Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/88/11. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The draft report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Barratt et al. This work was produced by Barratt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Barratt et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter includes material that has been adapted from the trial protocol, which has been published in BMJ Open. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Antibiotics are among the most frequently prescribed medicines for children worldwide. 2,3 In the UK, Italy and the Netherlands, almost 50% of children have received antibiotics by their second birthday. Annually, it is estimated that 30% of children aged 2–11 years receive antibiotics. 3

Of the possible indications in children aged < 5 years, the most common are acute respiratory tract infections, including community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). 4–6 CAP is one of the most common serious bacterial childhood infections. Although the majority of pneumonia deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, CAP is a major cause of morbidity in Europe and North America. 5,7 In the UK, 62% of all antibiotics prescribed for community-acquired infections are for CAP. 8 In the USA, respiratory symptoms, fever or cough are responsible for one-third of all childhood medical visits, and 7–15% of these children will be diagnosed with CAP. 9,10

Emergency department (ED) attendances and hospital admissions of children with respiratory complaints have increased in recent decades, mostly in preschool children. 9,11,12 According to Hospital Episode Statistics,13 children aged 0–4 years accounted for around 2.11 million ED attendances in 2017–18. More than 11,000 children aged < 15 years were admitted to hospitals in England with a diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia in 2008, and 9000 1- to 4-year-old inpatients with non-influenza pneumonia were recorded in 2012/13. 13,14

The bacterial pathogen most commonly associated with childhood CAP is Streptococcus pneumoniae, including in countries where pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) is routinely administered. 7,15–17 In 2010, PCV13 (which covers 13 S. pneumoniae serotypes) was introduced in the UK, with almost 95% uptake in young children. 18,19 However, despite an observed impact on invasive pneumococcal disease, a decrease in CAP-related hospital admissions in young children has not been observed. 11,14,20,21

What are the current challenges in the management of childhood community-acquired pneumonia?

There is no test capable of accurately distinguishing between bacterial and viral CAP. 22 Interobserver agreement for chest radigoraphic findings is poor, casting doubt on the usefulness of chest radiographs for identifying bacterial CAP, and culturing of microbiological samples, such as sputum, has low diagnostic value and samples are often difficult to take from young children. 23–25 Diagnosis of bacterial CAP presents a challenge for treating clinicians, who rely largely on clinical criteria. 22 Children presenting with fever, raised respiratory rate, focal chest signs and other respiratory signs and symptoms (such as cough) are commonly ascribed a diagnosis of bacterial CAP,10,26–28 whereas wheezing is associated with the absence of radiographic pneumonia and failure to detect bacteria in clinical samples. 26,29 If bacterial CAP is considered the likely diagnosis, treatment with antibiotics is instituted. 10,30 This diagnostic challenge is particularly problematic in secondary care, where the proportion of children presenting with serious bacterial infections is higher than in primary practice. 31,32

A further challenge for clinicians is severity assessment. Available validated predictive scoring systems for CAP severity include the Pneumonia Severity Index and the CURB-65 (confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and 65 years of age or older) score, but these are not applicable to children. 33,34 Pneumonia mortality risk scores for children have been developed in low-resource settings, but do not differentiate between viral and bacterial pneumonia. 35,36 Low oxygen saturation in room air is included as one component in these risk scores, and is an important factor for differentiating between non-severe and severe pneumonia. 37–39

Finally, assessing the efficacy of childhood CAP treatment is complex. Key measures in studies assessing efficacy early in the treatment course include lack of improvement or worsening of clinical symptoms and signs, such as respiratory rate and oxygen saturation. 40 According to British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidance, such criteria should trigger clinical review of children treated with oral antibiotics for CAP,22 including where the following features are present at 48 hours: (1) persistent high fever, (2) increasing or persistently increased effort of breathing and (3) persistent or increasing oxygen requirement to maintain saturations ≥ 92%. 22 Approximately 15% of children with CAP receive further antibiotics within 28 days of starting treatment because of symptoms that concern parents. 41–44 However, only half of children show recovery from symptoms of acute respiratory illness by day 9 or 10, and 90% of children recover by 3.5 weeks after symptom onset. 45–47

What are the current management recommendations for childhood community-acquired pneumonia?

Amoxicillin is the drug of choice for the treatment of childhood CAP according to the British National Formulary for Children (BNFc) and BTS and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, as well as several international guidelines,22,48–51 as it can effectively target and treat S. pneumoniae in the absence of high-level penicillin resistance. As a result, amoxicillin accounts for a very high proportion of overall oral antibiotic use among young children in many settings. Despite this, there is insufficient evidence to inform optimal treatment dose or duration.

What are the current dose recommendations?

Antibiotic dose selection should be driven by pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic considerations. The key pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameter for beta-lactams (including amoxicillin) is time spent above the minimum inhibitory concentration (T > MIC) (mainly focused here on pneumococcus). The recommended T > MIC is 40–50% of the dosing interval; however, the exact relationship between blood pharmacokinetics and concentrations of amoxicillin in the lungs is unclear. 48,52 The half-life of oral amoxicillin is about 1.0–1.5 hours and, on this basis, a three times daily regimen has been widely recommended. 53 However, there are few data to inform whether or not three times daily dosing is likely to achieve pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters better than twice-daily dosing. The available data suggest that, in the case of total amoxicillin doses of 25–50 mg/kg/day, twice-daily dosing should be sufficient to achieve adequate T > MIC53 and a Brazilian group recently demonstrated non-inferiority of twice-daily dosing compared with thrice-daily dosing in childhood CAP. 54 Together with a likely improvement in adherence to less frequent administration, twice-daily dosing is, therefore, widely recommended. 48–50,52 Currently, the BNFc recommends amoxicillin (250 mg) thrice daily for children aged 1–5 years with CAP, resulting in highly variable dosing, between approximately 40 mg/kg/day and 80 mg/kg/day, depending on the weight of the child. 55 Therefore, alternative strategies, such as weight-banded dosing, may be more appropriate. 56 Furthermore, much higher daily doses of amoxicillin, up to 200 mg/kg/day, are recommended for the treatment of severe infections. 55

What are the current duration recommendations?

Several large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have found shorter treatment courses in childhood CAP to be effective in low- and middle-income settings in terms of clinical cure, treatment failure and relapse rate. 57,58 However, these trials enrolled children with symptoms indicative of a viral infection not requiring antibiotics, and generalisability to the UK has, therefore, been questioned. 22 The BTS recognises that there are no robust data to inform guidance on duration of antibiotic treatment in childhood CAP. 22 The BNFc guidance relevant at the start of this trial recommended a 7-day course, whereas European and World Health Organization (WHO) guidance suggests a 3- to 5-day course. 48,55 In 2019, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence published guidance recommending stopping amoxicillin treatment after 5 days (250 mg thrice daily) for children aged 1–4 years, unless microbiological results suggest that a longer course length is needed or the patient is not clinically stable. 51

What is the impact of antimicrobial resistance in childhood community-acquired pneumonia?

In the UK, the rates of penicillin non-susceptibility of S. pneumoniae are relatively low, at approximately 15% for respiratory samples (mainly from adults) and 4–6% for blood culture isolates. 59 Penicillin resistance [i.e. minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) > 2 μg/ml] has not been observed in blood culture isolates and has been found in < 1% of respiratory S. pneumoniae isolates in the UK since 2010. 59 However, some worrying trends are observed in resistance of gut bacteria, and this situation will be exacerbated in a setting where antibiotics are used injudiciously. 60

The relationship between MIC (an in vitro phenomenon) and clinical outcome in CAP is complex, and data on the level of S. pneumoniae antimicrobial resistance that reduces amoxicillin effectiveness are limited. Harmonisation of European breakpoints (i.e. the MIC at which an isolate is considered susceptible, intermediate or resistant) attempts to provide a link between clinical impact and in vitro observation of resistance. 61 Clinical breakpoints are determined based on a variety of data, in addition to efficacy studies. This includes pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data, which for penicillin usually take T > MIC of 40% as the key exposure measure.

Children have high rates of bacterial colonisation, which often represents an increased level of carriage of resistant organisms62,63 These may be passed on to others in the community, especially within child-care settings. 64,65 Interventions to maintain a low level of antimicrobial resistance among colonising bacteria may, therefore, have population implications.

The limited existing data on the specific impact of duration and dose of antibiotic treatment on subsequent colonisation with resistant bacteria in vivo suggest a complex and dynamic relationship. 62–73 Experimental models suggest that insufficiently high dosing could promote selection of resistant pathogens. In addition, although most of the effect on bacterial load is achieved early during antibiotic exposure, resistant isolates emerge after 4 or 5 days. 74–78 RCTs assessing the effect of antibiotic duration and dose have been called for, as they will probably provide the strongest evidence for the relationship between antibiotic exposure and colonisation with resistant bacteria. 79 One such RCT found that higher-dose shorter-duration amoxicillin therapy for childhood CAP led to less colonisation with resistant bacteria after 4 weeks, and was associated with better treatment adherence. 72 However, mathematical modelling indicates that this may come at the price of selecting isolates with higher levels of resistance, and clinical efficacy was not addressed in the trial. 72,78

Trial rationale

Despite the reduction in incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease since the introduction of the conjugate vaccine,20 CAP remains one of the most commonly identified and treated childhood infections in the UK. Although there is clear agreement that amoxicillin should be the first-line treatment, there are insufficient data to inform selection of dose and duration, and the impact that different regimens have on antimicrobial resistance is unknown.

Effectiveness and resistance-outcome data pertaining to dose and duration of amoxicillin could inform antimicrobial stewardship strategies in the large group of children with a high likelihood of bacterial CAP targeted by CAP-IT (Community-Acquired Pneumonia: a protocol for a randomIsed controlled Trial). A better understanding of the relationship between dose and duration of antibiotic treatment, and the impact on clinical outcomes and antimicrobial resistance, would make it possible to formulate improved evidence-based treatment recommendations for childhood CAP.

Objectives

The main objective of CAP-IT was to determine the following for young children with uncomplicated CAP treated after discharge from hospital if:

-

a 3-day course of amoxicillin is non-inferior to a 7-day course, determined by receipt of a clinically indicated systemic antibiotic other than trial medication for respiratory tract infection (including CAP) in the 4 weeks after randomisation up to day 28

-

lower-dose amoxicillin is non-inferior to higher-dose amoxicillin under the same conditions.

Secondary objectives were to evaluate the impact of lower-dose and shorter-duration amoxicillin on antimicrobial resistance, severity and duration of parent/guardian-reported CAP symptoms and specified clinical adverse events (AEs).

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

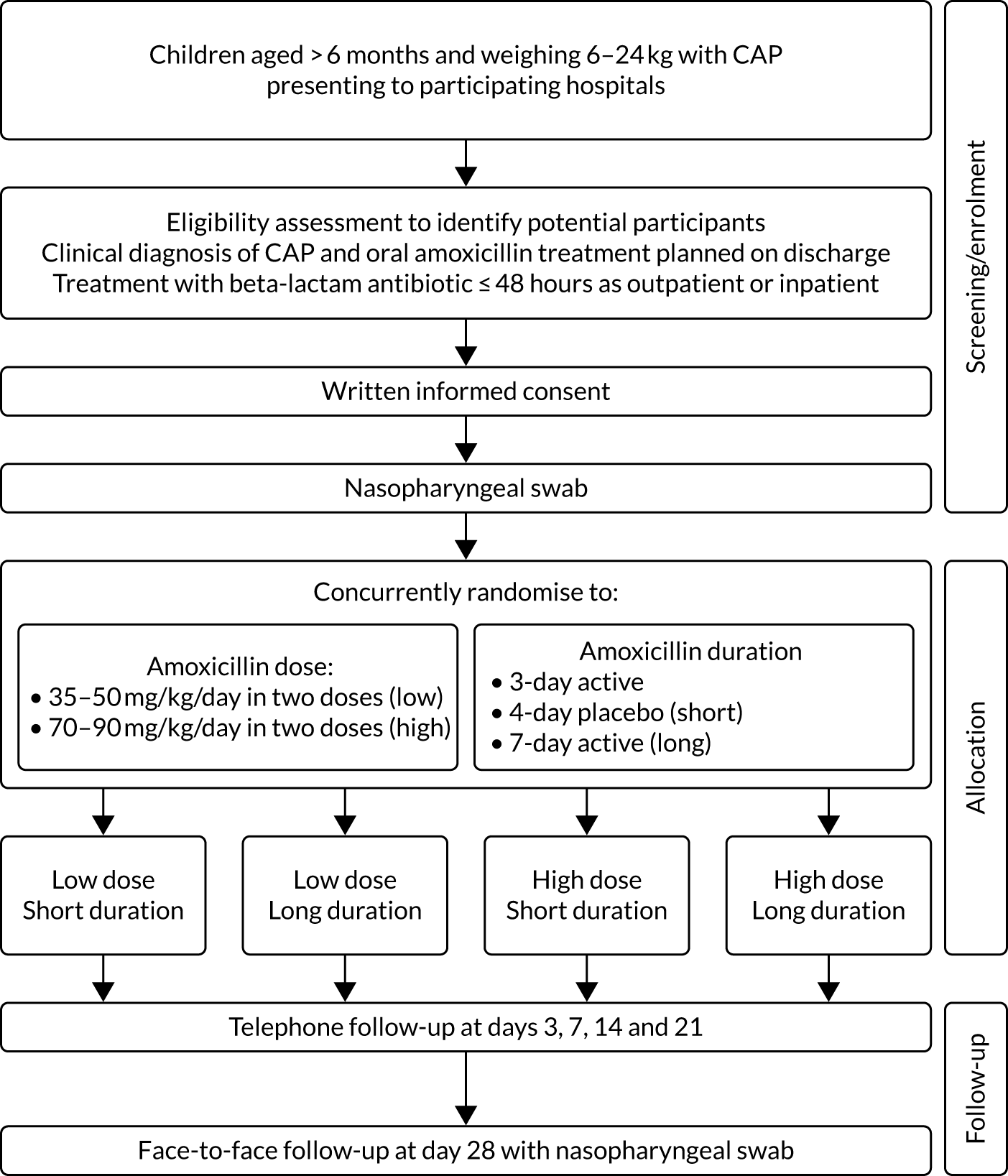

The CAP-IT study was a multicentre clinical trial with a target sample size of 800 participants in the UK and Ireland. In design, it was a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled 2 × 2 factorial non-inferiority trial of amoxicillin dose and duration in young children with CAP (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The CAP-IT schema.

Trial setting

Participants were recruited from 28 UK NHS hospitals and one children’s hospital in Ireland:

-

Alder Hey Children’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Liverpool, UK)

-

Barts Health NHS Trust (London, UK)

-

Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust (Birmingham, UK)

-

Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust (Brighton, UK)

-

Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK)

-

Children’s Health Ireland (Dublin, Ireland)

-

City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust (Sunderland, UK)

-

Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Chester, UK)

-

County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust (Darlington, UK)

-

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK)

-

Hull and East Yorkshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (Hull, UK)

-

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (London, UK)

-

King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK)

-

The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (Leeds, UK)

-

Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (Manchester, UK)

-

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (Nottingham, UK)

-

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Oxford, UK)

-

Southport and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust (Southport, UK)

-

Royal Hospital for Children (Glasgow, UK)

-

Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust (Sheffield, UK)

-

South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Middlesbrough, UK)

-

St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (London, UK)

-

University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (Bristol, UK)

-

University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust (Derby, UK)

-

University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust (Leicester, UK)

-

University Hospitals Lewisham (London, UK)

-

University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust (Southampton, UK)

-

University Hospital of Wales (Cardiff, UK).

Participating sites were tertiary or secondary hospitals with paediatric emergency departments (PEDs) and inpatient facilities, and were selected in collaboration with Paediatric Emergency Research in the UK & Ireland80 on the basis of clinical and research infrastructure, experience in clinical research and likely eligible population size.

Participants

Patients presenting to participating hospitals were identified in PEDs, assessment/observation units or inpatient wards. Potential participants were screened as early as possible during the initial clinical assessment. Informed consent was sought from a parent/guardian once eligibility had been confirmed, but only after full explanation of the trial aims, methods and potential risks and benefits. Discussions regarding the trial took place between families and clinical teams when the child’s clinical condition was stable, to minimise distress. Extensive information and recruitment materials were available for recruiting sites, including printed and video materials [accessible at URL: www.capitstudy.org.uk (accessed 29 July 2021)]. CAP-IT information film was designed to assist research teams in the recruitment process and provided information to parents/guardians about the purpose of the trial, the use of placebo and trial procedures. Parents/guardians could watch the film in their own time while in hospital, and research teams reported that the film was a useful tool during the recruitment process. The film was made with input from the trial patient and public involvement (PPI) representative and featured a site principal investigator and research nurse, as well as graphics to aid explanation of trial procedures. [It can be viewed at https://vimeo.com/217849985 (accessed 29 July 2021).] Families were able to decline participation in the trial at any time without providing a reason and without incurring any penalty or affecting clinical management.

Recruitment pathways

Children were recruited through two different pathways based on whether they received any inpatient antibiotic treatment (ward group) or not (PED group). Children in either group may have had up to 48 hours of oral or parenteral beta-lactam treatment before enrolment. The PED group contained children who had not received any in-hospital antibiotic treatment (but may have had up to 48 hours of beta-lactam antibiotics in the community), whereas the ward group contained children who received any in-hospital oral or intravenous beta-lactam therapy prior to randomisation. Children in the latter group may have received beta-lactam treatment in the community first and subsequently in hospital, without interruption, for a total of < 48 hours.

Inclusion criteria

Children were eligible if they had a clinical diagnosis of uncomplicated CAP, were aged > 6 months and weighed 6–24 kg, and treatment with amoxicillin as the sole antibiotic was planned on discharge. Box 1 shows the clinical criteria required for a diagnosis of CAP in CAP-IT.

Clinical diagnosis of CAP is defined as:

-

cough (reported by parents/guardians within 96 hours before presentation)

-

temperature ≥ 38 °C measured by any method or likely fever within 48 hours before presentation

-

signs of laboured/difficult breathing or focal chest signs (i.e. one or more of nasal flaring, chest retractions, abdominal breathing, focal dullness to percussion, focal reduced breath sounds, crackles with asymmetry or lobar pneumonia on chest radiograph).

Exclusion criteria

Children were excluded if they had received ≥ 48 hours of beta-lactam antibiotics or any non-beta-lactam agents, or if they had severe underlying chronic disease with increased risk of complicated CAP (including sickle cell anaemia, immunodeficiency, chronic lung disease and cystic fibrosis), documented penicillin allergy or other contraindication to amoxicillin, complicated pneumonia (including shock, hypotension, altered mental state, ventilatory support, empyema, pneumothorax and pulmonary abscess) or bilateral wheezing without focal chest signs.

Changes to selection criteria

During the trial enrolment period, eligibility criteria were modified based on emerging data to better reflect clinical management and facilitate inclusion of all children to whom the results of the trial may be of relevance.

Age and weight criteria were amended from ‘age from 1 to 5 years (up to their 6th birthday)’ in protocol v2.0 to ‘greater than 6 months and weighing 6–24 kg’ in protocol v3.0. Children recruited to protocol v2.0 were excluded if they were receiving systemic antibiotic treatment at presentation. This was modified in protocol v3.0 for the PED group and in protocol v4.0 for the ward group, such that children were eligible if they had received ≤ 48 hours’ systemic antibiotic treatment at trial entry, as per section 2.3 of the protocol.

