Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/35/99. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The draft report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Clarkson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction

The subsequent chapters of this monograph describe the INTERVAL (Investigation of NICE Technologies for Enabling Risk-Variable-Adjusted-Length) Dental Recalls Trial, a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded trial testing of the effectiveness and cost–benefit of dental check-ups at different recall intervals. The trial protocol has been published. 1

The reason for the trial

Background

Traditionally, patients have been encouraged to attend dental recall appointments at regular intervals of 6 months between appointments – irrespective of the individual’s risk of developing dental disease, the principal function of the dental recall being prevention and early detection of oral disease, in particular dental caries (tooth decay) and periodontal disease. 2 The traditional clinical rationale, developed at times of higher caries levels and progression rates, was the early detection of caries lesions while they were small in order to restore them before lesion progression resulted in extensive destruction of tooth tissue. This has evolved to a modern philosophy that seeks to detect small lesions at an early stage in order to provide preventative interventions prior to lesion cavitation. The preventative advice provided at recall examinations varies between practitioners and, indeed, between a practitioner’s individual patients and may incorporate instruction on appropriate oral hygiene practices and dietary advice for the prevention of dental disease, as well as advice aimed at modifying risk factors for oral disease such as smoking cessation advice and alcohol-related health advice. The dental recall examination may, therefore, be understood as having a dual function as a primary preventative (the prevention of oral disease before it occurs) and a secondary preventative (limiting the progression and effect of oral diseases at an early stage through early diagnosis) measure. The evolution of implementing the change from surgical to preventative treatment philosophies has been, and continues to be, complex and slow.

The recommendation of a 6-month recall interval has become established practice in primary dental care in many countries3–7 and has probably been a cornerstone of dental practice since it was mentioned by Pierre Fauchard in 1746. 8 There has been a longstanding international debate regarding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different recall intervals for routine dental check-up examinations,2,3,5,9–16 particularly in the light of changes in the epidemiology of dental diseases and in the interests of careful resource management. 9,17–19 This debate has been fuelled by conflicting evidence from observational studies on the effects of regular attendance and by the subsequent diverging interpretations of that conflicting evidence. 20

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory disease of the soft and hard tooth-supporting tissues. Periodontal diseases comprise gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is a reversible condition characterised by gingival redness and oedema, and absence of periodontal attachment loss. 21 The 2017 world workshop and classification system gives clear definition of a gingivitis site and a gingivitis case (patient). 21 A patient can be defined as a ‘gingivitis case’ when bleeding on probing at > 30% of sites is evident at a minimum of 10% of sites. 21 Bleeding at between 10% and 30% of sites is defined as localised gingivitis and bleeding on probing at > 30% of sites is generalised gingivitis. Gingival health is defined as bleeding on probing at < 10% of sites. Gingivitis is a pre requisite for periodontitis and is also a risk indicator for dental caries progression.

Periodontitis is the irreversible destruction of the tooth-supporting periodontal structures (periodontal ligament, cementum and alveolar bone) due to inflammation. 22 Periodontitis is characterised by periodontal pocket formation and gingival recession. In addition, tooth mobility and migration may occur as a result, as well as dentine hypersensitivity of the exposed root surface, root caries and, ultimately, tooth loss.

Gingivitis and periodontitis are a continuum of the same inflammatory disease process,23 with evidence that gingivitis is a risk factor for periodontitis,24 and that absence of gingival bleeding is a reliable predictor for the maintenance of periodontal health. 25 However, it is not currently possible to predict progression from gingivitis to periodontitis at either the individual or the site-specific level. Accumulation of microbial dental plaque is the primary aetiological factor for gingivitis and periodontitis, as well as dental caries. 26–28 Disease progression is also known to be affected by genetic factors (host defence mechanism), calculus, smoking and systemic comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes. 29–32

Despite the largely preventable nature of periodontal disease, it is considered the most common disease of mankind,33 remains the major cause of poor oral health globally and is the primary cause of tooth loss in older adults. 22,34 Global estimates of gingivitis range from 50% to 90% of populations. 35–37 Severe periodontitis is the sixth most prevalent human disease globally, with a prevalence of 11.2%,38 which appears to be rapidly increasing. 33

Dental caries is a multifactorial chronic oral disease that affects most populations globally and is considered the most important global oral health burden. 39 Dental caries results from production of organic acids by acidogenic bacteria within dental plaque (a biofilm formed on the tooth surface soon after tooth cleaning). Dental caries is considered a consequence of an ecological shift in the balance of the normally beneficial oral microbiota driven by a change in lifestyle and in the oral environment. 40 Organic acids can cause mineral loss from the tooth surface by removing calcium and phosphate ions from surface apatite crystals (demineralisation). In favourable conditions, a reversal of this process is possible (remineralisation). The development of a carious lesion is a dynamic process that may progress, halt or reverse. Progression of the carious lesion occurs where the demineralisation process prevails over remineralisation. Carious lesions can range from early non-detectable mineral loss restricted to enamel, through lesions that extend into dentine without any surface cavitations, to cavitated lesions visible as holes in the teeth. Progression rates of carious lesions appear to be more rapid in dentine than in enamel, with variable rates between individuals as well as between lesions within an individual. 41,42 Dental caries and its consequences are considered the most important burden of oral health, affecting up to 100% of adults in most countries. 43 It is not just a disease of children, but appears to occur at a relatively constant rate throughout the life course. 44

Where gingival recession has migrated apical to the amelocemental junction, the exposed root surface of the tooth may be susceptible to root caries. Like coronal caries, the main aetiological factor for the initiation and progression of root caries is the presence of a cariogenic biofilm and fermentable carbohydrates. Owing to the lower level of mineralisation of dentine, a smaller decrease in pH will induce demineralisation of the root surface. 45 As with coronal caries, the formation of root caries is a dynamic process of demineralisation and remineralisation, with progression of caries occurring where the balance of factors favours demineralisation. 46 Importantly, and unlike caries in enamel, coronal dentine and root caries both involve not only demineralisation but also collagen degradation,47 resulting in a demineralisation process that is approximately twice as rapid on enamel. 48

Root caries, like other forms of the disease, can be associated with pain, discomfort and tooth loss,49,50 which has the most significant impact on the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) of the elderly. 51,52 Although a well-recognised disease, its prevalence is increasing as populations age and retain more of their natural teeth into older life. 47,53,54 There is a wide range in the reported global prevalence of root caries for diverse populations ranging from 29% to 89%. 55

Individuals and dental care professionals have different roles to play in the prevention and control of periodontal diseases and dental caries. Consistent removal of the intraoral plaque biofilm by means of personal tooth brushing and interdental cleaning is considered the foundation of successful primary prevention of periodontal disease and dental caries. 56,57 The dental care professionals’ role in primary prevention involves assessment of an individual’s risk of developing oral disease and tailoring preventative advice, including oral hygiene and dietary advice based on this risk assessment, although the evidence relating to the beneficial effects of chairside provision of dental health education advice is conflicting. 58,59

In 2004, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a guideline entitled Dental Recall: Recall Interval Between Routine Dental Examinations,60 following a remit received from the Department of Health and Social Care and the Welsh Assembly Government. Within this guideline, the role of the oral health review, or dental check-up, in providing primary prevention and secondary prevention is highlighted. Subsequently, in 2011, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) published their guidance on oral health assessment and review. The SDCEP guidance was based on and was a tool to assist implementation of the NICE recommendations. 61

Given that the global burden of oral disease is not shared evenly, the risk of developing oral disease between patients is clearly variable. It has, therefore, been suggested that the preventative needs of patients are also variable and that intervals between oral health reviews should be appropriate for the needs of individual patients.

Dental check-ups at 6-month intervals have been customary in the general dental service (GDS) in the UK since the inception of the NHS. Although a recall interval of 6 months is not explicitly recommended by the NHS, this practice is implicitly recognised by NHS regulations that have remunerated dental practitioners for providing a dental check-up at 6-month intervals for decades, and, since 2006, the dental check-up has been free in Scotland. It has been argued that a 6-month dental recall policy is too rigid and that recall intervals should match the individual needs of patients more closely – needs that may change over time. Analysis of dental attendance patterns in NHS primary dental care using the Dental Practice Board’s longitudinal data demonstrates an attendance pattern that is variable, with many patients attending less frequently than every 6 months. 59 Data from the Information Services Division (ISD) in Scotland show that the vast majority of Scottish adults did not attend NHS primary care dental services on an annual basis, with only 23% attending at least once per year in each of the previous 6 years, and 21% not attending at all in the past 6 years. 62

In addition, it has been consistently observed that caries experience is generally more extensive in lower socioeconomic status groups,63 reinforcing the case for patient-specific recall intervals, based on an assessment of the patient’s risk of oral disease. 3,60,64 Evidence from the Dutch health system suggests that there is an increase in general dentists moving away from recalling all patients at the same interval in favour of applying an individualised recall interval, resulting in more frequent screening for periodontal disease than with those dentists using a fixed-period recall protocol. 65

One of the persistent arguments in favour of maintaining 6-month dental check-ups is that dentists may miss the opportunity to diagnose oral cancer lesions at an early stage in patients who attend at longer recall intervals. The incidence of oral cavity cancer in the UK is highest in Scotland, at 10.0 per 100,000 males,66 and has been relatively stable in Scotland since 2000 but rising in England and Wales. However, it has been reported that 53.7% of patients diagnosed with oral cancer had not attended an NHS primary care dentist in the 2 years preceding diagnosis,67 thus radically decreasing the opportunity for early detection. From these data it is estimated that a dentist potentially encounters one case of oral cancer every 10 years. 67 Brocklehurst and Speight68 reviewed the pros and cons of a national screening programme for mouth cancer, concluding that studies into mouth cancer screening have provided evidence to satisfy only 5 of the 20 criteria required by the UK Screening Committee, with no evidence of a test effective in the detection of oral lesions in the context of a screening programme,69 and that more research is needed to develop diagnostic tests more specific than conventional oral examination. 68 The authors also report that screening programmes have not resulted in a demonstrable reduction in mortality, apart from in high-risk groups, in which there is some evidence that screening may be effective and cost-effective. 68 Instead of asserting the need for shorter intervals between dental recall appointments, these papers67–69 highlight the need for oral health services to develop strategies to reach out to populations that do not attend primary care dental services regularly, instruct patients about high-risk habits including alcohol and tobacco use, and better network with other primary care services.

Evidence base

The recommendations in the NICE guideline on dental recall60 are designed to aid dentists in assigning individualised recall intervals to patients based on their risk of developing oral disease. The Guideline Development Group produced a checklist for use by dentists when assessing risk, including specific risk factors for consideration. 60 The guideline recommends an adjustable recall interval for adults, ranging from a minimum of 3 months to a maximum interval of 24 months between recall appointments for patients who have repeatedly demonstrated an ability to maintain oral health. The guideline panel recommended that the recall interval be regularly assessed, discussed and agreed based on each individual’s oral health risk profile and amended accordingly. The Guideline Development Group considered a balance of benefits and harms related to caries, periodontal disease and also oral mucosal lesions in making its recommendations. The recommendations are, however, based on low-quality evidence and the clinical experience of the Guideline Development Group. This lack of evidence has complicated the implementation of this guideline for dentists and health service commissioners.

Although the concept of assigning risk-based recall intervals has gained increasing standing internationally, the clinical effectiveness of this recall protocol is not supported by scientific evidence from clinical trials. Furthermore, there remains significant variation in professional recommendations within and between countries regarding the maximum time interval between dental check-ups that can reasonably be assigned for patients at low risk of oral disease. This can be considered inevitable given that many guideline recommendations regarding this issue have been informed primarily by professional consensus and are subject to variation in interpretation. 70

There is also a paucity of reliable scientific evidence to support the effectiveness of routine dental checks of differing recall frequencies in adults. The scientific basis for the 6-month dental examination was questioned more than 30 years ago. 2 Since then, systematic reviews investigating this key question have reported limited evidence of poor overall quality, which is insufficient to reach any conclusions regarding the potential beneficial and harmful effects of varying recall intervals between dental check-ups, and concluding that there is no evidence to support or refute the practice of encouraging patients to attend for dental check-ups at 6-month intervals. 71,72 The NICE guideline on dental recall reiterated the need for research in this area to examine the effects of varying dental recall intervals on oral health. 59 The NICE guideline also concluded that the research base was severely lacking in terms of determination of the optimal dental recall intervals on the basis of cost-effectiveness. 60

There is, therefore, an urgent need to assess the relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different dental recall intervals in a robust, sufficiently powered randomised control trial (RCT) in primary dental care.

The questions addressed by the INTERVAL trial

Aim

The aim of this trial was to compare the effectiveness and cost–benefit of dental check-ups at different recall intervals (fixed-period 6-month recall, risk-based recall or fixed-period 24-month recall) for maintaining optimum oral health in dentate adults attending general dental practice.

Objectives

The primary objectives were to compare the three recall strategies on:

-

gingival bleeding on probing

-

oral health-related quality of life

-

value for money in terms of (1) cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, (2) incremental net (societal) benefit and (3) incremental net (dental health) benefits.

The secondary objectives were to compare the three recall strategies on:

-

periodontal probing depths

-

dental caries

-

calculus

-

preventative and interventive dental treatment

-

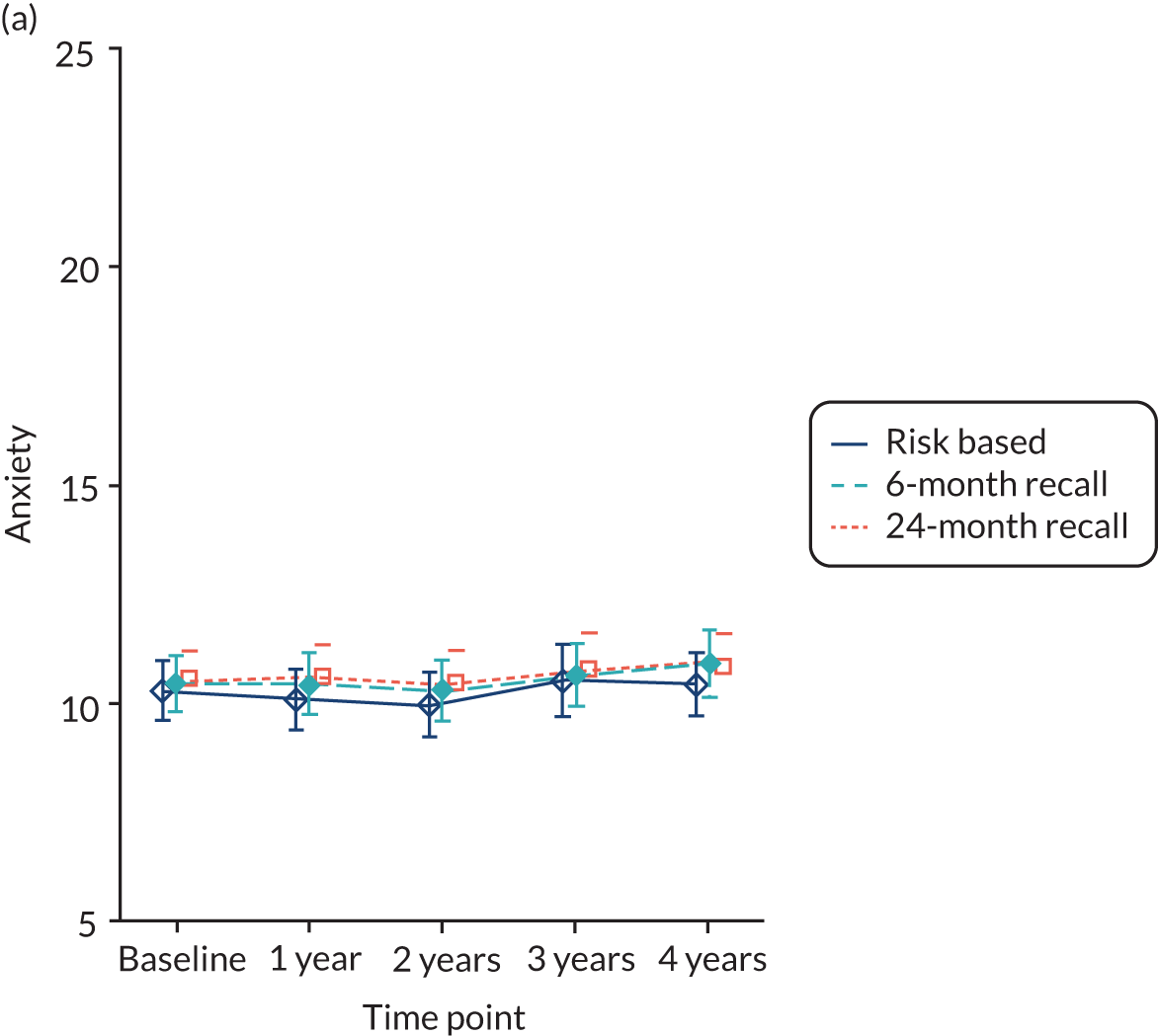

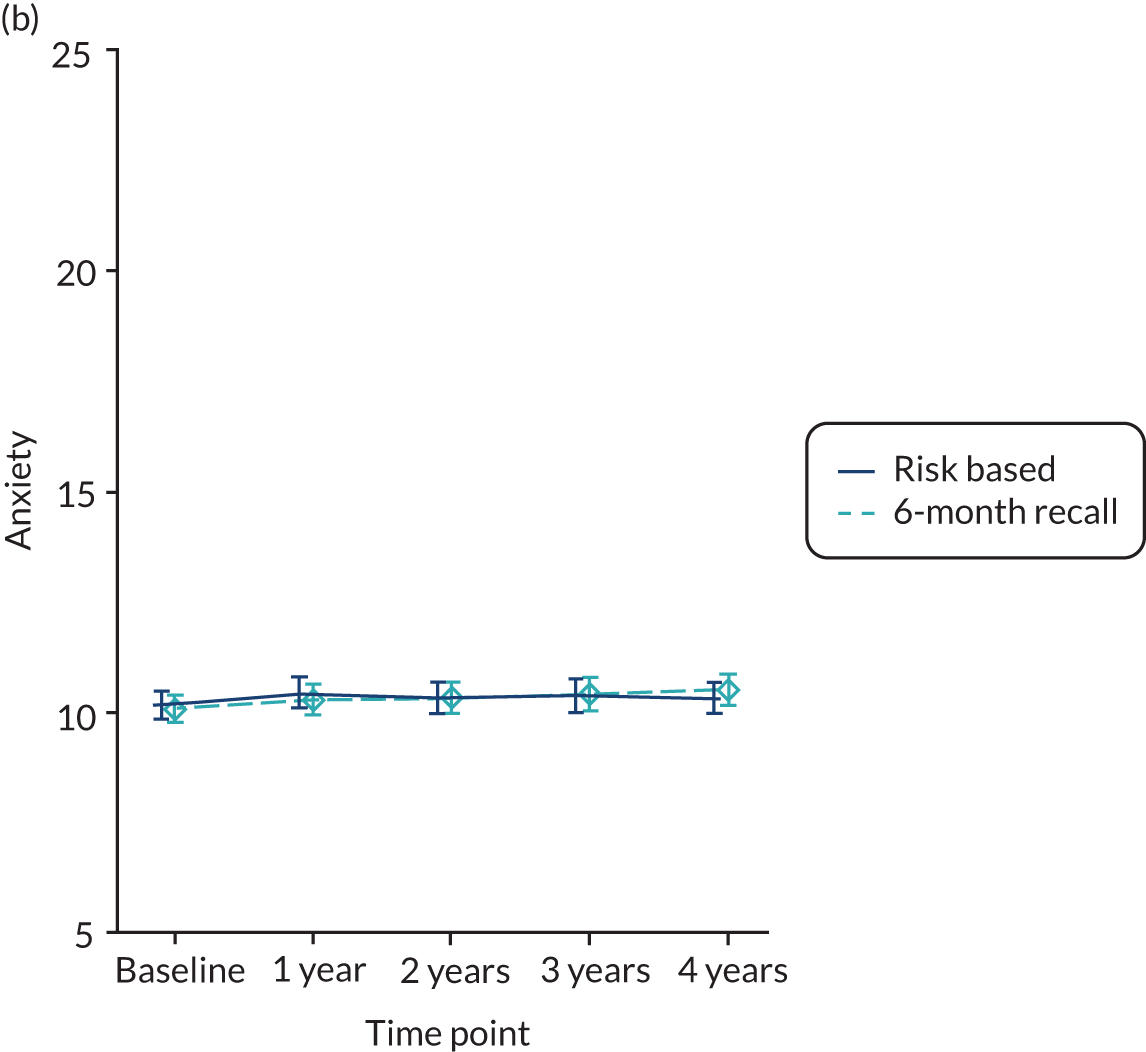

patient anxiety

-

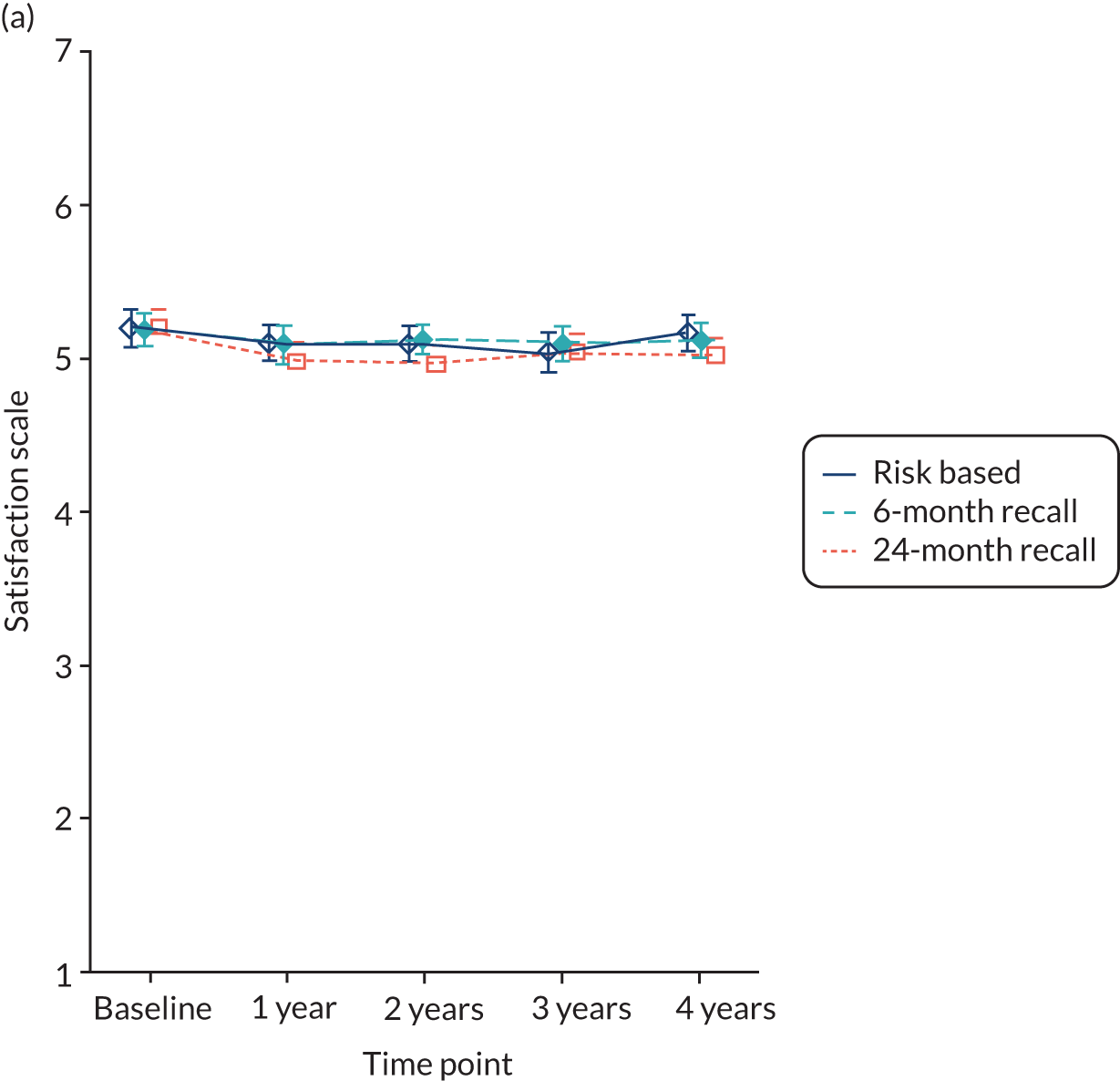

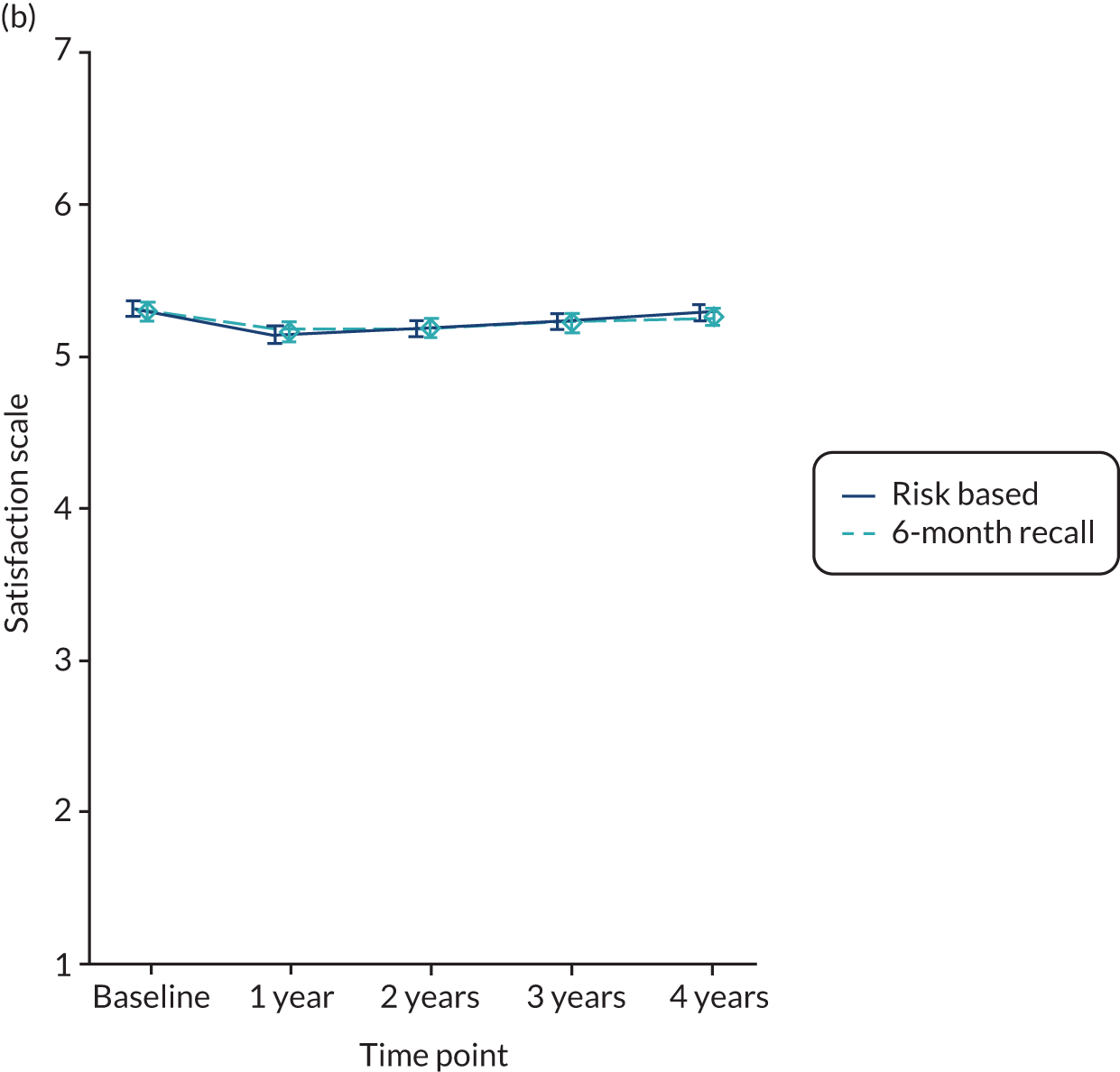

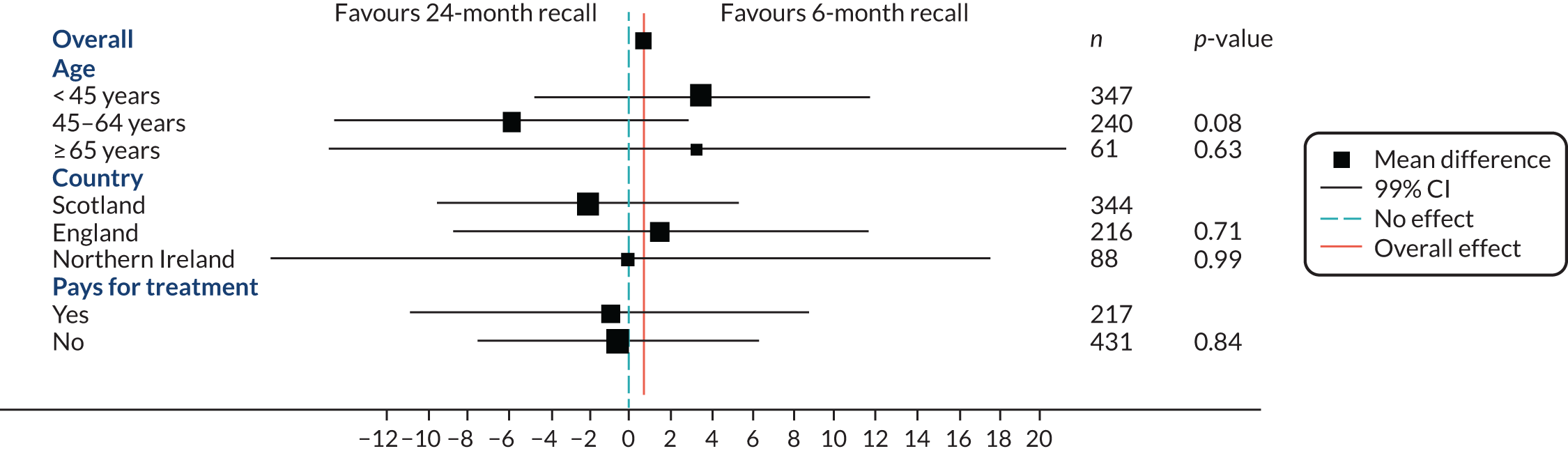

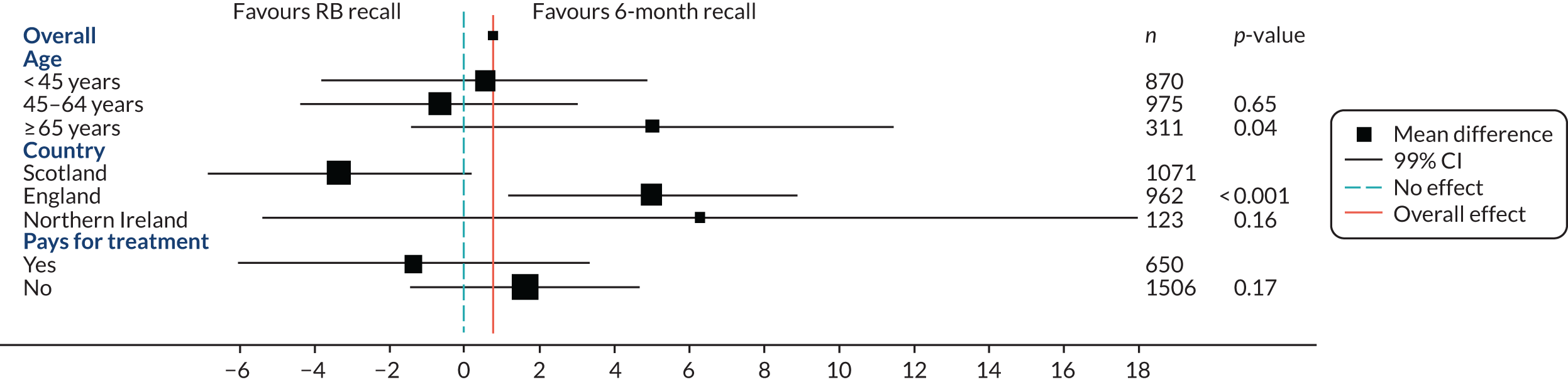

patient satisfaction with care

-

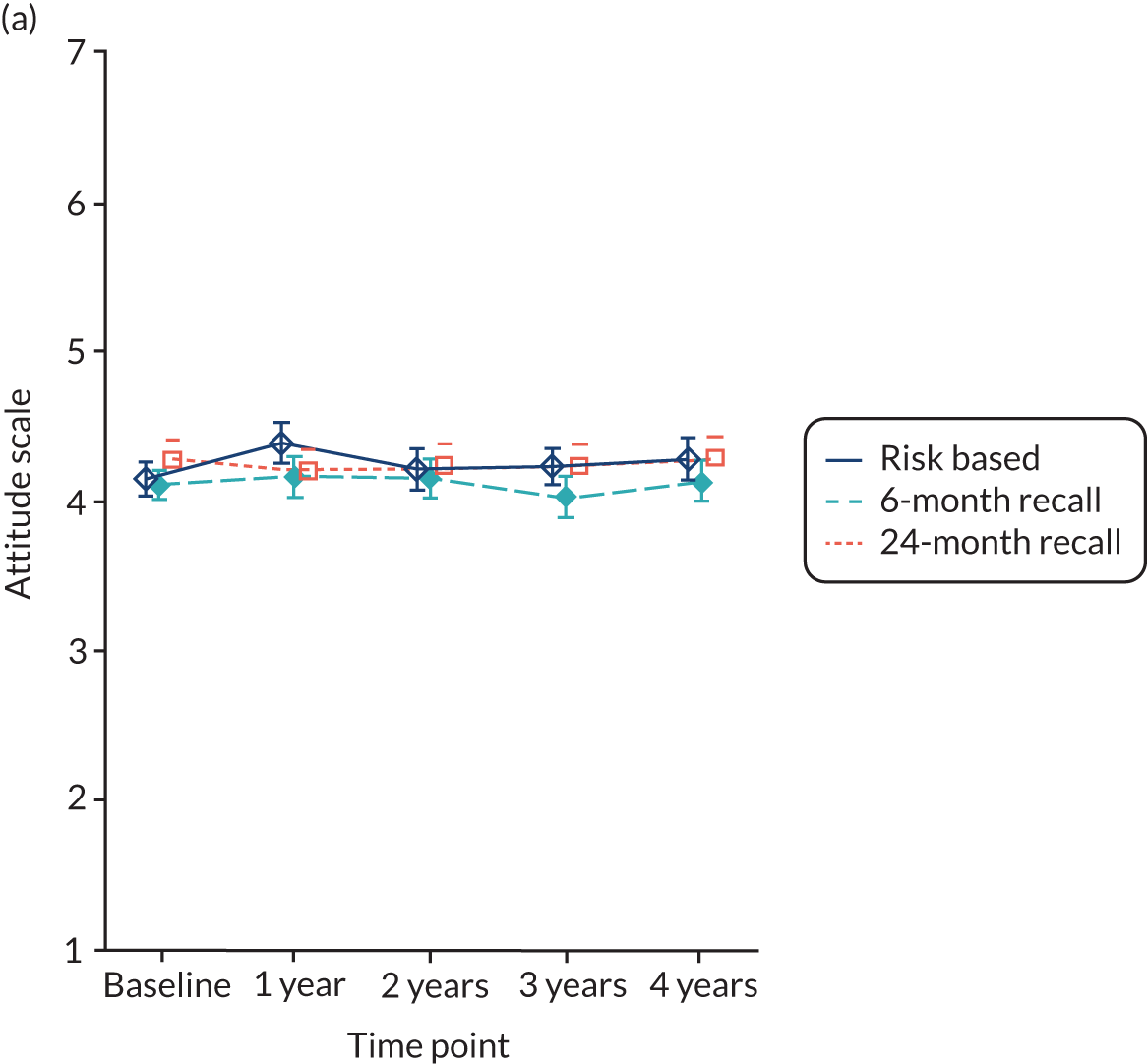

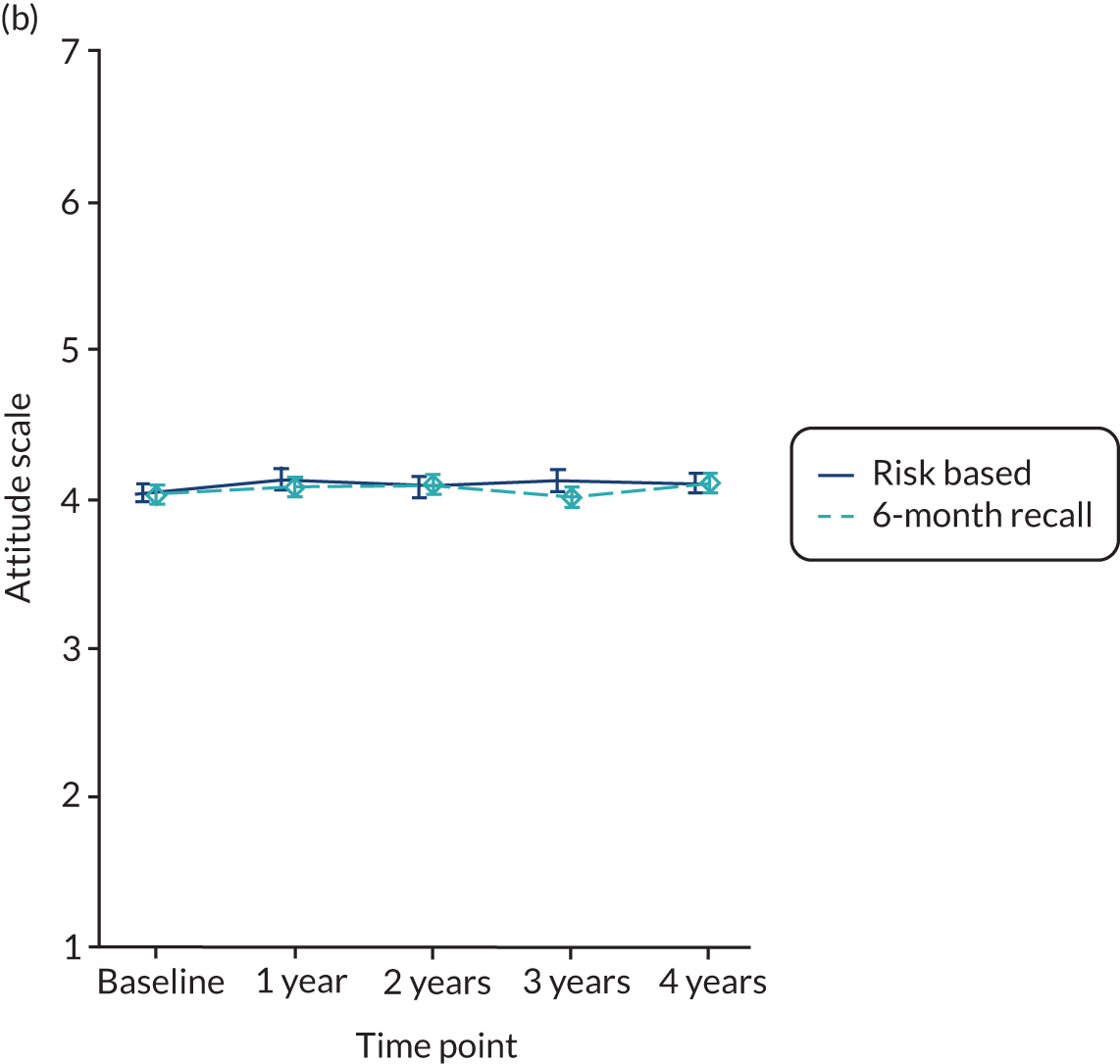

oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviours and to explore dentists’ attitudes towards dental recall intervals. 10

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

The trial was a UK-wide [England (London, Manchester, Birmingham, North East), Wales (Cardiff), Northern Ireland (Belfast, County Down) and Scotland] multicentre, parallel-group, RCT with blinded outcome assessment at 4-year follow-up.

