Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/28/02. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The draft report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Baker was a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline committee (CG157: hip, knee and shoulder replacement clinical guideline) (2018–2020). He is also a member of the NICE Quality Assurance Committee (2019 to present), is a HTA Commissioning panel member (Panel B) (2019 to present) and a Royal College of Surgeons Specialty Lead for Orthopaedics (2019 to present). Avril Drummond is a member of the Health Education England/National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Clinical Academic Programme Clinical Lectureship and Senior Clinical Lectureship Review Panel (2018 to present). Catriona McDaid is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Editorial Board (2017 to present). Catherine Hewitt is a member of the HTA Commissioning Board (2015 to present). Louise Thomson was a member of the NICE Public Health Advisory Committee on Workplace Health: long-term sickness absence and capability to work (NICE Guideline number 146) (2018–19). Amar Rangan is an NIHR grant holder [Partial Rotator Cuff Tear Repair (PRO CURE) trial, NIHR HTA project 128043 (co-investigator), subject to Department of Health and Social Care contracting; UKFROST, NIHR HTA project 13/26/01 (chief investigator); ProFHER) trial, NIHR HTA project 06/404/53 (chief investigator); HUSH trial, NIHR HTA project 127817 (co-investigator); Patch Augmented Rotator Cuff Surgery (PARCS) feasibility study, NIHR HTA project 15/103 (co-investigator); treatment of first time anterior shoulder dislocation, Clinical Practice Research Datalink analysis, NIHR HTA project 14/160/01 (co-investigator); SWIFFT, NIHR HTA project 11/36/37 (co-investigator); DRAFFT Trial, NIHR HTA project 08/116/97 (co-investigator); PRESTO feasibility study, NIHR HTA project 15/154/07 (mentor to chief investigator); and evidence synthesis on the frozen shoulder NIHR HTA project 09/13/02 (co-investigator)] and an Orthopaedic Research UK (London, UK) research grant holder, and research and educational grants were provided to his institution from DePuy Synthes [Raynham, MA, USA; a Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, NJ, USA) company].

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Baker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and study introduction

Is there a need for an occupational advice intervention for hip and knee replacement patients?

The impact of hip and knee osteoarthritis on employment

Decreased physical function associated with hip and knee osteoarthritis reduces the likelihood of employment, reduces household income and increases the number of missed workdays for those who are employed. 1 The magnitude of the impact varies according to the degree of activity limitation and disease severity. 2 A diagnosis of hip or knee osteoarthritis is associated with a reduction in work participation and productivity and an increased risk of work loss. 3,4 In a national study of patients in Finland, Kontio et al. 5 found that the age-adjusted incidence of disability retirement owing to knee osteoarthritis was 60 and 72 per 100,000 person-years for men and women, respectively. The highest rates of disability retirement in men were found in construction workers, electricians and plumbers, and in women they were found in building caretakers, cleaners, nurses and kitchen workers. 5

The cost of work-related musculoskeletal disorders that have an impact on a person’s ability to work is difficult to quantify. Direct (the cost of treatment) and indirect (costs related to the impact of the period of ill health) costs are borne by the individual (impact of ill health on quality of life), employers and society (loss of productivity, need for health care, rehabilitation and compensation). 6,7 The Health and Safety Executive calculates the annual cost of workplace injury and ill health on this basis by estimating both the financial cost and the ‘human’ cost. 7,8 The Health and Safety Executive estimates that the total annual cost of workplace ill health due to musculoskeletal disorders is £9.7B, equivalent to £18,400 per case. 7,8 However, these figures do not take account of non-work-related injuries and ill health and, therefore, are likely to be an underestimate of the total cost. In addition to its financial benefits, working has significant physical, mental and emotional health benefits. 9–11 Loss of employment is associated with a reduction in physical function, increased anxiety and depression and increased risk of mortality. 12,13 Therefore, earlier return to work (RTW) has potential health benefits as well as socioeconomic benefits.

The role of lower limb joint replacement in patients of working age

Lower limb joint replacements are successful and cost-effective treatments that relieve pain, restore physical function and improve health-related quality of life for patients with hip and knee arthritis. 14–17 Currently, > 1 million hip and knee replacements are carried out annually in the USA and > 190,000 are carried out annually in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 18 Projections from 2005 suggest that, by 2030, the number of primary total hip replacements (THRs) and total knee replacements (TKRs) carried out will increase by 174% and 673%, respectively. 19

Recent changes to the state pension age, combined with an ageing UK workforce, resulted in a steady increase in the numbers of hip and knee replacements being carried out in patients of working age between 2007 and 2017. 18 These changes are also reflected in data from North America, which suggest that over half of all hip or knee replacement procedures will be carried out in patients aged < 65 years by 2030. 19 International estimates suggest that between 15% and 45% of patients undergoing either hip or knee replacements are of working age. 20,21

According to data published by the National Joint Registry (NJR) for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 106,334 primary knee replacements22 and 96,717 primary hip replacements23 were carried out in 2017. Of the 91,923 hip replacement patients with available patient data, 18,812 (20.5%) were aged < 60 years (9778 females and 9034 males) and a further 26,295 were aged 60–69 years (28.6%; 15,375 females and 10,920 males). Of the 102,347 knee replacement patients with available patient data, 17,765 (17.4%) were aged < 60 years (10,259 females and 7506 males) and a further 33,523 were aged 60–69 years (32.8%; 18,161 females and 15,362 males).

Occupational advice for patients undergoing hip or knee replacement

There is currently a paucity of information and guidance to support patients returning to work after hip or knee replacement. Over the last 2 years [during the course of the Occupation advice for Patients undergoing Arthroplasty of the Lower limb (OPAL) study], the Royal College of Surgeons of England has produced written information resources to guide recovery including RTW after both hip replacement and knee replacement (example information is available at www.rcseng.ac.uk/patients/recovering-from-surgery/total-hip-replacement/returning-to-work; accessed 16 April 2019). We are not aware of any other currently available occupational advice or information resources specifically tailored to this patient group.

The UK Government currently funds the ‘Fit for Work’ service (in Scotland, the service is called ‘Fit for Work Scotland’). 24 This initiative is free for the public to use and is designed to support people in work with health conditions and help with sickness absence. It works alongside existing occupational health services and employer sickness absence policies. Patients can access this service via telephone line support, by visiting the ‘Fit for Work’ websites or by e-mailing the team. However, the patient-facing materials are generic and there is no specific information for hip or knee replacement patients. 24

Current evidence relating to return to work after hip or knee replacement

Two systematic reviews examined work status, time to return to work and determinants of RTW in patients undergoing hip or knee replacement. 20,21

The most recent and comprehensive review, by Tilbury et al. ,20 identified 19 articles:25–43 14 relating to hip replacements, four on knee replacements and one on both. All were cohort studies of either prospective (eight studies) or retrospective (11 studies) design and included the three studies from the earlier Kuijer et al. 21 review. Four of the included studies were from the UK. 38–41 Among these 19 studies, there was significant variation in the definition of work status both before surgery and after surgery. 20 The proportion of patients returning to work ranged from 25% to 95% at between 1 and 12 months after hip replacement and from 71% to 83% at 3–6 months after knee replacement. 20 Time to RTW ranged from 1.1 to 10.5 weeks after hip replacement and from 8 to 12 weeks after knee replacement. 20 Determinants of a worse ‘work outcome’ after hip replacement included female sex, older age, pain in other joints, failure of the procedure, employment involving physical work, unskilled work and being a farmer. 29,32,35 Better work outcomes after hip replacement were associated with younger age, a higher level of education, working within 1 month of surgery, primary osteoarthritis and earlier return of walking ability. 29,32,35 Determinants of a faster RTW after knee replacement included female sex, self-employment, better postoperative physical and mental health scores, a higher functional comorbidity index and a disability-accessible workplace. 42 Slower RTW after knee replacement was associated with the level of preoperative pain, a physically demanding job and being on workers’ compensation. 42

Of the work published in the UK, Mobasheri et al. 38 studied 86 hip replacement patients aged < 60 years at a mean of 3 years after surgery, of whom 51 were in work prior to surgery. After surgery, 49 patients (96%) returned to work and an additional 13 gained employment. 38 In a similar study, Lyall et al. 40 examined 56 knee replacement patients aged < 60 years at a mean of 5 years after surgery. Overall, 40 out of 41 (98%) patients who were employed before their operation returned to their previous work but none of the patients not working prior to surgery found work after their operation. Both studies suggest that high rates of RTW can be achieved in patients at mid-term follow-up (3–5 years). Of the 285 hip replacement patients aged < 65 years studied by Cowie et al. ,39 170 (71.1%) were working after their surgery and the mean time to RTW was 13.9 weeks. Of those who returned to work, 132 (78.1%) did so without any workplace restrictions. They also found a negative correlation between time to RTW and increasing age and body mass index (BMI). 39 Finally, Foote et al. 41 studied 109 patients aged < 60 years at a mean of 3 years post surgery who had previously had a total, unicondylar or patellofemoral knee replacement. The rate of and time to RTW varied by the type of operation, with the TKR (82% had returned to work at a median of 12 weeks) and unicondylar (82% had returned to work at a median of 11 weeks) patients returning significantly sooner than the patellofemoral knee replacement patients (54% had returned to work at a median of 20 weeks). 41

A number of additional studies examining RTW after hip or knee replacement have been published since these reviews.

Sankar et al. 44 studied RTW in a cohort of Canadian patients and found that the rate of RTW varied according to the joint replaced and the time since surgery. The proportion of patients returning to work was lower for knee replacement than for hip replacement at 1, 3 and 6 months, but by 12 months it was equivalent (1 month: TKR 24%, THR 34%; 3 months: TKR 57%, THR 66%; 6 months: TKR 78%, THR 85%; 12 months: TKR 85%, THR 87%). 44 They also reported that the time taken to return to work was improved in males and in patients with a higher level of education and in less physically demanding jobs. 44 Dutch researchers have also examined the rate of RTW, duration until RTW and determinants of RTW in patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement. 45,46 At 1 year post surgery, 90% of hip and 83% of knee replacement patients had returned to work, but 14% of the hip and 19% of the knee patients had returned to work on reduced hours. 45 The mean time to RTW was 12.5 [standard deviation (SD) 7.6] and 12.9 (SD 8.0) weeks for hip and knee replacement patients, respectively. 45 Factors associated with a RTW included self-employment and better preoperative activities of daily living subscale scores. 46 Preoperative absence from work reduced the chance of returning to work after surgery. 46

There have also been three recent publications from the UK. 47–49 Scott et al. 47 retrospectively reviewed 289 TKR patients aged < 65 years at a mean of 3.4 years after surgery. Overall, 261 patients (90%) were working prior to surgery, of whom 105 (40%) returned to work after surgery, with 89 (34%) returning to the same job at a mean of 13.5 weeks postoperatively. Factors predictive of a successful RTW included younger age and type of work undertaken. 47

Malviya et al. 48 summarised the qualitative and quantitative literature for RTW after hip or knee replacement. They found that patients have high expectations of the impact of joint replacement surgery on their ability to work and that unrealistic expectations lead to heightened frustration and a slower rate of recovery, preventing them from returning to work. In this setting, supportive care from health-care providers and family support after surgery were helpful in facilitating successful rehabilitation and satisfaction. 48 The same research team, Kleim et al. ,49 studied 83 patients undergoing hip or knee replacement who were employed prior to surgery. At review, 80 patients had returned to work at median of 12 (range 2–64) weeks. They found that those patients in more manual occupations, those without preoperative sick leave due to their hip or knee arthritis and those with a higher level of qualification returned to employment significantly quicker than the rest of the cohort. 49 In addition, hip replacement patients reported a greater improvement than patients after knee replacement did in terms of performance at work (63% vs. 44%) and job prospects (50% vs. 36%). 49

Summary of the current literature: key points

Current evidence suggests that:

-

A substantial proportion of patients undergoing hip or knee replacement are of working age and the majority are in work at the time of surgery. This number is set to increase in an increasingly aged workforce who will have to work for longer because of changes in the state pension age.

-

Lengthy sickness absence can have a negative impact on individual physical and mental health status.

-

The cost associated with sickness absence to the patient, employer and the state is significant.

-

Occupational advice interventions to support RTW after hip or knee replacement are limited.

-

The extent to which RTW is ‘full’ and ‘sustained’ is not known.

-

Given the lack of occupational advice interventions and associated resources, there is likely to be significant variation in the advice and information delivered to patients seeking to return to work after hip or knee replacement.

-

Return to work is influenced by a range of patient, health process and employment factors.

-

The underlying probability of employment varies by age, sex, education level and other factors, meaning that the economic implications of musculoskeletal limitations vary between patients and regions.

The OPAL study

In 2016, the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme commissioned a research call that asked ‘How feasible is a trial to evaluate whether occupational advice, initiated prior to planned surgery for major joint replacement within the lower limb, improves health outcomes in terms of faster recovery to usual activities, including work?’.

The Health Technology Assessment guidance described the need to develop a tailored occupational advice intervention that ensured targeted support and rehabilitation to facilitate RTW as part of this study. This intervention should be proactive and suitable for routine delivery in the NHS alongside the usual-care pathway. There was also a requirement to define the population group, describe usual care and explore important outcomes, such as time to RTW, health-related quality of life, health-care utilisation and proportion of patients requiring workplace occupational health interventions.

Preliminary work undertaken by the OPAL investigators demonstrated a number of evidence gaps related to RTW after major lower limb joint replacement that directed the format and direction of the study. These are described in the following sections.

Population

There is limited evidence about the population of patients undergoing hip or knee replacement who are in work and returning to work after surgery. Further information is required to understand the individualised workplace needs of this group, including an understanding of how job classifications (e.g. manual vs. non-manual), employment status (e.g. employed vs. self-employed), the type of employer (e.g. small and medium-sized enterprises vs. large companies; public- vs. private- or third-sector employer) and how the presence of an occupational health service within the organisational structure influences the potential for early RTW.

The target population for a clinical trial is, therefore, not clearly defined.

Intervention

-

Current recommendations guiding RTW are limited and inconsistent. Information is rarely individualised and generic information often fails to provide the patient, employers or health-care teams with the advice required.

-

The majority of patients undergoing hip or knee replacement undertake an integrated multidisciplinary team programme of education and rehabilitation spanning the surgical episode. The provision and utility of occupational advice within these ‘usual-care’ pathways is not established and the ability of this service to facilitate RTW has not been explored.

-

Studies suggested that the vast majority of ‘fit notes’ are not being used correctly. ‘Fit notes’ offer the patient and employer opportunities for early phased RTW. However, most are advising that patients are ‘not fit’ for work, with few doctors making use of the opportunity to advise on patient function and/or work modifications that might facilitate RTW after surgery. 50,51

-

There is limited information about the impact of addressing modifiable barriers that prevent RTW or how modifiable psychosocial factors influence RTW behaviours and the specific needs of the patients regarding perioperative care and advice. 48,52

There is, therefore, no appropriate occupational advice intervention available that could be used as the intervention in a clinical trial.

