Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/36/02. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Robinson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

There are 536,000 fragility fractures per year in the UK. 1 Reducing the burden of fragility fractures is, thus, a key health priority in the NHS. Osteoporosis is a silent disease of the skeleton that causes bone fragility and increases the risk of fracture.

Over one-quarter of people with osteoporosis have moderate or severe chronic kidney disease (CKD). 2 It is speculated that these numbers will increase as a result of improved detection and diagnosis, and sociodemographic changes. CKD stage is based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), with eGFR values separated into six categories: stage 1 (normal), an eGFR of > 90 ml/minute/1.73m2; stage 2 (mild CKD), an eGFR of between 60 and 90 ml/minute/1.73m2; stage 3A (moderate CKD), an eGFR of between 45 and 60 ml/minute/1.73m2; stage 3B (moderate CKD), an eGFR of between 30 and 45 ml/minute/1.73m2; stage 4 (severe CKD), an eGFR of between 15 and 30 ml/minute/1.73m2; and stage 5 (end-stage CKD), an eGFR of < 15 ml/minute/1.73m2. Formulae to calculate the eGFR based on serum creatinine are increasingly popular. According to routinely collected data from biochemistry tests in NHS settings, the proportion of UK patients tested for serum creatinine for whom eGFR measurements were estimated increased by almost 30% between 2004 and 2009. This led to a dramatic rise in the number of patients diagnosed with CKD. 3

Chronic kidney disease has been shown to predict low bone mass, which is a proxy for bone fragility, due to accelerated bone loss. 4 It also predicts fracture risk, with a doubled risk in patients with stage 3A CKD,5 a 2.5- to threefold increased risk in patients with stage 3B CKD6 and a fourfold higher fracture incidence in patients with stage 4 CKD7 or in renal replacement therapy for end-stage renal failure. 8

Although effective therapies exist to reduce the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis, the use of first-line anti-osteoporosis therapies (bisphosphonates) is restricted in patients with CKD. There are concerns that bisphosphonates raise the risk of worsening kidney function and other adverse events that are already increased in patients with CKD, such as severe hypocalcaemia,9 upper gastrointestinal events and acute kidney injury. As the biological mechanism by which CKD weakens bone differs from osteoporosis, it is uncertain whether or not bisphosphonates will have a similar beneficial effect in reducing fracture rates in CKD patients. 10 Efficacy data for bisphosphonates is scarce in CKD, as few patients with moderate or severe CKD were included in pivotal trials. For example, only 301 (of 4496) participants with an eGFR of < 30 ml/minute/1.73m2 (i.e. CKD stages 4 and 5) were recruited in the risedronate arms of nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 11 We have previously shown that the participants of these trials with CKD were healthier and had fewer comorbidities than patients with CKD in real-life settings. 12

About 40–45% of patients with end-stage renal disease,13,14 and an unknown proportion of those with stage 4 CKD, may suffer adynamic bone disease, which is a marked reduction in bone resorption activity. 15 As bisphosphonates are anti-resorptive therapies that also reduce this activity, bisphosphonate therapy in this setting could increase rather than decrease fracture risk. A recent systematic review of 13 trials and 9850 participants suggested that bisphosphonates could improve bone mineral density (BMD) as a proxy for bone strength in kidney transplant recipients, but their effects on fracture risk remained unclear. 16

Thus, despite good safety data from randomised trials of risedronate11 and alendronate,17 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines18,19 do not support the use of bisphosphonates in patients with eGFR under 35 (moderate to severe CKD). Drug regulators do not recommend alendronate20 for patients with an eGFR of < 35 ml/minute/1.732, or ibandronate21 or risedronate22 for patients with an eGFR of < 30 ml/minute/1.732, mainly because of a lack of evidence, rather than evidence demonstrating worse outcomes. 20 Alternative therapies, such as subcutaneous denosumab (Prolia®; Amgen Inc. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), have been proposed and used in recent years, but reports of severe and even life-threatening hypocalcaemia after denosumab injection in patients with moderate to severe CKD23–26 have limited the use of this therapy in this population.

This patient group is thus left with a very high fracture risk that is effectively untreatable. The most recent (2017) Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines27 do not rule out the use of bisphosphonates in patients with moderate to severe CKD, despite acknowledging the limited evidence available, but ask clinicians to use bisphosphonates with caution. The decision to treat with bisphosphonates should be made taking into account potential CKD progression, the severity of any biochemical abnormalities, fracture risk, and bone and mineral disorders related to CKD. 28

As the use of bisphosphonates is not supported for patients with CKD, new and more expensive treatments may be used instead. However, many CKD patients who are at a high risk of fracture are not offered any treatment. Bisphosphonates were contraindicated in patients with an eGFR of < 30 ml/minute/1.732, based on the information from the relatively few patients with an eGFR of < 45 ml/minute/1.732 included in the pivotal RCTs of bisphosphonates, a lack of data on the safety of bisphosphonates for patients with stage 3B or higher CKD, and information on the adverse events induced by intravenous zoledronate. Zoledronate is the most powerful of all bisphosphonates and its pharmacokinetics means it reaches a much higher maximal concentration in the blood than other bisphosphonates. Safety data on zoledronate are, therefore, unlikely to be generalisable to other bisphosphonates.

There is an urgent need for data on the risks and benefits of bisphosphonates for patients with moderate to severe CKD. Before embarking on a RCT, which is the gold-standard design to answer these questions, it is prudent to fully explore existing resources, given the concerns of randomising patients to treatments that are, formally, not recommended, or that may even be contraindicated.

Aims and objectives

We planned this study to answer a commissioned call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), with the aim to improve our understanding of the risks and benefits of bisphosphonate therapy in patients with stage 3B+ CKD (i.e. those with an eGFR of < 45 ml/minute/1.732). We proposed four work packages:

-

Work package (WP) 1 – to study the association between bisphosphonate use and CKD progression, defined as stage progression or the requirement of dialysis or transplantation (primary outcome). We also aimed to study the association between bisphosphonate use and the annualised rates of renal function loss, measured as the loss in eGFR over time (secondary outcome).

-

WP2 – to study the association between bisphosphonate use and fragility-related clinical (symptomatic) fractures.

-

WP3 – to study the association between bisphosphonate use and severe adverse events: hypocalcaemia or hypophosphataemia necessitating hospital admission, acute kidney injury necessitating hospital admission and upper gastrointestinal events necessitating hospitalisation or recorded in primary care records (symptomatic oesophagitis, ulcer, perforation or upper gastrointestinal bleeding).

-

WP4 – to study the association between bisphosphonate use and changes in BMD over time, measured as the annualised percentage change in BMD compared with baseline BMD. Change in femoral neck BMD was the primary outcome; changes in lumbar spine and total hip BMD were secondary outcomes.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 describes the data sources, defines the main exposure, gives the operational definition used to identify bisphosphonate use and describes the statistical method of propensity score matching used to account for confounding by indication.

The specific statistical methods and results of each WP are reported in Chapter 3 (WP1), Chapter 4 (WP2), Chapter 5 (WP3) and Chapter 6 (WP4).

We synthesise and discuss our findings, discuss the strengths and limitations of the study and interpret the data in Chapter 7.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter describes the data sources used for this research: the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) GOLD; this was linked to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality data, the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and the English Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) for WPs 1–3 and to the Odense University Hospital Databases (OUHD) from Denmark for WP4. The study sample and target population are also defined in this chapter.

Data sources

Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD

The CPRD GOLD data were used to define the patients who were eligible for the study cohorts in WPs 1–3 and characterise them in detail for adjustments in further modelling of the proposed outcomes. CPRD GOLD contains anonymised, routinely collected electronic health records for a UK-representative sample of > 11 million current and historic patients registered in 674 participating practices that use the Vision GP electronic medical records software (In Practice Systems Ltd, London, UK). 29

The CPRD GOLD covers all four countries in the UK: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. However, this study was restricted to patients registered in 375 English practices, representing 58% of the CPRD GOLD practices, for whom linked patient data collected in other data sets were also available. 29

Data were linked to hospital admission data in HES, mortality data from the ONS and deprivation area codes based on the IMD. These data sets are provided by CPRD fully anonymised and linkable to each other through a patient identification. For HES and ONS data, CPRD also produces a match rank value that evaluates the likelihood of linkage, based on an eight-step algorithm. Although CPRD provides data for patients with a match rank of between 1 and 5, we included only links with a match rank of 1 or 2 to improve data quality. CPRD also provides a HES general patient identification to identify and track individuals, as they may change practice during their lifetime.

Electronic health records in CPRD GOLD comprise clinical, referral and immunisation events; biochemistry results; and prescription records from primary care:

-

General practitioners (GPs) and primary care health professionals use the hierarchical coding system of Read Codes, initially developed by GP Dr James Read in the early 1980s. 30 Read Codes are used to record clinical, referral, test and immunisation events in primary care electronic medical records. Read Codes have been revised and expanded several times, but maintain their original hierarchical structure. Each character represents a more detailed, granular description of a clinical term, event or measurement. Read Codes are mapped individually to medCODES (Medical CRF Online Documentation and Evaluation System) in CPRD GOLD.

-

Biochemistry results are reported in CPRD GOLD with associated Read Codes or medCODES and/or with CPRD-specific entity types.

-

Prescription information in CPRD GOLD includes the product name, an associated product number (prodcode), the pharmaceutical substance, its strength and its British National Formulary code. Quantity and dosage are often incompletely recorded in CPRD GOLD as they are not mandatory fields in the Vision software. A CPRD-developed algorithm was used to calculate the numeric daily dose for each prescription in this study.

Hospital Episode Statistics

The HES data contain administrative and clinical details recorded for each hospital admission episode in England, including NHS hospitals and those in the independent sector that provide services commissioned by the NHS. At the time of writing, HES included admitted patient care data from 1997, outpatient data from 2003, accident and emergency data from 2007, diagnostic imaging data from 2012, and patient-reported outcome measures from 2009.

All data recorded in HES are submitted by contributing hospitals for reimbursement purposes. HES is an administrative data set, but has been used extensively for research purposes in recent years, including previous NIHR-funded work31 resulting in high-impact publications. 32 Validation studies have demonstrated that the health outcomes recorded in HES have high validity, including two of our chosen study outcomes: acute kidney injury and end-stage renal disease. 33,34

For each hospital admission recorded in HES, information is available on hospital diagnoses and procedures, administrative details (e.g. date of admission and discharge) and basic sociodemographic details (e.g. the region where the practice is located and the patient’s ethnic background). We used the admitted patient care records in HES, as these inpatient records had sufficient clinical detail for our study. They contain coded information on the primary reason for admission, secondary or concomitant diagnoses (comorbidity) and the procedure undertaken. The primary diagnosis and comorbidities are recorded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10). 35 Inpatient procedures are coded using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys – Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4). 36

Odense University Hospital Databases

We used OUHD for WP4 because there is no equivalent data framework in the UK. Some existing UK national data sources have incomplete and non-comprehensive BMD codification, such as CPRD GOLD. Others, such as existing nationally representative cohorts like the Hertfordshire and Chingford cohorts, are underpowered for studying bisphosphonate use in a relatively rare group of patients (here, those with a diagnosis of CKD) for whom the drug is to be used with caution.

The OUHD holds BMD data measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for the whole of the Funen region, the second largest island of Denmark. It includes 36,024 individuals examined between 1990 and 2015. The Odense University Hospital performs a standard panel of blood tests during routine assessment for osteoporosis that includes serum creatinine, from which eGFR can be calculated. This panel is also performed by the local general practices in the region. The general practices and Odense University Hospital use the same clinical biochemistry laboratory. Biochemistry values (including serum creatinine tests) and pharmacy drug dispensations can be tracked back to 1995.

Pharmacy dispensations are recorded using Anatomic Therapeutic Classification codes, and ICD-10 codes are used for diagnoses. The Odense Patient Data Exploratory Network provides a unique platform for linking clinical and biochemistry data and is an approved Statistics Denmark institutional partner for linking to national data on pharmacy dispensations and comorbid conditions. The facility has previously been used to link clinical biochemistry to fracture outcomes in the context of thyroid status and fractures. 37 Ad hoc extraction and linking to renal function from the Odense University Hospital clinical biochemistry database were done as part of this study using a similar approach.

In OUHD, > 10,000 patients, 30% of those examined, were recommended osteoporosis treatment. Alendronate is the first-line osteoporosis treatment in this setting. In Denmark, reimbursement for alendronate and other bisphosphonates requires a DXA assessment or a radiograph-verified spine or hip fracture.

UK Renal Registry

In our initial protocol (version 1.0), we planned to use the UK Renal Registry (UKRR) to obtain detailed information on relevant aspects of renal disease and treatment for end-stage renal disease. The UKRR collects data from the specialised treatment centres that treat most patients with end-stage renal disease.

The advantages of linking UKRR to the readily available CPRD GOLD–HES data set were obvious:

-

Access to this external data set would allow us to validate the diagnosis of end-stage renal disease and initiation of renal replacement therapies recorded in primary (CPRD GOLD) and secondary (HES) care records.

-

The UKRR contains more detailed and probably higher-quality information on dates and types of renal replacement therapies offered than CPRD GOLD–HES.

However, despite the early and full involvement of the UKRR in this study, we encountered difficulties that made it impossible to obtain approval for linkage by NHS Digital as a trusted third party to finalise this project on time. Nine months passed between the submission of our first application for linkage to NHS Digital and our decision to abandon this approach.

The steps followed and the difficulties encountered were as follows:

-

After some discussion, it was deemed necessary to apply for approval from the Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) and the Health Research Authority, through a Research Ethics Committee. We applied for both and were approved in March 2017 (reference numbers 17/CAG/0032 and 17/SC/0073).

-

We then needed to submit a Data Access Request Service (DARS) application to the Independent Group Advising on the Release of Data (IGARD) committee. CPRD offered to lead the application process and prepare the first draft as they had more experience, although the University of Oxford was the only data controller.

-

In August 2017 the first application was submitted. The lead applicant was changed from CPRD to the principal investigator of the study, as the CPRD information governance team had limited time available to track every step of the application. In November 2017, CPRD was added to the application as data controllers and the lead applicant changed back to the CPRD information governance team.

-

Once CPRD became the lead applicant, conversations and any modifications to the DARS application were in the hands of the CPRD and NHS Digital teams. It was not clear to us from this point onwards what other steps were needed to help progress the application, except for a CAG application from CPRD. The barriers were also unclear. We offered our assistance, but were assured that no other contributions were needed from us for the rest of the process.

-

The DARS application was deemed ready for submission by NHS Digital in May 2018. However, the implementation of the new European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)38 on 25 May 2018 required modifications to the application, causing delays. IGARD reviewed our DARS application and requested further amendments from CPRD and amendments to our fair processing notice to account for the new GDPR regulations.

-

We were informed by NHS Digital that they would prioritise our application and aim to obtain the UKRR data by the end of September 2018. We thus asked for a second extension to our contract with the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme in August 2018. However, we were then informed that a new version of the data-sharing framework contract was needed between the University of Oxford and NHS Digital before we could receive the linked data. Although our legal team tried to speed up the process, we felt that there was insufficient time to finalise this new contract and obtain the data by the end of September 2018.

For these reasons and to minimise an unnecessary delay in reporting our findings, we thus withdrew our extension submission and DARS application. In this report, as agreed with the HTA programme, we conducted all analyses using CPRD GOLD with linked HES data only. Data were extracted from the CPRD GOLD data set’s March 2016 release, with linkage to HES, ONS and IMD using linkage set 11.

Target population and statistical analyses

The target population of this study was patients with an eGFR of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 who were aged ≥ 40 years when biochemistry testing was done, in the period 1997–2014. The date of the first eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 in primary care (CPRD GOLD) was defined as the baseline date for all patients.

Patients were excluded if any of the following criteria applied:

-

CPRD GOLD participants with no possible linkage to HES.

-

Less than 1 year of run-in up-to-standard data available in CPRD GOLD before the index or baseline date (i.e. eGFR or creatinine measurement).

-

Use of any anti-osteoporosis medications in the year before index (except calcium and/or vitamin D supplements).

-

Use of any anti-osteoporosis medications other than bisphosphonates at any point (except calcium and/or vitamin D supplements; see Report Supplementary Material 3 for the code list).

We needed at least 1 year of CPRD GOLD data before baseline dates to ascertain whether or not an exclusion criterion applied to a patient. We also used this information in our propensity score modelling to minimise confounding by indication [e.g. age, sex, fracture history and body mass index (BMI)] by adjusting.

Main exposure: bisphosphonate use

Users of bisphosphonates were identified from primary care prescription records in CPRD for WPs 1–3 and from pharmacy dispensations data in the Danish Prescription Registers, linked as part of OUHD, for WP4. We included all bisphosphonates prescribed in primary care in the study period, of which alendronate, risedronate and ibandronate were the most common. Report Supplementary Material 1 lists the product names, corresponding British National Formulary codes and equivalent Prodcodes.

The data sources included information on drug prescriptions (CPRD GOLD) and dispensing (OUHD) instead of drug consumption. A prescription’s duration does not always reflect the true number of days over which the prescribed drug was used. Assumptions were made to account for non-adherence and non-compliance to define episodes of continuous exposure.

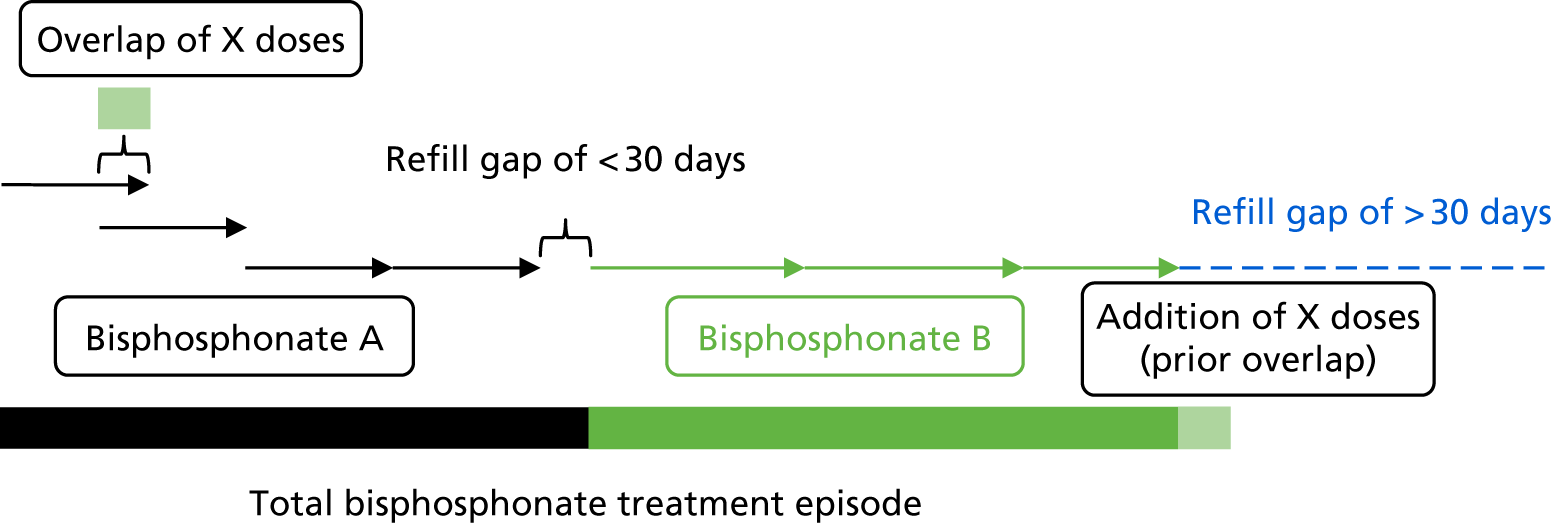

We assumed that any overlap between two prescriptions of the same bisphosphonate represented early collection of a repeat prescription. Any overlapping days between two prescriptions of the same drug were added to the end of the period covered by the two prescriptions. To define periods of continuous use of a study drug, any two prescriptions of the same drug were concatenated if the gap between the end of the first and the start of the second was < 30 days. Continuous use is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Construction of treatment episodes based on prescription data.

Immortal time bias

Immortal time bias is a common issue in pharmacoepidemiology. It appears when a study’s event of interest cannot occur for a certain time span because of the study design and/or the data analysis methods used. 39 In this study, immortal time could arise when the definition of drug use involved a delay or wait period during which follow-up time was accrued. For example, immortal time could arise when a participant waited for a prescription or drug dispensation after being discharged from hospital, when their discharge date represented the start of follow-up. 40

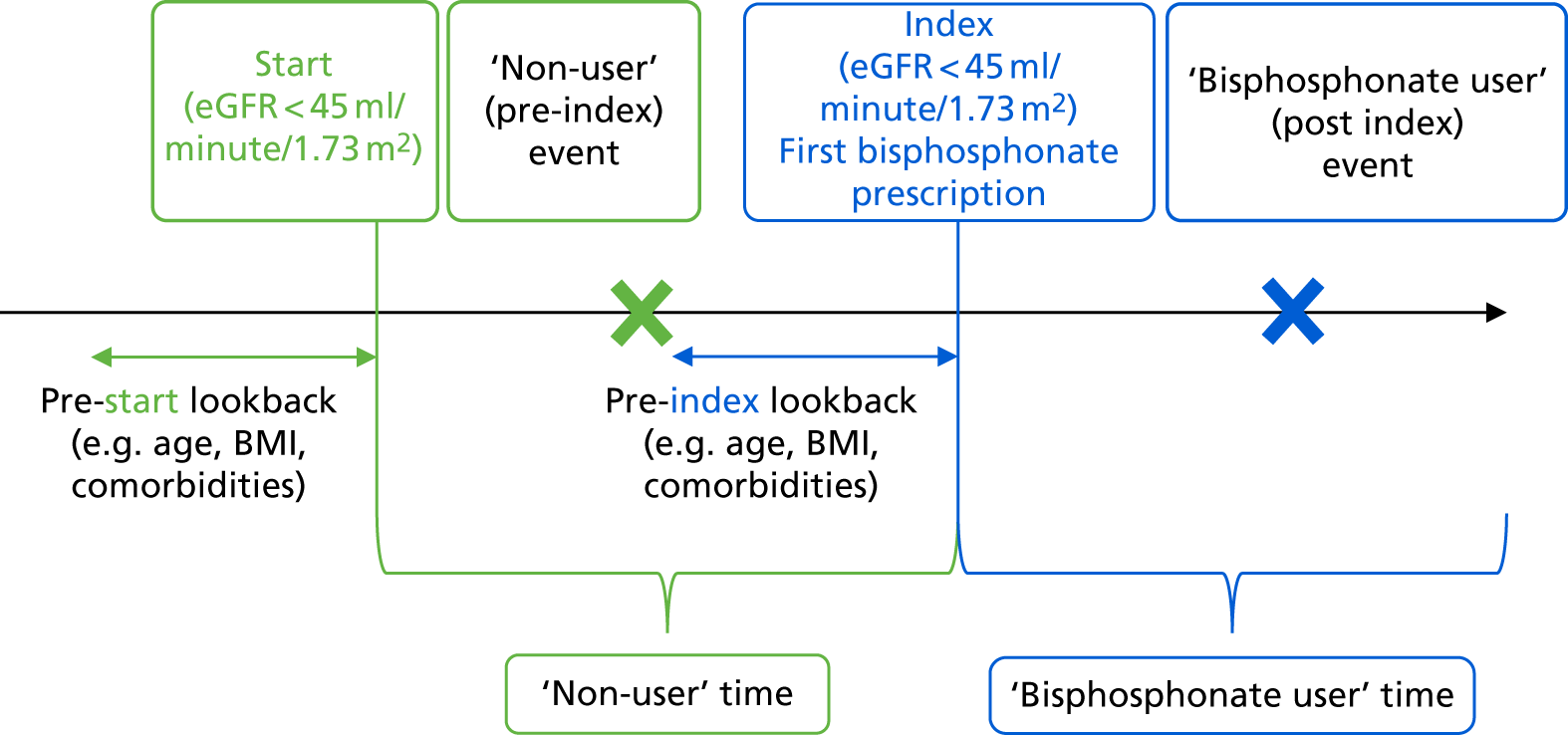

We used time-varying exposures, reclassifying the time before the first prescription of bisphosphonate as non-user person-years and classifying the time after the first prescription of bisphosphonate together with a recent eGFR of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 before that prescription as bisphosphonate user person-years. We have extensive expertise using this method,41–43 which is the most efficient at avoiding immortal time bias in pharmacoepidemiological studies. 44 Figure 2 demonstrates our implementation of time-varying exposures in our data management process.

FIGURE 2.

Time-varying exposure to avoid immortal time bias.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate measurement

Formulae to calculate eGFR based on serum creatinine are increasingly popular. According to routinely collected data on biochemistry tests in NHS settings, the number and proportion of UK patients tested for serum creatinine for whom eGFR measurements were calculated increased by almost 30% between 2004 and 2009. 3 Automated laboratory reporting of eGFR has also been increasingly used in UK primary care since 2006. 45 We used recorded eGFR from CPRD GOLD when available. When an automated laboratory report of eGFR was not available but serum creatinine data were recorded, we calculated eGFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease – Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula. 46 We chose this formula after consulting two renal epidemiologists.

Propensity score methods

The chosen study design is a propensity score-matched ‘real-world’ new-user cohort study. This is a standard pharmacoepidemiological design used to assess the intended (benefits) and unintended (risks) effects of drugs in drug safety observational research. Propensity scores are defined as the probability that a patient will receive the drug of interest (here, bisphosphonates) according to their baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Propensity scores have been proposed as a valid method for minimising confounding by indication in the absence of residual (unobserved) confounding.

