Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/31/04. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The draft report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Morrison et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Psychosis

The term psychosis is used to refer to a mental health problem that is characterised by a change to a person’s perceptions, beliefs and/or reality testing. This may include experiencing distressing perceptions that are not generated by an external stimulus, for example hearing a voice(s) speaking when another person is not present. It may also include holding fixed and distressing beliefs that others consider unusual: out of keeping with the social or cultural background of that person and lacking rational grounds. The former is typically referred to as a hallucination and may occur in auditory, visual, tactile, gustatory or olfactory sensory domains. The latter is typically referred to as a delusional belief. With regard to delusional beliefs, various types are frequently reported, including ones that are persecutory in nature,1 ideas of reference (seeing personal meaning in innocuous objects or events) and ideas of importance/grandiosity. 2 An individual with psychosis may experience both hallucinatory experiences and delusional beliefs, and sometimes the delusional beliefs will relate to the hallucinatory experiences.

Both the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),3 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),4 recognise hallucinations and delusions to be key features of psychosis spectrum diagnoses, such as schizophrenia. Thought disorder is considered a core cognitive symptom experienced by people with psychosis, involving abnormal features and patterns of speech that can lead to difficulties in communication. 5 Symptoms of thought disorder can be divided into positive (e.g. loosening of associations and illogicality) and negative (e.g. loss of goal and poverty of speech) symptoms. 5

Hallucinations, delusions and thought disorder are commonly referred to as positive symptoms of psychosis, as they are considered to be an additional perceptual or cognitive experience that are an addition to the person’s mental state. Alongside the positive symptoms of psychosis, negative symptoms may occur, which are considered to be the loss or absence of personal functions or characteristics. 6 In the DSM-5,4 negative symptoms are referred to as blunted affect (reduced emotional expressiveness), alogia (reduced/changed ability to have social conversations), asociality (decreased social contact), avolition (reduced energy/drive) and anhedonia (reduced pleasure from activities). 4,7 Negative symptoms, although considered a feature of psychosis and schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses, are also considered to be transdiagnostic and within DSM-54 they feature across diagnoses including bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and autism spectrum disorder. 8 Prevalence rates of negative symptoms vary, often owing to differing definitions,9 from 41% to 57%,10,11 with social withdrawal and emotional withdrawal most commonly reported in one study. 10

Psychotic experiences, such as hallucinatory experiences and delusional beliefs, have been shown to exist on a continuum, with psychosis-like experiences being reported by a significant proportion of the general population. 12,13 However, in the general population psychosis-like experiences may be less concerning for the individual experiencing them; they may be fleeting or transitory and not necessitate help-seeking or require support from services. 12–16 In addition, the symptoms of psychosis feature as part of other mental health conditions, including depression with psychotic features,17 bipolar disorder18 and autism. 19 The early stages of psychosis are sometimes referred to as the prodromal period, which tends to occur for 2–5 years before the onset of psychosis. 20,21 However, the term prodromal can be applied only once psychosis has been confirmed (i.e. retrospectively). A prospective approach is the identification of people who meet the criteria for an ultra high-risk (UHR) mental state. These criteria are commonly applied when state (attenuated psychotic symptoms or brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms) and/or trait factors (family history) for psychosis are present in the presence of a drop in function, indicating that development of psychosis is a risk, but is not inevitable. 22

A person experiencing psychosis may receive either an ICD-103 or a DSM-54 diagnosis, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, non-organic psychosis unspecified or a mood disorder with psychotic features. The DSM-54 criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia require the person to be experiencing two of the following: delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech, grossly disorganised or catatonic behaviour, or negative symptoms such as affective flattening or paucity of thought or speech for at least 6 months (although this can be at an attenuated level, so long as active psychotic symptoms have been present for 1 month). 4 In addition, these experiences must result in a deterioration in social, academic or vocational work and self-care functioning. In other instances, the term psychosis may be used more as an umbrella term, when a person may not have received a diagnosis but is experiencing symptoms that characterise psychosis, as outlined above. In the context of a first episode of psychosis (FEP) and the early intervention in psychosis service philosophy of embracing diagnostic uncertainty in the early phases of psychosis, the term psychosis is often applied in the absence of a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis.

First episode of psychosis in adolescence

FEP typically occurs in young adults. For those with a schizophrenia diagnosis, the age at onset is usually between 15 and 35 years. 23 However, data from community services for FEP in Australia,24 Finland25 and the UK26 indicate that the median age at onset lies between 22 and 23 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 19–27 years. When psychosis occurs before the age of 18 years the term ‘early-onset psychosis’ (EOP) is typically used in the literature. Epidemiological data regarding the prevalence of EOP are limited, and up-to-date estimates are required. 23,27,28 The limited data are partly because of challenges in the collection of epidemiological data on this population, including misdiagnosis,27 reliance on retrospective data and the absence of effective community-based systems for recording incidence from which accurate data can be obtained. 23 However, estimates from available data indicate that the prevalence of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses is 1.6 to 1.9 per 100,000 children and adolescents. 29–31 A useful data source to estimate the prevalence of psychosis in adolescents is the records of services that provide treatment for FEP. Although now somewhat outdated, information from the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) in Melbourne, Australia, which was collected between 1993 and 2000, suggests that just under one-fifth of those accepted into the service were aged ≤ 18 years. 24 Those in the service who were aged ≤ 18 years received a range of diagnoses, as follows: schizophrenia (39.3%), schizophreniform disorder (32.5%), bipolar I (9.4%), other psychoses (13.7%) and schizoaffective disorder (5.1%). Although we have some indication of the prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses in adolescence, data on the epidemiology of more broadly defined psychosis, in which diagnostic uncertainty is embraced, are lacking. Kirkbride et al. 32 used data from ÆSOP (Aetiology and Ethnicity in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses), a large population-based case–control study in three English sites, to examine variability in the incidence of psychotic illnesses across age, sex, ethnicity and site. They applied a broad diagnostic approach to their inclusion criteria, and the 568 people examined in this study included people with individual psychotic symptoms and those who met criteria for DSM-5 psychotic illnesses and schizophrenia subclasses. They found that the incidence rate of psychoses in women peaked between 16 and 19 years of age (in contrast to between 20 and 24 years for men). 32 In another study, Boeing et al. 33 examined data from child and adolescent mental health services, hospital case registers and admission and discharge data from the Scottish Executive in three areas of Central Scotland (covering a population of approximately 1.75 million people). Similarly to Kirkbride et al. 32 a broad diagnostic approach was taken to inclusion in the study, that is participants were eligible if they had ever been in contact with mental health services for a psychotic illness prior to their 18th birthday. The authors found a 3-year prevalence of 5.9 incidences of EOP per 100,000 people in the general population. 33 Boeing et al. 33 report that young people interviewed in their study were experiencing high levels of difficulty in both symptoms and functioning, as well as high levels of unmet clinical and social needs, suggesting the need for a national planning framework to ensure the delivery of assertive and integrative care across mental health, social care and educational/vocational services for young people with psychosis.

A key feature of early intervention in psychosis (EIP) is embracing uncertainty about diagnosis in the early stage of psychosis. 34–36 For this reason, inclusion criteria for EIP services have not specified a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. 37 It has been argued that the early course of psychosis can be characterised by changing symptoms and that application of a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis is difficult unless the person has been unwell for some time. 37 Meta-analysis of reliability of prospective diagnostic stability of FEP diagnoses demonstrates that both schizophrenia spectrum psychoses and affective spectrum psychoses have high prospective stability. 38 However, other FEP diagnoses have low diagnostic stability. 38 The validity of schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses in adolescence has been questioned and, although research indicates that a schizophrenia diagnosis made in adolescence is usually stable, other diagnoses, such as schizoaffective disorder and atypical psychoses, have been shown to have poor predictive validity. 38

Given the risk of stigma and discrimination related to psychiatric diagnoses, concern over false-positive diagnoses has been raised. 14 There is a recognition that embracing diagnostic uncertainty may result in some service users later being given conditions other than psychosis, such as personality disorders or post-traumatic stress disorder. However, McGorry et al. 36 argue that EIP services should ensure sufficient specialisation of staff to address the common needs of FEP service users and that EIP services should transcend traditional diagnostic barriers, reflecting the clinical reality of comorbidity and evolution of symptoms. 36 Although historically embracing diagnostic uncertainty has been part of EIP guidance and policy, there is a challenge for services in ensuring that this is carried out appropriately, that is not misattributing organic psychosis or drug-induced or subclinical experience of psychotic phenomena. 14 Marhawa et al. 39 note that EIP service users very frequently experience comorbid mental health problems and/or are in the process of normal developmental, educational or vocational transitions at the time of presenting to services. This combination of factors can make it challenging to assess service users’ needs while embracing diagnostic uncertainty,40 as do the realities of service provision in the context of limited resources and service boundaries and transitions. Harm caused by stigma, discrimination and the adverse effects of antipsychotic (AP) medication has led to concern that inaccurate inclusion of young people in EIP, who may later go on to be diagnosed with a mental health problem other than psychosis, is a risk of adopting a diagnostic uncertainty approach to identifying FEP. 14 This complexity may be compounded in young people, in whom the prevalence of unusual perceptual experiences is high, and differentiating psychosis from other conditions that are neurodevelopmental, organic or mental health-related may be difficult. 14,40

Personal, social and economic costs of psychosis in adolescence

Adolescence is a time of significant biological, cognitive and social development. People who develop psychosis in adolescence generally experience poorer long-term outcomes than those who develop psychosis as an adult. 28,41 In particular, the probability of full remission is lower, and the long-term outcomes poorer, among those who receive a schizophrenia diagnosis before the age of 18 years. 41,42 A systematic review of 21 studies of long-term functional outcomes among people who develop psychosis in adolescence found that schizophrenia diagnoses were associated with a significantly higher rate of poor outcomes than those with other psychotic disorders. 41 In addition, 50–60% of people with early-onset schizophrenia diagnoses had poor outcomes. 41 Premorbid difficulties and developmental delays are considered to be important predictors of long-term outcomes for those who develop psychosis in adolescence, as demonstrated by findings from two systematic reviews41,43 and one non-systematic review. 44 The most recent and comprehensive review, published by Diaz-Cadeja et al. ,43 utilised outcome data from longitudinal studies of participants with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (ICD-9 or ICD-10) diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic diagnoses that was made before the age of 18 years. A number of factors were found to be associated with a poorer outcome across clinical, cognitive and/or biological outcomes, including premorbid difficulties, higher symptom severity at baseline (in particular negative symptoms) and a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP). 43 Of concern, there is some indication that those who develop psychosis in adolescence may have longer DUPs. 24 The higher prevalence of negative symptoms and premorbid difficulties seen in those who develop psychosis in adolescence leaves young people at a greater risk of poor long-term outcomes. 43,45