Comparison

There is no information about how and when occupational advice is delivered and who is delivering it to hip and knee replacement patients. The rapid and inconsistent adoption of enhanced recovery and early-discharge pathways has led to variations in provision of perioperative care and advice.

‘Standard care’ is therefore not currently defined for use as a study comparator.

Outcome

-

There is currently no standardised method of recording RTW. Dichotomous recording of work status (yes/no) is blunt and does not address important aspects of workplace behaviour including absenteeism, presenteeism, return to usual activities and interference with activities. In the UK, > 20% of patients do not return to usual activities and have restrictions in their ability to work after hip replacement. 39 Measuring RTW should ideally consider specific elements of the job, the duties and the hours worked.

-

Assessment of workplace disability and productivity is poorly reported after hip or knee replacement. Validated tools exist (e.g. the Workplace Activity Limitations Scale and Work Limitations Questionnaire) but little is known about their applicability to the UK workforce and their utility as outcome measures for clinical trials. 53

The appropriateness of individual RTW measures for use as primary outcome measures in a clinical trial is currently unclear.

Summary

There is a need for preliminary research to generate relevant evidence and develop an occupational advice intervention to support a future clinical trial. The OPAL study was commissioned to facilitate this.

Objectives

This section is reproduced from Baker et al. 54 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The OPAL study had nine objectives:

-

to evaluate the specific needs of the population of patients who are in work and intend to return to work following hip or knee replacement

-

to establish how individual patients return to work; the role of fit notes, clinical and workplace-based interventions; and how specific job demands influence workplace disability and productivity

-

to establish what evidence is currently available relating to RTW/occupational advice interventions following elective surgical procedures

-

to understand the barriers preventing RTW that need to be addressed by an occupational advice intervention

-

to determine current models of delivering occupational advice, the nature and extent of the advice offered and how tools to facilitate RTW are being currently used

-

to define a suitable measure of RTW through systematic review and evaluation of specific measures of activity, social participation and including specific validated workplace questionnaires

-

to construct a multistakeholder intervention development group to inform the design and establish the necessary components of an evidence-based occupational advice intervention initiated prior to elective lower limb joint replacement

-

to develop and manualise a multidisciplinary occupational advice intervention tailored to the needs of this patient group

-

to test the acceptability, practicality and feasibility and potential cost of delivering the manualised intervention within current care frameworks and as a potential trial intervention.

Chapter 2 Methodological overview: the OPAL intervention mapping framework

The OPAL study employed an intervention mapping (IM) framework to deliver the objectives listed in Chapter 1, Objectives.

Intervention mapping

Intervention mapping is a framework for developing effective theory- and evidence-based behaviour change interventions. 55–59 IM was developed for, and is widely used in, health promotion, but the process has also been applied to many other fields, including traffic safety and energy conservation. 60 It has also been used in rehabilitation, for example in the management of osteoarthritis and back pain61 and stroke,62 as well as in work disability prevention. 63

The IM framework was first used in work disability prevention in 2007. Interventions developed using this methodology have included self-management at work of chronic diseases64 and upper limb conditions,65 but the majority (six separate interventions) have been designed to promote RTW. 66–71 However, only one study has focused on RTW following surgery. 68 Furthermore, in three of these studies69–71 an intervention has been designed but has yet to be implemented/evaluated.

Only three of the interventions to assist RTW developed using an IM framework have been formally evaluated in a randomised controlled trial (RCT); these are van Oostrom et al. ,72 Vermeulen et al. 73 and Vonk Noordegraaf et al. 68 The details of these studies are described in Chapter 3 and they suggest that the IM framework being employed in the OPAL study can facilitate the development of an effective occupational advice intervention.

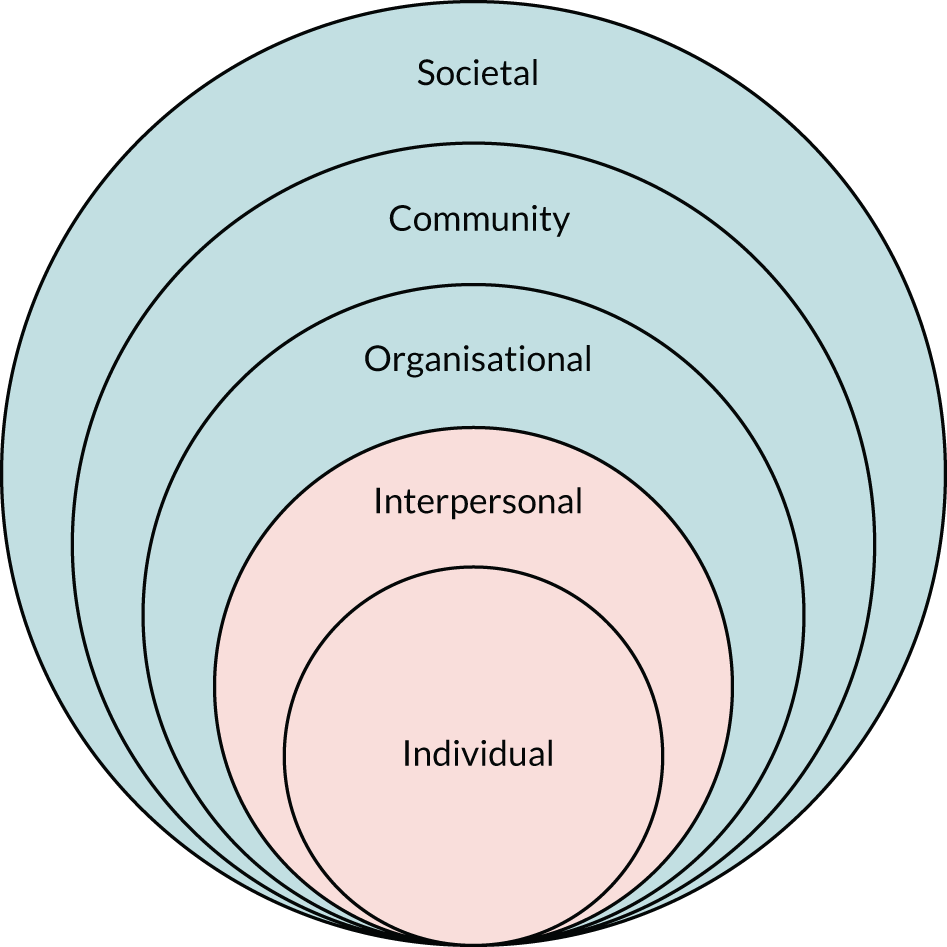

Intervention mapping is a useful approach as it acknowledges that health is a function of individuals and their environments. Many health-related behaviours are dependent on individual knowledge, motivation and skills, but are also determined by the actions of decision-making groups, such as organisations and health authorities. RTW interventions are complex and thus at higher risk of theory and/or implementation failure than simpler interventions, such as medication delivery or hospital-based rehabilitation. The main characteristics of the IM protocol are to consider the individual within all of the different levels of their environment, and to make explicit use of theories when defining the problem, the intended changes and how these changes will be achieved. In this way, IM has the potential to prevent both theory failures and execution failures when developing and implementing RTW interventions, with better chances of demonstrating effectiveness.

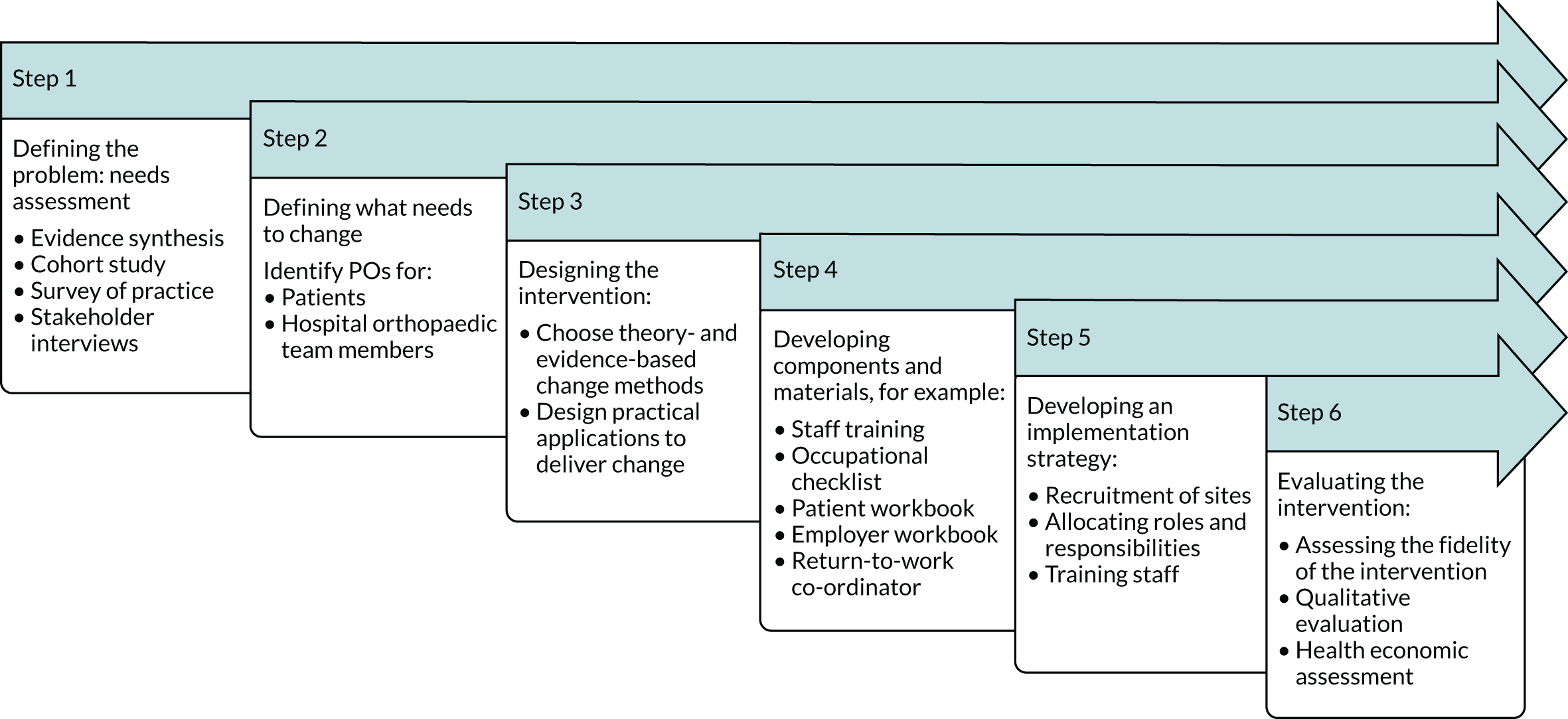

Intervention mapping is a stepwise approach to theory, evidence-based development and implementation of interventions. It consists of six stages: (1) needs assessment, (2) identification of intended outcomes and performance objectives (POs), (3) selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies, (4) development of intervention components, (5) development of an adoption and implementation plan, and (6) evaluation and feasibility testing.

The OPAL intervention mapping process

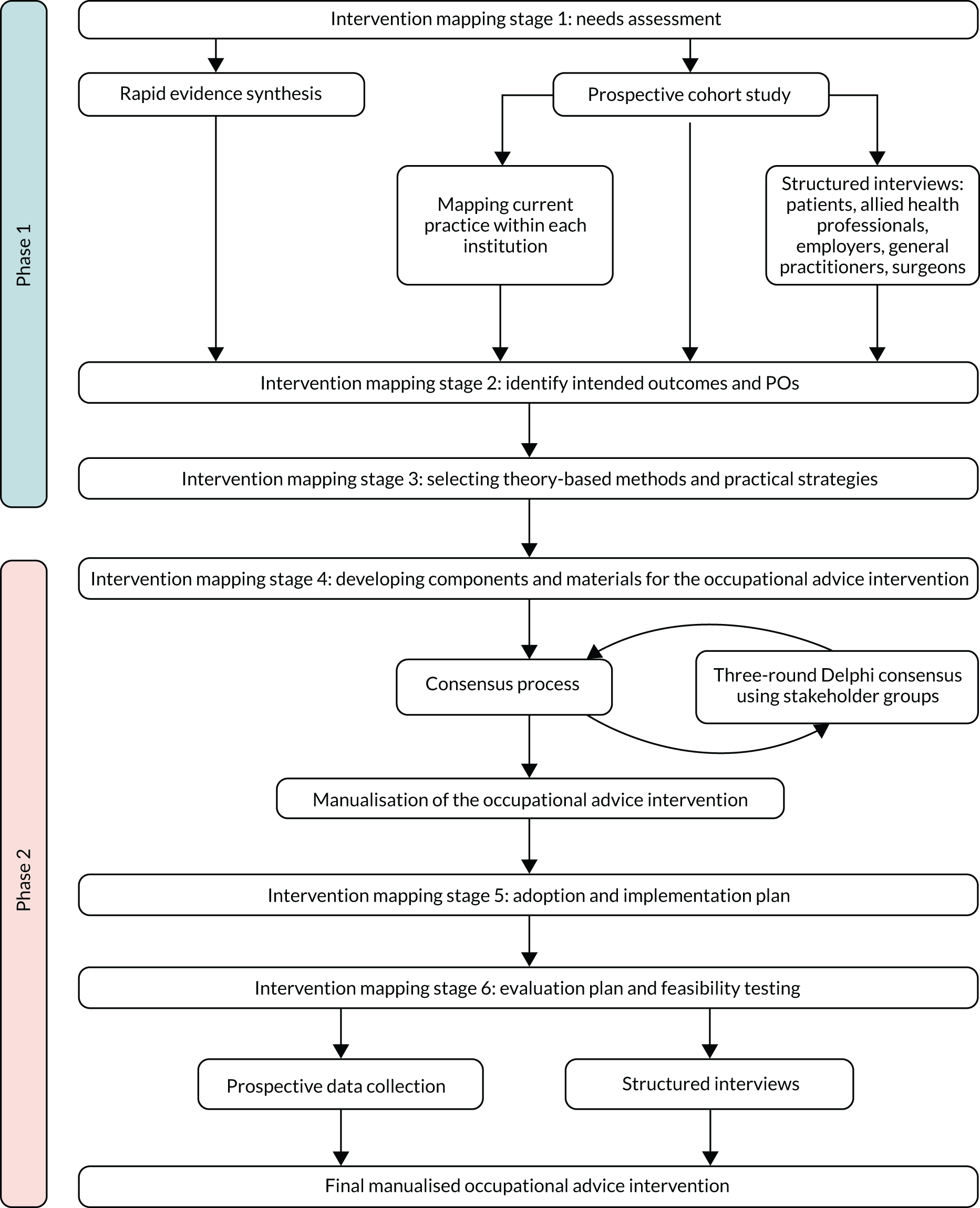

The OPAL study followed the six-stage IM approach (Figure 1). Stages 1–3 (phase 1) addressed objectives 1–6 (see Chapter 1, Objectives) by gathering information on current practice and barriers to change; stages 1–3 also provided a theoretical framework for intervention development. Stages 4–6 (phase 2) addressed objectives 7–9 (see Chapter 1, Objectives). An overview of the activity within each stage of the IM process is provided below, and further details can be found in each of the corresponding chapters.