Multivariable logistic regression equations were used to calculate one propensity score for each of the study outcomes of interest,47 as described in later chapters. A separate model was built for each of the outcomes, as the confounders and risk factors for different events might have differed. Prespecified predictors for each of these outcomes were included in each of the models. 48

The created propensity scores were used to match bisphosphonate users with comparable non-users using calliper matching, with a maximum calliper width of 0.02 standard deviations (SDs). Bisphosphonate non-users were thus only eligible to be matched if their propensity score fell within a bandwidth of 0.02 SDs of a bisphosphonate user’s propensity score. This method is one of the most efficient for minimising confounding by indication in pharmacoepidemiological studies. 49 Propensity score calliper matching typically excludes participants with extremely high or low risks for the outcome, if those extreme risk values are not seen in both intervention and comparator participant groups.

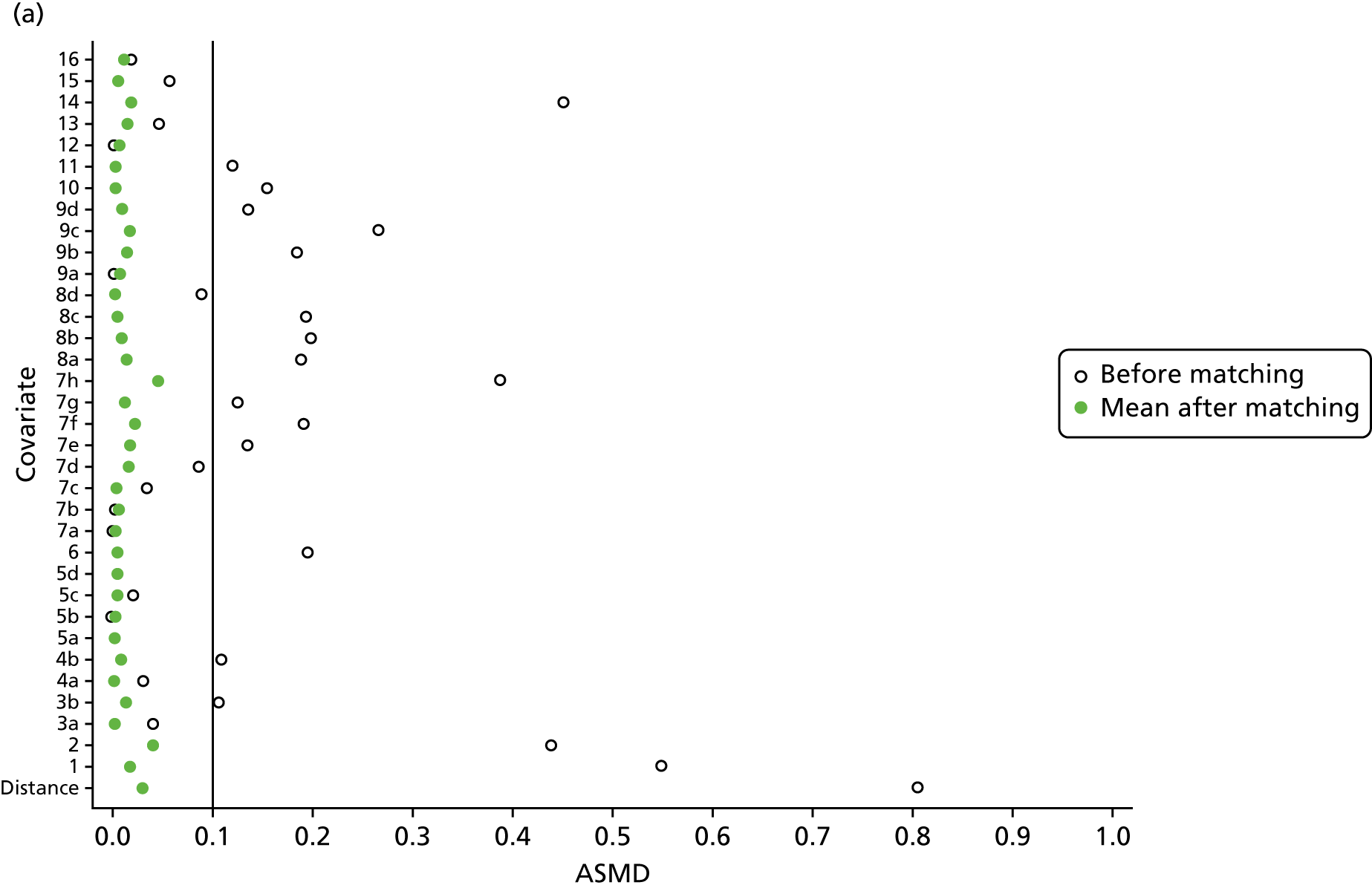

The imbalance in each of the listed confounders was assessed before and after matching using the absolute standardised mean difference (ASMD). An ASMD of < 0.1 was considered acceptable, based on previous literature. 50

Selection of confounders for inclusion in the propensity score equations

Previous methodological research has suggested that propensity scores should include true confounders (variables associated with the probability of treatment and the probability of the event of interest) and risk factors for the study outcomes. 51 We created a matrix of variables for inclusion in each of the propensity score equations created for each of the WPs. The list of variables to be included was defined as follows:

-

A list of all potential confounders and risk factors for each of the study outcomes was created by a postdoctoral epidemiologist based on a literature review and the availability of information recorded in the CPRD GOLD–HES data set.

-

The list was circulated to two clinician scientists, a GP and a rheumatologist, who added any potentially relevant variables not included in the list.

-

The amended list was sent to both clinician scientists, who independently highlighted the variables associated with each of the outcomes of interest.

-

Discrepancies in the highlighted lists were resolved in a consensus meeting involving the postdoctoral epidemiologist and both clinicians. The final lists of variables included in each of the propensity score equations are detailed in Table 1.

| Outcome events | WP1: CKD progression | WP2: symptomatic fracture | WP3: adverse events | WP4: change in DXA-measured hip BMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and/or clinical factors | ||||

| Age | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Sex | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Socioeconomic status | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Height, weight, and BMI | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Smoking status | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Alcohol drinking | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Number of GP visits/hospital visits in the previous year | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| BMD | ✗ | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index 5-year score | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Cancer | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| CKD | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Dementia | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| History of cardiovascular disease | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| History of fracture | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Previous jaw osteonecrosis or rickets | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Previous thromboembolic events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Varicose veins | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Kidney function (eGFR) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Peptic ulcer disease | ✗ | |||

| Renal disease | ✗ | |||

| Hypertension | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Hyperlipidaemia | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Liver disease | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Peripheral vascular disease | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Hyperthyroidism | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Co-medications | ||||

| Number of prescriptions in the previous year | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Hormone replacement therapy or contraceptives | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Calcium or vitamin D supplements | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Bisphosphonate use for > 1 year before index date | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Systemic corticosteroids | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Oral glucocorticoids | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Oral anticoagulants | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Proton pump inhibitors | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Low-molecular-weight heparins | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Aromatase inhibitors | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Antidepressants | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Statins/lipid-lowering drugs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Hypnotics | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Antiepileptics | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Diuretics | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Beta blockers | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ACE inhibitors | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Calcium channel blockers | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Other antihypertensives | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Digoxin | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Antihypertensives | ✗ | |||

| Antiarrhythmic agents | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Oral antidiabetic drugs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Insulin | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

The code lists of the included confounders can be found in Report Supplementary Material 4.

Missing data

We defined clinical characteristics according to consultation behaviour in primary care medical records. No consultation equates to the absence of a health problem, and no prescription equates to no drug use. This assumption is valid as, in the UK, GPs serve as the gatekeepers to authorise further medical services and are obliged to hold full records of their patients’ medical histories. However, some characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol drinking and BMI values, can be missing from these records.

We imputed this missing information for the propensity score (logistic) models using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) methods. As MICE assumes ‘at random’ missingness, we processed the data as follows:

-

We fitted logistic regression models using the whole data set to look for predictors of missingness for a specific variable (e.g. BMI). If such predictors were present in the data, then we assumed that missingness was not completely at random.

-

In the subset of patients with complete data for the same variable (e.g. BMI), we ran a different regression model (linear regression in this example) to look for predictors of that variable’s values. If we also identified predictors of such values, then we assumed that the data were ‘missing at random’.

-

We used the identified predictors of missingness (step 1) and values (step 2) in our MICE for imputation models.

-

As these steps confirmed the assumption of ‘at random’ missingness, we used MICE to impute missing values in each of the 10 imputed data sets. For each imputed data set, two propensity score-matched cohorts (bisphosphonate users and comparable non-users) were identified and analysed per study outcome.

-

Treatment estimates from each of the 10 imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules to obtain an overall outcome estimate. 52

Study outcomes

Detailed descriptions of each outcome are given in each work package chapter (see Chapters 4–7). In brief, the study outcomes were as follows:

-

CKD progression –

-

based on stage progression (changing to a worse CKD stage as defined by the KDOQI guidelines) or requiring haemodialysis or transplantation, as recorded in HES (primary outcome)

-

based on the change in eGFR over time (secondary outcome).

-

-

Clinical (symptomatic) fractures of osteoporotic sites (all but face, skull, fingers or toes), ascertained using prespecified Read code lists in CPRD GOLD.

-

Acute kidney injury, identified using ICD-10 codes recorded in HES.

-

Hospitalisation for hypocalcaemia or hypophosphataemia, identified using ICD-10 codes recorded in HES.

-

Upper gastrointestinal events, identified using ICD-10 codes recorded in HES and Read codes recorded in CPRD GOLD.

-

Change (percentage from baseline) in BMD over time –

-

in the femoral neck (primary outcome)

-

in the total hip and lumbar spine (secondary outcomes).

-

The follow-up windows are described in each WP chapter; see Chapters 4–7.

Data analysis

Detailed descriptions of the data analysis used in each WP are given in the relevant chapters. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.3.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) or Stata® version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), unless otherwise mentioned.

Ethics and scientific approval

No additional ethics approval was required as this study used anonymised routinely collected data from the UK’s CPRD GOLD with linked HES data and the Danish OUDH. To access these data sets, we submitted an application to and obtained approval from the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC) for CPRD GOLD/HES (WPs 1–3) (ISAC protocol number 15_153R2) and the Region of Southern Denmark (reference number 15/37999), the health trust accountable to the Data Protection Agency for oversight of research data at Odense University Hospital under the Danish Health Act (WP4).

Chapter 3 Work package 1: the association between the use of bisphosphonates and the progression of kidney disease

Introduction

Bisphosphonates and renal toxicity: mechanistic studies

Bisphosphonates are contraindicated in patients with stage 4+ CKD who have an eGFR of < 35 ml/minute/1.73 m2, because of a scarcity of risk–benefit data for these patients and a number of spontaneous reports suggesting nephrotoxicity.

Animal studies have identified a dose-dependent association between the administration of bisphosphonates and renal injury, identified by urinary (malate dehydrogenase)53 and serum (urea, nitrogen and creatinine) biomarkers. 54 Mice exposed to high doses of pamidronate expressed histological changes such as focal cellular necrosis, increased cellular vesicles and loss of tubular cell brush borders. 55 Similar effects have been reported for other bisphosphonates, including zoledronate and ibandronate. 56 Single-dose infusions of zoledronate or ibandronate in mice caused renal proximal tubular damage with loss of brush borders, cytoplasmic swelling, and cell necrosis. 57

Numerous human case reports of renal failure, acute kidney injury and nephrotic syndrome58 following the use of a bisphosphonate have been published. Subsequent renal biopsies have found focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), collapsing FSGS, and toxic acute tubular necrosis. 59–65 As expected, these spontaneous reports differ in sample size (reporting between one and seven patients) and scientific value. Some of the reports have claimed clinical and histological improvement after the bisphosphonate therapy was discontinued. 66

Evidence of renal toxicity from clinical trials

Data from RCTs are, in general, reassuring, suggesting that bisphosphonates are safe for use in fracture prevention for patients with normal renal function. 67,68 However, studies of high-dose bisphosphonate treatment for indications other than fracture prevention (e.g. treatment of bone cancer and metastasis) have been inconsistent. A Phase III trial of high-dose monthly intravenous pamidronate for multiple myeloma found no adverse renal effects in 203 treated participants compared with 189 placebo-exposed participants. 69 However, renal safety concerns have been reported in oncology RCTs of zoledronic acid. A Phase III RCT comparing zoledronic acid and pamidronate for multiple myeloma had to adjust treatment regimens and still found high incidences of nephrotoxicity of 9.3% and 8.1%, respectively. 70 Another trial in patients with bone metastases found a noticeable (although not statistically significant) 4.2% absolute risk increase in participants treated with zoledronic (10.9%) compared with placebo (6.7%). 71

Most of the participants in RCTs have a normal baseline renal function. A recent meta-analysis16 showed that none of the seven identified studies investigating the effect of bisphosphonate use in patients with stages 3–5 CKD or who required dialysis or kidney transplant reported a statistically significant difference between bisphosphonate users and non-users. However, the included studies generally contained low numbers of participants and were not powered to test for statistically significant differences in safety events such as eGFR stage change. The meta-analysis may not have been able to capture renal toxicity.

Work package 1 aimed to assess the association between bisphosphonate use and CKD progression (worsening) in real-world users of bisphosphonates with moderate to severe (stage 3B+) CKD.

Methods

Comparing Clinical Practice Research Datalink and Hospital Episode Statistics reporting of dialysis and transplant

As we were unable to acquire UKRR data, we cross-validated the recording of renal replacement therapy (dialysis or transplant) in CPRD GOLD and HES. HES was used as the gold standard for comparison, as previous linkage of HES to the UKRR found good validity and completeness of recording of both dialysis and kidney transplant in HES data, with quality improving further in recent years. 34

The positive predictive value and sensitivity of dialysis and transplant recording in CPRD GOLD and HES were calculated and compared. The number of events for which dates in CPRD GOLD and HES differed by less than 3 months (90 days) was also calculated.

Study participants and exposure

A new-user cohort analysis was conducted using data from CPRD GOLD linked to HES.

Patients recorded in CPRD GOLD who were aged > 40 years and had at least two eGFR measurements within 1 year of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 were eligible. Patients were excluded if they had received any bisphosphonate prescription in the year before their first eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, had previously used other (non-bisphosphonate) anti-osteoporosis therapies, were missing IMD data or had no follow-up eGFR measurements.

All participants initially joined the study unexposed to bisphosphonate on their second eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2. Participants could contribute to both exposed and unexposed time. They were followed up until one of the following occurred:

-

the end of enrolment in the database (due to moving out or death)

-

(exposed participants only) stopping treatment > 210 days, made up of the 30 days of the last prescription and a washout period of 180 days; they would not have any repeated prescription within 6 months

-

(exposed participants only) switching treatment to another osteoporosis medication and no repeated prescription of bisphosphonates within the next 6 months

-

incident recorded renal event, as defined under Study outcomes.

Exposure

The exposure of interest was bisphosphonate use. At first bisphosphonate use, a participant’s most recent eGFR measurement was assessed. Those with an eGFR of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 moved to the exposed category. Those with a bisphosphonate prescription and an eGFR of ≥ 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 were censored at the time of starting bisphosphonate therapy.

Bisphosphonate prescriptions were concatenated to create treatment (exposure) episodes as described in Chapter 2, Main exposure: bisphosphonate use. Exposed patients were censored 210 days (30 days to account for the last prescription, plus a 6-month washout period) after the last bisphosphonate prescription if this was earlier than their censor time, as specified in the previous section.

Study outcomes

The outcomes of interest were as follows:

-

primary (per-protocol) analysis – CKD stage worsening based on follow-up eGFR or start (first session or surgery) of renal replacement therapy

-

secondary (per-protocol) analysis – annualised eGFR change based on all follow-up eGFR measurements

-

post hoc analyses –

-

CKD stage worsening based on follow-up eGFR measurements

-

CKD stage change based on eGFR (compared with stable CKD)

-

increase (worsening) in CKD stage

-

decrease (improvement) in CKD stage.

-

-

As described in Chapter 2, Study outcomes, the outcome follow-up period ran from the baseline (second eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 within 1 year) or index date (first bisphosphonate treatment) until the earliest occurrence of any of the following:

-

end of enrolment in the database (due to moving out, death or the practice stopping follow-up)

-

therapy cessation (last prescription before a 6-month prescription gap) + 210 days, made up of the 30 days of the last prescription and a washout period of 180 days

-

switching to (or adding) another anti-osteoporosis medication

-

a dialysis, transplant or CKD stage-change event

-

10 years follow-up.

Chronic kidney disease stage was measured using eGFR records from CPRD GOLD. Dialysis and transplant events were identified in HES using ICD-10 and OPCS-4 codes, respectively. If a patient had more than one eGFR record within a calendar year, we used the latest one to represent the eGFR records for that follow-up year.

Code lists for dialysis and transplant outcomes are presented in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Statistical analysis

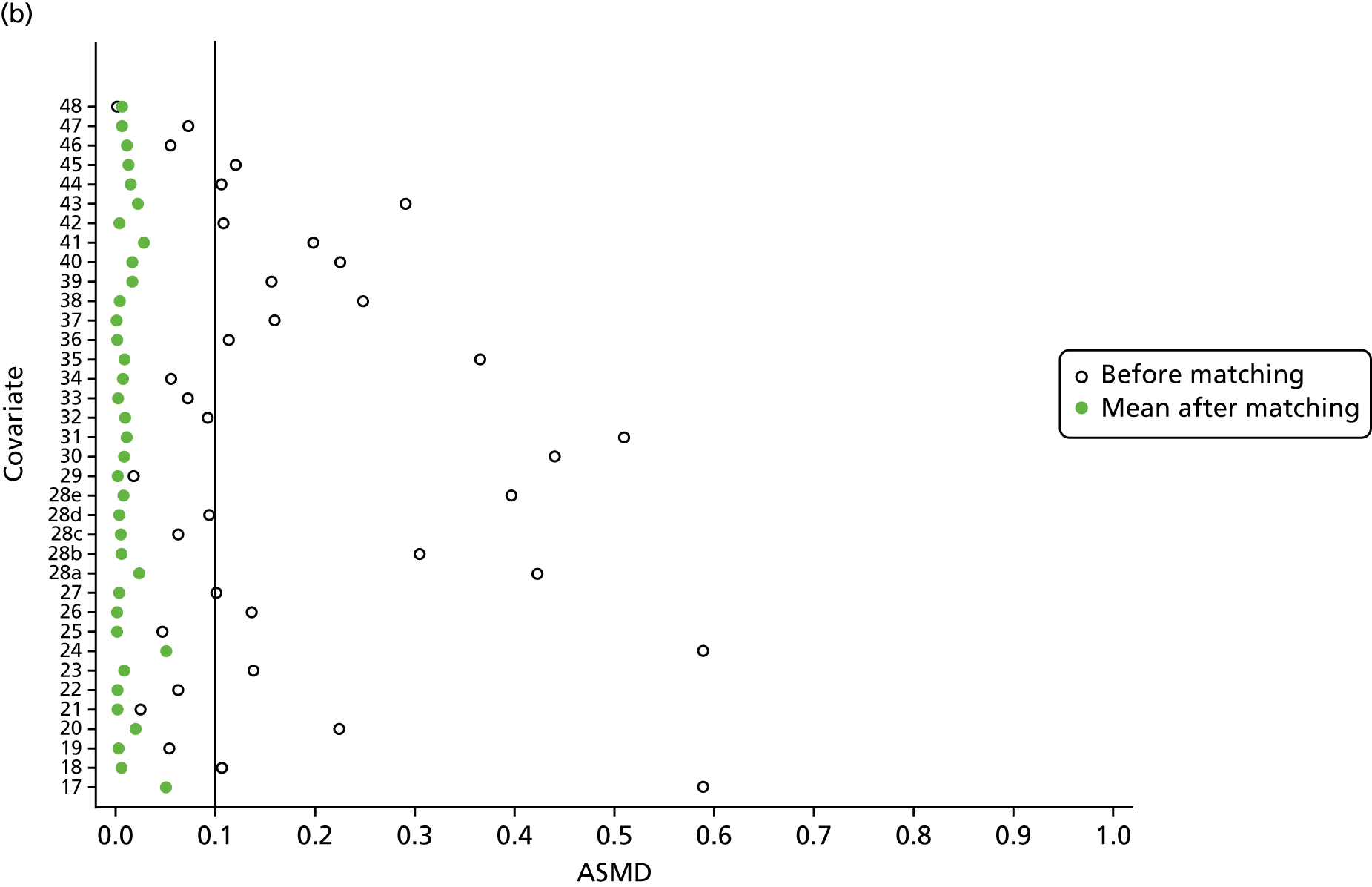

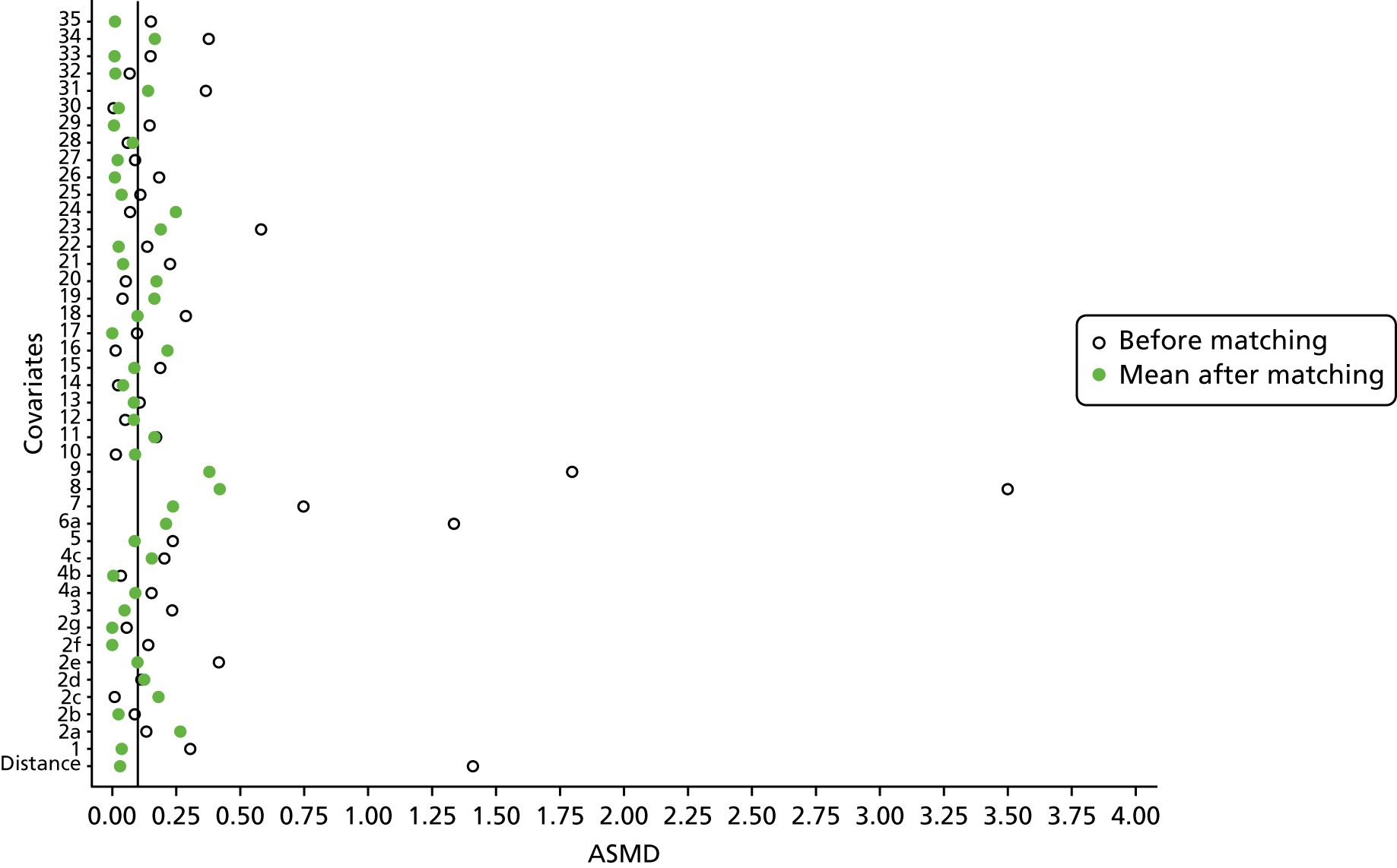

We conducted a stratified propensity score analysis to account for potential imbalance in the years of follow-up between bisphosphonate users and non-users. The stratification of years of follow-up was grouped into four categories: 1–2 years, 3–4 years, 5–6 years and 7–10 years. Each user was propensity matched with up to five non-users, all with the same follow-up period, based on 46 covariates (see Chapter 2, Propensity score methods). Balance before and after matching for each confounder was assessed using the ASMD with a cut-off point of 0.1.

The crude and age-sex specific incidence rates [and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] of each of the outcomes were estimated separately in the propensity score-matched cohorts for bisphosphonate users and non-users per 1000 person-years. Rates were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Average incidence rates were used to derive the absolute increase in risk and to calculate the number needed to harm in the primary analysis at 1, 3 and 5 years of treatment. 72 Kaplan–Meier plots were used to depict the predicted cumulative probability of each of the study end points according to bisphosphonate use.

