Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/49/34. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The draft report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Fiona Lobban reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study. Fiona Lobban and Lesley Chapman were involved in the design and development of the Relatives’ Education And Coping Toolkit (REACT); hence, this is not an independent evaluation. Bruce Hollingsworth reports that he was a NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioned Board member (2013–15). Paula Williamson reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study, and that the Clinical Trials Research Centre at the University of Liverpool was in receipt of NIHR Support Funding during the conduct of the study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Lobban et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter provides the background and rationale for the present study. We present an overview of the challenges faced by relatives of people with psychosis or bipolar disorder (BD), describe what support is currently available for this group and outline why we developed the Relatives’ Education And Coping Toolkit (REACT). We briefly describe previous work in developing REACT and explain the context for the current study.

This chapter draws on some material previously published by the report’s authors during the course of the study,1–3 and reproduced here under a Creative Commons licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Honary et al. 1 © Mahsa Honary, Naomi Ruth Fisher, Roisin McNaney, Fiona Lobban. Originally published in JMIR Mental Health (http://mental.jmir.org), 07.12.2018. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work, first published in JMIR Mental Health, is properly cited. The complete bibliographic information, a link to the original publication on http://mental.jmir.org/, as well as this copyright and license information must be included.

Challenges faced by relatives of people with psychosis or bipolar disorder

Psychosis is an umbrella term that covers many different conditions, the common feature of which is that people perceive or interpret the world around them very differently. The most frequent ways this manifests are having beliefs that are not shared by others and do not have a basis that is understandable to others (often called delusions); not being able to think clearly, and so sounding muddled and hard to follow (often called thought disorder); or experiencing, for example hearing or seeing, things that other people cannot (often called hallucinations).

As well as the presence of these unusual experiences, many people with psychosis also report a loss of valued experiences, most notably pleasure in everyday activities (anhedonia) and loss of motivation (apathy). These losses are sometimes referred to as ‘negative symptoms’, and are particularly challenging for relatives, not least because they are hard to differentiate from normal ‘teenage angst’, side effects of medication or depression. It is difficult to report exact figures on the number of people who will experience psychosis as many may never have contact with mental health services, but most recent estimates have calculated worldwide prevalence to be approximately 1 in 13 people (7.7%),4 and up to 10% of people in the UK report some kind of psychotic experiences. 5 Only a fraction of these people (approximately 1% of the general population) will ever come into contact with mental health services and receive a diagnosis of a mental health condition. In general, these are likely to be people for whom these experiences are particularly distressing or cause significant changes in behaviour.

Bipolar disorder is the third most common mental health cause of disability globally,6 affecting 1–4.5% of adults7 and costing the English economy £5.2B annually, largely owing to inadequate treatment. 8 BD is characterised by episodes of extreme low mood (depression) and extreme high or irritable mood (mania, or hypomania in its milder form). Challenging behaviours, such as increased self-harm and suicidal behaviour, excessive spending, sexual disinhibition and heightened irritability, can all occur during mood episodes, which are often accompanied by psychotic symptoms. Between episodes, functioning may return to normal levels, although many people report problematic subsyndromal levels of depression that affect their functioning and relationships. 9

Psychosis and BD present significant challenges to relatives, particularly in recognising and understanding what is happening, living with the elevated risk of suicide, the impact on relationships within the family, and having to balance caring, work and other family commitments. These challenges are exacerbated by difficulties in accessing mental health services, which delay access to effective treatment, leading to worse long-term outcomes. 10,11 It has been estimated that more than one-third of relatives of people with psychosis experience clinically significant levels of distress and burden,12 and estimates from more recent studies with relatives from early intervention in psychosis (EIP) services are even higher, at > 60%. 2,13

Almost half of relatives of people with psychosis experience post-traumatic stress symptoms associated with their caring roles,14 particularly linked to episodes of violence, disruptive behaviour and forced admission. 15

Key factors that increase the negative impact of psychosis on carers include being a female carer;16 living with the person with psychosis; young patient age and awareness of suicidal ideation;17 reduced social support and family resources;17,18 use of emotion-focused coping strategies;19 and beliefs that relatives hold about the psychosis, particularly those concerning cause and control. 20–22

In BD, symptoms associated with depressive episodes result in increased burden of caring, poorer general health, and depressive symptoms in carers. 23–25 The frequency of suicide attempts among the BD population is higher than in many other populations affected by mental health issues, creating a distressing situation for carers. 26 During periods of mania, extravagant spending, irritability and inappropriate and disproportionate behaviour become more frequent and extreme. 27–29 The challenge of learning to cope with symptoms associated with manic and depressive episodes can not only negatively affect the service user, but also diminish carers’ and their families’ quality of life, with carers expressing feelings of helplessness, anger and anxiety. 30,31

Importantly, many relatives also report positive aspects of caring for someone with a severe mental health problem, including identifying personal strengths; feeling a sense of love, caring and compassion; developing new insights about their lives and living; and greater intimacy with others as a result of their journey coping with mental illness. 32,33

We have chosen to focus on the needs of relatives of people with psychosis or BD together in the REACT project, as they face many common challenges. These include how best to support someone in their recovery journey, how to deal with a mental health crisis, how to manage difficult situations, how to manage stress and how to understand and navigate mental health services and the treatments they offer. Mental health services are often structured such that people with a diagnosis of psychosis or BD are managed in the same teams (e.g. community mental health teams, EIP teams). Therefore, having interventions to support relatives that work across these conditions also makes practical sense.

Support for relatives

Relatives of people with psychosis or BD provide a large amount of unpaid care,34,35 but at high personal cost in terms of distress and burden. 12,36,37 Without this unpaid care, the NHS would not be able to cope. Historically, the impact of severe mental health problems on relatives has been ignored, or included as a secondary outcome to service user outcomes. 38 However, more recently, there has been increasing recognition of the importance of understanding the impact on the carer of supporting someone with a mental health problem, and of the need for effective interventions to address this impact. 39

There is now good evidence that interventions that support relatives can improve outcomes both for service users38,40,41 and for carers. 39,42–44 The exact nature of these interventions for carers varies. Some are psychoeducational, aiming to empower relatives with information and coping strategies. 45 Others are more systemic and, in addition to psychoeducation, work with the family on approaches to problem-solving and communication (e.g. Miklowitz46). Interventions also vary in how many sessions are offered, over what period sessions are offered, whether or not the service user also takes part in the intervention and whether the programme is offered to individual families or in groups. To date, there are no good-quality data sets that determine which content or format is most effective.

The exact mechanism underlying the improvements in carer outcomes as a result of family-focused support is not well understood. However, studies have identified several factors associated with improved outcomes for relatives, including the following:

Implementing support for relatives

The UK government recognises the need to support relatives in a caring role,52 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that all relatives be given carer-focused education and support and offered a structured family intervention to enhance family coping and communication. 53,54

However, a recent national audit of EIP services in the UK showed poor implementation, with only 50% of relatives receiving a carer-focused education and support programme and only 31% being offered a structured intervention (of whom only 12% took up the offer). 55 A survey of > 1100 families across 22 European countries showed that half were dissatisfied with how they were involved by mental health services,56 suggesting that it is unlikely that services are better elsewhere.

The challenges services face in providing structured family interventions are likely to include cost and the practicalities of delivery. Many require two trained therapists, available at the same time weekly for up to 9 months with regular access to supervision, as well as a family whose members can all commit to attending face-to-face sessions, often during office hours, and have a sufficiently open and robust relationship with the service user.