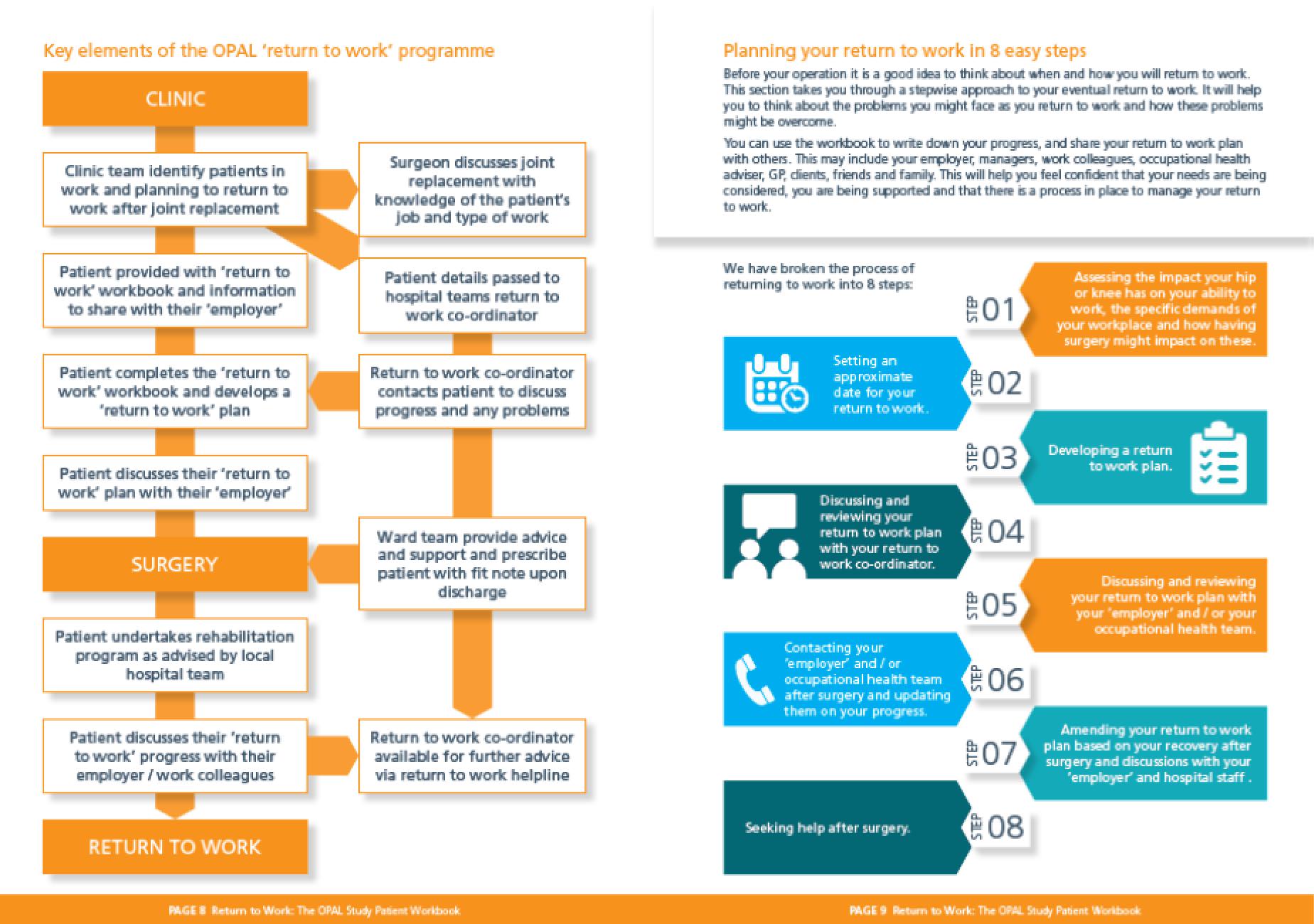

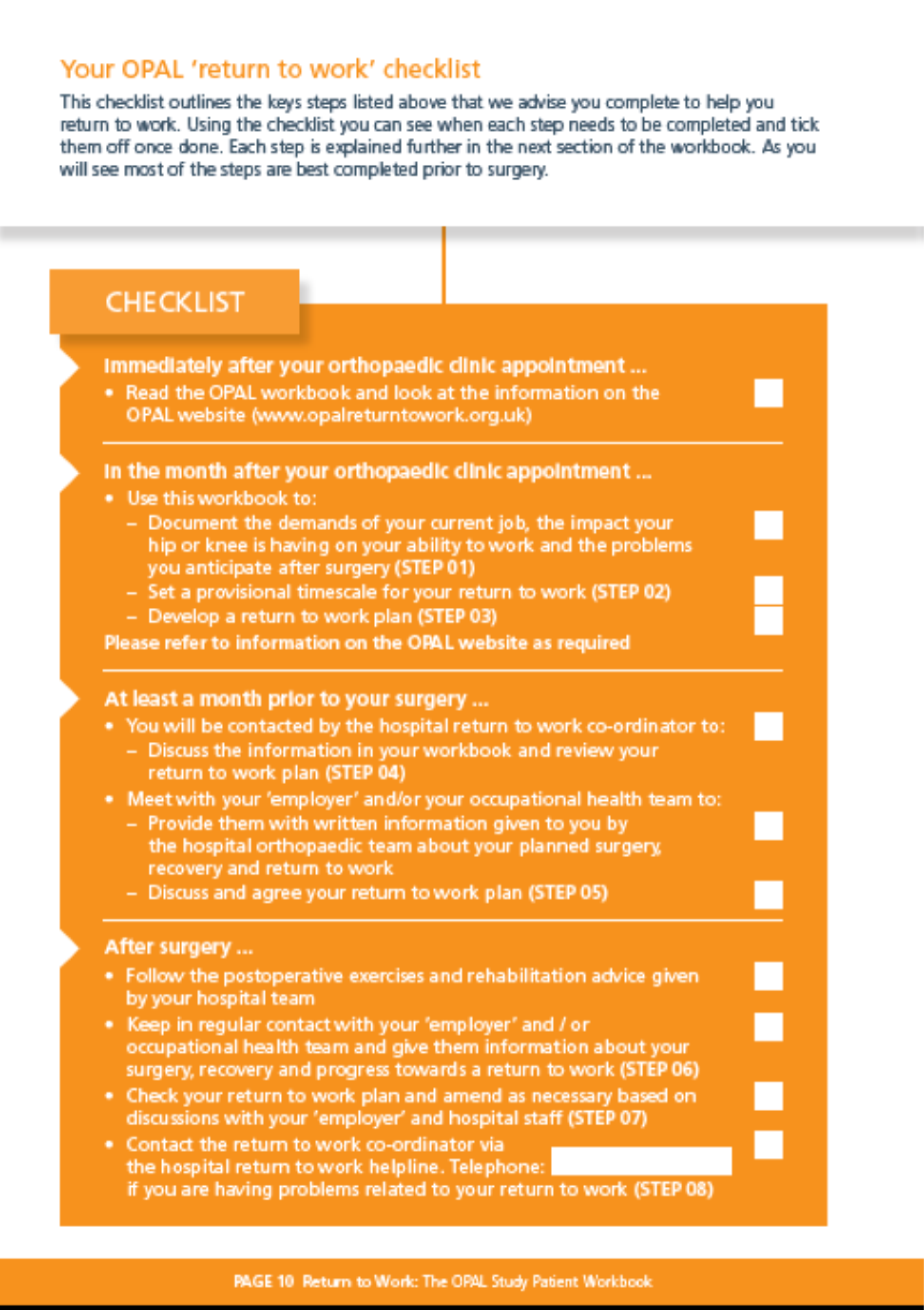

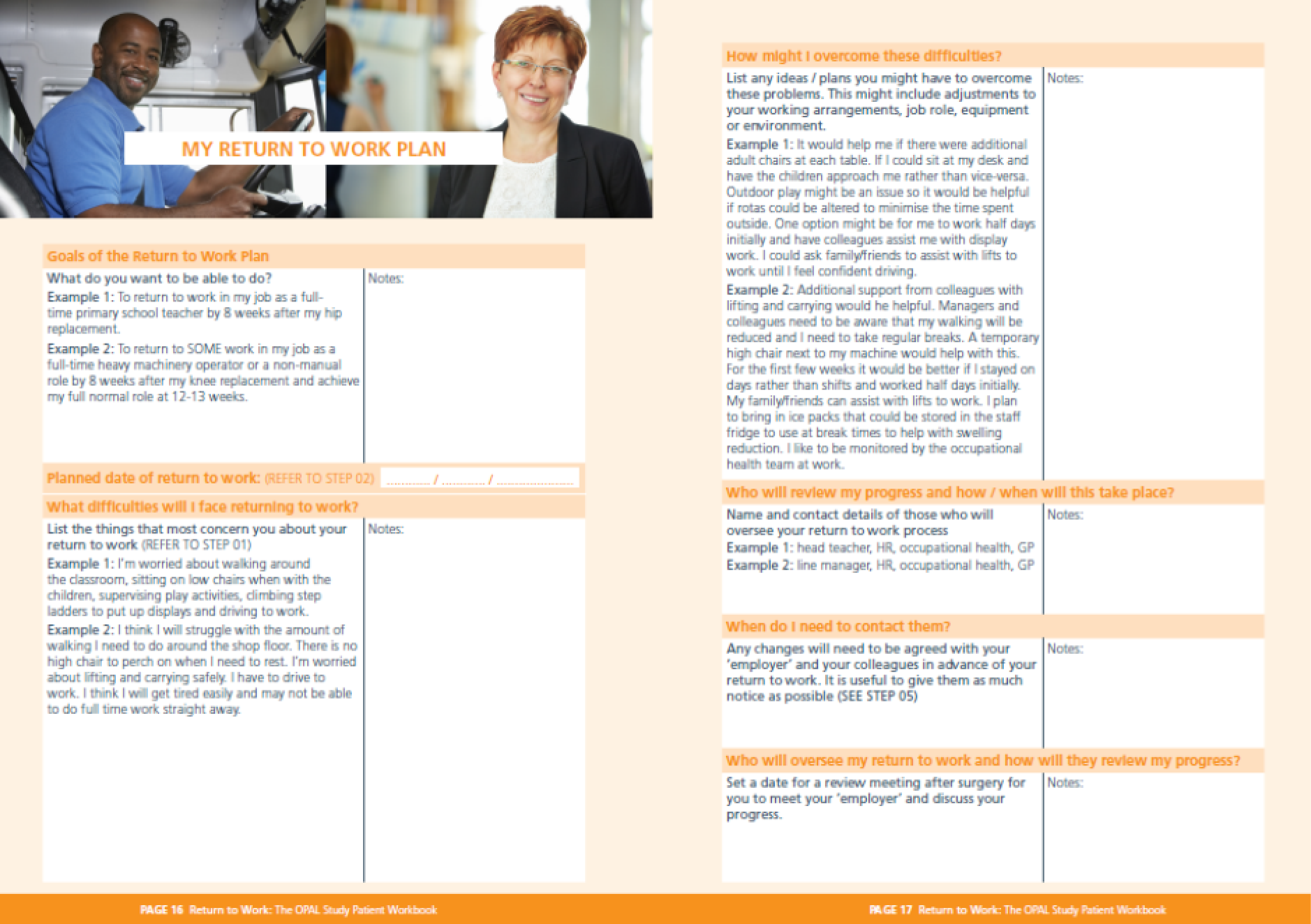

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the OPAL IM methodology.

Intervention mapping stage 1: needs assessment (see Chapters 3–6)

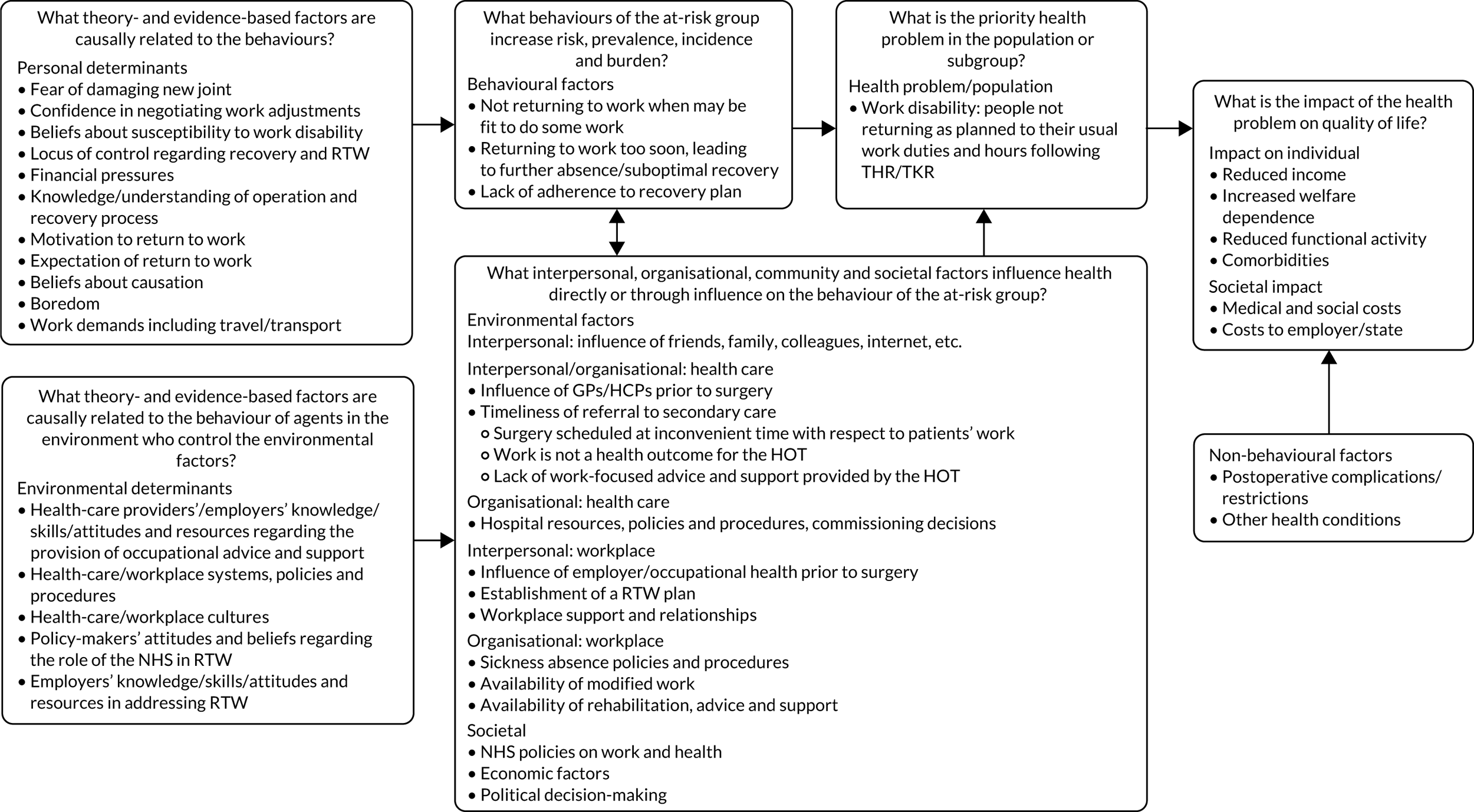

Intervention mapping stage 1 established the rationale for an occupational advice intervention within the target population by evaluating the discrepancy between current and desired practice. It utilised a variety of approaches including a rapid evidence synthesis (see Chapter 3), a cohort study (see Chapter 4), a national survey of practice (see Chapter 4) and patient (see Chapter 5) and stakeholder (see Chapter 6) interviews. This information was then used to create a logic model of the problem considering how the behaviours of the target population increase the risk, prevalence, incidence and burden of the problem and how interpersonal, organisational, community and societal factors influence RTW directly or through influence on the behaviour of the target population. These behavioural and environmental factors were then mapped to specific theory- and evidence-based factors and determinants to help provide an overview of the problem and a framework to address it.