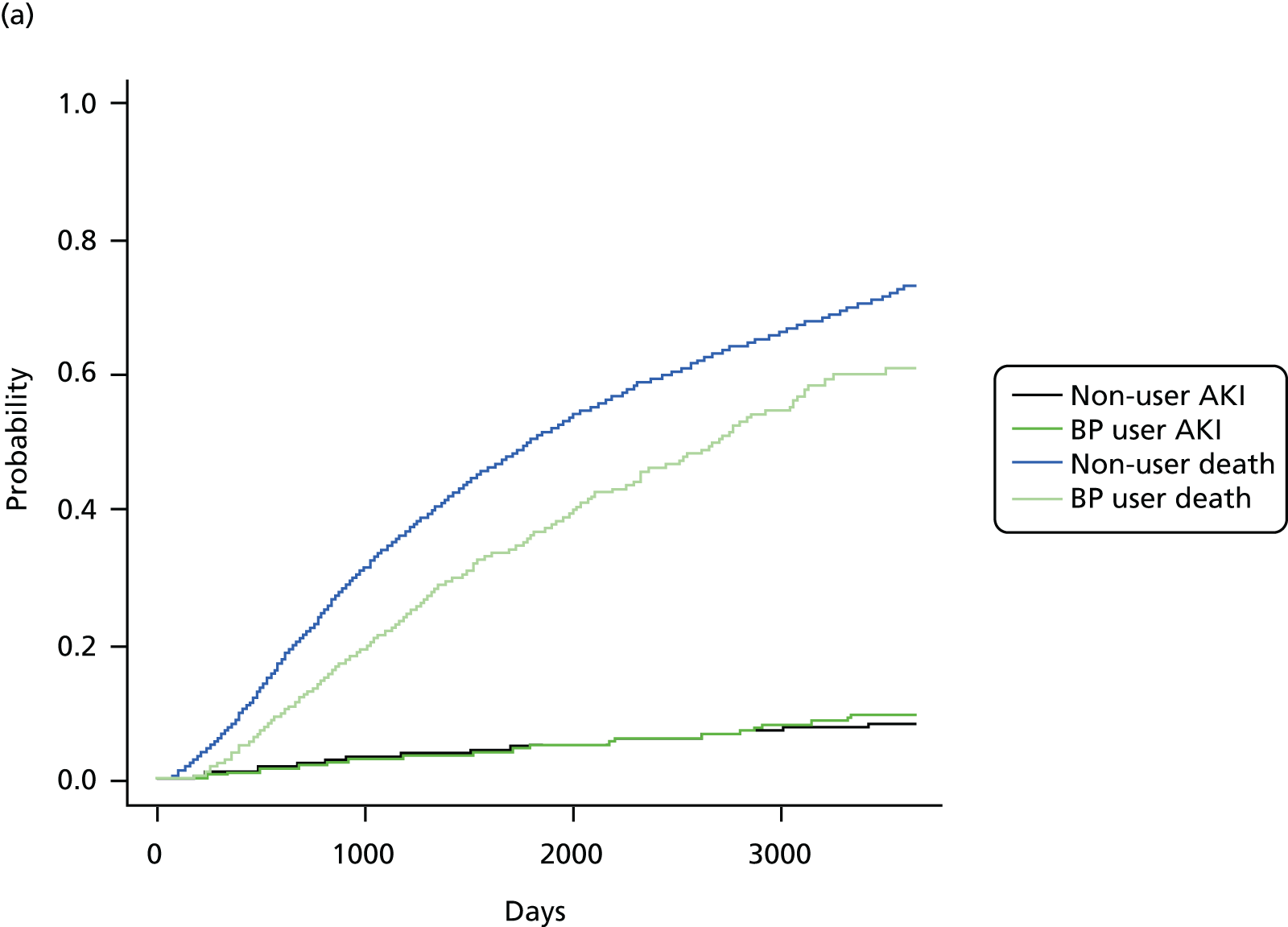

Initially, Cox proportional hazards models were used to compute the hazard ratio (HR) (and 95% CIs) for mortality according to drug use. These were fitted for the propensity score-matched cohorts of each imputation and combined using Rubin’s rules. 52 The assumption of proportionality was checked graphically using c-loglog plots. The model for mortality showed a reduced risk of death in patients using bisphosphonates (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.73). Therefore, competing risks analyses, both Fine and Gray and cause-specific hazards, were calculated. Because the results were similar, only Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard ratios (sHRs) are reported. Cumulative incidence function plots are shown in Appendix 1, Figure 25.

A post hoc multivariable analysis was undertaken on the full data set, as requested by the Steering Committee, using all of the covariates included in the propensity score. No difference in mortality was found in this model, and hence Cox proportional hazards were used.

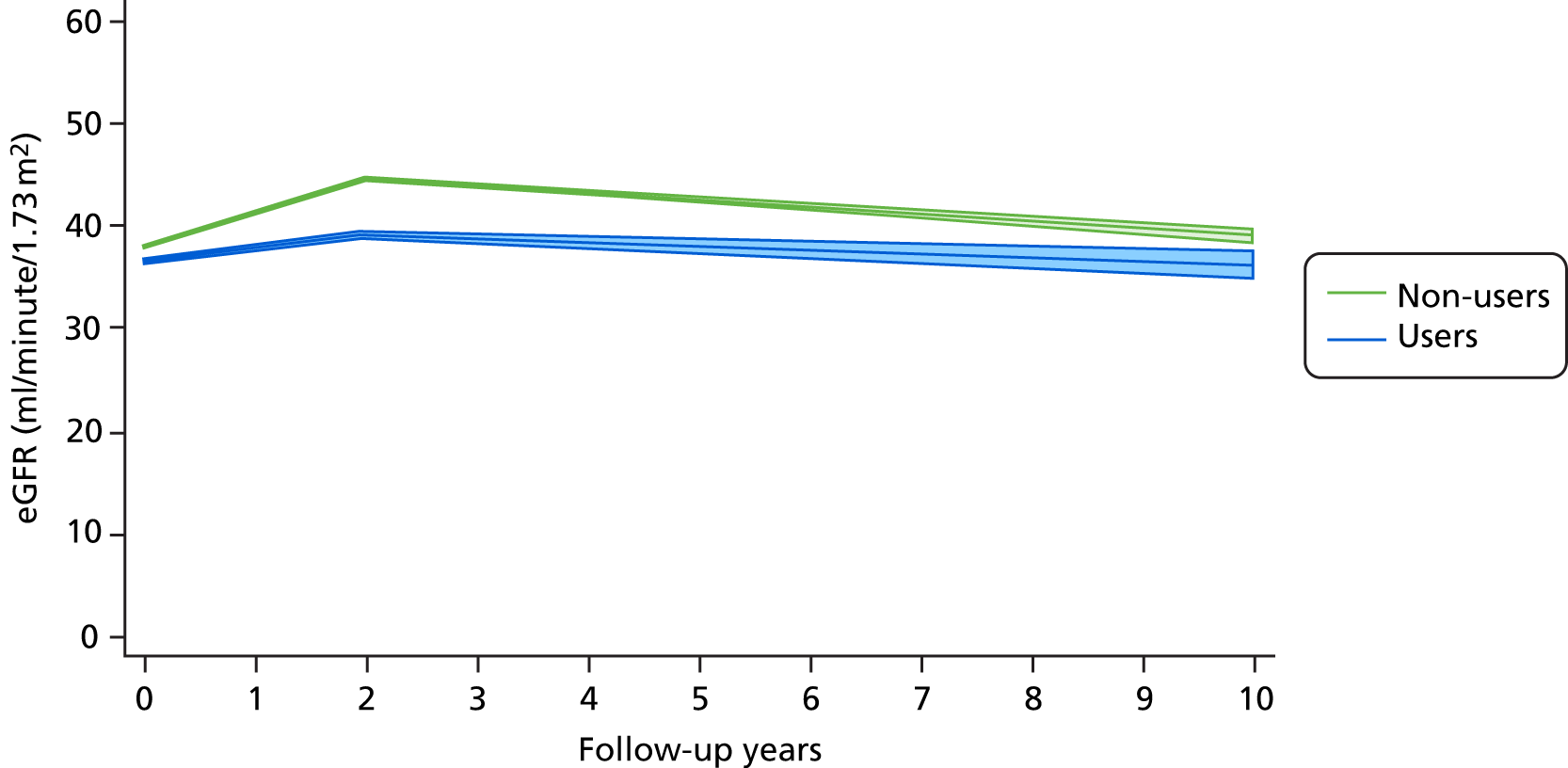

The rate of annual eGFR change was estimated using the slopes of a mixed-effects model with linear splines and an interaction between bisphosphonate use and time. Fractional polynomial models were used to identify the best-fitting shape of the non-linear association between the predictor (time) and the outcome (eGFR), based on the deviation chi-squared tests. An examination of the best-fitting fractional polynomial model was then used to identify the year when the linear rate diverges. This approach allowed us to interpret the rate easily as suggested by Tilling et al. 73 The models were fitted using the fp package in Stata version 15.

Sensitivity analyses

We tested for predefined interactions between the use of bisphosphonates and sex or history of previous fracture. Stratified analyses were reported if the interactions were significant. We did not test for an interaction with CKD starting stage. As a participant starting at CKD stage 5 cannot decrease in stage, the outcome would be highly associated with the interaction term. A Fine and Gray competing risk model was run to assess the competing risk of death. 74

One of the Bradford Hill causality criteria is that an observed association follows a gradient. 75 We tested the associations between bisphosphonate use and each of the outcomes by categorising bisphosphonate users into quartiles using their medication possession ratios (MPRs). The MPR was calculated as the number of defined daily doses prescribed over the total number of days of follow-up. Fine and Gray competing risk models were used to compare the sHR for each of the MPR quartiles with those of matched non-users. A mantel extension test was used to test for trend in the MPR quartiles.

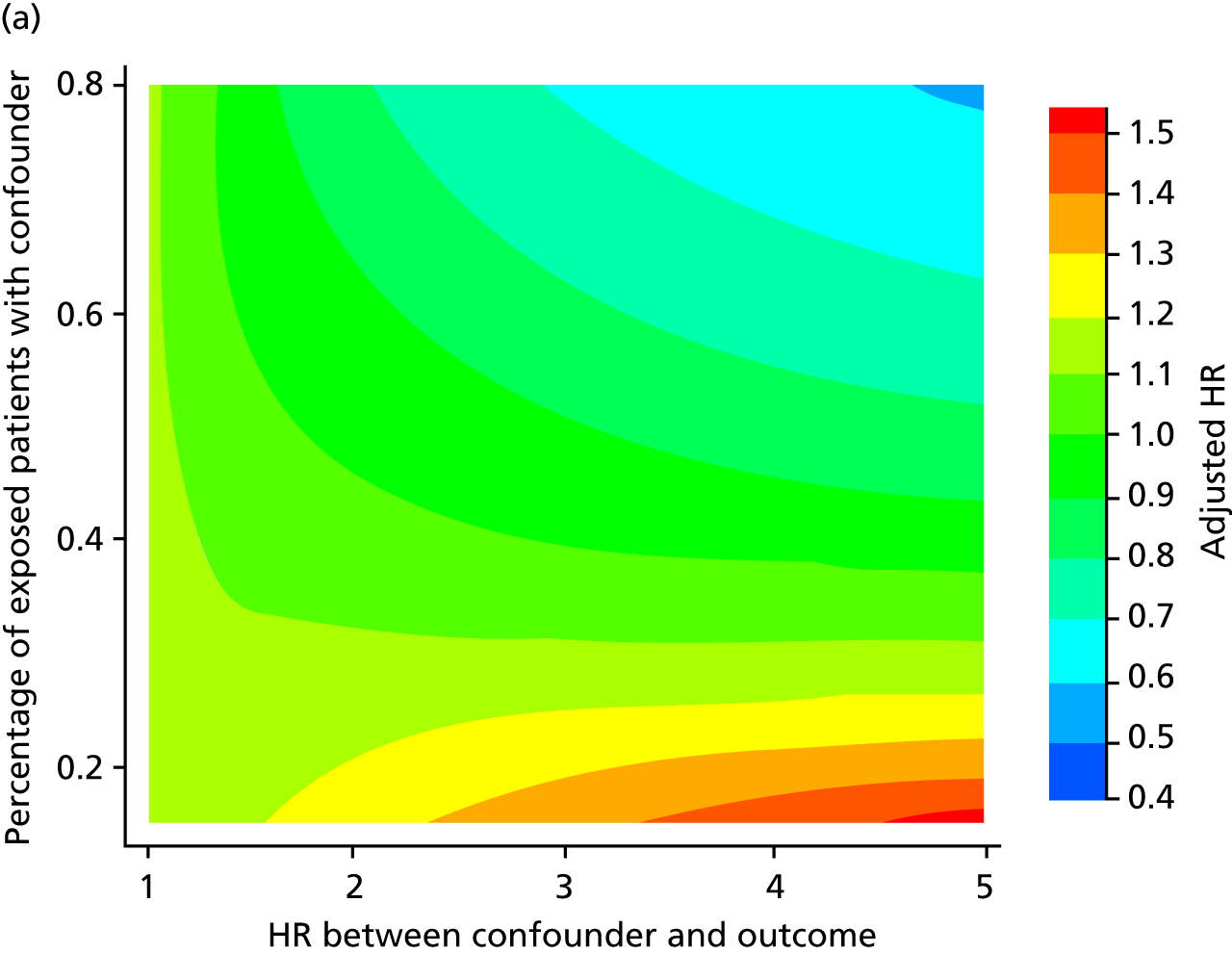

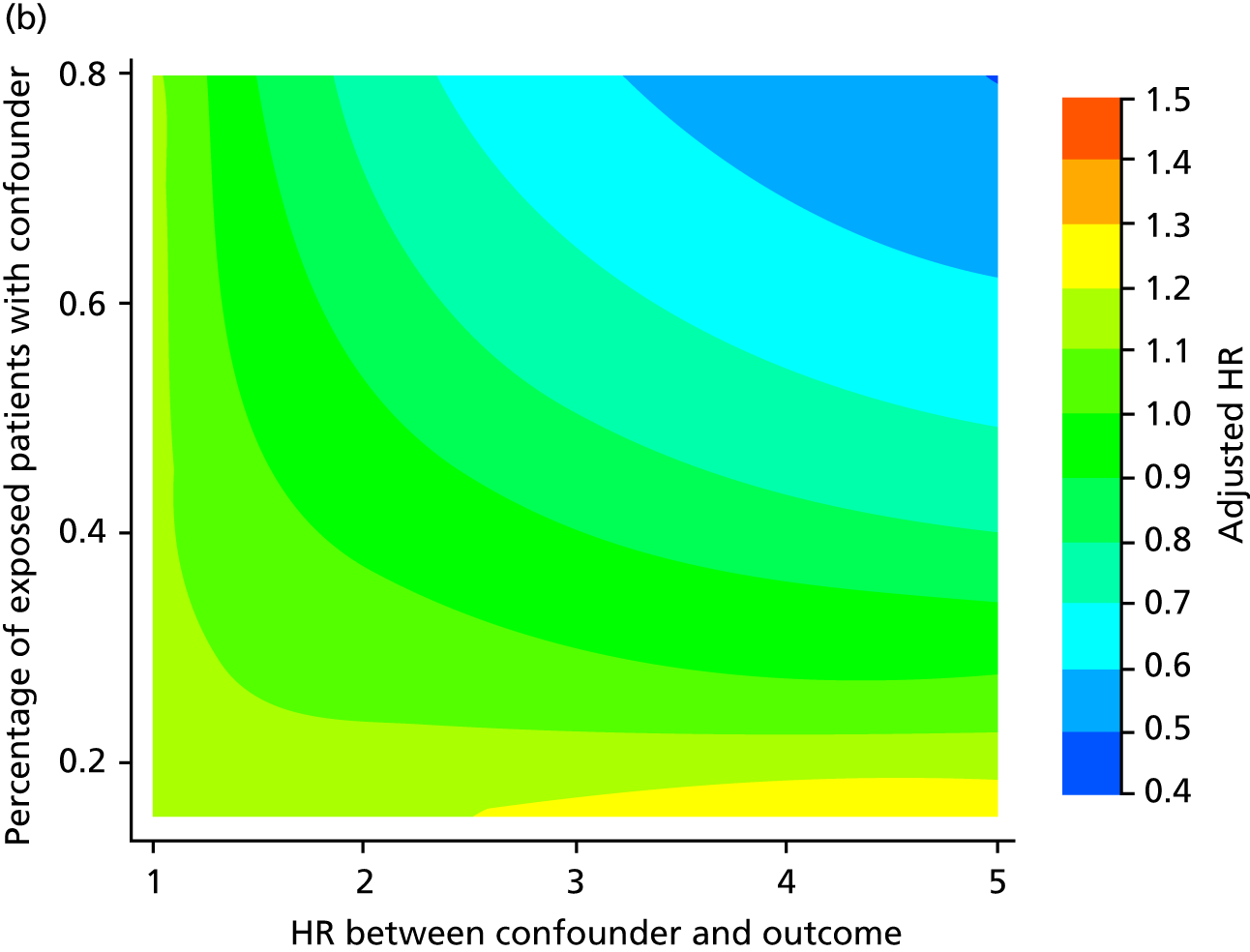

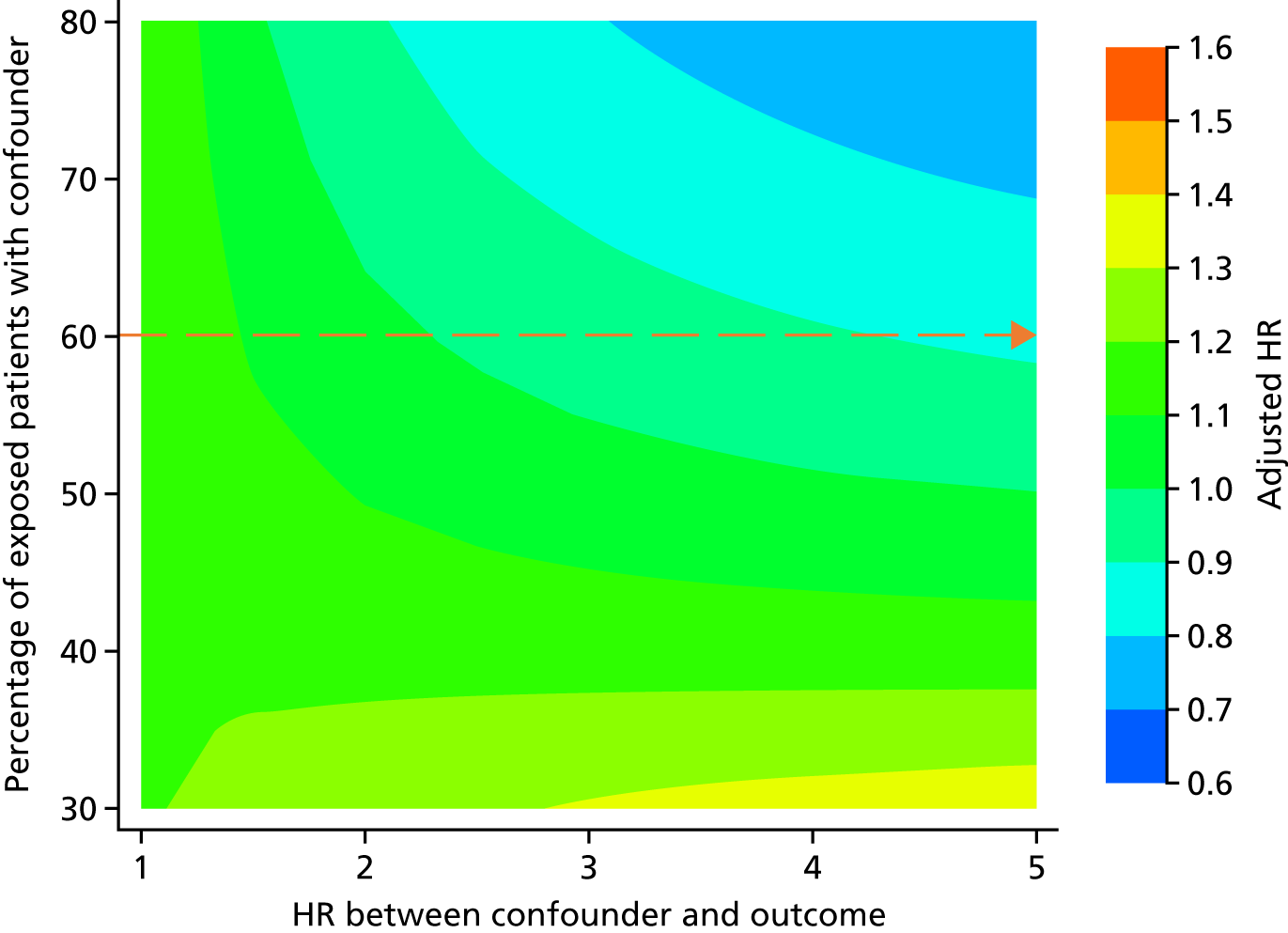

A post hoc array analysis was conducted to measure the potential impact of unmeasured confounding, as recommended by Schneeweiss,76 based on the competing risk analyses.

Results

Agreement between Clinical Practice Research Datalink and Hospital Episode Statistics reporting of dialysis and transplant

The agreement between CPRD GOLD and HES is reported in Table 2. The positive predictive value of CPRD GOLD reporting of dialysis in comparison with HES was high, at 80%. However the sensitivity of dialysis reporting was only 33%, suggesting that events would be lost if CPRD data were used alone. The positive predictive value of transplant reporting was also high, at 86%, with an acceptable sensitivity of 72%.

| CPRD | Dialysis (n) | Transplant (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HES: yes | HES: no | HES: yes | HES: no | |

| Yes | 1539 | 385 | 469 | 75 |

| No | 3084 | 222,043 | 182 | 226,325 |

When a 3-month window was used, the number of dialysis events in agreement between CPRD GOLD and HES dropped to 856 (55.6%), and the number of transplant events dropped to 440 (93.8%), again suggesting that CPRD GOLD and HES differ in their reporting of the numbers of, and the times and dates of initiation of, dialysis events.

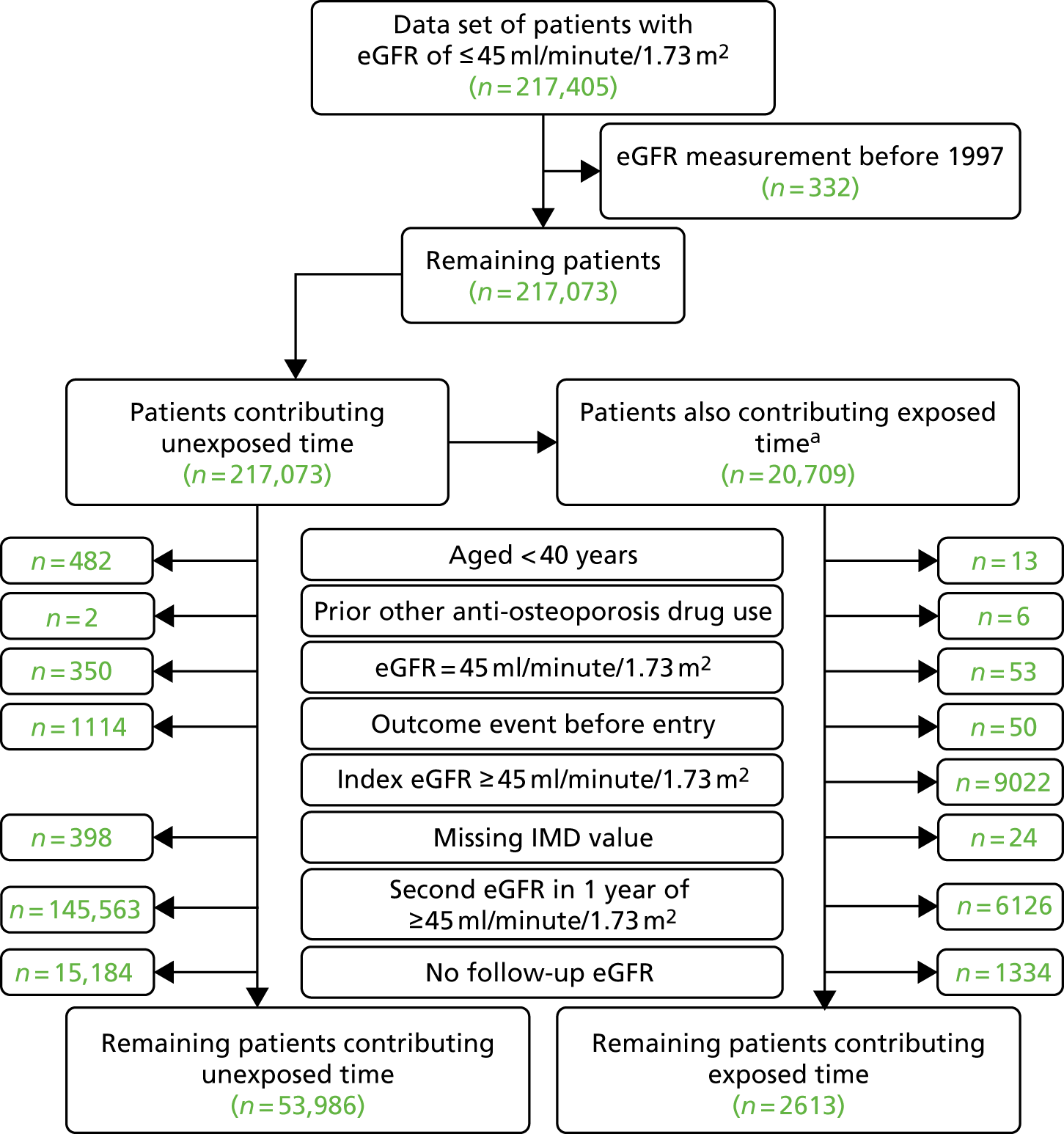

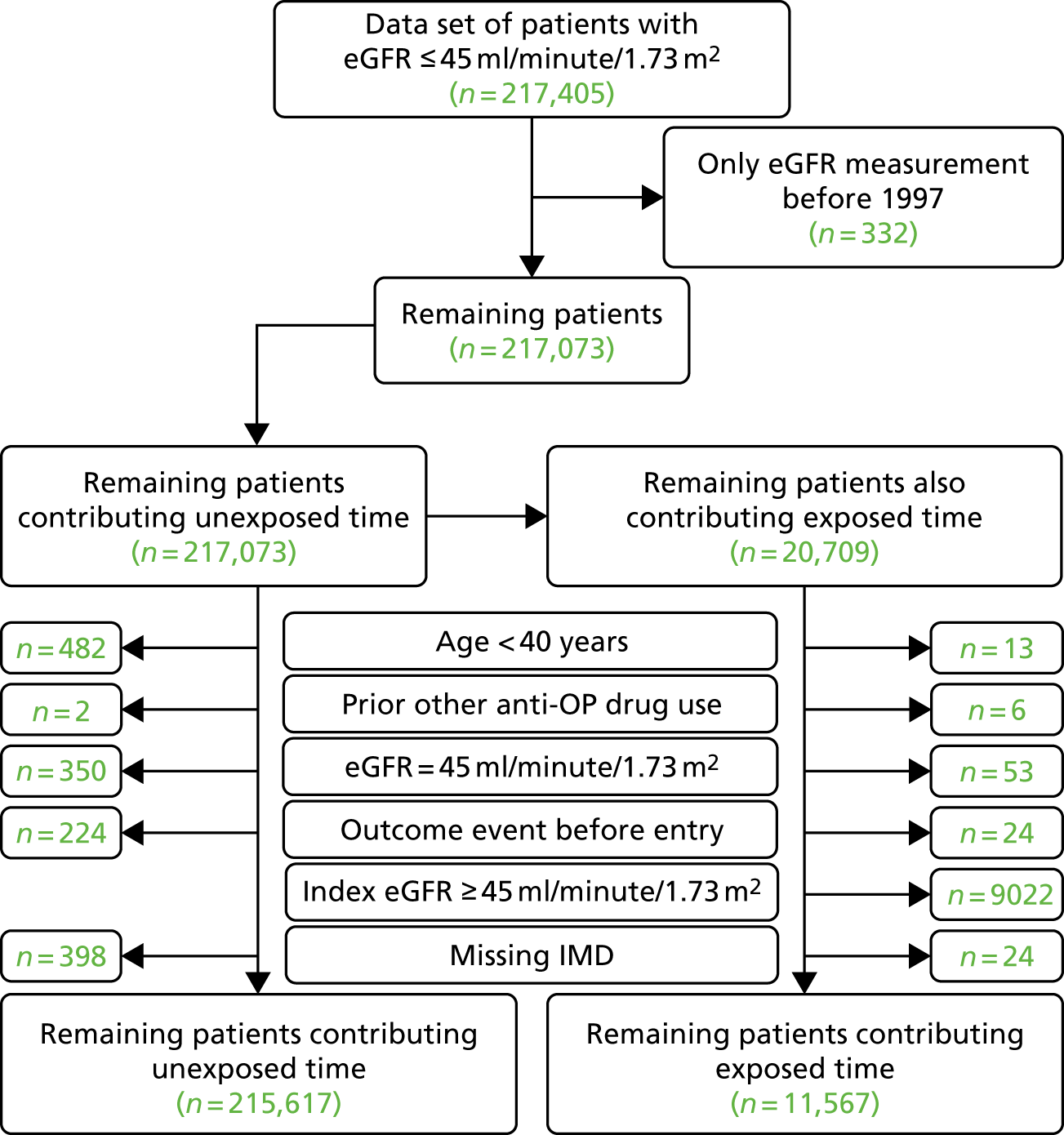

Identifying Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD patients during data extraction

