Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/127/134. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in November 2019 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Appleton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reused from Lyttle et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Parts of this chapter have been reused from Lyttle et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In addition, the exclusion criteria have been reused from the study ISRCTN registry. 3 This article is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Scientific background

Convulsive status epilepticus (CSE) is the most common life-threatening neurological emergency in children, with an incidence of 20 per 100,000 children per year. 4,5 It is the second most common reason for unplanned admission to paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) in the UK, accounting for 5.6% of all PICU admissions. 6 Mortality is low, but morbidity, including neurodisability, learning difficulties and de novo and drug-resistant epilepsy, may be as high as 22%. 7–10 Predictably, these may result in major long-term demands on acute and chronic health and social care resources. 4 The longer the duration of CSE, the more difficult it is to terminate and the greater the morbidity risk. 4,9,10

The current UK emergency care pathway for the management of childhood CSE is the stepwise algorithm that is advocated in advanced paediatric life support (APLS) guidance. 11 First-line treatment is two doses of a benzodiazepine given 10 minutes apart. A second-line anticonvulsant is administered if the child continues to fit 10 minutes after the second dose of benzodiazepine. APLS guidance recommends phenytoin (Epanutin, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) as the first-choice second-line anticonvulsant. Phenobarbital (AAH Pharmaceuticals, Coventry, UK) is recommended if the child is allergic to phenytoin, has previously not responded to it or has experienced a serious adverse event (SAE). Failure to stop CSE necessitates rapid sequence induction (RSI), intubation and admission to PICU, with consequent potential for iatrogenic consequences, including pneumonia, hospital-acquired infections and prolonged admission.

There is reasonable randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence to support the use of benzodiazepines as first-line anticonvulsants,12 but there is a dearth of evidence for second-line drug treatment and no high-quality RCT evidence to support any second-line treatment. 13 There is an absence of randomised evidence to support the use of phenytoin as the second-line anticonvulsant, despite its use as a standard intravenous (i.v.) anticonvulsant for the treatment of CSE since the 1940s. A retrospective case note review, in which 87% (331/381) of children administered a second-line anticonvulsant received phenytoin, reported seizure cessation in 190 cases (50%). 14 There is considerably more literature on phenytoin’s potential adverse effects, including potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (Tables 1 and 2). 15–18 The risk of a cardiac arrhythmia is related to the rate of infusion and, therefore, phenytoin must be infused over a period of at least 20 minutes. 18

| Eligibility criteria | Reason for ineligibilitya | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | ||

| 1 | Outside age range | 23 |

| 2 | Patient does not present with generalised tonic–clonic, generalised clonic or focal clonic status epilepticus that requires second-line treatment to terminate the seizureb | 656 |

| 3 | First-line treatment not administered in accordance with APLS guidelines or personalised rescue care plan to try and terminate the seizure | 133 |

| Exclusion | ||

| 1 | Absence, myoclonic or non-CSE, or infantile spasms | 100 |

| 2 | Known or suspected pregnancy | 0 |

| 3 | Contraindication or allergy to either trial treatment | 45 |

| 4 | Known renal failure (i.e. patients on peritoneal or haemodialysis, or with renal function that is < 50% expected for age) | 3 |

| 5 | Previous administration of a second-line antiepileptic drug prior to arrival in the ED | 7 |

| 6 | Had previously entered the EcLiPSE trial | 38 |

| Data recorded | Assumption | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Patient recorded as ‘no’ to inclusion criterion 2 and ‘yes’ to exclusion criterion 1, but their seizure continued after benzodiazepines | Patient had incorrect seizure type | 21 |

| Patient recorded as ‘no’ to inclusion criterion 2 and ‘no’ to exclusion criterion 1 and their seizure stopped after benzodiazepines | No second-line treatment was required (seizure stopped), but patient had correct seizure type | 533 |

| Patient recorded as ‘no’ to inclusion criterion 2 and ‘yes’ to exclusion criterion 1 and their seizure stopped after benzodiazepines | Patient had incorrect seizure type and no second-line treatment was required | 57 |

| Missing response for exclusion criterion 1 | No assumptions made: data confirmed as unobtainable | 3 |

| Patient recorded ‘no’ to inclusion criterion 2 and ‘no’ to exclusion criterion 1 and their seizure continued after benzodiazepines | No assumptions made: data suggested correct seizure type and seizure continuing | 11 |

| Patient has no benzodiazepines recorded | No assumptions made | 19 |

| Patient has missing benzodiazepine administration outcome | No assumptions made: data confirmed as unobtainable | 3 |

| Patient has other outcome recorded for benzodiazepines | No assumptions made | 9 |

| Total | 656 |

Levetiracetam (Keppra, UCB Pharma, Brussels, Belgium) is a broad-spectrum anticonvulsant that effectively treats focal and generalised tonic–clonic and myoclonic seizures. A growing body of evidence, predominantly, but not exclusively, anecdotal, suggests that i.v. levetiracetam is safe and effective in the treatment of acute repetitive seizures and both CSE and non-CSE, with reported seizure cessation rates between 76% and 100%. 19–27 There is limited evidence that i.v. levetiracetam may also be as effective as i.v. lorazepam (Ativan, Pfizer Inc.), which is the current first-choice first-line anticonvulsant in the treatment of CSE. Levetiracetam and lorazepam administered intravenously to 79 patients (the majority of whom were adults) were equally effective in terminating CSE {levetiracetam terminated CSE in 76.3% of patients and lorazepam in 75.6% of patients [relative risk 0.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44 to 2.13]}. 28 A systematic review of levetiracetam published in 201229 indicated that efficacy ranged from 44% to 94%, with reported higher rates in retrospective studies. Two RCTs, published in 2015, involving predominantly adults, directly compared i.v. levetiracetam with either i.v. phenytoin30 or i.v. phenytoin plus i.v. sodium valproate (Epilim, Sanofi, Paris, France)31 and showed no difference between the comparators. Chakravarthi et al. 30 reported on 44 patients who presented with ‘consecutive status’ and were randomised to treatment with phenytoin (20 mg/kg) or levetiracetam (20 mg/kg). Both drugs showed a similar efficacy in status termination within 30 minutes of commencement of drug infusion. Phenytoin achieved control in 15 out of 22 (68.2%) patients and levetiracetam in 13 out of 22 (59.1%) patients (p = 0.53). 30 In the study reported by Mundlamuri et al. ,31 the presenting seizure was controlled with lorazepam plus phenytoin infusion in 34 out of 50 (68%) patients, lorazepam plus valproate infusion in 34 out of 50 (68%) patients and with lorazepam plus levetiracetam infusion in 39 out of 50 (78%) patients. There was no statistically significant difference between the subgroups (p = 0.44). 31 Reported i.v. levetiracetam doses range from 20 to 60 mg/kg. Chakravarthi et al. 30 and Mundlamuri et al. 31 used doses of 20 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg, respectively. Adverse reactions (ARs) with levetiracetam seem to be infrequent and mild, even at high doses. These include dizziness, somnolence, headache and transient agitation, but there have been no reports of cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, tissue extravasation reactions, Stevens–Johnson syndrome or hepatotoxicity. 32–34 Levetiracetam can be infused over 5–10 minutes, which suggests that, theoretically, CSE may be terminated more rapidly than with phenytoin. Consequently, a reasonable hypothesis is that levetiracetam may be more effective and safer than i.v. phenytoin in terminating CSE. 13,35,36

Convulsive status epilepticus management was identified as a key priority area for research by a number of sources, including the Paediatric Emergency Research in the UK and Ireland (PERUKI)37,38 in its inaugural prioritisation exercise,38 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in its update of national epilepsy guidelines published in January 2012. 39 A high-quality RCT is, therefore, essential to determine whether phenytoin or levetiracetam is the better drug in managing CSE, as highlighted in a recent systematic review. 13 A meta-analysis published in 2014 concluded with the following statement:

The evidence does not support the first-line use of phenytoin. There is not enough evidence to support the routine use of lacosamide. Randomized controlled trials are urgently needed. 36

One RCT has recently been completed that evaluated the efficacy and safety of i.v. levetiracetam and phenytoin in the management of CSE in children aged 3 months to 16 years. 40,41 A second RCT recently evaluated i.v. fosphenytoin, levetiracetam and sodium valproate in the management of CSE in children (aged > 2 years) and adults. 42

The Emergency treatment with Levetiracetam or Phenytoin in Status Epilepticus in children (EcLiPSE) trial was a Phase IV, multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled open-label superiority trial comparing i.v. levetiracetam with i.v. phenytoin.

Rationale for research

Convulsive status epilepticus is the most common life-threatening neurological emergency in childhood. It can result in significant morbidity, with acute and chronic impacts on the family and health and social care systems. The current recommended first-choice second-line treatment in children aged ≥ 6 months is i.v. phenytoin (fosphenytoin, which is a pro-drug of phenytoin in the USA). However, this is not based on any robust RCT evidence and the drug is associated with significant and potentially serious adverse reactions (SARs). Emerging evidence suggests that i.v. levetiracetam may be effective as a second-line agent for CSE, and fewer ARs have been described. This trial was designed to determine whether i.v. phenytoin or i.v. levetiracetam is the more effective and safer drug in the treatment of childhood CSE.

Intervention

The EcLiPSE trial was an open-label trial using investigational medicinal products (IMPs) with marketing authorisation in the UK. These became IMPs only when the packaging was opened in the setting of this study. IMP provision was the responsibility of each site in accordance with standard clinical practice. Both IMPs were stored in line with local requirements for general medicine supplies.

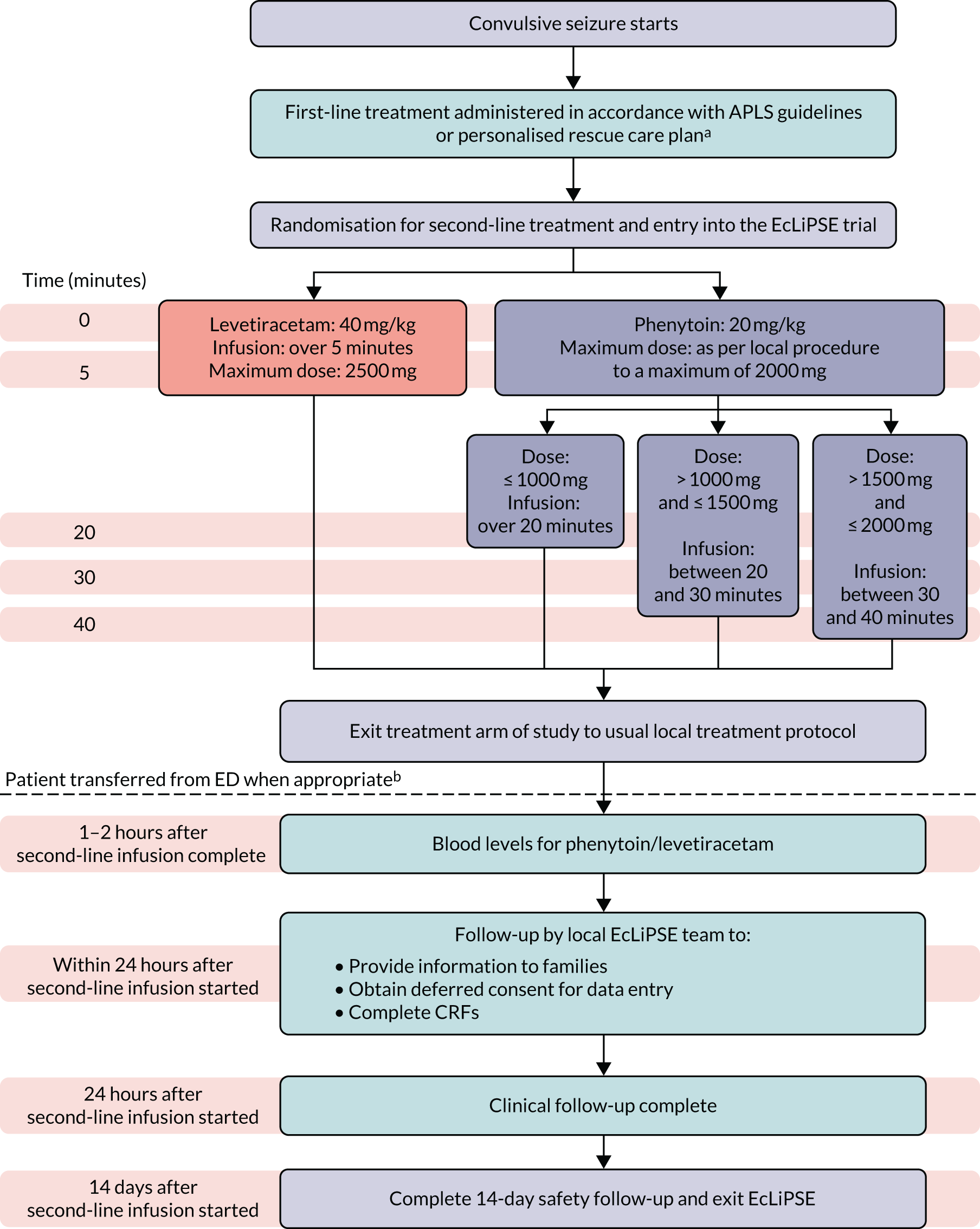

A single dose of the randomly allocated treatment was administered by i.v. infusion. The levetiracetam dose was 40 mg/kg (with a maximum dose of 2500 mg) over 5 minutes, diluted to a maximum of 50 mg/ml with 0.9% sodium chloride. The dose of 40 mg/kg was based on the available published data at the time of the full study application to the Health Technology Assessment programme in 2013. The phenytoin dose was 20 mg/kg (with a maximum dose of 2000 mg) at a rate not exceeding 1 mg/kg/minute (or > 20 minutes for doses of > 1 g), diluted with 0.9% sodium chloride to a maximum concentration of 10 mg/ml. This dose was based on national guidelines available in 2013. 11

The allocated treatment was prepared and administered in accordance with standard clinical care, with independent checking performed by two trained personnel. Trial-specific labelling was not required, rather an approved ‘i.v. additive label’ was used. If the randomised treatment was discontinued prior to administration of the full dose this was recorded. If CSE persisted at the end of the IMP infusion, further medical management was decided by the local clinical team independent of the trial protocol (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study design. a, Administration of the first-line treatment may have occurred prior to arrival in the ED. b, If a patient was randomised but not treated with a second-line anticonvulsant, follow-up would end at this point. ED, emergency department.

