Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/140/01. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The draft report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Outside this work, Paul Abrams reports grants and personal fees for being a consultant and speaker for Astellas Pharma Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and personal fees for being a consultant for Ipsen (Paris, France) and a speaker for Pfizer Inc. (New York City, NY, USA) and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd (Mumbai, India). He also reports personal fees from Pierre Fabre S.A. (Paris, France) and Coloplast Ltd (Peterborough, UK). Christopher Chapple reports being an author for Allergan plc (Dublin, Ireland) and Astellas Pharma; being an investigator for scientific studies/trials with Astellas Pharma and Ipsen; being a patent holder with Symimetics; receiving personal fees as a consultant/advisor for Astellas Pharma, Bayer Schering Pharma GmbH (Berlin, Germany), Ferring Pharmaceuticals (Saint-Prex, Switzerland), Galvani Bioelectronics (GlaxoSmithKline; Stevenage, UK), Pierre Fabre, Symimetics, TARIS Biomedical Inc. (Lexington, MA, USA), and Urovant Sciences (Irvine, CA, USA); and receiving personal fees as a meeting participant/speaker for Astellas Pharma and Pfizer. J Athene Lane was a member of the Clinical Trials Unit funded by the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of this trial. Marcus J Drake reports being on associated advisory boards and has received grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Allergan, Astellas Pharma and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. He has also received personal fees from Pfizer.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Lewis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The lower urinary tract (LUT) serves to store urine, relying on the bladder to act as a reservoir. People need to pass urine (known as voiding); this involves the expulsion of urine through the bladder outlet, which is a tube called the urethra. When storing urine, the urethra is held shut by a muscle called the sphincter. When the person wishes to void, they do so by relaxing the sphincter and increasing their bladder pressure by contraction of the main bladder muscle, called the detrusor, so that urine is actively expelled. In men, the genital tract also uses the urethra, and an important sexual gland, the prostate, encircles the urethra between the bladder neck and the sphincter.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are classified according to their relationship to the two main LUT functions of urine storage and voiding. The main storage LUTS are increased daytime urinary frequency (IDUF), nocturia, urgency and incontinence. The main voiding symptoms are slow stream, intermittency, hesitancy, straining and terminal dribbling. Some symptoms occur shortly after voiding has concluded. These ‘post-voiding LUTS’ are post-micturition dribble and a feeling of incomplete emptying. LUTS are a common clinical feature of ageing, with a high proportion of men aged > 50 years reporting at least one LUTS1 sufficient to impair quality of life (QoL), occupation and other activities.

Several mechanisms can give rise to LUTS:

-

Storage LUTS can arise if the bladder becomes ‘overactive’, leading to urgency and IDUF, and sometimes nocturia.

-

Storage LUTS can also arise if a patient develops an inflammation in the LUT, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI) or other abnormality.

-

Nocturia may occur if there is excessive urine production from the kidneys overnight, a problem that can be caused by a patient’s own habits or a range of medical problems.

-

Voiding and post-voiding LUTS might result if the prostate enlarges to constrict the urethra. Benign prostate enlargement (BPE) with ageing may cause partial bladder outlet obstruction (BOO), a situation known as benign prostatic obstruction (BPO). BOO can also be caused by pathologies narrowing the outlet, such as urethral stricture or bladder neck contracture.

-

Voiding and post-voiding LUTS can also be caused if the expulsion strength is impaired by weakening of the bladder, known as detrusor underactivity (DU).

Severe LUTS may require surgical treatment, which is one of the more common indications for surgery in the UK NHS, generally using transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or laser-based methods of enucleation or ablation. In 2016/17, > 18,000 TURPs were reported in England. 2 TURP is associated with morbidities such as blood loss, erectile dysfunction or incontinence, and a mortality rate of up to 0.25%. 3 Delayed-onset complications include urethral stricture and bladder neck contracture, and may affect almost 10% of men. 3

Each patient can have one or more of these causes of LUTS present; understanding of the underlying mechanisms is needed to optimise their treatment. Tests used in clinical practice to understand the issues in each individual with male LUTS include the following:4,5

-

Symptom scores are used to catalogue the LUTS present and their impact on the patient.

-

A digital rectal examination (DRE) is done to palpate outward enlargement of the prostate; this gives an indication of BPE but does not establish that BPO is present, as obstruction is caused by inward enlargement, compressing the urethra.

-

Urinalysis is undertaken to exclude infection.

-

Uroflowmetry is a basic test of voiding, evaluating the maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), voided volume (VV) and post-void residual (PVR). A threshold value for Qmax of 10 ml/second is commonly employed; for a well-conducted study, the specificity and positive predictive value for BOO may exceed 90%. 6 Other sources suggest that a Qmax of < 10 ml/second has a specificity of 70%, a positive predictive value of 70% and a sensitivity of 47% for BOO. 7

An additional test that can contribute insight to the underlying mechanisms is urodynamics (UDS), a term that principally covers observations made during multichannel cystometry, including filling cystometry to assess storage function and pressure–flow studies of voiding function. UDS requires urethral catheterisation for bladder filling and pressure measurement. Anal catheterisation is also done for measurement of abdominal pressure from the rectum. During the test, a computer calculates ‘detrusor pressure’, derived by subtracting abdominal from bladder pressure, to demonstrate whether or not bladder contraction is occurring. This test is the only routine clinical test able to distinguish BOO from DU, based on observation of a slow Qmax with a high detrusor pressure8 or with a low detrusor pressure,9 respectively. The clinical benefit of UDS is to ensure that interventions aimed at reducing outlet obstruction are used only in men who actually have BPO and also to identify other risk factors. As men are unlikely to accept TURP if they do not have BPO, widespread use of UDS may reduce interventional therapy for BPO in the NHS.

Urodynamics is not routinely included in standard clinical male LUTS assessment pathways in the UK. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline for this condition suggests that UDS should be offered to men with LUTS having specialist assessment if they are considering surgery. 5 The European Association of Urology (EAU) suggested that pressure–flow studies may be used for patients who cannot void > 150 ml, have a PVR of > 300 ml and in men aged > 80 years, and should be performed in men aged < 50 years when considering surgery. 4 Both organisations alluded to the weak evidence base when developing recommendations, and this was also identified in a Cochrane systematic review10 and other reviews. 11

Rationale

For older men, a slow urinary stream is a common problem. It can be caused by partial BOO, meaning that the conduit for passing urine is restricted. The most common cause is prostate enlargement due to the nodular growth of the gland in response to the male sex hormones. As the prostate is located around the upper end of the urethra, any inward enlargement will impede flow at the top end of the urethra, referred to as BPO. If sufficient obstruction occurs, voiding LUTS will result. The enlargement of the gland also can occur outwards; this can be felt by physical examination, done by feeling the prostate (i.e. a DRE). Other possible causes of BOO include a stricture (constricting scar of the urethra) or failure of relaxation of the bladder neck.

Voiding LUTS of a similar nature can also be a result of weakness of the bladder when a man is attempting to pass urine. This effectively means that the bladder does not mount enough contraction strength to overcome the innate resistance of the normal male bladder outlet and any co-existing BOO will exacerbate the situation. The associated LUTS are referred to as underactive bladder, which is now formally defined by the International Continence Society (ICS): ‘Underactive bladder is characterised by a slow urinary stream, hesitancy and straining to void, with or without a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying sometimes with storage symptoms’. 12

Storage LUTS are also a common feature for older men. These can result from a few possible mechanisms. Two situations are particularly important:

-

Overactive bladder syndrome (OAB), which is a symptom syndrome also defined by the ICS: ‘OAB is characterized by urinary urgency, with or without urgency urinary incontinence, usually with increased daytime frequency and nocturia, if there is no proven infection or other obvious pathology’. 13,14 By implication, this is a consequence of bladder dysfunction.

-

Nocturia, which is ‘the complaint that the individual has to wake at night one or more times to void’. 14,15 This may reflect OAB, but can also be due to the production of large volumes of urine from the kidneys overnight, referred to as ‘nocturnal polyuria’. Behavioural factors and medical problems can also give rise to nocturia, meaning that a symptom commonly referred to as a LUTS may actually reflect influences outside the LUT. 16,17

Thus, LUTS result from a range of underlying causes, including BOO, bladder dysfunction and factors outside the LUT. For many individuals, LUTS are very bothersome and men attend for medical attention in the hope of alleviating the impact of their symptoms. Furthermore, these issues are highly prevalent.

The treatment of LUTS aims to deal with the underlying mechanism. Diagnostic pathways are set up to map the severity and impact of the LUTS, to exclude serious conditions that could give rise to apparently similar presentations and to suggest mechanism. Details of the NICE guidance on the management of LUTS in men5 is provided in Box 1.

Specialist assessment refers to assessment carried out in any setting by a health-care professional with specific training in managing LUTS in men.

1.2.1 Offer men with LUTS having specialist assessment an assessment of their general medical history to identify possible causes of LUTS, and associated comorbidities. Review current medication, including herbal and over-the-counter medicines to identify drugs that may be contributing to the problem. [2010]

1.2.2 Offer men with LUTS having specialist assessment a physical examination guided by urological symptoms and other medical conditions, an examination of the abdomen and external genitalia, and a digital rectal examination (DRE). [2010]

1.2.3 At specialist assessment, ask men with LUTS to complete a urinary frequency volume chart. [2010]

1.2.4 At specialist assessment, offer men with LUTS information, advice and time to decide if they wish to have prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing if: their LUTS are suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction secondary to BPE or their prostate feels abnormal on DRE or they are concerned about prostate cancer. [2010]

1.2.5 Offer men with LUTS who are having specialist assessment a measurement of flow rate and post void residual volume. [2010]

1.2.6 Offer cystoscopy to men with LUTS having specialist assessment only when clinically indicated, for example if there is a history of any of the following:

-

recurrent infection

-

sterile pyuria

-

haematuria

-

profound symptoms

-

pain. [2010]

1.2.7 Offer imaging of the upper urinary tract to men with LUTS having specialist assessment only when clinically indicated, for example if there is a history of any of the following:

-

chronic retention

-

haematuria

-

recurrent infection

-

sterile pyuria

-

profound symptoms

-

pain. [2010]

1.2.8 Consider offering multichannel cystometry to men with LUTS having specialist assessment if they are considering surgery. [2010]

1.2.9 Offer pad tests to men with LUTS having specialist assessment only if the degree of urinary incontinence needs to be measured. [2010]

This information was accurate at time of access. © NICE 2018 Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management (CG97). 5 Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg97 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

The NICE guidance5 also recommends that men considering any treatment for LUTS be offered an assessment of their baseline symptoms with a validated symptom score [e.g. the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)], to allow assessment of subsequent symptom change. At initial assessment, the guidance5 suggests that men with LUTS a urine dipstick test to detect blood, glucose, protein, leucocytes and nitrites. The EAU guidelines4 include the same assessment components and, in addition, include the need to enquire about sexual function. Thus, two main diagnostic pathways relevant to practice in the UK include history and physical examination, including DRE; symptom score assessment; frequency–volume chart (also known as a bladder diary); flow rate testing with PVR measurement; and dipstick urinalysis. In both pathways, UDS testing is used selectively.

The potential contribution of UDS is principally in establishing if BOO is truly present. This is achieved by measuring the pressure the bladder generates when the flow rate is at its maximum. A high pressure generating only a slow flow is diagnostic of BOO and is quantified by the Bladder Outlet Obstruction Index (BOOI). A low pressure with slow flow rate indicates that reduced detrusor contraction strength is the cause, technically referred to as DU, and is quantified by the Bladder Contractility Index (BCI). Because of the nature of the way the UDS parameters are established, the test can identify if both mechanisms are present in one individual.

On the face of it, the confirmation of mechanism would make sense for guiding treatment choice. However, the prevalence of DU is lower than that of BPO; therefore, the chance of BPO as the explanation for voiding LUTS is considerably high. For men with a Qmax of < 10 ml/second, the chance that BOO is present is up to 90%, provided the test is undertaken and interpreted appropriately. 6 However, it becomes less reliable if the test is not done in adequate circumstances,18 or if the flow rate is > 10 ml/second.

Thus, two broad approaches have emerged:

-

use of UDS included in the diagnostic pathway to confirm whether BOO and/or DU is the cause of voiding LUTS in an individual man

-

omission of UDS from the pathway and presuming that BPO is the problem for a man with voiding LUTS.

This has important implications for decision-making, as someone evaluated under the second approach could be considered for surgery to relieve presumed BPO when actually they do not have BOO. Consequently, they would potentially experience the intervention and possible complications, and not benefit from improved symptoms. On the other hand, men evaluated under the first approach will be expected to undergo the invasive diagnostic test of UDS, gaining little benefit if the finding simply backs up the suppositions derived by the other tests in the pathway. Thus, both pathways have potential advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, many urological centres use symptom assessment, physical examination, urinalysis, flow rate and PVR measurement, and bladder diary, hereafter called the ‘routine care’ diagnostic pathway. They choose to omit UDS, because of a lack of relevant research evidence. Indeed, a Cochrane review found only two studies, one of which had to be excluded from analysis. 10 Accordingly, NICE highlighted the importance of identifying the role of invasive UDS, including clarifying whether or not it could improve the outcome of surgery and whether or not it should be recommended in the future. 5

When BPO is present or suspected, it can be treated by removing the obstruction. Relief of BOO can be attempted by various interventions. The following interventions were available during the course of the Urodynamics for Prostate Surgery Trial: Randomised Evaluation of Assessment Methods (UPSTREAM):

-

medications to relax the urethra, known as alpha-blockers (e.g. tamsulosin, alfuzosin or doxazosin)

-

medications to shrink the prostate enlargement, known as 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (e.g. finasteride or dutasteride)

-

a medication whose mechanism of action in LUTS has not been fully established and the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor tadalafil, which is also used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction

-

endoscopic resection or incision of the intruding part of the prostate [TURP or bladder neck incision (BNI)]

-

an endoscopic procedure to retract the prostate partly out of the way, known as UroLift® (NeoTract Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA)

-

laser enucleation of the nodular elements [e.g. holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP)]

-

laser vaporisation of the intruding part of the prostate (e.g. greenlight laser)

-

prostate artery embolisation to shrink the prostate by reducing its blood supply.

