Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/144/05. The contractual start date was in May 2020. The draft report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimers

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 McFadden et al. This work was produced by McFadden et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 McFadden et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and context

The frequency of feeding and volume of milk intake of healthy term-born infants is generally dictated by the infant’s appetite. Term infants exhibit feeding and satiation cues and adjust their volume of intake to compensate for differences in the nutrient density of various milks. 1 In contrast, enteral feeds for preterm infants are usually given as prescribed volumes at scheduled intervals. 2 However, there is some evidence that preterm infants can self-regulate their intake. 3 Furthermore, while feeding cues may be more difficult to detect in preterm infants, they may be sufficiently evident for a parent or caregiver to recognise and respond to,4 thereby supporting safer and more successful feeding experiences. Caregivers and parents can use infants’ physiological and behavioural channels of communication to inform their feeding decisions and actions. This may also set the scene for future feeding practices and success, as well as parent–infant interaction. Although studies have shown that cue-based (also known as responsive) feeding is feasible for preterm infants, the adoption of cue-based feeding has been constrained by the ‘schedule- and volume-driven culture’ in many neonatal units (NNUs). 5

Alternatives to scheduled interval feeding regimens that aim to respond to infant feed cues have been described. 6 These are relevant to the transition from gastric tube feeding to oral feeding,7 when preterm infants are developing periods of sustained alert activity and a suck–swallow–breathe pattern8 sufficient for oral feeding to commence. 1

Cue-based feeding is a co-regulated approach. 6 The enteral feeding process starts when the caregiver recognises infant cues that indicate readiness to feed and ends when the infant demonstrates satiation. The infant, therefore, determines the timing, duration and volume of intake. At each stage during transition to oral feeding, through understanding and interpretation of their cues, infants are supported in such a way that they can achieve all they are capable of with regards to oral feeding. Cue-based feeding occurs alongside supplementary tube feeding with the understanding that, developmentally, many preterm infants are not yet ready to fully sustain themselves by oral feeding. In modifications of cue-based feeding, caregivers may pre-set a maximum permitted duration of inactivity or sleep between feeds or a maximum volume of intake or modify feeding plans to consider the reduced endurance levels of preterm infants.

The transition to oral feeding is a critical developmental stage for preterm infants. Cue-based feeding may be considered a part of an integrated approach to providing ‘developmental care’ when infants are seen as individuals and caregivers are guided by the needs and behaviours of the infant. 9

Cue-based feeding may also increase rest between feeds promoting infant-led sleep and wake patterns. Potentially, infant-led feeding patterns will facilitate development of organised behaviour states leading to earlier establishment of oral feeding and thereby shortening hospital stay for preterm infants. 1

Reducing length of hospital stay has a direct effect on hospital costs and may also decrease cot occupancy in NNUs, thus reducing the need for inter-hospital transfer of women and infants. 10 Compared with a scheduled approach, cue-based feeding may support infant stability during oral feeds as infants’ cues will be responded to, resulting in fewer episodes of physiological instability, which could cause significant harm (e.g. aspiration, desaturation and bradycardia events). 11 As feeding an infant is a primary activity over the first year of life and a major preoccupation of parents, it is anticipated that there may be other benefits for the family and caregivers of cue-based feeding, principally allowing parents to feel more directly involved with their infant’s care and better understand their infant’s communication, together with increasing parental confidence and ability to recognise and respond to their infant’s needs during their hospital stay and beyond. Enhanced parental satisfaction is a key quality indicator in measuring the effectiveness of family-integrated care in neonatal services. 12

Potential adverse effects of cue-based feeding for preterm infants are recognised. These mainly relate to whether or not such a regimen can guarantee metabolic stability, particularly normoglycaemia, in this vulnerable group. Even at the point of discharge home from hospital, some preterm infants are known to be susceptible to hypoglycaemia if a scheduled enteral feed is omitted or delayed. 13 Concern exists that repeated or prolonged episodes of hypoglycaemia may impair longer-term growth and development. 14 There may be more acute problems relating to gastrointestinal immaturity, such as feeding intolerance and a higher risk of aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs, as well as concerns that allowing unrestrained volumes of enteral intake may increase the risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux or feed intolerance. However, there is a lack of evidence of these potential adverse effects and, indeed, some problems may be exacerbated by not responding to the infant’s cues. 11 Despite these concerns, and despite a lack of evidence of benefit, cue-based feeding is established in some NNUs in other countries (e.g. Sweden15,16 and the USA17,18) and is increasingly being used in NNUs in the UK. 19 Cue-based feeding for preterm infants is now recommended as a method to increase the duration of breastfeeding in the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI) ‘Ten steps to successful breastfeeding’. 20

