Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 96/20/99. The contractual start date was in June 2001. The draft report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Malcolm Mason reports personal fees from Sanofi (Paris, France), Bayer (Leverkusen, Germany) and Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium) outside the submitted work. Derek Rosario reports grants from Bayer and personal fees from Ferring Pharmaceuticals (Saint-Prex, Switzerland) outside the submitted work. Jane Blazeby was a member of the following during the project: National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials and Evaluation Committee (2009–2013), HTA NIHR Obesity (2010–2012), Commissioning Board for HTA Surgery Themed Call Board and the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) Standing Advisory Committee (2015–2019). Jenny Donovan was a member of the following during the project: HTA Commissioning Board (2006–12), Rapid Trials and Add-on Studies Board (2012), NIHR Senior Investigator panel (2009–12) and NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research board (Deputy Chairperson) (2010–11). Freddie C Hamdy was a member of the following during the project: HTA Commissioning Board (2007–12) and HTA Surgery Themed Call Board (2012–13). J Athene Lane was a member of the following during the project: CTUs funded by NIHR (2017 to present). Chris Metcalfe was a member of the following during the project: CTUs funded by NIHR (2010 to present). Tim Peters was a member of the following during the project: HTA Medicines for Children Themed Call (2005–6) and NIHR CTU Standing Advisory Committee (2008–14). John Staffurth reports support for travel to conferences and attendance on an advisory board from Bayer. Emma L Turner reports grants from Cancer Research UK (London, UK) during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Hamdy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in the UK. In 2014, there were 46,610 new cases of diagnosed prostate cancer, and 11,287 men died from the disease that year. Incidence rates for prostate cancer are projected to rise by 12% in the UK between 2014 and 2035, to 233 cases per 100,000 males by 2035. 1 The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer is one in eight for men in the UK, and, although it is often overtreated, many men are undertreated. In the USA alone, 26,730 deaths from the disease were expected in 2017. 2 It is estimated that there were approximately 330,000 men living with prostate cancer in the UK in 2015, and this number is expected to rise to around 830,000 by 2040. 3 The incidence of prostate cancer is increasing, with wider use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in asymptomatic men and with the population ageing, and has tripled over the past 35 years in many countries in Europe. 4 Although prostate cancer can be lethal, the majority of men who are diagnosed through PSA testing will not suffer clinically significant consequences from the disease during their lifetime, and evidence that treating such men improves survival or quality of life (QoL) is weak. Consequently, there are concerns that increasing PSA testing in the community is resulting in overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and an increasing burden on the NHS in the UK and other health providers elsewhere. Despite its high incidence and social and economic impact, prostate cancer continues to be under-researched, and only a limited number of studies are addressing the issues of screening and long-term comparison of treatment modalities.

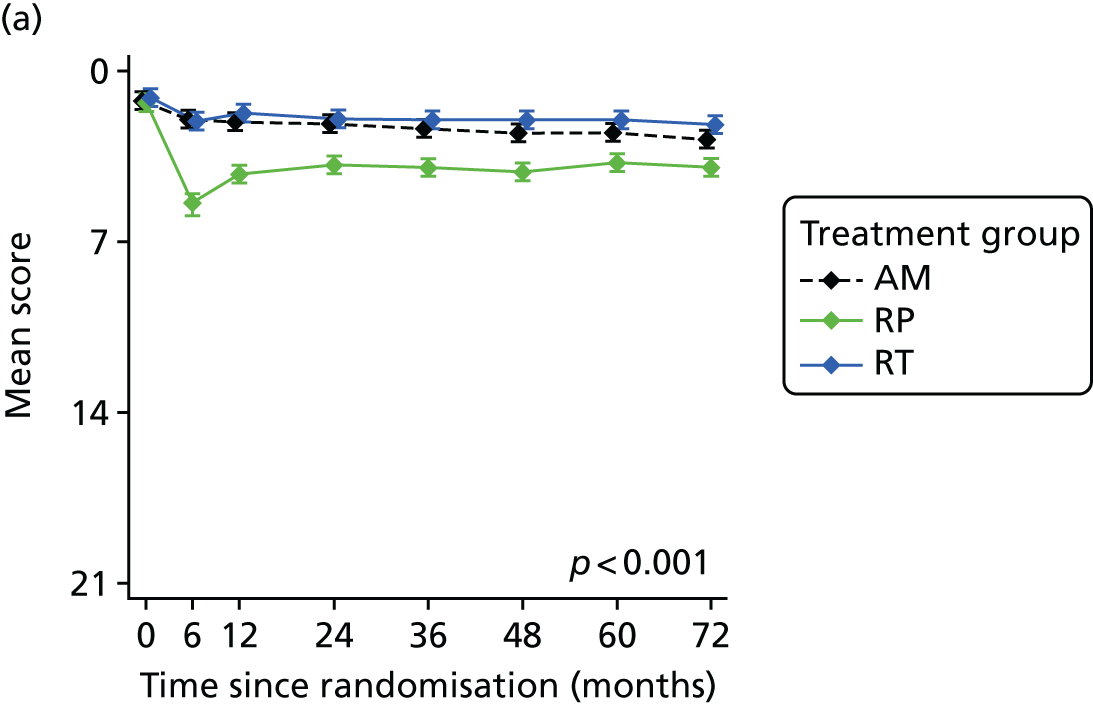

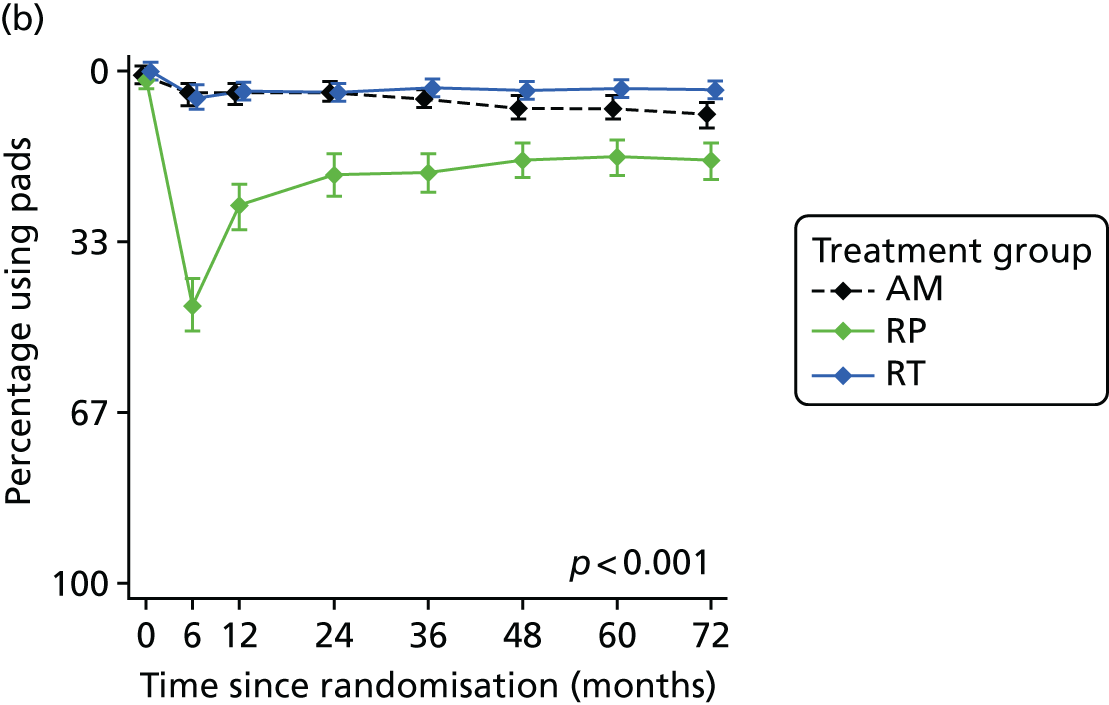

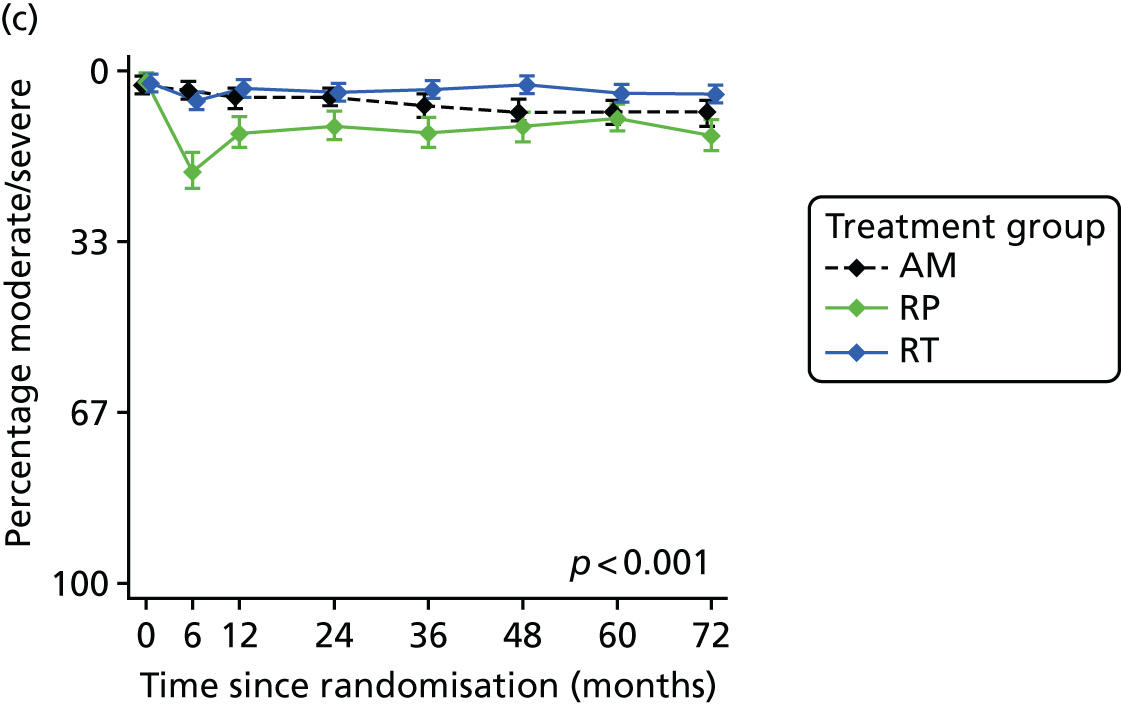

In particular, there have been very few studies of the longer-term impact on QoL of the major initial treatments for localised prostate cancer. Only one trial has reported on this: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 (SPCG-4) trial5 from the pre-PSA era comparing passive ‘watchful waiting’ with open prostatectomy for clinically detected prostate cancer. This trial’s follow-up, 12 years after randomisation, showed that urinary incontinence was persistently worse among those who had undergone prostatectomy rather than watchful waiting and sexual dysfunction was similarly poor in both groups. In addition, rates of sexual dysfunction, urinary leakage and anxiety were found to be much higher in SPCG-4 trial participants than in an age-matched cohort, with decreasing QoL reported from the increasing use of hormone therapy for progressing prostate cancer. 5,6 However, the SPCG-4 trial did not collect these data with a validated patient-reported outcome measure (PROM), the trial compared only surgery and passive ‘watchful waiting’ [not radiotherapy or active monitoring (AM)], participants had clinically detected not PSA-detected disease at diagnosis and treatments for advancing prostate cancer during their follow-up were very different from current options.

Most comparative cohort studies have analysed PROMs in only the short term,7 with only a small number extending this to the medium term of 5–6 years. 8–10 These cohort studies have produced somewhat contradictory findings, most likely because of baseline differences in PROMs between men receiving different treatments. Miller et al. 8 found that sexual, urinary and bowel dysfunction remained more prevalent and bothersome in men receiving surgery or radiotherapy than in an age-matched control group, and that sexual function remained stable after radical prostatectomy (RP) but continued to decline over time after radical radiotherapy (RT), whereas general QoL remained stable. They commented that they had found ‘evolving and potentially unexpected changes in long-term, patient-reported QoL as patients proceed from earlier to later phases of survivorship’ that required further research. 8 Potosky et al. 9 also reported large declines in sexual function following RT but Fransson and Widmark10 found no such worsening. There have been even fewer studies in the longer term, and these have also produced conflicting results. Resnick et al. 11 reported that differences in levels of urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction for RT and RP at 5 years reduced to become similar by 15 years, but noted that the specific contribution of prostate cancer treatments could not be distinguished from age-dependent changes in the longer term. In contrast, a population-based study12 comparing prostate cancer survivors with an age-matched control group found similar levels of global QoL in the longer term, but with prostate cancer survivors reporting severe and persistent urinary, bowel and sexual adverse effects, particularly if they had received combined treatments.

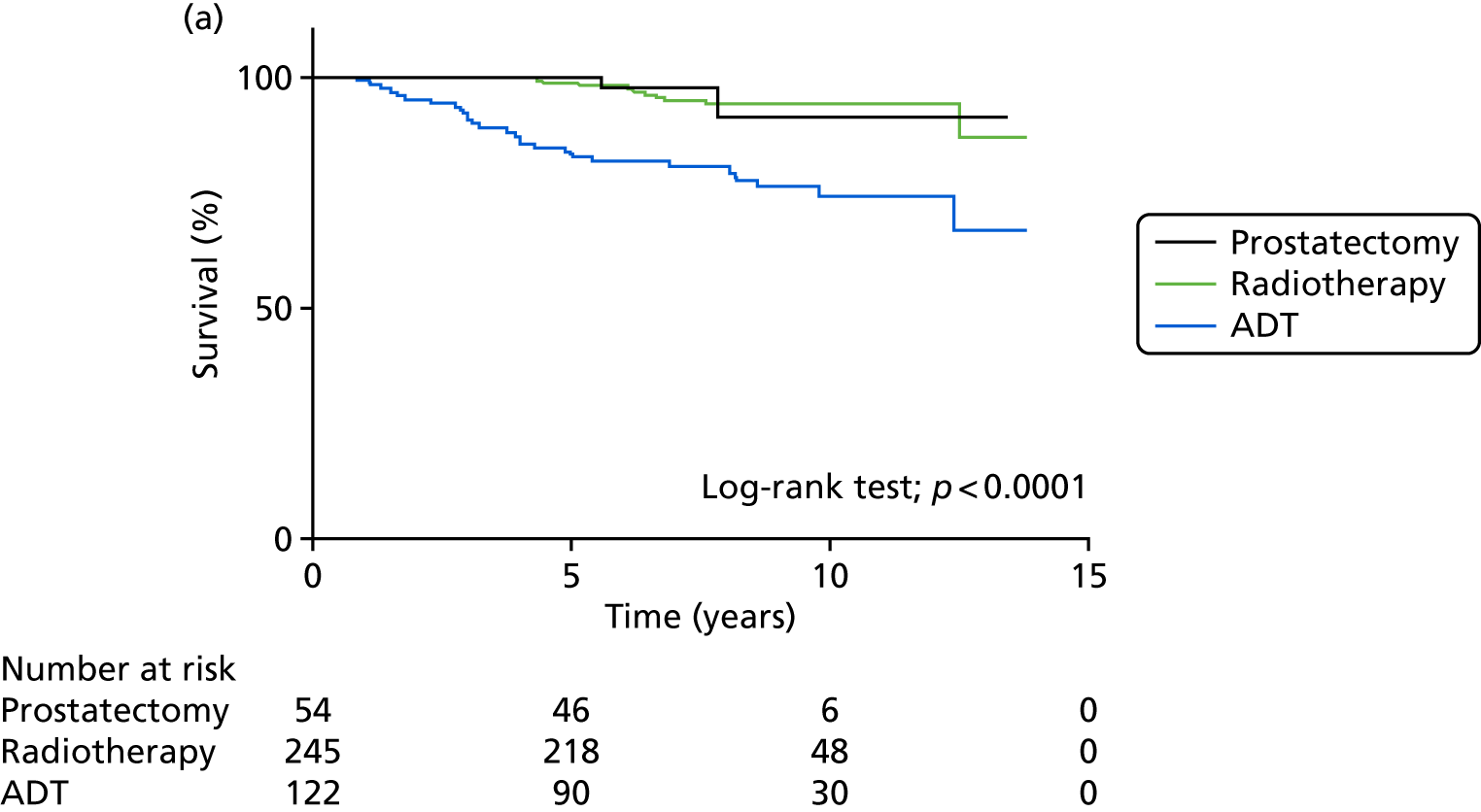

There is a paucity of research on the QoL impacts of progressing prostate cancer. Recent large trials have focused on mortality and clinical outcomes without parallel reporting of QoL impacts [e.g. CHAARTED (ChemoHormonal Therapy Versus Androgen Ablation Randomized Trial for Extensive Disease in Prostate Cancer)13]. This hinders men when making informed choices between treatments because there is a lack of information about the potential magnitude of QoL benefits or the likelihood of a man realising those benefits. A small number of older trials have included PROMs, and their results have been helpful. For example, the Medical Research Council RT01 trial14 found that sexual functioning deteriorated, urinary function did not change and there was a slight decline in physical well-being, although not in overall QoL, after androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was received in advance of high- or standard-dose RT. A pooled analysis showed that denosumab prevented progression of pain severity and pain interference more effectively than zoledronic acid in patients with advanced solid tumours (including some with prostate cancer) and bone metastases. 15 A systematic review concluded that effects on QoL of prostate cancer and its treatments varied across treatments and disease stage, and that there was a ‘pressing need for more research in men with advanced disease’. 16 There is some evidence that better information can improve patient satisfaction and even QoL. 17 A more recent review by the American Cancer Society18 noted that there remains very limited evidence to underpin guidelines for the long-term care of men with prostate cancer. The majority of articles found up to 2014 were case–control studies with fewer than 500 participants or reviews without PROMs, and there were only a small number of higher-quality studies using population-based data. In particular, the review stated that ‘the lack of clinical trials is a limitation of the current state of the science for survivorship’. 18

Diagnosis of prostate cancer

When the Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial was designed in the late nineties, prostate cancer was diagnosed following serum PSA testing, with transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsies in most cases. Although this allowed many early cancers to be detected, the majority represented low-risk disease, which does not tend to progress. Intermediate-risk, high-risk and locally advanced cancers were also detected, but in smaller numbers, and lethal cancers could be missed. More recently, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) technology and dissemination has been reaching a level at which accurate assessment of the location and grade of prostate cancer using imaging and biopsies is possible, as demonstrated in the recently published National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) PROstate Magnetic resonance Imaging Study (PROMIS);19 this was a definitive validating cohort study evaluating mpMRI as a triage test. PROMIS demonstrated higher levels of accuracy in the detection of clinically important disease, and found that ‘TRUS-biopsy performs poorly as a diagnostic test for clinically significant prostate cancer. mpMRI, used as a triage test before first prostate biopsy, could identify a quarter of men who might safely avoid an unnecessary biopsy and might improve the detection of clinically significant cancer’. 20 This is transforming the diagnostic pathway for prostate cancer, and it is likely that if it were available during the conduct of ProtecT, it would have had an impact on the disease-risk composition of our cohorts.

Screening and the linked CAP (Cluster randomised trial of PSA testing for Prostate cancer) trial

Evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in Europe [European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), n = 162,24321] and the USA [Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO), n = 76,69322] has not resolved the controversies surrounding PSA-based prostate cancer screening, resulting in different recommendations worldwide. 23,24 The prognosis for low- and intermediate-risk localised prostate cancer is excellent,25 and although there is fair-quality evidence that screening by PSA testing reduces prostate cancer deaths,26 debate continues about the trade-off between the mortality benefit and risks of harm from overdetection and overtreatment. 22–24

Current UK policy does not advocate screening. 27 The proposed 2017 update from the US Preventative Services Task Force recommends individualised decision-making for men between the ages of 55 and 69 years after a discussion of risks and harms with their physician. 26 This latest guidance comes amid concerns about the quality of previous evidence,24 favourable modelling projections,28 new secondary analyses,28 greater absolute risk (but not rate) benefits with long-term follow-up,29 the use of active surveillance (AS) to avoid radical treatment unless cancer is progressing30 and long-term data on the effects of different treatment options for localised prostate cancer. 25,30 The PLCO22 and ERSPC21 trials undertook repeated PSA testing at intervals of 1, 2 or 4 years. Less intensive strategies, such as longer screening intervals or one-off screens, have been predicted to reduce overdetection, overtreatment and costs relative to more frequent screening. 31,32 However, opportunistic screening may increase overdetection without reducing prostate cancer mortality. 33

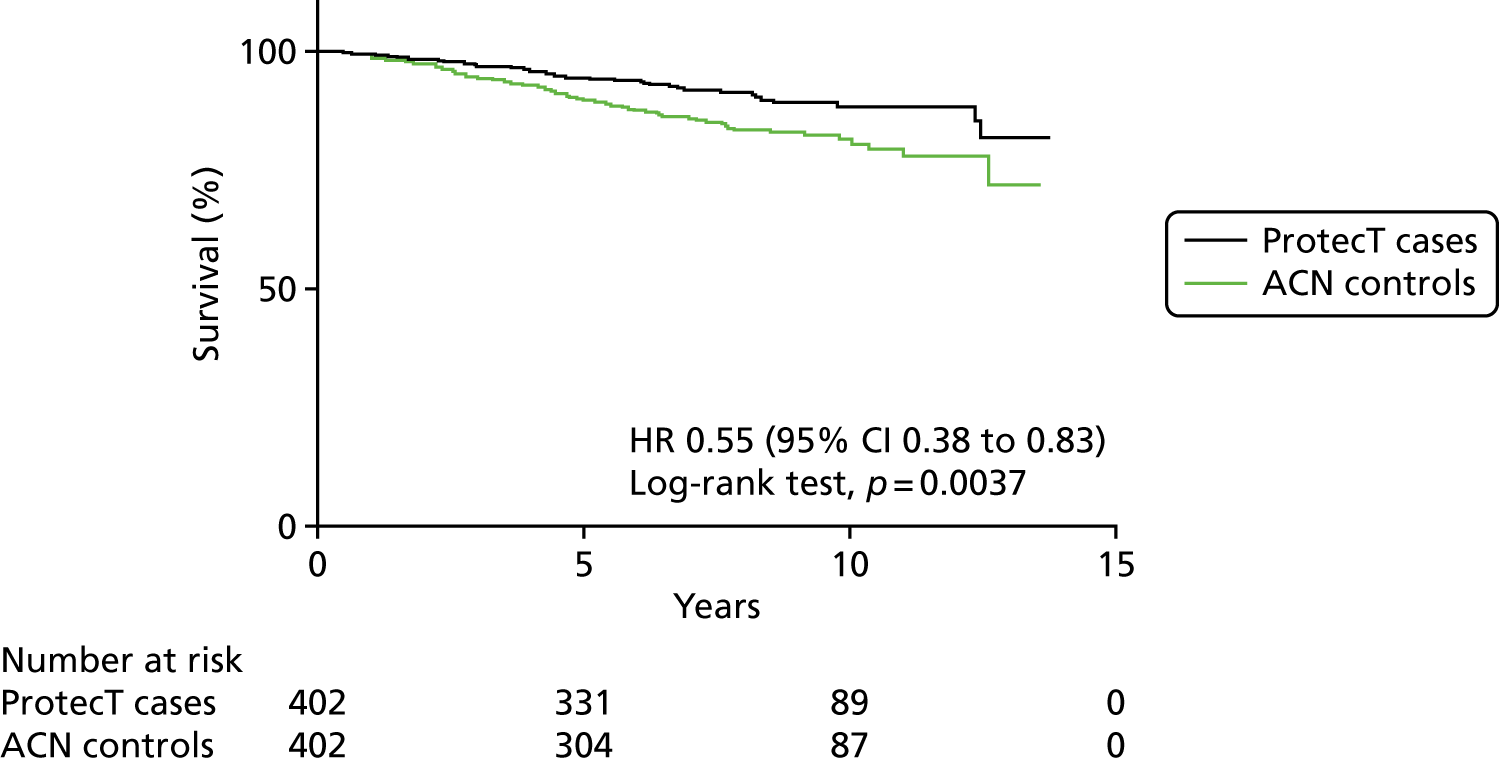

We undertook the primary-care-based Cluster randomised trial of PSA testing for Prostate cancer (CAP),34 within which the ProtecT trial of treatments for localised prostate cancer was embedded. CAP was designed to determine the effects of a low-intensity, single-invitation PSA test and standardised diagnostic pathway on prostate cancer-specific and all-cause mortality while minimising overdetection and overtreatment.

Between 2001 and 2009, general practices (the clusters) around eight hospital centres in England and Wales were randomised before recruitment (‘Zelen’ design) to intervention or control groups and approached for consent to participate. In the intervention group, men aged 50–69 years received a single invitation to a nurse-led clinic appointment (the intervention) at which they were provided with information about PSA testing and the treatment trial. Screened men with a PSA level of ≥ 3.0 ng/ml were offered a standardised 10-core TRUS-guided biopsy. Those diagnosed with clinically localised prostate cancer were offered recruitment to the ProtecT treatment trial comparing RP, radical conformal radiotherapy with neoadjuvant ADT and AM. 25 Control practices provided standard NHS management, with information about PSA testing provided to only men who requested it. 35

The primary outcome was prostate cancer mortality at a median of 10 years of follow-up (reached by March 2016), analysed by intention to screen. Prespecified secondary outcomes were diagnostic stage and grade of prostate cancers identified, all-cause mortality at 10 and 15 years, prostate cancer mortality at 15 years, health-related QoL, cost-effectiveness and instrumental variable analysis estimating the causal effect of attending PSA screening.

Study population

Parts of this section have been reproduced with permission from Martin et al. 36 JAMA 2018;319(9):883–95. Copyright © 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

In total, 911 general practices were randomised in 99 geographical areas. Of these, 126 were subsequently excluded as ineligible. 34 Consent rates among the remaining eligible intervention (n = 398) and control (n = 387) group general practices were 68% (n = 271) and 78% (n = 302), respectively; 195,912 and 219,445 men registered with these 573 practices were eligible for the intervention and control groups, respectively. After exclusions, the main analysis was based on 189,386 men in the intervention group and 219,439 men in the control group. There were some differences between numbers of participants in the intervention group of this trial and the published ProtecT study population. 25 There were no important differences between the measured characteristics of practices that did agree to participate and those that did not agree to participate. 34 There were also no important differences in measured baseline characteristics between intervention group and control group practices or men, indicating that post-randomisation exclusions did not introduce detectable selection biases.

Among 189,386 intervention group men in the CAP study, 75,707 (40%) attended the PSA testing clinic, 67,313 (36%) had a blood sample taken and 64,436 had a valid test result. Of these 64,436 men, 6857 (11%) had a PSA level of between 3 ng/ml and 20 ng/ml (eligible for ProtecT), of whom 5850 (85%) had a prostate biopsy. Intervention group men who attended PSA testing clinics were sociodemographically similar to non-attenders. 37 Cumulative contamination (PSA testing in the control group) was indirectly estimated at ≈10–15% over 10 years, based on previously reported diagnostic referral rates and ≈20% of follow-up being subsequent to a PSA test undertaken for screening. 38–40

The results of the primary analysis have been published. 36 After an average of 10 years of follow-up, there were 8054 (4.3%) cases of cancer in the screened group and 7853 (3.6%) cases in the control group. Crucially, both groups had the same percentage of deaths (0.29%). This demonstrated that the single PSA test followed by TRUS-guided biopsy diagnostic pathway does not appear to improve disease-specific survival at a median follow-up of 10 years, but longer follow-up is needed. Critically, the testing missed the diagnosis of an important number of lethal cancers, confirming the necessity to improve our diagnostic pathway, perhaps by incorporating imaging in the form of mpMRI upstream of biopsies, in order to triage men at risk of significant disease, and targeting significant cancers.

Treatment options for localised prostate cancer

Parts of this section are reproduced from Hamdy et al. 41 Reproduced with permission from JAMA 2017;317:1121–3. Copyright © 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Conventional treatment options for men with clinically localised prostate cancer include AM/AS, RP, now most commonly carried out as robot-assisted laparoscopic procedures, intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) and brachytherapy, which appear to have similar short- to medium-term oncological outcomes in non-randomised studies.

