Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/303/98. The contractual start date was in April 2007. The draft report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Helena Earl reports grants from Roche (Basel, Switzerland) and Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France), personal fees and travel expenses from Daiichi Sankyo (Tokyo, Japan), AstraZeneca plc (Cambridge, UK) and Intas Pharmaceuticals (Ahmedabad, India), travel expenses from Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) and Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) and personal fees from prIME Oncology (Atlanta, GA, USA), all outside the submitted work. Karen McAdam reports grants from Roche and personal fees from Roche, Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland), Pfizer and Eisai Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), all outside the submitted work. Daniel Rea reports personal fees and grants from Roche during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees from Novartis, Pfizer, Genomic Health (Redwood City, CA, USA) and Daiichi Sankyo, and grants from Celgene Corporation (Summit, NJ, USA), all outside the submitted work. Chris Plummer reports personal fees and non-financial support from Roche Products Limited, Novartis UK Limited, Pfizer UK Limited, Celgene and Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA) for attending education meetings. He also reports personal fees and non-financial support from Amgen Limited for attending education meetings and advisory boards, all outside the submitted work. Jean Abraham reports fees to her institution, and accommodation and travel expenses from AstraZeneca for session boards and advisory chairs, as well as fees to her institution, and accommodation and travel expenses from Pfizer for a lecture, all outside the submitted work. Carlos Caldas reports grants from Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA, USA), Roche, Servier Laboratories (Suresnes, France) and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work, and that he is a member of the AstraZeneca iMED External Science Panel. Peter Hall reports grants from Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Eisai and Daiichi Sankyo outside the submitted work. Christopher McCabe’s institution holds research contracts with Roche and reports grants from Roche, all outside the submitted work. David Miles reports personal fees from Roche/Genetech, outside the submitted work. Claire Hulme reports that she is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board. Andrew M Wardley reports personal fees from Roche, Napp Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Cambridge, UK), Amgen, Merck Sharp & Dohme (Hoddesdon, UK), Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Laboratoires Pierre Fabre (Paris, France), Accord (Barnstaple, UK), Athenex (Buffalo, NY, USA), Gerson Lehrman Group (New York, NY, USA), Coleman Research Expert Network Group (New York, NY, USA) and Guidepoint Global (New York, NY, USA). He also reports personal fees and other from Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and Daiichi Sankyo, all outside the submitted work. He is leading the National Cancer Research Institute Breast Group Initiative to develop the next de-escalation trial for HER2-positive breast cancer. David A Cameron reports funds to his institution from Novartis, Astrazeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Eli Lilly and Company, Puma Biotechnology (Los Angeles, CA, USA), Daiichi Sankyo, Synthon (Nijmegen, the Netherlands), SeaGen International GmbH (Zug, Switzerland), Zymeworks (Vancouver, BC, Canada), Elsevier (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), European Cancer Organisation (Brussels, Belgium), Celgene Corporation, Succinct Medical Communications (Wilmington, DE, USA), Immutep (Sydney, NSW, Australia), Oncolytics Biotech (U.S) Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), Celldex Therapeutics Inc. (Hampton, NJ, USA), San Antonio Breast Cancer Consortium (TX, USA), Highfield Communication (Oxford, UK), Samsung Bioepis Co. Ltd (Incheon, South Korea), prIME Oncology, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd, Prima Biomed Ltd, RTI Health Solutions (Research Triangle, NC, USA) and Eisai, all outside the submitted work. Janet A Dunn reports that she is a member of the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation funding board and an NIHR senior investigator.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Earl et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Breast cancer and biology of HER2-positive disease

Breast cancer is a significant health problem worldwide and is the most common cancer occurring in women in the UK, with an incidence of 54,700 diagnoses per year (figures from 2017). 1 This represents 31% of all new cancer diagnoses in women. Although breast cancer also occurs in men it is uncommon, accounting for only 390 cases per year in the UK. A total of around 11,400 deaths are due to breast cancer each year and in women this represents the second most common cancer cause, accounting for 15% of all cancer deaths. 1 Overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is recognised as a poor prognostic feature of breast cancer2 and has been found to be present in 12–15% of all breast cancer cases. Subsequently, the molecular intrinsic subtypes3 of luminal A and B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like have helped to define breast cancer prognosis more precisely and have improved clinical management and treatment decisions. These four main intrinsic subtypes are all found in HER2-positive disease, and dominate the biological and clinical phenotype. 4 Patients with HER2+/luminal A disease seem to have a relatively better outcome than patients with the other subtypes; in particular, patients with the HER2-enriched intrinsic subtype were found to have the worst prognosis, a finding confirmed in the integrative cluster of breast cancer analysis. 5

Trastuzumab treatment: metastatic and adjuvant

Significant HER2 overexpression leads to ligand binding and activation of cell division and tumour growth. Treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (Herceptin®; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was one of the first targeted cancer treatments to be developed and tested. It represented a major advance in the management of metastatic disease,6,7 producing significant improvements in response rates and survival. This signal of response soon led to registration studies of trastuzumab given with chemotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer early in the disease, and cure rates improved. A Cochrane review of all of the adjuvant trastuzumab studies published in 20128 demonstrated that there were 40% fewer cancer recurrences and 34% fewer deaths with adjuvant trastuzumab. The magnitude of this effect has also been demonstrated indirectly in molecular studies of tumours sampled before the introduction of adjuvant trastuzumab. 5,9 These showed that the HER2-enriched group without adjuvant trastuzumab had worse survival than those with nine other molecular subtypes, including basal-type triple-negative breast cancer.

Adjuvant trastuzumab studies

After the success of trastuzumab for treating metastatic disease, registration trials were carried out in the early disease setting. The duration of treatment used in these pivotal registration trials was 12 months, although no evidence existed to support this length of targeted treatment in the adjuvant setting.

HERA

HERA was an international, multicentre, randomised trial that compared 1 year or 2 years of trastuzumab given every 3 weeks with observation in patients with HER2-positive and either node-negative or node-positive breast cancer who had completed locoregional therapy and at least four cycles of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. A total of 1694 patients were randomised to 2 years of trastuzumab, 1694 were randomised to 1 year of trastuzumab, and 1693 were in the observation arm with chemotherapy alone. Results were first reported in the New England Journal of Medicine10 for 1 year of trastuzumab compared with chemotherapy alone. With a median follow-up of 1 year, 347 disease-free survival (DFS) events (recurrence of breast cancer, contralateral breast cancer, second non-breast malignant disease, or death) were observed: 127 events in the trastuzumab group and 220 events in the observation group. The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for a DFS event in the trastuzumab group compared with the observation group was 0.54 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.43 to 0.67; p < 0.0001], representing an absolute benefit in terms of DFS at 2 years of 8.4%. Symptomatic congestive heart failure (CHF), including severe CHF, developed in 1.7% of the women treated with trastuzumab.

Subsequent follow-up confirmed the beneficial effect. The 2-year analysis of the HERA trial demonstrated a benefit for overall survival (OS) as well as for DFS (HR for OS 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.91; p = 0.0115: updated HR for DFS 0.64, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.76; p < 0.0001). 11 These results confirmed that trastuzumab given sequentially after adjuvant chemotherapy has a significant benefit with a median follow-up of 2 years. The emergence of benefit after a median follow-up of only 1 year suggests that there is a significant effect from the first months of trastuzumab therapy. In addition, it is important to note that during the HERA trial trastuzumab was given sequentially after at least four cycles of standard chemotherapy, demonstrating the same degree of benefit as seen in the trials that used concurrent trastuzumab and chemotherapy.

Longer-term follow-up results of HERA have been published, confirming significant benefit for 12 months’ trastuzumab compared with observation at a median follow-up of 8 years. 12 This is despite nearly 50% of patients in the observation arm ‘crossing over’ to receive adjuvant trastuzumab after the early results were reported in 2005. There is no dispute about the significant benefit of adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer.

The HERA trial also tested 24 months’ trastuzumab compared with 12 months’ trastuzumab. The results for the 24-month arm showed no additional benefit in the 2013 publication after 8 years’ follow-up,12 or in the further publication in 2017 after 11 years’ follow-up. 13 Therefore, 12 months remained the standard of care throughout the world. In the accompanying editorial to the 2013 publication,14 Heikki Joensuu discussed the biology of HER2-positive breast cancer that leads to aggressive clinical behaviour and early cancer recurrence. He went on to say ‘The HERA results lend support to the hypothesis that patients with HER2 amplification do not benefit from long treatment durations with HER2-targeted therapy, but might be managed best with effective regimens of short duration’. 14 Interestingly, had the HERA trial been analysed and reported after only 3 years, a benefit for 2 years of trastuzumab would have been found. However, with longer follow-up,13 both 1- and 2-year DFS and OS are identical, and any earlier difference has disappeared.

NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831

The second paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine15 included the combined results of two US trials that compared adjuvant chemotherapy with and adjuvant chemotherapy without concurrent trastuzumab in women following surgery for HER2-positive breast cancer. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trial (NSABP B-31) compared group 1 (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel either every 3 weeks or weekly) with group 2 (the same chemotherapy plus 52 weeks of trastuzumab beginning with the first dose of paclitaxel). The North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) trial N9831 compared three regimens: group A (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by weekly paclitaxel), group B (the same chemotherapy followed by 52 weeks of trastuzumab after paclitaxel) and group C (the same chemotherapy plus 52 weeks of trastuzumab initiated concurrently with paclitaxel). The studies were amended to include a joint analysis comparing groups 1 and A (the control groups) with groups 2 and C (with trastuzumab given concurrently with taxanes). Group B was excluded from this first analysis because trastuzumab was not given concurrently with paclitaxel. The trial was reported when 394 DFS events had occurred, of which 133 were in the trastuzumab group and 261 were in the control group (HR 0.48; p < 0.0001). Three-year DFS was 87.1% in the trastuzumab group, compared with 75.4% in the control group, showing an absolute difference of nearly 12% in favour of trastuzumab. Trastuzumab therapy was associated with a 33% reduction in the risk of death (p = 0.015). The 3-year cumulative incidence of severe congestive heart failure or death from cardiac causes in the trastuzumab group was 4.1% in trial NSABP B-31 and 2.9% in NCCTG N9831.

Subsequently, longer-term follow-up16,17 confirmed the benefits of trastuzumab given for 12 months. At a median follow-up of 8.4 years, there was a 37% relative improvement in OS with the addition of trastuzumab (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.73; p < 0.001) and an increase in the 10-year OS rate from 75.2% to 84%. DFS rates also improved by 40% (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.68; p < 0.001), with an increase in the 10-year DFS rate from 62.2% to 73.7%. 17

Analysis of NCCTG N9831 on its own was able to address the comparison of the three arms. 16 The non-trastuzumab control arm was AC-paclitaxel (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel) chemotherapy, the second arm was AC-paclitaxel with sequential trastuzumab for 12 months, and the third arm was AC-paclitaxel with concurrent trastuzumab starting with paclitaxel and continuing afterwards to complete 12 months of weekly treatment. With a median follow-up of 6 years, the 5-year DFS rates were 80.1% and 84.4% for the second and third arms, respectively. There was an increase in DFS with concurrent trastuzumab and paclitaxel relative to sequential administration (HR 0.77, 99.9% CI 0.53 to 1.11), but the p-value of 0.02 did not cross the prespecified O’Brien–Fleming boundary (0.00116) required for this arm of the trial to be stopped early in the interim analysis. However, following the publication of these results in 2011, concurrent as well as sequential trastuzumab and chemotherapy were adopted as a ‘standard of care’ and, subsequently, concurrent treatment became the preferred option.

BCIRG-006

The Breast Cancer International Research Group (BCIRG) study of trastuzumab in women with HER2-expressing early breast cancer (BCIRG-006) examined concurrent treatment of trastuzumab with a non-anthracycline-containing chemotherapy regimen (docetaxel and either carboplatin or cisplatin). 18 In BCIRG-006, 3222 patients were recruited, and similar numbers of node-positive and high-risk node-negative women were randomised to each of three arms: adjuvant doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and then docetaxel plus trastuzumab (AC-TH) or doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and then docetaxel (AC-T), or docetaxel, carboplatin (or cisplatin) and trastuzumab (TCH). After a median follow-up of 65 months, there was significant benefit in DFS and OS in both groups treated with trastuzumab, compared with the group who received AC-T, who had a 5-year DFS of 75% and an OS of 87%. Among patients receiving AC-TH, the 5-year DFS was 84% (HR for the comparison with AC-T 0.64; p < 0.001) and OS was 92% (HR 0.63; p < 0.001). Among patients receiving TCH, the 5-year DFS was 81% (HR 0.75; p = 0.04) and OS was 91% (HR 0.77; p = 0.04). There was no difference between the two trastuzumab-containing arms, although the study was not sufficiently powered from a statistical point of view to confirm non-inferiority. There was a numerical trend for TCH showing a lower 5-year DFS (81% compared with 84% in the AC-TH arm), although there was significantly less cardiotoxicity among patients receiving TCH than among those receiving AC-TH.

FNCLCC-PACS-04

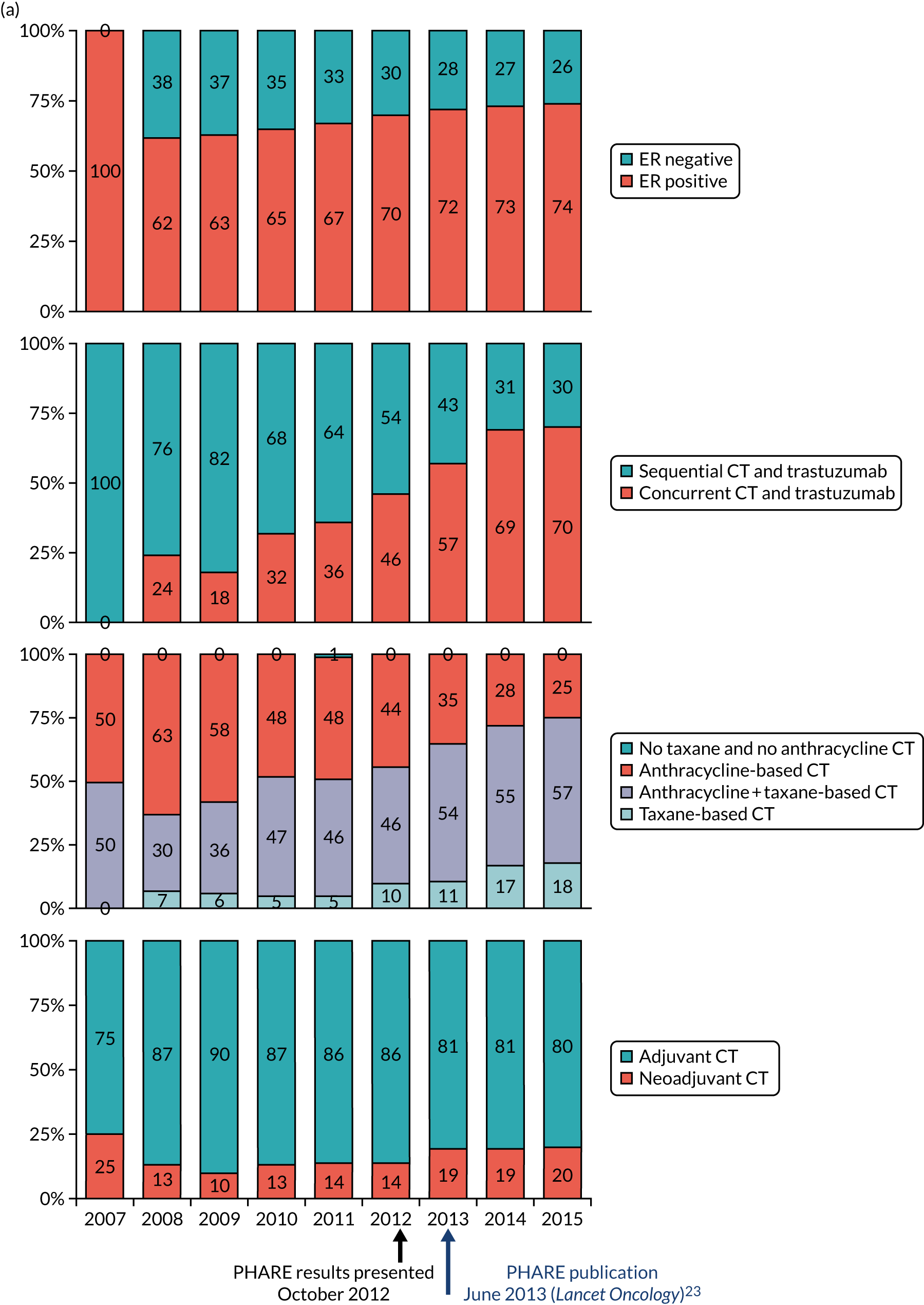

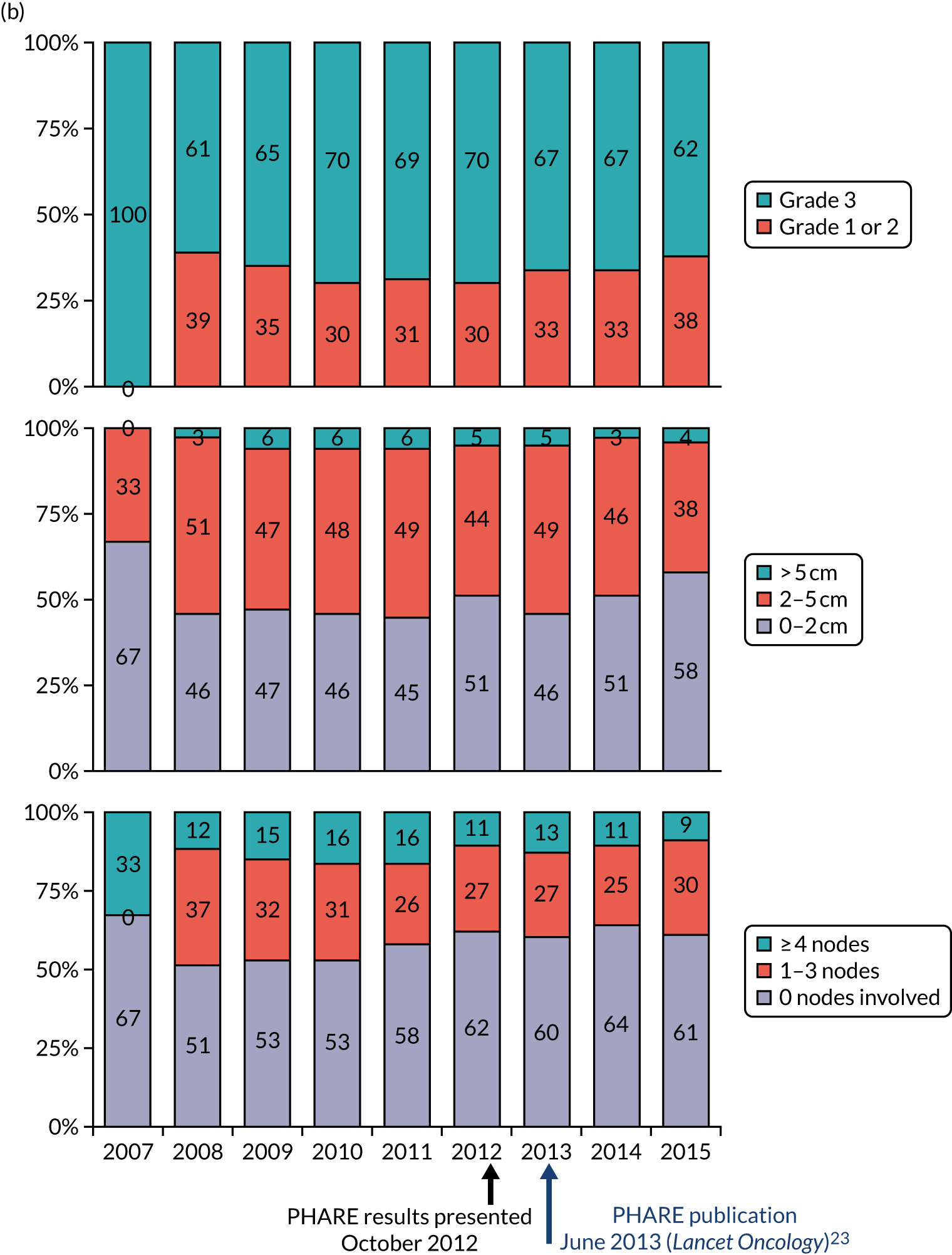

This was the only study that failed to demonstrate an advantage of adjuvant trastuzumab. 19 Five hundred and twenty-eight patients with operable node-positive breast cancer were randomised (1 : 1) to anthracycline-based chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab and, in a secondary randomisation, with or without docetaxel. The 3-year DFS rates were 78% (95% CI 72.3% to 82.5%) and 81% (95% CI 75.3% to 85.4%) in the observation and trastuzumab arms, respectively. There was a 14% reduction in the risk of relapse (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.22; p = 0.41, log-rank stratified on pathologic node involvement), which was non-significant. All patients in this trial received sequential trastuzumab, and this result, together with the NCCTG N9831 analysis,16 which was the only trial directly comparing concurrent with sequential trastuzumab, resulted in a gradual shift in UK practice to increase the numbers of patients receiving trastuzumab concurrently with chemotherapy. This coincided with the increasing use of anthracycline-with-taxane chemotherapy combinations, which were approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of node-positive breast cancer during the course of the trial.

Shorter-duration studies

FinHer

Soon after the results of the registration trials, the FinHer trial was published. 20 This study compared docetaxel with vinorelbine for the adjuvant treatment of patients with early breast cancer. In this trial, women with HER2-positive tumours were also randomised to receive chemotherapy with or chemotherapy without concurrent trastuzumab. Two hundred and thirty-two women were recruited who had axillary-node-positive or high-risk node-negative HER2-positive cancer. They were randomised to receive three cycles of docetaxel or vinorelbine with or without concurrent weekly trastuzumab for 9 weeks, followed by three cycles of 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC). In the subgroup of patients who had HER2-positive cancer, those who received trastuzumab had significantly better 3-year recurrence-free survival than those who did not (89% vs. 78%; HR for recurrence or death 0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.83; p = 0.01). Docetaxel was associated with more adverse effects than was vinorelbine. Importantly, despite trastuzumab being given immediately before anthracyclines, this arm was not associated with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) or cardiac failure. The FinHer trial demonstrated that a short course of trastuzumab administered concurrently with docetaxel or vinorelbine was effective in women with HER2-positive breast cancer.

Subsequently, at a median follow-up of 62 months,21 the benefit of 9 weeks’ trastuzumab was maintained in the exploratory comparison of docetaxel and trastuzumab followed by FEC with the same treatment without trastuzumab (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.89; p = 0.029). However, this was not the case in the comparison of vinorelbine and trastuzumab followed by FEC compared with the same treatment without trastuzumab (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.83; p = 0.82).

Hence, when the PERSEPHONE trial started in 2007, whether or not similar outcomes could be achieved with durations of trastuzumab treatment of < 12 months was an important question worldwide.

E2198

This was a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)22 that was set up to compare the cardiotoxicity of a short course of trastuzumab with that of the conventional 12 months of trastuzumab. This was not published until 2015 and therefore did not inform the design of the PERSEPHONE trial. In addition, it was not powered to demonstrate non-inferiority in the 12-week trastuzumab arm. The trial included 227 women with stage II or IIIa HER2-positive breast cancer. Patients were randomised to 12 weeks of paclitaxel and trastuzumab followed by four cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide or to the same treatment with a total of 1 year of trastuzumab (standard arm). The primary objective was to assess the safety of the different durations of trastuzumab therapy, in particular with regard to cardiac toxicity, which was defined as CHF or LVEF decrease of ≥ 10%. DFS and OS were secondary end points. The frequency or severity of cardiac toxicity did not increase; three patients in the experimental arm and four in the standard arm experienced CHF. There was no difference in 5-year DFS, which was 76% and 73% for the short and standard arms, respectively, with a HR of 1.3 (95% CI 0.8 to 2.1; p = 0.3). There was also no statistically significant difference in OS (HR 1.4; p = 0.3). The trial was not powered for efficacy; however, the longer duration of trastuzumab therapy did not demonstrate a signal for marked superiority. Retrospectively, this trial provided some additional evidence for the efficacy of shorter-duration trastuzumab.

