Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/104/501. The contractual start date was in September 2015. The draft report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Fowler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from the published trial protocol. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background

It is now widely recognised that most socially disabling chronic and non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems begin in adolescence, with 75% of all severe and chronic mental illnesses emerging between the ages of 15 and 25 years. 2,3 A series of retrospective studies have consistently shown that severe mental illness is often preceded by social decline, that this often becomes stable, and that such premorbid social disability is predictive of the long-term course of the disorder. 4 Between 3% and 5% of adolescents present with non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems associated with social disability. 2 The young people at highest risk of long-term social disability present with emerging signs of social decline, in association with low-level psychotic symptoms and emotional and behavioural disorder often accompanied by substance misuse problems, and risk to self and others. 2,3

Despite poor outcomes and the cost of disorders leading to social decline, young people with complex needs frequently do not access treatment, and less than 25% of young people and their families who have such needs access to specialist mental health services. 5–8 More complex cases are found in areas of social disadvantage and among those who are not in employment or education. 1 The economic costs of not addressing this disability are very high. 9 Persistent mental health problems associated with social disability in young people do not resolve naturally and may persist across the life course, resulting in severe distress and social disability, and high costs to health and a range of social and other services. 2,3 Health economic modelling of lifelong costs in this area is emerging. A recent estimate suggests that mental health problems in childhood and adolescence can result in problems across marital satisfaction, self-esteem and quality of life, and can lead to a 28% reduction in economic activity at age 50 years or a £388,000 lifetime loss per person. 10 Young people who have a combination of severe and persistent mental health needs and who are socially disabled present with problems that have the highest lifelong burden.

Several recent reports have highlighted that there is a major gap in identifying and managing the mental health problems of young people with non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems, particularly those at risk of social disability. 5,7,8,11–13 New approaches to detection and intervention are required to meet the needs of these young people. 1 There is a gap in the evidence base for these young people. 1 Several National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines have highlighted this issue, including those for social anxiety,14 depression,15 and detection of people at risk of psychosis, and the research recommendation deriving from the NICE guideline on psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people. 13

Young people who have non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems and who are socially disabled are complex. Thus, they tend not to be suitable for or respond to short-term evidence-based therapies for more discrete mental health problems, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for anxiety, depression and conduct disorder, which are available via the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies initiative. Moreover, although this group show clear evidence of social disability, they do not meet the criteria for first-episode psychosis (FEP) and so they are not suitable for Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) services, for which there is now considerable evidence of benefits on social functioning. 4,16,17

Our aim in the present project is to identify and target the group of young people who are socially disabled and have non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems and are at risk of long-term severe mental illness to offer them a new psychological intervention specifically tailored to their needs.

The most systematic service provision is often outside mental health services in statutory and voluntary sector provision for young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET). In these services, the focus is primarily on obtaining employment and, thus, the mental health problems that present barriers to activity, work, education and training may not be recognised. 18 However, the degree to which NEET status is associated with mental health problems is increasingly recognised. 18–24 Detection of this population therefore must focus on the screening of the mental health problems of young people who have links with NEET services and who are under primary mental health care, alongside seeking referrals from those referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and adult services. This group may be detected in services for those in the at-risk mental states for psychosis (ARMS), where these services are present.

Current evidence for effective interventions to address social disability among young people in the early course of severe mental illness is very limited. 4 A series of studies have been undertaken that aimed to identify people at ultra-high risk (UHR) of poor long-term outcomes associated with severe mental illness, focusing predominantly on risk of psychosis. 25–28 The success of the UHR studies is that they have shown that it is possible to set up services to identify and treat cohorts of young people who can be identified as having ARMS using defined operational criteria and structured assessment tools. 29 Furthermore, these studies have consistently identified that those who are at the highest risk are young people who present with social decline as well as subthreshold psychotic symptoms. 30,31 However, the focus of these studies has been on prevention of episodes or symptoms of psychosis, not social disability. 1 Recent studies have shown that cohorts identified using these criteria may have more transient problems than previously thought and that only a subset go on to have long-term socially disabling mental health problems. 30,31 Several prominent UHR researchers are now highlighting an alternative strategy, which is to examine functional outcome in the UHR group. This study is consistent with this strategy.

Systematic reviews of CBT for psychosis, including NICE guidelines, have consistently shown a moderate effect size on improvements in social disability where this has been assessed as a secondary outcome. 32 This has been confirmed in the recent review of the NICE guidelines for schizophrenia. 33 However, these studies have predominantly been carried out among chronic participants, not young people. 1 The feasibility of using CBT with young people who are at UHR of long-term poor outcomes has been shown in the recently completed, multicentre Early Detection and Intervention Evaluation for people at high-risk of psychosis 2 (EDIE-2) trial,34 which has shown reductions in the severity of psychotic symptoms. However, the focus of the therapy in EDIE-234 was symptom reduction,28 and this approach neither targeted nor had a significant benefit on social disability. EDIE-234 clearly demonstrated the ability of collaborating sites to recruit young people at high risk and successfully retain them in research and therapy. However, as described above, the group recruited in EDIE-234 were heterogeneous in terms of social disability. The present trial builds on EDIE-234 by focusing on a group that has a more homogeneous set of social disability problems, defined by low-activity levels, and targeting this group with a multisystemic intervention that specifically aims to address social disability.

Better outcomes on social disability and hopelessness can be obtained from a more targeted intervention specifically focused on improving social disability among those who have low functioning. We have developed a multisystemic form of CBT that targets social disability. 35,36 A successful Medical Research Council trial37 was carried out with a group of young people who had established chronic and severe social disability problems up to 8 years after a first episode of psychosis. This trial demonstrated gains in structured activity and hope, as well as reductions in symptoms,37 with evident long-term maintenance of gains in structured activity. 38 Clear indications of health economic benefits were demonstrated. 39 However, the trial was small and there was a high level of uncertainty associated with these estimates. A further, larger National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded trial demonstrated gains in structured activity and reductions in symptoms for EIP service users who were experiencing their first episode of psychosis. 40

The intervention used in this study has been refined from experience in previous studies to apply to socially withdrawn young people with non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems. 35,36 The intervention is considered developmentally appropriate for young people owing to evident gains for young people accessing EIP services. 40 Moreover, social recovery therapy (SRT) is a collaborative approach, led by the young person’s personally valued and meaningful goals. 36 This individualised goal focus means that SRT is in keeping with the adolescent and emerging adulthood stages of development, in which young people are beginning to individuate and separate from the family unit and to explore and develop their sense of self-identity. 41,42 Furthermore, SRT is in keeping with the youth perspective on social recovery, in which biographical disruption from mental health problems gives way to new meanings, identities and social connections. 43 To our knowledge, this trial was the first to specifically address both social disability and mental health problems among a high-risk population of young people presenting with social disability and non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from the published trial protocol. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aims and objective

We aimed to undertake a definitive randomised trial to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SRT plus enhanced standard care (ESC) compared with ESC alone in young people who present with social withdrawal and non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems, and who are at risk of long-term social disability and mental illness.

The primary hypothesis was:

-

In young people who are socially disabled and have non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems, SRT plus ESC is superior to ESC alone in improving social recovery [as measured by hours in constructive economic activity assessed on the Time Use Survey (TUS)] over a 15-month follow-up period.

The secondary hypotheses were:

-

SRT plus ESC is superior to ESC alone in terms of cost-effectiveness.

-

SRT plus ESC is superior to ESC alone in terms of effects on mental health symptoms [attenuated psychotic symptoms (APS) and emotional disturbance].

Design

This was a pragmatic, multicentre, single-blind, superiority RCT with ascertainment of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SRT delivered over a 9-month period plus ESC compared with ESC alone in young people (aged 16–25 years) with non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems and showing early signs of persistent social disability. Primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated at 15 months post randomisation (i.e. 6 months after the end of intervention or control) and limited assessment of longer-term outcomes was evaluated at 24 months post randomisation.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the former East of England Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire National Research Ethics Service Committee for recruitment to an internal pilot (12/EE/0311) and the Preston Research Ethics Committee (REC) North West (15/NW/0590) for recruitment to the definitive trial. All participants provided written informed consent before undertaking any trial procedures.

