Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/49/159. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Herrett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Herrett et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Statins effectively reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) in primary and secondary prevention among men and women across all age groups. 2,3 Meta-analyses have demonstrated the safety of statins. 4 Although severe adverse effects are rare, statins are known to be associated with a small increase in the risk of myopathy (absolute excess risk 1 case per 10,000 people treated per year), which can progress to more severe rhabdomyolysis (0.2 cases per 10,000 people treated per year). 4 Although the association between statins and these severe muscle disorders is well characterised, uncertainty persists about less severe muscle symptoms. Many people strongly believe that statins commonly cause muscle symptoms such as stiffness, pain and weakness. 5–7

This perception has been driven by unblinded observational studies7,8 and exacerbated by media reports worldwide. 9–11 The lack of blinding in observational studies means that patients taking a medication expect to experience adverse effects12 and, therefore, reporting of symptoms may be higher than in a comparable statin-free population. This phenomenon, the ‘nocebo’ effect, can lead to bias in unblinded studies. Because some patients think that their muscle symptoms are caused by statins, discontinuation is common,7–11,13 which leads to increased CVD and mortality14 and a substantial public health burden.

Previous research on statins and myalgia

In the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trial,15 statin-‘intolerant’ patients initially underwent a double-blind 4-week phase in which they received placebo. Interestingly, during this time, 7% dropped out because of myalgia. In the main phase of this three-arm trial [alirocumab (Praulent, Regeneron and Sanofi) vs. ezetimibe (Ezetrol, Merck Sharp and Dohme) vs. atorvastatin], rates of adverse events were the same across all groups, at roughly 80%, but dropped to 55% among the alirocumab patients when unblinded. 15 Therefore, in some trials of statins, expectation of adverse effects among both the placebo and the active treatment arms may have diluted any true effect of statins on muscle symptoms. A systematic review of randomised trials of statins found that the prevalence of myalgia varied from 0% to 30%, but was not different in the active and placebo arms. 16

There have also been two other important criticisms of the existing randomised controlled trial evidence. First, not all trials have collected data on subjective symptoms and recording may be inconsistent because of the definitions used. Studies have shown that adverse events are rarely fully presented in journal publications. 17 Second, although there have been trials among specific vulnerable patient groups,18–20 there is a perception that trial participants do not reflect the populations taking statins in routine care.

Need for trial

For any patient in routine clinical care, it is not easy for the clinician or patient to determine reliably whether or not muscle symptoms are caused by statins, despite available guidance and support. 21–23 There is currently no diagnostic tool that allows clinicians to empirically evaluate whether symptoms reported by an individual statin user are caused by the statin itself or by the ‘nocebo’ effect.

This creates a barrier to patients receiving the benefits of CVD prevention from statins. One way of overcoming this barrier is to undertake blinded N-of-1 trials among individual patients who are experiencing symptoms during statin use. N-of-1 trials are a type of randomised trial in individual patients24 and can provide further information to determine the best course of action for each individual. The trial addresses some of the criticisms of previous evidence. The trial will focus on muscle symptoms as a primary outcome, it will be blinded and placebo controlled to minimise bias and the sequence of statin and placebo treatments will be randomised to avoid confounding. When the results of a number of N-of-1 individuals are combined in analysis, the result can be used to demonstrate the overall effect of a treatment.

Using a series of N-of-1 trials comparing statin with placebo, StatinWISE (Statin Web-based Investigation of Side Effects) will seek to establish (1) the effect of statins on all muscle symptoms and (2) the effect of statins on muscle symptoms that are perceived to be statin related. The results of this work has also been published in the BMJ. 1

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The trial protocol has been previously published25 and parts of the published article are reproduced throughout this report. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

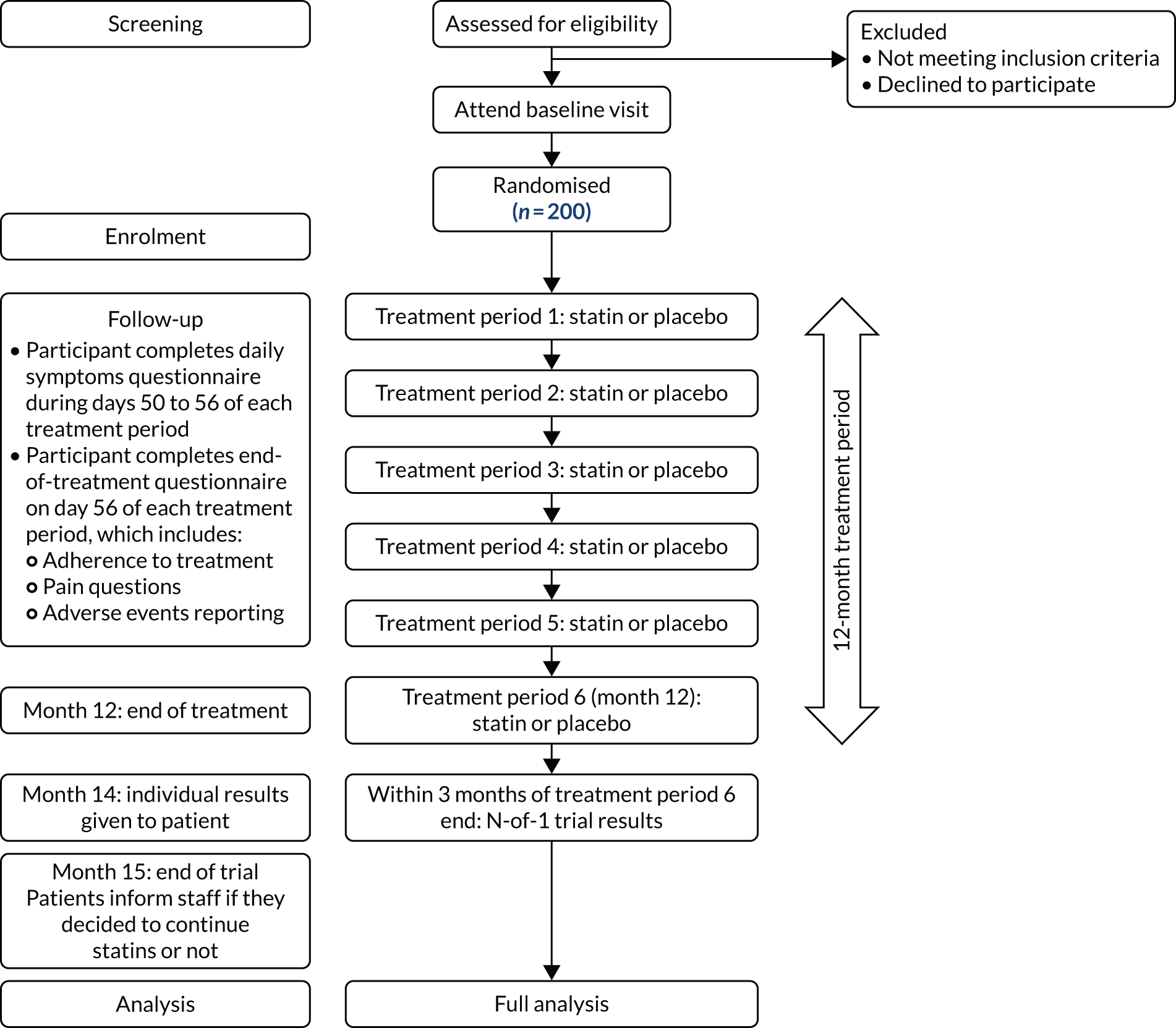

StatinWISE was a series of randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled N-of-1 trials. The overall duration of the trial was 1 year for each participant and comprised six 2-month treatment periods (three of placebo and three of active treatment) in a randomly allocated order (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The trial overview. This figure has been reproduced from Herrett et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Study participants

Participants were recruited from general practices in England and Wales and either were considering discontinuation of their statin because of muscle symptoms or they had stopped taking a statin in the last 3 years because of muscle symptoms.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient eligibility were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adults (aged ≥ 16 years).

-

Registered in a participating general practice.

-

Previously prescribed statin treatment in the last 3 years.

-

Stopped or considering stopping statin treatment because of muscle symptoms.

-

Provided fully informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Any previously documented serum alanine aminotransferase levels at or above three times the upper limit of normal.

-

Have persistent, generalised, unexplained muscle pain (whether or not this was associated with statin use) and have creatinine kinase levels greater than five times the upper limit of normal.

-

Any contraindications listed in the summary of product characteristics for 20 mg of atorvastatin (see Appendix 2).

-

Should not participate in the trial in the opinion of the general practitioner (GP).

Procedures

The trial treatment consisted of once-daily oral administration of 20-mg atorvastatin capsules, which was compared with a matching placebo (microcrystalline cellulose). The treatment phase of the trial consisted of six treatment periods of 8 weeks’ duration each (i.e. 56 daily capsules). During each treatment period participants received 20 mg of atorvastatin or placebo. A blinded placebo, identical in size, colour, smell and packaging to the active statin, was chosen to prevent knowledge of treatment from affecting symptom scores.

All treatment packs were stored in a temperature-monitored room with temperature-controlled refrigeration units at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Each 8-week supply of allocated treatment was posted to the patient by the trial team. Patients were contacted to ensure that they had received the correct treatment pack and to confirm the date when they would start the new treatment period. Alternatively, patients could access the trial electronic data capture (EDC) system themselves and enter their treatment pack number and start date.

The start date that was entered into the EDC system was used to calculate the dates for data collection for that treatment period. Reminder notifications for sending the next treatment pack were also generated by the EDC system, and the next treatment pack would be sent by the trial team. Patients were provided with prepaid stamped envelopes to return each treatment pack once completed. Patients were also given written instructions (included on the inside of the treatment pack) on how to take the study medication. A freephone telephone number was provided for patients to call if they had any questions.

Patients were asked to take one capsule orally once daily at a time of day that was convenient to them, and to try to take it at a similar time each day. If patients suffered any difficulties when taking the capsules, changing the time of the day that the medication was taken was an initial option offered to them. Stopping the medication with a short treatment break was also offered to patients if they were experiencing any adverse symptoms. Patients were advised to consult their GP if symptoms persisted.

Adherence to the study was monitored as part of the data collection. Monitoring returned packs for drug accountability against the reported data collection was also undertaken.

Dose selection

Atorvastatin is recommended by the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for lipid modification,26 and 20 mg is the recommended dose for primary prevention of CVD. Atorvastatin is also recommended by NICE for secondary prevention;26 for patients with a high risk of adverse events (our patient population), a dose of < 80 mg is recommended.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was self-reported muscle symptoms, defined as pain, weakness, tenderness, stiffness or cramp to the body of any intensity. The primary outcome was measured each day using a validated visual analogue scale (VAS) (range 0 to 10 cm)27 for the last 7 days of each treatment period. We aimed to collect symptoms using a web-based database or mobile phone app (application), but our patient representatives recommended that participants should also be permitted to submit their scores over the telephone or by paper questionnaire. Participants reporting by telephone were asked to score their symptoms on an analogue severity scale and, thus, did not use a VAS. Measuring symptoms during only the last week of each 2-month treatment period was designed to avoid any carryover effect.

Secondary outcomes were collected on the last day of each 2-month treatment period. These included whether or not patients reported that they believed their symptoms were caused by the study medication, the site of muscle symptoms and VAS scores for the effect of their muscle symptoms on general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, enjoyment of life, and any other symptoms that the patient believes were attributed to the study medication. Adherence to study medication was self-reported and verified by a count of returned treatment packs containing the trial medication. Three months after the end of the final treatment period, we determined if the participant continued or ceased statin treatment and the relationship to their primary outcome, as well as whether or not patients found their own trial result helpful in making the decision about future statin use.

Number of participants needed

A feasibility study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink indicated that, on average, 35 patients per practice per year would be eligible to take part in the trial. We anticipated an average uptake of 15% among primary care patients invited to participate in our trial. Therefore, we estimated that we would need to invite approximately 1300 patients from over 50 general practices to the trial to achieve our recruitment target of 200 patients.

Power calculations

Our power calculation was performed via simulation. 28 Data were generated under the proposed study design using the parameters detailed below. The generated data were analysed following the proposed primary analysis. The empirical power was determined as the proportion of such generated samples in which the p-value was < 0.05.

Minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score (10 mm, i.e. 1 unit)

This value was chosen to represent the smallest VAS change in pain that patients would perceive as being beneficial, and might therefore change the patient’s decision regarding subsequent statin use. Two studies conducted within an accident and emergency setting29–32 both concluded that the smallest change in VAS pain score corresponding to ‘a little more’ or ‘a little less’ pain was 13 mm, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of 10 to 17 mm and 10 to 16 mm, respectively. We took the lower limit of the CI to represent the smallest change likely to be perceived as beneficial.

Within- and between-participant variability in visual analogue scale pain score (302 and 352, respectively)

These values were obtained by fitting a mixed model to the data from a pilot series of N-of-1 trials for statin adverse effects33 (data obtained by approximation from figures presented in Breivik et al. 33). These variance components can be poorly estimated; therefore, we took values from the higher end of the CIs, giving conservative estimates of these components.

Sample size

A sample size of 64 participants provides approximately 90% power to detect a treatment effect of at least 10 mm, assuming a type I error of 5%. Allowing for loss to follow-up of 40% of participants through the trial inflates the required sample size to 107 participants.

