Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/20/02. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The draft report began editorial review in September 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Eke et al. This work was produced by Eke et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Eke et al.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

The acquisition of continence is an important milestone in child development. It involves planning, recognition of sensation, regulation, control, urinating and defecating in an appropriate place and cleaning and dressing afterwards. 1,2 Becoming continent involves the maturation of developmental domains, including sensory perception, cognitive and social understanding and motor planning, and there is wide variation in the age at which this occurs. Social, economic and environmental factors, parenting strategies and behaviour all affect the acquisition of continence.

Neurodisability describes a group of congenital or acquired long-term conditions that are attributed to the impairment of the brain and or neuromuscular system, creating functional limitations. 3 Impacts may include difficulties with movement, cognition, hearing, vision, communication, emotion and behaviour. Sensory disturbances may impair balance, proprioception and interoception. Children with neurodisability may often be referred to as children with special educational needs or children with disability.

Children with neurodisability have a higher incidence of delayed acquisition of continence (being clean and dry) and of incontinence (lower urinary tract and/or bowel dysfunction resulting in the involuntary leakage of urine or faeces) than other children, and may be slower to learn to manage going to the toilet, or they may not attain full independence. 4–7 Many children, however, can become continent with training. Factors that affect the ability of children with neurodisability to achieve continence include structural malformations and/or physiological impairments that can affect sensation and control, functional limitations (e.g. gross or fine movement or manual ability), learning difficulties and behavioural issues. These children may regress due to progressive impairment, psychological issues or the development of bladder or bowel dysfunction. Incontinence affects the quality of life (QoL) of the young person and that of their carers;8 the long-term physical, psychological and financial burden can be considerable. 9 There is also a cost to the NHS in terms of providing containment products for managing incontinence.

Not all children have the ability to become fully independent in toileting, but many can improve their continence. Assessing readiness for toilet training can be difficult; a child may display signs of readiness, or have the capability for readiness but not express it. Various factors can influence if and when toilet training commences. A key issue is whether or not families and professionals think that a child is ready and able to begin toilet training. Sometimes, unfortunately, assumptions are made about a child’s inability to train without a formal assessment being undertaken. There can be perceptions that the cause of any incontinence is either part of the child’s ‘condition’ or a reflection that they are ‘not ready’. This may result in the child with neurodisability not being offered the same comprehensive assessment that their typically developing peers, with similar problems, would be offered.

A variety of approaches to assessment, advice and intervention are available. 10 Children should be assessed systematically to see whether or not they are able to be trained and to identify any related medical problems that may inhibit the improvement of their continence. Toilet training strategies are complex interventions, and build on ideas initially proposed in the 1960s and 1970s. 11,12 Interventions to improve continence may include information/support, charts to monitor/feedback, scheduled drinks and toileting, cognitive–behavioural approaches, alarms, relaxation, psychotherapy, group-based programmes, medicines and surgery. 13 A systematic review14 identified limited evidence for toilet training strategies for children with physical and learning disabilities. Medication is sometimes used as part of treatment, and medications used for managing other impairments may have an impact on continence. Currently, there is uncertainty about the most effective ways to assess and promote continence in children with neurodisability.

Why this research is important

Pillar One of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) strategy for Adding Value in Research is to ensure that the questions being researched are those most important to patients, the public and clinicians. Research to evaluate ways to promote continence for children with neurodisability was ranked number 7 in a top 10 of topics by young people, parent carers, clinicians and charity representatives in the British Academy of Childhood Disability James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. 15 Improving continence can have a huge impact on the QoL of children and young people and their families, and can potentially reduce NHS expenditure in providing containment products for managing incontinence. Identifying current clinical practice in the NHS and summarising the available evidence for interventions allows us to make recommendations for research and practice for improving continence in children and young people with neurodisability.

The aim of the study was to summarise the available evidence for interventions and current practice relating to improving continence for children and young people with neurodisability. The methods in the commissioning brief were a survey of NHS practice and a systematic review. Fundamentally, we set out to examine what families and professionals were doing, and if there was any evidence that these approaches are effective. To be consistent with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) legislation,16 we considered any approaches taken to assess and promote continence for children and young people up to the age of 25 years.

Aims and objectives

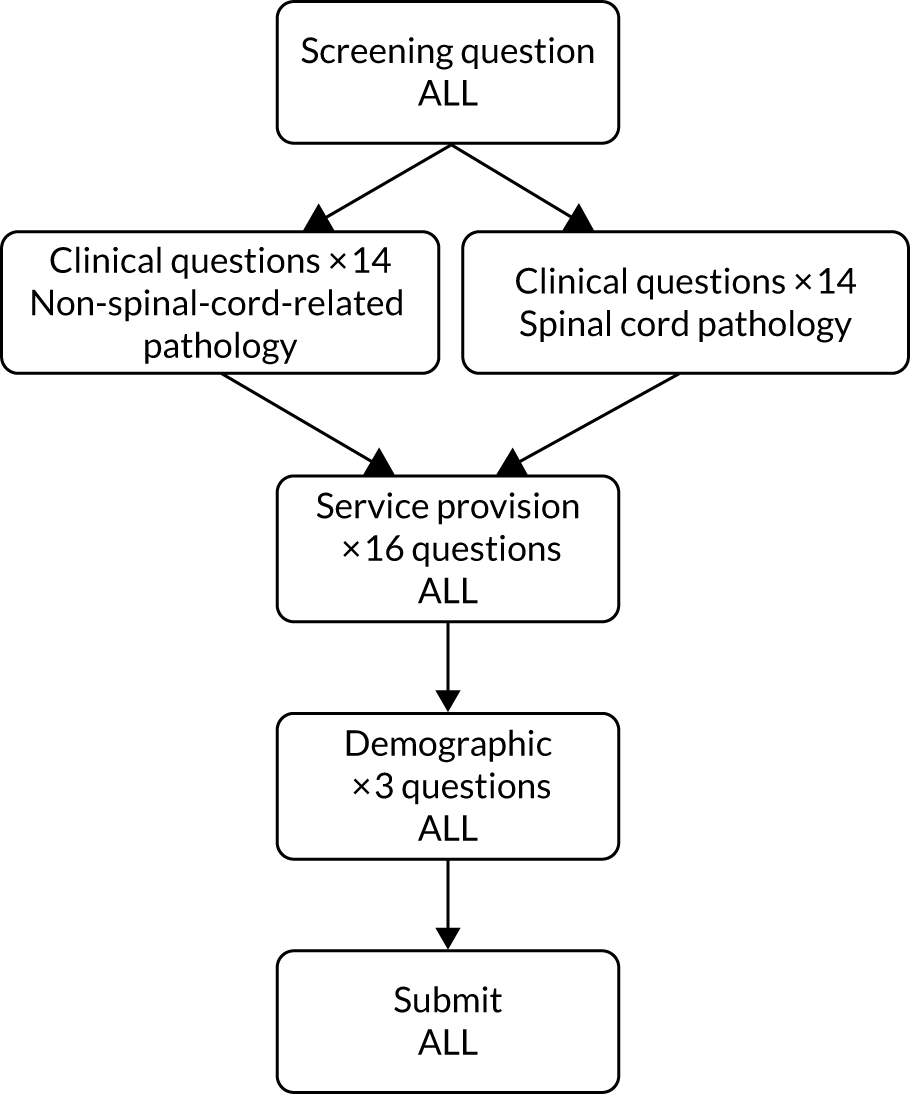

We aimed to find out how NHS staff assess and treat children with neurodisability to help those children become continent. To do this, an online survey was conducted with health professionals to describe clinical practice in the NHS, addressing the following research questions:

-

How do clinicians assess the bladder and bowel health of children and young people with neurodisability, their continence capabilities and their readiness for toilet training? Which clinicians are involved in assessments?

-

Which interventions do clinicians use or recommend to improve continence for children and young people with neurodisability and how are these individualised and evaluated and/or audited? Which clinicians recommend, deliver or evaluate interventions?

We also surveyed families, school and care staff about their experiences of using interventions to improve continence, addressing the following research questions:

-

How do families, school and social care staff consider and judge children’s readiness for toilet training and need for specialist assessment and/or interventions?

-

Which factors affect the implementation of interventions to improve continence, and what is the acceptability of strategies to children and young people and their carers?

Alongside the survey, we conducted an integrated systematic review of studies evaluating the (1) effectiveness, cost-effectiveness or implementation of interventions for improving continence for children and young people with neurodisability, and (2) views, experiences and perceptions of families and/or health professionals using and delivering interventions. The systematic review aimed to answer the following research questions:

-

What is the effectiveness of interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What are the factors that may enhance, or hinder, the effectiveness of interventions and/or the successful implementation of interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What are the views, experiences and perceptions of children and young people, their families, their clinicians and others involved in their care of delivering and receiving such interventions?