Participants were recruited from child, adolescent and adult primary and secondary care mental health services (including youth mental health, early detection and early intervention services), and from youth, social, education and third-sector (i.e. voluntary, charitable and community) services. Potential participants were approached by their care provider and asked for agreement to be contacted by the study team. Participants were provided with verbal and written information about the study using the participant information sheet (PIS) (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Interested participants were invited to provide written consent using an informed consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Under supervision and review by the Trial Management Group, research assistants (RAs) administered eligibility screening assessments. Eligible participants completed the remaining baseline assessment measures, were randomised to the intervention or control arm of the trial, and were followed up over the following 24 months. All participants were offered a thorough assessment summary report for them and their usual care provider. For those participants randomly allocated to SRT in addition to ESC, a SRT therapist made contact within 1 week to inform participants of their allocation and to arrange the first therapy appointment. Participants’ care providers (and referrers, if different) were informed of the allocation outcome.

Interventions

Social recovery therapy

The intervention was SRT plus ESC delivered by trial therapists who were clinical psychologists or qualified CBT therapists trained in the intervention. SRT is as described in a therapy manual. 36 SRT was delivered individually in face-to-face sessions, with interim telephone, text and e-mail contact. Sessions were delivered over 9 months. Sessions took place in participants’ homes, NHS premises, community and public locations. All sessions, except where conducted in public locations, were audio-recorded with participant consent.

Social recovery therapy is based on a cognitive–behavioural model that suggests that social disability evolves as a result of lifestyle patterns of low activity, which are adopted as functional behavioural patterns of avoidance and are maintained by lack of hope, a reduced sense of agency and low motivation. 36 The intervention involves promoting a sense of hopefulness, self-agency and motivation, and encouraging activity, while managing any psychotic and non-psychotic symptoms and neurocognitive problems. The approach combines multisystemic working with the use of specific CBT techniques. Multisystemic working may involve working with participants’ relatives and friends, and employment or education providers. Trial therapists adopt assertive outreach youth work principles and draw on successful social and vocational interventions, such as supported education and employment interventions.

Social recovery therapy involves three stages, which are flexibly tailored to each participant’s goals and problems:

-

Stage 1 involves assessment and developing a formulation of the person’s difficulties and barriers to social recovery. This often involves validation of real barriers, threats and difficulties, while focusing on promoting hope for social recovery.

-

Stage 2 involves identifying and working towards medium- to long-term goals guided by a multisystemic formulation of barriers to recovery. Identifying specific pathways to meaningful new activities and values is a central component of stage 2. This can include referral to appropriate vocational agencies and/or direct liaison with employers or education providers. Additional specific techniques used in stage 2 include cognitive work focused on promoting a sense of agency, consolidating a positive identity, and addressing feelings of stigma and negative beliefs about self and others.

-

Stage 3 involves the active promotion of social, work, education and leisure activities linked to personally meaningful goals, while managing symptoms. This involves specific cognitive–behavioural techniques, including behavioural experiments.

Social recovery therapy adherence and competence

Therapist adherence and competence to the SRT intervention were recorded and reviewed. All SRT therapists completed the SRT adherence checklist44 as soon as possible after each intervention session. The checklist involves indicating which components of the intervention were present during the session and briefly describing the delivery of this component to facilitate independent review. This was in addition to all SRT therapists’ recording their session notes, which further detailed the content of all SRT sessions and included additional records regarding all participant contacts beyond the sessions (including e-mail, telephone and text message contacts).

Social recovery therapy adherence was defined as follows:44 (1) full dose equated to at least six sessions that included the presence of an assessment and a social recovery formulation, and that involved at least two pieces of behavioural work conducted in the community (i.e. not in the participant’s home or a clinic room) with the therapist; (2) partial dose equated to at least six sessions, the presence of an assessment and formulation, and some behavioural work that does not meet full-dose criteria (e.g. conducted only as homework or in the clinic room, or planned but not completed); and (3) no dose reflected by fewer than six sessions and/or insufficient components to achieve a rating of partial or full dose.

Therapy cases were rated with respect to adherence (full dose vs. partial dose vs. none) by three raters. Raters reviewed the adherence checklists completed by each therapist for each session with each participant. Raters also consulted the additional session notes made by each therapist, again for each session. Inter-rater reliability of the application of adherence criteria was very high, confirming that adherence ratings were very concordant across raters [Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.9, bootstrapped 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87 to 0.98].

The competence of the SRT therapists was recorded using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale Revised45 (CTS-R). Competence was rated through all SRT therapists submitting session audiotapes, which were rated by multiple raters using the CTS-R.

Enhanced standard care

The control comparator was ESC alone. The aim of ESC was to provide the optimal combinations of currently available evidence-based medical, psychological and psychosocial treatments to this group. There was no restriction on access to existing NHS standard treatment for young people with non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems and social disability. ESC aimed to include provision of short-term individual and family psychological therapies, medication management, and support and monitoring within primary or secondary mental health services. Participants also received a range of education, social, training, vocational and youth work interventions from a variety of statutory and non-statutory service providers, including social services, voluntary agencies, and employment and education providers. ESC also involved a best practice manual (see Report Supplementary Material 3) for standard treatment, provided by the trial team to the referrer and usual care provider/case manager at referral and again at the end of the participant’s involvement in the study. This manual summarised good practice, including referral to a range of both statutory and third-sector mental health services and medication management, where appropriate. The best practice manual was produced by monitoring and mapping service contacts received across a range of services in the population of interest.

Participants and referrers and/or the usual clinical team, with participant consent, received an assessment summary report from the trial team pertaining to clinical (symptom and neurocognitive) and social problems and circumstances. Assessments identified risks to self or others and these were communicated to the referrer and/or usual care team to facilitate appropriate management. The best practice manual and the approach of the trial team were supported by service user groups and steering groups overseeing youth mental health provision in each region, and delivery was well received by participating services, with referrers keen to involve participants in both treatment and control arms.

Randomisation

Following pretrial assessments, consenting participants were randomised to trial arms stratified by age (16–19, 20–25 years); site (Sussex, East Anglia, Manchester); severity of social disability (low functioning = 16–30 hours of structured activity per week, very low functioning = 0–15 hours of structured activity per week); and whether or not they met symptomatic criteria for ARMS. A remote randomisation service allocated groups and was co-ordinated by the Norwich Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). Allocation was by preset lists of permuted blocks with randomly distributed block sizes (agreed with the trial statistician). The lists were generated by the Data Management Team at the NCTU.

The allocation process was web based and managed as part of the trial data management system (TDMS). The allocation sequence was hidden from TDMS users. Once allocated, the details were e-mailed to nominated individuals at the trial site to enable the allocation of treatment to be implemented. The allocation was not revealed to any other users of the database or other individuals.

Blinding

Research assistants collecting baseline and follow-up data were blinded to group allocation. This was successfully maintained in the pilot using a range of procedures, which were subsequently used in the definitive trial. 1 Following allocation to the treatment or control arm, all participants in the study, as well as their care co-ordinator/referrer and clinical team (if applicable), were asked not to reveal to the research assistant (RA) the group to which the participants were randomised. Participants and family members were asked at the beginning of each assessment interview not to disclose the group to which the individual was allocated. Outside the assessments, RAs were shielded from discussion of participants in study forums where the possibility of determining the allocation group of the participants could occur. A system of web-based data entry ensured that RAs did not have access to information in the database that would reveal the allocation group. Data entered into the TDMS by trial therapists that might inadvertently lead to unblinding were hidden from non-trial therapist users.

Reported blind breaks were managed to maintain blind outcome assessments by reallocating ‘blind’ RAs to collect and score study data, and thus did not bias results. Thirty-one blind breaks occurred during the trial, but all were managed by reallocating the assessment to a blind member of trial staff. Of these blind breaks, 16 were due to the participant or a family member informing the RA of the allocation, 14 were due to referrers or other clinical staff informing the RA of allocation and one was due to a trial staff administrative error.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) activity was led by Dr Rory Byrne. Young people with lived experience of mental health problems and NHS service use were initially recruited from EIP services in Norfolk. These young people were asked to inform the development of the original trial protocol,1 including advising on the feasibility and acceptability of the SRT intervention and the planned study assessment process.