Period effects (changes in underlying VAS pain score because of factors other than randomised treatment, e.g. seasonal, activity related), variability in individual statin effects across patients, imperfect adherence to the assigned treatment and potential non-normality of the distribution of VAS pain scores were investigated by further detailed simulations. These factors all have the effect of decreasing power, thus increasing the sample size required. An approximate 80% increase in the sample size required in the absence of these effects provided approximately ≥ 90% power across a plausible range of these potential effects; thus, we determined that a final sample size of 200 was required.

Multiple testing

Rather than making formal adjustments for multiple testing, we follow an approach advocated by Pocock34 of clearly specifying our primary analysis (which provides a single test for treatment effect), while explicitly presenting and interpreting all other tests as secondary analyses.

Power for individual N-of-1 trials

To increase the statistical power for the analysis of individual N-of-1 trials, we asked participants to report symptoms daily in the last week of each period, rather than once per period. Full adherence throughout the trial would provide between 55% and 70% power to detect effects of ≥ 10 mm for individual treatment comparisons.

Estimates of recruitment and retention rates

We anticipated that some patients will not provide complete data in each treatment period, and that some would not complete their 12-month follow-up. By designing this study as a series of N-of-1 trials, which offer individual participant benefit in the form of an individualised estimate of effect, we hoped to minimise this type of dropout. However, we accounted for this in our sample size calculation by allowing for 40% loss to follow-up.

Randomisation and masking

Randomisation codes were generated and held securely by the clinical trials unit (CTU) information technology (IT) team at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, which was independent of the StatinWISE trial management team, maintaining the blinded processes. Eight treatment sequences were defined (Table 1) and given an equal corresponding range of values between 0 and 1. Then, a series of random numbers between 0 and 1 were generated and matched to a treatment sequence, producing the randomisation list. The codes were made available to a Good Manufacturing Practice-certified clinical trial supply company (Sharp Clinical Services, Rhymney, UK) for the treatment packs to be manufactured in accordance with the randomisation list that was established in sequence from 1001 to 1200 in the EDC system.

| Sequence | Treatment period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | S | P | S | P | S | P |

| 2 | S | P | S | P | P | S |

| 3 | S | P | P | S | S | P |

| 4 | S | P | P | S | P | S |

| 5 | P | S | S | P | S | P |

| 6 | P | S | S | P | P | S |

| 7 | P | S | P | S | S | P |

| 8 | P | S | P | S | P | S |

Patients were randomly allocated to receive a sequence of blinded placebo or atorvastatin treatment by the research nurse/general practice trial team and entered into the EDC system and associated with a treatment sequence allocation. Treatment blocks were stratified to ensure that (1) all participants received one period of statin and placebo in their first two treatment periods (in a random order) and (2) no participant would be allocated to three sequential periods of the same treatment. Treatments were therefore allocated in three paired blocks (statin–placebo or placebo–statin) of treatment, with patients completing six treatment periods of 8 weeks’ duration each (i.e. 56 daily capsules). Each individual was randomly allocated (with equal probability) to one of the eight sequences (see Table 1).

Atorvastatin and the placebo were in capsule form and identical in appearance. DBcaps® capsules (Capsugel®, Morristown, NJ, USA), which have a unique locking mechanism to help with assuring the integrity of the blind, were used for overencapsulation of both the atorvastatin and the placebo treatments. The treatment packs were packaged in boxes of six, in line with the eight sequence options as per the randomisation code. Patients were recruited and allocated a sequence in order of entry on to the EDC system (see Table 1). Patients, general practice staff and trial staff were blind to the allocation in each period.

A visually matched placebo was chosen as an appropriate comparator for two reasons. First, patient expectation of symptoms when on statins is likely to affect their experience of symptoms. A placebo control should minimise bias arising from knowledge of allocation. Second, withholding statin treatment from patients during placebo treatment periods is justified because the trial recruited patients who had recently stopped using statins (and, therefore, were not currently receiving any benefit from statins) and those who wished to discontinue. If patients in the trial tolerate the active treatment periods with few symptoms, then this trial is likely to increase their use of statins in the long term.

Data collection

This trial was co-ordinated from the CTU at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and conducted at GP practices in England and Wales.

Baseline data were collected and entered online to the trial database provided by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine CTU. Follow-up data were collected directly from each patient at the end of each 2-month period.

Patients were allowed to choose the method of data collection that was most suitable for them from the following:

-

Bespoke mobile phone app that required patients to use their own smartphone.

-

Online database using a computer, mobile phone or tablet.

-

Paper forms that they received by post at the same time as their trial treatment and that they could complete themselves or with the help of a trial team member by telephone if they so requested. Trial staff would telephone the patient on each data collection day and complete the questionnaire based on the patient’s answers.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess any evidence of symptom scores varying between participants using different data collection methods.

For patients with a smartphone who chose to submit outcome data using the trial’s bespoke mobile app, the GP, principal investigator (PI) or research nurse helped the patient to install and set up the app. The GP, PI or research nurse also gave a demonstration to ensure that the patient understood how to use it. Each GP, PI or research nurse had access to the internet so that the patient could download the app without using their own mobile network (ensuring that download of the app was free of charge to the patient).

The GP or research nurse also showed the patient how to complete the symptoms data for the baseline form using their preferred method. Any questions were addressed at this stage. Once baseline procedures were completed and the patient was confirmed as being eligible and consented, the patient would then be allocated to a randomly selected sequence of treatments.

A screening log was used to record all patients who were identified as potentially eligible using the research site database, including those who were ineligible and those who declined participation. The screening log remained at the relevant research site and only anonymised information regarding number of screened patients and number and reasons for screen failure was shared with the CTU.

Data outlined on only the baseline, follow-up, end-of-trial and adverse events data forms were collected as part of the trial database.

Treatment phase follow-up data

In the seventh week of each treatment period, patients received reminders (format agreed at baseline) to alert them that follow-up data collection was approaching. During the eighth week of each treatment period, the patient questionnaire and VAS pain scale forms were completed by the patient. Patients could choose to receive daily reminders on each day that their data were due to be collected. Non-responders would automatically receive a reminder from the trial team 24 hours after the due date.

End-of-trial data

During the seventh week of treatment period 6, the GP, PI or research nurse contacted patients to thank them for their participation so far and to inform them that this was the last treatment period and inform them that they, together with their GP, the PI and research nurse, would receive their individual results at the beginning of month 14. The research nurse and patient arranged a telephone or face-to-face appointment to discuss the individual results during month 14. The research nurse also informed patients, that if they wanted to continue taking a statin without a break, they should arrange a separate clinical appointment with their GP prior to the end of the treatment period.

At month 15, trial staff contacted the patient to document their decision on future statin use and whether or not the results helped them to reach this decision. This was the last data collection point of the trial.

Throughout the trial, continued patient care was at the discretion of the patient’s GP. In primary care, the patient was recorded as having an ongoing statin prescription.

Where treatment with an interacting drug was needed and the duration was expected to be less than 1-month, the patient was be asked to stop the trial treatment for that period.

If treatment with an interacting drug was needed and was expected to be for more than 1 month, the patient was asked to withdraw from study treatment completely.

When a patient was randomised, a temporary Read code indicating StatinWISE participation was recorded in their primary care record. The code was removed at the end of the trial.

Patients were also given an alert card that identified them as a StatinWISE patient. Patients were asked to present this card to anyone providing medical care outside their usual general practice. This card had a link to the trial website and a trial contact number.

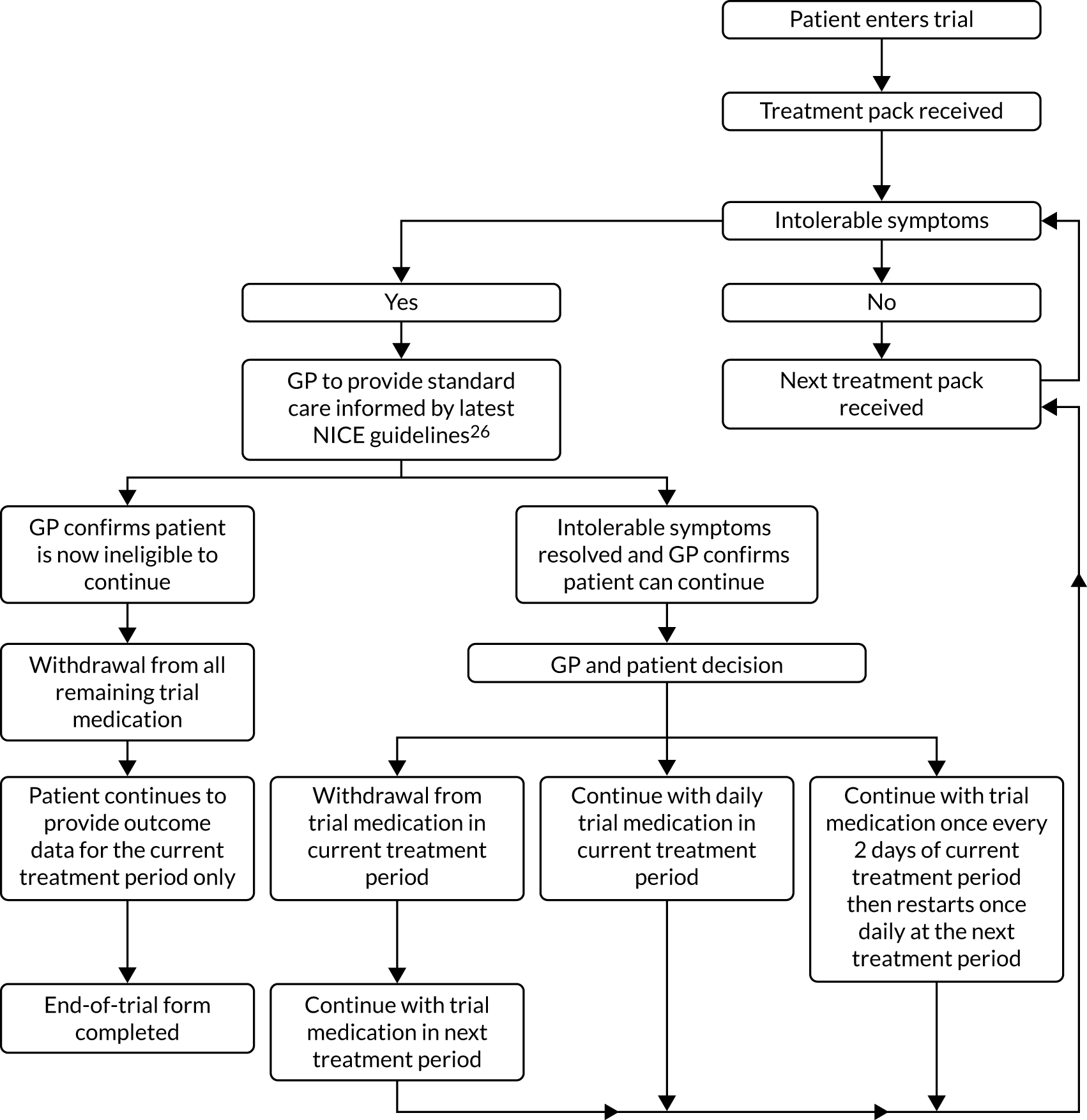

Patients reporting intolerable symptoms

The GP remained the first point of contact for patients during the trial for their care. Intolerable muscle symptoms were to be reported to the GP, who provided clinical care as directed by the appropriate NICE guidelines. Figure 2 shows the decision-making pathway for the GP and the patient in the case of patients reporting intolerable symptoms.

FIGURE 2.

Intolerable symptoms pathway. Note that withdrawal from the trial at any time is possible (the patient should visit their GP and complete a withdrawal form). This figure has been reproduced from Herrett et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

If patients experienced intolerable muscle symptoms and who did not want to be withdrawn early from the trial, the GP was asked to confirm that the patient still met the trial eligibility criteria. Patients who continued to meet the eligibility criteria could be offered the following options by the GP, depending on the GP’s clinical judgement:

-

continue with current treatment

-

reduce the frequency of tablet use to every other day rather than daily

-

stop for that treatment period and resume at the start of the next period.

Patients who withdrew from treatment temporarily or permanently were asked to inform the study team and report symptoms at the time of stopping, and to continue to submit outcome data for their current treatment period.

Early withdrawal of patients from the trial

Patients were free to change their minds about participation at any time. We advised that the patient see their GP to discuss future routine care. GPs were able to withdraw a patient at any time if clinical concerns arose or if the patient presented with any reason to stop atorvastatin as described in the summary of product characteristics for 20 mg of atorvastatin (see Appendix 2). In each case, an end-of-trial form was completed.

Statistical methods

Full details of the statistical analysis methods and the plan can be found on the project page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1449159/#/documentation; accessed May 2020).

Individual N-of-1 trials

At the end of the trial, patients were shown numerical and graphical summaries of their individual data in relation to their statin and placebo periods, and were asked if this was helpful and whether or not they would restart a statin. See the project page for an example of a personalised results document (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1449159/#/documentation; accessed May 2020).