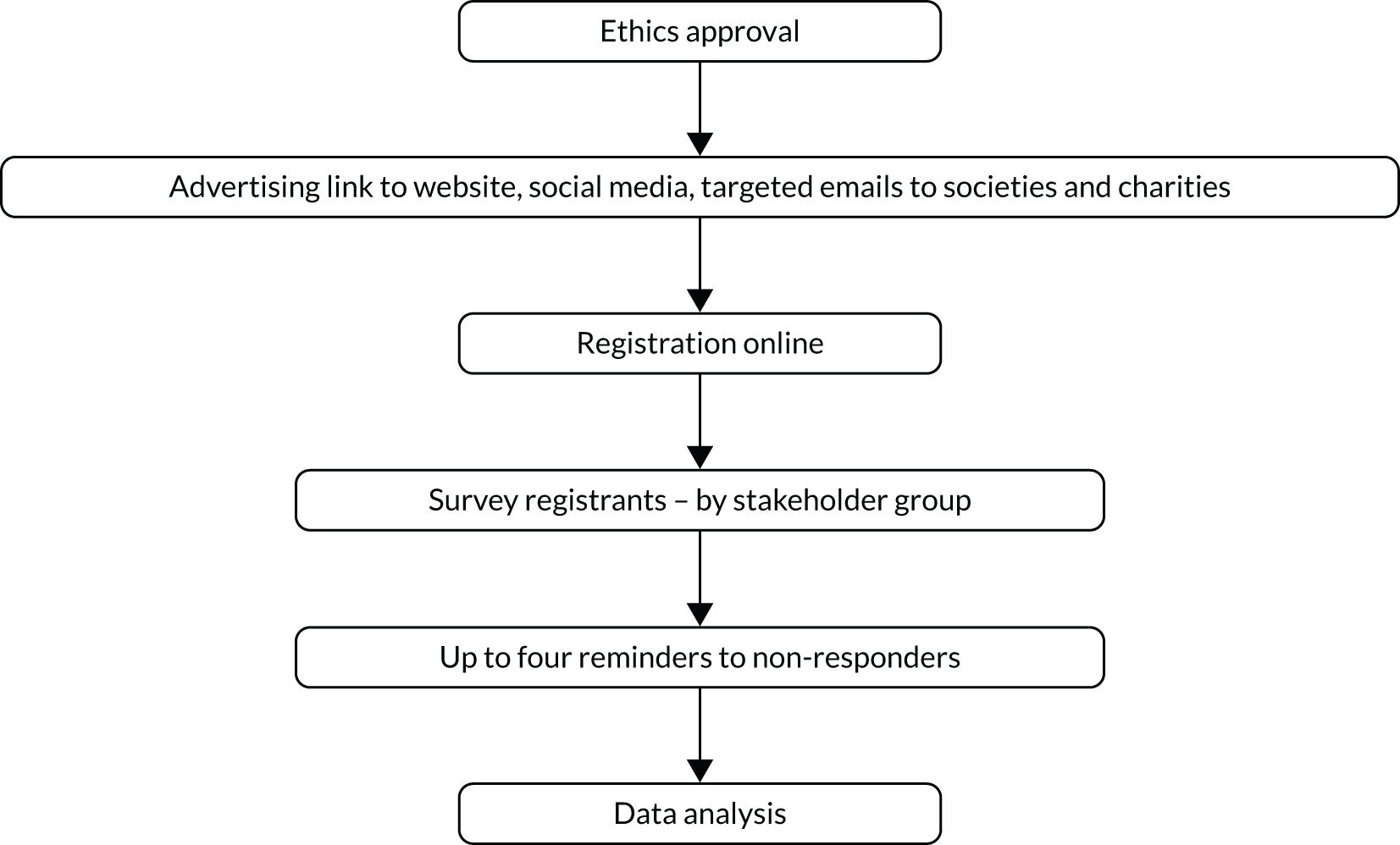

Chapter 2 Overview of methods

The project was designed with four interlinked phases: preparation, consultation, review and integration. During the preparation stage (months 1–3), key issues were discussed and explored with the study’s expert Professional Advisory Group and our Family Faculty group (our public involvement group) to produce, refine and finalise the protocols for the systematic review and the surveys. We also consulted on the design of the survey questionnaires, formatting, and the application for ethics approval. In the consultation phase (months 3–13), we conducted and analysed descriptive cross-sectional surveys with health professionals, school and care staff, parent carers, and young people in England. In parallel (months 3–13), for the review phase, we carried out the systematic review. Finally, during the integration phase (months 14–16), findings from the surveys and systematic review were collated and interpreted in consultation with the Professional Advisory Group, our Family Faculty group and young people with neurodisability.

Scope

The scope of this study focused on the following:

-

Population – children and young people with non-progressive neurodisability aged up to 25 years, consistent with the Department of Health and Social Care Special Educational Needs and Disabilities code of practice17 and the Children and Families Act 2014. 18

-

Interventions – assessments and interventions to improve continence, including structured training programmes, products and assistive technology, medicines and/or surgery.

-

Outcomes – (1) effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and implementation of interventions to improve continence; and (2) views and experiences of families and health professionals.

Complete and transparent reporting

To deliver a complete and transparent report of the research, we were mindful of the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public short-form;19 the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology: cross-sectional studies;20 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 21

Throughout the report, we endeavoured to use consistent terminology for continence, assessments, interventions and outcomes. We also referred to the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS)22 for bladder and bowel dysfunction terminology and to McComb23 for spinal cord pathology terminology.

Conceptual and theoretical frameworks

In terms of the conceptual frameworks underpinning this research, we were acutely aware of the need to take into account the complexity that comes with evaluating approaches to assess and interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability. We were mindful of the complexity of many of the relevant interventions as defined in the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework. 24 That is, salient interventions are multicomponent and context dependent, and the adoption and effectiveness of an intervention is reliant on the motivations and capabilities of children, parents and practitioners. Additionally, we considered the intricacies of the separate and combined health, education and care systems, the variable configuration of services, and the diversity of family cultures, resources and environments. 25,26

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) classifies components of health in domains of ‘body structures’, ‘body functions’, ‘activities and participation’, ‘environmental factors’ and ‘personal factors’. 1,2 The performance of activities and participation by an individual depends on their capacity and is mediated by personal and environmental factors. Thus, a health condition may involve impairments of body structures or functions, limitation in activities and/or restriction in participation; the relationships between these components are bidirectional and mediated by environmental and personal factors. Toileting is classified in the ICF as self-care (https://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/; accessed 19 October 2021). Following discussion, the team decided that menstruation was not in the scope of the commissioning brief.

Using the ICF classification, the bladder and bowel are body structures, urination and defecation are body processes, and the regulation of urination and defecation are classified as ‘self-care’ activities. Salient environmental factors include health services, systems and policies, products and technology for (1) education, (2) personal use in daily living (toilet adaptations, clothing adaptations), (3) communication, (4) personal indoor and outdoor mobility and (5) personal consumption (medicines). Not classified specifically are some medically assisted techniques and surgical approaches. Also pertinent are the designs of buildings for public and private use in terms of accessible toilets.

