Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/51/01. The contractual start date was in December 2009. The draft report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Langton Hewer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common life-limiting recessively inherited condition in white populations. It is a multisystem disorder in which the airways frequently become blocked with mucus, often associated with respiratory infections. These infections may lead to progressive respiratory failure and ultimately to death from breathing failure. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common infection in the lungs of patients with CF. The age-specific prevalence of P. aeruginosa in pre-school children is 9%, rising to 32% for 10- to 15-year-olds. 1 Early infection can be eradicated in the majority of patients. However, once chronic infection is established, P. aeruginosa is virtually impossible to eradicate and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. 2 Long-term infection is associated with poor outcomes, including more rapid decline in lung function, such as the amount of air expired in 1 second of forced expiration [forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)]. 3,4 New isolation of P. aeruginosa is treated with antibiotics in an attempt to eradicate the infection and to delay acquisition of chronic infection. 5 However, there is uncertainty about the best method to eradicate P. aeruginosa from the lower respiratory tract, and several different strategies are used, including oral quinolones such as ciprofloxacin, and intravenous (i.v.) and nebulised antibiotics. 6–10

There are clear differences between the available treatments in terms of the impact on the patient and their family, the use of resources and the cost of treatment. However, few studies have compared the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of these treatments.

Fourteen days of i.v. treatment will usually necessitate admission to hospital and siting of one or more i.v. lines for drug infusion. The siting of lines can be traumatic, especially for children and their families.

Intravenous aminoglycosides are commonly used and they require further blood tests for monitoring of plasma levels, and can be associated with kidney and inner ear damage. 11 No study has yet been conducted to investigate the therapeutic advantage of i.v. and oral treatment.

In 2005, the NHS National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) commissioned the Medicines for Children Research Network to assess the feasibility of conducting a randomised controlled trial to investigate the prevention of colonisation with P. aeruginosa in CF patients. This report was completed in 2007, having surveyed UK clinical practice, surveyed opinions of CF patients and families, and assessed the number of potentially eligible patients for such a trial. 12 The result of this feasibility study was to show that, generally, clinicians treat first or new growth of P. aeruginosa in accordance with the UK CF Trust guidelines13 and 95% of clinicians reported that they would consider i.v. treatment of first isolation of P. aeruginosa. In addition, 71% of clinician and 43% of consumer respondents would consider entry for themselves/their patients into a randomised controlled trial comparing oral with i.v. antibiotics. The conclusion of the study stated ‘[T]he clinical community are in equipoise when considering effectiveness of eradication therapy for treatment of P. aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis’ and recommended that it is feasible to consider the initiation of a randomised controlled trial investigating eradication therapy to treat P. aeruginosa in patients with CF.

This study has been conceived and designed in response to addressing this clinical equipoise and has been commissioned by the NIHR.

Rationale for research

There is equipoise about the best method to eradicate P. aeruginosa from the lower respiratory tract. Several strategies exist to treat early infection with P. aeruginosa. This includes the use of inhaled antibiotics, such as colistin and tobramycin,9,14,15 oral quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin,6,10 and i.v. antibiotics, usually consisting of a combination of an aminoglycoside with a beta-lactam.

Antibiotic strategies for eradication of P. aeruginosa in people with CF have been investigated in a systematic review of randomised clinical trials,16 which concluded that there is an urgent need for well-designed and well-executed trials. The review made the specific recommendation that any future trial should investigate the hypothesis to see if antibiotic treatment of early P. aeruginosa infection prevents or delays chronic infection, and whether or not this then results in an appreciable clinical benefit to patients, without causing them harm. The systematic review made the recommendation that the following outcomes be considered for any future randomised controlled trial: spirometric lung function; nutritional status;11 and socioeconomic outcomes, including quality of life.

The UK CF Trust has published guidance for antibiotic treatment for CF, including treatment for eradication of newly acquired P. aeruginosa infection. 11 This guidance recommends energetic treatment for a patient who has isolated P. aeruginosa where cultures have previously been negative and the report commented that there is no evidence favouring any particular regimen for eradication. The guidance states that appropriate treatment in this situation will include oral ciprofloxacin for the duration of treatment up to 3 months or i.v. treatment such as a beta-lactam antibiotic (e.g. ceftazidime or meropenem) or an anti-pseudomonal penicillin in combination with i.v. tobramycin. 11 Intravenous antibiotics are usually administered for 10–14 days in patients with CF, although there have been no randomised controlled trials of shorter treatment durations.

The rationale for choosing 14 days of i.v. treatment and for choosing 3 months for oral treatment is that both of these regimens are standard practice in many UK CF centres identified in the feasibility study,12 both are standard recommendations within the published UK guideline11 and they are believed to represent current best practice.

Interventions

Participants recruited into the study were randomised to one of the following treatment groups.

Group A

In this treatment group, participants received up to 14 days (recommended treatment duration of 14 days; minimum treatment duration 10 days) of i.v. antibiotics as follows:

-

Ceftazidime 150 mg/kg/day, in three divided doses (maximum of 3 g three times daily). Some centres used a once-daily continuous infusion (where the maximum daily dose would usually be 6 g/day) or twice-daily regimen for ceftazidime. These centres were permitted to continue using this regimen for the study and should have followed their local dosing guidelines.

-

Tobramycin 10 mg/kg/day once daily (maximum 660 mg/day). Some centres used a twice-daily or thrice-daily regimen for tobramycin. These centres were permitted to continue using their current regimen for the study and should have followed their local dosing guidelines.

Therapeutic drug monitoring was used to guide tobramycin dosing as per national guidelines11 and usual clinic procedures.

Group B

In this treatment group, participants received 3 months (12 weeks) of treatment oral ciprofloxacin twice daily. Ciprofloxacin dose was 20 mg/kg twice daily (maximum 750 mg twice daily). This was in line with the British National Formulary (BNF) for children. 17 Some clinicians preferred to use a lower dose of 15 mg/kg twice daily for children < 5 years, as used in national CF guidelines. 11

Both treatment arms received 3 months (12 weeks) of nebulised colistin in conjunction with the randomised treatment. The colistin dose was as recommended by the UK CF Trust: 1,000,000 units twice daily for children aged ≤ 2 years and 2,000,000 units twice daily for children aged > 2 years and adults. If the colistin was administered using an I-neb™ (Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA), then a lower dose of 1,000,000 units twice daily was used for all ages.

It was considered likely that during the study period a small proportion of participants would develop a further P. aeruginosa infection. These participants were treated as per local centre guidelines.

Objective

This study aimed to establish the superiority of 14 days of i.v. therapy compared with 3 months of oral therapy.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

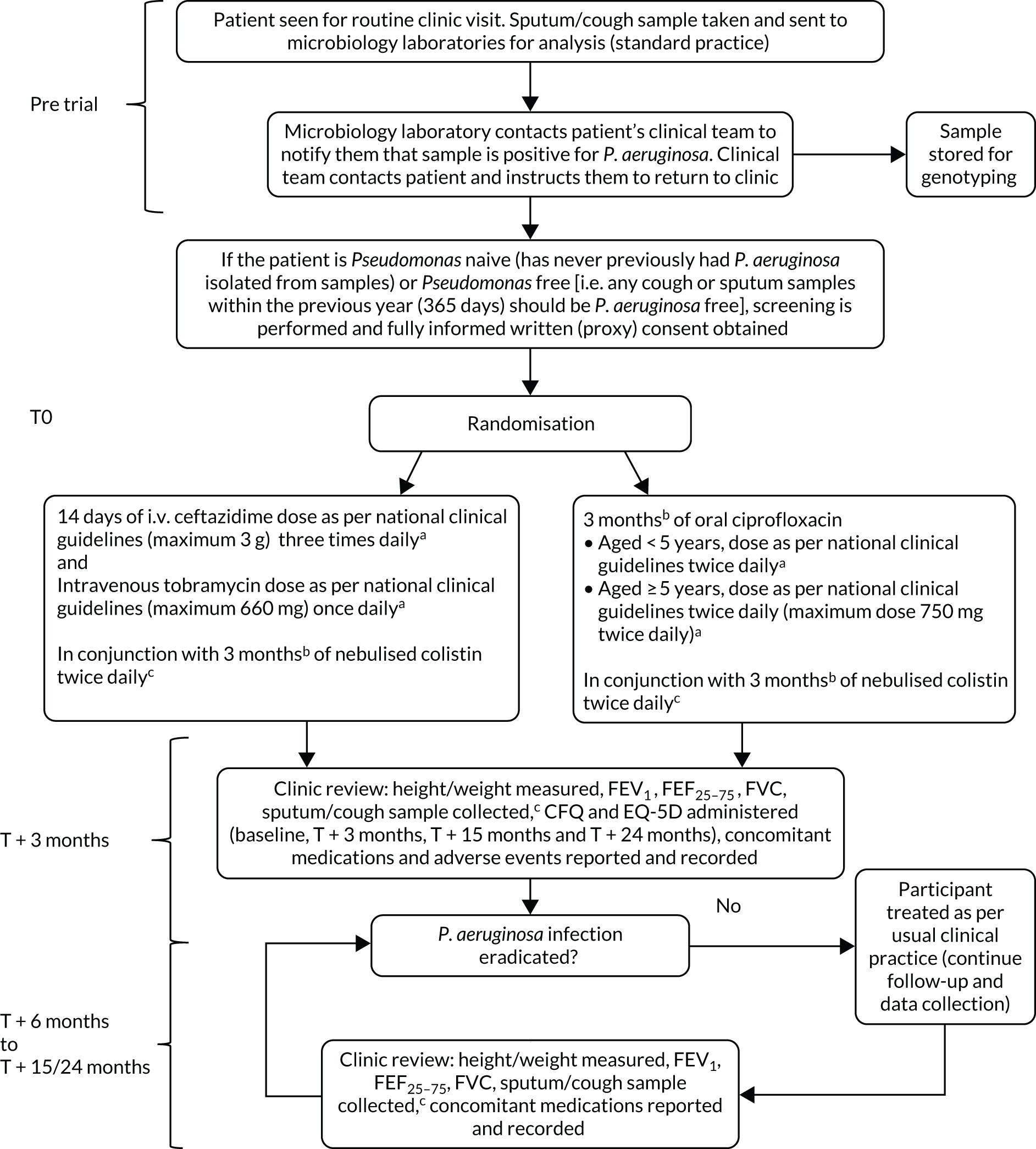

This study was a Phase IV, multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial comparing 14 days of i.v. antibiotic therapy with 3 months of oral antibiotic therapy for participants with CF (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The TORPEDO-CF study design. a, Sites that are unable to comply with the trial dosing regimen can use their current dosing regimen as long as the total daily dose administered is within national clinical guidelines; b, 3 months is defined as 12 weeks; and c, sample stored for genotyping.

Trial registration and ethics

The trial was registered on the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) database on 5 May 2009 (as EudraCT number 2009-012575-10) and received clinical trials authorisation from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency on 2 November 2009 (clinical trials authorisation reference 12893/0220/001). The trial and all subsequent protocol amendments were reviewed and authorised by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

The trial protocol was not initiated until it had received the favourable opinion of the National Research Ethics Committee (REC) (London REC reference 09/H0718/51) on 16 November 2009. It was then reviewed at the research and development offices at participating sites. All subsequent amendments were reviewed and approved by the National Research Ethics Committee, London REC.

The trial was listed on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry on 21 May 2009 as ISRCTN02734162.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Individuals with a diagnosis of CF.

-

Children over the age of 28 days, older children and adult CF participants (i.e. there was no upper age limit).

-

Competent adults who had provided fully informed written consent to participate in the trial.

-

Minors for whom proxy consent had been given by their parent or legal guardian and who had provided their assent to participate in the trial (where possible).

-

Individuals who had isolated P. aeruginosa and were either:

-

P. aeruginosa naive (i.e. never previously had P. aeruginosa isolated from samples) or

-

P. aeruginosa free [i.e. any cough or sputum samples within the previous year (365 days) were P. aeruginosa free].

-

-

Participants were able to commence treatment no later than 21 days from the date of a P. aeruginosa-positive microbiology report.

Exclusion criteria

-

Antibiotic resistance of the current P. aeruginosa sample to any of ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, tobramycin or colistin reported by local microbiology laboratory.

-

Known participant hypersensitivity to ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, tobramycin or colistin.

-

Other known contraindications to any of ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, tobramycin or colistin including previous aminoglycoside hearing or renal damage.

-

Participants in receipt of P. aeruginosa-suppressing treatment, in particular nebulised colistin or tobramycin, or oral ciprofloxacin for the previous 9 calendar months. Short courses of oral ciprofloxacin or i.v. antibiotics (with an anti-pseudomonal spectrum of action) were not a reason for exclusion unless given to treat proven infections with P. aeruginosa.

-

Treatment with other anti-pseudomonal nebulised antibiotics.

-

Pregnant and nursing mothers (women of child-bearing age were counselled on the risks of becoming pregnant during the trial and were offered a pregnancy test).

-

Previous randomisation in the Trial of Optimal TheRapy for Pseudomonas EraDicatiOn in Cystic Fibrosis (TORPEDO-CF).

-

Previous participation in another related intervention trial within 4 weeks of taking part in TORPEDO-CF.

Recruitment

The trial took place in 70 UK CF centres and two CF centres in Italy.

Recruitment commenced on 5 October 2010 and the final participant was randomised on 27 January 2017.

Informed consent

The trial recruited adults and minors (defined in statutory instrument 200418 No. 1031 as aged < 16 years). Informed consent procedures reflected the legal and ethical requirements for obtaining valid written informed consent in these populations.

Prior written informed consent was required for all trial participants. In obtaining and documenting informed consent, the investigator was required to comply with the applicable regulatory requirements, and adhered to the principles of good clinical practice (GCP) and to the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. 19

Potential participants and their families were provided information regarding the trial both verbally and in writing using the ethics-approved patient information sheets and consent forms (PISCs). They were given the opportunity to discuss the trial with the site team. The PISCs took into account the age of minors and their assent was obtained, where appropriate. Potential participants and their families were provided with a clear overview of the trial and details of the procedures, and the potential risks and benefits of all trial medications were carefully discussed.

Adequate time to consider trial entry (generally 24 hours, although it was acknowledged that some patients/families came to a decision sooner) was allowed and all participants were given the opportunity to ask questions, had the opportunity to discuss the study with their surrogates and had time to consider the information prior to agreeing to participate. All PISCs used in TORPEDO-CF were made available in the native language of the countries participating in the trial (with the exception of Wales, where the majority language was used).

All of the recruiting investigators were experienced CF physicians familiar with imparting information to the relevant trial populations. All investigators requesting consent to participate had attended GCP training. During the screening process, if a potential patient was identified, then they/their parent or the person with parental responsibility were approached by the investigator or a designated member of the investigating team. The trial and its objectives were then described to them, at which point any questions could also be answered. The treatment schedule and trial visits were in line with standard clinical care. The potential risks and benefits of the trial interventions were discussed, as well as what would happen if they chose not to enter the trial or had to withdraw from the trial for any reason.

The right of the patient (non-minors) or parent/legal guardian (for minors) to refuse consent to participate in the trial without giving reasons was respected. After the patient had entered the trial, the clinician remained free to give alternative treatment to that specified in the protocol, at any stage, if they felt that it was in the best interest of the participant. However, the reason for doing so was recorded and the patient remained within the trial for the purpose of follow-up and data analysis according to the treatment option to which they had been allocated. Similarly, the patient remained free to withdraw from the protocol treatment and trial follow-up at any time without giving reasons and without prejudicing their further treatment.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised using a secure (24-hour) web-based randomisation programme, which was controlled centrally by the Liverpool Clinical Trials Centre (LCTC), to ensure allocation concealment. Randomisation lists were generated in a 1 : 1 ratio using simple block randomisation, with random variable blocks of length of two and four after an initial block of length of three to reduce predictability. Randomisation was stratified by site, but this was not disclosed in the protocol to further reduce predictability.

Participant treatment allocation was displayed on a secure web page and an automated e-mail confirmation was sent to the authorised randomiser and the principal investigator (PI) or co-investigator (where applicable) at the randomising site. It was the responsibility of the PI or delegated research staff to inform the pharmacy department at their centre of the potential participant prior to randomisation to ensure that there was a sufficient supply of the study drugs.

In the event of an internet connection failure between the centre and the randomisation system, the centre contacted the LCTC to resolve the problem. In the event that site access could not be promptly reinstated, LCTC would attempt to centrally randomise the patient using the web system. Where this was not possible, LCTC would randomise the participant using a back-up randomisation envelope. Of the 286 participants who were randomised, four were randomised utilising a back-up randomisation envelope.

Interventions

Participants recruited into the study were randomised to one of the following treatment groups.

Group A

Up to 14 days (recommended treatment duration of 14 days; minimum treatment duration 10 days) of i.v. antibiotics as follows:

-

Ceftazidime 150 mg/kg/day, in three divided doses (maximum of 3 g three times daily). Some centres used a once-daily continuous infusion (where the maximum daily dose would usually be 6 g/day) or twice-daily regimen for ceftazidime. These centres were permitted to continue using this regimen for the study and should have followed their local dosing guidelines.

-

Tobramycin 10 mg/kg/day once daily (maximum 660 mg/day). Some centres used a twice-daily or thrice-daily regimen for tobramycin. These centres were permitted to continue using their current regimen for the study and should have followed their local dosing guidelines.

Therapeutic drug monitoring was used to guide tobramycin dosing as per national guidelines11 and usual clinic procedures.

Group B

Three months (12 weeks) of oral ciprofloxacin twice daily. Ciprofloxacin dose was 20 mg/kg twice daily (maximum 750 mg twice daily). This was in line with the BNF for children. 17 Some clinicians preferred to use a lower dose of 15 mg/kg twice daily for children < 5 years, as used in national CF guidelines. 11

Both treatment arms received 3 months (12 weeks) of nebulised colistin in conjunction with the randomised treatment. Colistin dose was as recommended by the UK CF Trust: 1,000,000 units twice daily for children aged ≤ 2 years and 2,000,000 units twice daily for children aged > 2 years and adults. If the colistin was administered using an I-neb™, a lower dose of 1,000,000 units twice daily was used for all ages.

During the study period, it was likely that a small proportion of participants would develop a further P. aeruginosa infection. These participants were treated as per local centre guidelines.

Data collection and management

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the successful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection 3 months after allocated treatment has started, and remaining infection free through to 15 months after the start of allocated treatment.

Secondary outcomes

-

Time to reoccurrence of original P. aeruginosa infection.

-

Reinfection with a different genotype of P. aeruginosa.

-

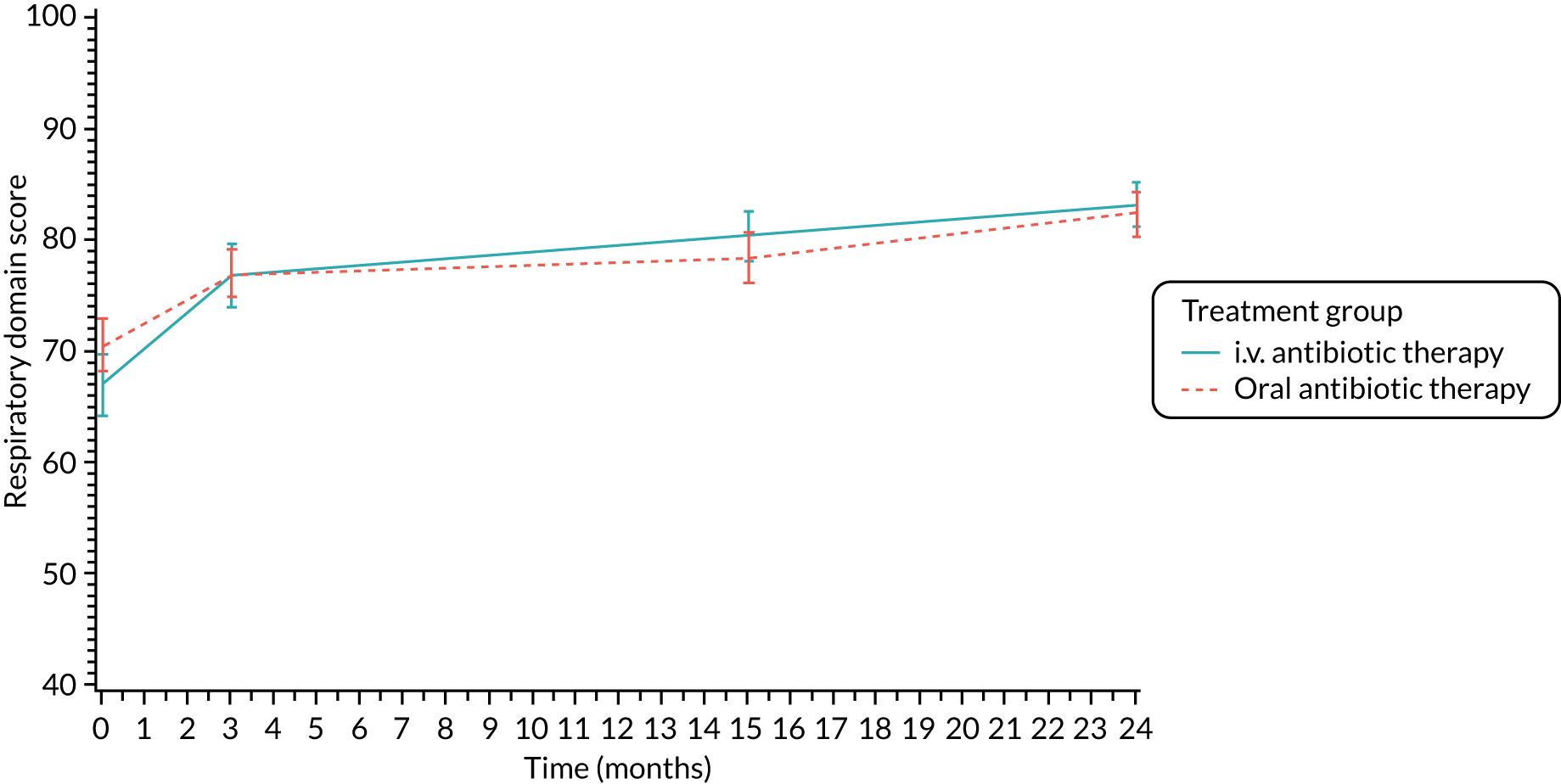

Lung function: FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory flow at 25–75% of forced vital capacity (FEF25–75).

-

Oxygen saturation.

-

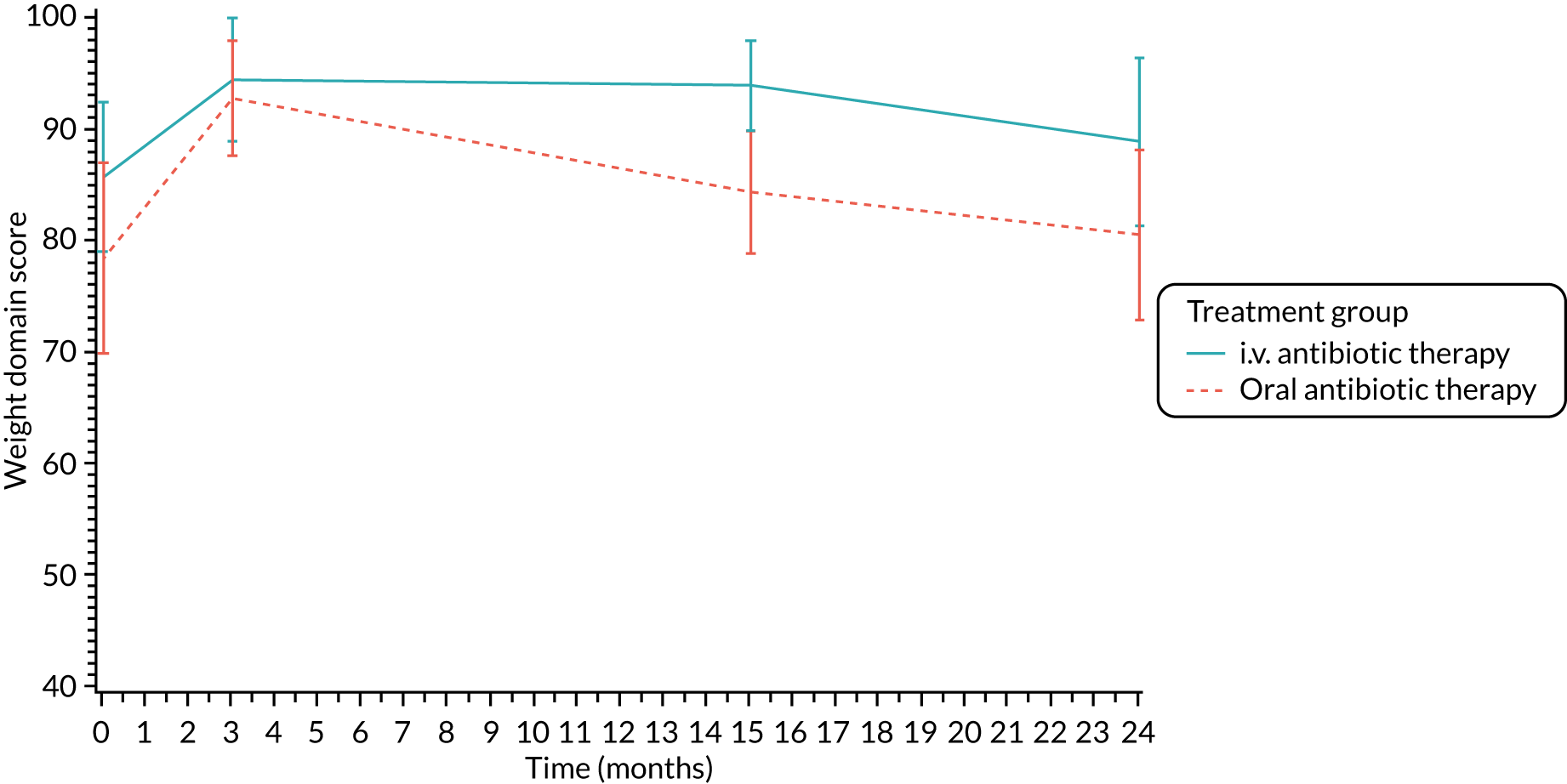

Growth and nutritional status: height, weight and body mass index (BMI).

-

Number of pulmonary exacerbations. (Definition of pulmonary exacerbation used guidelines by Rosenfeld. 20)

-

Admission to hospital.

-

Number of days spent as an inpatient in hospital during treatment phase and between 3 and 15 months after randomisation.

-

Quality of life [Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire (CFQ)].

-

Utility [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)].

-

Adverse events (AEs).

-

Other sputum/cough microbiology [meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Burkholderia cepacia complex, Aspergillus, Candida spp. infection].

-

Cost per patient (from an NHS perspective).

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) [cost per successfully treated patient, cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)].

-

Carer burden (absenteeism from education or work).

-

Participant burden (absenteeism from education or work).

The protocol wording for the outcome ‘[N]umber of days spent as an inpatient in hospital during treatment phase and between 3 and 15 months after randomisation’ is: ‘[N]umber of days spent as inpatient in hospital over the three-month period after allocated treatment has finished treatment, and between three months and 15 months after eradication treatment has finished-finished (other than 14 days spent on initial intravenous treatment)’. It has been changed in the list of secondary outcomes to aid clarity.