Overall, the evidence to support cue-based feeding is limited. A recent Cochrane review1 concluded that there was low-quality evidence that cue-based feeding compared with scheduled feeding leads to earlier transition to full oral feeding. The review authors noted that this evidence should be treated with caution owing to several methodological weaknesses. 1 Furthermore, there is a lack of strong or consistent evidence of the effect of cue-based feeding compared with scheduled feeding on important outcomes for preterm infants or their families. 1 Therefore, there is a need for rigorous evaluation of cue-based feeding for preterm infants within the NHS setting, based on the most up-to-date and complete evidence, and considering stakeholders’ (including parents’) views. The first step towards this is to assess if such an intervention trial is justifiable and feasible.

Research objectives

The overall aim of this study was to develop a manualised intervention and to assess whether or not it is feasible to conduct a clinical and cost-effectiveness study of cue-based compared with scheduled feeding for preterm infants in NNUs.

The study had eight research objectives:

-

to describe the characteristics, components, theoretical basis and outcomes of approaches to feeding preterm infants transitioning from tube to oral feeding, including by feeding type (breast milk, donor breast milk, formula, combined) and method (breastfeeding, bottle feeding)

-

to identify operational policies, barriers and facilitators, and staff and parents’ education needs in NNUs implementing cue-based feeding

-

to co-produce an evidence-informed, adaptable, manualised intervention, including staff and parent educational support for feeding preterm infants at the transition from tube to oral feeding in response to feeding cues and signs of infant stability

-

to appraise the willingness of parents and staff to implement and sustain the intervention

-

to assess the associated costs of implementing cue-based feeding in NNUs

-

to determine the feasibility and acceptability of conducting a future randomised controlled trial (RCT), including views on important outcomes of parents, staff and service commissioners

-

to scope existing data-recording systems and potential short- and long-term outcome measures (e.g. feeding outcomes, length of time to transition to full oral feeding, length of stay in NNUs, adverse events, infant growth, parent–infant attachment and well-being, and parent and staff satisfaction)

-

to determine key stakeholders’ views based on the evidence from our study (objectives 1–7) of whether or not a RCT of this approach is feasible and what the components of a future study would look like.