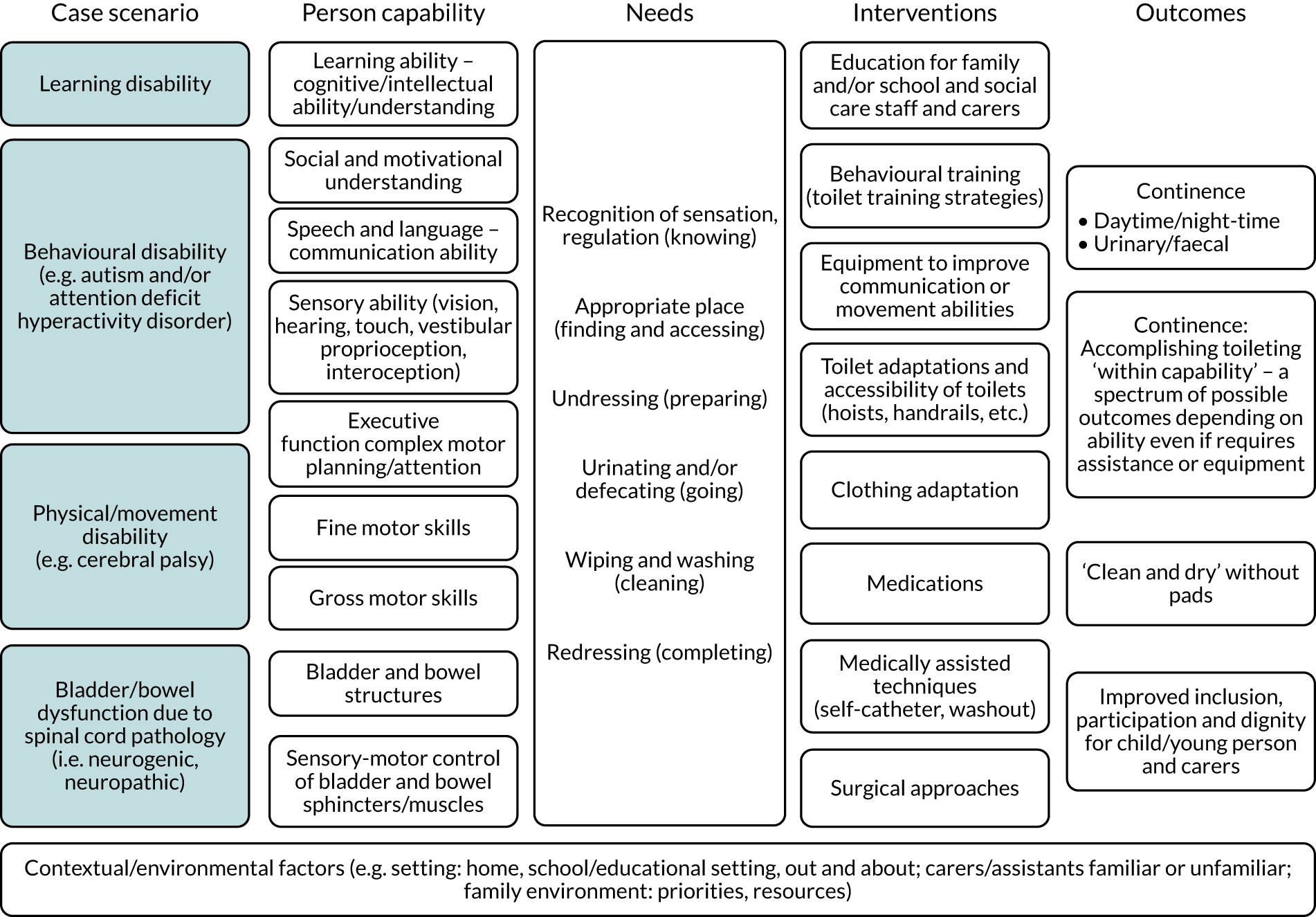

We sought to devise a study-specific conceptual framework diagram to inform and guide the research, and later to help integrate the findings of the systematic review and surveys (Figure 1). Initially, the framework took the form of the patient–intervention–outcome model; we identified the capabilities that individuals need to acquire for continence, the range of interventions that could be used and the ways in which the outcome of continence could be conceived. The framework outlines a logical process through which capability, needs, interventions and outcomes can be described and considered. The concepts are intended not to be linked sequentially but to be seen as interacting.

FIGURE 1.

Study-specific conceptual framework diagram to inform and guide the research. The concepts are not intended to be linked sequentially but seen as interacting.

The person capabilities at the fundamental level comprise (1) intact structure and physiological functioning of the bladder and bowel, and (2) sensorimotor control of the bladder and bowel sphincters and muscles. The other aspects of capability in our framework are a summary of the toilet training skills usually acquired sequentially in typically developing children: movement and manual ability, communication, and social and motivational understanding. Additionally, we included vision as vital for negotiating toileting, although children with limited vision are amenable to familiarisation and/or adaptation.

In order that the findings of this research might be readily generalised to children and young people with neurodisability, we posited four exemplar clinical case scenarios that capture different manifestations of the person capabilities. These were (1) spinal cord pathology (e.g. spina bifida), (2) learning disability, (3) movement disability (e.g. cerebral palsy) and (4) behavioural disability [e.g. autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)]. However, in practice this was problematic, as many children have complex conditions that are affected by components of all these difficulties. Therefore, as the project developed, we moved towards the main distinction being between children with spinal cord pathology and those with non-spinal-cord-related pathology indicating potential for bladder and bowel sensorimotor control.

As we progressed, and benefiting from input from our advisers, we found that our framework was underpinned best by a needs-based approach for toileting and capabilities for achieving continence:

-

KNOWING – understanding when needing to empty bladder and/or bowel

-

FINDING – waiting until finding a toilet

-

ACCESSING – being able to enter toilet

-

PREPARING – undressing and positioning

-

GOING – emptying bladder and/or bowel

-

CLEANING – wiping

-

COMPLETING – redressing and washing hands.

In terms of outcomes, the distinction between what the concept of continence means for those individuals with and those without spinal cord pathology affecting bladder and bowel sensorimotor control is crucial. Without sphincter control, there will often be a need for assistive technology or alternative approaches to emptying the bladder or bowel. Some children with profound learning disability will always need individual assistance with toileting, and so independence may not be safely realistic. By contrast, others may be able to accomplish toileting independently, provided that adequate accessibility and/or equipment is available. This way of conceptualising continence as an outcome emphasises that toileting techniques need to be adapted to the individual’s capability, that it will vary from person to person and that the individual may require assistance or equipment. However, the aim is to be ‘clean and dry’ and, therefore, not require incontinence pads.

We organised interventions into ICF categories as follows:

-

Products and technology for education –

-

Educational approaches focusing on enabling families and carers to understand the child’s capability and necessary modifications, for example attending to toileting at regular or timed intervals.

-

Behaviour change approaches focused on the child, for example increasing awareness.

-

-

Products for personal use in daily living –

-

Environmental modifications to make toilets more accessible and easier to use, for example handrails, positioning equipment and/or hoists.

-

Adaptation of clothing to increase independence, for example hook-and-loop fasteners rather than buttons, or enabling access to self-catheterise.

-

Continence products, such as pads/nappies, used for containment.

-

-

Products and technology for communication –

-

Equipment to improve communication about toileting.

-

-

Products and technology for personal indoor and outdoor mobility –

-

Equipment to enable movement in various environments.

-

-

Products for personal consumption (subset: drugs) –

-

Medications to help regulate toileting, for example anticholinergic medications to regulate bladder emptying or laxatives to treat constipation.

-

-

Medically assisted techniques and surgical approaches –

-

Alternative ways to empty the bladder and bowel, for example catheter or washout.

-

Surgery to change structures or enable catheterisation.

-

The assessment of children and young people by families and professionals plays a crucial part. Key to this is avoiding assumptions about ability, the need to assess each individual’s capabilities for achieving continence, their likely level of independence in achieving the identified needs, and deciding systematically which interventions and approaches are likely to be helpful. Assessments can include one or more of parent/carer reports, child/young person self-report, charting regularity and events, checklists, physical examination, ultrasound or other imaging, urodynamics or direct observation.

It is important to consider that children with neurodisability and non-spinal-cord-related pathology should have a typically developing bladder and bowel. However, they will be at least as susceptible to bladder and bowel issues that can affect any child or young person more generally. Common bladder problems include enuresis, which is the involuntary discharge of urine during sleep; overactive bladder, which is characterised by frequency, urgency and/or daytime wetting; and dysfunctional voiding, which is the habitual contraction of the urethral sphincter or pelvic floor during voiding. Furthermore, the commonest bowel problem, constipation, affects up to 30% of children at any one time. Children who have a neurodisability have an increased risk of this for a variety of reasons.

Our conceptual framework highlights the crucial influence of contextual factors. Therefore, assessment should take account of all the environments where the child or young person might need a toilet, for instance home, nursery/school or college/work, or out in the community. If assistance from a carer is necessary then familiarity may be influential, in terms of communicating a need to toilet and/or the carer understanding the individual’s need for assistance.

Project management

The whole team of co-investigators and researchers working on the project met at the beginning of the study and again once the survey and systematic review were largely completed. The co-investigators consisted of consultant paediatricians, specialist continence nurses and therapists. A subset of the core team based in Exeter comprised the researchers and leads for the systematic review and survey. The systematic review was led by the Evidence Synthesis Team of the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) South West Peninsula (known as PenARC). The survey and project management was led by the Peninsula Childhood Disability Research Unit (PenCRU). The core team met monthly and benefited from teleconferences with the whole team every 2 months. The study was also improved by our public and stakeholder engagement.

Patient and public involvement

In this study, members of the public involved as partners were predominantly parents of children and young people with neurodisability, and children and young people themselves. They were engaged in research through partnership with PenCRU. The aim of patient and public involvement in this study was to ensure that (1) the research was conducted in ways likely to be attractive and acceptable, (2) the research outputs were more likely to be perceived to be relevant and useful to families of children with neurodisability, and (3) our dissemination materials and methods were appropriate and relevant. We describe our public involvement using the elements recommended in the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) short-form. 19 This section describes how parents of children affected by neurodisability were involved in the study, and discusses the impacts that parent involvement had on the research. The patient and public involvement activities in which the parents and young people participated are described and their contribution to the study is reflected on.

Family Faculty group: parent carers

PenCRU carries out public involvement through a self-styled Family Faculty group and this is facilitated by the family involvement co-ordinator. Currently, around 200 parent carers of children with neurodisability are members of the PenCRU Family Faculty group. They have all signed up to be notified of opportunities to be involved as partners in aspects of the research cycle. For substantive projects such as this study, ‘working groups’ are convened. We e-mail all members with brief information about the topic, and those who are interested and available at the time can volunteer. Parent carers in the study-specific group participate in meetings and/or input into research by e-mail or telephone. We do not train members of the Family Faculty group, but we do identify individual learning needs and provide information and encouragement consistent with any member’s personal motivation and time available.

For this study, we e-mailed the Family Faculty group when we were preparing the outline funding application, and 24 members volunteered to join the project-specific working group. Their children had various diagnoses, including movement and/or learning disabilities, such as cerebral palsy and autism, and had experience of a range of issues relating to toileting and continence. Two of the more experienced Family Faculty group members volunteered to be co-applicants on the funding bid. Our Family Faculty group met in each academic term throughout the study. There were more frequent meetings when there was more opportunity for influencing the work, especially when we were developing the survey questionnaires and recruitment processes. All the working group members were invited to each study meeting, although, owing to balancing work and family life, not all attended every meeting. In total, 16 of the 24 members attended one or more of the study meetings. On average, seven members attended every meeting.

Pre-funding application stage

The Family Faculty group first met prior to funding being granted to help develop our ideas for designing the proposed study. The group met twice in June and October 2017 to advise on the stage 1 and stage 2 applications, respectively. Their input identified key contextual factors related to toileting for children with neurodisability, and influenced our evolving strategies for advertising and consultation with families through the survey, such as how to recruit participants, how to consult with children and young people, what information should be collected in the survey to describe the sorts of families who took part, and the types of questions that would help address the research question. The frequency of future meetings was also discussed. Crucially, surveying families was not part of the commissioning brief, which focused on current NHS practice; however, members of the group felt strongly that families should be consulted.

