Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/129/187. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Richard Gilson reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. Lewis J Haddow reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study, grants from the British HIV Association‘s Scientific and Research Committee and personal fees from Gilead Sciences, Inc. (London, UK) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Gilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Genital warts are benign lesions that present as lumps or raised plaques in the skin of the anogenital area. They are usually painless, but can cause irritation or bleeding. More commonly, they cause emotional distress, which is exacerbated by the need for prolonged, time-consuming and uncomfortable treatment. Relapse after apparently successful treatment occurs frequently. Surgery may be required in persistent or severe cases. About 90% of genital warts are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6 or 11, which are sexually transmitted. 1 These viruses are not believed to be associated with a risk of cervical or other genital cancer, and are therefore termed ‘low risk’. Other HPV types, particularly HPV types 16 and 18, are associated with a risk of cancer; indeed, these or one of the other ‘high-risk’ types are found in almost every case of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. However, high-risk types do not cause benign genital warts.

Of the 116,342 episodes of new or recurrent genital warts treated in sexual health services in England in 2017, 49% were recurrent episodes. 2 First-episode genital warts accounted for 15% of new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) diagnosed, making it the second most common STI after chlamydia infection. NHS treatment costs for anogenital warts in 2016 were estimated at £14M, of which about £6M was to treat recurrent episodes. 3

Since 2012, the HPV vaccine programme in 12- to 13-year-old girls has used the quadrivalent human papillomavirus (qHPV) vaccine, which is effective against HPV types 6 and 11, as well as the high-risk HPV types 16 and 18. The incidence of anogenital warts in young adults is beginning to fall, but the current programme is not predicted to result in elimination; therefore, effective treatment for warts will continue to be required.

The best first-line topical treatment for anogenital warts has not been established in clinical trials, so treatment guidelines lack a firm basis for their recommendations. The HPV vaccine is indicated to prevent infection; a therapeutic effect, although suggested, has not been established in a clinical trial.

The most clinically effective, and cost-effective, treatment for anogenital warts remains uncertain, so clinical guidelines lack a secure evidence base. 4–6 Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen can be used to treat anogenital warts. This treatment may be effective with a single application, but it requires equipment and facilities usually available only in specialist community settings and hospitals, and also requires appropriately trained staff. Repeated clinic attendance is often required for further applications of cryotherapy. Given the inconvenience for patients, and the burden it places on limited health service resources, most cases of warts are now treated with self-administered topical agents, of which podophyllotoxin (PDX) is the most common. 7 The plant extract podophyllin was used in clinics as an unlicensed product for the treatment of warts for many years. The standardised, purified product, PDX, is licensed and can be used safely by patients at home. It is more effective than podophyllin. PDX is a chemotherapeutic agent that probably acts by prevention of tubulin polymerisation required for microtubule assembly and by inhibition of nucleoside transport through the cell membrane. This leads to inhibition of growth of virally infected cells. Licensed forms include a cream and solutions. Efficacy has been demonstrated in randomised trials. 7–15 The cream Warticon® (GlaxoSmithKlein plc, Brentford, UK) contains the active compound at a concentration of 0.15%, whereas the solution is 0.5%. The cream is considered to be easier to apply, at least at some anatomical sites, and may be better tolerated. The consensus has been that the efficacy of the cream and the solution are similar, although a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the solution is slightly more effective. 16

The main alternative topical treatment is imiquimod (IMIQ). This is more expensive, although the price difference has reduced since the expiry of patent protection. Nonetheless, IMIQ is reserved in many clinics, and in guidelines, as a second-line therapy. IMIQ is available as a 5% cream (Aldara®; Meda Pharmaceutical, Tekely, UK). Some studies have suggested that IMIQ is associated with a lower recurrence rate after complete wart clearance, possibly as a result of its mode of action as an immune response modifier. 17,18 It is a toll-like receptor 7 agonist and stimulates tissue macrophages to release interferon alpha and other cytokines, which trigger a local cell-mediated response. IMIQ has no direct antiviral activity. The response to treatment may be slower than with PDX, and the licensed treatment duration is longer, at up to 16 weeks. Most patients will show a response by 8 weeks.

The efficacy of IMIQ compared with placebo or other treatment modalities has been investigated in a number of trials. 15,19–26 However, the efficacy of PDX and IMIQ as initial therapies for anogenital warts have never been compared in an appropriately powered trial. 5 The only randomised trial that directly compared these two agents was underpowered (n = 51) and did not report recurrence rates. 15 The clearance rates were similar but with wide confidence intervals (CIs): 75% clearance with IMIQ compared with 72% with PDX (95% CI 53% to 89% and 52% to 86%, respectively).

A systematic review of wart treatment undertaken for European guidelines for the treatment of genital warts5 suggested that PDX has a similar rate of initial clearance to IMIQ (43–70% at 4 weeks compared with 55–81% clearance at 16 weeks, respectively), but that recurrence rates may be lower with IMIQ (6–26% at 6 months for IMIQ compared with 6–55% at 8–12 weeks for PDX). The wide variation between reported studies may be related to differences in study design, including the outcome measures and timing. The review5 found no evidence for any single therapy being superior overall, largely owing to the lack of high-quality comparative studies. Those studies reported were heterogeneous in design, and often had high loss to follow-up. Large, well-designed randomised studies are required to make a firm recommendation on treatment. UK national guidelines recommend that the choice of first-line therapy is based on patient preference, morphology and distribution of lesions, with a clinic treatment algorithm to guide treatment. 4

The HPV vaccine is indicated to prevent infection; a therapeutic effect, although suggested, has not been established in a clinical trial. It is not known if the clearance rate of anogenital warts is increased when a HPV types 6 and 11 vaccine is given at the time of initiating either a topical treatment or cryotherapy. Similarly, whether or not recurrence of warts after clearance is reduced by the HPV vaccine has not been established.

Vaccines are currently licensed to prevent only HPV-associated anogenital warts and cancers; the qHPV vaccine Gardasil® (Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) is the only vaccine that also protects against the low-risk genotypes 6 and 11. This vaccine has been used in the national vaccination programme in the UK since 2012 for girls aged 12–13 years. Whether or not the vaccine has a therapeutic or secondary preventative effect for anogenital warts (or other HPV-associated diseases) has yet to be determined. Although there is no randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence yet, there are other types of evidence that there may be a therapeutic or secondary preventative effect.

There are case reports that clearance of anogenital warts may have been enhanced by the qHPV vaccine. 27,28 There is some evidence from placebo-controlled vaccine trials that found that women who are HPV seropositive but HPV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) negative for at least one HPV type at trial entry were protected against subsequent disease related to the HPV type to which they were previously exposed. 29 In addition, women with genital lesions treated surgically while in the vaccine trial were less likely to develop recurrent or progressive disease if they were in the vaccine arm than if they were in the placebo arm of the trial. 30 Patients with anogenital warts or genital intraepithelial neoplasia (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, vulval intraepithelial neoplasia or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia) have been shown to be at risk of reinfection with the same or different HPV types as well as relapse of existing infection. 31,32 Limited evidence also suggests that the qHPV vaccine (Gardasil) may reduce recurrences of respiratory papillomatosis in children,33 a condition usually caused by low-risk HPV types, principally 6 and 11. Similarly, anal intraepithelial neoplasia,34 caused by high-risk HPV types included in the vaccine, may be less likely to recur in vaccine recipients. Finally, vaccine antibody responses are stronger than those induced by natural infection;35 this means that boosting the immune response with vaccine could reduce the persistence of HPV types 6 and 11 infection and, therefore, the rate of disease recurrence. As an unmet need, the ability of vaccine to reduce the recurrence rate would be of greatest value to patients, given the estimated 30% recurrence seen with all treatments. Recurrence of warts after clearance by topical treatment is also the part of the disease process in which the vaccine is most likely to have activity.

Studies of the treatment cost and quality-of-life impact of genital warts, as well as economic analyses of vaccinating against HPV infection, have been conducted. 3,36,37 These studies have documented significant negative impacts on quality of life and substantial health-care service costs. The cost of IMIQ remains higher than that of PDX. If the effectiveness of IMIQ proves superior, then an economic analysis would allow an assessment of the maximum cost difference that would warrant its use as afirst-line therapy. All available treatments have significant failure and recurrence rates. By maximising initial response rates and reducing recurrence rates using first-line self-administered treatment, a RCT has the capacity to reduce this health and quality-of-life burden for patients and improve cost-effectiveness, now and in the future. Vaccination would add to the cost of treatment of patients with anogenital warts. If efficacy is demonstrated, an economic analysis could determine at which level the increased treatment costs would be justified by reduced future health-care costs and improved quality of life related to persistent or recurrent disease.

Objectives

The trial assessed the comparative efficacy of the two main topical treatments in current use, 0.15% PDX cream (Warticon) and 5% IMIQ cream (Aldara), and investigated the potential therapeutic benefit of a qHPV vaccine (Gardasil) in the management of patients with anogenital warts. The trial also evaluated the relative costs of the two topical treatments, as well as of the novel use of qHPV vaccination for both treatment and secondary prevention. The adoption of a pragmatic trial design with broad entry criteria for the comparison of the two topical therapies means that the results can be generalised to the large number of patients treated each year who present with anogenital warts. The topical therapies assessed and the potential (in the protocol) to use supplementary cryotherapy were closely aligned with current clinical practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter is adapted from Murray et al. 38 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Design

The study was a randomised, controlled, partially blinded 2 × 2 factorial-design trial of treatment for anogenital warts with an accompanying economic analysis. All participants received active, topical treatment with either PDX cream or IMIQ cream. They also received a course of qHPV vaccine or saline placebo injections. Participants were allocated in equal numbers to the four combinations of the two topical treatments and the vaccine or placebo: IMIQ cream plus qHPV vaccine, PDX cream plus qHPV vaccine, IMIQ cream plus saline placebo injection and PDX cream plus saline placebo injection. The primary outcome was clearance of warts at 16 weeks and remaining clear until the end of follow-up at 48 weeks. Analysis of the primary outcome was based on logistic regression. In the economic evaluation, we investigated the cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of the two topical treatments and the qHPV vaccine.

Ethics

The trial protocol was reviewed by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee B (reference number 13/SC/0638) and received a favourable opinion on 3 February 2014. Amendments to the protocol were subject to further review, including the decision to reduce the size of the trial, with its attendant impact on the likelihood of reaching a definitive conclusion.

Patient and public involvement

The research proposal was reviewed by a patient representative at the Mortimer Market Centre (Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust) before funding submission. The design of the study was discussed with a patient user group in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) clinical service during the development of the protocol. A lay representative was on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Setting

The trial was carried out in 22 sexual health clinics in England and Wales (see Appendix 1 for a list of participating sites). Sexual health clinics in the UK are open-access services, with most patients being self-referred. Approximately 80% of cases of genital warts treated in the NHS are treated in sexual health clinics.

Participants

The eligibility criteria for participants were adults, aged ≥ 18 years, presenting to participating clinics with external anogenital warts that, in the opinion of the investigator, could be appropriately treated with either self-administered IMIQ cream or self-administered PDX cream. Patients with a first episode of warts, and patients for whom this was a repeat episode, were eligible provided that they had not received treatment for warts in the previous 3 months.

Other exclusion criteria included patients who had previously had qHPV vaccine (but having had bivalent HPV vaccine was not an exclusion criterion). Patients with any contraindication to any of the products were excluded, which included previous intolerance to vaccines, pregnancy and lactation. Those with a total wart area of > 4 cm2 were excluded because the 0.15% PDX cream product information advice is to treat more extensive lesions only under medical supervision. Patients requiring topical steroids applied to the affected area, or on systemic immunosuppressive agents, were also excluded.

Initially, participants with known HIV infection were excluded, on the grounds that wart treatment and vaccine responses were reported to be impaired, with implications for the sample size. But, in December 2015, the entry criteria were modified to include patients living with HIV who were stable on antiretroviral treatment and had a cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count of > 350 cells/µl and those not on treatment with a CD4 count of > 500 cells/µl. This would exclude only those with more severe immunosuppression. Current evidence indicates that, in the majority of patients with HIV infection with well-preserved or restored immune markers, vaccine and treatment responses are not substantially impaired. 39–41

Interventions

The two topical treatments compared in the trial were 5% IMIQ cream and 0.15% PDX cream, both licensed products for the treatment of anogenital warts.

Participants randomised to IMIQ applied the cream to the warts in accordance with the licence, that is, 3 days of the week (every other day) at bed time, left on overnight, and the area of application washed after 6–10 hours. Duration of treatment was up to 16 weeks.

For participants randomised to PDX, the instruction was to apply the cream twice per day for 3 consecutive days followed by no treatment for 4 days, in weekly cycles. The licensed treatment duration is 4 weeks, but it is common practice to extend this period if there is a response to therapy. In the trial, we therefore allowed continued use of PDX cream for up to 16 weeks. No crossover of the topical treatment was permitted before 16 weeks.

Dose modifications of topical treatment were permitted if required for tolerability. For PDX, the weekly cycle of treatment could be postponed for 3 days, or longer if required, in which case it was restarted once daily. For participants unable to tolerate the standard regimen for IMIQ, the advice was to reduce the frequency of dosing to twice per week, and then to once weekly if tolerability was not improved. Any skin reaction requiring dose modification was reported as an adverse event (AE).

The qHPV vaccine was administered according to the schedule licensed for the prevention of HPV infection, with three doses administered at the time of randomisation and at 8 and 24 weeks. The vaccine volume is 0.5 ml and is presented in a pre-filled syringe. The placebo comparator for the vaccine was 0.5 ml of normal saline.

To retain participants in the trial without crossover of topical treatment before 16 weeks, adjunctive cryotherapy was permitted from week 4 (visit 2) onwards if, in the opinion of the investigator, this was in the best interests of the patient, and after assessment of the response to topical treatment to date.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to one of four groups:

-

IMIQ cream plus qHPV vaccine

-

PDX cream plus qHPV vaccine

-

IMIQ cream plus saline placebo injection

-

PDX cream plus saline placebo injection.

Allocation to the groups was carried out using minimisation with a random element, with gender, previous occurrence of warts and trial site as stratification factors. HIV status was added as a stratification factor when the eligibility criteria were changed. Participants were randomised 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 to the four groups. Trial participant number and randomisation group allocation were computer-generated and accessed by a secure online facility (Sealed Envelope™; Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK), which required entry of participant characteristics to allow the minimisation process to be completed.

Blinding

The differences in posology of the two topical treatments made a blinded comparison impractical. Therefore, the creams were dispensed in unblinded original packs.

The qHPV vaccine and saline placebo were dispensed in blinded packaging comprising an opaque plastic sleeve inside a cardboard box labelled with the trial details and a unique pack code number. Both were in pre-filled syringes, but it was not possible to source matching syringes to produce a fully blinded placebo. Therefore, the vaccine or placebo was administered by a member of staff who was not part of the trial team involved in the assessment of the participant.

Recruitment and consent

Members of the clinical team at participating clinics identified potential trial participants and referred them to the trial team. Participants were provided with the information sheet and gave written informed consent. Most participants were recruited at the same visit, but, if more convenient for the participant, the first visit, and treatment, were delayed for up to a few days.

