Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/184/14. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The draft report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Daley et al. This work was produced by Daley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Daley et al.

Chapter 1 Background to the research

Prevalence of obesity and its consequences for health

In 2015, the Global Burden for Disease Obesity Collaboration estimated that almost 603.7 million people globally were living with obesity; this equates to a global prevalence of around 12%. 1 Approximately two-thirds of the adult population in England are classified as overweight or obese. 2 Sex differences in the prevalence of overweight and obesity have been reported, with more women than men affected. 3 Obesity is known to have negative effects on the physical, mental and social health of the population and their economic productivity. 4 Public Health England have reported that, between 2014 and 2015, obesity cost the NHS approximately £6.1B in treating associated health conditions. During 2017 and 2018, NHS hospitals in England admitted 711,000 patients with a health condition associated directly or indirectly with obesity; this is a 15% increase from 2016 and 2017. 5,6 Some people who are obese may also experience stigmatisation, which can have a detrimental effect on their mental health, quality of life and well-being. 7,8

Prevalence of obesity and overweight in women of reproductive age

The main child-bearing years of women (aged 25–34 years) hold a higher risk of weight gain than any other age for women and all ages for men. 9 A pooled analysis of global body mass index (BMI) trends estimated that the average BMI for women increased by 0.59 kg/m2 (95% credible interval 0.49 to 0.70 kg/m2) each decade between 1975 and 2014, which equates to the global population becoming, on average, 1.5 kg heavier every 10 years. 10 It has been estimated that about 20% of women in the UK aged 25–44 years are living with obesity, and approximately 50–60% of women in this age category are overweight. 11 Evidence also suggests that women living in more deprived areas of the UK are more likely to be overweight or obese. 12,13 This prevalence of overweight and obesity among women in this age category may be explained by that fact that it coincides with women’s reproductive years.

Excessive gestational weight gain

Regardless of pre-pregnancy weight status, most women gain above the recommend weight during pregnancy. 14,15 A UK-based longitudinal study found that the number of women experiencing maternal obesity at an early stage of pregnancy had increased over a 15-year period, and that this was more common among women who experienced higher levels of socioeconomic deprivation. 16 It is estimated that, on average, women gain about 14–15 kg during pregnancy and at 1 year after birth 5–9 kg is retained, with an average BMI of 29.4 kg/m2. 2,17–20 One explanation for excess weight gain during pregnancy is the traditional ideology of ‘eating for two’,21,22 which is a common explanation given by women who feel that pregnancy is a time during which they can eat what they choose without restraint. The perceived social pressures placed on women to remain slim are also relaxed during pregnancy. 23 Physical activity levels also typically decrease during pregnancy, so energy expenditure is reduced. 24

Health effects of excessive gestational weight gain

The negative health outcomes of maternal overweight and obesity for the mother and the baby have been well documented. 25–28 Many of the health risks are inter-related and include the development of gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension in the mother. There may also be perinatal complications for the baby, such as macrosomia, newborn hypoglycaemia, jaundice, shoulder dystocia, asphyxiation and stillbirth. 29–31 A systematic review of 11 cohort studies that included data from almost 1 million women reported that an increase in BMI (by one unit or more) was associated with a 56% increased risk [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.48 to 1.96 adjusted odds ratio] of gestational diabetes in the next pregnancy. The risk of gestational diabetes was further exacerbated when maternal BMI increased by more than three BMI units between pregnancies. The review also reported that a moderate increase in BMI of two units or more increased the likelihood of a caesarean section by approximately 16%. 32 Between 2011 and 2013, approximately 50% of the women who died during pregnancy in the UK had complications associated with being overweight or obese. 33 Another systematic review and meta-analysis34 identified a 264% increase in the odds of child obesity when mothers have obesity before conception.

Postnatal weight retention

Many women report pregnancy as the critical period for the onset of excess weight, which can significantly increase the risk of later obesity and serious chronic diseases including type 2 diabetes, heart disease and cancer. 35–39 Most women will not lose all of their pregnancy-related weight gain. 17,36,40 A UK-based prospective cohort study (n = 2559) of postnatal women noted that, by 6 months postnatally, about 73% of women retained at least some of the weight gained during pregnancy. 41 Prospective observational studies have reported that, among women who have a healthy BMI prior to pregnancy, 30% are overweight 1 year after giving birth. Of women who are overweight prior to conception, 44% are obese by 1 year after giving birth, and 97% of women who are obese prior to pregnancy remain so 1 year postnatally. Studies have also suggested that women who gain excessive weight during pregnancy are more likely to retain or gain additional weight during the first 1–2 years following childbirth. 42 Of note, evidence has also indicated that women who lost all pregnancy weight within 6 months of giving birth, irrespective of breastfeeding status, were only 2.4 kg heavier 10 years after childbirth, whereas women who retained postnatal weight were 8.3 kg heavier at the 10-year follow-up. 43 Findings from a systematic review involving 17 studies44 reported that postnatal weight retention was more attributable to excessive gestational weight gain than pre-pregnancy BMI. This is important because many women will have successive pregnancies and their weight retention will pose risks to their long-term health, as well as increasing the risk of adverse outcomes for the infant during each pregnancy. 20,45,46 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance47 has highlighted gaps in the evidence about acceptable and effective weight management interventions for postnatal women. Of interest here, in 2018 the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists acknowledged that more women were conceiving when they were overweight or obese, and that women of childbearing age with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 should receive information and advice about the risks of obesity during pregnancy and childbirth, and be supported in losing weight before conception and between pregnancies, in line with NICE guidance. 47,48 More specifically, women should be supported in losing weight in the postnatal period, and women who are overweight should be offered referral to weight management services if available.

Postnatal weight retention and mental health

There is good evidence of an association between mood/postnatal depression and postnatal weight retention. 49,50 Low mood or elevated depressive symptomatology can negatively affect the bonding relationship between the mother and her child. 51 This relationship is more pronounced in women who were obese prior to pregnancy. 52 These findings are relevant because poor bonding can have long-term consequences for the child, including delays in social, cognitive and emotional development. 53

Parenthood often requires a shift in priorities. Qualitative evidence exploring the views of women has indicated that women may prioritise the care of their child over their own personal needs, and typically tend to be responsible for most child-care duties. 54–56 During the early postnatal period, there can be multiple demands and challenges associated with looking after a baby that have to be managed alongside adjustments to daily routines, changes in relationships with family and friends, recovery from childbirth, and the physical and emotional effects of recent pregnancy and childbirth. 57,58 The postnatal period can also be an emotionally delicate and demanding time for new mothers, and weight retention and/or poor self-image may be factors in the development of reduced mental health. 59,60

The postnatal period, particularly the first 6 months, is often characterised by sleep deprivation for the mother, which can consequently affect decisions about health behaviours. Evidence from systematic reviews has identified an inverse association between the amount of sleep and postnatal weight retention. 61 In addition, if women initiate poor health behaviours during the early postnatal period, there is a risk that these behaviours may become established in the mothers’ new routine with their baby and the wider family. 62,63 Moreover, studies64–66 involving a range of populations have shown that sleep deprivation is related to poor eating behaviours and weight gain. Sleep deprivation and fatigue are also likely to reduce women’s ability and motivation to engage in regular physical activity.

Weight management interventions

General populations and weight management interventions

A range of lifestyle interventions have been tested to support weight loss or prevent weight gain. The testing of interventions to facilitate weight maintenance is also a growing area of research endeavour. Lifestyle behavioural interventions usually involve asking participants to make changes to their dietary habits and/or increase their physical activity levels using cognitive and behavioural strategies, such as goal-setting, restraint of eating, self-regulation, relapse prevention and finding social support. A systematic review67 of weight loss interventions involving obese and overweight adults reported that a combination of a low-energy diet and participation in physical activity was more effective for weight loss than diet-only interventions.

Several systematic reviews have demonstrated the effectiveness of group-based commercial weight loss programmes. 68,69 The group setting of these programmes is preferred by many, as it instils group social support that can facilitate behaviour change. 70 In 2006, both NICE and the Department of Health and Social Care recommended that primary care clinicians identify people affected by overweight and obesity and offer assistance with weight management. 71,72 Despite the evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of commercial weight loss programmes, this approach is not currently offered as treatment by many Clinical Commissioning Groups. 73,74 However, NICE guidance still recommends that people living with obesity or those most at risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus should be referred by their general practitioner (GP) to locally available weight loss programmes. 75 Weekly attendance at these programmes may not be suitable for all patients, however, owing to the cost of attendance and the high level of commitment required to attend weekly group meetings. Furthermore, this approach might not be suitable for those who have caring responsibilities, such as postnatal women.