However, these factors do not account for the lack of more straightforward psychoeducational approaches and emotional support for relatives. It is likely that additional organisational factors also play a role in poor implementation.

For example, staff workload is often measured in terms of the number of service user contacts, which may not adequately recognise time spent with family members. Under pressure, this may be the first thing to go. As well as highlighting the need for organisation-wide change, a study by Eassom et al. 57 identified staff reservations about the level of involvement family members should be given in the recovery process, fear of negative outcomes as a result of involving family members and the need for an exclusive patient–professional relationship.

Attempts have been made to improve access to support for relatives. Achieving Better Access to Mental Health Services by 2020,58 published in October 2014 by NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care, sets a key standard that ‘more than 50% of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis will be treated with a NICE approved care package within two weeks of referral’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). This includes carer-focused education and access to structured family interventions. Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have been directed to allocate funding to EIP teams to support efforts to meet this standard, the success of which is being audited by the College Centre for Quality Improvement in the Royal College of Psychiatrists. 55

In addition to government policy, the Triangle of Care59 has been developed by the Carers Trust and the Mental Health Development Unit as a ‘guide to best practice’ to help mental health services improve collaboration and partnership with carers. The Triangle of Care sets out six key standards, which have already been adopted by a significant number of NHS trusts. However, the extent to which these are being met is currently monitored through self-audit only, which may limit their impact on practice.

In this context, our aim was to develop a user-friendly, easily accessible self-management intervention, based on the principles of psychoeducation and family intervention, that could overcome some of the identified barriers to implementation, and be made available to all relatives of people with psychosis or BD across the UK. Specifically, we were keen that the intervention would target key appraisals and coping strategies, be empowering for relatives, not require extensive staff time or training, be low-cost and require little input from mental health services. Self-management interventions that have the flexibility to be used alongside other work and family commitments and augment other forms of support are ideally suited to meet the needs of relatives, and have the potential to be widely available in an increasingly resource-restricted health service.

Initial development of REACT

REACT was first developed as a paper-based self-management intervention for relatives of people with psychosis in EIP services as part of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit-funded study. 60 The content was informed3 by:

-

our systematic review of interventions for relatives of people with psychosis,39 highlighting the distinguishing features of effective interventions

-

focus groups of relatives3

-

cognitive–behavioural therapy models highlighting the importance of helping relatives to understand psychosis and build on existing strategies

-

the research team’s own expertise.

REACT consisted of 13 sections, designed to be used flexibly depending on the individual needs of relatives. The 13 sections were as follows:

-

Introduction to REACT

-

What is psychosis?

-

Managing positive symptoms

-

Managing negative symptoms

-

Dealing with crises

-

Dealing with difficult behaviour

-

Managing stress: thinking differently

-

Managing stress: doing things differently

-

Understanding mental health services

-

Treatment options

-

The future

-

Resource directory (RD)

-

Jargon terms.

Through this combination of modules and the directory, the toolkit aimed both to support users directly, by providing advice, information and case studies, and to connect them to other sources of advice and support. The toolkit was printed in A5 format and given to each participant. It could also be read online or downloaded from a website made available to participants, although this was very little used and relatives made clear in feedback that they preferred a resource that they could hold in their hands. Most sections were < 24 pages: the shortest was 11 pages, the longest was the RD, at 43 pages. The large number of links to other services and resources meant that the toolkit required constant editing and updating to maintain its accuracy.

Support in using the toolkit came from EIP support workers, who conducted one-to-one introductory sessions with each participant, with ongoing support available for 6 months by telephone or e-mail, as preferred, limited to 60 minutes per week. Participants who did not contact their support worker or who missed appointments were called at least monthly to maintain engagement. The intention of this personalised support was to help relatives to identify their greatest challenges and to then navigate the toolkit to find information or useful strategies that could be used. The focus was on practical engagement rather than transmission of information, with relatives encouraged to adopt and adapt new strategies, acquire and use new skills and reflect on the results: an active rather than passive approach.

The feasibility and acceptability of the toolkit were tested in a randomised controlled trial (RCT), in which the toolkit was offered in addition to treatment as usual (TAU). Relatives’ distress and well-being outcomes were compared at 6 months’ follow-up against those receiving TAU. This trial showed that relatives were very keen to engage with the intervention, that staff could integrate delivery of REACT into existing EIP services, and that relatives who received REACT were significantly less distressed than those receiving TAU at 6 months, as measured by the General Health Questionnaire-28 items (GHQ-28)61 [regression coefficient –6.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) –12.55 to –0.64]. They also had higher levels of perceived support [measured using the Carer Well-being and Support (CWS) Questionnaire:62 regression coefficient 4.86, 95% CI 0.77 to 8.96] and perceived ability to cope (measured using the Family Questionnaire:63 regression coefficient –4.89, 95% CI –9.34 to –0.44) than those receiving TAU.

As well as strongly preferring the printed toolkit over the online version, relatives showed a slight preference for accessing support by telephone rather than e-mail. There were practical challenges in retaining trained NHS staff for the trial and in maintaining their allocated time to support the intervention.

Qualitative feedback from relatives who used REACT was extremely positive. 64 Relatives reported feeling less isolated and more supported as a result of REACT:

Say it were a Saturday night and they aren’t available, I still know, come Monday morning, I could ring that number, and that could help me through that weekend.

When asked what they felt REACT had changed for them, relatives reported changes in their ways of thinking about the service user’s behaviour:

[It] made me see things differently from a different point of view.

They also reported changes in their coping strategies:

I now know how to say things to David – rather than, I would have said, ‘Oh David, do you have to smoke? Your teeth are going to be yellow,’ I will say something now like, ‘Oh David, you know, you are so nice looking, you would be even nicer if you didn’t smoke because smoking can actually make your teeth go yellow.’ So I know how to word things more to make him feel not guilty about the smoking.

They also reported feeling more supported as a result of the intervention:

Oh, very reassuring. It [support] saved my life. I know that sounds melodramatic, but it saved my life; I feel as if it saved my sanity in a way.

Subsequent development of REACT

Based on qualitative feedback from relatives using REACT in the feasibility trial, as well as input from the patient and public involvement (PPI) group and from clinical academic experts in our research team, we proposed the following goals for the next version of the intervention:

-

to adapt REACT for a broader range of relatives, including those outside EIP and those supporting people with BD

-

to make a more interactive version of REACT, available online to relatives

-

to have expert relatives offer REACT support rather than NHS staff.

The reasons for these goals are explained in the following sections.

Adapt REACT for a broader range of relatives

Although targeted early interventions have been successful in improving outcomes, these improvements are not sustained when service users move from specialist EIP services into routine mental health services. 65,66 There are also many relatives supporting people with psychosis who are not accessing mental health services at all. There is an urgent need to develop interventions that can be extended beyond EIP services, to include relatives outside mental health services and to support people with a broader range of diagnoses.

A more interactive, online REACT

In the feasibility trial, relatives preferred the paper version of REACT. However, the online version was restricted to static Portable Document Formats (PDFs), with none of the advantages that interactive online interventions can offer. The paper version was also very difficult to update regularly, and had high production costs, which might limit dissemination.

