Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/201/09. The contractual start date was in November 2014. The draft report began editorial review in March 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sue Jowett is (from 2016 to present) a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Committee and reports personal fees as an independent advisor at the Pfizer (Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) chronic pain advisory board meeting in November 2018, outside the submitted work. Kate M Dunn reports grants from the Wellcome Trust (London, UK), during the conduct of the study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Foster et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The term sciatica is commonly used to describe symptoms of pain radiating from the lower back to the leg, often extending to the foot. 1,2 Patients may also have other leg symptoms such as pins and needles, numbness or leg muscle weakness. 1,2 Occasionally, there may not be any lower-back pain (LBP), and, commonly, the leg pain is worse than the LBP. 1,2 The most common reason for sciatica is compression or irritation of a lumbar spinal nerve root by a prolapsed or bulging disc; less often, it is due to tightening of the central or lateral spinal canal (spinal stenosis). 1,2 Some clinicians prefer to use only the terms lumbar nerve root pain, lumbar radicular pain or radiculopathy, to distinguish it from non-specific, referred leg pain, which may arise from spinal structures such as muscles, ligaments or facet joints, rather than compression of a nerve root. 3 However, the term sciatica is still used widely to indicate symptoms arising from lumbar nerve root compression, mainly from a disc prolapse,4 and this is the term used throughout this report.

There is significant variation in sciatica prevalence estimates in published studies, from 1.2% to 43%,5 depending on each study’s diagnostic criteria and sampling methods. 5–7 In clinically evaluated general population cohorts, the point prevalence of sciatica was estimated to be 4.8%. 8,9 In a 2015 primary care cohort in the UK, presenting with back and leg pain and attending a clinic for assessment, 74% of participants were suspected to have sciatic pain. 10 Although imaging tests were not used to inform the initial clinical diagnosis in the UK cohort, the prevalence estimate shows that sciatica is commonly encountered or suspected in primary care. 10

Research on characteristics potentially associated with outcome in sciatica has identified a limited number of prognostic factors independently associated with outcome, mainly in studies of secondary care cohorts. 11–14 Only pain and condition-specific disability are consistently associated with having spinal surgery, which, in this secondary care context, is taken as a proxy of poor outcome for natural course and conservative management. 13 In the UK primary care cohort of patients with suspected sciatica previously mentioned, the high impact of sciatic pain on patients and their expectation of non-improvement over time, were independently associated with non-improvement. 14

It is generally believed that, for most patients with sciatica, symptoms improve considerably within 12 weeks of onset, usually without any active treatment. 1,2 Results from both clinical trials and cohort studies involving sciatica populations and utilising a number of different outcomes and definitions of improvement show that the percentage of patients reporting improvement varies between 32% and 65%. 14–18 Therefore, at least one-third of patients continue to suffer with pain for ≥ 1 year. The personal, social and economic burdens are significant,19,20 with UK annual costs estimated at £268M in direct medical costs and £1.9B in indirect costs. 21

Treatments for, and current clinical management of, sciatica

The vast majority of patients with sciatica in the UK are assessed and managed in primary care. Current evidence,22–24 the updated UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance (2016)25 for the treatment of LBP and sciatica in those aged > 16 years and the National Low Back and Radicular Pain Pathway 201726 all support mainly a stepped-care management approach for most patients with sciatica, in the absence of suspected serious pathology. NICE25 recommends considering the use of stratification tools when assessing patients with sciatica to decide on the intensity of conservative management. Current management options may include advice about staying active; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); weak opioid or neuropathic pain medications; physiotherapy interventions, such as exercise, with additional options of manual therapy techniques; or psychological therapies. Most sciatica patients will improve over time and will not require specialist care or invasive management options. However, for patients with severe and/or non-resolving sciatica, steroid spinal epidural injections and/or surgery are recommended for pain relief, in the presence of concordant imaging findings, for example from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Of all the available treatments for sciatica, surgery has the most robust evidence from research studies; it provides rapid and substantial relief of pain, but outcomes for those having surgery and those managed conservatively have been shown to be similar in the longer term, with approximately one-fifth of patients reporting ongoing complaints, which fluctuate over time, irrespective of which treatment is received. 27 On average, although patients receiving surgical intervention improve rapidly and substantially, they still seem to report mild to moderate pain and disability 5 years after the surgery;28 however, evidence also shows that increased pre-treatment symptom duration is related to worse outcomes following both conservative and surgical management than receiving treatment earlier in a patient’s symptom presentation. 29

In practical terms, stepped care may include an initial ‘wait-and-see’ period in primary care, with advice and pain medication, with subsequent referral to physiotherapy or similar treatments/services (e.g. osteopathy, chiropractic), and, for those not improving or with severe and incapacitating pain, referral to specialist spinal services at the interface and/or the secondary care setting for investigations and further management. 26 In the UK NHS, it is in these specialist settings where treatment options such as spinal injections and/or surgery are considered. 26 However, an immediate referral of all sciatica patients to injections or surgery is not considered a cost-effective model of care,22,23,30 and it is unlikely that it is needed for all patients. Currently, only patients with possible serious spinal pathology are fast-tracked to specialist services. 25,26 For all other sciatica patients, there is variation in clinical practice in terms of referrals from general practice to physiotherapy and specialist services. The UK Spinal Taskforce31 highlighted problems in the management of sciatica caused by variation in clinical practice, specifically delays in the treatment of patients with severe pain, believed to be mainly caused by delays in referral to specialist services. The Spinal Taskforce31 highlighted the need for good-quality trial evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early referral of patients with severe symptoms for consideration of treatments such as surgery or spinal epidural injections. As early referral to surgical services for all sciatica patients cannot be recommended, better, and earlier, identification of patient subgroups in primary care for early matched treatment pathways [stratified care (SC)], including early referral to spinal specialist services for some sciatica patients, may be the key to improving outcomes for sciatica patients. The challenge for primary care clinicians [e.g. general practitioners (GPs) and physiotherapists] is how to identify, early in the presentation, patients who are likely to do well with conservative management in primary care and patients who may need early, fast-track referral to spinal specialist opinion for consideration of more invasive management options, such as spinal injections and surgery.

Stratified care model and rationale for the SCOPiC trial

In the field of non-specific LBP, a SC approach comprising two components – first, subgrouping according to risk of persistent back pain-related disability and, second, matching each subgroup of patients to treatment – demonstrated better clinical and health economic outcomes than non-SC. 32,33 In summary, the approach uses a brief self-report questionnaire, the Subgroups for Targeted Treatment (StarT) Back Screening Tool,34 developed for and validated with primary care patients with non-specific LBP (with and without leg pain), and allocates LBP patients to subgroups of low, medium or high risk of persistent back pain-related disability. The Subgroups for Targeted Treatment (STarT) Back Screening Tool has nine items: four focus on physical constructs and five focus on psychological constructs. A score of < 3 indicates that the patient is, most likely, at a low risk of future persistent back pain-related disability; a score of ≥ 4 of the five psychological items indicates that the patient is, most likely, at a high risk of persistent disability. 34 Any other score identifies patients as being at a medium risk of persistent disability. 34 By estimating the risk of persistent back pain-related disability, the STarT Back Screening Tool supports early clinical decision-making about conservative treatments for patients with non-specific LBP (such as GP care and physiotherapy management). Patients with sciatica have been shown to have more severe symptoms than those with non-specific LBP;20 management options such as injections and spinal surgery may be applicable to sciatica, but are not applicable to non-specific LBP. A SC approach for patients consulting with suspected sciatica in primary care may result in improved outcomes, but evidence is lacking.

Prior to the Sciatica Outcomes in Primary Care (SCOPiC) trial, no tool has yet been developed and tested with which to stratify care specifically for patients with sciatica early in the presentation of symptoms. In particular, it was not possible to predict which patients might benefit from early consideration for invasive treatment such as surgery. 35 In a cohort of sciatica patients with at least 6 weeks’ duration of symptoms, all of whom were surgical candidates, only high levels of pain and disability were associated with having surgery at some point. 12 The lack of clear and consistent factors predicting poor outcomes in patients with sciatica11,13,14 has made it challenging to design prognostic models that can guide early treatment decision-making. 13

In the absence of stratification approaches to help with clinical decision-making in early primary care management of patients with sciatica, we used information about the characteristics of patients referred to specialist spinal services from the only available UK primary care cohort of sciatica patients. 10 Using this, and working closely with clinicians, we developed an algorithm combining information about patients’ risk of persistent pain-related disability (using the STarT Back Screening Tool) and key findings from the clinical assessment that were associated with referral to spinal specialist services to allocate patients to matched care pathways, including an early, fast-track referral to MRI and specialist spinal opinion. 21 The stratification algorithm is described in Chapter 2.

Responding to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme commissioning call (12/201, February 2013) about research to improve the management and outcomes of patients with sciatica, the aim of this study was to test, in a definitive randomised trial, whether or not the use of a new stratification algorithm and the matched care pathways lead to better outcomes than non-stratified, usual care (UC) for patients consulting with suspected sciatica in primary care.

The SCOPiC trial aims and objectives

The overall aim of this trial was to investigate whether or not a new SC approach for sciatica that combines information on the risk of persistent disability with information about sciatica clinical severity to guide decision-making about matched care pathways results in better clinical and cost outcomes for patients consulting their GP with symptoms of suspected sciatica.

The two main aims were to investigate the:

-

clinical effectiveness of SC versus non-SC for patients consulting with suspected sciatica in primary care, in terms of patient-reported time to symptom resolution

-

cost-effectiveness of SC versus non-SC over a 12-month period.

Further objectives included investigating the clinical effectiveness of SC versus non-SC on sciatica-related disability, LBP, leg pain, quality of life, time lost from work, health-care use and patient satisfaction with care received, and the results of care. In addition, we investigated the impact of SC on service delivery, in terms of referrals to physiotherapy services and spinal specialist services, and the acceptability of this SC approach from the perspective of patients and clinicians.

Chapter 2 The SCOPiC trial methods

Design and setting

The SCOPiC trial was a multicentre, pragmatic, assessor-blinded, randomised controlled trial (RCT), with an internal pilot health economic evaluation and linked qualitative interviews. The trial’s setting included NHS primary care services (general practices), community physiotherapy services and spinal interface services between primary and secondary care.

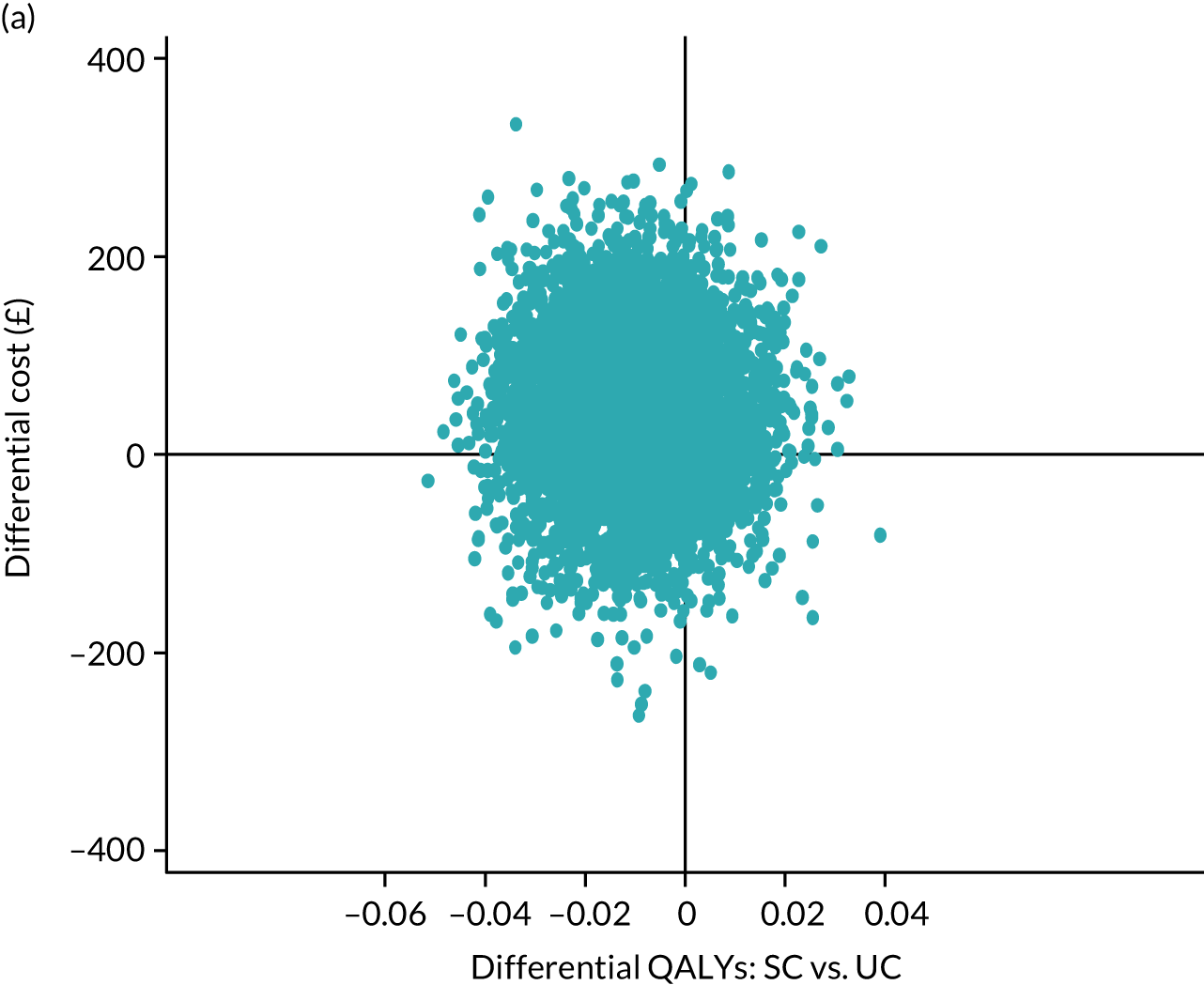

An economic evaluation was conducted alongside the RCT to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention over 12 months (see Chapter 4). A nested qualitative study was conducted to explore patients’ and clinicians’ views of the fast-track care pathway associated with the SC model tested in this trial (see Chapter 5).

General practices

We recruited patients from 42 general practices in the areas of North Staffordshire, North Shropshire/Wales and Cheshire. These areas were the three recruiting centres. We initially started with 30 general practices and then added a further 12 practices over the course of the trial, to recruit the number of participants required in the trial.

Physiotherapy sites

Five community NHS physiotherapy services were involved in the trial: two in Staffordshire, one in Shropshire, one in Wales and one in Cheshire. We initially started with three physiotherapy services (those in Staffordshire and Shropshire), then added a further two (in Wales and Cheshire) over the course of the trial.

Spinal specialist sites

Patients recruited to the fast-track pathway were seen by spinal specialists in either Staffordshire (Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Partnership NHS Trust), Shropshire (The Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust) or Cheshire (Leighton Hospital, Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Trust).

Ethics approval

The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry (ISRCTN75449581). Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service West Midlands – Solihull (reference number 15/WM/0078). Recruitment commenced in June 2015 and was completed in July 2017. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) provided independent oversight of the trial.

Participants

We recruited adults consulting in general practice with symptoms of sciatica of any duration and severity.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible to participate in the trial if the following criteria were satisfied:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

had a mobile phone that could receive and send texts or had access to a landline telephone

-

had consulted in general practice with back and/or leg symptoms, and the GP suspected sciatica

-

following clinical assessment in research clinics, the diagnosis of sciatica was confirmed with at least 70% diagnostic confidence by a physiotherapist

-

able to read and communicate in English (to give full informed consent and to complete the baseline and outcome assessments)

-

willing to participate.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were not eligible for participation in the trial if they:

-

had suspected serious spinal pathology or ‘red flags’ (e.g. cauda equina syndrome, progressive/widespread neurological deficit, spinal cord compression, suspicion of malignancy, infection, fractures, inflammatory spondyloarthropathy)

-

had had any previous lumbar spine surgery

-

were currently receiving ongoing care from, or had been in consultation with, a secondary care doctor or physiotherapist for the same problem in the previous 3 months

-

had serious comorbidity preventing them from attending the research clinic and/or being able to undergo assessment and interventions

-

had a severe, enduring mental health condition

-

were pregnant

-

were taking part, at the same time, in another research study relating to symptoms of back and/or leg pain (sciatica).

Interventions

Stratified care (trial arm)

We developed and utilised a stratification algorithm to direct the SC model tested in the SCOPiC trial. The algorithm was used to identify those sciatica patients likely to need a fast-track referral from primary care to specialist spinal services, those who might benefit from a course of physiotherapy treatment and those who may require only minimal intervention to support self-management. The algorithm combined prognostic information, using the STarT Back Screening Tool,34 and information on the following clinical examination findings: level of interference with ability to work (including work around the house), pain below the knee, intensity of leg pain and sensory changes in the painful leg such as loss of, or reduced, pin-prick sensation approximating a dermatomal distribution. The algorithm allocated patients to one of three groups and each group was matched with a care pathway. The matched care for participants in group 1 comprised one or two physiotherapy sessions. Participants in group 2 received a course of up to six physiotherapy sessions; the number and content of treatment sessions was tailored to participants’ individual needs. Participants in group 3 were fast-tracked to have imaging of the lumbar spine (MRI) and to see a spinal specialist, with the MRI results, for further assessment and management. The treatments offered to participants in group 3 (the fast-track pathway) after their appointment at the spinal specialist clinic formed part of current NHS care and were not influenced by the trial’s procedures. All participants in the SC arm received initial advice from the trial’s physiotherapists at the SCOPiC trial research clinic. Full details of the stratification algorithm and care pathways and treatments are given in Description of interventions.

Non-stratified care, usual care (control arm)

The control arm intervention of the SCOPiC trial was based on non-stratified UC, delivered by physiotherapists who were not involved in the delivery of the SC arm of the trial. All participants randomised to the UC arm received their first treatment in the SCOPiC trial research clinic. This included a one-off session of advice and education. If required, the treating physiotherapist could arrange a referral to the local NHS community physiotherapy or interface specialist spinal services, or discharge the patient to the care of their GP. Data were collected on referrals made and subsequent treatments received. The use of any stratification tools was prohibited for participants in the UC arm for the duration of the trial. This was agreed in advance with physiotherapy service managers and physiotherapists in the participating sites, and in sites that expected to see participants in the trial as part of UC.