Duration of trastuzumab studies

PHARE

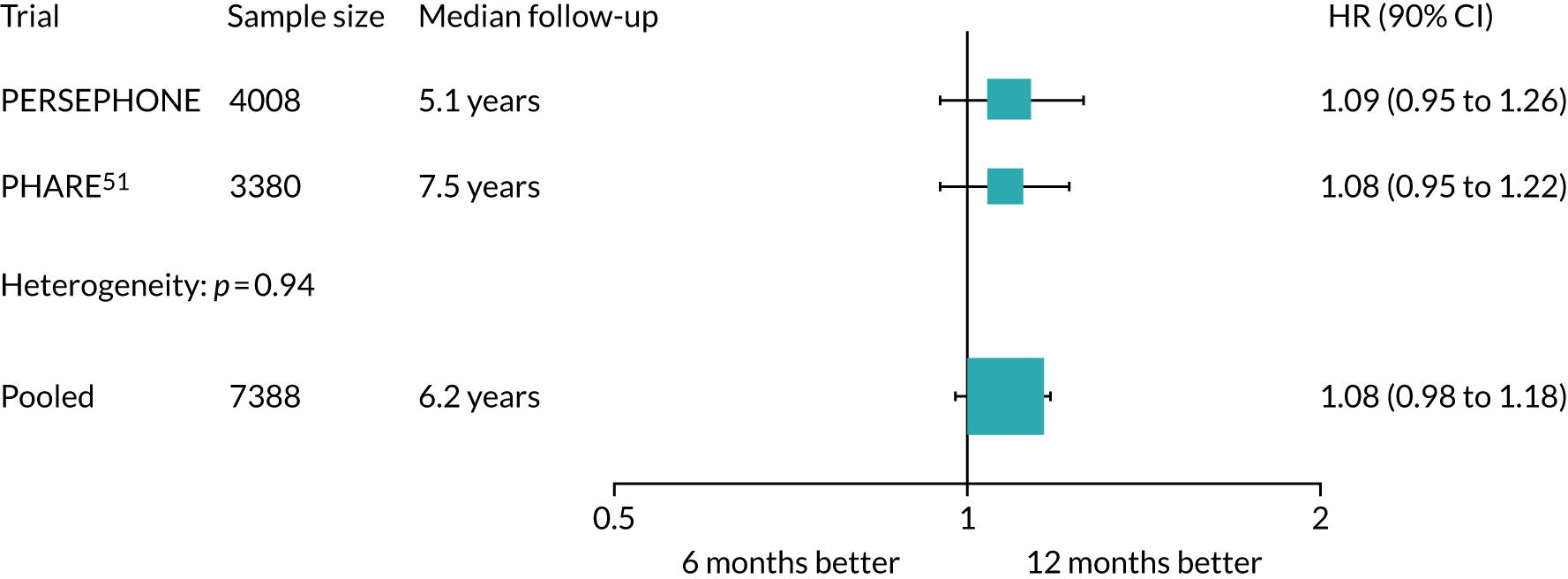

Based on the FinHer results, the French group Institut National du Cancer developed the PHARE clinical trial to compare 6 months’ trastuzumab with 12 months’ trastuzumab (Table 1). Randomisation into the PHARE trial occurred between 3 and 6 months after a patient had started trastuzumab, which was one of the differences between PHARE and PERSEPHONE. At the start of PERSEPHONE, all patients were randomised before starting trastuzumab, but subsequently randomisation was permitted at any time up to and including the ninth cycle of trastuzumab. In PHARE, patients were stratified by oestrogen receptor (ER) status (positive or negative) and concurrent or sequential trastuzumab and chemotherapy. It mapped on to standard practice in France and was carried out as a multicentre study recruiting 3384 patients: 1690 randomised to 6 months’ trastuzumab and 1690 randomised to 12 months’ trastuzumab. In the original statistical plan outlined in the first publication in 2013,23 a margin of non-inferiority of 2% was calculated on an assumed 2-year DFS of 85%. This was the 2-year DFS figure that had been predicted from the first results of the HERA trial. 10 The number of patients required was 7000 to have a 5% level of significance and 80% power to confirm non-inferiority of the experimental arm with an upper confidence limit below the HR, which was calculated at 1.15. In an international collaboration with the PHARE group, PERSEPHONE will carry out a pre-planned joint analysis of results, which will allow a non-inferiority comparison of 6 and 12 months’ trastuzumab with a margin of non-inferiority of 2%. This requires a total of at least 7000 patients to be entered into the two trials. The PHARE trial defined the HR of non-inferiority in the statistical analysis plan before the start of the trial, and then applied this when the analysis was carried out. This is an important difference between the statistical analysis of PHARE and that of PERSEPHONE. In the latter we defined non-inferiority as an absolute difference of no worse than 3% below the standard arm’s 4-year DFS rate, and the HR limit was to be calculated at the time of analysis using the real, observed DFS of the standard arm.

| Trial name/trial design | PERSEPHONE/duration of trastuzumab with chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer: 6 vs. 12 months | PHARE/protocol of Herceptin adjuvant with reduced exposure, a randomised comparison of 6 months vs. 12 months in all women receiving adjuvant Herceptin | HORG/6 vs. 12 months of adjuvant trastuzumab in combination with dose-dense chemotherapy for women with HER2-positive breast cancer: a multicenter randomised study by HORG | SOLD/randomised Phase III study comparing trastuzumab plus docetaxel (HT) followed by 5-FU, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) to the same regimen followed by single-agent trastuzumab as adjuvant treatments for early breast cancer | Short-HER/multicentric randomised phase III trial of two different adjuvant chemotherapy regimens plus 3 vs. 12 months of trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer patients |

| Duration of trastuzumab | 6 months vs. 12 months | 6 months vs. 12 months | 6 months vs. 12 months | 9 weeks vs. 12 months | 9 weeks vs. 12 months |

| Trial recruitment and location | October 2007 to July 2015, UK | May 2006 to July 2010, France | June 2004 to May 2012, Greece | January 2008 to December 2014, international | December 2007 to November 2012, Italy |

| Actual (n)/target (N) | 4088/4000 | 3384/3400 (revised from 7000) | 481/480 | 2174/2168 (revised from 3000) | 1253/2500 |

| ER positive (%) | 69 | 58 | 66 | 56 | 68 |

| Node negative (%) | 58 | 55 | 20 | 60 | 54 |

| Tumour size ≤ 2 cm (%) | 47 | 53 | – | 56 | 41 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy timing | 85 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Chemotherapy type | |||||

| Anthracyclines (%) | 41 | 16 | |||

| Taxanes without anthracyclines (%) | 10 | 10 | |||

| Anthracyclines and taxanes (%) | 49 | 74 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Trastuzumab timing | |||||

| Sequential | 54 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Concurrent | 46 | 57 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

HORG

The Hellenic Oncology Research Group (HORG) study24 randomised HER2-positive patients between 6 and 12 months (see Table 1). Randomisation occurred prior to the commencement of chemotherapy, which was dose-dense FEC given every 2 weeks for four cycles with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor support, followed by docetaxel given every 2 weeks with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. A total of 481 patients were randomised between trastuzumab for 6 or 12 months, and this was started concurrently with docetaxel chemotherapy. The non-inferiority margin was set with an absolute 8% boundary, and an estimated control arm 3-year DFS of 85%. The authors state that this produced a HR for the non-inferiority boundary of 1.53. With a type I error of 5% and 80% power, 239 patients were required to enrol in each arm within an accrual period of 3 years. The trial recruited 481 patients over nearly 8 years (between June 2004 and May 2012), which was longer than intended.

SOLD

The SOLD (Synergism or Long Duration) trial25 was co-ordinated from Finland and included international centres (see Table 1). This trial arose directly out of the FinHer trial and patients were randomised between standard 12 months’ trastuzumab and a shorter course of 9 weeks’ trastuzumab. All patients received single-agent docetaxel for three cycles concurrently with trastuzumab. This was followed by three cycles of FEC chemotherapy. Patients randomised to the standard arm completed 12 months’ trastuzumab following completion of chemotherapy, whereas patients randomised to 9 weeks’ trastuzumab did not receive more after chemotherapy was completed. Patients were randomised prior to any adjuvant treatment and all patients received the same chemotherapy; all therefore received trastuzumab concurrent with chemotherapy and upfront. Over nearly 7 years (January 2008 to December 2014), 2176 patients were recruited from seven countries. The SOLD trial was originally powered as a superiority trial, as it was anticipated that the standard 12 months’ treatment would lead to a significant increase in cardiac deaths, which was not the case. The original sample size calculation was for a trial of 3000 patients. The primary end point was changed to non-inferiority of DFS in the experimental arm, and a non-inferiority boundary of 4% on the true (observed) 5-year DFS rate of 88.7%. This resulted in a HR limit of 1.385, and the final sample size was 2168 patients (1084 patients in each group). The primary analysis was planned to be an event-driven analysis after 366 DFS events or when the last patient entered had been followed up for 2.0 years after randomisation, whichever occurred first.

Short-HER

Short-HER26 was an Italian government-sponsored trial with a similar design to the SOLD trial (see Table 1). The standard arm consisted of four cycles of anthracycline chemotherapy [doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) or epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (EC)] followed by four cycles of docetaxel with trastuzumab given 3-weekly, followed by completion of a full 12 months’ trastuzumab. The experimental arm was similar to the SOLD trial, with concurrent docetaxel and weekly trastuzumab for three cycles followed by anthracycline chemotherapy for three cycles (FEC) and then no further trastuzumab. This study was designed to assess if a shorter trastuzumab administration is non-inferior to the standard of 12 months with respect to DFS. Non-inferiority was defined before the trial started as an absolute difference of no worse than 3%, and the non-inferiority HR limit of < 1.29 was set. The sample size was estimated by setting an alpha of 5% and a power of 0.80, which resulted in a requirement for 372 events and 2332 patients. However, accrual of patients was slower than expected and, to comply with timelines set by the government funding body, the trial had to complete recruitment after 1256 patients had been enrolled. The data analysis was carried out after 198 events but, because of lower recruitment than planned, the study was underpowered for its DFS end point (statistical power 56%). As well as the standard frequentist approach, a Bayesian analysis was planned.

Pragmatic design mapping on to standard practice

The PERSEPHONE trial was a pragmatic trial set up in the NHS in 2007 and mapped on to standard practice in the NHS. Therefore, once study sites had been initiated, and had been set up with all the approvals necessary to be part of the trial, all patients who it was planned would receive chemotherapy and trastuzumab could be approached to take part. The advantage of this pragmatic approach is that it is a reasonable assumption that, following completion of the trial, the results would be implementable without concerns that the population of standard patients was in any way different from the population tested in the trial. In licensing trials the entry criteria are necessarily restricted and very tightly controlled to ensure a high level of medical fitness in the patients entered. We were clear that in the PERSEPHONE trial we aimed to investigate how 6 months’ trastuzumab compared with 12 months’ treatment in the patients whom recruiting clinicians on site would be treating as standard in their clinics.

Chapter 2 Methods: recruitment and study conduct

Trial design

PERSEPHONE was a UK prospective, randomised, non-inferiority, multicentre, open-label Phase III clinical trial to examine if the administration of 6 months of trastuzumab is non-inferior to 12 months in patients with histologically confirmed HER2-positive early invasive breast cancer receiving a standard chemotherapy regimen in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting.

The key aim of PERSEPHONE was to establish whether or not a shorter duration of trastuzumab (6 months/nine cycles) is non-inferior in terms of efficacy to standard of care (12 months/18 cycles). Eligible patients were randomised equally (1 : 1) to receive 12 or 6 months of trastuzumab as well as chemotherapy. After completing treatment, patients were followed up for 10 years.

The current standard of care for early breast cancer patients with HER2-positive disease is to give chemotherapy and 12 months of trastuzumab, which is given as 17 or 18 cycles depending on local protocols. At the start of the trial, trastuzumab was given mostly sequentially after chemotherapy (in the majority of cases, this was anthracycline based without taxanes), but practice gradually changed during the trial and trastuzumab was increasingly given concurrently with chemotherapy. PERSEPHONE had a safety stage built in to confirm that concurrent administration of chemotherapy and trastuzumab was safe during the trial. Data ‘in real time’ on serious adverse events (SAEs) and treatment delays for the first 100 patients of this cohort were collected and analysed before being discussed by the independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) (see outcome of the safety phase in Chapter 3, First 100 patients receiving concomitant trastuzumab and chemotherapy).

Research objectives/end points

To compare 6 months (nine cycles) of trastuzumab with 12 months (18 cycles) in terms of non-inferiority and safety in a prospective, randomised, non-inferiority, multicentre, open-label Phase III clinical trial, mapping on to standard practice in the UK.

Primary end point

-

To assess DFS non-inferiority of 6 months’ (nine cycles) compared with 12 months’ (18 cycles) trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer.

Secondary end points

-

To assess OS non-inferiority of 6 months’ (nine cycles) compared with 12 months’ (18 cycles) trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer.

-

To assess the expected incremental cost-effectiveness [cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)] of 6 months (nine cycles) of trastuzumab compared with 12 months (18 cycles) of trastuzumab.

-

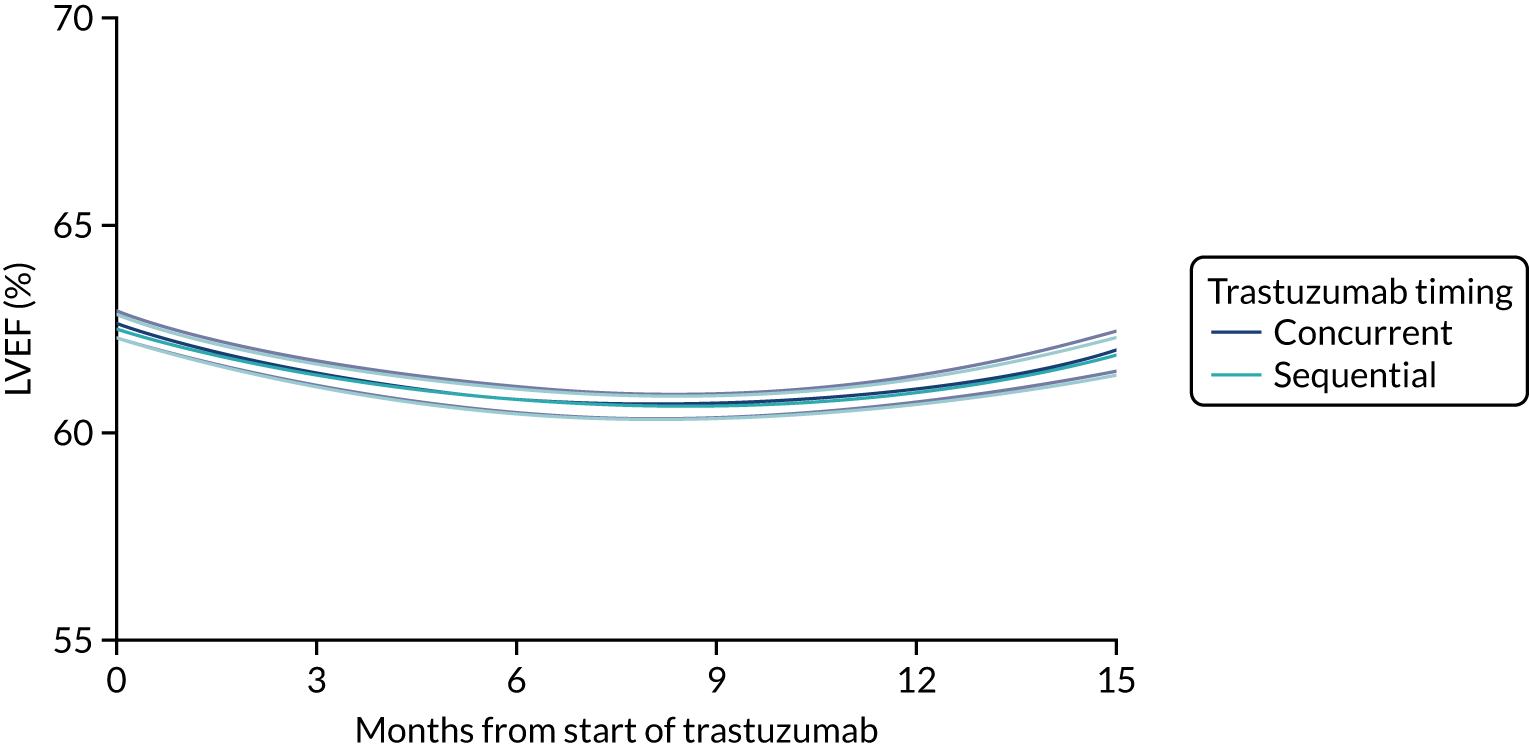

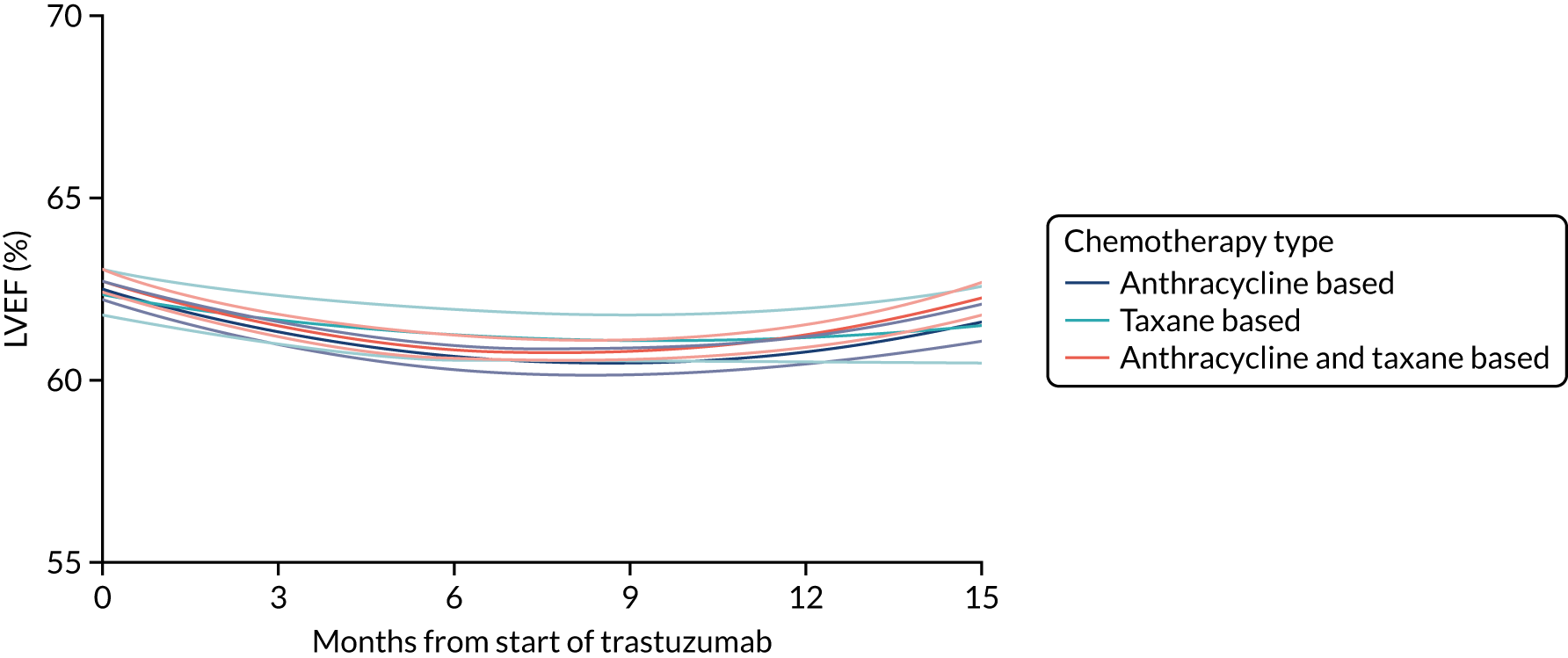

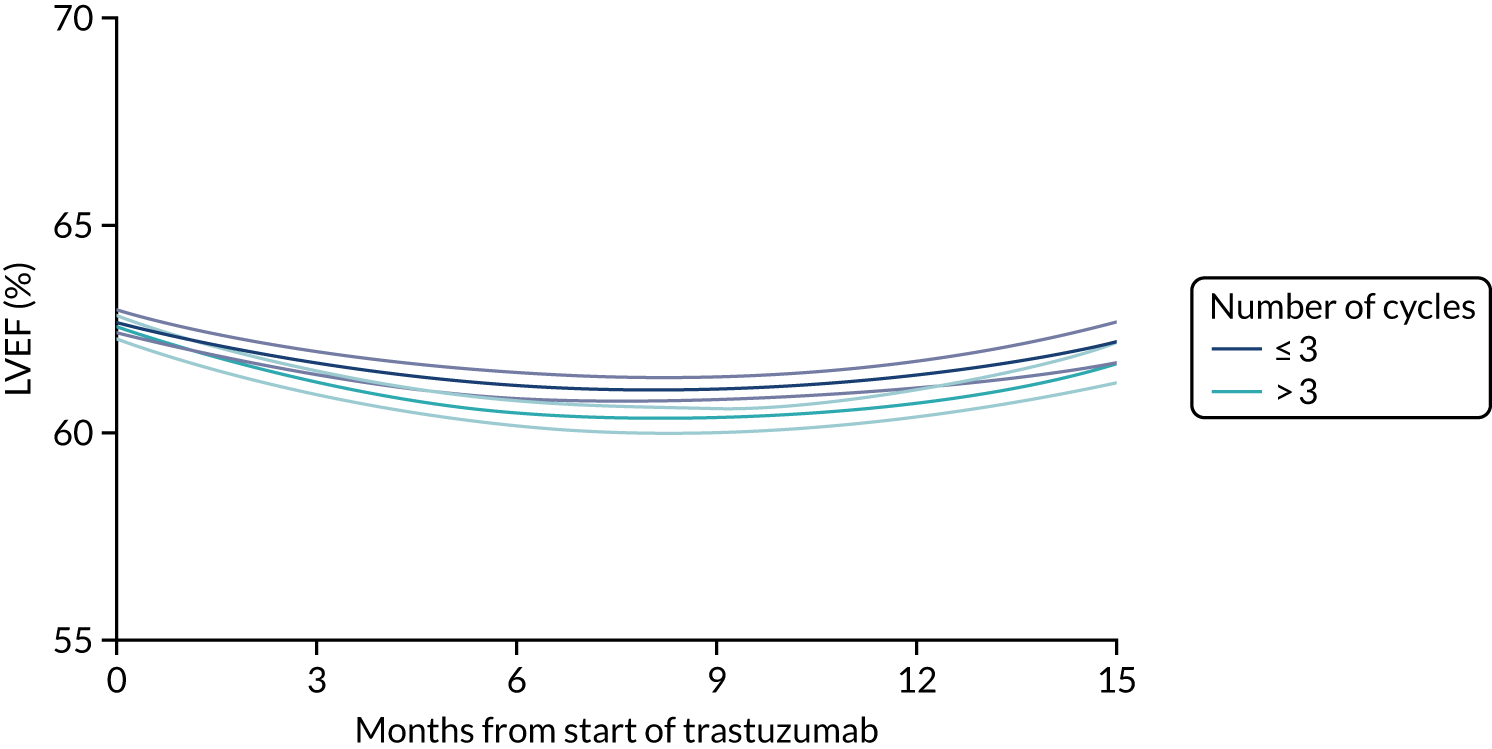

Cardiac function as assessed by LVEF during trastuzumab therapy, and analysis of predictive factors of development of cardiac damage.

Secondary objectives: substudies

-

Trans-PERSEPHONE: tumour blocks (paraffin-embedded) will be collected prospectively from patients in the study for molecular and candidate gene analysis as prognostic and predictive markers (separate protocol).

-

Trans-PERSEPHONE-SNPs: blood samples will be collected prospectively from patients in the study for single nucleotide polymorphism analysis to research genetic/pharmacogenetic determinants of inherited susceptibility to HER2-positive breast cancer, prognosis and trastuzumab response and toxicity (separate protocol).

Research hypotheses

-

Six months’ trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer is non-inferior to 12 months’ trastuzumab, which is the standard treatment.

-

The incremental cost-effectiveness of 6 months’ trastuzumab is significant when compared with 12 months’ trastuzumab.

-

Six months’ trastuzumab is significantly less toxic than 12 months’ trastuzumab in terms of clinical cardiac dysfunction, LVEF decrease, and rates of stopping treatment early for reasons of cardiac toxicity.

Study conduct

Sponsorship

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Cambridge are joint sponsors of PERSEPHONE.

Ethics, regulatory and research and development approvals

The trial was approved by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on 10 May 2007 and received a favourable opinion from the North West – Haydock Research Ethics Committee (REC) (previously named North West REC and then North West 5 REC – Haydock Park) on 9 August 2007. Local research and development department approval was obtained at each participating NHS trust before patients were randomised. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use,27 Good Clinical Practice (GCP),28 UK legislation,29,30 Cambridge and Warwick Clinical Trials Units Standard Operating Procedures and the REC and MHRA approved protocol. The current trial protocol is available online at the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit website. 31

Management of the trial

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, statisticians, translational scientists and patient advocates who had considerable expertise in all aspects of trial design, conduct, safety, quality assurance and analysis. This group was in charge of running the trial. The TMG met regularly by teleconference to discuss site set-up, recruitment targets, safety and all matters pertaining to efficient conduct of the trial. After recruitment was completed, the focus of the TMG was data collection and case report form (CRF) completion.

The overall supervision of the trial was provided by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) appointed by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (the funder of the PERSEPHONE trial). The independent TSC consisted of an independent chairperson (an oncologist) and two other independent members (a breast surgeon and a statistician) and members of the TMG. The NIHR HTA programme and the independent TSC monitored the trial conduct and progress through regular reports, face-to-face meetings and teleconferences about the trial.

The independent monitoring of the trial was undertaken by the independent DSMC, which was established to advise the independent TSC if there was evidence that or a reason why the trial should be amended or terminated based on recruitment rates or safety and efficacy. Reports containing recruitment, protocol compliance, safety data and interim analyses of outcomes (which were confidential and not shared with the investigators) were presented regularly for review along with results from other relevant trials. At each review, the independent DSMC considered whether or not the trial should be stopped prematurely for ethical or safety reasons, including unexpected frequency or severity of toxicity, early indication of an inferior outcome in the experimental arm, unsatisfactory futility analyses or the publication of new data.

At the design stage of the PERSEPHONE trial, it was agreed with the PHARE TMG that one member of the independent DSMC would serve on both trials’ independent DSMCs, with their roles and responsibilities clearly defined for each committee. Details of the membership of the independent TSC, TMG and independent DSMC can be found in the Acknowledgements.

Trial site set-up

A total of 158 hospitals from NHS trusts and health boards in England, Scotland and Wales participated in PERSEPHONE and 152 sites recruited patients (96%); three were screening sites only and three were opened for the purposes of patient follow-up only. A list of all participating sites can be found in the Acknowledgements. Before a site was activated to recruitment, a trial initiation meeting was held, in person or via teleconference, to provide study-specific training to all staff members working on the trial. Continued support was offered to both existing and new staff at participating sites to ensure that they remained fully aware of the trial procedures and requirements.

Monitoring

Several levels of monitoring were applied through the trial.

Remote monitoring of sites was carried out on several occasions and especially after amendments to ensure that the investigator site file (containing the instructional materials and documentation required for the conduct of the trial) was well maintained.

Central monitoring of all data was carried out throughout the trial. Data were routinely cleaned, and queries were sent to sites if needed after (1) automatic validation checks during data entry, (2) manual checks (discrepancies between forms) or (3) annual data freeze to generate interim data-cleaning reports.

To ensure that sites were competent, triggered on-site monitoring was carried out occasionally if serious breaches and/or safety issues were reported.

Since 2010, the sponsor’s regulatory team has been monitoring Addenbrooke’s Hospital on an ongoing 6-monthly basis. Addenbrooke’s has been the highest recruiter throughout the trial. Monitoring involves source data verification for consent, eligibility criteria, LVEF and SAEs. It also includes reviewing the investigator site and pharmacy files. Concurrently, the trial master file held by the Cambridge co-ordinators is reviewed, with a particular focus given to any SAEs and non-compliances reported by all participating sites.

The Warwick trial management file of the PERSEPHONE trial was audited by the MHRA in 2012 and the Cambridge trial management file was reviewed by an independent auditor on behalf of the sponsor in 2015. No critical findings were identified following these reviews.

Patient information and informed consent

Patients potentially eligible to participate in the trial according to the criteria (see Participants) were identified either during a multidisciplinary breast cancer meeting held at each of the sites or, more occasionally, from clinic lists if chemotherapy had already started.

Patients were invited to participate in PERSEPHONE during consultations in oncology clinics, where systemic treatment options were discussed. Here the local principal investigator or co-investigator, or another sufficiently trained individual at the discretion of the principal investigator, discussed the trial with the patient and provided her with a copy of the patient information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Patients were given sufficient time (at least 24 hours) to discuss participation in the trial with their family, friends and general practitioner (GP) and had the opportunity to ask questions. Patients who were willing to participate were asked to provide written informed consent (see Report Supplementary Material 1) to the principal investigator, co-investigator or other sufficiently trained individual.