People with psychosis often face public stigma and discrimination, and in adult psychosis populations the incidence of anticipated, experienced and internalised stigma has been shown to be high. 46,47 Many young people report that their experiences have been made worse by stigma and the negative stereotypes of psychosis that are reported by the media. 45 Indeed, research has indicated that young people who meet UHR criteria, even before the onset of psychosis, report internalised stigma that is associated with depression. 48

The risk of suicide and suicide attempts may be higher in adolescents with psychosis in young people with other mental health conditions. In one Swedish cohort,49 the long-term risk of suicide was 4.5% and the risk of attempting suicide was 25%. In the USA, data gathered from 102 young people admitted to an adolescent inpatient unit between 2003 and 2006 showed that, overall, those with psychosis had twice as many suicide attempts as those with other mental health conditions. 50

Adolescent-onset psychosis and schizophrenia are associated with significant economic costs. Young people with psychosis and schizophrenia accounted for 25% of adolescent psychiatric inpatient admissions in England and Wales between 1998 and 2004. 51

Although the evidence base for the personal and social costs points to worse outcomes for those who develop psychosis in adolescence than for those who develop psychosis in adulthood, there is some evidence to counter this. In a long-term follow-up of service users with a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis who received care from the EPPIC early intervention service, those who developed psychosis in adolescence had significantly better global, social, occupational and community functioning and less severe positive symptoms than those who developed psychosis in adulthood. 52

Service structure for the treatment of a first episode of psychosis in adolescence

In the UK, any adolescent aged ≥ 14 years who develops a FEP is eligible to receive treatment from EIP services. However, young people with psychosis may also receive care from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) both in the community and in psychiatric inpatient settings.

Early intervention in psychosis

The early treatment of psychosis is considered as essential for recovery, and research indicates that those who receive support from an EIP service have better outcomes than those who receive standard care. 53 As noted, this may be particularly indicated for young people, in whom the long-term effects of a delayed DUP on functioning are indicated to be higher.

Early intervention in psychosis services were first established in the UK in 2001, with the aim of providing holistic, evidence-based, biopsychosocial care for people aged 14–35 years with a FEP and their families. 53 For this reason, EIP services are a key provider of care for young people with a FEP. The structure of EIP services has been influenced by the World Health Organization (WHO)-endorsed consensus statement from the International Early Psychosis Association, which set standards and goals for the early intervention, detection and treatment of psychosis. 54 The objectives of the early psychosis declaration (EPD) were to increase access and care for people with FEP, raise awareness of the importance of early intervention, promote recovery, engage families and offer them support, and train primary care practitioners to both recognise psychosis and understand the importance of early detection of psychosis. The EPD sets out the values and ethos of EIP services, which are to promote recovery and hope by focusing on personal, social, educational and employment outcomes, reducing stigma and respecting the strengths of service users and their families.

Working with families is an essential component of EIP,54 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline [CG number 155 (CG155)]55 explicitly recommends family intervention (FI) to be delivered for all families of young people with psychosis. Unfortunately, the rate of delivery of FI is often low and, in the UK, an audit of EIP services found that 69% of families had not been offered FI in the first 6 months following acceptance into EIP services, and, where FI was offered, there was a relatively low uptake of 38%. 56 A systematic review57 of the literature on the barriers to and facilitators of implementing FI suggests that a number of factors may influence families’ interest in FI, including whether or not they identify as a caregiver, the relevance of the support offered to their needs, a desire to keep their family experiences private and the offer of FI being made after their family member’s psychosis had resolved. 57 The review also highlights that families require flexibility in FI in regard to the length, location and type (individual FI vs. group) of delivery. Furthermore, the review highlights that specific family needs should be considered, such as working hours and diversity in language and ethnicity. The same review reported that for EIP service staff a key concern was access to appropriate training, qualifications, supervision and resources to deliver FI. 57

Duration of untreated psychosis is associated with a number of functional outcomes,58 with positive symptoms58 and suicidality59 and reducing DUP as priorities for EIP services. An analysis of care pathways to EIP services found that people who received mental health support from CAMHS in the first instance had a substantially longer DUP and longer delays in access to EIP services than people who had received support initially from psychiatric hospitals or home-based treatment teams. 60 This indicates that an effective interface between EIP services and CAMHS is required to minimise treatment delay and avoid the adverse affect of a long DUP on prognosis for adolescences with psychosis.

Since the inception of EIP services in the UK, a number of guidance documents have been produced to inform EIP service delivery and practice. A total of 14 policy documents that were produced by the Department of Health and Social Care, the NICE and the Initiative to Reduce the Impact of Schizophrenia network were published between 2001 and 2016. 34 Thematic analysis of these documents indicates that the values set out by EPD are maintained as central to the delivery of EIP services; the core themes across these 14 policy documents are ethical practice (respect for informed consent, privacy and confidentiality), inclusivity (equal access to the service and reducing stigma and discrimination), being patient and family centred and providing appropriate recovery-orientated treatment (avoiding overuse of diagnosis, shared decision-making, responsibility and cost-effectiveness). 34

In 2016, an audit of EIP services reported that there were 56 EIP services established across England. 56 In 2015, the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health was commissioned by NICE and NHS England to develop a guide to the introduction of access and waiting time standards for EIP services. 37 The access and waiting time standards apply to people aged 14–65 years with a FEP. Eight standards have been set out for EIP services, which include allocation and engagement of people with confirmed or suspected FEP within a 2-week period of referral, offer of cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp), FI and educational and support programmes for carers, supported employment programmes, physical health assessments and interventions, and clozapine (Clozaril®, Mylan Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Canonsburg, PA, USA) prescribing. The 2016 Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership audit56 of the access and waiting time standards found that the proportion of people with FEP who had access to the NICE standards was low across many of the domains, but that it was particularly low in relation to engagement and assessment within 2 weeks, access to physical health assessments and interventions, and access to psychological interventions (PIs). In addition, the audit highlighted that there was considerable variation across the country in what was offered to service users.

Joint working between early intervention in psychosis services and child and adolescent mental health services

Child and adolescent mental health services are commissioned to provide care for young people up to the age of 18 years, and this includes young people with psychosis. 61 The NICE CG (CG155)55 recommends that primary care services make an urgent referral to either CAMHS (up to the age of 17 years) or an EIP service (aged ≥ 14 years) that has a consultant psychiatrist with training in child and adolescent mental health. The literature on the prevalence of psychosis cases in CAMHS is limited, so estimates are difficult to obtain. However, in 2011, audit data from Rethink (London, UK)62 indicated that just under half of the CAMHS teams who completed the survey were working with young people with psychosis who were aged < 18 years. CAMHS is structured in four tiers, with increasing complexity and specialism at each tier, as follows: non-mental health specialists working in the community with children (tier 1), CAMHS specialists in community primary care settings with children who experience mild mental health difficulties (tier 2), CAMHS specialists in multidisciplinary community child psychiatry outpatient settings (tier 3) and highly specialised CAMHS clinicians working in outpatient teams, day units or inpatient settings (tier 4).

UK policy for the treatment of psychosis stresses the importance of good communication between EIP services and other service providers, such as CAMHS, in ensuring appropriate assessment. 55 Examples of effective joint working include the provision of CAMHS psychiatry and prescribing for EIP service users aged ≤ 16 years; provision of EIP psychiatry for young people transitioning from CAMHS to adult mental health services (AMHS); input into CAMHS by EIP service team members, including training and attendance at CAMHS team meetings; and employment of FI therapists to work across CAMHS and EIP services. 62 Research conducted with UK primary care trusts (PCTs) and Strategic Health Authorities suggests that joint working is most effective when CAMHS and EIP service staff engage in joint training/education to align their philosophies, and that senior support from PCTs and Strategic Health Authorities is required to facilitate effective working. 62 Although there is evidence of effective working, a report published by Rethink62 found that 67% of EIP staff reported that they did not have training to work with 14- to 16-year-olds and 64% did not have training to work with 16- to 18-year-olds, and half of the EIP teams reported that CAMHS was not a source for identification of psychosis.

There is evidence to indicate that some young people may experience the transition from CAMHS to AMHS, such as EIP services, as an abrupt change that feels poorly planned. 63,64 Research has found that young people report largely negative experiences of the transition from CAMHS to AMHS, citing factors including feeling underprepared for the change in care provider, feeling abandoned by services and being unhappy with the quality of care received. 63–65 A recent Education Policy Institute report66 obtained data from 47 out of 60 CAMHS in England on their current waiting times for assessment and treatment. In 2017–18 the average median waiting time for treatment was 60 days. Waiting times varied substantially across the country, with the 10 CAMHS teams with the longest median waiting times to treatment reporting figures of 82–188 days in 2017–18. The authors concluded that there is still a postcode lottery in the access to time treatment from CAMHS. 66 Specifically, in relation to EIP services, several challenges have been reported in relation to joint CAMHS/EIP service working, including different philosophies,67 role confusion68 and different funding sources. 69 Although having separate EIP services and CAMHS is common across the UK, it has been argued that a unified service should be offered for young people up to the age of 25 years given the high risk of mental health issues starting between the ages of 15 and 25 years. 69 There are examples of such services developing in the UK, such as Forward-Thinking Birmingham (Birmingham, UK), which is an integrated service covering the age range 0–15 years including EIP.

Interventions for the treatment of a first episode of psychosis in adolescence

Access to evidence-based interventions for adolescents with psychosis is paramount. To date, the mainstay of research and treatment for psychosis in adolescence has been AP medication, with a limited number of studies of psychological treatments for people with psychosis who are under the age of 25 years. To understand the efficacy and safety of both pharmacological and psychological interventions, a number of helpful systematic reviews have been published that shall be considered here, along with updates to the literature following publication of these reviews. 70,71

Pharmacological treatment

Antipsychotic medication prescribing for young people with psychosis is increasing72 and, typically, AP medication is the main treatment available for adolescents with psychosis. 71 In the UK, NICE CG (CG155)55 recommends that for children and young people with FEP oral AP medication should be offered, and that the decision about the choice of AP medication should be made in collaboration with the young person and their parents/carers. 55

A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the topic of AP treatment of psychosis in young people have been published. 70,71 In relation to current treatment practice in the UK, the NICE CG (CG155) was informed by the systematic review and meta-analysis published by Stafford et al. 71 This review identified 19 studies of AP medication, seven of which were placebo-controlled trials and 12 of which were head-to-head trials. A meta-analysis was conducted on the seven placebo-controlled trials, with a total sample size of 1094 participants and a mean age of 15.5 years (range 15.4–20.0 years). The drugs that were compared with placebo were quetiapine (Seroquel®; AstraZeneca UK Ltd, Cambridge, UK), aripiprazole (Abilify®; Actavis Ltd, Dublin, Ireland), risperidone (Risperdal®; McGregor Cory Ltd, Bracknell, UK), paliperidone (Invega®; Janssen: Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, Beerse, Belgium; and Cilag AG, Schaffhausen, Switzerland), amisulpride (Solian®; Delpharm Dijon, Quetigny, France), olanzapine (Zyprexa®; Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and haloperidol (Haldol®; Ortho McNeil, Raritan, NJ, USA). Results of the meta-analysis showed small benefits of AP medication over placebo for positive and negative symptoms, depression and psychosocial functioning and large effects for global symptoms. However, data quality across the studies was considered poor and the authors highlight that the placebo groups also improved substantially.