During the internal pilot, a specific patient group [the PRODIGY Advisory Team (PAT)] was established. The PAT was fully integrated into the development and delivery of the internal pilot. The PAT contributed to the development and revisions of the trial protocol and all participant documentation. 1 Members of the PAT piloted trial assessments using role-play to inform the process of assessment selection and delivery. The PAT also provided consultation promotional materials and trial team training. The PAT improved recruitment to the internal pilot through advising on methods of engaging young people in the trial and in the provision of participant newsletters to facilitate ongoing engagement with the trial. In May 2014, the PAT reviewed the delivery of the internal pilot and contributed to the development of the funding application for the extension phase, most notably in the creation of the lay summary.

The extension phase comprised continued delivery of the trial protocol,1 as in the internal pilot, with no changes. Therefore, in the extension phase, PPI activity consisted of review of the delivery of the trial protocol by Dr Rory Byrne and Ms Ruth Chandler, lead for PPI for the extension phase sponsor, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. Dr Rory Byrne reviewed participant documentation, such as dissemination newsletters. Dr Rory Byrne continues to consult on dissemination activities.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was time use (hours per week engaged in structured activity) measured at 15 months post randomisation. This assessment was derived from the Office for National Statistics TUS interview,46 adapted for use with a clinical population. 47 Time use is an important marker of participation in structured activities that are robustly associated with reduced mental health problems and better mental health and well-being;48,49 thus, time use is a useful measure of the behavioural aspects of social recovery. 47 The TUS is validated for use with young people with mental health problems, is sensitive to discriminating between clinical and non-clinical groups,47 and shows convergent validity with measures of quality of life and social functioning. 37 Moreover, the derived outcome score is in the easily interpretable metric of weekly hours. Number of hours per week engaged in structured activity includes time spent in both constructive economic activity (e.g. paid and voluntary work, education, child care, housework and chores) and in structured leisure and sports activities. This total was also calculated without child care hours, as child care (especially of a new-born child) considerably inflates time in structured activity, but is an outlying, semirandom event that is unrelated to trial arm and is imbalanced towards female participants. In all relevant outcome models, time use was tested using the total with and without child care hours included.

Secondary outcomes

Further time use outcomes

Emotional disturbance using self-report questionnaires

-

Social anxiety [Social Interaction Anxiety Scale50 (SIAS) total score].

-

Depression (Beck Depression Inventory-II51 total score).

-

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms52 (SANS).

-

Global Assessment of Functioning53 (GAF).

-

Global Assessment of Symptoms54 (GAS).

-

Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale55 (SOFAS).

Levels of attenuated psychotic symptoms and associated psychopathology using the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States for psychosis

-

Transition to psychosis since last assessment was recorded as a dichotomous variable (transition or no transition).

-

Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States for psychosis (CAARMS) symptom scores were derived following the procedure used in EDIE-2:34

-

A CAARMS symptom severity score (0–144) was derived using the summed product of global severity (0–6) and frequency scores (0–6) across the four positive symptom subscales (unusual thought content, non-bizarre ideas, perceptual abnormalities and disorganised speech). Higher scores reflect more severe symptoms.

-

A CAARMS distress score was created by taking a mean average of subjective distress (0–100) across the four positive symptom subscales.

-

Change in difficulties experienced by participants in the study using the structured clinical interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV

-

Meeting diagnostic criteria for any mood disorders rated since last assessment point.

-

Meeting current month diagnostic criteria for up to two anxiety, somatoform or eating disorders for which diagnostic criteria were met at baseline.

Putative mediators

Putative moderators

Other outcomes

Health economic outcomes

-

Health Service Resource Use Questionnaire. 66

-

EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)]. 67

All outcomes were assessed at baseline and again at 9, 15 and 24 months post randomisation. The neurocognitive assessments were assessed only at baseline and at 15 months post randomisation. Further information regarding the timing of the assessments is shown in Appendix 2.

Participants

Sample size

The target sample size was 270 participants, providing 135 participants in each trial arm. The primary outcome was hours per week in structured activity on the TUS46,47 at 15 months, which was considered unlikely to follow a normal distribution, but potentially to have a positive skew. It was expected, therefore, that analyses would probably use logarithmically transformed data. The sample size was based on an effect size of 0.4 standard deviations (SDs) being considered a minimum clinically significant benefit. A total of 270 participants would provide > 90% statistical power to detect a 0.4 SD effect size using a two-sided 5% significance level; a total of 200 participants (i.e. accounting for > 25% loss to follow-up) would provide 80% statistical power for the same effect size. A total of 100 participants were recruited in the internal pilot phase (January 2013–February 2014) and 170 further participants were recruited in the definitive extension phase (September 2015–May 2017). The pilot participants were recruited on time and to target. A recruitment extension of 6 months was required to achieve the target of 170 participants for the extension phase. This delayed the planned end date of recruitment from November 2016 to May 2017. Follow-up assessment for the pilot 100 participants began in September 2013 and finished in March 2016. Follow-up assessment for the extension 170 participants began in June 2016 and finished in June 2019.

Inclusion criteria

-

Young people aged 16–25 years with non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems and showing early signs of persistent social disability.

-

Presence of impairment in social and occupational function indicated by patterns of structured and constructive economic activity of < 30 hours per week and a history of social impairment problems lasting for > 6 months.

-

Presence of non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems defined operationally as either of the following:

-

having APS that meet the criteria for ARMS

-

having non-psychotic severe and complex mental health problems which score ≤ 50 on the GAF scale (which indicates the presence of severe symptoms of at least two out of depression, anxiety, substance misuse, behavioural or thinking problems or subthreshold psychosis to the degree that they impair function), with at least moderate symptoms persisting for > 6 months.

-

Exclusion criteria

-

Active positive psychotic symptoms or history of FEP.

-

Severe learning disability problems (mild to moderate learning difficulties were not an exclusion criterion).

-

Disease or physical problems likely to interfere with ability to take part in interventions and assessments.

-

Non-English speaking to the degree that the participant is unable to fully understand and answer assessment questions or give informed consent.

Analytic plan

The analytic plan was detailed in the Statistical Analysis Plan (version 0.2, 4 July 2018) and approved by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). The primary analysis compared SRT plus ESC with ESC alone on time use at 15 months post randomisation. The primary analysis was on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (i.e. all participants were followed up for data collection irrespective of adherence to treatment and were analysed according to group allocation rather than intervention received). We also completed a per-protocol (PP) analysis of primary and secondary outcomes.

All hypothesis testing was at the two-sided 5% statistical significance level. CIs for parameter estimates were at the corresponding 95% level. Analyses were conducted by the trial statistician blinded to group identity (i.e. ‘subgroup’ blind). 1 Assuming a normal distribution (potentially of transformed values) for time use, a general linear model was constructed. This model included all stratification variables [i.e. recruiting site (as a random factor), age (16–19 years, 20–25 years), severity of social disability (withdrawn or extremely withdrawn) and meeting symptomatic criteria for an ARMS or not]. Time use at baseline was also included as a covariate. Logical memory at baseline was also included as a prognostic variable for long-term social recovery along with verbal fluency (total score). Treatment arm was included as a fixed effect. Estimation of model parameters was on the basis of ‘type III’ (or ‘adjusted’) least squares. The residuals from this model were examined to assess the normal distribution and homoscedastic assumptions. Transformations of the outcome were considered in the case that this assumption did not appear appropriate.

Secondary analyses were conducted in an analogous fashion through a generalised linear model, with an appropriate link and error term depending on the nature of the outcome of interest (e.g. a logistic regression model for binary outcomes). Stratification variables were again included in the model and, where available, the outcome variable at baseline was also included. Treatment group was included as a fixed factor.

The analytic plan included a consideration of the moderation of treatment effect with respect to the following baseline characteristics:

-

ARMS29 status

-

low or very low functioning according to structured activity hours per week at baseline46,47 Logical Memory I (Logical Memory Scaled Total Score61)

-

COWAT62 total score.