Because of the general increase in the use of the internet to access health-care interventions, the advantages of being able to update information quickly as required and the opportunity to add more interactive components and multimedia formats, such as video clips, we proposed delivering REACT as an online intervention, despite the preferences stated in the feasibility study.

Online interventions are well established for many mental health conditions, including depression and anxiety,67 and some have now been developed for psychosis68 and BD. 69 Such interventions are particularly suited to delivering standardised information together with a platform for sharing ideas through online forums. Online support is also being developed for relatives of people with other chronic health conditions,70 and may be particularly useful for these groups because of the flexibility of use and the empathy and support available from other carers. 71 There is some evidence that online interventions would be well received by carers,72 although acceptability, along with clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, needs further testing.

Have expert relatives offer the REACT support rather than NHS staff

Offering REACT to all relatives, including those not in contact with mental health services, and putting it online allowed us to develop a single dedicated team to support the intervention. This gave us greater control over the nature and design of the support. We chose to employ peer workers – relatives with lived experience of supporting someone with a mental health problem – for several reasons.

Our PPI group strongly favoured this approach. Our co-applicant (LCh) had worked with the charity Rethink for many years, sharing her knowledge and experience to support other relatives. There was a shared perception that peer workers would be highly knowledgeable, empathetic and motivated to support other relatives. This was reiterated in the design workshops that we conducted to develop the online version of REACT (see Chapter 2).

Qualitative and observational studies have identified a number of benefits of using peer workers, both for those receiving support and for the peers themselves. 73 For service users, these benefits include reduced admission rates; greater empowerment, empathy, acceptance and hope; better social functioning; and less stigma. Benefits reported by peer workers include support for their own recovery and personal growth, acquisition of new skills and the therapeutic effect of helping others. For paid peer workers, there are also financial benefits. 74,75 Employing relatives as REACT supporters to support the REACT website was an opportunity to develop the strategic role of service users and carers in delivery of services and explore the benefits and challenges of this role. It also circumvented the difficulty of identifying existing staff who had the expertise, time and support to take on this role. Developing the peer worker role as part of the NHS workforce was also consistent with recommendations from NICE in 2016. 76

Securing funding to evaluate REACT

In January 2013, we applied to NIHR for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme funding to deliver these adaptations and test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the new version of REACT in a large definitive trial. The application was rejected (13 December 2013), as the trial was seen as too expensive to deliver, at £2,032,667. Given the positive outcomes we had already demonstrated and the correspondence of the intervention to NICE guidance requirements to offer all carers psychoeducational and emotional support, the HTA programme funding committee suggested that we consider how best to deliver REACT in the NHS.

We then responded to the HTA programme efficient design call for RCTs that tested efficient trial designs to address the problem of the escalating costs of large-scale definitive trials. This offered the opportunity to test the online REACT intervention in an entirely online trial. Advantages of online trial design include the potential to reach a greater number and range of participants; to reach a population more representative of those likely to use an online intervention; to recruit more people over a shorter time frame; to simplify protocols for secure randomisation and data entry; and to deliver a trial much more cheaply because fewer staff are needed. 77 However, retention rates for such trials can be low,77,78 compromising internal validity of the trial.

This efficient design reduced the costs of the trial to £633,404. We were awarded funding for 36 months, to begin in October 2015.

In parallel, we applied to the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme for funding for an implementation study to identify the factors affecting successful delivery of an online intervention within EIP services. This study was also funded for 30 months, starting in March 2016. The two studies were complementary. The HSDR study explored factors affecting implementation of a clinician-supported intervention in EIP services in the NHS, in contrast to this study’s peer worker-supported intervention. It also included an evaluation of outcomes for the relatives, using the same measures and follow-up period as this study. We thus had the potential to compare both the reach and the outcomes achieved by providing REACT through two very different study designs. This allowed us to answer questions about which was likely to be the most effective service provision model, as well as to compare the effectiveness of peer worker- and clinician-supported approaches. The HSDR report was submitted for publication in December 2018.

Trial design

The REACT trial is a single-blind, parallel online RCT to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of REACT, including an online RD, compared with the RD only, for relatives of people with psychosis or BD. No changes were made to any other support that relatives received outside the trial. See Chapter 3 for the specific objectives of the trial.

Research team

The team included relatives, clinicians, academics and methodologists from a range of disciplines, with a common interest in developing and evaluating new ways to support people with mental health problems and their relatives. Team members were all UK based, and, although some had worked together previously, the team in its entirety came together specifically for this project. Although the team all differed in background, training, epistemological and ontological stance, some important factors underpinned the team in working together successfully:

-

a commitment to improving the lives of people with mental health problems and their relatives in non-stigmatising, empowering, and recovery-focused ways

-

a recognition of the huge role that relatives play in supporting people with health problems, and of the current lack of adequate support available to them

-

a belief in the importance of evidence-based health care and the need to carry out high-quality research to inform how NHS funding is spent

-

an interest in testing the potential of digital technology to increase accessibility and reduce costs of clinical interventions, while also exploring the challenges of and barriers to this approach

-

a commitment to identify efficient ways to carry out publicly funded research to provide value for money to the UK taxpayer.

Trial monitoring

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was involved in developing the trial ideas and was responsible for delivering the project. This group included the trial co-applicants: a relative with many years supporting a family member with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (LCh); two clinical academic psychologists (FL and SHJ) based in Lancaster; a clinical academic psychiatrist with a lead role nationally in EIP services (SJo) and a clinical academic general practitioner (GP) who is an expert in development and evaluation of digital health interventions (EM); a trial statistician who is director of the Clinical Trials Research Centre (CTRC) in Liverpool, which oversaw the data management and statistical analysis (PW); and a health economist based in Lancaster (CM).

The TMG met monthly and also included the trial managers (HR and BM), information technology (IT) experts who built and maintained REACT and the data collection systems (DA and AW) and lead and support statisticians who managed the data collection and recruitment and retention reporting, as well as conducting the final analysis (SD and NR). To accommodate the geographical spread, and consistent with our efficient design, all meetings took place by teleconference.

REACT was supported by a team of trained relatives [SF, Alison Hankinson (see Acknowledgements), LC, NA] and supervised by two clinical psychologists (SHJ, WS).

Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The trial was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and a separate Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). The TSC was chaired by an expert in clinical trials testing psychological interventions (Shirley Reynolds) and included two academic clinical psychologists (Gillian Hardy and Pete Langdon), a statistician (Alex McConnachie), a service user and a relative. It also included a representative of the sponsoring organisation Lancaster University (SD) and the NIHR Clinical Research Network (MW). The TSC met before the start of the trial, at 10 months to review progress with recruitment, at 15 months to determine whether or not the findings from the internal pilot supported the continuation of the trial, and then annually to the end of the trial.

The DMEC was chaired by a statistician who directs a clinical trials unit (Kerry Hood), and included another academic clinical psychologist with expertise in developing and evaluating digital health interventions (Cathy Creswell). The role of the DMEC was to monitor the data and, specifically, to assess whether or not we had met the stop/go criteria set for our internal pilot (see Chapter 3), and to monitor any ethics or safety concerns. The DMEC met before the start of the study, at 10, 12 and 15 months and then annually, timed to feed reports into meetings of the TSC. All meetings were by teleconference.

Patient and public involvement

Consistent with A Framework for Mental Health Research,79 this project was developed and conducted in partnership with service users and carers.

