Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/71/04. The contractual start date was in February 2019. The draft report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in April 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Bedford et al. This work was produced by Bedford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Bedford et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

New-onset atrial fibrillation (NOAF) is defined as atrial fibrillation (AF) that occurs in a patient with no known history of chronic or paroxysmal AF. 1 It is a common arrhythmia in critically ill patients. 2 It occurs in 5–15% of all patients admitted to a general intensive care unit (ICU),3,4 rising to 23% of patients with septic shock. 5

Organised atrial activity is important for ventricular filling and cardiac output. 6 NOAF is temporally associated with a reduction in cardiac output in non-ICU patients. 7 The haemodynamic impact of NOAF in critically ill patients is poorly understood, but limited data suggest that NOAF may precede haemodynamic instability8 and may be associated with increased rates of thromboembolism. 9 NOAF during critical illness is associated with an increased risk of death in an ICU and in hospital. 10,11 There is also a significant organisational impact of NOAF because it is associated with an increased length of ICU and hospital stay, and higher health-care costs. 12

New-onset atrial fibrillation during critical illness may carry a long-term burden. Patients who develop NOAF during sepsis and survive to hospital discharge have an increased risk of heart failure and stroke, and poorer 1-year and 5-year survival. 13,14 The long-term outcomes for patients who develop NOAF in an ICU remains unclear.

It is not known whether NOAF in patients in an ICU is causally related to worse outcomes or whether NOAF may be solely a marker of disease severity. However, there is clear mechanistic plausibility behind a causal association. This demonstrates the need for optimal prevention, management and follow-up. Although a recent scoping review has broadly described studies of NOAF treatment in patients in an emergency department or an ICU, or after major surgery,10 an in-depth review of NOAF in patients in an ICU focusing on treatment efficacy is required to put current treatment practices into context and to inform future comparative studies.

Clear guidelines exist for the management of AF in patients in the community. 15 However, there is a paucity of evidence for its management in the critical care setting, for which the balance of risks and benefits associated with different treatment options is unclear. Understandably, there is significant variation within and between units in the management of this common problem. 16 Many previous studies informing NOAF treatment in ICUs are small or inadequately adjusted for confounding factors. Well-conducted, multicentre, observational studies are required to highlight candidate interventions for clinical trials.

Overall aims and objectives of the study

Scoping review

-

To evaluate the evidence for the clinical effectiveness and safety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological NOAF treatments.

-

To provide guidance for the database analysis on:

-

NOAF definitions used for patients in an ICU

-

patient subgroups who develop NOAF in an ICU

-

inclusion/exclusion of specific treatments and potential confounders

-

-

determining barriers to future research.

Database analysis: RISK-II

-

To determine how common NOAF is in critical care.

-

To determine the typical characteristics of patients with NOAF in critical care and how they compare with other patients in critical care.

-

To increase the understanding of the outcomes of patients with NOAF in critical care and how they compare with other patients in critical care.

-

To investigate how much of the difference in outcomes is explained by differences in patient characteristics and comorbidities.

Database analysis: MIMIC-III and PICRAM

-

To compare the use and clinical effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological NOAF treatments.

-

To determine the incidence of short- and long-term NOAF complications.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was vital throughout the study. Valerie Keston-Hole and Rob Lawrence helped to develop the application, which was also reviewed by the Oxford Critical Care Patient Forum. The group strongly supported the use of existing databases for the purposes of undertaking the work. Valerie Keston-Hole sits on the group, which assesses applications for the use of the Post Intensive Care Risk-adjusted Alerting and Monitoring (PICRAM) data used in this work. Ian and Cathy Taylor provided us with a clear patient perspective when working with the expert panel and also helped us to choose research recommendations. Meetings went well and easy access to the chief investigator meant that things that were unclear could be explained by e-mail afterward and further thoughts considered. In discussion with Ian and Cathy Taylor, we identified that an area that we would improve in the future was how to present large numbers of initial data in a more comprehensible manner to our patient and public involvement (PPI) colleagues. A suggestion for the future would be to provide supplementary information that avoided technical terminology to help the understanding of the data by our PPI colleagues prior to the meetings. This would allow more spontaneous comments and discussion during the meeting. Our PPI work is not complete. We discussed our findings at the ICU patient forum. This helped us to understand how to clearly communicate our findings.

Chapter 2 Scoping review of treatments for new-onset atrial fibrillation

Parts of this chapter are adapted with permission from Drikite et al. 17 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scoping review methods

The scoping review followed the methodological framework described by Arksey and O’Malley,18 Levac et al. 19 and Daudt et al. ,20 and the reporting complies with the recently published Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines. 21

Literature searches

The search strategy was developed by an information specialist in MEDLINE (via Ovid®; Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) without any date or language restrictions. The search strategy included terms used to describe NOAF combined with a set of terms used for critical care.

An adapted MEDLINE search strategy was used to search the following databases in March 2019: MEDLINE, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science™ [Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA; including Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Clarivate Analytics)], OpenGrey, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; searched from 1994 to 2015). We were not able to search the National Guideline Clearinghouse, as suggested in our protocol,22 because this database was no longer available. The following clinical trial databases were searched for studies in progress or completed but not reported: International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN), ClinicalTrials.gov, the EU Clinical Trials register, additional World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) trial databases and the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Trials Gateway.

The search results were imported into EPPI-Reviewer 4 software (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK) and duplicates were removed. The search strategies can be found in Appendix 1. The reference lists of included review articles and studies were also reviewed to identify any relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria used to screen titles, abstracts and full-text articles were as follows.

-

Population:

-

Studies of adults (age ≥ 16 years) with NOAF (or without any history of AF, for prevention/prophylactic studies) admitted to general medical, surgical or mixed ICUs were included.

-

Studies of cohorts defined by a single disease or narrow disease group not normally admitted to a general ICU (e.g. myocardial infarction) and studies based on service-specific ICUs (e.g. cardiothoracic or neurosurgical) were excluded.

-

Studies in which a majority (> 50%) of patients belonged to a single, specific disease or operative cohort (e.g. liver resections or lung surgery) and cohorts with a known history of chronic or paroxysmal AF were excluded.

-

Studies of disease groups commonly admitted to an ICU, such as sepsis and septic shock, were included.

-

Studies of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias if AF constituted at least 70% of arrhythmias were included. Where these data were unavailable, we included studies that grouped AF and atrial flutter together if no other arrhythmia types were included.

-

Studies reporting on populations that were a mixture of NOAF and known AF were included only if data for the NOAF subgroup were reported separately.

-

Studies that included both ICU and non-ICU patients, but which did not present results separately, were included only if > 50% of the total cohort were ICU patients and if a valid method for confounding adjustment was used with ICU status included as a covariate.

-

-

Intervention:

-

Studies investigating pharmacological, electrical and other non-pharmacological (including electrolyte) treatment strategies for treatment or prevention of NOAF were included.

-

Studies of short- or long-term anticoagulation were included.

-

Studies of ablation or surgical interventions were excluded.

-

-

Comparators:

-

Any eligible intervention could be a comparator, including no treatment or ‘standard care’.

-

Placebo was also eligible.

-

-

Outcomes – any of the following outcomes were eligible:

-

rhythm and rate control

-

length of ICU and hospital stay

-

mortality (ICU, hospital, 30 days and long term)

-

arterial thromboembolism and adverse treatment effects

-

in the case of studies of preventative/prophylactic treatments, the incidence of NOAF had to be reported.

-

-

Study design – we included quantitative studies with the following designs:

-

randomised and non-randomised trials

-

cohort studies and case series containing five or more patients

-

practitioner surveys and opinion pieces (for research recommendations and interventions not otherwise identified) were also included.

-

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and potentially relevant full-text articles. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved either through discussion or by a third reviewer if necessary. Titles, abstracts and full-text articles were screened using EPPI-Reviewer 4 software. The screening of titles and abstracts was facilitated by use of the highlighting function in EPPI-Reviewer 4 (which highlights keywords associated with inclusion or exclusion criteria). This function allowed more prompt decisions to be made. After screening the titles and abstracts, all potentially relevant full-text articles were uploaded on Mendeley Reference Manager Software (1.19.5; Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) for easy access and sharing purposes.

Full-text articles that were not published in English included papers in French, German, Czech, Chinese and Spanish. These were screened by native speakers. None of the foreign language articles was eligible for the review.

Data charting

Data-charting forms were developed for the following study designs:

-

randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

-

prospective comparative studies (non-RCTs)

-

retrospective comparative studies

-

single-group studies.

The extracted data included the following:

-

details of the study (authors, country, setting, sample size and proportion of NOAF patients included in the study)

-

population characteristics (primary diagnosis; mean age; proportion of males; severity of illness; proportion of patients on vasopressors; proportion of patients with cardiovascular disease, acute renal failure, acute respiratory failure and mechanical ventilation; mean serum potassium levels; and authors’ definition of NOAF)

-

description of intervention and comparator(s)

-

methods to address confounding (for non-randomised studies)

-

results

-

any relevant recommendations for the future research.

The data-charting forms were piloted on a small number of studies and were adapted accordingly where necessary. Decisions about which population characteristics to extract were informed by a recent systematic review on risk factors for NOAF on the ICU23 and a retrospective observational study on predictors for sustained NOAF in the critically ill. 24 All data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by another member of the team; any disagreements would be referred to a third member of the team.

Critical appraisal

Randomised trials were evaluated using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (see Appendix 2). 25 Non-randomised comparative studies that fulfilled the following criteria were evaluated for risk of bias using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool:26

-

reported as full papers

-

included at least 100 patients per treatment arm

-

reported on methods to adjust for confounding.

The ROBINS-I tool was adapted for use in this scoping review by including a stopping rule: the risk-of-bias assessment stopped if a serious or critical risk-of-bias judgement was made for the ‘bias due to confounding’ domain. For the confounding domain, decisions regarding which covariates should be reported as being controlled for in analyses were made by the clinical experts in the CAFE (Critical care Atrial Fibrillation Evaluation) study team, with supporting references where possible, and are reported in Table 1, along with the risk-of-bias judgements.

| Studya | Confounding domain | Other domains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Results | Review prespecified covariates to be controlled or adjusted for | Risk-of-bias judgement | ||

| Launey 201927 | Incidence of NOAF | RD 11.9% (95% CI –23.4% to –0.5%) | Age, sex, preceding cardiovascular disease, acute renal failure, acute respiratory failure, APACHE score and the use of vasopressors23 | Serious:

|

NAc |

| RR 0.58 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.98) | |||||

| Walkey 201628 | Mortalityb | RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.15) | Sickness score (e.g. SOFA) or individual components of score | Serious:

|

NAc |

| RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.88) | |||||

| RR 0.67 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.77) | |||||

| Walkey 201629 | Stroke and bleeding | Stroke: RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.27) | Stroke: age, sex, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, carotid artery disease, hypercholesterolaemia | Serious for both outcomes:

|

NAc |

| Bleeding: RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.14) | Bleeding: ± illness severity, systemic inflammation, type and location of surgery, nutritional status, invasive devices, and acute coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia | ||||

Collating and summarising the results

The details of the primary studies were presented in structured tables categorised by study design. For each type of study design, the extent, range and nature of the identified research were described. Study parameters and results were then described and summarised narratively.

Expert panel review

We convened a face-to-face meeting of expert panel members to review our scoping review results and to inform our subsequent database analysis. We created a list of variables identified from our scoping review that may affect NOAF treatment choice. We then circulated this list among our expert panel where it was independently added to and refined. We collated a final list of these confounding variables, which was then ratified by our expert panel. We repeated this process with definitions of NOAF, interventions of interest and outcomes of interest.

Scoping review results

Quantity and quality of the research available

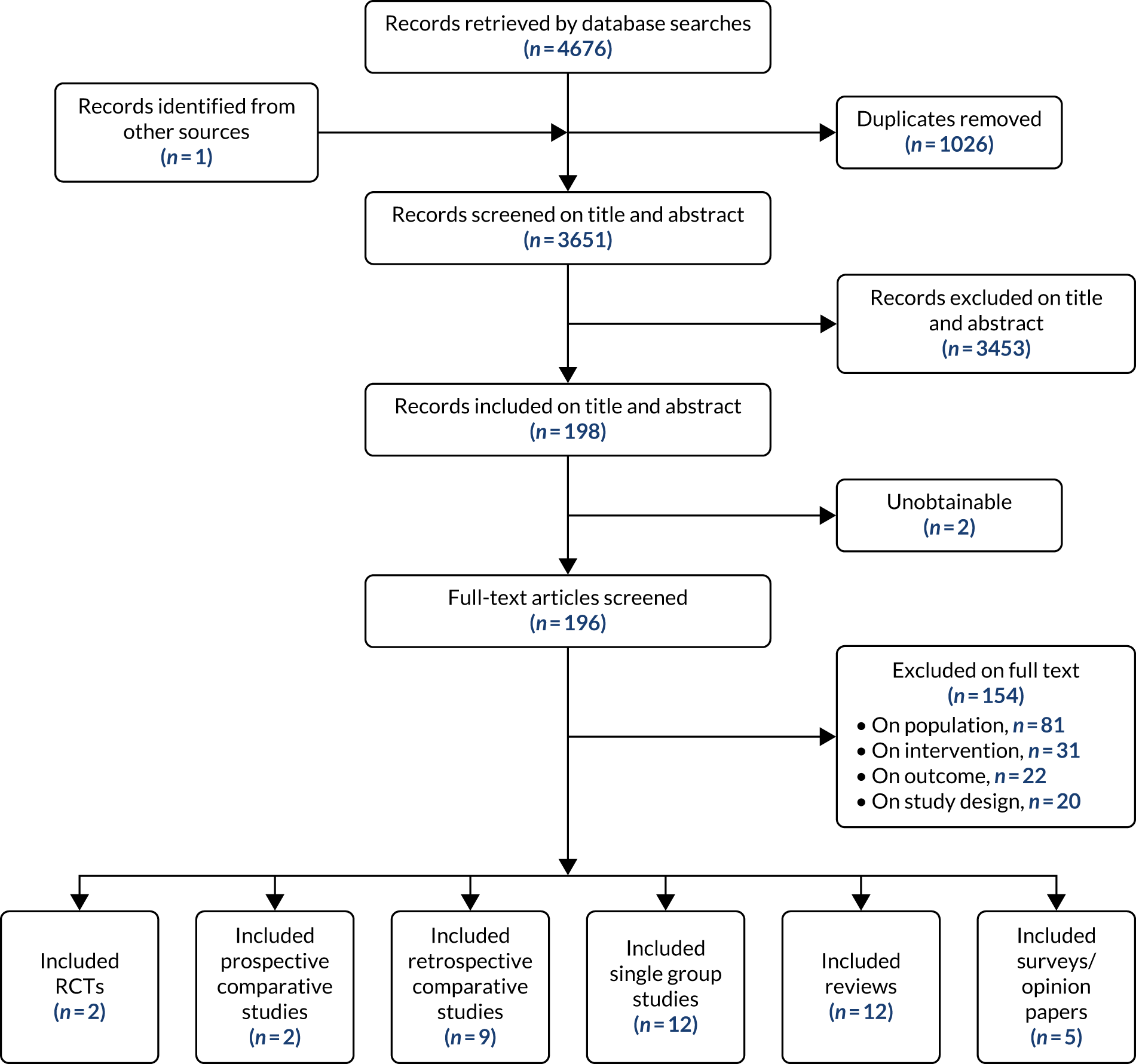

Following the removal of duplicates from the articles retrieved by database searches, 3651 articles were screened on their title and abstract. From those screened, 198 articles were identified as of potential interest and were screened on their full text. Two articles were unobtainable: a conference abstract published in 2000 and an old study from 1974 looking at amiodarone as a treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in critically ill patients. Therefore, copies of the 196 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion in the scoping review and 42 articles were included in the review. One eligible article was identified from checking the reference lists of included review articles. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of the articles throughout the review process and the number of included articles classified by study design. Studies excluded after full-text review are listed in Appendix 4, Table 19.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing the number of studies identified, excluded and eligible for inclusion in the scoping review.

Risk-of-bias assessments

Randomised controlled trials

Two RCTs were included. It was judged that the Balser et al. 30 trial gave rise to some concerns about possible bias, primarily owing to the lack of reporting of randomisation methods and the lack of blinding. The Delle Karth et al. 31 trial was judged to have a high risk of bias based on the lack of reporting of randomisation methods, coupled with baseline differences in sex and age. Moreover, the trial was not blinded with respect to investigators and caregivers.

Non-randomised comparative studies

Three non-randomised studies27–29 fulfilled the criteria (see Critical appraisal) to be evaluated using the ROBINS-I risk-of-bias tool.

All three of the large, non-randomised studies were judged to have a serious risk of bias owing to confounding. This was a result of either missing covariates in the propensity score matching or the risk of residual confounding as a result of the measurement of the covariates. The two studies by Walkey et al. 28,29 stated that some key data were recorded on admission, but that these studies used enhanced administrative data that lacked the detailed sequence of events. Some data relating to the admission time point may not be representative of the time point at which a treatment decision was made. The authors noted other limitations of these two studies, adding that the findings should be ‘considered hypothesis-generating and supportive of the need for future clinical trials to investigate optimal treatment of AF during sepsis’. 28

Primary studies of clinical effectiveness and safety

Table 2 presents an overview of the primary study evidence identified in the review. Further details are reported in the following sections, according to study design.

| Intervention | Study details | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | Prospective comparative study | Retrospective comparative study | Prospective single-group study | Retrospective single-group study | |

| Pharmacological treatments | |||||

| Amiodarone | Delle Karth 2001,31 n = 60 | Gerlach 2008,32 n = 61 |

Walkey 2016,28 n = 3174 Cho 2017,33 n = 448 Matsumoto 2015,34 n = 276 Balik 2017,35 n = 234 Mieure 2011,36 n = 126 Jaffer 2016,37 n = 65 Brown 2018,38 n = 33 |

Sleeswijk 2008,39 n = 29 Slavik 2003,40 n = not reported |

Liu 2016,41 n = 240 Mitrić 2016,42 n = 177 Kanji 2012,8 n = 139 Mayr 2004,43 n = 131 Burris 2010,44 n = 30 |

| Beta-blockers | Balser 1998,30 n = 55 | No studies |

Walkey 2016,28 n = 3174 Matsumoto 2015,34 n = 276 Balik 2017,35 n = 234 Mieure 2011,36 n = 126 Jaffer 2016,37 n = 65 Brown 2018,38 n = 33 |

Nakamura 2016,45 n = 16 |

Liu 2016,41 n = 240 Kanji 2012,8 n = 139 Burris 2010,44 n = 30 |

| Calcium channel blockers |

Delle Karth 2001,31 n = 60 Balser 1998,30 n = 55 |

Gerlach 2008,32 n = 61 |

Walkey 2016,28 n = 3174 Mieure 2011,36 n = 126 Jaffer 2016,37 n = 65 Brown 2018,38 n = 33 |

No studies |

Liu 2016,41 n = 240 Burris 2010,44 n = 30 |

| Propafenone | No studies | No studies | Balik 2017,35 n = 234 | No studies | No studies |

| Digoxin | No studies | No studies | Walkey 2016,28 n = 3174 | No studies |

Liu 2016,41 n = 240 Burris 2010,44 n = 30 |

| Ibutilide | No studies | No studies | No studies |

Hennersdorf 2002,46 n = 26 Delle Karth 2005,47 n = 17 |

No studies |

| Magnesium sulphate infusion | No studies | No studies | No studies | Sleeswijk 2008,39 n = 29 | No studies |

| Prophylactic treatments | |||||

| Hydrocortisone | No studies | Launey 2019,27 n = 261 | Kane 2014,48 n = 109 | No studies | No studies |

| Electrical treatments | |||||

| Direct-current cardioversion | No studies | No studies | No studies | Mayr 2003,49 n = 37 | No studies |

| Electrical cardioversion | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