This was to be achieved by using an interaction term (between the putative moderator and treatment arm) to formally assess differences in treatment effect. The sample size calculation did not include reference to hypothesis testing of interaction effects and this analysis was considered exploratory.

Missing data

For both the primary and secondary outcomes, the extent and patterns of missing data were checked and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods were used if the degree of missing data was < 50% of those randomised for any given analysis (i.e. when considering both missing outcome and prognostic variables in a model).

Multiple imputation (MI) methods were also used as another solution for missing data and for comparison with the FIML model. Factors to include in the imputation model were all those in the analytical model plus those considered likely to be related to the missing values. Any continuous variable exhibiting a strong asymmetric distribution was transformed to produce symmetry, following recommendations for MI. 68 The imputed analysis was based on 10 imputed data sets. Standard errors for parameter estimates were constructed using Rubin’s rules. The analysis using imputed data was a secondary sensitivity analysis with complete-case analysis being the primary analysis.

Full information maximum likelihood and MI methods are based on the assumption that data are missing at random. In the present study, there is clear evidence that there are consistently more missing data in the control arm than in the treatment arm. The level of missingness of data and the bias of missingness of data increases over time. This missingness of data is likely to be due to treatment, as therapy increases the engagement of those with more severe symptoms, who tend to drop out in the control group; therefore, this is likely missing not at random. The level of missingness of data and bias at 15 months was reviewed by the statistical team and, as the total level of missingness of data was < 20% and the bias was present but not extreme, it was agreed that the ITT analysis was the appropriate test of primary and secondary outcomes at that stage. At 24 months, the interpretation of results requires care. The bias assists a conservative assessment of the superiority of SRT and, indeed, may bias in favour of ESC. FIML and MI are reported as supportive analyses but, again, such missing data analyses cannot adjust for bias due to being missing not at random.

Additional analyses

The moderation of treatment effect on the primary outcome, time use at 15 months, was considered with respect to the following baseline characteristics:

-

Logical Memory I (Logical Memory Scaled Total Score61)

-

COWAT62 total score

-

at-risk mental state versus not-at-risk mental state from the CAARMS. 29

This was achieved by using an interaction term (between the putative moderator and treatment arm) to formally assess differences in treatment effect. The sample size calculation did not include reference to hypothesis testing of interaction effects and this analysis is considered exploratory.

Software

The analyses were carried out in SAS® software (version 9.4) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.

Chapter 3 Development and process evaluation

This report has been prepared using CHEERS (Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards) (see Report Supplementary Material 4) and CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) (see Report Supplementary Material 5) guidance. The completed checklists are provided as supplementary material.

Internal pilot statement

The internal pilot (NIHR reference 10/104/501) was funded in March 2012 and began recruitment in January 2013. The aims of the pilot were to (1) assess recruitment rate, quality of data collection and follow-up, (2) provide a final check on procedures in the protocol and (3) conduct a qualitative substudy to inform the objectives, using a qualitative, service user perspective. The following stop–go criteria were used to determine if it was appropriate for the pilot to be considered an internal pilot and progress to the definitive trial: (1) no necessity for substantive changes to the protocol, (2) recruitment of 80% of the planned total in the first 12 months, (3) retention of participants within the study with baseline and outcome assessments completed for > 80% of participants for the secondary and other outcomes and mediators, and for 90% of participants for the primary outcome, and (4) satisfactory delivery of competent and adherent therapy to > 80% of the treatment group.

The stop–go criteria were all satisfied. No changes to the trial protocol were necessary. The pilot recruitment was on time and to target. Primary and secondary outcome retention was excellent, achieving 92% at both 9- and 15-month assessment points. Primary and secondary outcome retention at the later-added 24-month assessment point necessitated a new consent procedure and a completion rate of 69% was achieved. Of those randomised to SRT (n = 47), 41 (87%) were deemed to have received competent and adherent therapy. The pilot DMEC and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) reviewed trial data in 2014 and supported confirmation of the pilot as an internal pilot. These two committees and the PPI representatives (the PAT) reached consensus that no changes to the trial protocol were required. The sponsor also performed a full Good Clinical Practice audit of the trial and concluded that no changes to trial procedures were needed. Additional funding was sought (NIHR reference 10/104/51) for the extension and was awarded in May 2015, with recruitment beginning in September 2015.

Process evaluation

The PRODIGY process evaluation was an evaluation of both the research and the intervention processes undertaken as three substudies, two involving patient participants and one involving SRT therapists, during the initial internal pilot phase. The patient process evaluation was conducted by a subresearch team led by a user researcher (RB) and an independent qualitative researcher (CN), neither of whom were involved in the development of SRT. Both parts of the patient process evaluation (i.e. research and intervention process substudies) were investigated using a qualitative methodology with qualitative interview data collection (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and thematic analytic methods. 69 These substudies were published as project outputs. 70,71 The final part of the process evaluation was conducted by a separate subresearch team during the non-pilot extension phase and focused exclusively on SRT therapist experiences of therapy delivery.

Research process evaluation

The research process evaluation was a qualitative exploratory substudy. All participants who had been randomised were invited to participate between April 2013 and mid-June 2013, resulting in a convenience sample of 13 participants. 71 An attempt was made to recruit substudy participants from both trial sites (East Anglia and Manchester) and both trial arms. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Interviews were conducted by a user researcher (RB) and a RA between 1 month and 3 months after study randomisation. The interview schedule was semistructured and designed to probe experiences relating to study participation. Data were analysed using an inductive thematic approach72,73 with a critical realist epistemic stance. 74 Themes are shown in Table 2.

| Substudy | Characteristic, n (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Sex | Allocation arm | Site | Social disability | At-risk mental states | |||||||

| 16–19 | 20–25 | Male | Female | SRT + ESC | ESC | Manchester | East Anglia | Very low | Low | At risk | Not at risk | |

| Research process: substudy 171 | 7 (54) | 6 (46) | 9 (69) | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | 7 (54) | 7 (54) | 6 (46) | 11 (85) | 2 (15) | 4 (31) | 9 (69) |

| Intervention process: substudy 270 | 11 (65) | 6 (35) | 8 (47) | 9 (53) | 8 (47) | 9 (53) | 8 (47) | 9 (53) | 11 (65) | 6 (35) | 6 (35) | 11 (65) |

| Study | Theme application | Themes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research process: substudy 171 | Across participants | Practicalities | Acceptance | Disclosure | Altruism | Engagement |

| Intervention process: substudy 270 | Across participants | ‘It’s just the speaking to someone’: the value of talking | ‘Just do it’: the importance of activity | Motivation to change | ||

| SRT + ESC | ‘She understood me on a personal level’: the therapeutic relationship | Flexibility | ‘It’s given me tools’: the CBT toolkit | No pain, no gain: SRT as difficult | ||

| ESC alone | Allocation ambivalence | No treatment, as usual | ‘I was the one who had to do everything to help overcome it’ | |||

The themes focused around key reflections on noteworthy aspects of participating in the PRODIGY trial. 71 First, ‘practicalities’ reflected the importance of RAs offering flexible research appointments. Flexibility on behalf of the researchers was seen as a manifestation of empathy and a person-centred approach. Second, ‘acceptance’ emphasised the position of openness from which participants approached their trial participation. Participants appeared to support the process of randomisation as a ‘fair’ way to allocate the intervention; they also appreciated the scientific importance of the ‘control’ group or comparator. The assessment process was described as acceptable even if questions were sensitive, again, within the context of a positive rapport with the RA. Third, ‘disclosure’ was positioned as a useful and therapeutic process within the context of assessment completion with the RA. The extent of their own disclosure, and the positive experience thereof, seemed to be a surprise for many participants. Fourth, ‘altruism’ appeared to be a key reason for participants wanting to be involved in the trial. This related to trial involvement in general and, more specifically, to participants being in support of the randomised controlled nature of the trial. A minority of participants appeared not to have a good understanding of randomisation. Finally, ‘engagement’ was a key theme that reflected the sense of being involved in the trial as a positive experience. Despite the main focus of the substudy being the research process, participants spoke of their thoughts and experiences in relation to the SRT intervention. Engagement in SRT was seen to be helpful; participants highlighted the benefits of understanding their experiences and how things could change for the better. Nevertheless, participants also described SRT as challenging.