Data collection tools

Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire

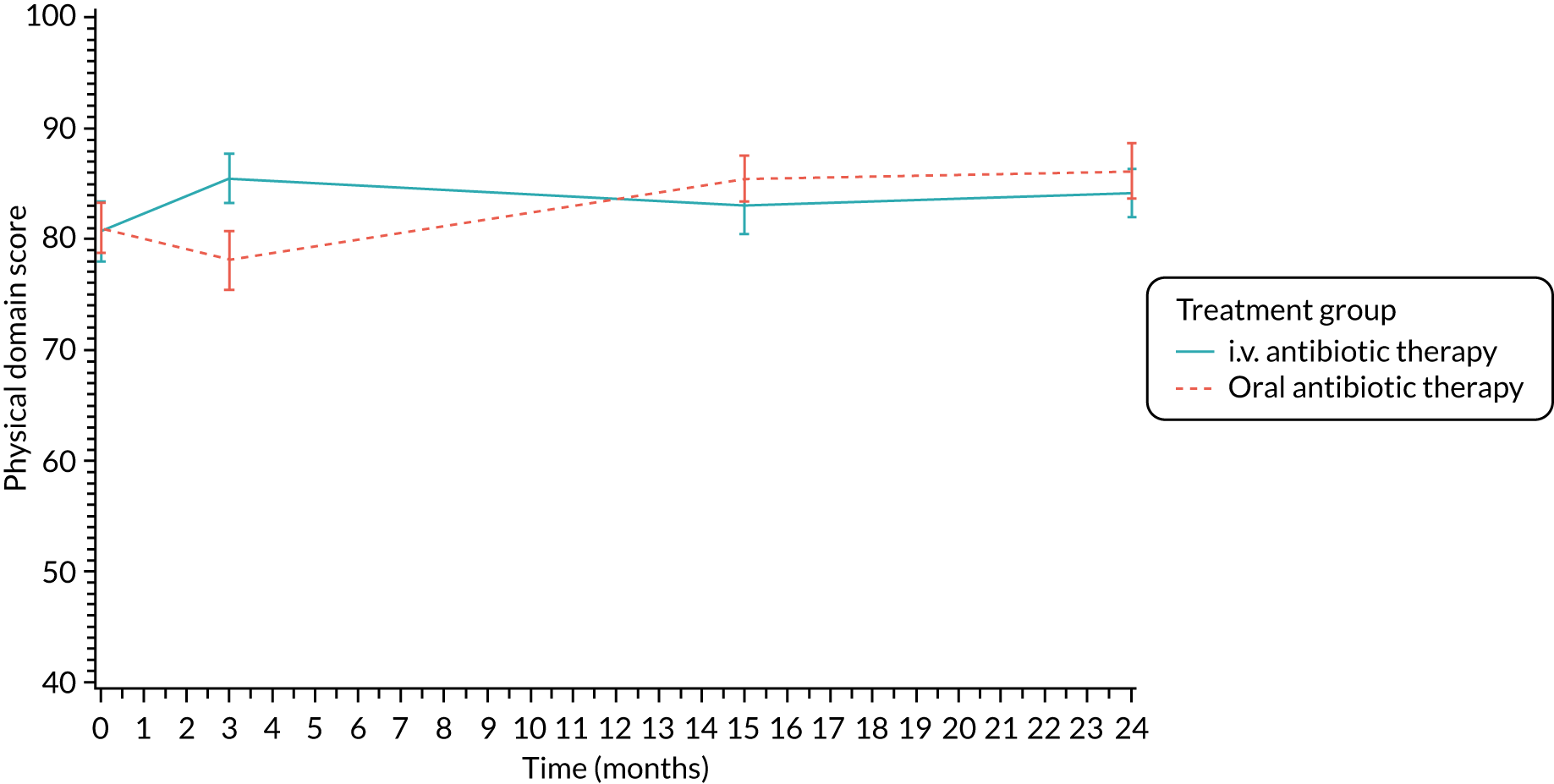

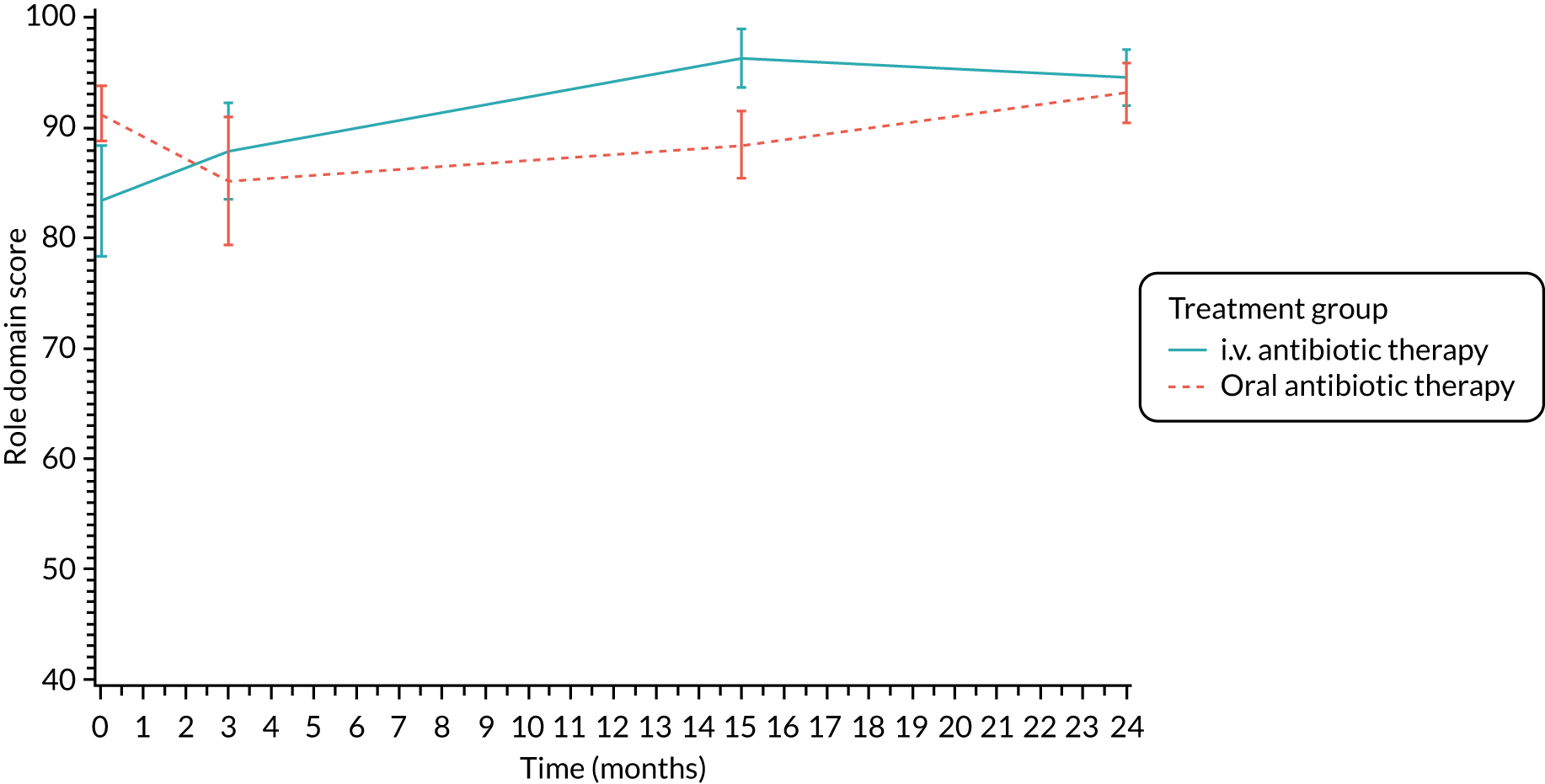

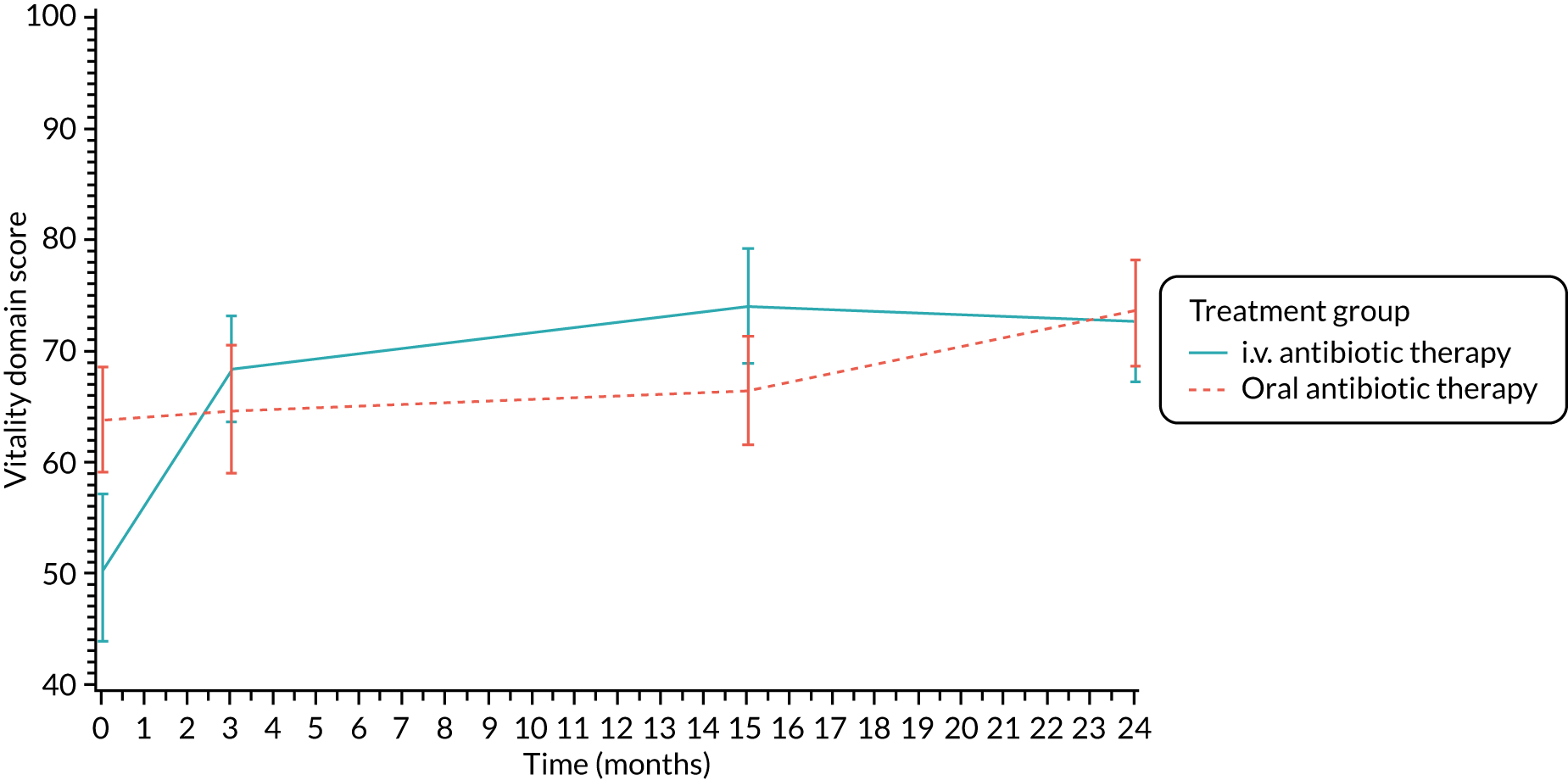

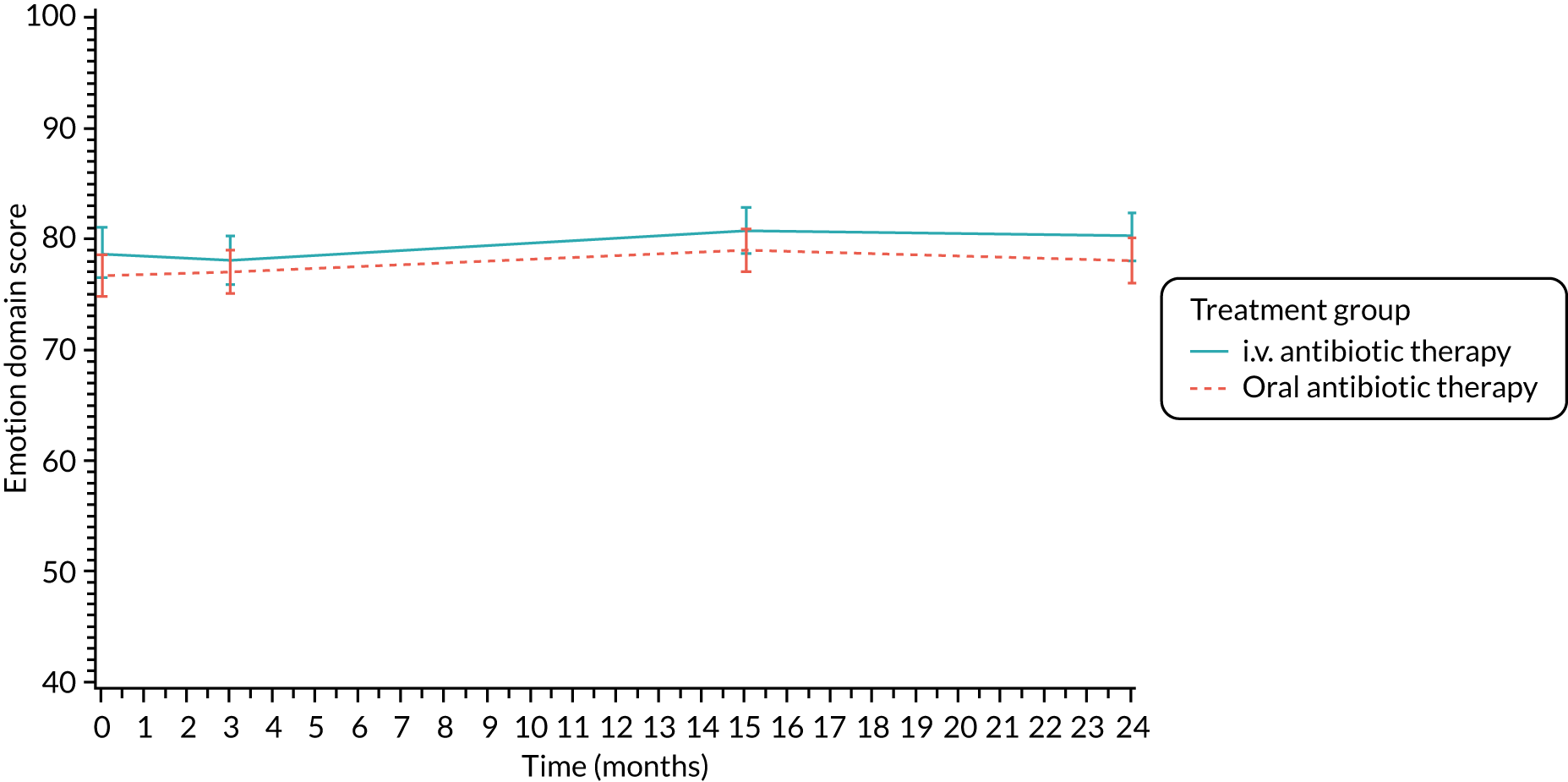

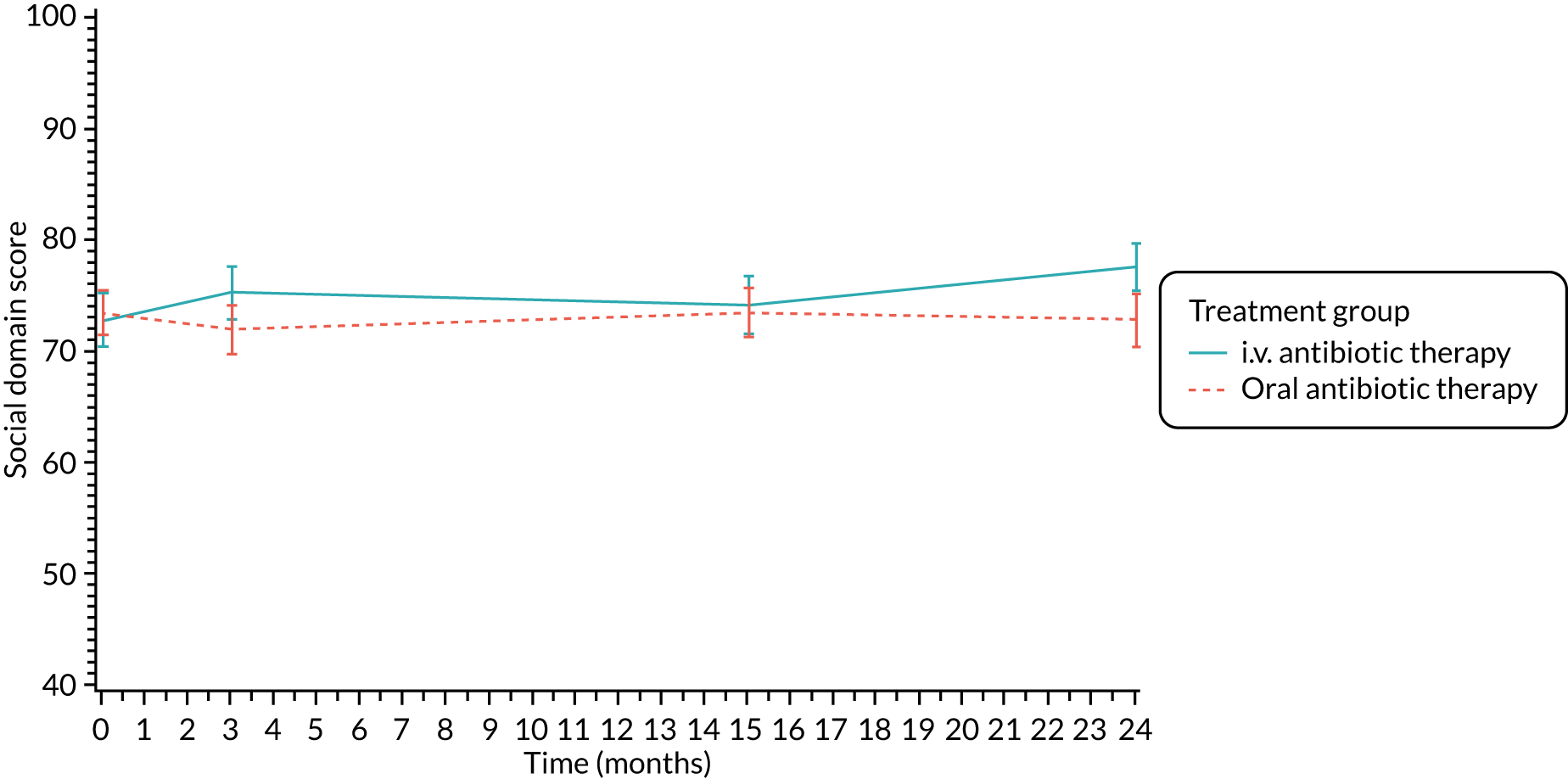

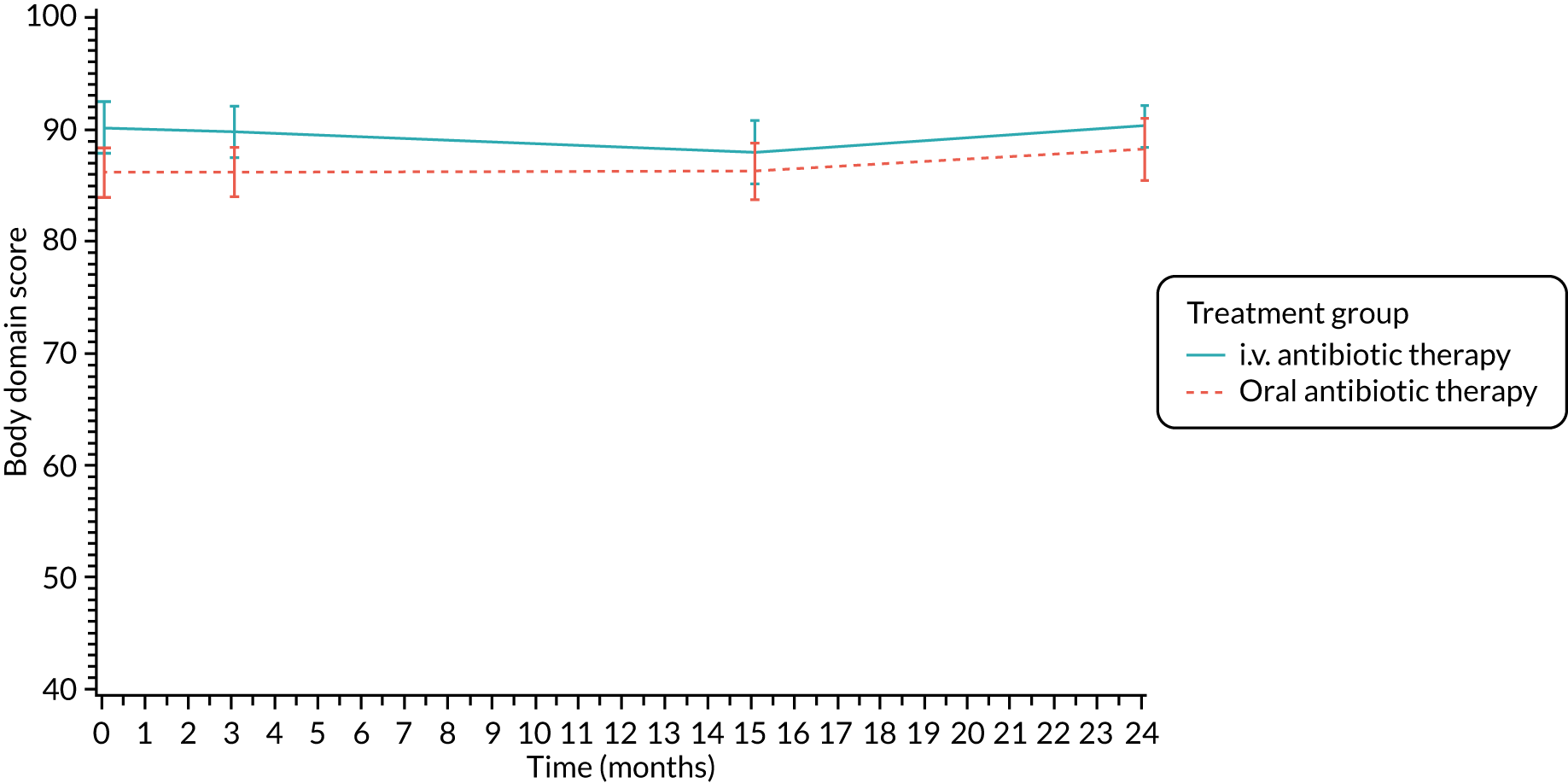

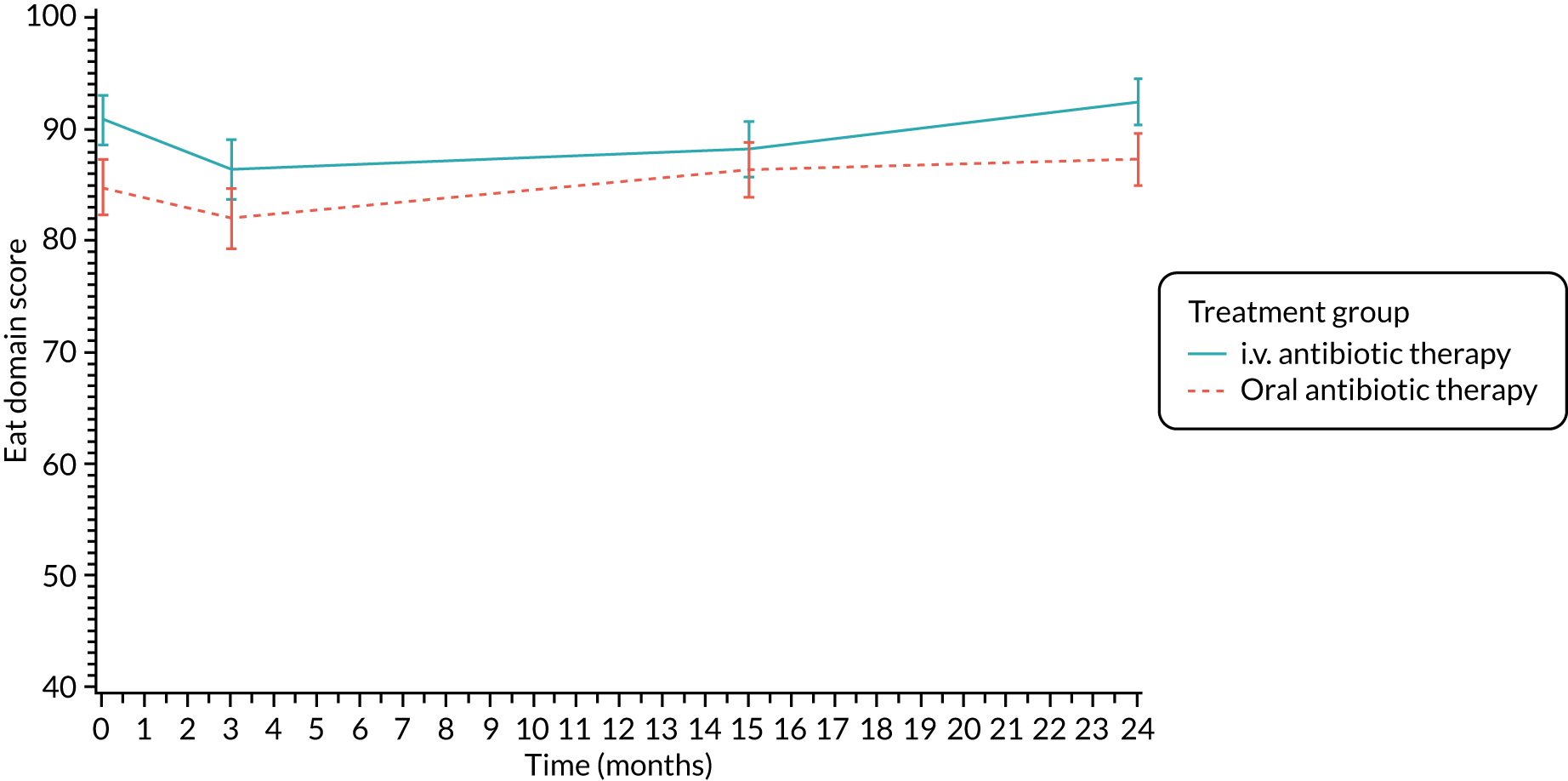

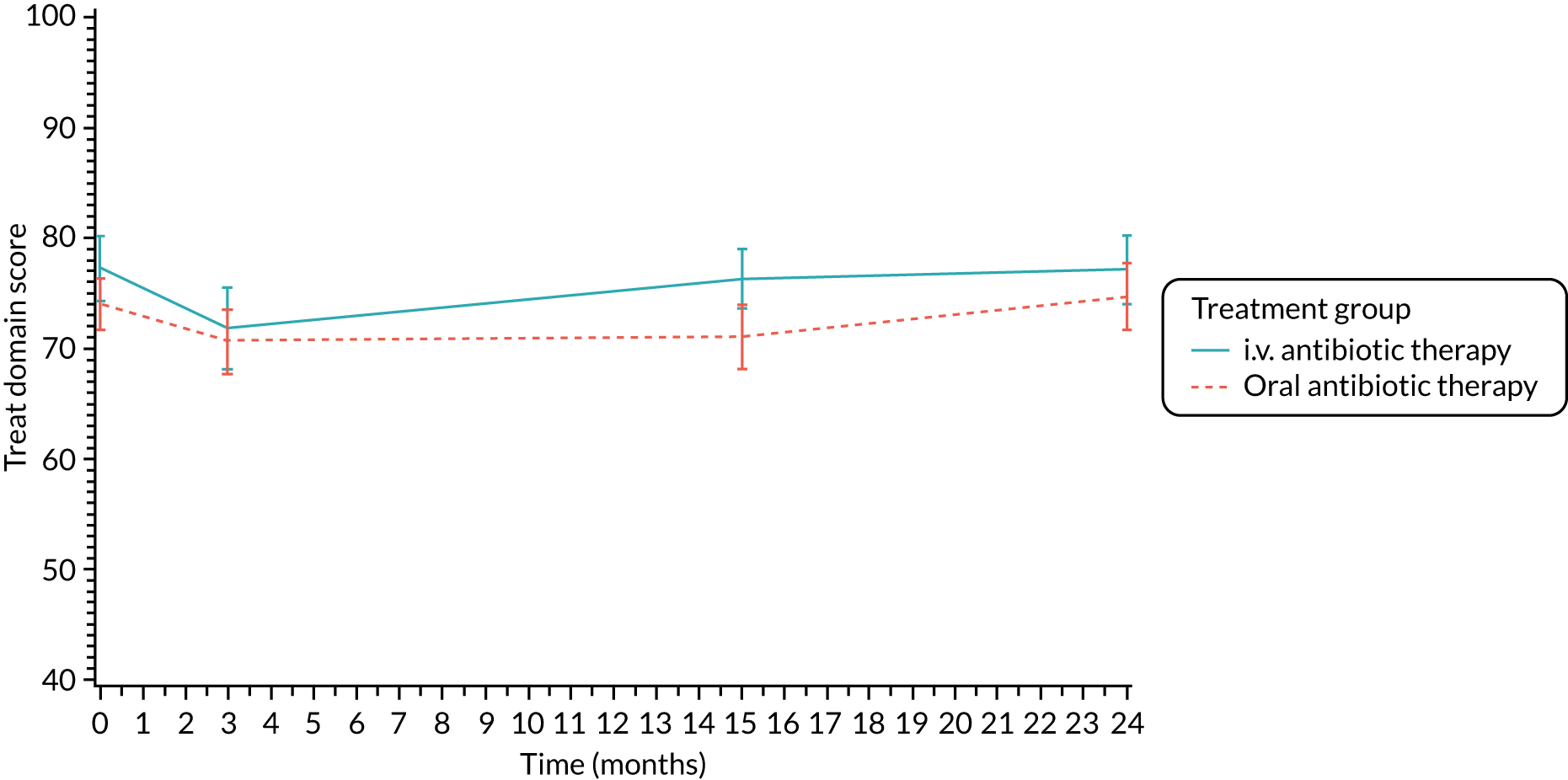

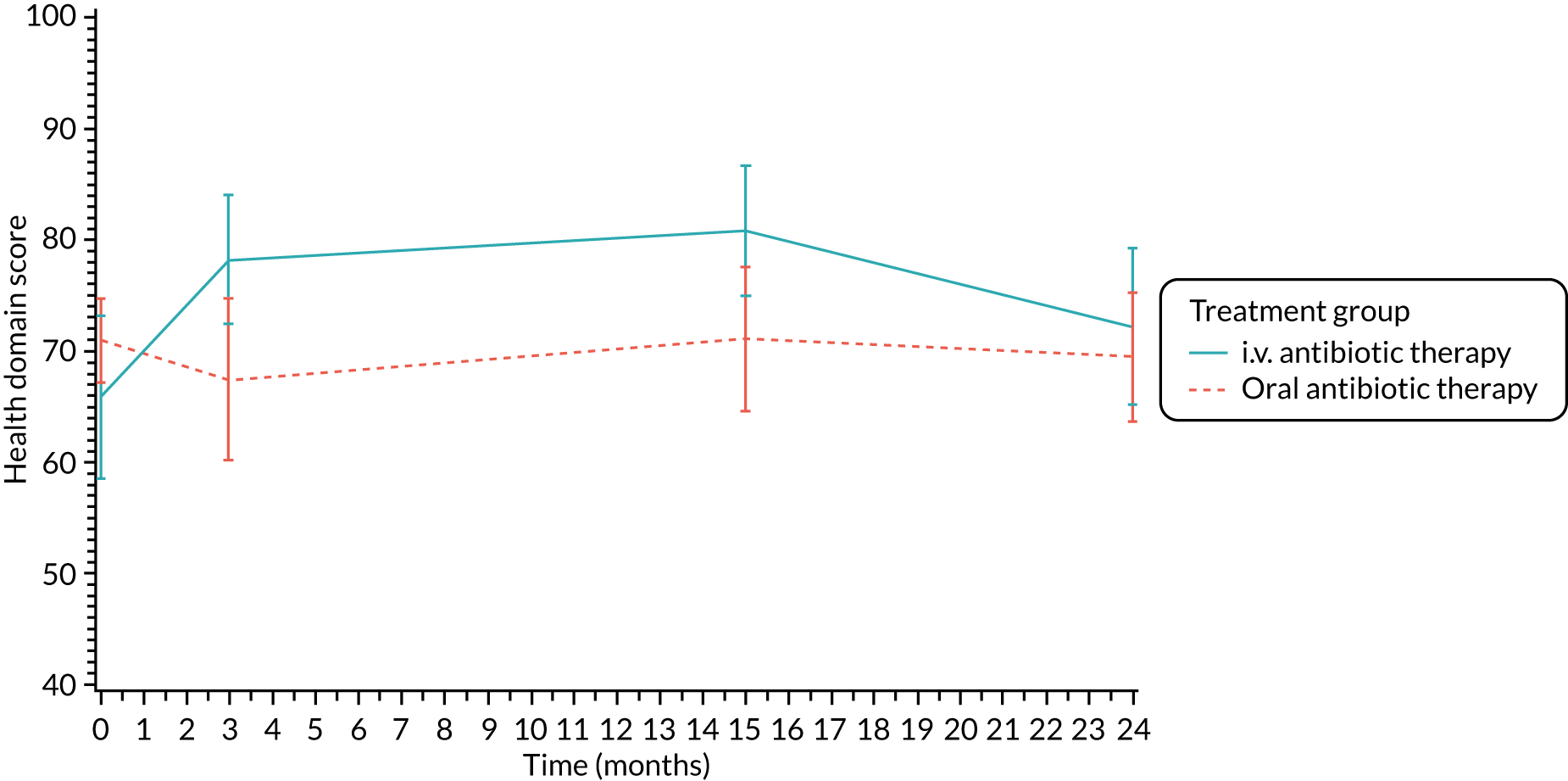

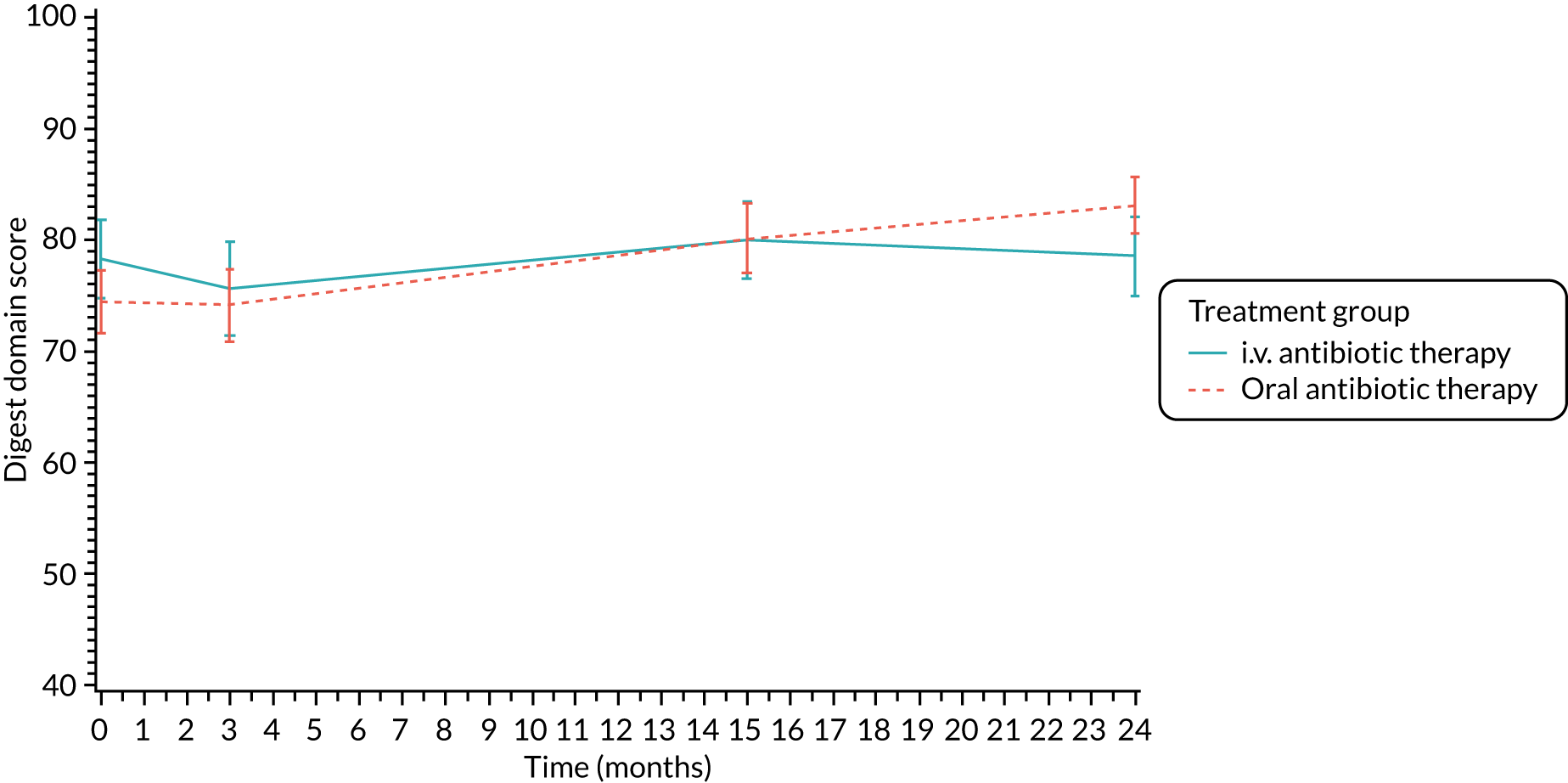

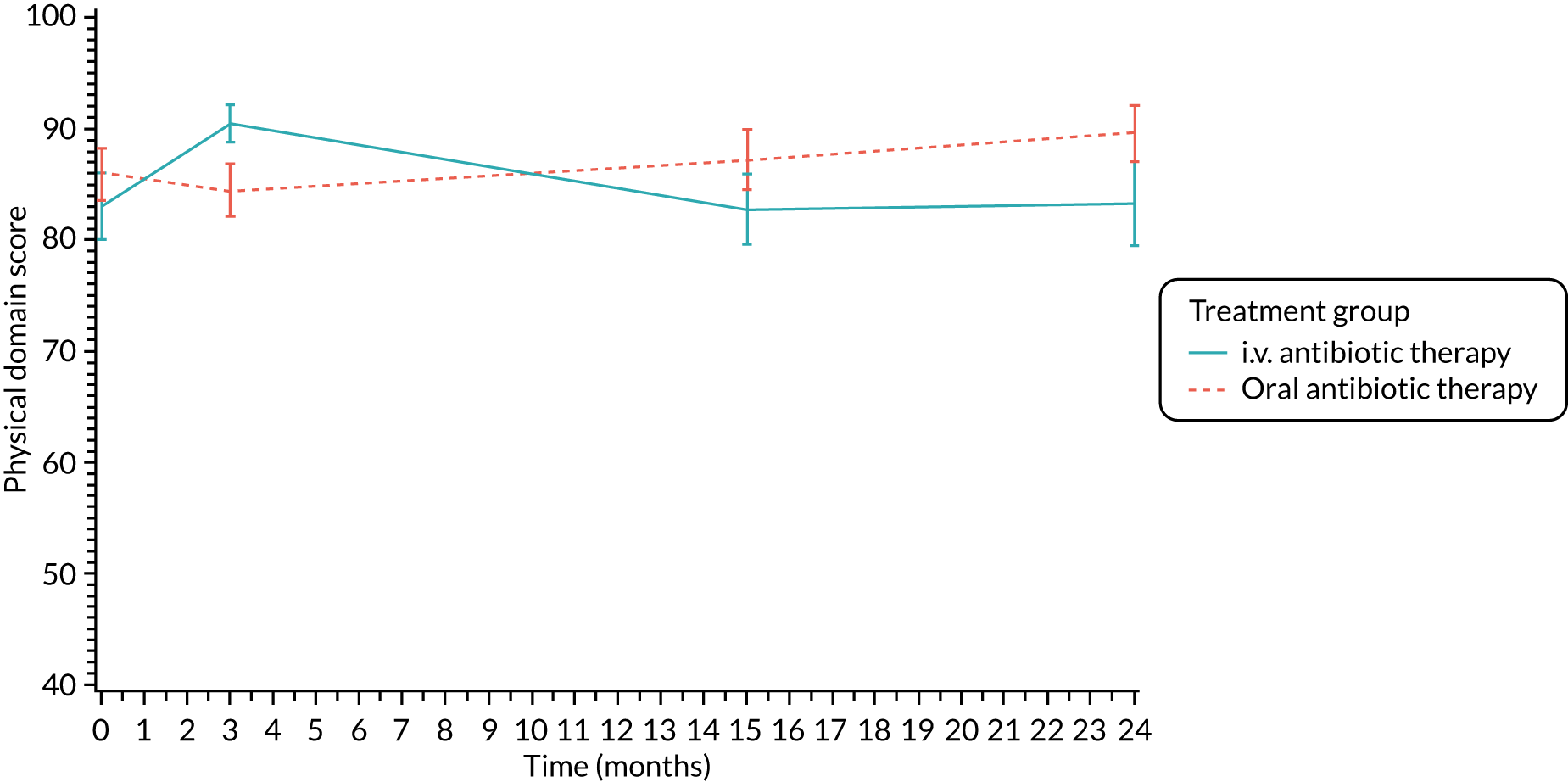

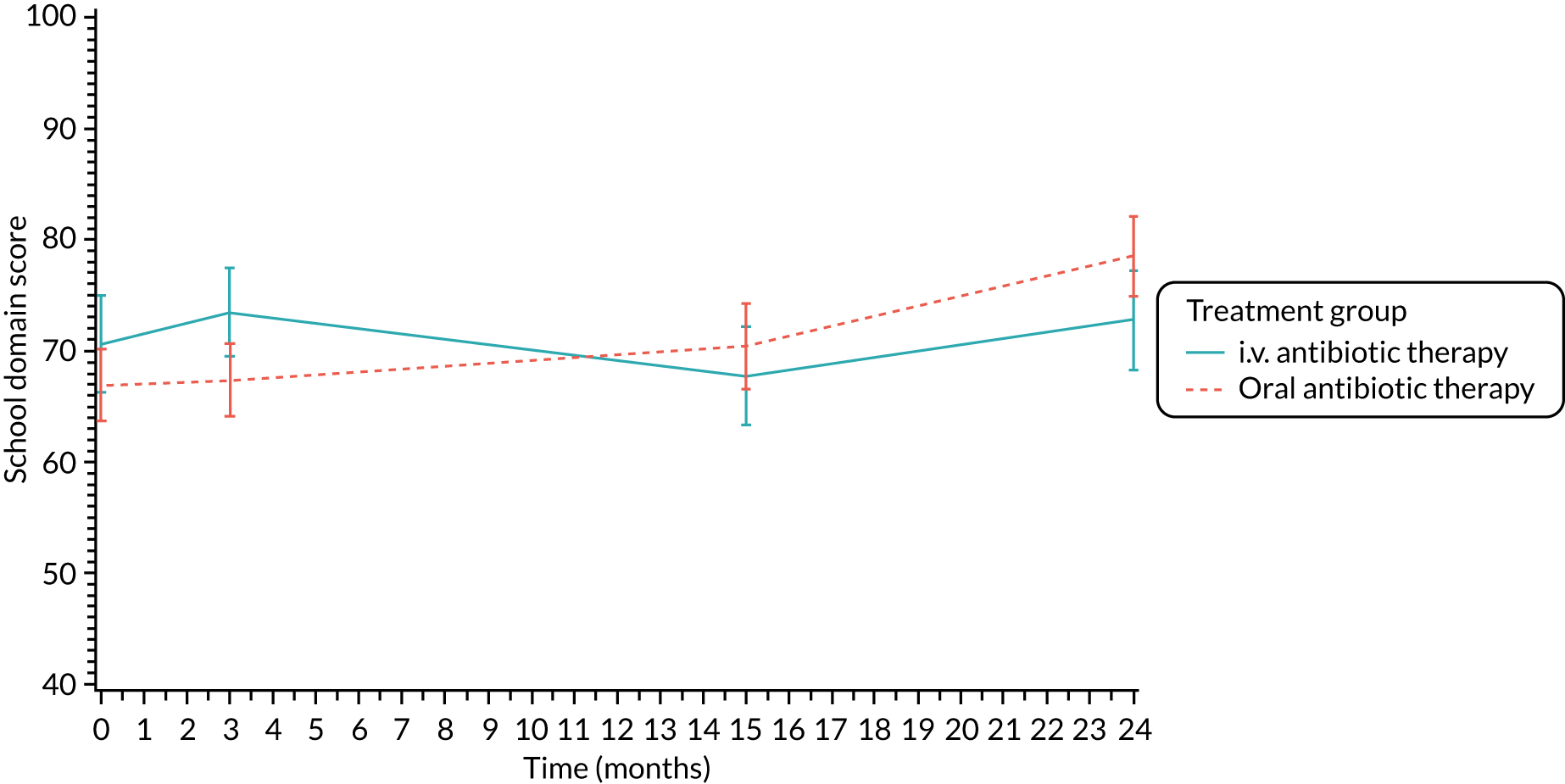

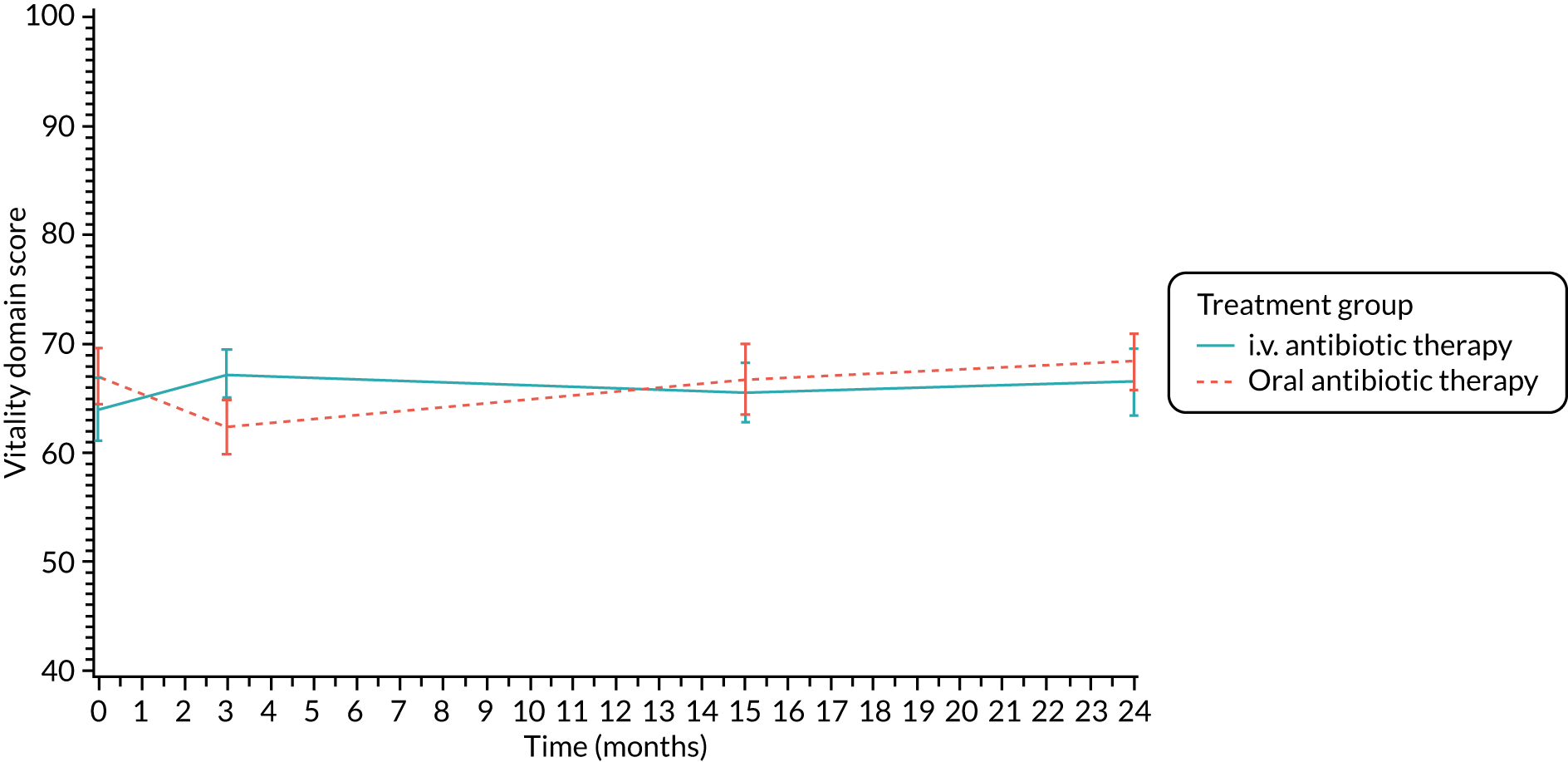

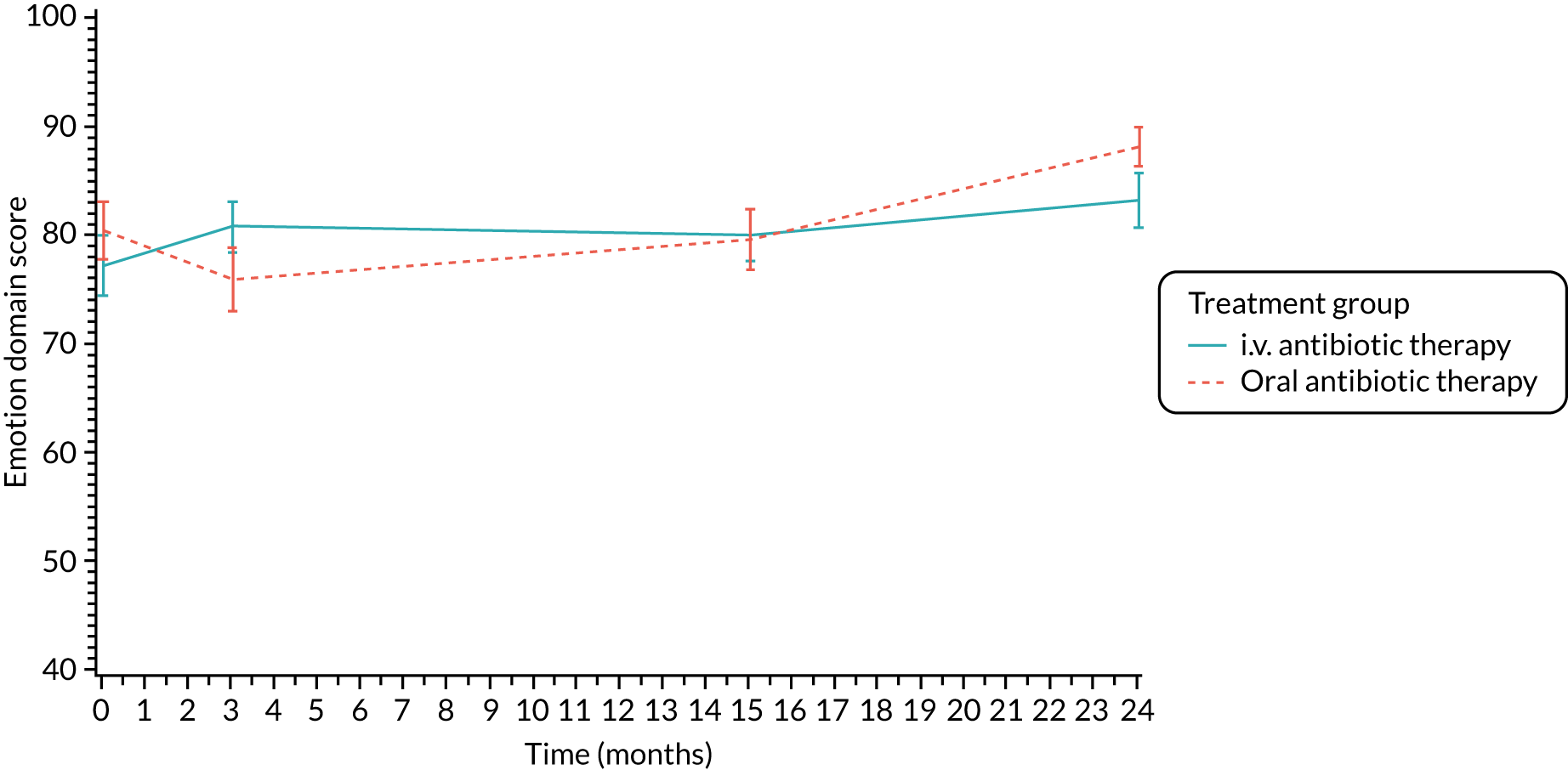

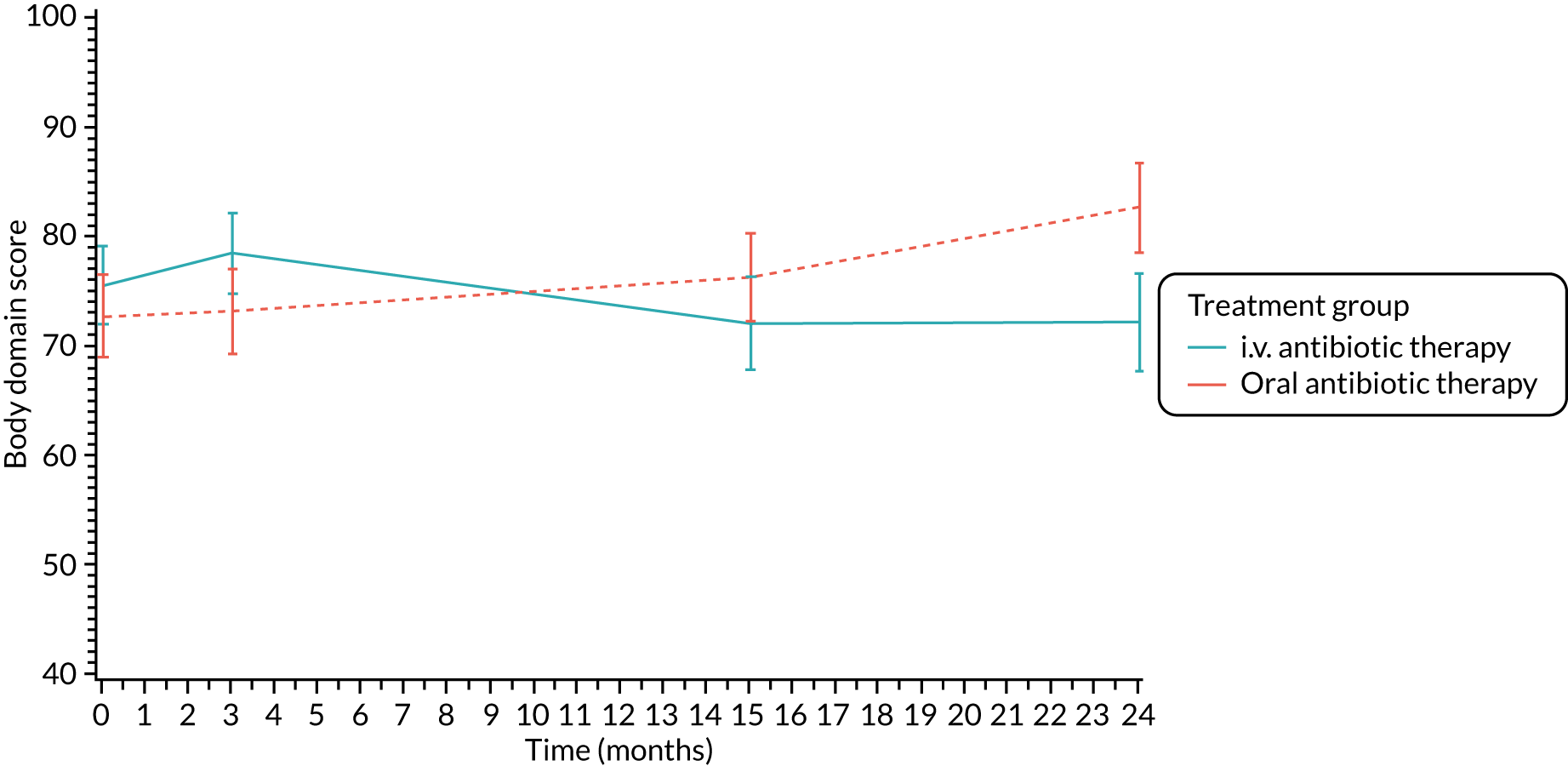

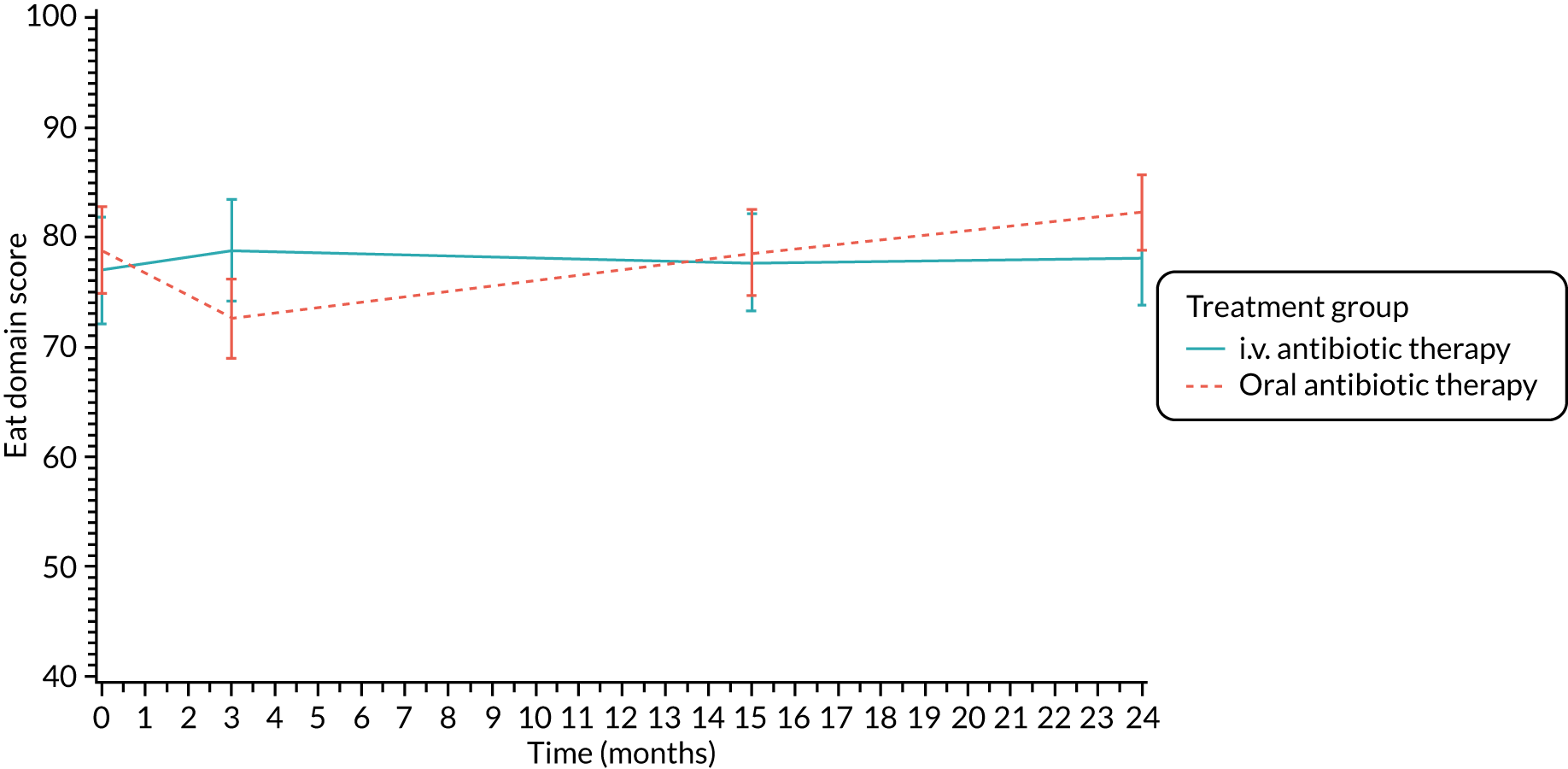

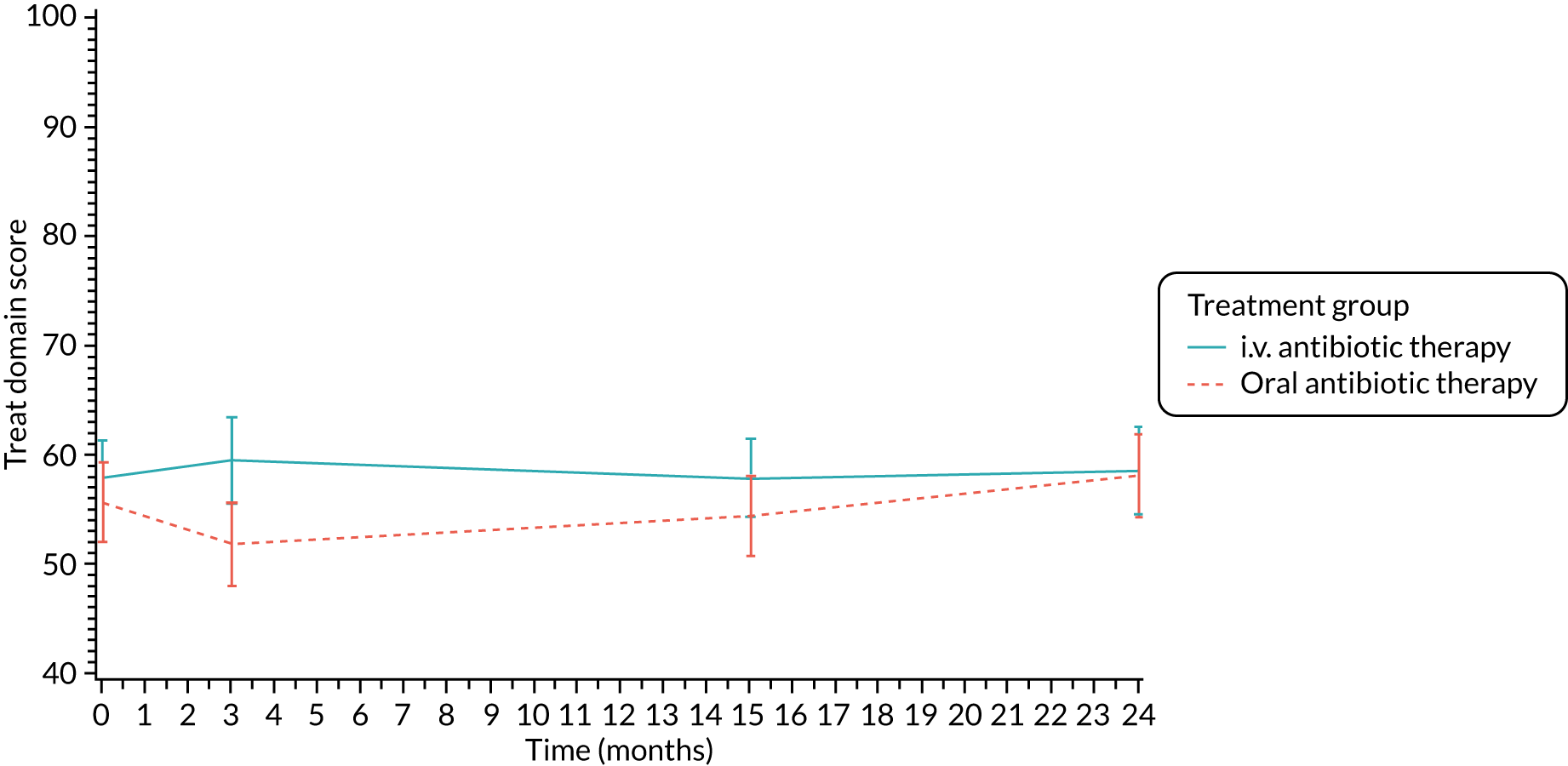

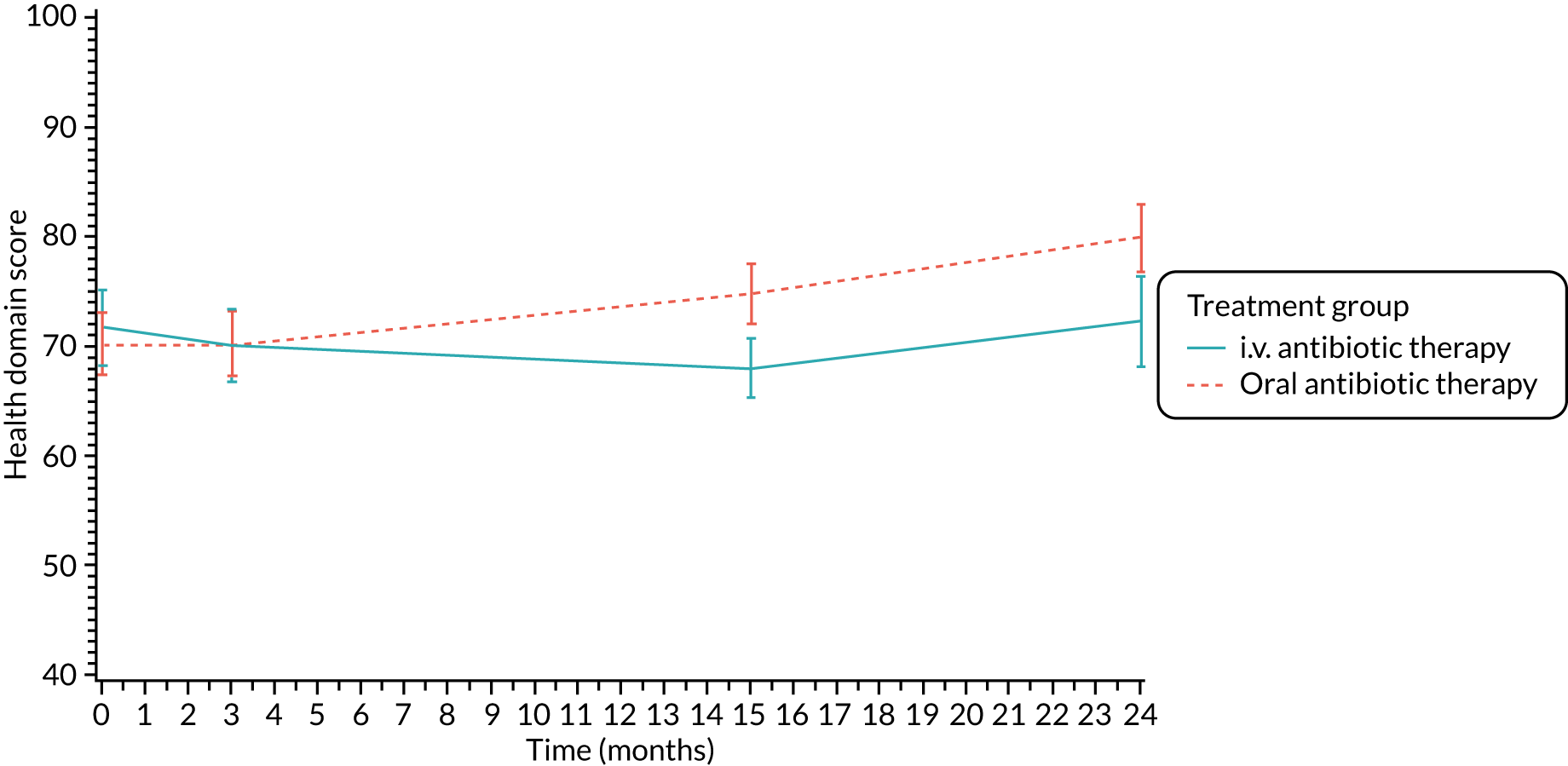

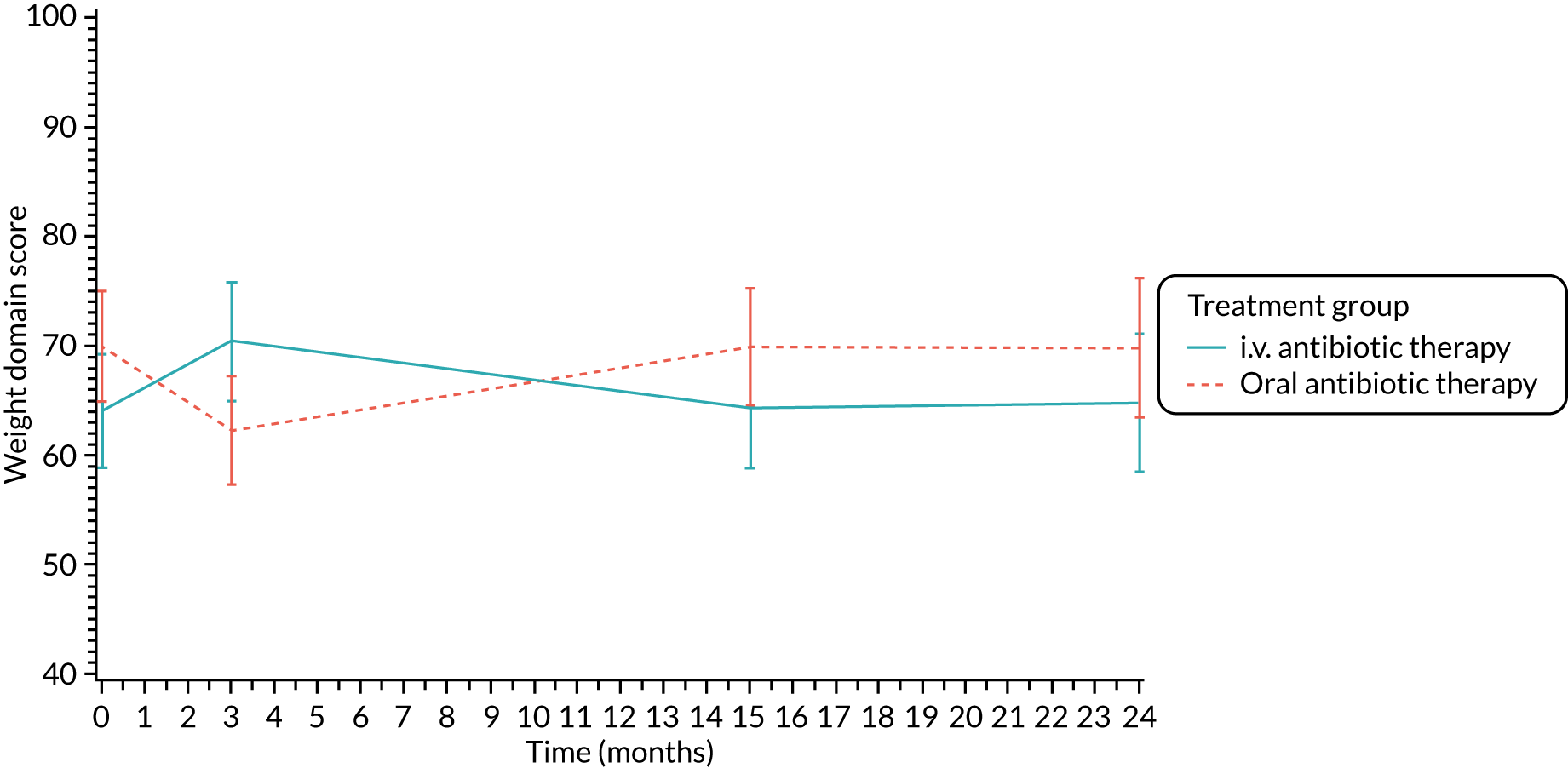