The trial interventions were three recall intervals – a fixed-period 24-month recall interval, a risk-variable adjusted-length recall interval (risk-based recall) based on the NICE guideline60 and a fixed-period 6-month recall interval.

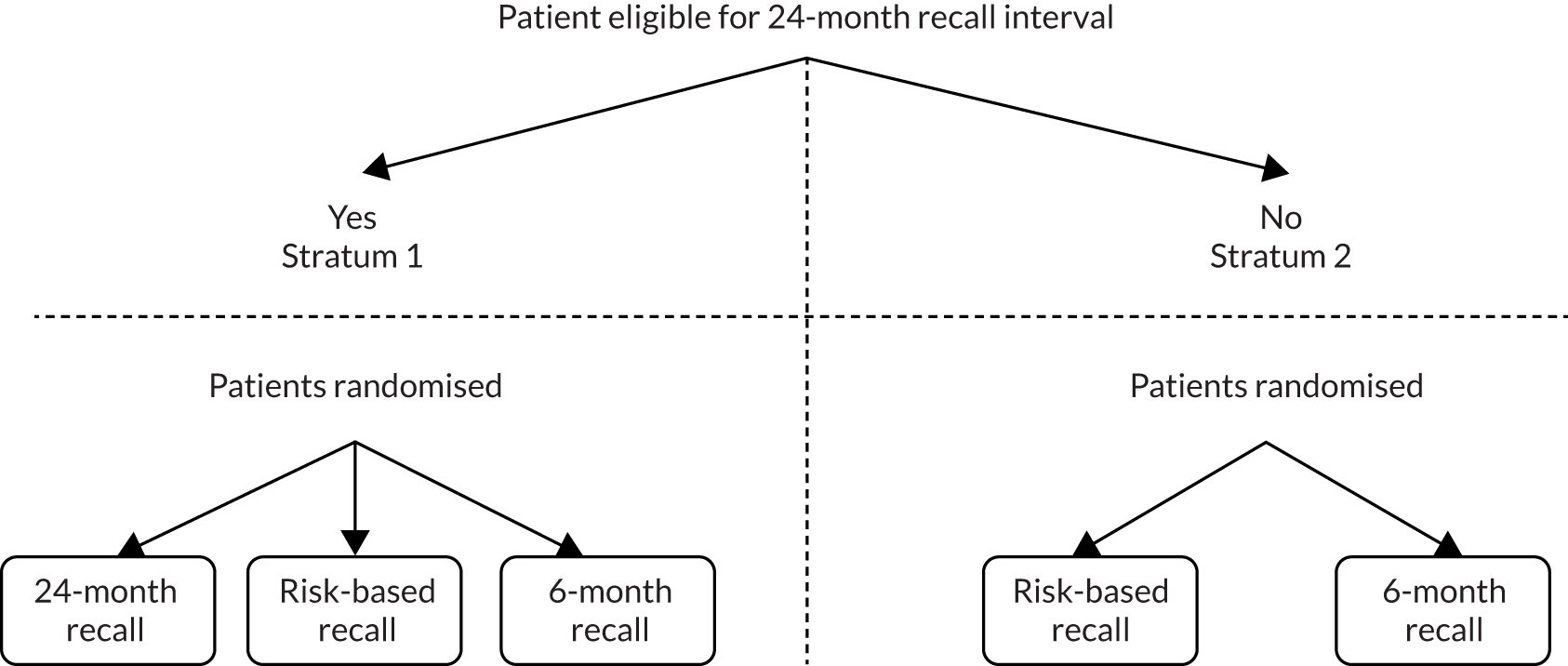

A two-stratum trial design was proposed to overcome potential ethical considerations and dental clinician and/or participant concerns. Participants were randomised to the fixed-period 24-month recall interval only if the recruiting dentist considered them clinically suitable.

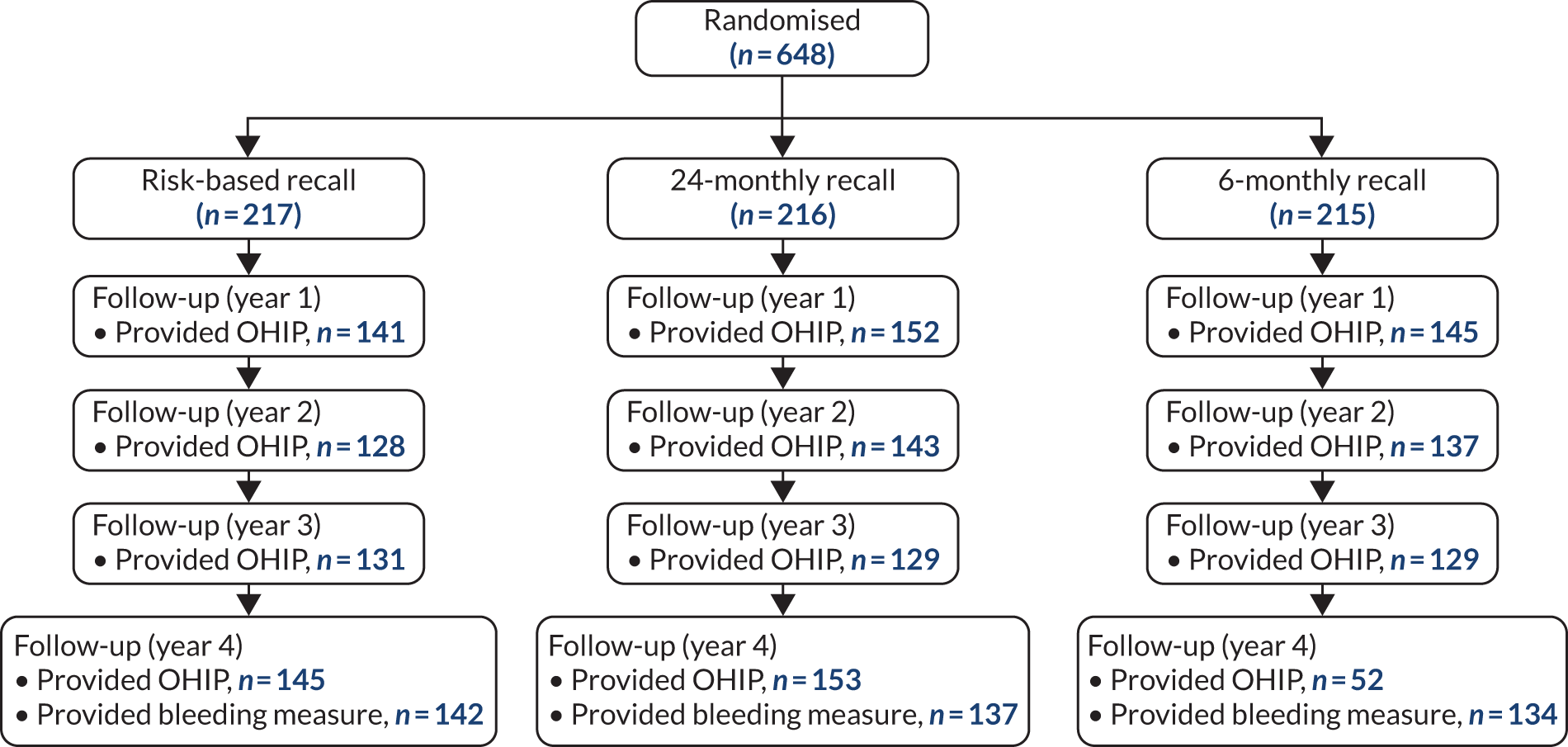

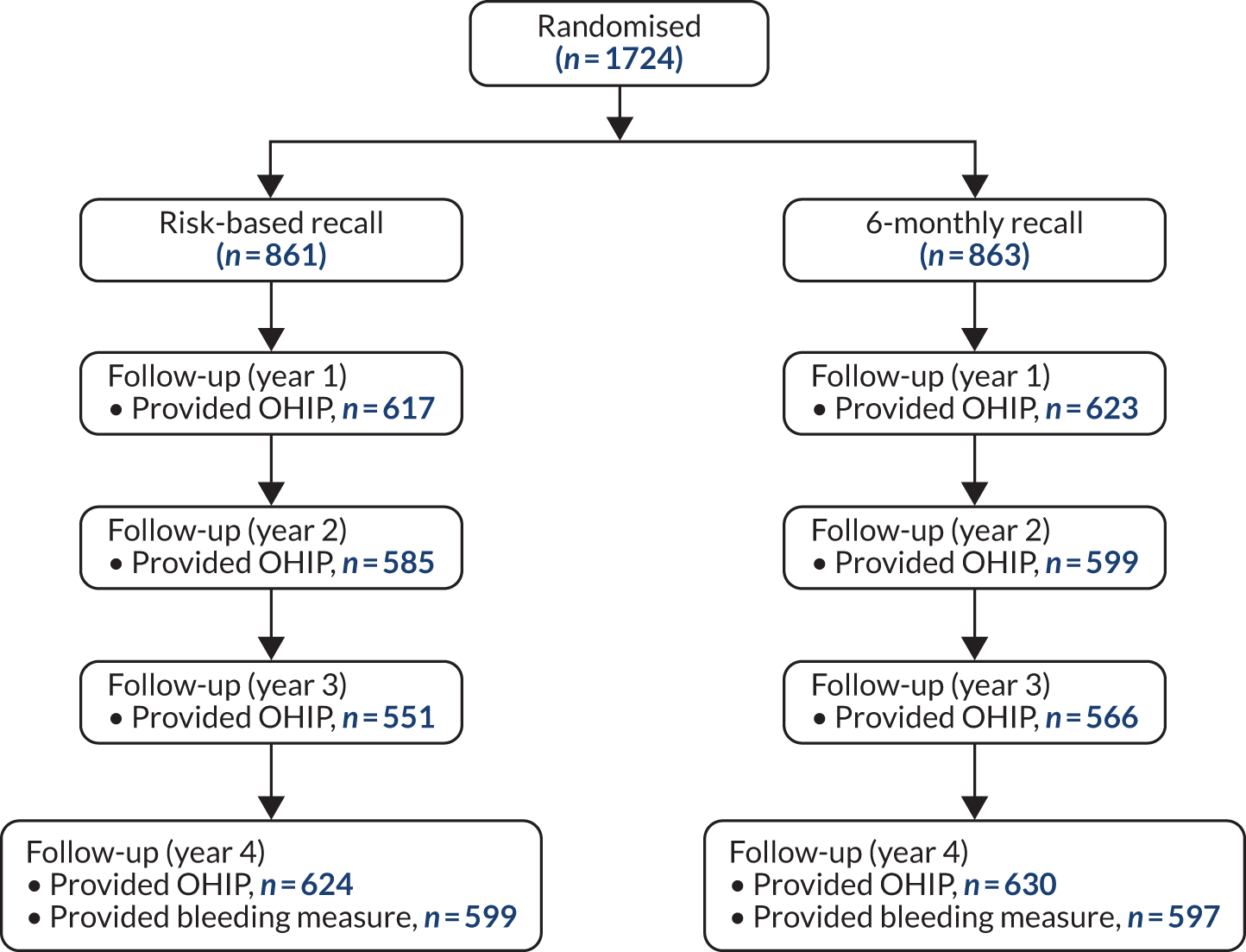

Randomisation was organised within the two strata (Figure 1):

-

For those participants considered suitable for a fixed-period 24-month recall (stratum 1), randomisation was to one of three groups:

-

Fixed-period 24-month recall versus risk-variable-adjusted-length recall (risk-based recall) versus fixed-period 6-month recall.