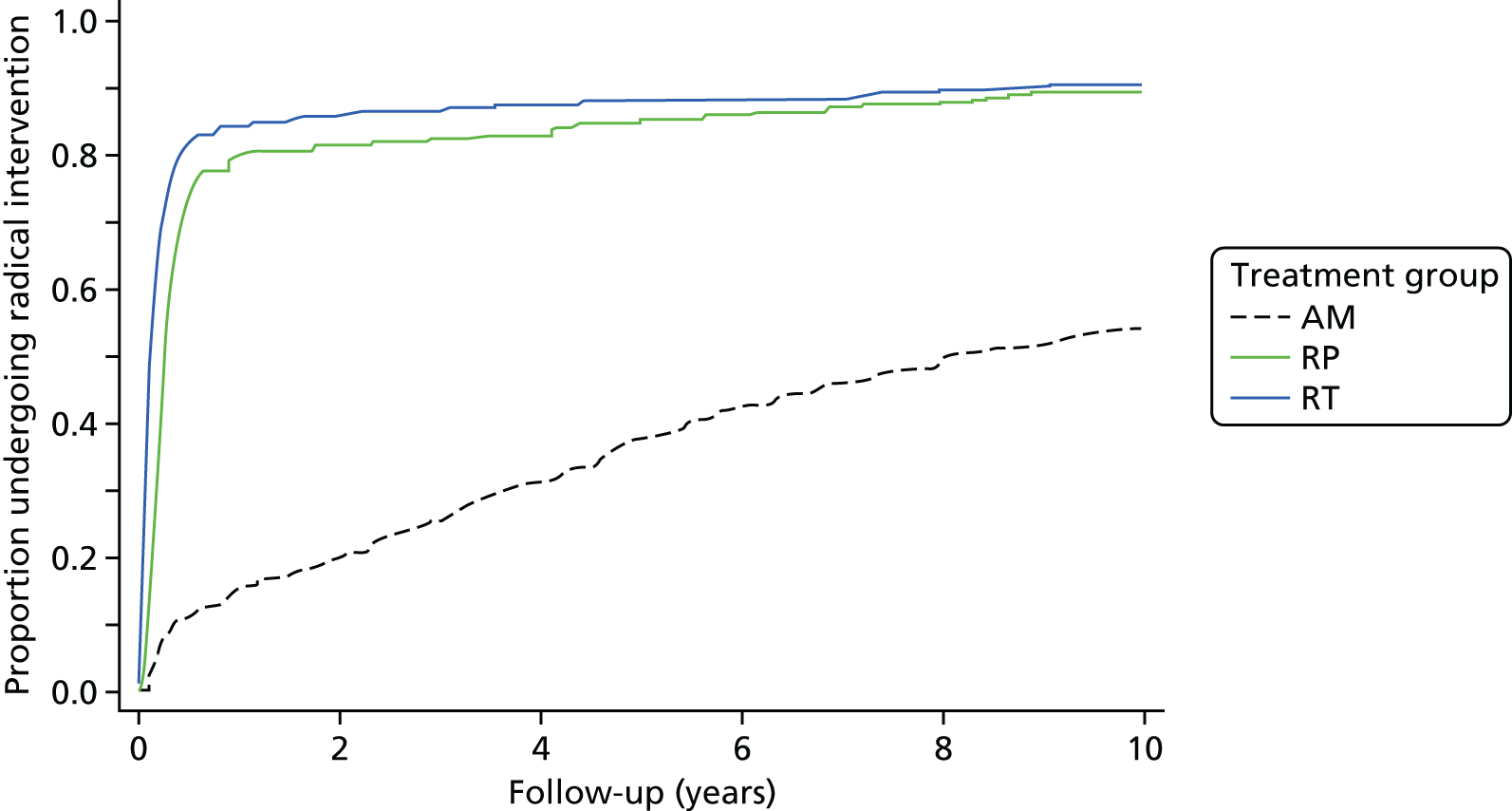

Active monitoring/surveillance protocols involve regular clinical examination, PSA measurements, mpMRI and repeat biopsies. If these parameters suggest the risk of progression, men are offered radical treatment. A number of Phase II studies have shown that delayed intervention due to signs of progression takes place in approximately one-third of AS groups within 5 years of diagnosis. 42,43 For those with intermediate disease, AM has been reported as conferring an 84% 5-year metastasis-free survival rate. 44 However, observational strategies can lead to significant anxiety. 45