Post-funding preparatory work

The Family Faculty group met more regularly during the preparation stage of the study, with four meetings held between November 2018 and May 2019. During these meetings, parent carers were consulted on the advertising materials, participant information forms and parent carer survey questionnaires that were all prepared for submission to the ethics committee. The Family Faculty group were consulted on ideas to engage and access potential participants for the school and care staff survey. They were keen to learn about and advise on aspects of the systematic review process.

In the earlier meetings, prior to commencement of the study, feedback from the Family Faculty group was that the response options in the survey for parent carers should be designed using mostly tick boxes or drop-down choices to enable the questionnaire to be completed quickly. Suggestions for the focus of the questions included toileting or continence interventions they had used, including any alternative therapies, rating their experience of strategies and/or whether the intervention had been successful or acceptable. They recommended providing a realistic estimate of how long it would take to complete the questionnaire, including a progress bar and ‘back button’. The Family Faculty group did not believe that a financial incentive was necessary and thought that this might lead to people taking part in the survey who did not have the correct motivation.

During the meetings between November 2018 and May 2019, the Family Faculty group assisted in revising the advertisement to share with organisations in terms of its appearance and the language used. The group provided additional suggestions of organisations or charities that could be contacted to aid recruitment. Members of the group piloted the registration process for the survey. Some members of the group felt that the registration process was an ‘extra step’ and might put people off. They noted that the process was simple and straightforward, although some had concerns that potential participants might be deterred by being asked to provide their e-mail addresses and queried whether or not a direct link to the survey might be preferable.

Members of the group commented and provided feedback on the study website design and content and made suggested changes to ensure clarity and understanding of the language used. They felt that the content was quite detailed and that a short animated video would be an easier and more accessible way for busy parents to quickly understand what the project was about and how they could get involved. Ideas for the video were developed, and suggestions included using humour and cartoon characters, keeping the video short and words limited to ensure that it was accessible to and understandable by all ages and abilities. A ‘script’ for the video narrative was proposed at a subsequent meeting and members made suggestions to add or remove content. It was agreed that a young person should narrate the video to provide an attractive voiceover to all ages. The video we produced was narrated by one of the children of a member of the Family Faculty group.

A pilot set of parent carer survey questions and response options was presented to the Family Faculty group, and members provided feedback on the questions (whether they could understand them clearly, whether the language would be readily understood) and they provided additional response options for some questions. Some felt that the parent carer questionnaire was quite long, and advocated for a shorter set of questions. Following refinements, the electronic survey questionnaire was created online. Members of the Family Faculty group piloted the survey online and provided feedback on the time they took to complete it, clarity of questions, the format and font. This further feedback was used to review and amend the questionnaire.

We developed a plain language summary protocol for the systematic review. The first draft of this was created by the researchers. Members of the Family Faculty group provided feedback on the text and format that influenced the final version. We communicated progress throughout the phases of the systematic review, asking for feedback on specific aspects such as terminology and interventions, and discussed parent carers’ views on the emerging findings.

Interpretation stage

Following completion of the survey and systematic review, the Family Faculty group met twice more during the integration stage of the study. In these meetings, the parent carers were asked to comment on and provide their interpretation of some initial findings from the systematic review and the survey, and they were consulted on potential ideas for disseminating the research findings.

Involving children and young people with neurodisability

We sought opportunities to consult children and young people with neurodisability about aspects of the study in the preparation stage, and again on the initial findings of the survey and systematic review in the integration stage of the study. A small number of PenCRU’s Family Faculty group members are young adults with neurodisability. Two of these young adults, a female group member with cerebral palsy who is profoundly deaf and a male group member with cerebral palsy, were invited to consult on various aspects of the study design. Both commented on the study website and the young person participant information sheets for the survey, and both also piloted the children and young people’s survey and offered feedback on the design, the language used and the questions asked.

The Pelican Project is a local community group in Exeter whose members work with young adults with disabilities, to assist them to make a contribution to the community. This group were approached and asked if any of their members would be willing to be consulted on their perspective of the children and young people’s survey. We met with four young adults with a range of disabilities who were assisted by their carers in the preparation stage of the study. The group were consulted on how we could access young people and encourage them to participate in the survey, and the group were also asked to review the information sheets for young people and the relevant study web pages for the survey.

Children and young people with neurodisability who attended a special school for children with severe learning difficulties were also invited to take part in the project through being consulted on our methods and findings. The group of four young people was convened with the assistance of the school advocacy lead and offered their comments and feedback regarding the questions in the survey for young people, the language used, and how they might feel about answering personal questions about their toileting ability. The advocacy lead also piloted the school and care staff survey and provided feedback.

Other stakeholder/end-user involvement

Professional Advisory Group

Our Professional Advisory Group was established in collaboration with ERIC (The Children’s Bowel & Bladder Charity). ERIC provides information and education and collaborates on research with children and young people and their families with continence challenges in the UK. With permission, we co-opted ERIC’s Professional Advisory Committee, which comprised expert professionals in the field of childhood bowel and bladder health who were keen to assist, plus one other professional who had expressed interest. Our Professional Advisory Group therefore consisted of 12 professionals who, collectively, had extensive experience in the field across medical, nursing and allied health professions.

During the preparation stage of the study, we convened the Professional Advisory Group and explained the study. Members were consulted about the study website, advertisements for the health professional survey, potential personal and organisational contacts for sharing adverts for the survey, and potential questions for consideration in the health professional survey. Following this initial meeting, the Professional Advisory Group members were consulted by e-mail regarding participant information sheets for health professionals, and they were also asked to assist with sharing advertisements for the survey once it had gone live. The Professional Advisory Group was convened again in May 2020 during the integration stage so that the members could help to interpret the findings from the survey and systematic review.

Oversight Group

The Oversight Group was approved by NIHR at the beginning of the project; it met with the core research team for the first time in May 2019. This group comprised two parent carers, a paediatrician, an allied health professional with considerable experience in neurodisability research, a psychologist with considerable experience in continence research, and another with expertise in systematic review methodology. This group met 3 months after the study commenced and provided valuable guidance, particularly in relation to adopting the needs-led approach in our conceptual framework.

Chapter 3 Systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve continence for children and young people with neurodisability

Research questions

-

What is the effectiveness of interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What are the factors that may enhance, or hinder, the effectiveness of interventions and/or the successful implementation of interventions to improve continence in children and young people with neurodisability?

-

What are the views, experiences and perceptions of children and young people, their families, their clinicians and others involved in their care of delivering and receiving such interventions?

Methods

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement. 21 The protocol was developed in consultation with the Family Faculty group and the Professional Advisory Group. The protocol is reported in accordance with PRISMA-P reporting guidelines27 and is registered on the International Database of Prospectively Registered Systematic Reviews in Health and Social Care (CRD42018100572; www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=100572; accessed 19 October 2021). We also produced a plain language protocol summary, which is available online (http://sites.exeter.ac.uk/iconstudy/files/2019/05/Systematic-Review-plain-language-protocol-summary.pdf; accessed 19 October 2021).

End-user involvement

In addition to consulting on our protocol, we discussed our search strategy, scoping searches and early findings with our Family Faculty group of parents who had lived experience of their children having continence issues and with the Professional Advisory Group. All discussions involved communicating progress throughout the phases of the systematic review, asking for feedback on specific aspects (e.g. terminology and interventions identified) and discussing views on findings as they emerged, such as what was surprising, what did people expect to see and how the results matched expectations.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched between 24 January 2019 and 1 February 2019: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo®, Health Management Information Consortium, Social Policy & Practice (all via OvidSP), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and CENTRAL (via Cochrane Library), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (via EBSCOhost), British Nursing Index and ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts) (via ProQuest), Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science) and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. The search strategy was developed and run by an information specialist (MR), with input from our Professional Advisory Group and Family Faculty group, who reviewed and commented on the search plans. Our strategy combined search terms for continence with terms for children and terms for quantitative and qualitative study types. The search strategy as designed for MEDLINE is shown in Box 1 and the adapted strategies for the other databases are available in Appendix 1, Tables 17–21. All database searches were updated on 21 and 22 April 2020.

-

Urinary Incontinence/

-

Fecal Incontinence/

-

toilet training/

-

continence.ti.

-

incontinen*.ti.

-

exp Enuresis/

-

enure*.ti.

-

encopresis.ti.

-

toilet*.ti.

-

wetting.ti.

-

bedwetting.ti.

-

dryness.ti.

-

potty.ti,ab.

-

(dysfunction* adj voiding).ti,ab.

-

or/1-14

-

child/

-

exp Nervous System Diseases/

Annotation: includes neural tubes defects, spina bifida, etc.

-

exp Autistic Disorder/

-

exp Neurologic Manifestations/

-

exp cerebral palsy/

-

exp autism/

-

or/17-21

-

16 and 22

-

(child or childs or children or childrens or childhood).ti,ab.

-

adolescen*.ti,ab.

-

teen*.ti,ab.

-

young people.ti,ab.

-

preschool*.ti,ab.

-

toddler*.ti,ab.

-

23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29

-

exp clinical trial/

-

randomly.ti,ab.

-

trial.ti,ab.

-

control group.ti,ab.

-

(group* adj5 compared).ab.

-

(randomised or randomized).ti,ab.

-

systematic*.ti,ab.

