Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/41. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The draft report began editorial review in June 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Bruce et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Falls and fractures are a major public health burden. Falls can be associated with loss of independence and reduced functionality and are a major contributor to premature admission to nursing home or long-term care. 1,2 The risk of falling increases with age. Half of people aged ≥ 80 years fall at least once per year. 3 Most falls result in no injury, but can lead to fear of falling and loss of confidence in mobility. Falls can cause serious injury: each year, fracture and hospitalisation occurs in about 5% of community-dwelling older adults with a history of falling. 4 In 2016, there were 255,000 falls-related emergency hospital admissions in England among people aged ≥ 65 years. Demographic change means that the number and proportion of older people in the population is rising. In 2016 there were 1.6 million people in the UK aged ≥ 85 years (2% of total population), and this is projected to double to 3.2 million by 2036. 5 Fractures in older people will become increasingly common and this will have a major impact on use of health-care resources and service provision.

Costs of fractures and fall-related injury

The health and social care costs associated with fractures and fall-related injuries are high. Fractures and falls in those aged ≥ 65 years account for 4 million bed-days per year in England alone, at an estimated cost of £2B. 6 Direct health-care and associated social costs arise from the management of these injurious falls and fractures (the majority of costs arise from hip fracture). 7 Mortality is high in people who sustain a hip fracture: 10% die within 1 month and 30% die within 1 year of fracture. 8

Falls services in the UK NHS

Falls are a hallmark of age and becoming frail. 1 Falls have a multifactorial aetiology, with many risk factors, some of which are modifiable. Risk factors include impairments or instability of gait and balance, visual problems, cardiac rhythm abnormalities and syncope, polypharmacy and certain classes of ‘culprit’ or psychotropic medication, cognitive impairment, multiple comorbidity, foot disorders, and home and environmental hazards. Early clinical trials from the USA targeted the assessment and treatment of multiple risk factors and intervention strategies, termed multifactorial falls prevention (MFFP). These early trials were promising, indicating that multiple risk factor intervention strategies reduced risk of falling among community-dwelling older people. 9 These studies from the 1990s provided the basis for the mandatory establishment of secondary prevention in the UK:10 falls services providing MFFP interventions for people with a history of falling were subsequently introduced in England. 11 Multifactorial risk assessment, followed by targeted treatment of individual risk factors, is recommended for falls prevention in the UK, supported by clinical organisations [e.g. the American Geriatrics Society, the British Geriatrics Society and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)]. 2,3 These UK NHS services vary considerably in terms of service design, models of delivery and professional skill mix. 12,13

Evidence of effectiveness of falls prevention interventions

At the time of preparing the Prevention of Falls Injury Trial (PreFIT), numerous small trials had investigated the effectiveness of alternative falls prevention strategies. A 2012 Cochrane review14 (59 trials, n = 13,264) of falls prevention strategies found that exercise programmes, particularly those focused on strength and balance retraining, reduced rate of falls (i.e. number of falls) by 30% and risk of falling (i.e. number of people falling) by 18%. 14 Certain strength and balance interventions were found to be effective, especially those including targeted, individualised programmes progressed over time. However, adherence to exercise remained a challenge. Among the 59 falls prevention trials investigating exercise, only six had recorded fractures outcomes, totalling 45 fracture events.

The same Cochrane review14 identified 40 trials (n = 17,195) of MFFP studies. The review identified evidence for weaker effectiveness of MFFP interventions on falls outcomes, reporting that these interventions may reduce the rate of falls but not number of fallers (falls risk). 14,15 Among the 40 falls prevention trials investigating MFFP, only 11 had recorded fracture outcomes (totalling 289 events), but some trials included non-fracture injury. 14 Typically, the interventions identified by the Cochrane review were too poorly specified to be reproducible. These Cochrane reviews have since been updated; however, the overall conclusions are unchanged. 16 The reviews continue to highlight methodological deficiencies in existing trials, with many studies being underpowered and lacking robust data on important outcomes, including quality of life (QoL), fracture, costs of intervention and cost-effectiveness.

There is a need for robust evidence, with economic evaluation, to justify NHS provision of these falls prevention services.

Rationale for the PreFIT

Falls prevention services are widely implemented throughout the NHS, yet gaps remain in evidence regarding the prevention of falls. One of the main purposes of falls prevention is to reduce fractures and other serious injuries. 17 Adequately powered studies are required to investigate the effectiveness of such initiatives on clinical and patient-reported outcomes. This cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) was designed to compare the effectiveness of alternative falls prevention strategies, using a screen-and-treat approach embedded within primary care, to investigate the prevention of falls and fractures in older adults.

The aim of the PreFIT was to determine the comparative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three alternative primary care-led fall and fracture prevention strategies for older people living in the community: advice only; advice with screening for falls risk, with referral to an exercise programme for those at higher risk; and MFFP. Outcomes included fractures, falls, QoL, mortality and health-care resource use.

Research objectives

To estimate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the three alternative falls prevention interventions (advice only; advice supplemented with risk screening and referral to either exercise; and MFFP) in older adults. Our intention was to conduct a pragmatic trial and to include a process evaluation and a within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis.

Overview of the report

This report is structured across six chapters. We present methods (see Chapter 2), intervention development and description (see Chapter 3) and trial results (see Chapter 4) and describe the findings of the economic evaluation (see Chapter 5). Finally, we provide an overarching discussion and conclusion of our findings (see Chapter 6).

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design and setting

We conducted a three-arm, pragmatic, cluster RCT design, with a parallel economic analysis. The setting was English primary care. We have published a detailed description of the trial protocol elsewhere. 18

Eligibility criteria

Cluster level

Practice identification and eligibility

We sought general practices (GPs) via existing research networks, including the Primary Care Research Network and Local Comprehensive Research Network. We placed advertisements in regional research newsletters and displayed posters at primary care events. We recruited triads of GPs in England with the infrastructure and services to support the trial. Specifically, we required practice agreement to adhere to a predetermined treatment pathway for the allocated intervention (advice, exercise or MFFP), local resources to deliver the active interventions and the technical capacity to undertake electronic searching to identify a random sample of older adults. We reimbursed practices for their time and postage costs.

Participant level

Participant eligibility

Community-dwelling older people aged ≥ 70 years and resident in the community or in sheltered housing were eligible for invitation by their GP. Exclusions included those housed in long-term residential or nursing care homes and those with terminal illness or expected shortened lifespan (defined as < 6 months). No specific restrictions or exclusions by age, sex, cognitive functioning, comorbidity or falls history were applied.

Participant identification

We sought to recruit an average of 150 participants per GP. A study researcher and/or practice staff member searched GP electronic databases to identify all people aged ≥ 70 years. A computer program selected a random sample of 400 of these. With an uptake rate of 35–40%, this would yield 140–60 participants per GP.

Participant exclusions by general practitioner

After generation of the random sample lists, general practitioners screened lists to remove patients who should not be approached (if not already removed via electronic search criteria). Predetermined reasons included any illness with an end-of-life prognosis of < 6 months or residence in nursing or residential accommodation.

Postal invitation and participant consent

Practices posted an invitation pack containing a participant information sheet, baseline questionnaire and consent form. We sought consent for multiple levels of access to medical data, including medical records and routine data held by the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) (NHS Digital from April 2016). At the time of trial launch, the wording of consent forms was appropriate for access to HSCIC data and approved by the Research Ethics Committee and relevant monitoring committees. Ethics issues were considered in relation to the cluster trial design. 18

Allocation sequence generation and randomisation

The unit of cluster randomisation was the GP. Once we had recruited approximately 150 participants from each of the three GPs, or no further responses were being received, GPs were then randomised. To ensure allocation concealment, we did this in blocks of three (one allocated to each treatment arm). No stratification was used. Randomisation was based on a computer-generated randomisation algorithm held and controlled centrally in Warwick Clinical Trials Unit by an independent programmer. Trial administration staff members were informed of GP allocation by e-mail. Treatment allocation was coded and unavailable to the trial management team.

Blinding

We adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement 2010 update extension for cluster randomised trials. 19 Owing to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind therapists or services delivering exercise or MFFP. Senior members of the research team were blind to GP and treatment allocation for the duration of the trial. We undertook data cleaning and fracture adjudication of suspected and confirmed events blind to treatment allocation.

Trial interventions (advice, exercise and multifactorial falls prevention)

We describe trial interventions in Chapter 3 and in two intervention development papers. 20,21 In brief, we randomised practices to deliver one of three interventions: advice leaflet only; advice leaflet supplemented with screening for falls risk, followed by exercise; or MFFP. The Age UK (www.ageuk.org.uk; accessed 21 April 2020) Staying Steady booklet22 was used for the advice intervention. This was mailed out after practice randomisation. Those randomised to active interventions received the Age UK advice leaflet with the falls risk balance screener. The exercise intervention was based on the Otago exercise programme (OEP), targeting lower-limb strength, balance retraining and walking. 23 Practices randomised to intervention invited participants identified to be at high risk of falling to attend a 6-month PreFIT exercise programme or the MFFP programme (Table 1). The MFFP intervention comprised an individualised, 1-hour falls assessment with appropriate onward referral for treatment, including referral to the PreFIT exercise intervention if gait or balance risk factors were identified. We based the MFFP intervention on evidence-based guidelines for falls risk assessment and treatment pathways. 2,11

| Referral: exercise programme | Therapist/venue | PreFIT exercise programme (6 months’ duration) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 3 | Week 6 | Month 3 | Month 4 | Month 5 | Month 6 | ||

| Participant invited to attend exercise |

Assessor: trained physiotherapist, occupational therapist or exercise specialist Venue: outpatient clinic, hospital, community clinic or participant’s home |

1-hour face-to-face baseline assessment Assess balance and strength, conduct CST and 4TBS, prescribe programme, provide ankle weights |

30-minute face-to-face appointment or 10-minute telephone call Review and progress |

30-minute face-to-face appointment or telephone call Review and progress |

10-minute telephone call Review and progress |

10-minute telephone call Review and progress |

10-minute telephone call Review and progress |

1-hour final assessment: face-to-face appointment Repeat assessment of strength and balance, repeat CST and 4TBS |

| Referral: MFFP intervention | Therapist/venue | Multifactorial Fall Prevention (MFFP) intervention | ||||||

| Falls assessment | Actions | Treatment | Checks of onward actions | |||||

| Participant receives written or telephone invitation to attend health check appointment |

Assessor: trained nurse, medical doctor or other falls specialist Venue: GP surgery, hospital falls service or community clinic |

1-hour face-to-face appointment for detailed falls assessment and screening of multiple risk factors | Any risk factor identified? | Follow recommended treatment protocol (e.g. onward referral to general practitioner/falls consultant/optician/secondary care services/occupational therapist depending on risk factor) | Searches undertaken on sample of GP systems to review documented treatment actions (e.g. medication reviews, referral to PreFIT exercise intervention) | |||

| Gait and balance problems referred to PreFIT exercise intervention | Follow as per exercise programme above | |||||||

Screening and referral to active intervention

All participants received the advice booklet by post. Advice arm GPs delivered no further trial interventions. We used a primary care screening approach to determine onward referral of participants to the active interventions of exercise or MFFP. A short self-complete falls risk screening survey, based on previous research,24 was posted from, and returned to, GPs. Participants were categorised as being at risk of falling based on responses to falls and balance questions (high risk = multiple faller; intermediate risk = one fall or balance problems). These participants were offered the opportunity to attend for further assessment and treatment, either exercise or MFFP. Participants deemed to be at low risk (no history of falls or balance problems) received no further intervention other than the advice leaflet.

Co-interventions

No restrictions were placed regarding other agencies or health-care services contacting participants about fall prevention strategies. At trial closure, participants continued with usual health care and no further ancillary care was provided.

Baseline data: practices and participants

Descriptive data collected on GPs included practice-level deprivation at randomisation, using the UK National Index of Multiple Deprivation, which scores from 1 to 10 (from most deprived to least deprived). 25 Baseline descriptive data on participants included mobility, difficulties with mobility, cognition and activities of daily living (ADL). Mobility questions, adapted from population surveys of older adults,26,27 captured difficulties when balancing on a level surface, ability to walk outside the house, average time spent walking and difficulties with balance when performing common ADL (e.g. taking a bath, dressing). A clock-drawing test cognitive screener was included at baseline only. 28 Scoring was a 6-point system according to visuospatial aspects and the correct denotation of time: normal cognition (score 6), minor visuospatial errors (score 5), mild (score 4), moderate (score 3) or severe (score 2) visuospatial disorganisation of time or no reasonable representation of a clock (score 1).

Outcomes

Selection of primary outcome

Given the burden of injury, disability and dependence associated with fractures in older people, we selected fractures, rather than falls or falls-related QoL, as the primary outcome for the trial.

Primary outcome: fracture rate

The primary outcome was the fracture rate over 18 months, expressed as per person per 100 years, from date of GP randomisation and per time period. Number of fractures per participant was based on fractures identified in Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and GP records, confirmed by adjudication panel. The fracture rate was derived for each participant, by accounting for time as an offset in statistical modelling.

Definition of fracture

We included all fractures, defined according to an internationally agreed definition:29 any fracture to bones in the peripheral (appendicular) skeleton, thus limbs, limb girdles, ribs and cranial and facial bones. We excluded compression fractures in the vertebral column that could not be attributed to a fall. Updates to the protocol are described in Monitoring and approval. We also estimated differences in number of proximal femoral (hip) fractures and fractures involving the distal radius or wrist to allow comparison with other reports from more recent fracture prevention trials. 30 We defined hip fractures as verified fractures with a specific description of neck of femur or proximal femur [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)31 code S72].

Fracture data sources

Fracture data were collected from three sources: HES, GP records and participant self-report postal questionnaires. Successive waves of NHS Digital data were purchased covering years 2010/11 to 2015/16. Fractures were screened and identified from the following sources:

-

HES acute patient care – searches of fracture codes in inpatient admissions using ICD-10 S00-T88 codes for ‘Injuries, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes’ and M/T/W codes (as reported in the statistical analysis plan).

-

HES accident and emergency (A&E) – fracture codes in A&E diagnosis and treatment codes, including diagnosis codes (three level) 052 and 053, treatment codes (two level) 05 and 33, and treatment codes (three level) 101 and 102.

-

HES outpatient data – orthopaedic and trauma clinic attendances (main specialty codes).

-

GP records – electronic searches of Read codes (clinical terms version 2 and 3: S/N/T code searches), with additional free-text searches undertaken for fracture/#. We extracted copies of any clinical records or correspondence relating to actual or suspected fractures.

-

Participant self-reports of fall-related fractures were captured via postal surveys administered at baseline (fractures in previous year) and at 4, 8, 12 and 18 months after randomisation.

We searched all data sources to identify any potential or suspected fracture report in HES acute patient care, HES A&E, GP records or self-report. Detailed searches on GP records were undertaken for all self-reported fractures. All events were identified for cross-checking against other sources by the adjudication panel. HES outpatient data were not used beyond the first wave because this data set did not yield usable fracture codes. Additional checks in the HES acute patient care data set were made for operations in the same hospital admission or adjacent time period by checking the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys’ Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures codes.

Fracture adjudication

Two clinically qualified members of the study team adjudicated fracture events (SEL and MU). When needed, further adjudication was made by KW. Adjudicators were blind to practice allocation and all personal-identifiable data were redacted before records were presented to the adjudication panel. A fracture event was included if it corresponded to the updated, revised fracture protocol. Fractures identified on HES acute patient care were considered confirmed with or without participant self-report or GP record; any fracture identified on HES A&E supported by a GP record was confirmatory with or without participant self-report. Primary care records were considered confirmatory when supported by hospital or clinic discharge letters or radiology (X-ray) reports confirming a fracture. Whenever possible, fractures ascertained from GP record searches were assigned an event date and corresponding ICD-10 fracture code by the panel. Fractures reported using self-report alone were discounted.

Secondary fracture outcomes

Fracture episodes

Some participants experienced multiple fractures from one fall. We characterised all fractures occurring on the same date as one episode. Statistical modelling was used to account for fractures occurring in the same individual and in the same episode.