Postnatal weight management interventions

Research shows that, irrespective of age or ethnicity, postnatal women would prefer to weigh less, are interested in implementing strategies to lose weight and would like help to do so. 76–78 During pregnancy and soon after childbirth, women may be more open to receiving support/advice about weight management; this may, therefore, be an ideal time to encourage the development of healthy lifestyle habits. 79 Weight management interventions may not only help women to lose any weight gained during pregnancy, but also have the potential to create a healthier environment for the whole family, providing further value and benefits. 80,81 Evidence has also highlighted that women would welcome additional weight management support after having a baby, as very little support is currently offered by the NHS. 82–84

Evidence from systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials in the postnatal period

Many studies, adopting a variety of methodological designs, have tested a range of weight loss interventions during the postnatal period. 85,86 To provide a comprehensive up-to-date quantitative summary of the evidence, the authors of this report (AD and HP) completed a systematic review86 in which the specific purpose was to both descriptively and statistically (using a mega meta-analysis) summarise the findings of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that have examined the effectiveness of behavioural lifestyle interventions for weight loss in postnatal women. A mega meta-analysis can be useful because it provides a comprehensive statistical summary of all of the available evidence across eligible systematic reviews. Mega meta-analysis is also helpful when previous systematic reviews have not been able to perform meta-analysis and/or subgroup analyses because of a lack of trials.