We identified 217,405 CPRD GOLD patients who had an index eGFR of ≤ 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 and were therefore eligible. As seen in Figure 3, patients were excluded if they had only one eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, had only eGFR measurements before 1997, had an eGFR of exactly 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, were aged < 40 years at the time of their first eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, had used bisphosphonates in the year before the index eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, had previously used any other anti-osteoporotic drug, had an adverse event of interest before study entry or had a missing IMD value. Exposed patients were also excluded if their most recent eGFR measurement before bisphosphonate exposure was ≥ 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of identification of CPRD GOLD participants using inclusion and exclusion criteria for renal and safety analyses. a, To avoid immortal time bias, unexposed participants could also contribute to exposed time. See Figure 2 for detailed explanations.

Time unexposed to bisphosphonates was contributed by 53,986 participants, with 2613 participants also contributing time as exposed to bisphosphonates.

Propensity score matching

Table 3 shows sociodemographic, clinical and prescription characteristics for the exposed and unexposed cohorts before and after propensity score matching. Before matching, participants exposed to bisphosphonates were older (80.6 years vs. 77.6 years), more likely to be female (77.2% vs. 56.9%), less likely to smoke (8.6% vs. 11.1%), less likely to drink alcohol (65.3% vs. 69.0%), had a lower eGFR [28.7% were in the highest category (40–44.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2) compared with 40.1% of unexposed participants], more likely to have been admitted to hospital in the previous year (60.9% vs. 38.2%), had a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score (36.8% vs. 14.9% with an index 3+) and had more polypharmacy (97.3% vs. 83.8% on more than three concomitant medications) than unexposed participants. They were also more likely to have a recorded diagnosis of CKD (52.9% vs. 15.3%), have a history of non-hip fracture (22.1% vs. 3.9%) and use calcium supplements (29.9% vs. 7.4%) or bisphosphonates (5.2% vs. 1.8%) more than 1 year before their index date.

| Category | Before matching, n (%) | After matching, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexposed | Exposed | Unexposed | Exposed | |

| Number | 53,986 | 2613 | 8931 | 2447 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 77.6 (9.8) | 80.6 (8.8) | 80.3 (9.1) | 80.4 (8.8) |

| Sex (male) | 23,280 (43.1) | 595 (22.8) | 2669 (29.9) | 584 (23.9) |

| IMD quintiles | ||||

| 1 – least deprived | 11,949 (22.1) | 637 (24.4) | 2127 (23.8) | 587 (24.0) |

| 2 | 12,649 (23.4) | 620 (23.7) | 2089 (23.4) | 585 (23.9) |

| 3 | 11,539 (21.4) | 550 (21.0) | 1881 (21.1) | 517 (21.1) |

| 4 | 10,771 (20.0) | 480 (18.4) | 1654 (18.5) | 452 (18.5) |

| 5 – most deprived | 7078 (13.1) | 326 (12.5) | 1180 (13.2) | 306 (12.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.6 (5.5) | 26.7 (5.2) | 26.9 (5.4) | 26.8 (5.3) |

| Smoking category | ||||

| No | 28,093 (52.0) | 1423 (54.5) | 4784 (53.6) | 1329 (54.3) |

| Ex | 19,910 (36.9) | 966 (37.0) | 3295 (36.9) | 906 (37.0) |

| Yes | 5983 (11.1) | 224 (8.6) | 852 (9.5) | 212 (8.7) |

| Drinking category | ||||

| No | 14,621 (27.1) | 781 (29.9) | 2663 (29.8) | 734 (30.0) |

| Ex | 2117 (3.9) | 126 (4.8) | 400 (4.5) | 118 (4.8) |

| Yes | 37,248 (69.0) | 1706 (65.3) | 5868 (65.7) | 1595 (65.2) |

| eGFR category (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | ||||

| 0–4.9 | 67 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| 5–9.9 | 362 (0.7) | 16 (0.6) | 60 (0.7) | 16 (0.7) |

| 10–14.9 | 616 (1.1) | 29 (1.1) | 116 (1.3) | 29 (1.2) |

| 15–19.9 | 1278 (2.4) | 81 (3.1) | 263 (2.9) | 73 (3.0) |

| 20–24.9 | 2541 (4.7) | 164 (6.3) | 537 (6.0) | 149 (6.1) |

| 25–29.9 | 4665 (8.6) | 327 (12.5) | 996 (11.2) | 299 (12.2) |

| 30–34.9 | 8417 (15.6) | 542 (20.7) | 1709 (19.1) | 498 (20.4) |

| 35–39.9 | 14,415 (26.7) | 704 (26.9) | 2378 (26.6) | 657 (26.8) |

| 40–44.9 | 21,625 (40.1) | 749 (28.7) | 2867 (32.1) | 725 (29.6) |

| Number of hospital visits | ||||

| 0 | 33,367 (61.8) | 1022 (39.1) | 4066 (45.5) | 988 (40.4) |

| 1 | 10,968 (20.3) | 737 (28.2) | 2368 (26.5) | 683 (27.9) |

| 2 | 4971 (9.2) | 399 (15.3) | 1170 (13.1) | 367 (15.0) |

| 3–5 | 3876 (7.2) | 371 (14.2) | 1078 (12.1) | 340 (13.9) |

| ≥ 6 | 804 (1.5) | 84 (3.2) | 249 (2.8) | 69 (2.8) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | ||||

| 0 | 30,485 (56.5) | 682 (26.1) | 3107 (34.8) | 671 (27.4) |

| 1 | 7723 (14.3) | 364 (13.9) | 1366 (15.3) | 350 (14.3) |

| 2 | 7719 (14.3) | 604 (23.1) | 1905 (21.3) | 565 (23.1) |

| 3–5 | 6468 (12.0) | 746 (28.5) | 2001 (22.4) | 666 (27.2) |

| ≥ 6 | 1591 (2.9) | 217 (8.3) | 552 (6.2) | 195 (8.0) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 532 (1.0) | 148 (5.7) | 171 (1.9) | 136 (5.6) |

| Varices | 3323 (6.2) | 316 (12.1) | 886 (9.9) | 281 (11.5) |

| Deep-vein thrombosis | 1895 (3.5) | 113 (4.3) | 388 (4.3) | 108 (4.4) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 6172 (11.4) | 404 (15.5) | 1304 (14.6) | 371 (15.2) |

| Dementia | 944 (1.7) | 79 (3.0) | 263 (2.9) | 74 (3.0) |

| CKD | 8245 (15.3) | 1381 (52.9) | 3479 (39.0) | 1225 (50.1) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4193 (7.8) | 320 (12.2) | 976 (10.9) | 299 (12.2) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1246 (2.3) | 88 (3.4) | 266 (3.0) | 80 (3.3) |

| Hypertension | 23,630 (43.8) | 1518 (58.1) | 4628 (51.8) | 1391 (56.8) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 5788 (10.7) | 459 (17.6) | 1289 (14.4) | 415 (17.0) |

| Liver disease | 224 (0.4) | 32 (1.2) | 73 (0.8) | 28 (1.1) |

| Peptic ulcer | 816 (1.5) | 65 (2.5) | 187 (2.1) | 58 (2.4) |

| Osteomalacia/rickets | 15 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| Cancer | 5415 (10.0) | 454 (17.4) | 1374 (15.4) | 416 (17.0) |

| Hip fracture | 440 (0.8) | 33 (1.3) | 125 (1.4) | 32 (1.3) |

| Non-hip fracture | 2088 (3.9) | 577 (22.1) | 1070 (12.0) | 482 (19.7) |

| Number of prescriptions | ||||

| 0 | 1527 (2.9) | 4 (0.2) | 72 (0.9) | 4 (0.2) |

| 1–3 | 6880 (13.3) | 61 (2.5) | 360 (4.3) | 61 (2.7) |

| 4–6 | 12,453 (24.0) | 230 (9.4) | 1104 (13.3) | 226 (9.9) |

| 7–9 | 12,408 (23.9) | 468 (19.2) | 1763 (21.2) | 451 (19.7) |

| 10–12 | 9019 (17.4) | 548 (22.5) | 1906 (22.9) | 519 (22.7) |

| 13 | 9524 (18.4) | 1129 (46.3) | 3125 (37.5) | 1026 (44.9) |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 2979 (5.5) | 244 (9.3) | 714 (8.0) | 228 (9.3) |

| Contraceptive | 38 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Calcium supplements | 3996 (7.4) | 782 (29.9) | 1818 (20.4) | 680 (27.8) |

| Bisphosphonate use more than 1 year before index date | 996 (1.8) | 136 (5.2) | 486 (5.4) | 122 (5.0) |

| Steroids | 9194 (17.0) | 1311 (50.2) | 3509 (39.3) | 1179 (48.2) |

| Anticoagulants | 7078 (13.1) | 486 (18.6) | 1567 (17.5) | 455 (18.6) |

| Heparin | 432 (0.8) | 61 (2.3) | 160 (1.8) | 51 (2.1) |

| Aromatase inhibitors | 265 (0.5) | 58 (2.2) | 122 (1.4) | 45 (1.8) |

| NSAIDs | 30,095 (55.7) | 1873 (71.7) | 5862 (65.6) | 1737 (71.0) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 19,596 (36.3) | 1593 (61.0) | 4795 (53.7) | 1465 (59.9) |

| Anxiols/sedatives/hypnotics | 10,488 (19.4) | 726 (27.8) | 2429 (27.2) | 668 (27.3) |

| Antidepressants | 14,578 (27.0) | 1118 (42.8) | 3386 (37.9) | 1032 (42.2) |

| Statins | 21,548 (39.9) | 1402 (53.7) | 4368 (48.9) | 1293 (52.8) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 23,668 (43.8) | 1507 (57.7) | 4683 (52.4) | 1392 (56.9) |

| ACE inhibitors | 32,246 (59.7) | 1907 (73.0) | 6142 (68.8) | 1773 (72.5) |

| Antiepileptics | 2251 (4.2) | 207 (7.9) | 631 (7.1) | 192 (7.8) |

| Diuretics | 38,403 (71.1) | 2164 (82.8) | 7139 (79.9) | 2023 (82.7) |

| Beta blockers | 25,175 (46.6) | 1395 (53.4) | 4461 (49.9) | 1302 (53.2) |

| Antidiabetics | 9507 (17.6) | 443 (17.0) | 1567 (17.5) | 420 (17.2) |

| Insulin | 2359 (4.4) | 127 (4.9) | 421 (4.7) | 120 (4.9) |

| Digoxin | 5839 (10.8) | 319 (12.2) | 1152 (12.9) | 310 (12.7) |

| Antihypertensives | 8608 (15.9) | 588 (22.5) | 1770 (19.8) | 548 (22.4) |

| Antiarrythmics | 7010 (13.0) | 447 (17.1) | 1418 (15.9) | 417 (17.0) |

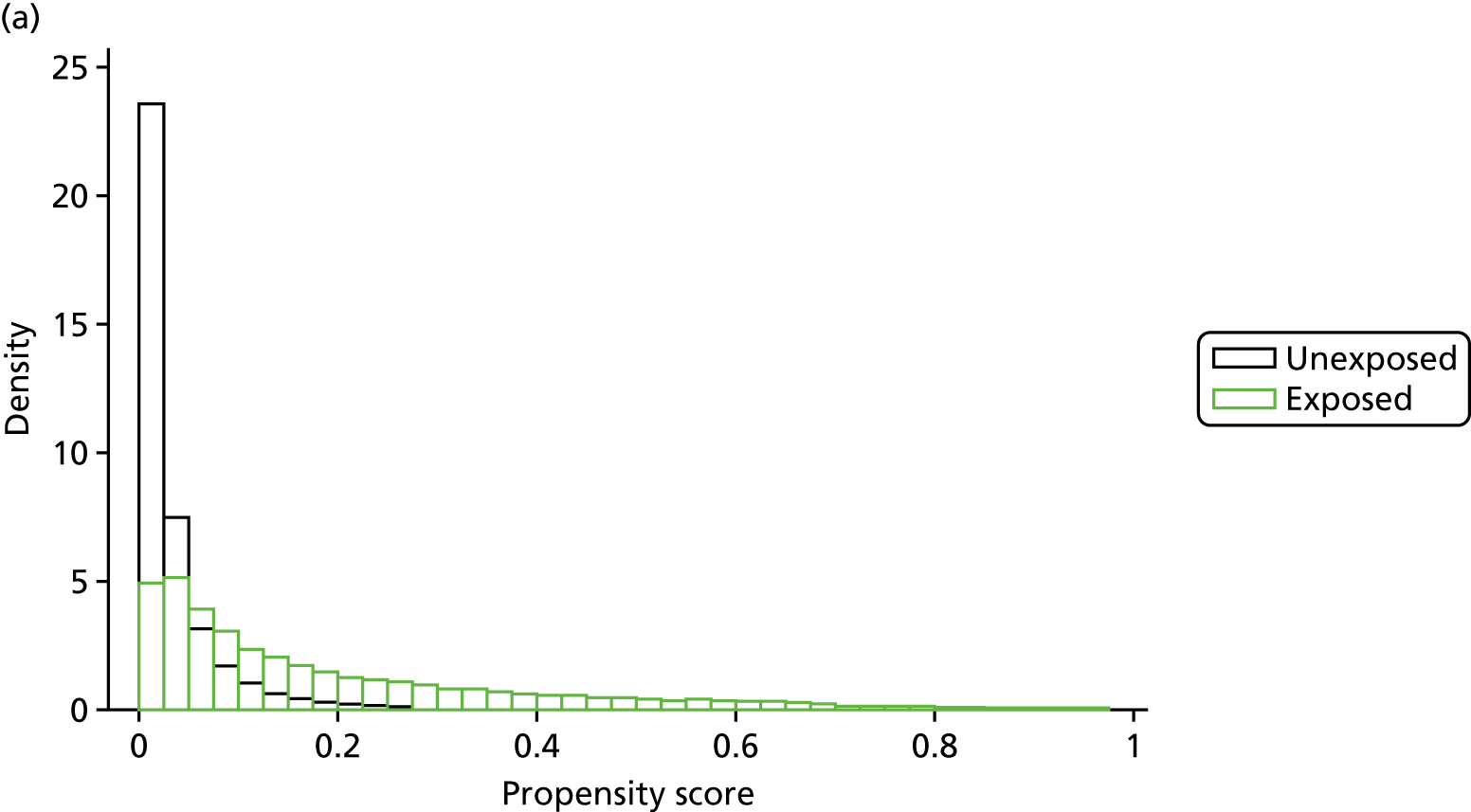

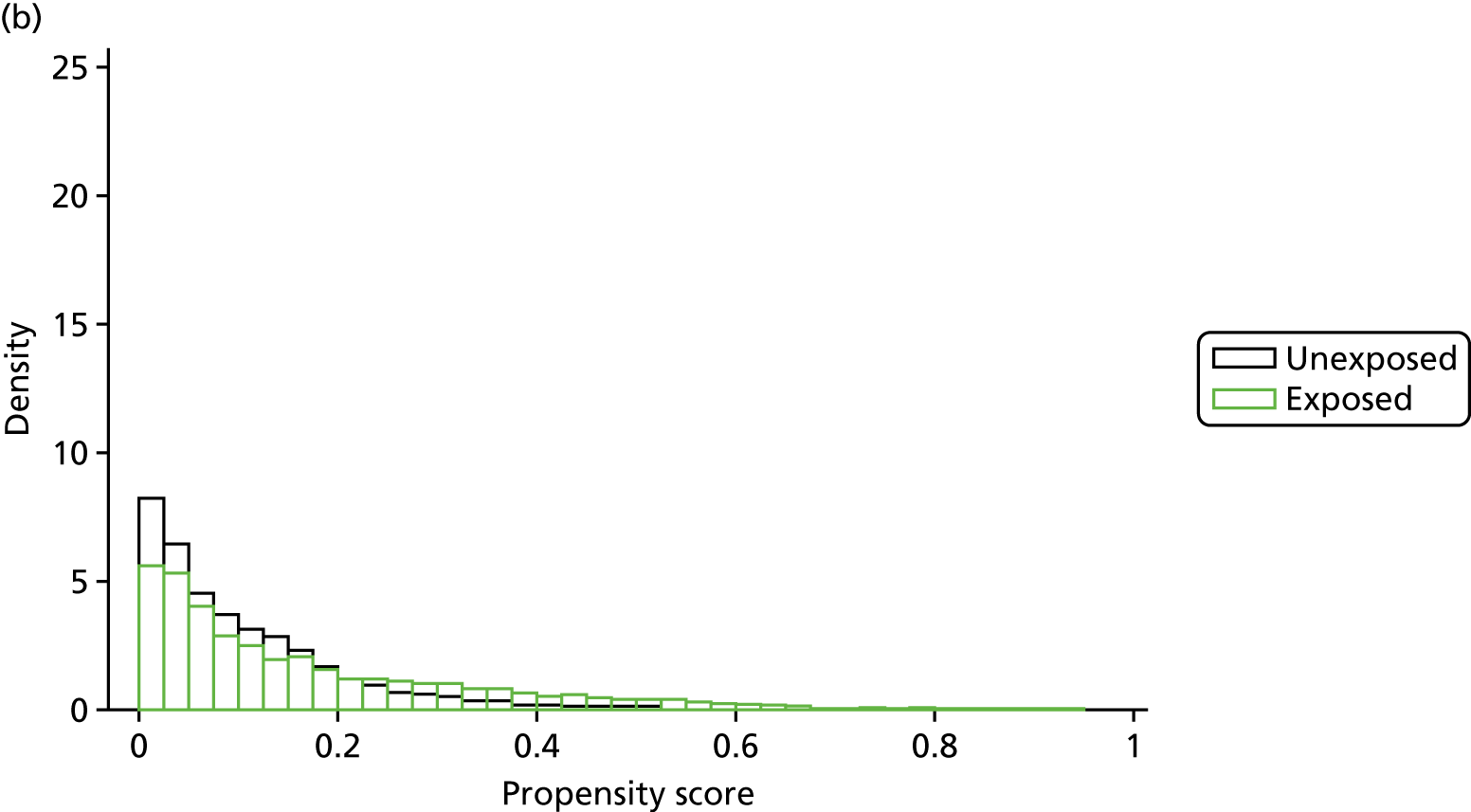

After matching, the remaining participants in both cohorts were more similar, with some remaining differences. Exposed participants started with a lower eGFR (29.6% had an eGFR of ≥ 40 ml/minute/1.73 m2 vs. 32.1%), more hospital visits (40.4% vs. 45.5% with zero hospital visits) and a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score (27.4 vs. 34.8 with a score of 0) than unexposed participants. They were more likely than unexposed participants to have diagnosed CKD (50.1% vs. 39.0%), a history of non-hip fracture (19.7% vs. 12.0%), more prescriptions (44.9% with ≥ 13 vs. 37.5% with < 13 prescriptions) and to receive calcium supplements (27.8% vs. 20.4%) and steroids (48.2% vs. 39.3%).

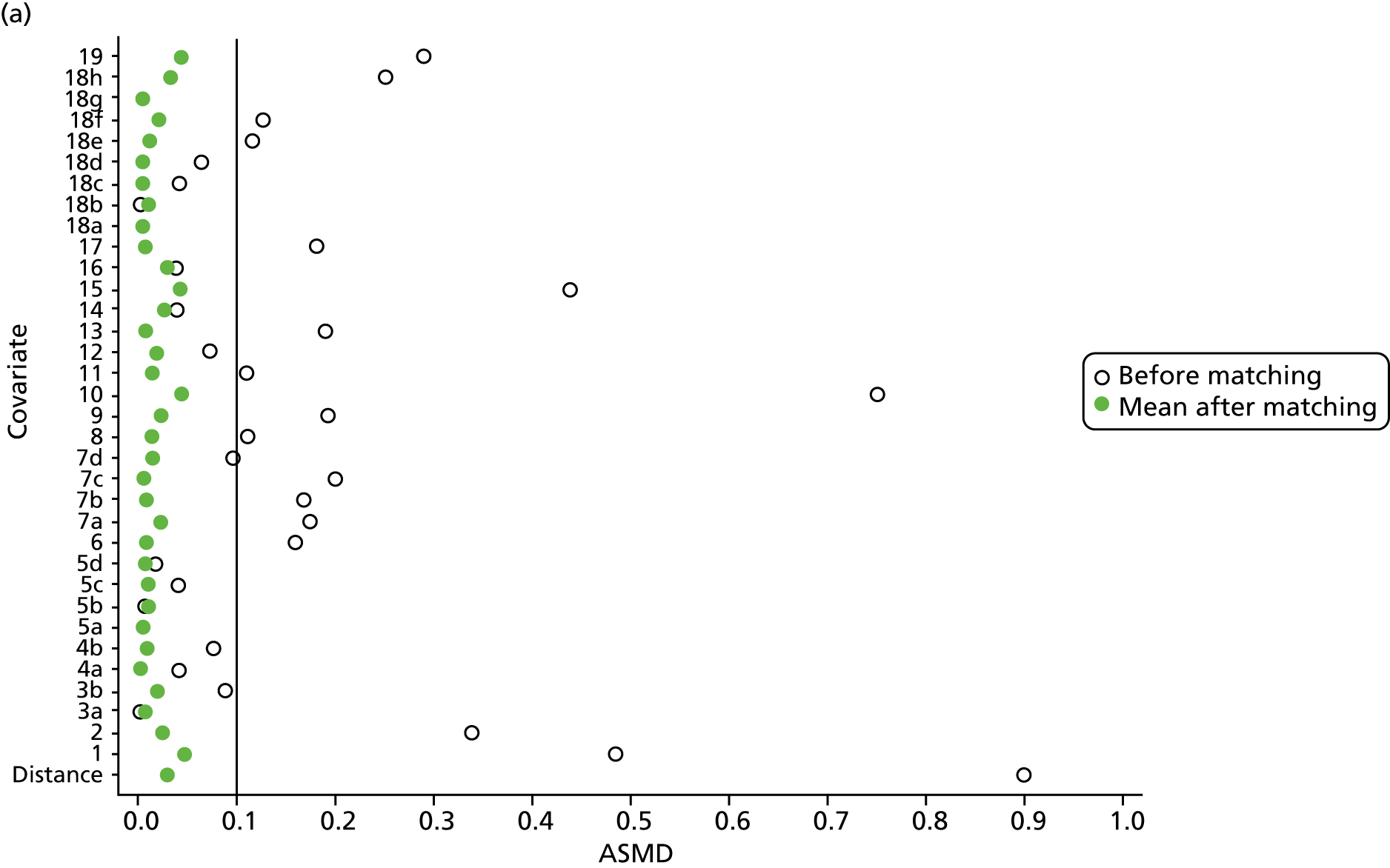

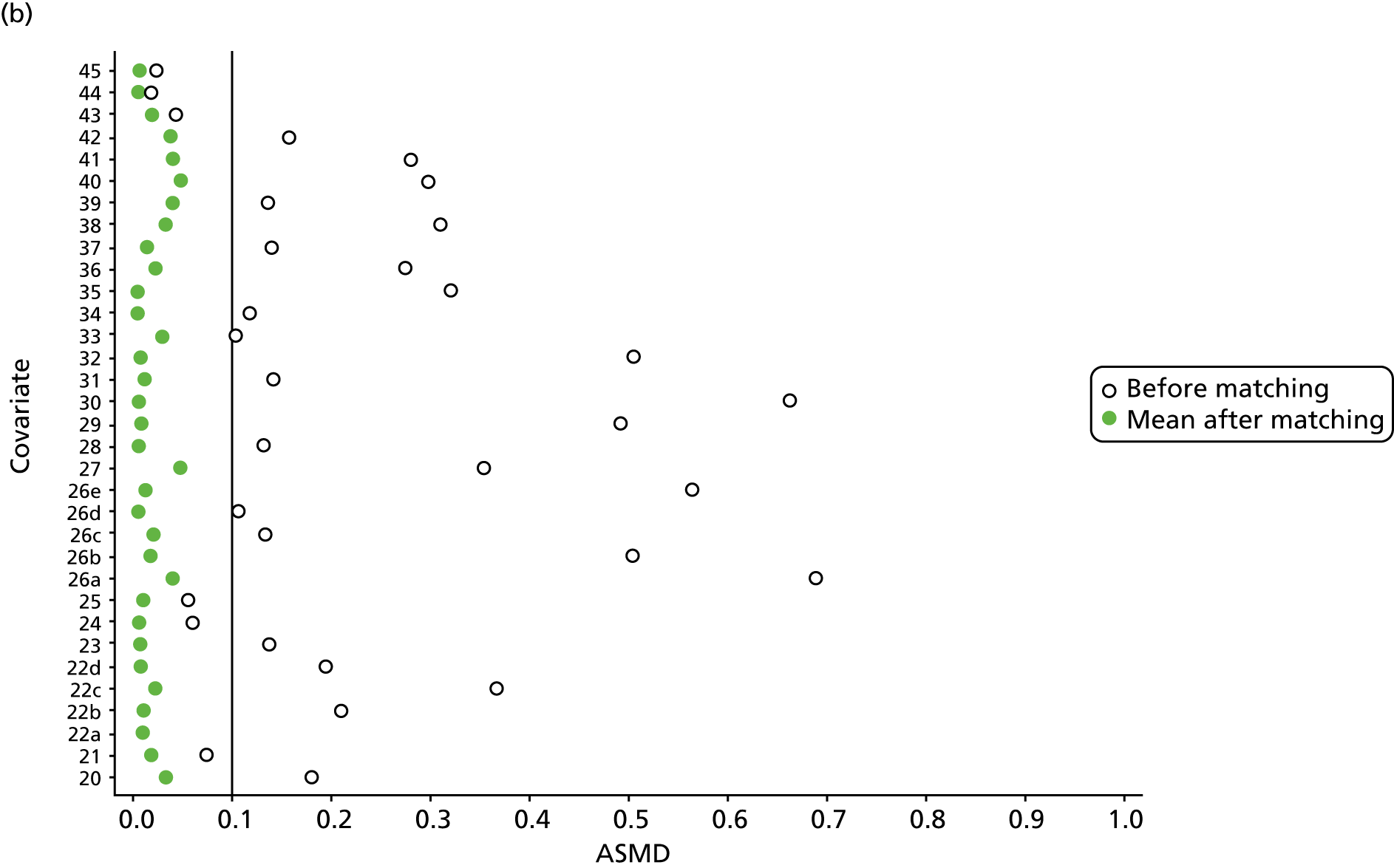

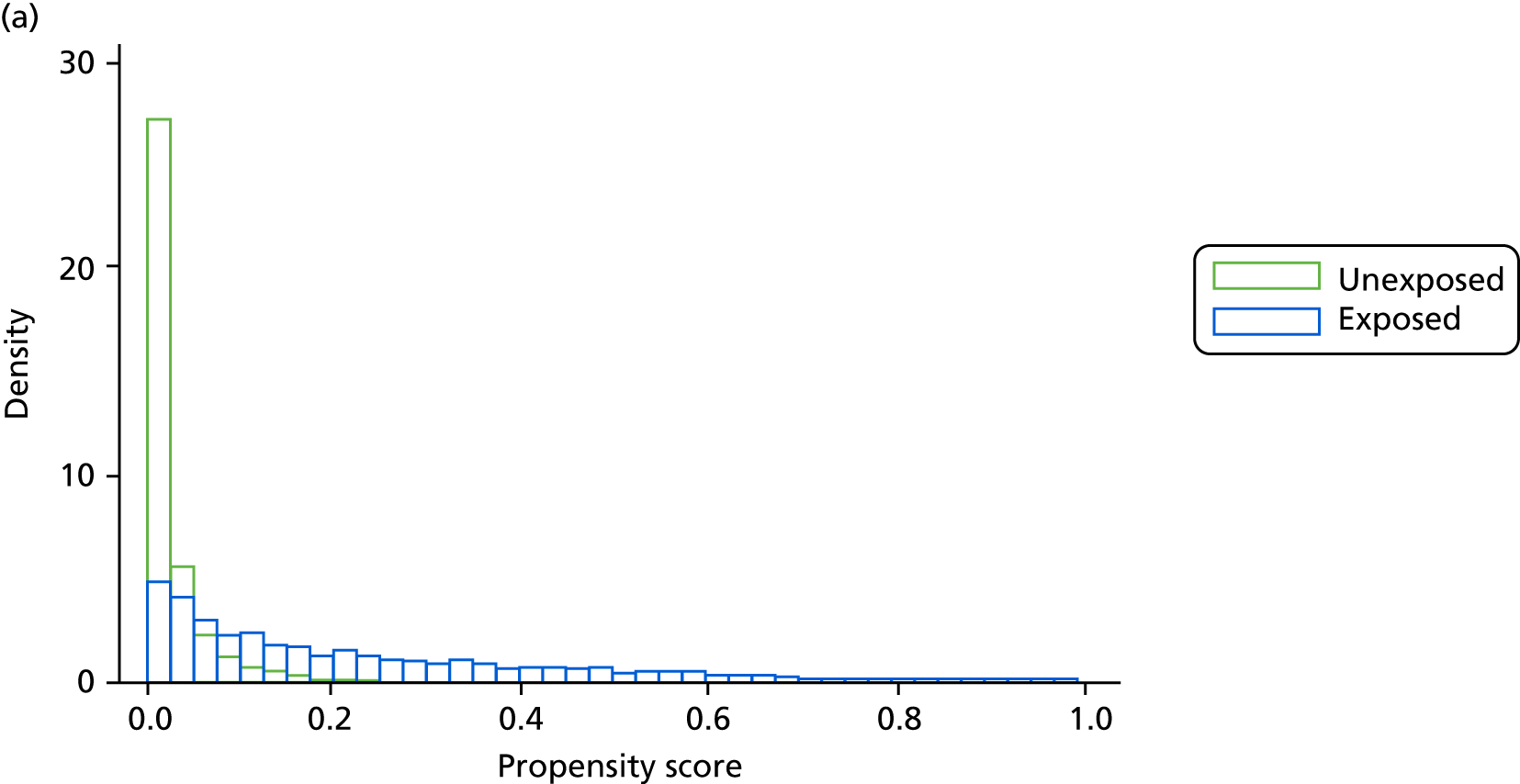

However, these differences were not great enough to influence the balance between the matched cohorts. Histograms show that the overlap in propensity score values was much improved after matching (see Appendix 1, Figure 24). Figure 4 shows ASMD values of < 0.1 for all covariates after matching, suggesting good balance.

FIGURE 4.

The ASMD of each covariate included in the propensity score matching for renal and safety outcomes before and after matching. (a) 1, Sex; 2, age; 3a, ex-smoker; 3b, current smoker; 4a, ex-drinker; 4b, current drinker; 5a, IMD quintile 2; 5b, IMD quintile 3; 5c, IMD quintile 4; 5d, IMD quintile 5; 6, BMI; 7a, 1 hospital visit in the previous year; 7b, 2 hospital visits in the previous year; 7c, 3–5 hospital visits in the previous year; 7d, ≥ 6 hospital visits in the previous year; 8, type 2 diabetes mellitus; 9, cancer; 10, CKD; 11, antiarrhythmic agents; 12, dementia; 13, cardiovascular disease; 14, hip fracture; 15, non-hip fracture; 16, deep-vein thrombosis; 17, varices; 18a, start eGFR value of 5–9.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18b, start eGFR value of 10–14.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18c, start eGFR value of 15–19.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18d, start eGFR value of 20–24.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18e, start eGFR value of 25–29.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18f, start eGFR value of 30–34.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18g, start eGFR value of 35–39.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 18h, start eGFR value of 40–44.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2; 19, hypertension; and (b) 20, hyperlipidaemia; 21, liver disease; 22a, 5-year Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 1; 22b, 5-year Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 2; 22c, 5-year Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 3–5; 22d, 5-year Charlson Comorbidity Index score of ≥ 6; 23, cerebrovascular disease; 24, peripheral vascular disease; 25, hyperthyroidism; 26a, 1–3 prescriptions in the previous year; 26b, 4–6 prescriptions in the previous year; 26c, 7–9 prescriptions in the previous year; 26d, 10–12 prescriptions in the previous year; 26e, ≥ 13 prescriptions in the previous year; 27, NSAIDs; 28, hormone replacement therapy; 29, calcium supplements; 30, steroids; 31, anticoagulants; 32, proton-pump inhibitors; 33, heparins; 34, aromatase inhibitors; 35, antidepressants; 36, statins; 37, antiepileptics; 38, diuretics; 39, beta blockers; 40, ACE inhibitors; 41, calcium channel blockers; 42, antihypertensives; 43, digoxin; 44, antidiabetics; 45, insulin. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Chronic kidney disease category changes

In the primary analysis of CKD stage worsening, bisphosphonate users were more likely to progress to a worse CKD stage (i.e. move to a higher stage) than non-users (22.8% vs. 21.5%). The number and percentage of participants changing CKD stage are shown in Table 4.

| Baseline CKD stage | Value | First change to a worse stage of CKD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphosphonate user | Bisphosphonate non-user | ||||||

| 3b | 4 | 5 | 3b | 4 | 5 | ||

| 3b | n | 1370 | 481 | 12 | 5257 | 1579 | 73 |

| % | 73.4 | 25.2 | 0.6 | 76.1 | 22.9 | 1.1 | |

| 4 | n | 0 | 473 | 65 | 0 | 1569 | 268 |

| % | 0 | 87.9 | 12.1 | 0 | 85.4 | 14.6 | |

| 5 | n | 0 | 0 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 185 |

| % | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |

In a post hoc analysis that also included improvements in CKD stage, 38.0% of non-users of bisphosphonate saw an improvement in their CKD after their first eGFR measurement of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, with an decrease in stage. Only 35.1% of bisphosphonate users improved their CKD severity (Table 5). The most common change in stage was a decrease (improvement) by one stage from the starting stage, seen in 31.3% of bisphosphonate users and 34.2% of non-users.

| Baseline category | Baseline CKD stage | Value | First change to a better or worse stage of CKD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3a | 3b | 4 | 5 | |||

| Unexposed | 3b | n | < 5 | 219 | 2316 | 2831 | 1473 | 69 |

| % | < 0.1 | 3.2 | 33.5 | 41.0 | 21.3 | 1.0 | ||

| 4 | n | 0 | 14 | 82 | 697 | 788 | 256 | |

| % | 0 | 0.8 | 4.5 | 38.0 | 42.9 | 13.9 | ||

| 5 | n | < 5 | < 5 | 9 | 8 | 37 | 125 | |

| % | < 2.7 | < 2.7 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 20 | 67.6 | ||

| Exposed | 3b | n | 0 | 58 | 534 | 800 | 460 | 11 |

| % | 0 | 3.1 | 28.7 | 42.9 | 24.7 | 0.6 | ||

| 4 | n | 0 | < 5 | 21 | 218 | 236 | 60 | |

| % | 0 | 3.9 | 40.5 | 43.9 | 11.2 | |||

| 5 | n | 0 | < 5 | < 5 | 8 | 13 | 21 | |

| % | 0 | 17.4 | 28.3 | 45.7 | ||||

Incidence rates of chronic kidney disease progression

In the primary analysis, participants exposed to bisphosphonates had a similar incidence rate of CKD stage worsening or starting renal replacement treatment (dialysis or transplant) to those not exposed to bisphosphonates, with incidence rates of 89.07 (95% CI 82.06 to 96.67) per 1000 person-years and 85.64 (95% CI 81.97 to 89.47) per 1000 person-years, respectively.

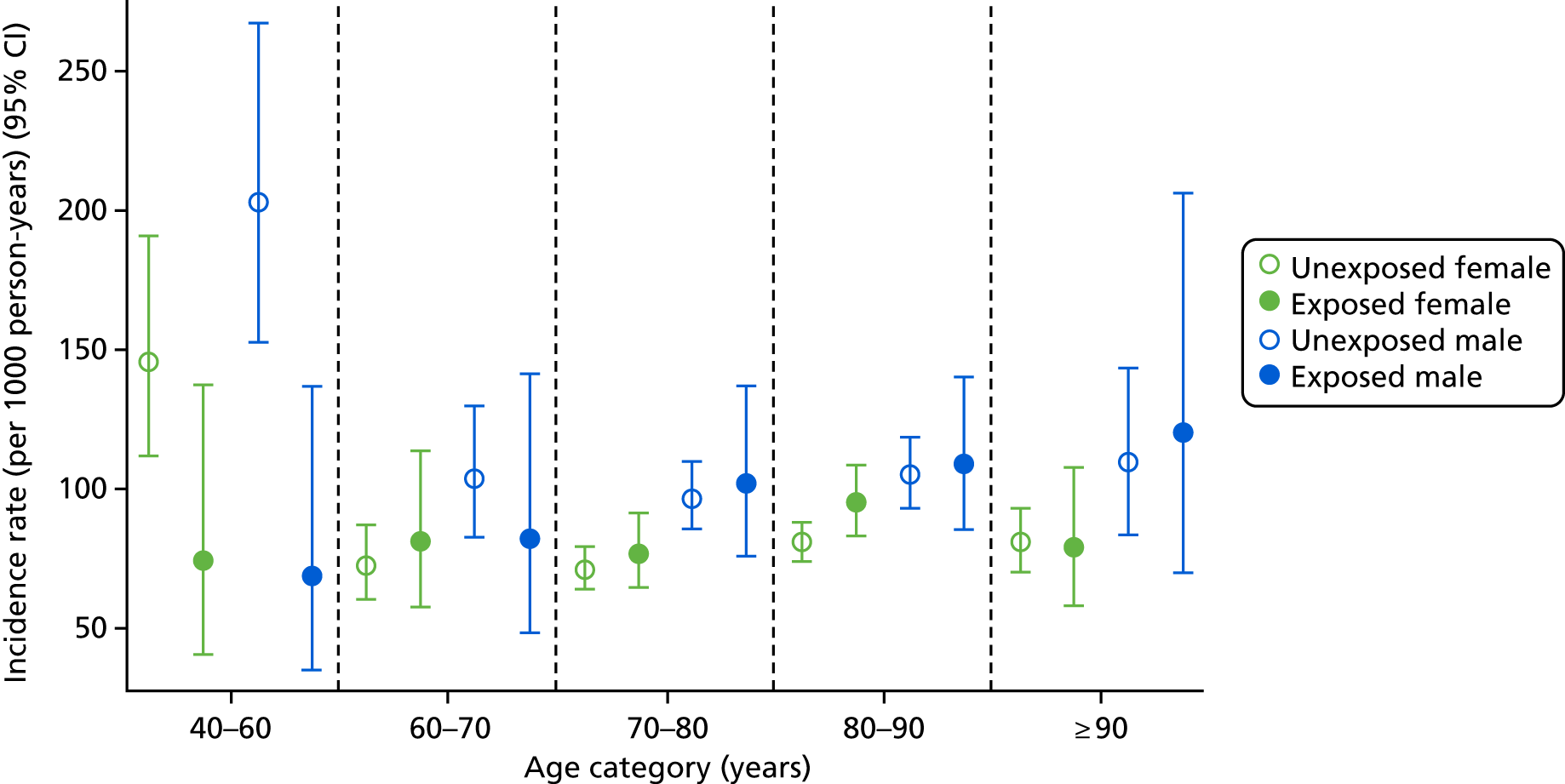

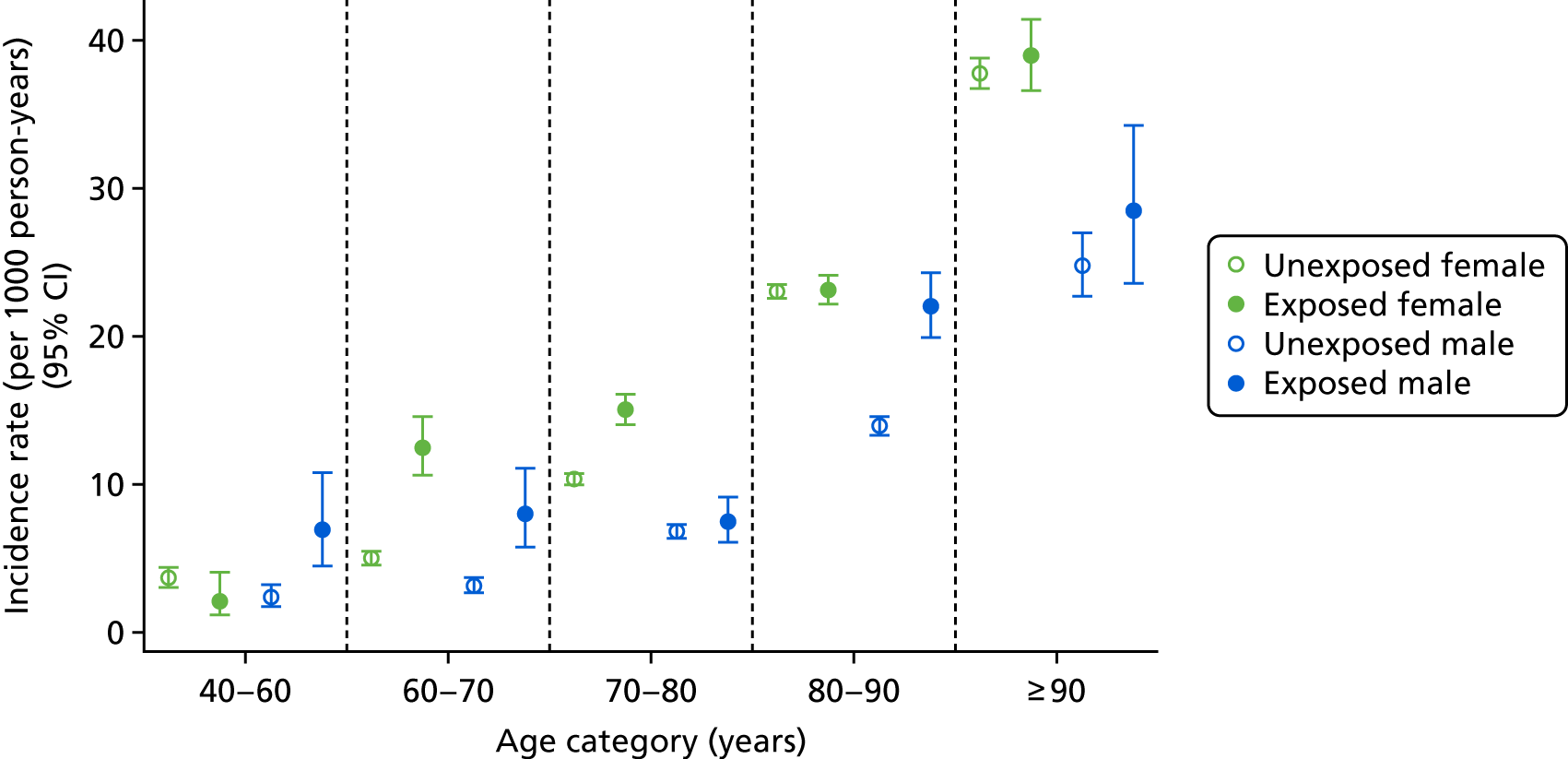

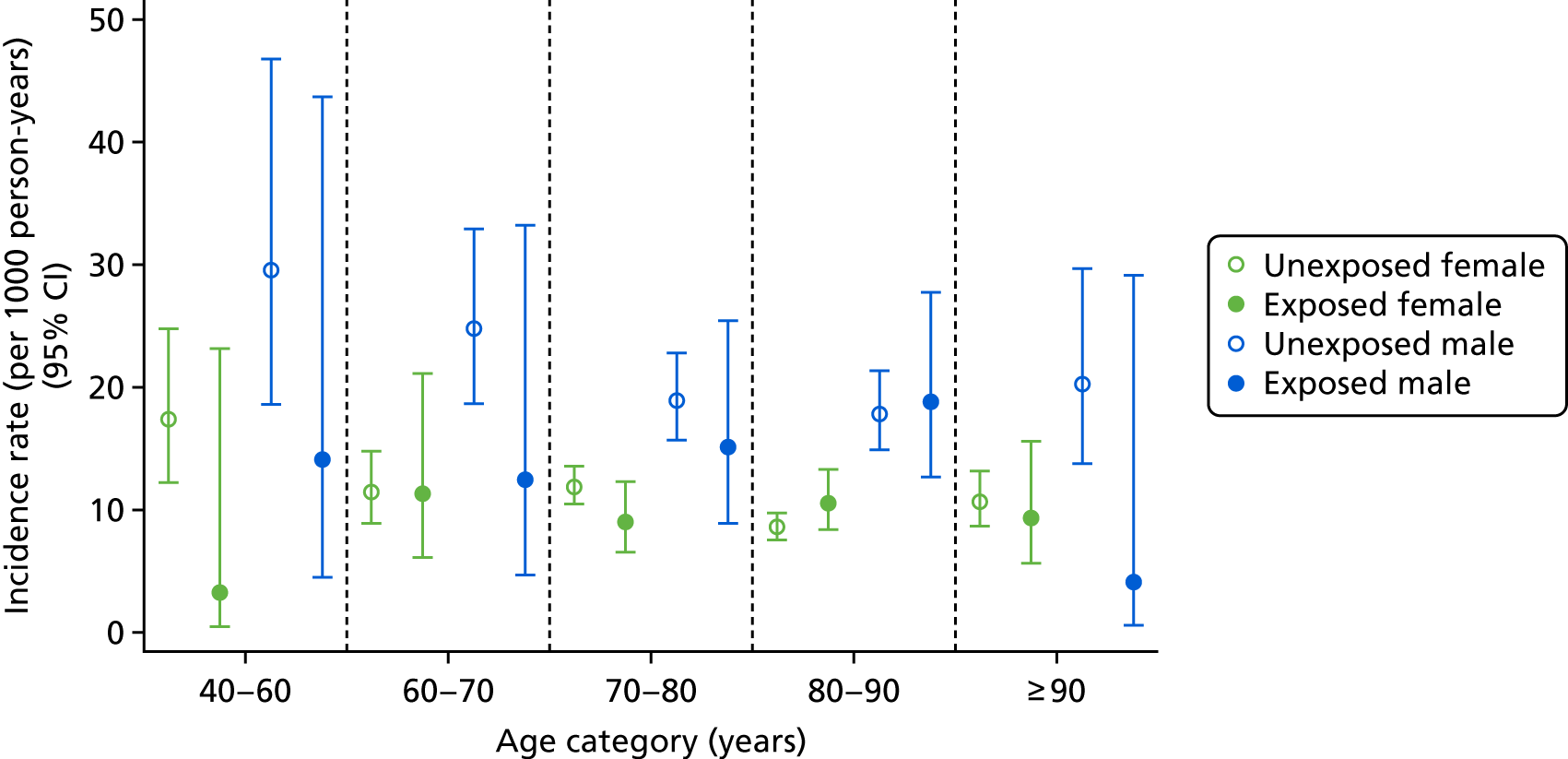

Age- and sex-specific incidence rates, stratified by bisphosphonate use, are shown in Figure 5. Men had a higher incidence of CKD worsening than women, with incidence rates of 100.82 (95% CI 85.38 to 119.06) per 1000 person-years for exposed men and 85.86 (95% CI 78.15 to 94.33) per 1000 person-years for exposed women.

FIGURE 5.

Male and female incidence rates of end-stage renal failure treatment or CKD stage worsening per 1000 person-years, stratified by exposure to bisphosphonate and age.

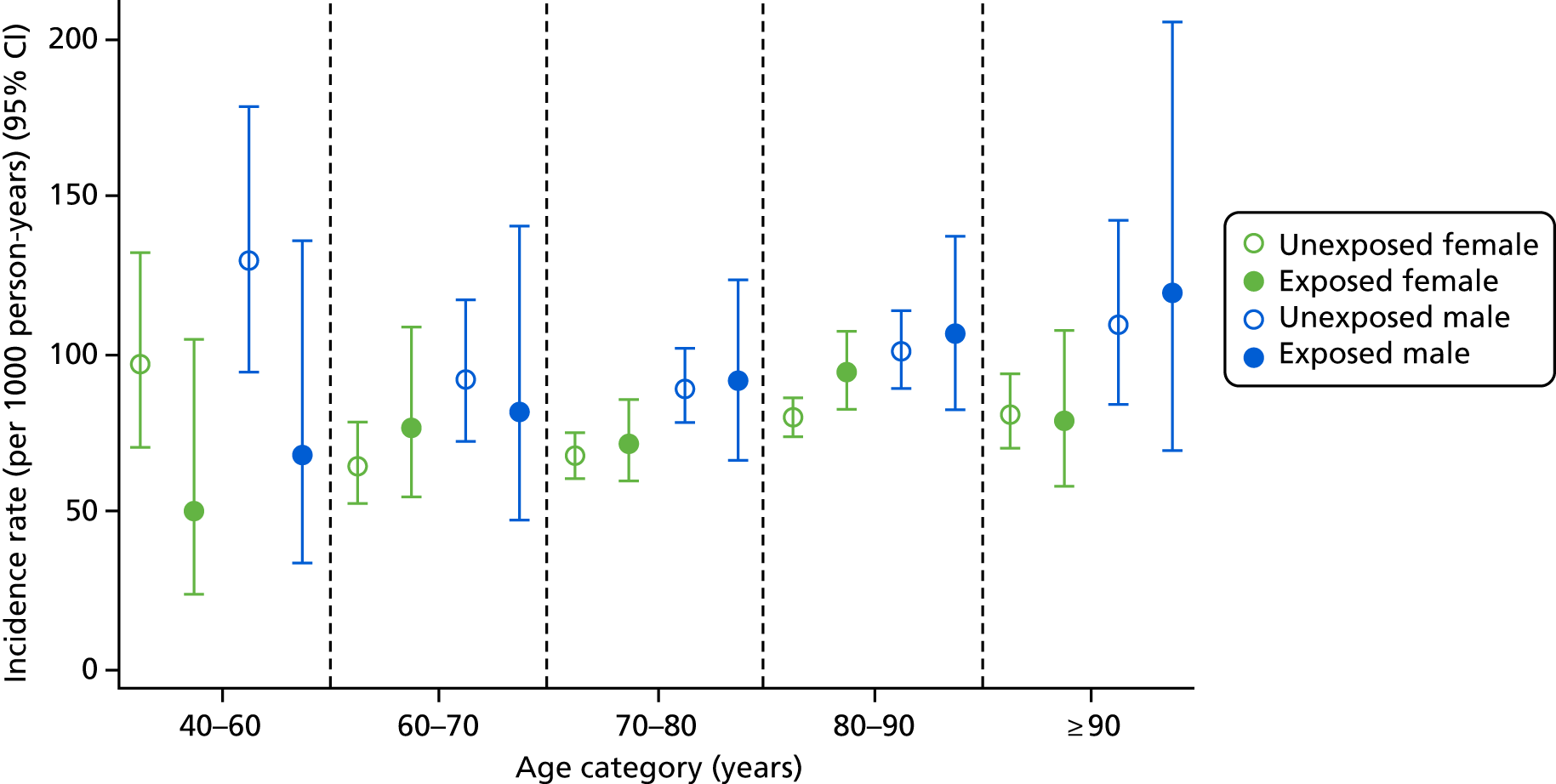

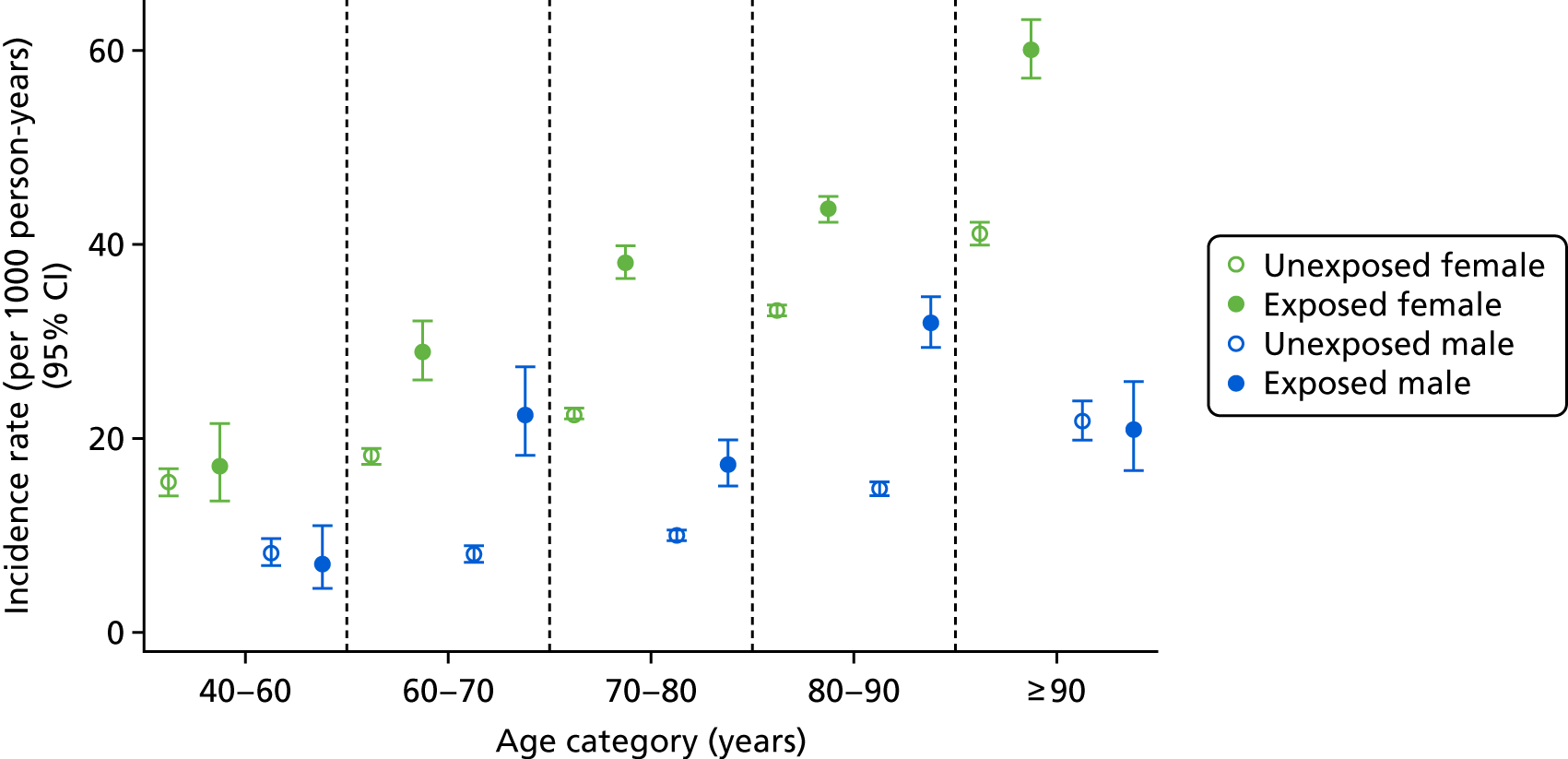

In the first post hoc analysis of CKD worsening based on eGFR measures alone, bisphosphonate users had a similar incidence rate to non-users [85.75 (95% CI 78.90 to 93.19) vs. 81.10 (95% CI 77.55 to 84.81) per 1000 person-years], agreeing with the results of the primary analysis. Age- and sex-specific incidence rates, stratified by bisphosphonate use, are shown in Figure 6. Few participants aged 40–60 years had an eGFR of < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2, resulting in wide CIs for this group. However, those aged > 60 years showed increased incidences of CKD worsening. For example, participants aged 60–70 years had an incidence rate of 78.38 (95% CI 58.52 to 104.98) per 1000 person-years for bisphosphonate users and 74.5 (95% CI 68.66 to 80.84) per 1000 person-years for non-users, whereas those aged > 90 years had an incidence rate of 86.14 (95% CI 65.81 to 112.75) per 1000 person-years for bisphosphonate users and 85.86 (95% CI 75.5 to 97.65) per 1000 person-years for non-users.

FIGURE 6.

Male and female incidence rates of CKD worsening, compared with participants who did not worsen in CKD stage, per 1000 person-years, categorised by exposure to bisphosphonate and age.

Men were more likely to experience worsening CKD, with incidence rates of 97.09 (95% CI 89.78 to 105.00) and 75.10 (95% CI 71.12 to 79.31) per 1000 person-years for unexposed men and women, respectively.

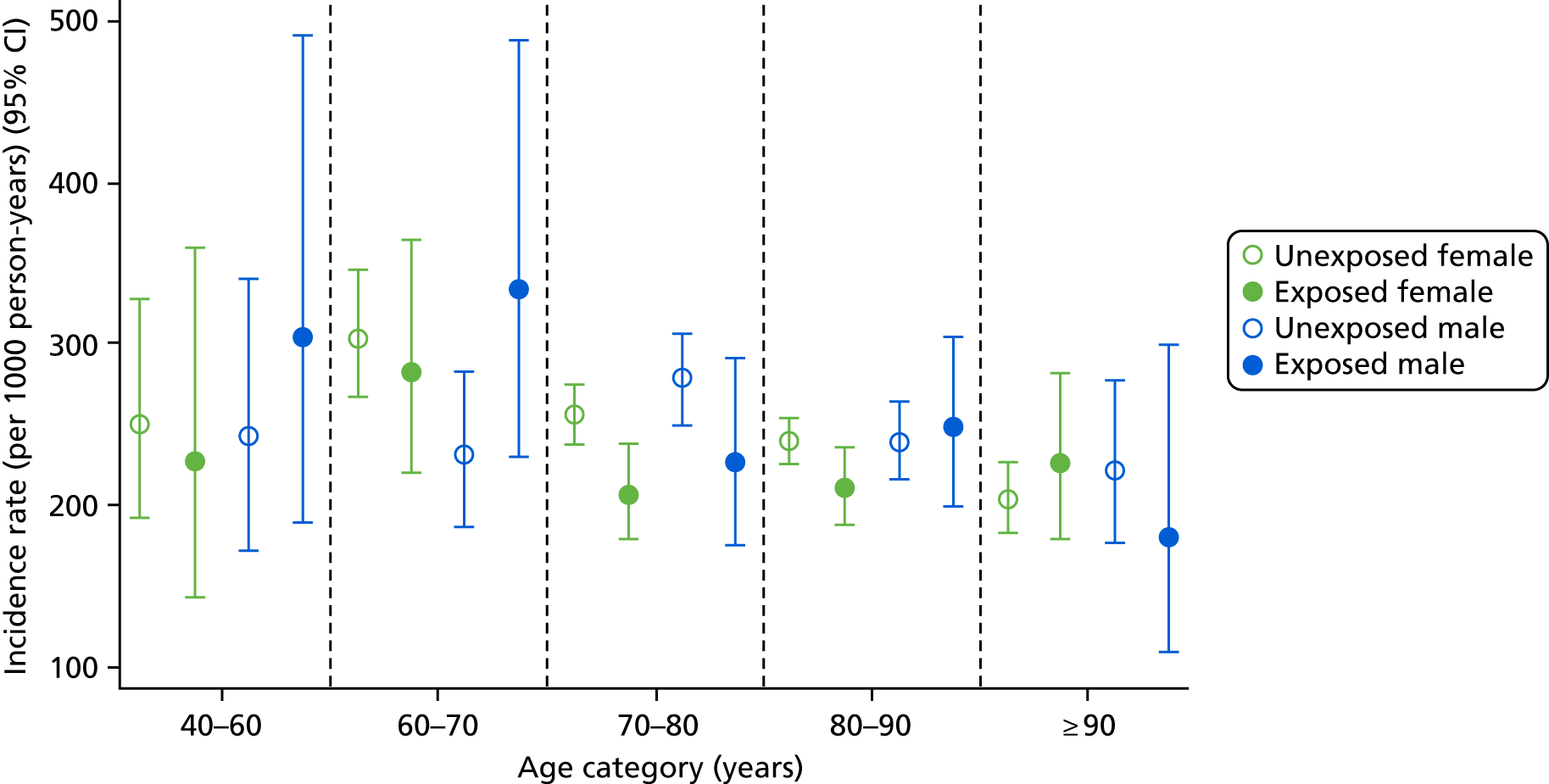

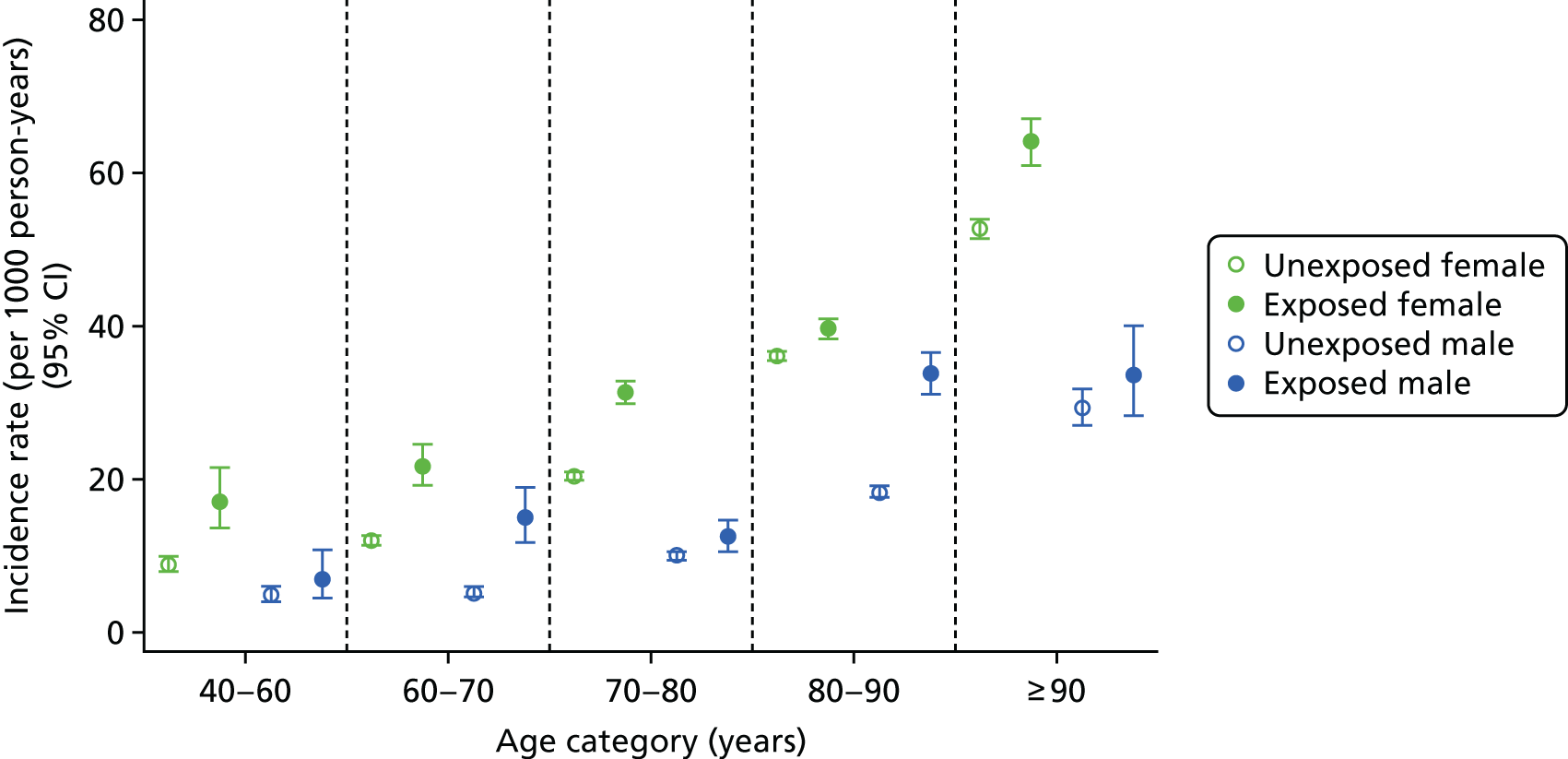

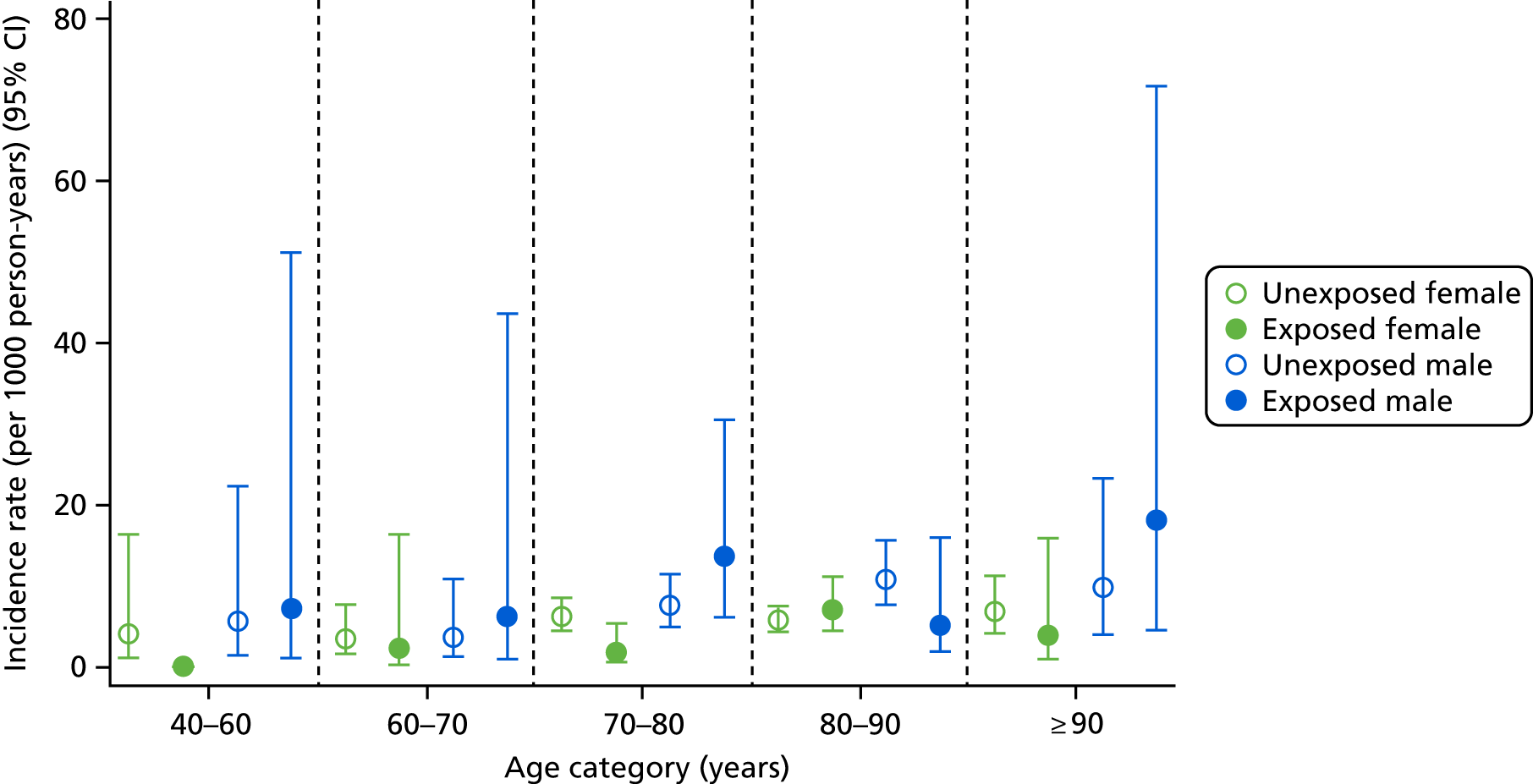

In a post hoc analysis focused on CKD improvement (i.e. reclassification to a less severe stage based on eGFR measures), improving CKD was slightly more frequent in participants who had not been exposed to bisphosphonates [incidence rate 246.83 (95% CI 238.66 to 255.28) per 1000 person-years] than bisphosphonate users [incidence rate 224.01 (95% CI 209.52 to 239.50) per 1000 person-years]. The age-, sex- and exposure-specific incidence rates for CKD stage improvement are shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Male and female incidence rates of CKD improvement per 1000 person-years, stratified by exposure to bisphosphonate, age and sex.

Improvement in men and women was similar, with relatively static incidence rates of improvement regardless of age and sex. Overall, men had a slightly higher rate of improvement than women [exposed men: incidence rate 246.92 (95% CI 215.41 to 283.05) per 1000 person-years; exposed women: incidence rate 217.64 (95% CI 201.57 to 234.99) per 1000 person-years]. The lowest rate of improvement was found in those aged > 90 years, with an incidence rate of 208.22 (95% CI 188.45 to 230.07) per 1000 person-years for unexposed participants. However, the incidence rates for participants exposed to bisphosphonate were constant across the following age groups: 70–80 years, 80–90 years and > 90 years; they were 211.7 (95% CI 187.2 to 239.4), 218.85 (95% CI 198.2 to 241.66) and 217.96 (95% CI 177.48 to 267.68) per 1000 person-years, respectively.

Fine and Gray competing risks model

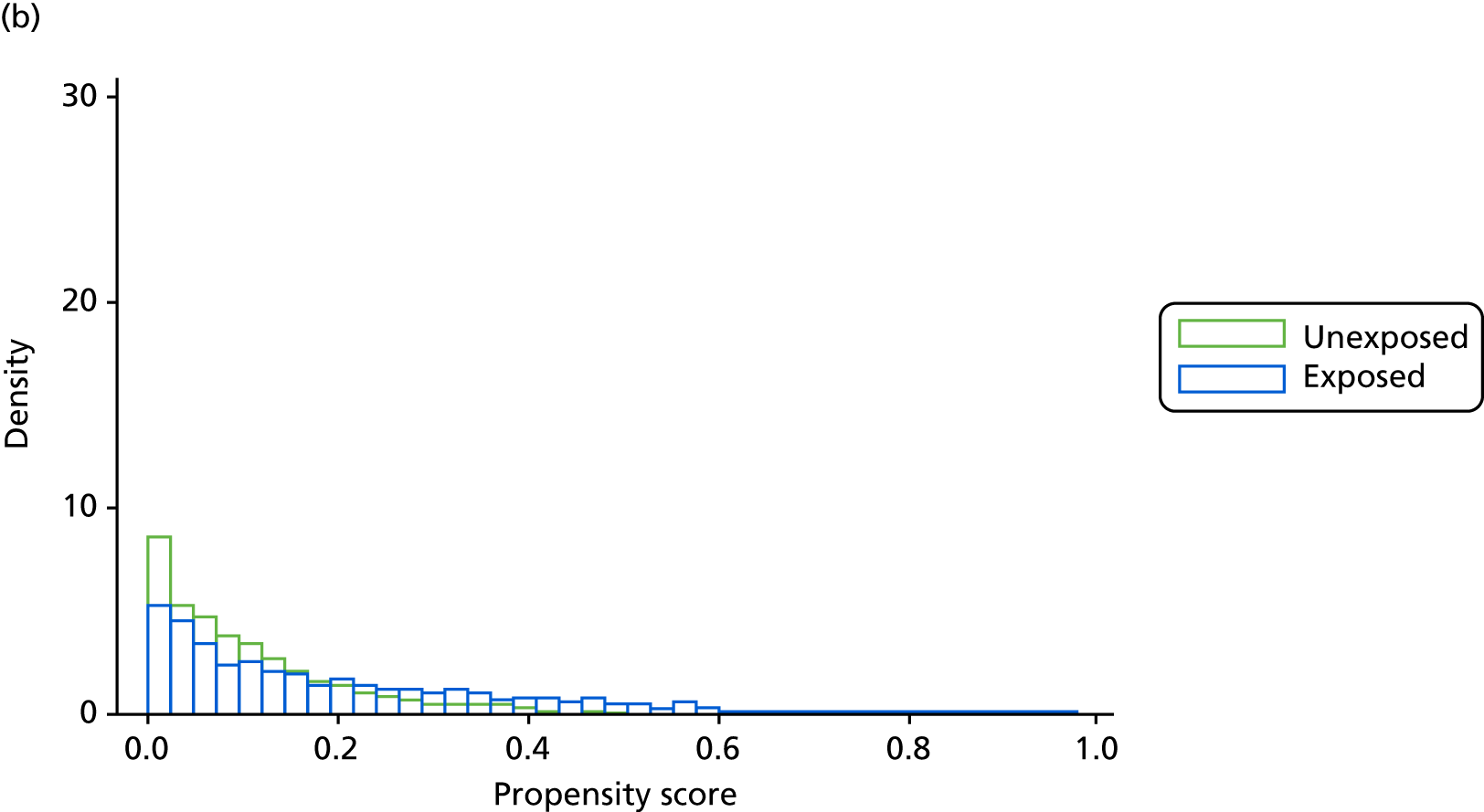

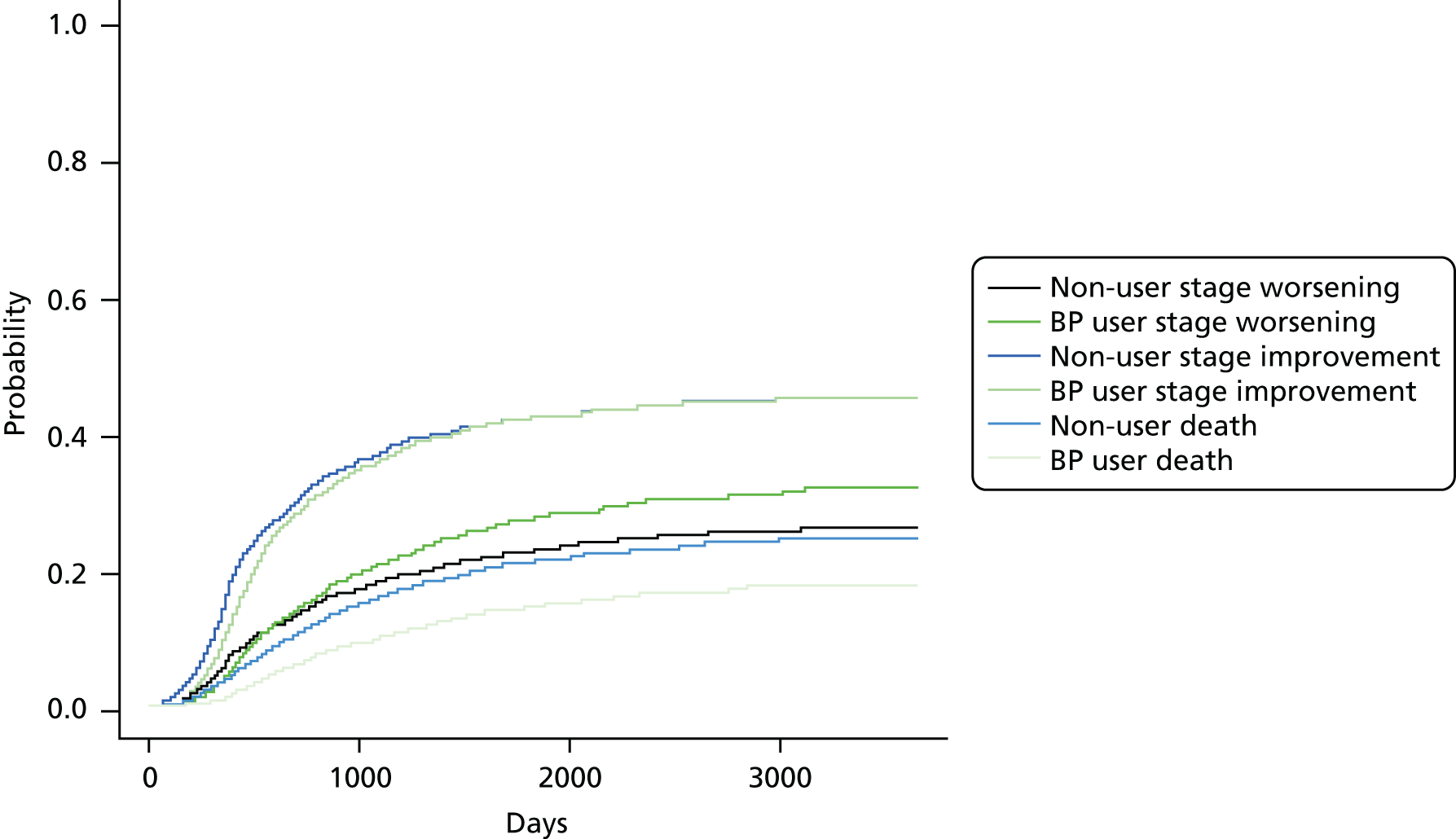

In the primary analysis, there were 576 events in the propensity-matched bisphosphonate user cohort: 36 end-stage renal failure events and 540 eGFR-based CKD stage-worsening events. The matched unexposed cohort reported 1996 events: 192 end-stage renal failure and 1804 eGFR-based CKD stage-worsening events. Cumulative incidence function plots are depicted in Figure 8.

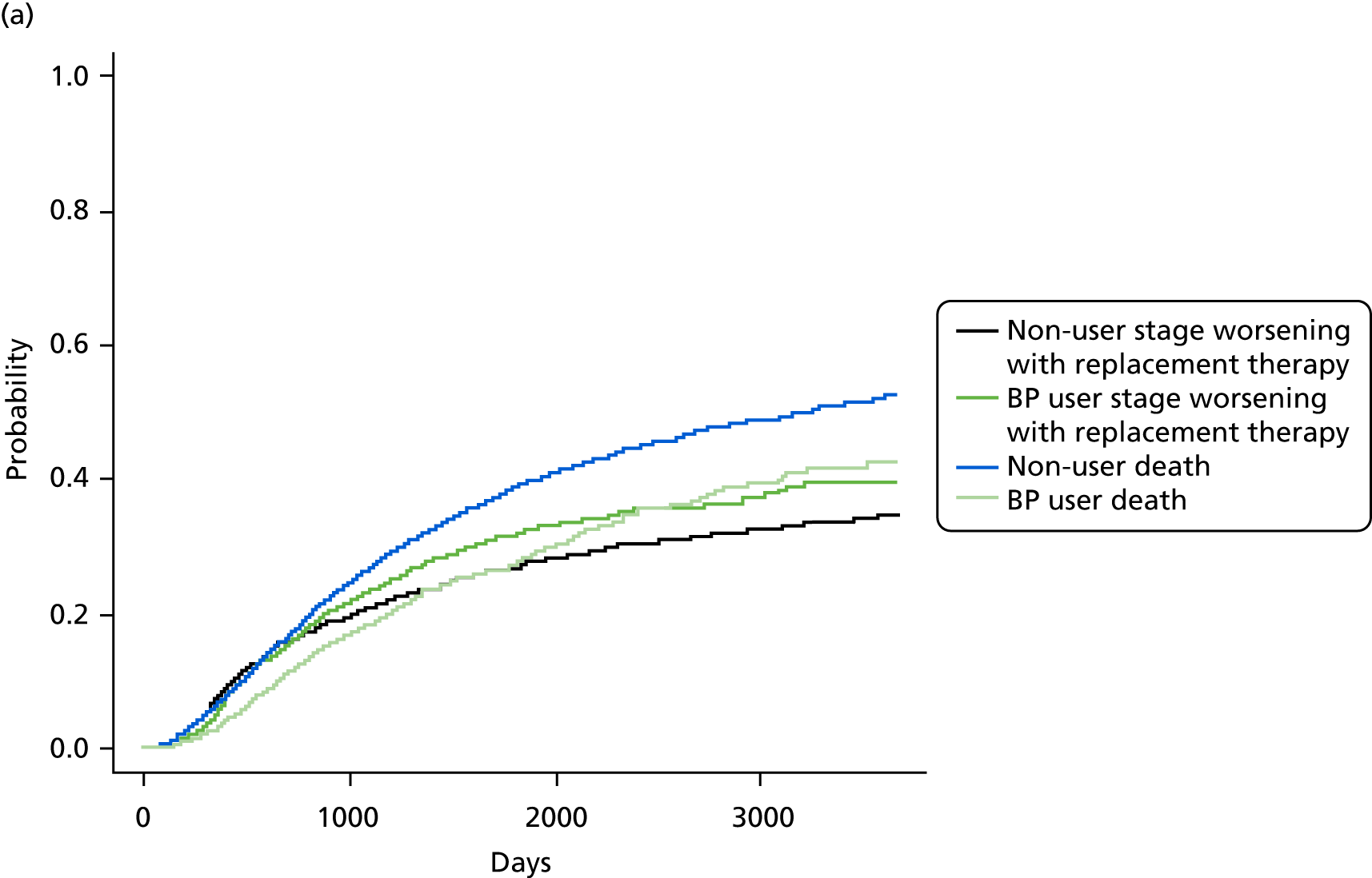

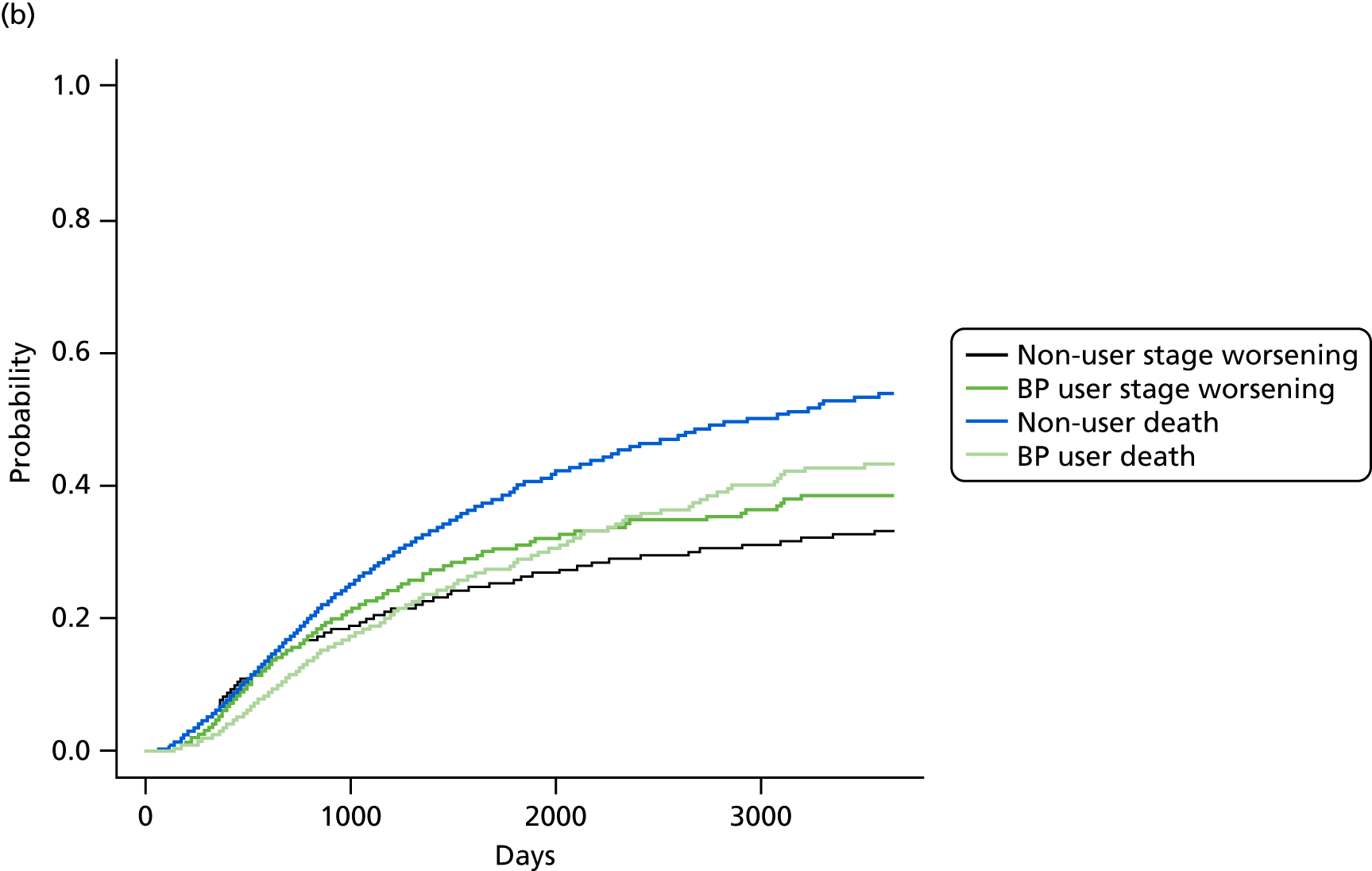

FIGURE 8.

Cumulative incidence plots of (a) CKD stage worsening or treatment for end-stage renal failure; and (b) only CKD stage worsening, stratified by bisphosphonate use or non-use.

Bisphosphonate use was associated with an increased risk of CKD progression, measured by stage worsening or receiving renal replacement therapy (sHR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.24). The results of the post hoc sensitivity analyses are detailed in Table 6.

| Outcome | Number of exposed events | Number of unexposed events | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-stage renal failure or CKD stage worsening | 576 | 1996 | 1.12 | 1.02 to 1.24 |

| CKD stage worsening | 559 | 1908 | 1.14 | 1.03 to 1.27 |

| CKD stage change | ||||

| Stable | 1057 | 3698 | Ref | Ref |

| Worsening | 534 | 1783 | 1.11 | 1.00 to 1.23 |

| Improvement | 858 | 3473 | 0.93 | 0.86 to 1.01 |

The first post hoc analysis defined CKD progression as only stage worsening. It gave results similar to the primary analysis, with 559 bisphosphonate users and 1908 non-users in the propensity-matched cohort changing to a worse eGFR-based stage (sHR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.27).

The second post hoc analysis used participants with stable CKD (no change in stage, neither improving nor worsening, during follow-up) as the reference group. Bisphosphonate users were at a higher risk of worsening CKD (sHR 1.11, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.23). There was a borderline significant reduction in their probability of improving: sHR 0.93 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.01).

See Figure 8 for the cumulative incidence plots of the primary and first post hoc analyses. Similar plots of the second post hoc analysis are shown in Appendix 1, Figure 25.

The cumulative incidence function of CKD stage worsening or treatment for end-stage renal failure gave a number needed to harm of 40.8 for a 3-year bisphosphonate treatment regimen, and of 20.7 for a 5-year bisphosphonate treatment regimen.

Interactions

Interactions were identified with history of fracture (p = 0.03) and sex (p = 0.04). Participants with a history of fracture were more likely to experience CKD stage worsening when exposed to bisphosphonates (sHR 1.32, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.66) than those without a history of fracture (sHR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.22). These CIs overlap, suggesting a non-significant difference without clinical relevance between the participants with and those without a history of fracture who experienced improved CKD. Women were also more likely to experience stage change than men after matching within sex, with sHRs of 1.24 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.38) and 1.00 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.21) for women and men, respectively.

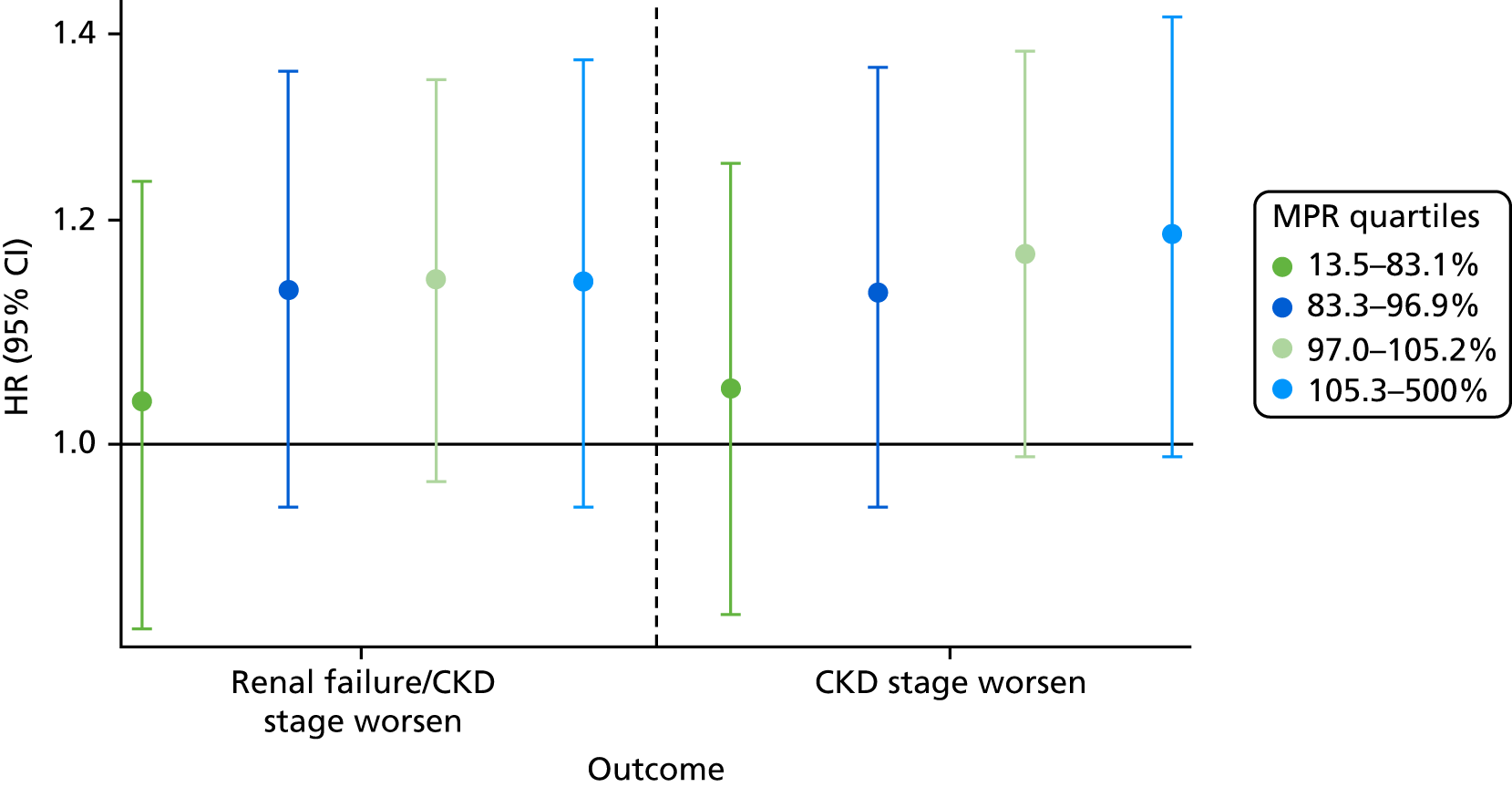

Medication possession ratio

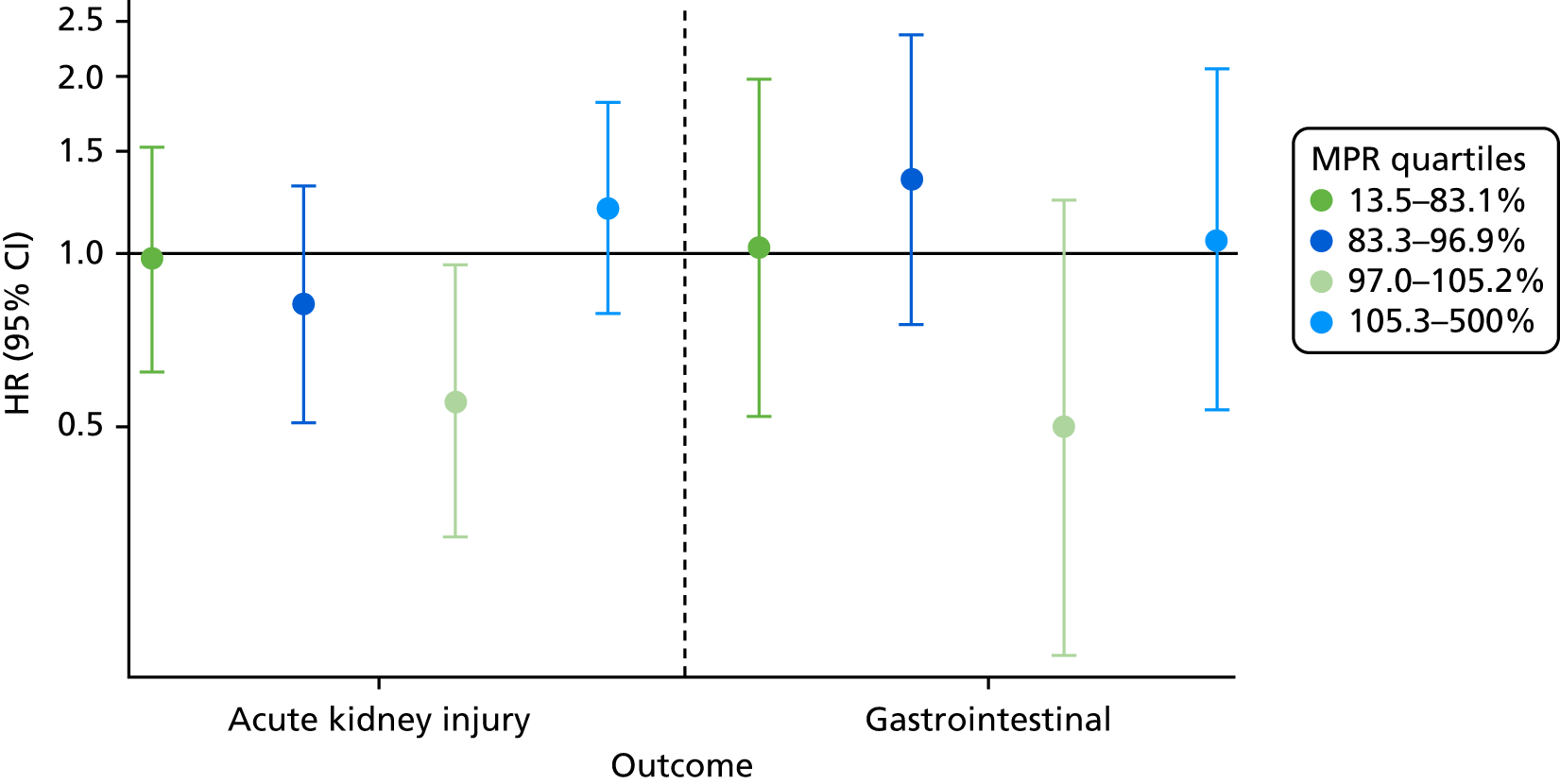

When the exposed participants were split into their MPR quartiles, there was little difference between the quartiles, with all CIs overlapping (Figure 9). Participants in the highest quartile were at increased risk of worsening CKD. The participants who were least likely to worsen in CKD stage were those in the lowest quartile, i.e., the participants least adherent to their prescribed bisphosphonate treatment. The Mantel extension test detected no difference between MPRs for renal failure/stage worsening (p-value 0.38) but a borderline significant difference (p = 0.07) for CKD progression based on eGFR stage change alone.

FIGURE 9.

Hazard ratios of each outcome, split into MPR quartiles.

Multivariable analysis

As requested by the Steering Committee, a multivariable analysis was used as a post hoc sensitivity analysis in place of propensity score matching. Bisphosphonate use was associated with an 18% increase in the risk of the primary outcome of CKD worsening, defined by stage change or end-stage renal disease (adjusted HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.29). The full results of this multivariable analysis are shown in Table 7.

| Covariate | Renal failure or CKD stage worsening | CKD stage worsening |

|---|---|---|

| Bisphosphonate use | 1.18 (1.08 to 1.29) | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.33) |

| Sex (female) | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.80) | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.80) |

| Age per year | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| Smoker | ||

| Non-smoker | Ref | Ref |

| Ex-smoker | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.10) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) |

| Current smoker | 1.19 (1.11 to 1.27) | 1.20 (1.12 to 1.29) |

| Alcohol | ||

| Non-drinker | Ref | Ref |

| Ex-drinker | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.08) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.09) |

| Current drinker | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.98) |

| IMD | ||

| 1 – least deprived | Ref | Ref |

| 2 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.02) |

| 3 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) |

| 4 | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.07) |

| 5 – most deprived | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18) |

| BMI (kg/m2) per 1 unit | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) |

| Baseline eGFR (ml/minute/1.73 m2) | ||

| 0.1–4.9 | 6.85 (5.09 to 9.22) | Not possible |

| 5–9.9 | 5.46 (4.72 to 6.30) | Not possible |

| 10–14.9 | 2.31 (2.01 to 2.67) | Not possible |

| 15–19.9 | 4.09 (3.76 to 4.45) | 3.74 (3.43 to 4.09) |

| 20–24.9 | 1.66 (1.53 to 1.79) | 1.60 (1.48 to 1.74) |

| 25–29.9 | 0.72 (0.66 to 0.78) | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.72) |

| 30–34.9 | 3.99 (3.82 to 4.16) | 4.02 (3.85 to 4.19) |

| 35–39.9 | 1.89 (1.81 to 1.97) | 1.89 (1.82 to 1.97) |

| 40–44.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Number of hospital visits | ||

| 0 | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.09) |

| 2 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14) | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) |

| 3–5 | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.19) | 1.13 (1.06 to 1.20) |

| ≥ 6 | 1.31 (1.16 to 1.49) | 1.28 (1.12 to 1.47) |

| 5-year Charlson score | ||

| 0 | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.15) | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14) |

| 2 | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.13) | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.12) |

| 3–5 | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.23) | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.22) |

| ≥ 6 | 1.34 (1.21 to 1.48) | 1.33 (1.20 to 1.48) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0.91 (0.85 to 0.96) | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.96) |

| Cancer | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) |

| CKD | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.96) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.97) |

| Dementia | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.13) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.14) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) |

| Hip fracture | 1.23 (1.02 to 1.49) | 1.21 (1.00 to 1.46) |

| Non-hip fracture | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.06) | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.05) |

| Deep-vein thrombosis | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.11) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.12) |

| Varices | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) |

| Hypertension | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.95) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.96) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) |

| Liver disease | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.19) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.15) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.04) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.04) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.14) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.15) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.17) | 0.88 (0.67 to 1.16) |

| Number of prescriptions | ||

| 0 | Ref | Ref |

| 1–3 | 0.90 (0.81 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.04) |

| 4–6 | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95) | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.99) |

| 7–9 | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.99) | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.03) |

| 10–12 | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.00) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.04) |

| ≥ 13 | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.04) | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.09) |

| NSAID | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.92) |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 0.81 (0.75 to 0.88) | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.89) |

| Calcium supplements | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.19) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.17) |

| Steroids | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.01) |

| Anticoagulants | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.97) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98) |

| Heparins | 1.21 (1.00 to 1.46) | 1.21 (0.99 to 1.47) |

| Aromatase inhibitors | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.26) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.30) |

| Antidepressants | 0.96 (0.92 to 0.99) | 0.96 (0.92 to 0.99) |

| Statins | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.96) | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.94) |

| Antiepileptics | 0.93 (0.86 to 1.02) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) |

| Diuretics | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.06) |

| Beta blockers | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.95 (0.91 to 0.98) |

| ACE inhibitors | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.13) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16) | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.16) |

| Antihypertensives | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) |

| Digoxin | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) |

| Antidiabetics | 1.44 (1.37 to 1.52) | 1.49 (1.41 to 1.57) |

| Insulin | 1.12 (1.04 to 1.20) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) |

Covariates associated with an increased risk included the following:

-

smoking –

-

HR 1.19 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.27) for current smokers

-

HR 1.05 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.10) for ex-smokers

-

-

socioeconomic deprivation –

-

HR 1.05 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.10) for IMD quartiles 3 and 4

-

HR 1.11 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.17) for IMD quartile 5

-

-

having a lower eGFR at baseline –

-

HR 6.85 (95% CI 5.09 to 9.22) for an eGFR of 0.1–4.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

HR 5.46 (95% CI 4.72 to 6.30) for an eGFR of 5–9.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

HR 2.31 (95% CI 2.01 to 2.67) for an eGFR of 10–14.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

HR 4.09 (95% CI 3.76 to 4.45) for an eGFR of 15–19.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

HR 1.66 (95% CI 1.53 to 1.79) for an eGFR of 20–24.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

HR 3.99 (95% CI 3.82 to 4.16) for an eGFR of 30–34.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

HR 1.89 (95% CI 1.81 to 1.97) for an eGFR of 35–39.9 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

-

high health resource use, as measured by hospital episodes in the year before index –

-

HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.08) for those with one admission

-

HR 1.08 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.14) for those with two admissions

-

HR 1.12 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.19) for those with three to five admissions

-

HR 1.31 (95% CI 1.16 to 1.49) for those with six or more admissions

-

-

comorbidity to as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index score –

-

HR 1.09 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.15) for a score of 1

-

HR 1.07 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.13) for a score of 2

-

HR 1.15 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.23) for a score of 3–5

-

HR 1.34 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.48) for a score of ≥ 6

-

-

history of hip fracture – HR 1.23 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.49)

-

treatment in the year before index with –

-

calcium supplements: HR 1.12 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.19)

-

heparins: HR 1.21 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.46)

-

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors: HR 1.09 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.13)

-

calcium channel blockers: HR 1.12 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.16)

-

other antihypertensives: HR 1.07 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.12)

-

digoxin: HR 1.10 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.17)

-

antidiabetics: HR 1.44 (95% CI 1.37 to 1.52)

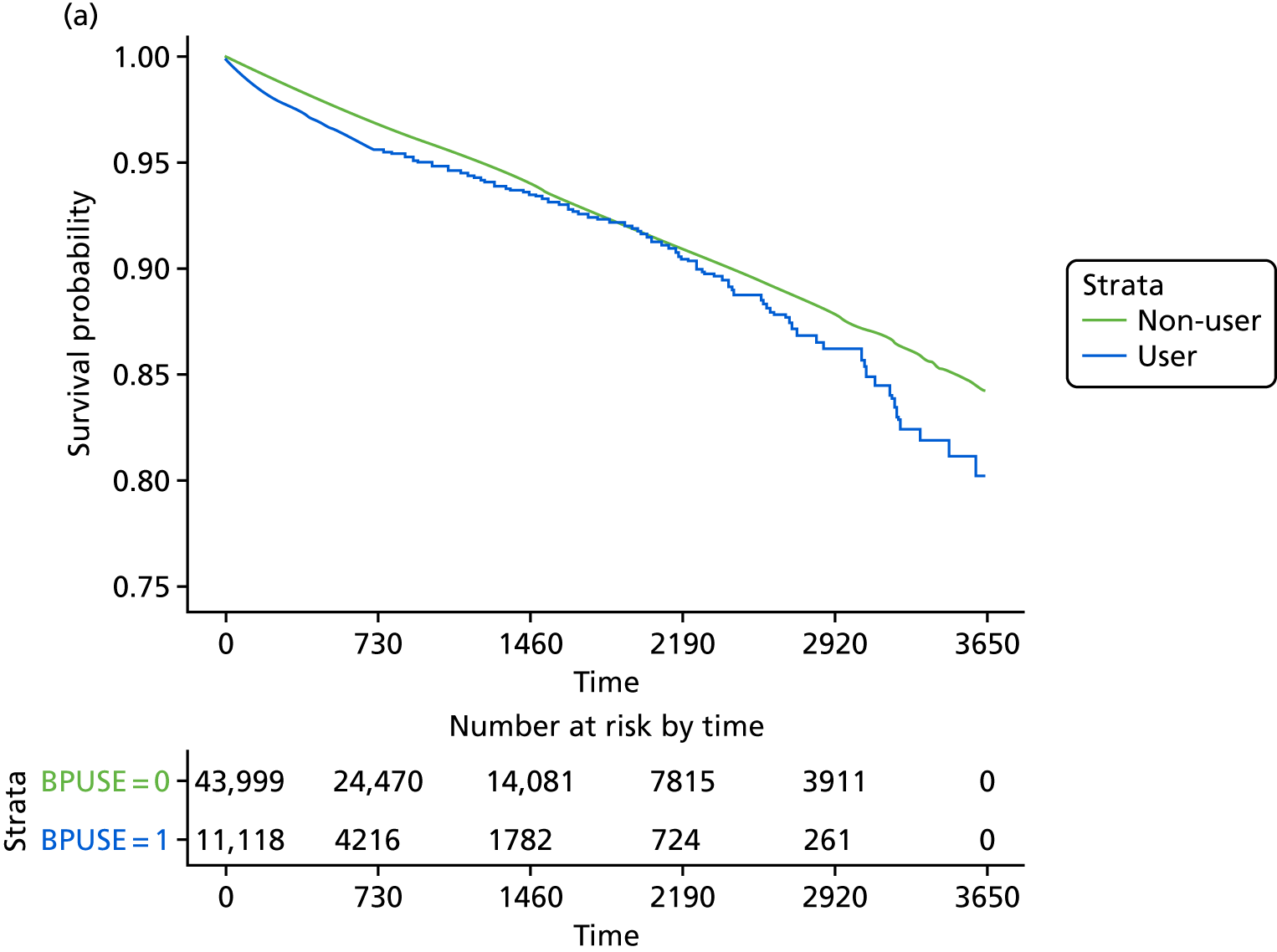

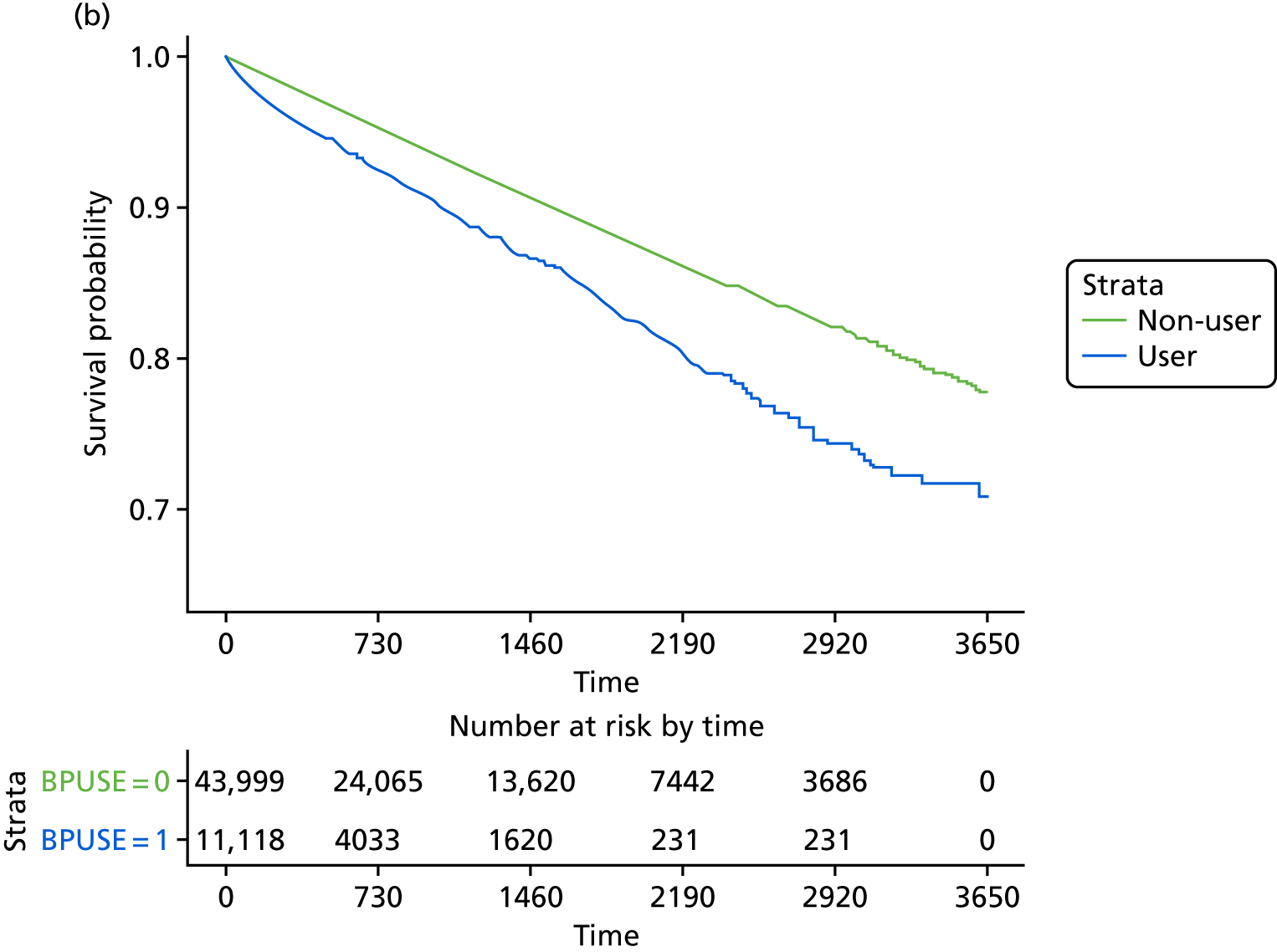

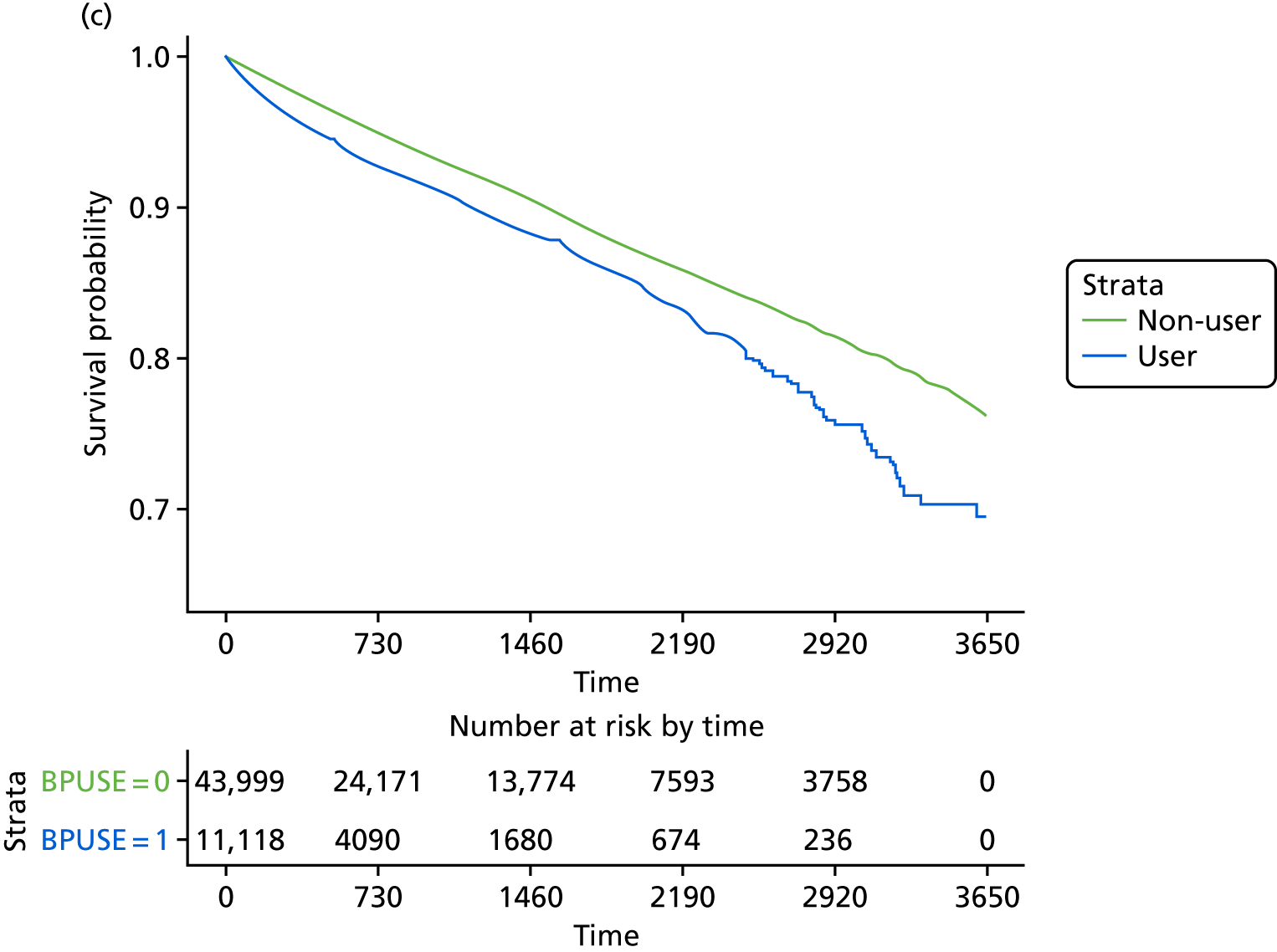

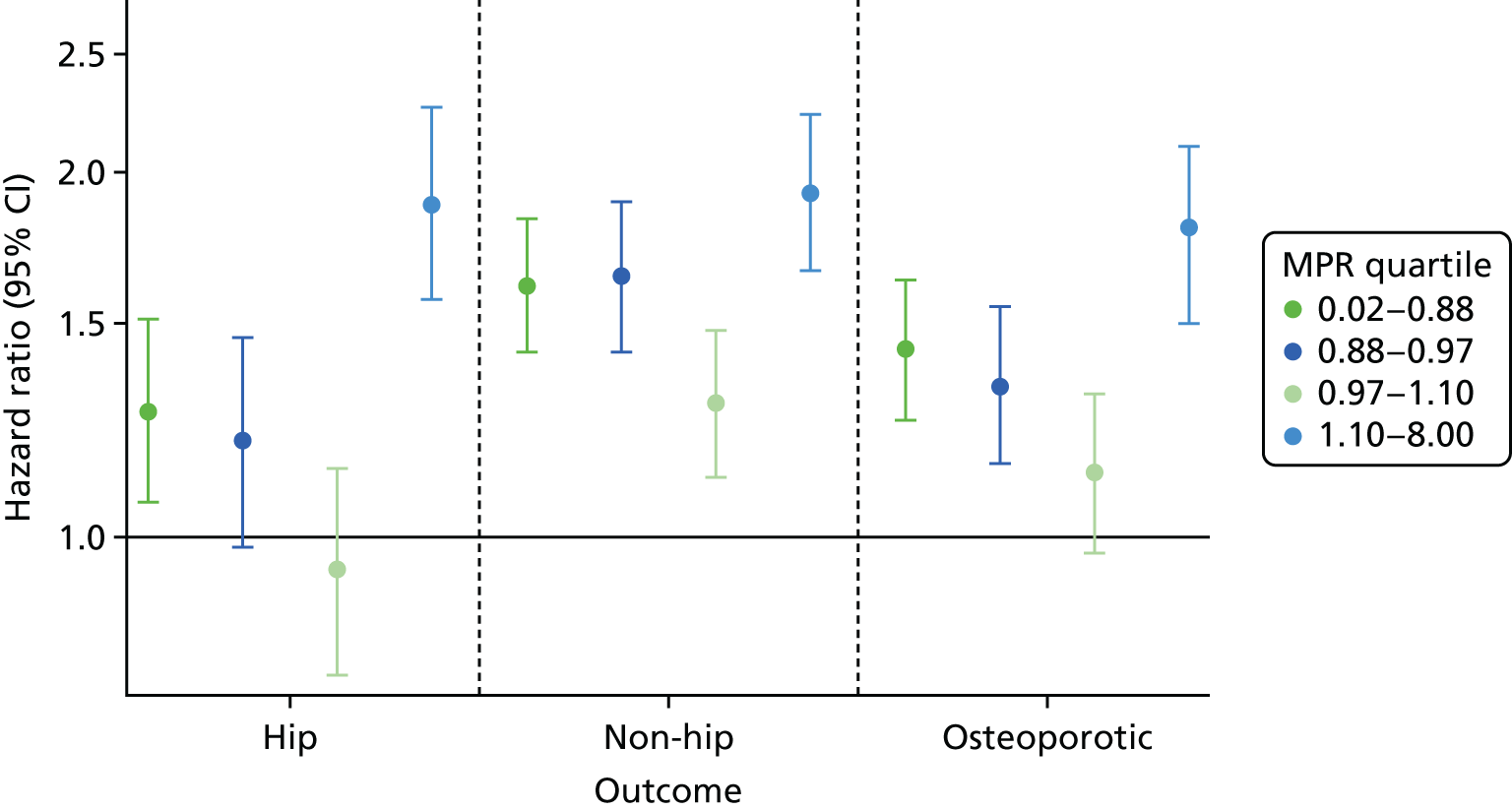

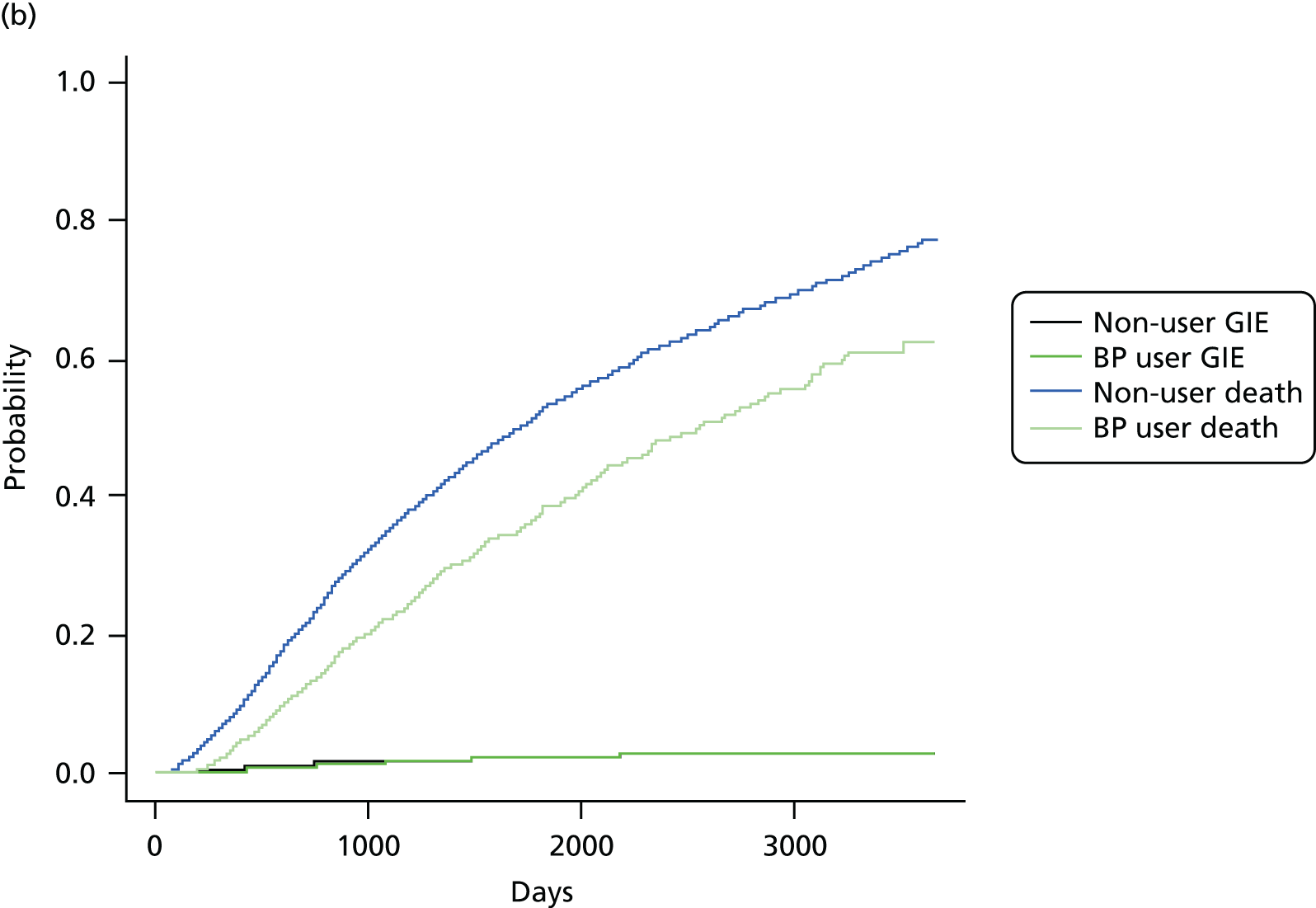

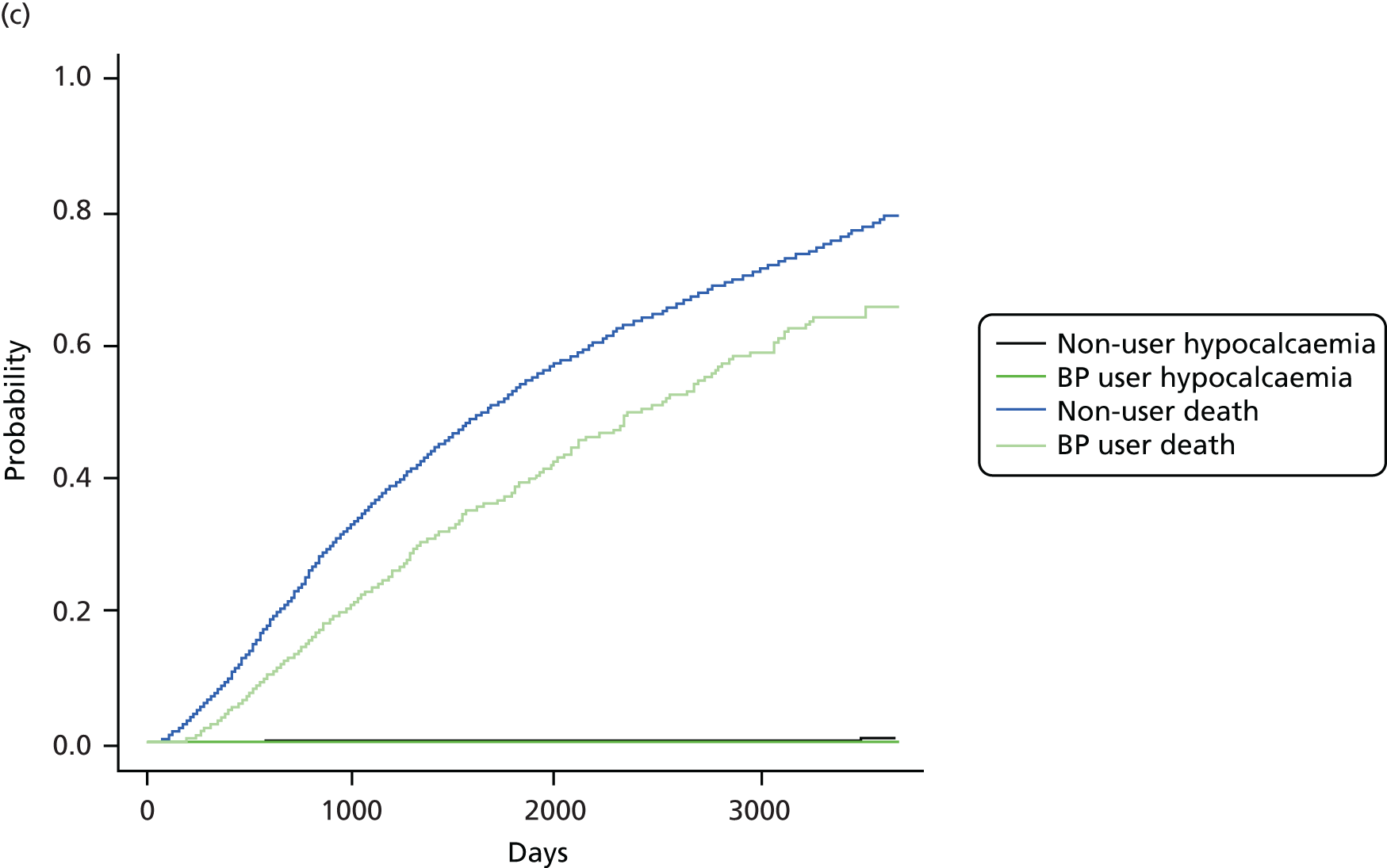

-