Liu 2016,41 n = 240 Kyo 2019,50 n = 85 |

| Anticoagulants | |||||

| Anticoagulants | No studies | No studies | Walkey 2016,29 n = 7522 | Slavik 2003,40 n = not reported | No studies |

Randomised controlled trials

Two small RCTs30,31 were identified as eligible and were included in the review. Both trials investigated pharmacological treatment strategies for rate control in patients with NOAF. Details of the RCTs are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Two further RCTs51,52 that studied supraventricular tachycardias were identified, but these were not eligible because < 70% of their study population were diagnosed with NOAF.

| Study details | Population characteristics | Intervention | Comparator | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

First author and year: Balser 199830 Setting: ICU Country: USA Sample size: n = 55 (esmolol, n = 28; diltiazem, n = 27) NOAF patients: n = 44 (80%) (esmolol, n = 22, 79%; diltiazem, n = 22, 81%) |

Primary diagnosis: non-cardiac surgical patients Primary diagnosisEsmolol (n)Diltiazem (n)GI/GU713Thoracic96Nonthoracic vascular43Neurosurgery23Other42No surgery20 Mean age: esmolol, 66 ± 15 years; diltiazem, 69 ± 11 years Male: esmolol, n = 14 (50%); diltiazem, n = 16 (59%) Severity of illness: APACHE III reported – esmolol, 59 ± 31; diltiazem, 65 ± 24 Patients on vasopressors: esmolol, n = 1 (3.57%); diltiazem, n = 3 (11%) Cardiovascular diseaseEsmolol, n (%)Diltiazem, n (%)Coronary artery disease10 (36)13 (48)Recent MI or ischaemia1 (3.57)2 (7)Left ventricular hypertrophy3 (11)1 (3.7) Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium: NR Definition of NOAF: ‘SVT present for as long as 24 hours’ |

Primary diagnosis | Esmolol (n) | Diltiazem (n) | GI/GU | 7 | 13 | Thoracic | 9 | 6 | Nonthoracic vascular | 4 | 3 | Neurosurgery | 2 | 3 | Other | 4 | 2 | No surgery | 2 | 0 | Cardiovascular disease | Esmolol, n (%) | Diltiazem, n (%) | Coronary artery disease | 10 (36) | 13 (48) | Recent MI or ischaemia | 1 (3.57) | 2 (7) | Left ventricular hypertrophy | 3 (11) | 1 (3.7) |

Esmolol: 12.5-mg i.v. bolus, followed by additional 25- to 50-mg boluses every 3–5 minutes until the heart rate was < 110 b.p.m. or a total loading dose of 250 mg was attained. The maintenance infusion was 50 µg/kg/minute for patients receiving > 30 mg. After 15 minutes, patients whose heart rate exceeded 110 b.p.m. received 1–4 boluses of 25 mg, followed by a 50 µg/kg/minute increment in their maintenance infusion. The authors reported that this was repeated after 30 minutes for patients whose heart rate was > 100 b.p.m. Beyond 30 minutes, infusion rates were adjusted by the treating physician to maintain heart rates between 80 and 100 b.p.m. If at any time a patient had symptomatic hypotension or their systolic blood pressure was < 80 mmHg, the infusion rate was decreased by 50% or a phenylephrine infusion was administered, or both Line of NOAF treatment: second line – adenosine given before the study treatment |

Diltiazem: loading infusion of 20 mg over 2 minutes, immediately followed by a 10 mg/hour maintenance infusion. After 15 minutes, patients whose heart rate was > 110 b.p.m. received an additional loading infusion of 25 mg and a 5 mg/hour increment in their maintenance infusion. After 30 minutes, patients receiving a maintenance infusion of < 15 mg/hour with a heart rate of > 100 b.p.m. received an additional 5 mg/hour increment in their infusion rate. Beyond 30 minutes, infusion rates were adjusted by the treating physician to maintain heart rates between 80 and 100 b.p.m. If at any time a patient had symptomatic hypotension or their systolic blood pressure was < 80 mmHg, the infusion rate was decreased by 50% or a phenylephrine infusion was administered, or both Line of NOAF treatment: second line – adenosine given before the study treatment |

| Primary diagnosis | Esmolol (n) | Diltiazem (n) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GI/GU | 7 | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thoracic | 9 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nonthoracic vascular | 4 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neurosurgery | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No surgery | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | Esmolol, n (%) | Diltiazem, n (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 10 (36) | 13 (48) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recent MI or ischaemia | 1 (3.57) | 2 (7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 3 (11) | 1 (3.7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Delle Karth 200131 Setting: ICU Country: Austria Sample size: n = 60 (diltiazem, n = 20; amiodarone bolus, n = 20; amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, n = 20) NOAF patients: n = 57 (95%) |

Primary diagnosis: Primary diagnosisDiltiazem (n)Amiodarone bolus (n)Amiodaron bolus + 24 hours (n)Congestive heart failure544Coronary artery disease22–Cardiac surgery6914Respiratory failure621Others131 Mean age: diltiazem, 64.8 ± 10 years; amiodarone bolus, 67.8 ± 9 years; amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, 71.2 ± 9 years Male: diltiazem, n = 15 (75%); amiodarone bolus, n = 17 (85%); amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, n = 11 (55%) Severity of illness: APACHE III score reported – diltiazem, 75.1 ± 35; amiodarone bolus, 76.7 ± 38; amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, 59.7 ± 8 Patients on vasopressors at the time of onset: diltiazem, n = 14 (70%); amiodarone bolus, n = 15 (75%); amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, n = 15 (75%) Patients with CVD: diltiazem, n = 13 (65%); amiodarone bolus, n = 15 (75%); amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, n = 18 (90%) Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: diltiazem, n = 6 (30%); amiodarone bolus, n = 2 (10%); amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, n = 1 (5%) Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: diltiazem, n = 15 (75%); amiodarone bolus, n = 17 (85%); amiodarone bolus + 24 hours, n = 14 (70%) Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: recent-onset tachycardic AF was defined as ‘atrial fibrillation with a rate consistently > 120 beats/minute over a 30-minute period’ |

Primary diagnosis | Diltiazem (n) | Amiodarone bolus (n) | Amiodaron bolus + 24 hours (n) | Congestive heart failure | 5 | 4 | 4 | Coronary artery disease | 2 | 2 | – | Cardiac surgery | 6 | 9 | 14 | Respiratory failure | 6 | 2 | 1 | Others | 1 | 3 | 1 |

Diltiazem: 25 mg of diltiazem by i.v. bolus infusion over 15 minutes followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 20 mg/hour for 24 hours Line of NOAF treatment: first line |

Amiodarone bolus: a bolus dose of 300 mg of amiodarone followed by i.v. infusion over 15 minutes Line of NOAF treatment: first line Amiodarone bolus + 24 hours: a dose of 300 mg of amiodarone followed by an i.v. bolus infusion over 15 minutes followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 45 mg/hour over 24 hours Line of NOAF treatment: first line |

|||||||||

| Primary diagnosis | Diltiazem (n) | Amiodarone bolus (n) | Amiodaron bolus + 24 hours (n) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congestive heart failure | 5 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 2 | 2 | – | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cardiac surgery | 6 | 9 | 14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respiratory failure | 6 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Study | Results | Adverse effects | Recommendations for/barriers to future research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balser 199830 |

|

No adverse effects | Although intuition suggests that ICU patients may benefit from accelerated conversion to sinus rhythm after operation, a much larger trial would be necessary to determine whether early conversion influences outcome |

| Delle Karth 200131 |

|

|

NR |

A RCT (n = 55)30 set in the USA compared esmolol (a beta-blocker) with diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker) in a non-cardiac surgical population. The proportion of patients diagnosed with NOAF was 79% in the esmolol group and 80% in the diltiazem group. Both esmolol and diltiazem were second-line treatments for NOAF because adenosine had been administered before the study treatments. The authors reported that loading and infusion rates were adjusted to achieve a degree of ventricular rate control similar to that achieved with standard dosing regimens used in their surgical ICU. The primary outcome that was reported was the rate of conversion to sinus rhythm. There was no statistically significant difference in conversion rate between the study groups within 2 hours for patients with NOAF: 59% in those who received esmolol and 27% in those who received diltiazem (p = 0.067). By 12 hours, 85% of patients who received esmolol had converted back to sinus rhythm, compared with 62% of patients who received diltiazem (p = 0.116). No adverse events were reported.

Delle Karth et al. 31 conducted a small RCT in Austria comparing diltiazem, an amiodarone (an anti-arrhythmic medication with multiple mechanisms of action) bolus and an amiodarone bolus in combination with 24 hours of infusion in a mixed ICU population. Ninety-five per cent of patients enrolled in the trial (n = 57) were diagnosed with NOAF. The first study group received a dose of 25 mg of diltiazem by an intravenous (i.v.) bolus infusion over 15 minutes, followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 20 mg/hour for a total of 24 hours. The second study group was given a bolus dose of 300 mg of amiodarone, followed by an i.v. infusion over 15 minutes. The third study group was given a dose of 300 mg of amiodarone followed by an i.v. bolus infusion over 15 minutes, which was then followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 45 mg/hour over 24 hours. Reported conversion rates within 4 hours were similar in both groups: 30% converted back to sinus rhythm in the diltiazem group, 40% in the amiodarone bolus group and 45% in the amiodarone bolus in combination with 24-hour infusion group. The authors reported a small number of adverse events (see Table 4).

Prospective comparative studies

We identified two prospective comparative studies, of which one32 investigated the effects of pharmacological treatments for NOAF and the other27 looked at prophylactic treatment to prevent NOAF in patients with septic shock. Details are presented in Tables 5 and 6.

| Study details | Population characteristics | Intervention | Comparator | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

First author and year: Gerlach 200832 Setting: surgical ICU Country: USA Sample size: n = 61 NOAF patients: n = 55 (90%) (diltiazem, n = 28; amiodarone, n = 27) |

Primary diagnosis Primary diagnosisDiltiazem (n)Amiodarone (n)Trauma59Gastrointestinal1511Vascular45Other surgery75 Mean age: diltiazem, 68.5 ± 14.6 years; amiodarone, 66.1 ± 16 years Male: diltiazem, n = 18 (58%); amiodarone, n = 21 (70%) Severity of illness: NR Patients on vasopressors at the time of onset: n = 11 (18%) (diltiazem, n = 8, 26%; amiodarone, n = 3, 10%) Patients with CVD: n = 11 (18%) (diltiazem, n = 5, 16%; amiodarone, n = 6, 20%) Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium: NR Definition of NOAF: NR |

Primary diagnosis | Diltiazem (n) | Amiodarone (n) | Trauma | 5 | 9 | Gastrointestinal | 15 | 11 | Vascular | 4 | 5 | Other surgery | 7 | 5 |

Intervention treatment given to patients during the first year of the study. Diltiazem: 0.25 mg/kg i.v. bolus, followed by continuous infusion of 5–15 mg/hour titrated to a heart rate of < 120 b.p.m. Decisions to continue, discontinue or change to oral therapy after 48 hours were at the discretion of the managing physicians Line of NOAF treatment: not specifically reported; however, no other treatments reported |

Comparator treatment given to patients during the second year of the study. Amiodarone: 150 mg i.v., over at least 10 minutes, followed by continuous infusion of 1 mg per minute for 6 hours then decreased to 0.5 mg per minute. The decision to continue, discontinue or change to oral therapy after 48 hours was at the discretion of the managing physicians Line of NOAF treatment: not specifically reported; however, no other treatments reported |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Primary diagnosis | Diltiazem (n) | Amiodarone (n) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trauma | 5 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 15 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vascular | 4 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other surgery | 7 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Launey 201927 Setting: five academic ICUs Country: France Sample size: n = 261 (hydrocortisone, n = 123; no hydrocortisone, n = 138) NOAF patients: NA |

Primary diagnosis: septic shock Infection siteHydrocortisone, n (%)No hydrocortisone, n (%)Intra-abdominal72 (59)72 (52)Thoracic24 (20)32 (23)Urinary17 (14)14 (10)Other10 (8)20 (14) Mean age: hydrocortisone, 65 ± 13 years; no hydrocortisone, 63 ± 15 years Male: hydrocortisone, 61%; no hydrocortisone, 58% Severity of illness: mean SOFA score (baseline) – hydrocortisone, 10 ± 4; no hydrocortisone, 8 ± 3 Mean SAPS II (baseline): hydrocortisone, 56 ± 20; no hydrocortisone, 50 ± 20 Mean SOFA score reported (during the first 24 hours of septic shock): hydrocortisone, 13 ± 0; no hydrocortisone, 10 ± 0 Patients on vasopressors VasopressorsHydrocortisone, n (%)No hydrocortisone, n (%)Noradrenaline122 (99)135 (98)Dobutamine29 (24)6 (4)Adrenaline15 (12)10 (7) Patients with CVD CVDHydrocortisone, n (%)No hydrocortisone, n (%)Coronary disease11 (9)12 (9)Valvular disease5 (4)7 (5) Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium: NR Definition of NOAF: AF was defined as 30 seconds or more of an irregular ventricular rhythm with absent P waves |

Infection site | Hydrocortisone, n (%) | No hydrocortisone, n (%) | Intra-abdominal | 72 (59) | 72 (52) | Thoracic | 24 (20) | 32 (23) | Urinary | 17 (14) | 14 (10) | Other | 10 (8) | 20 (14) | Vasopressors | Hydrocortisone, n (%) | No hydrocortisone, n (%) | Noradrenaline | 122 (99) | 135 (98) | Dobutamine | 29 (24) | 6 (4) | Adrenaline | 15 (12) | 10 (7) | CVD | Hydrocortisone, n (%) | No hydrocortisone, n (%) | Coronary disease | 11 (9) | 12 (9) | Valvular disease | 5 (4) | 7 (5) |

A hydrocortisone bolus of 100 mg followed by an infusion of 200 mg/day for 7 days followed by a short wean if the patient remained on vasopressors Line of NOAF treatment: not applicable as prophylactic treatment studied |

No prophylactic treatment |

| Infection site | Hydrocortisone, n (%) | No hydrocortisone, n (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Intra-abdominal | 72 (59) | 72 (52) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thoracic | 24 (20) | 32 (23) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Urinary | 17 (14) | 14 (10) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | 10 (8) | 20 (14) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vasopressors | Hydrocortisone, n (%) | No hydrocortisone, n (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Noradrenaline | 122 (99) | 135 (98) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dobutamine | 29 (24) | 6 (4) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adrenaline | 15 (12) | 10 (7) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CVD | Hydrocortisone, n (%) | No hydrocortisone, n (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronary disease | 11 (9) | 12 (9) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valvular disease | 5 (4) | 7 (5) |

| Study | Methods to address confounding | Results | Adverse effects | Recommendations for/barriers to future research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerlach 200832 | NR |

|

|

More studies including randomized controlled trials are needed to compare the use of diltiazem versus amiodarone for conversion of post-operative AF |

| Launey 201927 | The authors used inverse probability of treatment weighting using a multivariable logistic regression model to estimate the probability of treatment. Covariates included multiple measures of sepsis severity including admission severity scores and maximum doses of vasoactive medication |

|

NR | It would be interesting to study high-risk patients who develop AF and the short- and long-term outcomes in patients treated or not with hydrocortisone |

Pharmacological treatments

Gerlach et al. 32 conducted a small study (n = 61) that compared the effects of diltiazem with those of amiodarone in a surgical ICU population in the USA. 32 Ninety per cent of the included study participants were diagnosed with NOAF. Both study treatments were administered in accordance with the protocol developed by the participating surgical ICU medical team. The primary outcomes were conversion to normal sinus rhythm at 24 hours, time to conversion and adverse treatment effects. The lengths of ICU and hospital stays were also reported. The authors found no statistically significant differences between the study groups in the conversion rate at 24 hours and in the time to conversion. Similar lengths of ICU and hospital stays were also reported. One patient in the diltiazem group and two patients in the amiodarone group developed transient hypotension. This study was small and, therefore, probably underpowered to detect any treatment differences. No power calculations were reported and methods to account for confounding factors were not reported as being used in the analysis.

Prophylactic treatments

A study27 set in five French academic ICUs assessed the effect of hydrocortisone to prevent NOAF in 261 patients diagnosed with septic shock. Hydrocortisone was administered at the discretion of the attending physician, although a study treatment schedule was recommended. Patients who received hydrocortisone were more severely ill than those who did not. The unadjusted ICU and 28-day mortalities in the hydrocortisone group were higher than in the no-hydrocortisone group [37% vs. 24% (p = 0.018) and 38% vs. 26% (p = 0.036), respectively]. No relative risks (RRs) for ICU and 28-day mortality were reported in the study. However, in the propensity score-weighted analysis, patients who received hydrocortisone were less likely to develop NOAF than those who did not. The risk difference between the groups was 11.9% and the RR of developing NOAF was 0.58 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.35 to 0.98], which indicates a benefit of hydrocortisone.