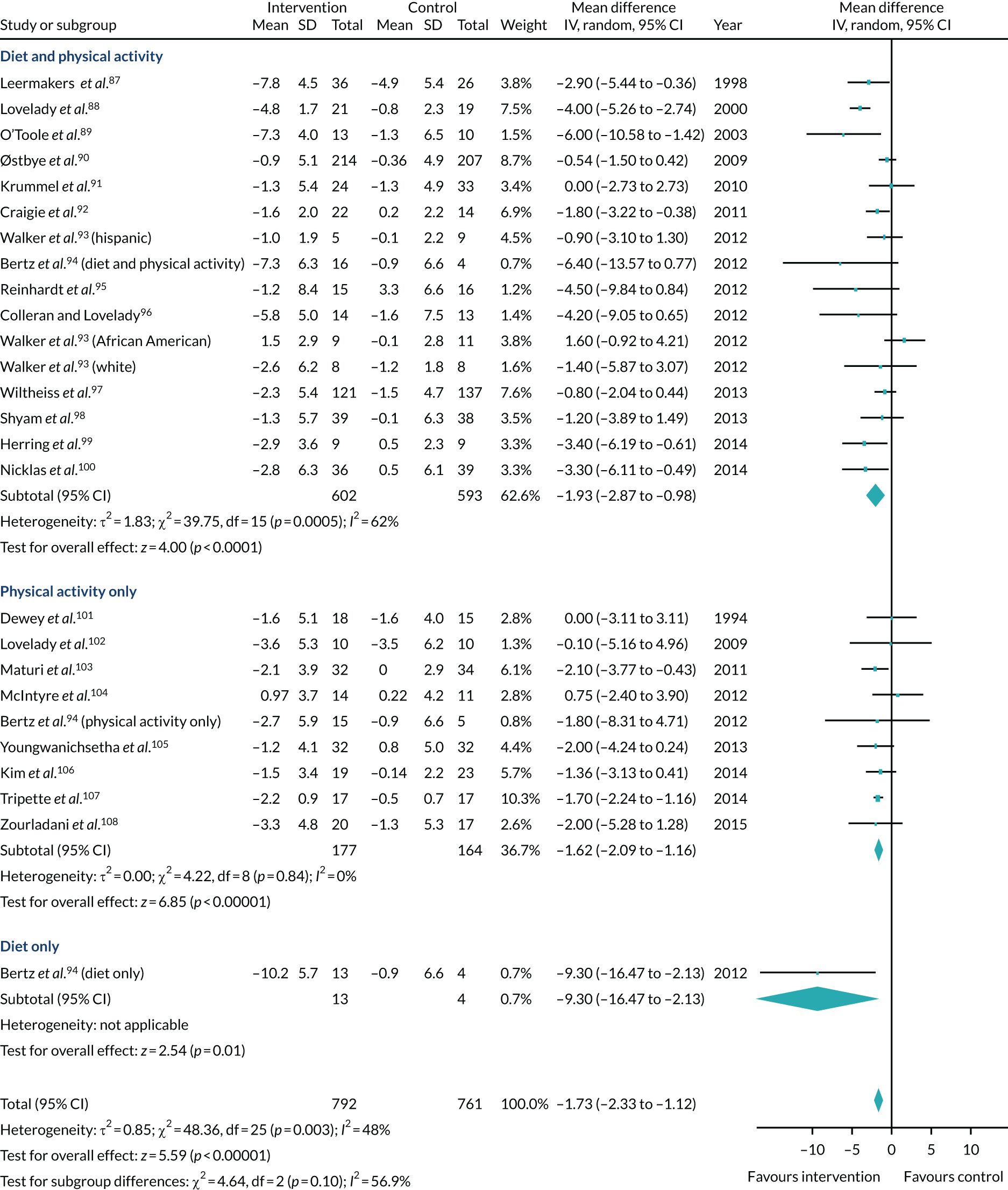

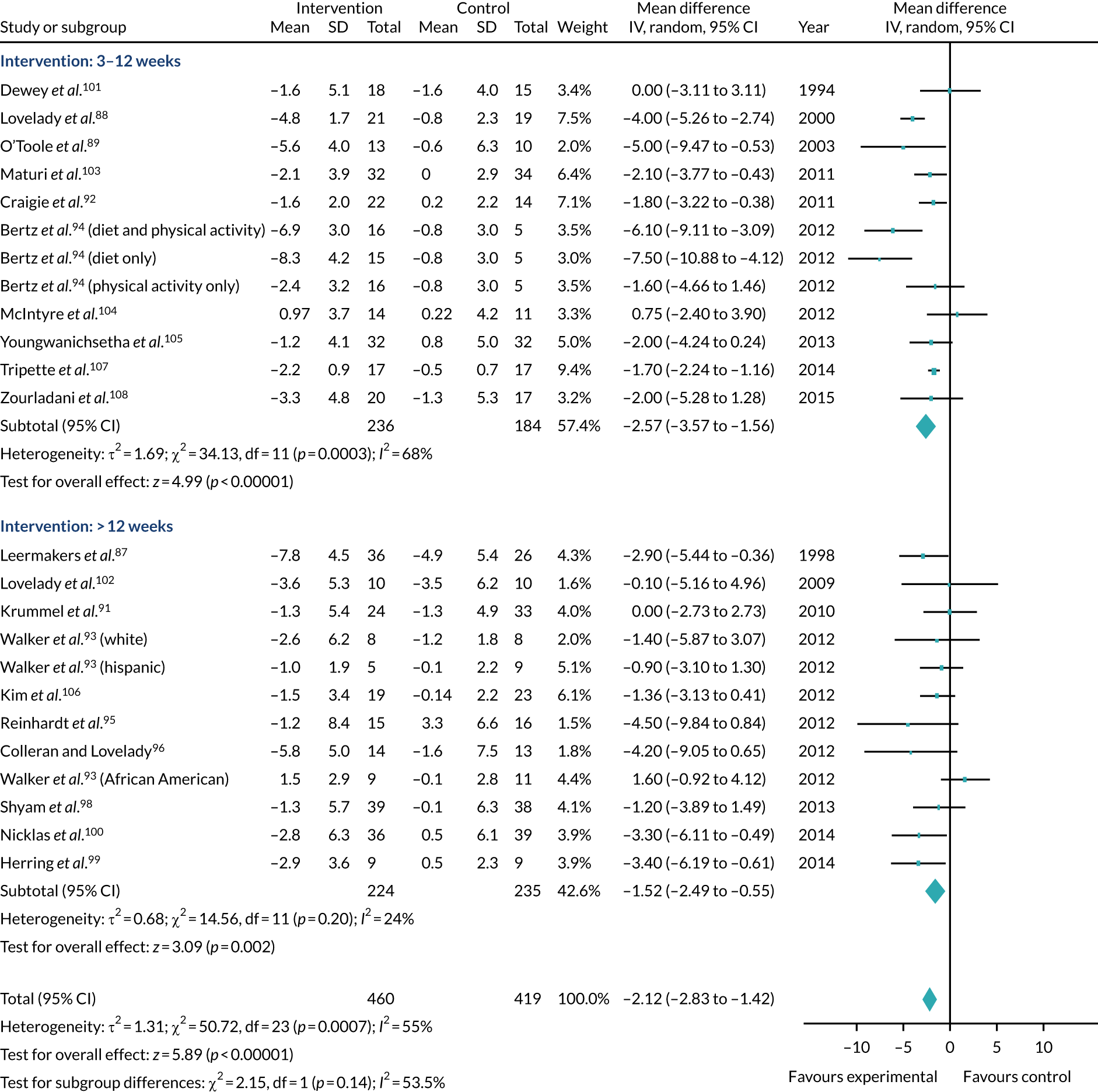

Nine systematic reviews of RCTs were eligible for inclusion in the review and 22 unique trials from across the nine systematic reviews were eligible for inclusion in the mega meta-analysis. Table 1 shows details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the review. Women who were randomised to a lifestyle intervention had a significantly lower body weight than comparators at the last follow-up visit (mean difference –1.7 kg, 95% CI –2.3 to –1.1 kg) (Figure 1). The results by subgroup are shown in Figure 2. Of interest here, the review did not find any RCTs that tested an intervention that was embedded in routine health-care appointments for postnatal women, and the review concluded that this might be a pragmatic way to offer support to all postnatal women who wish to lose weight after giving birth.

| Selection criteria | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Study type |

|

|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Main outcome |

|

FIGURE 1.

Overall mean difference in weight change (kg) and subgroup analysis (intervention type). This figure has been reproduced with permission from Ferguson JA, Daley AJ, Parretti HM. Behavioural weight management interventions for postnatal women: a systematic review of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. Obesity Reviews. 86 © 2019 World Obesity Federation.

FIGURE 2.

Mean difference in weight change (kg) by subgroup analysis (length of intervention). Note that this analysis was based on end-of-intervention weights recorded in the trials and two trials90,97 were excluded (as no end of data were reported). Therefore, the figures in this forest plot differ to those shown in Figure 1. This figure has been reproduced with permission from Ferguson JA, Daley AJ, Parretti HM. Behavioural weight management interventions for postnatal women: a systematic review of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. Obesity Reviews. 86 © 2019 World Obesity Federation.

Analysis showed that interventions that involved both diet and physical activity interventions, physical activity interventions alone and dietary interventions alone were moderately effective in reducing weight relative to comparator groups, although there was only one trial in the diet-only analysis. That said, the amount of weight loss does not need to be large to bring health benefits. 109,110 Modelling has shown that even if a small amount of weight is lost, this weight loss remains cost-effective if the weight regained occurs on a lower weight trajectory. 111 Furthermore, as the relationship between obesity and mortality is linear, even small amounts of weight loss may be clinically important. 38,112,113 Clinical guidance from NICE suggests that weight loss of approximately 2 kg can contribute towards a meaningful reduction in cardiovascular disease risk and type 2 diabetes mellitus. 109

It is important to highlight, however, that many of the RCTs included in the systematic reviews recruited small samples of participants, many of whom were white and middle class. 114,115 Furthermore, many of the tested interventions were intensive lifestyle-based programmes, were tailored to each individual woman and were frequently delivered by skilled health professionals, such as psychologists and dieticians. 116–118 Despite evidence suggesting that some of these interventions were effective, these intensive interventions require substantial resources to be scaled up to offer them to every postnatal woman in the UK who would benefit from them. Resource-intensive interventions cannot be delivered to all 820,000 women who give birth each year in the UK, 520,500 of whom will be overweight. 119 Furthermore, the acceptability of some of the interventions tested could be questioned given their reported high drop-out rates and/or poor levels of intervention attendance. 87,92,120 Attempts have been made to conduct studies that might be more appealing to a broader range of women from different ethnicities and socioeconomic backgrounds; however, they have also reported poor adherence and high drop-out rates. 121 Taken together, this evidence has highlighted the need for more high-quality RCTs that examine more acceptable and effective weight management interventions, designed to be suitable for postnatal women. 122 There is also a need for data regarding the cost-effectiveness of weight management interventions for postnatal women.

Self-management and self-regulation of weight

One solution that avoids the need for intensive resources to deliver postnatal behavioural weight management interventions is the provision of interventions that encourage self-management and self-regulation of weight. Research evidence has been inconsistent regarding the preferences of postnatal women for different types of weight management interventions, with some reporting that women prefer to attend group-based sessions123,124 and others reporting that home-based self-care interventions are preferred owing to issues such as time constraints, convenience and child care requirements. 92,125 Self-help interventions may, therefore, be attractive to this population of women, given that they are a low-cost, varied, flexible option that can be tailored to their specific needs. Given that many postnatal women may find it difficult to attend formal weight loss programmes and some have expressed a preference for home-based programmes, self-help interventions for postnatal weight loss are worthy of consideration. 86 In a systematic review126 of RCTs that aimed to determine the effectiveness of self-help interventions for weight loss (self-help defined as interventions that could be delivered without person-to-person support, including formats such as smartphone, web and print), analyses showed that self-help interventions that require no human input for delivery led to a small, but significantly greater, weight loss than unsupported attempts to lose weight at 6 months compared with minimal interventions (–1.9 kg, 95% CI –2.9 to –0.8 kg). However, results were variable and the reasons for this heterogeneity were unknown. In addition, in the small number of studies providing data at 12 months weight loss was no longer significant; the effect size was comparable with that achieved at 6 months, suggesting that self-help interventions on their own may not be useful for sustaining long-term weight loss, and that additional components within weight loss interventions are required. Nonetheless, given the potential scalability and relatively low cost of this type of intervention, self-help programmes may be a useful component within a broader intervention to treat women who are overweight in primary care.

Self-monitoring of weight

Trials of self-management interventions for weight loss can inform our knowledge about which types of self-directed weight loss strategies are most effective and which may be usefully highlighted to the public and policy-makers as scalable, low-cost interventions. One such intervention that has shown promise in helping people manage their weight is regular weighing to check progress against a target: a form of self-monitoring. Self-monitoring is defined as the procedure by which individuals record their own target behaviours. 127

The potential efficacy of regular weighing (either by the individual or by someone else) has been based on the principles of self-regulation theory. 128,129 Self-regulation has been described as a process that has three distinct stages: self-monitoring, self-evaluation and self-reinforcement. Self-monitoring is a method of systematic self-observation, periodic measurement and recording of target behaviours, with the goal of increasing self-awareness. The awareness fostered during self-monitoring is considered an essential initial step in promoting and sustaining behaviour change.

Strong evidence supports the role of self-monitoring as an effective strategy that leads to decreases in unwanted behaviours and increases in desired behaviours in many health areas, including diet and physical activity. 130 Self-monitoring is often described as a central component of behavioural treatment for weight loss,131 which may include monitoring food intake, physical activity and other outcomes, such as weight, size and body shape. 132 Reviews by Michie et al. 133,134 of effective behavioural techniques for healthy eating, physical activity and reduction in alcohol consumption reported that self-monitoring was effective alone, but when combined with other techniques the effect size nearly doubled. In a systematic review of RCTs by Madigan et al.,135 to examine the effectiveness of self-weighing as a strategy for weight loss, one of the included studies examined self-weighing as a single strategy and found it to be ineffective (–0.5 kg, 95% CI –1.3 to 0.3 kg); however, adding self-weighing/self-regulation techniques to programmes resulted in a significant difference of –1.7 kg (95% CI –2.6 to –0.8 kg). Multicomponent interventions, including self-weighing compared with no/minimal control, also resulted in mean differences of –3.7 kg (95% CI –4.6 to –2.9 kg). 135 With regard to postnatal women specifically, a systematic review to determine effective behaviour change techniques in physical activity interventions for this population found that effective interventions always included self-monitoring and goal-setting. 136

Accountability/audit and feedback for weight loss

External support for weight management has been shown to be a key factor in successful weight loss because of the feeling of accountability that it can foster. 137–139 Having to explain one’s actions to another individual can change behaviour and keep individuals motivated and focused on their weight loss goals. 140,141 In practical terms, if people know that their weight is being monitored externally, they may feel more obligated to try and adhere to their weight loss goals. Bovens142 has suggested that two concepts of accountability exist: one is a virtue and the other is a mechanism. Here the focus is on accountability as a mechanism and, therefore, consists of ‘an obligation to explain and justify conduct’. 142 The concept of accountability is well versed in the areas of business and organisational change management literature, in which it has been shown to keep individuals engaged and focused on their task and ensure that goals are achieved. In recent years, the role of accountability has also been applied in the health sector, particularly in relation to weight management. For example, research has shown that couples or ‘buddies’ can positively influence the health behaviours of the other partner. 143–145 In the review of self-weighing and weight loss by Madigan et al. ,135 there was some evidence suggesting that adding accountability to a self-weighing programme improves effectiveness.