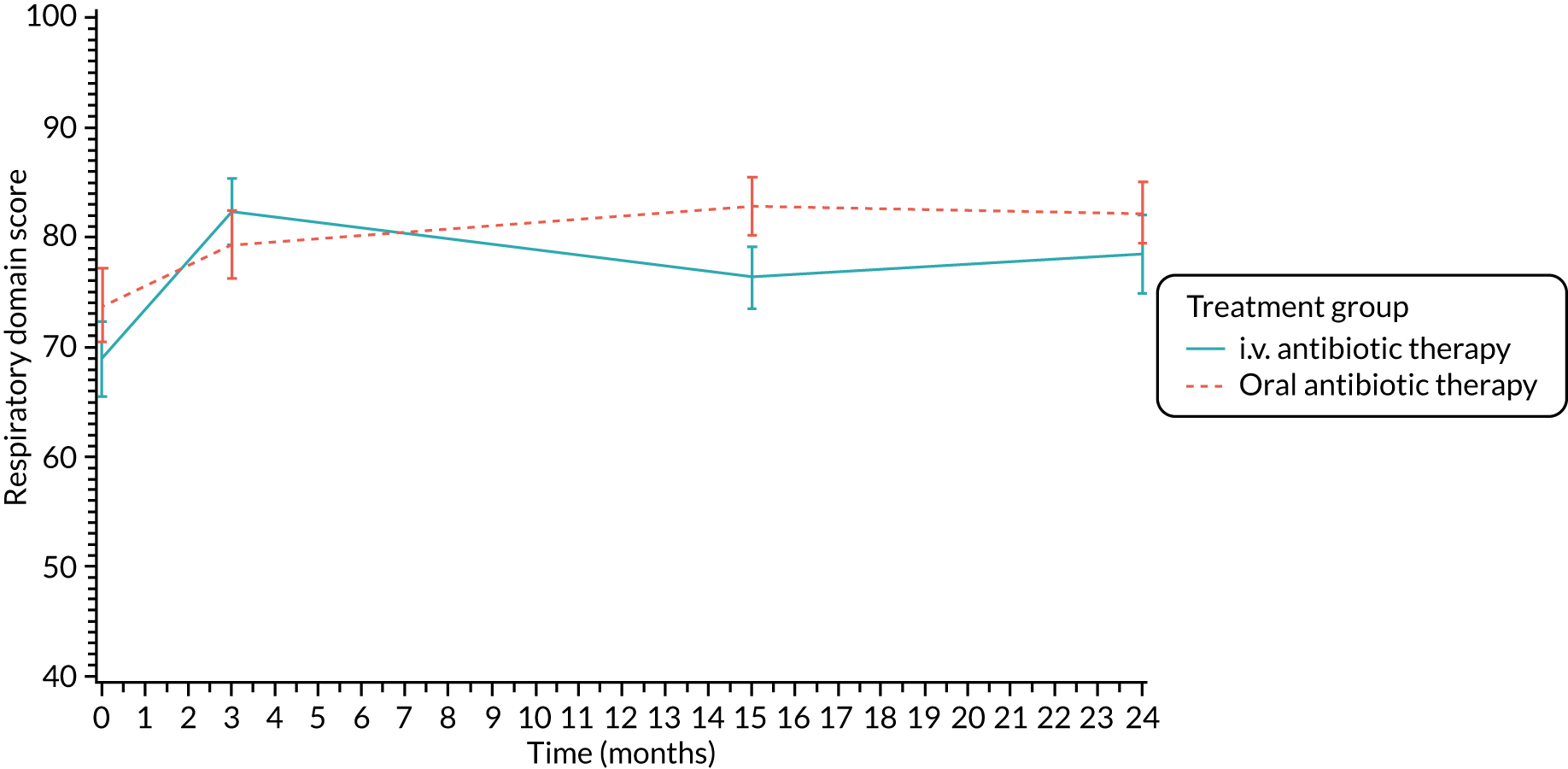

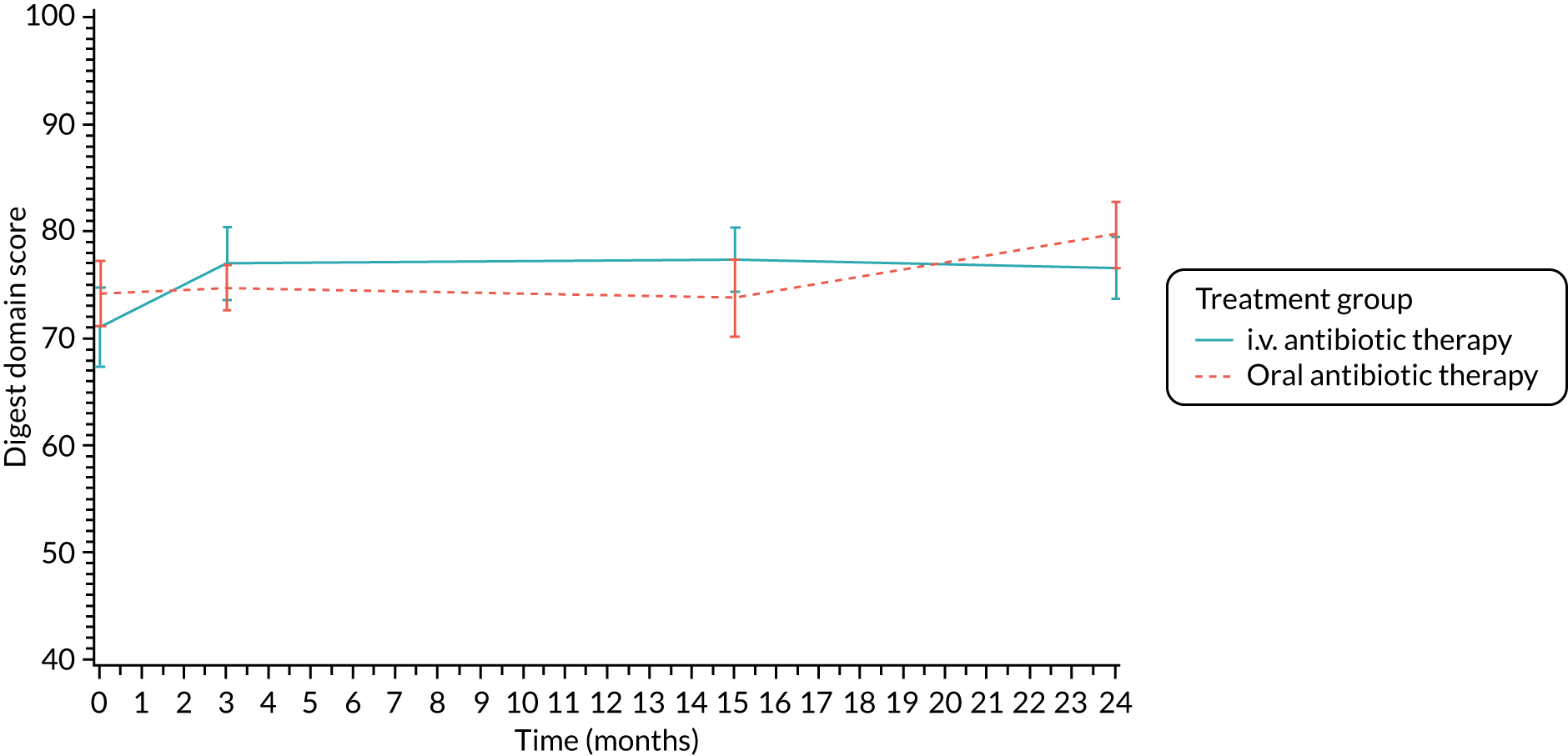

The CFQ is the only published, disease-specific measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for children (aged 6–13 years), adults and adolescents (aged ≥ 14 years) with CF. 21 Twelve domains of HRQoL are covered in a 44-item survey, which includes physical functioning, role functioning, vitality, health perceptions, emotional functioning and social functioning, as well as domains specific to CF: body image, eating disturbances, treatment burden, and respiratory and digestive symptoms. 22 Quality-of-life questionnaires (i.e. CFQs) were completed at baseline, and at 3, 15 and 24 months after the allocated treatment was started. (Note that the 24-month scores were collected for only those trial participants who started allocated treatment before 1 January 2016.)