A more recent systematic review and network meta-analysis identified 28 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of AP medication for children or adolescents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or schizophreniform disorder published from 1976 to 2017. 70 The total number of participants across the 28 RCTs was 3003, with a median age of 14.41 years (range 7.7–18.3 years). In total, the studies included in the network meta-analysis provided data on 17 AP medications but the most frequently studied were haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine. Results of the pairwise meta-analyses revealed that, compared with placebo, the following AP medications were significantly more effective in reducing overall symptoms: olanzapine, risperidone, lurasidone (Latuda®; AndersonBrecon Ltd, Hereford, UK), aripiprazole, quetiapine, paliperidone and asenapine (Sycrest®; Schering-Plough Labo N.V., Heist-Op-Den-Berg, Belgium). Results of the network meta-analysis indicated that clozapine was superior to all other AP medication for total, positive and negative symptoms. After clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone had the greatest effect sizes of –0.74 and –0.62, respectively. However, as olanzapine was associated with the highest weight gain, the authors recommended that it should be avoided in children and young people. Network meta-analysis revealed that haloperidol, trifluoperazine (Stelazine®; Mylan NV, Canonsburg, PA, USA), loxapine (Loxapine succinate®; Mylan) and ziprasidone (Geodon®; Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) were not more effective than placebo, and the authors recommended that these drugs should not be used in children and adolescents. Findings from this systematic review and network meta-analysis suggest benefits of AP medication over placebo (except for haloperidol, trifluperazine, loxapine and ziprasidone) and provide useful data to inform decision-making regarding the selection of AP medication and their relative superiority in comparison with each other. However, it should be noted that network meta-analysis relies on the use of indirect as well as direct evidence, and for clozapine the majority of the evidence was indirect. Krause et al. 70 also note limitations to the quality of data, with 50% of the RCTs providing inadequate information about the randomisation procedures and 75% not providing adequate information about allocation concealment. It should also be noted that inspection of the included studies indicates that 7 out of the 28 studies did not use either DSM or ICD-10 diagnostic criteria in application of clinical diagnoses; rather, the studies report that the diagnostic criterion was clinical diagnosis. This may draw into question the homogeneity of the participants included in the studies and the generalisability of the findings.

A review of the literature indicates that since publication of the systematic review and network meta-analysis by Krause et al. 70 two further trials of AP medication for young people with psychosis have been conducted. 73,74 The Tolerability and Efficacy of Antipsychotics (TEA) trial,74 conducted in Denmark, was a head-to-head, double-blind RCT comparing the safety and efficacy of quetiapine-extended release (ER) with aripiprazole in 12- to 17-year-olds with an ICD-10 schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. The total sample size, across seven university clinics, was 133 (55 allocated to quetiapine-ER and 58 to aripiprazole). The primary outcome was a positive Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score at 12 weeks, and the results of the trial indicated that there was no significant difference between medications in the primary outcome. However, in both groups positive PANSS scores significantly reduced from baseline to 12 weeks, by approximately 5 points, which is a modest reduction in PANSS score given that the minimum clinically important difference is thought to be about 15 points. 75 Quetiapine-ER and aripiprazole had differing adverse effect profiles. The Quetiapine-ER group had worse metabolic outcomes than aripirazole, with greater weight gain in the quetiapine-ER group. Furthermore, an analysis of the homeostatic model of insulin resistance favoured aripiprazole. However, there were significantly more cases of akathisia and sedation in the aripiprazole group. The number of adverse events (AEs) was high in both groups. In the quetiapine-ER group, the following percentages of AEs were reported: 79% experienced tremor, 92% had increased duration of sleep, 78% experienced orthostatic dizziness, 80% experienced depression, 69% experienced tension/inner unrest, 76% experienced failing memory and 87% experienced weight gain. In the aripiprazole group, 91% experienced tremor, 71% had increased duration of sleep, 81% experienced orthostatic dizziness, 77% experienced depression, 88% experienced tension/inner unrest, 77% experienced failing memory and 68% experienced weight gain. The results of the trial contribute to the relatively limited literature on head-to-head comparisons of AP medication for adolescents with FEP. However, concern has been expressed about the quality of this trial, including the limitations on the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the efficacy and safety given that one-third of participants were prescribed AP medication in addition to those being studied. 76 In the same year as the TEA trial, Correll et al. 73 published a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal-design trial of oral aripiprazole maintenance treatment. In this study, all 201 participants were cross-titrated to oral aripiprazole and were stabilised on this medication for 17–21 weeks before randomisation in a 2 : 1 ratio to either oral aripiprazole or placebo. The results showed that treatment with oral aripiprazole was associated with a significantly longer time to exacerbation of symptoms of psychosis than treatment with placebo. Interestingly, the rate of serious treatment-emergent adverse effects (TEAEs) and discontinuation because of TEAEs was lower in the medication arm, although not significantly so. 73

Adverse effects of pharmacological treatment

Antipsychotic medications are associated with a wide range of adverse effects, which include metabolic effects (i.e. weight gain), cardiovascular effects, hyperprolactinaemia, antimuscarinic side effects (dry mouth, blurred vision and cognitive impairment), sexual dysfunction and movement disorders. 77 The adverse effects of AP medication are associated with increased stigma, physical morbidity and mortality, poor adherence to medication and reduced quality of life. 77 A systematic review78 of the effects of AP medication on brain volume in adult populations concluded that some of the structural brain changes found in people with a schizophrenia diagnosis may be the result of AP medication. When considering the risk of adverse effects of AP medication for young people, there are biological differences between adolescents and adults that are important to consider. 79 Adolescence represents a time of social and educational change. Medication side effects may affect important educational milestones. The stigma of taking an AP medication may be challenging for a young person’s relationships. Compared with adults, young people may be more susceptible to the adverse effects of AP medication,80 particularly in relation to weight gain. 81 A study by Correll et al. 82 showed that 12 weeks of AP treatment in children and adolescents who had less than 1 week’s prior AP exposure was associated with significant rates of obesity and new-onset categorical glucose and lipid abnormalities. For example, a weight gain of > 7% occurred in 56% of participants taking quetiapine and in 84% of participants taking olanzapine. 82 Krause et al. 70 make an explicit recommendation that this medication should not be used in young people. Moreover, there is an indication that weight gain is associated with high rates of medication discontinuation. 71 In 2016, the NICE CG (CG155)55 was updated to include specific recommendations in relation to olanzapine, advising clinicians who are choosing between olanzapine and other AP medications to discuss with the young person and their parents or carers the increased likelihood of greater weight gain with olanzapine, and that this is likely to happen soon after starting treatment. 55

Summary of pharmacological treatment

Although there is some evidence to suggest benefits of AP medication over placebo for young people with psychosis,70,71 the quality of the evidence is low. 71 Head-to-head comparisons are limited and inferences are often indirect, which limits the extent to which comparisons can be drawn between AP medication. Study durations are short, which means that the long-term adverse effects of AP medication in young people are unknown. Furthermore, the evidence base for AP medication is significantly limited compared with the larger body of adult-derived data, the risks and benefits may be less favourable for young people and the additional benefit of AP medication over placebo is small. 71

Psychological intervention

Psychological interventions for young people with psychosis are recommended in the UK NICE guideline (GC155);55 specifically, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and FI. The current guidelines suggest that CBT and FI should be offered in conjunction with AP medication. However, if a young person and their parents wish to try PI alone, the NICE CG (CG155) suggests that the care team should advise that PIs are more effective when delivered in conjunction with AP medication, but offer individual CBT and FI if the young person and family wish to pursue that option. In the next sections we will review both CBT and FI, outlining the approaches, the evidence base and potential adverse effects.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Cognitive models suggest that the way that we interpret events has consequences for how we feel and behave, and that interpretations are often maintained by thinking biases and behavioural responses. Cognitive models of psychosis and psychotic experiences suggest that it is the way that people interpret and respond to psychotic phenomena that accounts for distress and disability, rather than the psychotic experiences themselves. 83–85 Key elements of CBT include a shared individualised formulation of the problem that can include reflection on life events that may contribute to the development and/or maintenance of psychosis (such as trauma and deprivation), evaluating unhelpful thoughts and conducting behavioural experiments. 83 Morrison et al. 83 place an emphasis on the importance of a strong therapeutic relationship, normalising information, collaboration between client and therapist and therapy being based on the client’s problem list and idiosyncratic goals. Brabban et al. 86 suggest 10 key ethical considerations for CBT to ensure that it is recovery orientated: (1) collaboration, (2) use of everyday language, (3) acknowledging the historical and developmental context of the client’s difficulties (i.e. adverse life experiences) so as not to minimise the impact of these, (4) evaluating rather than challenging beliefs, (5) applying caution with use of the stress-vulnerability model of psychosis and schizophrenia, (6) validating the client’s experience using a psychological formulation, (7) delivering hope to the client, (8) offering informed choice about engaging with CBT, (9) ensuring that CBT training is extensive and specialist and (10) ensuring that there is access to continued supervision.