Since 2010, consent for sample collections has been included in the main patient information sheet/consent document and made mandatory. This covers a blood sample and the use of the patient’s tissue archival samples removed at the time of surgery (and at diagnosis for neoadjuvant patients). The information and consent related to the collection of quality-of-life data are in a separate optional document.

HER2 testing

HER2 testing was carried out and reported in accordance with the UK Royal College of Pathologists’ HER2 testing guidelines. At the start of the trial, these were the 2004 guidelines,32 which were updated in 200833 and 2014. 34 All laboratories testing for HER2 on samples from NHS patients are required to carry out testing in accordance with this guidance and to be part of the National External Quality Assurance Scheme for both immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridisation (ISH). In the lifetime of the trial for recruitment (October 2007 to July 2015), three different guidelines were followed, depending on when a patient entered into the trial.

The 2004 guidelines32 for semiquantitative IHC stated that breast cancer samples should be considered to be HER2 positive if, on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections, strong, positive, complete membrane staining is apparent in > 10% of cancer cells. IHC was to be considered negative if there was no membrane staining (IHC score of 0), if < 10% tumour cells had membrane staining (IHC score of 0) or if > 10% tumour cells had membrane staining that was faint/barely perceptible and incomplete (IHC score of 1+). IHC was to be considered borderline (IHC score of 2+) when membrane staining was weak to moderate and present in > 10% of tumour cells. According to the guidelines, an IHC score of 2+ should be followed by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) and conventionally expressed as the ratio of HER2 signal to chromosome 17 signal (HER2 ratio). Tumours showing a ratio of ≥ 2 were considered positive and those with a ratio of < 2 were considered negative regardless of HER2 copy number.

The guidelines were updated in 2008. 33 Minimum workload recommendations were introduced and laboratories were required to perform at least 250 assays per year for IHC and 100 assays per year for ISH. IHC scores of 0 and 1+ were the same as in the 2004 guidelines. The cut-off point for IHC 3+, indicating a positive result, was increased to > 30% of cells with strong, complete membrane staining. The IHC 2+ category was expanded to include cases with 10–30% strong complete staining in addition to the previous definition of > 10% moderate staining. Categories for ISH and gene amplification were refined. A HER2 ratio of < 1.80 was considered HER2 non-amplified (negative). A HER2 ratio of 1.80–2.20 or HER2 gene copy number 4.0–6.0 signals/cell was considered borderline and the test was carried out again. If the HER2 ratio was 1.80–1.99, the tumour was considered non-amplified and therefore HER2 negative, and if the HER2 ratio was 2.00–2.20, the tumour was considered amplified and therefore HER2 positive; this was a subtle difference from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists guidelines, which did not further clarify the FISH borderline group. If the HER2 ratio was > 2.20 or the HER2 gene copy number was > 6.0 signals/cell, then the tumour was considered amplified and positive.

Further updates of the guidelines in 201434 redefined an IHC score of 3+ as > 10% strong, complete membrane staining, the same as in the 2004 guidelines. ISH was considered negative with a HER2/CEP17 ratio using a dual probe of < 2.0 and an average HER2 gene copy number of < 4.0 signals/cell. In tumours that were IHC 2+ (borderline), ISH testing was required. In these cases ISH was considered borderline/non-amplified when a dual probe HER2/CEP17 ratio was < 2.0 with either an average HER2 gene copy number of 4.0–6.0 signals/cell or a ratio of 1.80–1.99. In these cases the test was repeated and if the same result was obtained the tumour was regarded as HER2 negative, whereas a dual-probe HER2/CEP17 ratio of ≥ 2.0 or an average gene copy number of ≥ 6.0 signals/cell was considered to indicate HER2-positive cancer.

These changes over the course of the study would have affected only a small percentage of cases. In a review of the pooled data from the BCIRG breast cancer clinical trials, 0.5% of cases had a ratio of < 2.0 and a HER2 gene copy number of ≥ 6.0 (changed from negative to positive in 2008). 35

Screening and randomisation procedures

Sites were asked to screen patients with early breast cancer for their eligibility for the PERSEPHONE trial. We requested that screening logs be completed for all patients who were considered for the PERSEPHONE trial. We asked sites to record on the screening logs the date of screening, the patient’s date of birth, if the patient gave consent, if the patient was randomised and, in the event of patients not being consented or randomised, the reasons. These screening logs were requested from sites every 6 months for 6 years, and then annually for the last 2 years of recruitment.

The trial was an open-label, unblinded trial. Following the assessment of their eligibility during screening and collection of their written informed consent to be entered into the trial, patients were randomised (1 : 1) to either 12 months of trastuzumab (the standard treatment, comprising 18 cycles) or 6 months of trastuzumab (the experimental arm of the trial, comprising nine cycles). Randomisation was carried out by staff at each site telephoning the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit, where a central computerised minimisation procedure used the following stratification variables: ER status (positive or negative); chemotherapy type (anthracyclines without taxanes, anthracyclines with taxanes, taxanes without anthracyclines or neither anthracyclines nor taxanes); chemotherapy timing (adjuvant or neoadjuvant); and trastuzumab timing (concurrent or sequential).

Trial treatment and settings and locations

The trial treatment is trastuzumab and it is considered an Investigational Medicinal Product for the purpose of the PERSEPHONE trial, which is conducted with a Clinical Trial Authorisation in the UK.

Route

Trastuzumab was given intravenously to all patients until 2013, when the subcutaneous formulation became available in NHS hospitals.

Following the approval of amendment 11 by the MHRA at the end of 2013, the PERSEPHONE trial allowed participating sites to use the subcutaneous formulation. Switching between intravenous and subcutaneous administration was at the discretion of the treating clinician.

Setting

Trastuzumab was prescribed neoadjuvantly (pre surgery) or adjuvantly (post surgery).

Trastuzumab was prescribed with chemotherapy (concurrently) or post chemotherapy (sequentially). The PERSEPHONE trial recruited patients in both settings.

Dose

Patients were randomised to:

-

research arm – to receive nine cycles of trastuzumab (6-month arm)

-

standard arm – to receive 18 cycles of trastuzumab (12-month arm).

Each cycle had a 3 week duration with a loading dose given on day 1. Treatment was expected to be administered as per standard practice.

Intravenous route

The starting/loading dose of trastuzumab was 8 mg/kg.

The maintenance dose (6 mg/kg) was given 3 weeks after the starting/loading dose, and subsequent doses were given 3-weekly at 6 mg/kg.

Subcutaneous route

There is no loading dose for subcutaneous trastuzumab administration. Subcutaneous trastuzumab was given at a fixed dose of 600 mg in a volume of 5 ml as per the summary of product characteristics (SmPC).

Trastuzumab doses

The trial mapped on to standard practice and guidelines for dosing followed the SmPC for trastuzumab. In terms of cardiac guidelines, measurement of LVEF using either echocardiography (ECHO) or a multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan was recommended. At the start of the trial this was carried out every 3 months for 1 year in both arms, and then, after a protocol amendment, the interval between ECHO or MUGA scans was increased to 4-monthly. The guidance in the SmPC was to hold trastuzumab if LVEF fell by an absolute value of ≥ 10% below baseline and to < 50%. Cardiac medication could be started by the principal investigator; measurement of LVEF was repeated after 6 weeks, and trastuzumab could be restarted if LVEF was > 50%. The protocol stated that the maximum hold of trastuzumab for cardiac problems should be 12 weeks. If trastuzumab was restarted, then a reloading dose of 8 mg/kg intravenously was to be used with a delay longer than 7 days. In the second half of the study, some sites adopted new national guidelines to use cardiac medication and continue trastuzumab if the patient was asymptomatic and LVEF was > 40%. 36

Treatment location

Most patients were treated in chemotherapy units. However, to relieve these very busy hospital-based facilities, some participating sites started to administer trastuzumab outside chemotherapy units. Some patients were treated at home by an external clinical provider (Healthcare at Home Ltd). A few PERSEPHONE patients were treated in a GP surgery or a mobile unit (chemotherapy bus). As long as this was part of the standard practice at the site, it was allowed once the trials office had given its approval and made sure that the appropriate contracts, training and safety measures were in place.

Other treatments

Chemotherapy: commonly used regimens

Details of the chemotherapy regimens received by all patients (as per local institutional protocols) and whether trastuzumab was given concurrently with or sequentially to their chemotherapy were recorded in full, along with reasons for any early cessation of chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens were based on local protocols, which were informed by both licensing and NICE guidance.

Endocrine therapy

For women with ER-positive disease, systemic hormonal therapy is advised following completion of chemotherapy and definitive surgery. Concurrent hormone therapies could be administered with trastuzumab, although not with chemotherapy. The PERSEPHONE protocol stated that all endocrine therapy was at the discretion of the responsible clinician in accordance with standard local therapy protocols. However, the following guidelines were suggested: for women who remained pre-menopausal after completing chemotherapy, hormonal therapy options included ovarian suppression and tamoxifen. Entry into the Breast International Group EORTC trials SOFT (Suppression of Ovarian Function With Either Tamoxifen or Exemestane Compared With Tamoxifen Alone in Treating Premenopausal Women With Hormone-Responsive Breast Cancer Trial) or TEXT (Triptorelin With Either Exemestane or Tamoxifen in Treating Premenopausal Women With Hormone-Responsive Breast Cancer) was suggested. For postmenopausal women, tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors could be used for a minimum of 5 years (or tamoxifen for 2–3 years, switching to an aromatase inhibitor after 2–3 years). Adjuvant hormonal treatment received by the patient was recorded.

Surgery

The PERSEPHONE protocol did not stipulate surgery as part of the trial. Surgery was carried out in accordance with standard practice at each site. Primary surgery was carried out in all patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab, mostly consisting of either wide local excision and axillary surgery (sentinel lymph node biopsy with or without axillary nodal dissection) or mastectomy and axillary surgery. Some patients in the trial received neoadjuvant treatment, and in these patients definitive surgery with wide local excision or mastectomy and axillary surgery took place after chemotherapy was completed.

Radiotherapy

The PERSEPHONE protocol stipulated that radiotherapy should be given after definitive surgery according to local protocols. Radiotherapy could be given concurrently with trastuzumab. All radiotherapy treatment received by the patient was recorded.

Participants

The trial sought to recruit patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer who were or would be receiving trastuzumab. Patients were recruited from oncology departments in NHS hospitals covering England, Scotland and Wales.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with the following characteristics were eligible to enter the trial:

-

A histological diagnosis of invasive breast cancer.

-

No evidence of metastatic disease.

-

Known hormone receptor status.

-

Overexpression of HER2 receptor. Bilateral breast cancers were eligible provided that one of the tumours overexpressed the HER2 receptor.

-

Clear indication for neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy based on clinical and histopathological features.

-

Fit to receive neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab in the opinion of the responsible physician.

-

No previous diagnosis of malignancy unless:

-

managed by surgical treatment only, and disease free for 10 years

-

previous basal cell carcinoma, cervical carcinoma in situ or ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast.

-

-

Not pregnant and not lactating, with no intention of becoming pregnant during chemotherapy, and agreed to adopt adequate contraceptive measures if pre-menopausal and sexually active.

-

No concurrent medical or psychiatric problems that might prevent completion of treatment or follow-up.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Gave written informed consent for the study at any time before the 10th cycle of trastuzumab.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with the following characteristics were ineligible to enter the trial:

-

significant concurrent cardiac disease or significant concurrent comorbidity in the opinion of the responsible physician adding to the risks associated with trastuzumab or cytotoxic chemotherapy

-

unable to comply with protocol requirements

-

received more than nine cycles of trastuzumab

-

any other condition that, in the local investigator’s opinion, would make them unsuitable to participate in the trial.

Data collection

Schedule of assessments

Table 2 shows the schedule of assessments for patients considered for entry into the PERSEPHONE trial prior to randomisation, as well as for patients during their treatment and follow-up. Most of the assessments for PERSEPHONE were mapped on to standard practice.

| Event | Prior to randomisation | Trastuzumab treatment visit (every 3 months for a year after starting trastuzumab treatment; patients in the research arm MUST follow the same follow-up schedule as those in the standard arm) | Follow-up visits (every 6 months in year 2; annually thereafter for 8 years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent for trial | ✗ | ||

| ER status | ✗ | ||

| HER2 status | ✗ | ||

| Full blood count | ✗ | ||

| Biochemical screen | ✗ | ||

| Chest X-ray (or chest CT if standard practice) | If suspicion of metastases | ||

| Whole-body scintigraphy and liver ultrasound or abdominal CT scan | If suspicion of metastases | ||

| Medical history | ✗ | ||

| Physical examination, weight | ✗a | ✗a | ✗a,b |

| LVEF assessment | Done as per standard practice | ✗c | |

| ECOG performance status | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quality of life questionnaire | ✗d | ✗e | ✗f |

| Health-care resource used assessment questionnaire | ✗d | ✗e | ✗f |

| SAEs | ✗ | ||

| Survival/recurrence disease status | ✗ | ✗ | |

Toxicity

Based on the available data on the frequency of toxicities experienced with trastuzumab treatment, the 4000 patients recruited to PERSEPHONE were expected to adequately power the analysis of toxicity to allow detection of any clinically relevant differences between the treatment arms, if they existed.

A change in the eligibility criteria for PERSEPHONE was implemented on 11 September 2009 (after 316 patients had been randomised) to allow patients to be randomised before receiving their 10th cycle of trastuzumab. In the case of patients randomised into PERSEPHONE after the start of their trastuzumab treatment, we did not collect information on the toxicities or SAEs experienced during any treatment administered prior to randomisation. In the case of patients randomised before starting trastuzumab, we planned to collect all toxicities and SAEs experienced during their entire treatment.

Cardiac toxicity

Patients were assessed for symptoms or signs of congestive heart failure and information on new or altered cardiac medication was recorded during follow-up visits while on trastuzumab. Cardiac function was assessed using LVEF, either by ECHO or by MUGA scan depending on standard practice at each hospital. As per the recommendations from the trastuzumab SmPC, we requested scans for each patient at baseline and every 3 months for 12 months from the treatment start date. This was revised to standard practice (minimum of 4-monthly) in PERSEPHONE protocol version 4.0 on 31 October 2013.

Translational research collections

In parallel with the NIHR HTA programme funding, Cancer Research UK supported a translational collection of blood and archival tissue samples through the Trans-PERSEPHONE grant. 37 The patient information sheet detailed collection of blood samples and tumour tissue collection (from the surgical specimen in those receiving adjuvant trastuzumab and from the diagnostic biopsy and surgical specimen in those receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy). After patient consent was obtained, blood and tumour samples were requested.

Blood collection for pharmacogenetics/genetics study (Trans-PERSEPHONE-SNPs)

Trans-PERSEPHONE-SNPs aimed to collect two tubes of whole blood (2 × 9 ml) from patients, to be collected on one occasion at any time before, during or after treatment.

The purpose of collecting this was to build a bank of germline deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from breast cancer patients with HER2-positive disease and to carry out germline genome-wide sequencing for pharmacogenetics studies and prognostic and predictive candidate germline mutations. Analysis is planned of (1) germline single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) predisposing to cardiac and other toxicity from trastuzumab, (2) germline SNPs predisposing to HER2-positive breast cancer, and (3) germline SNPs linked to outcomes from adjuvant trastuzumab and any interaction with duration of therapy.

Archival tissue blocks collection (Trans-PERSEPHONE)

Trans-PERSEPHONE is a collection of archival tissue (formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue) from PERSEPHONE patients. As per standard of care, following surgery, several formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks per patient were made at sites for diagnosis purposes. One or two representative block(s) were requested from the site’s pathology department. This bank of HER2-positive tissue is to be used to investigate prognostic and predictive molecular signatures of HER2-positive breast cancer and, in particular, to explore this with respect to treatment duration (comparing 6 and 12 months of treatment). Analysis of tumour and normal tissue will involve (1) tissue microarrays for IHC of protein gene products and in situ hybridisation analysis and (2) whole-genome profiling using expression and DNA microarrays.

Safety

First 100 patients receiving concomitant trastuzumab and chemotherapy

PERSEPHONE had a safety stage built into the trial to confirm that concurrent administration of chemotherapy and trastuzumab was safe within the trial. Data ‘in real time’ on SAEs and treatment delays for the first 100 patients of this cohort were collected and analysed before being discussed by the independent DSMC (see outcome of the safety phase in Chapter 3, First 100 patients receiving concomitant trastuzumab and chemotherapy).

Serious adverse events/reactions

The definition of a SAE for the purpose of the PERSEPHONE trial was any untoward medical occurrence that at any dose resulted in:

-

death

-

a life-threatening experience

-

initial or prolongation of existing hospitalisation (Hospitalisation was defined as an inpatient admission, regardless of length of stay, even if the hospitalisation was a precautionary measure, for continued observation. Hospitalisation for a preexisting condition, including an elective procedure, that had not worsened did not constitute a SAE)

-

persistent or significant disability/incapacity

-

a congenital anomaly/birth defect

-

a new primary malignancy.

-

Any other event that was judged by the responsible investigator to warrant particular attention and for the purposes of the trial included symptomatic LVEF reduction.

Details of all SAEs were documented from the point of randomisation, and therefore not necessarily the start of the trastuzumab treatment, in the trial until 30 days from the last administration of trastuzumab.

SAEs occurring after a patient’s 30-day follow-up assessment were reported only if the investigator believed that the study drug or a protocol procedure may have caused the event.

Each principal investigator was advised to report SAEs using a specific SAE form within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event.

Assessments of all SAEs for expectedness and relatedness were made promptly by the chief investigator. A SAE was deemed to be a serious adverse reaction (SAR) when it was assessed as possibly, probably or likely to be related to trastuzumab.

Listing of SARs was submitted to the MHRA in accordance with national requirements on a yearly basis through development safety update reports/annual safety reports.

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions

When the nature and severity of the SAR was not consistent with the trial reference safety information, the event was unexpected and therefore classified as a suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR).

The reference safety information for the PERSEPHONE trial was the trastuzumab SmPC.

The PERSEPHONE Cambridge office reported SUSARs to the MHRA and REC within 7–15 days as per UK regulations.

Serious breaches

To ensure that appropriate action was taken to protect patients, maintain trial integrity and comply with legal requirements and any applicable regulatory guidance, protocol and GCP non-compliances were collected by the trial office before being assessed by the chief investigator and the sponsor.

Any departure from the protocol or regulatory requirements that was likely to affect to a significant degree either the safety of a trial patient or the scientific value of the trial was classified as a serious breach, queried, followed up and reported to the authorities (MHRA and REC) as per UK legislation.

Discontinuation of trial treatment

Patients’ trial treatment was discontinued in the following circumstances, which were reported on the withdrawal CRF:

-

The patient opted to discontinue their randomised treatment arm or chose not to comply with the trial procedures.

-

The patient was found to be ineligible (i.e. they had been randomised inadvertently without meeting the eligibility criteria).

-

The investigator decided that the patient’s trial treatment should be discontinued because of toxicity.

-

The patient did not recover from treatment-related toxicity to an extent that would have allowed further trastuzumab treatment.

-

The patient had disease progression (radiologically confirmed) while on trial treatment.

-

The patient became pregnant while receiving trial treatment and decided to continue her pregnancy.

-

During trial treatment the patient relocated to a site that was not participating in the trial.

Follow-up data were collected for all patients who discontinued treatment. Treatment data were collected for patients who had withdrawn but continued to receive trastuzumab up to 12 months, unless the patient had withdrawn because of relapse.

Withdrawal of consent

Patients could withdraw their consent to participate in the trial at any time by explicitly refusing to receive any further trial treatment, in which case no further trial treatment was given.

Additionally, patients could withdraw their consent for further data or samples to be collected, in which case no further data or samples were collected. However, data and samples collected up to the time consent was withdrawn were included in the data reported for the trial.

Database and data processing

The PERSEPHONE database is held at Warwick Clinical Trial Unit on a Microsoft SQL Server 2012 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) system with imposed rules for data entry, which include a valid range for responses, linked dates and patient identification numbers.

Data were single entered into the database by trained study personnel. The trial statistician carried out checks for missing data and plausibility of entered values to enable further queries to be resolved before freezing the data for scheduled analyses.

Protocol amendments

Protocol amendments as well as amendments to key documents such as the patient information sheet and informed consent forms were reviewed by the REC and/or the competent authority before these amendments were implemented. The amendments were also approved locally by sites’ research and development departments.

The key amendments are listed below.

Protocol amendment February 2009

In February 2009, version 2.0 of the protocol was submitted to the authorities. The alterations were to remove limitations of and offer more flexibility in the chemotherapy criteria and options available to patients, such as using the company Healthcare at Home Ltd to administer trastuzumab at patients’ domiciles.

Protocol amendment July 2009

In July 2009, a major amendment was made to the protocol to change randomisation to any point up to and including cycle 9 of the trastuzumab (6 months). Recruitment had been lower than expected and, after extensive consultation with the TMG, TSC, the PHARE group (French trial) and the funder, it was agreed that this was the best option to increase recruitment. As a result of this, changes to the health economic data collection were also made, streamlining it to the patient questionnaires. Detailed health resource use data were collected for the first 300–500 patients only, rather than for all 4000 patients. Mapping the trial on to standard practice also significantly reduced data collection for sites.

Protocol amendment July 2010

A new patient information sheet was designed and submitted to the authorities in July 2010 to improve patient acceptability. Not only was accrual less than expected, but < 60% of the patients consented for the translational substudies, which was lower than in other studies we have conducted. Both the TSC and the patient groups who were contacted for advice strongly believed that (1) the original patient information sheet was too long and complex and (2) when patients agreed to take part in the trial, the substudies should be incorporated into the study as a whole. The TMG, together with patient advisors, therefore developed a more patient-friendly patient information sheet that incorporated the two translational substudies.

Protocol amendment October 2013

The protocol was amended again in October 2013, mainly to reflect the changes to the environment of the trial:

-

A full update on recently published data was added to the introduction of version 4.0 of the protocol.

-

The long-term follow-up data of the HERA trial12 confirmed the significant benefit for 12 months’ trastuzumab compared with no trastuzumab control at median follow-up of 96 months (8 years) but also demonstrated that 24 months’ trastuzumab brought no additional benefit to 12 months’. Interestingly, had the trial been analysed and reported after only 36 months, a benefit of 24 months’ trastuzumab would have been found. However, with longer follow-up, both the 12- and the 24-month DFS and OS curves are identical.

-

Despite a relatively short follow-up, the preliminary results of PHARE were published and showed that the trial had not proven non-inferiority after a median follow-up of 42 months. The PHARE results23 did show that, in a prospectively stratified analysis of subgroups, only patients with ER-negative disease receiving sequential chemotherapy and trastuzumab appeared to be significantly disadvantaged by receiving 6 months of trastuzumab. An examination of the mature DFS and OS curves from the HERA trial shows a clear separation of the 24-month and 12-month curves after 36 months, which resolves with more prolonged follow-up. This time point was the same as that at which PHARE had been analysed.

In addition, following scrutiny of the published PHARE data, the PERSEPHONE Independent Data Monitoring and Safety Committee confidentially examined the data in the PERSEPHONE trial. As a result of this, the committee advised the TMG and Trial Steering Group that there were no adverse signals in the PERSEPHONE trial data and that the trial be continued.

-

The equivalence of the subcutaneous formulation of trastuzumab and the intravenous formulation was reported38 and therefore version 4.0 of the protocol stated that the use of the subcutaneous formulation was allowed.

-

This low-risk trial was made flexible, with the aim of making it as pragmatic as possible (i.e. following standard practice to facilitate recruitment). In particular, cardiac function, which was initially assessed every 3 months for 12 months, was subsequently evaluated at intervals up to 4-monthly in accordance with a change in standard practice guidelines. 36

Protocol amendment December 2018

Protocol version 5.0 included changes to account for the European Union General Data Protection Regulation, revised trial timelines and permission to follow up patients using sites’ standard practice, which could include telephone and e-mail follow-up.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 software. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.

Non-inferiority design

The non-inferiority design of clinical trials was introduced to evaluate new treatment approaches, drugs, devices, biologics and other medical treatments to demonstrate whether or not a new treatment is a ‘good substitute’ (i.e. has similar efficacy to that of an established treatment). 39 Increasing in use by a factor of 6 over a 10-year period, this design is especially useful when evaluating whether a new treatment offers greater safety, reduced toxicity and reduced cost, together with confirmation that efficacy is not effectively compromised. It is the favoured design for trials in oncology that seek to de-escalate treatments by reducing either the duration or the intensity and therefore reduce toxicity, improve safety and improve patient experience. Cancer trials that have used this design include the IDEA meta-analysis,40 which established that 3 months rather than 6 months of an adjuvant capecitabine/oxaliplatin regimen for colorectal cancer is non-inferior and significantly less toxic. The non-inferiority of outcomes for head and neck cancer was demonstrated for positron emission tomographic scanning surveillance followed by radical dissection if demonstrated positron emission tomographic scanning positive or equivocal results, rather than routine radical neck dissection. 41 The TAILORx study used a non-inferiority design to compare adjuvant chemotherapy and endocrine therapy with endocrine therapy alone in women with ER-positive, HER2-negative, node-negative breast cancer and a moderate recurrence risk (score of 11–25) on a genomic test (OncotypeDx; Genomic Health, Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA). The trial demonstrated that endocrine therapy alone was non-inferior to adjuvant chemotherapy with endocrine therapy. 42 All of the trials examining reduced durations of trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer have used non-inferiority designs. 23–26

Sample size and non-inferiority limit/margin

The PERSEPHONE trial was designed to allow the non-inferiority of the experimental arm (6 months’ trastuzumab) compared with the control arm (12 months’ trastuzumab) to be demonstrated in terms of the primary end point of DFS. The power calculations assumed that the DFS of the standard treatment of 12 months’ trastuzumab would be 80% at 4 years as this was the result available from the HERA trial. 10 The margin for non-inferiority was set as a 3% level, implying that the 4-year DFS of the experimental arm should not be below 77%, a difference equivalent to a HR of 1.17. On this basis, with 5% one-sided significance and 85% power, a trial randomising 4000 patients in total (2000 to each arm) would be able to prove the non-inferiority of the experimental arm.

The trial was expected to recruit for 4 years, with an additional follow-up period of 5 years, and allowed for loss to follow-up of up to 4%. The sample size was calculated by simulation assuming unadjusted analysis with a Cox’s proportional hazards model. The sample size also allowed for the 4-year DFS rate of the control arm to vary between 77% and 83%. The independent DSMC monitored the assumptions underlying the sample size calculation throughout the study.