Health Utility (EuroQol-5 Dimensions)

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)23 scores were collected at baseline, and at 3, 15 and 24 months post treatment commencement (24-month scores were collected for only those trial participants who started allocated treatment before 1 January 2016). Participants completed the baseline booklet before their treatment allocation was revealed.

The PI or delegated research staff were required to ensure that the randomisation number and time point at which the questionnaire booklet was administered were recorded and to notify LCTC if a participant was too unwell to complete the questionnaire booklet or missed an assessment. Participants who failed to complete their full treatment allocation were still given the questionnaire booklet to complete at the protocol-defined time points to avoid bias.

Sample size

Original trial sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome of initial eradication of P. aeruginosa following the start of allocated treatment and continued eradication until 15 months after the start of allocated treatment. Data dating back to 1995 on the eradication of P. aeruginosa 3 months after the start of treatment and 12 months following the end of treatment were obtained from an audit conducted on all current CF participants treated according to a standard UK CF trust protocol at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Liverpool (conducted by Louisa Heaf and Kate Davenport) (Louise Heaf and Kate Davenport, Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, 2008, personal communication). The data were treated in accordance with a standard UK CF Trust protocol. Data on 48 children were collected, with infection eradicated in 77% (37/48) of children at 3 months following the start of treatment and 58% (28/48) of children continuing to remain infection free at 12 months after the end of treatment (i.e. equivalent to 15 months after the start of allocated treatment in the proposed trial).

For 90% power, at a 5% level of significance, to detect an absolute difference between the control group (oral ciprofloxacin) and the treatment group (i.v.) of 20% (a difference of between 55% and 75%), 128 participants were required in each group. A 20% difference between the two treatment regimens was regarded to be of clinical importance, since the more intensive i.v. treatment would need to be justified by such a substantial benefit. Based on the experience of the TOPIC trial,24 in which five out of 244 (2%) participants who were randomised did not provide primary outcome data for the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, it was expected that the number of participants who would not provide data for the primary outcome during TORPEDO-CF would be quite small. Every effort was made to follow up all randomised participants, regardless of treatment tolerance, but the sample size was inflated to allow for 10% of participants not providing primary outcome data, increasing the total target sample size to 286 participants.

Based on the results of the feasibility study conducted for the Health Technology Assessment programme,12 it was found that the median rate per annum for the number of first or new growths of P. aeruginosa was 3% (range 1–8%) in adults and was 10% (range 2.5–23%) in children. Applying these estimates to the UK CF population (based on figures from 22 adult centres, 28 paediatric centres and two centres with combined populations) enabled a potential population of eligible adults and children of approximately 122 and 475, respectively, per annum. From the feasibility report, the consent rate was estimated to be 44%; therefore, the anticipated number of eligible participants was approximately 54 adults and 209 children per annum.

Patient and public involvement

TORPEDO-CF was conceived as a NIHR-commissioned call and thus had patient and public involvement (PPI) through this process. In addition, it benefited from a feasibility study that explored the importance, and acceptability, of the research question for children, young people and their parents, and adults with CF.

In its set-up, TORPEDO-CF profited from PPI involvement through the Young Persons Advisory Group of the Medicines for Children Research Network, which provided input on the design of documentation intended for the use of trial participants (e.g. information sheets and promotional materials).

During its conduct, TORPEDO-CF received support from the CF Trust and PPI representation within the Trial Management Group (TMG) was in the form of ad hoc representation through the CF Trust Special Adviser on Research and Patient Involvement, who advised on activities to enhance engagement with the CF community generally and with potentially eligible individuals in particular.

An important element of PPI involvement was provided by the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC). PPI representation on the committee provided reassurance that TORPEDO-CF remained of relevance to and in the interests of the CF community.

Changes to the protocol

The first site was opened to recruitment on 18 June 2010 and version 2.0 of the protocol was in operation at this time.

Over the course of the trial, eight substantial amendments were made to the protocol. Each amendment was assessed by the TMG and approved by the REC and by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The main corrections to the protocol included changes to the management of the trial and the addition of further guidance for participating sites. The definition of the primary outcome was also amended from ‘[S]uccessful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection at three months post randomisation, remaining infection free through to 15 months post randomisation’ to ‘[S]uccessful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection three months after allocated treatment has started, remaining infection free through to 15 months after the start of allocated treatment’ to eliminate any systematic bias due to the inevitable delay in starting i.v. treatment compared with oral treatment (caused by the need for the patient to be admitted to hospital to receive i.v. treatment).

The initial changes to the protocol were to provide clarification of the exclusion criteria and the secondary outcomes. Following site set up, several sites raised an issue with regard to differences in site dosing regimens compared with that specified in the protocol. The TMG confirmed that the changes were acceptable clinically and from a trial perspective.

Please refer to the trial protocol for a full list of protocol amendments (see NIHR Journals Library; www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk). A summary of amendments follows.

Protocol version 1.0 (21 August 2009) to version 2.0 (15 February 2010)

-

The length of treatment for the i.v. group was changed from 10 to 14 days to reflect clinical practice.

-

Inclusion criteria 1 and 3 clarified.

-

The inclusion criteria were amended: the text ‘has not isolated P. aeruginosa from cough, sputum or bronchoalvelolar lavage’ was replaced with ‘[A] minimum number of four consecutive cough or sputum samples should be P. aeruginosa free within a 12 month period to satisfy eligibility’ and the text ‘three weeks after the clinical team has been informed that P. aeruginosa has been isolated’ was replaced with ‘21 days’.

-

Clarification of text in exclusion criteria 1–5.

-

An extra exclusion criterion was added: ‘[P]revious participation in another intervention trial within four weeks of taking part in TORPEDO-CF’.

-

Secondary outcome ‘[T]ime to reoccurrence of P. aeruginosa infection’ amended to ‘[T]ime to reoccurrence of original P. aeruginosa infection’.

-

Secondary outcome ‘time to new P. aeruginosa infection’ replaced with ‘re-infection with a different genotype of P. aeruginosa’.

-

Secondary outcome ‘[C]arer burden (absenteeism from school or work)’ was clarified by changing to ‘[C]arer burden (absenteeism from education or work)’.

-

Clarifications made to section 6, ‘Trial treatments’.

-

Clarifications made to section 7, ‘Assessments and Procedures’.

Protocol version 2.0 (15 February 2010) to version 3.0 (1 September 2010)

-

Clarification text added to exclusion criterion 4: ‘[P]lease note, short courses of oral ciprofloxacin or intravenous antibiotics (with an anti-pseudomonal spectrum of action) are not an exclusion unless they are given to treat proven infections with P. aeruginosa’.

-

Primary end-point text amended from ‘[S]uccessful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection at three months post randomisation, remaining infection free through to 15 months post randomisation’ changed to read ‘[S]uccessful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection three months after allocated treatment has started, remaining infection free through to 15 months after the start of allocated treatment’.

-

Secondary end point 8 changed from ‘[N]umber of days spent as inpatient in hospital over the three-month period post-treatment and between three months and 15 months post-treatment (other than 14 days spent on initial intravenous treatment)’ to ‘[N]umber of days spent as inpatient in hospital over the three-month period post-randomisation and between three months and 15 months post-randomisation (other than 14 days spent on initial intravenous treatment)’.

-

In section 8.4 of the protocol, text in sample size calculation changed to reflect change in analysis from post randomisation to post treatment.

-

In section 9.7 of the protocol, change in the reporting timelines for AEs/serious adverse events (SAEs), beginning from the time allocation treatment started up to 28 days after treatment cessation.

Protocol version 3.0 (1 September 2010) to version 4.0 (13 December 2011)

-

Inclusion criterion 1 changed from ‘[D]iagnosis of cystic fibrosis (CF) (clinical feature + sweat chloride > 60 mmol/l and/or 2 CFTR [cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator] mutations)’ to ‘[D]iagnosis of cystic fibrosis (CF)’.

-

Trial treatment text (arm A) changed from ‘[F]ourteen days intravenous ceftazidime 50 mg/kg/dose (maximum three grams) three times daily and intravenous tobramycin 10 mg/kg/d (maximum 660mg) once daily’ to ‘[F]ourteen days intravenous ceftazidime dose as per national clinical guidelines (maximum three grams) three times daily and intravenous tobramycin dose as per national clinical guidelines (maximum 660 mg) once daily’.

-

Trial treatment text (arm B) changed from ‘[T]hree months oral ciprofloxacin < 5 years, 15 mg/kg twice daily, ≥ 5 years, 20 mg/kg twice daily (maximum dose 750 mg twice daily)’ to ‘[T]hree months oral ciprofloxacin, < 5 years, dose as per national clinical guidelines twice daily, ≥ 5 years, dose as per national clinical guidelines twice daily (maximum dose 750 mg twice daily)’.

Protocol version 4.0 (13 December 2011) to version 5.0 (11 January 2012)

-

Changes made to section 6, ‘Trial Treatments’, in relation to the provision of drug by home care companies.

Protocol version 5.0 (11 January 2012) to version 6.0 (17 October 2013)

-

Inclusion criterion 5b changed from ‘P. aeruginosa free (i.e. a minimum of four consecutive cough or sputum samples should be P. aeruginosa free within a 12 month period to satisfy eligibility.)’ to ‘P. aeruginosa free (i.e. any cough or sputum samples within the previous year (365 days) should be P. aeruginosa free.)’.

-

Exclusion criterion 4 changed from ‘previous 9 months’ to ‘previous 9 calendar months’.

-

Removing requirement for all SAEs to be reported on a SAE report form. Replaced with ‘[A]ll AEs that has been assessed and judged by the investigator to be not serious to be reported on an AE form and returned to MCRN CTU [Medicines for Children Research Network Clinical Trials Unit] as per routine schedule. All SAEs that have been assessed and judged by the investigator to be unrelated or unlikely to be related to be reported on an AE form and returned to MCRN CTU as per routine schedule. All serious adverse reactions (SARs) and Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) must be reported immediately by the investigator to the MCRN CTU on a SAR report form.’

Protocol version 6.0 (17 October 2013) to version 7.0 (12 August 2014)

-

Addition of University of Liverpool as co-sponsor; it will act as sole sponsor for international sites.

Protocol version 7.0 (12 August 2014) to version 8.0 (23 December 2015)

-

Clarifying follow-up period: patients who start randomised treatment before 1 January 2016 will continue follow-up for 24 months, patients who start randomised treatment on or after 1 January 2016 will continue follow-up for 15 months.

-

Clarification to section 6, ‘Trial Treatments’.

Protocol version 8.0 (23 December 2015) to version 9.0 (12 October 2016)

-

Updated number of patients to be enrolled.

Compliance with intervention

Participants’ compliance with trial treatment was monitored using participant-completed treatment diaries to record their daily treatment routine.

The majority of the trial treatment for participants in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group was anticipated to be administered during hospital in-patient visits, ensuring accurate monitoring of investigational medicinal product (IMP) compliance. Participants who had experience of administering i.v. antibiotics at home or those who preferred to have home i.v. were allowed to self-administer i.v. antibiotics at the discretion of their local PI. In this event, participants were asked to complete a home i.v. treatment diary each day to ensure compliance with the study medication. Any unused medication and the packaging of all used medication were to be returned at the next scheduled follow-up visit. All returned medication/packaging was destroyed as per local procedures.

Trial management and oversight

University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust was the sponsoring organisation, and delegated responsibilities to LCTC, the University of Liverpool and the chief investigator. LCTC was responsible for co-ordination of the trial (see Appendix 1).

University of Liverpool was co-sponsor, having no responsibility for the conduct of the trial in the UK, but acting as sole sponsor for non-UK centres (i.e. the University of Liverpool was legally responsible for the non-UK conduct of the trial).

Trial Management Group

The TMG was a multidisciplinary team comprising the chief investigators, scientific co-investigators, PPI representatives, sponsor representative, health economists and members of LCTC (see Appendix 1).

The TMG was responsible for the day-to-day clinical and practical aspects of the trial.

Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

The Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (IDSMC) comprised two independent clinicians and a statistician (see Appendix 2). The main responsibilities of the IDSMC were to safeguard the interests of the TORPEDO-CF participants, assess the safety and efficacy of the interventions during the trial, and monitor the overall progress and conduct of the trial. The IDSMC met at least annually during the trial and provided recommendations to the TSC. Reports to the IDSMC were produced by the statistical team at LCTC.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC comprised an independent chairperson, two independent physicians, two PPI representatives, an independent statistician and representatives from the TMG (see Appendix 2). An observer from the sponsor and from the funder were also invited to meetings. The TSC met at least annually throughout the trial, both by teleconference and by e-mail, shortly after the IDSMC met and its main role was to provide overall oversight of the trial.

Chapter 3 Statistical methods

General statistical considerations

The analysis and reporting of the study were undertaken in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)25 and the International Conference on Harmonisation E9 Guidelines. 26 The main features of the statistical analysis plan are included here with a full and detailed statistical analysis plan (available at www.uhbristol.nhs.uk/media/3933191/torpedo_final_analysis_statistical_analysis_plan_v2.pdf; accessed 8 October 2021). All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS® software version 9.3 or later (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A two-sided p-value ≤ 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance for all analyses, and all confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated at the 95% level. There were no adjustments for multiple testing; rather, all secondary analyses were treated as hypothesis generating.

The primary analysis followed the ITT principle as far as practically possible; all randomised participants were analysed on the basis of the treatment to which they were randomised, regardless of whether or not they received it. If consent for treatment was withdrawn but the participant was happy to remain in the study for follow-up, then they were followed up until completion. However, if they decided to withdraw consent completely, then the reasons for withdrawal of consent were collected (when possible) and reported for both groups.

Analysis of baseline data

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarised for each treatment group using descriptive statistics. No formal statistical testing was performed on these data. Descriptive statistics, including the number of observations, mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for discrete variables, were presented, as appropriate.

Analysis of compliance data

For i.v. antibiotic therapy, the number of daily doses that participants received varied by site. The protocol stated that patients should receive at least 10 days of treatment. For these reasons, compliance is presented in terms of the number of days on treatment rather than in terms of the number of doses received.

For oral antibiotic therapy, compliance is presented in terms of the number of doses received and a compliance rate [the percentage of the total doses (n = 168: two doses per day for three lots of 28 days) that were received].

For nebulised therapy, compliance is presented in the same way as oral antibiotic therapy. Data are presented split by treatment group.

All compliance data are presented descriptively [total (n), mean, SD, median, interquartile (IQR) range, range, minimum and maximum]. No formal statistical testing was undertaken.

Analysis of primary outcome

The primary outcome, successful eradication of P. aeruginosa 3 months after the start of treatment, and remaining infection free through to 15 months after the start of treatment, was a binary outcome. Participants were classified as a success if there was no record of P. aeruginosa on their microbiology case report form between 3 and 15 months after treatment commencement, and a failure if there was at least one record of P. aeruginosa on their microbiology report during this time.

To determine if a participant had eradicated P. aeruginosa at 3 months, they must have had a sample within 28 days on either side of their expected 3-month visit date (treatment commencement date + 84 days), which was at least 2 days after the last date of any anti-pseudomonal treatment. To determine if a patient had remained P. aeruginosa free at 15 months, they must have had either a positive sample within the primary outcome window (3–15 months) or a sample within 28 days either side of their expected 15-month visit date (treatment commencement date + 420 days). Participants who had not regrown P. aeruginosa and did not have a sample within the 15-month window (defined above) were not included in the primary analysis. If a patient was withdrawn before 15 months of follow-up was completed, they were included in the primary outcome analysis only if they had isolated P. aeruginosa; if there was no evidence that they had isolated P. aeruginosa prior to being withdrawn they were not included in the primary analysis.

The number and percentage of participants who were classified as a success and a failure for the primary outcome were presented for each treatment group. The difference between the groups was tested using the chi-squared test, and the relative risk and associated 95% CI are presented. The number and percentage of patients who had a positive sample at their 3-month follow-up visit are also presented for each treatment group. As a post hoc analysis, the difference between the groups at 3 months was also tested using the chi-squared test, the relative risk and associated 95% CI were calculated, and a sensitivity analysis was also carried out that extended the 3-month window to – 4 weeks/+ 10 weeks.

Six sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine the robustness of the results of the primary analysis:

-

All participants followed up past 3 months, but with no 15-month sample were classified as successes.

-

All participants followed up past 3 months, but with no 15-month sample were classified as failures.

-

All patients followed up past 3 months, but with no 15-month sample were classified as successes/failures according to the next sample taken after the end of the 15-month window.

-

Primary analysis adjusted for centre effect – a logistic regression model was fitted to investigate heterogeneity across centres and adjusted for centre as a random effect.

-

Analysis as per the primary analysis, but 3- and 15-month windows extended to 10 weeks either side of the expected visit dates: post hoc analysis.

-

Analysis as per the primary analysis, but 15-month window removed (any sample after 3-month window included): post hoc analysis.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Time to reoccurrence of the original P. aeruginosa infection was presented graphically using Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by treatment. The difference between the two treatment groups was tested using the log-rank test. Two analyses of this outcome were performed as a result of blind review. The first assumed that all patients who had had a reoccurrence of P. aeruginosa but did not have both a baseline and a follow-up sample (between 3 and 24 months) sent for genotyping did not have a reoccurrence of the original P. aeruginosa strain. The second assumed that these patients did have a reoccurence of the original P. aeruginosa strain.

Reinfection with a different genotype of P. aeruginosa and admission to hospital were analysed using the chi-squared test. The relative risk and 95% CI are also presented.

Lung function [percentage predicted FEV1, percentage predicted FVC and percentage predicted FEF25–75 (not measured in participants < 5 years)], oxygen saturation and growth and nutritional status [height z-scores (children only), weight z-scores (children only), BMI z-scores (children only) and BMI (adults only)] were analysed using a repeated-measures random effects model with a special power covariance structure. The baseline measurement, treatment group and time were included in the model as coefficients and a treatment-by-time interaction was also fitted. The treatment difference at 15 months and 95% CI are presented.

For the number of pulmonary exacerbations and the number of days spent in hospital, a Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test whether or not the distribution was the same in each treatment arm.

Quality of life (as measured by the CFQ – Revised) was analysed using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures with an unstructured covariance matrix. The baseline measurement, treatment group and time were included in the model as coefficients and a treatment-by-time interaction was also fitted. The treatment difference at 15 months and 95% CI are presented.

Whether or not participants had grown at least one positive culture of MRSA, Burkholderia cepacia complex, Aspergillus or Candida was analysed using the chi-squared test (where there were sufficient events), and the relative risk and 95% CI are presented. Other sputum microbiology was presented descriptively; no formal analysis was undertaken.

Carer and participant burden was analysed in two ways. Whether or not carers/participants had been absent from work/education was analysed using the chi-squared test and presented with a relative risk and 95% CI. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine whether or not there was a difference in the distributions of the number of days carers/participants were absent from work/education in each treatment group.

Analysis of safety data

The safety analysis data set contained all participants who were randomised and had commenced treatment. All events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA).

The number of occurrences of each AE [at the preferred term and System Organ Class (SOC) levels] and the number (and percentage) of patients experiencing each AE are presented for each treatment arm and overall. A similar table was produced for all SAEs reported under all versions of the protocol.

Each SAE reported under versions 1.0–5.0 of the protocol and each SAR reported under version 6.0 of the protocol onwards is presented in the form of line listings detailing:

-

SAE number

-

treatment

-

preferred term

-

SOC

-

date of onset

-

serious criteria (reporting of all that apply from seven possible options) (PI and chief investigator assessment)

-

severity (mild/moderate/severe) (PI assessment)

-

relationship to study drug (PI and chief investigator assessment)

-

expectedness (chief investigator assessment)

-

most likely cause (disease under study/other illness/prior or concomitant treatment/protocol procedure/lack of efficacy) (PI assessment)

-

outcome.

There was no formal statistical analysis of any safety data.

Post hoc analyses

Time to P. aeruginosa reoccurrence is presented graphically using Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by treatment. The difference between the two treatment groups was tested using the log-rank test. Two analyses of this outcome were performed; the first included all positive samples after 3 months and the second included samples post 3 months and prior to 15 months. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI were also calculated for the second analysis.

Additional analyses were performed on the lung function, oxygen saturation, growth and nutritional status, and quality-of-life outcomes. Where the interaction term was not significant in the original model, it was removed and an overall treatment difference and 95% CI are presented. Treatment differences at 3 and 24 months and the associated 95% CIs were also presented from the original model.

Chapter 4 Genotyping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates

Variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) are short nucleotide sequences that vary in copy number in bacterial genomes and are thought to occur through deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) strand slippage during replication. This variation in copy number may be exploited to generate a VNTR typing scheme comprising between 9 and 15 selected ‘loci’, or regions of the bacterial genome. Variation in the number of repeats at each locus generates a numerical code (representing the number of repeat units at each locus) that may be used to correlate with a bacterial strain type. This method of bacterial strain typing has been widely used for a range of different bacterial organisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacteroides abscessus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii and P. aeruginosa. 27–31

Selecting suitable loci for a VNTR typing scheme is critical for defining the scheme’s capacity for strain discrimination. Usually, loci are selected following specialised computer software analysis of whole-genome sequence(s) of isolate(s) of the species of interest. 32 Factors such as a small repeat size, choosing non-coding parts of the genome as well as areas that are not likely to contain insertions or deletions, and whole-genome coverage are important when choosing potential loci.

Use of variable number tandem repeat in a reference laboratory setting

Public Health England (PHE) has used VNTR analysis at nine loci as a method for P. aeruginosa strain typing since 2010 and, to date (May 2019), PHE has a national database of 31,028 profiles comprising CF, non-CF and environmental isolates from hospitals across the UK, providing a good national picture. Good concordance of this methodology was found on comparison with the gold standard, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). 31 In addition, as it is a polymerase chain reaction-based method, results can be generated rapidly and are portable between laboratories, making it preferable to PFGE, which is more laborious and not easily comparable between laboratories. Of the nine loci chosen for this scheme, the ninth is particularly discriminatory and may be used to evaluate relatedness between isolates from hospital outbreaks and in other settings among non-CF patients,33–36 but this locus is not always useful for CF isolate discrimination, as variation in copy number may be found in different colonies from the same sputum sample.

Examining the UK Pseudomonas aeruginosa population structure using variable number tandem repeat analysis

A study conducted by PHE in 2013 used VNTR analysis to examine the population structure of P. aeruginosa among UK CF patients, non-CF patients and hospital environmental isolates over a 2-year period. 37 In total, 3870 isolates were examined, comprising 726 environmental isolates from 47 hospitals and 2325 isolates from 2230 patients (of whom approximately 54% were CF patients) from 143 centres. The study highlighted the existence of VNTR profiles representing common clones present in both patient and environmental specimens, submitted from hospitals across the UK. Fourteen common types, each found in more than 24 patients within this 2-year period, were described. Among these were three well-characterised strains associated with transmissibility, which have been isolated almost exclusively from CF patients, namely the Liverpool, Manchester and Midlands 1 strains. 38,39 These were isolated from 6%, 1.7% and 1.5%, respectively, of 1204 CF patient isolates in the above-named study. 37

Four of the most common profiles were examined in more detail. Two of these correlated with previously well-established international clonal lineages, namely ‘PA14’ (VNTR profile: 12, 2, 1, 5, 5, 2, 4, 5, x, where the ninth locus is variable) and ‘clone C’ (VNTR profile: 11, 6, 2, 2, 1, 3, 7/8, 2/3, x, where the seventh, eighth and ninth loci may vary in copy number),40,41 which correspond to multilocus sequence types ST253 and 17, respectively. The other two types were ‘cluster A’ (VNTR profile: 8, 3, 4, 5, 2, 3, 5, 2, x), corresponding to ST27, and ‘cluster D’ (VNTR profile: 10, 3, 5, 5, 4, 1, 3, 7, x), where ‘x’ is variable (ST395). These four types were isolated from 6%, 5%, 3% and 2% of patients, respectively, and were geographically widespread, although they were not always isolated in large numbers in individual hospitals. PFGE analysis of representatives of each of these VNTR types from multiple hospitals separated the isolates into four broad clusters corresponding to their VNTR type with an overall similarity of approximately 70%. This led to the hypothesis that in most cases patients acquired these strains independently rather than by patient-to-patient transmission. Further evidence for the clonal nature of these four common profiles was found by examining the sequences for the intrinsic blaOXA-50-like gene.

To examine the hypothesis that these strains were often acquired independently, whole-genome sequences for 12 isolates of ‘cluster A’ from nine hospitals comprising six CF, five non-CF and one environmental isolate from geographically distant sites and separated in time were examined. The presence and absence of genes from the accessory genome detected 9454 variable sequences across the 12 isolates and the six reference genomes that were compared. A set of seven accessory genes were chosen from these, which were found to be variably present among a larger set of ‘cluster A’ isolates. Representatives from patients within a single centre mostly had distinct accessory gene profiles, suggesting that these patients acquired the strain independently, whereas those with clear epidemiological links shared the same profile. Profiles also varied between representatives from different centres.

Challenges in variable number tandem repeat analysis of cystic fibrosis isolates

Variable number tandem repeat analysis of CF isolates often poses additional challenges compared with the analysis of non-CF outbreaks, particularly, although not exclusively, among chronically infected patients. In addition to the variation at the last locus found between different colony types from the same sputum, variation of up to two repeats at one out of the first eight loci may also be found in some patient samples. There may also be variation between sequential isolates over time. Caution needs to be applied when inferring strain relatedness solely using VNTR analysis in certain cases. For example, it is unlikely to be sufficiently discriminatory when assessing whether isolates with similar profiles pre and post antibiotic therapy represent reinfection from an environmental/other source or therapeutic failure. In these cases, the greater discrimination provided through whole-genome sequencing of isolates may be required. Despite these drawbacks, this method has been successfully used by PHE to type P. aeruginosa isolates from hospitals throughout the UK since 2010, and has proved invaluable for highlighting outbreaks and aiding cross-infection decisions in CF clinics.

Chapter 5 Clinical effectiveness results

Participant recruitment

The first participant was randomised on 5 October 2010 and the final participant was randomised on 27 January 2017, when the recruitment target was met. The last follow-up visit occurred on 10 April 2018.

Sixty-one out of the 72 sites (see Appendix 3) that screened patients randomised at least one participant. Twenty-two sites randomised at least five participants.

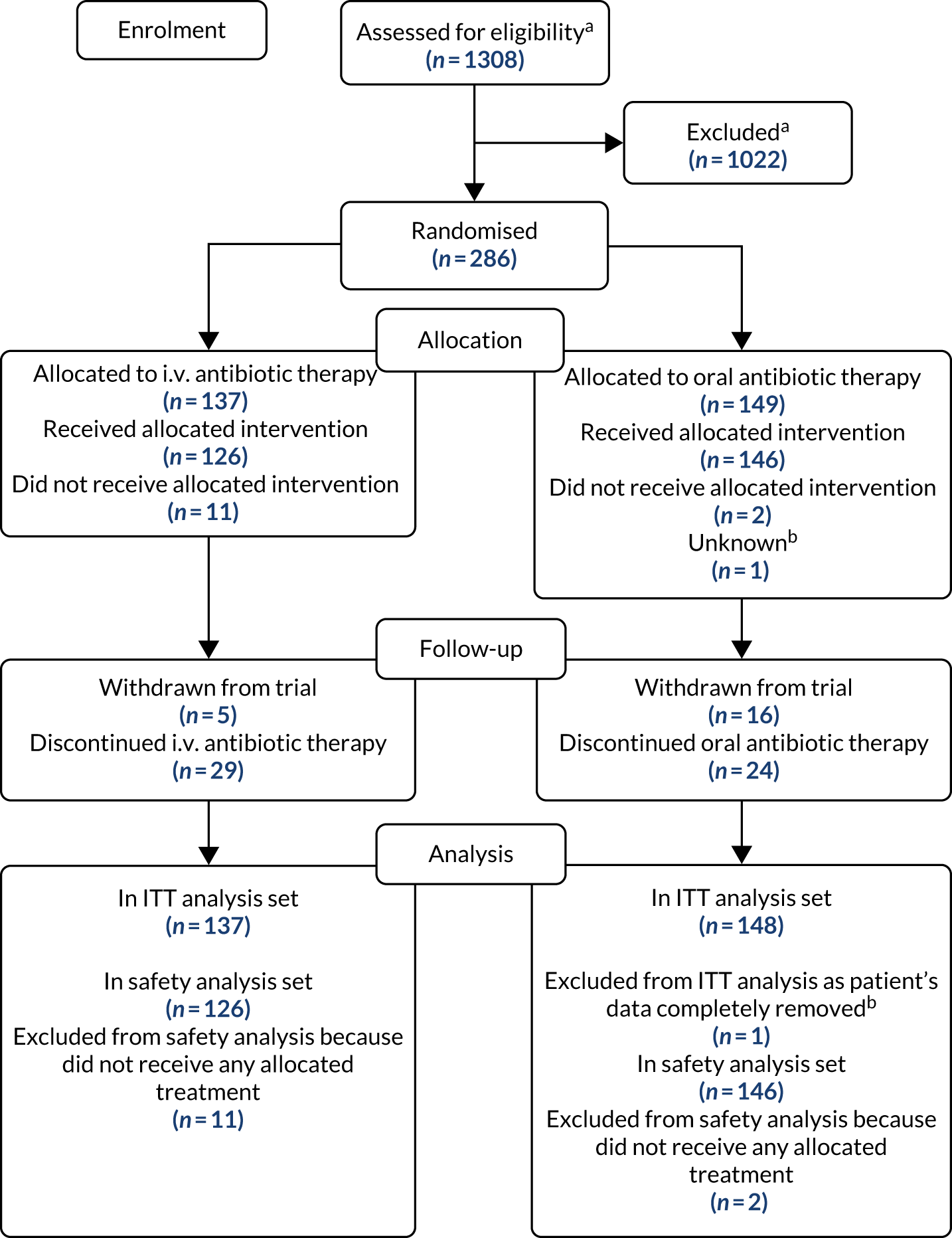

The flow of participants through the trial is presented in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 2). A total of 1308 patients screened for eligibility (patients could be screened on multiple occasions); 1022 did not undergo randomisation because they did not meet the eligibility criteria and 286 patients were randomised (137 to i.v. antibiotic therapy and 149 to oral antibiotic therapy). Detailed information on recruitment is provided in Appendix 4, Tables 28–32.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram for all trial participants. a, Multiple screenings allowed; b, Patient randomised by all data completely removed as PI sign off could not be obtained.

Analysis populations

The ITT analysis population included 285 of the 286 participants (99.7%) who were randomised; one participant’s data could not be included as PI approval could not be obtained despite every effort being made by the TMG to do so. The safety population included 272 of the 286 randomised participants (95.1%); 13 patients did not receive any of their allocated treatment and one participant’s data could not be included as PI approval could not be obtained. The analysis set for the primary outcome included 255 participants: 125 in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group and 130 in the oral antibiotic therapy group.

All participants who withdrew consent for trial continuation contributed outcome data up until the point of withdrawal.