-

(pubmed or medline).ab.

-

(review adj3 effectiveness).ti,ab.

-

(experiment or experimental).ti,ab.

-

(Quasi experiment* or quasi-experiment* or quasiexperiment*).ti,ab.

-

comparative study.ti,ab.

-

evaluation study.ti,ab.

-

(cross section* adj10 study).ti,ab.

-

crossover.ti,ab.

-

longitudinal study.ti,ab.

-

program* evaluation.ti,ab.

-

(control* adj5 compar*).ti,ab.

-

multicentre study.ti,ab.

-

observational study.ti,ab.

-

prospective.ti,ab.

-

retrospective.ti,ab.

-

cohort study.ti,ab.

-

qualitative research/

-

qualitative*.ti,ab.

-

interview*.ti,ab.

-

Economics/

-

exp “Costs and Cost Analysis”/

-

exp Economics, Medical/

-

Economics, Nursing/

-

Economics, Pharmaceutical/

-

cost effective*.ti,ab.

-

economic evaluation.ti,ab.

-

(cost adj2 evaluat*).ti,ab.

-

or/31-64

-

15 and 30 and 65.

Related systematic reviews were examined for other relevant studies through backwards citation searching, and forwards citation chasing was carried out via PubMed Central and Scopus using key papers. Unpublished studies were sought via conference proceedings databases (Conference Proceeding Citation Index – Science and Conference Proceeding Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities) and clinical trials websites (ClinicalTrials.gov and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform). OpenGrey and The British Library’s Explore catalogue were also searched.

Eligibility criteria

We sought to include any quantitative or qualitative study meeting the criteria below.

Population

The population was children and young people with non-progressive neurodisability aged up to 25 years, consistent with the Department of Health and Social Care Special Educational Needs and Disabilities code of practice and the Children and Families Act 2014. 18 We defined neurodisability as follows:

Neurodisability describes a group of congenital or acquired long-term conditions that are attributed to impairment of the brain and/or neuromuscular system and create functional limitations. A specific diagnosis may not be identified. Conditions may vary over time, occur alone or in combination, and include a broad range of severity and complexity. The impact may include difficulties with movement, cognition, hearing and vision, communication, emotion, and behaviour.

Interventions

Assessments including those to identify any underlying pathology and readiness for toilet training; and interventions to improve continence, including structured training programmes, products and assistive technology, medicines and/or surgery. Definitions around these categorisations are described fully in Chapter 2, Conceptual and theoretical frameworks.

Outcomes

Quantitative

Any outcome that could inform the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness or implementation of interventions to improve continence.

Qualitative

Views and experiences of families and health professionals; factors that may enhance, or hinder, the effectiveness of interventions and/or the successful implementation of interventions.

Setting

Any setting.

We had intended that only studies from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries would be included (listed in Appendices 2 and 3), but we also identified four eligible studies from the Islamic Republic of Iran that met all of the other inclusion criteria, so these were included. Particular consideration was given to the degree of transferability of findings from non-UK settings to the NHS context.

Study design

Any quantitative comparative study design, and any recognised method of qualitative data collection and analysis, including interviews, focus groups and observational techniques. This included stand-alone qualitative research, or evidence reported as part of a mixed-methods intervention evaluation. We also included process and outcome evaluations.

Study selection

At the title and abstract screening stage, we took an inclusive approach to evidence, meaning that if there was any doubt or ambiguity around whether a study was to be included or excluded, it should be included. Screening notes were created for the title and abstract screening process, which were piloted on two studies and refined following piloting. Title and abstract screening notes are available in Appendix 2. All definitions of key terms (The Children and Families Act 2014. Part 3: Children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities,17 list of OECD countries28) were included in the appendices of the screening notes (see Appendices 2 and 3). Titles and abstracts of references retrieved by the search were each screened independently by two reviewers (HH, MR, RW and JTC) using the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Screening decisions were recorded electronically in EndNote software [version X8; Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] and the master database was managed by our information specialist (MR). We shared the abstract and title screening results with the Family Faculty group and with the clinical specialists in the Professional Advisory Group, discussed the relevance of the conditions and terminology identified and asked for advice on the specific clinical details found in studies.

The full texts of potentially relevant studies were obtained and independently assessed for inclusion by two reviewers (HH, MR and RW). Screening notes were refined for the full-text phase, with coding guides included for screening in EndNote software. This process was again piloted with two papers, and the screening notes were refined accordingly (see Appendix 3, Tables 22 and 23). Screening decisions were recorded electronically in EndNote and the master database, managed by our information specialist (MR). Discrepancies around data extraction were resolved by discussion; reference to a third reviewer was planned but not necessary.

Data extraction

The data extraction form was created in consultation with our project team and clinical specialists, and in line with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 29 As we were interested in interventions and describing them in as much useful detail as possible, we used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist30 to guide the creation of our data extraction forms. TIDieR is a guide and reporting checklist developed to improve the completeness of reporting, and, ultimately, the replicability, of interventions. A blank quantitative data extraction form is available on reasonable request.

Quantitative data were extracted by one reviewer (HH or RW) and checked by another reviewer (HH or RW). As before, reference to a third reviewer was planned but not necessary. For qualitative studies, we extracted details of the study aim, the sample, and the type and nature of the intervention/programme. We also collected data on the theoretical approach, the methods used to collect the data and the analytic processes. This process was conducted by one reviewer (HH), with a second reviewer (RW) spot-checking extractions independently and both reviewers discussing the qualitative data.

Quality appraisal

We used the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP)31 quality assessment for quantitative data studies, and quality assessment was carried out alongside data extraction by one of two reviewers (HH or RW), with assessments checked by the other. The EPHPP tool enables the assessment of selection bias, study design, blinding, level of confounding, data collection methods and data analysis, providing an overall rating of weak, moderate or strong quality. For qualitative studies, we used the Wallace criteria to determine the quality of reporting and the appropriateness of the method used. 32 The assessed criteria included theoretical perspective, appropriateness of the question, study design, context, sampling, data collection, analysis, reflexivity, appropriateness, generalisability and ethics.

Quantitative synthesis

We used the methods of quantitative synthesis outlined in the Cochrane Handbook. 33 The included quantitative studies reported a range of outcomes, which we grouped into broad categories. Intervention descriptions were extracted as reported by study authors, and grouped into broad categories identified by the principal investigator (CM) within a conceptual framework developed at the beginning of the project and refined through discussion with the co-investigator team and the Professional Advisory Group. These categories were educational interventions, equipment to improve communication or movement abilities, toilet adaptations, clothing adaptations, medically assisted techniques, behavioural training, surgical approaches and medications.

Outcomes were recorded in an overarching Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet, and terminology of outcomes, interventions and medical conditions was recorded verbatim from study author descriptions. We then consulted with our clinical experts to identify any terms obsolete in current practice, conditions outside our remit and other anomalous terminology, and we refined the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet accordingly. Outcomes relating directly to effectiveness of interventions were then grouped broadly into continence, incontinence and equipment related (e.g. diaper/nappy, anal plug use).

This research uses current accepted standardised terminology as described by the International Children’s Continence Society22 for bladder and bowel dysfunction, McComb23 for spinal cord pathology and Morris et al. 3 for neurodisability. As all terms were drawn directly from the included study literature, some of which dated back to 1965, there was a need to rationalise and redefine terms for the purposes of this paper. We therefore carried out a series of consultations with topic experts on our project team to check terminology and refine and condense these categories where it made sense to do so. This resulted in the development of two overarching groupings: one describing non-spinal-cord-related conditions and the other describing conditions with underlying spinal cord pathology. Non-spinal-cord-related conditions included autism, ADHD, developmental disability, learning disability (reworded from mental disability) and ‘mixed conditions’ (including Down syndrome, epilepsy, ‘primary genetic’, infant autism and postnatal infection). Spinal cord pathology conditions include all forms of myelodysplasia (defective development of any part of the spinal cord), including myelomeningocele, spina bifida and tethered cord syndrome, and associated neurogenic dysfunction (including neuropathic bladder and/or bowel, also referred to as neurogenic bladder and/or bowel, and neurogenic detrusor overactivity).

There were insufficient homogeneous data across studies to allow a formal meta-analysis for any outcome. As part of the synthesis process, we extracted data into tables to allow greater comparison and contrast across different features of interest, including age range of participants, type of continence (faecal/urinary/both), medical condition (Table 1) and study type (RCT, before-and-after/cohort, case–control, case reports, crossover). From a single overarching summary table, we created individual topic tables and summarised the effectiveness of results narratively, grouping outcome measures by their broad intervention category (e.g. medication), by medical condition (e.g. autism) and by study design.

| Overarching group | Summary group (where relevant) | Subgroup (where relevant) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-spinal cord related | Autism | – |

| ADHD | – | |

| Developmental disability | Angelman syndrome | |

| Learning disability | – | |

| Mixed conditions | – | |

| Spinal cord pathology | Myelodysplasia | – |

| Spina bifida | Myelomeningocele, and spina bifida with anorectal malformations, tethered cord syndrome | |

| Neurogenic dysfunction | Neuropathic bladder/bowel; neurogenic bladder/bowel; neurogenic detrusor overactivity |

Qualitative synthesis

All qualitative outcome data were extracted in the form of quotations, themes and concepts identified by study authors, and themes and concepts identified by a reviewer (HH) and reviewed by a second reviewer (RW). The data were read and re-read and the findings were organised into subthemes. The subthemes were then grouped into main themes and reported according to the condition category.