Objectives

The study objectives were to determine:

-

whether i.v. phenytoin or i.v. levetiracetam is the more efficacious second-line anticonvulsant for the emergency management of CSE in children

-

whether or not i.v. levetiracetam is associated with fewer ARs or adverse events (AEs) than i.v. phenytoin

-

the potential barriers and solutions to recruitment and consent in the EcLiPSE trial to inform future trials with regard to recruiter training and trial conduct in this clinical setting (i.e. a nested consent study).

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial registration and ethics

The trial was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West – Liverpool Central on 3 March 2016 (reference 15/NW/0090). The trial is registered as ISRCTN22567894 (registered 27 August 2015) and EudraCT identifier 2014-002188-13 (registered on 21 May 2014).

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

The full study protocol was published in 2017. 2

Inclusion criteria

-

Males and females aged 6 months to 17 years 11 months (inclusive).

-

The presenting seizure was generalised tonic–clonic, generalised clonic or focal clonic status epilepticus that requires second-line treatment to terminate the seizure.

-

First-line treatment was administered in accordance with APLS guidelines or the child’s personalised rescue care plan to try and terminate the presenting seizure.

Eligibility notes

Patients with the following features were eligible for inclusion in the trial, assuming that all other inclusion and exclusion criteria were met.

-

Patients administered more than two doses of benzodiazepines, which is above the recommended dose in APLS guidelines.

-

Patients whose personalised rescue care plan included rectal paraldehyde as the first-line treatment.

-

Patients receiving oral phenytoin or levetiracetam as part of their regular oral antiepileptic drug regime.

Exclusion criteria

-

Absence, myoclonic or non-CSE, or infantile spasms.

-

Patients with a known or suspected pregnancy.

-

Patients with known contraindication or allergy to levetiracetam or phenytoin. This included when the child’s personalised rescue care plan stated that the child never responded to, or had previously experienced a SAR to, phenytoin, levetiracetam or both.

-

Patients with known renal failure (i.e. patients on peritoneal or haemodialysis, or with renal function that is < 50% expected for age).

-

Previous administration of a second-line antiepileptic drug prior to arrival in the emergency department (ED).

-

Patients known to have previously been treated as part of the EcLiPSE trial.

Recruitment

Thirty EDs (‘sites’) throughout Great Britain and Northern Ireland participated in the study. The sites were selected from the membership of PERUKI [a collaborative paediatric emergency medicine (PEM) research network]. 37 Participating sites included tertiary or district general hospitals with EDs that treat children only, or children and adults. A full list of participating centres is included in Appendix 3. Centres were selected based on factors such as membership of PERUKI, site research infrastructure, projected number of recruits based on the local population and proposed training strategy.

Screening commenced once a child arrived in the ED and received their first-line treatment for CSE. A unique participant screening form was used and included an eligibility assessment and reasons for non-randomisation where appropriate. If eligible, the participant was randomised to the trial.

Informed consent

The trial used research without prior consent (RWPC), also known as ‘deferred consent’, because of the time-critical management of CSE, in accordance with regulatory requirements, RWPC guidance and pre-trial research. 43,44 Parents/legal representatives/patients (hereafter termed ‘participants’) were approached once the child’s clinical condition was stable. This was ideally within 24 hours of randomisation and prior to discharge from hospital, at which point written informed consent was sought to continue data collection and use data already collected.

If consent was not sought prior to discharge the participant would be contacted within 5 working days of randomisation by a delegated member of the research team and informed of the participant’s involvement and details of the trial. Written information and a consent form were posted to the family. The covering letter asked participants to return the enclosed form, indicating their consent for use of the data already collected and continued participation in trial follow-up, within 4 weeks of the date of the letter. If no response was received within 4 weeks, the covering letter verified that the participant was included within the trial.

If the participant died before consent was sought, the site research team obtained information from colleagues and bereavement counsellors to establish the most appropriate time and the most appropriate practitioner to notify the parents/legal representative of their child’s involvement in the research study.

When it was considered inappropriate to seek consent prior to the parent/legal representative’s departure from hospital, the parent/legal representative was notified by a personalised letter and written information about the trial from the most appropriate practitioner 4 weeks after randomisation. Wherever possible, this practitioner would already be known to the family. The letter explained the EcLiPSE trial, reasons for deferred consent, how to opt in or out of the trial and provided contact details if parents wished to discuss the trial with a member of the research team (either in person or by telephone).

A second letter was sent to the bereaved family if there had been no response within 4 weeks of the initial letter. The second letter included information about the EcLiPSE trial, reasons for deferred consent and how to opt in or out of the trial. It also provided contact details if parents wished to discuss the EcLiPSE trial with a member of the research team, either in person or by telephone. Finally, it informed the family that the participant’s data would be included in the trial if no consent form was returned within 4 weeks of the letter being sent, unless the family first notified the site team.

Finally, there was also a qualitative mixed-method study involving participants to explore approaches to recruitment and deferred consent. This is outlined in Chapter 4.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to levetiracetam or phenytoin in a ratio of 1 : 1 using random variable block sizes of two and four. A computer-generated randomisation schedule was produced by an independent statistician who had no further involvement in the trial. Randomisation was stratified by centre for logistical purposes. Centres were provided with sequentially numbered and EcLiPSE trial-labelled randomisation packs. These were stored in an appropriate secure location within the ED for ready access on presentation of eligible patients.

Randomisation packs were opaque brown cardboard tamper-proof A4 envelopes. The construction was resistant to accidental damage or tampering and contents could not be viewed without fully opening the envelope. Each pack was sequentially numbered and during randomisation the clinician/nurse used the next sequentially numbered pack.

The case report form (CRF) that was completed at the patient’s bedside while the patient was in the ED was included in the randomisation pack. The CRF was prepopulated with the centre code, participant randomisation number and the randomly allocated treatment.

The randomisation pack should have been opened only once eligibility was confirmed on the screening form. However, because of the time required to prepare the randomised treatment for infusion, this was undertaken prior to when the infusion was required to avoid trial participation creating a delay in treatment. This meant that some randomised participants would experience seizure cessation while the infusion was being prepared.

Once randomised, the patient was administered the randomly allocated treatment, as required clinically, to terminate seizure activity.

If the participant was randomised but the seizure terminated prior to infusion of the randomly allocated treatment, the patient could subsequently be treated with the randomised treatment allocation if the patient’s seizure restarted while still in the ED. However, if the patient’s seizure restarted after leaving the ED, the randomised treatment could not be given.

If the randomised treatment was not administered while the patient was in the ED and instead the comparator second-line was administered in error, the participant was still considered as recruited and the randomisation number applied. The treatment administered was recorded, along with reasons why it had not been possible to treat as per allocation.

If the patient had been given a RSI prior to administration of any second-line treatment the decision to administer a second-line treatment was outside the EcLiPSE trial and the patient was treated as per the site’s routine care.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind the trial interventions in the EcLiPSE trial because of the different times required for their infusion. Although a double-dummy approach was considered, this would have increased complexity during a paediatric emergency situation. Therefore, this was an open-label study.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was time from randomisation to cessation of all visible signs of convulsive seizure activity. All ‘visible signs of convulsive seizure activity’ was defined by cessation of all continuous rhythmic clonic activity.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

the need for further anticonvulsants to manage CSE after administration of the trial treatment

-

the need for RSI because of ongoing CSE

-

the need for admission to a critical care unit (i.e. a high-dependency unit or a PICU)

-

the occurrence of SARs, including death, airway complications, cardiovascular instability (e.g. cardiac arrest, arrhythmia and hypotension requiring intervention), extravasation injury (e.g. ‘purple glove syndrome’) and extreme agitation.

Data collection

Follow-up

There were three time points for data collection in the EcLiPSE trial (see Figure 1). The first was in the ED during the acute CSE treatment phase. The second was at 24 hours following the administration of the randomised treatment, wherein data collected included further seizures, concomitant anticonvulsants that may have been required to treat other acute seizures and ARs. The third and final time point was undertaken 14 days after administration of the randomised treatment through review of hospital notes and a single-sheet four-question questionnaire completed by the child’s parents. The questionnaire included information on further hospital admissions and organ failure.

Blood samples

Samples were taken 1–2 hours after completion of the randomised treatment to measure drug levels, a common practice when giving phenytoin. 45 Levetiracetam levels were measured as part of trial conduct by an accredited central laboratory. Measurement of phenytoin levels was undertaken in the laboratory of each participating site as part of routine care.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated on the basis of published seizure cessation rates for phenytoin (50–60%)14 and levetiracetam (76–100%). 19–27 A sample size of 140 randomised and consented participants per group, with a total of 183 events of CSE cessation, was required for a 0.05-level two-sided log-rank test for equality of survival curves to detect an increase in seizure cessation rates from 60% to 75% [a constant hazard ratio (HR) of 0.661] at 80% power. The sample size was increased to 308 participants to allow for 10% loss to follow-up, which proved unnecessary. The final sample size was 286 participants and the Independent Data and Safety and Monitoring Committee (IDSMC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) were consulted before the decision to stop recruitment because of low attrition and completeness of data. The difference to detect was influenced by the size of difference deemed to be clinically important and convincing to change clinical practice. Although smaller differences could also have been considered important, they needed to be balanced against the costs of the medicinal products and the experience of delivering them within emergency care setting.

Trial management and oversight

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for the day-to-day practical and clinical aspects of the trial. The team was multidisciplinary (see Appendix 2) and included the chief investigator, several co-investigators, sponsor representatives, a patient and public involvement (PPI) contributor (see Appendix 5) and members of the clinical trials unit.

Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

The IDSMC was responsible for safeguarding the interests of the EcLiPSE trial participants, assessing the efficacy and safety of the interventions throughout the trial and monitoring the overall progress and conduct of the trial. The IDSMC comprised an independent paediatrician, an independent professor of neurology and an independent statistician (see Appendix 1). The IDSMC met annually during the course of the trial and provided recommendations to the TSC. The Haybittle–Peto approach was used by the IDSMC as a guide to consider stopping the trial within interim reports with 99.9% CIs.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was responsible for providing overall oversight of the trial. The TSC comprised an independent paediatrician, an independent consultant in PEM, an independent statistician and a representative from the TMG (see Appendix 1). Co-sponsor representatives were invited to meetings as observers. The TSC met annually throughout the study and remained masked to accumulating data until the end of the trial. The TSC remained happy with trial progress and received monthly updates of recruitment and progress. The TSC met in December 2017.

Both chairpersons of the TSC and the IDSMC supported a joint final meeting that was arranged to coincide with the final results meeting. This meeting took place in Manchester on 9 July 2018 and the results of the study were presented to all EcLiPSE trial team members of each participating site.

Internal pilot

The EcLiPSE trial included an 18-month internal pilot and involved five centres.

The 18-month period was chosen to allow five centres to be opened, be fully up to speed with trial procedures and be achieving the optimal recruitment rate (assumed to be achieved 3 months after opening). This time frame also allowed each site a minimum of 6 months of active recruitment at the optimal level to demonstrate their recruitment rates and support prediction of trial activity into the main phase of the trial.

Success criteria of the pilot were based on the below.

Recruitment

-

If the predicted recruitment period is ≤ 36 months, then proceed to main trial.

-

If the predicted recruitment period is between 36 and 48 months, then consider, and introduce, ways to reduce this (e.g. increase the number of centres, address training needs or determine if new evidence suggests that eligibility criteria could be widened) then proceed to main trial with amendments.

-

If the predicted recruitment period is > 36 months and no obvious solutions exist, then abandon the plan for the main trial.

Deferred consent

-

If the deferred consent rate is ≥ 80%, then proceed to the main trial.

-

If the deferred consent rate is between 60% and 80%, and there is no clear association between provision of deferred consent and the child’s outcome, then analyse reasons why patients/guardians do not want to participate to identify any aspects amenable to change and proceed to the main trial, as amended.

-

If deferred consent is < 60%, then analyse reasons why patients/guardians do not want to participate. If consent declination is associated with poor patient outcome (e.g. death), abandon the main trial.

Completeness of primary outcome data

-

If primary outcome data are available for > 90% of randomised and consented participants, then proceed to the main trial.

-

If primary outcome data are available for between 70% and 90% of randomised and consented participants, then analyse reasons for missing data and identify whether or not any aspects are amenable to change and proceed to the main trial, as amended.

-

If primary outcome data are available for < 70% of participants randomised and consented, then abandon the plan for the main trial.

Statistical methods

A detailed statistical analysis plan is available online [see NIHR Journals Library project web page URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/12127134/# (accessed 25 September 2020)]. All analyses were undertaken with SAS® software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The primary analysis was based on a modified intention-to-treat principle. All randomised and consented participants who received a second-line treatment were included in the analysis according to their allocated treatment. Children who were randomised but whose CSE stopped without requiring second-line treatment (and did not restart in the ED) were excluded. The safety analysis included the same participants, grouped according to the actual treatment received. To avoid double counting, SAEs were reported separately from AEs.