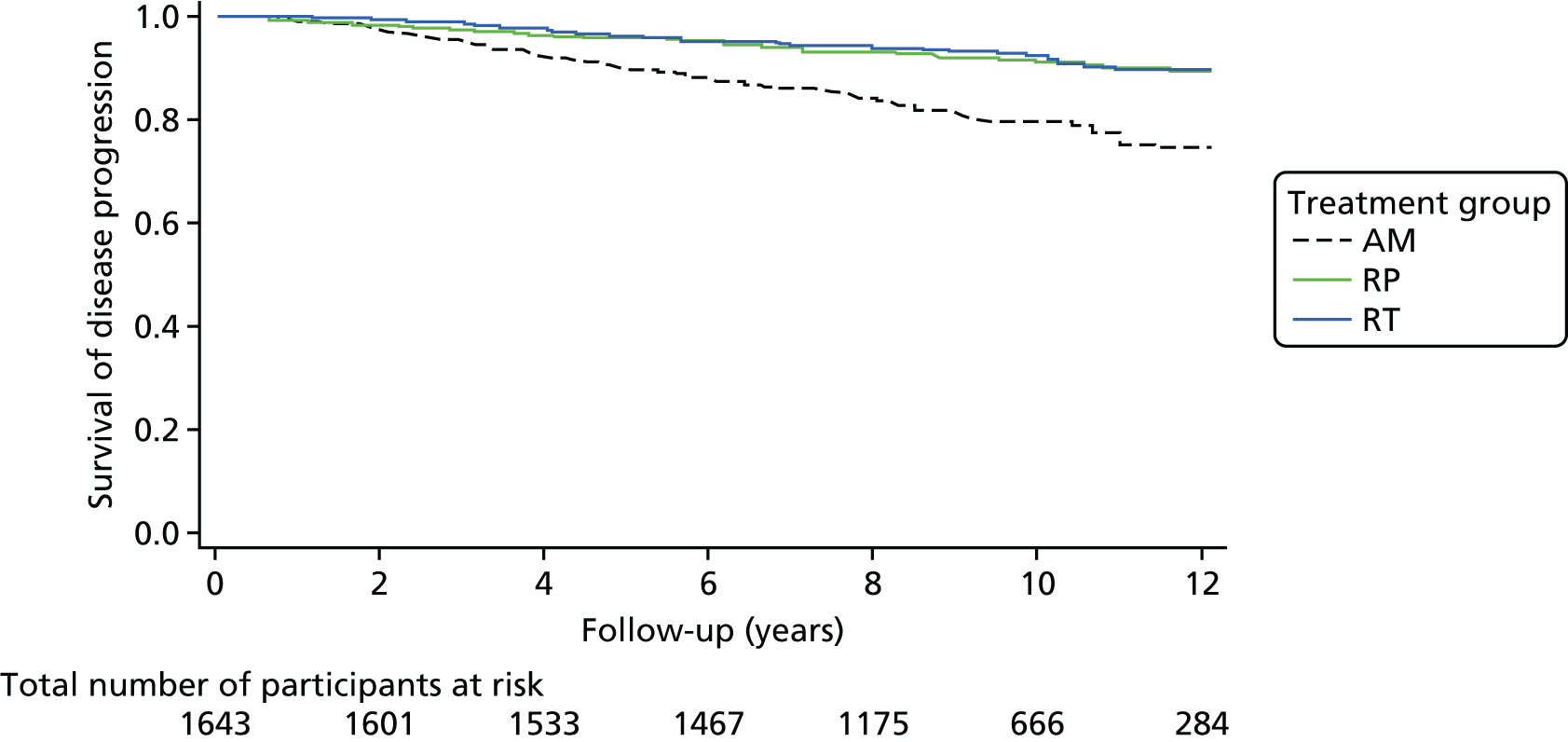

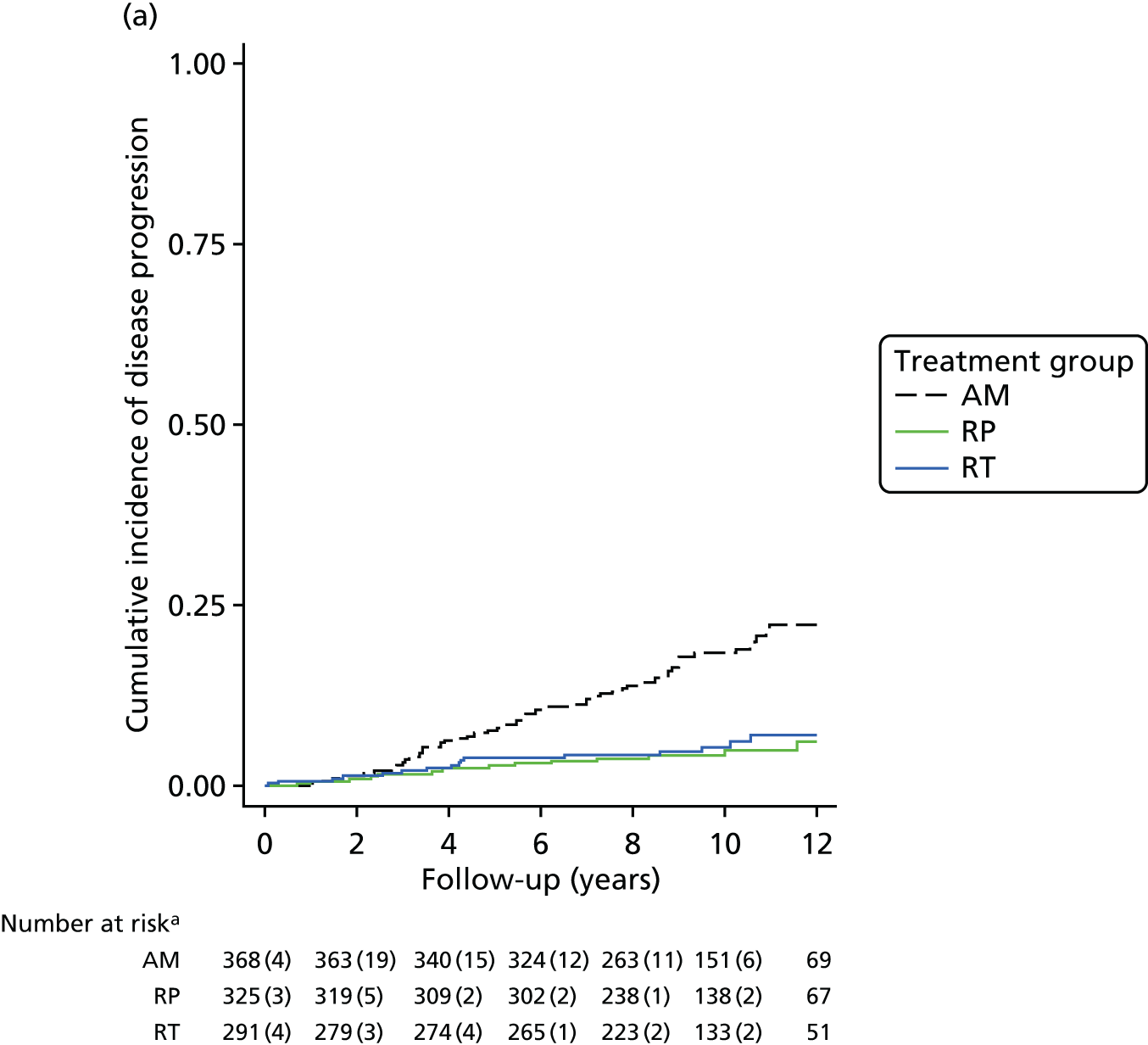

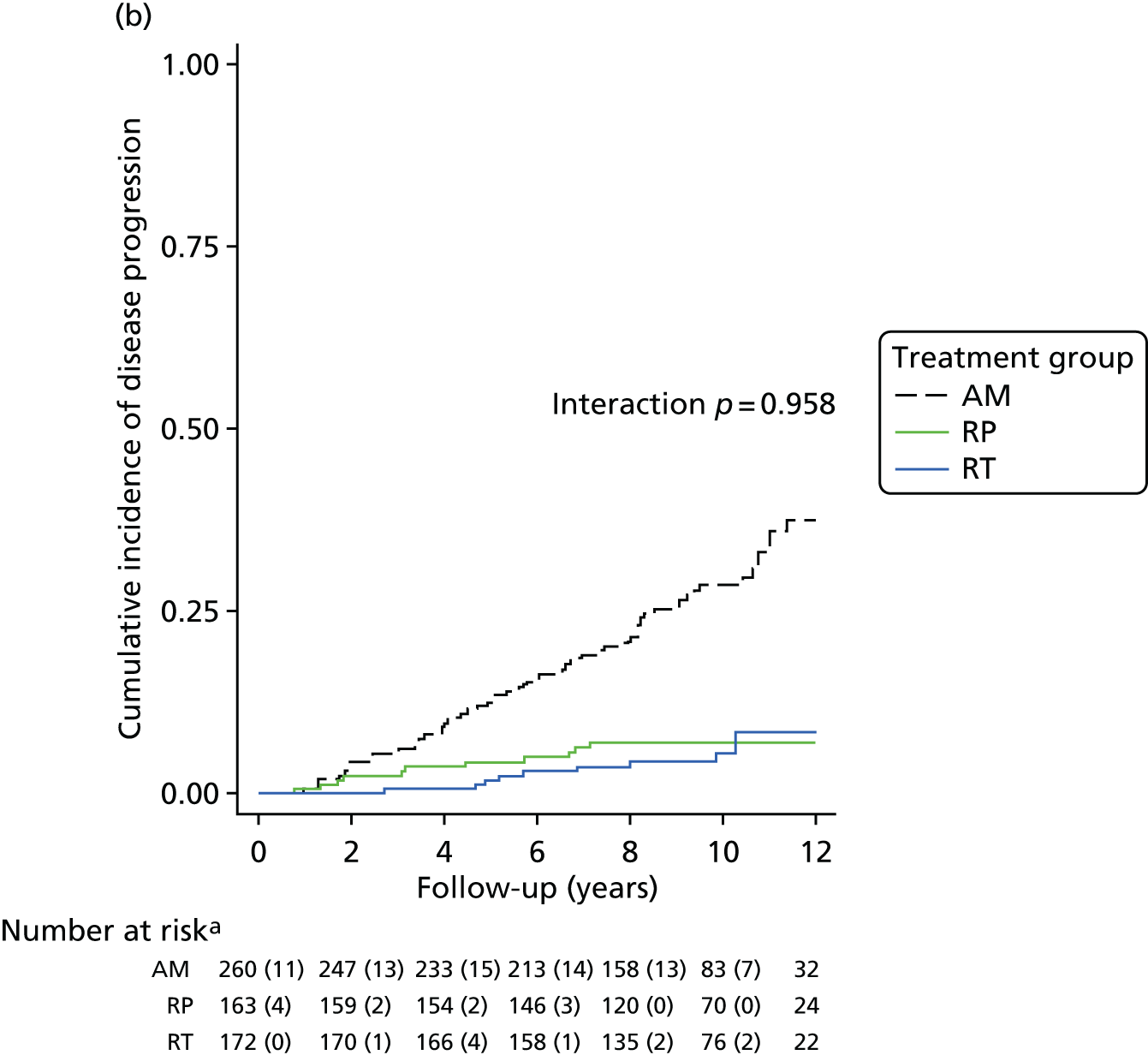

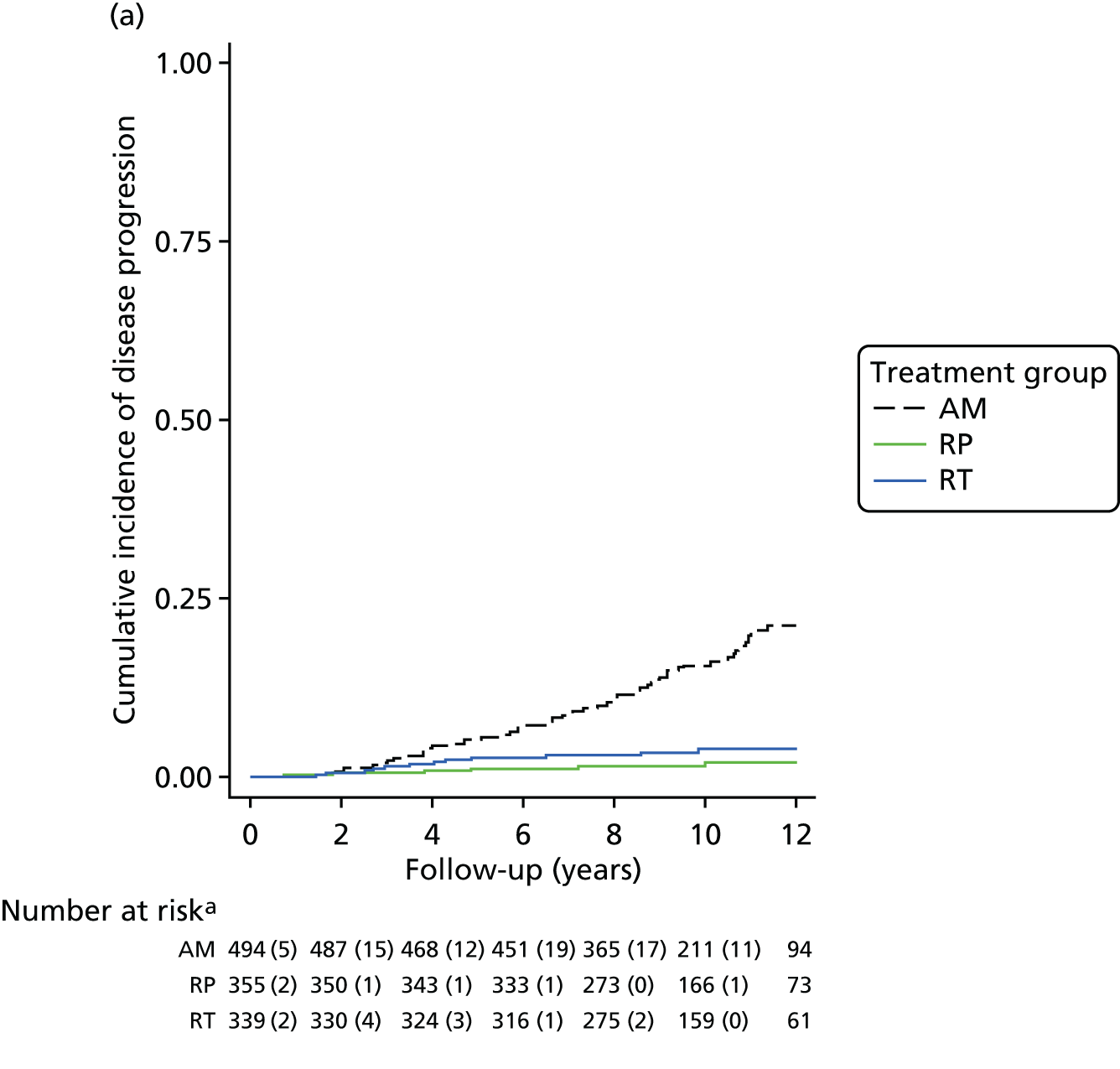

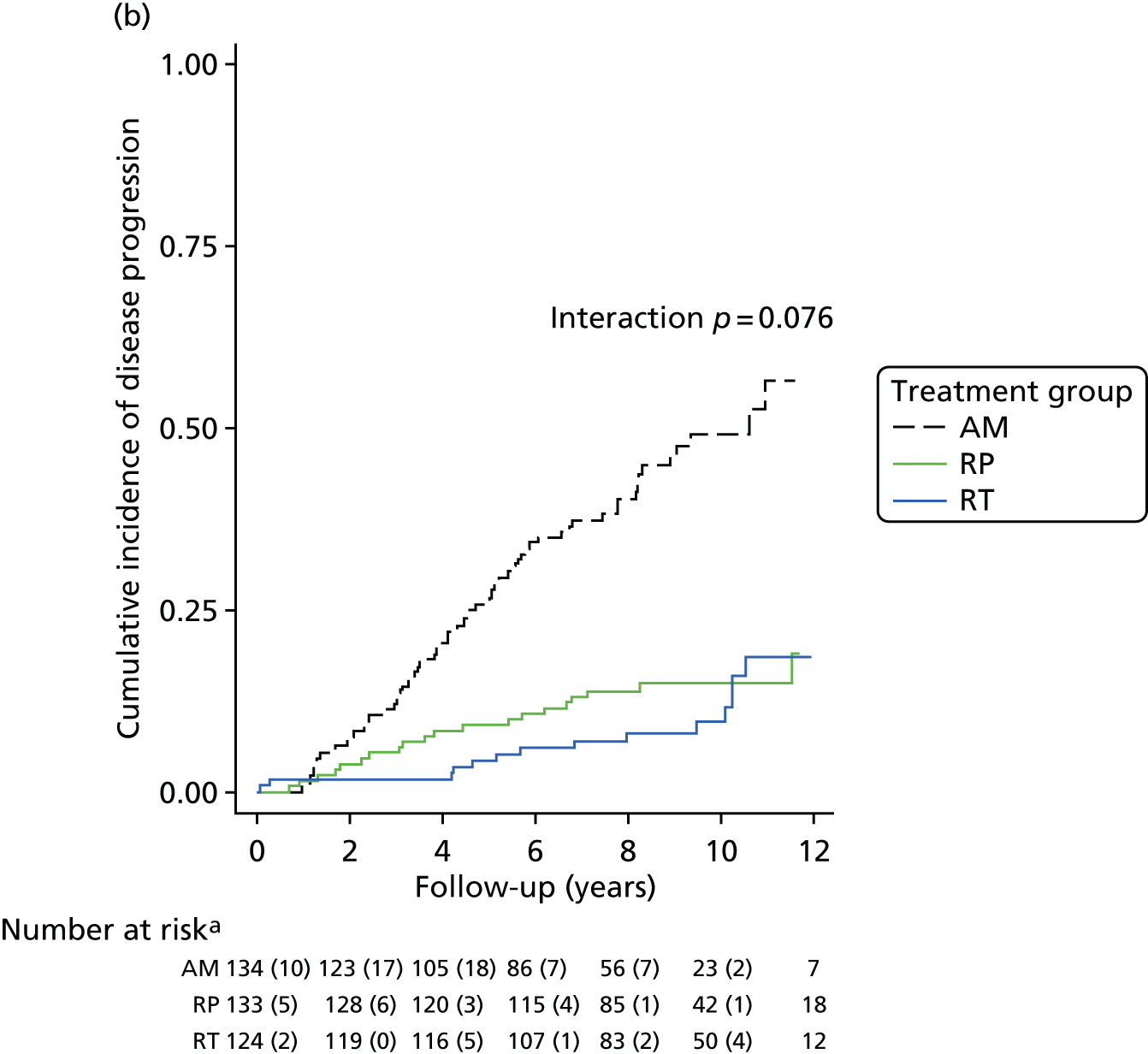

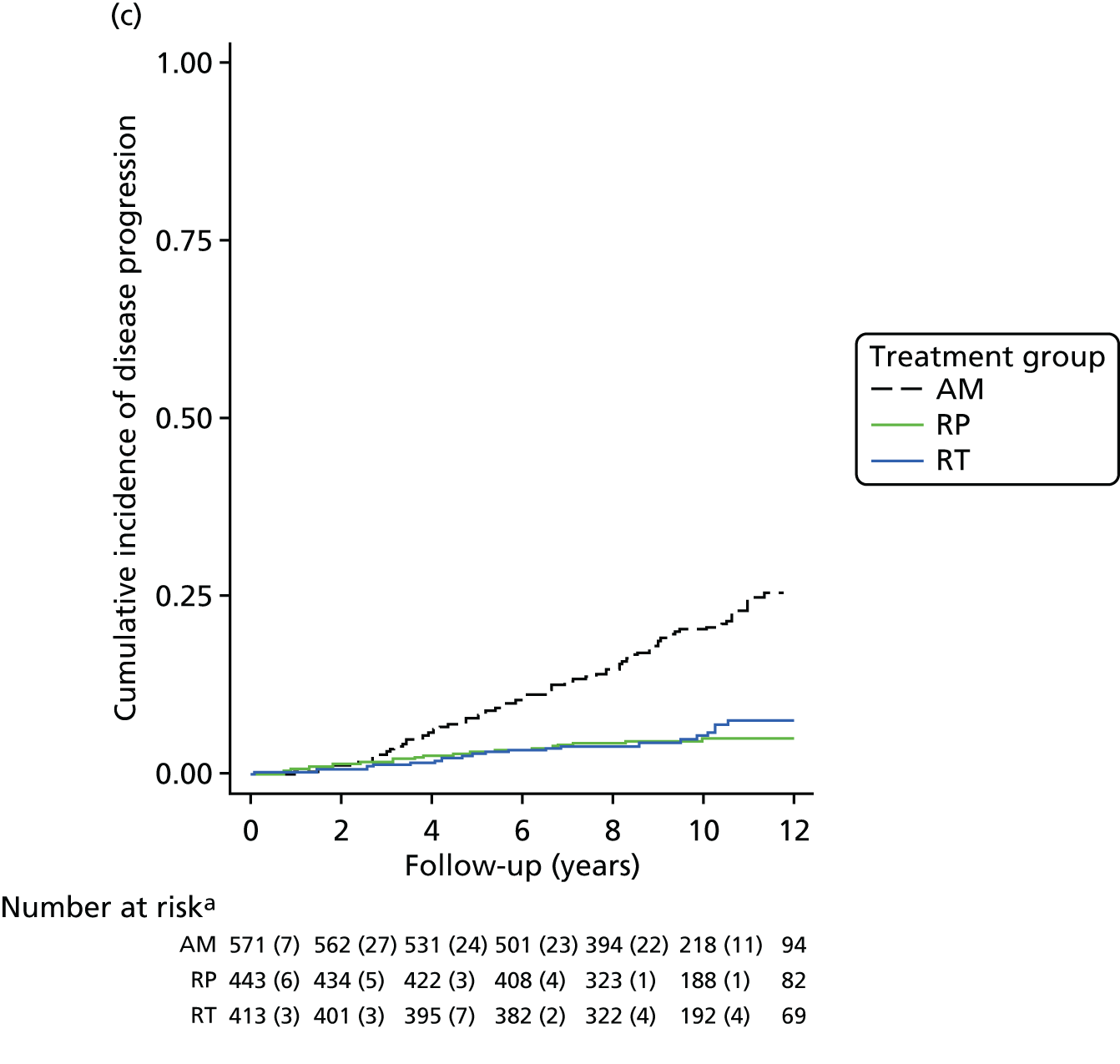

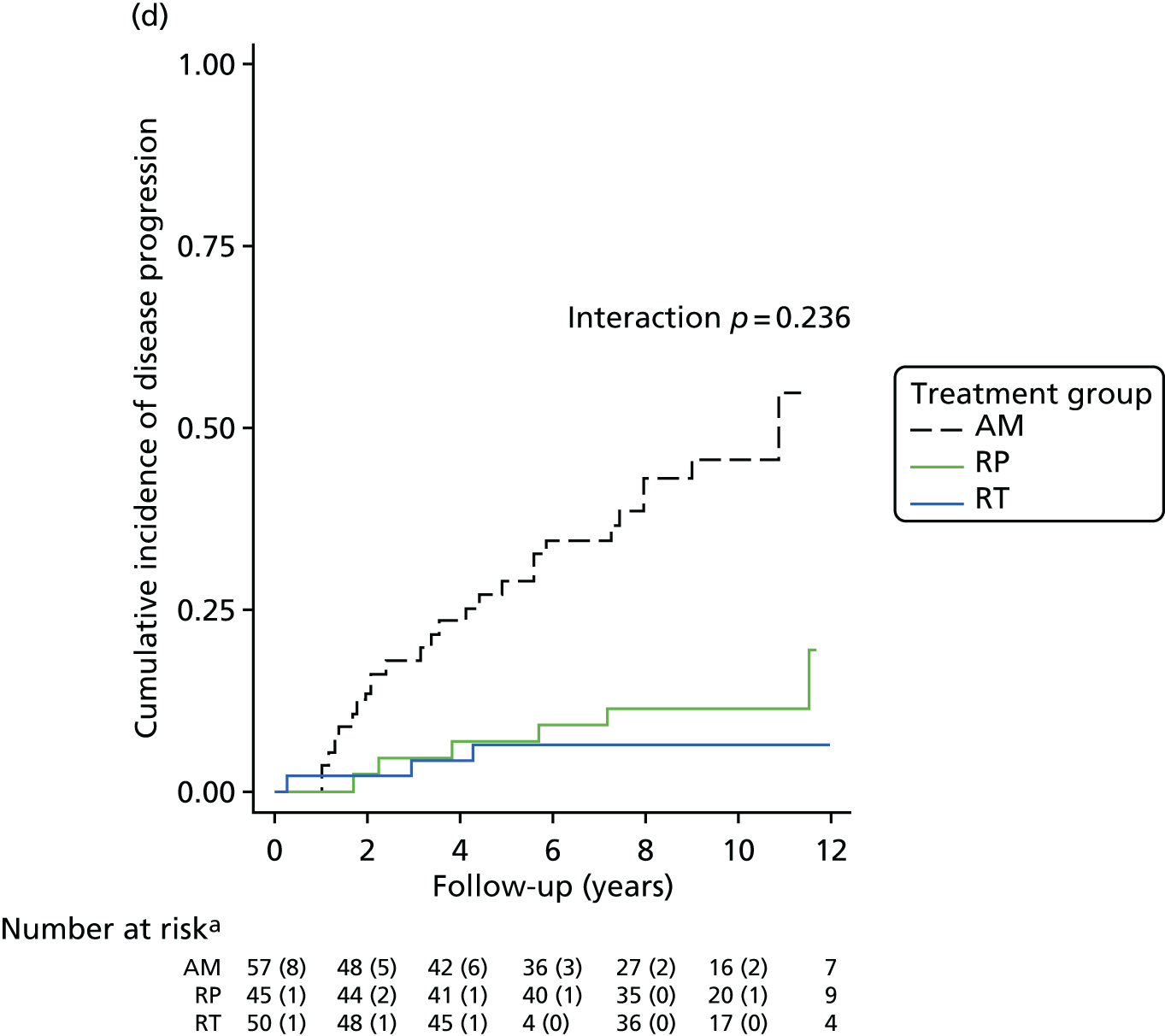

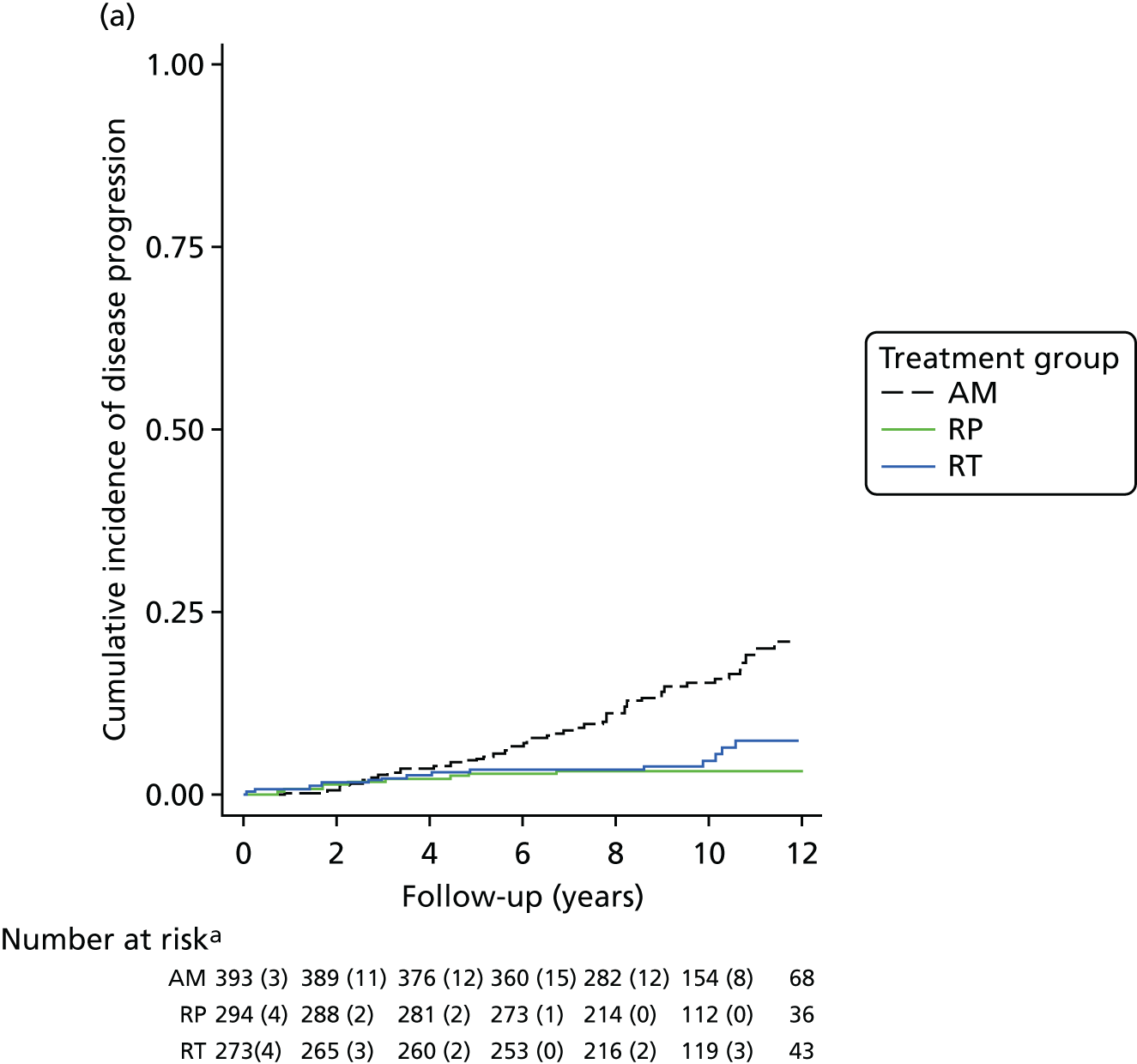

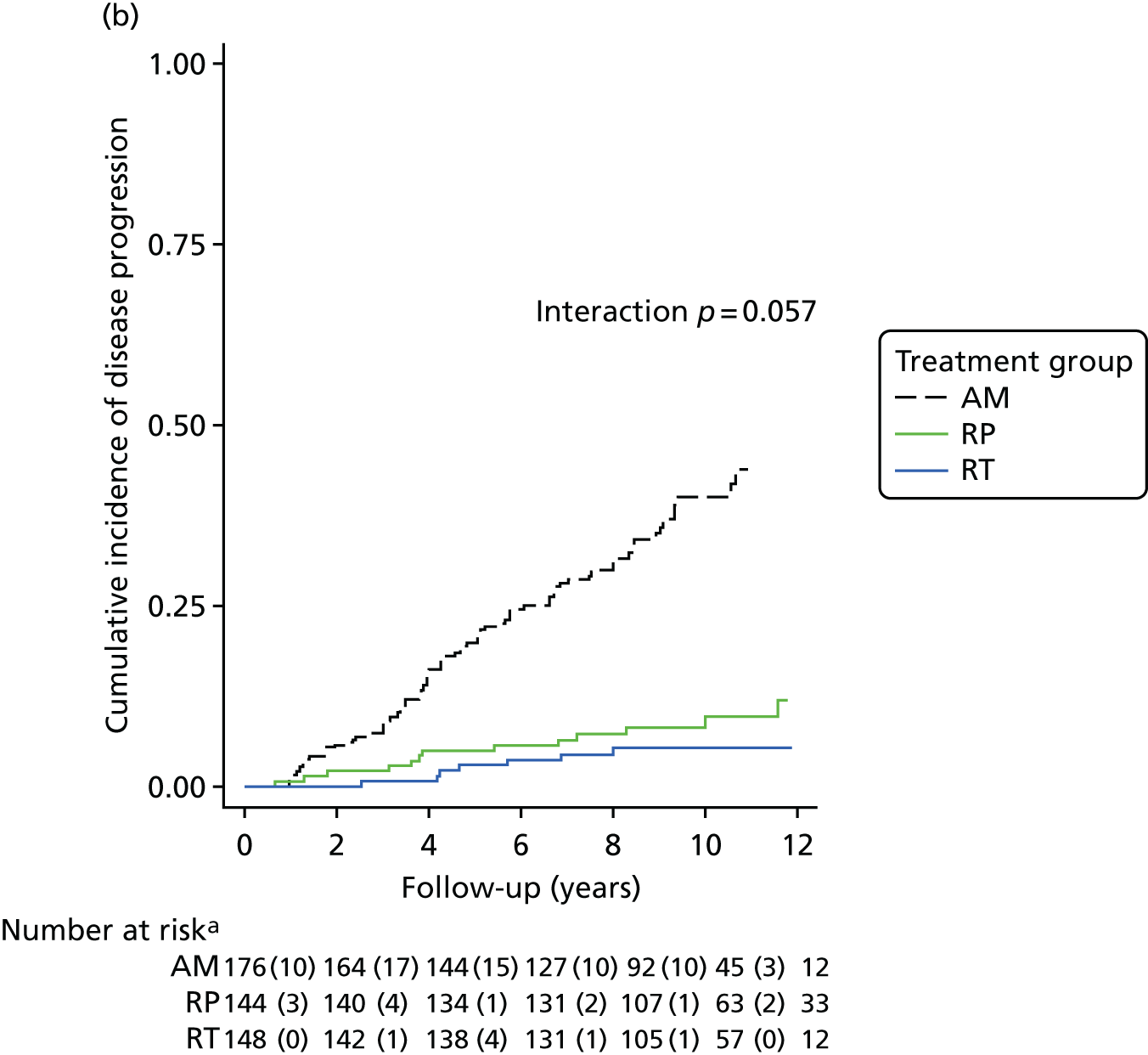

Active monitoring has been tested in clinically-localised prostate cancer in the context of the ProtecT study,46 which reported that although RP and radiotherapy were associated with lower rates of disease progression, 44% of men assigned to AM did not receive radical treatment and, thus, avoided side effects. Men with newly diagnosed, localised prostate cancer therefore need to consider the critical trade-off between the short-term and long-term effects of radical treatments on urinary, bowel and sexual function and the higher risks of disease progression with AM, as well as the effects of each of these options on QoL.

Radical prostatectomy involves total open, laparoscopic or robot-assisted surgery to remove the entire prostate gland and seminal vesicles. The proportion of prostate cancer patients receiving surgery varies with age: 8% of prostate cancer patients receive a major surgical resection as part of their cancer treatment, with fewer resections in the oldest age group (0% in those aged ≥ 85 years) than in the youngest age group (29% in those aged 15–54 years). 1 Until recent years, most RPs were carried out using conventional open surgery. Laparoscopic RP was developed in the nineties, and evolved to robot-assisted techniques, which are now used almost exclusively. A recent RCT compared open with robotic techniques and showed no differences in short-term oncological and functional outcomes. 47

Radical radiotherapy in the form of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) is a common treatment in the UK for men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer. It is usually preceded by 3–6 months of neoadjuvant androgen suppression, and is given in daily fractions over 4–8 weeks as an outpatient. In large reported series, EBRT conferred a 5-year disease-free survival of between 78% and 80%, or 88% and 94% in combination with hormone therapy. 48–51 IMRT, an optimised form of EBRT, is delivered in some centres. 52

Brachytherapy can be given either as permanent radioactive seed implantation or as high-dose brachytherapy using a temporary source. For localised prostate cancer, the 5-year biochemical failure rates are similar for permanent seed implantation, high-dose (> 72 Gy) external radiation, combination seed/external irradiation and RP. 53

Radical, extensive treatments carry the potential for significant short-, medium- and long-term morbidity, such as urinary leakage, erectile dysfunction and radiotherapy toxicity. At present, there is little difference between RP and RT in terms of cancer control in the short to medium term; much of the decision-making process that governs treatment allocation is based on the differences in the side effect profiles associated with the various interventions. 52 The recently published clinical and patient-reported outcomes from the ProtecT study30,41 demonstrated that each treatment option has a particular pattern of adverse effects on QoL in the short term. Urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction were worst after surgery, followed by recovery but persistent difficulties for some men; bowel problems were worst after radiation, with sexual dysfunction mostly related to neoadjuvant ADT. Although adverse effects of interventions can be avoided initially with AS, there is a natural decline in urinary and sexual function symptoms over time, and the adverse impacts of radical treatments will be experienced when those treatments are received. 30,41 Findings from the ProtecT trial described in this report have therefore established the true side effect profiles of the various treatment options. 54 These side effect profiles have been consistently described even with more modern and contemporary radical treatment options, such as robot-assisted surgery, and different forms of radiation, including brachytherapy. It is therefore true to state that contemporaneous men who are treated with current forms of radical therapy will continue to suffer from the now well-described and well-documented side effect profile patterns related to these treatments, substantiated by more recent PROMs reported by two large prospective observational cohorts from the USA. 55,56

Alternatives to conventional therapies

Alternative, targeted focal ablative therapies are being developed in an attempt to reduce treatment burden, improve QoL and reduce adverse events associated with radical treatment, while retaining at least equivalent cancer control. Focal therapies should minimise morbidity by lowering the chance of damage to the neurovascular bundles responsible for erectile function, and the urinary continence mechanism, and may help to avoid the psychological morbidity associated with surveillance, but their long-term oncological effectiveness remains untested.

These alternative technologies are being used as primary ablative therapy in a number of centres worldwide, but have been introduced without robust Phase III RCT validation. Examples include high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), cryotherapy, vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy (VTP), radiofrequency interstitial tumour ablation (RITA), laser photocoagulation and irreversible electroporation. Each one is at a different stage in its evaluation and application to clinical practice. The current evidence for focal therapy for prostate cancer is mostly provided from non-randomised Phase I and II trials in single centres and from case series with small numbers of patients. 57 A previous Phase I/II study has demonstrated that as few as 5% of men suffered from genitourinary side effects after focal therapy, with absence of clinically significant cancer in all treated patients. A manufacturer-sponsored Phase III RCT of VTP versus AS in 413 men with very low-risk disease has been recently published with 2-year follow-up data; this is discussed later in this section. 58

High-intensity focused ultrasound uses ultrasound energy focused by an acoustic lens to cause tissue damage as a result of thermal coagulative necrosis and acoustic cavitation. The procedure is undertaken using a transrectal approach and may be carried out under general or spinal anaesthesia as a day-case procedure.

Cryotherapy is the localised destruction of tissue by extremely low temperatures followed by thawing, and may be undertaken under general or regional anaesthesia. Cryoneedles or probes are inserted into the prostate via the perineum, using image guidance.

Vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy uses light to activate an intravenously administered photosensitising drug to produce instantaneous vessel occlusion and subsequent tissue necrosis. The light is delivered by optical fibres placed transperineally under transrectal ultrasound guidance. VTP is given under general anaesthesia and can be undertaken as a day-case procedure.

A manufacturer-sponsored Phase III RCT of VTP versus AS in 413 men with very low-risk disease has been recently published, with 2-year follow-up data. 59 It found VTP to be safe and effective, with a 66% reduced risk of treatment failure [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24 to 0.46] compared with AS; however, the VTP group experienced more frequent and severe side effects, although these were mostly mild and of short duration.

Other ablative technologies are currently under evaluation but without sufficient evidence to be used within the context of a RCT. Examples include radiofrequency ablation, which acts by converting radiofrequency waves to heat, resulting in thermal damage. RITA has recently been proposed for the treatment of prostate cancer. 60–63 Interstitial laser photocoagulation was reported by Amin et al. ,64 who described a percutaneous technique for local ablation. Irreversible electroporation is a new non-thermal ablation modality that uses short pulses of DC (direct current) electric current to create irreversible pores in the cell membrane, thus causing cell death. 65,66

These newer techniques have been evaluated in a systematic review by Ramsay et al. ,67 who conclude that they have not been evaluated with sufficient reliability to inform their utilisation in the NHS.

Ongoing and recently completed studies clearly indicate that the evidence base for partial ablation therapies is increasing, particularly the evidence for focal ablative therapies. However, the quality of the evidence base will not improve substantially given that the majority of these studies are case series. Research efforts in the use of ablative therapies in the management of prostate cancer should focus on conducting more rigorous, high-quality studies. A NIHR HTA feasibility trial was completed successfully by the authors of this report to assess rates of recruitment and randomisation to a trial comparing radical treatments with partial ablation of the prostate,68 and a full RCT application is currently being reviewed by the NIHR HTA programme.

Implications for research

The lack of RCT-based evidence for the treatment effectiveness of radical therapeutic options with AM for PSA-detected clinically localised prostate was the main driver for the inception and conduct of the ProtecT trial. The overarching aim was to provide robust evidence to inform patients, clinicians and policy-makers to develop optimal guidelines and recommendations for the management of this common and ubiquitous disease.

At the same time, NIHR supported a feasibility study of creating an overarching screening trial to provide the recruitment framework for ProtecT. A previous trial, ERSPC,21 had shown a 20% reduction in mortality after 13 years with repeated PSA testing, but with unacceptable levels of overdetection and overtreatment. In 2003, Cancer Research UK agreed to support the CAP trial. The goal of CAP, with its low-intensity, one-off PSA testing, was to try to avoid unnecessary detection of low-risk cancers while still identifying men with dangerous disease for whom screening and early treatment could be beneficial. The trial’s median 10-year outcomes have been summarised earlier in this section. 36

A further important strategy, which remains untested, is to use novel technologies to target and treat all clinically significant cancers in the gland focally, with careful follow-up and repeat treatments as necessary, particularly of emerging new lesions detected by biopsy. The strategy may obviate the need for any radical therapies.

Identifying men at high risk of harbouring significant prostate cancer is essential to achieve a reduction in overdetection, subsequent overtreatment as well as improving undertreatment of aggressive cancers. This requires comprehensive high-throughput platform investigation of large, well-phenotyped cohorts of men and their biobanked material with accurate and long-term follow-up, which the ProtecT cohort offers, and the investigators are poised to undertake this next critical step in patient stratification pending appropriate funding for the research.

Rationale for the ProtecT trial and summary of the feasibility study

Rationale for the ProtecT trial

The discovery and wide clinical use of serum PSA for over three decades to detect asymptomatic cancers in fit men, combined with the continuous refinement of curative radical treatments including anatomical RP, has led to a substantial increase in the detection and treatment of early prostate cancer. In countries where PSA testing has been encouraged, overdetection and overtreatment of prostate cancer has prevailed, with unnecessary adverse events caused by treatments and cost pressures for health-care providers. Unlike most developed countries, the UK’s policy on screening for prostate cancer has been not to recommend its use.

The ERSPC21 investigated the effects of screening versus no screening in a large multicentre European cohort. The study reported an advantage in favour of screening, which improved survival and reduced disease progression, but at a substantial cost of overdetection and overtreatment. 31,69 In contrast, the US screening study (PLCO22) showed no beneficial effect of screening for prostate cancer, but suffered serious limitations because of contamination in both groups. 70

In large reported series, RP conferred a 5-year disease-free survival of between 69% and 84%. 71–75 The Scandinavian SPCG-4 RCT comparing surgery and watchful waiting showed an absolute risk reduction in preventing cancer mortality within 8 years of 5% (from 14% to 9%). 76 An update has shown that this absolute difference remains unchanged with longer follow-up of 14 years. 77,78 However, the Prostate Intervention versus Observational Treatment (PIVOT) study in the USA compared RP with watchful waiting in over 700 men with localised PSA-detected prostate cancers,79 concluding that RP did not significantly reduce all-cause or prostate cancer mortality, compared with observation, through at least 12 years of follow-up. There were fewer prostate cancer deaths with RP (21/364 for RP vs. 31/367 for watchful waiting, HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.09; p = 0.09). In other large reported series, radiotherapy conferred a 5-year disease-free survival of 78–94% in combination with hormone therapy. 48–51

Although prostate cancer can be lethal, the majority of men who are diagnosed through PSA testing will not suffer clinically significant consequences from the disease during their lifetime, and evidence that treating such men improves survival or QoL is weak. Consequently, there have been serious concerns that increasing PSA testing in the community is resulting in overdiagnosis, overtreatment and an increasing burden to the NHS. Despite its high incidence and social and economic impact, prostate cancer continues to be under-researched and only a limited number of studies are addressing the issues of screening and long-term comparison of treatment modalities. Following a successful feasibility study, described in the following section, the NIHR HTA ProtecT study conducted by the authors of this report aimed to test the value of a single round of PSA testing in the community, and compared the effectiveness of the three conventional treatment options of AM, RP and EBRT in clinically localised disease at all risk levels. A large prostate cancer detection programme was essential to conduct the main RCT of treatment, in order to diagnose men and counsel them in advance of the diagnostic pathway, which allowed them to become well-informed participants to the treatment trial.

The ProtecT feasibility study

The ProtecT feasibility study, conducted between 1999 and 2001, was undertaken in three clinical centres to provide evidence to underpin the design and conduct of the main ProtecT trial. The methods of the study and its findings have been published in detail. 80 In brief, the feasibility study showed that men aged 50–69 years could be identified in primary care practices, invited to attend a prostate check clinic appointment to discuss having a PSA test and potentially participating in a RCT of treatment, and that sufficient numbers would attend and follow the diagnostic pathway to feed into the proposed treatment trial. By the end of the feasibility study, 8505 men from 18 primary care centres attended clinics (56% of those invited) and 7383 had a PSA test. Of these men, 861 (12%) had a raised PSA level and, after biopsy, 224 were found to have prostate cancer, with 165 clinically localised and eligible for the treatment RCT. These response rates were largely reflected in the main trial. The feasibility study also showed that men were willing to complete detailed questionnaires before the PSA test and biopsy. These questionnaires comprised patient-reported outcomes that were then used in the main trial.

As it was expected that recruitment to the trial would be extremely difficult, the feasibility study was innovatively embedded in a qualitative research study to explore a wide range of issues with the urologists and nurses undertaking recruitment and among men participating in the study. 81 In addition, the feasibility study included a RCT comparing the effectiveness and efficiency of recruiting with nurses or urologists. In total, 167 men with localised prostate cancer were identified and 150 (90%) took part. There was a 4.0% difference between nurses and surgeons in recruitment rates (67% nurses, 71% urologists, 95% CI −10.8% to +18.8%; p = 0.60). Cost minimisation analysis showed that nurses spent longer with patients but surgeon costs were higher and nurses often supported surgeon-led clinics. We concluded that nurses were as effective and more cost-effective recruiters than surgeons, and so nurses became the major recruiters in the main RCT.

The qualitative research involved in-depth interviews with 39 men before and after the PSA result, case studies of four men interviewed several times after the PSA result as they progressed through the study, 20 audio-recorded recruitment appointments and subsequent interviews, and 15 other audio-recordings of recruitment appointments with nurses or urologists attempting to recruit men to the treatment trial. Findings from these data included:

-

Men perceived the offer of PSA testing as an opportunity to discover cancer early, most did not want to consider the implications of a positive result and most expected to receive a negative test result. 82

-

Although most men could recall and understand the reason for the treatment RCT, they did not always find it acceptable, and most found the concept of randomisation difficult to accept. However, those who understood and were able to believe in clinical equipoise were most likely to consent to randomisation. 83 These findings formed a detailed basis for developing suitable and effective trial information in relation to clinical equipoise in the main RCT.

-

In recruitment appointments, surgeon and nurse recruiters initially found it difficult to present the treatment options equivalently and many were not in equipoise, particularly in relation to the non-radical treatment group. These findings were documented and fed back to recruiters. A plan to improve recruitment was designed by Jenny L Donovan and implemented by Freddie C Hamdy: to change the order of presenting treatments to encourage greater emphasis on equivalence, avoiding terms commonly misinterpreted by patients (such as ‘trial’ and ‘watchful waiting’) and describing a redefined and reconceptualised ‘active monitoring’ group. Presentations about the plan and workshops on recruitment practice were followed by the randomisation rate increasing from 40% to 70%. In further analyses of appointments, treatments were described more clearly and with greater balance, patients became better informed and the three-group trial (including AM) became the preferred design. Embedding the trial recruitment process within this innovative and detailed qualitative research study enabled efficient recruitment that was acceptable to patients and clinicians in the three feasibility study centres. 81

The feasibility study thus showed that, against all expectations, it was possible to introduce PSA testing in primary care practices, implement a standardised diagnostic pathway, identify sufficient numbers of men with clinically localised prostate cancer and mount a full-scale three-group RCT to evaluate the major treatment options: radical surgery, radiotherapy and a reconfigured ‘active monitoring’.

Aim and objectives of the main ProtecT trial

Aim

The overarching aim of the main ProtecT trial was to provide robust evidence of the comparative treatment effectiveness of the three conventional treatment options in the management of clinically localised prostate cancer.

Objectives

-

To evaluate the comparative treatment effectiveness of the three conventional options (AM, RP and RT) for men with clinically localised prostate cancer, with a first analysis at the 10-year median follow-up.

-

To assess QoL measures and patient-reported outcomes related to the three treatment options.

-

To inform patients, clinicians and policy-makers about the optimal management of patients with clinically localised prostate cancer.

-

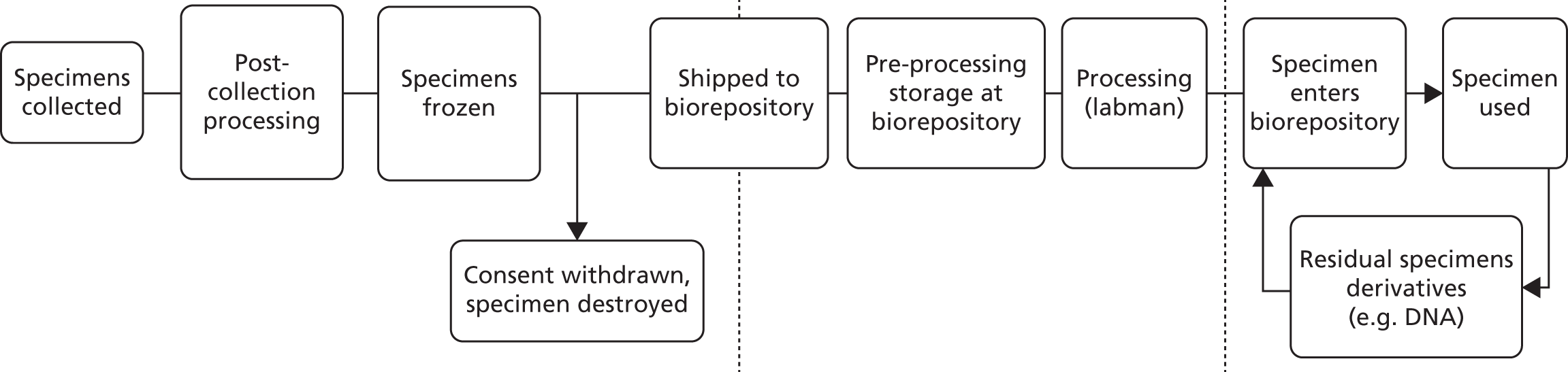

To develop a comprehensive biorepository of biobanked material donated by patients, associated with an electronic clinicopathological database for conducting effective translational prostate cancer research.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design, ethics approvals and management

Trial design

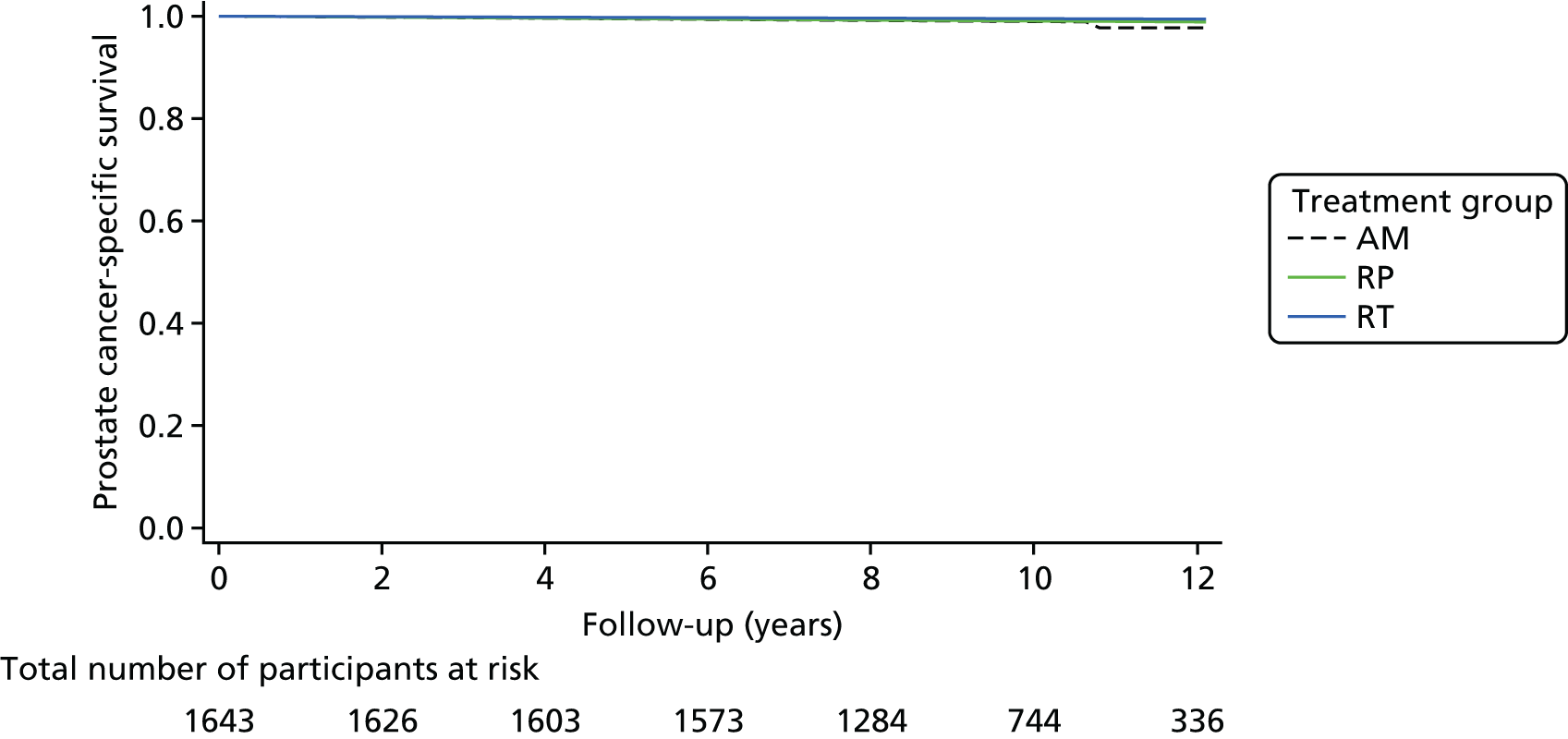

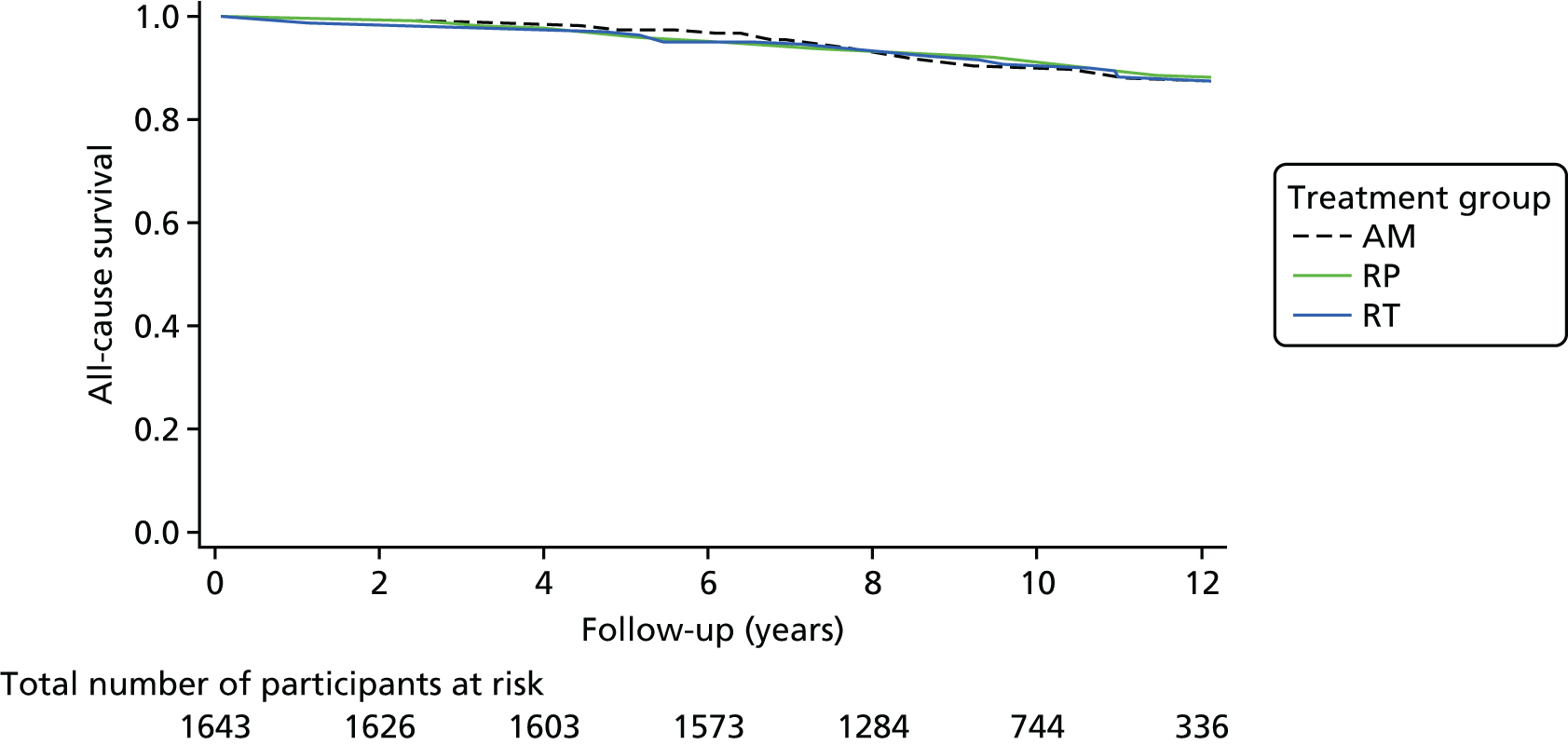

ProtecT is a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel-group RCT that compared RP, external beam three-dimensional (3D)-conformal radiotherapy and AM for clinically localised prostate cancer detected through population-based PSA testing in primary care. The trial was conducted in nine UK centres based at hospitals. A feasibility trial conducted at three centres between June 1999 and September 2001 preceded the main trial, which recruited until January 2009, with follow-up for the primary analysis completed in November 2015. The primary outcome of prostate cancer-specific mortality was evaluated at a median of 10 years’ follow-up. Secondary outcomes analysed included disease progression and patient-reported outcomes, as well as cost-effectiveness.

Ethics approvals and research governance

The trial was approved by the NHS Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (Trent Multicentre Research Ethics Committee reference number 01/04/025). An independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) oversaw the trial to the primary outcome analysis and met annually. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC), with an independent chairman and seven independent members, monitored the conduct and progress of the trial annually. The DMC would have recommended changes to the TSC if clear evidence (of the order of p < 0.001) of a positive or negative balance of risks and benefits emerged for one intervention in comparison with the others. Study training programmes (described in Research nurses’ role in recruitment, randomisation and follow-up and The ProtecT recruitment story) and on-site monitoring visits were used to standardise trial conduct. 84 The main trial is registered with Controlled Clinical Trials ISRCTN20141297 (feasibility trial: ISRCTN08435261). The protocol is available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/962099/#/.

Study setting and participants

The feasibility study recruitment was conducted in three English cities (in 24 primary care centres linked to three hospitals) from June 1999 to September 2001. The main phase of recruitment was conducted from October 2001 to January 2009 in nine cities (seven in England, one in Scotland and one in Wales) where around 100,000 men were recruited in primary care.

