Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/50/02. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The draft report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Gathercole et al. This work was produced by Gathercole et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 The authors

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report are reproduced with permission from Leroi et al. 1 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Parts of this report are reproduced with permission from Howard et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background

There are approximately 850,000 people with dementia in the UK3,4 and an estimated 700,000 people who provide unpaid care for them. Many of these people with dementia will require accommodation in nursing or residential care homes when their illness has progressed to the point at which they can no longer live safely and independently in their own homes. It has been estimated that, over the next two decades, the number of people aged ≥ 85 years will increase by two-thirds. 5 Over half of all users of adult social care services are aged ≥ 65 years,6 and a steep rise in the numbers of people living with dementia is expected over the next few decades. The financial cost of caring for people with dementia is considerable,3 as is the social and psychological cost to unpaid caregivers (generally a relative or friend, subsequently referred to as ‘caregivers’). Caregiver breakdown is a common reason for the unplanned admission of older people (many of whom will have dementia) to permanent nursing or residential care. 7

Living Well with Dementia, the theme of the 2009 National Dementia Strategy for England,8 involves helping people with dementia to retain their independence while living in their own homes, and to maintain their quality of their life. People living with dementia who move from their own homes into institutional care often experience a loss of independence and quality of life. To minimise this possibility, the NHS and councils with adult social services responsibilities (CASSRs) in England aim to support people with dementia to live safely in their own homes for as long as possible.

Assistive technology and telecare (ATT) offer relatively new means of delivering care and support to people with social care needs by helping to manage the risks facing older people with dementia who wish to remain living independently at home. It is claimed that sensors (e.g. to detect falls, floods or the presence of gas from an unlit appliance in someone’s home), passive monitoring that uses sensors placed in a home environment to detect movement, and alerting devices to relay information from the person’s home to a remote site such as a call centre support the independence of people with social care needs,9,10 reduce the burden on caregivers11–15 and save money for CASSRs. 16 By addressing risks associated with independent living for people with dementia, it is claimed that ATT help reduce the need for community care, prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and delay or prevent admission to residential or nursing care. 12,17–19 The evidence to support such claims is limited, and based largely on qualitative evidence or uncontrolled quantitative studies. 20,21 There is, therefore, an urgent need to provide evidence to inform decisions about whether or not to provide ATT in the homes of people with dementia.

The first use of electronic ATT in the UK, in the 1990s, was to provide support for people with dementia and their caregivers. 17,22–25 Within a decade, interest in ATT has developed from a fringe interest for a handful of enthusiasts to a multimillion-pound industry commanding government support, a Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) strategy26 and, increasingly, the use of ATT in CASSR settings as a mainstream service (see Woolham et al. 25). However, as interest in ATT has increased, the specific focus on its application for those living with dementia has diminished. 13 The performance indicators that followed the Preventative Technology Grant (given to CASSRs in 2008 by the DHSC26) were intended to promote the widest possible use of telecare. The DHSC did not, however, offer a clear indication of what this grant was supposed to ‘prevent’. Although Woolham12 has drawn attention to the cost-effectiveness of telecare for people with dementia by closely matching ATT with assessed need, thereby preventing the need for more expensive forms of care, Poole27 has argued that CASSRs should see ATT as a long-term investment, deploying it at an early stage without expecting immediate savings. This has contributed to a situation in which CASSRs have implemented ATT across several different care groups without always referring to the needs of the specific groups, such as people with dementia. The current economic situation, and a significant reduction in government CASSR funding, has led to increasing numbers of CASSRs developing an interest in ATT. Some have developed local strategies to use it, whereas others already have well-developed ATT services that can be deployed alongside, or instead of, non-institutional forms of support, often known as ‘community care’ in the UK.

Despite growing ATT use, the evidence to support its use is limited. The Whole System Demonstrator (WSD) study was funded by the DHSC in 2008 to investigate the impact and effectiveness of ATT in England. 28–35 However, individuals with dementia were not specifically included. This, together with the relative dearth of dementia-specific studies relating ATT, means that a significant gap in the evidence remains. Although there are relatively large numbers of qualitative studies, audits and service evaluations, there are few studies with sufficient rigour and appropriate design to offer any degree of generalisability21 or agreement about how ‘success’ can be measured. 36 One study25 has suggested that, when used appropriately, ATT are highly cost-effective, but limitations in design and methodology constrain the generalisability of this study’s findings. A Cochrane review in 201737 found no research evaluating assistive technology for people via a randomised controlled trial (RCT), with the exception of this Assistive Technology and Telecare to maintain Independent Living At home for people with dementia (ATTILA) trial, which was in progress at the time of publication of the Cochrane review. 37 Evidence from a well-designed trial such as ATTILA is clearly needed to guide future policy direction.

The DHSC’s ‘Building Telecare’ strategy in 200513 provided generic advice to CASSRs. As part of this strategy, a Preventative Technology Grant, which CASSRs were required to spend on developing local ATT services, was made available. England’s 2009 National Dementia Strategy8 recommended a ‘watching brief’ for emerging evidence of the impact of telecare, stating:

However, with respect to more recent innovations, this is not an area where the strategy is able at this time to make specific recommendations. Instead, central, regional and local teams should keep in touch with initiatives in the areas of housing and telecare and make appropriate commissioning decisions as data become available, for example from the Department’s large-scale field trials of telecare and assistive technology.

Aims and objectives of the trial

The ATTILA trial was designed to answer questions about the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of ATT, with relevance for those who commission and provide care for people with dementia.

The aims of the ATTILA trial were to test the following hypotheses:

-

that the application of ATT will significantly extend the time that people with dementia can continue to live independently and safely in their own homes

-

that ATT interventions are cost-effective in the management of risk and maintenance of independence for people with dementia living in their own homes

-

that provision of ATT interventions to people with dementia living at home will significantly reduce the number of incidents involving serious risks to safety and independent living, particularly those involving acute admissions to hospital

-

that ATT interventions will reduce burden and stress in family and other caregivers and increase quality of life for people with dementia.

These hypotheses were tested by the following primary and secondary objectives:

-

Primary objective – to establish whether or not ATT assessments and interventions extend the time that people with dementia can continue to live independently in their own homes and whether or not this is cost-effective.

-

Secondary objectives –

-

to establish whether or not these technologies can significantly reduce the number of incidents involving serious risks to safety and independent living, including acute admissions to hospital

-

to reduce burden and stress in family and other caregivers, and increase quality of life for people with dementia and their caregivers

-

to collect qualitative and quantitative data from people living with dementia, their paid and unpaid caregivers, and members of the NHS and CASSR teams about their experience of using these technologies.

-

Structure of the report

In Chapter 2, we provide a summary of the trial methods. In the chapters that follow, we set out the methods and results of the research, beginning with work carried out to describe the intervention (see Chapter 3). In subsequent chapters, we report on participant outcomes, cost-effectiveness, caregiver outcomes and ethnographic research with participants and caregivers. In Chapter 8, we summarise the findings, reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of the research and make recommendations for future research and practice.

Deviations from the protocol

We did not conduct one proposed cost-effectiveness analysis. It was proposed that an analysis of the change in EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), score over 2 years would take into account the costs of permanent care home and hospital stays of those admitted to care homes over that period. This analysis was not conducted because no outcomes and costs data were collected from caregivers when participants were permanently admitted to care during the 2-year follow-up.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial objectives

The ATTILA trial was a pragmatic RCT comparing outcomes for people with dementia who received a full ATT package with the outcomes for people with dementia who received equivalent community services but ATT were limited to a pendant alarm, non-monitored smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, and key safes. Assistive technology is defined as ‘any item, piece of equipment, product or system, whether acquired commercially, off the shelf, modified or customised, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities of individuals with cognitive, physical or communication difficulties’. 22 Telecare can include many different interventions, including those aimed at delivering care and monitoring remotely. 38 For the purposes of this trial, these devices had to be provided to support challenges related to memory problems and recommended by a health or social care professional.

The primary objectives of the trial were to establish whether or not:

-

ATT assessments and interventions can extend the time that people with dementia can continue to live independently and safely in the community

-

ATT interventions are cost-effective in the management of risk and maintenance of independence in people with dementia living in their own homes.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

establish whether or not these technologies can significantly reduce the number of incidents involving serious risks to safety and independent living, including acute admissions to hospital; reduce stress in family and other caregivers; and increase quality of life for those with dementia and their caregivers

-

collect qualitative and quantitative data from people living with dementia and their formal caregivers about their experience of using these technologies.

Trial design

The ATTILA trial was a multicentre, pragmatic RCT, conducted over 260 weeks, that took place in the homes of people living with dementia who were eligible to receive a package of care. The trial compared outcomes in two groups of participants randomised to one of the two trial arms: (1) receiving an assessment of needs followed by the installation of appropriate ATT devices and response services to be deployed by the CASSR or NHS (a full ATT package) or (2) receiving an assessment of needs followed by the installation of an ATT package restricted to smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, a key safe and a pendant alarm if indicated, also arranged by the CASSR (a basic ATT package). The co-primary outcomes were time to institutionalisation and cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

The trial was not funded to source, assess for, or deploy ATT. Our approach was to work alongside CASSRs who were charged by the Department of Health and Social Care with responsibility for establishing and developing local ATT services.

Site identification and recruitment

Recruitment of local authority Adult Social Care Department (ASCD) sites to the trial was opportunistic because of anticipated difficulties in securing permissions. Sites known to have well-established telecare services were identified, as well as those located in geographical areas close to the place of employment of research team members. This also meant that participating ASCDs were geographically widely spread across England, and that all types of local authority were represented. Telephone contact was usually first made with a telecare manager in identified sites. In most cases, this person referred our request to the departmental senior management team or to the director. In some sites, repeated visits were needed to discuss the request. Several ASCDs declined to take part in the main trial, either because they did not feel that they had the resources to do so or because of lack of fit between the trial aims and the strategic priorities of the service.

Participants

Participants were people with any dementia diagnosis, or suspected dementia, who were living in the community and were from one or more of three constituencies:

-

people who sought help or support from local authority social care services in the areas that had agreed to support the trial (Barnsley, Blackburn, Blackpool, Cambridgeshire, Croydon, Lambeth, Lancashire, Nottingham, Norfolk, Oxfordshire, Southwark and Suffolk) and who met local ASCD eligibility criteria for their support

-

people who were supported by the services of the NHS and were referred to an ASCD and met local ASCD eligibility criteria

-

people who were recruited from the caseload of NHS services for older adults and referred to local social services and met local ASCD eligibility criteria.

Those referred from the NHS usually had to meet eligibility criteria for social care because this often determined if ATT could be provided.

Most participants (n = 431, 87.1%) did have a dementia diagnosis, but some of those referred by LAs had not yet had a formal diagnosis. In these cases, clinical judgement was used by the research worker and health or social care staff involved to decide whether or not the cause of the potential participant’s memory impairment was dementia. If necessary, the research worker could discuss further with the local principal investigator.

Screening for eligibility and the preliminary information visit

All trial procedures, including the initial visit and consent visit, took place in participants’ homes. At the first appointment, participants were assessed for eligibility based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Had any dementia diagnosis, evidence of memory difficulties or possible dementia.

-

Had a professionally assessed need for ATT from a health or social care professional.

-

Was resident in a community.

-

Lived in a dwelling suitable for the installation of ATT.

Exclusion criteria

-

Had already received an ATT intervention (excluding non-linked smoke detector or carbon monoxide detector, key safe or pendant alarm) or ATT had been previously provided but was not used.

-

Was unlikely to comply with follow-up, for example owing to an unstable medical or psychiatric condition.

-

Was participating in another clinical trial involving an intervention for dementia.

-

Had an urgent need for a care package owing to immediate and severe risks to self or others.

-

Did not have a suitable caregiver.

-

Was living in accommodation unsuitable for the provision of ATT.

Selection and recruitment

There were several routes for participant recruitment. Most participants were referred from local authority social services, but other referring services included not-for-profit organisations providing ATT; charitable organisations such as Age UK and the Alzheimer’s Society; and NHS mental health, community care and primary care services. Those referred from the NHS had to meet eligibility criteria for social care provision.

After assessing eligibility of new referrals for both social care support and the ATTILA trial, participating services asked if a potential participant’s contact details could be made available to a named individual in the local research team. Once identified, the research worker contacted this person and arranged to visit them and a caregiver who knew them well. Those meeting the eligibility criteria had the possible benefits and risks of participation in the trial explained to them. Following this, the participant was given a general outline of three possible options: (1) taking part in the ATTILA trial with the intervention (i.e. ATT package or regular support package without ATT) decided by randomisation, (2) declining to participate in the ATTILA trial and (3) taking more time to consider their decision about whether or not to participate. Those who were interested in taking part in the trial were provided with participant and caregiver information leaflets to find out more about the trial before deciding whether or not to participate. After a full explanation of the intervention options and the manner of treatment allocation, all suitable participants were invited to take part in the randomised component of the trial. If urgent provision of support services was required, then consent was sought at that visit so that they could be immediately randomised. Otherwise, information about the trial could be left with the prospective participant and, if they required more time to consider participation, the researcher would return at a later date to take consent and subsequently randomise the participant. Consent was also obtained from the caregiver using the caregiver consent form in the trial folder. If a participant lacked capacity, a professional or personal consultee was involved to ensure that participation in the trial was in the person’s best interests (according to guidelines established in the Mental Capacity Act 2005: Code of Practice39). When appropriate, data-sharing agreements were agreed with the CASSRs and health services concerned to ensure that the transfer of personal data from the local authority to the research team was lawful. If consent was not given, the participant was not included and any personal data were removed from research team records and destroyed. Reasons why those who were potentially eligible did not consent to take part were recorded on a screening log in the ATTILA trial folder. After randomisation, assessment for ATT and provision of ATT services (within limits set by randomisation) were left entirely up to the local authority or health service operational teams concerned.

Outcome measures

The co-primary trial outcomes were (1) time to institutionalisation and (2) the cost-effectiveness of the ATT intervention. Table 1 shows the schedule of all assessment points and the measures used at each.

| Assessment | Time point | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week –1 | Eligibility and randomisation screening | Follow-up assessments | |||||||||||

| Face to face | Telephone | ||||||||||||

| Week 0 | Week 12 | Week 24 | Week 52 | Week 104 | Week 130 | Week 156 | Week 182 | Week 208 | Week 234 | Week 260 | |||

| Participant information | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Inclusion criteria | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| ATT needs assessment at home | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Capacity assessment | ✗ | ✗ (prior to consent) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Randomisation data | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Inform local authority of randomisation outcome | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Install intervention (ATT or alternatives)a | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| SMMSE | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| BADLS | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| EQ-5D-5L Proxy (carer) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| STAI-6 (carer) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| CES-D-10 (carer) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| ZBI (carer) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| SUTAQ (carer) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||

| CSRI (carer) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Follow-up form | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| ATT checklist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

Time in days from randomisation to institutionalisation

This was defined as permanent transition of a participant from living in their own home to living in a nursing or residential care home or to admission to an acute care facility that results in permanent placement in a residential care or nursing home. Caregivers were asked to report the date of this transition; if necessary, health or social care results would also be consulted. Analyses were by intention to treat, with all randomised participants included in the comparison and analysed according to their randomised allocation, including those who discontinued the trial. The primary outcome of time to institutionalisation was compared between intervention and control arms using survival analysis methods. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were created for graphical representation of the time to event comparisons (see Figures 4, 5 and 7). Statistical significance was determined by the log-rank test. Analyses included all events, even those occurring after 2 years. Participants who died, withdrew from follow-up or were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of withdrawal from the trial.