Statistical methods

All randomised patients were included in all analyses where possible. Patients were analysed according to the treatment group to which they had been randomised on an intention-to-treat basis. Analyses were guided by the PERSEPHONE statistical analysis plan, which was prepared before data were available, and subsequently agreed by the PERSEPHONE independent DSMC.

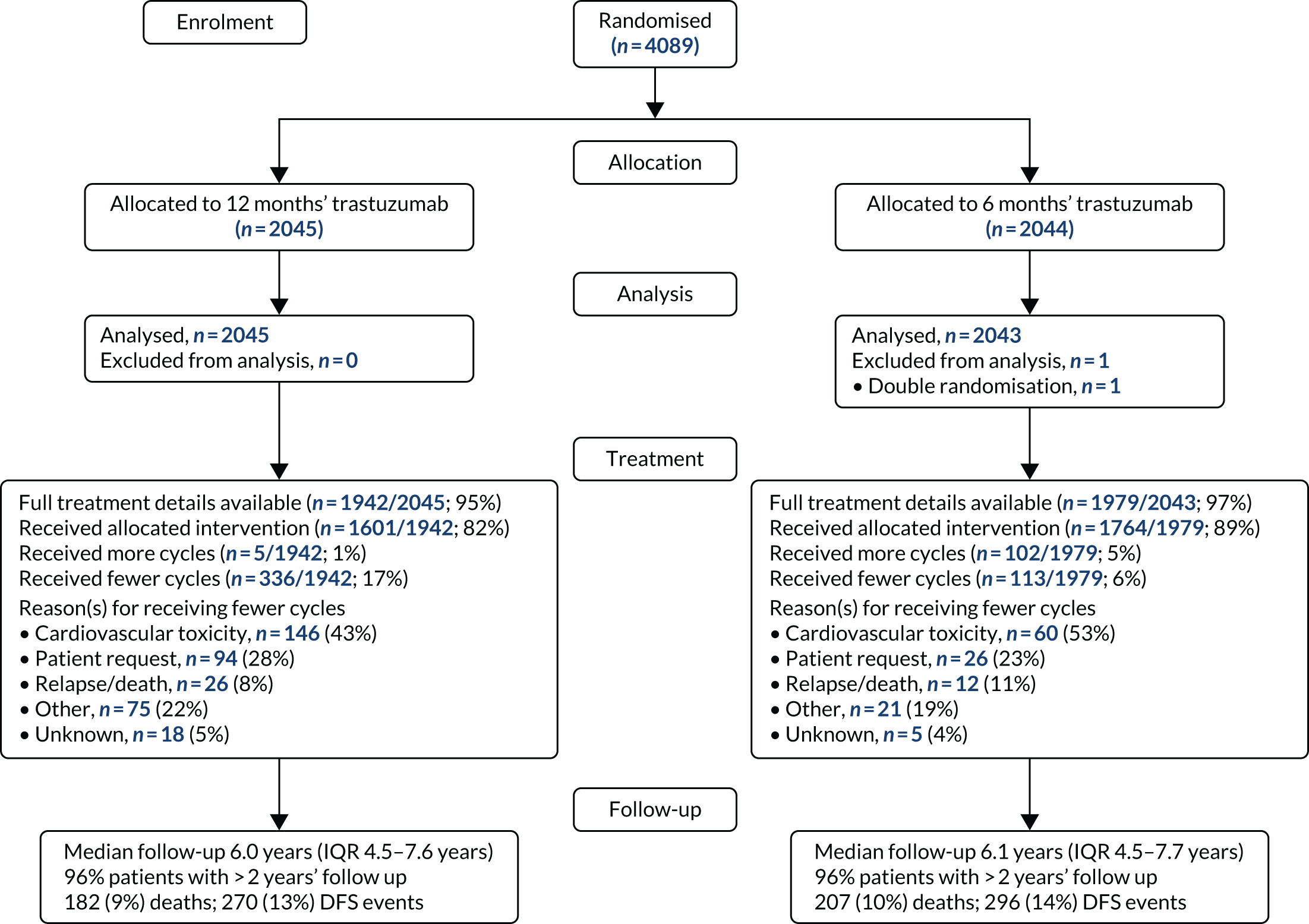

Patient and tumour characteristics were presented to evaluate the comparability of the treatment arms and also the generalisability of the results to clinical settings. Categorical variables were presented using counts and percentages, and continuous variables were presented using either mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median [interquartile range (IQR)] depending on normality, and all were tabulated by treatment arm. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram43 was also presented (see Chapter 3).

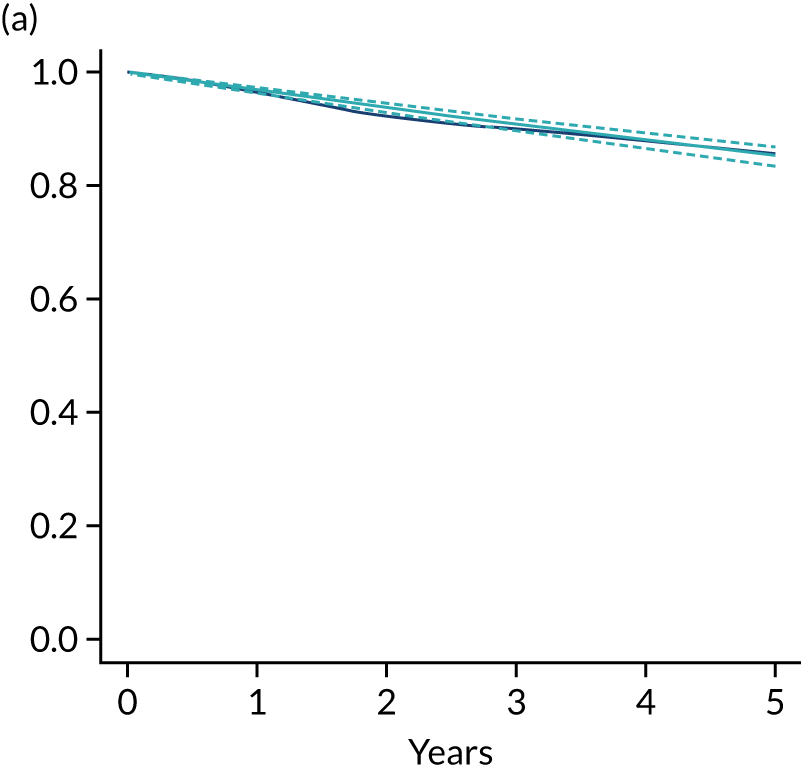

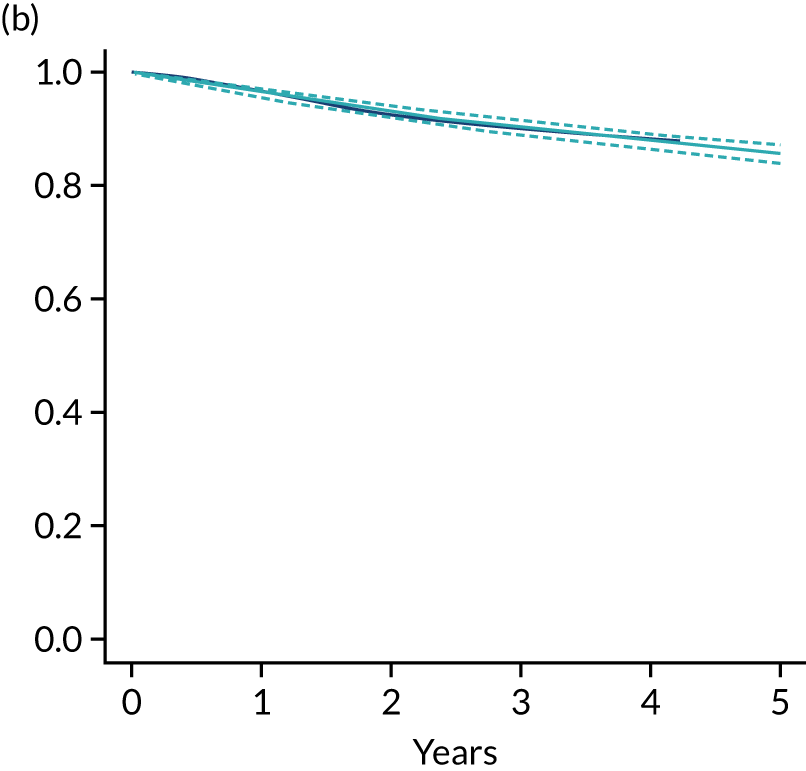

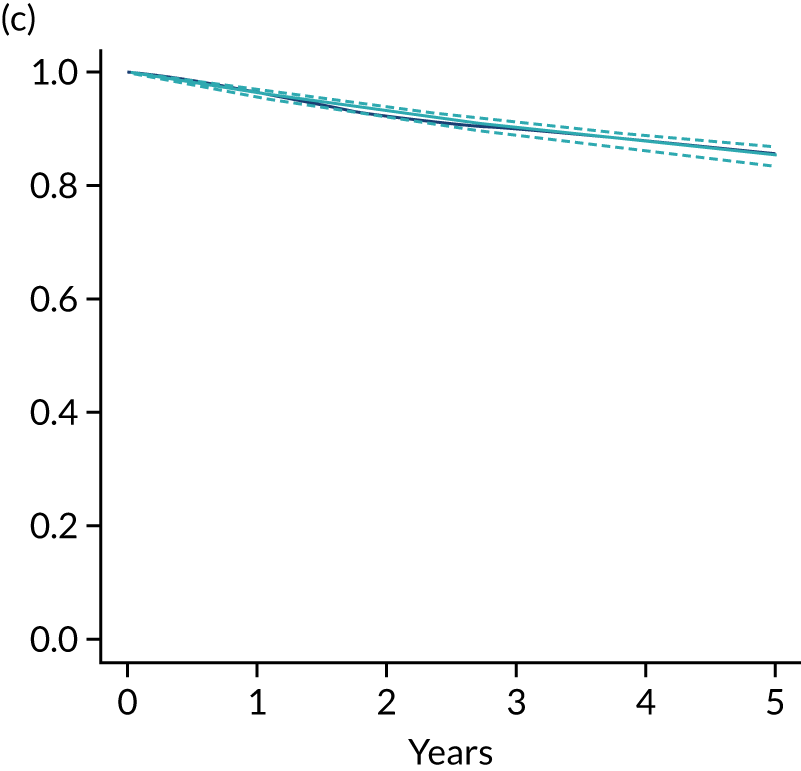

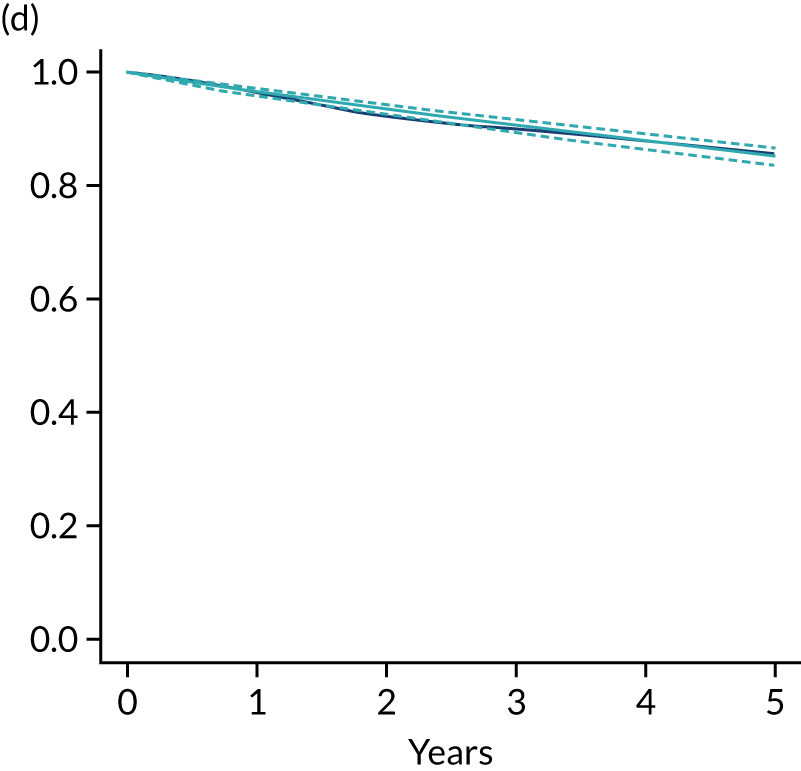

Primary end point: disease-free survival

The primary end point of DFS was measured for every patient from the date of diagnosis to date of first relapse (local or distant) or death. Patients who were disease free and either on follow-up or lost to follow-up were censored at the latest date at which they were known to be alive and disease free. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method. Non-inferiority was defined as no worse than 3% below the control arm’s 4-year DFS rate. To test the non-inferiority of the experimental arm (i.e. 6 months’ trastuzumab), the HR was estimated using a Cox’s proportional hazards model containing only the trial treatment effect. If the 95th percentile of the estimated HR was less than the critical value, then the experimental arm (6 months’ trastuzumab) was regarded as non-inferior. Critical values were calculated for different scenarios with regard to the observed 4-year DFS on the control arm, as follows:

-

With a 4-year DFS on the control arm of 80%, the critical value to be used was 1.1712853.

-

With a 4-year DFS on the control arm of 85%, the critical value to be used was 1.2210943.

-

With a 4-year DFS on the control arm of 88%, the critical value to be used was 1.2713341.

-

With a 4-year DFS on the control arm of 90%, the critical value to be used was 1.3217671.

Proportionality of hazards was checked using an assessment of log–log plots.