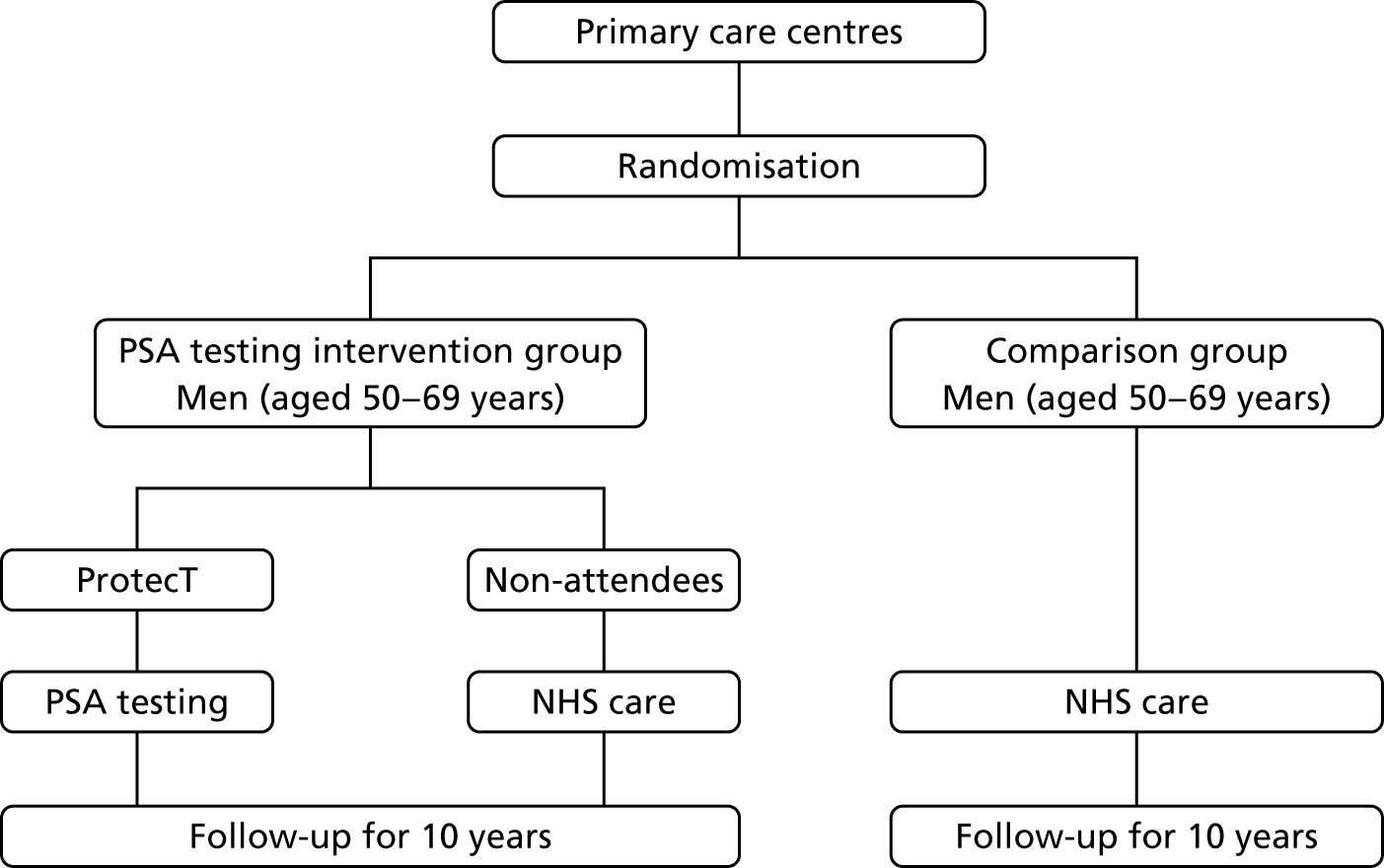

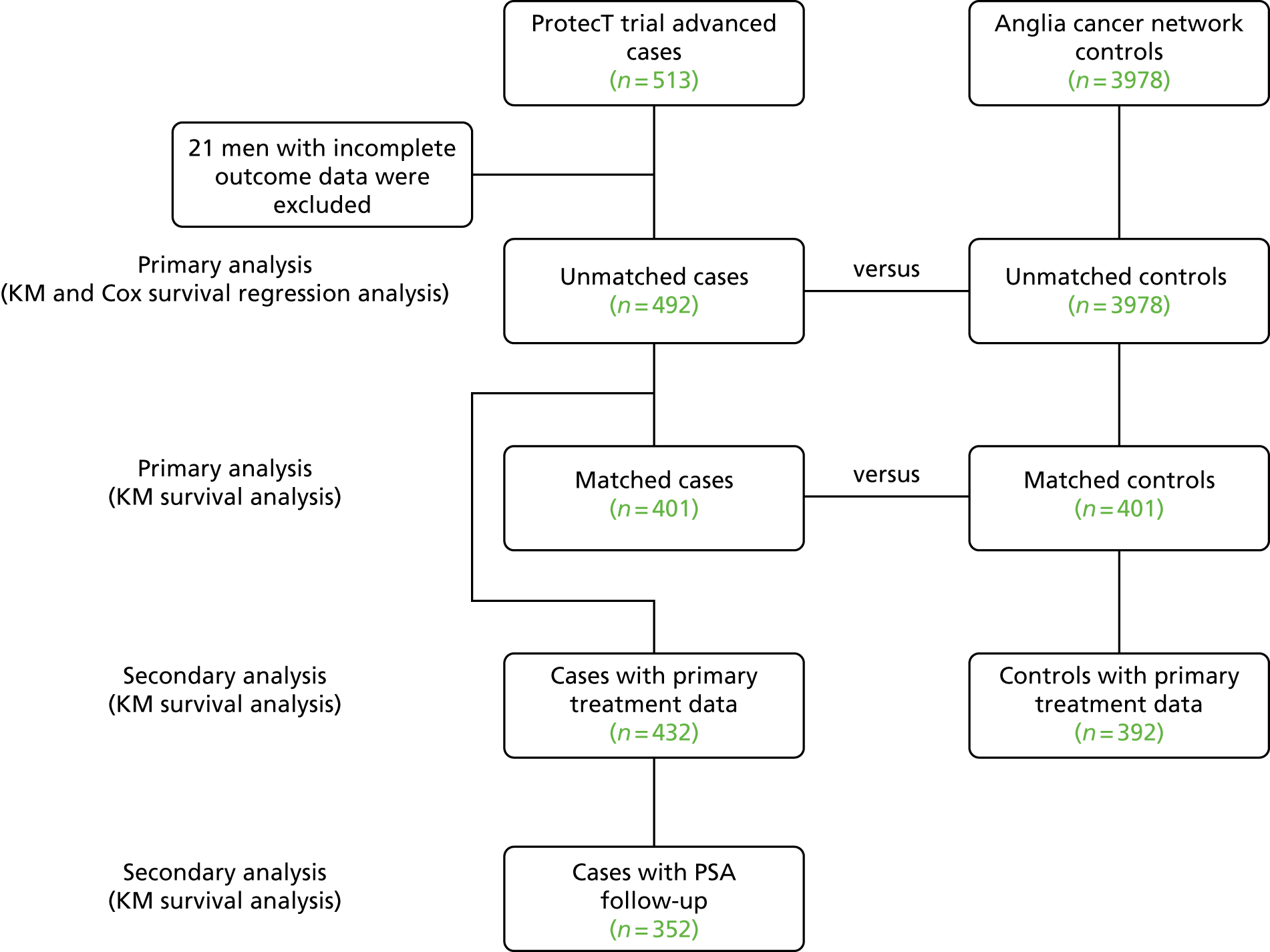

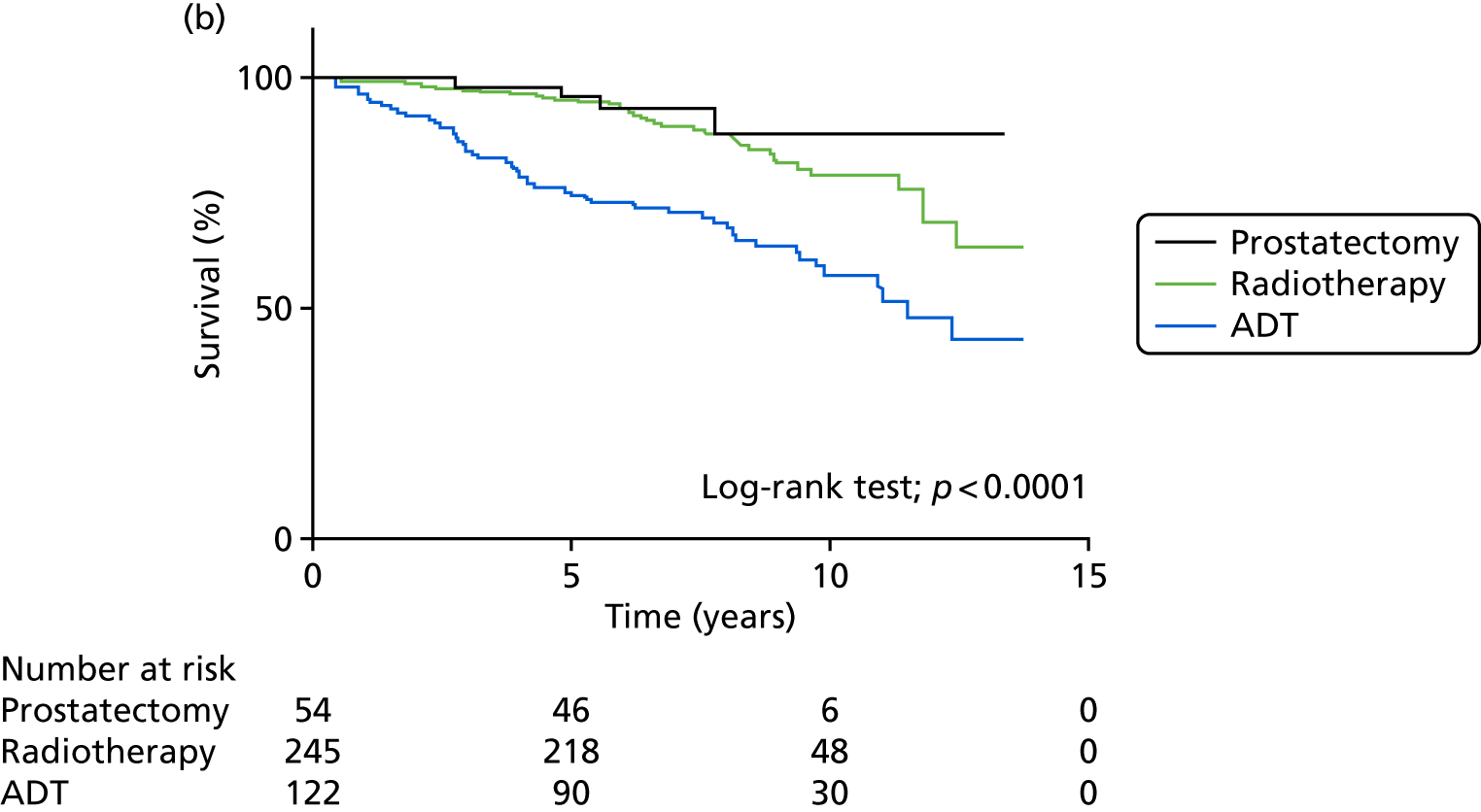

The CAP trial (ISRCTN92187251)34 commenced in 2001; it randomly assigned 911 primary care centres in eight UK centres to undertake either the ProtecT trial or standard UK NHS management to assess population-based screening for prostate cancer (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the ProtecT and CAP trials.

A written invitation was sent by 337 primary care centres participating in the ProtecT trial to registered men aged 50–69 years (inclusion criterion). Trial exclusion criteria were a previous malignancy (apart from skin cancer), renal transplant or current renal dialysis, major cardiovascular or respiratory comorbidities, bilateral hip replacement or an estimated life expectancy of < 10 years. Men who responded received a ProtecT patient information sheet and an appointment with a specialist research nurse, who explained the complexities of PSA testing, assessed trial eligibility and sought written informed consent. Previous PSA test results were checked in the medical records (not an exclusion criterion). On postal receipt of a second consent form, total PSA level was analysed at hospital laboratories audited by the NHS External Quality Assessment Service.

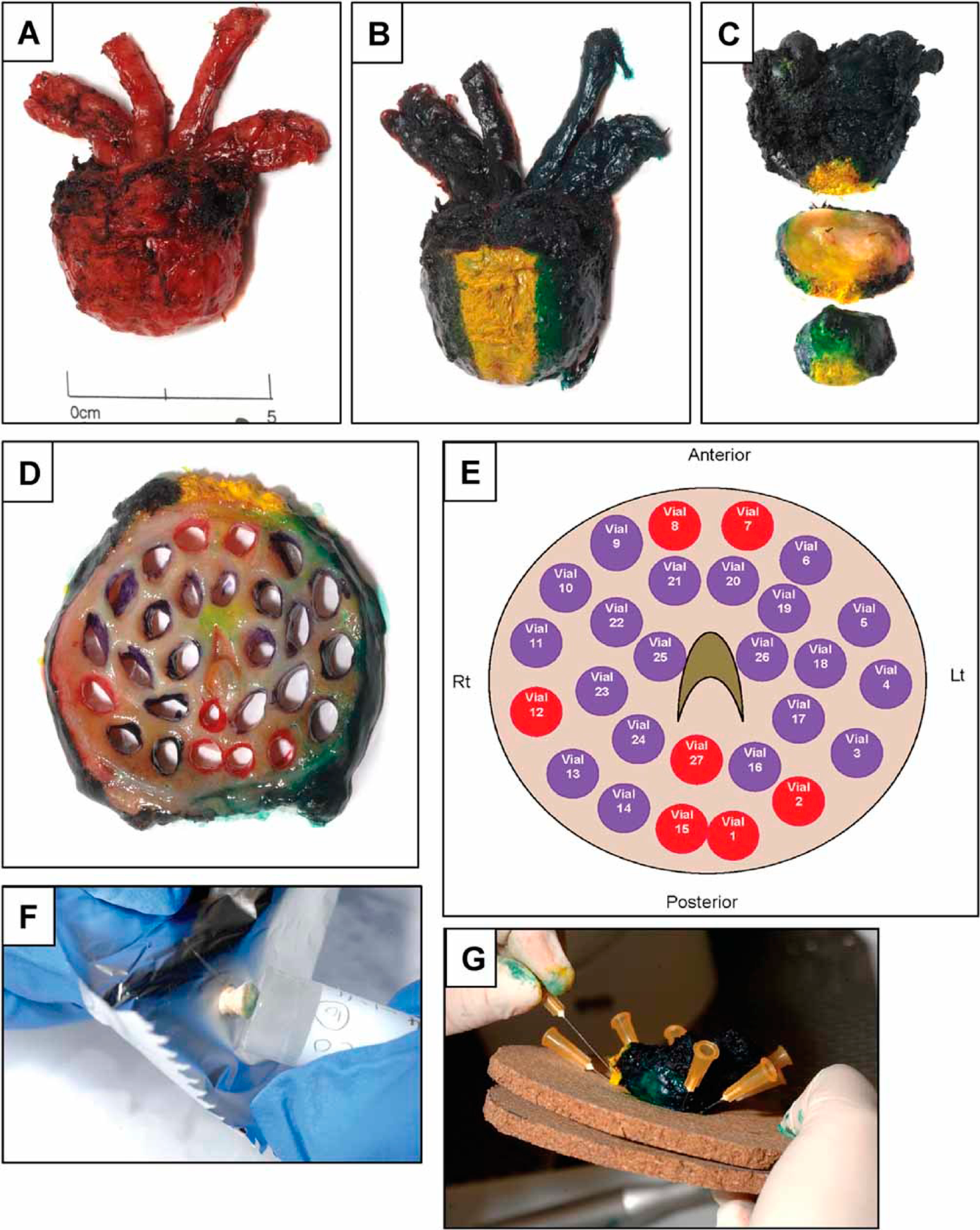

Diagnosis of prostate cancer

Participants with a PSA concentration of ≥ 3.0 µg/l were invited to attend secondary care centres within the nine participating cities for a physical and digital rectal examination and standardised 10-core TRUS-guided prostate biopsies. Participants with an initial PSA concentration of ≥ 20.0 µg/l at diagnosis were excluded because of the high likelihood that they had more advanced cancer. Patients were staged using a combination of digital rectal examination, PSA concentration, TRUS-guided biopsies and isotope bone scanning (if their PSA level was ≥ 10 µg/l). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used for staging at the discretion of individual investigators because this imaging technique was not available in all centres during recruitment. Men diagnosed with clinically localised prostate cancer and deemed fit for radical treatment received a ProtecT treatment patient information sheet and were subsequently invited to discuss randomisation with the specialist nurses. Men with a PSA concentration of ≥ 10µg/l or a Gleason score of ≥ 7 points underwent an isotope bone scan to exclude metastatic disease. Men who initially had benign biopsy samples or who were diagnosed with locally advanced or advanced prostate cancer were managed in the NHS and excluded from the trial. Men with a benign first biopsy sample and a free-to-total PSA ratio of < 11%, or atypical small acinar proliferation or high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, were offered further biopsies; if these repeat biopsy samples were benign, these men were managed in primary care and excluded from the trial. No further trial follow-up took place after the one round of PSA testing or identification of cancers after referral to the NHS. Histopathologists at each site reported pathology findings on standardised forms and participated in trial quality-control processes and those of the NHS Uropathology External Quality Assessment Scheme. At baseline, height and weight were measured and blood samples were taken (whole blood, plasma and serum). Biopsy and prostatectomy tissue, if relevant, were biobanked for participants who also entered the ongoing linked translational Prostate Mechanisms of Progression and Treatment study (see Chapter 7).

Interventions

Participants were randomised to one of three treatments: AM, radiotherapy or RP.

In the AM group, the aim was to avoid immediate radical treatment while assessing the disease over time, with radical treatment offered if disease progression was evident. PSA concentrations were reviewed every 3 months in the first year and twice yearly thereafter (frequency was changed as indicated). The specialist nurses also met with participants yearly to assess their overall health and discuss graphical displays of PSA results and any concerns raised, overseen by each centre’s local clinical investigator. Changes in PSA concentrations were assessed at each visit, and a rise of ≥ 50% during the previous 12 months triggered repeat testing within 6–9 weeks. If the PSA concentrations were persistently raised, or the patient had any other concerns, a review appointment was made with the centre urologist for discussion of further tests including re-biopsy and all relevant management options. A site monitoring and review team comprising trial research nurses and the trial manager visited sites annually; these visits included observation of the nurse-led AM appointments as per the protocol. 85

In radiotherapy, neoadjuvant androgen suppression was given for 3–6 months before and concomitantly with 3D-conformal radiotherapy delivered at 74 Gy in 37 fractions at each of the nine centres. Quality assurance followed RT01 trial procedures. PSA concentrations were measured every 6 months for the first year and then yearly. The study oncologist held a review appointment with participants if the PSA concentrations rose by ≥ 2.0 µg/l post nadir or if concerns were raised about disease progression. Management options were discussed, including monitoring, tests and salvage, radical or palliative treatments as indicated. 34

The predominant approach for RP was open retropubic with individual-level quality assurance to published standards at each of the nine centres. 86 Participants with a baseline PSA concentration of ≥ 10 µg/l or a biopsy Gleason score of at least 7 points received bilateral lymphadenectomy. Postoperatively, PSA concentrations were measured every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the subsequent 2 years and then yearly. Adjuvant radiotherapy was discussed and offered to patients with positive surgical margins or extracapsular disease. The centre urologist held a review appointment with participants if their postoperative PSA concentrations reached ≥ 0.2 µg/l to discuss adjuvant radiotherapy.

In all treatment groups, ADT was offered when serum PSA reached a concentration of 20.0 µg/l, or less if indicated. Imaging of the skeleton was recommended if the serum PSA level reached 10.0 µg/l, using isotope bone scintigraphy, plain radiographs and MRI as necessary.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was definite or probable prostate cancer mortality, including intervention-related deaths, evaluated at a median of 10 years’ follow-up. Participants were linked to the NHS national registry for vital status information, which was updated quarterly. The process used to assess cause of death was adapted from the PLCO algorithm,70,87 used in the CAP and ProtecT trials. In brief, hospital medical records were summarised by trained CAP researchers onto vignettes, anonymised and reviewed by an independent endpoint committee masked to the ProtecT and CAP trials. 34

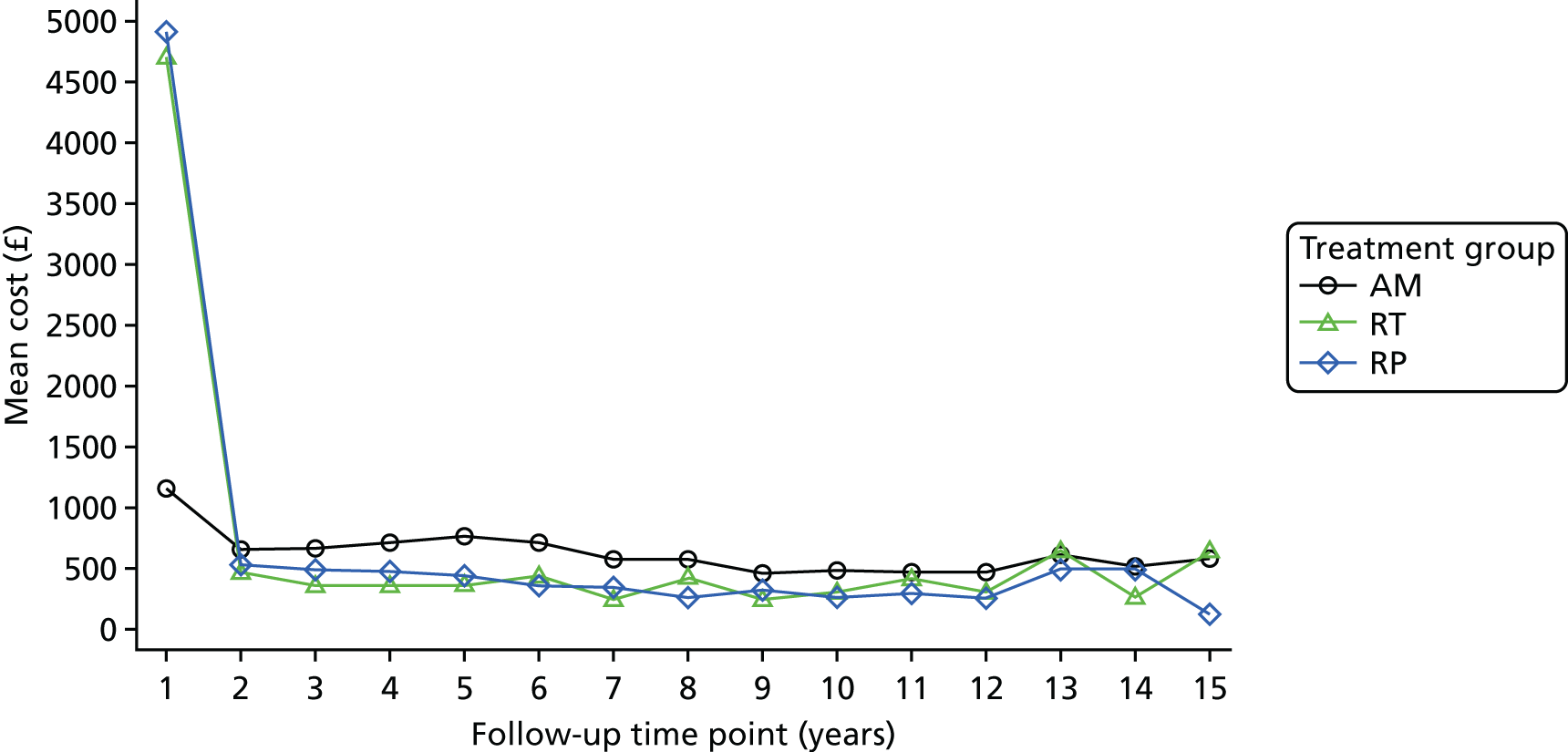

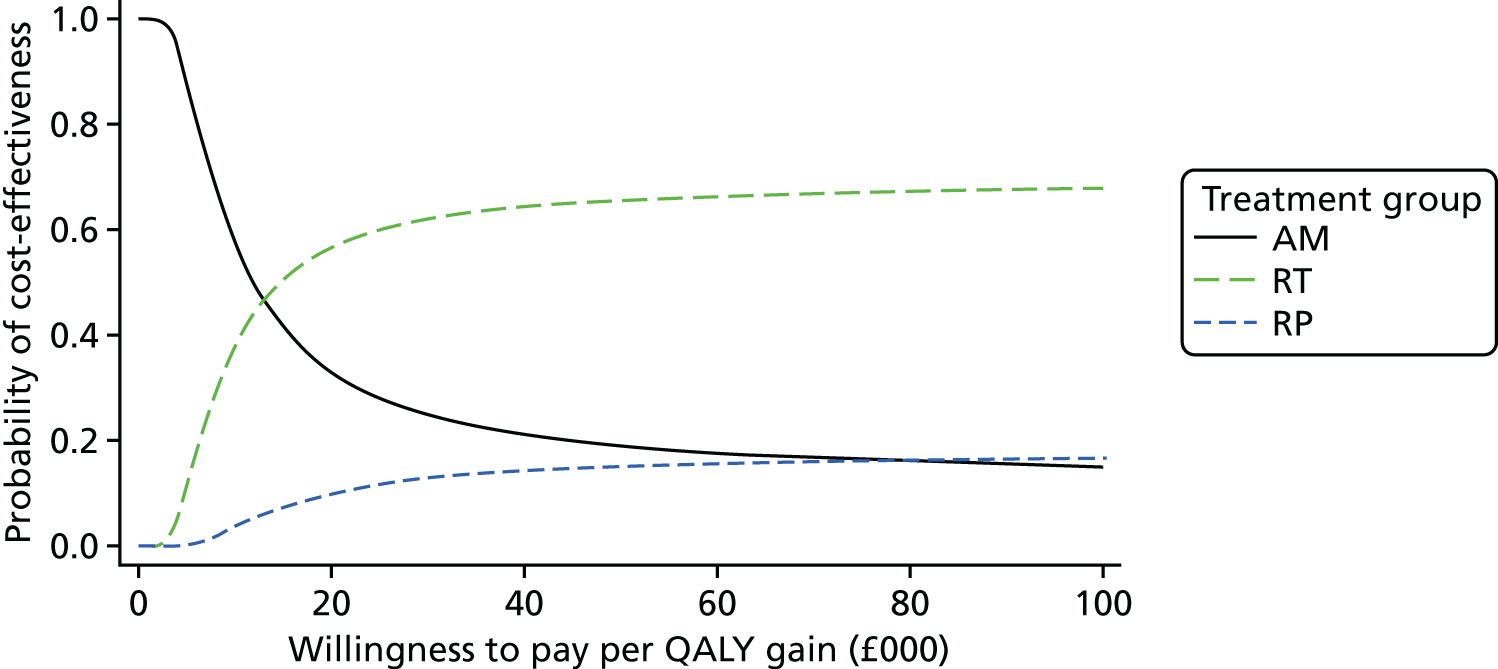

Secondary outcomes

These outcomes were analysed at a median of 10 years and included overall mortality (from death certificates), metastases, disease progression, treatment complications (including adverse events) and resource use for the cost-effectiveness analysis (described in Chapter 5). Outcomes were collected on case report forms (CRFs) by research nurses annually, based on medical record reviews and participant information gained at an appointment.

