Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/25/20. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft report began editorial review in January 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

As described elsewhere,1 evidence-based guidelines recommend both aerobic training and strength training for improving health markers and quality of life among those people with common chronic metabolic conditions1–5 and musculoskeletal conditions. 6 To prevent or reduce depression, mostly aerobic exercise is recommended. 7 Public health guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate activity per week (accumulated in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes) or 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week are met by only 66% of men and 58% of women aged ≥ 19 years in England,8 which is similar to results from the Scottish Health Survey 20149 (68% men; 59% women), based on self-report data from a national representative survey. The guidelines also highlight the importance of reducing sedentary behaviour and regularly doing bouts of resistance exercise. Physical inactivity, based on data from 2013–14, collected by Clinical Commissioning Groups in the UK, costs the NHS £455M. 10

Even small increases in physical activity (PA) and reduced sedentary time, especially among the least active,10 are likely to provide health benefits. 11,12 Patients with obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis and depression do less PA than the general population2 and report greater barriers to increased PA.

Exercise referral schemes in the UK

A variety of approaches have been explored to promote PA within primary care, such as referring patients to ‘exercise on prescription’ [i.e. an exercise referral scheme (ERS)]. As described previously,1 in the UK, ERSs have been popular, with an estimated 600 schemes involving up to 100,000 patients per year in 2008. 13 There is currently no single model for ERSs in the UK, but they mainly involve referral to a programme (e.g. 10–12 weeks) of structured, supervised exercise at an exercise facility (e.g. gym or leisure centre) or a counselling (and signposting) approach to support patients to engage in a variety of types of PA. 13 ERSs operate diversely to accommodate patient choice and local availability of facilities, the common goal being to reduce the risk of long-term metabolic, musculoskeletal and mental health conditions due to physical inactivity.

Evidence from a meta-analysis of eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving 5190 participants eligible for ERSs14 indicated only a small increase in the proportion of participants who achieved 90–150 minutes of PA of at least moderate intensity per week, compared with no exercise control, at the 6- to 12-month follow-up among at-risk individuals. However, uncertainty remains regarding the effects for patients with specific medical conditions, no study assessed long-term PA objectively and many of the eight studies reviewed had relatively small sample sizes.

A review15 reported that the average ERS uptake (attendance at the first ERS session) ranged from 66% in observational studies to 81% in RCTs, and average levels of ‘adherence’ ranged from 49% in observational studies to 43% in RCTs. Predictors of uptake and adherence have been explored; women were more likely than men to begin an ERS, but less likely to adhere to it, and older people were more likely to begin and adhere to an ERS. 15 As an example of a large observational retrospective study,16 of 6894 participants who had attended an ERS over 6 years, 37.8% (n = 2608) dropped out within 6 weeks and 50.03% (n = 3449) dropped out by the (final) 12th week, and males (p < 0.001) and older people (p < 0.001) were more likely to adhere than females and younger people, respectively. ERSs may help patients to become familiar with medical conditions17 and target key processes of behaviour change. However, the following features of an ERS may reduce uptake and adherence: inconvenience, cost, limited sustainable PA support (e.g. for 10 weeks) and low appeal for structured exercise and/or the medical model (i.e. ‘exercise on prescription’), which may in some schemes do little to provide autonomous support or empower patients to develop self-determined behaviour to manage chronic medical conditions. 13,18,19

It therefore appears that additional support may be needed that is accessible and is low cost, can be tailored to support a wide range of individual needs and empowers patients to develop and use self-regulatory skills (e.g. self-monitoring, goal-setting) to self-manage their chronic conditions. In one study, training for ERS staff to foster self-determined behaviour increased PA more than when the ERS was delivered by untrained staff at 3 and 6 months. 20 Similarly, training of ERS staff in behaviour change techniques and motivational interviewing led to small additional changes in self-reported PA after 12 months17 compared with no ERS. Challenges in training staff across a wide geographical area across Wales and monitoring intervention fidelity were noted.

Intervention technologies to promote physical activity

To address the challenges with face-to-face promotion of PA noted above and to encompass the growing use and availability of new technologies, a wide variety of online and mobile support has been developed and used to promote PA.

As described previously,1 there is growing evidence on the effectiveness of technology-based interventions for promotion of PA. 21,22 Studies include a wide range of interventions (from quite simple self-monitoring to interventions with multiple complex behaviour change components), targeted at different clinical groups with different baseline levels of PA, with various PA outcomes reported (very few using objective measures), and with mostly short-term follow-ups. In addition, some comparisons are between intervention versus no intervention and others are versus human contact, although none reports on the effects of adding web-based support to complement face-to-face support provided by ERSs. The impact of web-based and technology interventions on increasing PA is small to moderate (effect size ≤ 0.4). However, there is evidence from more rigorous studies that interventions with more behaviour change components and ones targeting less active populations are more effective. 21,22 A systematic review23 highlighted the importance of maximising sustained engagement in web-based interventions for enhancing change in the target behaviour. A recent study24 highlighted that self-monitoring of PA and tailored feedback were important to increase engagement, and periodic communications helped to maintain participant engagement.

The LifeGuide© (version 1.0.7.30, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK; www.LifeGuideonline.org/; accessed 25 February 2020) platform has been extensively used to develop and evaluate the acceptability and impact of online behaviour change and self-management interventions with a variety of clinical groups, including in primary care. 25–27 As an example, when adding online LifeGuide support to face-to-face support there was a greater lasting reduction in obesity than with face-to-face dietetic advice alone. 28 The LifeGuide platform provides a researcher-led tool to develop theory-driven interventions and evidence of the effectiveness of techniques. 29,30 It also provides the opportunity to capture intervention engagement and assess the utility of different behaviour change components.

The potential for e-coachER

Following iterative development work and user group testing and involvement, drawing on some online modules used in other LifeGuide interventions, for example in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease,25 we developed a bespoke intervention. We called the intervention ‘e-coachER’ and it was designed to support patients with chronic physical and mental health conditions who have been referred from primary care to an ERS to receive face-to-face support. 1 The overarching aim of the e-coachER intervention was to facilitate long-term PA by promotion of evidence-based self-regulatory skills and to encourage interaction with others (including the ERS professional, family and friends), and founded on self-determination theory31 to build a sense of competence in managing PA, autonomy or control over PA, and connection or relatedness with others. We wanted to encourage uptake and adherence to the ERS but if that was not acceptable or feasible for participants then we offered support to find alternative ways to be physically active in a way that may support their needs as someone who was inactive. It was also important that the intervention could be scaled up to promote PA for patients with obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis and risk of depression at probably low cost32,33 and also potentially make it available for patients with other chronic medical conditions (e.g. low back pain, heart disease and cancer).

Developing the e-coachER intervention

The intervention development included the piloting of the welcome pack and development of an initial version of e-coachER, built on wide-ranging experiences from the development of other self-management interventions using the LifeGuide platform34 and beta testing over 7 months. Co-applicants and researchers then provided feedback on a time-truncated version, and ERS users provided feedback on a real-time version for 5 months before the website was locked for the RCT.