UPSTREAM studied men with bothersome LUTS who were referred to urology departments when surgery was potentially being considered. Men were randomised to the specified intervention (UDS plus routine care) or comparator (routine care alone), and the trial was powered to ascertain significant difference in non-inferiority in symptoms at 18 months after randomisation. The key secondary outcome was surgery rates, as men in the UDS arm identified as not having BOO would not be recommended for surgery. A non-inferiority assessment was selected because men not receiving surgery would see no improvement or modest improvement in symptoms.

Transurethral resection of the prostate requires a median hospital stay of 2 days, and additional NHS costs can result from delayed discharge from hospital, readmissions and increased primary care utilisation. Significant risks may be associated with TURP: mortality is up to 0.25% and there is risk of blood loss, erectile dysfunction or incontinence. Late complications, notably urethral stricture, can affect almost 10% of men. 3 Lower surgery rates would potentially have the advantages of reduced adverse effects and resource use, so a health economic analysis was included. Qualitative interviewing was also employed to explore user acceptability and influences on decisions made by the participating men and the surgeons.

Aim and objectives

Using invasive UDS to categorise LUT function should improve patient selection for surgery compared with a pathway with no invasive UDS testing. Identifying men with LUTS who do not have BOO will reduce men’s willingness to undergo surgery, which should reduce risk of surgical complications and substandard symptom outcomes.

Aim

The aim was to determine whether a care pathway including UDS is no worse for symptom outcome than one in which it is omitted, at 18 months after randomisation. The primary clinical outcome was the IPSS at 18 months after randomisation. Influence of UDS on rates of bladder outlet surgery was a main secondary outcome.

Objectives

-

Does invasive UDS deliver similar or better symptomatic outcomes for LUTS measured by the IPSS at 18 months after randomisation?

-

Does invasive UDS influence surgical decision-making, as reflected in differing surgery rates in the two diagnostic pathways?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of the two diagnostic pathways?

-

What are the relative harms of UDS and the subsequent therapy?

-

What subsequent NHS services are required (including repeat surgery or catheterisation for acute urinary retention) for men in each arm?

-

What are the differential effects on QoL?

A qualitative component examined patients’ and clinicians’ views and experiences of UDS for male BOO and BOO surgery. The qualitative component considered the following questions:

-

What is the acceptability and experience of UDS and how satisfied are men with the diagnostic pathways?

-

What are clinicians’ opinions in relation to the value of UDS for male BOO?

-

How does UDS affect decision-making for both surgeons and men with bothersome LUTS?

-

What are the experiences and attitudes of men regarding male BOO surgery and recovery?

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

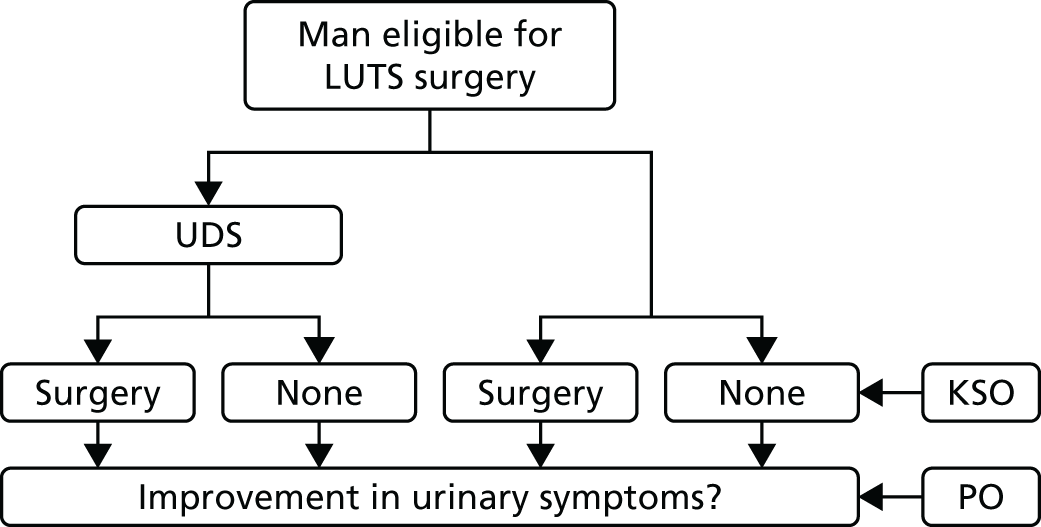

This trial was a two-arm, multicentre, randomised controlled trial, randomising men seeking further treatment, which may include surgery, for their bothersome LUTS, to either a care pathway that includes UDS testing or a care pathway without it (i.e. routine care). UPSTREAM was designed as a non-inferiority trial to establish non-inferiority in symptom severity 18 months after randomisation, which was the primary outcome, measured using the IPSS. It derived from the assumption that UDS would decrease the need for surgery, as it would provide useful information regarding bladder function and better predict success of surgery. Surgery rates were measured (to establish superiority) as a key secondary outcome (Figure 1). Both the trial protocol19 and statistical analysis plan (SAP)20 are published and detail the trial background and intentions.

FIGURE 1.

The UPSTREAM interventions and key outcomes. KSO, key secondary outcome; PO, primary outcome.

Ethics approval and research governance

The National Research Ethics Service Committee South Central – Oxford B reviewed and approved the trial on 10 July 2014 (reference number 14/SC/0237). Centre-specific assessments were completed by each of the participating NHS trusts (as listed in the protocol19) and all the necessary approvals were granted, including subsequent approvals for amendments (identified in Table 1). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry (ISRCTN56164274) and sponsored by North Bristol NHS Trust (NBT) (reference number 3250).

| Amendment (date) | Brief description of amendment |

|---|---|

| Minor 1 (September 2014) |

|

| Minor 2 (December 2015 and January 2016) |

|

| Minor 3 (November 2016) |

|

| Minor 4 (April 2017) |

|

| Minor 5 (April 2017) |

|

| Substantial 1 (February 2015) |

|

| Substantial 2 (May 2015) |

|

| Substantial 3 (September 2016) |

|

The trial was conducted in accordance with the UK Research Governance Framework21 and the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. 22 All men who agreed to take part in the trial provided written informed consent and any adverse event (AE) classified (and confirmed) as serious, related and unexpected was reported to the sponsor and Research Ethics Committee within 15 days. All AEs were summarised and reviewed regularly by the sponsor and Trial Management Group (TMG), including the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Amendments

Table 1 summarises the minor and substantial amendments to the trial after the original ethics approval was granted, all of which the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme supported. Amendments were made, following feedback from patients and centre staff, to improve understanding of, uptake of and involvement with the trial (e.g. clarifying the inclusion criteria). Furthermore, slower than anticipated recruitment rates at the beginning resulted in an extension (i.e. substantial amendment 3).

Patient and public involvement

UPSTREAM included patient and public involvement throughout its lifecycle, via mixed methods (e.g. remote communication and face-to-face meetings).

During the funding application and development (design) of the trial, a user (patient) panel of eight volunteers from NBT’s research and innovation department provided insight and feedback, and 15 men were consulted at flow rate/UDS clinics at two hospitals about the procedures that would, and could, occur during the trial. All these patient representatives regarded invasive UDS as acceptable, to gain information relevant to treatment decisions. Experiencing the test did not alter this attitude: it was ‘less unpleasant than anticipated’. For a care pathway omitting invasive testing, all men understood how sufficient information for treatment could be obtained. One man said that ‘free-flow rate testing is time-consuming’ and recommended keeping the diagnostic pathway short. Thirteen of the 15 patient representatives would accept random allocation to a diagnostic pathway. One said, ‘he did not want any tubes inserted without general anaesthetic’; another said he was ‘convinced of the benefits of the test and a more accurate diagnosis’. The men emphasised that the care pathway should not be prolonged. This pre-trial feedback from patient and public representatives helped develop the initial trial design.

Members of the same panel also contributed to the design of the letter of invitation to participate, and the patient information sheet, as well as contributing during the recruitment period of the trial. We sought insight about ways to improve the trial experience for men, resulting in changes to documentation and processes (e.g. consent and questionnaire completion methods; see Amendments). There was also direct involvement in an early press release, which aimed to increase the trial profile.

Throughout the trial, there was a continued presence of two patient representatives at TMG and TSC meetings. They advised on trial progress, participant retention, newsletters (i.e. content, design and frequency) and continued development, as well as assisting with ideas surrounding the reporting and dissemination of findings.

Participants

Urological departments from 26 NHS hospitals across England recruited men from October 2014 to December 2016.

Inclusion criteria

Given the pragmatic nature of this trial, eligibility criteria were minimal and consisted of recruiting men (aged ≥ 18 years) who were seeking further treatment, which may include surgery, for their bothersome LUTS. Men who were already on surgery waiting lists were also eligible, providing they were willing to have UDS first, if assigned to that arm, and to reconsider treatment options if deemed appropriate following the UDS assessment.

Exclusion criteria

Men were not eligible if they met any of the following exclusion criteria:

-

inability to pass urine without a catheter [excluding clean intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC) after passing urine, in order to complete emptying of their bladder]

-

have a relevant neurological disease (such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease or spina bifida)

-

currently undergoing treatment for prostate or bladder cancer

-

previously had prostate surgery

-

not medically fit for surgery

-

do not consent to being randomised or comply with essential trial procedures.

Interventions

Men were randomised to a diagnostic pathway based on routine care (i.e. assessment as set out in the NICE clinical guidance on male LUTS:5 routine care control arm) or a pathway that included UDS (routine care plus UDS: intervention arm). UDS is a diagnostic test to evaluate bladder function, assessing how well a person’s bladder stores urine and how well they pass urine (voiding). The test used catheters to measure bladder and abdominal pressures during bladder filling and passing urine. Any change in abdominal pressure was also detected in the bladder and a computer calculated the difference between bladder and abdominal pressure throughout the test. Detrusor pressure was then derived and used to assess voiding function and urine storage. This knowledge was then used to detect whether or not BOO is present. Once voiding function was tested, an opinion on surgery effectiveness in treating the man could be made.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The IPSS, a well-established and validated patient-reported outcome, was collected at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months after randomisation. Men filled in a questionnaire concerning their LUTS, which produced a score from 0 to 35 (with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms).

Secondary outcomes

Key secondary (surgery)

The number of men having surgery within 18 months was recorded in each arm and the proportion of men having surgery was calculated using the number of men with a completed 18-month case report form (CRF) as the denominator. Men who withdrew consent for a notes review to be carried out at 18 months, or who died, were removed for this outcome. As a pragmatic trial, standard practice for the centres were followed, relating to the type of surgery, LUTS medications or other treatments.

Adverse events

The number of AEs were recorded in each arm, as well as the severity, expectedness and relationship to testing and treatment. Box 2 provides the definition of a serious adverse event (SAE) and lists expected and related AEs. When events were related to surgery, they were given a Clavien–Dindo classification,23 of which there are five grades (plus two subgroups for grades 3 and 4); see Dindo et al. 23 for further details.

An AE was defined as serious if one of more of the following applied to the AE:

-

resulted in the death of the participant

-

was life-threatening (i.e. an event whereby the participant was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event that, hypothetically, may have caused death if it were more severe)

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatient hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent/significant disability/incapacity

-

was considered medically significant by the investigator (i.e. important AEs that were not immediately life-threatening or did not result in death or hospitalisation, but may have jeopardised the subject or required intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed above, may also be considered serious; medical judgement was exercised in deciding whether or not an AE is serious in other situations).

-

UTI.

-

Bacteriuria.

-

Haematuria.

-

Urinary retention.

-

Discomfort.

-

Dysuria.

-

Urethral trauma.

-

Excess blood loss (of > 500 ml).

-

Blood transfusion.

-

Urethral injury.

-

Bladder injury.

-

Bowel injury.

-

Injury to blood vessels or nerves.

-

Anaesthetic complications.

-

Thrombosis/deep-vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

-

Prolongation of postoperative catheterisation.

-

Recatheterisation.

-

UTI.

-

Other infection (sepsis, septicaemia, abscess).

-

New urinary tract symptoms.

-

Constipation.

-

Discomfort/pain.

-

New sexual problems.

-

Death.

Reproduced from Bailey et al. 19 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

All AEs (serious and non-serious) were reviewed by an independent clinician, including the relatedness to testing and treatment and Clavien–Dindo scoring for surgery-related events, to ensure uniformity in the classifications across the centres and check for bias in the classifications. Any disagreements with the assignment or classification were revised when appropriate.

Patient-reported outcome measures: ICIQ-MLUTS

In the 18-month questionnaire, men were asked to fill out the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-MLUTS). [Note that copies of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaires can be requested via the website, URL: www.iciq.net (accessed 29 May 2019).] Both a voiding and incontinence score were generated from this questionnaire as well daytime and night-time voiding frequency data. This information was also collected at baseline and at 6 and 12 months.

Patient-reported outcome measures: ICIQ-MLUTSsex

In the 18-month questionnaire, men were asked to fill out the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Sexual Matters associated with Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-MLUTSsex). The ICIQ-MLUTSsex contained data on erection and ejaculation quality and how bothersome this was for them. This information was also collected at baseline and at 6 and 12 months.

International Prostate Symptom Score quality of life

As part of the IPSS questionnaire, men were asked how they would feel if they were to spend the rest of their life with their urinary condition, rated on a scale from 0, ‘delighted’, to 6, ‘terrible’.

Maximum urinary flow rate

Uroflowmetry, evaluating the Qmax, VV and PVR, was measured as part of the 18-month clinic. When men did not turn up to the clinic, this measure was collected using case note reviews and the measurements closest to 18 months after randomisation were utilised. If two measures were taken on the same day, the higher flow rate was used. Uroflowmetry data (Qmax, VV and PVR) were also collected at baseline; if men had recently had a uroflowmetry test prior to joining the trial, these data were used to avoid unnecessary repetition for the patient. Additional uroflowmetry data were collected for men undergoing surgery in both arms, approximately 4 months after surgery (± 1 month).

Patient-reported outcome measures: ICIQ-UDS-S

Overall satisfaction with the UDS assessment was captured using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – urodynamics satisfaction (ICIQ-UDS-S), which asked about the details of the procedure, patient satisfaction and whether or not they would recommend the test. Although not a testable outcome, the satisfaction with the UDS procedure was explored descriptively.