Overview of the study and structure of the report

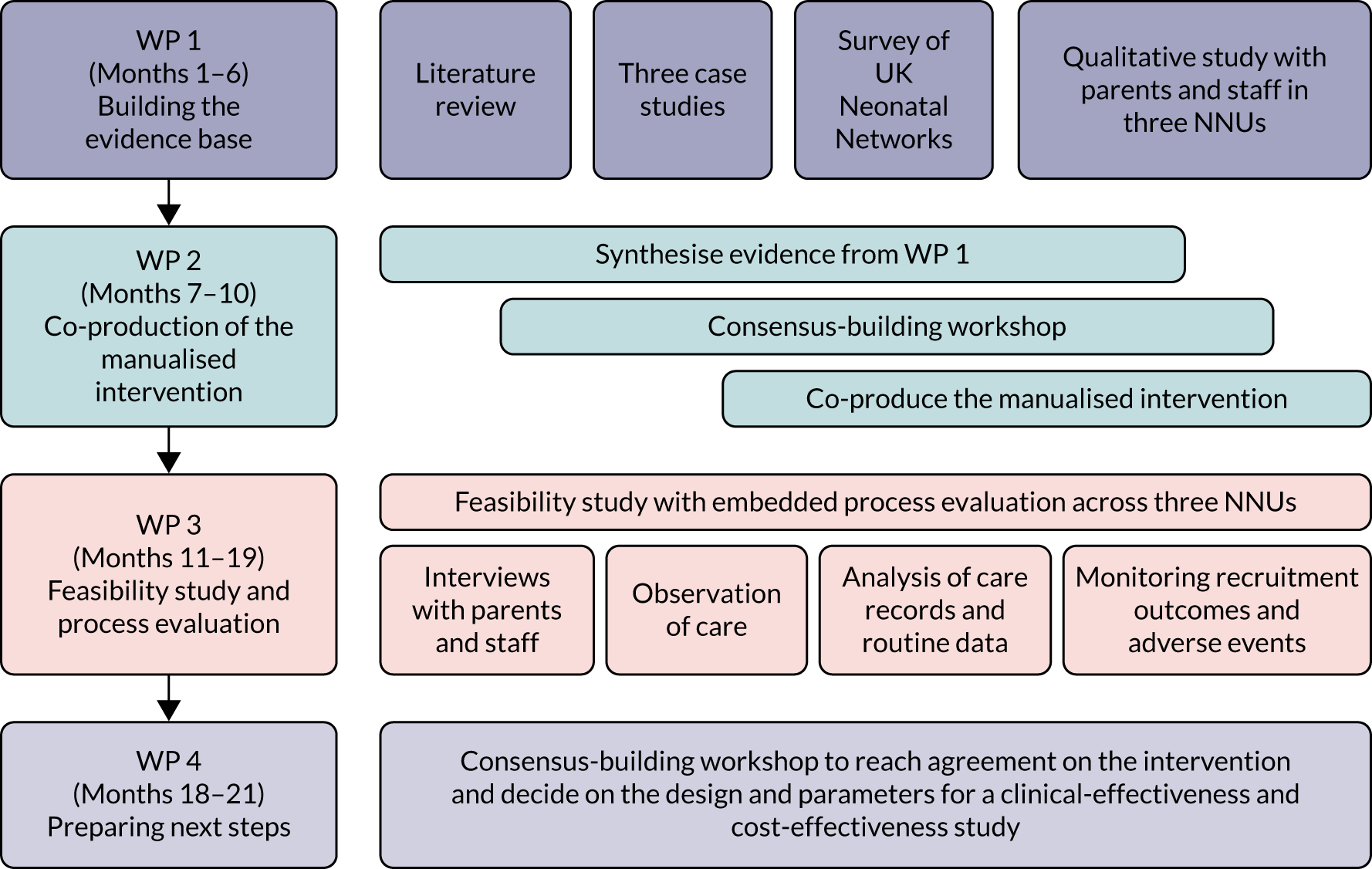

The study comprised four work packages (WPs) based on the Medical Research Council principles for developing and evaluating complex interventions21 and process evaluations. 22 The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

Work package 1: building the evidence base

To inform the content and methods of the manualised intervention, WP 1 comprised a systematic literature review; three case studies of NNUs with embedded cue-based feeding; telephone interviews with senior members of staff from NNUs across the UK to assess variation in approaches to the transition from tube to oral feeding; and qualitative research with parents and staff in three NNUs to gain their perspectives on cue-based feeding. The findings of this WP are presented in Chapters 3–6.

Work package 2: co-production of the intervention

To develop an evidence-informed, adaptable, manualised intervention, WP 2 comprised the synthesis of the evidence from WP 1; a consensus-building workshop with relevant stakeholders, including parents and third-sector organisations, to agree the intervention components; and co-production of the manualised intervention including behaviour change techniques (BCTs), training packages and commissioning of a short film of infant cues. A description of the methods and the final intervention are presented in Chapter 7.

Work package 3: feasibility study and process evaluation

To determine feasibility, WP 3 comprised a feasibility study with an embedded process evaluation22 to assess the willingness of parents and staff to implement the intervention, explore the design of a future study, and determine the feasibility and acceptability of conducting a future RCT. The intervention was implemented in three NNUs across the UK. The methods and findings of this WP are presented in Chapters 8–10.

Work package 4: preparing next steps

Work package 4 comprised synthesising the findings of the previous WPs and a stakeholder workshop to explore preferences, reach agreement on the manualised intervention and produce a framework for decision-making on the design, feasibility and acceptability of a future clinical and cost-effectiveness study of cue-based compared with scheduled feeding for preterm infants. We used the ADePT (A process for Decision-making after Pilot and feasibility Trials) to guide our analysis. The process and outcomes of this WP are presented in Chapter 11.