Retrospective comparative studies

Nine retrospective comparative studies28,29,33–38,48 were identified, with sample sizes ranging between 33 and 7522 patients. Seven studies28,29,33–36,48 had a sample size of > 100 patients. Six studies took place in the USA,28,29,36–38,48 two in Asia33,34 and one in Europe. 35 All studies were published after 2010. Five studies33,34,36,37,48 were available only as conference abstracts; therefore, limited data were available. None of the studies reported treatment adverse events. Details of these studies can be found in Tables 7 and 8.

| Study details | Population characteristics | Intervention | Comparator | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

First author and year: Balik 201735 Setting: 15-bed general ICU Country: Czechia Sample size: n = 234 (amiodarone, n = 177; propafenone, n = 42; metoprolol, n = 15) NOAF patients: n = 163 (69.7%) |

Primary diagnosis: septic shock Primary sources of septic shock: respiratory (57.3%), abdominal (25.2%), urosepsis (7.3%), wound/surgical (5.2%), catheter related (4.2%), maxillofacial (0.4%), neuroinfection (0.4%) Mean age: amiodarone, 67.8 ± 11.4 years; propafenone, 66.8 ± 11.3 years; metoprolol, 60.9 ± 8.3 years Male: n = 139 (59.4%) Severity of illness at the start of the anti-arrhythmic therapy: APACHE II – amiodarone, 25 ± 11.4; propafenonel, 23.2 ± 11.1; metoprolol, 19.4 ± 11.9 SOFA – amiodarone, 11.1 ± 4; propafenone, 10.2 ± 4; metoprolol, 7.0 ± 4.2 Patients on vasopressors: VasopressorAmiodarone, n (%)Propafenone, n (%)Metoprolol, n (%)Dobutamine24 (16.9)6 (7.7)–Vasopressin10 (7)2 (2.6)– Patients with CVD: n = 117 (50%) (amiodarone, n = 79, 56%; propafenone, n = 34, 43.6%; metoprolol, n = 4, 28.6%) Patients with acute renal failure: n = 64 (27.4%) Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: n = 232 (99.1%) (although does not specify whether or not this was at the onset) Serum potassium level (mmol/l): amiodarone, 4.4 ± 0.6; propafenone, 4.4 ± 0.6; metoprolol, 4.3 ± 0.5 Definition of NOAF: NR |

Vasopressor | Amiodarone, n (%) | Propafenone, n (%) | Metoprolol, n (%) | Dobutamine | 24 (16.9) | 6 (7.7) | – | Vasopressin | 10 (7) | 2 (2.6) | – |

Propafenone: the median total dose of propafenone was 2.5 g (IQR 1.0–4.0 g). The length of therapy was 5.0 days (IQR 2.0–8.5 days) Line of NOAF treatment: first and second line |

Amiodarone: median total dose of amiodarone was 3.0 g (IQR 1.8–4.6 g), given by infusion over 4 days (2–6 days) Line of NOAF treatment: first and second line Metoprolol: the median i.v. metoprolol dose was 84 mg/day (48–120 mg/day) The median length of therapy was 5 days (2–9 days) Line of NOAF treatment: first line |

||||||||||||||||||

| Vasopressor | Amiodarone, n (%) | Propafenone, n (%) | Metoprolol, n (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dobutamine | 24 (16.9) | 6 (7.7) | – | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vasopressin | 10 (7) | 2 (2.6) | – | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Cho 201733 (conference abstract) Setting: medical ICU Country: Republic of Korea Sample size: n = 448 NOAF patients: 100% |

Primary diagnosis: sepsis Mean age: 68.2 years Male: 68.9% Severity of illness: median CHA2DS2-VASc score, 3; median APACHE II score, 24 Patients on vasopressors: 59.9% (at the time of NOAF onset) Patients with CVD: NR Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: 84.5% Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: NR |

Rhythm control (43.5% patients): amiodarone used in 95.4% of rhythm control cohort Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

Rate control (56.7% patients) Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Jaffer 201637 (conference abstract) Setting: ICU Country: USA Sample size: n = 65 NOAF patients: 100% |

Primary diagnosis: septic shock Mean age: NR Male: 56% Severity of illness: NR Patients on vasopressors: NR Patients with CVD: NR Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: NR |

Amiodarone (administered to 49% of patients) Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

Calcium channel blockers (administered to 15% of patients) and beta-blockers (administered to 12% of patients) Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Kane 201448 (conference abstract) Setting: ICU Country: USA Sample size: n = 109 (hydrocortisone, n = 39) NOAF patients: not applicable as prophylactic treatment studied |

Primary diagnosis: septic shock Mean age: NR Male: NR Severity of illness: mean APACHE IV score reported, 97 ± 32.5 Patients on vasopressors: NR Patients with CVD: NR Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: NR |

Hydrocortisone (median duration 4.2 days, IQR 1.1–8.1 days) Line of NOAF treatment: not applicable as prophylactic treatment studied |

No treatment Line of NOAF treatment: not applicable |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Matsumoto 201534 (conference abstract) Setting: ICU Country: Japan Sample size: n = 276 (amiodarone, n = 116; landiolol, n = 160) NOAF patients: 100% |

Primary diagnosis: NR Mean age: NR Male: NR Severity of illness: NR Patients on vasopressors: NR Patients with CVD: NR Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: NR |

Amiodarone: a loading infusion of 150 mg over 30 minutes followed by a continuous infusion of 20 mg/hour Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

Landiolol: a bolus infusion of 7.5 mg followed by continuous infusion of 2.5–7.5 mg/hour Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Brown 201838 Setting: surgical ICU Country: USA Sample size: n = 33 Initial treatment: beta-blockers, n = 22; amiodarone, n = 6; calcium channel blockers, n = 2; no treatment, n = 3 NOAF patients: 100% NOAF with rapid ventricular rate |

Primary diagnosis: oesophagectomy, n = 8; intra-abdominal surgery, n = 9; other surgery, n = 9, trauma n = 7 Sepsis at the time of onset: n = 16 (48.5%) Mean age: median age (IQR) 71 (64–80) years Male: n = 19 (58%) Severity of illness: NR for baseline or onset characteristics Patients on vasopressors (within 24 hours of NOAF onset): n = 12 (36%) Patients with CVD: coronary artery disease, 20%; stroke, 12%; peripheral vascular disease, 9% Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset (only reported for within 24 hours of onset): n = 5 (15%) Serum potassium level: patients with serum potassium of < 4 mmol/l on first laboratory after AF onset, n = 15 (45%) Definition of NOAF: AF occurring in any patient with no documented history of AF |

Beta-blockers Line of NOAF treatment: first line |

Amiodarone and calcium channel blockers Line of NOAF treatment: first, second and third Sixteen patients (48%) received a second medication owing to failure to restore sinus rhythm, with amiodarone being the most common (n = 13, 81%) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Mieure 201136 (conference abstract) Setting: ICU Country: USA Sample size: n = 126 (amiodarone, n = 61; diltiazem, n = 41; metoprolol, n = 24) NOAF patients: 100% |

Primary diagnosis: NR Mean age: NR Male: NR Severity of illness: NR Patients on vasopressors: NR Patients with CVD: NR Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: ‘onset 120 beats per minute’ |

Amiodarone Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

Diltiazem Line of NOAF treatment: not specified Metoprolol Line of NOAF treatment: Not specified |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Walkey 201628 Setting: 20% of hospitals in the USA Country: USA Sample size: n = 39,693 (calcium channel blockers, n = 14,202; beta-blockers, n = 11,290; digoxin, n = 7937, amiodarone, n = 6264) NOAF patients: n = 3174 Note: outcomes reported separately for NOAF patients |

Primary diagnosis: sepsis Infection siteBeta-blocker, n (%)Calcium channel blocker, n (%)Digoxin, n (%)Amiodarone, n (%)Respiratory3583 (31.7)5882 (41.4)3118 (39.3)2369 (37.8)Gastrointestinal2107 (18.7)1692 (11.9)1030 (13.0)896 (14.3)Urinary tract4173 (37.0)5439 (38.3)3008 (37.9)1980 (31.6)Skin or soft tissue982 (8.7)1217 (8.6)696 (8.8)507 (8.1)Primary bacteraemia or fungaemia140 (1.2)150 (1.1)82 (1.0)76 (1.2) Mean age: beta-blockers, 75.7 ± 11.3 years; calcium channel blockers, 75.6 ± 11.4 years; digoxin, 77.1 ± 10.7 years; amiodarone, 73.1 ± 11.7 years Male: beta-blockers, 50.4%; calcium channel blockers, 47.4%; digoxin, 48.5%; amiodarone, 55.1% Severity of illness: NR Patients on vasopressors on first hospital day: beta-blockers, 29.1%; calcium channel blockers, 26.5%; digoxin, 44.1%; amiodarone, 64.0% Patients with CVD: NR Patients with acute renal failure: NR Patients with acute respiratory failure: NR Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: AF that was not documented on hospital admission |

Infection site | Beta-blocker, n (%) | Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | Digoxin, n (%) | Amiodarone, n (%) | Respiratory | 3583 (31.7) | 5882 (41.4) | 3118 (39.3) | 2369 (37.8) | Gastrointestinal | 2107 (18.7) | 1692 (11.9) | 1030 (13.0) | 896 (14.3) | Urinary tract | 4173 (37.0) | 5439 (38.3) | 3008 (37.9) | 1980 (31.6) | Skin or soft tissue | 982 (8.7) | 1217 (8.6) | 696 (8.8) | 507 (8.1) | Primary bacteraemia or fungaemia | 140 (1.2) | 150 (1.1) | 82 (1.0) | 76 (1.2) |

Intravenous beta-blocker (metoprolol, esmolol, atenolol, labetalol, propranolol) Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

Intravenous calcium channel blocker (diltiazem, verapamil) Intravenous digoxin (cardiac glycosides, digoxin, digitalis) Intravenous amiodarone Line of NOAF treatment: not specified |

| Infection site | Beta-blocker, n (%) | Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | Digoxin, n (%) | Amiodarone, n (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respiratory | 3583 (31.7) | 5882 (41.4) | 3118 (39.3) | 2369 (37.8) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 2107 (18.7) | 1692 (11.9) | 1030 (13.0) | 896 (14.3) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Urinary tract | 4173 (37.0) | 5439 (38.3) | 3008 (37.9) | 1980 (31.6) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skin or soft tissue | 982 (8.7) | 1217 (8.6) | 696 (8.8) | 507 (8.1) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primary bacteraemia or fungaemia | 140 (1.2) | 150 (1.1) | 82 (1.0) | 76 (1.2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First author and year: Walkey 201629 Setting: non-federal US hospitals Country: USA Sample size: n = 38,582 (pre-existing AF, n = 31,060) NOAF patients: n = 7522 (n = 5585 analysed with propensity score approach) Note: outcomes reported separately for NOAF patients |

Primary diagnosis: sepsis Mean age: anticoagulation, 73.2 ± 11.7 years; no anticoagulation, 75.8 ± 11.7 years Male: anticoagulation, n = 6941 (51%); no anticoagulation, n = 12,035 (42.2%) Severity of illness mean (SD) CHA2DS2-VASc score reported: anticoagulation, 3.4 (1.5); no anticoagulation, 3.6 (1.5) Patients on vasopressors: anticoagulation, n = 5084 (37.4%); no anticoagulation, n = 10,002 (40.1%) Patients with CVD Cardiovascular diseaseAnticoagulation, (N = 13,611) (35.3%), n (%)No anticoagulation, (N = 24,971) (64.7%), n (%)Heart failure5712 (42.0)9792 (39.2)Coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction4532 (33.3)7970 (31.9)Valvular heart disease2010 (14.8)3348 (13.4) Patients with acute renal failure: anticoagulation, n = 7612 (55.9%); no anticoagulation, n = 15,814 (63.3%) Patients with acute respiratory failure: anticoagulation, n = 5308 (39.0%); no anticoagulation, n = 9442 (37.8%) Mechanical ventilation at NOAF onset: NR Serum potassium level: NR Definition of NOAF: ‘incident AF that was not present on admission’ |

Cardiovascular disease | Anticoagulation, (N = 13,611) (35.3%), n (%) | No anticoagulation, (N = 24,971) (64.7%), n (%) | Heart failure | 5712 (42.0) | 9792 (39.2) | Coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction | 4532 (33.3) | 7970 (31.9) | Valvular heart disease | 2010 (14.8) | 3348 (13.4) |

Intravenous or subcutaneous administration of therapeutic-dose anticoagulant (including i.v. heparin, SC enoxaparin, SC dalteparin, SC fondaparinux) Patients who received oral anticoagulants as their initial anticoagulant were excluded in the primary analysis Line of NOAF treatment: not applicable as NOAF treatment not studied |

No anticoagulation Line of NOAF treatment: not applicable |

||||||||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | Anticoagulation, (N = 13,611) (35.3%), n (%) | No anticoagulation, (N = 24,971) (64.7%), n (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heart failure | 5712 (42.0) | 9792 (39.2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction | 4532 (33.3) | 7970 (31.9) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valvular heart disease | 2010 (14.8) | 3348 (13.4) |

| Study | Methods to address confounding | Results | Recommendations for/barriers to the future research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balik 201735 | Linear regression analysis involving univariate and multivariate testing |

|

NR |

| Cho 201733 (abstract) | Propensity matching |

|

NR |

| Jaffer 201637 (abstract) | None |

|

Further investigation into the management of arrhythmias in septic shock is needed to further elucidate the potential benefits and harms of various pharmaceutical agents |

| Kane 201448 (abstract) | Multivariate regression |

|

Given the incidence rate of AF in septic shock, a preventative study using [hydrocortisone] may be appropriate. Furthermore, future studies using [hydrocortisone] in this patient population should include AF as a secondary endpoint |

| Matsumoto 201534 (abstract) | NR |

|

NR |

| Brown 201838 | Markov chain analysis to account for patients who have achieved the outcome (sinus rhythm restoration). This analysis recognises that the outcome can be achieved by different medication. No other methods to address confounding were reported |

|

Future studies are needed to further explore this and determine many unknowns including optimal dosing and route, need for anticoagulation, and duration of treatment |

| Mieure 201136 (abstract) | NR |

|

A large randomized controlled trial designed to determine the optimal therapeutic strategy for a heterogeneous cohort of patients with new onset AF with RVR [rapid ventricular rate] is needed |

| Walkey 201628 | Propensity score matching approach using over 30 covariates covering specific patient demographics, hospital characteristics, prevalent comorbidities, type of acute organ failure and type of infection |

|

Our outcome findings should be considered hypothesis generating and supportive of the need for future clinical trials to investigate optimal treatment of AF during sepsis |

| Walkey 201629 | A propensity score approach was used to adjust for variables representing hospital characteristics, patient demographics, comorbidities, use of intensive care, measures of acute organ dysfunction, source of infection and year of hospitalisation | The authors reported RR of in-hospital ischaemic stroke associated with anticoagulation as 0.85 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.27) for patients with newly diagnosed AF. The RR of bleeding associated with parenteral anticoagulation was reported as 0.97 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.14) for patients with newly diagnosed AF | Whereas current evidence suggests that benefits may not outweigh risks of parenteral anticoagulation for AF during sepsis, further study is warranted to determine optimal timing for restarting treatment with oral anticoagulants among patients with pre-existing AF and long-term anticoagulation strategies after hospitalisation for patients with newly diagnosed AF during sepsis |

Pharmacological treatments

Seven studies28,33–38 investigated the effects of pharmacological treatments. Four studies included patients with sepsis28,33 or septic shock35,37 as their primary diagnosis. One study38 was conducted in a surgical population and two studies34,36 did not clearly specify the type of ICU and study population. A study by Walkey et al. 28 was not limited to an ICU population. A large proportion of studies did not report on the dose28,33,36–38 or the mode of administration33,36–38 of any treatment given. One study33 investigated the treatment effects of rate and rhythm control strategies, but the conference abstract did not report which specific interventions were studied. Outcomes reported included cardioversion to sinus rhythm,33–36,38 mortality28,33,35,37 and lengths of ICU and hospital stays. 37

Most of the larger studies28,34–36 (sample size > 100 patients) compared amiodarone with beta-blockers (e.g. landiolol and metoprolol). A large study28 from the USA reported that patients treated with amiodarone were more likely than patients treated with beta-blockers to be critically ill with septic shock. The RR of hospital mortality for patients who received beta-blockers compared with patients who received amiodarone was 0.67 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.77) after adjustment for confounding, which indicates a better outcome for patients with beta-blockers. However, the patient characteristics between these groups were different and the matching of groups in the NOAF cohort was not reported. Balik et al. 35 reported higher ICU mortality in patients receiving amiodarone (40%) than in patients receiving metoprolol (21%); however, this was reported as being not statistically significant. Three studies34–36 compared conversion rates between amiodarone and beta-blockers, and found that rates of conversion to sinus rhythm were slightly, but not significantly, higher in patients receiving beta-blockers. However, Balik et al. 35 did not adjust for confounding factors such as sickness score. Matsumoto et al. 34 and Mieure et al. 36 did not report the methods used for the analysis.

Walkey et al. 28 compared outcomes in patients who received digoxin and those who received beta-blockers. Following propensity score matching (n = 1932), the RR of hospital mortality for patients who received beta-blockers compared with patients who received digoxin was 0.75 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.88), which indicates a better outcome for patients treated with beta-blockers. 28 However, only around 60% of patients in the propensity score-matched cohorts were ICU patients, and the study was restricted to patients with sepsis; therefore, this study’s results should not be considered applicable to a broad ICU population. Moreover, the study was judged as being at a serious risk of bias owing to confounding (see Risk-of-bias assessments).

Four studies28,36–38 investigated the effects of calcium channel blockers (e.g. diltiazem). Walkey et al. 28 found no statistically significant difference in mortality between patients who received beta-blockers and patients who received calcium channel blockers (RR 0.99, 95% CI 86 to 1.15). Similarly, a conference abstract by Jaffer et al. 37 reported no statistically significant difference in death at discharge between patients administered beta-blockers and patients administered calcium channel blockers. Two studies36,38 compared conversion rates between patients who were administered calcium channel blockers and patients who were administered either amiodarone36 or beta-blockers. No meaningful conclusions from the results of these two studies could have been made owing to the small sample sizes. In addition, the Mieure et al. 36 study was available only as a conference abstract in which the study methods and population characteristics were not reported.

Prophylactic treatments

A small (n = 109 patients) study48 assessed the association of hydrocortisone with NOAF in patients who were diagnosed with septic shock. The authors concluded that administering hydrocortisone was associated with a reduction in the incidence of NOAF (20.5% in patients who received hydrocortisone vs. 42.9% in those who did not; p = 0.022). 48 No evidence of a difference in mortality and length of stay between the study groups was reported. This study was published as a conference abstract; therefore, limited data were available on the study population and analysis.

Anticoagulants

One large study29 (n = 7522) included a subgroup of patients who developed NOAF during sepsis in hospital, of whom just over 60% of whom were treated in an ICU. Rates of in-hospital stroke were low (n = 104, 1.9%). Given that the length of hospital stay was not reported, the duration of exposure was unclear. Following propensity score matching (n = 5585 analysed) there was no evidence of a difference in rates of in-hospital ischaemic stroke events between patients who did and those who did not receive parenteral anticoagulation (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.27). Given the low event rate, the study may have had inadequate power to determine whether or not a statistically significant difference exists. There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of bleeding associated with parenteral anticoagulation between the groups (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.14).

Prospective single-group studies

Six prospective single-group studies39,40,45–47,49 were included in the review. The sample sizes of the included studies39,45–47,49 ranged from 16 to 37 patients; one study40 did not report the sample size. Four studies were undertaken in Europe,39,46,47,49 one in Asia45 and one in North America. 40 Five articles39,40,46,47,49 were published between 2002 and 2008, and one article45 was published in 2016. One publication40 was available only as a conference abstract.

One study45 was conducted in a mixed ICU and one study40 was conducted in a general ICU. Two studies47,49 were conducted in specialty ICUs, such as surgical or medical ICUs. The type of ICU was not clearly specified in two studies. 39,46 Four studies39,45–47 investigated the treatment effects of pharmacological treatments and one study49 looked at electrical treatments. One study40 reported both the treatment effects of pharmacological treatments and the preventative effects of anticoagulation for stroke prophylaxis. Details of the prospective single-group studies can be found in Appendix 3, Tables 15 and 16.

Pharmacological treatments

Pharmacological treatments such as amiodarone,40 ibutilide,46,47 beta-blockers45 and MgSO4–amiodarone step-up scheme39 were investigated. Four studies39,40,46,47 reported conversion to sinus rhythm as the primary outcome and one study45 looked at mortality as an outcome.

Slavik et al. 40 investigated the treatment effects of amiodarone; however, results were not clearly reported in this conference abstract.

A study45 (n = 16) set in Japan investigated the effects of switching therapy from landiolol to the Bisoprolol patch (Bisono® tape, Toa Eiyo Corp, Tokyo, Japan) in a mixed ICU population. This study reported that survival was achieved in 81% of the patients in whom switching therapy was introduced. Another very small study39 (n = 29) investigated the effects of a new treatment protocol consisting of the infusion of magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) as a first-line therapy and amiodarone as a second-line therapy in the case of no conversion. The study population was mixed and comprised medical and surgical ICU patients who were diagnosed with NOAF. Study treatments were administered as per institutional protocol based on MgSO4–amiodarone step-up scheme, for which infusion of amiodarone was started if conversion to sinus rhythm or reduction in the ventricular rate of < 110 beats per minute (b.p.m.) within 1 hour after the start of MgSO4 infusion was not achieved. The authors reported that amiodarone was required in 13 MgSO4 non-responders, of whom 11 converted to normal sinus rhythm within 24 hours. No adverse events were reported.

Two very small studies46,47 investigated the treatment effects of ibutilide. Both studies administered i.v. ibutilide, with a maximum dose of 2 mg. Hennersdorf et al. 46 (n = 26) reported slightly lower conversion rate to sinus rhythm than Delle Karth et al. 47 (n = 17) (71% vs. 82%, respectively).