Co-investigator

One of the trial investigators and co-author is a parent of someone living with psychosis and was extensively involved in the development of REACT, the RD and the data collection processes. She was part of the supervisory team for the REACT supporters. She was also invited to attend the TMG meetings.

Development of REACT

Relatives were involved in the development of the initial content for the toolkit,80 and in subsequent iterations to develop an online toolkit;1 see Chapter 2.

Relatives’ advisory group

At the start of the project, we set up the relatives’ advisory group (RAG) of 13 relatives or close friends of someone with BD and/or psychosis and one individual with lived experiences of BD. Their role was to provide consultative input to each stage of the research.

Consistent with the online nature of the trial, members of the group worked mainly remotely, providing detailed feedback on REACT (reviewing its content and format) and the online data collection process (including selection of questionnaires and items used for eligibility screening), and advising on strategies for maximising recruitment and retention.

In addition to independent review work, the group met three times during the trial: before the start of the trial, to familiarise themselves with the REACT and trial and data collection tools; at 12 months, to review the recruitment strategy; and at 22 months, to advise on the follow-up strategy. The first meeting was held face to face at Lancaster University; the other meetings were held online, which facilitated the involvement of people from a wider geographic area and a greater diversity of relatives’ experiences. RAG members were also invited to write blogs for the website to stimulate discussions on the REACT forum. The results of the trial have been presented to the RAG members, and work continues with this group on interpretation and broader dissemination of the data.

The RAG members received a high-street shopping voucher for £10–50 (depending on the length of the task undertaken) as a thank-you for their time.

The REACT supporter role

The REACT supporters were relatives with lived experience of supporting someone with psychosis or BD. They were employed by the host NHS trust as NHS band 5 staff. See Chapter 2 and the project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/144934/#/ (accessed 28 October 2019)] for more details on their role.

Trial Steering Committee

One relative and one service user were appointed to the TSC at the start of the trial. They both had experience of using services, but also had research expertise. The service user was employed as a research associate on another NIHR-funded study, and the relative was a retired academic.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Introduction

In this chapter, we describe how the paper-based REACT intervention (see Chapter 1) was adapted to an online version, and describe the resulting content. The three key adaptations, based on learning from the feasibility trial, were to:

-

broaden REACT to make it suitable for relatives outside EIP services and for relatives supporting people with BD

-

make REACT more interactive and directly available online to relatives

-

offer REACT with support from trained relatives.

In the feasibility trial of the paper-based REACT, modules were posted online as PDFs to aid availability. Clearly, this is not the same as an online intervention, which would typically be more structured, self-guided, interactive, visually rich and personally tailored. Therefore, considerable work was needed.

Following guidance from the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials of Electronic and Mobile HEalth Applications and onLine TeleHealth (CONSORT-EHEALTH) checklist, version 1.6.1,81 we describe the history, development and initial formative evaluations of REACT, details of how the dynamic components worked and how the site was updated. We provide relevant screenshots and have archived the site (access available on request). We also present the development and content of the RD that was offered as our active control intervention. As required by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT), we identify the sponsorship and ownership of the site.

The aim was to involve relatives, clinicians and the clinical academic team in co-developing content and design to ensure that both would be of high quality, user friendly, meet the needs of relatives and engender confidence in potential referrers. The importance of understanding the needs of users and involving them in design has been well reported. 82 We carried out a series of workshops with users (relatives) and drew on the expertise within our clinical academic team to develop a list of design features, which guided our development of REACT.

Understanding user perspectives: method

We held two workshops (workshops 1 and 2, with 13 and 11 participants, respectively) to explore the needs of relatives outside EIP services, and their views about how REACT should be developed. We aimed to recruit participants from diverse backgrounds in terms of age, gender, relationship with the service user, length of experience as a caregiver and computer literacy. Workshop participants were invited if they identified as supporting a relative or close friend with psychosis or BD. Our recruitment strategy was to advertise locally to obtain a convenience sample that could attend face-to-face workshops. Advertisements were circulated via Lancaster University’s Spectrum Centre for Mental Health Research,83 using e-mail, social media and post. The Spectrum Centre is a multidisciplinary research centre focusing on the development and evaluation of psychosocial interventions for people with long-term mental health problems.

In accordance with our approval from the Lancaster University Ethics Committee, those who indicated interest were sent an information sheet by e-mail or post before the workshop, allowing them to raise any questions in advance. This information included the purpose of the workshop, its location and duration, that participation was voluntary, and what would happen to their audio-recorded data.

Participants were offered a £20 Amazon (Amazon.com, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA) voucher in recognition of their time and input. Two researchers facilitated each workshop, using a semistructured topic guide to lead discussion and ask open questions to elicit a range of views.

First, the participants were encouraged to reflect and share their lived experiences as caregivers of people with psychosis or BD. This included how their relative was first diagnosed, how they became involved as caregivers, the impact of mental health problems on their family and daily life, and their current sources of support, as well as the types of support or strategies they found most useful.

Second, they were asked their views on gaps in the support system for caregivers, how to fill these and whether or not online support could play a role in this. Finally, they reviewed the REACT booklets together and discussed whether or not and how these could be redesigned as a web-based intervention, and what additional support might be needed to facilitate REACT’s use online. Each workshop was audio-recorded with participants’ permissions, and transcribed verbatim for later analysis (see the data analysis section).

We conducted an additional workshop (workshop 3) with two participants to scope the types of features that could be included in the web-based REACT intervention. Both participants were comfortable using computers, used social media frequently and were interested in helping with the design of REACT. Before the workshop, participants were given access to the website of the PDFs. They were also asked to identify other websites that they liked or disliked, both related and unrelated to mental health. We explored their aesthetics and functionalities together. This was followed by a visual demonstration of a series of design prototypes for the web-based REACT intervention, based on our findings from workshops 1 and 2. The prototypes were developed in conjunction with a web design company and mainly focused on aesthetic aspects of the web interface, such as logo, font style and size, navigation menu, colour scheme and multimedia choices.

We wanted to know how to translate the values and needs that participants had highlighted in workshops 1 and 2 into functionalities. In particular, we wanted to understand how best to give users a positive experience. We therefore asked participants in workshop 3 to discuss how to design the web-based REACT to be more engaging, what features might motivate users to keep returning and what types of support could be offered only online.

A full description of the findings of all three workshops is reported elsewhere,1 and is summarised in the next section.

Understanding user perspectives: results

The majority of participants in workshops 1 and 2 were female, aged > 45 years, parents and infrequent computer users. Most had had many years’ experience of caring for relatives with severe mental illness (on average, about 10 years). In workshop 3, one participant had taken part in workshop 1 and was typical of that group, whereas the second participant was aged 21 years and new to the study. In total, 25 participants took part in this qualitative study across all three workshops (18 females, age range 21–75 years, n = 20 parents). Participants comfortably shared their experiences, and no prompting was required for conversation to flow. Key findings covered their caregiving experiences, the support that they believed was needed, the potential role of online interventions and the design of such interventions.

Caregiving experiences

Identity as a carer

Relatives talked about feeling a loss of sense of self in their journey to becoming a carer. They felt that they had been pushed into a ‘carer’ role and found it hard to maintain their identity as a father, wife, etc:

I don’t want to be a carer, I don’t like the word. I’m a mother. I know somebody has me down as a carer even if they don’t give me a decision. But in my head, I’m not.