Intervention process evaluation

The focus of the intervention process evaluation was on both arms of the trial (i.e. SRT plus ESC, and ESC alone). Participants were purposively sampled from those involved in the trial (pilot 100 participants only) aiming to balance across sex, study site (East Anglia and Manchester), allocation and baseline ARMS status. Attempts were also made to involve participants reflecting maximum variation in age and prior service use, and to include looked-after children. 70 Nineteen people participated, and their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Participants were interviewed by one of two researchers using a semistructured interview schedule. Questions focused on experience of psychological difficulties and previous service use, experience of trial participation and interventions received, and perceived outcomes and thoughts about future well-being. Data were analysed with an inductive thematic analysis approach69,72 taking a critical realist epistemic stance. Themes are shown in Table 2.

There were three themes common to the accounts of all participants. 70 First, “‘It’s just the speaking to someone’: the value of talking” reflected participants in both arms perceiving there to be a therapeutic value in talking to someone (RA or therapist) during their trial involvement. Many participants felt that they had avoided or not had the opportunity to do so before their trial involvement. Subthemes reflected that talking to someone helped in two main ways: ‘it’s not boiled up in me no more’ and ‘it helped me recognise the things that I wanted to change’. Second, “‘Just do it’: the importance of activity” reflected the sense of importance placed on meaningful activity by participants in both trial arms. For SRT plus ESC participants, doing these activities reflected an important part of the intervention. Yet for ESC-alone participants, increasing their occupational activity also seemed important, and several participants described making clear efforts to increase their activity levels. Finally, ‘motivation to change’ reflected a sense that determination to make positive changes in their lives was a key feature across the accounts of all participants.

There were four themes corresponding to participant experiences of the SRT intervention. 70 First, “‘She understood me on a personal level’: the therapeutic relationship” emphasised the centrality of the relationship with the SRT therapist to the participant’s experience of SRT. Participants emphasised the informal yet boundaried relationships developed with SRT therapists, which produced a sense of collaborative engagement. Second, the ‘flexibility’ theme reflected participant appreciation for the flexible way in which the intervention was delivered, for example with respect to timing and location. Third, in “‘It’s given me tools’: the CBT toolkit” participants spoke of how SRT equipped them with tools for managing their own distress and increasing their activity levels. Commonly described ‘tools’ included behavioural activation and behavioural experiments. Most participants felt that they could use the tools they had gained to their benefit beyond the intervention, although one participant felt that the intervention period was too short to allow them to use the same techniques independently. Finally, ‘No pain, no gain: SRT as difficult’ reflected that participants experienced the SRT intervention as challenging and even at times painful or overwhelming. Participants tended to emphasise that the ‘pain’ was worth it as they needed to push themselves to complete challenging exercises in order to improve their situations.

There were three themes corresponding to the experience of treatment as usual (i.e. ESC) only. 70 First, most participants expressed ‘allocation ambivalence’ and did not seem to hold negative views about having been randomised to ESC. Some expressed relief at not having to attend therapy, which they appeared to feel would have been anxiety-provoking. However, two participants did express negative views. Second, the theme ‘No treatment, as usual’ spoke to the experience of young people in the ESC-alone arm of the trial as reflecting an absence of care and support provision. Only two participants reported having received specialist mental health care since their involvement in the trial. Some participants did report support from their general practitioner (GP), although they were not particularly satisfied with the nature of this support. Finally, ‘I was the one who had to do everything to help overcome it’ reflected ESC-alone participants’ sense that they had to manage their mental health independently, in the context of not being offered SRT and the perceived lack of treatment offered by standard mental health services. Some participants did emphasise that there had been considerable improvement in their mental health despite feeling unsupported by any services, conveying a sense of pride and achievement in improving without this additional support.

Therapist experience process evaluation

The focus of the therapist experience process evaluation was to explore therapist experiences of delivering SRT, with a particular focus on therapist hopefulness in the face of engaging with patients with complex presentations. All SRT therapists involved in therapy delivery in the extension phase of the trial, including two therapists who had also been involved in therapy delivery in the internal pilot, were invited to participate. Information about participation was shared verbally and using a PIS (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Ten SRT therapists participated in a semistructured individual interview following the provision of consent using an informed consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The interview guide focused on asking therapists to reflect on their experiences of delivering SRT, including experiences where therapy had gone ‘well’ and experiences where it had not gone ‘well’. Therapists were also asked about their experiences of informal and formal support and supervision. Data were analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis. 75 Coding and analysis were performed by a SRT therapist experienced in SRT delivery but not involved in the inception or design of SRT and by a non-therapist researcher.

The finding of the therapy process evaluation was that SRT therapists emphasised the importance of working with this complex client group. In standard services, therapists reported that these young people would typically not be seen, because the typically protracted period needed to engage these young people is usually not possible within the services’ policies and practices. SRT therapists reported that, with this complex group, understanding and formulating treatment ambivalence and disengagement was essential, as was the pursuit of meaningful connection with these young people. SRT therapists also spoke of the difficulty of finding and sustaining their own hopefulness in the face of participants’ sense of ambivalence, hopelessness and ‘stuckness’. Sources of hope and scaffolds for its maintenance included access to expert and hopeful supervision, and opportunities to engage in peer supervision with other SRT therapists.

Process evaluation limitations and conclusions

The key limitations of the process evaluation substudies are that, because of the nature of the convenience sampling methods, the conclusions cannot be said to be generalisable to the whole trial sample or population beyond the trial. Nevertheless, the epistemic stance and qualitative methodologies taken were such that we sought not generalisability, but rather the unique experiences of individual participants of interest. Despite this the findings do show consistency with the wider literature, for example a previous study involving young people with ARMS. 76 Further limitations of the process evaluation substudies include the apparent weighting of the intervention arm participants towards those who had engaged with the therapy. Only one participant was included who had not received a ‘dose’ of the intervention. Although the majority of participants in the trial did receive a dose, those who did not are an under-represented group and their experiences are particularly important in understanding both research and therapy processes.

Key conclusions of the process evaluation centred around the apparent value of having someone with whom to talk and reflect on mental health and well-being. This value was identified for both the research assessments and SRT. With respect to contact with RAs, the perceived value of the research assessment process seems to reflect the notion of therapeutic assessment77 (i.e. that assessment alone can have a therapeutic effect on patients). In the first substudy, all but two participants indicated at least some degree of past mental health service involvement, ranging from CAMHS or youth mental health services to school, university, private or third-sector counselling. Nevertheless, these participants still appeared to experience their trial involvement as reflecting a novel sense of ‘opening up’. This appears to reflect the particularly in-depth nature of the research assessments and also the flexible, engaging and skilled nature of RAs’ interactions with trial participants. It is also notable that in both substudies70,71 SRT participants emphasised the difficult and challenging nature of the intervention.

Chapter 4 Results

Participant flow

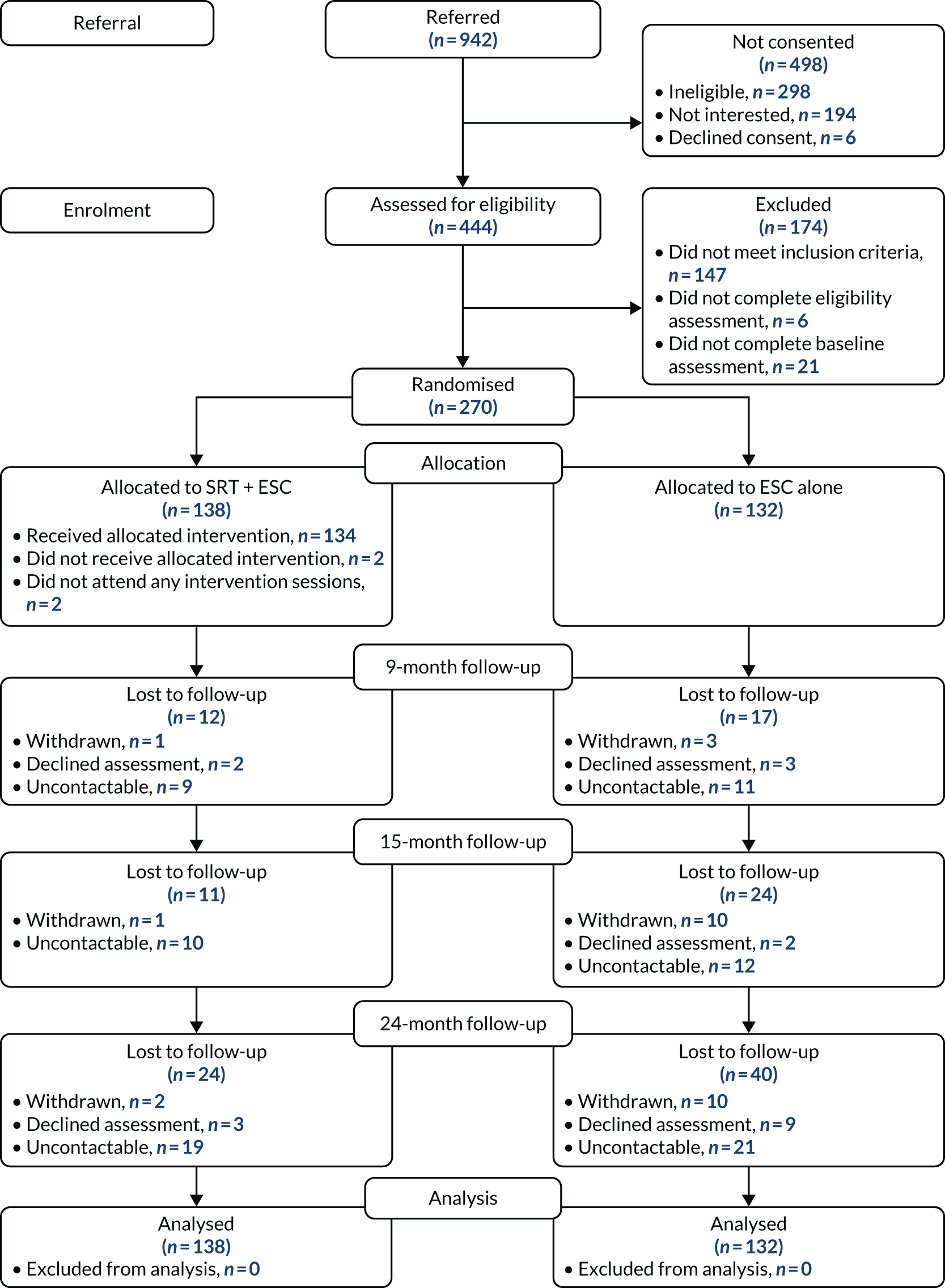

Participant flow through the trial is depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

Participant non-entry

As shown in Table 3, the majority of participants who were ineligible (1) did not meet entry criteria regarding no history of or current active psychosis evidenced by symptoms and/or prescription of threshold dosage of antipsychotic medication, (2) had insufficient social impairment and/or (3) were not eligible for unknown reasons. The third group included early referrals from clinicians of potential participants who did not reach formal eligibility assessment. As shown in Table 4, the majority of participants who declined to participate for lack of interest did not give further reasons for their decision or were categorised as not interested because they and/or their referrers were not contactable (disengaged).

| Reasona | Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Age < 16 years or > 25 years | 6 |

| + Severe learning difficulties | 1 |

| Historical or active psychotic symptoms or first episode (or taking antipsychotics at above therapeutic dose) | 63 |

| + Social impairment insufficientb | 6 |

| Severe learning difficulties | 3 |

| Disease or physical problems likely to interfere with ability to take part | 4 |

| Non-English speaking | 0 |

| Social impairment insufficientb | 76 |

| Mental health problems insufficient | 32 |

| + Social impairment insufficientb | 1 |

| Out of area | 11 |

| Risk/safety concerns | 9 |

| Re-referral of young person who had already participated | 3 |

| Reason for unsuitability unknown | 91 |

| Reasona | Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Not interested (detail unknown) | 91 |

| Not help-seeking | 19 |

| Not interested in research participation | 10 |

| + Not interested in SRT | 9 |

| + Project too much commitment | 3 |

| + Not interested in SRT, not help-seeking | 3 |

| Not interested in SRT | 2 |

| Project too much commitment | 8 |

| Unable/unwilling to engage due to mental health problem(s) | 7 |

| Young person disengaged from referrer | 54 |

| Young person disengaged from the PRODIGY trial | 64 |

| Referrer disengaged from the PRODIGY trial | 70 |

| Recruitment ended | 4 |

Characteristics of randomised participants

Table 5 provides baseline demographic characteristics of the sample by trial arm conditions and as per the ITT and PP analyses. The aim was to recruit a sample of withdrawn young people with low activity and comorbid complex severe mental illness. There was little difference between the two groups, with both groups showing a majority of participants aged 16–19 years, with a mean age around aged 20 years, of white ethnicity, who were single, unemployed, heterosexual and living in rented accommodation. The ESC sample is evenly balanced between sexes, although there was a predominance of male participants in the SRT group.

| Characteristic | Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ITT | PP | ||

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | SRT + ESC (N = 91) | |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |||

| 16–19 | 79 (57) | 75 (57) | 51 (56) |

| 20–25 | 59 (43) | 57 (43) | 40 (44) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 20.1 (2.5) | 20.0 (2.7) | 20.1 (2.4) |

| Missing, n | 6 | 5 | 2 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 54 (39) | 66 (50) | 34 (37) |

| Male | 84 (61) | 66 (50) | 57 (63) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 127 (92) | 114 (86) | 83 (91) |

| Non-white | 11 (8.0) | 18 (14) | 8 (8.8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Partner | 18 (13) | 17 (13) | 9 (9.9) |

| Separated | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (2.2) |

| Single | 118 (86) | 115 (87) | 80 (88) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Paid work | 5 (3.6) | 6 (4.6) | 3 (3.3) |

| Voluntary work | 3 (2.2) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (3.3) |

| Student | 34 (25) | 31 (24) | 22 (24) |

| Unemployed | 95 (69) | 91 (69) | 62 (69) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sexual orientation, n (%) | |||

| Heterosexual | 98 (74) | 107 (82) | 64 (74) |

| Homosexual | 6 (4.5) | 6 (4.6) | 3 (3.5) |

| Bisexual | 16 (12.1) | 13 (9.9) | 9 (10.5) |

| Unsure | 6 (4.5) | 1 (0.8) | 5 (5.8) |

| Other | 6 (4.5) | 4 (3.1) | 5 (5.8) |

| Missing, n | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Accommodation, n (%) | |||

| Accommodation with support | 8 (5.9) | 4 (3.0) | 4 (4.5) |

| Homeless/temporary accommodation | 5 (3.7) | 7 (5.3) | 2 (2.2) |

| Mobile accommodation | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Owner occupied | 48 (36) | 41 (31) | 32 (36) |

| Rented (local authority/housing association) | 45 (33) | 55 (42) | 27 (30) |

| Rented (private) | 29 (22) | 24 (18) | 24 (27) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Social functioning, n (%) | |||

| Low functioning | 40 (29.0) | 40 (30) | 21 (23) |

| Very low functioning | 98 (71) | 92 (70) | 70 (77) |

| Mental state, n (%) | |||

| At risk | 69 (50) | 64 (49) | 49 (54) |

| Not at risk | 69 (50) | 68 (52) | 42 (46) |

Of note is the severity of social disability, and psychopathology anxiety and depression present in the sample at baseline. Around half of the participants (n = 133) met the criteria for ARMS. One hundred and fourteen (86%) of the 133 participants with ARMS were categorised as experiencing APS, 11 (8.3%) were categorised as experiencing APS and vulnerability, four (3.0%) were categorised as experiencing vulnerability, three (2.3%) were categorised as experiencing APS and brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms and one (0.8%) was categorised as experiencing brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms. Around two-thirds of the sample entered the trial with very low functioning according to stratification. The mean structured activity level was around 11 hours, which, when compared with > 64 hours in an age-matched non-clinical sample, suggested extreme withdrawal. 47 Levels of social disability were in the severe range and > 95% of participants were unemployed. Functional status according to GAF and SOFAS similarly suggested severe functional disability. 53,55 Levels of global symptoms, depression, social anxiety and hopelessness were in the severe range,50,51,54,78 with comorbidity in the majority of cases. Alcohol and drug disorders, aggression and suicidality were also severe and prevalent. 29,63,64