Premature discontinuations

Premature discontinuation of treatment (either IMP or non-IMP) occurred in 40 of the 137 participants in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group (29.2%) and 26 of the 148 participants in the oral antibiotic therapy group (17.6%). The most common reasons for premature discontinuation of treatment in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group were withdrawal of consent (n = 9; 22.5%), venous access problem (n = 7; 17.5%) and long-line failure (n = 5; 12.5%), and in the oral antibiotic therapy group the reasons were AE (n = 13; 50%) and withdrawal of consent (n = 4; 15.4%). Reasons for premature discontinuation of treatment are summarised in Table 1.

| Reason | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy | Oral antibiotic therapy | ||

| AE | 1 (2.5) | 13 (50.0) | 14 (21.2) |

| Withdrawn consent | 9 (22.5) | 4 (15.4) | 13 (19.7) |

| Venous access problem | 7 (17.5) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (10.6) |

| Long-line failure | 5 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.6) |

| Missing | 4 (10.0) | 1 (3.8) | 5 (7.6) |

| Clinician decision | 3 (7.5) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (6.1) |

| Othera | 3 (7.5) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (6.1) |

| SAE/reaction | 1 (2.5) | 3 (11.5) | 4 (6.1) |

| Errorb | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.5) |

| Bed not available | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) |

| Insufficient medication supplied | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (3.0) |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Poor adherence | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (1.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Total | 40 | 26 | 66 |

Withdrawal from follow-up occurred in 5 of the 137 participants in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group (3.6%) and 16 of the 148 participants in the oral antibiotic therapy group (10.8%). The most common reason in both groups was that participants were lost to follow-up [three participants in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group (60%); nine participants in the oral antibiotic therapy group (56.3%)]. Reasons for withdrawals from follow-up are summarised in Table 2.

| Reason | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy | Oral antibiotic therapy | ||

| AE | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (4.8) |

| Lost to follow-up | 3 (60.0) | 9 (56.3) | 12 (57.1) |

| Othera | 1 (20.0) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (14.3) |

| Withdrawn consent | 1 (20.0) | 4 (25.0) | 5 (23.8) |

| Total | 5 | 16 | 21 |

Baseline characteristics

The demographic baseline data of the 285 randomised participants were comparable between the two groups. The proportion of infants and toddlers was slightly larger in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group (30.7%, compared with 18.9% in the oral antibiotic therapy group). The proportions of male and female participants were approximately the same across the two treatment groups, with slightly more female than male participants (Table 3).

| Baseline characteristic | Treatment group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy (N = 137) | Oral antibiotic therapy (N = 148) | |

| Age groupa | ||

| Infants and toddlers (28 days–23 months) | 42 (30.7) | 28 (18.9) |

| Children (2–11 years) | 71 (51.8) | 92 (62.2) |

| Adolescents (12–17 years) | 18 (13.1) | 19 (12.8) |

| Adults (18–64 years) | 6 (4.4) | 9 (6.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 63 (46) | 67 (45.3) |

| Female | 74 (54) | 81 (54.7) |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| Naive | 81 (59.1) | 93 (62.8) |

| Free | 56 (40.9) | 55 (37.2) |

| Other micro-organisms detected | ||

| Candida albicans | 11 (8) | 17 (11.5) |

| MRSA | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.4) |

| Other organisms | 26 (19) | 31 (20.9) |

| Genotype | ||

| p.Phe508del/p.Phe508del | 70 (51.1) | 90 (60.8) |

| p.Phe508del/other | 40 (29.2) | 43 (29.1) |

| p.Phe508del/unknown | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.4) |

| Other/other | 12 (8.8) | 7 (4.7) |

| Unknown | 11 (8.0) | 3 (2) |

| Pulmonary exacerbation present | 18 (13.1) | 17 (11.5) |

| BMI z-score (paediatric), n, mean (SD) | 125, 0.3 (1) | 131, 0.3 (0.9) |

| BMI (adults) (kg/m2), n, mean (SD) | 6, 24.6 (1.8) | 9, 23.2 (2.3) |

| Time from P. aeruginosa isolation to treatment initiation (days), n, mean (SD) | 126, 8.8 (5.3) | 145, 6.8 (5.3) |

| FEV1% predicted (l), n, mean (SD) | 67, 86.6 (15.8) | 70, 85.7 (16) |

| FVC% predicted (l), n, mean (SD) | 67, 92.2 (15.5) | 70, 95.1 (14.5) |

| FEF25–75% predicted (l), n, mean (SD) | 44, 72.7 (26.6) | 53, 70.6 (30.3) |

| Oxygen saturation (%), n, mean (SD) | 118, 97.7 (1.4) | 133, 97.7 (1.7) |

Body mass index, lung function and oxygen saturation were similar across the two treatment groups. The proportions of patients who were naive or free from P. aeruginosa for the preceding 12 months and who had experienced a pulmonary exacerbation were also comparable across the two groups. There were fewer patients in the i.v. antibiotic therapy that had a diagnosis based on a homozygous delta f508 mutation (60.8%, compared with 51.1% in the oral antibiotic therapy group). Similar numbers of participants in each treatment group had other microorganisms detected at baseline (see Table 3).

Protocol deviations

Protocol deviations were monitored centrally by evaluating inclusion/exclusion criteria at trial entry and throughout the trial. A total of 284 participants (99.6%) had at least one major protocol deviation. The most common protocol deviations related to visits occurring outside the protocol-specified visit windows; 282 participants (98.9%) had a visit outside the window at 3 or 15 months (major deviation) and 280 participants (98.2%) had a visit outside the window at 6, 9, 12, 18, 21 or 24 months (minor deviation). All protocol deviations were agreed with the co-chief investigators prior to them seeing any unblinded results (Table 4).

| Deviation | Treatment group, n (%) | Total, n (%) (N = 285) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy (N = 137) | Oral antibiotic therapy (N = 148) | ||

| Any protocol deviation | 137 (100.0) | 148 (100.0) | 285 (100.0) |

| At least one major deviation | 137 (100.0) | 147 (99.3) | 284 (99.6) |

| Consent not obtained | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Inclusion of patient previously randomised into TORPEDO-CF | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Treatment non-compliance (< 10 days of i.v. treatment or 120 doses of ciprofloxacin) | 35 (25.5) | 6 (4.1) | 41 (14.4) |

| Premature discontinuation of randomised treatment because of safety | 2 (1.5) | 16 (10.8) | 18 (6.3) |

| Premature discontinuation of randomised treatment because of patient preference | 15 (10.9) | 5 (3.4) | 20 (7.0) |

| Scheduled visits at 3 and 15 months occurring outside appropriate time frame (3 months should be more than 48 hours after and no more than 14 days after; 15 months should be no more than 7 days before and 14 days after) | 136 (99.3) | 146 (98.6) | 282 (98.9) |

| At least one minor deviation | 134 (97.8) | 146 (98.6) | 280 (98.2) |

| Outside age range | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Patient starting treatment > 21 days after a positive microbiology report | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (1.4) |

| Inclusion of patient who has not been clear of P. aeruginosa for 12 months | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Scheduled visits at 6, 9, 12, 18, 21 and 24 months occurring outside appropriate time frame (no more than 7 days either side) | 134 (97.8) | 146 (98.6) | 280 (98.2) |

Compliance

Intravenous antibiotic therapy

Serum creatinine levels prior to the administration of the first dose of tobramycin are presented in Table 5, along with tobramycin serum concentrations prior to the administration of the second dose and after 1 week. Table 6 provides summary statistics for the number of days that participants received i.v. treatment.

| Summary statistic | Serum creatinine level (mmol/l) prior to first tobramycin dose administration | Tobramycin serum levels (mg/l) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to second dose administration | After 1 week | ||

| n | 109 | 112 | 102 |

| Mean | 35.6 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| SD | 17.7 | 1.3 | 4.3 |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 33 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Maximum | 132.6 | 8.7 | 41 |

| Missing (n) | 28 | 25 | 35 |

| Summary statistic | Number of days on treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Ceftazidime | Tobramycin | |

| n | 137 | 137 |

| Mean | 11.5 | 11.0 |

| SD | 5.3 | 5.1 |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 14 | 14 |

| Maximum | 16 | 16 |

| Missing (n) | 0 | 0 |

Oral antibiotic therapy

Table 7 provides summary statistics for the number of doses that participants received along with a compliance rate based on a denominator of 168 doses [two doses per day for 84 days (3 × 28 days)]. As some participants remained on treatment for longer than the required 84 days, this information was updated (post hoc) to include only those doses taken in the first 84 days.

| Summary statistic | All doses | Doses from first 84 days | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of doses | Compliance rate (%) | Number of doses | Compliance rate (%) | |

| n | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Mean | 167.1 | 99.5 | 156.6 | 93.2 |

| SD | 32.8 | 19.5 | 29 | 17.27 |

| Minimum | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Median | 173 | 103.0 | 166 | 98.8 |

| Maximum | 230 | 136.9 | 168 | 100 |

| Missing (n) | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 |

| Summary statistic | Compliance rate (%) using all doses | Compliance rate (%) using doses from the first 84 days | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy | Oral antibiotic therapy | i.v. antibiotic therapy | Oral antibiotic therapy | |

| n | 97 | 105 | 97 | 105 |

| Mean | 87.8 | 97.7 | 82.1 | 91.6 |

| SD | 34.4 | 21.4 | 31.5 | 19.0 |

| Minimum | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Median | 100.6 | 101.2 | 98.2 | 98.2 |

| Maximum | 125 | 136.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Missing (n) | 40 | 43 | 40 | 43 |

Colistin therapy

Table 8 provides summary statistics for the compliance rate based on a denominator of 168 doses [two doses per day for 84 days (3 × 28 days)]. As some participants remained on treatment for longer than the required 84 days, this information was updated (post hoc) to include only those doses taken in the first 84 days.

Time from randomisation to treatment commencement

The median (IQR) time from randomisation to treatment commencement was 3 (1–6) days in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group and 0 (0–1) days in the oral antibiotic therapy group.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome (successful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection 3 months after allocated treatment has started and remaining infection free through to 15 months after the start of allocated treatment) was achieved by 55 of the 125 participants (44.0%) in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group and by 68 of the 130 participants (52.3%) in the oral antibiotic therapy group. Participants who were randomised to the i.v. antibiotic therapy group had a reduced chance of having successful eradication of P. aeruginosa 3 months after the start of treatment and remaining infection free through to 15 months (relative risk 0.84, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.09; p = 0.184). Results from five of the six sensitivity analyses to address missing data can be found in Table 9, which details the number of patients included in each analysis, the number in each treatment group in whom eradication was or was not observed, the relative risk, 95% CI and the p-value from the chi-squared test. The results from all five sensitivity analyses are consistent with the results from the primary analysis, indicating that the original results are robust with regard to the assumptions that were made. The additional sensitivity analysis not reported in Table 9 applied all of the same assumptions as the primary analysis, but used a logistic regression model to adjust for centre as a random effect. The adjustment to the model for centre did not significantly affect the results (p = 0.218), indicating that there was no statistically significant effect of centre on the primary results. Results from a post hoc subgroup analyses in P. aeruginosa naive and P. aeruginosa free patients are also reported in Table 9. A Mantel–Haenszel test for interaction was conducted and the relative risks were not significantly different in the two subgroups (p = 0.19).

| Analysis | Treatment group, n/N (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy | Oral antibiotic therapy | |||

| Primary outcome: successful eradication of P. aeruginosa infection 3 months after allocated treatment has started, remaining infection free through to 15 months after the start of allocated treatment | ||||

| Primary analysis | 55/125 (44) | 68/130 (52.3) | 0.84 (0.65 to 1.09) | 0.184 |

| Sensitivity analysis 1: all participants followed up past 3 months with no 15-month sample classified as success | 66/136 (48.5) | 85/144 (56.9) | 0.85 (0.68 to 1.07) | 0.159 |

| Sensitivity analysis 2: all participants followed up past 3 months with no 15-month sample classified as failure | 55/136 (40.4) | 68/144 (47.2) | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.12) | 0.253 |

| Sensitivity analysis 3: all participants followed up past 3 months with no 15-month sample classified as success/failure in accordance with the next sample taken after 15-month window | 66/136 (48.5) | 81/144 (56.3) | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.08) | 0.196 |

| Sensitivity analysis 4: as primary analysis, but 3- and 15-month windows extended to – 4 weeks/+ 10 weeks of the expected visit dates | 61/132 (46.2)a | 73/139 (52.5)a | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.12)a | 0.299a |

| Sensitivity analysis 5: as per primary analysis, but 15-month window removed (any sample after 3-month window included) | 58/136 (42.7)a | 70/144 (48.6)a | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.13)a | 0.317a |

| Subgroup analysis 1: P. aeruginosa free participants | 23/49 (46.9) | 21/50 (42.0) | 1.12 (0.72 to 1.74) | NR |

| Subgroup analysis 2: P. aeruginosa naive participants | 32/76 (42.1) | 47/80 (58.8) | 0.72 (0.53 to 0.99) | NR |

| Unsuccessful eradication of P. aeruginosa 3 months after allocated treatment has started | ||||

| Primary analysis | 13/110 (11.8) | 5/116 (4.3) | 2.74 (1.01 to 7.44)a | 0.037a |

| Sensitivity analysis: as primary analysis, but 3-month window extended to –4 weeks/+10 weeks of the expected visit date | 22/124 (17.7)a | 12/135 (8.9)a | 2.00 (1.03 to 3.86)a | 0.035a |

The number of participants who did not eradicate P. aeruginosa 3 months after the start of treatment was 13 (11.8%) in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group and five (4.3%) in the oral antibiotic therapy group. Participants who were randomised to the i.v. antibiotic therapy had an increased risk of unsuccessful eradication of P. aeruginosa 3 months after the start of treatment (relative risk 2.74, 95% CI 1.01 to 7.44; p = 0.037) (post hoc analysis). The results of this analysis were supported by a sensitivity analysis in which the 3-month window was widened to – 4 weeks/+ 10 weeks of the expected 3-month visit date (relative risk 2.00, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.86; p = 0.035).

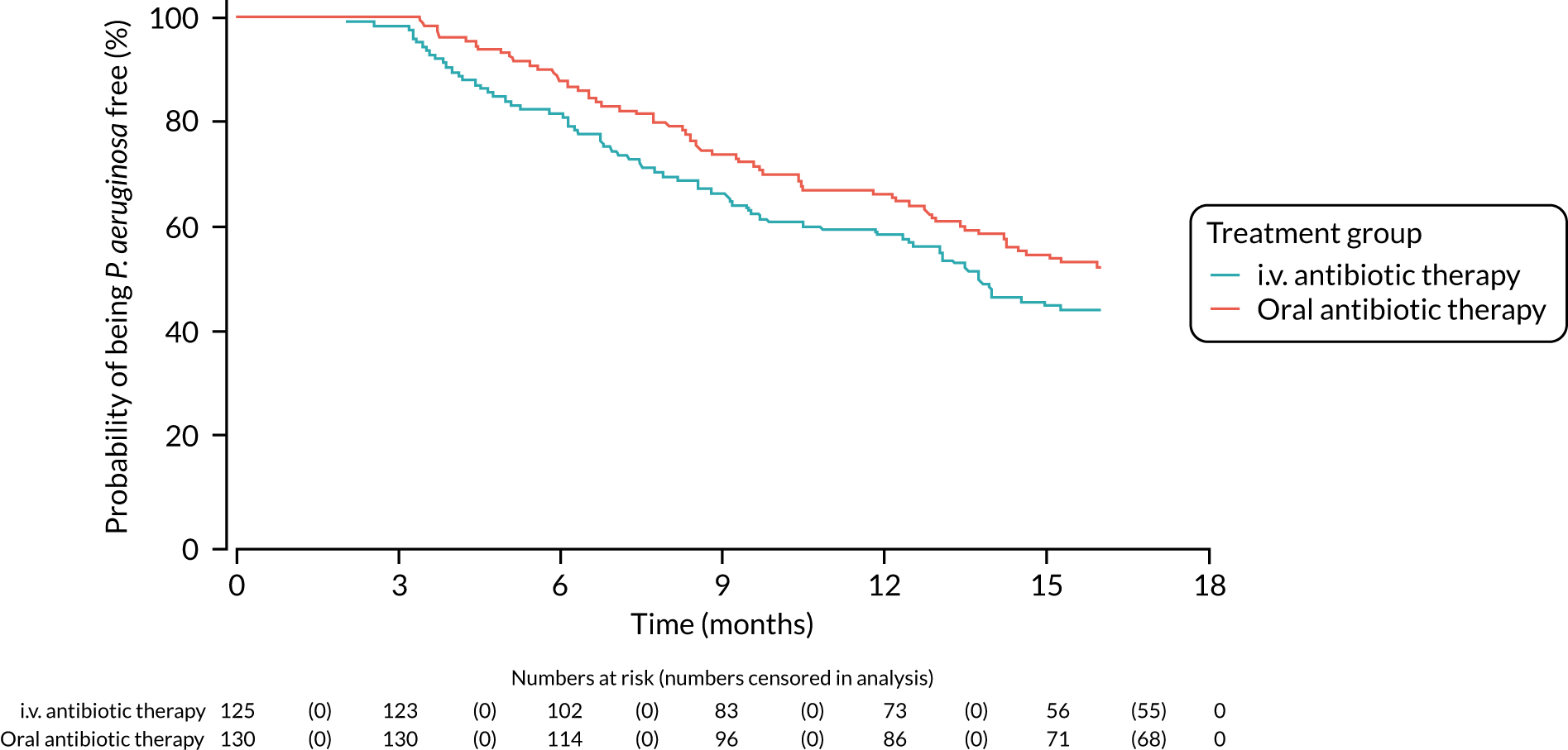

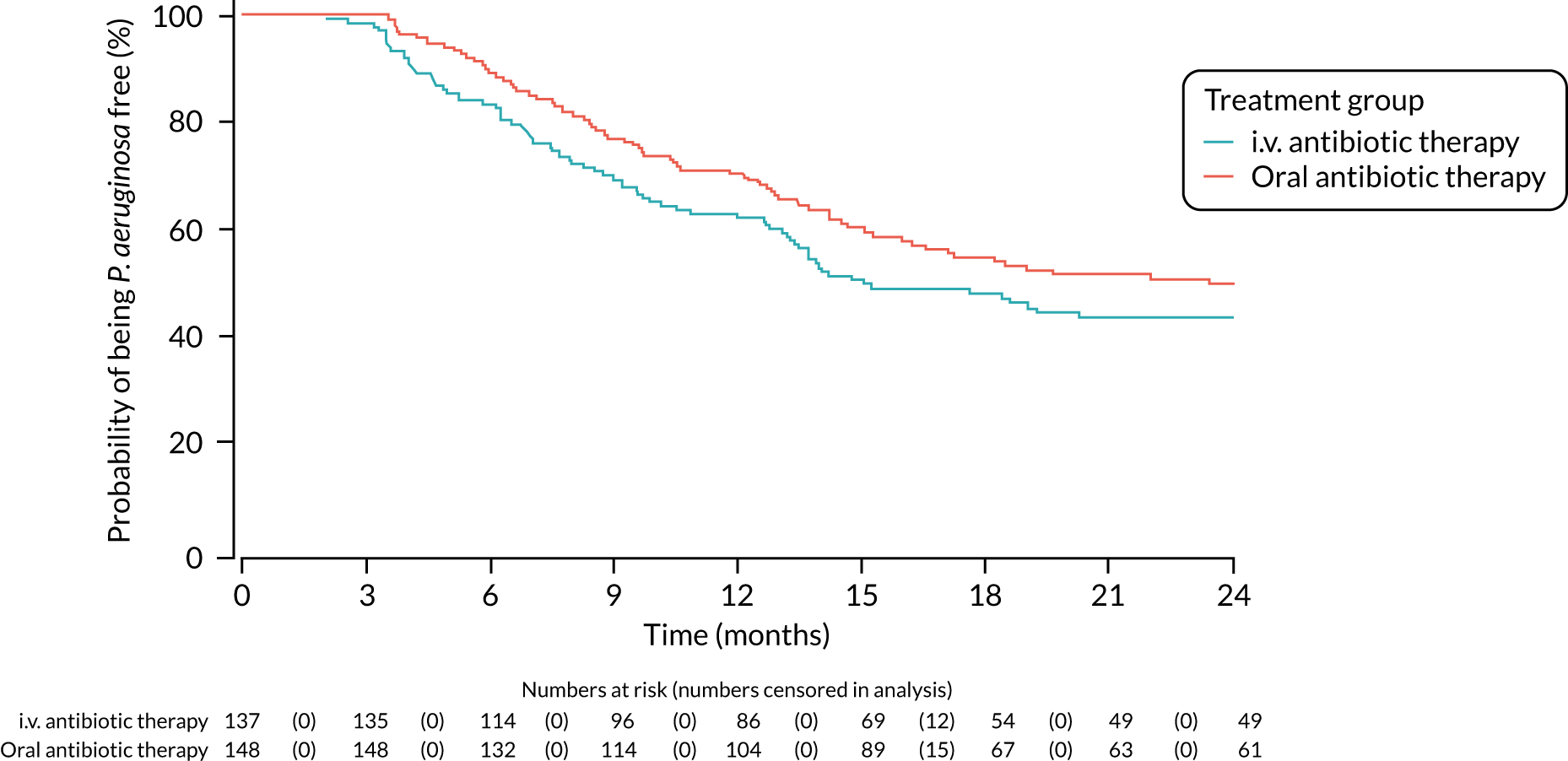

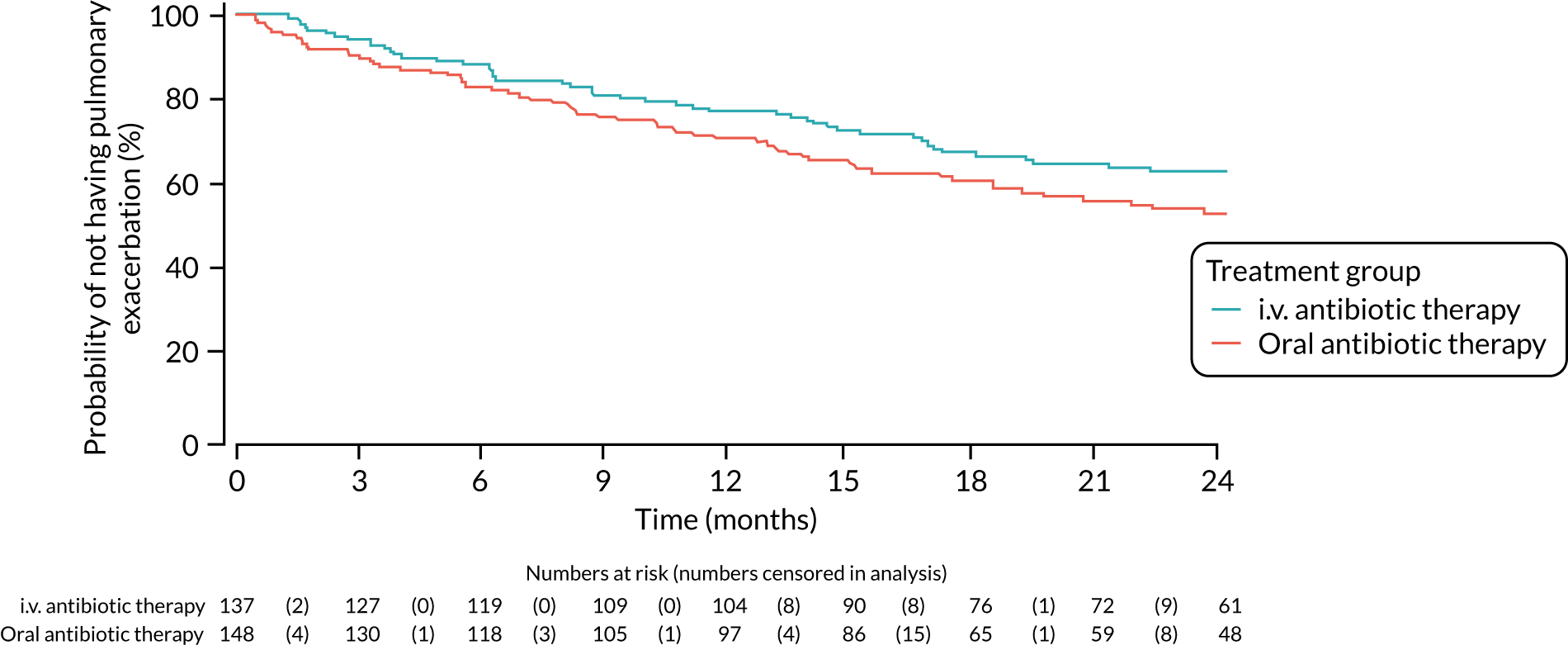

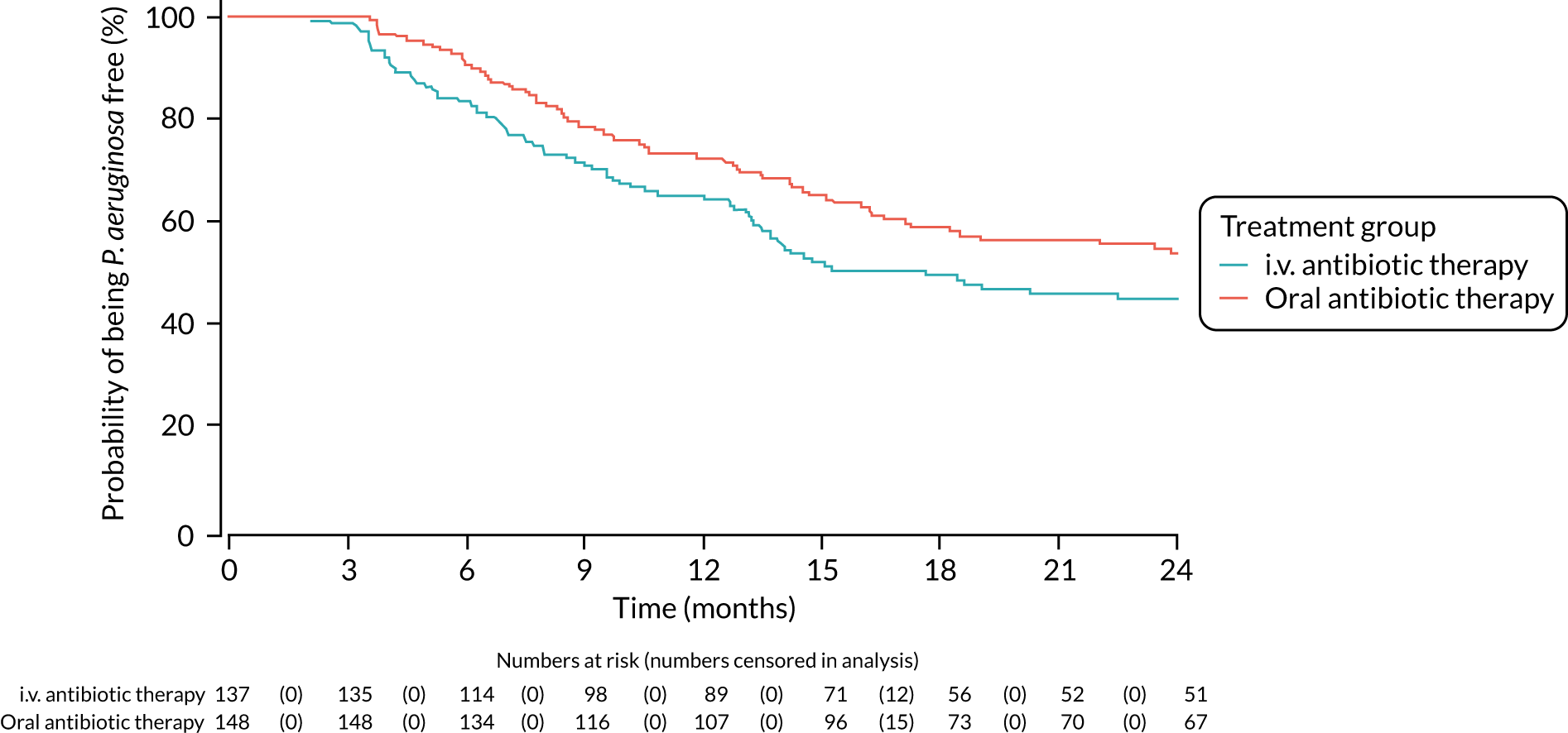

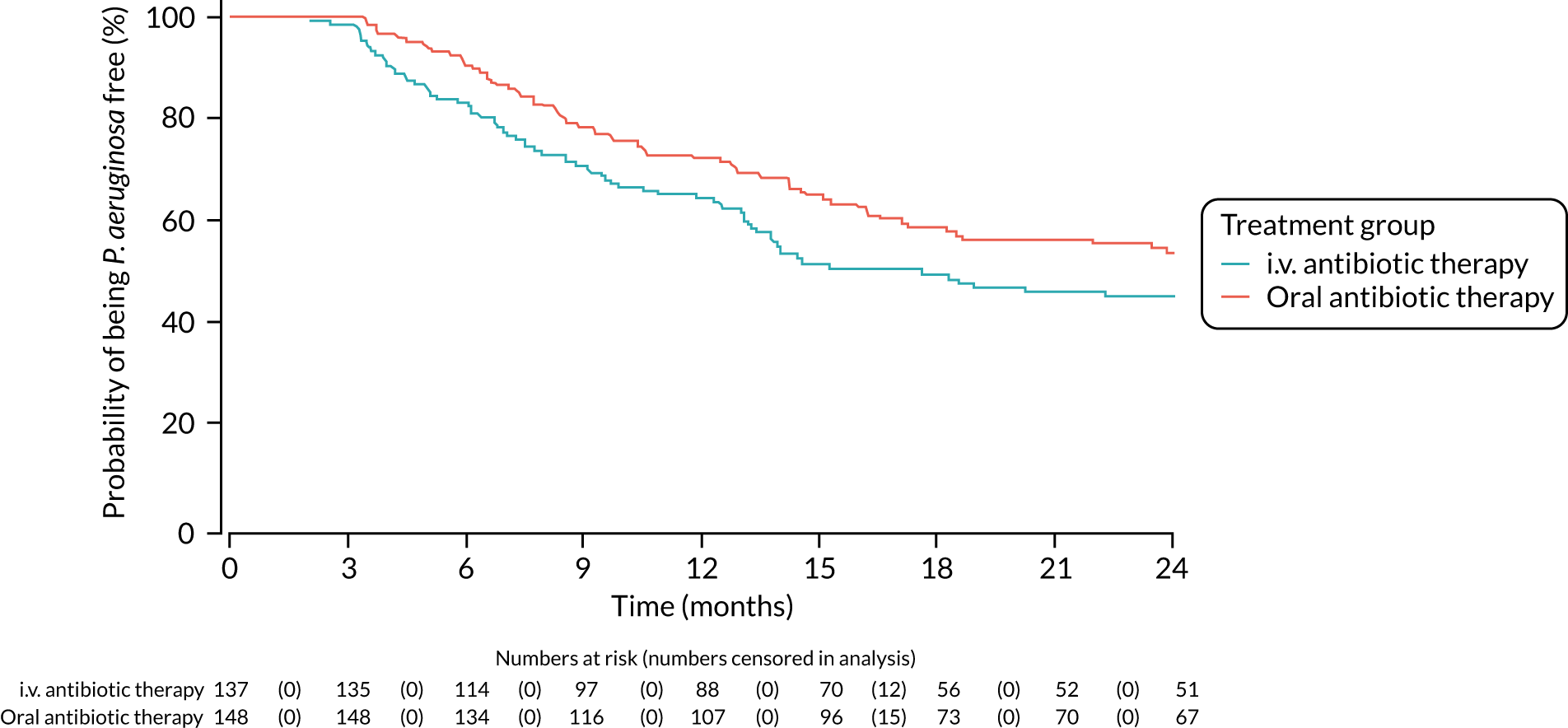

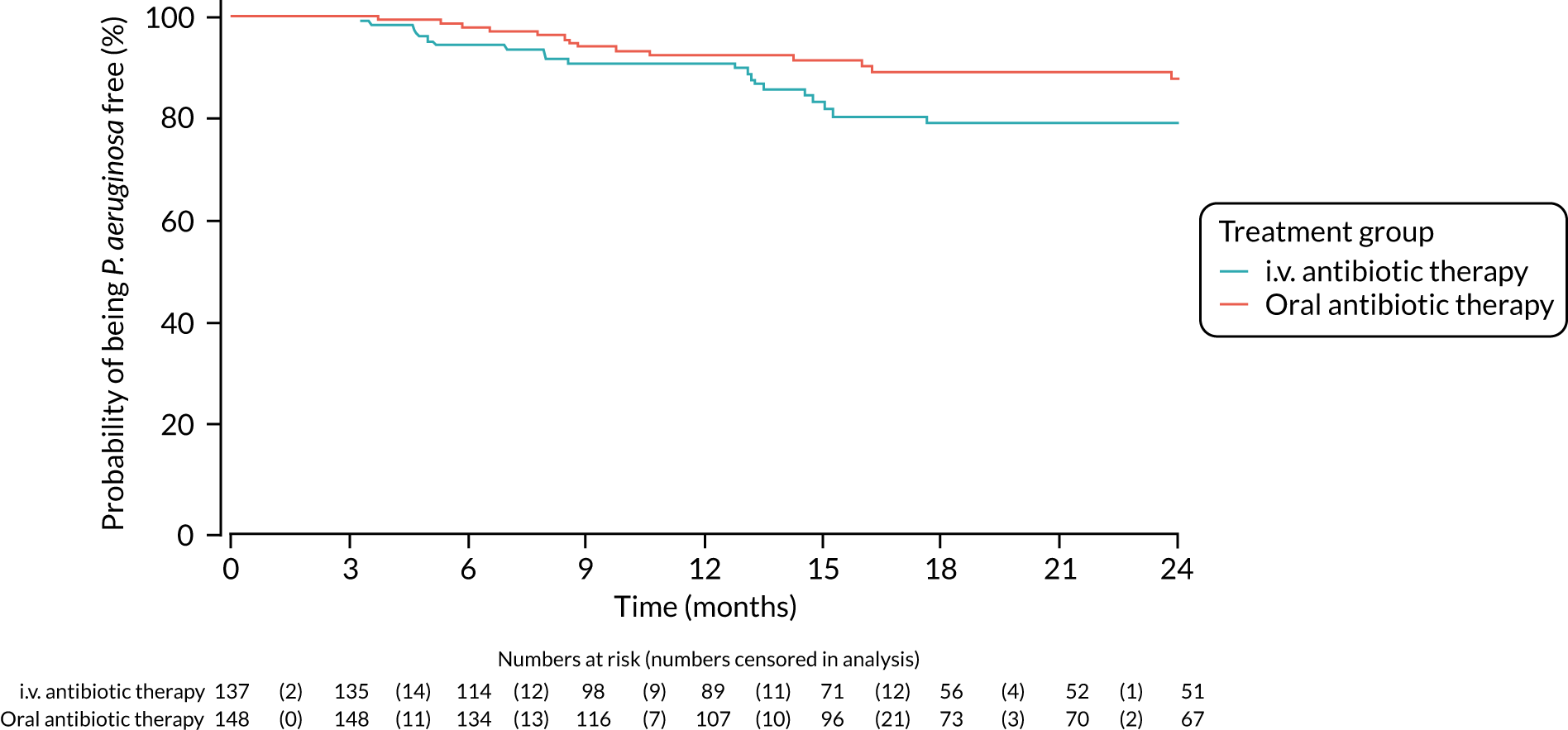

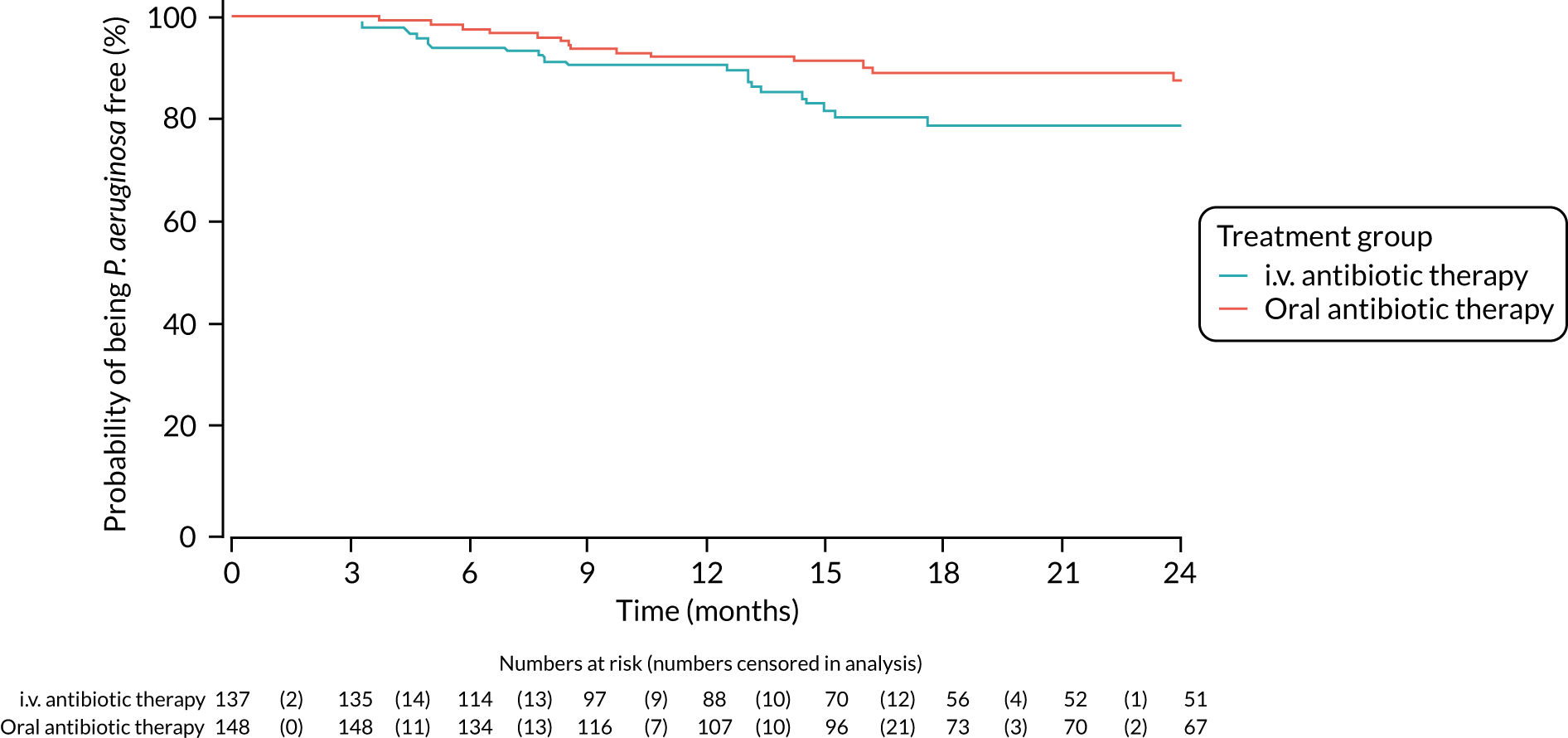

A post hoc analysis was performed on time to P. aeruginosa reoccurrence. Figure 3 is the Kaplan–Meier plot for time to P. aeruginosa reoccurrence up until the end of the 15-month window. This analysis included the 255 participants included in the primary analysis. Oral antibiotic therapy delayed time to P. aeruginosa reoccurrence compared with i.v. antibiotic therapy; however, the effect was not statistically significant (HR 1.31, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.85; p = 0.119). Figure 4 is the Kaplan–Meier plot for time to P. aeruginosa reoccurrence up until the end of the 24-month follow-up period.

