Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/23. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The draft report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Pickard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction: background and objectives

Material from Stephenson et al. 1 Open urethroplasty versus endoscopic urethrotomy – clarifying the management of men with recurrent urethral stricture (the OPEN trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:600; Whybrow et al. 2 Equipoise across the patient population: optimising recruitment to a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:140; and Whybrow et al. 3 How men manage bulbar urethral stricture by concealing urinary symptoms. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1435–42 have been used within this report under Creative Commons Licenses.

Scientific background

Urethral stricture disease

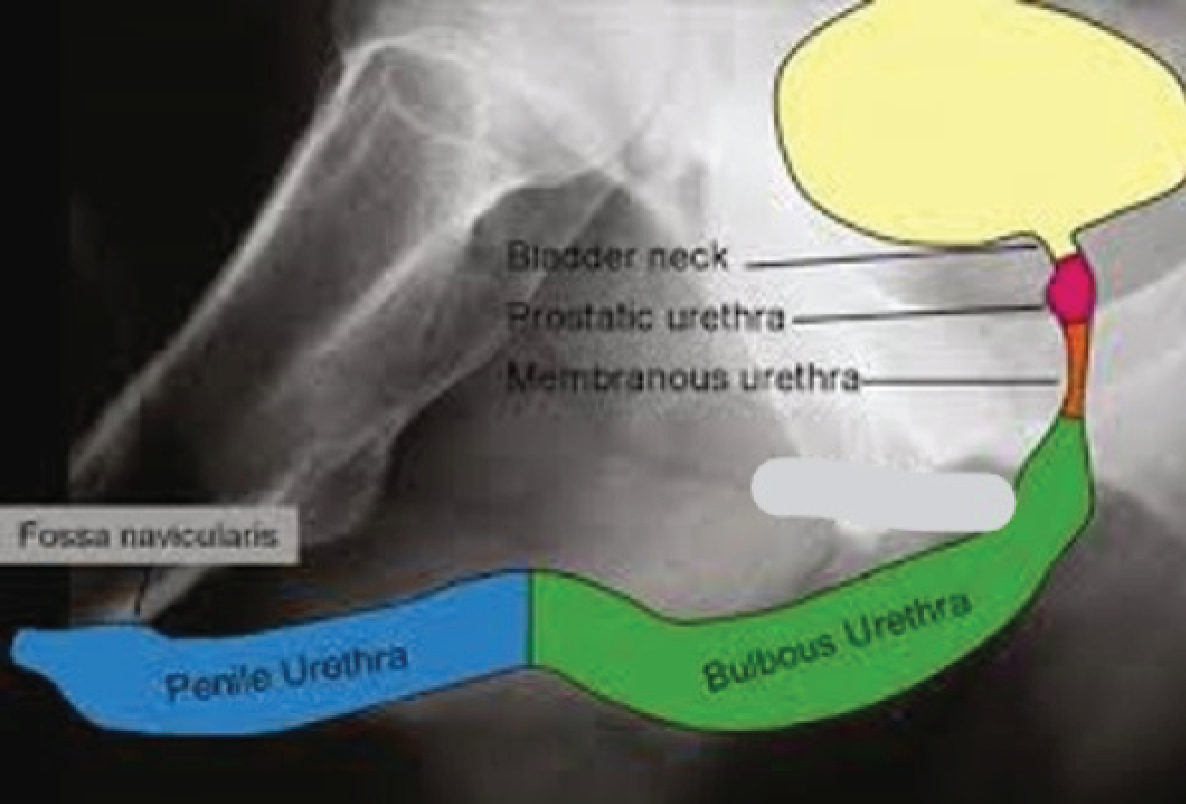

The male urethra is an epithelium-lined tube enveloped by smooth muscle erectile tissue (corpus spongiosum) and an outer layer of striated muscle (bulbospongiosus). It runs from the bladder outlet (neck), through the prostate gland, perineum and the ventral (under) aspect of the penis, opening at the fossa navicularis at the penile tip (external urethral meatus). It is anatomically divided (from proximal to distal) into prostatic, membranous, bulbous and penile segments (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Pictorial representation of male urethra. This figure was published in Surgery, Vol. 35, Watkin and Patel,4 The diagnosis and management of acquired urethral stricture disease, pp. 313–23, © Elsevier 2017. Reproduced with permission.

It functions as an active conduit to void urine and thereby empty the urinary bladder when desired. 5 It is also the conduit for ejaculation and emission of semen, which enters the urethra from ejaculatory ducts running through the prostate.

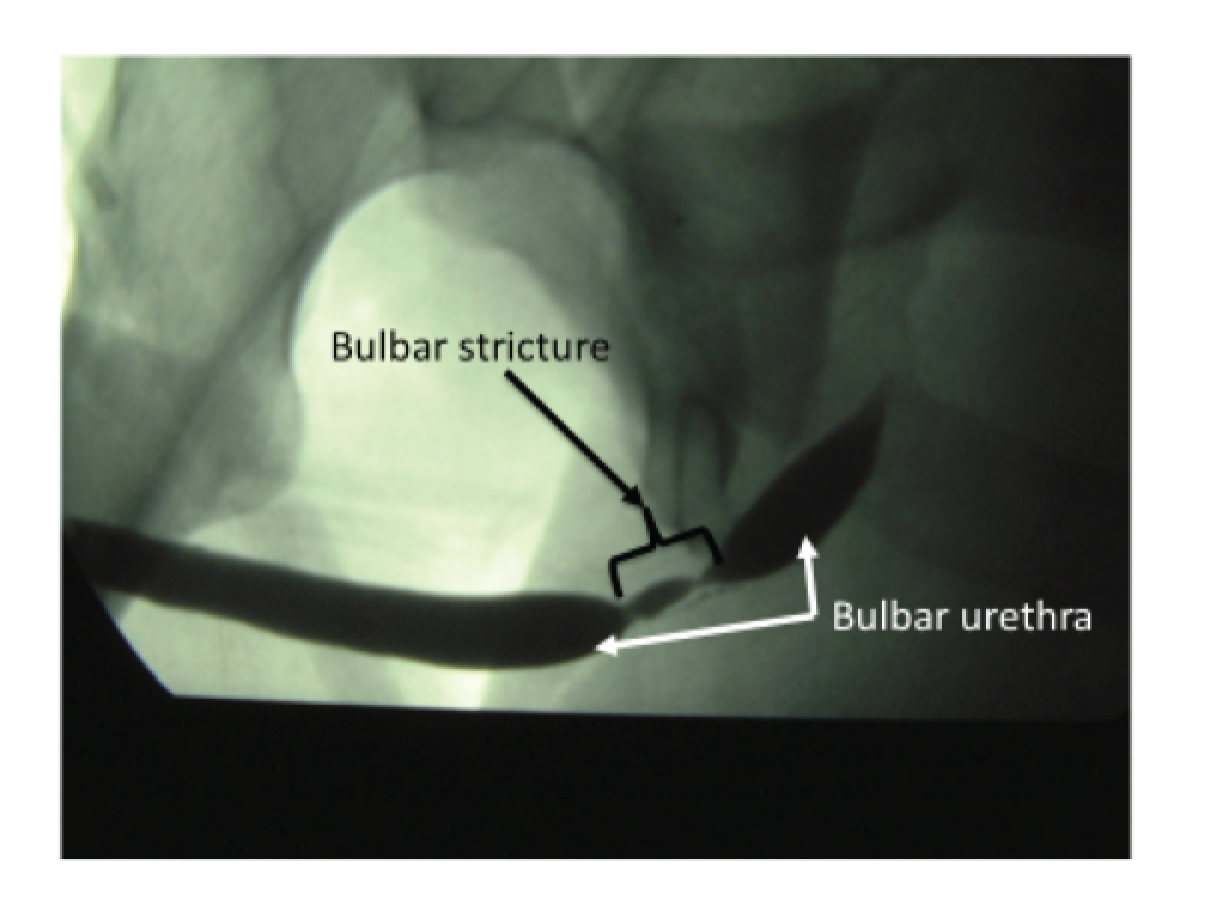

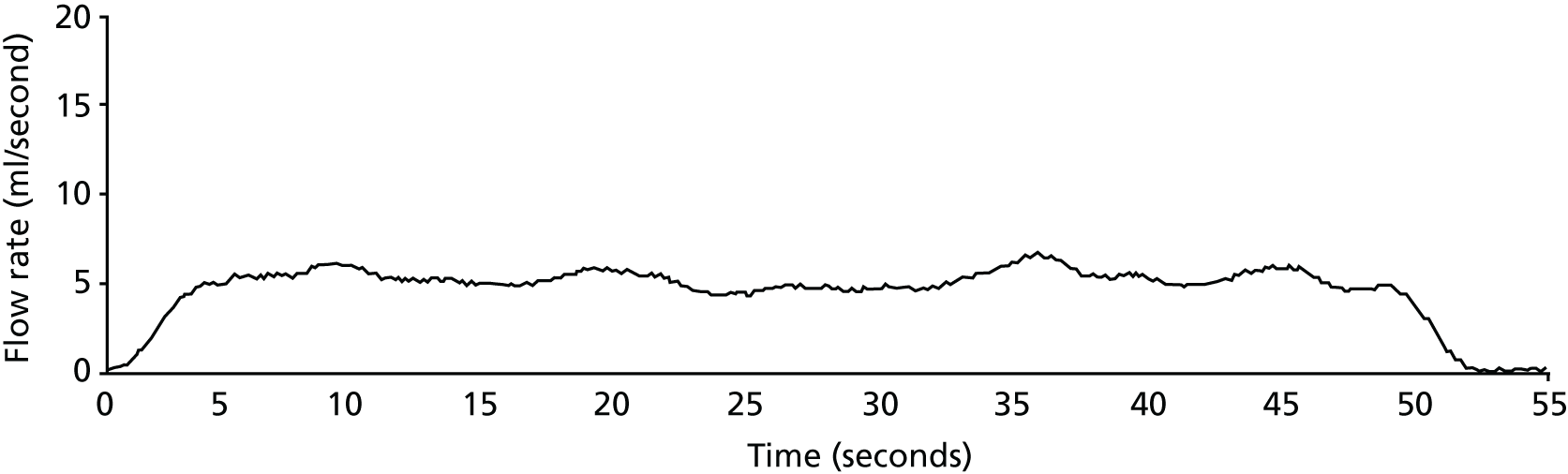

Urethral stricture is caused by annular scar formation in the epithelium and underlying smooth muscle layers, resulting in narrowing of the lumen, loss of propulsive muscle action and restriction of urine flow. Published estimates of the prevalence of urethral stricture disease among adult men derived from hospital activity registries in the USA include 0.6%6 and 0.9%. 7 Urethral stricture disease (OPCS Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 3 – character primary diagnosis code N35) resulted in > 17,000 admissions of men to NHS hospitals in England during 2016–17. 8 Men notice a reduction in the strength of urinary stream, prolonged voiding time and slow emptying of the urethra, often with dribbling of urine after micturition. When these symptoms become intolerable men seek medical help and are generally assessed by a urology specialist. Stricture site and length are evaluated by performing either a telescopic (urethroscopy) or radiological (urethrography) examination of the urethra or both (Figure 2). Severity of urinary obstruction is assessed by measurement of maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) and residual urine after voiding (Figure 3). Most strictures are located in the bulbar segment of the urethra between the pelvic floor and penoscrotal junction. The cause of stricture formation is most often unknown, but it may result from previous injury or infection (urethritis).

FIGURE 2.

Ascending urethrogram showing 2-cm bulbar urethral stricture. Courtesy of Nick Watkin, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

FIGURE 3.

Uroflowmetry record of man with bulbar urethral stricture. The flow is slow up to a maximum of 6 ml/second (normal ≥ 15 ml/second) and prolonged. Courtesy of Alison Bray, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Treatment options for bulbar urethral stricture

Men with bulbar urethral stricture have two management options: (1) endoluminal treatment, in which the stricture is disrupted from within the urethral lumen (urethrotomy or dilatation); or (2) open surgery (urethroplasty), in which the stricture is approached through an incision in the perineal skin and excised or bridged by interposition of a healthy tissue graft. Unless there are complicating factors, men with a first stricture occurrence generally choose to undergo an endoscopic urethrotomy, as it is a straightforward procedure and can be carried out under the same anaesthetic following diagnostic urethroscopy. A review of case series suggested that following this first urethrotomy the rate of recurrence at 2 years was 40% and 60% at 8 years. 9 For those men whose stricture recurs, the choice is between further urethrotomy (or simple dilatation for short flimsy strictures) and open urethroplasty. Urethroplasty is a more complex procedure, but case series suggest a lower stricture recurrence rate of around 15% at 2 years and 20% at 6 years. 10–12 Management discussions between urologists and men with recurrent bulbar stricture centre around the choice between these two strategies: (1) planning and carrying out urethroplasty surgery with a view to longer-term freedom from recurrent stricture, or (2) further urethrotomy repeated as needed at stricture recurrence. The relative efficiency of these two strategies for the management of recurrent bulbar urethral stricture in men is the focus of this trial.