Family intervention

As noted above, a FEP often occurs in adolescence, which is a time when young people are typically living with family members. For this reason, families often play a key role in supporting a person who is experiencing psychosis, and the level of support may be greater in early psychosis and when people are younger in age. FI is considered to be a psychoeducational intervention based on the behavioural family therapy and cognitive behavioural approaches. 87 This approach includes an assessment of family understanding and appraisals of presenting difficulties; sharing the emerging psychological formulation and agreeing a problem list and FI goals; psychoeducation to develop a common understanding, including normalising and recovery-orientated information on presenting difficulties; problem-solving; communication skills training; and relapse prevention planning. 88 Families are often given between-session tasks and are encouraged to hold family meetings to support skills practice. 87 Family members are also given information about local services and signposted to support for themselves, where appropriate. The NICE CG (CG155) recommends that FI should be recovery focused; offer support, education, problem-solving and crisis management; and be delivered over 10 sessions to the family and young person (assuming that inclusion of the young person is practical). 55

Efficacy and safety of psychological intervention for adolescents with psychosis

Although there is an established evidence base for CBT in adult psychosis populations,89–92 the availability of studies to determine its efficacy in children and young people is limited. 71,93 In adult populations, meta-analyses show CBT to have small to moderate effects when delivered in combination with AP medication. 89–92 In relation to FI, NICE conducted a review of the literature for FI for adults with psychosis and found that FI reduced the risk of relapse, the risk of hospital admission during treatment and the severity of symptoms both during and up to 24 months following the intervention. 92 To inform the NICE CG (CG155),55 Stafford et al. 71 conducted a systematic review of PIs for the treatment of psychosis and schizophrenia in children, adolescents and young adults. Searching the literature up to July 2013, Stafford et al. 71 identified eight trials of PI, of which seven included a treatment arm with CBT or FI (one trial was of movement therapy vs. dance therapy). However, no trials of PI (i.e. CBT or FI) carried out exclusively in an under-18 population were identified; rather, the studies included in the review included participants up to the age of 25 years (mean age 23.2 years, range 15–24 years). Meta-analysis of the data from these studies indicates no evidence of treatment effects on symptoms and low-quality evidence for the combination of CBT and FI on the number of days to relapse. In addition to the limited evidence base, the quality of studies in under-25-year-olds was questionable, with a risk of detection bias from inadequate concealment of allocation across all studies and four trials at high risk of selective reporting. 71

Since the publication of the review by Stafford et al. ,71 a further review has been produced by Anagnostopoulou et al. 93 that included studies of PIs published up to 2017. The aim of the review was to evaluate the efficacy of PIs for young people with EOP (before the age of 18 years) in relation to positive and negative symptoms, cognitive functioning and psychosocial functioning. The authors included papers in which the study was a RCT and the participants were aged 12–18 years and had received a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. The review identified one controlled trial of CBT versus FI94 and one RCT of a psychoeducational group intervention for adolescents with psychosis and their families,95 both in a strictly under-18-year-old population.

In their pilot controlled trial of CBT versus FI versus treatment as usual (TAU), Browning et al. 94 recruited 30 adolescents with psychosis who had been admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit and allocated them to receive CBT and TAU (n = 10), FI and TAU (n = 10) or TAU only (n = 10). TAU included, as a minimum, medication (although the authors do not specify whether this was AP medication or other mental health medications), a nursing care plan and group-based activities on the unit. CBT was adapted for young people by delivering shorter sessions twice per week. Participants allocated to receive CBT could access 10 sessions. FI comprised five 1 hour-long sessions and was delivered over 4–10 weeks. The study conducted by Browning et al. 94 provides data to suggest that it may be feasible to recruit young people to a study comparing PIs. However, there was a high risk of selection bias owing to the non-randomised design and the numbers recruited were too small to make any inferences regarding efficacy, although there was an encouraging signal from the data that participants in the PIs reported greater satisfaction ratings than those receiving TAU alone.

A secondary analysis of the SoCRATES trial,96 which recruited people with psychosis who had a recent first or second inpatient admission, found that participants under the age of 21 years who had supportive counselling showed significantly greater improvements at 3 months on the PANSS positive, PANSS general and the PSYRATS (Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scales) delusions subscales than those who received CBT or TAU. 97 In addition, among those under the age of 21 years, the therapist-rated therapeutic alliance was significantly poorer in the CBT group than in the supportive counselling group. 97 The authors concluded that PIs for people with early psychosis may need to consider age-related factors. 97 Although these findings contribute to the literature, it should be noted that this is a secondary analysis of the SoCRATES study, which was not designed to evaluate these treatments specifically in young people with psychosis, and so the conclusions that can be drawn are limited.

In their RCT of a group-based psychoeducational intervention for young people with psychosis and their families, Calvo et al. 95 recruited 55 young people and their families and randomly allocated them to either a psychoeducational problem-solving group arm (n = 27) or a time-matched control arm (n = 28). At the end of the intervention, young people in the psychoeducational intervention arm had significantly fewer visits to accident and emergency and lower negative symptom scores than those in the control arm; however, these results were not sustained at 2-year follow-up. 95 The results of this study are a signal that, as with adult populations, FI with adolescent populations and their families may be effective in reducing relapse. However, to our knowledge, the study by Calvo et al. 95 represents the only trial of FI in an under-18-year-old population, and any inferences that can be drawn from this study with a small number of participants is limited.

Overall, there is a paucity of evidence from which conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of CBT and FI for psychosis in children and young people. In producing the UK NICE CG (CG155),55 the guideline development group considered if there were grounds for recommending that treatment with PIs in young people should be any different from that in adults. Given the paucity of evidence for CBT and FI in young people, the guideline development group utilised the data from the much larger adult evidence base to make the recommendation to offer CBT and FI in conjunction with AP medication. CBT trials have been criticised for poor reporting of adverse effects98 and data on the safety of PIs for adolescents are lacking. There clearly remains an important need to address the question of efficacy and safety of CBT and FI for this population.

Psychological intervention in the absence of antipsychotic medication

It has been argued that evidence from meta-analyses of adult psychosis studies demonstrates that the superiority of AP medication over placebo has been overestimated and that the adverse effects of AP medication have been underestimated. 99 For this reason, there has been a growing interest in the efficacy and safety of PIs in the absence of AP medication. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial treatment with a time-limited postponement of AP medication versus initial AP treatment found that psychosocial treatment may be effective in the absence of AP medication, with psychosocial treatment having a small–medium effect size advantage over AP medication. 100 Although the findings from Bola et al. 100 suggest that it is feasible to conduct research into psychosocial interventions in the (short-term) absence of AP medication, the quality of the studies is limited, with only one RCT, and the psychosocial interventions evaluated varied across the studies and represented treatment programmes rather than specific PIs, such as CBT or FI.

In relation to CBT, Morrison et al. 101 demonstrated that it was feasible and safe to recruit adults who chose not to take AP medication to a RCT of CBT and TAU versus TAU alone. Data from this trial showed that CBT may be effective in reducing symptoms in adults who choose not to take AP medication, particularly in participants under 21 years old. However, the trial was not definitive and conclusions about the efficacy of CBT in this population are limited. The COMPARE (Cognitive behaviour therapy Or Medication for Psychosis – A Randomised Evaluation) trial,102 a three-arm RCT for people aged ≥ 16 years with FEP, allocated participants to AP monotherapy, CBT monotherapy or a combination of both treatments. The results showed that over the 12-month follow-up period the PANSS scores were significantly lower in the combined treatment group than in the CBT monotherapy group, but there was no significant difference between AP medication and CBT, or between combined treatment and AP medication. 102 Participants who received CBT monotherapy had fewer non-neurological side effects and less weight gain than those in the AP monotherapy and combined treatment groups, which may indicate that CBT monotherapy leads to fewer adverse effects. 102 However, although one-fifth of participants in the COMPARE trial (15/75) were aged 16–18 years, there are no head-to-head studies of PI versus AP medication in young people and, therefore, no data on which to draw conclusions about the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PI versus AP medication versus a combined treatment in young people with psychosis. 102 The COMPARE trial also did not include FI as a component of the PI.

Summary

In summary, when the UK NICE CG (CG155)55 was produced it was concluded that the available evidence, including that from adult populations, was sufficiently strong to recommend a combination of AP medication, CBT and FI as treatment for young people with psychosis. 88 However, for young people with psychosis, the risk-to-benefit ratio of AP medication appears less favourable, and research is required to establish the potential for psychological treatments alone and in combination with AP medication in this population. Consequently, CG15555 recommends research to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychological treatment alone, compared with AP medication and compared with psychological treatment and AP medication combined. 55

Rationale for the research

In response to the NICE guideline research recommendation, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme put out a commissioned call to answer the question of how feasible it is to conduct a study to examine the effectiveness of PI, AP medication or a combination of the two in adolescents with a FEP. Managing Adolescence first-episode Psychosis; a feasibility Study (MAPS) was commissioned by the HTA programme to answer the research question from this commissioned call.

Chapter 2 Methods

Used with permission from Morrison et al. 103 This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

To answer the question of feasibility we employed both quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Objectives

We had six specific objectives across the main trial and qualitative work to enable a strong understanding of the feasibility of running a definitive trial, as follows:

-

to identify the willingness of clinicians to refer to the trial, the proportion of young people referred who are eligible and are willing to consent to the study, and the proportion of participants who comply with the treatment allocation

-

to assess the rate of attendance at follow-up assessments

-

to identify characteristics of trial participants (to clarify selection criteria)

-

to determine how feasible and acceptable the interventions are for participants, parents and clinicians, and the appropriateness of our treatment protocols

-

to assess the suitability of our randomisation and blinding procedures

-

to determine the relevance and validity of the measures to decide their acceptability for use in a definitive trial.

We also aimed to estimate ranges of sample size parameters, finalise treatment manuals and outcome measures, determine training/supervision requirements for research assistants (RAs) and therapists, and assess the possibility for economies for scale.

Role of the funding source

MAPS (both main trial and qualitative studies) was funded by the NIHR HTA programme following a commissioned call (15/31/04). The call specified the interventions, population, setting, comparator, study design and important outcomes.

Approval

MAPS (both main trial and qualitative studies) was approved by the North West – Greater Manchester East Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 6 February 2017 (reference 16/NW/0893). The trial was also prospectively registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) clinical trial registry (reference ISRCTN80567433) on 27 February 2017.

Patient and public involvement

Two MAPS co-applicants and one user-led researcher provided patient and public involvement (PPI), contributing substantially to numerous facets of the trial. Rory Byrne contributed to the trial participant information sheets and leaflets. Rory Byrne wrote the Plain English summary of the study for the ISRCTN. The nested qualitative study was user led, with Rory Byrne contributing to the development of the topic guide and participant information sheet, and informing the sampling approach and data analysis. Rory Byrne conducted many of the participant, family/carer and clinician interviews. Transcription, coding and analysis of qualitative interviews was led by Rory Byrne with support from Wendy Jones.

Rory Byrne and Wendy Jones attended weekly team meetings in the central site (Manchester) to provide input on processes and issues as they arose. A PPI representative sat on our independent Data Monitoring Committee (iDMC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and contributed to trial oversight and recommendations.

Throughout the course of MAPS, we sought consultation and recommendations on trial processes from the Psychosis Research Unit service user reference group, all members of which have personally experienced psychosis. For example, the service user reference group provided feedback on the outcome measures used in MAPS and documents such as consent forms, participant information sheets and the trial feedback sheet.