Baseline visit

The baseline assessment included a record of previous wart episodes and treatments, history of STIs and comorbidities, history of recent sexual contacts, concomitant medication and a quality-of-life questionnaire [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)].

The location of warts present was recorded and the approximate number of warts present was recorded in categories: 1–5, 6–10, 11–20 and > 20. The maximum diameter of the largest wart was recorded, measured against a size gauge. A symptom-directed general physical examination was performed, if appropriate.

A swab from the wart lesions and a blood sample were collected and archived for mechanistic studies, subject to separate review and funding. The details of the baseline and follow-up assessments are tabulated in Appendix 2.

Randomised treatments were then prescribed or administered and participants were supplied with information on their use, risks and side effects. Participants were offered safer-sex advice and access to other sexual and reproductive health services as per routine care. For women of child-bearing potential, a pregnancy test was performed. Diary cards were provided to the participant to remind them when the treatment should be applied and to record its use, if and when warts cleared and any symptoms related to the topical treatment. These were reviewed at follow-up study visits.

Follow-up assessments and treatment

Trial follow-up was for 48 weeks, with scheduled visits at weeks 4, 8, 16, 24 and 48. Presence of warts was determined on examination by a member of the trial clinical team at each of these visits and at any unscheduled visit. Further topical treatment was supplied according to the randomised allocation at weeks 4 and 8 if required. Blinded vaccine or placebo was administered at weeks 8 and 24, regardless of the response to topical treatment.

If warts recurred within the first 16 weeks, the participant was prescribed the treatment to which they were randomised at baseline. Participants were asked to return to the clinic early for an extra visit if they noticed a recurrence of warts after complete clearance so that this could be documented and a swab from the new or recurrent lesion collected.

Cryotherapy was offered at the discretion of the local investigator if this was considered to be in the best interests of the patient and after assessment of response to topical treatment to date. Investigators were encouraged not to give cryotherapy before 4 weeks to allow for assessment of the initial response to topical treatment alone in all cases.

If a participant was unable to tolerate the allocated treatment during the first 16 weeks, and after dose modifications as appropriate, alternative treatment could be administered at the discretion of the investigator. For the purposes of the trial, use of alternative treatments other than additional weeks of PDX or cryotherapy before 16 weeks was considered a topical treatment failure. In the event of treatment failure, participants were still followed up and received vaccine or placebo in accordance with protocol.

After week 16, topical treatment for any persistent or recurrent warts was at the discretion of the investigator, including a switch to the other randomised topical treatment.

The timing of wart clearance was recorded for the secondary outcomes analysis. If there were additional visits for clinical care between weeks 16 and 48, a record was made of whether or not warts were present.

Routine visits included a review of adherence to the treatment regimen, tolerability and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Participants were also asked about work days lost as a result of clinic visits. Diary cards were collected from participants and reviewed by site staff.

A blood sample was collected at week 48 from all those who attended, and a lesion swab for later HPV DNA detection was collected and stored if warts were present.

To reduce the loss to follow-up rate, a small financial incentive was provided to those participants who attended the week 16 and week 48 visits in the form of Love2shop Gift Cards (highstreetvouchers.com, Birkenhead, UK).

Safety

All AEs and adverse reactions (ARs) were recorded and reported according to procedures specified in the protocol. The severity of AEs and ARs were graded and reported using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was a combined end point of wart clearance 16 weeks after starting treatment and remaining wart free between weeks 16 and 48. This captured both the initial clearance efficacy and the impact on relapse or recurrence.

Secondary outcomes

The two components of the combined primary end point were considered as factor-specific, clinically important secondary outcomes:

-

for topical treatment, the proportion that were wart free at week 16

-

for vaccination, the proportion that remained wart free between weeks 16 and 48 in those with wart clearance at week 16.

There were a number of other secondary outcomes specified in the protocol:

-

proportion that were wart free at the end of the assigned treatment course (4 or 16 weeks)

-

proportion that were wart free at the end of the assigned treatment course (4 or 16 weeks) without receiving additional treatment

-

quantity of additional treatment (e.g. number of cryotherapy applications) required to achieve clearance by week 16

-

proportion that were wart free at week 16 without receiving additional treatment

-

proportion that experienced complete wart clearance at any time, up to week 48

-

proportion that experienced wart recurrence or relapse after complete wart clearance

-

time to complete first wart clearance

-

time from complete wart clearance to recurrence or relapse

-

AEs

-

HRQoL as measured by the EQ-5D-5L

-

symptom scores

-

cost of treatment including prescribed agents and clinic visits.

Sample size

The trial was originally designed with a sample size of 1000 participants with equal numbers randomised to each of the two topical treatment arms, and each of the two vaccine or placebo groups, in a 2 × 2 factorial design. After allowing for 20% loss to follow-up, 800 participants would contribute primary outcome data. The anticipated proportion achieving the primary end point in the less favourable topical treatment group was estimated at 35%, assuming a wart clearance rate of 50% within 16 weeks and a subsequent recurrence rate of 30%. This sample size would have provided 80% power (at the 5% significance level) to detect an increase to 45% achieving the primary end point with the better treatment. It would also have provided 80% power to detect an increase from 35% to 45% in the primary end point as a result of an effect of vaccination, as would arise if vaccination reduced the recurrence rate from 30% to 10% while leaving the wart clearance rate unchanged at 50%.

Owing to a lack of feasibility to achieve the proposed recruitment target of 1000 participants, a revised sample size of 500 participants was proposed to the funder in February 2016. With 15% loss to follow-up, this would now provide 52% power (at the 5% significance level) to detect the prespecified difference in the combined primary end point. Even with a reduction in the loss to follow-up rate, which would, in itself, be challenging, the study would be substantially underpowered for its combined primary end point.

The statistical power for the components of the primary end point were therefore also evaluated. It was expected that the main effect of the topical treatment would be on wart clearance and the main effect of vaccination would be on wart recurrence. The power of the study to detect a clinically important difference in each of these secondary outcomes was calculated for the proposed reduced trial size.

The reduced sample size would provide 80% power at the 5% significance level, assuming 15% loss to follow-up, to evaluate each of the two components of the primary outcome: the proportion wart free at week 16 and the proportion of those who were wart free at week 16 remaining wart free at week 48. For the week 16 topical treatment outcome, a difference of 14% in wart clearance (57% wart clearance in the imiquimod group vs. 43% wart clearance in the podophyllotoxin group) could be detected. For the week 48 vaccine outcome, a difference of 16% in recurrence (12% recurrence in the vaccine group vs. 28% recurrence in the placebo group) could be detected. These differences were considered to be clinically important and sufficient to be likely to influence management guidelines. A 5% significance level was still used for these calculations, as there was a different outcome for each of the two factors, to answer two independent questions.

Data collection and management

Data were entered at the Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit (CCTU) into a MACRO v4.0 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) database, which incorporated validation checks to improve data quality. Data verification, consistency and range checks were performed during data entry, as were checks for missing data. Data queries were resolved by site staff before database lock and final analysis. Additional data checks were performed when the data sets for analysis were constructed before the final statistical analysis commenced. All variables were examined for unusual, outlying, unlabelled or inconsistent values.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted on a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. We included all consented randomised participants for whom at least one follow-up visit was available regardless of their adherence to treatment because the HIPvac [Human papillomavirus infection: a randomised controlled trial of Imiquimod cream (5%) versus Podophyllotoxin cream (0.15%), in combination with quadrivalent human papillomavirus or control vaccination in the treatment and prevention of recurrence of anogenital warts] trial was a pragmatic study concerned with the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of topical therapy with or without the addition of qHPV vaccination.

All CIs are 95% and two sided. Statistical tests used a two-sided p-value of 0.05 unless otherwise specified. The analysis for both factors (PDX vs. IMIQ and qHPV vaccine vs. placebo) was based on comparisons at the margins of the 2 × 2 table, such that all participants randomised to PDX were compared with all participants randomised to IMIQ, and all participants randomised to qHPV vaccine were compared with all participants randomised to the placebo injection.

We did not anticipate a substantial interaction between topical treatment and vaccination. However, as a secondary analysis, we performed a prespecified interaction test between the two factors, and present results from a four-arm analysis (in which each of the four treatment combinations is regarded as a separate treatment arm), as recommended for factorial trials.

We adjusted the analyses for the stratification variables HIV status, gender and whether or not the participant had had a previous episode of warts by including them as fixed-effect covariates. Trial site was included in the mixed-effects models as a random effect (random intercept) to account for any possible variation by site. Treatment effects were then estimated, conditional on HIV status, gender and previous occurrence of warts, and account for variation between sites.

In a pragmatic clinical trial over a 48-week time frame, some patients are inevitably lost to follow-up. Outcomes for such patients are, therefore, only partially observed. This can lead to a loss of power, biased estimates and standard errors, and a loss of efficiency. To reduce the potential impact of bias, and to maximise the power to detect a treatment effect, multiple imputation by chained equations42 was used to impute data from missing follow-up visits. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR), conditional on all variables included in the imputation model, and so independent of the values of the unobserved data themselves. The analyses for all primary and secondary outcomes were performed on fully imputed data sets.

Three separate sets of imputed data were generated; in each case, enough imputed data were generated such that the Monte Carlo error of the treatment effects estimated in the subsequent analyses was minimised. Each of the three multiple imputation sets included the following as (fully observed) explanatory variables in the imputation model: gender, HIV status, previous warts, trial site, allocated treatment, total number of visits attended, number of additional visits attended (over and above scheduled visits), an indicator of non-compliance and an indicator of any additional treatment given. The first set imputed 120 sets of the week 16 wart clearance outcome, the week 48 recurrence outcome and the outcomes wart free by week 4 and wart free by week 16. The primary outcome is a combination of the week 16 wart clearance outcome and the week 48 wart recurrence outcome, and was not directly imputed but determined from the imputed outcomes at weeks 16 and 48. The second set imputed 50 sets of the outcomes wart clearance (at any time) and wart recurrence (at any time). The final set imputed 50 sets of the quality-of-life outcomes [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) health utilities index and visual analogue scale (VAS)] at each time point.

Sensitivity analyses investigated the impact of the MAR assumption and missing data for all participants.

Changes to the protocol

The major change to the protocol was the reduction in the sample size as described in Statistical methods.

Active vaccine comparator

When funding for the trial was awarded, the design included the hepatitis A virus (HAV) vaccine as an active comparator for the qHPV vaccine. This was to be used to ensure effective blinding of the study, because some local reactogenicity would be expected to occur in both arms, whereas the HAV vaccine would have no activity in treating or preventing HPV infection, unless there was any non-specific immune stimulant effect, which was deemed to be unlikely. This design might also have helped recruitment, because the HAV group could also derive benefit from participating, if they were not already immune to the HAV. There is no contraindication to receiving the HAV vaccine in those who are already immune.

This design was predicated on the availability of matching the qHPV and HAV vaccines, as used in a number of HPV vaccine efficacy studies. This methodology had to be changed when the pharmaceutical company support for the HIPvac trial was withdrawn, and it was clear that the additional costs and delays that this immediately imposed on the trial would be exacerbated by trying to source a matching HAV vaccine control.

Blinding

Without pharmaceutical company support for the trial, it was necessary to contract with an independent pharmacy manufacturing facility to make a blinded placebo, using normal saline as the only feasible ‘matching’ placebo. Although syringes identical to the bespoke syringes used for the commercial stock of qHPV vaccine were procured, there were technical difficulties in filling these. To minimise delay to the initiation of the study, an amendment that allowed non-matching placebo syringes to be used for the first 250 participants was submitted and approved. The non-matching syringes were of similar size but not identical in design to the qHPV vaccine. Each syringe (qHPV vaccine or placebo) was therefore packed in an opaque plastic sleeve, and then in a plain cardboard container, labelled with the trial details and a unique vaccine code number. Until the packaging was opened, the allocation would remain blinded. A member of the clinical team who was not involved in any other aspect of the assessment of the participant was instructed to open the package and administer the vaccine, taking care to avoid unblinding any member of the research team.

Although this arrangement was intended to be temporary for the first 6 months of the trial only, further technical problems with the filling of the matching syringes led to the decision to continue the use of non-identical syringes for the remainder of the trial. The protocol was amended accordingly.

Inclusion of participants with HIV infection

Initially, participants known to be living with HIV were excluded on the grounds that wart treatment and vaccine responses were reported to be impaired in this group, with implications for the sample size. But, in December 2015, at the suggestion of the lay member of the TSC, the entry criteria were modified to include participants living with HIV who were stable on antiretroviral treatment with a CD4 count of > 350 cells/µl and those not on antiretroviral treatment with a CD4 count of > 500 cells/µl. This would exclude only those with more severe immunosuppression. Existing evidence indicated that vaccine and treatment responses in the majority of patients living with HIV with a well-preserved or restored CD4 count are not substantially different from those in patients without HIV. 39–41 It was concluded that those living with HIV and fulfilling these criteria should not be excluded. It was estimated that 80% of participants living with HIV with warts would be eligible. It would also be of benefit to observe if the response to the topical wart treatments and the vaccine was comparable in those with and those without HIV, although it was acknowledged that the power to detect any such effect would be limited. As a precaution, HIV status was added as a stratification variable. Finally, given that the accrual to the study was behind schedule and that the prevalence of anogenital warts was higher in those living with HIV, it was hoped that the protocol change would help the trial to meet the overall recruitment target.

Trial oversight

A TSC was established comprising five independent members and the trial chief investigator as the only non-independent member. Membership included a patient and public representative. The day-to-day management of the trial was the responsibility of the University College London CCTU, with oversight by a Trial Management Group responsible for the design, co-ordination and strategic management of the trial and chaired by the chief investigator. An Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) was appointed with three independent members: a clinician with expertise in HPV, a clinical triallist with experience of HPV trials and a statistician as chairperson. All oversight committees had agreed terms of reference.

During the course of the trial, the TSC and IDMC met together six times; the IDMC met once to review blinded data in connection with a decision to revise the sample size. The TSC and IDMC also made a recommendation to allow inclusion of participants living with HIV.