-

-

For those participants not considered suitable for a fixed-period 24-month recall (stratum 2), randomisation was to one of two groups:

-

Risk-variable-adjusted-length recall (risk-based recall) versus fixed-period 6-month recall.

-

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

An economic evaluation to determine the cost-effectiveness of different recall intervals and to compare NHS and patient-incurred costs and benefits is included in Chapter 5.

Ethics approval and protocol amendments

Favourable ethical opinions were granted for the INTERVAL Dental Recalls Trial by the Fife and Forth Valley Research Ethics Committee (feasibility study Research Ethics Committee reference number 09/S0501/1; main study Research Ethics Committee reference number 09/S0501/1).

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomisation Controlled Trial Register (ISRCTN), reference number 95933794.

Amendments to the protocol were made after recruitment of practices and participants, and on conclusion of the feasibility study. These included an increase of more than one dentist per practice able to participate in consenting, recruiting, randomising and establishing risk-based recall intervals for participants in the risk-based arm and the assistance of dental postgraduate research networks to identify and recruit potential dentists and identify and approach potential participants.

Additional amendments, notified to the funder, included an increase in the number of practices recruited and increased numbers of participants per practice, extension of the recruitment period, changes of Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) members, lengthening from 3 to 4 months plus or minus the 4-year anniversary of participant randomisation for final year assessments, and adaptions to study administrative processes. All changes were in accordance with approved contract variations.

Recruitment and consent of dental practices

The trial sought to recruit general dental practitioners/practices from across the UK (i.e. England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland), representing a cross-section of practitioners in terms of urban/rural areas, community-level sociodemographics and fluoridated or non-fluoridated communities.

Dentists were recruited through local postgraduate dental research networks, by advertising in professional dental publications and through presentations at dental conferences and dental events. Trial information and recruitment evenings were organised in Birmingham and Cardiff and across Scotland.

The Trial Office in Dundee (TOD) sent potential dentist participants a personalised invitation letter for the dentist and their staff to attend a local information and recruitment session, at which the reasons for and design of the trial and practice involvement were described. Dental professionals were given the opportunity to discuss participation with the trial team. For dentists and teams that could not attend, information packs about the trial were posted/e-mailed from the TOD.

Trial team members telephoned dental practices to follow up the notes of interest of involvement. A site briefing/training session was arranged with the dentist, practice staff and TOD staff (see Training of dentists). Following the site briefing, dentists who were interested in the trial were asked to provide written consent to participate, a signed declaration agreeing to adhere to the trial protocol and a completed clinician beliefs questionnaire (see the NIHR project web page for details: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/063599/#/documentation; accessed October 2020). Original signed and dated dentist consent forms and declarations were held securely as a part of the trial site file at the TOD. Copies were made and returned to dentists.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: dental practices

The inclusion criteria were:

-

NHS provider for adult patients

-

primary care provider: salaried service, corporate and independent operators

-

willingness to follow trial protocol.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

providing only private dental services to adults

-

unwilling to follow trial protocol.

Recruitment and consent of participants

Recruitment of patient participants was achieved through standard procedures and agreements for primary care research in the four nations. In some areas of England, Wales and Northern Ireland, regional Clinical Local Research Networks assisted dental practice staff to identify eligible patients and facilitate an approach by including information about the trial in the appointment letter for their routine dental examination. In Scotland, co-ordinators from the Scottish Primary Care Research Network, when invited, provided a similar service. The appointment letter included an invitation to participate, the patient information leaflet and the baseline patient and cost questionnaires (see the project web page for copies of questionnaires: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/063599/#/documentation).

In instances where the Clinical Local Research Networks and Scottish Primary Care Research Network were not available at an agreeable time, or practices did not request or require assistance, practice staff undertook the duties of identifying and contacting eligible patients and inviting them to participate in the trial using the same paperwork.

At the routine appointment, discussion about the trial was held between the dentist and patient. If agreeable, potential participants were screened for suitability prior to their routine dental examination. Patients who contacted the practice to advise that they were not interested in taking part in the trial were reassured that they would still receive a dental examination appointment with their dentist as per practice policy.

There are a variety of patient recall appointment management strategies utilised within dental practices across the UK. Some dental practices arrange routine examination appointments for their patients up to 6 months or a year in advance. Some practices send letters, e-mail, telephone or text reminders to their patients when their routine dental examinations are due, asking them to contact the dental practice to make an appointment, whereas other practices pre-allocate the date and time of appointments and ask patients to contact the practice if the appointment is not suitable. The INTERVAL Dental Recalls Trial utilised a flexible and pragmatic participant recruitment strategy that aimed to be suitable for each practice’s usual recall procedure.

Eligibility of those who expressed an interest in taking part was confirmed against the trial inclusion and exclusion criteria. The dentist confirmed consent with those eligible and willing to participate in the trial. A signed participant consent form was obtained in triplicate. The participant retained a copy, the practice retained a copy in the patient’s notes in the site file, and the original copy was sent to the TOD.

Following consent, the dentist clinically examined the participant to establish suitability for randomisation to the 24-month arm (see Randomisation). If participants had not completed the questionnaires provided with the appointment letter, they were asked to complete the baseline questionnaire and cost questionnaire in the waiting room of the dental practice before placing them in a sealed opaque envelope and returning them to practice staff. Questionnaires were returned to the TOD by the dental practice in a sealed envelope.

The TOD staff did not have access to any participant data prior to the participants consenting to take part in the trial.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: participants

The inclusion criteria were adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) who:

-

were dentate

-

had visited their dentist in the previous 2 years

-

received their dental care in part or fully as an NHS patient, including dental examination.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

patients who had a medical condition indicating increased risk of bleeding

-

immunocompromised patients.

Participants whose medical condition changed during the follow-up period were not prohibited from continuing in the trial. Provision was made for dentists to record changes and rationale to the length of the recall interval, on the patient attendance data (PAD) form, but such participants remained within the allocated stratum.

Training of dentists

In England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, the process of training recruited dentists took the same format.

Training in trial procedures

Trial staff visited the practice by arrangement for a 1- to 2-hour site briefing/training session at an agreed and convenient time, attended by the participating dentist and practice staff. After a brief review of the trial aim and objectives, trial procedures were described and discussed.

Recruited dentists were defined as local investigators within the dental practice, and were responsible for recruiting, consenting and protecting the personal data of trial participants within the dental practice. Local Investigators signed an agreement to conduct the trial in compliance with applicable legislation including (1) the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guideline73 and (2) the Department of Health and Social Care’s Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (April 2005)74 or the Scottish Executive Health Department’s Research Governance for Health and Community Care (2nd edition 2006),75 whichever was relevant.

Dentists and practice staff were advised at the trial briefing/training and in monthly practice newsletters that the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guideline training was available in their local area and that attendance at these sessions could be arranged through the TOD. The TOD also signposted to the online NIHR Introduction to Good Clinical Practice e-learning (primary care) module. 76

Training in determining risk-based recall intervals

Following the site briefing/training session, each dentist was sent a link to an online training package. The online training package presented risk-based recall interval determination according to the NICE guideline,60 with written instruction, audio and video components, examples and test assessments. It described a systematic approach dentists could follow to consider setting and review of individualised patient recall intervals and to enable discussion and explanation between patient and dentist of the risk-based recall interval. Dentists were instructed to complete this training before screening any potential patient participants for the trial, and reminders via letter, e-mail, telephone and trial newsletter requested that dentists complete it on an annual basis during follow-up.

On completion of the online training package, and before being awarded with a certificate of training and 2 hours continuing professional development (CPD), dentists were required to complete an evaluation form that asked users to measure to what extent they felt that the training programme met the learning objectives, and how easy it was to access and understand. They were also asked to suggest improvements regarding content, design, navigability and length.

Feedback from users was mixed; some found it difficult to access and to navigate, whereas others found it user-friendly and were reassured that they could use the tool with patients. Some users found the content appropriate, easy to understand and a good support for participating in the trial, whereas others found some aspects to be basic to a practising dentist or felt that it could be shortened for the experienced practitioner.

For additional reference on risk-based interval determination, practices in England, Wales and Northern Ireland were provided with a link to the NICE guideline Dental Recall: Recall Interval Between Routine Dental Examinations. 60 Practices in Scotland were supplied with an electronic link and hard copy of the SDCEP Oral Health Assessment and Review (OHAR) guidance. 60,61 Both documents contained templates for checklists to record variables identified as potential modifying factors (risk variables) that influence the setting of recall intervals (see Trial interventions for more detail on risk-based templates).

Clinical outcome assessor training

The clinical outcome training was delivered by trial collaborators with expertise and experience of training assessors in periodontal and caries measures. The clinical outcome assessors and scribes for this trial were qualified, General Dental Council-registered dentists, dental hygienists/therapists and dental nurses employed by the trial.

The emphasis of the training was consistency of the examination process and agreement of scoring criteria. Following the didactic face-to-face and online training, the outcome assessors, with their research nurse, examined 15 patient volunteers in a clinical setting similar to that of a dental practice. The cohort of patient volunteers were similar in age and dental attendance behaviour to those recruited to the trial. The clinical outcome assessments were conducted at Dundee Dental Hospital and School, and each participant was examined by all outcome assessors.

The processes of clinical outcome assessment were agreed in advance, including the order of outcome measure assessment, time allocation, sequence around the mouth and moisture control. The primary clinical outcome of gingival bleeding on probing is a measure of gingival inflammation. It is described as ‘gingival inflammation/bleeding on probing’ in the study protocol;1 for clarity within this report it will be described as gingival bleeding on probing, the definition and outcome measurement remaining the same as outlined in the protocol. This clinical outcome does not allow for repeat assessment; therefore, neither intra-assessor nor interassessor reliability measurements were possible. Training77 for the primary outcome involved face-to-face discussion with the assessors and scribes about the assessment technique and scoring criteria. Prior to the assessment of the cohort of volunteer patients by the outcome assessment teams, a slide presentation developed for training in commercial clinical trials was presented by a periodontal clinical trial expert, and this was supplemented with group discussion about clinical photographs and clinical cases. Periodontal training included positioning, angulation of instrument and pressure of the University of North Carolina-15 (UNC15) periodontal probe, to ensure a standardised approach by the outcome assessors. Periodontal probing depths were recorded at six sites on erupted teeth using a probing force of approximately 25 g.

Training in caries assessment consisted of several components that have been developed and used in other clinical trials and epidemiological studies. This included an online training programme for the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS), a half-day of slide presentations and discussions of the ICDAS codes and protocol for the clinical examination. The assessor training included both theoretical aspects and discussions regarding patient participants within the clinical trial setting. Practical training included simulation of the assessment protocol on extracted carious teeth representing carious lesions at all stages of lesion progression included in the ICDAS scale, as well as clinical assessment of a cohort of volunteers similar to the trial population, who had been specifically recruited for trial assessor training. All training in the use of ICDAS was completed under the supervision of a trial collaborator experienced in the use of ICDAS in clinical research.

The caries detection elements of the ICDAS criteria are now well tested and are advocated for general use as well as for use in the clinical trials and in dental epidemiology. 78,79 The ICDAS criteria measure both early stages of caries and more advanced stages of caries. For early caries, ICDAS measures the surface changes and potential histological depth of carious lesions by relying on surface characteristics related to the optical properties of sound and demineralised enamel prior to cavitation. Advanced stages are recorded when cavitation is evident. The trial utilised a modified ICDAS as clinical data were collected only on the caries experience. Restorations and non-carious tooth loss were not recorded.

The intensive face-to-face and online training was provided a month before the first trial outcome assessment to provide sufficient time for additional training if required. The training was repeated mid-way through the INTERVAL trial clinical outcome assessment period, to reinforce standardisation in the process and clinical measures. Throughout the clinical outcome collection period, the assessment team met regularly to confirm the outcome assessment processes and data collection methods to achieve the highest level of standardisation possible.

Randomisation

Eligible and consenting patient participants were clinically examined by their dentist to determine suitability for randomisation to the 24-month recall arm (yes/no). The decision that a patient was eligible for a 24-month recall was based on routine clinical examination and risk assessment. Dentists were instructed not to apply the detailed risk-based variable assessment unless randomised to the risk-based arm in either stratum.

There were separate, identical algorithms in the trial design for the two strata. Eligible participants were randomised in equal numbers within each of the two strata according to a minimisation algorithm including:

-

dentist

-

participant age (18–40 years/≥ 40 years)

-

filled teeth (n ≤ 8/n > 8)

-

absence of gingival bleeding on probing (yes/no)

-

exempt from dental charges (yes/no).

Random allocation occurred via telephone, after the decision by the dentists about the patient’s suitability for a 24-month recall. The trial utilised the automated central randomisation service at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), University of Aberdeen, which had 24-hour telephone access. The service prompted dental practice staff to enter and confirm details by entering numbers (i.e. 1 = yes, 0 = no) on the telephone touch pad.

The dentist communicated the allocation outcome and confirmed trial details with the participant. Participants randomised to a fixed-period recall interval, either 24 or 6 months, were managed according to routine practice regarding the practice recall management system. For participants randomised to receive a risk-based recall, further history taking, examination and assessments were undertaken, if required, to determine the appropriate variable risk-based recall interval. This was discussed and agreed with the patient participant prior to the recall interval being entered into the routine practice management system (see NICE guideline60).

Owing to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind participants and dentists to allocated recall intervals. TOD staff received an e-mail notification when a successful randomisation had taken place, providing practice and participant ID numbers, and trial arm allocation. Following randomisation, dental practice staff were asked to send the original signed patient consent form, baseline patient questionnaire and cost questionnaire, and screening/patient case report form (PCRF) to the TOD.

Trial interventions

The trial interventions recall intervals were a fixed-period 24-month recall interval, a risk-variable-adjusted-length recall interval based on the NICE guideline60 and a fixed-period 6-month recall interval.

Fixed-period recall intervals (24 months, 6 months)

Patient participants allocated to the fixed-period 24-month recall interval and the fixed 6-month recall interval groups attended their dentist at the scheduled time intervals for a routine dental check-up. The content of this check-up remained as per current practice. A recognised definition of a routine NHS dental check-up is clinical examination, advice, charting including monitoring of periodontal status and report. 71

Risk-variable-adjusted-length recall interval (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline)

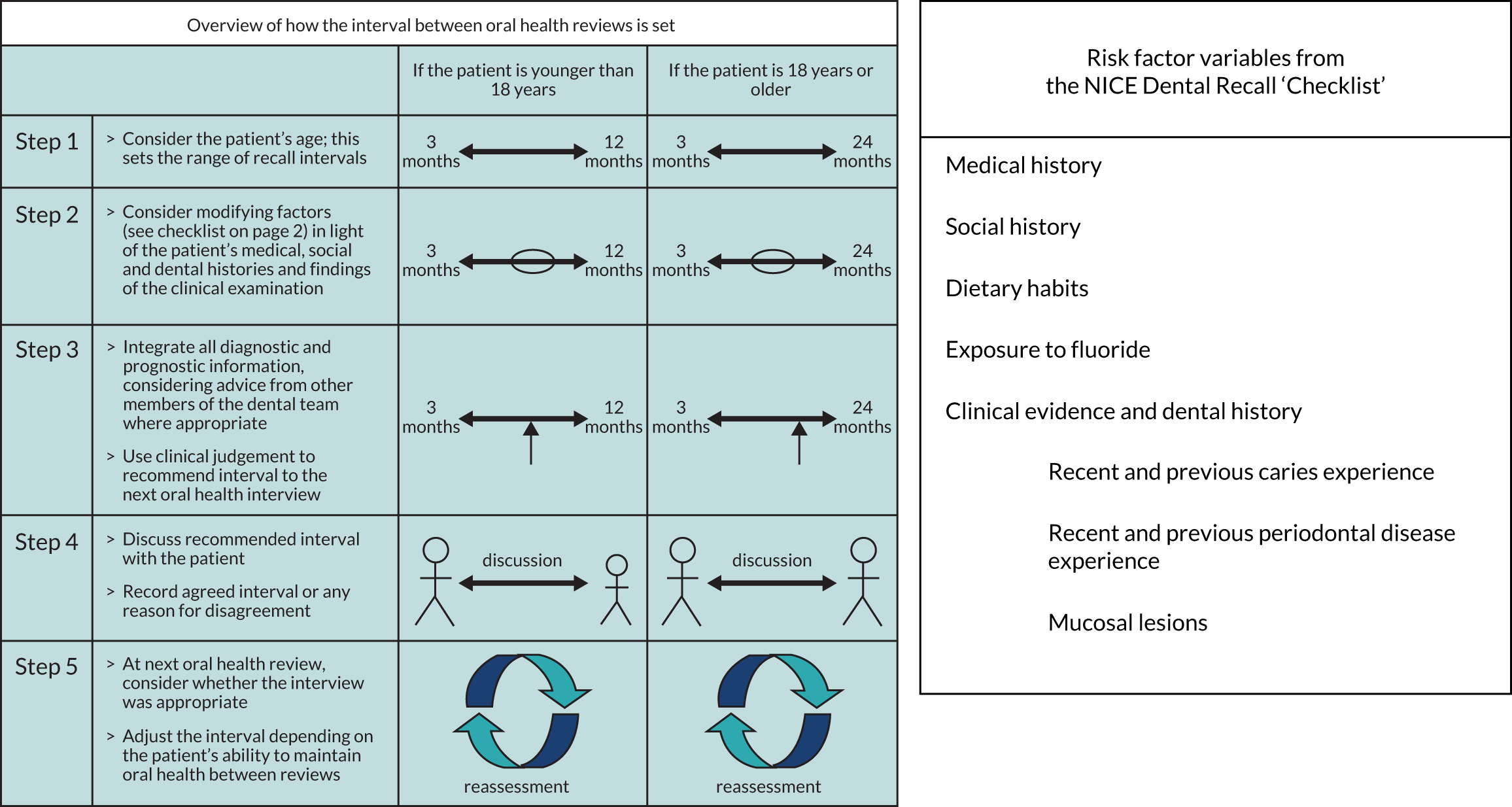

Patient participants allocated to the risk-based recall interval group attended their dentist at time intervals determined by the evidence-based process outlined in the 2004 NICE guideline on dental recall. 60 The essential steps of the procedure and the risk factors collected at recall examinations are outlined (from the guideline) in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The NICE risk-based dental recall procedure and risk factors. Reproduced with permission. © NICE 2004 Dental Recall – Recall Interval Between Routine Dental Examinations. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg19/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-193348909. 80 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

The recommended steps in establishing the appropriate recall interval were:

-

Consider the age range – in the case of this trial, all patients were adults of ≥ 18 years.