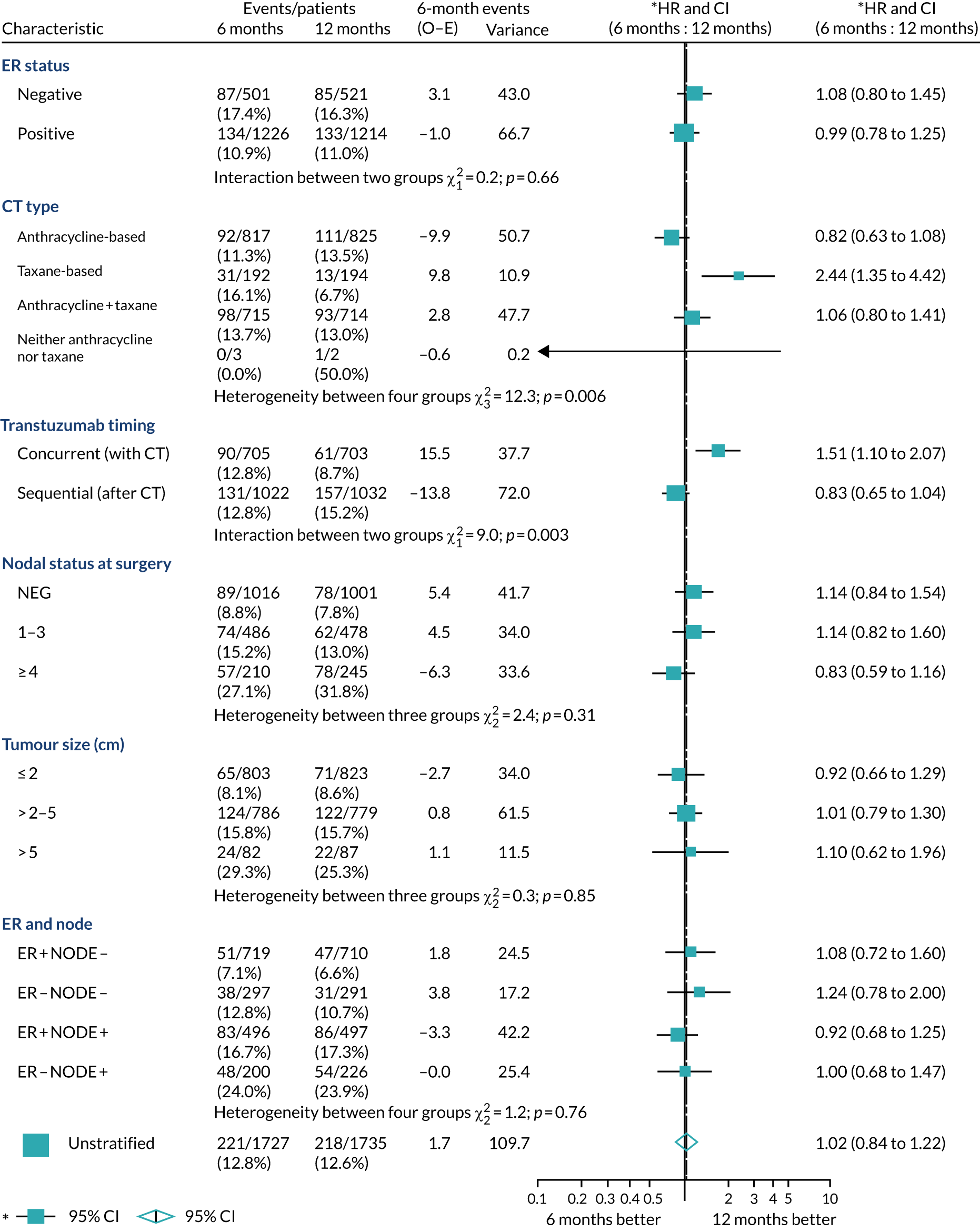

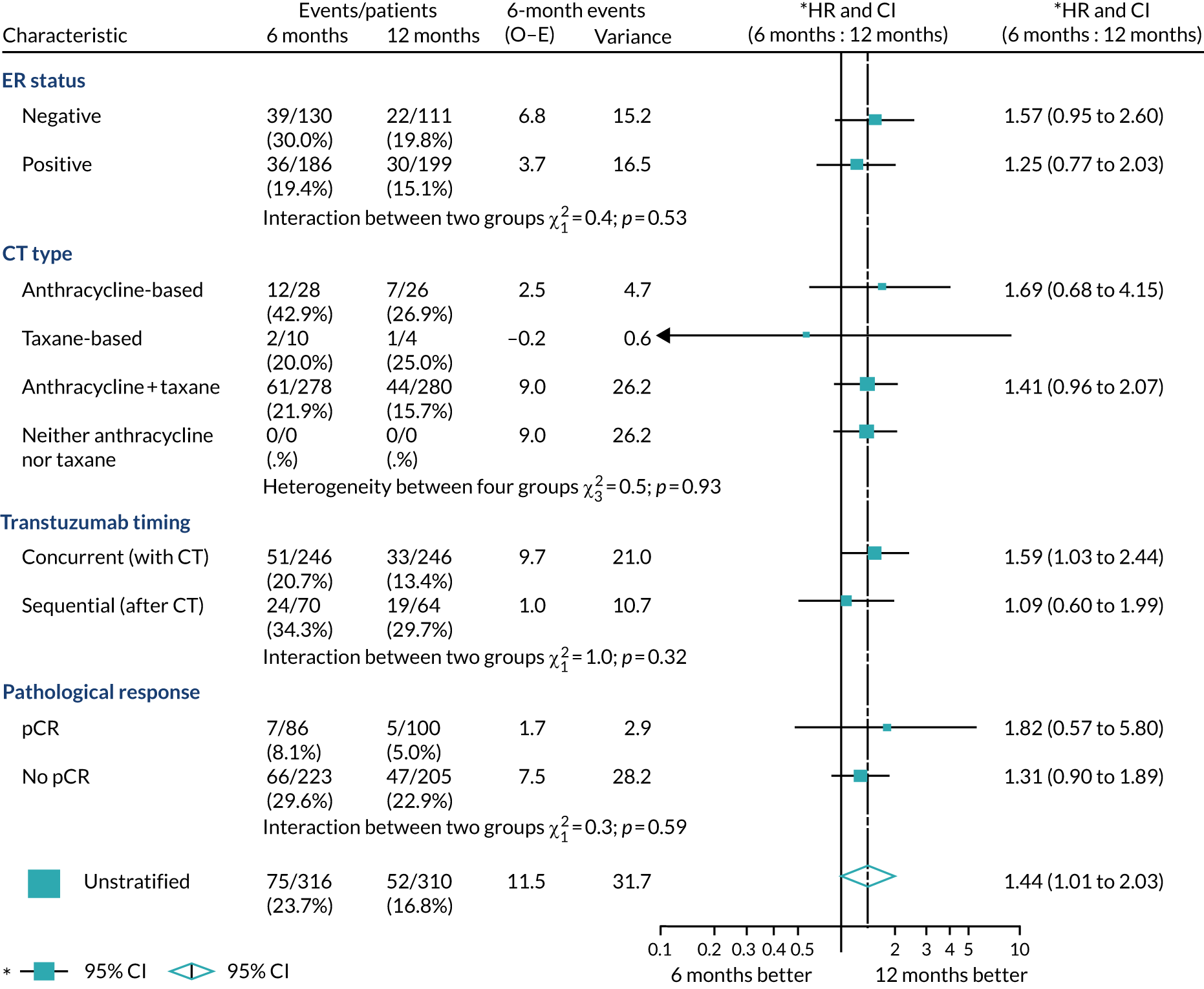

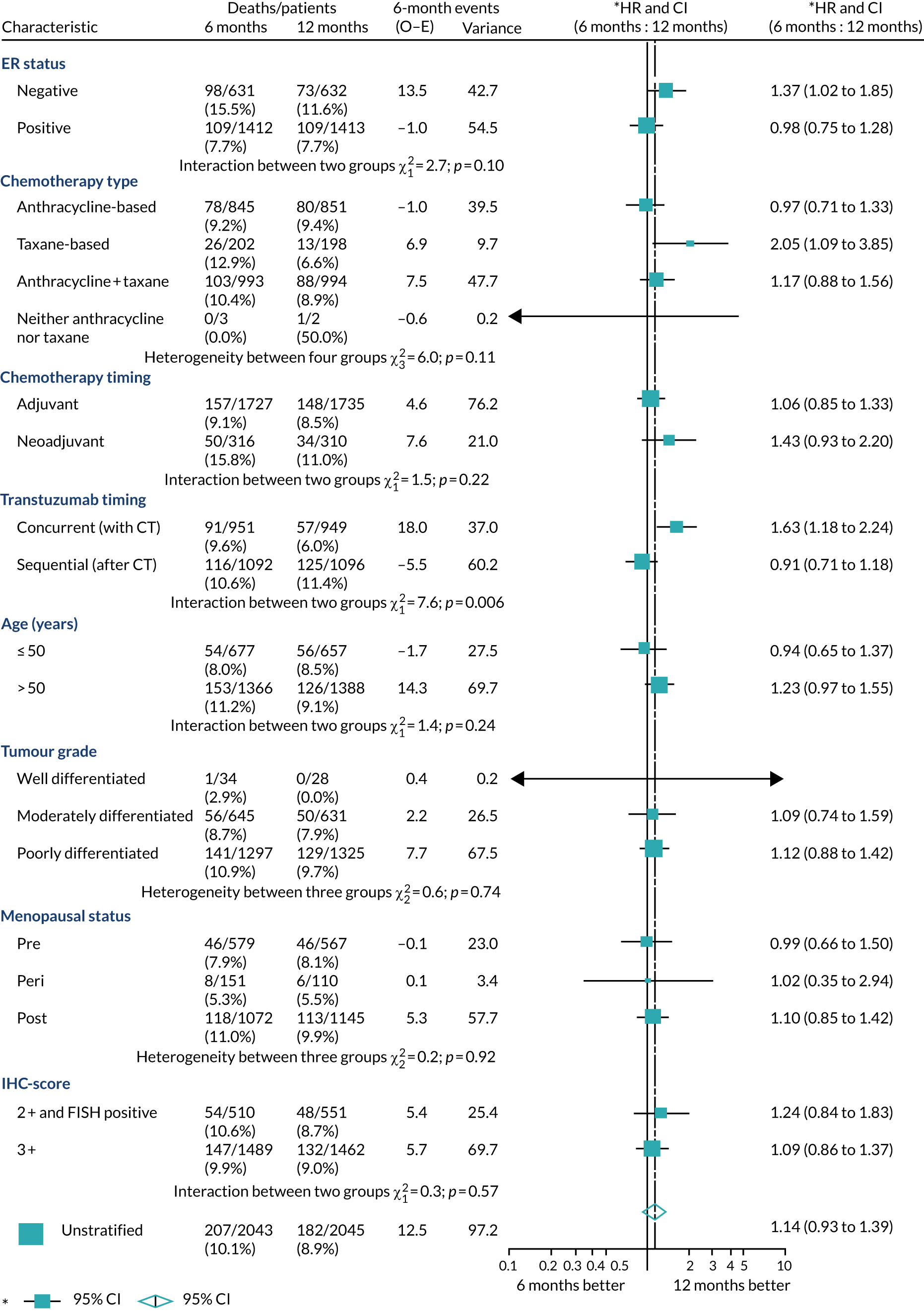

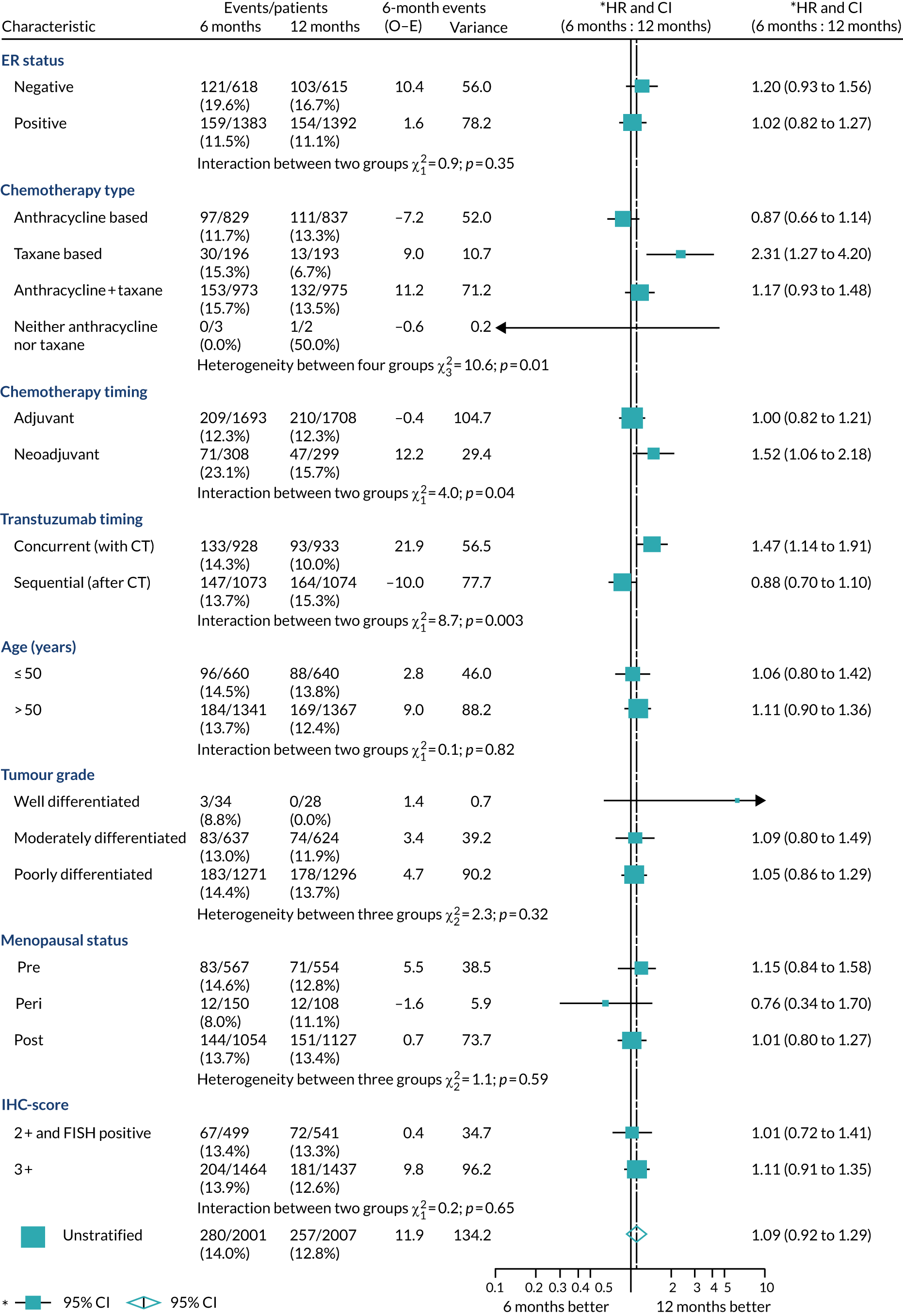

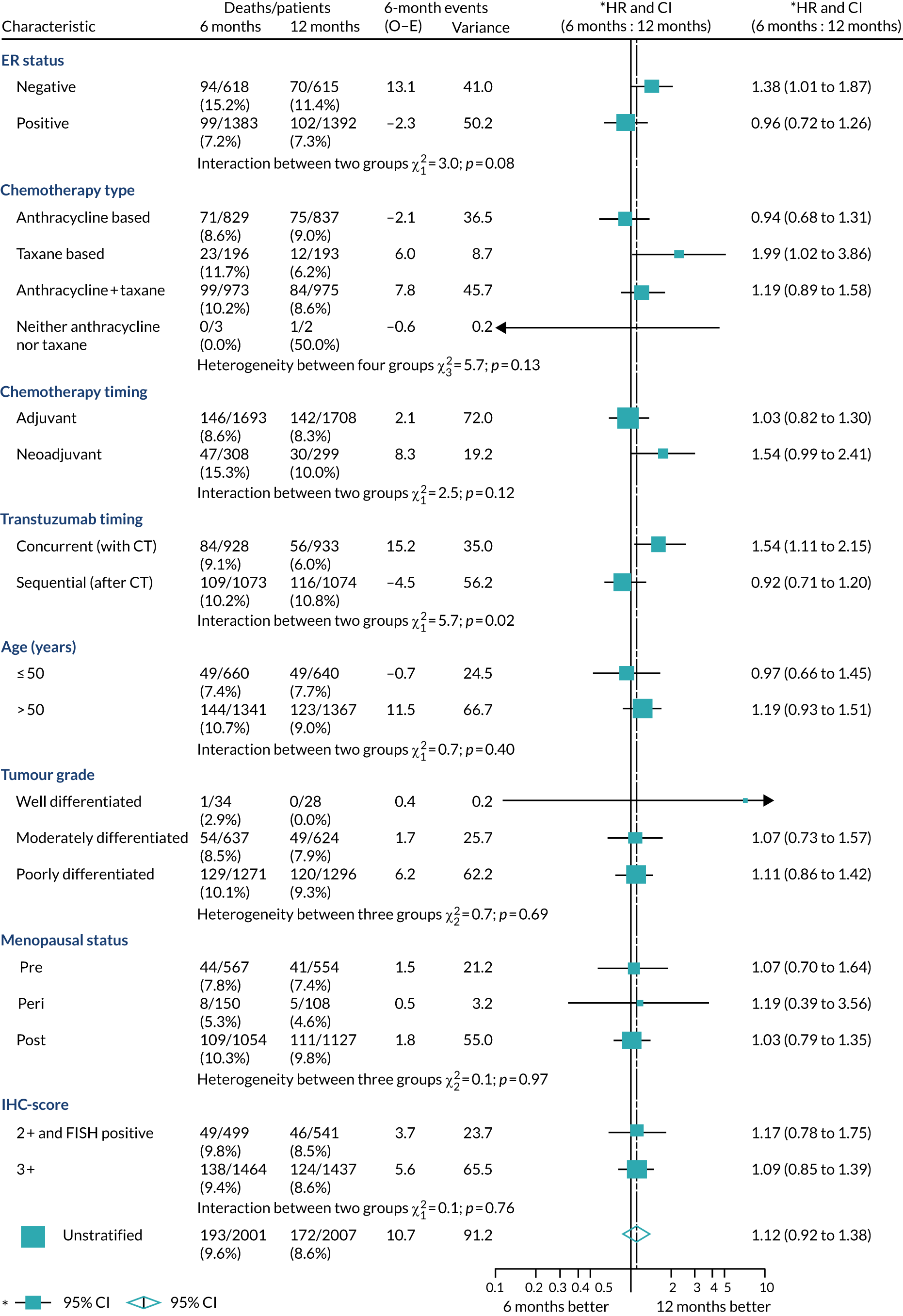

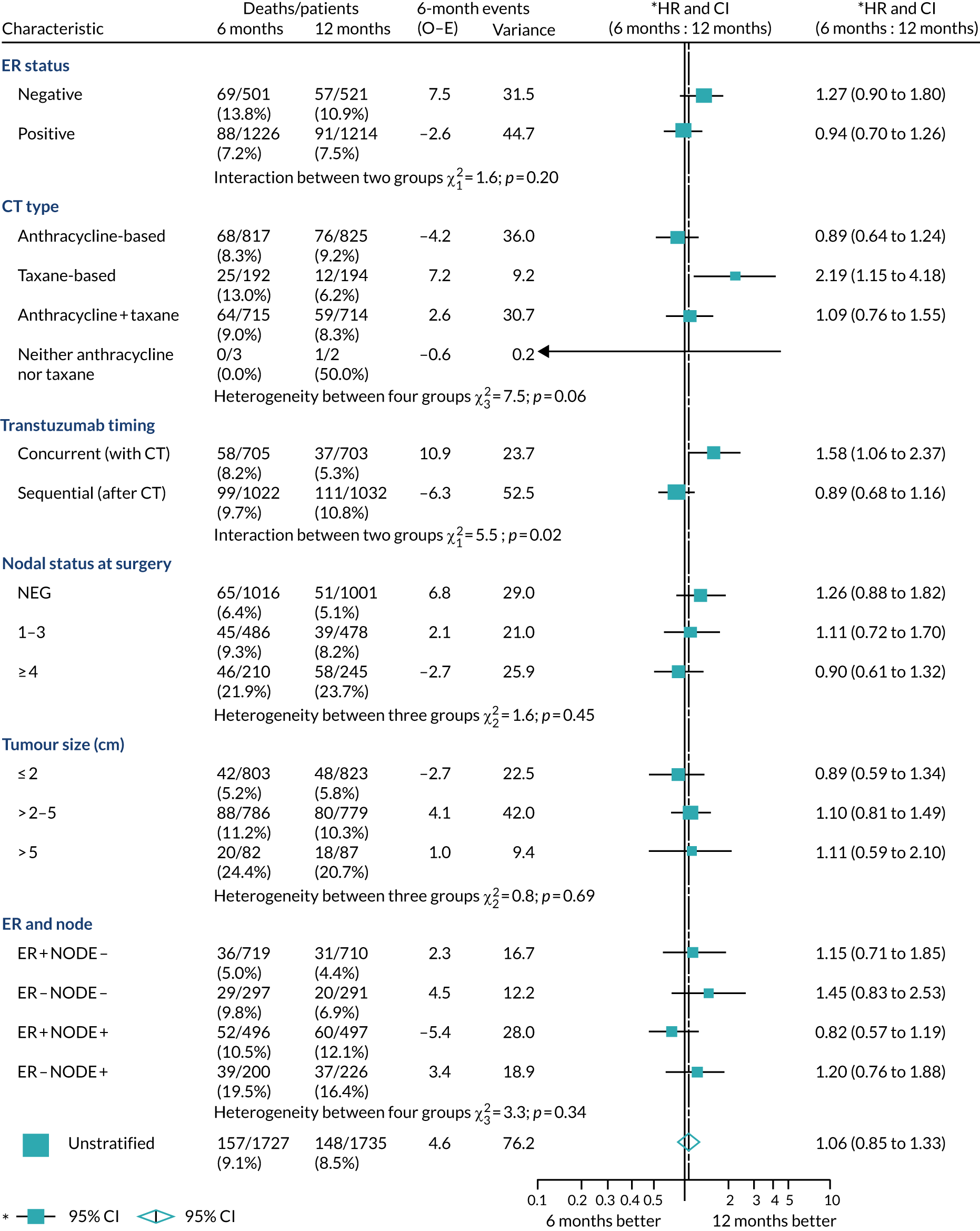

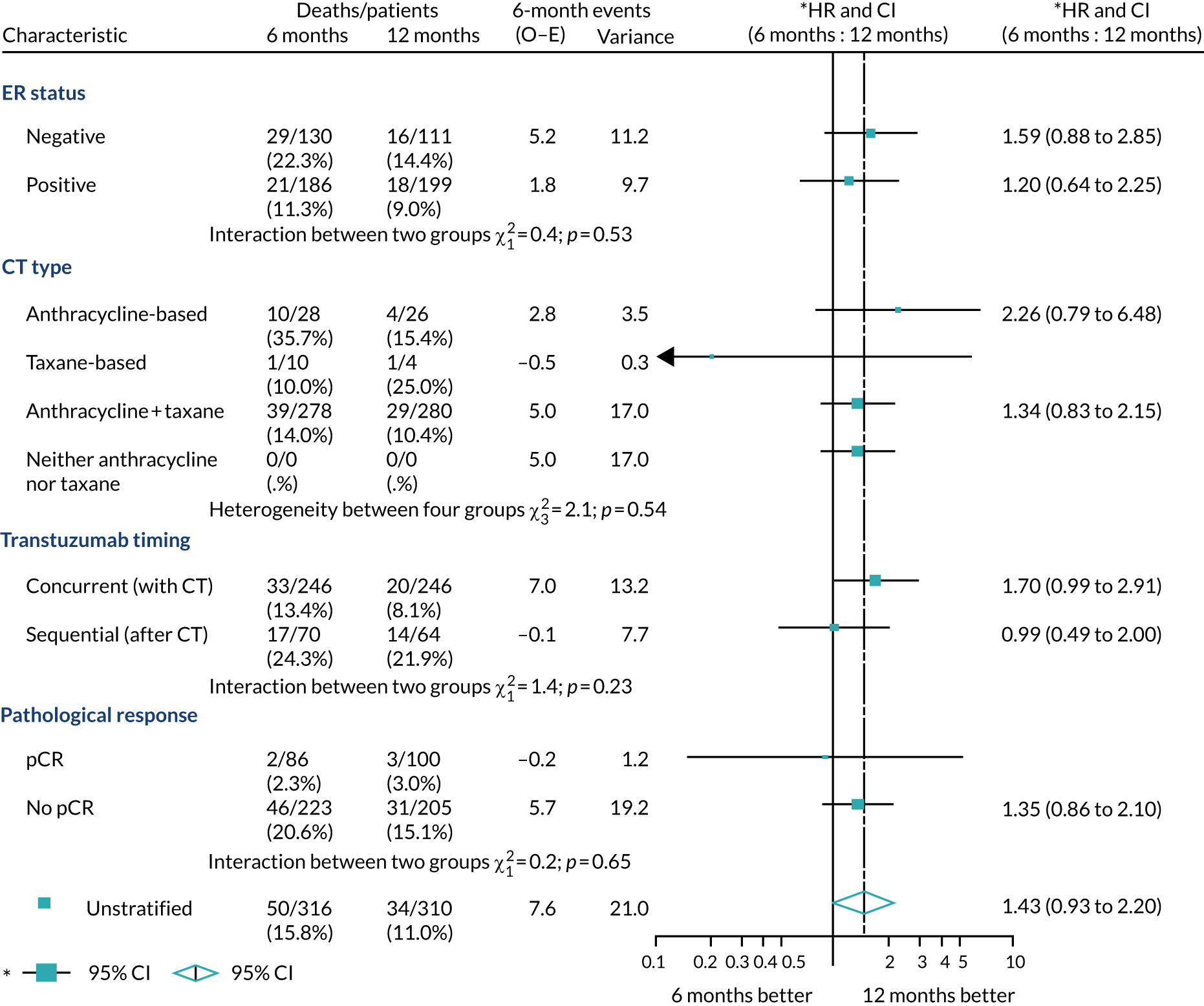

A secondary analysis adjusting for stratification and baseline prognostic factors was planned. The treatment effect on DFS was also presented for stratification variables (ER status, chemotherapy type, chemotherapy timing and trastuzumab timing) using HR plots with interaction statistics using methods described by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group in 1990. 44