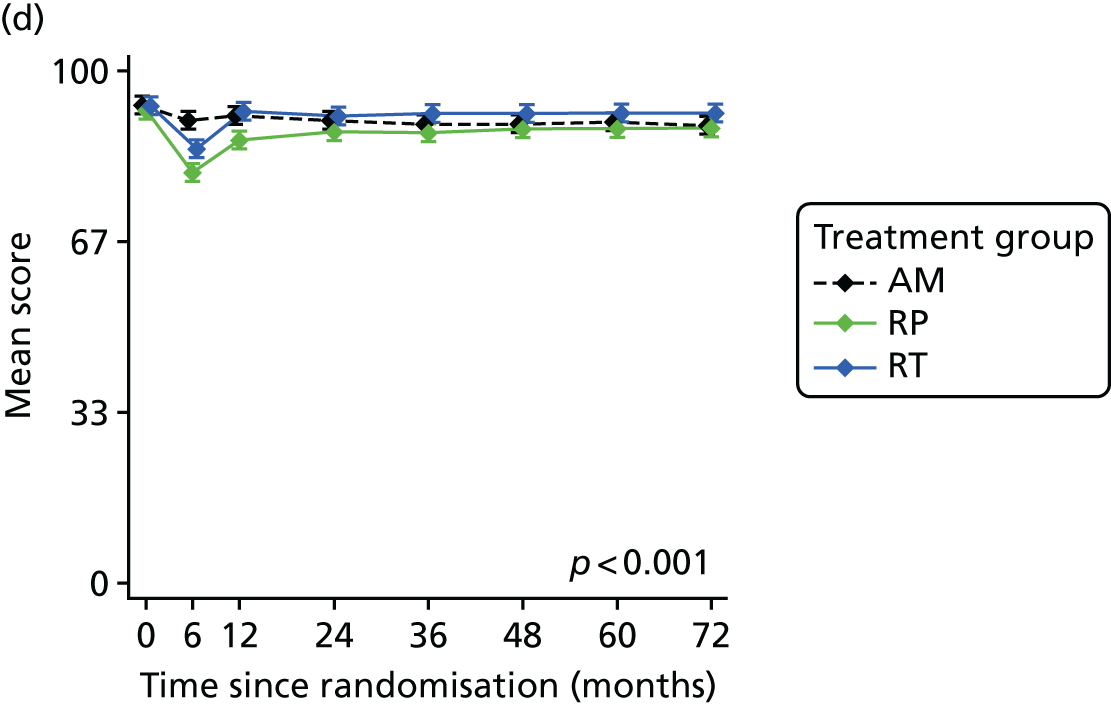

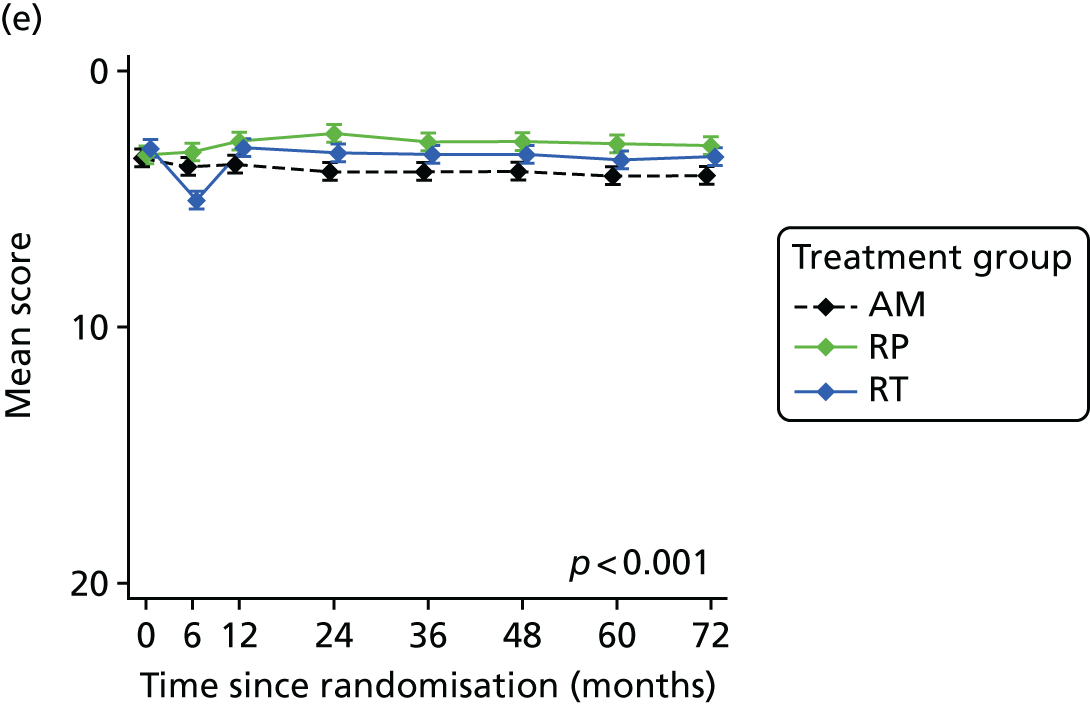

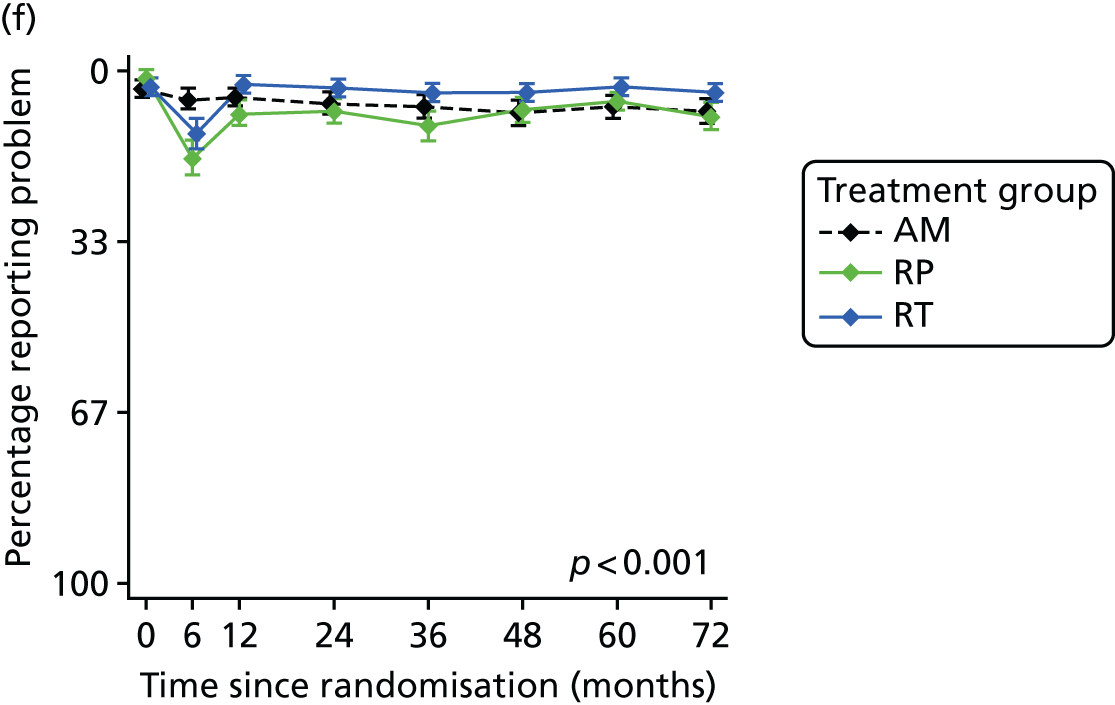

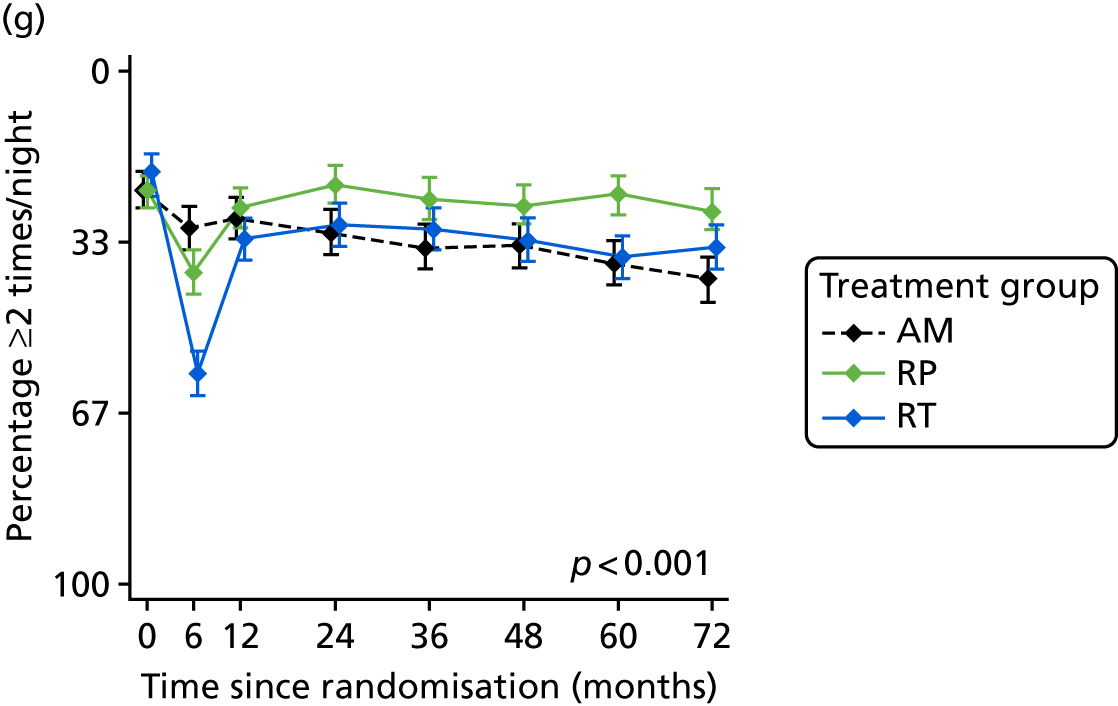

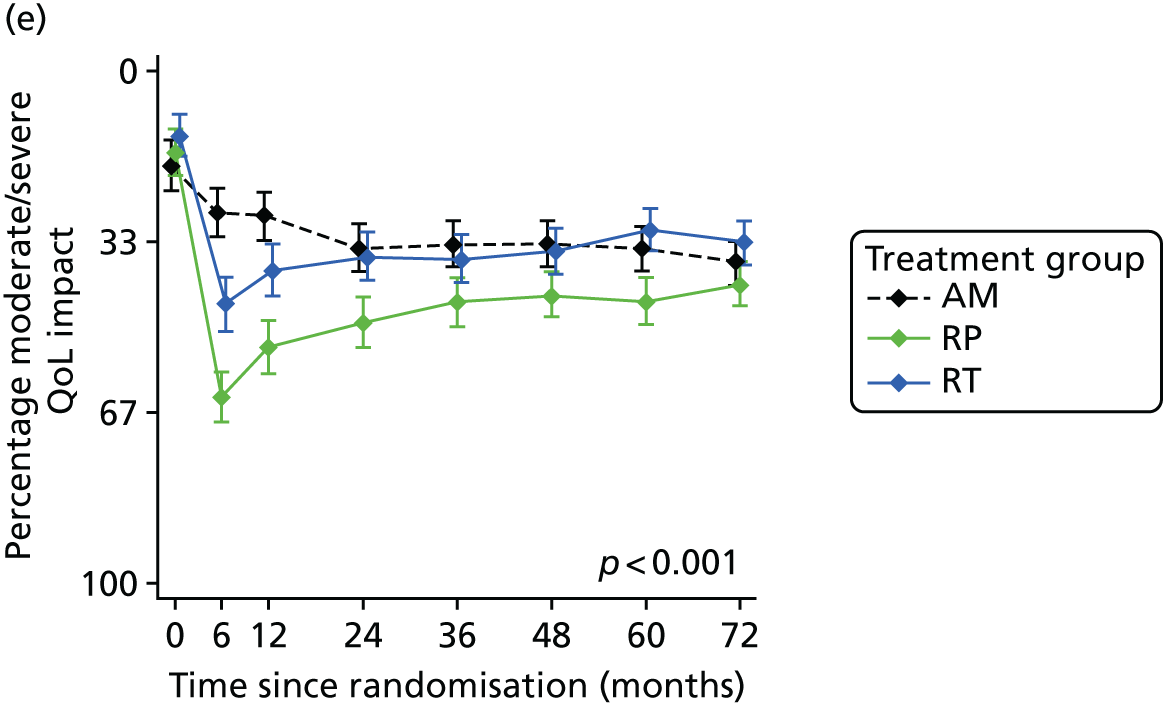

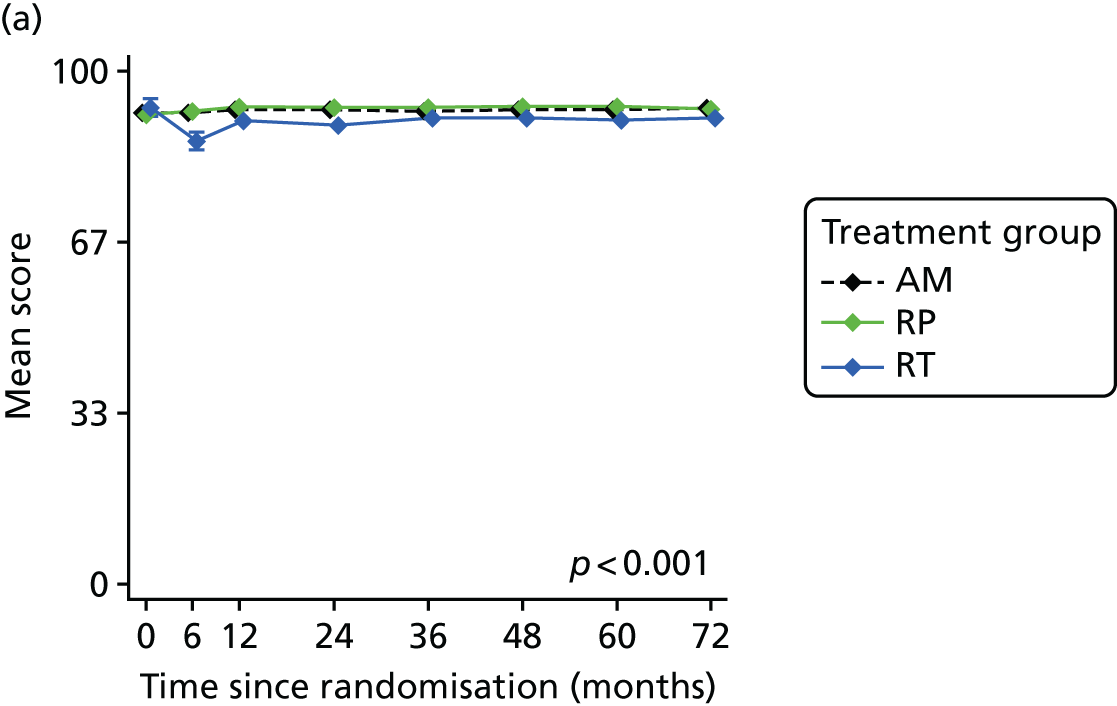

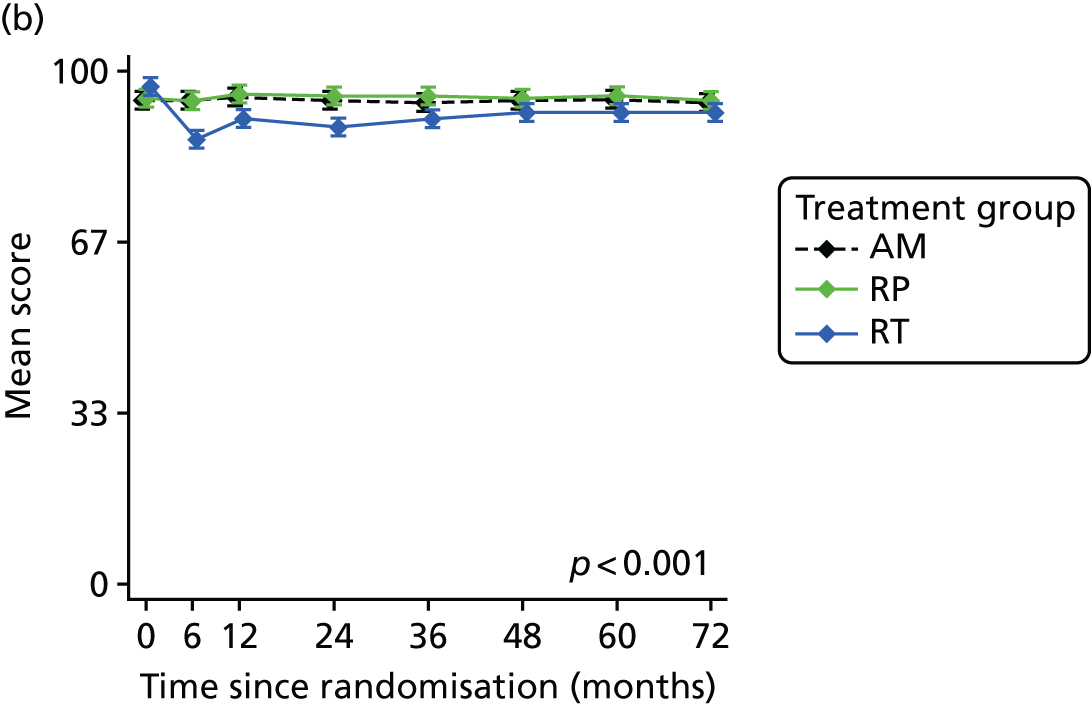

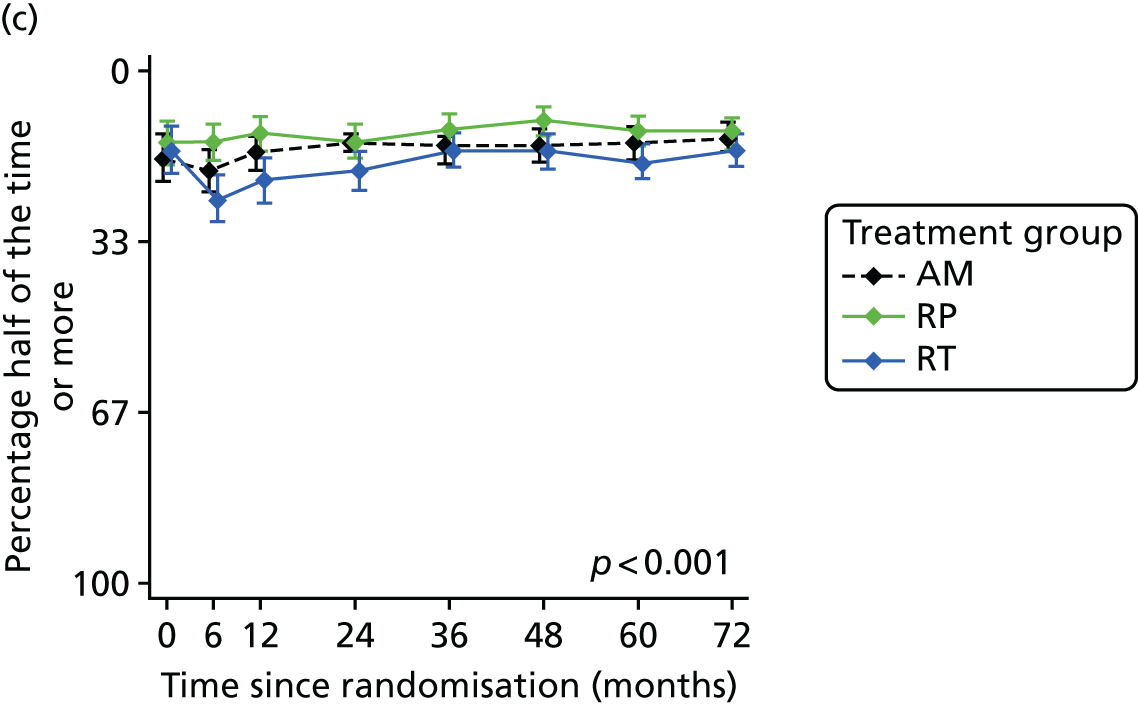

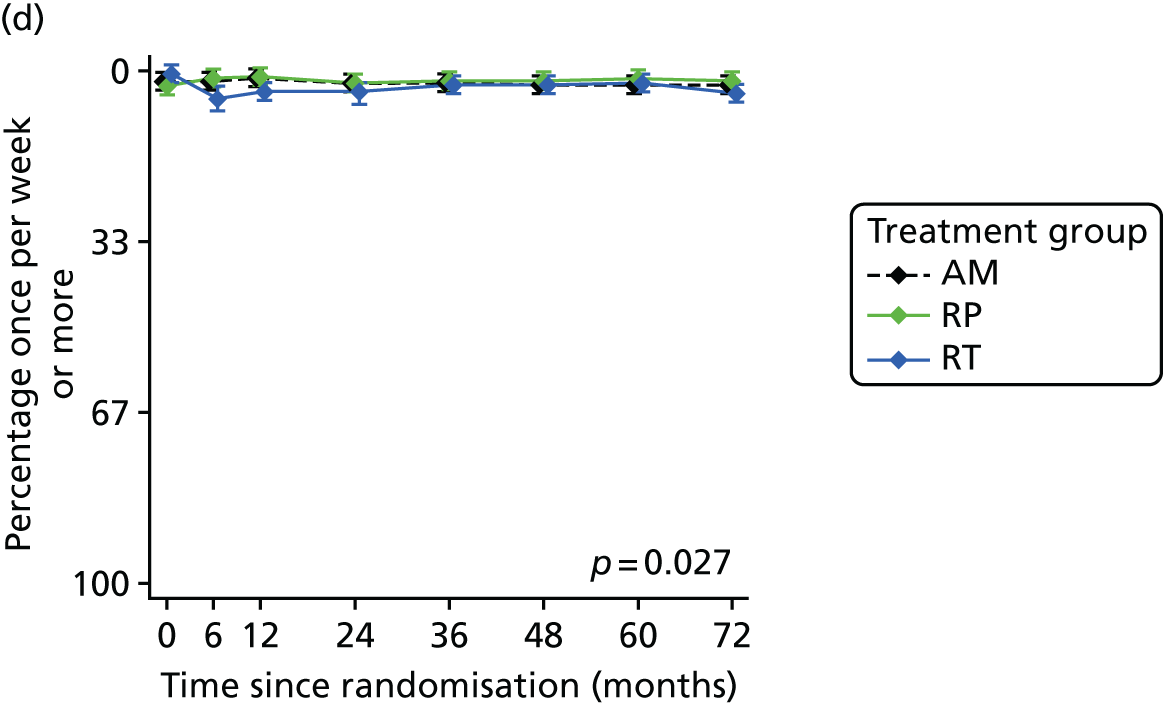

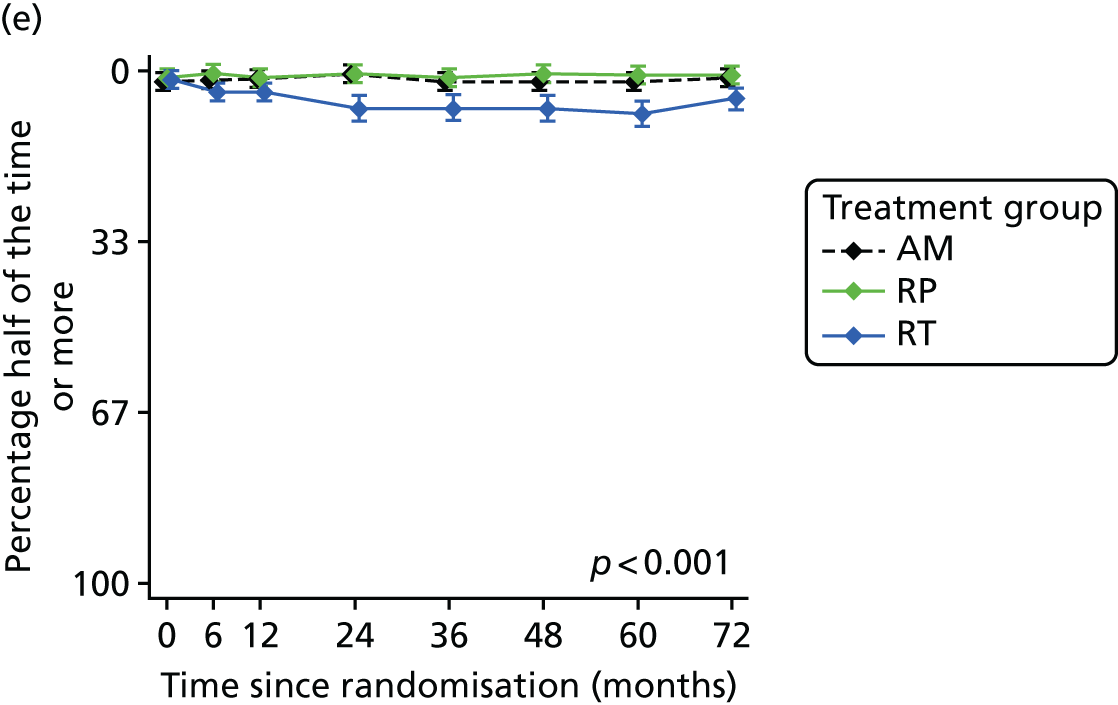

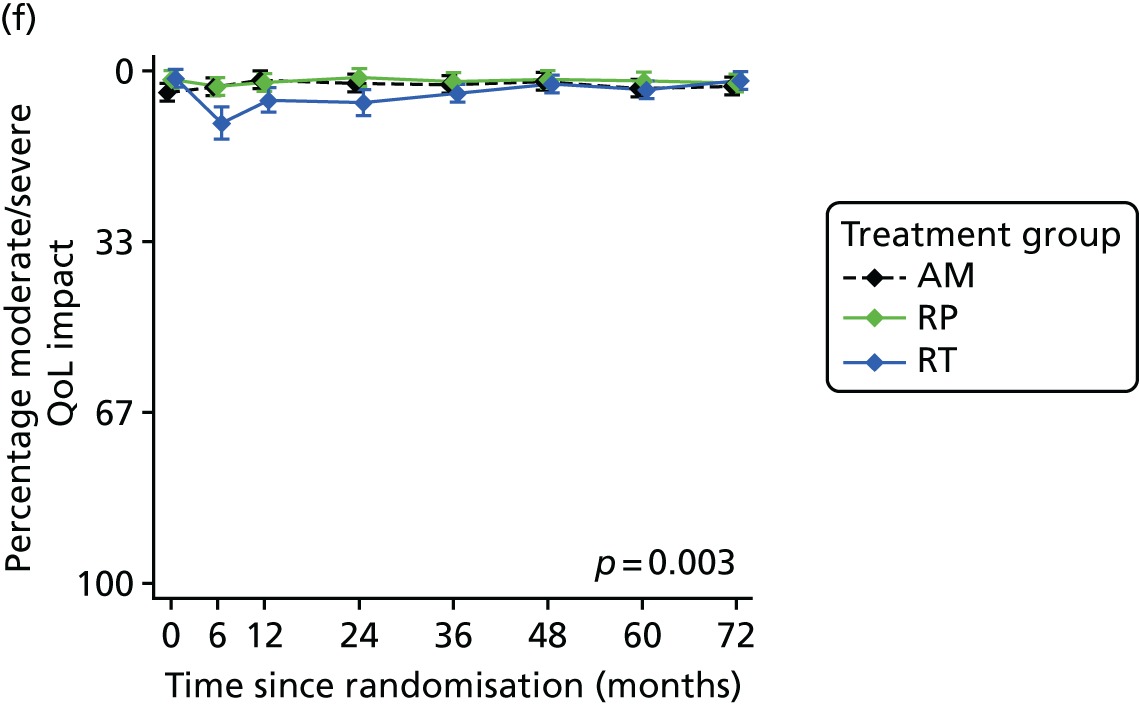

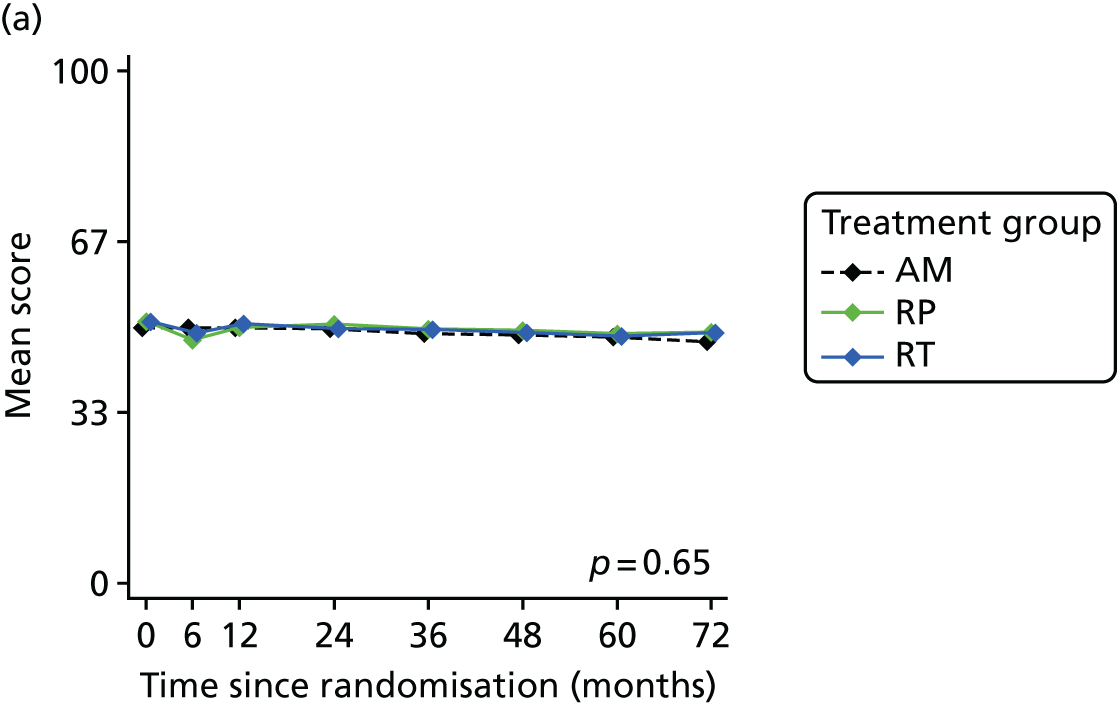

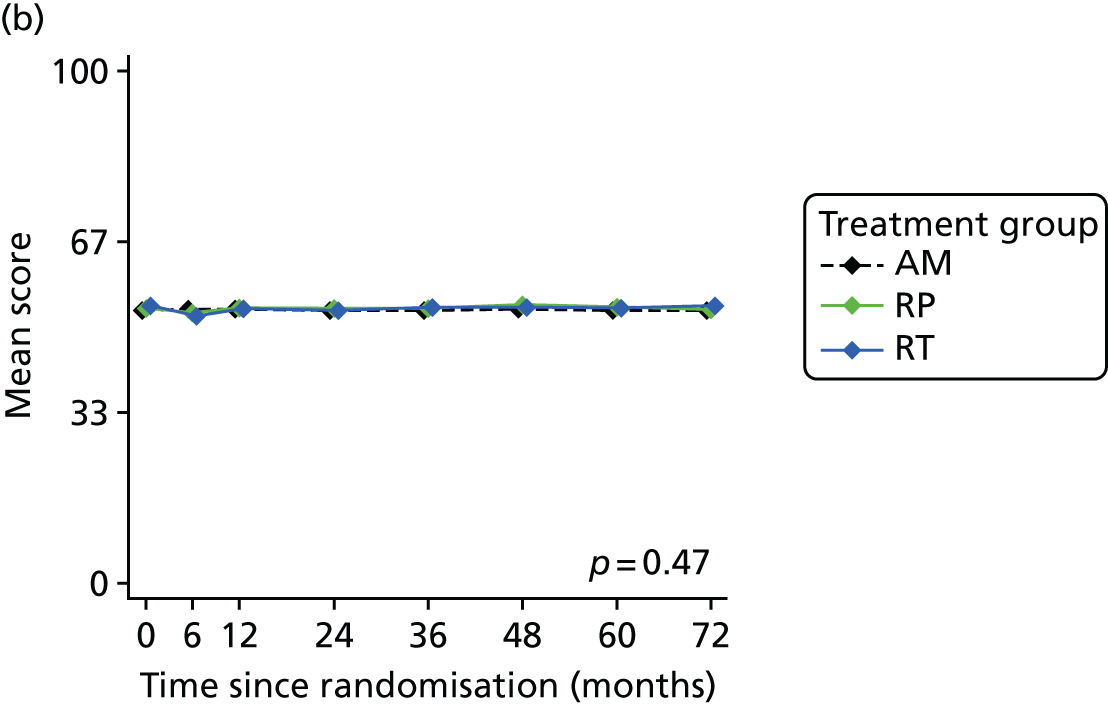

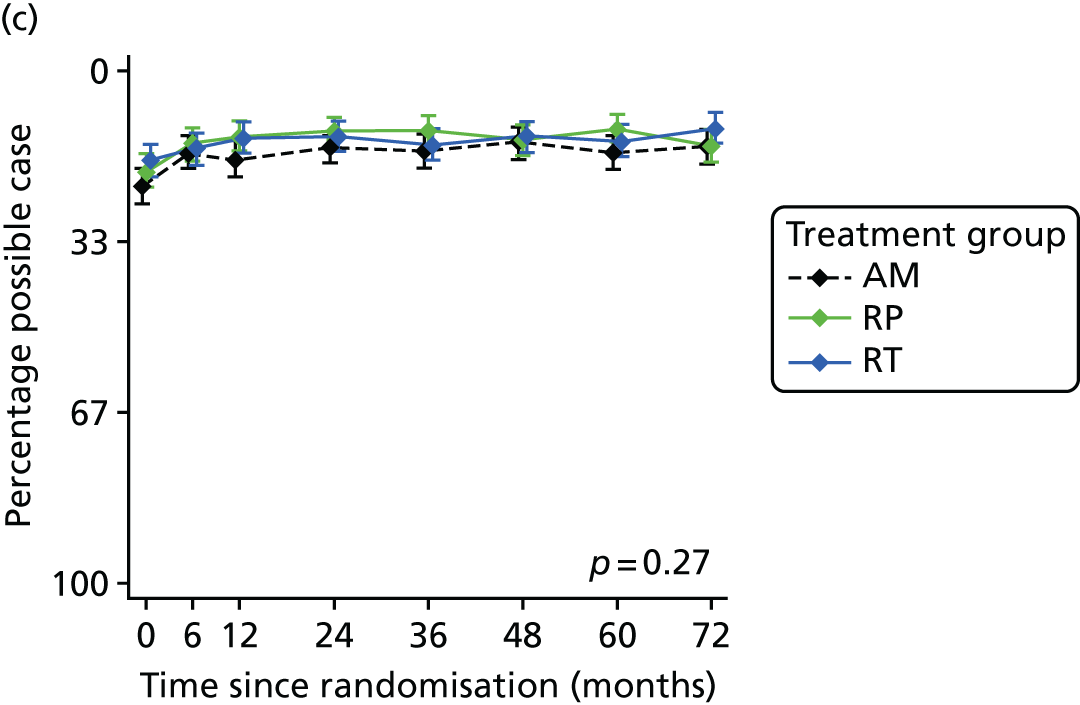

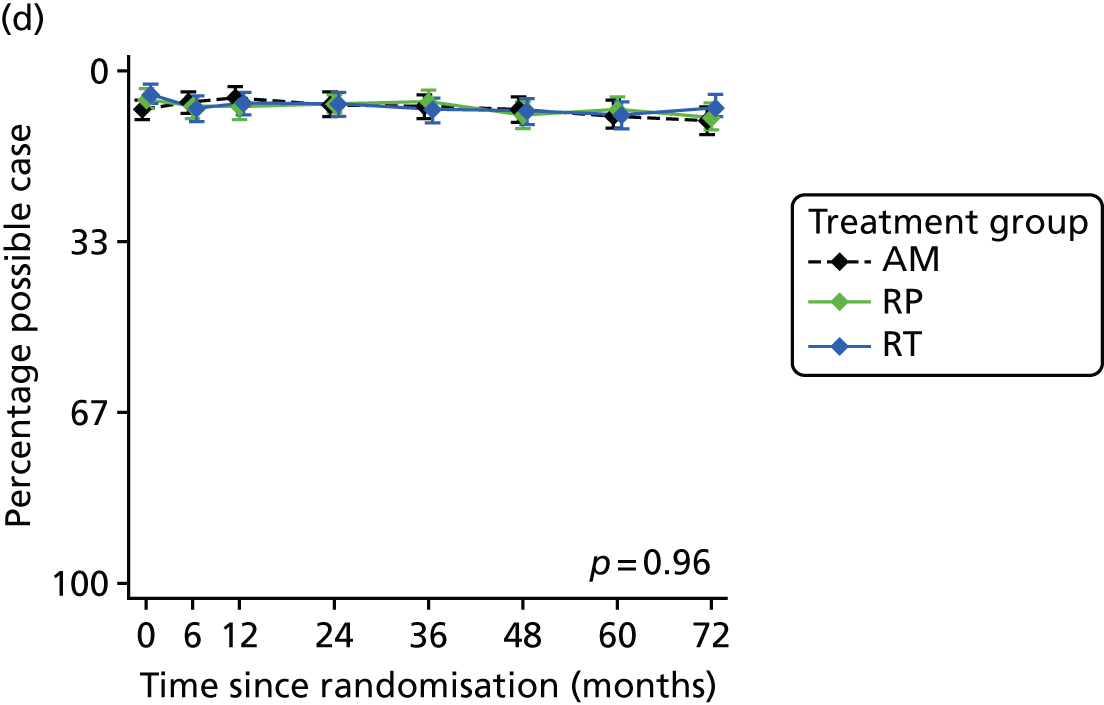

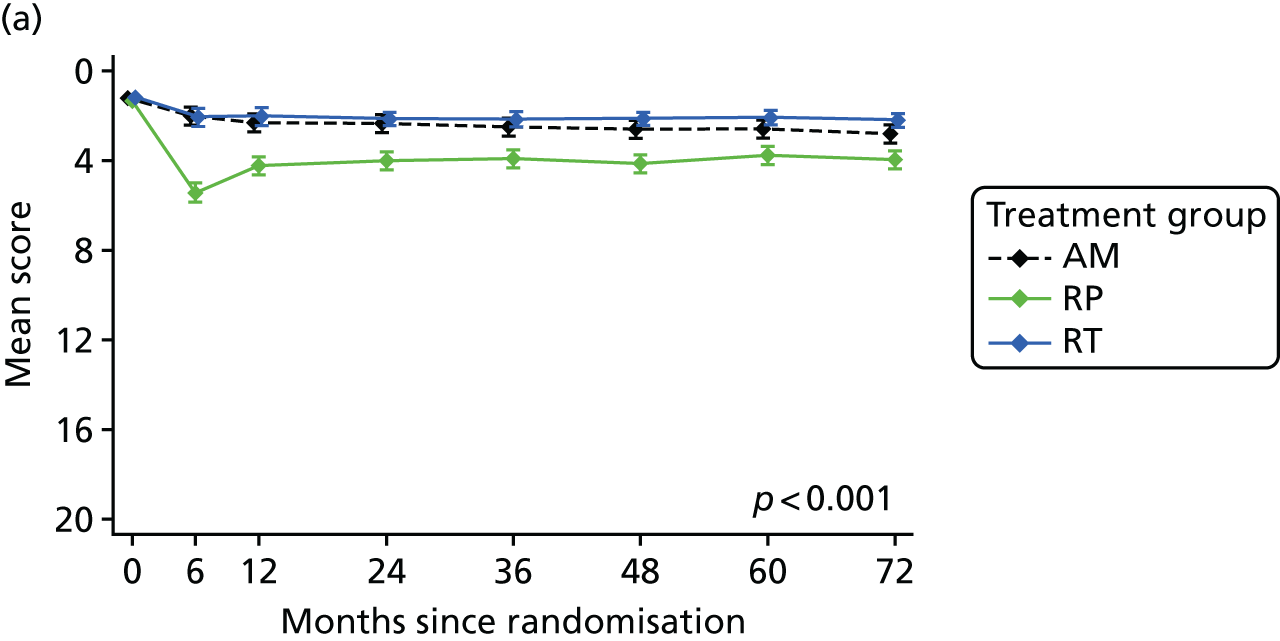

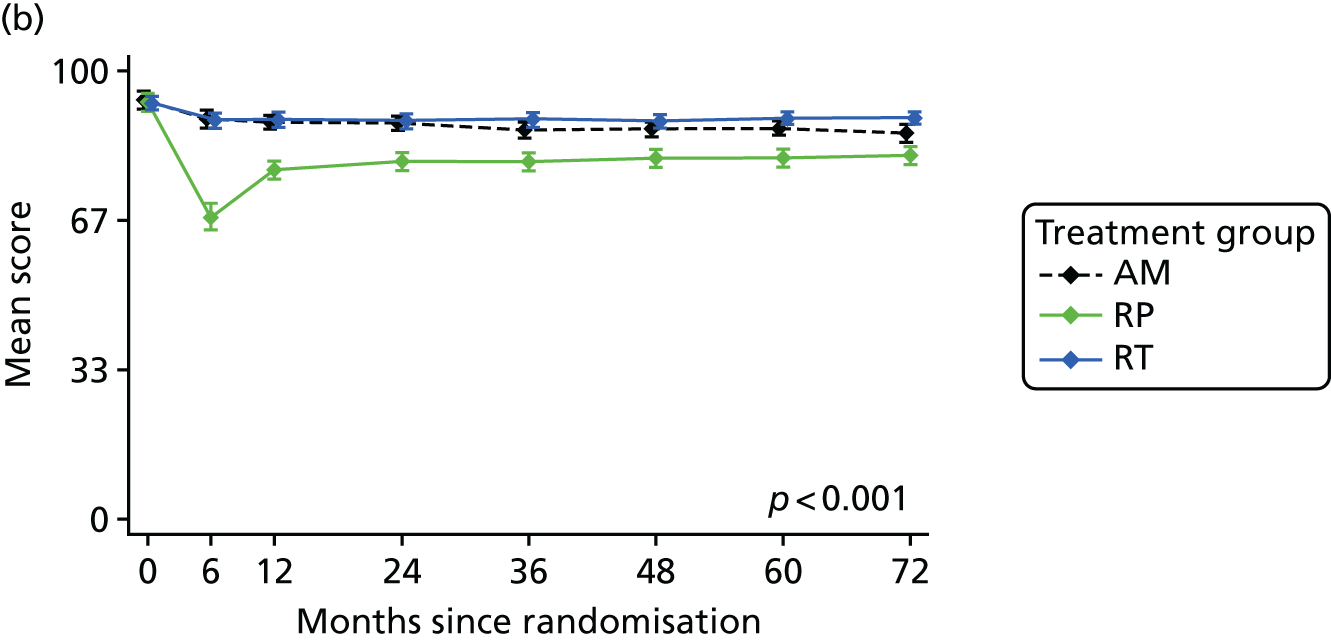

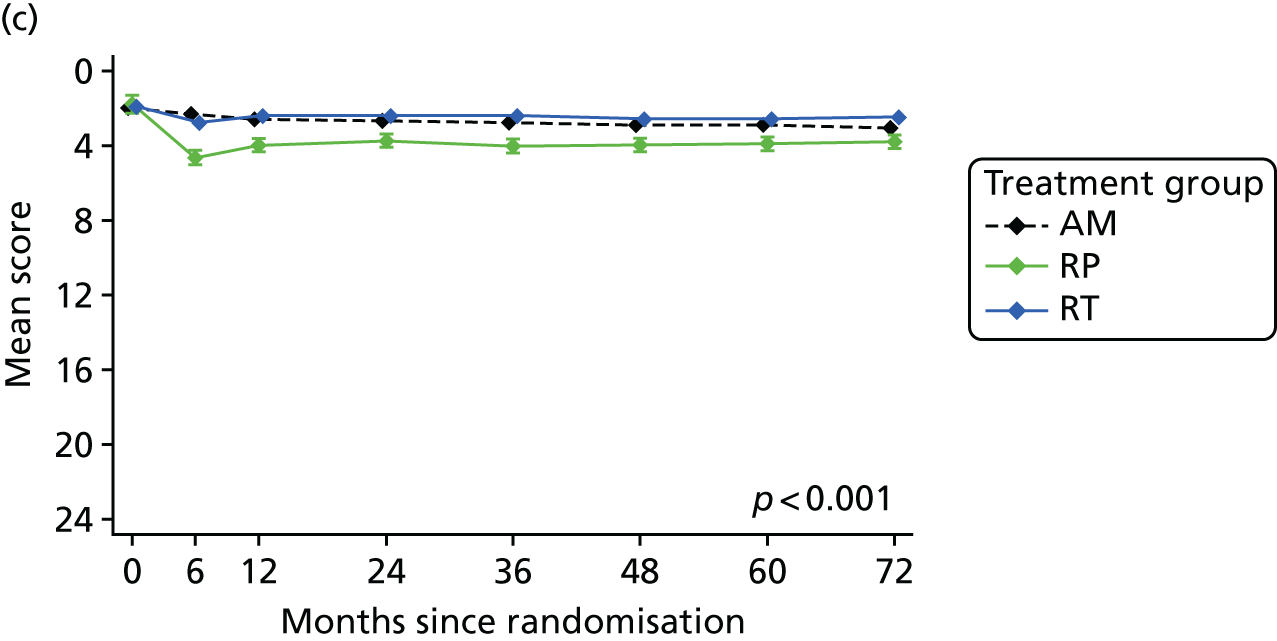

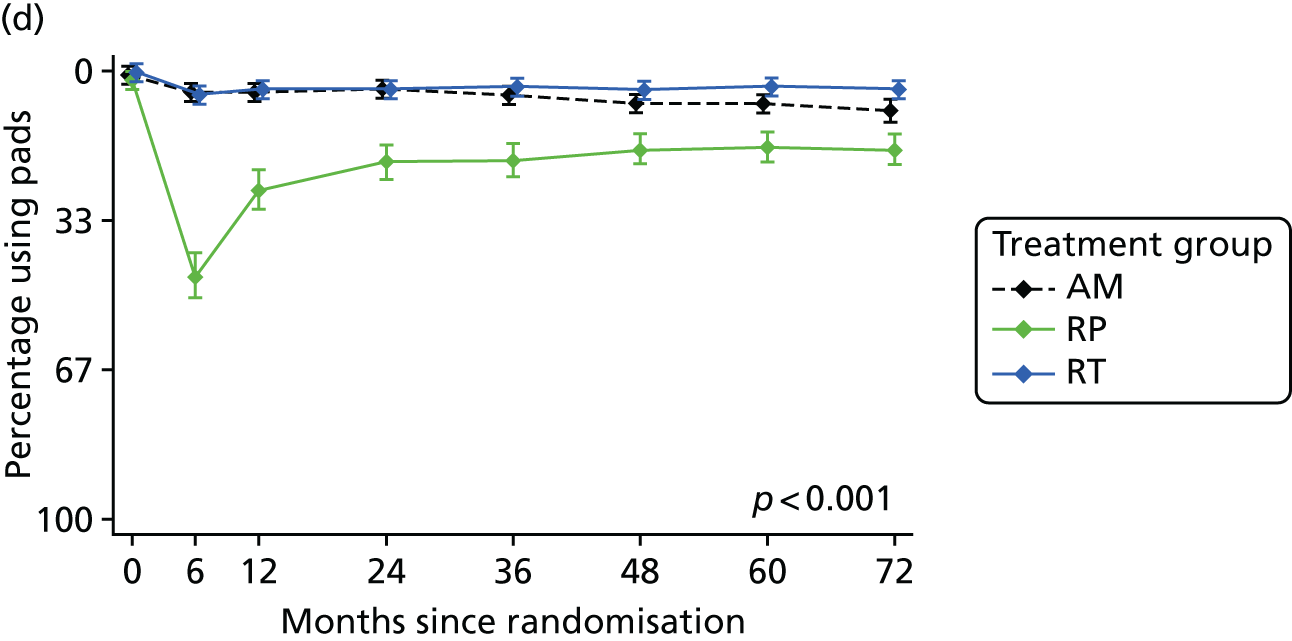

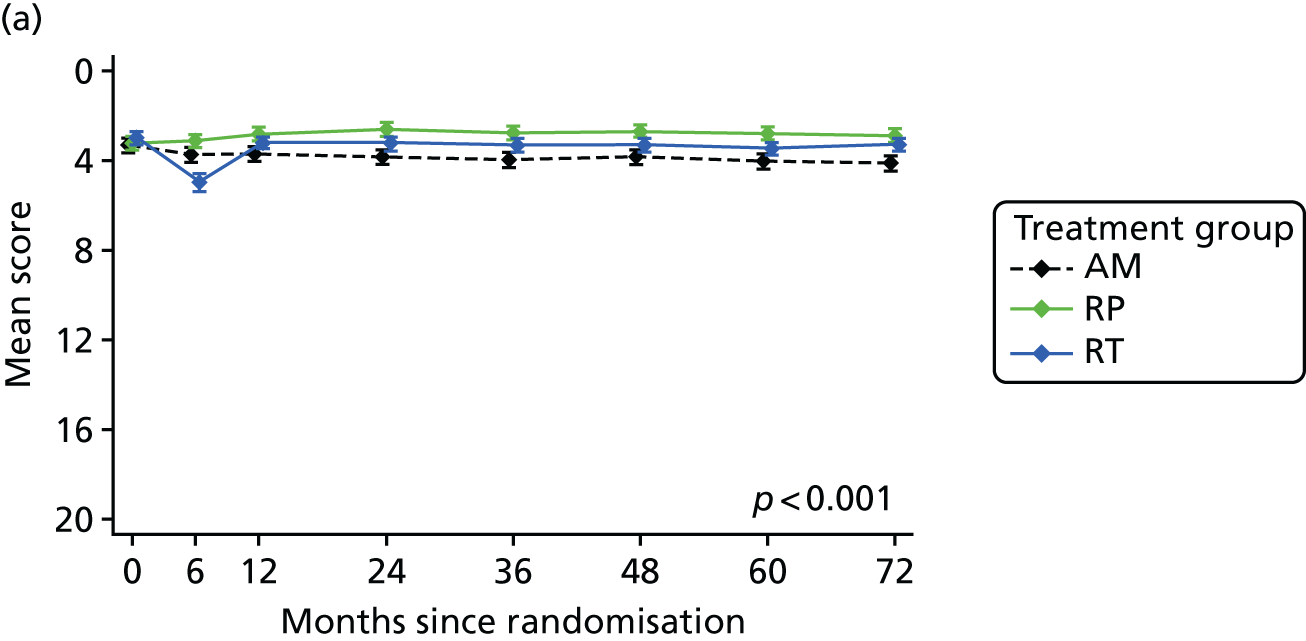

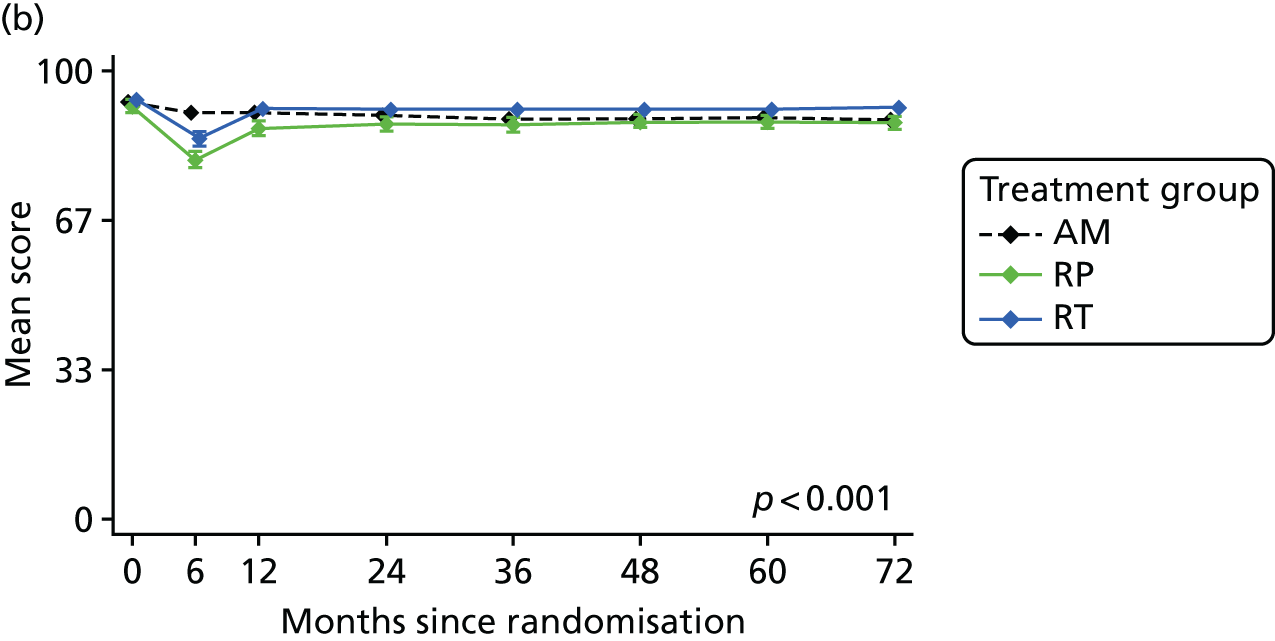

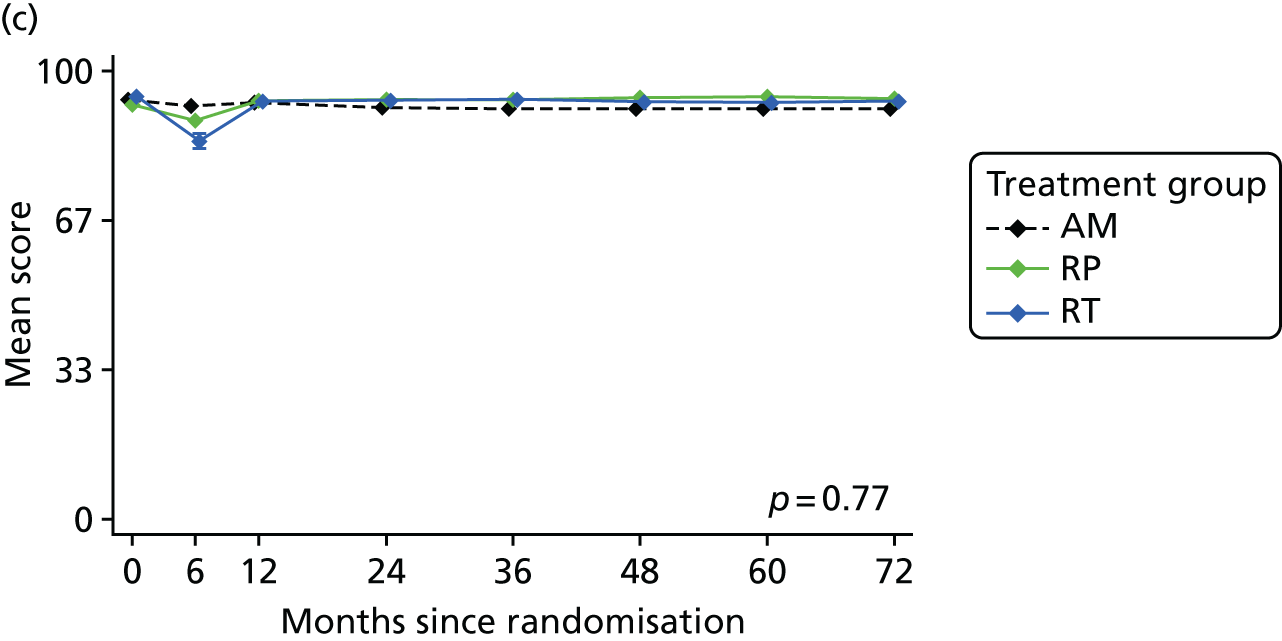

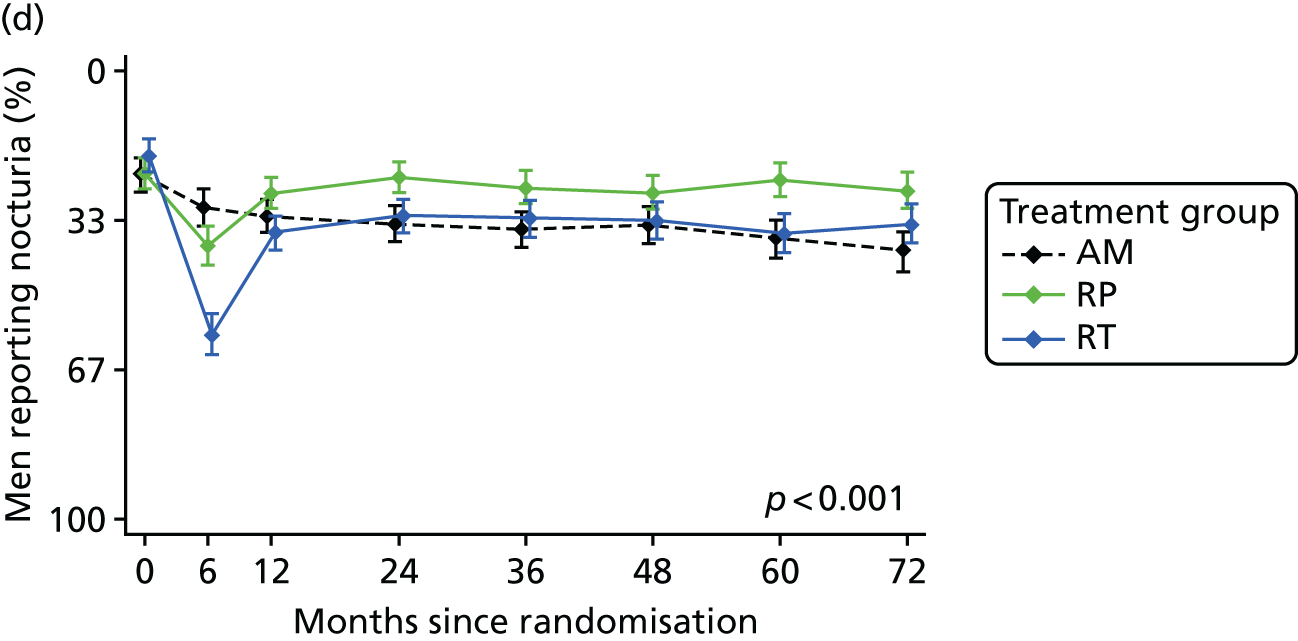

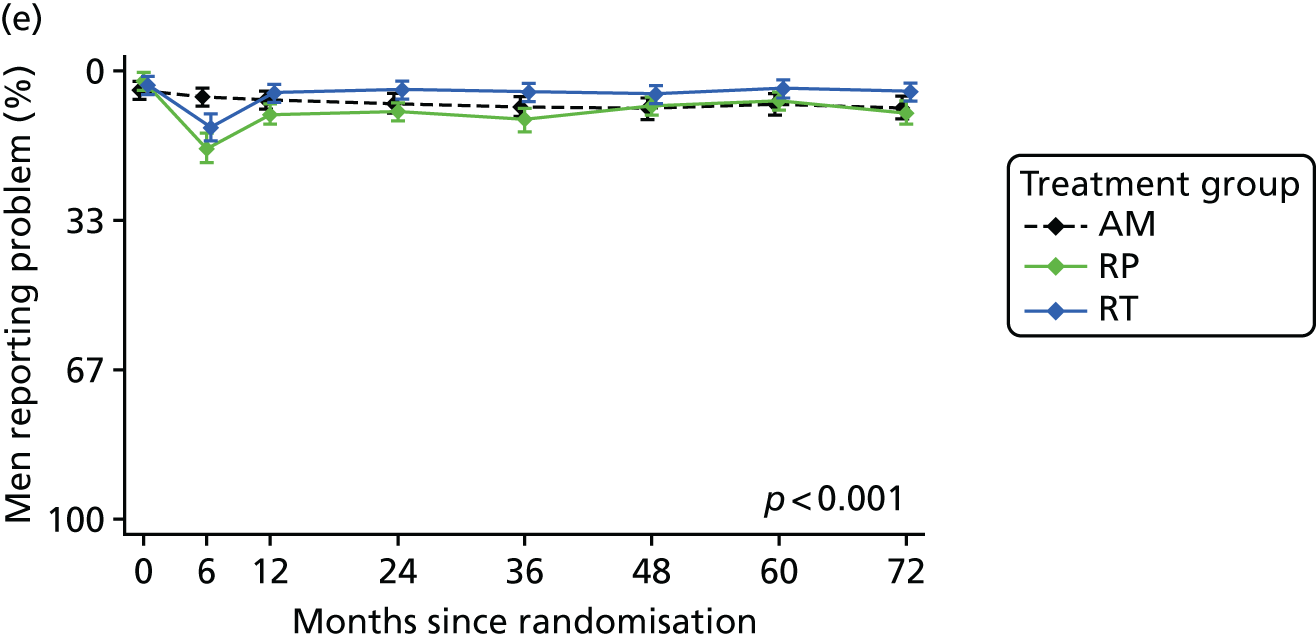

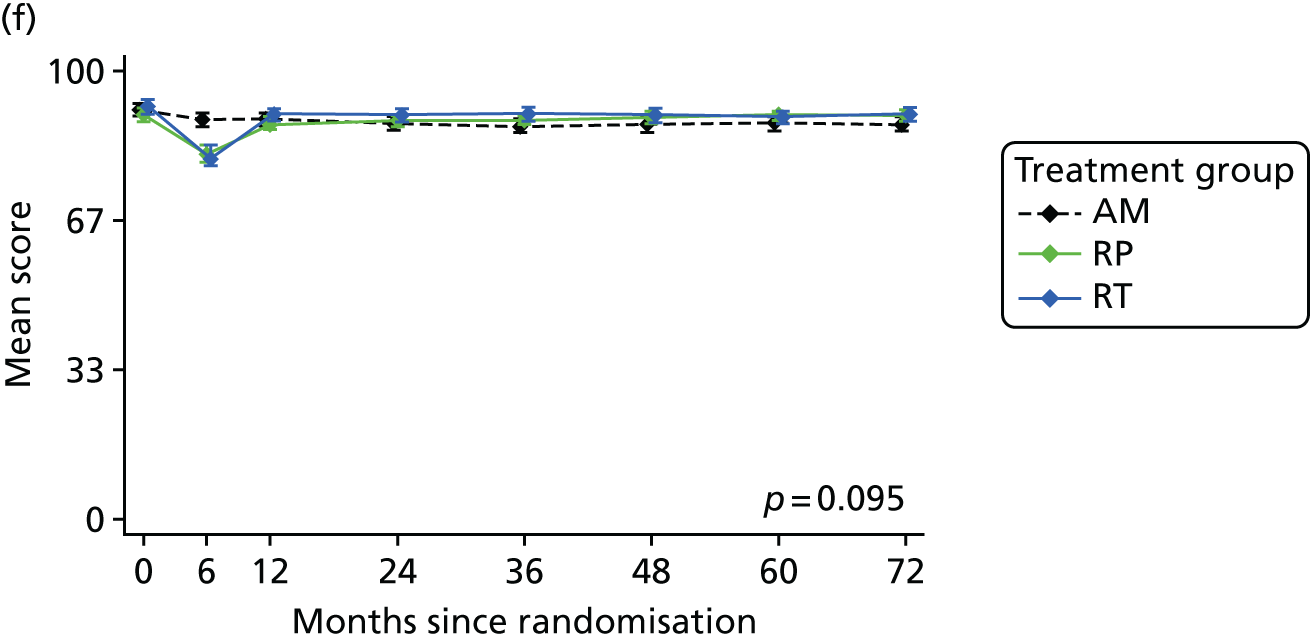

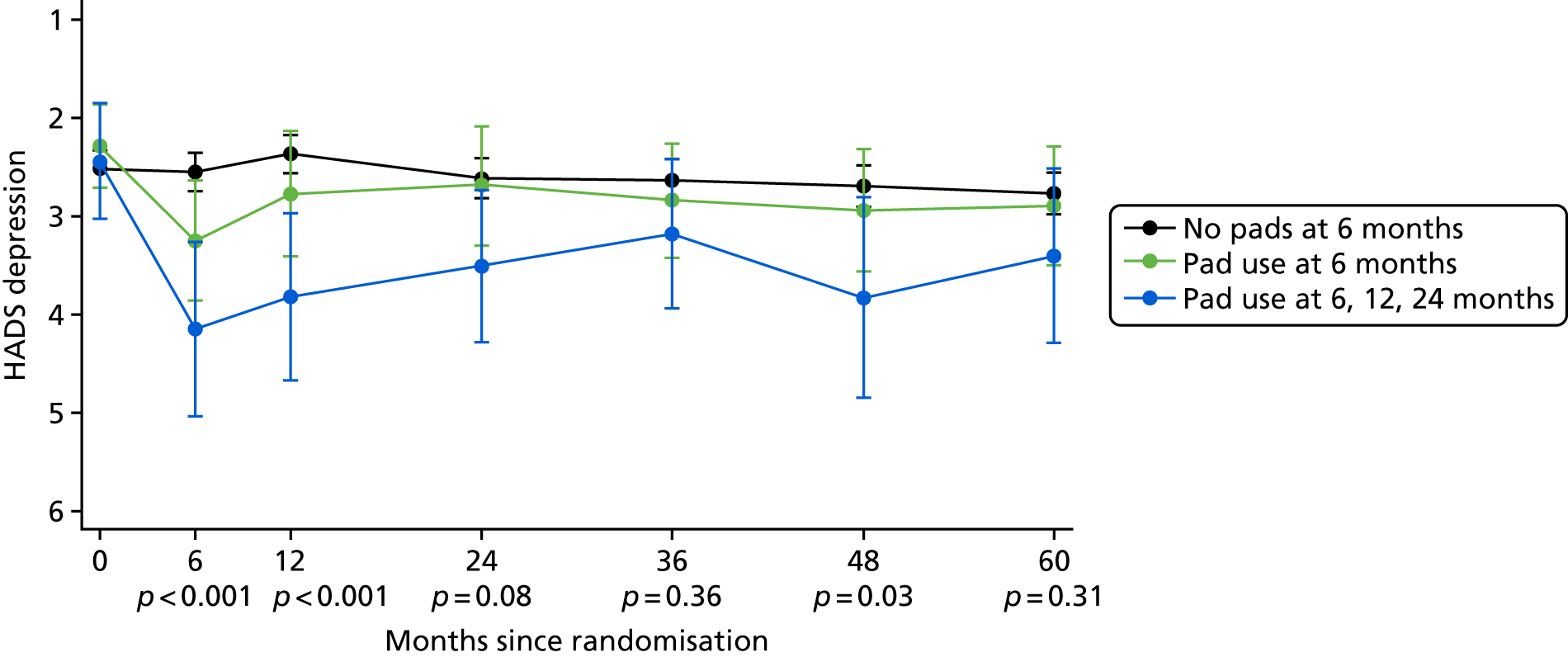

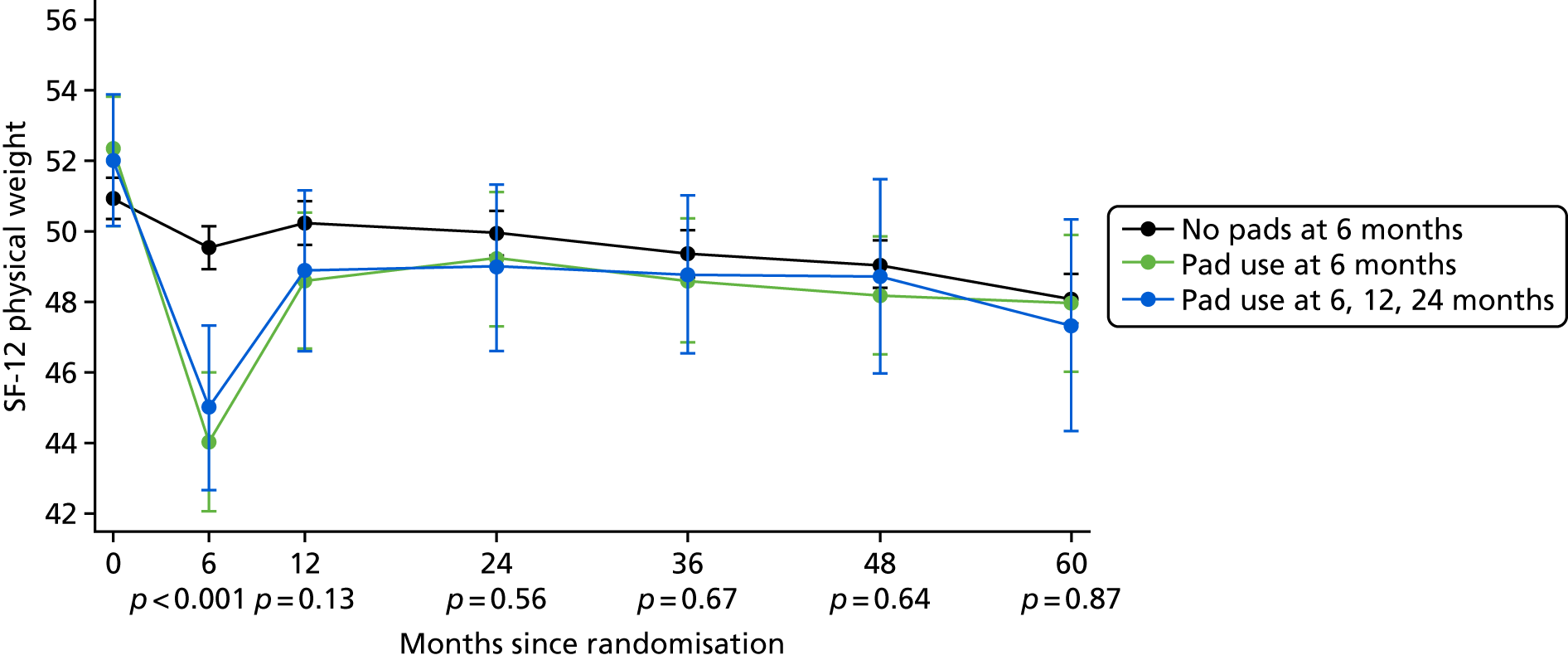

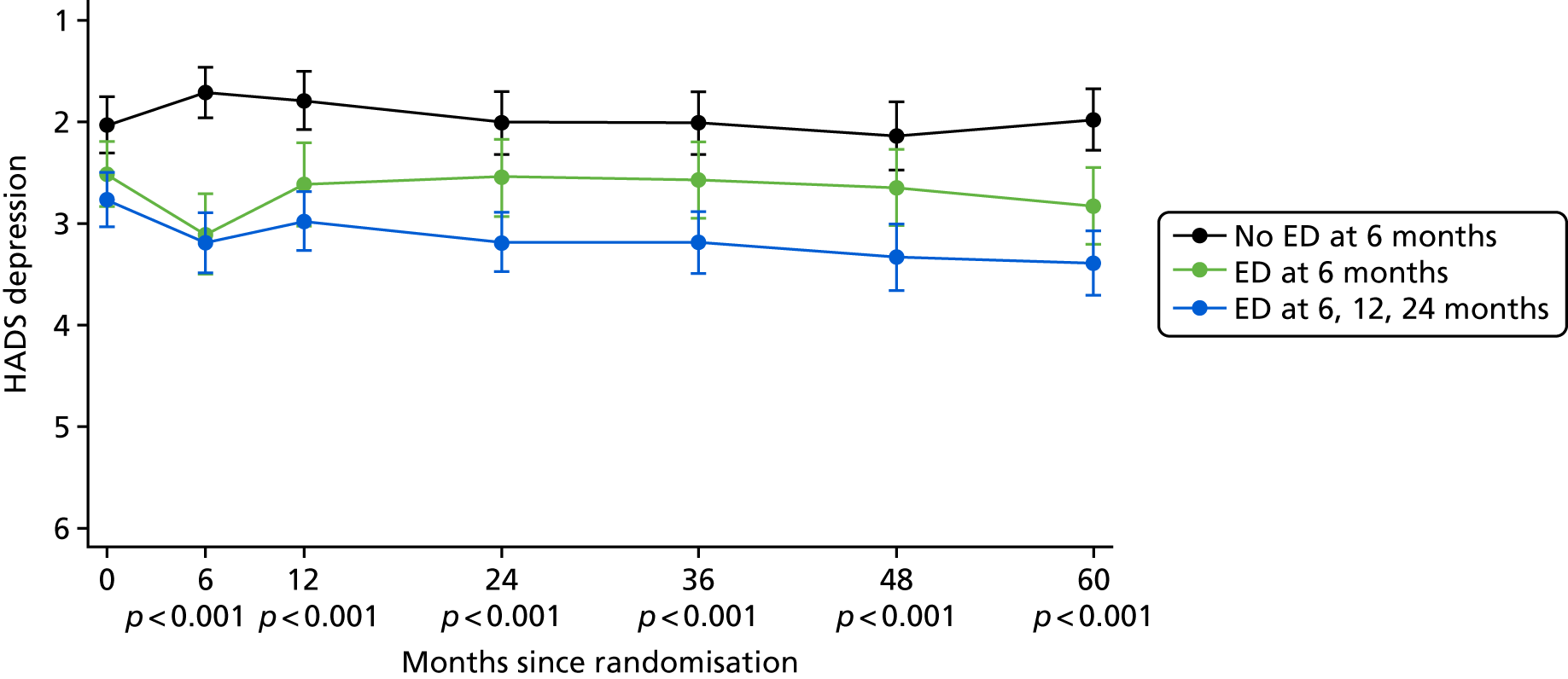

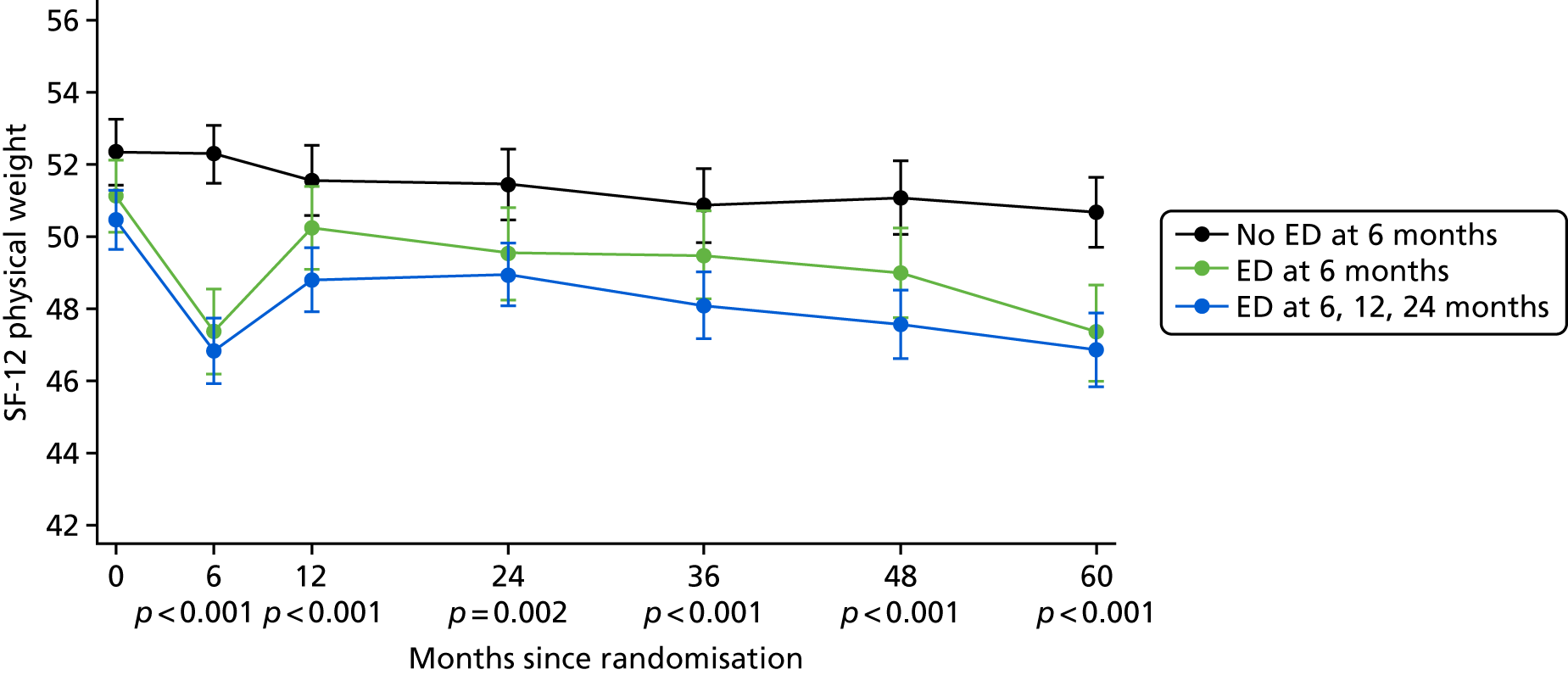

Patient-reported QoL outcomes were focused on symptoms, condition-specific and overall QoL and psychological status. The measures and their foci are summarised in Table 1 and included the Expanded Prostate Index Composite (added in 2005 for rectal complications), the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ), the International Continence Society (ICS) urinary ICSmaleSF (International Continence Society male Short-Form) and sexual function ICSsex measures, the EORTC-QLQ Q30 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire–Core 30 module) (added in 2007 for cancer-specific effects), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for psychosocial effects and the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions generic health status measures. 88–94 These validated questionnaires were completed at recruitment and at first biopsy appointments then at 6 months after randomisation and yearly thereafter for at least 10 years (see Table 1).

| Outcome | PROM and its focus (time frame)a | PROM scales/items presented in main analysis (range/categories) [domain MID utilised or calculated] | Completion rate (n completed/n given the PROM)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | ICIQ-UI: incontinence (4 weeks) |

|

82% (1244/1508) |

| EPIC: prostate cancer treatment (4 weeks) |

|

88% (745/849) | |

| ICSmaleSF: LUTS (4 weeks) |

|

86% (1413/1643) | |

| Bowel | EPIC: prostate cancer treatment (4 weeks) |

|

88% (748/849) |

| Sexual | EPIC: prostate cancer treatment (4 weeks) |

|

85% (719/849) |

| Psychological | HADS: anxiety and depression (1 week) |

|

85% (1399/1643) |

| SF-12: overall mental health (4 weeks) | Mental component subscore (0–100) [3.8] | 77% (1260/1643) | |

| Physical | SF-12: overall physical health (4 weeks) | Physical component subscore (0–100) [4.0] | 77% (1260/1643) |

| Generic health | EQ-5D-3L: health utility (today) | Health utility score (–0.594 to 1.0 scored as perfect health) [0.09] | 86% (1413/1643) |

| Cancer-related QoL | EORTC-QLQ Q304,126 (1 week) | Global health, five functional and three symptom scales, five single items, completed after randomisation |

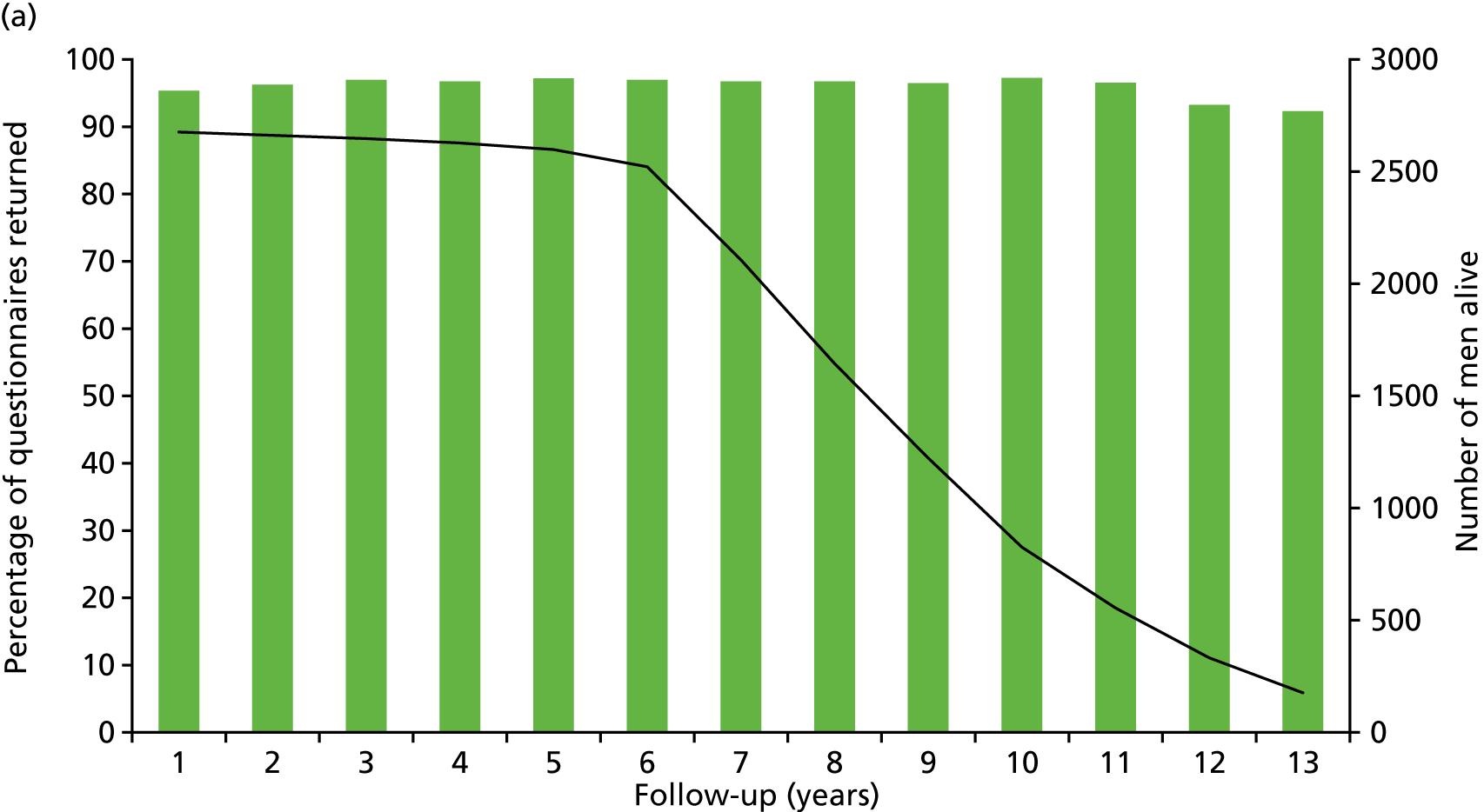

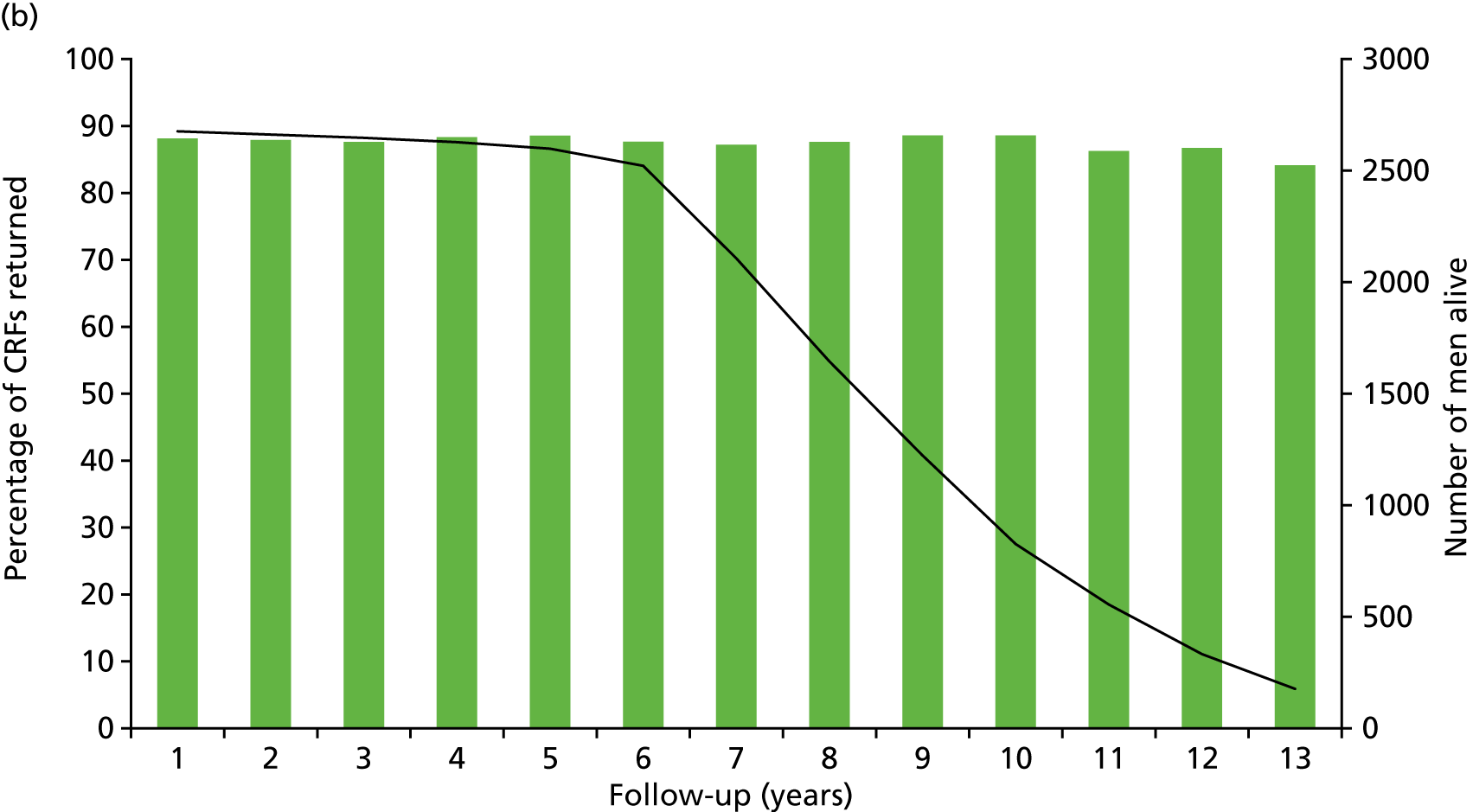