Workshop 1, participant 9

The role of carer was particularly unappealing as it came with no formal training or guidance, so, as well as being imposed, it was also very challenging. Many relatives described it taking years for them to learn strategies to cope with the impact of psychosis or BD on the rest of the family.

Impact on the whole family

Participants described the very broad impact mental health problems had on the wider family, and the need for support for all family members:

Our youngest son didn’t understand what his brother was going through . . . It must have been terrible for him and, in fact, not long ago, he actually left the family.

Workshop 1, participant 1

In addition, caregivers discussed needing support, not just as caregivers, but as individuals in their own right, with other responsibilities in their lives:

I might have had a right morning with my son, threatening suicide or wrestling for my own life. And I’d have to go in work . . . change into my uniform and drive to work and I’ve got a lump in my throat. And I’d phone my partner [saying] ‘I’m going to cry’.

Workshop 2, participant 3

Social isolation

Caregivers of people with physical illness may have little opportunity for social interaction because of the need for constant caring. In mental health, social isolation can be further exacerbated by stigma and lack of public awareness about mental health. Participants talked about finding it difficult to open up to their friends and families:

My children used to say to me ‘what do we say to our friends about [relative]?’ And I told them to [deny relative has a mental health problem], which I don’t know is right, because I thought they’ll get bullied. Or otherwise they will say your relative’s crazy or . . .

Workshop 2, participant 10

Many had found it challenging initially to find others with similar lived experiences. Once they were in contact with other caregivers, they found this invaluable not only for emotional support, but also for signposting to important information and guidance. Many were part of charity-run face-to-face peer support groups facilitated by an ‘expert caregiver’:

The person who runs our small group is a godsend. What’s worrying is, if she couldn’t do that job, what would we do with it? That’s what I always think about, because there’s got to be a system there that does what she does.

Workshop 1, participant 1

Although valuable, these groups were considered scarce, and almost invisible to newly diagnosed caregivers.

Support needed

Information

Participants reflected on the knowledge and information that they wished they had had as they first adapted to the caregiver role:

We’ve been caring for so many years, I thought there’s nothing I can learn now. I know it all. But actually a lot of what was in [the REACT booklet] was kind of new to me and if somebody had told me that at the beginning, you know, how to – how to break through the system, then I think things wouldn’t have got so bad.

Workshop 1, participant 1

They acknowledged that it could take years for relatives to learn about the mental health condition, and, on reflection, identified three types of educational sources that newly diagnosed caregivers would greatly benefit from:

-

A comprehensive list of available sources of support, such as local support groups and national charities –Workshop 1, participant 6

This exists. That exists. You can read this. You can read that. You can go here. You can go there. You’ve got a right to this – this is practical help, not the general pat you on the back and say everything’s alright and happy clappy, and let’s be friends, but actual hard practical, meaningful.

-

Information about medication, including types, side effects and how to manage doses –Workshop 2, participant 5

We’re never given, sort of, like, a comparative – information about the various antipsychotics. They had awful side effects.

-

Legal rights –Workshop 1, participant 1

I think actually what carers are entitled to under the law is very different from what they get in real life. And you’ve got to know.

Overall, participants agreed that knowledge is power and that less experienced relatives would benefit from guidance on how to get help, and from being directed to trusted and up-to-date resources.

Emotional support

Participants talked about the emotional impact of supporting someone with psychosis, and the importance of emotional, as well as practical, support:

I had some professional experience [in mental health], but it’s completely different when you are emotionally involved . . . It’s literally like somebody’s just parachuted you into a foreign country. You’ve no idea of what should be happening, what is available. And you need to know that sometimes, to be able to get it.

But the peer support is about emotional support. And I think what health professionals sometimes don’t understand is, by the time you get to them, you’ve been doing this for months, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. And the emotional toll on you . . .

Workshop 2, participant 2

They talked about the importance of hearing that their experiences were not unique, as well as the need for explicit reassurance that the development of mental health problems within the family was not their fault and that they were doing all they could to manage the situation:

My mum never forgets this nurse who said to her ‘it could happen to anybody. This is not your fault. You’re doing everything you can’. And that just lifted that guilt off my parents. But sadly that was the only time.

Workshop 2, participant 7

Opportunities to have social contact with similar caregivers, to share experiences and feel connected and supported, were particularly valued:

There’s nothing better than seeing that somebody else has had the same fears and guilt to start with. Worries about the future and practical travel problems.

Workshop 3, participant 1

A recovery-focused approach

Although most of the discussion revolved around the challenges relatives faced, the need to focus on positive outcomes was also evident. One participant explained how she desperately struggled to find positive role models for her son:

Then I realised that the positive role models don’t want to go back and look again. And there’s got to be thousands of recovered or people who are managing their condition but they don’t really want to join the club. And that would be priceless, to have more positive role models. People who have managed and are managing their conditions or have completely recovered.

Workshop 3, participant 1

There was a general feeling that caregivers and service users would benefit from hearing positive stories to give them hope that recovery was possible.

The role of online interventions

For the majority of relatives, online support was seen as part of a ‘big scary virtual world’. They described several practical challenges regarding using the internet, including limited access and skills:

I live in the country and my internet doesn’t work half the time and my computer is probably my biggest source of stress.

Workshop 1, participant 10

However, it was not only practical issues that concerned them. There was a lot of fear associated with online activity, and many relatives felt reluctant to post personal information on any website. They feared that, once shared, it could never be removed and would always be ‘Googleable’. There was also an ethical dilemma that, in sharing their experiences online, they could also be sharing their relatives’ experiences, without their explicit consent. Participants felt that it was often unclear ‘whose story’ it was:

I don’t mind saying anything about my own medical symptoms or if I had a mental health problem, but . . . if my anxiety and stress and my needs are because my relative’s issues aren’t being addressed, then it is about me, but it’s still about her . . . But everybody’s different, so I think there needs to be a number of ways to access this information.

Workshop 1, participant 10

This dilemma was exacerbated by fear of the impact their posts might have on their relative if they saw them:

If my relative happened to get access to it, it could trigger a major episode.

Workshop 1, participant 8

This led to limits in how open relatives felt they could be online:

My relative has now got access to all my Facebook [Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA] discussions. But I’ve always feared letting [my relative] know how I’m feeling about things . . . I’m not sure how far we can open up.

Workshop 1, participant 5

Overall, participants had mixed views about the value of online support, but felt that people in the generation after them might be more positive, and might even be put off by paper-based support:

We’re all of a certain age. And what I’m finding is that, the people in the group who are a lot younger are actually perfectly happy to go all over Facebook.

Workshop 1, participant 1

It’s often a generational thing, and a lot of younger carers are siblings and would never dream of getting something off paper; they would automatically go online.

Workshop 2, participant 6

Online design of REACT

Most of the specific ideas for design features came from workshop 3, whose two participants were more frequent and confident users of computers. The key design issues that they identified are summarised in this section.

The paper-based REACT PDFs are too text-heavy for online

Initially, participants were presented with the website containing the PDF versions of the REACT booklets. Unsurprisingly, they found these too text-heavy, and felt that relatives would not have time to read them and would quickly lose interest. Their suggestion was for much more use of video to convey factual information and sharing of experiences.

Importance of vicarious learning in addition to didactic instruction

One challenge of a self-management toolkit for long-term health conditions is that it is difficult to make concrete recommendations when there is often no right or wrong answer. One participant felt that a limitation of many sites they had reviewed was that they tried to provide checklists:

A lot of websites will say, ‘oh why don’t you try meditation [or] going for a walk’.