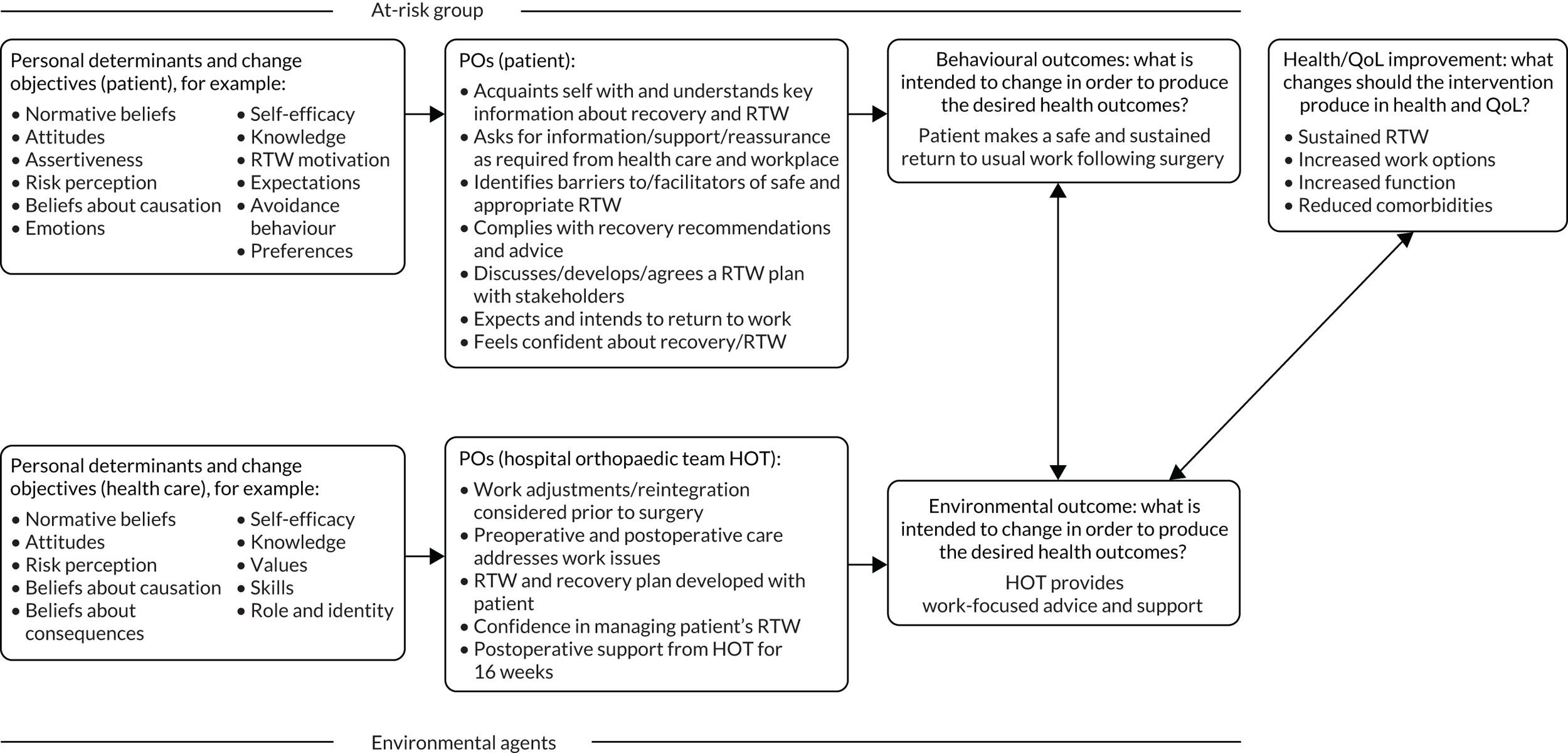

Intervention mapping stage 2: identify intended outcomes and performance objectives (see Chapter 7)

Stage 2 used the findings from stage 1 to specify who and/or what needs to change for patients to make a successful RTW following hip/knee replacement. A provisional matrix of POs for key stakeholder groups was constructed outlining the personal determinants, external determinants and expected outcomes for each objective.

Intervention mapping stage 3: selecting theory-based methods and practical strategies (see Chapter 7)

In stage 3, a list of possible components matched to each performance objective/determinant was generated. Using theory, evidence, experience and consensus, the most practical ways to implement these interventions were identified. These intervention ‘components’ formed the basis of the statements presented to stakeholders as part of the Delphi consensus process (see the next section on IM stage 4) and helped to develop the first iteration of the developed occupational advice intervention.

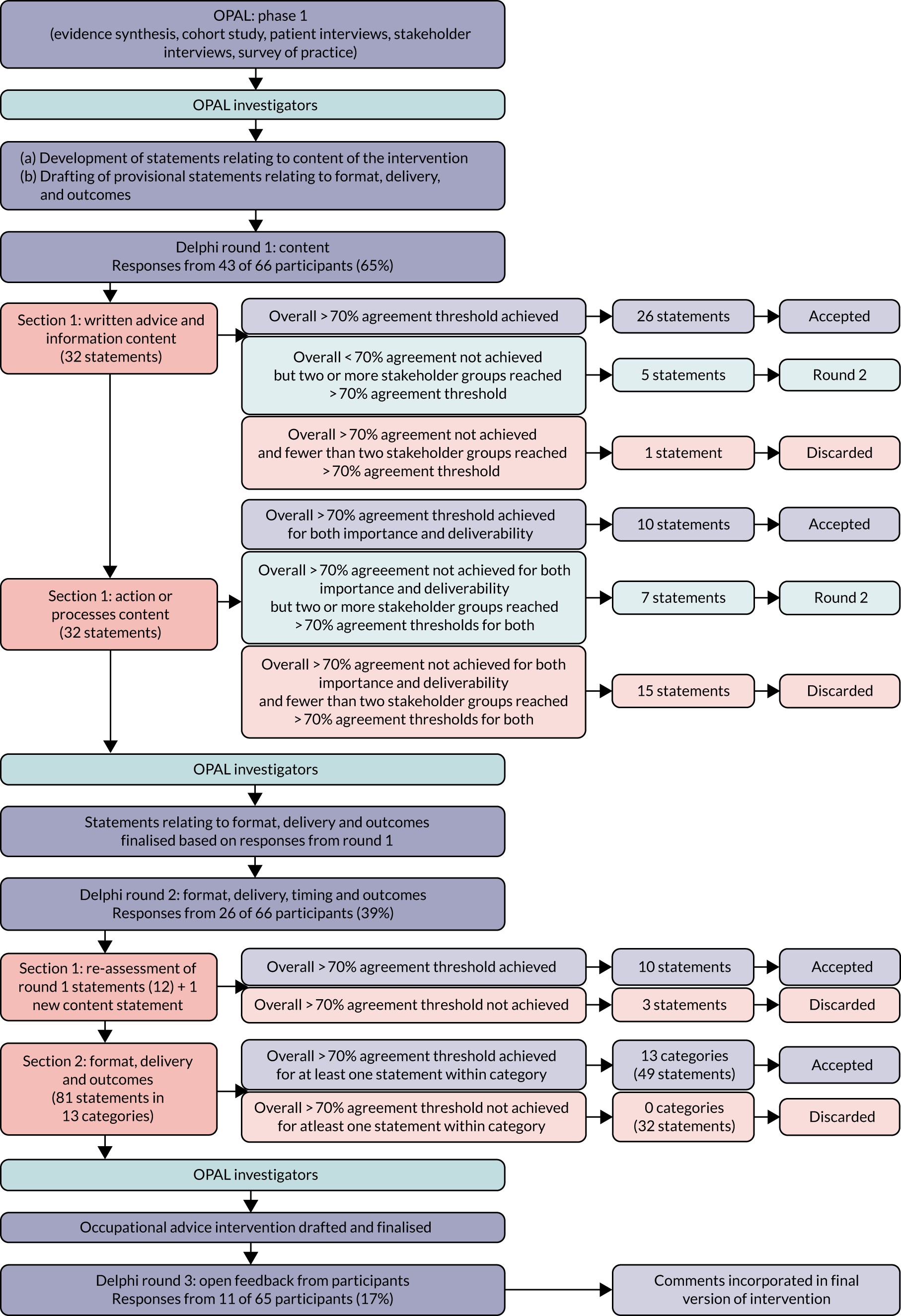

Intervention mapping stage 4: development of intervention components (see Chapters 8 and 9)

Stage 4 used the information and associated occupational advice strategies identified in the first three IM stages to develop specific tailored tools and materials. To help refine these components, a multistakeholder intervention development group was created to reach agreement about the design, content, delivery, format and timing of the proposed occupational advice intervention. To facilitate this process, a modified three-round Delphi consensus process was employed. Information from the Delphi consensus process was then used to refine and finalise the occupational intervention.

Intervention mapping stage 5: adoption and implementation plan (see Chapter 10)

In stage 5, strategies for the implementation and adoption of the intervention were developed. This stage ran concurrently with the final stages of intervention development as the content, format and method of delivery became finalised. The implementation plan focused on the delivery of the intervention within the realities of the NHS. Therefore, the intervention and the associated implementation plan had to be adaptable to current practice, infrastructure and staffing at each of the three feasibility sites. This flexibility permitted delivery alongside current ‘standard’ care while stipulating the achievement of specified POs, against which the fidelity of the intervention was assessed.

To facilitate the implementation and adoption of the intervention, education and training materials were developed for each of the staff groups involved in its delivery. Appropriate support and training systems were developed and an implementation plan was constructed to assist adoption at each site, which included a site visit and ongoing support from the OPAL investigators.

Intervention mapping stage 6: evaluation plan and feasibility testing (see Chapter 10)

The final stage of the IM process evaluated the intervention by assessing four complementary aspects of its delivery and performance:

-

assessment of intervention fidelity – quantitative evidence that the intervention was delivered against specific POs for both the hospital orthopaedic team (HOT) (staff objectives) and the patient (patient objectives)

-

assessment of intervention quality – qualitative assessment of the intervention delivery obtained by interviewing patients and staff groups about what worked and what did not, why it did not work or why it went well

-

assessment of feasibility data – preliminary comparison of outcomes using data obtained from IM stages 1 (pre intervention) and 6 (post intervention)

-

assessment of economic data – approximate cost estimates for the intervention using derived health economic data.

In addition, the feasibility stage collected information that would help to shape the design and development of a future clinical trial by assessing screening, recruitment, consent and follow-up procedures and rates at each of the study sites. A formal pilot study was not undertaken at this stage as per the commissioning brief.

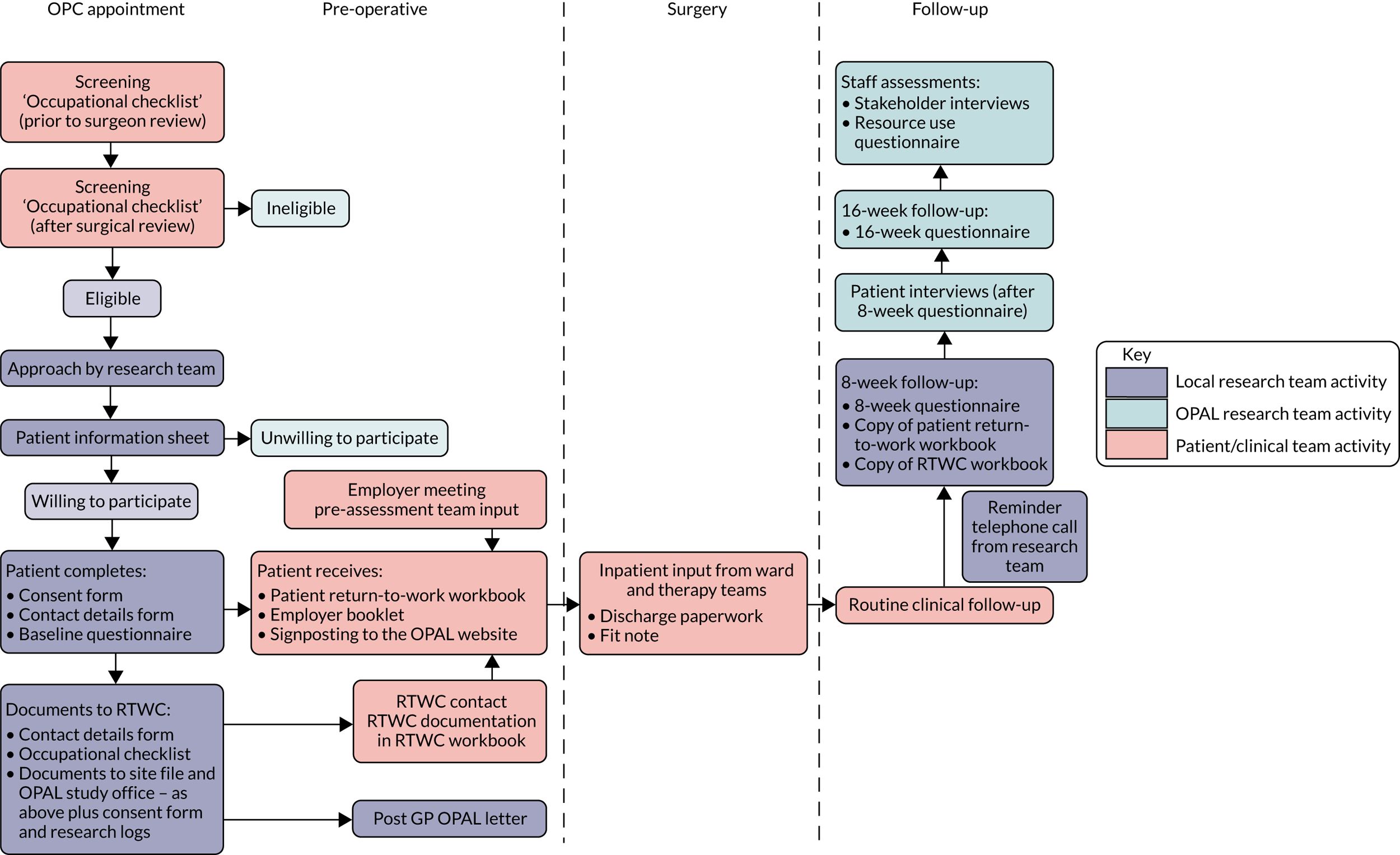

The OPAL IM approach described above is outlined in Figure 1 and a diagram describing development of the OPAL occupational advice intervention is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of the stages of development of the OPAL occupational advice intervention.