Interventions under study

The experimental intervention strategy is open urethroplasty. 13 The bulbar urethra is approached through a longitudinal incision in the perineal skin behind the undersurface of the scrotum. The bulbar urethra is dissected free and the strictured segment incised in either the dorsal or ventral surface. The area of the stricture is then either removed and the cut ends rejoined (anastomotic urethroplasty) or augmented by insertion of a tissue graft. 14 The tissue graft (typical dimensions 5 × 2 cm) is harvested from the mucosa of the mouth. The urethra is then retubularised and the repaired area protected by passage of a urethral catheter to drain urine. Urethroplasty requires a general anaesthetic, takes 2–3 hours to perform and is followed by a 2-week period of urethral catheterisation postoperatively. Median hospital stay in the UK NHS is 2 days. 8

The control intervention strategy is endoscopic urethrotomy (also known as direct visual internal urethrotomy, internal urethrotomy or optical urethrotomy). 15 This procedure involves passing an endoscope under direct vision down to the distal end of the stricture. 16 The narrowed area is then progressively incised from distal to proximal with a straight longitudinal cut, either using a steel blade (‘cold knife’) mounted on the endoscope17 or under endoscopic control with a diathermy needle or laser fibre (‘hot knife’). Once the lumen has been incised sufficiently to restore a normal calibre (approximately 6 mm diameter) the endoscope is withdrawn and a urethral catheter passed to tamponade bleeding from the cut area and provide reliable urine drainage during the postoperative period. If the stricture is short and flimsy, simple dilatation with the endoscope or graduated dilators may suffice without incising the urethral mucosa and underlying corpus spongiosum. Endoscopic urethrotomy requires a general anaesthetic and takes approximately 45 minutes to perform. The median hospital stay in the UK NHS is 1 day. 8 The urethral catheter is typically removed 24–48 hours postoperatively. Men having repeated urethrotomy may be offered training for a programme of intermittent self-dilatation, using an appropriately sized soft plastic catheter. This adjunctive intervention appears to lessen the risk of recurrence over the subsequent 12 months. 18

Both procedures have a similar spectrum of complications, predominantly bleeding from the wound site and urinary infection. If an oral mucosal graft is used to augment the urethra, then there are specific complications related to the donor site in the mouth.

Current management guidance

Evidence for effectiveness of optical urethrotomy and open urethroplasty for treatment of bulbar urethral stricture has been summarised in four systematic reviews. 13,15,19,20 The Cochrane review,19 up to June 2012, found no randomised trials comparing outcomes after urethrotomy and urethroplasty and could not make any conclusion regarding comparative effectiveness. An updated Cochrane search performed to August 2017 found no more recent relevant completed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or any other RCTs in progress. Reviews underpinning published guidelines, sponsored jointly by the Société Internationale d’Urologié, the International Consultation on Urologic Disease13,15 and by the American Urological Association,20 included non-randomised studies, predominantly of retrospective cohort design. Guideline formulation subsequent to these reviews was predominantly based on expert opinion and panel consensus. Guidance from the Société Internationale d’Urologié15 suggests that optical urethrotomy is an appropriate management option for initial treatment of bulbar urethral stricture, with an overall long-term success rate of about 50%. The guidance also states that the first recurrence of bulbar stricture could be treated with urethrotomy as long as no adverse factors, such as recurrence at < 3 months post surgery, are present. Success rates in terms of up to 2 years freedom from recurrence in the case series varied from 53% to 95%. Buckley et al. 15 recommended that urethrotomy should not be used for second or subsequent recurrences. Urethroplasty with scar excision and primary mucosal anastomosis or use of an interposition graft of oral mucosa was recommended for complex or recurrent bulbar stricture. 13 The more recent systematic review and guideline from the American Urological Association also did not find any robust evidence on which to base clinical practice recommendations. 20 Wessells et al. 20 suggested that both optical urethrotomy and urethroplasty were appropriate initial procedures for men with bulbar urethral stricture. For those men with recurrent stricture, they considered that only urethroplasty would potentially give long-term symptom control. Further recurrence after repeat urethrotomy was regarded as highly likely and therefore should be considered only as a palliative management option. There is little published qualitative research on patient experience of living with and managing the condition. Patients do appear most concerned regarding the impact of their urinary symptoms, particularly difficulty voiding and post-micturition dribbling, on their daily activities. 21 Agreement between patients and specialist clinicians regarding ranking of importance of particular symptoms is poor. 21

Evidence regarding choice of urethrotomy and urethroplasty

Guidance from two professional urologist organisations, the Société Internationale d’Urologie and the American Urological Association, is clear that open urethroplasty is the recommended option for men with recurrent bulbar stricture. However, this recommendation is based on low-level evidence and expert opinion. Both guideline panels were predominantly made up of urologists specialising in urethroplasty, without general physician or patient representation. Registry studies suggest that optical urethrotomy is more frequently used than urethroplasty for recurrent strictures. 22 Case series from a number of health-care systems also suggest that repeated urethrotomy is preferred in practice for recurrent bulbar strictures,23–26 with urethroplasty reserved for complex strictures. Reasons for the more frequent choice of urethrotomy for treatment of recurrent bulbar stricture may include patient and clinician preference, restricted availability of urethroplasty, health service organisational issues and lower cost to the patient and health-care provider. Information regarding management of men with urethral stricture disease and costs in the UK, derived from NHS England hospital activity and tariff data8 from April 2016 to March 2017, showed a total cost of £17.8M, comprising 742 urethroplasty procedures [OPCS Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4) M73.6], with a mean tariff cost of £4157 (Healthcare Resource Group code LB29A), 5074 endoscopic urethrotomy procedures (OPCS-4 M76.3) and 5838 male urethral dilatation procedures (OPCS-4 M76.4/M79.2), both with a mean tariff cost of £1468 (Healthcare Resource Group code LB55A). A number of studies have made cost comparisons between the two procedures accounting for procedure costs derived from personally funded health-care provision and risk of recurrence derived from cohort studies. A UK-based cost comparison suggested that a strategy of initial urethrotomy followed by urethroplasty at first recurrence was least costly. 27 US decision-analytic models, using cost minimisation28 and cost-effectiveness29 methodology, suggest that initial urethrotomy (providing a success rate of > 40%) followed by urethroplasty on recurrence is the most efficient treatment strategy for men with bulbar urethral stricture, although utility weights were not used and parameter estimates were from non-comparative studies.

Summary with implications for trial design

Decisions for men and their clinicians regarding how to best manage recurrent bulbar stricture continue to be based on low-level evidence with no robust comparative studies of clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness. A strategy of urethrotomy repeated as necessary has the attraction of being a straightforward, widely available procedure practised by 95% of urologists. 24 It is characterised by a short hospital stay and rapid recovery. It does not appear to be a curative procedure, meaning that multiple subsequent interventions may be needed during the man’s lifetime. A strategy of open urethroplasty, on the other hand, requires longer operating time and the need for specific expertise, restricting availability. However, it appears to be associated with lower recurrence rate and longer duration of symptom relief. At present, men with recurrent bulbar stricture are guided by clinician experience and preference, together with their own past experience of interventions and their individual values and preferences. Decisions by health-care providers regarding investment in, and provision of, specialist urethroplasty services are also made difficult by this evidence gap.

Aims and objectives

This trial aimed to determine whether or not a strategy of urethroplasty is superior to one of urethrotomy for alleviation of urinary symptoms in men with recurrent bulbar stricture over 24 months and whether or not it is cost-effective for the UK NHS. The trial hypothesis was that the difference in the control of voiding symptoms over 24 months after randomisation was > 10%. To achieve these aims we set the following objectives.

Primary objectives

-

Determine the relative impact on symptoms over 24 months.

-

Determine the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) over 24 months.

Secondary objectives

-

Determine the relative rate of need for reintervention.

-

Determine the relative change in Qmax at 24 months.

-

Establish the safety profile of each procedure.

-

Model the incremental cost per QALY of the most effective treatment over 10 years.

-

Qualitatively assess the views of men with urethral stricture and their clinicians regarding the disease, the available treatment interventions and participation in the trial.

-

Determine the factors that men trade-off in deciding between the two strategies.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter covers trial design and methods, statistical analysis and governance. Details of the methods and findings of the parallel qualitative study and economic evaluation are provided in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively.

Summary of study design

We designed an open-label, patient-randomised, parallel-group superiority trial comparing an experimental strategy of open urethroplasty against a control strategy of endoscopic urethrotomy in men with recurrent bulbar stricture, primarily in terms of symptom control over 24 months. Both strategies are in routine use in the UK NHS. For urethroplasty, there is a need for specialist referral for further assessment and counselling regarding harvesting of an oral mucosal graft. Because of this complex and variable care pathway, we chose a pragmatic design without blinding of clinicians or participants. Clinical trials unit staff entering and managing trial data were blinded to participant allocation. Men in both groups received standard perioperative care, including consent for the surgical intervention that they were allocated to and/or underwent. Inclusion criteria were made as broad as possible within the constraint of subjects having to be able and willing to undergo either procedure and agreeing to random allocation. The trial was set in the UK – England, Wales and Scotland – recruiting participants from NHS hospitals providing operative urological procedures for men with urethral stricture.

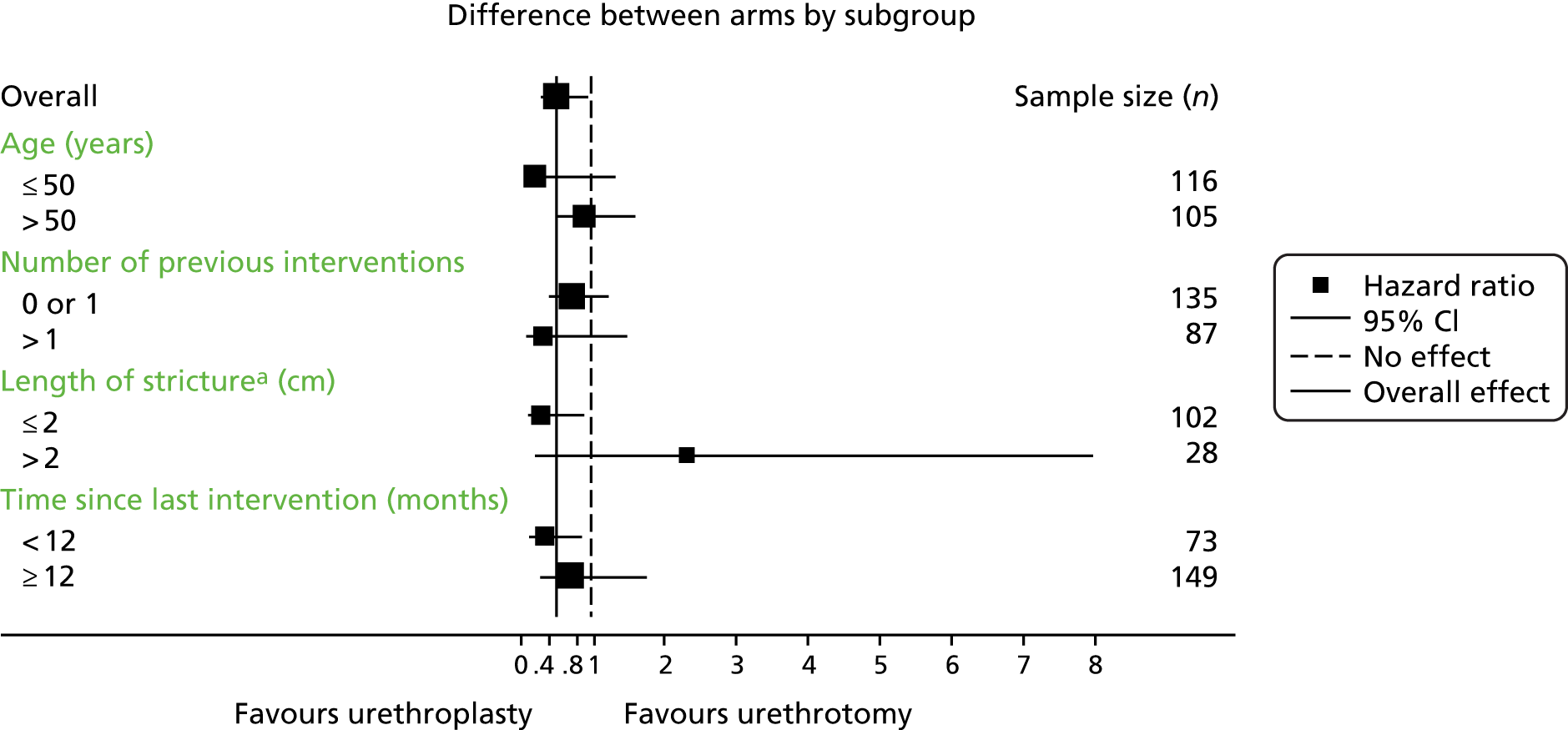

Sites

From 18 February 2013 to 5 March 2015 we progressively established 53 research sites (38 recruited at least one participant), all being NHS secondary care providers affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network in England and equivalent organisations in Scotland and Wales, which agreed to host the study locally. We initially concentrated on sites that could undertake both urethrotomy and urethroplasty. Subsequently, we set up sites that offered only urethrotomy. Those sites required delineation of routine referral pathways to a previously established trial site that offered urethroplasty (Table 1).

| Study intervention and outcome data collection component | Visit 1: initial screen | Visit 2 | Visit 3: intervention (according to site processes) | Visit 4: 3-month clinical follow-upa | Postal: 6 monthsa | Postal: 9 monthsa | Remote: 12 months follow-upa | Postal: 18 monthsa | Visit 5: 24-month follow-upa | Postal: 24 months after surgery | End of study (November 2017) | Pre and post reintervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | Baseline | Randomisation | ||||||||||||

| Eligibility checklist | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Trial discussed and patient information sheet provided | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| USS-PROMa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Resource use questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Further intervention questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Uroflowmetry | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Process of care | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| AEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Additionally, four participant identification centres were opened between August and September 2014 to support recruitment to the trial.

