Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/42/08. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The draft report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Lois et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK. Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from our published protocol: Lois et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. Parts of this report have been reproduced from Lois et al. 2 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

2021 2019 2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO The authors The authors

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from our published protocol: Lois et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Lois et al. 2 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most common microvascular complication of diabetes and a leading cause of sight loss in people of working age. 3 Patients with DR may lose their vision as a result of the development of diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and/or proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), which are the major complications of DR. DMO and PDR can happen in the same person and even in the same eye.

Diabetic macular oedema

Diabetic macular oedema is caused by the accumulation of fluid, often accompanied by lipid (and occasionally blood), in the central part of the retina, the macula, which is responsible for the generation of detailed central vision. Thus, DMO results in people progressively losing central sight and experiencing difficulties reading, recognising faces and doing any work for which detailed central vision is required (Figure 1).

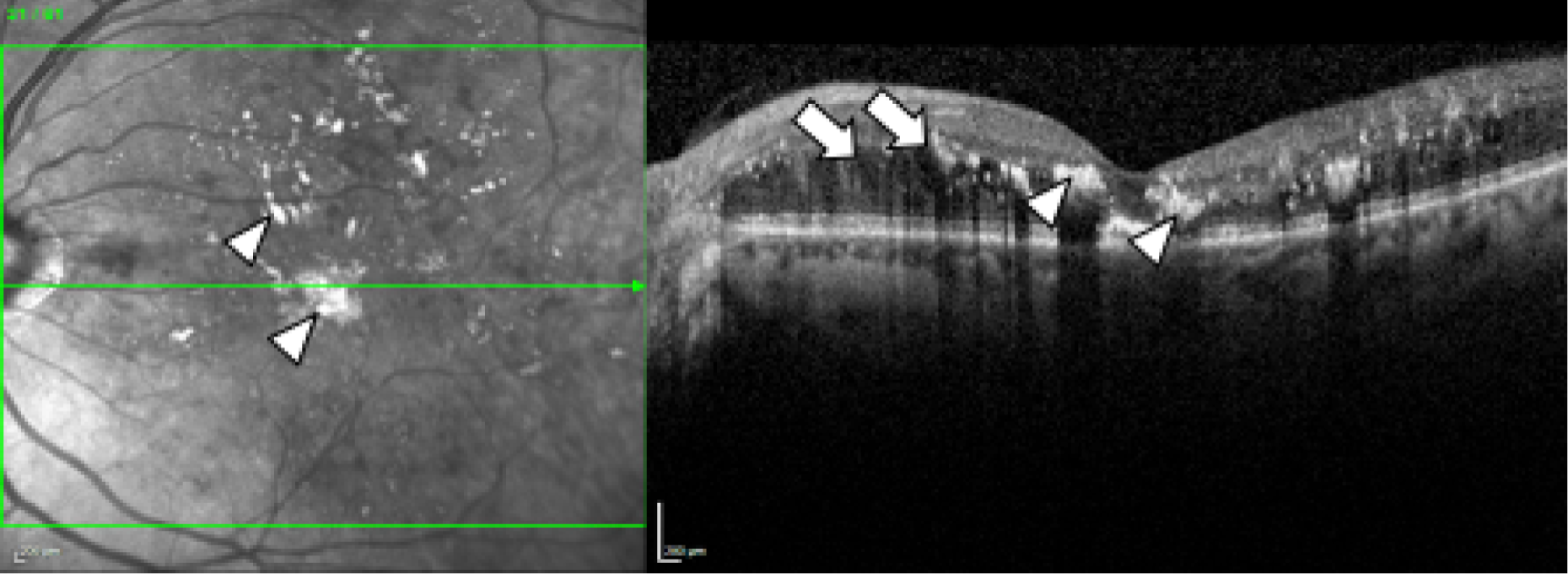

FIGURE 1.

Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography in DMO. Fundus image (left) and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scan (right) of the left eye of an individual with diabetes and DMO (top) and, for comparison, of someone with diabetes but no DMO (bottom). Lipid (the so-called ‘hard exudates’) (arrowheads; hard exudates appear as white areas on the images) and fluid (arrows; fluid appears as black areas on the image) are present in DMO (top). The normal structure of the macula (the central area of the retina, marked approximately with the circle on the bottom image, left) and of the fovea (the central area of the macula, marked approximately with a circle in the bottom image, right) is observed in the eye with no DMO (bottom).

In 2010, the prevalence of DMO in England was estimated to be 7% of all people with diabetes. 4 An individual participant data meta-analysis that included 22,896 individuals from 35 studies conducted in Asia, Australia, Europe and the USA found a very similar estimate of prevalence of DMO, with an overall age-standardised prevalence of 6.8%. 5 Based on these estimates and considering the prevalence of diabetes in the UK,6 it can be presumed that there are a minimum of 273,000 people in the UK affected by DMO.

In the UK, treatments for DMO include focal or grid macular laser, eye injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapies and eye injections of steroids. All treatments aim to dry the macula and improve or maintain vision. Macular laser is advised and offered when the central retinal thickness (CRT), measured by means of spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) is < 400 µm, which may be considered mild DMO. Patients in whom there is drop-out of perifoveal capillaries contiguous to the area of leakage causing DMO, as determined by fundus fluorescein angiography, are not good candidates for macular laser. Patients with more severe DMO (CRT on SD-OCT of ≥ 400 µm) are eligible to receive anti-VEGFs; currently, the anti-VEGFs approved by the NHS are ranibizumab (Lucentis®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, London, UK) and aflibercept (Eylea®; Bayer plc, Reading, UK) (Figure 2). 7,8 Bevacizumab (Avastin®; Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA) is also available off label. Intraocular steroids are reserved for patients with DMO who do not respond to macular laser or anti-VEGFs and are pseudophakic (i.e. have had their cataracts removed). 9

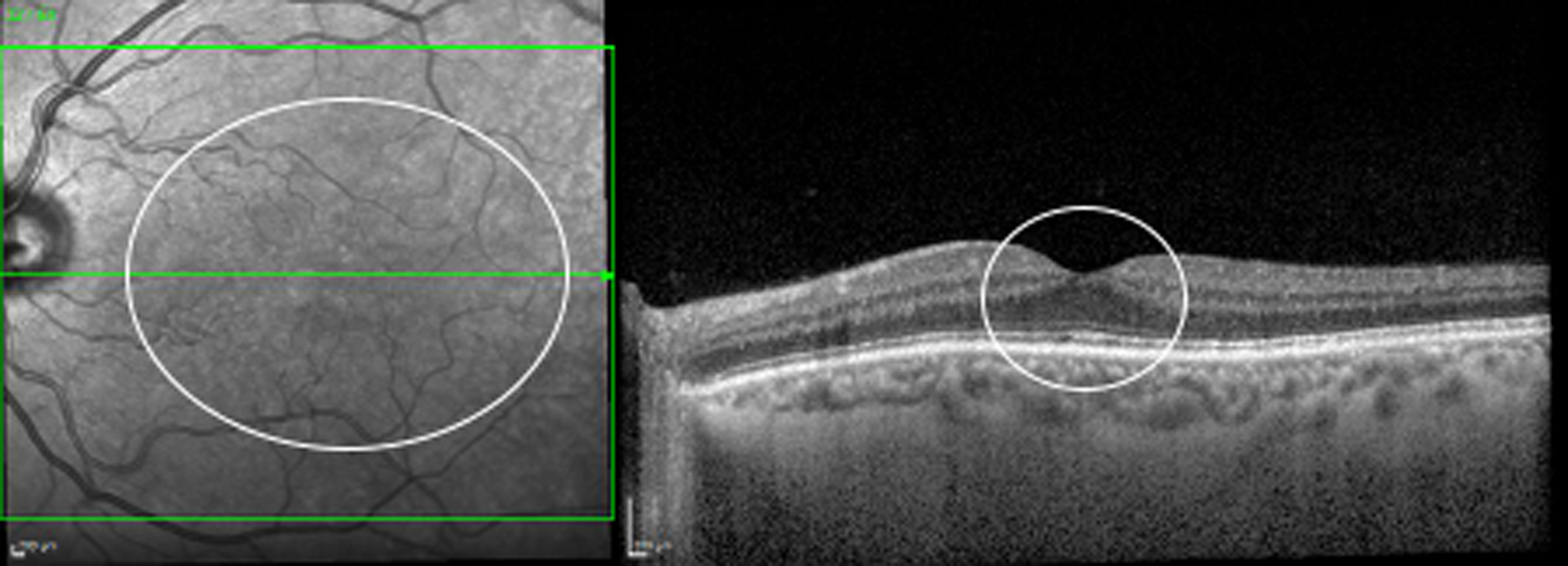

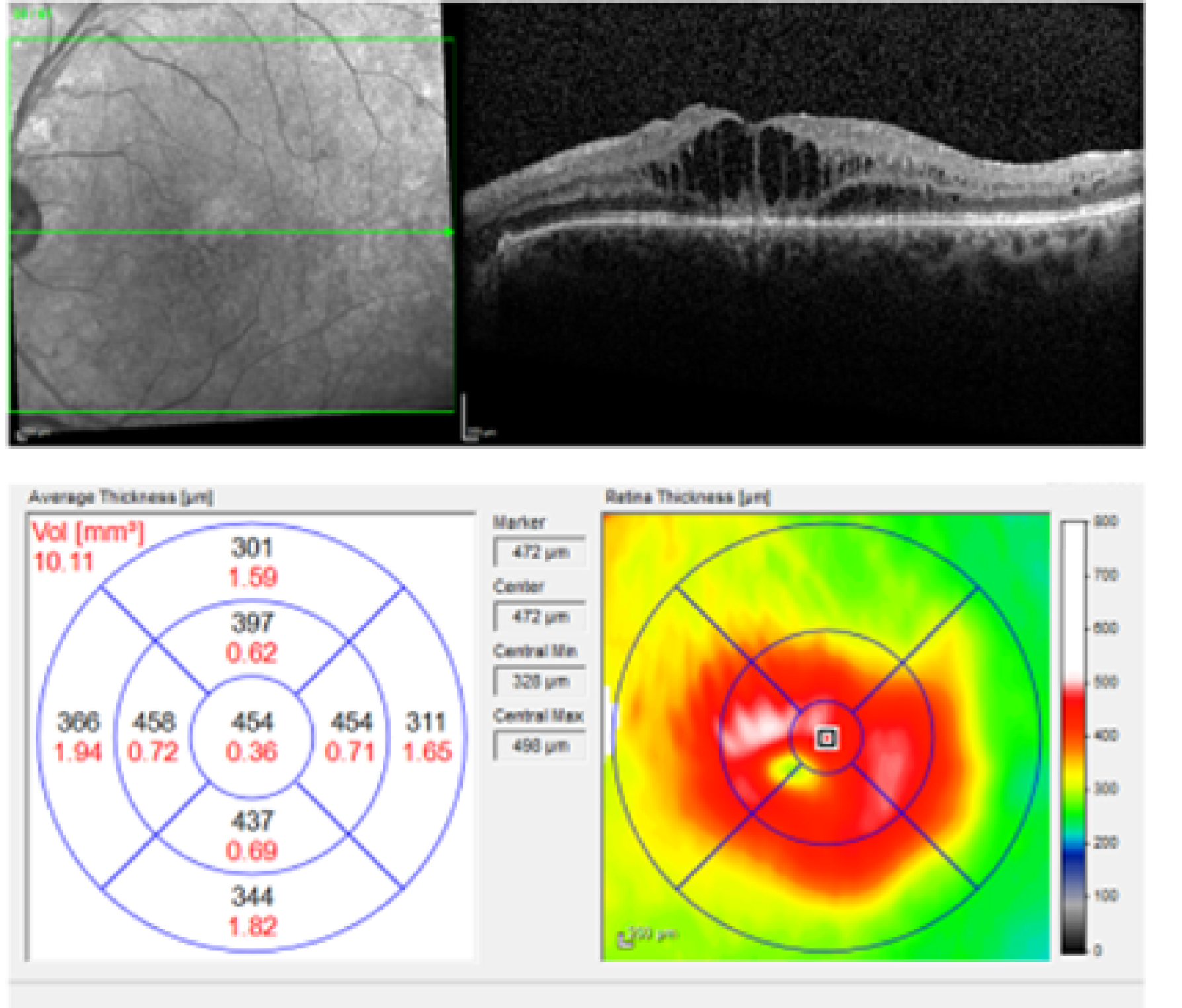

FIGURE 2.

Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography in DMO with CRT of > 400 µm. Fundus image (top left) and SD-OCT scan (top right) of the left eye of a patient with severe DMO, with > 400 µm CRT (454 µm in the central 1 mm field, bottom left). Thickening of the retina is shown in red in the colour map (bottom right).

Macular laser is delivered in a single session. Re-treatments may be required to clear DMO and are usually given at no earlier than 3- to 4-month intervals. Anti-VEGF injections are given monthly until the macula is dry (i.e. DMO clears). Once patients have been treated successfully (i.e. DMO is no longer present), long-term follow-up is required, as DMO may recur. Typically, once dried, patients are followed up every 3–4 months following laser treatment for DMO; patients are followed up monthly initially and every 1–3 months thereafter following treatment with anti-VEGFs. 10 Follow-up continues for the rest of the patient’s life.