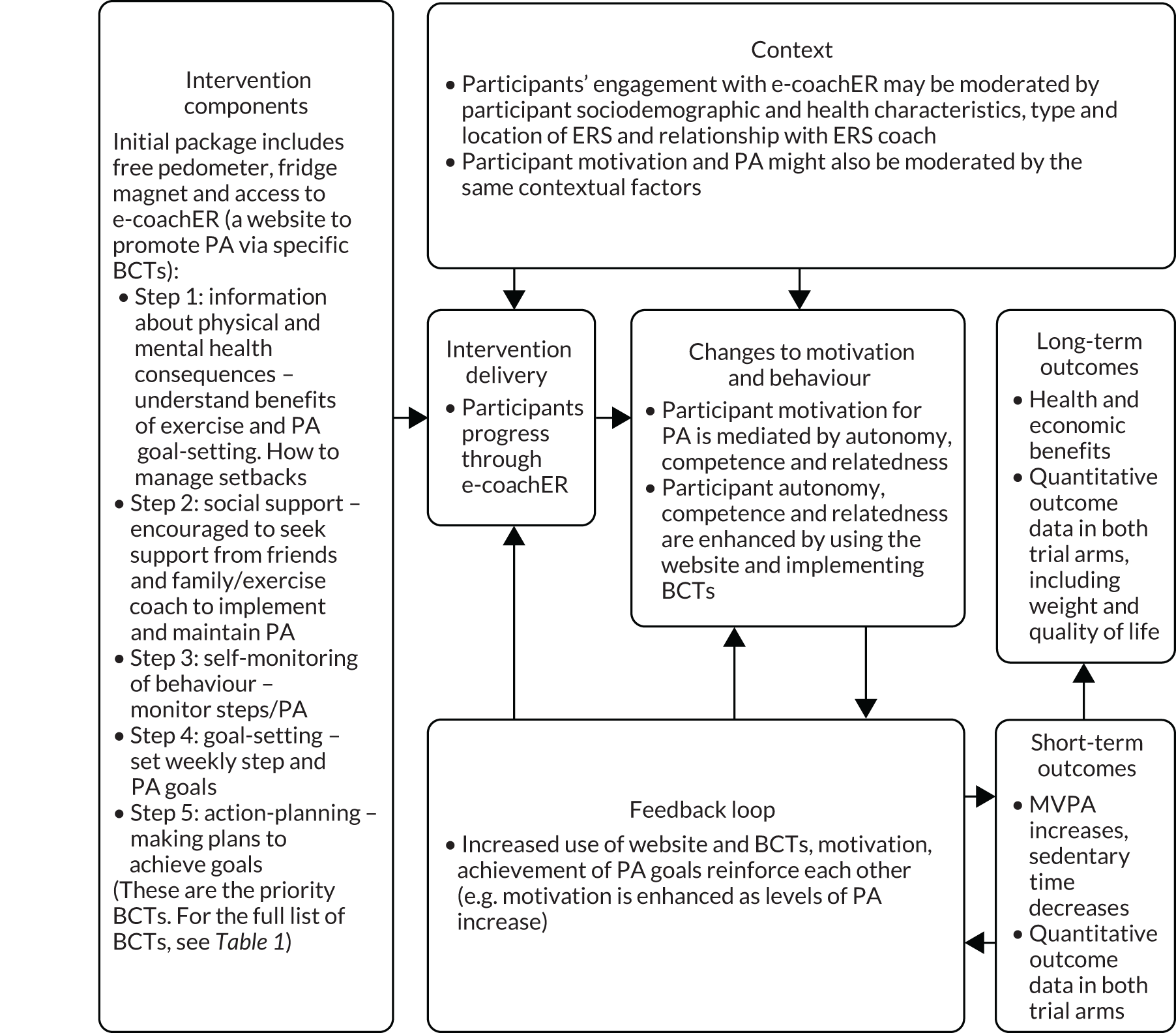

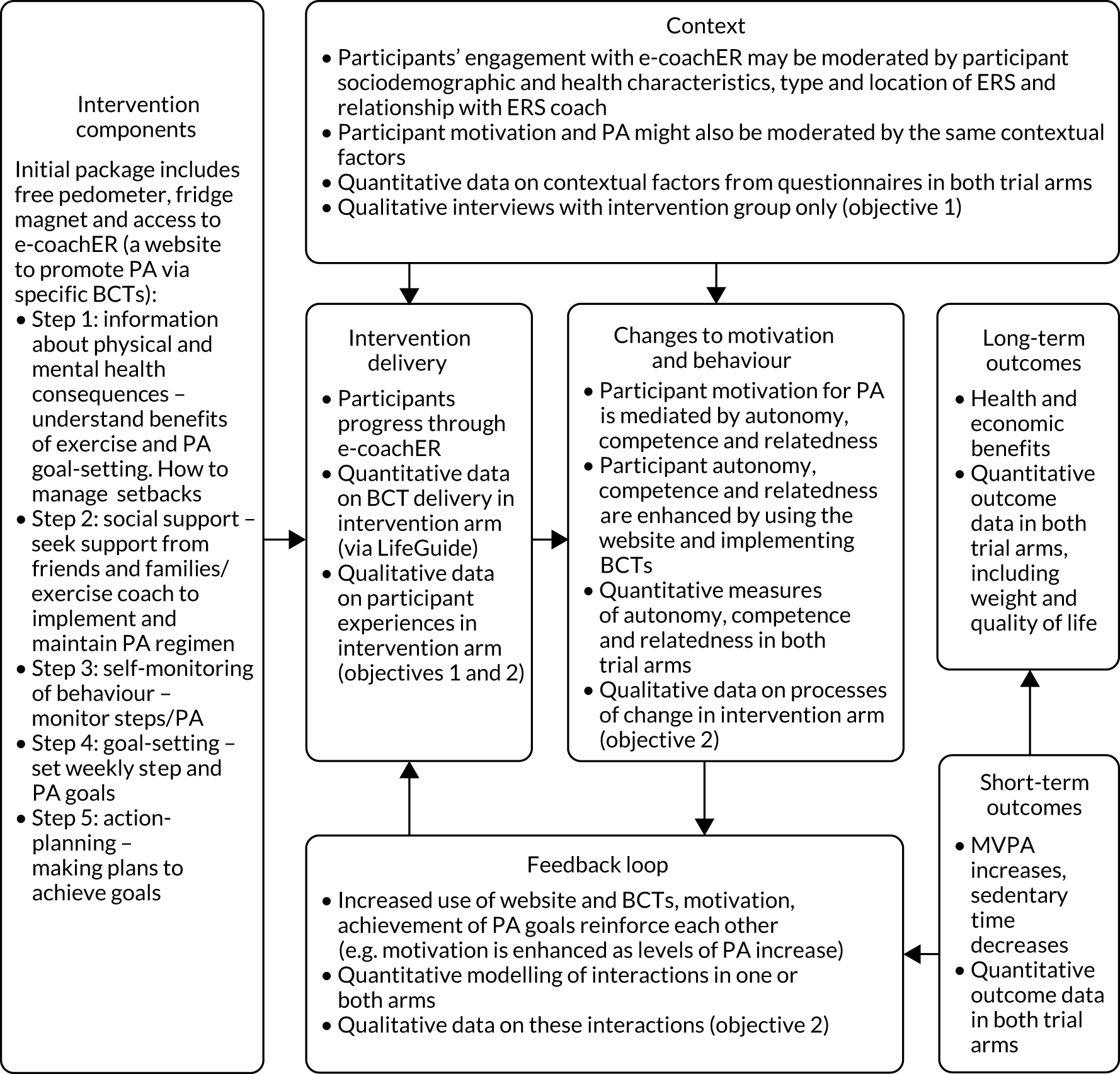

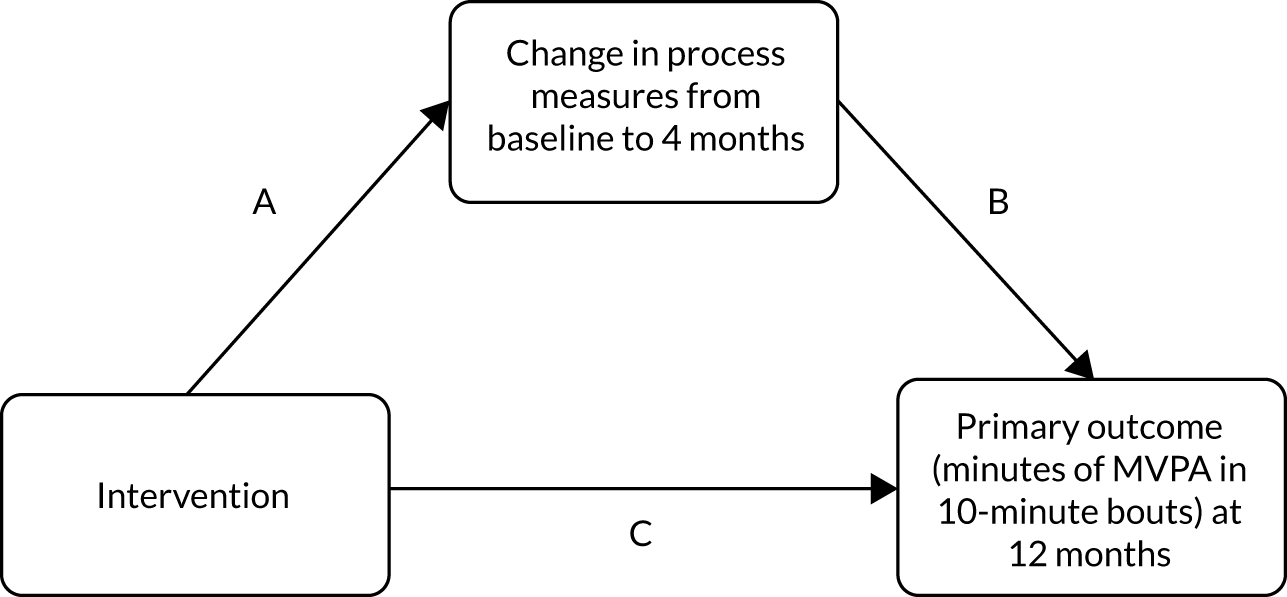

The development of all components of the e-coachER intervention followed a logic model as shown in Figure 1. 1

FIGURE 1.

Logic model for the e-coachER intervention. BCT, behaviour change technique; MVPA, moderate and vigorous physical activity. Reproduced with permission from Ingram et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The key components of e-coachER include the following:

-

On allocation to the intervention, all participants received a ‘welcome pack’ (Figure 2) that contained a user guide and the participant’s unique user log-in and registration details to access the e-coachER website, a simple pedometer (step counter) with instruction sheet and a fridge magnet with tear-off sheets to record daily PA (complete with trial branding and e-coachER helpline number). Participants were encouraged to use the pedometer and the PA record sheets for self-monitoring and goal-setting in conjunction with the website.

-

The e-coachER support system, hosted on the LifeGuide platform, provided support through seven ‘steps to health’ lasting approximately 5–10 minutes each, as shown in Table 1.

-

The steps were designed to do the following: encourage participants to think about the benefits of PA (motivation); seek support from an ERS practitioner, friends/family and the internet (support/relatedness); set progressive goals; self-monitor PA with a pedometer and upload step counts or minutes of moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (self-regulation, building confidence/autonomy); and find ways to increase PA more sustainably in the context of day-to-day life and deal with setbacks (building confidence). The sequential content, objectives and how this was implemented were mapped against a taxonomy for behaviour change techniques shown in Table 1. 35 The website content is illustrated in Appendix 1.

-

Participants were encouraged to use e-coachER support as an interactive tool by using pre-set or personally set reminders to upload step counts or minutes of MVPA, and messages of encouragement. A lack of engagement (e.g. not reviewing a goal by entering step counts 1 week later, or not signing into the website for 1, 2 and 4 weeks) triggered reminder e-mails. Participants were reminded by prompts to review goals the next day.

-

An avatar was used throughout the content to avoid having to represent a range of individual characteristics, such as age, gender and ethnicity. The avatar delivered brief narratives to normalise and support behaviour change and encourage the use of e-coachER. Automatic and user-defined e-mails generated by the LifeGuide system promoted ongoing use of functions such as recording weekly PA and goal-setting. Participants were provided with links to reputable generic websites for further information about the chronic conditions of interest and lifestyle, links to other websites and apps (applications) for self-monitoring health behaviour and health, as well as modifiable listings of local opportunities to engage in PA.

-

The only webpages that were not ‘locked’ after the initial participant began the intervention were pages for the respective recruitment sites that displayed links to the following websites: (1) local community opportunities for engaging in PA, (2) disease-specific (e.g. Diabetes UK, Royal College of Psychiatrists) informational sites about the role of PA in preventing and managing the condition, and (3) sites about other methods to optimise ways to be physically active (e.g. more sophisticated technologies to self-monitor).

-

Our aim was to maximise accessibility and use. Therefore, a local researcher provided technical support if requested, but did not support behaviour change directly. If participants did not register on the e-coachER website within the first few weeks, they were followed up with a telephone call to offer support to use e-coachER. If technical support to resolve any user operational issues with the website (e.g. re-issuing passwords) was needed, participants were referred to a centralised technician within the LifeGuide team for further support.

Trial aim and objectives

The overarching aim was to determine if e-coachER online support combined with usual ERS provided a clinically effective and cost-effective approach to supporting increases in PA in people referred to an ERS with a range of chronic conditions.

The specific objectives were to:

-

determine whether or not there is an increase in the total weekly minutes of MVPA at 12 months post randomisation in the intervention group compared with the control group

-

determine whether or not there is an increase in the proportion of participants in the intervention group compared with the control group who:

-

take up the opportunity to attend an initial consultation with an exercise practitioner

-

maintain objectively assessed PA at 4 and 12 months post randomisation

-

maintain self-reported PA at 4 and 12 months post randomisation

-

have improved health-related quality of life at 4 and 12 months post randomisation

-

-

quantify the additional costs of delivering the intervention, and determine the differences in health utilisation and costs between the intervention and control groups at 12 months post randomisation