Trial management

The central trial office was established at the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU), Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. The NCTU was responsible for obtaining approvals, trial registration, trial management and organising the collection of outcome measures. The health economic evaluation and qualitative research teams were also based in Newcastle. The randomisation service, database construction and management, and statistical analysis were based in the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) at the University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK.

Participants

Adult men with a history of urethral stricture disease having previously undergone at least one intervention for bulbar urethral stricture were identified at the time of clinic presentation with recurrent symptoms and from health-care records at each site. Clinicians were encouraged, through the NIHR Clinical Research Network, local and national meetings, and relevant professional organisations, including the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) and the British Association of Genito-urethral Surgeons, to introduce the study to men under their care. Patients were approached and introduced to the study by clinical staff at site. If men were interested, an eligibility check was carried out by local research staff at each site according to the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

-

Men aged ≥ 16 years.

-

Stricture located predominantly in the bulbar urethra.

-

Undergone at least one previous intervention for bulbar urethral stricture.

-

Clinician and patient agreement that intervention was required.

-

Suitable for general or regional anaesthesia of up to 3 hours’ duration.

-

Willingness to have a catheterisation period of up to 2 weeks.

Exclusion criteria

-

Current perineal sepsis and/or urethrocutaneous fistula.

-

No previous intervention for bulbar stricture.

-

Inability to adhere to the trial protocol.

-

Previous participation in the study.

Consent procedures

Men who were eligible and in provisional agreement for participation were seen by local research staff and given trial information. Trial eligibility was checked for each potential subject using information from the prospective participant and from his clinical record. Sites kept a screening log documenting non-identifiable information and reasons for non-participation. The right to refuse to participate without giving reasons was respected.

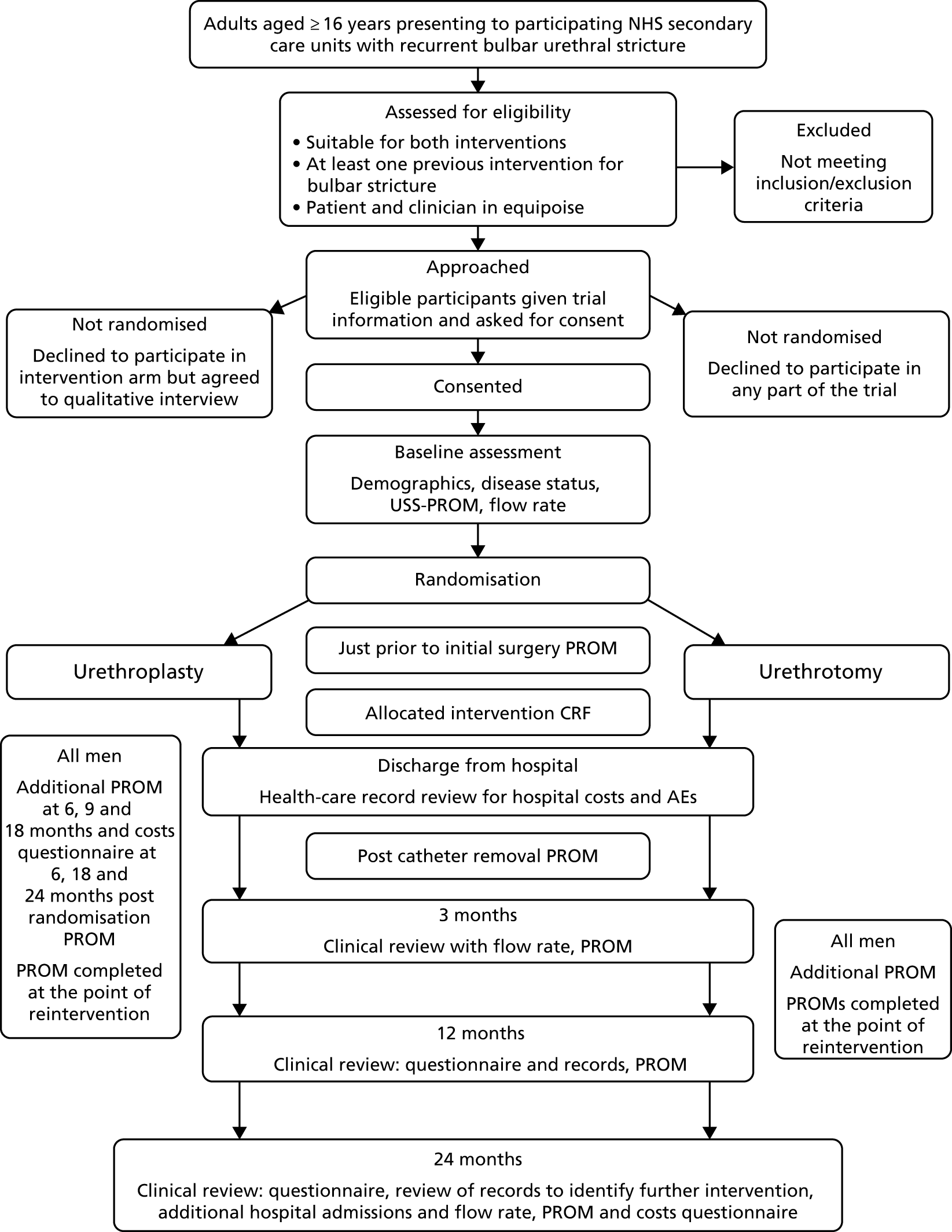

Following a period of at least 48 hours post provision of trial information, interested and eligible patients were then contacted using their preferred means of communication (surface mail, e-mail, telephone or text) and reviewed by local research staff to explain fully the purpose and conduct of the study, including the need for randomisation to allocate them to either procedure. If they agreed to take part they gave written consent to be randomised to either open urethroplasty or endoscopic urethrotomy by signing and dating the study consent form, which was witnessed and dated by a member of the research team with documented, delegated responsibility to do so. The timing of randomisation was usually at the time of trial consent, provided that there was agreement between patient and clinician that intervention for recurrent bulbar stricture was required. Standard local arrangements concerning preoperative assessment, hospital admission, consent for surgery, conduct of surgery and after care continued unaffected by study participation. Men eligible for the study who were not willing to consider randomisation were asked to consent to being approached by a qualitative researcher, regarding participation in an interview-based study. Urologists participating in trial recruitment were also asked to give expressions of interest in participating in this qualitative study. The recruitment timetable is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Chart showing flow of participants through the trial. AE, adverse event; CRF, case report form; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; USS-PROM, urethral stricture surgery – patient-reported outcome measure.

Randomisation

Participant allocation

Consented men were allocated to urethroplasty or urethrotomy using a centralised, automated, randomisation application hosted by CHaRT and accessed by telephone or through the internet. The algorithm allocated participants to urethroplasty or urethrotomy in a 1 : 1 ratio, with recruitment site and time since last procedure (< 12 months or ≥ 12 months) as minimisation covariates. The final allocation algorithm was set by a statistician not involved in trial planning or analysis and included a random component. Participants were informed of their allocated treatment group immediately following randomisation.

Progress on study

The schedule of events for trial participants is shown in Table 1. Baseline data were collected by site research staff just prior to randomisation to minimise any biases that might result from knowledge of the allocated intervention. We aimed for participants to undergo their allocated procedure as soon as possible and preferably no longer than 12 weeks after randomisation, subject to participant and clinician preference and health-care provider service constraints. At 3, 12 and 24 months post intervention, research staff at site contacted participants for a follow-up to complete case report forms (CRFs), face to face or by telephone, with supplementation by health-care record review.

Participant expenses

Expenses incurred by participants as a result of extra attendances outside standard local NHS care were reimbursed. Participants were given £25 thank-you gift vouchers to cover any unforeseen additional costs at the time of randomisation, 24 months after randomisation and on receipt of a completed end-of-trial questionnaire in December 2017.

Withdrawal

Consented participants remained on study unless they withdrew their consent or trial staff deemed that further participation by an individual was not appropriate. Participants who declined their allocated procedure after randomisation were kept on study, including those men who underwent the alternative procedure and those men who did not undergo an intervention. The reason for withdrawal was recorded if the participant agreed.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to funding application, we discussed the rationale of the trial with a patient with urethral stricture who had experienced both urethrotomy and urethroplasty. He agreed to be a co-investigator and reviewed the funding application from a patient perspective. Subsequently, he reviewed and commented on trial documents relevant to patients prior to submission for ethics approval. He contributed to discussions at trial management meetings, particularly at the start of recruitment and at the end of the study. As part of governance of the trial, we recruited a member of the public through the Northern Regional Public Involvement in Medical Research Network to act as a lay member of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).He attended and contributed to TSC meetings throughout the trial, offering very helpful lay input into trial oversight and management. Both individuals critically appraised the final report from a lay perspective.

Outcome measurement

Participant-reported outcomes for the OPEN trial were collected through a specific trial questionnaire completed by participants. The questionnaire, urethral stricture surgery – patient-reported outcome measure (USS-PROM), has been validated in this patient group in English,30 German,31 Turkish,32 Russian,33 Spanish34 and Portuguese. 35 It comprised six questions on voiding symptoms and their impact on daily activities, self-rating of urine flow strength (using a pictorial guide) and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), questionnaire measuring health status. For the purposes of this trial, a single-item question, overall satisfaction with sexual function, was added from the validated International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire. 36 Participant completion of trial questionnaires at baseline, prior to allocated intervention and 1 week after catheter removal following intervention were prompted and overseen by local research staff at site. Subsequently, participants were automatically sent a letter enclosing a questionnaire and instruction for completion at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 months following the date of allocated intervention and at 18 and 24 months after the date of randomisation. A final questionnaire was sent out to all randomised participants for completion at the end of the study in November 2017. Participants also had the option to complete the questionnaires online with automatic upload to the trial database, or by telephone call with trial management staff. Need for completion was prompted by letter from the trial office at NCTU. We scheduled additional collections of outcome measures just prior to and at 1 month subsequent to any further surgical procedure for bulbar urethral stricture.

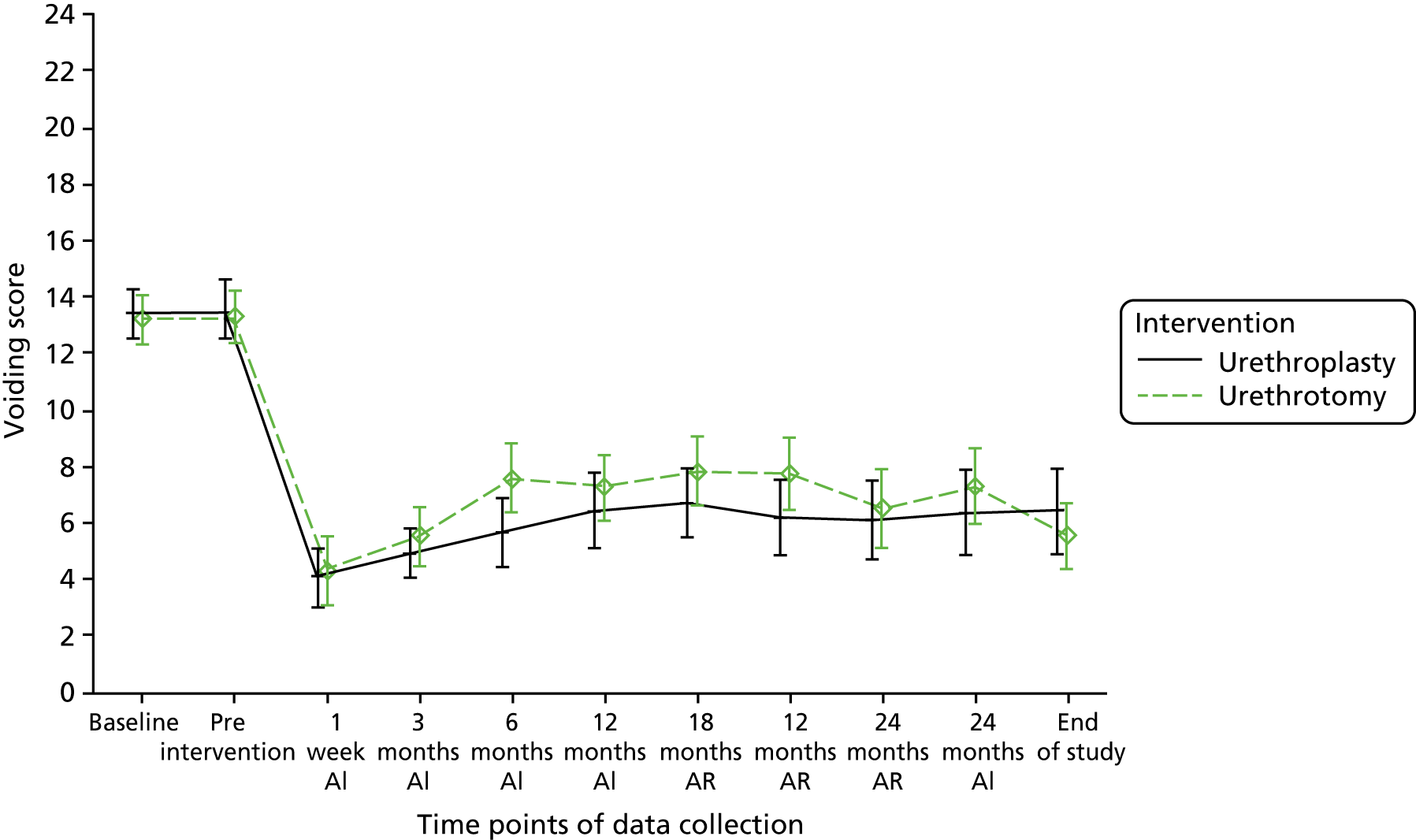

Primary effectiveness outcome

The primary outcome for the OPEN trial was the area under the curve (AUC) of the urinary voiding symptom score component of the USS-PROM, repeatedly measured over 24 months following randomisation. The voiding symptom measure comprised six questions each scored from 0 (symptom not present) to 4 (symptom present all of the time), giving a range of total score of 0–24. The completed questionnaires were returned to the trial office at NCTU for data entry.