Statistical tests were two-sided at a 5% significance level and results are presented with 95% CIs. The primary outcome was analysed using the log-rank test and is presented as a Kaplan–Meier curve. All participants were followed up to cessation of CSE, with censoring used in the event of RSI or death. If RSI was administered, time was censored at RSI plus 12 hours (i.e. 720 minutes). In patients who died before cessation of CSE, time was censored at the time of death plus 48 hours (i.e. 2880 minutes). RSI and death represent informative censoring and, therefore, the censoring times were inflated to signify the negative outcome for the child with further sensitivity analyses. The sensitivity analyses considered the robustness of the results to the primary analysis approach and included Gray’s test, treating RSI as a competing risk, calculating time to cessation of CSE from start of infusion instead of randomisation and censoring participants at the time of an additional second-line treatment after no response to the allocated treatment. Additional analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for baseline characteristics of weight (i.e. < 12 kg, 12–36 kg or > 36 kg), sex and whether or not this was the child’s first seizure. Two covariates (i.e. site of infusion and additional anticonvulsants given in parallel) specified in the analysis plan were not included because they were measured after randomisation. Additionally, centre (i.e. the site) could not be included as a factor in the Cox model because of the lack of convergence. Schoenfeld residual plots were used to check the assumption of proportionality. The binary secondary outcomes of need for further anticonvulsants, RSI and admission to critical care were analysed using the chi-square test and presented with relative risks. Logistic regression models were fitted as additional analyses to the primary chi-square tests, with adjustments as per the Cox proportional hazards model. No adjustment was made for multiplicity for the secondary outcomes. Baseline categorical data and AE data are summarised using numbers and percentages, and continuous data are summarised as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). A post hoc analysis was undertaken for the reasons underlying the further management of the presenting episode of CSE, the assessment of which was carried out without knowledge of the allocated intervention.

Role of the funding source

The trial funder monitored trial progress and approved oversight committee membership, but had no role in trial design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the trial.

Changes to the protocol

The EcLiPSE trial opened to recruitment on version 3.0 of the protocol and closed on version 5.0. Changes to the protocol are summarised in Appendix 4. In summary, the key changes from version 1.0 to version 2.0 included increasing the follow-up period to 14 days to collect longer-term safety data, adding information that the primary outcome would be calculated from the time of randomisation and providing additional clarifications on eligibility criteria. Amendments between subsequent versions included clarification on dose, safety reporting, questionnaire administration and consent process.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness results

Parts of this chapter have been reused from Lyttle et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a total of 30 sites, all EDs. Although 30 sites were formally opened, two subsequently closed with neither site having recruited any participants. The first participant was recruited from Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Liverpool, on 22 July 2015 under version 3.0 of the protocol and the last participant was recruited from Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, on 7 April 2018 under version 5.0 of the protocol.

The five top-recruiting sites recruited 124 out of the 286 (43.4%) participants.

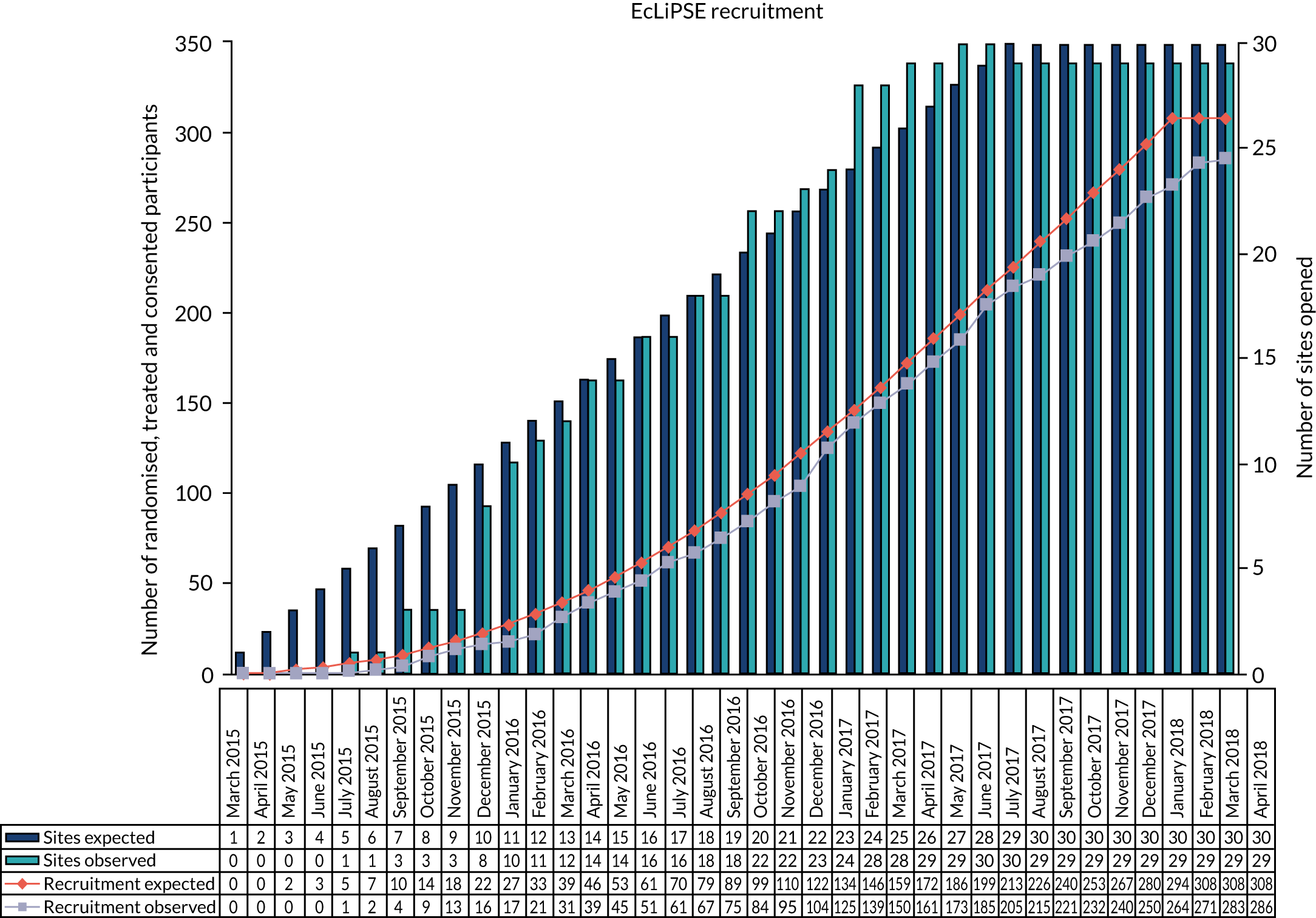

The observed site opening and participant recruitment rates closely followed those predicted (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment graph.

Study commencement was delayed by approximately 6 weeks because of contractual issues between the two co-sponsors of the study and, therefore, recruitment closed 6 weeks later than planned, on 10 April 2018.

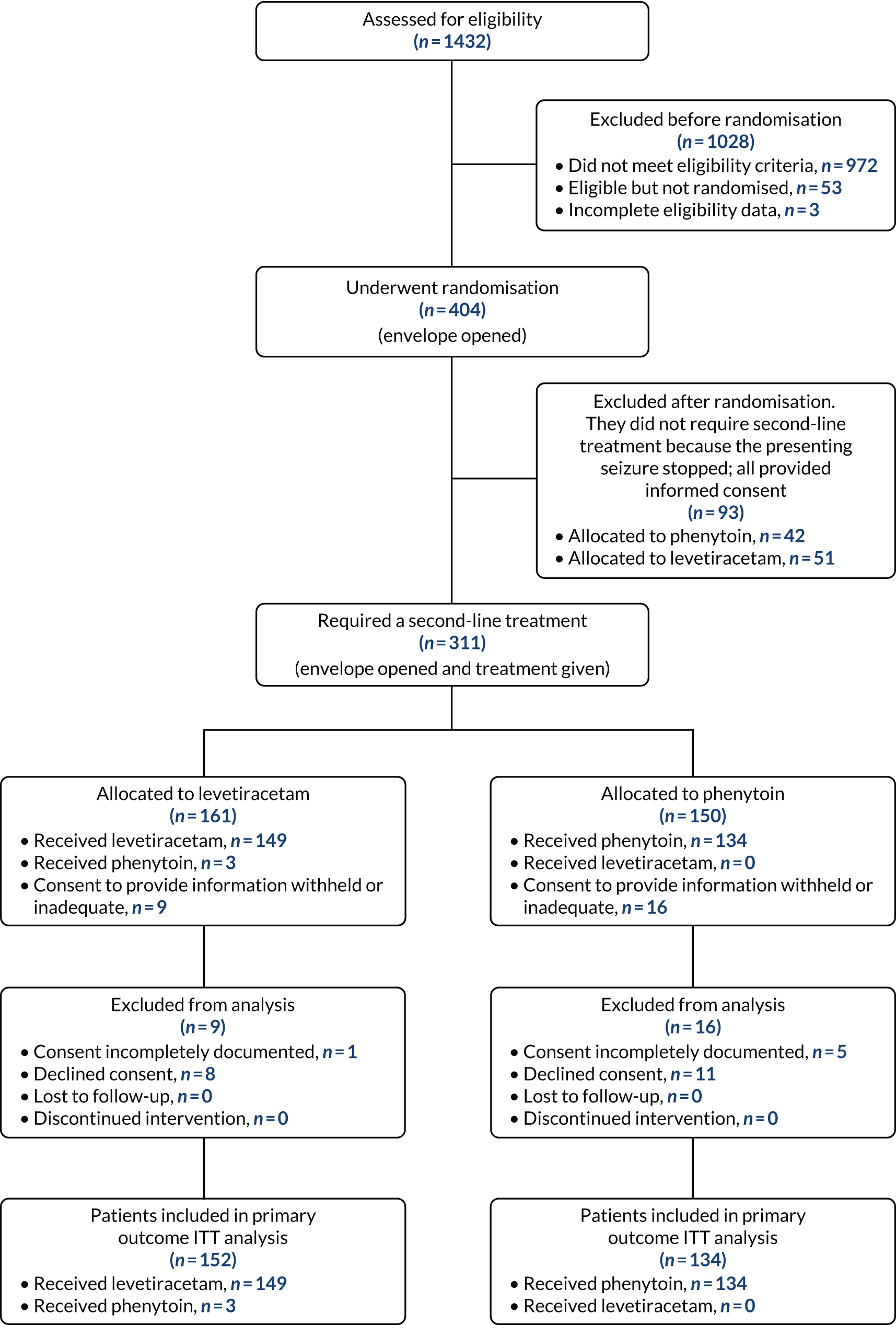

Participant screening and throughput are summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. ITT, intention to treat.

Of the 1432 children screened for eligibility, 404 were randomised (i.e. the randomisation pack was opened). A total of 1028 children were excluded before randomisation, including 972 children who did not meet the eligibility criteria (see Tables 1 and 2). Reasons for not randomising 53 children who were considered eligible included no trial-trained doctor available, loss of, or failure to, achieve i.v. access, clinical judgement (e.g. child too sick) and treatment given before random allocation.

Inclusion criterion 2 (see Table 1) combined seizure type with the need for second-line treatment. Table 2 looks at this inclusion criteria in greater detail to distinguish eligibility owing to seizure type and ongoing need for second-line treatment.

Of the 404 children randomised, 93 did not require a second-line treatment. Of those children randomised who did require a second-line treatment, 25 were excluded from the analysis as consent was either incompletely documented (n = 6) or declined (n = 19). Table 3 provides the reasons why consent was declined.

| Reason consent declined | Group | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam | Phenytoin | ||

| Dad did not like the idea of being interviewed for the consent study. When it was explained again that this was optional dad said he did not like the idea | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Dad felt that he had been deceived and that consent should have been asked first | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Father did not want information to be used | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mum did not want sponsors or regulatory authorities to have access to the child’s medical records | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Not happy with DOB or gender to be used or have mum’s name written on consent form | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Parents felt patient had been through enough | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Parents would like to put upsetting time in past | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Too much going on and does not want any of their details collected | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Language barrier – mum given information and understood brief concepts but not enough to give informed consent | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Not interested | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Unclear reason. Parents have been given lot of information and patient was diagnosed with a new condition since admission. Information overload | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Stressed, patient very unwell | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Do not like signing things | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Social worker explained that this is a complex social care case – currently with courts and they are unable to consent without court approval | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Taken advice from solicitor due to ongoing litigation in respect to birth injury | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| No reason given | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 8 | 11 | 19 |

Compliance with the intervention

Data on compliance (adherence) with treatment are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Patients randomised and consented | Group, n (%) | Total (N = 379), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 203) | Phenytoin (N = 176) | ||

| Received no second-line treatment | 51 (25.1) | 42 (23.9) | 93 (24.5) |

| Received allocated treatment | 149 (73.4) | 134 (76.1) | 283 (74.7) |

| Received other second-line treatment to that allocated | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Received treatment followed by a second second-line treatment | 22a (14.5) | 13a (9.7) | 35a (12.2) |

| Compliance data | Group, n (%) | Total (N = 286), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 152) | Phenytoin (N = 134) | ||

| Patient given lower dose of trial treatment | 8 (5.3) | 4 (3.0) | 12 (4.2) |

| Patient given higher dose of trial treatment | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) |

| Dose administration shorter than expected | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Dose administration longer than expected | 27 (17.8) | 34 (25.4) | 61 (21.3) |

| Treatment prematurely discontinued | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (0.7) |

| Unauthorised route of administration (intraosseous) | 6 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.1) |

| Received initial second-line treatment other than that allocated | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Received further second-line treatmenta | 22 (14.5) | 13 (9.7) | 35 (13.6) |

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study participants were comparable (Table 6). However, the levetiracetam-treated group comprised more participants in whom the presenting episode of CSE [n = 69 (45%) vs. n = 49 (37%)] represented their first convulsive seizure ever, with a lower proportion of participants with a chronic epilepsy, as evidenced by participants taking oral maintenance antiepileptic drugs [n = 51 (34%) vs. n = 55 (41%)].