Participants in group weight loss programmes often report that it is the weekly weigh-in that is the most salient component of the programme that provides external accountability and keeps them committed to their diet and physical activity plan. 146 In practical terms, if a person knows that their weight will be monitored they are more likely to make healthy lifestyle choices and, therefore, are more motivated to stick to their weight loss goals. Related to this, Gardner et al. 147 have conducted a systematic review examining similar behaviour change techniques to accountability, called audit and feedback. They investigated whether or not audit and feedback changed health-care professionals’ behaviour and found a significant effect (odds ratio 1.43 kg, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.61 kg). Audit and feedback are similar to accountability in that participants are aware of being observed. Based on this evidence, it can be hypothesised that adding accountability/audit to self-help and self-monitoring interventions could further facilitate weight loss.

Raising the topic of weight

Health professionals working in primary care have access to a wide proportion of the population and the ability to offer a range of important information as a trusted source of advice and support; therefore, they are well positioned to address overweight and obesity in the population, as most people are registered with a general practice. NICE Clinical Guideline 189109 suggests that health-care providers should use their clinical judgement to decide when to opportunistically weigh patients, but few do. 148 NICE gives guidance on the appropriate weight management advice and treatment options to offer to patients who are overweight or obese; however, this tends to occur at the discretion of the health-care provider. Evidence has suggested that GPs and nurses are apprehensive about raising the topic of weight with their patients. 149 Some of the reasons given for this reluctance include a fear of causing offence, not feeling that they have the skills to raise the topic and a lack of appropriate treatment pathways. 150–153 Research has also identified that health professionals consider weight management unrewarding and are pessimistic about patients’ motivation to lose weight. 153

The provision of more weight management interventions in primary care settings may enable more people to receive treatment. Furthermore, it may also make it easier for the topic to be discussed because it ‘normalises’ the process of raising the topic. Having these conversations more routinely may also help to remove some of the societal stigma associated with overweight and obesity. 154,155 It is also interesting to highlight that research with GPs has suggested that, when raising the topic of weight, most patients are not offended, with such discussions being perceived as helpful by patients. 156

The use of a brief intervention by health professionals to raise a specific health topic has been shown to be 10 times more useful for initiating a behaviour change programme than leaving the responsibility exclusively to the patient. 157 The use of brief interventions involving health-care professionals signposting patients presenting in primary care to seek weight management support shows promise of effectiveness. This trial found that a simple approach of GPs raising the topic of weight and referring obese adult patients to commercial weight management programmes during routine consultations was effective in facilitating weight loss. 156 Nevertheless, postnatal women are a unique subgroup of the population who experience many challenges and barriers that may impact their ability, willingness and motivation to regularly attend commercial weight loss programmes, for example availability of child care, cost, child-feeding routines, reduced mental health and disrupted sleeping patterns.

Technology and weight management

Various health policies have identified digital technologies as a promising vehicle for health behaviour change. NHS England’s Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View158 strategy highlighted that better use of information and technology to help people manage and improve their own health can help meet the health need of the growing and ageing population, and reduce pressure on services. 158 The use of technology for behaviour change has also been identified as an opportunity in Public Health England’s 5-year strategy. 159 Observational studies have reported that, irrespective of age or socioeconomic status, about 91% of new mothers use the internet as a source of information, with weight loss as the fourth most-searched topic. 160 Technology-based interventions offer self-regulatory features with the opportunity to promote self-awareness of health behaviours, and they can include a tracking system to enhance self-evaluation and self-reinforcement through monitoring devices. 161,162 Moreover, technology offers the potential to offer women a flexible approach to the management of their weight, providing the opportunity to access regular help and support.

Systematic reviews of eHealth or web-based interventions163–166 for weight loss and/or maintenance in adults have found that these interventions can result in modest weight loss in overweight/obese adults. For example, a systematic review (n = 224 studies)164 reported that internet/mobile telephone interventions improved diet, physical activity, obesity, tobacco use and alcohol use up to 1 year. Health professional involvement may also improve the effectiveness of digital or mHealth interventions. 165 More specifically, a systematic review166 reported that internet-based weight management interventions for postnatal women appeared to be beneficial in reducing weight. This evidence suggests that it would be appropriate and potentially beneficial to include the assistance of technology in the development of weight management programmes for postnatal women.

Primary care settings, child immunisations and weight management

Primary care serves as a gateway into the NHS for the population, which means that the public have regular contact with health professionals in this context. As primary care operates throughout the UK, it can provide the opportunity and framework through which large-scale weight management interventions can be delivered, with the added potential of being able to access hard-to-reach populations, thereby reducing health inequalities. Public Health England recommends that all children under the age of 5 years in the UK receive a schedule of routine immunisations that include measles, mumps, rubella, polio, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, meningococcal groups B and C, hepatitis B, rotavirus gastroenteritis and pneumococcal disease (13 serotypes). 167 These immunisations are provided by general practices and are usually administered by practice nurses. During their first year, babies receive immunisations when they are 8, 12 and 16 weeks old, as well as at 1 year. In 2019, 92.1% of children had completed the primary course of immunisations by their first birthday. 167 Each child is provided with a personal child health record book, or ‘red book’ at birth, in which health-related information, including immunisations, is recorded. Parents are asked to bring this red book with them to each child immunisation appointment so that delivery of the immunisation can be recorded. Given that the vast majority of postnatal women will have regular contact with primary care services to have their child immunised, these types of contacts provide an opportunity to reach all postnatal women to offer weight management interventions. This also aligns well with the ambition of the NHS to ‘Make Every Contact Count’: to deliver health behaviour change interventions to the population during routine health-care consultations.

Trial rationale

Given the consequences of obesity, the large numbers of women having babies each year who retain weight gained during pregnancy and the NHS resource implications of later health-care needs, there is a need to evaluate pragmatic, low-cost interventions that could facilitate postnatal weight loss at a population level. Moreover, NICE has highlighted the low quality of previous research as a limitation to developing clinical guidance in this area. 47,168 There is a need to intervene routinely and early in the postnatal period, to help women to manage their excess weight after having a baby and to minimise the long-term physical and mental health risks. This may also have additional benefits by reducing weight at the start of subsequent pregnancies. Interventions to promote a healthy diet and physical activity may also raise awareness of the importance of healthy lifestyle habits that will also be of benefit to the baby. Developing and testing postnatal interventions is also important, given that lifestyle interventions during pregnancy have had only modest success to date in preventing excessive gestational weight gain. 169,170

The intervention proposed here will be delivered in the context of the national child immunisation programme in primary care to minimise the costs to the NHS and to avoid the need for additional contacts with health professionals at this busy time in women’s lives. In the UK, infants are vaccinated four times in the first year of life as part of the child immunisation programme, which has a coverage rate of 92%. 167 We propose to embed a simple and brief intervention into this national child immunisation programme. The intervention does not require additional visits or expenses for postnatal women; thus, the sustainability of the intervention is likely to be high and income and/or ethnicity will not be barriers to participation. This approach also provides the opportunity for early intervention to reduce the possibility of women gaining further weight after childbirth. Although we expect our intervention approach to result in a smaller effect than the intensive interventions tested in previous trials, because of its widespread applicability and scalability it could have a larger population-level impact.

Aims of this study

The primary aim of this study was to produce evidence that a large-scale Phase III cluster RCT of a weight management intervention in which women engage in managing their own weight, by self-monitoring their weight and by accessing an existing online weight loss programme for support, is feasible. Should the intervention be feasible and acceptable, the ambition was to undertake a large-scale Phase III cluster RCT to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention in facilitating long-term weight loss.