Baseline scores for the outcome measures were fairly similar across both groups (see Table 6). The intervention group reported slightly greater social anxiety (SIAS) and slightly lower functioning (SOFAS) at baseline. The average scores for the CAARMS interview variables at baseline were fairly similar between the control and the intervention groups. The symptom severity and average distress scores were very similar; however, the intervention group showed a slightly lower aggression severity score and a slightly higher suicidality severity score. These results are tabulated in Table 7. The diagnostic characteristics of both groups (Tables 8 and 9) were similar at baseline, although ESC-alone participants appeared to be slightly more likely to have current panic disorder or panic with agoraphobia, and slightly less likely to report a current major depressive episode. Scores on ‘other’ outcomes at baseline were similar across groups, although the ESC-alone arm scored slightly lower for hopelessness (Table 10).

| Outcome | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ITT, mean (SD) | PP, mean (SD) | ||

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | SRT + ESC (N = 91) | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| Structured activity (hours per week) | 11.3 (8.0) | 11.3 (8.6) | 9.8 (7.4) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Structured activity (minus child care) (hours per week) | 11.0 (7.8) | 11.2 (8.6) | 9.7 (7.3) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary time use outcome | |||

| Constructive economic activity (hours per week) | 8.6 (7.1) | 8.1 (7.0) | 7.3 (6.4) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary emotional disturbance outcomes | |||

| SIAS | 52.1 (14.1) | 48.1 (16.1) | 53.9 (12.6) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| BDI-II | 30.4 (12.8) | 30.3 (12.4) | 30.3 (11.8) |

| Missing, n | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| GAF | 37.9 (5.6) | 38.2 (5.5) | 37.8 (4.6) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GAS | 43.1 (7.3) | 43.2 (7.5) | 43.5 (7.0) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SOFAS | 41.6 (7.6) | 43.3 (7.0) | 40.5 (6.8) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Outcome | Allocation arm | |

|---|---|---|

| SRT + ESC, mean (SD) (N = 138) | ESC alone, mean (SD) (N = 132) | |

| CAARMS symptom severity score | 26.2 (16.5) | 26.1 (15.9) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 2 |

| CAARMS average distress score | 52.5 (27.0) | 52.1 (23.1) |

| Missing, n | 6 | 6 |

| CAARMS aggression severity score | 6.3 (5.4) | 7.7 (6.0) |

| Missing, n | 5 | 1 |

| CAARMS suicidality severity score | 6.7 (6.5) | 5.9 (6.4) |

| Missing, n | 7 | 1 |

| Outcome | Allocation arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | |

| Current major depressive episode | 72 (52.2) | 65 (49.2) |

| Past major depressive episode | 33 (23.9) | 41 (31.1) |

| Current mania | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| Past mania | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.8) |

| Current hypomania | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) |

| Past hypomania | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Dysthymia | 16 (11.6) | 15 (11.4) |

| Bipolar at risk | 25 (18.1) | 14 (10.6) |

| Bipolar I | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.8) |

| Bipolar II | 4 (2.9) | 1 (0.8) |

| Major depressive disorder | 95 (68.8) | 93 (70.5) |

| Outcome | Allocation arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | |

| Panic disordera | 6 (4.4) | 6 (4.6) |

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia | 18 (13) | 25 (19) |

| Agoraphobia without panic | 21 (15) | 31 (24) |

| Social phobia | 62 (45) | 54 (41) |

| Specific phobia | 10 (7.3) | 4 (3.0) |

| OCD | 12 (8.7) | 11 (8.3) |

| PTSD | 14 (10) | 16 (12) |

| GAD | 36 (26) | 44 (33) |

| Hypochondriasis | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.3) |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | 14 (10) | 10 (7.6) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| Bulimia nervosa | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Binge-eating disorder | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Anxiety disorder NOS | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.3) |

| Outcome | Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ITT, mean (SD) | PP, mean (SD) | ||

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | SRT + ESC (N = 91) | |

| BHS | 13.4 (5.8) | 12.7 (5.2) | 13.7 (5.6) |

| Missing, n | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| AUDIT | 5.0 (6.3) | 5.2 (6.3) | 4.3 (5.6) |

| Missing, n | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| DUDIT | 3.6 (7.2) | 3.9 (7.8) | 3.2 (7.1) |

| Missing, n | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Rates of retention

Table 11 depicts the proportion of participants assessed at follow-up in each of the three trial sites. Proportions of follow-up are broadly similar. The higher rate of 24-month follow-up in the Sussex site reflects the fact that this site participated in the extension phase only and, thus, all participants consented to this follow-up at the outset.

| Time point | Site | Proportion of participants assessed at follow-up, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | Uncontactable | Declined | Withdrawn | ||

| 9 | Sussex | 53 (93) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) |

| East Anglia | 102 (94) | 5 (4.6) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Manchester | 86 (83) | 13 (13) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Total | 241 (89) | 20 (7.4) | 5 (1.9) | 4 (1.5) | |

| 15 | Sussex | 50 (88) | 4 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.3) |

| East Anglia | 98 (90) | 4 (3.7) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (5.5) | |

| Manchester | 87 (84) | 14 (14) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Total | 235 (87) | 22 (8.1) | 2 (0.7) | 11 (4.1) | |

| 24 | Sussex | 49 (86) | 4 (7.0) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.3) |

| East Anglia | 84 (77) | 11 (10) | 8 (7.3) | 6 (5.5) | |

| Manchester | 73 (70) | 25 (24) | 3 (2.9) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Total | 206 (76) | 40 (15) | 12 (4.4) | 12 (4.4) | |

Intervention results

Description of enhanced standard care

Data regarding participant health and support service use were collected at each assessment point. The reporting period at baseline covered the 6 months prior to the assessment date. At each follow-up assessment, the reporting period covered the time since the previous assessment point.

Mental health service use was recorded as the number of contacts (Table 12). Overall, high incidence of mental health service use is noted and, in most cases, incidence is highest in the ESC-alone arm. Of particular note is the especially large number of individuals in the ESC-alone arm who received psychological therapies between baseline and the 9-month assessment point: 44% of participants received, on average, almost nine therapy sessions. Furthermore, the majority of participants in both arms reported 6–8 sessions of psychological therapy in the 9-month period leading up to trial entry (see Table 12). The majority of participants in both arms reported GP contacts at baseline and throughout the trial, and the majority of participants in both arms were taking antidepressant medication (see Table 12). A sizeable minority of participants also had case management, psychiatrist input and additional medication; case management was higher for SRT plus ESC participants across the trial, and psychiatrist input and additional medication were more frequent for ESC-alone participants.

| Resource | Time point, n (%)/mean (SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | 15 months | 24 months | |||||

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | SRT + ESC (N = 124/138) | ESC alone (N = 108/132) | SRT + ESC (N = 124/138) | ESC alone (N = 100/132) | SRT + ESC (N = 107/138) | ESC alone (N = 83/132) | |

| GP | ||||||||

| Presence | 94 (68%) | 105 (80%) | 92 (74%) | 69 (64%) | 87 (70%) | 68 (68%) | 79 (74%) | 55 (66%) |

| Contacts | 5.4 (7.7) | 4.1 (3.5) | 4.9 (5.8) | 5.3 (4.4) | 3.0 (3.5) | 4.2 (3.7) | 4.6 (7.1) | 5.3 (6.1) |

| Psychiatrist | ||||||||

| Presence | 27 (20%) | 37 (28%) | 22 (18%) | 23 (21%) | 13 (10%) | 18 (18%) | 16 (15%) | 14 (17%) |

| Contacts | 2.9 (3.6) | 2.85 (3.0) | 2.0 (1.5) | 2.6 (2.2) | 3.2 (3.2) | 1.4 (0.51) | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.6 (2.9) |

| Psychological therapiesa | ||||||||

| Presence | 71 (51%) | 73 (55%) | 33 (27%) | 47 (44%) | 26 (21%) | 25 (25%) | 30 (28%) | 26 (31%) |