| Demographic | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 152, 53%) | Phenytoin (N = 134, 47%) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 75 (49) | 72 (54) |

| Female | 77 (51) | 62 (46) |

| Age | ||

| 6 months to < 2 years, n (%) | 65 (43) | 53 (40) |

| 2–11 years, n (%) | 81 (53) | 74 (55) |

| 12–17 years, n (%) | 6 (4) | 7 (5) |

| Median (years) (IQR) | 2.7 (1.3–5.9) | 2.7 (1.6–5.6) |

| Range (years) | 0.6–16.1 | 0.6–17.9 |

| Weight (kg) | ||

| < 12, n (%) | 52 (34) | 42 (31) |

| 12–36, n (%) | 86 (57) | 80 (60) |

| > 36, n (%) | 14 (9) | 12 (9) |

| Median (IQR) | 12.1 (10.0–19.0) | 12.0 (10.0–18.0) |

| Range | 7.5–70.0 | 6.0–66.0 |

| Participant’s first seizure, n (%) | 69 (45) | 49 (37) |

| Presenting seizure type, n (%) | ||

| Generalised tonic–clonic | 107 (70) | 105 (78) |

| Generalised clonic | 12 (8) | 7 (5) |

| Focal clonic | 33 (22) | 22 (16) |

| Seizure cause, n (%)a | ||

| Febrile convulsion | 63 (41) | 58 (43) |

| Seizure (pre-existing epilepsy) | 46 (30) | 46 (34) |

| First afebrile seizure | 16 (11) | 12 (9) |

| Central nervous system infection | 6 (4) | 7 (5) |

| Intracranial vascular event (bleed/stroke) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 0 | 0 |

| Substance misuse | 1 (< 1) | 0 |

| Indeterminate | 10 (7) | 7 (5) |

| Other | 27 (18) | 26 (19) |

| Maintenance antiepileptic drugs at presentation, n (%)a | ||

| Levetiracetam | 29 (15.9) | 26 (19.4) |

| Sodium valproate | 16 (10.5) | 19 (14.2) |

| Carbamazepineb | 12 (7.9) | 10 (7.5) |

| Clobazamc | 9 (5.9) | 9 (6.7) |

| Topiramated | 4 (2.6) | 8 (6.0) |

| Phenytoin | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 11 (7.2) | 18 (13.4) |

Protocol deviations

Protocol deviations were comparable across both treatment groups. Major and minor deviations are shown in Table 7.

| Protocol deviation | Group, n (%) | Total (N = 286), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 152) | Phenytoin (N = 134) | ||

| Any protocol deviation | 52 (34.2) | 51 (38.1) | 103 (36) |

| At least one major deviation | 10 (6.6) | 8 (6) | 18 (6.3) |

| At least one minor deviation | 43 (28.3) | 45 (33.6) | 88 (30.8) |

Major protocol deviations comprised:

-

premature discontinuation of randomised treatment (none in the levetiracetam-treated group and two in the phenytoin-treated group)

-

duration of infusion shorter than expected (none in the levetiracetam-treated group and one in the phenytoin-treated group)

-

lower dose of the intervention administered (eight in the levetiracetam-treated group and four in the phenytoin-treated group)

-

missing data for primary outcome (two in both the levetiracetam- and phenytoin-treated groups).

Primary outcome

Seizure cessation was achieved in 106 out of the 152 (70%) levetiracetam-treated participants and in 86 out of the 134 (64%) phenytoin-treated participants.