Stakeholder engagement strategy

Five key stakeholder groups central to the development of an occupational advice intervention were identified: (1) patients, (2) employers and their associated occupational health departments, (3) allied health professionals (AHPs) (occupational therapists and physiotherapists) and nurses, (4) orthopaedic surgeons and (5) general practitioners (GPs).

To maximise engagement with these stakeholder groups, nominated OPAL investigators were responsible for the identification and engagement of stakeholders within their area of expertise. This included stakeholder recruitment from a number of professional bodies and employment institutions, providing the breadth of opinion and insight required to ensure generalisability and acceptability of findings and assist with dissemination of findings at various stages of the study (Table 1).

| Stakeholder group | Nominated OPAL investigator | Participants recruited via |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Mrs J Fitch |

|

| Employers and occupation health services | Professor S Khan |

|

| Orthopaedic surgeons | Mr I McNamara |

|

| AHPs and nurses | Dr D McDonald and Dr C Coole |

|

| GPs | Mr P Baker and Professor A Rangan |

|

Data collection and handling

Personal data collected during the trial were handled and stored in accordance with the 199875 and 2018 Data Protection Acts. 76 All electronic patient-identifiable information was held on a secure, password-protected database accessible to only essential study personnel. Only OPAL investigators (University of York and University of Nottingham), the sponsor (South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) and the recruiting NHS trust had access to the personal data. Written consent was taken for collected data to be linked to routinely collected health data stored in national databases (via NHS Number), although this activity did not form part of this research project.

Project management

The South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was the sponsor for this project. This study was compliant with the research governance framework77 and Medical Research Council good clinical practice guidance. 78 The Trial Steering Committee, which met approximately 6-monthly during the OPAL study, oversaw the study.

Ethics approval

The OPAL study was approved by the East Midlands – Derby Research Ethics Committee (Integrated Research Application System ID 200852) on 18 August 2016. The employer/workplace representative interviews were approved by the University of Nottingham Ethics Committee on 25 July 2016. Health Research Authority approval was received on 4 October 2016. For ethics approvals and Health Research Authority correspondence documents, see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/152802/#/ (accessed 2 May 2020).

Project registration

-

Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN27426982 (date registered: 20 December 2016); URL: www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN27426982 (accessed 16 April 2019).

-

International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) registration number CRD42016045235 (date registered: 4 August 2016).

Protocol management and version history

See study protocol version 4.0, which has been published. 54 Protocol version history is provided in Appendix 1.

Patient and public involvement

Active patient and public involvement (PPI) was ensured throughout the study. During the development of the grant application, PPI was sought from the NJR patient network and the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) Patient Liaison Group. Six patients who had a joint replacement contributed to the initial proposal.

A recurring concern during initial discussions with patients was that a ‘one size fits all’ approach could be too generic. Other issues raised were variations across hospitals in the support provided; the needs of specific occupational groups, such as self-employed; different expectations among people about RTW; and the impact of the employer perspective, coupled with concerns about how early RTW interventions may result in pressure for people to return too early.

To address these concerns, the OPAL study specifically assessed individual patients’ experiences to enable an individualised intervention to be developed. Patient interviews explored individual patients’ needs, concerns and expectations related to the RTW process. This information, along with information from other stakeholders, shaped the development of the intervention during the rest of the study. In phase 2, patients were included in the Delphi consensus process, ensuring that we understood and addressed issues pertinent to them within the intervention. In addition to patients, engagement from other stakeholders was ensured during both phases of the OPAL study as part of the study design, maximising their engagement in the design and development of the intervention.

The study investigators included a patient representative as co-applicant (Mrs Judith Fitch). Mrs Fitch was involved in the ongoing management of the study through her involvement with the Trial Management Group, and intervention development meetings. In addition, a lay member sat on the Trial Steering Committee. Throughout the project, we continued to work with the NJR PPI group and the BOA patient network as well as PPI groups local to the sponsor site (South Tees). These groups helped us to develop study materials for the cohort study, patient interviews, Delphi consensus process and feasibility elements of the OPAL study. This included refining the study screening and consent processes, and developing the content of all patient-facing materials, ensuring that they were ethically sound, participant friendly and acceptable to the patient population. PPI members had the opportunity to contribute to the OPAL study via face-to-face meetings with the investigators and via telephone, e-mail or post. The costing for all PPI activity was calculated using the guidelines on the INVOLVE website. 79 PPI members were informed of the various resources and opportunities available for patient and public engagement with the NHS and research.

Once the study was complete, the chief investigator held a patient and public focus group meeting at which an outline of the study and the study outcomes were presented; this meeting included hip and knee arthroplasty patients, a carer and a patient ambassador. The intervention that was developed and its associated resources (patient and employer workbooks, and POs) were discussed and queries about specific aspects of the study findings and intervention were answered. The group agreed that the designed intervention was highly valuable to the patient population. They agreed that it should be tested in a larger setting and commented on its potential to be adapted to other areas. The group also discussed dissemination plans for the research findings and future research. The Plain English summary in this report was reviewed and edited by the group.

Chapter 3 Intervention mapping stage 1: needs assessment – rapid evidence synthesis

Introduction

A rapid evidence review of existing quantitative and qualitative evidence on occupational advice interventions for people undergoing any type of elective surgery was undertaken. This was to ensure that the best available evidence informed the OPAL occupational advice intervention. All elective surgery populations were included as it was considered likely that there would be some generalisability across different surgery populations. However, due to the paucity of information available on this population, established following initial screening of the database searches, the review was widened, following the advice of the Trial Steering Committee. It also therefore included systematic reviews evaluating occupational advice interventions supporting RTW for individuals with chronic musculoskeletal problems.

Objectives

The rapid evidence review supported study objectives 3–6 (see Chapter 1, Objectives).

Methods

Overview

A rapid review methodology was used. Given that the commissioner had already identified an evidence gap relating to occupational advice interventions for patients undergoing hip or knee replacement, and the need for primary research and a future trial (if feasible), a full systematic review was not warranted. The purpose of the rapid review was to identify interventions that showed evidence of benefit (or a signal of benefit where the study is underpowered) to explore the content of the interventions and identify aspects that could inform the development of the intervention for people undergoing lower limb joint replacement.

The term ‘rapid review’ covers a range of methods and there is no generally accepted definition, although generally the approach addresses a trade-off between time and methodological rigour and comprehensiveness of the end product. 80 We focused on the systematic review evidence in the first instance, included only English-language articles published in the last 20 years, restricted the range of databases searched and double-checked a proportion of the literature searches, rather than 100% (which is accepted practice for a full systematic review). The protocol for the rapid review is available on PROSPERO (protocol registration number CRD42016045235). 81

Literature searches

There were two sets of searches: one for systematic reviews and one for primary studies reported outside the search dates or remit of the reviews identified.

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Database of Reviews of Effectiveness were searched in August 2016 for systematic reviews up to 2015. Additional supplementary searches were undertaken for the period 2015 to July 2016 in MEDLINE and EMBASE. The search combined various terms for ‘occupational advice’ and ‘return to work’ with terms for ‘systematic reviews’. There was no restriction for type of population (e.g. elective surgery) so that the searches were as comprehensive as possible. The following five databases were searched for primary studies in August 2016: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE and OTseeker. The strategy combined terms for ‘surgery’ and terms for ‘return to work’ and ‘occupational advice’. The full search strategies are reported in Appendix 2.

An information specialist undertook the searches. Both sets of searches were restricted to English-language studies published in the previous 20 years (since 1996). Records were downloaded, added to EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) bibliographic software and deduplicated.

In addition, reference and citation checking of included studies was undertaken to identify further potentially relevant records.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria that were applied are displayed in Table 2. We anticipated the literature outside elective surgery to be vast and dominated by RTW following mental ill health and musculoskeletal problems, such as back and neck pain, where generalisability to hip and knee surgery is less certain; hence, we initially excluded studies in which the participants were not undergoing an elective surgical procedure.

| Criteria | Review of systematic reviews | Review of primary studies |

|---|---|---|

| Study type | Systematic reviews with no restriction on the types of primary studies they included | RCTs, non-randomised designs (e.g. non-randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after and interrupted time series studies) and qualitative studies that explore process issues, such as barriers to and facilitators of implementation, and stakeholder perspectives |

| Population |

|

People who have been on a period of sickness absence or where a prolonged absence is anticipated following an elective surgical procedure |

| Interventions | Any occupational advice intervention, where occupational advice includes occupational therapy advice and/or occupational health advice. No restriction on when the intervention was provided | |

| Comparator | No restriction on the types of comparators included in reviews | No intervention, usual care or another occupational advice intervention. Qualitative studies were not required to have a comparator |

| Context | Studies delivered in any setting were included (i.e. primary, secondary, community and workplace). This was to capture the widest evidence to inform the development of the intervention | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes of interest were those related to RTW, return to normal activities and social participation. Condition-specific measures were excluded, except where they were specifically related to people with hip or knee functional limitations. Also included were any process measures related to the delivery of interventions, such as barriers and facilitators, and any data on stakeholder perspectives. There was not a single primary outcome for the review, given its broad aims | |

However, following an initial screening of the search results, where only a small number of studies were identified for elective surgical populations, we widened our inclusion criteria for the population. Hence, the review also included systematic reviews that evaluated occupational advice interventions, aiming to support RTW, targeted at participants with chronic musculoskeletal problems as this population was considered most similar to our target population of interest. Owing to resource constraints, it was not feasible to widen the inclusion criteria in a similar way for the supplementary primary study searches.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the literature search were screened for inclusion by one reviewer, with 30% screened by a second researcher. The full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed for eligibility by a single reviewer, with 100% also being assessed by a second reviewer, following the development and piloting of a screening tool. Any disagreement between the reviewers regarding this sample was resolved via discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

A standardised data extraction form was developed and piloted to record key information, such as population, study design, intervention details, outcomes, surgical procedure type and results. Items related to the intervention followed the Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare,82 with outcome data extracted from the primary studies, and summary information provided for the systematic reviews. The data extraction forms can be found in Appendix 2. Data extraction was undertaken by a single reviewer, and checked by a second reviewer.

-

For primary quantitative studies, the data extraction form recorded information including population; intervention (e.g. content of the intervention, material and tools used for delivery, who delivered, setting and any theoretical basis, such as behaviour change theory); process measures related to the delivery of interventions, such as barriers and facilitators; stakeholder perspectives (i.e. patients, health-care professionals and employers); study methods (e.g. study design, how outcomes were measured and length of follow-up); outcomes (e.g. what outcome measures are used in studies to assess RTW, return to normal activities and social participation?); and surgical procedure type.

-

For primary qualitative studies, data were extracted for the following items: population; study objective; surgical procedure type; method of evaluation and underpinning methodology, views and experiences (related to return to work, normal activities and social participation); and process measures related to delivery of interventions.

-

For reviews, the data extraction form also collected information such as objectives of the review; search strategies (e.g. searched databases, date of literature search, languages and inclusion/exclusion criteria); number of studies included in the review, sample sizes and details of data synthesis; types of studies included/setting, population, interventions assessed and outcomes assessed; quality assessment tools used; analysis (e.g. meta-analysis); results of the review; key conclusions; and limitations.

Assessment of risk of bias

Careful consideration was given to the risk-of-bias tools that were selected for use in our evidence synthesis, with a recent systematic review noting there being several limitations of existing tools regarding their scope, guidance for judgements on the risk of bias, and measurement properties. 83 Each of the tools listed below was considered to be appropriate for the different study type to adequately capture biases, with further information provided in the corresponding references for each tool. The quality of the included studies was assessed at the study level by one researcher and checked by a second. Specifically:

-

for systematic reviews – the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool,84,85 a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews

-

for RCTs – the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool86

-

for non-randomised studies (including non-randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after and interrupted time series studies) – the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions) tool87

-

for qualitative studies – the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist. 88

Data synthesis

Details of studies were tabulated and presented in a narrative synthesis to address the review questions. A meta-analysis was not possible owing to heterogeneity of studies and limited availability of RCTs. Key study characteristics have been tabulated, and the outcome domains investigated in the studies and specific outcome measures used have been mapped.

Many of the included systematic reviews had broad inclusion criteria and included primary studies outside the remit of interest (i.e. occupational advice interventions). Therefore, for the systematic reviews, the relevant primary studies were pulled out for closer examination, with the studies reported according to whether they featured a (1) surgical population or (2) wider musculoskeletal population. Mapping of the content of the interventions was also undertaken to allow exploration of all intervention components, materials and tools, any underlying theoretical basis, and any issues related to delivery and implementation. Data were explored and described by individual review question. No subgroup analysis was planned as part of this review.

Results

The results of the review are presented in two sections: the first relates to the included systematic reviews, for both surgical and musculoskeletal evidence, and the second refers to the review of primary studies of elective surgery populations.