Non-inferiority margin

A non-inferiority design was chosen to assess whether or not men randomised to receive UDS would have patient-reported urinary symptoms that were better than routine care or no worse than an acceptable number of symptoms. The sample size calculation was based on the consideration that men randomised to UDS should have symptoms that are non-inferior to those who are randomised to routine care. For the primary outcome, a lower IPSS in the intervention arm, or of no more than 1 point higher, was hypothesised as suggesting non-inferiority. The team felt that these were appropriate for the following reasons:

-

The minimally clinically important difference for the IPSS is generally accepted to be a 3-point difference;24 however, given that a difference smaller than this may involve a substantial difference on an individual subscale, it was felt that the non-inferiority margin should reflect a more sensitive change.

-

A single void per night has shown to not be too much of a problem for men suffering with nocturia. 25 However, at least two voids have been shown to be substantially bothersome; therefore, a 1-point difference would be able to detect this subtle but pivotal change.

-

A difference of 1 point is much more conservative than a difference of 2 or 3 points, requiring a much larger sample size, and would therefore reduce the risk of falsely claiming non-inferiority.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the non-inferiority primary outcome of IPSS at 18 months after randomisation, as well as the key secondary outcome of surgery rate. The non-inferiority margin was set at 1 point and a one-sided t-test with common standard deviation (SD) of 5, 80% power and 5% alpha gave a required sample size of 310 participants per arm. It was estimated that 20% of participants would be lost to follow-up or withdraw (attrition); therefore, the sample size was inflated to 388 men per arm (776 men in total).

The key secondary outcome was based on a superiority outcome of surgery, for which it was anticipated that the UDS procedure may reduce the proportion of men having surgery. Using hospital audit data from Bristol, for 5670 men presenting with LUTS suggestive of poor or obstructive urine flow,19 the team sought to find an absolute difference of 13% based on 73% of men in the routine care arm having surgery compared with 60% in the UDS arm. To achieve 90% power with a two-sided alpha of 5% required a sample size of 291 men per group. Inflating for anticipated attrition rates led to a sample size of 364 men per arm, smaller than for the primary outcome. Therefore, the team aimed for a recruitment total of 800 men.

Randomisation and implementation

Eligible men were randomised using ‘simple randomisation’, whereby trained staff (e.g. research nurse, administrators) utilised a telephone- and web-based randomisation system that randomised men to UDS or routine care, with no stratification or minimisation techniques. Randomisation was carried out in the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC). Originally, the trial team planned to stratify the randomisation by centre, but, given the use of simple randomisation, this was not the case. It was, however, adjusted for in all analyses.

Blinding

Given the nature of UDS, men were not blinded to their trial arm. The trial manager and administrative staff, although unblinded to enable individual data collection and AE reporting, were blinded to aggregate data. Centre (hospital) staff had access to unblinded data to enable them to make clinical decisions about the management of a man’s LUTS, including the appropriateness of surgery.

All investigators remained blinded to aggregate data throughout recruitment and analysis. The senior statistician (PSB) had not seen any data when writing the SAP and remained blinded until the analysis had been finalised. The junior statistician (GJY) had unblinded access to the data to report safety and outcome data to the DMC. The protocol was written before recruitment ended and published in a peer-reviewed journal. 19 The SAP was written and agreed by the trial team, DMC and TSC in September 2016 prior to recruitment end. It was submitted for publication on the 14 December 2016 and underwent minor revisions before being published on 3 October 2017. 20

Data collection

Data were collected at certain points from various data collection forms (Table 2). The primary outcome (IPSS) was collected at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months after randomisation. The ICIQ-MLUTS and ICIQ-MLUTSsex questions were also asked at these time points. A 3-day bladder diary was distributed at baseline and 18 months; and will be analysed separately at a later date as an exploratory analysis.

| Data collection tool | Baseline | UDS only | Surgery only | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After | Perioperative | 4 monthsa after | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||

| CRF | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| IPSS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ICIQ-MLUTS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ICIQ-MLUTSsex | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ICIQ-UDS-S | ✓ | ||||||

| Flow rate/PVR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bladder diary | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Case note review | ✓ | ||||||

As some CRFs and questionnaires were completed earlier/later than their scheduled time in the follow-up, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was added that included questionnaires only from within a specific time frame (prior to analysis, the team established a time frame for which questionnaires would be included in this sensitivity analysis). An 18-month questionnaire would be accepted only if it was within the window of 16–20 months from the date of randomisation. The baseline questionnaire, which was adjusted for, was accepted only if it was within 6 months of the randomisation date.

Statistical methods

The main statistical analyses were prespecified using a SAP, which was completed prior to recruitment end. 20 The database was closed on the 20 August; final analysis started soon after and finished in October 2018. Stata® 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analyses in this trial. Binary outcomes were presented as n (%), whereas continuous outcomes were presented as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Any deviations from these methods were considered ‘post hoc’ analyses and clearly labelled as such.

Primary analysis

The IPSS was collected from the 18-month questionnaire. The primary analyses were conducted under the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle using multivariable linear regression. Both centre and the baseline IPSS were adjusted for in the primary analysis. Results were based on the non-inferiority margin prespecified in the trial design process. As the primary analysis tested non-inferiority, interpretation of the primary analysis results focused on observed differences, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the between-group comparisons. When CIs lay below the non-equivalence margin, the two arms were deemed to be equivalent.

H0: routine care leads to IPSSs that are at least 1 point lower, on average, than in the UDS arm (higher IPSSs signify a poorer outcome).

H1: UDS is non-inferior to routine care, with IPSSs that are lower than in the routine care arm or less than 1 point higher.

Secondary analyses

In a similar way to the primary analysis, all secondary analyses were conducted using ITT and adjusting for centre and baseline measures (when appropriate). However, all secondary analyses tested for superiority as opposed to non-inferiority.

The key secondary outcome was surgery rates at 18 months. Using logistic regression, the proportion of men receiving surgery for BOO was compared between the two arms. The denominator for this outcome was the number of men who were followed up at 18 months, either by clinic appointment or by case notes review. The proportion having surgery by their 18-month follow-up was recorded via perioperative CRFs and 18-month CRFs. If men withdrew before their 18-month time point, or did not attend their clinic appointment, details were obtained via notes review, when permissible. We also explored whether or not men agreed with their doctor’s recommendation on listing for surgery.

Adverse events were collected throughout each man’s 18-month period of follow-up. The relationship to diagnostic testing and/or treatment was considered, as well as the severity and expectedness. When events were deemed related to surgery, a Clavien–Dindo score23 was assigned. The number of deaths and the number of acute urinary retention cases were also recorded separately in each arm. Events were compared using logistic and ordinal logistic regression.

Each of the following patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were compared between the arms at 18 months, using linear and logistic regression:

-

IPSS QoL

-

ICIQ-MLUTS (voiding scale, incontinence scale, daytime frequency and nocturia)

-

ICIQ-MLUTSsex (erection and ejaculation quality, painful ejaculation and overall effect on sex life).

The following dichotomous variables were created from the ICIQ-MLUTS for ease of reporting and interpretation:

-

Daytime frequency (eight or more times): question 13a, coded as 1 if the man ticked ‘9 or 10 times’, ‘11 or 12 times’ or ‘13 or more times’.

-

Nocturia (one or more times per night): question 14a, coded as 1 if the man ticked ‘two’, ‘three’ or ‘four or more’.

Dichotomous variables were also created from the ICIQ-MLUTSsex:

-

Erections (reduced or none): question 2a, coded as 1 if the man ticked ‘yes, with reduced rigidity’, ‘yes, with severely reduced rigidity’ or ‘no, erection not possible’.

-

Ejaculation (reduced or none): question 3a, coded as 1 if the man ticked ‘yes, reduced quantity’, ‘yes, significantly reduced quantity’ or ‘no ejaculation’.

-

Painful ejaculation (yes): question 4a, coded as 1 if the man ticked ‘yes, slight pain/discomfort’, ‘yes, moderate pain/discomfort’ or ‘yes, severe pain/discomfort’.

-

Urinary symptoms affected sex life: question 5a, coded as 1 if man ticked ‘a little’, ‘somewhat’ or ‘a lot’.

Ordinal scales were also analysed to ensure that the dichotomisation did not mask any of the findings.

Maximum urinary flow rate was collected at 18 months, either at the 18-month clinic visit or via case note review. When multiple measures were recorded, the measure closest to the 18-month time point (548 days after randomisation) was used. Linear regression was used to compare flow rates between the arms, adjusting for baseline urinary flow rate and centre.

Satisfaction with UDS was explored descriptively as it was collected only for those men who had UDS.

Additional cost-effectiveness and qualitative analysis outcomes are described and presented in Chapters 4 and 5.

Sensitivity analyses

Several prespecified sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results from the statistical analyses to increase understanding of the relationship between the dependent and independent variables for the primary analysis and, in some circumstances, the key secondary analysis:

Per-protocol analysis

The primary and key secondary analyses were repeated, analysing men who received UDS, having been allocated to it, against those who did not receive it, having been allocated to routine care. Therefore, any men who had not complied with their randomised pathway were excluded from the analyses.

Complier-average causal effect analysis

The complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis used the data from those men who did receive their randomised treatment but, unlike the primary analysis, incorporated the treatment-received variable as the independent variable and randomisation as an instrumental variable, using the ‘iv regress sls’ command in Stata.

Mixed-effects model

This analysis allowed us to look at the total 18-month impact of the intervention and whether or not there was a difference between the two arms. The mixed-effects repeated measures approach was adopted to assess the total 18-month impact, while accounting for missing data at each 6-month time point.

Imputation using 6- and 12-month data

When baseline IPSSs were missing, the 6-month scores were utilised if no intervention procedures had taken place (e.g. surgery). When 18-month scores were missing, the 12-months scores were utilised if all intervention procedures had taken place by this time point, if they were scheduled to take place.

Imputation for missing data

Men included in the analysis were compared with those men who were not followed up at 18 months. The missingness mechanism was assessed and multiple imputation methods were adopted. The randomisation seed was prespecified (648) to allow reproducible results and reduce any tampering.

Adjustment for clinically important confounders

When the trial was designed, the clinicians produced a list of clinically important confounders that should be considered in the analysis of the primary outcome. These were centre, age, comorbidities and symptom severity. Therefore, these were adjusted for in a sensitivity analysis.

Adjustment for imbalance at baseline

A prespecified measure of imbalance was used to compare the arms and any continuous measures that were at least 0.5 SDs apart, or had an absolute difference of 10% (for binary and categorical outcomes), were adjusted for.

Adjustment for time from surgery

When UPSTREAM was designed, the team envisaged that the 18-month follow-up would incorporate a 6-month post-surgery gap that would allow any side effects of treatment to subside. It became apparent that assessment and treatment pathways across the 26 hospitals varied, and waiting lists for surgery were longer than anticipated, potentially influencing the 18-month symptom scores. Therefore, the time between surgery and the 18-month questionnaire was calculated, imputing a time of 1000 days when no surgery occurred.

When the 18-month time points were scrutinised during follow-up, the team chose to conduct a post hoc sensitivity analysis that excluded follow-up outside a certain trial window (16–20 months). This was done to ensure that the results we achieved were truly reflective of an 18-month follow-up.

Subgroup analyses

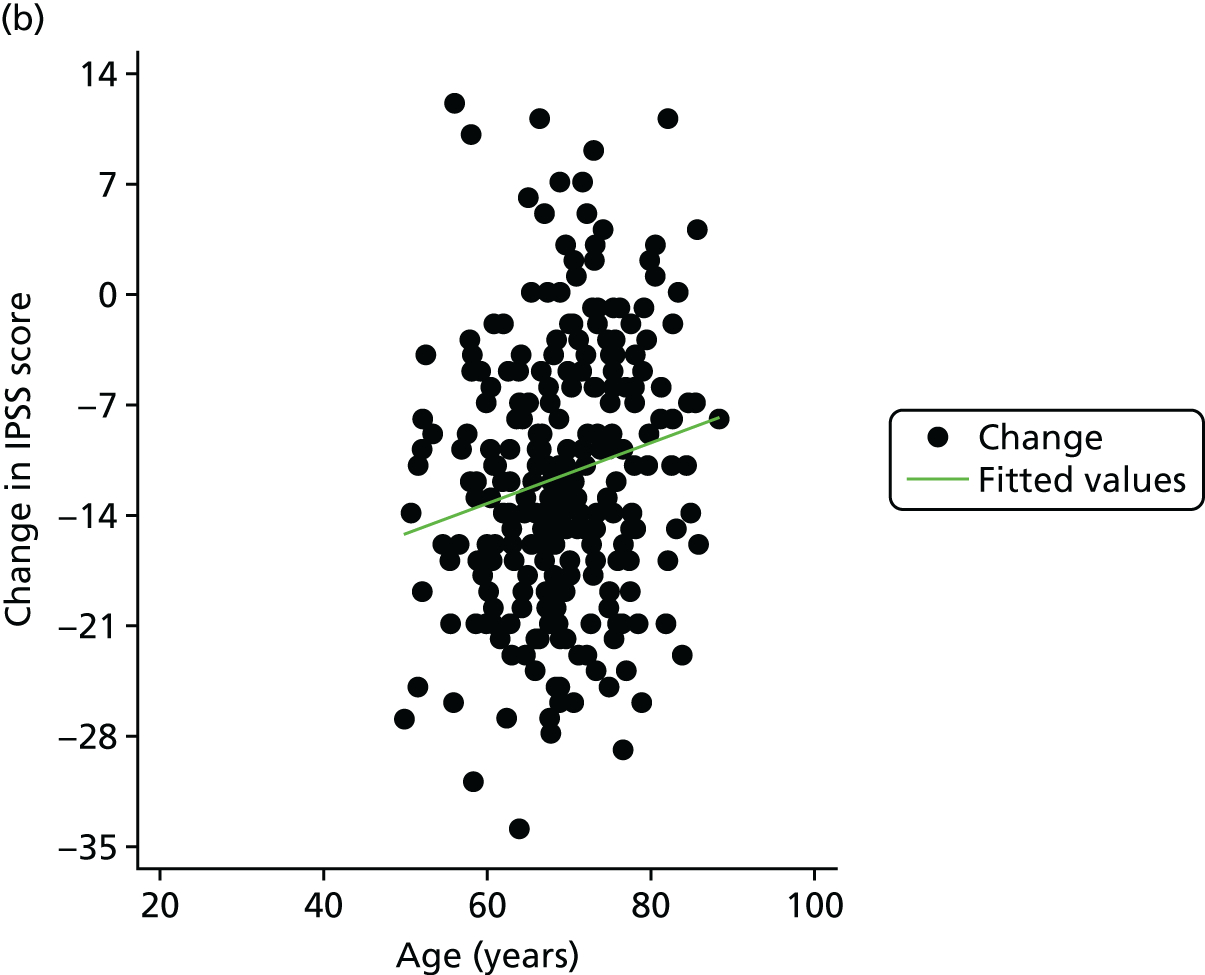

Prespecified subgroups were used to test whether or not the differences between the two arms were more pronounced in certain subgroups of men. Although underpowered, tests of interaction between the dichotomised/categorical variables and trial arm were carried out to test whether or not the treatment effect differed between subgroups. These interaction terms were added to the primary analysis model.