Trial procedures

Recruitment methods

Two methods were used to identify potentially eligible participants for the SCOPiC trial: (1) electronic ‘pop-up’ prompts in general practice computer software fired by appropriate Read codes (the Read code system is a clinical coded dictionary used for recording consultations in the UK primary care information technology systems)36 for back and/or leg pain and (2) weekly reviews of practice consultation records for those practices not using electronic ‘pop-ups’, with the list of potential participants screened by the GP who identified patients who should be excluded. Patients consulting with a health-care professional (HCP) other than a GP at a general practice (e.g. a practice nurse) could also be recruited using the aforementioned recruitment methods. The list of Read codes used were checked with each general practice. Initially, only Read codes indicative of sciatica were included, but some general practices requested the addition of generic LBP Read codes as well, because a number of GPs used the LBP codes to record sciatica presentations. The list of Read codes used for the trial are presented in Appendix 1.

In the method using electronic ‘pop-up’ prompts, when a patient with back and/or leg pain consulted their GP, and the GP entered an appropriate Read code on the computer system, a ‘pop-up’ screen asked the GP if they thought that the patient might have sciatica, and, if so, to consider whether or not the patient was suitable (yes/no) to be invited to the SCOPiC trial sciatica clinic, taking into account trial inclusion/exclusion criteria. By entering ‘yes’ on the computer system, those patients thought to be suitable for invitation to the clinic were flagged. The GP could briefly inform the patient about the clinic and the study, although this was not a requirement in order to send invitations to potential participants. In addition to using the ‘pop-up’ method for participant identification, the ‘pop-up’ screen asked GPs to record their preferred approach to management of the patient: (1) keep patient under GP care, (2) refer patient to physiotherapy or (3) refer patient to a specialist. This information was intended for use in the SCOPiC trial research clinics for the UC arm treatment decisions, if appropriate, and for descriptive purposes, to compare GP decision-making about management options at first consultation with sciatica patients, versus physiotherapist decision-making in the SCOPiC trial research clinic.

Once a potential participant had been identified, with either method, an invitation letter (on general practice-headed notepaper) and an information sheet about the SCOPiC trial sciatica clinic were posted to them. The letter explained that there was a research study in sciatica and potentially eligible participants were invited, if interested, to telephone an administrator to make an appointment at the SCOPiC trial sciatica clinic to see a physiotherapist. During that telephone call, the administrator carried out a brief check for preliminary eligibility for the trial, to establish the following: presence of leg pain, aged ≥ 18 years, ability to communicate in English, not currently receiving treatment for the same problem by a physiotherapist or secondary care doctor, had not seen a secondary care doctor or physiotherapist for the same problem in the previous 3 months, not currently participating in any other back pain and/or sciatica research study, had not undergone lumbar spine surgery and was not pregnant. Potentially eligible participants receiving or having had received care from alternative or complementary health-care practitioners, such as osteopaths, chiropractors or acupuncturists, were not excluded but were advised, if possible, to keep co-treatments to a minimum during the treatment phase of the trial. The reasons for decline/exclusion were documented. Potential participants were offered a clinic appointment within 10 working days. A letter was then sent to potential participants confirming their appointment details; the pack included the participant information sheet, explaining the SCOPiC trial, and the baseline questionnaire. Approximately 2 days before the clinic appointment, potential participants were telephoned by a clinic administrator to remind them about their appointment and to ask those who were interested in taking part in the trial to bring their completed questionnaire.

Baseline assessment, eligibility screening and informed consent

The SCOPiC trial sciatica clinics were operated as integrated research and NHS service clinics. At these clinics, trial physiotherapists explained the purpose of the clinic and answered questions about the clinic and the trial. Potential participants expressing interest in participating in the trial proceeded to have a standardised clinical assessment by the physiotherapist to confirm the clinical diagnosis of sciatica. The assessment was documented on a standard pro forma. In the context of the trial and according to literature37,38 and clinical guidelines,25 sciatica is, in most cases, indicative of nerve root entrapment due to a disc prolapse, and, less frequently, due to spinal stenosis. 1 Therefore, as well as patients with symptoms thought to be due to disc prolapse, we also included patients with symptoms thought to be due to spinal claudication. Eligibility for the trial was based on the assessing physiotherapist being ≥ 70% confident in their diagnosis of sciatica. We also asked the assessing physiotherapists to record a specific diagnosis of disc prolapse or stenosis for the sciatic symptoms. At least one of the following signs and symptoms contributing to the clinical diagnosis of sciatica7,39,40 had to be present: leg pain approximating a dermatomal distribution; leg pain worse than, or as bad as, back pain; leg pain worse with coughing/sneezing/straining; subjective sensory changes approximating a dermatomal distribution; objective neurological deficits indicative of nerve root compression; positive neural tension test; and (specifically for spinal claudication/spinal stenosis) leg pain worse with weight-bearing activities and better with sitting. Patients were excluded if the assessing physiotherapist thought that the leg pain was a result of causes other than sciatica (e.g. referred leg pain, hip pathology, vascular claudication), if diagnostic certainty was < 70% or if potentially serious pathology was suspected (e.g. malignancy, cauda equina syndrome). All reasons for exclusion were documented.

For those patients who were eligible and interested in taking part in the trial, the trial physiotherapist explained the trial in detail, answered any questions and took written informed consent. The information required from self-report and clinical examination to allocate patients to one of the three groups based on the stratification algorithm was recorded by the assessing physiotherapist on a standard pro forma. Patients had completed and brought with them the baseline questionnaire, or completed the questionnaire during the research clinic visit, along with a second baseline questionnaire. The clinic administrator checked the baseline questionnaires for missing data while the patient was in the clinic.

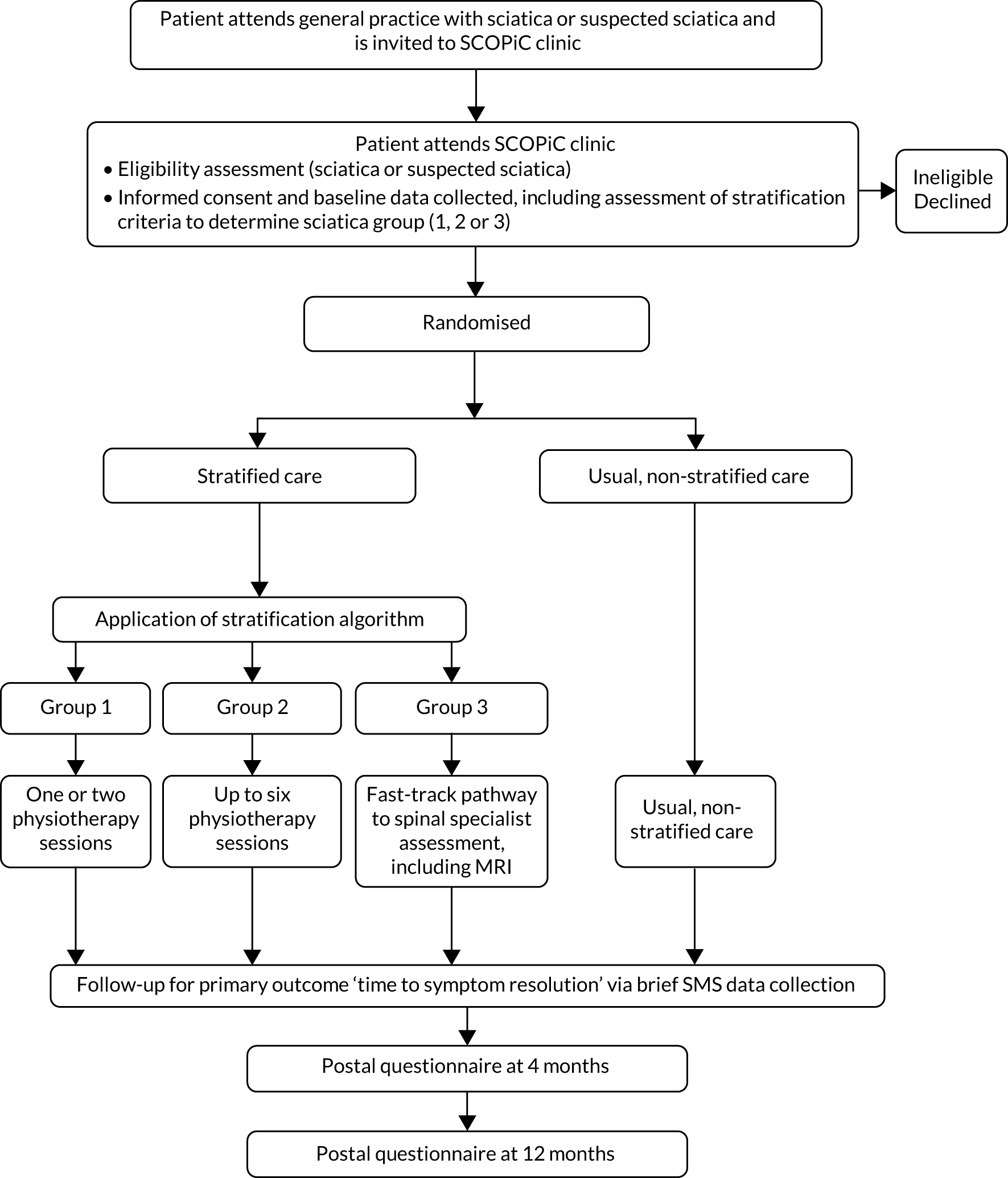

Patients who did not wish to participate or who were ineligible received advice and education from the physiotherapist in the clinic, with the option to be referred for further treatment as appropriate, outside the trial. GPs received information (by a standard letter generated by the trial management database) of the outcome of their patients’ attendance to the SCOPiC trial research clinic, and their care plan. Figure 1 outlines the SCOPiC trial recruitment procedures.

FIGURE 1.

The SCOPiC trial recruitment procedures.

Randomisation

Eligible patients who consented to take part were randomised to one of the two trial arms, in a 1 : 1 ratio, using a web-based randomisation service from Keele Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), which ensured allocation concealment, operated by the clinic administrator. There was a back-up process to telephone the CTU randomisation service in the event of web access failure. The assessing physiotherapist gave the clinic administrator the completed standard pro forma, which included the sciatica group the participant was allocated to according to the stratification algorithm. In each recruiting centre, the clinic administrator used the randomisation service and individual participants were randomised, stratified by centre (North Staffordshire, North Shropshire/Wales and Cheshire) and group allocation according to the stratification algorithm, using random permuted blocks of varying size (two, four and six), to either SC or UC. With three centres and three groups equating to nine stratified cells, participants were randomised in block sequences with random selection from the following blocks: AB, BA, AABB, ABAB, ABBA, BAAB, BABA, BBAA, AAABBB, AABABB, AABBAB, AABBBA, ABAABB, ABABAB, ABABBA, ABBAAB, ABBABA, ABBBAA, BAAABB, BAABAB, BAABBA, BABAAB, BABABA, BABBAA, BBAAAB, BBAABA, BBABAA, BBBAAA.

If a participant was randomised to the SC arm of the trial, the administrator informed the assessing trial physiotherapist, who saw the participant and commenced the care matched to each group. If a participant was randomised to the UC arm of the trial, the administrator informed the physiotherapist delivering care for the UC arm, who saw the patient and initiated treatment. Different physiotherapists delivered treatment to participants in each trial arm, at the research clinic and during subsequent appointments. Information about which arm of the trial a participant was allocated to was not disclosed to either the participant or their GP. A participant’s GP was informed in writing that the individual was participating in the trial, but GPs were not informed about which arm of the trial the participant had been randomised to. Usual clinician-to-clinician correspondence continued as per usual practice; the research did not interfere with this. Each participating general practice had a site file containing contact details of the trial team.

Blinding

The main issue in the SCOPiC trial was the concealment of the stratification algorithm and its use in matching participants to care pathways. Participants were told that the trial was comparing two primary care approaches for the treatment of sciatica: one based on matching patients to treatment using a simple tool that helps to decide on the treatment pathway most likely to help them and one based on the treatment needed as discussed and agreed by the physiotherapist and themselves. To further help with allocation concealment, participants randomised to the UC arm of the trial were seen by physiotherapists who had not carried out their detailed clinical assessment and eligibility screen for the trial. Therefore, physiotherapists in the UC arm remained blinded to both the details of the stratification algorithm and the individual patient’s sciatica group status, hence avoiding contamination between the two trial arms. It was not possible for physiotherapists treating participants in the SC arm to remain blinded. To further protect against contamination, no physiotherapists treating participants in the SC arm were involved in the treatment of participants in the UC arm. Research nurses blinded to treatment allocation conducted the minimum data collection (over the telephone) at 4 and 12 months’ follow-up for participants who did not respond to questionnaires. The risk of contamination from GPs knowing to which arm a participant was randomised was deemed to be very low. In qualitative interviews with the GPs (as part of the nested qualitative interviews), we collected data on whether or not involvement in the trial contributed to changes in GPs’ referral decisions for patients with sciatica (see Chapter 5). Initially, we planned to collect information about GP referral patterns before and during the trial, using anonymised general practice electronic records, to check whether or not trial participation influenced referral patterns for sciatica patients, but this was not technically possible to do.

Statisticians and health economists were blinded to treatment arm during the development of the statistical analysis plan (SAP) (the SAP was agreed in advance with the TSC members) and through monitoring phases of the trial, including the interim data analysis specified in the internal pilot phase of the trial. Furthermore, two statisticians performed the primary analysis of the main trial independently and both were blinded to treatment arm allocation. The trial statistician carrying out further key analyses of primary and secondary outcomes was blinded up to the point of conducting the per-protocol analysis (a sensitivity analysis). Treatment allocation was stored in a secure computer server accessible only by authorised CTU staff, for whom blinding was not relevant. For the quantitative data analysis, throughout the monitoring period, the treatment arm variable was blind dummy-coded until the key primary and secondary data had been analysed.

Follow-up

For the primary outcome, time to resolution of sciatica symptoms, data collection via text messages occurred weekly for the first 4 months for all participants, starting on the first Sunday following the participant’s randomisation at the SCOPiC trial research clinic. Then, between 4 and 12 months’ follow-up, the text message data collection changed to once every 4 weeks, or until ‘stable resolution’ of symptoms (stable resolution was defined as 2 consecutive months’ responses of ‘completely recovered’ or ‘much better’; see Outcome measures and assessments for details on the primary outcome). Once stable resolution occurred, data collection for the primary outcome via text message, beyond the first 4 months, ceased. Non-responders to the first week’s text message received a reminder text 48 hours later, and those who still did not respond were mailed a postcard the next day. Non-responders to the second week’s text message received a reminder message 48 hours later, and those who still did not respond received a telephone call from a research nurse after at least a further 24 hours. For subsequent non-response reminders, the processes described above were repeated. For those participants not providing any response using text messages, there was an option to transfer to data collection by brief telephone call with a research nurse. A small number of participants chose to receive only phone calls for collection of the primary outcome (n = 49).

The secondary clinical outcomes and health economic outcomes were collected at 4 and 12 months using participant self-completed postal questionnaires. Participants who did not respond to the postal questionnaires were sent a reminder postcard after 2 weeks of non-response. After a further 4 weeks, participants received a repeat full postal questionnaire and a short version if they had not responded by 6 weeks. If a total of 8 weeks had passed and no data had been received, the participant was contacted by a research nurse blinded to treatment allocation to collect a minimum data set over the telephone.

Quality assurance

For quality assurance purposes, we implemented monitoring procedures to ensure that all personnel involved in the trial adhered to the trial’s protocol and procedures. All physiotherapists involved in taking participant consent were observed at least once by a senior member of the research team. All physiotherapists involved in eligibility assessment were observed at least once in the research clinic. Administrators involved in the preliminary eligibility criteria checking over the telephone were also observed by a senior member of the research team. Standardised pro formas were used for all trial documentation, to minimise variation in trial procedures. We did not encounter significant problems during quality control monitoring.

Outcome measures and assessments

Baseline

Participants completed a self-report questionnaire at baseline (the questionnaire was posted to participants and they were asked to complete it and bring it with them to the clinic; if they forgot, they were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire in the SCOPiC trial clinic). Following final eligibility screening in the SCOPiC trial clinic, eligible participants completed a second questionnaire, in the SCOPiC trial clinic, prior to randomisation. Demographic data were collected via the baseline questionnaire, and baseline information on analgesic medication was collected during the clinical assessment for eligibility, and recorded on a standard pro forma. Clinical data were also collected prior to randomisation, as part of the eligibility process.

Follow-up

Follow-up for the primary outcome, time to symptom resolution, was carried out via text messages (or brief telephone calls if participants preferred this). Secondary outcomes were collected via postal questionnaires at 4 and 12 months from the baseline clinic appointment.