Changes to outcomes post trial commencement

Throughout the course of the trial, there were a number of changes to the trial protocol, including changes to the trial outcomes as agreed with our iDMC and TSC. Summaries of these changes are shown in Table 1.

| Amendment number | Date of amendment | Summary of amendment | Date of REC approval | Protocol version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substantial amendment 1 | 22 February 2017 | Objectives in the protocol amended to state that we will:

|

3 March 2017 | V2: 22 February 2017 |

| Substantial amendment 2 | 27 April 2017 |

|

11 May 2017 | V3: 29 March 2017 |

| Substantial amendment 3 | 22 September 2017 | Addition of an educational film about MAPS | 25 September 2017 | V3: 29 March 2017 |

| Substantial amendment 4 | 19 October 2017 |

|

19 October 2017 | V3: 29 March 2017 |

| Substantial amendment 5 | 12 March 2018 |

|

Rejected by the REC on 12 April 2018 | V3: 29 March 2017 |

| Substantial amendment 5 modified | 18 May 2018 |

|

12 June 2018 | V4: 12 March 2018 |

| Substantial amendment 6 | 31 July 2018 |

|

21 August 2018 | V5: 17 July 2018 |

Feasibility randomised controlled trial

Trial design

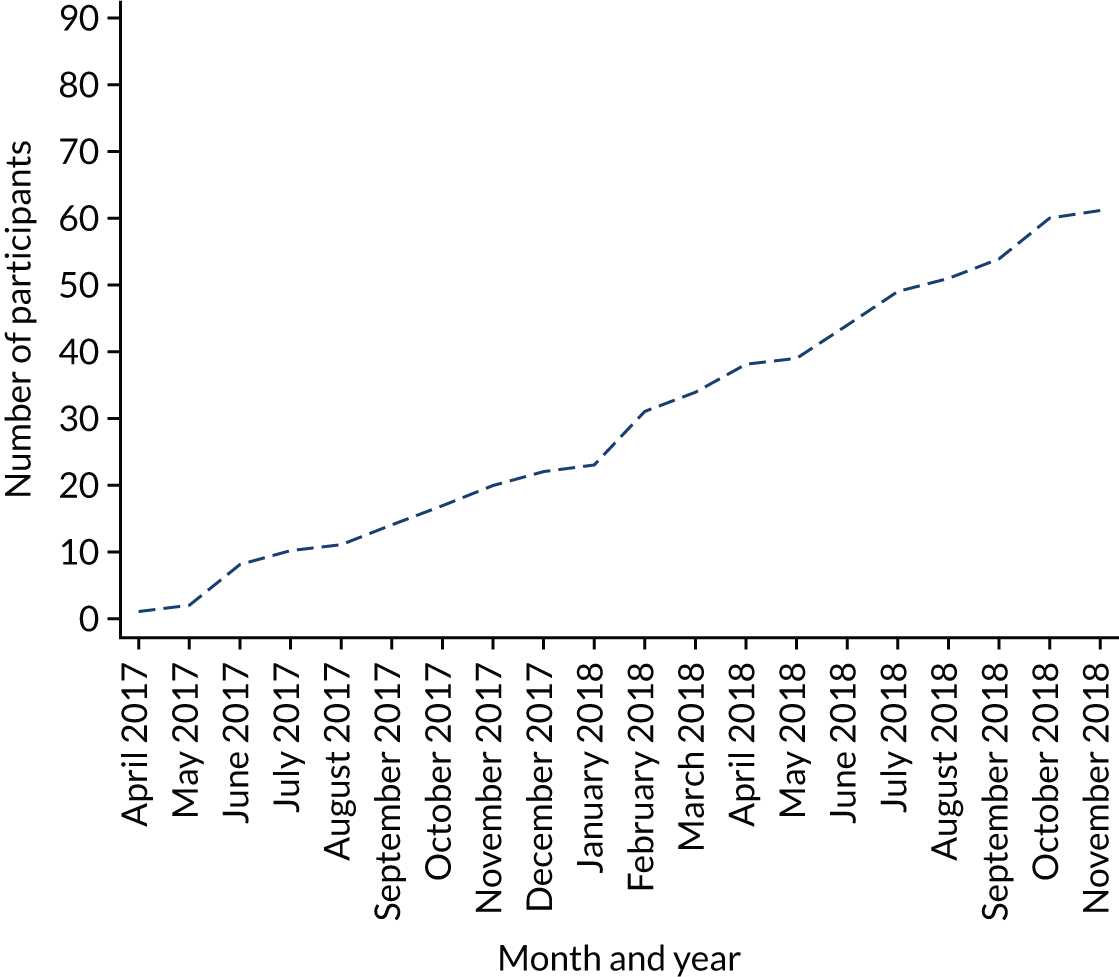

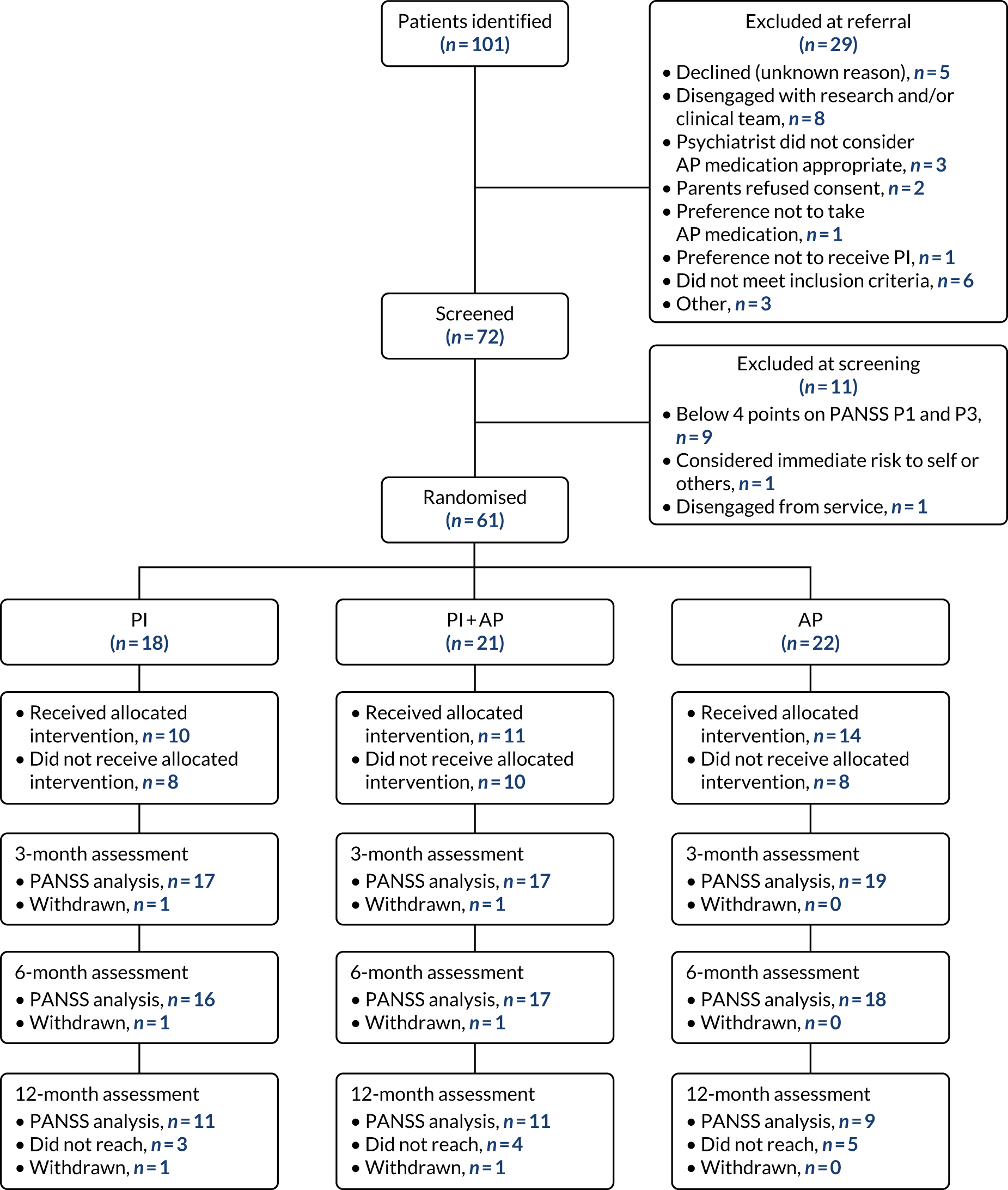

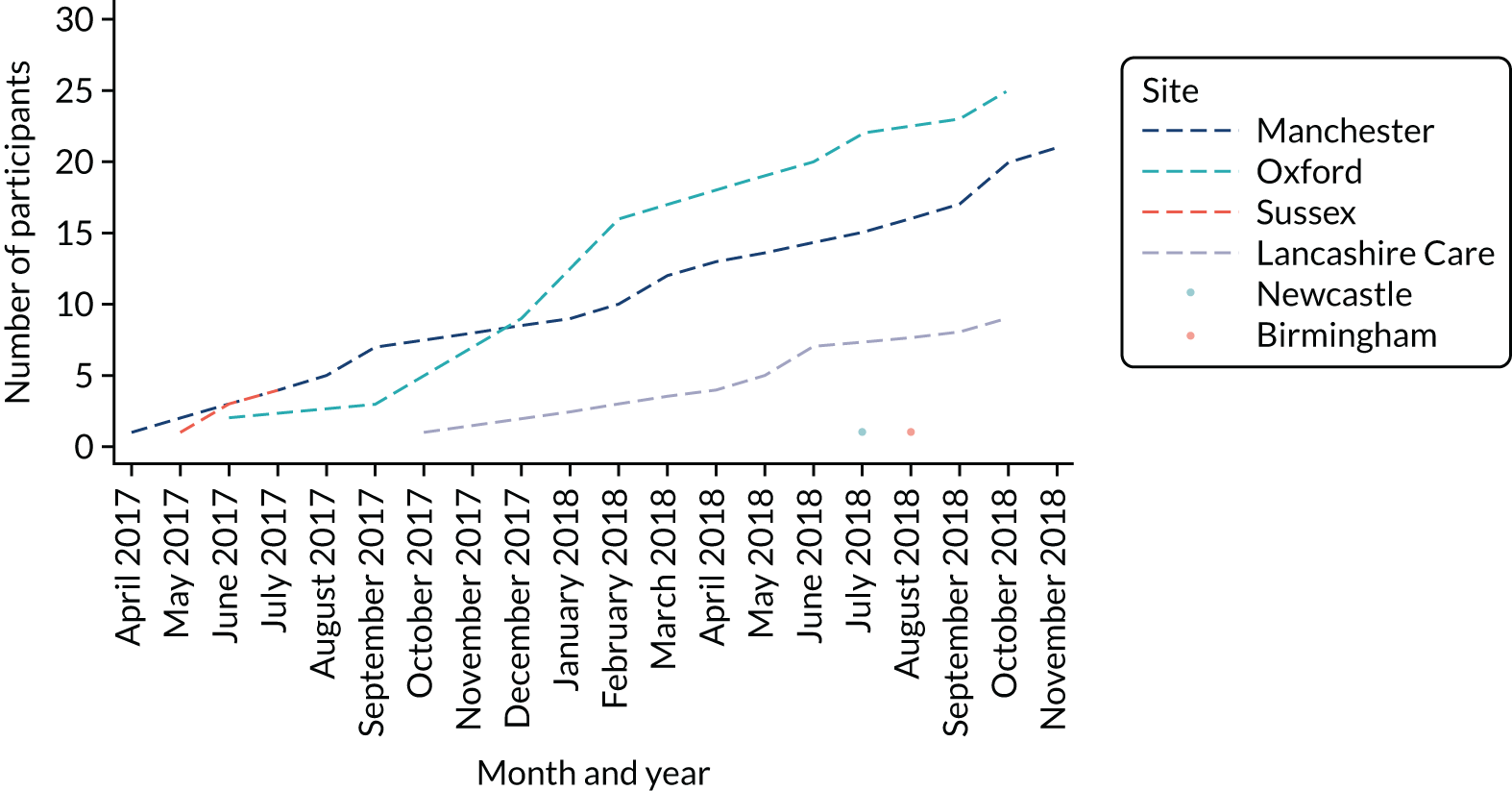

MAPS was a Prospective Randomised Open Blinded Evaluation (PROBE) to explore the feasibility of running a definitive trial of three treatment options for FEP in 14- to 18-year-olds. Participants were allocated in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to receive AP medication monotherapy, PI monotherapy or a combination of both treatments. MAPS was conducted over 27 months across seven UK sites. The recruitment window ran from 1 April 2017 to 31 October 2018. All follow-up assessments were finalised by 31 May 2019. The current REC-approved trial protocol is available at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/153104/#/.

Settings

MAPS was conducted within NHS secondary care mental health services, namely EIP services and CAMHS. The seven UK sites were Manchester (central site); Birmingham; Lancashire; Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire; Norfolk and Suffolk; Northumberland, Tyne and Wear; and Sussex. The study started with four sites: Manchester, Sussex and Oxford all commenced recruitment on 1 April 2017 and Lancashire commenced recruitment on 8 June 2017. The remaining three sites were added in 2018 to determine the feasibility of replicating effective recruitment approaches from the initial four sites. Norfolk and Suffolk commenced recruitment on 9 May 2018, Birmingham on 31 May 2018 and Northumberland on 20 June 2018.

MAPS sites differ considerably in their characteristics, including the levels of urbanisation and deprivation. For example, the 2015 English Indices of Deprivation104 rank Birmingham and Greater Manchester third and fifth, respectively, in having the highest proportions of neighbourhoods that are in the most deprived 10% of areas nationally, whereas Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire have some of the lowest proportions (35th and 38th, respectively, out of 39 Local Enterprise Partnerships).

Participants

Sixty-one participants were recruited from EIP services and CAMHS in six sites: Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire (n = 25 randomisations), Manchester (n = 21), Lancashire (n = 9), Sussex (n = 4), Birmingham (n = 1) and Northumberland, Tyne and Wear (n = 1). No participants were recruited in Norfolk and Suffolk.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included young people who met all of the following criteria:

-

aged 14–18 years (up until their 19th birthday)

-

presented with FEP (defined as being within 1 year of presenting to services with psychosis)

-

under the care of an EIP service or/and CAMHS

-

scored ≥ 4 points on the PANSS105 for delusions and/or hallucinations at the baseline assessment to ensure current symptoms of psychosis

-

met the ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder (as diagnosed by the treating consultant) or met the entry criteria for an EIP service

-

able to provide written, informed consent and if under 16 years old have a parent/guardian willing to provide additional consent for the MAPS team to contact the young person (for ethics reasons).

To ensure that our sample was representative of young people with FEP as a primary problem, we excluded those who:

-

had a diagnosis of ICD-10 organic psychosis

-

had a moderate/severe learning disability

-

had primary alcohol/substance dependence

-

were non-English speaking (to ensure that participants were able to engage in assessments and therapy)

-

scored ≥ 5 points on the conceptual disorganisation item of the PANSS (as above)

-

presented with immediate risk to themselves or others at the time of referral

-

had received AP medication or structured PI within the last 3 months (to ensure treatment naivety).

Exclusion did not include comorbid diagnoses, such as autism spectrum disorders, personality disorders or use of substances (e.g. cannabis or alcohol) (unless this was a primary alcohol/substance-dependence diagnosis, as outlined above).

Data collection

Potential participants were informed of MAPS by a member of their care team and, if interested, were asked for a verbal agreement for basic referral details to be provided to the research team and for a member of the research team to contact them. For people under 16 years of age, the MAPS protocol required the care team member to ask the young person’s parent/guardian to provide verbal consent to be contacted by the research team initially. If verbal consent was provided, the care team member shared with the RA basic referral information for the young person and contact details for the parent. The RA would then contact the young person (aged 16–18 years) or parent (for under-16-year-olds) to describe the study briefly and send them a participant information sheet. Each young person or parent was given at least 24 hours to consider the participant information sheet. If interested, RAs would arrange to meet the young person or parent at their preferred venue [including the individual’s home, school/college, mental health services, general practitioner (GP) surgeries or youth offending services]. If there were any concerns about the individual’s home environment or risk to others, the initial meeting would take place at an NHS site.