-

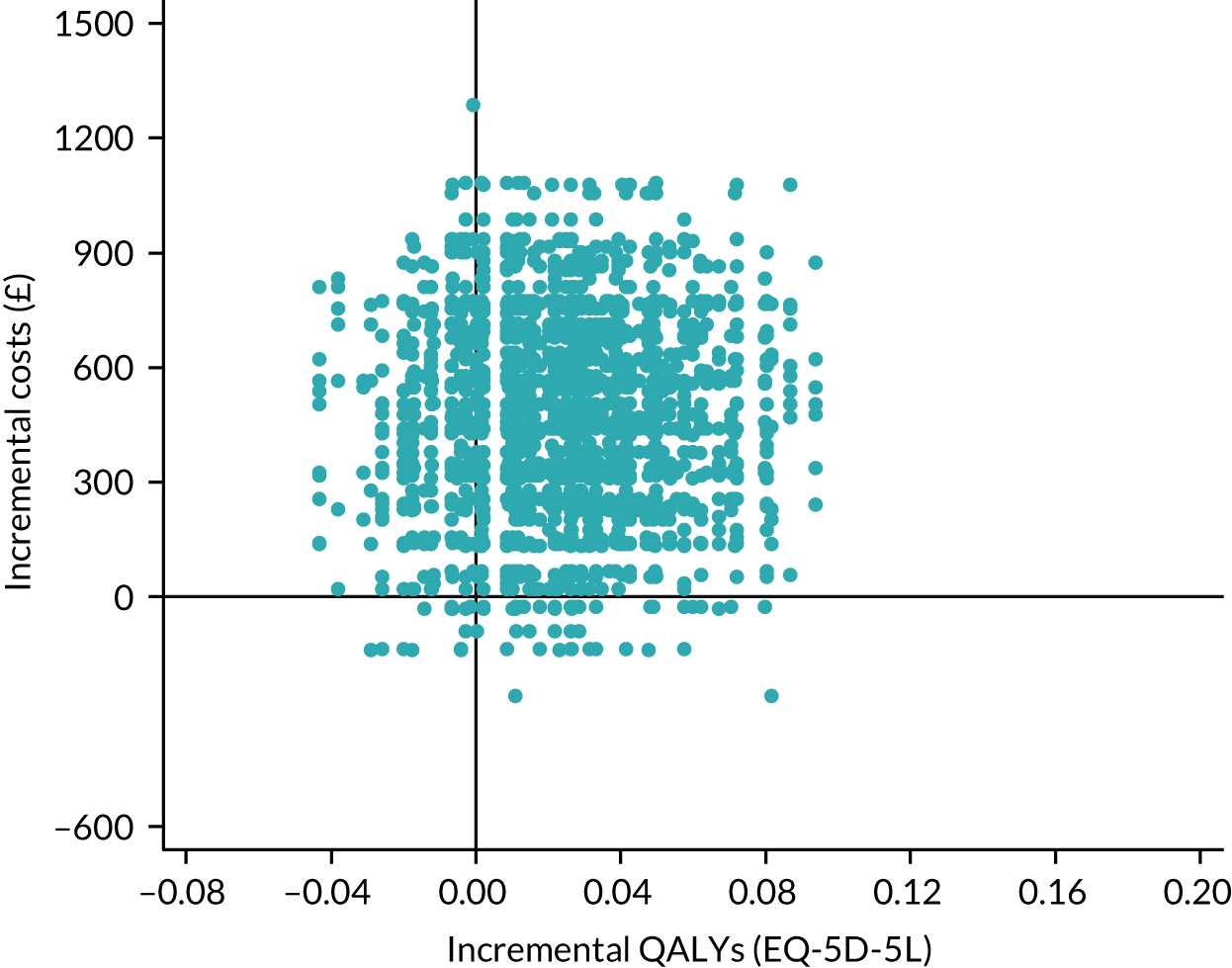

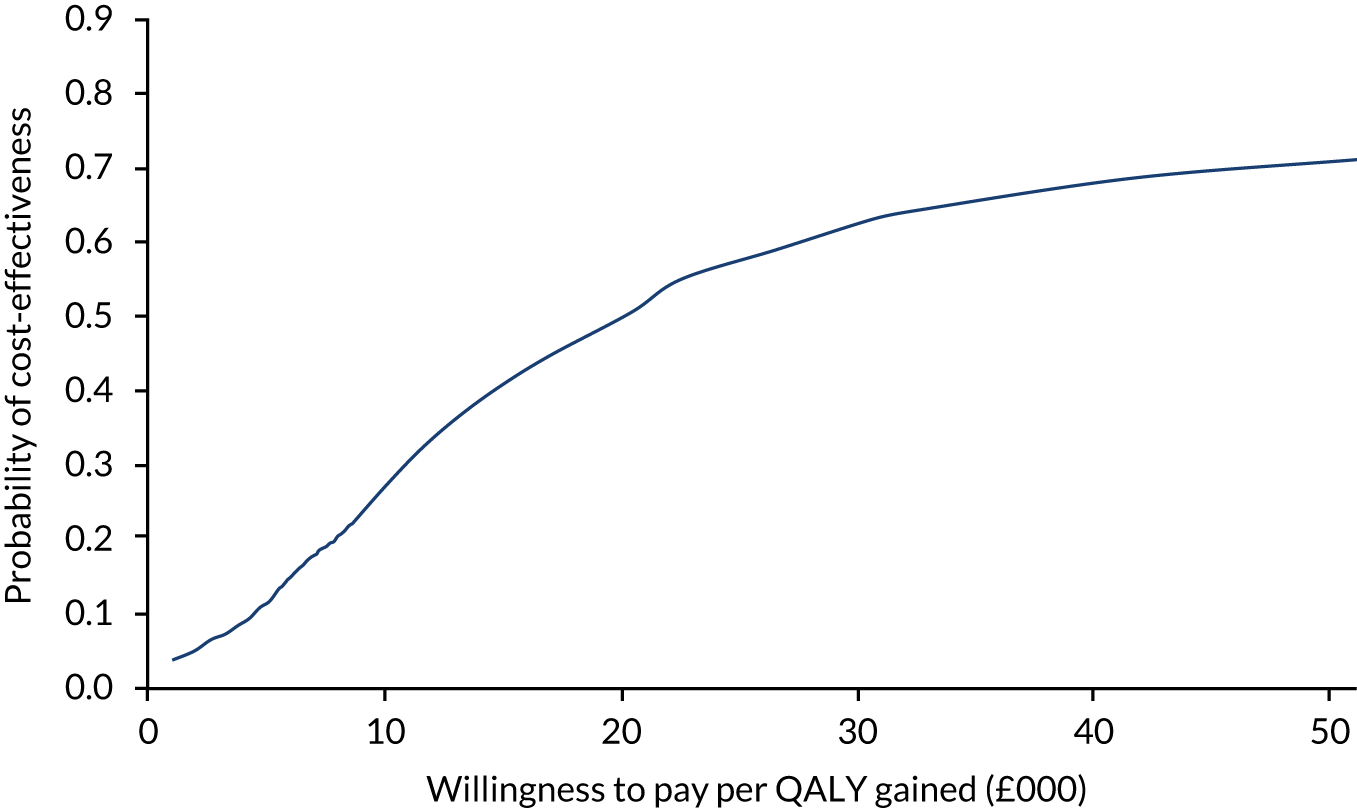

assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with control at 12 months post randomisation [incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)] using a previously developed decision model to estimate future costs and benefits

-

quantitatively and qualitatively explore whether or not the impact of the intervention is moderated by medical condition, age, gender, socioeconomic status, information technology (IT) literacy or ERS characteristics

-

quantitatively and qualitatively explore the mechanisms through which the intervention may have an impact on the outcomes, through rigorous mixed-methods process evaluation and mediation analyses (if appropriate).

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

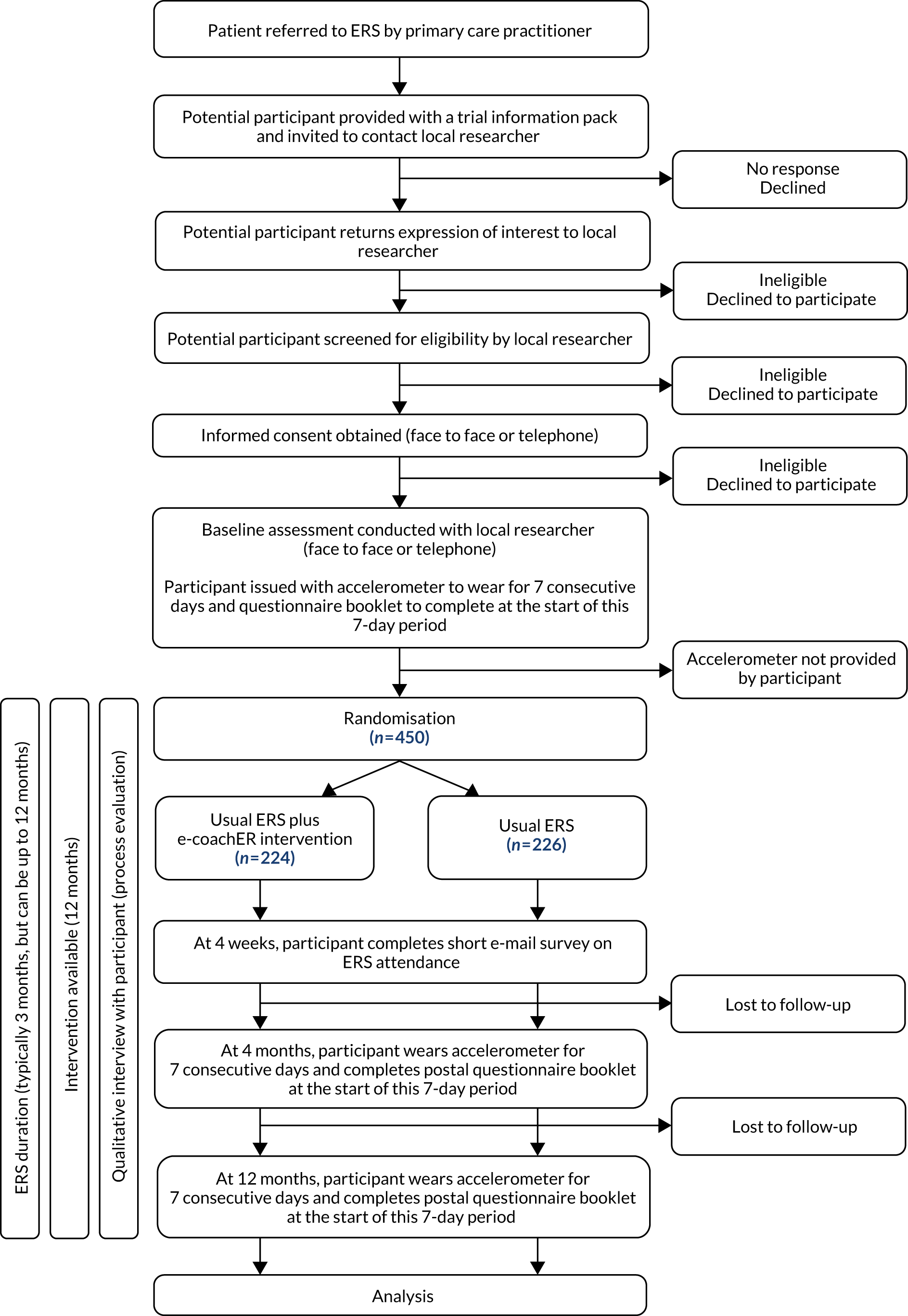

This was a multicentre, parallel, two-arm RCT with participant allocation to usual ERS alone (control) or usual ERS plus web-based behavioural support (intervention) with parallel economic and mixed-methods process evaluations. 1 The trial design is summarised in Figure 3, from Ingram et al. 1

FIGURE 3.

Participant pathway. Reproduced with permission from Ingram et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Recruitment to the trial took place over a 21-month period (July 2015 to March 2017) in three areas in the UK: Greater Glasgow, West Midlands and South West England (including Plymouth, Cornwall and Mid Devon). The majority of participants lived in urban locations. Further information about the characteristics of the cities involved and the respective ERSs to which participants were referred is given in Ingram et al. 1

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was granted by North West Preston NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) in May 2015 (reference 15/NW/0347). Approval for activity at non-NHS sites was obtained from the same REC for the following ERSs: Everyone Active (Plymouth), Teignbridge District Council (Cornwall), Tempus Leisure (Cornwall), Be Active Plus (West Midlands) and Live Active (Glasgow) in December 2015, and Docspot (West Midlands) in November 2016.

NHS Research and Development approval was granted by the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust Shared Management Service for the Plymouth site (July 2015); NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) West Midlands for the Birmingham site (July 2015); and the NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Health Board for the Glasgow site (January 2016).

Prior to commencing recruitment, the trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN) under reference number 16900744 and NIHR CRN Portfolio 19047. A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is given later in this chapter.

Patient and public involvement

Aim

The aim was to involve public representatives throughout the study to ensure that the intervention and trial methods were appropriate for the target population.

Methods

The target trial population was composed of patients with one or more physical and mental health conditions; there was no single patient support group or user group that could be invited to contribute as patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives. Hence, PPI representatives with diverse clinical conditions were sought from an ERS provider in Plymouth. Others involved in the delivery of ERSs as managers or practitioners were also consulted to ensure that the methods and intervention were aligned with the usual ERS, especially in the recruitment locations.

There was comprehensive PPI in intervention development. PPI representatives provided critical feedback in informal focus groups on the e-coachER website and registration processes, and on the use of the pedometer and the fridge magnet (with recording strips) as a motivational tool in the e-coachER support package.

Patient and public involvement representatives with experience of ERSs also contributed to the study via their membership of the e-coachER Project Management Group and Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Results

Notable benefits included having access to PPI representatives’ perspectives on (1) participant-facing documents, such as the e-coachER invitation materials and participant newsletter, (2) usability of the e-coachER intervention package and (3) suggestions to overcome barriers to recruitment.

Discussion

One PPI representative was influential with regard to including a ‘personal message’ from an ERS user in the periodic participant newsletter, the aim being to convey the importance and value of taking part in the study from the perspective of someone who has been referred to an ERS. There were no negative aspects of the PPI activities undertaken in the study.

Reflections

Being a resident of Plymouth, one PPI representative was able to attend all of the meetings held at the chief investigator’s institution in person. Face-to-face contact with the PPI representative meant that a rapport was more readily generated than would have been possible if teleconferencing had been used.

The PPI representative on the TSC provided a welcome contribution to the various discussions on the problems faced with recruitment in the pilot phase of the trial. He took a keen interest in the wider issues faced by the trial team, such as ERS provision in the UK, national guidelines for PA and the choice of cut-off points for accelerometer-derived data that informed the primary outcome. The PPI representative provided a ‘real-life’ perspective on such matters, as he saw them.

Participants

The study population was composed of patients who had been referred to an ERS administrator, or were about to be referred, mostly by a general practitioner (GP), and occasionally by a nurse to a local ERS for a programme of support to increase PA.

Patients were eligible for the study if they were aged between 16 and 74 years, inclusive, were contactable via e-mail, had some experience of using the internet and had one or more of the following conditions:

-

obesity [i.e. a body mass index (BMI) of 30–40 kg/m2]

-

a diagnosis of hypertension

-

prediabetes

-

type 2 diabetes

-

lower limb osteoarthritis

-

current or recent history of treatment for depression

-

categorised as ‘inactive’ (i.e. 0 hours per week of physical exercise and in a sedentary occupation) or ‘moderately inactive’ (i.e. some activity but < 1 hour per week and in a sedentary occupation, or 0 hours per week of physical exercise and in a standing occupation) according to the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ). 36

Patients were excluded for the following reasons:

-

They did not meet the eligibility criteria for their local ERS.

-

They had an unstable, severe and enduring mental health problem.

-

They were being treated for an alcohol or drug addiction that may have limited their involvement with the study.

-

They were unable to use written materials in English, unless they had a designated family member or friend to act as translator.

Intervention

All participants had been offered usual ERS. Participants allocated to the intervention group were additionally offered access the e-coachER web-based support package. Development and delivery of the intervention is fully described in Chapter 1, Developing the e-coachER intervention.