Currently in the NHS, patients with previously treated DMO are evaluated in clinic during follow-up appointments with ophthalmologists who have expertise in retinal diseases, even if DMO is no longer present. At each visit, patients receive a visual acuity test, which is most often undertaken by a nurse or a visual acuity technician, before having a SD-OCT scan, obtained by a photographer or by an imaging technician, and then being seen by an ophthalmologist. The ophthalmologist checks the back of the eye using slit-lamp biomicroscopy and, most often, a non-contact fundus lens, and determines, also using SD-OCT scans, whether DMO is present or absent (Figure 3). SD-OCT is a non-invasive, user-friendly, fast and safe imaging technology that obtains scans of the back of the eye. SD-OCT allows the CRT to be measured (which is often increased when DMO is present) and visualises fluid in the retina, which is the hallmark of DMO (see Figures 1 and 2). SD-OCT has been extensively used in clinical trials and clinical practice to determine the presence of DMO, select treatment and monitor the patient’s response to treatment. 11–16

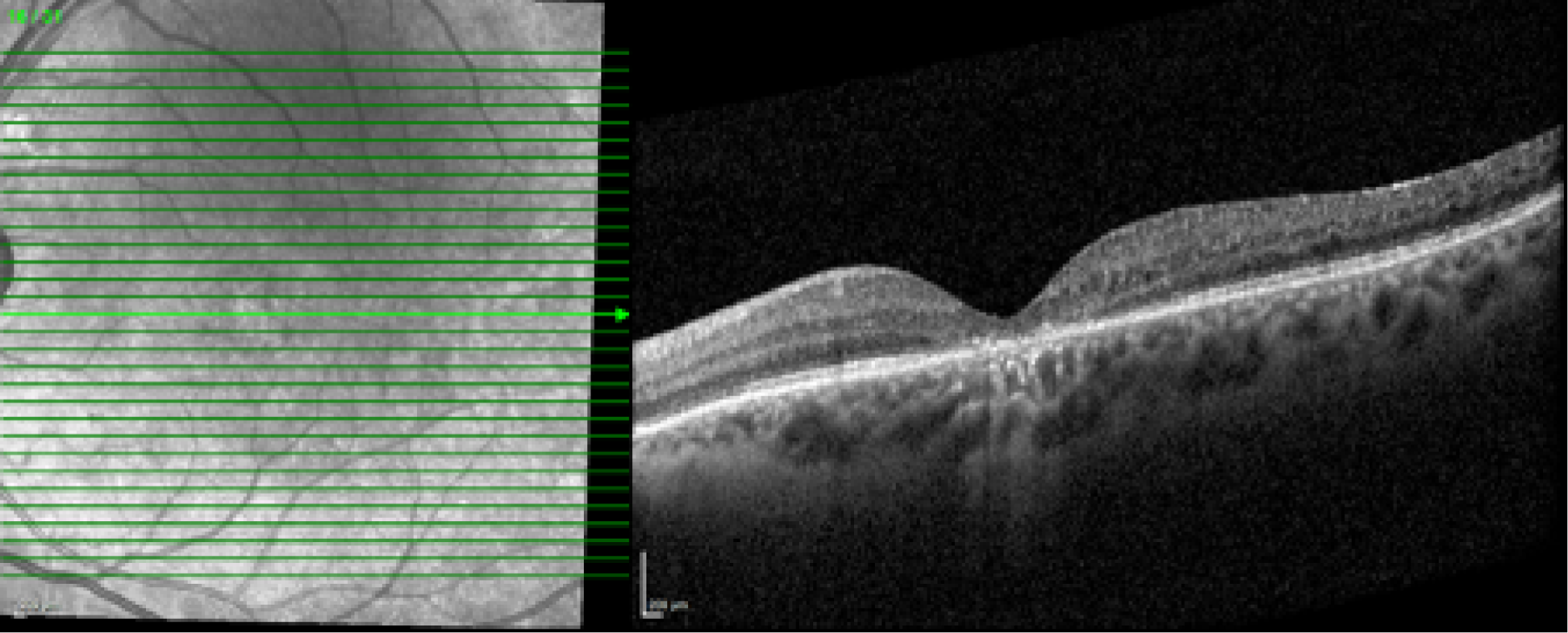

FIGURE 3.

Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography following resolution of DMO. Fundus image (left) and SD-OCT scan (right) of the left eye of the patient shown in Figure 2 following anti-VEGF treatment. The DMO has resolved (no DMO present).

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

In PDR, abnormal, newly formed blood vessels (‘new vessels’) grow on the optic nerve head [the so-called new vessels in the disc (NVD)] and/or on the surface of the retina [the so-called new vessels elsewhere (NVE)] and towards the inside of the eye (i.e. the vitreous cavity) (Figure 4). These blood vessels may bleed, causing what is called a vitreous haemorrhage. They can also lead to the formation of scarring tissue that could then contract and pull on the retina and detach it from the wall of the eye, causing a tractional retinal detachment (TRD). Both vitreous haemorrhage and TRD can lead to loss of not only central but also peripheral vision. Once it occurs, vitreous haemorrhage may clear spontaneously or may require surgery (vitrectomy). If TRD affects or threatens the macula it will require surgery, which is often very challenging. Furthermore, visual outcomes following TRD repair may be disappointing.

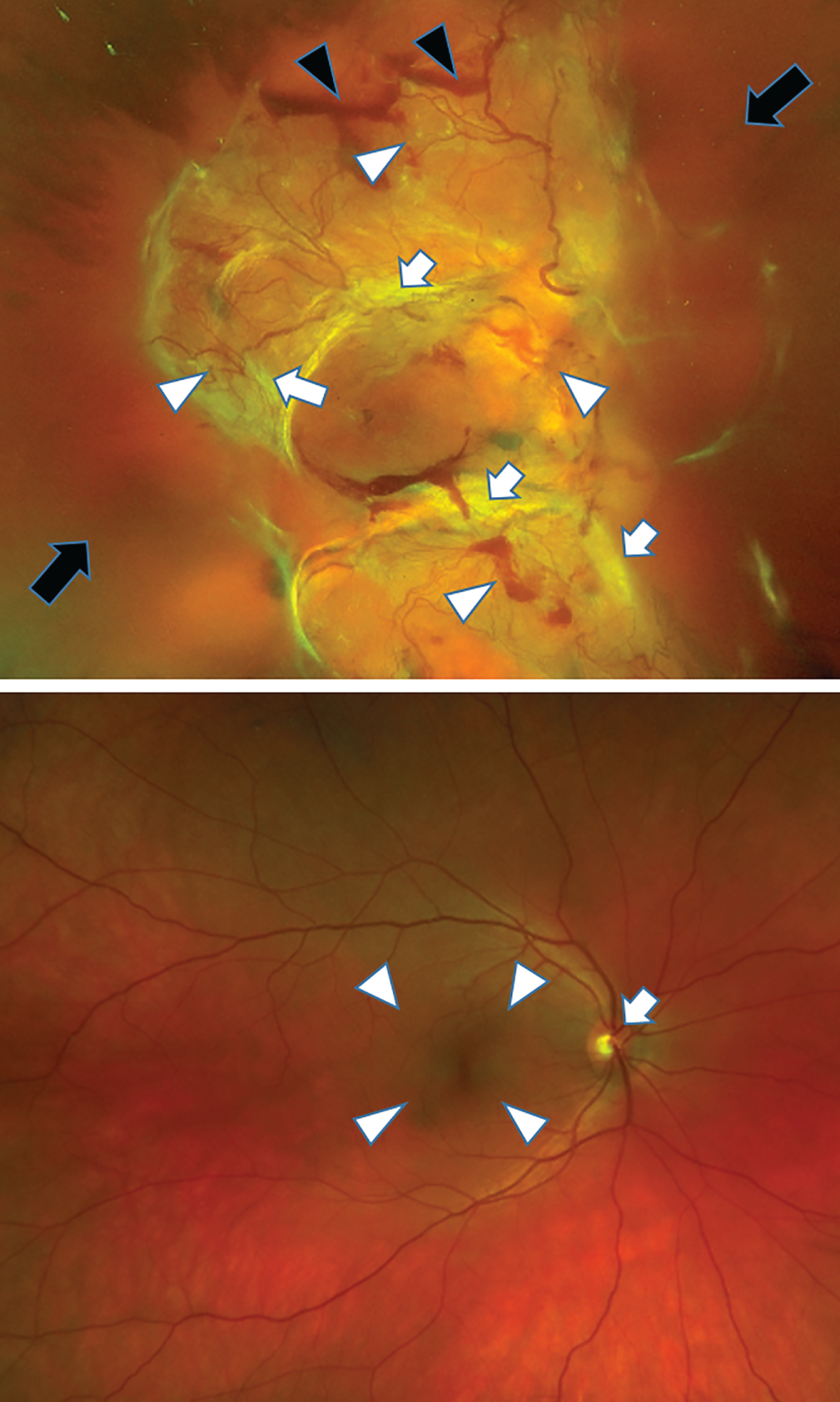

FIGURE 4.

Fundus images of an eye with HRC PDR and a healthy eye. Fundus image of the right eye (top) of a patient with PDR and very large new vessels (white arrowheads) and scarring (white bands seen on the image, white arrows), pre-retinal haemorrhages (black arrows) and vitreous haemorrhage (black arrowheads) obscuring the view of the retina. For comparison, a fundus image of a healthy eye is shown (bottom). The optic nerve (white arrow) and macular area (white arrowhead) are healthy.

The estimated prevalence of PDR in the individual participant data meta-analysis referred to above was 6.96%. 5 Based on the prevalence of diabetes in the UK,6 it could be assumed that there are ≈ 271,440 people in the UK affected by PDR.

The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS)17 demonstrated the value of scatter laser panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) for the treatment of PDR. Following the results of the ETDRS, immediate treatment is recommended for all patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes when high-risk characteristics are present, including NVD of a certain size (more than one-third to one-quarter of the disc area) and/or any new vessels if pre-retinal haemorrhage or vitreous haemorrhage are detected. 17 Treatment at earlier stages could be considered in selected cases (e.g. poor attendance at clinics) and especially in people with type 2 diabetes. The cost-effectiveness of applying PRP at earlier stages than the presence of high-risk characteristics (i.e. when there is PDR but not reaching high-risk characteristics and when there is severe non-proliferative disease and before new vessels develop) is unclear, and cannot be recommended for all patients at present. 18 PRP is delivered as an outpatient procedure, under topical anaesthetic or sub-Tenon’s (local) anaesthesia. Most often, treatment is completed in two sessions. Laser PRP is usually undertaken following ETDRS guidelines. For some time, an argon laser was the only laser type used to perform PRP, but recently other types of laser, including the so-called ‘pattern’ laser, have been introduced. However, there is no evidence to date of the efficacy and safety of any lasers other than the argon laser, and of any laser protocols/strategies other than the ETDRS. 19 In this regard, it is important to note that a recent, large, well-conducted randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing laser PRP with anti-VEGF therapies for the treatment of PDR found that, in the PRP arm, eyes receiving ‘pattern’ PRP were at a higher risk of worsening PDR [60% vs. 39%; hazard ratio (HR) 2.04, 99% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 4.08; p = 0.008] than those receiving conventional single-spot PRP laser. 20

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is expected to appraise anti-VEGFs for the treatment of PDR in the next year or two. Anti-VEGFs are not currently used to treat PDR in the UK.

Once scatter laser PRP is complete, patients require follow-up (Figure 5). Initially, immediately after treatment, patients are followed up at a shorter time interval (e.g. 4–8 weeks) to ensure that regression of the disease occurs. However, once the disease is stabilised and regression occurs, patients are often followed up every 6–8 months or even at longer intervals. Follow-up is required as new vessels in PDR could return and vitreous haemorrhage and TRD could still ensue. Closer follow-up should be considered if PRP is performed using a ‘pattern’ laser, given the information provided above.

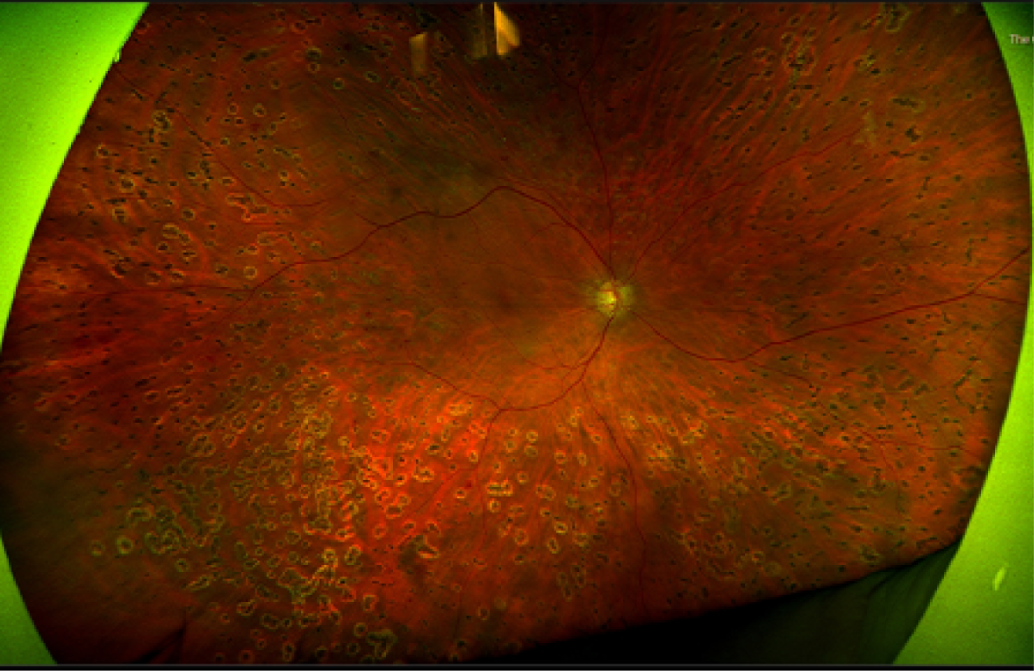

FIGURE 5.

Fundus image of an eye treated with laser panretinal photocoagulation and with regressed PDR. Ultra-wide field fundus image of the right eye of a patient with PDR following laser panretinal photocoagulation. Laser scars (small, black areas surrounding by clearer ‘halos’) throughout the retina are seen.