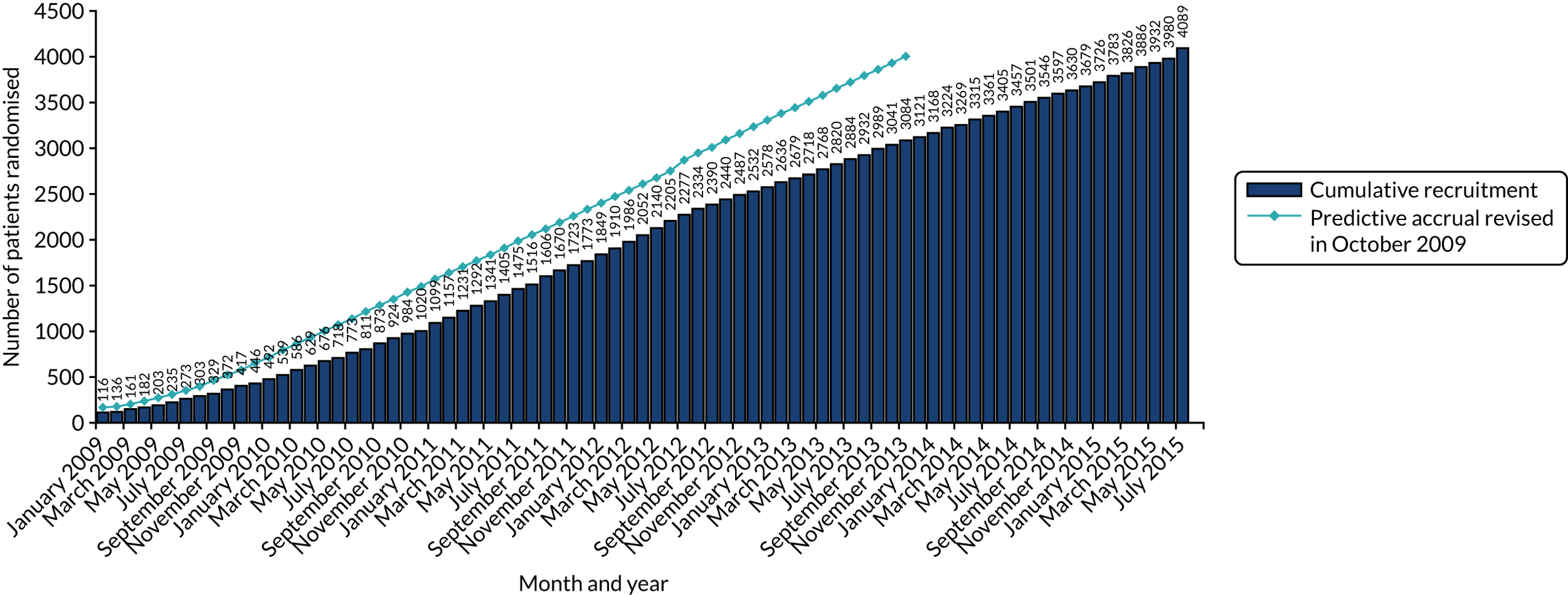

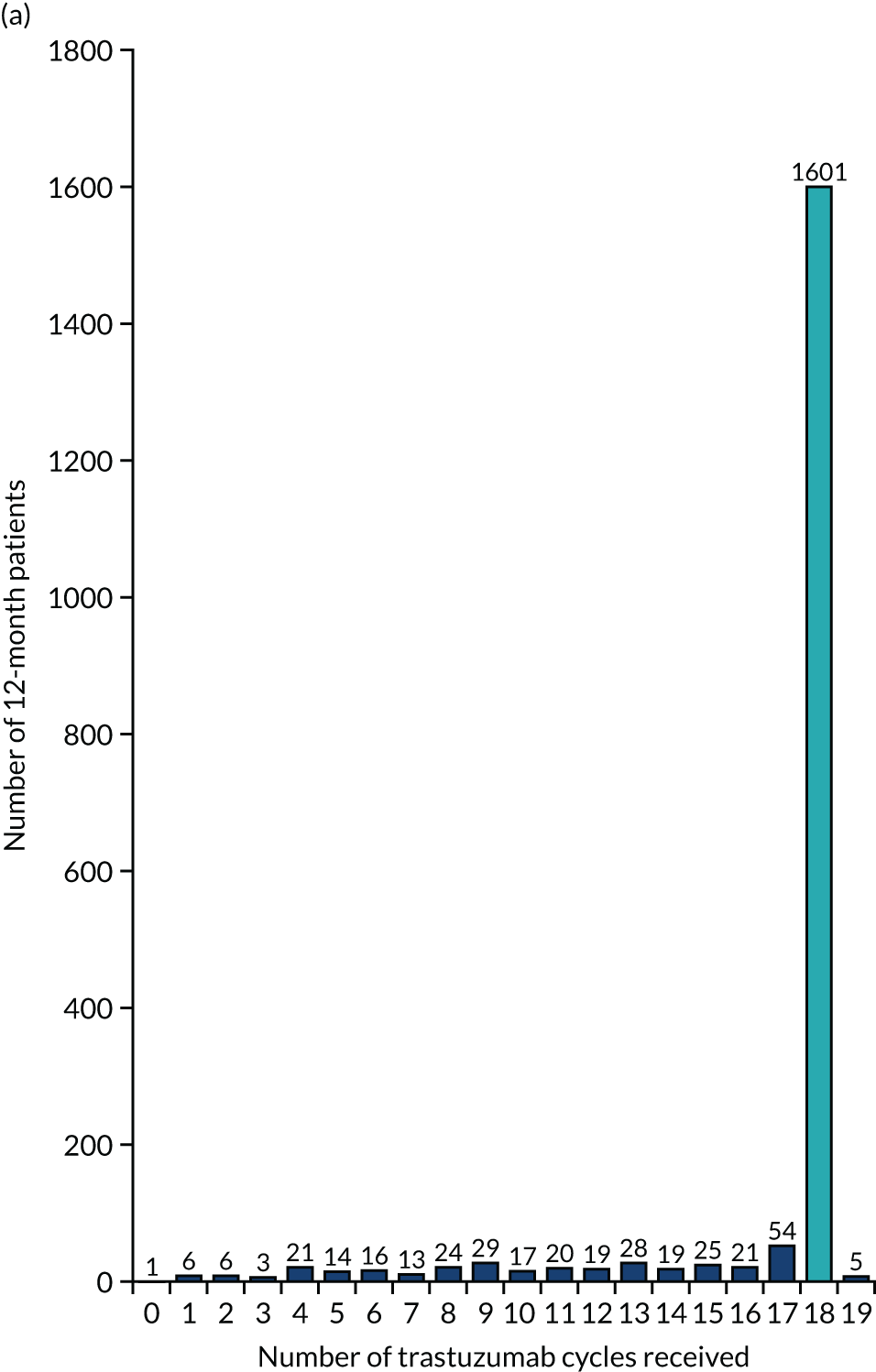

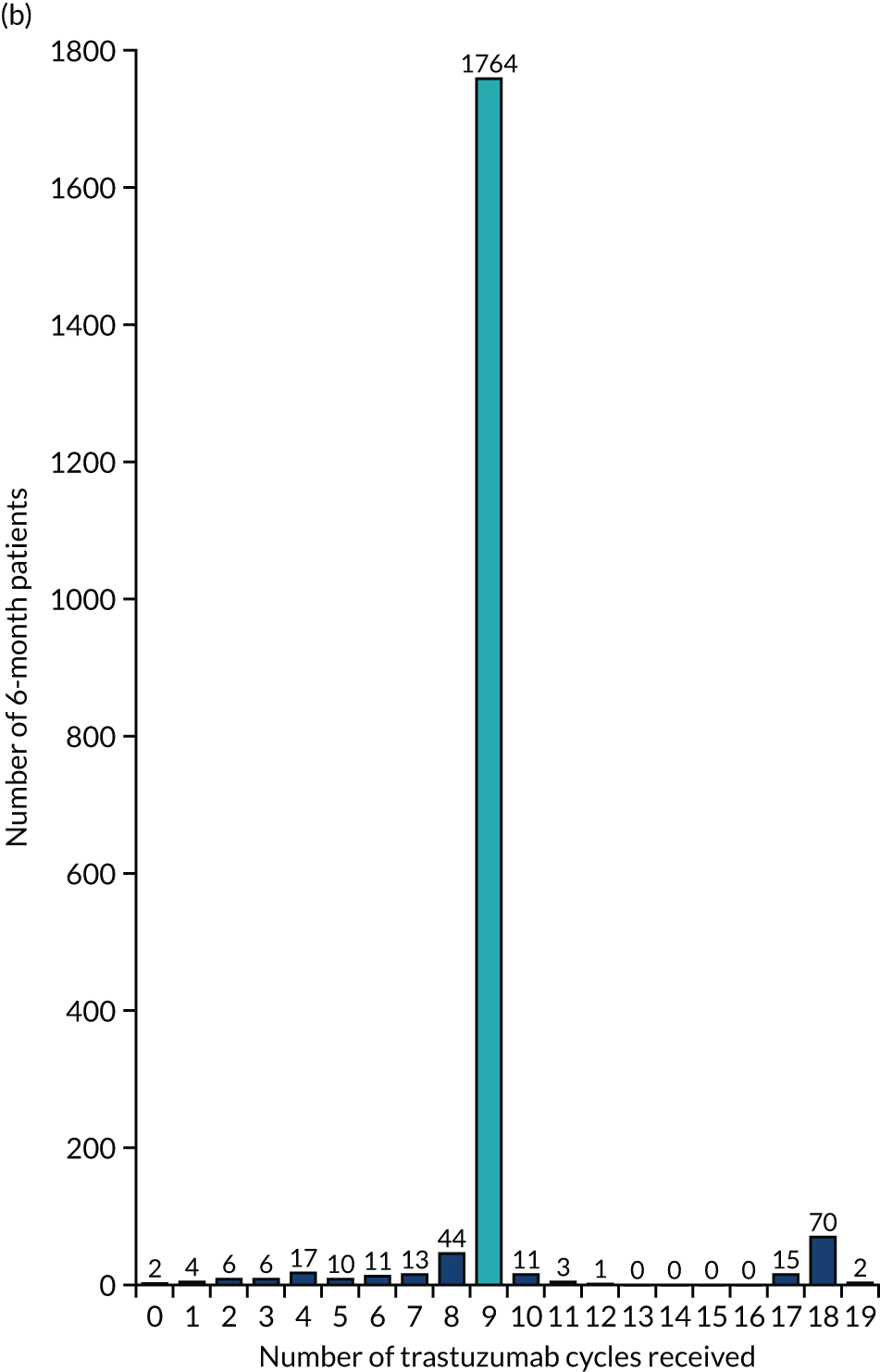

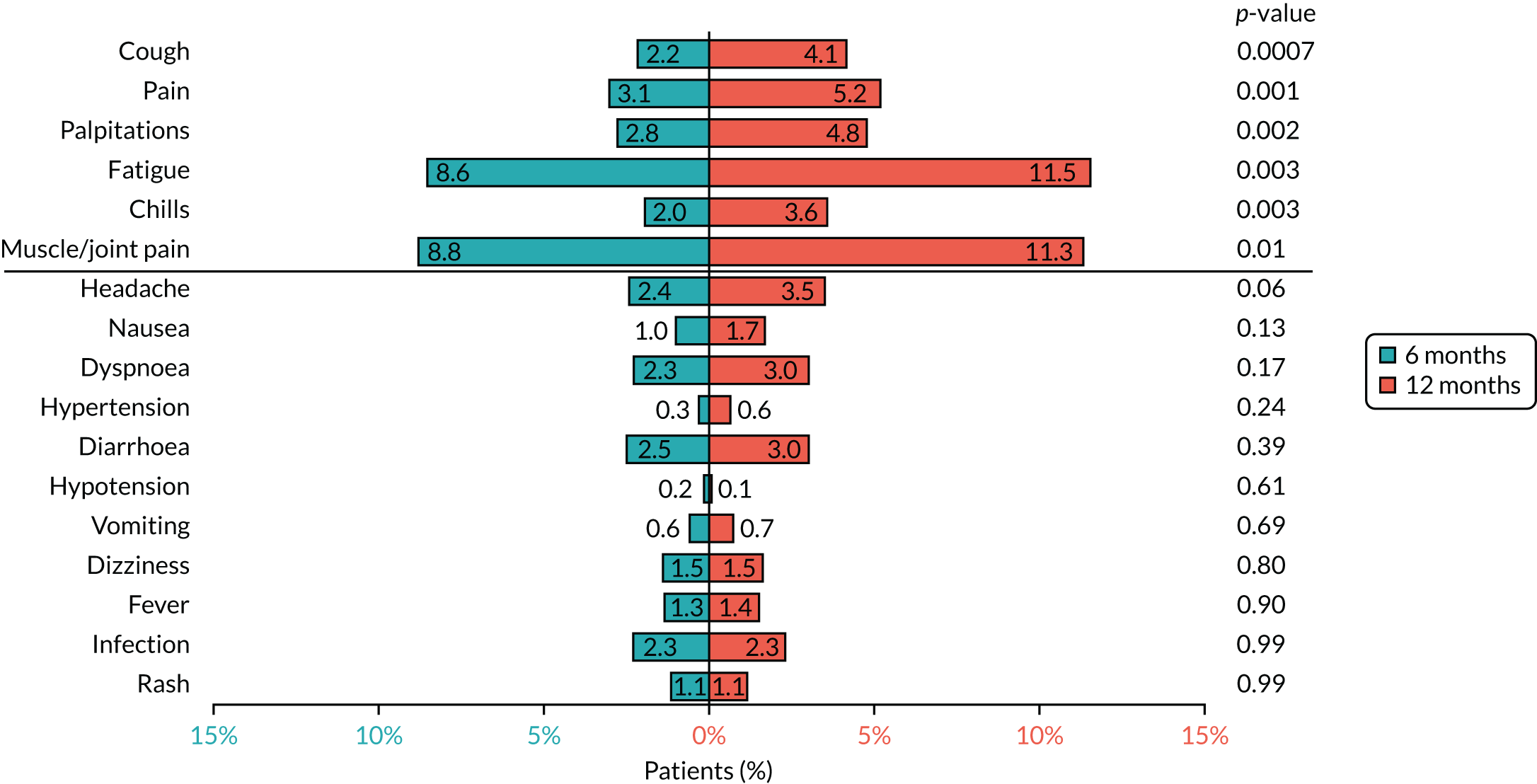

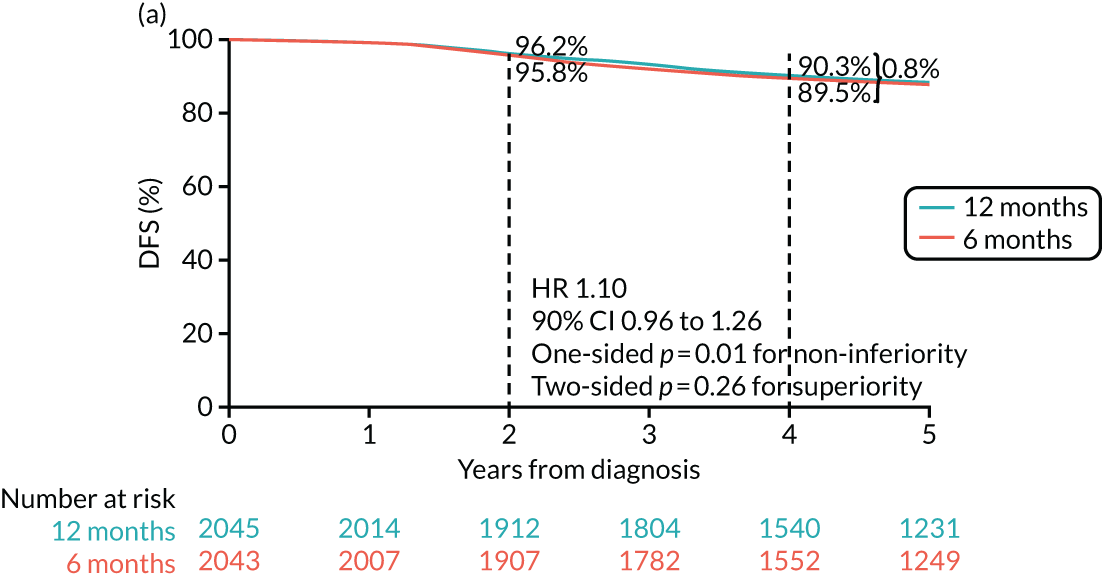

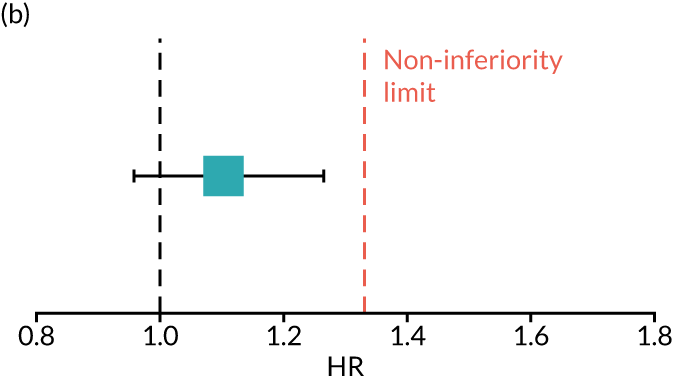

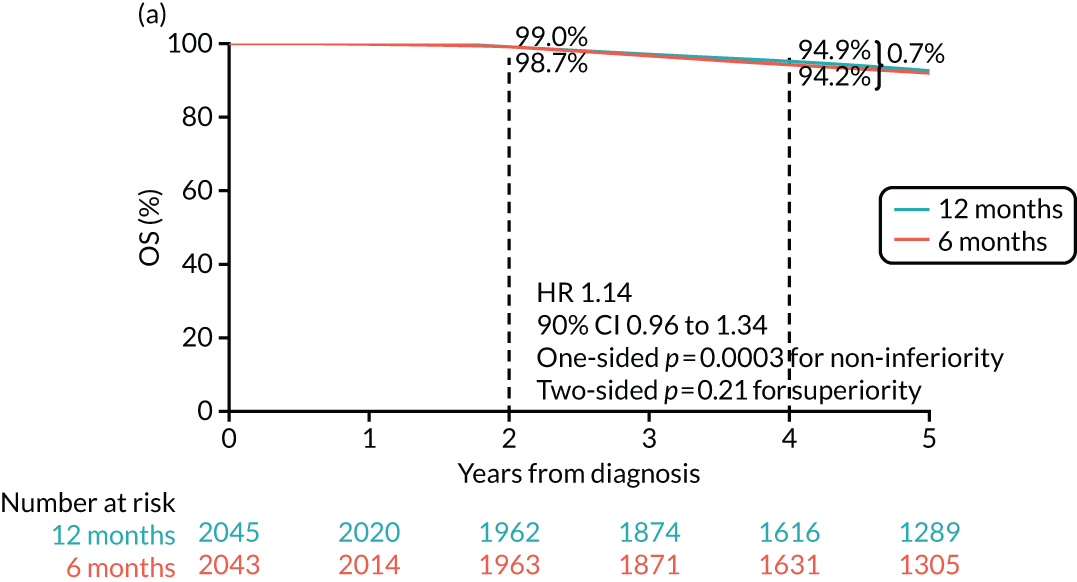

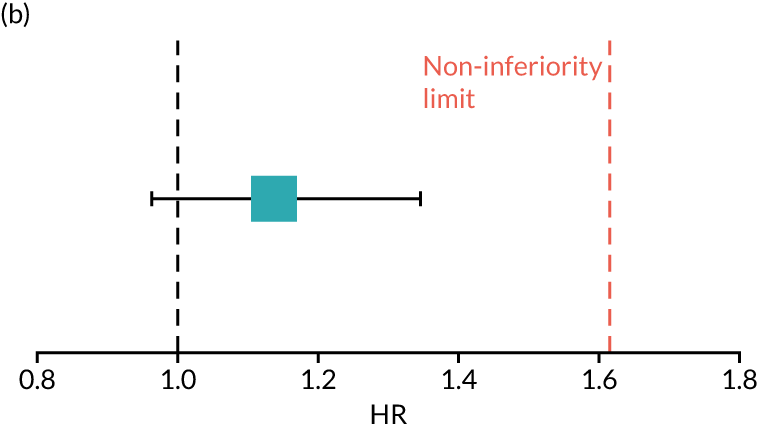

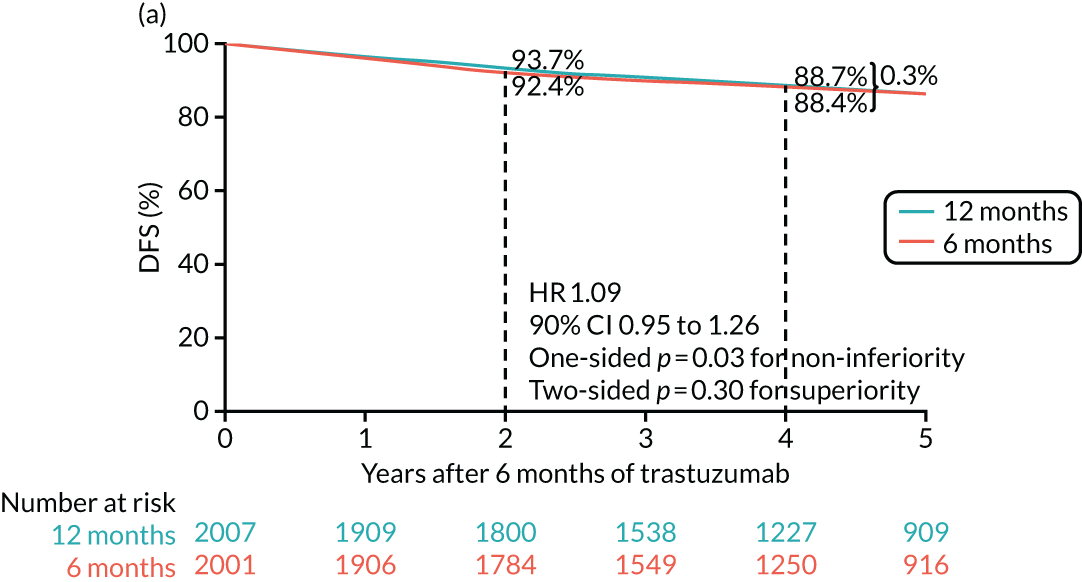

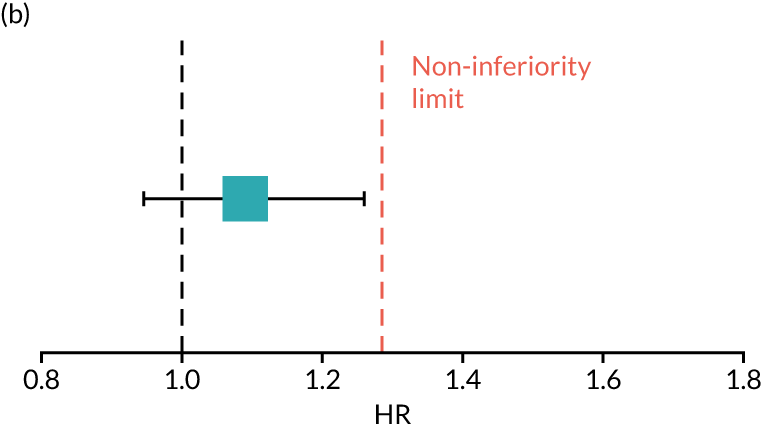

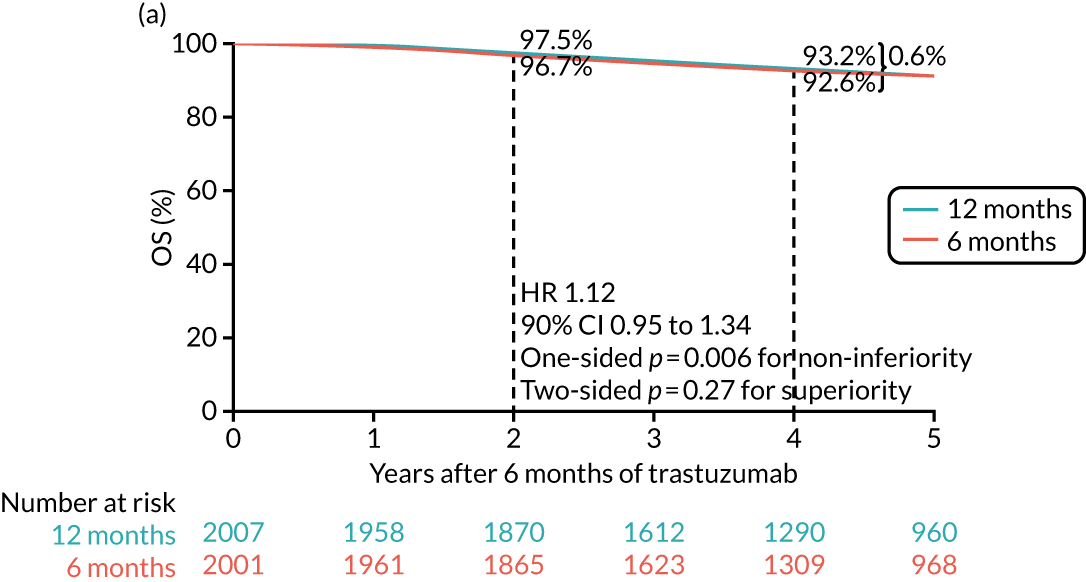