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcome

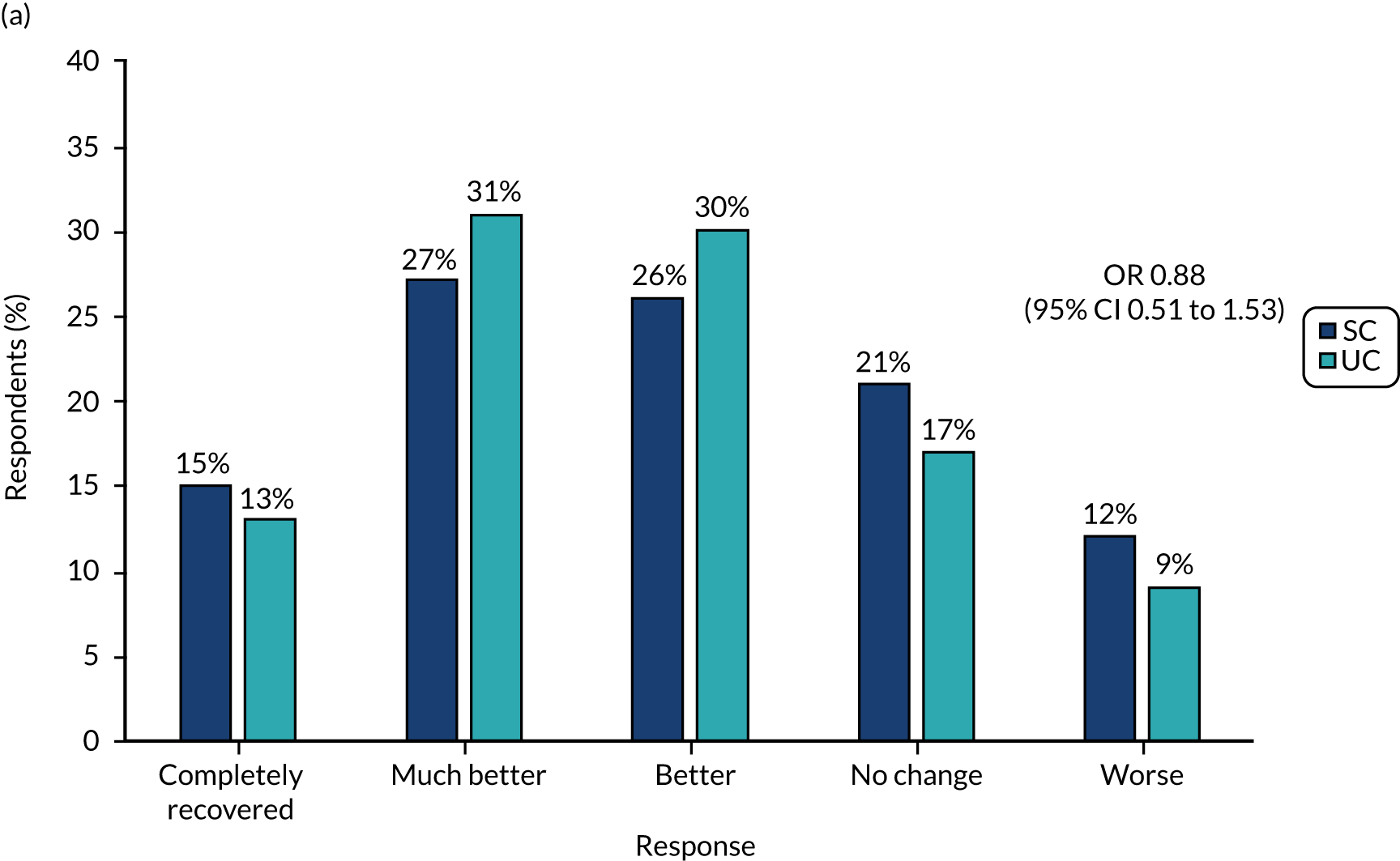

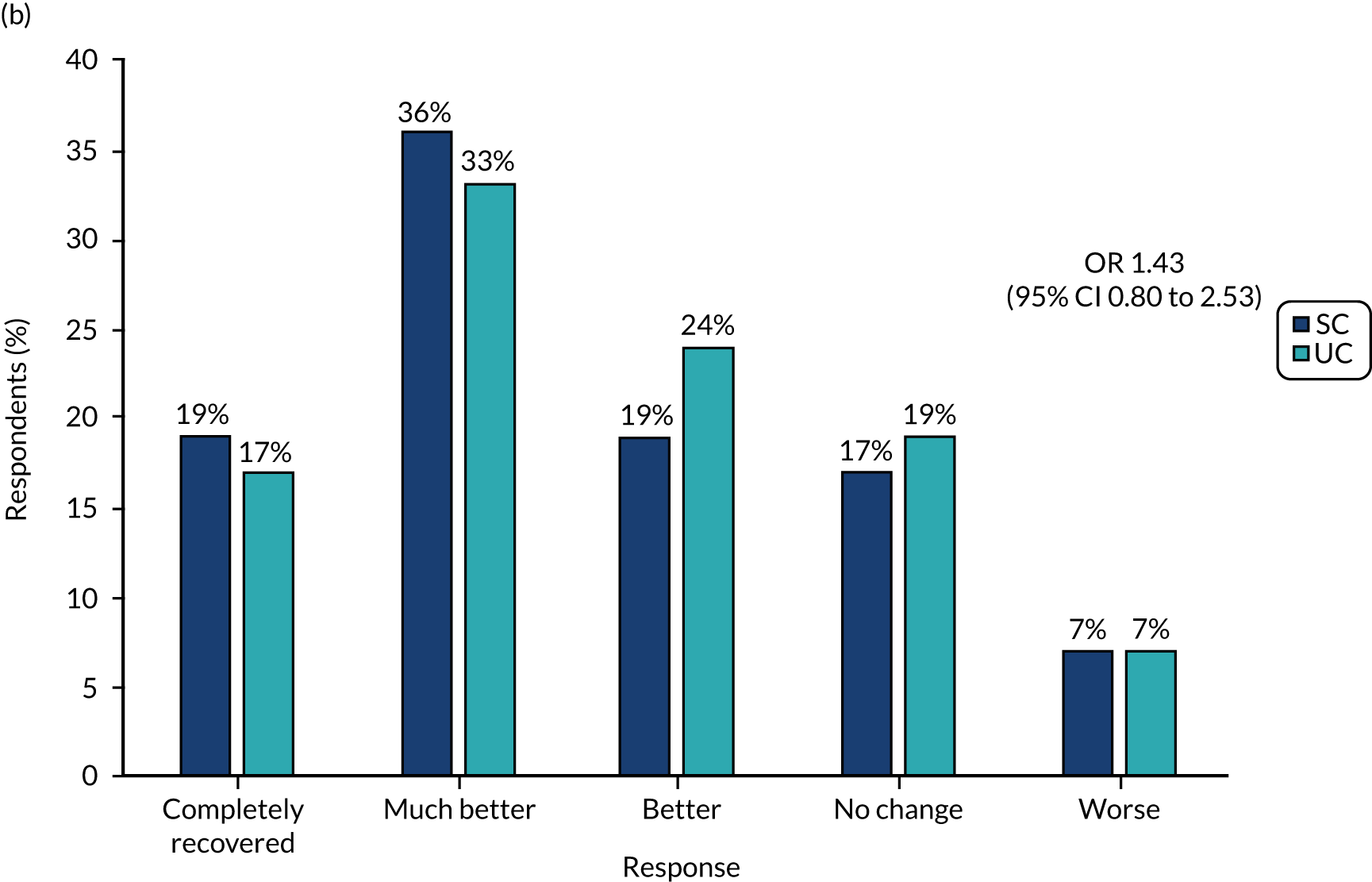

The primary outcome measure, collected with text messages, was time to first resolution of symptoms of sciatica, measured on a six-point ordered categorical scale: ‘completely recovered’, ‘much better’, ‘better’, ‘same/no change’, ‘worse’ and ‘much worse’. The scale’s anchor was a participant’s baseline symptoms when he/she attended the SCOPiC trial research clinic. The text message read: ‘Compared to how you were at the SCOPiC clinic X weeks/months ago, how are your back and leg symptoms today?’. This outcome, whereby participants are asked about the change in symptoms compared with baseline assessment, is commonly used in primary care research of musculoskeletal disorders, and was used in a trial comparing early surgery with conservative care for patients with severe sciatica. 4 Patient-reported resolution of symptoms was defined as a response of either ‘completely recovered‘ or ‘much better‘.

Secondary outcomes

We collected secondary clinical outcomes at 4 and 12 months using participant self-completed postal questionnaires, to evaluate pain intensity, function, psychological health, general health status, work status, days lost from work, work productivity loss due to sciatica, satisfaction with care and care results, and quality of life. We also collected information on adverse events (AEs). Resource use information for the duration of the follow-up period of 12 months was also collected for the health economic analysis. This included self-reported information on primary care consultations (GPs and practice nurses, physiotherapists), secondary care consultations (e.g. hospital consultants), prescriptions, hospital-based tests and procedures (investigations such as MRI and blood tests, and procedures such as spinal epidural injections and spinal surgery for sciatica), nature and length of inpatient stays, over-the-counter purchases by participants and out-of-pocket expenses. Participants were asked to distinguish between UK NHS and private provision. Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics collected, the domains measured, the measures used and the time points of measurement.

| Outcome measure | Instrument | Time points (months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Global perceived change | Six-point Likert scale | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Physical disability | Modified RMDQ for sciatica41 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sciatica symptoms | SBI42 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pain intensity (usual pain) | NRS for back and leg pain43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sleep interference | Jenkins Sleep Questionnaire44 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Risk of poor outcome | STarT Back Screening Tool34 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Anxiety and depression | HADS45 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fear of movement | TSK46 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Neuropathic symptoms | S-LANSS47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Employment | Questions on employment status and work absence (days) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Presenteeism (productivity) | Performance at work: single question with NRS response (0–10 scale) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| General health | Short Form 148 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| AEs | Identified by clinicians and through patient self-report via their questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Patient satisfaction with care and results of care | 5-point scale | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Economic measures | EQ-5D-5L49 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Health-care use questions | ✓ | ✓ | ||

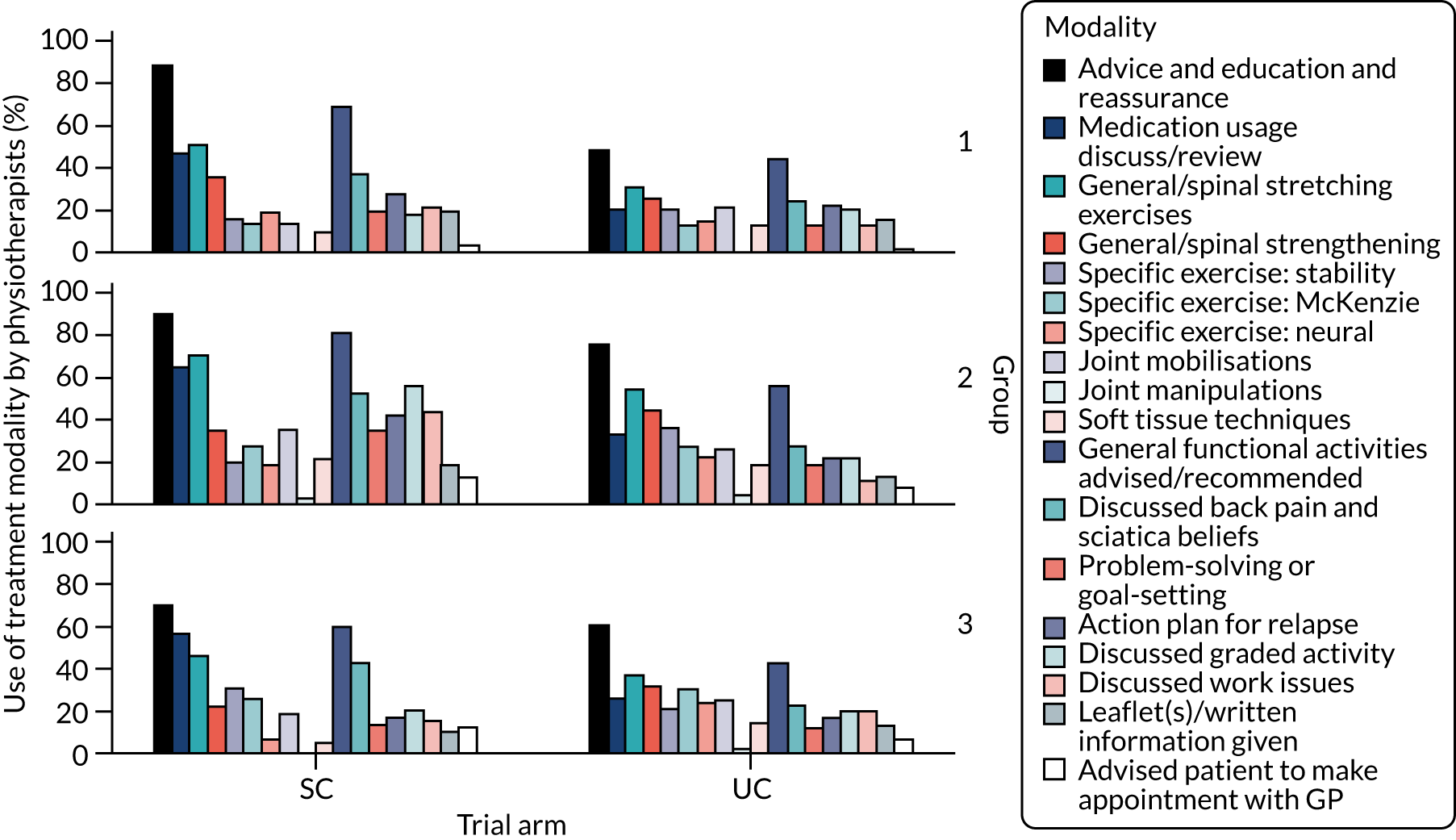

Process outcomes

Process outcomes were collected to investigate the impact of SC on service delivery for both physiotherapy and specialist spinal services. With the use of case report forms (CRFs), data were collected, in each arm of the trial, on the number of participants referred to physiotherapy services, the number of physiotherapy sessions received, treatments provided and the number of participants referred to specialist spinal services and/or secondary care settings. The timing of referral and treatment were also captured, when possible. In addition to CRFs, we captured information on health-care use from participant questionnaires and hospital record reviews from participating NHS specialist services.

Description of the interventions

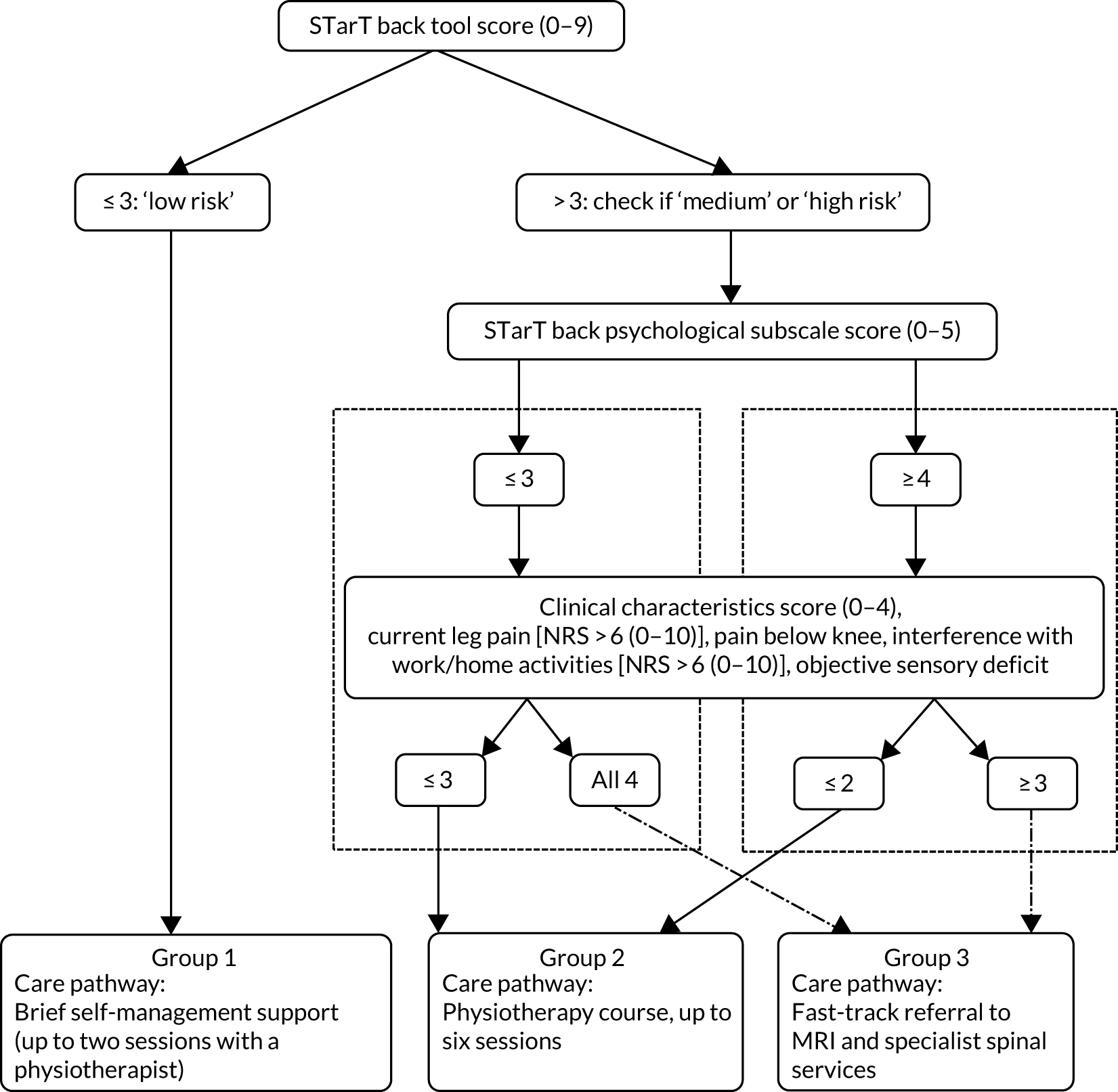

Stratification algorithm

Figure 2 shows the stratification algorithm used to direct participants’ care in the stratified arm of the trial. The algorithm utilises information on the risk of a poor prognosis from the STarT Back Screening Tool and information on factors associated with referral to spinal specialists to allocate participants with clinically diagnosed sciatica to one of three sciatica groups, each matched to a care pathway, with one of the care pathways being fast-track referral for MRI and to a consultation with a spinal specialist for opinion. We briefly describe here the decisions and methods utilised to derive the stratification algorithm. Full details of the development and internal validation of the stratification algorithm for primary care patients with sciatica are available in a separate peer-reviewed paper. 50

FIGURE 2.

Stratification algorithm for allocating patients to groups and matched care pathways.