Usual care

There is currently no single model for ERSs in the UK, but the predominant mode of delivery involves referral to a programme (e.g. 10–12 weeks) of structured, supervised exercise at an exercise facility (e.g. gym or leisure centre) or a counselling approach to support patients to engage in a variety of types of PA. 13 ERSs operate diversely to accommodate patient choice and local availability of facilities, the common goal being to reduce the risk of long-term metabolic, musculoskeletal and mental health conditions as a result of physical inactivity. The three participating sites were selected from different regions of the UK (different ERS providers) to provide diversity of approach; the schemes are described in Ingram et al. 1

Recruitment procedures

Patients were identified as potentially eligible for the trial in a number of ways.

-

By health-care professionals in primary care at the point of being actively referred to an ERS or having been opportunistically found to be eligible for an ERS at a consultation with the primary care practitioner.

-

Via a search of patient databases at the participating GP practices (conducted by the local NIHR Primary Care Research Network team).

-

Via patient self-referral to the GP arising from community-based publicity for the trial.

-

By the ERS programme administrator on receipt of an ERS referral form from a GP practice.

-

By exercise advisors at the ERS service at enrolment on the ERS. With the patient’s consent, the exercise advisor provided the local researcher with the patient’s contact details for the purposes of the trial.

Potentially eligible patients were approached by the primary care practitioner or the local researcher, depending on how the patient had been identified. Some patients self-referred to the local researcher in response to publicity campaigns. These various means of identification and approach were designed to accommodate the variation in usual-care referral pathways to ERSs across the participating sites and individual GP practices.

Amenable patients were offered a study-specific participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1) by post, by e-mail or by hand (the route used largely depended on the preference of the participating GP practice or ERS service). Interested patients were asked to communicate their expression of interest to the local researcher via a prepaid reply slip, by telephone or by e-mail. On receipt of an expression of interest, the local researcher contacted the potential participant by telephone to discuss the trial, confirm eligibility and seek informed consent.

Informed consent

Informed, written consent (see Report Supplementary Material 2) was obtained prior to undertaking the baseline assessment, either over the telephone or at a face-to-face visit, depending largely on the patient’s preference but also on the availability of suitable venues, such as the GP practice. The original completed informed consent forms were held securely at the site and a copy was given to the participant.

In the case of telephone consent, the researcher was required to sign and date the informed consent form, but the participant was not required to sign or date their copy.

Patients who were deemed to be ineligible for inclusion in the study were informed of this outcome.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

On receipt of the baseline accelerometer at the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU) (after 1 week of wear), participants were randomised to usual ERS or usual ERS plus access to e-coachER in a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified by site with minimisation by participant’s perception of main medical referral reason (i.e. weight loss, diabetes control, reduce blood pressure, manage lower limb osteoarthritis symptoms, manage low mood/depression) and by self-reported IT literacy level on a visual analogue scale (i.e. lower or higher confidence).

To maintain concealment, the minimisation algorithm retained a stochastic element.

Randomisation was conducted by means of a secure, password-protected web-based system created and managed by the clinical trials unit (CTU).

Blinding of participants was not possible, given the nature of the intervention. Given that the primary outcome was an objective measure of PA recorded by accelerometer, and the secondary outcomes were assessed by a participant self-completed questionnaire, the risk of assessor bias was considered to be negligible in this study. However, to minimise any potential bias, the statistical analysis was kept blinded and the code for group allocation was not broken until the primary and secondary analyses had been completed. The ERS practitioners would not have been aware of trial participants’ treatment allocations.

Process evaluation: qualitative interviews

Participants who had engaged with the e-coachER website (i.e. logged on to the website, as a minimum) were invited to participate in one or more qualitative interviews to inform the process evaluation (see Chapter 4, Qualitative process evaluation).

Data collection and management

Data were collected and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 199837/General Data Protection Regulation 2016. 38

Participant numbering

Following receipt of an expression of interest, each patient was allocated a unique identification number and was then identified in all study-related documentation by this number and their initials. A record of names, addresses, telephone numbers and e-mail addresses linked to participants’ identification numbers was stored securely on the study database at the CTU for administrative purposes only.

Data collection

Data were recorded on study-specific paper-based case report forms (CRFs) by the local researcher, and participants completed a paper-based questionnaire booklet comprising validated and non-validated self-report outcome measures.

Accelerometers [GENEActiv™ Original accelerometer (version 3.0_09.02.2015), Active Insights Kimbolton, UK; www.geneactiv.org/ (accessed 26 February 2020)] were configured for use prior to being issued to participants by the local researcher at baseline and the CTU thereafter, using GENEActiv software. A recording window of 10 days, starting at midnight of the day of issue and recording at 75 Hz, was pre-set, thus accounting for transits in the post while optimising the battery life of the device.

Accelerometers received by the CTU following 1 week of wear by the participant were physically cleaned with liquid detergent in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions before data were downloaded and linked to the participant identification number (see Accelerometer data processing). Accelerometers were then issued to other participants in the trial as required.

Data on participants’ uptake of the ERS were collected via participant self-report at 4 weeks post baseline and 4 months post randomisation, and via the ERS service provider.

Recording and reporting of non-serious adverse events (AEs) in this study were not required. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported to the CTU via the self-report questionnaire booklet administered at 4 and 12 months, but were also reported to the CTU or local researcher by the participant (or relative) outside these time points, until the end of follow-up. SAEs were categorised using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Terminology Systems Organ Classification List Internationally Agreed Order Version 19.0, March 2016 (www.meddra.org/sites/default/files/guidance/file/intguide_19_0_english.pdf; accessed 26 February 2020).

All persons authorised to collect and record study data at each site were listed on the study site delegation logs, which were signed by the principal investigator.

Data processing

Accelerometer data processing

Accelerometer data were downloaded using the GENEActiv and analysed in software R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using package GGIR version 1.2–8 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GGIR/index.html). 39 GGIR performs autocalibration with the reference of local gravity. 40 Raw acceleration data are used to compute Euclidean norm minus one (ENMO in mg). 41 Data were analysed from the first to the final midnight using 5-second epochs. Participants were included in the main analysis if they achieved a minimum of 16 hours of wear-time for a minimum of 4 days (including at least 1 weekend day). Non-wear was detected if the standard deviation (SD) of two axes was < 13 mg with a range of < 50 mg in windows of 60 minutes. Time spent in activity intensities was established using published thresholds. 42

Computed variables included average daily MVPA accumulated in any 5-second epochs. Ten-minute bouts of MVPA were detected when at least 80% of a 10-minute period was above the MVPA intensity threshold. 43 Total time accumulated in bouted and unbouted MVPA minutes was calculated by multiplying the average daily values by 7 to represent 1 full week.

Diurnal activity and nocturnal periods of inactivity were also estimated to determine if the intervention had an effect on reducing daytime inactivity and increasing sleep. Sleep duration was established using sustained nocturnal inactivity bouts. An inactivity bout occurred when no change in arm angle > 5° was observed for at least 5 minutes. 44 Diurnal inactivity represents the sustained inactivity bouts (> 5 minutes) that occur in the day,43 which includes naps, but omits other inactivity that results in measurable movement. 45 However, it is likely that some misclassification of this inactivity may occur. 43

To explore if different ways of processing accelerometer data influenced the findings, four additional wear-time criteria were calculated:

-

≥ 16 hours over any 4 days (irrespective of weekday/weekend day)

-

≥ 10 hours for 4 days (including at least 1 weekend day)

-

≥ 10 hours over any 4 days (irrespective of weekday/weekend day)

-

a minimum wear criterion of 1 day for 10 hours but with individuals weighted by the number of valid days with ≥ 10 hours of wear.

Case report forms and questionnaire booklets

Original CRFs and questionnaire booklets were posted to the CTU, with copies of the CRF retained at the site. All data were double-entered by CTU staff into a password-protected Structured Query Language Server database and encrypted using Secure Sockets Layer (version V3, QuoVadis Global SSL ICA G3, QuoVadis Online Limited, Lincolnshire, UK). Double-entered data were compared for discrepancies using a stored procedure, and discrepant data were verified using the original CRF. Incomplete, incoherent, unreadable or other problem data in the CRF pages were queried with site staff by staff at the CTU during data entry to ensure a complete and valid data set. Self-reported data in the questionnaire booklet were not queried with participants.

The CTU staff completed further validation of data items and performed logical data checks after data collection had been completed. After all data-cleaning duties had been performed at the CTU, the final export of anonymous data was transferred to the statistician and health economist for analysis.

Baseline assessment

Consented participants attended a baseline assessment with the local researcher. This assessment was conducted over the telephone or in person at a suitable venue in the community.

Demographic data were collected (i.e. age, gender, BMI, blood pressure, ethnic group, relationship status, domestic residence status, smoking status, employment status, education status, GPPAQ score, internet use capability, requirement for translator for trial purposes and clinical condition).

Information technology literacy level was determined using a visual analogue scale for self-reported ‘confidence using the internet’, where 1 = not at all confident and 10 = totally confident. Arbitrarily, scores of 1–5 were set to indicate a low literacy level and scores of 6–10 indicated a high literacy level, for the purposes of stratification.

‘Clinical condition’ was the participant’s perception of the reason for referral to the ERS; where more than one medical condition was stated, the participant ranked these in order of importance and the most important reason was used as a stratification variable.

The participant was issued with the wrist-worn waterproof accelerometer to wear constantly for 1 whole week (day and night), and a self-report questionnaire booklet to complete at the beginning of the week-long period. At the face-to-face baseline assessments, the accelerometer was fitted by the local researcher; at telephone visits, the accelerometer (and self-report questionnaire booklet) were posted to participants. All participants were provided with a bespoke guidance sheet for wearing the accelerometer (see Report Supplementary Material 3), including instructions to wear the accelerometer on the wrist of the non-dominant hand (i.e. the hand not favoured for writing). After 1 week of wear, participants were required to post the accelerometer and completed questionnaire to the CTU in a preaddressed padded envelope provided. A prepaid postal service was used so as not to incur costs to the participant.

The measures collected at baseline are summarised in Table 2.

| Measure | Baseline | 4 weeks post baseline | 4 months post randomisation | 12 months post randomisation | On completion of participants’ ERS programme at site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ✗ | ||||

| Engagement with the ERS: self-reported | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Engagement with the ERS: ERS service provider’s record | ✗ | ||||

| Accelerometer-recorded MVPA | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Self-reported MVPA | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Self-reported health and social care resource use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Self-reported quality-of-life measure (EQ-5D-5L) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Self-reported Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Self-reported process evaluation outcomes (confidence to be physically active; importance of being physically active, perceived frequency and availability of support; perceived autonomy over choices; involvement in self-monitoring and action-planning PA) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Qualitative interviews as part of the process evaluation focusing on participants’ experiences with the ERS and the intervention (optional for participants) | ✗ | ||||

| Engagement with e-coachER (captured from the LifeGuide platform) | ✗ | ||||

Follow-up assessments

The measures collected at follow-up are summarised in Table 2.

At 4 weeks post baseline, a short survey on initial uptake of the ERS was administered via e-mail.

At 4 and 12 months post randomisation, participants were sent an accelerometer (along with the guidance sheet on how to wear it), a questionnaire booklet, and a pre-addressed, prepaid envelope to return the items to the CTU.

To maximise data completeness at follow-up assessments, participants were sent standard letters from the CTU: (1) 7 days before delivery of the accelerometer, (2) 3 days into the 10-day recording window as a prompt to begin wearing the accelerometer (if not already doing so) and (3) at 3 and 5 weeks after issue as a reminder to post the accelerometer to the CTU (for those participants who had not already done so). If a participant had not sent the accelerometer back to the CTU after 6 weeks, the local researcher telephoned the participant to remind them to return the device. Participants who returned the accelerometer to the CTU were provided with a £20 voucher for an online store as a token ‘thank you’ to maximise response rates.

Once a participant’s involvement in the ERS had concluded, the ERS service providers completed a simple pro forma to confirm whether or not the participant attended an appointment with the exercise specialist and, if so, how many appointments were available to the participant.

Measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the number of weekly minutes of MVPA, in ≥ 10-minute bouts, measured objectively using the GENEActiv Original accelerometer,46 over 1 week at 12 months post randomisation, compared with the control group. To be included, participants had to have provided activity recorded over 4 days, including a weekend day, for at least 16 hours per day.

Secondary outcome measures

-

Total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts, measured objectively using an accelerometer, over 1 week at 4 months.

-

Achievement of at least 150 minutes of MVPA, measured objectively by accelerometer, over 1 week at 4 and 12 months.