Questionnaires in the follow-up period were posted with a Freepost envelope, with a reminder questionnaire sent after 3 weeks, a telephone call from research nurses after another 3 weeks and a short version of the questionnaire sent at around 8 weeks if there was no reply. Qualitative interviews investigated participants’ experiences of treatments and outcomes over time and are described fully in Chapter 3.

Data-collection schedule

The data-collection schedule related to trial outcomes is summarised in Appendix 1, Table 23.

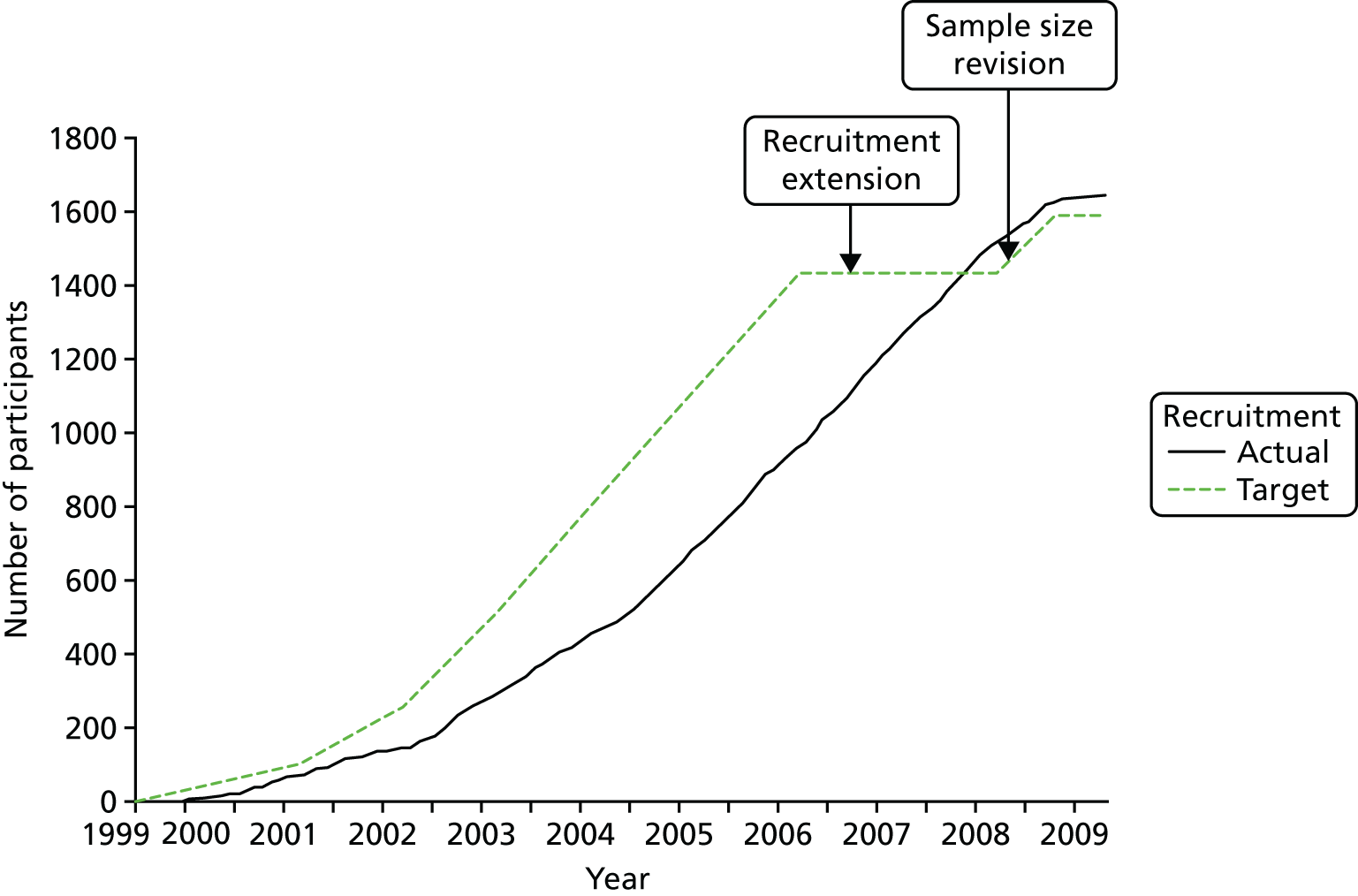

Sample size

Before the start of the trial, a sample size target of 1434 randomly assigned men (478 in each group) was identified as sufficient to estimate the absolute difference in mortality probability between two treatment groups with a 95% CI of ±0.045, on the basis of an assumed prostate cancer mortality risk of 15% at 10 years, consistent with prostate cancer-specific mortality in men aged 55–69 years, with clinically detected disease managed conservatively at that time and a difference that would be deemed clinically significant by the NHS. The pilot study recruitment data were used to calculate the number of sites and duration of recruitment needed to meet the sample size target. However, more-recent data suggested that disease-specific mortality with non-radical treatment was likely to be closer to 10% at 10 years because of improvements in disease management. 34 As a result, the DMC advised in 2008 that recruitment should continue to the planned end date, with 1590 men (530 per group) expected to be randomly allocated by that point. This sample size would enable a 46% relative reduction in prostate cancer mortality to be detected with 80% power at a 5% significance level for a pairwise comparison of a radical treatment with AM. This calculation assumes a 10% prostate cancer-specific mortality at 10 years with AM, and hence a 5.4% risk with radical treatment (an absolute difference very similar to the margin of error specified in the first calculation). These sample size targets are based on differences in and ratios of risk rather than the HRs planned for the primary analysis, because the resulting calculations are simpler and more flexible. When a high survival rate is expected, calculations based on risk ratios will be a close approximation to those based on HRs.

Randomisation

Patients were randomised on an equal basis (1 : 1 : 1) to AM, surgery or radiotherapy by a remote randomisation service. Allocation concealment was assured by the treatment being assigned only after the nurse telephoned the research centre and participant identifiers and key baseline data were logged on the computerised randomisation system held at the University of Bristol. Allocations were computer generated as required for each participant, originally using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) functions and subsequently in C++ by an independent programmer, stratified by site with stochastic minimisation (maintaining a random element to the allocation) to improve the balance across the groups in relation to age at primary care patient-identification date, Gleason sum score (< 7, 7 or 8–10 points) and mean of baseline and first biopsy PSA results (< 6.0, 6.0–9.9 or > 9.9 µg/l). The allocation was revealed after the entry of participant details and given to the participant by the nurse. Men who declined randomisation were offered trial follow-up and formed a comprehensive cohort. 95

Blinding