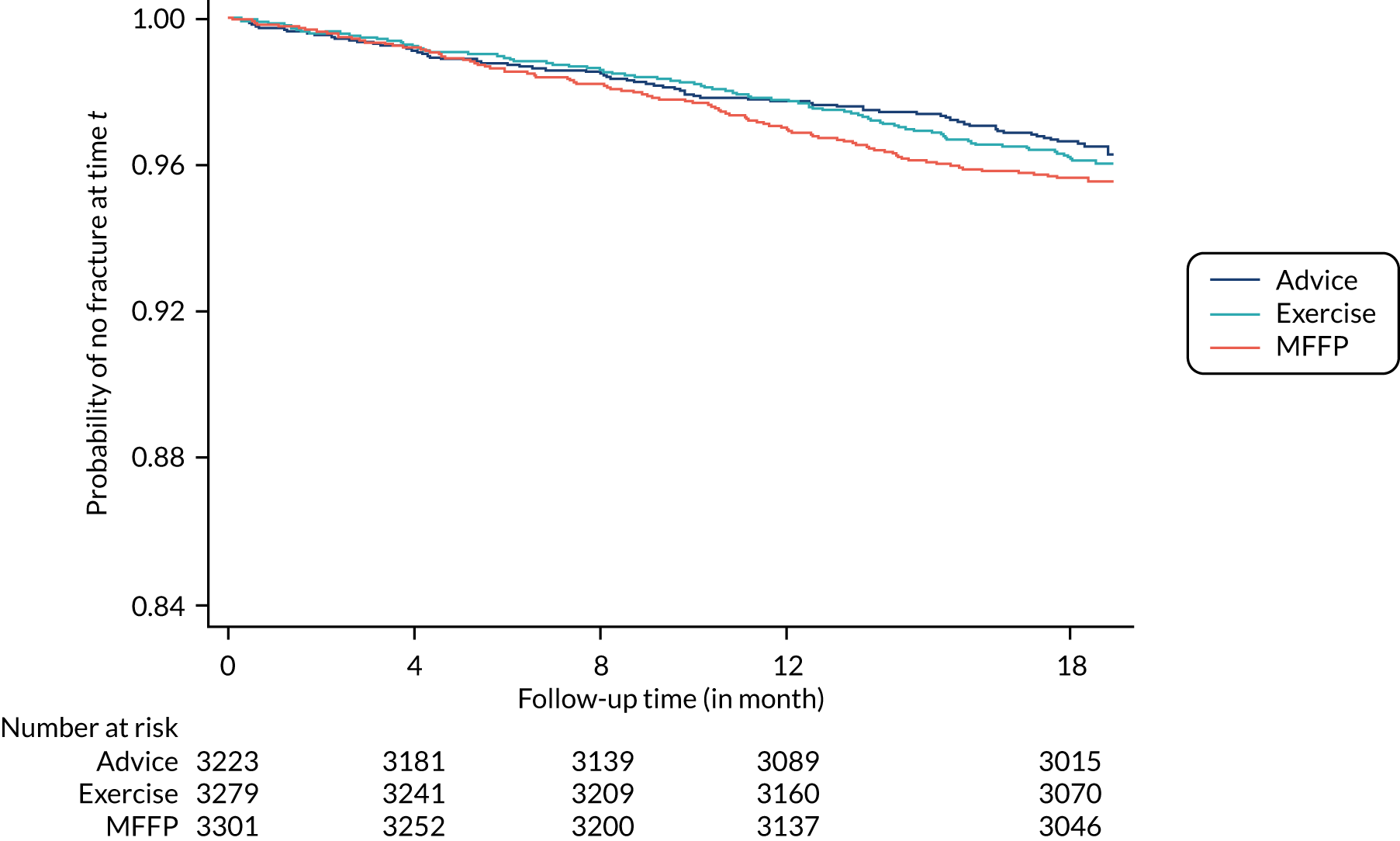

Time to first fracture

The adjudication panel dated all fractures using HES, GP data and self-report. When data were not available on the date of fracture, then date of hospital admission or attendance was taken as date of fracture. Time to first fracture was defined as the interval, in days, between randomisation and first fracture in the study period.

Proportion of people sustaining one or more fractures or fracture episodes over 18 months

As participants might have multiple fractures as a result of one or more falls during the 18-month follow-up, the proportion of participants with at least one fracture episode was calculated.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included falls, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), frailty, mortality and health-care resource use.

Falls

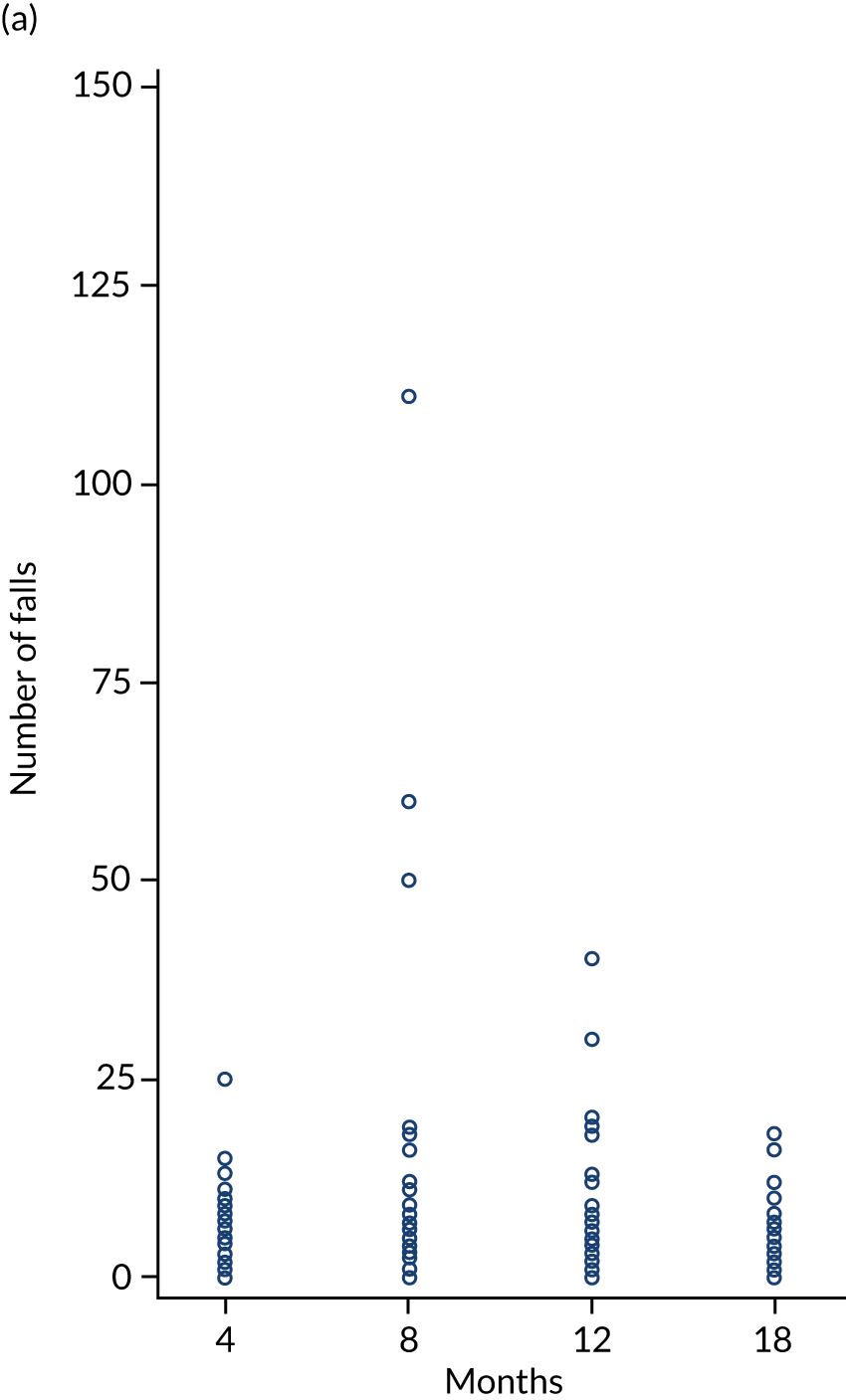

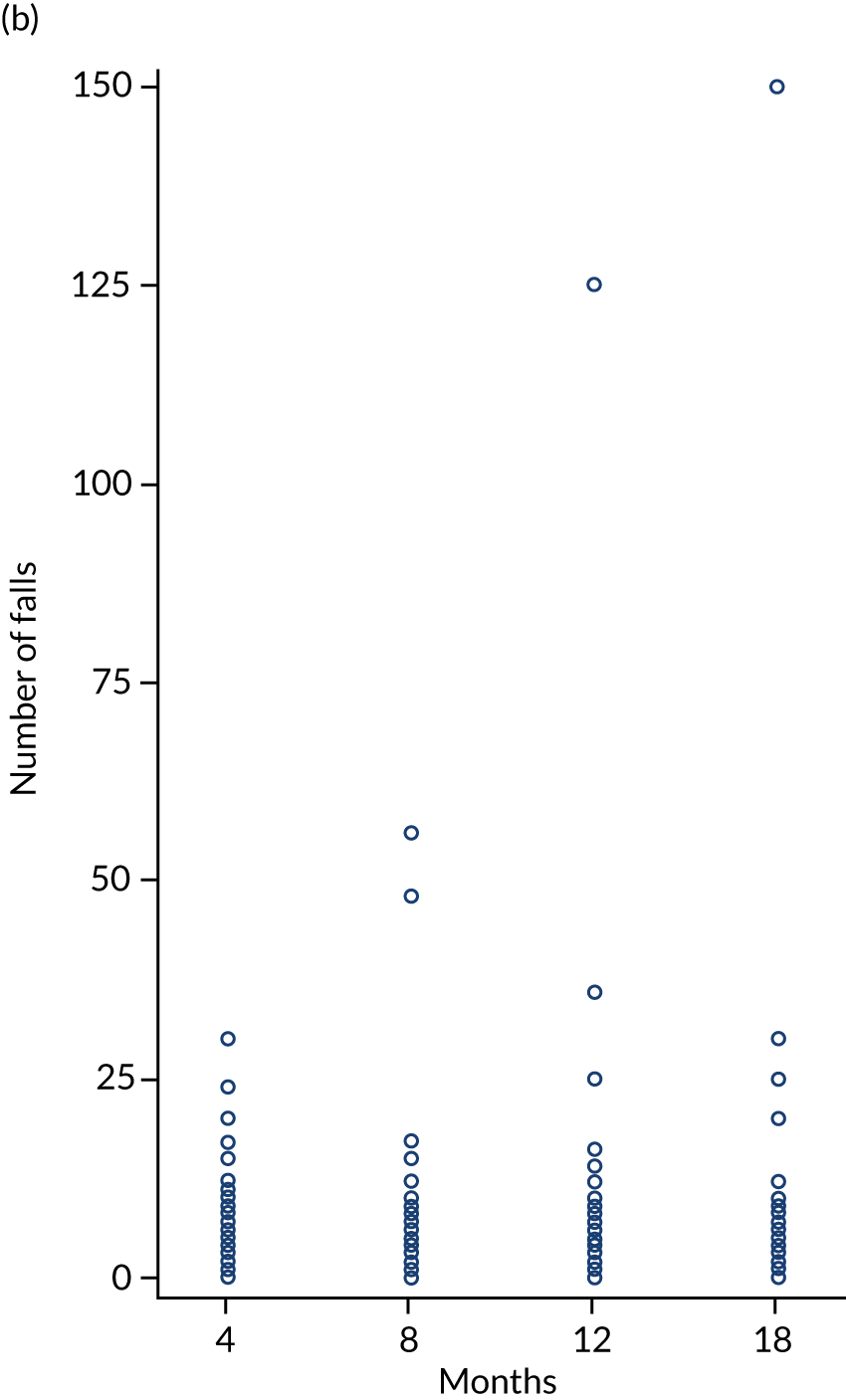

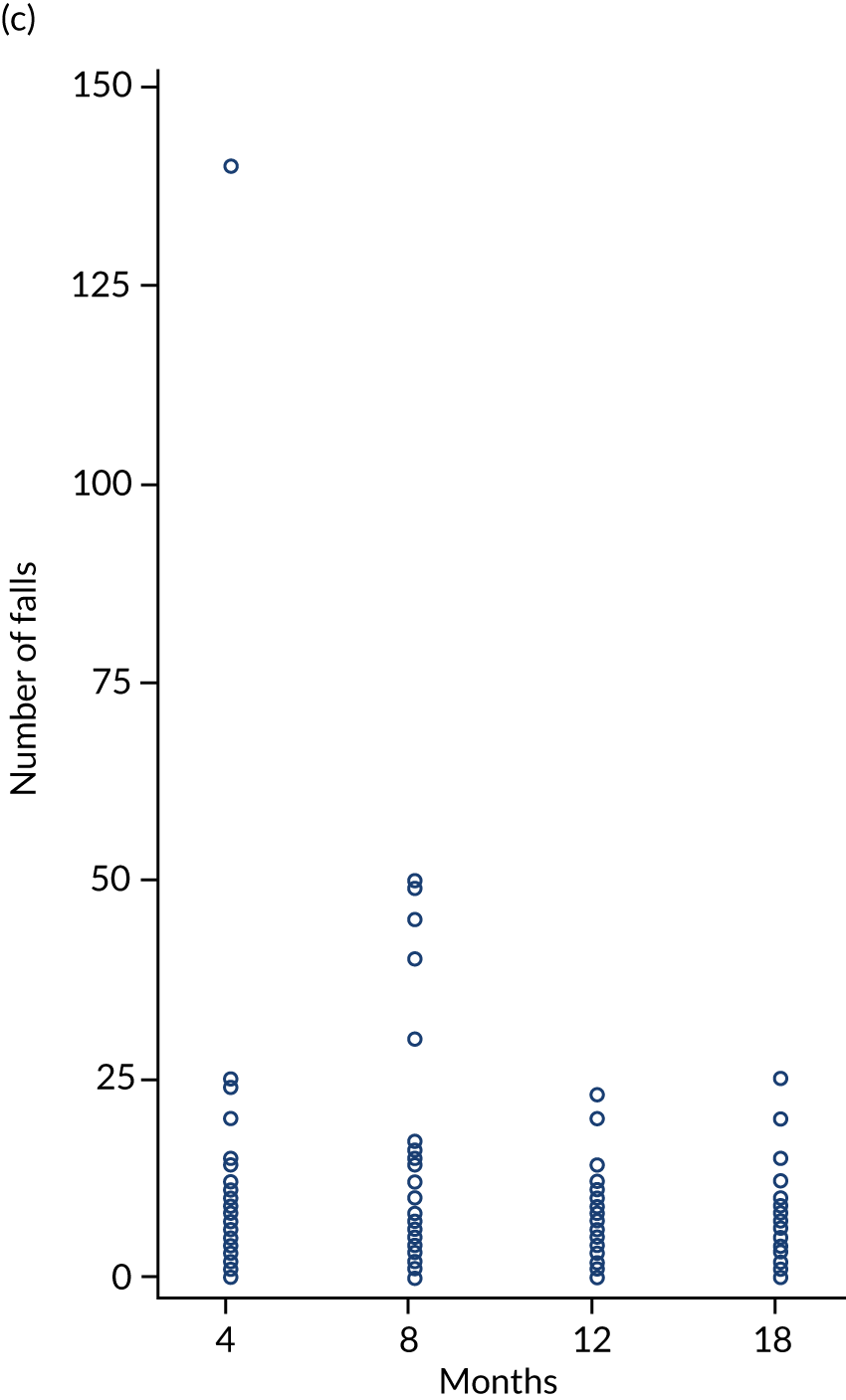

Rate per 100 person-years observation over 18 months and per time period

Our primary falls outcome was the falls rate, expressed as falls per person per 100 years, over 18 months from date of practice randomisation. The definition for falls was consistent with the Prevention of Falls Network Europe (ProFaNE) consensus. 29 The number of falls per participant was based on retrospective self-report in postal questionnaires, recorded at baseline (falls in the last 12 months) and at each follow-up time point, by asking about falls in the previous 4 months. This was the primary method of falls data collection. The number of falls between each of the follow-up time points and the number of people sustaining one or more falls were also reported.