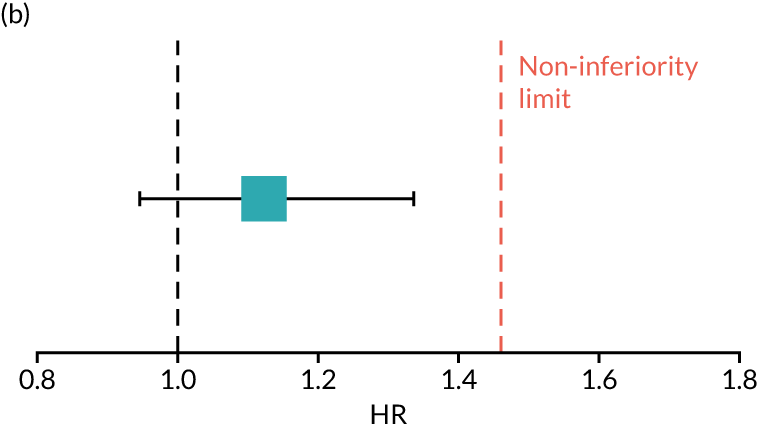

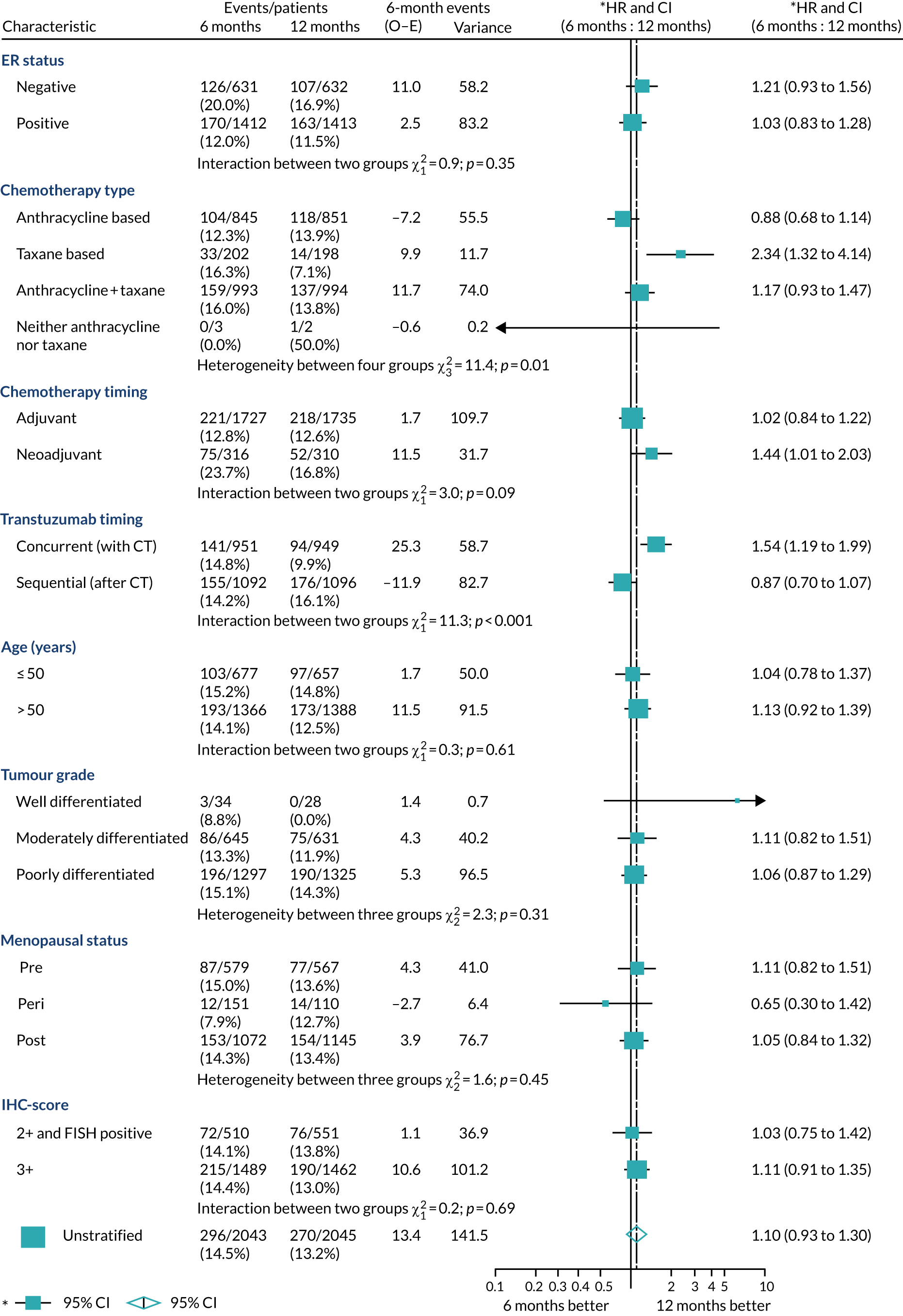

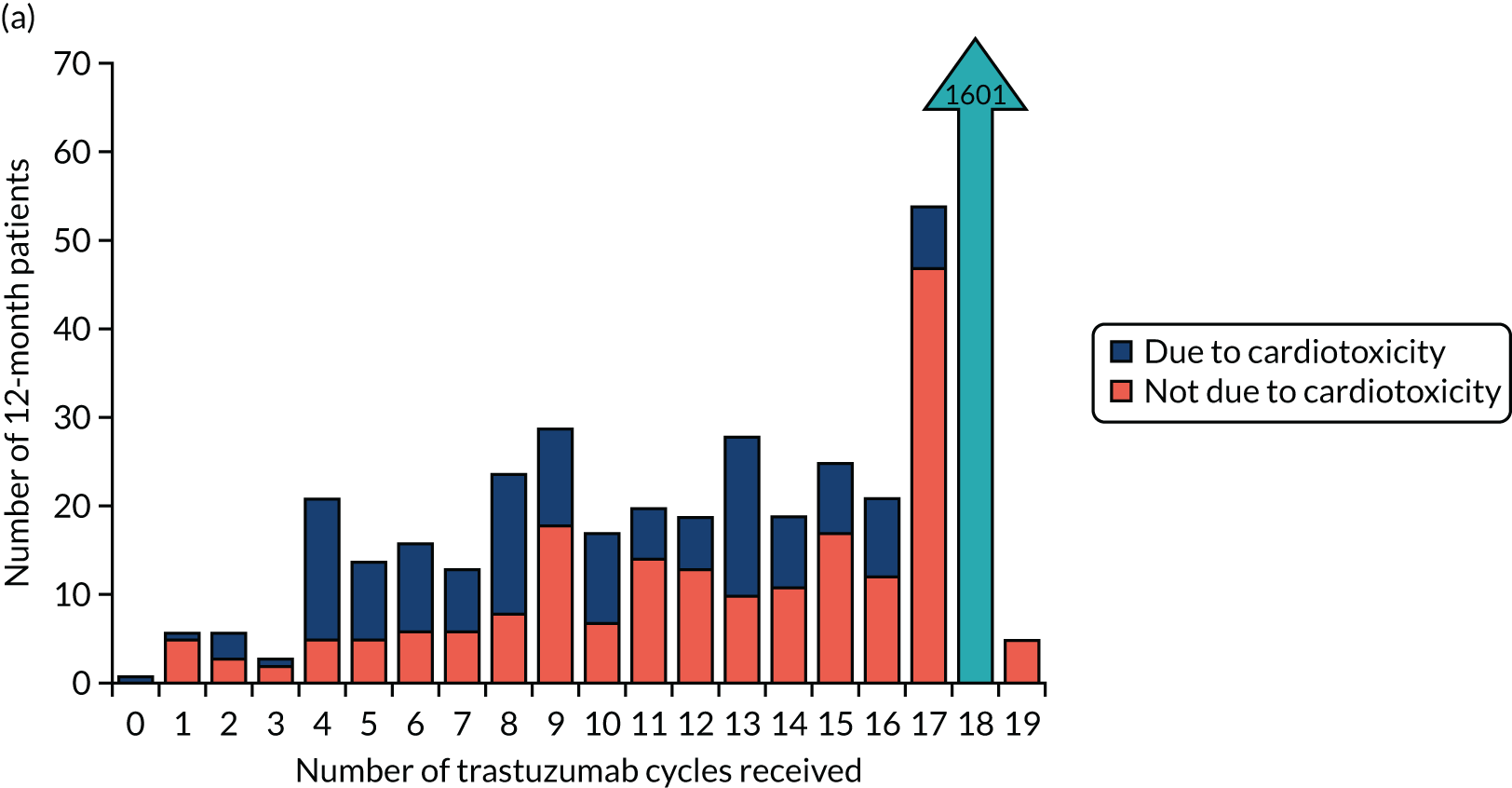

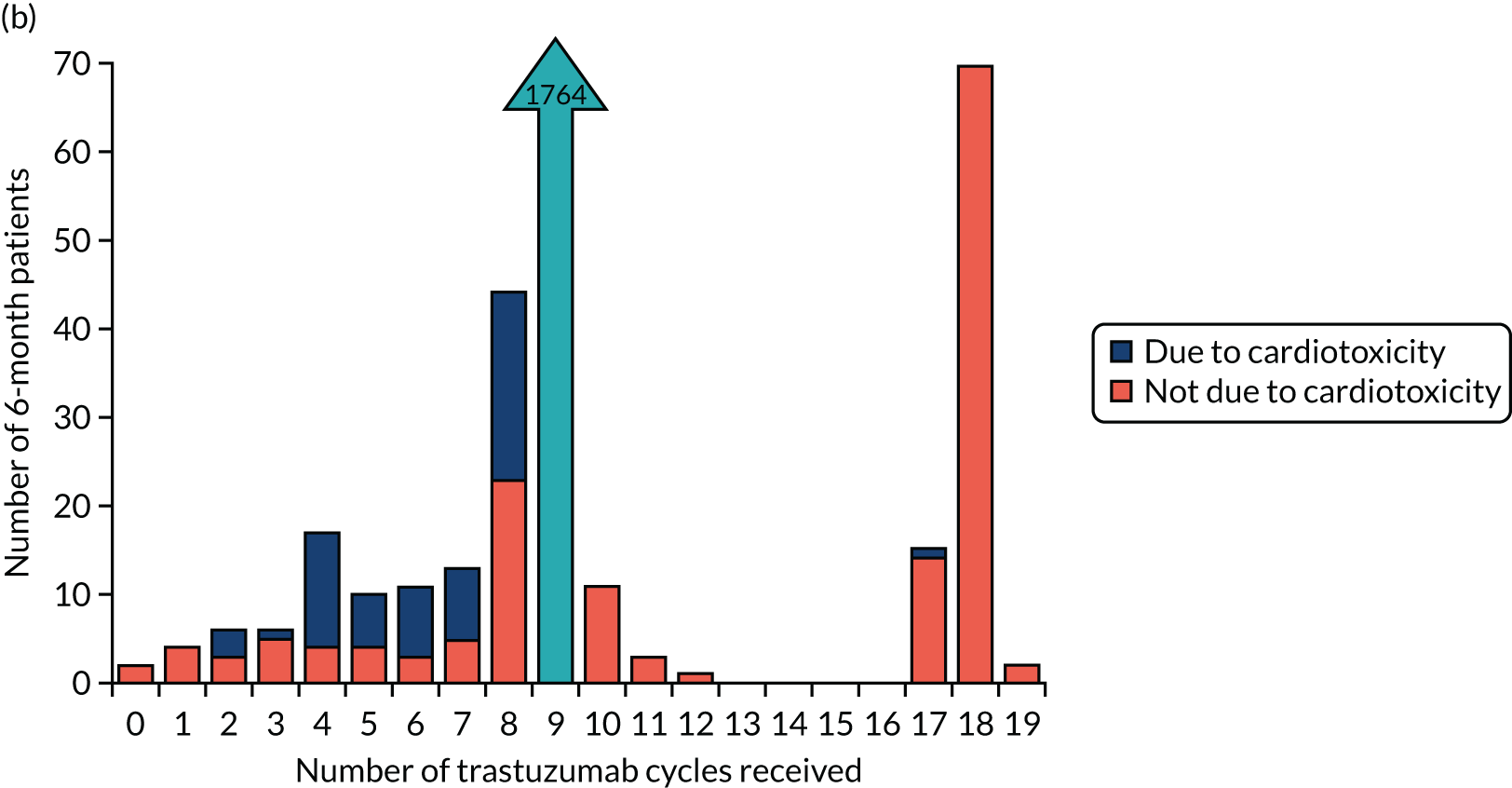

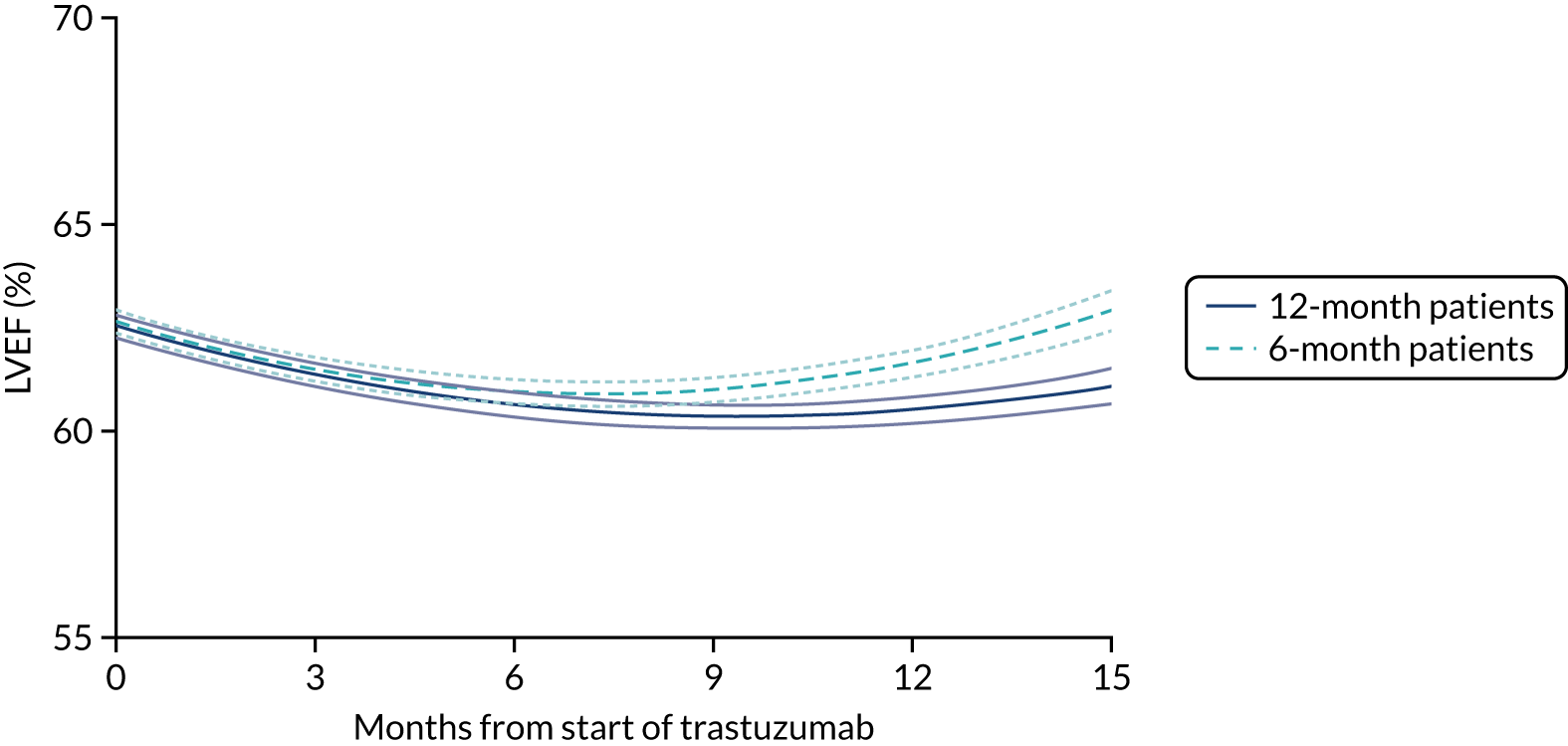

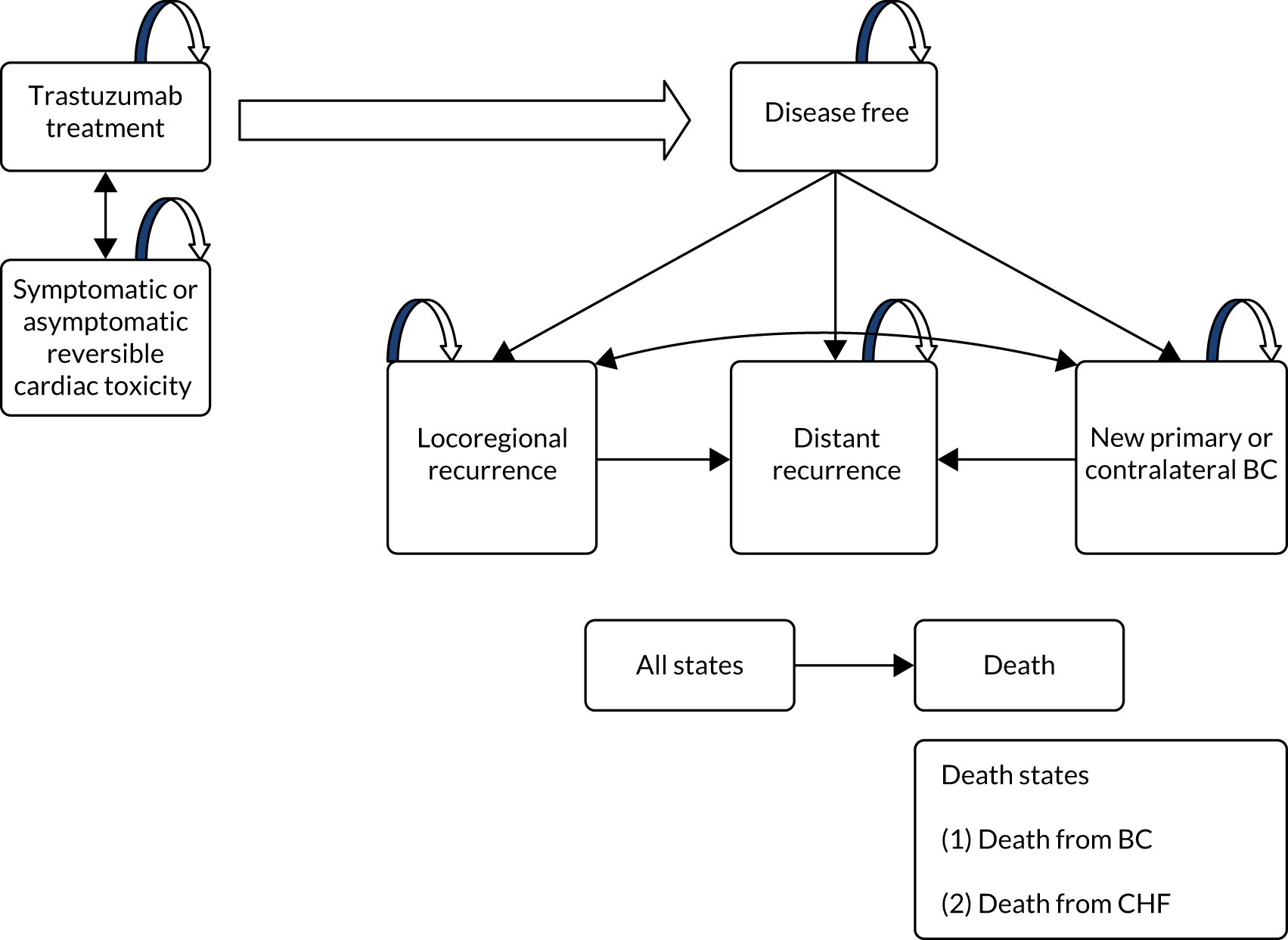

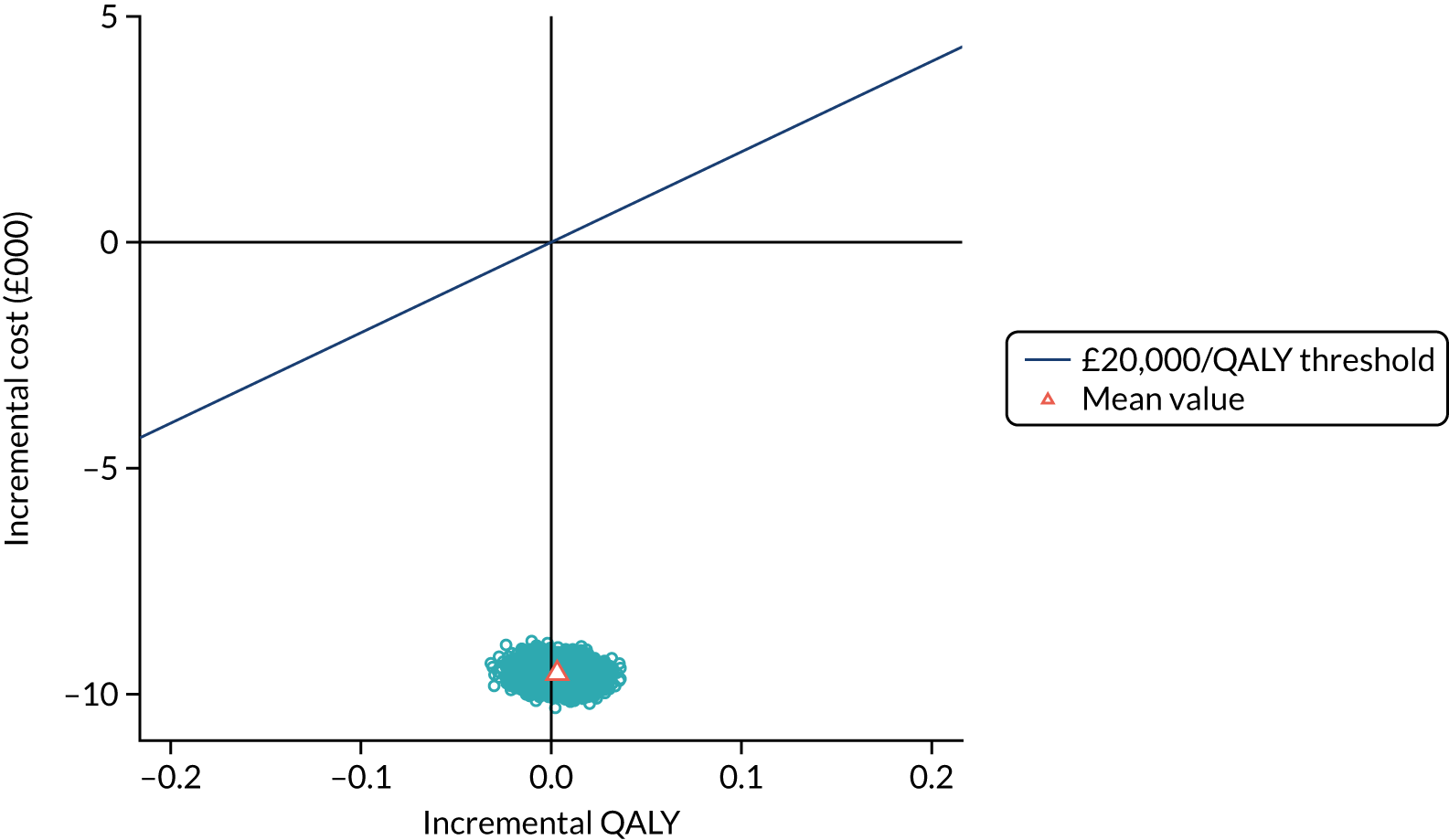

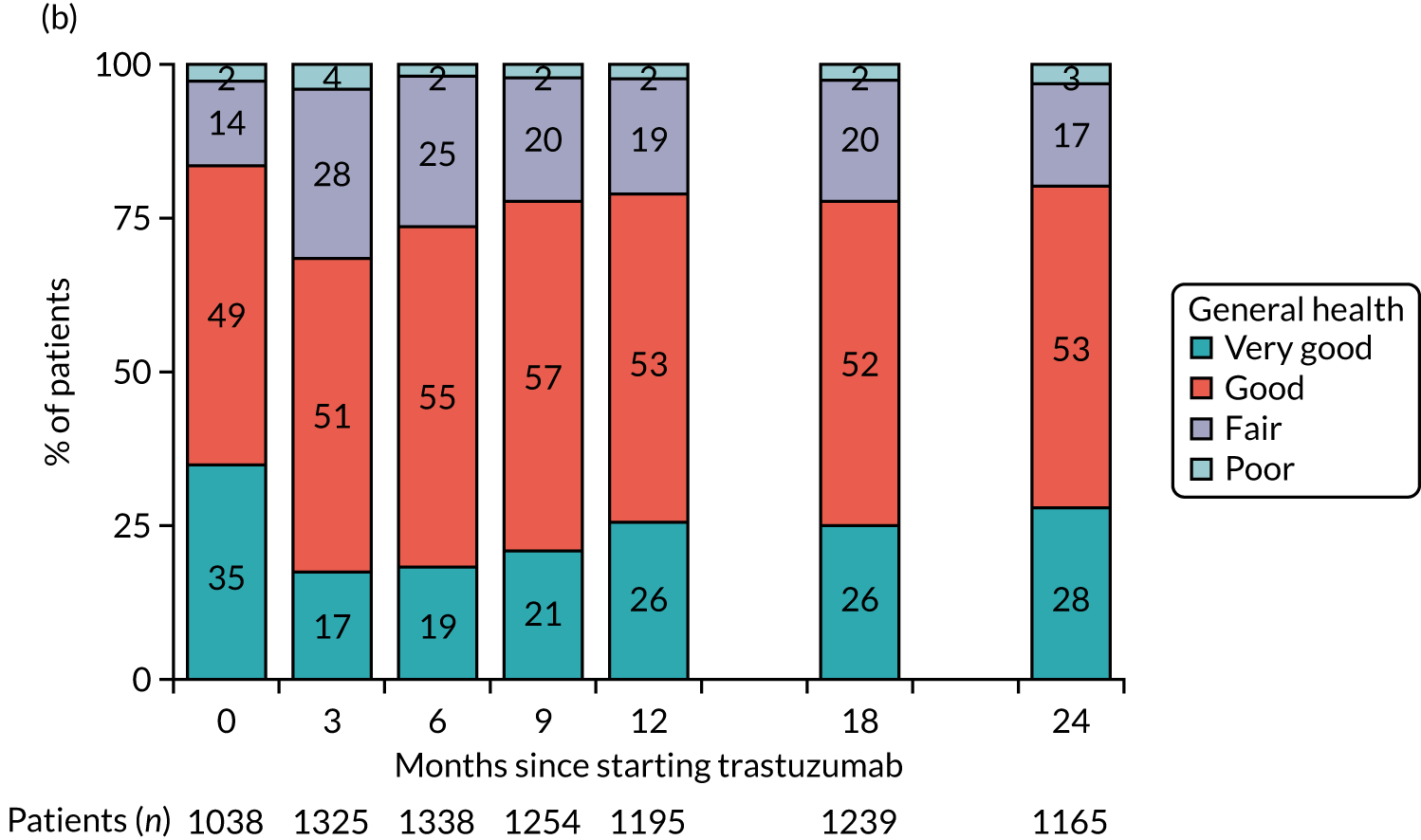

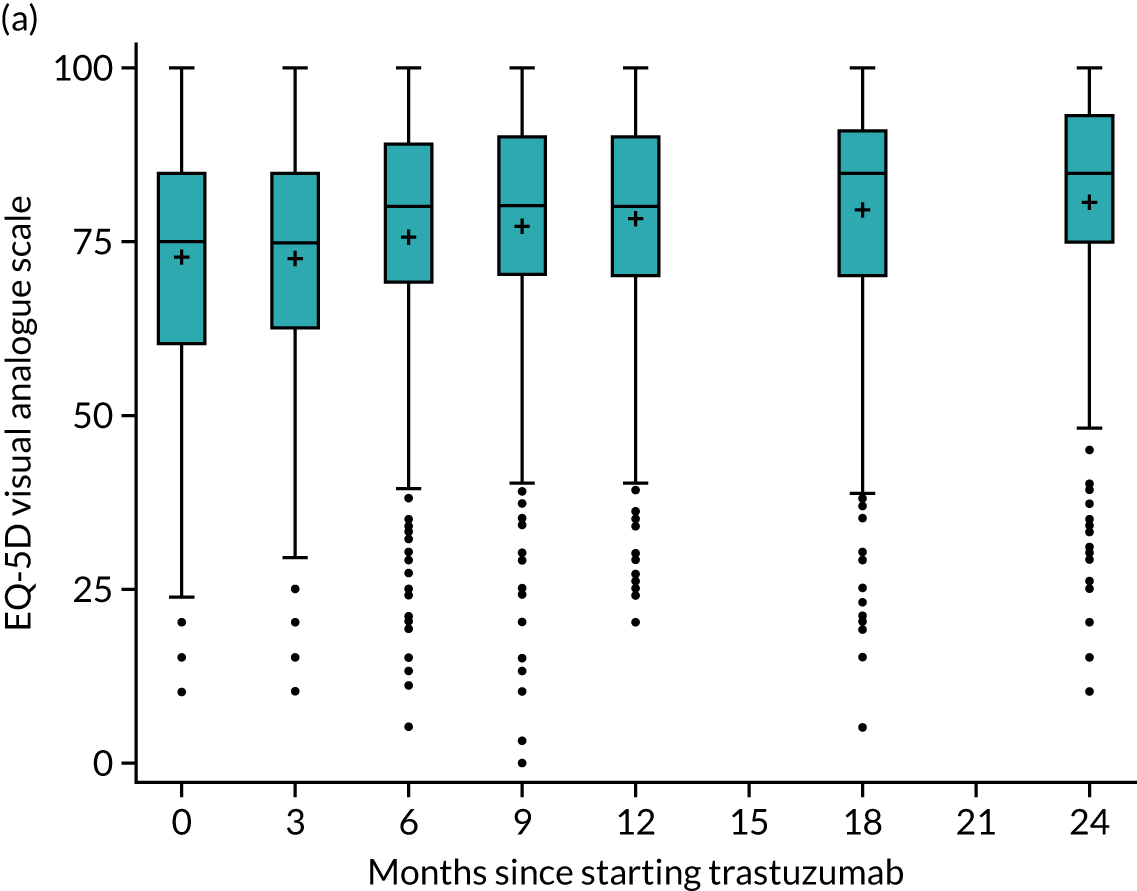

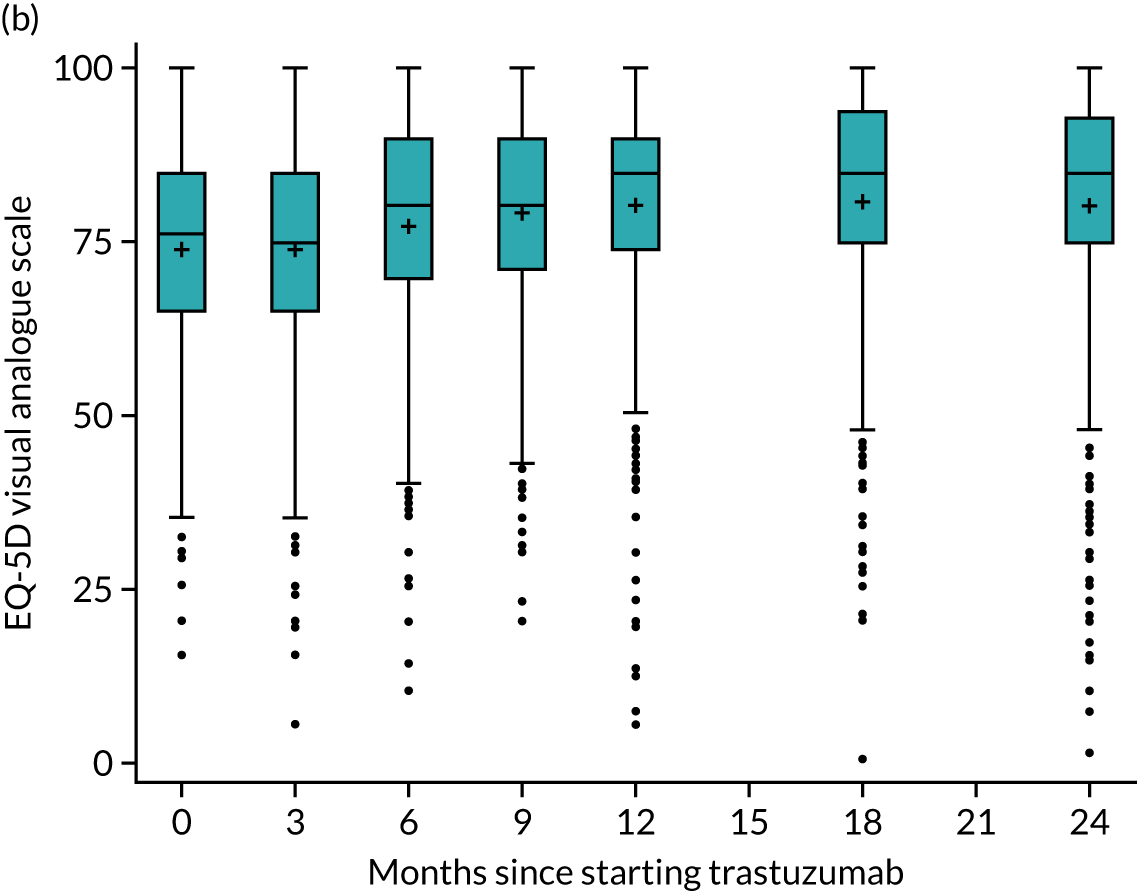

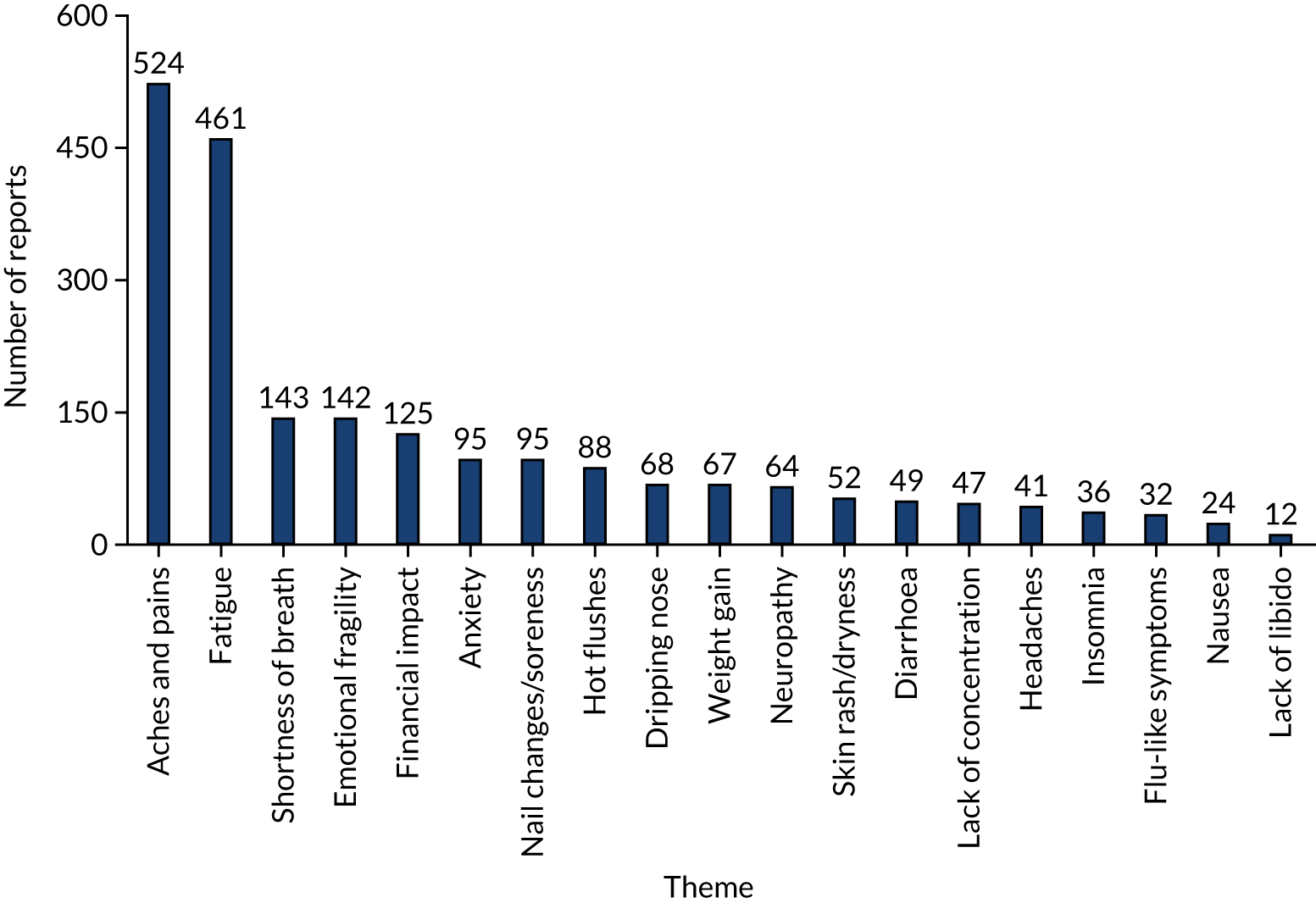

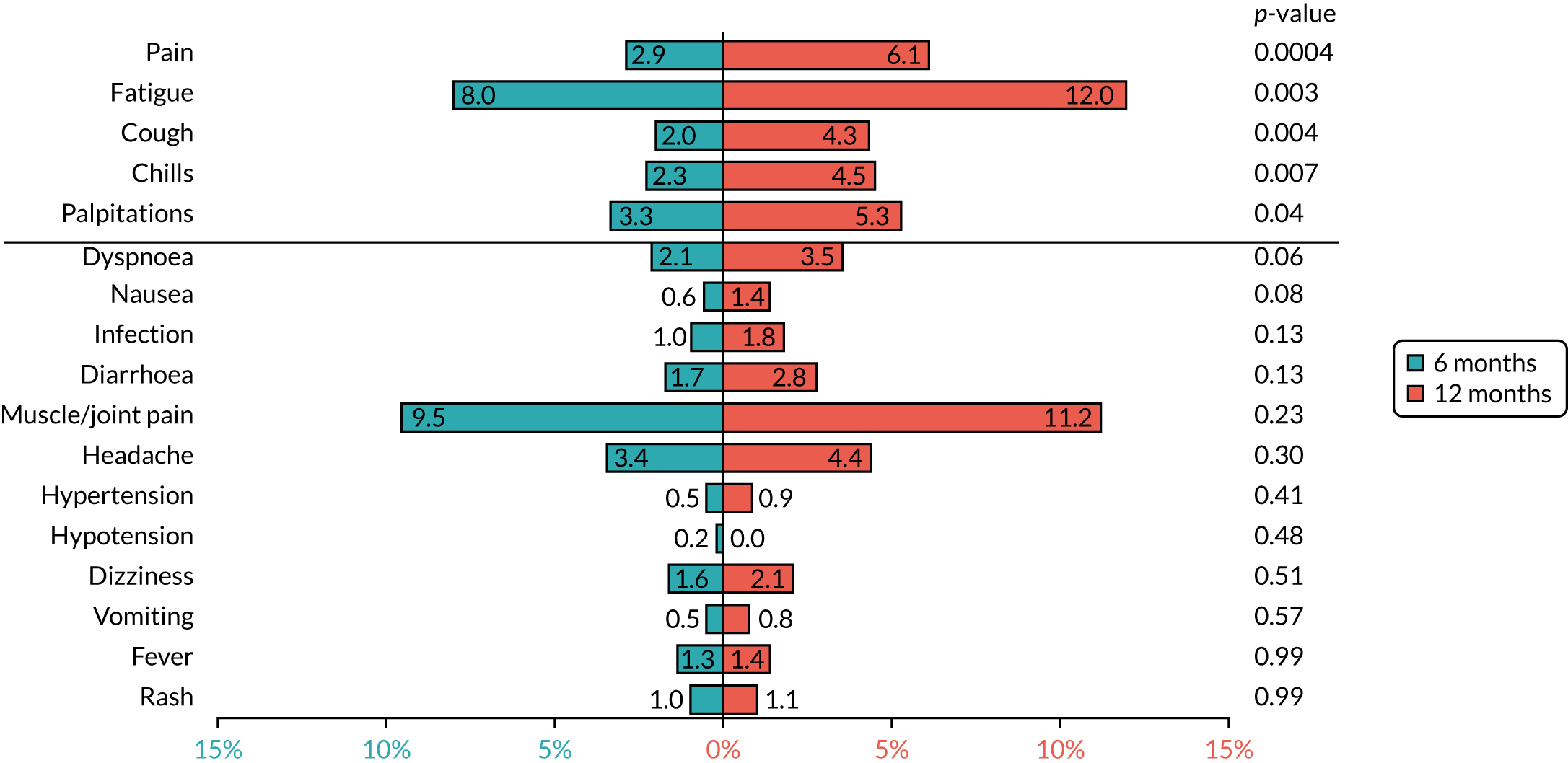