Workshop 3, participant 2

Instead it was suggested that online support needed to be thought-provoking, to facilitate ‘thinking and reflecting’ exercises that enabled users to learn problem-solving strategies that could then be applied to their own particular context:

Stuff that helps you ask questions and helps you think about what you’re feeling rather than, like, ‘try this, try [that]’, because there’s only, like, so much a hot bath can cure.

Workshop 3, participant 2

Sometimes relatives had questions for which Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), and online interventions, could provide no useful answer:

How much am I supposed to do? What’s too much? What’s not enough? How strict am I supposed to be? When’s the point when I back off? And that’s not really a question that I felt I could ask Google, ‘cause I’m not going to get anything useful from that.

Workshop 3, participant 2

Need for a personalised record of support

Supporting someone with a mental health problem is often a long, episodic journey. Participants suggested offering a personal space where relatives could save useful and interesting information to revisit easily:

Like some kind of like scrapbook section . . . where, like, people just put different stuff in.

Workshop 3, participant 2

The value of this would be not only having a useful place to store things, but also facilitating a process of reflection on progress over time:

It’s very affirming to go back to some of the earlier learning content to realise that you have learnt, you know, I’ve acted correctly. You have been a good carer.

Workshop 3, participant 1

Attractive, appealing and easy-to-navigate design

Participants were keen that we retain the colour-coded modular design of the toolkit, and suggested more emphasis be given to the invitation to dip in and out in an order and frequency of the user’s choosing, without the need to complete modules in sequence:

Instead of having to go through it in, like, a sequence, you can just, like, go onto the ones you choose . . . Like you can do it quite easily with the hard copy.

Workshop 3, participant 1

They recommended including a ‘how to use the intervention’ section to explain that REACT covered a wide range of topics and to encourage shorter sessions, selecting the modules that were most relevant to the challenges they faced at that time.

When asked about frequency and mode of delivery of prompts, participants felt that this would vary and that users should be able to customise this. They both disliked receiving too many prompts and would feel ‘suffocated’ or ‘pressured’, especially if they were having a good day. They therefore recommended ‘reject’ and ‘unsubscribe’ buttons. They also preferred to receive person-centred prompts:

What’s your question this week? What are you worrying about this week? You never get any e-mails that just say, ‘How are you doing? How are you?’

Workshop 3, participant 2

Participants recommended using colourful, positive images and artworks throughout the toolkit:

I’m just thinking right the way back to 2000; I think probably what my family were given were ‘Here’s these leaflets’, which weren’t even colour leaflets at that point, you know. You can imagine what it was like [to] read that info[rmation].

Workshop 3, participant 1

Trustworthiness

The design of the toolkit was felt to be very important in engendering a sense of trust in participants. Simplicity, ease of navigation and a professional look were all seen as qualities that would attract users by assuring them that the intervention was legitimate:

’Cause you look at it and you go ‘Oh wow, this looks legitimate’, like, ‘I can trust this’. And then you start building up that trust and start using it.

Workshop 3, participant 2

Participants compared the look of a website to a building and suggested aiming, not for a slick look, like a building with shiny floors that felt corporate, but instead for something simple and professional that provided information.

Creating the design brief

Based on these findings, we drew on the expertise of the TMG to create a design brief for building REACT. The TMG included a relative with extensive experience of supporting other relatives through a leading charity, and a consultant psychiatrist, two consultant clinical psychologists and a GP, all with expertise in supporting people with mental health problems and their families, and some with expertise in designing and delivering digital health interventions (SJo, EM). The brief was as follows.

The modules

The content of the paper versions of the modules was updated and rewritten for a broader range of relatives. Large sections of text were replaced by video material whenever possible. Videos included experts sharing their clinical expertise on each topic, and actors sharing the personal experiences of relatives and service users.

We were very keen to ensure that the personal experience videos felt authentic to people using the site. We considered filming real relatives and service users, but were concerned that subjects might change their mind over time about sharing their story, and that removing a story already uploaded to the internet might not be possible. Relatives’ questions in workshops about the ownership of stories also made us wary. We therefore invited relatives and service users to talk on video, and then, supplemented by face-to-face discussions with relatives and service users at the Spectrum Centre in Lancaster University, worked with the actors to create hybrid characters who shared their ‘experiences’ on camera.

Additional modules were added, including ‘What is bipolar disorder?’ and ‘Managing mood swings’, and new introductory sections were created: a welcome page, ‘meet the team’ and a ‘how-to’ module that outlined the aims and structure of REACT and how it could be used. All new and revised modules were shared with the RAG, which gave detailed feedback on the language and structure.

Signposting

We specified the need for a comprehensive signposting page, which could be updated regularly, containing direct links to other useful organisations and websites providing information or support.

Peer-to-peer support

The strong desire to meet and learn from the lived experiences of other relatives led to us specifying the need for an online function to allow this. We chose to allow people to be anonymous in this space, because of their fears around confidentiality. We were also keen that this be moderated to ensure that any negative responses could be managed, and any risk issues quickly identified and responded to (see Protocols and policies).

Confidential support

In addition to peer-to-peer support, we also specified the need for direct, confidential support for those relatives who did not want to share their experiences with peers, but had specific questions they wanted answered.

A place to store the history

We really liked the idea of an online place where relatives could securely store any documents they found relevant to their supporting role and might want to revisit. We hoped this would also allow them to reflect on their caring journey by providing reminders of events over time and the challenges they had overcome.

Look and feel

The site should be simple and easy to use, create a positive tone and include images relevant to the content. We reused many of the images from the paper-based toolkit. Furthermore, one of the relatives who took on a REACT supporter role was a professional artist and created additional images for the site.

Building and hosting the REACT intervention

REACT was initially built in WordPress (Automattic Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) by a web design and hosting company local to Lancaster; initially, the plan was for the company to host and maintain the REACT site during the trial. However, owing to difficulties in establishing a sustainable plan to do this, the site was brought in-house and is now located on a dedicated virtual server at Lancaster University. It is maintained and updated bimonthly by a digital technology developer from the REACT team (AW).

To meet the design brief, the WordPress site required a number of plug-ins. These included standard ones, such as bbPress (Automattic Inc.) to run the REACT group forum, and some built bespoke for the REACT site.

REACT

The content of the toolkit was informed by family intervention models that underpin effective face-to-face treatments for people with psychosis. 84–88 The key components of the toolkit were as follows: 12 information modules, a comprehensive RD, and peer support through a group forum and a confidential direct messaging service. A ‘meet the team’ page ensured that relatives were fully informed about who was delivering the content of the site. Logos for Lancaster University, Lancashire Care NHS Trust, University College London, Liverpool CTRC, and the McPin Foundation (London, UK) were prominently displayed on the log-in page. ‘Mytoolbox’ offered users a confidential space to save links to any information they might want to access easily later, including specific toolkit content, their self-reflection tasks and external web links. A blog page offered a flexible space for additional communication with site users, which could be edited by the REACT supporters.

The REACT information modules

Each of the 12 modules contained evidence-based written information, videos of clinical experts and/or content from experts by experience to illustrate key points, and self-reflection tasks to ensure that content was personalised to the user. The 12 modules were as follows:

-

What is psychosis? – information about psychosis, what it feels like, possible causes and common misconceptions.