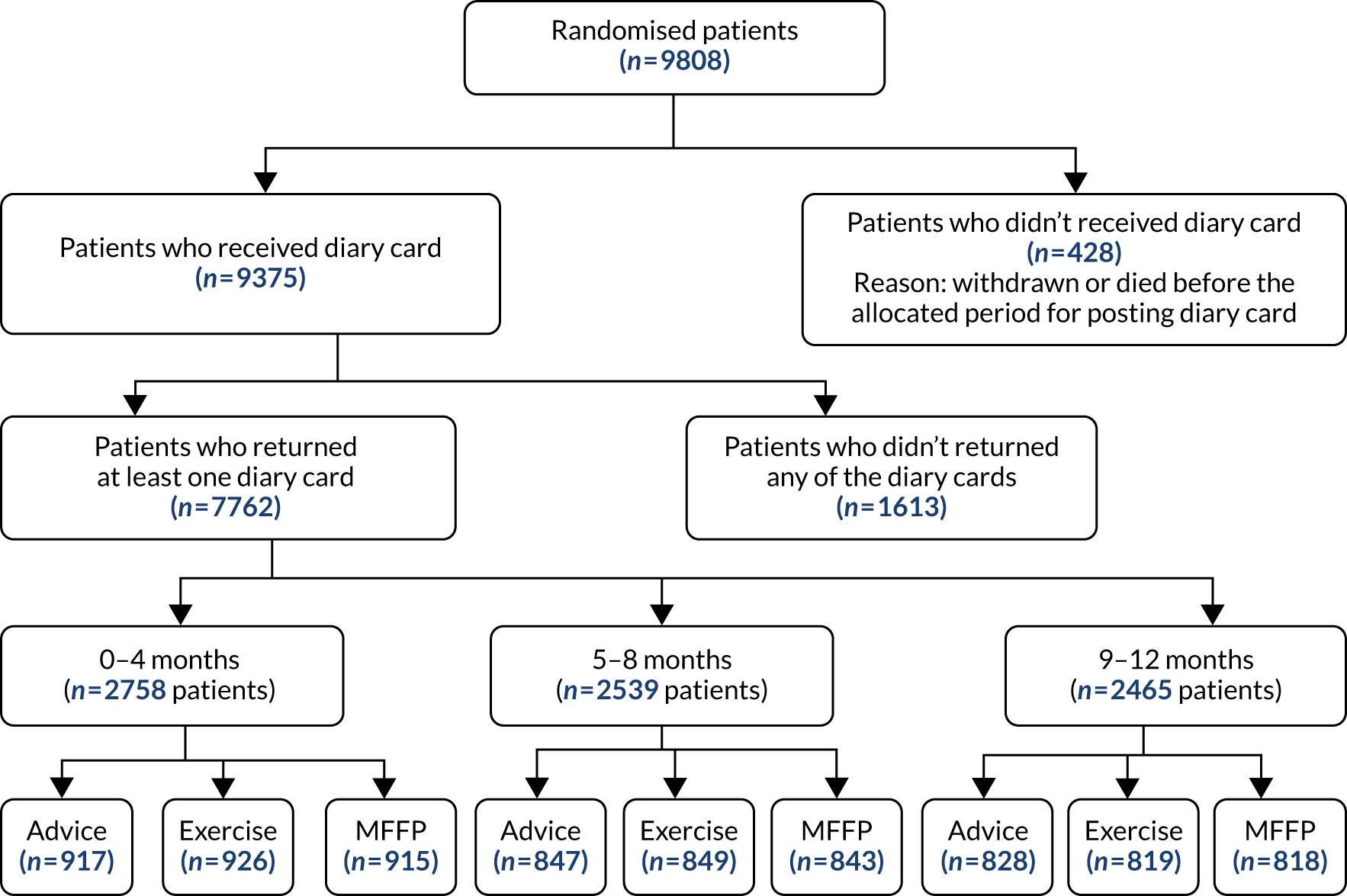

Prospective diary

All participants were asked to complete monthly prospective falls diaries for a period of 4 months during the first year of the trial. Prospective data collection is considered the gold-standard method for falls recording, but given the large sample size this was not practical. We allocated participants to one of three time periods (randomisation to 4 months, 5–8 months or 9–12 months after randomisation) using random sampling without replacement. Prepaid postal diaries were completed daily and returned to the research office every month.

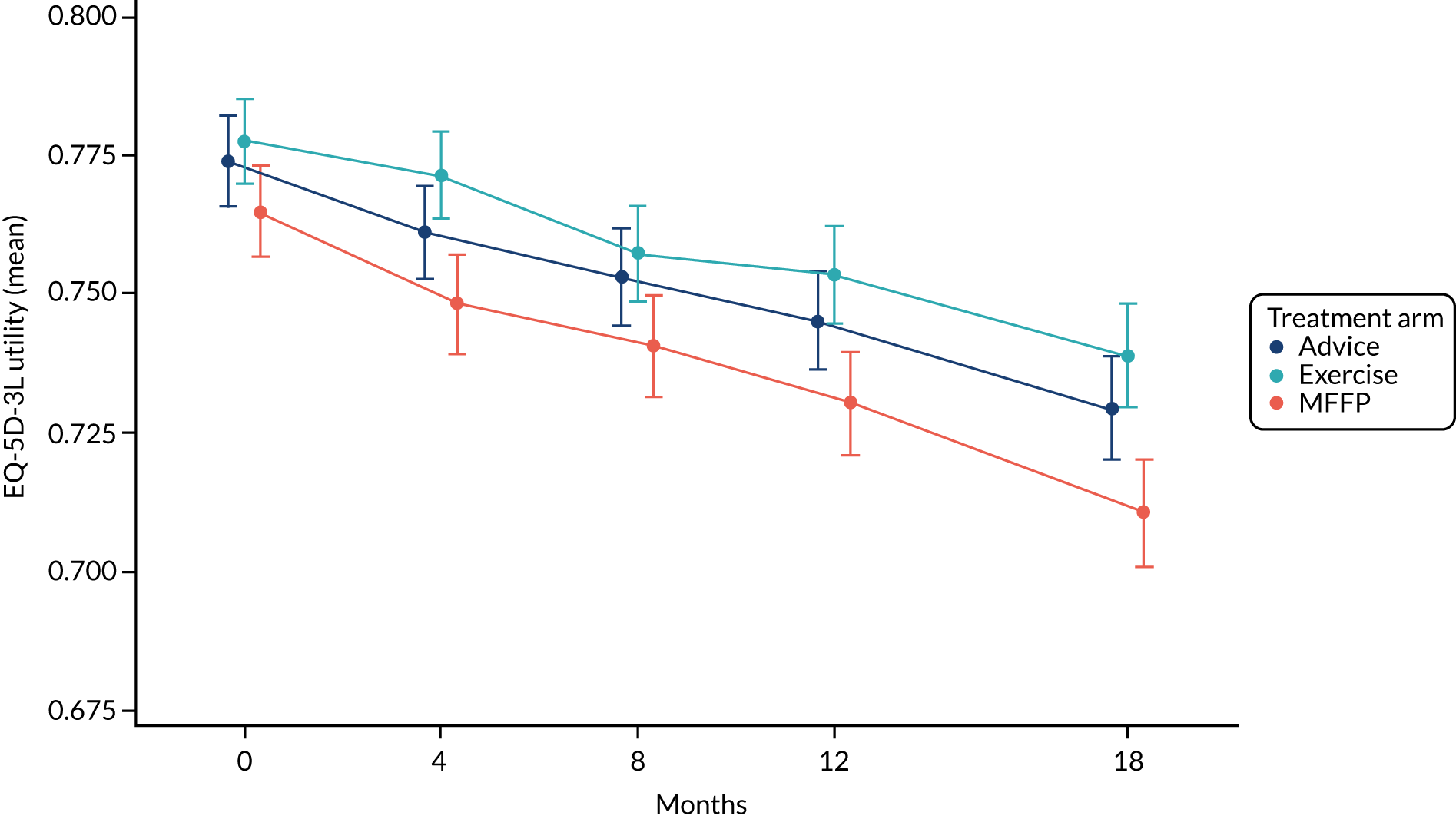

Health-related quality of life: measured over 18 months and each time period

The Short-Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) measures physical function, engagement in usual activities and mental functioning. 32 The physical health composite scale (PCS) and mental health composite scale (MCS) combined items allow comparison with national norms [mean score 50.0, standard deviation (SD) 10.0]. The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), is a standardised measure of self-reported HRQoL that includes five domains: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression. 33

Frailty: measured at baseline and 18 months

Frailty was measured using the Strawbridge questionnaire, a 16-item questionnaire comprising four frailty subdomains: (1) physical (four items), (2) nutritional (two items), (3) cognitive (four items) and (4) sensory (six items). 34 Scoring is on a four-point ordinal scale (rarely or never, sometimes, often, or very often), with those scoring ≥ 3 on at least one item being considered to have a problem or difficulty in that domain. Participants were classed as ‘frail’ if they reported having problems in two or more domains. 35

Mortality: over 18 months

Date of death was obtained from multiple sources, including notifications to the study team from family members or from primary care, HES data and searches of practice medical records on completion of the trial.