Combined analysis of N-of-1 trials

To estimate the population-average estimate of the trial treatment on VAS muscle symptom scores, data from each N-of-1 trial were aggregated. The primary analysis included all patients who provided a daily VAS symptom score at least once during a treatment period with the statin and at least once during a treatment period with placebo. The primary analysis was a linear mixed model for VAS muscle symptom scores with random effects for participant and treatment. Residual errors were modelled using a first-order auto-regressive error structure within each treatment period to account for correlation between the seven daily measurements, with robust standard errors to account for non-normality of the VAS scores. Although VAS muscle symptom scores are not normally distributed, analysing such data using normal-based methods is likely to be a sufficiently robust approach. 27 All tests were two-sided, with a p-value of < 0.05 being considered as statistically significant.

Period effects and robustness of conclusions to the correlation structure of residual errors were explored in a sensitivity analysis. The length of treatment periods in our study was chosen so that carryover effects would be avoided.

Secondary analyses

The single binary measure of whether or not the participant reported having muscle symptoms during that treatment period was assessed using a logistic mixed model with random participant and treatment effects. This binary measure was then combined with the follow-up question pertaining to attribution, to obtain a single binary measure of whether or not the participant reported having muscle symptoms that they attributed to the study medication, and was analysed using a logistic mixed model with random participant and treatment effects. We also repeated the primary analysis, setting patients’ pain scores to zero if they reported that their symptoms had a non-statin-related cause.

Secondary outcomes measured using VASs relating to the impact of the statin on other aspects of life were analysed in a similar manner to the primary outcome, omitting the auto-regressive correlation structure because these secondary outcomes were measured once per treatment period. Whether or not the excess muscle symptoms (if any) that were experienced during treatment periods with the statin appeared to be concentrated in multiple sites was investigated.

Graphical and descriptive summaries were used to explore how discontinuation and adherence related to the statin and placebo periods. Linear mixed models for continuous measures of adherence with random participant and treatment effects were fitted.

We related the patients’ decision regarding future statin use, and whether or not the participant found their own result helpful in making their subsequent treatment decisions, to their individual estimated effect of the statin.

Protocol changes

Prior to any patients being randomised to the trial, an addition was made to the exclusion criteria: excluding any patients with any contraindications to the summary of product characteristics for 20 mg of atorvastatin.

Adverse events were also changed to be reported if they met the outlined criteria for a serious adverse event on the protocol, and not only those resulting in a hospitalisation/death.

After an initial slow period of recruitment, an advertising campaign was launched to promote the trial in GP practices. Patients could contact the CTU at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine directly, expressing their interest in participating. They would then be sent a letter requesting their GP’s details. The CTU would then contact the GP for confirmation of the patient’s suitability for the trial. Patients would then be screened at William Harvey Heart Centre at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London. The recruitment pathway for the trial was subsequently updated to incorporate this process, as well as amendments made to the patient information sheet. However, only one patient was recruited via this pathway. The recruitment period was also extended after recruitment began, although working to the same sample size.

The consent form was also amended so that consent to participate in the optional genetic study was captured on a separate form to that of consent to participate in the trial itself.

Patient and public involvement

Three patient representatives were on the Trial Steering Committee (see Appendix 1). A StatinWISE patient involvement group provided feedback on the trial design, patient information sheet and data collection tools. Their input and views shaped aspects of the design, specifically around the logistics of drug postage and return, the drug packaging, the phrasing of questions for the outcome measures, the format of the data collection tools that were patient facing, and the content and wording of the patient information sheet. The group continued to be involved throughout the course of the trial, including providing substantial input into the individual participants’ results feedback document. Patient representatives also provided active input into the interpretation of the results and their presentation. They will also play an important role in designing materials for dissemination.

Approvals

StatinWISE was given a favourable opinion by the South Central Hampshire Research Ethics Committee (16/SC/0324) and regulatory approval (17072/0009/001-0001).

Role of the funding source

The trial was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The writing committee had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Chapter 3 Main results

Recruitment and participant flow

Two hundred patients were recruited between December 2016 and April 2018. The first patient was enrolled on 20 December 2016 and the last patient’s last follow-up took place on 5 July 2019.

Baseline data

The median age was 69.5 years [interquartile range (IQR) 63–76 years] and 115 (57.5%) participants were male (Table 2). Fourteen participants (7.0%) were current smokers, 105 (52.5%) were ex-smokers, 33 (16.5%) had diabetes and 140 (70.0%) had a history of CVD. The mean total cholesterol level was 5.4 mmol/l [standard deviation (SD) 1.4 mmol/l].

| Characteristic | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 200 | 100 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 69.1 (9.5) | |

| Age category (years) | ||

| 35–49 | 7 | 3.5 |

| 50–64 | 49 | 24.5 |

| 65–79 | 115 | 57.5 |

| ≥ 80 | 29 | 14.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 85 | 42.5 |

| Male | 115 | 57.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 11 | 5.5 |

| Black | 8 | 4 |

| Other | 2 | 1 |

| White | 179 | 89.5 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 14 | 7 |

| Ex-smoker | 105 | 52.5 |

| Non-smoker | 81 | 40.5 |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 167 | 83.5 |

| Yes | 33 | 16.5 |

| CVD history | ||

| No | 60 | 30 |

| Yes | 140 | 70 |

| Cholesterol level (mmol/l)a | ||

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 5.3 (4.4, 6.2) | |

| QRISK2® (ClinRisk Ltd, Leeds, UK) score for participants with no history of CVD | ||

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 18.3 (9.6, 28.8) | |

Table 3 shows the numbers of participants allocated to each sequence of treatment over the six trial periods.

| Allocated sequence over the six periods | Frequency (n = 200) | % |

|---|---|---|

| PSPSPS | 18 | 9.0 |

| PSPSSP | 24 | 12.0 |

| PSSPPS | 29 | 14.5 |

| PSSPSP | 26 | 13.0 |

| SPPSPS | 22 | 11.0 |

| SPPSSP | 22 | 11.0 |

| SPSPPS | 27 | 13.5 |

| SPSPSP | 32 | 16.0 |

Data collection methods

Table 4 shows the details of the method chosen to collect outcome data. Around half of the participants chose to collect data using the paper form. A total of 88 participants (44%) chose to fill in the online form and 17 participants (8.5%) submitted data by telephone.

| Collection method | Frequency (n = 200) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile app | 2 | 1.0 |

| Online | 88 | 44.0 |

| Paper | 93 | 46.5 |

| Telephone | 17 | 8.5 |

Numbers analysed

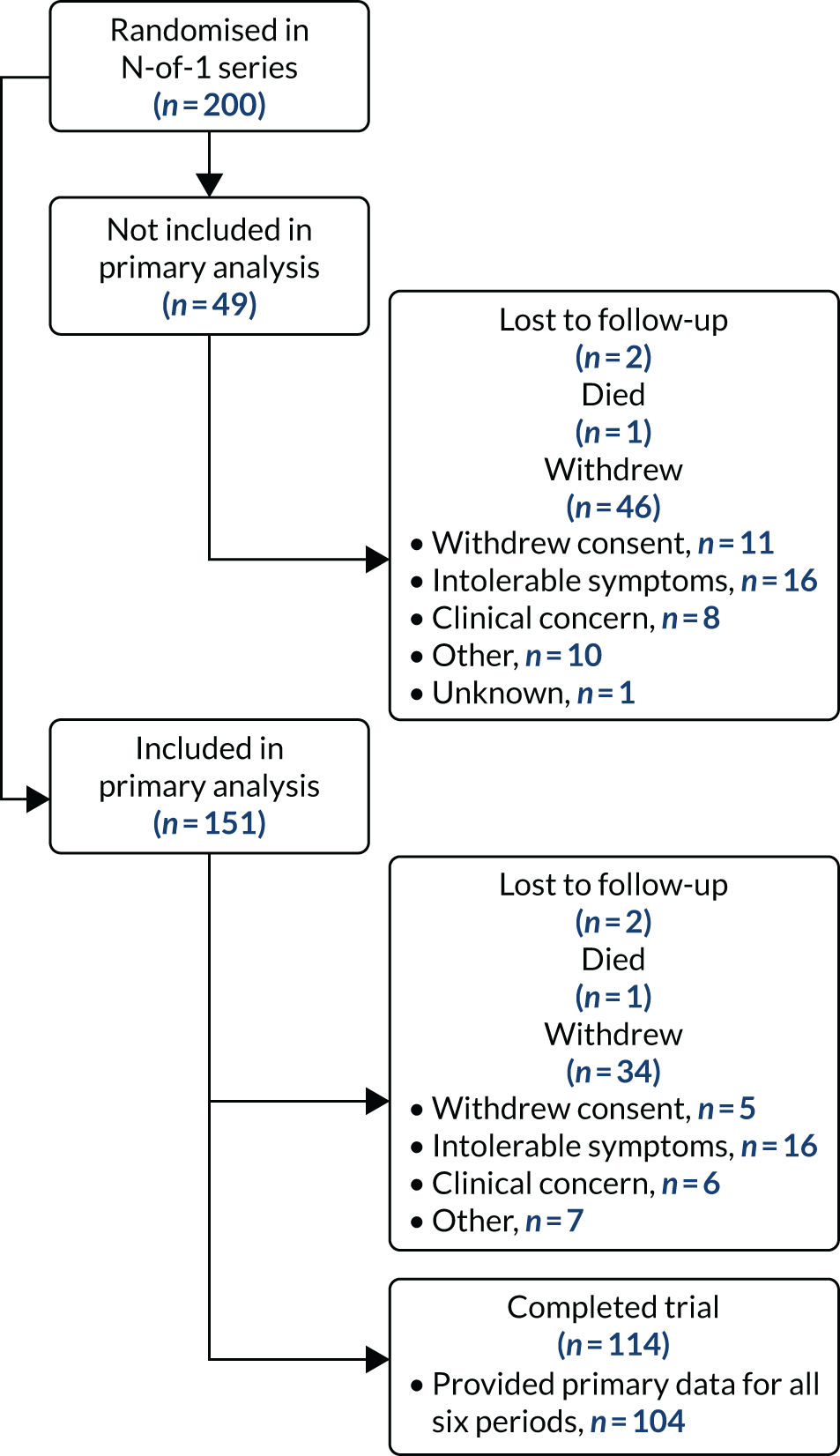

Figure 3 describes participant flow through the trial. A total of 151 out of 200 (75.5%) randomised participants provided one or more VAS measurements in a placebo period and one or more in a statin period and are therefore included in the primary analysis. A total of 86 (43.0%) participants did not complete the whole trial (two died, four were lost to follow-up and 80 withdrew).

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment and patient flow. This figure has been reproduced from Herrett et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

For the primary analysis of the daily muscle symptom scores, the linear mixed model was fitted on 151 participants, who contributed 5214 individual symptom score measurements (placebo, n = 2576; statin, n = 2638). The mean number of scores per participant was 34.5 (range 8–42). In period 1, 164 participants (82.0%) provided at least one daily report of muscle symptoms, which dropped to 149 participants in period 2 (74.5%) and 115 in period 6 (57.5%).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

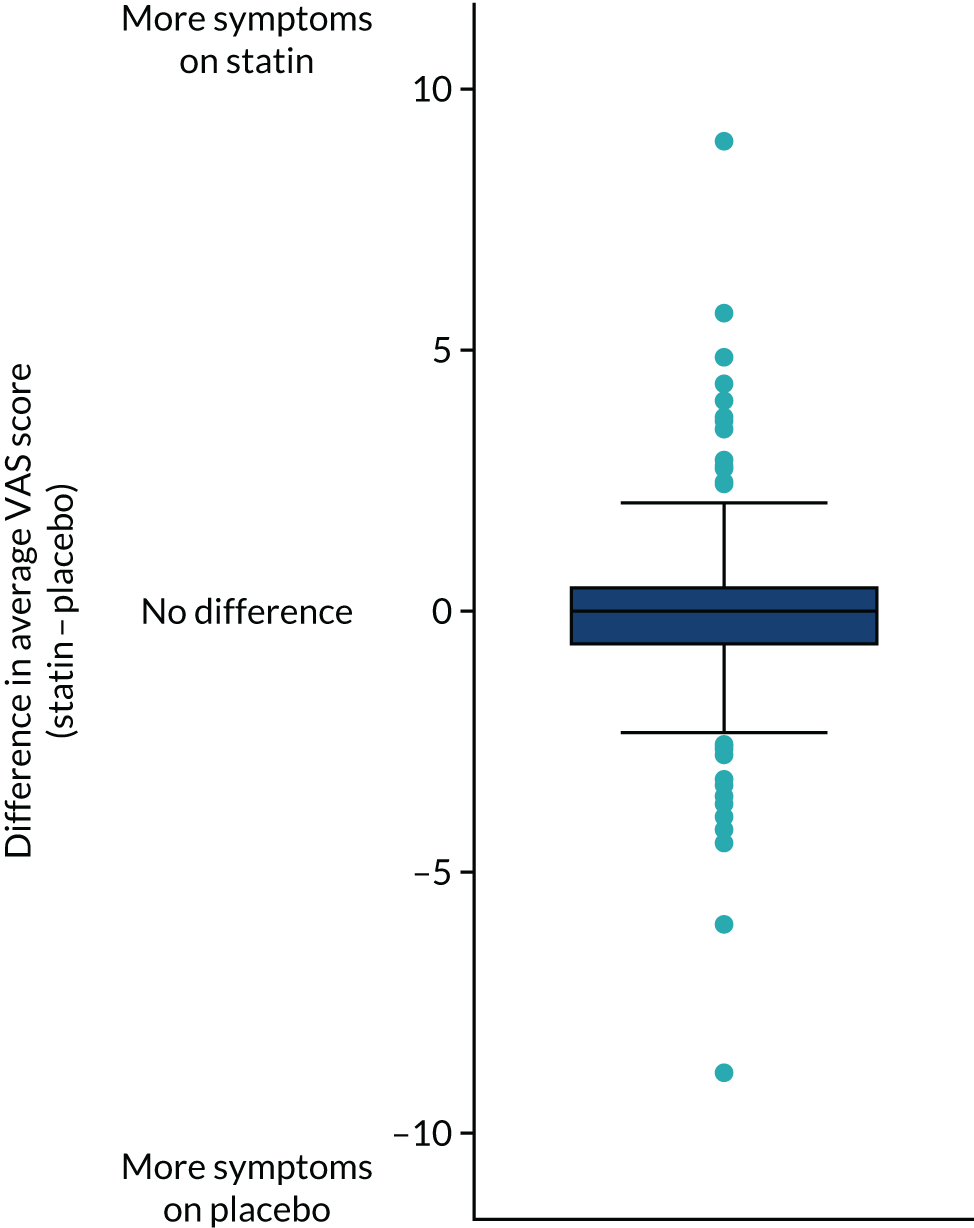

Among the 151 patients who reported at least one primary outcome measure during a statin period and at least one primary outcome measure during a placebo period, there was no evidence of a difference in mean muscle symptom scores between statin and placebo periods (Figure 4; estimated mean difference statin minus placebo –0.11, 95% CI –0.36 to 0.14; p = 0.398). The observed mean muscle symptom score was lower during statin treatment periods (mean 1.68, SD 2.57) than during placebo periods (mean 1.85, SD 2.74).

