Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/201/10. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Wilby et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Sciatica can be described as a symptom rather than a diagnosis. It is broadly defined as leg pain in the distribution of a lumbosacral nerve root and has already been subject to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) review of treatment guidance. 1 Estimates of caseload vary substantially within the literature because of difficulties in definition and poor data capture. A UK epidemiological study suggests a lifetime prevalence of up to 43%, an annual incidence of 5% and a point prevalence of up to 13%. 2 Over 90% of sciatica is due to a prolapsed intervertebral disc (PID), with the average age of patients being early 40s. 3 As patients affected are typically young, working adults, it may be helpful to consider two categories of sciatica: (1) acute sciatica that lasts < 6 weeks and may be self-limiting with little or no impact on the patient’s work, and (2) persistent sciatica that persists > 6 weeks and has a tremendous impact on the patient’s working ability.

Although the duration of pain may vary considerably, and the natural history of sciatica is favourable within 1 or 2 years, many patients have pain that persists beyond 6 weeks that could have a considerable impact on their employment and lives. It is generally accepted that pain persisting beyond 6 weeks is unlikely to get better imminently and requires further patient investigation and treatment. Treatment options include drugs, injections of drug combinations into the spine and surgical techniques to remove the prolapsed disc. UK guidelines recommend non-routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning after lifestyle modifications and simple treatments. 1

Spinal injection involves the administration of a mixture of local anaesthetic and steroid into the spine via one of three main routes: (1) through the base of the spine (i.e. a caudal epidural), (2) through the back of the spine (i.e. a interlaminar injection) or (3) through the nerve tunnel (foramen) directly adjacent to the prolapsed disc [i.e. a transforaminal epidural steroid injection (TFESI)]. The last mode (i.e. TFESI) is reported to be the most successful. 4 This specific use of a steroid (for spine injection) is outside the marketing authorisation (off-label). However, it is a commonly used and a widely accepted treatment for sciatica, although the success rate reported is highly variable because of inconsistent patient population and route, type and dose of steroid administration. Although TFESI is recommended by a number of expert review groups, including the UK NICE guideline1 (low back and radicular pain), a recent review from Danish experts on behalf of the Danish Health Authority recommends against its use for sciatica > 12 weeks’ duration. 5,6 Of the surgical techniques, microdiscectomy to remove the prolapsed disc is considered highly successful, with reported success rates of 90%. 7 However, as sciatica has a favourable natural history, there is potential that the treatment administered in the form of injection may render surgery excessive.

There is currently no care pathway in the NHS that recommends any one particular treatment over another, and no direct comparison exists between microdiscectomy to treat sciatica secondary to PID and nerve root blocks, such as TFESI. In addition, no international consensus agrees the use of TFESI for sciatica within 12 weeks’ duration. This trial aims to address that by comparing surgical microdiscectomy with steroid and local anaesthetic administered accurately to the source of leg pain against various objective outcomes.

Scientific background

Sciatica is a common condition. In the UK, in 2010/11, > 25,000 therapeutic epidural steroid injections (ESIs) were administered and > 9000 surgical procedures to remove herniated lumbar disc prolapses were performed for sciatica [Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data]. 8 In the USA, > 200,000 microdiscectomies are performed per year. 9 In the UK, the cost to the NHS is estimated to be £700 per TFESI and approximately £4500 for surgical microdiscectomy (which requires patients to be hospitalised for 2 nights, on average).

Previous studies of surgical microdiscectomy for sciatica

Surgical removal of the PID is believed to be the treatment of choice for symptomatic PID, with > 90% success rates, return to work within 1 month in the majority of cases and complications of around 2%. 10 Several trials have attempted to compare surgical microdiscectomy with non-operative treatments, but with notable methodological flaws. Population studies have suggested that surgery is more effective than non-surgical treatments, but these studies were affected by selection bias and lacked clear definitions of the non-operative treatment arm. 3,11–13 The two most notable studies are large, prospective case series studies, the Maine Lumbar Spine Study12 and the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial,11 and are worthy of specific mention.

Recruiting > 500 patients treated by spinal specialist teams across Maine, almost an equal number of surgical patients were compared with non-surgical patients with sciatica. 12 Surgery was deemed effective in 71% of patients compared with 43% of non-surgical patients. The non-surgical group was, however, quite heterogeneous, with only 18% of non-surgical patients receiving ESI. In addition, the study was observational and, therefore, suffered from selection bias.

The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial11 had two main arms: an observational reporting group in which patients selected their treatment (surgical or not) and a randomised arm. Owing to a large degree of treatment crossover in the randomised section, intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses showed no significant difference in outcomes. However, the as-treated analysis favoured surgery. Once again, however, the non-surgical treatments being compared with surgery were heterogeneous.

To our knowledge, only one previous study14 (n = 100) has directly compared surgery with ESI (interlaminar route) and this study reported that ESI could prevent surgery in approximately 50% of cases. This study was a single practitioner cohort, but randomisation was employed in design of the study.

Previous studies of epidural steroid injections for sciatica

Epidural steroid injections are known to improve patients’ sciatica, but their efficacy varies widely throughout the literature. 15 A wide variation in practice exists across the UK in the methods of administration of the ESI.

Epidural steroid injections involve the administration of a mixture of local anaesthetic and steroid into the epidural space via one of three main routes: (1) through the base of the spine (i.e. a caudal epidural), (2) through the back of the spine (i.e. a interlaminar injection) or (3) through the nerve tunnel directly adjacent to the prolapsed disc (i.e. transforaminal injection). In the past, the most widely used injection therapy route was ESI, by either the interlaminar route or the caudal route. However, placing the needle through the bony tunnel through which the lumbar nerve root exits the spine can accurately place the drug closer to the target site (i.e. TFESI). Currently, ESI is not commissioned by all local commissioning groups within the NHS in the UK for sciatica, whereas TFESI is. This technique routinely requires X-ray guidance or computerised tomography (CT) scanning guidance and most pain clinics in the UK are able to offer this treatment.

Although randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have tested ESI for acute sciatica, these trials have not included comparisons between TFESI and interlaminar ESI. However, prospective and case–control studies have compared the two techniques and demonstrated a superior efficacy of TFESI. 13,16,17 A comprehensive review of the literature has recently been published by the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. 15 Only one small RCT14 (n = 100) directly compared interlaminar ESI with surgery for sciatica secondary with PID and suggested that ESI could prevent 50% of surgical interventions. One previous UK RCT, the Wessex Epidural Steroid Trial (WEST)18 (n = 228), funded by the HTA programme, compared interlaminar injection of steroid with placebo (i.e. injection of saline between the spinous processes) in patients with sciatica ranging in duration from 4 weeks to 18 months and found no benefit of steroid injections beyond 3 weeks of follow-up. However, in this study, MRI was not undertaken as part of the trial to confirm pathology, with this relying on clinical findings alone. These possibly could be some of the factors contributing to less than promising results for ESI. Various other studies have shown that ESIs have only a small short-term effect on leg pain and disability compared with placebo, and no effect in the long term. 19 These poor medium- to long-term results have given ESIs poor perceived efficacy and hence they are not commissioned or recommended in the treatment and clinical pathway of sciatica secondary to PID management.

A prospective randomised study20,21 reported that transforaminal administration of the drug mixture into the epidural space (i.e. TFESI) under fluoroscopic guidance is the most successful route (more so than injection of saline or local anaesthetic into the epidural space, or intramuscular steroid or saline injection), and this route was used in this study. Relief of pain was corroborated by significant improvements in function and disability, and reductions in use of other health care.

Transforaminal epidural steroid injection is believed to be superior in efficacy to interlaminar administration of ESI, as the drug is delivered more accurately and closer to the site of the pathology/disc prolapse. A prospective study17 of TFESI (n = 48) for acute sciatica suggests long-term pain reduction in > 80% of patients. One RCT published in 201120 (n = 150) compared the outcomes of selective nerve root injection and local anaesthetic, local anaesthetic alone, normal saline and intramuscular injection of steroid or normal saline. The only radiological feature associated with successful outcome was the grade of nerve root compression. Of patients with low-grade root compression (n = 71), 75% responded favourably to selective nerve root injection and avoided surgery by 54 weeks’ follow-up.

Although there are few data directly comparing TFESI with interlaminar steroid injections for sciatica, during the recruitment stage of this trial a number of ongoing studies throughout the world were specifically looking at this. However, these studies were experiencing recruitment difficulties because of the lack of a surgical treatment arm. 22,23 One recent study24 (n = 238) reported that 65% of injections were effective at follow-up of > 6 months (based on patient-reported measures).

Adverse events (AEs) associated with TFESI procedures are rare, typically < 1%, but can be severe and include paraplegia, infection, haematoma, intravascular injection of medication, direct nerve trauma, subdural injection of medication, air embolism, disc entry, urinary retention, radiation exposure and hypersensitivity reactions.

The advantages of spinal injections include:

-

The injections are a relatively cheap and low-risk procedure compared with surgery.

-

Success rates have been estimated to be as high as 75%.

-

Injections are delivered as a day-case procedure and, therefore, require no hospital admission and can be easily repeated.

-

There is a range of treatment providers, including radiologists, surgeons and pain physicians.

The disadvantages of spinal injections include:

-

The true success rate of injections is largely unknown. The injections may work well in the short term, but pain may return some weeks later.

-

Injections are not able to prevent physical nerve root compression and are inappropriate for massive disc prolapses that cause motor weakness or numbness in the leg.

Economic background

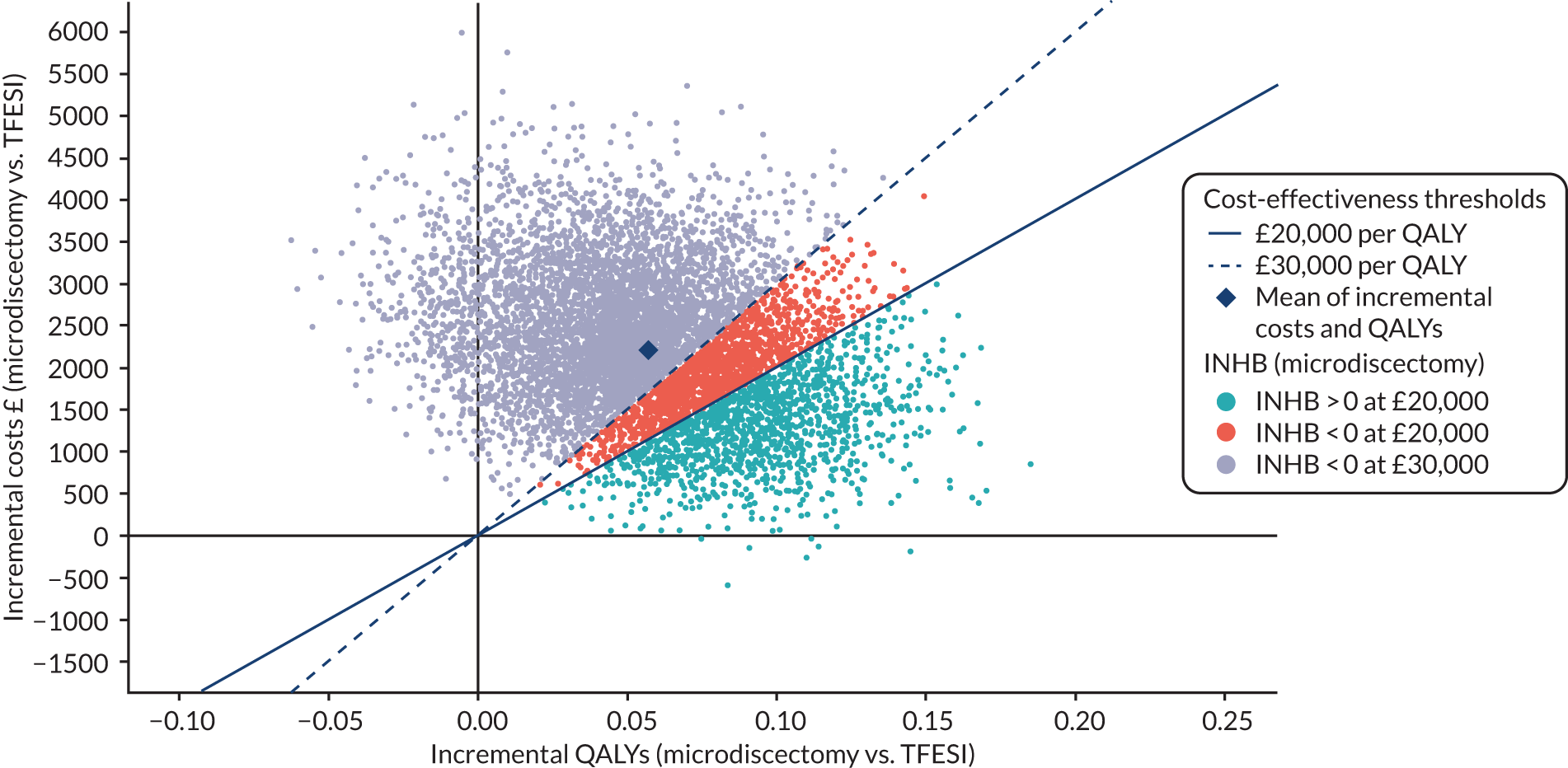

Although there are a number of published economic evaluations of interest in the treatment of sciatica, they are of limited applicability, as none has directly compared microdiscectomy with TFESI. A recent systematic review25 of economic evaluations in sciatica included 16 decision-analytic models that compared a selection of management strategies. The review25 found that analyses were generally associated with poor modelling techniques, analytical methods and data quality, specifically in terms of health state representation, time horizons and utility values. Uncertainty associated with the clinical evidence populating the models was an identified contributor to these limitations.

A number of the US studies identified by Hall et al. 25 compared surgical techniques with epidural injection techniques in the treatment of sciatica. Parker et al. ,26 taking a payer perspective, including the cost of patient care (i.e. index procedures and any follow-up care or repeat procedures), reported a cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) of US$16,300 (2014 US$) when comparing interspinous spacer surgery with conservative care (which could include steroid injection). Skidmore et al. 27 compared spacer surgery with conservative care (including ESI) and, in taking a broader cost perspective (i.e. patient, physician or payer, but excluding productivity losses), reported a cost per QALY of US$17,894 (2009 US$). Udeh et al. 28 estimated the cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive lumbar decompression as US$37,758 per QALY gained (2013 US$) compared with ESIs from a Medicare payer’s perspective. An evaluation29 including societal costs associated with lumbar disc herniation surgery and non-surgical treatments (including ESI) for privately insured, working patients identified that after fully accounting for the effects of disc herniation surgery on worker productivity (based on changes in earnings and missed work days) the cost per QALY gained of surgery reduced from US$52,416 to US$35,146 (2009 US$), based on a 4-year time horizon.

Economic evidence from the UK is limited. Lewis et al. 15,30 estimated the cost-effectiveness of alternative management strategies for sciatica using a deterministic model informed by an evidence synthesis based on a review of > 100 potential treatment scenarios. A 12-month time horizon was selected on the basis that patients would be managed through one of three treatment pathways: (1) primary care, (2) stepped approach or (3) immediate referral to more invasive treatments (i.e. epidural and disc surgery). Utilities derived from the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) were sourced from a Dutch study31 comparing prolonged conservative care with early surgery, and costs were based on clinical opinion and derived from published UK cost sources (2008/9 prices). The results indicated that stepped-care approaches to patient management based on initial treatment with non-opioids were likely to represent the most cost-effective approach relative to strategies that involved direct referral for disc surgery.

Vertuani et al. 32 assessed the cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery for lumbar spinal fusion in the treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal conditions. Using published data derived from a number of sources and UK costs (subsequently converted to euros), the results indicated that minimally invasive surgery was the dominant strategy, yielding both cost savings and improved health outcomes. A cost saving of €1666 (2013 costs) per procedure was estimated, based on shorter length of hospital stay, reduced blood loss and fewer complications, and with a corresponding improvement of 0.04 QALYs over 2 years.

Price et al. 18 conducted an economic evaluation of ESI compared with placebo within a 12-month double-blind placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial in four UK hospitals. A bottom-up costing approach was applied, with resource use estimated from data on drugs, equipment, pathology and radiology services collected within the trial and supplemented by a survey of non-RCT patients for clinical staff time-based activities. QALYs were derived from Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions preference-based utilities from the Short Form questionnaire-36 items questionnaire over the initial 12-week period. Taking a provider perspective, an incremental cost per QALY of £44,701 was estimated for up to three injections over a 12-week period, reducing to £25,745 per QALY gained if only one injection was administered, on the basis that there are no significant health benefits beyond the first injection (2002/3 prices). An alternative perspective, reflecting the charge levied on the purchaser as opposed to the actual resource cost, yielded incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) of £354,171 and £167,145 per QALY gained for up to three injections and only one injection, respectively.

However, by the nature of their setting, perspectives, interventions and comparators, these studies are unlikely to be directly generalisable or informative to the present decision problem concerning the cost-effectiveness of microdiscectomy compared with TFESI in the setting of the NHS in England.

The aim of the economic evaluation conducted as part of the NErve Root Block VErsus Surgery (NERVES) trial was to establish which intervention, microdiscectomy or TFESI, for the treatment of sciatica secondary to PID herniation offered greater value for money from the perspective of the NHS in England.

Rationale for research

To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence comparing steroid injections given via the nerve foramen with any other form of treatment (i.e. surgical microdiscectomy). Neither has a robust economic analysis been performed for this condition and these treatment paradigms.

Intervention

The technologies compared are standard surgical lumbar microdiscectomy (i.e. microdiscectomy) and fluoroscopically guided TFESI of a standard combination of local anaesthetic and steroid drug.

Objectives

The NERVES trial is a pragmatic, multicentre, Phase III randomised trial comparing microdiscectomy with TFESI for persistent sciatica caused by a PID of < 12 months’ duration. An internal pilot was completed with two trial centres as part of an initial feasibility study.

Primary objective

-

To compare the clinical effectiveness of microdiscectomy with TFESI at 18 weeks post randomisation.

Secondary objectives

-

To compare the clinical effectiveness of microdiscectomy with TFESI up to 1 year post treatment.

-

To compare the cost-effectiveness of microdiscectomy with TFESI.

-

To compare quality-of-life (QoL) outcomes for both treatments.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

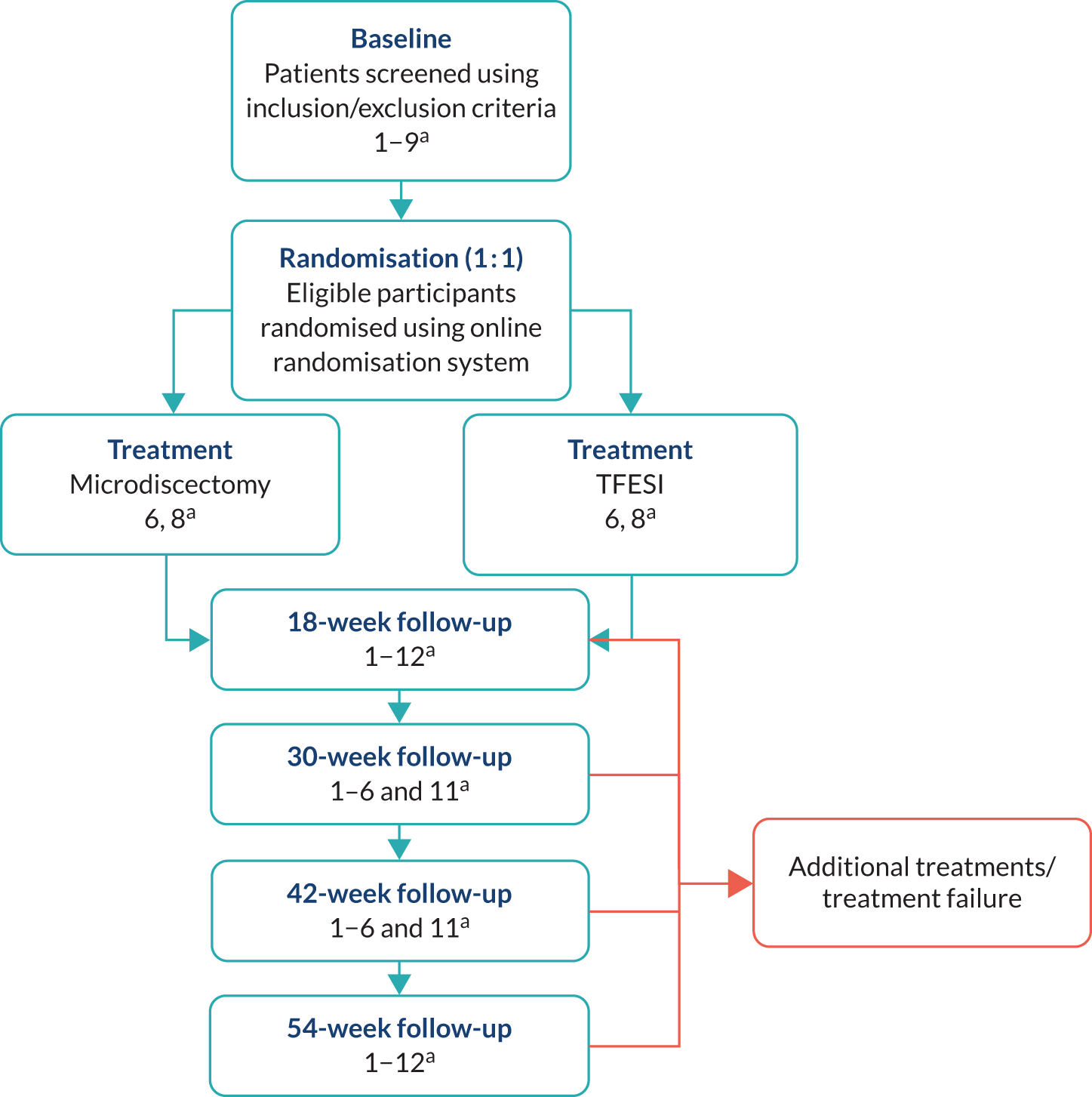

Figure 1 shows the NERVES trial design.

FIGURE 1.

The NERVES trial design. a, Trial-specific outcome assessments undertaken at each time point: (1) Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (primary outcome at the 18-week follow-up); (2) modified Roland–Morris outcome score for sciatica; (3) Core Outcome Measures Index score; (4) visual analogue scale scores for leg and back pain; (5) EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; (6) Resource Use Questionnaire; (7) physical examination; (8) pregnancy; (9) concomitant medications; (10) return to work; (11) treatment satisfaction (Likert scale); and (12) AEs. Orange indicates the possibility or option of additional treatment if primary treatment deemed unsuccessful.

Trial registration and ethics

This trial falls within the remit of the European Union Directive 2001/20/EC, transposed into UK law as the UK Statutory Instrument 2004 number 1031: Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 as amended. This trial has been registered with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and has been granted a Clinical Trial Authorisation. The Clinical Trial Authorisation reference is 21322/004/001 and the EudraCT number is 2014-002751-25.

Ethics considerations

The trial abided by the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. 33

Both of the treatments offered as part of the trial are standard NHS practice. As such, there were no major ethics concerns. When treatment has been considered to be unsuccessful, participants had full access to additional treatment needed as per routine care. Participation in the trial did not prevent access to additional treatments needed.

The specific issues pertaining to this trial are:

-

requirement for an additional visit

-

patients were randomised and, therefore, were unable to choose their own treatment.

Funding was in place to allow reimbursement of financial costs incurred by the trial participant to attend an additional appointment (i.e. a 54-week follow-up appointment post randomisation).

Patients provided informed consent to participate, with information provided about the randomisation process, data collection and other trial processes.

Ethics approval

The trial protocol received the favourable opinion of a Research Ethics Committee prior to initiation at the Liverpool Clinical Trials Centre (LCTC) and underwent independent review at the research and development (R&D) offices of participating centres. Local R&D offices were sent the appropriate centre-specific information form to complete with the necessary authorisation signatures, plus any other documentation requested for review. A copy of local R&D approval was forwarded to the LCTC before the centre was initiated and patients recruited.

Consent from patients was obtained prior to participation in the trial and after a full explanation had been given of the treatment options, including the conventional and generally accepted methods of treatment. Patients were asked to read and review a patient information sheet and consent form (PISC) containing key information about the trial, and then complete, sign and date the consent form if they consented to take part in the trial. The right of the patient to refuse consent to participate in the trial without giving reasons was respected. After the patient entered the trial, the clinician remained free to give alternative treatment to that specified in the protocol, at any stage, if he/she felt it to be in the best interest of the participant. However, the reason for doing so was recorded and the participant remained within the trial for the purpose of follow-up and data analysis, according to the treatment option to which they have been allocated. Similarly, participants remained free to withdraw at any time from the protocol treatment and trial follow-up without giving reasons and without prejudicing further treatment.

Selection of centres/clinicians

The trial was run in NHS outpatient neurosurgical, pain and orthopaedic clinics and community-based services. Patients were recruited from units receiving patients from pooled tertiary referrals from general practitioners (GPs), allied health professionals and non-spinal consultants.

Participating centres were initiated once all regulatory approvals and trial-specific conditions (e.g. training requirements) had been met, and all necessary documents had been returned to the LCTC.

Centre/clinician inclusion criteria

-

TFESI performed according to protocol requirements (i.e. specified pharmaceutical agents available from pharmacy via local routine prescription routes).

-

Able to provide both treatments within 12 weeks of randomisation.

-

Principal investigator can be a representative of either neurosurgery or pain management (note that both specialties should be represented within the local research team).

-

Clinical equipoise.

-

Local R&D approval.

-

Completion and return of a ‘delegation of authority and signature log’ to the LCTC.

-

Completion and return of centre suitability assessment to the LCTC.

-

Signed contract between centre and sponsor.

-

Receipt of evidence of adherence to points (a) to (g) by the LCTC.

-

Complete progression through the green light checklist.

Centre/clinician exclusion criteria

-

Not meeting the inclusion criteria listed above.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the trial if they met the following criteria:

-

They had been diagnosed with lower extremity radiculopathy (sciatica).

-

They had sciatica secondary to prolapsed intervertebral disc (proven by magnetic resonance imaging).

-

The duration of their symptoms was between 6 weeks and 12 months. [Note that, if symptoms were episodic, then ‘duration of symptoms’ refers to the initial incidence of severe symptoms (i.e. the disc prolapse). It does not refer only to the most recent episode.]

-

They had leg pain non-responsive to conservative, non-invasive management.

-

They were aged 16–65 years.

-

They had previously undergone at least one form of conservative (non-operative) treatment (including but not limited to medication, physiotherapy and modification of daily activities) but this had not provided adequate relief of pain/symptoms.

-

They provided written, informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the trial if they met any of the following criteria:

-

They had a serious neurological deficit (e.g. foot drop/possible cauda equina compression).

-

They had previously undergone spinal surgery at the level of the prolapsed intervertebral disc.

-

Their current episode of sciatica had lasted longer than 12 months.

-

They were aged < 16 years or > 65 years.

-

They had not previously undergone any form of conservative treatment.

-

Patients with a contraindication for surgery and/or injection.

-

They were known to be pregnant.

Contraindications for both groups of treatment were assessed on a case-by-case basis by the health-care team, as per routine NHS practice and according to local policy.

Changes to the eligibility criteria

During the course of the trial the following changes were made to the eligibility criteria.

Protocol v3.0, 15 December 2014, wording amended for clarity

-

Inclusion criterion: ‘Newly diagnosed sciatica secondary to PID (proven on MRI)’ changed to ‘Newly diagnosed lower extremity radiculopathy (sciatica)’.

-

Inclusion criterion: ‘Diagnosed with lower extremity radiculopathy (sciatica) secondary to a lumber disc herniation’ changed to ‘Sciatica secondary to prolapsed intervertebral disc (PID) (proven on MRI)’.

-

Exclusion criterion: ‘Pregnancy’ changed to ‘Patient known to be pregnant’.

-

Exclusion criterion: ‘Not attempted conservative non-operative treatment for a minimum of 6 weeks’ changed to ‘Patient has not attempted any form of conservative treatment’.

Protocol v4.0, 5 May 2015, wording amended for clarity

-

Inclusion criterion: ‘Newly diagnosed lower extremity radiculopathy (sciatica)’ changed to ‘Diagnosed lower extremity radiculopathy (sciatica)’.

-

Inclusion criterion: ‘Severe leg pain non-responsive to conservative, non-invasive management’ changed to ‘Leg pain non-responsive to conservative, non-invasive management’.

-

Exclusion criterion ‘Neurological deficit (foot drop/possible cauda equina compression)’ changed to ‘Serious neurological deficit (e.g. foot drop/possible cauda equina compression)’.

Protocol v6.0, 21 March 2016, wording amended to improve recruitment

-

At trial inception, 6 months was believed to be an appropriate cut-off point because the main issue governing the selection of symptom duration was in terms of getting patients back to work faster, and for this reason the shorter time point of 6 months was selected. During the course of the trial, screening logs showed that the most common reason for subject ineligibility was pain duration of > 6 months. On review, the Trial Management Group (TMG) believed that there was clinical equipoise up to 12 months of symptom duration, after which time the disc prolapse itself was unlikely to change significantly radiologically and there may not be equipoise. It was therefore agreed that it was appropriate to extend the duration of symptoms to 12 months.

-

Inclusion criterion: ‘Duration of symptoms between 6 weeks and 6 months’ changed to ‘Duration of symptoms between 6 weeks and 12 months’.

-

Exclusion criterion: ‘Sciatica presentation for longer than 6 months’ changed to ‘Sciatica presentation for longer than 12 months’.

Protocol v7.0, 25 October 2017, wording amended for clarity

-

Inclusion criterion: ‘Patient willing and able to give consent’ changed to ‘Patient has provided written, informed consent’.

Recruitment

Screening

All patients who attended a participating trial centre following referral for sciatica secondary to PID (previously proven by MRI scanning) were prospectively screened for trial eligibility. Trial information was provided to patients at, or prior to, the clinic appointment. Potentially eligible patients (i.e. those who met the eligibility criteria listed in Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria) were invited to participate in the trial. At the clinic appointment, the patient was allowed time to discuss the trial, ask questions and decide whether or not to consent to take part in the trial. Owing to the pragmatic nature of the trial, patients provided written, informed consent at the initial visit without requiring further time to consider participation. Patients requiring additional time to consider consent were managed on a case-by-case basis at a centre level and an additional visit occurred if required.

A screening log was maintained at each trial centre to record all individuals screened for the trial and the eventual outcome. Reasons for non-recruitment were documented (e.g. not eligible, declined consent) and the information was used for monitoring purposes. Patients were asked if they would like to provide a reason for non-consent, although they were not obliged to do so. Reasons for non-participation that relate to patient preference were recorded with the undesired treatment listed when possible.

Baseline and eligibility

After obtaining written, informed consent, the baseline case report form (CRF) was completed to assess and confirm eligibility. The baseline CRF included a medical and neurosurgical history based on source data in the participant’s notes and eligibility was confirmed by an appropriately qualified doctor. The details of recruitment into the NERVES trial were recorded appropriately in the participant’s notes [i.e. details of eligibility confirmation (when and by whom), consent and entry into the trial].

Participants were also asked to complete a questionnaire booklet [incorporating the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ); modified Roland–Morris (MRM); Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI); visual analogue scale (VAS) for leg and back pain; the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L); and a Resource Use Questionnaire (RUQ)], with support from a health-care professional if needed. The participant-completed questionnaires were completed prior to randomisation, but after provision of consent. The ODQ collected primary outcome data for the trial and so it was important that it was completed accurately. Therefore, it was checked by centres and assistance was provided in completing it if required.

Informed consent

Informed consent is a process initiated prior to an individual agreeing to participate in a trial and continues throughout the individual’s participation. Informed consent is required for all patients participating in LCTC co-ordinated trials. In obtaining and documenting informed consent, the investigators were required to comply with applicable regulatory requirements and adhere to good clinical practice and to the ethics principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki.

There was discussion about the objectives, risks and inconveniences of the trial, and the conditions under which the trial would be conducted were provided to patients by staff with experience in obtaining informed consent. Patients were provided with a PISC describing in detail the trial interventions/products, trial procedures and risks (which was approved by an Independent Ethics Committee), and were asked to read and review it.

After the patient had read the document, the investigator explained the research trial, emphasising that participation in the trial was voluntary and that the participant could withdraw from the trial at any time and for any reason. All patients were given the opportunity to ask any questions and to discuss the trial and were given time to consider the information prior to agreeing to participate. A contact point where further information about the trial could be obtained was included in the PISC.

Patients who agreed to participate then signed and dated the informed consent document. Both the person taking consent and the patient personally signed and dated the form. A copy of the informed consent document was given to the patient for their records. The original copy was filed in the patient’s notes and a further copy of the signed consent form retained in the investigator centre file. One final copy of the consent form was sent to the co-ordinating centre (i.e. the LCTC). Centres were instructed to send the consent form within 7 days of informed consent being provided.

Patients were invited to participate in the trial at their clinical visit. Consent was sought at this initial visit, as there are no immediate routine follow-up visits. When patients requested longer to consider their decision about whether or not to participate, the local research team managed this. Potential participants could be invited to return to the clinic to provide consent at a later date, but the cost of attending the visit was not reimbursed as part of the trial. This is a reflection of current NHS practice, in which a patient would be given their treatment options and, in consultation with their health-care provider at that same appointment, would make a decision about how they wished to proceed.

The participant could, without being subject to any resulting detriment, withdraw from the trial at any time by revoking the informed consent. The rights and welfare of the patients were protected by emphasising to them that the quality of medical care would not be adversely affected if they declined to participate in this trial.

Randomisation

Patients were not randomised until:

-

fully informed written consent had been obtained from the patient

-

the baseline CRF had been accurately completed

-

full eligibility had been confirmed by a doctor.

Participants were randomised between groups in a 1 : 1 ratio, with variable block randomisation stratified by centre. Randomisation lists were created by a statistician who was not part of the main trial team.

Participants were randomised using an online web randomisation system. Designated members of the trial team at site, as detailed on the delegation of authority and signature log, were given training to use the online system and then provided with unique log-in details. Data captured on the baseline CRF were entered into the online system to confirm eligibility of the participant and provide information needed for treatment allocation. Randomisation occurred at the initial clinic appointment, if possible.

The online system allocated a unique randomisation number to the participant together with their treatment allocation. The LCTC received an e-mail notification that randomisation had taken place.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the interventions, blinding was not possible.

Trial treatments

Ionising radiation

In accordance with the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000,34 participants in the trial received a small exposure to ionising radiation in both groups of the trial. This was required to provide imaging for verification of the treatment level for both microdiscectomy and TFESI. The ionising radiation exposure required was part of the normal care pathway and the same exposure would be necessary outside this clinical trial context. There was no additional ionising radiation exposure to participants as a result of trial participation.

Group A: transforaminal epidural steroid injection

Standard nerve root blockade was completed, as per local policy/technique, using the lateral, foraminal portal of entry. All fluoroscopically guided techniques (e.g. CT or X-ray screening) were permitted to specify the correct level. Treating specialists included pain specialists, radiologists, anaesthetists, surgeons and other appropriately qualified medical professionals, as long as radiological level confirmation was incorporated into the procedure.

The NERVES trial is a pragmatic trial and, as such, the agents used were obtained and prescribed via normal NHS routes. The following injection regimen was followed when possible to minimise variability across the participating centres:

-

Injectate:

-

steroid [20–60 mg of triamcinolone acetonide (KENALOG™; Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals, Uxbridge, UK)]

-

local anaesthetic [0.25% levobupivacaine hydrochloride (2 ml) (Chirocaine®; AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA)].

-

As the NERVES trial is a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product, information regarding the pharmaceutical products used was provided to the MHRA. The following active ingredients were notified to the MHRA and, therefore, are also accepted for use if appropriate:

-

Steroid:

-

dexamethasone

-

methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrone®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA).

-

-

Local anaesthetic:

-

bupivacaine hydrochloride

-

lidocaine hydrochloride.

-

For the purpose of participant safety, centres were instructed to ensure that maximum doses were not exceeded (Table 1).

| Injectate | Maximum dose (mg) |

|---|---|

| Triamcinolone acetonide (e.g. KENALOG) | 80 |

| Levobupivacaine hydrochloride (e.g. Chirocaine) | 10 |

| Dexamethasone | 20 |

| Methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrone) | 80 |

| Bupivacaine hydrochloride | 10 |

| Lidocaine hydrochloride | 40 |

Note that, if the maximum dose was exceeded, then a data query form was produced at the LCTC and sent to the centre with a request for justification.

All participants randomised to group A received at least one therapeutic injection. As per local policy, participants could receive another injection if there was a favourable but partial response that could be boosted by further injections. Information about any further injections was collected.

The steroid/anaesthetic combination used in the TFESI was distributed from pharmacy via routine processes and so specific trial labelling was not required as per MHRA Exemption Regulation 46 of the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trial) Regulations 2004. 35 It is an off-label use of steroid, but is commonly accepted practice within the NHS and in the further medical field.

Group B: microdiscectomy

Standard microdiscectomy was performed as per local treatment protocols.

Treatment specialists at centres identified the correct side (left or right) and level prior to treatment, with level localisation advised as per local treatment protocols. Information on site and level was collected.

Treatment specialists were an orthopaedic or neurosurgical consultant or consultant equivalent (i.e. associate specialist), or a specialist trainee directly supervised by a consultant.

For both groups, treatment was given within 6 weeks of randomisation when possible and centres were instructed that treatment should occur within 12 weeks of randomisation to ensure valid collection of primary outcome data at the 18-week follow-up visit.

Additional treatments

The NERVES trial protocol allocated only initial treatment for sciatica, either microdiscectomy or TFESI. During the course of follow-up, some participants required further intervention for sciatica, as per routine NHS practice. Further clinical intervention was permitted for trial participants without the participant having to withdraw from the trial.

If a participant received additional treatment, information on the type of intervention (i.e. microdiscectomy or TFESI), the details of the treatment received and the reason were collected, and they remained in the trial.

Trial participants were able to cross over prior to receiving their initial treatment allocation without withdrawing from the trial (e.g. if they became unsuitable for the treatment they were initially randomised to). This was recorded on the treatment CRF with the reason for crossover indicated.

Schedule for follow-up

All follow-up visits were scheduled from the date of randomisation.

Each participant was followed up for 54 weeks following randomisation. During this time, participants attended scheduled follow-up visits. Table 2 shows the follow-up schedule. Any additional procedures provided to the participant and completed at the trial centre during this period were documented.

| Procedure | Screening/baseline (T = 0) | Follow-up schedule | Unscheduled visitsc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention T = 6 weeksa | T = 18 weeks | T = 30 weeksb | T = 42 weeksb | T = 54 weeks | |||

| Signed consent form | ✓d | ||||||

| Assessment and confirmation of eligibility criteria | ✓d | ||||||

| Review of medical history | ✓d | ||||||

| Review of concomitant medications | ✓d | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| ODQ | ✓d | ✓ | ✓b | ✓b | ✓ | ||

| RUQ | ✓d | ✓ | ✓ | ✓b | ✓b | ✓ | |

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓d | ✓ | ✓b | ✓b | ✓ | ||

| VAS scores for leg and back pain | ✓d | ✓ | ✓b | ✓b | ✓ | ||

| MRM outcome score for sciatica | ✓d | ✓ | ✓b | ✓b | ✓ | ||

| COMI score | ✓d | ✓ | ✓b | ✓b | ✓ | ||

| Trial intervention | ✓ | ||||||

| Pregnancy assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Physical examination | ✓d | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Treatment satisfaction (Likert scale) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Return to work | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Assessment of related AEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Assessment of additional interventions given to the participant during the trial period | ✓ | ✓ | ✓c | ||||

| Telephone follow-up of non-responders | (✓)e | (✓)e | |||||

Normal clinical practice would typically include a 3-month post-treatment follow-up. Therefore, participants were followed up at approximately 18 weeks post randomisation to align with routine clinical practice, and then again at 30, 42 and 54 weeks. To maintain feasibility, the 18-, 30- and 42-week visits could take place within a 2-week visit window on either side. The 54-week visit had an acceptable window of 54–62 weeks post randomisation. Participants could be seen at other times, as clinically indicated. Additional visits outside the trial protocol were recorded.

After randomisation, scheduled treatment and follow-up stages were as follows.

Treatment visit

Treatment details were recorded and the participant was presented with a RUQ booklet and asked to fill it in prior to their treatment. The centres co-ordinated provision of the RUQ booklet to the participants in preoperative assessment. Contraindications to treatment (such as pregnancy) were assessed by centres as per NHS policy and, therefore, no additional trial-specific assessments were conducted at this visit.

When a participant chose to not proceed with their allocated treatment prior to treatment being given, the participant was still expected to continue with trial follow-up and attend the follow-up visits. If a participant did not wish to continue in the trial then the date and reason for trial withdrawal were recorded.

The 18- and 54-week visits

-

A face-to-face follow-up visit (postoperative for the week 18 visit).

-

Centres were responsible for organising the follow-up within the visit window (specified in the e-mail when the participant was randomised).

-

Visits were ideally arranged to occur within the first 2 weeks of the visit window, when possible, giving the centre time within the visit window to take action if the participant did not attend their appointment.

-

Participants underwent a physical examination and data were collected, including concomitant medications, related AEs, additional treatments and work status.

-

Participants completed a questionnaire booklet (incorporating the ODQ, the MRM outcome score for sciatica, the COMI, a Likert scale for treatment satisfaction, VAS scores for leg and back pain, the EQ-5D-5L for QoL and the RUQ for costs).

-

Pregnancy was assessed when applicable.

Participants not attending visits (weeks 18 and 54)

The primary outcome data for the trial were collected at the week 18 visit and so centres were reminded of the importance of participants attending the week 18 visit throughout the recruitment period. Participants were contacted as per trust policy to urge them to attend.

When these attempts failed, centres were instructed to e-mail the LCTC to seek approval to post out the questionnaire booklet, explaining the circumstances.

Centres were instructed that visits should be arranged initially for the first 2 weeks of the visit window to give time for the questionnaire booklet to be sent out by post and completed by participants within the visit window in cases of non-attendance and then returned in a pre-paid envelope to the LCTC.

When visits did not take place, centres were instructed to telephone the participant to try and retrieve as much information as possible over the telephone.

For the week 18 visit, centres could use a telephone call to collect primary outcome data (i.e. the ODQ section within the questionnaire booklet) in exceptional circumstances, with agreement from the LCTC.

Weeks 30 and 42 (postal)

-

Centres posted the questionnaire booklet to participants at the start of the weeks 30 and 42 window, with a pre-paid envelope for the participant to return the completed booklet to the LCTC.

-

The date that the questionnaire booklet was posted was recorded by centres.

-

When a response had not been received (notified by the LCTC), the centre research nurse telephoned the participant to prompt completion and return of the questionnaire booklet and offer any help required to ensure that the questionnaire booklet was completed accurately.

Data collection and management

Data collection tools

Procedures for assessing efficacy

Efficacy of trial treatment was measured through the period of the trial using a number of outcome measures:

-

ODQ at 18 weeks after randomisation (approximately 3 months post treatment).

-

ODQ at 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

-

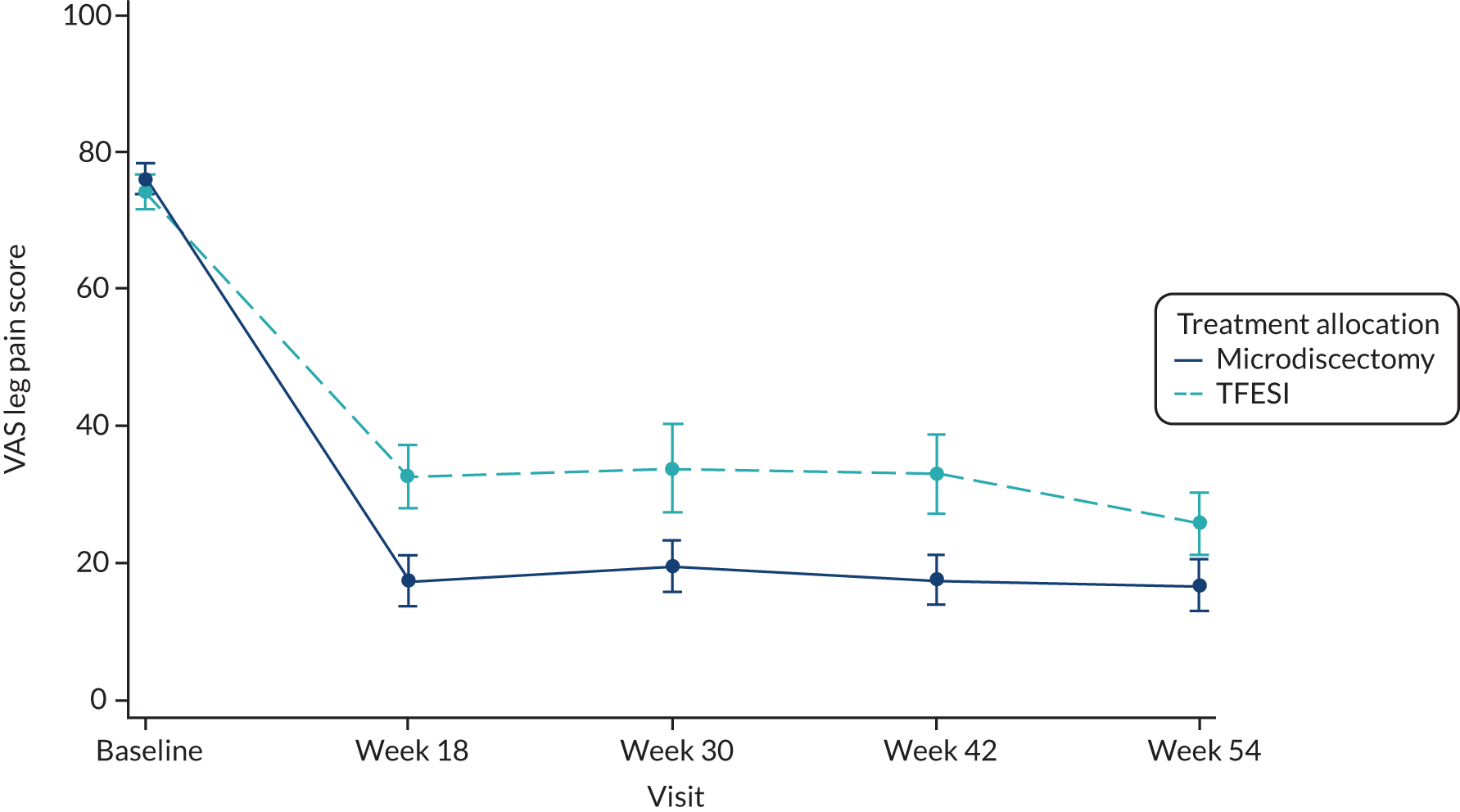

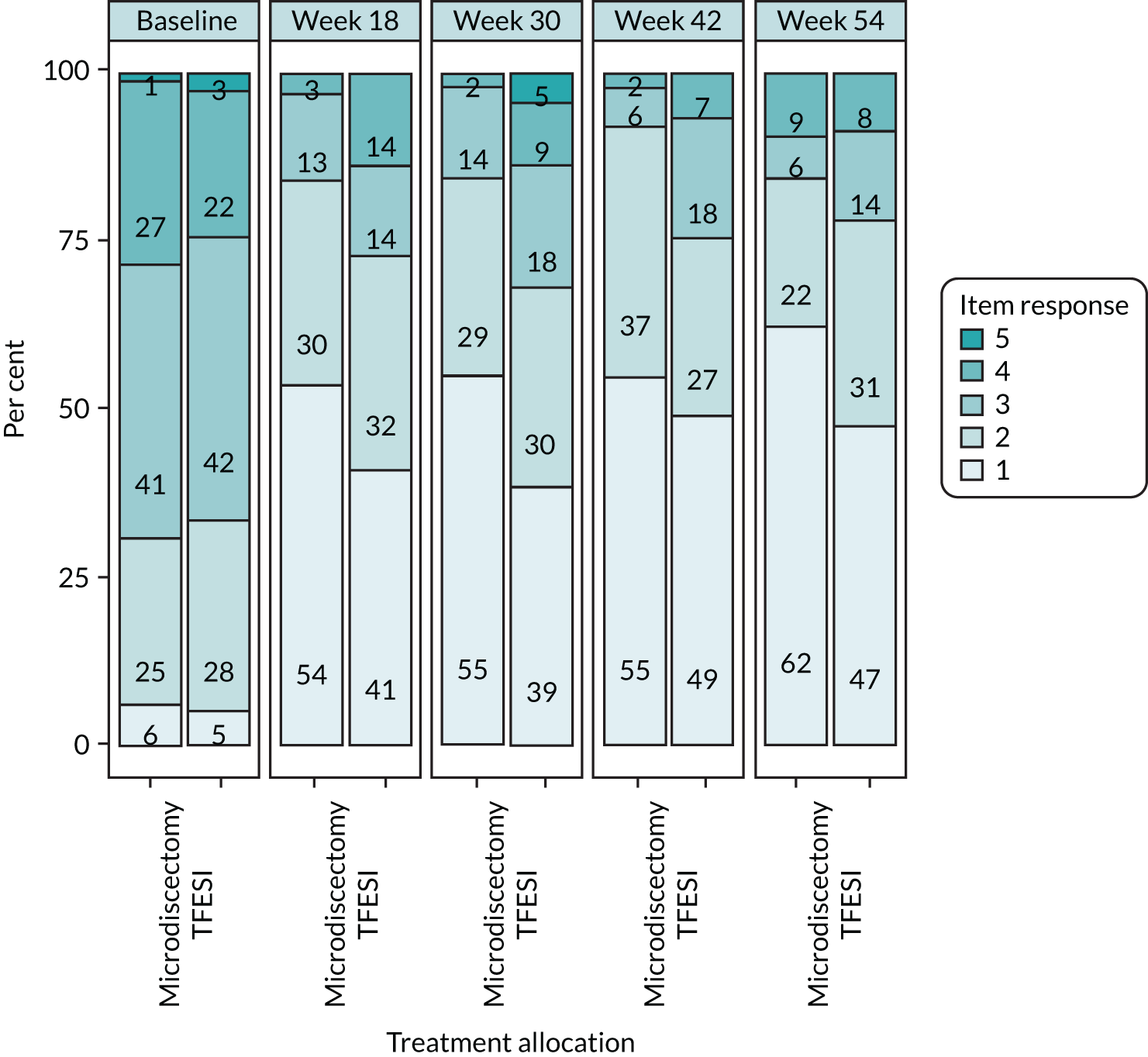

VAS for leg pain at baseline and at 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

-

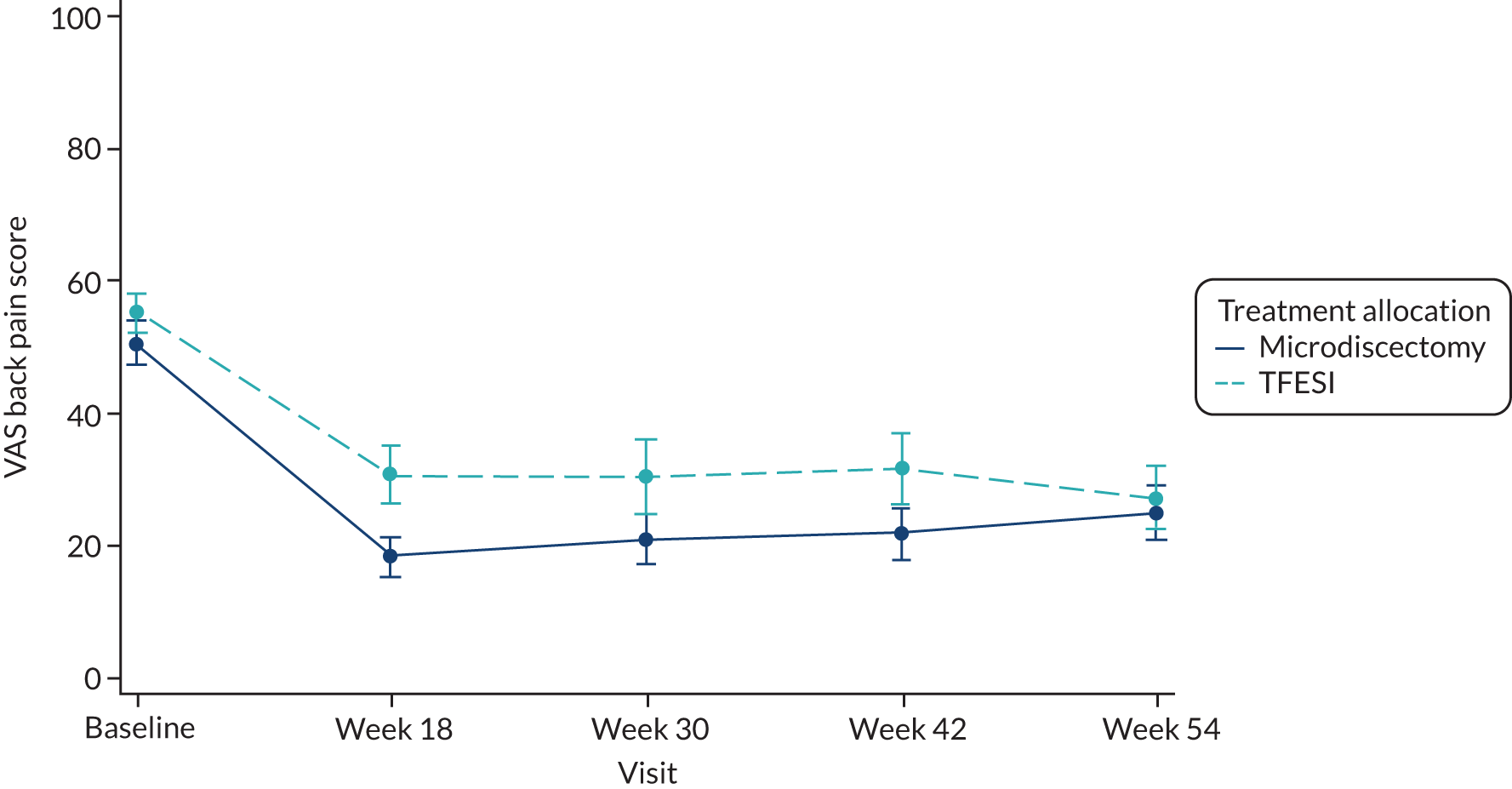

VAS for back pain at baseline and at 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

-

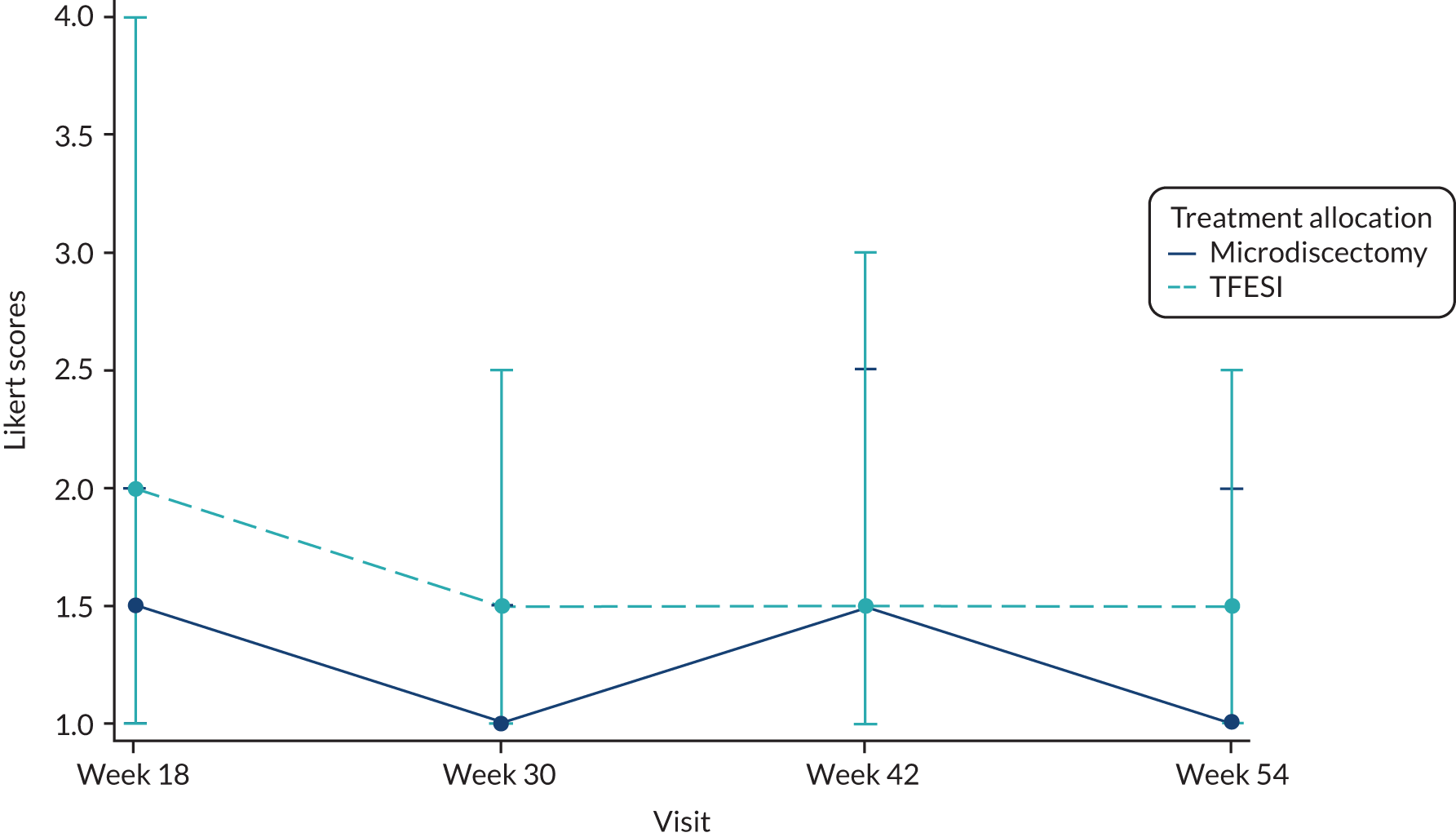

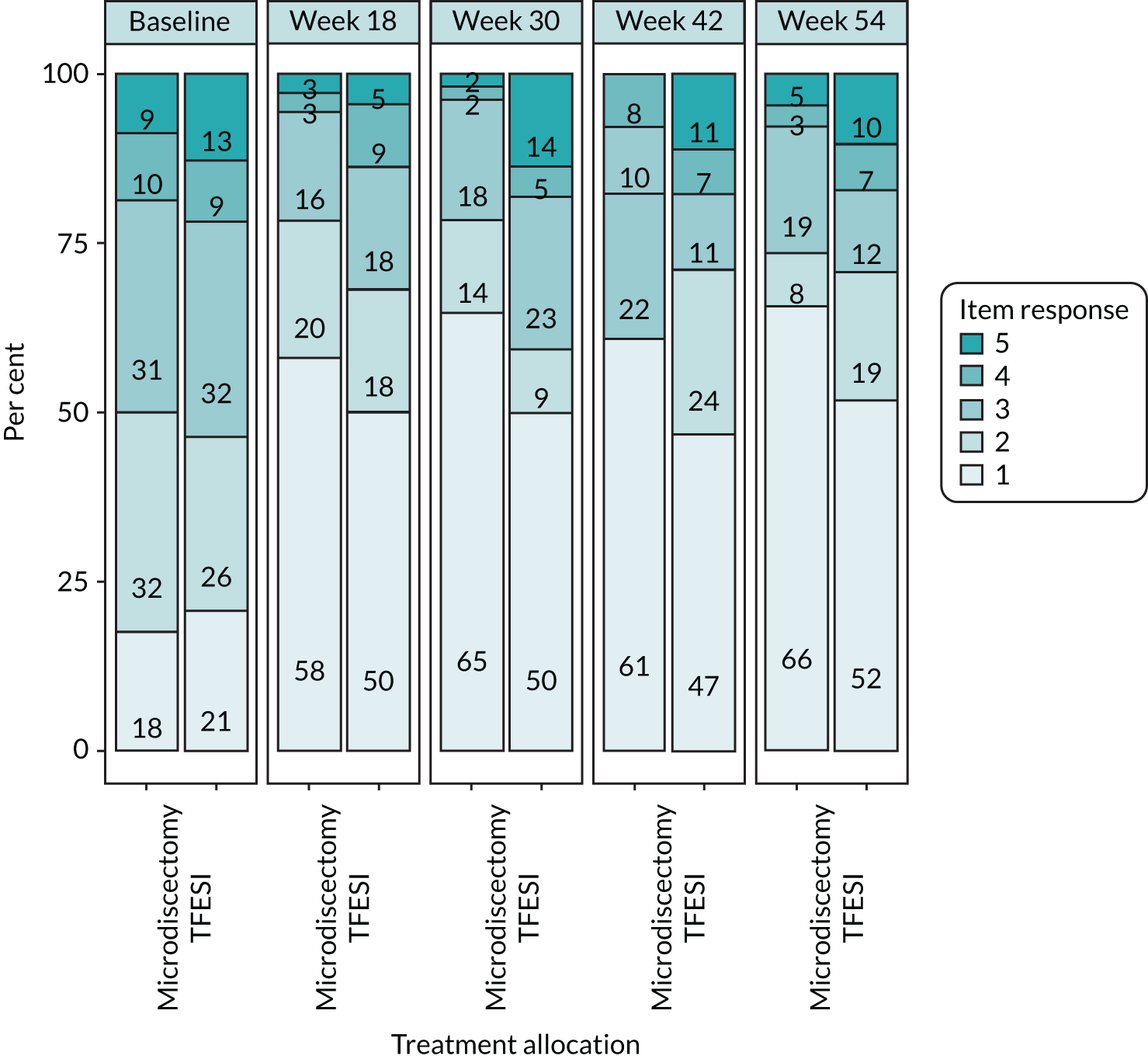

Likert scale to assess patient treatment satisfaction at 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

-

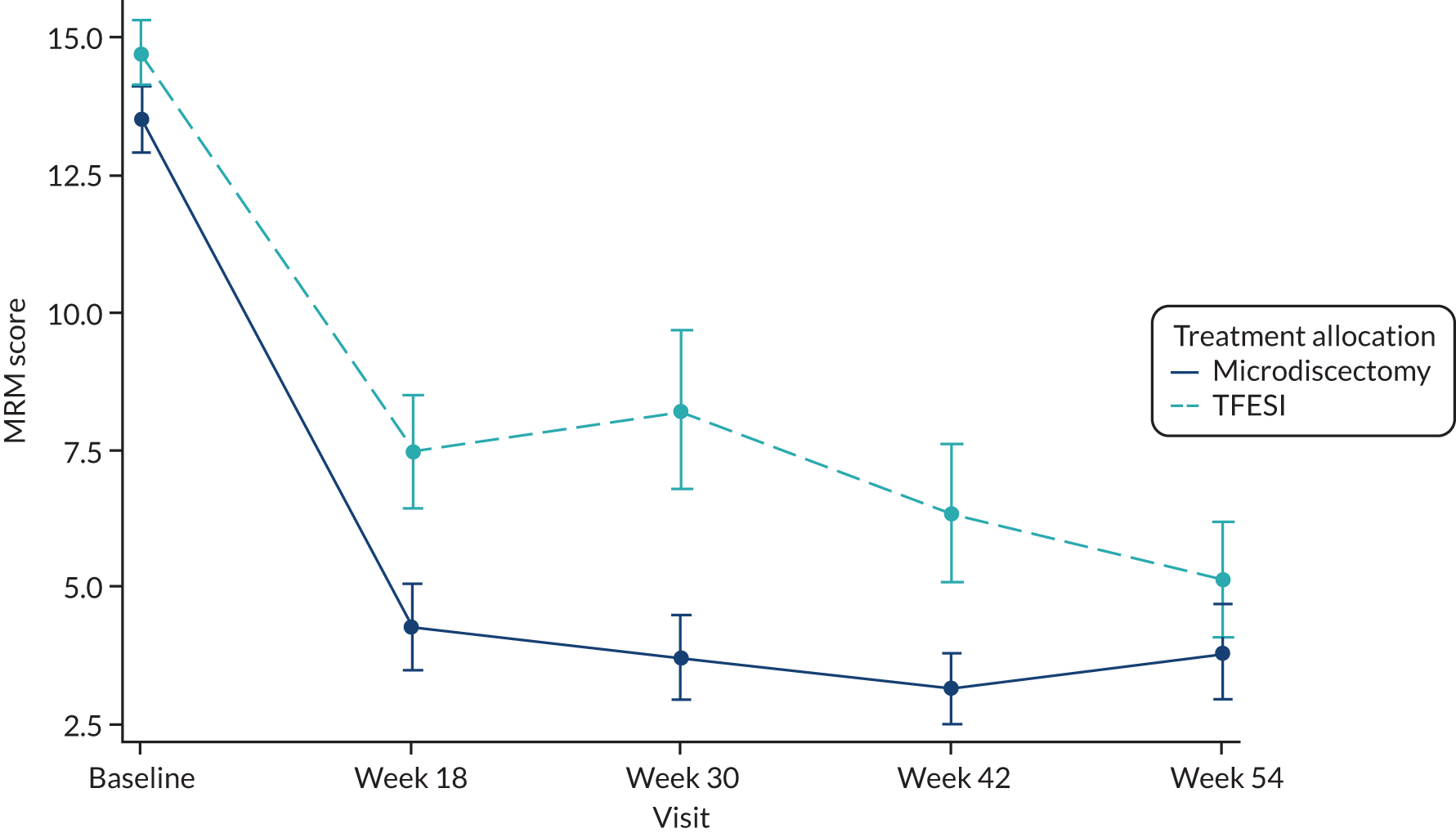

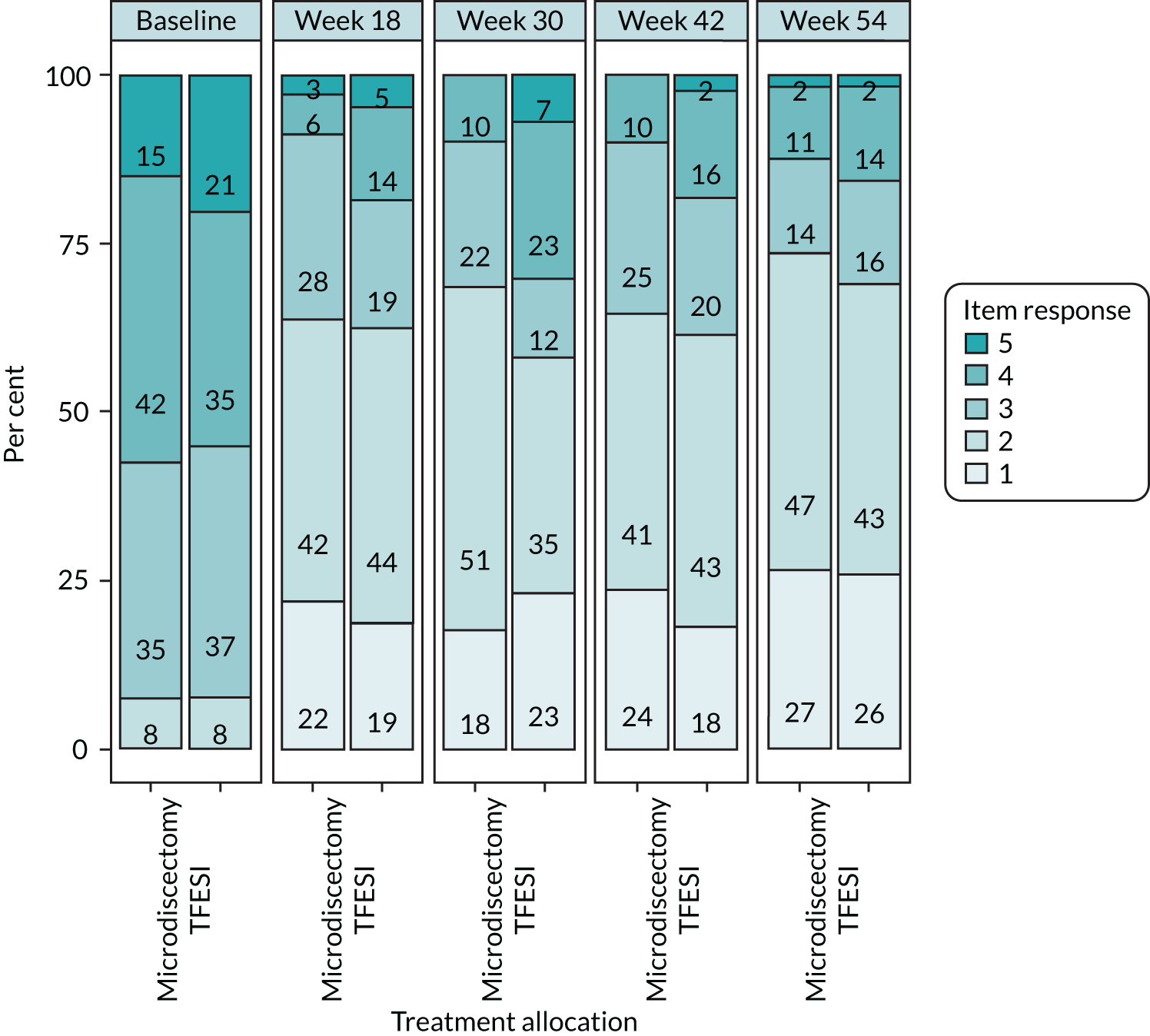

MRM score for sciatica at baseline and at 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

-

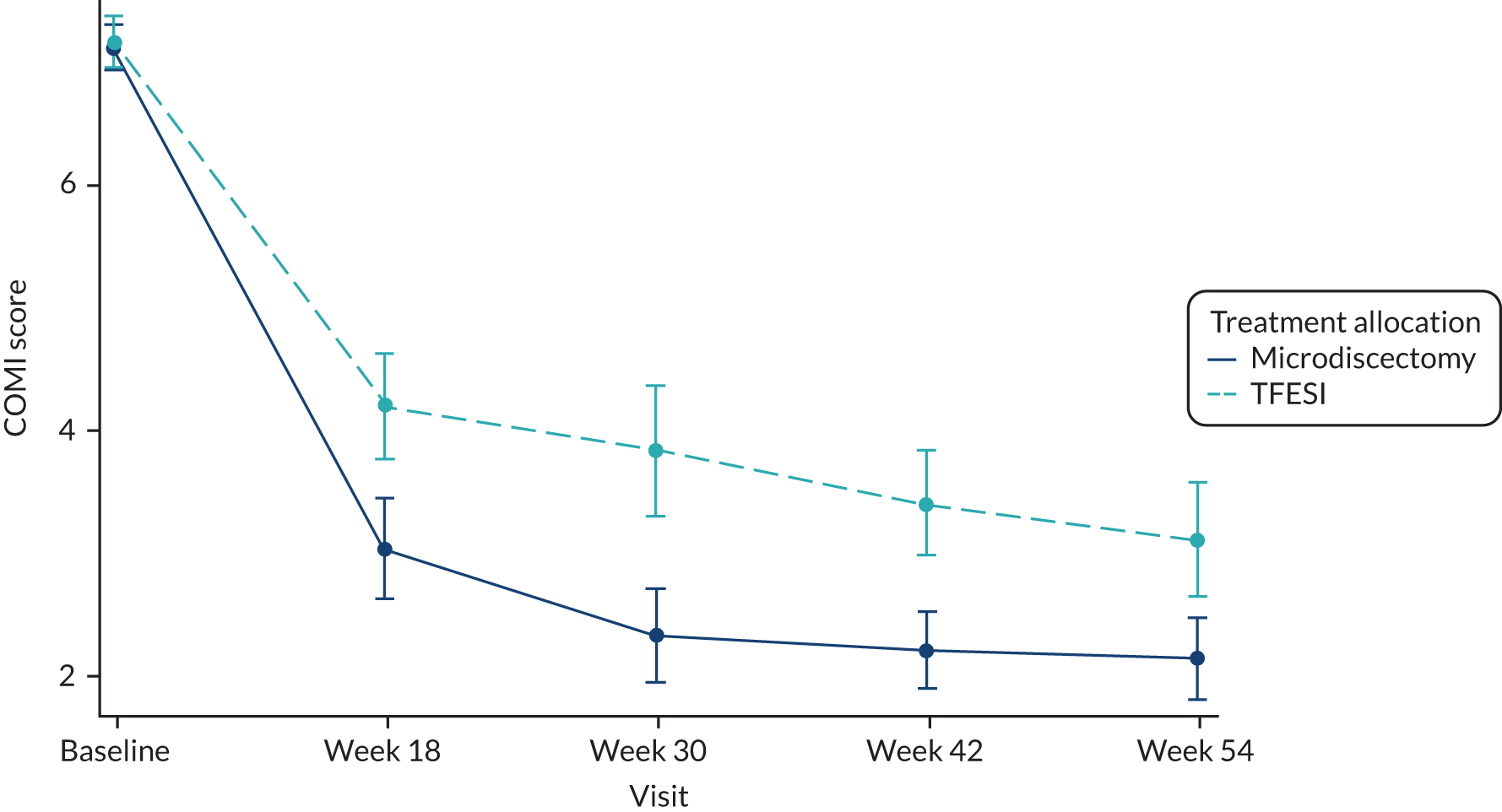

COMI score at baseline and at 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

-

work status (i.e. return to work and work days lost) at baseline and at 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks after randomisation.

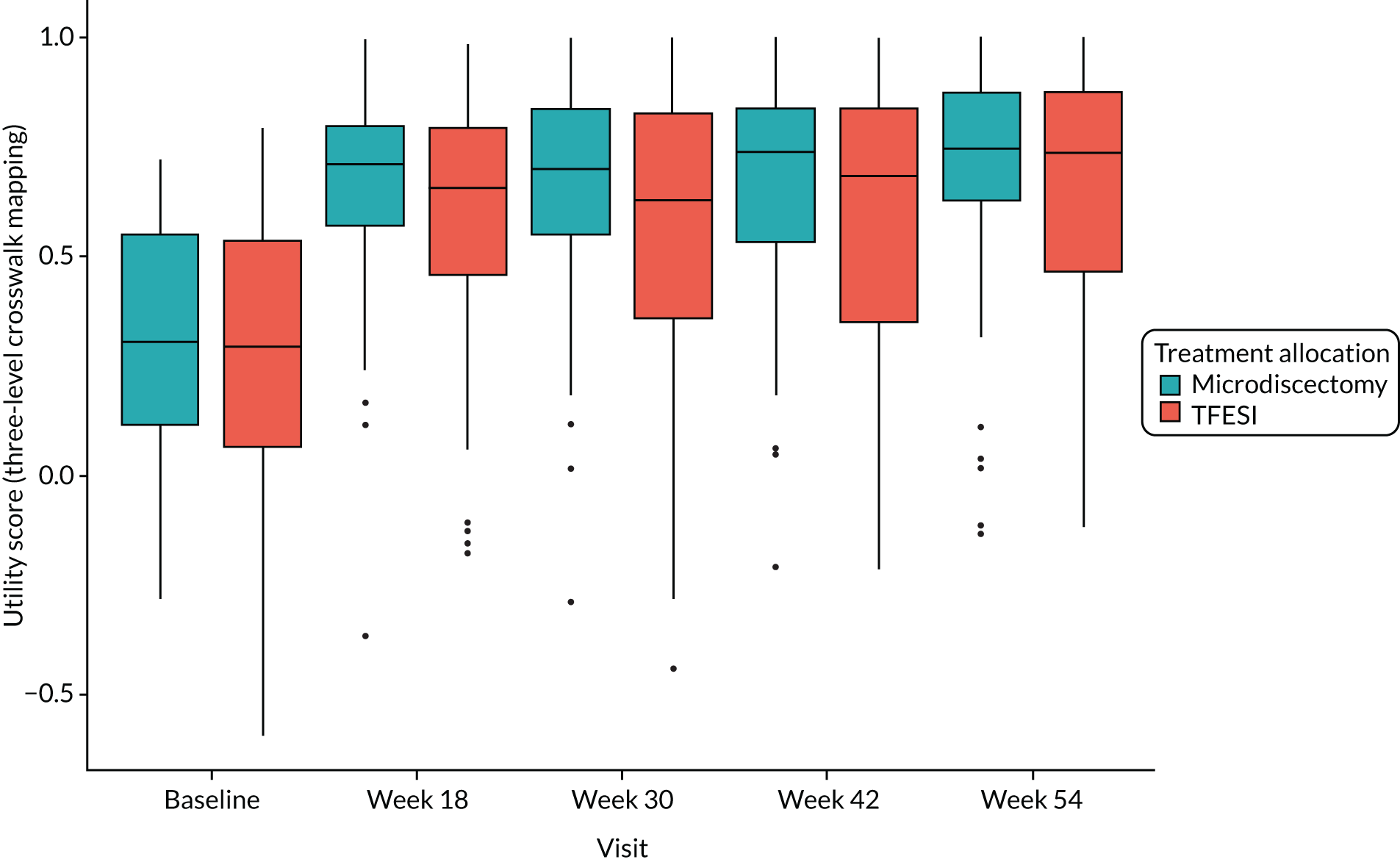

The cost-effectiveness of trial treatment, expressed as the incremental cost per QALY, was based on the following measures:

-

EQ-5D-5L questionnaire

-

RUQ

-

HES

-

concomitant medications.

Procedures for assessing safety

An assessment of AEs was undertaken at each trial clinic visit post treatment. These reviews were carried out by the principal investigator or delegated research staff.

Participant-reported outcomes

Participants were asked to complete the following participant-reported outcome measures at baseline, 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks post randomisation:

-

ODQ

-

MRM outcome score for sciatica

-

COMI score

-

Likert scale for treatment satisfaction

-

EQ-5D-5L

-

VAS scores for leg and back pain

-

health-care resource use and participant costs (including time off work).

The questionnaire booklet was provided to the participant at the scheduled clinic visits (at baseline and at the 18- and 54-week follow-ups) and completed in clinic. The RUQ booklet was completed at the treatment visit before treatment and was provided to the participant in preoperative assessment.

Completion of these questionnaires was an important part of the trial. Particular emphasis was given to part 1 of the questionnaire booklet (i.e. the ODQ) because it was used to collect primary outcome data for the trial. It was therefore crucial that research staff at centres offered any necessary support to participants to ensure the questionnaires were completed correctly and returned to the LCTC either by centres or by the participant in accordance with the schedule for follow-up. The questionnaires took approximately 15 minutes to complete and participants were advised of the extended visit time prior to their appointment.

All questionnaires completed at baseline were completed after consent had been provided and prior to randomisation.

Sample size

The primary outcome measure of ODQ has > 30 years of validation and is supported by Outcome Measures in Rheumatology, an independent initiative of international health professionals and patient research partners interested in outcome measures and measurement methodology, especially in rheumatology. Deyo et al. 36 has recommended the use of ODQ as part of the core outcome measures for low back research, along with the use of EQ-5D. The scale ranges from 100 (extreme disability) to 0 (extreme ability). A change of 10 points has been widely regarded in the literature as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). One study,37 specifically addressing this issue, has suggested a range of 10.5–15 points as clinically important. ODQ has > 30 years of validated, published data pertaining to low back pathology and radicular symptoms. It has formed the basis for previous HTA trials exploring sciatica and will allow useful comparisons to be made with previous data. A recent study by Chiarotto et al. 38 has sought to specify a core outcome set for low back pain (not specifically sciatica) and the authors have recommended the use of four items: (1) physical functioning (either ODQ or MRM scores), (2) numerical pain rating score for pain intensity, (3) health-related QoL assessment (although no consensus reached, the Short Form questionnaire-12 items or Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System were recommended) and (4) mortality. Although published after our trial conception, we have collected all of these outcomes apart from EQ-5D-5L for the health-related QoL and VAS for the pain intensity score.

Original trial sample size calculation

A total of 172 participants was required to detect a difference of 10 points between the two groups on the ODQ at a 5% significance level with 90% power. This assumed a standard deviation (SD) of 20 points based on similar populations in previous published trials. 18,36,37,39,40 The previous large and well-carried out WEST, based in the UK, suggested a baseline ODQ SD of between 16 and 18 points. 18 Baseline ODQ data were collected on 11 potentially eligible patients from the fast-track sciatica clinic at the Walton Centre, Liverpool, and this generated a SD of 14.4 points, well under the assumed value. The initial target sample size for the trial was 200 patients, which would allow for a 10% rate of missing outcome data. Of the originally planned seven centres involved, allowing for one to have difficulties opening, this would require recruitment of 30 patients in total from each participating centre and 50 patients from the lead centre.

Revised sample size calculation for the primary outcome

The original sample size calculation did not assume any correlation between baseline and follow-up ODQ scores, as no data were available to estimate this. The sample size calculation was revisited during the trial with the agreement of the trial oversight committees. Based on a blinded analysis of the correlation between baseline and follow-up ODQ scores in the first 47 trial participants to have outcome data available, the correlation was estimated as 0.49.

Using this estimate, our revised sample size to achieve 90% power was 66 participants per group. Allowing for 10% loss to follow-up gives a revised target of 74 participants per group (i.e. 148 participants total).

Internal pilot study

An internal pilot study was included in the trial design. The study targeted two centres to open first to collect 6 months of recruitment data before progressing to a full trial. These centres, the Walton Centre, Liverpool, and Salford Royal, Manchester, were identified to cover recruitment of participants within specialty and mixed care settings.

The aim of the internal pilot study was to assess the feasibility of recruitment and the rates of potential crossover due to patient preference or treatment failure. The criteria for progression to a full trial were:

-

at least 30 patients recruited

-

a consent rate of ≥ 40% or more

-

< 10% of patients unhappy with allocation and receive the alternative treatment

-

< 50% of patients in the injection group proceed to surgery.

Changes to the protocol

The protocol has been previously published. 41 The study opened on protocol version 3.0 and the final approved version was 8.0, which contains a detailed list of the protocol changes [see www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/12/201/10 (accessed 16 July 2020)]. Table 3 lists the key protocol changes.

| Protocol version (date) | Key amendment |

|---|---|

| 3.0 (15 December 2014) |

Minor amendment Eligibility criteria changes: inclusion criteriaEligibility criteria changes: exclusion criteriaAdditional expected AEs associated with microdiscectomy and TFESI added Removal of requirement for investigators to assess expectedness when recording AEs ‘Do not include’ list for SAEs reporting updated Minor amendments for clarity and minor corrections |

| 4.0 (5 May 2015) |

Minor amendment Eligibility criteria changes: inclusion criteriaEligibility criteria changes: exclusion criteriaCentre inclusion criteria addedClarification of treatment timelines addedAddition of an expected TFESI regimen specifically:Addition of text clarifying AE reporting requirements specifically defining ‘reactions’ (related to IMP) vs. ‘events’ (related to procedures) Minor amendments for clarity and minor corrections |

| 5.0 (19 August 2015) |

Substantial amendment Addition of statistician sign-off and addition of IRMER |

| 6.0 (21 March 2016) |

Substantial amendment Eligibility criteria changes: inclusion criteriaEligibility criteria changes: exclusion criteriaAddition of CT scanning for guidance of the TFESI injection Addition of text outlining the procedures for follow-ups at weeks 18, 30, 42 and 54 weeks and clarification of the process for dealing with non-attendance at weeks 18 and 54 Addition of text clarifying SAE assessment of expectedness process, specifically that the chief investigator will undertake the assessment Addition of ‘Recurring prolapse of the disc’ to expected list of events for microdiscectomy table Process of reporting AEs has been reduced to one flow chart to clarify the procedure. The flow chart includes requirements to report pregnancies and any deaths Minor amendments for clarity and minor corrections |

| 7.0 (25 October 2017) |

Substantial amendment Target population changed from 200 to 148 participants Eligibility criteria changes: inclusion criteriaStudy duration changed from ‘54 weeks’ to ‘54–60 weeks’ List of accepted active ingredients for use in the TFESI group added Table of expected maximum doses for each active ingredient used in the TFESI group added Section added providing guidance on what should be done when participants do not attend the 18- and 54-week visits Option for collection of week 18 primary outcome data to be collected by telephone as ‘last resort’ added ‘Pregnancy’ section added allowing assessment of pregnancy throughout trial Statement added clarifying patients should not be withdrawn unless specifically requested ‘Revised Sample Size’ section added Pharmacovigilance section modified throughout for clarification:Definitions and responsibilities defined for assessment of expectedness: chief investigator’s responsibility (not the principal investigator) based on relevant safety information available at the time Expected AE tables reworked for clarity Addition of expected AEs ‘anaphylaxis’ and ‘low-pressure headache’ added to expected AE tables ‘Overdose of any medication without signs or symptoms’ added to non-reportable list Safety reporting period defined as ‘from intervention up to and including the week 54 follow-up visit’ Process for completing SAE forms amended as per the LCTC processes Addition of ‘urgent safety measures’ and ‘protocol deviations and serious breaches’ sections Minor amendments for clarity and minor corrections |

| 8.0 (10 April 2019) |

Substantial amendment Change in lead sponsor contact/signatory Minor amendments for clarity and minor corrections |

Patient and public involvement

The trial team collaborated with patient contributors throughout the trial, all of whom had personal experience of the condition and/or interventions being examined.

-

Prior to funding application submission, a patient representative reviewed the trial design to confirm agreement with the principle of the trial.

-

Patient representatives reviewed the full funding application prior to submission.

-

Members of the public were involved in the development of the PISC by providing feedback.

-

Patient representatives were recruited to the TMG and Trial Steering Committee (TSC), both of which were actively involved at the start of the trial.

-

Once the centres had been opened and recruitment was under way we entered a phase of the trial in which the TMG discussions focused on issues relating to governance and internal trial management. During this period, it was more difficult to engage our patient representatives and to ensure that the discussions were relevant and interesting to them. The TMG patient representative stopped attending meetings during this period and the TSC patient representative resigned in March 2017.

-

In December 2018, two patient representatives were recruited to join the TMG [via the INVOLVE website (URL: www.invo.org.uk)] with the purpose of helping us to design our end-of-trial information and ensure that the results from the trial are understandable and accessible, particularly to those who have suffered from sciatica.

-

The new TMG patient representatives have reviewed this report and we intend to involve them in producing our end-of-trial information. We hope to encourage patient representative co-authorship and co-presenting of our findings to patient and clinical audiences to ensure that the impact of the findings are maximised.

Compliance with Intervention

The LCTC monitored compliance with the randomised trial intervention through completion of CRFs at centres recording the intervention given and the allocation provided by the online randomisation system. Any deviations from the randomised intervention were explored with centres. As the NERVES trial was a pragmatic trial and the interventions were expected to reflect local NHS policy, the rates of compliance with the interventions were expected to vary between NHS sites.

Trial oversight and role of funders

Trial Management Group

The TMG was a multidisciplinary team that comprised the chief investigators, several co-investigators, patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives, a sponsor representative, health economists and members of the LCTC. The TMG was responsible for the day-to-day clinical and practical aspects of the trial.

Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

The Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (IDSMC) comprised an independent chairperson, an expert in the field of pain and two independent members (one was an expert in the field of neurosurgery and one was an expert in medical statistics). The main responsibilities of the IDSMC was to safeguard the interests of the NERVES trial participants, assess the safety and efficacy of the interventions during the course of the trial, and monitor the overall progress and conduct of the trial. The IDSMC met at least annually during the course of the trial and provided recommendations to the TSC. Reports to the IDSMC were produced by the statistical team at the LCTC.

Trial Steering Committee

The membership of the TSC included an independent chairperson, an independent expert in the field of pain, an independent expert in the field of neurosurgery and an independent statistician, as well as representatives from the TMG. Observers from the sponsor and the funder were also invited to meetings. The TSC met at least annually, shortly after the IDSMC met and their main role was to provide overall oversight of the trial.

Trial funder

The membership of the oversight committees was suggested by members of the TMG to the trial funders and appointed by the funders with their constitution following funder requirements.

Statistical methods

The main features of the analyses were specified in the protocol and a separate detailed statistical analysis plan (see Report Supplementary Material 1) was developed prior to randomisation codes being released.

All efficacy outcomes were analysed using the intention-to-treat principle as far as practically possible. Safety outcomes were reported based on actual treatment received. All applicable statistical tests were two-sided and used a 5% significance level. No adjustments for multiplicity were made for the secondary outcomes.

Baseline data for continuous variables are presented as both means and SDs, and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables are presented using frequencies and percentages.

The primary outcome variable (i.e. ODQ at 18 weeks) was compared between groups using a linear regression model, adjusting for the stratification variable centre and baseline ODQ. The potential impact of missing data on the primary outcome results was explored using multiple imputation analysis. An extended model was also fitted, adjusting for age, sex, duration of symptoms, body mass index (BMI) and estimated volume of canal occupied by disc prolapse as shown on MRI scan. An additional post hoc model added an adjustment for level of disc prolapse.

The secondary outcomes measured at multiple time points were analysed using repeated measures random-effects models, adjusting for baseline outcome score, time (as a continuous variable) and a time–treatment interaction. The time–treatment interaction term was dropped in models when it was found to be non-significant (p > 0.05). A post hoc analysis using joint modelling of the same longitudinal outcome data and the time to study dropout was undertaken. The aim was to assess sensitivity of the results for potentially informative dropout from the study.

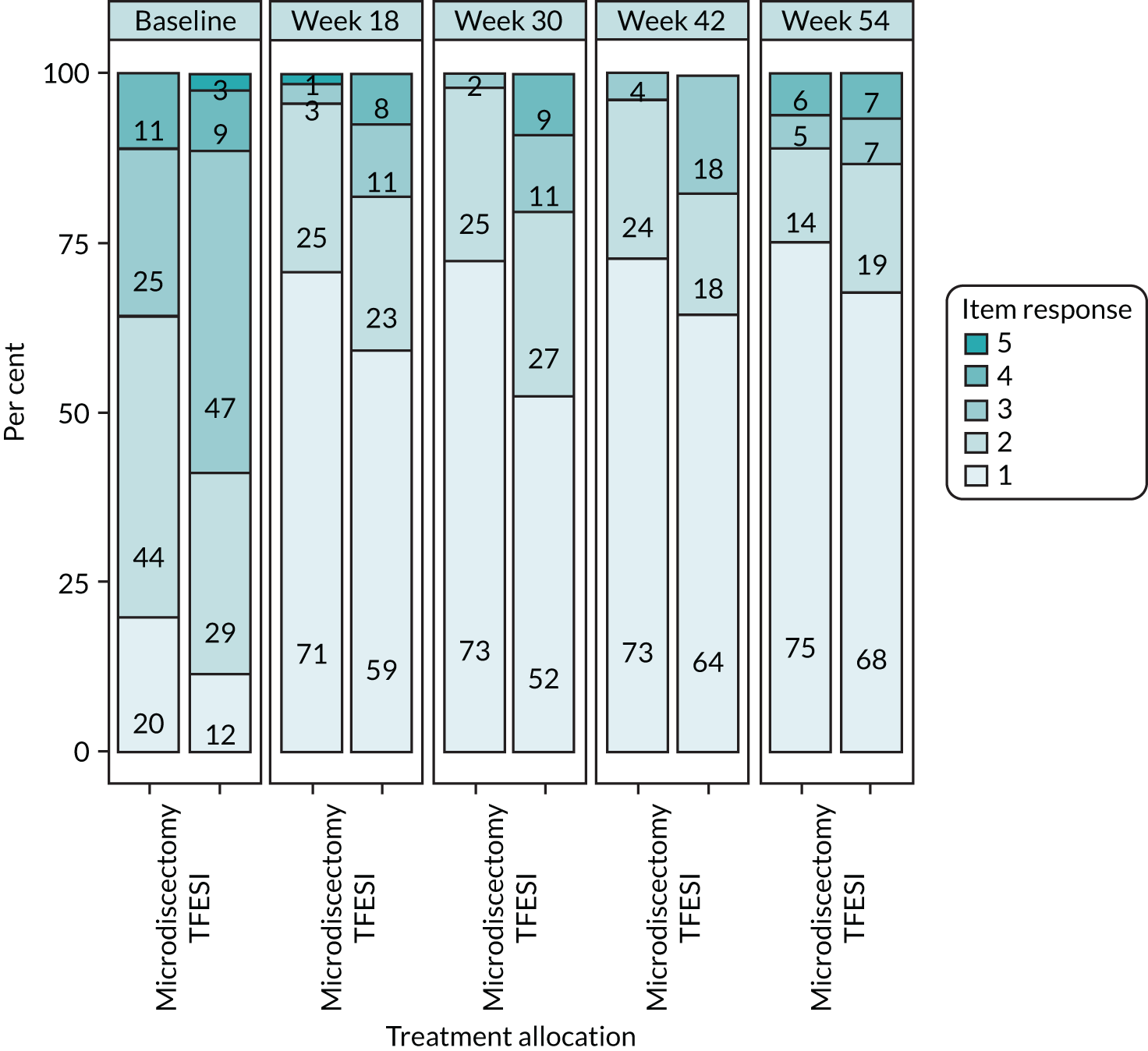

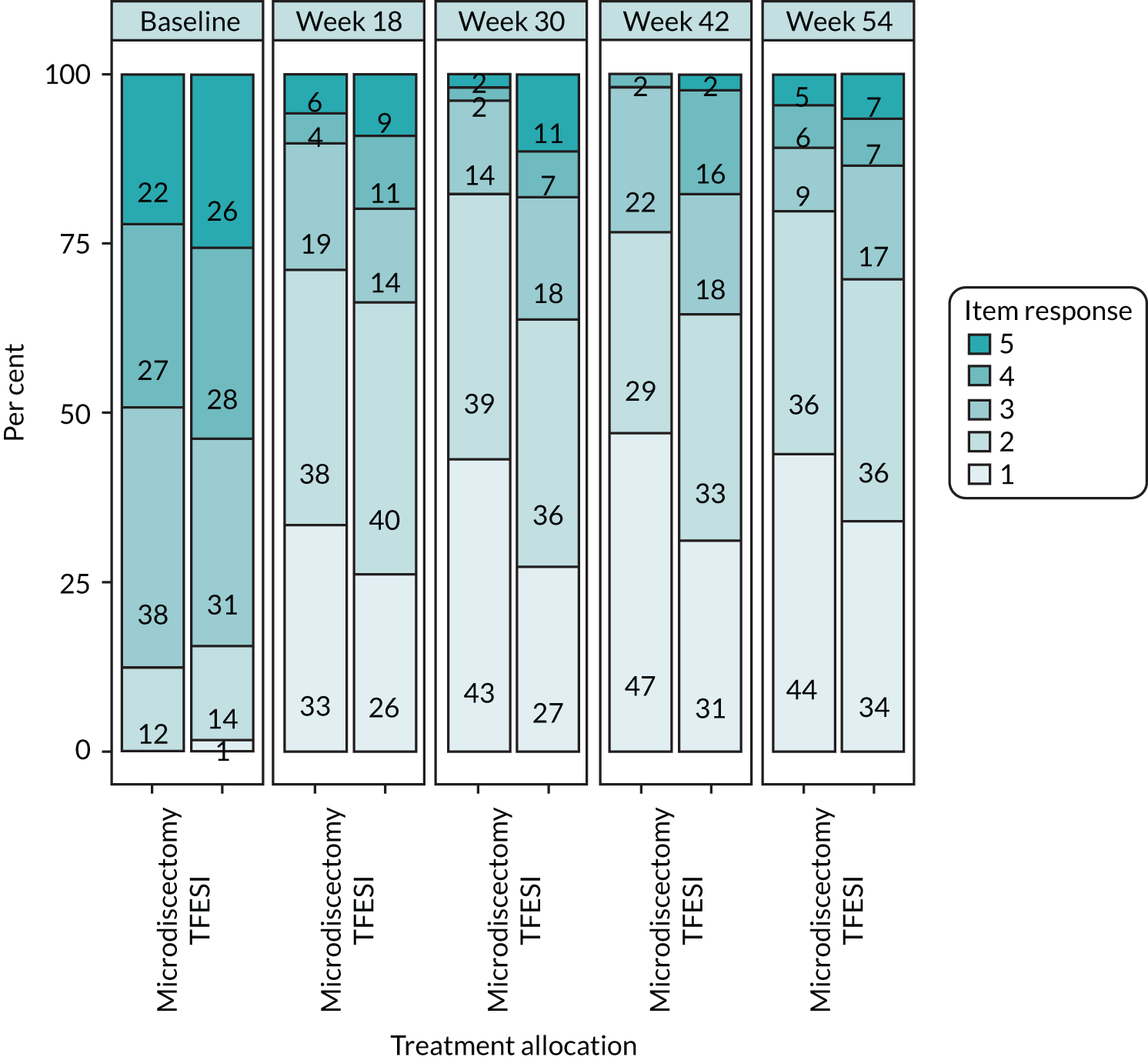

The secondary outcome of participant satisfaction was compared between groups using a Mann–Whitney U-test. The satisfaction with care outcome was measured using a two-item questionnaire with a 1- to 5-point Likert scale. The average of the two items was taken, with possible values ranging from 1 to 5 and lower values indicating higher levels of satisfaction. The return-to-work status was compared using a chi-squared test.

Safety data on AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) are presented descriptively, with no inferential statistics.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness results

Screening and recruitment

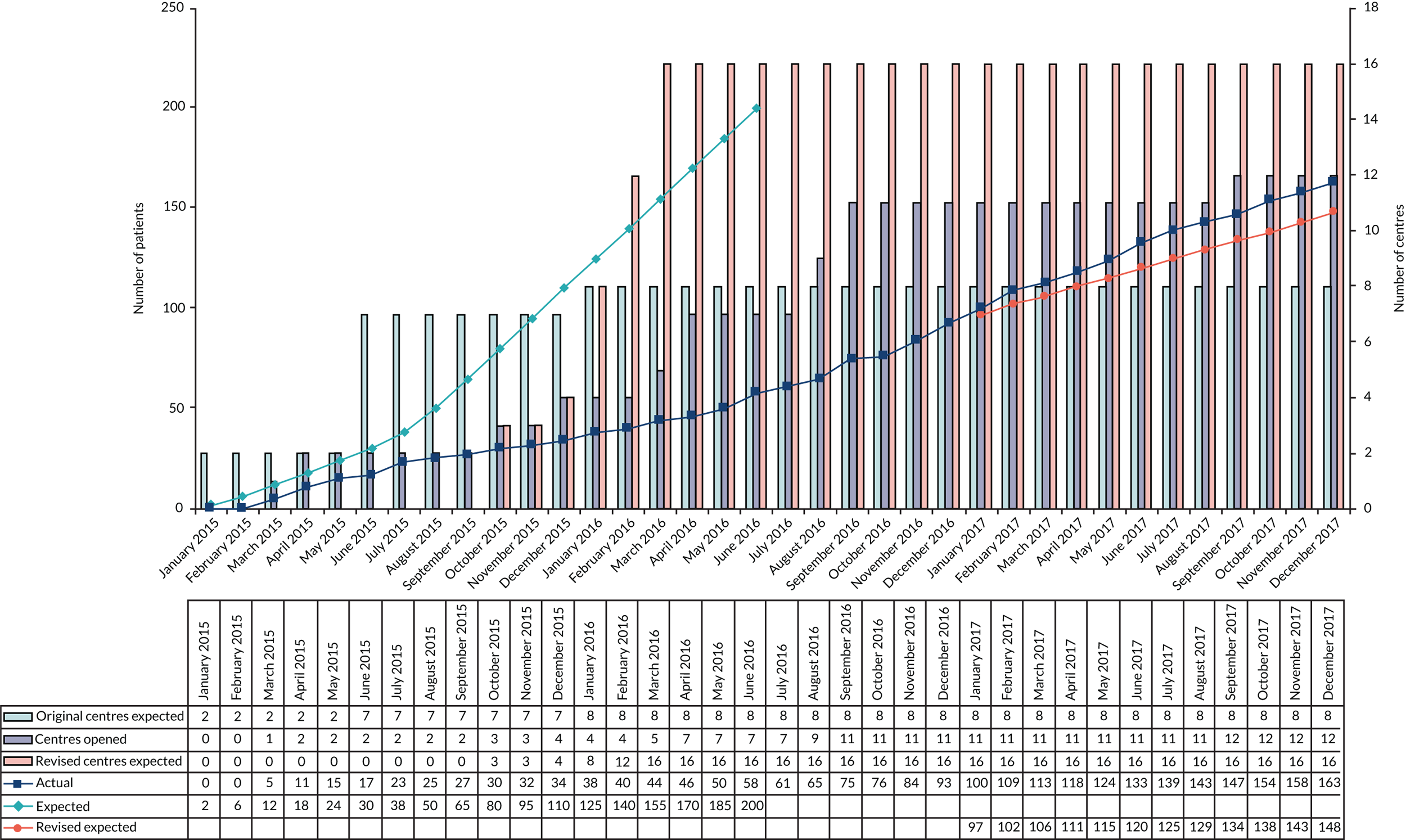

The trial opened to recruitment on 4 March 2015 and closed on 9 July 2018 after the final follow-up of all participants had been completed. A total of 1055 participants were screened for eligibility from 12 centres and a total of 163 participants were randomised from 11 of the 12 centres. Of the participants screened for eligibility, 723 (69%) were found to be ineligible. Of those eligible and approached for consent, 163 (49%) consented and were randomised into the trial.

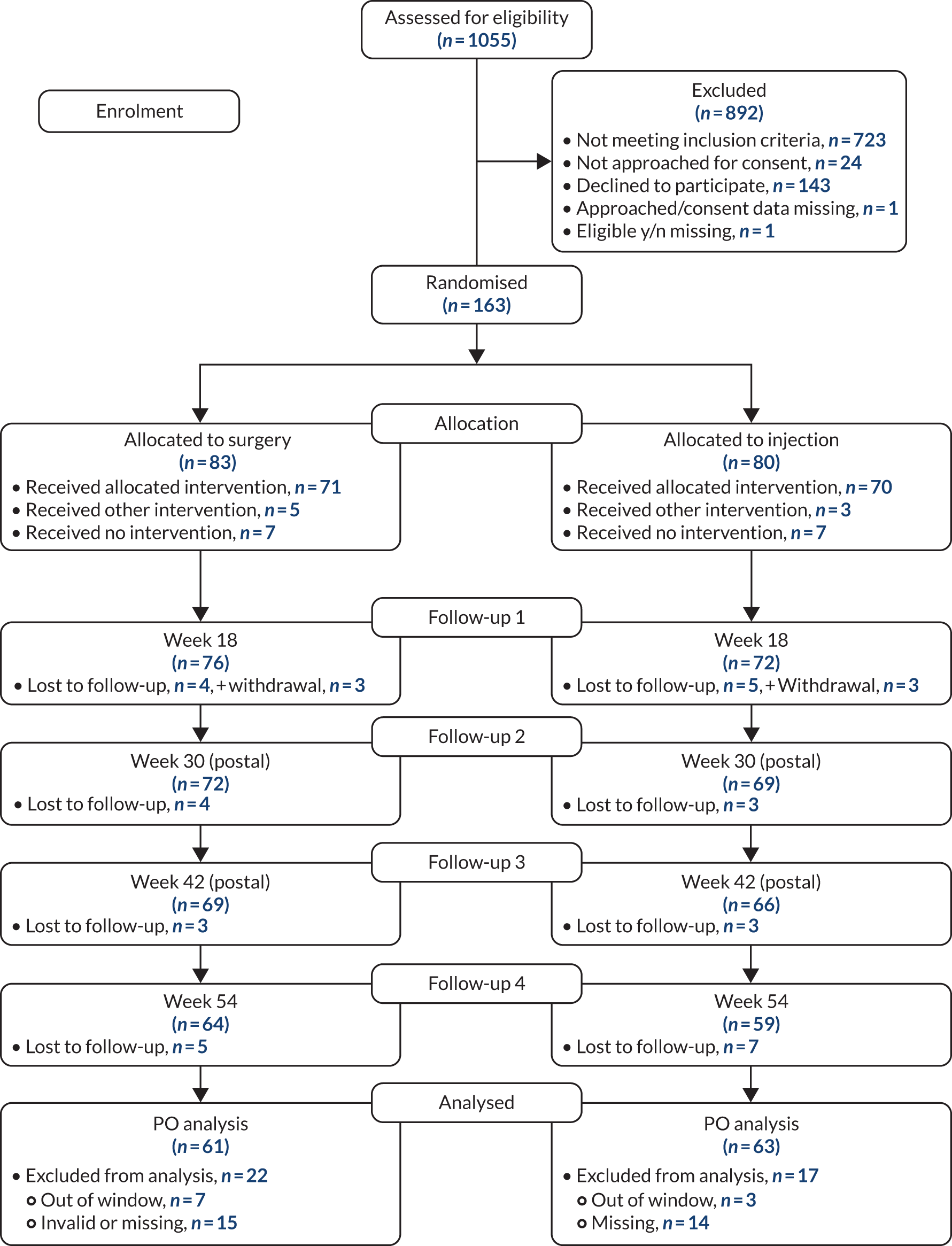

Figure 2 shows the participant flow from screening to consent and randomisation.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for all trial participants. PO, primary outcome; y/n, yes/no.

Internal pilot

The internal pilot phase of the trial was reviewed by the IDSMC in September 2015 after 25 participants were recruited from two centres. The committee assessed the recruitment, consent rates, treatment switches and crossover rates, and recommended that the trial continue with the remaining centres being opened.

Baseline comparability

Tables 4–6 summarise baseline participant characteristics, details of management and impact of sciatica, and relevant clinical characteristics, by randomised group. The randomised groups were generally similar in their baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Summary | Microdiscectomy | TFESI | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants randomised | 83 | 80 | 163 | |

| Sex | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| Female, n (%) | 46 (55.4) | 40 (50.0) | 86 (52.8) | |

| Male, n (%) | 37 (44.6) | 40 (50.0) | 77 (47.2) | |

| Age (years) | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 43.5 (9.9) | 41.2 (8.6) | 42.4 (9.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 42.8 (34.9–50.5) | 41.4 (35.2–47.0) | 42.2 (35.2–48.9) | |

| Range | 23.2–65.6 | 23.3–59.8 | 23.2–65.6 | |

| Of reproductive potential (female only) | n (missing) | 46 (0) | 40 (0) | 86 (0) |

| No, n (%) | 11 (23.9) | 5 (12.5) | 16 (18.6) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 35 (76.1) | 35 (87.5) | 70 (81.4) | |

| Weight (kg) | n (missing) | 75 (8) | 71 (9) | 146 (17) |

| Mean (SD) | 83.7 (16.8) | 81.4 (20.7) | 82.6 (18.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 82.0 (72.0–95.1) | 77.1 (67.0–94.0) | 79.3 (69.8–94.0) | |

| Range | 54.0–134.0 | 51.7–154.0 | 51.7–154.0 | |

| Height (cm) | n (missing) | 76 (7) | 71 (9) | 147 (16) |

| Mean (SD) | 171.7 (10.7) | 172.6 (9.5) | 172.2 (10.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 170.1 (164.0–180.7) | 173.0 (167.0–180.0) | 171.5 (165.0–180.0) | |

| Range | 147.0–197.0 | 150.0–192.0 | 147.0–197.0 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | n (missing) | 74 (9) | 68 (12) | 142 (21) |

| Mean (SD) | 28.2 (5.3) | 27.2 (6.4) | 27.7 (5.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 26.9 (24.5–31.3) | 25.6 (22.9–29.4) | 26.4 (24.1–30.7) | |

| Range | 18.9–44.3 | 17.1–47.1 | 17.1–47.1 |

| Treatment | Summary | Microdiscectomy | TFESI | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants randomised | 83 | 80 | 163 | |

| Taking anticoagulant medication | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| No, n (%) | 82 (98.8) | 79 (98.8) | 161 (98.8) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Number of weeks with symptoms | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 21.5 (10.7) | 21.1 (11.2) | 21.3 (10.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 17.0 (14.0–28.0) | 18.0 (13.0–27.0) | 18.0 (14.0–28.0) | |

| Previous surgery at disc level | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| No, n (%) | 82 (98.8) | 80 (100.0) | 162 (99.4) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 1a (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Taken medication for pain and symptoms | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| Yes, n (%) | 83 (100.0) | 80 (100.0) | 163 (100.0) | |

| Modified activity | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| No, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 83 (100.0) | 79 (98.8) | 162 (99.4) | |

| Attended physiotherapy | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| No, n (%) | 15 (18.1) | 16 (20.0) | 31 (19.0) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 68 (81.9) | 64 (80.0) | 132 (81.0) | |

| Other conservative treatment | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 (0) |

| No, n (%) | 49 (59.0) | 43 (53.8) | 92 (56.4) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 34 (41.0) | 37 (46.3) | 71 (43.6) | |

| Currently employed | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 79 (1) | 162 (1) |

| No, n (%) | 21 (25.3) | 13 (16.3) | 34 (20.9) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 62 (74.7) | 66 (82.5) | 128 (78.5) | |

| Currently unable to work because of sciatica (of those employed) | n (missing) | 62 (0) | 66 (0) | 128 |

| No, n (%) | 41 (66.1) | 34 (51.5) | 75 (58.6) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 21 (33.9) | 32 (48.5) | 53 (41.4) | |

| Currently taking analgesics/steroids/anticoagulant medication | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 |

| No, n (%) | 7 (8.4) | 7 (8.8) | 14 (8.6) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 76 (91.6) | 73 (91.3) | 149 (91.4) |

| Clinical characteristic | Summary | Microdiscectomy | TFESI | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants randomised | 83 | 80 | 163 | |

| Estimated volume of canal occupied by disc prolapse | n (missing) | 83 (0) | 80 (0) | 163 |

| < 25%, n (%) | 43 (51.8) | 44 (55.0) | 87 (53.4) | |

| 25–49%, n (%) | 36 (43.4) | 34 (42.5) | 70 (42.9) | |

| ≥ 50%, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.5) | 6 (3.7) | |

| Level of disc prolapsea | n (missing) | 75 (8) | 73 (7) | 148 (15) |

| L2/3, n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| L3/4, n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (1.8) | |

| L4/5, n (%) | 27 (32.5) | 25 (31.3) | 52 (31.9) | |

| L5/S1, n (%) | 46 (55.4) | 46 (57.5) | 92 (56.4) |

Adherence to treatment, additional treatments and retention

Withdrawals

There were a total of six withdrawals from the trial (three from the microdiscectomy group and three from the TFESI group).

The reasons given for withdrawal in the TFESI group were:

-

patient unwilling to have microdiscectomy or TFESI

-

site exhausted all means of communication with participant

-

chest infection and investigation for possible bowel cancer.

Reasons given for withdrawal from the microdiscectomy group were withdrawal of consent for follow-up, participant not happy with the process (one withdrawal) and withdrawal of consent for follow-up, no additional reason (two withdrawals).

Treatment compliance

A further 14 participants did not initially receive any treatment (seven randomised to microdiscectomy and seven to TFESI). Table 7 shows all combinations of treatments received by participants.

| Detail | Microdiscectomy (N = 83), n (%) | TFESI (N = 80), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Received randomised treatment initially | ||

| Single randomised treatment | 65 (78.31) | 40 (50) |

| Repeated randomised treatment | 3a (3.61) | 2 (2.5) |

| Randomised treatment then the alternative treatment at least once | 3 (3.61) | 28 (35) |

| Received alternative treatment initially | ||

| Single alternative treatment | 3 (3.61) | 3 (3.75) |

| Repeated alternative treatment | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| Alternative treatment then the randomised treatment | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| Lateb/no treatment | ||

| No treatment recorded during trial | 4 (4.82) | 4 (5) |

| Late randomised treatment | 0 | 1 (1.25) |

| Late alternative treatment(s) | 3 (3.61) | 2 (2.5) |

Eight participants did not receive their randomised treatment, but were given the alternative treatment instead (five randomised to microdiscectomy and three randomised to TFESI). Of the five participants randomised to microdiscectomy, three changed because of participant preference, one because of safety concerns from the anaesthetist and one because their symptoms had improved and microdiscectomy was thought to be unnecessary. Of the three participants randomised to TFESI, two changed to microdiscectomy because of participant preference and the other was reported as a surgeon decision.

Additional treatment

The rows in italics in Table 7 indicate participants who have received the alternative trial treatment after their initial treatment. The largest group (28 participants) includes those who received the TFESI initially and subsequently went on to receive microdiscectomy as an additional treatment. The first row in italics denotes those who received their allocated treatment first and then the alternative treatment. The second row in italics denotes those who initially received a treatment to which they were not allocated, but then subsequently additionally received the original planned allocation. Table 8 summarises the timing of treatments for those patients who received both TFESI and microdiscectomy.

| Timing | Microdiscectomy (N = 83), n (%) | TFESI (N = 80), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Received other treatment after primary outcome | 2 (2.41) | 13 (16.25) |

| Received other treatment before primary outcome | 2 (2.41) | 13 (16.25) |

| Received both treatments, but no primary outcome available | 0 | 2 (2.50) |

| Total | 4 (4.82) | 28 (35.00) |

Protocol deviations

Prespecified protocol deviations are summarised in Table 37. The most common major protocol deviations were missing primary outcome data (n = 28) and treatment compliance (i.e. receiving randomised treatment) (n = 22).

Analysis sets

Table 9 gives the number of participants in the analysis sets. The ITT data set included all randomised participants. The safety data set included every participant who received one of the trial interventions. Note that safety outcomes are analysed based on actual treatment received, rather than randomised groups.

| Population | Microdiscectomy, n | TFESI, n | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised | 83 | 80 | 163 |

| ITT | 83 | 80 | 163 |

| Safetya | 105 | 82 | 155 |

Primary outcome: Oswestry Disability Questionnaire at 18 weeks

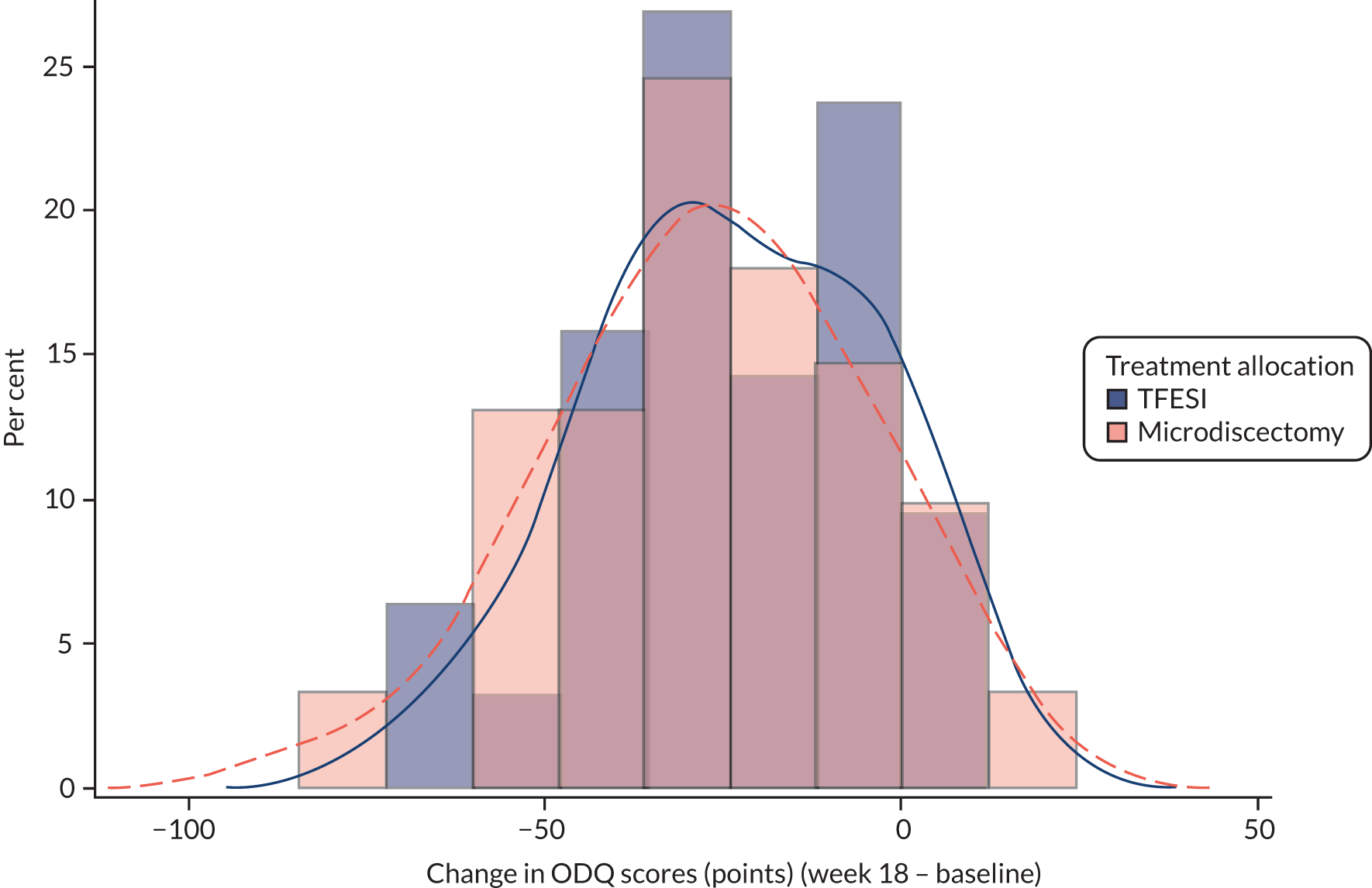

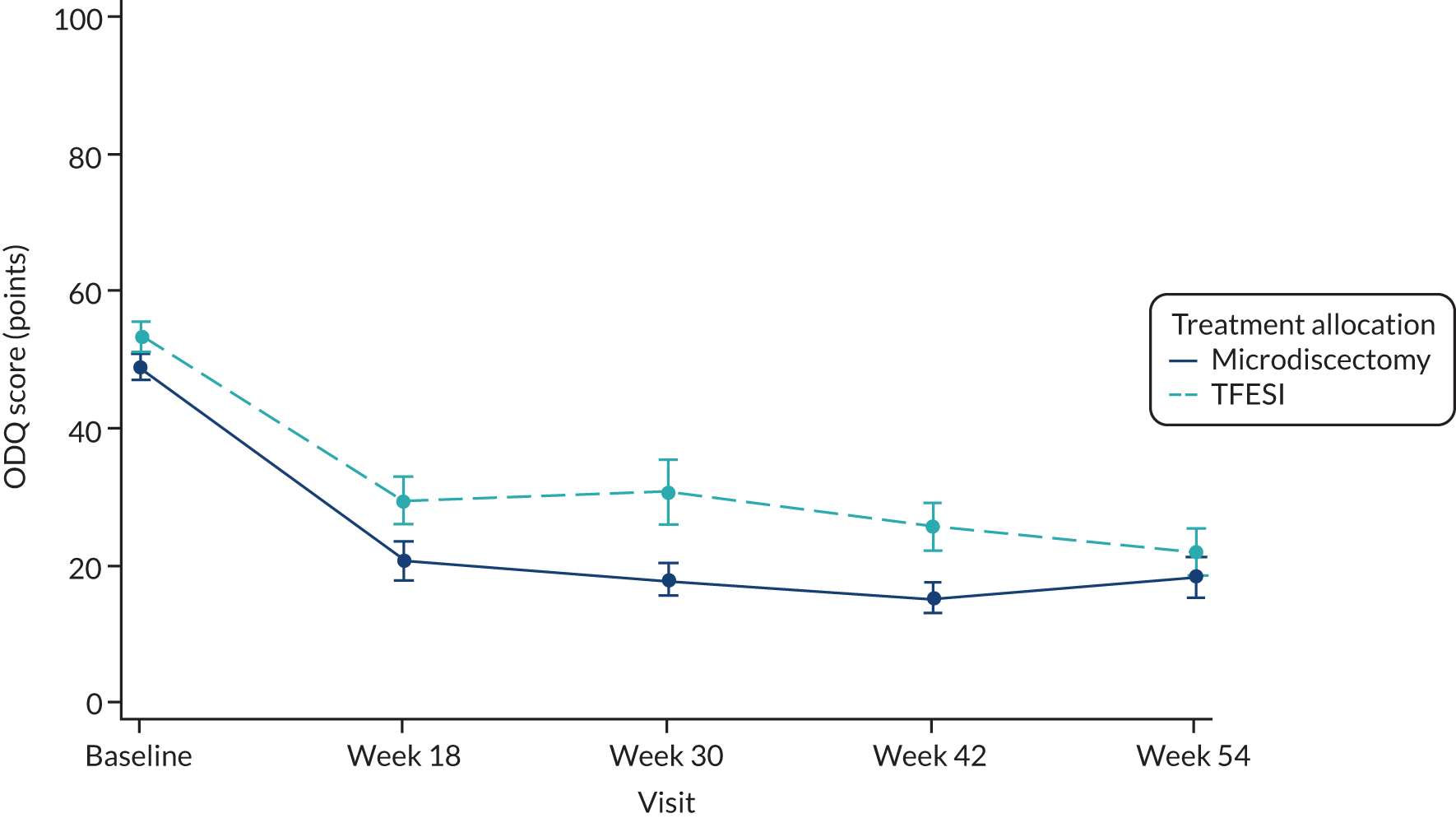

The primary outcome was the ODQ measure at 18 weeks after randomisation. Questionnaires completed within a window of 6 weeks either side of 18 weeks (i.e. 12–24 weeks) were included in this analysis. The ODQ is a 10-item questionnaire; item 8 (‘sex life’) may not be applicable. If the number of items answered is fewer than eight items then this questionnaire was excluded from the analysis and considered invalid (as specified in the statistical analysis plan, see Report Supplementary Material 1). Table 10 shows descriptive statistics of the ODQ at baseline and at week 18, including the difference between baseline and week 18 values. The differences are also categorised into those who improved by ≥ 10 points (considered clinically significant), those who improved < 10 points but at least 0 and those for whom the symptoms got worse.

| Time point | Summary | Microdiscectomy | TFESI | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n | 83 | 79 | 162 |

| n missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.39 (17.81) | 53.74 (19.35) | 51.51 (18.64) | |

| Median (IQR) | 46.67 (36.00–62.22) | 54.00 (40.00–71.11) | 50.00 (38.00–66.00) | |

| Week 18 | n | 61 | 63 | 124 |

| n missing/invalid | 22 | 17 | 39 | |

| Mean (SD) | 22.30 (19.83) | 30.02 (24.38) | 26.22 (22.51) | |

| Median (IQR) | 18.00 (6.00–36.00) | 22.22 (10.00–50.00) | 20.00 (9.00–37.89) | |

| Difference | n | 61 | 63 | 124 |

| n missing/invalid | 22 | 17 | 39 | |

| Mean (SD) | –26.74 (21.35) | –24.52 (18.89) | –25.61 (20.09) | |

| Median (IQR) | –26 (–40 to –8.89) | –26 (–38 to –6) | –26 (–39 to –8) | |

| 95% CI | –32.21 to –21.27 | –29.28 to –19.76 | –29.18 to –22.04 | |

| Difference category | n | 61 | 63 | 124 |

| Improvement of ≥ 10 points, n (%) | 45 (73.8) | 43 (68.3) | 88 (71.0) | |

| Improvement of < 10 points, n (%) | 8 (13.1) | 14 (22.2) | 22 (17.7) | |

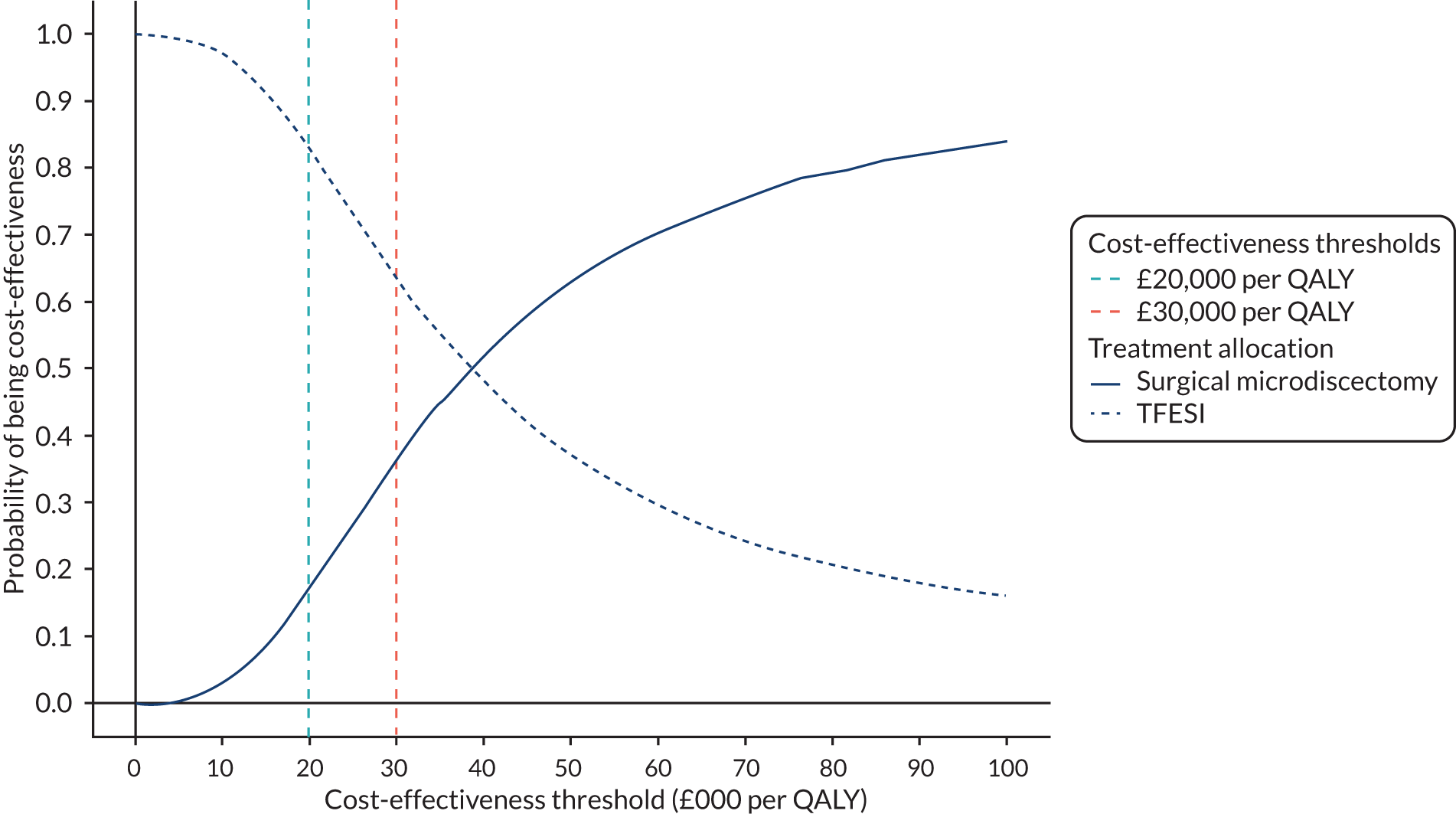

| Deterioration in symptoms, n (%) | 8 (13.1) | 6 (9.5) | 14 (11.3) |