FIGURE 3.

Time to reoccurrence of P. aeruginosa infection (any strain) up to the end of the 15-month window.

FIGURE 4.

Time to reoccurrence of P. aeruginosa infection (any strain) up to the end of the 24-month follow-up period.

Following database lock and the unblinding of the treatment allocations, it was found that one participant (who had withdrawn from the trial and was not included in the primary analysis) had a positive sample for P. aeruginosa on the day that they had stopped treatment. The definition in the statistical analysis plan stated that any samples taken in the 48-hour window following treatment cessation should be excluded and this was executed for the primary analysis shown above; however, this should have stated that only samples that were negative for isolation of P. aeruginosa in this period should be excluded – positive samples should have been included. Further investigation identified no other occurrences of this; in a post hoc analysis that included this participant, there was no impact on the primary analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Time to reoccurrence of original Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection

A total of 50 participants (n = 28 in the i.v. antibiotic therapy group; n = 22 in the oral antibiotic therapy group) had P. aeruginosa genotyping performed on both a baseline and a follow-up sample over the course of the trial. Owing to the limited numbers of participants with genotyping results, two analyses were performed on this outcome, in which assumptions were made around whether any reoccurring P. aeruginosa infections were the same strain or different. Both analyses included all 285 participants.

In the first analysis, in which participants who had regrown P. aeruginosa but did not have genotyping performed were assumed to have regrown the same strain, there was no statistically significant difference between oral antibiotic and i.v. antibiotic therapy treatment groups in time to reoccurrence of infection with the original P. aeruginosa strain (HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.91; p = 0.061) (Table 10, and Appendix 4, Figure 6). The results from a sensitivity analysis using time from treatment commencement, rather than time from randomisation, confirmed this finding (HR 1.38, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.92; p = 0.060) (see Table 10 and Appendix 4, Figure 7).

| Analysis | Treatment group, n (%) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. antibiotic therapy (N = 137) | Oral antibiotic therapy (N = 148) | |||

| Unknown strains assumed to be the same as baseline | ||||

| Time from randomisation | 74 (54.0%) | 66 (44.6%) | 1.37 (0.99 to 1.91) | 0.061 |

| Time from treatment commencement | 74 (54.0%) | 66 (44.6%) | 1.38 (0.99 to 1.92) | 0.060 |

| Unknown strains assumed to be different from baseline | ||||

| Time from randomisation | 21 (15.3%) | 14 (9.5%) | 1.85 (0.94 to 3.64) | 0.075 |

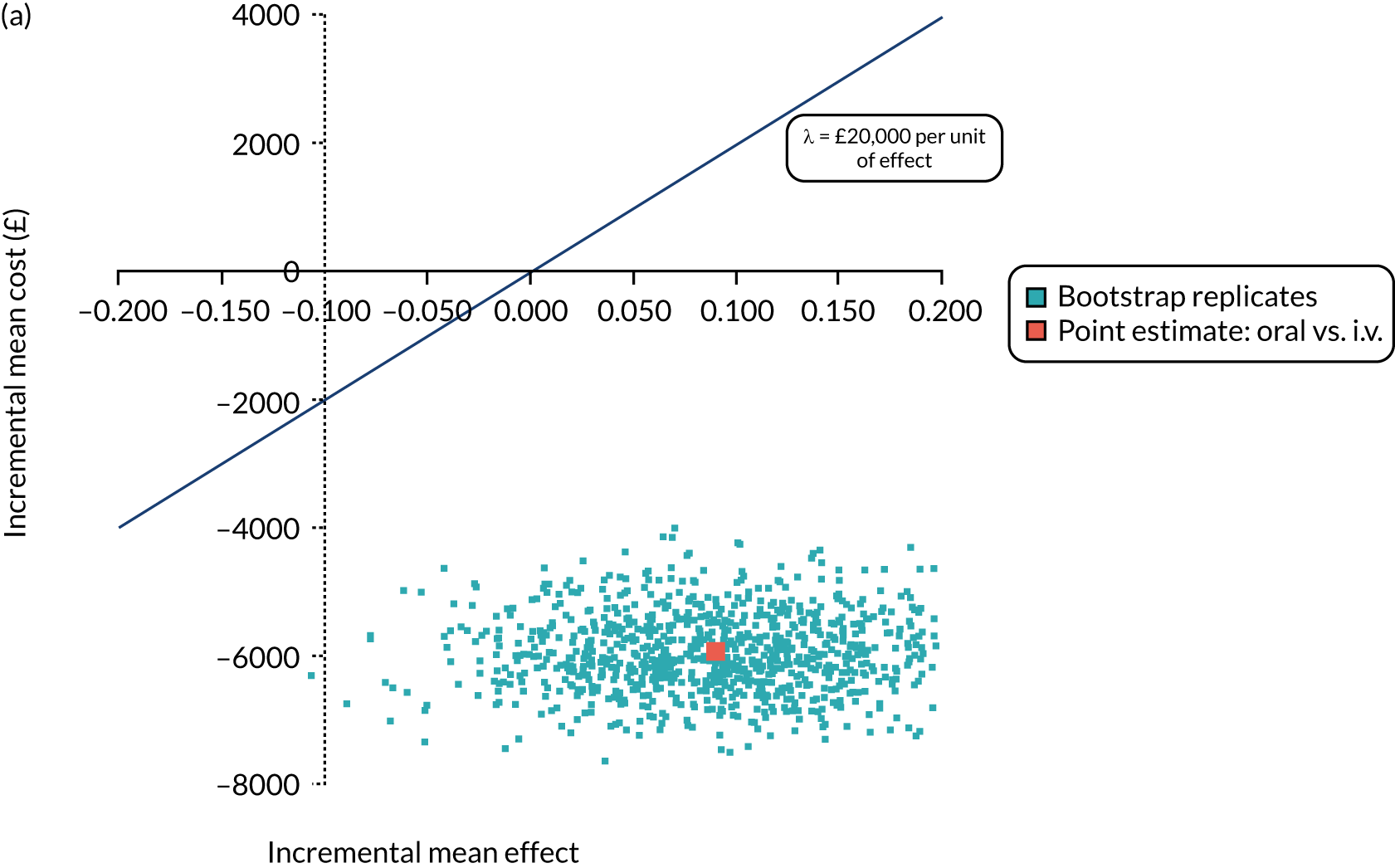

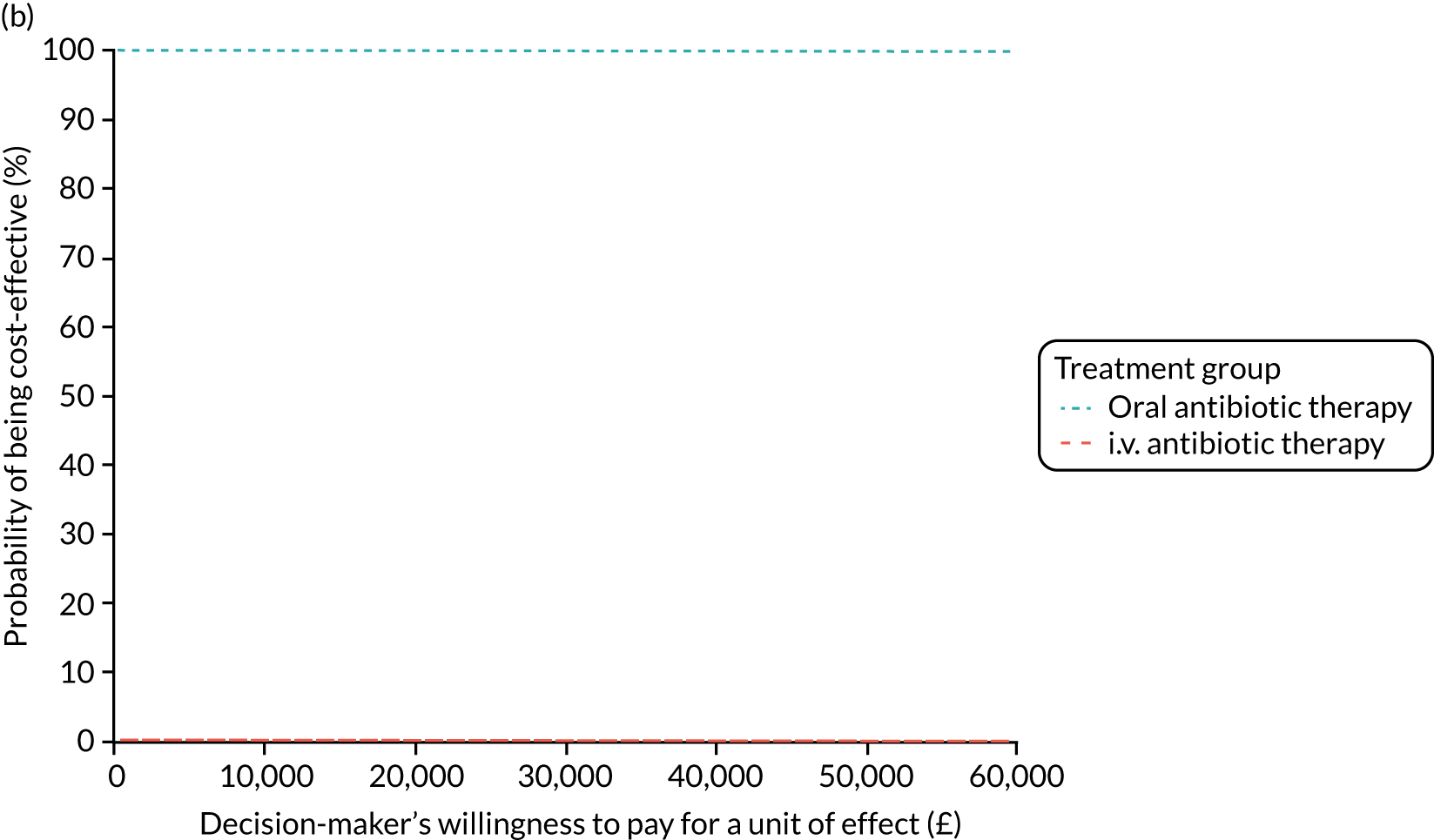

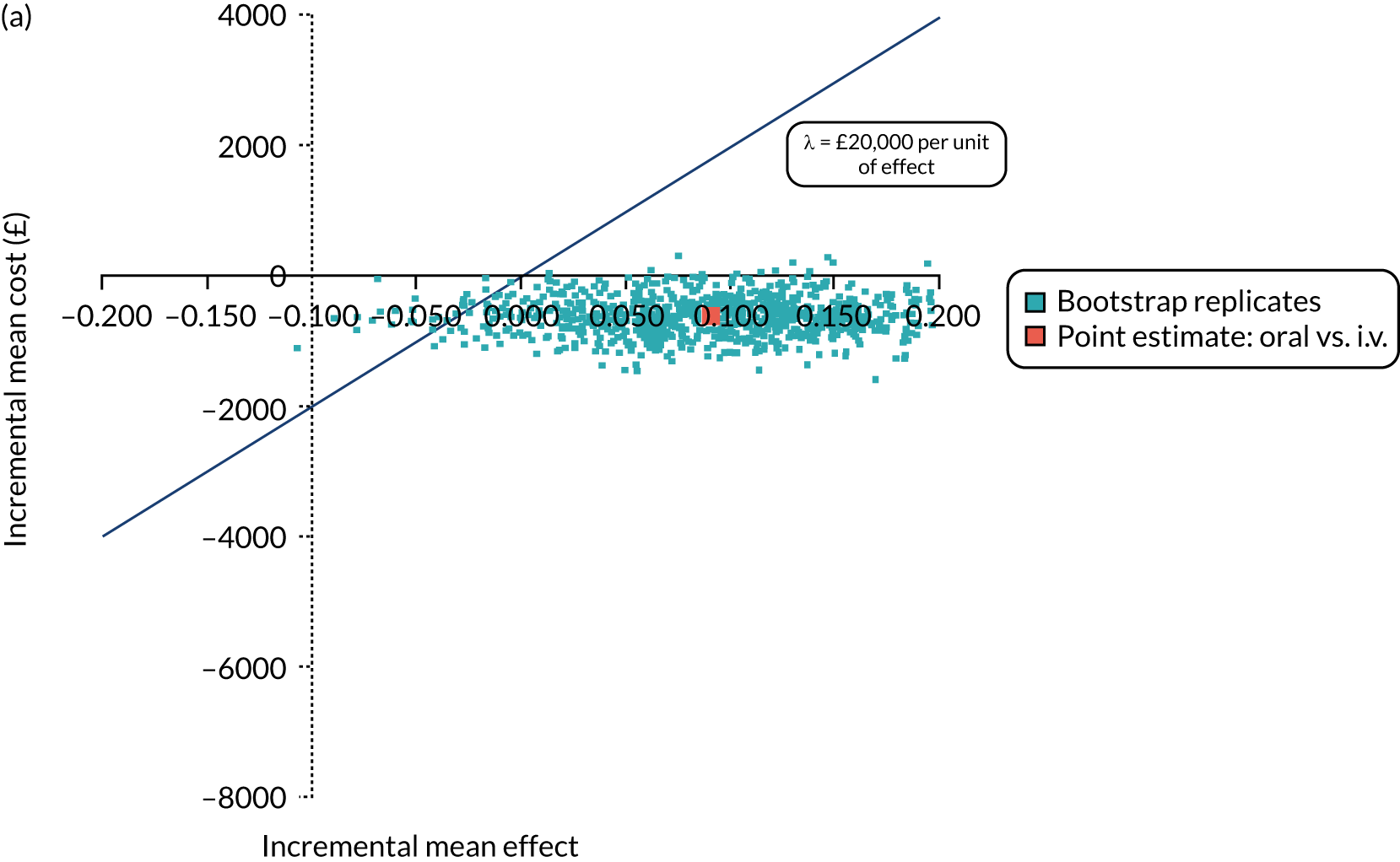

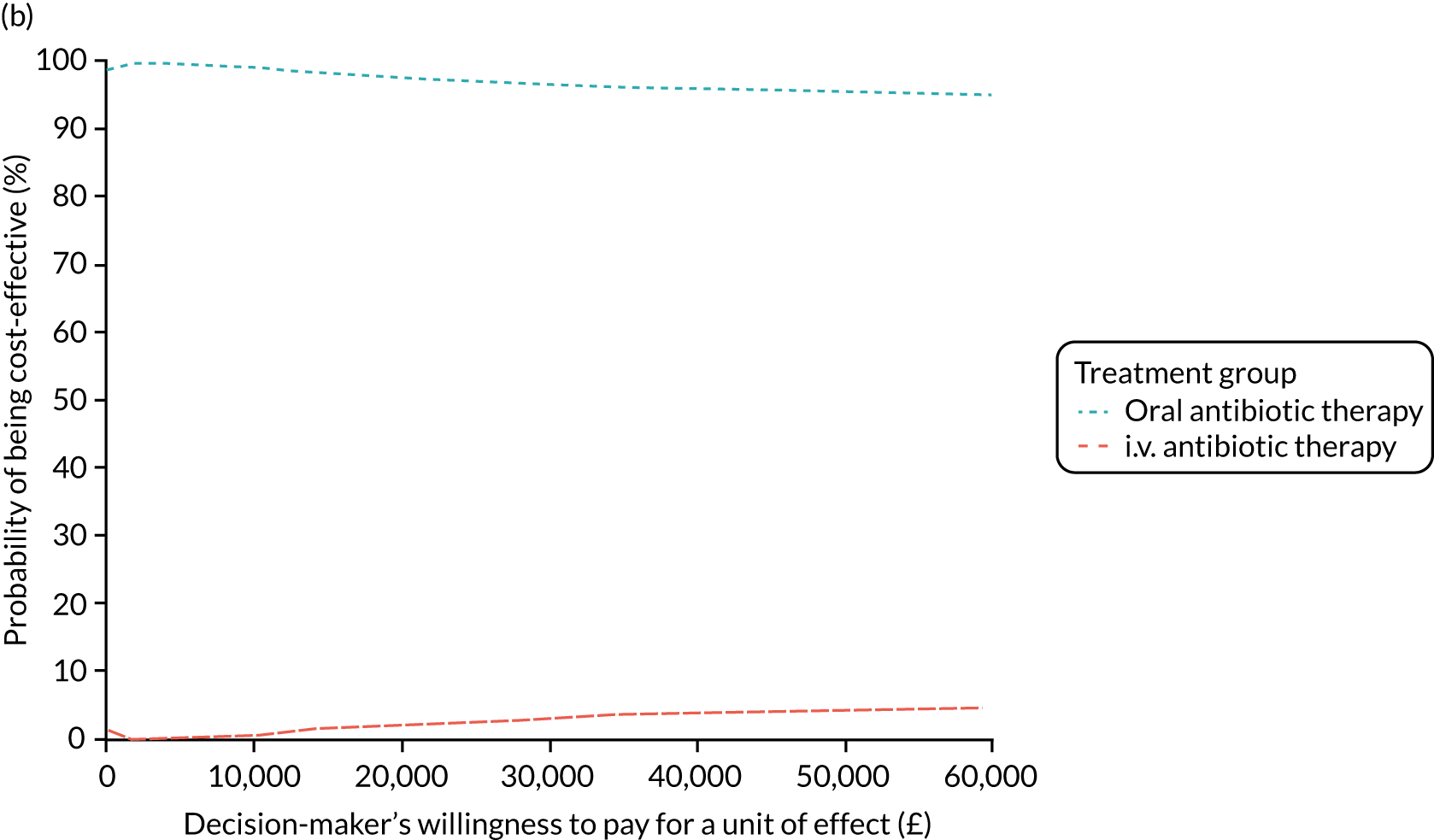

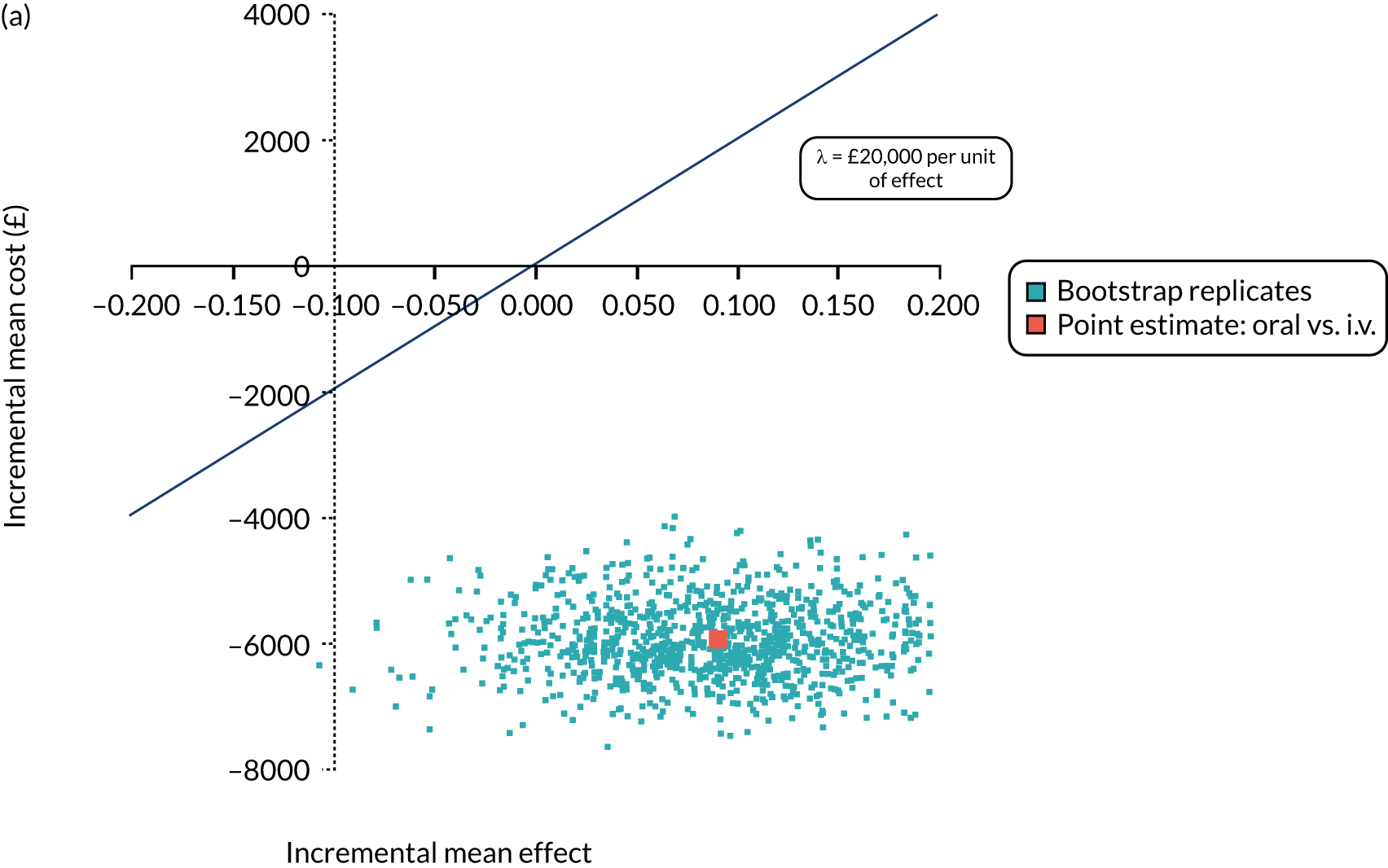

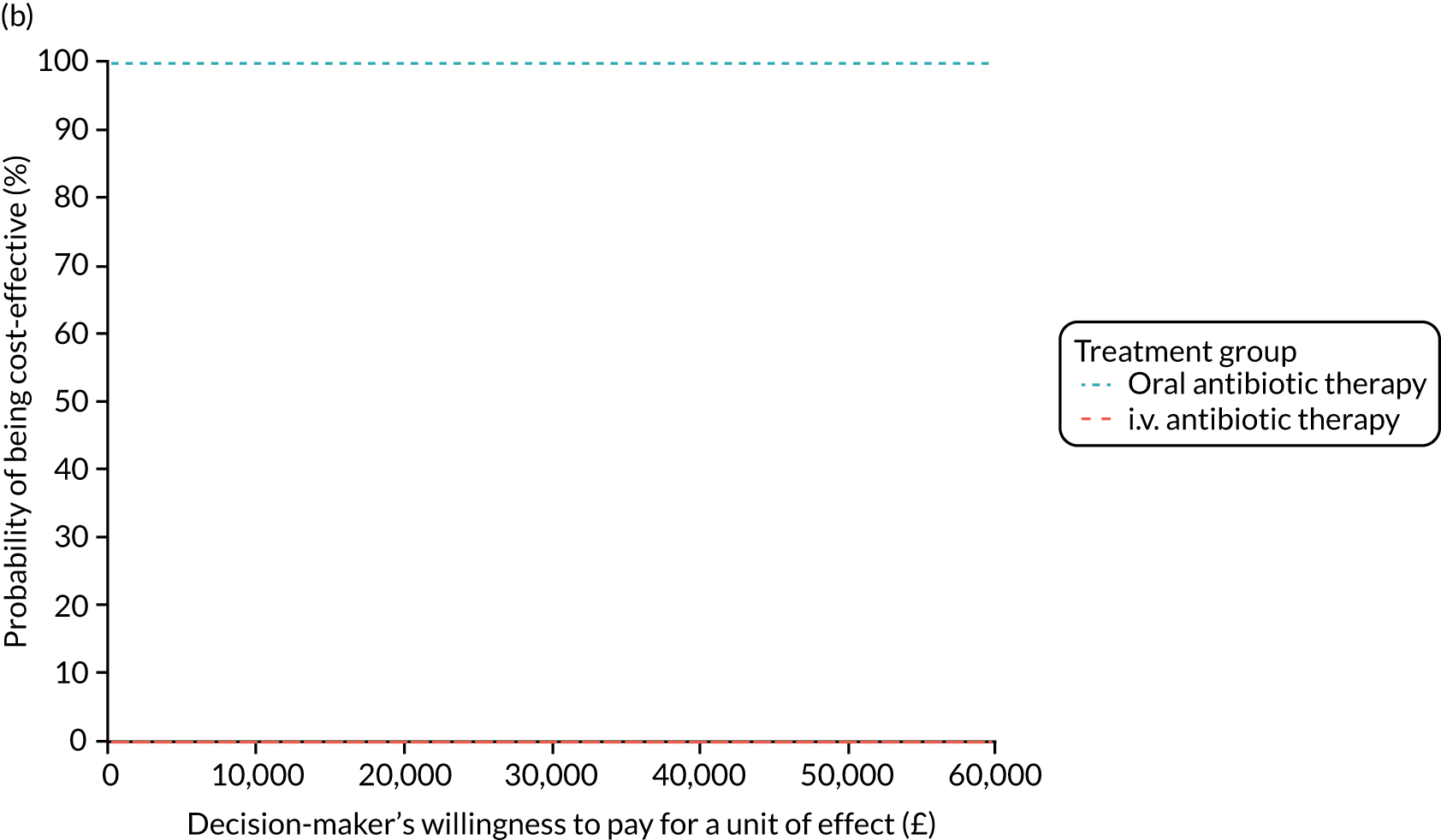

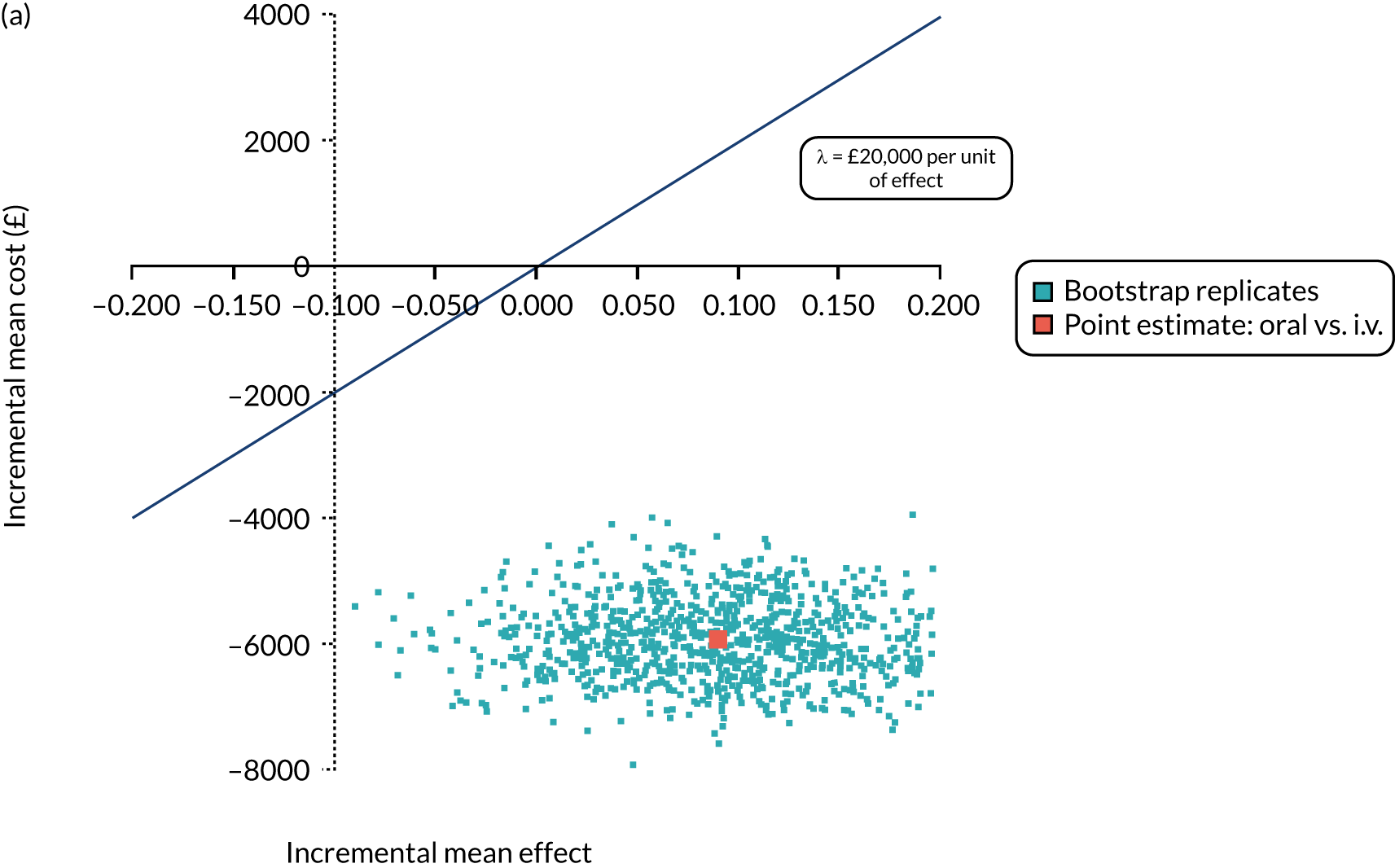

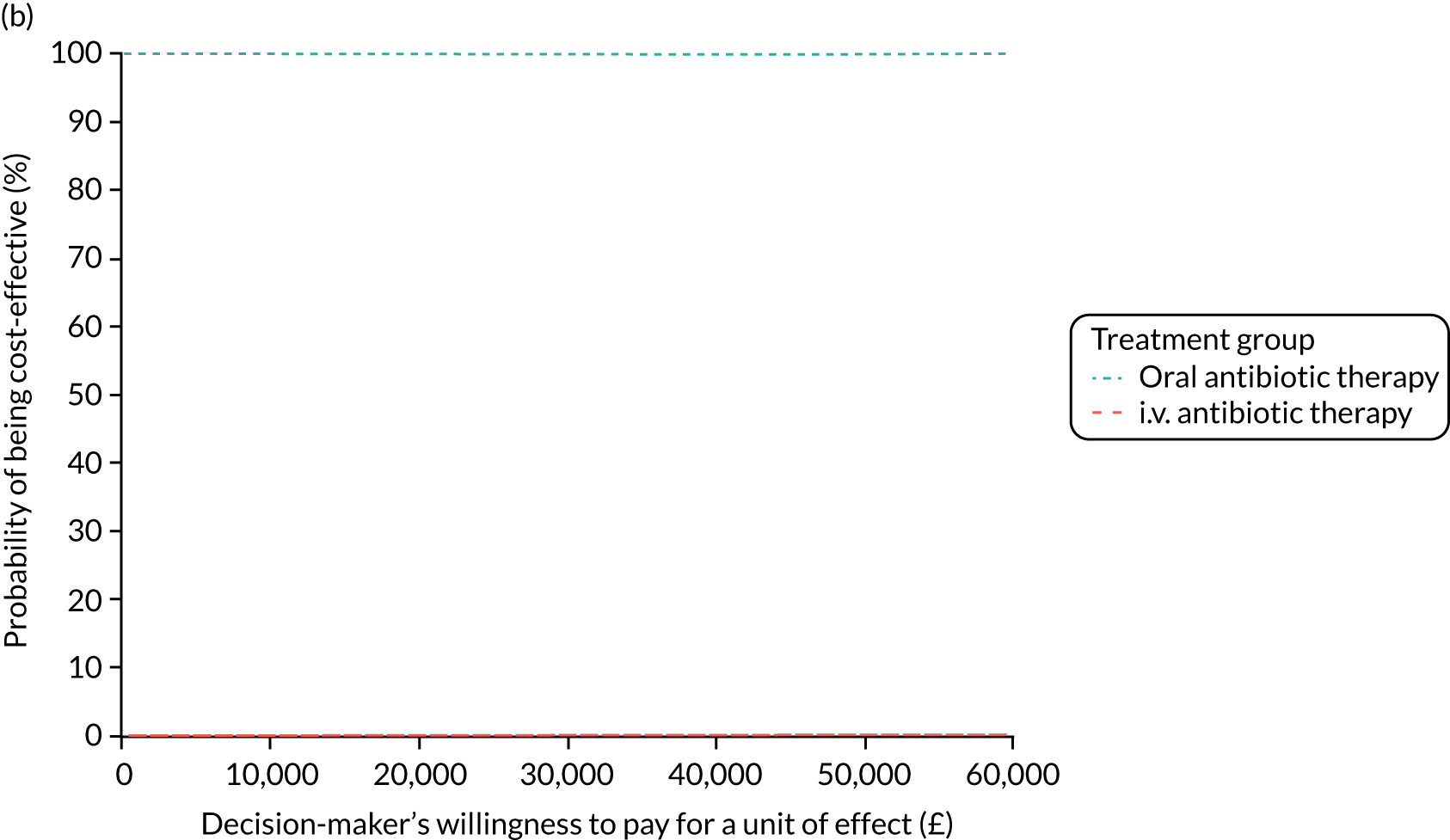

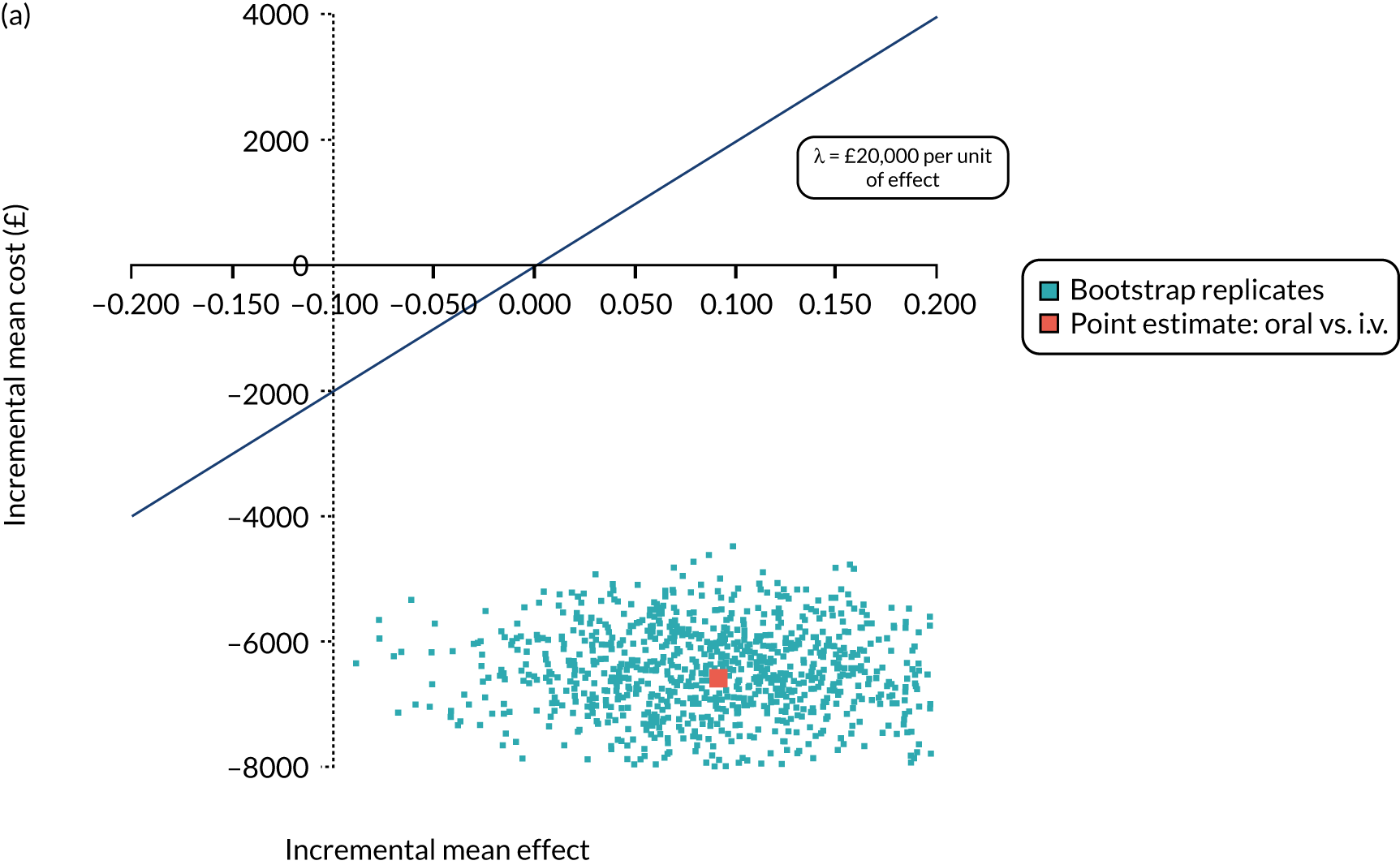

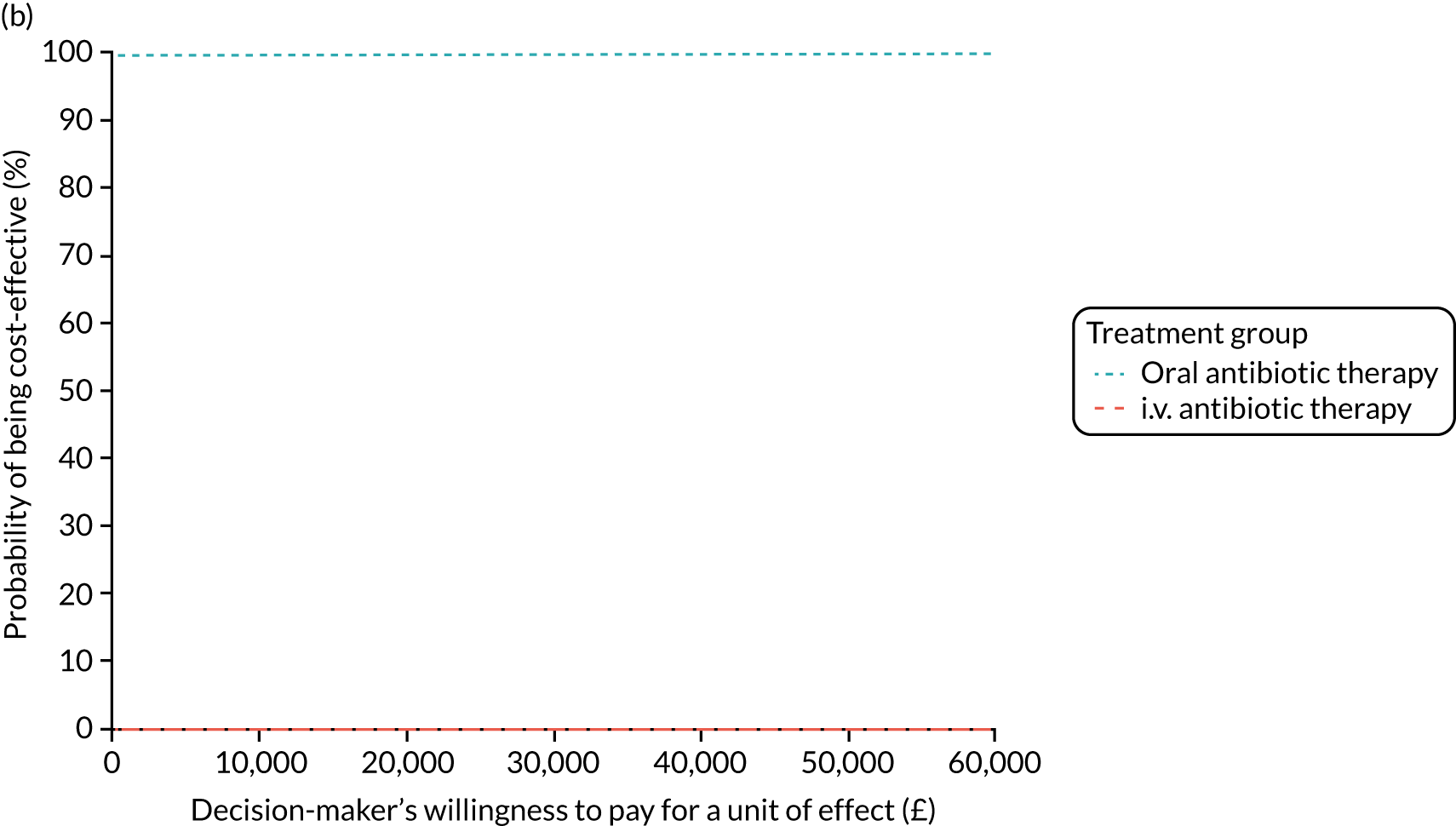

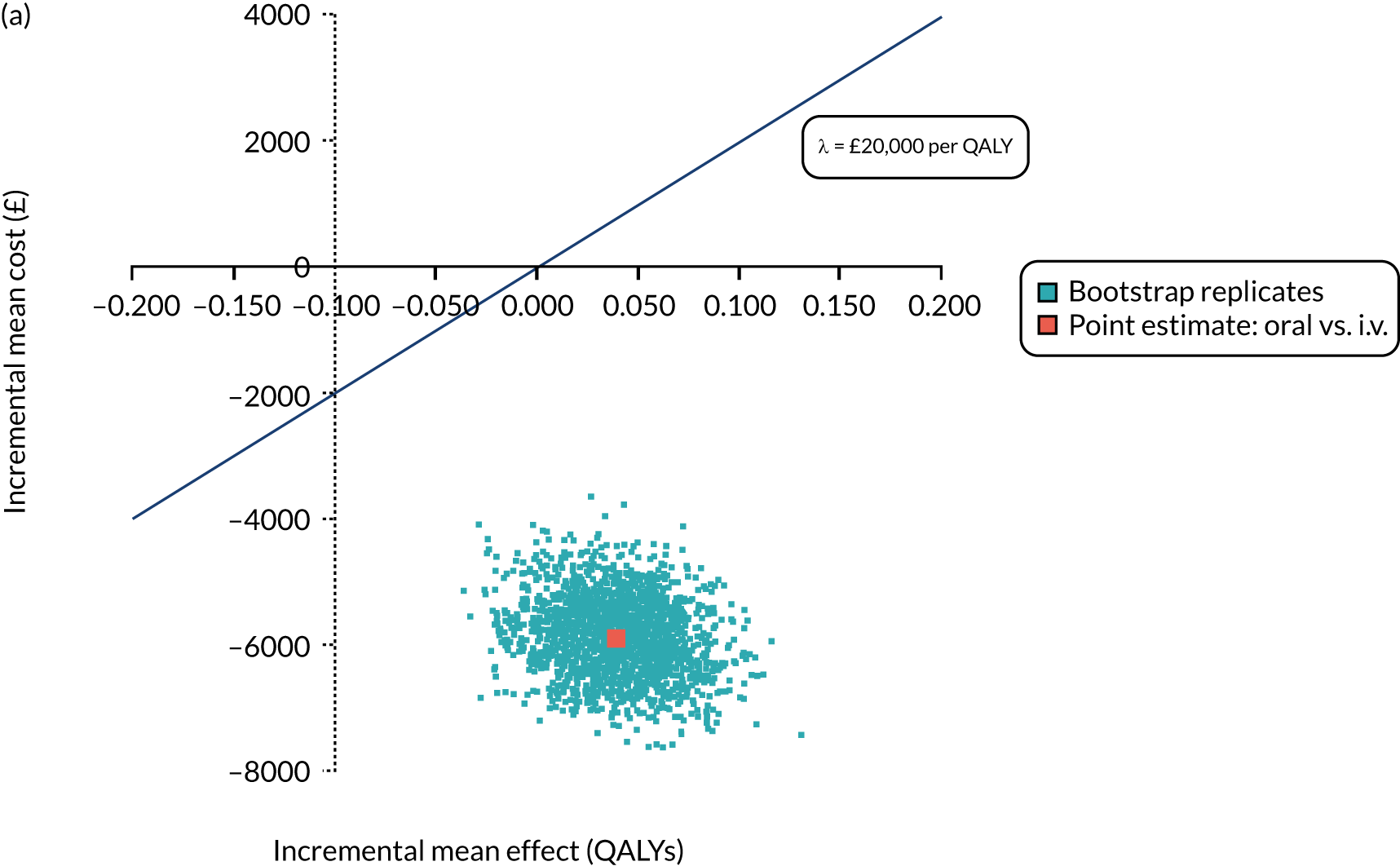

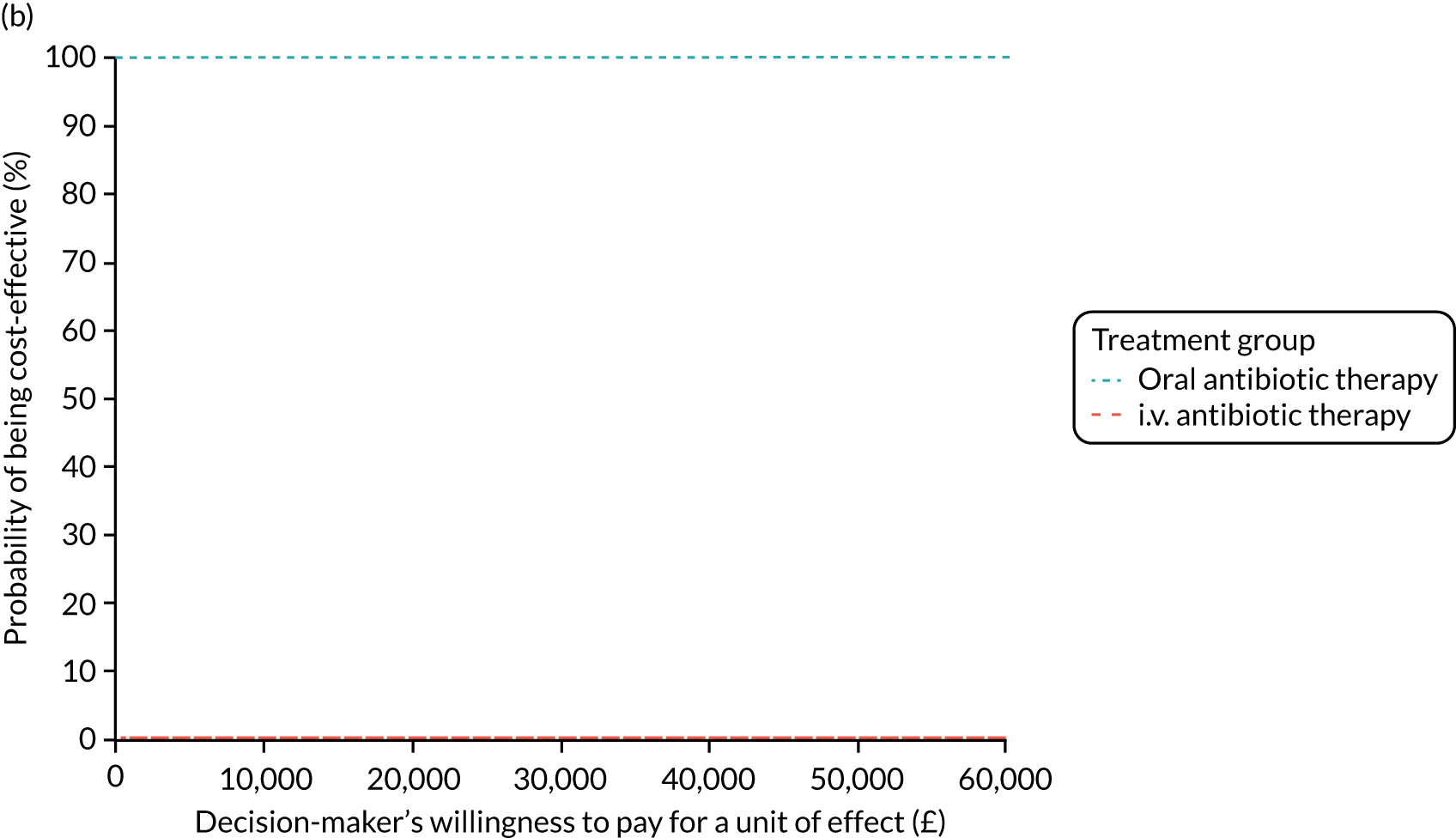

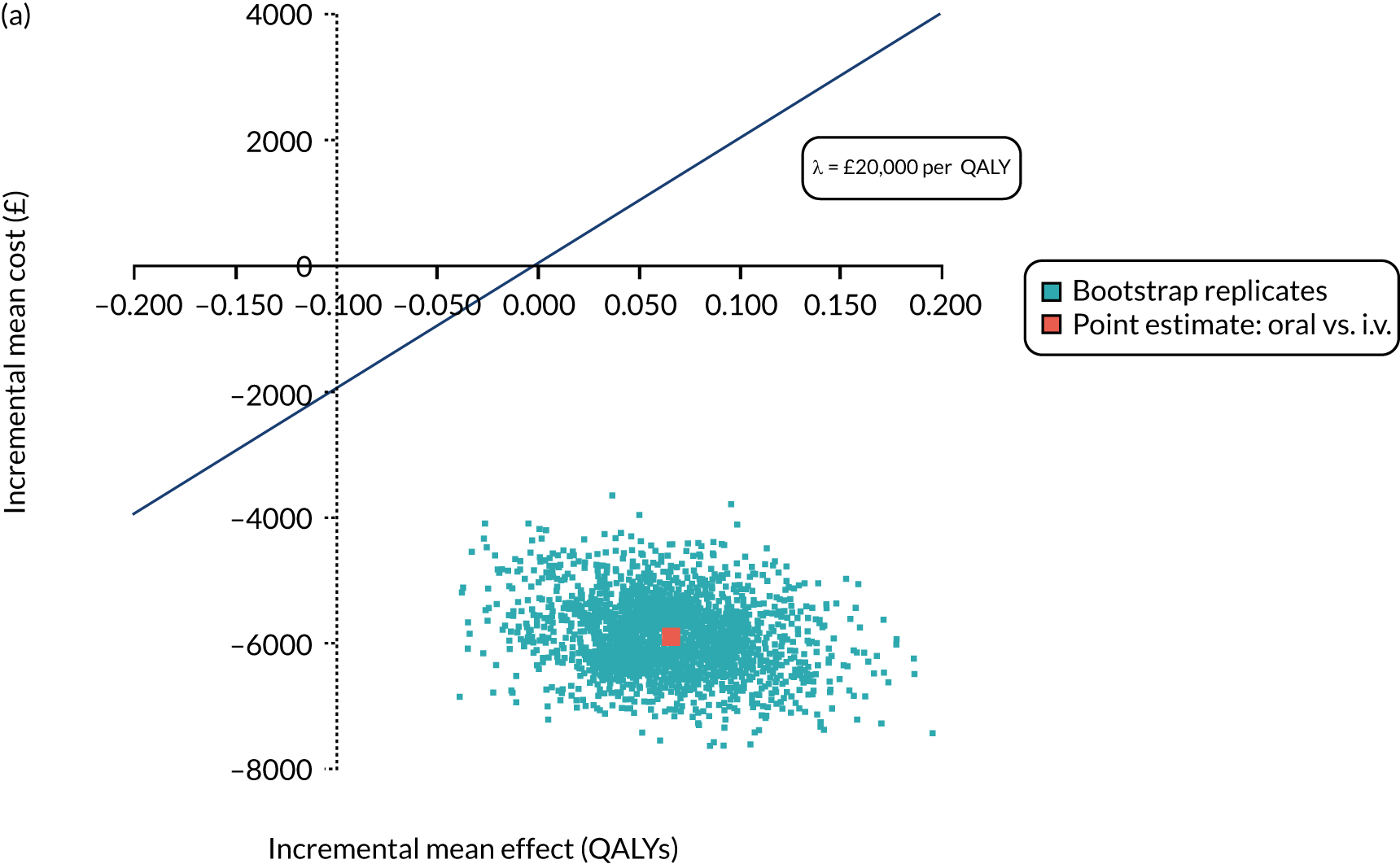

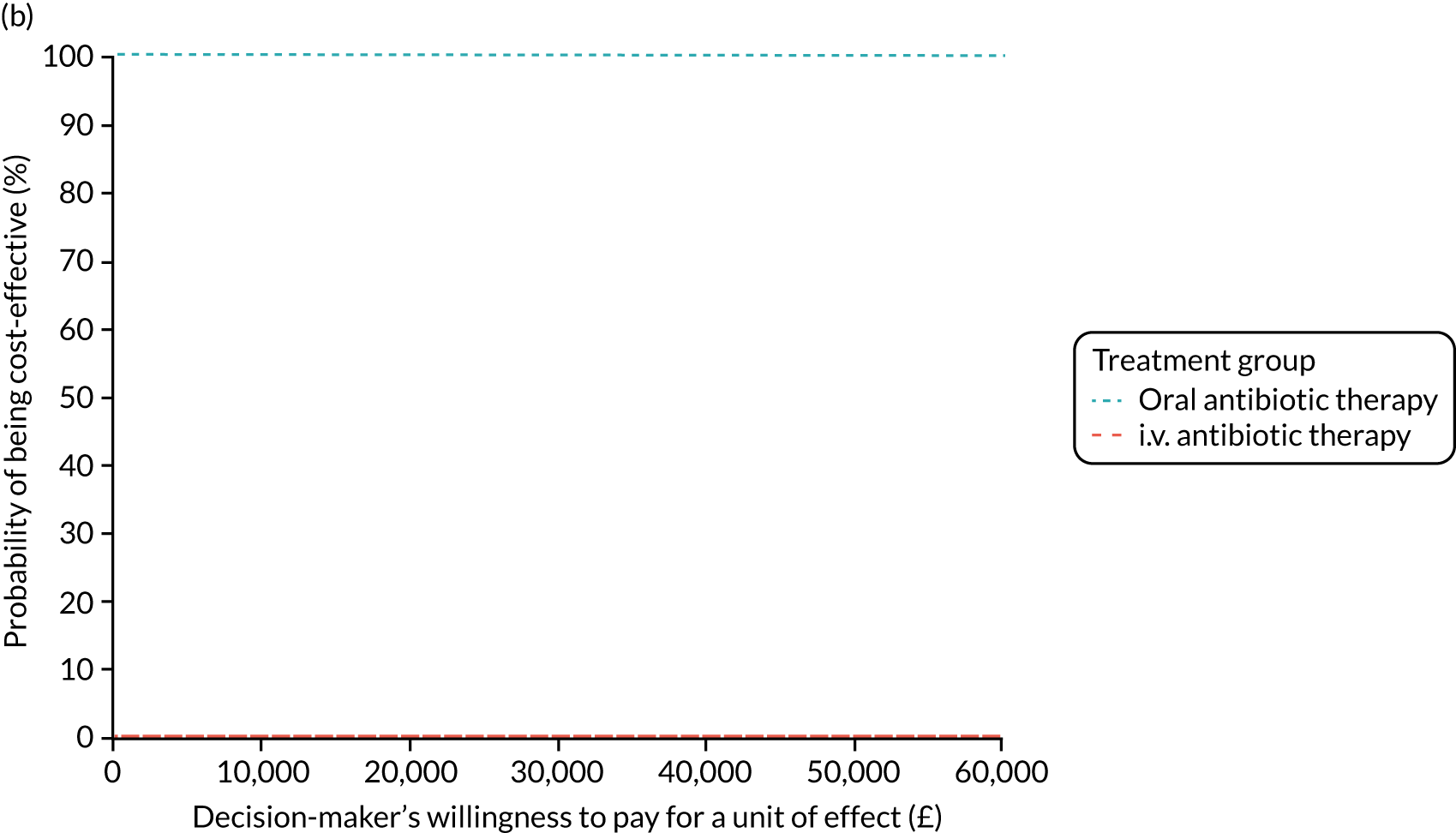