Clinicians, participants and researchers were not masked to group assignment. All investigators remained blinded to outcomes by group throughout recruitment and analysis. The statistical analysis plan was written by the senior statistician and was agreed by the trial team post recruitment end but prior to any statistical analysis. 96 The primary outcome was assessed by a committee independent of the trial team. 97

Statistical methods and analysis plan

The primary analyses utilised an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach comparing three treatment groups as allocated. At a median of 10 years of follow-up (November 2015), the primary outcome measure of prostate cancer mortality was compared between treatment groups using a survival analysis (Cox proportional hazards regression model) adjusted for stratification and minimisation variables. The estimated relative treatment effect for each pairwise comparison of treatments was captured as a HR, and presented with a 95% CI. Pairwise significance tests were planned if a test of an equal 10-year disease-specific mortality risk across all three groups yielded a p-value of < 0.05. 98 This was used for event-based secondary outcomes (i.e. grouped analyses of definite, probable or possible prostate cancer, all-cause mortality and metastatic disease).

Pairwise comparisons of symptom burden utilised multilevel models for repeated measures to estimate the average treatment effect over the median 10-year follow-up. Further analyses will investigate the relative burden between treatment groups over time. Prespecified subgroup analyses will investigate whether treatment effectiveness in the reduction of prostate cancer-specific mortality is modified by clinical stage, Gleason score, age or PSA concentration using stratified analyses for descriptive statistics and by formally including interaction terms in the relevant regression models. Secondary analyses will estimate the efficacy of radical treatment versus AM in the reduction of prostate cancer mortality in individuals who complied with their allocated treatment, by using a method to derive an unbiased estimate in parallel with the per-protocol analysis originally specified in the trial protocol. 99,100

Data from the recruitment, diagnostic and randomisation phases are summarised, and categorisation of continuous variables was based on either clinical thresholds (e.g. for PSA) or the aim of equal group sizes (other measures). Resident area-based material and social deprivation scores (the proportion of people living in an area of material deprivation) were derived using lower super output areas, each equating to around 1500 residents, for England, Scotland and Wales separately. Analyses were carried out in Stata® version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Summary of changes to the protocol

The main changes in chronological order were:

-

An alternative two-group randomisation between RP and radiotherapy was stopped in 2003 by the TSC because of limited uptake (24 participants in total).

-

An additional exclusion criterion of bilateral hip replacement (precluded radiotherapy) was added in 2003.

-

A pilot study of men aged 45–49 years in one centre that recruited around 1300 participants between 2003 and 2005 was discontinued because of lower recruitment and identification of mostly low-risk disease. 101

-

There was a recruitment extension from June 2006 to June 2008 resulting from contractual delays in opening centres in the main trial.