Objectives

The objectives of this research were to:

-

assess the feasibility of delivering an intervention to promote self-management of weight loss through self-monitoring of weight and signposting to an online weight management programme by practice nurses as part of the UK child immunisation programme in women who have recently given birth

-

assess recruitment to ensure that a full-scale Phase III cluster trial is feasible

-

determine levels of adherence to the intervention (acceptability)

-

determine the extent of participant burden in completing the trial questionnaires

-

collect data on immunisation uptake rates (to check that the study does not have a detrimental effect on rates)

-

determine the potential risk for intervention contamination (whether or not participants in the control group have spontaneously accessed the online programme) to assess if the main trial sample size will need to be adjusted to account for this

-

provide estimates of the variability in the primary outcome (weight) to inform the sample size for the Phase III trial

-

assess the impact of the intervention on breastfeeding rates and psychological health in both groups

-

explore practice nurses’ views about delivering the intervention and explore any variation in intervention delivery to ascertain if any adjustment to nurse training is required using semistructured interviews

-

explore the acceptability of the intervention based on feedback from participants through semistructured interviews

-

explore the acceptability/validity of the ICEpop CAPability measure for adults (ICECAP-A) for the cost-effectiveness analysis in the Phase III trial.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design considerations

Before undertaking a large-scale Phase III cluster RCT to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intervention, it is important to assess the feasibility and acceptability of such a trial. Although individually randomised trials can be less prone to selection bias and cheaper than cluster trials, a cluster design helps avoid the possibility of contamination in the comparator group. In this trial, practice nurses were trained to deliver the intervention. If an individual-randomisation design had been used, nurses could potentially use aspects of their training with participants assigned to the usual-care group. It is also possible that women registered at the same practice or living near each other (by virtue of being registered at the same practice) could potentially share information or intervention resources. Cluster randomisation helps to avoid the possibility of this contamination in usual-care participants.

Practices (clusters) were randomised to either the weight management intervention or the comparator trial group. To avoid the possibility of selection bias, which can be a concern in cluster trials, it is recommended that the randomisation of the clusters (in this case practices) occurs once the participants have been identified and recruited into the trial. In this trial, it was not possible to allocate practices to the trial groups after participants were recruited because the required number of births per practice could occur over several months, meaning that we would miss the immunisation visits in which the intervention is being delivered.

Setting

This trial took place in Birmingham, where about one-third of the population are of non-white ethnicity (compared with 13% in England). Birmingham has high levels of socioeconomic deprivation, with 40% of the population living in super output areas in the 10% most deprived areas in England.

Ethics approval and study sponsor

Favourable ethics approval for this study was obtained from Black Country Ethics Committee (reference number 236462). The University of Birmingham (UoB) was the sponsor for this trial. The day-to-day management of the trial was co-ordinated by the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU) at the UoB. BCTU is fully registered as a UK Clinical Research Collaboration clinical trials unit.

Trial Steering Committee

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) met six times during the course of the study to assess its progress. The TSC included five independent members.

Patient and public involvement

As part of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care – West Midlands, a maternity Public and Researchers Involvement in Maternity and Early Pregnancy (PRIME) group was established to support and guide maternity-related research. The application proposal for this study was presented to six members of the PRIME group prior to submission and their views were incorporated into the application. Two members of the public, both of whom were married, mothers to three children, of white ethnicity and employed, were invited to join the study management group and attended all of the TSC meetings either in person or occasionally by teleconference. Their purpose and role were to help guide the research team and offer their experiences during both the trial and the qualitative study. Both patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives had recently given birth and were, therefore, able to offer feedback based on their very recent experiences of attending their general practice to have their child immunised. One of the representatives also had a personal interest in weight management after giving birth. All of the patient-facing trial documentation was viewed and commented on by the PPI representatives, and their feedback was incorporated into the documents. The PPI representatives were consulted regularly throughout all stages of the study, particularly regarding their views about different approaches to participant recruitment, their thoughts on the questions to be included in the interview topic guide and their views on planning for a subsequent Phase III trial. The research team found the feedback from the PPI representatives very useful; it kept the team ‘grounded’ and realistic in their expectations of participants. In a future trial, it would be important to invite mothers from non-white ethnic backgrounds to join the PPI group, to ensure that the views of women from a range of ethnic backgrounds are embedded in the management of the trial. The PPI representatives were reimbursed in line with the INVOLVE guidelines.

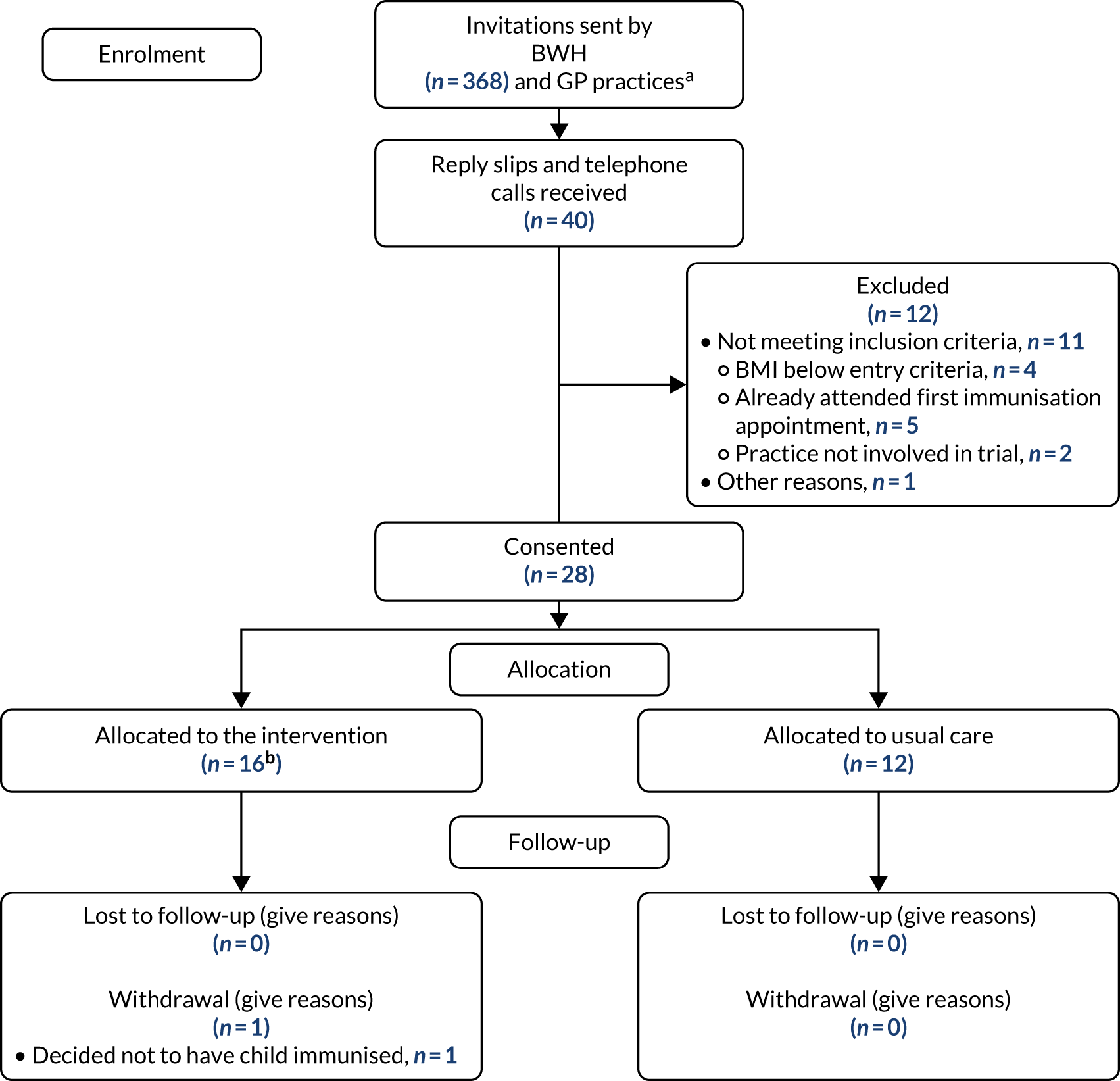

Design

A cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial design was used to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. General practice was the unit of randomisation. All women who had recently given birth and registered at participating practices were invited to take part. Group allocation was concealed from participants until baseline data were collected. To mitigate against selection bias, all women registered at general practices who gave birth at Birmingham Women’s Hospital (BWH) were sent an invitation letter inviting them to take part in the study. The trial has been reported in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for the reporting of trials.