| Contacts | 8.0 (9.1) | 6.3 (5.6) | 11.8 (19.8) | 8.9 (6.3) | 6.9 (10.1) | 6.8 (11.4) | 10.3 (11.9) | 8.8 (10.9) |

| Case managementb | ||||||||

| Presence | 54 (39%) | 75 (57%) | 58 (47%) | 41 (38%) | 45 (36%) | 39 (39%) | 33 (31%) | 31 (37%) |

| Contacts | 10.3 (14.4) | 9.7 (17.5) | 11.5 (13.7) | 11.3 (13.9) | 9.02 (11.3) | 10.8 (11.4) | 10.6 (12.1) | 10.0 (13.7) |

| Medication | ||||||||

| Antidepressant | 78 (57%) | 78 (59%) | 71 (57%) | 59 (55%) | 61 (49%) | 49 (49%) | 60 (56%) | 41 (49%) |

| Antipsychotic | 16 (12%) | 5 (3.8%) | 14 (11%) | 3 (2.8%) | 13 (10%) | 4 (4.00%) | 12 (11%) | 2 (2.4%) |

| Other | 24 (17%) | 35 (27%) | 18 (15%) | 18 (17%) | 20 (16%) | 22 (22%) | 26 (24%) | 17 (20%) |

| Additional anxiolytic | 12 (8.7%) | 19 (14%) | 10 (8.06%) | 15 (14%) | 11 (8.9%) | 12 (12%) | 16 (15%) | 10 (12%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 7 (5.07%) | 7 (5.3%) | 7 (5.7%) | 4 (3.7%) | 7 (5.7%) | 4 (4.00%) | 4 (3.7%) | 2 (2.4%) |

| Mood stabilisers | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.3%) | 1 (0.81%) | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (0.81%) | 3 (3.00%) | 1 (0.93%) | 2 (2.4%) |

| Stimulantsc | 5 (3.6%) | 11 (8.3%) | 5 (4.03%) | 5 (4.6%) | 4 (3.2%) | 5 (5.00%) | 5 (4.7%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Psychiatric admissionsd | ||||||||

| Number of people | 11 (7.9%) | 4 (3.03%) | 5 (4.03%) | 1 (0.93%) | 6 (4.8%) | 2 (2.00%) | 7 (6.5%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Number of visits | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.8 (1.8) | 4.00 (–) | 1.3 (0.82) | 3.00 (2.8) | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.00 (0.00) |

| Total days | 11.6 (26.1) | 1.7 (1.2) | 5.00 (4.3) | 6.00 (0.00) | 23.2 (39.4) | 6.00 (4.2) | 10.4 (14.7) | 1.00 (0.00) |

| Accident and emergency contacts (non-admission) | ||||||||

| Number of people | 21 (15%) | 14 (11%) | 15 (12%) | 18 (17%) | 14 (11%) | 18 (18%) | 16 (15%) | 13 (16%) |

It is also noteworthy that a higher proportion of participants in the SRT plus ESC arm (12%) than in the ESC-alone arm (4%) were taking antipsychotic medication at trial entry (see Table 12). The slightly higher rate in the SRT plus ESC arm was notable across the follow-up points. In addition, the rate of psychiatric admission (8% vs. 3%) and length of stay (11.6 vs. 1.7 days) were slightly higher in the SRT plus ESC arm than in the ESC-alone arm at baseline, and this pattern continued across follow-ups. A higher rate of accident and emergency visits was reported in the SRT plus ESC arm than in the ESC-alone arm at baseline (15% vs. 11%); however, this pattern reversed across the follow-up periods (see Table 12).

With respect to ‘packages’ of care (Table 13), participants allocated to SRT plus ESC (38% at 9 months and 54% at 15 months) were more likely than those assigned to ESC alone (30% at 9 months and 42% at 15 months) to have no NHS mental health service provision. Where provision did occur, the ‘packages’ of care appeared similar across both trial arms during the trial [other than the ESC-alone arm being more likely than the SRT plus ESC arm to have therapy during the 9-month intervention window only (21% vs. 9%)].

| Care ‘package’ | Time point, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | 15 months | 24 months | |||||

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | SRT + ESC (N = 124/138) | ESC alone (N = 108/132) | SRT + ESC (N = 124/138) | ESC alone (N = 100/132) | SRT + ESC (N = 107/138) | ESC alone (N = 83/132) | |

| No NHS mental health provision | 18 (13) | 23 (17) | 47 (38) | 32 (30) | 66 (54) | 42 (42) | 52 (49) | 38 (46) |

| Care co-ordinator/keyworker only | 29 (21) | 23 (17) | 30 (24) | 19 (18) | 25 (20) | 21 (21) | 16 (15) | 13 (16) |

| Psychological therapy only | 33 (24) | 40 (30) | 11 (8.9) | 23 (21) | 11 (8.9) | 12 (12) | 17 (16) | 9 (11) |

| Psychological therapy plus care co-ordinator/keyworker | 21 (15) | 19 (14) | 14 (11) | 11 (10) | 8 (6.5) | 7 (7.00) | 7 (6.5) | 7 (8.4) |

| Psychiatrist only | 7 (5.07) | 6 (4.5) | 6 (4.8) | 6 (5.6) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (3.00) | 5 (4.7) | 2 (2.4) |

| Psychological therapy plus care co-ordinator/keyworker plus psychiatrist | 11 (7.9) | 6 (4.5) | 6 (4.8) | 7 (6.5) | 6 (4.9) | 2 (2.00) | 5 (4.7) | 6 (7.2) |

| Care co-ordinator/keyworker plus psychiatrist | 13 (9.4) | 8 (6.06) | 8 (6.45) | 4 (3.7) | 6 (4.9) | 9 (9.00) | 6 (5.6) | 3 (3.6) |

| Psychological therapy plus psychiatrist | 6 (4.4) | 7 (5.3) | 2 (1.61) | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.00) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) |

Personal and support services were recorded in terms of the number of participants accessing such services and the duration of support, in hours (Table 14). It is notable that one-quarter to one-third of participants in both arms reported multiple hours of employment support across the trial period. Large SDs for the mean average values (see Table 14) suggest that the number of hours of personal and social support that individuals receive is extremely variable, with some individuals having received very high amounts of personal and social support over the reporting periods, especially with respect to youth and statutory service provision and social support group attendance.

| Service use | Time point, n (%)/mean (SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 9 months | 15 months | 24 months | |||||

| SRT + ESC (N = 138) | ESC alone (N = 132) | SRT + ESC (N = 124/138) | ESC alone (N = 108/132) | SRT + ESC (N = 124/138) | ESC alone (N = 100/132) | SRT + ESC (N = 107/138) | ESC alone (N = 83/132) | |

| Employment support | ||||||||

| Presence | 33 (24%) | 36 (27%) | 42 (34%) | 43 (34%) | 39 (31%) | 27 (27%) | 32 (30%) | 25 (30%) |

| Duration (hours) | 10.07 (25.2) | 5.00 (7.01) | 8.5 (13.3) | 9.0 (19.3) | 8.4 (17.6) | 11.5 (17.9) | 56.1 (173.0) | 7.9 (10.8) |

| Youth services | ||||||||

| Presence | 9 (6.5%) | 15 (11%) | 16 (13%) | 12 (11%) | 5 (4.03%) | 4 (4.00%) | 4 (3.7%) | 5 (6.02%) |

| Duration (hours) | 13.2 (24.2) | 6.3 (4.4) | 8.2 (9.8) | 36.7 (97.4) | 18.2 (20.8) | 52.2 (43.7) | 27.1 (51.9) | 16.3 (11.6) |

| Statutory services | ||||||||

| Presence | 17 (12%) | 19 (14%) | 9 (7.3%) | 9 (8.3%) | 4 (3.2%) | 4 (4.00%) | 5 (4.7%) | 4 (4.8%) |

| Duration (hours) | 4.6 (6.2) | 5.1 (6.6) | 2.1 (2.3) | 21.8 (52.32) | 5.00 (1.7) | 161.5 (320.1) | 27.1 (52.0) | 61.5 (119.0) |

| Telephone support | ||||||||