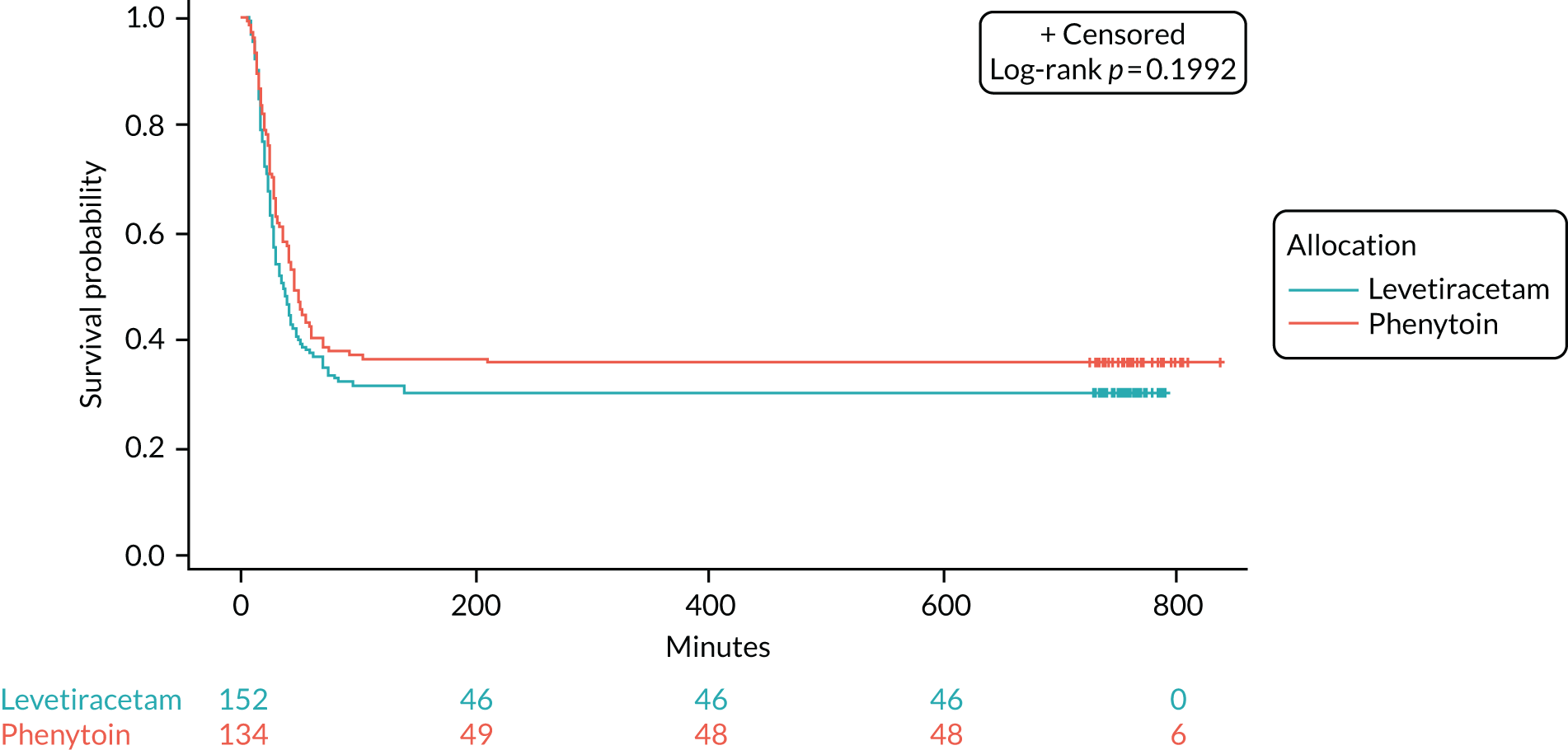

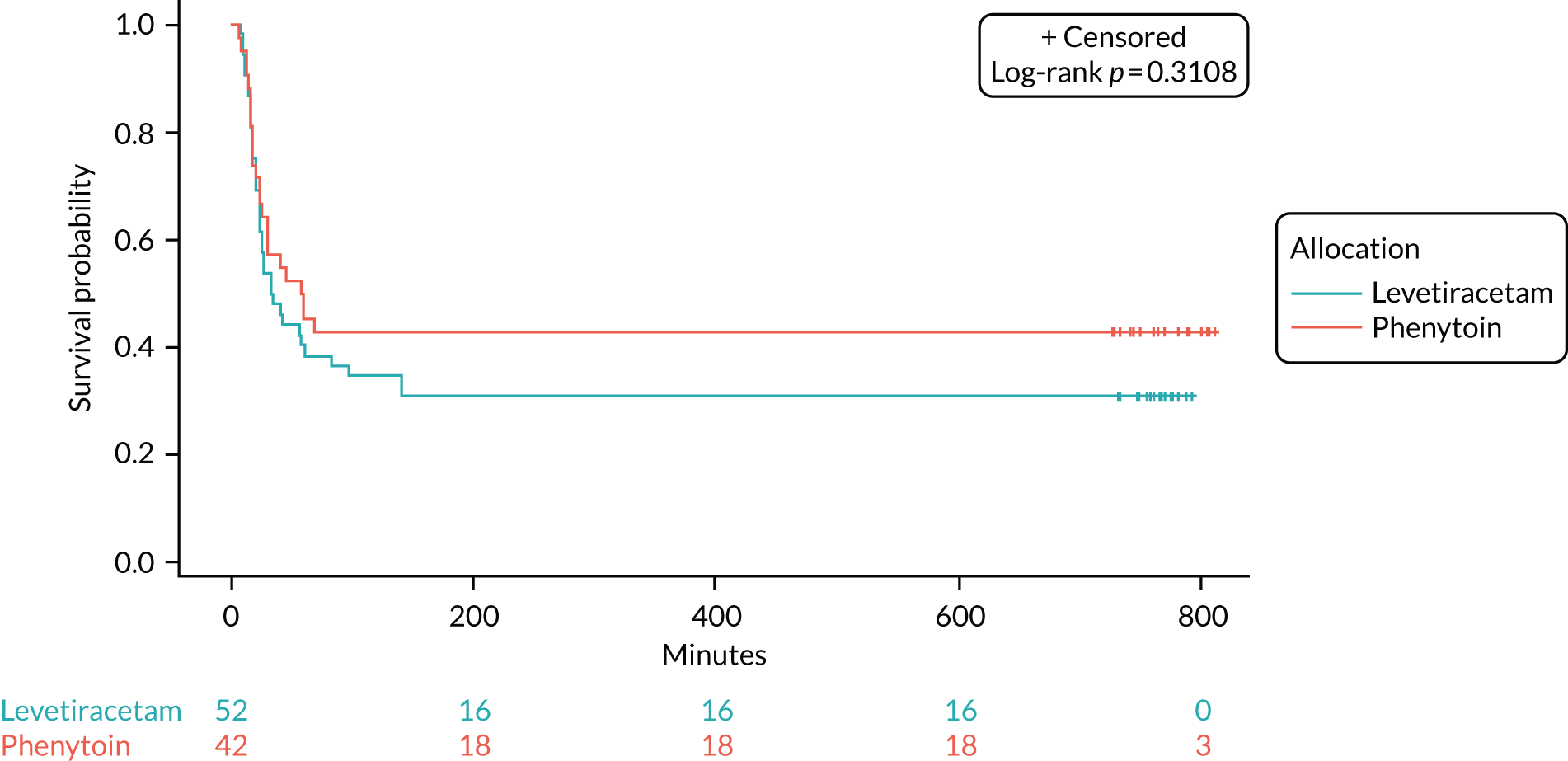

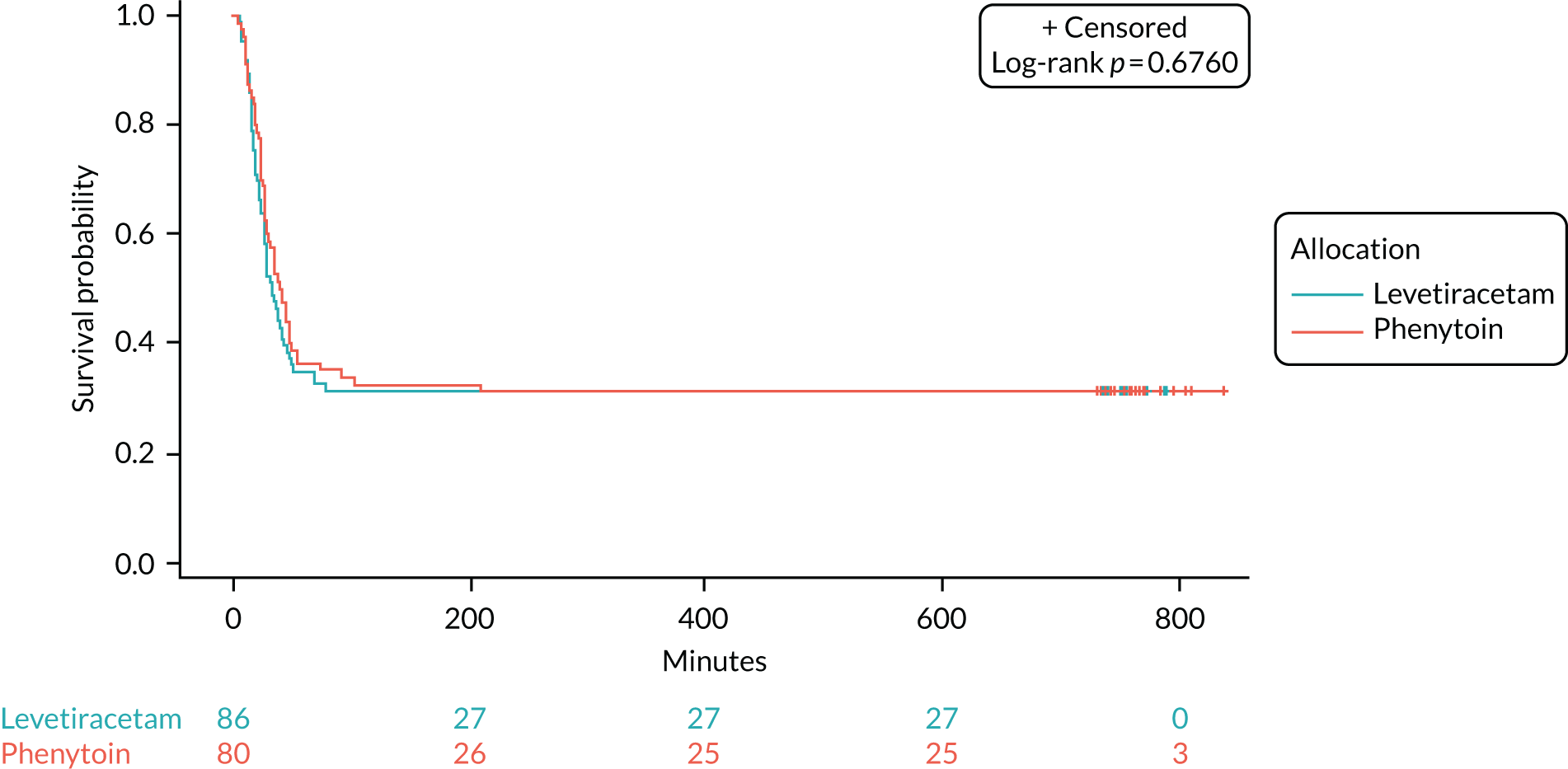

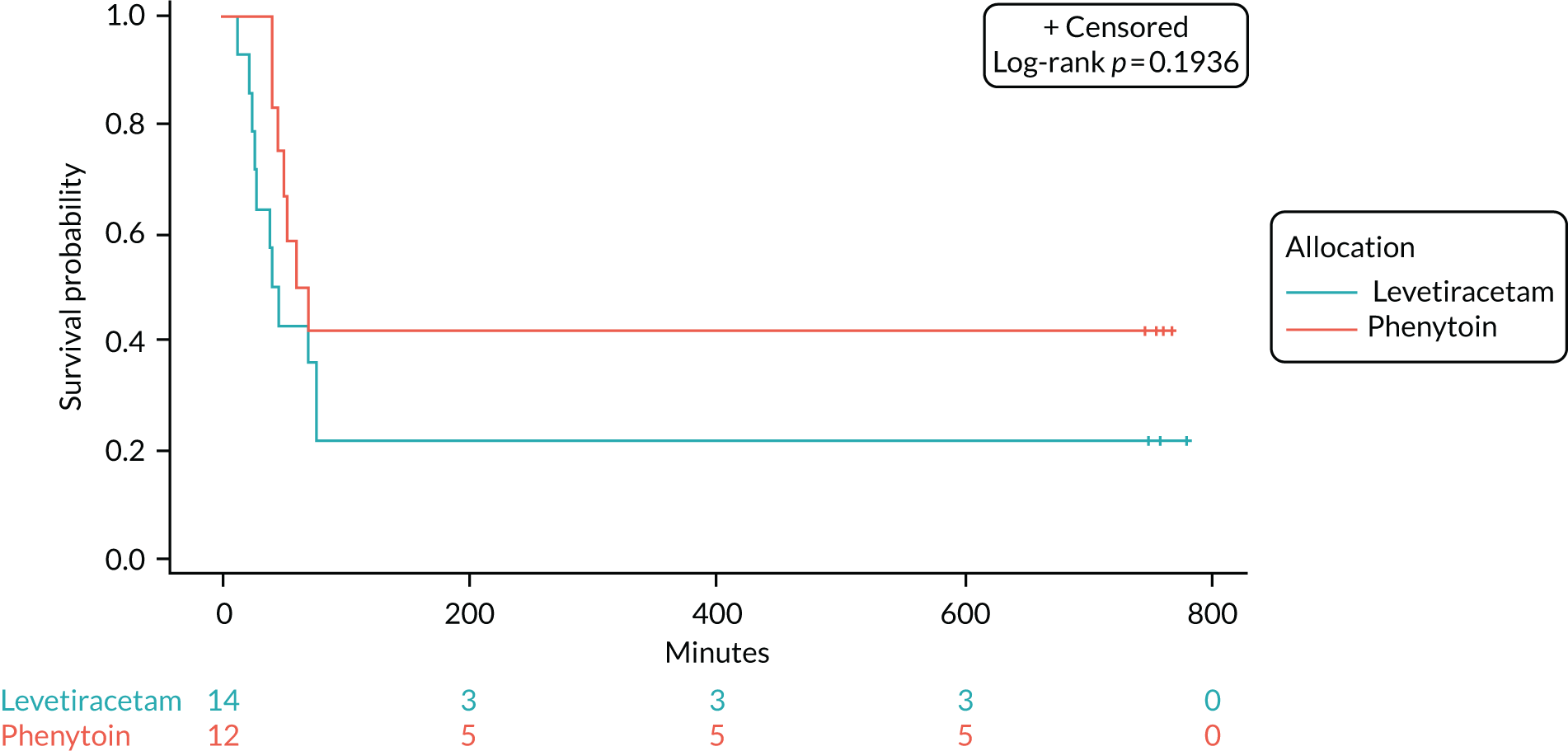

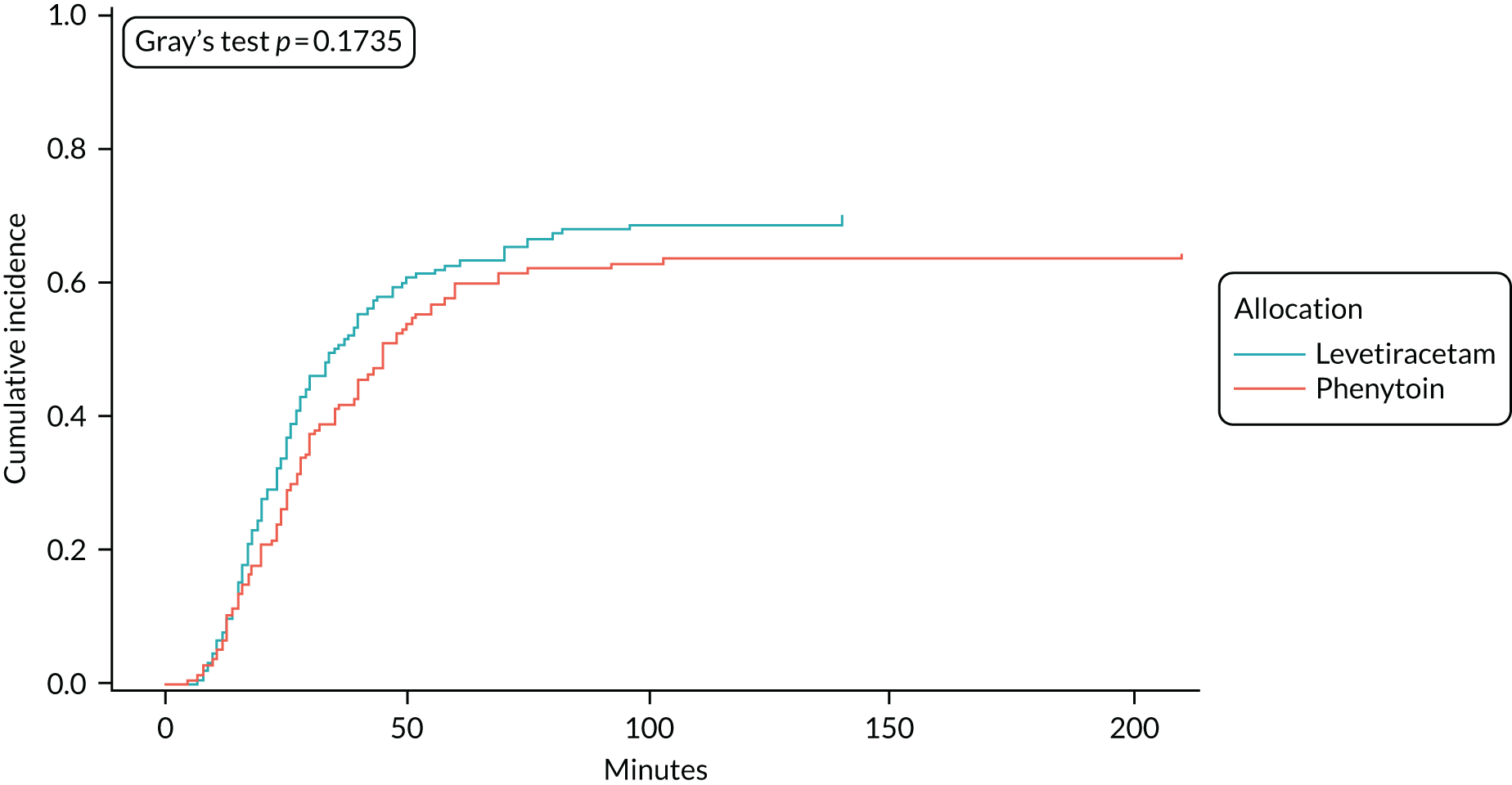

Table 8 provides the median time to seizure cessation from randomisation and Figure 4 shows the Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test. As the event of interest (i.e. seizure cessation) is positive, the lower curve indicates a shorter time to seizure cessation; however, there is no statistically significant difference between the treatment arms (log-rank p-value > 0.05).

| Event | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 152) | Phenytoin (N = 134) | |

| Number of events (seizure cessation), n (%) | 106 (69.7) | 86 (64.2) |

| Number of censored times (RSI), n (%) | 46a (30.3) | 48b (35.8) |

| Median time (minutes) to cessation of seizure from randomisation (IQR) | 35 (20–NAc) | 45 (24–NAc) |

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier plot time from randomisation to seizure cessation. Product-limit survival estimates with number of subjects at risk. This figure been reused from Lyttle et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The unadjusted HR was 1.2 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.6; p = 0.2) in favour of levetiracetam. The Schoenfeld residuals for the unadjusted model (p = 0.72) indicated the independency of time and the validity of the proportionality assumption. The Schoenfeld residuals for the adjusted model indicated that the assumption of proportionality for weight was not met (p = 0.05, p-value ranged from 0.27 to 0.71 for other variables). The data were subgrouped according to weight category as per the baseline table (i.e. < 12 kg, 12–36 kg and > 36 kg) and estimates from the adjusted model calculated (see Appendix 6, Tables 15–29). The proportionality assumption within each subgroup of data was supported by the Schoenfeld residuals. Direction of treatment effect was consistent across subgroups, CIs were wide and results were not statistically significant. The treatment effect was increased for children in the > 36 kg subgroup, but remained non-significant and numbers within this group are small.

A range of sensitivity analyses were considered to assess seizure cessation from the start of the infusion, rather than from randomisation (see Appendix 7, Table 32) and the impact censoring regarding RSI and death. The results demonstrated robustness of conclusions and are presented in Appendices 6 and 7.

Secondary outcomes

The study comprised four secondary outcomes. These assessed the efficacy and safety of the two trial interventions (Table 9).

| Secondary outcome | Group, n (%) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 152) | Phenytoin (N = 134) | |||

| Need for further anticonvulsantsa | 57 (37.5) | 50 (37.3) | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.36) | 0.97 |

| Need for further anticonvulsants for the presenting CSEb | 24 (15.8) | 20 (14.9) | 1.06 (0.61 to 1.83) | 0.84 |

| Need for further anticonvulsants for a subsequent seizure (within 24 hours)b,c | 14 (9.2) | 17 (12.7) | 0.72 (0.37 to 1.4) | 0.33 |

| RSI to terminate an ongoing seizure | 44 (30.0) | 47 (35.1) | 0.83 (0.59 to 1.16) | 0.27 |

| Admission to critical care | 97 (63.8) | 72 (53.7) | 1.19 (0.97 to 1.45) | 0.08 |

| SAR | 0 | 2d | ||

| 14-day follow-up | ||||

| Discharged from hospital | 145 (95.4) | 130 (97.0) | ||

| Readmitted to hospital | 12 (7.9) | 10 (7.5) | ||

| Patient died | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Organ failure | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

One participant who was allocated and received phenytoin experienced a SAR. This was profound hypotension, which was considered to be immediately life-threatening and responded to emergency treatment. This participant also experienced a severe unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR), which manifested as a large increase in seizure frequency and marked sedation within 24 hours of receiving phenytoin. The SUSAR was considered medically significant and the participant required admission to the intensive care unit. The SUSAR resolved without complication.

Safety, tolerability and compliance

Two patients died in the study, but neither death was considered related to the randomised treatment. One participant presented to the ED in a generalised tonic–clonic seizure and unconscious. Resuscitation was immediate. The participant received levetiracetam (the randomised treatment) and then phenytoin, followed by RSI with thiopentone (Archimedes, Reading, UK) because of abnormal posturing. The participant died 36 hours following admission and a post-mortem examination revealed severe brain oedema secondary to encephalitis. Consent for recruitment into the study was subsequently obtained from the participant’s carers. The death was considered to be unrelated to the randomised treatment by the principal investigator and chief investigator.

The second participant received phenytoin. The participant died and the results of the post-mortem examination were not available prior to closure to recruitment to the study. The principal investigator and chief investigator considered the death to be unrelated to the randomised treatment. Consent was sought from the participant’s carers but had not been obtained by the time recruitment to the study closed on 10 April 2018 and, therefore, this participant’s data are not included in the analysis.

Adverse events and serious adverse events

A total of 51 AEs were reported in 39 out of the 286 participants. Some participants experienced more than one AE. Forty-one of the AEs were classified as mild, nine as moderate and one as severe. Sixteen out of 130 levetiracetam-treated participants, 18 out of 132 phenytoin-treated participants and four out of 24 participants who received both drugs experienced at least one AE. Each individual AE had a prevalence of < 10%. In the levetiracetam-treated group (20 AEs in 16 participants), a psychiatric AE was reported in 12 participants (agitation in 11 and hallucinations in one). In the phenytoin-treated group (23 AEs in 18 participants), a cardiovascular AE was reported in eight participants, an extravasation/administration site reaction AE in seven (severe in one) and an agitation AE in four. In the group that received levetiracetam and phenytoin (eight AEs in four participants), an extravasation/administration site reaction was reported in three. The full list of reported AEs is shown in Table 10.

| AE | Group | Total (N = 286) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam (N = 132) | Phenytoin (N = 130) | Both drugs (N = 24) | ||||||

| Events, n | Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Patients, n (%) | |

| Agitation | 11 | 11 (8.3) | 4 | 4 (3.1) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 15 | 15 (5.2) |

| Hypotension | 2 | 2 (1.5) | 3 | 3 (2.3) | 1 | 1 (4.2) | 6 | 6 (2.1) |

| Catheter site related | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 3 | 2 (8.3) | 5 | 4 (1.4) |

| Extravasation | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 4 | 4 (3.1) | 1 | 1 (4.2) | 5 | 5 (1.75) |

| Tachycardia | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 3 | 3 (2.3) | 1 | 1 (4.2) | 5 | 5 (1.75) |

| Rash | 2 | 2 (1.5) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 3 | 3 (1.1) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 2 | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 2 | 2 (0.7) |

| Reaction to ceftriaxonea | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (4.2) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Confused | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Decreased consciousness | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Hallucination | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Infusion site erythema | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Mechanical ventilation complication | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Pallor | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Stridor | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (4.2) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Wheezing | 1 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.4) |

| Total | 20 | 16 (12.1) | 23 | 18 (13.9) | 8 | 4 (16.7) | 51 | 38 (13.3) |

Five SAEs were reported in four participants [including one participant who experienced two SAEs (participant 00133027)]. In three participants, the SAE was considered unrelated to the intervention, and one each was considered to be possible and probable (Table 11).

| SAE number | Description | Preferred term (System Organ Class) | Treatment received | Seriousness | Severity | Expectedness | Relationship assessment | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal investigator | Chief investigator | ||||||||

| 00133007-001 | Attended ED fitting. Randomised to levetiracetam, but given phenytoin. Stopped self-ventilating and required RSI and was intubated. CT showed fractured VP shunt and required urgent shunt revision. Taken to theatre 25 November 2015 at 02.45. Shunt revision complete. Admitted to PICU for < 24 hours. Admitted to neurosurgical ward until 30 November 2015 | Device malfunction (general disorders and administration site conditions) | Phenytoin | Prolonged existing hospitalisation | Moderate | Unexpected | Unrelated | Unrelated | Resolved |

| 00133027-005 | Patient weaned off sedation on 22 March 2017. At 13.55 patient started having seizure episodes. Documented in notes that the patient had approximately 40 seizures until phenobarbital given at 18.10, 22 March 2017. No further seizures but conscious level decreased until 18.00, 26 March 2017 | Seizure (nervous system disorders) | Phenytoin | Medically significant or important | Moderate | Unexpected | Unlikely | Possibly | Resolved |

| 00133027-006 | Patient became hypotensive at 01.45, 22 March 2017. Patient given fluid boluses as documented on concomitant medication form. Patient remained hypotensive and so given adrenaline infusion. Hypotension resolved completely (26 March 2017). No further problems | Hypotension (vascular disorders) | Phenytoin | Immediately life-threatening | Moderate | Expected | Possibly | Probably | Resolved |

| 00133029-008 | Patient randomised and given levetiracetam. Noted to have only slight twitching after. Patient then started having decorticate/decerebrate posturing. RSI. Desaturated and bradycardia owing to ET tube problems. No ETC02 reading, reintubated but ventilation difficult causing desaturation and bradycardia. Arrest CPR commenced | Cardiac arrest (cardiac disorders) | Levetiracetam |

Immediately life-threatening Prolonged existing hospitalisation |

Severe | Unexpected | Unrelated | Unrelated | Resolved |

| 00243026-002 | Attended the ED fitting and unconscious. Pupils equal and reactive but sluggish. Tolerating airway. CT showed massive raised intracranial pressure. Pupils become fixed and dilated just before being taken to emergency theatre. Oral secretions positive for mycoplasma pneumoniae | Intracranial pressure increased (nervous system disorders) | Phenytoin and levetiracetam | Immediately life-threatening | Severe | Unexpected | Unrelated | Unrelated | Fatal |

An additional follow-up questionnaire was completed by sites and the families of participants who had been randomised, treated and consented to take part in the study. The questionnaire was completed 2 weeks following randomisation. Results are shown in Table 12.

| Follow-up | Allocation | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Information not provided in patient notes, n (%) | Unknown or missing, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged from hospital | Levetiracetam | 145 (95.4) | 7 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 152 (53.15) |

| Phenytoin | 130 (97) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 134 (46.9) | |

| Total | 275 (96.1) | 11 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 286 (100) | |

| Readmitted to hospital | Levetiracetam | 12 (7.9) | 81 (53.3) | 25 (16.4) | 34 (22.4) | 152 (53.1) |

| Phenytoin | 10 (7.5) | 64 (47.8) | 19 (14.2) | 41 (30.6) | 134 (46.9) | |

| Total | 22 (7.7) | 145 (50.7) | 44 (15.4) | 75 (26.2) | 286 (100 | |

| Patient died | Levetiracetam | 1 (0.7) | 111 (73) | 22 (14.5) | 18 (11.8) | 152 (53.1) |

| Phenytoin | 1 (0.7) | 93 (69.4) | 20 (14.3) | 20 (14.9) | 134 (46.9) | |

| Total | 2 (0.7) | 204 (71.3) | 42 (14.7) | 38 (13.3) | 286 (100) | |

| Organ failure | Levetiracetam | 1a (0.7) | 110 (72.4) | 20 (13.2) | 21 (13.8) | 152 (53.1) |

| Phenytoin | 0 (0) | 98 (73.1) | 16 (11.9) | 20 (14.9) | 134 (46.9) | |

| Total | 1 (0.3) | 208 (72.7) | 36 (12.6) | 41 (14.3) | 286 (100) |

Only 74 (25.9%) families completed their 14-day follow-up questionnaire. As documented in the internal meeting minutes, 8 May 2018, details for these questionnaires are not presented within this report because of the low response rate.

Laboratory parameters (haematological, biochemical analysis and urinalysis)

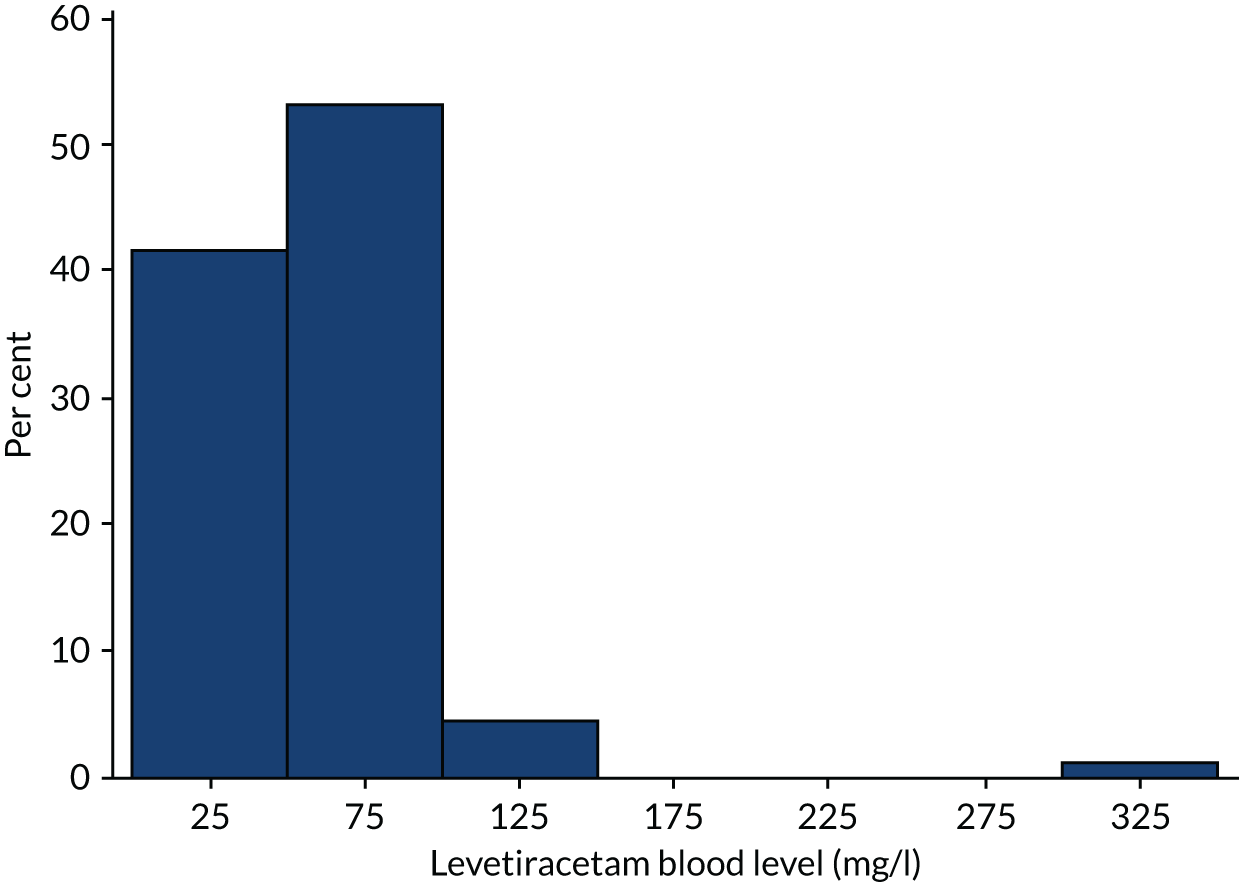

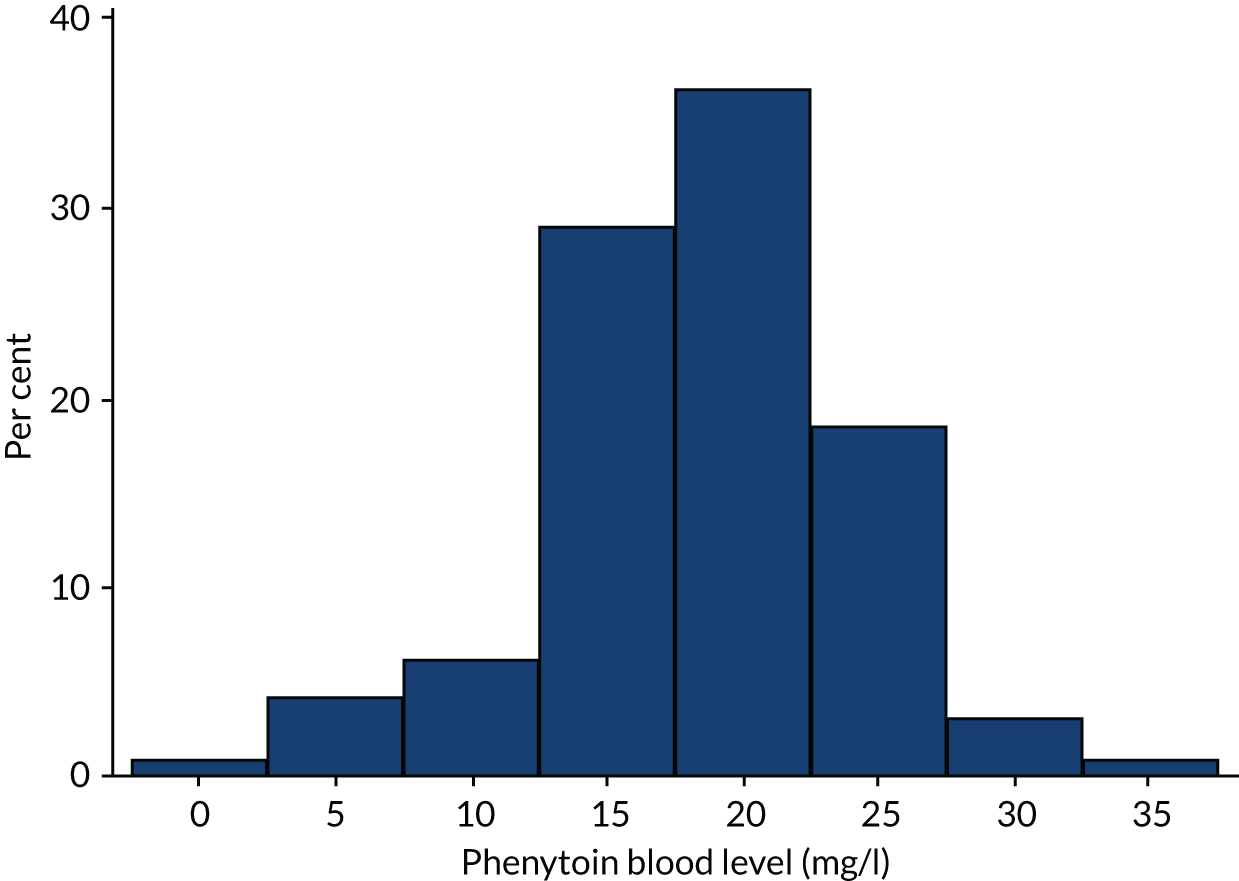

Laboratory analyses in the trial protocol were limited to measurements of blood levels of levetiracetam and phenytoin in the randomised, treated and consented participants. Blood samples were obtained between 1 and 2 hours after completion of infusion of the two treatments. Biochemistry laboratories in each site processed the samples in accordance with their standard operating procedures. The reference ranges for blood levels of levetiracetam were provided by a single central laboratory that analysed all of the samples of levetiracetam-treated participants. The reference ranges for blood levels of phenytoin were provided by the biochemistry department of each participating site that analysed samples of its phenytoin-treated participants.

A total of 192 participants underwent measurement of a blood level [96 participants in the levetiracetam-treated group (63.2%) and 96 participants in the phenytoin-treated group (77.7%)] and the results are shown in Figures 5 and 6.

FIGURE 5.

Levetiracetam blood levels.

FIGURE 6.

Phenytoin blood levels.

Chapter 4 Nested consent study

Background

Convulsive status epilepticus is a medical emergency that has insufficient time to obtain informed consent within the therapeutic window. The use of RWPC (also known as deferred consent) in the EcLiPSE trial was supported by parents who took part in trial feasibility work. 43

A nested study was designed to identify potential barriers and solutions to recruitment and consent in the EcLiPSE trial, and to inform recruiter training on recruitment, consent, trial conduct and future trials in this setting.

Objectives

Consent study objectives were to explore:

-

how information about the trial and RWPC was exchanged during recruitment discussions

-

parents’ and practitioners’ views and experiences of RWPC and consent decision-making

-

the impact of an unblinded trial design.