-

Self-reported achievement of at least 150 minutes of MVPA over 1 week using the 7-day recall of PA47 (7-day Physical Activity Recall questionnaire) at 4 and 12 months.

-

Self-reported weekly minutes of MVPA at 4 and 12 months.

-

Average daily hours of sedentary behaviour measured objectively using an accelerometer over 1 week at 4 and 12 months.

-

Self-reported average daily hours of sleep over 1 week at 4 and 12 months.

-

Self-reported health-related quality of life, assessed using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),48 at 4 and 12 months.

-

Self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression, assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),49 at 4 and 12 months.

-

Uptake of the ERS according to the attendance records held by the ERS service provider, with imputed participant-reported attendance at 4 weeks and/or 4 months where the ERS service data are missing.

-

Adherence to PA using a composite measure to describe the proportion of participants in each arm of the trial who achieved at least 150 minutes of MVPA in bouts of at least 10 minutes at 4 months and were still doing so at 12 months.

Self-reported survey process measures

The following survey items were adapted from existing measures or originally developed, using processes to be reported elsewhere in more detail, and were used as process measures:

-

importance and confidence to be physically active (single items)

-

perceived competence in being regularly physically active (four items)

-

autonomous in decisions about PA (four items)

-

availability of support (three items)

-

frequency of support (three items)

-

action-planning (five items)

-

self-monitoring (two items).

The respective measures were not validated but exploratory analysis, to be reported in more detail elsewhere, indicated that Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all scales were ≥ 0.77, using data from participants included in the primary analysis.

In the intervention group, we measured engagement with e-coachER. This included whether or not the participant visited the website at least once and whether or not they reached a stage of the online support to indicate that they have set and reviewed at least one PA goal [i.e. step 5 – users make their specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound (SMART) activity plan and then review their step goal and SMART activity goal].

Sample size

In the absence of a published minimally important difference for MVPA, assuming a ‘small’ to ‘moderate’ standardised effect size of 0.35, we estimated that 413 participants were required, with 88% power and a two-sided alpha of 5%, assuming 20% attrition, or 90% power at a two-sided alpha of 5% allowing for 16% attrition [using ‘sampsi’ in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA)]. Given that the intervention was delivered at the level of the individual participant, clustering was not factored into the sample size calculation. Based on the baseline SD for MVPA total weekly minutes in ≥ 10-minute bouts of 104–113,50 an effect size of 0.35 corresponds to a between-group difference of 36–39 minutes of MVPA per week.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation guideline 9 (ICH-9) statistical guidelines51 for clinical trials and updated Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines52,53 for non-drug trials. All primary and secondary analyses were undertaken and reported in accordance with a prespecified detailed statistical analysis plan that was agreed with the Project Management Group, TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC).

Following data lock by the CTU data manager, the statistician undertook primary analyses blinded to group (i.e. randomised groups were coded ‘A’ or ‘B’). Following the blinded presentation of the primary results to the Project Management Group and agreed interpretation of the results, the groups were unblinded.

Descriptive analyses

A summary of baseline characteristics and baseline outcome values in the intervention and control groups was undertaken and between-group equivalence was assessed descriptively. Because differences between randomised groups at baseline could have occurred by chance, no formal significance testing will be conducted.

Interim analysis

No interim inferential analysis was planned and none was conducted.

Inferential analyses

Definition of comparison groups

Intention to treat (ITT), complete case: groups according to original randomised allocation in participants with complete data (i.e. meeting required accelerometer wear-time) at 12-month follow-up.

Intention to treat, imputed: groups according to original randomised allocation in all participants.

Per protocol [complier-average casual effect (CACE)]: ITT complete-case participants who have completed step 5 – making your activity plans.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis using a linear model (continuous outcomes – using Stata ‘regress’) or logistic model (binary outcomes – using Stata ‘logistic’ command) compared primary and secondary outcomes between groups according to the principle of intention to treat (i.e. according to original randomised allocation) in participants with complete outcomes at 12 months. This adjusted for baseline outcome values and stratification (by site) and minimisation variables (participant’s perception of main medical reason for referral to the ERS and IT literacy level). Given that age and gender are known to be predictive of PA, these baseline characteristics were also added to the adjusted model.

Given the overdispersion and high frequency of the primary outcome, the primary mixed-effects model was found to be a poor fit. Therefore, alternative post hoc regression models were explored for the analysis of the primary outcome. These included a log-transformed mixed-effects model (with a constant added), a mixed-effect model (with outliers removed), negative binomial models and zero-inflated binomial models.

Secondary analyses

Secondary analyses were undertaken to compare groups at follow-up across all follow-up points, using a mixed-model repeated-measures approach (using Stata ‘xtmixed’ command). Secondary per-protocol analysis using a CACE approach (using Stata ‘ivregress’ command) was undertaken to examine the impact of adherence to the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes at 12 months post randomisation.

Subgroup analyses

The primary analysis model was extended to fit interaction terms to explore possible subgroup differences in intervention effect in stratification and minimisation variables for the primary outcome at 12 months post randomisation. Given the relatively low power for testing interactions, these results were to be considered as exploratory only.

Sensitivity analysis to test the effects of different ways of processing accelerometer data

Sensitivity analysis was undertaken using four additional wear-time criteria:

-

≥ 16 hours over any 4 days (irrespective of weekday/weekend day)

-

≥ 10 hours for 4 days (including at least 1 weekend day)

-

≥ 10 hours over any 4 days (irrespective of weekday/weekend day)

-

a minimum wear criterion of 1 day for 10 hours but with individuals weighted by the number of valid days with ≥ 10 hours of wear.

Handling of missing data

Missingness was defined as those participants with the absence of data at follow-up for one or more outcomes. Given that the proportion of patients with missing accelerometry data out of the total number of participants who fulfil the criteria of includable PA data (n = 243) was small (i.e. 0–10 participants or < 5%), no imputation was undertaken for the primary outcome or any of the derived secondary outcomes. For EQ-5D-5L and HADS, missing data were replaced using multiple imputation using the covariates of age, gender, reason for referral and confidence in IT, and assuming that unobserved measurements were missing at random (using Stata ‘mi’ command). Using the same primary analysis model as described above, between-group outcomes were compared in ITT complete-case and imputed data sets for primary and secondary outcomes at 12 months post randomisation.

Adverse events

Safety data and AEs were listed descriptively by group and include details of the event and the likely relatedness to either treatment.

Data presentation

Results were reported as between-group mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs); global p-values were provided with regard to categorical explanatory variables. The threshold for determining significant effects was p < 0.05. No adjustment of p-values was made to account for multiple testing, although the implications of multiple testing were considered when evaluating the results of the analyses.

Model checking and validation

All analyses were undertaken using Stata version 14.2.

Stata coding for the primary analysis was prepared independently and the analyses were cross-checked.

Checks were undertaken to assess the robustness of models, including an assessment of model residual normality and heteroscedasticity.

Changes to the project protocol

Primary outcome measure and sample size

The original protocol featured an internal pilot. During the internal pilot phase, 180 participants were to be recruited over 3 months to provide sufficient information to justify progression to a main trial. Progression from the internal pilot to the main trial was dependent on recruitment rate and engagement with the intervention according to the scenarios in Table 3. In the main trial, an additional 1220 participants were to be recruited, giving a total of 1400 participants (recruited over 16 months).

| Criteria | Scenario 3 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of internal pilot sample size target (180 participants) recruited (%) | < 65 | 65–79 | ≥ 80 |

| Intervention engagement (% participants who access e-coachER at least once) | < 65 | 65–79 | ≥ 80 |

| Proposed action | No progression | Discuss with TSC and funder about progression and resources needed to achieve target | Proceed to full trial |

The recruitment rate during the internal pilot phase was lower than expected as a result of limitations on the time that primary care practitioners had available to approach potential participants, a delayed start at one of the research sites, poor uptake when patients were approached via a postal mailshot and a high ineligibility rate among patients who were identified via a primary care database.

In response to poor recruitment, the following strategies to increase recruitment were introduced in November 2015:

-

The inclusion criterion for BMI was aligned with the ERS entry (upper BMI limit for the trial was originally 35 kg/m2 and was raised to 40 kg/m2), and prediabetes was included as an inclusion criterion.

-

Provision was made for the Birmingham and Plymouth sites to recruit participants via the ERS service (a strategy already in place at the Glasgow site), in addition to recruitment via primary care.

-

Incentive payments to participants (for returning an accelerometer) were increased from a maximum of £40 per participant (£10 at baseline, £10 at 4 months and £20 at 12 months) to a maximum of £60 per participant (£20 at each of the aforementioned time points).

Having implemented these measures, the conditions for progression in terms of recruitment rate and engagement with the intervention were not met by the end of the internal pilot phase, despite a 4-month extension period. A ‘recovery plan’ was developed in collaboration with the funders, based on amending the choice of primary outcome.

The original primary outcome was achievement of at least 150 minutes of MVPA measured objectively by accelerometer over 1 week at 12 months. This outcome was based on the findings of a systematic review of ERSs14,54 demonstrating that trials had primarily reported their outcomes according to percentage of participants reaching the NICE guidelines for PA level (i.e. 150 minutes of MVPA per week). We estimated that recruiting 700 participants per group would allow us to detect a difference at 12-month follow-up of at least 10% (intervention group 53% vs. control group 43%), assuming an attrition rate of 20% and small effect of clustering (intracluster correlation coefficient 0.006) at 90% power and 5% alpha. Thus, the original sample size was 1400 participants to be recruited over a 16-month period.

From the outset, the TSC and DMC had recommended that this dichotomous primary outcome measure be replaced with a continuous variable (i.e. total weekly minutes of MVPA). This was because:

-

A continuous primary outcome measure would be more relevant in this study population, in terms of detecting a small but clinically significant increase in minutes of MVPA.

-

Based on sample size calculations, this would offer greater statistical power than to the categorical assessment of whether or not participants reach a threshold of 150 minutes of MVPA. This would therefore afford a reduction in sample size.

The TSC and funders agreed to these changes (in August 2016) and the original sample size was reduced in accordance with this new primary outcome measure and revised sample size calculation, from 1400 to 413 participants (to be recruited over 21 months). A similar reduction in sample size was incorporated into the qualitative component of the process evaluation work.

The primary outcome was subsequently specifically defined as total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts recorded objectively by accelerometer over 1 week at 12 months, in participants with activity recorded for at least 16 hours per day on at least 4 days, including 1 weekend day.

Capture of exercise referral scheme attendance data

Initially, uptake of the ERS was solely self-reported, captured via an e-mailed survey at approximately 4 weeks and a postal questionnaire at 4 months. Owing to poor compliance (especially at 4 weeks), data were sought from the ERS service providers, in addition to the self-reported data. Participants consented to the ERS service sharing their attendance data for the purposes of the trial.

Omission of Short Form questionnaire-12 items data analysis

Owing to an error in the compilation of the participant self-report questionnaire booklet, the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) data collected could not be analysed in this study. We had intended to administer the SF-12 version 2 at each of the study time points but it transpired that a number of the response options for SF-12 version 1, instead of SF-12 version 2, had been printed in the questionnaire booklet in error.

Chapter 3 Trial results: quantitative results

Participant recruitment

A total of 450 participants were recruited (randomised) to the trial over a 20-month period (3 September 2016 to 10 April 2017).