Overarching synthesis

We created a simple overarching synthesis to link the quantitative and qualitative evidence. We used the interweave method of data synthesis,34 whereby data are incorporated across multiple sources of evidence through a process of ‘interweaving’ the findings of individual studies and combining categories to produce insight and promote understanding of the evidence base in its entirety. We used the intersubjective questioning approach to interrogate the evidence and draw links between and across both the qualitative and the quantitative evidence identified in this systematic review.

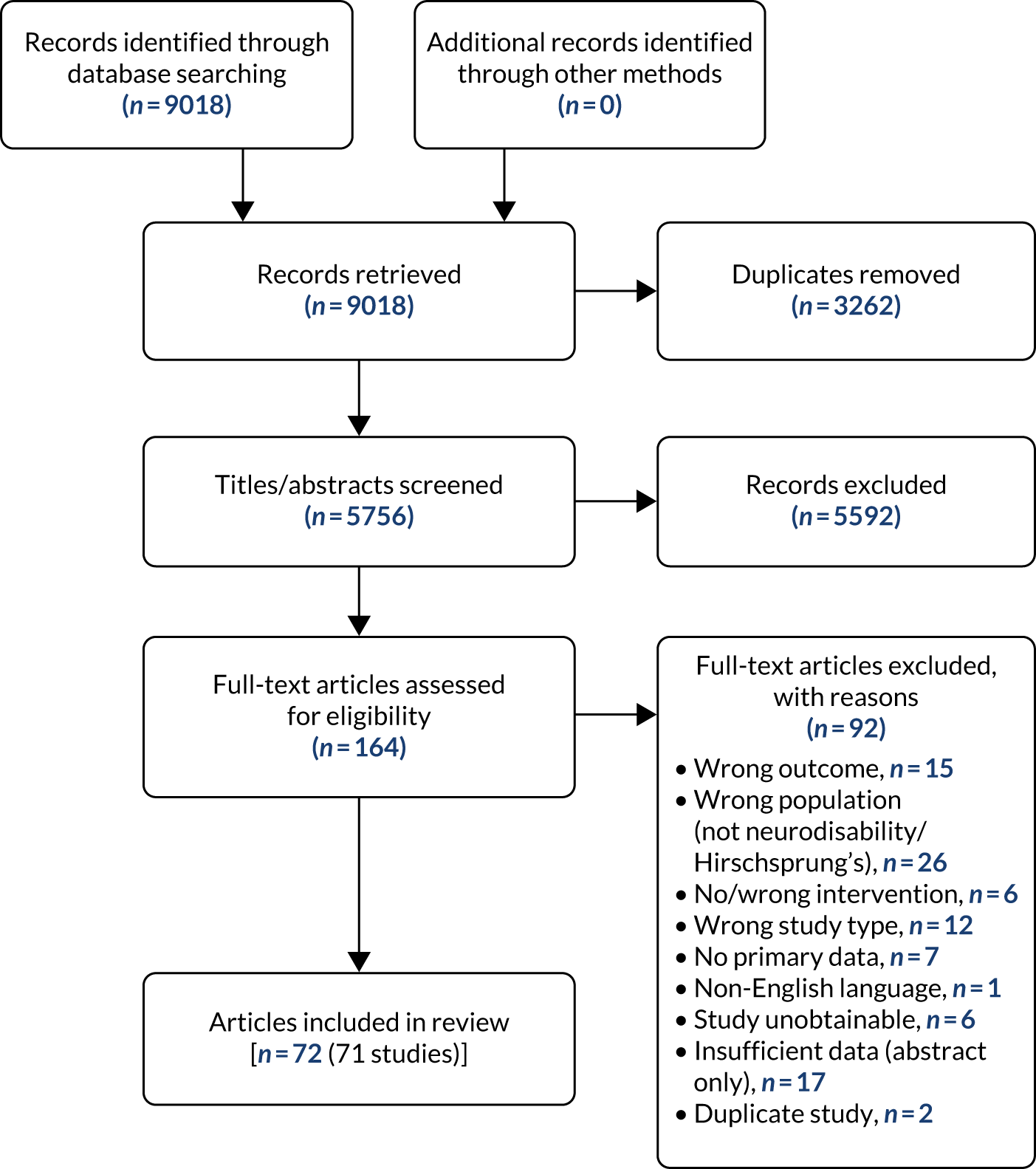

Results

We identified 9018 records, which resulted in 5756 individual references following the removal of duplicate records. At the title and abstract screening stage, we excluded 5592 articles, and we retrieved the full texts of 164 for scrutiny at the full-text screening phase.

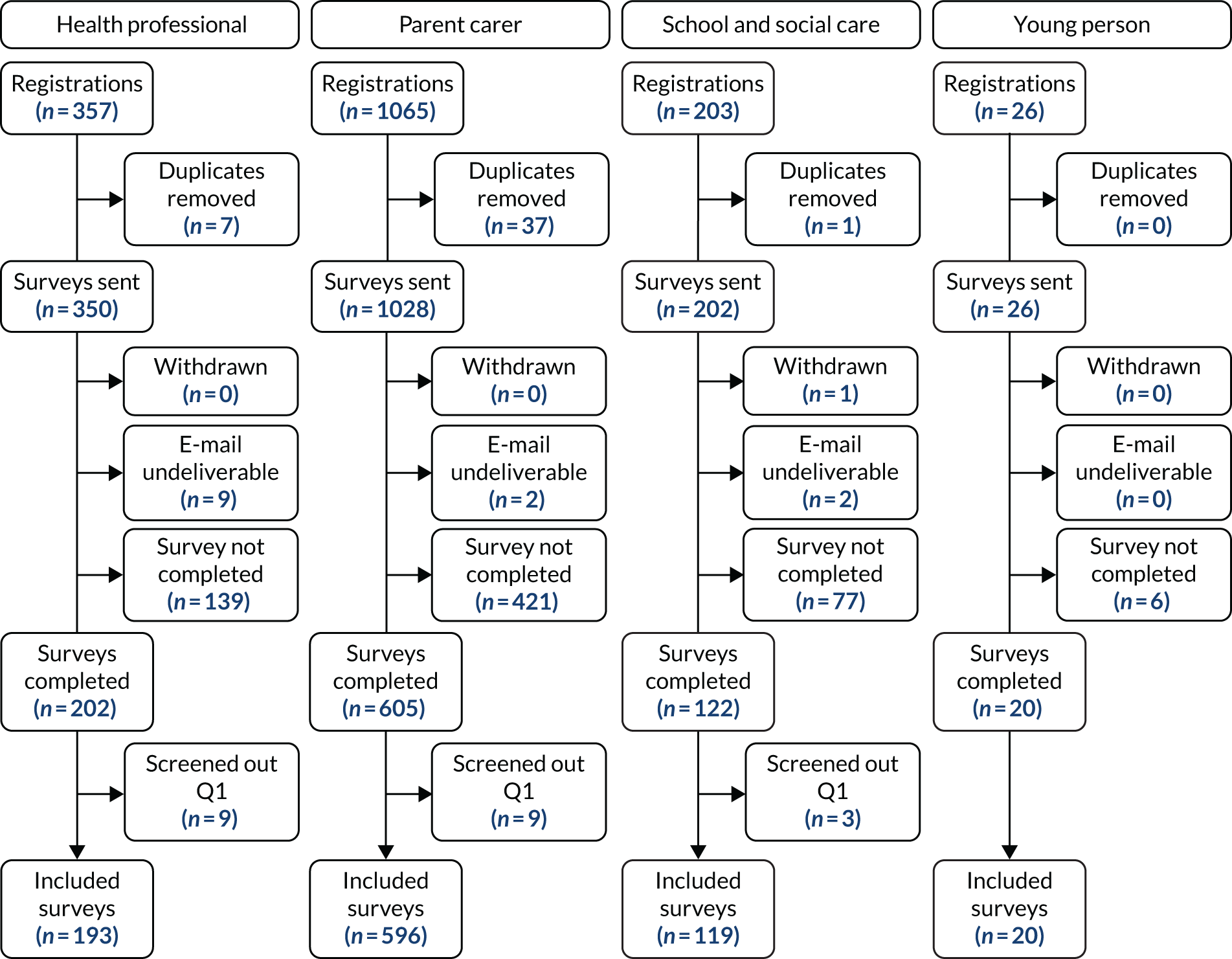

Following full-text screening, we included 71 studies from 72 articles in the final analysis (see Tables 2 and 3 and Appendix 4). Of these, 68 articles contained quantitative outcome data and three articles contained exclusively qualitative outcome data. The reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram showing the study screening and selection process.