To identify the group of sciatica participants likely to need fast-track referral to imaging tests and a spinal specialist assessment and opinion, we used data on patients with a sciatica clinical diagnosis from the Assessment and Treatment of Leg pain Associated with the Spine (ATLAS) study,10 a prospective, treatment cohort of primary care patients with back and leg pain. The ATLAS cohort included patients with symptoms of any duration and severity, and excluded patients with potential serious pathology. All patients without contraindications to MRI had the scan after their baseline clinical assessment. In the development of the algorithm, ATLAS study participants clinically diagnosed with sciatica with diagnostic confidence of ≥ 70% (as reported by the assessors) were included. The outcome definition was referral to NHS spinal specialist services (yes/no) at some point over the course of 12 months’ follow-up in the ATLAS study. Potential predictors of referral to specialist services that were informed from the literature more broadly and that were available in the ATLAS study data set comprised self-report and clinical examination findings. The selected factors were categorised into five domains: impact of condition, pain levels/symptoms, psychological factors, symptom behaviour and presentation (e.g. increased leg pain with coughing, reporting of numbness in the leg), and clinical examination findings. Logistic regression (univariable and multivariable) was used to determine the association between each factor and the outcome of referral to spinal specialist services. The factors derived from the statistical models as being most strongly associated with referral to specialist services, within each domain and overall, were discussed with clinical and research experts (epidemiologists, triallists, statisticians, spinal surgeons, spinal physiotherapy specialists, rheumatologists, pain specialists, GPs). The final list of factors thought to be most relevant to the decision to refer to spinal specialists was agreed by all clinical stakeholders, and included the following: effect of lower-back and/or leg pain (sciatica) on ability to do one’s job or ability to do jobs around the house [Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of 0–10, with a cut-off point of > 6], current leg pain intensity (NRS of 0–10, with a cut-off point of > 6), sensory deficits in a dermatomal distribution recorded during the clinical examination (yes/no) and pain below the knee (yes/no). The first three factors were derived from the statistical analyses. The binary cut-off points (NRS scores of > 6) for impact and pain intensity were considered to be reasonable thresholds for pain and functional limitations, and had face validity when considering early referral to specialists. Presence of pain below the knee was subsequently added to the list as it is considered the best proxy indicator of leg pain due to nerve root involvement;37 the clinical experts considered this to be important to combine with the other factors to guide referral decisions for patients with sciatica.

Data from the ATLAS study cohort showed that only one participant (out of 52) with a STarT Back Screening Tool score of up to 3 (out of a total of 9), indicative of low risk of poor prognosis, was referred to spinal specialist services. On the basis of that, patients at a low risk of poor prognosis (STarT Back Screening Tool score of up to 3), irrespective of clinical characteristics, were not considered for referral to specialists or for a full course of physiotherapy management. For the remaining participants, we considered a number of possibilities in terms of combinations of factors from the clinical assessment and information on risk of poor prognosis, using the STarT Back Screening Tool score, for identifying which participants with sciatica should be fast-tracked to spinal specialist services. For each combination of factors, we considered the implications for sensitivity in terms of identifying observed referrals, and feasibility and practicality in relation to use in clinical practice. For all scenarios, sensitivity/specificity, positive/negative predictive values and percentage of the sample fast-tracked were calculated. Based on the results of this analysis, participants at a medium risk of poor prognosis who had all four clinical characteristics described above, and participants at a high risk of poor prognosis with any three of the clinical characteristics, were allocated to group 3 and matched to the care pathway of fast-track referral to MRI and specialist opinion. The remaining participants were allocated to group 2 and matched with a course of physiotherapy management of up to six sessions. Sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) of the algorithm for participant allocation to the fast-track pathway (group 3) were 51%, 73% and 22%, respectively. The algorithm, applied to the ATLAS study cohort, allocated 12% of participants to group 1, 57% to group 2 and 31% to group 3.

Stratified care

Group 1

Participants in this group were expected to have an overall good prognosis and to require only brief support for self-management. However, in contrast with participants with non-specific LBP who have a low risk of poor outcome (according to the STarT Back Screening Tool), patients with sciatica tend to have more severe symptoms; therefore, we decided to offer a brief intervention delivered by physiotherapists for this group of participants. The recommended physiotherapy treatment input was to provide up to two 30-minute sessions, with a target of delivery of 4 weeks, in order to permit review when needed, but no further sessions were advised. The biopsychosocial paradigm guided the care delivered by the physiotherapists, which was tailored to the individual participant’s presentation and specific needs to support self-management and reduce disability. This included advice, information, appropriate reassurance and education about sciatica and focused on the expected good outcome without the need for further tests or investigations. It reinforced the maintenance of activity levels, including return to work, when appropriate; lifestyle advice such as general activity and weight control, as appropriate; and guidance on self-management and the management of future flare-ups of sciatica. Pain relief and discussion about appropriate medication were also part of the treatment, and any suggested changes in analgesia were communicated to the participant and their GP for consideration. A sciatica booklet, developed from existing educational materials, was given to participants along with an information sheet of local contacts for exercise venues, such as swimming pools, exercise classes and physical activity opportunities.

Group 2

Participants allocated to this group received a course of physiotherapy treatment, tailored to their individual needs. This matched treatment package was delivered in up to six sessions of 30 minutes each, over a suggested period of 6–12 weeks. The number and content of treatments were tailored to each participant’s individual needs. The main aims of treatment were to reduce pain and disability and address psychological obstacles to recovery. The STarT Back Screening Tool and clinical assessment findings guided the treating physiotherapist in targeting management towards the physical and psychosocial factors that were found to be particular problems for each patient. Management plans included some or all of the following: advice, explanation, reassurance and education, medication review and advice (suggestions on analgesia were communicated to the participant and their GP for consideration), exercise (e.g. McKenzie ‘directional preference exercises’, muscle-strengthening stability exercises, general fitness and mobility exercises, and guidance on pacing using graded activity principles as applicable), manual therapy techniques (joint and/or soft tissue), advice about and plans for return to normal activities and work as appropriate, and guidance on self-management and the management of future flare-ups. Psychological obstacles to recovery, such as fear-avoidance beliefs, pain-related low mood and distress or anxiety, unhelpful or erroneous beliefs about back pain and sciatica, and catastrophising were also addressed as part of the physiotherapy treatment. The sciatica booklet and information sheet of local contacts for exercise venues, as mentioned in Group 1, were also given to participants in group 2.

Care delivery for groups 1 and 2

The care pathways for groups 1 and 2 were delivered in primary care by NHS physiotherapists. Participants were able to access care via their GP, as per normal. Physiotherapists treating participants in group 1 were able to break protocol and see a participant for more than the recommended two treatment sessions, or refer them to specialist spinal services if they strongly felt that this was clinically necessary. Similarly, physiotherapists treating participants in group 2 could refer a participant to specialist spinal services if it was deemed clinically necessary. Protocol deviations first had to be discussed with the team’s consultant spinal physiotherapist and co-author (KK), and documented.

Group 3

Participants allocated to group 3 were fast-tracked for lumbar spine MRI, providing there were no contraindications to MRI, and for an appointment at the spinal interface service to see a specialist for further assessment and opinion about management. The results and report of the MRI were available to the specialist at the time of the clinic appointment. All MRI was reported by an NHS consultant radiologist. The participant was expected to have the MRI and their appointment at the spinal interface service within 4 weeks from randomisation. Participants with contraindications to MRI were still referred to the spinal interface services to see the spinal specialist, who would decide on alternative imaging tests as necessary.

In the SCOPiC trial, the fast-track pathway to the spinal interface services was for a specialist assessment and opinion about clinical management. After a participant’s assessment at the spinal interface clinic, any referrals required to other services, such as spinal orthopaedics, injections, pain clinic or physiotherapy services, were at the discretion of the treating clinician. The waiting time to treatments offered by those services could not be influenced by the fast-track pathway; however, by ensuring that suitable participants joined these waiting lists earlier than in the UC arm, participants were expected to have these treatments (if they were suitable for them and they wanted to have them) sooner than participants in the UC arm. The spinal interface services in the participating NHS services were specialist clinics at the primary/secondary care interface. In the centres participating in the SCOPiC trial, these services are predominantly delivered by extended scope spinal physiotherapy specialists, who have close links with secondary care spinal services, such as orthopaedics. Specialist physiotherapists working in the spinal interface services collaborating in delivering the SCOPiC trial assessed participants allocated to group 3.

Non-stratified usual care

The control arm of the trial was based on non-stratified primary care and was delivered by different physiotherapists to those who delivered the SC arm of the trial. Patients attending the research clinic and randomised to the UC arm were seen by a physiotherapist in the clinic for an initial physiotherapy session. Then the physiotherapist, in consultation with the patient, decided on further management. Options included discharge back to the care of their GP, referral to community physiotherapy services for further treatment or referral to specialist spinal services. As mentioned previously, no stratification tool was used in the physiotherapist decision-making and delivery of treatment for patients in the UC arm. The physiotherapist was aware of the information on the management options stated by the GP, but did not have to follow the recommendation.

Training and auditing

All personnel (i.e. administrators, trial physiotherapists for intervention and control arms, research nurses) involved in the trial received training in the trial’s procedures and documentation. For audit purposes, treatments delivered to participants in the intervention and control arms of the trial were recorded in a standardised format on CRFs. The information recorded included dates of start and completion of treatment, number of treatments received and types of interventions (i.e. exercise, advice, manual therapy) and the physiotherapist’s clinical grade (NHS Agenda for Change banding). Protocol deviations in both trial arms were recorded and reported. Physiotherapy record reviews were conducted in the cases of missing or incomplete CRFs for both SC and UC participants.

Details of the care of participants in group 3, the fast-track pathway (e.g. referrals for physiotherapy or surgical or injection procedures), were collected from the clinical letters generated in the specialist clinics for each participant and recorded on CRFs. Following the 12-month follow-up, data on treatments actually received for sciatica and the time frame of any interventions delivered were supplemented by reviews of the hospital records at the participating NHS trusts whenever possible. Given that participants could choose to have treatments in other NHS sites, we anticipated that we would not be able to retrieve hospital record data for all participants.

Physiotherapists’ training processes

Physiotherapists who participated in the trial attended training workshops prior to the start of recruitment and treatment. All participating physiotherapists had expertise in assessing and treating musculoskeletal problems, including previous training in the assessment and management of psychological obstacles to improvement, as part of their normal practice. Those delivering the treatment session in the SCOPiC trial clinic for participants in the control arm (eight physiotherapists at NHS band 6, and two at grade 7) took part in a half-day workshop that focused on trial procedures, the importance of avoiding contamination between trial arms and the completion of trial CRFs.

Those physiotherapists involved in the assessment of patients’ eligibility for the SCOPiC trial, who determined the sciatica group status of participants (according to the stratification algorithm) and who delivered matched care pathways in the SC arm attended 3 days of training. Nine physiotherapists at band 6, five at band 7 and six at band 8a participated. Training focused on the standardised assessment to identify sciatica patients for participation in the trial, the stratification algorithm, taking informed consent, the delivery of evidence-based physiotherapy interventions in line with the biopsychosocial model of care and the procedures of the trial, the importance of avoiding contamination between arms, and details of how to complete the trial’s CRFs.

The training was supplemented by comprehensive written material on the trial procedures, practice guidelines and evidence-based management options for the assessment and treatment of patients with sciatica. To maximise protocol fidelity, physiotherapists providing the matched care pathways for participants in groups 1 and 2 had support as required (face to face, over the telephone or by e-mail), provided by the research team’s spinal physiotherapy specialists from the NHS spinal interface services participating in the trial. One refresher training session of 3 hours was held approximately 4 months after the trial commenced.

Adverse events

It was considered unlikely that participants in the SCOPiC trial would be at risk of serious adverse events (SAEs). The trial investigated the approach of matching appropriate care pathways to three groups of sciatica patients. The treatments themselves, in each of the three care pathways, were all part of routine clinical practice. SAEs were defined as those that resulted in death, unscheduled hospitalisation or significant disability as a result of the trial’s interventions or procedures. Any SAEs were documented in CRFs and reported immediately to the trial team. Any SAEs that were considered to be related to the trial procedures or interventions were reported to the Research Ethics Committee by the chief investigator within 15 days of the chief investigator becoming aware of the event, and to the TSC and DMC. We also documented SAEs during hospital records reviews, carried out as part of the trial’s data collection procedures.

Possible potential AEs included worsening of symptoms, for example as a result of an exercise programme prescribed by the physiotherapist. Physiotherapists treating participants in the SCOPiC trial were asked to report potential AEs on the CRFs or to the trial team. Participants were also asked about AEs in the follow-up questionnaires.

Sample size justification

A total sample size of 470 participants was required to test for superiority of SC compared with UC, to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of between 1.4 and 1.5 for time to resolution of symptoms (primary outcome) with 80–90% power (given a two-tailed significance level of 5%), assuming an event (resolution) rate of ≥ 60%, a 20% drop-out rate and intraclass correlation (ICC) for clustering by physiotherapist at the level of 0.01 and allowing for a coefficient of variation in physiotherapist cluster size of 0.65 (Eldridge et al. 51). The sample size allows for a least conservative HR of 1.4 in median survival times with 90% power (if all participants in the trial are recovered by the 12-month follow-up and ICC for physiotherapist effect is < 0.001), and a most conservative HR of 1.5 in median survival times with 80% power (if 60–65% of participants in the trial are recovered by the 12-month follow-up and ICC for physiotherapist effect is 0.01, given an average cluster size of around 12–15).

In this context, a HR of > 1 (denoting a higher ‘successful’ event rate) is a positive outcome.

The sample size of 470 would also provide > 80% power to detect a ‘small’ to ‘moderate’ standardised mean difference (effect size) of 0.3552 between the two trial arms in respect of sciatica-related physical disability [measured using the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), a key secondary outcome], at the 12-month follow-up, allowing for physiotherapist effect and 20% attrition. The trial was not powered to detect differences between the sciatica groups between the trial arms.

Internal pilot phase

The internal pilot phase of the trial was designed to assess participant recruitment and follow-up rates over the first 8 months of recruitment; the success of general practice recruitment and retention; the success of physiotherapy site recruitment, including training and engagement; adherence to the treatment protocols; the proportion of participants allocated to each of the three groups according to the stratification algorithm; the time to MRI and specialist opinion for those in the fast-track pathway (group 3); the event rate of the primary outcome; and rate of missing data (text messages) for the primary outcome up to the 4-month follow-up for all participants recruited during the 8 months of the pilot trial phase.

The following were set as criteria for progression to the main trial from the internal pilot phase, and were agreed with the DMC and TSC:

-

recruitment rate of ≥ 70% of that anticipated; specifically, ≥ 90 patients would need to be recruited over the first 8 months of recruitment (where 130 would have been expected across the centres, taking into account staggered general practice recruitment and set-up)

-

overall loss to follow-up including non-response and dropouts (e.g. withdrawals, deaths, departures) in the primary outcome measure (resolution of symptoms) not exceeding 25% (based on 4 months’ follow-up of participants recruited during the first 7 months).

In the first success criterion, the expected number of 130 participants recruited in the trial for the duration of the internal pilot phase was based on the total number of 470 adults who were to be recruited from approximately 30 general practices over a 22-month recruitment period (or approximately 0.7 participants recruited per practice per month). Recruitment of centres was staggered; active recruitment was expected to start with the first centre (North Staffordshire), from five general practices, during the first month of recruitment, then increase at the first centre with an additional 10 practices by end of the second month. Recruitment would then start at the second centre (North Shropshire) from five practices by end of the third month, and increase at the second centre with an additional 10 practices by end of month 4, with full patient recruitment thereafter. Therefore, expected patient recruitment was (practices × months recruiting in first 8 months × recruitment rate):

The internal pilot did not involve formal interim analysis of between-group effects on the primary or any other outcomes. A review of the internal pilot phase data was undertaken by the Trial Management Group (TMG) and shared with the DMC, which reported their recommendations on progression to the TSC and funder.

Data management

Databases

Electronic data for the trial were stored in a Microsoft SQL Server (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database, hosted in a secure infrastructure at Keele CTU. Access to patient-identifiable data was regulated using predefined roles and privileges, and restricted views of the data ensured that authorised trial team members could see only the data required to carry out their role. Data access and entry was fully auditable within this system.

Data verification

Data-checking was carried out on all variables to identify data entry errors and missing data. Any identified errors were cross-checked against returned questionnaires. All manually entered data were verified through a random 10% double-entry validation process (across all returned baseline and follow-up questionnaires). The data entry was considered valid if complete agreement of data entry was verified across ≥ 90% of the (randomly chosen) test questionnaires and if any errors were spread across several variables (as opposed to being present on certain variables). In the case of consistent errors limited to one or a few variables, the team investigated and put in place an appropriate strategy for data entry for the variable(s) in question. If > 10% of questionnaires had one or more data entry errors, then necessary training and re-entry of data were carried out (and further verification checks put in place). All discrepancies were investigated and corrected prior to the final analysis.

For the primary outcome, all data from the text responses were electronically transmitted to the secure patient database. Any telephone responses were manually entered into the patient database by one assessor, blind to intervention allocation.

Missing data

The number of missing data for the primary outcome measure (perceived change in symptoms) was reported by trial arm. Primary data were utilised to the point of ‘resolution of symptoms’ (’completely recovered’ or ‘much better’) or censoring. Participants with no available outcome data were ‘right-censored’ at week 1, and withdrawals/dropouts were ‘right-censored’ on the day they last provided data. In the primary analysis, any missing primary outcome data prior to a recording of ‘resolution of symptoms’ were treated as indicative of no ‘resolution’ of symptoms.

The degree of missingness of primary outcome data was assessed by calculating two statistics, stratified by trial arm. First, the percentage of complete cases (those patients providing full data up to the point of resolution of symptoms or the end of the follow-up period) was reported. Second, we derived the completeness of follow-up (expressed as a percentage): the total observed person-time follow-up relative to the potential person-time follow-up. 53 Both statistics were assessed against baseline characteristics to check the missingness pattern.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted and reported following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 54–56 The primary analysis was by ‘intention to treat’ (ITT), with analysis being carried out as per randomised allocation.