Secondary effectiveness outcomes

Patient reported

The USS-PROM questionnaire also included measurements assessing the outcomes of urine stream strength, impact of urinary symptoms on daily activity and overall health status. The single-item visual scale of urinary stream strength was scored from 1 (strong stream) to 4 (weak stream). The question regarding impact of urinary symptoms on daily activities was scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot). The USS-PROM questionnaire measured health status using the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. 37 Each domain was scored 0 (no problem) to 4 (extreme or incapacitating problem), giving a total ranging from 0 to 20. This measure was accompanied by the EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS), on which participants rated their overall health between 0 (the worst health imaginable) and 100 (the best health imaginable). An additional single-item question, overall satisfaction with sexual function, was scored from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). 36 All measures included in the USS-PROM were self-completed by participants at the same multiple time points as the primary outcome.

Clinical

Maximum urinary flow rate was measured for each participant by asking them to void at least 150 ml of urine into a commercial, calibrated uroflowmeter available at site. This measurement was scheduled to take place at baseline, at 3 months post intervention, and between the 12 and 24 months’ post-intervention visits. An increase in Qmax of ≥ 10 ml/second compared with baseline was categorised as a successful outcome. 38 If participants underwent a further intervention for bulbar urethral stricture subsequent to the allocated trial procedure (excluding self-dilatation), this was documented at the 3-, 12- or 24-month follow-up, completed by research staff at site. Additionally, site staff were asked to complete a reintervention CRF. Participants were asked to provide information regarding any further interventions for recurrent bulbar stricture in the further intervention questionnaire sent to all participants at 24 months post surgery and at the end of the study (November 2017). Recurrence of bulbar stricture but without a planned or completed further intervention was recorded in the 24-month follow-up CRF, using information from symptom report, urine flow rate and documentation in the health-care record. We considered that a stricture was likely to have recurred if at least one of the following conditions were met during the 24 months after intervention: a reintervention had occurred or was scheduled, the Qmax had deteriorated to the preintervention value or the voiding score had deteriorated to baseline value.

Harms

Harms arising from trial participation, principally related to the procedure undergone, were collected through CRFs completed by research staff at site at the time of, and shortly after, the trial intervention, at 3, 12 and 24 months after intervention, and at the time of, and shortly after, reintervention. They were categorised as being expected adverse events (AEs), as listed in the trial protocol, or unexpected AEs. The trial office were notified of any AE deemed serious [i.e. a serious adverse event (SAE)] via an e-mail alert originating from the CHaRT database, triggered by data entry at site. The SAEs were then adjudicated by the chief investigator in discussion with other members of the trial team and, when required, by the site principal investigator (PI), to decide if the SAE was indeed serious and whether it was related or unrelated to participation in the OPEN trial.