Table 4 shows the number (%) of participants who entered the trial by referral source (i.e. by mailout from the GP or opportunistically in primary care, at the point of initial contact with the ERS providers, or by word of mouth or community advertisement) across the different sites.

| Referral source | Site, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plymouth | Birmingham | Glasgow | ||

| ERS | 38 (25) | 109 (71) | 141 (100) | 288 (64) |

| Primary care | 102 (66) | 45 (29) | 0 (0) | 147 (33) |

| Self-referral | 15 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (3) |

| Total | 155 (100) | 154 (100) | 141 (100) | 450 (100) |

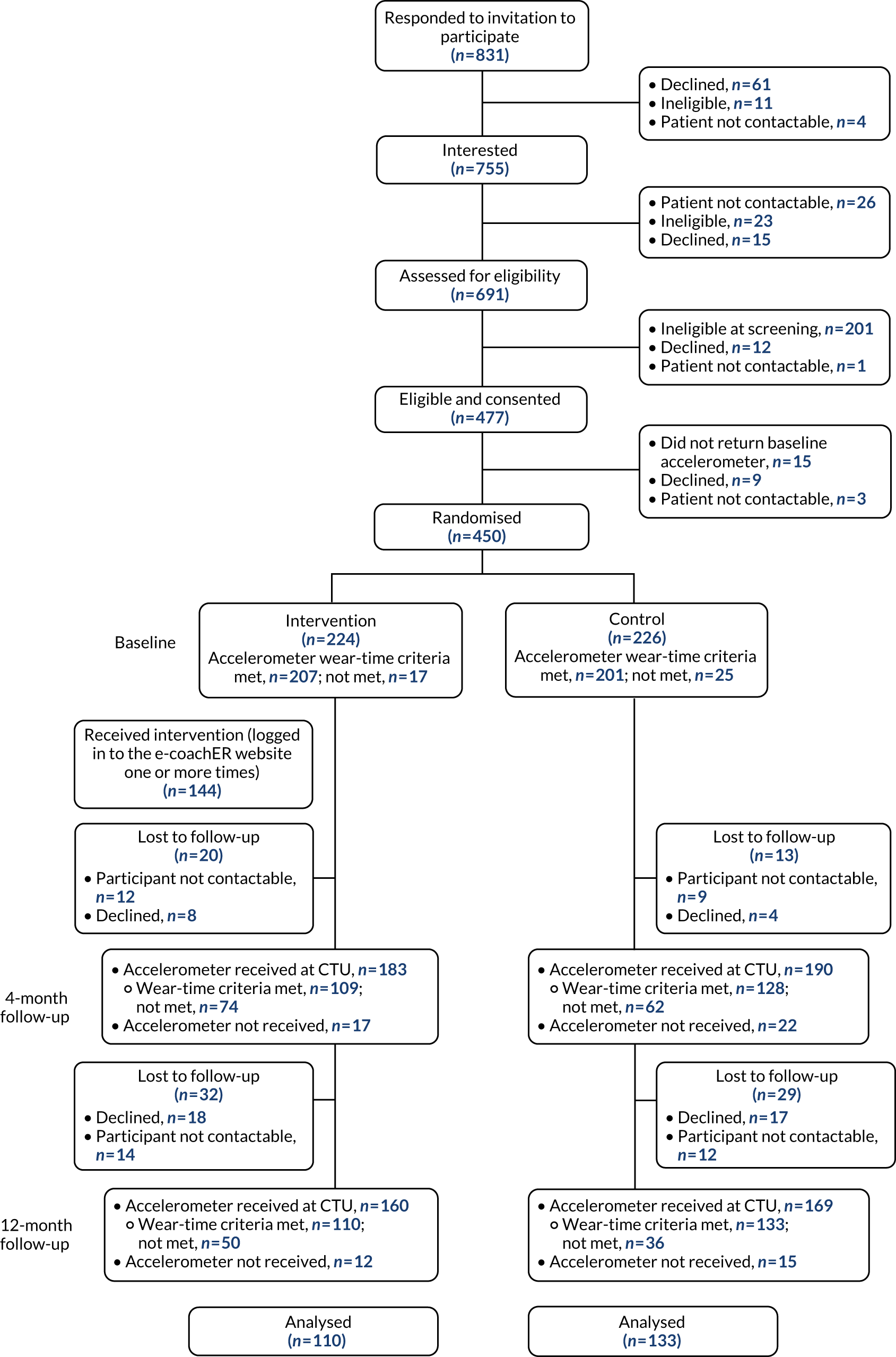

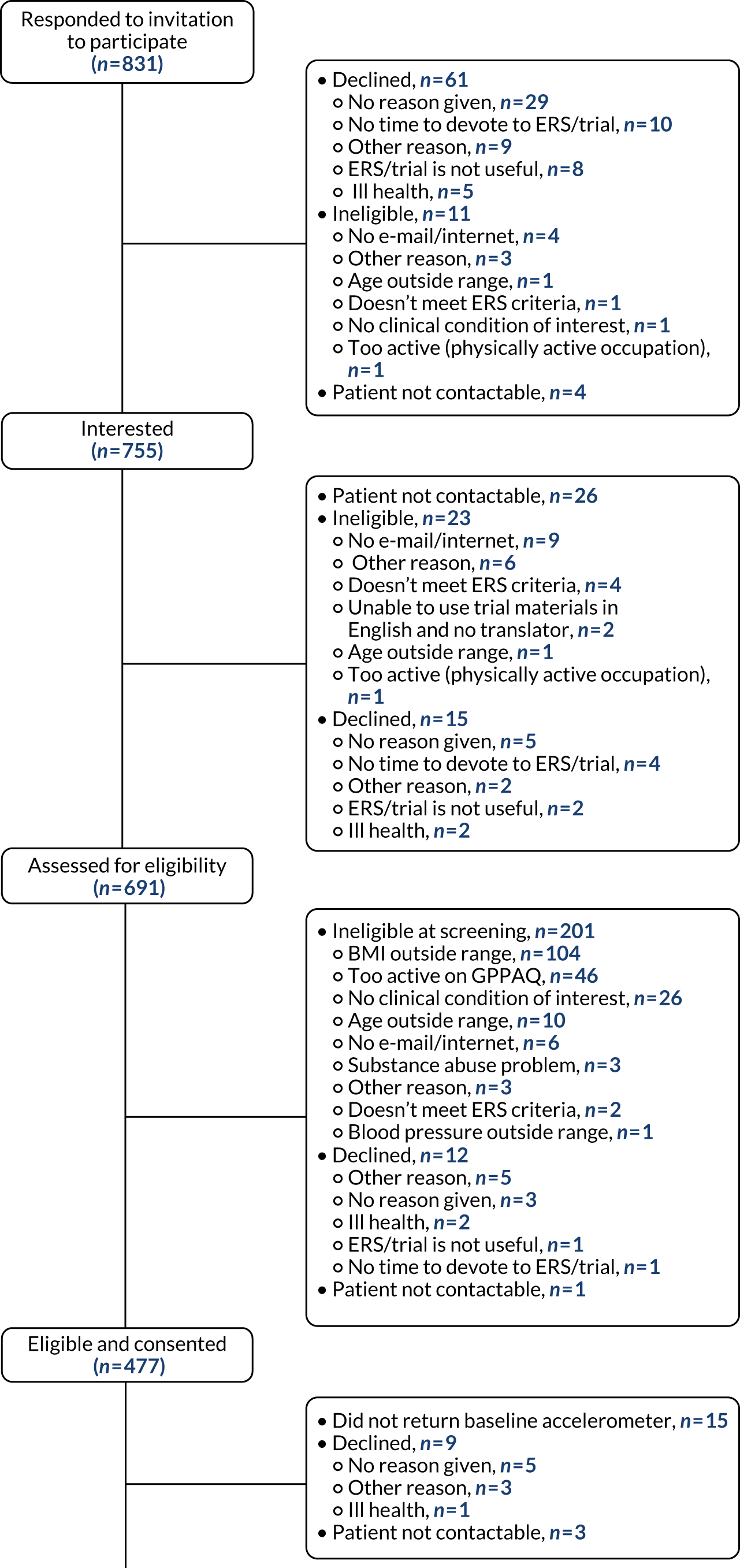

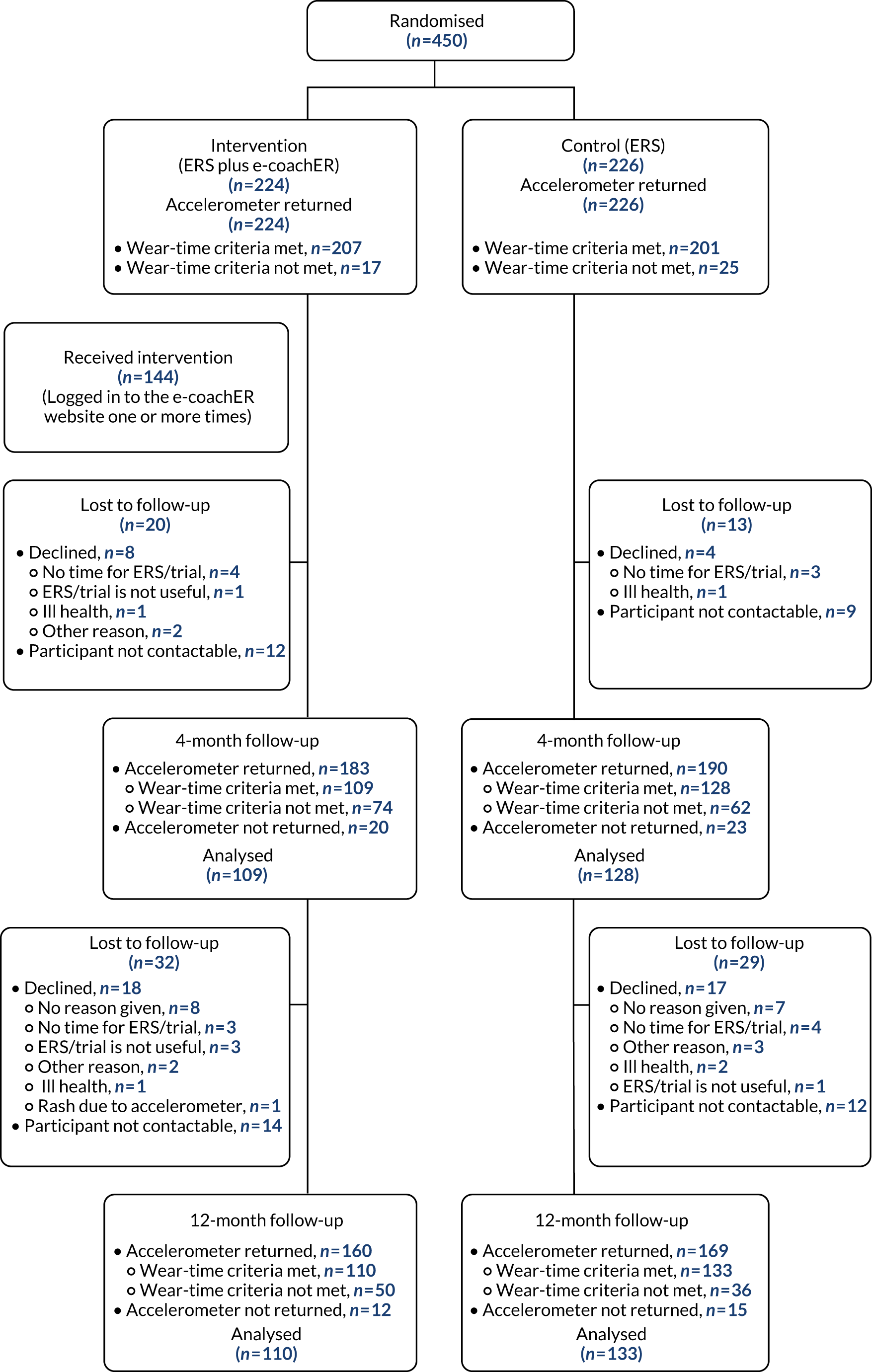

Flow of participants in the trial

Figure 4 shows the flow of participants through the trial. Of those expressing an interest in participating, 477 (63%) individuals were eligible. The main reasons for ineligibility were BMI being too high (n = 104, 14%), being too active according to the GPPAQ (n = 47, 6%) and clinical condition of interest not being present (n = 26, 3%). An additional 27 individuals (4%) could not be contacted following their expression of interest. A detailed CONSORT flow diagram is given in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 4.

Participant flow.