-

What is BD? – an overview of BD, its main features, different presentations and how it feels to experience it.

-

Managing ‘positive’ symptoms – an explanation of the term ‘positive symptoms’, how these might be experienced, how they might appear to relatives and friends and how they can be managed.

-

Managing ‘negative’ symptoms – a detailed description of signs that make up ‘negative symptoms’, how these can manifest and how relatives can spot them, how they might make relatives feel and suggestions for helping the person experiencing these symptoms.

-

Managing mood swings – how to help people avoid extreme lows and highs, maintain a stable mood and support a relapse prevention or a staying-well plan, with suggestions for creating a low-stress environment in a friendly, non-judgemental way.

-

Dealing with difficult situations – describes the difficult situations that relatives and friends can encounter, including risky, illegal or embarrassing behaviours, and suggests ways to manage these.

-

Managing stress – doing things differently – helps relatives consider what stresses they have in their own lives and how to adapt their behaviour to manage.

-

Managing stress – thinking differently – helps relatives to consider how they think about the stresses in their lives, and whether or not different perspectives might help reduce their distress; explores the many common thinking traps, such as jumping to conclusions or mind-reading; and helps relatives to test their own thoughts.

-

Understanding mental health services – supports relatives in navigating services, helping to ensure that they talk to the right people to get the right information and the support they need.

-

Treatment options – information on the medication, psychological interventions and other therapies that people with psychosis or BD and their relatives should be offered, according to the NICE guidelines53,54; aims to empower relatives by outlining choices.

-

Dealing with crisis – clear suggestions about what to do in a crisis, where to turn to for help and what to expect from services; creates a useful personalised ‘what to do in a crisis’ plan.

-

The future and recovery – focuses on supporting recovery, with useful tips on how to help people with BD or psychosis to develop confidence and gain independence, including finding a balance between support and enabling independence, looking for positive changes to celebrate, accepting new goals and challenges and focusing on the bigger picture.

The resource directory

The RD provided to participants in the REACT and control arms of the REACT trial contained a comprehensive list, with website addresses and telephone numbers, of national organisations that support people with psychosis or BD and their relatives [e.g. Rethink (London, UK), Mind (Stratford, UK), Carers UK (London, UK) and Bipolar UK (London, UK)] and organisations that provide support for related conditions [e.g. Anxiety UK (Manchester, UK) and Samaritans (Ewell, UK)]. The RD also listed government websites that offer information and guidance about mental health and related topics, such as NHS Choices, Care Quality Commission, NICE guidelines and the Department of Work and Pensions, and gave contact details for emergency services and Samaritans, and a link for finding contact details for each user’s local NHS mental health services out-of-hours crisis team.

The RD given to those in the REACT arm of the trial also contained additional elements, including extensive information on topics such as advance directives, advocacy, benefits, direct payments, carer’s allowance, carer’s breaks, confidentiality, mental health law and an interactive map of support groups in different geographical areas. This content was developed in consultation with the REACT supporters and the RAG, and was added to over the period of the trial in response to information from users.

Support

Support was offered through confidential direct messaging with trained relatives (REACT supporters), and peer support was provided through a moderated online forum. The REACT supporters were available on the site Monday–Friday, from 09.00 to 16.30, excluding bank holidays and university holiday closures. Their key role was to provide emotional support and to guide relatives to relevant parts of the toolkit or other resources, as appropriate. They were also trained to moderate the forum and could hide posts or withdraw access in response to inappropriate use. They were trained to identify and report risk, and were supervised by two clinical psychologists and an expert relative. A REACT supervision manual and a REACT supporter manual [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/144934/#/ (accessed 28 October 2019)] were provided.

Reminders

Participants allocated to REACT were e-mailed reminders to visit the website after a week of inactivity. Participants could change the frequency of these reminders or turn them off.

Appearance

Screenshots in Figure 1 show the look and feel of the REACT intervention.

FIGURE 1.

Screenshots of the REACT intervention website.

The REACT supporters

The role, training and supervision of the REACT supporters are briefly summarised in the following paragraphs. The detailed manuals for the REACT supervisors and the REACT supporters, as well as the REACT risk protocol, can be found on the project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/144934/#/ (accessed 28 October 2019)].

Role

The REACT supporters were carers with lived experience of supporting a relative with psychosis or BD. Their role was to offer support to REACT participants through forum posts, direct messages and blogs. The REACT supporters did not give direct advice, but provided empathetic support while helping participants access relevant information and resources. They also moderated forum activity to ensure that there were no inappropriate posts and checked forums and direct messages for risk (see Protocols and policies). Carers, rather than clinicians, were selected to support the intervention so that supporters had personal experience of the issues raised by people using the site, and so could readily empathise with these issues in a sensitive and appropriate manner.

Training

The primary focus of the REACT supporter training was on familiarising supporters with REACT’s content and functions and giving them confidence to make timely forum posts and respond to personal messages from relatives while logging any risk issues. There were three intended domains for training: clinical, technical and co-worker sharing.

Clinical training was provided by the clinical supervisor (SHJ) and chief investigator (FL) before REACT was launched, and supplemented with ongoing clinical supervision (see Supervision). As the REACT supporters were able to draw on their personal experience of caring, clinical supervision helped train them in providing empathetic support and guiding relatives to the best use of the toolkit and associated resources to deal with their concerns.

Technical training was provided by the IT/digital support lead (AW) and clinical supervisor (SHJ). This was intended to ensure that the REACT supporters were very familiar with the REACT site and module content, the RD and how to access the automated e-mails informing them about posts.

Co-worker sharing was intended to offer a supportive environment in which supporters could share information and learning and develop ideas to increase site activity.

The REACT supporter role was relatively novel and there were, therefore, few training and supervision models to draw on at the beginning of the programme. The REACT supporters indicated that they would have appreciated more in-depth structured training in how to moderate peer-to-peer interactions on the forum and offer support, more detail on site functionality and longer access to training around clinical issues in mental health. Although the REACT supporters did successfully execute their roles with the training provided, the REACT supporter and supervision manuals provide additional information on how such training could be improved in future.

Supervision

Supervision was led by an experienced clinician fortnightly for up to 1.5 hours to provide a space for the REACT supporters to discuss relevant issues in a supportive environment. Issues typically covered in supervision included clinical issues, site cover and supporter well-being, with other issues discussed as required. Supervisors and the REACT supporters would review topics raised in direct messaging and the forum, including any risk issues. Urgent risk issues between sessions were dealt with in accordance with the risk protocol (see Protocols and policies).

Site cover issues included planned site closures such as Christmas, as well as staff leave, training and sickness absence. It was important to ensure that adequate time was allocated to supporter well-being. This included consideration of how personal and work factors might affect different supporters at different times and reviewing approaches to address this. Other issues covered as required included reviews of planned blog posts, ideas for updates, refinement of site materials, technical issues and site promotion.

Protocols and policies

All forum posts and private messages were reviewed by REACT supporters for potential risk, in accordance with the risk protocol [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/144934/#/ (accessed 28 October 2019)]. Risk was categorised as being low or high. Low-risk posts and messages were defined as showing no indication of immediate or serious threat of severe harm or risk to life, but showing either:

-

clear evidence of high levels of distress

-

concerns about risk of harm or abuse towards participants or others (safeguarding risks).