At the initial appointment, the RA discussed the participant information sheet with the young person or parent and asked them to reflect on the information, ask questions and raise concerns to ensure that the information was understood. Once the RA and individual were satisfied that all of the information had been provided and understood, they would complete the parent/guardian consent to approach form (parents of under-16-year-olds) or the participant consent form (16- to 18-year-olds). The RA read out each statement on the form to the individual, checked their understanding and asked individuals to sign their initials next to each statement if they agreed with it. Finally, the RA and young person/parent provided their signatures and the date of consent at the bottom of the form. For individuals under 16 years old, once the parent/guardian had provided consent for their child to be contacted about MAPS, the RA could meet the young person to complete the consent form, as described above. All participants, regardless of their age, provided written informed consent to enter the trial.

Following the consent appointment, the RA completed the baseline assessment. RAs were advised to minimise participant burden, that is ideally keep appointments to a maximum of 1.5 hours, avoid multiple appointments for any one time point and prioritise participant choice. It was recognised that for some participants the assessment battery may not be complete in full should the participant choose to decline an assessment or opt for a single appointment. Participants completed the PANSS first, before completing other self-report and physical health measures. Each participant was given a personalised crisis card with details of their care co-ordinator, GP and other crisis support numbers (e.g. Samaritans, Ewell, UK). All participants who attended baseline assessments received £10 for their time and contribution to the research.

We designed a follow-up period of variable length, such that participants recruited in the first 16 months were offered assessments at 3, 6 and 12 months post baseline, and those recruited thereafter were offered assessments up to the end of treatment (6 months). RAs contacted participants or their parents (with the participants’ consent) by telephone to arrange assessments. RAs confirmed and documented ongoing consent with participants prior to completing any measures. RAs began with the PANSS before moving on to the other measures. Participants were given another copy of the personalised crisis card and were compensated £10 at each follow-up appointment.

The RAs telephoned participants at 1.5, 4.5 and 9 months to maintain ongoing contact and engagement with the follow-up appointments, and ascertain any changes in contact details (no clinical outcome data were collected). RAs posted £5 gift cards to participants for their choice of shop after completion of these telephone calls.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Given that MAPS was a feasibility study, our key outcomes for informing a definitive trial were referral and recruitment rates, therapy attendance and medication adherence (including discontinuation rates), and completion of follow-up appointments and questionnaires.

Our iDMC, TSC and funder agreed a three-stage progression criterion to determine how successfully each outcome was achieved and help make recommendations about proceeding to a definitive trial. Recruitment, retention and adherence to PI and AP medication were evaluated and determined as meeting one of three success levels:

-

‘green’ – indicating that progression to a definitive trial is possible without needing to substantially change design or delivery

-

‘amber’ – indicating a need for more resources and/or new ideas for recruiting and retaining participants and supporting treatment adherence

-

‘red’ – indicating that a definitive trial may not be economically viable.

Recruitment success was measured by determining the proportion of the target sample size achieved: green criterion ≥ 80%, amber criterion 79–60% and red < 60%. Retention success was measured by the proportion of participants who completed an end-of-treatment PANSS assessment: green criterion ≥ 80%, amber criterion 79–60% and red < 60%. Satisfactory delivery of adherent therapy was determined by the proportion of participants allocated to PI who received six or more sessions of CBT: green criterion ≥ 80%, amber criterion 79–60% and red criterion < 60%. Satisfactory delivery of AP medication was determined by the proportion of participants receiving an AP medicine for ≥ 6 consecutive weeks: green criterion ≥ 80%, amber criterion 79–60% and red criterion < 60%. It should be noted that we included an AP dose below the limits in the British National Formulary (BNF) given that this is frequently the approach for young people owing to the drugs being licensed for adults.

Secondary outcomes

The RAs collected secondary outcomes from participants via semistructured interviews and self-report measures at each appointment to assess their acceptability and usefulness for inclusion in a definitive trial, rather than assessing the efficacy or safety of treatments. RAs completed the measures in a prioritised order that was agreed by the chief investigator. The measures are described below in order of priority.