Eligibility criteria

A complete list of all of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is detailed in the following sections, and these were applied at various stages during the recruitment process.

Inclusion criteria

-

Women aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Women who were at least 4-weeks postnatal and who had not yet attended their first child immunisation appointment.

-

Women planning to have their child immunised as part of the national immunisation programme.

-

Women with a BMI of ≥ 25kg/m2 at the time of recruitment at the baseline home visit.

-

Women able and willing to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Women whose babies had died or had been removed from their care at birth.

-

Women who indicated that they were already actively involved in a weight loss programme or weight management trial to lose weight.

-

Women who were unwilling to give consent to notify their GP of their involvement in this study.

-

Women who had been diagnosed with a serious mental health difficulty requiring hospitalisation or with anorexia and/or bulimia in the past 2 years.

Methods of recruitment

Screening via Birmingham Women’s Hospital

Computerised systems at BWH allowed for systematic identification of all postnatal women who had recently given birth, regardless of socioeconomic status and ethnicity, which reduced the potential for recruitment and selection bias. Every 2 weeks, BWH conducted searches of women aged ≥ 18 years who had recently given birth and were registered at participating practices. A trial invitation letter and participant information sheet were mailed to these women from BWH asking them to contact the study researchers if they were interested in the trial. Women did not receive their letter of invitation until at least 4 weeks post delivery. BWH applied the following initial screening criteria before sending study letters of invitation to women:

-

confirmed that the participant was aged ≥ 18 years

-

confirmed that the participant had given birth at least 4 weeks previously

-

confirmed that the participant was registered at one of the participating practices

-

excluded mothers whose babies had died or had been removed from their care at birth.

The invitation letter and participant information sheet included a telephone number that potential participants could call if they were interested in the trial. Alternatively, potentially eligible participants were asked to complete a screening reply slip and return it to the research team in the post using a free-post envelope. Between September and December 2018, women who had not responded within 10 days of being sent the invitation letter and participant information sheet received a follow-up call from the research team at BWH to ask if they were interested in taking part. As the study was recruiting from practices mostly located in high-deprivation communities with ethnically diverse patient lists, it was felt that women may respond better to a telephone call in which they could talk to a researcher regarding the trial rather than by a letter alone, particularly if their literacy was low. Further screening by telephone was conducted by the research team prior to the baseline home visit. Assessment of full eligibility was completed at the baseline home visit (see Establishing full eligibility at the baseline home visit and informed consent).

Direct recruitment through general practices

Towards the end of the study recruitment period, recruitment via BWH was supplemented with recruitment strategies directly via practices. Posters advertising the trial were displayed in waiting rooms at participating practices. Posters were also made available for viewing on general practice waiting room television screens. Participants who heard about the trial through this route were asked to telephone the research team for further information, and the study invitation letter and participant information sheet were mailed to interested women, if women had not already received one. If women were still interested after receiving the invitation/participant information sheet, they contacted the research team again, either by telephone or by returning a reply slip sent to them requesting a follow-up call. During this second telephone call, initial eligibility screening checks were completed. If all initial screening eligibility criteria were met, an appointment was made for a researcher to visit potentially eligible participants at home to fully confirm eligibility and collect baseline data.

There was also the opportunity for participants to be informed about the trial directly from baby check clinics, from postnatal check-ups or at any other appointment with the GP or other health-care professional post delivery and prior to the 2-month immunisation appointment. Some GPs in participating practices were asked to give a letter of invitation and participant information sheet directly to participants whom they may have seen at postnatal check-up consultations and who may have been eligible. In practices that held baby clinics, a researcher attended these clinics on an ad hoc basis. In this instance, the researcher attending the baby clinics was not the first point of contact for participants, as these participants had already received at least one letter of invitation from BWH and/or a health-care professional at their practice. When this occurred, the researcher provided potential participants with the letter of invitation and participant information sheet directly, either to read at the practice or to take home. If, after having read these documents, women remained interested, they were screened at the practice by the researcher or telephoned at a later time to establish initial eligibility (see Screening prior to baseline home visit). If all of the initial screening criteria were met, an appointment was made for a researcher to visit their home to fully confirm eligibility and collect baseline data.

Screening prior to baseline home visit

Regardless of how women were notified about the trial or how they were approached, prior to the baseline home visit all potential participants were initially screened for eligibility by a researcher over the telephone, when verbal permission was requested to collect some screening information to establish eligibility. Screening by the researcher prior to the baseline home visit established the following:

-

reconfirmed that the participant was aged ≥ 18 years

-

reconfirmed that the participant had given birth at least 4 weeks previously

-

reconfirmed that the participant was registered at one of the participating general practices

-

collected self-reported data on participants’ height and weight to calculate an approximate BMI

-

confirmed that participants were planning to have their child immunised

-

confirmed that participants had not yet attended the first child immunisation appointment

-

confirmed that participants were not already actively involved in a weight loss programme or a weight management trial to lose weight

-

confirmed that participants were willing to give consent to notify their GP of their participation in the trial.

An appointment was arranged for a researcher to visit the home of participants who fulfilled the initial screening criteria and who were interested in taking part in the study. The baseline visit was arranged to take place between 6 and 7 weeks postnatally, no earlier than 4 weeks and before the first immunisation visit at 2 months.

Establishing full eligibility at the baseline home visit and informed consent

Written informed consent was a two-stage process. At the baseline home visit, prior to any trial measurements being undertaken, a researcher obtained written informed consent to collect further screening data to fully confirm eligibility. If women consented to screening, the researcher measured participants’ height and weight to confirm the BMI eligibility criteria. As part of the eligibility criteria, the researcher confirmed that participants had not been diagnosed with a serious mental health difficulty requiring hospitalisation or been diagnosed with anorexia and/or bulimia in the past 2 years. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about the trial before signing and dating the screening informed consent form. Written informed consent was obtained from participants not deemed eligible at the home visit to keep any data collected about them from the screening process.

Participants who met all of the eligibility criteria at the baseline home visit were asked if they consented to be enrolled into the main trial. The trial was explained to them again verbally, and written informed consent was obtained for enrolment. The baseline assessments were then undertaken. Participants were then notified of the trial group to which their general practice was allocated. Researchers stressed to women that participation was voluntary and that they were free to refuse to take part and could withdraw from the trial at any time.

Written informed consent was obtained for the qualitative studies with women and practice nurses/GPs after they had completed either receiving or delivering the intervention.

Randomisation

The unit of randomisation was the practice (cluster). Linked practices that shared clinical staff were considered a single practice/cluster. Linked practices that did not share staff were considered independent practices. Practices in Birmingham and Solihull were invited to participate in the trial. The practices were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to the weight management intervention or to no intervention (usual care), using minimisation for practice list size (large, ≥ 6000 patients; small, < 6000 patients) and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score. The IMD was based on the postcode of the practice; the IMD score ranges from 1 to 32,844 and was divided into tertiles of high, medium and low levels of deprivation. The trials unit created a computer-generated randomisation list to allocate practices to the two trial groups. The randomisation list was held securely by the clinical trials unit. Once all of the necessary approvals were in place, practices were randomised centrally at BCTU by the trial statistician, and those practices randomised to the intervention group received the required training to deliver the intervention prior to opening for the trial. To maintain allocation concealment at the start of the study, randomisation of the first practices occurred when three practices were ready to open (except for need for trial intervention training). Thereafter, practices could be randomised sequentially.

Masking

It was not possible to mask participants or those providing the intervention to group allocation. It was also not possible to mask the outcome assessor, as the researcher needed to undertake both the baseline and the follow-up home visit to collect data. We do not believe that this would have introduced bias because the aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of undertaking a large Phase III cluster RCT, and these outcomes are not affected by knowledge of group allocation, and the data relating to the feasibility outcomes were not collected during the home visits.