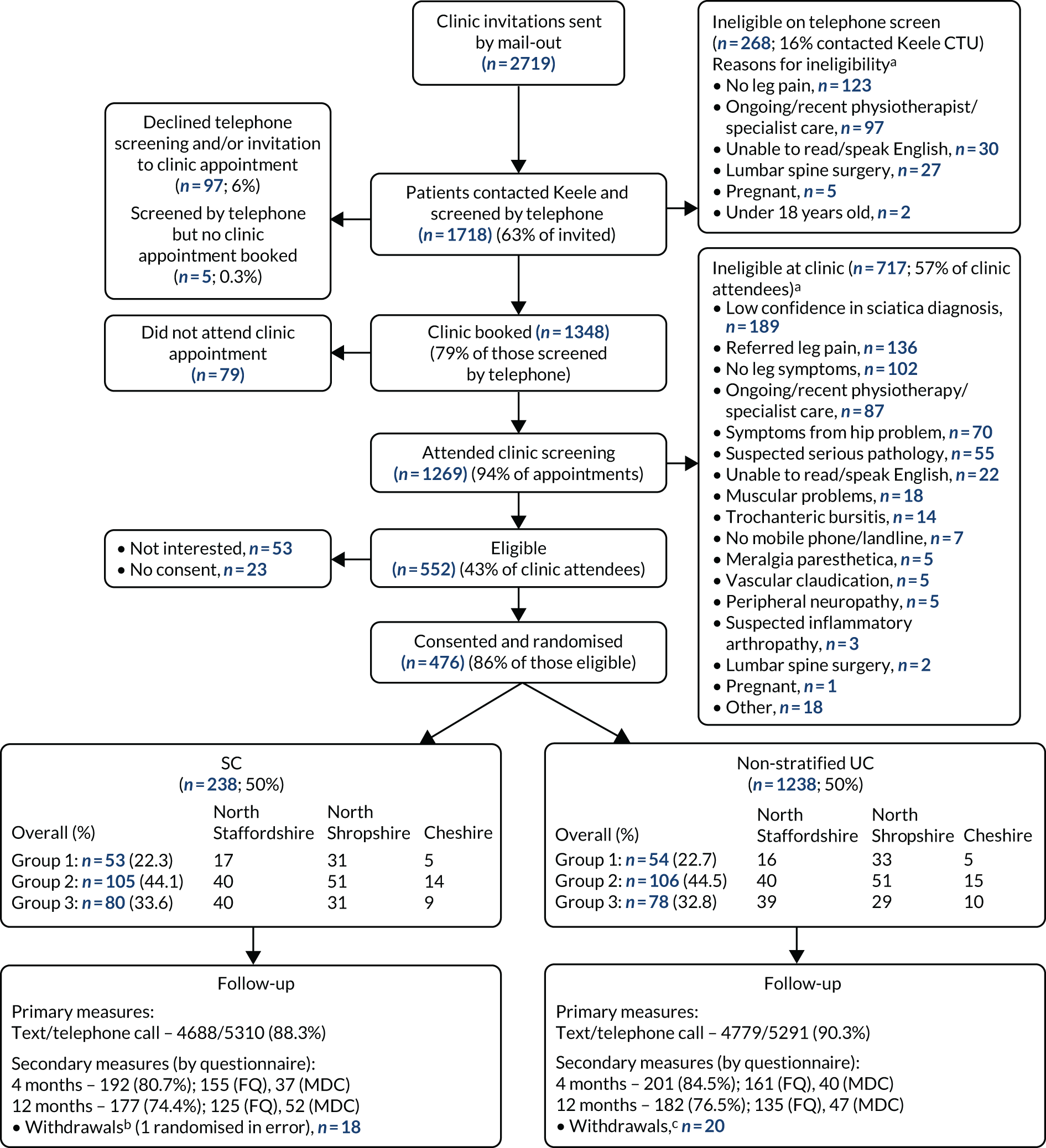

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram

The CONSORT flow diagram shows the numbers and percentages of participants recruited to the trial. It gives the details of preliminary and full eligibility assessment and exclusion reasons at each stage, details the numbers (and percentages) of participants in the two arms of the trial and according to sciatica group (1, 2 or 3) and the follow-up numbers, including the numbers providing data via full questionnaires and via minimum data collection processes.

Baseline data analyses

Participants are described by trial arm with respect to baseline sociodemographic and health-related characteristics (including randomisation stratification variables). Numerical variables are summarised by their mean values [and standard deviation (SD)] or median [and interquartile range (IQR)], depending on skewness of the distribution. Categorical variables are summarised through presentation of their frequency counts and per cent per category (calculated using the number of participants for whom data were available as the denominator). There are no tests of statistical significance of baseline variables between trial arms.

At the suggestion of the TSC, we included comparisons, at baseline, of differences in group allocation (using the stratification algorithm) numbers (percentages) by trial arms, between the three recruitment centres (North Staffordshire, North Shropshire/Wales and Cheshire), by cross-tabulating group by recruitment centre. At the TSC’s suggestion, to explore reasons for any differences, we examined, first, the association between group and socioeconomic status of the participants from each centre (based on the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification57 derived from the job title), and second, area-level deprivation of the participants in each centre.