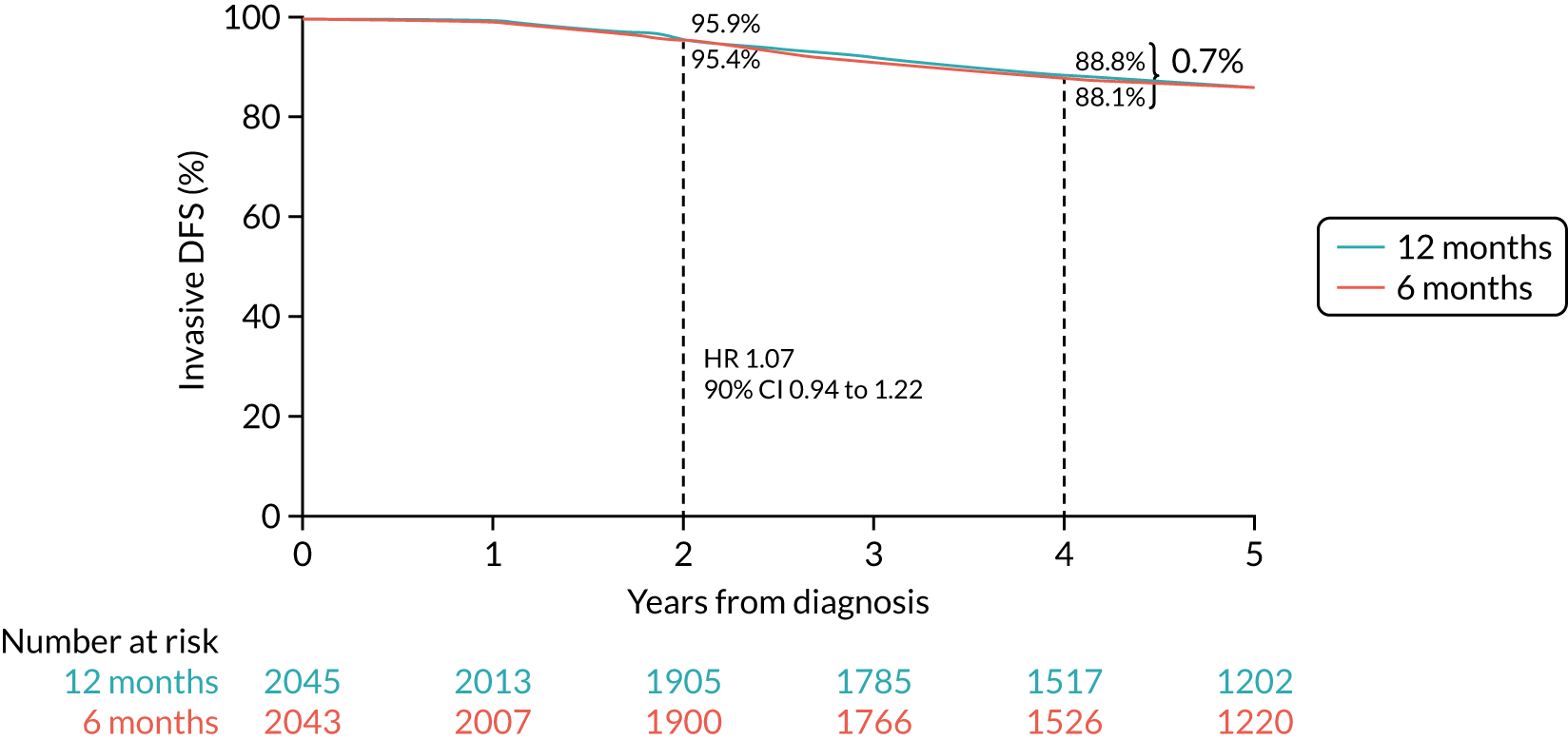

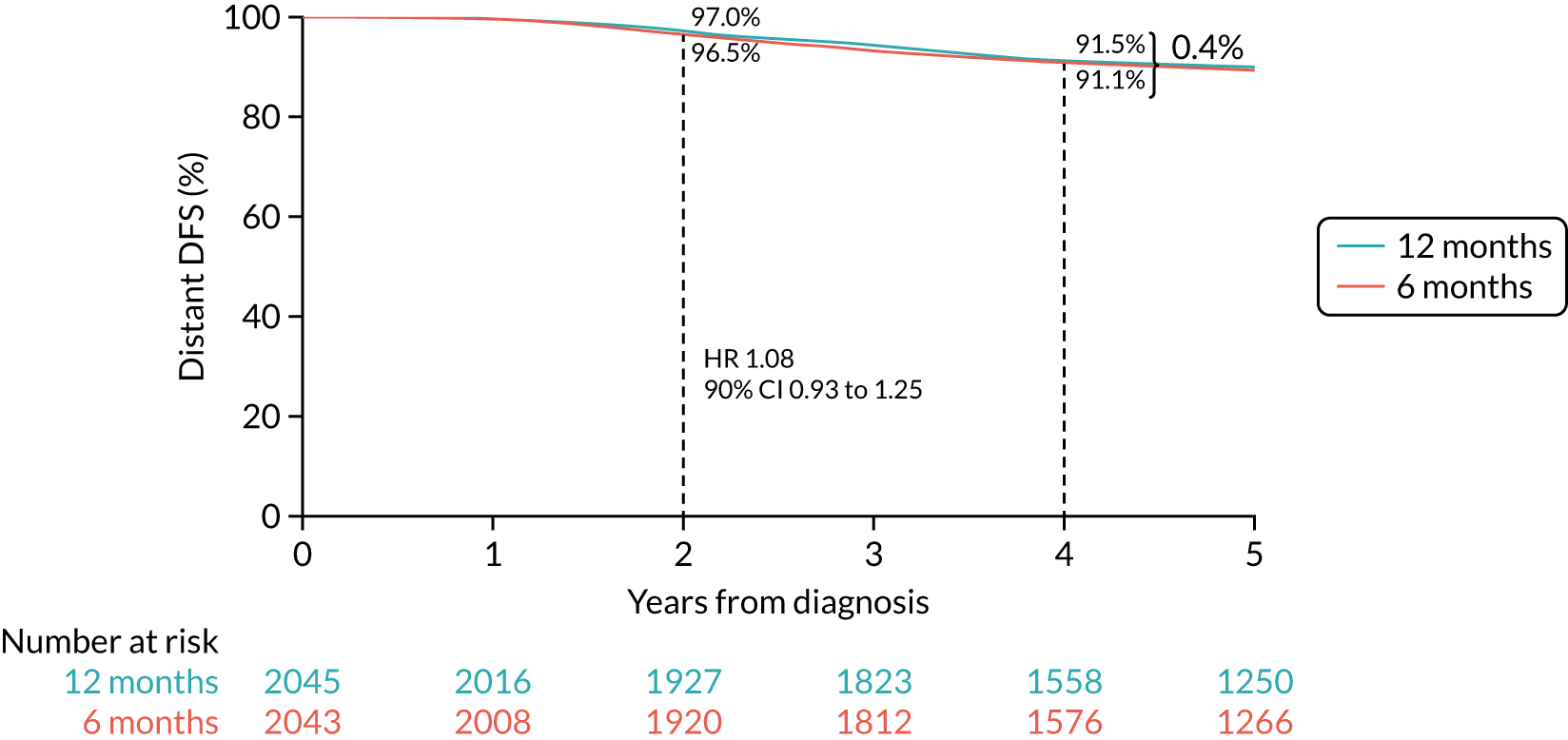

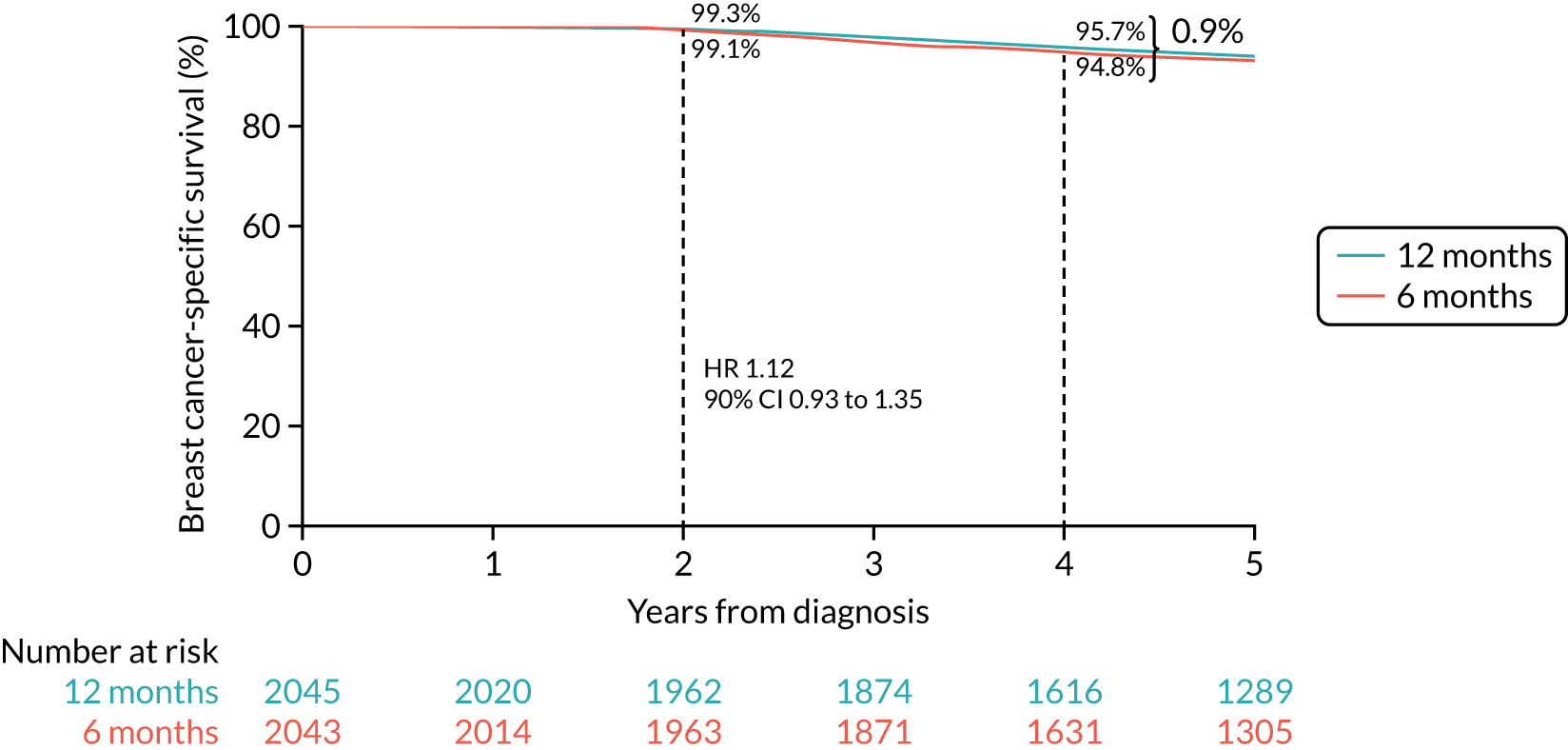

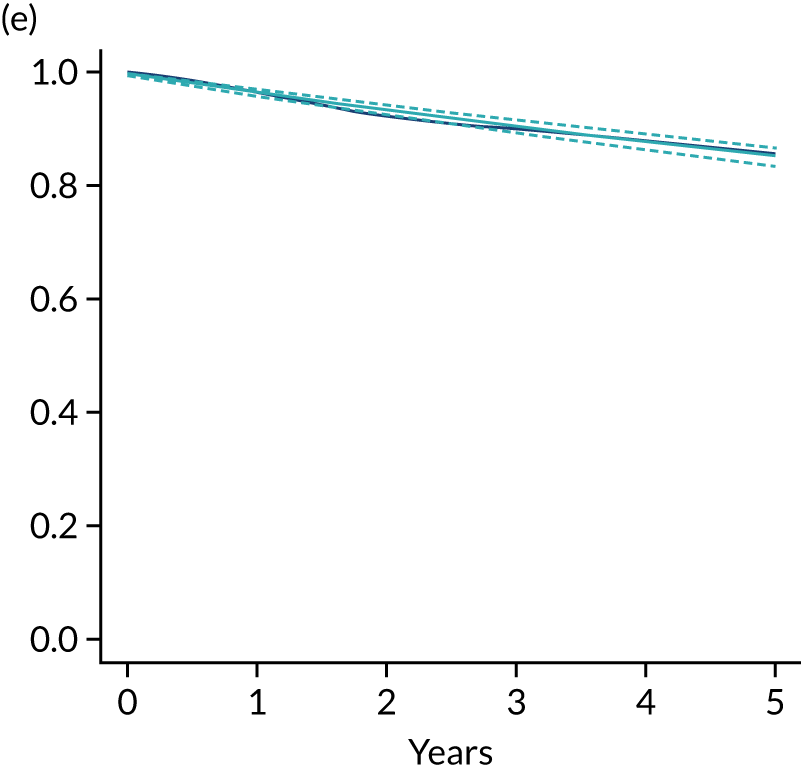

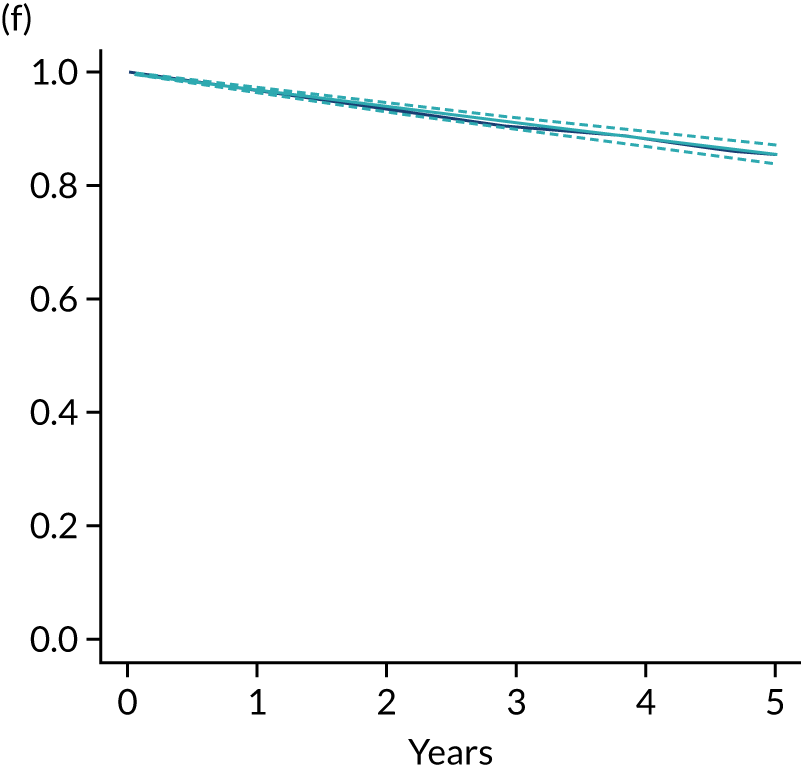

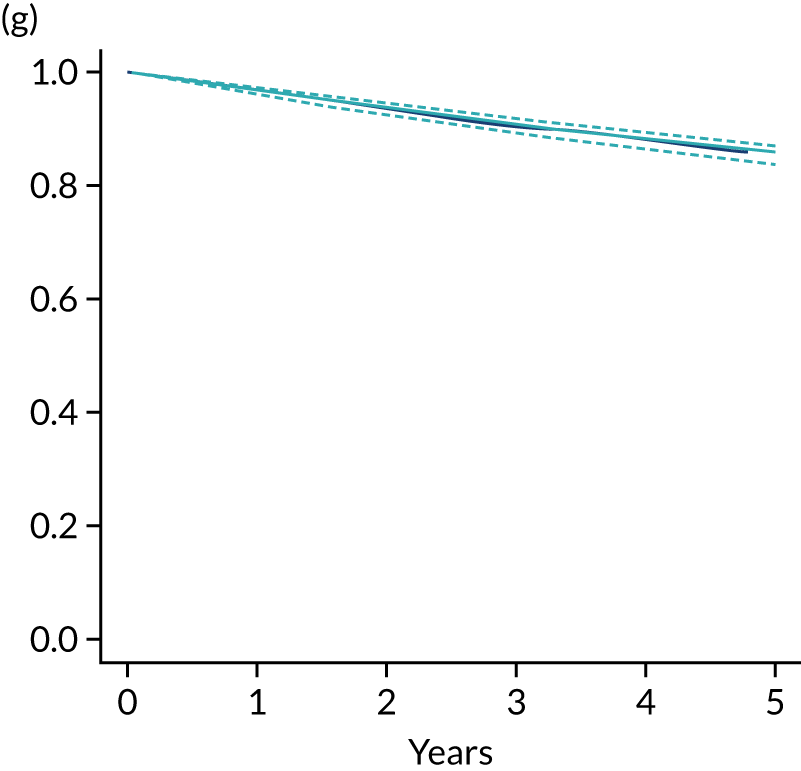

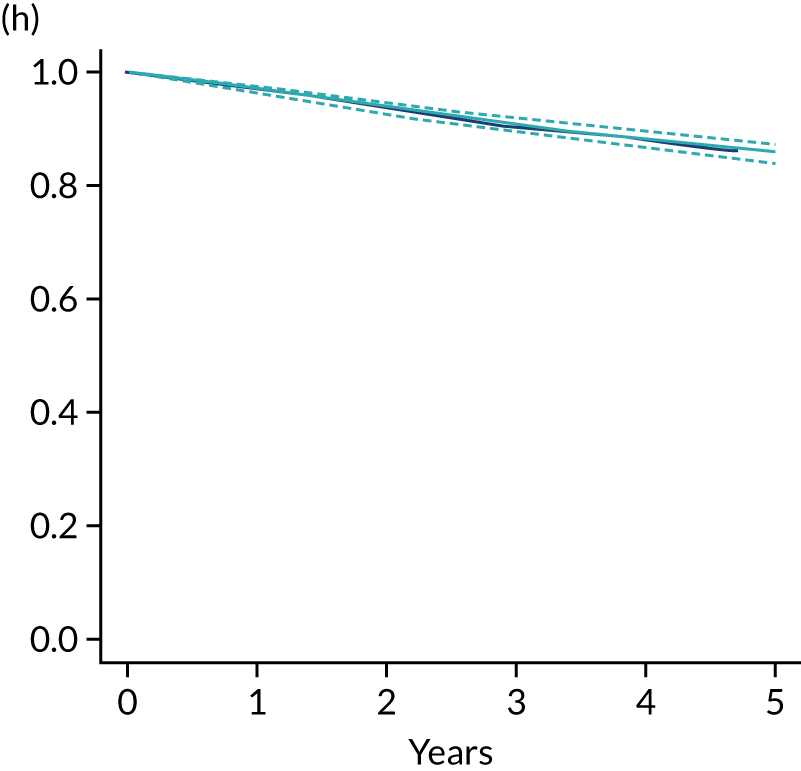

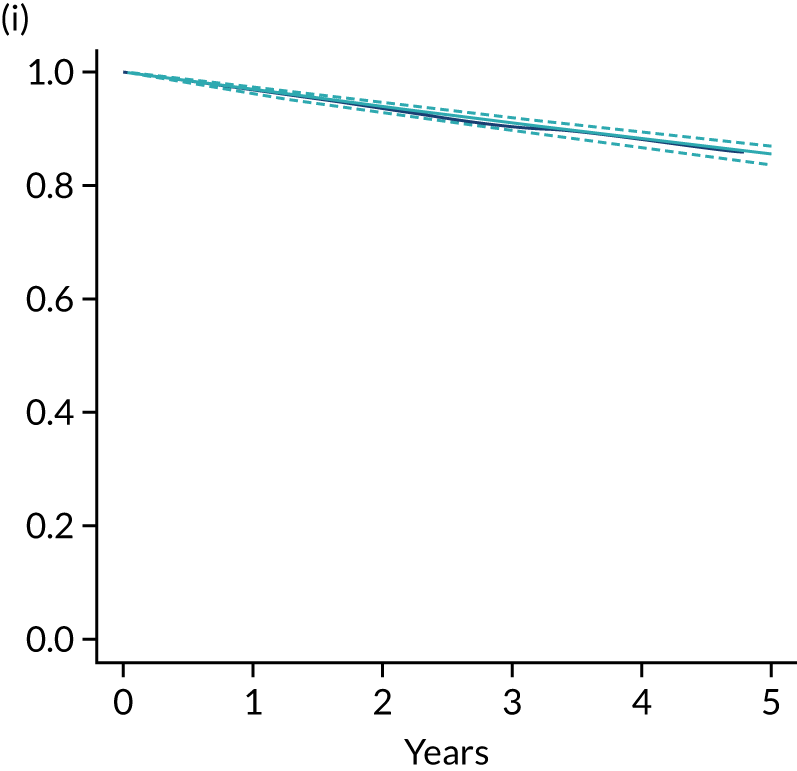

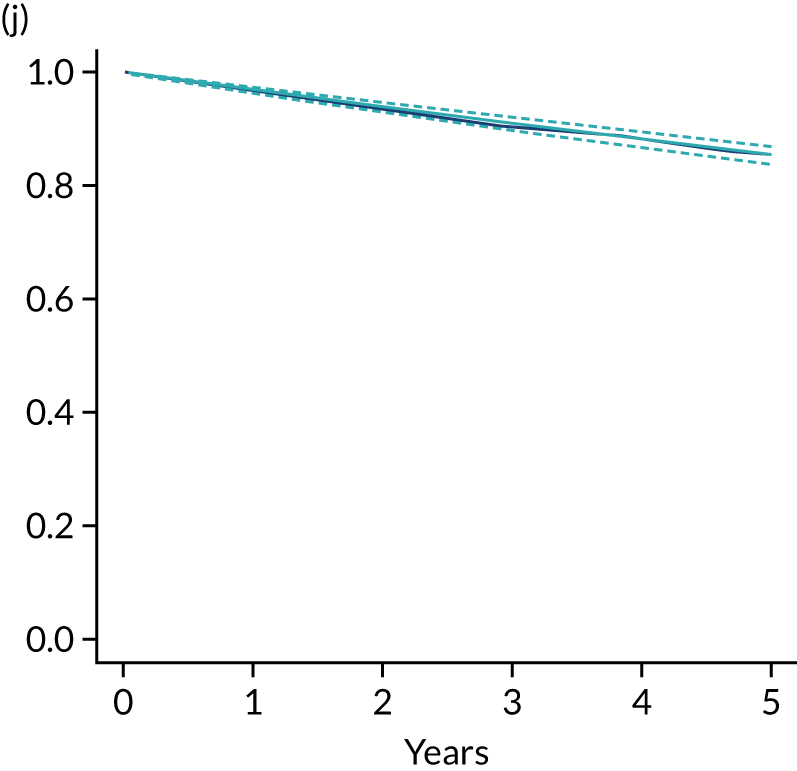

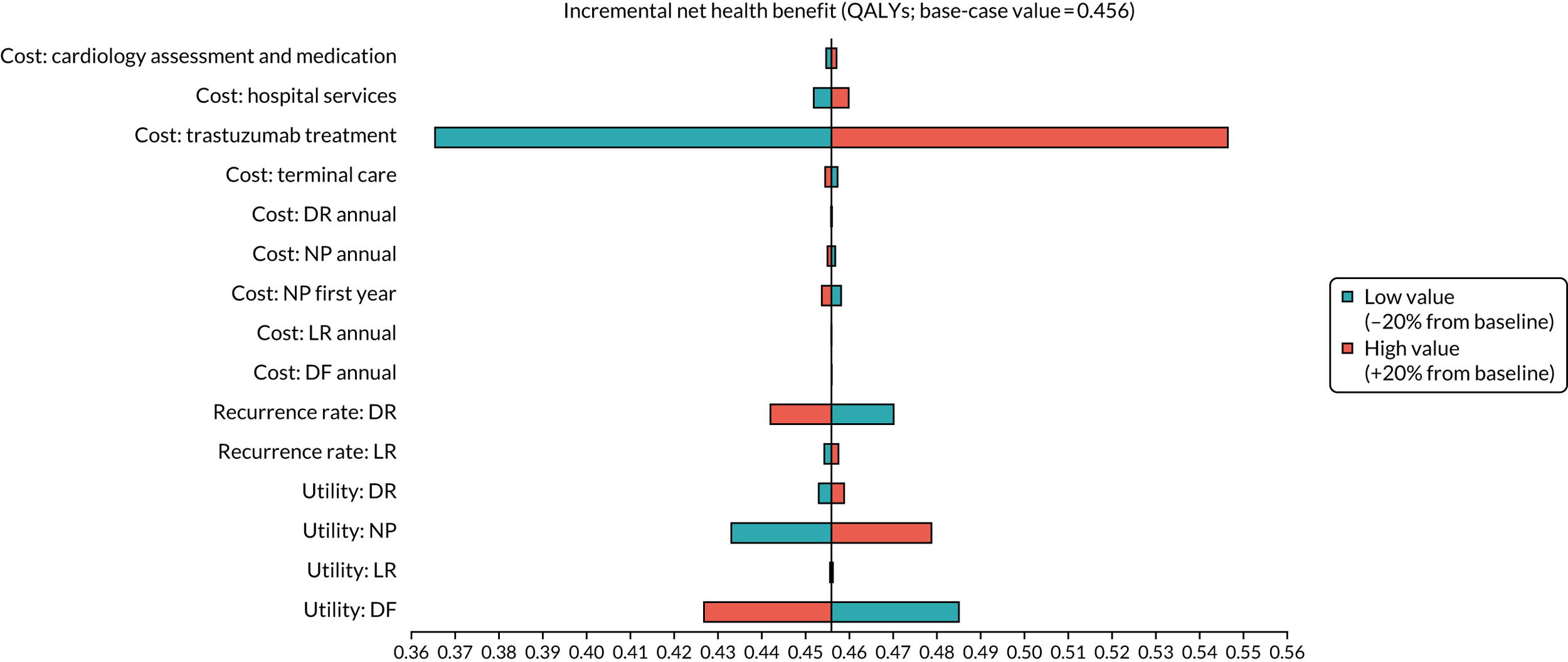

Timing of primary analysis of primary end point