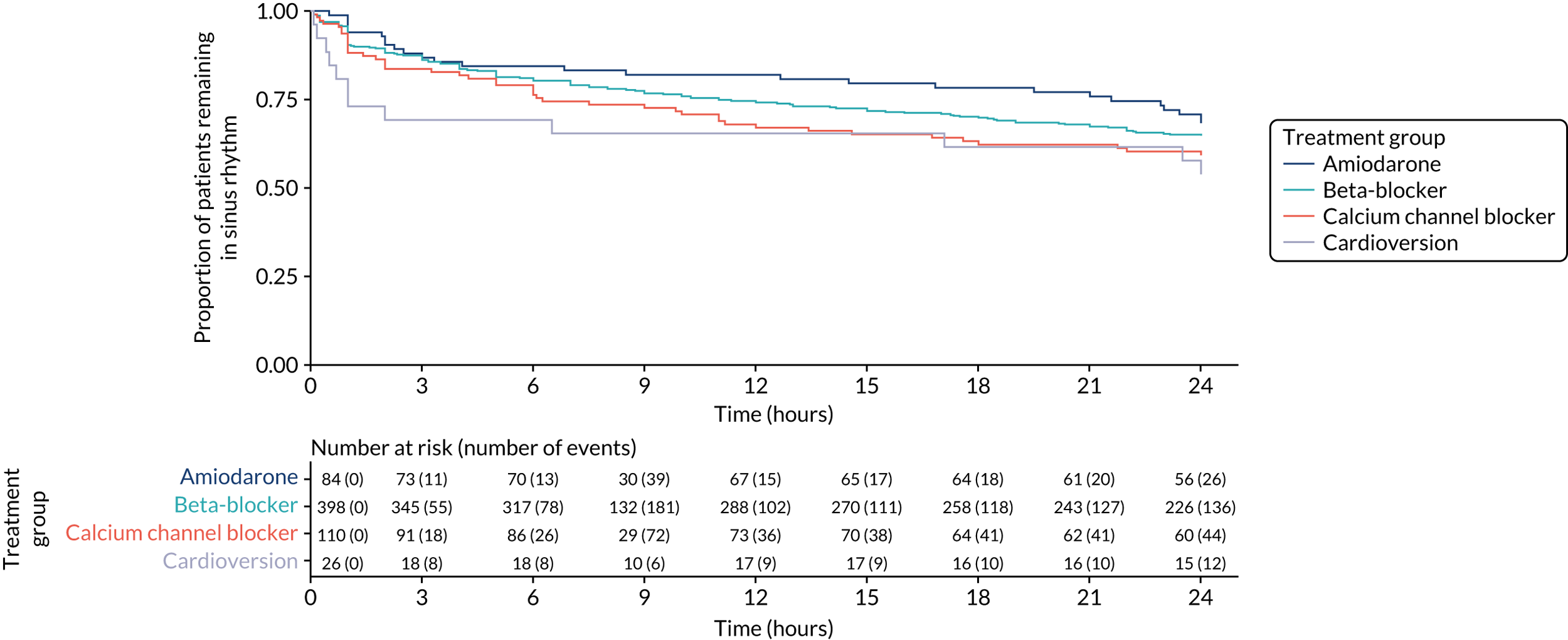

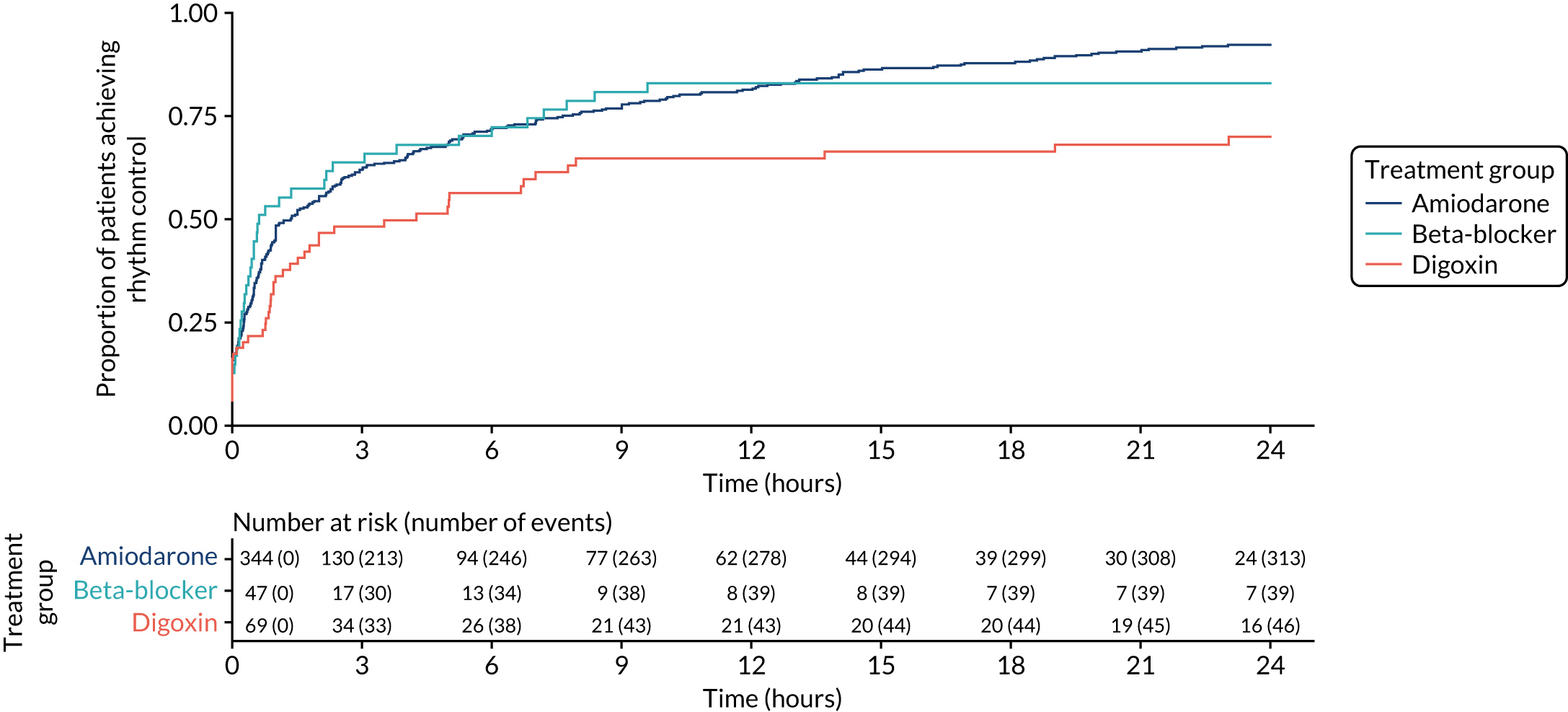

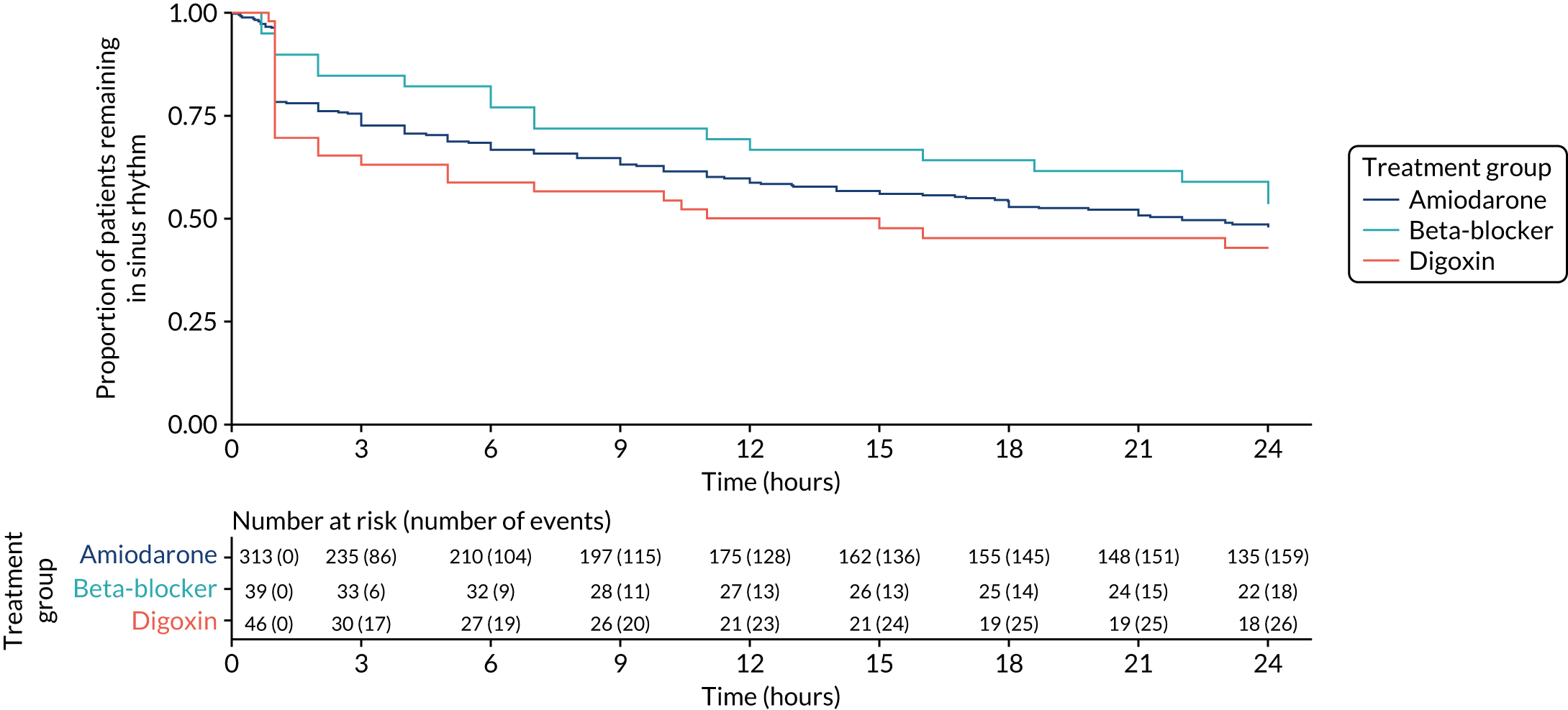

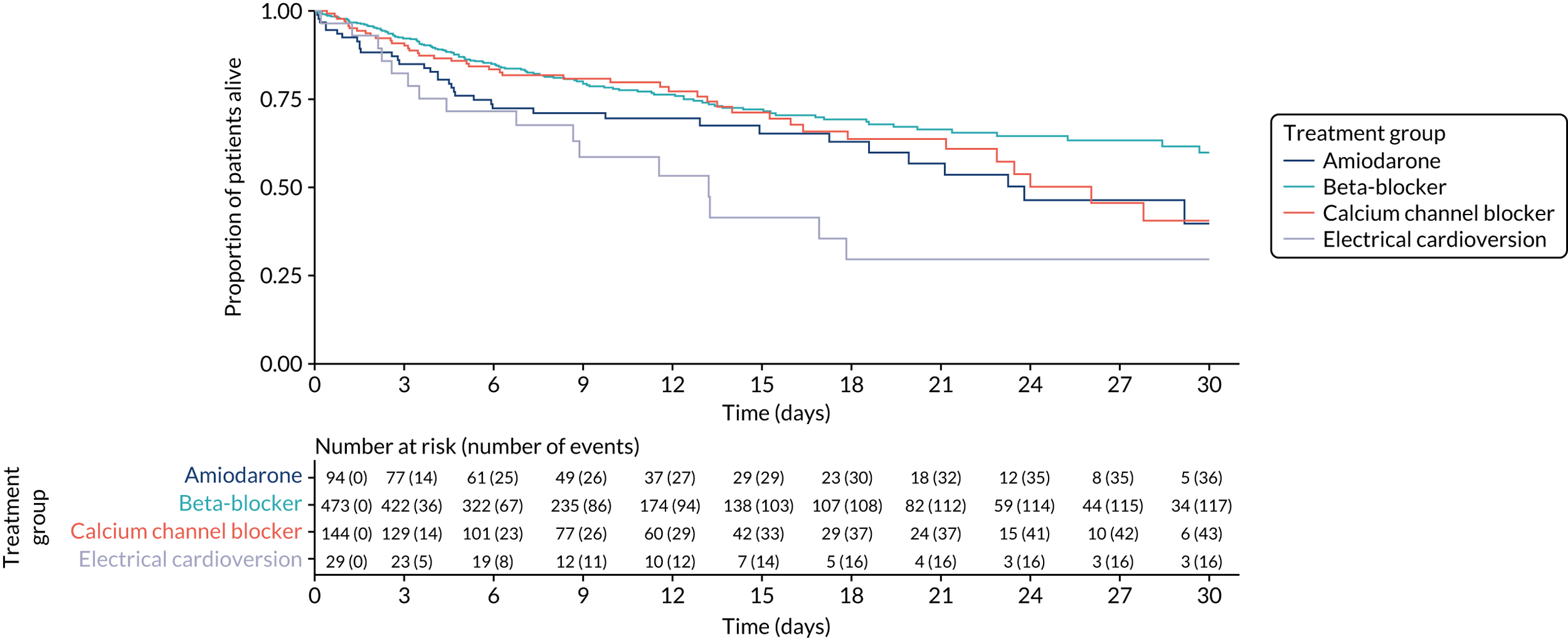

Electrical treatments

A small study49 (n = 37) assessed the effect of direct current cardioversion (DCC) in a surgical ICU population. The treatment for patients with regular supraventricular tachyarrhythmia consisted of a maximum of four consecutive cardioversions with an energy delivery of 50 J, 100 J, 200 J and 300 J. For patients with irregular supraventricular tachycardia, cardioversion was performed with an energy delivery of 100 J, 200 J and 360 J. Thirty-five per cent of patients (n = 13) primarily responded to DCC with restoration of sinus rhythm for ≥ 5 minutes, of whom 62% (n = 8) remained in sinus rhythm at 1 hour. At 24 and 48 hours, 16% and 13.5% of patients remained in sinus rhythm, respectively.

Anticoagulants

Slavik et al. 40 studied i.v. heparin as a prophylactic treatment for stroke; this was used in 36% of NOAF episodes. The authors did not report which anticoagulant was used in the other 64% of NOAF cases. It was reported that stroke prophylaxis was achieved in 91% of NOAF episodes. The authors concluded that the appropriateness of therapy for stroke prophylaxis was ‘optimal’. This was decided using prespecified study definitions. Five per cent of the study population experienced major bleeding as a side effect of i.v. heparin. 40 It must be noted that only an abstract was available for this study; therefore, limited data were obtained. Moreover, the definition of ‘appropriateness of therapy assessed as optimal, appropriate and inappropriate’ was not provided.

Retrospective single-group studies

Six retrospective single-group8,41–44,50 studies were identified, with sample sizes ranging from 30 to 240 patients. Four studies8,41–43 had a sample size of > 100 patients. Two studies were set in each of North America8,44 and Asia,41,50 one in Europe43 and one in Australia. 42 One article43 was published in 2004 and five articles8,41,42,44,50 were published between 2010 and 2019.

Four studies8,42,43,50 were conducted in mixed ICUs, one study in a surgical ICU44 and one study in a medical ICU. 41 Three studies investigated the treatment effects of pharmacological treatments,8,42,43 one study investigated electrical treatments50 and two studies looked at both pharmacological and electrical treatments. 41,44 The details of the retrospective single-group studies can be found in Appendix 3, Tables 17 and 18.

Pharmacological treatments

The following pharmacological treatments were investigated in the included studies: amiodarone,8,41–44 beta-blockers (e.g. metoprolol, esmolol and sotalol),8,41,44 calcium channel blockers (e.g. diltiazem)41,44 and digoxin. 41,44 Two studies41,44 did not report on the dose and mode of administration of the treatments studied.

Four larger studies8,41–43 (n > 100 patients) investigated the treatment effects of amiodarone. Conversion rates to normal sinus rhythm ranged from 65% to 87%. 8,41,43 Studies reported different time points for conversion rates; for example, at some point while receiving amiodarone8 and during the first 48 hours of amiodarone therapy. 43 Maintenance of normal sinus rhythm in patients who had converted back while receiving amiodarone ranged from 49% to 59% at the time of ICU discharge. 8,42 The studies reported different time points at which maintenance of sinus rhythm was achieved, such as until discharge from the ICU. 42 It should be noted that, where reported, the dose and administration of amiodarone were heterogenous between the studies. 8,42,43 One study43 reported on treatment adverse effects associated with amiodarone, finding increases in serum concentrations of creatinine and bilirubin.

A study41 undertaken in a population with sepsis reported that 76% of patients who were given beta-blockers (n = 88), 71% of those who were administered calcium channel blockers (n = 66) and 55% of those who were given digoxin glycosides (n = 27) converted back to sinus rhythm within 7 days after the onset of NOAF. Although some authors also studied the treatment effects of beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers and digoxin, the sample sizes were too small to make any meaningful conclusions8,44 or the results were not clearly reported. 44

Electrical treatments

Kyo et al. 50 investigated the effect of electrical cardioversion in a mixed ICU population (n = 85). A median of one shock per electrical cardioversion session was reported and the delivered electrical cardioversion energies in the first and second shocks were ≤ 100 J in 91% and 83% of all electrical cardioversion patients, respectively. The authors reported successful electrical cardioversion, defined as conversion to sinus rhythm for at least 5 minutes after an electrical cardioversion session, in 48% of patients, and 13% of these patients maintained sinus rhythm until ICU discharge.

Liu et al. 41 administered electrical cardioversion to eight patients and reported that 50% of these patients converted back to normal sinus rhythm. No more details on the intervention and outcome were available.

Reviews and guidelines

Twelve review articles53–64 were included in the current review. Of these, two were systematic reviews,53,56 six were narrative review articles54,57–59,62,64 and four were review articles55,60,61,63 that proposed a treatment algorithm based on available evidence. Most of the included reviews53–55,57–61,63,64 (n = 10) were published after 2012. No guidelines were identified in this scoping review.

Systematic reviews

Yoshida et al. 53 conducted a systematic review of the epidemiology, prevention and treatment of NOAF in critically ill patients. One database was searched and eligibility criteria were specified for study inclusion in the systematic review. The authors assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. 65 No studies on NOAF prevention were included in the systematic review and five studies8,30,39,66,67 investigating treatments for NOAF were eligible. Of the five studies identified by Yoshida et al. ,53 three 8,30,39 were eligible for this scoping review and two66,67 were excluded on outcome. The five included studies, of which one was a RCT,30 evaluated the clinical effectiveness of NOAF treatments, such as amiodarone, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, magnesium sulphate and DCC. However, no conclusive findings on the treatment strategies were reported. The authors concluded that the current evidence for the management of NOAF in a general ICU population is very limited and further research is urgently required.

In 2008, Kanji et al. 56 published a systematic review of RCTs to assess the treatments of NOAF in non-cardiac ICU patients. Three databases were systematically searched, the study eligibility criteria were clearly specified and a quality assessment of each included RCT was conducted using a basic rating instrument (the Jadad scale68). Four RCTs30,51,52,69 that assessed the efficiency of procainamide (a sodium-channel blocker), flecainide (a sodium-channel blocker), esmolol, amiodarone, verapamil, diltiazem and magnesium were included in the Kanji et al. 56 review. Only one RCT 30 identified by Kanji et al. 56 was included in this scoping review. Two RCTs51,52 had a study population consisting of < 70% of NOAF patients (and so were not eligible for this scoping review). The other study69 included in the Kanji et al. 56 review investigated patients with AF; however, it was not clear whether or not these patients had NOAF (therefore, this study was excluded on population in this scoping review). The authors were not able to make evidence-based recommendations for pharmacological rhythm conversion strategies for a general ICU NOAF population owing to considerable methodological heterogeneity of the included RCTs. The authors emphasised the need for well-designed and adequately powered RCTs to evaluate treatment strategies for critically ill patients with NOAF. Moreover, they recommended that future research should address treatments of choice and goals of care using a standardised outcome measure of success.