FIGURE 4.

Box plot of mean difference in primary outcome (VAS daily symptom scores), comparing statin with placebo.

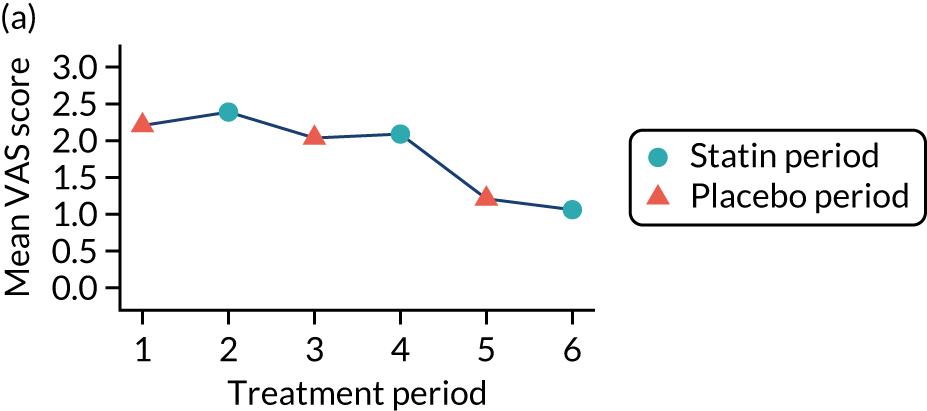

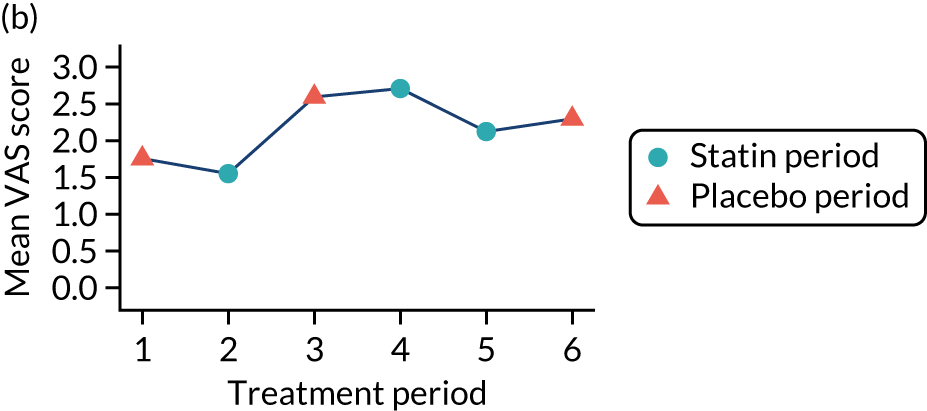

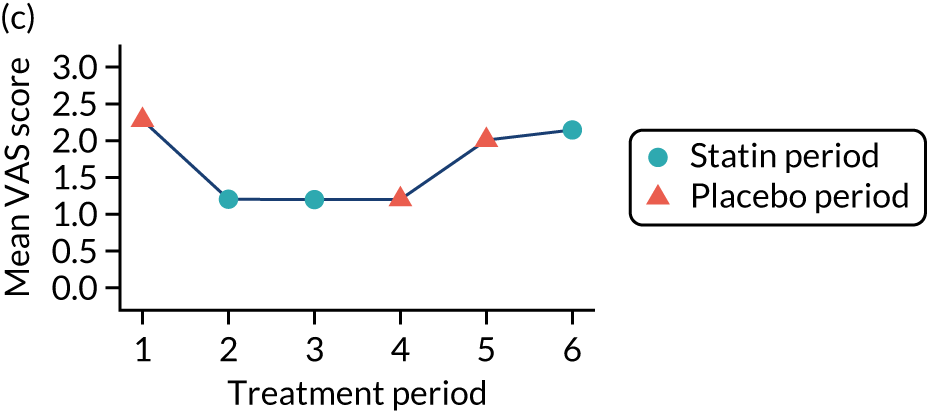

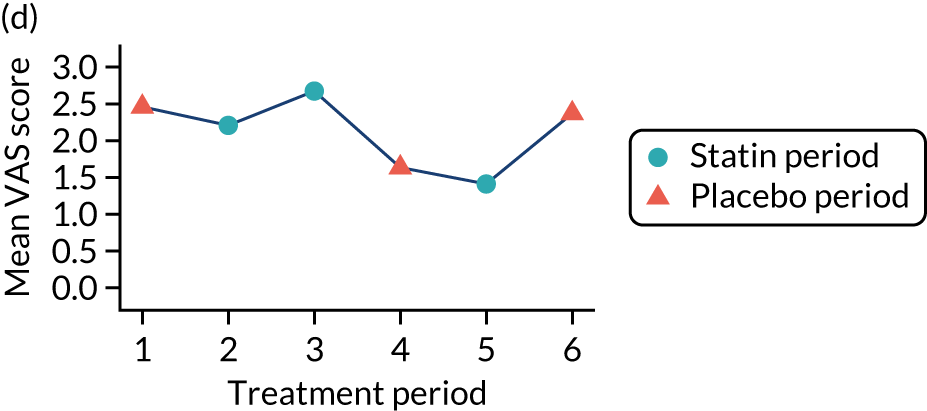

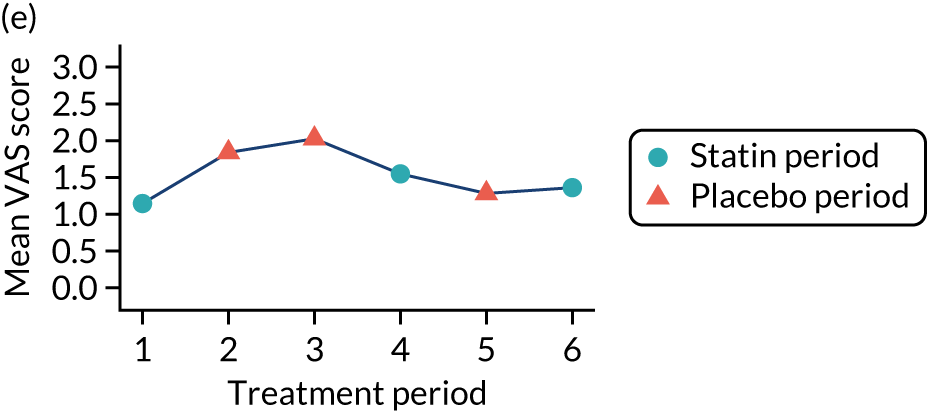

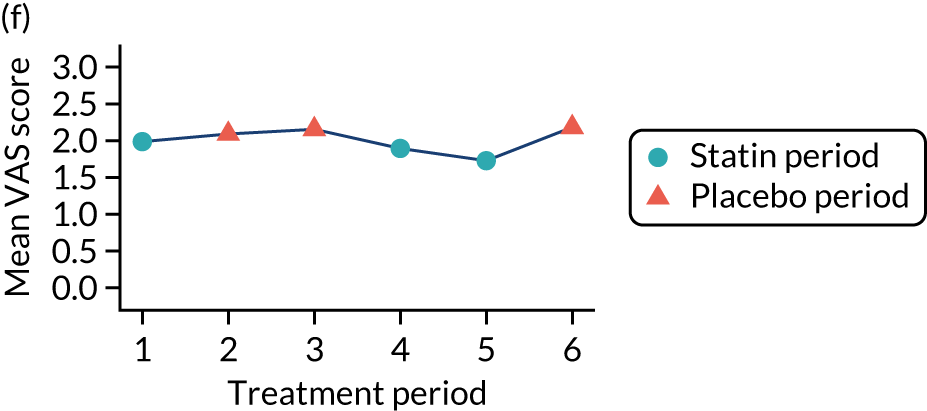

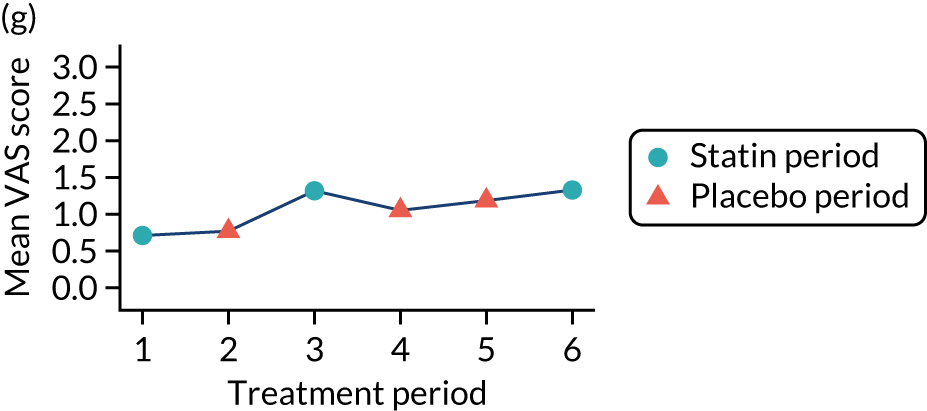

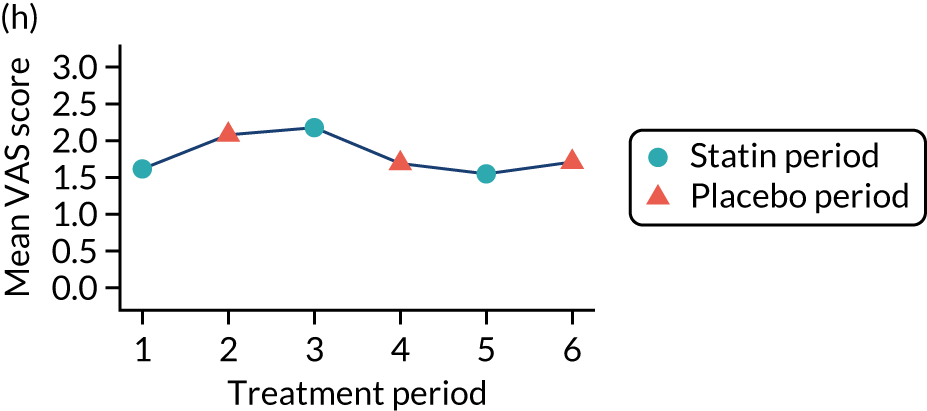

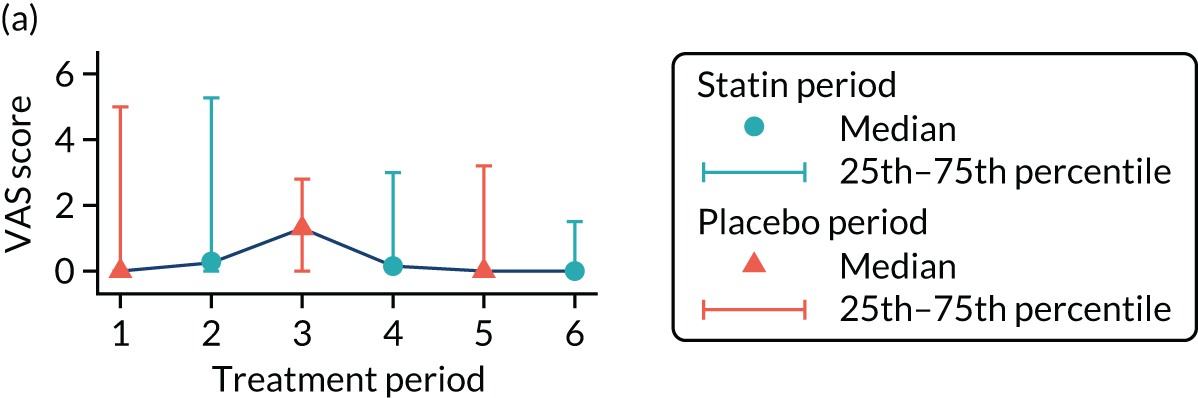

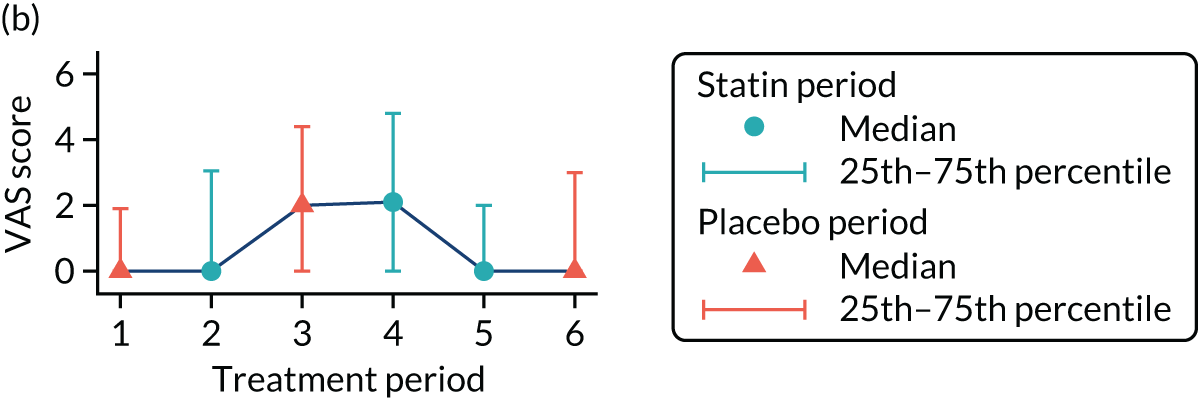

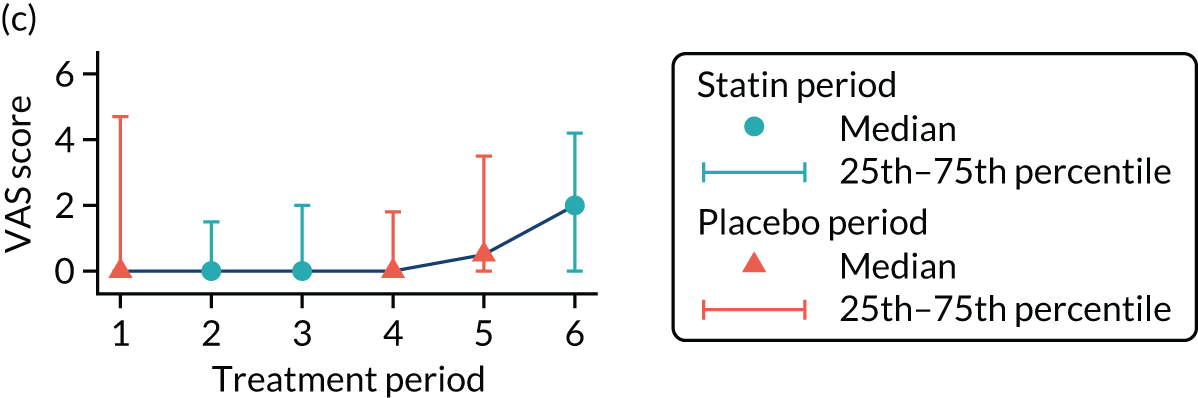

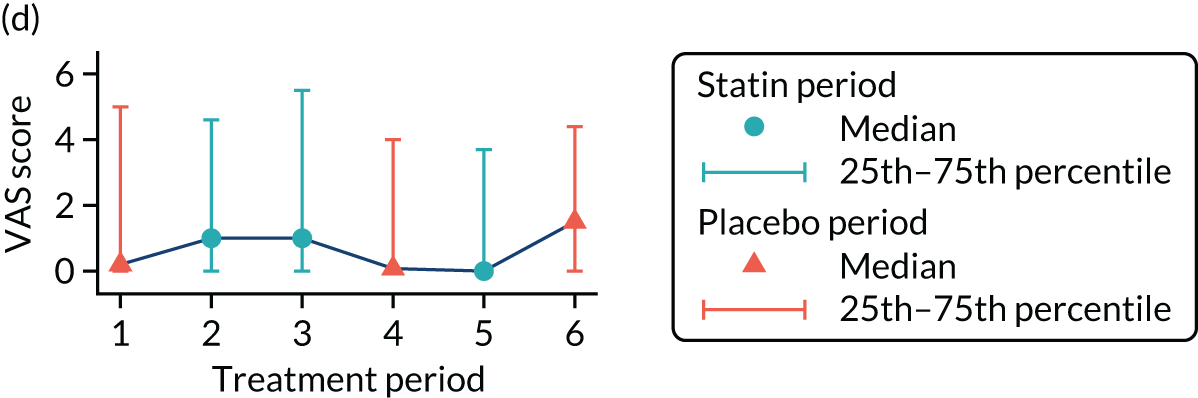

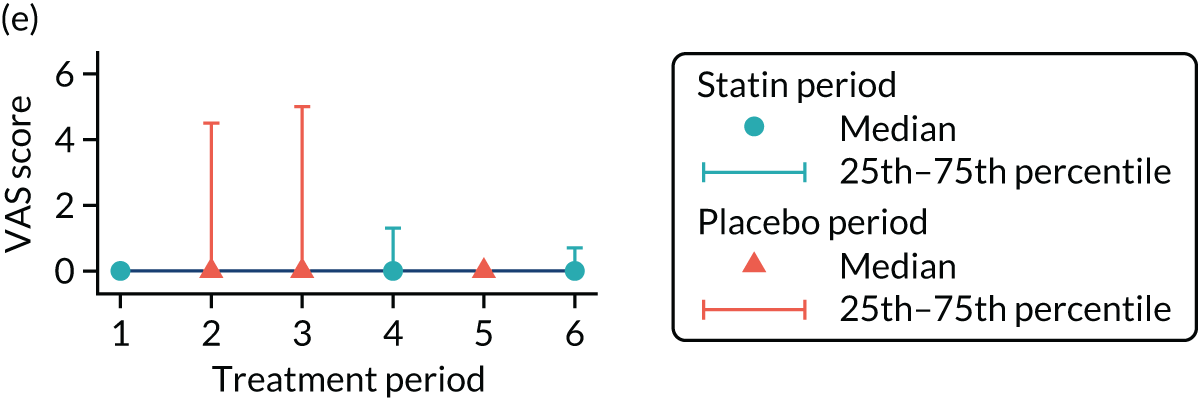

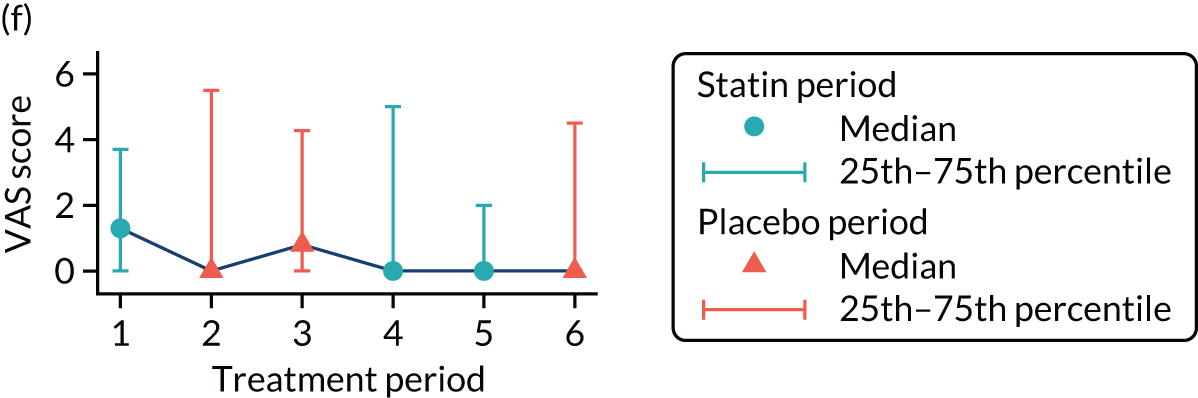

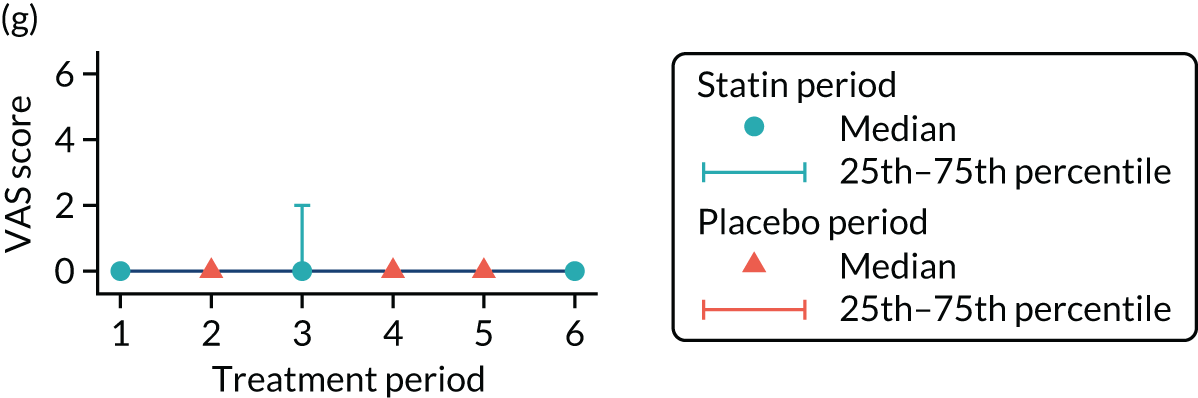

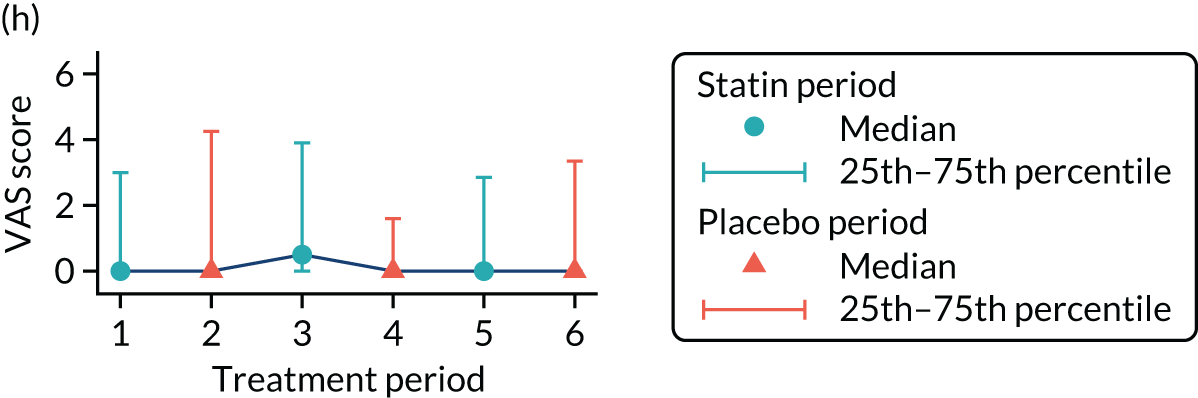

The effect of statins on the primary outcome was not modified by the method of data collection (Table 5). Figures 5 and 6 display summaries of the primary outcome measure (i.e. VAS scores) by period and randomisation sequence. Figure 5 shows the trajectory of mean scores (daily patient VAS scores are averaged across the week and an overall mean is then calculated for each period in each sequence). Figure 6 