Cost-effectiveness

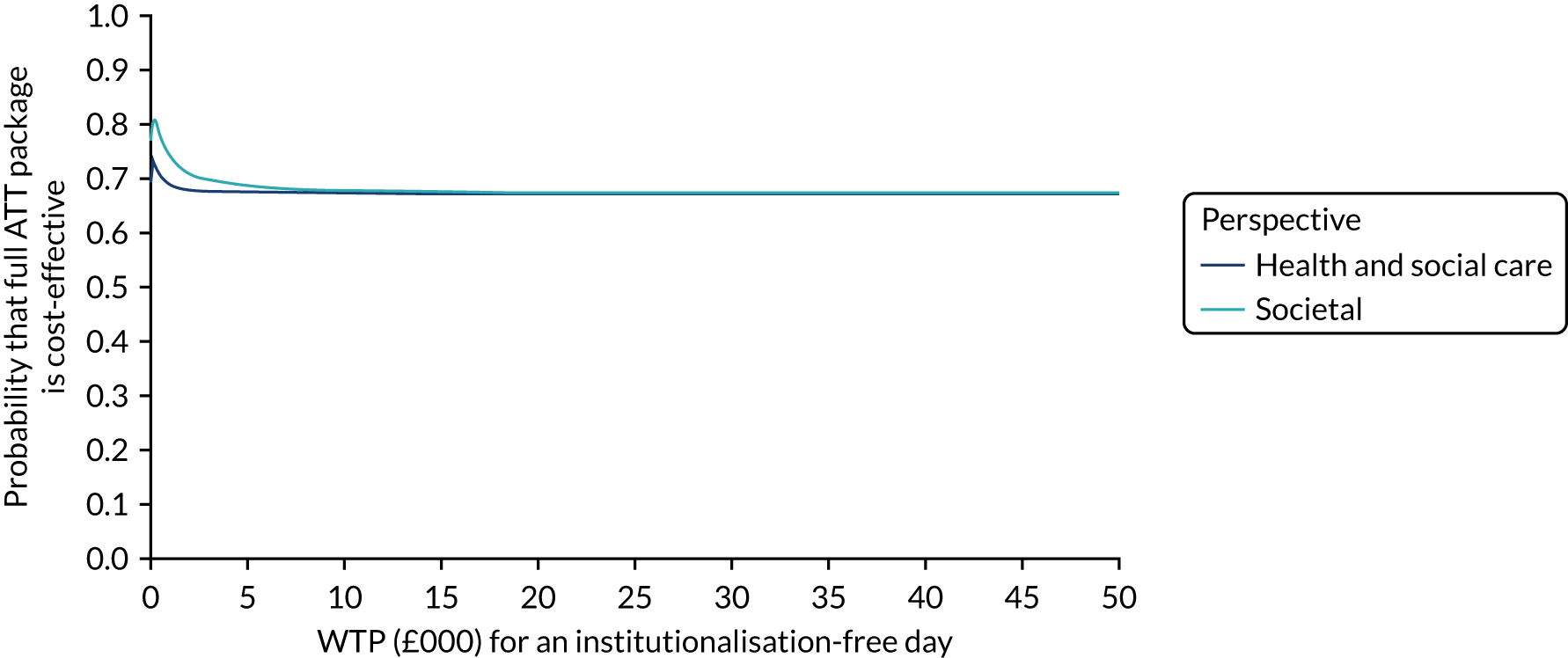

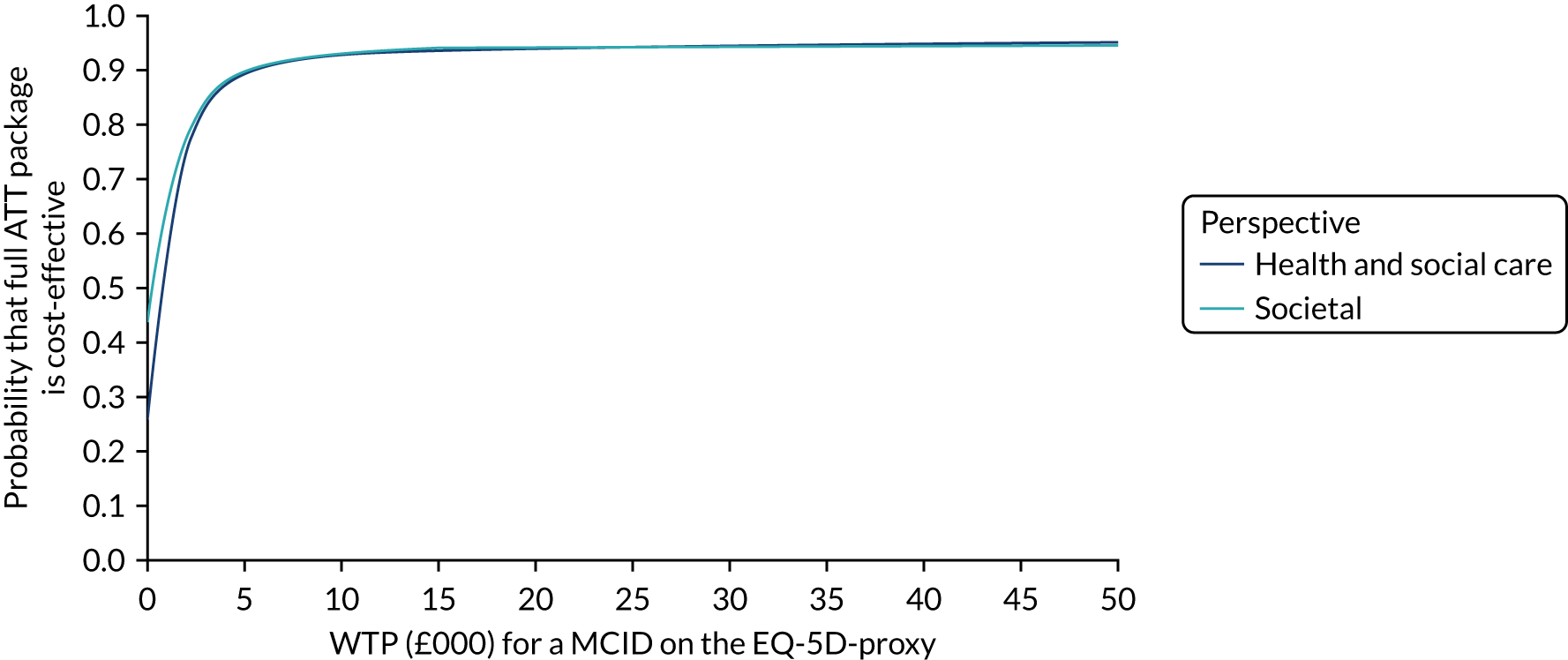

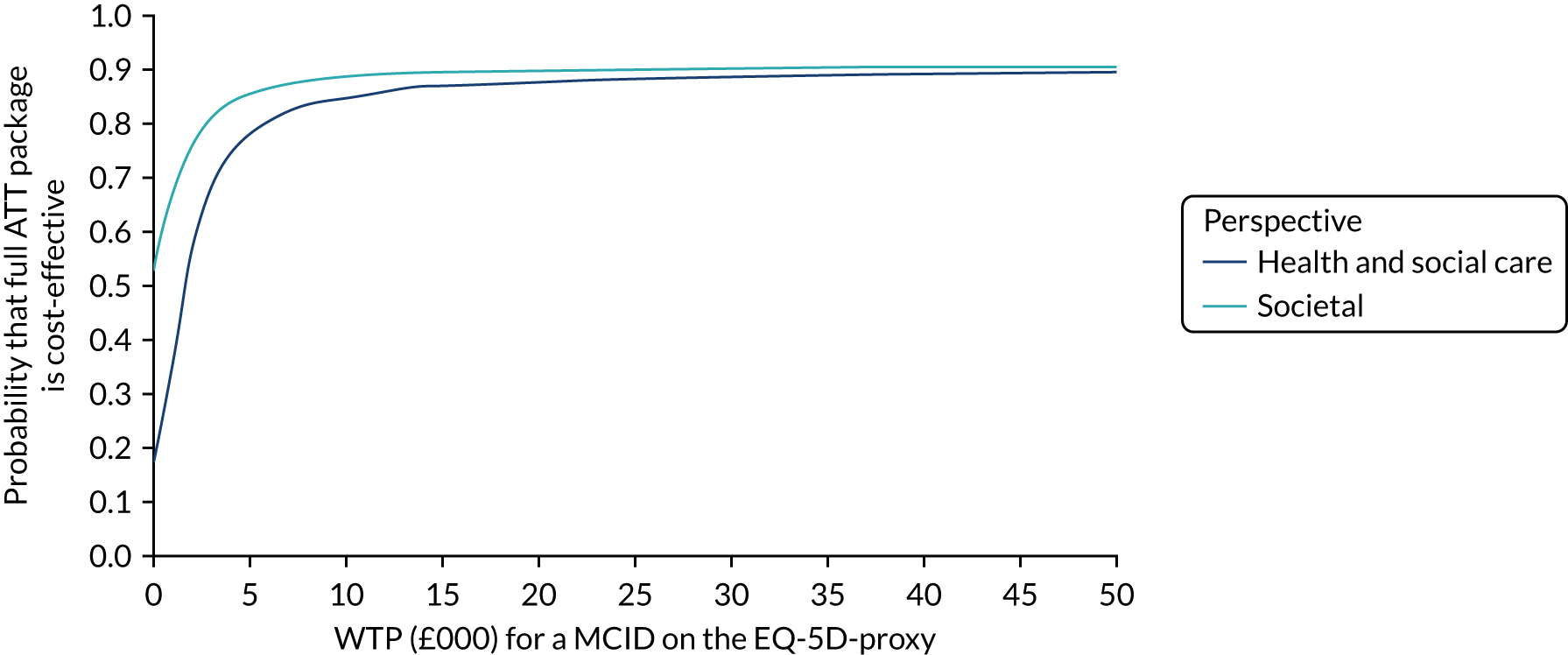

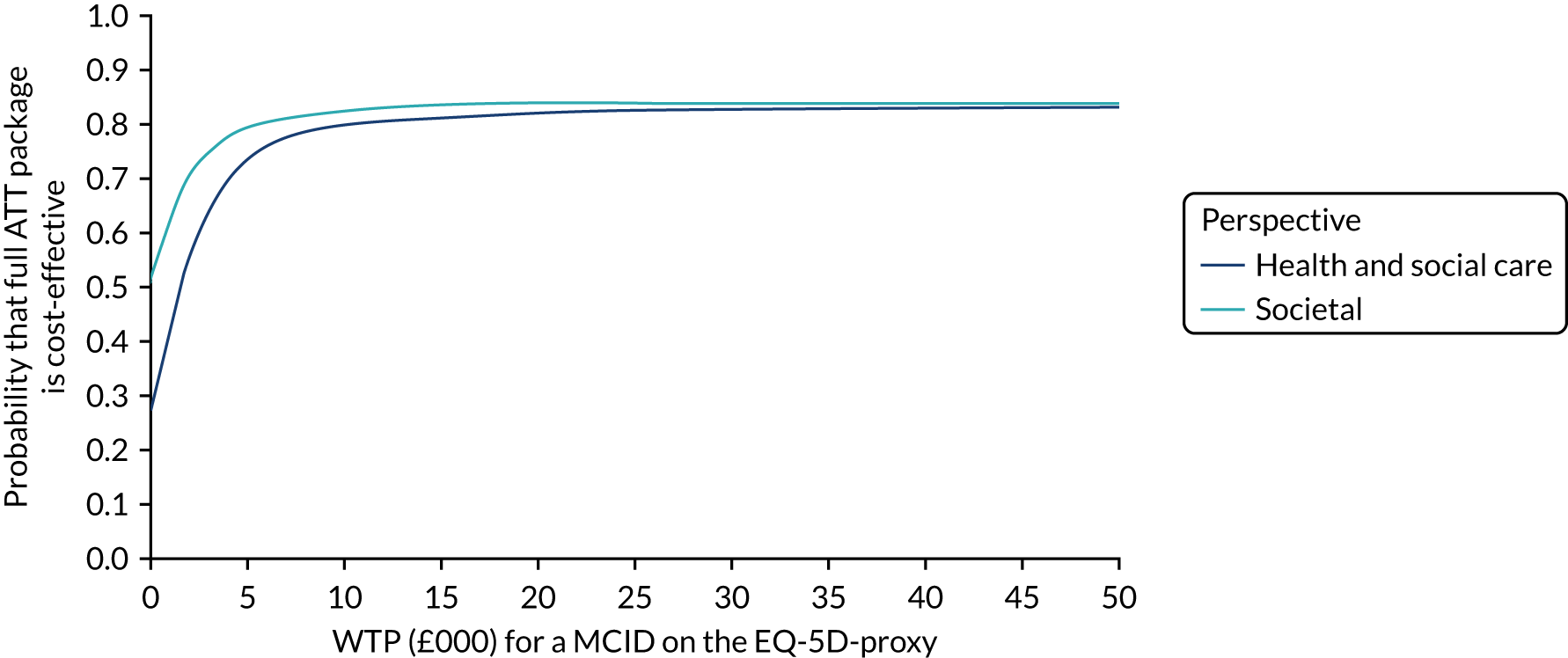

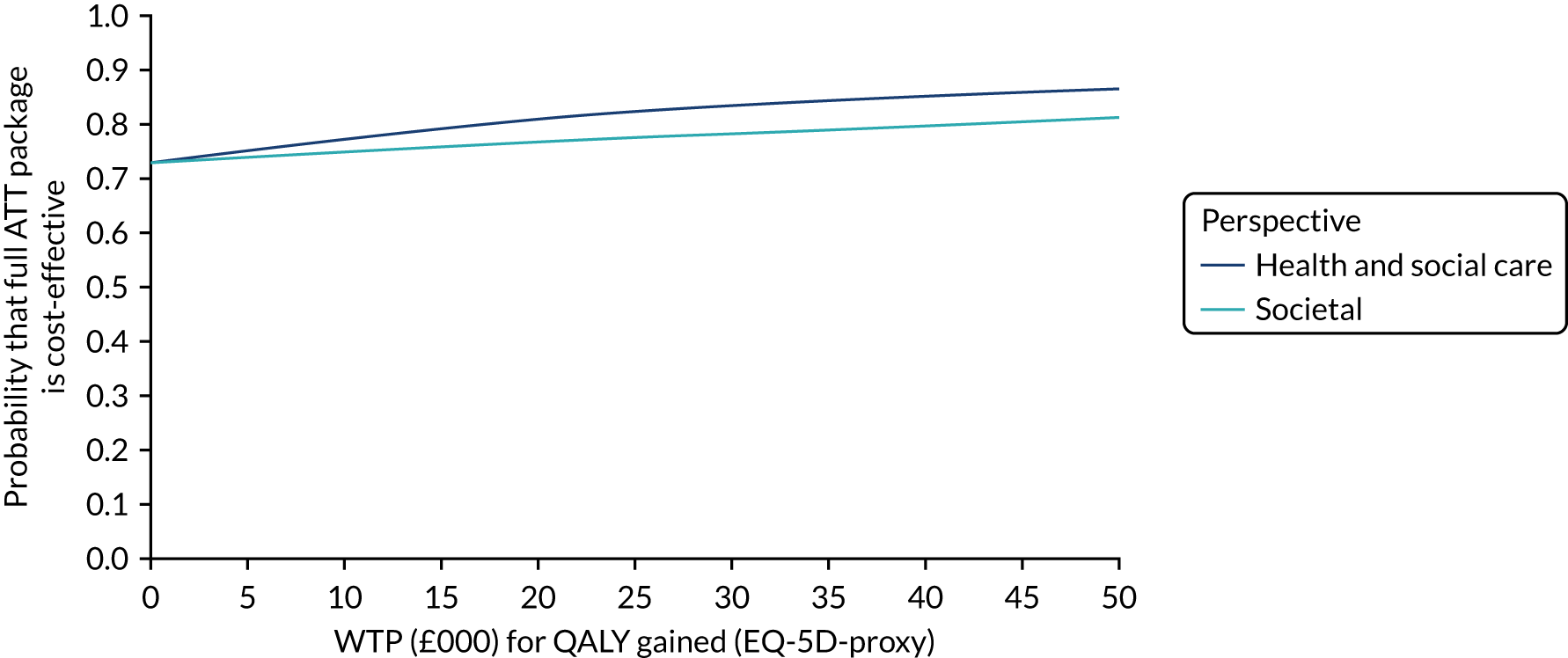

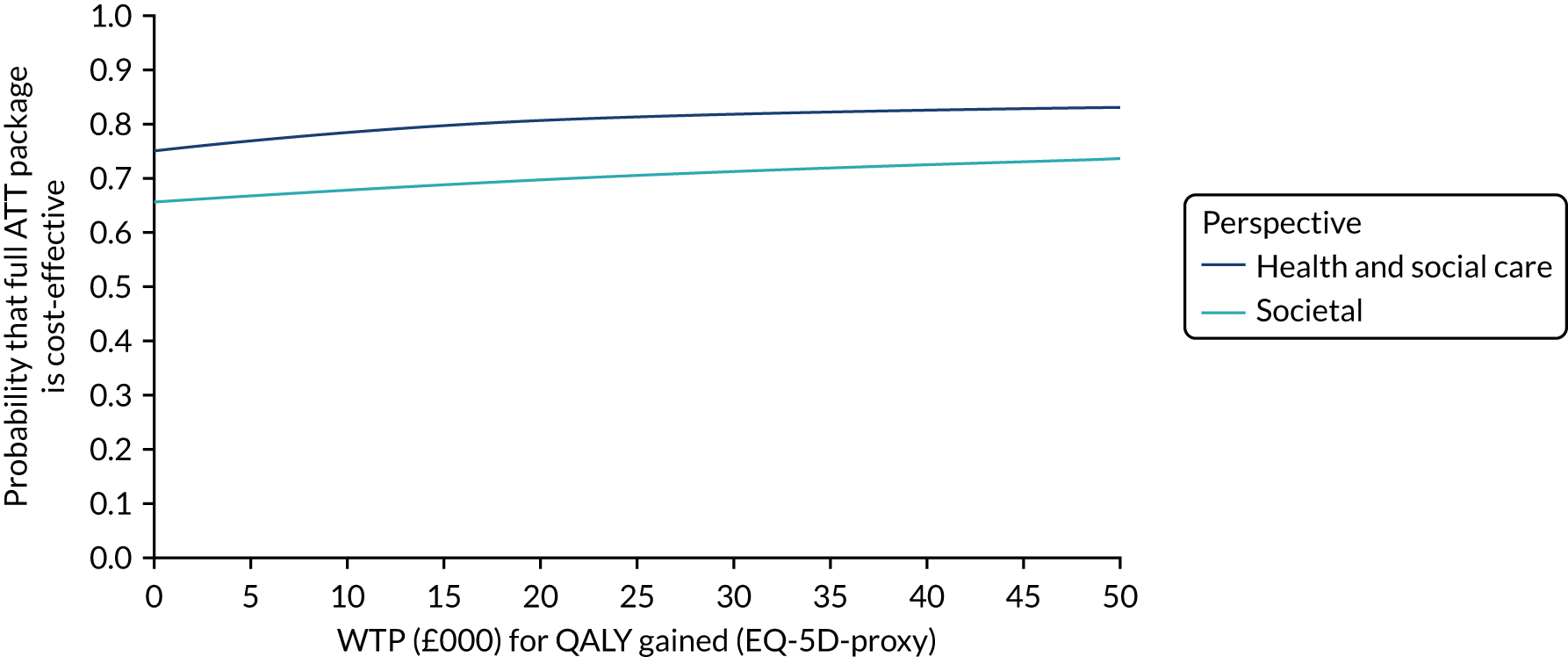

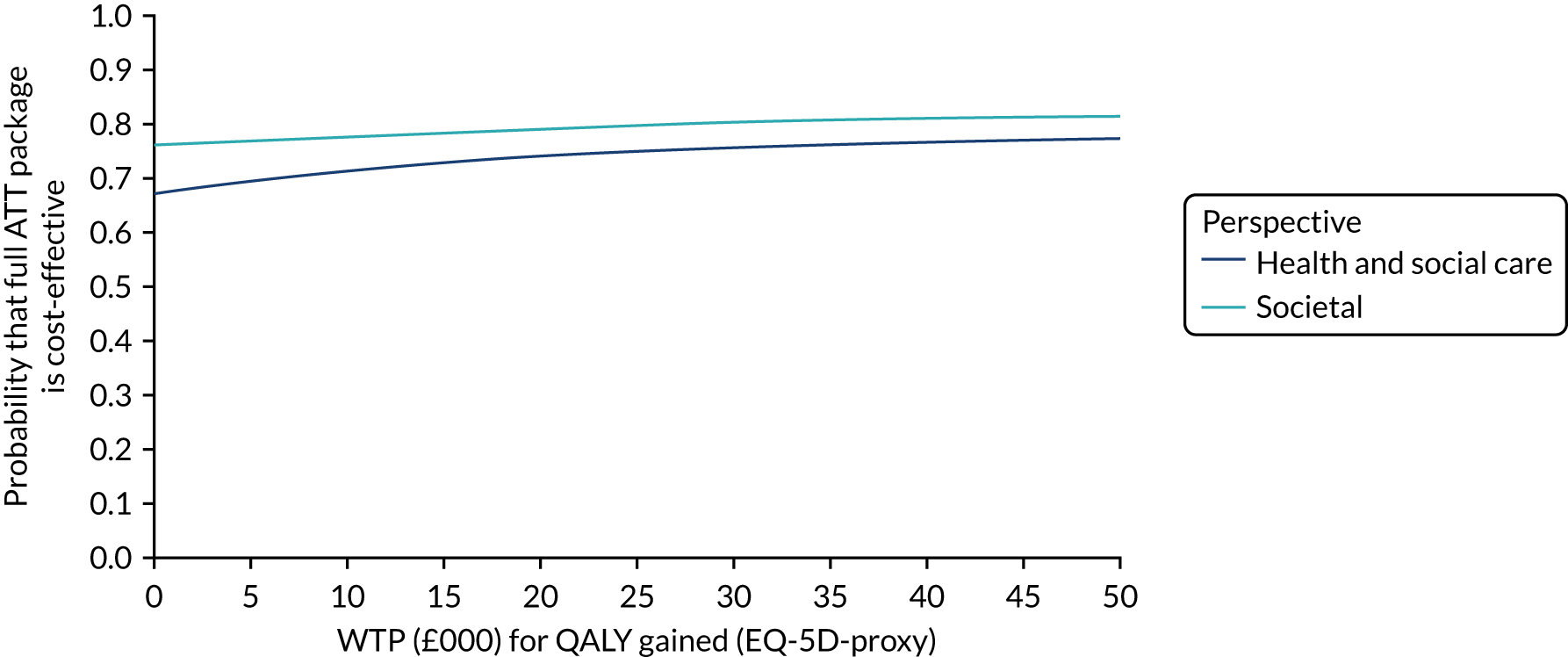

Economic evaluation methods (see Chapter 5) included cost-effectiveness and cost–utility analyses. The evaluation considered three outcomes: days to institutionalisation, change in the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) index40,41 and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted from two perspectives: (1) health and social care and (2) societal. Costs were calculated by attaching nationally applicable unit cost measures to health and social service use. 42,43 These data focused on ATT, health-care and other service use patterns and caregiver inputs, and were collected at baseline and at 12, 24, 52 and 104 weeks for each participant using a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 44 Data on caregiver time and task inputs came from the CSRI and were valued using (and comparing, in sensitivity analyses) replacement wage and opportunity cost approaches. ATT intervention costs were calculated drawing on sources including key informant interviews about the production of ATT in ATTILA trial sites, and from price data drawn from procurement contract databases of the Northern Housing Consortium (NHC). Difference-in-difference analyses of EQ-5D change, with non-parametric bootstrapping, were performed; institutionalisation-free days and QALY outcome analyses employed a combination of population-averaged generalised gamma and survival models with non-parametric bootstrapping. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were computed and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were plotted over a range of values of willingness to pay (WTP) for each outcome.

Secondary efficacy parameters

Caregiver burden

We measured both burden associated with caregiving and levels of psychological distress among the principal caregivers of participants at baseline and at 12, 24, 52 and 104 weeks. The 22-item short version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) questions caregivers about their experiences in terms of emotional, physical and social strains or difficulties that result from their role as a caregiver. Items include topics such as feeling that one’s own health has suffered, feeling that caregiving has affected relationships with family and friends and how burdened one feels. Caregivers respond by indicating how often they experience each item and responses are scored on a five-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘frequently’. Higher burden is indicated by a higher score and the combined 12 items have high reliability (alpha = 0.86). 45 We also assessed psychological distress with the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) and the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).

Number and severity of serious adverse events