Subgroup analyses included:

-

age (split by median age)

-

flow rate (> 12 ml/second vs. ≤ 12 ml/second)

-

maximum VV (< 200 ml vs. ≥ 200 ml)

-

storage dysfunction/nocturia (yes vs. no)

-

severity of storage LUTS, questions 2, 4 and 7 in the IPSS questionnaire (split by median).

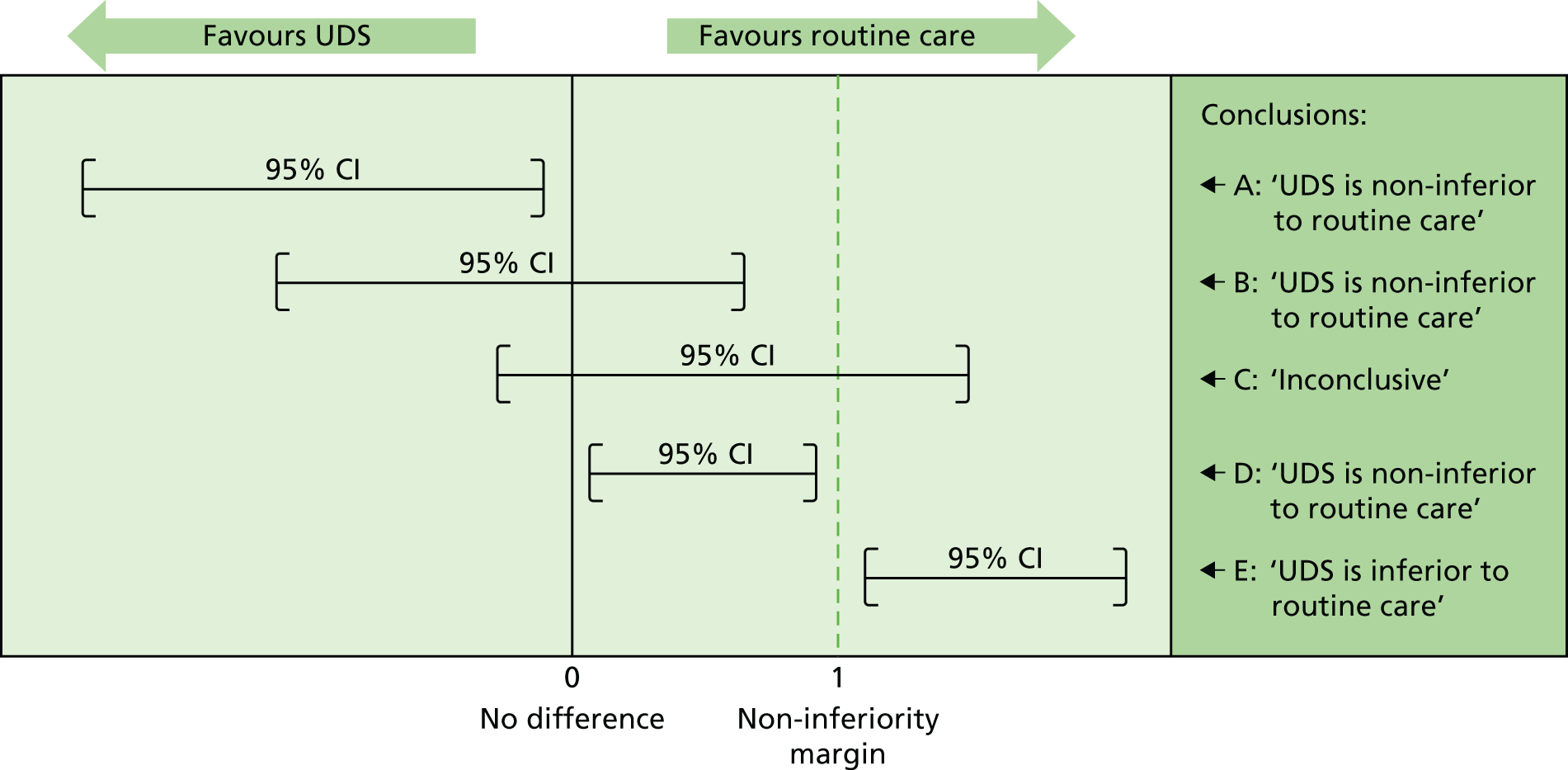

Assessing non-inferiority

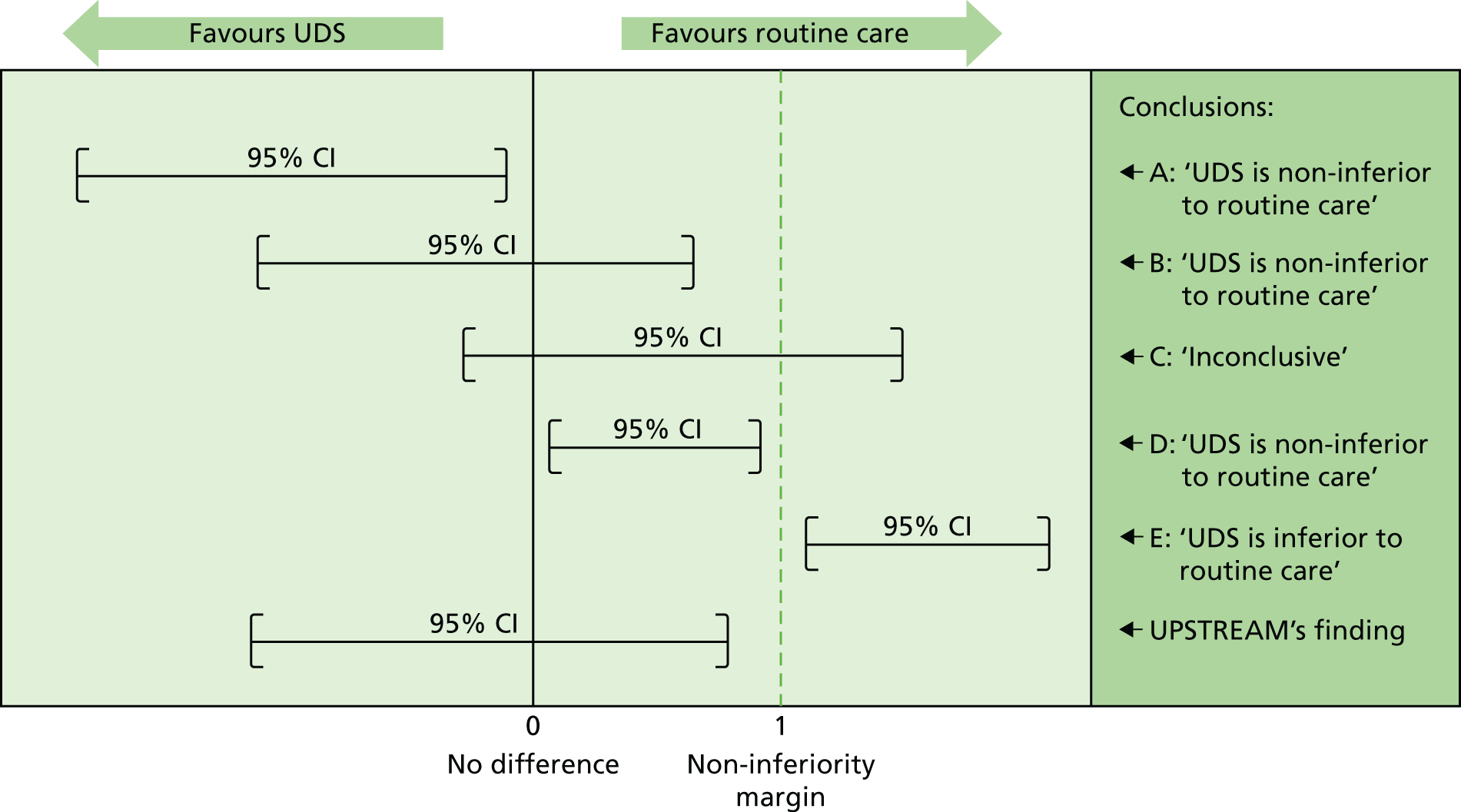

Although a p-value can be very helpful in determining superiority, it cannot determine non-inferiority or equivalence. Therefore, for the primary outcome of this trial, emphasis was placed on the 95% CIs and their positioning around the non-inferiority margin. The variety of potential conclusions are demonstrated in Figure 2 (adapted from Schumi and Wittes26).

FIGURE 2.

Assessing the potential non-inferiority conclusions for UPSTREAM. Treatment difference (UDS – routine care). Adapted from Schumi and Wittes26 © 2011 Schumi and Wittes; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Future analysis plans

A bladder diary analysis plan has been prespecified, which will look at clinical characteristics of the men, such as average sensation score, total urgency and frequency score, and VV. It will assess the quality of the bladder diary by comparing it with the measures from the trial, for example VV, as well as measures from the validated questionnaires (e.g. IDUF and nocturia). By looking at the daytime frequency and nocturia, we can also assess the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire and IPSS to see whether or not one is more closely related to the results from the bladder diary.

The treatment pathways are of interest to the trial team, so it is probable that they will go through each of the men’s treatments, both surgical and conservative, to gain an understanding of a typical pathway for the treatment of LUTS.

UPSTREAM has been awarded further follow-up funding to assess the longer-term impact of LUTS and its treatment.

Chapter 3 Results

Some of the work reported in this chapter may overlap with content published in dedicated journal papers, which we wish to acknowledge. 27–29

Some text has been based on Drake et al. 28 Reprinted from Eur Urol, Drake MJ, Lewis AL, Young GJ, Abrams P, Blair P, Chapple C, et al. , Diagnostic assessment of lower urinary tracts symptoms in men considering prostate surgery; a non-inferiority randomised controlled trial of urodynamics in 26 hospitals [published online ahead of print June 30 2020], Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier. Some text has also been based on Aiello et al. 29 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

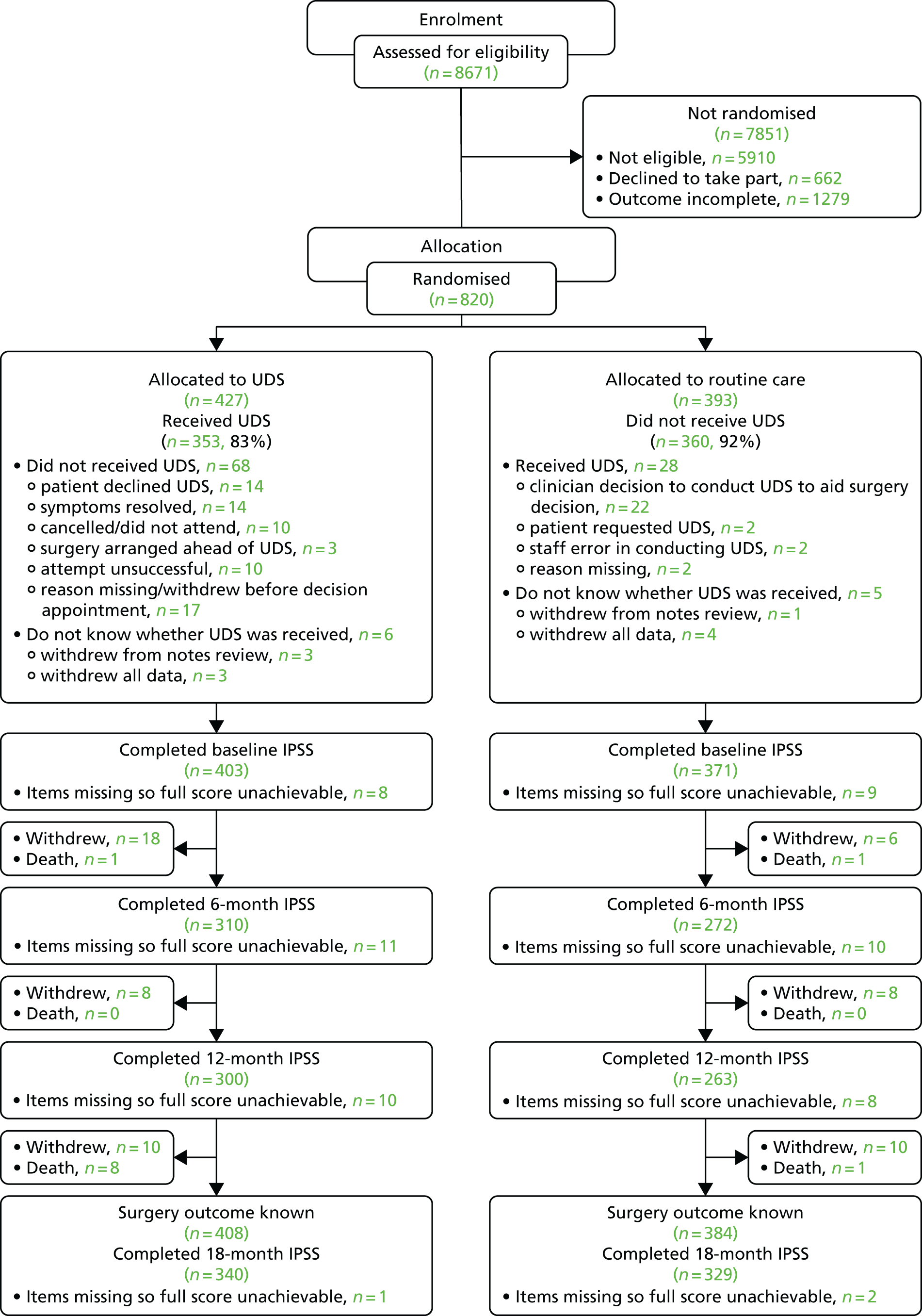

Participant flow

Figure 3 shows the layout of the trial and the different levels of dropout and analysis. Overall, 67 men withdrew from the trial within 548 days (18 months) of randomisation (seven of whom requested complete data withdrawal), with a median withdrawal time of 8 months (of 60 men with an available date). A further nine men from each arm withdrew after 548 days; however, these men were not included in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. There were 18 withdrawals in the UDS arm between randomisation and 6 months, but only six withdrawals in the routine care arm. When looking at the reasons for withdrawal, two did not like their randomised allocation and six did not give an explanation; neither of these reasons was given in the routine care arm. There were nine deaths in the UDS arm, compared with only two in the routine care arm; all were unrelated to trial procedures (see Table 8). We were also made aware of four unrelated deaths that occurred after men withdrew (two in the UDS arm and two in the routine care arm), but no further details were given. For the IPSS, 80% and 84% of men had available data at 18 months, in the UDS and routine care arms, respectively. After adjustment for centre and baseline IPSS, 328 and 313 men were analysable at 18 months for the UDS and routine care arms, respectively. The sample size calculation had estimated that 310 men per group would provide 80% power to answer the primary research question.