-

Consider risk variables – identification of the pertinent risk and protective factors present for each patient from both the checklist and a comprehensive oral health assessment, leading to the evaluation of the impact of these factors in the context of the patient’s past levels of oral health and current disease experience, and then consideration of a likely range of recall intervals.

-

Integrate prediction of recall need – use of all the information obtained by the dental team in order to predict the potential level of threat to maintaining oral health and controlling disease for this patient and, from this, judge the most appropriate next recall interval.

-

Discuss with patient – to explicitly discuss the recommended recall interval with the patient, explain the influencing factors in setting the recall and record the agreed interval (or any reason given by a patient in disagreement).

-

Review – at each check-up review (oral health review), the appropriateness of the preceding interval is reviewed by the dentist and patient and the recall interval is reset according to the experience from the last period along with any change in the risk and protective variables identified at re-examination.

The frequency of recall interval appropriate for an individual patient depends on the likelihood that specific diseases or conditions may develop or progress beyond the control of secondary prevention. The selection of an appropriate recall interval for a patient is a multifaceted clinical decision that involves judgement and cannot be decided mechanistically.

The NICE guideline60 was developed using extensive consensus methods and the limited evidence available. The recommendation was that the recall interval range for adults should vary from 3 to 24 months according to risk.

The NICE guideline checklist60 was intended to be used as a guide to assist the dentist in setting an appropriate recall interval. It is not an exhaustive list of all factors that may influence the choice of a recall interval for a patient. There is insufficient evidence to assign a ‘weight’ to individual factors in the checklist and dentists must use their clinical judgement to weigh the risk and protective factors for each patient. The same checklist is in the SDCEP Oral Health Assessment and Review guidance61 and, therefore, for dentists across the UK guidance is consistent with the content of the trial training material including the online resource.

It was anticipated that by taking a comprehensive history and carrying out a comprehensive oral health assessment the dentist would be better informed to provide an accurate risk assessment and more appropriate preventative and interventive treatment recommendations including advice.

It was envisaged that, once trained, the time taken to complete this process would be 20 minutes for the first risk-setting visit and 15 minutes for subsequent recall examinations (oral health reviews).

Outcome measures

All primary and secondary outcome measures were measured at 4 years’ follow-up and are outlined below.

Primary outcomes

Clinical:

-

gingival bleeding on probing.

Patient centred:

-

OHRQoL [Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14)]. 81

Secondary outcomes

Clinical:

-

dental caries

-

periodontal probing depth

-

calculus

-

preventative and interventive care.

Patient centred:

-

dental anxiety82

-

oral health-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours

-

generic quality of life, measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)

-

use of, and reason for use of, dental services

-

satisfaction with care.

Economic outcomes

-

NHS costs.

-

Patient-incurred costs.

-

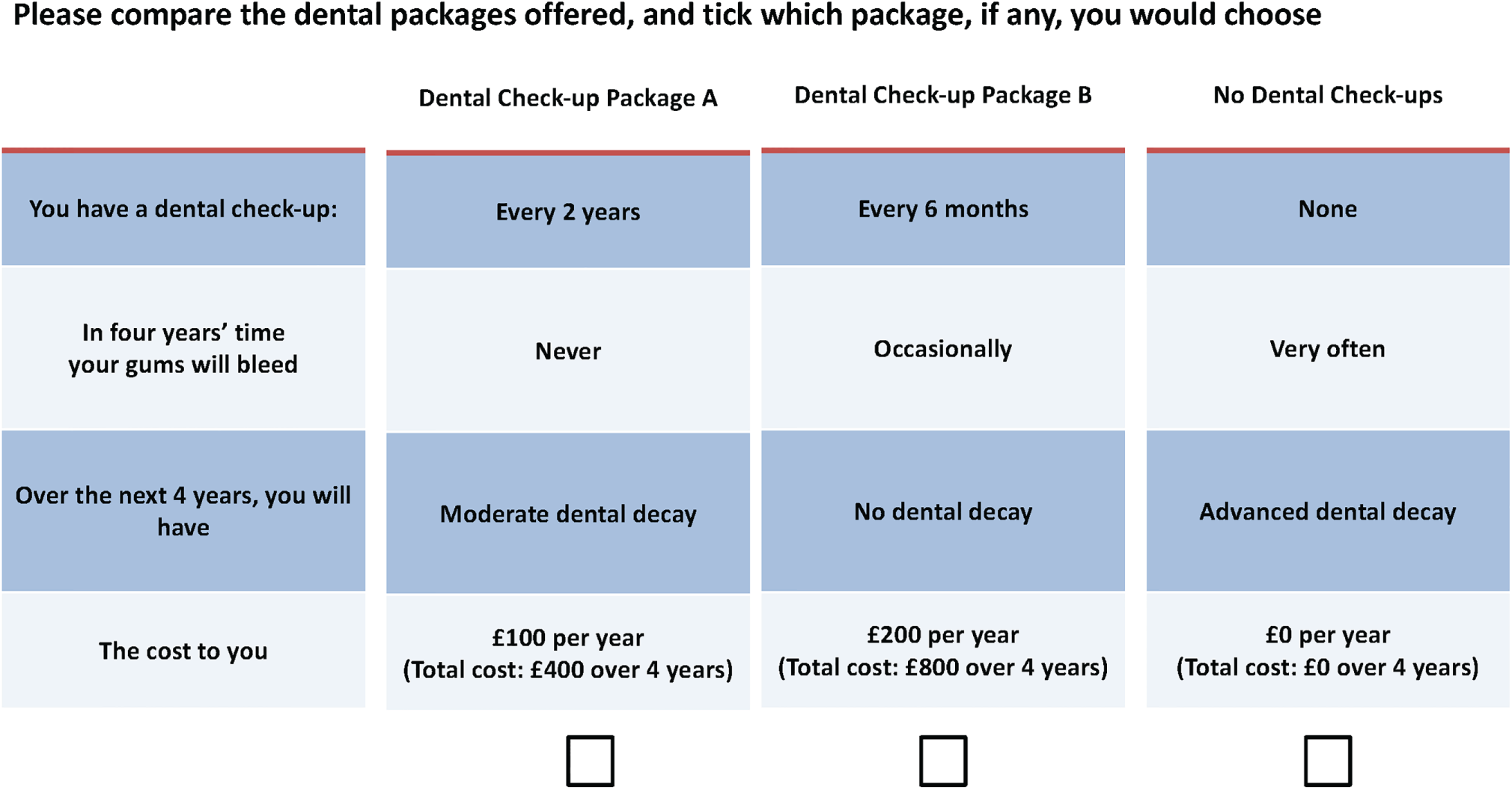

General population preferences, willingness to pay (WTP) calculated from a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to value service delivery and outcomes.

-

Incremental net benefits (INBs) (WTP minus costs), measured as societal net benefit (WTP for health and non-health aspects) and dental health net benefit (WTP for health outcomes, bleeding on brushing and caries experience only).

-

Generic quality of life, measured using the EQ-5D-3L.

-

QALYs.

-

Incremental cost per QALY.

(See Chapter 3 for further details.)

Service provider measures

-

Dentist attitude towards dental recall strategies.

Post hoc outcomes

-

Self-reported bleeding.

Measurement of clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes were assessed at 4 years post randomisation ± 4 months by trained outcome assessors who were blinded to allocation. The blinding of the outcome assessors was achieved by non-disclosure of the practice or patient to the allocated recall interval. The flexibility around the 4-year anniversary was to accommodate participant and practice factors influencing the convenience of attending the outcome assessment visit. Each tooth was examined, except third molars, unless a second molar was absent and the third molar tooth had drifted mesially to occupy the second molar position. The periodontal examination was performed first and the sequence of assessment was gingival bleeding on probing, periodontal probing depths and calculus. Teeth then were cleaned with a manual toothbrush by the outcome assessor and an ICDAS caries examination was carried out. More details on clinical data collection are outlined below.

Periodontal

Gingival bleeding on probing was measured according to the Gingival Index of Löe83 by running a colour-coded UNC15 periodontal probe circumferentially around each tooth just within the gingival sulcus or pocket. After 30 seconds, bleeding was recorded as being present or absent on the buccal and lingual surfaces. The primary outcome was calculated by adding all the sites where bleeding was observed and dividing it by the number of sites (twice the number of teeth) and was presented as a percentage.

Periodontal probing depth was measured using a colour-coded UNC15 periodontal probe. Clinical probing depths were measured for all teeth at six sites per tooth (mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual/palatal, midlingual/palatal and distolingual/palatal). Clinical probing depth was calculated as the mean of the six sites measured per tooth and is presented in millimetres.

Calculus was detected using a colour-coded UNC15 periodontal probe as being present or not. Calculus was calculated by adding all the sites where calculus was observed and dividing it by the number of teeth and presented as a percentage.

Caries

We measured caries at the enamel and dentine threshold using ICDAS. After manual tooth brushing by the outcome assessor, an examination of clean and wet/dry teeth (according to ICDAS procedure) was performed. Examination was aided by a ball-ended explorer used to remove any remaining plaque and debris and to check for surface contour, minor cavitation or sealants. All surfaces of all teeth were examined and the status of each recorded in terms of caries detection. A score between 0 and 6 was recorded for each surface.

Preventative and interventive care

Practice-reported data were collected throughout the 4-year trial including recall appointments on the PAD forms completed by practice staff. The PAD form was used to collect data on intended recall appointment dates, actual date of appointment, any rescheduling, length of time of appointment, any further treatment required as an outcome of the recall and, if known, the reason why a participant had not adhered to the recall interval. It also captured the expected date of the next recall appointment, after taking into account any course of treatment that might be required.

NHS routine data reported details of the treatment provided under the NHS during the trial period and was accessed through the routinely collected data in all participating regions in the UK, NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) England and Wales, Business Services Organisation (BSO) Northern Ireland and ISD Scotland. Further details are provided in Chapter 3.

Measurement of patient-centred outcomes

Patient-centred outcomes were measured at 4 years and also collected annually, including at baseline, through a self-administered questionnaire.

Annual questionnaires were mailed to participants from the TOD on the anniversary of their randomisation. A Freepost envelope was included for ease of return. If the questionnaire had not been returned within 4 weeks, a reminder letter and another copy of the questionnaire were sent to the participants.

The full details of the calculations used to generate each patient-centred outcome are shown in Appendix 1, Table 26. We used the relevant publication to inform the calculation of validated scores, such as OHIP-14 and the dental anxiety scale.

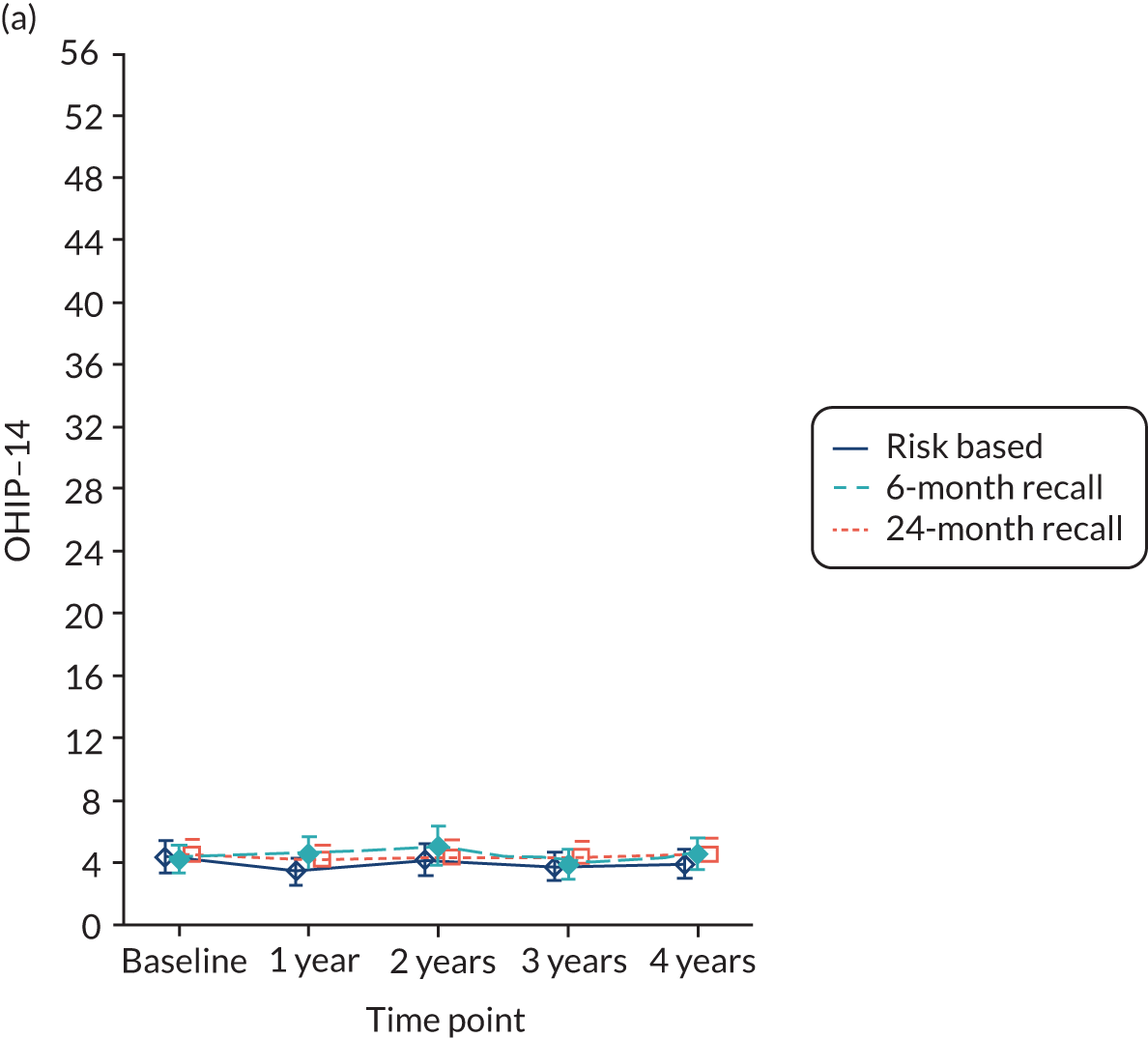

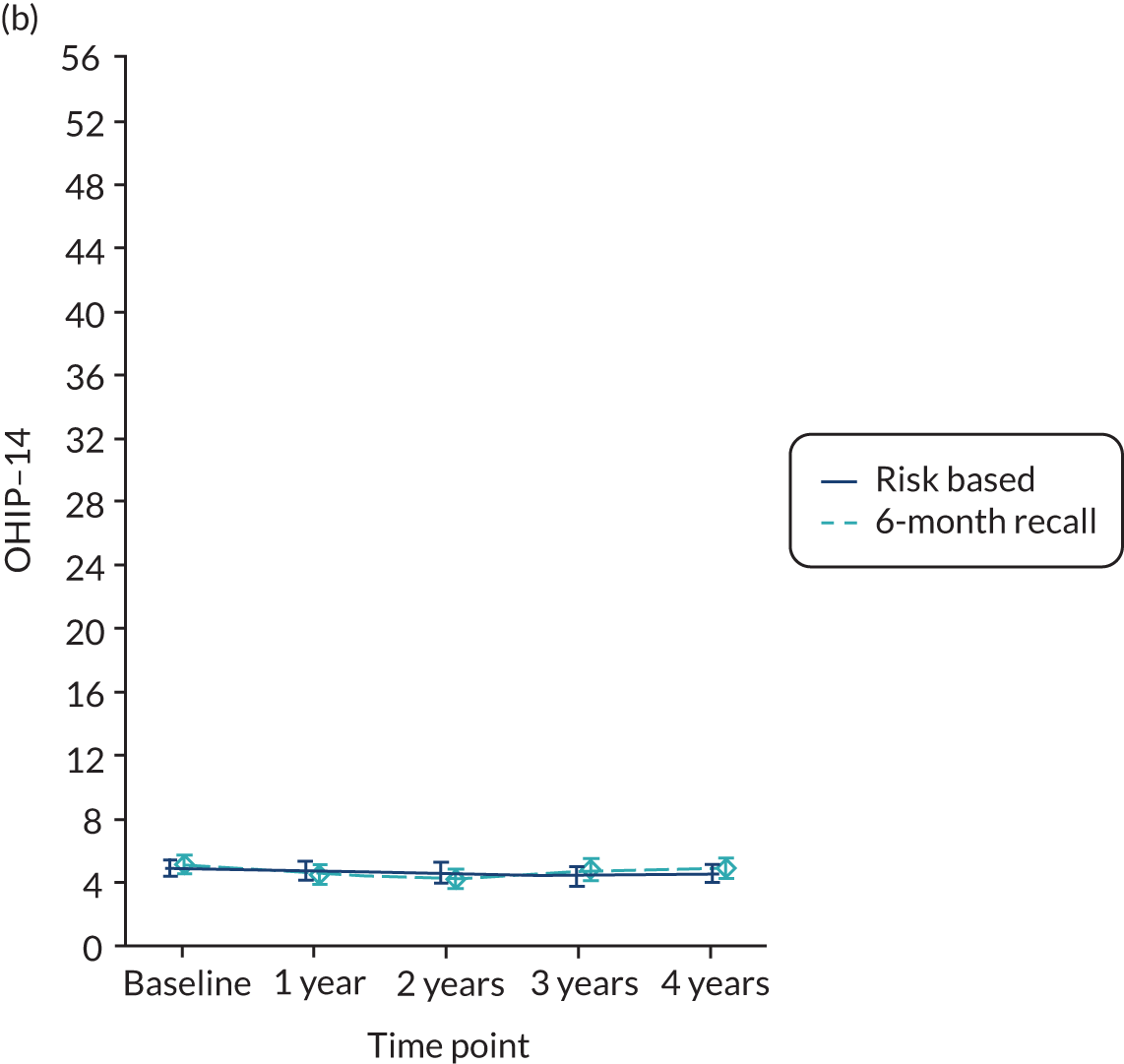

Oral health-related quality of life

Quality of life was measured using OHIP-14. 81 The OHIP-14 is a 14-question oral health-specific patient-centred measure referring to symptoms in the past 12 months. The questions are scored from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) and summed to produce a score ranging from 0 to 56, with 56 being the worst outcome.