Systematic reviews

Study selection

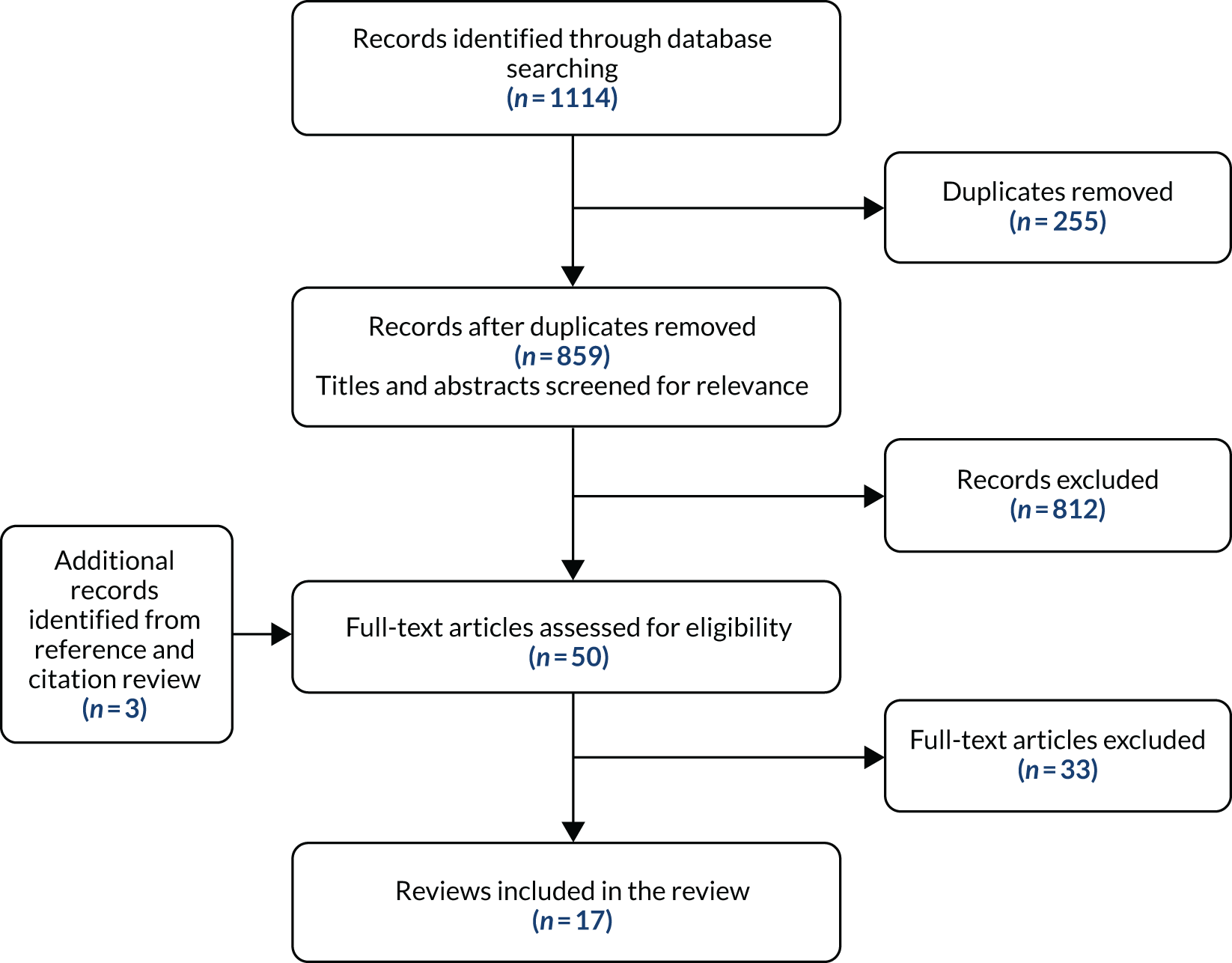

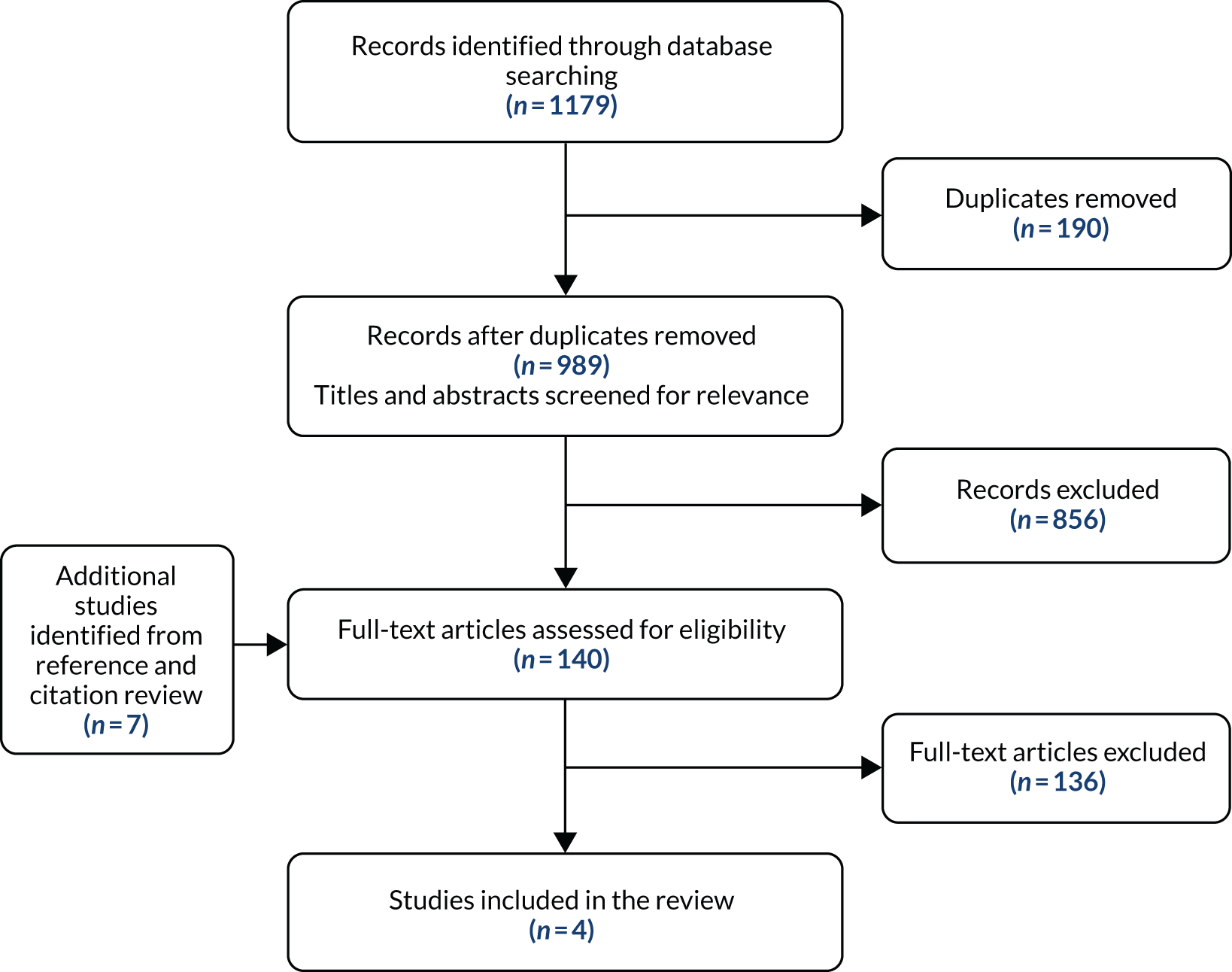

There were 859 records that were screened for relevance following deduplication of the results of the searches for systematic reviews (Figure 3). On reviewing titles and abstracts, 812 records were excluded, with 50 obtained in full-text form to assess eligibility for inclusion. A total of 17 systematic reviews were included, as listed in Appendix 2. The 33 excluded reviews and their associated reasons for exclusion are available in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 3.

Study selection for the review of systematic reviews.

Overview of included studies and reviews

The 17 systematic reviews included a total of 188 unique studies (242 before removing duplicated studies). Appendix 2 summarises the key review characteristics, the eligibility criteria, the work-related outcomes assessed and a summary of the review authors’ conclusions. The AMSTAR scores for the included systematic reviews are also provided in Appendix 2 alongside scores for individual items. These ranged from 3 to 9 out of a total of 11 possible points. The majority of reviews used robust methods to reduce risk of error and bias in study selection, data extraction and assessment of risk of bias. For some of the reviews, it was not possible to locate a protocol to verify that the review was conducted following a protocol. From the 188 included studies in the reviews, 30 were considered to be relevant to our review questions.

Only a single review was identified that focused on elective surgery (lumbar disc surgery patients);89 the remaining 16 included a range of musculoskeletal conditions:90–105 back pain (n = 6), neck and shoulder pain (n = 1), musculoskeletal issues/conditions more generally (i.e. musculoskeletal-related sickness absence and non-specific musculoskeletal complaints) (n = 2), neck pain (n = 1), repetitive strain injuries (n = 1) and fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal pain (n = 1). The remaining four reviews took a broader approach regarding the population, for example by specifying that individuals were of working age and participated in a rehabilitation programme, or by including patients with a range of permanent disabilities, or focusing on workers who were off work for reasons as specified in the review.

Type of return-to-work interventions

Almost half of the RTW interventions featured in the included reviews were of a multidisciplinary nature in a health-care setting, with seven involving multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes,89,92,95–97,101,106 four of which featured a biopsychosocial element. 95–97,106 A further seven reviews focused on specifically workplace-based interventions,90,91,94,100,102,104,105 with the remaining three involving other types of interventions: one related to physical conditioning as part of a RTW strategy,103 one investigated secondary prevention for back disorders93 and the other featured interventions that fell into five different categories (detailed in Other interventions). 99

Workplace-based interventions

One review included interventions conducted at the workplace only (clinical and health-care interventions outside the workplace were excluded), which were either group based or individual and which were aimed at modifying body function, activity performance, participation, environmental factors or personal factors. 90 The interventions could comprise either a single strategy or a combination of strategies. The review by Franche et al. 94 included studies whose interventions were provided by the workplace, by an insurance company or by a health-care provider in very close collaboration with the workplace. Nevala et al. 100 focused on interventions comprising workplace accommodation, occupational rehabilitation, vocational rehabilitation and assistive technology interventions. Studies featuring workplace interventions implemented directly by the employer, including involvement from occupational health services, were included in the review by Vargas-Prada et al. 104

The review by Carroll et al. 91 considered interventions that featured either full or partial involvement of the workplace, or involved the intervention being delivered via direct employer/representative contact. Williams et al. 105 reviewed studies that featured interventions undertaken at the workplace, in addition to studies involving secondary prevention interventions for the condition under consideration. The review by Palmer et al. 102 focused on interventions delivered in a workplace or primary care setting, or in collaboration with employers or primary care providers.

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme interventions

Désiron et al. 92 focused on occupational therapy interventions as part of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme, with the review by Norlund et al. 101 specifying that the multidisciplinary interventions should involve two or more health-care disciplines. The surgical review89 included studies that focused on active rehabilitation programmes, where these included exercise therapy, strength and mobility training, physiotherapy and multidisciplinary programmes.

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation programme interventions

The review by Kamper et al. 95 included studies that featured multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation interventions, defined as involving a physical component and at least one of the following elements: biopsychosocial, social or occupational. The reviews by Karjalainen et al. 96,97,106,107 focused on studies whose interventions featured a biopsychosocial multidisciplinary inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation programme, specifically stating as part of their eligibility criteria that the programme should consist of a physician’s consultation, in addition to a psychological, social or vocational intervention, or a combination of these. Studies featuring rehabilitation interventions that were solely or predominantly medical were excluded. Note that the 1999 Karjalainen et al. 96 review did not state the word ‘biopsychosocial’ in the intervention description; however, the intervention was set out to incorporate the same elements, and because it was derived from the review on common musculoskeletal disorders by the same authors,97 it has been placed in the biopsychosocial category.

Other interventions

In their review, Elders et al. 93 included interventions relating to a secondary prevention intervention in a non-health-care setting for back pain or disorders. These comprised either organisational or administrative interventions (including modified work and early RTW); technical, engineering or ergonomic interventions; or personal interventions. The review by Meijer et al. 99 featured interventions that fell into the following five categories: knowledge conditioning, physical conditioning, psychological conditioning, social conditioning and work conditioning (e.g. vocational training and workplace-based interventions). Physical conditioning interventions, as part of RTW strategies, were reviewed by Schaafsma et al. ,103 which were specified as comprising advice about exercises for restoration of functionality (neurological, musculoskeletal, systemic or cardiopulmonary), with an intended improvement in work status, and a relationship between the intervention and functional job demands. In addition, the intervention could include further components, such as advice on RTW and workplace involvement.

Individual relevant studies from the included reviews

The systematic reviews were included based on the scope of the reviews and their inclusion criteria meeting the eligibility criteria for our rapid review. However, the primary studies that were identified and included in the reviews did not necessarily all provide relevant data or fit with our review question (i.e. have an occupational advice intervention). Hence, if conclusions were to be drawn solely from the overall messages of each of the reviews, this would not be of use for our review, as several irrelevant studies would be feeding into this. As a result, we screened the list of included studies in each review and the key details from the studies identified as being relevant have been extracted and summarised in Appendix 2, regarding work-related outcomes.

Effectiveness of interventions

The interventions that showed evidence of benefit are summarised in Appendix 2, comprising 14 musculoskeletal studies and one surgical study. The intervention content within the musculoskeletal studies varied, but generally featured rehabilitation, with multidisciplinary team involvement. The studies tended to relate to back pain or musculoskeletal pain in general. Specifically, six studies related to low back pain,108–115 one was for work-related thoracic/lumbar pain,116 one for upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders117 and one for rheumatic disease. 118 More generally, four studies related to musculoskeletal disorders/pain119–122 and one study investigated soft-tissue injuries,123 which involved back, shoulder, lower extremity, neck and thoracic pain.