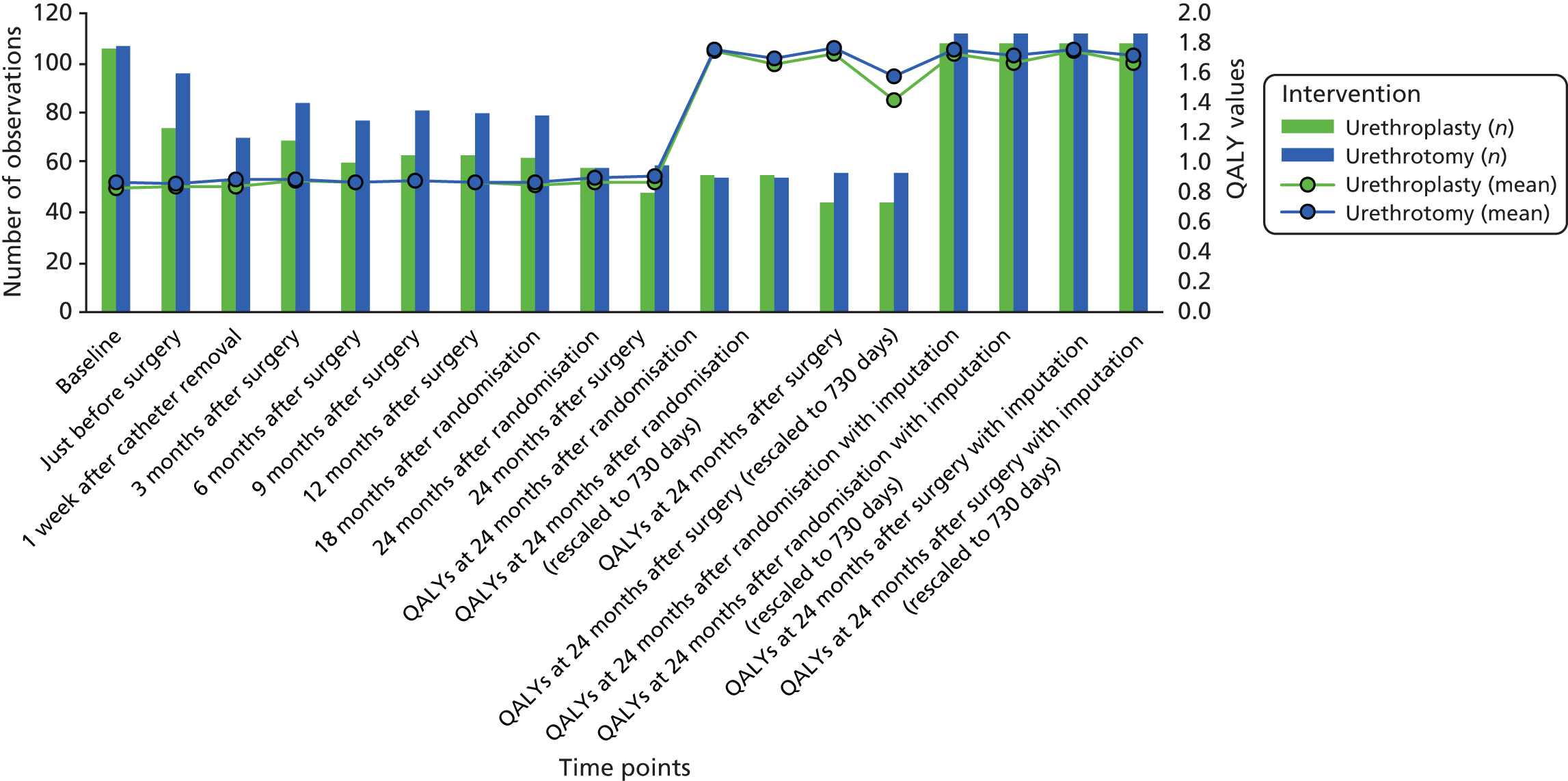

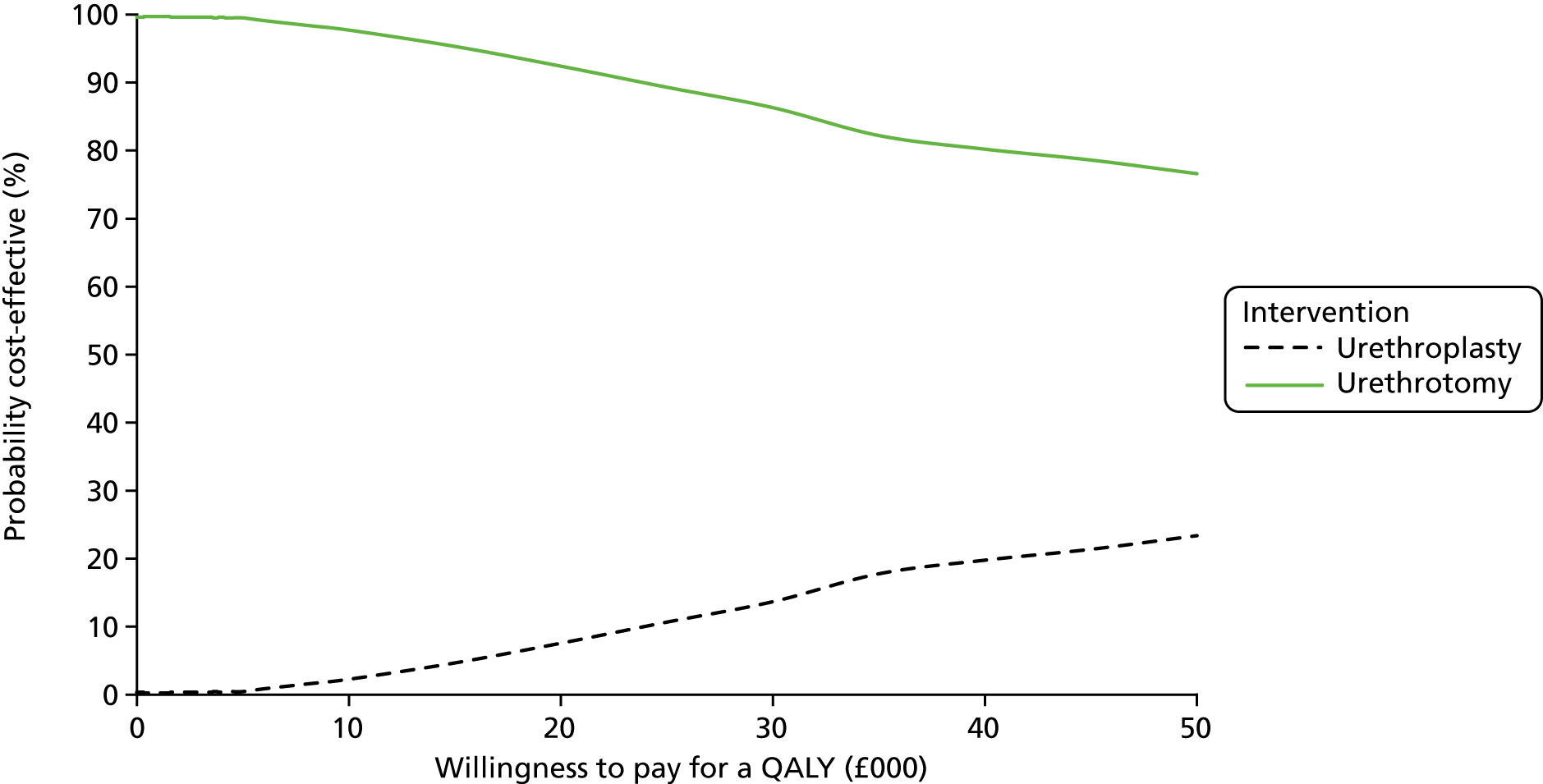

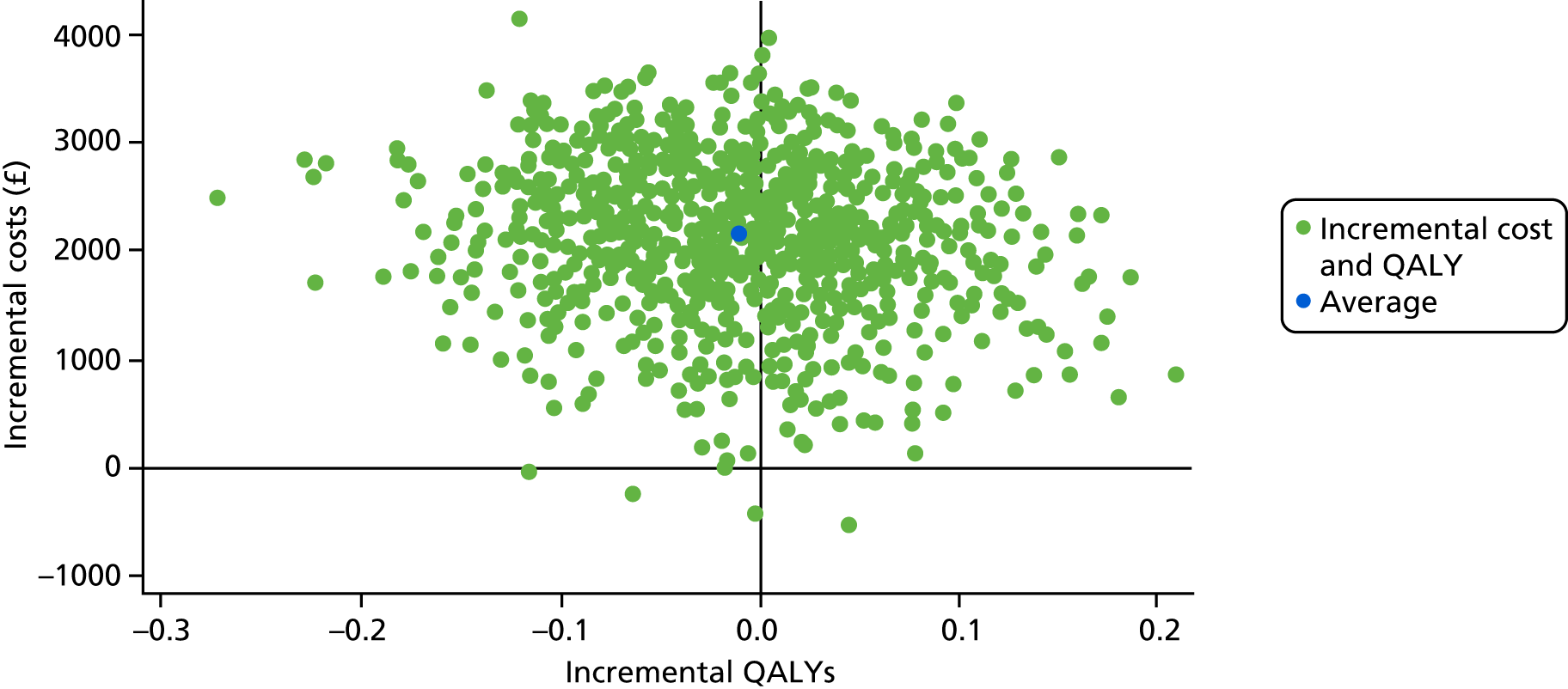

Primary cost-effectiveness outcome

The primary outcome of the health economic evaluation was cost–utility, assessed as the incremental cost per QALY at 24 months after randomisation. Health-care costs were calculated from hospital visits recorded by research staff at site on CRFs completed at 3 and 24 months, and from use of primary care services as reported by participants on a patient’s cost questionnaire completed at 6 and 12 months after allocated intervention and at 18 and 24 months after randomisation. Patient costs were collected through a questionnaire completed at 6 months after allocated intervention. Responses to the EQ-5D-5L health status questionnaire were transformed using UK population tariffs39 to produce a health state utility score for each participant.

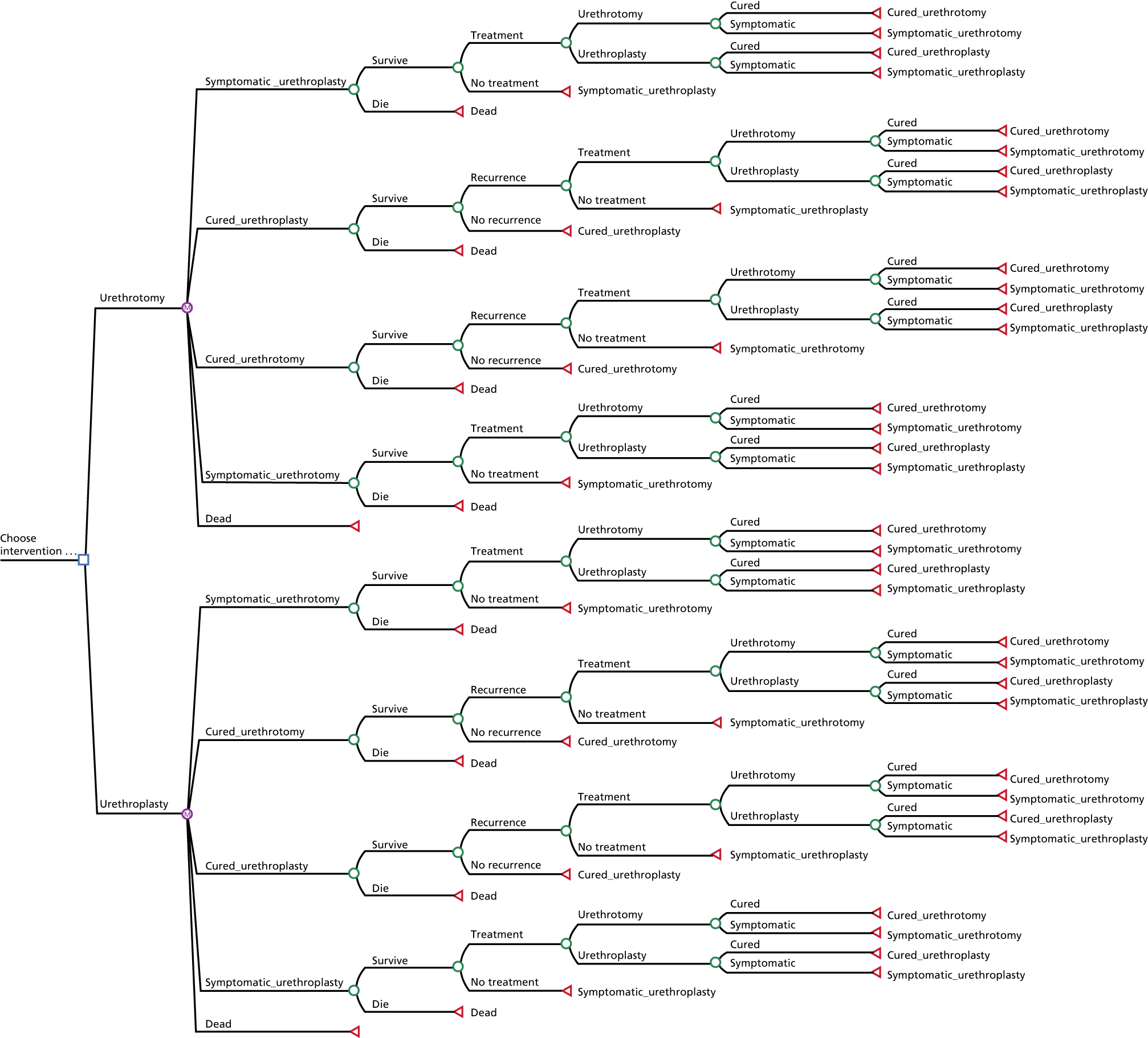

Secondary cost-effectiveness outcome

To complement the primary cost–utility analysis, the health economic evaluation included a time trade-off (TTO) experiment to better understand choices made by men with urethral stricture and assess the likely short-term disutility of the procedures that would not be measured at the EQ-5D-5L time points, and also a Markov model to project observed differences in outcome and their impact on cost-effectiveness over a 10-year time horizon. The health economic evaluation carried out as part of the OPEN trial is fully described in Chapter 5.

Data collection

Summary

Data from trial CRFs were entered by research staff at site through a password-protected portal onto the internet-based data management system developed, set up, hosted and maintained by CHaRT. Participant-completed questionnaires from catheter removal post intervention onwards were collated at the central trial office and entered into the trial database by NCTU staff, whereas patient-reported outcomes at baseline and just prior to intervention were entered at site by research staff. Staff in the NCTU trial office in Newcastle worked closely with the local research teams at site and the trial team at CHaRT in Aberdeen to ensure that data were complete and accurate. We made concerted efforts to chase and complete any missing data entries through contact with the sites. Participants’ details were stored securely in the CHaRT study database under the guidelines of the Data Protection Act 1998. 40 Participants were allocated an individual specific trial number and all data, other than personal data, were identified only by this unique study number. Data collected during the course of the research were kept strictly confidential and accessed only by members of the trial team.

Trial events

The schedule of events for the OPEN trial is shown in Table 1.

Screening

After identification by clinical staff, men potentially eligible for the trial and who were willing to consider participating were introduced to research staff at site. General demographics and eligibility were checked and anonymised data entered on a screening log. Trial Information was provided and potential participants were given at least 48 hours to consider participation in the study. Following review, at a mutually convenient time, those men who wanted to take part, who fulfilled the entry criteria and who understood the rationale and conduct of the trial provided written consent witnessed by research staff at site with delegated approval to do so. The participant and local research staff then completed baseline data collection.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed as close as possible to the date of consent (normally immediately thereafter) and the participant and clinical staff responsible for their care informed. For participants allocated to urethroplasty, recruited at urethrotomy-only sites, onward referral to the appropriate specialist centre was organised by the responsible clinician and the trial office informed. Details of baseline assessment and allocated intervention were entered on the web-based data management system baseline and randomisation CRF.

Intervention

Research staff at site liaised with the clinical team caring for the individual participant regarding arrangements for undergoing the allocated intervention (urethroplasty or urethrotomy). The protocol anticipated a maximum 12-week delay between randomisation and surgery. A more extended time awaiting allocated intervention was nonetheless allowed. This resulted from uncertainty regarding assessment required prior to anaesthesia and surgery, clinical prioritisation, need for onward referral for some men allocated to urethroplasty and time waiting for surgery. Just prior to intervention, participants were asked to again complete the trial questionnaire. Research staff at site recorded details of the intervention given, together with any AEs during surgery, the subsequent postoperative hospital stay and during the period of postoperative catheterisation in the allocated intervention CRF. Participants completed a further trial questionnaire 1 week after catheter removal, which was generally performed in hospital.

Follow-up

When possible, the 3-monthly trial follow-up visits carried out by research staff at site coincided with routine or extra clinical visits. If appropriate, the trial participant reviews could be completed by telephone in conjunction with the review of health-care records. Local research staff recorded any deviations in standard care, such as reinterventions for bulbar urethral stricture, AEs, unscheduled outpatient visits and any hospital stays. Owing to slower than planned recruitment, longer than anticipated waiting times for surgery and the need to complete the trial within the funded period, a final review of all participants was arranged at the end of the study during November and December 2017, 24 months after the date of the last randomisation. This consisted of participant completion of a trial questionnaire and a further intervention questionnaire. Uroflowmetry was carried out at baseline and at 3 and 24 months after surgery.

Data handling and record keeping

Data were recorded by site staff on electronic CRFs in a bespoke electronic database within a software package designed and maintained by CHaRT in Aberdeen. In certain cases, data were initially recorded on paper CRFs prior to transfer to the study database. The database was accessed by research staff at site through a password-protected portal unique to that site. Participant questionnaires returned by post to the trial office in NCTU were entered by NCTU staff who remained blind to participant allocation. Participants had the option of completing the questionnaire online with immediate electronic transfer to the database. Participants who chose this option at baseline were sent the web address to the participant area and a unique login identifier for that participant to gain access to the area. Once logged in, the participant would then be able to complete the questionnaire for the relevant time point. Participant data collected under a unique identifier were kept confidential and accessed only by members of the trial team. Extensive efforts were made to ensure completion and collection of trial questionnaires at each time point. Regular checks were carried out and missing data pursued with research and clinical staff at site and with participants through their preferred means of communication. Up to three reminders to complete questionnaires were sent at each scheduled time point. Essential data will be retained for a period of at least 10 years following close of study, in line with sponsor policy and the latest European Directive on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) (2005/28/EC). Data were handled, digitalised and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 40

Details of study interventions

General

Study design was pragmatic, in that, apart from randomised allocation of intervention and outcome data collection, standard care pathways for each procedure at individual sites were followed. These included type of anaesthesia, use and regimen of antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical instrumentation, closure or non-closure of oral mucosal graft donor site, duration of postoperative urethral catheterisation and clinical follow-up schedule, including use of investigations to detect stricture recurrence. The interventions were funded by the NHS in accordance with local contracting mechanisms. The NHS excess treatment costs were approved by the sponsor (Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) and the host NHS organisation at each participating site.

Urethroplasty (experimental)

For urethroplasty, men were positioned supine on the operating table with hips and knees held in an abducted and flexed position by suitable leg supports. A longitudinal skin incision was made in the perineum above the anus and towards the base of the scrotum. The bulbar urethra was localised and mobilised from its attachments. The stricture segment was incised longitudinally on the dorsal or ventral surface according to surgeon preference. The surgeon then decided if the stricture could be excised with or without transection of the corpus spongiosum and a primary anastomosis made (typically, proximal strictures < 2 cm in length with limited fibrosis) or if an oral mucosal graft should be placed without stricture excision in an augmented repair (typically, fibrotic strictures ≥ 2 cm in length). The oral mucosal graft was harvested from the inner cheek, defatted and sutured to the cut urethral edges, then stabilised against the corpora cavernosa if dorsally placed or the corpus spongiosum if ventrally placed. A 16-French silicone Foley urethral catheter was then placed and left in situ for free drainage of urine for a postoperative period of approximately 2 weeks. Once recovered, the patient was discharged home to return at a planned later date for a urethrogram to check that there was no leakage from the area of repair, catheter removal and trial of voiding. The median stay from NHS England hospital activity data at the time of the trial was 2 days. 8 Clinical follow-up was usually by wound and symptom review at 3 months and urinary flow rate measured at 3 and 24 months post intervention.