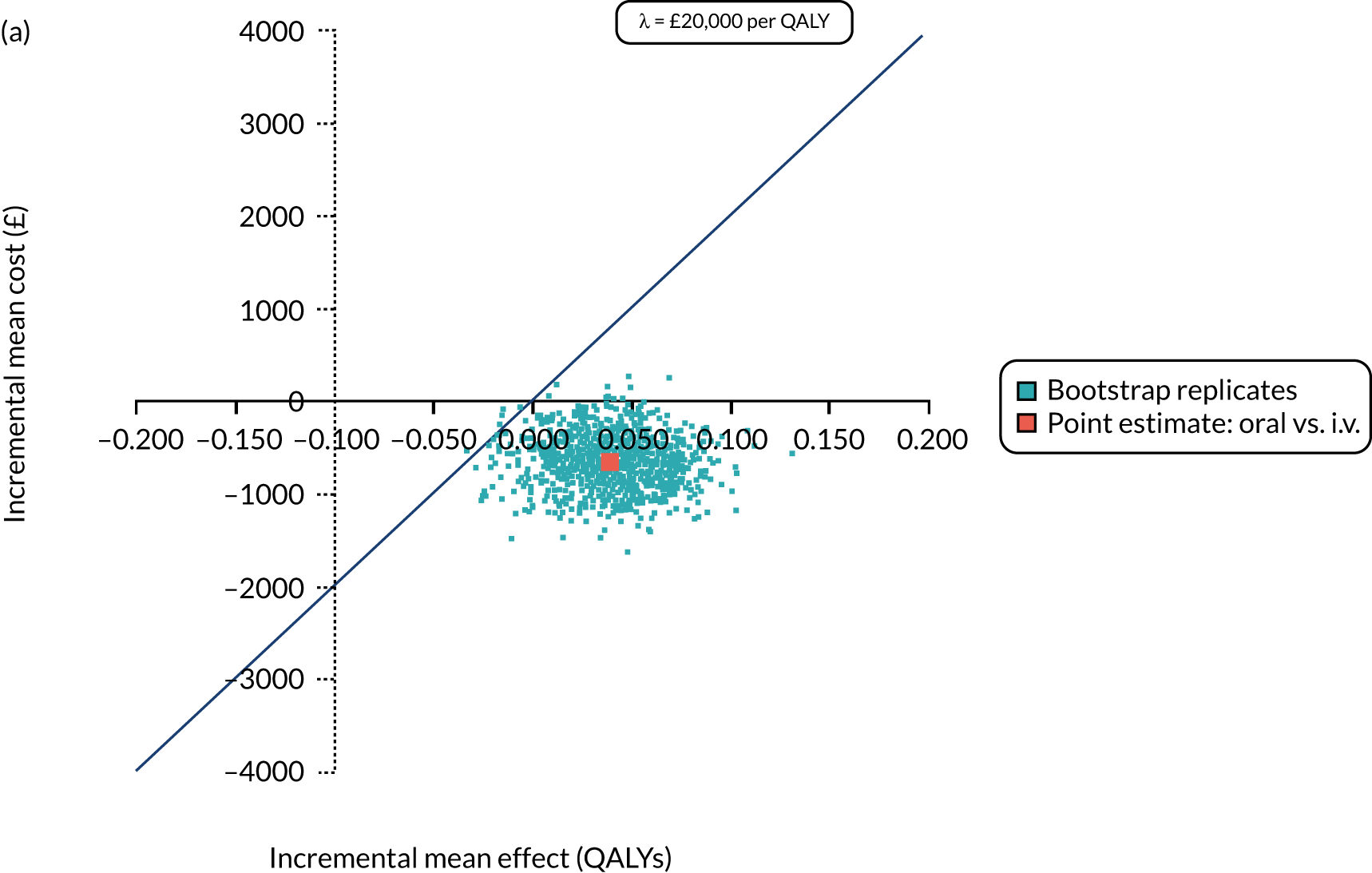

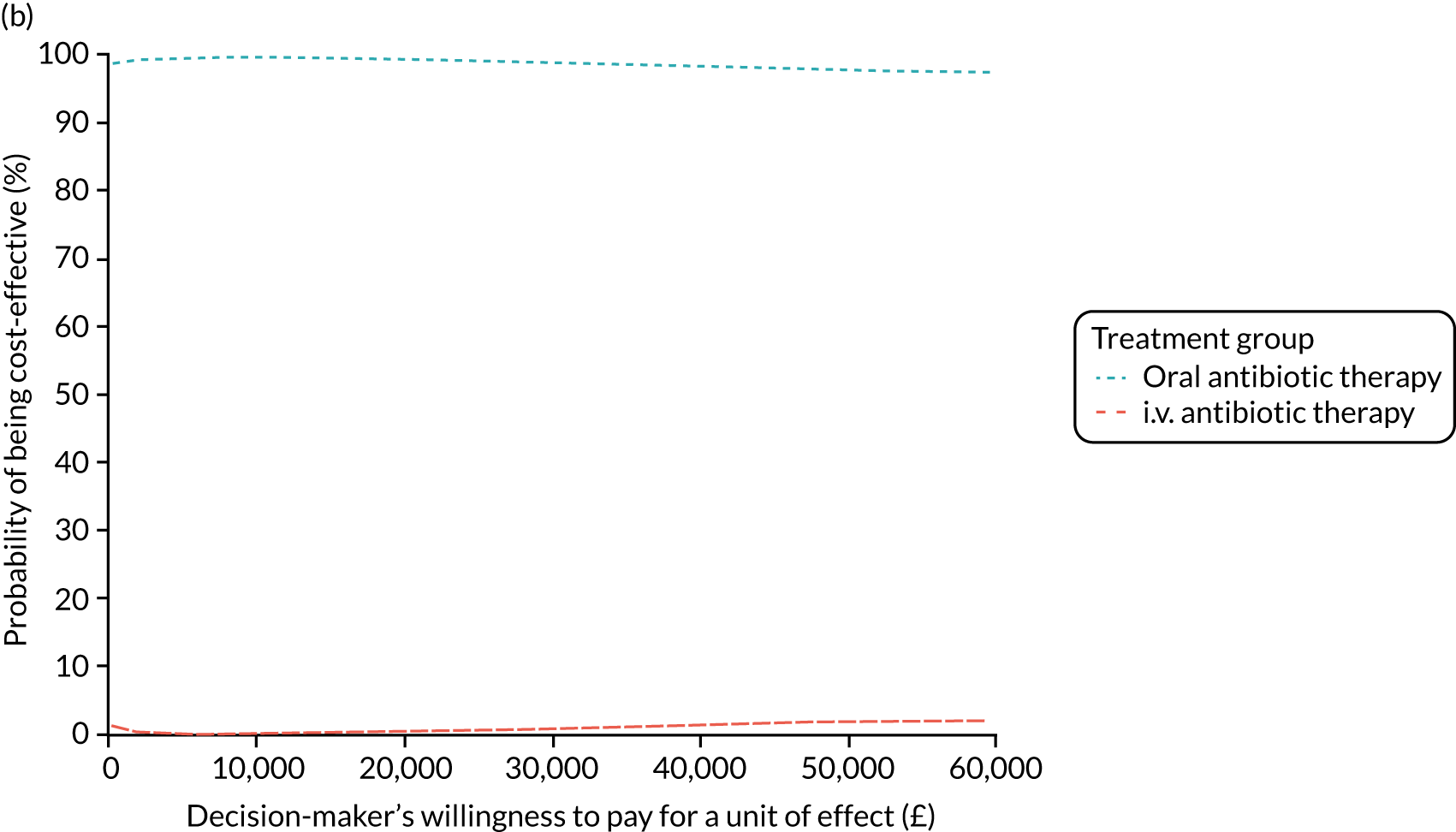

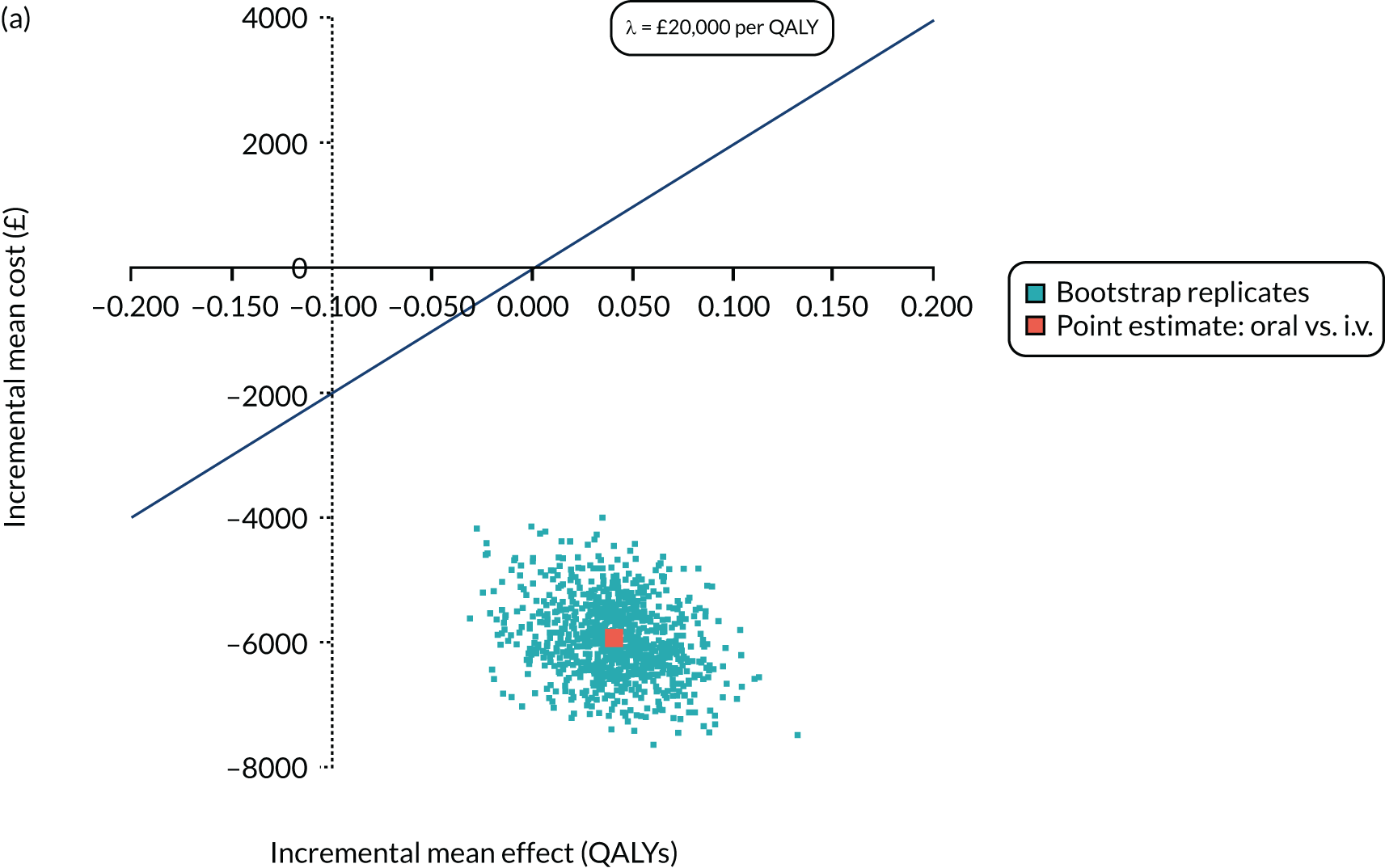

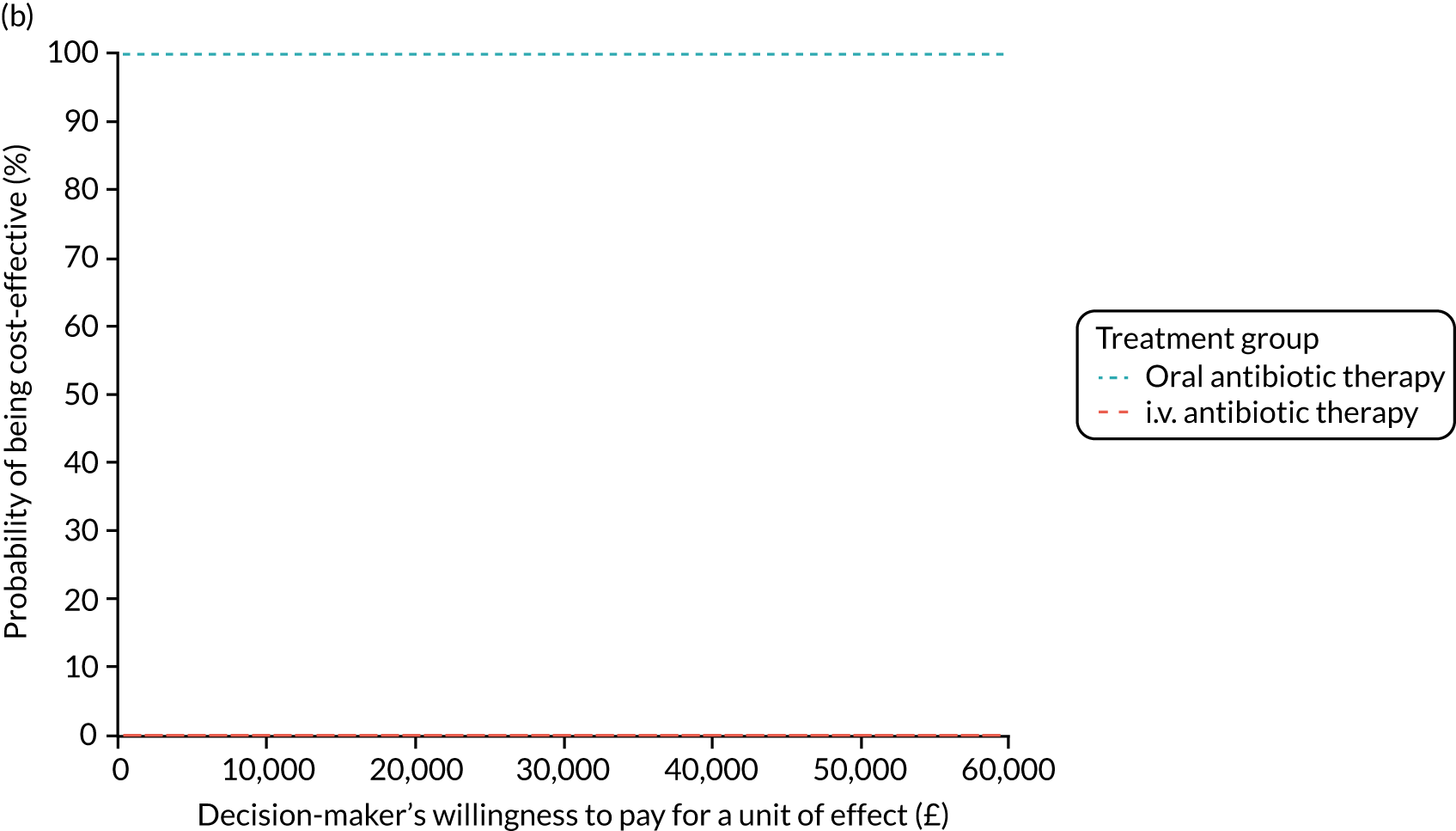

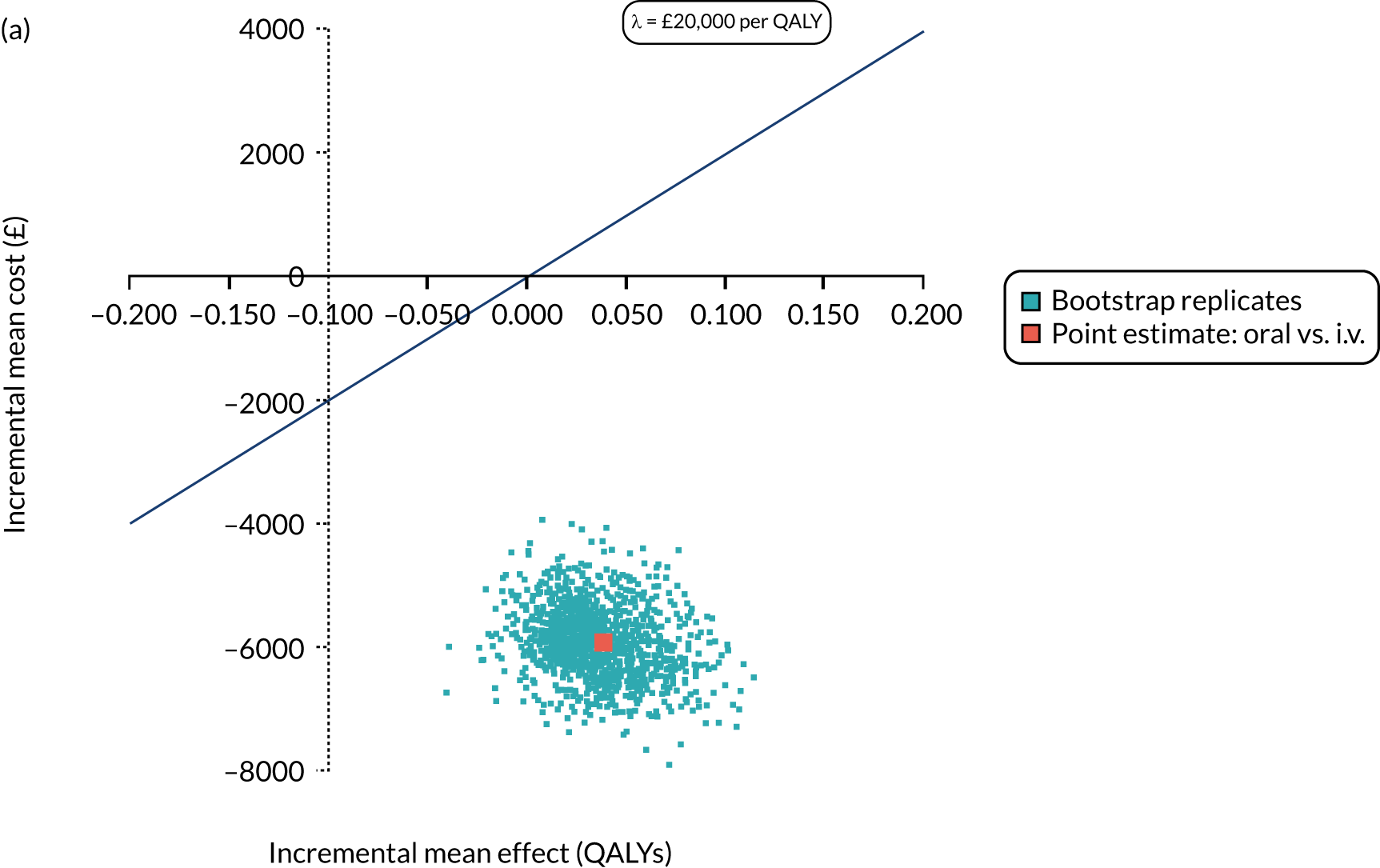

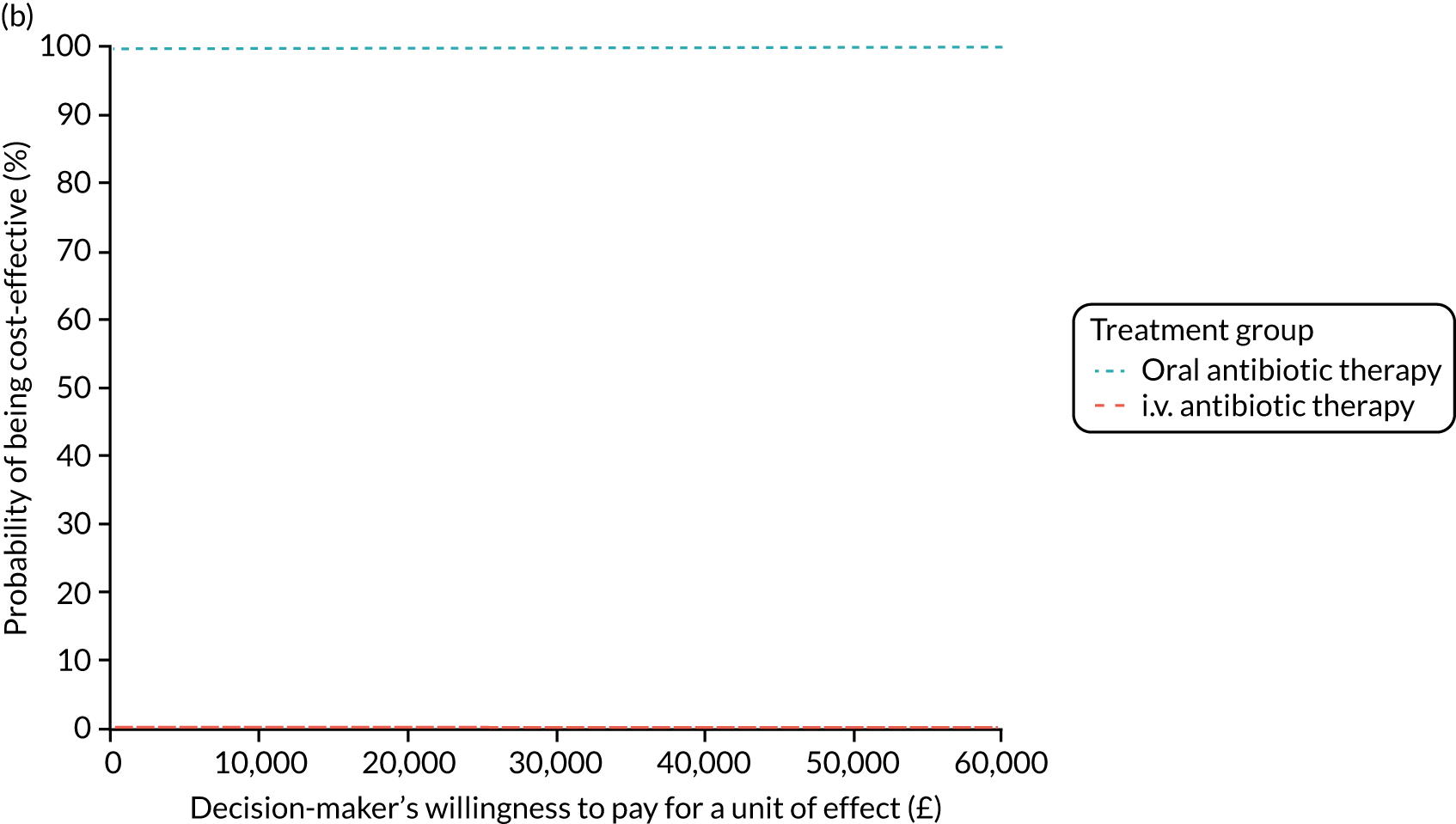

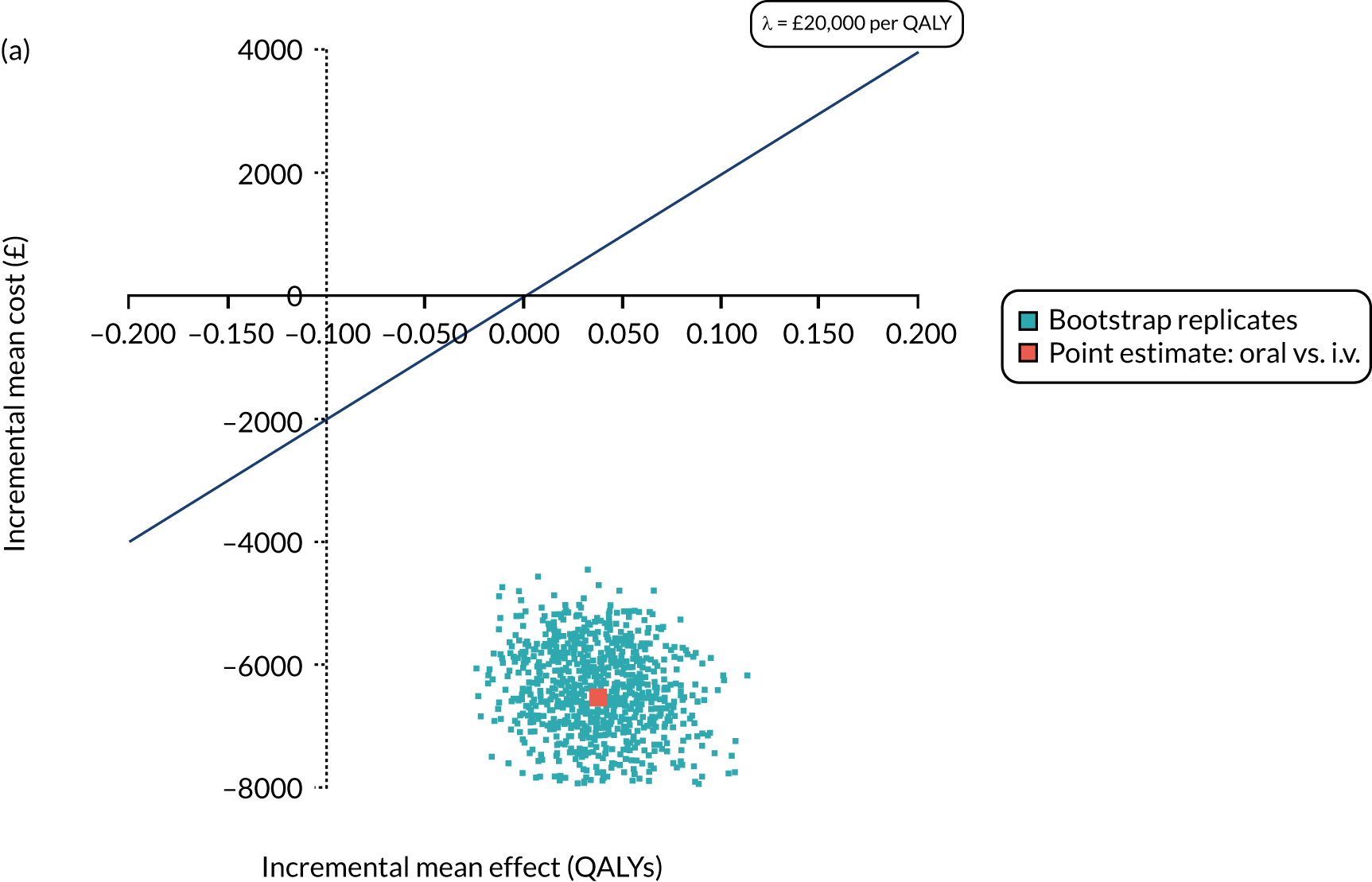

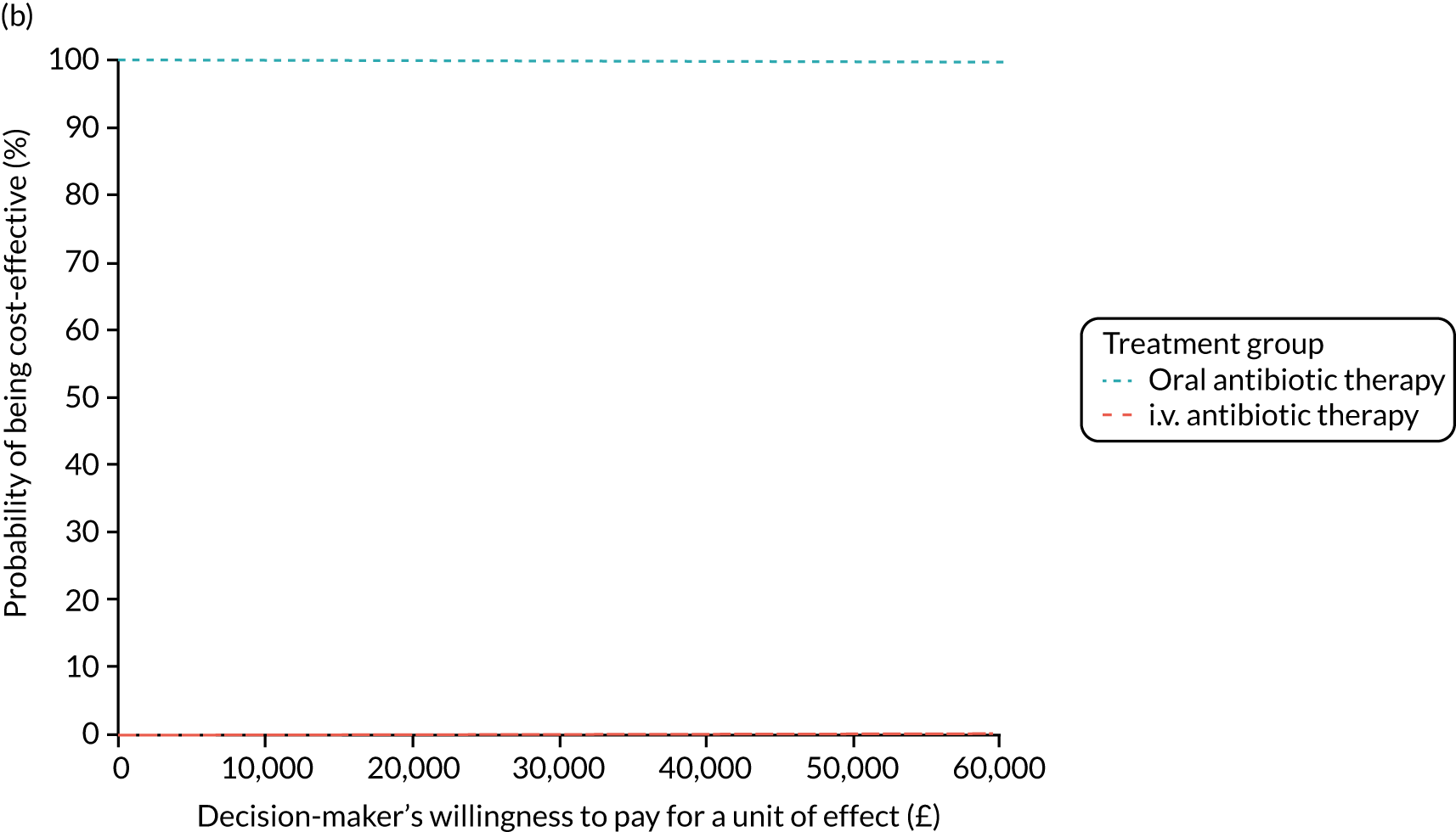

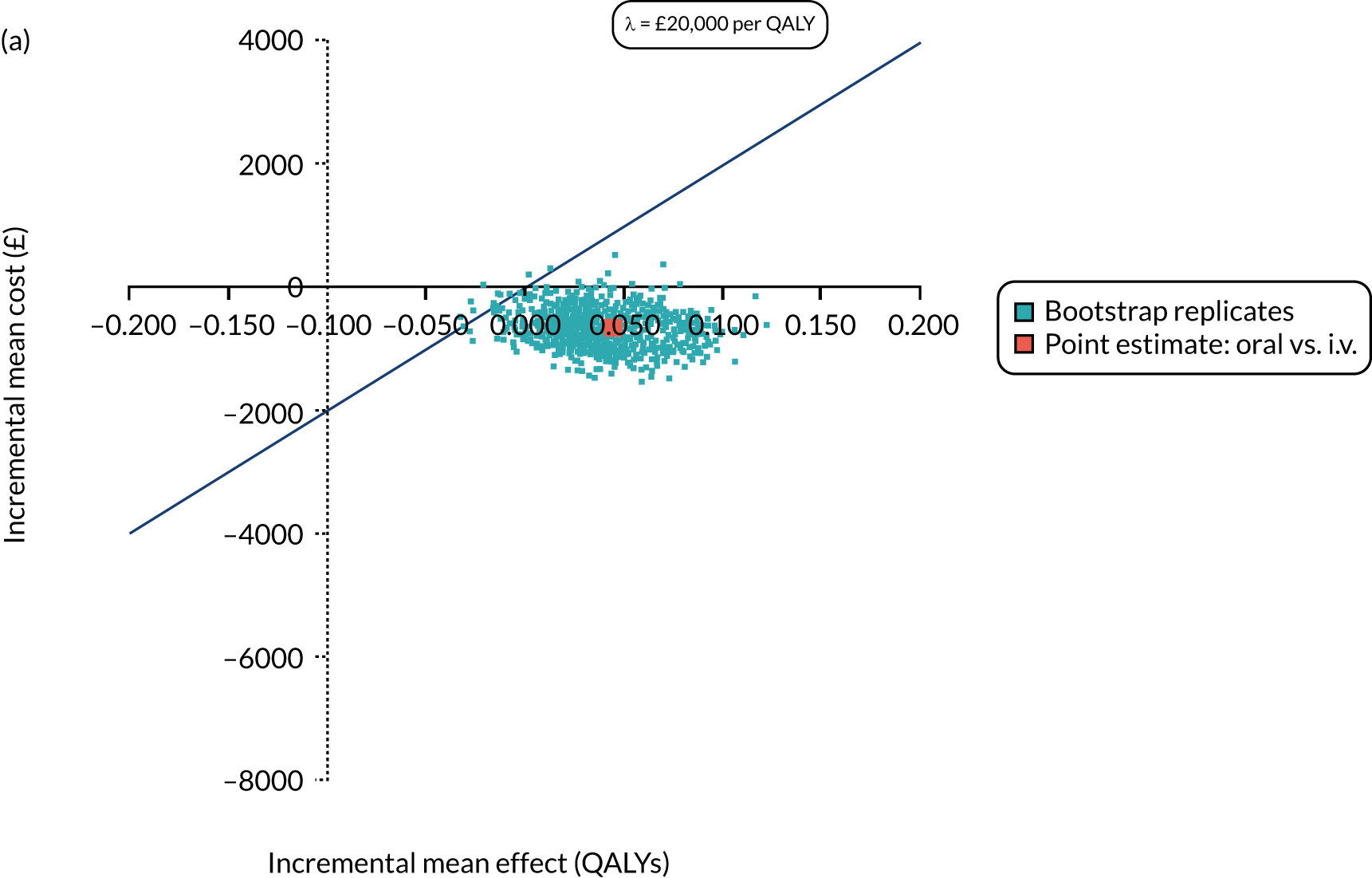

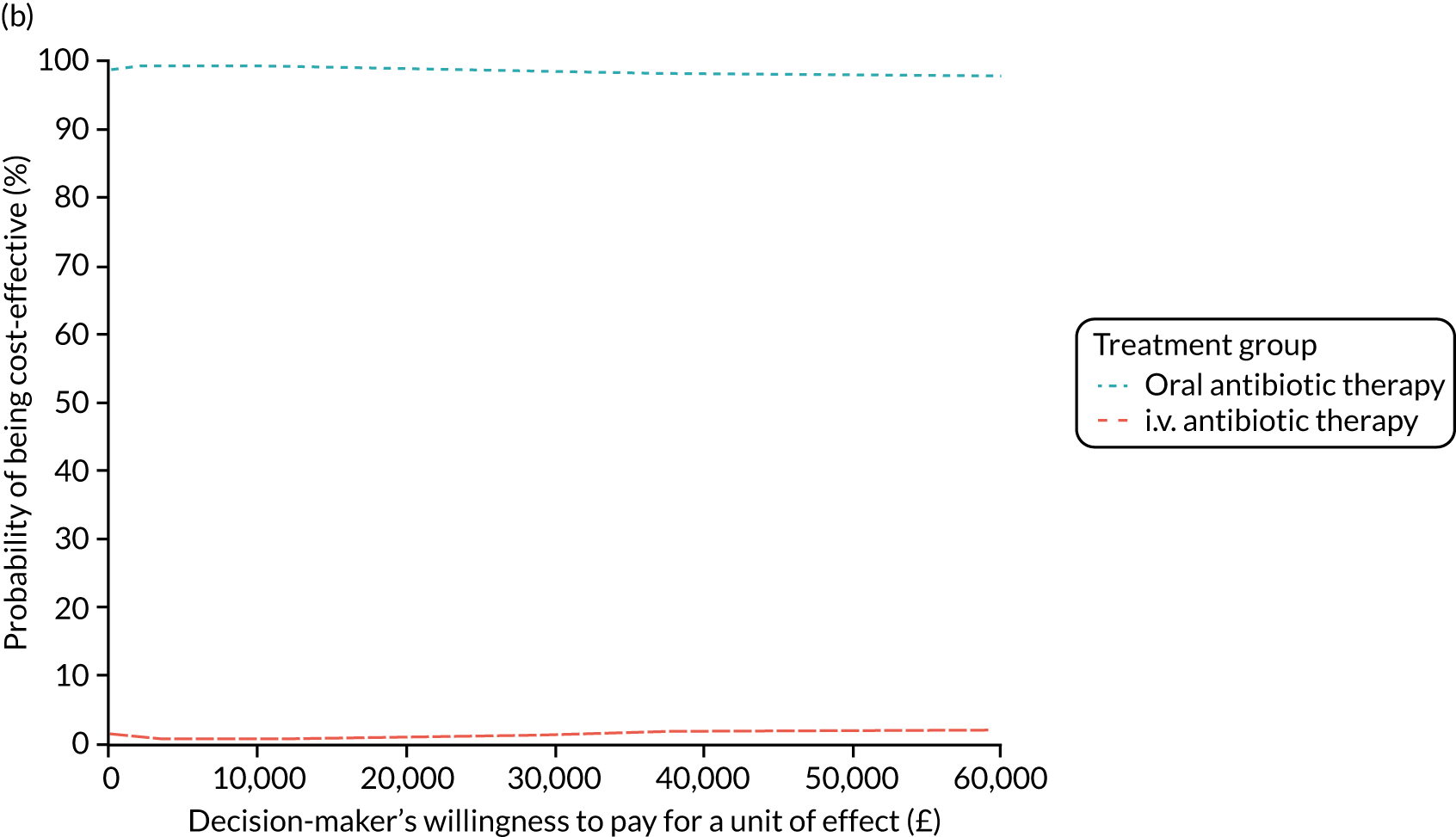

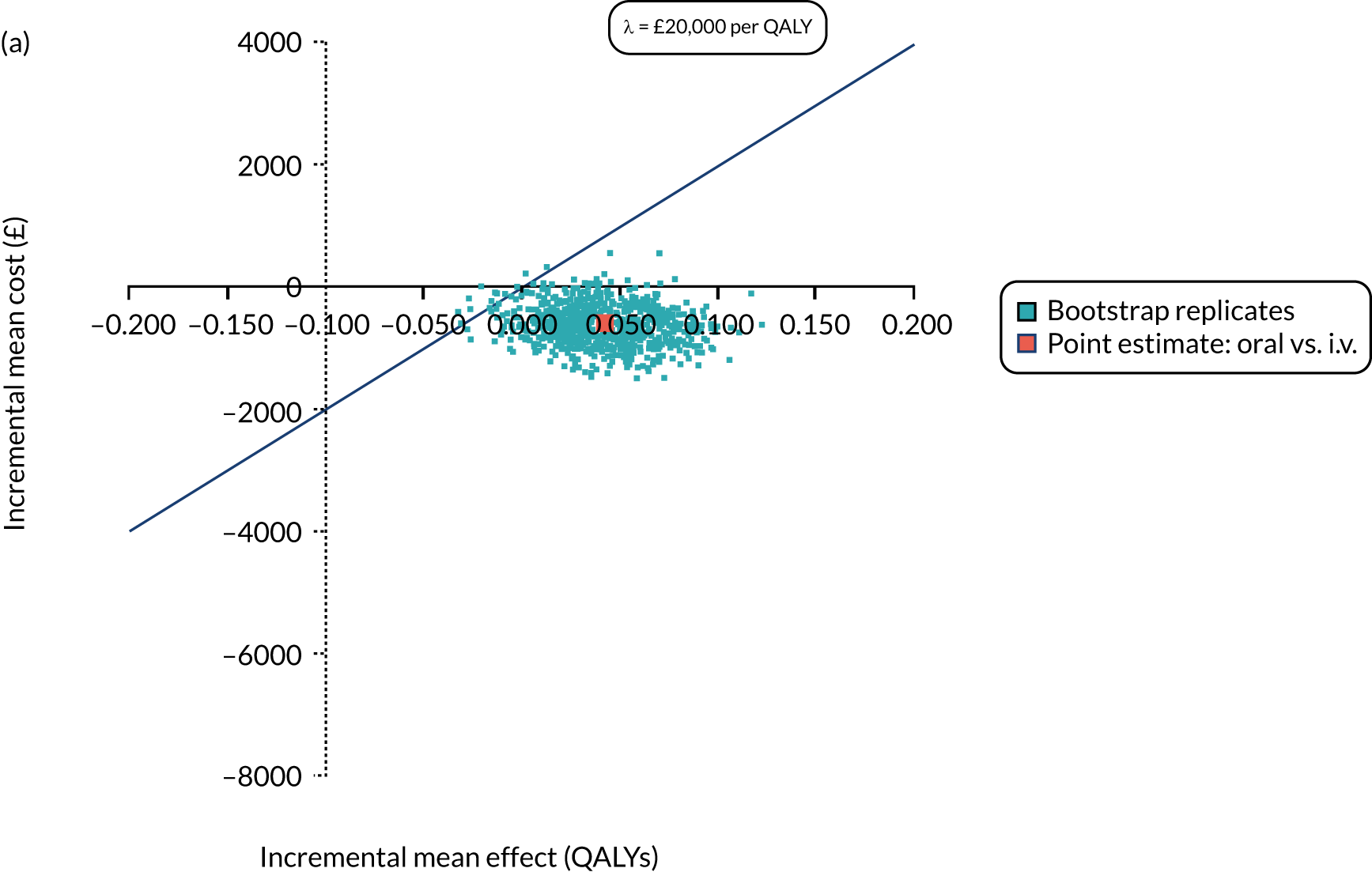

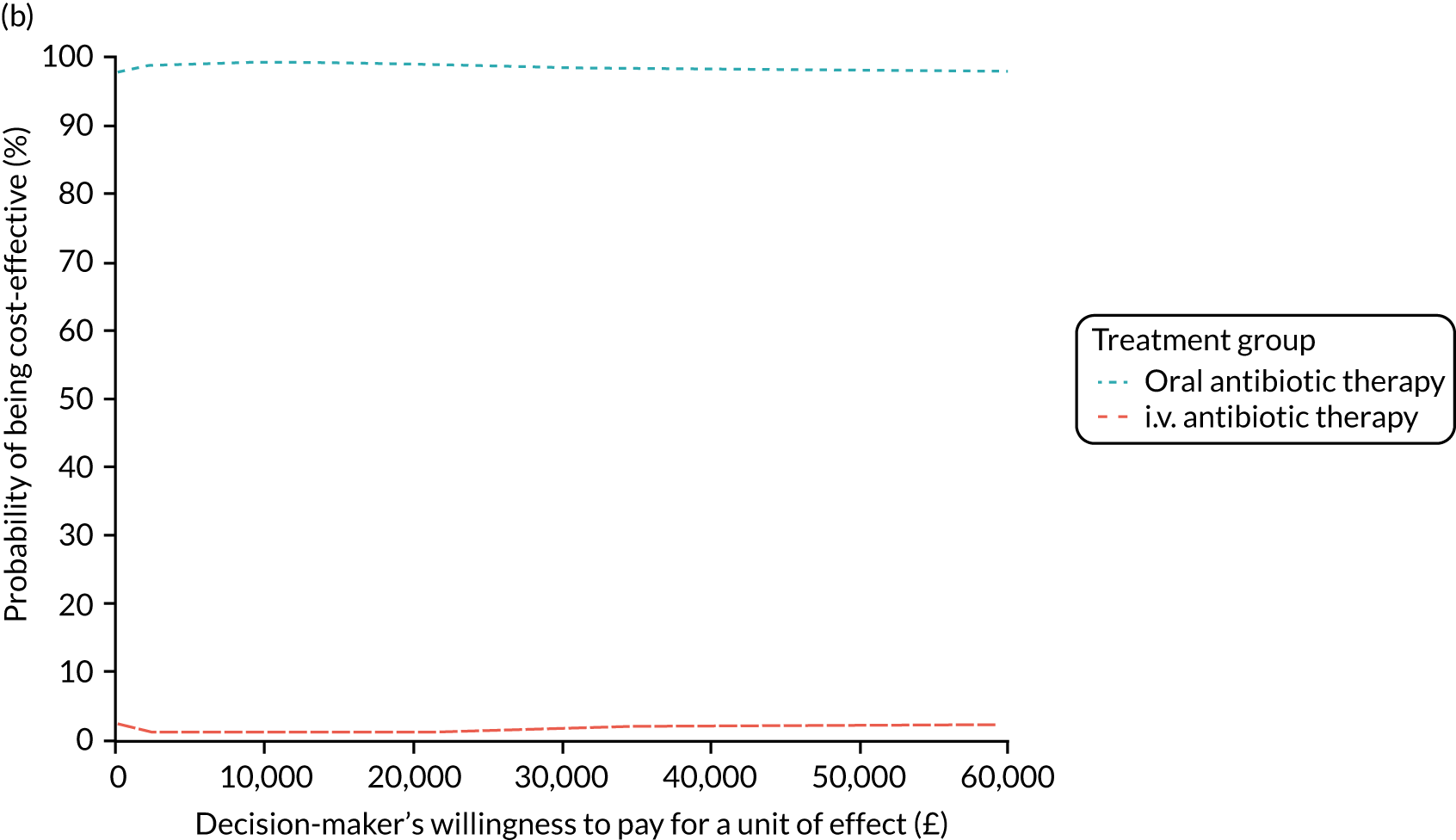

| Time from treatment commencement | 21 (15.3%) | 14 (9.5%) | 1.85 (0.94 to 3.64) | 0.074 |