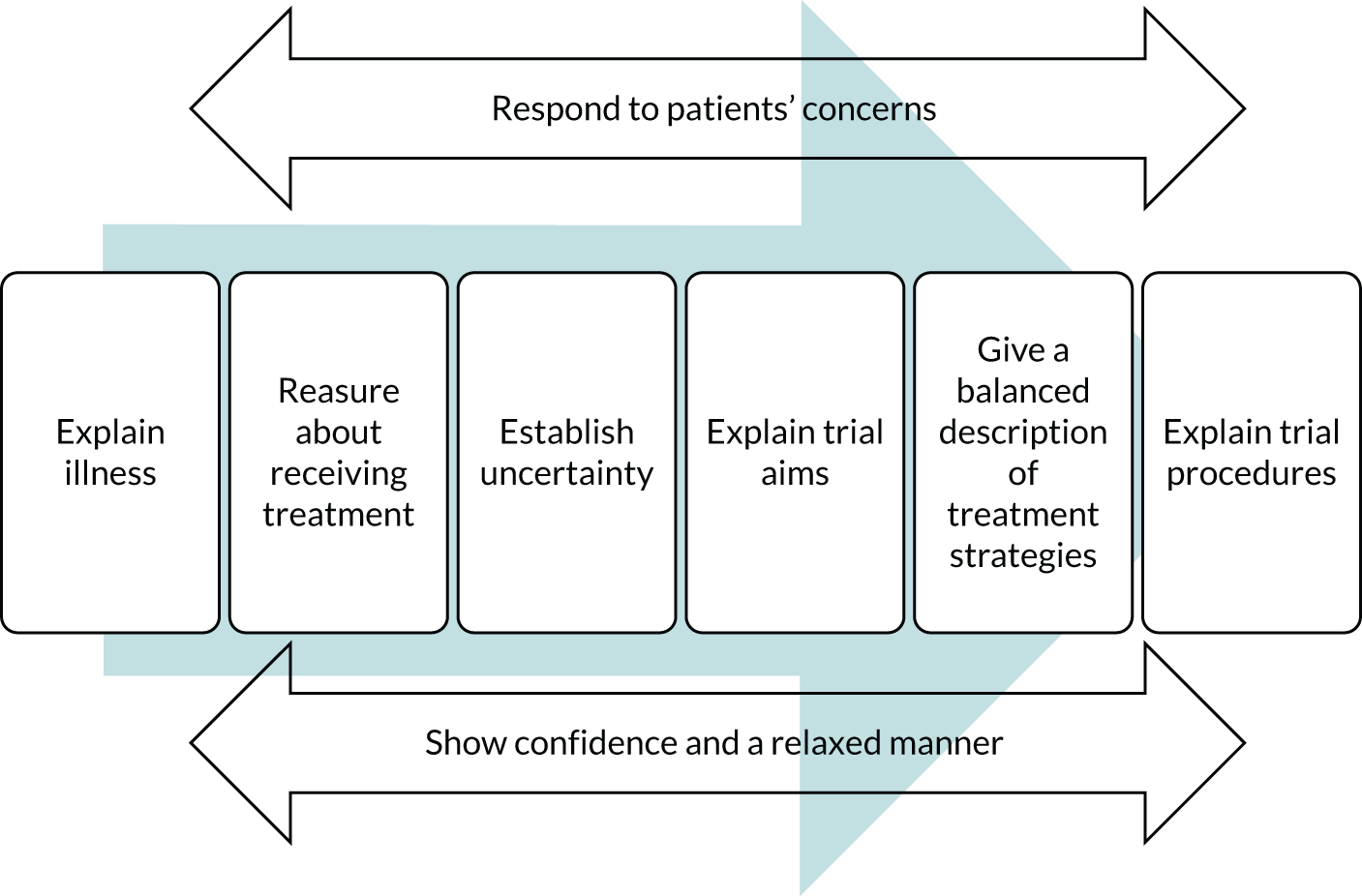

We included a strand of work that aimed to develop trial recruiter training on RWPC using recommendations made by parents in the feasibility study and related guidance. 43,46–49 Our objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of the EcLiPSE trial site initiation visit (SIV) training on practitioners’ confidence in recruitment, consent and trial conduct.

Methods

Study design

The consent study used a mixed-methods approach,50,51 involving parents of randomised participants and EcLiPSE trial practitioners. The design and development of the consent study, including recruitment strategy, questionnaires and topic guides, were informed by previous work43,46 in paediatric emergency and critical care in the NHS. EcLiPSE trial feasibility work43 was used to develop participant information and practitioner training materials.

All EcLiPSE trial sites were eligible for inclusion in the consent study, which involved the following research methods:

-

recorded trial recruitment and consent discussions between parents and EcLiPSE trial practitioners

-

parent questionnaires completed after EcLiPSE trial consent discussions (including those who decline consent)

-

telephone interviews with parents approximately 1 month after hospital discharge

-

telephone interviews with the site principal investigator or research nurse within the first 12 months of site opening

-

focus groups with practitioners at the end of the first year

-

a semistructured questionnaire with practitioners administered before and after SIV training

-

an online questionnaire of practitioners in final phase of the trial (approximately 8 months before trial closure).

Participants

We aimed to collect parent questionnaires at all sites throughout trial recruitment. Based on previous research,43,44 we anticipated interviewing approximately 15–25 parents/legal representatives, conducting 6–10 focus groups and 10 additional practitioner interviews to reach data saturation (i.e. the point where no new major themes are discovered in analysis). We planned to collect recorded trial discussions at all sites for the first 4 months of the trial or until data saturation point. We aimed to include practitioners at all sites in the online survey and all staff attending each SIV in the training evaluation.

Eligibility

Parents

Parents (including legal representatives) who did and did not consent to their child’s participation in the trial were eligible to take part in the consent study, unless they were unable to speak or read English.

Practitioners

All practitioners involved in screening, recruiting, randomising and consenting parents/legal representatives during the trial were eligible to take part in the consent study. Those not intending to stay for the full SIV training were excluded from the SIV questionnaire element.

Recruitment

Recruitment to recorded trial discussions, parent questionnaires and interviews

As described in Chapter 2, the principal investigator, research nurse or other designated member of the site research team approached the parent/legal representative to discuss the trial and seek consent as soon as possible after completion of trial treatment (ideally within 24 hours of randomisation). During this discussion, the principal investigator/research nurse briefly explained the aims of the consent study and sought verbal permission for audio-recording of trial discussions. If permission was declined the recruitment discussion was not recorded. If permission was given the recruiter activated an audio-recorder. Written consent was then sought for all consent study elements as part of the EcLiPSE trial consent process. This included written consent for the use of recorded trial discussion data, as well as consent to complete a questionnaire before their child was discharged from hospital and to take part in an interview approximately 1 month later.

Parents were asked to place the completed questionnaires in a sealed, stamped, addressed envelope and return it to the EcLiPSE trial practitioner to post to the consent study team. There was also a link to an online version of the questionnaire at the top of the paper questionnaire, enabling parents to complete the survey online if preferred. Recruitment for questionnaires took place throughout the active trial recruitment phase. In the rare instance that consent was not sought prior to discharge or before the participant was transferred to another hospital, the questionnaire was sent to parents/legal representatives along with the parent/legal representative information sheet and consent form to complete. We asked trial recruiters to record all trial discussions (e.g. an initial discussion followed by a full trial discussion after the family had considered the trial information), which were then uploaded to a secure website for transcription. LR made contact with families to arrange telephone interviews within 1 month of consent. Initially, parents’ expressions of interest to participate were responded to in sequential order. As trial recruitment progressed, we stopped interviewing parents from high-recruiting sites and purposively sampled across all recruiting sites to help ensure sample variance.

Recruitment to practitioner focus groups and interviews

LR e-mailed selected sites and invited practitioners to participate in a telephone interview or focus group. Selection of sites was based on accrual rates (i.e. high and low rates) and recruitment issues identified in the ongoing analysis of recorded trial discussion, parent questionnaires and interviews. Verbal consent was sought, including consent for recorded trial discussions. All focus groups were facilitated by LR who sought audio-recorded verbal consent from participants before each focus group began.

Recruitment to the site initiation visit evaluation

The trial co-ordinator (AH) liaised with the site principal investigator or research nurse to invite all relevant staff to the SIV. KW, LR or AH provided a brief description of the evaluation before the opening presentation and invited practitioners who intended to stay for the full training to participate by completing part A of the questionnaire before training and part B at the end of training. Questionnaire completion was taken as indication of consent. Personal details were not requested to ensure anonymity.

The trial co-ordinator (AH) e-mailed all eligible sites (28 out of 30 sites because two had closed) 8 months before the scheduled trial end date, and invited staff involved in the EcLiPSE trial to complete an online questionnaire [see appendix on the NIHR Journals Library project web page: URL www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/12127134/#/ (accessed 28 September 2020)]. MDL sent e-mail reminders on behalf of the trial team and PERUKI. It was anticipated that some of the same staff who took part in a telephone interview or focus groups would also complete the online questionnaire.

Conduct of interviews and focus groups

LR began interviews and focus groups with parents and practitioners with a description of the consent study aims. The interview commenced using an interview topic guide (see Appendix 8). Respondent validation was used to add unanticipated topics to the topic guide as interviewing and analysis progressed. After the interview, participants were thanked for their time.

Any distress during the parent interviews was managed with care and compassion and participants were free to decline to answer any questions that they did not wish to answer or to stop the interviews at any point.

Transcription

Digitally recorded trial discussions were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company (VoiceScript Ltd, Bristol, UK). Transcripts were anonymised and checked for accuracy. All identifiable information, such as names (e.g. of patients, family members or the hospital their child had been admitted to), were removed.

Data analysis

Qualitative data

LR (a psychologist) led the analysis with assistance from KW (a sociologist). Qualitative focus group and interview data analysis was interpretive, and iterative analysis was based on thematic analysis, a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (or themes) within data. Utilising a thematic analysis approach, the aim was to provide accurate representation of parent and practitioner views to address the study aims and objectives. This approach allows for themes to be identified at a semantic level (i.e. surface meanings or summaries) or at a latent level (i.e. interpretive, theorising the significance of the patterns and their broader meanings and implications). 50 NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to assist in the organisation and coding of data.

Quantitative data

LR entered all parent and practitioner online questionnaire and SIV training questionnaire data into SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented with percentages and the chi-squared test for trend.

For the SIV training questionnaire analysis, we used paired samples t-test and Wilcoxon signed-ranks test (95% CI), as appropriate. Questionnaires with recruitment and consent-related data missing were excluded from the analysis. To investigate the presence of informative missing data, the results of those who completed only part A of the questionnaire were compared with those who completed parts A and B of the questionnaire. This was also undertaken for those who completed only the ‘after’ questionnaire.

Data synthesis

Our approach to synthesising qualitative and quantitative data52 drew on the constant comparative method. 53,54 As part of an iterative process, KW and LR used early findings during trial conduct to create updates via newsletters for EcLiPSE trial recruiters and brief feedback sessions at the end of each focus group. These outputs contained recommendations to assist ongoing approaches to recruitment and consent in the EcLiPSE trial.

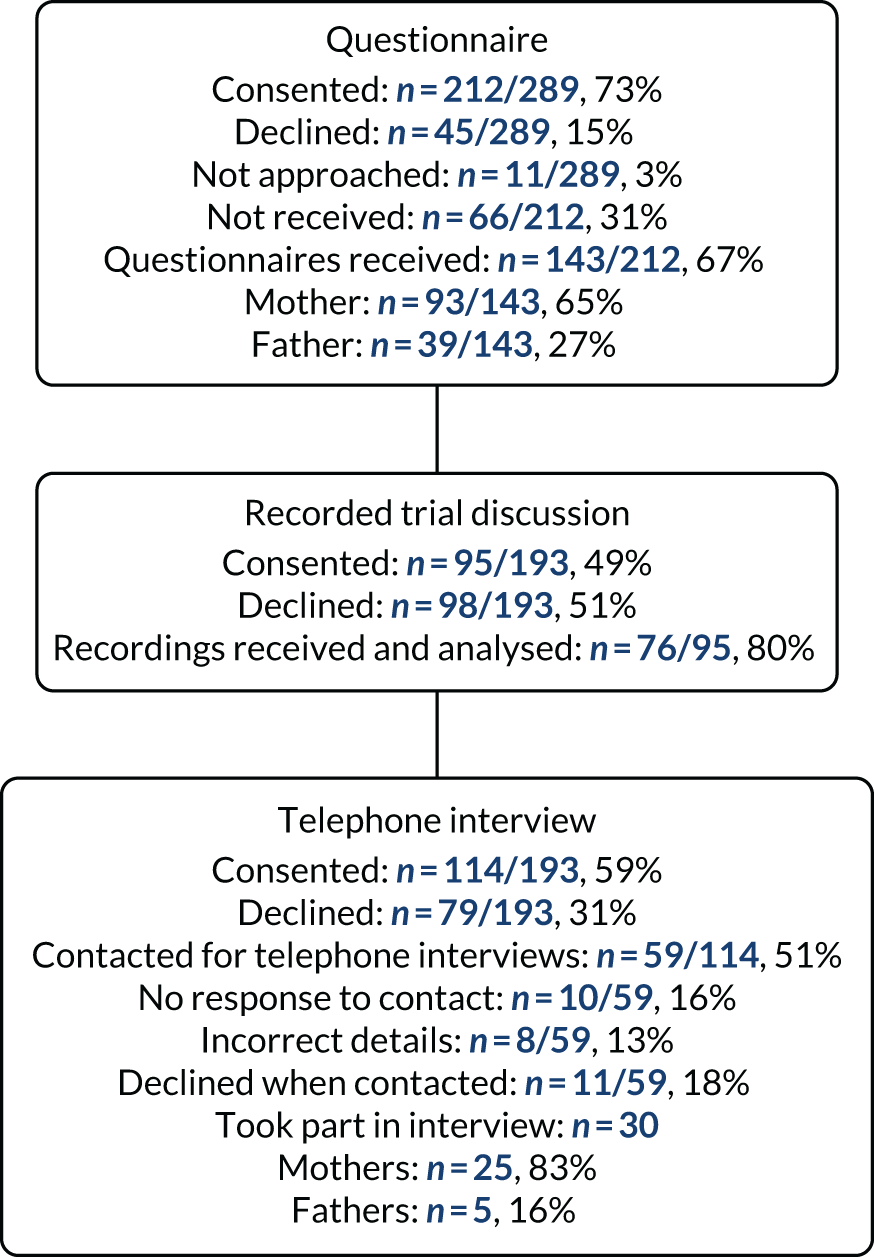

Results

Participants: parents

Two hundred and eighteen parents of the 289 (75%) children randomised and treated in the EcLiPSE trial consented to participate in some aspect of the consent study. A total of 212 out of 218 (97%) parents consented to complete a questionnaire and in 13 instances two parents completed a questionnaire for one child. A total of 143 out of 212 (67%) paper-version questionnaires were received (Figure 7). No parents chose to complete the questionnaire using the online version.