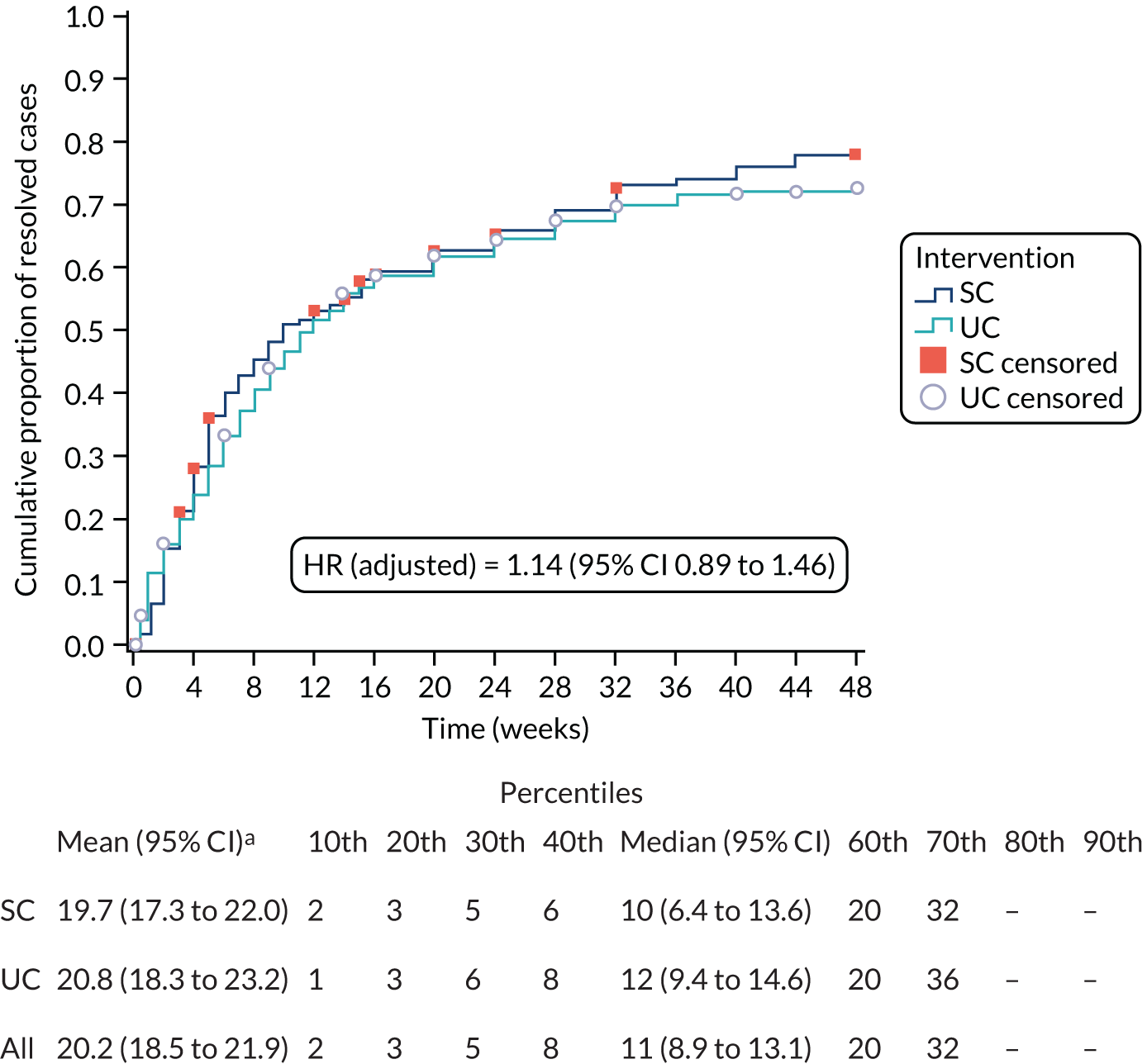

Primary analysis

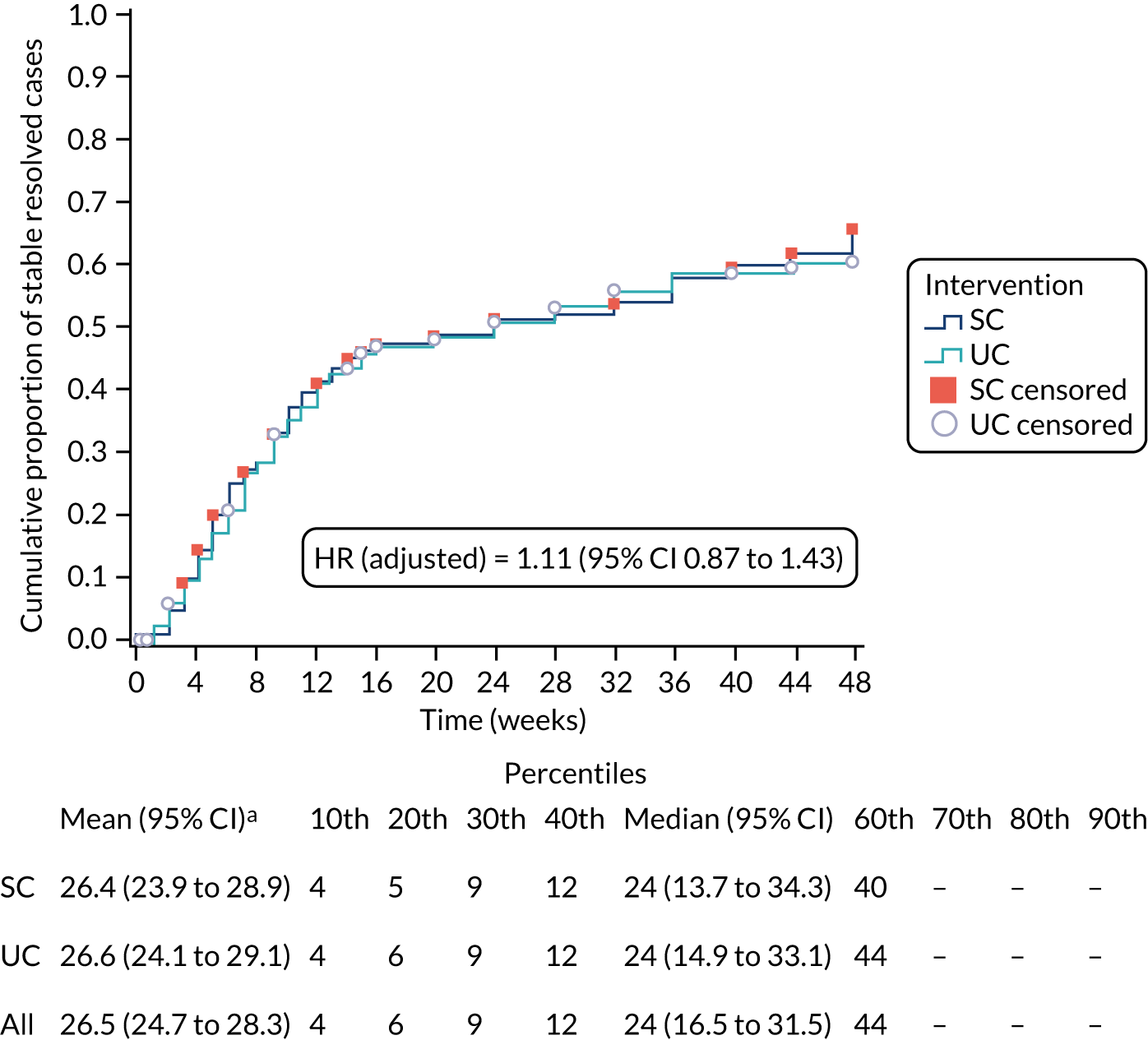

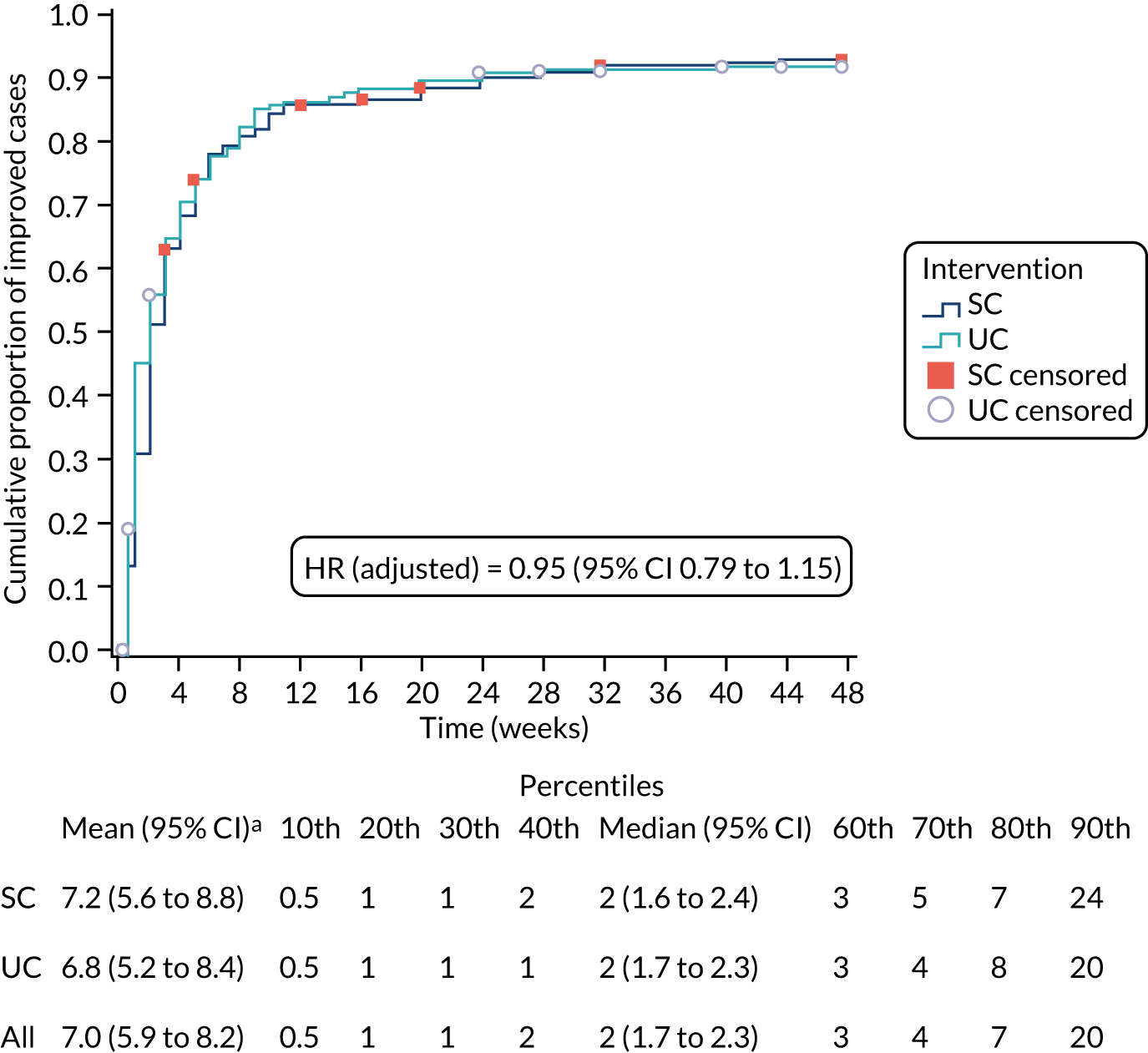

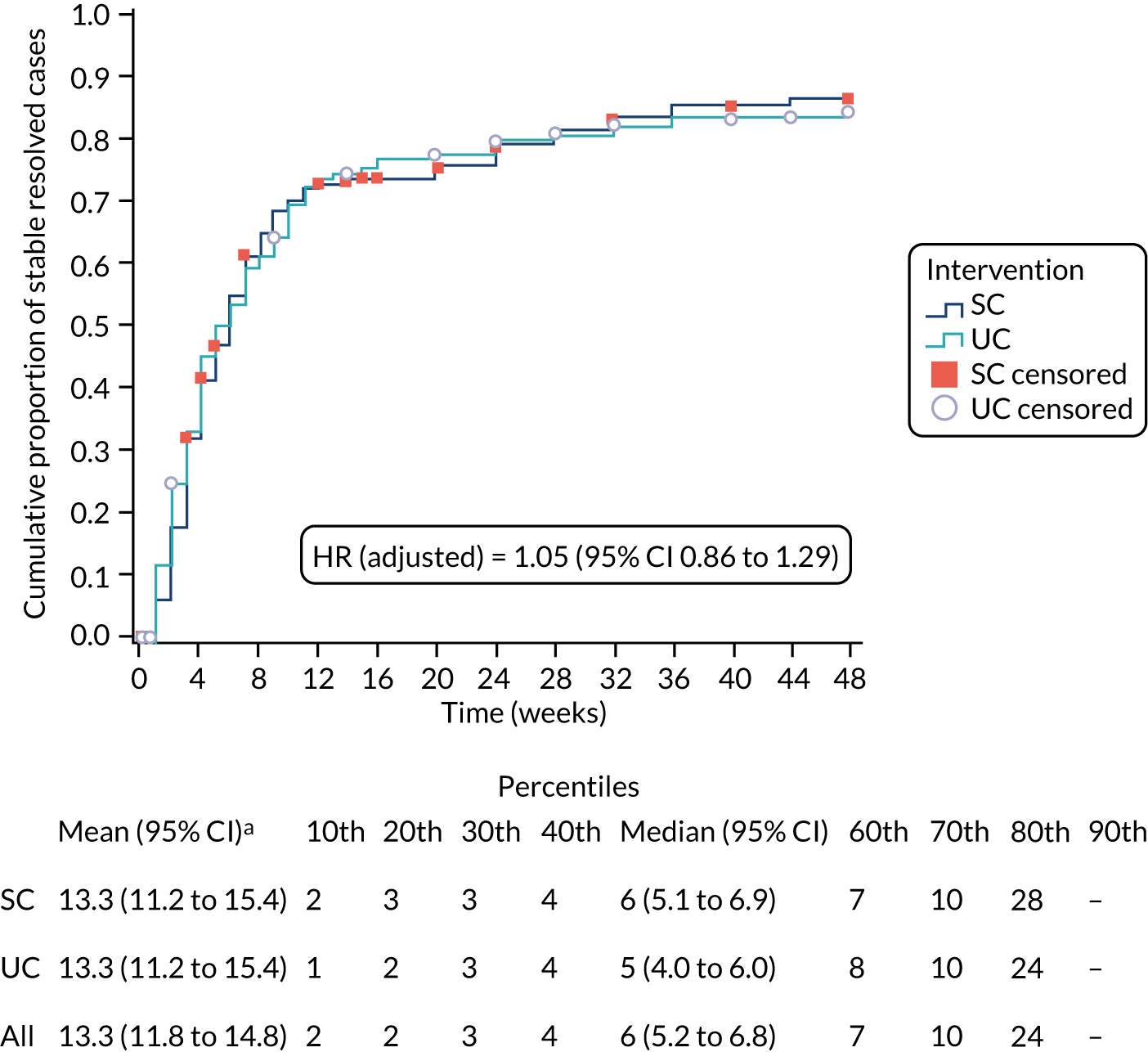

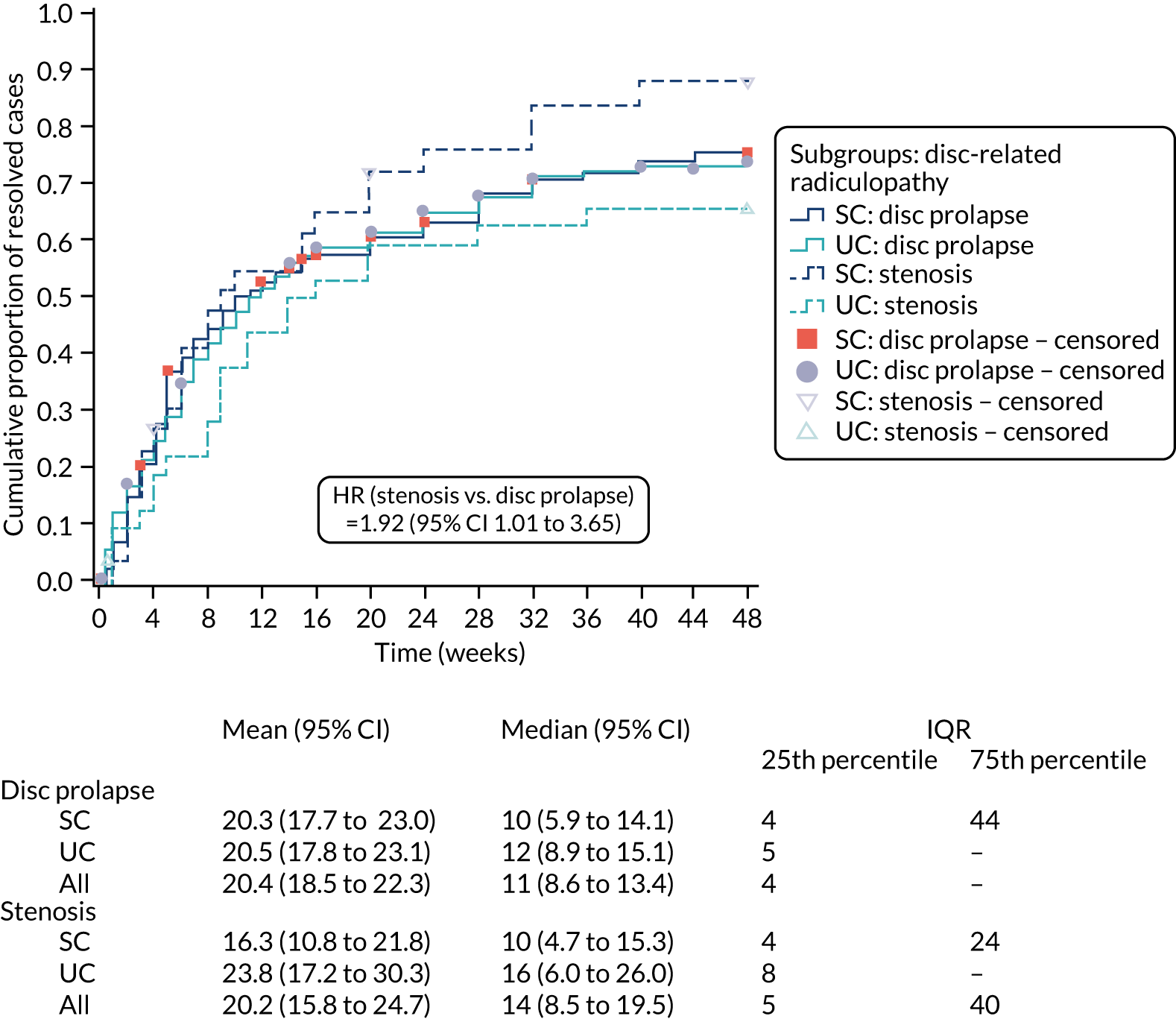

The primary analysis was a time-to-event analysis comparing the times to self-reported resolution of symptoms (’completely recovered’ or ‘much better’) between stratified care and usual care arms over 12 months of participant follow-up. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis estimated the time from randomisation until reporting of first resolution of sciatica symptoms. A life-table review was also carried out to show cumulative event rate over discrete periods. Participants who dropped out of the trial through active withdrawal were censored at the time interval of occurrence, whereas participants who did not respond at any time point continued to be followed up until the point of any notification of withdrawal. From the Kaplan–Meier analysis, we derived and compared the relative mean and median survival times of the two trial arms. A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was carried out comparing the time to resolution between trial arms by estimating the HR for the rate of resolution along with 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates (and corresponding p-values), adjusted for centre, sciatica group (stratifying variables) and pain duration (fixed effects), and accounting for clustering by physiotherapist (frailty/random effect). A p-value of < 0.05 (two-tailed), based on the Wald test statistic, signified rejection of the null hypothesis of no difference in the rate of recovery across time between the two trial arms. A p-value of < 0.05 along with a HR of > 1 indicated a statistically significant shorter time to recovery (and increased recovery event rate) for the trial arm (SC) than for the control arm (UC). By contrast, a statistically significant p-value (p < 0.05) with a HR of < 1 indicated a (statistically) significantly longer time to recovery for the trial arm (and lower recovery event rate) than for the control arm. The primary analysis was double-analysed by two statisticians working independently (from the source data) following the final agreed SAP [with any differences resolved through consensus agreement and involvement of a third independent statistician (blinded to treatment arm allocation), if needed].

Secondary analysis

Intention-to-treat analyses of between-group differences in secondary outcomes at 4 and 12 months were carried out using longitudinal mixed-effect regression models, as appropriate to the outcome data being analysed (linear regression for numerical measures and logistic regression for categorical measures), adjusting for centre, group (stratifying variables) and pain duration (fixed effects), and accounting for clustering by physiotherapists (random effect). Time-by-trial arm interactions were included, as well as time-by-(baseline) covariates to account for potential attrition bias. Descriptive summaries of mean scores and frequency counts or per cent (as appropriate to the data) are presented for the two trial arms. For the between-trial arm comparisons, mean differences (numerical outcomes) and odds ratios (ORs) (categorical outcomes) are presented, along with 95% CIs and p-values for the test of statistical association.

Per-protocol analysis

Participants in the SC arm who did not receive the matched care pathways were excluded; the remaining sample formed the per-protocol analysis. The physiotherapy session at the initial research clinic was not included in the calculation of total number of physiotherapy contacts. We defined protocol violations or deviations for the participants allocated to the SC arm as follows: (1) those allocated to group 1 who received more than two physiotherapy treatment sessions, (2) participants allocated to group 2 receiving fewer than three physiotherapy treatment sessions, (3) participants allocated to group 3 not referred to (or not attending) spinal specialist services and (4) participants allocated to groups 1 or 2 and referred to spinal specialist services.

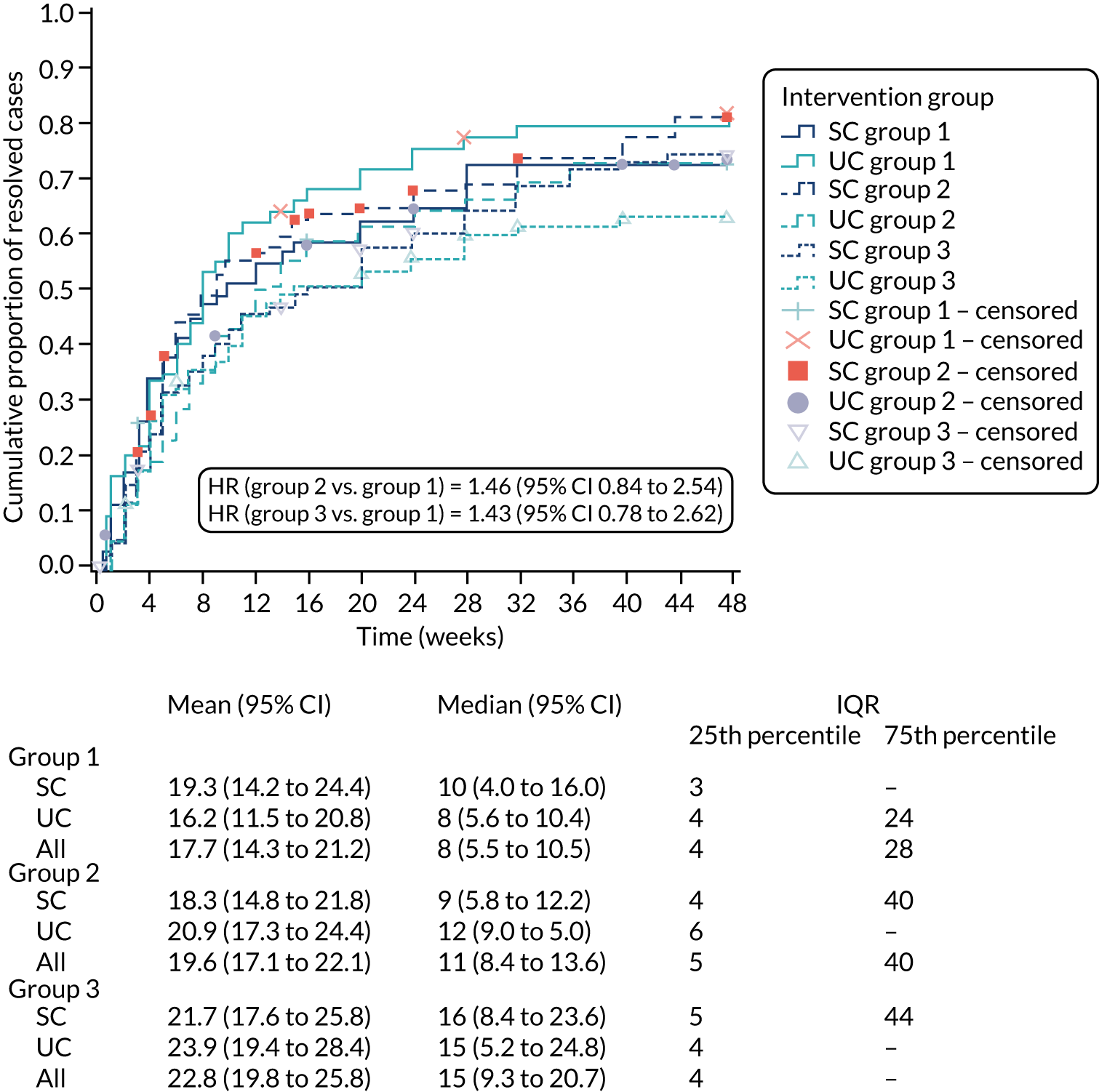

Subgroup analyses

Two subgroup analyses were prespecified in relation to re-analysis of the primary outcome: (1) treatment by group evaluation (SC/UC by sciatica groups 1, 2 and 3) and (2) treatment by disc-related sciatica/stenosis ascertained by clinical assessment in the SCOPiC trial research clinic (SC/UC by clinical diagnosis of disc prolapse/stenosis). Descriptive statistical summaries were provided through mean and median time to resolution per trial arm per participant-specified subgroup. The adjusted Cox proportional hazards frailty model was repeated including additional interaction terms for trial arm (SC/UC) by subgroups within the models. Tests of statistical significance were obtained from the p-values for the interaction term for the product of subgroup variable by treatment arm within the Cox model.

Sensitivity analyses

A number of prespecified sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome were carried out to test the rigour and robustness of the main evaluation through the following evaluations:

-

Alternative definitions of good outcome. We used three separate classifications of the self-report data on resolution of symptoms from the text messages based on ‘stable resolution’, ‘improvement’ and ‘stable improvement’. The primary definition of patient-reported resolution of symptoms was defined as a first response of either ‘completely recovered’ or ‘much better’. Sensitivity definitions comprised (1) two consecutive recordings of ‘completely recovered’ or ‘much better’, which was considered indicative of ‘stable resolution’; (2) first response of ‘completely recovered’, ‘much better’ or ‘better’, which was considered indicative of ‘improvement’; and (3) two consecutive recordings of ‘completely recovered’, ‘much better’ or ‘better’, indicative of ‘stable improvement’.

-

Alternative assumptions regarding missing data. For the primary evaluation, missing data were assumed to be synonymous with non-recovery and event definitions were based on ‘recovery’ at the first point of a positive response. Any missing data immediately preceding this response were assumed to be indicative of ‘non-recovery’. Sensitivity analyses set the time interval of recovery as the mean time between the last patient’s response (indicating ‘non-resolution’) and the time at which ‘resolution’ was first classified (for different classifications for the event as noted above). More relaxed sensitivity analyses took the contrary view on missingness, in which it was equated to, and imputed as, an event had occurred, that is ‘resolved’ or ‘improved’ case.

-

Alternative assumption regarding interval-censoring. As we knew only the interval of time during which the resolution occurred and not the exact time (especially after the first 16 weeks, when outcome data were collected monthly rather than weekly), further time-to-event sensitivity analyses were carried out to estimate between-arm comparison of HR that allowed for both left and right censoring through interval-censoring analysis.

-

Alternative (parametric) modelling. Weibull, exponential and log-normal distributions58,59 were considered instead of the Cox proportional hazards approach.

-

Alternative (non-parametric) testing. The log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test, Breslow (Generalised Wilcoxon) and Tarone–Ware tests were carried out.

-

Analysis of groups of participants who completed follow-up (not including censoring) and per-protocol analysis, as previously outlined.

Assumption-checking

For the evaluation of the primary time-to-event analysis, the Cox regression model assumption of proportional hazards was examined in two ways. First, by assessment of the graphs of the survival curves, and, second, through inclusion of a time–trial arm interaction in the regression model, with statistical significance of this term signifying an important deviation from the proportional hazards assumption. In the event that the proportional hazards assumption was not met, greater emphasis on front-line testing would be given to the distribution-free, non-parametric log-rank test result.

For the secondary outcomes, we examined the normality of the residuals in respect of the linear models (in the event of any reasonable violation, we planned to use a suitable data transformation function). In the longitudinal mixed models, we explored different covariance structures to assess for the best goodness-of-fit by comparing likelihood with Bayesian Information Criterion.