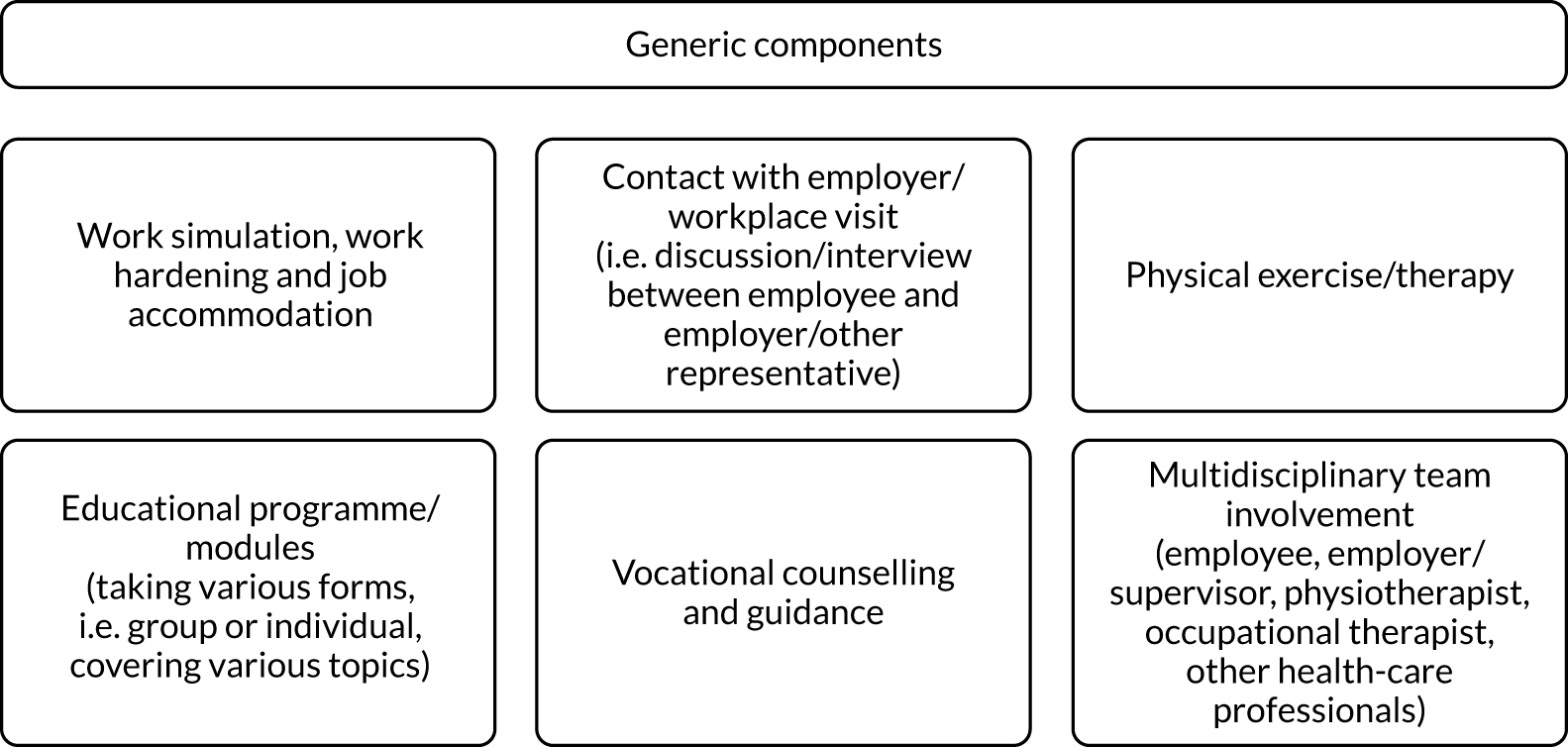

Duration and timing of the interventions varied, with participants often being on sick leave at entry to the programme. Some interventions were more intensive,108–111,114,115,117,121–123 for example being 6 hours per day, 5 days per week, for 5 weeks,110 whereas others involved only a few visits or sessions at longer time intervals. All of the interventions were delivered face to face. The multidisciplinary team involved in the effective interventions tended to comprise an occupational therapist, physiotherapist, other health-care professionals and the employer/workplace supervisor, in collaboration with the employee. The majority of the rehabilitation interventions included components such as job accommodation, work hardening/simulation, physical therapy/exercises, vocational advice, workplace visits and educational classes, with some covering pain management.

The intervention that featured in the one surgical study of herniated lumbar disc surgery124 followed a rehabilitation-orientated approach used by medical advisors to motivate patients and treating physicians towards social and professional reintegration. It was delivered face to face by medical advisors, with patients first visiting at 6 weeks post operation and then attending monthly follow-up consultations. The intervention also involved contacts with treating physicians and case discussion with medical advisors’ colleagues (see Appendix 2).

What components of the interventions are likely to be generic across conditions and surgical procedures and, therefore, generalisable to an occupational advice intervention prior to planned surgery for hip or knee replacement?

The effective interventions tended to involve rehabilitation programmes, which took a multidisciplinary approach in general. In the majority of cases, it was not possible to disentangle the separate elements to determine whether certain components were playing more of a role in the effectiveness than others. The key components of the interventions that kept appearing irrespective of the condition and/or surgical procedure under consideration are summarised in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of key components across effective interventions.

Outcome measures for return to work, return to normal activities and return to social activities

The outcome measures used in the relevant primary studies from the systematic reviews are mapped in Appendix 2 by study and type of outcome measure. Outcome measures were grouped in the following categories to aid mapping, although in reality there is overlap between these categories: (1) non-standardised return to work/activities measures, standardised scales for return to work/usual activities, measures focusing on musculoskeletal symptoms, quality-of-life measures, psychological measures and other measures.

Studies most commonly used some type of measure of RTW, although how this was assessed varied between studies. In some studies, the measure distinguished between whether participants returned to work at full capacity or whether this was in an altered capacity, whereas other studies had a more blunt measure, such as the proportion of participants who returned to work. Number of days of sick leave was also commonly used as an outcome measure. Patient-reported outcome measures tended to focus more broadly on activities of daily living, such as the disability component of the low back pain rating scale developed by Manniche et al. 125 This component of the scale assesses ability to perform daily activities, such as working, sleeping, housework, walking, sitting, lifting, dressing, driving and running. Other outcome measures focusing on ability to perform activities of daily living were the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)126 and the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire. 127 There are multiple versions of the ODI and not all contain questions related to employment, and none of the multiple versions of the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire contains questions related specifically to employment. Two studies128,129 used measures that focused specifically on work using the Graded Reduced Work Ability Scale developed by Haldorsen et al. 130

Primary studies (surgical)

Study selection

The literature search of electronic databases identified 1179 potentially relevant records for the primary studies (Figure 5). After removal of duplicates, 989 primary studies were screened for relevance. A total of 856 primary studies were excluded on the basis of title and abstract and 140 full papers were retrieved for more detailed evaluation, which included seven obtained via reference and citation checking. A total of 136 papers were excluded and four studies met the inclusion criteria, with the included primary studies listed in Appendix 2. One of these studies had already been identified in the review of reviews and was also included here for the sake of completion so that it was quality assessed and discussed in conjunction with the only other identified study of a surgical population. 124 Details of excluded studies are also provided in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 5.

Study selection for review of primary studies.

Overview of included studies

The four included primary studies comprised two RCTs (n = 925 participants) conducted in the Netherlands131 and Belgium124 and two qualitative studies undertaken in England132 and Texas, USA. 133 The main study characteristics are presented in Appendix 2.

One RCT involved individuals who had undergone lumbar disc herniation surgery124 and the other featured participants following gynaecological surgery. 131 One of the qualitative studies explored perspectives of patients who had undergone knee replacement surgery,132 and the other focused on cancer care. 133

Risk of bias

The risk-of-bias assessments are reported in Appendix 2. The qualitative studies were of variable methodological quality; one study132 met all of the CASP criteria with the exception of one area being unclear regarding whether or not the relationship between researcher and participants had been adequately considered. The other study133 lacked detail in relation to data collection considerations, ethics issues and the researcher–participant relationship. One of the two RCTs was at an unclear risk of bias due to limited reporting on several elements of study design124 and the other was at unclear risk of bias due to lack of information about allocation concealment. 131

Type of return-to-work interventions

One RCT evaluated a personalised eHealth intervention in terms of the effect on recovery and RTW,131 and the second assessed a rehabilitation-oriented approach that focused on early mobilisation and early resumption of professional activities in terms of the effect on RTW. 124 The Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare82 were used for the interventions in the included studies (see Appendix 2).

The qualitative studies explored factors affecting RTW from the perspective of the patient following knee replacement,132 and factors influencing work disability following mastectomy through involvement of patients, therapists and employers. 133 Rather than discuss a defined intervention as such, both studies instead discuss individuals’ experiences of advice or education and rehabilitation received from health-care professionals132 and employers133 regarding RTW, among other issues relating to RTW.

Effectiveness of interventions

The RCT by Donceel et al. ,124 of early mobilisation and early resumption of professional activities versus usual practice (control) for lumbar disc surgery, reported that, at 52 weeks after surgery, a smaller proportion of patients in the intervention group (10.1%) than in the control group (18.1%) had not resumed work. The difference between the groups was found to be statistically significant (log-rank test: p < 0.001), with the intervention group being more successful (i.e. a higher rate of RTW was found for the intervention group).

When evaluating a personalised eHealth programme compared with a control website for recovery and RTW following gynaecological surgery, Vonk Noordegraaf et al. 131 estimated a hazard ratio of 1.43 (95% confidence interval 1.003 to 2.040; p = 0.048) in their adjusted intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses of RTW in favour of the eHealth intervention. Findings were comparable for the adjusted per-protocol analyses, but for the univariate crude ITT analyses, findings were not statistically significant.

Further details of the interventions are provided in Appendix 2. The two interventions (a rehabilitation-oriented approach and a personalised eHealth intervention) were very different in terms of the surgical population under consideration (lumbar disc surgery and hysterectomy) and the content of the interventions. The modes of delivery varied between studies, from the intervention being delivered face to face to being delivered purely online. In terms of the timing of the interventions, one was delivered 6 weeks after surgery whereas the other was delivered both before and after surgery.

Taken collectively, the two studies124,131 suggest that a multicomponent intervention with a focus on assisting RTW for individuals undergoing elective surgery is beneficial. However, owing to there being only two interventions from the included studies and because these were heterogeneous in nature, it was not possible to examine the components of the interventions that are likely to be generic across conditions and surgical procedures.

Outcome measures for return to work, return to normal activities and return to social activities

Donceel et al. 124 assessed the proportion of patients who had returned to work at 12 months’ follow-up. In Vonk Noordegraaf et al. ,131 the primary outcome was duration of sick leave until a full sustainable RTW, defined as the duration of sick leave in calendar days from the day of surgery until a full RTW to the same job, or to other work with equal pay, for at least 4 weeks without recurrence (partial or full). Other outcomes assessed in this study were quality of life (assessed by the RAND Short Form questionnaire-36 items), general recovery [measured by the Recovery Index 10 (RS-10), a validated recovery-specific quality-of-life questionnaire134] and pain intensity (measured by a visual analogue scale questionnaire).

Barriers to and facilitators of intervention delivery and stakeholder perspectives

Truncated data extraction tables from the two qualitative studies on stakeholder perspectives are provided in Appendix 2.

One UK study of 10 employed patients who had undergone TKR identified several facilitators and barriers from the patient perspective. 132 Three key themes were identified that have relevance for delivery of an occupational advice intervention:

-

Delays in surgical intervention and impact on work participation preoperatively. Patients felt that their employment status and need to remain in employment were not fully taken into consideration in the decision-making process about whether surgery should take place or be delayed until they were older. Perceived delays in surgery due to their age had a negative impact on their work before surgery and had the potential to have a negative impact on future employability.

-

Limited and inconsistent advice from health-care providers to optimise RTW. Patients reported that the advice they received focused mainly on the needs of an older retired population and covered the inpatient stay and immediate postoperative period but not RTW. Some patients thought that they should not return to work until they were advised to do so. Some reported that they could have returned to work earlier. Advice appeared to be generic rather than tailored.

-

Rehabilitation to optimise recovery and RTW. Patients reported that the postoperative rehabilitation they received was variable, that their need to return to work was not routinely considered and that they would have benefited from a more tailored approach. However, rehabilitation staff played an important role in giving them confidence to progress in their recovery.

One US study obtained the views of 31 mastectomy patients, 18 physical or occupational therapists and five employers. 133 Information provided about patients’ views on RTW was very limited. It is noteworthy that, although ‘many women’ described physical impairments that interfered with their ability to work, only one woman reported being asked by a health-care professional about the physical requirements of her job. However, 81% of therapists reported that job requirements were addressed in their treatment goals. Employers reported that they had written guidelines in place appropriate for people returning to work following surgery but that they would find it useful to have more tailored information about their employee’s physical restrictions, better patient education about expectations for recovery, more counselling services and better timing of clinic appointments to reduce disruption to work schedules. The authors commented that a common theme from all three stakeholder groups was the perceived dependence on doctors to guide the recovery process. It was suggested that some of this responsibility could be delegated to other health-care professionals.

Chapter 4 Intervention mapping stage 1: needs assessment – cohort study, health economic analysis and national survey of practice

Introduction

A cohort study was undertaken to collect information about the population of working patients undergoing elective primary hip or knee replacement and the care they currently receive. A national survey of current national practice was conducted concurrently to provide additional information about current practice.

Objectives

The cohort study and survey of practice supported study objectives 1, 2 and 5 (see Chapter 1, Objectives).

Methods

Cohort study

Overview

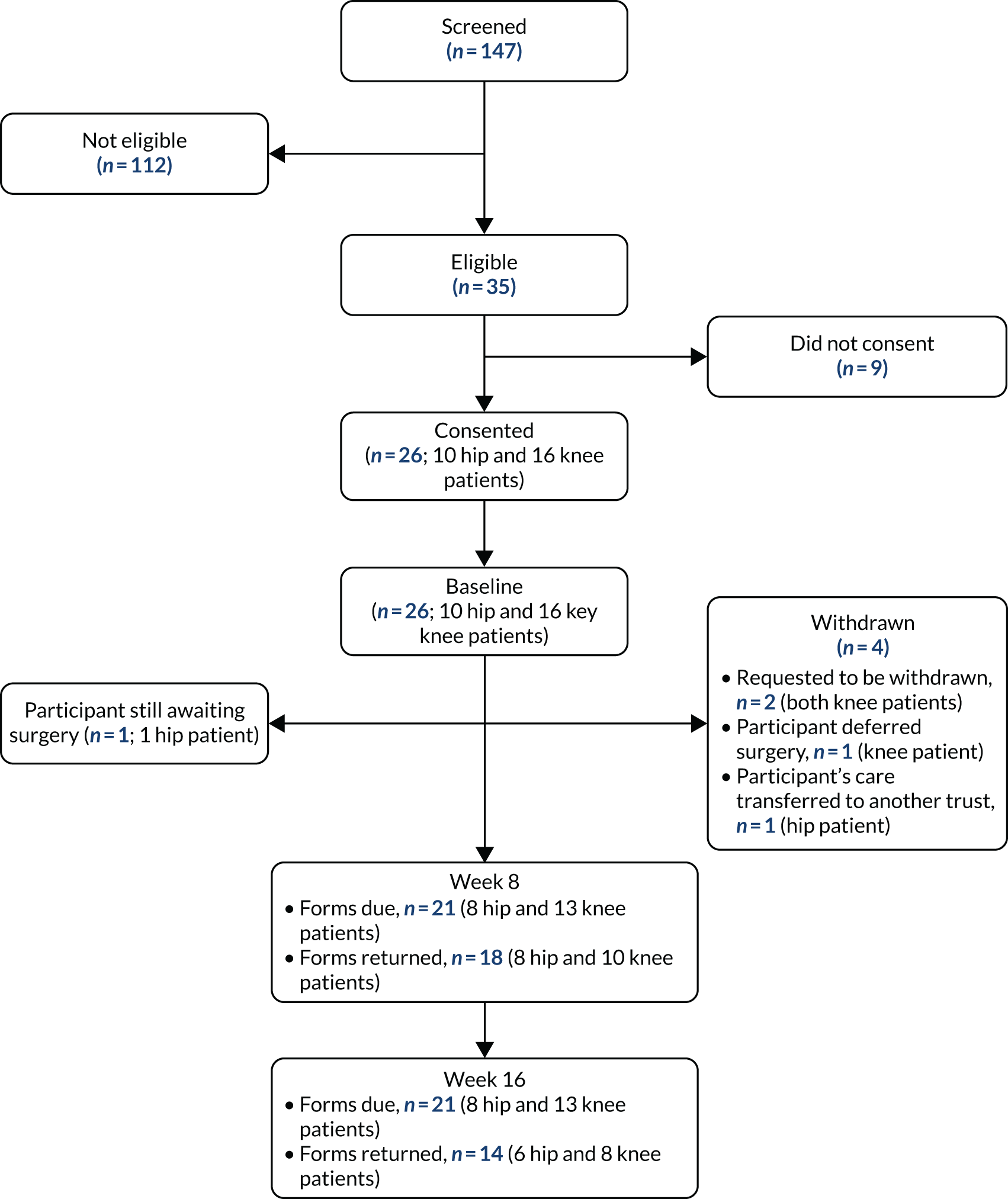

Participants undergoing hip or knee replacement (or who were on the waiting list) who had been working in the 6 months prior to surgery were prospectively recruited over a 5-month period at four centres (Middlesbrough, Nottingham, Norwich and Northumbria). Potential patients were identified by the clinical teams and screened by the local research teams at each site. Eligible patients were approached and given a patient information sheet (see Appendix 3), had an opportunity to ask the research team questions and then, if appropriate, were consented into the study.

Questionnaires were completed at baseline (either postoperatively on the inpatient ward or preoperatively in a pre-assessment clinic) and at 8 and 16 weeks post surgery (postal), and, for a subsample, at 24 weeks post surgery. Baseline questionnaires included:

-

patient demographic data

-

functional status in the workplace (Work Limitations Questionnaire135,136 and Workplace Design Questionnaire137)

-

health-related quality of life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)]

-

depression and anxiety [Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-2 item (GAD-2)]

-

Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)

-

joint specific functional outcomes [Oxford Hip Score (OHS) or Oxford Knee Score (OKS)]

-

employment details

-

expectations of recovery and RTW after surgery.

Follow-up questionnaires included the same measures plus information about RTW, adaptions to hours and the workplace environment, use of fit notes, health-care utilisation, interaction with occupational health services and return to normal activities. The baseline hip questionnaire and postoperative knee questionnaire documents are available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/152802/#/ (accessed 2 May 2020).

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for patients recruited into the cohort study were:

-

aged ≥ 16 years

-

on the orthopaedic ward undergoing a primary hip or knee replacement or on the waiting list for a primary hip or knee replacement

-

in work in the 6 months prior to their joint replacement.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

lack of mental capacity

-

did not understand written and/or spoken English

-

emergency surgical procedure (e.g. surgery for an indication of trauma)

-

currently undergoing surgery for cancer

-

currently undergoing surgery for infection.

Sample size

A sample size of 150 patients was used as this number is sufficient for representative estimates within an 8% margin of error. 138 In addition, based on the rule of thumb of 10 events per variable in logistic and Cox regression, a sample size of 150 would allow a maximum of seven predictor variables to be included in the regression analyses, assuming that 50% of participants experienced the outcome of interest.

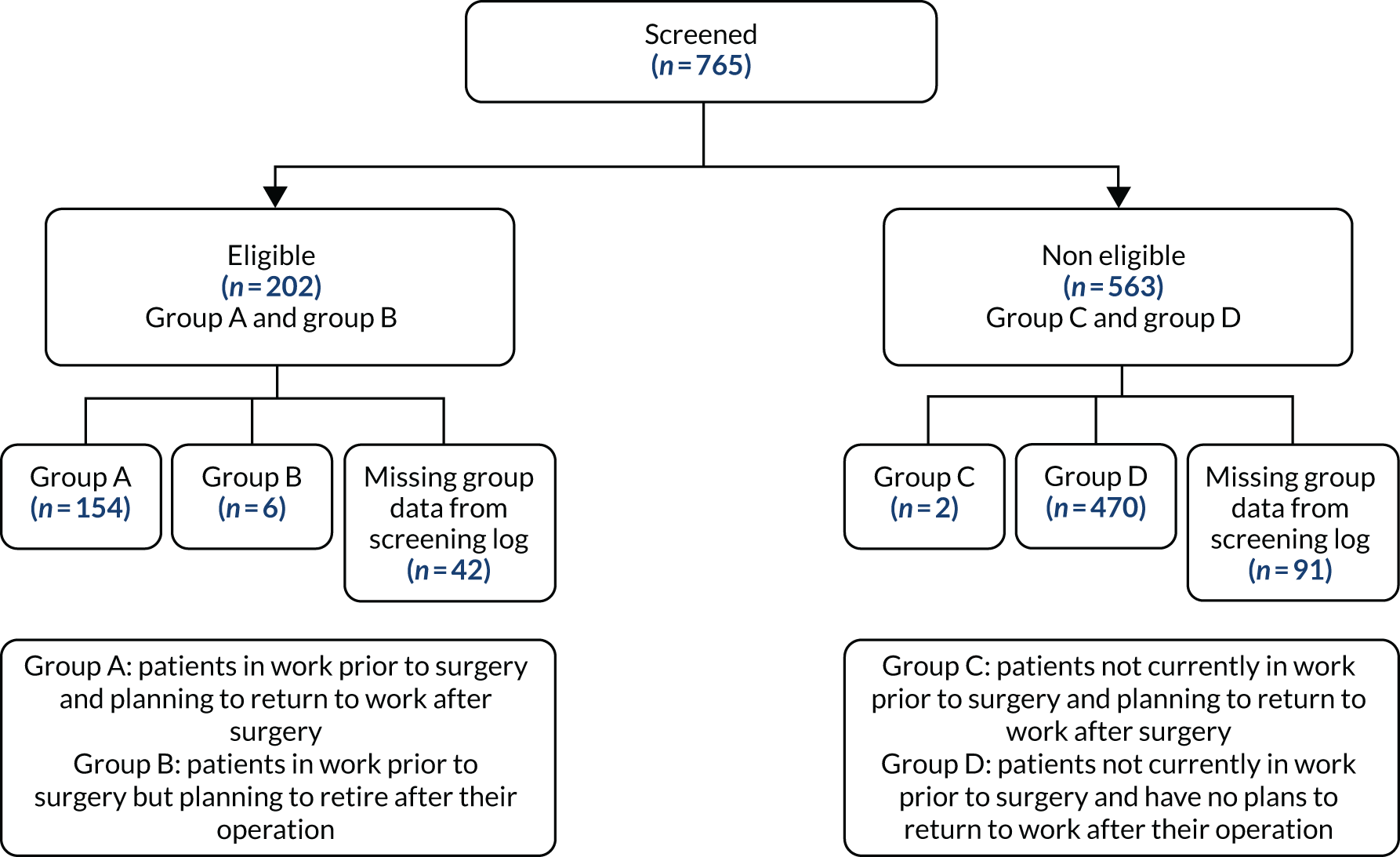

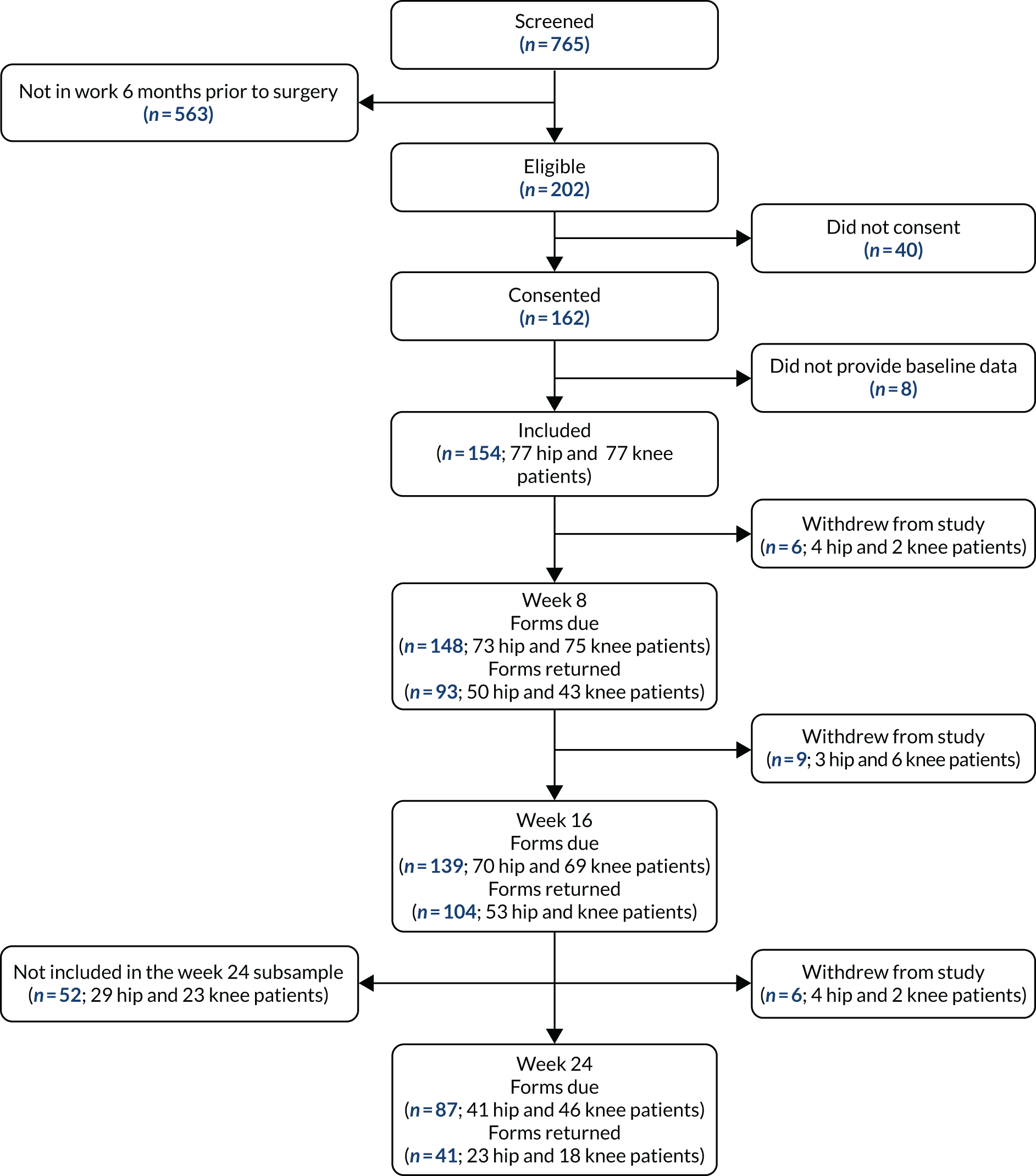

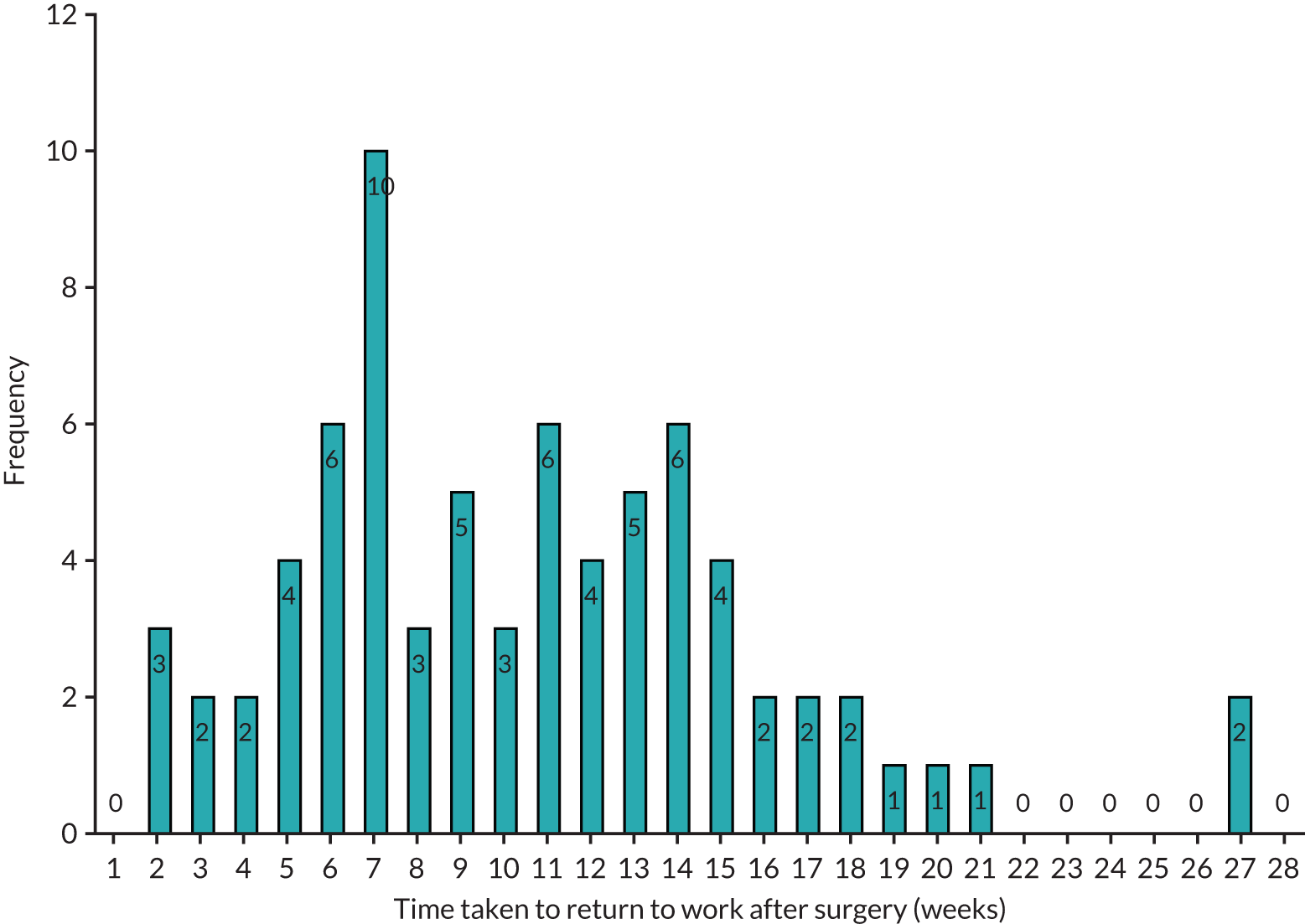

Data checking and transfer