The REACT supporters who detected low-risk posts in which distress was the primary issue responded with a standardised e-mail to the carer. For potential safeguarding issues, the supporter consulted their clinical supervisor and used their NHS trust safeguarding team to discuss potential risks, if appropriate.

High-risk posts and messages were defined as those with clear evidence of immediate and serious risk to life or child welfare. If immediate risk of severe harm or death was detected, the protocol stipulated that an emergency call should be made to police (risk to life) or social services (other risk to child). Any concerns that might constitute a risk issue but that fell outside these definitions were discussed as urgent with the clinical supervisor to decide on a course of action. All risks were logged by the relevant REACT supporter on the REACT system to provide a record of the level of risk identified, where the risk was identified (forum post, direct message or other source), which supporter identified the risk, what action was undertaken and what follow-up actions were performed, including the name of the clinical supervisor consulted. Steve Jones was the lead clinical supervisor. To allow for leave and other commitments, a rota of alternative clinically qualified contacts was employed, including William Sellwood, Sonia Johnson and Fiona Lobban. Fiona Lobban was the contact of last choice, to avoid unblinding, and was never required. Steve Jones and William Sellwood dealt with the vast majority of risk queries, none of which met the high-risk criterion.

As part of their role, REACT supporters also monitored the site for inappropriate posts in line with an agreed posting policy [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/144934/#/ (accessed 28 October 2019)]. If the supporter believed a post might cause significant distress to participants, they had authority to remove it temporarily. It was then discussed with the clinical supervisor at supervision, or at an earlier ad hoc meeting if required. This discussion was used to reach a final decision as to whether the post would be removed permanently or reinstated.

Resource directory-only intervention

Participants allocated to the RD arm logged in to the same website, but were able to see only the ‘meet the team’ and RD pages. At the end of the trial, those in the RD-only arm were given access to the modules, without the forum or direct messaging.

Logic model for REACT

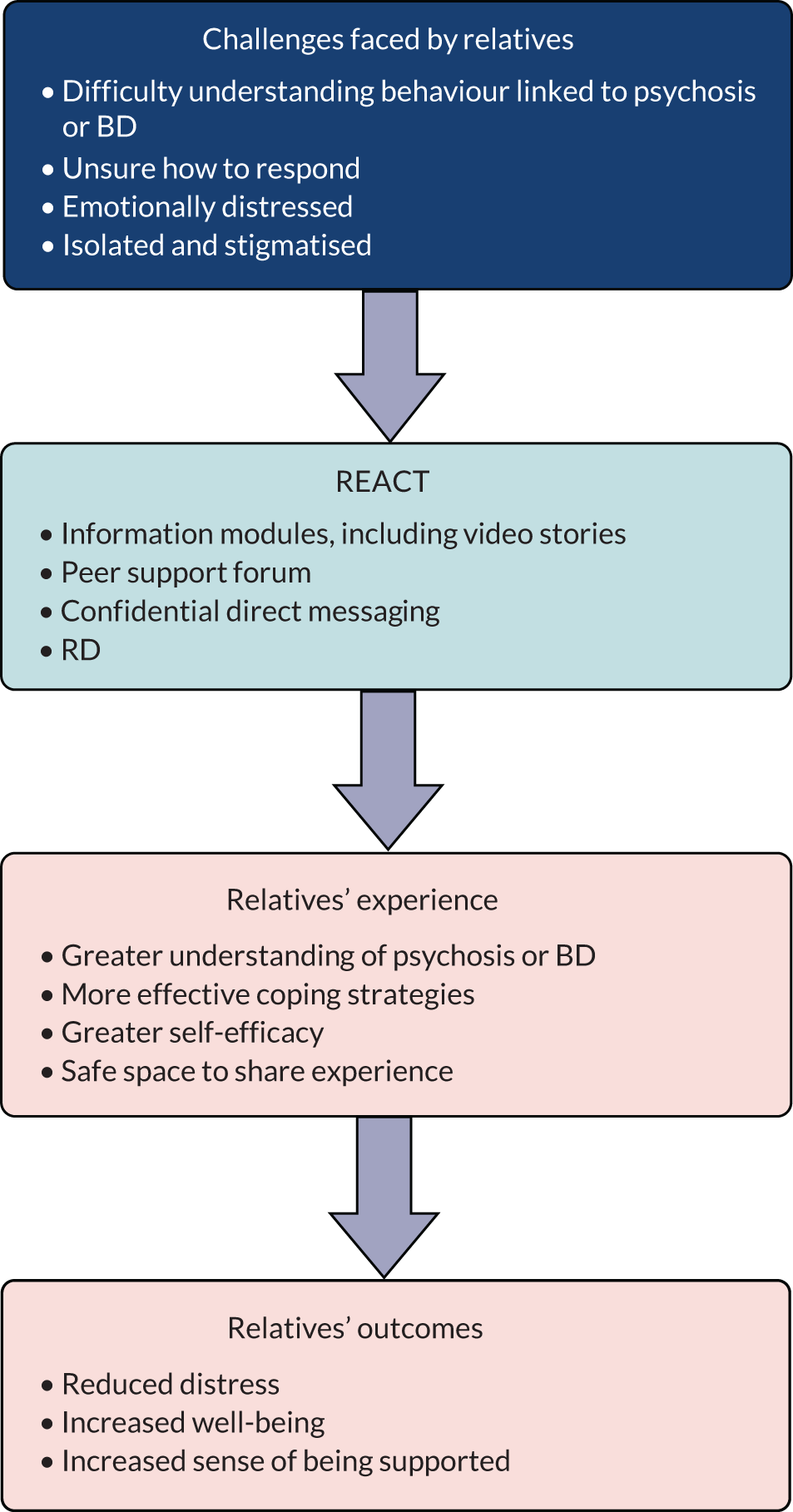

For any intervention, it is important to make explicit the underlying theoretical basis. Figure 2 outlines the process by which we hypothesised that REACT would benefit relatives.

FIGURE 2.

Hypothesised mechanism for REACT.

Reflections on developing REACT

REACT drew on evidence-based cognitive and behavioural psychological theories and clinical practice. The content had been developed and refined over many years, with extensive input from relatives, clinicians and service users in an early-intervention context. Therefore, in building the online version, we already had a good idea of the problems faced by relatives and an understanding of the processes underlying these difficulties and the strategies that could be successfully used to address them.

Even so, in broadening the reach of REACT to relatives of people outside EIP services and those with bipolar experiences, we felt that it was important to explore further what challenges these groups experienced and what support they valued. We also wanted to investigate relatives’ views about online interventions. This information was invaluable in helping us to build a design brief, and, ultimately, to develop the online version of REACT in time to start the trial. However, there were many challenges along the way, and we learnt a lot in overcoming them.

The drive to translate REACT from a paper-based to digital intervention came primarily from the practical need to have something that was easy to update, cheap to deliver and consistent with the NHS’ direction of travel towards digital NHS. 89 However, the extent to which service users and relatives wanted to receive support online was not clear. Many studies showed support for digital health interventions (DHIs) in mental health, but none of the studies was from representative samples of the service-using population, and most studies had recruited small convenience samples of people interested in digital health. 90,91 The relatives in our workshops were also a convenience sample, but were invited to the study to talk more broadly about their experiences of supporting someone with a mental health problem, and so may have been less biased in their views about online support. They had many reservations about the use of online interventions, but also suggested that this might be a cohort effect, and that a younger population would perhaps be less concerned and more comfortable with this mode of delivery.