shows the trajectory of median scores (daily patient VAS scores are summarised for each period by the median and the overall median is then calculated for each period in each sequence). To indicate variability of the outcome measure, Figure 6 also shows the IQR.

| Data collection method | Estimated mean difference | 95% CI | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statin (method: online) | 0.008 | –0.358 to 0.373 | 0.968 |

| Statin interaction parameters | 0.594 | ||

| App | –0.065 | –0.704 to 0.574 | |

| Paper | –0.159 | –0.676 to 0.358 | |

| Telephone | –0.681 | –1.680 to 0.318 | |

| Collection method | |||

| Online | Reference | ||

| App | 0.563 | –0.223 to 1.349 | 0.161 |

| Paper | 0.604 | –0.081 to 1.289 | 0.084 |

| Telephone | 1.949 | 0.352 to 3.545 | 0.017 |

| Constant | 1.441 | 1.053 to 1.829 | < 0.001 |

FIGURE 5.

Trajectory plot of mean VAS scores by randomised sequence. (a) PSPSPS; (b) PSPSSP; (c) PSSPPS; (d) PSSPSP; (e) SPPSPS; (f) SPPSSP; (g) SPSPPS; and (h) SPSPSP.

FIGURE 6.

Trajectory plot of median VAS scores with IQRs by randomised sequence. (a) PSPSPS; (b) PSPSSP; (c) PSSPPS; (d) PSSPSP; (e) SPPSPS; (f) SPPSSP; (g) SPSPPS; and (h) SPSPSP.