Baseline comparability

The baseline characteristics of the whole sample (n = 450) and those who were included in the primary analysis (n = 232) are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. The groups were well balanced.

| Variable | Control group | Intervention group | Both groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 226 | 224 | 450 |

| Gender, n male (%) | 84 (37) | 76 (34) | 160 (36) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) [range] | 51 (14) [18–75] | 50 (13) [20–73] | 50 (12) [18–75] |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) [range] | 32.5 (4.4) [18.8–40.5] | 32.7 (4.5) [18.8–40.4] | 32.6 (4.4) [18.8–40.5] |

| Requirement for translator for trial purposes, n (%) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (1.3) |

| GPPAQ score, n (%) | |||

| 2 (inactive) | 144 (63.7) | 149 (66.5) | 293 (65.1) |

| 3 (moderately inactive) | 82 (36.3) | 75 (33.5) | 157 (34.9) |

| Participant’s perception of any medical reason(s) for referral to ERS – prevalence, n (%) | |||

| Prediabetes | 8 (4.0) | 15 (7.7) | 23 (5.8) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 47 (20.8) | 42 (18.8) | 89 (19.8) |

| Osteoarthritis | 64 (28.3) | 45 (20.1) | 109 (24.2) |

| Weight loss | 182 (80.5) | 182 (81.3) | 364 (80.9) |

| Low mood | 122 (54.0) | 121 (54.0) | 243 (54.0) |

| High blood pressure | 79 (35.0) | 68 (30.4) | 147 (32.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 195 (86.3) | 179 (79.9) | 374 (83.1) |

| Black Caribbean | 3 (1.3) | 8 (3.6) | 11 (2.4) |

| Black African | 3 (1.3) | 6 (2.7) | 9 (2.0) |

| Black other | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.8) | 5 (1.1) |

| Indian | 4 (1.8) | 12 (5.4) | 16 (3.6) |

| Pakistani | 7 (3.1) | 4 (1.8) | 11 (2.4) |

| Bangladeshi | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Chinese | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 13 (5.8) | 10 (4.5) | 23 (5.1) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 78 (34.5) | 78 (34.8) | 156 (34.7) |

| Married | 97 (42.9) | 110 (49.1) | 207 (46.0) |

| Civil partnership | 5 (2.2) | 2 (0.9) | 7 (1.6) |

| Divorced or dissolved civil partnership | 35 (15.5) | 25 (11.2) | 60 (13.3) |

| Widowed or surviving civil partnership | 11 (4.9) | 9 (4.0) | 20 (4.4) |

| Domestic residence status (live with), n (%) | |||

| Live alone | 59 (26.1) | 48 (21.4) | 107 (23.8) |

| Partner | 120 (53.1) | 130 (58.0) | 250 (55.6) |

| Parent | 11 (4.9) | 13 (5.8) | 24 (5.3) |

| Child aged < 18 years | 66 (29.2) | 67 (29.9) | 133 (29.6) |

| Child aged ≥ 18 years | 39 (17.3) | 53 (23.7) | 92 (20.4) |

| Other family | 10 (4.4) | 8 (3.6) | 18 (4.0) |

| Non-family | 9 (4.0) | 12 (5.4) | 21 (4.7) |

| Education status, n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 52 (23.0) | 29 (12.9) | 81 (18.0) |

| GCSEs | 146 (64.6) | 162 (72.3) | 308 (68.4) |

| A level | 71 (31.4) | 96 (42.9) | 167 (37.1) |

| First degree | 36 (15.9) | 54 (24.1) | 90 (20.0) |

| Higher degree | 22 (9.7) | 20 (8.9) | 42 (9.3) |

| Other | 108 (47.8) | 104 (46.4) | 212 (47.1) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Smoker | 34 (15.0) | 32 (14.3) | 66 (14.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 90 (39.8) | 89 (39.7) | 179 (39.8) |

| Never smoked | 102 (45.1) | 103 (46.0) | 205 (45.6) |

| IT literacy level, n (%) | |||

| Low | 36 (16) | 35 (16) | 72 (16) |

| High | 190 (84) | 189 (84) | 379 (84) |

| Site, n (%) | |||

| Birmingham | 78 (34) | 76 (34) | 154 (34) |

| Glasgow | 69 (31) | 72 (32) | 141 (31) |

| Plymouth | 79 (35) | 76 (34) | 155 (35) |

| Participant-reported main reason for referral, n (%) | |||

| High blood pressure | 19 (8) | 18 (8) | 37 (8) |

| Low mood | 42 (18) | 42 (19) | 84 (19) |

| Osteoarthritis | 27 (12) | 26 (12) | 53 (12) |

| Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes | 24 (11) | 25 (12) | 49 (11) |

| Weight loss | 114 (50) | 113 (50) | 227 (50) |

| Variable | Control group | Intervention group | Both groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 124 | 108 | 232 |

| Gender, n male (%) | 44.0 (35.5) | 36.0 (33.3) | 80 (34.4) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) [range] | 52.1 (13.4) [18.0–74.7] | 49.9 (12.9) [20.6–72.9] | 51.1 (13.2) [18.0–74.7] |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) [range] | 32.3 (4.3) [18.8–40.5] | 32.6 (4.9) [18.8–40.4] | 32.4 (4.6) [18.8–40.5] |

| Requirement for translator for trial purposes, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (1.3) |

| GPPAQ score, n (%) | |||

| 2 (inactive) | 82 (66.1) | 70 (64.8) | 152 (65.5) |

| 3 (moderately inactive) | 42 (33.9) | 38 (35.2) | 80 (34.5) |

| Participant’s perception of any medical reason(s) for referral to ERS – prevalence, n (%) | |||

| Prediabetes | 4 (3.7) | 4 (4.3) | 8 (4.0) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 26 (21.0) | 15 (13.9) | 41 (17.7) |

| Osteoarthritis | 40 (32.3) | 22 (20.4) | 62 (26.7) |

| Weight loss | 100 (80.6) | 84 (77.8) | 184 (79.3) |

| Low mood | 65 (52.4) | 57 (52.8) | 122 (52.6) |

| High blood pressure | 47 (37.9) | 38 (35.2) | 85 (36.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 109 (87.9) | 95 (88.0) | 204 (87.9) |

| Black Caribbean | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.8) | 5 (2.2) |

| Black African | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.8) | 5 (2.2) |

| Black other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Indian | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.8) | 4 (1.7) |

| Pakistani | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.7) |

| Bangladeshi | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Chinese | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 6 (4.8) | 4 (3.7) | 10 (4.3) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 40 (32.3) | 37 (34.3) | 77 (33.2) |

| Married | 57 (46.0) | 50 (46.3) | 107 (46.1) |

| Civil partnership | 3 (2.4) | 2 (1.9) | 5 (2.2) |

| Divorced or dissolved civil partnership | 19 (15.3) | 13 (12.0) | 32 (13.8) |

| Widowed or surviving civil partnership | 5 (4.0) | 6 (5.6) | 11 (4.7) |

| Domestic residence status (live with), n (%) | |||

| Live alone | 30 (24.2) | 29 (26.9) | 59 (25.4) |

| Partner | 69 (55.6) | 58 (53.7) | 127 (54.7) |

| Parent | 6 (4.8) | 6 (5.6) | 12 (5.2) |

| Child aged < 18 years | 39 (31.5) | 26 (24.1) | 65 (28.0) |

| Child aged ≥ 18 years | 19 (15.3) | 25 (23.1) | 44 (19.0) |

| Other family | 4 (3.2) | 3 (2.8) | 7 (3.0) |

| Non-family | 3 (2.4) | 6 (5.6) | 9 (3.9) |

| Education status, n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 29 (23.4) | 11 (10.2) | 40 (17.2) |

| GCSEs | 84 (67.7) | 83 (76.9) | 167 (72.0) |

| A level | 39 (31.5) | 50 (46.3) | 89 (38.4) |

| First degree | 18 (14.5) | 28 (25.9) | 46 (19.8) |

| Higher degree | 16 (12.9) | 9 (8.3) | 25 (10.8) |

| Other | 59 (47.6) | 49 (45.4) | 108 (46.6) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Smoker | 13 (10.5) | 12 (11.1) | 25 (10.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 52 (41.9) | 51 (47.2) | 103 (44.4) |

| Never smoked | 59 (47.6) | 45 (41.7) | 104 (44.8) |

| IT literacy level, n (%) | |||

| Low | 17 (13.7) | 14 (13.0) | 31 (13.4) |

| High | 107 (86.3) | 94 (87.0) | 201 (86.6) |

| Site, n (%) | |||

| Birmingham | 43 (34.7) | 34 (31.5) | 77 (33.2) |

| Glasgow | 29 (23.4) | 34 (31.5) | 63 (27.2) |

| Plymouth | 52 (41.9) | 40 (37.0) | 92 (39.7) |

| Participant-reported main reason for referral, n (%) | |||

| High blood pressure | 10 (8.1) | 10 (9.3) | 20 (8.6) |

| Low mood | 15 (12.1) | 22 (20.4) | 37 (15.9) |

| Osteoarthritis | 18 (14.5) | 13 (12.0) | 31 (13.4) |

| Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes | 14 (11.3) | 10 (9.3) | 24 (10.3) |

| Weight loss | 67 (54.0) | 53 (49.1) | 120 (51.7) |

Study attrition

Loss to follow-up

A total of 450 participants were randomised. A total of 94 participants (21% of those randomised) were lost to follow-up: 47 (10%) participants declined to participate further and 47 (10%) participants were non-contactable (see Appendix 2).

There were no differences in age, BMI, gender, IT literacy and educational attainment between participants who were included in the primary analysis and those who were not.

Accelerometer and questionnaire booklet return rates

Accelerometer and questionnaire booklet return rates are given in Table 7. Receipt of the baseline accelerometer at the CTU was a prerequisite for randomisation; therefore, there is a 100% return rate for this accelerometer.

| Time point | Sent to participant (n) | Returned to CTU, n (% of sent) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Total | Intervention | Control | Total | |

| Accelerometer | ||||||

| Baseline | 224 | 226 | 450 | 224 (100) | 226 (100) | 450 (100) |

| 4 months | 203 | 213 | 417 | 183 (90) | 190 (89) | 373 (89) |

| 12 months | 172 | 184 | 356 | 160 (93) | 169 (92) | 329 (92) |

| Questionnaire | ||||||

| Baseline | 224 | 226 | 450 | 220 (98) | 220 (97) | 440 (98) |

| 4 months | 204 | 213 | 417 | 166 (81) | 183 (86) | 349 (84) |

| 12 months | 172 | 184 | 356 | 155 (90) | 170 (92) | 325 (91) |

At 12 months, 329 participants returned the accelerometer (return rate of 92%). The wear-time criteria were met by 243 participants, this being 54% of those randomised (Table 8). At this time point, 325 participants returned the questionnaire booklet (return rate of 91%), that is 72% of those randomised.

| Number of valid weekdays | Number of valid weekend days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | |

| 0 | 181 | 181 | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 3 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 18 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 10 | 31 | 47 | ||

| 5 | 5 | 30 | 77 | 16 | 2 | 130 |

| 6 | 2 | 49 | 7 | 58 | ||

| 7 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Total | 203 | 50 | 172 | 23 | 2 | 450 |

In Table 8, purple shading denotes the number of participants meeting the wear-time criteria. A day was ‘valid’ when the accelerometer was worn for ≥ 16 hours on that day. Participants who did not meet the ‘valid’ criterion (n = 181) were 94 participants lost to follow-up prior to the 12-month time point, 60 participants who returned an accelerometer at 12 months but failed to meet the wear-time criteria and 27 participants who remained in follow-up but did not return the accelerometer at 12 months.

Losses to follow-up and non-compliance in returning the accelerometer were balanced across the two trial groups. Failure to meet the wear-time threshold was less consistent across the two trial groups.

Intervention engagement

Table 9 shows the level of engagement in the various steps offered online.

| Stage started | Summary of content | Number (% of 224 in intervention group) |

|---|---|---|

| Did not register | 81 (36) | |

| Step 1 | Quiz on benefits of PA | 144 (64) |

| Step 2 | Support to get active | 133 (59) |

| Step 3 | Encourage self-monitoring of steps | 107 (48) |

| Step 4 | Setting SMART step-count goals for next week | 99 (44) |

| Step 5 | Setting SMART goals for any PA for next week | 96 (43) |

| Goal review | Review goal and personalised feedback | 81 (36) |

| Step 6 | Ways to achieve goals/overcoming barriers (optional) | N/A |

| Step 7 | Overcoming setbacks (optional) | N/A |

The sample was evenly split, with 36% of participants not registering and logging in to e-coachER and 36% progressing through the support to record at least one goal review (i.e. having set a PA goal review, the participant logged back in about 1 week later to record PA against the goal and obtain feedback on the PA achieved against the goal set). Participants were routinely ‘locked out’ of accessing the web-based support to ensure that they did not complete it in one or two visits to the website, and then reminded by e-mail after 1 week to log in and continue with the steps and later record their PA in minutes, set goals and review them. Reaching step 5 involved > 4 weeks of intervention engagement.

Among all participants allocated to the intervention group, the mean number of goal reviews was 2.5 (SD 4.5), with a range of 0–52. Among the 144 participants who registered for e-coachER, they logged in for a mean and median number of times of 14.1 (SD 16.7) and 6, respectively, with a range of 1–101. Of these participants, 81 (36%) completed a goal review; the mean and median number of reviews was 14.4 (SD 13.8) and 4.5, respectively, with a range of 1–52.