FIGURE 3.

The UPSTREAM trial Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

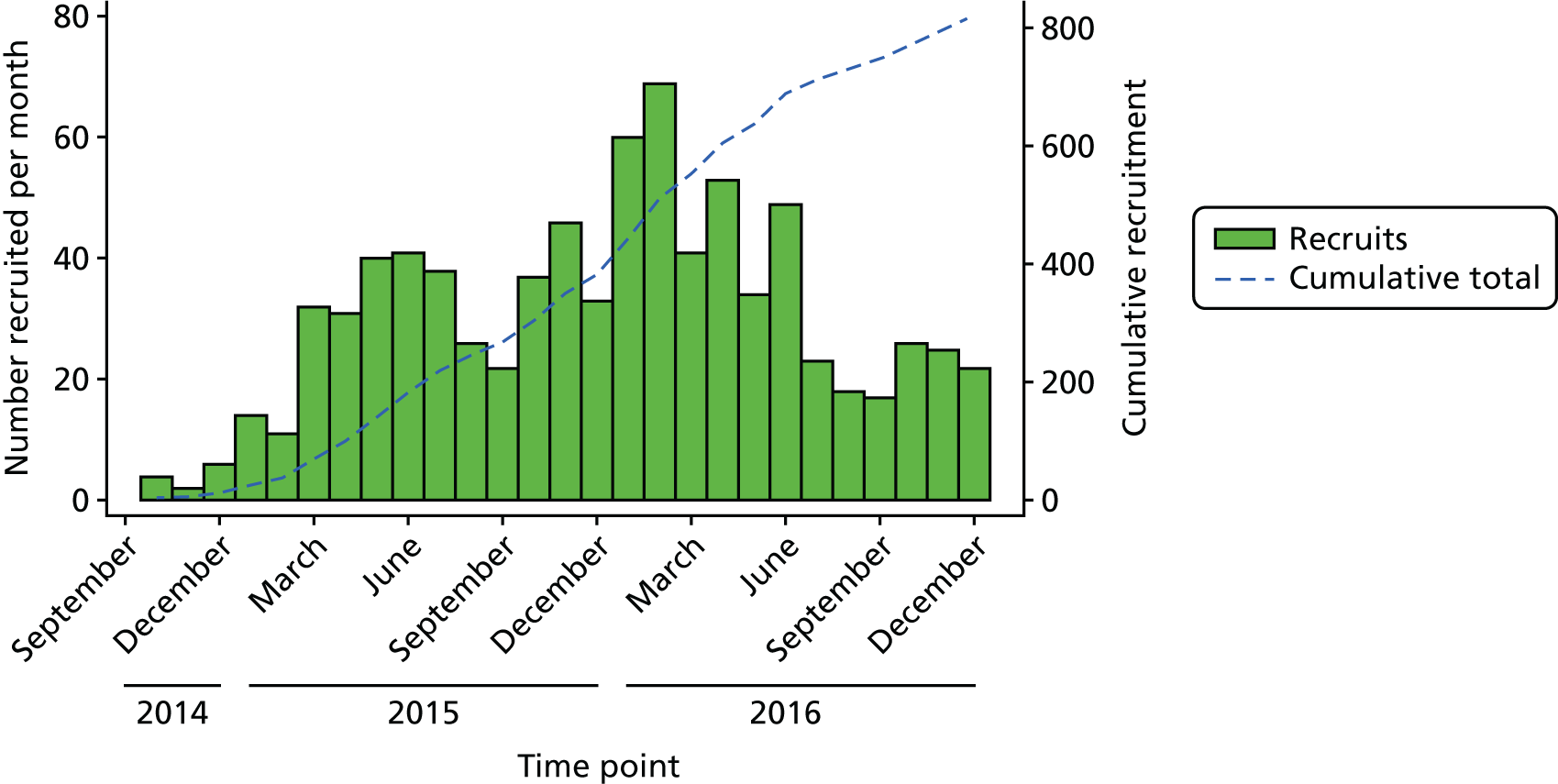

Recruitment

Of the 8671 men screened for eligibility, 1482 (17%) were considered eligible, of whom 820 (55%) were randomised to UPSTREAM (427 men in the UDS arm and 393 men in the routine care arm). Further details of patient screening are provided in Appendix 1 (see Tables 34–36). The first man was randomised in October 2014 and the last man in December 2016. There was no obvious seasonal variation; however, recruitment was slower during school holidays, when fewer recruiting staff were available (e.g. August, September, December) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

The UPSTREAM recruitment chart.

Baseline data

Baseline comparisons for UPSTREAM are given in Tables 3 and 4. The team prespecified in the analysis plan20 that any baseline characteristics that differed by > 10% (categorical variables) or by more than 0.5 SDs (continuous variables) would be adjusted for in a sensitivity analysis. None of the baseline characteristics met these criteria, so the sensitivity analysis was not carried out. The two arms were well balanced with respect to baseline characteristics, suggesting that allocation concealment in randomisation was successful.

| Baseline sociodemographics | N a | UDS | N a | Routine care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of participants | 427 | 393 | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 424 | 67.51 (9.59) | 389 | 67.81 (8.79) |

| Centre,b n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 56 (13) | 58 (15) | ||

| 2 | 12 (3) | 20 (5) | ||

| 3 | 35 (8) | 27 (7) | ||

| 4 | 29 (7) | 26 (7) | ||

| 5 | 29 (7) | 18 (5) | ||

| 6 | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | ||

| 7 | 17 (4) | 9 (2) | ||

| 8 | 9 (2) | 12 (3) | ||

| 9 | 17 (4) | 14 (4) | ||

| 10 | 11 (3) | 6 (2) | ||

| 11 | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | ||

| 12 | 16 (4) | 17 (4) | ||

| 13 | 424 | 15 (4) | 393 | 11 (3) |

| 14 | 17 (4) | 19 (5) | ||

| 15 | 14 (3) | 13 (3) | ||

| 16 | 21 (5) | 23 (6) | ||

| 17 | 24 (6) | 13 (3) | ||

| 18 | 14 (3) | 12 (3) | ||

| 19 | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | ||

| 20 | 15 (4) | 16 (4) | ||

| 21 | 13 (3) | 13 (3) | ||

| 22 | 9 (2) | 7 (2) | ||

| 23 | 13 (3) | 21 (5) | ||

| 24 | 10 (2) | 9 (2) | ||

| 25 | 11 (3) | 9 (2) | ||

| 26 | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 377 (91) | 356 (93) | ||

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British | 8 (2) | 6 (2) | ||

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 415 | 17 (4) | 383 | 11 (3) |

| Asian/Asian British | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Other ethnic group | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | ||

| Disclosure declined | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | ||

| IMD scores 2015 (based on postcodes) | ||||

| IMD score 2015,c median (IQR) | 411 | 14 (8–22) | 383 | 14 (8–24) |

| Quintile 1 (most deprived), n (%) | 43 (10) | 61 (16) | ||

| Quintile 2, n (%) | 75 (18) | 49 (13) | ||

| Quintile 3, n (%) | 92 (22) | 91 (24) | ||

| Quintile 4, n (%) | 106 (26) | 86 (22) | ||

| Quintile 5 (least deprived), n (%) | 95 (23) | 96 (25) | ||

| Clinical baseline characteristic | N a | UDS | N a | Routine care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities at baseline, n (%) | 420 | 281 (67) | 383 | 260 (68) |

| DRE findings,b n (%) | ||||

| No abnormality | 395 | 108 (27) | 375 | 120 (32) |

| Benign enlargement | 395 | 312 (79) | 375 | 287 (77) |

| Suspected prostate cancer | 395 | 16 (4) | 375 | 8 (2) |

| Other | 395 | 22 (6) | 375 | 20 (5) |

| Uroflowmetry,c median (IQR) | ||||

| Qmax (ml/second) | 402 | 10.20 (7.40–15.00) | 371 | 11.00 (7.90–58.30) |

| PVR (ml) | 401 | 100.00 (40.00–180.00) | 373 | 100.00 (45.00–189.00) |

| VV (ml) | 405 | 215.00 (133.00–318.00) | 376 | 214.00 (149.50–316.00) |

| Additional (discretionary) tests, n (%) | ||||

| PSA test | 57 (14) | 57 (15) | ||

| Cystoscopy | 44 (11) | 25 (7) | ||

| Urinalysis | 59 (14) | 59 (15) | ||

| Urea and electrolytes | 413 | 18 (4) | 383 | 17 (4) |

| Kidney ultrasound | 14 (3) | 11 (3) | ||

| Voiding urology cytology | 2 (< 1) | 2 (1) | ||

| Prostate volume measurement | 15 (4) | 7 (2) | ||

| IPSS: symptom severity at baseline, mean (SD) | ||||

| Total IPSS | 403 | 18.52 (6.90) | 371 | 19.39 (7.14) |

| Incomplete emptying | 411 | 2.64 (1.71) | 379 | 2.88 (1.72) |

| Frequency | 411 | 3.36 (1.35) | 379 | 3.56 (1.30) |

| Intermittency | 411 | 2.58 (1.69) | 379 | 2.65 (1.62) |

| Urgency | 409 | 2.60 (1.68) | 379 | 2.80 (1.66) |

| Weak stream | 409 | 3.17 (1.57) | 379 | 3.16 (1.61) |

| Straining | 408 | 1.56 (1.56) | 377 | 1.67 (1.66) |

| Nocturia | 410 | 2.60 (1.32) | 379 | 2.72 (1.28) |

| IPSS QoL | 411 | 4.07 (1.36) | 379 | 4.20 (1.25) |

| ICIQ-MLUTS | ||||

| Voiding score,d mean (SD) | 394 | 8.88 (4.04) | 370 | 9.30 (4.38) |

| Incontinence score,e mean (SD) | 395 | 5.01 (3.37) | 369 | 5.19 (3.27) |

| Daytime frequency (eight or more times), n (%) | 398 | 160 (40) | 374 | 169 (45) |

| Nocturia (one or more times per night), n (%) | 398 | 300 (75) | 374 | 301 (80) |

| ICIQ-MLUTSsex, n (%) | ||||

| Erections (reduced or none) | 389 | 277 (71) | 362 | 275 (76) |

| Ejaculation (reduced or none) | 383 | 300 (78) | 359 | 295 (82) |

| Painful ejaculation (yes) | 359 | 56 (16) | 343 | 71 (21) |

| Urinary symptoms affected sex life? | 378 | 259 (69) | 358 | 233 (65) |

Although stratified randomisation (by centre) was planned, simple randomisation was employed. It was observed mid-trial that more men were being recruited to the UDS arm, and this was not equally distributed across centres. Although this could not be adjusted, examination of the randomisation system confirmed that it was functioning correctly and that any imbalance was due to chance and not significant. This was also reviewed by the TSC, which agreed with this conclusion.

When comparing the characteristics of those men analysed at 18 months with those who withdrew or were lost to follow-up (not analysed), we see very similar characteristics (Table 5). There were more men with comorbidities among those not analysed (71%), which was not surprising given that that this was one of the main reasons for withdrawal. The only baseline measures that differed by the prespecified 10% and 0.5 SDs were the proportions of men who had a cystoscopy or PSA test at baseline. Of the 35 men who had a PSA test, 15 withdrew (seven because of poor health). Of the 26 men who had a cystoscopy, five withdrew because of poor health and two died.

| Baseline characteristics | N a | Analysed at 18 months | N a | Not analysed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 641 | 67.79 (8.46) | 172 | 67.14 (11.62) |

| Clinical baseline characteristic, n (%) | ||||

| Comorbidities | 633 | 421 (67) | 170 | 120 (71%) |

| Additional tests, n (%) | ||||

| PSA test | 639 | 79 (12)b | 157 | 35 (22)b |

| Cystoscopy | 639 | 42 (7)b | 157 | 27 (17)b |

| Urinalysis | 639 | 85 (13) | 157 | 33 (21) |

| Kidney ultrasound | 639 | 15 (2) | 157 | 10 (6) |

| Cytology | 639 | 4 (1) | 157 | 0 (0) |

| Prostate volume measurement | 639 | 14 (2) | 157 | 8 (5) |

| Urea and electrolytes | 639 | 24 (4) | 157 | 11 (7) |

| IPSS: symptom severity at baseline, mean (SD) | ||||

| Total IPSS | 641 | 18.83 (7.05) | 133 | 19.47 (6.89) |

| IPSS QoL | 640 | 4.09 (1.31) | 150 | 4.31 (1.30) |

| ICIQ-MLUTS | ||||

| Voiding score,c mean (SD) | 621 | 9.10 (4.15) | 143 | 9.03 (4.49) |

| Incontinence score,d mean (SD) | 622 | 5.01 (3.27) | 142 | 5.47 (3.47) |

| Daytime frequency (eight or more times), n (%) | 626 | 262 (42) | 146 | 67 (46) |

| Nocturia (one or more times per night), n (%) | 626 | 484 (77) | 146 | 117 (80) |

| ICIQ-MLUTSsex, n (%) | ||||

| Erections (reduced or none) | 613 | 449 (73) | 138 | 103 (75) |

| Ejaculation (reduced or none) | 605 | 489 (81) | 137 | 106 (78) |

| Painful ejaculation (yes) | 574 | 106 (18) | 128 | 21 (16) |

| Urinary symptoms affected sex life? | 600 | 397 (66) | 136 | 95 (70) |

Numbers analysed

The numbers who had outcome data were also relatively balanced between the groups; however, the number adhering to the diagnostic pathway (i.e. trial arm) to which they were assigned differed; p < 0.001 (Table 6). A larger proportion of men in the routine care arm adhered to the care pathway (93%) than those randomised to UDS (84%), with reasons for non-adherence shown in Figure 3. As also seen in Figure 3, the number of withdrawals within 548 days was 67 and the number of deaths was 11.

| UDS, n/N (%) | Routine care, n/N (%) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers of withdrawals and losses to follow-up | |||

| Number randomised | 427 | 393 | – |

| Number that adhered to their randomised allocationb | 353/421 (84) | 360/388 (93) | < 0.001 |

| Withdrew from the trial (within 548 days) | 39/427 (9) | 28/393 (7) | 0.294 |

| Deaths (within 548 days) | 9/427 (2) | 2/393 (1) | 0.047 |

| Analysable sample | |||

| IPSS at baseline | 403/427 (94) | 371/393 (94) | 0.989 |

| IPSS at 6 months | 310/427 (73) | 272/393 (69) | 0.286 |

| IPSS at 12 months | 300/427 (70) | 263/393 (67) | 0.304 |

| IPSS at 18 months | 340/427 (80) | 329/393 (84) | 0.131 |

| Analysable for IPSS | 328/427 (77) | 313/393 (80) | 0.327 |

| Analysable for surgery rate | 408/427 (96) | 384/393 (98) | 0.089 |

For the surgery rate outcome, the following men were removed from the final analysis: 7 who completely withdrew; 11 men who died prior to their 18-month follow-up time point; and 10 men who withdrew before their 18-month follow-up time point and declined permission to obtain a notes review. Owing to the higher number of deaths in the UDS arm (p = 0.047), a lower number of men were analysable for surgery rate (96% vs. 98% for the UDS and routine care arms, respectively).