Summary characteristics

Summary study characteristics are shown in Tables 2 and 3, laid out by intervention type and then by study type. Further details of study results are provided in Appendix 5 (see Tables 24–28).

| First author, year (country of study), study design | Intervention group | Setting | N; age | Intervention | Duration of intervention; follow-up | EPHPP quality appraisal | Urinary/faecal/both; outcomes reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | |||||||

| Yang,35 2015 [Taiwan (Province of China)], B&A | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 68; 5–12 years | Drug therapy – desmopressin | 4 weeks; 1 month | Moderate | Both (enuresis and lower urinary tract symptoms):

|

| Chertin,36 2007 (Israel), case–control | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 54; average 8 years | Combination therapy with desmopressin and oxybutynin vs. the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine | 1 year; NR | Weak | Urinary (enuresis):

|

| Gor,37 2012 (USA), cohort | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 671; mean 8.6 years | Desmopressin or anticholinergic treatment | 9 months; NR | Weak | Urinary (enuresis and daytime voiding symptoms):

|

| Autism | |||||||

| Lomas Mevers,38 2020 (USA), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 20; 5–16 years | Liquid glycerin suppositories and reinforcement | 6 weeks; 4 weeks | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Mruzek,39 2019 (USA), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 32; 3–6 years | Wireless moisture pager intervention | 12 weeks; 3 months | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Mruzek,39 2019 (USA), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 33; 36–72 months | Wireless moisture pager intervention | 12 weeks; 3 months | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Ardic,40 2014 (Turkey), B&A | Behaviour | Special education unit | 3; 3–4 years | Azrin and Foxx adaptation (modified intensive toilet training method) | 6 hours; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Keen,41 2007 (Australia), case–control | Behaviour | Kindergarten, special education unit, preschool | 5; 4 years 5 months to 6 years 9 months | Operant conditioning plus video | 7 days; 165 days | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Cicero,42 2002 (USA), case study | Behaviour | School | 3; 4–6 years | Azrin and Foxx adaptation | 22 days; 6 months and 1 year | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Developmental/learning disability | |||||||

| Edgar,43 1975 (USA), RCT | Behaviour | Special education unit | 20; 4–12 years | Behavioural training and device (electric belt, toilet with buzzer plus relaxation training) | 2 weeks; NR | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Hundziak,44 1965 (USA), RCT | Behaviour | Special education unit | 29; 7–14 years | Operant conditioning vs. operant conditioning and conventional training vs. no treatment | 27 days; NR | Moderate | Both:

|

| Sadler,45 1977 (USA), RCT | Behaviour | Special education unit | 14; 7–12 years | Azrin and Foxx method | 4 months; NR | Weak | Both:

|

| Van Laecke,46 2009 (Belgium), B&A | Education | Special education unit | 111; 4–15 years | Adequate fluid intake | 6 weeks; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Barmann,47 1981 (USA), B&A | Behaviour | Home, residential care | 3; 4–8 years | Azrin and Foxx adaptation | 10 days; 2 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Rinald,48 2012 (Canada), B&A | Behaviour | Home, community centre, university | 6; 3 years 3 months to 5 years 11 months | Azrin and Foxx adaptation | 4–12 days; NR | Moderate | Both:

|

| Lomas Mevers,49 2018 (USA), case study | Behaviour | Paediatric clinic | 44; 2–20 years | Behavioural intervention | 2 weeks; 6–24 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Angelman syndrome | |||||||

| Didden,50 2001 (the Netherlands), cohort | Behaviour | Residential facility; home | 6; 6–19 years | Azrin and Foxx adaptation | 2 days; 2.5 years | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Mixed | |||||||

| Valentine,51 1968 (UK), RCT | Medication | Hospital, at home | 16; NR | Imipramine | 3 weeks; 6 weeks | Weak | Urinary:

|

| First author, year (country of study), study design | Intervention group | Setting | N; age | Intervention | Duration of intervention; follow-up | EPHPP quality appraisal | Urinary/faecal/both; outcomes reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spina bifida | |||||||

| Kajbafzadeh,52 2009 (Islamic Republic of Iran), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 30; 5.6 years | Pelvic floor interferential electrostimulation | 6 weeks; 18 months | Moderate | Both:

|

| Kajbafzadeh,53 2014 (Islamic Republic of Iran), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 30; 6.7 years (range 3–13 years) | Transcutaneous functional electrical stimulation | 1 week; 6 months | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Loening-Baucke,55 1988 (USA), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 28; 7–21 years | Biofeedback training | Approximately 2 weeks; 12 months | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Marshall,56 2001 (UK), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 77; 4–18 years | Transcutaneous electrical field stimulation – Duet Continence Stimulator | 6 weeks-5 months; NR | Moderate | Both:

|

| Steinbok,57 2016 (Canada), RCT | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 21; 5–18 years | Filum section + medical therapy | 1 day; 3,6 and 12 months | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Van Winckel,58 2006 (Belgium), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 7; 4–13 years | Anal plug (Conveen®, Coloplast, Humlebaek, Denmark) | 3 weeks; NR | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Choi,59 2013 (Republic of Korea), B&A | Behaviour | Paediatric clinic | 53; 3–13.8 years | Stepwise bowel management programme | 3 months; NR | Moderate | Faecal:

|

| Dietrich,60 1982 (USA), B&A | Behaviour | Paediatric clinic | 55; 5.6–18.9 years | Bowel training | 1 week; 1.2 years | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Aksnes,61 2002 (Norway), B&A | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 20; 6.3–17 years | MACE procedure | 1 day; 16 months | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Ausili,62 2010 (Italy), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 62; 6–17 years | TAI; The Peristeen® Anal Irrigation System (Coloplast A/S Kokkedal, Denmark) | 3 months; NR | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Ausili,63 2018 (Italy), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic, home | 74; 6–17 years | TAI; Peristeen | Up to 24 months; unclear | Moderate | Faecal:

|

| Choi,64 2015 (Republic of Korea), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 47; 3–18 years | Irrigation cone-based transanal irrigation system (Colotip, Coloplast) or catheter-based TAI system (Peristeen anal irrigation system) | 3 months; 33 months | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Hascoet,65 2018 (France), B&A | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 53; 8.5 years | IDBTX-A 6–8 weeks | 6–8 weeks (varied by site); 3.7 years | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Kajbafzadeh,66 2006 (Islamic Republic of Iran), B&A | Surgery | Paediatric clinic and home | 26; 6.9 ± 2.6 years | IDBTX-A | 12 hours; 4 months | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Killam,67 1985 (USA), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 8; 7–19 years | Urodynamic biofeedback treatment | 9–51 weeks; NR | Weak | Both:

|

| Ladi-Seyedian,68 2018 (Islamic Republic of Iran), B&A | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 24; 9 years | Intravesical electromotive BoNTA ‘Dysport’ | 1 day; 1 year | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Lima,69 2017 (Brazil), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 25; 5–18 years | ISRD | 6 months; NR | Moderate |

Urinary: QoL Daily number of diapers used per day |

| Mattsson,70 2006 (Sweden), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 40; 10 months–11 years | Transrectal irrigation | 1.5 years; 8 years | Moderate | Faecal:

|

| Shoshan,71 2008 (Israel), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 20; 12 years | Anal plug | 4 weeks; NR | Moderate | Faecal:

|

| Horowitz,72 1997 (USA), B&A | Medication | Paediatric clinic, home | 18; 10.5 years (range 7–16 years) | Desmopressin | 6 weeks; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Tarcan,73 2014 (Turkey), cohort | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 31; 7.95 years | Intradetrusor injections of onabotulinum toxin-A | One injection; 12–42 weeks | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Palmer,74 1997 (USA), cohort | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 55; 2–14 years | Transrectal bowel stimulation | 9 weeks; NR | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Radojicic,75 2019 (Serbia), case–control | Behaviour | Paediatric clinic | 70; 4–16 years | Bowel management programme | 12 months | Weak | Both:

|

| Snodgrass,76 2009 (USA), case–control | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 41; 3–14 years | Bladder neck sling with and without enterocytoplasty | 1 day; 1 year | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Han,77 2004 (Republic of Korea), case study | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 24; 3.9–13.2 years | Intravesical electrical stimulation | 4 weeks; 3–6 months | Weak | Faecal:

|

| King,78 2017 (Australia), case study | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 20; 14.5 years | Transanal irrigation (Peristeen) | Unclear; 4.1 years | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Petersen,79 1987 (Denmark), case study | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 10; 8–12 years | Transurethral intravesical electrical stimulation | 3–4 weeks; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Vande Velde,80 2007 (Belgium), case study | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 80; 5–18 years | Stepwise bowel management programme | 1 week; NR | Moderate | Faecal:

|

| Bar-Yosef,81 2011 (USA), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 21; 6–22 years | MACE | 1 day; 4.7 years | Weak | Both:

|

| Ibrahim,82 2017 (Nigeria), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 23; 3.5–17.8 years | ACE | 1 day; 2.6 years | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Matsuno,83 2010 (Japan), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 25; 4–23 years | Retrograde colonic enema (RCE); Malone anterograde continence enema | 1 day; 23–31 months | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Snodgrass,84 2016 (USA), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 37; 3–18 years | Bladder neck sling | 1 day; 60 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Van Savage,85 2000 (USA), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 16; 12 (4–21 years) | ACE | I day; NR | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Wehby,86 2004 (USA), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 60; 3–18 years | Section of the filum terminale | 1 day; 13.9 months | Weak | Both:

|

| Schletker,87 2019 (USA), case study | Behaviour | Paediatric clinic | 22; 2–24 years | Bowel management programme | 1 week; no follow-up | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Neurogenic dysfunction | |||||||

| Haddad,88 2010 (France), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 33; mean age 12.22 years | Sacral neuromodulation | 6 months; 13 months | Moderate | Both:

|

| Borzyskowski,89 1982 (UK), controlled trial | Medically assisted | Hospital, possibly home | 43; 7 years | Clean intermittent catheterisation plus drug therapy | 3 months; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Corbett,90 2014 (UK), B&A | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic | 24; 4–16 years | TAI (Peristeen) | 1 week; 1 year | Weak | Faecal:

|

| Schulte-Baukloh,91 2006 (Germany), B&A | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 20; 8.9 years | Propiverine | 12 hours; 3–6 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Schulte-Baukloh,92 2012 (a longer-term follow-up of Schulte-Baukloh 200691) (Germany), B&A | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 17; 13 years | Propiverine | 12 hours; 36 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Guys,93 1999 (France), cohort | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 33; 13 (7–17 years) | Endoscopic injection of PDMS | 6–18 months; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Guys,94 2006 (France), cohort | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 49; 14 years (SD 4.8 years) | Endoscopic injection of PDMS | 6–18 months; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Silveri,95 1998 (Italy), cohort | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 23; 6–17 years | Collagen injection | 1 hour; 19 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| González,96 2002 (USA, Canada and Austria), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 27; 4–23 years | Artificial urinary sphincter with seromuscular colocystoplasty | 1 day; 1.1 years | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Do Ngoc Thanh,97 2009 (France), case study | Surgery | Paediatric clinic | 7; 6.5–15.5 years | Botulinum type A injections | 24 hours; 12 months | Moderate | Urinary:

|

| Myelodysplasia | |||||||

| Boone,98 1992 (USA), RCT | Medically assisted | Paediatric clinic; at home | 36; 6–12 years | Transurethral intravesical electrotherapy | 18 weeks; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Åmark,99 1992 (Sweden), RCT | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 10; 6–18 years | The alpha-adrenoceptor agonist phenylpropanolamine | 1 week; 13 weeks | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Mixed | |||||||

| Åmark,100 1998 (Sweden), B&A | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 39; 0.5–18 years | Intravesical oxybutynin | 1 day; 6 months | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Naglo,101 1979 (Sweden), B&A | Medication | Paediatric clinic | 13; 6–18 years | Drug therapy plus continence training | 9 weeks; NR | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Faure,102 2017 (France), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 59; 7.6 years (1.9–17.5 years) | Young–Dees bladder neck reconstruction, with bladder neck injection as a follow-up | 1 day; 16 years | Weak | Urinary:

|

| Jawaheer,103 1999 (UK), case study | Surgery | Paediatric surgery | 18; 3–14 years | Pippi Salle bladder neck repair | 1 day; 2 years | Weak | Urinary:

|

Included quantitative studies were conducted in the USA (n = 23), France (n = 6), the UK (n = 5), Sweden (n = 4), the Islamic Republic of Iran (n = 4), Republic of Korea (n = 3), Italy (n = 3), Canada (n = 3), Belgium (n = 3), Australia (n = 2), Israel (n = 2) and Turkey (n = 2), and one was conducted in each of the following countries: Austria (combined with Canada and the USA), Brazil, Denmark, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Serbia and Taiwan (Province of China). The years studies were conducted ranged from 1977 to 2020, although this information was not reported in 32 studies. Sample population sizes ranged from 3 to 150 participants.

Of the three qualitative studies, two took place in the UK and one took place in the USA. Study years were 2004, 2009 and 2014. Sample populations included 7, 18 and 40 participants, with two studies focused on the experiences of parents and caregivers and one paper focused on the experiences of children and young people.

Intervention categories

We found no studies that met our criteria under the categories of equipment to improve communication or movement abilities, toilet adaptations or clothing adaptations. We identified 24 studies that reported on interventions relating to medically assisted techniques, such as self-catheterisation. Interventions related to behavioural training (e.g. Azrin and Foxx-style104 training approaches) were identified in 14 studies. Interventions using surgical approaches such as MACE procedures were reported in 20 studies, and nine studies (reported in 10 papers) reported interventions relating to medications such as oxybutynin. One study reported an educational intervention. Details of complex interventions can be found in Appendix 6 and further details of the recorded adaptations made to the Azrin and Foxx intervention can be obtained on request.

Faecal and urinary continence

Thirteen studies focused on both faecal and urinary incontinence, with the remaining studies focused on either urinary or faecal incontinence. Faecal and urinary intervention focus across the included studies is shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Intervention category | Urinary (n) | Faecal (n) | Both (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational | 1 | – | – |

| Equipment | – | – | – |

| Toilet adaptations | – | – | – |

| Clothing adaptations | – | – | – |

| Behavioural training | 7 | – | 3 |

| Medically assisted techniques | 2 | 1 | – |

| Medications | 3 | – | 1 |

| Surgical approaches | – | – | – |

| Intervention category | Urinary (n) | Faecal (n) | Both (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational | – | – | – |

| Equipment | – | – | – |

| Toilet adaptations | – | – | – |

| Clothing adaptations | – | – | – |

| Behavioural training | – | 3 | 1 |

| Medically assisted techniques | 5 | 12 | 4 |

| Medications | 5 | – | – |

| Surgical approaches | 14 | 4 | 2 |

Neurological conditions

The conditions of children and young people in the studies identified by study authors included ADHD, autism, myelodysplasia, ‘developmental disability’, ‘mental disability’, spina bifida (including myelomeningocele, and spina bifida with anorectal malformations), Angelman syndrome, neurogenic dysfunction, neurogenic detrusor overactivity, neuropathic bowel/bladder, occult tethered cord syndrome and mixed conditions that appeared to fit neurodisability definitions.

Table 6 shows the number of studies reporting results for each intervention category in each condition.

| Intervention category | Condition (n) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-spinal-cord-related pathology | Spinal cord pathology | ||||||||

| ADHD | Autism | Angelman syndrome | Developmental/learning disability | Mixed | Spina bifida | Neurogenic dysfunction | Myelodysplasia | Mixed | |

| Educational | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Equipment | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Toilet adaptations | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Clothing adaptations | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Behavioural training | – | 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 | – | |||

| Medically assisted techniques | – | 3 | – | – | 17 | 3 | 1 | – | |

| Medications | 3 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Surgical approaches | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 5 | – | 2 |

The majority of interventions identified were in the medically assisted techniques category, with the majority of populations of interest formed of children and young people with spina bifida. The next largest group of studies identified were in the surgical approaches intervention category, again with the majority of participants in the populations of children and young people with spina bifida. We identified no studies of interventions that fell into the categories of toilet adaptations, clothing adaptations or equipment.

Age ranges of included study populations

Educational interventions (one study) covered the ages of 4–15 years; behavioural training interventions (14 studies) covered the ages of 2–24 years; medically assisted interventions (24 studies) covered the ages of 36 months to 19 years; medication interventions (nine studies) covered the ages of 6 months to 18 years; and surgical interventions (20 studies) covered the ages of 3–23 years.

Study designs

Included studies used a range of study designs. These included 16 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), one controlled trial, 30 before-and-after or cohort studies, 17 case studies, four case–control studies and three qualitative studies. Where reported, the majority of before-and-after and cohort studies recruited participants prospectively. This information was not reported widely in other studies. The range of study designs used across the intervention categories is shown in Table 7.

| Intervention category | Study design (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | CT | B&A/cohort | Case–control | Case study | |

| Educational | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Equipment | – | – | – | – | – |

| Toilet adaptations | – | – | – | – | – |

| Clothing adaptations | – | – | – | – | – |

| Behavioural training | 3 | – | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| Medically assisted techniques | 10 | 1 | 9 | – | 4 |

| Medications | 2 | – | 6 | 1 | |

| Surgical approaches | 1 | – | 8 | 1 | 10 |

Study quality

None of the included studies reporting quantitative evidence was assessed as high quality using the EPHPP quality assessment tool. 31 Quality of the quantitative studies was assessed as ‘moderate’ in 22 studies and ‘weak’ in 46 studies (Tables 8 and 9).

| First author (year); study type | Intervention group | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection method | Withdrawals and dropouts | Analysis | Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | |||||||||

| Yang, 2015;35 B&A | Medications | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Chertin, 2007;36 case–control | Medications | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Gor,37 2012; cohort | Medications | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Autism | |||||||||

| Lomas Mevers,38 2020; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Mruzek,39 2019; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Mruzek,39 2019; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Ardic,40 2014; B&A | Behavioural | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Keen,41 2007; case–control | Behavioural | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Cicero,42 2002; case report | Behavioural | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Developmental/learning disability | |||||||||

| Edgar,43 1975; RCT | Behavioural | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | strong | Moderate |

| Hundziak,44 1965; RCT | Behavioural | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Sadler,45 1977; RCT | Behavioural | unclear | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Unclear | Moderate | Weak |

| Van Laecke,46 2009; B&A | Educational | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Barmann,47 1981; B&A | Behavioural | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Rinald,48 2012; B&A | Behavioural | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Lomas Mevers,49 2018; case report | Behavioural | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Angelman syndrome | |||||||||

| Didden50, 2001; cohort | Behavioural | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |

| Mixed | |||||||||

| Valentine,51 1968; prospective RCT | Medications | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| First author (year); study type | Intervention group | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection method | Withdrawals and dropouts | Analysis | Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spina bifida | |||||||||

| Kajbafzadeh,52 2009; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Kajbafzadeh,53 2014; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Loening-Baucke,55 1988; RCT | Medically assisted | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Marshall,56 2001; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Steinbok,57 2016; RCT | Surgery | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Van Winckel,58 2006; RCT | Medically assisted | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Choi,59 2013; B&A | Behavioural | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Dietrich,60 1982; B&A | Behavioural | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Aksnes,61 2002; B&A | Surgery | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak |