Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/50/49. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in November 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Adamson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

There are > 9000 new cases of oesophageal cancer and 8000 oesophageal cancer deaths in the UK each year. 1 Oesophageal cancer is the seventh most common cause of cancer deaths (the fourth most common in men) and accounts for 5% of the UK total. The majority of cases occur in those aged ≥ 60 years and overall prognosis is poor, with 5-year survival rates of only 15%. 1 Worldwide there are > 450,000 new cases of oesophageal cancer per year and > 400,000 deaths. Over 80% of new cases, and deaths, occur in low- and middle-income nations. 2

The majority of patients present with incurable disease and mean survival in advanced disease is 3–5 months. 3 The emphasis of treatment for most patients is therefore on effective palliation. Between 70% and 90% will require intervention for dysphagia. 4,5 This particular symptom has a profound impact on physical independence, social functioning and other aspects of health-related quality of life. Interventions to improve swallowing must, therefore, aim to produce prompt and lasting palliation of dysphagia while minimising the need for late reinterventions and hospitalisation. Interventions should produce these benefits without causing significant impairment of other aspects of quality of life and be accessible at scale to this patient population.

Evidence base for palliation of dysphagia in advanced oesophageal cancer

Although the optimal palliative intervention remains to be established, oesophageal stenting using self-expanding metal stents (SEMSs) is the most widely used treatment option for providing prompt relief of severe dysphagia. Shenfine et al. ’s6 2005 Health Technology Assessment (HTA) evidence review and prospective study confirmed the efficacy of SEMS placement and also highlighted that delayed complications are common and result in later reinterventions. The pragmatic randomised controlled trial (RCT) randomised 215 patients between SEMS and a variety of non-SEMS treatments. 7 It found that SEMS is an effective one-treatment strategy for palliation of dysphagia but highlighted higher initial pain scores and lower quality of life in the SEMS-treated arm.

Notably, 35% (38/108) of SEMS patients in the study required reintervention, with the risk of stent-related complications increasing over time. The analysis of survival data in Shenfine et al. ’s7 study suggested that there was longer survival in patients treated with non-stent therapies (median survival: non-stent, 172 days; 18-mm SEMS, 86 days; 24-mm SEMS, 94 days; p = 0.04).

The study also confirmed the need for better evidence relating to combination therapies, survival – particularly where treatment combinations are investigated – and more robust evidence on quality of life. A literature review conducted as part of the Shenfine et al. 7 report found that only 0.55% of papers published since 1966 on oesophageal cancer considered quality-of-life issues, despite the inherently palliative nature of treatment options for the majority of patients. It also highlighted that the methodological quality of studies reporting quality-of-life data was very poor.

The two most recent Cochrane systematic reviews8,9 confirm the efficacy of SEMS in providing safe, effective and quicker initial relief of dysphagia when compared with other intervention modalities, such as rigid plastic tube insertion, endoscopic chemical and thermal ablation or external beam radiotherapy/chemoradiotherapy. However, they too highlight a continuous decline in quality of life in SEMS-treated patients, possibly related to poorer pain scores, and that non-stent modalities may be associated with improved survival. Dai et al. ’s9 updated review in 2014 included 3684 patients in 53 RCTs. It reported significant variability in the quality of evidence, with only 25% of studies graded as high quality. 9 In general, studies recruited small numbers and used varied scales and outcomes – which precluded meta-analysis – and few studies provided data on combined interventions. It also reported a lack of well-designed studies containing robust assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) or costs. The conclusion of the review was that no absolute superiority of any intervention was shown, but that combinations of different modalities might provide better treatment outcomes. Like Shenfine et al. 6 and Sreedharan et al. ,8 Dai et al. 9 called for high-quality RCTs of combination treatments, particularly of SEMS with either brachytherapy or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT).

Dai et al. 9 concluded that, of the non-stent interventions, high-dose intraluminal brachytherapy may be considered an appropriate alternative to SEMS, particularly in patients with longer survival. This conclusion was based on two studies comparing SEMS insertion with brachytherapy using validated patient-reported measures of dysphagia and HRQoL. 10,11 SEMS provided more rapid onset of relief. In Homs et al. ’s10 larger study of 209 patients, 18% of patients receiving brachytherapy alone had persistent problems with dysphagia 2–4 weeks after the procedure, compared with none in the SEMS arm. However, dysphagia-free survival was longer in the brachytherapy arm [median of 115 days, compared with 82 days with SEMS; mean difference 33 days, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1 to 64 days; p < 0.05]. There was also evidence in Homs et al. ’s10 study that late upper gastrointestinal (GI) haemorrhage occurred significantly less frequently in the brachytherapy arm than in the SEMS arm. In both studies, other aspects of HRQoL appeared to be more stable in the brachytherapy arm over time.

More recently, Rosenblatt et al. 12 reported a multicentre international RCT of EBRT at a dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions combined with high-dose-rate intraluminal brachytherapy compared with high-dose-rate intraluminal brachytherapy alone in 219 patients. The study reported an absolute difference in dysphagia relief experience of 16% at 100 days and 18% at 200 days in favour of the combination arm. There was no difference in survival between the two arms. Description of the toxicities was limited, although this was reported as not significantly different between the arms. Importantly, only patients with limited locoregional disease were eligible, limiting the relevance of the finding to the broader population of patients who were receiving a stent.

There have been no large-scale trials combining stent plus brachytherapy. In a single-arm safety study of brachytherapy followed by biodegradable stent placement, Hirdes et al. 13 reported early termination of the study as the safety threshold was exceeded, with 47% of patients suffering major complications. By contrast, Amdal et al. 14 have reported a RCT of brachytherapy following SEMS placement versus brachytherapy alone. However, the trial was closed because of slow recruitment, with only 42 patients randomised and insufficient statistical power to draw robust conclusions.

One prospective multicentre Chinese RCT combining endoluminal radiotherapy and stent in a single modality has been reported by Zhu et al. 15 Compared with conventional stenting (n = 75), patients treated with 125I irradiation stents (n = 73) had longer survival (median 177 days vs. 147 days) and consistently lower dysphagia scores over time, although recurrent dysphagia due to occlusion was not different between arms (28% vs. 27%). No health economic analysis was included and the expertise required for irradiation stent placement and care is not widely available. Tian et al. ’s16 non-randomised study in the same health-care economy suggested that the cost associated with irradiation stents is almost four times that of conventional stents.

Implications for NHS practice

Therefore, the available evidence suggests that SEMS is an appropriate intervention for rapid dysphagia relief in incurable oesophageal cancer, and is widely implemented as first-line management of dysphagia in the NHS in this group. 17

Brachytherapy represents an appropriate alternative to SEMS, particularly in those with longer predicted survival, as, although the onset of dysphagia relief is slower, brachytherapy provides a longer duration of dysphagia relief, improves quality of life over time and requires fewer reinterventions.

However, throughout the UK, experience of and access to brachytherapy is very limited. Indeed, only 2.5% of all cancer patients requiring radiotherapy,18 including those with oesophageal cancer, are treated with brachytherapy. National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audits17,19 consistently report that only 15% of English Cancer Alliances treating these patients have access to brachytherapy, with no improvement over a 5-year period, and in the 2017 report17 < 30 brachytherapy episodes were recorded compared with > 2000 stent insertions for palliation. Brachytherapy, therefore, does not currently have a role in the routine palliation of oesophageal cancer dysphagia in NHS settings either alone or as an option for combination with stenting.

The efficacy of SEMS alone, however, is limited by early problems with pain, decline in general aspects of quality of life and later complications, such as haemorrhage and tumour overgrowth. Median time to recurrent dysphagia in stent comparator studies20,21 and in Homs et al. ’s10 SEMS versus brachytherapy study is 11–12 weeks. Reinterventions not only impose a significant burden on NHS resources but also decrease the quality of life and functioning of an unwell, predominantly elderly, population with a median survival of 12–20 weeks. This is consistent with estimations that health-care costs in general in the last year of life account for 20–30% of overall health-care budgets. 22 This is also consistent with data that demonstrate that, among cancer patients, patients with upper GI cancer have high rates of health and social care usage in the last 12 months of life. 23

Research rationale

In line with Cochrane Review research recommendations,8,9 the combination of SEMS with other treatments might reduce costs and patient burden by reducing adverse events and reinterventions at a time when patients are approaching the last weeks of life.

This study was developed in response to a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) call for research proposals into aspects of palliative care to address uncertainties in the evidence base for interventions combined with SEMS.

In contrast with the lack of availability and higher cost of brachytherapy, EBRT is readily accessible by patients at regional cancer centres across the UK, although its use in the immediate post-stent period has not been rigorously studied.

Only one prospective RCT of EBRT in combination with SEMS versus SEMS alone has been reported. 24 Javed et al. ’s24 single-centre Indian study recruited 84 patients and reported more sustained dysphagia relief in the SEMS plus EBRT group (7 months vs. 3 months) and longer survival (180 vs. 120 days). However, there was no a priori statistical plan described, no power calculation and no reporting of missing data, which resulted in low-quality evidence.

Study aim and objectives

This study aimed to assess whether or not the addition of EBRT reduces the risk of recurrent dysphagia, improves quality of life and reduces health economic and personal burden in patients undergoing SEMS placement.

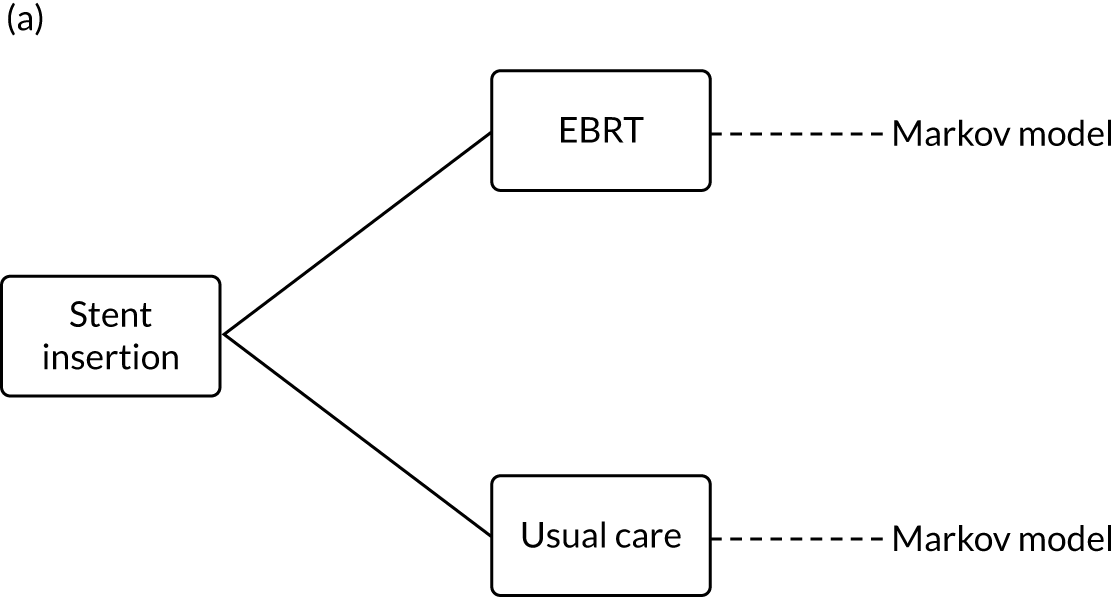

The Radiotherapy after Oesophageal Cancer Stenting (ROCS) study was funded by NIHR as part of its HTA programme. The study was composed of:

-

a RCT, with internal pilot, in which palliative radiotherapy at a dose of 20 Gy in five fractions or 30 Gy in 10 fractions delivered following SEMS placement was compared with SEMS placement alone

-

an embedded qualitative study to explore patient and carer experience of participating in the randomised study, of receiving the radiotherapy intervention, and of their lived experience of advanced oesophageal cancer and dysphagia

-

an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of delivering the radiotherapy intervention, and of the resource use associated with advanced oesophageal cancer.

Intervention development

The radiotherapy intervention was intended to reflect current practice in the centres recruiting to this trial, rather than to be closely prescriptive. This would allow the findings to be readily and directly applicable to current UK practice. EBRT is routinely available at regional cancer centres across the UK. For palliation of oesophageal cancer, a radiotherapy course delivering a tumour-absorbed dose of 20 Gy in five fractions or 30 Gy in 10 fractions is generally recommended by the Royal College of Radiologists. 25 The study team suggested a dose of 20 Gy in five fractions, which was the most commonly used dose across the UK at the time of study design,19 with the 30 Gy in 10 fraction dose chosen at the discretion of the treating physician. Recent audit data suggest that both of these doses remain the most commonly used palliative regimens in advanced oesophageal cancer in England, accounting for 63% of palliative radiotherapy delivered. 17

Self-expanding metal stents are the most common intervention used in the UK and internationally for the palliation of malignant dysphagia. Audit data for 2014–16 confirm that they constituted 94.5% of all stents placed for oesophageal cancer dysphagia in England. 17 They can be placed at a single endoscopic or radiological session. There are several designs with a variety of delivery devices and, for this trial, SEMS insertion was undertaken in accordance with standard local protocols. Covered or partially covered metal stents were permitted and the length, type and mode of stent placement were selected by the treating clinician.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The study was designed as a pragmatic RCT of EBRT in addition to stent insertions versus stent insertion alone. Participants were those clinically assessed as requiring stent insertion for relief of dysphagia caused by inoperable oesophageal cancer. An internal pilot was included to assess rates and methods of recruitment as it was expected that the trial would be challenging in studying a palliative population approaching the last months of life.

To ensure a multiperspective analysis of efficacy and address previously highlighted evidence gaps, the trial also included an embedded qualitative study and a health economics component to interrogate the cost-effectiveness of radiotherapy intervention, and to capture in detail health and social care resource use across both arms of the trial.

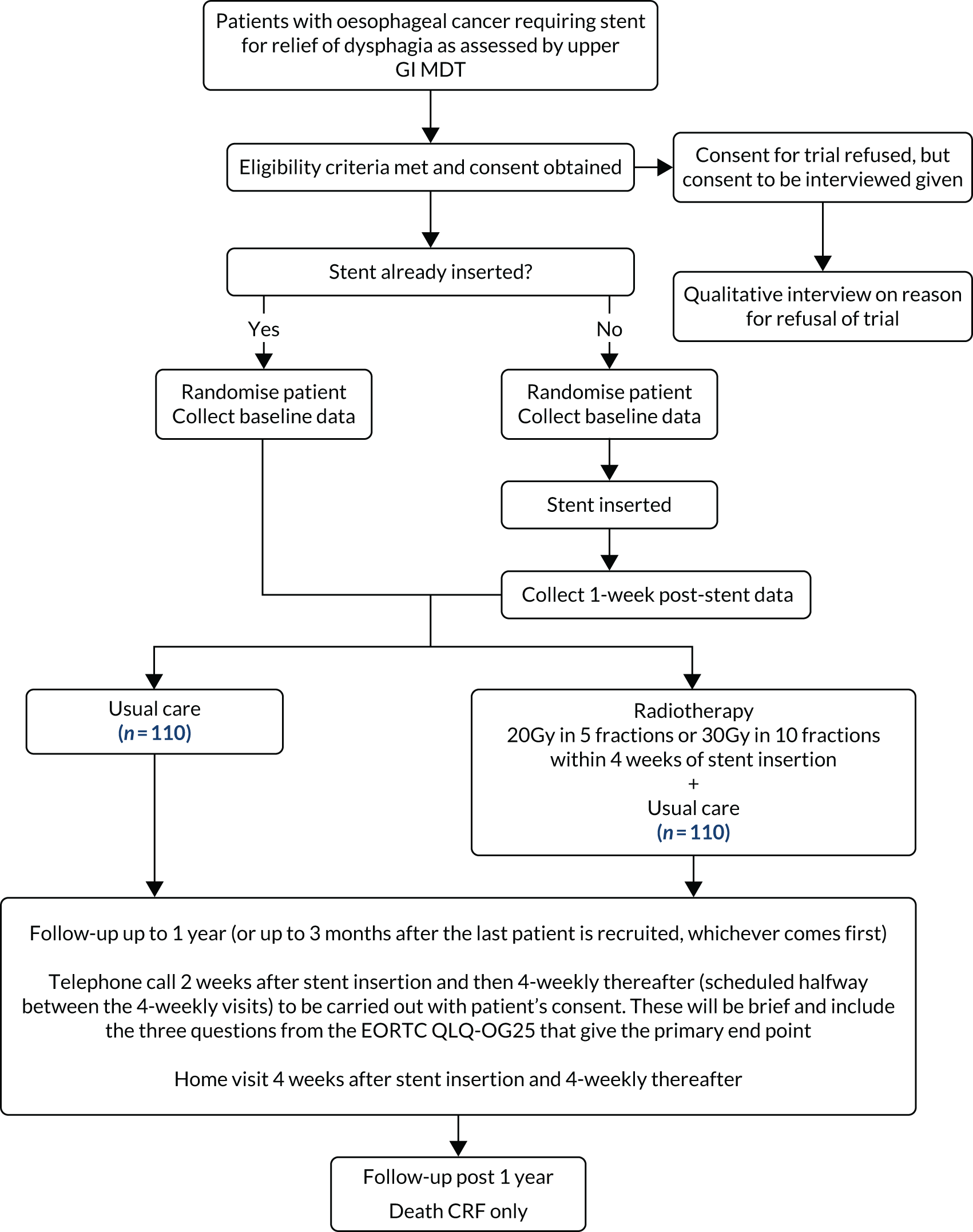

A description of the trial protocol has previously been published. 26 The trial schema is detailed in Figure 1. A full summary of protocol amendments is included in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema showing randomisation and follow-up. CRF, case report form; EORTC QLQ-OG25, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire oesophago-gastric module; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

| Change to protocol | Date |

|---|---|

| Exclusion criterion removed: planned endoscopic treatment of the tumour (e.g. laser) in the immediate peri-stenting period | April 2013 |

| Inclusion criterion added: patient has completed baseline QLQs added in the inclusion criteria | April 2013 |

| Companion PIS and consent form introduced in the qualitative study | September 2014 |

| Dedicated face-to-face follow-up specified as preferred to ensure optimum support for patients; telephone or postal follow-up for questionnaire completion also permitted depending on patient’s choice | September 2014 |

| Additional level of withdrawal added: option for participants to stop home visits and questionnaires but follow-up | September 2014 |

| Qualitative study added interviews with research nurses responsible for recruiting patients to the trial | September 2014 |

| Randomisation allowed within 2 weeks after stent insertion, but preferably within 1 week of stent insertion | April 2015 |

| Baseline assessments for those patients consented following stent insertion, ideally baseline assessments will occur within 1 week, but not > 2 weeks, following the procedure | April 2015 |

| Clarification of time zero owing to consent also possible after stent insertion | April 2015 |

| Secondary outcome added: determine the haemostatic effect of radiotherapy on tumour bleeding | March 2016 |

| Inclusion criterion of oesophageal carcinoma widened to include clinical and/or radiological evidence of invasive tumour (as agreed by MDT consensus) and at least high grade dysplasia of a non-small cell type on histology | March 2016 |

| Interim telephone calls introduced 2 weeks after stent insertion and 4-weekly thereafter to be scheduled halfway between the 4-weekly assessment visits | March 2016 |

| Dysphagia card was introduced with a list of questions asked during the telephone calls | March 2016 |

| Follow-up until death reduced to 1 year, follow-up post 1 year is death CRF only | March 2016 |

| Primary outcome amended: assess the impact that radiotherapy has in addition to stent placement on time to progression of patient-reported dysphagia or other dysphagia-related event in a patient population unable to undergo surgery | February 2017 |

| Final accrual reduced from original 496 to 220 | December 2017 |

| Primary outcome amended: to assess the impact that radiotherapy has in addition to stent placement on difference in event rate of patient-reported dysphagia or other dysphagia-related event at 12 weeks following stent insertion in a patient population unable to undergo surgery | December 2017 |

| Originally it was intended to perform a time-to-event analysis. However, in collaboration with the IDMC in response to recruitment difficulties, the primary outcome analysis has been amended and will now be based on proportion of events at week 12. An event is defined as a progression in self-reported dysphagia (see above) or other dysphagia-related event | |

| Follow-up for 1 year or up to 3 months after the last patient is recruited, whichever comes first | December 2017 |

| New secondary outcome – measure hospital admission rates | December 2017 |

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was given by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 2 in October 2012 (reference number 12/WA/0230). Global Research and Development approval was given in January 2013. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Registry (ISRCTN) under the reference number ISRCTN12376468 and also with Clinicaltrials.gov under the reference number NCT01915693.

Participants

The study recruited patients referred for an oesophageal stent as primary palliation for advanced oesophageal cancer dysphagia. Patients were recruited from 23 cancer centres and acute hospitals across Scotland, England and Wales (see Appendix 1). Recruitment was limited to five sites in the first 18 months to allow for the embedded pilot phase and review.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were considered for inclusion if they:

-

had oesophageal carcinoma with either of the following –

-

histological confirmation (excluding small cell carcinoma)

-

clinical and/or radiological evidence of invasive tumour [as agreed by multidisciplinary team (MDT) consensus] and at least high-grade dysplasia of a non-small cell type on histology

-

-

were not suitable for radical treatment (oesophagectomy or radical chemoradiotherapy) because of either patient choice or medical reasons

-

had dysphagia clinically assessed as needing a stent insertion as primary treatment of the dysphagia

-

were aged ≥ 16 years

-

had a treatment decision made by discussion with an upper GI MDT for stent insertion

-

were deemed suitable for radiotherapy

-

had an expected survival of at least 12 weeks

-

could provide written informed consent

-

had completed baseline quality-of-life questionnaires (as a minimum patients had to have completed the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) oesophago-gastric module (OG25).

Exclusion criteria

Patients were not considered for exclusion if they:

-

had small-cell carcinoma

-

had tumour length of > 12 cm

-

had tumour growth within 2 cm of the upper oesophageal sphincter

-

had endoscopic treatment of the tumour, other than dilatation, planned in the peri-stent period

-

had a tracheo-oesophageal fistula

-

had a pacemaker in proposed radiotherapy field

-

had previous radiotherapy to the area of the proposed radiotherapy field

-

were pregnant.

Recruitment procedure

Patients were identified in secondary care by their treating clinician or by members of the local upper GI MDT. Patients were then approached prior to stent insertion by the local research nurse, who introduced the ROCS study, provided them with a participant information sheet (PIS) and completed eligibility checks. The research nurses received specific training on information provision to include the radiotherapy intervention and the consent process.

Comprehensive screening log data were collected throughout the trial to track proportions of patients who were eligible, approached and randomised. This was used to feed back to participating centres, the Trial Management Group (TMG), the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) and the funding body throughout the duration of the study.

During the trial pilot phase, screening logs demonstrated that the number of patients requiring stent insertion was as predicted by the trial team and that the 64% acceptance rate was above the 50% initially predicted. However, eligibility was 33% compared with the 70% predicted. The reasons for ineligibility included previous radiotherapy and capacity to consent issues. The screening data also highlighted that a significant number of patients were being stented before trial teams became aware (14%). Data from the qualitative study additionally identified individual patient distress at being approached prior to stenting. Together these data resulted in a protocol amendment to allow randomisation up to 2 weeks after stent insertion, and eventually 66% of the overall 220 patients were randomised post stent insertion. Following review of the comprehensive pilot data, the funder approved trial continuation and the number of centres was increased.

Informed consent

Once trial eligibility was confirmed, informed written consent was obtained after a full explanation had been given and further questions answered. The consent was taken by an appropriately trained research nurse or delegate. The original signed and dated consent forms were held securely as part of the trial site file, with a copy provided to the participant. Patients and informal caregivers were consented separately for the embedded qualitative study by the qualitative researcher.

Patients were also asked to consent to NHS Information Centre flagging so that the date and cause of death could be collected without longer-term follow-up. This was optional and additional to the standard informed consent.

Randomisation and concealment

Eligible and consenting participants were randomised centrally via the Wales Cancer Trials Unit [now the Centre for Trials Research (CTR), Cardiff University] randomisation telephone line using an online trial management database with a manual backup available. The outcome of the randomisation procedure was communicated to the participant by the research nurse together with details of the allocated treatment. As indicated, the initial protocol stipulated randomisation prior to stent insertion, but was amended to allow post-stent randomisation after the pilot phase.

Participants were randomised to a trial arm using the method of minimisation with a random element (80 : 20). Minimisation was stratified to ensure balanced allocation for a number of potential confounding factors: centre, stage at diagnosis (I–III vs. IV), histology (squamous or other) and MDT intent to give chemotherapy (yes or no). Randomisation was carried out using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio.

Study interventions

Self-expanding metal stents: both arms

Following the decision by the MDT to proceed with stenting as the primary treatment for oesophageal cancer-related dysphagia, stent insertion was performed as per the standard procedures of the treating centre. The length and type were determined and recorded by the treating clinician. It was advised that, where possible, the length of stent should be chosen to ensure that at least 2 cm of normal oesophagus was covered by the stent above and below the tumour stricture. The following were also recorded: whether the stent was inserted under sedation or general anaesthetic, whether dilatation was required before or after stent insertion and whether or not radiological imaging was used.

Patients who were offered any endoscopic treatment of the tumour, other than oesophageal dilatation used as part of the centre’s normal procedure for stent insertion, were excluded from the study, unless an emergency required such procedure. Use of such procedures was recorded on the case report form (CRF). Patients in whom brachytherapy or EBRT was planned routinely for after stent insertion were also excluded.

External beam radiotherapy trial arm: intervention

The study protocol mandated that the radiotherapy begin within 4 weeks of stent insertion and preferably within 2 weeks. Radiotherapy treatment was delivered to the primary tumour and significant treatable lymphadenopathy, as defined by the treating oncologist. Treatment dose was either 20 Gy in five fractions over 1 week or 30 Gy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks using daily fractionation and the centre’s normal radiotherapy treatment procedures. The 20 Gy in five fractions regimen was the preferred option but the dose and fractionation schedule were chosen by the treating clinical oncologist.

Patients were withdrawn from the trial if they missed > 7 consecutive calendar days during radiotherapy treatment and any further treatment given was at their treating clinician’s discretion. In the unlikely event of radiotherapy side effects severe enough to interfere with treatment delivery, the treating clinician had the option to temporarily stop treatment and allow a break of no more than 7 calendar days prior to recommencement.

Radiotherapy quality assurance

Radiotherapy quality assurance was carried out by the Cardiff National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Radiotherapy Trial Quality Assurance (RTTQA) Group. The ROCS radiotherapy quality assurance group consisted of a radiation oncologist and radiotherapy physicist from the Cardiff NCRI RTTQA Group, who gave information and guidance regarding implementation of the protocol, monitored compliance with the protocol and, where necessary, provided feedback on the radiotherapy quality assurance accreditation.

Pre-trial quality assurance

A process document containing information on set-up, verification and beam arrangement was required from all radiotherapy sites prior to being opened to recruitment. This was reviewed by the ROCS radiotherapy quality assurance group.

On-trial quality assurance

Following entry of the first patient into the trial at each radiotherapy treatment site, a set of computerised tomography (CT) images or simulator images, together with information concerning the treatment fields (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine-RadioTherapy file or hard copy) and treated volumes, were requested to ensure compliance.

Data collection and management

Pre-stent and 1 week post stent insertion

Patients randomised prior to stent insertion were seen before stenting for a pre-stent assessment at which the following data were collected: World Health Organization (WHO) performance status, questionnaires, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-OG25, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03. See Appendix 2 for the QLQs.

All patients, including those randomised post stent insertion, were seen 1 week post stent insertion, when the above data were collected, in addition to stent morbidity data, bleeding and transfusion episodes, and resource use. This formed the baseline against which future deterioration was measured.

Follow-up

Every 4 weeks after the 1-week post-stent insertion assessment, and until death, the following assessments were conducted and data were collected: WHO performance status, questionnaires (EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-OG25, EQ-5D-3L), toxicity assessment (CTCAE), stent morbidity data, bleeding and transfusion episodes, and resource use. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were monitored in real time.

The funded study included costs for additional research nurse time to allow all follow-up visits to occur in the home setting, or place of patient choice. The aim was to minimise the burden of study processes for patients and their families and to maximise data capture in participants who were at an advanced stage of illness. The challenges of capturing self-reported health data from patients with poor health and life expectancy are well documented,27 with recommendations for dedicated research staff collecting the quality-of-life (QoL) data via home visits where possible. 10 Face-to-face follow-up was preferred in our trial to ensure optimum support for patients in completing assessments and to minimise disruption for them; however, where patients specifically declined face-to-face follow-up visits but expressed a preference to have telephone or postal follow-up for questionnaire completion, follow-up assessments were undertaken in this way.

Information was captured in the CRFs on whether or not patients required support from research practitioners or family members/informal carers to complete patient-reported outcome questionnaires and reasons for missing data were also recorded.

As part of their regular data reviews, the IDMC highlighted that, despite excellent CRF returns, there were missing data owing to participants becoming too frail to complete questionnaires or dying without the ROCS primary outcome data being collected. Subsequently, the study protocol was amended in consultation with the research nurse teams to introduce interim telephone calls to participants scheduled halfway between the 4-weekly follow-up visits, aiming to ensure that dysphagia deterioration was assessed more frequently and that data were available in all patients. The telephone call assessments were brief and included the specific OG25 dysphagia questions only. For ease of call administration, participants were given a dysphagia card with details of the three questions that they were expected to answer.

Trial and data management

Paper-based CRFs were completed at sites within 4 weeks of the follow-up visit and a copy sent to the CTR for clinical database entry in MACRO Electronic Data Capture (InferMed, London, UK) version 4.9. A range of data validation checks were carried out to minimise erroneous and missing data throughout the trial. These consisted of checks programmed into MACRO Electronic Data Capture and more complex consistency checks (central monitoring) programmed in Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) version 16 (e.g. comparing toxicities reported on CRFs with toxicities reported through the SAE pharmacovigilance system). Data cleaning was an ongoing process and central monitoring was conducted prior to IDMC meetings and to commencing the final data analysis. Where central monitoring highlighted concerns at particular centres, site monitoring could be triggered and source data verification performed.

The TMG met once every 3 months to review screening and recruitment data and trials processes and receive Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and IDMC reports and advice. They oversaw all reporting and governance responsibilities and advised on all amendments to the protocol. The TSC and IDMC met once every 6 months to review trial progress and safety.

Investigator meetings were planned on a 6-monthly basis to facilitate peer support and motivate recruitment among principal investigators and particularly research nurses. The meetings allowed identification of both generic and site-specific trial process issues, sharing of good practice, and feedback from the qualitative researcher on patient experiences of being approached, informed about and consented into the trial. The knowledge and experience of the research nurses and the qualitative patient feedback resulted in real-time changes to, and improvements in, the protocol and data capture including:

-

changes to CRF design and content

-

changes to the wording of the PIS and description of the intervention by research nurses

-

changes to the timing of randomisation to include after stent placement

-

the inclusion of ‘between-visit’ telephone calls to capture primary outcome data

-

an additional level of withdrawal to allow ongoing case note data capture

-

the inclusion of research nurse interviews regarding non-consent.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome in this trial was a revised binary measure of deterioration in dysphagia symptoms, or death, by 12 weeks.

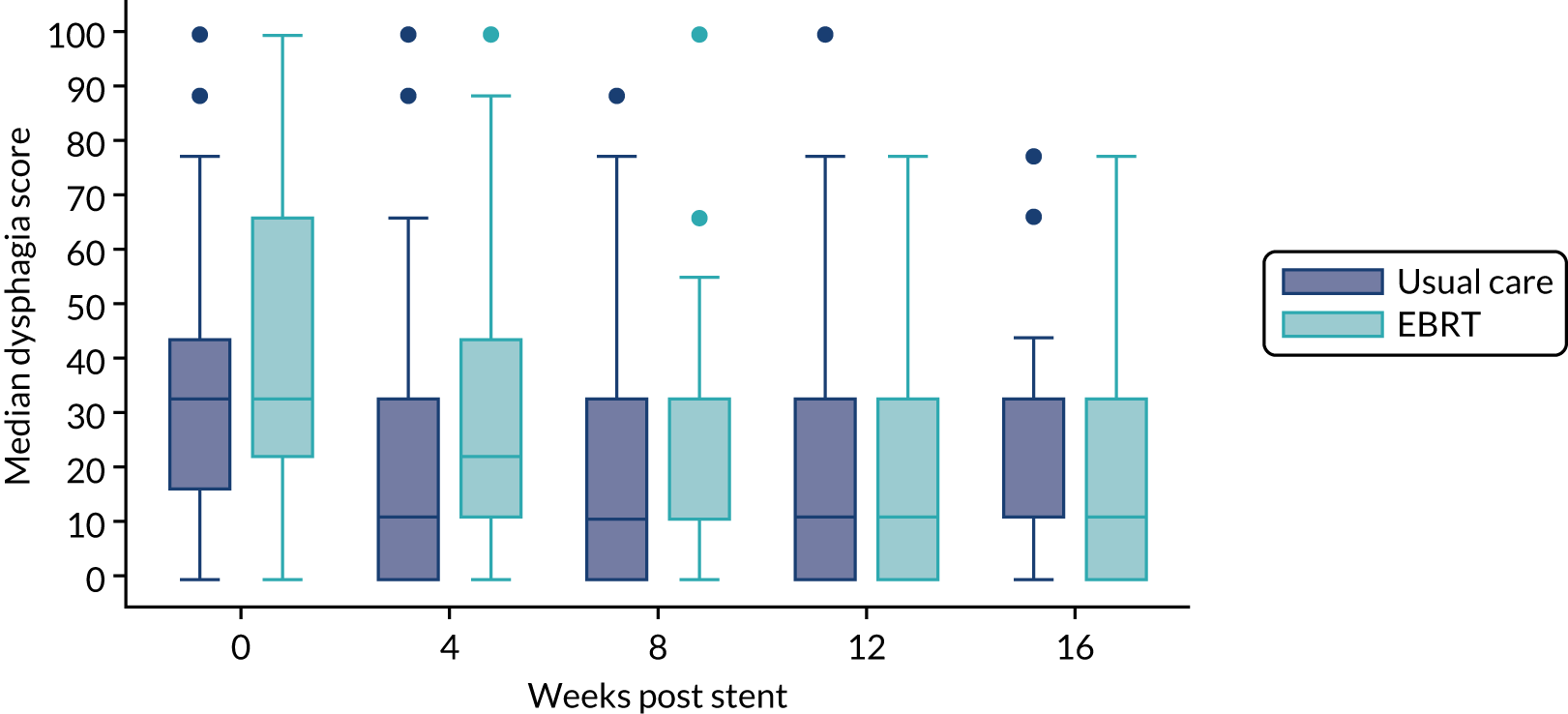

Patient-reported dysphagia was measured at each time point using the EORTC QLQ-OG25,28 which amalgamates the widely used EORTC scales to assess HRQoL in patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer. 29,30 In the earlier EORTC scales, problems with the validity of the dysphagia scale were noted, with patients finding the response categories confusing. The EORTC QLQ-OG25 resolved this issue and combined both oesophageal and gastric modules to ensure that HRQoL issues relevant to both groups of patients and that patients with oesophagogastric (junctional) tumours were included. The questionnaire has six scales; the dysphagia scale is scored from 0 to 100 and a change of 10–15 points in mean score is considered to be clinically significant. 31

Relief of dysphagia is expected in the majority of participants following stent insertion so the dysphagia score taken 1 week after stent insertion (prior to EBRT in treatment arm) formed the time zero measurement for the main end point of the study. A worsening in score of 11 compared with time zero at any subsequent time point was taken as deterioration. However, it is possible that patients undergoing radiotherapy may have a temporary worsening of dysphagia secondary to radiation-induced oesophagitis and other temporary changes may occur. To ensure that EBRT did not bias the primary outcome, definitive deterioration in dysphagia was defined as an 11-point change on two consecutive occasions, with the first being taken as the event time point.

To ensure that all primary events were captured, all CRF data related to toxicities and SAEs were reviewed to identify any additional dysphagia-related primary events that may have occurred between assessments. These events were reviewed blindly by the two co-chief investigators and by a gastroenterologist independent of the study (see Primary analysis).

Secondary outcomes

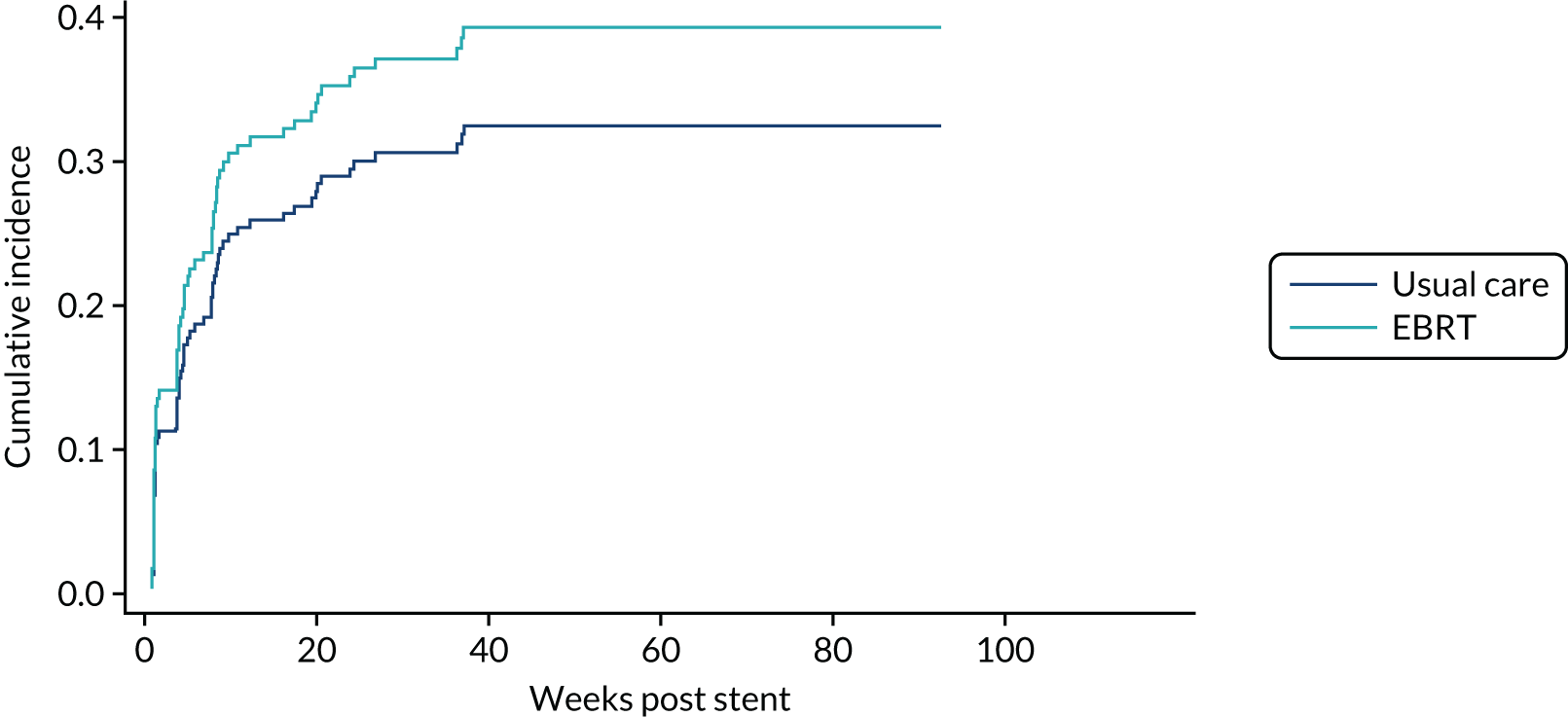

Overall survival

Notification of death was collected and overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of stent insertion to the date of death from any cause.

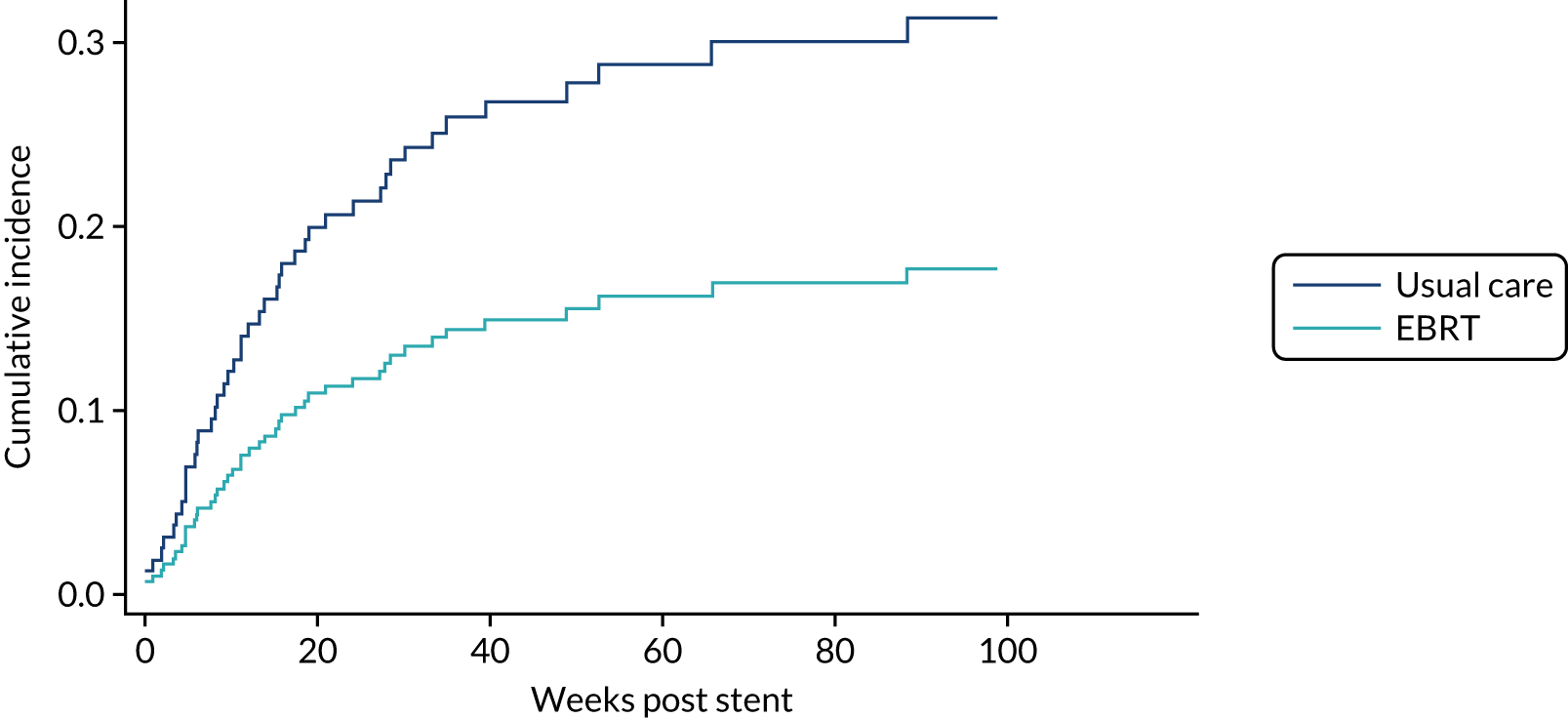

Dysphagia deterioration-free survival

Dysphagia deterioration-free survival (DDFS) was calculated from the date of stent insertion to the date of deterioration in dysphagia symptoms (as per the primary outcome definition).

Health-related quality of life

Quality of life was measured using the EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-OG25 and EQ-5D-3L at the specified assessment time points.

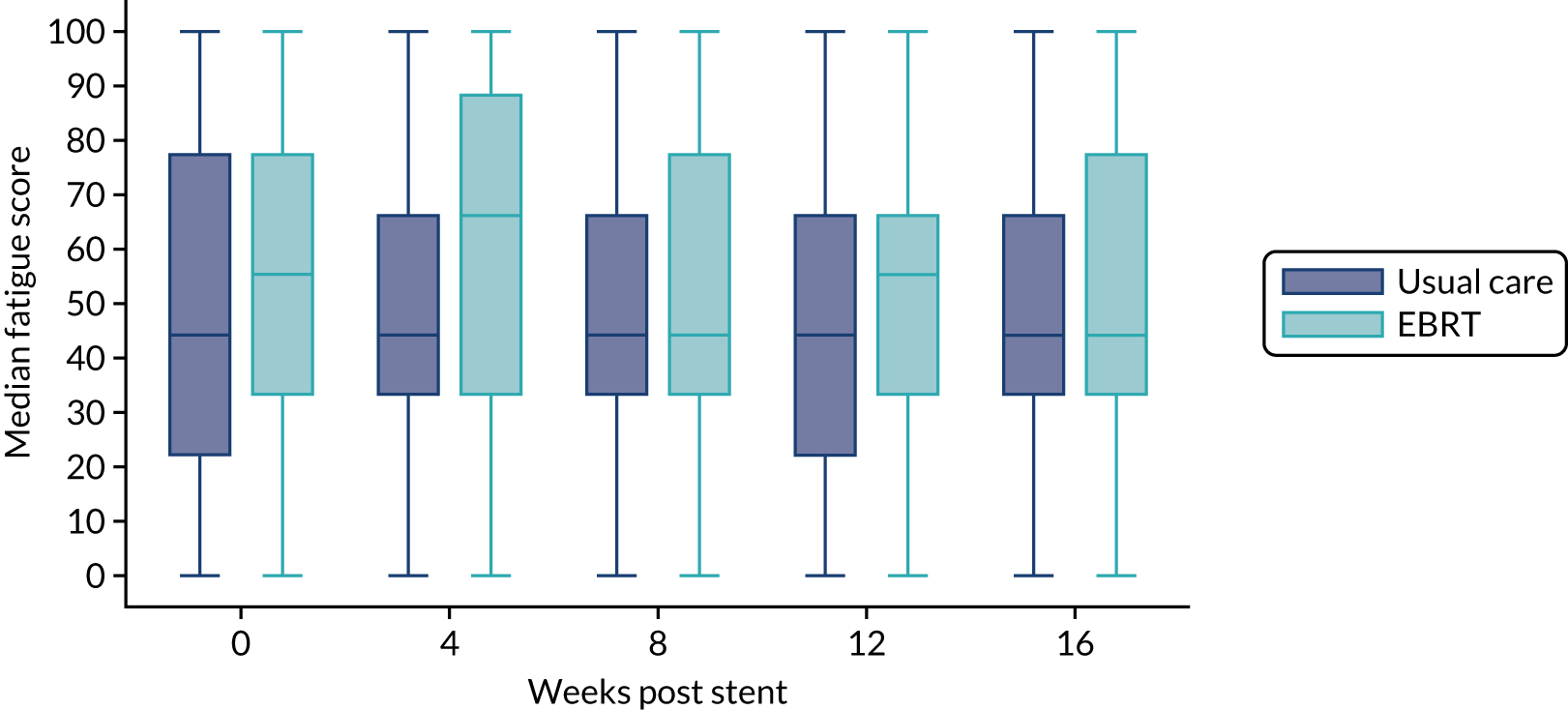

Health-related quality of life was assessed using generic instruments: the EORTC QLQ-C-30, which assesses global QoL, functional domains (physical, emotional, social, role and cognitive) and symptoms (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulty) that commonly occur in patients with cancer; and the EORTC QLQ-OG25. Both tools (the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the EORTC QLQ-OG25) were employed, as validation of the EORTC QLQ-OG25 demonstrated that it measures separate HRQoL issues and it is likely that dysphagia accounts for only a proportion of the impact on QoL. 32 All of the scales and single-item measures range in score from 0 to 100; a higher score represents a higher (‘better’) level of functioning, or a higher (‘worse’) level of symptoms.

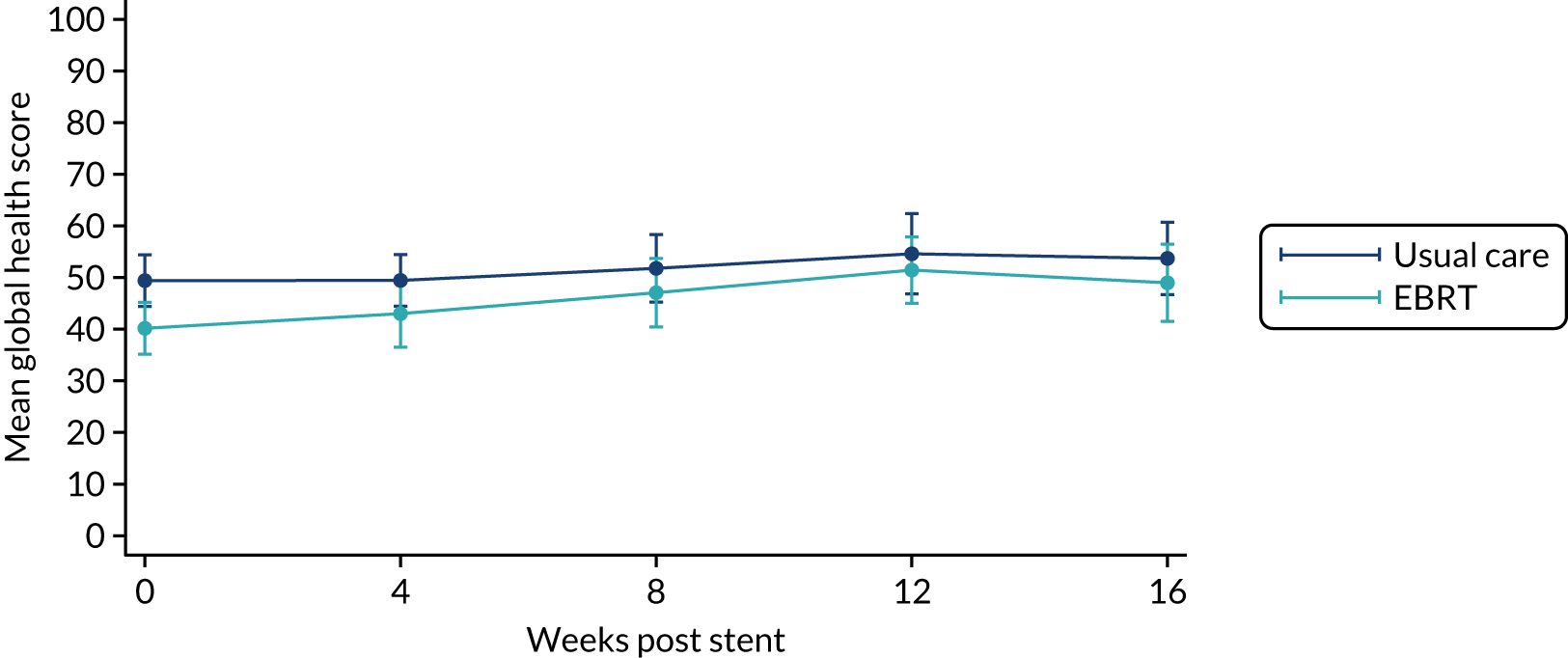

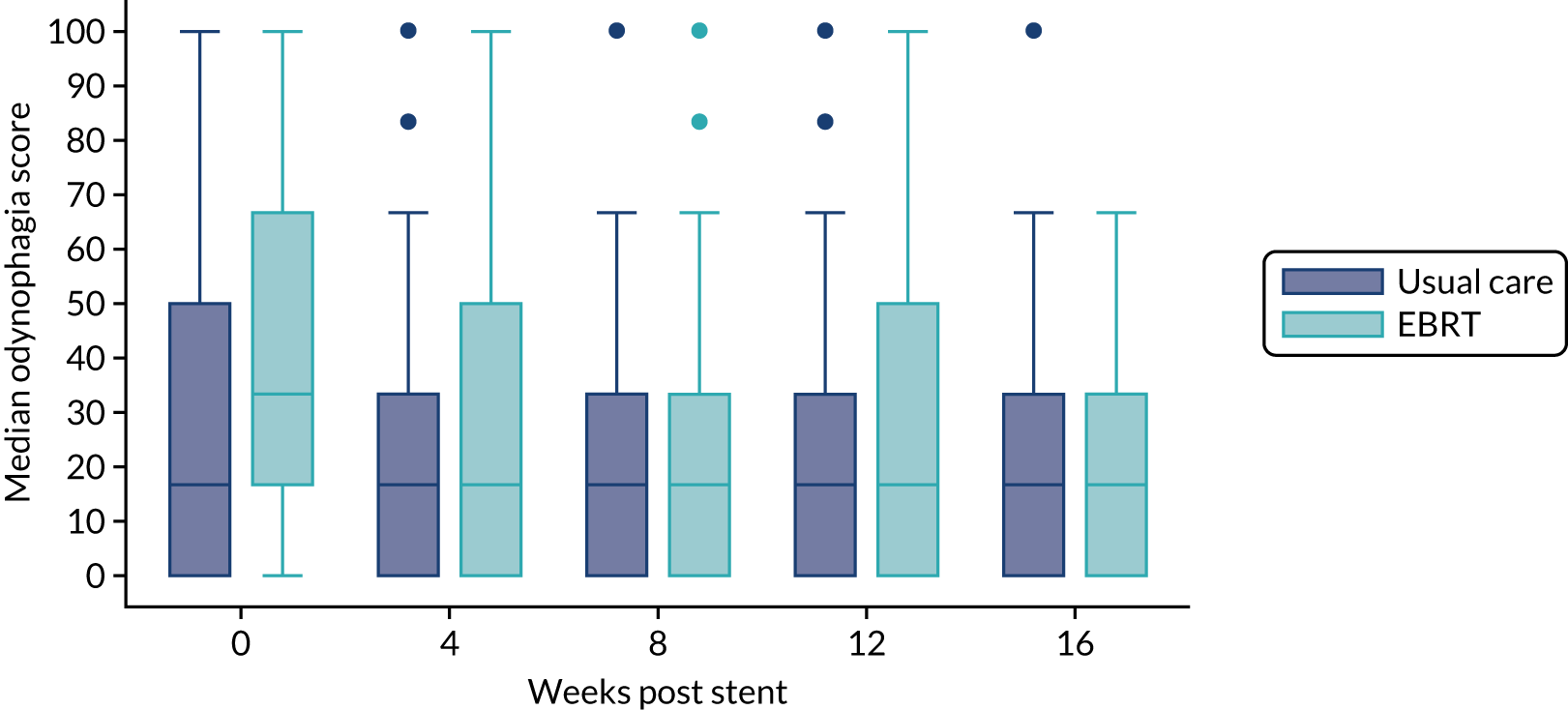

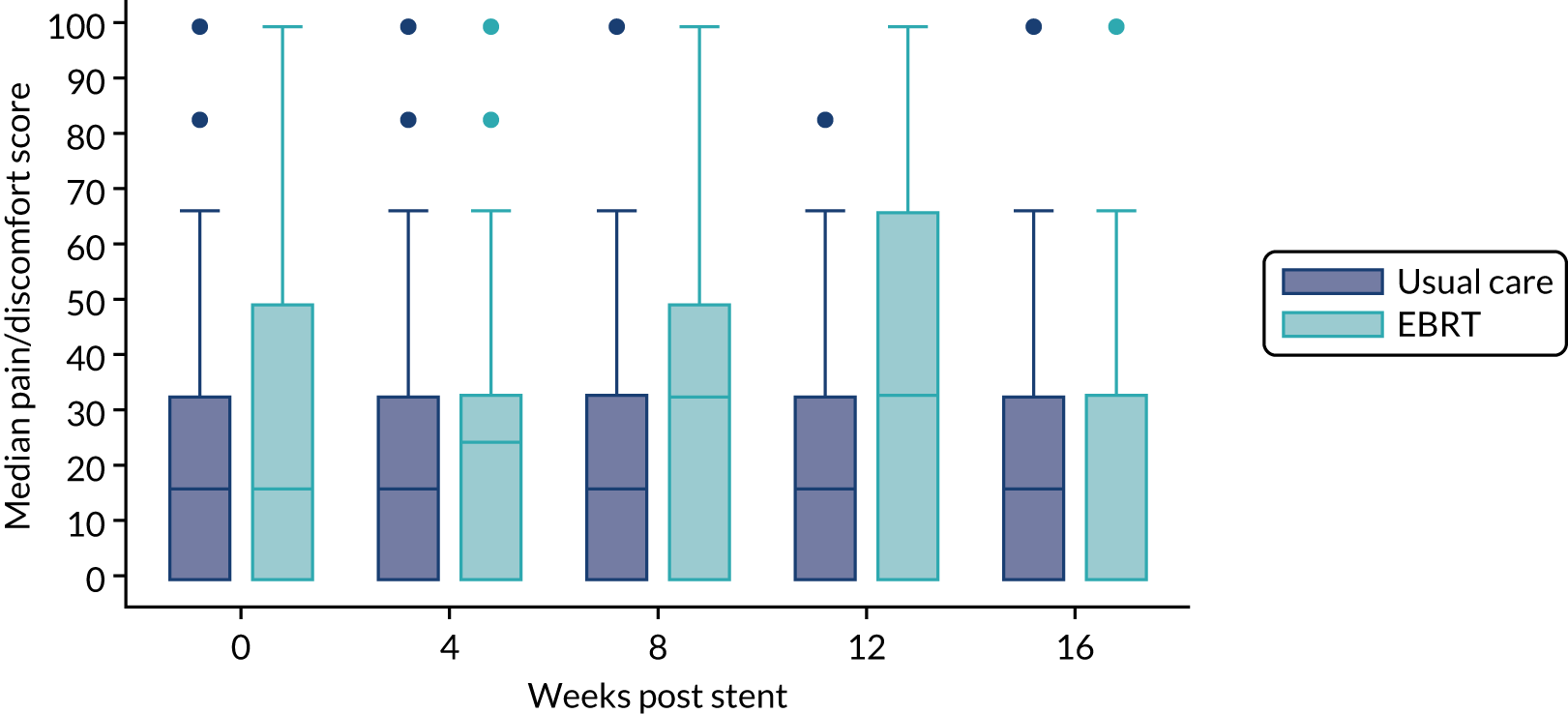

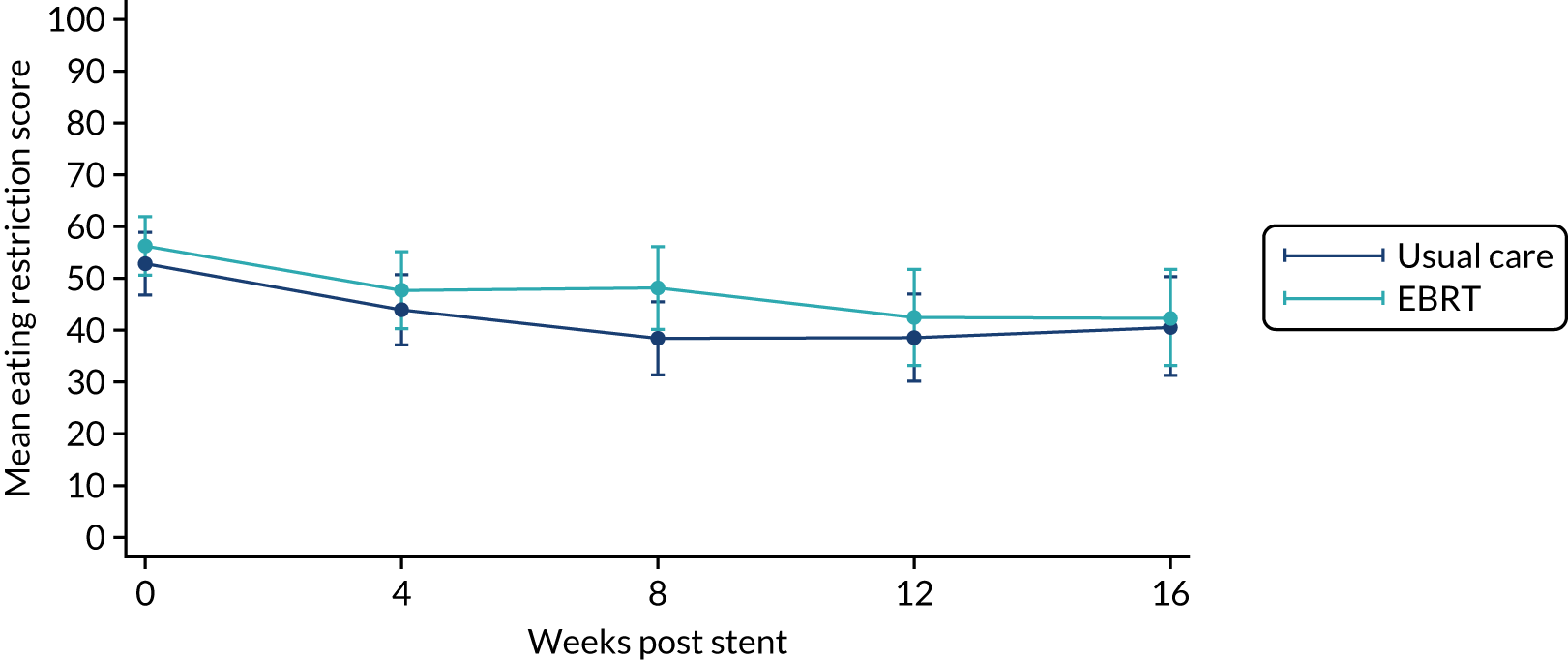

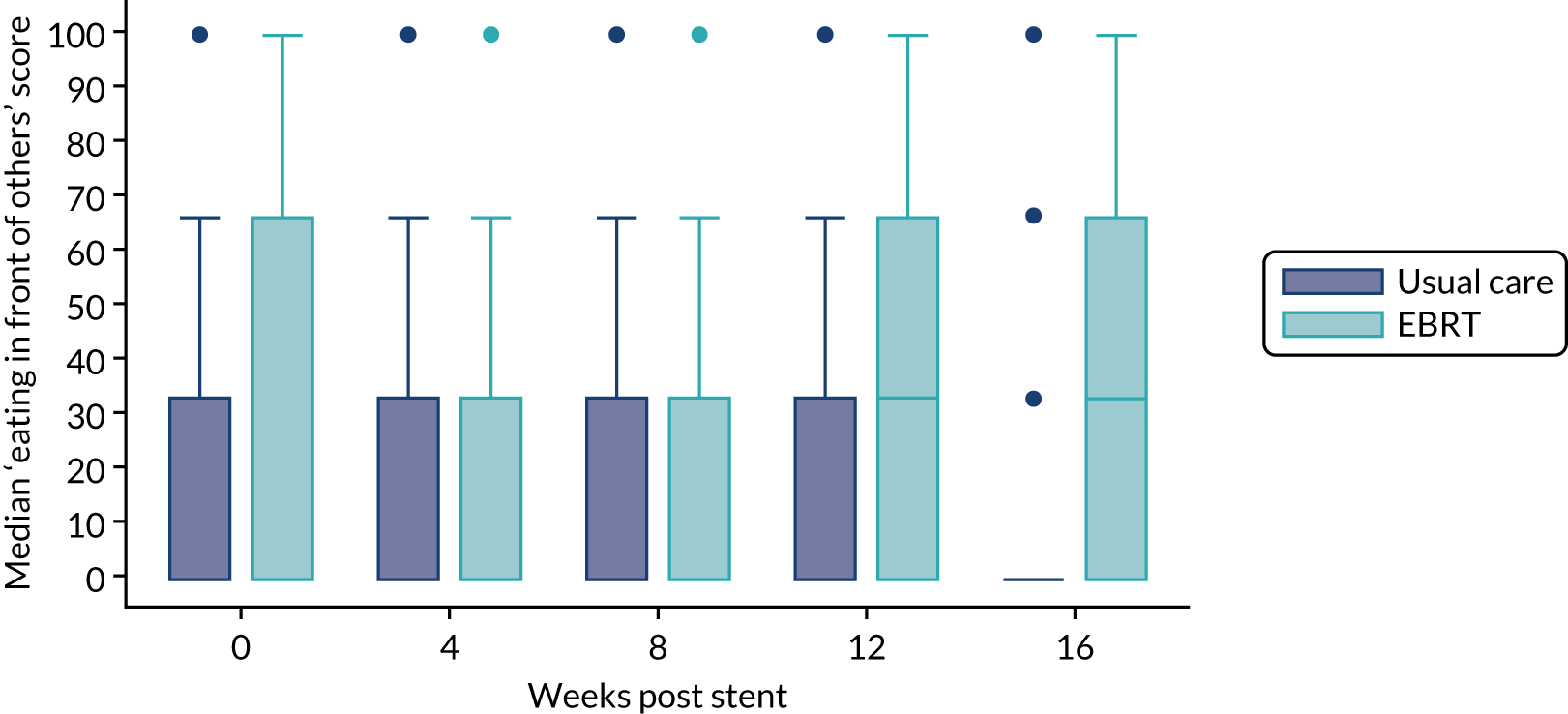

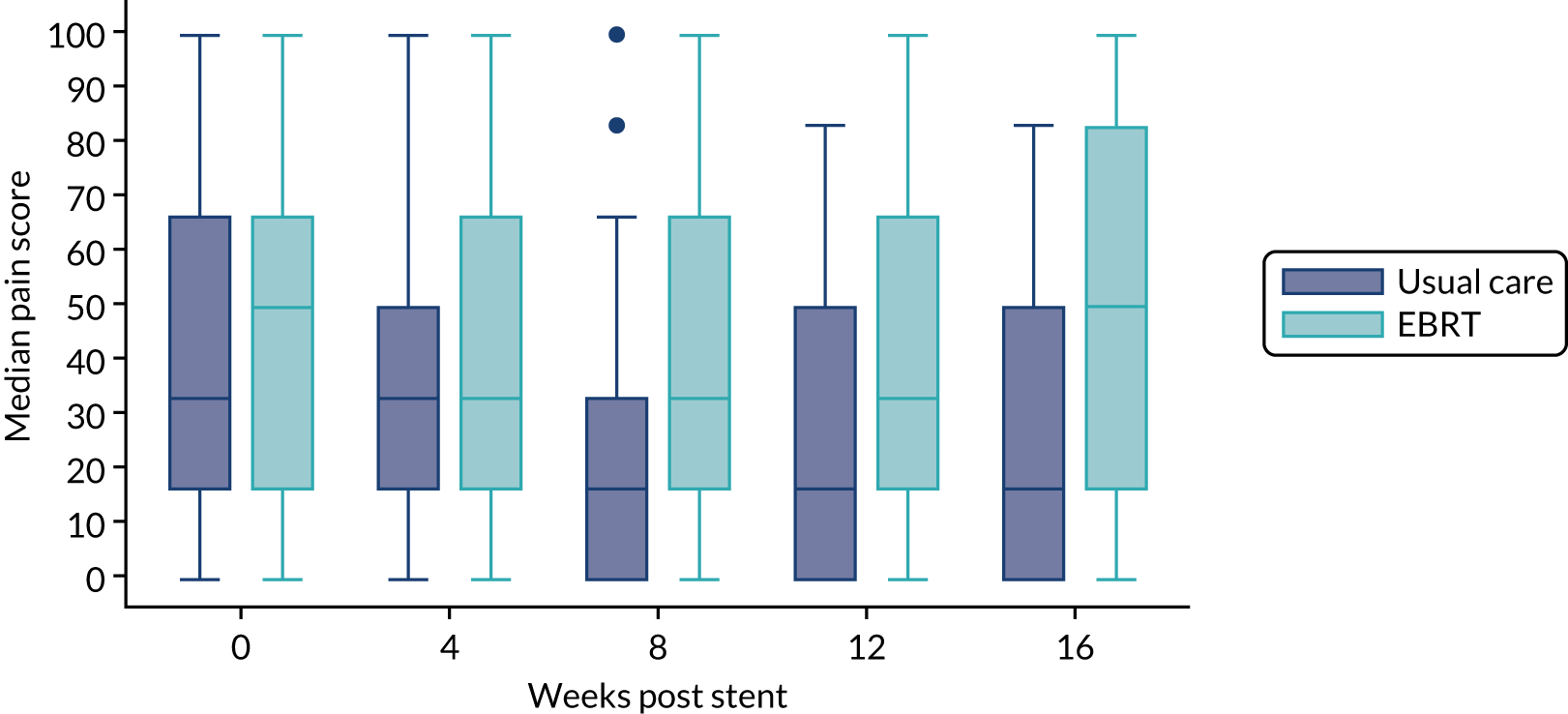

The prespecified main patient-reported outcome items that were identified a priori to be of relevance were the global health score from the EORTC QLQ-C30 and four scales from the EORTC QLQ OG25 questionnaire: odynophagia, pain/discomfort, eating restrictions and eating in front of others.

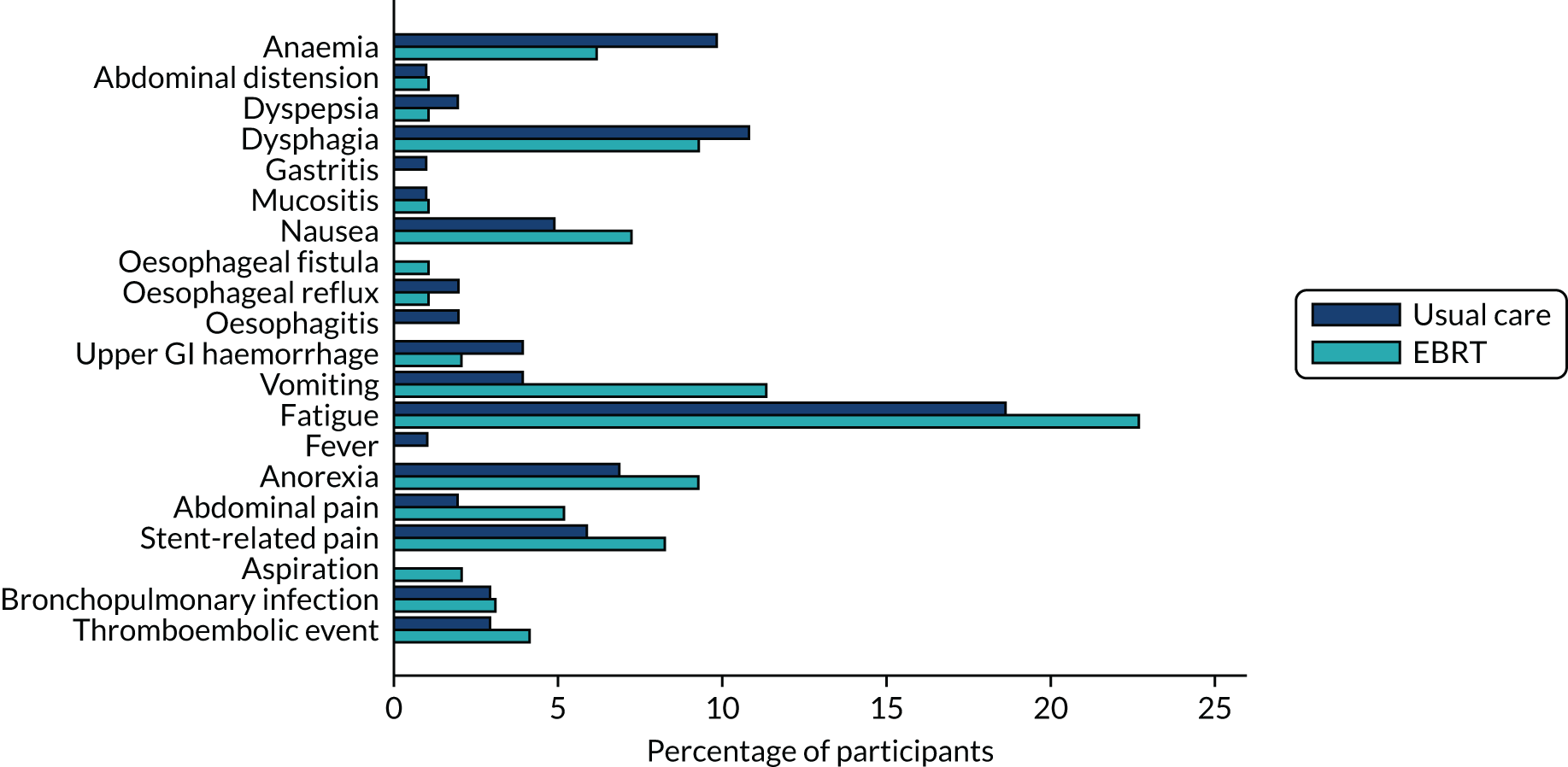

Toxicity

Toxicity data were scored using the National Cancer Institute CTCAE at baseline, during treatment and at the prespecified time points during follow-up.

Morbidity

Tumour bleeding

Upper GI bleed events were confirmed by the chief investigators, who were blinded to the study arm, and reviewed by an independent gastroenterologist. These included blood transfusion, haematemesis, upper GI haemorrhage or bleed, melaena and interventions related to bleeding (e.g. argon plasma coagulation or additional radiotherapy). If there was no clinical evidence that anaemia was due to a bleed, then it was not considered.

Dysphagia-related stent complications and reinterventions

Stent complications were defined as re-stenting, repeat endoscopy, overgrowth of stent, undergrowth of stent, stent blockage, stent fracture and stent slippage. Reinterventions were defined as additional stent insertion, stent removal, endoscopic intervention (including laser therapy and alcohol injection) and other palliative radiotherapy (including brachytherapy and additional EBRT for dysphagia).

Stent-related pain

A stent-related pain event was defined as grade 2+ stent-related pain reported on the toxicity CRF.

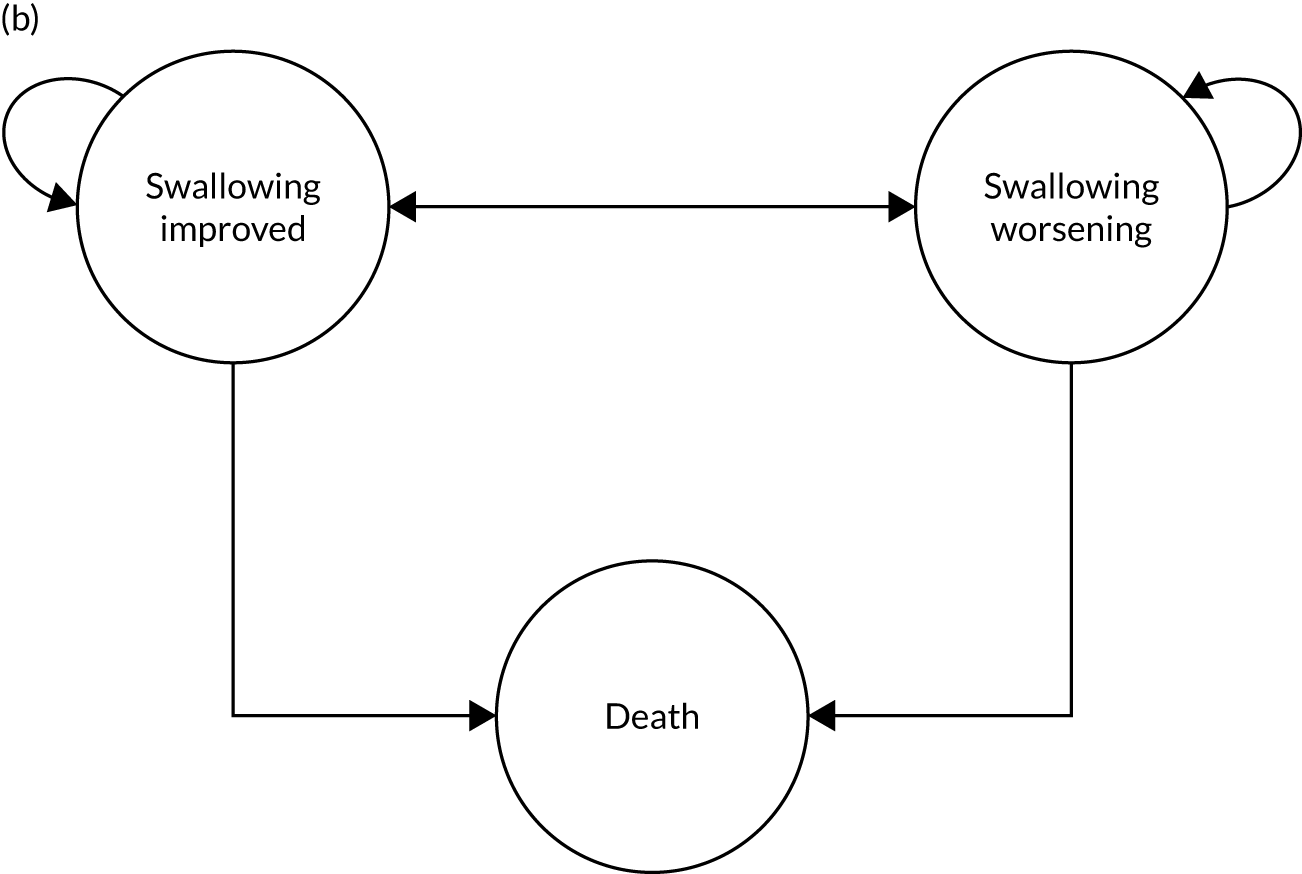

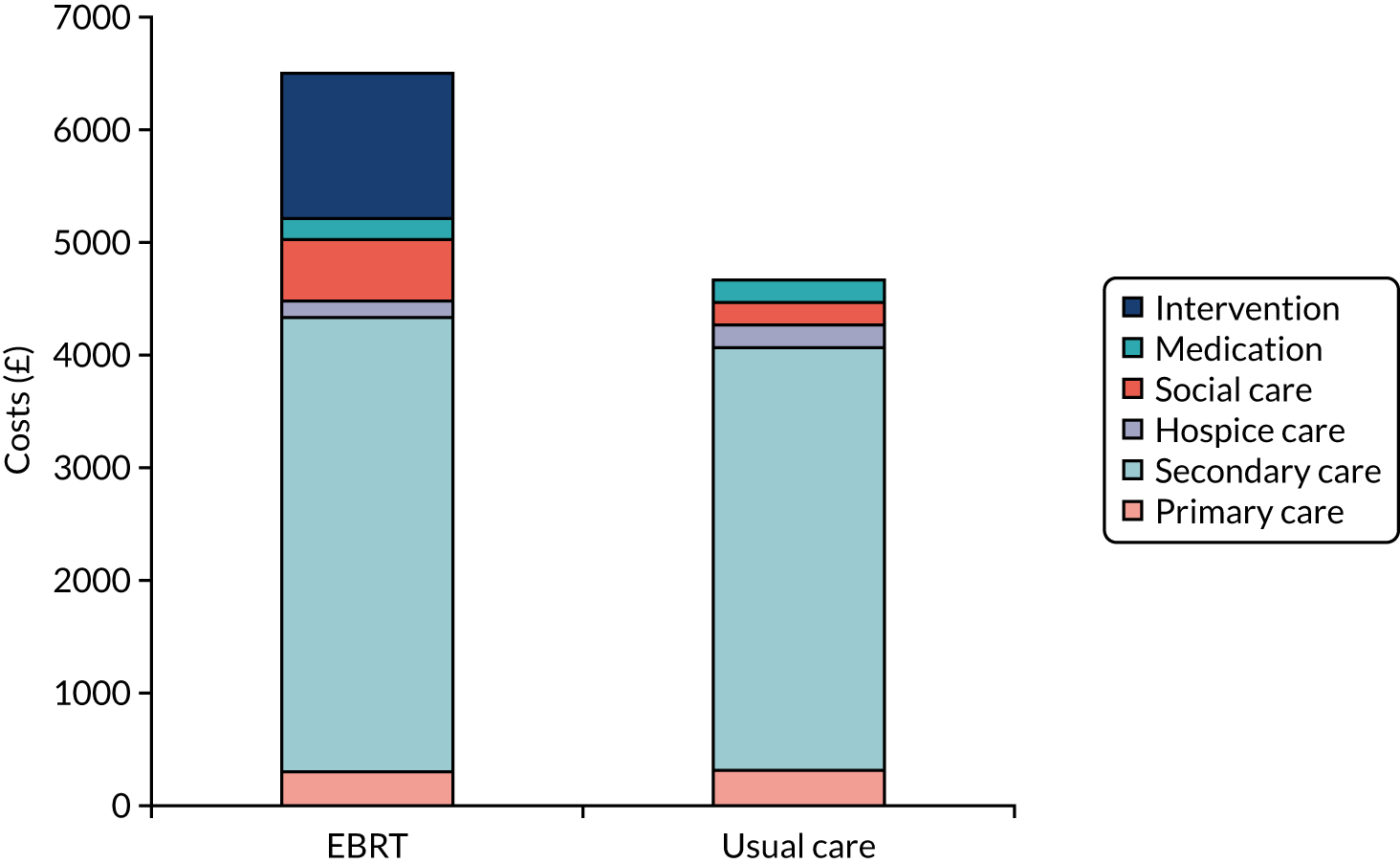

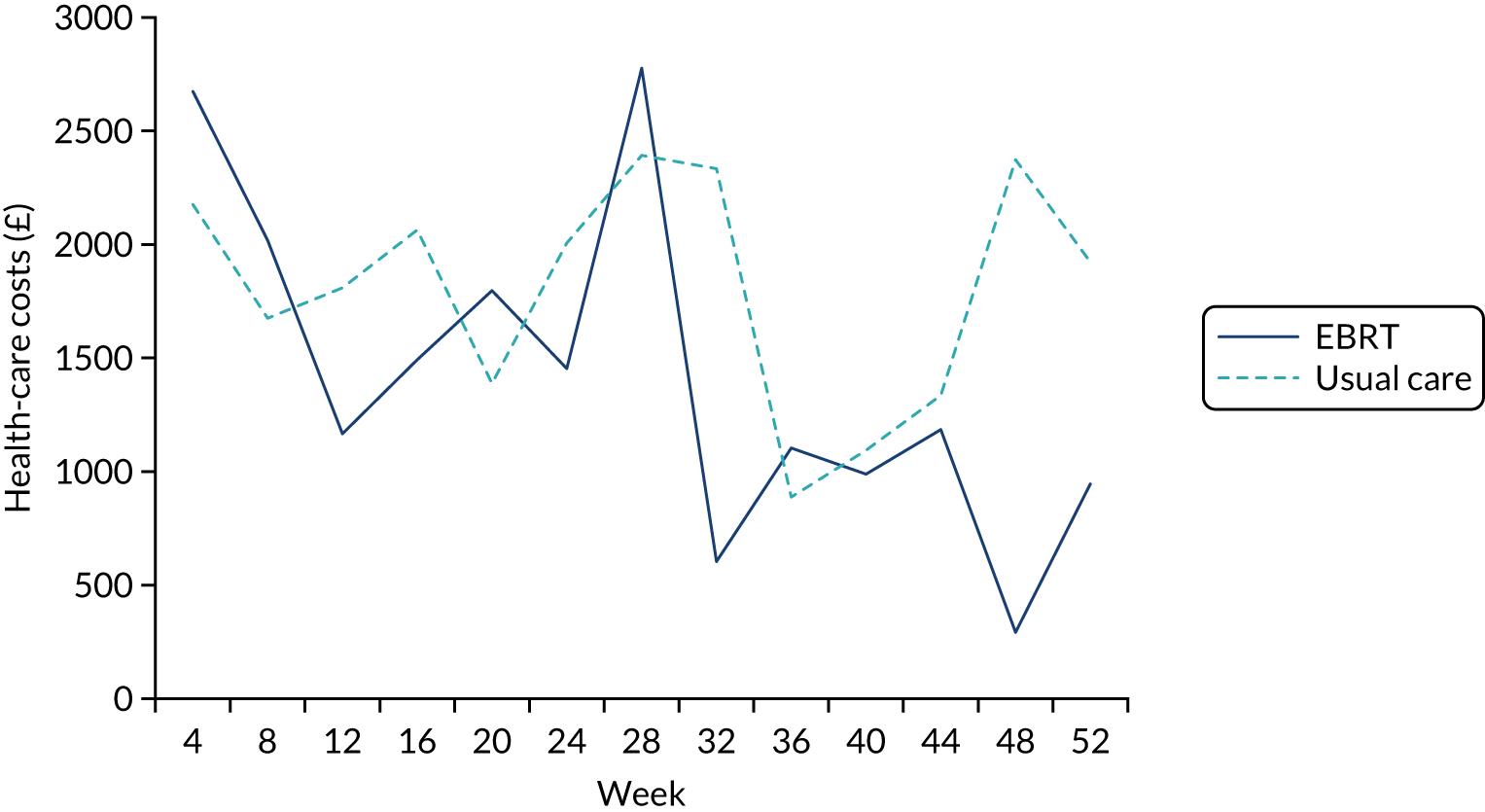

Cost-effectiveness

The economic valuation was in the form of a cost–utility analysis (CUA) assessing total costs against differences in health outcome expressed as quality-adjusted-life-years (QALYs), with utilities derived from the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire responses. 33–35 EQ-5D-3L has been used previously on patients with inoperable oesophageal cancer. 7 CUA is the health economic method preferred by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 33 In line with NICE guidance, the analysis was undertaken from an NHS and Personal Social Services perspective. Details of the health economic evaluation are reported in Chapter 5.

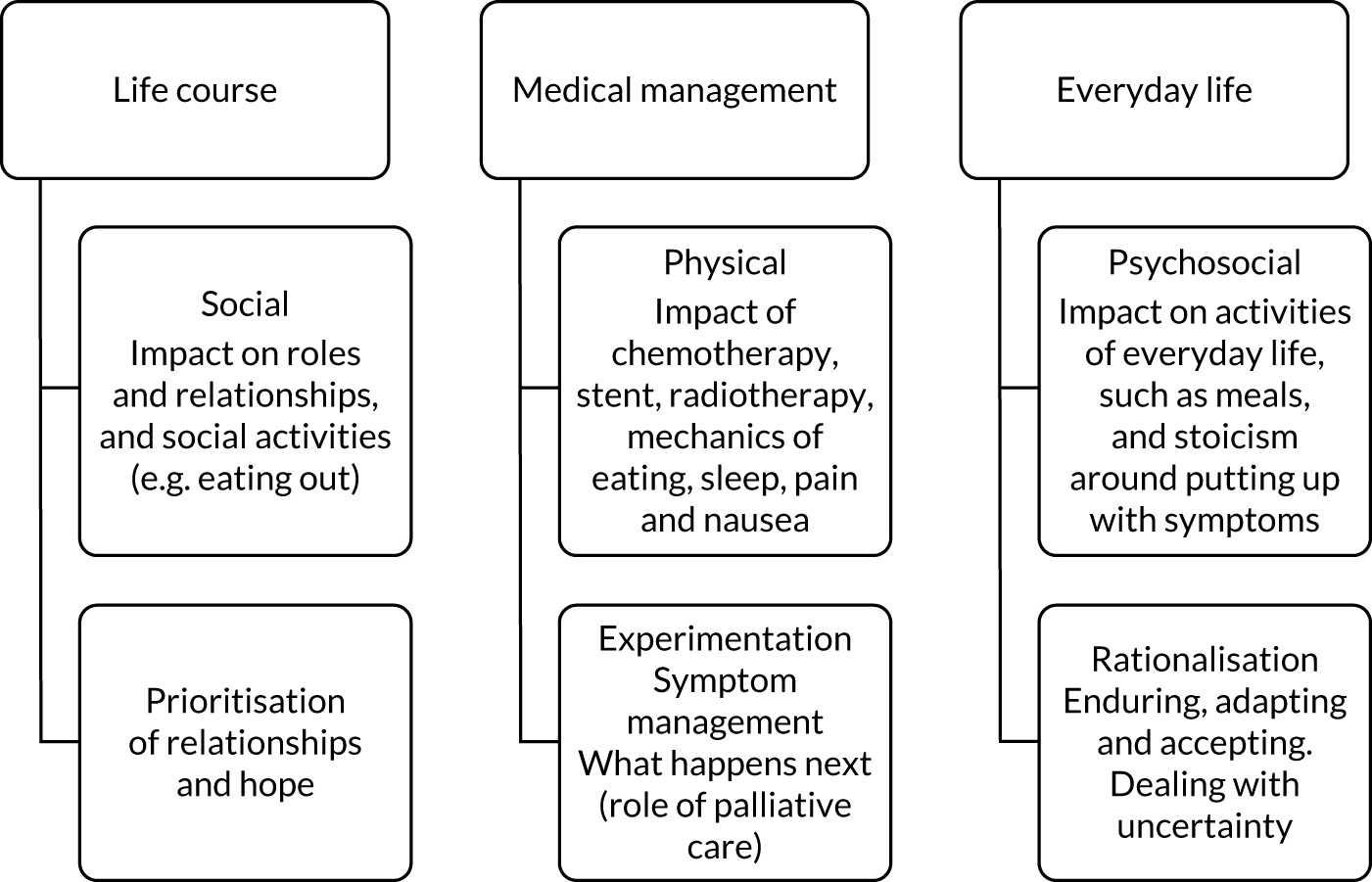

Patient perspectives

The embedded qualitative study was designed to explore the feasibility of patients’ recruitment to the trial by examining their experience of consent and recruitment, to highlight the reasons for non-consent and to examine patients’ motivation to accept randomisation to an intervention that may include extra radiotherapy. It also provided the opportunity to understand patients’ experience of living with advanced oesophageal cancer and dysphagia and how they negotiated interventions – particularly in terms of trade-offs between perceived burdens and benefits. The qualitative methodology is described in detail in Chapter 4.

Sample size

Original sample size justification based on time to event

In a population with a median survival of approximately 4 months, an increase in median time to deterioration in self-reported dysphagia of 4 weeks was considered clinically meaningful. This was based on previous results10 and expert multidisciplinary clinical and service user opinion. Sample size was therefore originally calculated, based on a time-to-event analysis, to detect an increase in median time to deterioration in self-reported dysphagia of 4 weeks: from 12 to 16 weeks [equivalent to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.75 and a difference in 12-week event rate of 50% vs. 60%]. For 80% power with alpha = 0.05 based on a two-sided log-rank test, 198 patients per arm would be required: 396 in total, which is a total of 384 events. Assuming 20% attrition, a total of 496 participants would be required.

Time to event would be calculated from the time of stent insertion to the time of deterioration or death. Patients who did not achieve an improvement from the pre-stent measure of at least 11 points31 on the OG25 dysphagia subscale at the first week assessment after stent insertion (time zero) would be included and followed up but assumed to have failed at time zero. Those who were deterioration free and alive would be censored at the time last seen.

Revised sample size justification based on proportions of events at 12 weeks post stent

In view of the challenging nature of the study in recruiting a palliative population towards the end of life, the IDMC undertook 6-monthly reviews of recruitment and data returns. Although the consent rate continued to approach the predicted rate of 50%, the proportion of eligible patients remained significantly lower than originally predicted (43.6% vs. the 70% predicted). Missing data also increased significantly beyond 12 weeks, despite high CRF returns, reflecting the increasing frailty of the patient population. In view of these combined issues the IDMC recommended a revised sample size calculation based on comparison of proportions with a dysphagia event at week 12. To reduce this proportion from 40% to 20% required 164 patients (80% power, 5% alpha two-sided). This difference in proportions is in line with the difference sought in other studies of stent or non-stent interventions for malignant dysphagia. 9,12,36 To allow for a 25% loss to follow-up required 220 patients to be randomised. This is equivalent to the largest sample size recruited into intervention RCTs for advanced oesophageal cancer dysphagia. The changes were approved by the independent TSC and ratified by the funder following independent review.

Statistical analysis

Analysis and reporting of this trial were undertaken in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 37 All statistical analyses were performed using Stata following a predefined statistical analysis plan agreed with the IDMC. The modified intention-to-treat (ITT) population was defined as all patients who had a stent inserted and returned a baseline EORTC QLQ-OG25 (OG25) questionnaire. The per-protocol population was defined as the subgroup of the modified ITT population that was alive and who had not withdrawn from trial treatment at 4 weeks post stent insertion, that was not found to be ineligible, had no protocol deviation or other reason for exclusion and (in the radiotherapy arm) received at least one fraction of radiotherapy.

Primary analysis

Analysis of the primary binary end points of deterioration in dysphagia symptoms by 12 weeks was primarily conducted in the modified ITT population with complete-case data. Complete cases were defined as having complete data for the dysphagia subscale of the EORTC QLQ-OG25 questionnaire at time 0, week 4, week 8 and week 12 or having died with complete data prior to week 12. Single missing time points were permitted under the rules described below.

Primary end point events were based on:

-

Two consecutive deteriorations in patient-reported dysphagia score.

-

One deterioration and no more data possible (i.e. patient withdrew completely or died before next visit).

-

One deterioration, missing next visit; withdrew or died within 4 weeks of missing visit.

-

Additional dysphagia-related primary events (additional stent insertion, dysphagia on clinical assessment or documented as reason for hospital admission, overgrowth or undergrowth of stent, grade 3+ dysphagia on toxicity form or SAE or additional radiotherapy to oesophagus/stent region). All additional primary events were assessed blindly and confirmed by the chief investigators and reviewed by an independent gastroenterologist, as a dysphagia-related event.

-

Death prior to week 12.

In the absence of a documented dysphagia-related event, missing dysphagia scores between two non-event dysphagia scores were assumed to be no event.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to adjust for randomisation stratification factors and the adjusted odds ratio (OR) was presented along with 95% CIs and p-values for the primary analysis and all sensitivity analyses. Where there were fewer than five patients per centre, these patients were combined into a new centre to ensure that all patients’ data were used in the adjusted model. Three sensitivity analyses were performed:

-

using the same complete-case population but treating death by 12 weeks without prior deterioration as no deterioration

-

imputing missing data using a best-case scenario that assumed no deterioration in a missing OG25 form immediately prior to an OG25 form that showed deterioration (or additional primary event confirmed by the chief investigator), or missing OG25 data immediately prior to death

-

imputing missing data using a worst-case scenario that assumed deterioration in a missing OG25 form immediately prior to an OG25 form that showed deterioration (or additional primary event confirmed by the chief investigator), or missing OG25 data immediately prior to death.

Additional sensitivity analyses of the main results and the three sensitivity analyses above were performed in the per-protocol population.

Secondary analyses

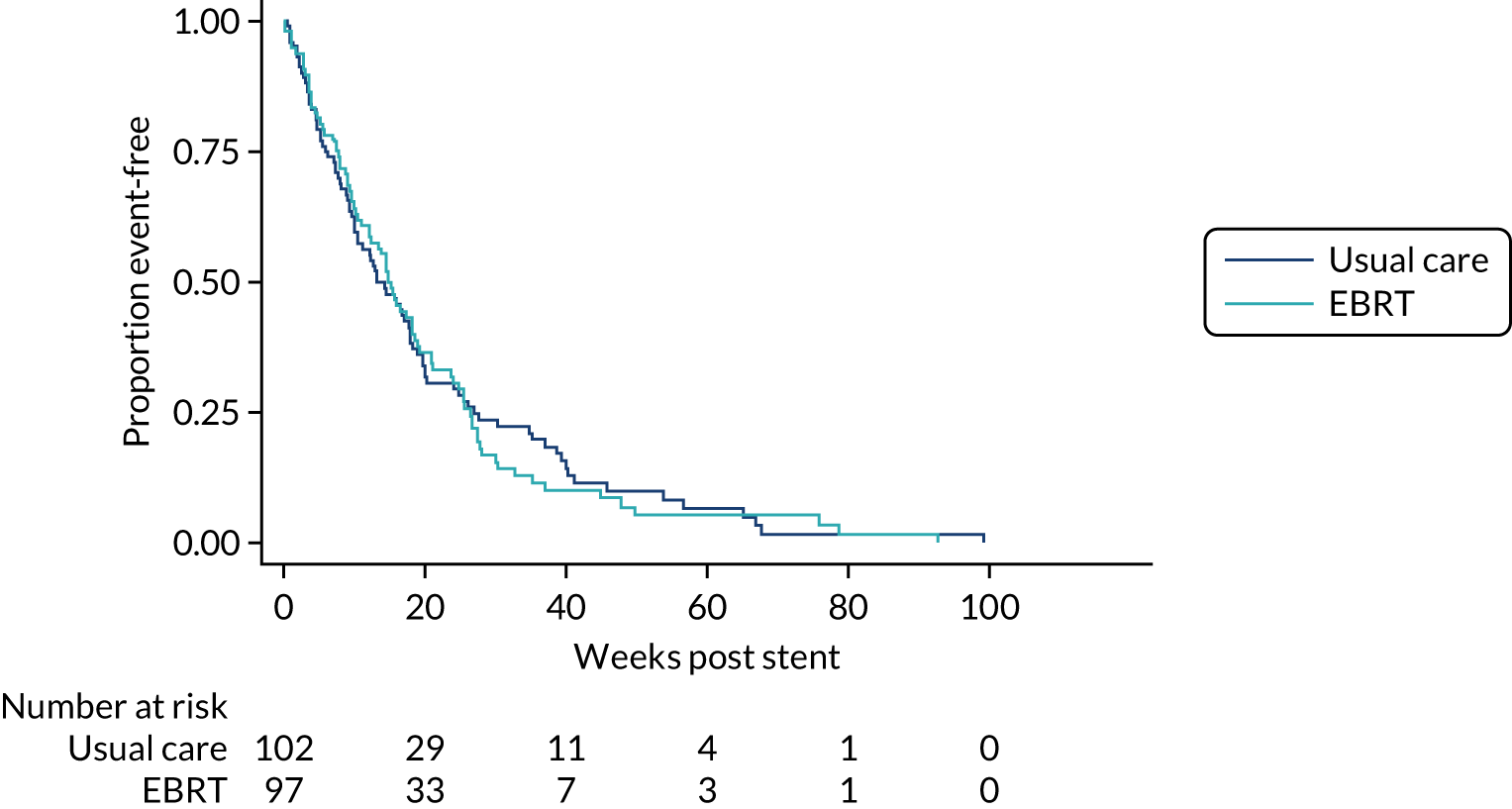

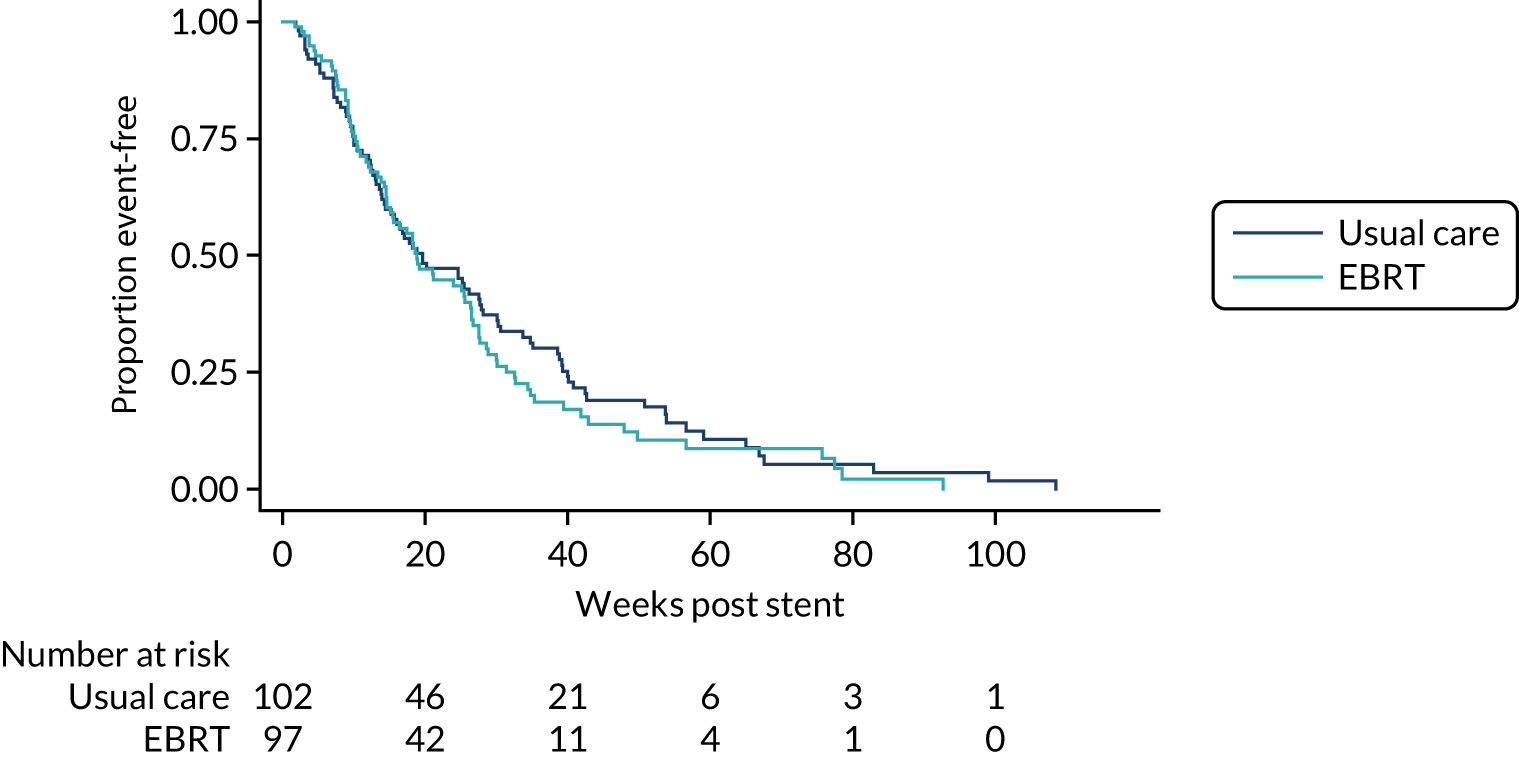

Overall survival, follow-up and dysphagia deterioration-free survival

Overall survival and DDFS were analysed by time-to-event methods (Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox regression), with those without events being censored at time last seen. The Cox regressions were adjusted for randomisation stratification factors with treating centre also included as a shared frailty. For those with uncensored data, the reverse Kaplan–Meier approach was used to present follow-up post-stent insertion in each arm. DDFS events were calculated as per the method used for the primary end point above. As a sensitivity analysis, the DDFS analysis was repeated, but data were censored at death with no prior dysphagia event.

Quality of life and World Health Organization performance status

All EORTC QLQ-C30 items were scored for each patient according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 38 Data were imputed according to EORTC guidance if fewer than half of the items in a scale were missing. Where data were missing from more than half of the items in any scale, these scales were excluded from the analyses. When a complete questionnaire was missing, the reason for the missing questionnaire was ascertained and categorised. The same methods were used for analysing the QoL data and the WHO performance status scores.

The distribution of the baseline scores was tested for normality using kernel density plots, normal probability plots, normal quantile plots and the Shapiro–Wilk test to determine which graphical method to use to display scores over time [median and interquartile range (IQR) if not normal, mean and 95% CIs if normal]. Questionnaires that were returned within 2 weeks (plus or minus a specified time point) were selected for each time point measure.

Linear mixed models were used to compare differences between trial arms for each subscale or single item. Time was included as a categorical covariate using the week of observation from 0 (time zero) to 16, after which the proportion of missing data became too high. If an intermediate value was missing, the corresponding time was skipped. Covariates included trial arm, age, time zero score and randomisation stratification factors. For each subscale or single item, the interaction of treatment by time of assessment was tested.

To assess goodness of fit of the linear mixed models, the fixed effects for determining the selection of linear mixed model for each subscale or item were evaluated using Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the model with the lowest AIC and BIC is presented.

Morbidity

The same analytical method was used for the following morbidity events:

-

upper GI bleed events

-

dysphagia-related stent complications and reinterventions

-

additional stent insertion

-

repeat endoscopy

-

overgrowth or undergrowth of stent

-

stent-related pain.

Time to first morbidity event was compared between trial arms using competing risks regression, with death as a competing risk, adjusted for randomisation stratification factors and cumulative incidence functions plotted by trial arm.

Missing data

The potential for missing data was significant in this trial given the study population. Plans to reduce the number and impact of missing data centred on:

-

maximising data capture

-

handling of missing data

-

analysis and reporting.

Significant efforts were made to reduce the number of missing data. As described, they included additional research nurse time to collect all follow-up data at home, multidisciplinary input to trial and CRF design to optimise the type and number of data captured and reasons for missing data, implementation of between-visit telephone calls, and an additional level of withdrawal to allow continued case note data capture.

The handling and investigation of the potential influence of missing data through sensitivity analyses are described in Primary analysis and in Chapter 3.

Patient and public involvement

Aim

The involvement of patients and members of the public as research partners was underpinned by a comprehensive strategy within the CTR and the Marie Curie Research Centre (MCRC) at Cardiff University, which was responsible for the conduct of the main trial and the embedded qualitative component. The ROCS study had research partner involvement from the initial concept and outline design phase, through study delivery as part of the TMG and as a core component of the dissemination phase. There were specific objectives in relation to:

-

research partner advertisement and recruitment onto the TMG by interview

-

research partner training and integration in to the trial team and TMG

-

ongoing support and assessment of impact of the contribution of the research partners

-

involvement in publications and dissemination plan.

Methods

One member of the public, Jim Fitzgibbon, had a lead role for development of patient and public involvement (PPI) strategy in the CTR alongside Annmarie Nelson as academic lead for PPI. Together they developed the strategy for PPI in the trial. They developed a role description and bespoke recruitment and training plans. An additional member, Stephen Thomas, was appointed following successful grant capture and set-up of the TMG.

Support

Research partners were introduced to, and integrated into, the trial team. Both research partners became familiar with the trial unit environment, and trial staff received training on the importance of the research partner role and specific aspects of support. Reimbursement of expenses was offered, as were honoraria for their time, in keeping with the local strategy for research partner support.

Impact

Both lay members of the TMG were fully involved as the trial progressed. Particular areas where they had an impact were:

-

Jim Fitzgibbon was involved in initial trial design and grant submission as co-applicant, as well as the protocol publication.

-

Jim Fitzgibbon and Stephen Thomas directly influenced protocol design and subsequent amendments, particularly in relation to patient-reported outcomes and recruitment strategy.

-

Jim Fitzgibbon and Stephen Thomas directly supported development of trial materials, particularly the PIS and consent form, and the formatting and content of CRFs.

-

They made sure that the trial was conducted in a participant-friendly and ethically acceptable way, which included changes in timing of consent, the introduction of a patient card containing the primary outcome dysphagia questions in support of telephone data capture, and introduction of additional 2-weekly telephone assessments between the scheduled 4-weekly face-to-face assessments.

-

They were involved in the interpretation and reporting of the trial results for this monograph.

It is anticipated that they will also be involved in:

-

disseminating results through publication, UK and international presentations, and knowledge transfer through national and regional clinical and academic organisations and patient groups.

Conclusions and reflections

The involvement of our lay research partners was core to the successful development and implementation of the ROCS study. Their inputs have had an impact throughout the trial and have supported wider integration of research partners in the trials unit environment. Although the involvement predates the NIHR standards, we followed forefront processes in recruitment, training and support. Although it has been possible to describe and list some of the impact that research partners have had, we recognise the need in future to utilise more considered and timely ways of recording it and to undertake a ‘study within the study’ of how best to capture and describe research partner impact. Work is proceeding in the CTR to develop a practical system and tool to enable this to happen.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and randomisation

A total of 220 participants were recruited to the ROCS study by 23 centres (see Appendix 1) between 16 December 2013 and 24 August 2018. In total, 112 participants were allocated to the usual-care arm and 108 participants were allocated to the EBRT arm.

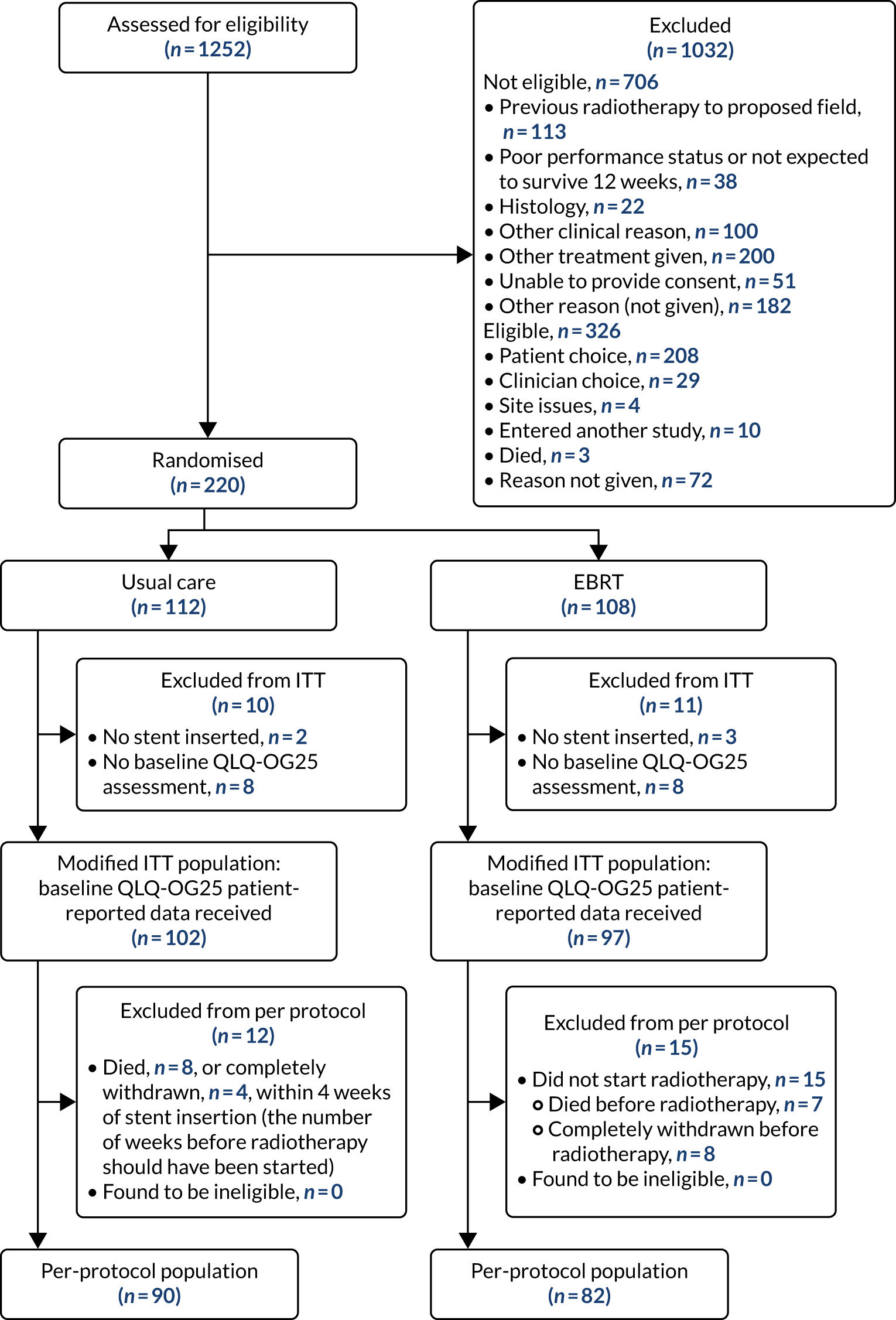

Flow of participants through the trial

The CONSORT flow diagram is shown in Figure 2 and summarises patient flow from eligibility screening and randomisation to stent insertion (either before or after randomisation) and inclusion in the ITT and per-protocol populations. Unless otherwise stated, all analyses are for the modified ITT population. In total, 43.6% (546/1252) of screened patients were eligible and, of those, 40.3% (220/546) gave consent.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Characteristics of the study sample

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The randomisation stratification factors of tumour type, stage at diagnosis and intended chemotherapy after stent insertion were well balanced between trial arms, as were other baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Usual care (N = 102) | EBRT (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR), n | 73.5 (65.4–81.5), 102 | 72.0 (65.3–79.9), 97 |

| Randomisation time point, n (%) | ||

| Before stent | 39 (38.2) | 36 (37.1) |

| After stent | 63 (61.8) | 61 (62.9) |

| WHO performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 10 (9.8) | 10 (10.3) |

| 1 | 61 (59.8) | 59 (60.8) |

| 2 | 27 (26.5) | 27 (27.8) |

| 3 | 4 (3.9) | 1 (1.0) |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Tumour type, n (%) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 68 (66.7) | 61 (62.9) |

| Squamous | 33 (32.4) | 34 (35.1) |

| Undifferentiated/other | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Overall length of primary tumour (endoscopic assessment), median (IQR), n | ||

| Measured length (cm) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0), 64 | 6.0 (4.0–8.0), 57 |

| Estimated length (cm) | 6.0 (4.5–8.0), 28 | 7.0 (5.0–8.0), 33 |

| Measured/estimated length (cm) | 5.9 (4.0–7.0), 92 | 6.0 (4.5–8.0), 90 |

| Missing | 10 (9.8) | 7 (7.2) |

| Alternative method for assessing length, n (%) | ||

| PET | 5 (4.9) | 7 (7.2) |

| CT | 23 (22.5) | 23 (23.7) |

| Barium | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| None | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Site of predominant tumour, n (%) | ||

| Upper | 3 (2.9) | 3 (3.1) |

| Middle | 24 (23.5) | 25 (25.8) |

| Lower | 75 (73.5) | 68 (70.1) |

| If lower, involvement of GOJ | 38 (37.3) | 38 (39.2) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Extension across GOJ (if involvement of GOJ), n (%) | ||

| Siewert type 1 | 21 (20.6) | 20 (20.6) |

| Siewert type 2 | 15 (14.7) | 13 (13.4) |

| Missing | 2 (2.0) | 5 (5.2) |

| T stage | ||

| 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| 2 | 4 (3.9) | 7 (7.2) |

| 3 | 61 (59.8) | 54 (55.7) |

| 4 | 29 (28.4) | 31 (32.0) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Missing | 4 (3.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| N stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 17 (16.7) | 10 (10.3) |

| 1 | 46 (45.1) | 46 (47.4) |

| 2 | 20 (19.6) | 20 (20.6) |

| 3 | 15 (14.7) | 17 (17.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Missing | 3 (2.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| M stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 46 (45.1) | 41 (42.3) |

| 1 | 49 (48.0) | 50 (51.5) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Missing | 5 (4.9) | 5 (5.2) |

| Overall stage, n (%) | ||

| 1–3 | 51 (50.0) | 46 (47.4) |

| 4 | 51 (50.0) | 51 (52.6) |

| Chemotherapy | Usual care (N = 102) | EBRT (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|

| Previous chemotherapy given, n (%) | ||

| No | 87 (85.3) | 74 (76.3) |

| Yes | 15 (14.7) | 23 (23.7) |

| EOX | 6 (5.9) | 7 (6.9) |

| ECX | 4 (3.9) | 3 (2.9) |

| Cisplatin + capecitabine | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.9) |

| CX; OxCap | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| OxCap | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Carboplatin + capecitabine + epirubicin | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Cisplatin; 5FU | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Cisplatin + epirubicin | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| CX | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| CX + herceptin; docetaxel | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Docetaxel; irinotecan | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| ECF | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| ECX neoadjuvant; EOX | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| EOX; docetaxel | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| If had prior chemotherapy, intended number of cycles, median (IQR), n | 6.0 (4.0–8.0), 15 | 4.0 (3.0–6.0), 21 |

| Intended number of cycles missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) |

| Number of prior chemotherapy cycles given, median (IQR), n | 3.0 (2.0–6.0), 15 | 4.0 (3.0–6.0), 23 |

| MDT intended chemotherapy after stent? n (%) | ||

| Yes | 36 (35.3) | 34 (35.1) |

| No | 66 (64.7) | 63 (64.9) |

Allocation of treatments

Treatment adherence

Table 4 shows a summary of stent insertion, including clinical characteristics and complications. There were no reports of oesophageal or other GI tract perforation. Radiotherapy administration is shown in Table 5 for those randomised to stent plus radiotherapy. Of the 97 patients randomised to receive radiotherapy, 15 died or withdrew before radiotherapy treatment could be given. One participant chose a reduction to the planned radiotherapy, from 30 Gy in 10 fractions to 15 Gy in five fractions. All remaining participants received the planned radiotherapy except one participant who received 8 Gy in one dose, as this was the local practice. This was classified by the TMG as a minor deviation as this is an appropriate palliative dose and this patient was kept in the per-protocol population.

| Stent characteristic | Usual care (N = 102) | EBRT (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of stent, n (%) | ||

| Fully covered stent | 31 (30.4) | 24 (24.7) |

| Covered stent with anti-reflux valve | 5 (4.9) | 3 (3.1) |

| Partially covered stent | 55 (53.9) | 58 (59.8) |

| Partially covered stent with anti-reflux valve | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Uncovered | 9 (8.8) | 9 (9.3) |

| Missing | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Length of stent (cm), median (IQR), n | 10.2 (8.0–13.0), 100 | 10.3 (8.0–13.0), 92 |

| Dilatation required, n (%) | ||

| Before stent insertion | 4 (3.9) | 10 (10.3) |

| After stent insertion | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Not required | 95 (93.1) | 80 (82.5) |

| Missing | 3 (2.9) | 5 (5.2) |

| Radiological imaging used, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 69 (67.6) | 46 (47.4) |

| No | 33 (32.4) | 48 (49.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.1) |

| Post-insertion oesophagogram performed, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 10 (9.8) | 13 (13.4) |

| No | 92 (90.2) | 84 (86.6) |

| If yes, any stent slippage, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) |

| No | 10 (100.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Number of nights in hospital post stent, median (IQR), n | 1.0 (0.0–2.0), 102 | 1.0 (0.0–2.0), 95 |

| Acute airway compression, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 99 (97.1) | 96 (99.0) |

| Missing | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.0) |

| Oesophageal or other GI tract perforation, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 101 (99.0) | 97 (100.0) |

| Missing | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| CT scan performed post stent insertion, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (2.9) | 7 (7.2) |

| No | 99 (97.1) | 90 (92.8) |

| Chest X-ray performed post stent insertion, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 23 (22.5) | 21 (21.6) |

| No | 79 (77.5) | 76 (78.4) |

| Radiotherapy compliance | EBRT (N = 97) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients receiving radiotherapy, n (%) | 82 (84.5) |

| Reasons if radiotherapy not received, n (%) | |

| Withdrew before radiotherapy | 7 (7.2) |

| Died before radiotherapy | 8 (8.2) |

| Planned dose 20 Gy in five fractions | 64 (78.0) |

| Planned dose 30 Gy in 10 fractions | 17 (20.7) |

| Planned dose 8 Gy in one fraction | 1 (1.2) |

| Reduction to planned dose | 1 (1.2) |

| Radiotherapy delays | 10 (12.2) |

| Toxicity | 1 (10.0) |

| Patient choice | 1 (10.0) |

| Logistical/machine breakdown | 3 (30.0) |

| Other | 5 (50.0) |

| Been hospitalised hydration | 1 (10.0) |

| Felt ill | 1 (10.0) |

| Weekend break | 1 (10.0) |

| Bank holidays | 1 (10.0) |

| Not known | 1 (10.0) |

| Average number of days delayed, median (IQR; range), n | 2.0 (1.0–2.0; 1.0–5.0), 10 |

| Field size (cm), median (IQR), n | |

| X | 12.0 (10.0–14.0), 81 |

| Y | 11.4 (8.3–14.0), 81 |

| Field definition, n (%) | |

| CT simulator | 77 (93.9) |

| Conventional simulator | 5 (6.1) |

| Field arrangement, n (%) | |

| Parallel pair (anteroposterior, posteroanterior) | 76 (92.7) |

| Other | 5 (6.1) |

| 3D conformal radiotherapy | 2 (40.0) |

| 4 – field | 1 (20.0) |

| 5 – field | 1 (20.0) |

| Conformal ‘4’ field box | 1 (20.0) |

| Missing | 1 (1.2) |

| Number of beams, median (IQR), n | 2.0 (2.0–2.0), 82 |

| Beam 1, n (%) | |

| 6 | 56 (68.3) |

| 10 | 25 (30.5) |

| Missing | 1 (1.2) |

| Beam 2, n (%) | |

| 6 | 56 (68.3) |

| 10 | 25 (30.5) |

| Missing | 1 (1.2) |

| Beam 3, n (%) | |

| 6 | 5 (6.1) |

| 10 | 1 (1.2) |

| Missing | 76 (92.7) |

| Beam 4, n (%) | |

| 6 | 5 (6.1) |

| 10 | 1 (1.2) |

| Missing | 76 (92.7) |

| Contrast applied, n (%) | |

| Yes | 17 (20.7) |

| No | 65 (79.3) |

| Dose calculation method used, n (%) | |

| Tables | 43 (52.4) |

| TPS | 37 (45.1) |

| Other | 2 (2.4) |

| First calculation check done in RADCALC (Computer) | 1 (50.0) |

| OMP planning system | 1 (50.0) |

| Inhomogeneity correction used, n (%) | |

| Yes | 18 (22.0) |

| No | 64 (78.0) |

Missing data, compliance with follow-up and return of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 and OG25 questionnaires

The return of EORTC QLQ-OG25 and C30 questionnaires over time, including missing reasons where known, is shown in Table 6 and Appendix 3, Table 28, respectively. Although there was very good questionnaire return in early visits, missing questionnaire data substantially increased over time. Sensitivity analyses were used to take account of missing primary end-point data, and these are detailed in the primary outcome analysis below. Around 50% of participants required help to complete questionnaires, and this stayed fairly constant over time. Fewer participants needed a carer to complete the questionnaire for them (0–8% prior to week 32). The main reasons for missing questionnaires in both arms were that the patient was too ill, refused or withdrew consent, or the patient took the questionnaire away and did not return it. However, for many of the missing questionnaires no reason is given.

| Time point | Usual care (N = 102), n (%) | EBRT (N = 97), n (%) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not expecteda | Expected | Actually received | Help needed to complete questionnaire | Carer completed | Missing reasons | Not expecteda | Expected | Actually received | Help needed to complete questionnaire | Carer completed | Missing reasons | |||||||

| Patient too ill, refused or withdrew consent | Patient did not return | Admin error | Reason missing | Patient too ill, refused or withdrew consent | Patient did not return | Admin error | Reason missing | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 0 | 102 | 102 (100.0) | 46 (45.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 97 | 97 (100.0) | 38 (39.2) | 7 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 week post stent insertion | 0 | 39 | 39 (100.0) | 21 (53.8) | 6 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 36 | 36 (100.0) | 11 (30.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 4 weeks post stent insertion | 11 | 91 | 78 (85.7) | 36 (46.2) | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (76.9) | 6 | 91 | 75 (82.4) | 28 (37.3) | 3 (4.0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | 12 (75.0) |

| 8 weeks post stent insertion | 23 | 79 | 61 (77.2) | 32 (52.5) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (77.8) | 17 | 80 | 62 (77.5) | 27 (43.5) | 4 (6.5) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (77.8) |

| 12 weeks post stent insertion | 37 | 65 | 46 (70.8) | 18 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (73.7) | 34 | 63 | 49 (77.8) | 21 (42.9) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (78.6) |

| 16 weeks post stent insertion | 49 | 53 | 41 (77.4) | 24 (58.5) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (66.7) | 45 | 52 | 40 (76.9) | 20 (50.0) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| 20 weeks post stent insertion | 57 | 45 | 34 (75.6) | 19 (55.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (72.7) | 55 | 42 | 35 (83.3) | 15 (42.9) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| 24 weeks post stent insertion | 58 | 44 | 27 (61.4) | 14 (51.9) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (82.4) | 58 | 39 | 26 (66.7) | 11 (42.3) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (92.3) |

| 28 weeks post stent insertion | 65 | 37 | 21 (56.8) | 11 (52.4) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (81.3) | 70 | 27 | 19 (70.4) | 10 (52.6) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) |

| 32 weeks post stent insertion | 72 | 30 | 14 (46.7) | 9 (64.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (62.5) | 76 | 21 | 12 (57.1) | 6 (50.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (100.0) |

| 36 weeks post stent insertion | 76 | 26 | 13 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (92.3) | 81 | 16 | 10 (62.5) | 7 (70.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| 40 weeks post stent insertion | 79 | 23 | 12 (52.2) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (54.5) | 82 | 15 | 8 (53.3) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| 44 weeks post stent insertion | 85 | 17 | 6 (35.3) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (81.8) | 83 | 14 | 7 (50.0) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| 48 weeks post stent insertion | 84 | 18 | 7 (38.9) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (81.8) | 84 | 13 | 5 (38.5) | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (87.5) |

| 52 weeks post stent insertion | 86 | 16 | 4 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (83.3) | 85 | 12 | 5 (41.7) | 2 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) |

Baseline characteristics of participants missing versus not missing primary end-point data

Baseline characteristics of those participants missing and those not missing primary end-point data were reasonably well balanced, as shown in Table 7 and in Appendix 3, Table 29.

| Characteristic | Complete data up to week 12 (N = 149) | Missing data up to week 12 (N = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR), n | 72.2 (64.8–80.2), 149 | 75.0 (68.4–83.3), 50 |

| Randomisation time point, n (%) | ||

| Before stent | 59 (39.6) | 16 (32.0) |

| After stent | 90 (60.4) | 34 (68.0) |

| WHO performance status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 17 (11.4) | 3 (6.0) |

| 1 | 93 (62.4) | 27 (54.0) |

| 2 | 37 (24.8) | 17 (34.0) |

| 3 | 2 (1.3) | 3 (6.0) |

| Tumour type, n (%) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 96 (64.4) | 33 (66.0) |

| Squamous | 51 (34.2) | 16 (32.0) |

| Undifferentiated/other | 2 (1.3) | 1 (2.0) |

| Overall length of primary tumour (endoscopic assessment) | ||

| Measured length (cm), median (IQR), n | 5.0 (4.0–7.0), 93 | 5.3 (4.3–7.0), 28 |

| Estimated length (cm), median (IQR), n | 6.0 (5.0–8.0), 42 | 7.0 (5.5–9.0), 19 |

| Measured/estimated length (cm), median (IQR), n | 6.0 (4.0–8.0), 135 | 6.0 (5.0–8.0), 47 |

| Missing, n (%) | 14 (9.4) | 3 (6.0) |

| Alternative method for assessing length, n (%) | ||

| PET | 9 (6.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| CT | 33 (22.1) | 13 (26.0) |

| Barium | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| None | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Site of predominant tumour, n (%) | ||

| Upper | 5 (3.4) | 1 (2.0) |

| Middle | 34 (22.8) | 15 (30.0) |

| Lower | 109 (73.2) | 34 (68.0) |

| If lower, involvement of GOJ | 60 (40.3) | 16 (32.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Extension across GOJ (if involvement of GOJ), n (%) | ||

| Siewert type 1 | 32 (21.5) | 9 (18.0) |

| Siewert type 2 | 26 (17.4) | 2 (4.0) |

| Missing | 2 (1.3) | 5 (10.0) |

| T stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2.0) |

| 2 | 7 (4.7) | 4 (8.0) |

| 3 | 87 (58.4) | 28 (56.0) |

| 4 | 45 (30.2) | 15 (30.0) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.3) | 2 (4.0) |

| X | 6 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| N stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 20 (13.4) | 7 (14.0) |

| 1 | 68 (45.6) | 24 (48.0) |

| 2 | 29 (19.5) | 11 (22.0) |

| 3 | 27 (18.1) | 5 (10.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 2 (4.0) |

| X | 4 (2.7) | 1 (2.0) |

| M stage, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 63 (42.3) | 24 (48.0) |

| 1 | 77 (51.7) | 22 (44.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 2 (4.0) |

| X | 8 (5.4) | 2 (4.0) |

| Overall stage, n (%) | ||

| 1–3 | 70 (47.0) | 27 (54.0) |

| 4 | 79 (53.0) | 23 (46.0) |

Primary outcome

Modified intention-to-treat population

There were 102 versus 97 patients (usual care vs. EBRT) in the modified ITT population with 74 versus 75 patients (usual care vs. EBRT) having complete data at week 12 for the primary end point (Table 8). The complete-case analysis, which included deaths up to week 12 with complete data as an event, showed no evidence of a difference in the proportion of patients experiencing a primary event up to week 12 post stent by trial arm [36/74 (48.6%) vs. 34/75 (45.3%); adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.82, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.68; p = 0.587]. The sensitivity analysis, treating death by week 12 without prior event as no event, also showed no evidence of a difference between trial arms [21/74 (28.4%) vs. 21/75 (28.0%); adjusted OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.25; p = 0.893].

| Characteristic | Usual care (N = 102), n (%) | EBRT (N = 97), n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI; p-value, n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete-case data at week 12 | |||

| Completely withdrew with no event | 6 (5.9) | 5 (5.2) | |

| Died with incomplete data and no event | 8 (7.8) | 6 (6.2) | |

| Alive at week 12 with incomplete data and no event | 14 (13.7) | 11 (11.3) | |

| Reasons for complete withdrawal | |||

| Participant choice | 3 (2.9) | 4 (4.1) | |

| Other | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Informed by CNS on family’s behalf | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Transferred to another area due to relocation | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Complete-case data at week 12 | |||

| Total with complete data | 74 (72.5) | 75 (77.3) | |

| Died with complete data | 20 (19.6) | 22 (22.7) | |

| Alive at week 12 with complete data | 54 (52.9) | 53 (54.6) | |

| Complete-case analysis (death as an event) | |||

| Number of primary events or deaths | 36 (48.6) | 34 (45.3) | 0.82 (0.40 to 1.68; 0.587, 149) |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||

| Complete-case analysis (death as non-event) | |||

| Number of primary events | 21 (28.4) | 21 (28.0) | 1.05 (0.49 to 2.25; 0.893, 149) |

| Best case | |||

| Total with complete data | 90 (88.2) | 88 (90.7) | |

| Number of primary events or deaths | 40 (44.4) | 36 (40.9) | 0.85 (0.44 to 1.62; 0.612, 178) |

| Worst case | |||

| Total with complete data | 90 (88.2) | 88 (90.7) | |

| Number of primary events or deaths | 53 (58.9) | 46 (52.3) | 0.73 (0.38 to 1.40; 0.345, 178) |

Imputation of missing data under the best- and worst-case scenarios resulted in 90 versus 88 patients in the denominator for the associated sensitivity analyses. Those with remaining missing data were missing two or more questionnaires and no deterioration had been confirmed prior to this. There was no evidence of a difference in the primary end point between trial arms under either the best-case (p = 0.612) or the worst-case (p = 0.345) scenario.

Per-protocol population

There were 90 versus 82 patients in the per-protocol population with 66 versus 64 (usual care vs. EBRT) having complete data at week 12 for the primary end point (Table 9). The complete-case analysis, which included deaths up to week 12 with complete data as an event, showed no evidence of a difference in the proportion of patients experiencing a primary event up to week 12 post stent by trial arm [28/66 (42.4%) vs. 26/64 (40.6%); adjusted OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.14; p = 0.972]. The sensitivity analysis, treating death by week 12 without prior event as no event, also showed no evidence of a difference between trial arms [19/66 (28.8%) vs. 19/64 (29.7%); adjusted OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.71; p = 0.666]. The complete cases in the per-protocol population all completed full planned radiotherapy.

| Characteristic | Stent (N = 90), n (%) | Stent plus radiotherapy (N = 82), n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI; p-value, n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete case data at week 12 | |||

| Completely withdrew with no event | 2 (2.2) | 3 (3.7) | |

| Died with incomplete data and no event | 8 (8.9) | 5 (6.1) | |

| Alive at week 12 with incomplete data and no event | 14 (15.6) | 10 (12.2) | |

| Reasons for complete withdrawal | |||

| Participant choice | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Informed by CNS on family’s behalf | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Loss to follow-up | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Complete-case data at week 12 | |||

| Total with complete data | 66 (73.3) | 64 (78.0) | |

| Died with complete data | 12 (13.3) | 14 (17.1) | |

| Alive at week 12 with complete data | 54 (60.0) | 50 (61.0) | |

| Complete-case analysis (death as an event) | |||

| Number of primary events or deaths | 28 (42.4) | 26 (40.6) | 0.99 (0.45 to 2.14; 0.972; 130) |

| Complete-case analysis (death as non-event) | |||

| Number of primary events | 19 (28.8) | 19 (29.7) | 1.20 (0.53 to 2.71; 0.666; 130) |

| Best case | |||

| Total with complete data | 82 (91.1) | 76 (92.7) | |

| Number of primary events or deaths | 32 (39.0) | 28 (36.8) | 0.96 (0.48 to 1.93; 0.910; 158) |

| Worst case | |||

| Total with complete data | 82 (91.1) | 76 (92.7) | |

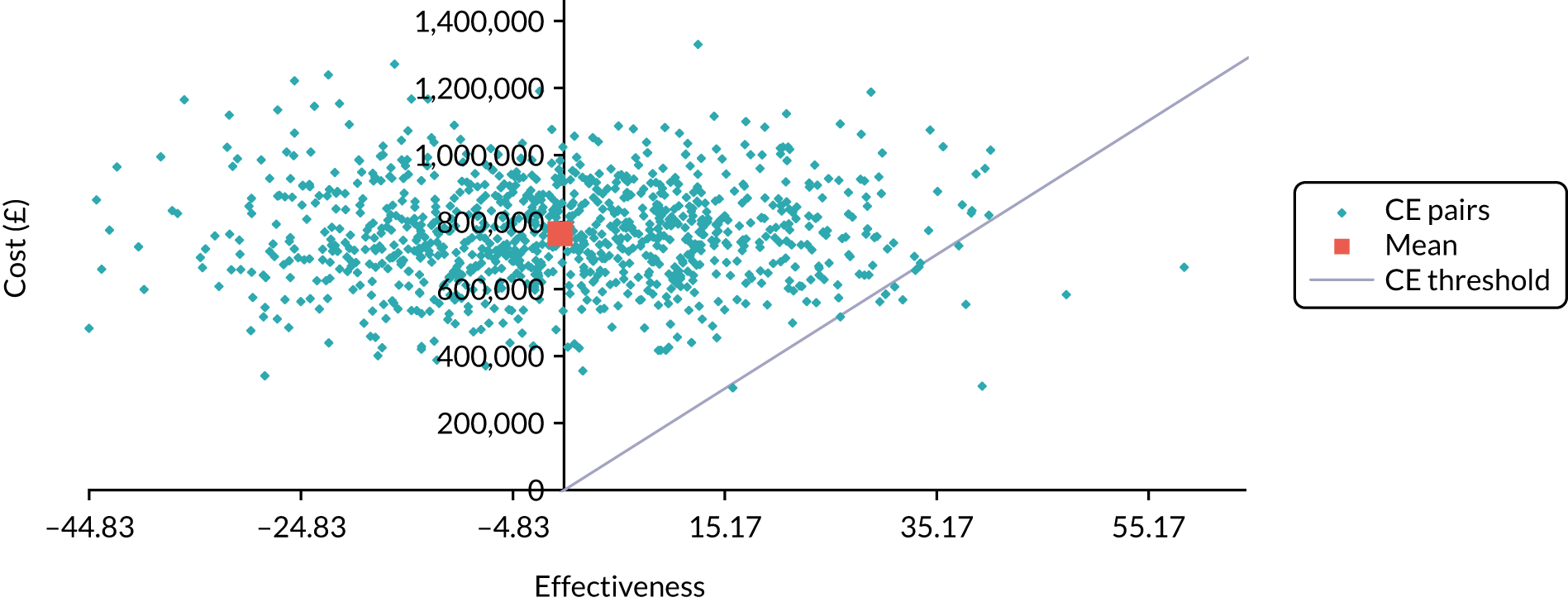

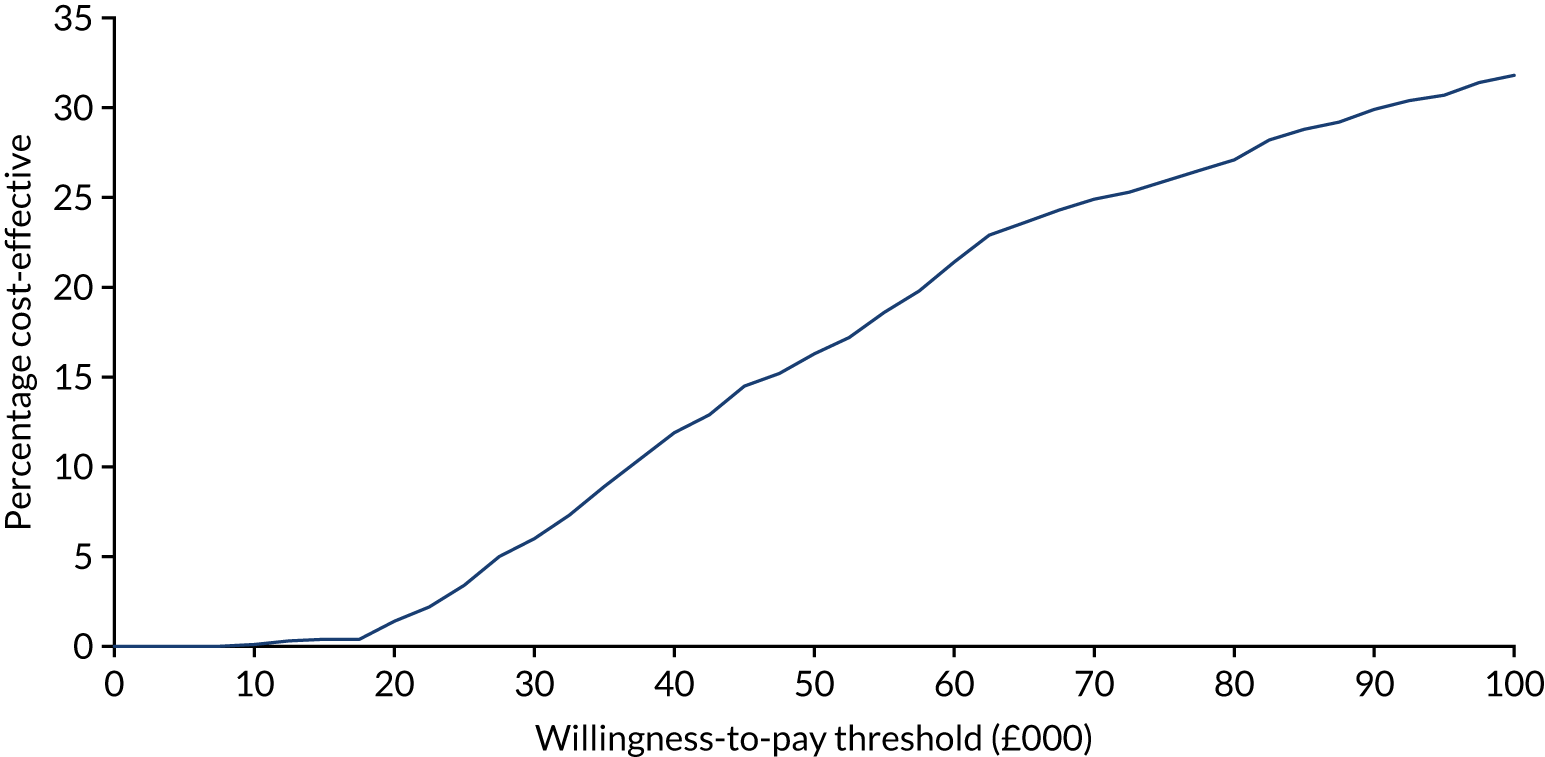

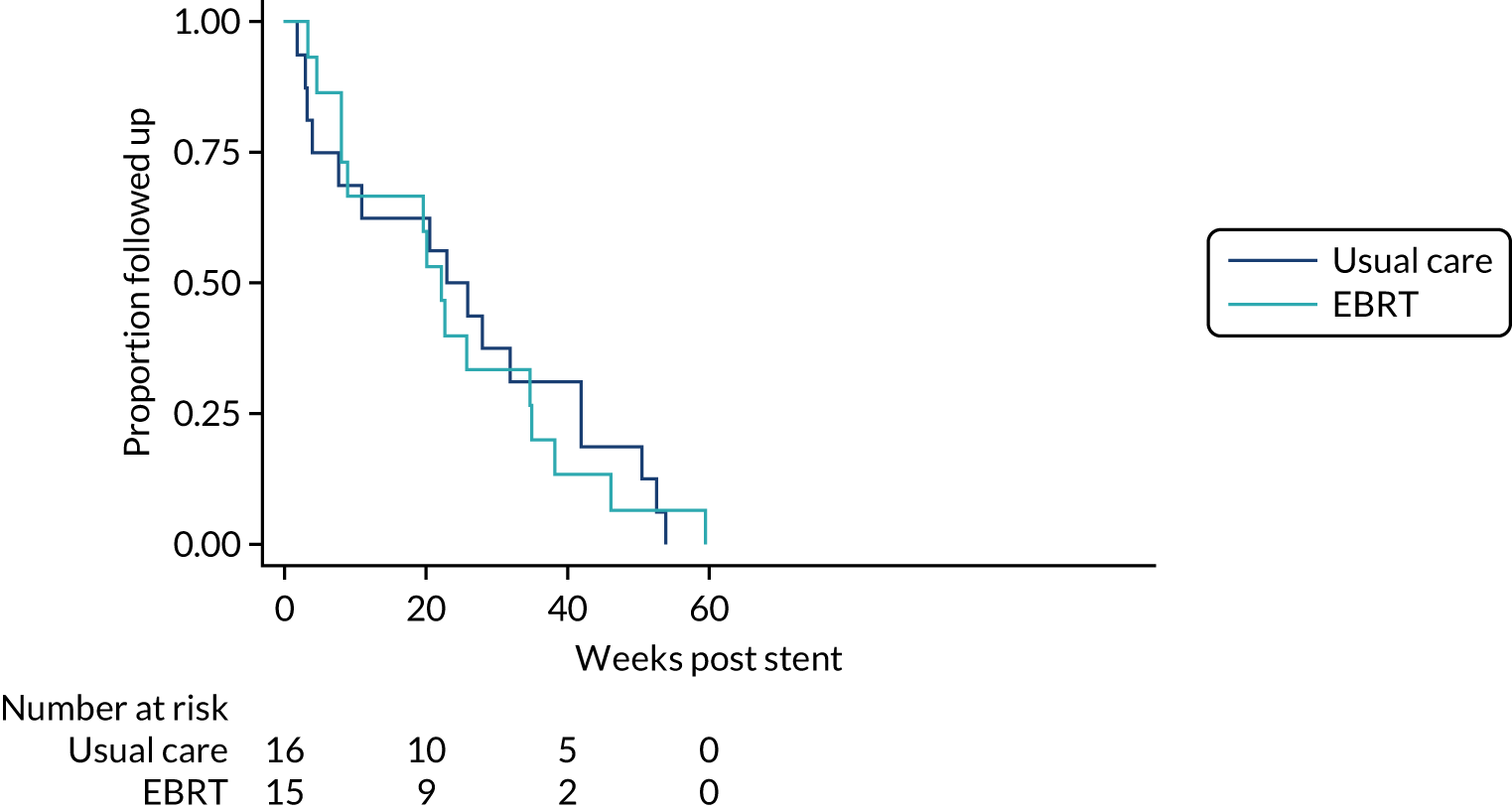

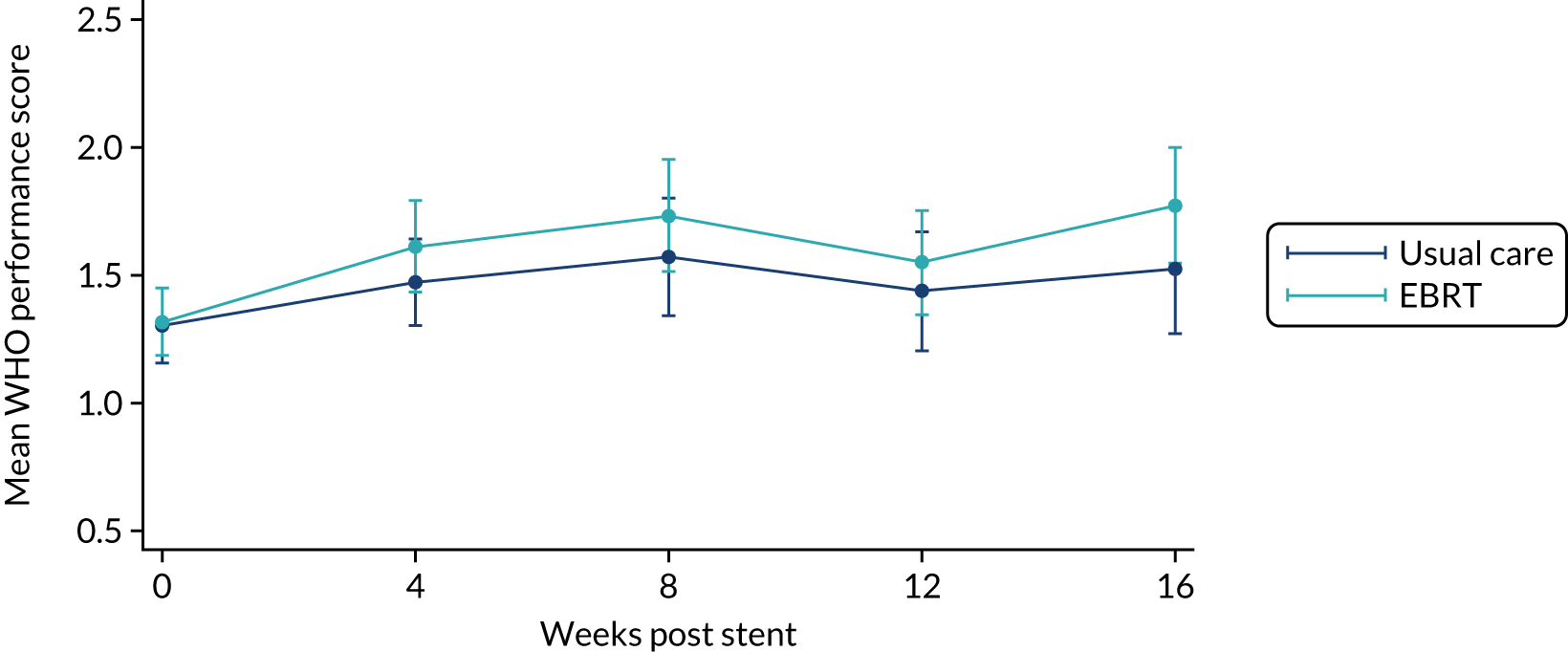

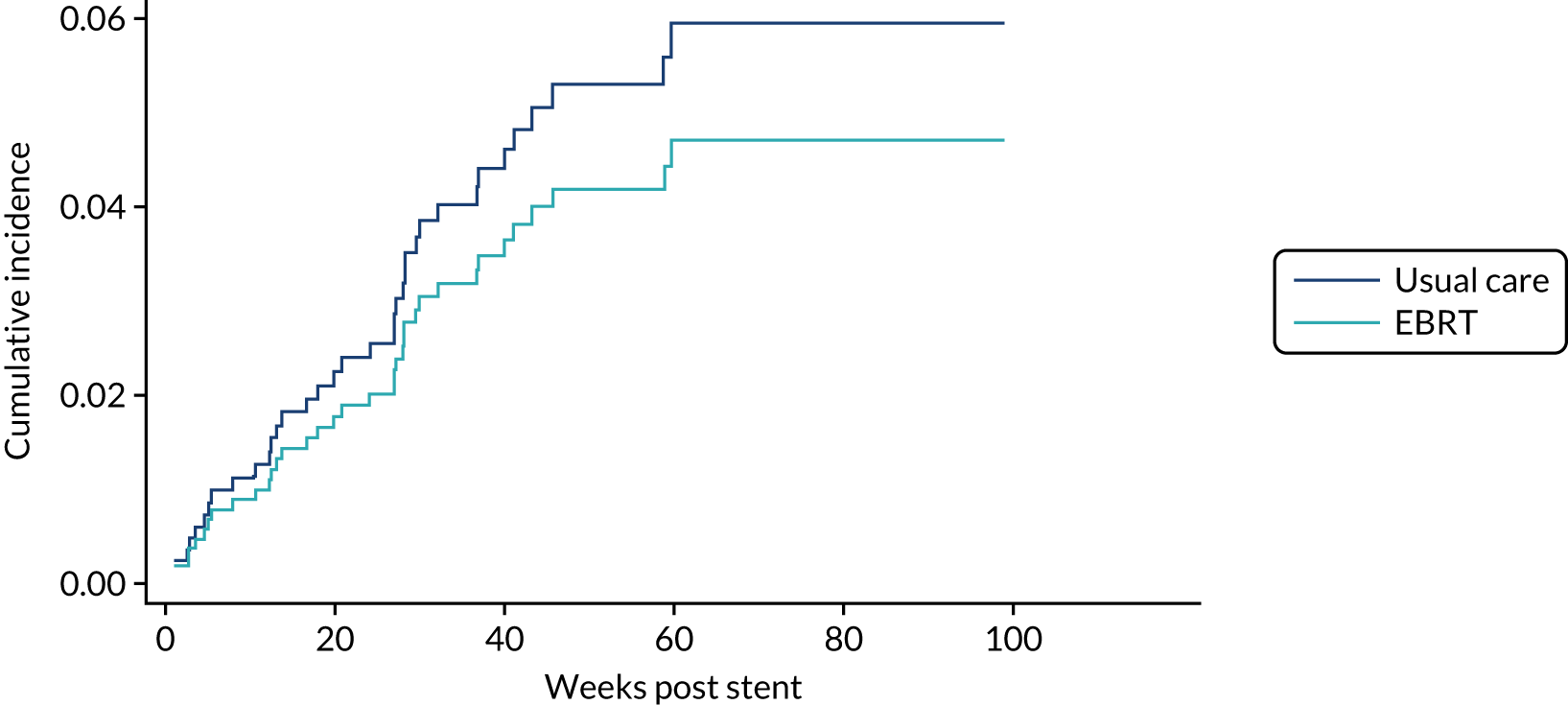

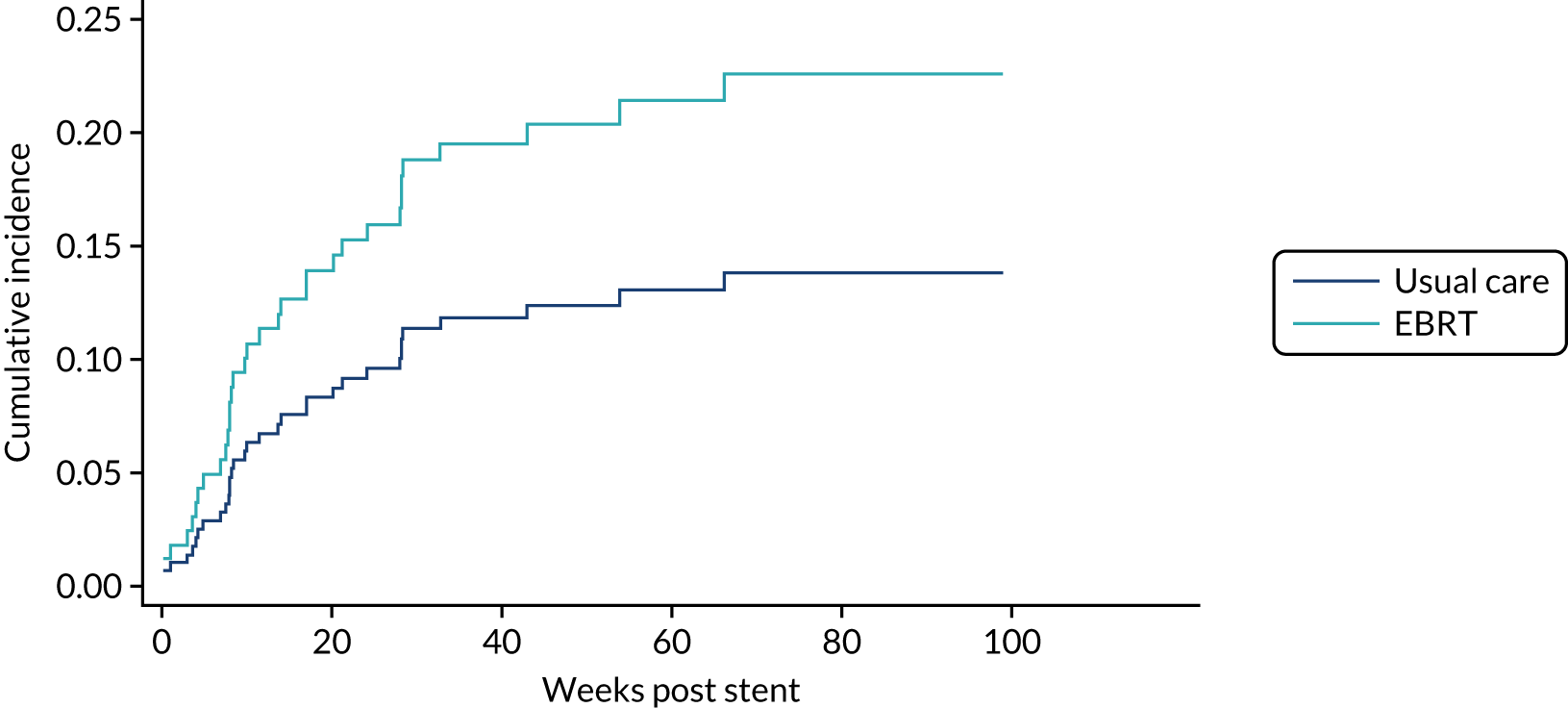

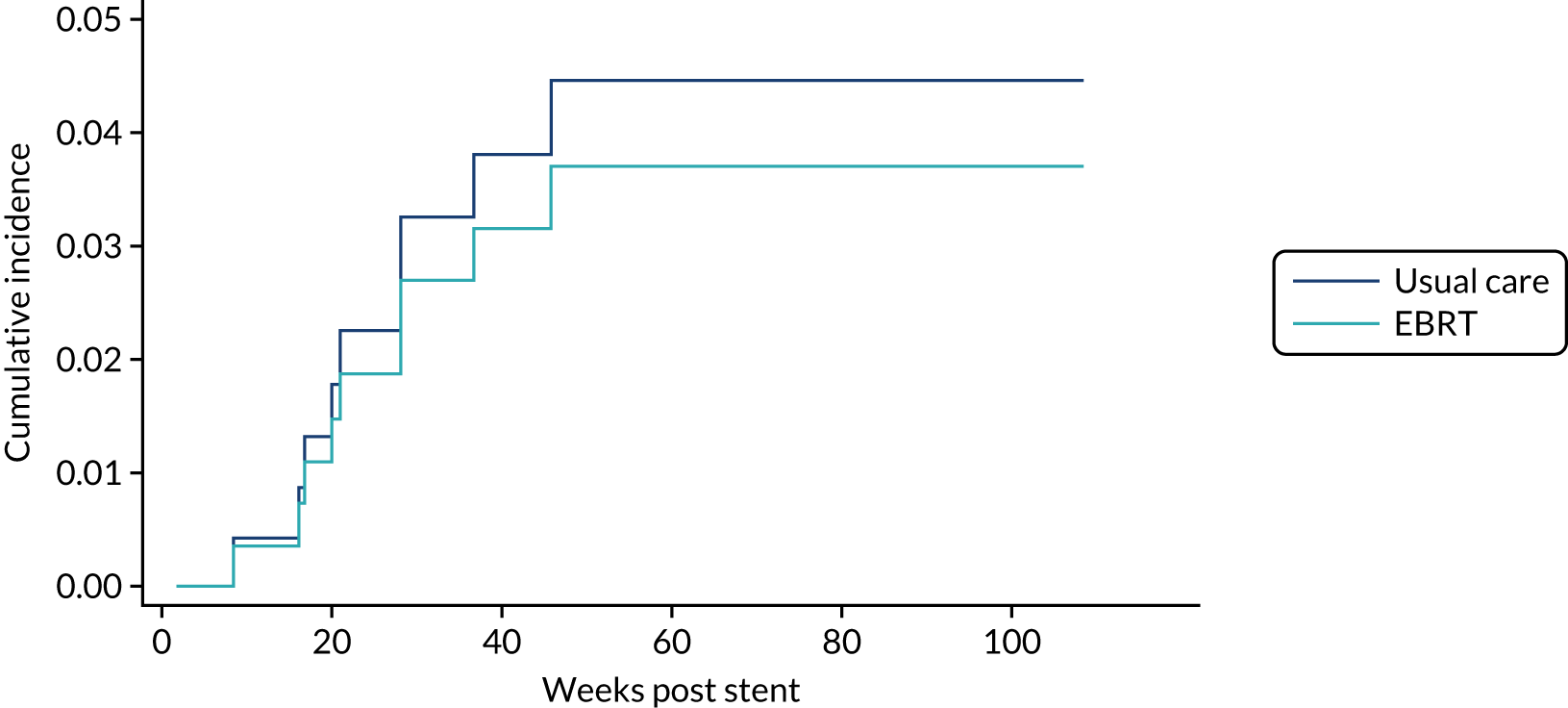

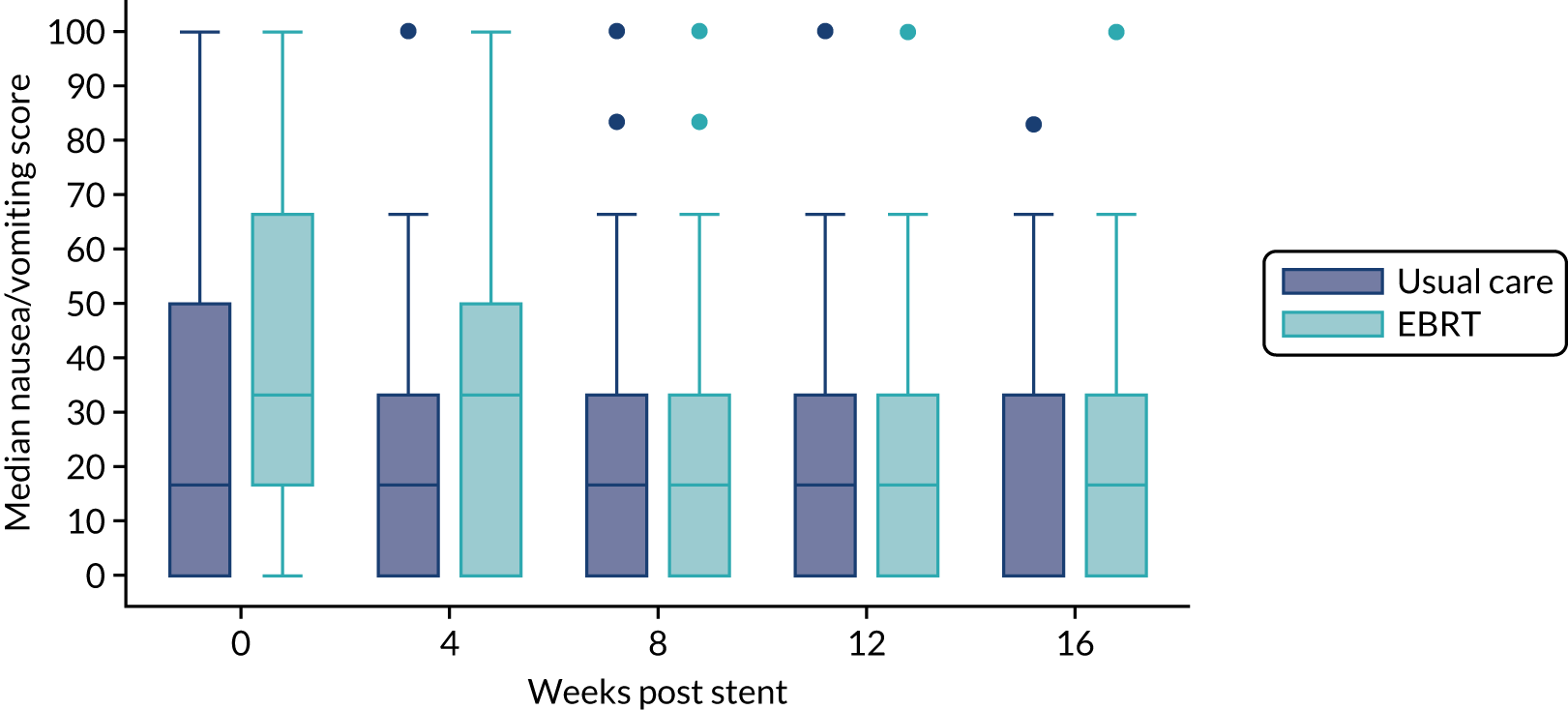

| Number of primary events or deaths | 45 (54.9) | 37 (48.7) | 0.80 (0.41 to 1.58; 0.527; 158) |