Children in the ward group were excluded in protocol v2.0 if they had ‘current oxygen requirement’ or ‘current age-specific tachypnoea’; however, these criteria were removed in protocol v3.0 and replaced with the inclusion criterion ‘child is considered fit for discharge at randomisation’.

The CAP diagnostic criterion relating to fever changed from ‘temperature ≥ 38 °C measured by any method OR history of fever in last 24 hours reported by parents/guardians’ in protocol v2.0 to ‘temperature ≥ 38 °C measured by any method OR likely fever in last 48 hours’ in protocol v3.0 to account for the accompanying parent/guardian not measuring temperature in the preceding 24 hours.

Interventions

The investigational medicinal product (IMP) for treatment at home was provided as a powder to be suspended on the day of randomisation. Children received oral amoxicillin suspension twice daily, commencing on the day of randomisation. All children were weighed during eligibility screening and was used to determine dose volume according to seven weight bands (Table 1).

| Weight range (kg) | Dosing intructions |

|---|---|

| ≤ 6.4 | 4.5 ml twice a day |

| 6.5–8.4 | 6 ml twice a day |

| 8.5–10.4 | 7.5 ml twice a day |

| 10.5–13.4 | 9.5 ml twice a day |

| 13.5–16.9 | 12 ml twice a day |

| 17.0–20.9 | 15 ml twice a day |

| 21.0–24.0 | 16.5 ml twice a day |

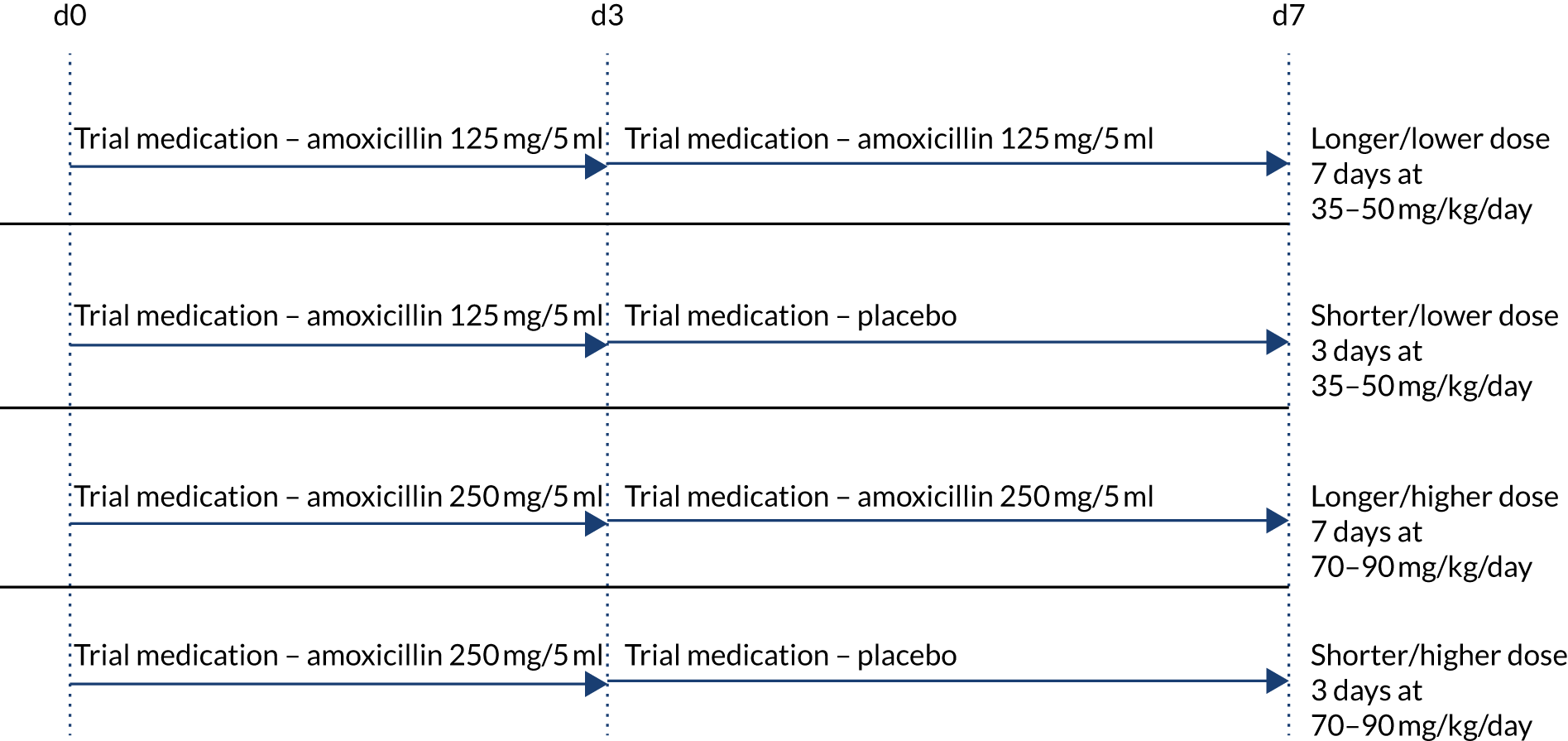

Participants were randomised to receive either a lower (35–50 mg/kg/day) or a higher (70–90 mg/kg/day) dose, concealment of which was achieved by using amoxicillin products of two different strengths (125 mg/5 ml and 250 mg/5 ml). Therefore, children in each dose arm in the same weight band were administered the same volume of suspension .

Participants were simultaneously randomised to receive either 3 or 7 days of amoxicillin treatment at home. A placebo manufactured to match the characteristics of oral amoxicillin suspension was used to blind parents/guardians and clinical staff to the duration allocation. Both active drug and placebo formed a yellow-coloured similar-tasting suspension. However, because of difficulties in exactly taste-matching the placebo suspension to amoxicillin, one brand of amoxicillin was used for the first 3 days of treatment followed by a second brand for days 4–7 when duration of treatment was 7 days. Parents were instructed to expect a taste change between bottles, but they did not know whether this was due to moving to placebo or to a new brand of amoxicillin. Allocated treatment duration to be given after discharge from hospital was fixed at 3 or 7 days independently of any antibiotics received before randomisation, with up to 48 hours of oral or parenteral beta-lactam treatment permitted before enrolment.

This resulted in four treatment arms, as shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Treatment arms.

The hypothesis is that higher doses of amoxicillin given for a longer duration are non-inferior to lower doses of amoxicillin given for a shorter duration for the treatment of children attending hospital with CAP in terms of antibiotic retreatment.

The objective is to conduct a RCT in children attending hospital with CAP comparing higher and lower doses of amoxicillin given for 3 or 7 days.

Drug substitutions and discontinuations of trial treatment

Substitution of an alternative amoxicillin formulation or another antibiotic was permitted where tolerability issues could not be overcome by improving acceptability (e.g. by mixing the suspension with formula milk, other liquids or foods) or where a clinical need for continued treatment persisted. In situations of toxicity, for example if an allergic reaction to penicillin was suspected, substitution with an alternative class of antibiotic was permitted.

Discontinuation of trial treatment was permitted if, on clinical review, a change in the child’s condition justified discontinuation or modification of trial treatment, if use of a medication with a known major or moderate drug interaction with amoxicillin was essential for the child’s management or if the parent/guardian withdrew consent for treatment.

In situations where retreatment was deemed necessary, the choice of antibiotic was left to the treating clinician.

Trial assessments and follow-up

Participants were screened as described in Participants, and, following receipt of informed consent, randomisation was performed at the point of discharge from hospital. Following randomisation, all participants were followed up for 29 days for evaluation of the primary and secondary end points described in Outcomes. The timing and frequency of assessments are summarised in the trial schedule (Table 2) and described below.

| Assessment | Pre randomisation:a ≤ 48 hours before randomisation | Days in trial | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 (randomisation) | Day 3 | Days 7–9 (week 1) | Days 14–16 (week 2) | Days 21–23 (week 3) | Days 28–30 (week 4) | Any acute event | ||

| Trial participation | ||||||||

| Parent/guardian information sheetb | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | |||||||

| Drug supply dispensing | ✗ | |||||||

| Adherence questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | (✗) | |||||

| Adherence review (returned medication) | ✗ | |||||||

| Clinical assessment | ||||||||

| Medical historyb | (✗) | ✗ | ||||||

| Physical examinationb | (✗) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Symptom reviewb | (✗) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EQ-5D | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Use of health services | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Laboratory assessment | ||||||||

| Nasopharyngeal swabc | (✗) | ✗ | ✗ | (✗) | ||||

| Haematology | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||||

| Biochemistry | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||||

| Virology | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||||

| Radiological assessment | ||||||||

| Chest radiography | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | |||||

| Parent-completed diary | ||||||||

| Symptom diary | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Ancillary subgroup studies | ||||||||

| Stool samplec | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

Enrolment and randomisation

Following identification, screening and informed consent of eligible patients, baseline information was obtained through interview with the parent/guardian. This included demographic information, such as sex and ethnicity, medical history, including review and duration of symptoms (e.g. cough, temperature and respiratory symptoms), underlying diseases and antibiotic exposure in the preceding 3 months. Details of the physical examination, including weight and vital parameters (e.g. temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate and oxygen saturation in room air), were recorded and a baseline nasopharyngeal swab was obtained.

No additional tests were mandated, but results were collected if tests were performed as part of clinical care, including haematology tests (e.g. haemoglobin, platelet count, leucocyte count, neutrophil count and lymphocyte count), biochemistry tests (e.g. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and electrolytes), virology [rapid testing for respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A/B (any method)] and chest radiography.

Parents/guardians were provided with trial materials, including a symptom diary, participant information sheet, IMP administration instructions and contact details for the trial team. The symptom diary collected data pertinent to the primary and secondary outcomes and was completed by parents for 14 days following randomisation.

Follow-up

Telephone contact was made with participants on days 3, 7–9, 14–16 and 21–23, with a face-to face visit within 2 days of day 28. At these contacts, primary and secondary end points were reviewed, including additional antibiotic treatment, clinical signs and symptoms, adverse treatment effects and IMP adherence. During face-to-face visits (final or unscheduled) a nasopharyngeal swab was collected, and, if CAP symptoms were ongoing, physical examination findings and physiological parameters were collected. If a hospitable face-to-face visit was not possible for final follow-up, it was attempted by telephone or as a home visit. If this failed, despite reasonable efforts, primary end-point data were sought through contact with the general practitioner (GP) where consent had been given to do so.

If participants required acute clinical assessment for ongoing/re-emerging symptoms during the follow-up period, the treating clinician’s judgement determined if investigations, treatment or hospitalisation was required. On premature discontinuation of IMP, irrespective of reason, parents/guardians were encouraged to remain in follow-up. However, parent/guardian decisions were respected, and if follow-up was stopped prematurely, then data and samples already collected were included in the analysis unless parents/guardians requested otherwise.

Data collection and handling

Data were recorded on paper case report forms and entered onto the CAP-IT database by clinical or research staff at each site. Staff with data entry responsibilities completed standardised database training before being granted access to the database. Data were exported into Stata® (v15.1) (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis.

Randomisation

Eligibility was confirmed by CAP-IT site investigators through completion of an eligibility checklist. Patients were randomised simultaneously to each of the two factorial randomisations in a 1 : 1 ratio. Randomisation was stratified by group (PED and ward) according to whether or not they had received any non-trial antibiotics in hospital before being enrolled.

A computer-generated randomisation list was produced by the trial statistician based on random permuted blocks of eight. Each block contained an equal number of the four possible combinations of dose and duration in random order. The IMP supplier packaged the trial medication into kits that were grouped into blocks of eight, in accordance with to the randomisation list specification. Blinded IMP labels were applied to each kit, which contained the kit identifications (IDs). Kit IDs were made up of four numerical digits, the first three of which represented the block ID and fourth specified the kit ID within the block. Blinded randomised blocks of IMP were delivered to trial sites and participants were randomised by dispensing the next sequentially numbered kit within the active block.

Blinding

All treating clinicians, parents/guardians and outcome assessors [including End-Point Review Committee (ERC) members] were blinded to the allocated treatment. The use of placebo, as well as the permuted block randomisation strategy and blinded drug kits, ensured that parents and clinic staff remained blinded to amoxicillin duration and dose.

Access to the randomisation list was restricted to trial statisticians and IMP repackagers, and unblinded data were reviewed confidentially only by the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) (annually) and trial statisticians. The Trial Management Team remained blinded until after the trial end and completion of the statistical analysis in accordance with the prespecified statistical analysis plan (SAP).

Unblinding was possible in situations where a treating clinician deemed it necessary, for example in the case of a significant overdose. This could be performed using an emergency unblinding system accessible through the CAP-IT website. Only the treating clinician would then be informed of the child’s allocation, maintaining the blinding of the trial team.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome for CAP-IT was defined as any clinically indicated systemic antibacterial treatment prescribed for respiratory tract infection (including CAP) other than trial medication up to and at week 4 final follow-up (i.e. day 28). Prescription of non-trial medication when the primary reason was (1) illness other than respiratory tract infection, (2) intolerance of or adverse reaction to IMP, (3) parental preference or (4) administrative error did not constitute a primary end point.

An ERC, comprising doctors independent of the Trial Management Group and blinded to randomised allocations, reviewed all cases of a participant being prescribed non-trial systemic antibacterial treatment. The main role of the ERC was to adjudicate, based on all available data, whether or not the primary outcome was met. The ERC classified non-trial systemic antibacterial treatment as being for respiratory tract infection with likelihoods of ‘definitely/probably’, ‘possibly’, ‘unlikely’ or ‘too little information’. Those infections categorised as ‘CAP’, ‘chest infection’ or ‘other respiratory tract infection’ with a treatment likelihood assessment of ‘definitely/probably’ or ‘possibly’ were regarded as fulfilling the primary end point.

Information on additional antibacterial treatments was collected from parents through follow-up telephone contact with parents on days 3, 7, 14 and 21, at the final visit contact and finally through a daily diary completed by parents on days 1–14.

During enrolment, parents were asked to provide consent for the research teams to contact their child’s general practice to collect information regarding antibacterial treatment given during the follow-up period. This additional information supported the ERC in accurately adjudicating events. In addition, this allowed the collection of primary outcome data where contact with participants had been lost prior to completion of the follow-up period.

Changes to primary end point

The primary end-point definition was clarified in protocol v3.0 to specify that ‘systemic antibacterial’ treatments should avoid inclusion of topical antibiotics, which were not of interest. In protocol v4.0, the primary end point was refined further, resulting in the definition in Primary outcome. This definition specified that the systemic antibacterial must be clinically indicated and prescribed for a respiratory tract infection (including CAP), as adjudicated by the ERC.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included measures of morbidity, antimicrobial resistance and trial medication adherence.

Morbidity

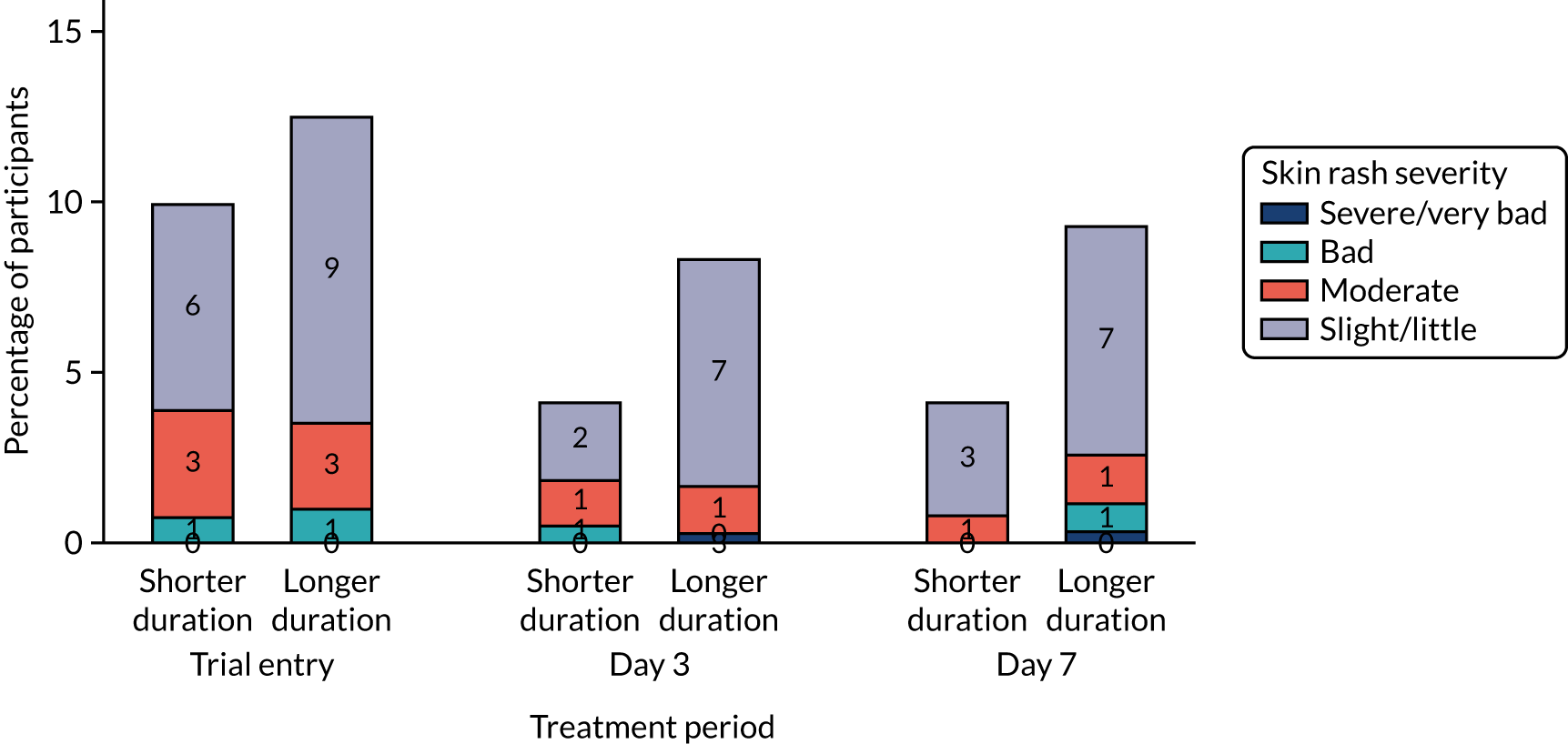

Morbidity secondary outcomes included severity and duration of parent/guardian-reported CAP symptoms and specified clinical AEs.

The following CAP symptoms were elicited at baseline, in follow-up telephone calls at days 4, 8, 15 and 22 and at the final visit, as well as at unscheduled visits: cough, wet cough (i.e. phlegm), breathing faster (i.e. shortness of breath), wheeze, sleep disturbed by cough, vomiting (including after cough), eating/drinking less and interference with normal activity. Parents/guardians were asked to grade each symptom using the following five categories: (1) not present, (2) slight/little, (3) moderate, (4) bad and (5) severe/very bad. Date of start and resolution were also elicited. Symptoms and their severity (using the same categories) were obtained daily on the symptom diary for 14 days from randomisation.

Information about diarrhoea, skin rash and thrush was collected and graded in the same way as CAP symptoms. In addition, AEs related to the stopping of trial medication or the start of non-trial antibiotics were recorded.