Reasons for withdrawal were relatively balanced between the arms. There were more deaths in the UDS arm, but these did not appear to be related to the intervention, or any UPSTREAM pathway procedure/treatment; therefore, this appears to be a chance finding (Tables 7 and 8). There were four men in the routine care arm who felt that there were too many questionnaires, compared with no men in the UDS arm.

| Reason for withdrawal | UDS, n/N (%) | Routine care, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Too many questionnaires | 0/427 (0) | 4a/393 (1) |

| Poor health | 12a/427 (3) | 9/393 (2) |

| Relocation | 1/427 (< 1) | 1/393 (< 1) |

| Declined treatment allocation | 3/427 (1) | 0/393 (0) |

| Personal reasons | 5/427 (1) | 3a/393 (1) |

| Symptoms improved | 2a/427 (< 1) | 1/393 (< 1) |

| Deceased within 18 monthsb | 9/427 (2) | 2/393 (< 1) |

| Deceased after withdrawal (that were recorded) | 2/427 (< 1) | 2/393 (1) |

| Confirmed ineligible | 1/427 (< 1) | 1/393 (1) |

| Work commitments | 3/427 (1) | 1/393 (< 1) |

| Did not want hospital involvement | 2/427 (< 1) | 1a/393 (0) |

| Centre error | 1/427 (< 1) | 0/393 (0) |

| No reason given | 9a/427 (2) | 7/393 (2) |

| Trial arm | Time to death from randomisation (months) | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|

| Routine care | 0.62 | Cardiac arrest before any trial interventions organised or carried out |

| Routine care | 13.44 | Ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease |

| UDS | 12.89 | Multiple organ failure |

| UDS | 17.87 | Metastatic synovial sarcoma |

| UDS | 14.82 | Metastatic oesophageal cancer |

| UDS | 15.61 | Unverified, but no trial treatment/procedures within 30 days prior to the event. Patient previously removed from surgery list because of breathlessness/bronchiectasis |

| UDS | 12.13 | Pneumonia and metastatic renal cell carcinoma |

| UDS | 13.18 | Lung cancer with lung and liver metastases |

| UDS | 14.16 | Metastatic pancreatic cancer |

| UDS | 5.41 | Subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| UDS | 13.11 | Pneumonia, with no trial-related procedures within 30 days prior to the event |

Statistical outcomes and estimation

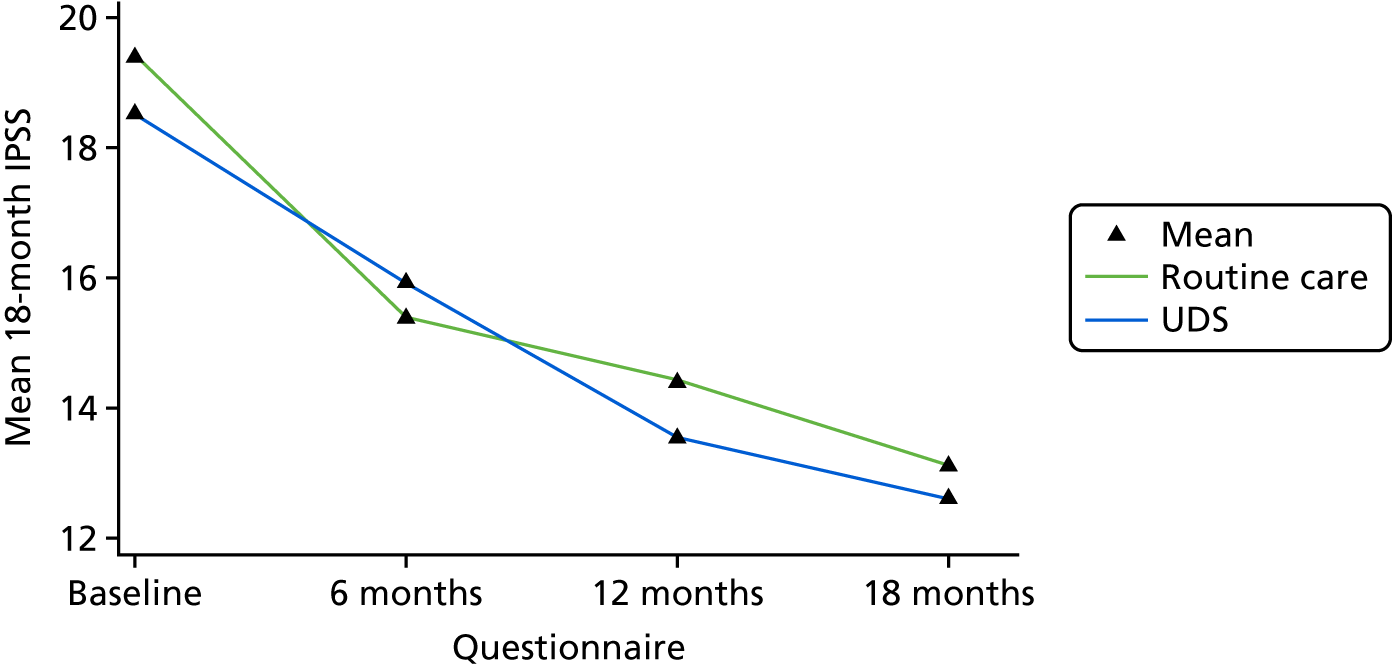

International Prostate Symptom Scores

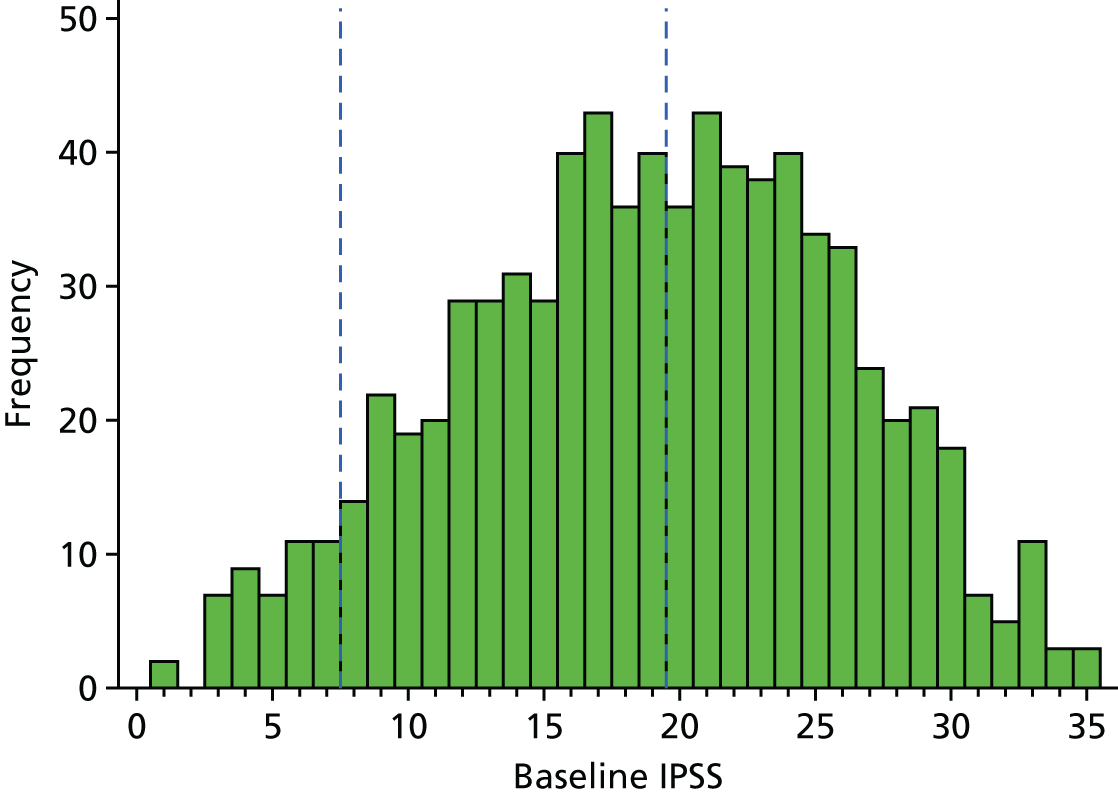

The primary outcome of IPSS at 18 months was analysed using linear regression. The scores at baseline were normally distributed, presented in Figure 5. Current guidelines for the measure advise that a score of 1–7 suggests mild urinary symptoms, 8–19 suggests moderate symptoms and 20–35 suggests severe symptoms. At baseline, the largest percentage of men was in the severe symptoms category (48%), followed by the moderate category (45%), whereas only 6% were in the mild symptoms category.

FIGURE 5.

Histogram of IPSSs at baseline.

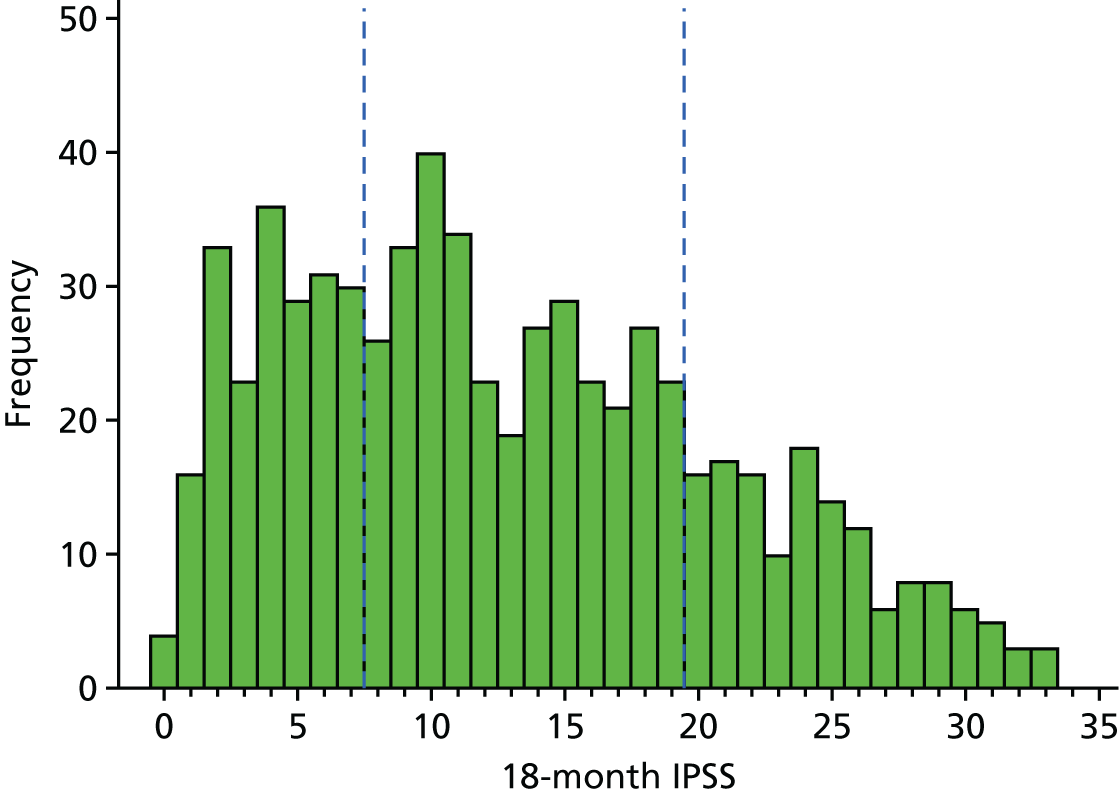

When we look at the histogram of scores at 18 months, we can see a large drop in IPSSs, so the majority are now in the less severe categories. Thirty per cent of men were in the mild symptoms category, 49% in the moderate symptoms category and 21% in the severe category (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Histogram of IPSSs at 18 months.

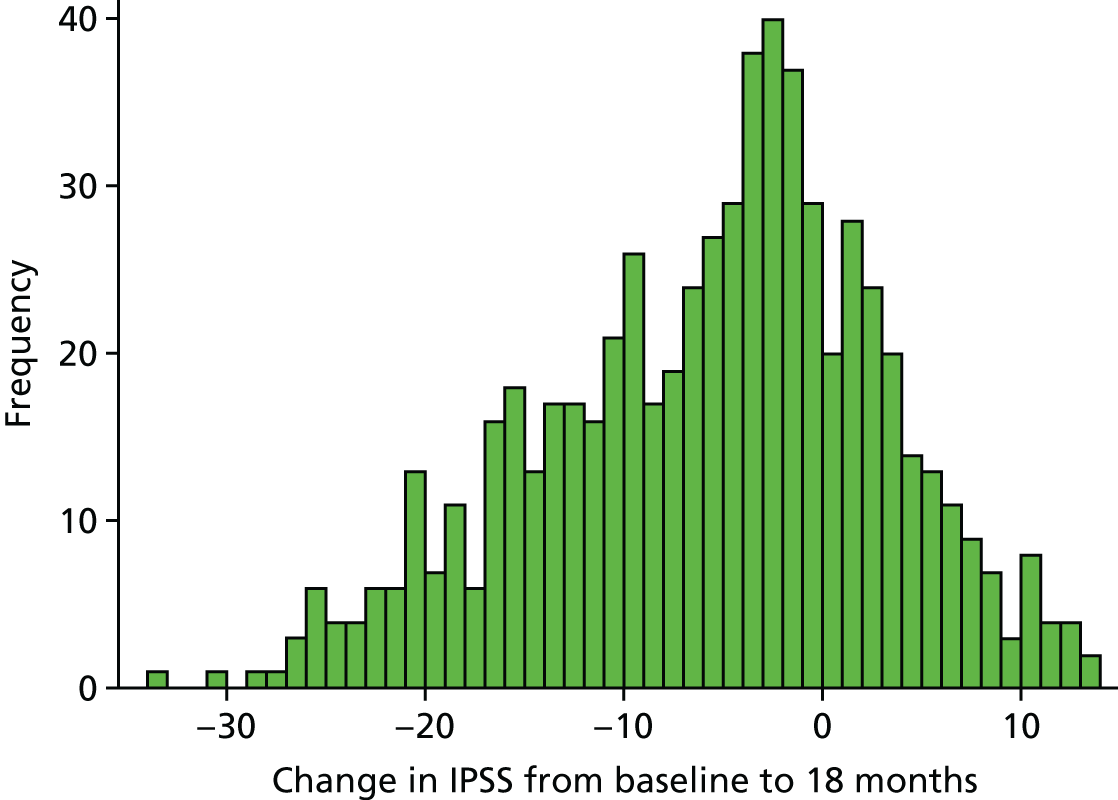

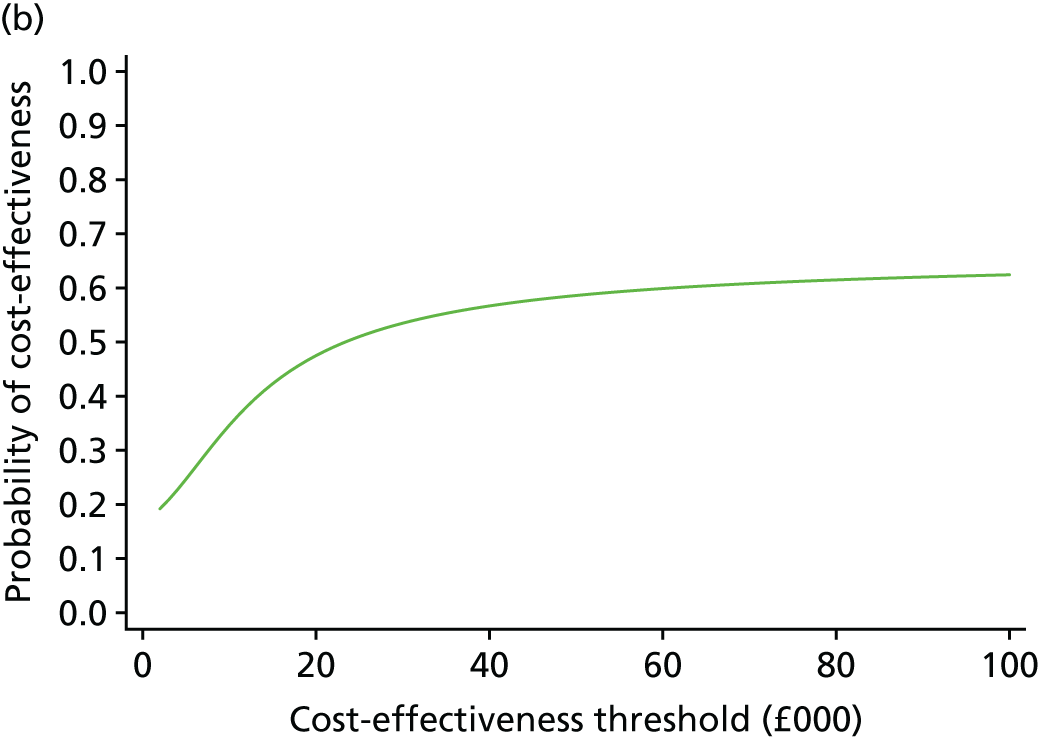

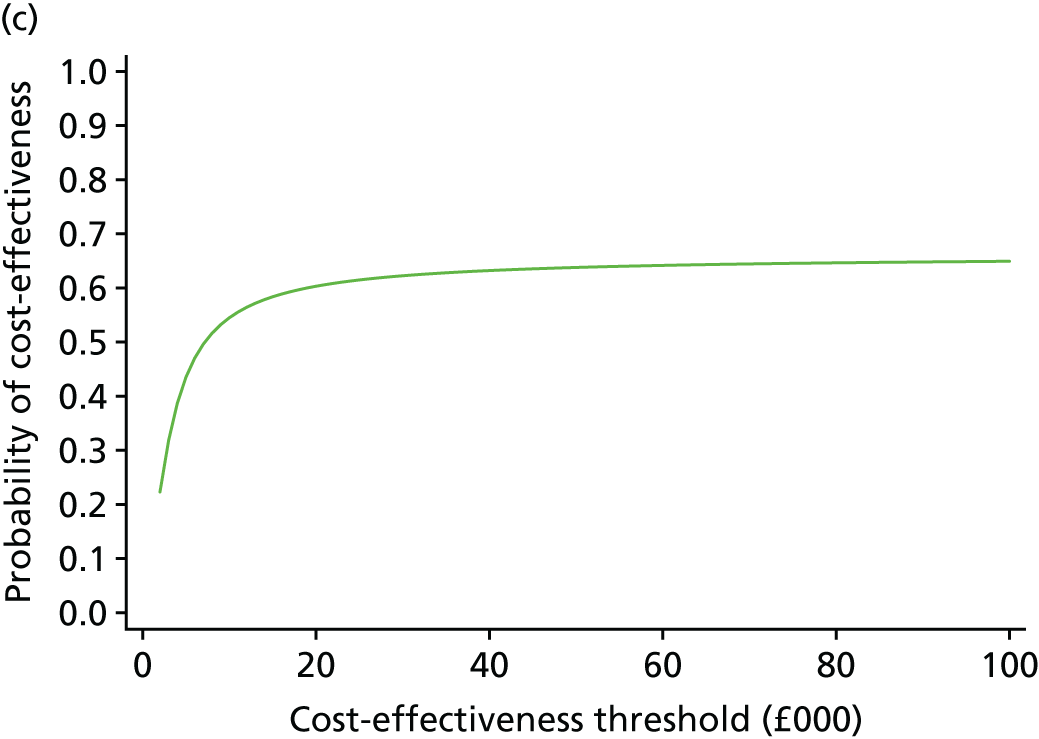

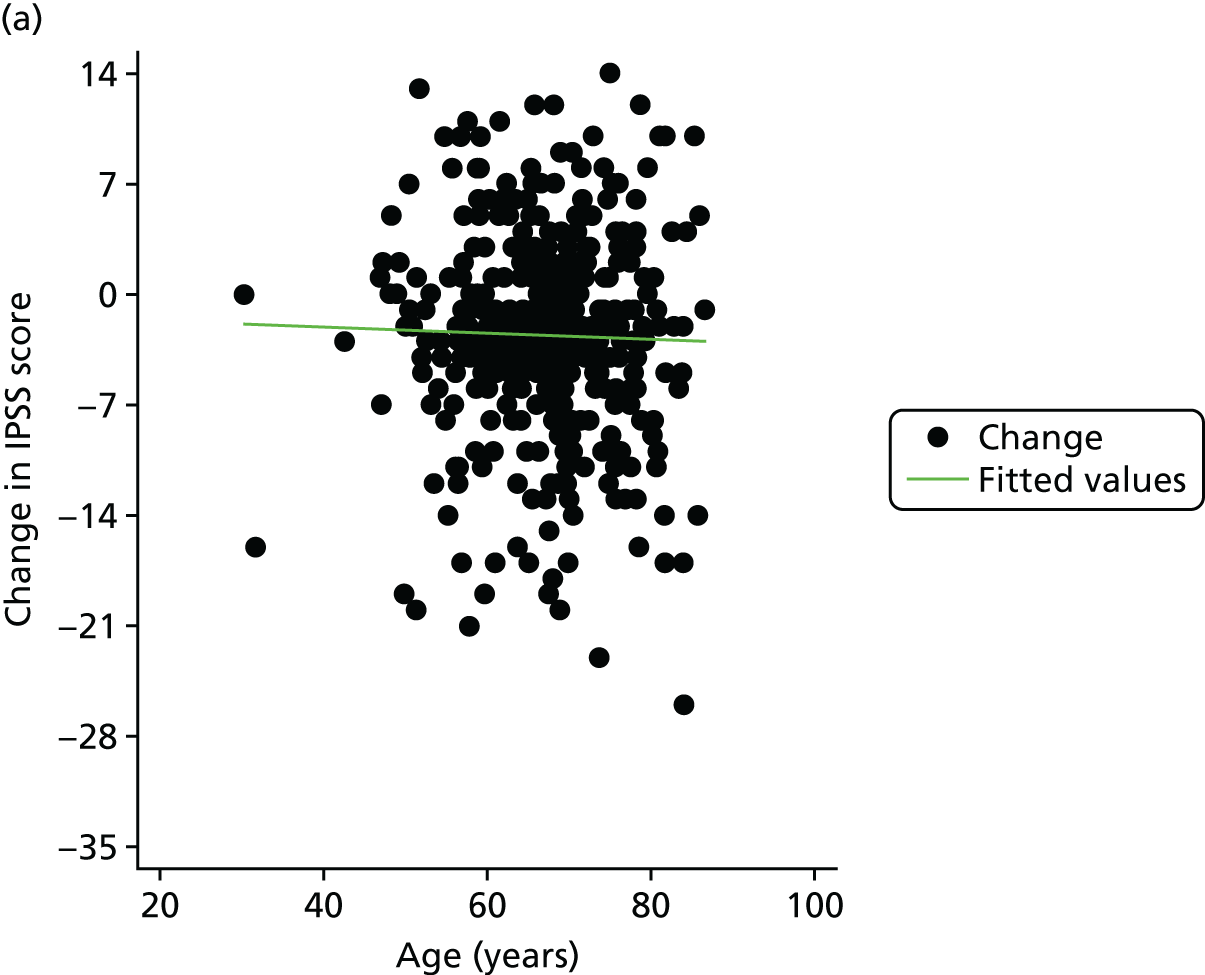

The median change in IPSS was –5, with a 25th and 75th percentile of –12 and 0, respectively. There were 147 men who had an IPSS that increased over the 18 months, a negative outcome. Of these, 53% underwent UDS and only 14% underwent surgery (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Histogram of change in IPSS.

The change in QoL score had a similar distribution to the change in overall IPSS. The median change in QoL was –1, with 25th and 75th percentiles of –3 and 0, respectively. There were 91 men who had a QoL score that increased (worsened) over the 18 months. Of these, 58% received UDS and 21% received surgery. This was explored in more detail in Appendix 2.

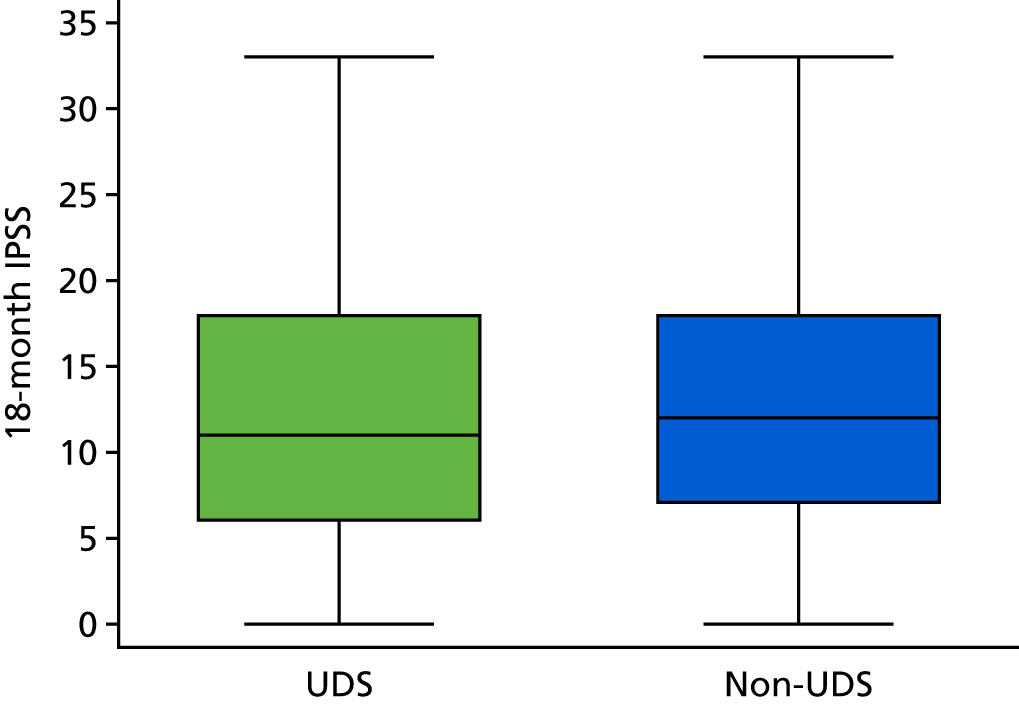

When looking at the 18-month scores across the trial arms, we see that they are very similar with respect to their distributions (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Box plot of IPSSs at 18 months, by arm.

There was a similar decrease in the IPSS QoL question (on a scale of 0–6 where 0 is ‘delighted’ and 6 is ‘terrible’).