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded and reported. Researchers systematically enquired about changes in participants’ health, any compromises of participant safety or changes in living circumstances between assessments. Safety was assessed by the researcher at the 12-, 24-, 52- and 104-week assessments, and then at the 130-, 156-, 182-, 208-, 234- and 260-week telephone calls to participants’ caregivers. The adverse event (AE) reporting arrangements that apply to investigational medicinal products were not applicable, or appropriate, for the ATTILA trial. The focus was to capture as complete information as possible on compromises of participant safety that might have been preventable by the use of ATT. An adapted version of the AE reporting scheme was therefore used in the ATTILA trial.

A SAE was any compromise of participant safety that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

necessitated hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

necessitated the intervention of emergency services

-

resulted in admission to permanent residential care.

Assessment of preventability

The potential preventability of a SAE by the use of ATT was also assessed and categorised by the local researcher and principal investigator into one of the following five categories:

-

Not preventable with assistive technology – the event or its consequences would have been the same with or without ATT.

-

Unlikely to be preventable – the event or its consequences were unlikely to be altered by ATT.

-

Possibly preventable – it is possible that the event or its consequences might have been prevented or mitigated by ATT.

-

Likely to be preventable – it is reasonable to believe that the event or its consequences might have been prevented or mitigated by use of ATT.

-

Definitely preventable – the event or its consequences would have been prevented or mitigated by ATT.

In the analysis, ‘possibly’, ‘likely’ and ‘definitely’ preventable categories were considered as preventable. Throughout the trial, the local ASCD retained responsibility for the ATT and any other support provided, and retained full case responsibility. The trial team had a duty of care to report relevant issues if the ASCD involved were not already aware and would signpost when necessary, but it did not provide equipment, care or support to trial participants.

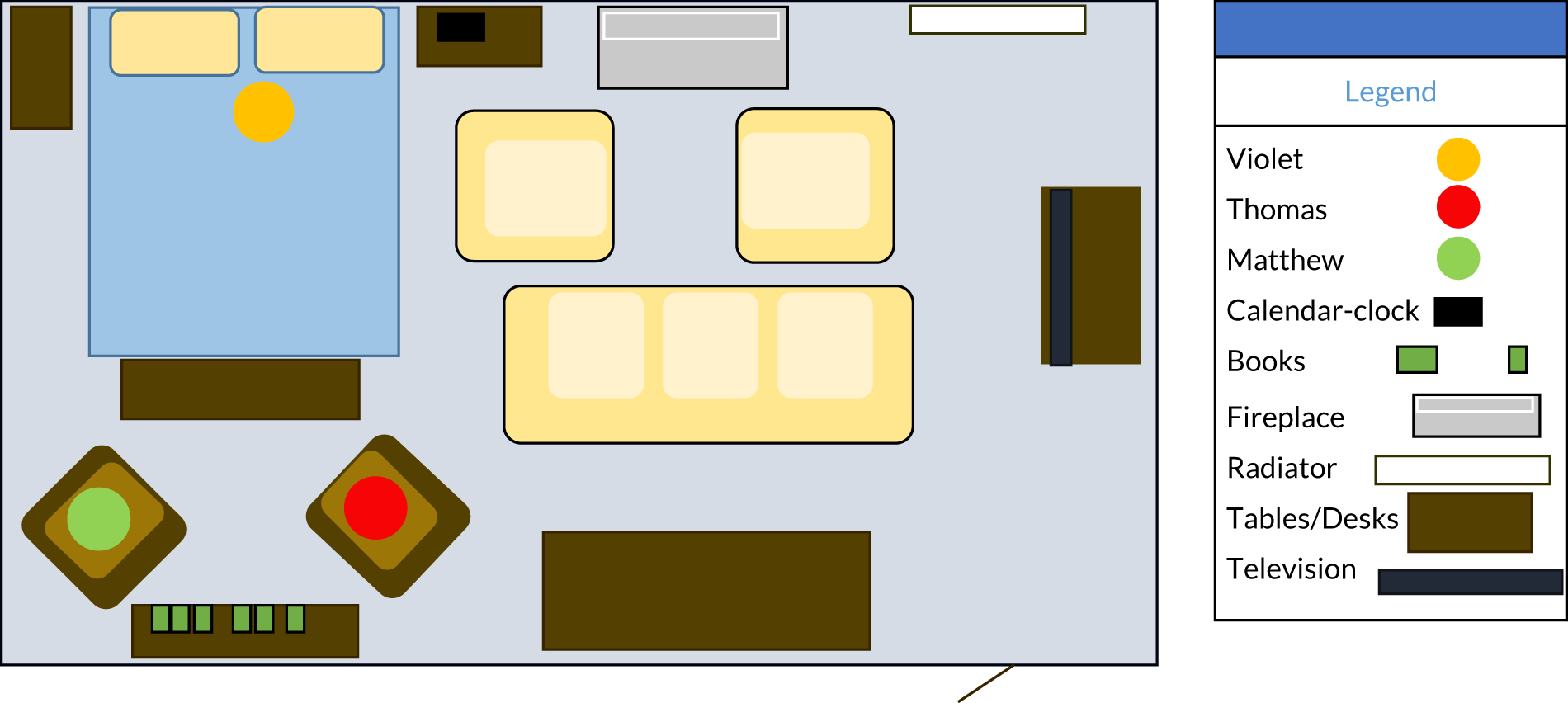

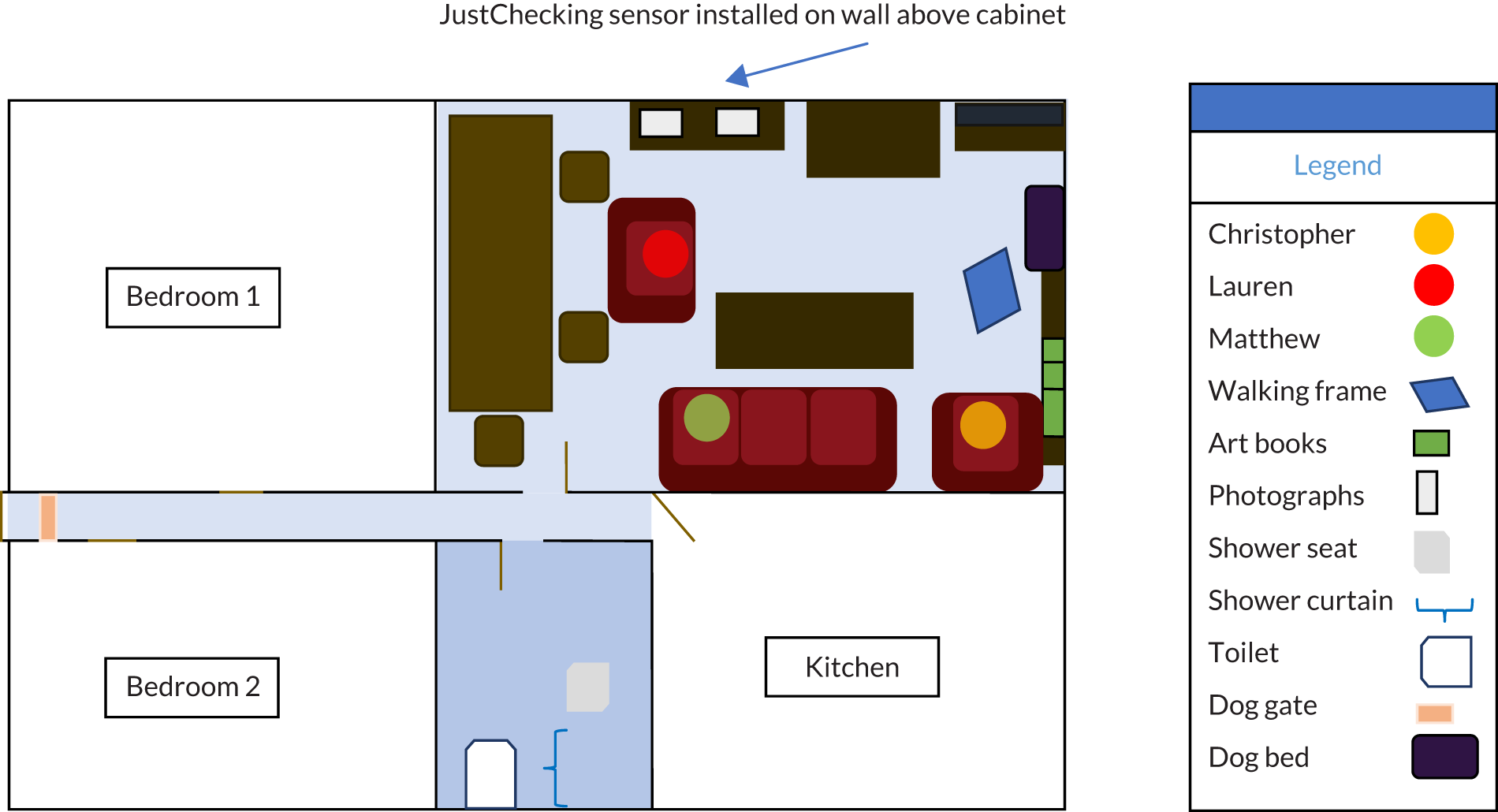

Quantitative and qualitative data

Data on the acceptability, applicability and reliability of ATT intervention packages were collected using the Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire. This questionnaire was validated using data from the WSD project. 46 We anticipated that unpaid caregivers’ experiences would provide examples of ways that their lives, well-being and caregiver roles had been enhanced and/or undermined by the use of these technologies. Longitudinal qualitative data were collected through an embedded ethnographic study with a subset of the ATTILA trial participants to observe how people with dementia and their caregivers actually used (or chose not to use) ATT in their everyday routines and built environments. This methodology allowed for the team to investigate changes in participants’ technologically enabled care practices over time, as the care needs of people with dementia became more acute.