Other AEs meeting the criteria for seriousness [i.e. serious adverse events (SAEs)] were reported within 24 hours of research sites becoming aware of the event. SAEs were classified by system organ class and lower-level term in accordance with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®; version 21.1) and were graded using the Division of Aids (DAIDS) Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Paediatric Adverse Events. 81

Antimicrobial resistance

The antimicrobial resistance secondary end point was defined as phenotypic resistance to penicillin at week 4 measured in S. pneumoniae isolates colonising the nasopharynx. Carriage and resistance of S. pneumoniae isolates were assessed by analysis of nasopharyngeal samples, collected from participants at baseline, at the final visit (i.e. day 29) and at any unscheduled visits during the follow-up period.

Phenotypic penicillin susceptibility was determined for S. pneumoniae isolates by microbroth dilution across a dilution range for penicillin of 0.016–16 mg/l and interpreted in accordance with EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) clinical break-point tables v10.0 for benzylpenicillin and S. pneumoniae (infections other than meningitis) [i.e. sensitive (MIC ≤ 0.064 mg/l), non-susceptible (MIC 0.125–2 mg/l) or resistant (MIC > 2 mg/l)]. 82 The same approach was taken for amoxicillin susceptibility testing [isolates with MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/l were sensitive and isolates with MIC > 1 mg/l were resistant). S. pneumoniae ATCC® 49619™ (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was used for quality control. 82

Adherence

Data on IMP adherence were elicited during follow-up telephone calls, at the final visit (where follow-up telephone calls were not performed) and at unscheduled visits. At each time point, parents/guardians were asked if IMP had been stopped early, and, if so, the date of the last dose taken and for which of the following reasons: CAP improved/cured, CAP worsened/not improving or gagging/spitting out/refusing. In addition, parents/guardians were asked how many doses of each bottle were either missed or were less than the full prescribed volume.

Sample size

The sample size was based on demonstrating non-inferiority for the primary efficacy end point for each of the duration and dose randomisations. Although inflation factors have been advocated for factorial trials to account for interaction between the interventions, or a reduction in the number of events, this is not necessary if either randomised intervention (dose or duration) has a null effect (i.e. the underlying hypothesis with a non-inferiority design), as marginal analyses can then be conducted.

The expected antibiotic retreatment rate was originally assumed to be 5%. However, data emerging during the enrolment phase suggested that the primary outcome event rate was considerably higher, at approximately 15%. This necessitated a change in the non-inferiority margin, which was increased from 4% to 8%. This is still lower than the European Medicines Agency’s recommendation of a 10% non-inferiority margin for adult CAP trials. 83 Assuming a 15% event rate, 8% non-inferiority margin (on a risk difference scale) assessed against a two-sided 90% confidence interval (CI) and 15% loss to follow-up, the sample size was calculated as 800 children to achieve 90% power.

Statistical methods

Analysis principles

The primary analysis adopted a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, that is it included all patients enrolled and analysed in accordance with the group to which they were randomised, regardless of treatment actually received. One modification to the strict ITT principle prespecified in the trial SAP was the exclusion of randomised patients who did not take any IMP. Owing to the blinded nature of the trial, the risk of introducing bias by exclusion of these patients was considered minimal. A secondary on-treatment analysis was performed that excluded ‘non-adherent’ participants, defined as having taken < 80% of scheduled trial medication, based on (1) all trial medication including placebo and (2) active drug only.

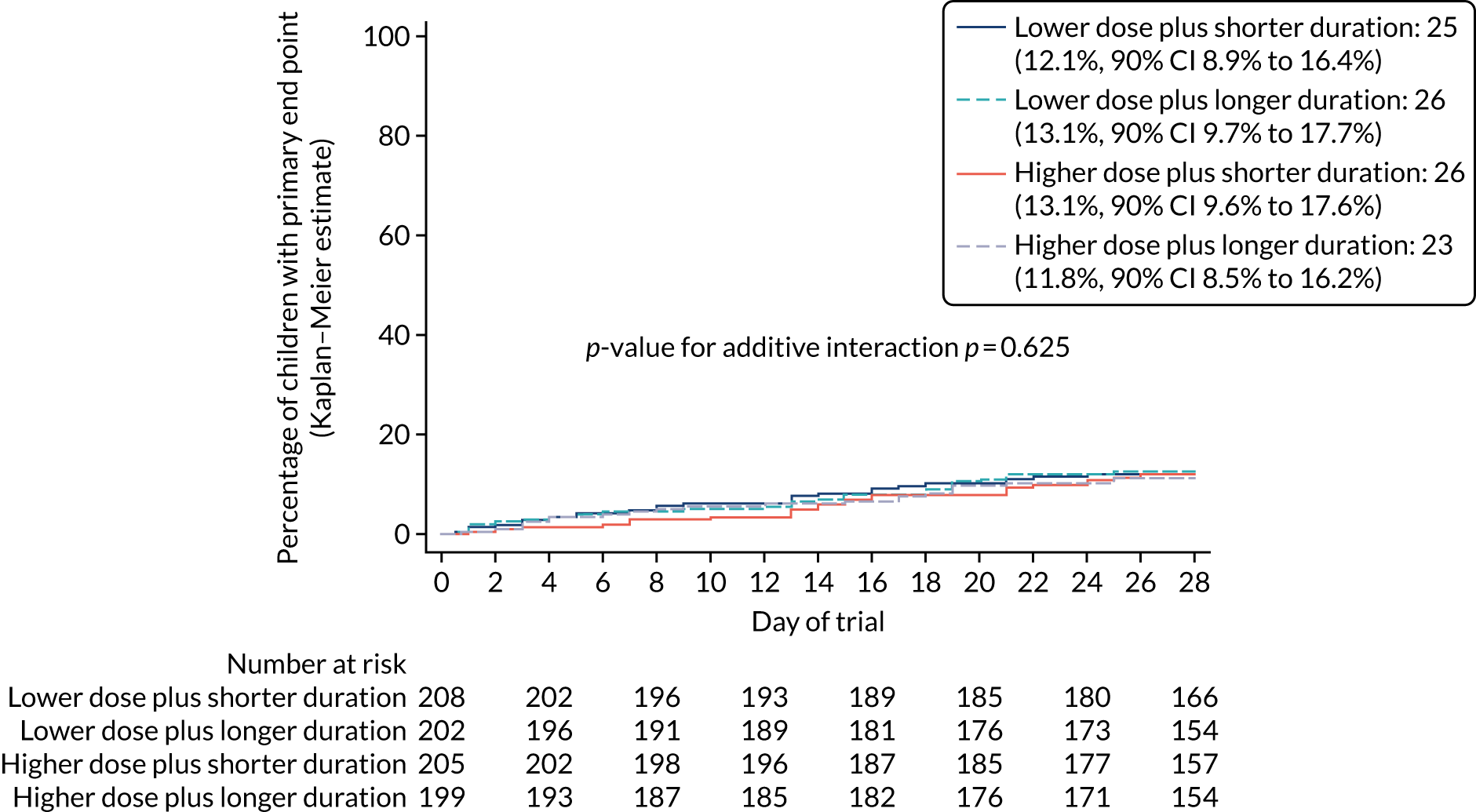

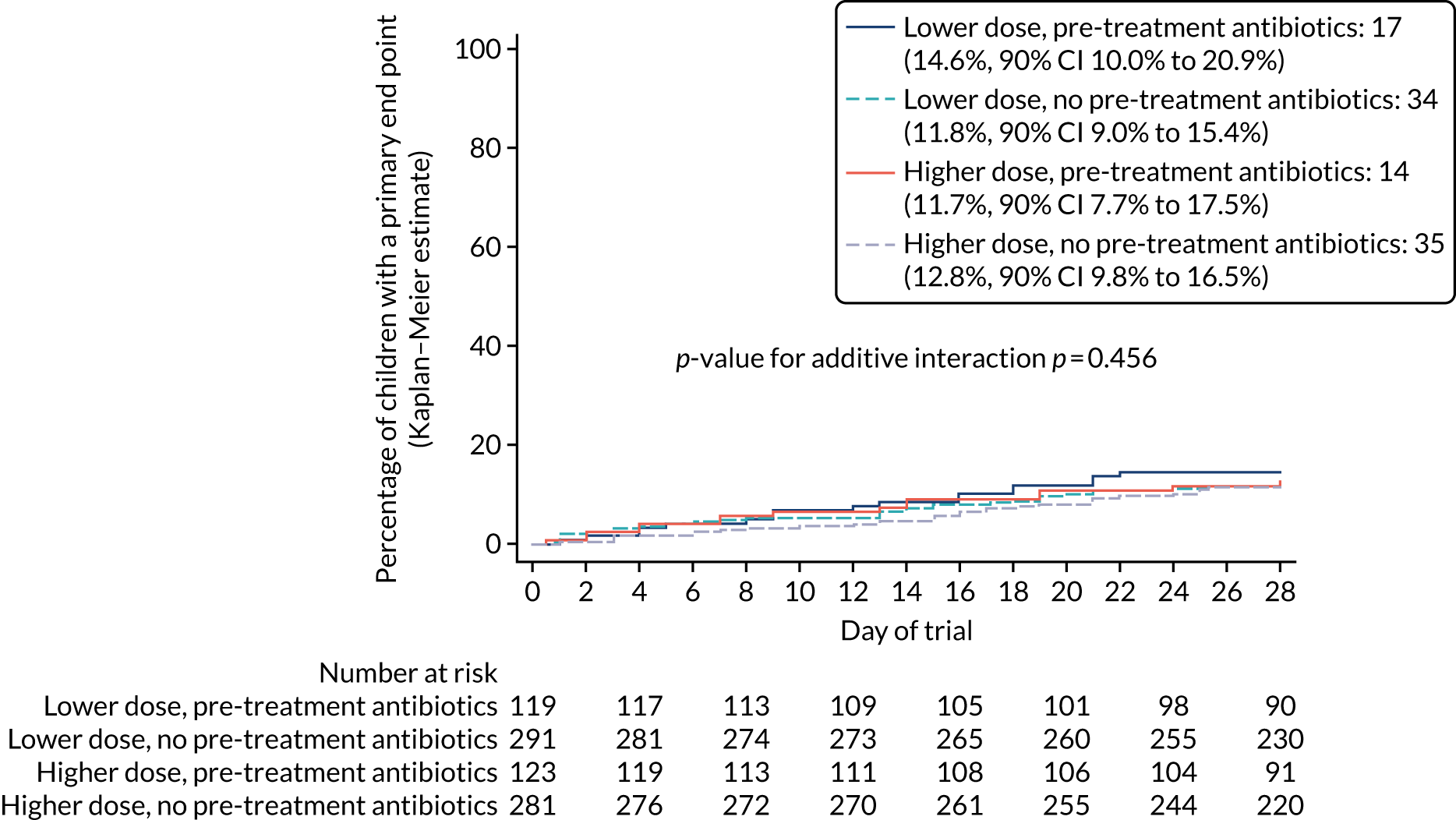

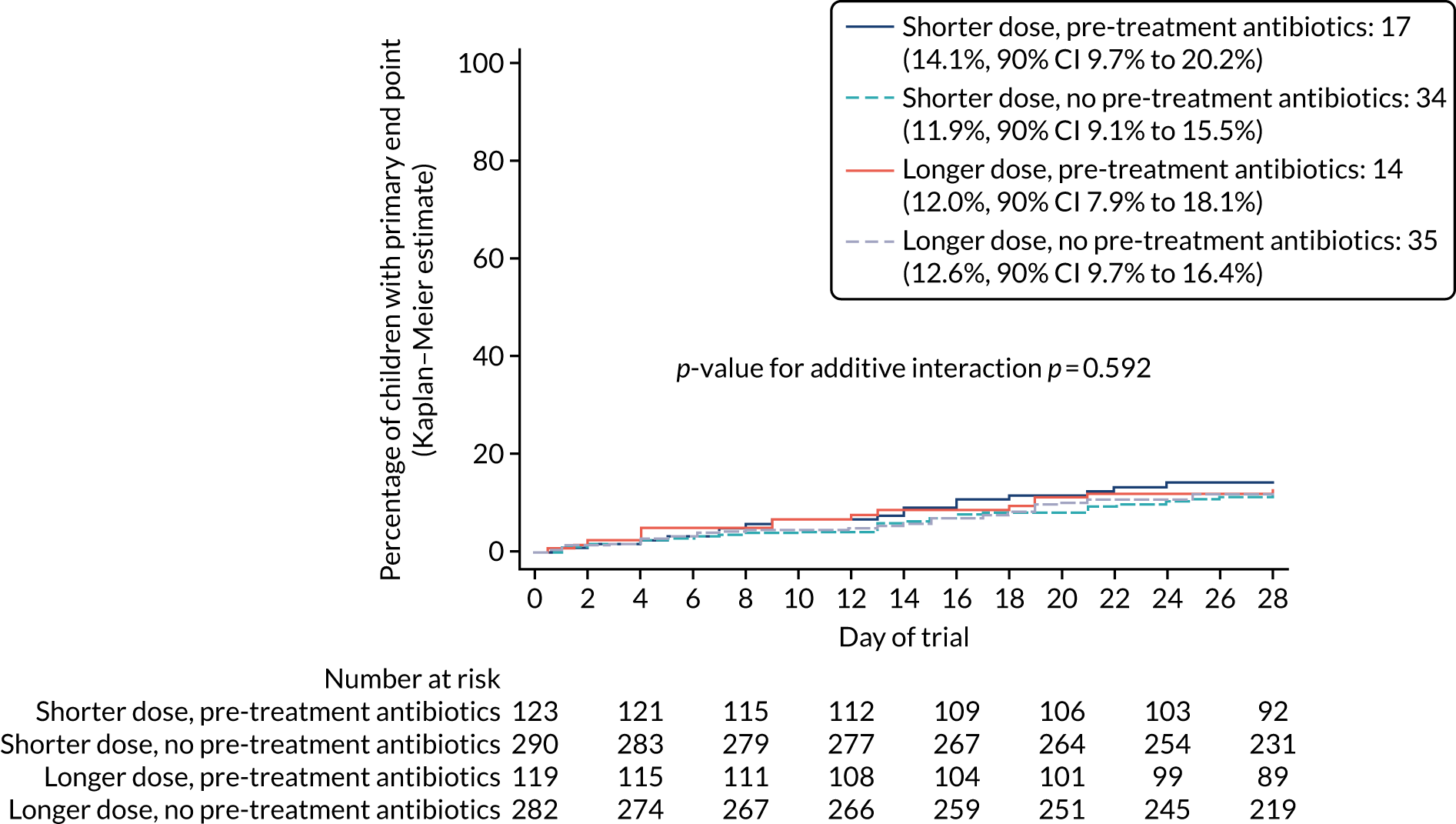

In the primary and secondary analyses, the main effect for each randomisation was estimated by collapsing across levels of the other randomisation factor, supplemented by tests for interaction between the two randomisations and with previous systemic antibacterial exposure. Interaction was assessed on an additive scale.

For continuous variables, the mean (with standard deviation) or median [with interquartile range (IQR)] of absolute values and of changes in absolute values from baseline were reported by scheduled telephone calls/visits and by randomised group.

For binary and categorical variables, differences between groups at particular time points were tested using chi-squared tests (or exact tests, if appropriate). For ordered variables, differences between groups at particular time points were tested using rank tests.