Intervention

Overview summary

The intervention group were offered brief support that encouraged active self-management of weight in the postnatal period when they attended their practice to have their child immunised during the first year of life. In their first year, babies are routinely immunised at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age; the intervention was embedded in these routine immunisation contacts, so no additional visits by participants were required. The intervention involved nurses who encouraged participants to make healthier lifestyle choices through self-monitoring of their weight and signposting to an online weight management programme [Positive Online Weight Reduction (POWeR)] for support. 171 Nurses were asked not to provide any lifestyle counselling; their role was to only provide encouragement, provide regular external accountability (i.e. so that women were mindful that their weight was being monitored by someone else) and signpost women to the POWeR programme for weight loss information. The intervention was deliberately designed to be multicomponent because evidence suggests that such interventions lead to more favourable weight management during the postnatal period. 172

The intervention behaviour change techniques were mapped in accordance with the CALO-RE taxonomy checklist (Table 2). 173 The content of the intervention has also been mapped against the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 174

| Behavioural technique | Definition |

|---|---|

| Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | The practice nurse instructed participants to weigh themselves once per week. Participants were encouraged to weigh themselves on the same day and at the same time every week. The POWeR online programme also encouraged regular self-weighing, as well as giving information on how to make changes to eating and physical activity |

| Credible source | Participants were given an information leaflet at the start of the trial and were directed to the POWeR online programme |

| Social support (general) | Advice on using social support was included in the POWeR programme as were ‘POWeR stories’ from previous successful users of the programme |

| Goal-setting (behaviour) | Participants were asked to self-weigh and record their weight once per week. The POWeR online programme also allowed personalised eating and physical activity goals to be set each week |

| Goal-setting (outcome) | Participants were advised to aim for 0.5- to 1-kg weight loss per week, as advised by NICE for a general population |

| Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour | Participants were instructed to record their weight once per week on a record card that was attached to their child’s red book. Participants could also record their weight weekly on the POWeR online programme |

| Feedback of outcome(s) of behaviour | Participants were weighed at each immunisation appointment by the practice nurse and given feedback by the nurse with their weight recorded on the record card attached to their baby’s red book. The POWeR online programme also gave feedback on participant’s own review of their weekly self-weight |

| Review behaviour goal(s) | Previously set personalised eating and physical activity goals were reviewed in the POWeR online programme |

| Use of follow-up prompts | Participants were directed to the POWeR online programme, which provides weekly e-mail messages to prompt participants to access the programme. Participants were also prompted to self-weigh when seen by the nurse at the child immunisation appointments |

Women were asked to weigh themselves weekly and record this on a weight record card that was attached to their child’s health record red book, in which infant immunisations are recorded, or using the online programme. This is because nurses needed to be able to check that women were weighing themselves regularly, and the POWeR programme provides personalised information based on weight gain/loss progress. The intervention ran until the third immunisation (when the child was approximately 4 months old).

Weight loss goals

No clinical guidelines that specify rates of healthy weight loss for postnatal women are available, but for the general adult population NICE recommends 0.5–1 kg per week. 75 Participants were, therefore, advised to aim for 0.5- to 1-kg weight loss per week until they had achieved a BMI of < 25 kg/m2 and were no heavier than their pre-pregnancy weight.

Accountability

As outlined above, practice nurses did not provide any counselling about diet/physical activity; they simply weighed participants at each child immunisation visit and recorded this weight, as a source of regular external accountability for weight monitoring. Someone who is regularly weighed is more likely to maintain weight goals when they know that their progress will be monitored by another individual.

Online weight loss programme (POWeR)

Nurses signposted women to the POWeR online weight loss programme for weight loss support and assistance with goal-setting, action planning and implementation of changes to their lifestyle (https://powerpimms.lifeguidehealth.org; accessed July 2019). Women were given their own unique username and were asked to set their own secure password. The POWeR programme is an existing programme and has been shown to result in clinically effective weight loss in overweight primary care patients when combined with brief nurse support. 171 The POWeR programme is a self-guided, online, theory- and evidence-based intervention to support weight management over 12 months, and was designed to be appropriate for people in most situations, including postnatal women. Participants choose either a low-energy eating plan (a reduction of around 600 calories per day) or a low-carbohydrate eating plan. Users are also encouraged to increase their physical activity levels by choosing either a walking plan or a self-selected mixture of other physical activities. The POWeR programme focuses principally on fostering users’ self-regulation skills for autonomously self-managing their weight, rather than providing detailed dietetic advice. Users of the programme are taught active cognitive and behavioural self-regulation techniques (‘POWeR tools’) to overcome problems, such as low motivation, confidence and relapse. Evidence is provided for the effectiveness of these techniques and examples given of how others have successfully used them (‘POWeR stories’). The POWeR programme emphasises forming healthy eating and physical activity habits that should become non-intrusive and require little effort to sustain. Information about breastfeeding and weight loss was added to the programme for the purpose of this trial.

Participants were encouraged to continue to use the website weekly to track their weight, set and review eating and physical activity goals, and receive personalised advice. After entering their weight and whether or not they had achieved the goals they had set themselves the previous week, users received tailored feedback giving encouragement if they had maintained their weight loss (e.g. reminders of health benefits accrued) and met their goals. Weight gain and failing to meet goals triggered automated personalised advice, such as appropriate goal-setting and planning, boosting motivation, overcoming difficulties and recovering from lapses.

Training of practice nurses

All nurses who administered child immunisations at intervention practices were trained to deliver the intervention following a standard protocol. Training took about 20–25 minutes to complete, given that nurses’ involvement was very simple and brief. Nurses were also trained in the research trial procedures. A training manual provided information on the importance of adhering to the protocol, information on the consequences of postnatal weight retention, instructions about how to weigh and record weight in the appropriate place in the child health red book, and tips and phrases for encouraging women to weigh themselves weekly (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The nurse training also addressed any concerns nurses may have had about raising the topic of weight.

Intervention fidelity

Written informed consent was obtained from participants to audio-record their immunisation/intervention consultations so that intervention fidelity against a checklist could be assessed. Only the parts of the consultation relevant to the intervention were recorded. This process was also included to allow assessment from a practical and logistical perspective on how well the intervention fitted within immunisation visits and to also inform nurse training for any subsequent main trial. This also allowed the research team to calculate how long the intervention took nurses to deliver.

Usual-care comparator group

Women allocated to the usual-care comparator group received brief written information about following a healthy lifestyle and no other intervention at the baseline home visit.

Outcome measures and trial procedures

Primary outcome

The primary aim of the trial was to assess the feasibility of undertaking a full-scale Phase III cluster RCT. This was assessed via specific questions:

-

whether or not the trial was appealing to postnatal women (via assessment of the recruitment rate to ensure that a full Phase III trial is feasible)

-

whether or not the intervention was acceptable (via assessment of adherence to weekly self-weighing and registration with the POWeR online weight management programme)

-

whether or not the intervention had any adverse impact on infant immunisation rates (recorded attendance by practices)

-

the number of women who completed the trial and completed the trial questionnaires (follow-up).

BodyTrace weighing scales

The intervention group were given a set of real-time weight-tracking scales (BodyTrace scales, BodyTrace Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) as an objective process measure of adherence to weekly self-weighing (www.bodytrace.com/; accessed 12 November 2019). Each time a participant used the scales to weigh themselves, their data were sent to the research team in real time via wireless cellular data transfer. Participants who did not have wireless internet access in their homes, or did not want their weight to be transmitted to the team in real time, were given UPS ION scales (ION Health, Richmond, UK) that store 100 weight recordings on a Universal Serial Bus (USB) stick attached to the scales; with participants permission, these weight data were downloaded from the scales at the follow-up visit. The scales were delivered to participants’ homes and were set up by the research team. Women were informed that their weight data would be transferred to the research team but that they would not receive feedback regarding their weight from the research team.

Other outcomes

Although this feasibility trial was not powered to detect meaningful differences in outcome measures, it provided the opportunity to ensure that there were no issues with the completion of these measures in preparation for the main trial. All measures were assessed at baseline and follow-up in both groups unless stated otherwise. Weight and body fat were assessed using a Tanita SC-240MA analyser (Tanita Europe BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Depression and anxiety were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 175 Body image was measured using the Body Image States Scale (BISS). 176 Self-reported physical activity was assessed using the postnatal version of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ). 177 Weight control strategies were assessed at follow-up [Weight Control Strategies Scale (WCSS)]. 178 Using the revised Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ), the variables of conscious cognitive energy restraint of eating, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating were measured. 179 Questions from Steinberg et al. ’s180 perceptions of self-weighing questionnaire were used to measure perceptions of regular monitoring in the intervention group at follow-up only. 180

Health economics

Relative to routinely used economic quality-of-life measures, such as the EuroQol-5 Dimensions,181 the ICECAP-A has only recently been developed. 182 We assessed the acceptability of the ICECAP-A in the feasibility trial to inform the economic evaluation design in a full trial. It was seen as an important measure to include, as the benefits of weight loss are not confined to health alone and ICECAP-A offers the potential to capture well-being benefits in an economic framework.

Adverse events and serious adverse events

The collection and reporting of adverse events (AEs) was conducted in accordance with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care and the requirements of the Health Research Authority (HRA). The investigator assessed the seriousness and causality (relatedness) of all AEs experienced by trial participants, and if AEs occurred they were documented in the source data with reference to the protocol. No risks were expected to arise from taking part in the trial. The intervention was considered low risk, given that it consisted only of self-monitoring of weight, goal-setting and using an online weight loss programme, all of which have been used in other populations and settings without evidence of harm. There may be certain AEs that are commonly expected in participants undergoing a weight management programme. However, as these events are well characterised, it was highly unlikely that this trial would have revealed any new safety information relating to this intervention. Therefore, AEs were not collected. AEs related to the newborn baby were not collected either.

No serious adverse events (SAEs) were anticipated as a consequence of participation in the study, but reporting requirements were outlined in the trial protocol. Safety was assessed continuously throughout the study. The following were expected SAEs and were not reported as SAEs:

-

SAEs that were related to a pre-existing condition (pre-existing conditions are medical conditions that existed before entering the trial, as we intend to monitor the safety of the intervention by capturing severe, unexpected occurrences, in relation to the intervention).

-

Death as a result of a pre-existing medical condition. The protocol stipulated that all deaths should be reported to the trials office immediately on becoming aware so that no correspondence (patient questionnaires or queries, etc.) were sent to the participant or their family.

Investigators were required to only report SAEs that were attributable to the trial intervention. The above events were not considered related to the trial intervention and were, therefore, excluded from notification to the trial office as SAEs. The protocol was that these events should be recorded in the medical records in accordance with local practice.

Demographic-, lifestyle- and pregnancy-related information (both groups)

Information on age, ethnicity, pre-pregnancy weight, timing of cessation of breastfeeding, infant feeding practices and sleeping patterns of the mother were collected. Some women resume smoking and alcohol consumption after pregnancy, which might affect their weight; therefore, these behaviours were recorded. Data on whether or not participants in both groups had attended any formal weight loss programmes during their involvement in the trial were collected, as were data on any specific weight loss strategies or diets that participants might have used. Data relating to participants’ mode of delivery, participants’ pregnancy complications and how many children they had given birth to were collected. Data on marital status were collected to ascertain participants’ general level of social support in their lives. Data on employment status and financial status were collected to provide descriptive profile data on women who agreed to participate.

Objective assessment of self-weighing (intervention group)

As an objective measure of adherence to self-weighing, the intervention group were given weighing scales (BodyTrace, www.bodytrace.com/; accessed 12 November 2019) that objectively recorded their weight every time they weighed themselves, and this information was remotely transmitted back to the research team by wireless transfer. These weighing scales were given to women at the baseline home visit by researchers. These scales were included as an objective process measure to assess adherence to frequency of self-weighing in the intervention group; we did not provide any feedback to participants, nor did we monitor fluctuations or changes in weight during the trial.

Weight record cards (intervention group)

The intervention group were asked to complete weight record cards that were collected from participants as a measure of intervention implementation at the end of the intervention. The record cards allowed us to measure how much of the intervention was delivered per protocol by practice nurses. We obtained data from the POWeR programme for participants who chose instead to record their weight on the online programme.

Use of the POWeR online programme (intervention group)

Using participants’ e-mail addresses the online POWeR software automatically recorded their usage of the website (i.e. registration, number of logins, time spent on the POWeR website, progress through the POWeR programme and the number and value of weight measurements entered).

Attendance at immunisation appointments

The intervention was delivered at child immunisation appointments at 2, 3 and 4 months postnatally. Monitoring of immunisation uptake rates in the intervention group was an explicit role of the TSC. Practices were asked to provide data on all immunisations attended by both groups, and any missed appointments were investigated and a reason allocated. We also collected patient-reported attendance at the immunisation appointments at the follow-up visit.

Intervention fidelity via audio-recording of immunisation appointments

If consent to do so was provided, immunisation appointments were audio-recorded to gauge delivery of the intervention to protocol by practice nurses. These consultations were transcribed by a researcher (NTM) and read to assess, by use of a checklist, whether or not the nurses were delivering the intervention in accordance with their training and the protocol. The specific criteria checklist for nurses were as follows:

-

weighed and recorded participants’ weight on weight record card

-

checked that participants had been weighing themselves on a weekly basis

-

asked participants if they had accessed the POWeR website

-

verbally signposted participants to the POWeR website.

Intervention contamination

The possibility of intervention contamination in the usual-care group was assessed by asking participants if they knew any other women participating in the trial and whether or not they had accessed the POWeR website.

Trial procedures

Table 3 outlines all of the assessments and outcomes measured in this trial, the time points at which they were measured and the groups that were assessed. Baseline home visits took place between 6 and 7 weeks postnatally and before the first child immunisation visit at 2 months, and took about 30–45 minutes to complete. Participants were visited at home by a researcher, where:

-

Screening consent was obtained.

-

Height, weight and percentage body fat were measured, and BMI was calculated.

-

Eligibility (inclusion/exclusion criteria) was reviewed.

-

Informed consent was obtained for eligible participants.

-

The baseline health questionnaire booklet was completed/collected. The baseline questionnaire booklet was posted prior to the baseline home visit to allow the participant to complete the booklet in their own time prior to the visit.

-

Participants were informed which group of the trial they were allocated to.

-

The usual-care group were issued with the healthy lifestyle leaflet and advised that they would receive usual care at their child immunisation appointments.

-

The intervention group were issued with the healthy lifestyles leaflet, the weight record card was attached to the red immunisation book, a trial sticker was placed on the front of the red book, and participants were given BodyTrace scales and instructed on use (issued instruction leaflet). The intervention group were provided with details instructions and individual login details for the online weight management programme.

| Assessment | Visit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening: 4 weeks postnatally (no earlier than 4 weeks) | Baseline home visit: 6–7 weeks postnatally (before the first immunisation) | Immunisation visits at general practice (intervention group only) (postnatally) | Follow-up home visit: 3 months post randomisation (–1 week to approximately 4 weeks) | Post follow-up | |||

| 2 months | 3 months | 4 months | |||||

| Identification of potential participants | ✗ | ||||||

| Eligibility check | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Valid informed consent for screening | ✗ | ||||||

| Height (cm) | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Weight (kg) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Per cent body fat | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Valid informed consent for full trial | ✗ | ||||||

| Pregnancy and family details | ✗ | ||||||

| Feeding of baby | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Sleep patterns | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Marital status | ✗ | ||||||

| Employment and financial status | ✗ | ||||||

| Smoking status | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Alcohol consumption | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| HADS175 | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| ICECAP-A questionnaire182 | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| TFEQ179 | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| BISS176 | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| PPAQ177 | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| WCSS178 | ✗ | ||||||

| Immunisation record from participant | ✗ | ||||||

| Weight loss resources used | ✗ | ||||||

| Intervention group only: self-weighing data | ✗ | ||||||

| Intervention group only: BodyTrace weight data | ✗ | ||||||

| Intervention group only: POWeR programme171 data | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Intervention group only: trial acceptability | ✗ | ||||||

| Immunisation records from GP | ✗ | ||||||

| Qualitative study interviews | ✗ | ||||||

Follow-up home visit

Follow-up visits took place 3 months after participants entered the trial and took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Participants were visited at home by a member of the research team and the following tasks were completed:

-

Weight and percentage body fat measured, BMI calculated.

-

Follow-up questionnaires collected. Questionnaires were posted to participants 5–7 days in advance (for collection by the researcher).

-

Confirmation of attendance at immunisation appointments obtained.

-

Intervention group only – willingness to participate in a semistructured interview about experiences of participating in the study; collection or photograph of the weight record card; collection of BodyTrace weighing scales.

Participant incentives

A £20 high-street shopping voucher was offered to all participants as reimbursement for any inconvenience that trial participation may have caused them. This voucher was offered at the follow-up home visit once all follow-up clinical report form (CRF) questions and health questionnaires had been completed.

Data monitoring

Given that this was a feasibility trial that was designed to test whether or not a definitive trial was feasible, a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee was not established. Oversight of the trial was provided by the TSC.

Data management