Dental anxiety

Patient dental anxiety status was measured using recognised and validated psychological inventories [Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS)]. 82,84 Five questions relating to different dental treatments and situations were posed. The answers are scored on a scale from not anxious (rated as 1) to extremely anxious (rated as 5). The range of the summed total of five items was 5–25.

Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviours

The questions for measuring patient-centred belief outcomes and beliefs [attitude and perceived behavioural control (PBC)] outcomes were derived from social cognitive theory and the theory of planned behaviour. 85,86

Oral health knowledge outcome

Knowledge was measured using four questions related to oral health (frequency of brushing, duration of brushing, frequency of flossing and frequency of interdental brush usage). The best value between flossing and interdental brush usage was used as a measure of interdental cleaning knowledge. Each response varied from 0 to 3, with a score of 3 being the highest level of knowledge. The responses were summed to produce a total score ranging from 0 to 9, with 9 being the best outcome.

Oral health beliefs (attitude and perceived behavioural control) outcomes

Oral health-related attitude was measured using a 7-point scale varying from 1 to 7 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and the higher the score, the better (i.e. the more positive) the attitude. The scale comprised seven questions and the final score was the average of the individual item scores.

Perceived behaviour control was measured using a 7-point scale varying from 1 to 7 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) with higher scores indicating more perceived behaviour control. The scale comprised four questions and the final score was the average of the individual item scores.

Oral health behaviours

Patient-reported oral health behaviour outcomes were measured using four questions (frequency of brushing, duration of brushing, frequency of flossing and frequency of interdental brush usage). Each response ranged from 0 to 3, with a score of 3 being the best possible behaviour. The best value between flossing and interdental brushes was used as a measure of interdental cleaning behaviour. The responses for each question were summed to produce a total score ranging from 0 to 9, with 9 being the best outcome.

Use of and reason for use of dental services

A question within the annual patient questionnaire asked participants to record the number of times they had attended the dental practice and the type of treatment received (NHS, private or combination), and their payment cost of this treatment. Questions were also asked about frequency and treatment data on non-scheduled attendance at services for dental problems (e.g. hospital accident and emergency, hospital outpatients or general medical practitioners).

Satisfaction with care was a score averaging 12 items, each varying on a scale of 1 to 7 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and the higher the score, the more satisfied participants were with care. The satisfaction measure was developed with dental patients in Scotland.

Service provider measures

Dentists were asked to complete a clinician belief questionnaire at baseline prior to the online risk-based training and randomisation of participants.

The questionnaire collected data on the dentist’s professional history and profile, practice profile, professional engagement and factors such as decision-making, confidence and workplace stress. The majority of questions (n = 21) related to their attitude towards dental recall interval, ease of its determination and the consequence for patients. A 7-item scale was developed from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Full details of the calculations used to generate dentist belief outcomes are shown in Appendix 1, Table 27.

Post hoc outcome

Self-reported bleeding was included as a post hoc outcome and measured via patient questionnaire at 4 years post randomisation. It was measured by asking patients ‘Have you had bleeding from your gums when brushing your teeth?’ The answer could vary from 0 (never) to 4 (very often).

Demographic characteristics

Participant demographic characteristics were collected at baseline and annually using a self-administered postal questionnaire. The demographic characteristics included the most recent visit to the dental practice, type of attender (regular/non-regular), type of toothbrush (manual/electric) and smoking status. Participants also provided details on difficulty of travelling to the dental practice, which was scored from 1 to 7 on a Likert scale, where the higher the score, the easier participants found travelling to their dentist. Demographic characteristics are presented by year and randomised group, using either mean, standard deviation (SD) or n (%) as appropriate.

Fidelity measures

Dental practice compliance with the protocol was monitored through face-to-face practice visits by a member of the trial office team, regular telephone contact from the TOD to practices and an audit of six participants per practice at the mid-point in the trial. The PAD forms were reviewed as part of the audit and a judgement was made on whether or not they were compliant with the allocated recall interval. Dentists were also reminded to complete the online risk-based variable training package annually to reinforce the review needed for the participants randomised to a variable risk-based recall.

The audit of six participants (two participants from each of the three recall intervals or three each from risk-based and 6 months if no participants had been allocated to 24 months) was conducted with each practice to check if participants had been contacted to attend an appointment according to their allocated treatment group. If ≥ 50% of these random six participants had not been contacted or invited to attend, this triggered a telephone call to the practice to check the trial processes and, if required, a visit to review protocol.

All practices received at least one face-to-face visit. This was to ensure practice compliance with the protocol and confirm staff understanding of their role. It provided a valuable opportunity to answer any queries the practice staff had and to build and maintain a rapport to ensure a smooth transition into the follow-up phase of the trial. Practice staff were encouraged to flag INTERVAL participants in their electronic system as an aide-mémoire to following up participants.

Regular telephone calls were made by TOD administration staff to designated main contacts in practices during the course of follow-up to keep practice staff on board and on track, to provide an opportunity to discuss queries and for TOD staff to seek updates on PAD forms where necessary. Practices were encouraged to contact the TOD for guidance on any aspect of the trial.

An INTERVAL-branded site folder was prepared for each practice containing copies of their completed screening log/PCRFs and participant consent forms, and a section in which to file copies of completed PAD forms.

The TOD e-mailed and posted monthly newsletters to practices to remind dentists and staff of procedures and processes for recruitment and training, and trial updates.

Number of check-ups received (routine data and patient attendance data forms)

The PAD forms were used to collect information on intended and actual appointment dates. The information about the first intended appointment date per recall group was used to assess dentists’ intended compliance with the protocol.

Routine treatment data were obtained from the NHSBSA in England and ISD in Scotland for the time period 2010 to 2018. 62 The routine data provided information about the number of dental recalls received throughout the trial by counting the number of claims for treatment made by dentists for each participant.

Data collection

Baseline

Dentists were asked to complete the baseline clinician belief questionnaire after consenting to participate in the trial.

Patient-centred outcomes were collected at baseline using a self-administered questionnaire. Questionnaires were returned to the TOD by the dental practice in a sealed envelope.

Ongoing

Recall appointment dates and times and further treatment information were collected by practices on PAD forms. Routine NHS treatment data were obtained from national-level dental claims data held by the ISD (Scotland), NHSBSA (England) and BSO (Northern Ireland).

Annual follow-up

Patient-centred outcomes were collected annually using self-administered postal questionnaires.

The annual follow-up questionnaire combined questions on patient-centred outcomes, OHRQoL (OHIP-14), generic health (collected using the EQ-5D-3L), dental anxiety, oral health-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviours, use of dental services and satisfaction with care.

Questions collecting descriptive measures were also included in this questionnaire. The annual patient questionnaire also included questions for the health economic analysis, relating to patient-incurred dental costs, and patient attendance at general NHS services (e.g. hospital accident and emergency) for dental-related problems. Questionnaires were issued annually to participants at their home address from the TOD with a covering letter and a Freepost envelope for return of the completed questionnaire.

Those participants who failed to return their questionnaire within 4 weeks were sent a reminder, a further copy of the questionnaire and a Freepost envelope.

On the second anniversary of their recruitment to the trial, participants were sent a £15 gift voucher for their participation in the trial.

Final/fourth-year follow-up

Dentists completed the end-of-trial clinician belief questionnaire after all clinical assessments had been completed in their practice.

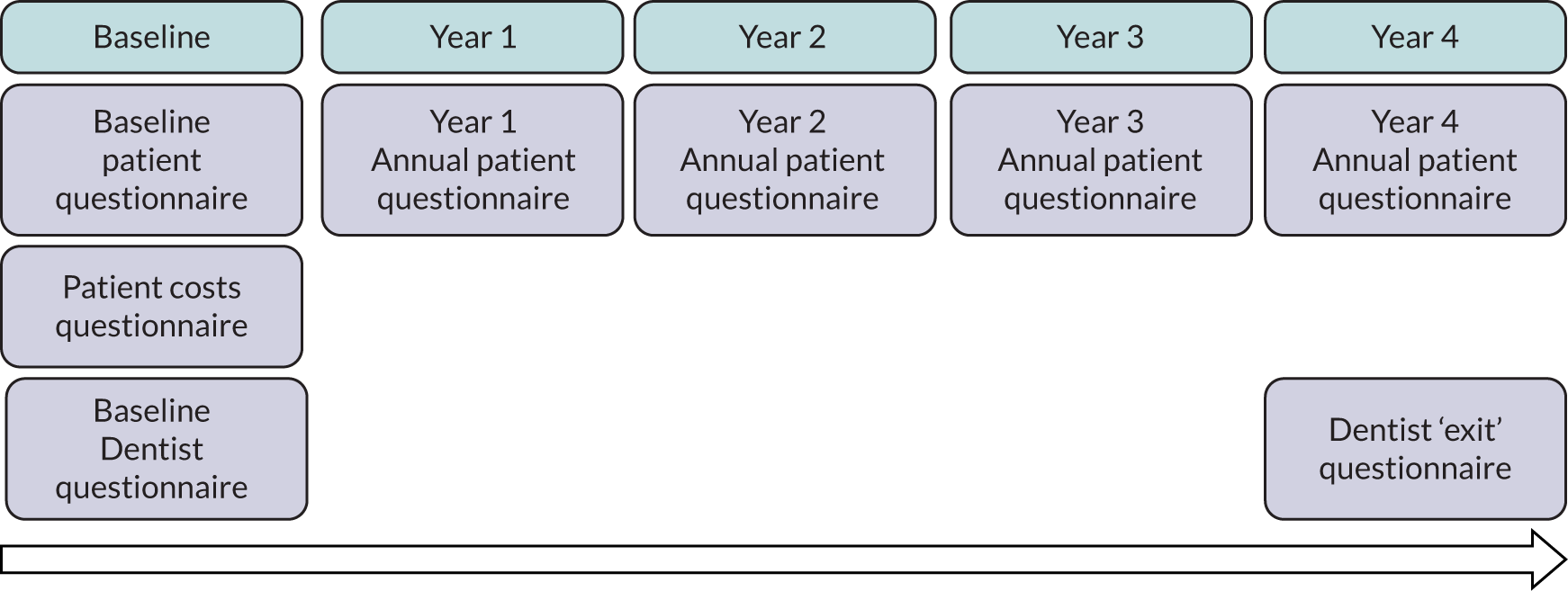

Patient-centred outcomes were collected at 4-year follow-up using the annual patient questionnaire. To maximise return, the final questionnaire was sent to participants at least 6 weeks before the date of their final year clinical assessment appointment, with a reminder sent 2 weeks before the appointment. Participants who had not returned a questionnaire by the time of their follow-up assessment appointment were asked to complete the questionnaire at that appointment prior to being assessed. A summary of the data collection items and time point is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Data collection schedule summary.

All participants were invited to attend a trial final-year clinical assessment appointment by their dental practice either at the time of their routine check-up or as a separate appointment. A brief medical history was undertaken about bleeding disorders or immunocompromised disorders. The assessor also confirmed continuing consent with the participants. Gingival bleeding on probing scores, periodontal probing depths, calculus and caries detection were measured by the assessors and recorded on a clinical chart by the dental research nurse, who was a member of the trial team.

Participants who could not attend were contacted and given the option of attending at least one other day or time. Patients who were no longer registered at the practice were offered the opportunity to return to the practice (with practice permission) for an assessment examination, or at another INTERVAL practice (if appropriate) or at a suitable satellite location.

All participants who attended the follow-up assessment received a letter of appreciation for their participation in the trial, details of where the trial results would be published and a final £15 gift voucher in recognition of their contribution. Letters and vouchers were subsequently posted, where possible, to participants who did not attend a follow-up assessment.

Sample size

An exploratory trial in a similar population reported that 35% of gingival sites were bleeding on probing (SD 25%). 87 The Cochrane review of periodontal instrumentation (PI) suggested that 6-month PI versus no PI reduces bleeding sites by 15%. 88 The recall interval was expected to produce an effect lower than this given that the majority of participants in all arms would still receive PI at some time during follow-up. Assuming that either risk-based versus 24-month recall or 6-month versus 24-month recall could reduce/increase the percentage of sites bleeding by 7.5%, the study with 235 participants in each arm could detect such a difference with 90% power at 5% significance, and, likewise, detect a difference of 0.3 of the SD of the OHIP-14 score or any other global measure of OHRQoL. For the caries clinical outcome, assuming a SD of 3.5, the study with 235 participants per arm would detect a shift in white spot lesions (from 3.3 to 4.2) at 80% power and 5% significance. 79 We combined the two strata, without introducing bias, to estimate this comparison. We anticipated smaller effect sizes for the 6-month versus risk-based recall comparison than 6-month versus 24-month recall given that many of the participants in the risk-based group would be seen more frequently than 24 months. A study with 750 participants in each arm could detect a difference in bleeding scores of 4.5% with at least 90% power and a 5% significance level,89 and likewise detect a difference of 0.17 of the SD of the OHIP-14 score. For the caries clinical outcome, assuming a SD of 3.5, a study with 750 participants per arm could detect a 20% relative shift in white spot lesions from 3.3 to 3.9 at 90% power and 5% significance. 79 Although there was no reason to be concerned about contamination effects in this trial or clustering by dentist, the sample size was conservatively estimated such that if contamination occurred with 15% of the control participants or the intracluster correlation was 0.03, the study would still have 80% power to detect the hypothesised changes in the bleeding score. Our sample size calculations indicated that we needed to randomise 705 participants to stratum 1 (235 in each arm) and 1030 to stratum 2 (515 in each arm).

Contamination effects

There were no obvious mechanisms for contamination to occur in this trial. Our experience of simultaneously conducting an educational cluster and patient randomised trial in dentistry suggested that contamination occurred in at most 15% of participants (if any);89 therefore, fewer participants are required to perform a patient randomised trial than a cluster randomised trial. 90 There is no perceived direct influence of skill on the patient outcomes and, even if that were hypothesised, the intracluster correlation would be very low (< 0.03).

The sample size has been conservatively estimated such that, if contamination occurred with 15% of the control participants or the intracluster correlation was 0.03, the study would still have 80% power to detect the hypothesised changes in the bleeding score.

Statistical analyses of outcomes

Baseline data were explored to better understand dentists’ decision-making process when allocating participants to different strata (eligible to be randomised to 24-month recall vs. not eligible). The primary analysis used an intention-to-treat framework and all participants with available data remained in their allocated groups. The participant outcomes listed above were compared between 24-month, risk-based and 6-month recall groups (for the stratum eligible for a 24-month recall) and risk-based versus 6-month recall (for the stratum ineligible for a 24-month recall). Outcomes collected at year 4 (clinical outcomes, behaviour, knowledge and PBC scores) were analysed using a generalised linear model with a random effect for dental practice. Outcomes collected at years 1, 2, 3 and 4 were analysed using a mixed-effects model with two random effects: participant and practice. A time by treatment interaction term was included in the models. The appropriate effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were derived. All analyses were adjusted for the protocol minimisation variables [age, dentist, filled teeth (≤ 8 or > 8) and absence of gingival bleeding on probing]. Stata 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to undertake the analysis.

Missing data

Missing items in scales were dealt with as recommended in the literature by their authors, when recommendations were available. Otherwise, a complete-case approach was used where, in the presence of any missing items in a patient’s score, the score was considered missing. Continuous missing data at baseline were imputed for modelling purposes as recommended in the literature,91 and categorical missing data at baseline used the missing indicator method. 92 The primary intention-to-treat analysis was on observed data.