Table 6 provides descriptive summaries of the primary outcome by allocated sequence across the three paired treatment blocks.

| Period | Placebo | Statin | Difference (statin – placebo) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | Mediana (25th, 75th percentiles) | Number of participants | Mediana (25th, 75th percentiles) | Number of participants | Mediana (25th, 75th percentiles) | |

| All patients with reported scores | ||||||

| 1 and 2 | 158 | 0.4 (0, 3.9) | 155 | 0.2 (0, 2.4) | 145 | 0 (–1, 0.6) |

| 3 and 4 | 121 | 0.6 (0, 3.2) | 128 | 0.8 (0, 3.4) | 118 | 0 (–0.4, 0.6) |

| 5 and 6 | 115 | 0.3 (0, 3.4) | 116 | 0.1 (0, 2.8) | 115 | 0 (–0.5, 0.1) |

| Patients with at least one report in a statin period and at least one in a placebo period (i.e. included in the primary analysis) | ||||||

| 1 and 2 | 147 | 0.4 (0, 3.8) | 148 | 0.4 (0, 2.4) | 145 | 0 (–1, 0.6) |

| 3 and 4 | 121 | 0.6 (0, 3.2) | 128 | 0.8 (0, 3.4) | 118 | 0 (–0.4, 0.6) |

| 5 and 6 | 115 | 0.3 (0, 3.4) | 116 | 0.1 (0, 2.8) | 115 | 0 (–0.5, 0.1) |

Secondary outcome

Muscle symptoms without attribution to other causes

Among the 152 patients who contributed at least one secondary outcome measurement in a placebo period and one in a statin period (note that one additional participant provided secondary outcome data compared with primary outcome data), there was no evidence of an effect of statins on muscle symptoms overall [odds ratio (OR) 1.11, 99% CI 0.62 to 1.99], nor was there evidence of an effect of statins when restricting to muscle symptoms that could not be attributed to another cause (OR 1.22, 99% CI 0.77 to 1.94) (Table 7). In the case of the other secondary outcomes (e.g. general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, sleep and enjoyment of life), there was no evidence of a difference in symptom scores between the statin and placebo periods.

| Outcome | Participants analyseda | OR (99% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle symptoms | 152 | 1.11 (0.62 to 1.99) |

| Muscle symptoms, not attributed to other causes | 152 | 1.22 (0.77 to 1.94) |

| Mean difference (99% CI) | ||

| General activity | 152 | 0.09 (–0.25 to 0.42) |

| Mood | 152 | 0.26 (–0.04 to 0.56) |

| Walking ability | 152 | 0.11 (–0.22 to 0.43) |

| Normal work | 152 | 0.15 (–0.17 to 0.46) |

| Relations with other people | 152 | 0.15 (–0.09 to 0.39) |

| Sleep | 152 | –0.02 (–0.32 to 0.29) |

| Enjoyment of life | 152 | 0.13 (–0.22 to 0.48) |

Location of symptoms and other details

In total, there were 493 reports of muscle symptoms during a treatment period arising from 140 participants. Of these 493 reports, 481 (97.6%) included the location of the muscle symptoms. Table 8 shows that the majority of reports (65%) were in the lower limbs, with comparatively fewer reports in the head and neck (3.7%).

| Location | Frequency (n = 481) | % of reports |

|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 18 | 3.7 |

| Lower limbs | 312 | 64.9 |

| Trunk | 73 | 15.2 |

| Upper limbs | 78 | 16.2 |

Among the 481 reports of location of muscle symptoms, 312 had a report of multiple sites attached. Table 9 shows a summary of these reports.

| Location | Multiple sites reported | Total (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Head and neck | 15 | 83.3 | 3 | 16.7 | 18 |

| Lower limbs | 190 | 60.9 | 122 | 39.1 | 312 |

| Trunk | 60 | 82.2 | 13 | 17.8 | 73 |

| Upper limbs | 47 | 60.3 | 31 | 38.7 | 78 |

Table 10 shows that, of the 493 reports, 71 also reported other symptoms that may be due to the study medication. Those reporting no other symptoms or ‘don’t know’ have no further details recorded. Table 11 shows descriptive summaries of the secondary outcome by allocated sequence, across the three paired treatment blocks. Appendix 3 shows the other symptoms listed in the 71 reports mentioning other symptoms. No attempt has been made to analyse these data.

| Other symptoms reported? | Frequency (n = 493) | % of reports |

|---|---|---|

| No | 248 | 50.3 |

| Yes | 71 | 14.4 |

| Don’t know | 174 | 35.3 |

| Symptoms | Periods | Placebo | Statin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | Frequency (%) | Number of participants | Frequency (%) | ||

| Any muscle symptoms experienced? | |||||

| Muscle symptoms | 1 and 2 | 156 | 95 (60.9) | 157 | 97 (61.8) |

| 3 and 4 | 125 | 78 (62.4) | 129 | 89 (69) | |

| 5 and 6 | 115 | 69 (60) | 117 | 65 (55.6) | |

| Any muscle symptoms experienced, not attributed to other causes? | |||||

| Muscle symptoms due to study drug | 1 and 2 | 156 | 76 (48.7) | 157 | 83 (52.9) |

| 3 and 4 | 125 | 65 (52) | 129 | 78 (60.5) | |

| 5 and 6 | 115 | 61 (53) | 117 | 58 (49.6) | |

Withdrawals

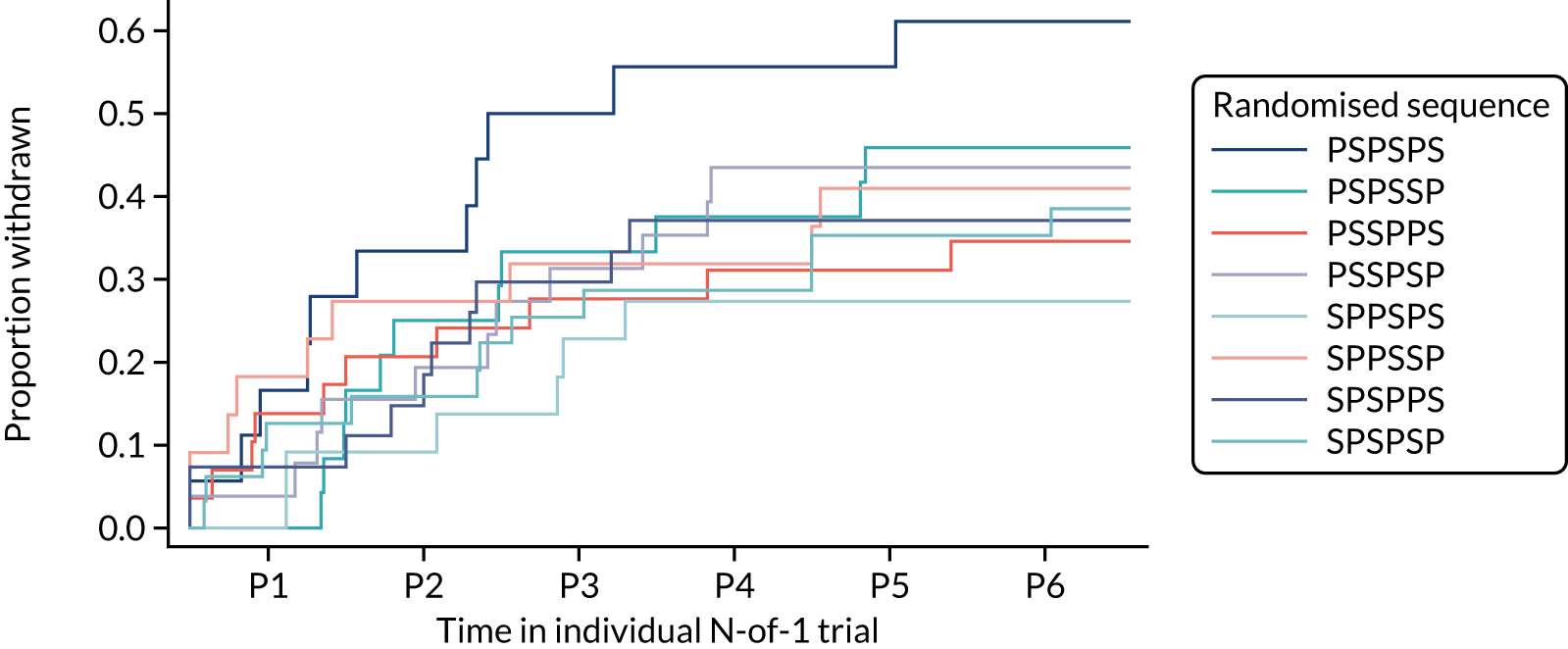

Overall, 80 patients (40%) withdrew from the trial before the end of the 12-month treatment period. A total of 16 of these 80 patients (20%) withdrew informed consent, 32 (40%) reported intolerable muscle symptoms, 14 (17.5%) withdrew because of clinical concerns raised by their GP and 18 (22.6%) withdrew for other or unknown reasons. Of the 80 withdrawals, 34 (42.5%) were during a statin period, 39 (49.75%) during a placebo period and seven (8.75%) after randomisation but prior to any study medication being taken.

More participants withdrew because of intolerable symptoms during a statin period (n = 18) than because of intolerable symptoms during a placebo period (n = 13). Conversely, the number of participants withdrawing because of clinical concern was greater during a placebo period (n = 9) than during a statin period (n = 4).

Figure 7 shows the withdrawal of patients broken down by treatment period and randomised sequence.

FIGURE 7.

Withdrawals for each treatment period by randomised sequence. P, placebo; P1, period 1; P2, period 2; P3, period 3; P4, period 4; P5, period 5; P6, period 6; S, statin.