Endoscopic urethrotomy (control)

For urethrotomy, men were positioned supine on the operating table with legs supported in an abducted and flexed position. The endoscope (Sachse urethrotome) was passed retrogradely through the urethral lumen under direct vision until the distal end of the stricture segment was encountered. A fine-calibre guidewire was placed through the stricture into the bladder to aid incision planning. The stricture was progressively incised longitudinally under vision using the steel blade (‘cold knife’) mounted on the endoscope until healthy mucosa signalling the proximal end of the stricture was reached. Alternatively, a diathermy needle mounted on the endoscope or a laser fibre passed through the endoscope was used to make the incision (‘hot knife’). For short flimsy strictures, dilatation with the endoscope or graduated dilators could be used rather than formal urethrotomy. A 16-French silicone Foley catheter was then placed for free drainage of urine during the postoperative period. It was typically removed at 24–48 hours postoperatively, with a trial of voiding prior to discharge or following hospital reattendance after discharge. Follow-up was by outpatient review and urinary flow measurement 3 and 24 months postoperatively. According to patient and clinician decision, a standardised programme of intermittent self-dilatation could be initiated 1 week after catheter removal, as this can delay time to recurrence. 18

Delivery of interventions

All procedures were carried out by accredited consultant urologists or senior trainees in urology. Competency in performing endoscopic urethrotomy is a mandatory component of training as urologists and is regularly performed by approximately 95% of practising urologists. 24 Urethroplasty is a specialised technique requiring extra training. Specialist surgeons with recognised expertise working in specific UK centres were identified through BAUS and acted as PIs for the trial at these sites. The precise technique of urethroplasty used for each participant was decided by the operating surgeon. Details of each intervention were recorded by research staff at site on a CRF.

Changes to study design

Changes made to the protocol during the trial are listed in Table 2. Owing to slow recruitment, the trial protocol was adjusted over the period October 2014 to February 2015. The sample size required to detect a 10% difference in voiding symptom score was recalculated using primary outcome data collected up to September 2014, without unblinding of allocated groups. This gave a revised target recruitment of 210 men. To take into account the prolonged recruitment period and differing waiting times for surgery, we reprofiled timing of collection of the primary outcome, anchoring the timing of participant completion of trial questionnaire completed during the last 6 months of the study to the date of randomisation, rather than the date of allocated intervention. In line with these changes, the end of recruitment period was put back to December 2015 and the end of study to December 2017.

| Description | Protocol version | Date |

|---|---|---|

|

Justification of sample size for the secondary outcome of need for further intervention in case of poor recruitment (104 rather than 500 men) Inclusion of two extra trial questionnaire completions (just prior to the procedure and at 1 week after catheter removal) Addition of validated single-item global sexual function question to the PROM |

1.1 | 15 November 2012 |

|

Protocol contacts page updated Emergency contact details updated Removal of SF-12 and clarification of the time points that the resource use questionnaires will be completed Clarification of what participant data will be stored on the trial database AE reporting had been written according to the regulations for CTIMP studies. As trial is not a CTIMP, amended with guidance from the National Research Ethics Service website |

1.2 | 15 February 2013 |

|

Amended protocol appendix (with no changes to the main protocol) to include the second qualitative phase, a TTO evaluation Addition of site monitoring centrally when possible Amended protocol and consent form to ask site to fax a copy of the consent form to the central trial office |

1.3 | 12 January 2014 |

|

Changes to members of the health economics team Change of trial manager Typographical changes |

1.4 | 20 February 2014 |

|

Addition of online advertisement URL: www.trialreach.com, which feeds information to URL: www.patient.co.uk. Basic trial information to be advertised online Addition of video demonstrating a model trial consultation on the OPEN trial electronic CRF website Clarification in the protocol and patient information sheet that there is a limit to the amount of patient travel expenses that can be claimed: £25 per visit, when the visit occurs outside routine care Length of archiving altered to 10 years in line with the clinical trial agreement and sponsor practice Alteration of the number of recruiting sites and locations within the UK |

1.5 | 16 July 2014 |

| Change to end of recruitment date from 31 October 2014 to 27 February 2015 to reflect the delayed opening of the study | 1.6 | 22 October 2014 |

|

Change to the length of recruitment period. Recruitment to close 31 December 2015. End of follow-up therefore December 2017 Reduction in the sample size required from 500 to 210 Change of the timing of 18- and 24-month post-surgery questionnaires to be 18 and 24 months after randomisation to mitigate bias from different waiting times for surgery Addition of two secondary objectives: (1) looking at the symptom control and quality of life over the study period and (2) need for reintervention over the study period (median time from intervention) Participant follow-up by questionnaires will be increased with two additional time points: 24 months after surgery and at the end of study (December 2017) Introduction of a reintervention questionnaire for participants to complete at 24 months post surgery and at the end of study (December 2017) Addition of a third ‘thank you’ voucher at trial end Update to the TTO substudy protocol (see Appendix 1) Change to trial manager contact details Typographical changes |

1.7 | 17 February 2015 |

|

Clarification of study procedures and analysis for participants who did not receive their randomised allocated intervention Update to SAE reporting procedure (introduction of paper SAE form) Administrative changes |

1.8 | 3 October 2016 |

Sample size calculation

We aimed to detect at least a 0.1 (10%) difference in the AUC of the voiding symptom score calculated from the plotting of repeated measurements over 24 months for both trial groups and using a 0–1 utility scale. This conservatively assumed a standard deviation (SD) score of < 0.33 based on the finding of a SD of 0.15 in a previous shorter-term study among men undergoing bulbar urethroplasty. 30 For 90% power this would require 500 men to be randomised. Following the trial feasibility phase, it was clear that this sample size was not achievable in a fundable time frame. We therefore recalculated the SD of the symptom score in August 2014, using trial data collected from the first 69 men randomised who had completed at least one score following intervention (220 measurements in total), while maintaining blinding of allocated intervention. This recalculation gave a SD of 0.165, which reduced to 0.15 when adjusted for baseline score and trial site. Using these data we updated our sample size estimate assuming a reduced SD of ≤ 0.21. This indicated a requirement of 170 men to be randomised to have 90% power for detection of a 10% difference at a two-sided 5% level. We inflated the figure to 210 to allow an up to 19% loss to follow-up rate. When interpreting actual trial data we found results more straightforward to consider by scaling the AUC to the USS-PROM scale minimum and maximum over 24 months, in which a score of 0 indicated a complete lack of symptoms over the trial and a score of 24 indicated full symptoms throughout the trial. Rescaling the AUC did not change the assumptions of the sample calculation.

Statistical analysis

Primary outcome

The primary analysis was based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, with participant groups compared according to randomly allocated intervention using available data in a complete-case ‘modified’ ITT analysis. Details of the planned analyses were documented prior to the end of the trial in a statistical analysis plan (SAP) [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105723# (accessed 26 June 2019)].

Additional planned analyses using a per-protocol definition and inclusion of more men enabled by data imputation in a further ITT sensitivity analysis were detailed in an additional SAP [see URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105723#/ (accessed 26 June 2019)].

Baseline and follow-up data were summarised using mean (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] when appropriate for continuous variables. Discrete variables were summarised with numbers and percentages. Treatment effects were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The primary outcome measure, AUC for the repeated measurement of voiding symptom score contained in the USS-PROM trial questionnaire over 24 months following randomisation, was analysed using linear regression adjusted for the minimisation covariates of site and stricture severity, defined as the time duration between the last previous intervention for bulbar stricture and the date of randomisation (< 12 months or ≥ 12 months). Voiding score was measured at baseline; prior to intervention; 1 week after catheter removal; 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after intervention; and 18 and 24 months after randomisation. Additionally, participants were asked to complete the trial questionnaire 24 months after intervention and at the end of study (November 2017). Trial questionnaires were also completed before and after any reintervention for stricture recurrence. The AUC was constructed using the trapezoidal rule, which assumes a constant increment (or decrement) in score between two points when outcome is measured. The AUC was divided by total duration of the trial for each participant up to 24 months post randomisation to facilitate interpretation. The original sample size calculation introduced the AUC in its usual format, 0–1 utility; however, in our results we decided to multiply the scale by 24 in order to present it in the same scale as the voiding score (0–24) and therefore facilitate interpretation.

For the primary analysis, all participants who had surgery and completed at least three voiding scores, comprising one baseline measure prior to trial intervention, one early measure up to 12 months after intervention and one later measure up to 24 months post randomisation, were included. Participants who did not have a late measure but had returned an end of study or a 24 months post intervention measure were included if this measure was collected within 6 months after their 24 months post randomisation time point. For the two participants without a baseline or preintervention measure, we used imputation based on the mean score observed at that site.

Sensitivity analyses detailed in the additional SAP were conducted to assess the robustness of the primary treatment effect estimate. This was done by relaxing and tightening the minimum number of measures needed to be included in the analysis. When available, all observed data were used across all time points. However, for many participants, data were missing at various time points. The assumptions of the data inclusion for the primary analysis and proposed sensitivity strategies are outlined below for each group of measurement time points.

Baseline

If either of the baseline and prior to surgery measurements were missing but the other was available, we assumed a constant score between these two time points and imputed one with the other. If both were missing, we imputed the site mean for each time point to allow calculation of the AUC for the primary analysis.

Early

If the 1 week after catheter removal measure was missing we did not impute a value; in these circumstances the AUC calculation was made between the baseline and first available early measure. As the 1 week after catheter removal measure could occur at any real time point throughout the trial, we used real time (in months) to incorporate this into the relevant time section of the AUC. Only one of the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month post-surgery measures was required. The AUC calculation used the notional time, in weeks, between the last available time point prior to 3 months and the first of these time points. If one or two time points were missing, we did not impute a value for those missing time points, but assumed constant increment (or decrement) in score between those points where outcomes were measured.

Late

Only one of the 18- and 24-month post-randomisation time points was required to calculate the AUC. If the 18-month time point was missing but the 24-month time point was measured, we did not impute a value for 18 months. Rather, the AUC calculation used the notional time (in months) between the last available measurement prior to 18 months and assumed constant increment (or decrement) in score between these two time points. If the 18-month time point was measured but the 24-month time point was missing, we carried the 18-month measurement forward to 24 months to allow calculation of the AUC. If there was a 24-month post-intervention or end of study measurement closer in time to the 24-month post-randomisation measure than the 18-month time point, we used that rather than the 18-month measure.

Accounting for occurrence of reintervention

For participants who underwent reintervention and submitted outcome measures prior to or following this intervention, we incorporated these into the relevant time section of the AUC by inserting the extra observations between notional time point measures. When reintervention clashed with a scheduled outcome measurement, the reintervention reported measurements were used. If a reintervention took place but the associated outcome measures were missing, we used index intervention outcome data for that participant. We assessed the appropriateness of this assumption empirically with observed data.

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary outcomes were recorded:

-

difference in condition-specific quality-of-life trajectory, measured from 0 to 3 by the AUC for the single item on the USS-PROM

-

difference in global sexual functioning trajectory, measured from 1 to 5 by the AUC for the single-item male sexual satisfaction score from Index of Erectile Function questionnaire

-

difference in generic quality-of-life trajectory, measured by the AUC for the EQ-5D-5L total score based on responses to 5-dimension items and using UK population valuations (0 death to 1 full health)39 and VAS score (0 worse possible health state to 100 best possible health state)

-

difference in rate of improvement of Qmax, measured at baseline, 3 months, and between 12 and 24 months with an increase in Qmax ≥ 10 ml/second from baseline taken to signify a successful outcome

-

difference in rate of need for further intervention, recorded from the clinical record for those participants returning to the care of their original specialist with recurrent stricture, by patient questionnaire for participants seeking care elsewhere and checked by the local trial research staff at the final 24-month assessment.

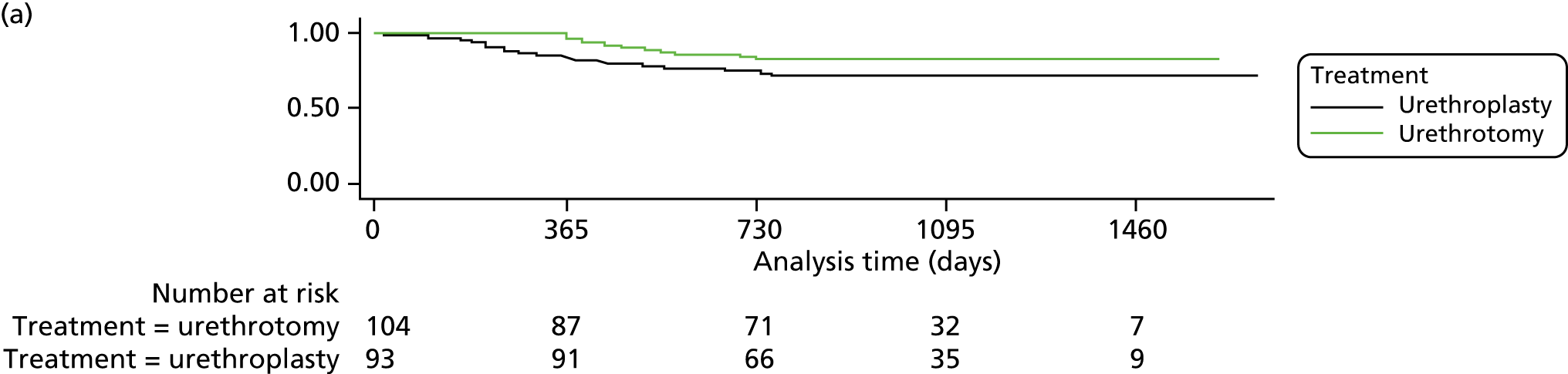

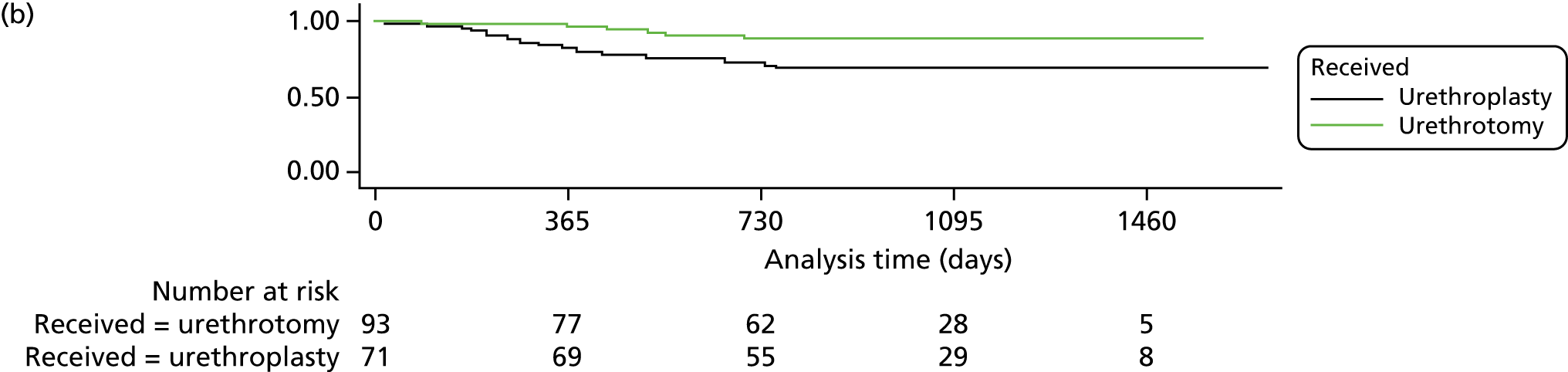

Secondary outcomes were analysed using generalised linear models appropriate for the distribution of the outcome, with adjustment for minimisation and baseline variables as appropriate. Reintervention was analysed as a time-to-event outcome using Cox regression and adjusting for minimisation variables and centre. Hazard ratios and 95% CI were calculated with the model. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated. Participants were included in the analysis using the observation time available until database closure (at least 2 years and up to 4 years). Box regression with multiple failure time data used the Andersen–Gill model.