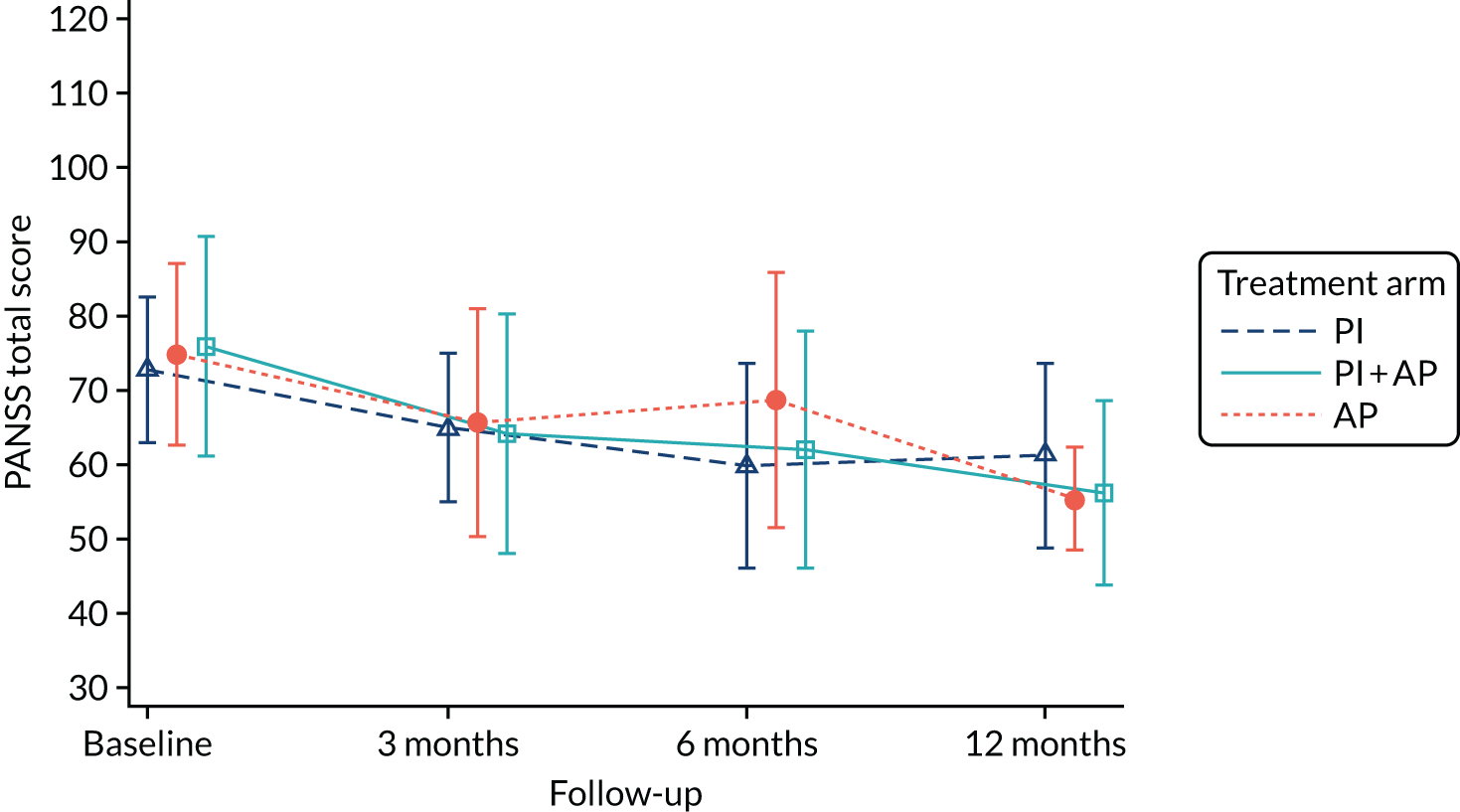

Symptoms of psychosis

Symptoms of psychosis, as assessed by the total score on the PANSS,106 are our provisional choice of primary outcome measure for a definitive trial, although quantitative and qualitative data from this trial will help inform the final decision. The PANSS is a semistructured assessment administered by interview that assesses the severity of symptoms experienced by people with psychosis. PANSS score is a commonly used primary outcome measure in studies of treatment for psychosis spectrum difficulties, which enables comparability with other relevant trials and inclusion of our results in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as appropriate. The PANSS has 30 items that are scored from 1 (‘absent’) to 7 (‘extreme’). Seven items pertain to positive symptoms (e.g. delusions and hallucinations), seven to negative symptoms (e.g. blunted affect and social withdrawal) and 16 to general psychopathology (e.g. anxiety and depression). We used the five-factor PANSS model developed by van der Gaag et al. ,107 which divides the items into five subscales: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, disorganisation, excitement and emotional distress. This model has been found to be more stable and represent a more complex factor model than those previously published.

Demographic information

We developed a brief demographic questionnaire that participants were asked to complete at each assessment. The questionnaire required participants to select statements that best characterised their gender, highest level of education, current employment status, marital status, living arrangements, ethnicity and religion/belief; participants were also asked to report their date of birth.

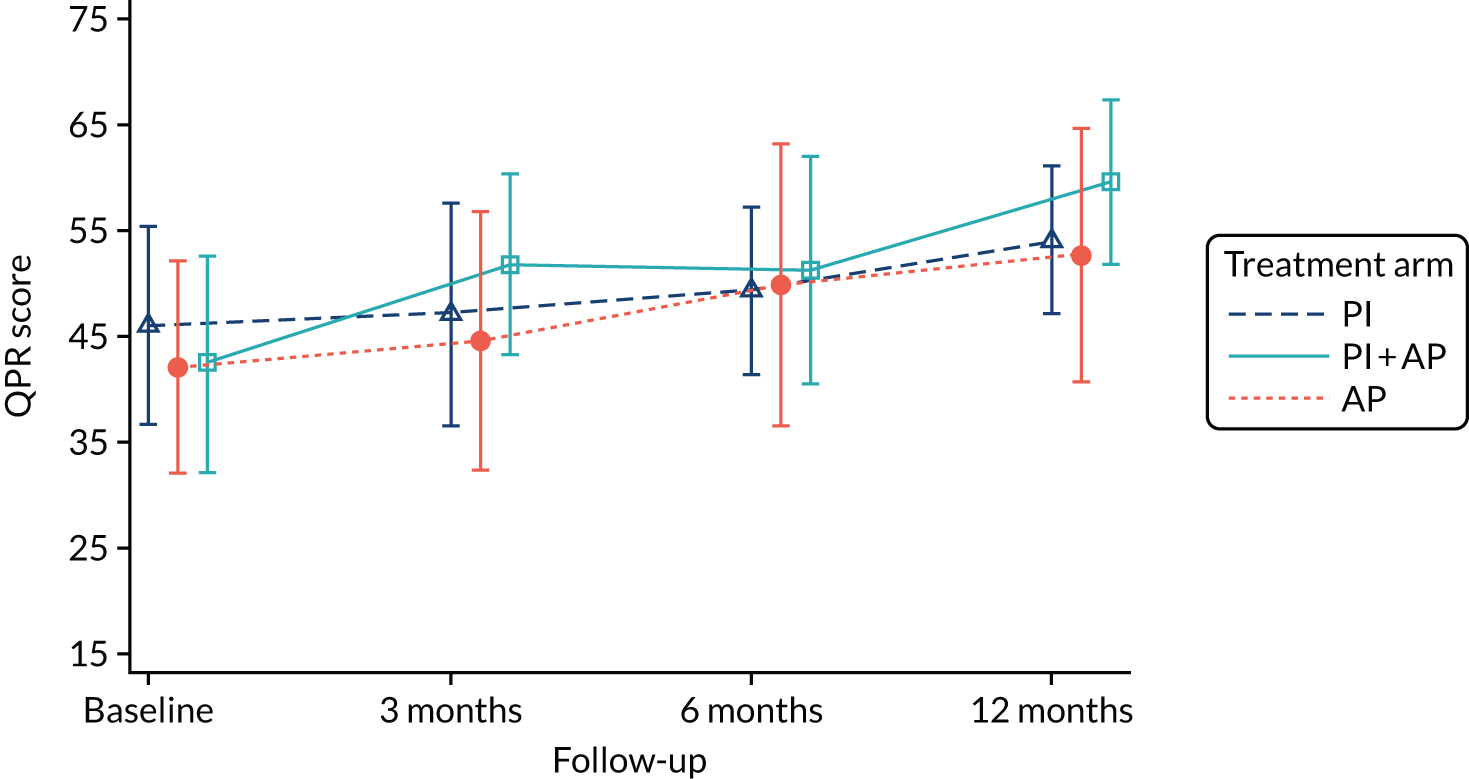

Recovery

We used the shortened 15-item version of the Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR),105 which was developed collaboratively with service users to assess recovery from psychosis. Participants respond to the statements (such as ‘I feel that my life has a purpose’) on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, according to their experiences in the last 7 days.

Duration of untreated psychosis

At the baseline appointment only, RAs completed a semistructured interview with participants to identify when symptoms of psychosis began and when they first sought help. DUP was operationalised as the number of months between the emergence of symptoms and the date participants received CBTp/AP medication from their clinical service or were randomised into the trial (if they were treatment naive).

Anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)108 is a reliable, valid measure of anxiety and depression symptoms over the past 7 days. Statements include ‘I feel tense or wound up’ and ‘I feel cheerful’. Participants rate the frequency/intensity of their symptoms using one of four multiple-choice response options for each of the 14 statements. Anxiety and depression scores are calculated separately.

Social and educational/occupational functioning

The First Episode Social Functioning Scale (FESFS)109 was developed for use with people with FEP. It has good reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. The FESFS assesses nine areas of functioning: ‘Living skills’, ‘Interacting with people’, ‘Friends and activities’, ‘Intimacy’, ‘Family’, ‘Relationships and social activities at work’, ‘Work abilities’, ‘School relationships and social activities at school’ and ‘Educational abilities’. Participants are asked to rate their perceived capability and frequency of engaging in these areas using four-point scales (e.g. from totally agree to totally disagree or from never to always). Higher scores correspond to better social and educational/occupational functioning.

Autism spectrum disorders

At the baseline appointment only, participants completed the 10-item version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ-10),110 which is recommended by NICE to measure diagnostic symptoms for autism spectrum conditions in young people. Participants respond to statements including ‘I find it difficult to work out people’s intentions’ on a four-point scale from ‘definitely agree’ to ‘definitely disagree’. The scoring instructions provide a threshold score that indicates a possible need for a specialist autism assessment.

Health economic data

We used an economic patient questionnaire that was adapted from previous studies conducted by the authors111,112 to gather information about the types of health and social care services used by participants and the frequency of their contact with these services. We also used the EuroQol-Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), health status questionnaire, a valid measure of health outcomes in people with a schizophrenia diagnosis. 113 Participants are asked to rate their mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression on the present day on a five-point scale from no problems to extreme problems.

Substance use

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was developed by WHO114 and is a reliable measure for people with FEP. 115 Participants respond to 10 statements about their alcohol use habits, with predefined answers scored from 0 to 40. Higher scores correspond to more severe alcohol use problems. The scale includes threshold scores for dangerous drinking habits. Participants also completed the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST). 116 Participants responded ‘yes/no’ to the 10 items, including ‘Are you always able to stop using drugs when you want to?’.

Dimensions of psychosis experiences

Participants completed the Specific Psychotic Experiences Questionnaire (SPEQ),117 which was developed for use with young people. It has five subscales each containing 8–15 items, which assess paranoia, hallucinations, cognitive disorganisation, grandiosity and anhedonia. Participants are asked to rate their belief in or frequency of experiences from predefined response options. Each subscale is scored separately, with higher scores corresponding to more severe symptoms.