Sample size

The two primary outcome measures were time to transition to institutional care and cost-effectiveness. It was anticipated that 50% of participants with a Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS)47 score of ≥ 15 would transition to institutional care after 24 months, based on observed institutionalisation rates in participants from the AD2000 (Alzheimer’s disease) cohort. 48 A reduction in the estimated 24-month transition to care home rate by 30% (i.e. 50% institutionalised at 2 years reduced to 35%) would require the involvement of 500 participants, allowing for 10% attrition due to death while still community resident. This equated to an average of 55 days more of independent home life for each participant who received ATT. The trial would therefore be powered to detect a mean institutionalisation delay of just under 8 weeks. Expert opinion suggests that 8 weeks is close to the minimum clinically important difference in delaying institutionalisation.

Trial interventions

As the trial design was pragmatic, all aspects of the intervention (ATT assessment, funding, choice of devices, or ordering and installation of devices) were determined by staff from participating LAs or telecare providers. We worked alongside these teams, which have been charged by the Department of Health and Social Care with responsibility for establishing and developing local ATT services. The trial was not funded to source, assess for or deploy ATT.

Each participant underwent an assessment with the ATT provider to determine the level of need and what services that they required. The intervention involved the installation of simple, battery-operated, standalone technologies and/or telecare (a range of devices and sensors that communicate and relay messages to an external call centre where an appropriate response is arranged). The installation and selection of the technology to be deployed was the responsibility of the LAs involved. Those in the control arm were limited to a pendant alarm, non-monitored smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, and a key safe, as recommended by the health or social care professional assessing their needs. Both arms could use additional support services, such as paid care, meals on wheels and day centres.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised in a one-to-one ratio, using telephone-based randomisation and a computerised data entry portal provided by the Oxford Clinical Trial Service Unit. Treatment allocation was via a minimised randomisation procedure stratified by the following variables to reduce the risk of chance imbalances between arms. This information was obtained by the local trial team following consent and during the screening process. Variables were as follows:

-

sex

-

age (< 65, 65–80 or > 80 years)

-

risk of wandering or leaving the home inappropriately (low, moderate or high risk)

-

safety risk in the home (low, moderate or high risk)

-

level of caregiver support available (live-in caregiver, caregiver visits at least once daily or caregiver visits less often than daily).

This stratification procedure was reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee after the first 100 randomisations.

Blinding

Blinding was not undertaken for participants or trial staff collecting data as it was not practicable or ethical to conceal allocation of ATT. The staff who entered the data were unaware of which arm a participant had been allocated to.

Patient and public involvement

The Alzheimer’s Society was involved in devising the research question and in the production of the trial materials. Two service user representatives sat on the Trial Steering Committee.

Ethics approval

The trial was conducted and designed in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki49 and the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). 50 All researchers working on the trial received training in ICH-GCP guidelines. The integrated form for both site-specific information and research and development approval at all participating NHS sites was approved prior to recruitment at each site. Annual progress and safety reports and a final report at conclusion of the trial were submitted to the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and the Health Technology Assessment programme within the timelines agreed.

The trial was approved by the NHS Health Research Authority National Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/LO/186) and is registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry (ISRCTN86537017).

Sponsorship

The trial was sponsored by South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

Chapter 3 Describing the intervention

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Forsyth et al. 51 Reprinted from Alzheimers & Dementia, 5, Forsyth K, Henderson C, Davis L, Singh Roy A, Dunk B, Curnow E, et al. , Assessment of need and practice for assistive technology and telecare for people with dementia – The ATTILA (Assistive Technology and Telecare to maintain Independent Living At home for people with dementia) trial, 420–30, 2019, with permission from Elsevier.

Introduction

A detailed exploration of the intervention under investigation is needed to give insight into the fidelity of the intervention and to allow for replication. 52 The aim, therefore, was to provide an overview of routine ATT practice and the systems in place to deliver ATT for people with dementia.

Method

We adhered to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)53 checklist in describing the components of the ATTILA trial intervention, in terms of what happened; who was involved; how, where and when the intervention happened; how much ATT was provided; and whether or not it was tailored to participants.

Assistive technology and telecare delivery systems

To describe the delivery systems for ATT deployment, interviews were conducted by staff with key informants from local authority operational/commissioning teams and telecare monitoring centre managers in the seven sites from which the majority of trial participants were recruited (n = 484). Invitations were sent to 21 potential key informants, resulting in 14 interviews covering six sites (no key informants were available for interview in one site) between June and September 2016. Interviews were not recorded but written notes were taken; interviewees were also asked for supporting documentation that might help in understanding the policies and procedures in relation to ATT deployment. Data were also collected on ATT assessment and delivery processes via pro formas completed by local researchers in 2015 and via a follow-up desk-based search in 2017. Data were examined using NVivo version 11 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Data were first structured into five production stages within a framework analysis:54 assessment, equipment procurement/ordering, installation, call monitoring, and response to sensor activations. To identify commonalities in local systems for delivering ATT to trial participants, we took an approach based on value network role analysis. 55,56 Production inputs and processes observed in each site were mapped onto value network frameworks.

Assistive technology and telecare

The ATT intervention was defined for the purposes of the ATTILA trial as a two-stage process:

-

an ATT assessment, with subsequent ATT recommendation(s)

-

the installation of ATT devices alongside monitoring services, as appropriate.

Framework analysis

We assumed that social services departments in each ATTILA trial site had distilled local and national guidelines on best practice in ATT assessment when constructing local assessment templates. To establish a practice standard for ATT assessments in the ATTILA trial sites, ATT assessment templates and guidance were sourced from each site between August 2013 and August 2016. Sites were asked to resend documentation if there were changes during the lifetime of the trial; as a result, two sets of new documentation were submitted. Framework analysis54 to identify common assessment themes across sites was applied to this documentation, using the Model of Human Occupation Screening Tool (MOHOST). 57 The MOHOST is designed to detail people’s values, insight, interests, routines, communication, cognitive and physical skills, and physical and social environment to gain a detailed picture of an individual’s life. The resultant ATT assessment standard consisted of a set of 14 ATT assessment areas (Table 2). A 4-point scale was developed for each assessment area in the ATT assessment standard, where 4 = no risk when doing daily activity, 3 = mostly risk free when doing daily activity, 2 = some risk when doing daily activity and 1 = significant multiple risks when doing daily activity. Specific definitions were developed for rating each assessment area (see Appendix 2). ATT needs were identified when an assessment area received a rating of 1 (significant multiple risks when doing daily activity) or 2 (some risk when doing daily activity).

| Key themesb | ATTILA trial site exemplar questionsc |

|---|---|

Motivation

|

1. Insight

|

2. Values

|

|

Routines

|

3. Wandering/disorientation

|

4. Daily activity

|

|

Communication skills

|

5. Conversation

|

6. Express needs

|

|

Cognitive skills

|

7. Memory

|

8. Problem solving

|

|

Physical skills

|

9. Mobility

|

10. Grip/dexterity

|

|

Physical environment

|

11. Space

|

12. Resources

|

|

Social environment

|

13. Social support

|

14. The way an activity is completed

|

Fidelity of assistive technology and telecare assessment to assessment standard

Locally completed ATT assessments for each participant were reviewed against the ATT assessment standard to assess whether or not locally completed ATT assessments across ATTILA trial sites addressed the ATT assessment areas identified by the templates. Fidelity to this standard was determined by two trial practitioners with experience in dementia care and ATT assessment, who independently classified the content of each locally completed ATT assessment against the ATT assessment standard and assigned risk ratings. They then reviewed ratings together and resolved discrepancies.

Assistive technology and telecare taxonomy/checklist

There is no recognised taxonomy of ATT for people with dementia; therefore, a taxonomy was developed in collaboration with Trent Dementia Services Development Centre and the ‘atdementia’ initiative (www.atdementia.org.uk; accessed 13 July 2018), an independent online ATT resource. This taxonomy was then developed into two identical technology checklist forms (one for recommended ATT and one for installed ATT), which covered the following ATT functions: (1) reminder or prompting devices, (2) devices to support safety, (3) safer walking technologies, (4) communication devices, (5) devices that support meaningful use of leisure time and (6) monitoring and response information. The form also recorded data about which type of assessor had assessed for ATT (ATT assessor, health or social care professional, other), the method of assessment (in person, at home; in person, not at home; telephone assessment; using case notes; other), whether or not ATT were monitored (yes/no) and who would respond to ATT alerts (direct to responder or via a call centre). Two trial practitioners with experience in dementia care and ATT assessment collaboratively classified each device recommended in the locally completed ATT needs assessment using the technology checklist (for recommended ATT).

Assistive technology and telecare installations

Assistive technology and telecare checklist

Local trial researchers used the technology checklist (for installed ATT) during home visits at weeks 12, 24, 52 and 104.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were summarised in percentages and numbers of observations. Correlations between count variables were tested using non-parametric methods (Kendall rank correlation coefficient, τ). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to assess if there were statistically significant differences between multiple groups for outcomes. Freidman’s test was used to determine the significance of change over time in the count variables. In the case of categorical variables, differences between observed and expected frequencies were tested using Pearson’s chi-squared test for independence, or, alternatively, Fisher’s exact test, when the assumption of minimum expected cell count in contingency tables was not met. 58 Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE) scores were categorised into stages of dementia59 for the purposes of analysis (30 = no dementia, 26–29 = questionable dementia, 21–25 = mild dementia, 11–20 = moderate dementia and 0–10 = severe dementia). Effective tailoring of the intervention was described through the strength of the correlation60 between ATT needs and ATT recommendations at baseline and between ATT recommendations and ATT installation by 24 weeks. We also compared the ATT that were recommended in the needs assessment with subsequent installations for each participant in the intervention arm up to 24 weeks. Any installation after 24 weeks was considered unrelated to the baseline ATT assessment.

Results

Participants

A total of 495 participants were randomised to the ATTILA trial (intervention group, n = 248; control group, n = 247). Of these, 451 had a documented needs assessment. A total of 209 intervention group participants had documented ATT installations.

Assessment

Of the 451 documented ATT needs assessments available, 413 contained an ATT recommendation. Of the 248 participants recruited to the intervention arm, data from 209 participants were available for analysis of ATT installations.

In total, 60% of assessment responses identified an ATT need, with 4.4 ATT needs (range 0–12) identified per participant (Tables 3 and 4). The mean number of ATT needs identified varied, ranging from two to six per site (p < 0.001). The areas of concern most frequently identified as triggering the need for ATT were daily activities (93%), memory (89%) and problem-solving (83%). Health and social care professionals identified more ATT needs than ATT assessors (p = 0.047). More ATT needs were identified through in-person, at-home assessments than through telephone assessment methods (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference between ATT needs in men and women (p = 0.337). The number of ATT needs identified for each participant differed depending on the risk of wandering (p = 0.005): a medium risk of wandering was associated with more ATT needs than a low risk of wandering (p = 0.016). ATT needs varied by category of SMMSE score (p < 0.001): participants with severe dementia had more ATT needs than those with mild (p < 0.001), those with moderate (p = 0.002) or those with questionable dementia (p < 0.001).

| Site ATT assessment areas/standard | Fidelity with ATT assessments standard | ATT needs (i.e. responses rated as ‘at risk’) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| 1. Insight | 241/451 | 53 | 151/241 | 63 |

| 2. Values | 245/451 | 54 | 100/245 | 41 |

| 3. Wandering/disorientation | 284/451 | 63 | 219/284 | 77 |

| 4. Daily activity | 321/451 | 71 | 298/321 | 93 |

| 5. Conversation | 226/451 | 50 | 100/226 | 44 |

| 6. Express needs | 175/451 | 39 | 24/175 | 14 |

| 7. Memory | 320/451 | 71 | 284/320 | 89 |

| 8. Problem-solving | 218/451 | 48 | 181/218 | 83 |

| 9. Mobility | 335/451 | 74 | 224/335 | 67 |

| 10. Grip/dexterity | 147/451 | 33 | 18/147 | 12 |

| 11. Space | 140/451 | 31 | 47/140 | 34 |

| 12. Resources | 128/451 | 28 | 26/128 | 20 |

| 13. Social support | 325/451 | 72 | 183/325 | 56 |

| 14. The way the activity is completed | 162/451 | 36 | 118/162 | 73 |

| Total responses | 3267/6314 | 52 | 1973/3267 | 60 |

| Characteristic | Fidelity with ATT assessments standard | Number of ATT needs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean | % | Median | Mean | % | |

| Participant characteristic | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 8 | 7.67 | 62 | 4 | 4.46 | 60 |

| Male | 5 | 6.65 | 38 | 3 | 4.25 | 40 |

| p = 0.027 | p = 0.337 | |||||

| Risk of wandering | ||||||

| Low | 7 | 6.93 | 70 | 4 | 4.10 | 68 |

| Medium | 9 | 8.37 | 23 | 5 | 5.04 | 23 |

| High | 6 | 7.24 | 7 | 4 | 5.24 | 9 |

| p = 0.038 | p = 0.005 | |||||

| SMMSE score of 18 points | ||||||

| Questionable dementia (26–29) | 7 | 7.22 | 13 | 3 | 3.38 | 10 |

| Mild dementia (21–25) | 7 | 6.6 | 27 | 4 | 3.9 | 27 |

| Moderate dementia (11–20) | 7 | 7.38 | 45 | 4 | 4.27 | 44 |

| Severe dementia (0–10) | 8.5 | 7.96 | 15 | 5.5 | 5.79 | 19 |

| p = 0.309 | p < 0.000 | |||||

| Assessment characteristic | ||||||

| Assessors | ||||||

| Health and social care professionals | 8 | 7.85 | 68 | 4 | 4.66 | 67 |

| ATT assessor | 5.5 | 6.51 | 29 | 3 | 3.86 | 29 |

| p = 0.051 | p = 0.028 | |||||

| Assessment method | ||||||

| In person, at home | 10 | 9.14 | 85 | 5 | 5.06 | 82 |

| In person, not at home | 5 | 6.43 | 8 | 3 | 3.38 | 8 |

| Telephone | 2 | 3.42 | 6 | 2 | 2.71 | 9 |

| Case notes | 3 | 3.33 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 1 |

| p < 0.000 | p < 0.000 | |||||

| Service structure | ||||||

| Public telecare provider | 7 | 7.59 | 73 | 4 | 4.41 | 70 |

| Not-for-profit telecare provider | 6 | 6.41 | 25 | 4 | 4.31 | 28 |

| p = 0.026 | p = 1.00 | |||||

| Mean fidelity with ATT assessment standard per participant: 7.2 assessment areas addressed (range 0–13) | Mean number of responses per participant rated as an ATT need: 4.4 ATT needs (range 0–12) | |||||

Fidelity of assessment

The local ATT assessment fidelity with the ATT assessment standard was 52% (7.2 assessment areas were addressed per assessment) (see Tables 3 and 4). Of 451 ATT assessments reviewed, 99 (22%) addressed 0–2 areas of assessment. There was higher fidelity to assessment areas relating to ‘mobility’ (74%), ‘social support’ (72%), ‘daily activity’ (71%) and ‘memory’ (71%). Fidelity varied across sites: the mean number of assessment areas addressed ranged from two to 13 per site (p < 0.001), with public telecare providers addressing more assessment areas than not-for-profit telecare providers (p = 0.026). Health and social care professionals addressed more assessment areas than ATT assessors (p = 0.046). Fidelity varied across assessment methods (p < 0.001), with the in-person, at-home assessment method addressing more assessment areas than in-person, not-at-home (p = 0.003), telephone (p < 0.001) and case notes assessment methods (p = 0.003). Women had more assessment areas addressed than men (p = 0.027). More assessment areas were addressed for participants at medium risk of wandering than for participants at low risk of wandering (p = 0.028).