Primary analysis result

The primary analysis model included all men who answered all IPSS questions in the 18-month questionnaire and baseline questionnaire. Results are presented on an ITT basis and using complete cases. Adjusted analyses are based on a smaller sample size, as men needed to have completed both the baseline and 18-month questionnaire to be included. There were 12 and 16 men excluded from the primary analysis, from the UDS and routine care arms respectively, due to missing baseline IPSS data.

The overall SD for the 18-month IPSSs was 7.89, which was higher than the anticipated SD of 5 used in the sample size calculation. Despite this, the CI for the difference in means was still small. The non-inferiority margin was prespecified as 1 point on the IPSS scale, to demonstrate non-inferiority in the UDS arm. The lower CI level shows that, in the population, those receiving UDS have scores that are no more than 1.47 points lower than the scores of those men in the routine care arm (Table 9). Conversely, the upper CI level shows that those men who underwent UDS have scores that are no more than 0.80 points above the scores of those in routine care arm (a worse outcome for the UDS arm). Therefore, UPSTREAM has demonstrated that PROMs in men randomised to UDS are non-inferior to those randomised to routine care, with respect to IPSSs.

| Variable | n (UDS : routine care) | UDS, mean (SD) | Routine care, mean (SD) | Crude difference in means (95% CI) | Adjusted difference in meansa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSS symptom questionnaire | |||||

| Total IPSS | 340 : 329 | 12.61 (7.92) | 13.11 (7.86) | –0.49 (–1.69 to 0.70) | –0.33 (–1.47 to 0.80) |

| QoL score | 343 : 332 | 2.72 (1.69) | 2.74 (1.64) | –0.02 (–0.28 to 0.23) | –0.07 (–0.32 to 0.18) |

Comparing this with the scenarios explained in the methods section (see Assessing non-inferiority), we can see that our results conform to ‘scenario B’, concluding that UDS is non-inferior to routine care with regards to the IPSS (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

The non-inferiority conclusion for UPSTREAM. Treatment difference (UDS – routine care). Adapted from Schumi and Wittes26 © 2011 Schumi and Wittes; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Key secondary result: surgery recommendation

In the care pathways, whether or not a man actually received surgery was as a result of several steps:

-

Recommendation – whether surgery or interventional treatment was recommended by the surgeon, as opposed to behavioural therapy or medications (conservative therapy).

-

Acceptance or refusal of the recommendation by the man. If the man accepted, the surgeon would then place him on the waiting list for surgery (‘listing’). In the trial, the duration of wait for surgery varied between centres.

-

Surgery – the ‘surgery rate’ key secondary outcome reflects the number of men who actually received interventional treatment, implying prior recommendation and listing.

The difference between the recommendation rate and the surgery rate reflects two main factors: (1) men who declined surgery that was recommended to them and (2) men kept on the waiting list for a long time.

The total number of men who were initially recommended surgery by their surgeon was 378 (49%) [196 men (49%) and 182 men (48%) for the UDS and routine care arms, respectively]. One centre recommended surgery to all seven of their patients (4 : 3, UDS and routine care); this was dropped from the analysis when adjusting for centre (Table 10).

| Variable | UDS, n (%) | Routine care, n (%) | ORa (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon recommendation | ||||

| Surgery | 196 (49) | 182 (48) | 1.02 (0.76 to 1.38) | 0.872 |

| No surgery | 201 (51) | 196 (52) | ||

| Surgeon recommended surgeryb | ||||

| Patient agreement | 159 (82) | 153 (84) | ||

| Patient disagreementc | 36 (18) | 29 (16) | ||

| Surgeon did not recommend surgeryd | ||||

| Patient agreement | 200 (> 99) | 190 (97) | ||

| Patient disagreemente | 1 (< 1) | 5 (3) | ||

| Outcome of decision-making appointment | ||||

| Listed for surgery | 156 (41) | 147 (41) | ||

| Not listed for surgery | 220 (59) | 211 (59) | ||

Men did not necessarily agree with the recommendation for or against surgery and this view on agreement can also be found in Table 10. Recommendations were reviewed in a post hoc analysis, using criteria prespecified in consultation with urologists not taking part in UPSTREAM, before looking at the data, and agreed by the co-applicant urologists, to allow for a more uniform approach. Further details on this and the reasons for recommending surgery can be found in Appendix 3. The proportion of men actually listed for surgery following their decision-making appointment was 41% in both arms. Of those men listed, 264 (87%) had the surgery, 34 (11%) did not have surgery and for 5 (2%), we do not know if they received surgery (because of withdrawal/death/unable to access medical notes). Of those men initially not listed for surgery, 405 men (94%) did not have surgery, 21 men (5%) did go on to have surgery and for 5 men (1%), we do not know if they received surgery (because of withdrawal/death/unable to access medical notes).

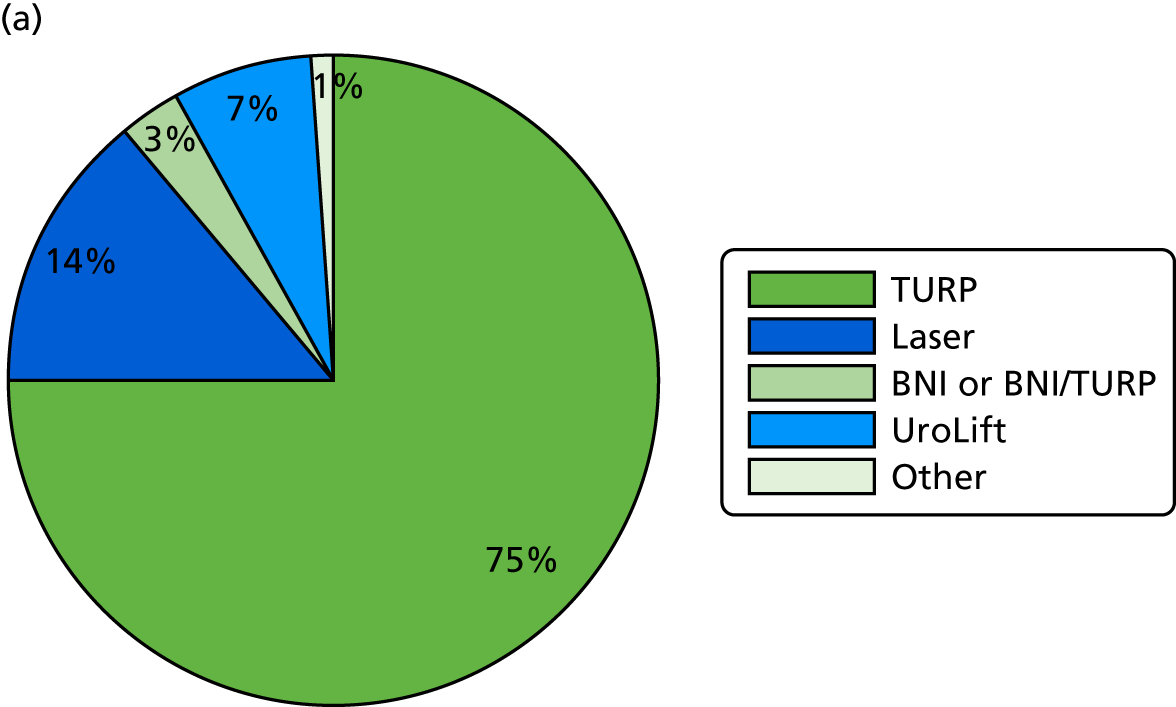

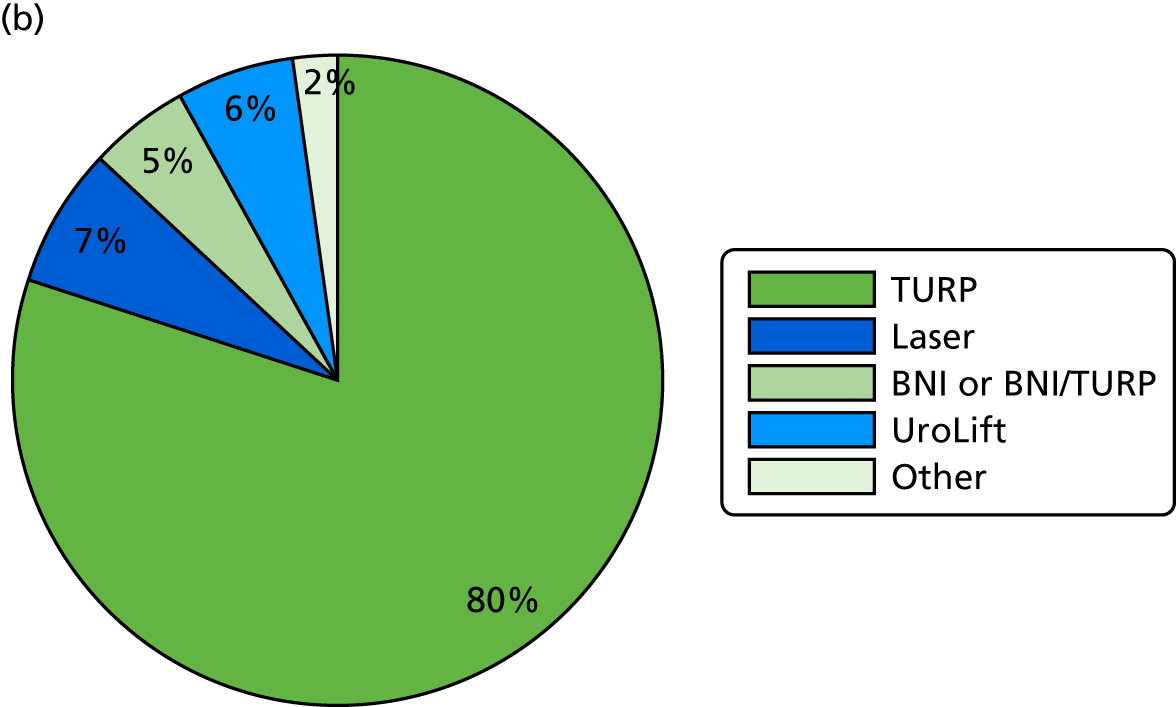

Key secondary result: surgery rates

The proportion of men receiving surgery, regardless of surgery recommendation or listing, can be found in Table 11. The key secondary hypothesis for this trial was that surgery rates would be reduced in the UDS arm. The results show that there was no difference in the surgery rate at 18 months [153/408 (38%) men in the UDS arm had surgery, compared with 138/384 (36%) in the routine care arm]. This was well below the estimated surgery rate used in the sample size calculation (60–73%). We know the recommendation and surgery outcome for 748 men in total, and 26% of men who were recommended to have surgery did not receive it. Of those men not initially recommended for surgery, 4% did go on to receive it (e.g. after additional review due to prolonged symptoms). Of those men listed for surgery, 34 men (11%) did not undergo surgery during the 18-month follow-up; at least 10 of these 34 participants were still awaiting their surgery at their 18-month follow-up appointment (see Time to surgery).

| Variable | UDS, n (%) | Routine care, n (%) | ORa (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery outcome | ||||

| Surgery conducted | 153 (38) | 138 (36) | 1.05 (0.77 to 1.43) | 0.741 |

| No surgery | 255 (63) | 246 (64) | ||

| Surgery outcome (if matching the surgeon’s recommendation)b | ||||

| Surgery conducted | 143 (44) | 132 (41) | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.54) | 0.578 |

| No surgery | 185 (56) | 189 (59) | ||

| Recommended surgery | ||||

| Surgery conducted | 143 (75) | 132 (73) | ||

| No surgery | 47 (25) | 48 (27) | ||

| Not recommended surgery | ||||

| Surgery conducted | 10 (5) | 6 (3) | ||

| No surgery | 185 (95) | 189 (97) | ||

Time to surgery

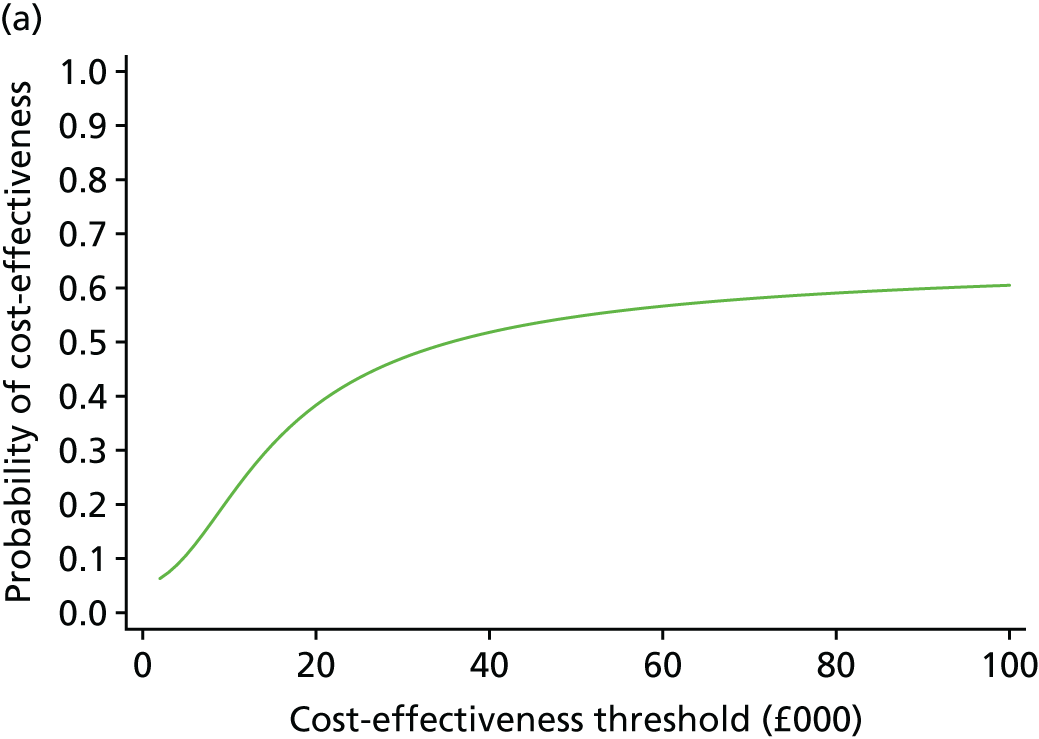

There were 291 men who had surgery for LUTS during UPSTREAM. In the UDS arm, the median time from randomisation to surgery was 216 days (7 months). In the routine care arm, the median time from randomisation to surgery was 177 days (6 months).