Other types of review

The evidence on pharmacological54,55,57–63 and electrical55,59,62,63 treatment strategies for NOAF was discussed in the other review articles. Four articles54,57,59,63 discussed the management of NOAF in sepsis patients and six articles57,60–64 reviewed the literature on anticoagulation strategies for critically ill patients with NOAF. Four articles55,60,61,63 proposed an algorithm for the management of NOAF in an ICU setting based on the available evidence.

Pharmacological treatments

It is widely reported that the management of arrhythmias in critical care settings is a major problem59,62 and that research on optimal therapeutic strategies for critically ill patients with NOAF is urgently needed. 54,55,57–59,61–63 Some articles55,58,61 argued that beta-blockers may be a reasonable first-choice treatment given the current evidence of decreased mortality55 and improved heart rate control. 55,58 By contrast, some authors discussed amiodarone as being a potentially effective treatment54,57,59,60,62 based on current evidence and its widespread use; however, it was also recognised that amiodarone has potentially significant side effects. 54,60,62 Other pharmacological treatments, such as propafenone,54,62 calcium channel blockers,55,62,63 digoxin54,55,62 and ibutilide,62 were discussed, but no conclusive findings were made. Four articles55,60,61,63 proposed a treatment algorithm, but the algorithms should be interpreted cautiously because they were developed based on limited evidence that was not identified and critiqued systematically.

Electrical treatments

Reviews suggested that DCC might often be unsuccessful55 and might also be associated with a high relapse rate. 55,62 More evidence in critically ill populations is required to support this62 and the current findings should be used to guide research in therapy and mechanisms.

Anticoagulants

A review article62 concluded that there was no clear evidence of whether or not stroke risk reduction outweighs the increased risk of bleeding when using therapeutic anticoagulation in critically ill patients with NOAF. Labbe et al. 64 reported a high frequency of major bleeding events and recommended that anticoagulation therapy should be administered only in patients with the highest risk of arterial thromboembolic events. This assertion of high bleeding rates referenced one study that did not compare bleeding events between patients who received anticoagulation and patients who did not, and one study that found no significant difference in bleeding events between these two patient groups. A patient-centred single-case decision approach of whether or not to use anticoagulant therapy was also suggested in another review. 57 Sibley and Muscedere61 recommended that anticoagulation therapy should be initiated if AF persists for > 48 hours and in patients with a high risk of arterial thromboembolic events. 61 Only one review article61 discussed which drug would be appropriate to use for anticoagulation in ICU patients. Unfractionated heparin was reported to be the drug of choice for critically ill patients owing to its short half-life and reversibility with protamine; however, it must be noted that the authors of the review61 did not provide any references for this statement.