Sensitivity analysis

We explored differences between responders and non-responders to inform our missing data model. As a sensitivity analysis, missing primary outcome data were imputed using a predictive mean matching multiple imputation approach. 92

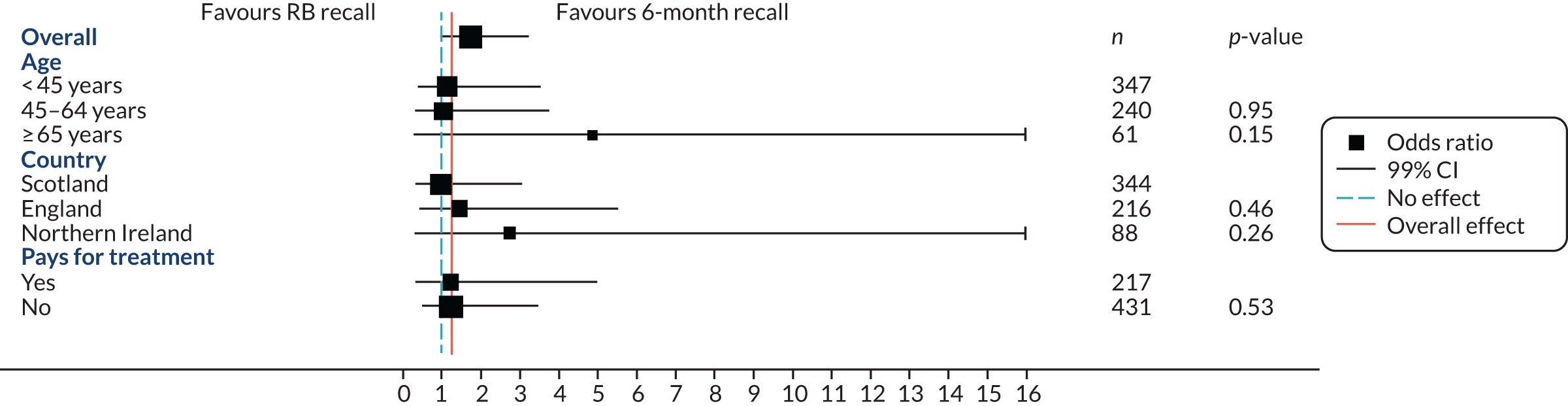

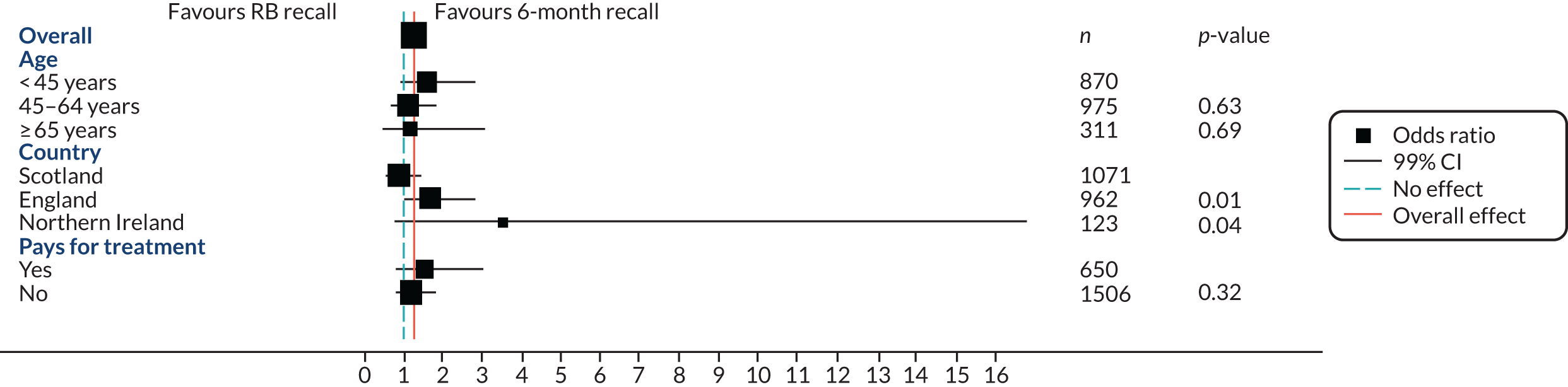

Subgroup analysis

A pre-planned subgroup analysis explored the effect modification of age (< 45 years, 45–64 years, ≥ 65 years) and social class (exempt from payment and not exempt from payment) by including a subgroup-by-treatment interaction term in the primary clinical outcome model described in Statistical analyses of outcomes. Further pre-planned subgroup analyses included residence in a fluoridated area, and dentist characteristics were included in the protocol; however, there were too few participants (2%) in fluoridated areas to make a subgroup analysis meaningful. The dentist characteristics subgroup analysis was an error in the protocol. A post hoc subgroup analysis by country was also included.

Trial oversight

The University of Dundee acted as the sponsor for the study. The trial was co-ordinated from the TOD in the Dental Health Services Research Unit, Dundee, which provided day-to-day support for the dental practices and outcome assessors/research nurses. The TOD was responsible for issuing and collecting trial documentation from practices and participants (including annual questionnaires and reminders) and co-ordination of participant follow-up. The TOD was also responsible for the entry of collected data into the database, including screening logs/PCRFs, PAD forms, baseline, costs and annual patient questionnaires, baseline and follow-up dentist questionnaires and clinical data from outcome assessments. Clinical data were entered by the dentally qualified assessment team.

CHaRT, in the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, provided the database applications and information technology programming for the trial, and hosted the randomisation system, provided experienced trial management guidance, and took responsibility for all statistical aspects of the trial (including interim reports to the TSC and the DMC).

Trial Operational Committee meetings were held weekly and attended by Co-Chief Investigators, the Trial Manager and key TOD staff.

The Operational Management Committee met monthly, chaired by one of the Co-Chief Investigators, and comprised co-investigators in TOD and CHaRT.

The Trial Management Committee (TMC) met approximately annually, chaired by the Co-Chief Investigators, and comprised co-investigators, key members of the TOD and CHaRT and a lay representative.

The TSC comprised an independent chairperson and two further independent members, plus a member of the public acting as a lay patient representative. The TSC met approximately annually.

The DMC comprised an independent chairperson and two further independent members. The DMC met approximately annually.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to the start of the trial, advice on the design and conduct of the study was sought from members of the public partnership groups and from similar patient groups in other parts of the UK sourced under guidance from INVOLVE (UK National Advisory group).

These independent public partnership groups comprise volunteers who work in partnership with NHS Tayside and aim to provide a conduit for the views of people about their local services.

Patient advisors were a valuable resource at the outset of the trial and helped to ensure good conduct and patient-friendly practice throughout the duration of the trial. Patient advisors were involved with the trial design and provided invaluable feedback on trial recruitment and communication strategies. Patient advisors also contributed to the content and layout of trial invitation, trial newsletters and the design of patient participant questionnaires. This ensured that trial participants could understand and easily complete these materials.

As quality of life was a primary outcome of the trial, patient advisors’ input to the proposed questionnaire design was essential. Qualitative work with patients was carried out to ensure that the outcome measures were patient centred.

Lay representatives on the TSC and TMC actively contributed to trial oversight, processes and procedures, including helping to interpret the trial findings, preparation of the monograph and assisting with the review of the Plain English summary.

Chapter 3 Health economics methods

Introduction

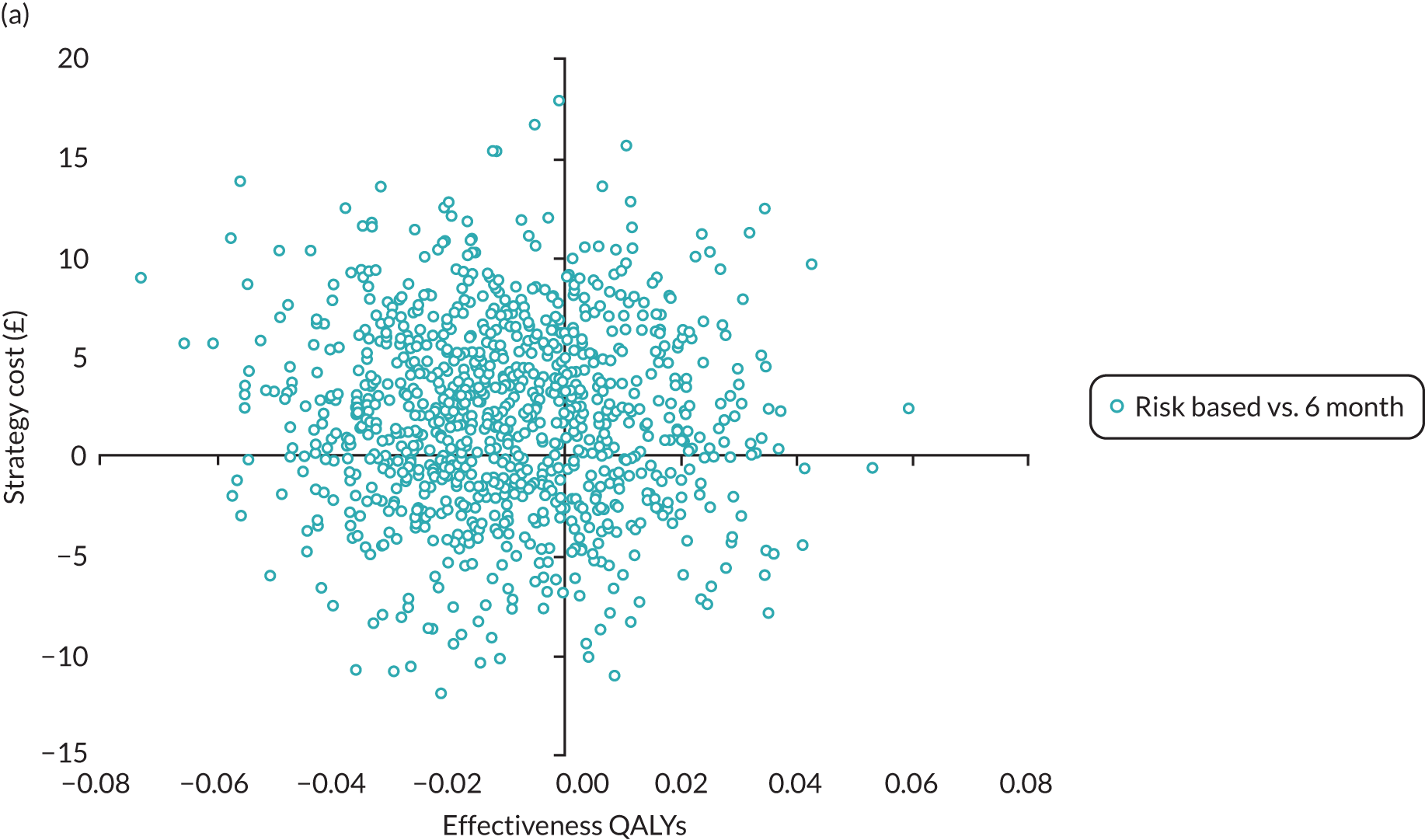

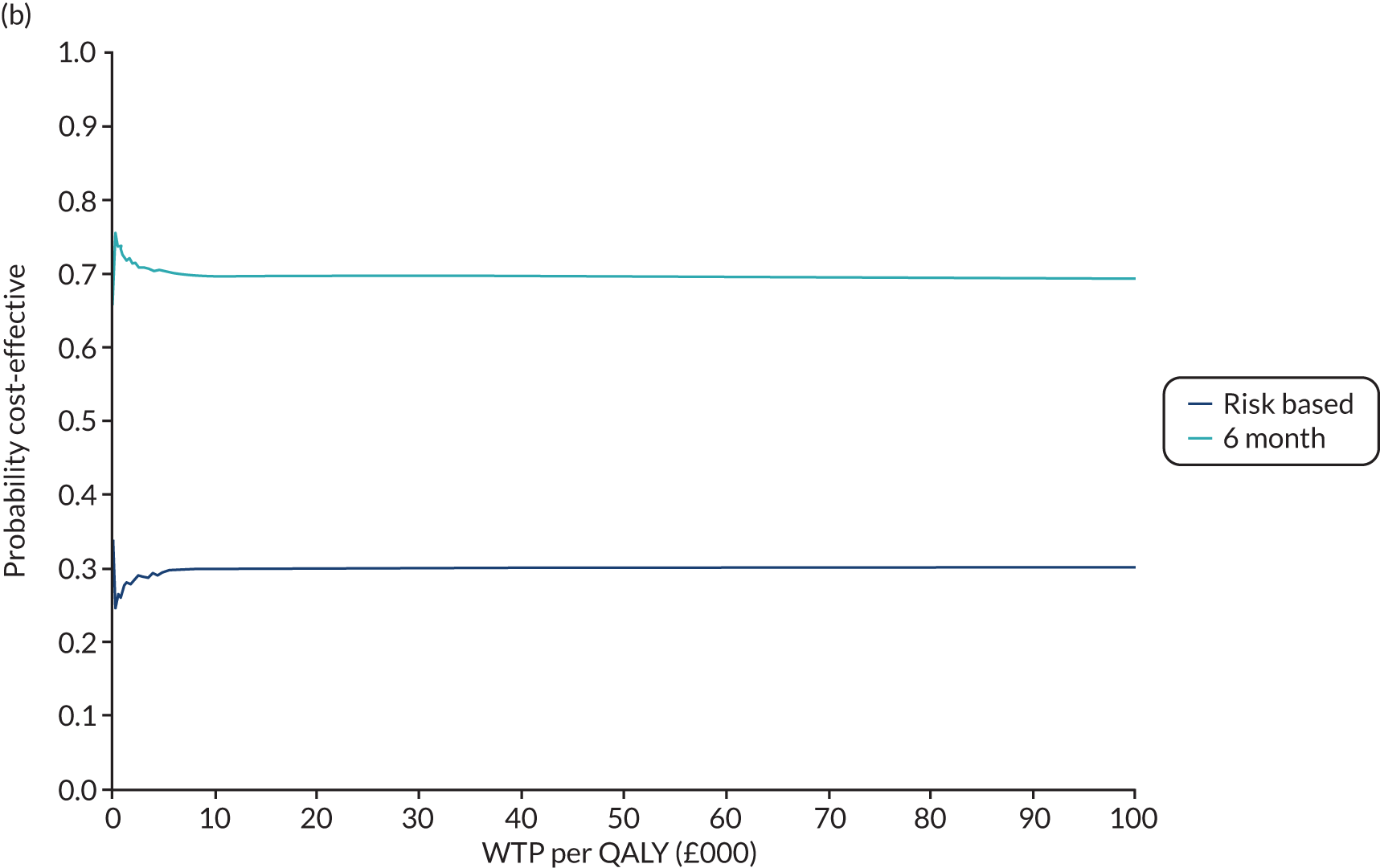

In this chapter we report the methods used to conduct the within-trial health economic analysis comparing different dental recall strategies as follows: eligible for 24-month recall – 24-month versus risk-based versus 6-month recall; and ineligible for 24-month recall – risk-based versus 6-month recall. All analyses are completed according to the intention to treat principle at 4 years’ follow-up. The health economic analysis compares the costs and benefits of different dental care recall strategies. The results are presented using different perspectives. Economic evaluations to inform UK health-care decision-making, for example through NICE, typically take the form of cost–utility (i.e. cost per QALY) analyses, reporting incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). However, in the context of dentistry, there are concerns that generic EQ-5D-3L-based QALYs lack the sensitivity to capture the processes and outcomes of care that are of value to patients and decision-makers. 93 Furthermore, it is argued that the time dimension embedded in QALY calculations may underestimate the impact of acute health effects such as painful caries. 94,95

Similarly, from a cost point of view, dentistry is unique within health care as the majority of patients pay a contribution towards their NHS care. It is, therefore, crucial to consider both the costs falling directly on the NHS dental budget and the impact on patients in terms of co-charges for NHS care and the opportunity cost of time and travel to dental care appointments when making recommendations about the most efficient dental recall strategy.

For these reasons, it is necessary to consider different frameworks of evaluation that (a) are sensitive to changes in important dental health outcomes such as bleeding or caries, (b) value outcomes that are relevant to service users and (c) capture the full cost burden to both patients and the NHS of different recall strategies. Providing results from a range of perspectives of benefits and cost is essential to equip decision-makers with all the relevant information necessary to reach informed decisions about the efficient allocation of scarce dental care resources.

In terms of the benefits, the scopes are WTP for dental recall interval and associated outcomes [cost–benefit analysis, including all benefits (health and non-health) that are important to individuals], QALYs and WTP for dental health outcomes (caries and self-reported bleeding gums). The preferred analysis depends on what outcome a decision-maker wishes to maximise: social welfare, QALYs or (WTP for) defined dental health (caries and bleeding). In terms of costs, the perspectives are NHS dental budget, NHS total budget and societal perspective (NHS and participant).

Resource use and costs

Resource use and cost data are collected from an NHS and dental patient participant perspective. NHS costs include provision of dental care services (obtained from data linkage to routinely collected claims data) and costs of attending non-dental health professionals for dental problems (obtained from participant questionnaires). Patient participant costs include co-payments for dental care, purchase of dental care products, and the travel costs and the opportunity cost of time spent attending dental appointments obtained from a combination of routinely collected data and participant self-reported questionnaires.