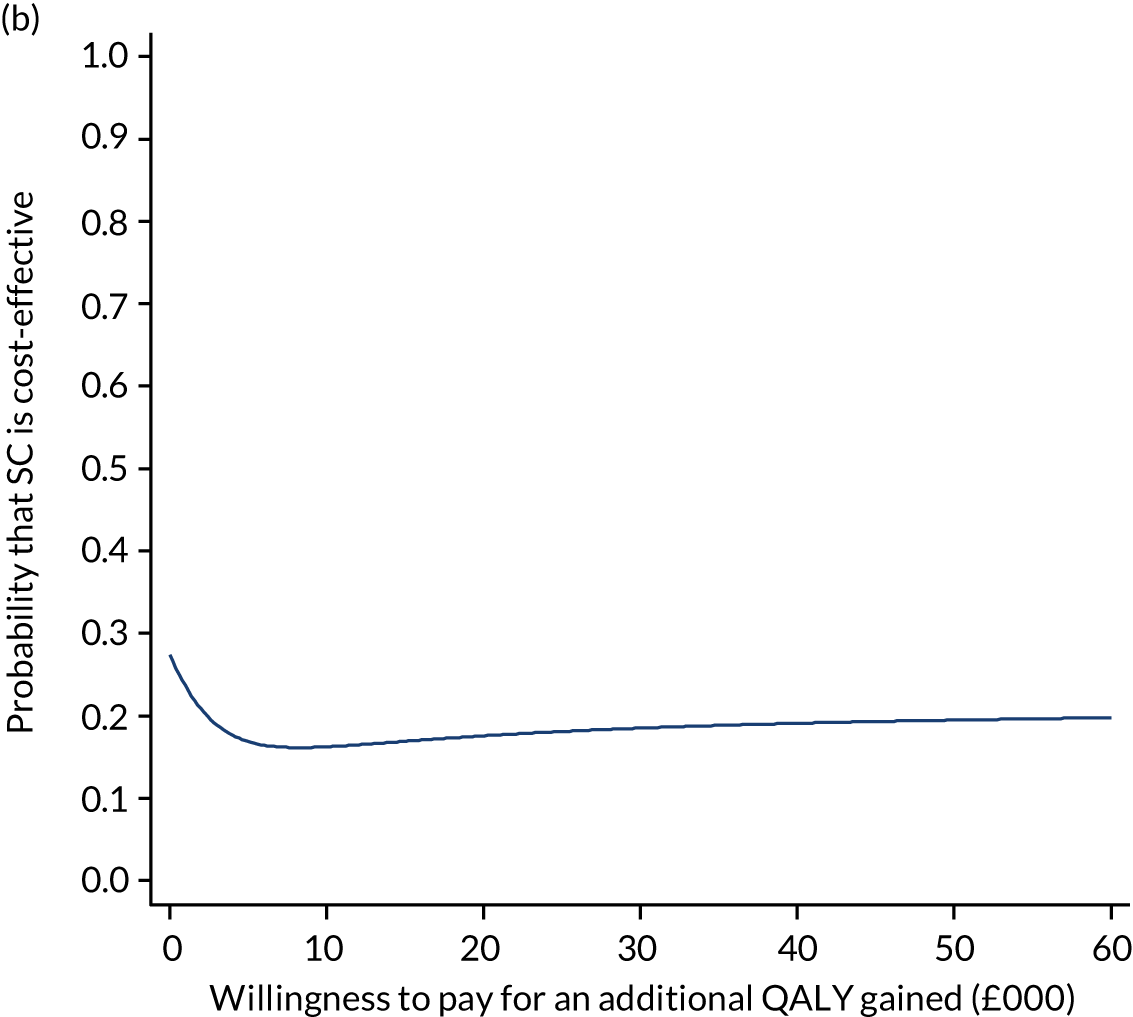

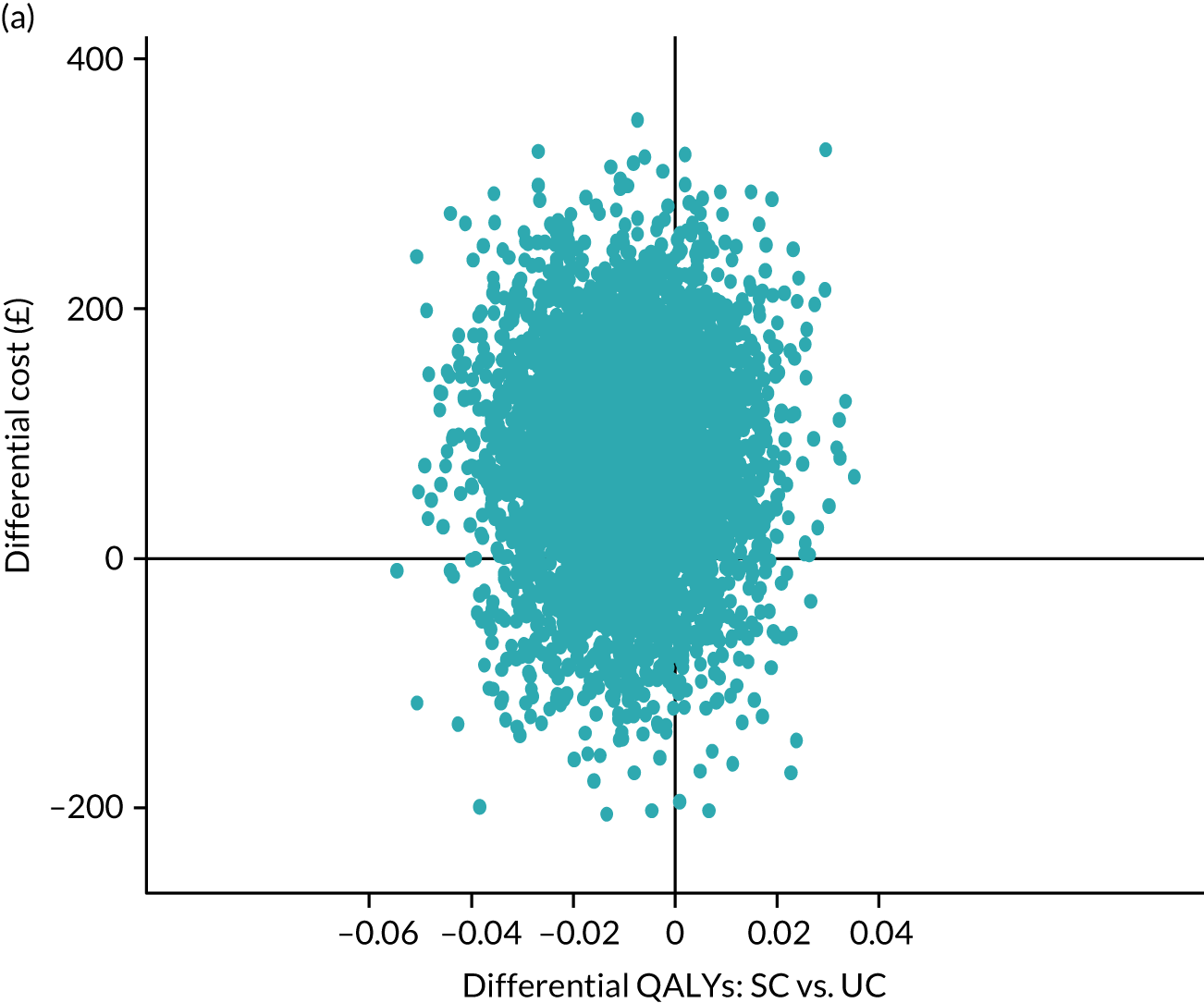

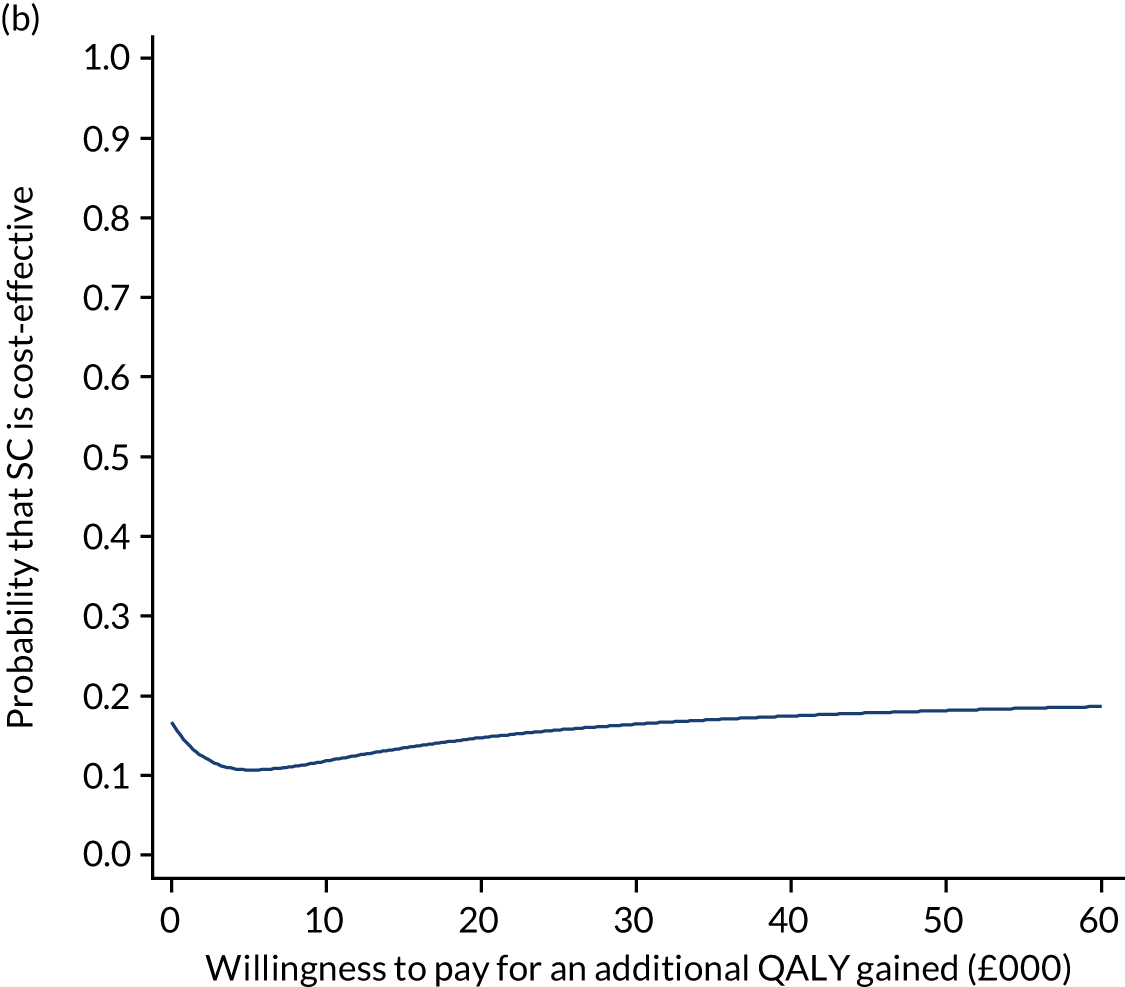

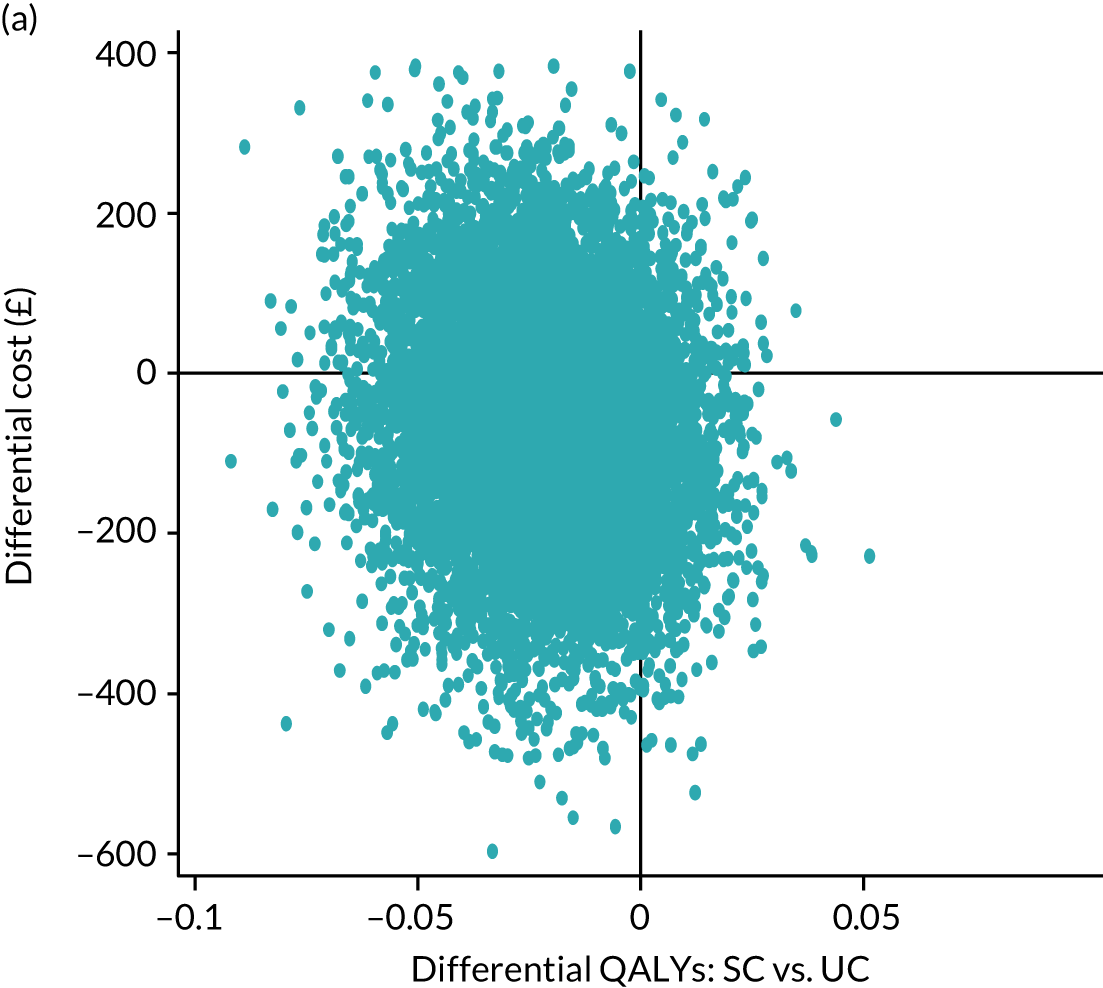

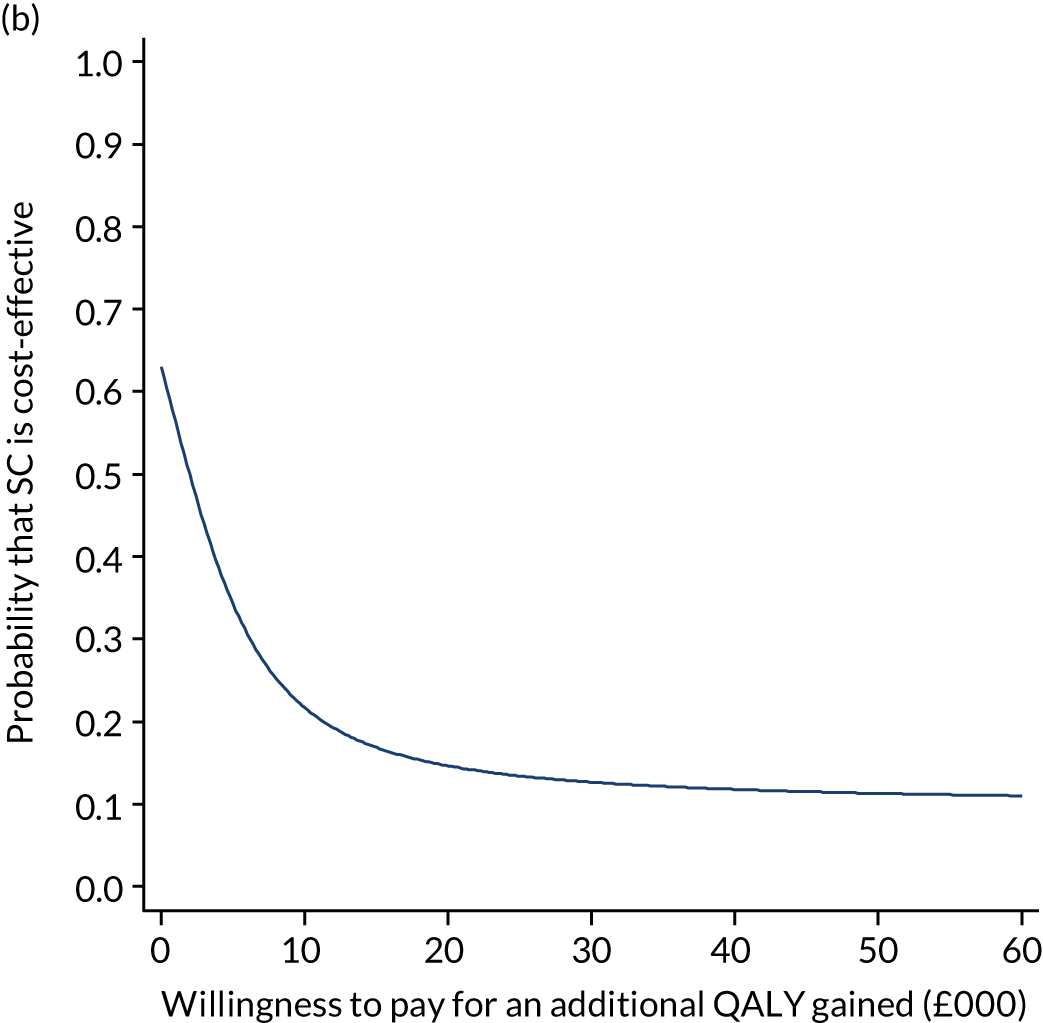

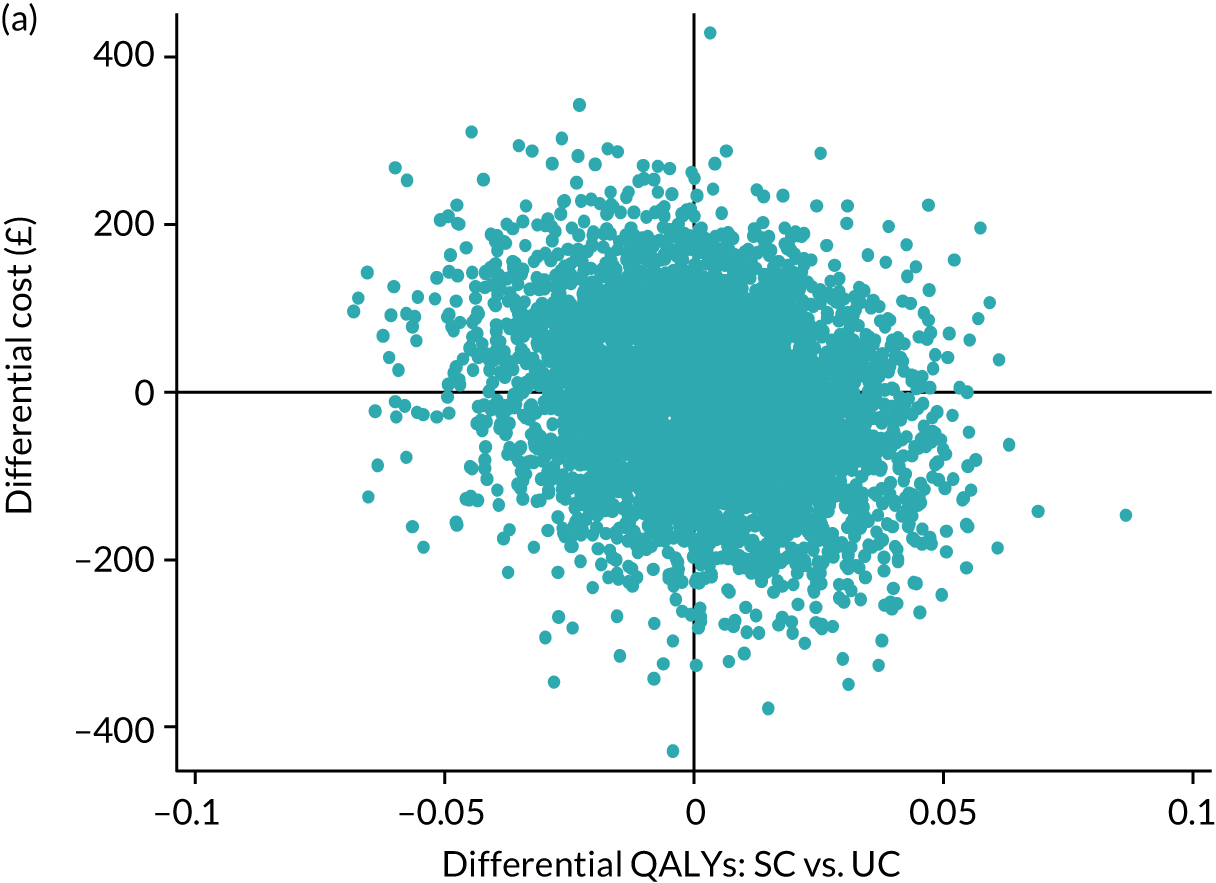