Surveys and opinion pieces

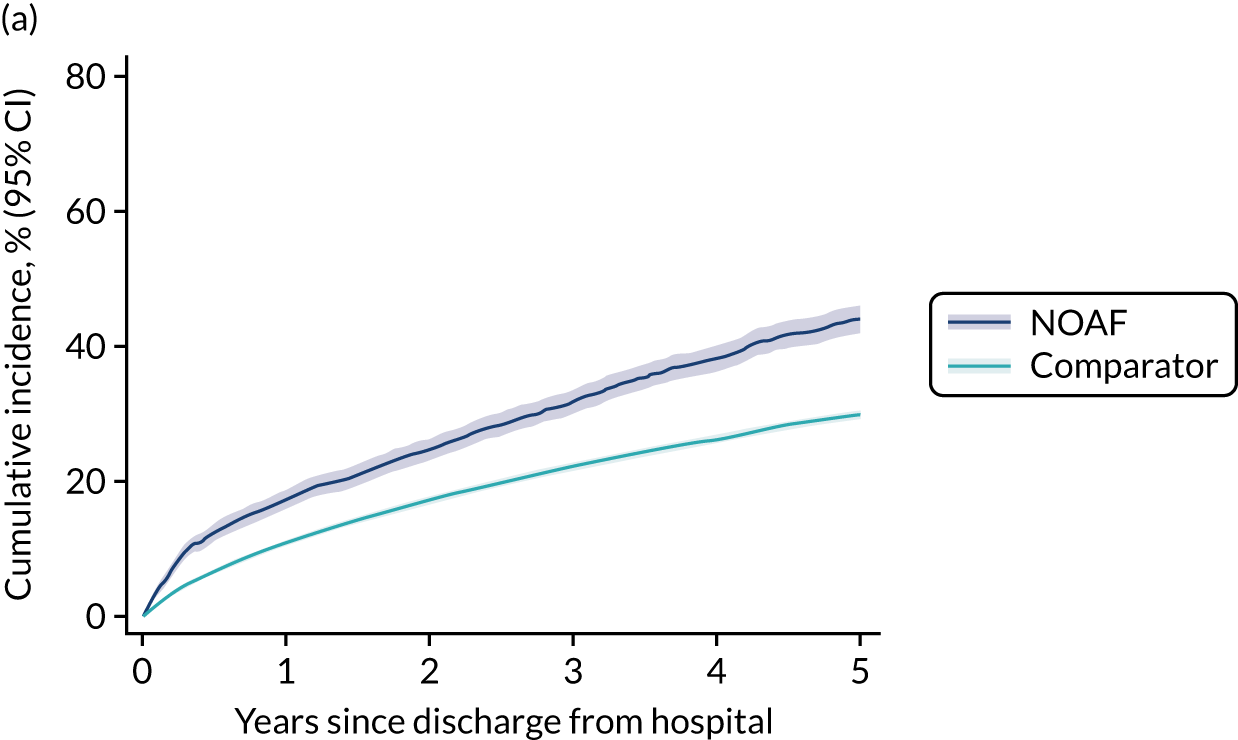

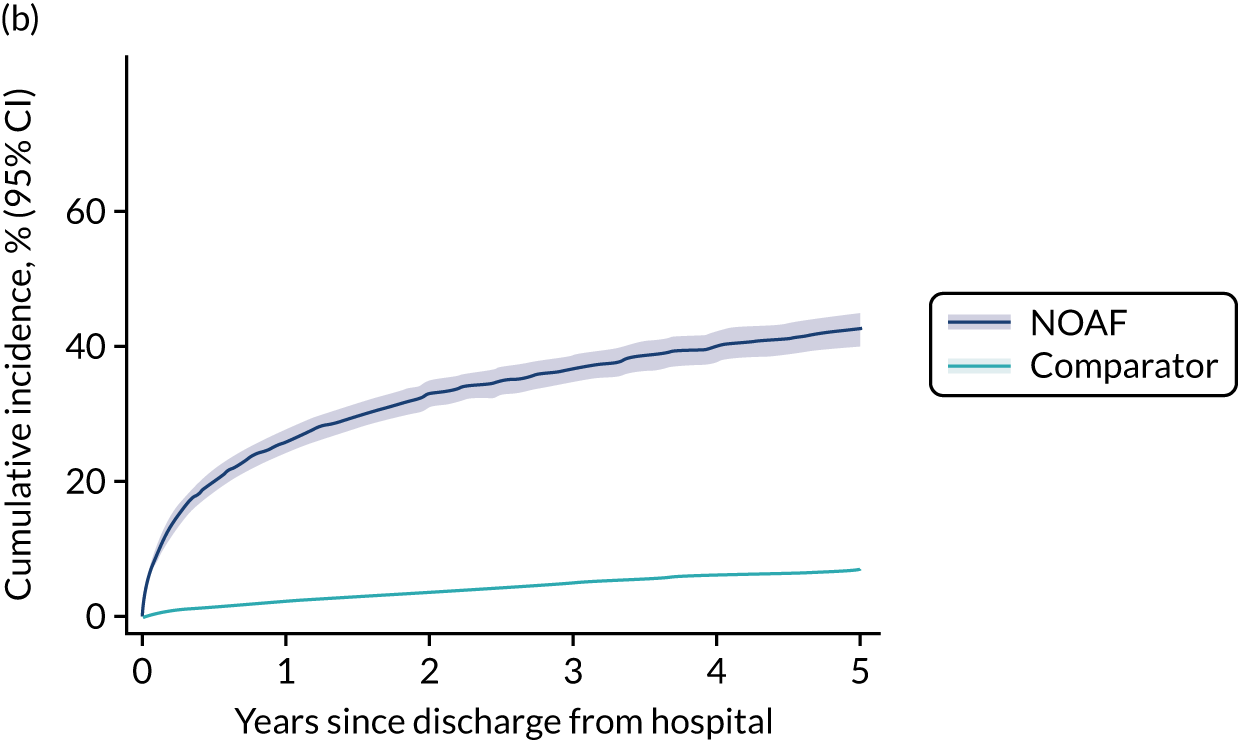

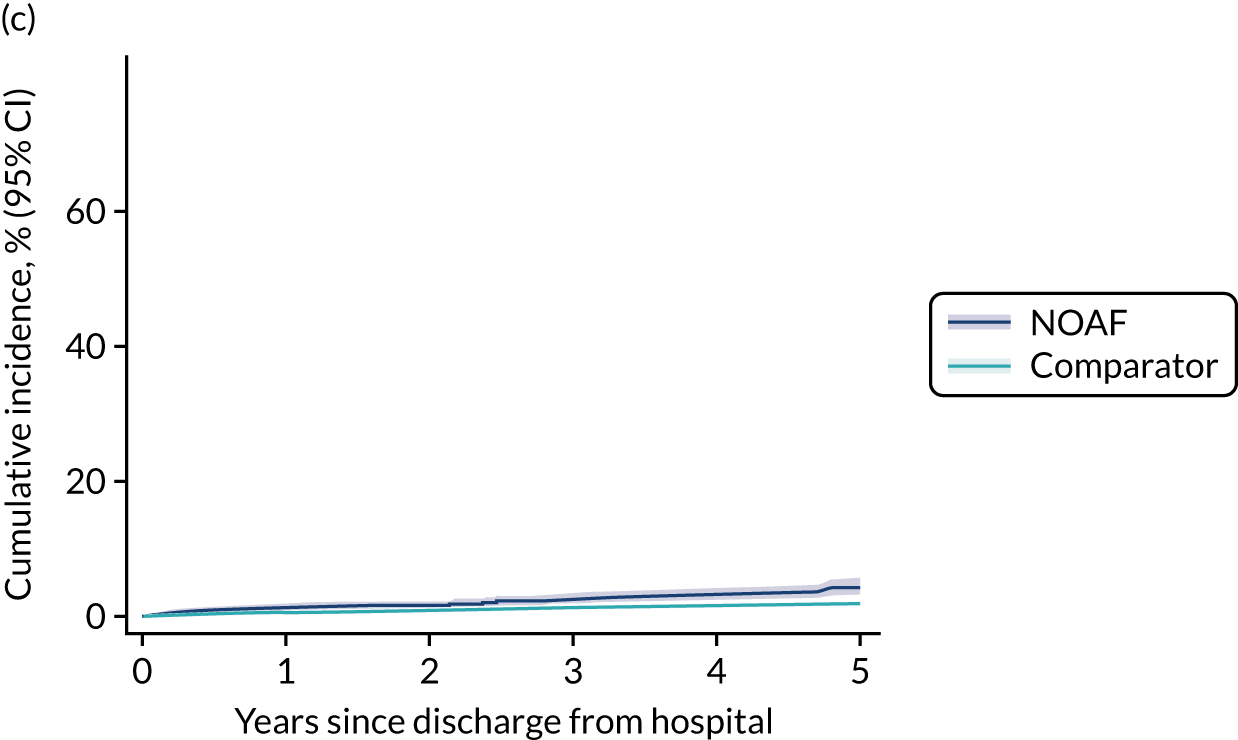

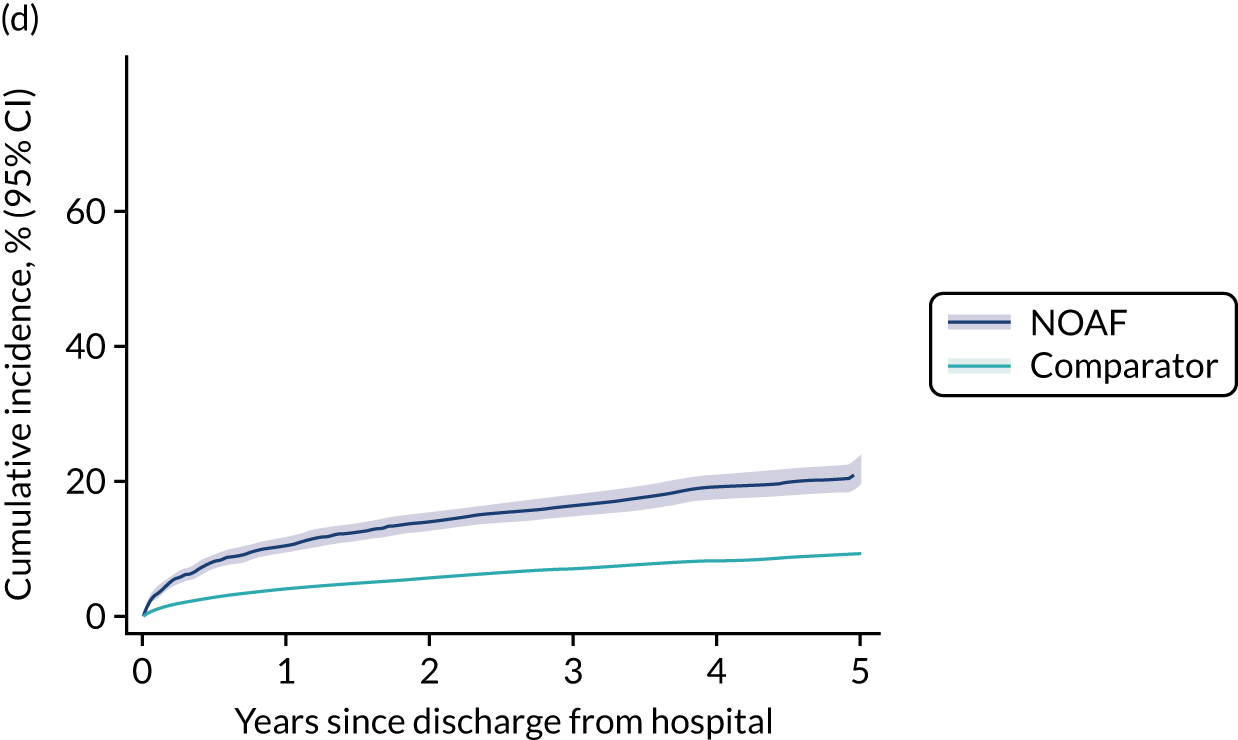

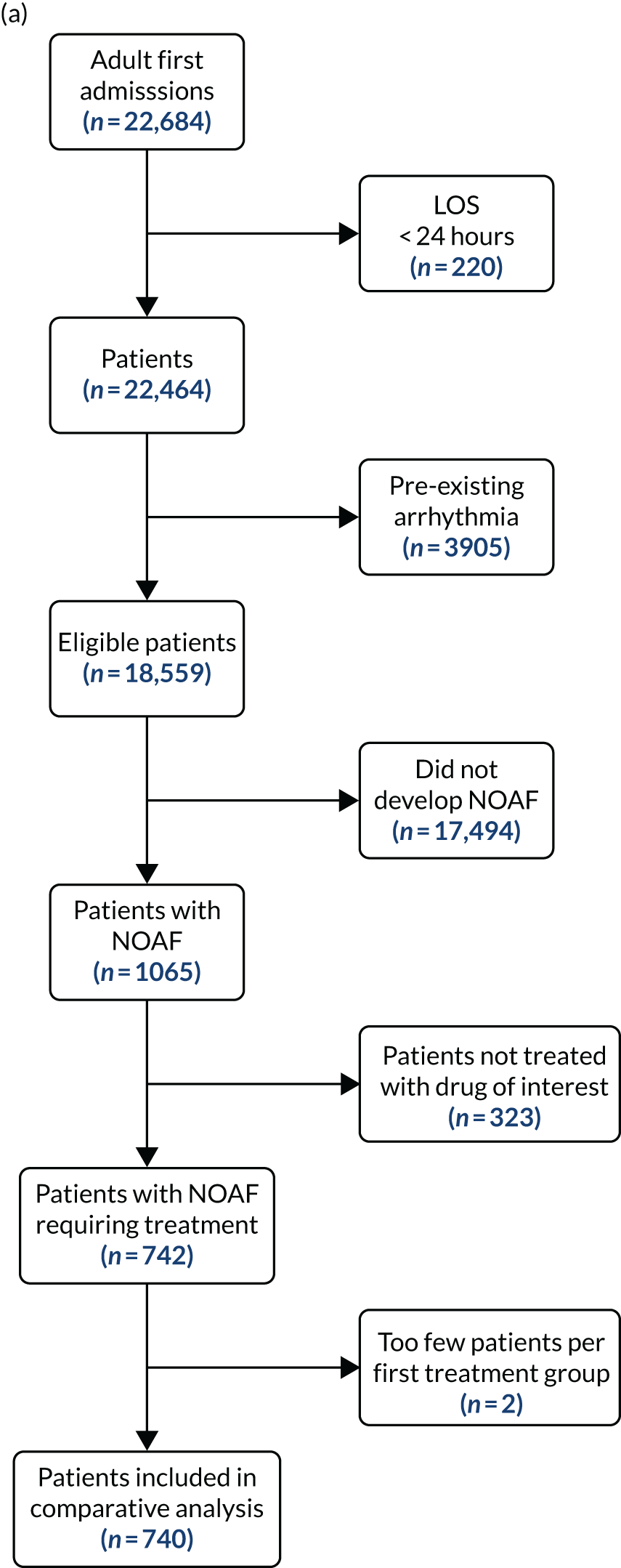

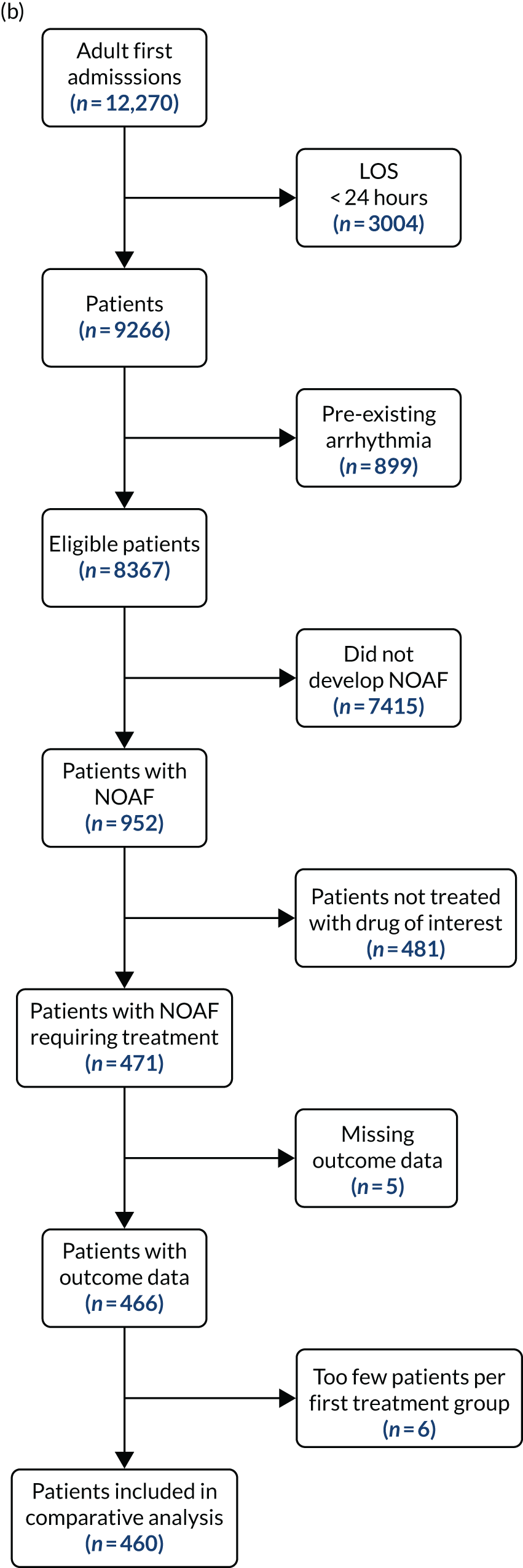

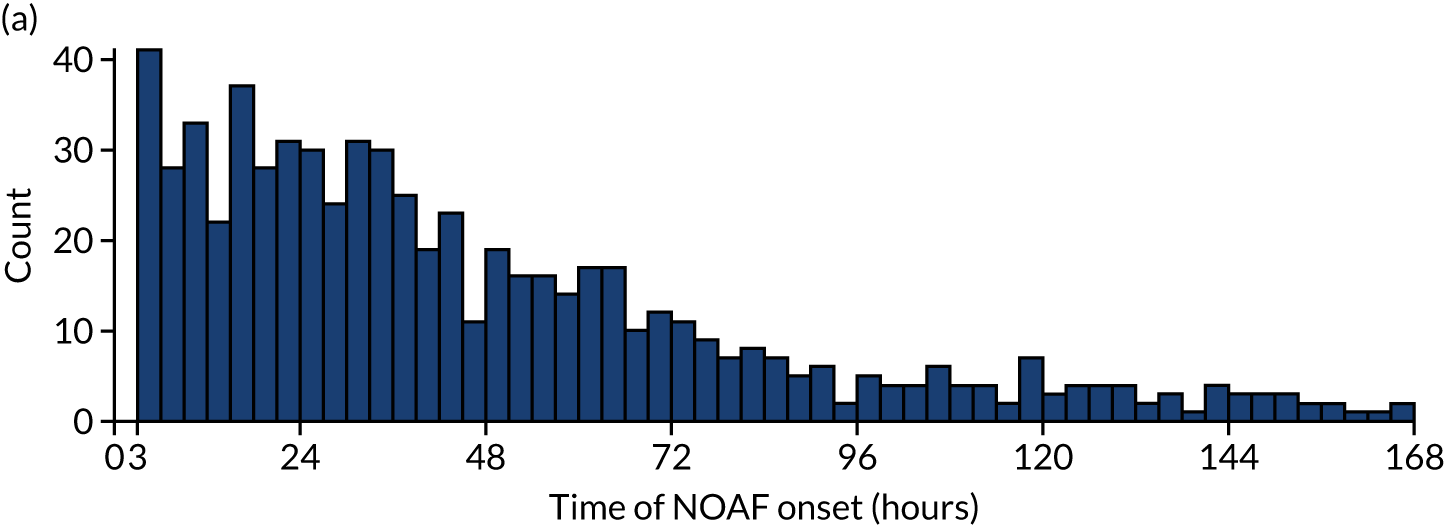

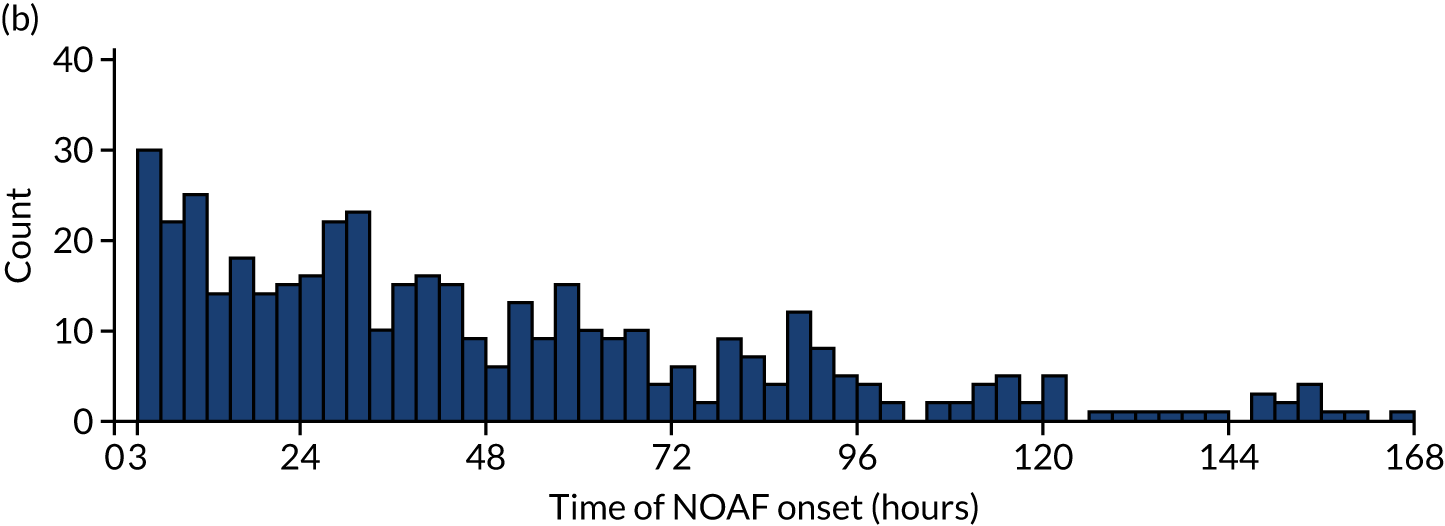

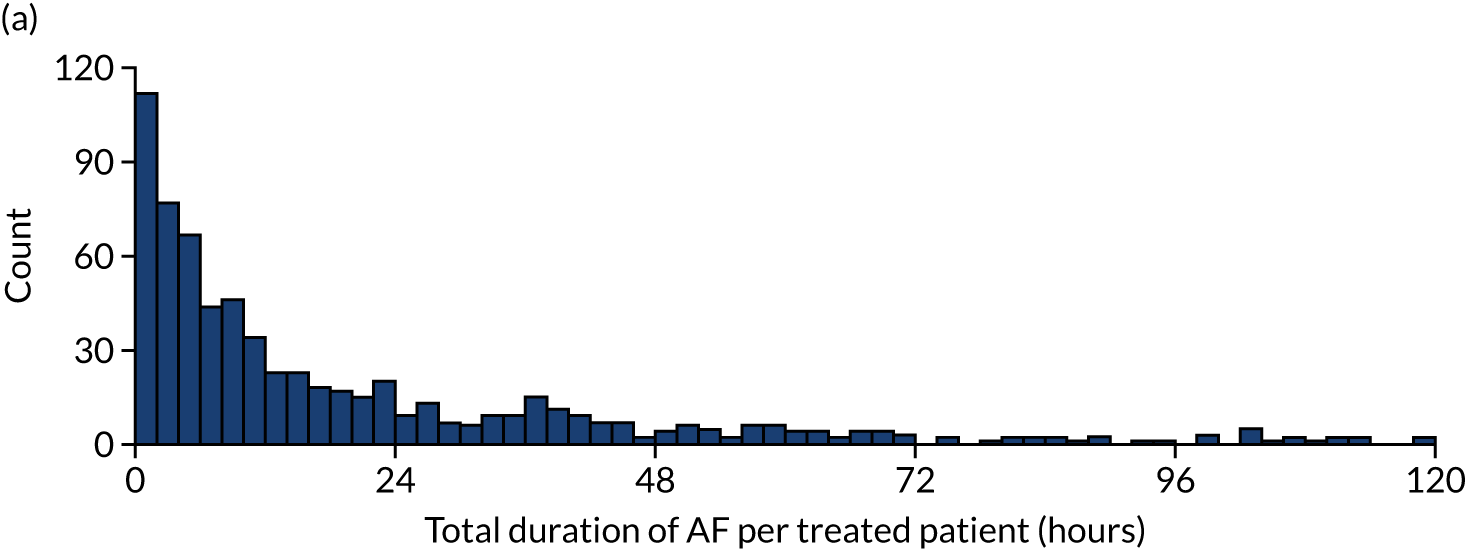