NHS dental costs

Resource use and costs associated with the use of NHS dental services are obtained through data linkage for each randomised trial participant to national-level dental claims data held by the ISD (Scotland), NHSBSA (England) and BSO (Northern Ireland). For the 13 participants recruited from a single Welsh practice, resource use is obtained from practice note data extraction. The actual cost to the NHS of providing treatments, the split of cost burden between the NHS and the patient, and the level of granularity of data available for analysis is dependent on different remuneration systems and contracting arrangements in place for payment of NHS dental care across different UK countries. For example, dentists in Scotland and Northern Ireland are reimbursed on the basis of fee for service, whereas in England contract payments are based on banded categories of treatment complexity. This means that there is a greater granularity of data available for Scotland and Northern Ireland to inform resource use and costing. There are also differences in patient co-charges for dental check-ups ranging from £0.00 (Scotland) to £19.70 (England), which have implications for the interpretation of NHS versus patient perspective costs across the regions. Tables 1 and 2 describe the NHS and patient breakdown of treatment charges across the UK regions for fee-paying adults. All cost data are reported in 2016/17 values based on the regional dental payment contracts. Regional specific variation in the dental payment systems is discussed in the following paragraphs.

| England and Wales activity-based banding96,97 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | Number of UDAs | UDA unit value | Band treatment value | England (2016/17 charges)a,b | Wales (2016/17 charges)a,b | ||

| Patient charge | NHS charge | Patient charge | NHS chargec | ||||

| 1 (e.g. check-up/X-ray/advice/PI) | 1 | £25 | £25 | £19.70 | £5.30 | £13.50 | £6.20 |

| 2 (band 1 treatments + fillings, extractions, root canal treatments) | 3 | £25 | £75 | £53.90 | £21.10 | £43.00 | £10.90 |

| 3 (band 1 and 2 work + crowns, dentures and bridges) | 12 | £25 | £300 | £233.70 | £66.30 | £185.00 | £48.70 |

| Urgent | 1.2 | £25 | £30 | £19.70 | £10.30 | £13.50 | £6.20 |

| Scotland/Northern Irelanda | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Patient charge (2016/17 charges) | NHS charge (2016/17 charges) |

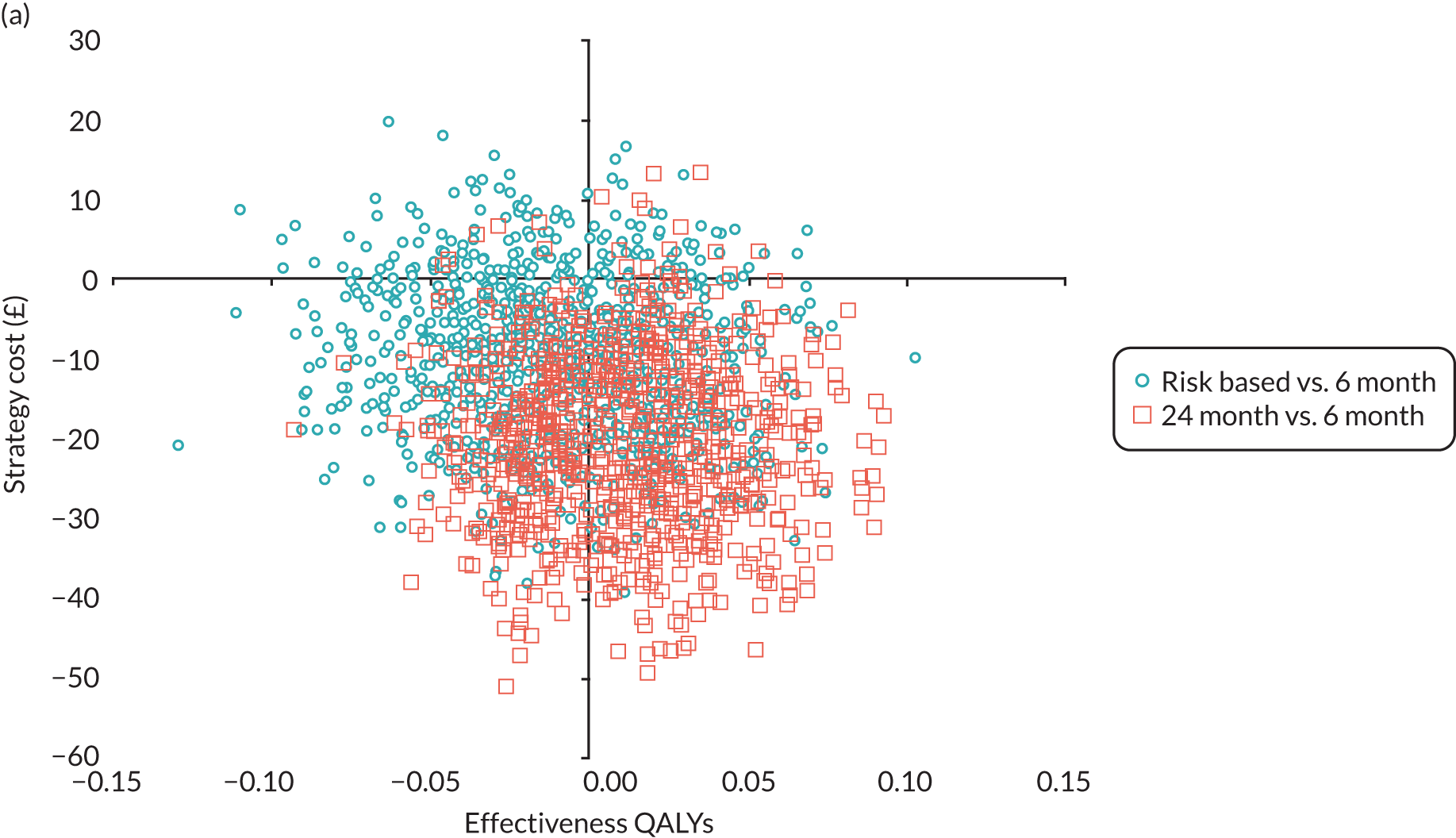

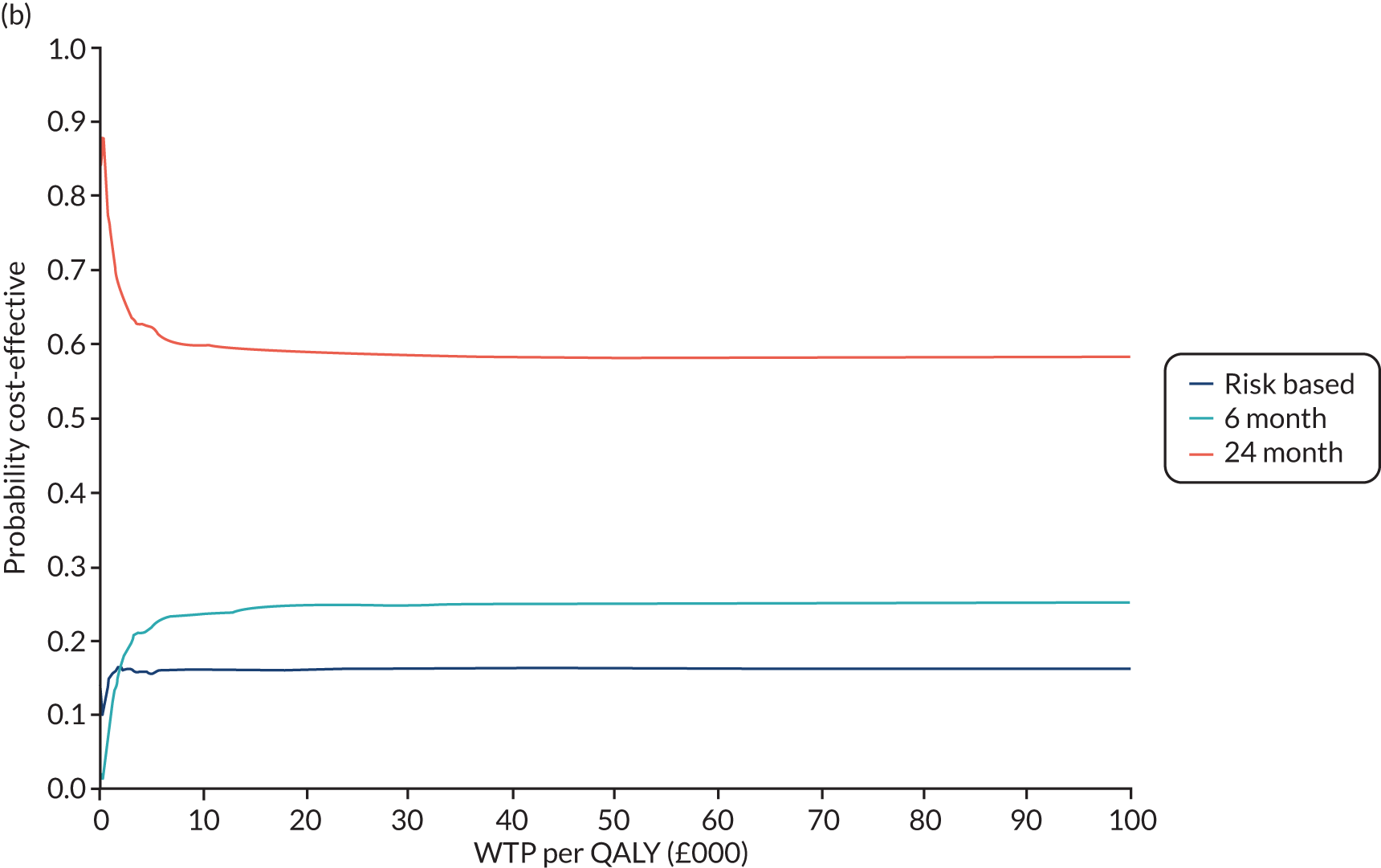

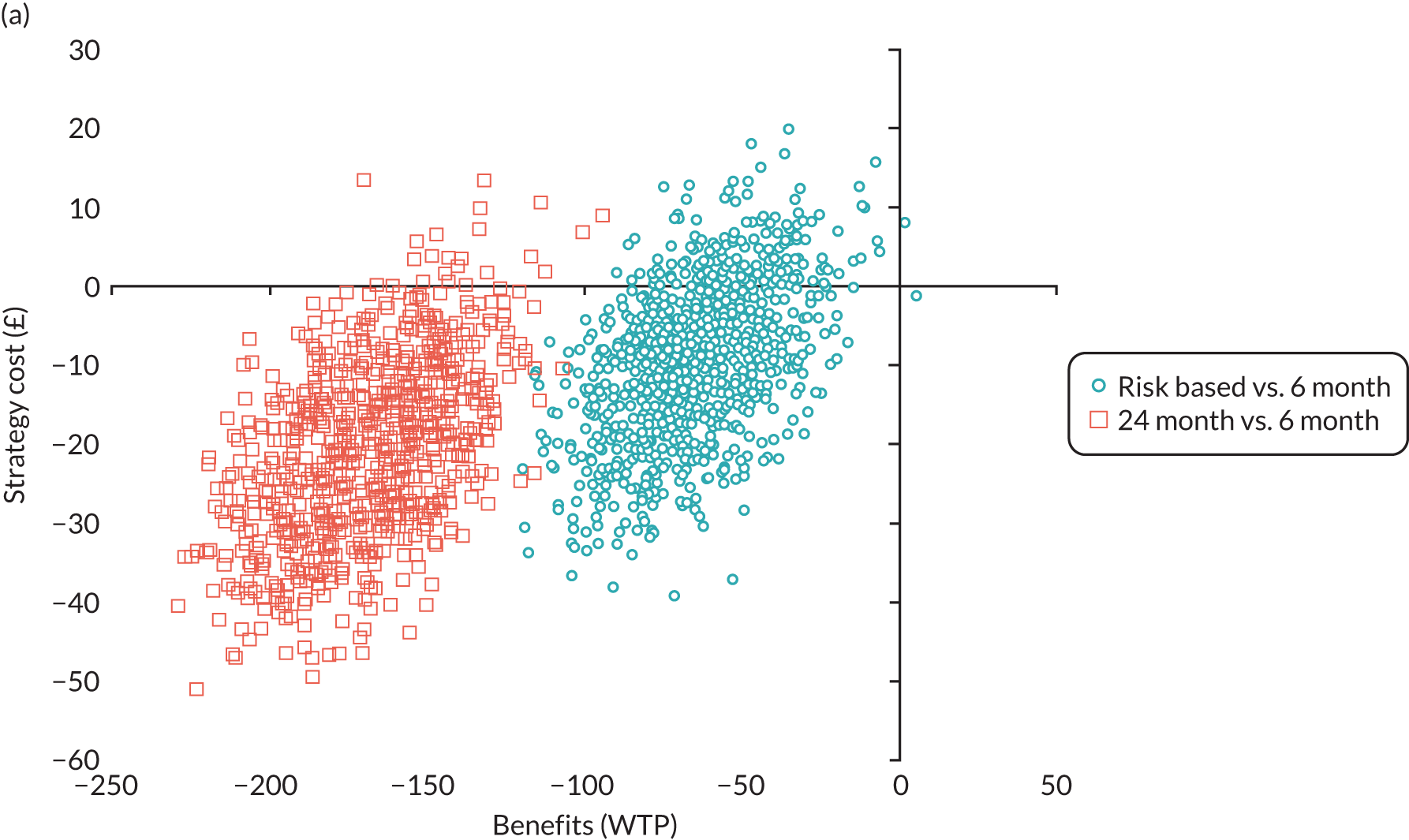

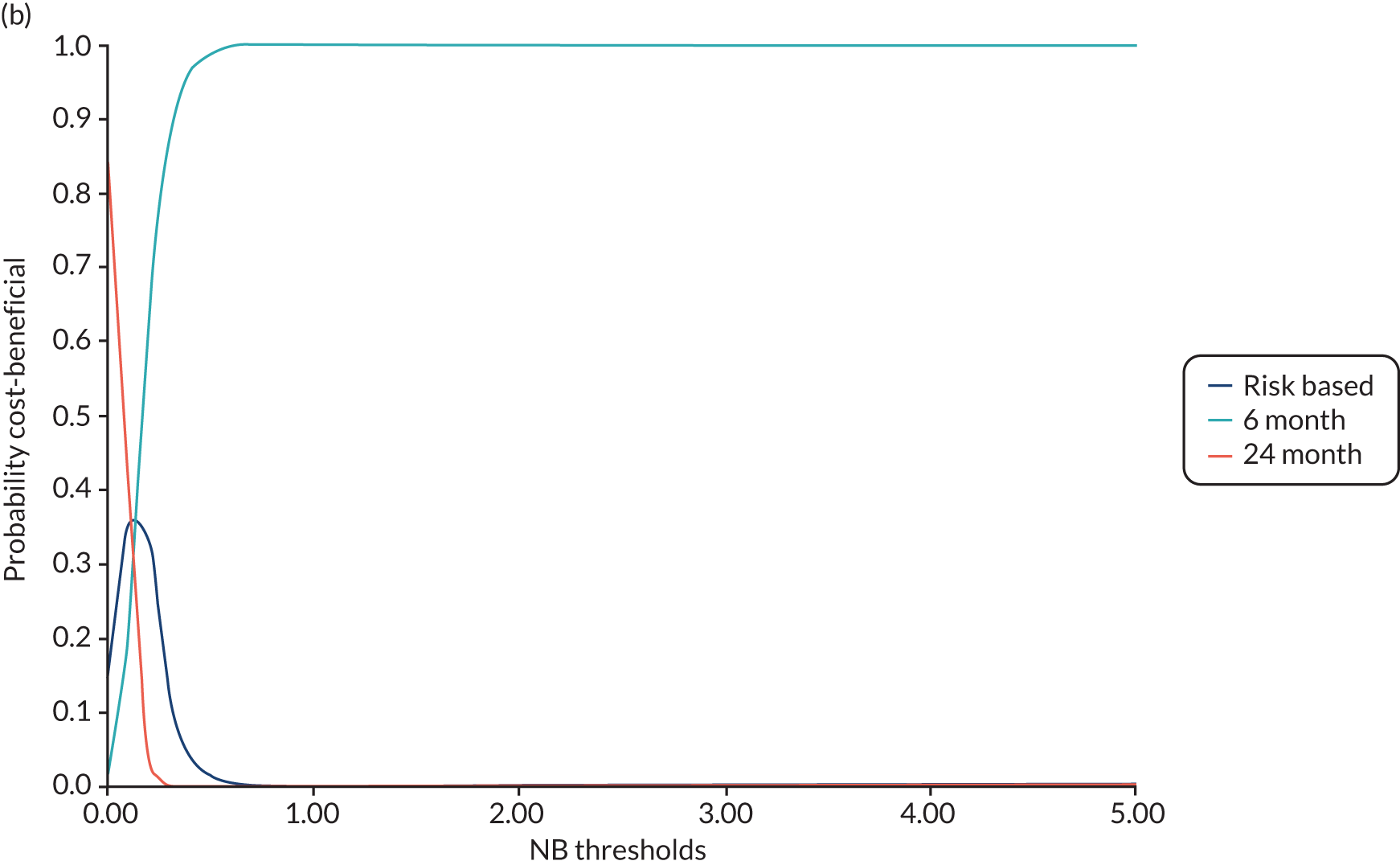

| Check-ups and case assessments | Scotland: 0% of full cost | Scotland: 100% of full cost |