In Chapter 2 we describe how stakeholders, including parents, were involved in the study. In Chapter 12 we discuss the findings of the study, its strengths and weaknesses, and the implications of our work for taking forward the Cue-based versus scheduled feeding (Cubs) intervention.

Chapter 2 Patient, public and wider stakeholder involvement

This chapter provides an overview of our approach to patient and public involvement and wider stakeholder engagement including health-care professionals, third-sector organisations and researchers. Throughout this report, we use the term parent involvement instead of patient and public involvement. There is further detail of how parent and stakeholder involvement contributed to the implementation of the research threaded through the remainder of the report.

Pre submission of the funding application

We involved parents in preparing the application for funding to conduct the study. Through two third-sector charitable organisations [Bliss (London, UK) and TAMBA (Twins and Multiple Births Association) (now Twins Trust, Aldershot, UK)] which support parents and infants in NNUs, we discussed the study design with five women with recent experience of the transition from tube to oral feeding with a preterm infant in a NNU. The women had experienced scheduled feeding moving to cue-based feeding near discharge from the NNU. These discussions highlighted the importance of education for parents so that they understand the rationale for cue-based feeding and can identify their infant’s feeding cues. We learned that staff training is needed so that information and support for parents is consistent while also tailored to individual need. The women highlighted the need for the intervention to support breastfeeding as well as formula feeding and suggested important outcomes were time to discharge from the NNU and breastfeeding rates. The research team included a co-investigator from the neonatal charity Bliss, who contributed to the design of the study (in particular, the parent involvement component and suggestions to incorporate parents’ recording of outcome data in the intervention).

Parent involvement

Bliss was critical to facilitating parent involvement in the Cubs study. As well as having a member of Bliss on the research team, Bliss hosted the Parents’ Panel and the Bliss research team member attended all the research team meetings, Stakeholder Advisory Group meetings, and the workshops in WP 2 and WP 4.

Through an advertisement on the Bliss website, we recruited six parents with relevant experience of having an infant in a NNU to form a Parents’ Panel. Over the course of the study, three teleconferences were held with the Parents’ Panel. Activities of the Parents’ Panel included reviewing the participant information sheets prior to submission for ethics approval, co-designing the ‘Our Feeding Journey’ document that was an integral part of the intervention, and reviewing the intervention components including the posters and film. The Parents’ Panel reviewed and made many suggestions for the script of the film. The Parents’ Panel also suggested solutions to some of the challenges encountered during WP 3, for example offering alternatives to the telephone follow-up. Members of the Parents’ Panel attended the workshops in WPs 2 and 4.

Two members of the Parents’ Panel were also members of the Stakeholder Advisory Group and the Study Steering Committee. They were involved in all Stakeholder Advisory Group meetings including the final one at which they contributed to discussion of the findings, and options for optimising the intervention and research.

Stakeholder involvement

Other than parents, the main stakeholders for our work were health-care practitioners working in NNUs and researchers with an interest in neonatal care and/or intervention development and feasibility studies. We involved these stakeholders through our Stakeholder Advisory Group and the two study workshops (WPs 2 and 4). The Stakeholder Advisory Group comprised two neonatal care practitioners (one from England and one from Scotland), a representative from UNICEF UK BFI National Neonatal Network, an associate professor from Sweden with an interest in neonatal care and three researchers (a health economist, a statistician and an expert in using the ADePT framework, all from Scotland). The group met four times during the study and provided advice on the intervention and the research, including suggesting solutions to overcome challenges (e.g. slow recruitment). Wider stakeholder engagement was also achieved through the consensus-building workshops in WPs 2 and 4. The methods and findings of these workshops are reported in Chapters 7 and 11.

The parental and wider stakeholder involvement was critical to the study and had many benefits, as can be seen throughout this report. Parental engagement was better at the beginning of the study; for example, five parents attended the first workshop but only one parent attended the final workshop. However, engagement with the Parents’ Panel remained consistent.