Table 10 shows the mean, SD and median time spent during the respective stage (session) for the 144 participants who registered or 81 participants who completed at least one goal review. These data come with the limitation that participants may have left their browser open after some sessions rather than logging off, which leads to an overestimation of time spent. ‘n’ refers to the number of visits used to estimate the descriptive data for the time in sessions 1–5, the number of visits when a goal was first set and the number of sessions when a goal was reviewed.

| Status | Mean (minutes) | SD (minutes) | Median (minutes) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visited steps 1–5 (from 144 participants who registered) | 9.53 | 9.68 | 6.45 | 539 |

| Goal-setting initial session (from 91 participants who set a goal) | 7.81 | 7.54 | 5.92 | 91 |

| Goal review session (from 81 participants doing ≥ 1 goal review) | 4.75 | 5.25 | 3.18 | 1034 |

| Total | 6.47 | 7.45 | 4.08 | 1664 |

On the basis that participants spent approximately 6 minutes logged in for steps (sessions) 1–5, and for 3 minutes for each goal review, for those 144 participants who registered, the total mean and median time that participants spent on steps 1–5 was 24.1 (SD 5.9) minutes and 30 minutes respectively.

For those 81 participants who completed at least one goal review, the overall mean and median time that participants spent doing goal reviews was 43.3 (SD 37.3) minutes and 21 minutes respectively. The 144 participants who registered spent a total mean and median time of 48.4 (SD 41.9) minutes and 36 minutes respectively. The range was 6–186 minutes.

Descriptive data for the primary and secondary outcomes by group and time

The descriptive statistics for the primary and secondary outcomes at baseline and 4- and 12-month follow-up are shown in Table 11 for all participants who provided data.

| Variable | Baseline | 4-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Intervention group | Control group | Intervention group | Control group | Intervention group | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts,a n (mean); SD | 201 (30.2); 105.8 | 207 (31.8); 53.7 | 128 (30.9); 64.5 | 109 (38.4); 74.5 | 133 (18.7); 37.6 | 110 (35.4); 78.3 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Average daily minutes of MVPA,a n (mean); SD | 201 (45.6); 35.6 | 207 (53.1); 35.9 | 128 (46.3); 37.8 | 109 (58.3); 35.9 | 133 (42.6); 30.1 | 110 (51.9); 36.6 |

| Weekly achievement of at least 150 minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts,a n/N (%) | 8/201 (4) | 9/207 (4) | 2/128 (2) | 7/109 (6) | 3/133 (2) | 6/110 (5) |

| Weekly achievement of at least 150 minutes of MVPA,a n/N (%) | 149/201 (74) | 178/207 (86) | 98/128 (76) | 99/109 (91) | 99/133 (74) | 93/110 (85) |

| Weekly achievement of at least 150 minutes of MVPA self-reported, n/N (%) | 83/220 (37) | 77/220 (48) | 94/183 (51) | 88/166 (53) | 76/170 (45) | 76/154 (49) |

| Average daily diurnal inactivity (hours),a n (mean); SD | 199 (1.7); 1.1 | 205 (1.5); 1.1 | 125 (1.4); 1.1 | 109 (1.4); 0.9 | 99 (1.4); 1.0 | 78 (1.5); 1.0 |

| Average daily sleep (hours),a n (mean); SD | 199 (6.8); 1.5 | 205 (6.9); 1.2 | 125 (6.7); 1.3 | 109 (6.7); 1.4 | 128 (6.8); 1.5 | 110 (7.0); 1.5 |

| EQ-5D-5L (Devlin values), n (mean); SD | 216 (0.74); 0.24 | 215 (0.76); 0.23 | 162 (0.72); 0.26 | 148 (0.76); 0.25 | 158 (0.72); 0.26 | 138 (0.73); 0.27 |

| HADS-D, n (mean); SD | 217 (7.6); 4.5 | 214 (7.4); 4.7 | 164 (7.4); 4.8 | 147 (6.0); 4.7 | 156 (7.1); 4.8 | 139 (6.3); 5.1 |

| HADS-A, n (mean); SD | 217 (8.7); 4.6 | 214 (8.6); 5.1 | 164 (8.5); 4.8 | 146 (7.5); 5.0 | 156 (8.4); 4.8 | 139 (7.6); 5.2 |

The groups were well balanced at baseline. Only 4% of participants achieved at least 150 minutes of accelerometer-recorded MVPA (in ≥ 10-minute bouts) over 1 week at baseline and the average weekly minutes of MVPA (not in 10-minute bouts) was 49 minutes, which reflects our success in recruiting inactive or moderately inactive participants with chronic conditions. In contrast, 80% achieved 150 minutes of accelerometer-recorded MVPA without regard for ≥ 10-minute bouts at baseline. Cassidy et al. 55 have also shown lower levels of accelerometer-recorded MVPA minutes when data are processed using ≥ 10-minute bouts compared with bouts of at least 1 minute. This proportion drops to 36% for self-reported MVPA, reflecting the way that the 7-day Physical Activity Recall questionnaire (7-D PAR) measure focuses on only discrete bouts of memorable MVPA. There were also no baseline differences between groups for the EQ-5D-5L and the two HADS scales.

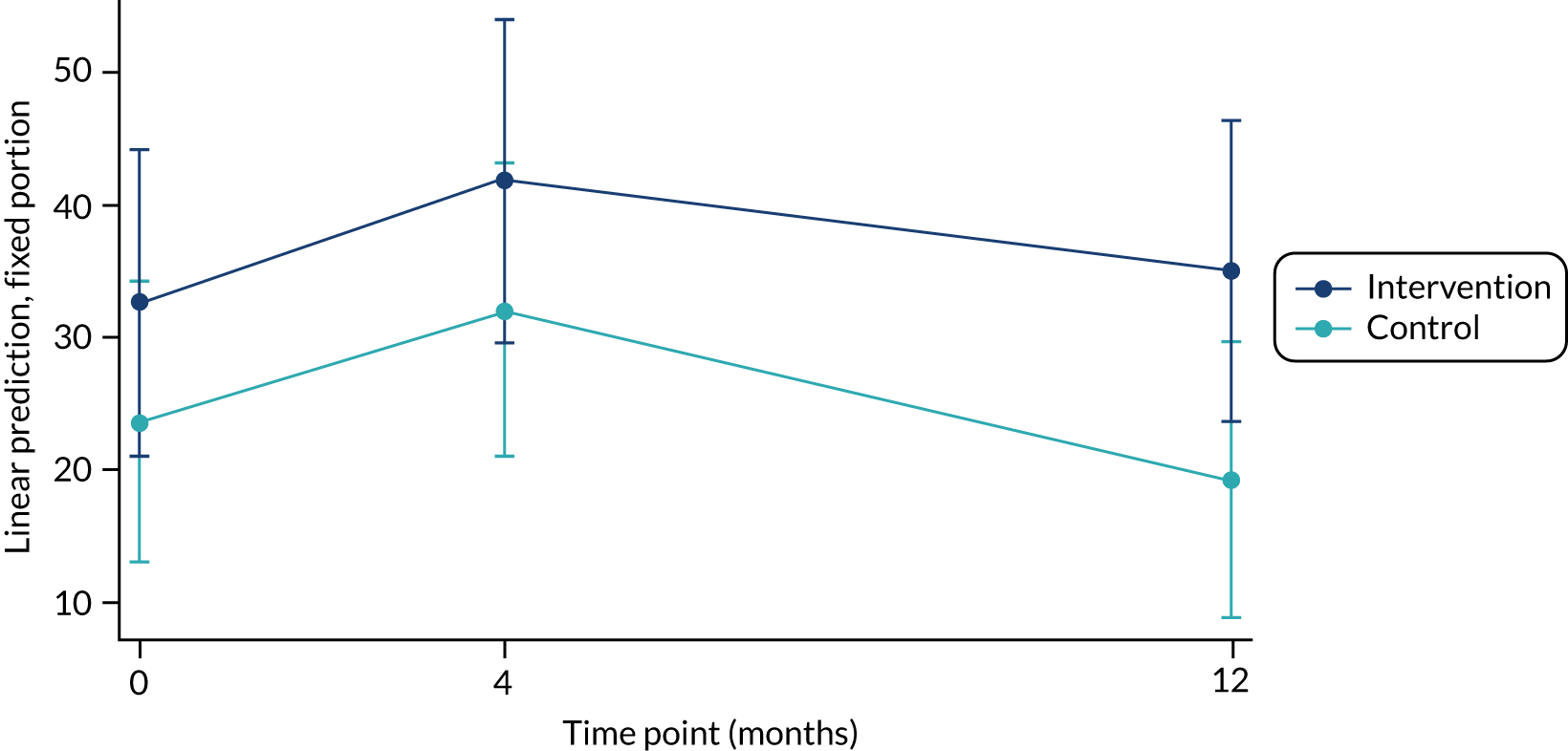

Descriptive data for PA and participant-reported outcomes are also shown in Table 11 for those providing data at baseline, 4 and 12 months by trial arm, without controlling for baseline or other covariates. Qualitatively, the intervention group was more active than the control group at 4 and 12 months for all primary and secondary outcomes. The intervention group also qualitatively had higher well-being (EQ-5D-5L) and lower depression and anxiety scores than the control group at 4 and 12 months.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome, ITT complete-case analysis showed a weak indicative effect in favour of the intervention group in the primary outcome at 12 months (mean difference 11.8 weekly minutes of MVPA, 95% CI –2.1 to 26.0 minutes; p = 0.10) (Table 12). A plot of the repeated-measures model estimates for the primary outcome over time for the intervention and control groups is shown in Appendix 3. Although the alternative model p-values varied somewhat, a similar pattern of results was seen across alternative post hoc models. In interpreting these results, it is important to recognise the limitations of all these models: lack of fit of the predefined primary and post hoc models, and the need to assume data as counts with both negative binomial and zero-inflated binomial models.

| Primary outcome | Primary analysis | Secondary analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITT complete-case comparison at 12 months, n, coefficienta (95% CI); p-value | ITT imputed comparison at 12 months | Complete-case comparison at all follow-up points, p-value for interaction between intervention effect and time | |

| Total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts | 232, 11.8 (–2.1 to 26.0); 0.10b | Not calculated | 0.63 |

| 223, 2.5 (–5.8 to 10.7); 0.55c | |||

| 232, 1.2 (0.8 to 1.5); 0.27d | |||

| 232, RR 1.90 (0.90 to 4.00); 0.09e | |||

| 232, RR 1.59 (1.13 to 2.25); 0.01f | |||

The results of the CACE analysis for the primary outcome were consistent with the ITT results (Table 13). In other words, when controlling for whether or not intervention participants completed a prespecified ‘dose’ of the intervention [i.e. they completed a goal review (reached step 5)], this made no difference to the findings, but qualitatively the difference between the intervention and control groups did appear to be larger (in favour of the intervention).

| Variable | Between-group difference, n, mean difference (weekly minutes) (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|

| Total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts | 232, 22.9 (–3.4 to 47.8); 0.09 |

As Table 14 shows, there was no evidence of any interactions between stratification variables and age and gender with the intervention effect for the primary outcome at 12 months. The ITT complete-case model was adjusted for stratification variables age, gender and baseline scores, and random effects for site and fulfil the criteria of includable PA data.

| Variable | Interaction p-value | Subgroup coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.10 | –0.9 (–1.2 to 0.2)a |

| Gender | 0.91 | |

| Male | 16.7 (–5.2 to 38.7) | |

| Female | 10.3 (–7.8 to 17.9) | |

| Trial site | 0.20 | |

| Plymouth | 4.3 (–15.2 to 23.9) | |

| Birmingham | 19.4 (–9.8 to 48.8) | |

| Glasgow | 9.0 (–9.8 to 27.8) | |

| Participant’s perception of main medical referral reason | 0.33 | |

| Control diabetes | 11.9 (–0.1 to 24.1) | |

| Weight loss | 7.3 (–9.5 to 24.2) | |

| Lower blood pressure | 20.6 (–5.9 to 27.2) | |

| Manage lower limb osteoarthritis symptoms | 21.1 (–8.1 to 32.2) | |

| Manage mood/depression | 25.1 (–32.4 to 82.7) | |

| IT literacy level | 0.59 | |

| Lower confidence | 2.3 (–6.4 to 11.0) | |

| Higher confidence | 13.5 (–2.2 to 29.2) |

Table 15 shows the descriptive data for participants included in the primary analysis (n = 232). Data shown for the 4-month assessment are from participants who were included in the primary analysis and also had complete data at 4 months. The intervention group had qualitatively greater mean weekly minutes of MVPA than the control group at baseline.

| Variable | Baseline | 4 months | 12 months | |||