Chapter 3 Trial results

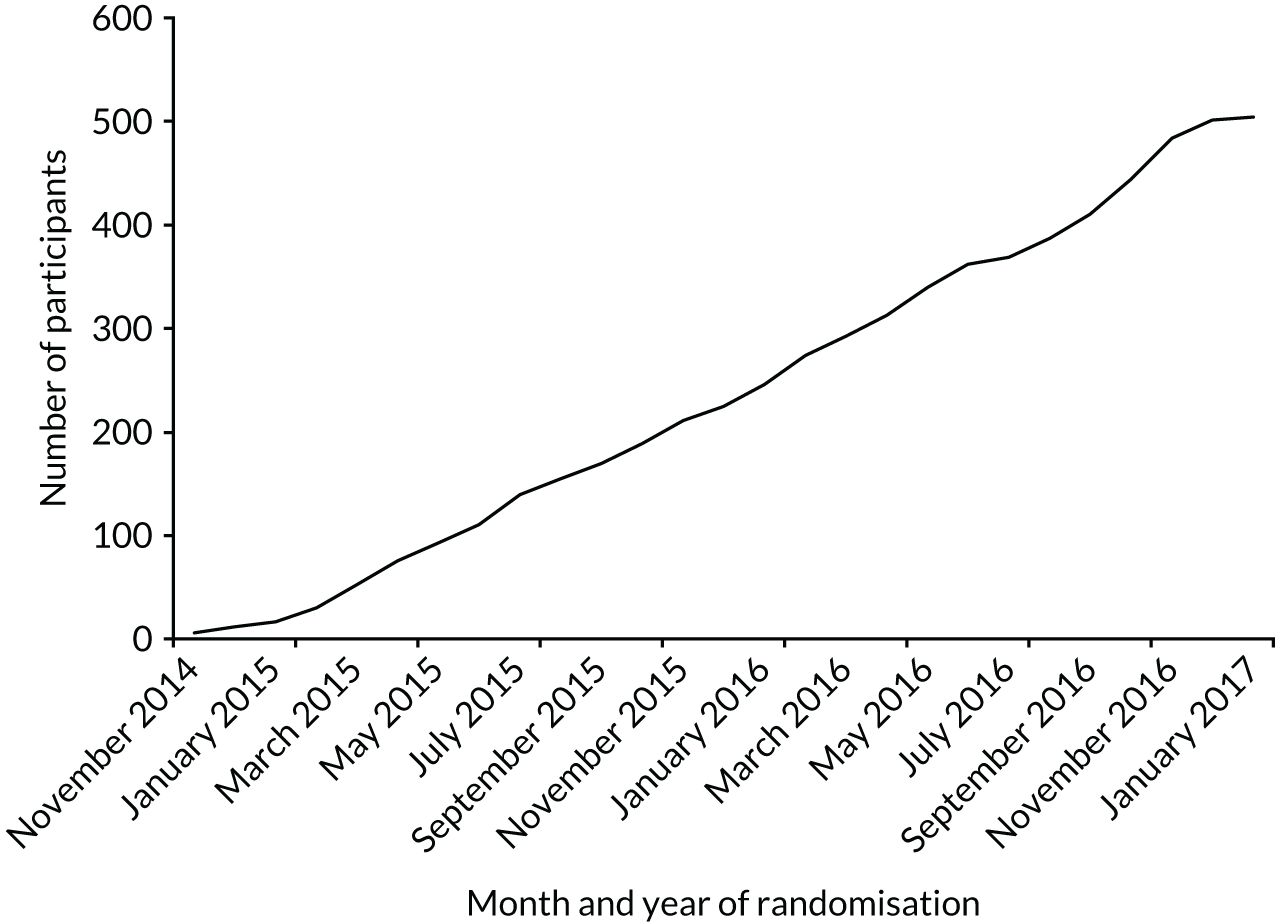

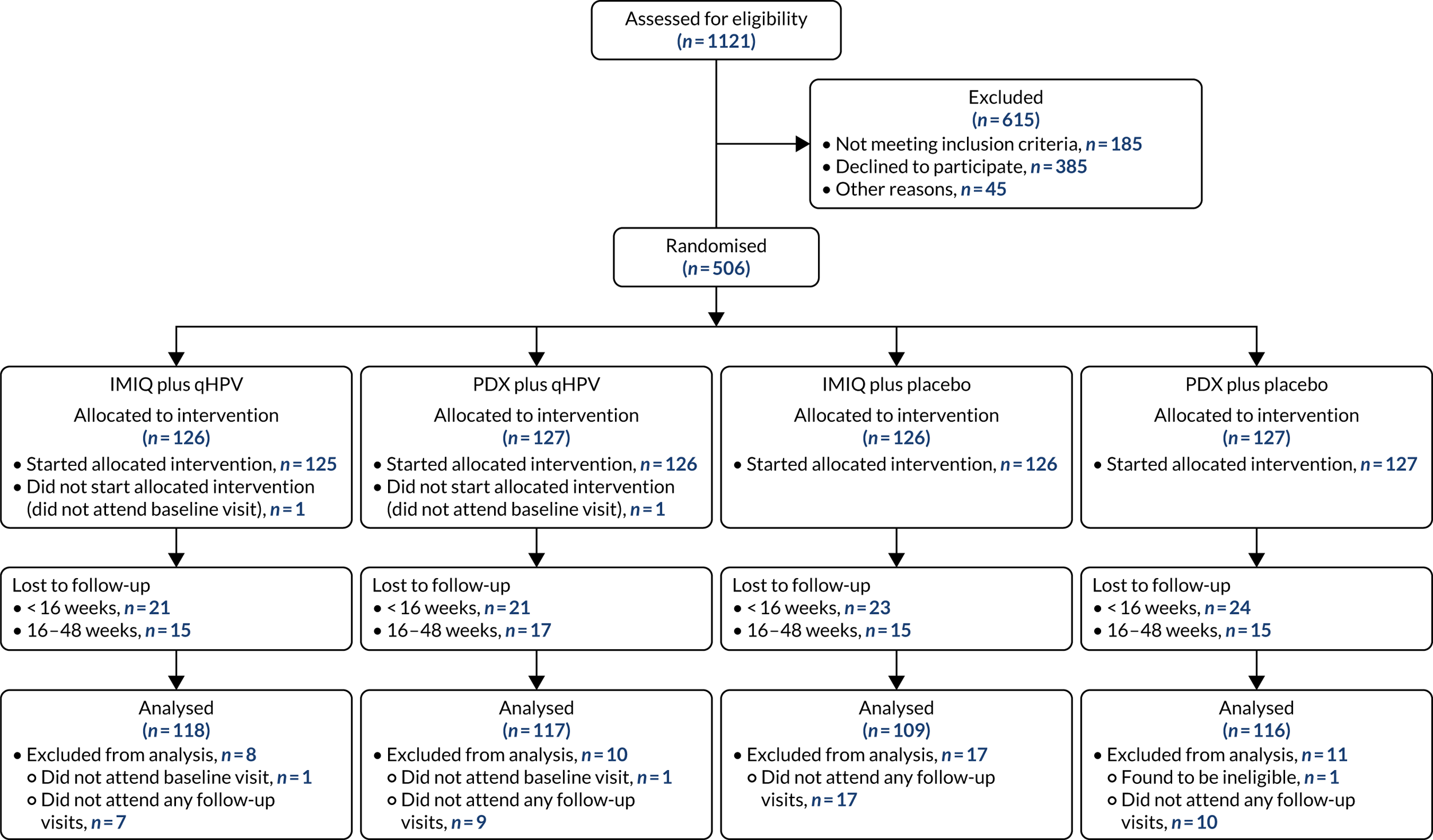

The trial was designed in 2012 and funding was confirmed in 2013. Because of issues with investigational medicinal product manufacture of the blinded vaccine, site activation was delayed; the first site was opened to recruitment on 5 November 2014. Participants were recruited to the trial between November 2014 and December 2016, with the last participant randomised in January 2017 (Figure 1) (see Appendix 1 for recruitment numbers by site). The last scheduled participant follow-up visit was in January 2018. In all, 506 participants consented and were randomised into the trial, of whom 503 are included in the analysis. Three participants did not start the treatment or did not attend any follow-up and are therefore excluded from all analyses. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram summarising the recruitment and follow-up of participants in each group is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment graph by date of randomisation.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram showing participant recruitment and the flow of participants in the trial. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Baseline characteristics of participants

Of the 503 participants included in the analysis, 333 (66%) were male, 170 (34%) were female and the median age was 31 years. A total of 410 (82%) participants were heterosexual, 67 (13%) were homosexual and 25 (5%) were bisexual. Half of the participants (n = 251; 50%) reported one or more previous episodes of warts. A total of 12 participants (2.4%) were HIV positive. Under one-third of participants (n = 151; 30%) were current smokers, reporting cigarette smoking at least daily; 59 (12%) smoked cigarettes less than daily; 118 (23%) were ex-smokers; and 173 (34%) were lifelong non-smokers Information on smoking status was missing for just two participants (0.4%).

The complete data for participant baseline characteristics according to treatment group allocation are shown in Table 1. In general, all baseline characteristics were evenly distributed between the four treatment groups.

| Characteristic | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (N = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (N = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (N = 126) | PDX plus placebo (N = 126) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 31 (10) | 31 (10) | 32 (10) | 30 (10) |

| Stratification variables | ||||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 83 (66) | 84 (67) | 83 (66) | 83 (66) |

| Female | 42 (34) | 42 (33) | 43 (34) | 43 (34) |

| Previous occurrence of warts, n (%) | ||||

| No | 63 (50) | 63 (50) | 63 (50) | 63 (50) |

| Yes | 62 (50) | 63 (50) | 63 (50) | 63 (50) |

| HIV positive, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| No | 123 (98) | 122 (97) | 123 (98) | 123 (98) |

| Quantity of warts | ||||

| Diameter of largest wart (mm), median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) |

| Total number of warts, n (%) | ||||

| 1–5 | 63 (50) | 80 (63) | 66 (52) | 57 (45) |

| 6–10 | 26 (21) | 23 (18) | 38 (30) | 32 (25) |

| 11–20 | 24 (19) | 15 (12) | 17 (13) | 21 (17) |

| > 20 | 11 (9) | 8 (6) | 5 (4) | 16 (13) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Position of warts, n/N (%)a | ||||

| Male | ||||

| Penile, shaft | 48/83 (58) | 45/84 (56) | 41/83 (49) | 52/83 (63) |

| Penile, glans | 9/83 (11) | 6/84 (7) | 10/83 (12) | 3/83 (4) |

| Penile, foreskin | 15/83 (18) | 16/84 (19) | 15/83 (18) | 20/83 (24) |

| Perineum | 3/83 (4) | 3/84 (4) | 5/83 (6) | 0/83 (0) |

| Anal/perianal | 20/83 (24) | 17/84 (20) | 20/83 (24) | 19/83 (23) |

| Other | 22/83 (27) | 25/84 (30) | 28/83 (34) | 20/83 (24) |

| Female | ||||

| External genitalia | 26/42 (62) | 29/42 (69) | 33/43 (77) | 29/43 (67) |

| Perineum | 11/42 (26) | 13/42 (31) | 12/23 (28) | 19/43 (44) |

| Anal/perianal | 9/42 (21) | 11/42 (26) | 9/43 (21) | 9/43 (21) |

| Other | 9/42 (21) | 5/42 (12) | 7/43 (21) | 5/43 (12) |

| Sexual orientation and history | ||||

| Male, n (%) | ||||

| Heterosexual | 65 (78) | 63 (75) | 62 (75) | 62 (75) |

| Homosexual | 15 (18) | 19 (23) | 16 (19) | 16 (19) |

| Bisexual | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | 5 (6) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Female, n (%) | ||||

| Heterosexual | 39 (93) | 39 (93) | 40 (93) | 40 (93) |

| Homosexual | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bisexual | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 3 (7) | 3 (7) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Number of partners in the previous 3 months, median (IQR) | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 1) |

| Sexual practices in the previous 3 months, n (%)a | ||||

| Vaginal sex | 91 (73) | 81 (64) | 86 (68) | 92 (73) |

| Passive oral sex | 75 (60) | 73 (58) | 83 (66) | 78 (62) |

| Performed oral sex | 73 (58) | 77 (61) | 82 (65) | 77 (61) |

| Anal-receptive sex | 12 (10) | 21 (17) | 17 (13) | 13 (10) |

| Insertive anal sex | 14 (11) | 22 (18) | 22 (17) | 20 (16) |

| Current contraception (female), n/N (%)a | ||||

| Condoms | 10/43 (24) | 9/42 (21) | 15/43 (35) | 12/42 (29) |

| Hormonal contraception (e.g. pill, IUS, implant, injection) | 20/42 (48) | 21/42 (50) | 16/43 (37) | 22/42 (52) |

| Not sexually active | 4/42 (10) | 4/42 (10) | 5/43 (12) | 2/42 (5) |

| Other | 7/42 (17) | 6/42 (14) | 6/43 (14) | 3/42 (7) |

| None | 1/42 (2) | 2/42 (5) | 0/43 (0) | 1/42 (2) |

| N/A (not of child-bearing potential) | 0/42 (0) | 0/42 (0) | 1/43 (2) | 2/42 (5) |

| Health history | ||||

| Had previous episode(s) of warts, n (%) | 65 (52) | 68 (54) | 63 (50) | 64 (51) |

| Had previous treatment for warts (in those with a previous episode), n/N (%) | 64/65 (98) | 67/68 (99) | 63/63 (100) | 62/64 (97) |

| Wart treatment for most recent episode, n/N (%)a | ||||

| PDX | 18/64 (28) | 16/67 (24) | 14/63 (22) | 17/61 (28) |

| IMIQ | 18/64 (28) | 13/67 (19) | 16/63 (25) | 12/61 (20) |

| Cryotherapy | 48/64 (75) | 47/67 (70) | 43/63 (68) | 42/62 (68) |

| Surgery | 2/64 (3) | 2/67 (3) | 6/63 (3) | 1/62 (2) |

| Other | 1/64 (2) | 3/67 (4) | 1/63 (2) | 4/62 (6) |

| Previous bivalent HPV vaccine, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10 (8) | 12 (10) | 8 (6) | 13 (10) |

| No | 115 (92) | 114 (90) | 118 (94) | 110 (87) |

| Number of doses of vaccine in those previously vaccinated, median (IQR) | 3 (3–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (3–3) | 3 (3–3) |

| Previous STI excluding anogenital warts, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 41 (33) | 43 (34) | 40 (32) | 44 (35) |

| No | 82 (67) | 82 (65) | 86 (68) | 82 (65) |

| Type of STI, n/N (%)a | ||||

| Chlamydia | 24/41 (59) | 25/43 (58) | 24/40 (60) | 28/44 (64) |

| Gonorrhoea | 11/41 (27) | 15/43 (36) | 7/40 (18) | 11/44 (25) |

| Syphilis | 2/41 (5) | 2/43 (5) | 2/40 (5) | 1/44 (2) |

| Herpes | 13/41 (32) | 7/43 (16) | 9/40 (23) | 8/44 (18) |

| Other | 7/41 (17) | 8/43 (19) | 7/40 (18) | 9/44 (20) |

| Number of STI episodes, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Daily | 42 (34) | 33 (26) | 36 (29) | 40 (32) |

| Less than daily | 13 (10) | 15 (12) | 10 (8) | 21 (17) |

| Ex-smoker | 32 (26) | 27 (21) | 34 (27) | 25 (20) |

| Never smoked | 37 (30) | 50 (40) | 46 (37) | 40 (32) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Quality of life | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L: health utility | ||||

| n | 110 | 116 | 119 | 112 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.94 (0.11) | 0.92 (0.13) | 0.94 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.10) |

| EQ-5D-5L: VAS | ||||

| n | 111 | 115 | 119 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 83 (12) | 82 (13) | 82 (14) | 82 (15) |

Adherence to treatment and receipt of additional treatment

Over the 48-week duration of the study, 34 (15%) participants required a switch in topical treatment from IMIQ and 41 (18%) from PDX. Only four switches in topical treatment occurred before the end of the licensed duration of the allocated treatment (4 weeks for PDX and 16 weeks for IMIQ). A total of 139 out of 227 (61%) participants allocated to IMIQ and 29 out of 233 (12%) participants allocated to PDX completed less than the licensed duration of each topical treatment. A total of 167 out of 233 (72%) participants allocated to PDX extended their topical treatment beyond 4 weeks (the denominator is the number of participants who attended at least one follow-up visit).

Over half of participants (54%) received cryotherapy treatment at any time during the study. The use of cryotherapy was very similar, overall, between the groups: 117 out of 227 (52%) participants in the IMIQ group and 130 out of 233 (56%) in the PDX group; and 118 out of 235 (50%) and 129 out of 225 (57%) in the qHPV and placebo groups, respectively.

Cryotherapy prior to week 16 of the study was administered to 76 out of 460 (17%) participants: 27 out of 227 (12%) in the IMIQ group and 49 out of 233 (21%) in the PDX group. Cryotherapy use occurred earlier in the PDX group, probably owing to the shorter licensed duration of this treatment.

Complete data on participants’ adherence to the allocated treatments, switching of topical treatment and use of additional cryotherapy is shown in Table 2.

| Treatment characteristic | Treatment group | Topical treatment group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV | PDX plus qHPV | IMIQ plus placebo | PDX plus placebo | IMIQ | PDX | |

| Number randomised | 125 | 126 | 126 | 126 | 251 | 252 |

| Number analysed (attended at least one follow-up visit) | 118 | 117 | 109 | 116 | 227 | 233 |

| Topical treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Switched treatment at any time, yes | 15 (13) | 15 (13) | 19 (17) | 26 (22) | 34 (15) | 41 (18) |

| Timing of first treatment switch | ||||||

| Before 4 weeks | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Between 4 and 16 weeks | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 5 (2) | 7 (3) |

| After 16 weeks | 12 (10) | 12 (10) | 15 (14) | 20 (17) | 27 (12) | 32 (14) |

| Completed less than maximum licensed duration of topical treatment | 71 (60) | 13 (11) | 68 (62) | 16 (14) | 139 (61) | 29 (12) |

| Extended PDX beyond 4 weeks | 87 (74) | 80 (69) | 167 (72) | |||

| Any cryotherapy received | 56 (47) | 62 (53) | 61 (56) | 68 (59) | 117 (52) | 130 (56) |

| Timing of first cryotherapy | ||||||

| Before 4 weeks | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1) |

| Between 4 and 16 weeks | 17 (14) | 24 (21) | 9 (8) | 22 (19) | 26 (11) | 46 (20) |

| After 16 weeks | 39 (33) | 37 (32) | 51 (47) | 44 (38) | 90 (40) | 81 (35) |

| Has the patient had any other treatment at their treatment centre other than cryotherapy at any time | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 4 (4) | 9 (8) | 9 (4) | 13 (6) |

| Has the patient had any treatment from a source outside their treatment centre | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 5 (5) | 6 (5) | 10 (4) | 11 (5) |

| Vaccine, n (%) | ||||||

| Number of vaccine doses given | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 11 (9) | 13 (11) | 7 (6) | 15 (13) | 18 (8) | 28 (12) |

| 2 | 17 (14) | 15 (11) | 11 (10) | 13 (11) | 28 (12) | 28 (12) |

| 3 | 89 (75) | 89 (76) | 91 (83) | 88 (76) | 180 (79) | 177 (76) |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the study was a combination of being wart free at 16 weeks and remaining wart free at 48 weeks from the start of treatment. This was achieved in 35 out of 101 (35%) participants allocated to receive IMIQ plus the qHPV vaccine, 38 out of 99 (38%) of those allocated to receive PDX plus the qHPV vaccine, 25 out of 98 (26%) of those allocated to IMIQ plus the placebo vaccine and 30 out of 99 (30%) of those allocated to PDX plus placebo. The denominator in each group is those participants who provided follow-up data at week 48.

Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) were calculated to estimate the topical treatment and vaccine effects after adjustment for gender, previous wart recurrence and HIV status, and included imputed data for those with missing data. The aOR for the topical treatment effect for IMIQ relative to PDX was 0.81 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.23). The aOR for the effect of vaccine relative to placebo was 1.46 (95% CI 0.97 to 2.20).

The data for the primary outcome are shown in Table 3.

| Outcome | Treatment group, n/N (%) | Treatment effects, aOR (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (N = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (N = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (N = 126) | PDX plus placebo (N = 126) | IMIQ vs. PDXb | qHPV vs. placeboc | |

| Wart free at week 16 and remaining wart free between weeks 16 and 48d | 35/101 (35) | 38/99 (38) | 25/98 (26) | 30/99 (30) | 0.81 (0.54 to 1.23) | 1.46 (0.97 to 2.20) |

Secondary outcomes

Clinically important secondary outcomes

Clinically important secondary outcomes were defined as (1) the proportion of participants who were wart free at week 16 (of those not lost to follow-up by this time point) and (2) the proportion of participants remaining wart free at week 48 (of those who had achieved clearance at 16 weeks and were followed up until week 48). To estimate the topical treatment and vaccine effects for each outcome, aORs were calculated and included imputed data for missing follow-up visits.

The proportion of participants who were wart free at week 16 was 58 out of 104 (56%) of those allocated to IMIQ plus qHPV vaccine, 70 out of 105 (67%) of those allocated to PDX plus qHPV vaccine, 56 out of 103 (54%) of those allocated to IMIQ plus placebo vaccine and 57 out of 102 (56%) of those allocated to PDX plus placebo. The aOR for the topical treatment effect for IMIQ relative to PDX was 0.77 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.14). The aOR for the effect of vaccine relative to placebo was 1.30 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.91).

The proportion of participants remaining wart free at week 48 of those with clearance at week 16 was 35 out of 43 (81%) of those allocated to IMIQ plus qHPV vaccine, 38 out of 53 (72%) of those allocated to PDX plus qHPV vaccine, 25 out of 39 (74%) of those allocated to IMIQ plus placebo vaccine and 30 out of 42 (71%) of those allocated to PDX plus placebo. The aOR for the topical treatment effect for IMIQ relative to PDX was 0.98 (95% CI 0.54 to 1.78). The aOR for the effect of vaccine relative to placebo was 1.39 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.63). The data for the clinically important secondary outcomes are shown in Table 4.

| Outcome | Treatment group, n/N (%) | Treatment effects, aOR (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (N = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (N = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (N = 126) | PDX plus placebo (N = 126) | IMIQ vs. PDXb | qHPV vs. placeboc | |

| Wart free at week 16d | 58/104 (56) | 70/105 (67) | 56/103 (54) | 57/102 (56) | 0.77 (0.52 to 1.14) | 1.30 (0.89 to 1.91) |

| Remaining wart free at week 48 after clearance at week 16e | 35/43 (81) | 38/53 (72) | 25/39 (74) | 30/42 (71) | 0.98 (0.54 to 1.78) | 1.39 (0.73 to 2.63) |

Other secondary outcomes measuring treatment effectiveness

Other secondary outcomes that measured treatment effectiveness were (1) the proportion of participants who were wart free at the end of the licensed duration of their assigned topical treatment (4 weeks for PDX and 16 weeks for IMIQ), (2) the proportion of participants wart free at any time during the 48-week trial period, (3) the proportion of participants who experienced wart recurrence after achieving complete clearance, (4) the proportion of participants who were wart free at week 16 without additional procedures (cryotherapy or surgery), (5) the proportion of participants who were wart free at the end of the licensed duration of their assigned topical treatment without additional procedures (cryotherapy or surgery), (6) the time to complete wart clearance (days) and (7) the time from complete wart clearance to recurrence (days). To estimate the topical treatment and vaccine effects for binary or ordinal outcomes, aORs were calculated and included imputed data for missing follow-up visits. Hazard ratios were calculated for time to event data (outcomes 6 and 7).

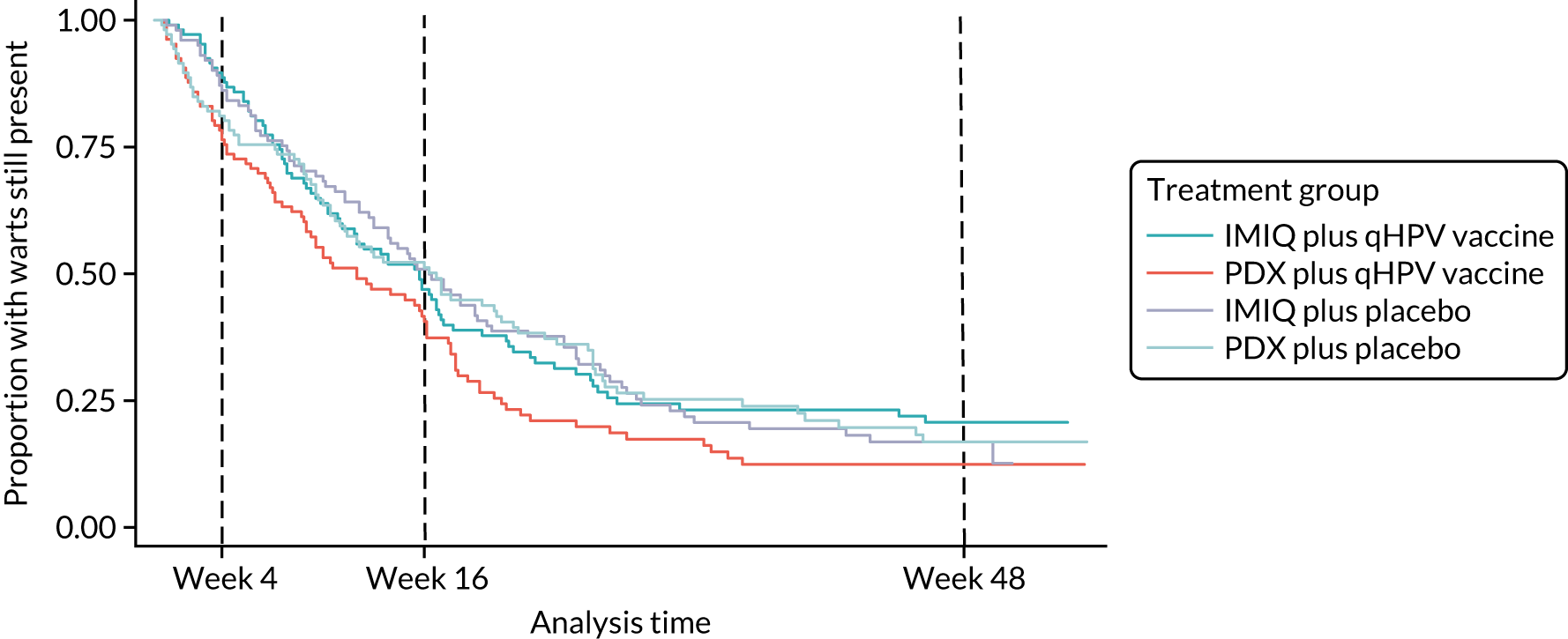

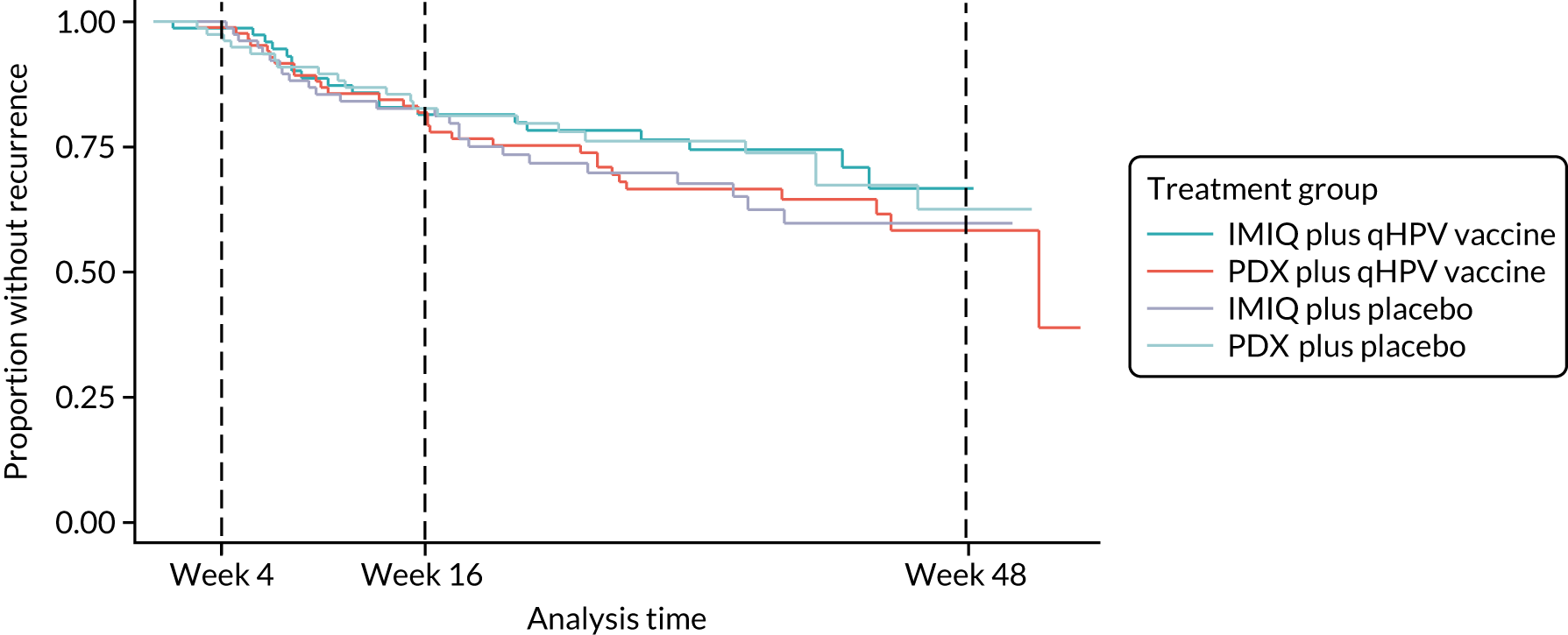

The results for the secondary outcomes measuring treatment effectiveness are shown in Table 5. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for time to wart clearance and recurrence are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

| Outcome | Treatment group | Treatment effects, aOR (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (N = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (N = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (N = 126) | PDX plus placebo (N = 126) | IMIQ vs. PDXb | qHPV vs. placeboc | |

| Wart free at the end of the assigned treatment course (4 or 16 weeks), n/N (%)d | 54/104 (52) | 23/117 (20) | 48/103 (47) | 19/116 (16) | 2.92 (1.75 to 4.87) | 1.13 (0.72 to 1.77) |

| Proportion experiencing complete wart clearance at any time during the 48-week trial period, n/N (%)e | 79/118 (67) | 86/117 (74) | 82/109 (75) | 79/116 (68) | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.34) | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.80) |

| Proportion of patients experiencing wart recurrence/relapse after complete wart clearance, n/N (%)f | 19/79 (24) | 30/86 (35) | 26/82 (32) | 21/79 (27) | 0.84 (0.52 to 1.37) | 1.16 (0.72 to 1.88) |

| Wart free by week 16 without additional treatment, n/N (%)g | 34/104 (33) | 38/105 (36) | 37/103 (36) | 26/102 (25) | 1.11 (0.73 to 1.69) | 1.20 (0.80 to 1.81) |

| Wart free at the end of the assigned treatment period (4 or 16 weeks) without additional treatment, n/N (%)h | 29/104 (28) | 19/117 (16) | 29/103 (28) | 16/116 (14) | 1.63 (0.98 to 2.71) | 1.04 (0.67 to 1.62) |

| Treatment effects, adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)a | ||||||

| Time to complete wart clearance (days), median (95% CI) | 110 (77 to 120) | 84 (63 to 112) | 114 (91 to 138) | 117 (77 to 144) | 0.77 (0.60 to 0.97) | 1.24 (0.99 to 1.56) |

| Time from complete wart clearance to recurrence/relapse (days), 20th percentile (95% CI) | 149 (61 to 295) | 113 (67 to 183) | 122 (56 to 179) | 150 (76 to 273) | 1.07 (0.66 to 1.73) | 0.72 (0.42 to 1.24) |

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for time to wart clearance.

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for time to wart recurrence in participants who achieved wart clearance.

Adverse events

There were no serious adverse events (SAEs) of grade 4 severity in any of the groups. There were 21 SAEs of grade 3 severity, eight of which occurred in participants allocated to IMIQ plus qHPV vaccine, four in participants allocated to PDX plus qHPV vaccine, three in participants allocated to IMIQ plus placebo vaccine and six in participants allocated to PDX plus placebo vaccine. Of the eight SAEs in the IMIQ plus qHPV vaccine group, six occurred in a single participant and all eight were judged to be unrelated to either the topical treatment or vaccine by the local investigator. Of the four SAEs in the PDX plus qHPV vaccine group, three were judged to be unrelated to either the vaccine or placebo and one was judged unlikely to be related to vaccine and unrelated to topical treatment. Of the three SAEs in the IMIQ plus placebo vaccine group, all three were judged to be unrelated to either topical treatment or vaccine. Of the six SAEs in the PDX plus placebo group, two were in a single participant; four were judged to be unrelated to either topical treatment or vaccine, one was judged unlikely to be related to both topical treatment and vaccine and one was judged unlikely to be related to topical treatment and unrelated to vaccine.

There was one serious adverse reaction to the topical treatment, of grade 3 severity (skin ulceration). This occurred in a patient in the IMIQ plus qHPV vaccine group and was judged to be definitely related to topical treatment.

There was one suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction, which occurred in the PDX plus placebo vaccine group and was judged to be possibly related to vaccine and unrelated to topical treatment.

In addition, two pregnancies were reported (notifiable AEs), one in the PDX plus qHPV vaccine group and one in the PDX plus placebo group.

The number of SAEs by group allocation is shown in Table 6.

| Event | Treatment group (n) | Total (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV | PDX plus qHPV | IMIQ plus placebo | PDX plus placebo | ||

| SAE | 8 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 21 |

| SAR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SUSAR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 9 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 23 |

For further details of the SAE reports and reasons for withdrawal, see Appendix 3, Tables 17–23.

Symptom scores of adverse effect severity from topical treatment

Participants self-rated the maximum intensity of any adverse effects from their allocated topical treatment since their previous visit as none, mild, moderate or severe. Their symptom scores are shown in Table 7. To estimate the topical treatment and vaccine effects on symptom scores, aORs were calculated from an ordinal logistic regression model and included imputed data for missing follow-up visits. There were no significant differences in symptom scores according to topical treatment or vaccine.

| Time point | Severity of most severe side effects (patient reported) | Treatment group, n/N (%)a | Treatment effects, aOR (95% CI) (calculated from ordinal logistic regression model)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (N = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (N = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (N = 126) | PDX plus placebo (N = 126) | IMIQ vs. PDXc | qHPV vs. placebod | ||

| Week 4 | None | 33/109 (30) | 36/109 (33) | 44/105 (42) | 39/107 (36) | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.26) | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.91) |

| Mild | 38/76 (50) | 40/73 (55) | 30/61 (49) | 41/68 (60) | |||

| Moderate | 23/76 (30) | 27/73 (37) | 22/61 (36) | 20/68 (29) | |||

| Severe | 15/76 (20) | 6/73 (8) | 9/61 (15) | 7/68 (10) | |||

| Week 8 | None | 37/81 (46) | 44/77 (57) | 42/85 (49) | 29/78 (37) | 0.85 (0.57 to 1.29) | 0.91 (0.60 to 1.38) |

| Mild | 18/44 (41) | 19/33 (58) | 29/43 (67) | 33/49 (67) | |||

| Moderate | 18/44 (41) | 14/33 (42) | 9/43 (21) | 14/49 (29) | |||

| Severe | 8/44 (18) | 0/33 (0) | 5/43 (13) | 2/49 (4) | |||

| Week 16 | None | 21/46 (46) | 32/52 (62) | 25/56 (45) | 16/47 (34) | 0.76 (0.45 to 1.30) | 0.62 (0.36 to 1.06) |

| Mild | 14/25 (56) | 13/20 (65) | 17/31 (65) | 22/31 (71) | |||

| Moderate | 7/25 (28) | 6/20 (30) | 11/31 (35) | 8/31 (26) | |||

| Severe | 4/25 (16) | 1/20 (5) | 3/31 (10) | 1/31 (3) | |||

| Week 24 | None | 18/32 (56) | 15/26 (58) | 15/34 (44) | 20/35 (57) | 0.75 (0.37 to 1.49) | 0.84 (0.42 to 1.68) |

| Mild | 10/14 (71) | 6/11 (55) | 13/19 (68) | 11/15 (73) | |||

| Moderate | 2/14 (14) | 4/11 (36) | 4/19 (21) | 4/15 (27) | |||

| Severe | 2/14 (14) | 1/11 (9) | 2/19 (11) | 0/15 (0) | |||

| Week 48 | None | 13/20 (65) | 8/13 (62) | 6/12 (50) | 12/14 (86) | 0.45 (0.13 to 1.51) | 0.93 (0.29 to 3.03) |

| Mild | 7/7 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 4/6 (67) | 1/2 (50) | |||

| Moderate | 0/7 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 1/6 (17) | 0/2 (0) | |||

| Severe | 0/7 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 1/6 (17) | 1/2 (50) | |||

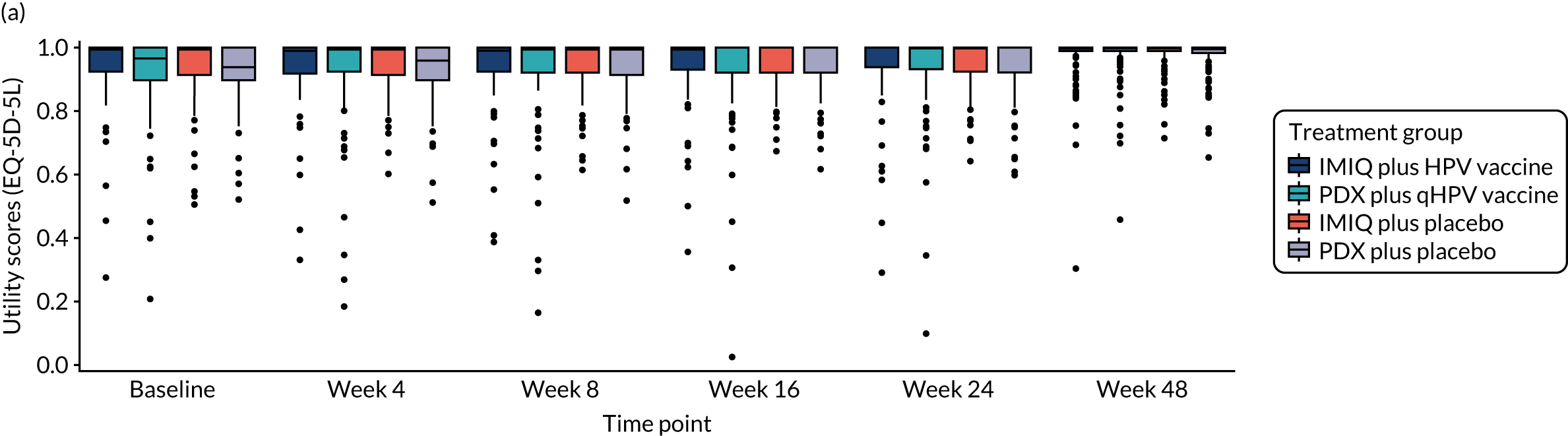

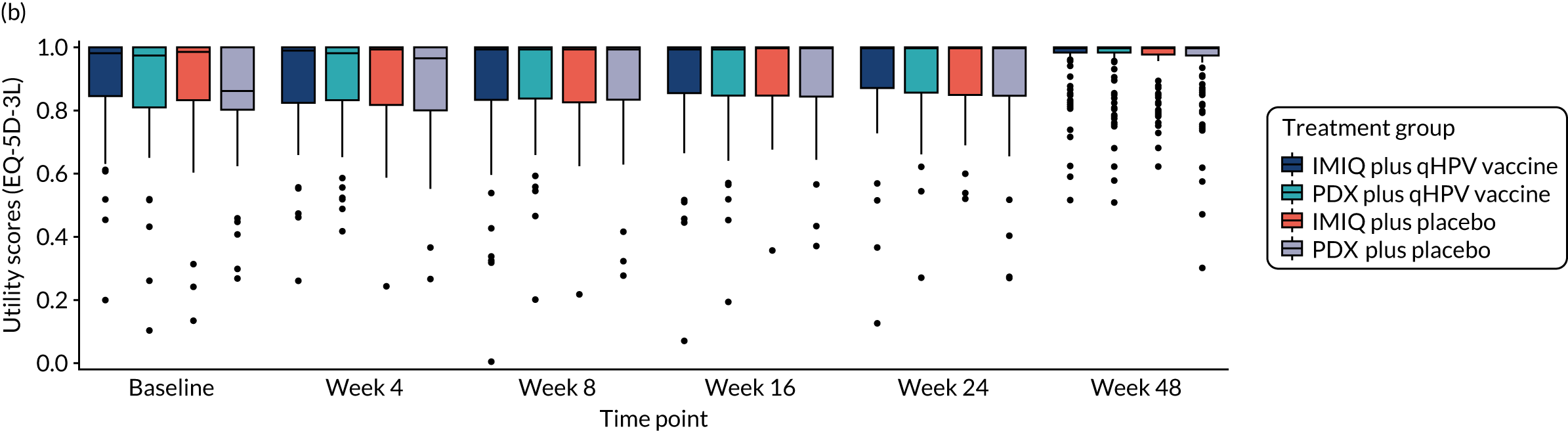

Health-related quality-of-life outcomes

Heath-related quality-of-life outcome data, as measured by EQ-5D-5L health utility and VAS ratings, are shown in Table 8.

| Measure | Treatment group, mean (SD) | Treatment effects, adjusted coefficient (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (n = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (n = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (n = 126) | PDX plus placebo (n = 126) | IMIQ vs. PDX | qHPV vs. placebo | |

| EQ-5D-5L: health utility | ||||||

| Week 4 | 0.95 (0.08) | 0.94 (0.13) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.93 (0.10) | ||

| Week 8 | 0.95 (0.09) | 0.93 (0.14) | 0.94 (0.09) | 0.94 (0.10) | ||

| Week 16 | 0.95 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.16) | 0.96 (0.06) | 0.95 (0.08) | ||

| Week 24 | 0.94 (0.14) | 0.95 (0.12) | 0.96 (0.08) | 0.93 (0.10) | ||

| Week 48 | 0.94 (0.14) | 0.93 (0.15) | 0.95 (0.09) | 0.95 (0.09) | ||

| Area under the curve: health utility | ||||||

| Multiple imputation analysis | 45.6 (4.71) | 44.5 (6.74) | 45.9 (3.05) | 45.2 (3.77) | 0.14 (–0.63 to 0.91)a | –0.31 (–1.06 to 0.45)a |

| Complete-case analysis | 0.64 (–0.59 to 1.87) | –0.24 (–1.48 to 1.00) | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L: VAS | ||||||

| Week 4 | 85.0 (9.7) | 83.2 (14.2) | 82.2 (14.1) | 81.2 (15.6) | 1.05 (–1.55 to 3.65)a | 2.14 (–0.66 to 4.94)a |

| Week 8 | 85.8 (12.0) | 82.6 (13.9) | 82.4 (13.5) | 84.8 (13.3) | –0.10 (–2.46 to 2.26)a | 0.22 (–2.27 to 2.71)a |

| Week 16 | 86.1 (11.6) | 83.3 (14.2) | 85.6 (13.0) | 85.7 (11.2) | 0.39 (–2.12 to 2.90)a | –0.43 (–2.80 to 1.94)a |

| Week 24 | 87.3 (12.5) | 86.4 (14.5) | 85.0 (15.3) | 85.6 (13.5) | 0.32 (–2.50 to 3.14)a | 1.38 (–1.21 to 3.97)a |

| Week 48 | 88.0 (11.9) | 85.2 (17.1) | 84.5 (14.4) | 87.8 (11.2) | –0.62 (–3.04 to 1.81)a | –0.26 (–2.97 to 2.45)a |

Further analyses

A complete-case analysis (CCA) was performed for the primary outcome and clinically important secondary outcomes without the use of imputed data (see Appendix 3, Table 24, for details of missing data). The results are shown in Table 9 and are consistent with the main results shown in Tables 3 and 4.

| Outcome | Treatment group, n/N (%) | aOR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (n = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (n = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (n = 126) | PDX plus placebo (n = 126) | IMIQ vs. PDXa | qHPV vs. placebob | |

| Wart free at week 16 and remaining wart free between week 16 and 48c | 35/101 (35) | 38/99 (38) | 25/98 (26) | 30/99 (30) | 0.82 (0.53 to 1.27) | 1.55 (1.00 to 2.41) |

| Wart free at week 16d | 58/104 (56) | 70/105 (67) | 56/103 (54) | 57/102 (56) | 0.76 (0.51 to 1.13) | 1.31 (0.88 to 1.95) |

| Remaining wart free at week 48 after clearance at week 16e | 35/43 (81) | 38/53 (72) | 25/39 (74) | 30/42 (71) | 0.97 (0.48 to 1.95) | 1.80 (0.90 to 3.63) |

The results of a four-arm analysis are presented in Table 10. Effectively, this approach considers each treatment combination as a separate treatment arm and is an analysis that is recommended for factorial trials. The reference group was the group allocated to receive PDX plus placebo vaccine, so each of the other three treatment groups were compared with the reference group. The odds of achieving the primary outcome for participants allocated to IMIQ plus qHPV vaccine is 1.18 times (18% higher than) the odds for those allocated to PDX plus placebo (95% CI 0.66 to 2.12); the odds of achieving the primary outcome for the other treatment groups compared with the reference group can be interpreted in a similar way.

| Outcome | Treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIQ plus qHPV (N = 125) | PDX plus qHPV (N = 126) | IMIQ plus placebo (N = 126) | PDX plus placebo (N = 126) | |

| Participants achieving end point/participants not lost to follow-up at week 48 (%) | 35/100 (35) | 38/99 (38) | 25/98 (26) | 30/99 (30) |

| aOR of remaining wart free at week 16 and remaining wart free between weeks 16 and 48a | 1.18 (0.66 to 2.12) | 1.37 (0.78 to 2.41) | 0.76 (0.42 to 1.38) | Reference |

In addition, we fitted a model for the primary outcome that contained the two main effects (topical treatment and vaccine) and an interaction term (Table 11). The interaction term was not significant (p = 0.76).

| Effect | aOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Topical main effect (IMIQ vs. PDX for participant receiving vaccine placebo) | 0.76 (0.42 to 1.36) | 0.35 |

| Vaccine main effect (qHPV vaccine vs. placebo for participants receiving PDX) | 1.38 (0.78 to 2.41) | 0.27 |

| Interaction effect (IMIQ × qHPV vaccine) | 1.14 (0.51 to 2.53) | 0.76 |

The interpretation of the interaction effect is that the topical treatment effect is no different in the presence or absence of the qHPV vaccine.

Three subgroup analyses were specified a priori: gender (male vs. female), previous occurrence of warts (no previous occurrence vs. one or more previous occurrences) and HIV status (HIV positive vs. HIV negative) and performed by adding interaction terms to the model for the primary outcome for each factor (topical treatment and vaccine). The resulting six interaction terms were tested separately (topical treatment and gender, topical treatment and previous occurrence of warts, topical treatment and HIV status, vaccination and gender, vaccination and previous occurrence of warts, and vaccination and HIV status). There was no evidence of any interaction; all p-values for the interaction terms outlined above were > 0.35. Complete data are shown in Appendix 3, Table 25.

As detailed in the statistical analysis plan, further analyses were undertaken to explore the sensitivity of results to the MAR assumption. As the MAR assumption cannot be tested directly, imputation was undertaken under various scenarios that might occur if the data were not MAR and to see if the results obtained are consistent with the primary analysis. We proceeded as follows: we defined π0 as the proportion of unobserved individuals experiencing the primary outcome (complete wart clearance at week 16 and remaining wart free at week 48); we defined π1 as the corresponding proportion in the observed individuals; we defined θ as the odds ratio for the primary outcome for the observed individuals compared with that for the unobserved individuals, adjusting for covariates in the analysis model.

Under the MAR assumption θ = 1, it may be reasonable to expect that those individuals who have a good outcome (wart clearance) are less likely to attend follow-up visits (π0 > π1; therefore, θ < 1), but π1 > π0 and θ > 1 is also plausible, although perhaps somewhat less so. We therefore generated three sets of imputed data for the sensitivity analysis, with values of θ equal to 0.6, 0.8 and 1.25 using the Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) impute command for a logistic model with an offset. Each of the three sets of imputed data for the three scenarios outlined above (θ = 0.6, 0.8 and 1.25) was generated using a logistic imputation model with the offset equal to ln(θ) and combined using Rubin’s rules. The results were compared with those from the multiple imputation analysis performed under the assumption of MAR and with the CCA. No substantive differences were found; the analyses were entirely consistent with the multiple imputation analyses carried out under the MAR assumption and the CCA. Therefore, we are confident that our primary results generated under the MAR assumption are robust to plausible deviations from that assumption.

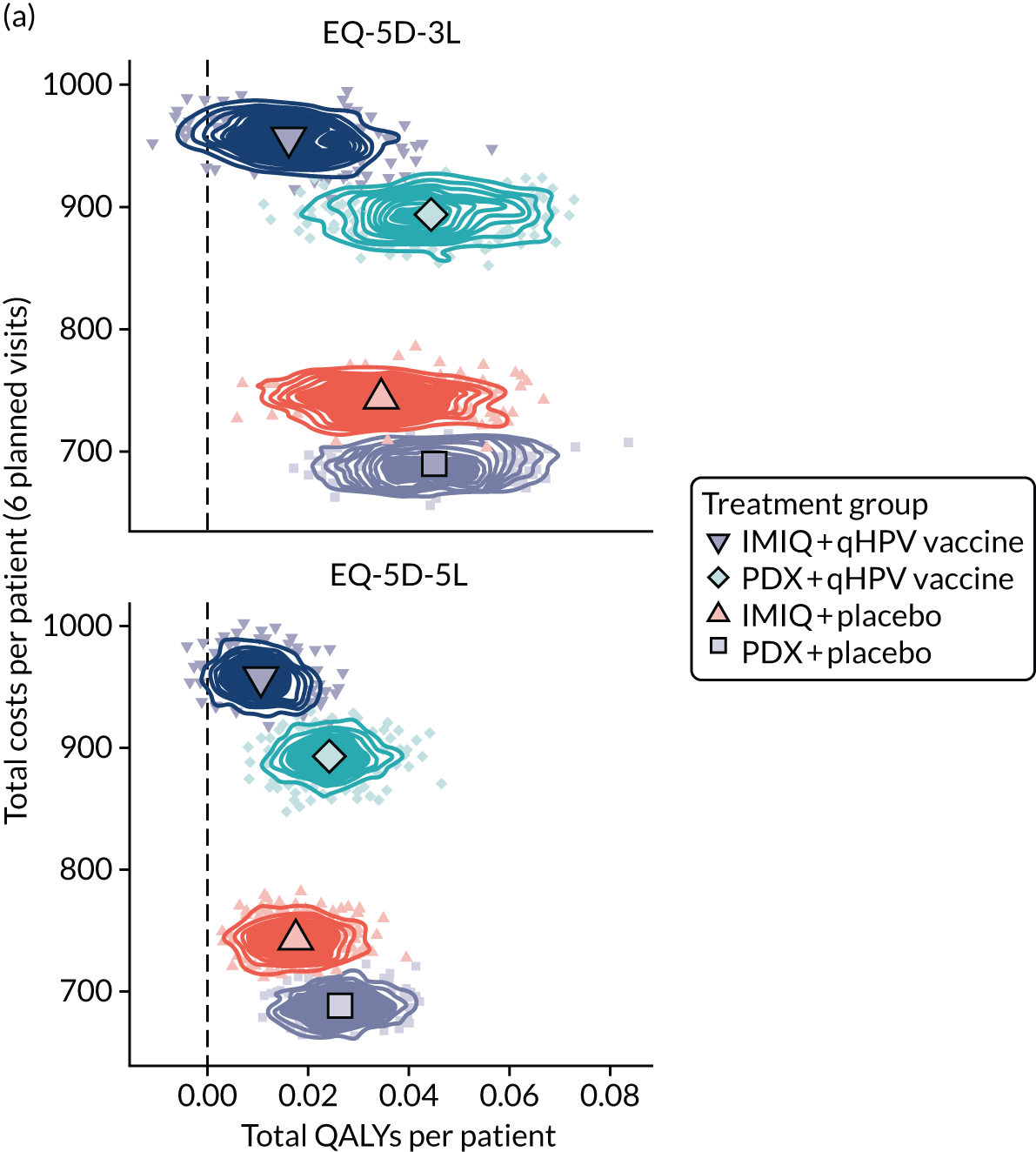

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Introduction

In this chapter, we present the results of an economic evaluation conducted alongside the randomised trial. We investigated the cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of the two topical treatments, as well as the qHPV vaccine, in patients with anogenital warts.

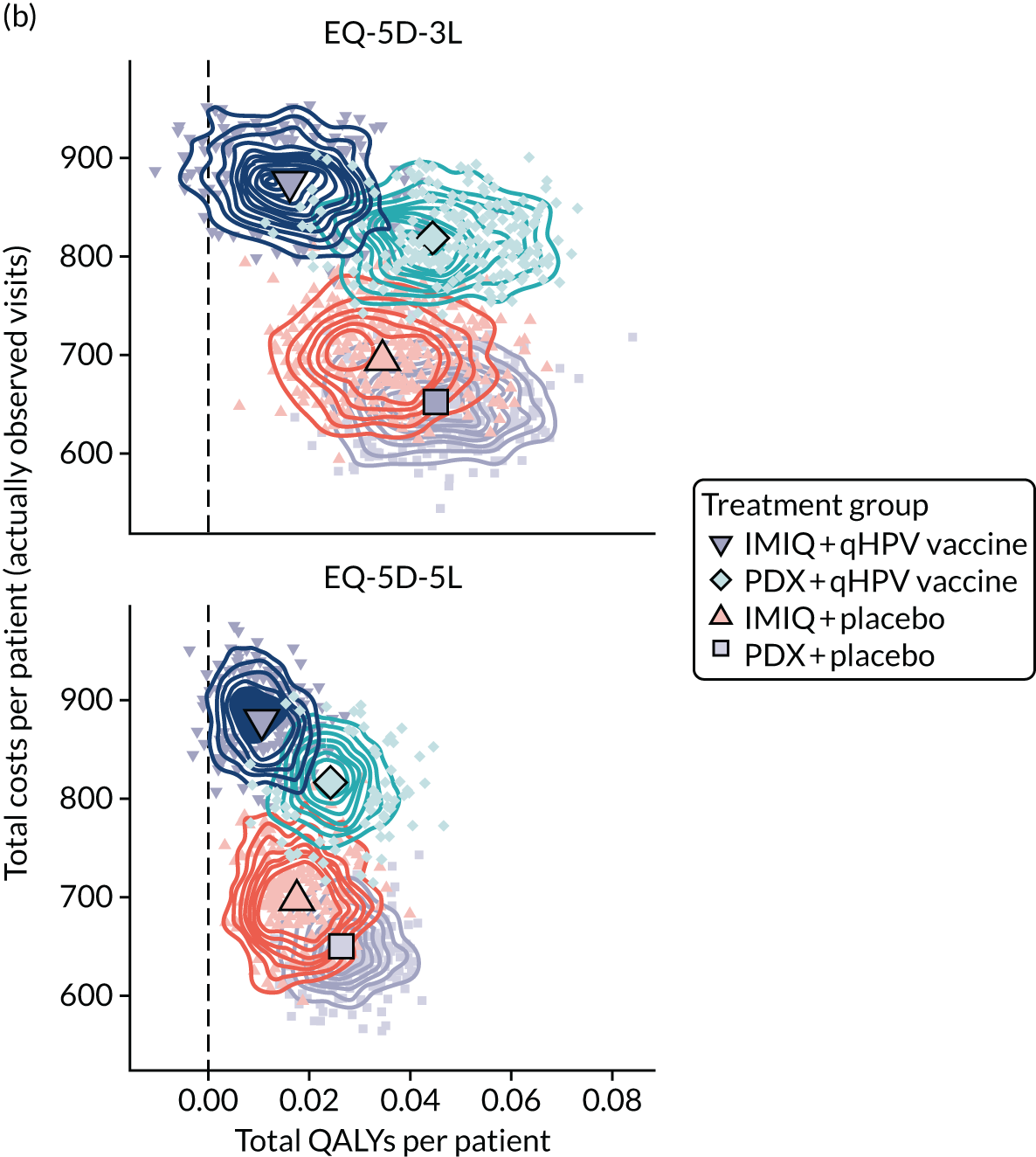

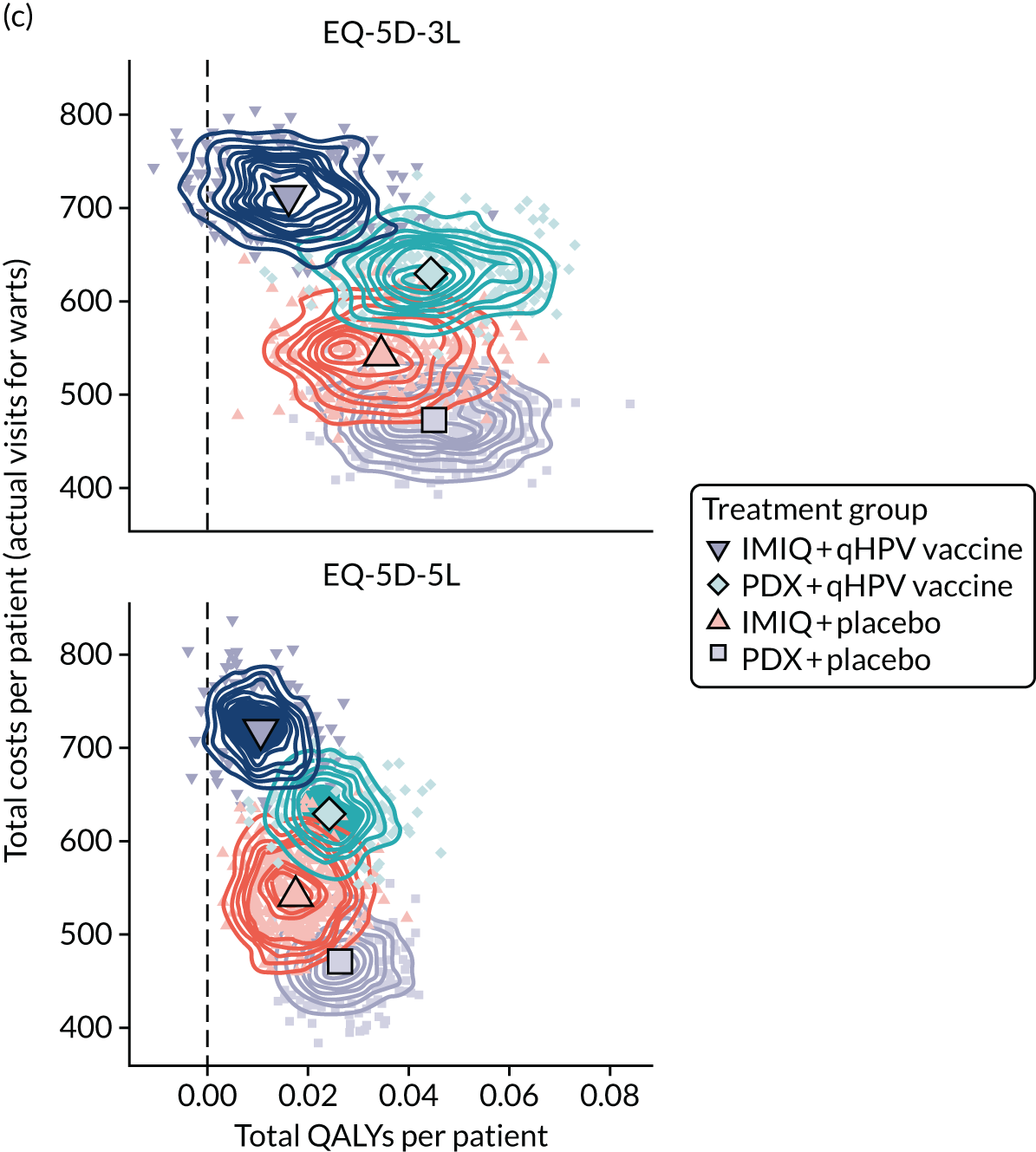

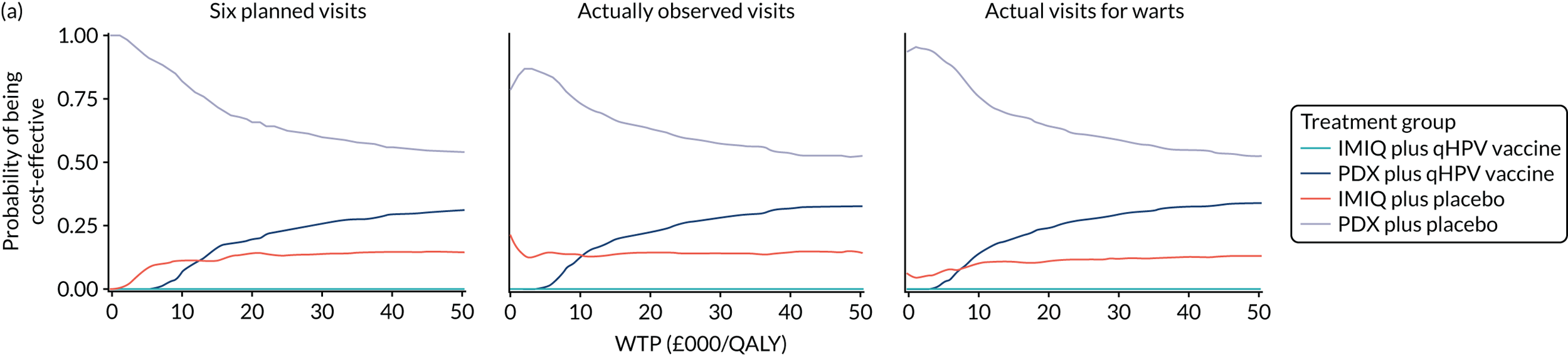

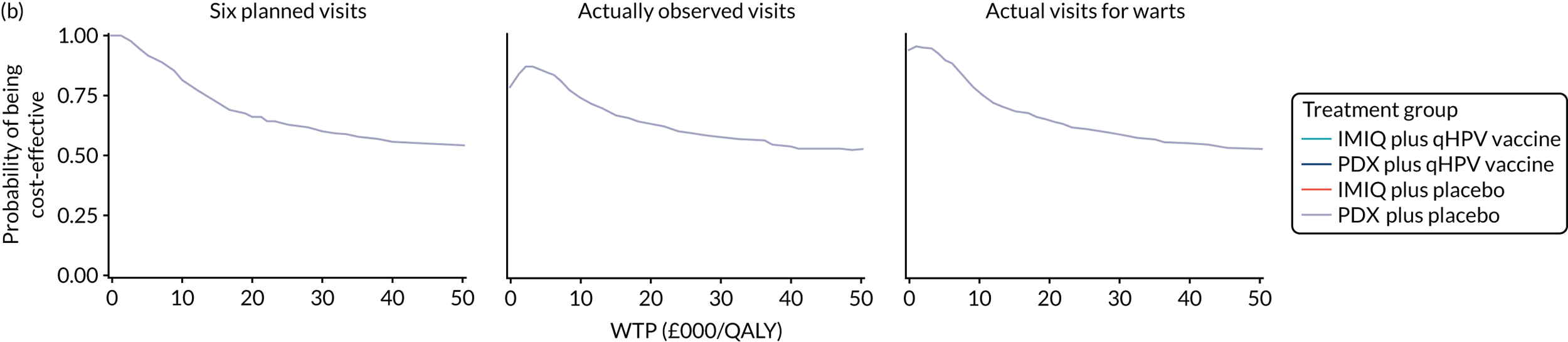

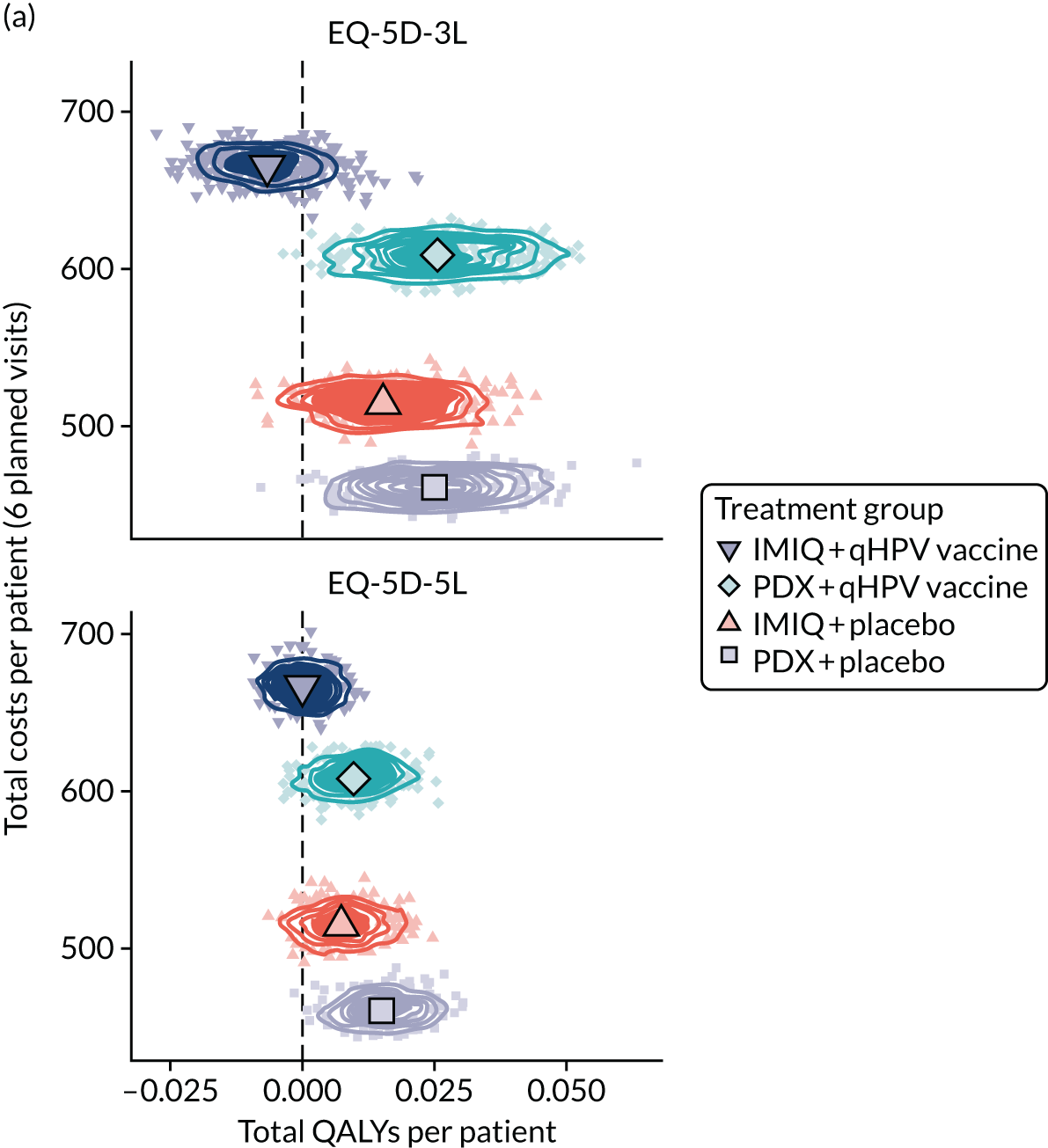

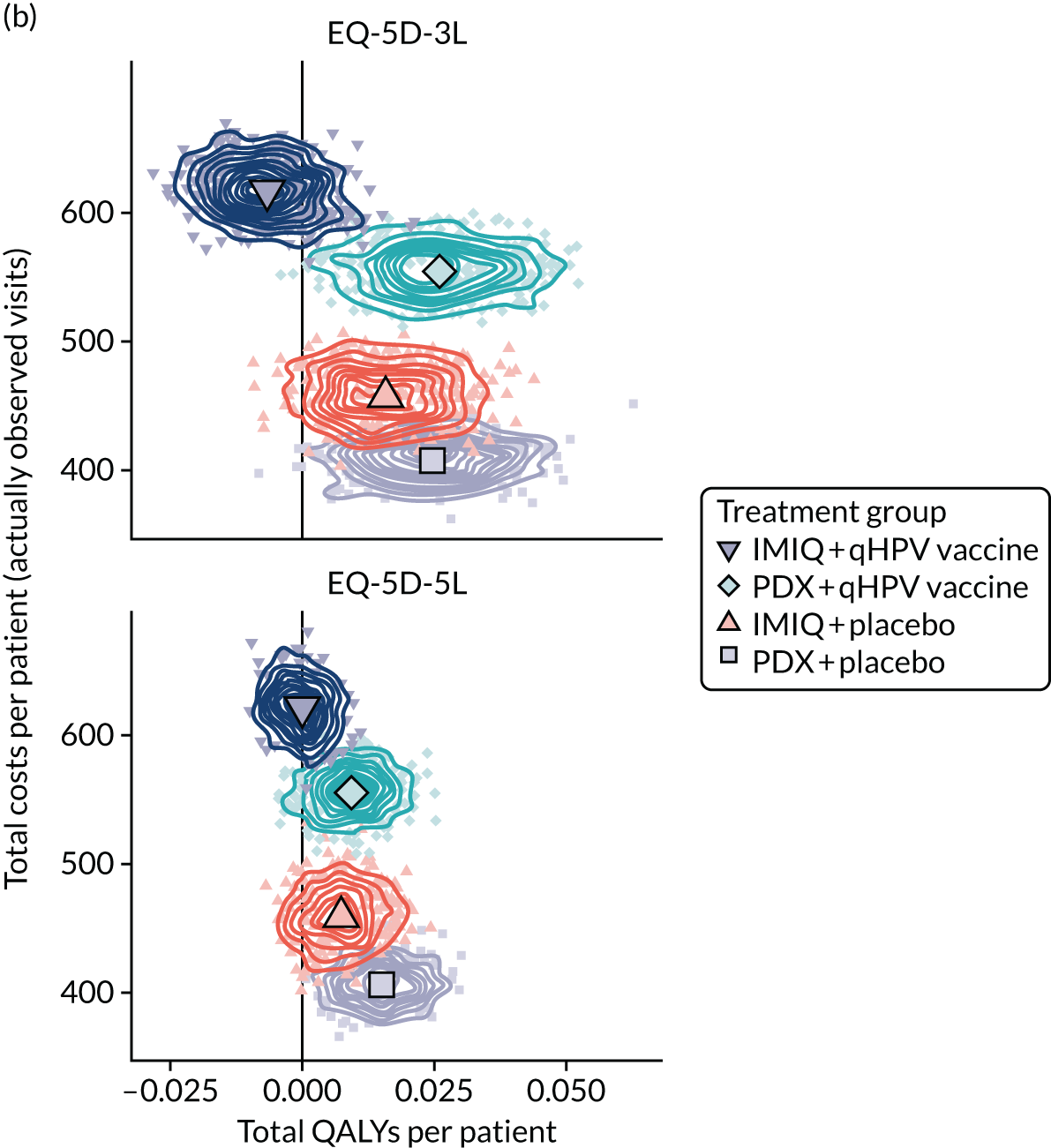

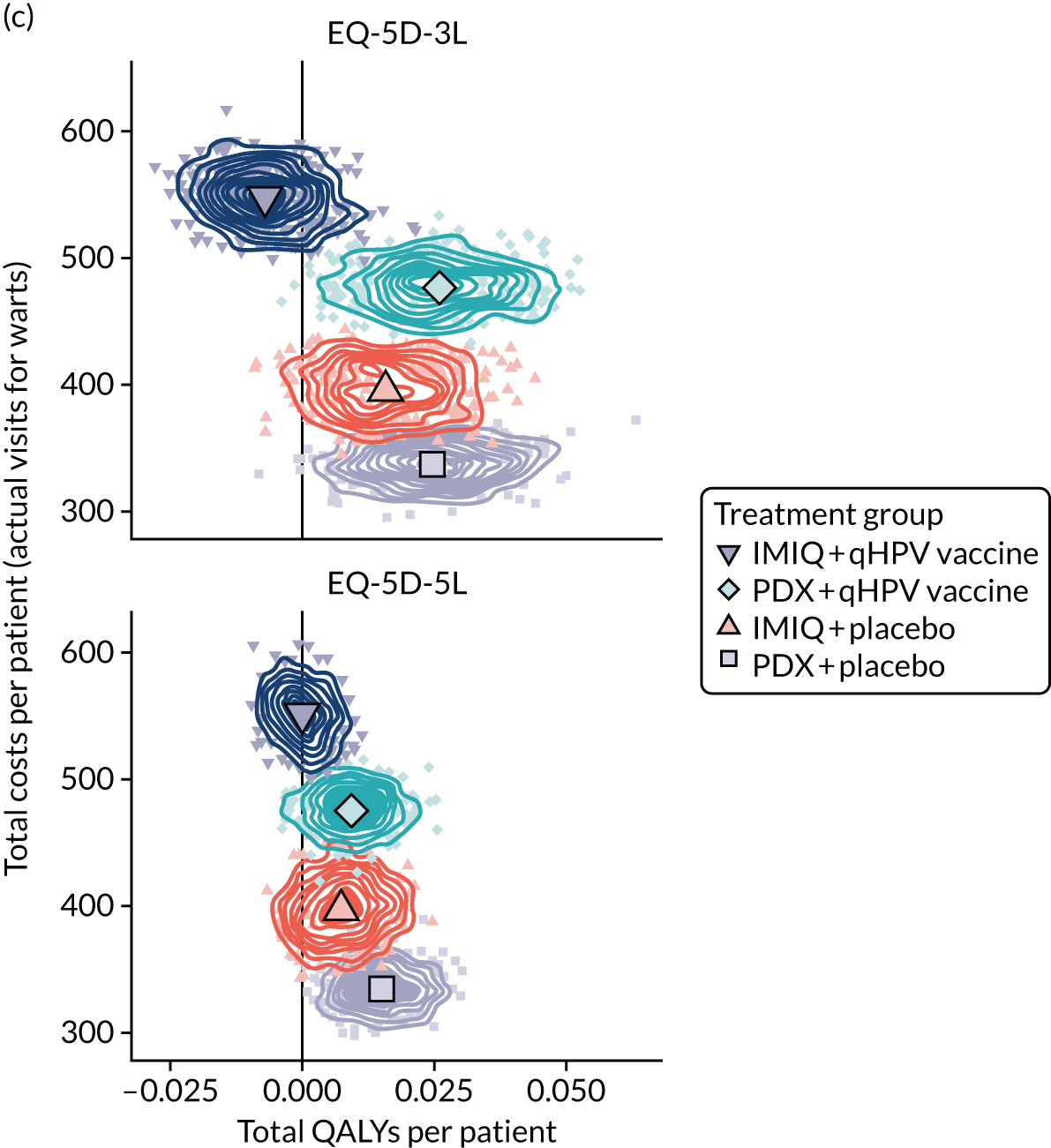

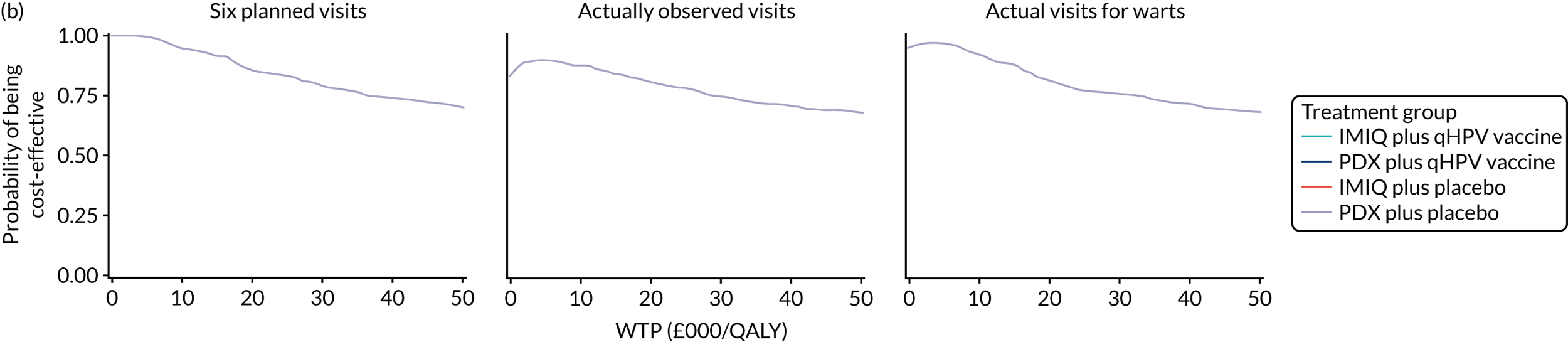

We explored a range of scenarios in the economic evaluation, representing different design choices:

-

factorial design – (1) each of the treatment arms in the 2 × 2 table; (2) qHPV vaccine versus placebo or PDX cream versus IMIQ cream

-

utility values – (1) values based on the EQ-5D-5L instrument used in the trial; (2) values based on mapping values to the EQ-5D-3L

-

trial population – (1) ITT population; (2) a population restricted to those who had never changed from their allocated topical treatment; (3) a complete-case population based on the utility scores

-

data interpolation – (1) interpolating missing data by assuming it is MAR; (2) interpolating missing data by assuming it is missing not at random (MNAR)

-

costs for health-care visits – (1) planned study visits to align with the ITT principle; (2) total number of visits in the trial; (3) number of visits with warts present

-

outcomes – (1) incremental costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained; (2) incremental costs per additional patient clearing warts by week 16; (3) incremental costs per avoided recurrence up to 48 weeks after starting treatment.