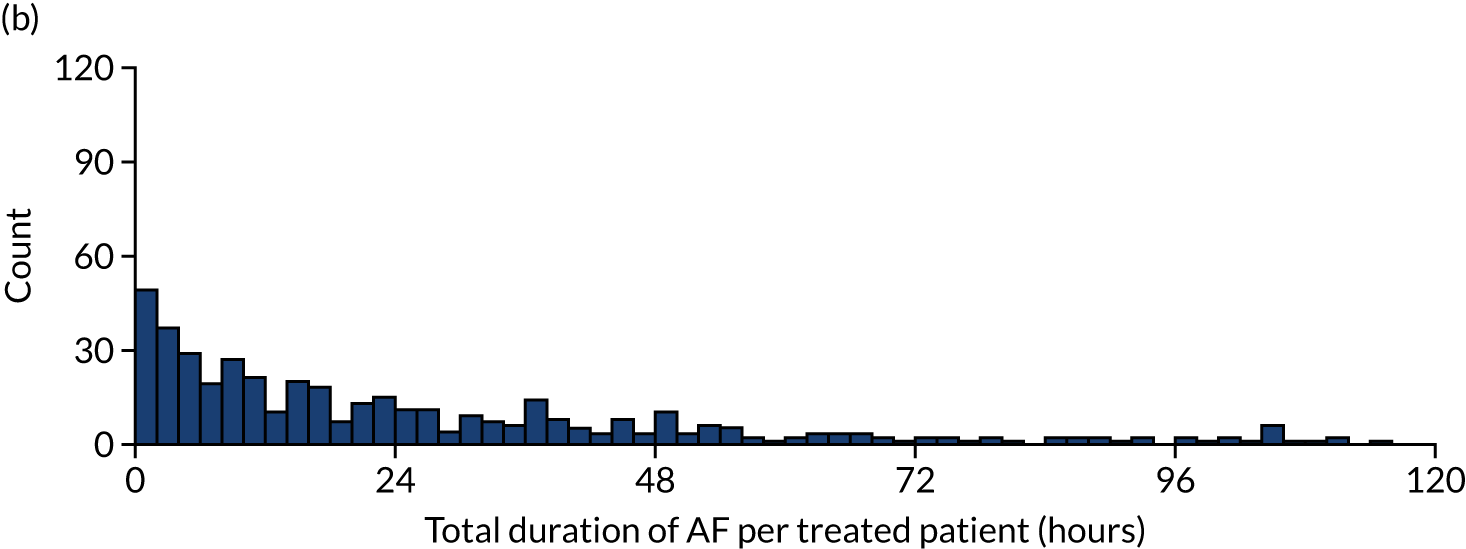

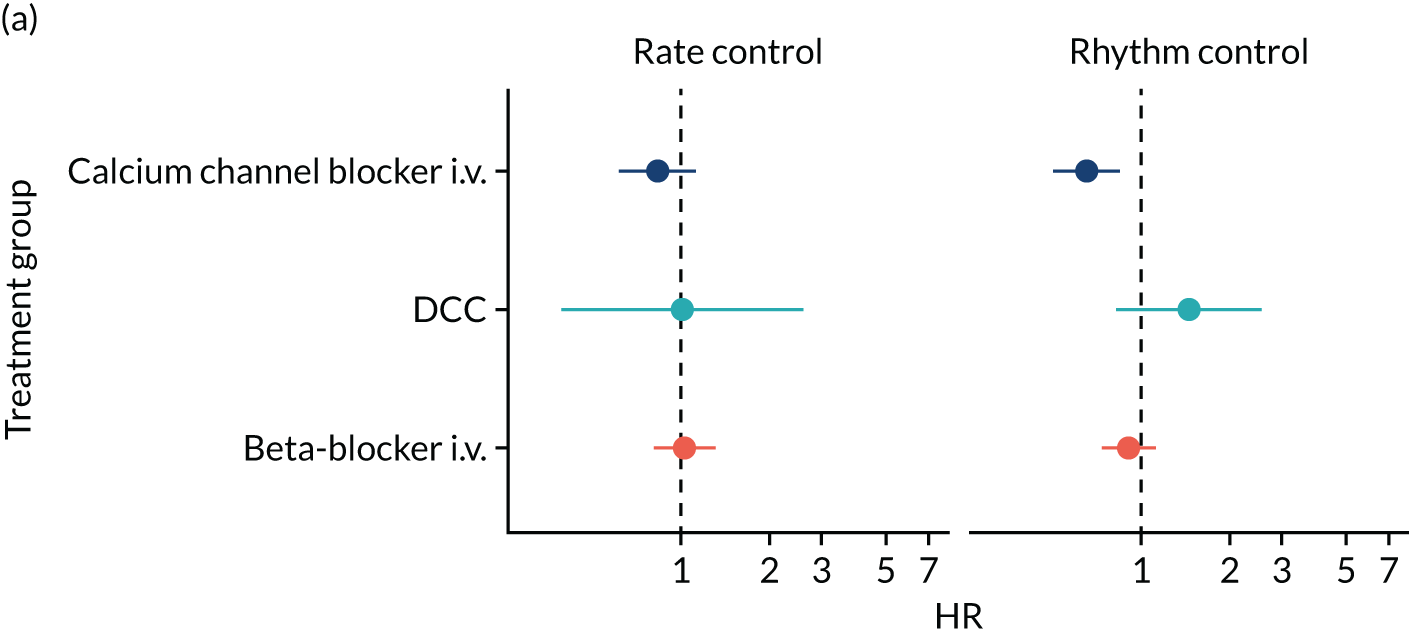

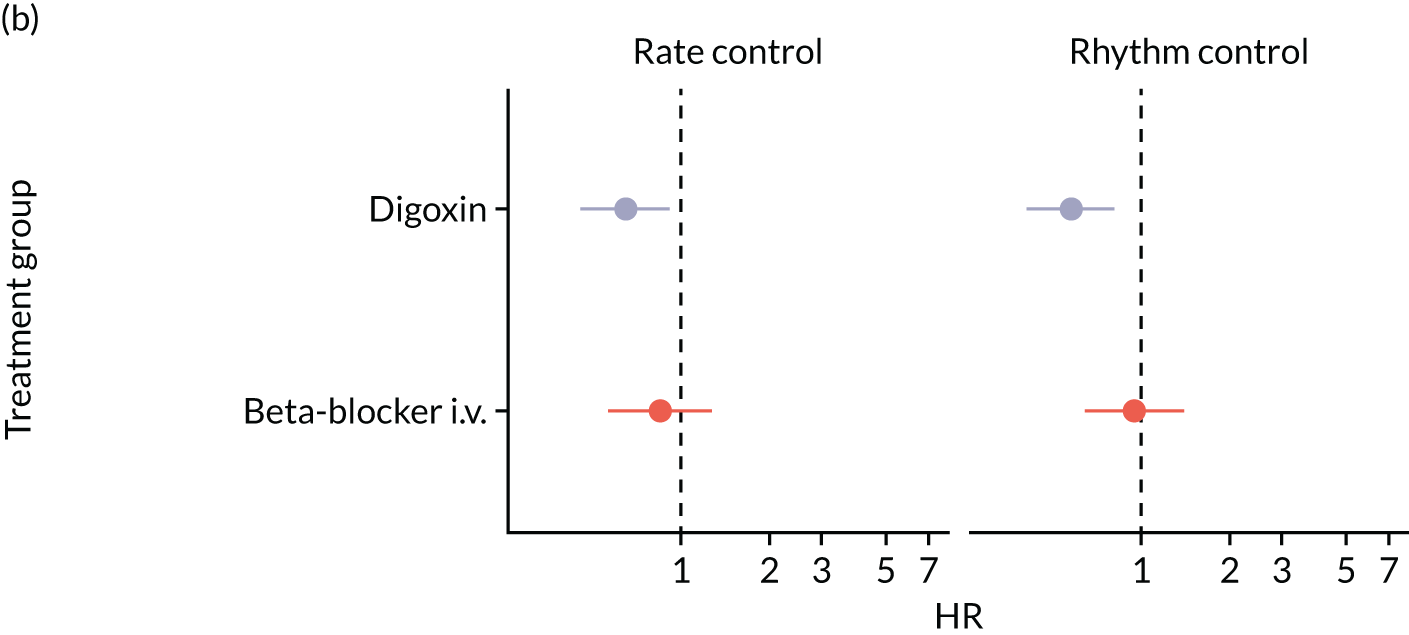

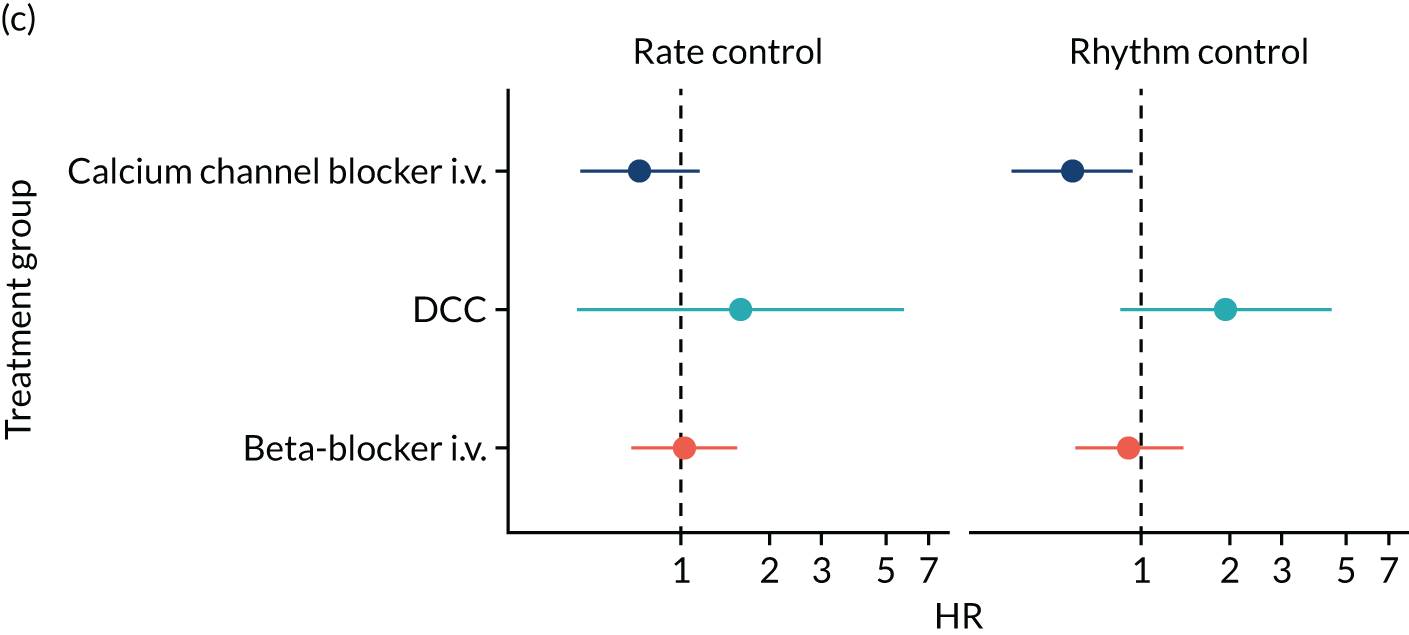

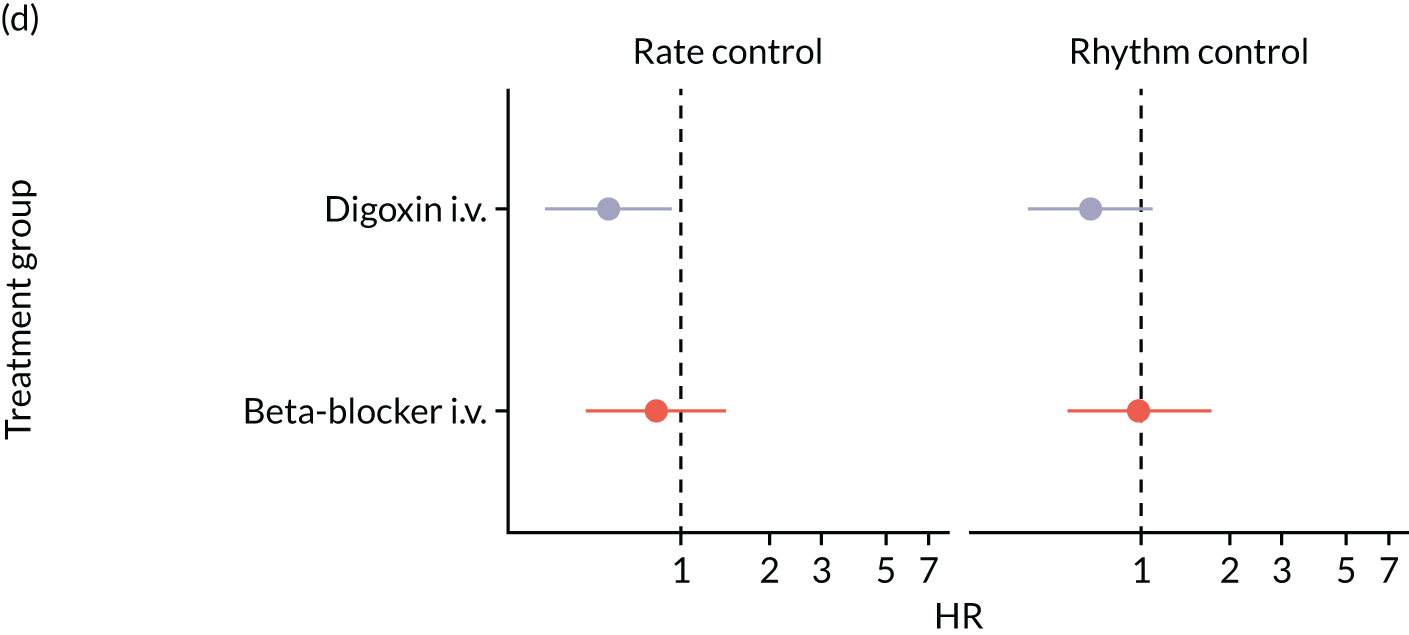

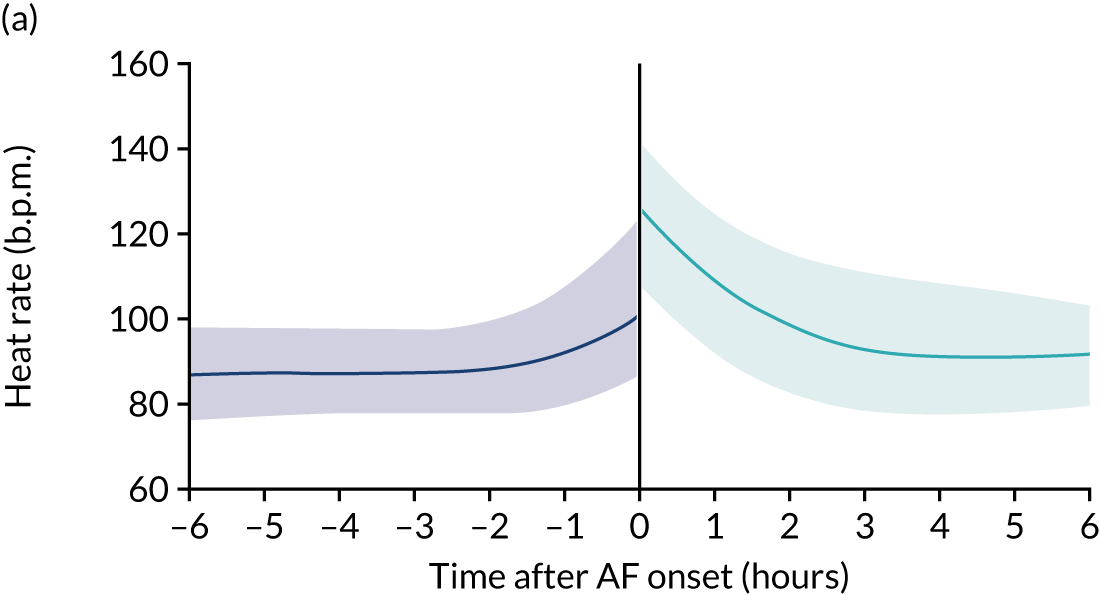

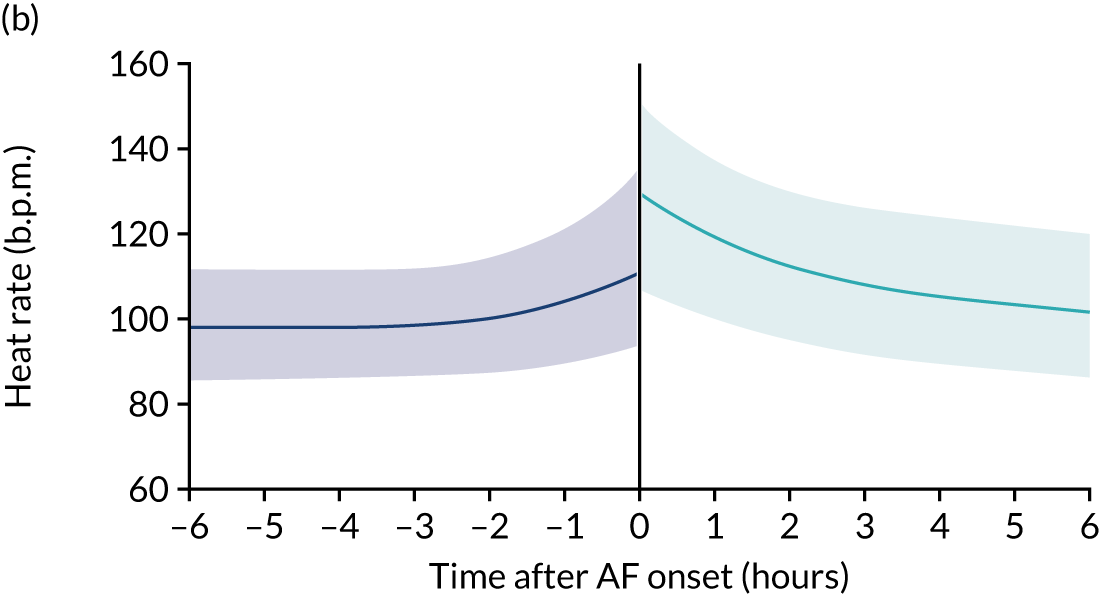

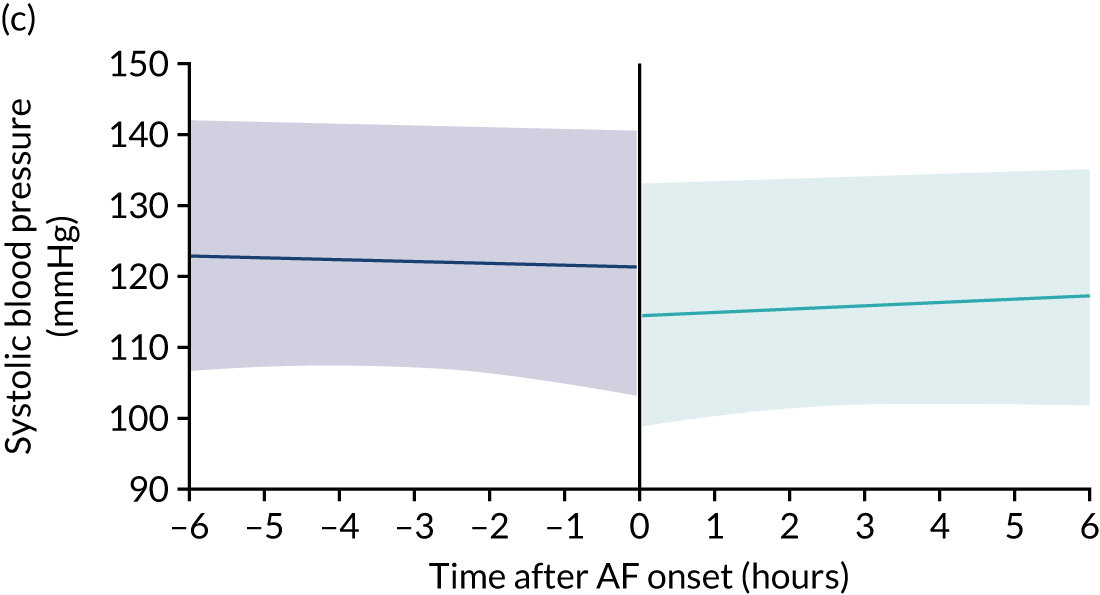

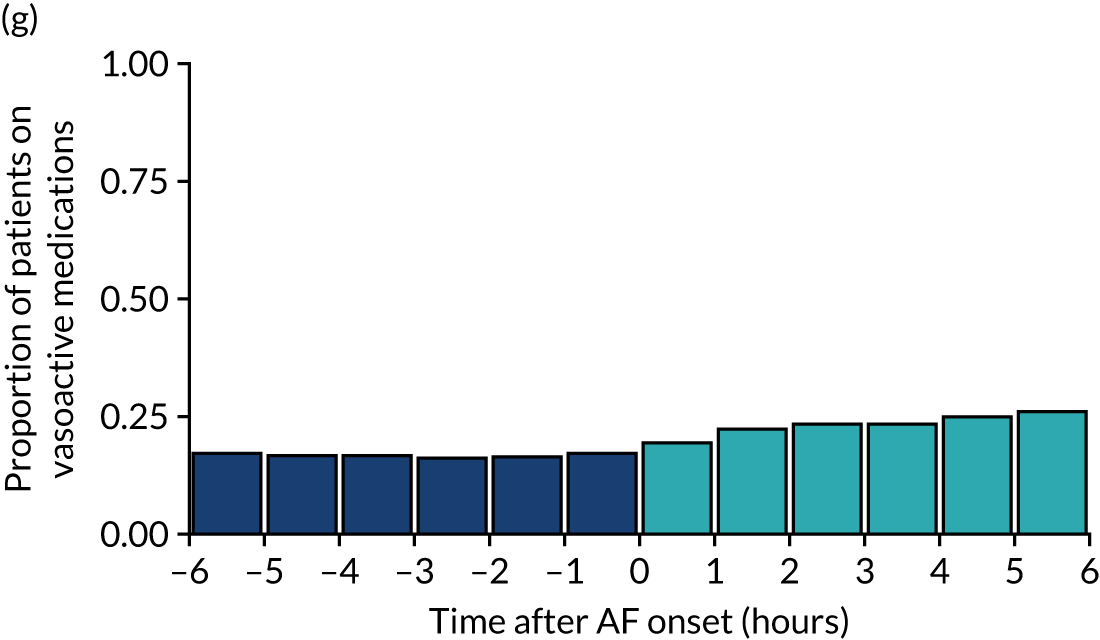