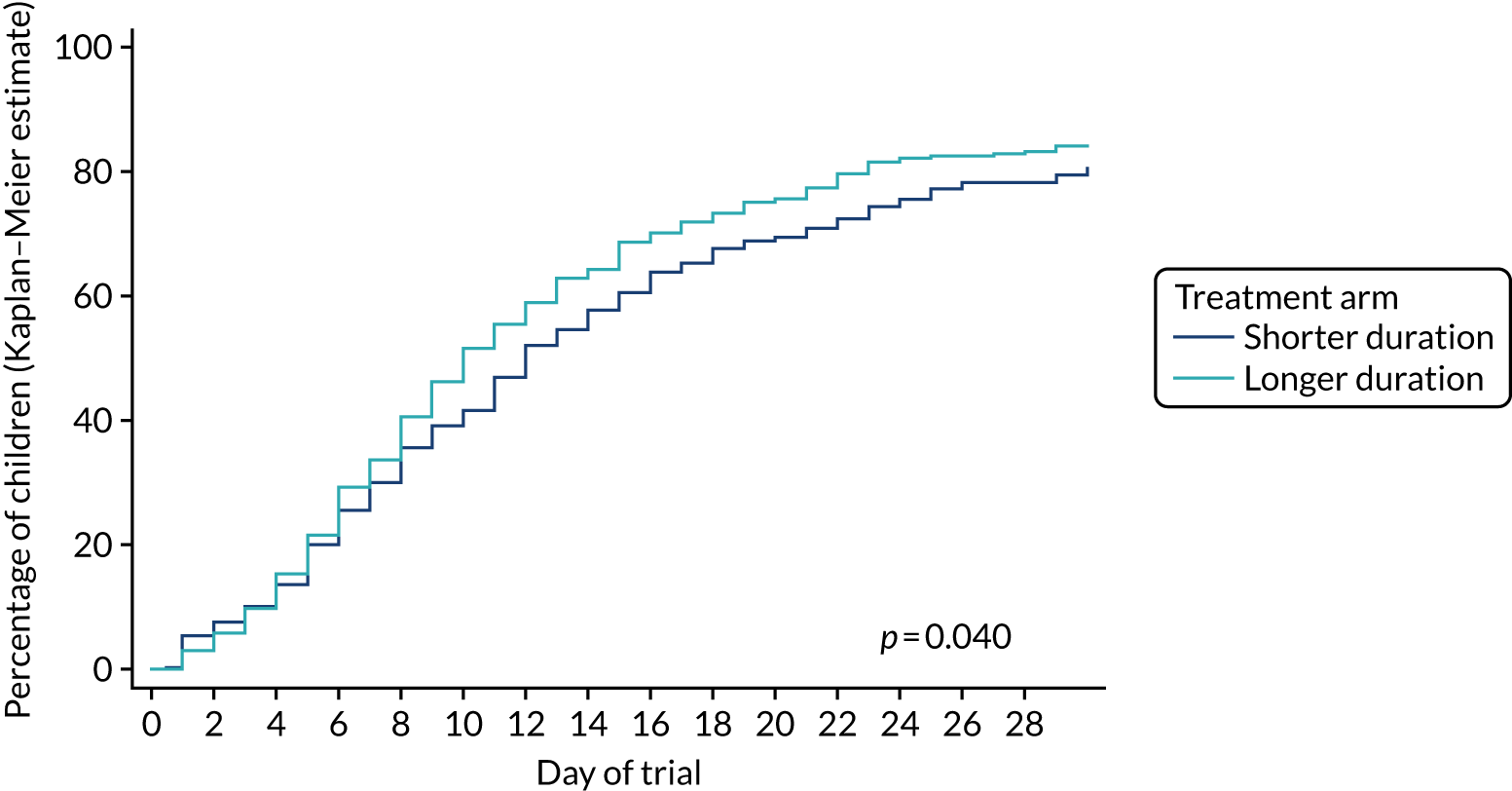

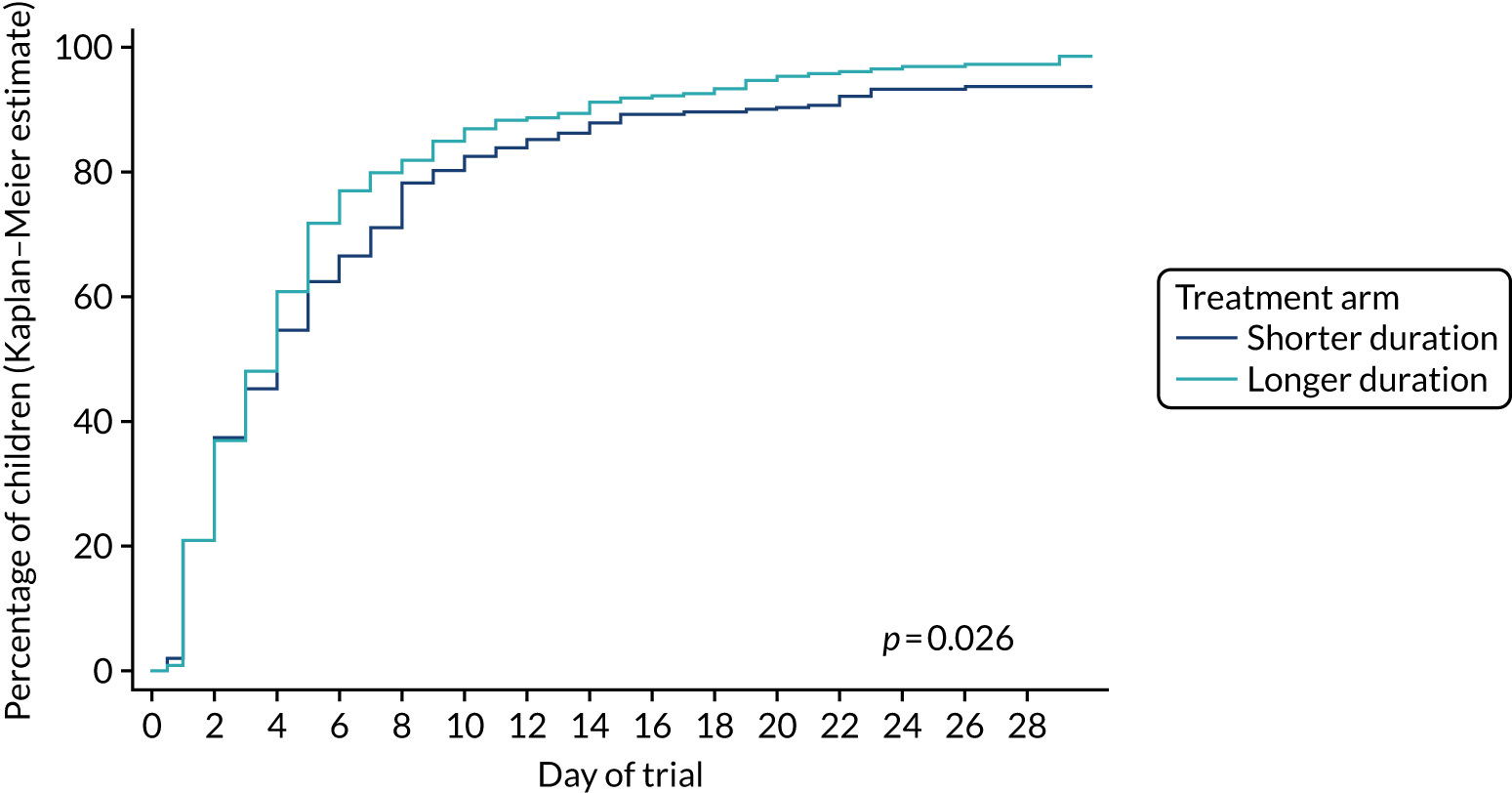

For time-to-event outcomes, the time from baseline to the event date was used, applying Kaplan–Meier estimation. Where participants did not experience an event, data were censored at the date of last review of that event. Differences between groups were tested using a log-rank test.

Formal statistical adjustment for multiple comparisons (particularly pertinent for some of the secondary end points) were not applied, and significance tests should be interpreted in the context of the total number of related comparisons performed.

The primary end point was analysed within a non-inferiority framework, where significance testing has no clear role (with emphasis instead on CIs). Secondary outcomes were analysed within a superiority framework (i.e. assessing the null hypothesis of no difference). All estimates, including differences between randomised groups, are presented with two-sided 90% CIs (rather than the more conventional 95%) to achieve consistency with the reporting of the primary end point.