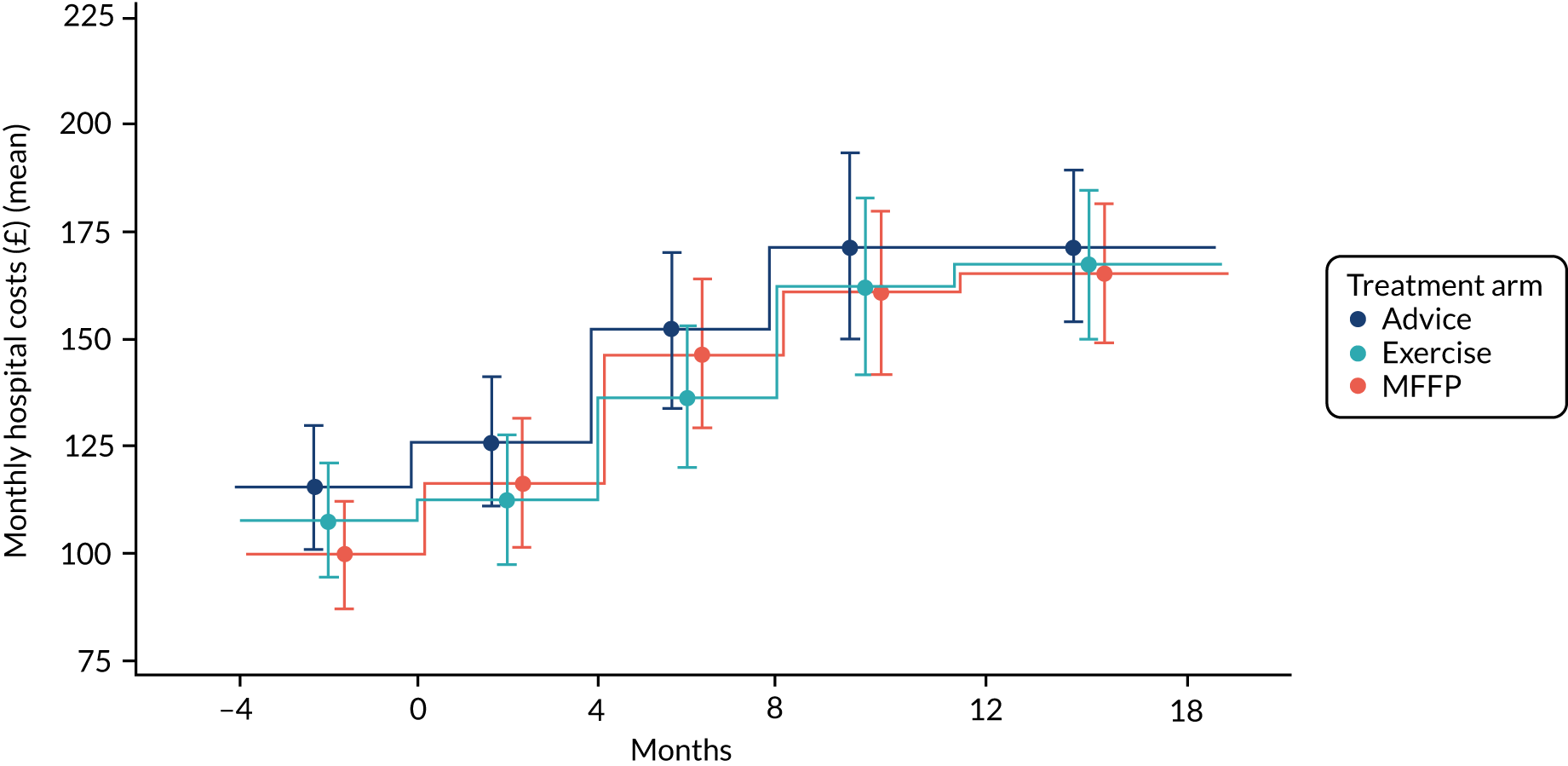

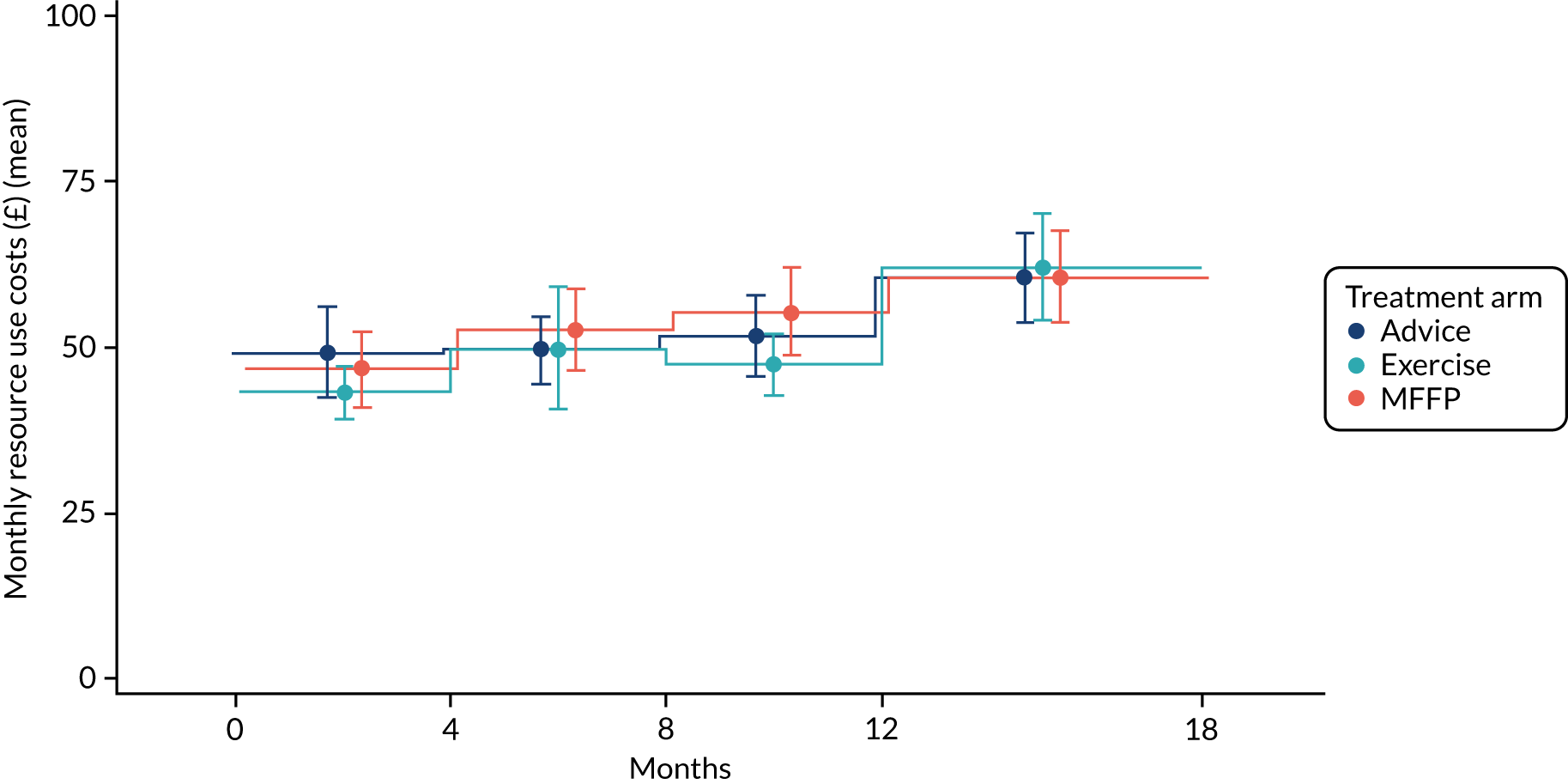

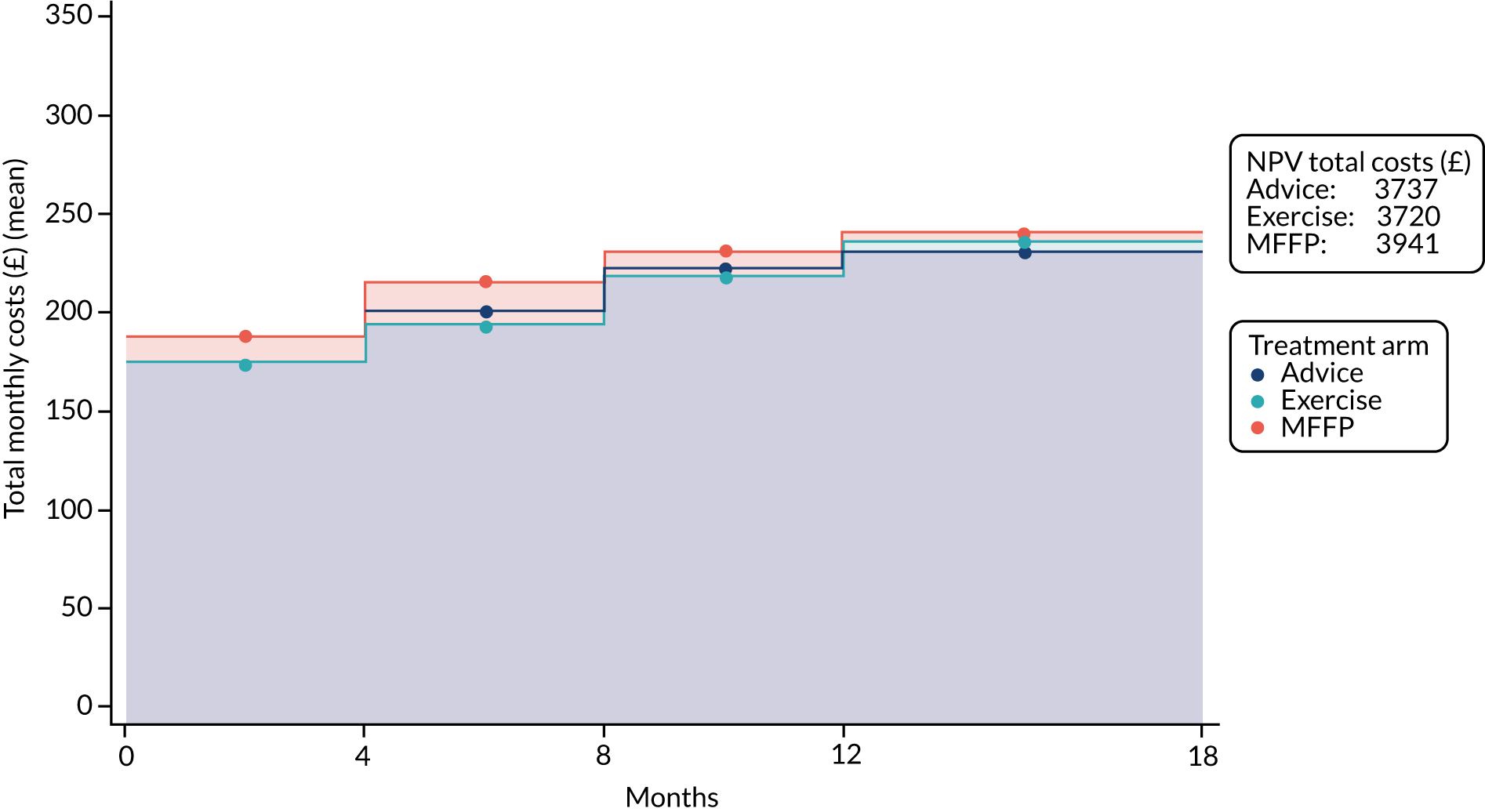

Health-care resource use (baseline and at 4, 8, 12 and 18 months)

We describe these data in more detail in Chapter 5. In brief, questions addressed attendance at health-care services, including GP, the district nurse, any time spent in a nursing or residential home and contact with physiotherapy services.

Data collection: postal questionnaires

Questionnaires were printed in large font, with a freephone number on the front page of the booklet and final free-text section for comments. Draft versions were modified after feedback from older people attending a community social group. We posted questionnaires with an explanatory cover letter. We collected core outcome data on fractures, falls, mobility, EQ-5D-3L and health-care resource by telephone if no response was received after one postal reminder. Any participant who reported a fracture event in the questionnaire was sent a separate questionnaire to elicit date, site of fracture (e.g. upper arm, wrist) and details of any hospital admission and/or radiographs taken. Participants reporting more than one fracture were contacted by telephone for further details.

Process evaluation

We measured a range of process evaluation indicators relating to intervention uptake and delivery, including time from randomisation to postal risk screener administration, uptake and predictive utility of the postal screener, uptake of active interventions, and duration and ‘dose’ of treatments delivered by exercise therapists or MFFP assessors.

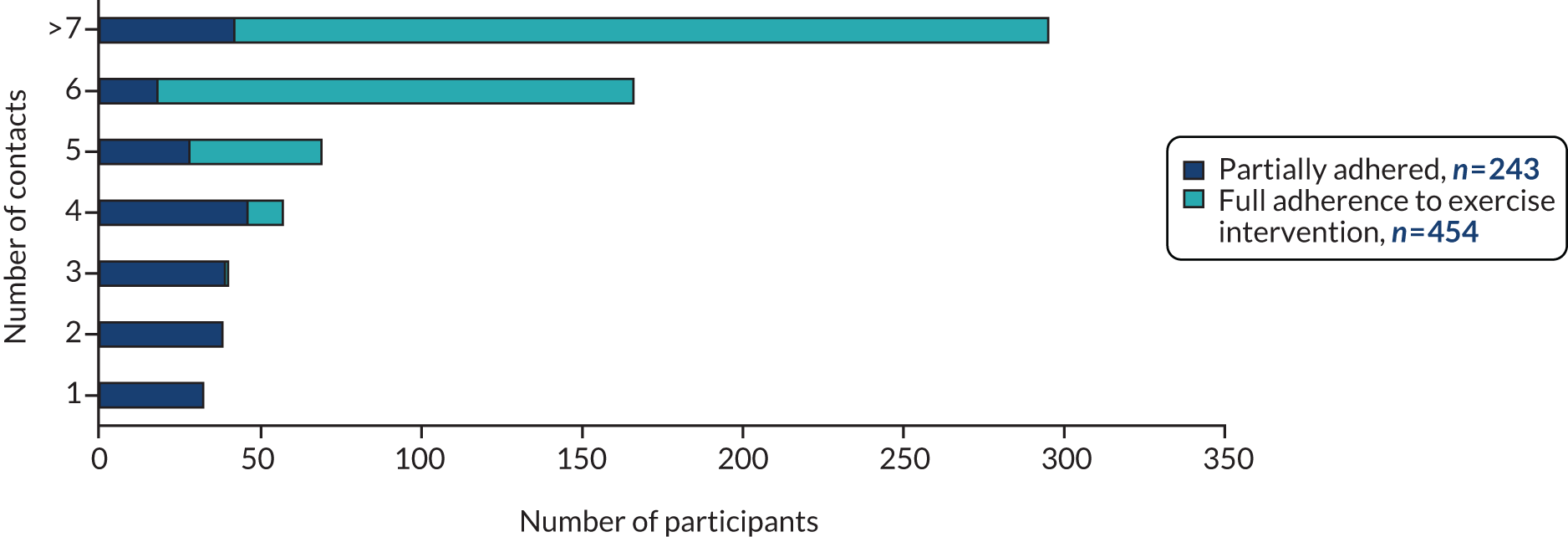

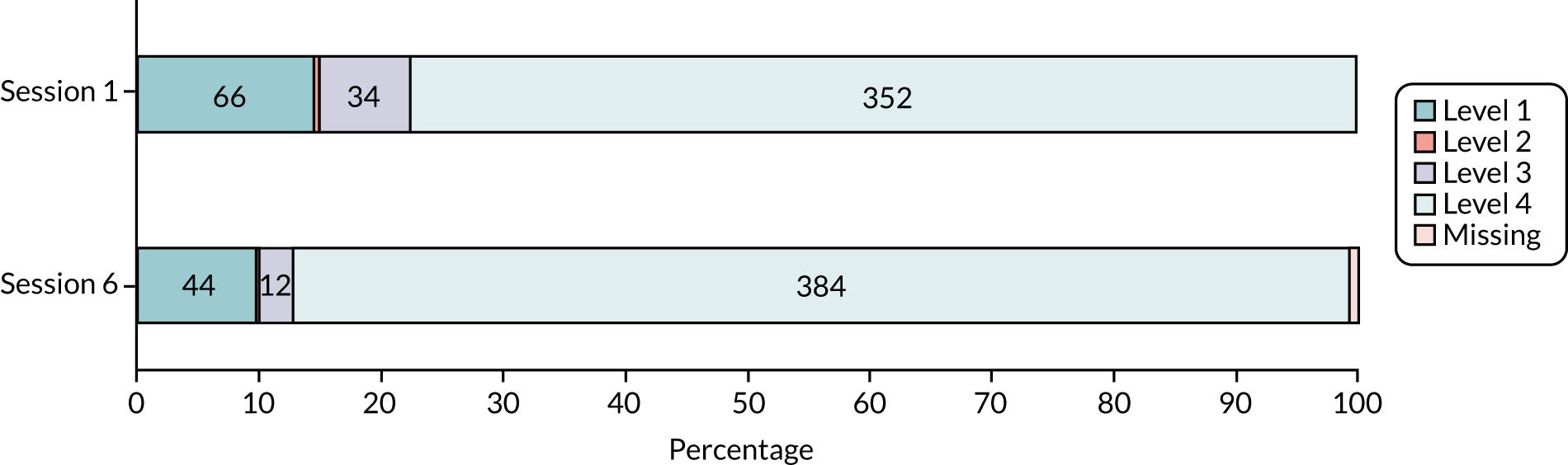

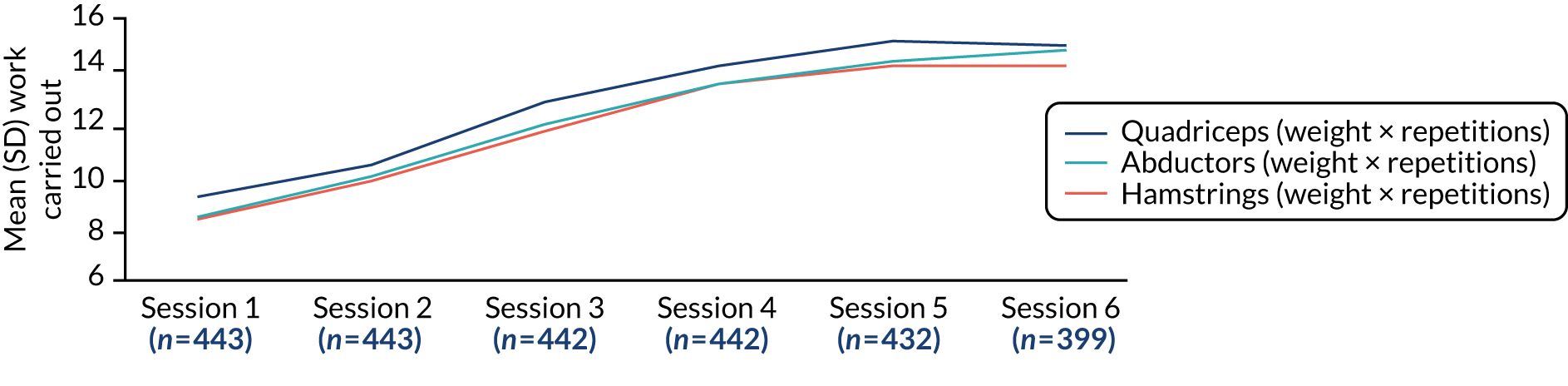

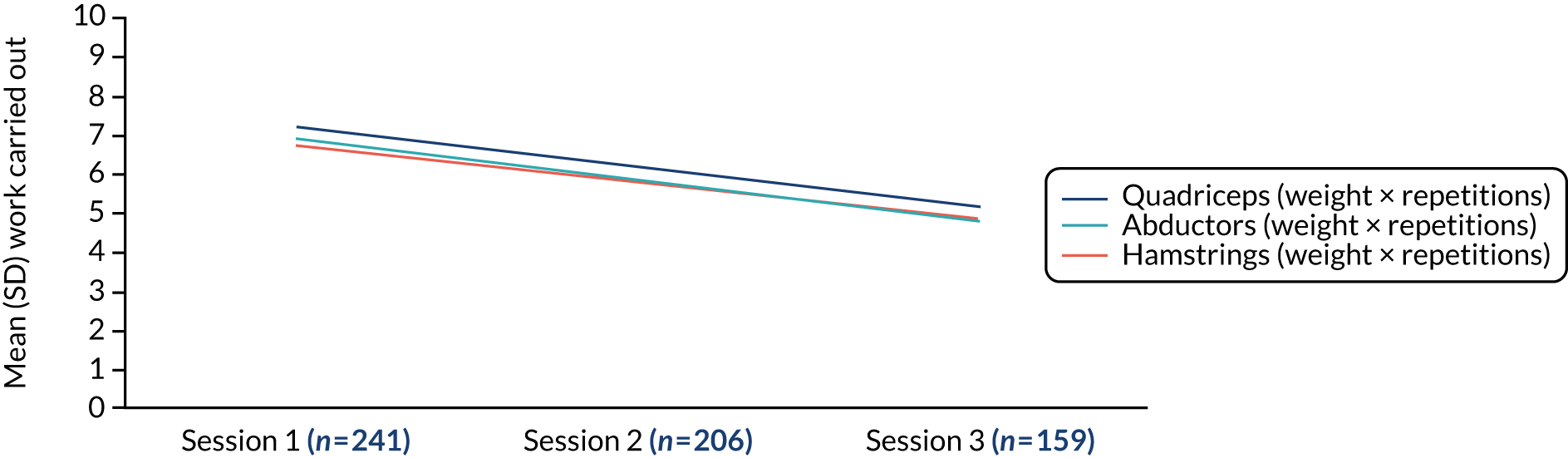

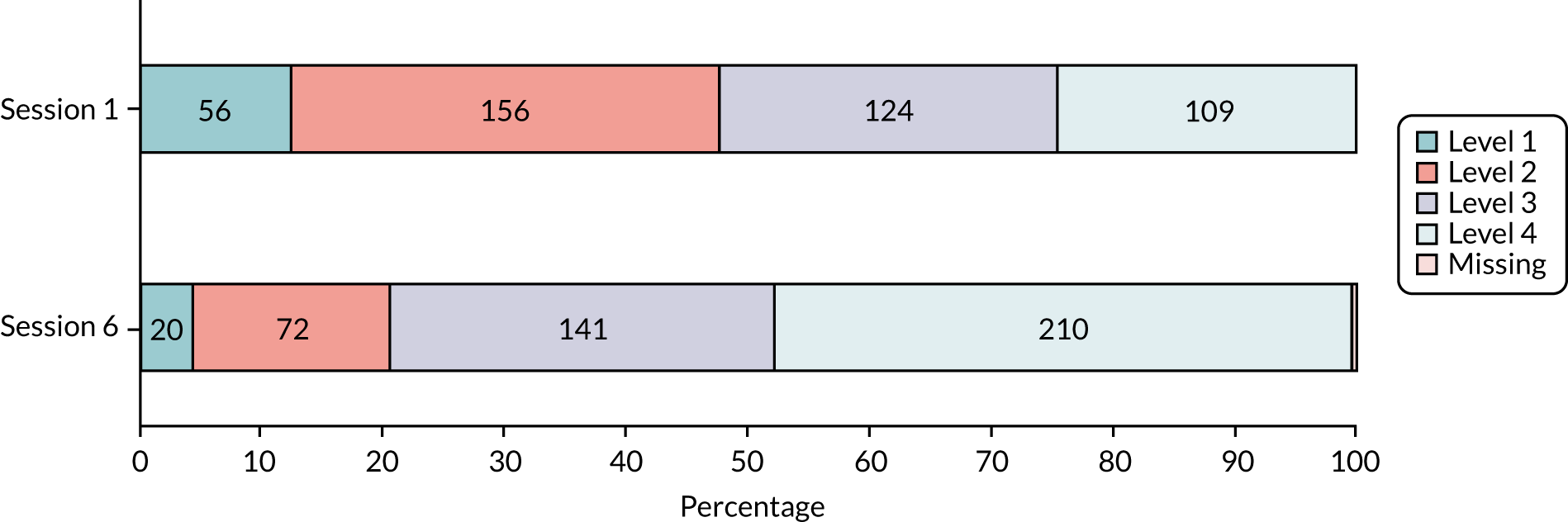

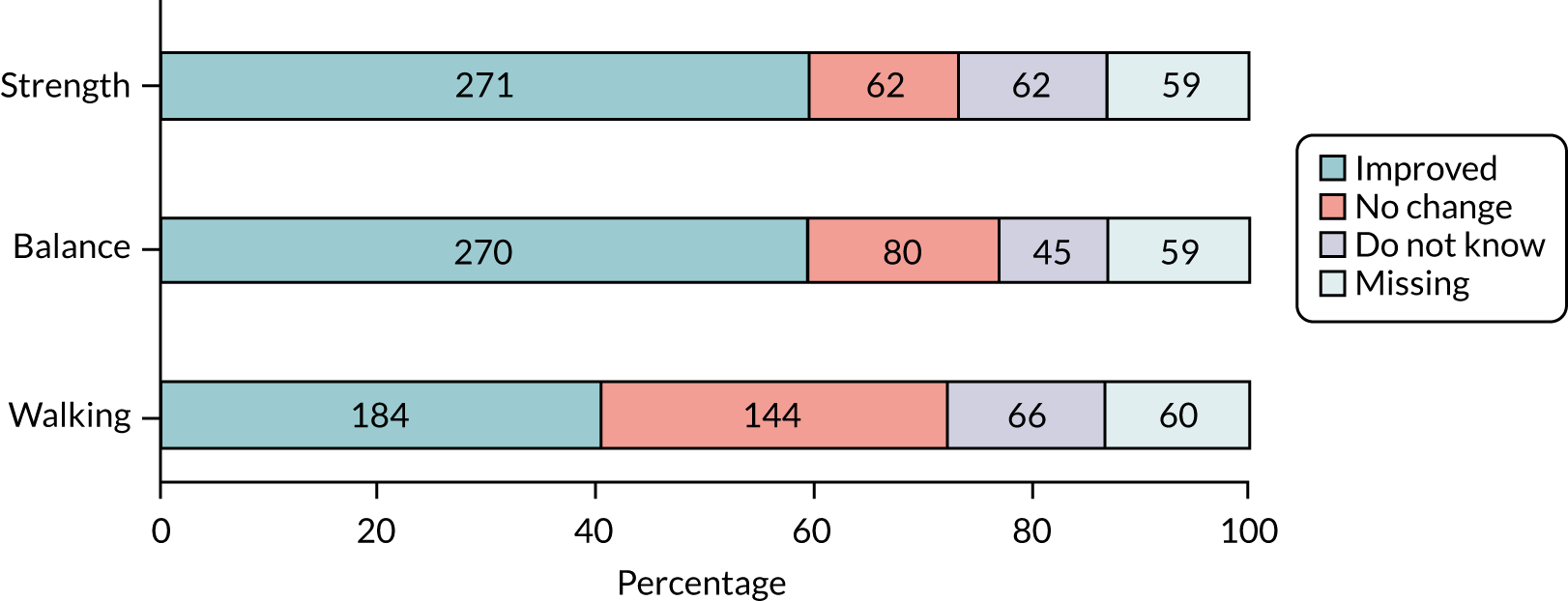

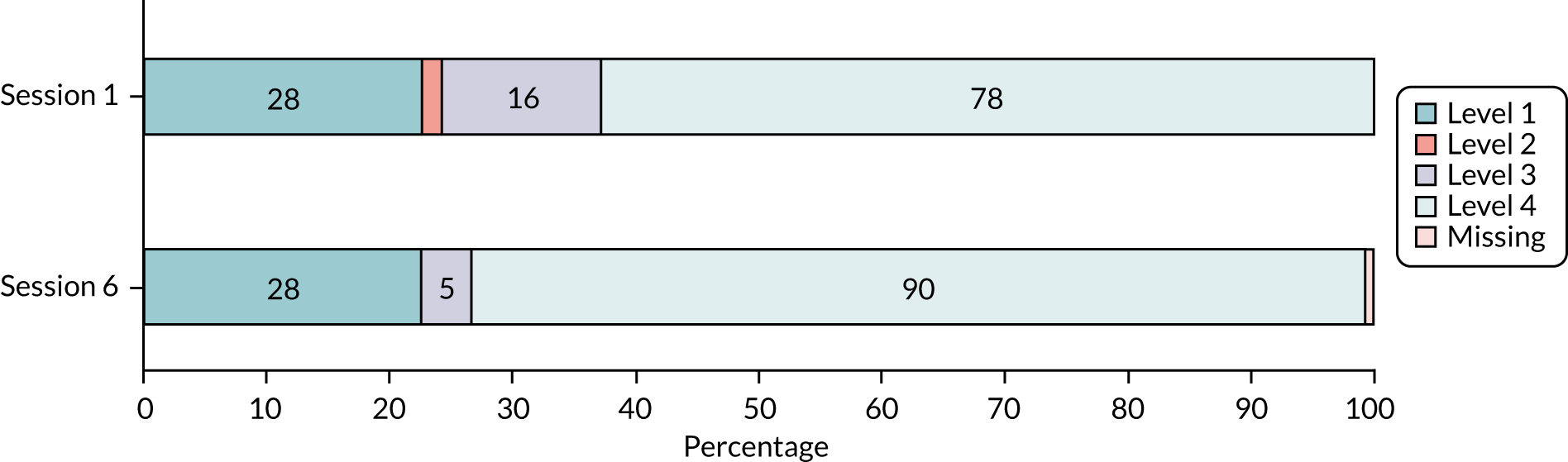

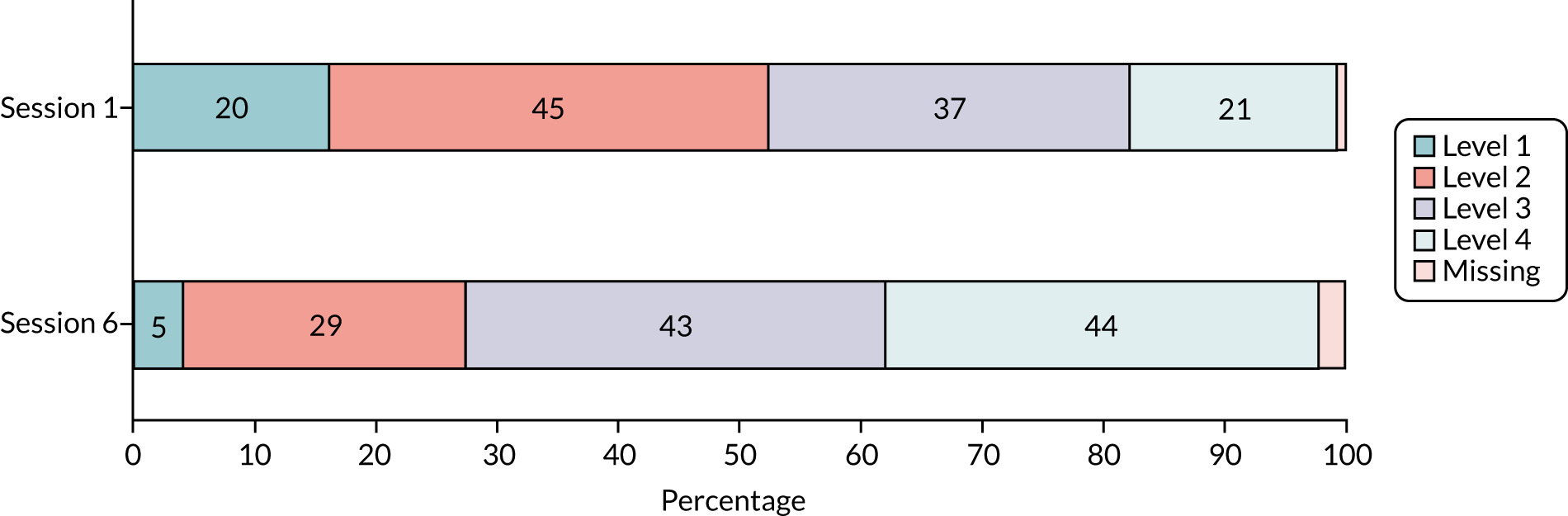

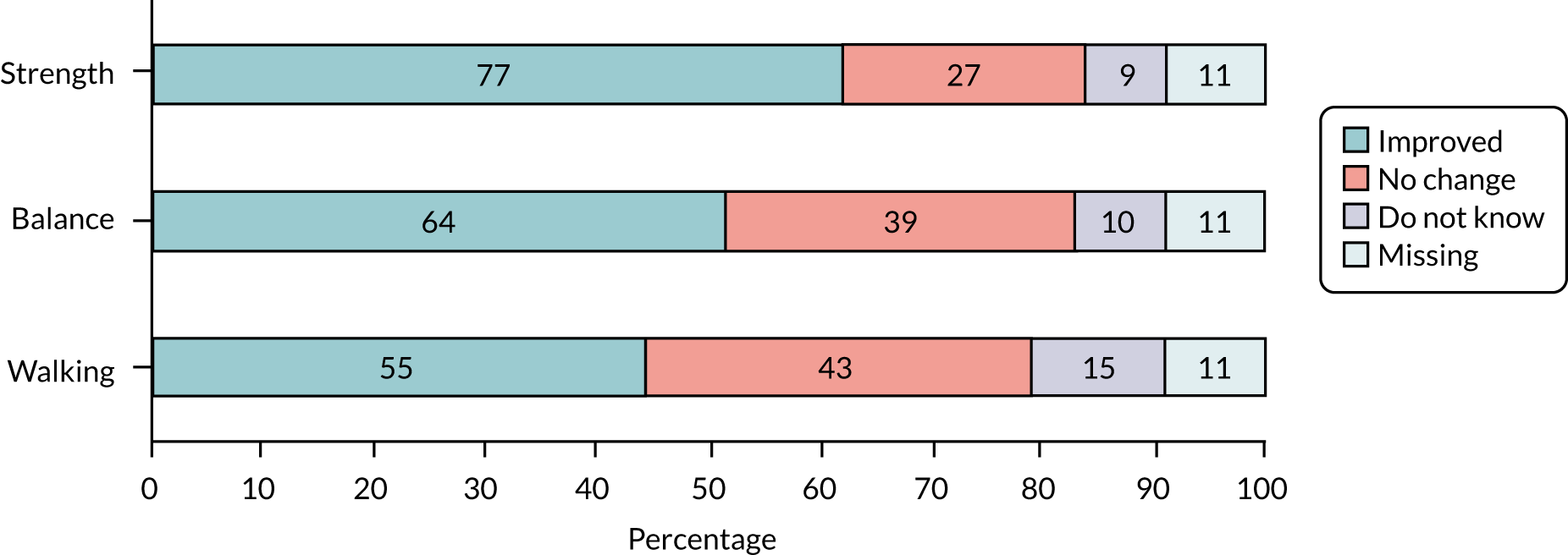

The response rate to postal falls risk screeners was assessed for screening yield and utility by assessment of prediction of falls over 12 months, using area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as per recommended guidance for evaluation of prediction models. 36 Intervention-related process measures for exercise included changes in strength and balance over time; thus, first and final assessments using the chair stand test (CST), the 4-test balance scale (4TBS), weights (kg) and repetitions were prescribed. We defined ‘work’ done as the product of the number of repetitions and amount of weight prescribed at each contact point (weights × repetitions). 37 We recorded the number of contacts and reported participants as having either fully or partially adhered to the exercise programme (fully adhered = six contacts or until discharge by therapist; partially adhered = fewer than six contacts). We recorded the number of MFFP assessments among those invited to attend. The skill mix of assessors was recorded by region, and participant uptake of interventions was explored by region.

Process evaluation: general practice medication prescribing

We extracted prescribing data for selected medications from GP records for two time periods captured 1 year apart: 3 calendar months pre randomisation and from 9 to 12 months post randomisation. The aim was to determine the rate of prescriptions of culprit medications (i.e. those targeted in any of the interventions) over time. In addition, we estimated the use of bisphosphonates and mineral supplementation as contextual data. We planned to undertake drug data searches on a random subsample of GPs stratified by intervention arm, but pilot searches suggested that this would be unreliable owing to differences in primary care electronic systems, which resulted in variation in format and quality of drug data. Therefore, medication searches were undertaken at all GPs. We developed a medication search protocol detailing Read codes for two drug classes of interest: (1) psychotropics and psychotropic-related medication and (2) bisphosphates and mineral supplementation. Psychotropics can increase risk of falling, and we included antidepressants, psychotropics, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics and antimanic medications, as per British National Formulary38 classes 4.1.1—4.3.1. Bisphosphonates (British National Formulary class 6.6.2), are often prescribed with mineral supplementation (calcium and vitamin D preparations that include calcium carbonate, British National Formulary classes 5.1 and 9.6.4), as can slow bone loss and may decrease the risk of fractures. We collected data at practice level only, on the total number of trial participants prescribed psychotropics and bone protection drugs (mean/proportion participants per practice) and changes pre–post randomisation. Completeness of data varied by practice electronic system.

Data management

Questionnaires were scanned using FORMIC FUSION™ software (Formic Ltd, Staines, UK), which includes internal system validation checks. All scanned questionnaire entries were manually checked by the research office. All other data were manually entered by data clerks onto the bespoke database designed for the trial. All data were validated using range checks, outliers, missing data and date discrepancies. Anomalies were checked against original data sources for rectification.

Data analyses

Definition of higher falls risk

We established risk of falling using two methods, based on responses to (1) the GP-administered postal falls risk screener mailed to treatment arms only and (2) the baseline questionnaire completed by all participants. Details of response options used to classify risk of falling for each data source are provided on the project webpage (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/081441/#/; accessed 16 March 2020). The risk algorithm from the baseline questionnaire used falls and balance difficulty questions analogous to the falls risk screener, but this enabled identification of risk across the full trial population. Comparisons of risk of falling were made across treatment arms.

Sample size calculation

As reported in the published protocol,18 the study was powered using the proportion of people with at least one fracture. We used a conservative method of estimating the sample size based on a comparison in the proportion of people with fractures, recognising that this would be more than adequate for comparison of both proportions and fracture rates per person over 18 months of follow-up. There were surprisingly few data available from which to draw estimates of fracture rates for the UK older population. The sample size was based on the annual fracture incidence from UK statistics, estimated to be 6 per 100 (6%) for people aged > 70 years. 39 We prespecified a target of reduction to 4% in the intervention arm.

A total of 5700 participants, thus 1900 per arm, were required to achieve 80% power for detecting a statistically (p < 0.05) and clinically relevant (2%) reduction in proportion sustaining a fracture, from 6% to 4%, for the comparisons of advice compared with exercise and advice compared with MFFP. We aimed to recruit an average of 150 participants from each GP. To adjust for varying degrees of modest clustering, intracluster correlation (ICC) set at 0.003 inflated this sample size estimate from 5700 to 7800, or 2600 per arm. The choice of ICC was driven by data reported by Smeeth and Ng,40 who, although they did not provide information relating to fractures, reported ICC related to an outcome of ‘at least one fall’. This estimate was 0.0061. We used a slightly smaller ICC of 0.003, as the number of fracture events would be lower than number of falls. Allowing for 15% loss to follow-up, this yields a minimum target sample size of 9000 participants from a minimum of 60 practices. To reduce the possible effects of variable cluster size on statistical power, we sought to keep final cluster sizes in the range of 129 to 179.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using StataSE® version 15 and 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two sided and performed at the 5% significance level. We undertook three levels of analysis: (1) intention to treat (ITT), (2) a nested ITT on data from those at higher risk of falling and (3) complier-average causal effect (CACE) analyses. Unadjusted and adjusted estimates were obtained for all statistical regression models. Adjustment was made for the corresponding baseline variable (participant age, sex, falls history and GP deprivation score). The main ITT analysis included all randomised participants. In a nested ITT analysis, we compared treatments just among those at higher risk of falling, classified in accordance with the baseline questionnaire.

Treatment comparisons

The primary analysis compared all participants randomised to advice with all participants randomised to exercise and, separately, all participants randomised to advice with all participants randomised to MFFP. Only if there was evidence of a statistically or clinically important difference for either of these did we plan to proceed with comparing exercise with MFFP.

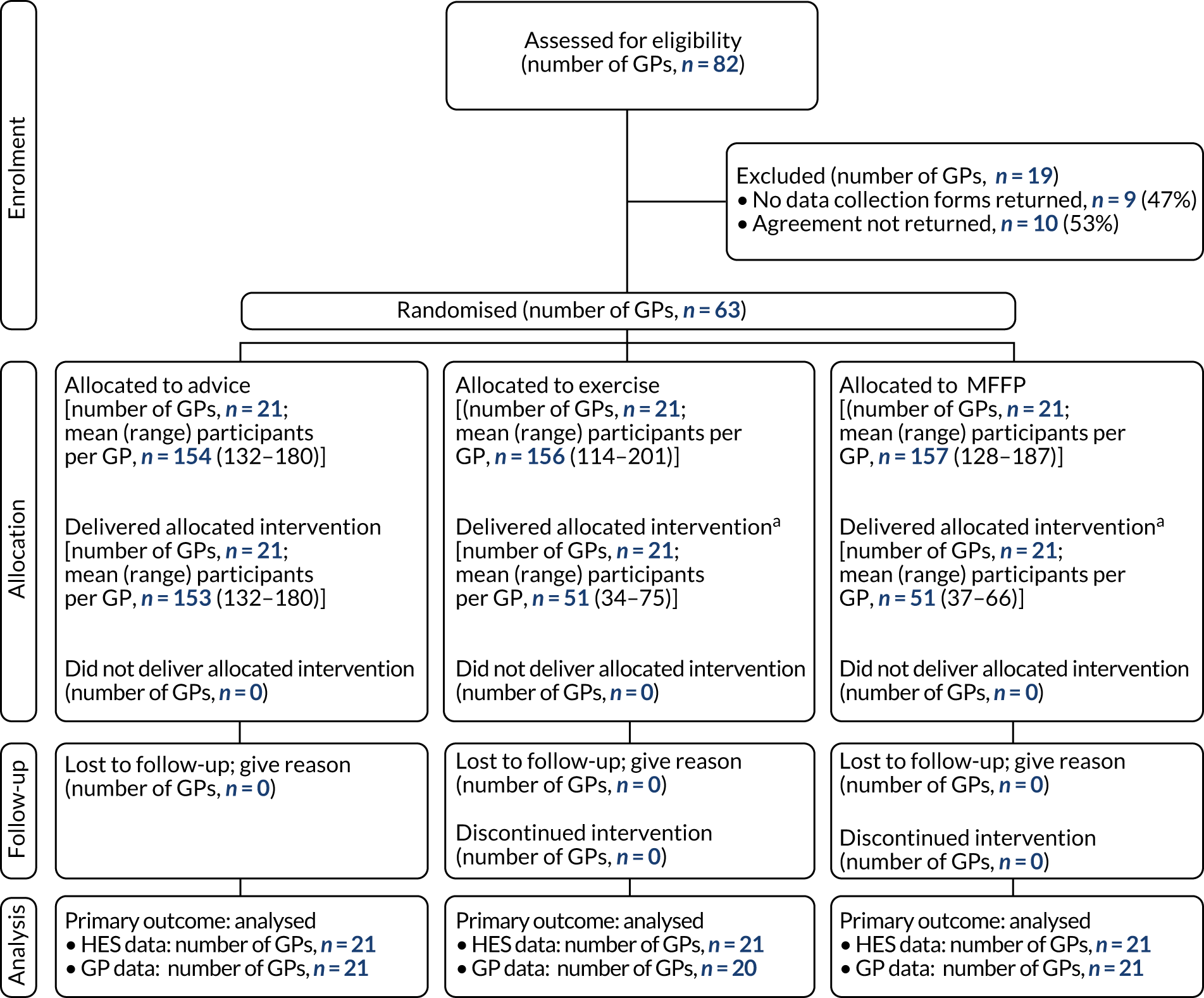

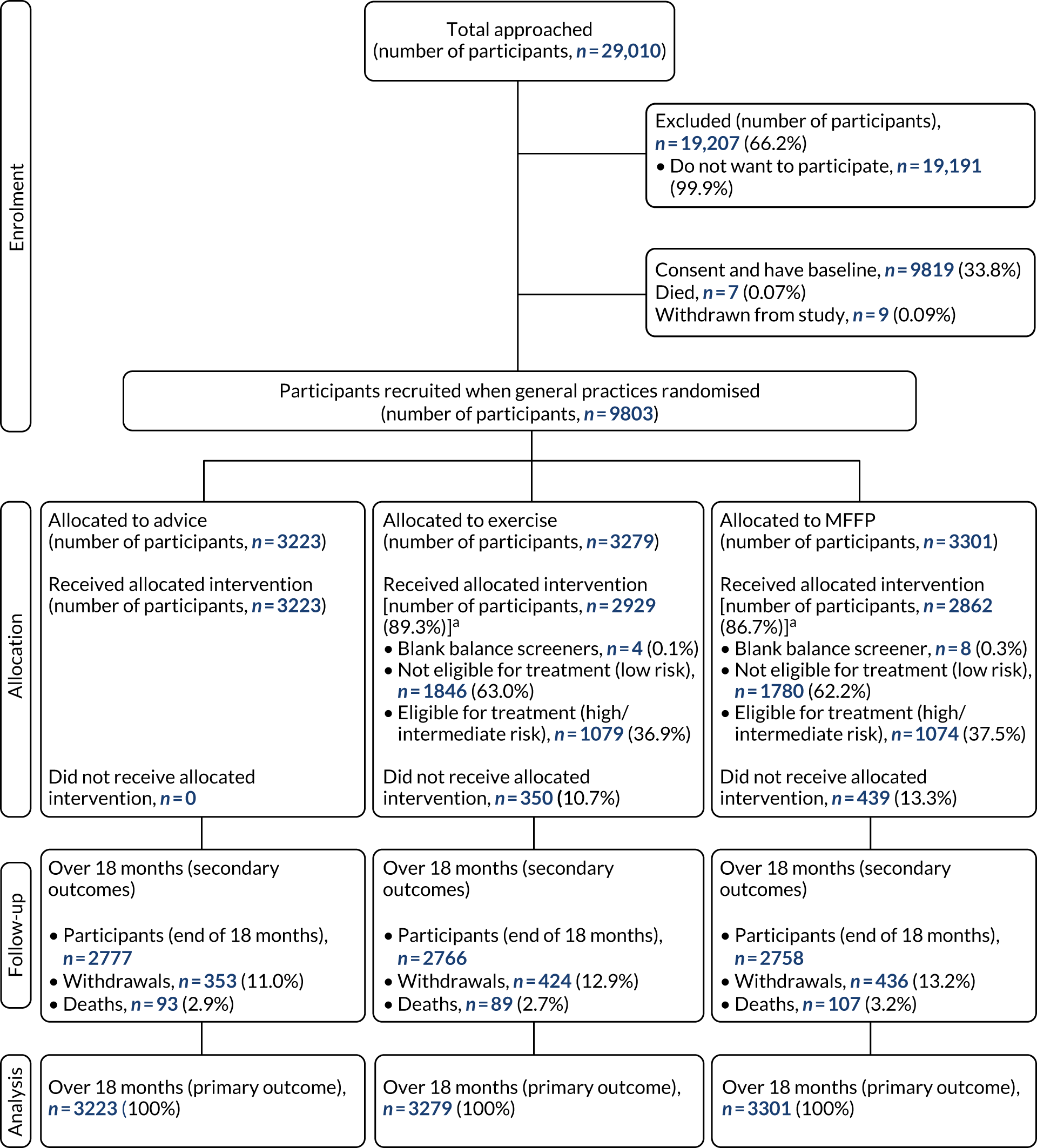

Descriptive analyses

Data were summarised and reported in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines for cluster RCTs. 19 Recruitment and participant flow are reported using CONSORT flow diagrams at the level of GP and participants in Chapter 4 (see Figures 1 and 2). Participant data from randomisation to 18 months were analysed by treatment arm and by risk classification using falls and balance questions from the baseline questionnaire. Sociodemographic variables were summarised by intervention arm, with mean (SD), median (range) and missingness reported for continuous variables, and number (%) for categorical variables. Unadjusted and adjusted estimates were obtained for all statistical regression models. Adjustment was made for the corresponding baseline variables: GP deprivation score, participant falls history, age and sex.

Primary analyses

Cook and Major41 reviewed two different approaches to the analysis of events per person-years, examining estimation of the rate by (1) dividing total number of events across all participants by total duration of participant follow-up and (2) fitting a random-effect Poisson model to accommodate the expected variation in the rate between different participants. 41 They found that the events-per-person method substantially underestimated variation in the data and felt that this method was not appropriate to summarise the incidence of rate-related data. 41 Others have described different statistical models to assess count data when there is overdispersion and excess zeros. 42–44 These models include the Poisson, negative binomial, zero-inflated Poisson, zero-inflated binomial, hurdle Poisson, hurdle binomial, Andersen–Gill and marginal Cox regression models. There is consistent evidence to suggest that the negative binomial models provide the best fit. 42 We therefore used these to analyse fracture and falls rates per person time observation.

Fractures were expressed as the fracture rate per person per 100 years of observation. Using the negative binomial model, we incorporated the random effect for GP, and this provided the unadjusted and adjusted estimates of the fracture rate per person per 100 years, taking account of all data collected over 18 months. The adjusted model accounted for baseline falls, sex, age and GP deprivation score. An offset variable was incorporated to account for the time the participant was in the study. In the light of the extremely skewed distribution of the baseline falls count, the log of the baseline falls count was used. 45 The fracture rates per person per 100 years of observation (with 95% CIs) are presented by treatment arm. The rate ratio (RaR) (95% CI) is given for advice compared with exercise and advice compared with MFFP. The standard errors (SEs) for the rates were obtained using bootstrapping methods. Model fit was assessed using the likelihood ratio (LR) test, which compared the random-effect model with the standard negative binomial model.

The fracture rate based on per person per time period was also computed for each follow-up time point to 18 months. Negative binomial models were fitted similar to those described above but without an offset variable, because the time interval was standard for all participants.

Secondary analyses

The proportion of participants who sustained one or more fractures over 18 months was analysed using random-effects logistic regression models, with the random effect as GP. Responses were taken as ‘no fracture’ (0) and ‘at least one fracture’ (1) where one or more fractures were recorded. Model fit was assessed using the LR test, comparing the standard with the random-effect logistic regression model. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) (95% CI) for the odds of incurring at least one fracture compared with no fracture were calculated.

Time to first fracture was analysed using survival methods, accounting for the random effect (GP) and other key predictors, as above. A Cox proportional hazards model was fitted to the data to compare time to first fracture across treatment arms; assumptions for models were checked. The total number of fracture episodes and rate of fracture per episode were summarised by treatment arm. Frequency and proportion of hip and wrist or forearm fractures were compared by treatment arms using the chi-squared test.

Secondary outcomes

Falls analyses

Using the negative binomial model with random effect for GP, unadjusted and adjusted falls rates per 100 person-years were calculated using all data collected over 18 months. The adjusted model accounted for baseline falls, sex, age and GP deprivation score. An offset variable was incorporated into the model to account for time in the study. In the light of the extremely skewed distribution of the baseline falls count, the log of the baseline falls count was used. 45 The negative binomial model provided a rate per participant per month, expressed as per 100 person-years of observation. The falls rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) was calculated by treatment arm. The RaR (95% CI) was calculated for exercise compared with advice and for MFFP compared with advice. The SEs for rates were obtained using bootstrapping methods. Model fit was assessed using the LR test, which compared the random-effect model with the standard negative binomial model.

We analysed the proportion of participants who sustained one or more fall over 18 months, similar to the fracture analyses. At 18 months, the questionnaire time period covered 6 months (from 12 to 18 months). However, the written question enquired about falls in the previous 4 months; therefore, 4 months was used for rate calculations. Only reported data were used in rate calculations. For example, when a participant returned falls data at 4, 12 and 18 months but had not responded at 8 months, then the falls rate was based on the observation periods for data returned (in this example, 4, 12 and 18 months).

The number (proportion) of fallers was calculated. In addition, the falls rate (per 100 person-years) was calculated as a 4-monthly rate for each time interval analysed using random-effect negative binomial models. The falls rate per person per month based on diary card responses was summarised and analysed using similar methods for each time interval (baseline to 4 months, 4 to 8 months and 8 to 12 months). A comparison was made by method of reporting (retrospective vs. prospective).

Other secondary outcomes and baseline measures

Other clinical outcomes and baseline measures were summarised by treatment arm (SF-12, EQ-5D-3L, frailty, mobility and difficulties with ADL, cognitive impairment and self-reported health conditions). Mean values (SD), median (range) and missingness were reported for continuous variables, and number (%) for categorical variables. For secondary analyses, we estimated treatment effects by age, sex, falls history, frailty and cognition. Frailty status was fitted using the random-effect logistic regression model, unadjusted and adjusted, with the odds of being frail compared with non-frail by each active treatment arm compared with advice modelled. We followed validated scoring guidelines for all measures. Descriptive data for the cognition test were summarised as having higher compared with lower cognitive functioning. An additional secondary analysis was undertaken on fractures occurring after the 18-month follow-up period for the entire observation period for which HES data were available. For these events, confirmed fractures were based on only hospital statistics, as GP and self-report were not gathered beyond 18 months. We report events from the extended period as per events for the main trial.

Nested intention-to-treat analysis

In a nested ITT analysis, we compared treatment just in those at higher risk of falling, classified according to responses to falls and balance questions in the baseline questionnaire, completed by all trial participants before randomisation. This provided information on those at higher risk of falling across all three treatment arms, including the advice only group, who did not receive the falls risk screener.

Complier-average causal effect analysis

In a CACE analysis we assessed treatment effect in compliers compared with non-compliers. We defined a ‘complier’ as a participant who returned a postal falls risk screener who was deemed at risk of falling and attended their first exercise or MFFP assessment or one who returned the falls risk screener but had a low risk of falling. We defined non-compliers as those who returned a falls risk screener and were at risk of falling but did not attend treatment, or who did not return a falls risk screener.

Subgroup analyses

We prespecified subgroup analyses to explore intervention effectiveness by age, sex, falls history, cognitive impairment and frailty. 46,47 We did not expect to include large numbers of community-dwelling older people with severe cognitive impairment, but mild to moderate cognitive impairment may affect ability to engage in falls prevention strategies. Subgroup effects were tested through formal interaction tests. 48 Random-effects negative binomial models were fitted using the interaction of treatment and subgroup as the covariates. We did not adjust for other baseline covariates. RaRs (95% CI) were obtained for the treatment comparisons for advice compared with exercise and advice compared with MFFP, respectively.

Missing data

As fracture data were available for all participants from combinations of HES and GP records, we had no missingness for the primary outcome. We assessed missing data for the falls outcome. It was not possible to perform multiple imputation (MI) owing to skewness in the distribution of the data. Instead, we assessed missingness (no response) by looking at the proportion of missing data across treatment arms for the falls data within each time interval.

Adverse event reporting

A safety-reporting protocol for related and unexpected serious adverse events (SAEs) and directly attributable adverse events (AEs) was developed. An AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant that did not necessarily have a causal relationship with treatment. All participants were aged ≥ 70 years; thus, we expected common chronic diseases associated with age (e.g. osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal conditions). It was expected that some participants would experience uncomfortable effects from exercising, such as muscle or joint discomfort. These effects were anticipated and, provided they were short-lived, were not reported as AEs. AEs were reported if they occurred during any contact time with the therapist or assessor delivering an intervention, during an intervention session or when undertaking prescribed exercise, either supervised or unsupervised. All AEs were reported to the trial team and chief investigator within the required timelines, in accordance with the PreFIT safety-reporting protocol. A SAE was an AE occurring as a direct consequence of treatment that resulted in death, threat to life, hospitalisation, disability or incapacity. Any event that required professional medical attention included, but was not restricted to, serious sprains, joint dislocation, falls or other injuries occurring as a direct consequence of the intervention. All events were reported to the trials unit immediately after the therapist became aware of them, within 24 hours for SAEs. The SAEs and AEs were recorded in the trial database. Any event related to trial interventions was referred to and reviewed by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Pilot phase and protocol revisions

A pilot phase was undertaken in one locality from September 2010 to March 2012. Key changes during the pilot phase included to increase postal mail-out from 300 to 400 people to increase yield from initial invitation. Other changes over time included an update to the primary outcome. The original trial protocol defined peripheral fracture as any fracture to bones in the appendicular skeleton, thus limbs and limb girdles as well as cranial and facial bones, but with exclusion of compression fractures in bones constituting the vertebral column (lumbar, thoracic and cervical vertebrae, sacrum and coccyx). This definition of appendicular skeleton also excludes the thoracic cage (sternum and ribs), as per the internationally agreed definition published by the ProFaNE network. 29 However, the definition of fracture events had evolved since protocol development. There was broad recognition among the clinical community that the ProFaNE consensus, published in 2005, required updating to reflect the contemporary epidemiology of trauma-related fractures in older people. 49 As populations age, the incidence of trauma-related skull, rib, vertebral and facial fractures increases. 50–53 During the pilot phase, we had developed methods for extracting accurate fracture data from both HES and GP records. It was apparent that fracture reporting was of sufficient quality to distinguish compression fractures of the vertebral column. We updated the PreFIT protocol and trial registry to include these fractures from HES and GP records when these were clearly consistent with a trauma mechanism. Therefore, when there was a clear description of trauma or fall, or when the fracture presentation was consistent with trauma and clearly mapped to the ICD-10, falls codes were generated from HES. Reports of vertebral osteoporotic compression fractures in GP records were excluded unless clearly linked to a report of trauma or fall.

Statistical models were revised from generalised estimating equations to generalised linear mixed-method models to account for data type and dispersion. These model revisions (updated from the original application) were reported in the prespecified analysis plan, approved by external committees and described in the published trial protocol. 18

Monitoring and approval

Regional and site-specific approvals were obtained from regional NHS research and development departments. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service (Research Ethics Committee reference 10/H0401/36, version 3.1, 21 May 2013), with approval granted by the Derbyshire Research Ethics Committee on 29 April 2010 (Table 2). Funder-led monitoring meetings to review pilot study recruitment and intervention data were held on 4 April 2012 and 14 September 2012, and written approval to proceed to the main trial was received in October 2012. Of the amendments approved by the Research Ethics Committee, seven were substantial and one was non-substantial.

| Date amendment approved | Overview of modifications |

|---|---|

| 29 April 2010 | Ethics approval for trial |

| 16 March 2011 | Sample size refinement, edits to primary outcome data collection, refinements to postal questionnaires and related participant materials |

| 17 August 2011 | Amendments relating to HES data |

| 1 March 2012 | Participant materials and consent form |

| 7 September 2012 | Post-pilot protocol revisions. Increase in invitations from 300 to 400 per practice. Extension of follow-up to 18 months |

| 24 June 2013 | Participant materials for 18-month follow-up |

| 7 April 2017 | Protocol addendum for additional follow-up |

| 22 August 2017 | Approval for a related PhD study |

Patient and public involvement

User groups and patient public representatives were involved in the design of materials and implementation of the trial. Older people attending a community support group and social lunch group in the Warwickshire region were invited to review patient-facing materials, including questionnaires, balance screening, cover letters and patient information sheets. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) included an independent lay member. A patient dissemination event, attended by 48 participants and their partners or carers, was held at a University of Warwick conference centre on completion of the trial.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was responsible for monitoring and supervision of trial progress.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

The independent DMEC monitored ethics, safety and data integrity aspects of the trial. Pilot data were reviewed by the TSC and DMEC; we proceeded to the main trial after approval by the DMEC, TSC and funder.

Chapter 3 Trial interventions

Introduction

This chapter presents a description of the trial interventions; sections are based on published work describing the exercise and MFFP interventions. 20,21 Intervention development was undertaken using Medical Research Council guidance54 for the development of complex interventions and following methodology used in other rehabilitation trials supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme. 55,56 A key consideration was the selection of interventions suitable for testing and implementation in the UK primary care setting.

Advice intervention

A scoping survey of UK falls services, referral pathways and information materials for older people had been completed before we started the PreFIT. 12 Falls prevention leaflets for older adults were reviewed for content and clarity. The Age UK’s Staying Steady booklet22 was selected for the advice intervention because of the positive emphasis on remaining steady and physically active. The Age UK leaflet contained useful advice about improving strength and balance rather than focusing on the consequences of falling. This 29-page colourful booklet provides clear information about eyesight, hearing, foot care, managing medications, checking the home environment for falls risks and dealing with anxiety about falling. It contains practical advice on seeking help from the NHS, contact details and telephone numbers for other organisations for older people and links to further reading. The leaflet was provided free of charge by Age UK. All trial participants received this booklet by post after the GP was randomised. Those randomised to the advice arm received a booklet with a covering letter only, then no further planned intervention.

Rationale and scientific principles for the exercise intervention

Evidence for exercise type and dose

Multiple systematic reviews have explored exercise type and dosage, finding that programmes that included balance training programmes and those delivering higher doses of exercise had the greatest effect on falls reduction. 57,58 Programmes of walking-only interventions and those without any balance challenge were ineffective in preventing falls. These systematic reviews led to best-practice recommendations that exercise-based falls prevention programmes should provide a moderate to high balance challenge, should be undertaken for at least 2 hours per week and should be delivered in either a group format or home-based setting. 58 Programmes should be of sufficient dose to induce changes in muscle strength and neuromuscular function and be delivered by either trained health professionals or suitably qualified exercise instructors. Other public health guidance for maintaining musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory health in older adults from the World Health Organization59 and American College of Sports Medicine60 recommended that strength training, or resistance exercises, targeting the major muscle groups should be undertaken two or three times per week. Given these recommendations, we reviewed the theoretical principles of balance and strength exercises during the process of selecting a suitable programme for testing in the PreFIT. A detailed description of the PreFIT exercise intervention is presented elsewhere. 21 An overview of principles and definitions used is given here.

Balance control in older age

Balance control is a prerequisite for successful mobility. Balance is defined as the ability to maintain the projection of the body’s centre of mass within manageable limits of the base of support, as in standing, sitting or in transit to a new base of support. 61,62 Balance is also a generic term describing the dynamics of body posture to prevent falling,61 and it can be quantitatively assessed by measuring the body’s centre of mass in relation to the base of support (e.g. sway on a force platform). It can also be measured using self-report or by using observation and functional testing. 62

Our ability to maintain balance depends on many inter-related processes (e.g. sensory information received from visual, vestibular, proprioceptive and exteroceptive sources). 62,63 Ageing is associated with a loss of reserve capacity in several bodily systems engaged in the control of balance and gait. Walking patterns change with increasing age: steps become shorter, push-off power is decreased and landing becomes more flat-footed. 64

Balance retraining in older people

For balance to improve, it should be challenged. 65 Progression to dynamic balance exercises is recommended, as static balance training is less likely to translate into improvements in balance during functional activities and ADL. 66 Many daily activities involve balance, such as moving from a sit to stand position, turning while walking or bending to retrieve objects from the floor. Traditional balance ‘challenges’ include reducing the base of support or moving the body’s centre of gravity out of the base of support, or a combination of both. Balance retraining exercises can lead to improvements in physical activity and function. Systematic reviews have found that balance training in older adults is most effective when exercises are performed three times per week and for at least 3 months. 58,67

Evidence for strength training in older people

Evidence for strength training in older adults was also considered. Muscle strength is greatest when young, with maximum strength peaking at age 20–40 years. By the age of 50 years, about 10% of muscle mass has gone and, thereafter, the rate of decline accelerates. 60,68 This decline is thought to be due, in part, to decreasing levels of physical activity. The consequences of loss of muscle mass include increased susceptibility to falls and fractures, and inability to perform everyday tasks.

Strength training is a system of physical conditioning in which muscles are exercised by being worked against an opposing force to increase strength. 62 There is good evidence to show that sedentary older adults, with support and regular training, can achieve a two- to threefold increase in muscle strength after 3 months of training. 60 In addition to effects on muscle mass, strength training can also lead to improvements in insulin action, bone density, energy metabolism, functional status and physical activity. 60,69 There is debate about the reasons why muscles become weak and atrophied over time; lack of use may be the major contributory factor rather than the ageing process alone. However, this may be a new concept for many older people and for some health-care professionals. Strength training challenges our accepted view of activity in older populations.

Selection of a suitable exercise intervention

Given the robust evidence base supporting the effectiveness of interventions targeting balance and strength, we aimed to incorporate these elements of best practice into the exercise intervention. The process for selection of the most suitable exercise intervention has been described in detail elsewhere. 70 In brief, we reviewed all exercise interventions reported in clinical trials included in systematic reviews published up to 2011. We considered all exercise interventions and programmes, although many interventions were not reported in sufficient detail to allow replication. Three established exercise programmes were shortlisted for consideration for the PreFIT: (1) the Tinetti et al. 9 exercise programme, (2) the Falls Management Exercise Programme (FaME)71 and (3) the OEP. 23,72

The Tinetti et al. 9 exercise programme, developed in the USA, includes progressive strength and balance exercises, gait and transfer training and a range of motion exercises. 9 The intervention also includes upper-limb exercises, with general recommendations for weights and progression. Starting-level exercises are predominantly chair based, and the programme also targets training in how to transfer from lying to sitting and sitting to standing, etc. This exercise programme is not widely used in the UK.

FaME, developed in the UK, is a 36-week group and home exercise programme incorporating fitness with progressive ‘chain’ exercises (movement sequences to get up and down to the floor), functional exercises and adapted tai chi. 71 The FaME intervention had been tested in one secondary prevention trial71 and was effective in reducing falls among frequent fallers when participants were provided with transport to attend classes (this encouraged attendance). The programme was not widely used in the UK setting at the time of the design stage of this trial. It has subsequently been proven to be an effective primary prevention falls intervention that also increases habitual physical activity. 73,74

The OEP, developed in New Zealand, is a programme of muscle-strengthening and balance-retraining exercises delivered at home or in the clinic setting by trained health professionals. This programme had been tested in four community-based primary prevention RCTs by the original research team,75–78 with two of these trials77,78 undertaken with those aged ≥ 80 years. The programme is individually prescribed by a physiotherapist or trained nurse and delivered via a series of home visits. It is based on robust physiological principles, incorporating progressive lower-limb strengthening exercises using ankle weights and moderate- to high-challenge balance exercises, and includes a walking plan. A meta-analysis by the Otago group of its own trials, totalling 1016 adults aged 65–97 years, randomised to either the OEP or control, reported a 35% reduction in falls (incidence RaR 0.65, CI 95% 0.57 to 0.75) and a reduction in fall-related injuries (OR 0.56, CI 95% 0.44 to 0.71). 79 A subsequent meta-analysis from an independent research group also found that the OEP reduced rate of falls compared with non-exercise control intervention (six studies; incidence RaR 0.68, CI 95% 0.56 to 0.79). 80

Rationale for selection of Otago exercise programme

In addition to the evidence base and consideration of essential components for inclusion in an exercise programme, we reviewed models and configurations of service delivery identified from a national survey of health and social care-funded UK falls services. 81 The 2007 national scoping audit of UK falls clinics reported that most localities provided group or home programmes, usually two sessions per week, over approximately 8–12 weeks. 81 As PreFIT was designed to be pragmatic rather than explanatory, we wanted to test an exercise intervention suitable for our proposed screen-and-treat approach in primary care, thus deliverable to older people living in the community. After further consultation with clinical experts in falls prevention and rehabilitation, we selected the OEP for PreFIT. In addition to the robust evidence base for clinical effectiveness, in terms of reducing falls, with clear guidance for prescription and progression, the OEP was familiar and recognised by many services and was implemented across a number of regions; in addition, established training schedules for different health-care personnel already existed (a range of national accreditations were available). We also informed the original research group from Otago, New Zealand, of our intention to test in the UK setting (approval from Professor John Campbell, University of Otago, Otago, New Zealand, 2011, personal communication). Public Health England has since recommended both OEP and FaME as cost-effective interventions for use in the UK. 82

Content of the PreFIT exercise intervention

Overview of programme

The PreFIT exercise intervention was entirely based on the OEP, with adaptions to the duration of the programme to reflect the commonly used formulations in the NHS setting. 81 It consisted of three core components: (1) strength training, (2) balance retraining and (3) a walking plan. It was a home-based programme, individually prescribed, adapted and progressed by ability. We delivered the programme over a 6-month period, with support provided by trained physiotherapists, occupational therapists, therapy assistants or exercise assistants. A menu of five strength exercises and 12 balance exercises was available, with exercises prescribed according to ability. Participants were assessed at the first appointment and then reviewed at regular intervals and progression introduced over time. We recommended six contacts over 6 months: three face-to-face appointments and three telephone contacts. Further details of the exercise plan, training intensity, progression and procedures are described below, along with minor adaptations made for trial delivery.

Prescription of strength exercises

Five strength exercises were undertaken three times per week, allowing for rest days in between. Exercises targeted the main muscle groups in the lower limbs, including the knee flexors, knee extensors, hip abductors, ankle dorsiflexors and ankle plantarflexors. Strength training was achieved using ankle cuff weights starting from 0.5 kg and body weight as resistance. The aim was for participants to achieve moderate- to high-intensity training.

Level of intensity in the PreFIT

The therapists were trained in all aspects of the programme, including how to assess intensity and progress in individual participants. The aim was for participants to work at a moderately difficult or difficult level during leg exercises. 62 For a training stimulus to be effective, completion of 10 repetitions should be moderately difficult or hard without loss of quality of contraction. If the leg exercises were too easy, then the starting weight was insufficient, and if very hard, then the weight was too high. The physiotherapist observed a participant undertaking 10 repetitions of leg exercises in a slow, controlled manner, holding the position and then returning to the start position in a controlled way. If the participant started to hurry movements, or used trick movements (compensation), then the weight was adjusted. Number of repetitions and weights prescribed were based on baseline assessment using the CST to assess lower-leg strength, as recommended in the original programme.

Principles of progression

Progression of exercise is necessary to maintain improvement and to prevent plateau or potential reversal of training effects. Progression refers to the training load or overload, with overload meaning having to work longer or harder than normal; this is required for adaptation. The body gradually adapts to exercise repetitions and increasing weights over time; thus, overload should be applied again to progress and improve further. 83 If prescribed exercises are increased too quickly, this can hamper progression, lead to demotivation and result in injury. Related to progression, the principles of rest and recovery are also important because the amount of rest between different sets of resistance exercises can affect the metabolic, hormonal and cardiovascular response to exercise. Overexercising can lead to pain and muscle injury; thus, it was important to ensure that rest days were included in the programme, to allow muscle fibres a chance to rebuild and recover.

Prescription of balance exercises

The OEP includes a menu of 12 static and progressively dynamic balance exercises of varying levels of challenge. Balance exercises are done on at least 3 days per week, although they can be done every day. Exercises at appropriate level were prescribed according to ability during the first appointment and assessment using the 4TBS. These exercises progressed from supported balance challenge movements, (e.g. tandem stand holding onto a work surface) to more complex, unsupported movements (e.g. backwards heel-to-toe walking).

Prescription of a walking plan

Research investigating the effectiveness of walking-only interventions has found no impact on falls or fall-related injuries. Indeed, some studies have reported an increased risk of falls in certain environments, such as walking outdoors on uneven pavements. 84 However, general public health guidance and the American College of Sports Medicine recommend that older people should walk 5 days per week. 60 The OEP includes a walking plan of 30 minutes at least twice per week to increase physical capacity. The PreFIT adhered to the original programme; thus, it recommended walking, but only in conjunction with the strength and balance exercises. The walking plan advice was to walk at the usual pace for up to 30 minutes at least twice per week. Outdoor walking was recommended if the physiotherapist felt that it was safe for participants. Walks could be broken up into shorter sessions (e.g. three 10-minute daily walks) and recommendations were given about how to incorporate walking into daily activities.

Procedures for delivery of the PreFIT exercise intervention

Staff expertise and training

To ensure standardisation of intervention delivery, two research physiotherapists became fully qualified OEP leaders [Vivien Nichols and Susanne Finnegan; Later Life training (Later Life Training Ltd, Killin, UK) completed 2012]. Training was supported by the research team (JB; Later Life training completed March 2011). Trial staff members provided a 5-hour structured staff training session to all therapists responsible for delivering the exercise intervention. Therapists included physiotherapists, occupational therapists, therapy assistants and exercise therapists or instructors. Training included the key skills and competencies for delivery, including correct exercise techniques, motivational and support strategies for adherence, and the roles and responsibilities expected of therapists participating in a research trial. Each therapist received a comprehensive manual containing a detailed description of all intervention procedures along with a training certificate for continuing professional development.

Location of intervention delivery

We designed the exercise intervention for completion by participants at home, but exercises could be undertaken in a group venue or exercise class led by the trained therapist if this option was available within a region. However, it was a prerequisite that any group-based session delivered the exact PreFIT programme, with individual adaption for each participant.

Recommended number of contacts throughout the intervention

In the original OEP trials every trial participant received up to five home visits (after the assessment) over 12 months. This model of multiple home visits to older people was not feasible in the UK NHS setting. For the PreFIT, six contacts were recommended, of which at least three were to be face-to-face sessions (including the assessment) in the outpatient or community clinic setting and the remainder could be telephone calls. The first and final appointments were individual clinic appointments to last for 1 hour, with interim appointments being shorter (up to 30 minutes each). The purpose of the follow-up sessions was to assess progress, to increase resistance by providing heavier ankle weights or increasing repetitions and to prescribe more challenging balance exercises.

Duration of PreFIT exercise intervention

We recommended a 6-month supported exercise programme. This is longer than current usual NHS practice: most services provide strength and balance training for between 8 and 12 weeks. 12,13 There is good evidence to suggest that exercise programmes of longer duration, that is > 3 months, are required to sustain physical benefits. 58 We considered our 6-month programme to be the most we could reasonably expect the NHS to provide.

First appointment with trial participant

The first 1-hour appointment was arranged in an outpatient clinic, community venue or at home. The purpose of the first assessment was to conduct a brief health check, undertake baseline tests of strength and balance and to prescribe the exercise programme. The therapist first assessed general health, current fitness and walking ability before undertaking strength and balance tests. General health was screened by asking about any cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, chronic lung disease or Parkinson’s disease, cerebrovascular disease and whether or not an inhaler or angina spray was used. The baseline tests were simple and quick, and valid and reliable tests of lower-limb strength and balance were used to determine starting level of exercise prescription. 85

Assessment of strength: chair stand test

The CST, a proxy measure of lower limb strength, was used to inform the prescription of strength exercises and to determine the starting level of ankle cuff weights. The test involves timing how long it takes to perform five consecutive sit-to-stand movements starting in a sitting position in a straight-backed firm chair, preferably with no arms, placed against a wall for safety. 23 We developed a detailed trial intervention protocol to standardise all procedures and tests. 21 The findings of the CST were used to determine starting weight and/or repetitions based on performance during the test (Table 3).

| Level | CST: criteria for prescribing strength exercises | 4TBS: criteria for prescribing balance exercises | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Poor strength: completed CST using arms or took > 2 minutes with arms folded (failed test). These individuals are very weak Weight: start with a light weight (e.g. 0.5 kg) and possibly no weight at all Repetitions: consider a lower number of repetitions (e.g. five to eight repetitions) |

Failed balance test: poor balance, has difficulty with feet together stand or can only achieve feet-together stand Select from only level 1 balance exercises |

1 |

| 2 |

CST successfully completed between 1 and 2 minutes: able to stand from chair but still fairly weak Weight: start with a lighter weight (e.g. 0.5 kg) Repetitions: aim for 8 to 10 repetitions if comfortable |

Managed some of balance test. Fairly good balance. Can achieve semi tandem stand Start by selecting level 2 balance exercises and moderate according to how the participant manages |

2 |

| 3 |

CST successful: good strength (e.g. five stands within 1 minute) Weight: use a reasonable starting weight (e.g. 1 kg) Repetitions: prescribe either one or two sets of 10 repetitions |

Managed most but not all of balance test. Good balance. Can achieve semi-tandem stand and can partially or completely hold the tandem stand Start by selecting both level 2 and 3 balance exercises and moderate according to how the participant manages |

3 |

| 4 |

CST successful: very good strength (e.g. five rises within 30 seconds) Weight: use heavier weights (e.g. 1 kg or possibly 1.5 kg) Repetitions: you may need to prescribe more than 10 repetitions for patients to feel that the challenge has been moderately difficult |

Balance test successful. Excellent balance that will need quite a challenge to improve it. Can achieve single-leg stand Consider starting with level 4 exercises, but moderate the prescription according to how the participant manages |

4 |

Balance assessment: 4-test balance scale

The 4TBS, used in the original programme, involves four increasingly difficult, timed, static balance challenges: (1) the feet-together stand, (2) the semi-tandem stand, (3) the tandem stand and (4) a single-leg stand. 66,85 The test is performed with the participant in bare feet, standing close to a wall or solid object for safety, but without aids. The assessor can help the participant assume the correct foot position, but progression to the next test is allowed only if a stance can be held independently for 10 seconds (see Table 3). If this is not achieved, or if support is required, then the test is then stopped and the participant is scored at the level that can be completed.

Overview of exercises

Strength and balance exercises were carried out three times per week, but balance exercises could be undertaken daily.

Warm-up exercises

Warm-up exercises comprised five gentle mobility movements of the neck, shoulders, trunk, hips, knees and ankles, and it was recommended that these be undertaken before any strength and balance exercise.

Strength exercises

Strength exercises included front and back knee strengthening (knee extensors and flexors), side strengthening (hip abductors), and calf and toe raises (ankle plantarflexors and dorsiflexors). Ankle cuff weights were used for the knee and hip exercises, with training in how to safely apply and remove weights.

Balance exercises

Twelve static and dynamic balance exercises of four levels of difficulty were included, from a tandem stand with support (level 1) to backwards heel-to-toe walking without support (level 4).

The programme took approximately 30 minutes to complete, excluding the walking plan. The therapist explained and demonstrated each prescribed exercise and observed the participant performing the exercises to ensure that participants were confident in undertaking them independently at home.

Materials given to trial participants

At the first appointment, participants received an A5-sized PreFIT exercise folder with pictures and instructions for every exercise, with supporting information written in large font. The folder included exercise diaries and general advice about physical activity and walking. The therapist could personalise each folder by adding his/her name, contact details, details of next appointments and any additional instructions about which exercises to focus on from the longer menu, according to ability. A set of ankle cuff weights were provided and these were replaced with heavier weights as people progressed over time.

Follow-up appointments and telephone calls

Follow-up appointments were recommended at 3 and 6 weeks and at 3, 4 and 5 months, with a final assessment at 6 months. The purpose of the follow-up contacts was to modify exercise prescription and to review, adapt and progress exercises when appropriate. Progression was essential to ensure that physiological challenges continued as fitness and functional ability improved. 58 Therapists were encouraged to provide additional behavioural support to encourage compliance and motivation. 23 Follow-up telephone calls were expected to last approximately 10 minutes, although actual duration varied. The Otago research team recommended a schedule of regular telephoning to enhance compliance. 66 We provided therapists with a simple checklist of points to discuss during follow-up telephone calls.

Final appointment

The final face-to-face appointment, lasting 1 hour, was arranged at approximately 6 months after the initial appointment and baseline tests were repeated. On discharge, participants were encouraged to continue with their exercise programme and were given a ‘staying active’ leaflet, which was designed for the trial. This leaflet outlined information about purchasing weights, the benefits of continued exercise and details of other opportunities for exercising in the local area.

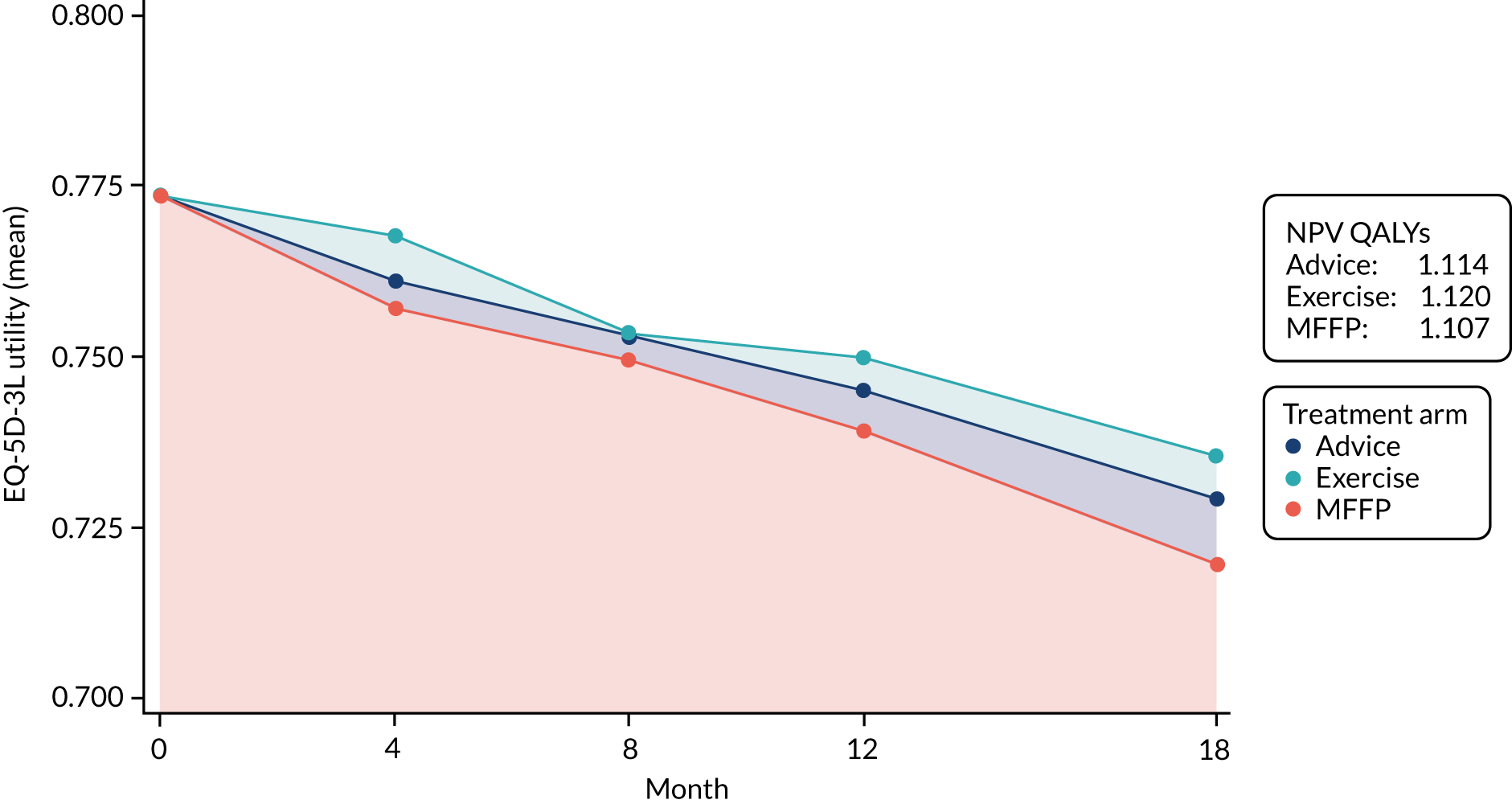

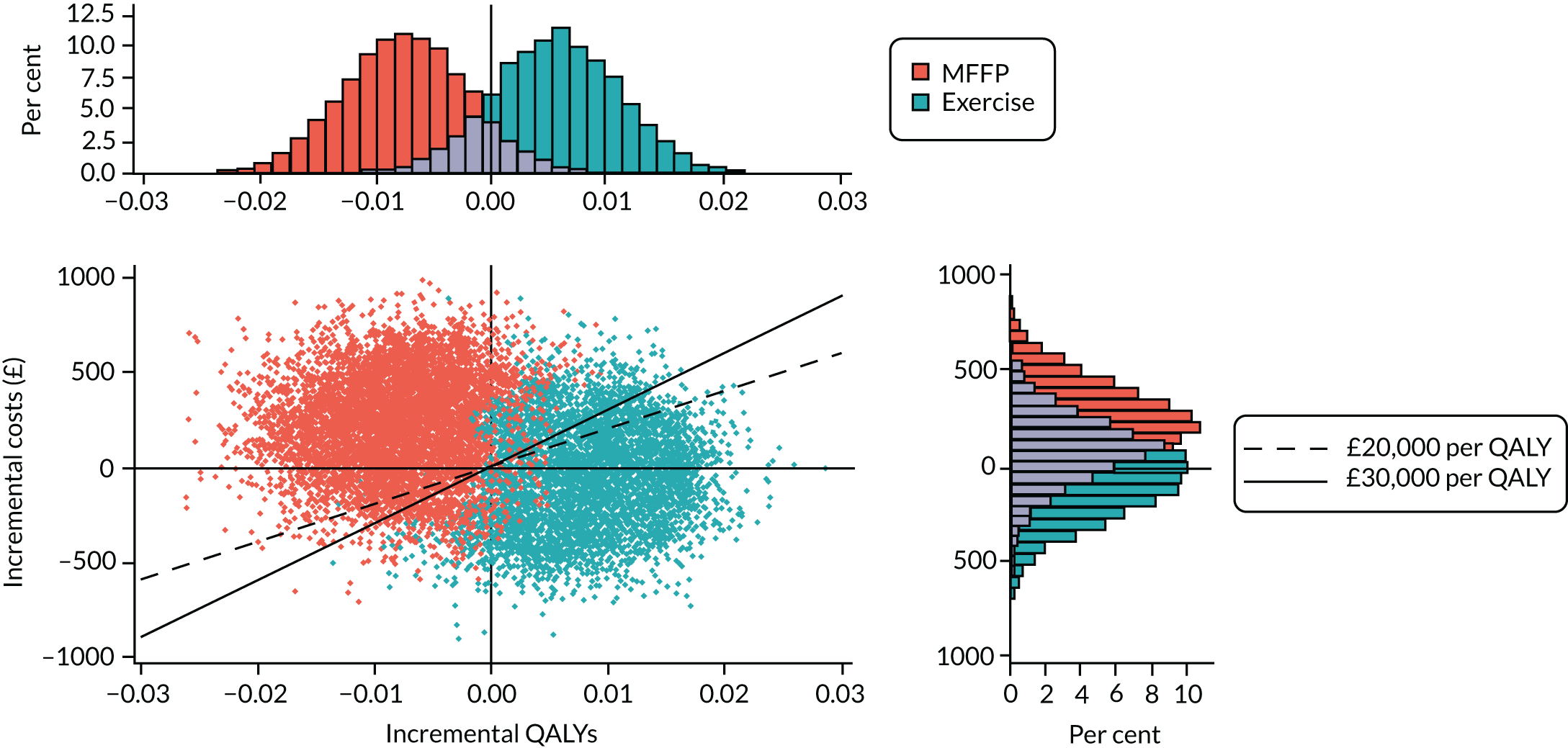

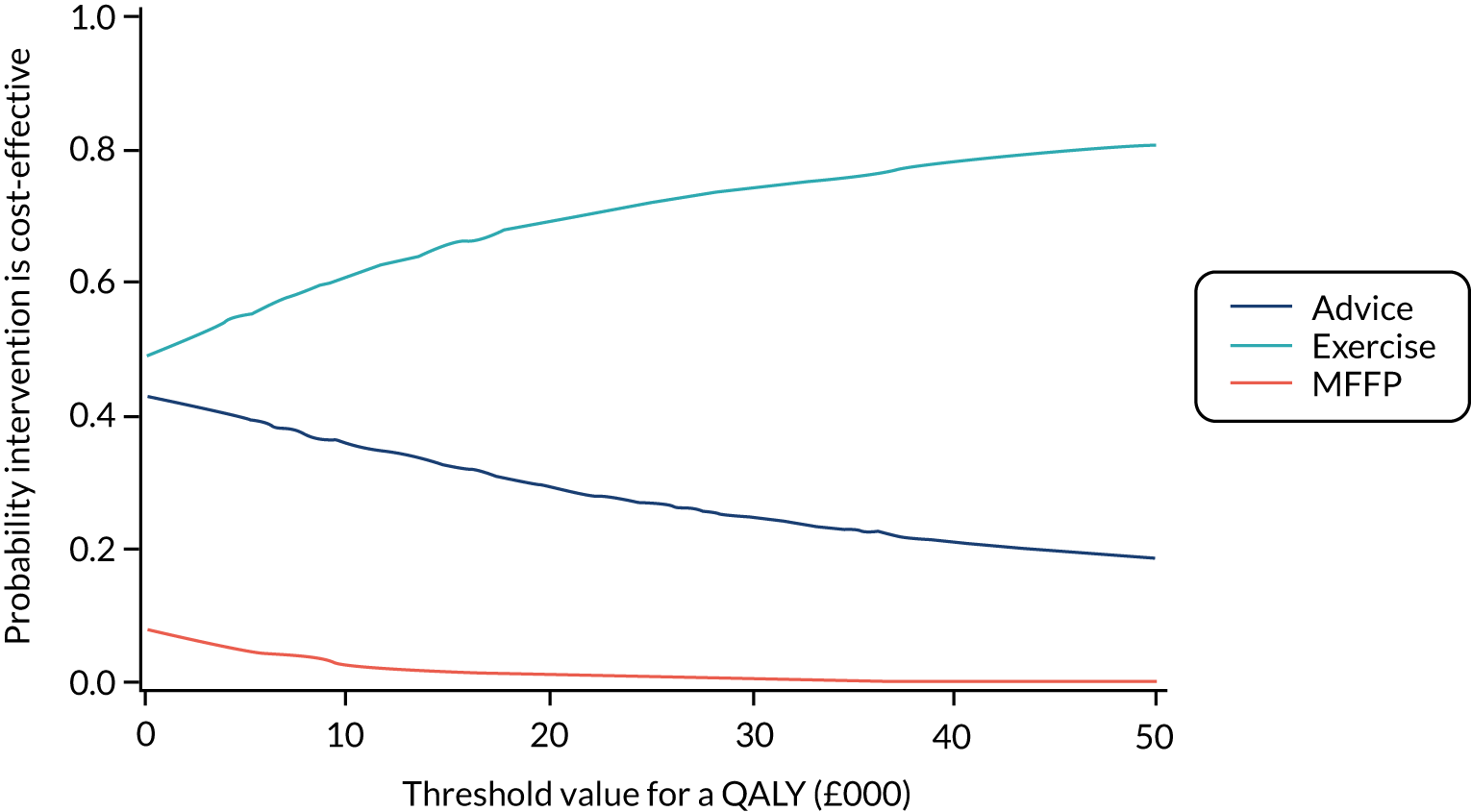

Comparison between the PreFIT intervention and original Otago exercise programme