-

Additional PROMs were added for bowel effects [Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) added in 2005] and cancer-specific QoL (EORTC-QLQ Q30 in 2007).

-

Sample size calculation changed on the advice of the DMC and TSC, as described earlier in 2008.

-

The 5-year survival analysis was removed in 2009 on DMC advice.

-

The chief investigator (and trial sponsorship) moved from the University of Sheffield to the University of Oxford in 2010.

The role of research nurses in recruitment, randomisation and follow-up

Establishment, development and preservation of the local ProtecT teams

The results of the feasibility study102 provided an opportunity for nurses, with the support of secretaries, to be involved in all aspects of the trial: initial recruitment of general practitioner (GP) surgeries (later taken on by the CAP study34), recruitment of participants, assisting with the diagnostic/eligibility phase, randomisation and follow-up. Although commonplace now, at the time this level of involvement by nurses was unusual. Each centre had a senior ProtecT ‘lead nurse’, research nurses (during recruitment) and a trial secretary. The feasibility study showed that nurses were as effective as urologists in randomising participants and they became central to the success of the main trial. The nurses helped recruit general practices, enrolled participants in primary care, assisted with the cancer diagnosis phase, offered randomisation to participants and conducted AM follow-up and research follow-up. At the start of the trial in the early 2000s, nurses rarely took consent, which was questioned by at least one local ethics review board when opening the centres and also by the sponsors. Recruitment took place mainly at GP surgeries, but on occasions at other venues such as sports centres or church halls, requiring the nurses to be adaptable and autonomous. In addition, the nurses sometimes travelled widely during recruitment, particularly where there were few surgeries near the hospital or if they had taken part early on in recruitment.

In order to increase trial activity, particularly recruitment, six additional clinical centres were added at the start of the main trial in two separate three-centre ‘waves’. Practical on-site support was provided to these clinical centres by two of the lead nurses who had gained experience of the trial during the feasibility phase. These ‘co-ordinating’ lead nurses assisted with the initial office set-up, appointment of new staff and on-site staff training: at times this included recruitment of the first participants at a fledgling centre while the team settled into their new role. Each centre first employed a dedicated lead nurse and lead secretary and then new team members were added as trial workload increased. Although each centre was different and had its own challenges, once established these new teams became integrated within the urology department. In order to keep recruitment on schedule and to deal with increasing numbers of men in follow-up, each centre had a team of four or five nurses and two or three secretaries; numbers in centres varied depending on the ratio of full- and part-time staff and the number of participants in follow-up. At the height of recruitment, there were around 45 nurses working across the UK. In total, more than 80 nurses were involved in the trial at some point. Some staff stayed for only a few weeks, leaving once they realised that the repetition of recruitment was not for them; others stayed for many years, often citing the annual nurse-led follow-up clinics and the strong bonds that they subsequently established with the participants as a major factor in their decision to continue working on the trial.

Many of the nurses had previous urology experience when they started on the trial; few had previous research experience. National training meetings were provided by the research hub at the University of Bristol for new and existing staff, with an initial focus on recruitment/randomisation, standard operating procedure (SOP) development, data collection and research methods. As the trial matured, the training increasingly focused on the treatment pathways and research/clinical follow-up issues. The training meetings were an opportunity for nurses and secretaries from across the UK to meet and share experiences and ideas.

Two trial-specific ‘jamborees’ brought together staff from all disciplines and further engendered a national and team approach. Centralised training for nurses was also delivered on an individualised basis as the appointments with participants who had been newly diagnosed with prostate cancer and considering entry into the main treatment trial (‘information appointment’) were, with the participant’s consent, audio-recorded. This material provided a platform for individual and group feedback to improve randomisation. 102

A small peer-review team was established to visit clinical centres and provide on-site support and training, audit, increase protocol/good clinical practice adherence, maintain ‘target’ recruitment/follow-up and to help with any centre-specific issues. 85 The training and on-site review meetings were on a rolling programme to accommodate changes in staff and different phases of the trial. Lead nurse meetings were chaired by the trial co-ordinator and hosted by the University of Bristol (three per year) to encourage cross-centre support, provide feedback on performance, assist with trial development/protocol changes and to work through current issues of concern. In addition, each centre had a nurse attend the national trial meetings, for instance the investigator and radiotherapy meetings. During the follow-up phase, a third co-ordinating lead nurse was added to help develop the trial in the light of new challenges, for instance national changes to trial governance, the move from paper to electronic records across NHS trusts and the complexities of maintaining high follow-up rates in an ageing population. A summary of current ‘nursing issues’ was presented annually at the TSC meetings, at which the emphasis of discussion moved from recruitment to follow-up as the trial matured.

Many teams remained quite constant over time, often citing the trial follow-up clinics and strong bonds that they established with participants as major factors in continuing to work on the trial. ProtecT staff were respected within urology departments for their research and clinical experience, and they advised on other trials and helped to train staff. Several nurses undertook additional qualifications, such as nursing diplomas, Bachelor of Science degrees and one Master of Science degree.

Recruitment/randomisation

Drawing on the experience of the feasibility study, recruitment was carried out by qualified nurses and took place mainly in primary care/community settings, such as GP surgeries, sports centres and church halls. Recruitment centred on the main ProtecT research office/urology department, graduating outwards to ensure that recruitment targets were met. Towards the end of the recruitment phase, many of the nurses regularly had a daily commute of up to 80 miles, particularly to reach centres with a smaller core population, such as Cambridge. The timing and content of appointments were as described in the feasibility report. Methods to ensure standardisation across centres are described previously. Additional support was provided to centres that were underperforming in relation to recruitment and/or randomisation. One centre was withdrawn from recruitment 2 years ahead of the other centres owing to futility despite intensive support, but then became, by default, a pilot for the follow-up phase.

Follow-up

Annual nurse-led follow-up clinics were driven by the trial protocol and were developed using the ‘treatment pathways’ and SOPs as the focus of activity. Each centre ensured that clinics were compliant with local hospital and urology/oncology policies. Follow-up included face-to-face (including ‘outreach’) and telephone appointments and were tailored to the circumstances and wishes of participants. The individualised approach to follow-up facilitated continued participant contact even in the event of participants moving ‘out of area’, helping to reduce levels of trial attrition. In addition to the annual research follow-up, the nurses were responsible for the ‘clinical’ follow-up of the AM cohort, with accountability/oversight provided by the local investigator. In some centres, the nurses provided ongoing clinical support to participants following primary surgery and radiotherapy treatments. The clinical component was perhaps the most important factor in ensuring job satisfaction of the nurses working on the trial. ProtecT nurse-led clinics were demonstrated as being acceptable to patients, nurses and investigators owing to the perceived quality and continuity of service provided. 103 If trial participants moved away, the nurses tried to conduct research follow-up remotely; with participants who lived overseas, this was when they returned to visit the area. Several urology nurse-led clinics have been established at these hospitals using the ‘ProtecT model’. In some centres, nurses who left the trial have drawn on experiences from the ProtecT study and there are examples of departmental-led, nurse-led clinics run on the ‘ProtecT model’. At the time of the primary analysis, plans were being made for a ‘transition’ phase whereby participants would be referred back to usual NHS follow-up – this will be described in the next HTA report.

Chapter 3 Trial results at baseline and randomisation

Participant flow

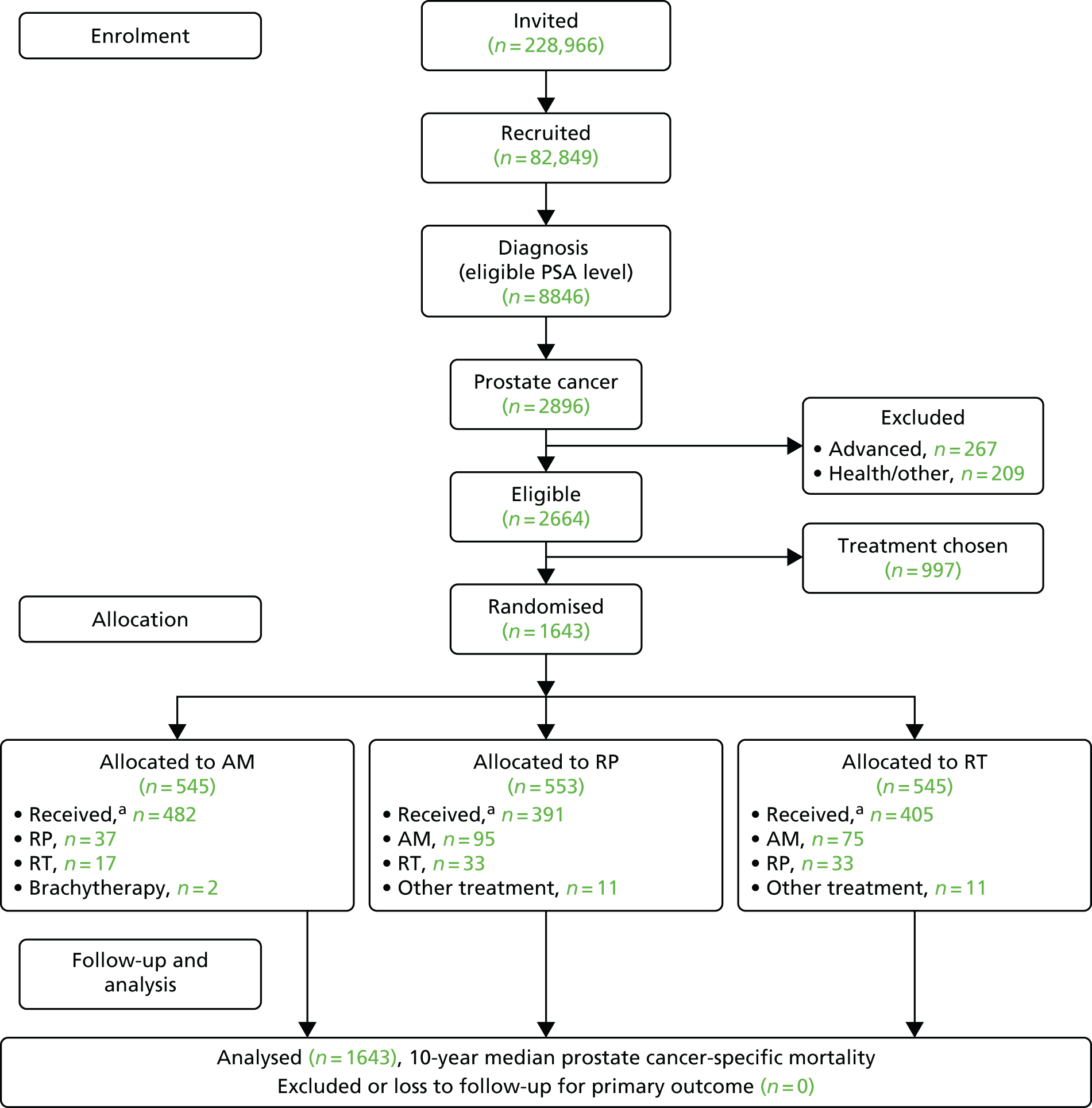

The CONSORT flow chart is presented in Figure 2. All participants were included in the primary outcome analysis, which was based on follow-up from June 1999 to November 2015.

FIGURE 2.

The ProtecT CONSORT flow chart. a, Within 9 months of randomisation.

The ProtecT recruitment story

Recruitment in the feasibility study

Figure 2 shows the flow of participants through the ProtecT study. The recruitment process through the prospective cohort of PSA testing and prostate cancer diagnosis has been described elsewhere. 95,104 This section details the process and outcome of recruitment to the ProtecT trial from the feasibility study until completion in January 2009.

The ProtecT feasibility study was undertaken in three clinical centres from 1999 to 2001 to explore the issues that were expected to make recruitment challenging, if not impossible. The feasibility study was innovatively embedded in a qualitative (ethnographic) study of the perspectives of recruiters and potential participants, identifying obstacles and challenges to successful recruitment. Recruitment in the feasibility study was not easy, but it was eventually successful. The findings produced several recommendations for the main trial: that research nurses should undertake most recruitment activities, supported by urologists who would conduct the ‘eligibility’ assessment appointments; that the comparison should be between three treatments – surgery, radiotherapy and ‘active monitoring’ (as reconceptualised by the qualitative research); that AM should be presented first in the list of treatments; and that nurses would be trained to present the study in a carefully balanced way, avoiding terms such as ‘trial’ and ‘random’ and attempting to explain equipoise and randomisation clearly. 80,83,105 At the beginning of the feasibility study, recruitment struggled, with only 30–40% of eligible patients consenting to randomisation, and 60–70% accepting the allocation, but this rose to a randomisation rate of 70% (95% CI 62% to 77%) by the end of the feasibility study in May 2001, with around 70% accepting the allocation (Table 2).

| Dates | Number of eligible patients | Eligible patients consenting to randomisation, n (%) | Randomised patients immediately accepting the allocation, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 1999–May 2000 | 30 | 9–12 (30–40) | 18–21 (60–70) |

| June 2000–August 2000 | 45 | 23 (51) | 18 (78) |

| September 2000–November 2000 | 67 | 39 (58) | 30 (77) |

| December 2000–January 2001 | 83 | 51 (61) | 38 (75) |

| February 2001–May 2001 | 155 | 108 (70)a | 76 (70) |

Recruitment to the main ProtecT trial: 2001–9

The feasibility study had been undertaken in three clinical centres; the main trial required the addition of six further clinical centres. The target for accrual was to randomise 1590 men with localised prostate cancer (including the 146 recruited in the feasibility study). The clinical centres were set two simultaneous targets:

-

Achieve randomisation of at least 60% of eligible patients.

-

Ensure that participants were well informed so that at least 70% would accept the random allocation.

The recruitment intervention that had been successful in the feasibility study was further developed and extended into a complex intervention in the main trial. 102 Initially, the following actions were proposed as part of the intervention, building on the findings from the feasibility study:

-

regular training for nurses

-

centre reviews if study targets were not met

-

provision of documents to support recruitment

-

individual feedback to recruiters as required.

In addition, the lead investigators in the clinical centres were interviewed to capture their views about participating in the trial and confidence with eligibility assessments and recruitment, and their ‘eligibility’ appointments were audio-recorded if recruitment rates fell below the target rate. Nurses were asked to audio-record all of their recruitment appointments. Patient consent for audio-recording was almost universal. Recordings were selected for scrutiny when staff commenced recruitment or when rates of randomisation or acceptance of allocation fell below study targets. Some recordings were selected at random for trial monitoring, or consecutively for analysis in particular studies. Audio-recordings and interviews were analysed in accordance with methods of constant comparison based on grounded theory, with thematic methods used for interviews and a mixture of content, thematic and targeted conversation analysis methods used for audio-recordings. Centres failing to reach both study targets were selected for review, in which J Athene Lane undertook an audit of consent procedures and Jenny L Donovan completed a focused qualitative analysis of recruitment practice.

Figure 3 shows numbers of patients agreeing to randomisation over time and Table 3 shows recruitment over time according to the rates of randomisation and immediate acceptance of allocation. By the end of 2001, although the randomisation rate was ahead of the target of 60%, the rate of acceptance of allocation had slipped to 64%. The TSC advised that all efforts should be devoted to improving the acceptance rate, and suggested the need to aim to reach a rate of 75–80%. This was investigated in detail through reviews of two recruiting centres with recruitment considerably lower than the targets: centre A with 45% randomisation and 55% acceptance rates, and centre B at 50% and 65%, respectively. Details of the reviews have been reported elsewhere. 102 In brief, after these reviews, rates of randomisation and acceptance of allocation increased markedly to 86% and 78% for randomisation and 67% and 87% for acceptance, with evidence of improvement beyond chance after 12 months. These changes were sustained at 24 months, although numbers were small. In one of the centres, most of those declining randomisation chose surgery, and so training and feedback were targeted towards clearer explanation of all treatments. In the other centre, the nurse recruiters referred to prostate cancer as ‘early’, leading to men expressing a preference for AM (radical treatment was seen as using ‘a sledgehammer to crack a nut’), with nurses then accepting their preference without further discussion. These issues were dealt with by avoiding the term ‘early’ and referring instead to mostly ‘small’ or ‘slow-growing’ cancers, asking patients to keep an ‘open mind’ while they listened to information about treatments, and by acknowledging the need for nurses to explore the reasons for patients’ preferences.

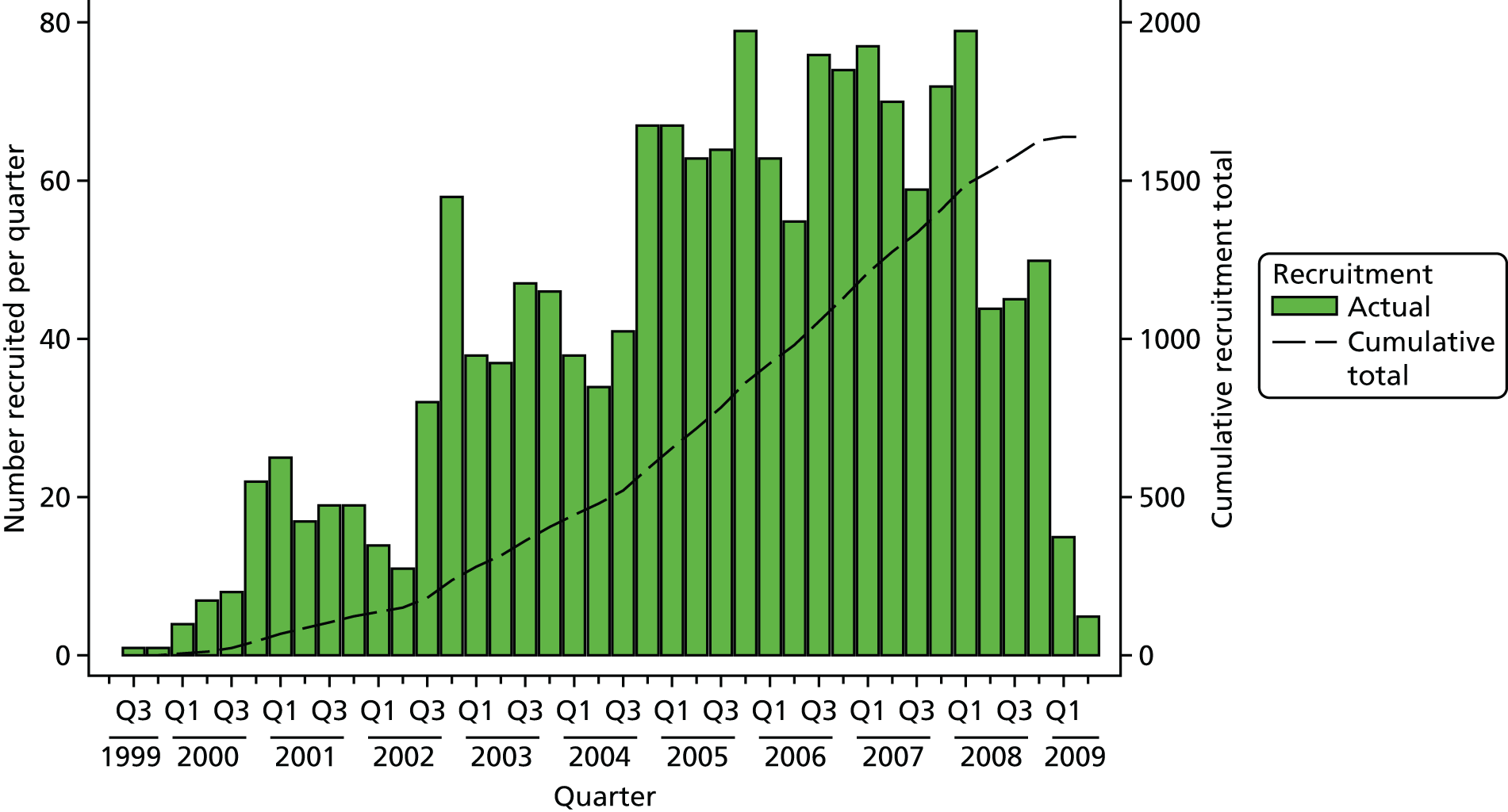

FIGURE 3.

Numbers of patients agreeing to randomisation over time. Q, quarter.

| Year(s) of recruitment | Cumulative number of eligible men with clinically localised prostate cancer | Cumulative number (%) of eligible men agreeing to randomisation | Cumulative number (%) of randomised men accepting allocation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2001 (includes feasibility) | 200 | 137 (69) | 88 (64) |

| 2002 | 381 | 263 (69) | 173 (66) |

| 2003 | 622 | 430 (69) | 303 (71) |

| 2004 | 914 | 621 (68) | 455 (76) |

| 2005 | 1319 | 889 (67) | 702 (79) |

| 2006 | 1762 | 1153 (65) | 918 (80) |

| 2007–9 | 2664 | 1643 (62) | 1336 (81) |

Information about these issues was then included in nurse training sessions that were held in March 2002, February and June 2003, January and October 2004 and annually thereafter. In October 2002, the training was supplemented with a document of ‘tips’ for recruitment, which was sent to all nurse recruiters and urologists carrying out eligibility appointments. This document advised:

-

mentioning the purpose of the study and randomisation early in the appointment

-

avoiding the use of terms such as ‘early’ to avoid misunderstanding

-

describing the treatments succinctly and with balance, including potential advantages as well as adverse effects

-

eliciting and exploring participants’ treatment preferences, particularly if based on incorrect information (such as radiotherapy resulting in hair loss)

-

providing details about what would happen next after advising the participant of the treatment allocation.

A further document (‘Tips 2’) was produced in December 2004, focusing more on the structure and content of appointments, with the following advice:

-

Explain the purpose and rationale of the study, inform patients about advantages and disadvantages of treatments so that they could perceive them as equivalent in terms of outcomes in the long term, obtain consent from randomisation only after checking that the participant was likely to accept all three treatments and ensure that they were comfortable with the conduct and outcome of the appointment.

-

Conduct appointments in three basic stages: opening (points 1–3 above, and empathising with the patient’s situation), process (point 4 above) and ending (ensure that all preferences are addressed, explain purpose and advantages of randomisation, only gain consent if patient indicates willingness to accept all options – or arrange preferred treatment).

-

Examples of difficult situations were given.

-

Essential things to do and avoid were given.

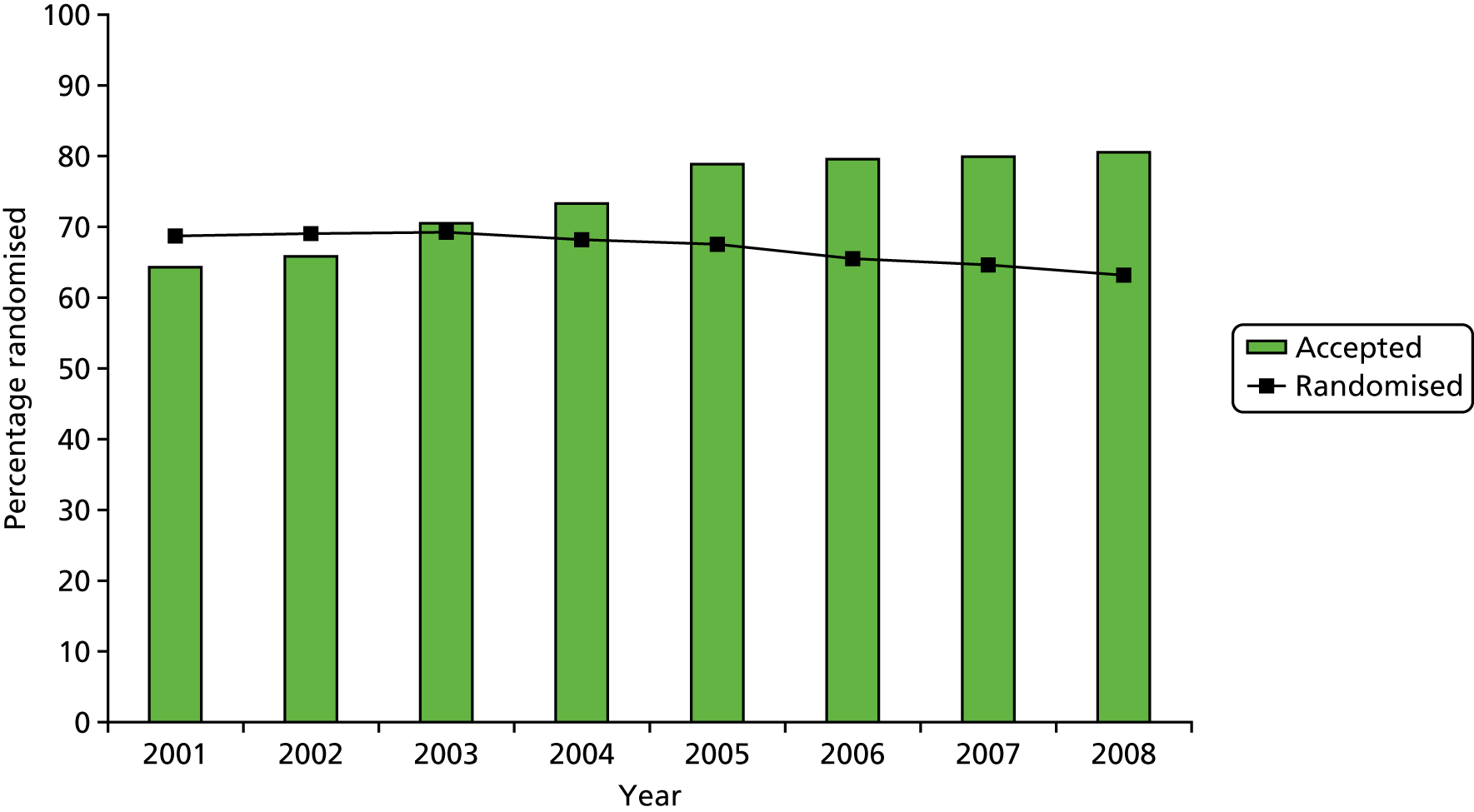

As can be seen in Table 3 and Figure 4, the rate of acceptance of allocation increased sharply in 2002 and continued to increase, reaching 70% in 2003 and rising to 80% in 2005, before stabilising at that level to the end of recruitment. The rate of randomisation began to decline gradually from its high point of 69% in 2003 as the acceptance of allocation increased. Both original targets were thus met from 2003 onwards, as was the revised TSC target for acceptance of allocation from 2005 onwards.

FIGURE 4.

Randomisation and acceptance of allocation over time.

Years

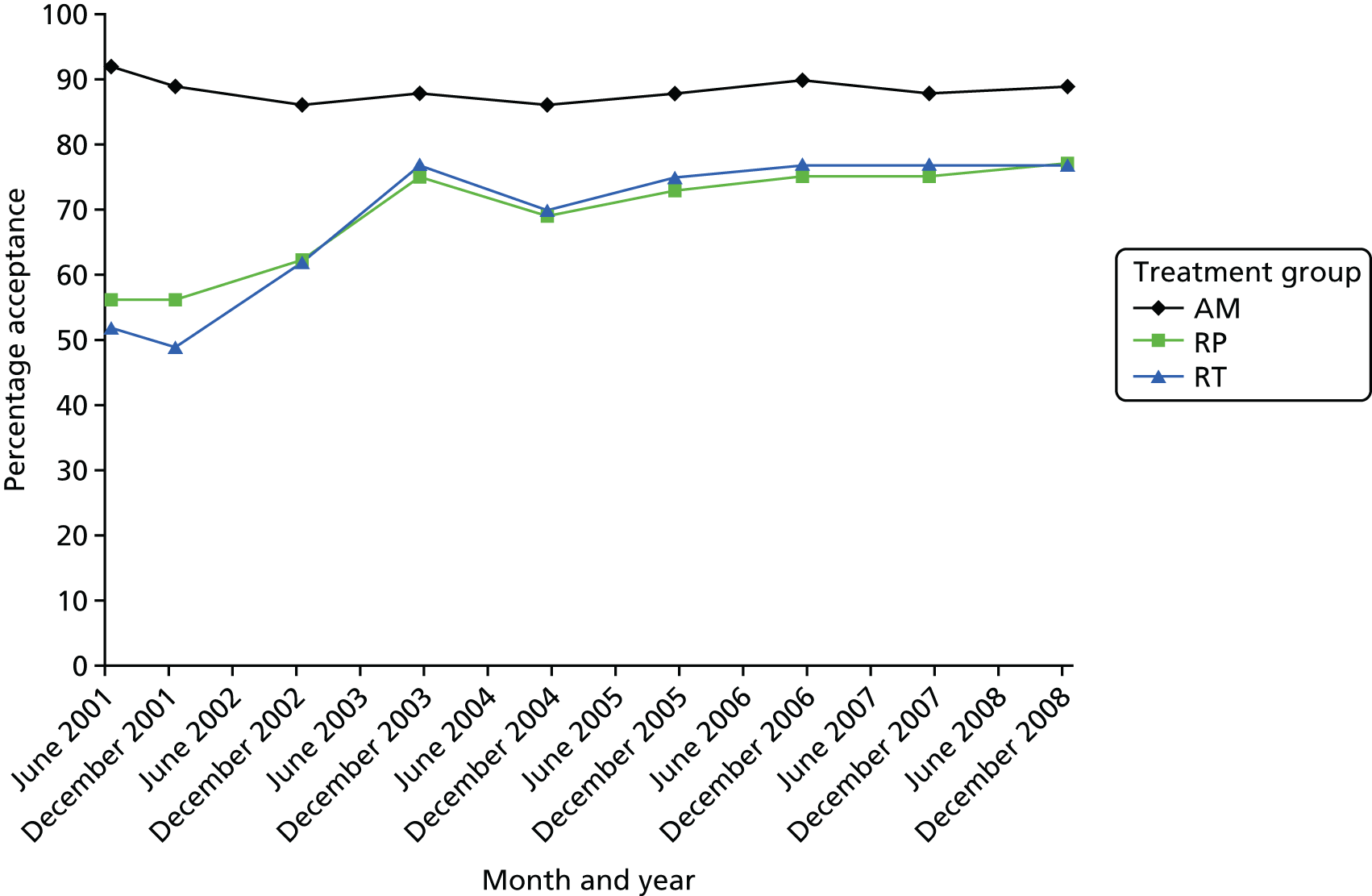

We also investigated acceptance of allocation by group. Figure 5 shows how the low level of acceptance in 2001 was related to the radical treatments, particularly radiotherapy. Nurses were encouraged to visit oncology units and improve information provision about radiotherapy in addition to providing more balanced information about all three treatments. As can be seen in Figure 5, the acceptability of allocation to both radical treatments became similar to but remained somewhat lower than the rate for AM, reflecting the differences in the immediate consequences of these options.

FIGURE 5.

Acceptance of allocation by group over time.

Development and refinement of the ProtecT recruitment intervention

The centre reviews, nurse training, provision of ‘tips’ documents and individual confidential feedback constituted the ProtecT trial recruitment intervention. The intervention was further developed through two qualitative research studies undertaken alongside the recruitment:

-