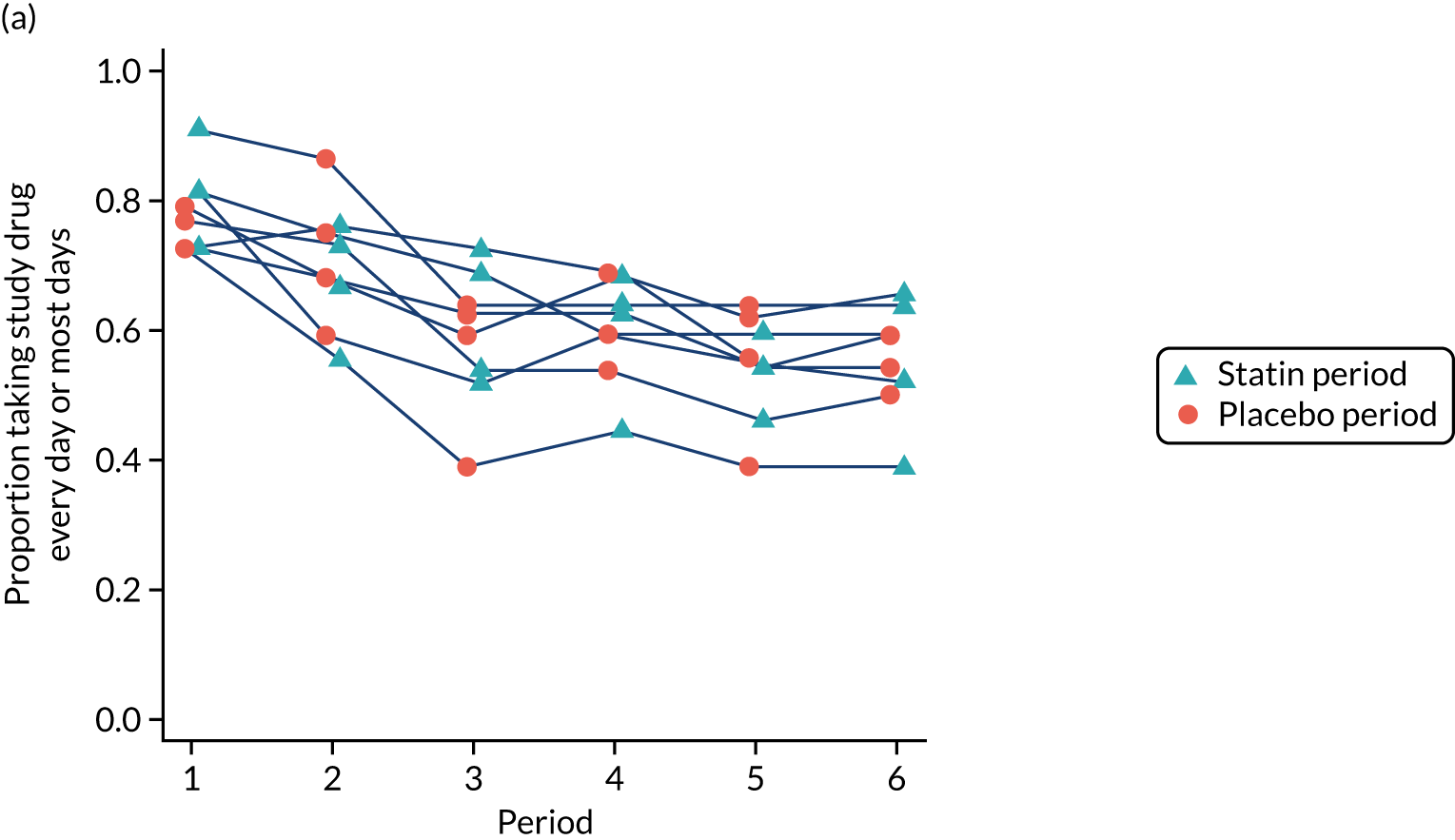

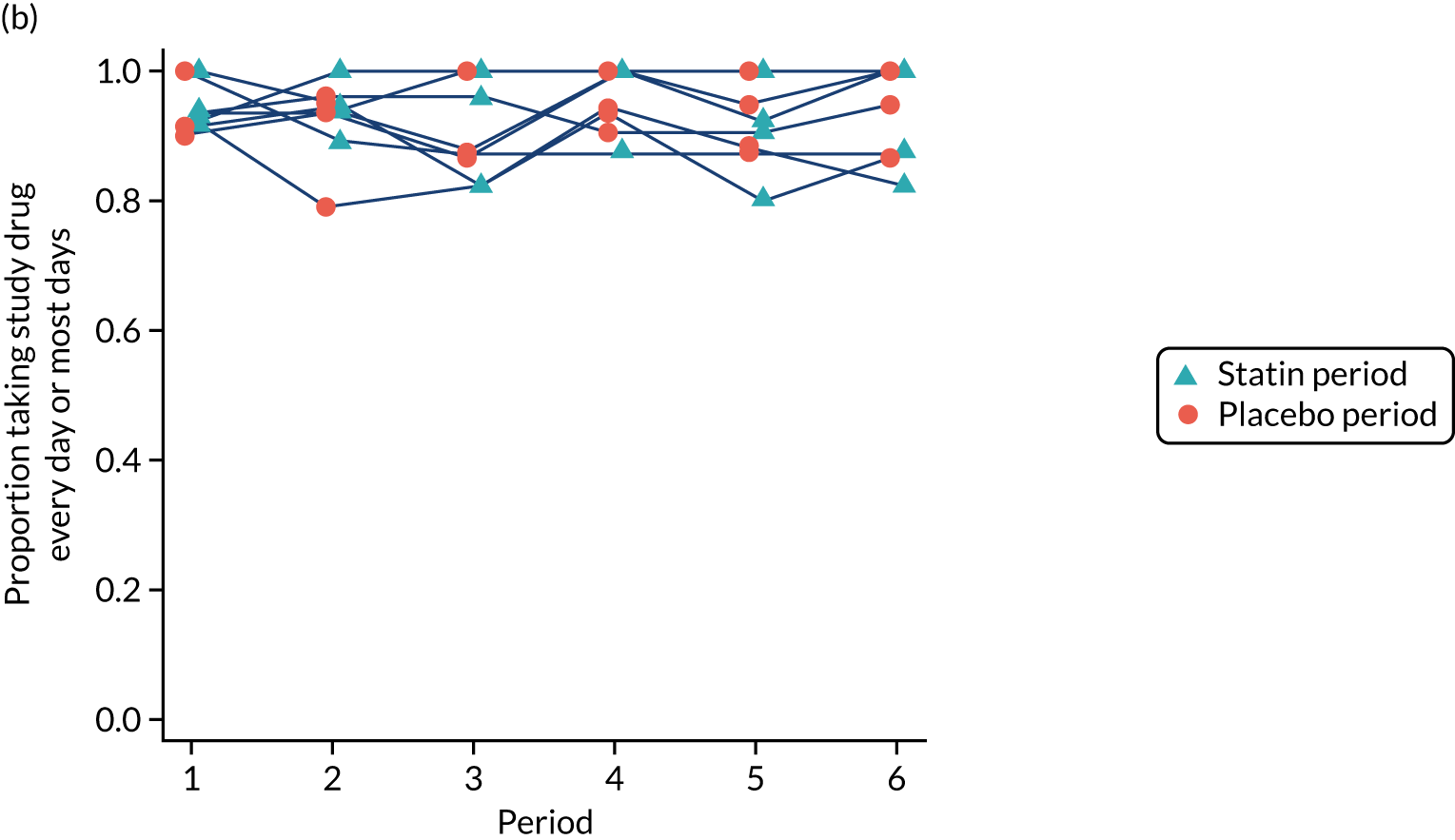

Adherence

Participant-reported adherence was confirmed through verification of the number of pills remaining in returned medication packs. Adherence to the study medication was high, with the proportion of participants reporting taking their study medication ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ being at least 80% during each period among participants who had not yet withdrawn (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Adherence to study medication by period and sequence for (a) all recruited participants; and (b) those who had not yet withdrawn. This figure has been reproduced from Herrett et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Of the 114 patients who completed the full six treatment periods, 113 received their results during an end-of-trial discussion (56.5% of randomised participants) (one participant did not attend). At 15 months, 58 (51.3%) of these 113 participants had a prescription for statins, 74 (65.5%) said that they intended to resume statins and 99 (87.6%) said that their trial had been helpful (Table 12).

| Experience | Frequency (%) (n = 113) |

|---|---|

| Participant had a subsequent prescription for statin (by 15 months’ follow-up) | 58 (51.33) |

| Does participant intend to resume statins following trial?a | |

| No | 25 (22.1) |

| Yes | 74 (65.5) |

| Don’t know | 14 (12.4) |

| Patient found their trial helpful? | |

| No | 13 (11.5) |

| Yes | 99 (87.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.9) |

Adverse effects

During the trials there were 13 serious adverse events but none was considered attributable to the study medication. There were two fatal events (one during statin treatment and one after the end of treatment) and 11 non-fatal events (five during statin treatment and six during placebo).

No emergency treatment unblinding was needed.

Chapter 4 Discussion

This series of N-of-1 trials recruited participants who either were considering discontinuation of their statin due to muscle symptoms or had stopped taking a statin due to muscle symptoms. We showed that, for the majority of participants, there were no differences in the frequency or severity of muscle symptoms between periods using statins and periods using placebo, among those who received at least one treatment period of each. In addition, there were no differences between statin and placebo periods for a range of secondary outcomes related to the effect of the muscle symptoms on aspects of participants’ daily life. Although 25% of participants did not complete sufficient treatment periods to contribute to the primary analysis, missing outcome data for treatment periods were equally distributed between statin and placebo periods, so it is unlikely that muscle symptoms contributed to missed outcome data collection. In addition, the study remained powered for the primary outcome. The majority of participants (87.6%) said that their N-of-1 trial had been helpful, with nearly two-thirds of participants reporting that they intended to resume statins or already had after the trial.

Thirty-two participants withdrew from the trial because of intolerable symptoms, and two further participants withdrew consent with support of their GP because of perceived muscle side effects. This was more common during statin periods and, therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that a minority of patients may experience muscle symptoms caused by their statin. Crucially, among this highly selected population of participants who identified themselves as experiencing symptoms on statins that were severe enough to discontinue, withdrawal because of intolerable symptoms was uncommon and the excess comparing statins and placebo was only 2%.

Comparison with other literature

StatinWISE, along with the concurrent SAMSON trial,35 are the first large-scale N-of-1 trials to investigate the effect of statins on muscle symptoms. Our findings largely support evidence from large systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials, which have shown no effect of statins on muscle symptoms in the absence of myopathy,3,4,22 despite being powered to have detected extremely rare and serious side effects of statins (e.g. rhabdomyolysis, myopathy, haemorrhagic stroke and diabetes4). An ongoing meta-analysis36 is investigating adverse event data from statin trials, aiming to provide a complete understanding of any other statin side effects. Although our trial cannot exclude the possibility of side effects among a minority of participants, it clearly indicates that the majority of patients taking statins do not experience symptoms because of their statin, and highlights the importance of blinding when assessing side effects.

Observational studies have frequently reported muscle side effects,37 and patients’ experience of muscle symptoms during statin use frequently causes them to discontinue use. Various explanations have been offered for the high frequency of symptoms found in observational studies and clinical practice. First is the nocebo effect, in which expectations of adverse effects may have led patients to attribute muscle symptoms occurring during statin use to the statins themselves. 12 Second, muscle aches and pains are common among the age group taking statins, and so occur by chance during statin use, causing patients to misattribute their pain to statins. 38 Lack of randomisation and blinding in observational studies means that spurious effects of statins are more likely. Given the proportion of patients who intended to resume statin use after their trial, our result is also in agreement with observational data showing that statin re-challenge can be tolerated. 39,40

Strengths

We collected data on muscle symptom side effects of statins as a primary outcome, in the setting of a blinded, placebo-controlled series of trials with randomised order of treatments to minimise bias and confounding. The within-patient design created superior power that was boosted in our study by repeated measurements in each treatment period, thus allowing us to investigate differences between statin and placebo with more precision.

Owing to the within-participant trial design, we were able to feed back to individual participants about whether their muscle symptoms occurred more frequently with statins or placebo and allowing them to decide for themselves whether or not to continue on statin treatment.

In delivering this series of trials, we have created a diagnostic tool allowing patients to empirically evaluate whether or not their symptoms are caused by statins. The N-of-1 trial is a complex design, but was made easy for patients as trial medications were delivered directly to patients through the post. This pathway of care could be adopted by clinicians who are looking to establish the best course of treatment for patients who present with statin intolerance.

Limitations

Although the overencapsulated statin and placebo were identical in appearance, we cannot exclude the possibility that a determined participant may have opened the capsules and unblinded themselves based on taste.

Of the 200 randomised participants, 86 did not complete the trial, of whom 49 did not provide sufficient data to contribute to the primary analysis. Adherence was similar between statin and placebo periods, and the trial was adequately sized to account for this level of dropout. Although overall withdrawals were not related to statin or placebo periods, withdrawal due to intolerable symptoms was more common during statin periods, and although it is recommended that GPs measure creatine kinase among patients experiencing such symptoms, this was not part of our trial protocol.

For simplicity and pragmatism, the trial assessed the effect of statins on muscle symptoms using 20 mg of atorvastatin only, so we are unable to extrapolate our results to other types of statins, to other dosages or to other outcomes that have been suggested to be statin related. 41

Although we intended to collect outcomes using web-based methodology, over half of the participants preferred to report their symptoms on paper or by telephone.

Generalisability

Our results are generalisable to patients who are considering discontinuing statins or have already discontinued statins due to muscle symptoms, and who are willing to re-challenge or participate in an N-of-1 trial. The N-of-1 methodology is applicable to other clinical situations in which the causal effect of a drug on a transient symptom is questioned.

Chapter 5 Conclusions

The evidence from StatinWISE suggests that, on re-challenge among patients who have previously experienced muscle symptoms that they attribute to statins, 20 mg of atorvastatin has no effect on muscle symptoms at the population level. Among a group of patients selected as having reported muscle symptoms when previously taking a statin, a proportion did have more muscle symptoms while taking a statin rather than the placebo and decided not to continue with a statin in the long term.

Among individual patients, a majority of those completing the trial decided to restart statins. Therefore, the N-of-1 trial design could be a useful method of encouraging patients to find out whether or not statins are causing their pain and guide individual therapy.

Implications for practice

The evidence from our series of N-of-1 trials suggests that this methodology could be a useful tool to aid decision-making about future statin use and encourage patients to find out whether or not statins are causing their symptoms.

General practitioners who are managing patients who believe that they are experiencing muscle symptoms as a result of the statin that they are taking should be aware that the majority of StatinWISE participants did not experience a difference in symptoms between statin and placebo, although a small proportion did have more muscle symptoms during statin treatment.

Recommendations for future research

-

We would recommend that series of N-of-1 trials be undertaken for other types of statins, higher dosages and non-muscle symptoms that are frequently attributed to statins. In particular, we would recommend this methodology among patients with existing CVD who require higher statin doses than tested in our series of N-of-1 trials.

-

We would recommend that N-of-1 trials be used in the context of transient symptoms that occur during the use of other medications.

Acknowledgements

Contributions of authors

Emily Herrett (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9425-644X) (Assistant Professor) was involved in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting phases.

Elizabeth Williamson (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6905-876X) (Associate Professor of Medical Statistics) was involved in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting phases.

Kieran Brack (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8100-8949) (StatinWISE Trial Manager) was involved in the design and conduct phases.

Alexander Perkins (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9817-2390) (StatinWISE Trial Manager) was involved in the conduct, analysis and reporting phases.

Andrew Thayne (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9702-1662) (Data Assistant) was involved in the design, conduct and reporting phases.

Haleema Shakur-Still (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6511-109X) (Professor of Global Health Clinical Trials) was involved in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting phases.

Ian Roberts (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1596-6054) (Professor of Epidemiology and Public Heath) was involved in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting phases.

Danielle Prowse (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7470-4823) (Assistant Data Manager) was involved in the design and conduct phases.

Danielle Beaumont (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2530-9608) (Senior Trial Manager/Research Fellow) was involved in the design and conduct phases.

Zahra Jamal (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3817-6795) (Trial Assistant) was involved in the reporting phase.

Ben Goldacre (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5127-4728) (Senior Clinical Research Fellow) was involved in the design and reporting phases.

Tjeerd van Staa (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9363-742X) (Professor in Health e-Research) was involved in the design and reporting phases.

Thomas M MacDonald (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5189-6669) (Professor of Molecular and Clinical Medicine) was involved in the design phase.

Jane Armitage (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8691-9226) (Professor of Clinical Trials and Epidemiology) was involved in the design phase.

Michael Moore (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5127-4509) (Trial Steering Committee Chairperson) was involved in the design, conduct and reporting phases.

Maurice Hoffman (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8860-4786) (Patient Representative on the Trial Steering Committee) was involved in the conduct and reporting phases.

Liam Smeeth (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9168-6022) (Professor of Clinical Epidemiology) was involved in the design, conduct, analysis and reporting phases.

Publications

Herrett E, Williamson E, Beaumont D, Prowse D, Youssouf N, Brack K, et al. Study protocol for statin web-based investigation of side effects (StatinWISE): a series of randomised controlled N-of-1 trials comparing atorvastatin and placebo in UK primary care. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016604.