Measurement of adverse events and potentially unwanted effects of trial participation

We used a number of methods to ensure a rigorous approach to recording and reporting adverse physical health effects, adverse and serious adverse events (SAEs), and potentially unwanted effects of trial participation throughout participants’ time in the trial, described in detail below.

Adverse effects of medication

At each assessment, RAs completed the Antipsychotic Non-Neurological Side Effects Scale (ANNSERS)118 with participants. This is a 44-item semistructured interview that determines the presence and severity of side effects associated with AP medication, which are categorised into different subscales including cardiovascular, autonomic and sleep problems. Each item represents a known side effect from AP medication and, if present, is allocated a rating of mild, moderate or severe. Owing to the blind nature of the trial, all participants were offered the ANNSERS interview regardless of allocation. Therefore, RAs were required to rate each item regardless of whether that particular side effect was attributable to AP medication, unless there was a very clear non-medication cause. For example, in the example of a skin rash, if a participant with a known skin allergy to a particular substance reported that only after coming into contact with the known allergen, a score of absent would be applied. Medically trained clinicians on the MAPS team were sought for consultation on scoring when required.

Metabolic side effects

At each assessment, RAs completed physical cardiovascular and metabolic screenings to determine any changes since baseline that may be related to AP medication. RAs measured participants’ height and weight [to calculate their body mass index (BMI)], waist circumference and blood pressure. In addition, RAs took three samples of blood for analysis of total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), triglycerides, prolactin, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG). The blood test results were sent to participants’ psychiatrists (or other responsible clinician) at each time point. If RAs were unable to obtain a blood sample or if the participant declined a test, participants’ psychiatrists were also notified.

Serious adverse events and adverse events

Consistent with Health Research Authority (HRA) guidelines, we determined all of the following as SAEs:

-

death

-

an event that is life-threatening

-

an event that requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

an event that results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

an event that consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

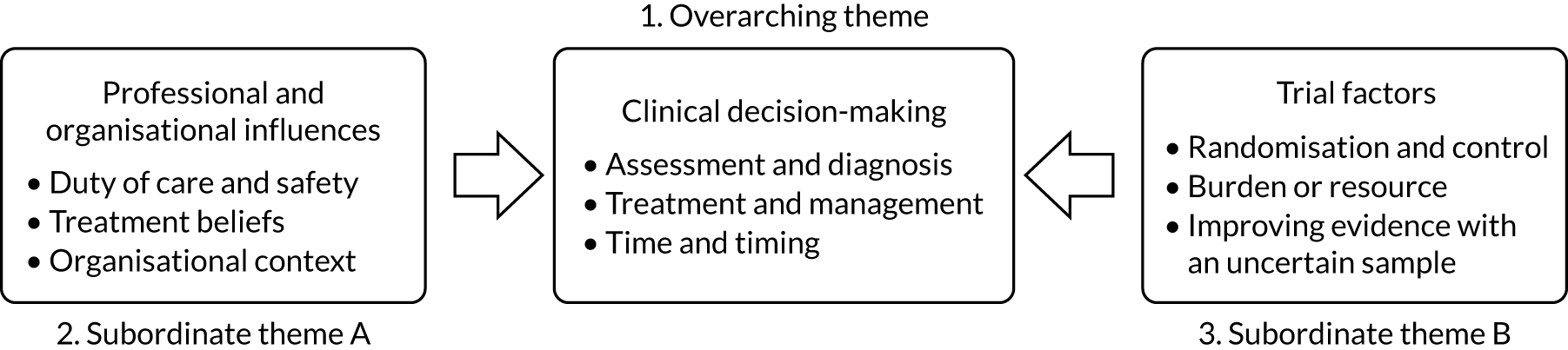

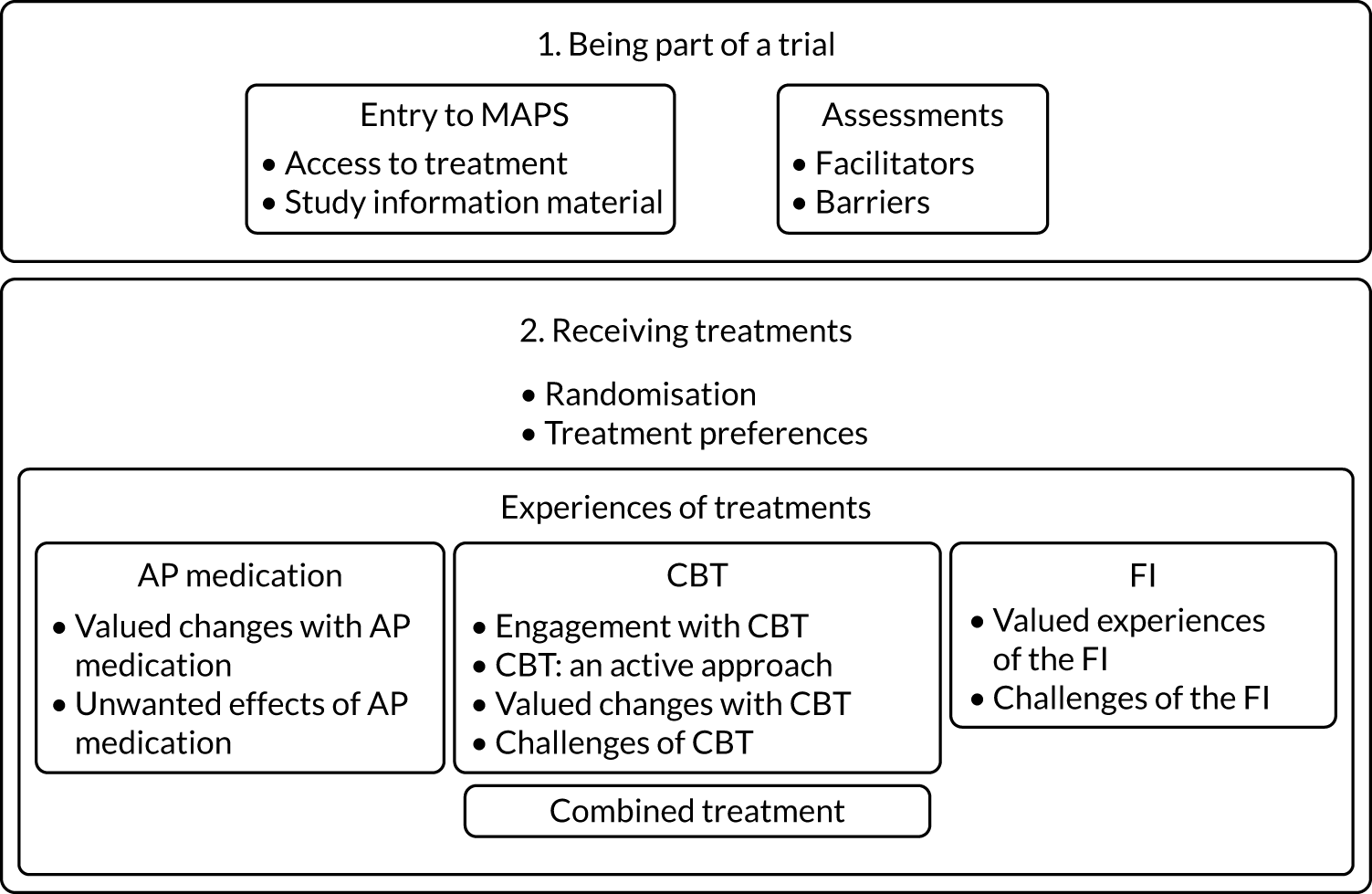

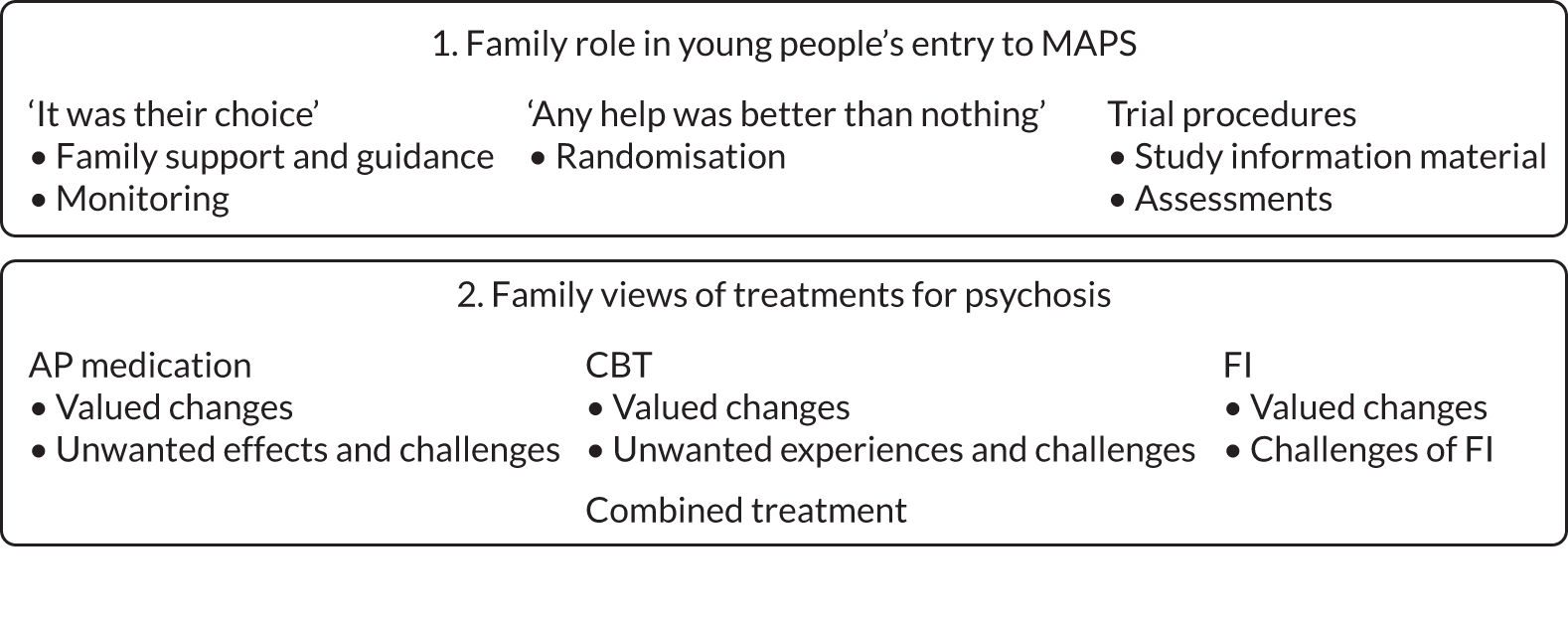

an event that is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.