For assessment of the primary outcome, missing follow-up data were estimated in sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation models for participants who had missing time points. We explored differences between responders and non-responders to inform our missing data model. We calculated an AUC for each imputation and combined these using Rubin’s rules under a missing at random assumption. 41,42 We also explored, using pattern mixture models, imputation of a range of values estimated from observed data using different missing not at random scenarios. Measures of the primary outcome collected at 24 months post intervention and at the end of the study were also included, when applicable, as a sensitivity analysis of the calculation of the AUC.

There were no planned or requested interim outcome analyses. The analyses were performed in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

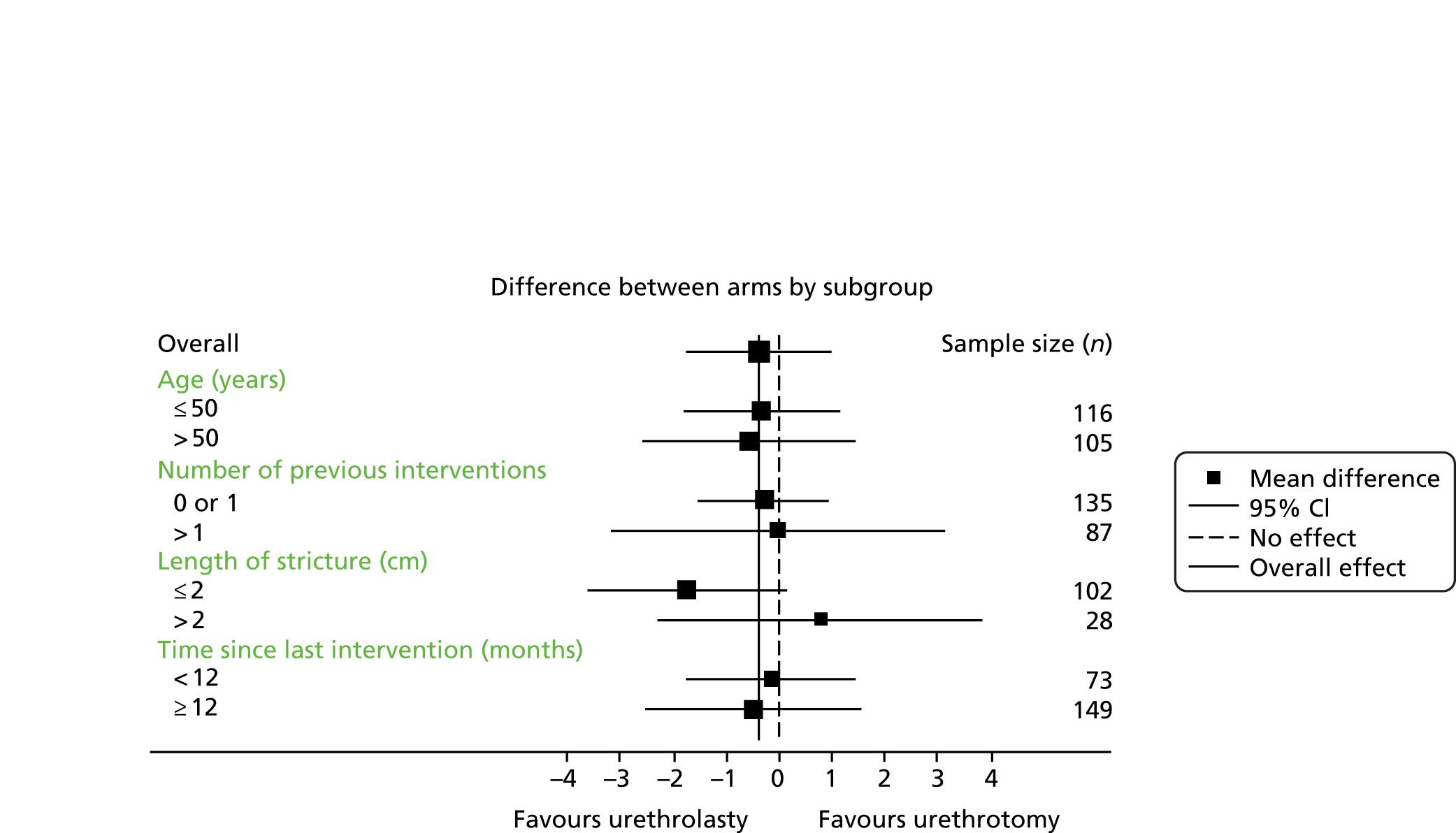

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses explored the possible modification of treatment effect by clinically important factors: time since last procedure (< 12 months or ≥ 12 months) as a global measure of stricture severity, age, stricture length and number of previous interventions. This was done by including treatment-by-factor interactions in the model and they were classified as exploratory analyses. No adjustment of the significance level was applied and findings should not be considered definitive but require replication.

Adverse events

An AE may be defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a subject to whom a study intervention or procedure has been administered, including occurrences which are not necessarily caused by or related to that intervention.

For the purposes of this trial:

-

all AEs were recorded at time of initial or reintervention surgery, and at 3, 12 and 24 months after initial intervention, and categorised by trial staff according to expectedness, relatedness, severity and, for postoperative complications, according to the Clavien–Dindo classification. 43

Please refer to the protocol [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105723/#/documentation (accessed 26 June 2019)] for more information about AE classification and reporting.

Qualitative substudy

Qualitative work was undertaken to establish factors determining willingness of patients and support of their clinicians to consider participation. Timely and successful completion of the planned qualitative study first established that the aims of the trial were important to men eligible to participate, given the troublesome and chronic nature of their symptoms, and to both general and specialist clinicians; these findings reinforced the rationale and need for the trial. As part of this work, we found that men eligible for inclusion were most likely to be willing to participate when their symptoms had first recurred and this was the point at which they expressed most uncertainty as to which option would be best for them as individuals. Both general and specialist clinicians were also very supportive of the aims of the trial given the uncertainty of guidance on best treatment, but expressed concerns regarding delivery of balanced information to men eligible for participation. To assist men eligible for participation in making a decision about participation, appropriate written guidance and an example video were provided, supported by personal contact from the trial team.

Trial progress and monitoring

The study initially set out to progressively build to a target of 500 participants over 24 months. This included an initial 12-month feasibility study, during which recruitment and patient adherence to the intervention were evaluated. Feasibility of recruitment was analysed after 9 months of active recruitment (trial month 12) and reported in August 2014 to the TSC and the funder, with an additional safety report reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). Recruitment continued to be monitored by the Trial Management Group (TMG) through returns to the randomisation website. The funder and TSC requested a recovery plan to mitigate the slow recruitment and ensure that the trial was completed over a fundable period of time. The recovery plan, which principally involved a re-estimation of required sample size using early observed data to 210 randomised participants, opening of additional sites and the recruitment window increasing from 24 months to 35 months, was submitted and approved by the TSC and funder in December 2014.

Sources of bias

To allow randomisation, both the eligible participant and the responsible clinician needed to be sufficiently uncertain whether the experimental or control strategy was best for management of the individual’s recurrent urethral stricture. Given the lack of high-level evidence as to which was the more effective intervention, trial information was provided illustrating the uncertainty and the need for a definitive trial. This aimed to ensure that any selection bias in terms of differing characteristics of men with recurrent bulbar urethral stricture willing to be randomised compared with those men who were eligible but not willing to participate was minimised. As far as possible and within the limits of data protection legislation, we recorded reasons for declining randomisation, but patients were free to decline participation and randomisation without giving a reason.

Trial literature for men eligible for participation or who were participating in the trial included the following: the OPEN trial participant information sheet and consent form v1.5 (main trial), the OPEN trial participant information sheet and consent form interview study v1.3, the OPEN trial website synopsis v1.1, the OPEN trial patient end of study questionnaire letter v1.0, the OPEN trial patient questionnaire letter v1.2, the OPEN trial patient invitation letter main study v1.0, the OPEN trial contact card v1.0 and participant flowchart v1.0. These documents are available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105723#/ (accessed 26 June 2019).

Definition and end of study

The end of study, defined as the 24-month post-randomisation follow-up for the last recruited participant, was originally planned for 28 February 2017. Owing to slow recruitment, an extension was granted in December 2014 by the funder and approved by the TSC to a new end date of 31 January 2018. A further extension to 30 April 2018 was approved in December 2017 by the funder and TSC in consultation with the DMC to allow more time to consider the primary result of the trial in the light of additional analyses prior to report submission. Active participation in the trial ended on 23 December 2017.

Compliance and withdrawal

Outcome data were collected remotely whenever feasible by participant completion of the trial questionnaires. Local research staff made use of planned routine clinical visits to check completion of trial documentation, with reference to the trial database and participants’ health-care record. Adherence to the allocated group (urethroplasty or urethrotomy) was checked by completion of an intervention CRF at the time of surgery. Reasons why participants chose not to have their allocated intervention but underwent the alternative procedure instead or who did not have any intervention were recorded. These participants continued to complete trial questionnaires and trial visits according to protocol to allow them to be included in the complete-case ITT primary analysis. The trial statistician monitored attrition rate against the anticipated maximum of 19% and reported to the TMG, TSC and DMC as appropriate.

Data monitoring, quality control and assurance

Quality control was maintained through adherence to standard operating procedures governing the work of sponsor (Research and Development Directorate, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), NCTU, CHaRT and local research teams, and in accordance with the study protocol, the principles of GCP, research governance and clinical trial regulations. An independent DMC was set up comprising one methodologist, one clinician not connected to the trial and one statistician (chairperson). The purpose of this committee was to monitor efficacy and safety end points. It operated in accordance with written terms of reference linked to the DMC’s lessons, ethics, statistics charter. 44 Only the DMC and the trial statistician preparing reports to the DMC had access, prior to completion of the trial, to data separated by allocated group. The DMC met at the start and completion and four times during the study. The DMC meetings were also attended by the trial statistician.

A TSC was established to provide overall supervision of the trial. The TSC consisted of an independent clinician who acted as chairperson, two further independent clinicians, an independent statistician, a lay representative and the chief investigator. Other members of the TMG attended as required or as requested by the chairperson. The committee met approximately every 6 months during recruitment and annually thereafter for the duration of the trial.

Monitoring of study conduct and collected data followed a written monitoring plan, informed by a risk assessment and agreed with sponsor. It was performed by a combination of central review and site monitoring visits to ensure that the study was conducted in accordance with GCP. Study site monitoring was undertaken by appropriately trained members of the NCTU. The main areas of focus were consent, eligibility, SAEs and completeness of the investigator site file at each site and the trial master file held at NCTU. Audit of data entry using a random 10% sample of trial questionnaires showed a 3% error rate, below the threshold of 5% that would have triggered a full audit.

Ethics and governance

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development Directorate sponsored the trial (reference 6332). Favourable ethics opinion for the trial was obtained on 16 October 2012 from the NHS Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 (reference 12/NE/0343) and subsequent research and development and Caldicott Guardian approvals were granted by each participating site. Approval was sought and obtained for all substantive protocol amendments (see Table 2).