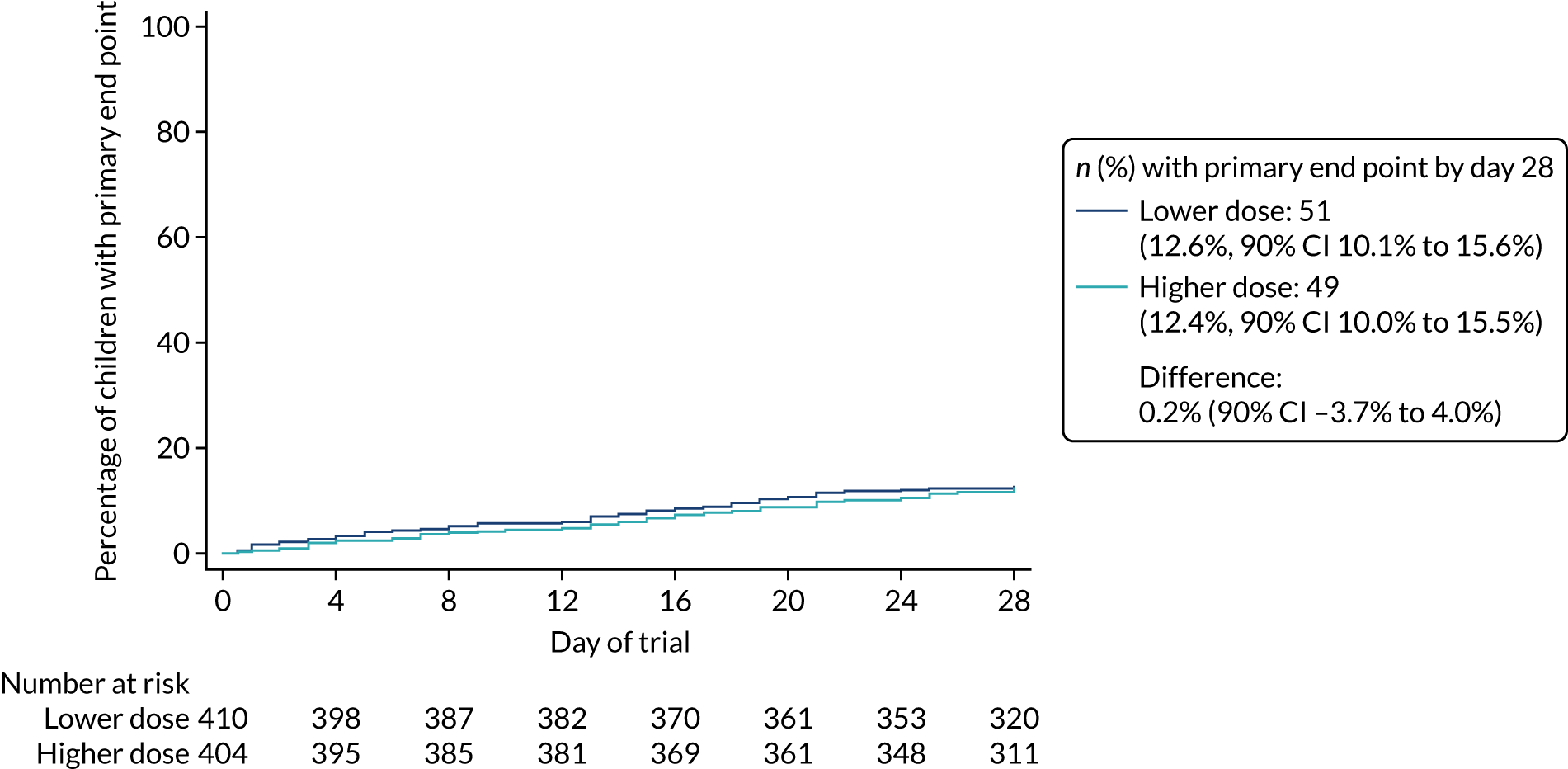

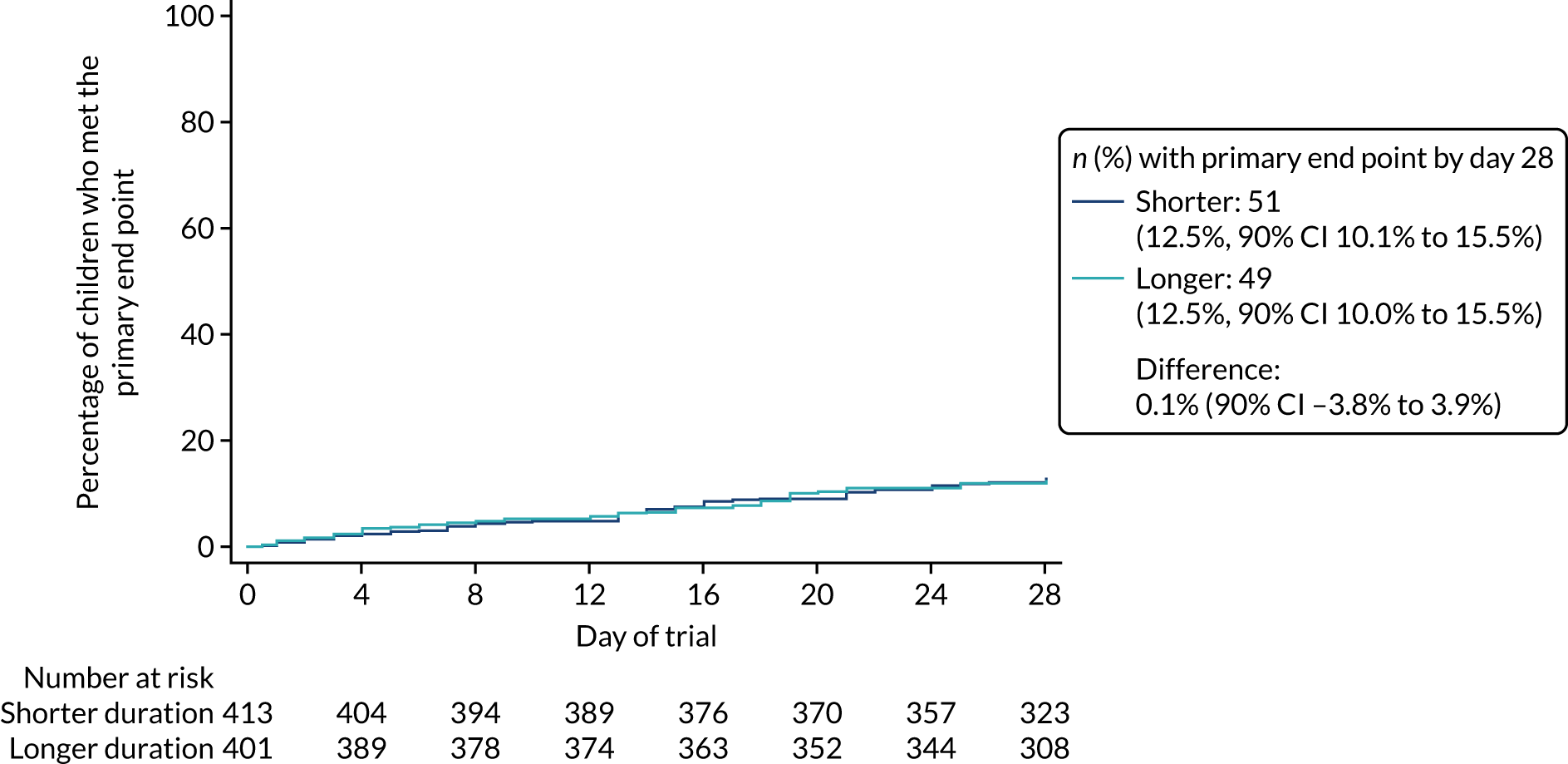

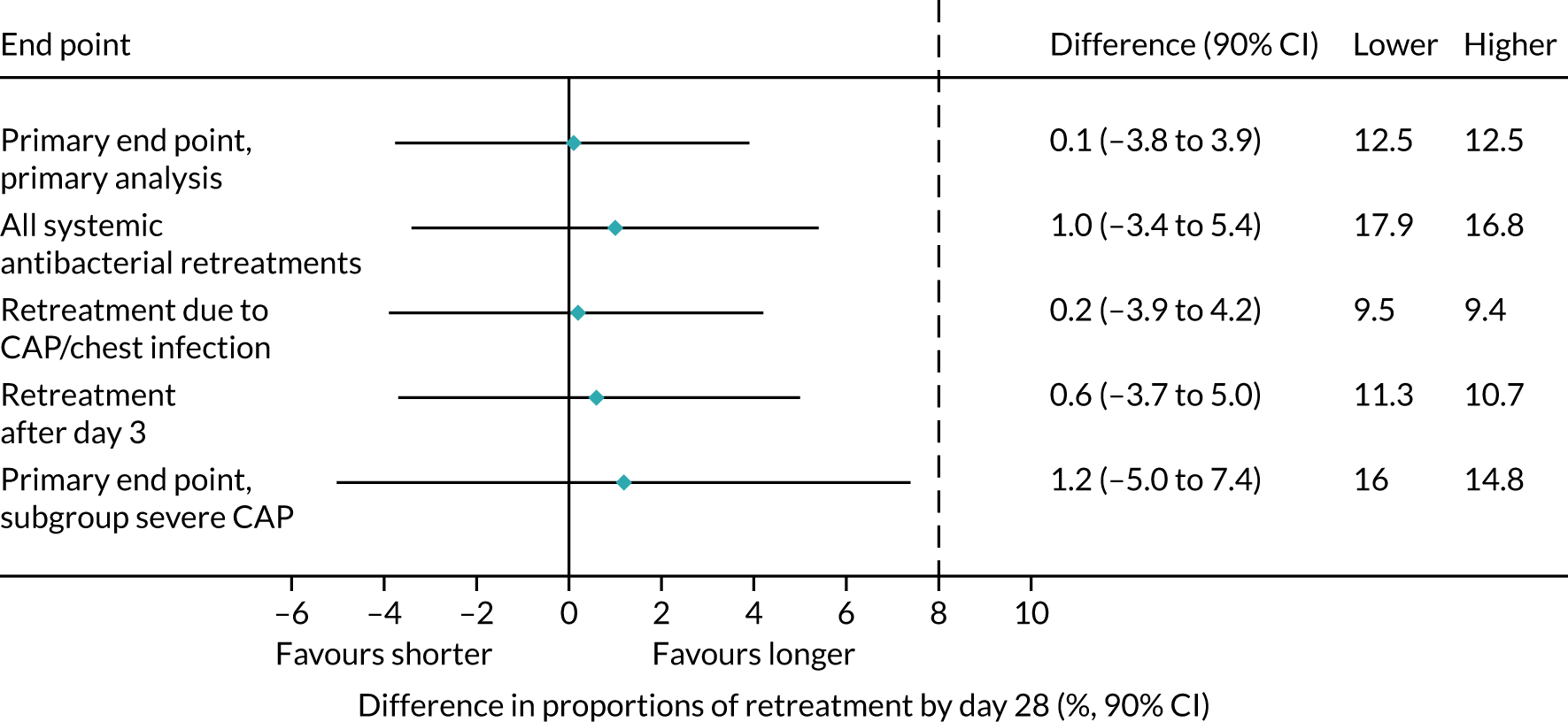

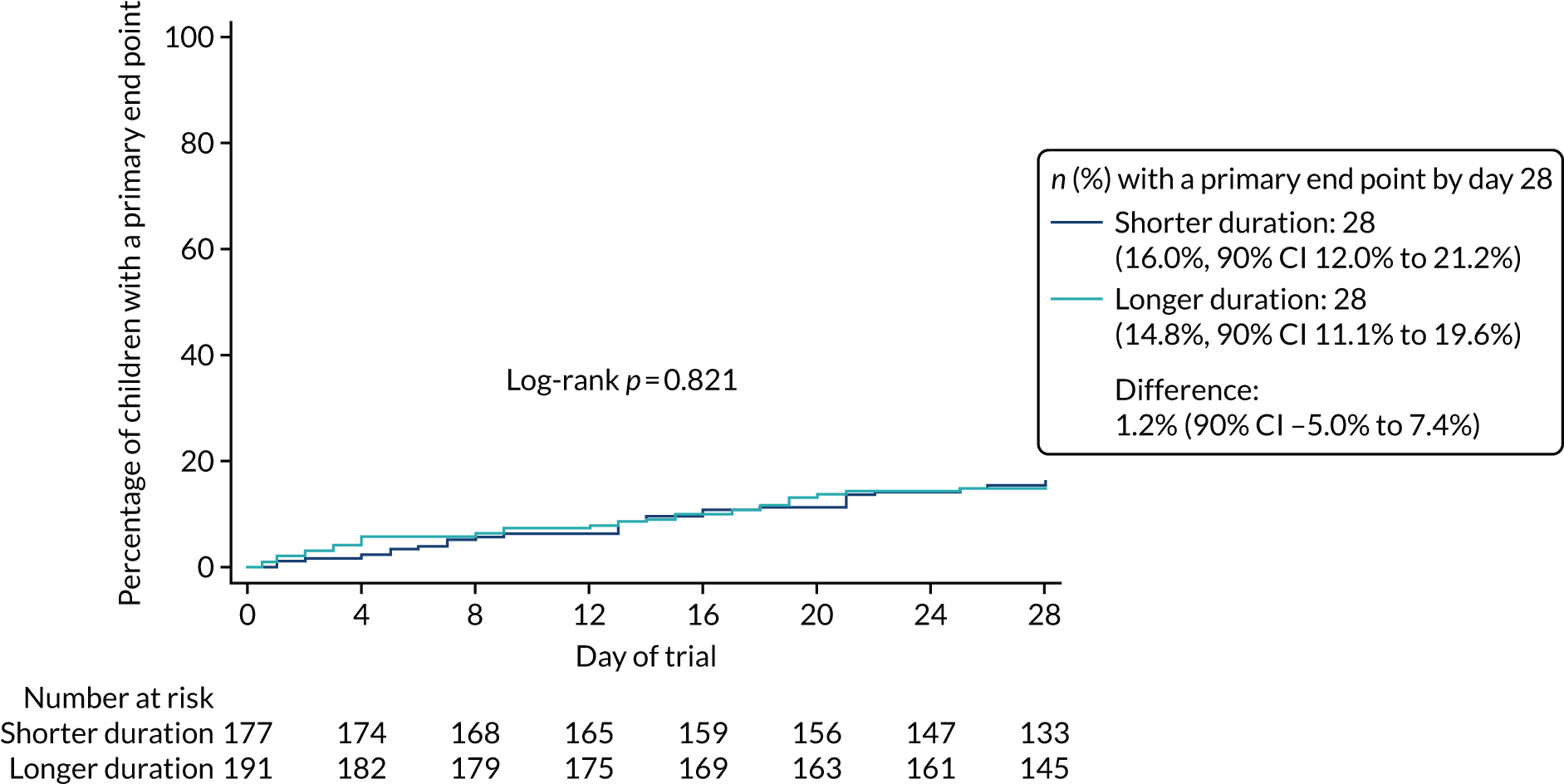

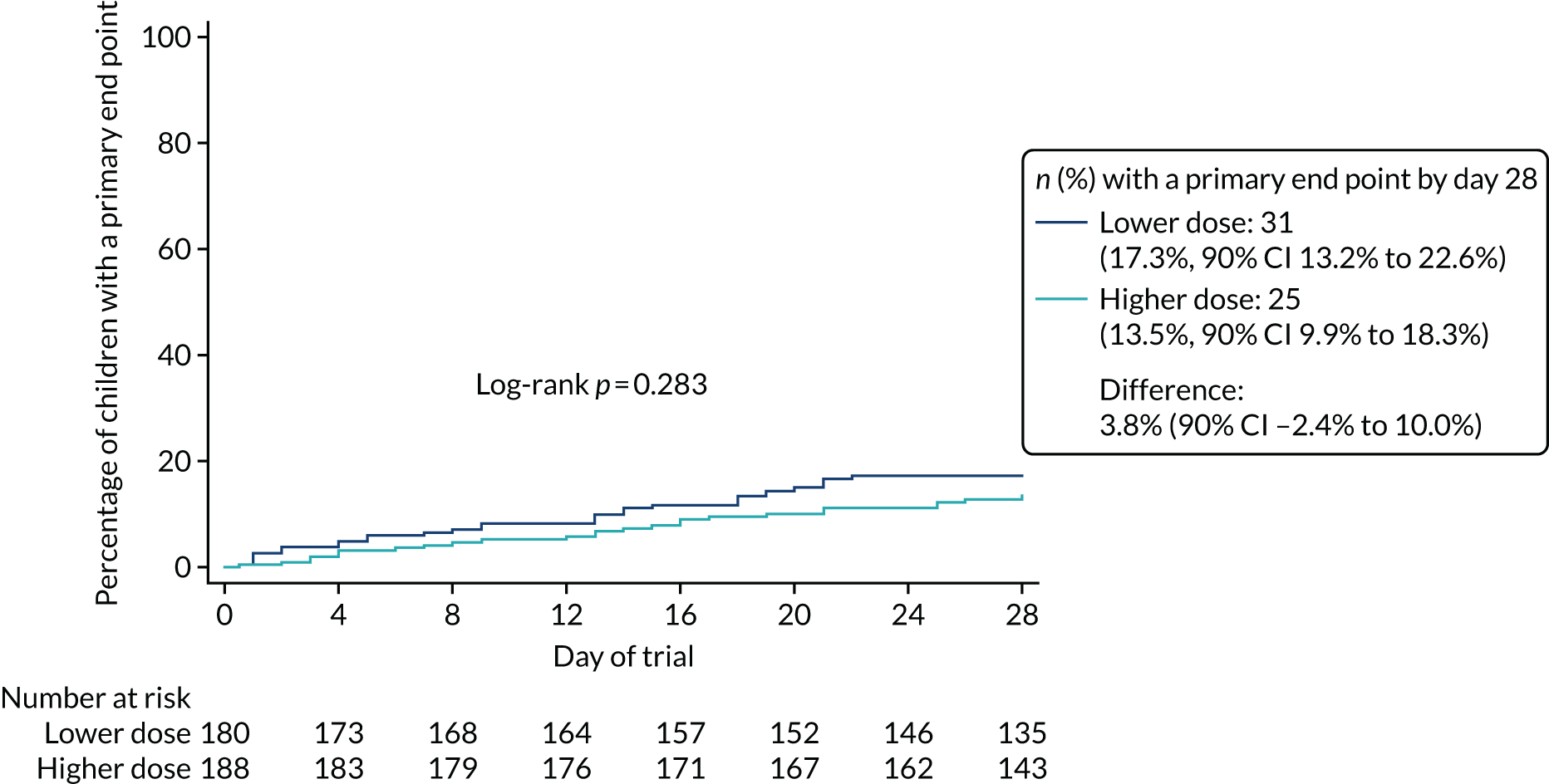

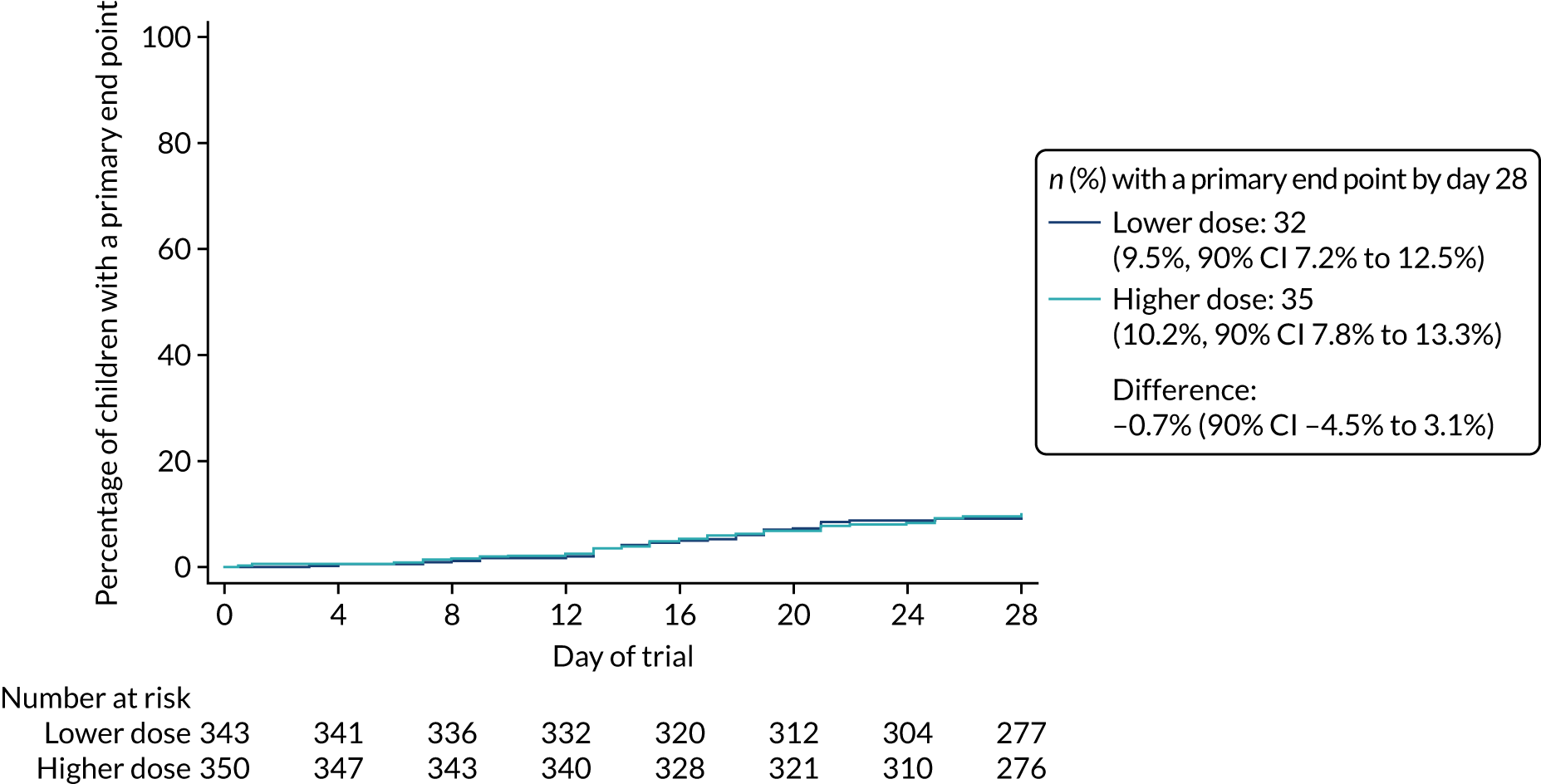

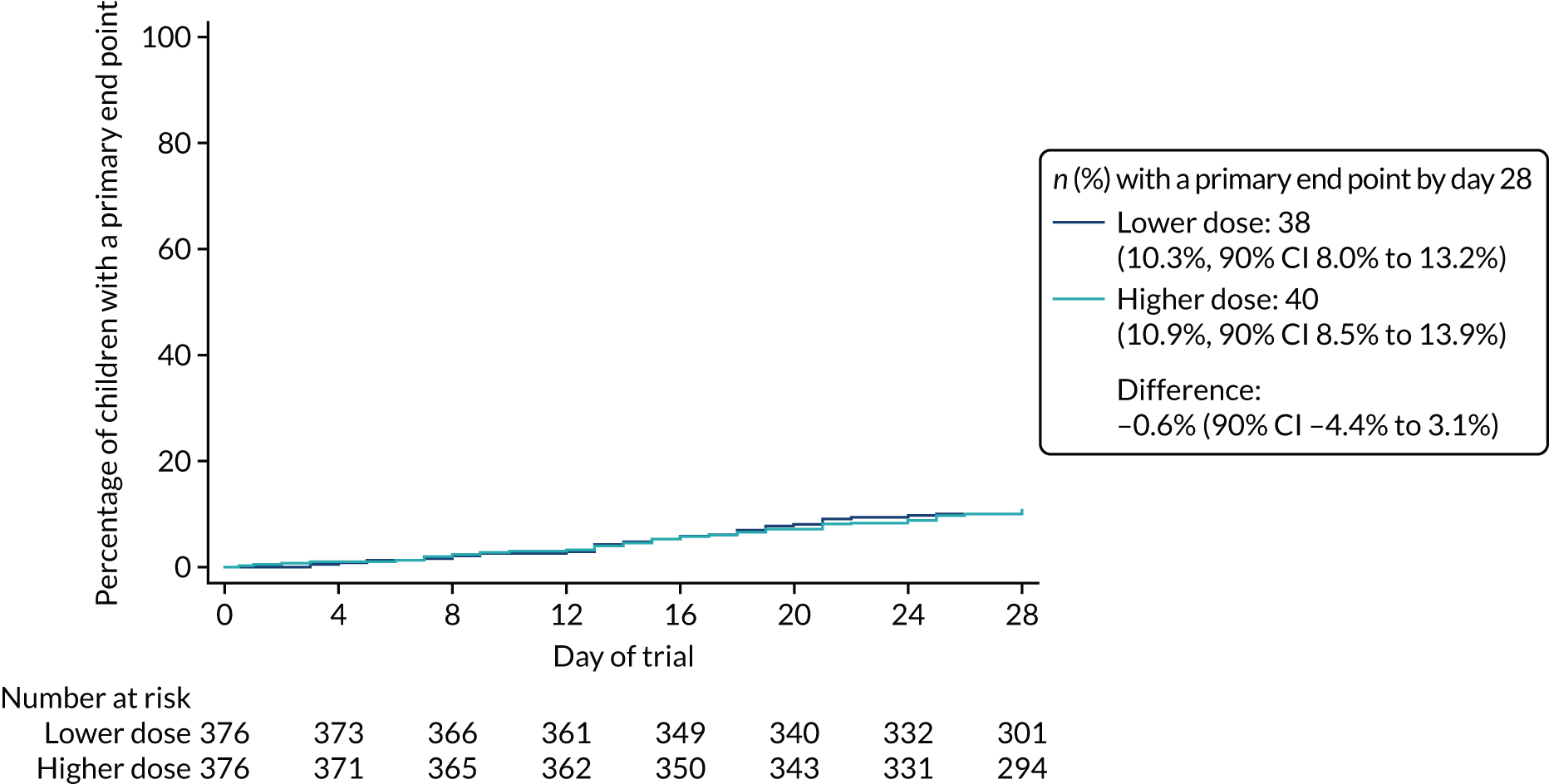

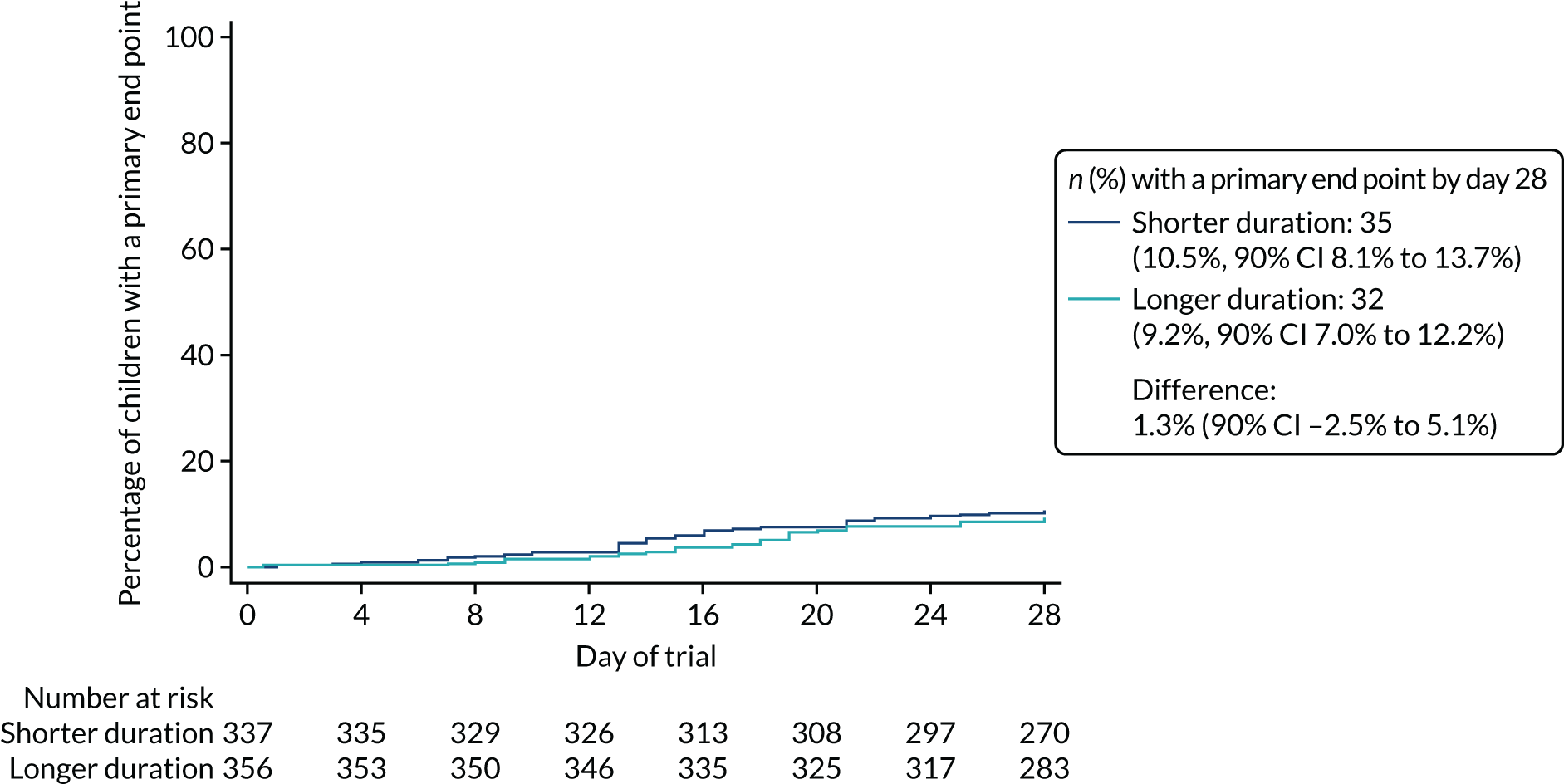

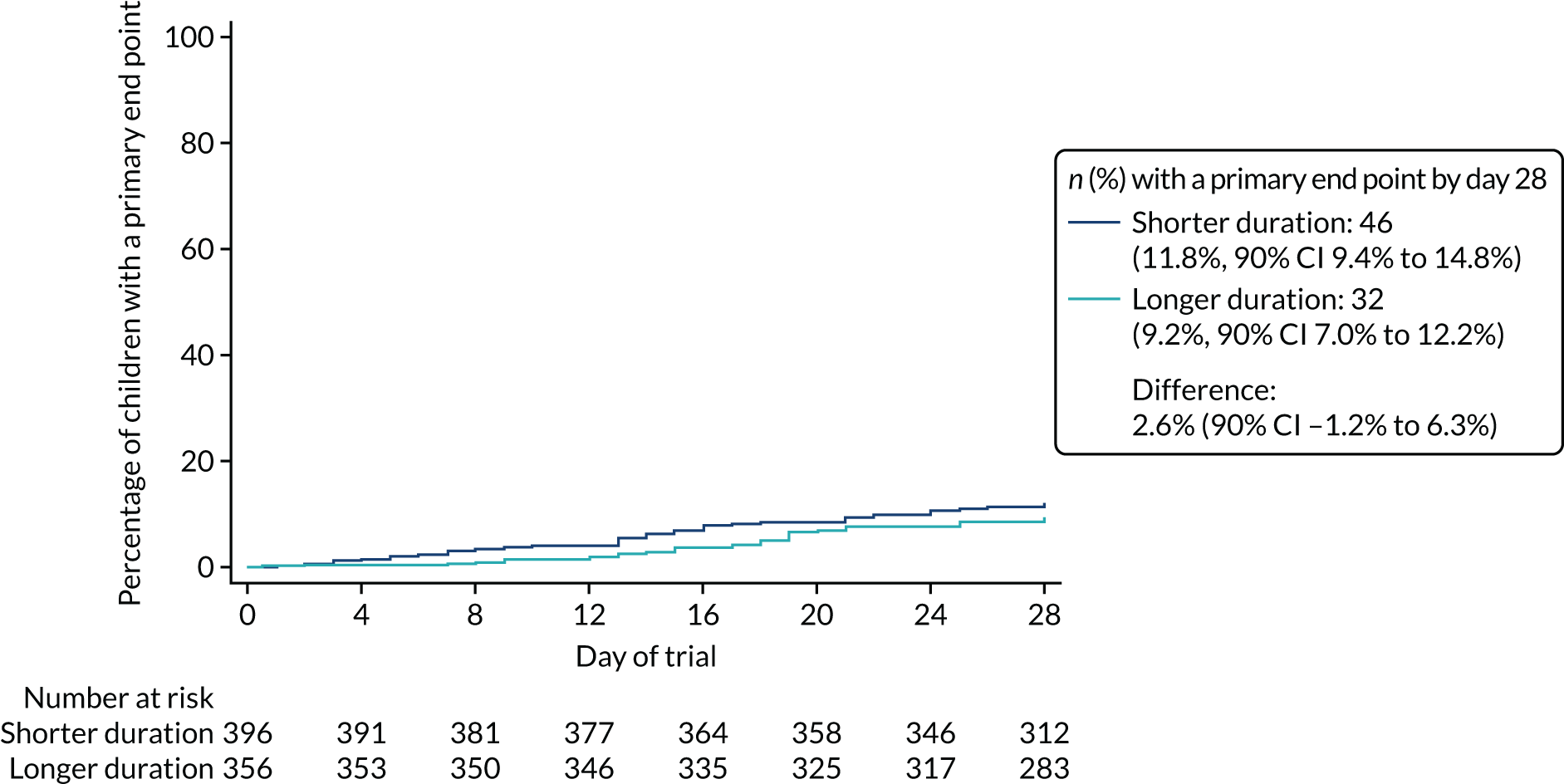

Primary outcome

The proportion of children meeting the primary end point was obtained from the cumulative incidence at day 28, as estimated by Kaplan–Meier methods (i.e. accounting for the differential follow-up times). Participants with incomplete primary outcome data (e.g. as a result of a missed final visit) were censored at the time of their last contact. In the case of participants who missed the final visit but whose GP confirmed that no additional antibacterials were prescribed during the follow-up period, day 28 was used as the censoring date.

Kaplan–Meier estimates were used to derive the risk difference between the randomised groups for the primary end point, and standard errors and CIs for the risk difference were derived from the estimated standard errors of the individual survival functions.

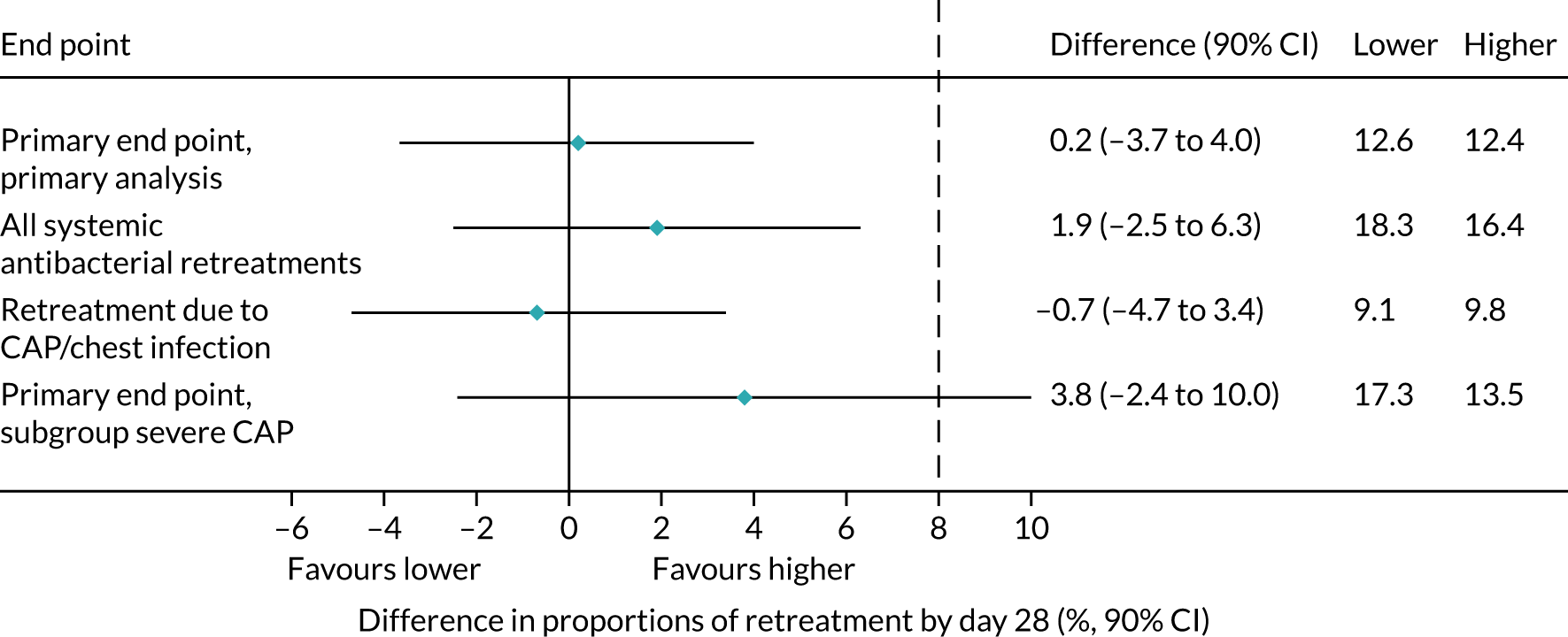

Lower-dose treatment and shorter-duration treatment were considered ‘non-inferior’ to higher-dose treatment and longer-duration treatment, respectively, if the upper limit of the two-sided 90% CI for the difference in the proportion of children with the primary end point at day 28 was less than the non-inferiority margin of 8%. Although the non-inferiority margin was important to the design of the trial, it is less relevant to its interpretation, which should be based on observed estimates and CIs.

Sensitivity analyses

As described in Primary outcome, the primary analysis included only end points confirmed by the ERC as clinically indicated antibacterial treatment for respiratory tract infection (including CAP). To improve confidence in the primary analysis, the following sensitivity analyses were performed for the primary end point:

-

including all systemic antibacterial treatments other than trial medication regardless of reason and indication

-

including only ERC-adjudicated clinically indicated systemic antibacterial treatment where either CAP or ‘chest infection’ was specified as the reason for this treatment (rather than any respiratory tract infection)

-

as above, but also including, as an end point, all systemic antibacterial treatments for CAP or ‘chest infection’ where the clinical indication was ‘unlikely’, as adjudicated by the ERC

-

disregarding systemic antibacterial prescriptions occurring within the first 3 days from randomisation, as these events cannot be related to the treatment duration randomisation, to allow comparison of shorter and longer treatment.

Subgroup analyses

Two subgroup analyses were performed. The first considered severity of CAP at enrolment to provide reassurance that a potential null effect was not due to dilution arising from inclusion of children with mild disease. The main efficacy analysis was repeated, but included only participants with severe CAP, defined as two or more of the following abnormal signs/symptoms at enrolment: raised respiratory rate (> 37 breaths/minute for children aged 1–2 years; > 28 breaths/minute for children aged 3–5 years), oxygen saturation < 92% in room air and presence of chest retractions.

The second subgroup analysis considered the potential for seasonal changes in infections, by including only primary end points occurring in the two winter seasons spanned by CAP-IT. This was based on Public Health England reports of circulating viruses/bacteria in the winter seasons spanned by CAP-IT.

Community-acquired pneumonia symptoms

The severity of the symptoms (detailed in Morbidity) were reviewed by the number (%) of symptoms in each severity category at each scheduled contact visit and analysed as described for ordered outcomes in Analysis principles.

Duration of a symptom was measured as time from baseline to resolution, defined as the first day the symptom was reported as not present. This was analysed as a time-to-event outcome, as specified in Analysis principles. Where a symptom was not present at enrolment, participants were excluded from the analysis of that symptom.

Clinical adverse events

Solicited clinical AEs, specified in Morbidity, were analysed overall and by randomised arm. Analysis considered total number of events, number of participants with at least one event, the number of participants with at least one new event and event severity. These variables were analysed as described for binary outcomes in Analysis principles.

In addition, the number of participants experiencing at least one SAE were compared as a binary outcome (see Analysis principles).

Antimicrobial resistance

Descriptive analyses of baseline samples were analysed as follows: proportion of samples with positive S. pneumoniae culture, frequency distribution of broth microdilution MIC values and proportion of samples classified as S – susceptible, standard dosing regimen; I – intermediate, increased exposure; and R – resistant (see Secondary outcomes).

S. pneumoniae carriage, determined by tabulation of the proportion of samples with positive S. pneumoniae culture at the final visit by randomisation group, was compared using tests for binary variables, as described in Secondary outcomes. S. pneumoniae culture results at the final visit were cross-tabulated with baseline culture results (including missing values).

For the antimicrobial resistance analysis, a descriptive analysis of the proportion of samples with resistance to penicillin (S – susceptible/I – intermediate/R – resistant categorisation) at the final visit was performed using both cut-off points (penicillin and amoxicillin) described in Secondary outcomes. This analysis was repeated, first, including only samples with a positive S. pneumoniae culture result and, second, including all samples. Randomised groups were compared by tests for binary variables, and cross-tabulation of penicillin resistance at the final visit compared with penicillin resistance at baseline was performed as a descriptive analysis.

Finally, the change in broth microdilution MIC (in patients for whom this was measured at both the baseline and the final visit) was analysed with randomisation group as factors and after adjusting for baseline MIC.

Interim analyses

The trial was reviewed by the CAP-IT IDMC. They met three times over the course of the trial: once at a joint meeting with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) in June 2017 and twice in strict confidence in January 2018 and January 2019. The IDMC reviewed unblinded safety and efficacy data and made recommendations through correspondence to the TSC following each meeting.

Patient and public involvement

Parents of young children were involved during the development and delivery of CAP-IT. A PPI representative was a member of the TSC, contributing at meetings and in an ad hoc fashion when required. When considering the research question, the trial team were advised by parents that shorter antibiotic courses would be welcomed if equally effective, because of difficulties in giving medicine (due to palatability or challenges with day care and daytime doses). For the same reasons, parents supported the twice-daily dosing of the CAP-IT. Multiple PPI representatives reviewed and provided input on the patient information materials, including the CAP-IT information film, to ensure that they were clear, easy to understand and not off-putting to parents, while still providing sufficient detail to allow informed consent. Valuable input was provided from the PPI representative on the CAP-IT TSC on the plan for dissemination of the CAP-IT results.

Protocol amendments

The CAP-IT protocol v.2.0 was active when recruitment to CAP-IT commenced in January 2017. Two protocol amendments were completed subsequently, with version 3 implemented in September 2017 and version 4 in December 2018. Amendments were largely in relation to selection criteria (see Exclusion criteria) and the SAP (to which three significant updates were made on the basis of accumulating trial data). First, a stratified analysis was originally planned based on the PED and ward groups. This was changed to a joint analysis in protocol version 3 because of significant clinical overlap (see Appendix 1 for more details) Second, the primary end-point definition was made more specific in protocol version 3 and further refined in version 4 (see Changes to primary end point). Finally, the non-inferiority margin was adjusted, as the primary end-point event rate had been substantially underestimated. The trial and all substantial amendments were approved by the London – West London & GTAC Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/LO/0831).

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

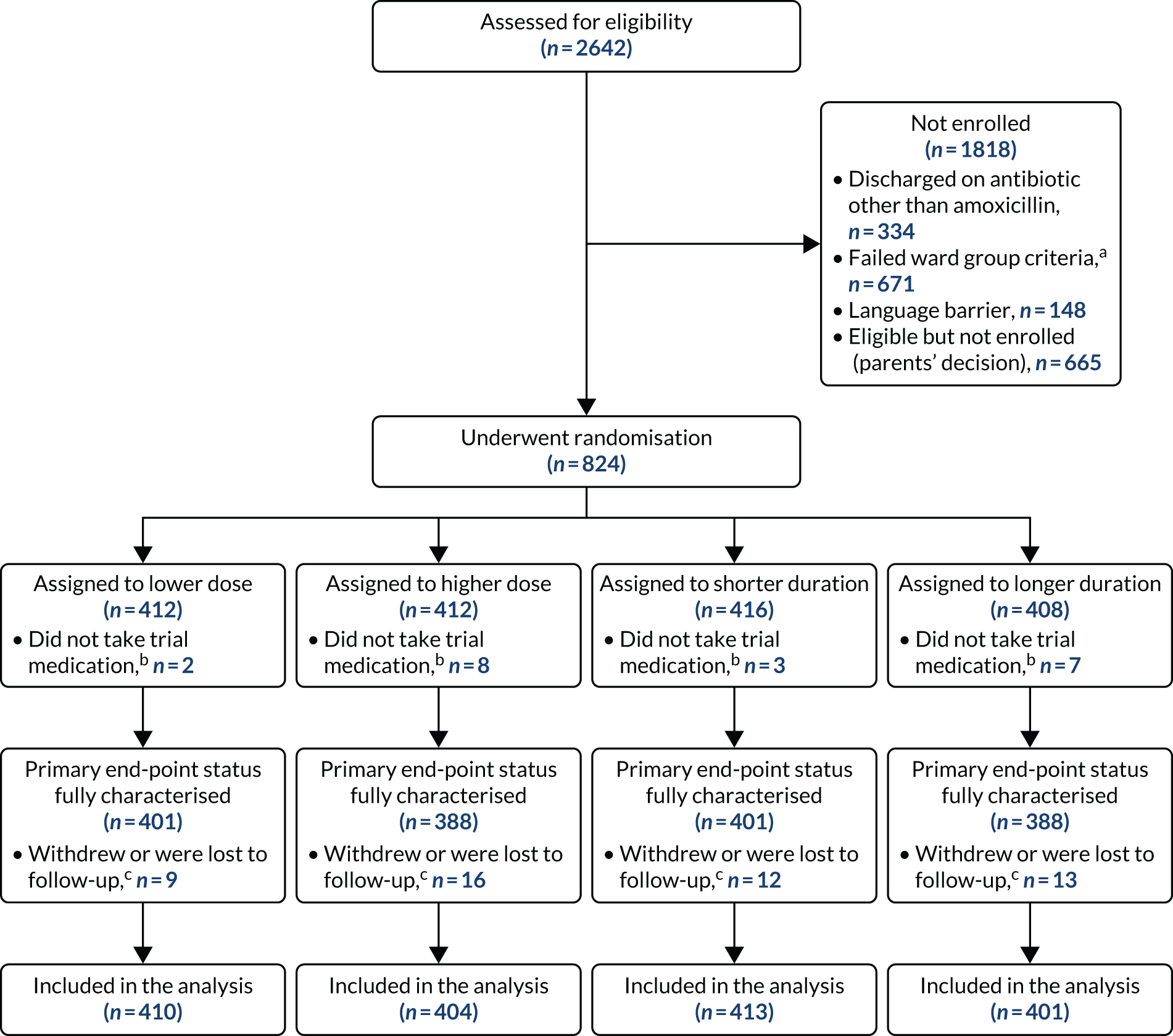

Between 1 February 2017 and 23 April 2019, a total of 2642 children were assessed for eligibility and 824 were randomised. Ten patients were randomised but received no trial medication (owing to, for example, a change of mind by parent/guardian or administrative error) and were, therefore, excluded from the analysis, resulting in an analysis population of 814 patients.

A total of 591 participants had no pre-treatment antibiotic at trial entry. A total of 223 (mainly following admission to assessment units of wards) had received beta-lactam antibiotic pre-treatment for no more than 48 hours. The final follow-up visit occurred on 21 May 2019, which was considered the trial end date.

Six participants were randomised in error but were included in the analysis in accordance with the ITT principle. Of these participants, five did not have all the required symptoms to fulfil the criteria for CAP diagnosis (see Box 1). One patient did not have a cough reported in the previous 96 hours at presentation, two patients did not have a reported fever in the previous 48 hours at presentation and two patients lacked documentation of signs of laboured/difficult breathing and/or focal chest signs at presentation. In one of the final two patients, chest radiography was suggestive of lobar pneumonia, prior to this being added to the inclusion criteria as part of protocol version 4.0, and in the other participant pneumonia was diagnosed on chest radiography, but was documented as patchy infiltrate, which did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. The final patient randomised in error received an antibiotic other than a beta-lactam (clarithromycin) before discharge (Table 3).

| Reason for ineligibility | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Known violation of any inclusion/exclusion criterion | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 6 (0.7) |

| No presence of cough | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| No presence of fever | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| No presence of CAP signs | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pre-treatment with non-beta-lactams | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Excluded from analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Participants were well distributed between arms, with 208 (25.6%) participants receiving 3 days of lower-dose treatment, 202 (24.8%) participants receiving 7 days of lower-dose treatment, 205 (25.2%) participants receiving 3 days of higher-dose treatment and 199 (24.4%) participants receiving 7 days of higher-dose treatment (Figure 3 and Table 4).

FIGURE 3.

A CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram. a, Inpatient stay > 48 hours and treated with non-beta-lactam antibiotics as inpatients; b, these children have been excluded from all analyses; and c, follow-up included up to time of withdrawal or no further contact.

| Outcome | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PED (N = 591) | Ward (N = 223) | ||

| Randomisation arm | |||

| Lower dose plus shorter duration | 153 (25.9) | 55 (24.7) | 208 (25.6) |

| Lower dose plus longer duration | 150 (25.4) | 52 (23.3) | 202 (24.8) |

| Higher dose plus shorter duration | 146 (24.7) | 59 (26.5) | 205 (25.2) |

| Higher dose plus longer duration | 142 (24.0) | 57 (25.6) | 199 (24.4) |

| Dose randomisation | |||

| Lower | 303 (51.3) | 107 (48.0) | 410 (50.4) |

| Higher | 288 (48.7) | 116 (52.0) | 404 (49.6) |

| Duration randomisation | |||

| Shorter | 299 (50.6) | 114 (51.1) | 413 (50.7) |

| Longer | 292 (49.4) | 109 (48.9) | 401 (49.3) |

Baseline

Patient characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics were well balanced between the randomisation groups (see Table 4). The median age of participants was 2.5 (IQR 1.6–3.7) years, with a minimum and maximum age of 0.5 and 8.8 years, respectively, and 52% were male (Table 5).

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | Total (N = 814) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.6–3.7) | 2.4 (1.6–3.7) | 2.5 (1.7–3.7) | 2.5 (1.5–3.7) | 2.5 (1.6–3.7) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.5, 8.8 | 0.5, 8.5 | 0.5, 8.5 | 0.5, 8.8 | 0.5, 8.8 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 210 (51) | 211 (52) | 217 (53) | 204 (51) | 421 (52) |

| Female | 200 (49) | 193 (48) | 196 (47) | 197 (49) | 393 (48) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White | 275 (67) | 279 (69) | 283 (69) | 271 (68) | 554 (68) |

| Asian or British Asian | 55 (13) | 51 (13) | 53 (13) | 53 (13) | 106 (13) |

| Black or black British | 40 (10) | 36 (9) | 40 (10) | 36 (9) | 76 (9) |

| Other | 40 (10) | 38 (9) | 37 (9) | 41 (10) | 78 (10) |

| Number (%) of households with smokers | 69 (17) | 62 (16) | 61 (15) | 70 (18) | 131 (16) |

Medical history

One-third of participants (30.7%) reported an underlying diagnosis of asthma or use of an asthma inhaler within the past month. The second most common comorbidity (affecting 20% of participants) was eczema, followed by food or drug allergies (9.6%) and hay fever (9.1%). Routine vaccinations had been received by 95% of participants; the remaining 5% either had not had routine vaccinations (3.2%), or were of unknown vaccination status or had been vaccinated outside the UK (1.8%).