Assistive technology and telecare delivery system

Value networks

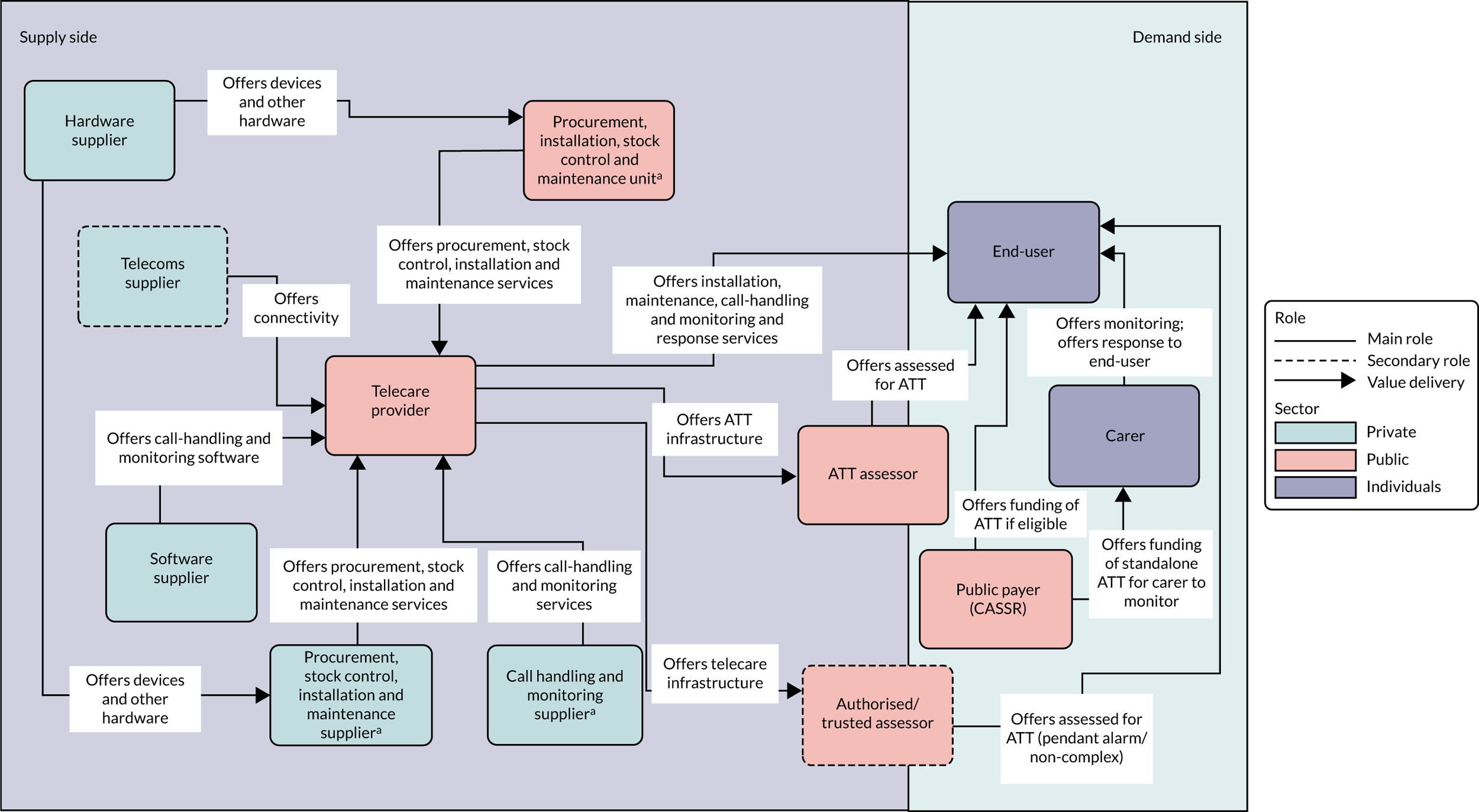

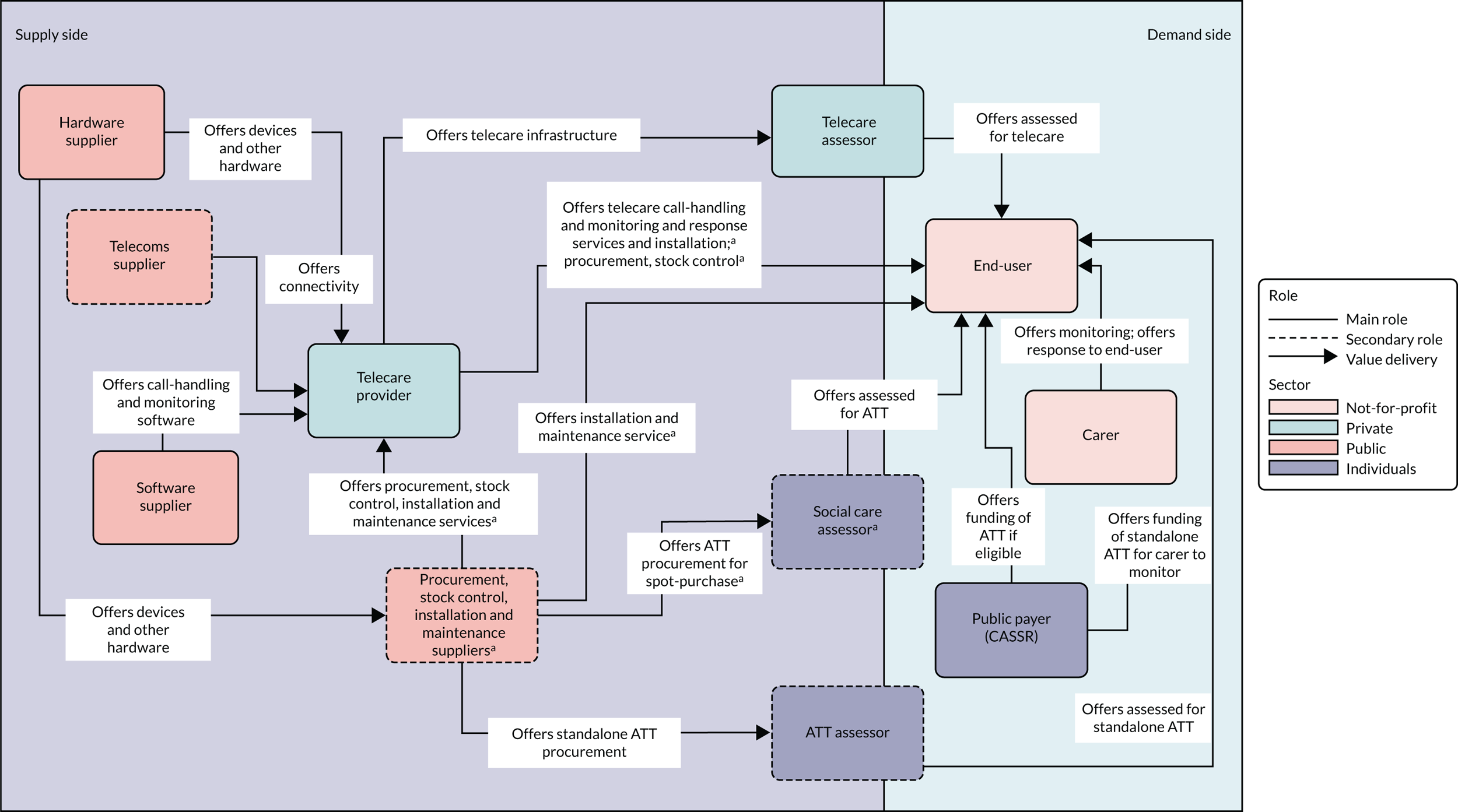

Networks delivering services (offering value) to participants in ATTILA trial sites were classified into two types (Figures 1 and 2). First were ‘public telecare provider networks’ (n = 4), for which two assessor roles were identified: the ATT assessor and the authorised (or trusted) assessor (health or social care professional). ATT assessors were employed by public agencies (NHS or CASSRs); their primary role was to assess for a full range of ATT devices [‘networked’ (monitored by a telecare call centre or caregiver) or ‘standalone’]. Authorised assessors could offer first-generation telecare (pendant-only systems) or straightforward ATT (e.g. adding on an additional sensor or providing a memo minder), depending on their level of experience and local permissions; they performed ATT assessment as a secondary role. In these networks, most or all of the ATT infrastructure for procurement, installation, stock control and maintenance of ATT devices fell to units in the CASSR. The second type of networks were ‘not-for-profit provider networks’ (n = 3). Three assessor roles were identified across these ‘not-for-profit telecare networks’. Telecare assessors working for not-for-profit telecare providers assessed for AT that was networked to providers’ call-monitoring centres. Assessment for standalone assistive technology fell to assessors in the CASSR. A ‘social care ATT assessor’ role was also identified; these assessors could assess for ATT (networked or standalone) and work with a choice of suppliers to procure and arrange the installation of ATT devices. Private companies offered combinations of procurement and stock control, installation, and maintenance services to the not-for-profit telecare providers.

FIGURE 1.

Public assessor value networks. a, Featured in some but not all networks.

FIGURE 2.

Not-for-profit value networks. a, Featured in some but not all networks.

Assistive technology and telecare recommendations

A documented ATT recommendation was given for 413 participants, with 1090 ATT devices recommended at baseline [mean three devices (range 1–14 devices)]. For 57% (n = 235) of participants, just one or two ATT devices were recommended. The correlation between the ATT needs and the ATT recommendations identified in local ATT assessments was weak (τ = 0.242; p < 0.001). Most recommendations were for safety-related devices (59%, 644/1090), followed by reminder/prompting devices (25%, 269/1090). ATT devices required monitoring in 62% (673/1090) of recommendations, and 67% (353/526) of monitored devices with an identified responder required a formal (call centre) response.

Assistive technology and telecare installations

Frequency of assistive technology and telecare categories

By 24 weeks, a mean of 3.5 devices had been recommended for participants in the intervention arm. Of the ATT devices recommended, 53% (306/572) were not installed.

Relationship of assistive technology and telecare installations to assistive technology and telecare recommendations

A total of 62% (438/704) of the ATT devices that were installed had not been recommended in the needs assessment (Table 5). There was a moderate negative correlation between number of recommendations and number of installations per participant per ATT category (τ = –0.470; both p < 0.001).

| ATT technology checklist | ATT devices, n/N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended | Recommended and installed by 24 weeks | Recommended but not installed | Installed by 24 weeks | Not recommended but installed | |

| Control group technology | |||||

| Pendant alarm | 44/572 (8) | 22/44 (50) | 22/44 (50) | 89/704 (13) | 67/89 (75) |

| Non-monitored smoke detector | 0/572 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 68/704 (10) | 68/68 (100) |

| Non-monitored carbon monoxide detector | 1/572 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 1 (100) | 36/704 (5) | 36/36 (100) |

| Key safe | 18/572 (3) | 9/18 (50) | 9/18 (50) | 89/704 (13) | 80/89 (90) |

| Activity monitors assessment only | 8/572 (1) | 4/8 (50) | 4/8 (50) | 5/704 (1) | 1/5 (20) |

| Other devices | 1/572 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 1/1 (100) | 6/704 (1) | 6/6 (100) |

| Intervention group technology | |||||

| Reminder or prompting devices | |||||

| Date and time reminders | 31/572 (5) | 13/31 (42) | 18/31 (58) | 46/704 (7) | 33/46 (72) |

| Item-locator devices | 9/572 (2) | 8/9 (89) | 1/9 (11) | 11/704 (2) | 3/11 (27) |

| Medication reminders/dispensers | 56/572 (10) | 25/56 (45) | 31/56 (55) | 33/704 (5) | 8/33 (24) |

| Voice recorders and memo minders | 46/572 (8) | 27/46 (59) | 19/46 (41) | 38/704 (5) | 11/38 (29) |

| Other reminder/prompting devices | 1/572 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 1/1 (100) | 6/704 (1) | 6/6 (100) |

| Devices to promote safety | |||||

| Activity monitors – ongoing monitoring | 5/572 (1) | 1/5 (20) | 4/5 (80) | 6/704 (1) | 5/6 (83) |

| Fall detectors | 75/572 (13) | 31/75 (41) | 44/75 (59) | 53/704 (8) | 22/53 (42) |

| Continence management devices | 1/572 (0) | 1/1 (100) | 0/1 (0) | 1/704 (0) | 0/1 (0) |

| Alarm and pager units | 5/572 (1) | 2/5 (40) | 3/5 (60) | 5/704 (1) | 3/5 (60) |

| Flood detectors and water temperature monitor | 14/572 (2) | 9/14 (64) | 5/14 (36) | 11/704 (2) | 2/11 (18) |

| Gas detectors | 21/572 (4) | 8/21 (38) | 13/21 (62) | 19/704 (3) | 11/19 (58) |

| Monitored carbon monoxide detectors | 25/572 (4) | 8/25 (32) | 17/25 (68) | 22/704 (3) | 14/22 (64) |

| Monitored smoke detectors | 59/572 (10) | 39/59 (66) | 20/59 (34) | 47/704 (7) | 8/47 (17) |

| Monitored extreme temperature sensors | 26/572 (5) | 18/26 (42) | 15/26 (58) | 19/704 (3) | 8/19 (42) |

| Lighting devices | 2/572 (0) | 1/2 (50) | 1/2 (50) | 8/704 (1) | 7/8 (88) |

| Other safety and security devices | 15/572 (3) | 2/15 (13) | 13/15 (87) | 9/704 (1) | 7/9 (78) |

| Safer walking technologies | |||||

| To locate the user | 43/572 (8) | 20/43 (47) | 23/43 (53) | 28/704 (4) | 8/28 (29) |

| To alert the responder to movement | 59/572 (10) | 25/59 (42) | 34/59 (58) | 37/704 (5) | 12/37 (32) |

| Communication devices | |||||

| Intercoms | 2/572 (0) | 0/2 (0) | 2/2 (100) | 1/704 (0) | 1/1 (100) |

| Telephones | 3/572 (1) | 0/3 (0) | 3/3 (100) | 7/704 (1) | 7/7 (100) |

| Communication aids | 0/572 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 1/704 (0) | 1/1 (100) |

| Other communication devices | 1/572 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 1/1 (100) | 0/704 (0) | 0/0 (0) |

| Devices that support meaningful use of leisure time | |||||

| Computer aids | 0/572 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dementia-friendly television/radio/music players | 0/572 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Electronic photograph albums/electronic reminiscence aids | 0/572 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Electronic games | 0/5572 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 1/551 (0) | 1/1 (100) |

| Other devices | 1/572 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 1/1 (100) | 2/551 (0) | 2/2 (100) |

| Total | 572 | 266/572 (47) | 306/572 (53) | 704 | 438/704 (62) |

Week 12–104, assistive technology and telecare devices installed (intervention arm only)

From week 12 to week 104, 888 ATT devices were installed for 209 participants in the intervention arm, which is a mean of 4.2 devices per participant (range 1–15 devices). Of the devices installed for intervention participants (Table 6), 42% (374/888) involved the types of technology provided to control arm participants (e.g. non-monitored smoke detectors). Installations decreased over time (p = 0.031), with 79% (704/888) of ATT installed by week 24. Intervention participants’ ATT devices were most frequently installed for safety reasons (38%) or for reminder/prompting (18%). ATT assessors were most frequently identified as having assessed for the installed devices (32%), followed by health and social care professionals (20%), but 40% of assessors’ backgrounds were unknown. A total of 41% of installations followed an in-person home visit (41%), but in 42% of cases participants could not report the method of assessment. Nearly half (47%) of the ATT devices installed required monitoring; 38% of monitored devices were networked to a call centre (so that any alerts would receive an initial response from paid services).

| Week, n (%) | Total (weeks 12–104), n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 24 | 52 | 104 | ||

| Control group technology installed | |||||

| Basic ATT | 235 (41) | 58 (47) | 45 (52) | 36 (37) | 374 (42) |

| Intervention technology installed | |||||

| Reminder/prompting | 116 (20) | 18 (15) | 9 (10) | 17 (18) | 160 (18) |

| Safety | 220 (38) | 45 (36) | 30 (35) | 43 (44) | 338 (38) |

| Communication | 8 (1) | 1 (0) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 12 (2) |

| Support leisure time | 1 (0) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (0) |

| Any other devices | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total installed | 580 (100) | 124 (100) | 87 (100) | 97 (100) | 888 (100) |

| Assessor | |||||

| Health or social care professional | 126 (22) | 20(16) | 13 (15) | 17 (18) | 176 (20) |

| ATT assessor | 152 (26) | 58 (47) | 23 (26) | 45 (46) | 278 (32) |

| Other | 68 (12) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 4 (4) | 75 (8) |

| Unknown | 234 (40) | 46 (37) | 48 (55) | 31 (32) | 359 (40) |

| Total installed | 580 (100) | 124 (100) | 87 (100) | 97 (100) | 888 (100) |

| Assessment method | |||||

| In person, at home | 216 (37) | 70 (57) | 30 (34) | 55 (57) | 371 (41) |

| In person, not at home | 7 (1) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 15 (2) |

| Telephone | 50 (9) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 59 (7) |

| Using case notes | 7 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 9 (1) |

| Other | 56 (10) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 59 (7) |

| Unknown | 244 (42) | 46 (37) | 53 (61) | 32 (33) | 375 (42) |

| Total installed | 580 (100) | 124 (100) | 87 (100) | 97 (100) | 888 (100) |

| Monitoring | |||||

| Yes | 292 (51) | 56 (45) | 32 (37) | 42 (43) | 422 (47) |

| No | 147 (25) | 45 (36) | 25 (29) | 40 (41) | 257 (29) |

| Unknown | 141 (24) | 23 (19) | 30 (34) | 15 (16) | 209 (24) |

| Total installed | 580 (100) | 124 (100) | 87 (100) | 97 (100) | 888 (100) |

| Response | |||||

| Formal services | 104 (36) | 29 (52) | 15 (47) | 14 (33) | 1622 (38) |

| Informal services | 79 (27) | 11 (20) | 8 (25) | 16 (38) | 1142 (27) |

| Mixed services | 106 (36) | 14 (25) | 8 (25) | 12 (29) | 1402 (33) |

| Unknown | 3 (1) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 62 (2) |

| Total installed | 292 (100) | 56 (100) | 32 (100) | 42 (100) | 422 (100) |

Summary

The findings are the first to describe assistive technology for people with dementia. The components of the ATTILA trial intervention have been described, in terms of what happened, who was involved, how, where and when the intervention happened, how many devices was provided and whether or not the intervention was tailored to participants. Value networks operating in ATTILA trial sites were characterised as either public or not-for-profit telecare provider network types. The ATTILA trial intervention is summarised in Table 7, using the TIDieR format.

| TIDieR format | Current ATT practice for people with dementia |

|---|---|

| When? | |

| When did assessments, recommendation and installations happen? | Baseline (week 0): assessment and recommendations |

| Weeks 12, 24, 52 and 104: assessment and installation | |

| What? | |

| What areas of assessment, in local ATT assessments, had higher fidelity to the ATT assessment standard? | Daily activity, memory, mobility and social support |

| What areas of assessment more frequently triggered the need for ATT? | Daily activities, memory and problem-solving |

| What ATT devices were recommended more frequently in local ATT assessments? | Devices for safety issues and to remind/prompt with monitoring/formal response |

| What ATT devices were installed more frequently? | Devices for safety issues and to remind/prompt with monitoring/formal response and control arm devices (e.g. non-monitored smoke detectors) |

| How much? | |

| How much of the ATT assessment was completed? | 52% of the ATT assessment areas were completed |

| 7.2 ATT assessment areas were addressed, on average (range 0–13) | |

| How many ATT needs were present? | 4.4 ATT needs, on average (range 0–12 needs) |

| How many ATT recommendations were identified? | 3 ATT devices, on average (range 1–14 devices) |

| 57% of participants had one or two ATT devices recommended | |

| How many installations were conducted? | 4.2 ATT devices were installed, on average (range 1–15 devices) (including control arm devices) |

| 79% were installed by week 24, with a reduction in installation over time | |

| How much monitoring and response happened? | 47% of installed ATT devices required monitoring, of which 38% required a formal response |

| Who? | |

| Who were the participants? | > 80 years of age, female, widowed, white British, not living alone and had moderate dementia |

| Who were the assessors of the installed devices? | Baseline:

|

Weeks 12–104:

|

|

| Where? | |

| Where did the ATT assessment take place? | 41% of assessments were in-person, at home |

| Where did the installations take place? | Participant’s homes |

| Tailoring | |

| Were the devices tailored to the participants? | There was an expectation that ATT installations would be tailored to participants by the baseline ATT assessment; however, there was weak to moderate tailoring between (1) baseline ATT needs and ATT recommendations (τ = 0.242; p < 0.000) and (2) ATT recommendations and the ATT installed (τ = –0.470; p < 0.000); 62% of devices were installed for ATT needs that had not been identified in the assessment process, and 53% of the devices recommended as a result of assessment were not installed by week 24 |

Chapter 4 Primary outcome results

Recruitment

Eleven sites in England were opened for recruitment to the ATTILA trial. The first participant was randomised on 14 August 2013; recruitment ended on 26 October 2016. The ATTILA trial randomised over a period of 38 months, with an average recruitment rate of 13 participants per month. Yearly recruitment per site is shown in Table 8.

| Site | Year (number of participants recruited) | Total number of participants recruited | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||

| Croydon | 4 | 21 | 13 | 10 | 48 |

| Lambeth | 5 | 13 | 28 | 17 | 63 |

| Southwark | 3 | 21 | 21 | 26 | 71 |

| Cambridge | 2 | 49 | 37 | 51 | 139 |

| Oxford | 0 | 18 | 8 | 4 | 30 |

| Suffolk | 3 | 23 | 24 | 11 | 61 |

| Lancashire | 1 | 14 | 35 | 22 | 72 |

| Blackpool | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Nottingham | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Barnsley | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Blackburn | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Yearly total | 18 | 162 | 171 | 144 | 495 |

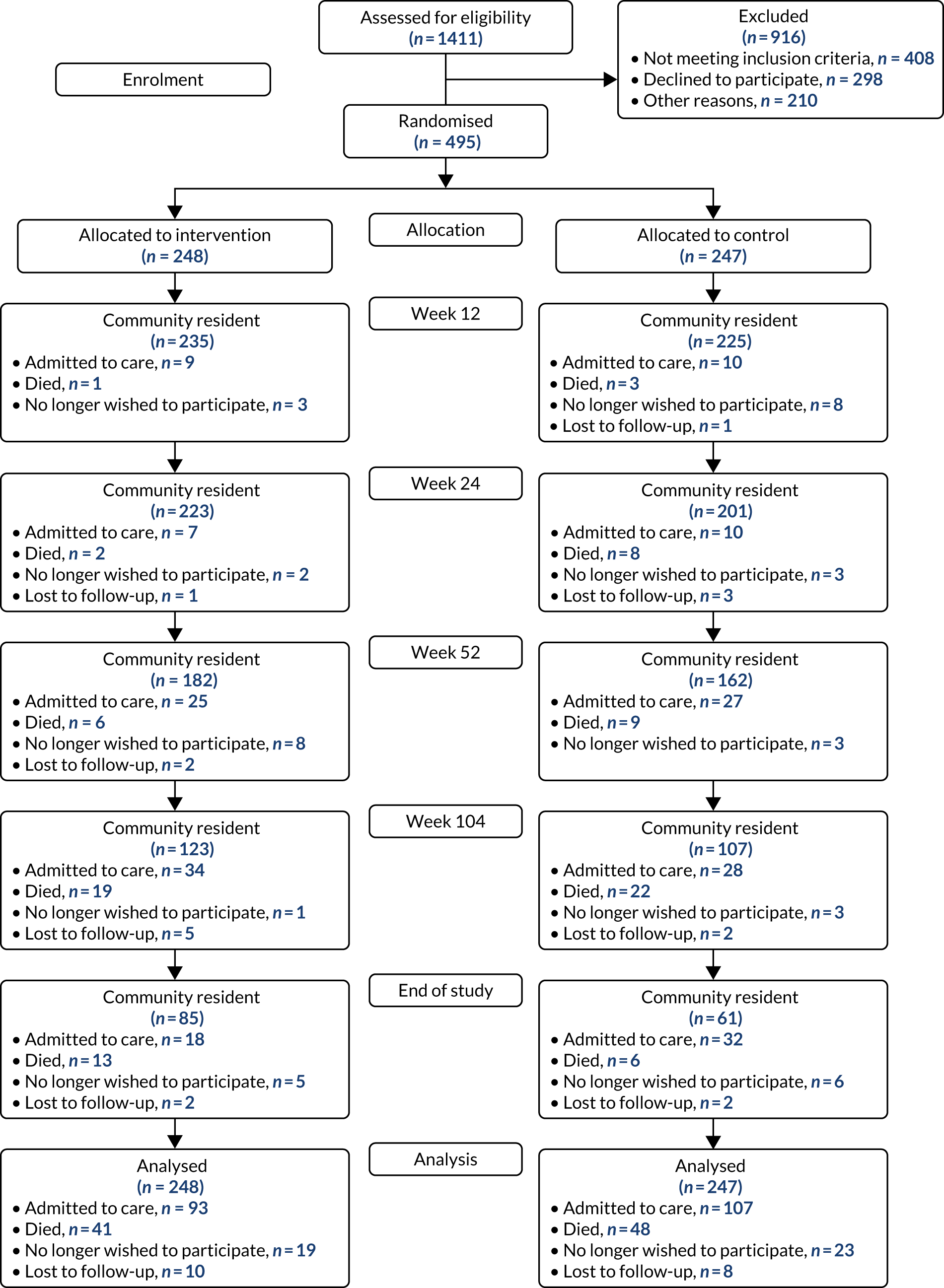

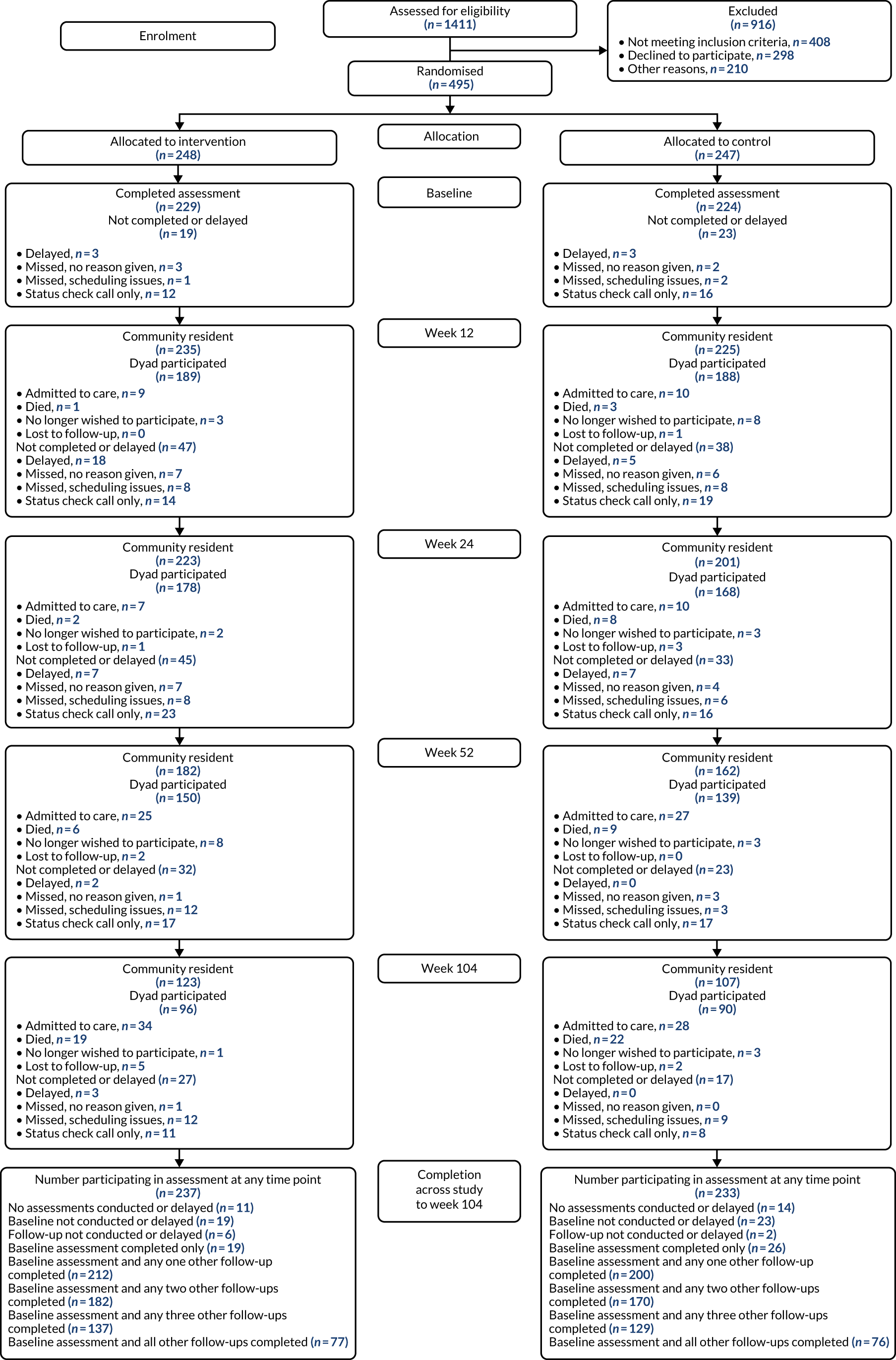

A total of 1411 people were assessed for trial eligibility; of these, 495 were randomised across the 11 sites: 248 were randomised to receive ATT and 247 were randomised to the control arm. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram of participants through the ATTILA trial is shown in Figure 3, and Table 9 shows the participant status at the end of the trial.

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram.

| Status | Trial arm, n (%) | Total (N = 495), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 248) | Control (N = 247) | ||

| Admitted to care | 93 (37.5) | 107 (43.3) | 200 (40.4) |

| Death while a community resident | 41 (16.5) | 48 (19.4) | 89 (18.0) |

| Withdrew from further follow-up | 19 (7.7) | 23 (9.3) | 42 (8.5) |

| Lost to follow-up (unable to contact) | 10 (4.0) | 8 (3.2) | 18 (3.6) |

| Finished trial living in the community | 85 (34.3) | 61 (24.8) | 146 (29.5) |

Those people who declined to consent did so because they wanted ATT (n = 53), because they did not want ATT (n = 83) or because they did not want to participate in research (n = 162). Other reasons for being excluded were, primarily, that the researcher was unable to contact the potential participant (n = 131) or because participation was deemed inappropriate (n = 48).

During the follow-up of the ATTILA trial, in total, 200 participants were admitted to care, 89 participants died, 42 withdrew from further follow-up and 18 were lost to follow-up. This resulted in 146 participants finishing the trial living independently in the community: 85 in the intervention arm and 61 in the control arm. Relatively few participants (3.6%) were lost to follow-up, as, once randomised, every effort was made to follow up participants throughout the trial to obtain all follow-up forms and outcome assessments. Of the 18 lost to follow-up, 10 were in the intervention arm and eight were in the control arm. Once a participant was admitted to care, the follow-up was terminated and no outcome assessments were collected. Table 10 displays a comparison of the key participant characteristics of the 495 participants randomised.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 248) | Control (N = 247) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 65, n (%) | 11 (4) | 4 (2) |

| 65–80, n (%) | 89 (36) | 93 (38) |

| > 80, n (%) | 148 (60) | 150 (61) |

| Mean (SD) | 81.0 (8.2) | 80.8 (7.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 102 (41) | 103 (42) |

| Female | 146 (59) | 144 (58) |

| Risk of wandering/leaving home inappropriately, n (%) | ||

| Low | 178 (72) | 180 (73) |

| Medium | 52 (21) | 48 (19) |

| High | 18 (7) | 19 (8) |

| Safety risks within home identified, n (%) | ||

| Low | 125 (50) | 124 (50) |

| Medium | 104 (42) | 101 (41) |

| High | 19 (8) | 22 (9) |

| Level of caregiver support, n (%) | ||

| Live in | 119 (48) | 121 (49) |

| Once daily | 60 (24) | 61 (25) |

| Less than once daily | 69 (28) | 65 (26) |

| SMMSE scorea | ||

| 0–9, n (%) | 23 (10) | 34 (15) |

| 10–19, n (%) | 79 (36) | 96 (43) |

| 20–25, n (%) | 87 (39) | 74 (33) |

| 26–30, n (%) | 32 (14) | 19 (9) |

| Mean (SD) | 18.7 (6.6) | 16.9 (6.9) |

| BADLS scoreb | ||

| 0–4, n (%) | 17 (7) | 10 (4) |

| 5–14, n (%) | 72 (31) | 64 (28) |

| 15–29, n (%) | 95 (41) | 102 (45) |

| 30–60, n (%) | 46 (20) | 49 (22) |

| Mean (SD) | 19.5 (11.3) | 20.4 (10.9) |

All characteristics appear to be reasonably well balanced across the two randomised arms. The average age was 80.9 years, 59% (290/495) were female and 48% (240/495) had a live-in caregiver. The majority of participants, 72% (358/495), were classified as being at low risk of wandering or leaving their home inappropriately. Half of the participants (249/495) were deemed to have low safety risks identified within the home. The average SMMSE score was 18.7 points in the intervention arm and 16.9 points in the control arm, so participants in the intervention arm had a slightly higher baseline SMMSE score than those in the control arm. The average BADLS score was 19.5 in the intervention arm and 20.4 in the control arm. The missingness of these data was similar between the two arms.

Primary outcomes

Time to institutionalisation

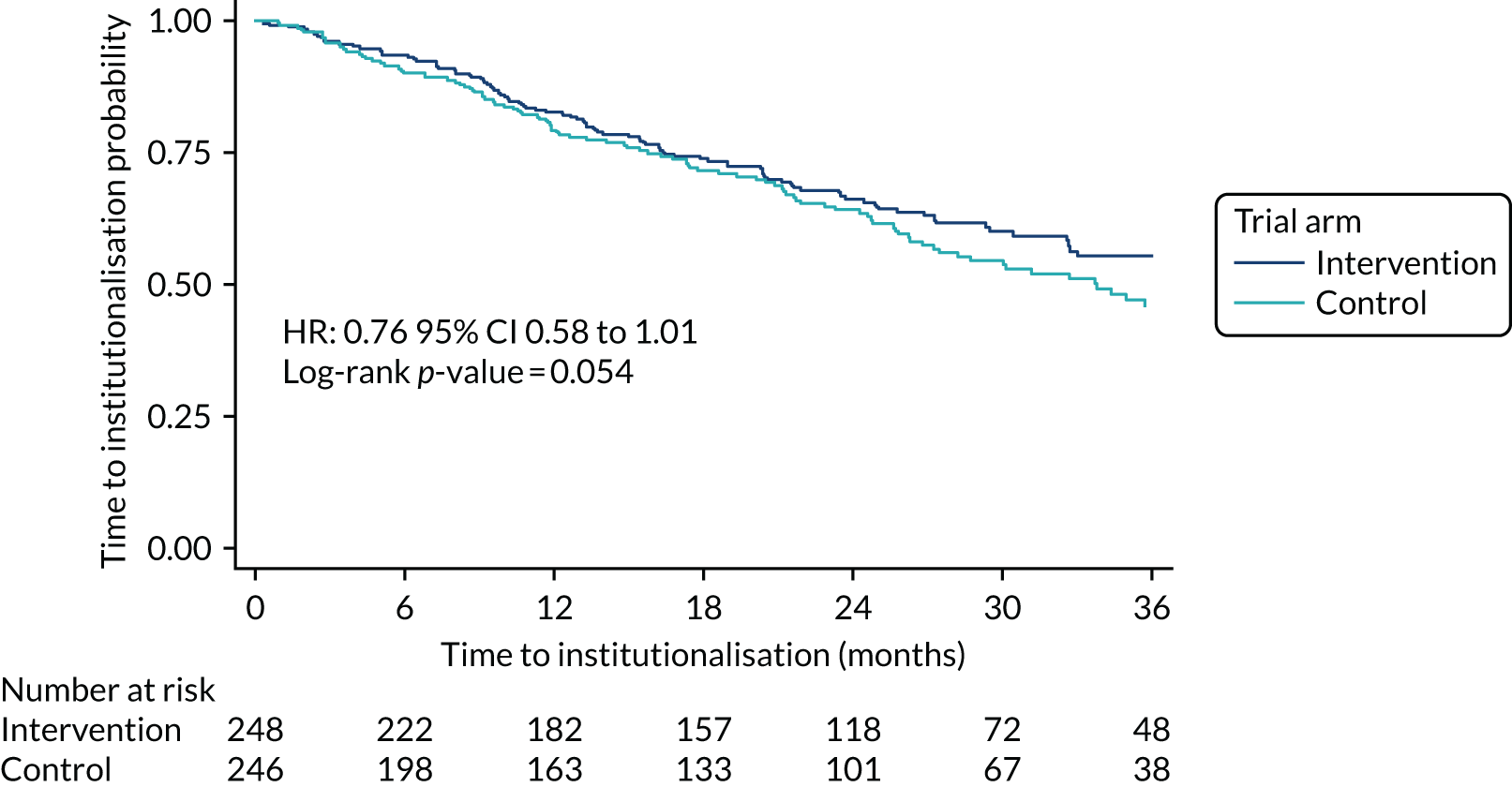

The primary analysis of admission to care was defined as a permanent transition from living in a participant’s own home to living in nursing or residential care, or admission to an acute care facility that resulted in permanent placement. The end point was compared between the intervention and control arms using survival analysis. Kaplan–Meier curves are for graphical representation of time to an event. Statistical significance was determined through log-rank test. The primary analysis was conducted according to intention to treat, and participants who have died, withdrawn from follow-up or who were lost to follow-up were censored at the date of withdrawal. The time to admission to care, split by randomised arm, is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve: time to admission to care by randomised arm, unadjusted analysis.

The intervention and control arms showed a similar pattern of time to admission to care over the 3-year period plotted. Comparing the ATT arm with the control arm, the hazard ratio is 0.76 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.58 to 1.01; p = 0.054]. This unadjusted analysis showed a borderline significant difference in slowing the time to admission to care with ATT use when compared with the control. At 2 years, the admission to care rate for the ATT arm was 65.6% (95% CI 58.8% to 71.5%), compared with 63.4% (95% CI 56.3% to 69.7%) for the control arm.

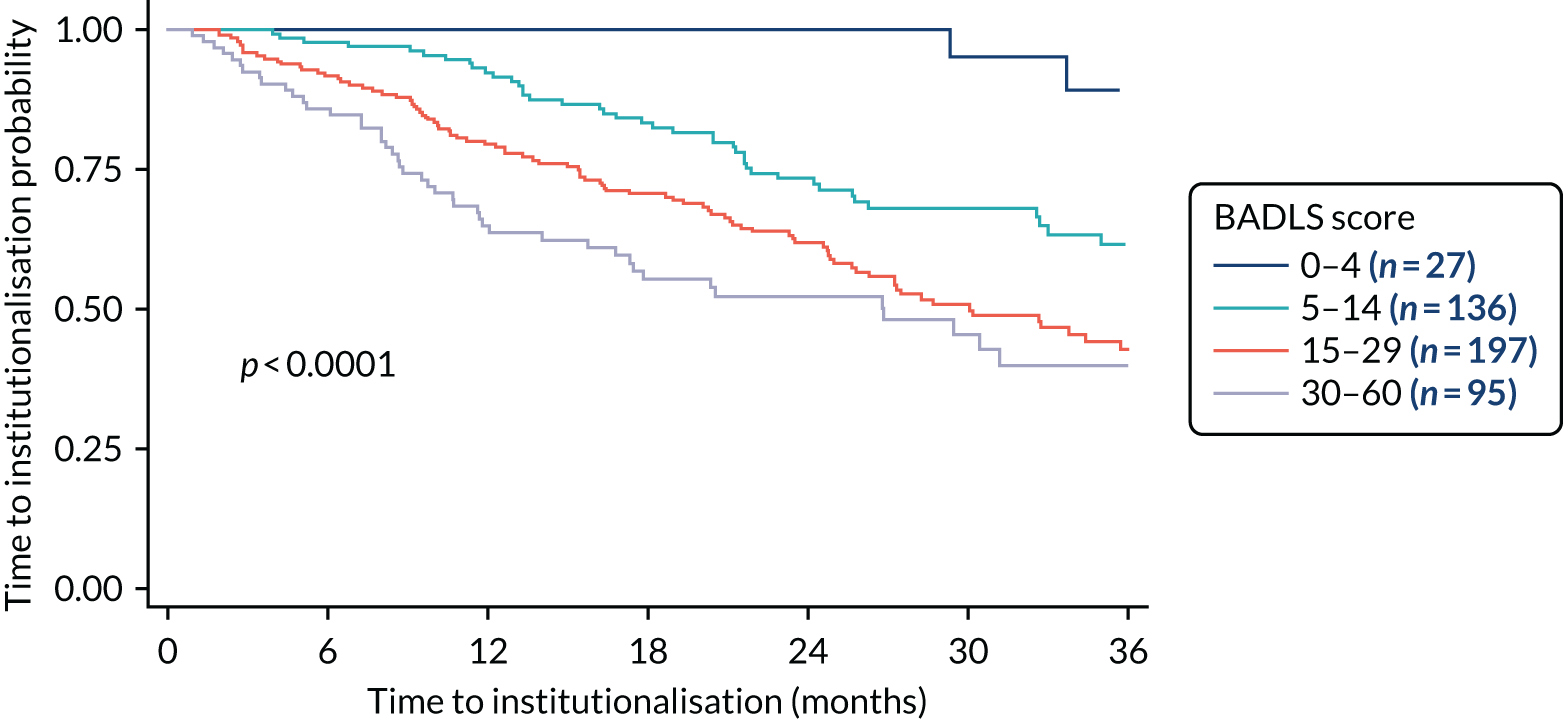

The rates of admission to care can be affected by participants’ functional ability. This was measured using the BADLS. BADLS scores range from 0–60, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. Figure 5 shows the time to admission to care split by BADLS scores 0–4, 5–14, 15–29 and 30–60.

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve: time to admission to care by baseline BADLS score.

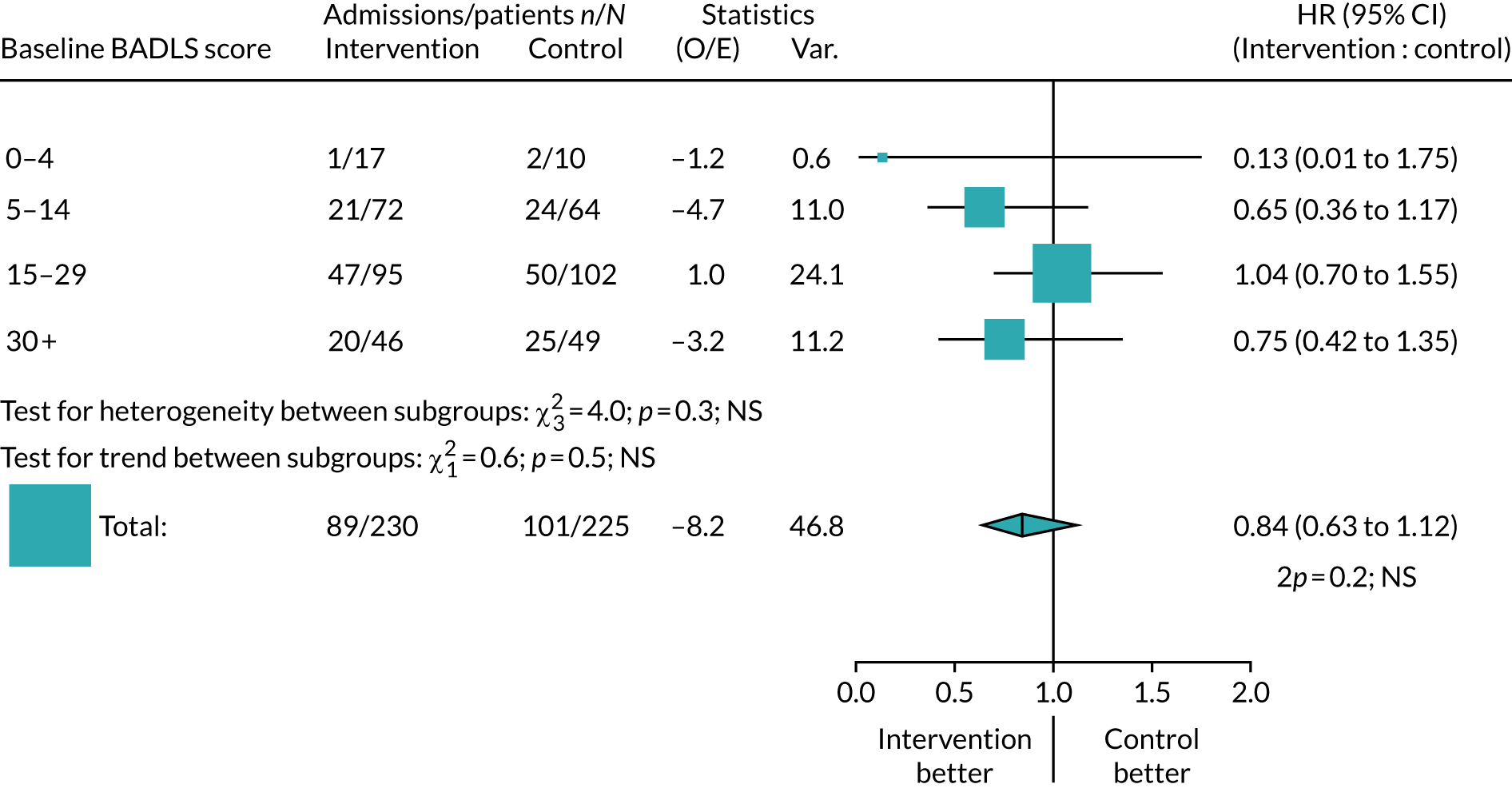

There was a highly significant difference in the time to admission to care when comparing baseline BADLS scores. Participants with a higher baseline BADLS score were more likely to be admitted to care (p < 0.0001). Baseline BADLS scores are presented in Table 10 and shows an imbalance in baseline scores. More participants in the intervention arm than in the control arm had a lower baseline BADLS score. As Figure 5 showed that participants with a higher baseline BADLS score are more likely to be admitted to care; this difference at baseline was adjusted for in the primary analysis. A forest plot split by baseline BADLS score is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot: admission to care by randomised arm, adjusted for baseline BADLS score. NS, not significant; O/E, observed over expected; Var., variance.

When adjusting for baseline BADLS scores, there is no significant difference in the time to admission to care between those in the intervention group and those in the control group (hazard ratio 0.84, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.12; p = 0.20).

The reasons for admission to care are usually multifactorial. To determine whether or not ATT might have helped prevent admissions to care, the reasons given for institutionalisation have been categorised as having any mention of safety, then any mention of wandering and then falls, with others classified as inability to perform activities of daily living (ADL), behaviour, other medical condition, deterioration (unspecified), caregiver health, other and unknown. This can give only an approximate classification, given the complexity of Alzheimer’s symptoms, but the breakdown of the most likely causes is given in Table 11.

| Categorised reason | Trial arm (number of participants) | Total number of participants (N = 495) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 248) | Control (N = 247) | |||

| Safety concern | 12 | 4 | 16 | 0.043 |

| Wandering | 5 | 13 | 18 | 0.054 |

| Falls | 13 | 13 | 26 | 0.990 |

| Loss of ADL | 14 | 29 | 43 | 0.016 |

| Behaviour | 8 | 10 | 18 | 0.630 |

| Other medical condition | 7 | 6 | 13 | 0.790 |

| Deterioration (unspecified) | 14 | 11 | 25 | 0.540 |

| Caregiver health | 9 | 3 | 12 | 0.081 |

| Other | 6 | 8 | 14 | 0.580 |

| Unknown | 5 | 10 | 15 | 0.190 |

| Any cause | 93 | 107 | 200 | |

The most common reason for admission to care is the inability to perform ADL. Institutionalisation for safety concerns, which might have been expected to be reduced by ATT, is actually more common in the intervention group (12 vs. 4 participants; p = 0.043). By contrast, the risk of wandering, which might, again, be mitigated by appropriate ATT, was reduced in the intervention group (5 vs. 13 participants; p = 0.054). There was also a significant reduction in the number of participants moving into residential care because of the inability to perform ADL (14 vs. 29 participants; p = 0.016). A total of 15 admissions to care were classified as being for an unknown reason.

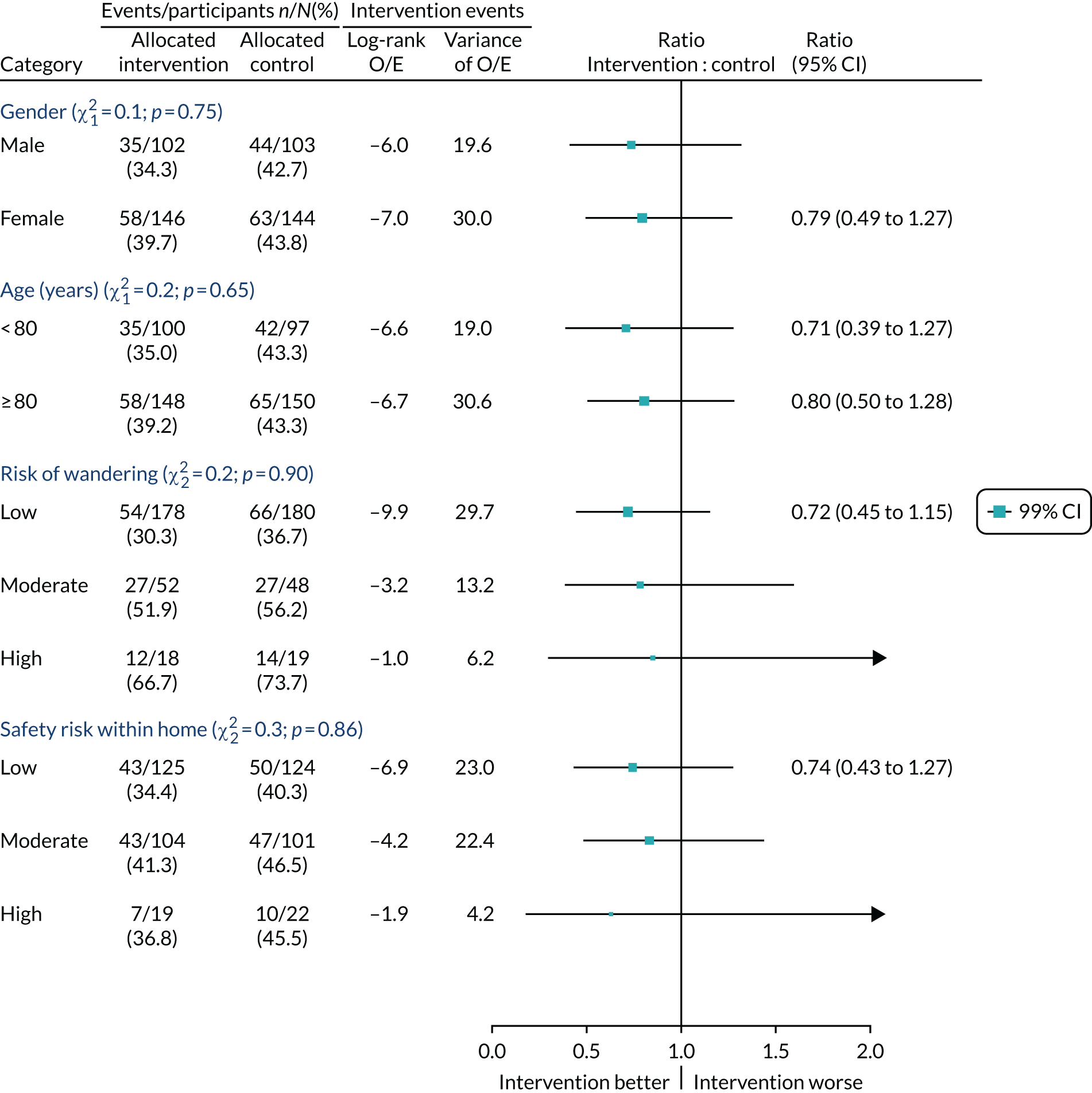

Subgroup analysis

To investigate whether or not ATT use varied by baseline characteristics, we did subgroup analyses of admission to care in the ATT group compared with admission to care in the control group by gender, age, risk of wandering from home and safety risk within the home (Figure 7). As there were no significant differences seen, there is no indication of any benefit from ATT use in any of these subgroups.

FIGURE 7.

Subgroup analyses of admission to care for the ATT group vs. the control group, by baseline characteristics. O/E, observed over expected; Var., variance.

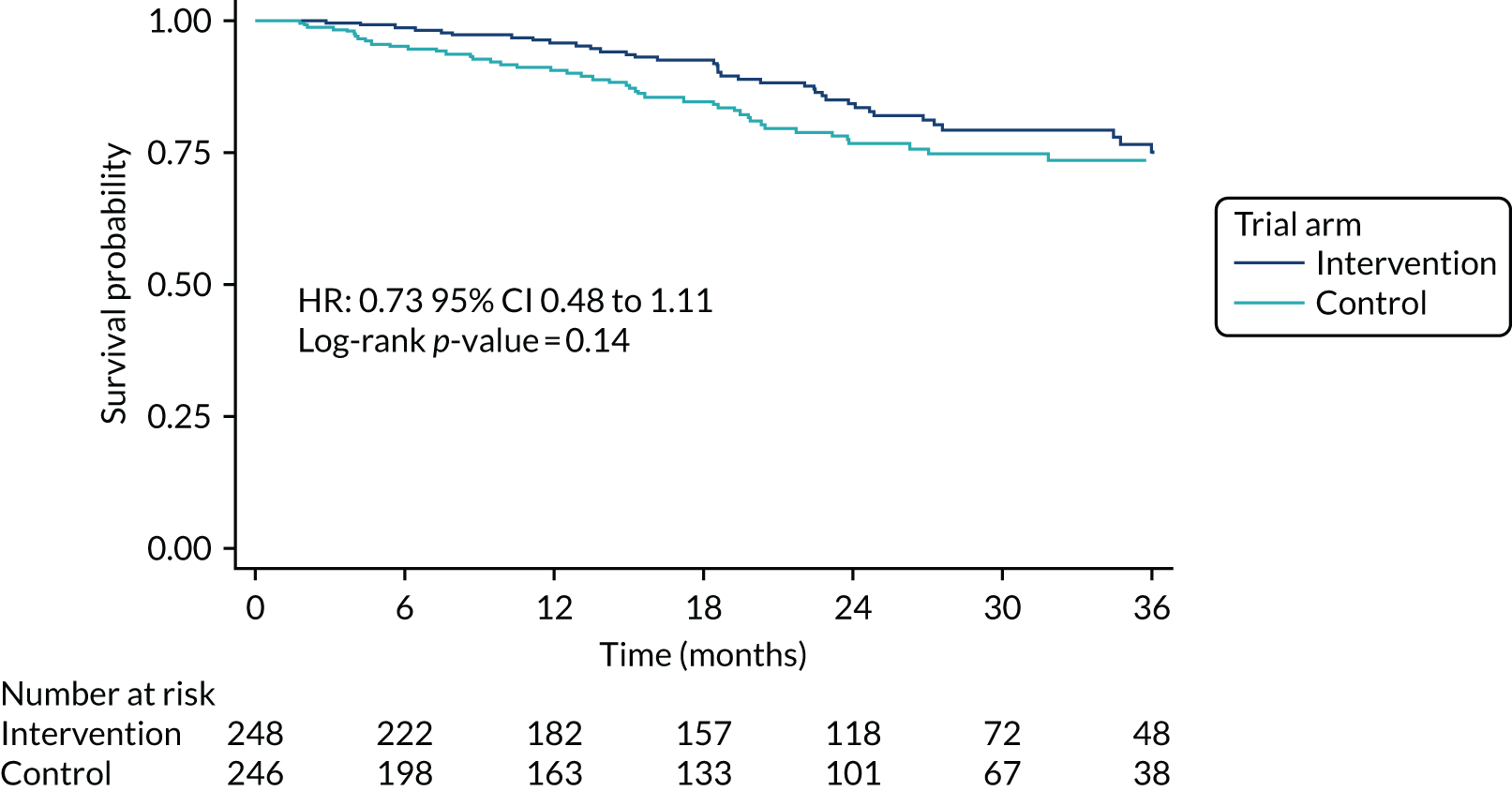

Deaths while in the community

Eighty-nine participants died while in the community. Figure 8 is the Kaplan–Meier graph of time to death while community resident and Table 12 shows the categorised reasons for cause of death. In the Kaplan–Meier analysis, participants who had been admitted to care, withdrawn from follow-up or lost to follow-up were censored at the date of withdrawal.

FIGURE 8.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve: time to death while community resident, by randomised arm.

| Cause of death | Trial arm (number of participants) | Total number of participants (N = 495) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 248) | Control (N = 247) | |||

| Health/dementia deterioration | 8 | 4 | 12 | 0.25 |

| Pneumonia/respiratory failure | 4 | 10 | 14 | 0.10 |

| Heart attack/heart failure | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0.13 |

| Stroke | 7 | 5 | 12 | 0.56 |

| Cancer | 7 | 4 | 11 | 0.36 |

| Infection | 6 | 4 | 10 | 0.53 |

| Other | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0.41 |

| Unknown | 4 | 9 | 13 | 0.16 |

| Total | 41 | 48 | 89 | |

There were no significant differences seen overall (p = 0.14) or in the grouped categories for cause of death (see Figure 8 and Table 12).

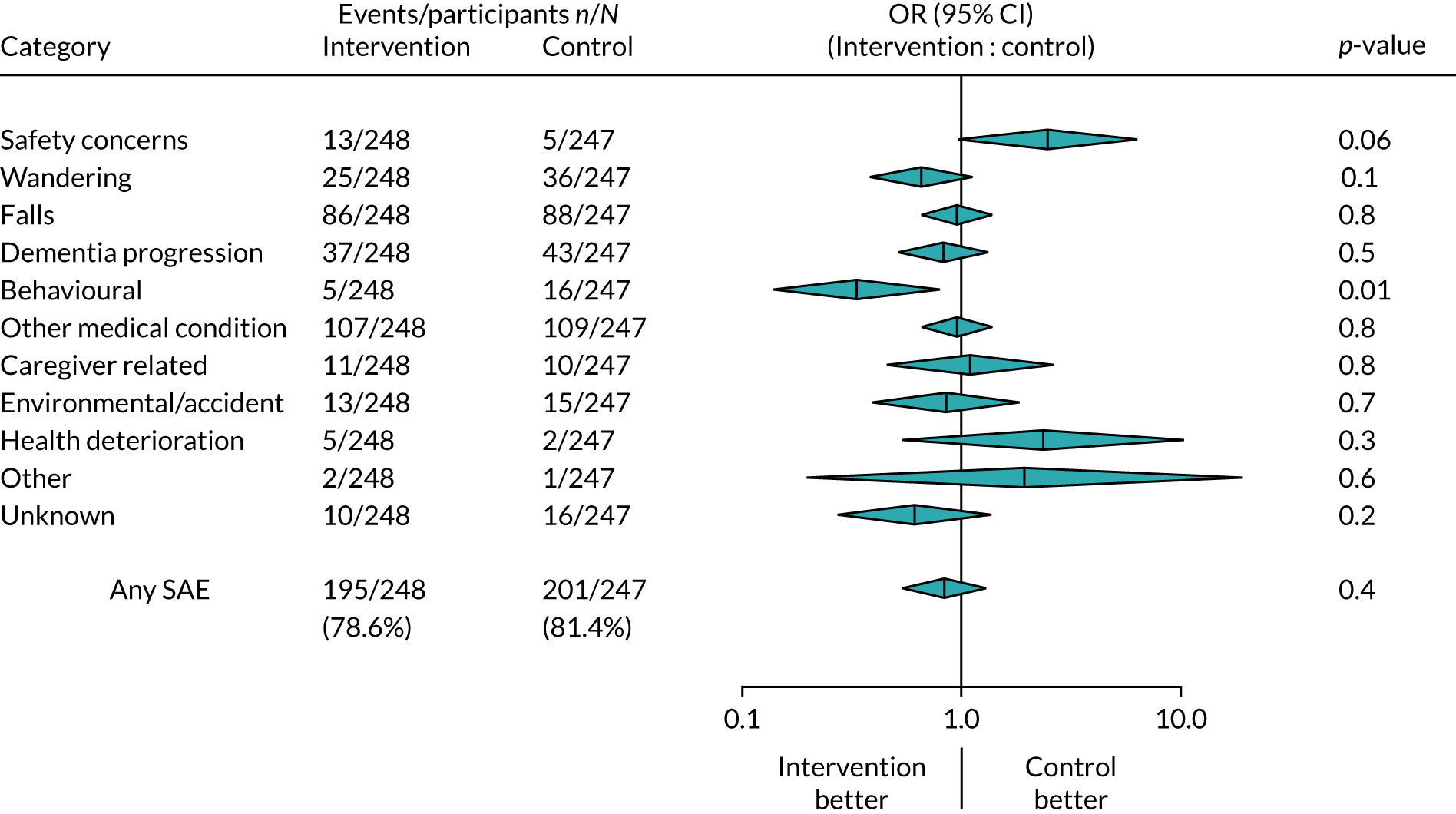

Serious adverse events

Serious adverse events have been grouped into broad categories and are summarised in Tables 13 and 14. The categories were decided on by members of the ATTILA trial team with clinical expertise and were categorised separately by two members of the team, then assessed for consistency. Any differences were discussed, and input sought from a clinical expert in the team. Raters were unaware of treatment allocation of the participants involved. Table 13 presents the counts of SAEs recorded and Table 14 presents the number of participants reporting the SAEs, as participants can report multiple SAEs. Similarly to the reasons for admissions to care, SAEs could be multifactorial. The categories are any mention of safety concerns, wandering, falls, dementia progression, behaviour, other medical condition, caregiver related, accidents, health deterioration, other and unknown.

| Categorised SAE | SAE count (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | Control arm | Total | |

| Safety concerns | 15 | 5 | 20 |

| Wandering | 36 | 71 | 107 |

| Falls | 182 | 187 | 369 |

| Dementia progression | 37 | 46 | 83 |

| Behaviour | 5 | 21 | 26 |

| Other medical condition | 214 | 220 | 434 |

| Caregiver related | 11 | 10 | 21 |

| Environmental/accident | 14 | 21 | 35 |

| Health deterioration | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Unknown | 10 | 18 | 28 |

| Total count of SAEs | 532 | 603 | 1135 |

| Categorised SAE | Number of participants | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | Control arm | Total | ||

| Safety concerns | 13 | 5 | 18 | 0.06 |

| Wandering | 25 | 36 | 61 | 0.13 |

| Falls | 86 | 88 | 174 | 0.83 |

| Dementia progression | 37 | 43 | 80 | 0.45 |

| Behaviour | 5 | 16 | 21 | 0.01 |

| Other medical condition | 107 | 109 | 216 | 0.83 |

| Caregiver related | 11 | 10 | 21 | 0.83 |

| Environmental/accident | 13 | 15 | 28 | 0.69 |

| Health deterioration | 5 | 2 | 7 | 0.26 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.57 |

| Unknown | 10 | 16 | 26 | 0.22 |

| Total | 195 | 201 | 396 | 0.45 |