Trial registration and protocol availability

The trial was registered as ISRCTN98009168 on 29 November 2012 and in the UK NIHR Portfolio (reference 13507). The latest version (1.8) of the full protocol is available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/105723/#/ (accessed 14 February 2017) and a published version is also available. 1

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

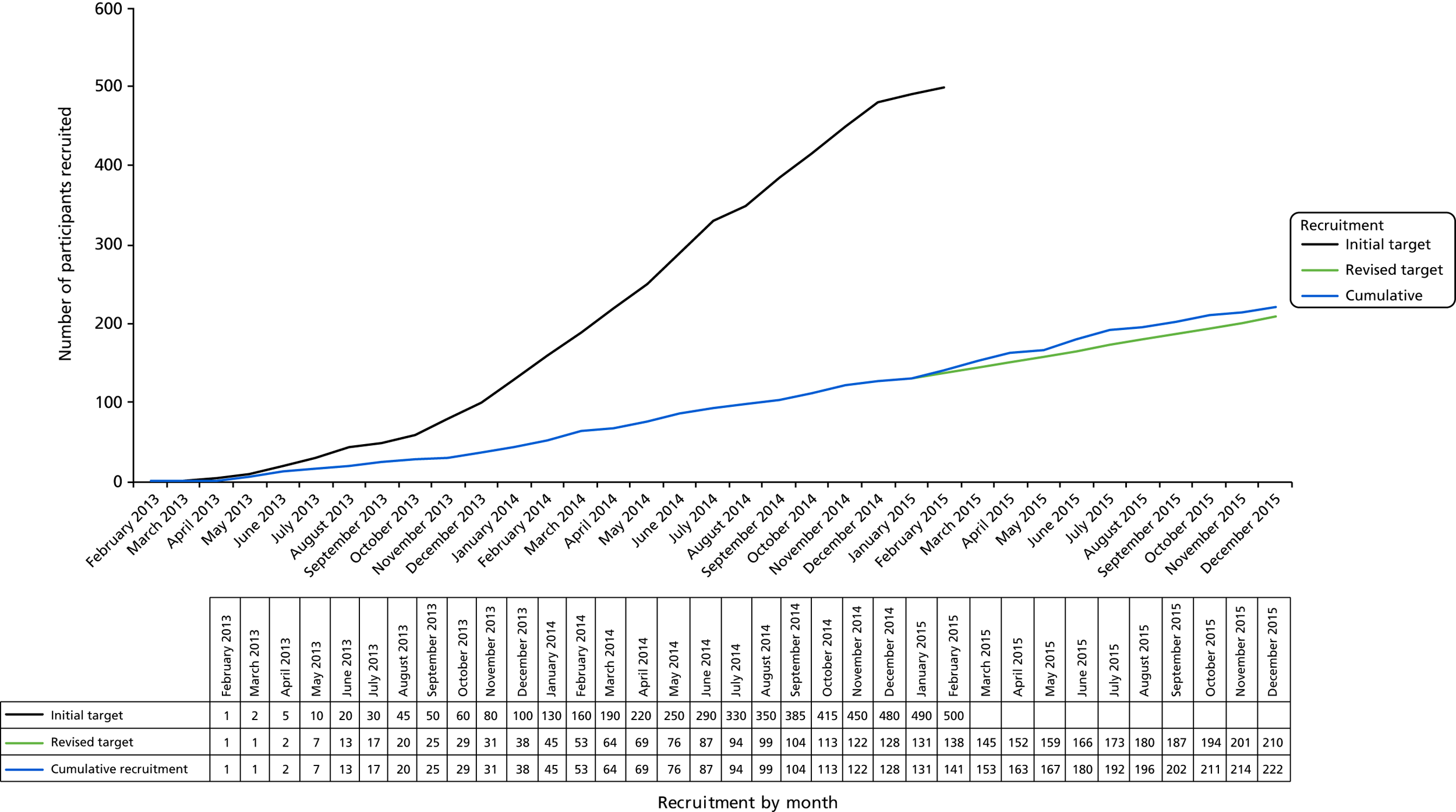

The trial recruited from 38 NHS hospital sites across the UK (England, Scotland and Wales). The first participant was randomised on 27 February 2013 and the last on 23 December 2015. The planned recruitment window was extended by 12 months to 35 months to allow the opening of further sites and to achieve the revised recruitment target (Figure 5). Participants were identified when attending hospital urology clinics. The recruitment strategy was first to open specialist sites where both urethroplasty and urethrotomy were carried out and subsequently to open general urology sites where only urethrotomy was provided, with urethroplasty accessed by referral to a previously established specialist site. Overall, 222 participants were recruited and randomised [58 (26%) from general sites and 164 (74%) from specialist sites] (Table 3).

FIGURE 5.

Planned and actual recruitment trajectory for the OPEN trial.

| Site of recruitmenta | Number of participants randomised at site |

|---|---|

| Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne | 21 |

|

1 |

|

5 |

| St George’s Hospital, London | 12 |

|

3 |

|

2 |

| University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London | 4 |

|

1 |

|

9 |

|

6 |

|

6 |

|

2 |

| Russells Hall Hospital, West Midlands | 17 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth | 11 |

| St Richard’s Hospital, Chichester | 4 |

| Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester | 0 |

|

5 |

| St James’s University Hospital, Leeds | 3 |

|

3 |

| Weston General Hospital, Weston-super-Mare | 2 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

2 |

| Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge | 31 |

| Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield | 1 |

| Aintree University Hospital, Liverpool | 8 |

| Stepping Hill Hospital, Stockport | 2 |

|

1 |

| Kent and Canterbury Hospital, Canterbury | 13 |

| Southampton General Hospital, Southampton | 12 |

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen | 5 |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland | 9 |

| Guy’s Hospital, London | 5 |

| Charing Cross Hospital, London | 1 |

| Princess of Wales Hospital, Bridgend | 2 |

|

1 |

| Western General Hospital, Edinburgh | 5 |

| Total randomised | 222 |

Participant flow

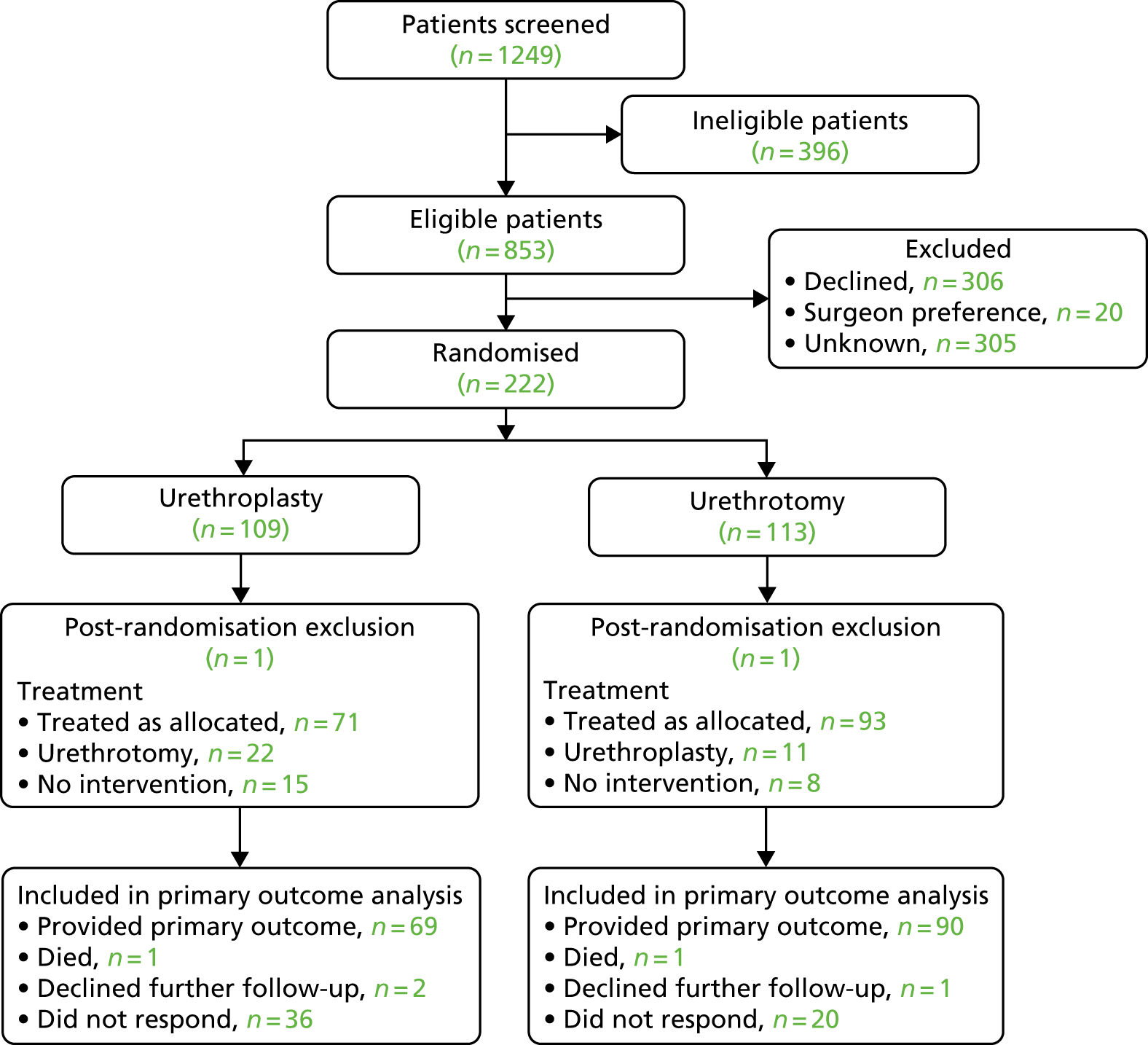

The flow of participants enrolled in the study is shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 6). A total of 1249 men were identified by study sites (83% of the target of 1500 men) and screened for eligibility. Of these men, 1027 (82%) were either deemed ineligible to take part by local research staff or declined to participate in the trial (Tables 4 and 5). Following completion of written consent and collection of baseline data, 222 participants (106% of revised target) were randomised, with 109 men allocated to open urethroplasty and 113 men to endoscopic urethrotomy.

FIGURE 6.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing progress of participants through the study. Reprinted from European Urology, vol. 78, Goulao B, Carnell S, Shen S, MacLennan G, Norrie J, Cook J, et al. , Surgical treatment for recurrent bulbar urethral stricture: a randomised open-label superiority trial of open urethroplasty versus endoscopic urethrotomy (the OPEN trial), pp. 572–80,45 Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier.

| Participants approached | Total (N = 1249; 100.0%), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ineligible | 396 (32) |

| Age < 16 years | 4 (0.3) |

| Stricture in penile urethra | 66 (5.3) |

| No previous intervention for stricture | 101 (8.1) |

| Intervention not required | 65 (5.2) |

| Unwilling to have 2-week catheterisation | 1 (0.1) |

| Unable to give consent | 13 (1.0) |

| Perineal sepsis or fistula | 7 (0.6) |

| Previous participation in the OPEN trial | 5 (0.4) |

| Unable to have 3-hour anaesthetic | 22 (1.8) |

| Inability to adhere to trial protocol | 11 (0.9) |

| Ineligible, no reason stated | 101 (8.1) |

| Patient declined participation | 306 (24.5) |

| Preference for open urethroplasty | 185 (14.8), 60% of those men who declined |

| Preference for endoscopic urethrotomy | 79 (6.3), 26% of those men who declined |

| Potential adverse effects of urethroplasty | 6 (0.5) |

| Potential adverse effects of urethrotomy | 1 (0.1) |

| Need for urethrogram for urethroplasty | 2 (0.2) |

| Unable to fulfil protocol commitments | 19 (1.5), 6% of those men who declined |

| Patient did not attend follow-up | 14 (1.1) |

| Surgeon preference | 20 (1.6), 7% of those men who declined |

| Unknown | 305 (24.4) |

| Reason for withdrawal | Intervention (n) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urethroplasty (N = 109) | Endoscopic urethrotomy (N = 113) | ||

| Withdrawal by participant | 5 | 5 | |

| No longer requires treatment | 1 | 1 | |

| Withdrawn by clinician | 1 | 1 | |

| Participant did not accept allocation and wished to have alternative (crossover) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Participant referred to specialist site where urologist was not available to perform procedure | 2 | 2 | |

| Participant not suitable for surgery | 1 | 1 | |

| Participant deceased | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| No reason recorded/given | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 12 | 6 | 18 |

Numbers analysed

Primary analysis

In the primary complete-case ITT analysis we included 159 (72%) of the randomised participants using the criteria of having completed primary outcome questionnaires on a minimum of three occasions: at baseline, during the first year after intervention and at 18–24 months after randomisation. This was 94% of the pre-set target of 170 participants providing data on the primary outcome in our revised sample size calculation. The total of 159 men comprised 69 men (63% of those men randomised) allocated to the urethroplasty group and 90 men (81% of those men randomised) allocated to urethrotomy. A total of 25 men allocated to urethroplasty had urethrotomy and a further 15 men had no intervention. From the urethrotomy group, 11 men had urethroplasty and 8 men did not have any intervention. Accordingly, 19 men (17%) allocated to urethrotomy did not receive urethrotomy and 40 men (37%) allocated to urethroplasty did not receive urethroplasty. All participants who ‘crossed over’ or did not have any intervention but who remained in active follow-up and provided sufficient completed trial questionnaires were analysed according to allocated group (complete-case ITT analysis). Reasons for exclusion from the primary analysis are detailed in Table 6.

| Intervention (n) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Urethroplasty (N = 108) | Urethrotomy (N = 112) | |

| Included | ||

| All three required questionnaires received | 69 | 90 |

| Excluded | ||

| At least one required questionnaire missing | 39 | 22 |

| Intervention performed in those men excluded | ||

| Allocated intervention | 17 | 13 |

| Alternative intervention (crossover) | 7 | 1 |

| No intervention performed | 15 | 8 |