Vital parameters and clinical signs

Participant vital parameters were measured at presentation and were similar between randomisation groups (Table 6). The median temperature was 38.1 °C (IQR 37.2–38.8 °C) and median oxygen saturation was 96% (IQR 95–98%). The median number of days for which a child had a cough at presentation was 4 (IQR 2–7) days, and the median number of days for which a child had a temperature was 3 (IQR 1–4) days. The median weight was 13.5 (IQR 11.2–16.4) kg.

| Medical history | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Asthma or inhaler use within past month | 119 (29) | 136 (34) | 125 (30) | 130 (32) | 255 (31) |

| Hay fever | 34 (8) | 40 (10) | 37 (9) | 37 (9) | 74 (9) |

| Food or drug allergy | 38 (9) | 40 (10) | 37 (9) | 41 (10) | 78 (10) |

| Eczema | 84 (20) | 79 (20) | 78 (19) | 85 (21) | 163 (20) |

| Prematurity | 43 (10) | 43 (11) | 51 (12) | 35 (9) | 86 (11) |

| Routine vaccinations? | |||||

| Yes | 388 (95) | 385 (95) | 394 (95) | 379 (95) | 773 (95) |

| No | 14 (3) | 12 (3) | 15 (4) | 11 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Not sure (or vaccinated outside UK) | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | 4 (1) | 11 (3) | 15 (2) |

| Other underlying disease | 37 (9) | 19 (5) | 21 (5) | 35 (9) | 56 (7) |

The most common baseline clinical signs were coryza [affecting 599/814 (73.6%) participants] and chest retractions [affecting 483/814 (59.3%) participants] (Table 7). Other baseline clinical signs were less common (enlarged tonsils or pharyngitis, 22.5%; pallor, 20.9%; nasal flaring, 9.3%, inflamed/bulging tympanic membrane or middle ear effusion, 9%; and stridor, 1.2%).

| Parameter/clinical sign | Treatment arm | Total (N = 814) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 13.6 (11.2–16.8) | 13.3 (11.1–16.2) | 13.8 (11.5–16.4) | 13.2 (10.9–16.4) | 13.5 (11.2–16.4) |

| Temperature (°C), median (IQR) | 38.1 (37.3–38.9) | 38.0 (37.2–38.6) | 38.0 (37.1–38.7) | 38.1 (37.3–38.8) | 38.1 (37.2–38.8) |

| Temperature ≥ 38 °C, n (%) | 227 (55) | 214 (53) | 221 (54) | 220 (55) | 441 (54) |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.), median (IQR) | 146 (131–160) | 143 (130–158) | 144 (131–158) | 146 (130–162) | 145 (130–160) |

| Abnormal heart rate,a n (%) | 307 (75) | 271 (67) | 282 (68) | 296 (74) | 578 (71) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/minute), median (IQR) | 37 (30–44) | 38 (32–44) | 36 (30–43) | 38 (32–45) | 37 (30–44) |

| Abnormal respiratory rate,b n (%) | 270 (66) | 258 (64) | 262 (64) | 266 (67) | 528 (65) |

| Oxygen saturation (%), median (IQR) | 96 (95–98) | 96 (95–98) | 96 (95–98) | 96 (95–98) | 96 (95–98) |

| Abnormal oxygen saturation,c n (%) | 18 (4) | 25 (6) | 18 (4) | 25 (6) | 43 (5) |

| Nasal flaring, n (%) | 33 (8) | 42 (10) | 35 (9) | 40 (10) | 75 (9) |

| Chest retractions, n (%) | 239 (58) | 244 (60) | 239 (58) | 244 (61) | 483 (59) |

| Pallor, n (%) | 82 (20) | 87 (22) | 93 (23) | 76 (19) | 169 (21) |

| Stridor, n (%) | 4 (1) | 6 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Inflamed/bulging tympanic membrane or middle ear effusion, n (%) | 37 (9) | 35 (9) | 39 (10) | 33 (8) | 72 (9) |

| Coryza, n (%) | 291 (71) | 308 (76) | 304 (74) | 295 (74) | 599 (74) |

| Enlarged tonsils or pharyngitis, n (%) | 95 (24) | 86 (22) | 92 (22) | 89 (23) | 181 (23) |

Multiple vital parameters and clinical signs differed at presentation between the children previously exposed and unexposed to antibiotics (see Table 7).

Chest examination

Chest examination findings at presentation were reported as absent, bilateral or unilateral. Unilateral findings were present in 691 (85%) participants overall, featuring as crackles/crepitations in 562 (71%) participants, reduced breath sounds in 336 (44%) participants, bronchial breathing in 103 (15%) participants and dullness to percussion in 59 (13%) participants. The proportions of the four chest examination variables were very similar among the randomisation arms (Table 8).

| Chest examination finding | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Dullness to percussion | |||||

| Absent | 194 (86) | 186 (86) | 198 (86) | 182 (86) | 380 (86) |

| Unilateral | 32 (14) | 27 (13) | 31 (13) | 28 (13) | 59 (13) |

| Bilateral | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Bronchial breathing | |||||

| Absent | 283 (82) | 263 (82) | 276 (83) | 270 (81) | 546 (82) |

| Unilateral | 53 (15) | 50 (16) | 49 (15) | 54 (16) | 103 (15) |

| Bilateral | 10 (3) | 7 (2) | 8 (2) | 9 (3) | 17 (3) |

| Reduced breath sounds | |||||

| Absent | 202 (52) | 187 (49) | 202 (51) | 187 (50) | 389 (50) |

| Unilateral | 168 (43) | 168 (44) | 174 (44) | 162 (43) | 336 (44) |

| Bilateral | 20 (5) | 26 (7) | 20 (5) | 26 (7) | 46 (6) |

| Crackles/crepitations | |||||

| Absent | 69 (17) | 65 (17) | 71 (18) | 63 (16) | 134 (17) |

| Unilateral | 287 (71) | 275 (70) | 290 (72) | 272 (69) | 562 (71) |

| Bilateral | 48 (12) | 52 (13) | 42 (10) | 58 (15) | 100 (13) |

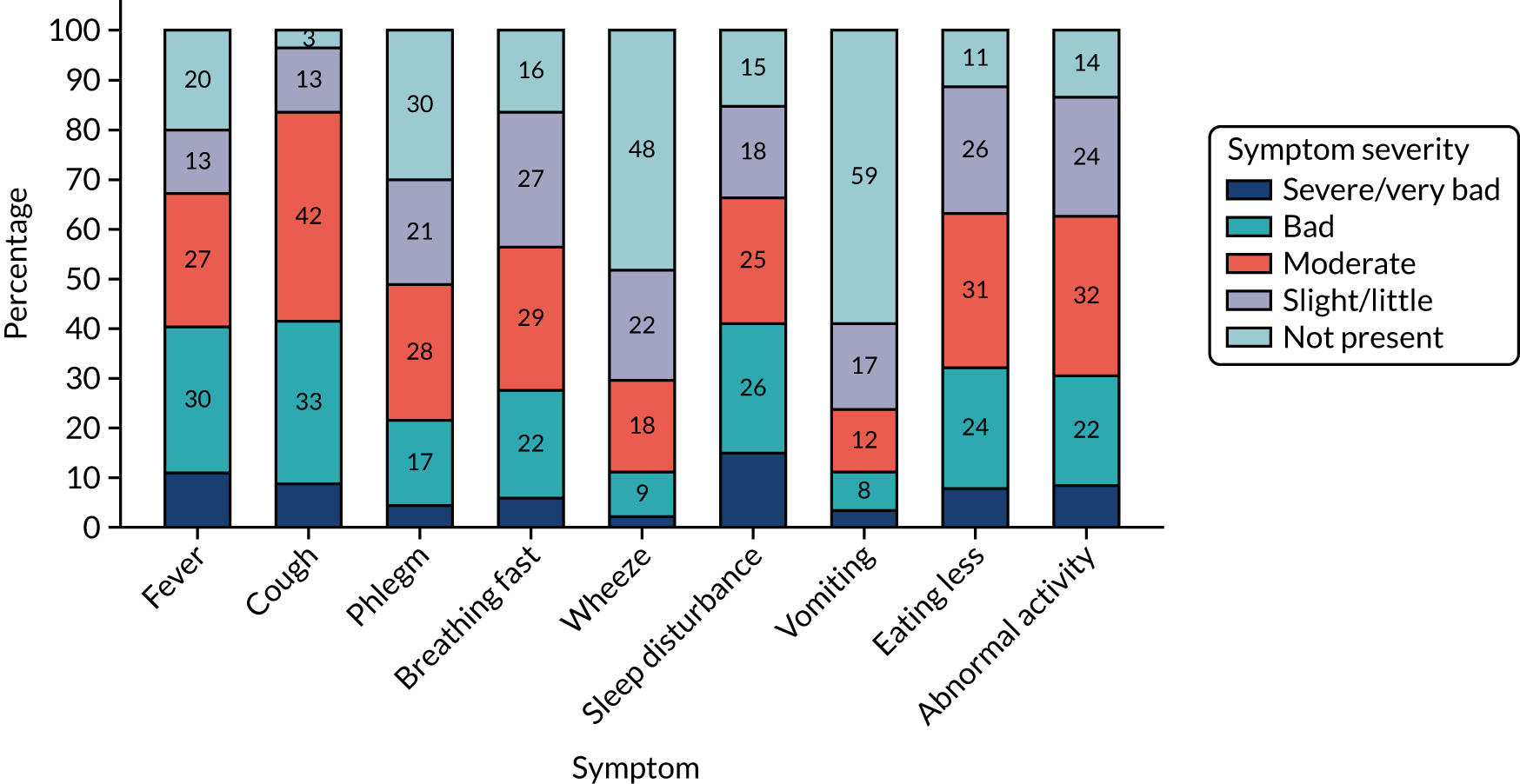

Parent/guardian-reported community-acquired pneumonia symptoms

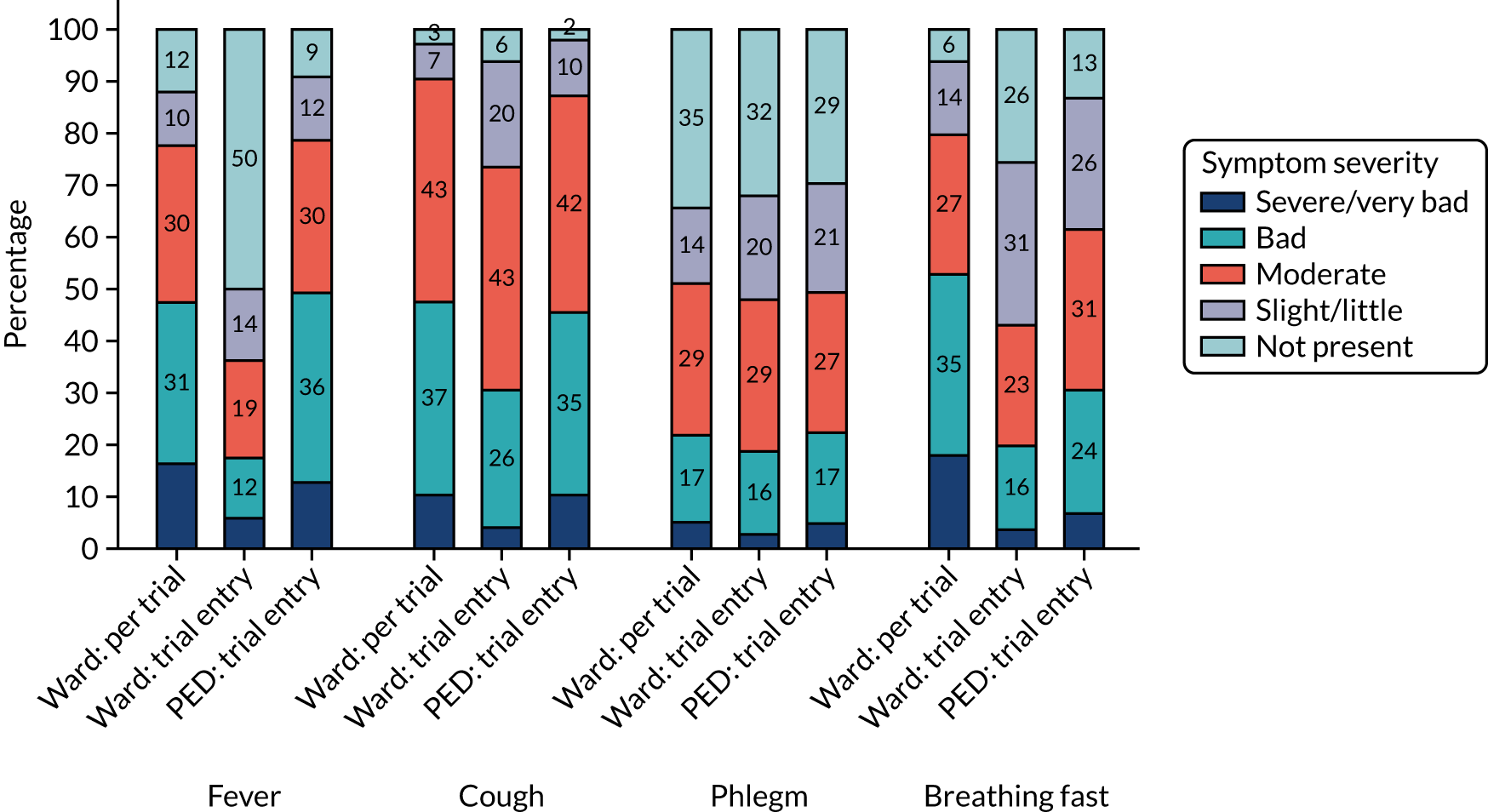

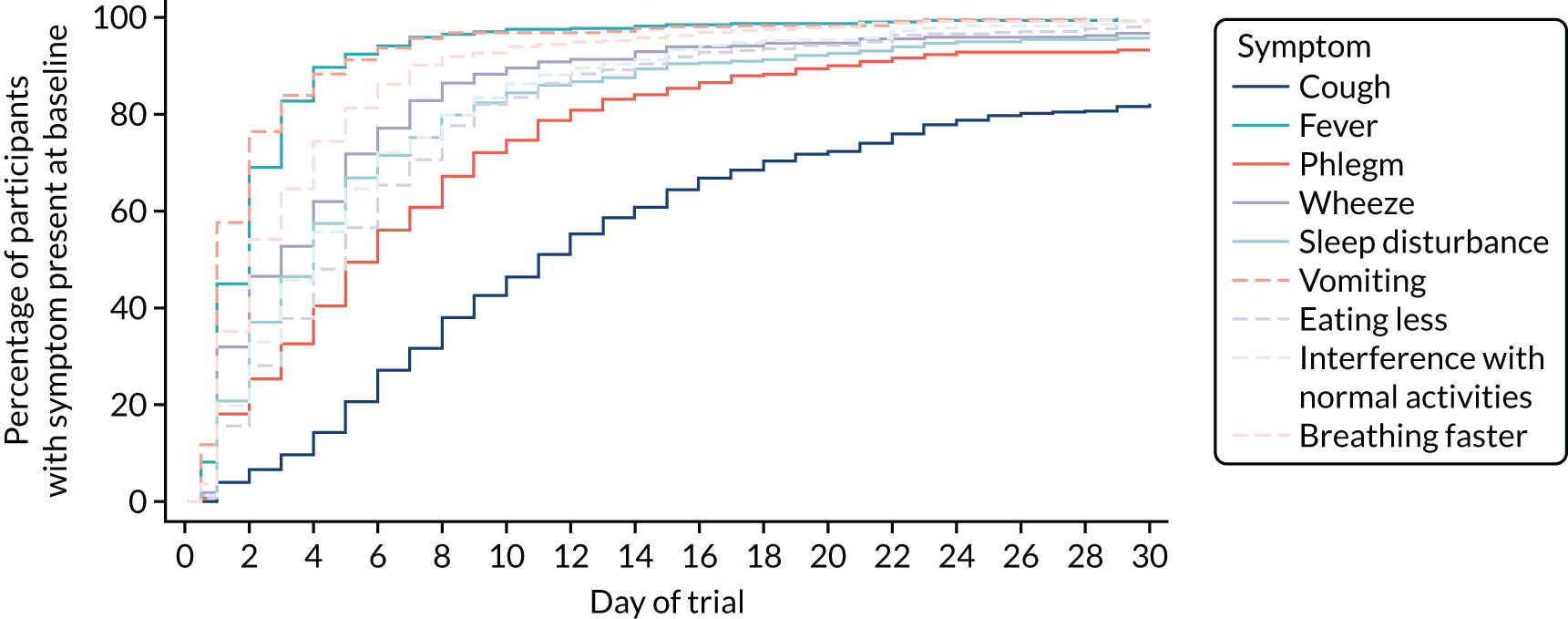

Parent/guardian-reported symptom severity at trial entry is shown in Figure 4. The most common clinical symptom was cough, reported by 96.5% of participants. Fever and fast breathing were reported for 79.6% and 83.5% of participants, respectively, and the least common symptoms at baseline were vomiting and wheeze, reported in 41.1% and 51.8% of participants, respectively. Sleep disturbance, eating less and interference with normal activity were reported in between 80% and 90% of participants.

FIGURE 4.

Symptoms at trial entry.

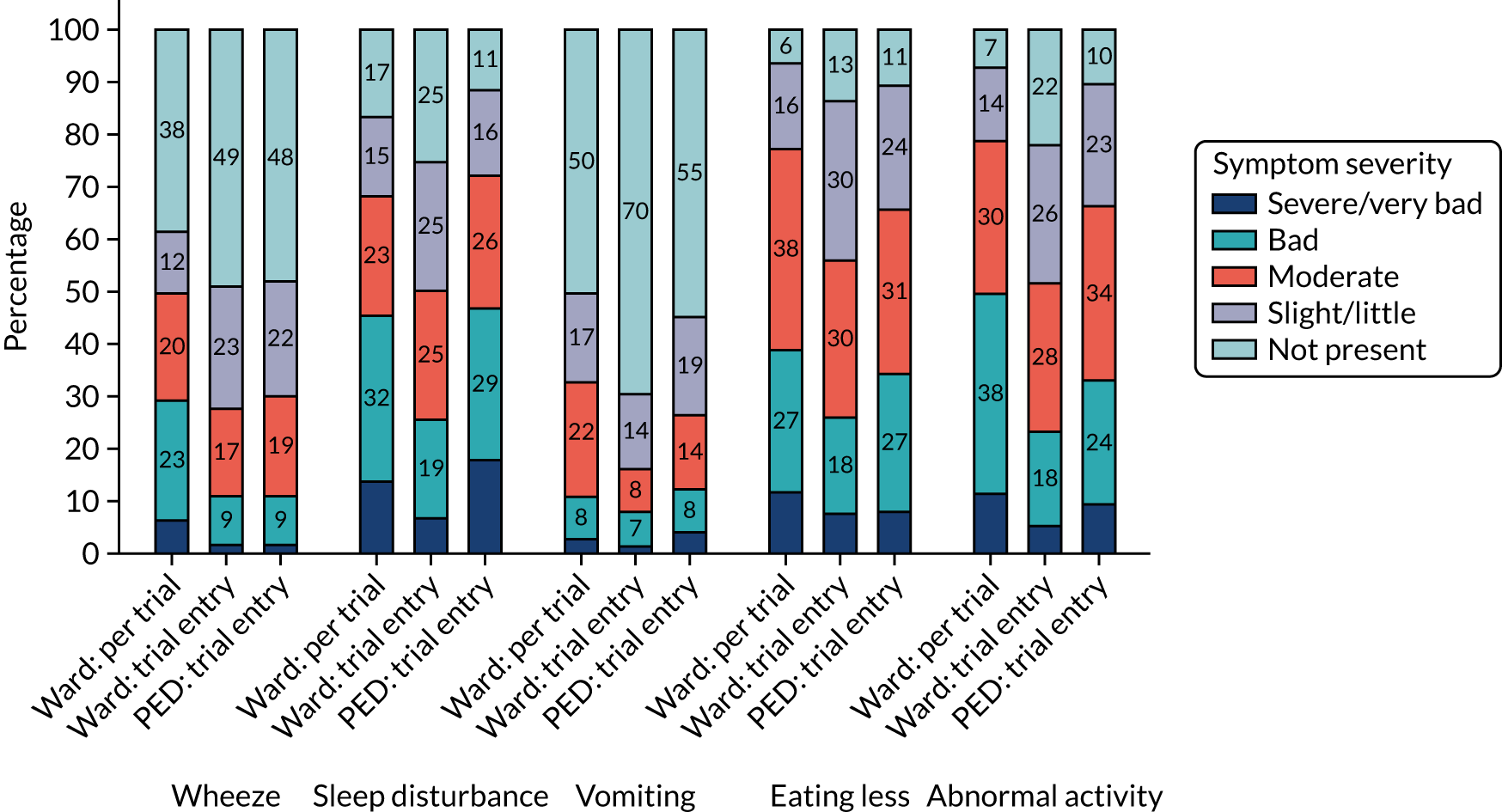

Clinical symptoms in patients who received in-hospital antibiotics prior to trial entry (i.e. the ward group) were reported by parents/guardians at presentation (pre trial) and at baseline (trial entry). Figures 5 and 6 show parent/guardian-reported clinical symptom severity both pre trial and at trial entry for the ward group and at trial entry only for the PED group. For the ward group, the proportion of participants with presence of symptoms at any level of severity decreased between pre trial and trial entry for all symptoms except wet cough (phlegm). The greatest proportional decrease was for fever, for which the proportion of participants with a severity of slight/little or greater decreased from 87.9% to 50.2%.

FIGURE 5.

Clinical symptoms (i.e. fever, cough, phlegm and breathing fast) at trial entry, by group.

FIGURE 6.

Clinical symptoms (i.e. wheeze, sleep disturbance, vomiting, eating less and abnormal activity) at trial entry, by group.

Community-acquired pneumonia symptoms at trial entry, by stratum, are shown in Appendix 2, Table 27.

Clinical investigations

Clinical investigations, including chest radiography, haematology assessment, biochemistry assessment, blood culture and respiratory samples, were not mandatory in CAP-IT. However, if any of these investigations were undertaken, results were reported.

Chest radiography was the most common investigation and was undertaken in 391 (48%) participants (Table 9). Haematological and biochemical assessments were undertaken in 81 (10%) and 82 (10.1%) participants, respectively, while blood cultures and respiratory specimens were obtained in 41 (5%) and 46 (5.7%) participants, respectively.

| Result of chest radiography | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 391), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 192) | Higher dose (N = 199) | Shorter duration (N = 196) | Longer duration (N = 195) | ||

| Suggestive of pneumonia: lobar infiltrate | 65 (33.9) | 69 (34.7) | 64 (32.7) | 70 (35.9) | 134 (34.3) |

| Suggestive of pneumonia: patchy infiltrate | 72 (37.5) | 82 (41.2) | 84 (42.9) | 70 (35.9) | 154 (39.4) |

| Unsure if suggestive of pneumonia | 21 (10.9) | 16 (8.0) | 15 (7.7) | 22 (11.3) | 37 (9.5) |

| Other diagnosis | 7 (3.6) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.1) | 6 (3.1) | 12 (3.1) |

| No finding/not suggestive of pneumonia | 27 (14.1) | 27 (13.6) | 27 (13.8) | 27 (13.8) | 54 (13.8) |

Of the 46 respiratory samples taken, 44 samples underwent virology assessment and 11 samples underwent bacteriology assessment (Table 10). All 11 of the respiratory samples subjected to bacteriological assessment showed no significant growth.

| Assessment result | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 44), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 19) | Higher dose (N = 25) | Shorter duration (N = 24) | Longer duration (N = 20) | ||

| Type of respiratory sample for virology | |||||

| Nasopharyngeal | 13 (68) | 21 (84) | 20 (83) | 14 (70) | 34 (77) |

| Oropharyngeal | 6 (32) | 4 (16) | 4 (17) | 6 (30) | 10 (23) |

| Respiratory sample for virology: result | |||||

| Rhinovirus | 5 (26) | 7 (28) | 6 (25) | 6 (30) | 12 (27) |

| Influenza A/B | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 2 (5) |

| Adenovirus | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Rhinovirus plus adenovirus | 2 (11) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (7) |

| Rhinovirus plus enterovirus | 4 (21) | 5 (20) | 5 (21) | 4 (20) | 9 (20) |

| Rhinovirus plus enterovirus plus adenovirus | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Rhinovirus plus enterovirus plus coronavirus | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Human metapneumovirus | 1 (5) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (7) |

| No viral isolate present | 5 (26) | 7 (28) | 7 (29) | 5 (25) | 12 (27) |

Finally, of the 40 blood samples taken for culture, 37 (93%) returned a negative result. The three positive results were considered probably due to contamination, with two identifying as coagulase-negative staphylococci and one identifying as Gram-positive cocci (not further differentiated).

Prior antibiotic exposure

A total of 242 (29.7%) children received antibiotics for up to 48 hours prior to enrolment, of whom 241 received beta-lactam antibiotics and one received a macrolide. Amoxicillin was the most common antibiotic taken prior to trial entry (209/242, 86.4%), followed by co-amoxiclav (20/242, 8.3%). In children receiving antibiotics prior to enrolment, the median number of doses was 2 (IQR 1–3). More than half of children (55%) were enrolled within 12 hours of commencing antibiotic treatment, with 24.8% enrolled within 12–24 hours, 12.4% within 24–36 hours and 7.9% within 36–48 hours (Table 11).

| Prior exposure | Treatment arm | Total (N = 814) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Any systemic antibiotic in last 3 months, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 64 (16) | 65 (16) | 66 (16) | 63 (16) | 129 (16) |

| No | 346 (84) | 339 (84) | 347 (84) | 338 (84) | 685 (84) |

| Antibiotics received in last 48 hours?, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 119 (29) | 123 (30) | 123 (30) | 119 (30) | 242 (30) |

| No | 291 (71) | 281 (70) | 290 (70) | 282 (70) | 572 (70) |

| Class of prior antibiotic, n (%) | |||||

| Beta-lactam | 118 (99) | 123 (100) | 123 (100) | 118 (99) | 241 (100) |

| Macrolide | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Prior antibiotic, n (%) | |||||

| Amoxicillin | 103 (87) | 106 (86) | 104 (85) | 105 (88) | 209 (86) |

| Benzylpenicillin | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Ceftriaxone | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 6 (2) |

| Cefuroxime | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Clarithromycin | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Co-amoxiclav | 9 (8) | 11 (9) | 13 (11) | 7 (6) | 20 (8) |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Number of prior antibiotic doses, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) |

| Prior antibiotic: route, n (%) | |||||

| Intravenous | 15 (13) | 10 (8) | 17 (14) | 8 (7) | 100 (41) |

| Oral | 103 (87) | 110 (89) | 106 (86) | 107 (90) | 85 (35) |

| Intravenous plus oral | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 28 (12) |

| Duration (hours) of prior antibiotic treatment, n (%) | |||||

| < 12 | 67 (56) | 66 (54) | 68 (55) | 65 (55) | 133 (55) |

| 12–24 | 27 (23) | 33 (27) | 33 (27) | 27 (23) | 60 (25) |

| 24–36 | 13 (11) | 17 (14) | 13 (11) | 17 (14) | 30 (12) |

| 36–48 | 12 (10) | 7 (6) | 9 (7) | 10 (8) | 19 (8) |

Other medical interventions in exposed group

In addition, 54.3% of children in the ward group received supportive measures, including oxygen (49.3%), nasogastric feeds or fluids (2.7%), parenteral fluids (8.5%) and chest physiotherapy (2.7%). Finally, 82.1% of children in the ward group received pharmacological treatment other than antibiotics in hospital, including salbutamol inhalers (58.3%), paracetamol (52.1%), steroids (22.9%), ibuprofen (15.7%) and ipratropium bromide (8.3%).

Follow-up

Of the 814 patients included in the analysis, 642 (79%) completed the final assessment. Where possible, this final assessment was carried out face to face at hospital or at home, but if this proved impossible (e.g. if parents/guardians were unable to attend an appointment), then the assessment was completed by telephone. Overall, 25% of final assessments were performed by telephone, 74% were performed in hospital and 1% were performed at home. In 172 (21%) participants, the final assessment was not conducted with the family. Of these 172 participants, 11 had withdrawn consent and a further 161 could not be contacted. However, 150 of these participants (87%) had provided consent for collection of the primary outcome via hospital and GP records, and primary outcome data were successfully collected in 144 of these participants. This ensured that primary outcome data were available for 786 (97%) participants, and only 28 participants (3%) were considered withdrawn or lost to follow-up (Table 12).

| Final visit and follow-up data | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Attendance | |||||

| Final visit completed | 329 (80) | 313 (77) | 315 (76) | 327 (82) | 642 (79) |

| Previously withdrawn | 8 (2) | 3 (1) | 6 (1) | 5 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Not withdrawn but not completed | 73 (18) | 88 (22) | 92 (22) | 69 (17) | 161 (20) |

| Where/how did final visit take place? | |||||

| Hospital | 242 (74) | 236 (75) | 231 (73) | 247 (76) | 478 (74) |

| Home | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Telephone call | 84 (26) | 74 (24) | 81 (26) | 77 (24) | 158 (25) |

| Consent for further data collection? | |||||

| Yes | 71 (88) | 79 (87) | 87 (89) | 63 (85) | 150 (87) |

| No | 10 (12) | 12 (13) | 11 (11) | 11 (15) | 22 (13) |

| Day 28 data received from GP? | |||||

| Yes | 70 (99) | 74 (94) | 84 (97) | 60 (95) | 144 (96) |

| No | 1 (1) | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 3 (5) | 6 (4) |

| Final visit status | |||||

| Completed | 329 (80) | 313 (77) | 315 (76) | 327 (82) | 642 (79) |

| Not completed, but GP data received | 70 (17) | 74 (18) | 84 (20) | 60 (15) | 144 (18) |

| Withdrawn/lost | 11 (3) | 17 (4) | 14 (3) | 14 (3) | 28 (3) |

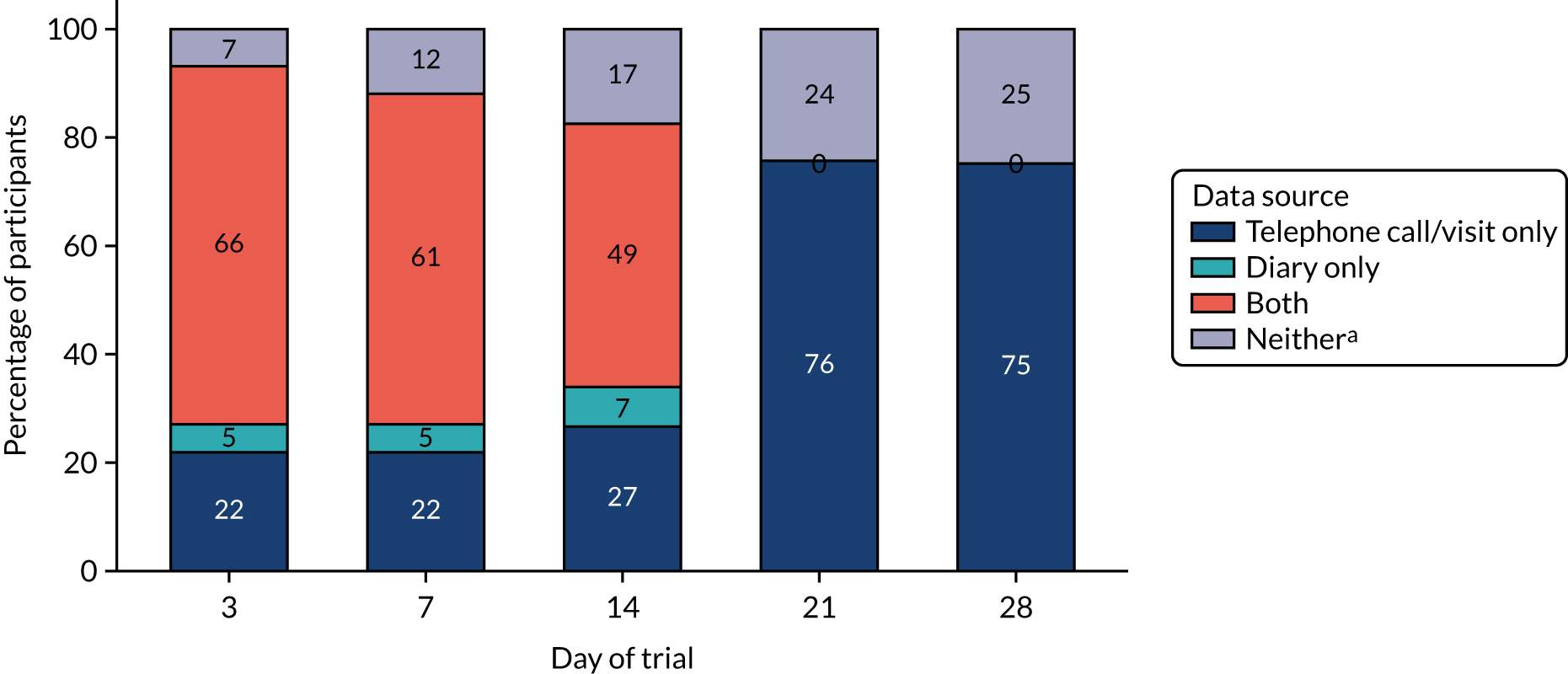

Follow-up data were also collected by telephone at days 3, 7, 14 and 21 (Table 13). Follow-up rates were 88% at day 3, 75% at day 14 and 76% at day 21. A total of 443 (54%) parents/guardians of participants completed all telephone calls and the final visit, with 153 (19%) parents/guardians of participants missing one follow-up visit, 95 (12%) parents/guardians of participants missing two follow-up visits, 51 (6%) parents/guardians of participants missing three follow-up visits and 48 (6%) parents/guardians of participants missing four follow-up visits. Twenty-four (3%) parents/guardians of participants missed all telephone calls and visits.

| Follow-up | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Trial entry | 410 (100) | 404 (100) | 413 (100) | 401 (100) | 814 (100) |

| Day 3 | 355 (87) | 360 (89) | 365 (88) | 350 (87) | 715 (88) |

| Day 7 | 332 (81) | 343 (85) | 342 (83) | 333 (83) | 675 (83) |

| Day 14 | 314 (77) | 299 (74) | 307 (74) | 306 (76) | 613 (75) |

| Day 21 | 315 (77) | 302 (75) | 303 (73) | 314 (78) | 617 (76) |

| Final visit (day 28) | 329 (80) | 313 (77) | 315 (76) | 327 (82) | 642 (79) |

A symptom diary was to be completed daily by parents/guardians for the first 14 days after trial entry. Completed diary data were available for 406 (49.9%) participants and no diary data were available for 227 (27.9%) participants. Parents/guardians were assigned to complete symptom diaries either electronically (42.5%) or on paper (57.5%) using pseudorandomisation. Summary data on diary completion are presented in Table 14.

| Diary completion | Treatment arm, n (%) | Total (N = 814), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||

| Diary status | |||||

| Completed: all days | 201 (49.0) | 205 (50.7) | 212 (51.3) | 194 (48.4) | 406 (49.9) |

| Completed: partly | 97 (23.7) | 84 (20.8) | 79 (19.1) | 102 (25.4) | 181 (22.2) |

| No diary data available | 112 (27.3) | 115 (28.5) | 122 (29.5) | 105 (26.2) | 227 (27.9) |

| Number of days completed | |||||

| None | 112 (27.3) | 115 (28.5) | 122 (29.5) | 105 (26.2) | 227 (27.9) |

| 1–4 | 26 (6.3) | 11 (2.7) | 14 (3.4) | 23 (5.7) | 37 (4.5) |

| 5–8 | 27 (6.6) | 32 (7.9) | 33 (8.0) | 26 (6.5) | 59 (7.2) |

| 9–12 | 44 (10.7) | 41 (10.1) | 32 (7.7) | 53 (13.2) | 85 (10.4) |

| 13 | 201 (49.0) | 205 (50.7) | 212 (51.3) | 194 (48.4) | 406 (49.9) |

| No diary data: reason | |||||

| Withdrawal | 7 (6.3) | 2 (1.7) | 5 (4.1) | 4 (3.8) | 9 (4.0) |

| Paper: no final visit | 40 (35.7) | 48 (41.7) | 49 (40.2) | 39 (37.1) | 88 (38.8) |

| Paper: final visit as telephone call | 23 (20.5) | 18 (15.7) | 17 (13.9) | 24 (22.9) | 41 (18.1) |

| Lost/forgot | 21 (18.8) | 19 (16.5) | 24 (19.7) | 16 (15.2) | 40 (17.6) |

| Technical/password issue | 8 (7.1) | 13 (11.3) | 11 (9.0) | 10 (9.5) | 21 (9.3) |

| No time | 4 (3.6) | 6 (5.2) | 6 (4.9) | 4 (3.8) | 10 (4.4) |

| Site error | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 9 (8.0) | 8 (7.0) | 9 (7.4) | 8 (7.6) | 17 (7.5) |

Adherence

A total of 240 (29.5%) participants deviated from the prescribed IMP regimen for reasons including taking fewer doses or a lower volume, taking too many doses or a greater volume, or deviation in timing (Table 15).

| Adherence to trial medication | Treatment arm, n (%) | p-value | Treatment arm, n (%) | p-value | Total (N = 814), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower dose (N = 410) | Higher dose (N = 404) | Shorter duration (N = 413) | Longer duration (N = 401) | ||||

| Early cessation of trial treatment | |||||||

| Trial treatment completed | 355 (86.6) | 366 (90.6) | 0.10 | 358 (86.7) | 363 (90.5) | 0.015 | 721 (88.6) |

| Early cessation for clinical improvement | 7 (1.7) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.7) | 8 (1.0) | ||

| Early cessation for clinical deterioration | 16 (3.9) | 11 (2.7) | 10 (2.4) | 17 (4.2) | 27 (3.3) | ||

| Early cessation for other reason | 32 (7.8) | 26 (6.4) | 40 (9.7) | 18 (4.5) | 58 (7.1) | ||

| Day of last dose of trial medication | |||||||

| Day 0 or 1 | 11 (20) | 4 (11) | 0.62 | 9 (16) | 6 (16) | 0.61 | 15 (16) |

| Day 2 or 3 | 17 (31) | 15 (39) | 16 (29) | 16 (42) | 32 (34) | ||

| Day 4 or 5 | 22 (40) | 15 (39) | 24 (44) | 13 (34) | 37 (40) | ||

| Day 6 or after | 5 (9) | 4 (11) | 6 (11) | 3 (8) | 9 (10) | ||

| Bottles received | |||||||

| Taken bottle A but not bottles B/C | 30 (7.3) | 16 (4.0) | 0.038 | 21 (5.1) | 25 (6.2) | 0.48 | 46 (5.7) |

| Taken bottle A and bottles B/C | 380 (92.7) | 388 (96.0) | 392 (94.9) | 376 (93.8) | 768 (94.3) | ||

| Overall: fewer doses taken than scheduled | |||||||

| Yes | 86 (21.0) | 77 (19.1) | 0.49 | 85 (20.6) | 78 (19.5) | 0.69 | 163 (20.0) |

| No | 324 (79.0) | 327 (80.9) | 328 (79.4) | 323 (80.5) | 651 (80.0) | ||

| Overall: fewer doses or less volume taken than scheduled | |||||||

| Yes | 104 (25.4) | 95 (23.5) | 0.54 | 113 (27.4) | 86 (21.4) | 0.050 | 199 (24.4) |

| No | 306 (74.6) | 309 (76.5) | 300 (72.6) | 315 (78.6) | 615 (75.6) | ||

| Overall: any deviation (including too many doses/volume or timing deviations) | |||||||

| Yes | 128 (31.2) | 107 (26.5) | 0.14 | 133 (32.2) | 102 (25.4) | 0.033 | 235 (28.9) |