Methods

We performed a cost-effectiveness analysis (using the trial primary end points) and cost–utility analysis (using QALYs) based on the recommended ITT population. 43 The analysis compared the four randomisation arms, allowing for interaction between the topical treatments and the vaccine. The analysis also compared the topical treatment and vaccine separately, assuming no interaction and mirroring the efficacy analysis. In addition, a per-protocol analysis (PPA) was undertaken, considering patients who had been treated with the allocated topical treatment only (i.e. no change in allocated topical treatment over the course of the trial), and we explored, in a CCA, the impact of missing utility values.

The analysis was defined prior to release of the final data set as an economic evaluation analysis plan. 38 When possible, this economic evaluation followed the reference case of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and guidelines for economic evaluations from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation,44,45 as well as the recommendations of economic evaluations to be conducted alongside clinical trials. 43

In line with this national guidance,44,45 we adopted the perspective of the NHS. Because the trial follow-up was only 48 weeks, mortality did not occur and there was close similarity of end points in all four treatment arms; therefore, we adopted the time frame of the trial and did not discount future costs or outcomes.

Outcomes

We performed a cost–utility analysis of the incremental costs per QALY gained by each intervention. We performed a full incremental analysis in which both dominated and extendedly dominated interventions were removed. 46 We also calculated the net monetary benefit (NMB), which can be defined as the difference in the value of monetised economic benefits (health outcomes and costs saved) in each arm, where the health outcome is expressed in monetary units using a range of willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds. 47,48

An additional threshold analysis was conducted to estimate the threshold price at which the qHPV vaccine would become cost-effective should the vaccine be more effective than placebo.

In scenario analyses, we used both components of the combined primary end point of the trial as the denominators in the cost-effectiveness analysis,43 that is the incremental costs per additional patient clearing warts by week 16 and avoiding recurrence up to week 48 after starting treatment.

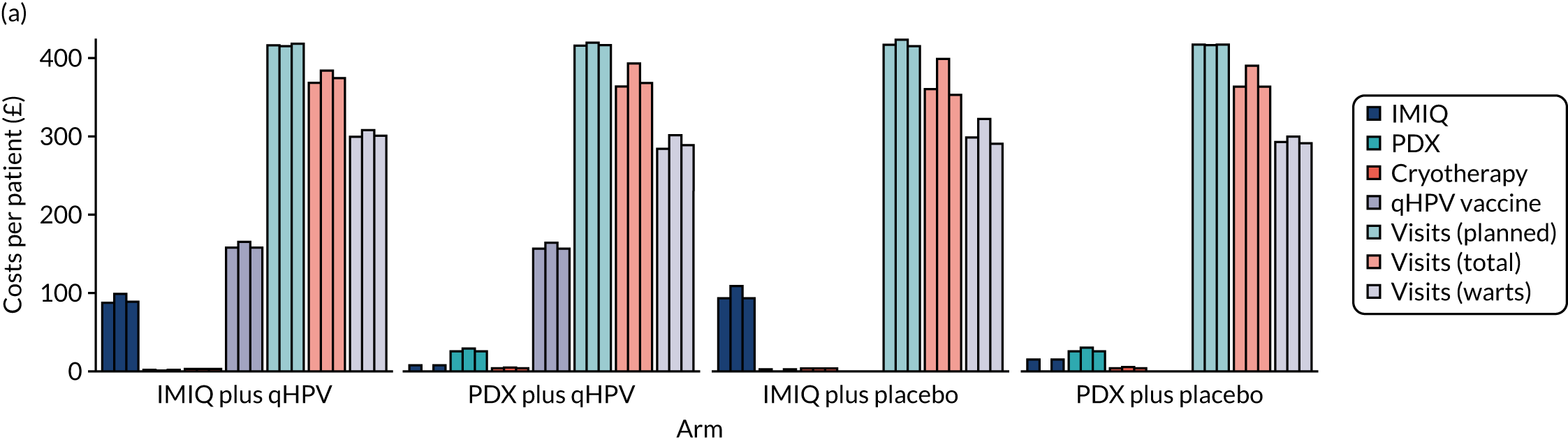

Resource use and costs

The total costs per patient consisted of the costs of the study medication (topical treatment and vaccine), the (optional) cryotherapy and the care episodes. For the two topical treatments, we calculated costs based on the number of applications of each treatment. For the qHPV vaccine, we considered the actual number of administered vaccine doses, despite the fact that some patients did not receive all three doses as planned, which is likely to reflect real-world clinical practice. If cryotherapy had been applied, we also used the actual number of applications. The number of care episodes was estimated based on three scenarios: (1) the planned study visits (four within 16 weeks and six within 48 weeks), (2) the actual number of planned and additional visits and (3) the number of visits when warts were reported to be present. We considered these three different cost values because (1) the planned study visits align well with the ITT principle, (2) the total number of observed visits is in line with the other estimated resources based on the trial, but is probably an overestimate of the number of clinic visits seen in clinical practice and (3) the number of visits when warts were present may be regarded as most closely approximating the number of visits seen in clinical practice. Note that the cost scenarios are listed in order of the total number of visits involved (from highest to lowest), rather than in order of which scenario is deemed the most valid or probable.

For the costs of the two topical treatments, we used the NHS Business Services Authority Drug Tariff price [£48.60 for 12 sachets of IMIQ (50 mg/g); £17.83 for 5 g of PDX cream (1.5 mg/g)]. 49 For the qHPV vaccine, we obtained the NHS indicative price for Gardasil of £86.50 per dose from the British National Formulary. 50 For the costs per cryotherapy treatment round (£4.95), we took the costs from the Quality Of Life In patients with GENital warts (QOLIGEN) observational study of anogenital wart treatment in sexual health clinics. 36 For the costs of care episodes (men, £92.80; women, £126.40), we multiplied the number of clinic visits by the sex-specific mean costs per episode of care from the QOLIGEN study. 36 Finally, we assumed that each patient would have had one STI screen, irrespective of treatment randomisation, which is why the costs of STI screens were not included in the costs of our economic analysis.

The base year of the analysis was 2017/18; therefore, we inflated values to Great British pounds (GBP) 2017/18 when appropriate. 51 Similar to the procedure for natural outcomes, we separated costs at weeks 16 and 48 to allow for separate evaluations of wart clearance by week 16 and avoided recurrence up to week 48.

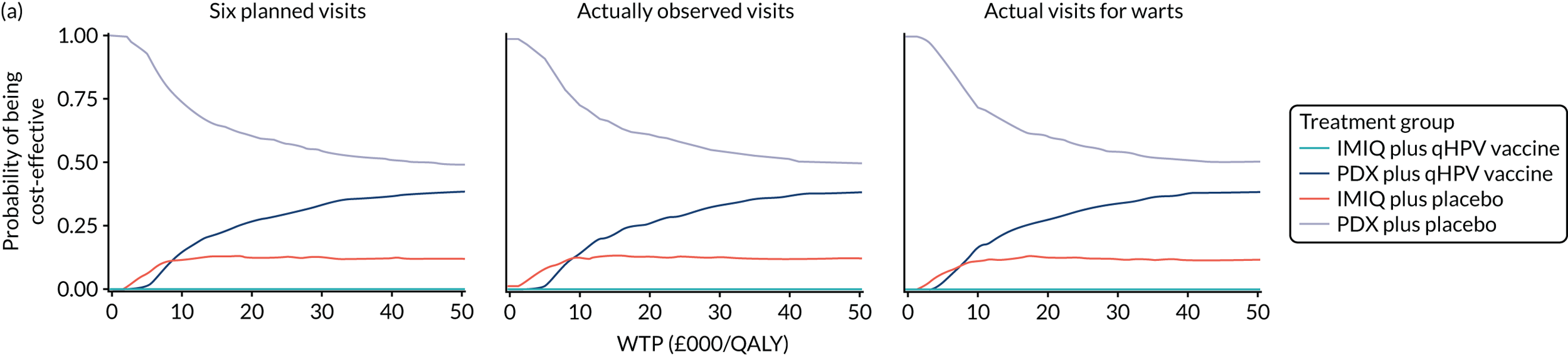

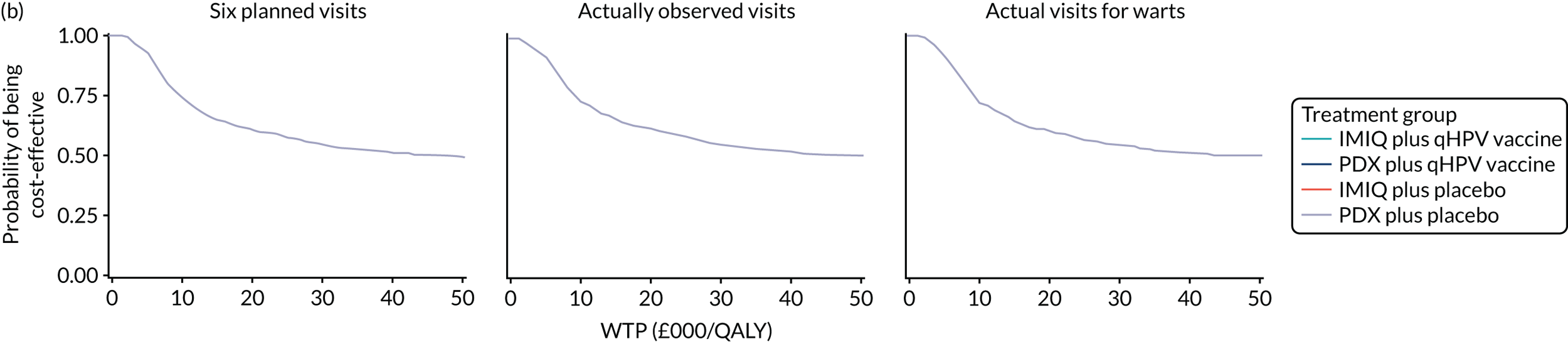

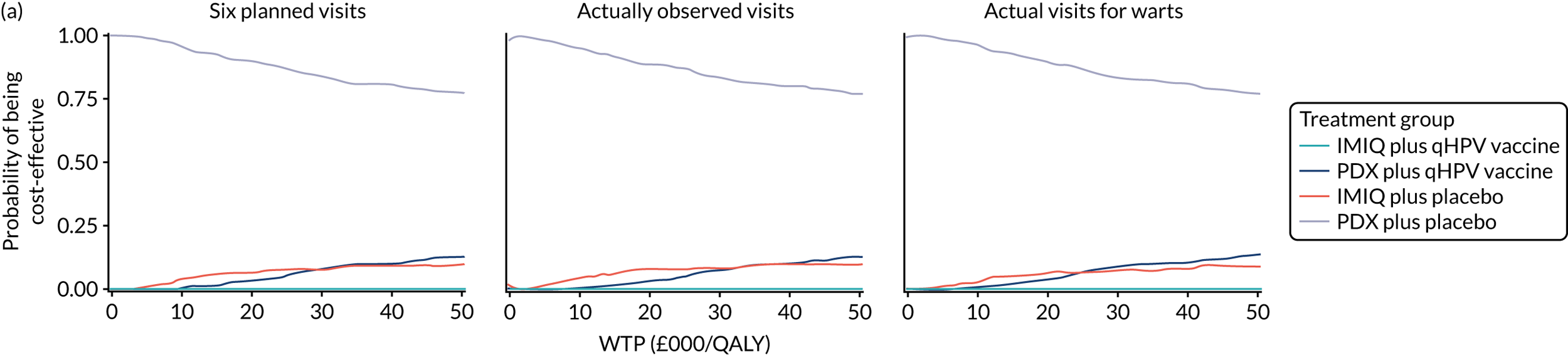

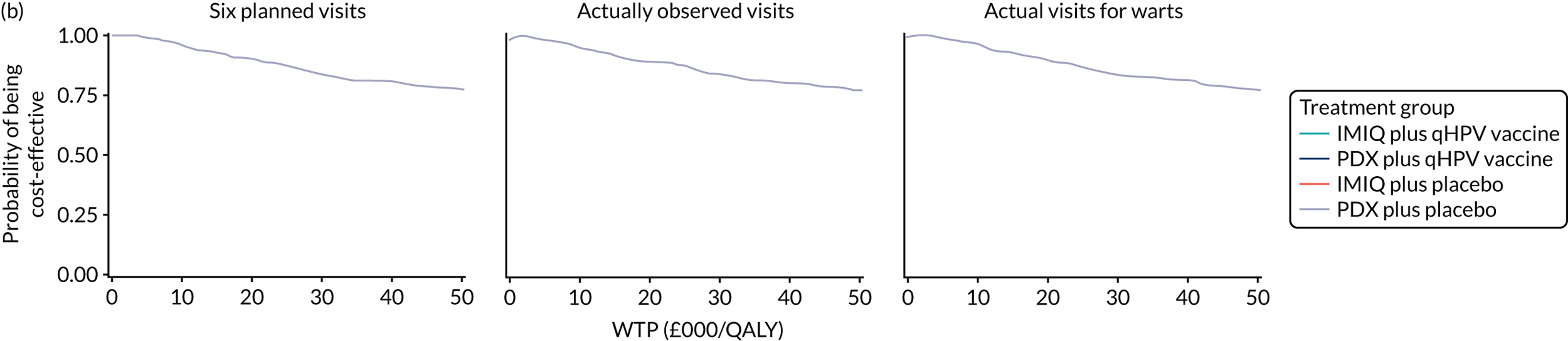

Measurement of health-related quality of life