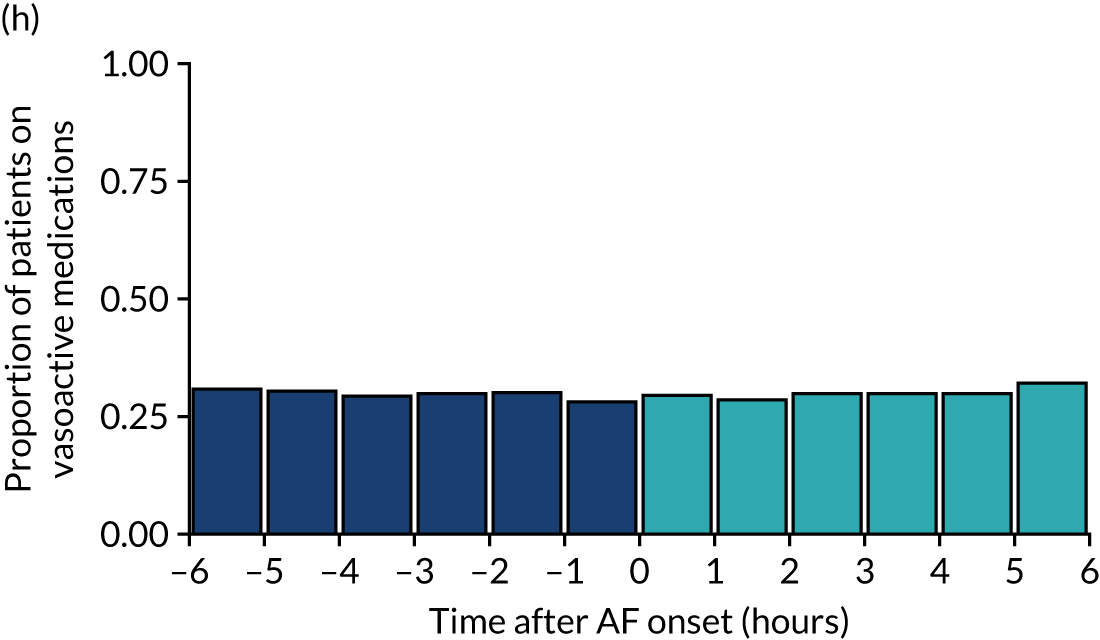

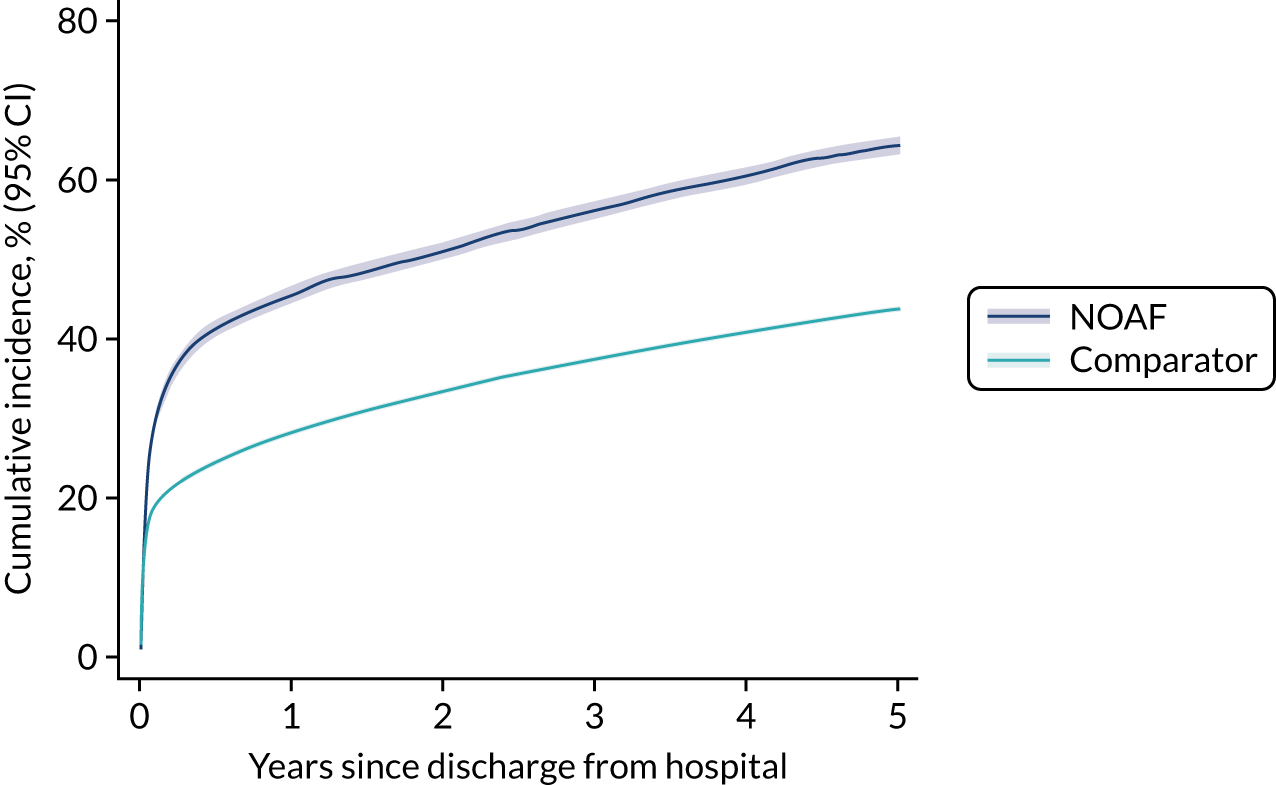

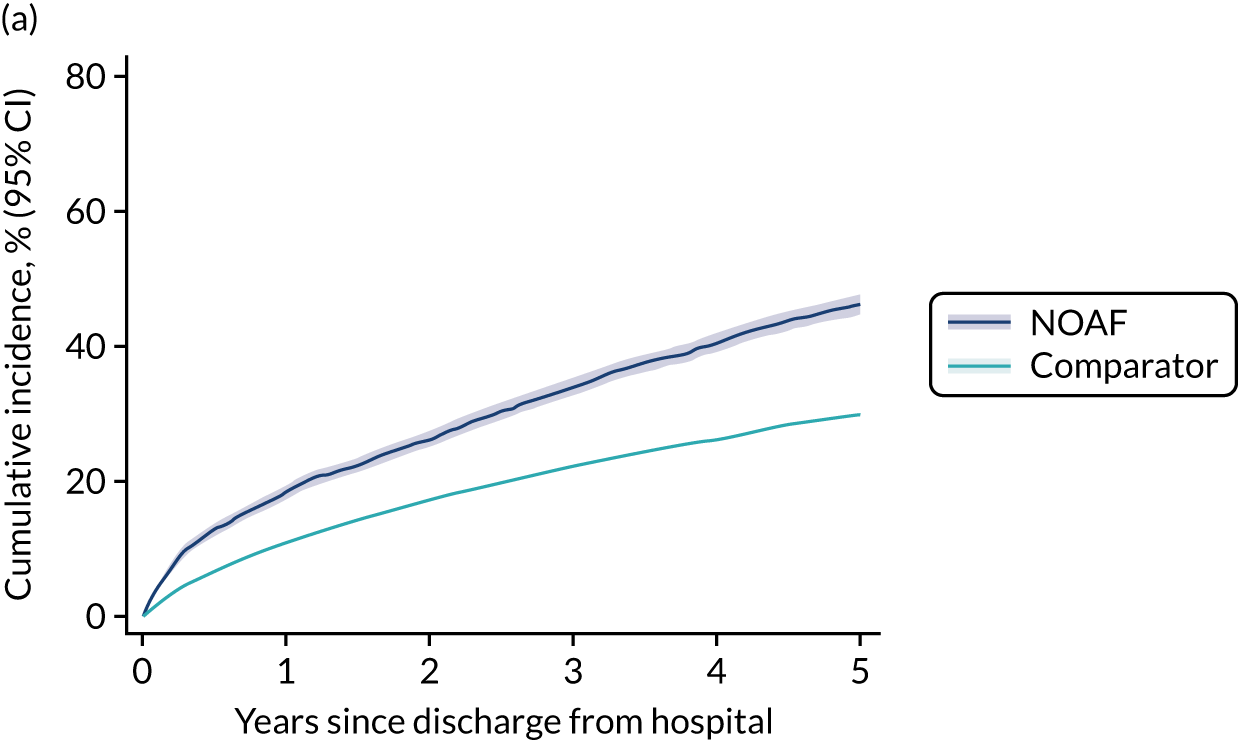

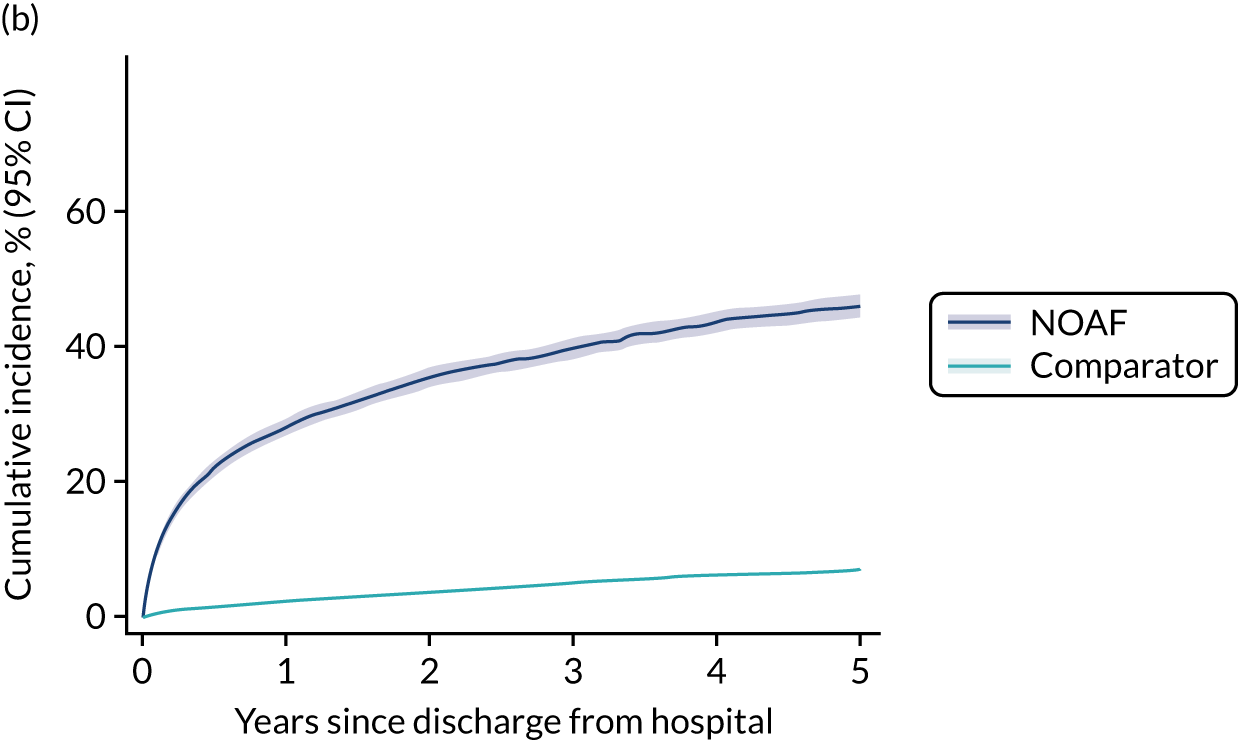

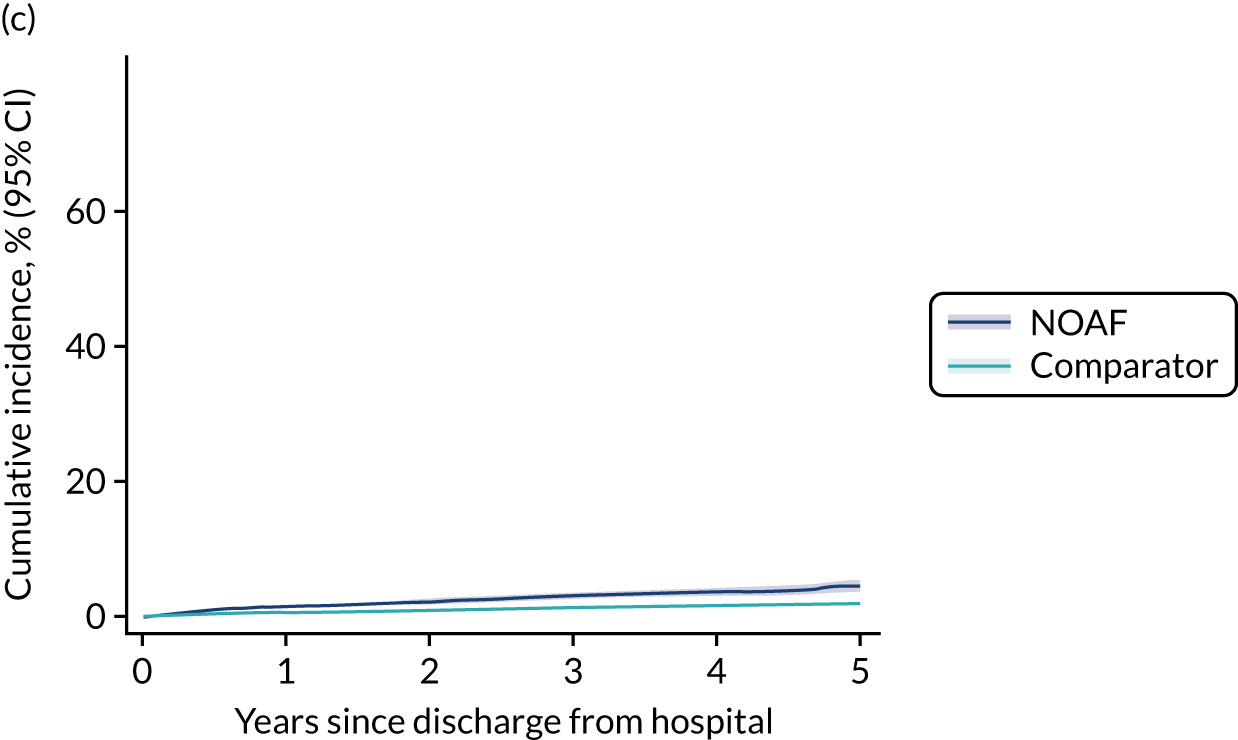

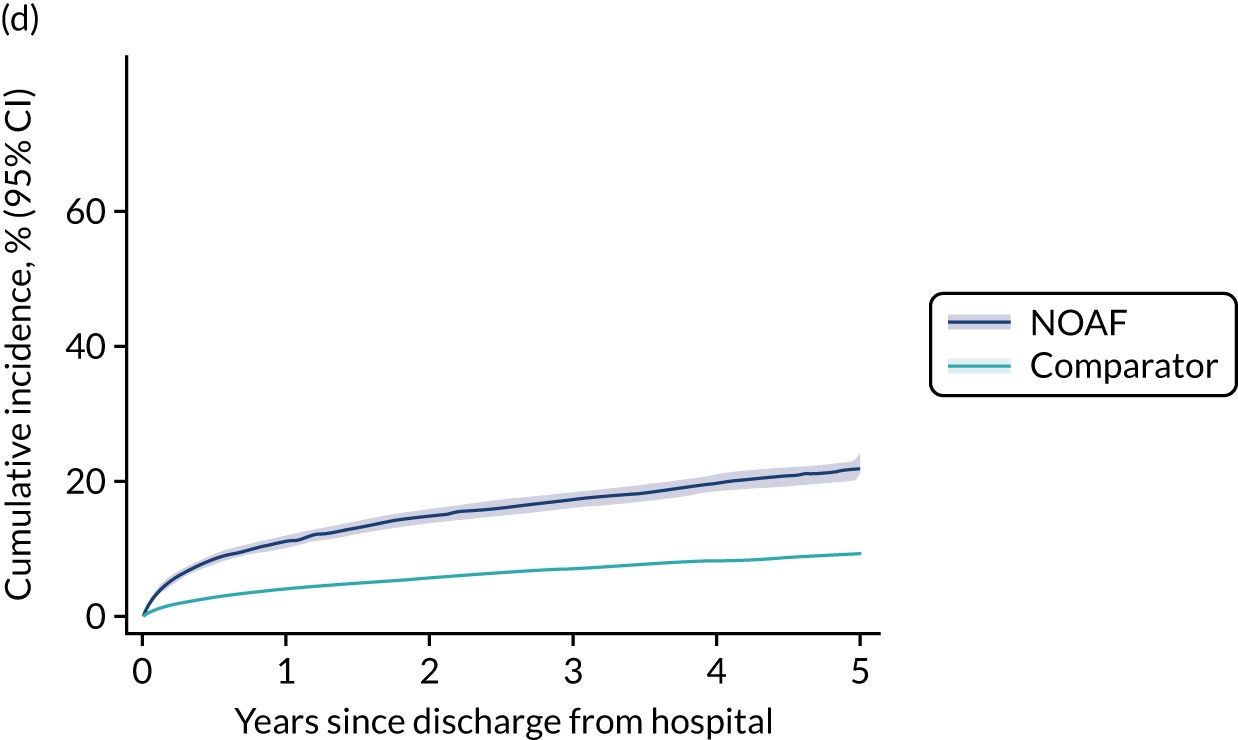

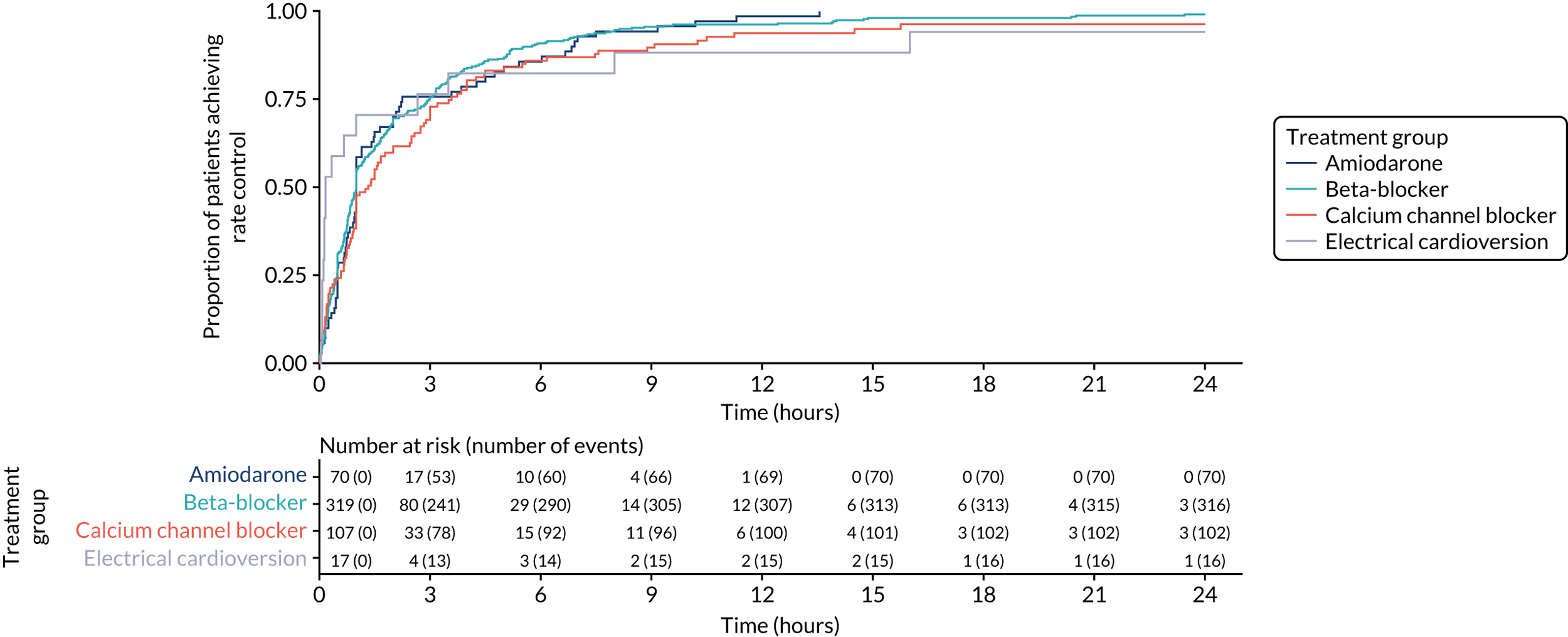

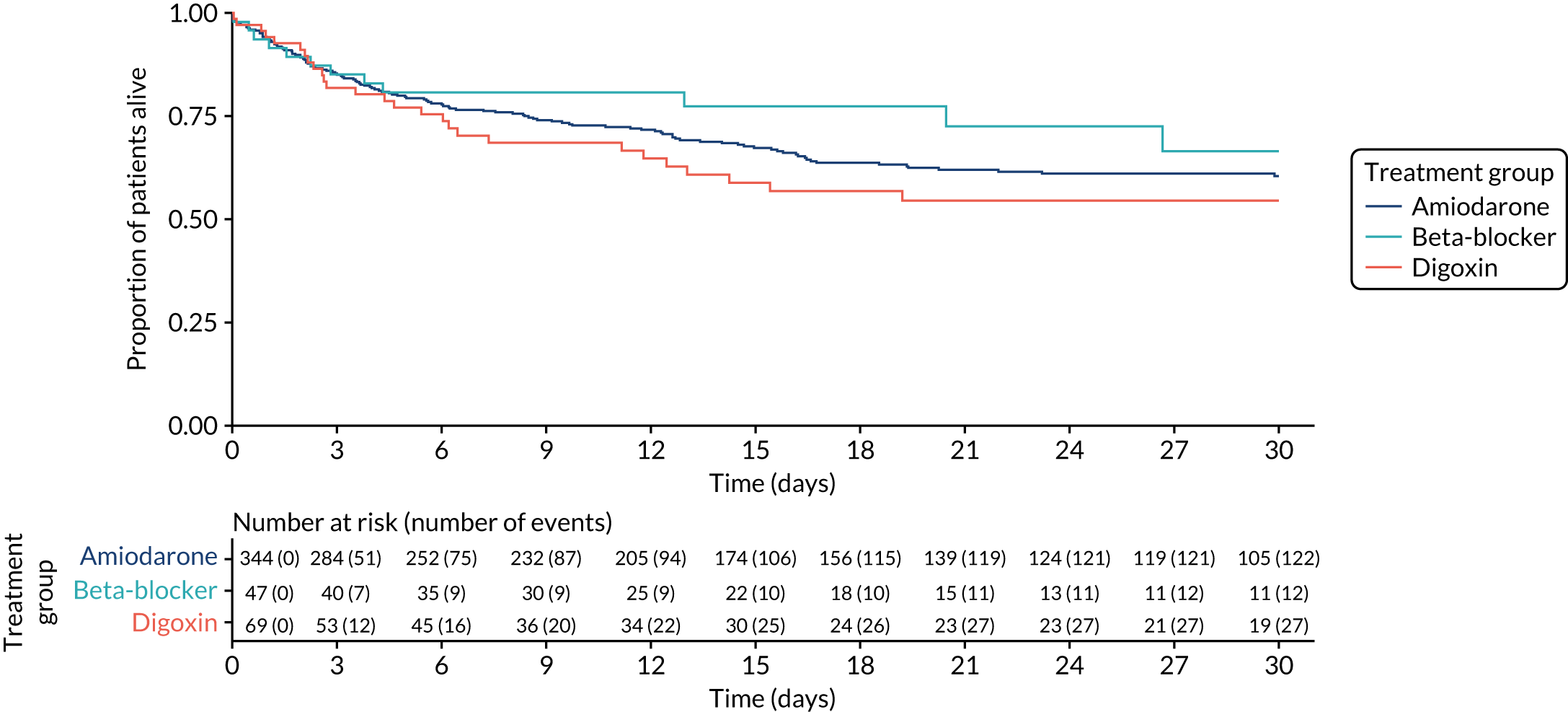

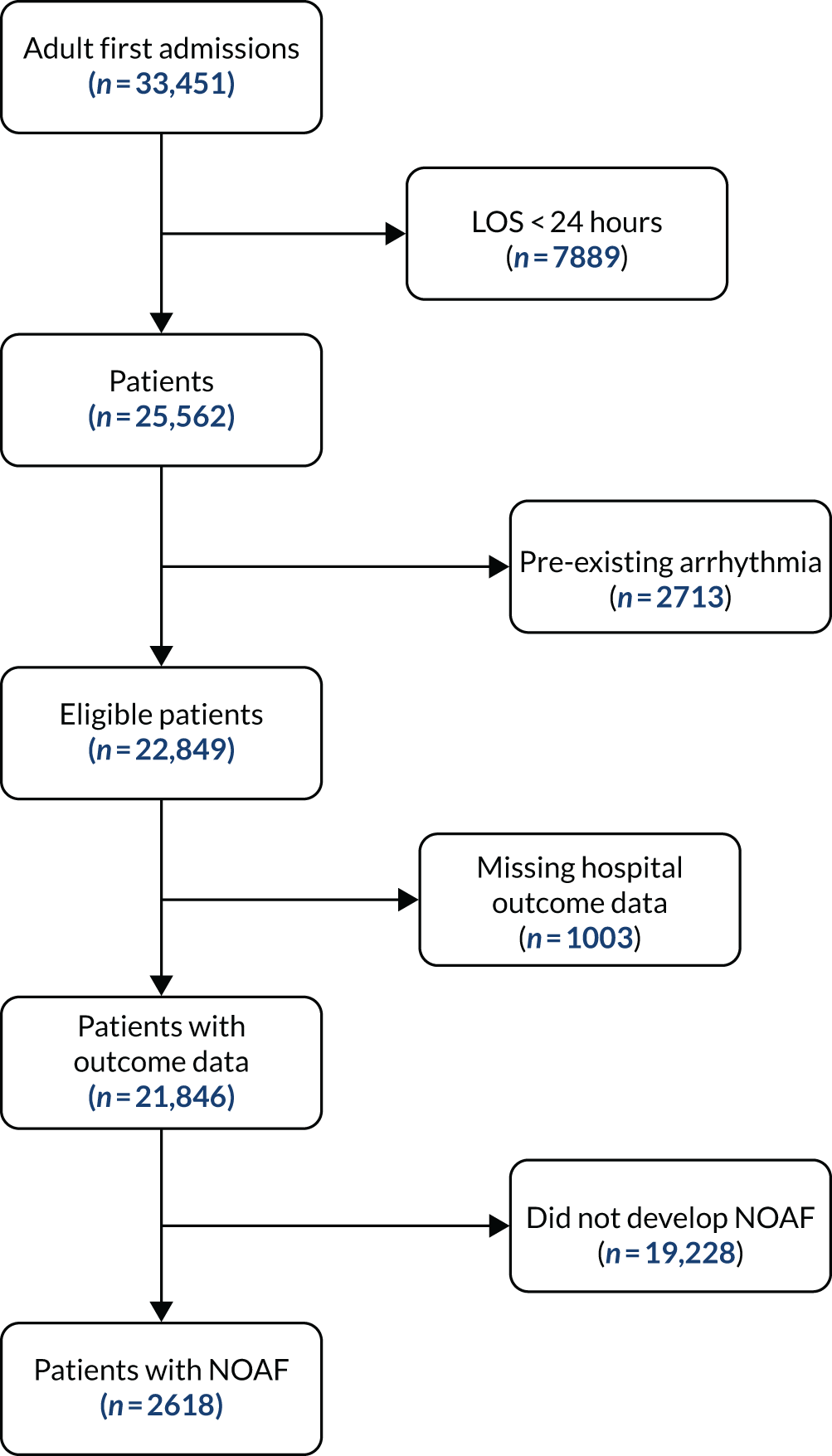

Surveys