Currently in the NHS, most patients with treated and stable PDR are followed up in clinic by ophthalmologists. In fact, it has been shown that a high proportion of all patients with DR reviewed in hospital eye services have treated and stable PDR. 21 At each follow-up visit, patients receive a visual acuity test, which is most often undertaken by a nurse or a visual acuity technician, followed by a SD-OCT scan, which is obtained by a photographer/imaging technician, to rule out the presence of concomitant DMO; they are then seen by an ophthalmologist, an expert on retinal diseases. The ophthalmologist examines the patient by slit-lamp biomicroscopy using, most often, a non-contact fundus lens, and determines whether there is active PDR or the disease remains stable. Fundus photographs (photographs of the retina) are not routinely obtained in clinic to determine whether or not active PDR is present, although they may be taken in selected cases.

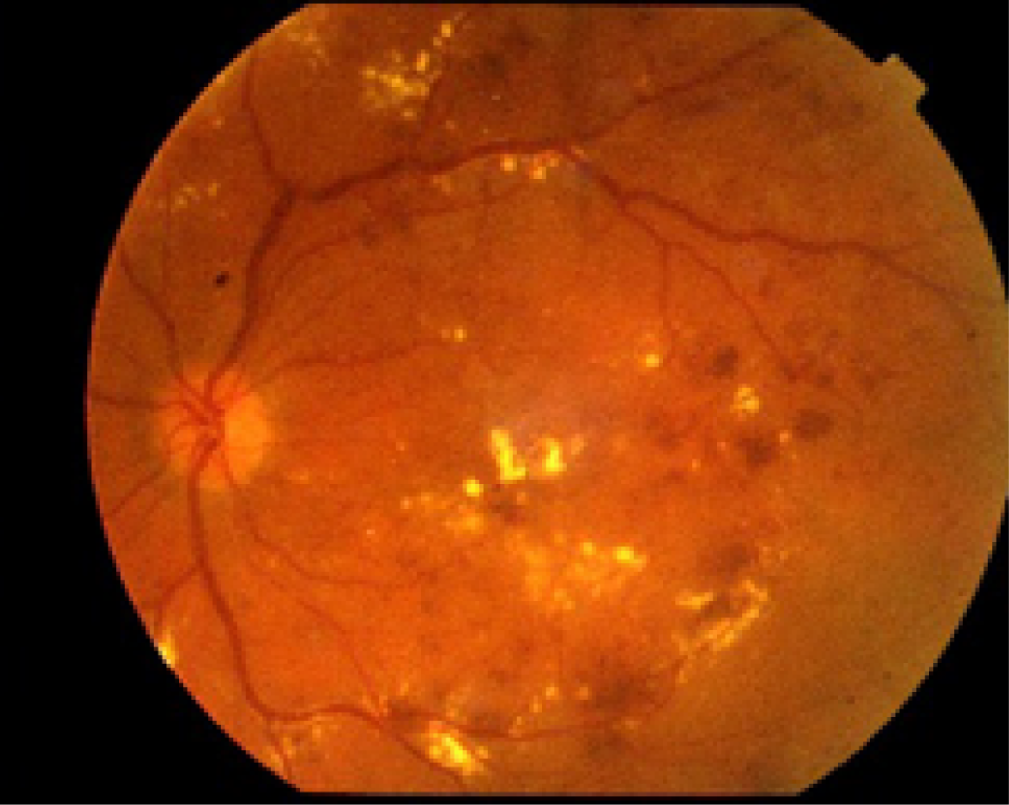

If required, fundus photographs can be obtained with standard cameras that provide 30- to 45-degree images to allow imaging of the central part of the retina, including the macula (Figure 6). To visualise other areas of the retina using these standard cameras, the patients are asked to look up, left, down and right so that images of the superior, nasal, inferior and temporal retina can be obtained, for example, when imaging a right eye. However, even when this is carried out, the peripheral retina cannot be imaged.

FIGURE 6.

Standard fundus image in a patient with DMO. Standard fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with DR and macular oedema. With a single image, only the central retinal area is visualised.

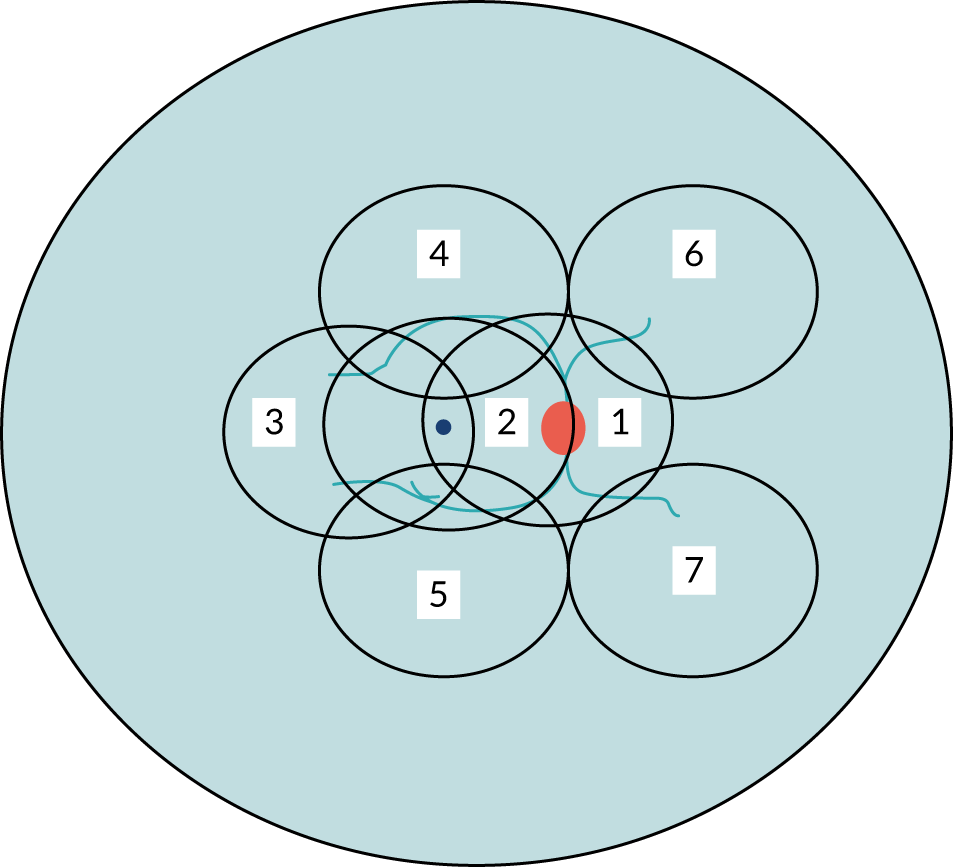

To date, most of the research studies on DR have used seven-field ETDRS imaging to document the status of the retina. Seven-field ETDRS imaging consists of seven fields that are located in the mid-peripheral retina as follows (Figure 7):

-

field 1 – centred at the optic nerve head

-

field 2 – centred at the fovea

-

field 3 – temporal to the fovea

-

field 4 – superotemporal

-

field 5 – inferotemporal

-

field 6 – superonasal

-

field 7 – inferonasal.

FIGURE 7.

Scheme demonstrating the seven-field ETDRS fields.

Seven-field imaging takes some time to be obtained and, similarly, to be evaluated; for this reason, it is impractical and not used in routine clinics.

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 7, much of the retina remains uncovered (i.e. not photographed) when seven-field ETDRS fundus images are used. More recently, ultra-wide field imaging has become available. The first ultra-wide field fundus technology developed, which remains the widest field imaging system in existence, is produced by Optos (Dunfermline, UK). Using a scanning laser ophthalmoscope, a view of nearly the entire retina (200 degrees) can be obtained in a single image (Figure 8). To visualise the far peripheral superior and inferior retina as well, patients are asked to look up and down. With the three images (centre, superior and inferior) the whole retina is covered. Ultra-wide field imaging allows identification of DR lesions in the peripheral retina that would not be imaged if seven-field ETDRS was used instead; this could have important prognostic implications. 22

FIGURE 8.

Ultra-wide field fundus images. Full visualisation of the superior (top), central (centre) and inferior (bottom) retina.

The burden of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular oedema and proliferative diabetic retinopathy and NHS pressures to meet service demands

Diabetes is on the rise. The estimated prevalence of diabetes in the UK was 3.9 million in 2019, over 100,000 more than in 2018. 6 If nothing changes, 5 million people in the UK will have diabetes by 2025. 6 The increasing number of people with diabetes will translate to a larger number of individuals with DMO and PDR. Given that patients are required to return to clinics at short intervals to receive treatment (until their disease has been controlled), and that these visits are required for the rest of their lives, the already excessive workload in hospital eye services related to DMO/PDR is expected to worsen. This poses major problems for the ability of ophthalmic clinics to evaluate and treat patients in time, especially because of the shortage of ophthalmologists. Delaying appointments may subsequently lead to poorer visual outcomes for patients; such delays are widespread in the UK, as recently highlighted by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. 23 Hospital eye services are further stretched by the fact that anti-VEGFs have been introduced not only for DMO but also for other conditions, including age-related macular degeneration and retinal vein occlusion, and frequent evaluation and treatment is required for these groups as well. Thus, it is imperative that new ways to increase efficiency and capacity in the NHS are identified and, if safe and acceptable, implemented.

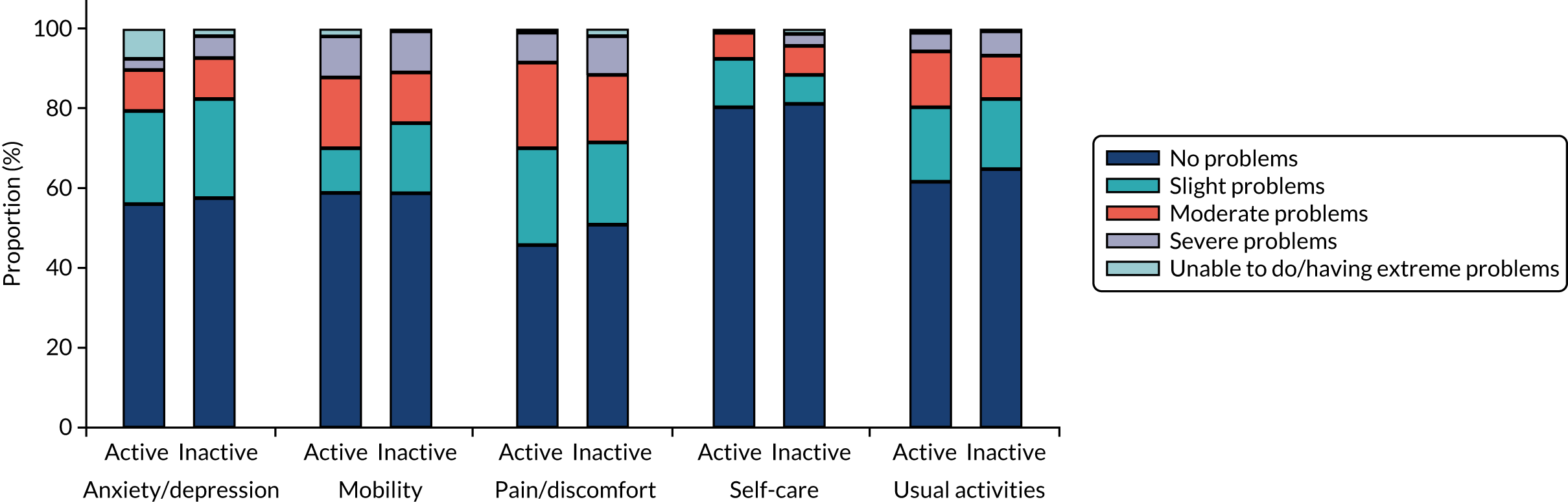

With the above in mind, EMERALD (Effectiveness of Multimodal imaging for the Evaluation of Retinal oedema And new vesseLs in Diabetic retinopathy) was conceived with the purpose of determining whether or not patients who had previously received treatment for DMO and/or PDR and in whom treatment had been successful [i.e. DMO cleared and PDR became quiescent (inactive)] could be followed up with multimodal retinal imaging and review of these images by a trained ophthalmic grader, rather than by ophthalmologists, as is currently standard practice.

Chapter 2 Diagnostic accuracy

The purpose of EMERALD was to determine the diagnostic accuracy, acceptability to patients and health-care professionals, and cost-effectiveness of a new care pathway, the ophthalmic grader pathway, when compared with the current standard of care (standard care pathway) for the surveillance of people with previously successfully treated DMO and/or PDR.

Methods

EMERALD was designed as a case-referent, cross-sectional diagnostic study with both sampling (selection) of patients and data collection carried out prospectively. 24 This approach provides both a cost-efficient study design and a low risk of bias in terms of diagnostic accuracy. 25

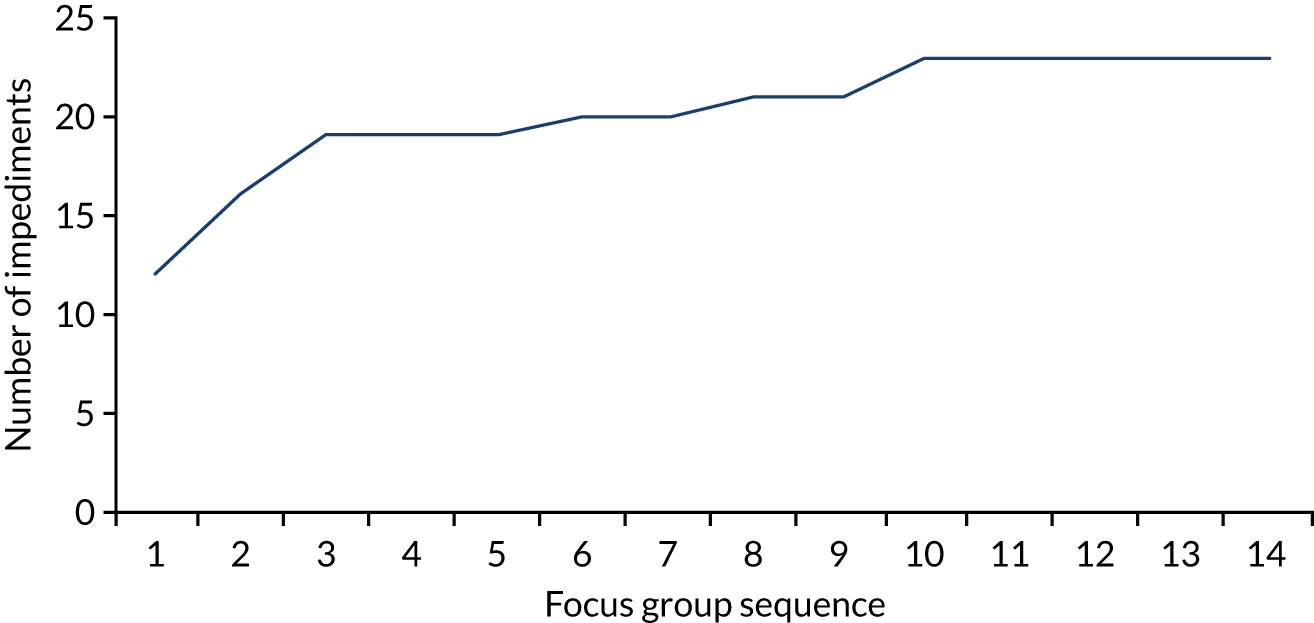

At the time of study conception, a patient and public involvement (PPI) group was established. EMERALD was presented to the PPI group and the plans for the study discussed. The PPI group confirmed the research question was important and that the tests proposed were adequate and feasible to patients. The PPI group provided essential input to all patient-related materials elaborated for the study (patient information sheet and consent form). The PPI group will also be actively involved in the dissemination of the results.

Setting

EMERALD was conducted in 13 specialised hospital eye services in the UK. Participating sites were in England (n = 11), Scotland (n = 1) and Northern Ireland (n = 1). All participating sites had extensive experience in the management of people with DR, DMO and PDR.

Population

Patients with DR and DMO and/or PDR were eligible for EMERALD if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

Adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and with previously successfully treated DMO and/or PDR in one or both eyes, and in whom, at the time of enrolment in the study, DMO and/or PDR was active or inactive. Patients could be recruited into the study only once.

Active DMO was defined as a CRT of > 300 µm on SD-OCT and/or by the presence of intraretinal/subretinal fluid on SD-OCT owing to DMO. Inactive DMO was defined as the lack of intraretinal/subretinal fluid at the macula on SD-OCT. Active PDR was defined as the presence of subhyaloid/vitreous haemorrhage and/or active new vessels (new vessels with a lack of fibrosis on them), whether in the disc (NVD) or elsewhere in the retina (NVE). Inactive PDR was defined as the lack of preretinal/vitreous haemorrhage and the lack of active NVD or NVE.

The exclusion criteria used were as follows:

-

patients unable to provide informed consent

-

patients unable to read, speak or understand English.

Pathways evaluated

Ophthalmic grader pathway

The new care pathway tested, the ophthalmic grader pathway, consisted of reviewing SD-OCT images to detect DMO and the review of seven-field ETDRS/ultra-wide field fundus images to detect PDR; this was carried out by trained, tested and certified ophthalmic graders (see Selection of ophthalmic graders and training). Following evaluation of these images, graders determined whether there was active DMO/PDR, inactive DMO/PDR or whether they were unsure or unable to grade (ungradable), in which case patients would be referred to an ophthalmologist for assessment. If there was no DMO and/or inactive PDR only, the grader would arrange a review appointment for the patient in the ophthalmic grader pathway at a pre-determined interval.

Standard-of-care pathway

The standard-of-care pathway considered in EMERALD was the current standard of care, as follows:

-

for people with DMO – ophthalmologist evaluating patients in clinic by slit-lamp biomicroscopy and with access to SD-OCT scans

-

for people with PDR – ophthalmologist evaluating patients in clinic by slit-lamp biomicroscopy.

For the purpose of EMERALD, and owing to ethics considerations, all patients were first evaluated through the standard care pathway, as explained in Patient flow in EMERALD.

Enhanced reference standard for proliferative diabetic retinopathy

It is possible that ophthalmologists could miss new blood vessels when evaluating patients by slit-lamp biomicroscopy. To account for this, EMERALD also evaluated an ‘enhanced’ reference standard for PDR that consisted of the reference standard (i.e. evaluation of the patient by slit-lamp biomicroscopy by an ophthalmologist) supplemented by the evaluation of seven-field ETDRS and ultra-wide field fundus images, which were reviewed by an ophthalmologist who was an expert in DR. If active PDR was detected in one of these three evaluations (slit-lamp biomicroscopy, seven-field ETDRS fundus images and ultra-wide field fundus images), it was considered that there was active PDR based on the enhanced reference standard (ERS). To obtain masking to the reference standard, ophthalmologists did not grade images from their own centre. Seven-field ETDRS and ultra-wide field images of the same participant were not reviewed by the same ophthalmologist to avoid the reading of one imaging technology influencing the reading of the other.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the sensitivity of the new pathway (ophthalmic grader pathway) in detecting active DMO/PDR, using the standard care pathway as the reference standard.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were:

-

specificity, concordance (agreement) between the new pathway (ophthalmic grader pathway) and the standard care pathway, and positive and negative likelihood ratios

-

cost-effectiveness

-

acceptability

-

proportion of patients requiring subsequent full clinical assessment

-

proportion of patients unable to undergo imaging, with inadequate quality images or indeterminate findings.

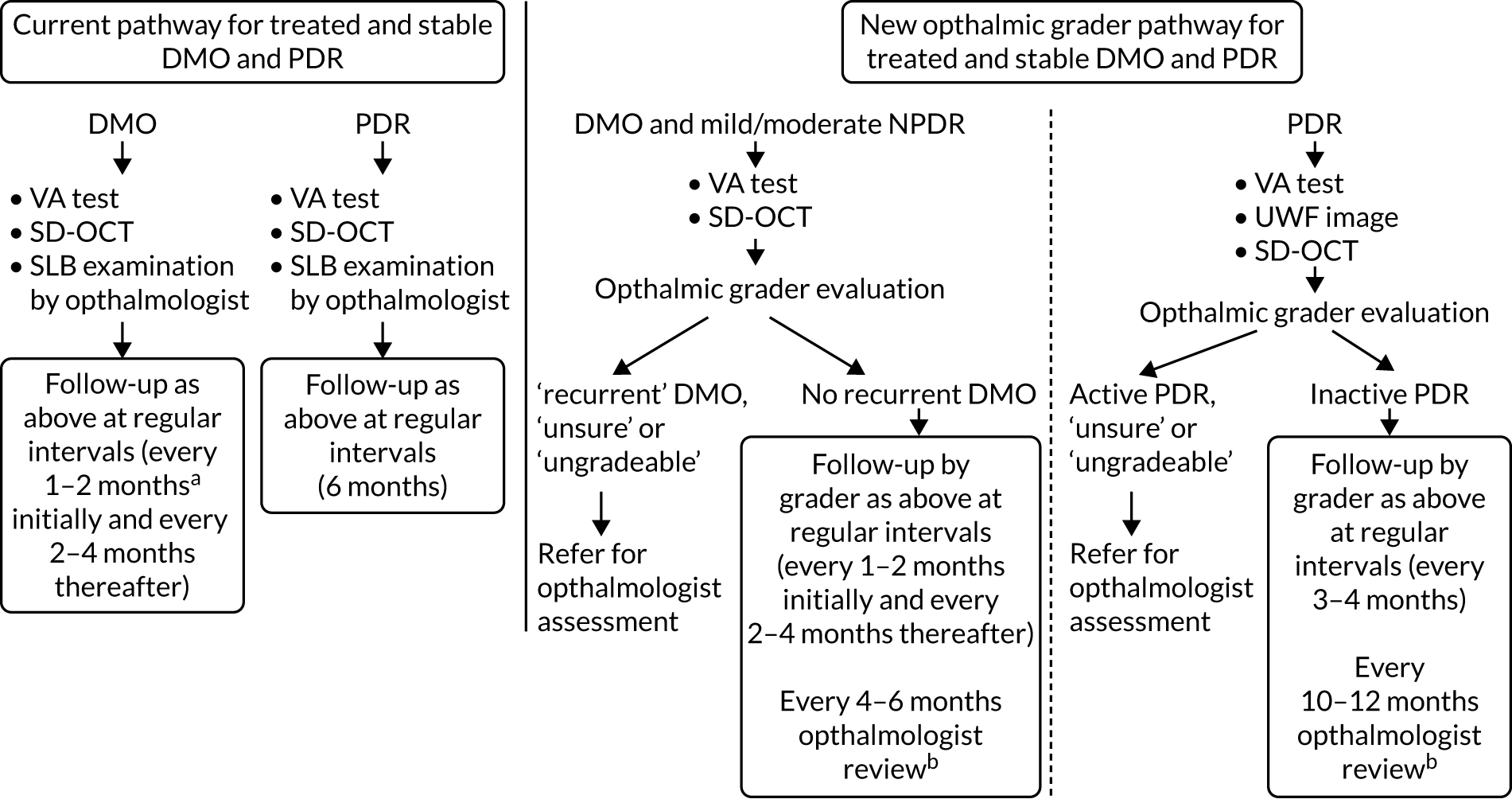

Selection of ophthalmic graders and training

Currently, ophthalmic photographers/imaging technicians obtain images and interpret them routinely, but make no decisions on the care of patients. In ophthalmic services, there are also ophthalmic graders that have been trained to interpret findings on fundus images for the purpose of undertaking DR screening.

For EMERALD, the ophthalmic graders at each participating site were selected as follows. To start, local principal investigators (PIs) provided names of individuals that they believed had experience of obtaining and/or grading images of patients with DMO and PDR; these individuals were approached to confirm their interest and willingness to participate in EMERALD. Some ophthalmic graders who were selected for EMERALD were already involved in the grading of images for DR screening.

Graders identified by the PIs were asked to fill in questionnaires detailing their experience of imaging/grading DMO/PDR, their experience of recognising features of DMO/PDR and whether or not they felt confident identifying DMO on SD-OCT and new vessels on fundus images. Graders who stated that they did not have experience of imaging/grading DMO/PDR and those stating that they could not recognise features of DMO/PDR were not invited to take part in EMERALD as graders.

Formal training was then provided to potential EMERALD graders; during training sessions, features of active/inactive DMO/PDR were reviewed and discussed and extensive clinical examples were presented. This training was provided to all EMERALD ophthalmic graders prior to the initiation of the study. Thus, prior to the initiation of the study, a 2-day face-to-face course was provided to potential graders. This was followed by two additional half-day training sessions.

A web-based teaching module with examples of DMO/PDR was prepared so that graders could consolidate their knowledge. Clear guidelines on when patients would need to be referred for an assessment by an ophthalmologist were also given.

To ensure that the graders who were selected had the required level of experience to undertake the task of grading images, all potential graders were required to take a test involving the reading of optical coherence tomographies (OCTs) and fundus images. Only graders who reached a minimum of 80% of correct answers in detecting the presence of DMO (active DMO) and active PDR, when present, were invited to act as graders. Graders were allowed to undergo further training and take the test a second time, but if the minimum number of correct answers was not reached at this second test they were not selected to be graders for EMERALD and did not carry out this role for the study.

Patient flow in EMERALD

Patients with previously successfully treated DMO/PDR were identified from clinical records, electronic databases or in clinic. Verbal and written information about the study was given to all potential participants and their questions, if any, were answered. At their review appointment, an ophthalmologist confirmed patient eligibility, obtained informed consent and determined whether or not DMO was present and whether there was active or inactive PDR, setting the reference standard. All participants underwent visual acuity testing, SD-OCT scans and fundus examination, as undertaken per routine standard practice. In some participating sites, 159 (40%) patients were evaluated in ‘research’ clinics, and in others 238 (60%) patients were evaluated fully within usual NHS clinics.

Once the reference standard was set, non-stereoscopic seven-field ETDRS and ultra-wide angle fundus images were obtained. These images were then coded (identifiers removed), uploaded to a central facility [the Central Administrative Research Facility (CARF), Queen’s University, Belfast] and allocated randomly to the EMERALD ophthalmic graders. Graders did not grade images from their own centre (to ensure masking to the reference standard) and did not grade seven-field ETDRS/ultra-wide fundus images from the same patient to prevent the grading of one technology influencing the grading of the other. For each patient/imaging modality, graders judged whether there was active/inactive DMO and/or active/inactive PDR, or if they were uncertain about this. Graders also determined, based on their findings, whether patients needed referral to an ophthalmologist for review/treatment or they could continue their care in the ophthalmic grader pathway.

Schedule of assessments for EMERALD

Case report forms (CRFs) were specifically designed to collect all of the information required for the purpose of the EMERALD study. The following information was obtained during the standard care pathway and recorded:

-

medical and ophthalmic history, including previous treatments for DMO/PDR

-

best-corrected visual acuity

-

ophthalmologists’ findings on slit-lamp biomicroscopy, including:

-

presence of anterior segment neovascularisation and possible determinants of poor-quality images, including media opacity and small pupillary size

-

presence/absence of DMO and/or active/inactive PDR

-

presence/absence and location of active/inactive NVD and NVE in the retina and/or pre-retinal haemorrhage/vitreous haemorrhage

-

presence of any other co-existent eye disease (e.g. glaucoma)

-

proposed plan for the patient (observation or treatment).

-

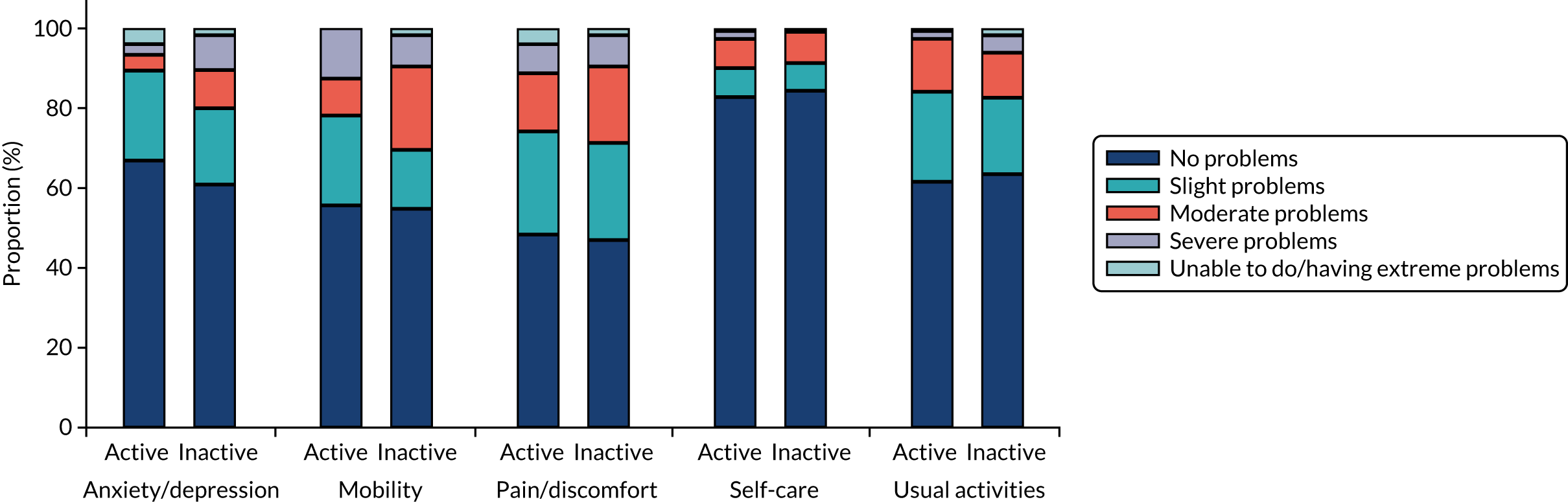

While in clinic, patients completed the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), National Eye Institute Visual Function-25 (NEI VFQ-25) and Vision and Quality of Life (VisQoL) questionnaires. Those willing to participate in the focus group (FG) discussions were asked for their consent and informed that they might be contacted at a later date for this purpose.

Patients underwent seven-field ETDRS and ultra-wide field imaging. Images were obtained following the guidelines provided in the standard operational procedures, as set in the EMERALD study manual. Once obtained, fundus photographs and SD-OCT images were anonymised and transferred to the CARF of Queens’ University Belfast, where they were uploaded to an electronic website developed for the study and randomly allocated and made accessible to the EMERALD ophthalmic graders and ophthalmologists determining the ERS for PDR. Images (SD-OCTs for graders and seven-field ETDRS and ultra-wide field fundus images for graders and ophthalmologists) were viewed in an ophthalmic viewer platform (Ophthalsuite, BlueWorks, Coimbra, Portugal) and graded by ophthalmic graders and ophthalmologists.

Ophthalmic graders determined and recorded in the appropriate CRF:

-

whether there was active/inactive DMO/PDR or if they were unsure or unable to grade presence of the disease (ungradable)

-

the presence/absence, location and activity of new vessels or whether they were unsure or unable to grade presence of the new vessels (ungradable)

-

the presence/absence and degree of completeness (partial or complete) of previous laser PRP

-

the presence/absence of pre-retinal haemorrhage and vitreous haemorrhage

-

the presence and type of other abnormalities, if observed

-

whether the patient could continue surveillance in the ophthalmic grader pathway or if an assessment by an ophthalmologist was required and the reasons why.

Similarly, ophthalmologists who were determining the ERS determined and recorded the following information in the appropriate CRF:

-

whether there was active/inactive PDR or if they were unsure or unable to grade presence of the disease (ungradable)

-

presence/absence, location and activity of new vessels or whether they were unsure or unable to grade presence of the new vessels (ungradable)

-

presence/absence and degree of completeness (partial or complete) of previous laser PRP

-

presence/absence of pre-retinal haemorrhage and vitreous haemorrhage

-

presence and type of other abnormalities, if observed

-

whether or not the patient could continue surveillance in the ophthalmic grader pathway or if an assessment by an ophthalmologist was required and the reasons why.

Masking

Ophthalmic graders and ophthalmologists evaluating images for the ERS were masked to the results of the reference standard. To ensure this, graders and ophthalmologists did not interpret images from patients recruited in their own centres; they did not have access to the results of the reference standard. Ophthalmologists undertaking the standard-of-care evaluation were also masked to the findings/decisions made by the ophthalmic graders (who reviewed the images at a later date). Patients were also masked to the findings/decisions made by the ophthalmic graders (these were not available at the time of the clinical visit for the study).

Data collection and quality checks

As stated above, CRFs were specifically prepared for the purpose of EMERALD and used to collect study data. Monitoring was undertaken during the study to check the accuracy of entries in CRF’s against source documents, adherence to protocol and procedures and adherence to the International Conference of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines26 and regulatory requirements. Monitoring visits were carried out by a monitor from the Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit (NICTU). Training on the protocol and study procedures was provided by the chief investigator and the NICTU to research staff at all participating sites prior to the initiation of the study.

Study data were transferred from CRFs to a web-based clinical trial database, which was elaborated for the purpose of EMERALD, by NICTU personnel and processed electronically. Data quality-control checks were carried out by a data manager to ensure accuracy. Data errors were documented in quality control reports and corrective actions implemented. Data validation and discrepancy reports were generated following data entry to identify discrepancies, such as data out of range, inconsistencies or protocol deviations, based on the data validation checks programmed in the clinical trial database.

Sample size

The sample size was determined by setting a target number of people with reactivated (active) DMO and PDR required to enable sensitivity to be tested against a prespecified target level of 80%. The required sample size was calculated using formula T1 from Obuschowski27 in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA); this was a Wald test-based calculation. This target level was considered to be the minimum acceptable for the new pathway (ophthalmic grader pathway) to be clinically viable. A lower specificity was considered acceptable; a target level of 65% was used to confirm sufficiency of the sample size to assess specificity. Eighty-nine participants with DMO/PDR that had reactivated (active DMO/PDR) was sufficient to detect if the sensitivity of the new pathway is 10% and 12% higher than the 80% minimal target set with 80% and 90% power, respectively, at the two-sided 5% significance level. 28 Ninety-three participants who have not reactivated would enable detection with a specificity 15% higher than the 65% target with 90% power. A 95% confidence interval for the sensitivity and specificity of the ophthalmic grader pathway would have a confidence interval (Wilson method) with a width of 10–20% depending on the observed level. 29 Allowing for 10% of missing/indeterminate results, 104 individuals who have reactivated and 104 who have not reactivated were required (208 individuals for each DMO and PDR), which led to a need for a maximum of 416 participants in the study. Because some participants had both DMO and PDR, and they contributed to both DMO and PDR targets, the number of patients required was smaller than 416.

Statistical analyses

Overview of principal analyses

The statistical analyses were conducted in accordance with the study protocol1 and the statistical analysis plan, which was signed off and made publicly available on the EMERALD website (www.nictu.hscni.net/emerald-trial/; accessed March 2020) prior to data analyses. Additional analyses conducted beyond those planned for in the statistical analysis plan are identified as such in this chapter (as well as in Chapter 4). To address the primary objective, the principal analyses were carried out with DMO and PDR patients assessed in two separate sets of analyses at the person level, one for each disease (see Table 2). Analyses were focused on the participant being considered eligible for the new pathway by virtue of having previously successfully treated DMO/PDR in one or both eyes (‘Patients eligible for new pathway’). The main analysis was according to the ophthalmic graders decision to refer to an ophthalmologist (irrespective of the reason, i.e. active disease or if the grader was unsure or unable to grade; referred to throughout this chapter as ‘referral’ = ‘active’ + ‘unsure’ + ‘ungradable’); this would be what would occur if the ophthalmic grader pathway were to be implemented. The reference standard was standard care: slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination by an ophthalmologist [referred to throughout this chapter as ophthalmologists face-to-face (O-FTF)] with access to SD-OCT images (referred to as O-FTF + OCT) for DMO, and slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination by ophthalmologist (O-FTF) for PDR to detect the presence of active disease (active DMO or active PDR) in either eye. For PDR only, an ERS was used for some analyses. This consisted of the combined findings of ophthalmologist slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination (O-FTF), ultra-wide field fundus images (referred to throughout this chapter as O-OPTOS) and seven-field ETDRS fundus images (referred to throughout this chapter as O-ETDRS). Positive detection of active PDR constituted a positive ERS result. The diagnostic performance of the new ophthalmic grader pathway was quantified and compared with that of the standard care pathway. For PDR, there were two sets of results: one using ultra-wide field fundus imaging-based assessment (referred to as OPTOS) and one using the seven-field ETDRS-based assessment (referred to as ETDRS). The impact of using either OPTOS or ETDRS on the diagnostic performance of the new pathway was formally compared.

Table 1 summarises all of the analyses undertaken in EMERALD. Tables 2 and 3 summarise the planned principal analyses (main and sensitivity analysis) and the unplanned additional principal analyses undertaken.

| Disease(s) | Image(s) | Population | Level of analysis | Analysisa | Location in report | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure | Table number(s) | Appendix 1 | |||||

| DMO | SD-OCT | Eligible patients for new pathway | Person | Main analysis | Figure 10 | Tables 2, 7, 9, 12 and 13 | |

| SENA1 | |||||||

| SENA2 | |||||||

| SENA3 | |||||||

| SENA6 | |||||||

| PDR | UWF OPTOS and seven-field ETDRS | Eligible patients for new pathway | Person | Main analysis | Figure 11 | Tables 2, 8, 10, 14, 15, 16 and 17 | |

| SENA1 | |||||||

| SENA2 | Figure 11 | Tables 2, 8, 10, 14 and 15 | |||||

| SENA4 | |||||||

| SENA5 | |||||||

| SENA6 | |||||||

| Additional 1 | Figure 11 | Tables 3, 8, 10, 14 and 15 | |||||

| Additional 2 | |||||||

| Additional 3 | |||||||

| Combined diseases | SD-OCT and UWF OPTOS/seven-field ETDRS | All patients | Person | SECA2A | N/A | Tables 5, 18 and 19 | |

| Additional 4 | |||||||

| SECA2B | |||||||

| SECA2C | |||||||

| DMO | SD-OCT | All patients | Eye | SECA1A | N/A | Table 5 | Table 41 |

| SECA1B | Table 42 | ||||||

| PDR | UWF OPTOS/seven-field ETDRS | All patients | Eye | SECA1A | N/A | Table 5 | Table 41 |

| SECA1C | Table 42 | ||||||

| Analysis name | Level of analysis | DMO | PDR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index test positive | Reference standard | Index test positive | Reference standard | ||

| Main | Person | OCT-based ophthalmic grader referralb for either eye | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO in either eye | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | |||||

| SENA1 | Person | OCT-based ophthalmic grader identification of active disease in either eye | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO in either eye | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader identification of active disease in either eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader identification of active disease in either eye | |||||

| SENA2 | Person | OCT-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO in either eye requiring treatment | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye requiring treatment |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | |||||

| SENA3 | Person | OCT-based ophthalmic grader identification of central-involving DMO in either eye | O-FTF + OCT assessment of central-involving DMO in either eye | N/A | N/A |

| SENA4 | Person | N/A | N/A | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR with pre-retinal or vitreous haemorrhage in either eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | |||||

| SENA5 | Person | N/A | N/A | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | Enhanced standard |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | |||||

| SENA6 | Person | OCT-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye (participants assessed in routine clinic setting only) | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO in either eye (participants assessed in routine clinic setting only) | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye (participants assessed in routine clinic setting only) | O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye (participants assessed in routine clinic setting only) |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye (participants assessed in routine clinic setting only) | |||||

| Analysis name | Level of analysis | DMO | PDR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index test positive | Reference standard | Index test positive | Reference standard | ||

| Additional 1 | Person | N/A | N/A | OPTOS-based ophthalmologist identification of active disease in either eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmologist identification of active disease in either eye | |||||

| Additional 2 | Person | N/A | N/A | OPTOS-based ophthalmologist identification of active disease in either eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR with pre-retinal or vitreous haemorrhage in either eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmologist identification of active disease in either eye | |||||

| Additional 3 | Person | N/A | N/A | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referralb for either eye | O-FTF assessment + ophthalmologist OPTOS images of active PDR in either eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for either eye | O-FTF assessment + ophthalmologist ETDRS images of active PDR in either eye | ||||

Eligible participants for the EMERALD ophthalmic grader’s pathway

Eligible participants contributed to the principal analyses under the new pathway for DMO (see Table 2) if they had at least one eye with DMO that was eligible (i.e. previously successfully treated). Similarly, eligible participants contributed to the principal analyses under the new pathway for PDR (see Tables 2 and 3) if they had at least one eye with PDR that was eligible (i.e. previously successfully treated).

Participants in EMERALD, however, could have one or both eyes with ‘active DMO’ or ‘active PDR’ (‘recurrent’, ‘de novo’ or ‘persistent’; see below for definitions), or ‘inactive DMO’ or ‘inactive PDR’, or ‘no DMO’ or ‘no PDR’ according to the diagnosis established at the standard care pathway.

Definitions

‘Active, recurrent DMO/PDR’ refers to previously successfully treated DMO/PDR that was present at the time of the EMERALD examination.

‘Active, de novo DMO/PDR’ refers to DMO/PDR never present before but observed at the time of the EMERALD examination.

‘Active, persistent DMO/PDR’ refers to DMO/active PDR that was present before, never cleared (e.g. unsuccessfully treated) and was present at the time of the EMERALD examination.

‘Inactive DMO/PDR’ refers to inactive disease at the time of the EMERALD examination.

Note that some eyes with inactive DMO/PDR would have been previously successfully treated and would be considered eligible eyes; others, however, may not have had previously successfully treated disease, but at the time the patient attends the EMERALD visit their disease may be inactive and, thus, would be considered ineligible eyes (see Eye-level classification).

‘No DMO/PDR’ refers to DMO or PDR never present and not detected at the time of the EMERALD examination.

Eye-level classification

The eye-level classification was based on the following six scenarios:

-

‘Scenario 1 – Previous Active, successfully treated, Today Active’ (corresponding to ‘recurrence’) – also defined as ‘Eligible eye’ for the analysis of new pathway.

-

‘Scenario 2 – Previous Active, successfully treated, Today Inactive’ (corresponding to ‘inactive’) – also defined as ‘Eligible eye’ for the analysis of new pathway.

-

‘Scenario 3 – Previous Active, not successfully treated, Today Active’ (corresponding to ‘persistence’) – also defined as ‘Ineligible eye’ for the analysis of new pathway.

-

‘Scenario 4 – Never present, Today Active’ (corresponding to ‘de novo’, i.e. newly diagnosed) – also defined as ‘Ineligible eye’ for the analysis of new pathway.

-

‘Scenario 5 – Previous Active, not successfully treated, Today Inactive’ – (corresponding to ‘inactive’) also defined as ‘Ineligible eye’ for the analysis of new pathway.

-

‘Scenario 6 – DMO/PDR never present, Today No DMO/PDR’ (i.e. no disease) – also defined as ‘Ineligible eye’ for the analysis of new pathway.

Participant-level classification

All participants who were included in the EMERALD study were at least eligible for the new DMO or the new PDR pathway, or eligible for both the DMO and the PDR pathways. Each eye for each EMERALD participant was assessed with regard to the status of PDR and DMO, irrespective of whether or not they were ‘eligible’ for both cohorts. What data were included varies according to the analysis (see Tables 2 and 3 for a full list). The statement ‘eligible participants’ for the new pathway refers to analyses from data obtained from participants contributing with one or both eligible eyes (one or both eyes had to have previous successfully-treated DMO or PDR, respectively) (Scenario 1 or 2 in one or both eyes).

To be eligible for the new DMO pathway (see Table 2), participants needed to have at least one eye with previously successfully treated DMO (i.e. ‘eligible’). At the time of the EMERALD examination, if DMO was present in one or both eyes they were classed as having active DMO (‘recurrent DMO’), and if neither eye had DMO then participants were classed as having inactive DMO. Inactive DMO includes patients who have one previously successfully treated eye in which DMO is inactive at the time of examination and who have no DMO in the other eye. It also includes those for whom one or both eyes had been previously successfully treated for DMO, but both eyes were inactive at the time of examination. Participants who did not have an eye that had been previously successfully treated were ineligible for the new DMO pathway.

To be eligible for the new PDR pathway (see Tables 2 and 3), participants needed to have at least one eye with previously successfully treated PDR (i.e. ‘eligible’). At the time of the EMERALD examination, if PDR was active in one or both eyes they were classed as having active PDR (‘recurrent PDR’), and if neither eye had active PDR then participants were classed as having inactive PDR. Inactive PDR includes patients who had one previously successfully treated eye in which PDR is inactive at the time of examination and who had no PDR in the other eye. It also includes those in whom one or both eyes had been previously successfully treated for PDR but both eyes were inactive at the time of examination. Participants who did not have an eye that had been previously successfully treated were ineligible for the new PDR pathway.

Definition of grader’s assessments of optical coherence tomography, OPTOS and ETDRS

A grader’s decision on whether or not to refer the patient, an inherently person-level decision, was used, rather than an assessment of the single eye. The basis of the referral decision was the grader’s assessment of the corresponding disease (DMO/PDR). Furthermore, to more closely reflect how the new pathway would function in practice, a patient whom graders classified as having DMO or PDR within the eye under the category ‘unsure’ or ‘ungradable’ were considered alongside those classified as ‘active’, as both would be anticipated to require further examination by an ophthalmologist under the main analysis (referral = ‘active’ + ‘unsure’ + ‘ungradable’). How the ophthalmic graders decision was tested varied according to the analysis (see Tables 2 and 3 for a full list). Table 4 shows the graders decision of person-level active status based on the combination of eye-level results. Only those samples in which there was an overall classification available were included in the sensitivity analyses.

| Eye-level active status | Person-level active status | |

|---|---|---|

| Main | SENA1/SENA3 | |

| ‘Both’ eyes ‘Active’ or ‘either’ eye ‘Active’, no matter the status of the other eye | Referrala | Active |

| ‘Both’ eyes ‘Unsure’ or ‘Ungradable’ | Referrala | Not Active |

| One eye ‘Unsure’ or ‘Ungradable’, while the other eye ‘No’ disease, ‘Ungradable’ or ‘Unsure’ | Referrala | Not Active |

| One eye ‘Unsure’ or ‘Ungradable’, while the other eye ‘Missing’ | Referrala | Missing |

| ‘Both’ eyes ‘No disease’ or ‘Inactive disease’ | Not Active | Not Active |

| One eye ‘No disease’ while the other eye ‘Inactive disease’ and neither eye ‘Missing’ | Not Active | Not Active |

| ‘Both’ eyes ‘Missing’, and none of the eyes would be referral | Missing | Missing |

| One eye ‘No disease’ or ‘Inactive disease’, while the other eye ‘Missing’ | Missing | Missing |

Diagnostic performance of the EMERALD ophthalmic graders

The diagnostic performance of the EMERALD ophthalmic graders was assessed against the standard care reference standard to determine:

-

sensitivity (the proportion of patients determined by the ophthalmologist to suffer from active DMO/PDR who had been correctly referred/identified by EMERALD ophthalmic graders)

-

specificity (the proportion of patients determined by the ophthalmologist to suffer from inactive DMO/PDR who had been correctly referred/identified by EMERALD ophthalmic graders)

-

overall agreement (a measure of how well the ophthalmic graders’ assessment agrees with the ophthalmologist assessment)

-

positive likelihood ratio (the probability that a patient with active DMO/PDR is correctly assessed by the ophthalmic graders, divided by the probability that a patient with inactive DMO/PDR is incorrectly assessed by the ophthalmic graders as being active)

-

negative likelihood ratio (the probability that a patient with active DMO/PDR is incorrectly assessed by the ophthalmic graders as being active, divided by the probability that a patient with inactive DMO/PDR is correctly assessed).

Agreement between assessment methods was also quantified, where appropriate.

Diagnostic performance analysis methods

For all diagnostic accuracy analyses the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios were calculated (with appropriate 95% CIs). The difference in sensitivity and specificity between OPTOS and ETDRS fundus images, as assessed by the ophthalmic graders, was compared with corresponding 95% CIs produced using Newcombe’s method for paired data30 and McNemar’s test. 31

Sensitivity analyses of diagnostic performance

In addition to the main analysis for DMO and PDR, a number of sensitivity analyses were conducted (listed in Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis (SENA)1 assessed the impact of the ‘unsure’ and ‘ungradable’ test classifications and of the ophthalmic grader’s grade on the diagnostic performance by defining the index test positive as definite assessment of the active disease (in contrast to allowing referral for ‘unsure’ or ‘ungradable’). The reference standards of the O-FTF + OCT assessment for DMO and the O-FTF for PDR of those present with active disease were used.

SENA2 assessed the ophthalmic graders’ referral assessments against the reference standard of those requiring treatment for both DMO and PDR. For DMO only, SENA3 focused on diagnostic performance for assessment among patients considered to possess a form of DMO that would be more important to recognise earlier, central-involving DMO (in contrast to non-central-involving DMO against the reference standard of O-FTF + OCT assessment). For PDR only, SENA4 assessed the diagnostic performance of the ophthalmic grader against the reference standard of O-FTF assessment to detect active PDR with pre-retinal or vitreous haemorrhage (i.e. high risk PDR). For PDR only, SENA5 assessed the diagnostic performance of the ophthalmic grader against the ERS (O-FTF assessment supplemented by ophthalmologist evaluation using OPTOS and ETDRS images) to detect active PDR. A further sensitivity analysis (SENA6) assessed diagnostic accuracy for a subset of participants only, who were assessed in a ‘typical’ NHS clinic setting, in contrast to a research clinic, but otherwise under the same conditions as the main analysis.

For PDR only, three additional post hoc analyses (see Table 3) that were not listed in the statistical analysis plan were also conducted in the light of the main PDR results, to further understand the content and potential value of the two imaging modalities evaluated (ultra-wide field and seven-field fundus images) along with the reliability of the O-FTF reference standard for PDR. ‘Additional 1’ compared the ophthalmologists’ identification of active PDR by OPTOS or by ETDRS in either eye with the reference standard of O-FTF assessment for active PDR. ‘Additional 2’ compared the ophthalmologists’ identification of active PDR by OPTOS or by ETDRS in either eye with the reference standard of O-FTF assessment for patients with more severe disease (i.e. PDR with pre-retinal or vitreous haemorrhage). ‘Additional 3’ compared the ophthalmic graders’ referral for either eye by OPTOS or by ETDRS with the reference standard of O-FTF assessment + ophthalmologist OPTOS assessment of active PDR in either eye or O-FTF assessment + ophthalmologist ETDRS assessment of active PDR in either eye.

Secondary analyses of diagnostic accuracy

In addition to the principal analyses that were conducted separately at the person level for DMO and PDR, two distinct secondary analyses of diagnostic accuracy were planned (Table 5). Both of these secondary analyses focused on the entire EMERALD participant population (‘All participants’), whether or not they were eligible for a disease (DMO/PDR) pathway. First, a limited set of eye-level analyses were carried out using the positive identification of active disease at the eye level [secondary analysis (SECA) 1A–C]. A random eye was selected when two eyes were eligible, with ophthalmic grader eye-specific assessment against the reference standard. Second, person-level analyses were carried out for the overall referral status of a patient, irrespective of whether it was active DMO or PDR that required referral (SECA2A–C). SECA2A utilised an ophthalmic grader referral assessment for either disease; for DMO, OCT assessment was used, and for PDR the OPTOS and ETDRS assessment were used in turn (i.e. two sets of results). The reference standards of O-FTF + OCT assessment for DMO and O-FTF assessment for PDR for those present with active disease were used (either disease constituting active disease at the person level). SECA2B was the same as SECA2A, except that a visual acuity of less than 6 out of 12 would also be considered a valid reason for referral. SECA2C was the same as SECA2A, except the reference standard was an ophthalmologist’s assessment of the presence or absence of active disease that required treatment. Diagnostic performance for both secondary analyses was assessed using the same outcomes and methods as for the principal analyses.

| Analysis name | Level of analysis | DMO index test positive | DMO reference standard | PDR index test(s) positive | PDR reference standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SECA1A | Eye | OCT-based ophthalmic grader assessment of active DMO in the randomly selected eye | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO in the randomly selected eye | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader assessment of active PDR in randomly selected eye | O-FTF assessment of active PDR in the randomly selected eye |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader assessment of active PDR in randomly selected eye | |||||

| SECA1B | Eye | OCT-based ophthalmic grader identification of central-involving DMO in either eye | O-FTF + OCT assessment of central-involving DMO in either eye | ||

| SECA1C | Eye | N/A | N/A | OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral | Enhanced standard |

| ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral | |||||

| Combined DMO/PDR test positive | Combined DMO/PDR reference standard | ||||

| SECA2A | Person | Ophthalmic grader referralc based on OCT for DMO and either OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral for PDR or ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for PDR (referral for either disease will be considered a referral for the combined test) | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO and O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye | ||

| Additional 4b | Person | Ophthalmic grader assessment of active DMO based on OCT and either OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader assessment of active PDR or ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader assessment of active PDR | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO and O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye | ||

| SECA2B | Person | Ophthalmic grader referral based on OCT for DMO and either OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral or ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for PDR, and visual acuity of < 6/12 (or ETDRS equivalent letter) (referral for either disease, or owing to visual acuity, will be considered a referral for the combined test) | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO and O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye | ||

| SECA2C | Person | Ophthalmic grader referral based on OCT for DMO and either OPTOS-based ophthalmic grader referral or ETDRS-based ophthalmic grader referral for PDR, and visual acuity of < 6/12 (or ETDRS equivalent letter) (referral for either disease, or owing to visual acuity, will be considered a referral for the combined test) | O-FTF + OCT assessment of active DMO and O-FTF assessment of active PDR in either eye requiring treatment | ||

One additional post hoc analysis (‘Additional 4’) that was not listed in the statistical analysis plan was also conducted to further understand the content and the potential implementation method of the new pathway. The test results for Additional 4 were graders’ assessment of active disease(s) in either eye rather than graders’ referral [which would include active disease(s), unsure or ungradable] in either eye (SECA2A). Both SECA2A and Additional 4 would be of interest to how the new pathway would function in clinical practice.

Results

Participant characteristics

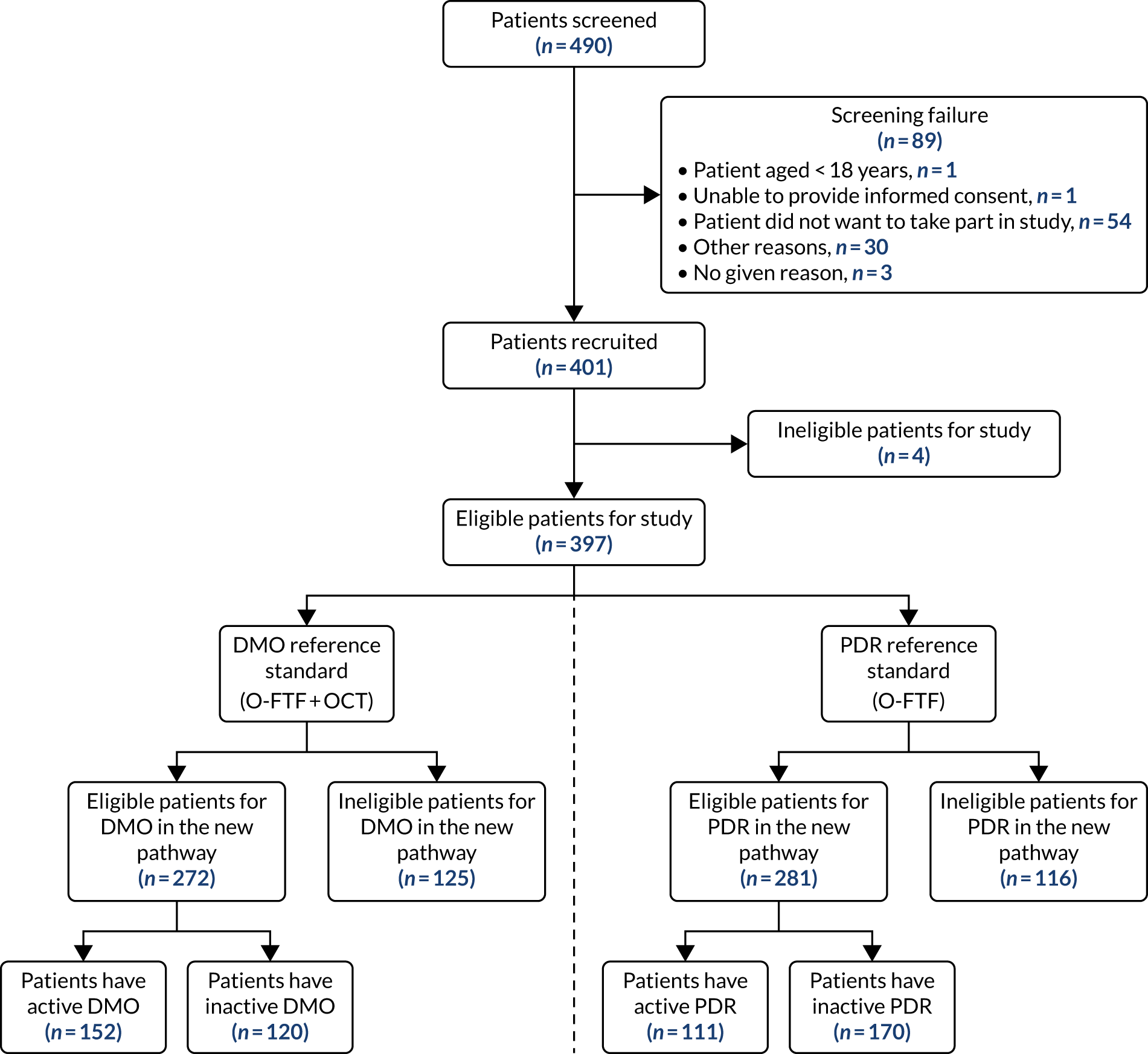

A flow diagram is provided (Figure 9) that shows the flow of participants and the O-FTF assessment reference standard for each disease. In total, 490 patients were screened, of whom 401 (82%) consented and were recruited. A total of 397 patients were eligible to participate in the study and four patients were ineligible. Five eyes could not be assessed and were excluded at eye-level assessment, but were included at patient-level assessment (assessed the other eye only): one right eye could not be assessed owing to blindness; four left eyes could not be assessed owing to blindness (n = 2), total retinal detachment (n = 1) and artificial eye (n = 1).

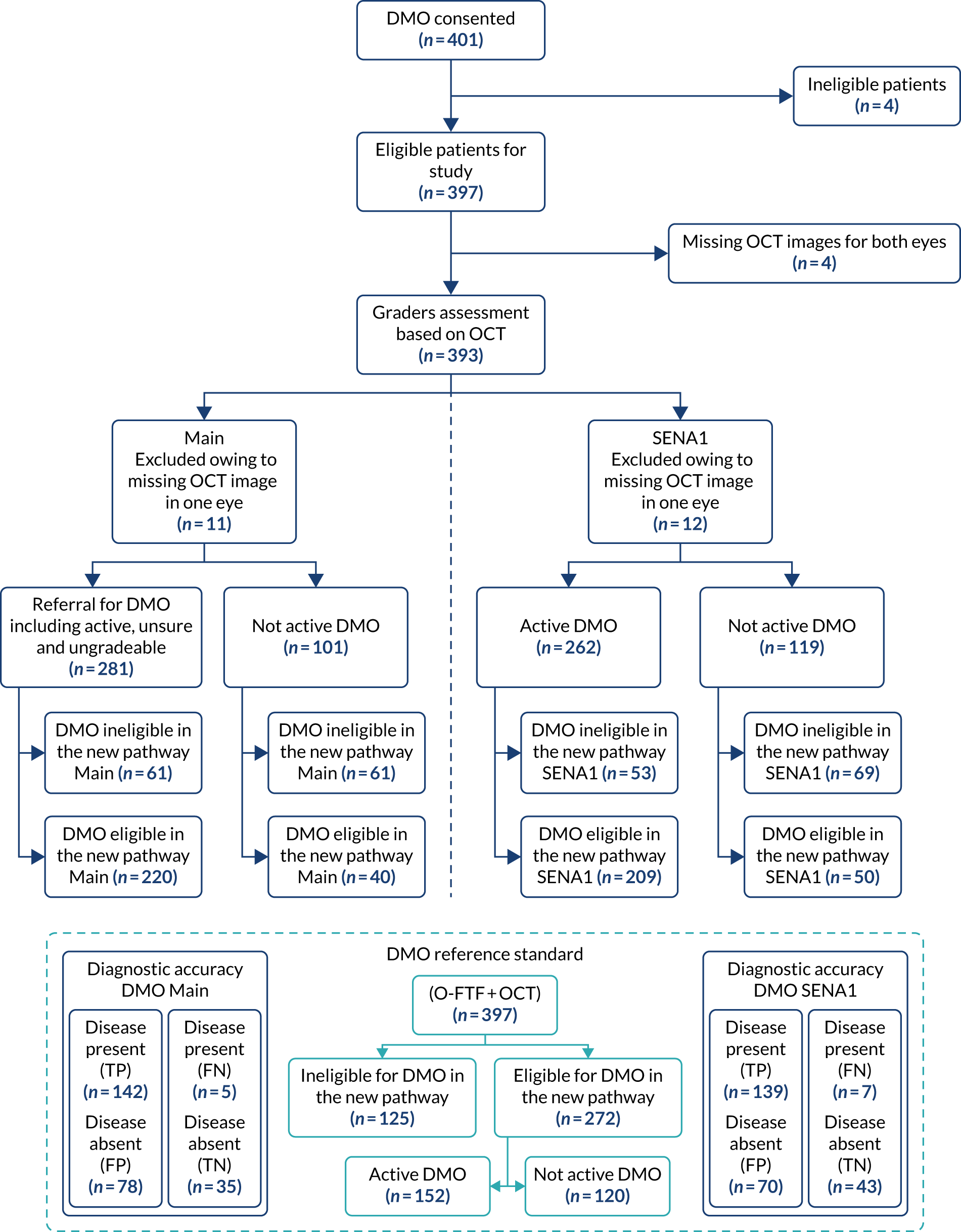

FIGURE 9.

Study flow diagram.

Sample description

Baseline characteristics of participants

The median age of the 397 patients included in EMERALD was 60 (range 18–103) years. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of the patients were male and the majority (86%) were of white ethnicity. In total, 317 (80%) patients had a diagnosis of DMO and of these 182 (57%) were from the older (≥ 60 years) age group. A total of 287 (72%) patients had a diagnosis of PDR and of these 136 (47%) were from the older age group (Table 6). The participants’ characteristics by active diseases status are summarised in Appendix 1, Table 36.

| Characteristic | Patients with DMO (N = 317), n (%) | Eligible for DMO in the new pathway (N = 272), n (%) | Patients with PDR (N = 287), n (%) | Eligible for PDR in the new pathway (N = 281), n (%) | Total (N = 397), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 205 (65) | 175 (64) | 187 (65) | 185 (66) | 257 (65) |

| Female | 112 (35) | 97 (36) | 100 (35) | 96 (34) | 140 (35) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 18–59 | 135 (43) | 113 (42) | 151 (53) | 148 (53) | 188 (47) |

| ≥ 60 | 182 (57) | 159 (58) | 136 (47) | 133 (47) | 209 (53) |

| Ethnic origin | |||||

| White | 274 (86) | 240 (88) | 240 (84) | 234 (83) | 340 (86) |

| Black | 20 (6) | 17 (6) | 19 (7) | 19 (7) | 26 (7) |

| Asian | 16 (5) | 11 (4) | 20 (7) | 20 (7) | 22 (6) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Other | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) |

Reference standard diagnosis characteristics

Tables 7 and 8 display the EMERALD population at eye level and at person level based on the six patient classification scenarios for DMO and for PDR, respectively. The reference standard was determined at both the eye and person level. Of the 397 patients included in the analyses, 272 (80%) were eligible for DMO in the new pathway and these patients were used in the principal person-level diagnostic accuracy analyses for DMO. Of these, 152 (56%) had DMO at least in one eye that was previously successfully treated and was active (i.e. had recurrence of DMO) when evaluated in the EMERALD study visit (i.e. when entering the study). A total of 120 (44%) had DMO in at least one eye that had been previously successfully treated and remained inactive (i.e. had no DMO present) when evaluated in the EMERALD study visit (i.e. when entering the study) (see Figure 9 and Table 7). In total, 281 (71%) of the 397 patients were eligible for PDR in the new pathway and these patients were used in the principal person-level diagnostic accuracy analyses for PDR. Of these, 111 (40%) had PDR in at least one eye that was previously successfully treated and was active (i.e. had recurrence of active PDR) when evaluated in the EMERALD study visit (i.e. when entering the study). A total of 170 (60%) patients had PDR in at least one eye that had been previously successfully treated and remained inactive when evaluated in the EMERALD study visit (i.e. when entering the study) (see Figure 9 and Table 8). In total, 272 (69%) out of the 397 participants had active DMO or active PDR, and 49 (12%) had active DMO and active PDR according to the ophthalmologists assessments (see Appendix 1, Table 36).

| DMO status | Eye level | Person level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right eye (N = 396),a n (%) | Left eye (N = 393),a n (%) | Person (either eye) (N = 397), n (%) | ||

| Active | Previously successfully treated (scenario 1) | 97 (24) | 92 (23) | 152 (38) |

| Previously unsuccessfully treated (scenario 3) | 30 (8) | 17 (4) | – | |

| Newly diagnosed (scenario 4) | 15 (4) | 11 (3) | – | |

| Inactive | Previously successfully treated (scenario 2) | 113 (29) | 119 (30) | 120 (30) |

| Previously unsuccessfully treated (scenario 5) | 19 (5) | 23 (6) | – | |

| No disease | Scenario 6 | 121 (31) | 127 (32) | – |

| Unclassifiableb | 1 (< 1) | 4 (1) | – | |

| Owing to no view of fundus: cataract | 1 (< 1) | – | ||

| Owing to no view of fundus: haemorrhage | – | 3 (1) | – | |

| Owing to no view of fundus | – | 1 (< 1) | – | |

| Ineligible for new DMO pathwayc | – | – | 125 (31) | |

| PDR status | Eye level | Person level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right eye (N = 396),a n (%) | Left eye (N = 393),a n (%) | Person (either eye) (N = 397),a n (%) | ||

| Active | Previously successfully treated (scenario 1) | 72 (18) | 71 (18) | 111 (28) |

| Previously unsuccessfully treated (scenario 3) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | – | |

| Newly diagnosed (scenario 4) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | – | |

| Inactive | Previously successfully treated (scenario 2) | 180 (45) | 171 (44) | 170 (43) |

| Previously unsuccessfully treated (scenario 5) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | – | |

| No disease | (Scenario 6) | 134 (34) | 140 (36) | – |

| Unclassifiableb | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | – | |

| Owing to no view of fundus: cataract | 1 (< 1) | – | – | |

| Owing to no view of fundus: corneal graft | – | 1 (< 1) | – | |

| Owing to no view of fundus: reason not specified | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | – | |

| Ineligible for new PDR pathwayc | – | – | 116 (29) | |

Eye characteristics and eye comorbidities of participants

Appendix 1, Tables 37 and 38, describes other findings (abnormalities) that were identified by ophthalmologists when undertaking slit-lamp biomicroscopy and were recorded as potential factors that could lead to inadequate image quality, as well as comorbidities noted. Comorbidities were uncommon in EMERALD participants. The most common comorbidities were epiretinal membrane and glaucoma (reported in approximately 3% of eyes) (see Appendix 1, Table 38).

Grading results diagnosis characteristics

Table 9 displays the OCT-based ophthalmic graders’ grading results at eye level against the reference standard for assessing DMO. OCT images were available for 385 (97%) right eyes and 380 (97%) left eyes. Of these, only a very small number, six (2%) right eyes and five (1%) left eyes, were considered ungradable. In a similarly small number of eyes, the grader was unsure if DMO was present [13 (3%) right eyes and 12 (3%) left eyes]. A total of 198 (51%) right eyes and 188 (49%) left eyes were identified as having DMO, and there were 168 (44%) right eyes and 175 (46%) left eyes with no DMO.

| DMO grading | Graders OCT (G-OCT) | Reference standard (O-FTF + OCT) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | |

| Total DMO present (active) | 198 | 188 | 142 | 120 |

| No DMO | 168 | 175 | 253 | 269 |

| Unsure if DMO present | 13 | 12 | – | – |

| Ungradeable | 6 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| No images | 11 | 13 | – | – |

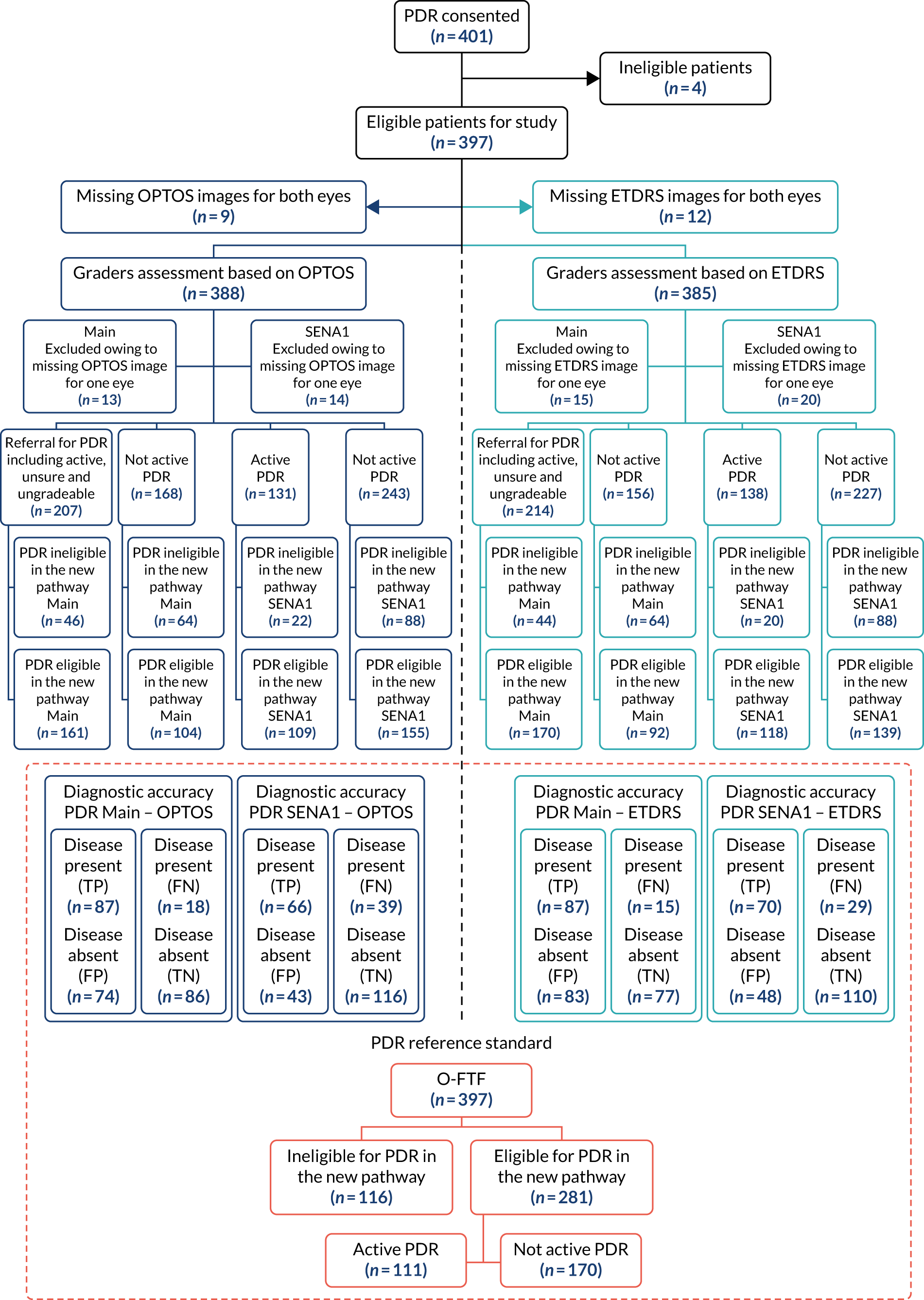

Table 10 displays the UWF OPTOS and seven-field ETDRS-based ophthalmic graders’ and ophthalmologists’ grading results for PDR patients at eye level against the reference standard. Seven-field ETDRS images were available for 376 (95%) right eyes and 362 (92%) left eyes. Of these, a small number [19 (5%) right eyes and 27 (7%) left eyes] were considered ungradable. In a similarly small number of eyes, the grader was unsure if PDR was present [20 (5%) right eyes and 17 (5%) left eyes]. A total of 88 (23%) right eyes and 83 (23%) left eyes were identified as having active PDR based on seven-field ETDRS images. There was a small number of eyes in which PDR was identified, but the grader stated that they were unsure if there was active disease or not [12 (3%) right eyes and 14 (4%) left eyes]. A total of 71 (42%) right eyes and 65 (40%) left eyes were classified by the graders as having inactive PDR, and 166 (44%) right eyes and 156 (43%) left eyes were classified by the graders as having no PDR. UWF OPTOS images were available for 379 (96%) right eyes and 374 (95%) left eyes. Of these, a small number [16 (4%) right eyes and 21 (6%) left eyes] were considered ungradable. In a similarly small number of eyes, the grader was unsure if PDR was present [20 (5%) right eyes and 21 (6%) left eyes]. A total of 85 (22%) right eyes and 73 (20%) left eyes were identified as having active PDR based on UWF OPTOS images. There was a small number of eyes in which PDR was identified but the grader was unsure if there was active disease or not [11 (3%) right eyes and 16 (4%) left eyes]. A total of 95 (25%) right eyes and 81 (22%) left eyes were identified as having inactive PDR, and 152 (40%) right eyes and 162 (43%) left eyes were identified as having no PDR, based on UWF OPTOS images.

| PDR grading | Graders seven-field (G-ETDRS) | Ophthalmologist seven-field (O-ETDRS) | Graders UWF (G-OPTOS) | Ophthalmologist UWF (O-OPTOS) | Reference standard (O-FTF) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | Right eyea (n = 396) | Left eyea (n = 393) | |

| Total PDR present | 171 | 162 | 185 | 185 | 191 | 170 | 206 | 213 | ||

| Active | 88 | 83 | 58 | 60 | 85 | 73 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 79 |

| Inactive | 71 | 65 | 98 | 106 | 95 | 81 | 117 | 121 | 180 | 172 |

| Unsure if active | 12 | 14 | 29 | 19 | 11 | 16 | 19 | 17 | – | – |

| No PDR | 166 | 156 | 150 | 137 | 152 | 162 | 143 | 125 | 134 | 140 |

| Unsure if PDR present | 20 | 17 | 30 | 31 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 23 | – | – |

| Ungradable | 19 | 27 | 9 | 10 | 16 | 21 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 2 |

| No images | 20 | 31 | 22 | 30 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 20 | – | – |

Missing test images

Table 11 displays the reasons for missing test images in EMERALD at the person level. Of the 397 patients included in the analyses, 345 (87%) had SD-OCT, seven-field ETDRS and ultra-wide field fundus images for each eye available for assessment. A total of 52 patients had at least one imaging assessment missing. Of these, 17 (33%) would be considered as not assessable by images and, therefore, the patient would need to be referred to clinical practice (e.g. media opacity). In total, 35 (67%) patients would be considered as missing for the EMERALD study and would also be considered as missing in practice (e.g. patient does not attend for the taking of the image). The details of eye-level missing images by assessment are summarised in Appendix 1, Table 39.

| Number of participants (n = 397) | |

|---|---|

| All images are available (all threea imaging modalities for both eyesb) | 345 |

| Missing at least one imaging assessment | 52 |

| Image missing: patient would need referral | 17 |

| No view of fundus: vitreous haemorrhage | 2 |

| No view of fundus: corneal graft | 1 |

| Poor pupillary dilatation | 4 |

| Patient unable to co-operate with imaging | 1 |

| Patient unable to sit at the camera | 2 |

| Media opacity | 5 |

| Patient could not stand the light | 1 |

| Unable to see fundus owing to pathology | 1 |

| Image missing: missing | 35 |

| Patient does not attend for the taking of the image | 9 |

| Only one eye image capturedc | 5 |

| Images not recorded correctly | 11 |

| Other unknown reason | 10 |

Diagnostic performance of the imaging tests

The results of the diagnostic performance of the EMERALD ophthalmic graders are presented in the following three sections:

-

Diagnostic performance for DMO patients eligible for the new ophthalmic grader pathway.

-

Diagnostic performance for PDR patients eligible for the new ophthalmic grader pathway.

-

Secondary sensitivity analyses on combined diseases (DMO and PDR) for all patients.

Diagnostic performance for diabetic macular oedema patients eligible for the new ophthalmic grader pathway

Summary of ophthalmic graders’ grading results for diabetic macular oedema

Table 12 displays the OCT-based ophthalmic graders’ grading results at the person level against the reference standard. The graders’ decision on whether or not to refer the patient, an inherently person-level decision, was used rather than an assessment of the single eye. Furthermore, to address how the new pathway would function in practice, graders’ assessment results of DMO of ‘unsure’ and ‘ungradable’ were considered alongside those classified as ‘active’ to be referred to an ophthalmic clinic for ophthalmological assessment. Of the 272 DMO patients who were eligible for the new pathway, 152 (56%) were identified by the ophthalmologists’ slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination with access to SD-OCT images (O-FTF + OCT is the reference standard) as having DMO that was active at the time of recruitment, whereas 120 (44%) were identified by the O-FTF + OCT reference standard as having DMO that was inactive at the time of recruitment. Compared with this reference standard, 220 (81%) out of the 272 patients under graders’ assessment (G-OCT) were referred for further ophthalmological examination; of these, 209 (209/220; 95%) were referred because graders (G-OCT) identified active DMO (i.e. active DMO present in their opinion) and 11 (11/220; 5%) because graders were unsure or considered OCT images ungradable.

| Classification | Reference standard (O-FTF + OCT) | G-OCT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active DMOa | Active DMO requiring treatmentb | Central-involving active DMOc | Referrald for DMOe | Active DMOf | Central-involving active DMOg | |

| Positive | 152 | 85 | 132 | 220 | 209 | 177 |

| Negative | 120 | 187 | 139 | 40 | 50 | 80 |

| Missing/cannot classify | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 13 | 15 |

The flow of study participants who followed the new pathway of graders’ assessment for DMO based on OCT is shown in Figure 10. Of the 397 EMERALD participants, four (1%) had missing OCT images for both eyes and were excluded from the analyses. Eleven (3%) participants were excluded from the main analysis and 12 (3%) were excluded from SENA1 because of missing OCT images for one eye, which led to no overall graders assessment result at the patient level. Of the 382 participants who had valid grading results from the graders to be included in the main analysis, 281 (74%) were identified by the graders as referring for DMO (i.e. having active DMO or unsure or ungradable), of whom 220 (78%) were eligible for the new DMO pathway. In total, 101 (26%) of the 382 participants were identified by the graders as not having active DMO (including no DMO and inactive DMO), of whom 40 (40%) were eligible for the new DMO pathway. Of the 381 participants who had valid grading results from the graders to be included in SENA1, 262 (69%) were identified by the graders as having active DMO (i.e. excluding unsure and ungradable), of whom 209 (80%) were eligible for the new DMO pathway. In total, 119 (31%) out of the 381 participants were identified by the graders as not having active DMO, of whom 50 (42%) were eligible for the new DMO pathway. The diagnostic performance for the main analysis and sensitivity analyses for DMO patients are given in Table 13. Results from the main analysis and SENA1 are also presented in the flow diagram (see Figure 10). Owing to missing OCT images that led to no overall graders assessment result, the grader’s diagnostic performance under main analysis was tested with a slightly smaller number of referral for DMO [disease present, n = 147; true positive (TP), n = 142; false negative (FN), n = 5] than the O-FTF-OCT (ophthalmologist face-to-face examination with access to optical coherence tomography scans) examination of active DMO (n = 152), and a slightly smaller number of not active DMO [disease absent, n = 113; false positive (FP), n = 78; true negative (TN), n = 35] than the O-FTF-OCT examination of not active DMO (n = 120). The grader’s diagnostic performance under SENA1 was also tested with a slightly smaller number of active DMO (disease present, n = 146; TP, n = 139; FN, n = 7) than the O-FTF-OCT examination of active DMO (n = 152), and a slightly smaller number of not active DMO (disease absent, n = 113; FP, n = 70; TN, n = 43) than the O-FTF-OCT examination of not active DMO (n = 120).

FIGURE 10.

Flow diagram: diagnosis as determined by the ophthalmic graders for DMO patients – main and SENA1. Note that this flow diagram presents only the grading results from the graders’ assessment based on SD-OCT images. FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

| Test positive | Reference standard | Diagnostic parameter | n/N | Estimate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main | G-OCT referrala for DMO | O-FTF + OCT examination of active DMO in either eye | Sensitivity (%) | 142/147 | 97% (92% to 99%) |

| Specificity (%) | 35/113 | 31% (23% to 40%) | |||

| Positive likelihood ratio | – | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.59) | |||

| Negative likelihood ratio | – | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.27) | |||