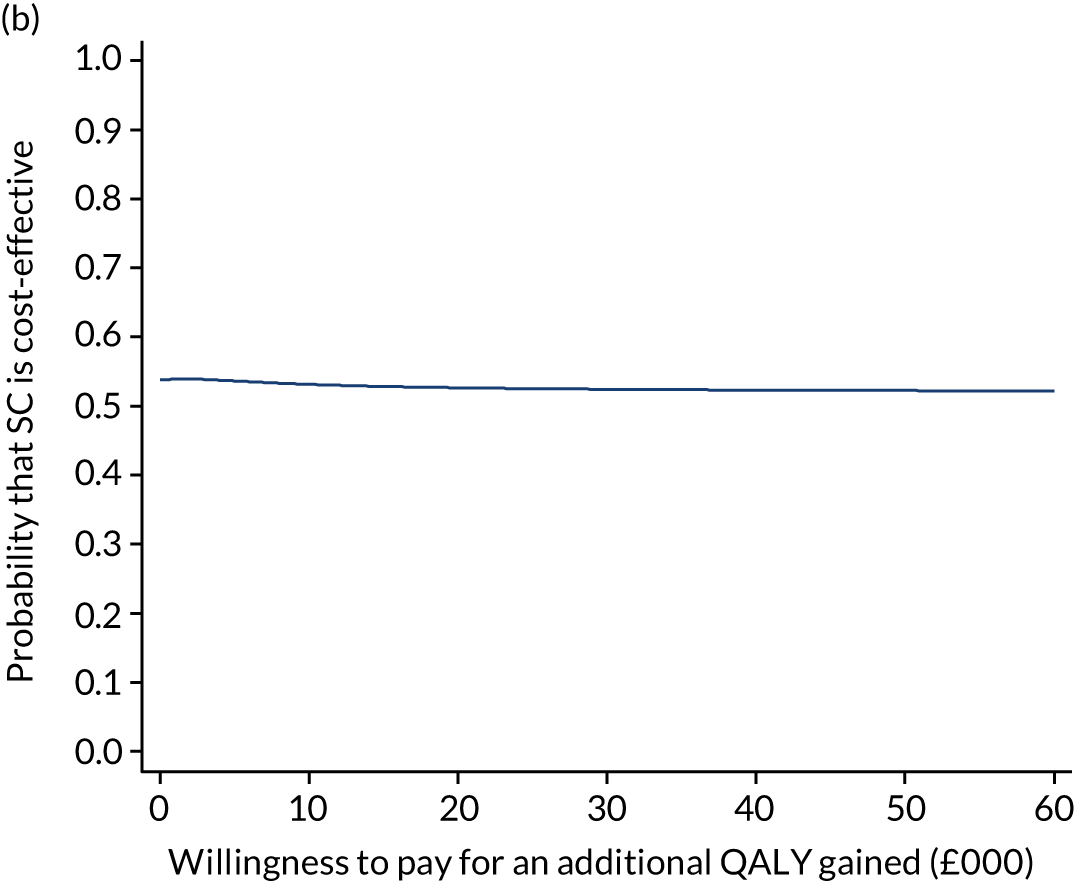

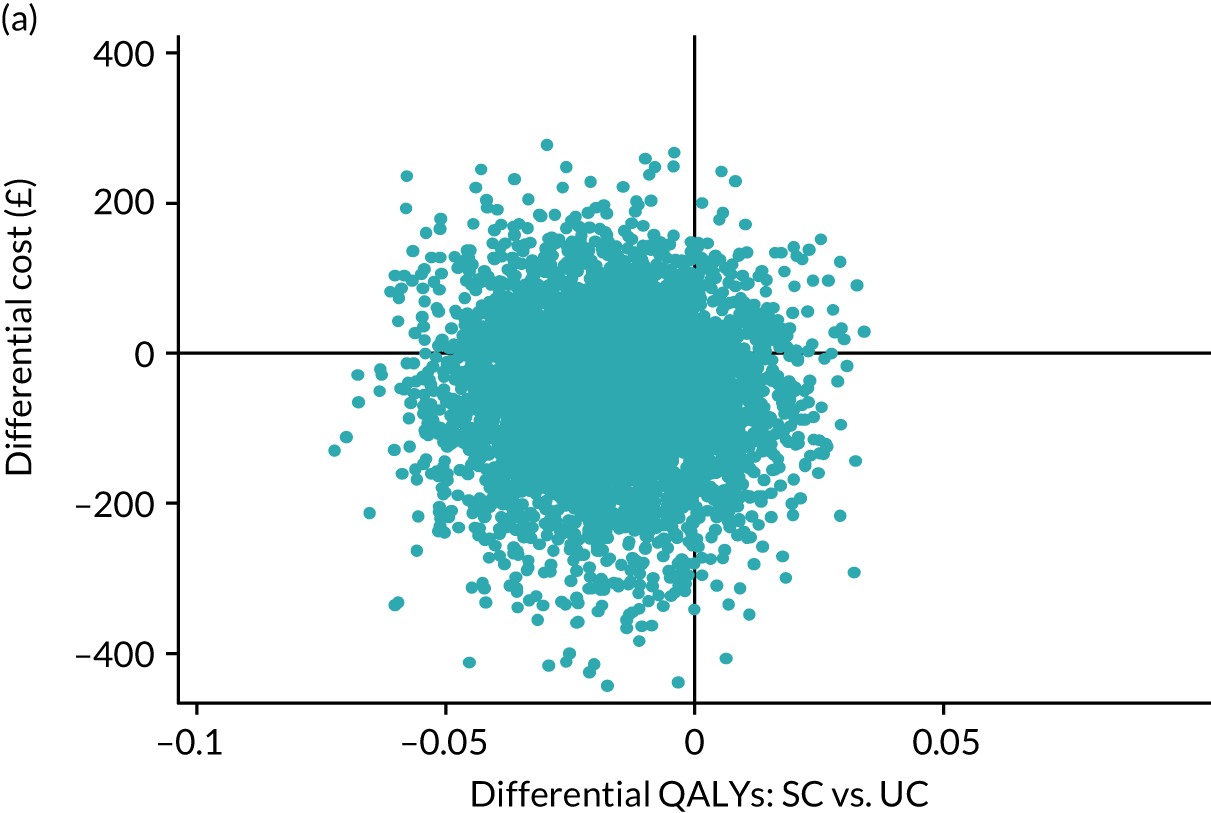

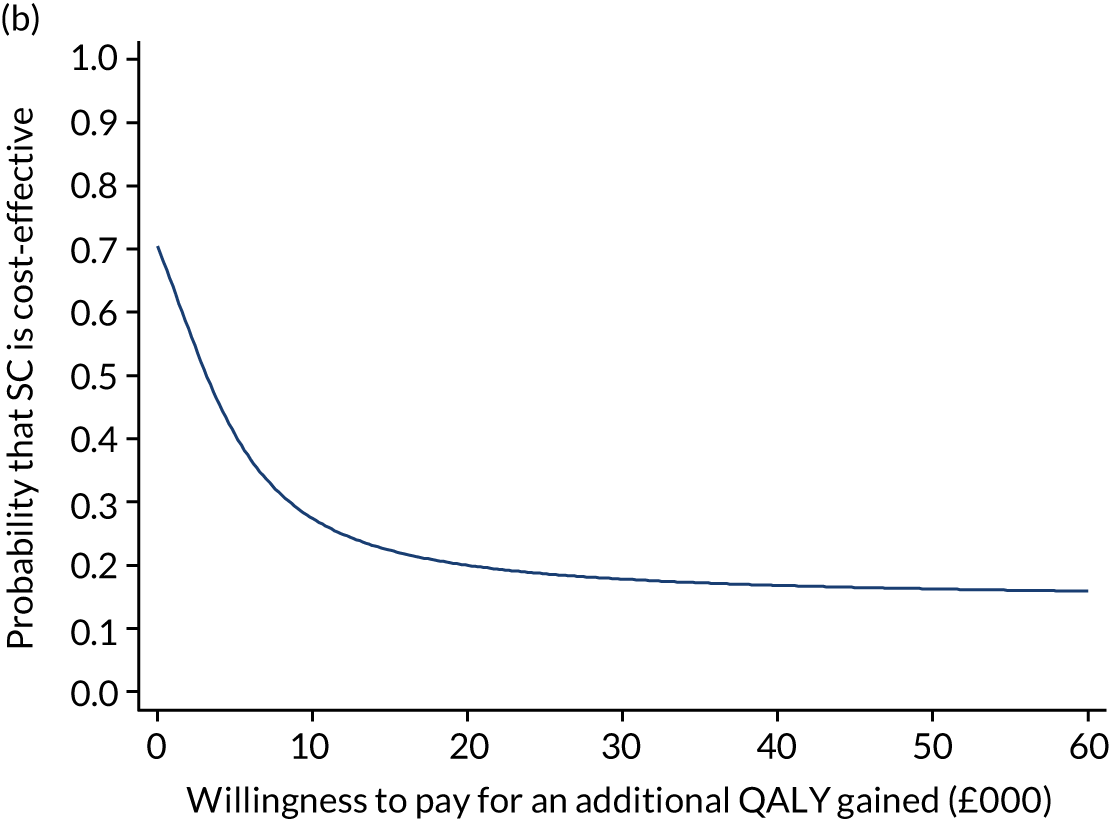

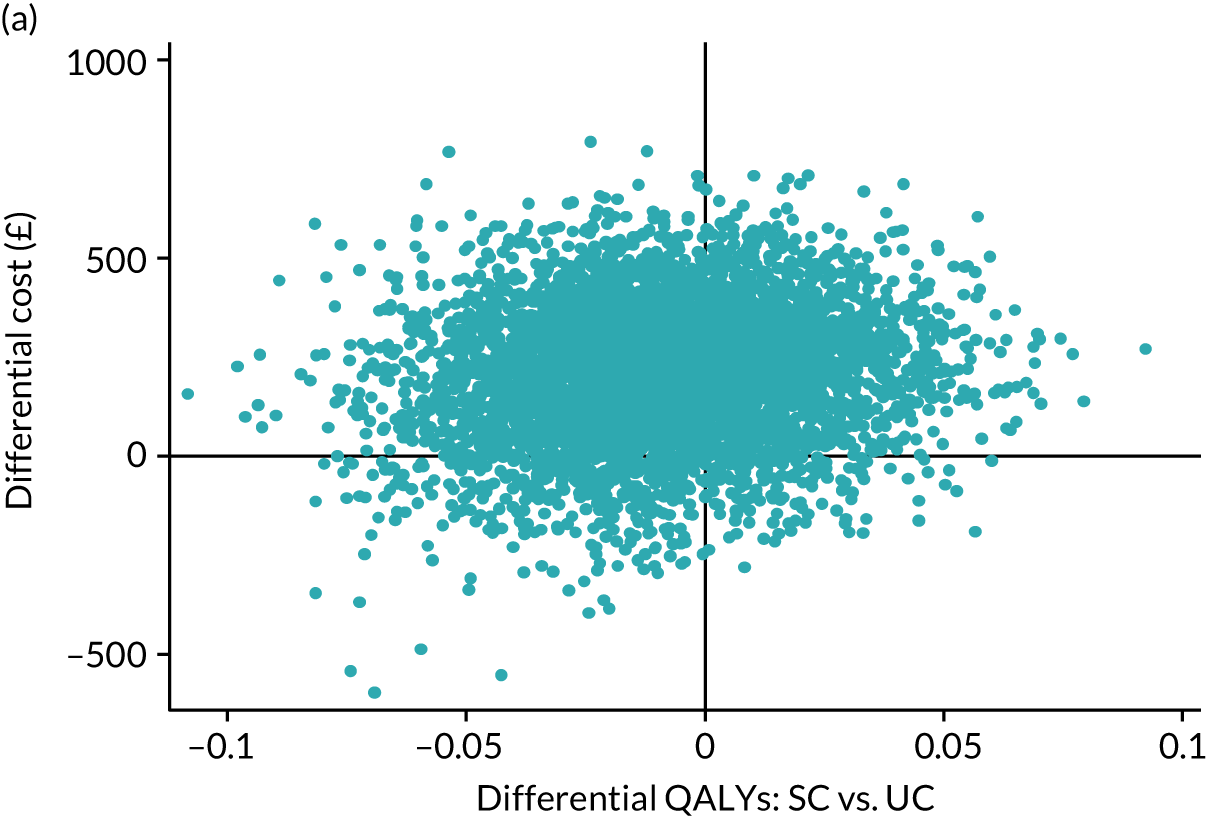

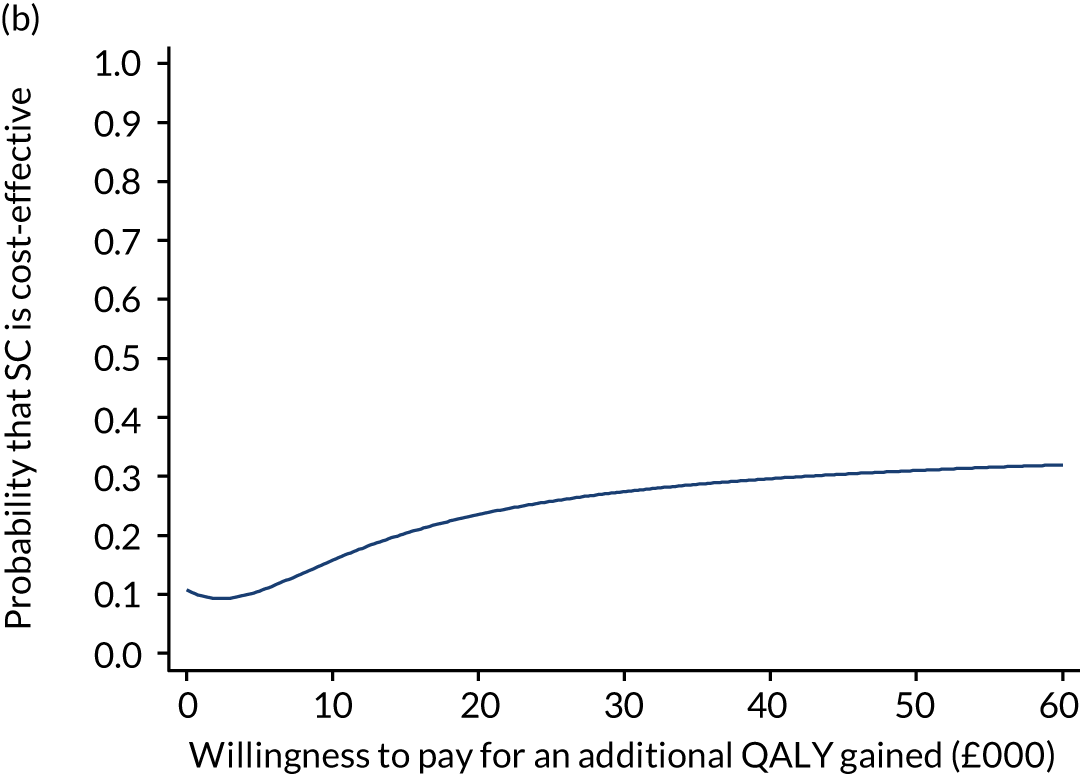

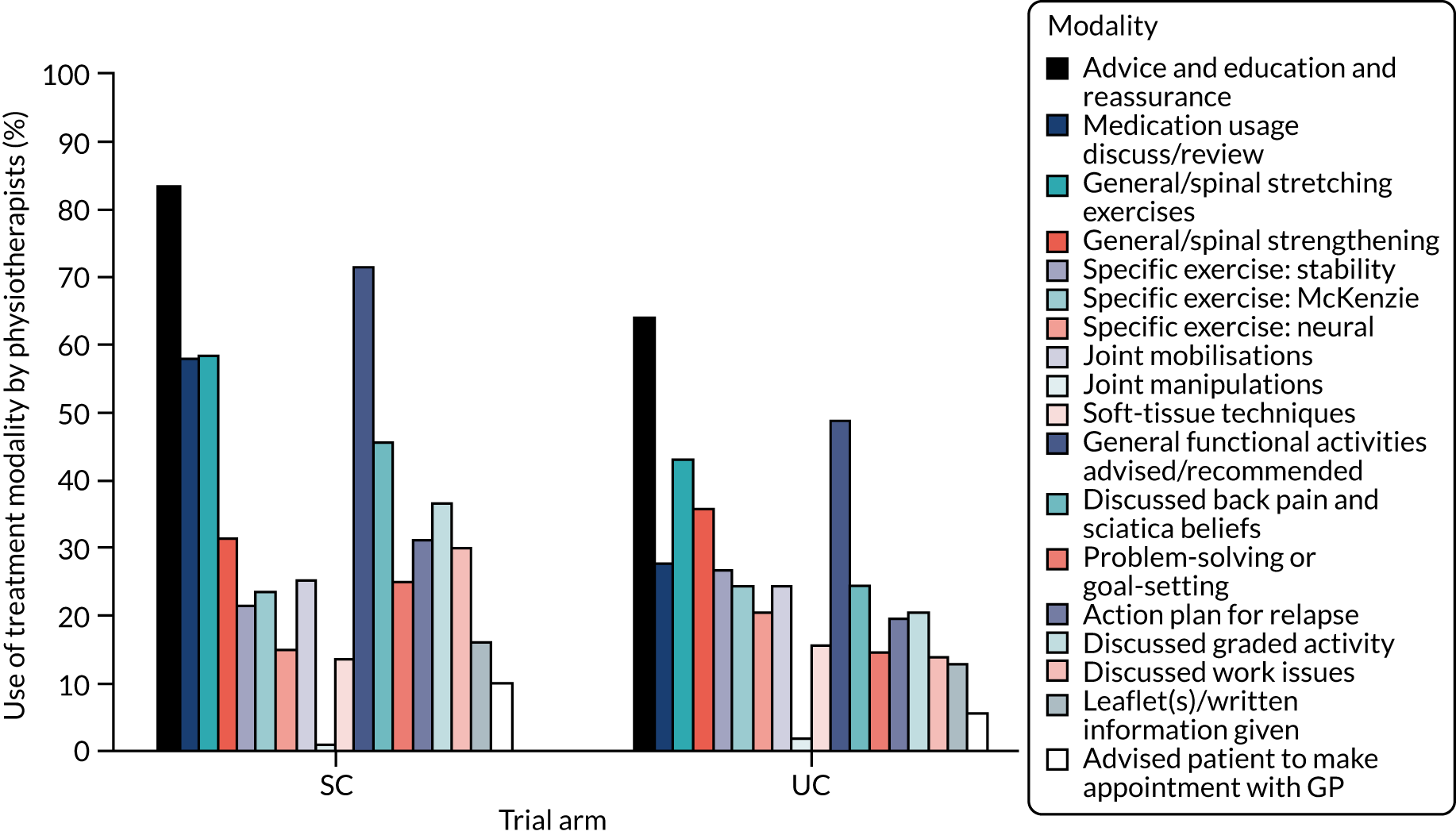

Process outcomes analysis