Herrett E, Williamson E, Brack K, Beaumont D, Perkins A, Thayne A, et al. Statin treatment and muscle symptoms: series of randomised, placebo controlled n-of-1 trials. BMJ 2021;372:n135.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety, and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it’s important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. #datasaveslives You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Herrett E, Williamson E, Brack K, Beaumont D, Perkins A, Thayne A, et al. Statin treatment and muscle symptoms: series of randomised, placebo controlled n-of-1 trials. BMJ 2021;372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n135.

- Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Mihaylova B, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2015;385:1397-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61368-4.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2016;393:407-15.

- Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, Armitage J, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet 2016;388:2532-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5.

- Abramson JD, Rosenberg HG, Jewell N, Wright JM. Should people at low risk of cardiovascular disease take a statin?. BMJ 2013;347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6123.

- Malhotra A. Saturated fat is not the major issue. BMJ 2013;347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6340.

- Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, Morrison F, Mar P, Shubina M, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:526-34. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00004.

- Garavalia L, Garavalia B, Spertus JA, Decker C. Exploring patients’ reasons for discontinuance of heart medications. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2009;24:371-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ae7b2a.

- Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Negative statin-related news stories decrease statin persistence and increase myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J 2016;37:908-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv641.

- Schaffer AL, Buckley NA, Dobbins TA, Banks E, Pearson SA. The crux of the matter: did the ABC’s catalyst program change statin use in Australia?. Med J Aust 2015;202:591-5. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja15.00103.

- Matthews A, Herrett E, Gasparrini A, Van Staa T, Goldacre B, Smeeth L, et al. Impact of statin related media coverage on use of statins: interrupted time series analysis with UK primary care data. BMJ 2016;353. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3283.

- Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, Borus JF. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. JAMA 2002;287:622-7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.5.622.

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Brindle P, Hippisley-Cox J. Discontinuation and restarting in patients on statin treatment: prospective open cohort study using a primary care database. BMJ 2016;353. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3305.

- De Vera MA, Bhole V, Burns LC, Lacaille D. Impact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:684-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12339.

- Moriarty PM, Thompson PD, Cannon CP, Guyton JR, Bergeron J, Zieve FJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab vs ezetimibe in statin-intolerant patients, with a statin rechallenge arm: the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE randomized trial. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:758-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2015.08.006.

- Kashani A, Phillips CO, Foody JM, Wang Y, Mangalmurti S, Ko DT, et al. Risks associated with statin therapy: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials. Circulation 2006;114:2788-97. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624890.

- Wieseler B, Wolfram N, McGauran N, Kerekes MF, Vervölgyi V, Kohlepp P, et al. Completeness of reporting of patient-relevant clinical trial outcomes: comparison of unpublished clinical study reports with publicly available data. PLOS Med 2013;10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001526.

- Kjekshus J, Apetrei E, Barrios V, Böhm M, Cleland JG, Cornel JH, et al. Rosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2248-61. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706201.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group . MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3.

- Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, Emberson J, Wheeler DC, Tomson C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:2181-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3.

- Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, Vladutiu GD, Raal FJ, Ray KK, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel statement on assessment, aetiology and management. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1012-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043.

- American College of Cardiology . Statin Intolerance Tool n.d. http://tools.acc.org/StatinIntolerance/#!/ (accessed 10 October 2019).

- Laufs U, Filipiak KJ, Gouni-Berthold I, Catapano AL. SAMS expert working group . Practical aspects in the management of statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS). Atheroscler Suppl 2017;26:45-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1567-5688(17)30024-7.

- Guyatt G, Sackett D, Taylor DW, Chong J, Roberts R, Pugsley S. Determining optimal therapy – randomized trials in individual patients. N Engl J Med 1986;314:889-92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198604033141406.

- Herrett E, Williamson E, Beaumont D, Prowse D, Youssouf N, Brack K, et al. Study protocol for statin web-based investigation of side effects (StatinWISE): a series of randomised controlled N-of-1 trials comparing atorvastatin and placebo in UK primary care. BMJ Open 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016604.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Assessment and Reduction, Including Lipid Modification 2014.

- McCormack HM, Horne DJ, Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med 1988;18:1007-19. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700009934.

- Sakaeda T, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Statin-associated muscular and renal adverse events: data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. PLOS ONE 2011;6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028124.

- Todd KH, Funk JP. The minimum clinically important difference in physician-assigned visual analog pain scores. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:142-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03402.x.

- Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:633-8. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2001.118863.

- Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol 2012;6:208-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2012.03.003.

- Keech A, Collins R, MacMahon S, Armitage J, Lawson A, Wallendszuset K, et al. Three-year follow-up of the Oxford Cholesterol Study: assessment of the efficacy and safety of simvastatin in preparation for a large mortality study. Eur Heart J 1994;15:255-69. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060485.

- Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:17-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen103.

- Pocock SJ. Clinical trials with multiple outcomes: a statistical perspective on their design, analysis, and interpretation. Controlled Clin Trials 1997;18:530-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00008-1.

- Wood FA, Howard JP, Finegold JA, Nowbar AN, Thompson DM, Arnold AD, et al. N-of-1 trial of a statin, placebo, or no treatment to assess side effects. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2182-4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2031173.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration . Protocol for analyses of adverse event data from randomized controlled trials of statin therapy. Am Heart J 2016;176:63-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.01.016.

- Macedo AF, Taylor FC, Casas JP, Adler A, Prieto-Merino D, Ebrahim S. Unintended effects of statins from observational studies in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2014;12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-51.

- Gupta A, Thompson D, Whitehouse A, Collier T, Dahlof B, Poulter N, et al. Adverse events associated with unblinded, but not with blinded, statin therapy in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial and its non-randomised non-blind extension phase. Lancet 2017;389:2473-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31075-9.

- Zhang H, Plutzky J, Shubina M, Turchin A. Continued statin prescriptions after adverse reactions and patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:221-7. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-0838.

- Mampuya WM, Frid D, Rocco M, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL, et al. Treatment strategies in patients with statin intolerance: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Am Heart J 2013;166:597-603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.06.004.

- He Y, Li X, Gasevic D, Brunt E, McLachlan F, Millenson M, et al. Statins and multiple noncardiovascular outcomes: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:543-53. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0808.

Appendix 1 StatinWISE trial organisation

Trial Steering Committee

Michael Moore, Maurice Hoffman, Rebecca Harmston, Brian MacKenna, David Symes, Haleema Shakur-Still and Liam Smeeth.

Data Monitoring Committee

John Norrie (a member of the NIHR HTA and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board), Nicholas Mills and Hannah Castro.

Protocol Committee

Emily Herrett, Elizabeth Williamson, Danielle Beaumont, Danielle Prowse, Nabila Youssouf, Kieran Brack, Jane Armitage, Ben Goldacre, Tom MacDonald, Tjeerd van Staa, Ian Roberts, Haleema Shakur-Still and Liam Smeeth.

Trial Co-ordinating Team

Liam Smeeth (Chief Investigator), Elizabeth Williamson (Statistician), Alexander Perkins (Trial Manager), Andrew Thayne (Data Assistant), Haleema Shakur-Still (CTU Co-director), Ian Roberts (CTU Co-director), Danielle Prowse (Assistant Data Manager), Danielle Beaumont (Senior Trial Manager), Nabila Youssouf (Trial Manager), Kieran Brack (Trial Manager), Collette Barrow (Trial Administrator), Sergey Kostrov (IT Systems Officer) and Hakim Miah (IT Manager).

Trial Collaborators

Please see Appendix 4 for a list of GP practices involved in the research.

The following staff were involved in the trial at the GP practices:

Eve Thacker, Melissa Baldey, Eleanor Sowerby, Nicola Harding, Gail Timcke, Alison Macleod, Karen Lomax, Nigel Wells, Emma Pierre, Tom Baker, Carla Bratten, Karen Forshaw, Daniel Clark, Selina Fox, Rachel Hubbard, David Crichton, Nabeel Alsindi, Mandy Hayes, Keith (Peter) Elliot, Robin Fox, Jane Stanford, Emily Ackland, George Strong, Debbie Kelly, Dev Malhotra, Dipti Gandhi, Gillian Foster, Diane Exley, Dawn Brayford, Theresa Nuttall, Clare Corbett, Nicola Anderton, Gwyn Hughes, Sian Turner, Sarah Roberts, David Brown, Susan Fairhead, Karen Sutcliffe, Mark Boon, Paula Dirienzo, Kay Ellor, Hasan Chowhan, Amy Townrow, Tracey Rowles, Debbie Hipps, Geoffrey Perry, Amanda Ayers, Rebecca Cooper, Sara Harley, Lesley Parsons, Ann Selby, Regan Hood, Elizabeth Zoon, Lucy Wraith, Vicky Peterson, Jackie Pretty, Narinder Dhillon, John Wearne, Sandra Moss, Kate Maitland, Catherine Edge, Susan Brown, Stuart Mackay-Thomas, Heather Pearson, Ewan Deas, Lesley Yelland, Helen Jones, Stephen Rogers, Ian Huckle, Carsten Dernedde, Caroline Mansfield, Heather Leishman, Jordan Howard, Chris Wright, Mark Ashworth, Satinder Kumar, Catarina Guerreiro, David Hartley, Sally Gordon, Carolyn Forrest, Andy Gibson, Laura Howe, John Whitwell, Irwin Nazareth, Letitia Coco-Bassey, Kate Walters, Jaqueline Mburu, Crystal Chetwood, Lynne Dowding, Alison Williams, Nikki Richards, Mini Nelson, Emma Chadwick, Helen Mingaye, Mehul Mathukia, Jacqueline Mburu, Anna Swinburn, Janeth Tomakin, Valentina Valasevich, Hywel Jones, Joanne Bannister, Emma Edwards, Morag McDowall, Beverley Hall, Helen Permain, Nigel Peacock, Carol Harrison, Lorraine Parsons, Chuin Kee, Paula McLaren, Sherard Le Maitre, Helen Nash, Stephanie Evans, Rachel Evans, Stephen Miller, Pooja Agarwal, Oliver Booth, Victoria Mayhew, Alison Peat, Maqsood Manzur, Umesh Chauhan, Lesley Miller, Katie O’Connell-Binns, Simon Wetherell, Sam Moon, Sarah Bland, Julia Leach, Mark Sloan, Christine Shepherd, Ross Dyer-Smith, Maarten Derks, Karen Read, Jodie Button, Martin Hadley-Brown, Sandra Smith, Caroline Hutson, Barbara Stewart, Karen Norcott, Andrew Slattery, Davinder Singh, Rose Fells, Susie Foster, Liz Tomlinson, Michaela Coutts, Kathryn Morgan, David Cowling, Joanna Beldon, Caite Guest, Bruce Helme, Daniel Tacagni, Nikki Davies, Angela Sanders, Paul Harris, Angela Juhasz, Anne Jenkins, Kirsteen Rakin, Tracey Hayward-Allingham, Samantha Kirby, Kumani Jeyarajah, Beata Guss, Dorota Daukszewicz, Yesim Ozcan, Jaisun Vivekanandaraja, Preeti Pandya, Stella Oldham, Lindsey Roberts, Julie Fuller, Murtaza Khanbhai, Jonathan Barnett, Veridiana Toledo, David Collier, Anne Zak, Rebecca James, Yasmin Choudhury, Mary Feely, Manish Saxena, Julian Shiel, Julia Colclough, Elizabeth Butterworth, Alison Crumbie, Jill Barlow and Nicola Jayne Pascall.

Appendix 2 Summary of product characteristics for 20-mg atorvastatin tablets

Appendix 3 List of other symptoms reported

The other symptoms reported were as follows:

Aches in fingers.

Annoying itching under shoulder blades.

Blood sugar levels is quite high I never had diabetic problems but since I have taken these tablet my blood sugar level is high.

Calves on both legs have been very swollen, hard and very tender.

Cough.

Cramp – very slight for 2 or 3 days. Not bad.

Cramp, nose bleeds.

Cramps in leg. Muzzy head.

Dry mouth sometimes.

Experiencing a lot of cramps. Pains shooting through body. But seem to have a bit more energy and motivation.

Feet losing sensation. This is why I gave up Atorvastatin in the first place. My feet appear to have stabilised since abandoning the medication but not gone back to their original state. But I am really not sure whether there is any effect so far on this regime.

Forgetfulness.

From Day 4 to Day 24 I had a headache, joint, muscle pain, burning. Pins and needles in my hand. After Day 24 it eased off, but still had pins and needles but not so bad. In the past 7 days the pins and needles have almost gone, my energy levels are up, as at past few weeks were low.

Further difficulty rising from chair.

Giddiness.

Giddiness. Caused to have a couple of falls.

Have pain in knees at times also.

Have to think about going shopping etc as legs stiff when I get up after sitting and just don’t walk far as I my legs just don’t feel right.

Headache. Tingling in fingers and toes and also a very warm feeling in fingers and toes. Lumber area just above the hips. Very dry throat. Calves on both legs. Diarrhoea. Dry throat. Very little sleep. Aching in all leg joints. Very unwell feeling.

I also have problems with my discs in my neck, and the pain in that area has been a lot worse.

I am becoming very sleepy and lethargic. Could this be caused by your medication?

I am characteristically very active. The symptoms I suffer from is tiredness and lethargy.

I am irritable, muzzy head ache and lack of energy.