FIGURE 7.

Parent characteristics by method.

Recorded trial discussions and interview elements closed in August 2017 (with 193 patients treated and randomised at that stage of the trial) as we reached the data saturation point. 55 Just under half (95/193, 49%) of eligible parents gave consent for the recorded trial discussion. Of these recorded discussions, 76 out of 95 (80%) were received and analysed. Of 114 (59%) of the 193 eligible parents who agreed to be approached for interview, 59 (51%) were invited to participate in an interview by telephone or e-mail. Of these, eight (13%) had incorrect contact details, 10 (16%) did not respond and 11 (18%) declined to interview on telephone contact. Interview and recorded trial discussions data were obtained from 17 out of 25 (68%) sites. Of these, 36 out of 76 (47%) recorded trial discussions were led by doctors and 19 out of 76 (25%) conversations were led by nurses or research nurses. Most (45/76, 60%) practitioners recorded one trial discussion, 24 out of 76 (31%) recorded two parts of a trial discussion and 7 out of 76 (9%) recorded three or more parts. In 37 (49%) cases, it was clear that only the second part of the conversation had been recorded. We obtained a full data set (i.e. the questionnaire, recorded trial discussions and parental interview) for 19 families.

Participants: practitioners

We interviewed EcLiPSE trial principal investigators (n = 4) and lead research nurses (n = 6) who were the main staff involved in recruitment discussions with parents within their first year of site opening. Telephone interviews took place 8–18 months post SIV training (mean 11 months, 345 days; range 260–577 days) and 5–16 months after site opening (mean 8 months, 265 days; range 168–490 days).

A total of 36 practitioners (i.e. 20 nurses and 16 doctors) took part in one of six focus groups held 13–18 months post SIV (mean 14 months, 455 days; range 400–574 days) and a mean of 12 months (mean 374 days; range 329–420 days) after site opening.

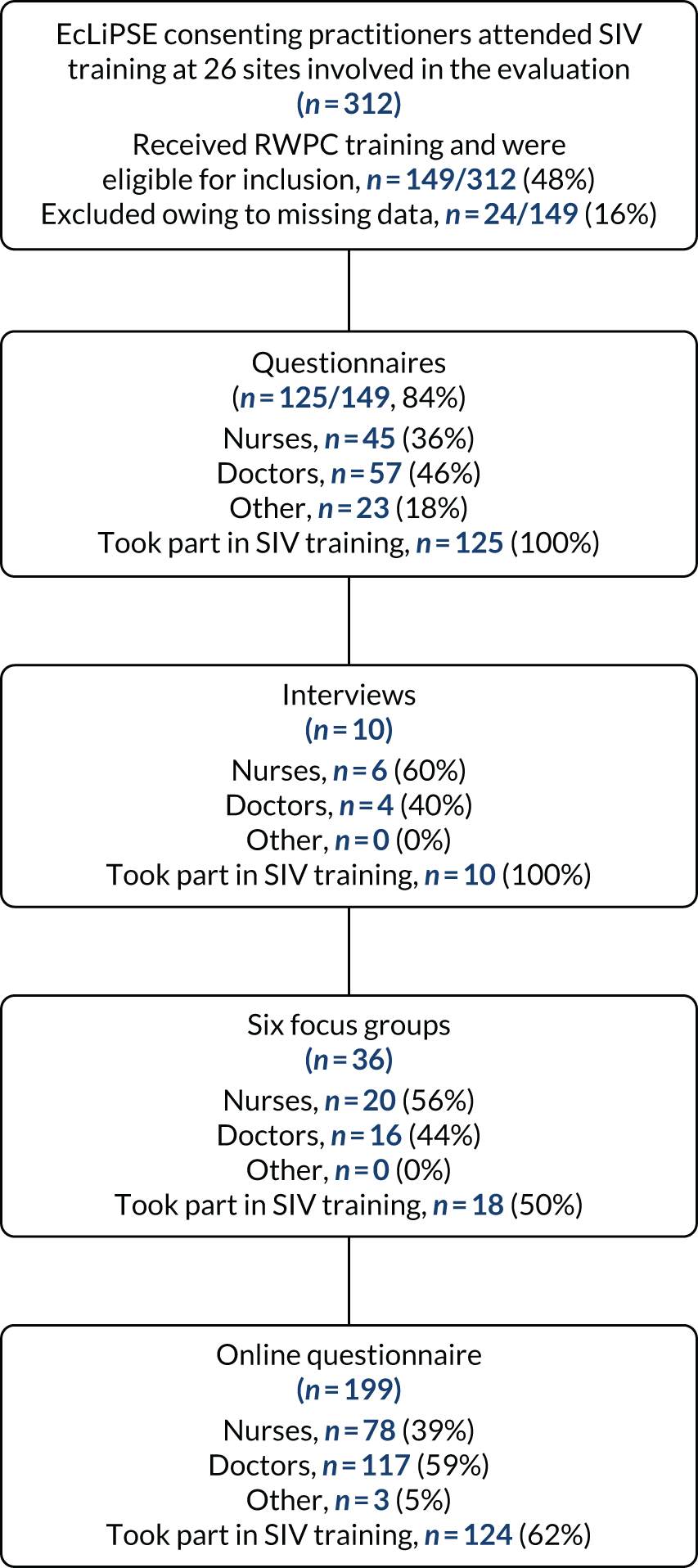

The SIV evaluation involved 26 out of 30 (87%) sites. A total of 149 out of 312 (47%) staff were eligible for inclusion, as they anticipated staying for the full site initiation meeting and completed a questionnaire. Clinical commitments had an impact on staff’s ability to attend the entire SIV. Consequently, 24 out of 149 (16%) questionnaires were partially completed and excluded from the analysis because of missing data.

A total of 199 practitioners from 29 out of the 30 (97%) sites completed the online questionnaire approximately 8 months before the end of the trial.

See Appendix 10 for consent study participant characteristics.

We present consent study findings under key themes identified in the analysis of parent and practitioner data.

Trial acceptability and challenges: practitioner perspectives

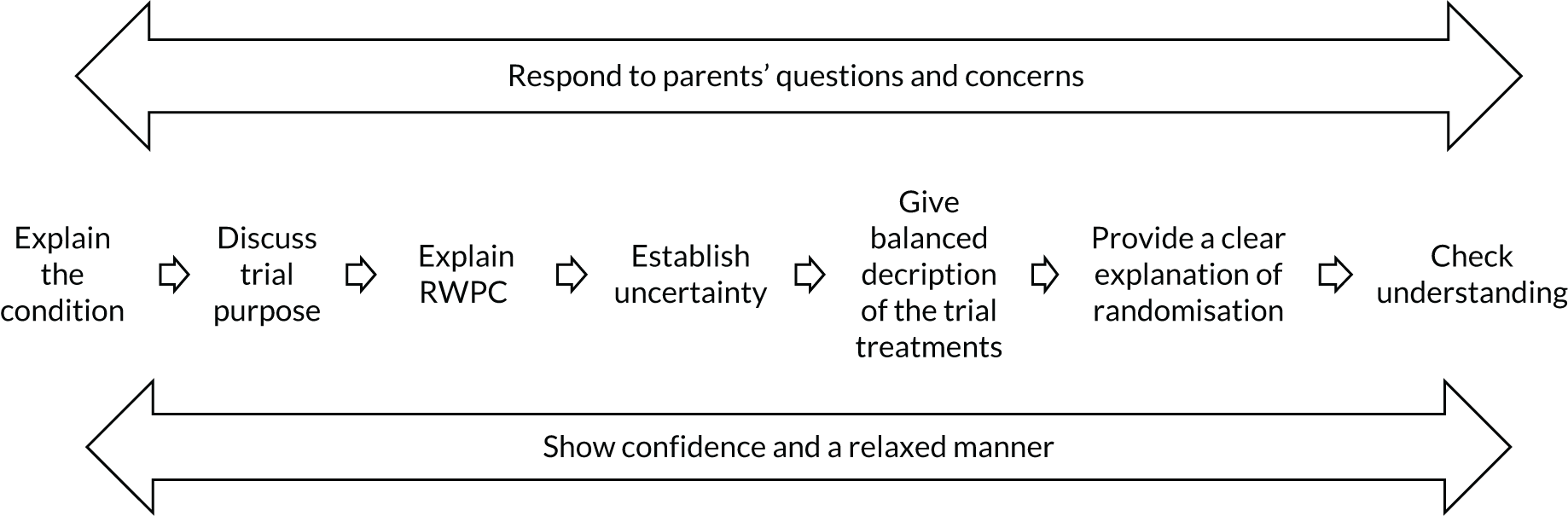

For many hospitals, the EcLiPSE trial was the first clinical trial to be led by their ED. In the early stages of the design of the EcLiPSE trial, the trial team recognised practitioner concerns about the acceptability of RWPC. A training package was, therefore, developed using parents’ perspectives from the EcLiPSE feasibility study40 and CONseNt methods in paediatric Emergency and urgent Care Trials (CONNECT) guidance. 48 The aim was to help provide practitioners with confidence in recruitment and RWPC in the EcLiPSE trial.

Practitioner perspectives before trial recruitment

Before site initiation training, 33 out of 118 (28%) practitioners who completed a questionnaire indicated that they had concerns about recruiting participants to the trial. A higher proportion of practitioners (48/120, 40%) was concerned about seeking RWPC (Table 13). During interviews and focus groups practitioners described how their concern arose from lack of knowledge and experience of RWPC. Some staff were apprehensive about the acceptability of RWPC and ‘quite concerned how parents would take that [RWPC]’ (focus group 4, female, nurse, P1) and about ‘how to approach it with the parents’ (practitioner telephone interview, female, lead research nurse, P3) after their child had been entered into the trial.

| Question | Yes, n (%)a | No, n (%)a | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have any concerns about recruiting to the EcLiPSE trial? | 33 (28) | 85 (72) | |||

| Experienced in RWPC | 4 (19) | 17 (71) | 0.54 | 1.17 to 1.74 | 0.296 |

| Not experienced in RWPC | 28 (30) | 64 (70) | |||

| Do you have any concerns about seeking consent for the EcLiPSE trial? | 48 (40) | 72 (60) | |||

| Experienced in RWPC | 6 (26) | 17 (74) | 0.46 | 0.17 to 1.30 | 0.128 |

| Not experienced in RWPC | 40 (43) | 52 (57) |

Interestingly, previous experience with RWPC was not associated with concerns about recruitment or seeking consent, suggesting that concerns may have arisen from issues other than the consent process. Sixty-nine out of 115 (60%) practitioners who completed the questionnaire anticipated that there would be practical or logistical difficulties in conducting the EcLiPSE trial. This included concerns about adequate research support to conduct consent discussions with families, particularly ‘over the weekend’ (SIV questionnaire part A, female, doctor, P55), as well as the challenge of training all relevant staff across departments. In focus groups, doctors discussed their concerns about using a trial protocol in an emergency resuscitation situation, while not compromising the clinical care of critically ill children:

I thought, oh God, this sounds horrendous. Literally I was thinking, how is this going to work? This is going to be a nightmare.

Focus group 3, female, doctor, P3

As the number of eligible patients per site was expected to be fairly small (i.e. approximately 0.5 patients per month), practitioners referred to the anticipated challenge of maintaining trial awareness to ensure that eligible patients were not missed. Principal investigators were most concerned about engaging and motivating all staff to maximise trial success:

Difficult to control for other people who may be less interested in our department being involved.

SIV questionnaire part A, female, doctor, P121

Practitioner perspectives after training and experience of recruitment

As shown in Appendix 9, Tables 38 and 39, improved levels of confidence were observed for all four questionnaire statements, regardless of whether or not practitioners had prior experience of RWPC. It was notable that following training 82 (66%) practitioners felt that their confidence in explaining the study to families had improved, whereas 90 (72%) practitioners felt more confident in explaining RWPC to families. Approximately half of the practitioners also indicated that their confidence in explaining randomisation (47%) and addressing parents’ objections to randomisation (51%) had improved.

Questionnaire part B (after training) free-text responses, as well as interview and focus group discussions, indicated that the EcLiPSE trial training had addressed many of the practitioners’ concerns about recruitment and RWPC. After training, many described how the trial and its approach to consent seemed more ‘feasible’ (SIV questionnaire part B, female, doctor, P128) and ‘logical and straightforward’ (SIV questionnaire part B, female, nurse, P30). Research nurses, in particular, valued the examples of tailored communication, such as the ‘terminology used to explain this to families’ (SIV questionnaire part B, female, nurse, P109), as well as ‘see how nurse handled difficult questions’ from parents (SIV questionnaire part B, female, nurse, P27). During telephone interviews, research nurses also commented on the training:

There are some good sort of one-line quotes that you can take from it.

Practitioner telephone interview, female, lead research nurse, P4