Chapter 3 Literature review

In this chapter we report the aims, methods and findings of the systematic review of the literature and the analysis of cue-based policies and guidelines. The review was conducted to update and build on the existing Cochrane review. 1 Although Watson and McGuire1 included only RCTs, our review included studies of any design to synthesise additional information on underpinning theories, components, characteristics and outcomes of interventions, and economic evaluations.

Review aims and questions

The aims of the systematic review were to synthesise existing evidence on the components, characteristics, theoretical basis and associated BCTs23 of interventions, infant and parent outcomes and any economic evaluations.

The specific review questions were as follows.

In studies examining the effectiveness of approaches to feeding preterm infants transitioning from tube to oral feeding:

-

What are the study characteristics (participants, interventions, comparisons, context)?

-

What are the specific components of the interventions?

-

What, if any, is the theoretical basis of any intervention being tested?

-

What specific outcomes have been tested and what is the magnitude and direction of any effect?

We examined the nature of the evidence regarding the feeding type adopted (i.e. mother’s breast milk, donor breast milk, formula, any combination of these) and by feeding method (breastfeeding, bottle feeding, other methods such as cup feeding).

Review methods

The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42018097317).

Search strategy

The search strategy was informed by the existing Cochrane Review. 1 Searches were conducted in August 2018. We initially searched for existing systematic reviews from Cochrane, Campbell and Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)/Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) databases. This was followed by searches of key online databases to identify other kinds of intervention studies (e.g. cohort studies; controlled trials; interrupted time series designs; controlled before-and-after studies; and programme evaluations). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE; EMBASE; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR); Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); Social Science Citation Index; PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA); Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC); Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA); Social Policy and Practice; Bibliomap; Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER); Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (TRoPHI); Social Care Online; British Nursing Index; Research Councils UK; OAIster and OpenGrey. We also carried out searches using the Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) advanced interface to identify relevant research on NHS and UK government sites. The search strategy used subject headings (specific to each database), key words and free-text search terms. We also used truncation and wild cards in order to increase sensitivity. No language restriction was applied to the search; however, studies were excluded at the full-text screening stage if an English translation was not available. The search architecture is shown in Box 1. The full search strategy for Ovid databases is presented in Appendix 1.

-

Pre-term/neonates OR synonyms.

-

Cue-based feeding OR synonyms.

-

1 and 2.

-

Limit to 6 years.

-

Remove duplicates from 4.

Study selection

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were set a priori and were informed by the trials included in the previous Cochrane review. 1 Publications were included if they reported empirical findings of an investigation that aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness of any intervention designed to support developmentally normal preterm infants born before 37 weeks’ gestation to transition from tube to oral feeding. To be included, infants had to be clinically stable, at least partially enterally fed and have an intragastric tube in place at the start of the study. Studies of multiple births were also included. We excluded studies of infants > 37 weeks’ gestation, preterm infants who had transitioned to full oral feeding, infants with major congenital anomalies, gastrointestinal disorders (e.g. necrotising enterocolitis), congenital infections and major neurological conditions (e.g. cerebral palsy, seizures, grade III–IV intracranial haemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia) and infants whose parent(s) did not give consent for inclusion in the study. Studies were also excluded if they did not report methods and data.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently for inclusion by two reviewers. The full texts of relevant studies were retrieved and screened independently by two members of the research team. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Data extraction and synthesis

All included studies were categorised based on their methodology and research questions. Data were extracted regarding (1) study country, (2) design, (3) characteristics (participants, interventions, comparisons, context), (4) intervention components, (5) theoretical basis for the intervention including BCTs and (6) outcomes including the magnitude and direction of any effect. Intervention BCTs were coded independently by two reviewers using the BCT taxonomy. 24 Coders were trained in BCT coding through an online course (URL: www.bct-taxonomy.com; accessed 9 December 2020), a 93-item taxonomy to identify BCTs within behavioural interventions. After initial coding, coders met to cross-verify coding and reach consensus when there were differences.

Quality assessment

All included studies were assessed for methodological quality according to individual elements of quality. The Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias tool was used to assess risk of bias in RCTs. 25 As there is no universal tool to encapsulate all domains of risk of bias in non-randomised trials, we used the recommendations of chapter 13 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 24

Synthesis

Owing to the diversity of the evidence, the findings have been synthesised narratively.

Results

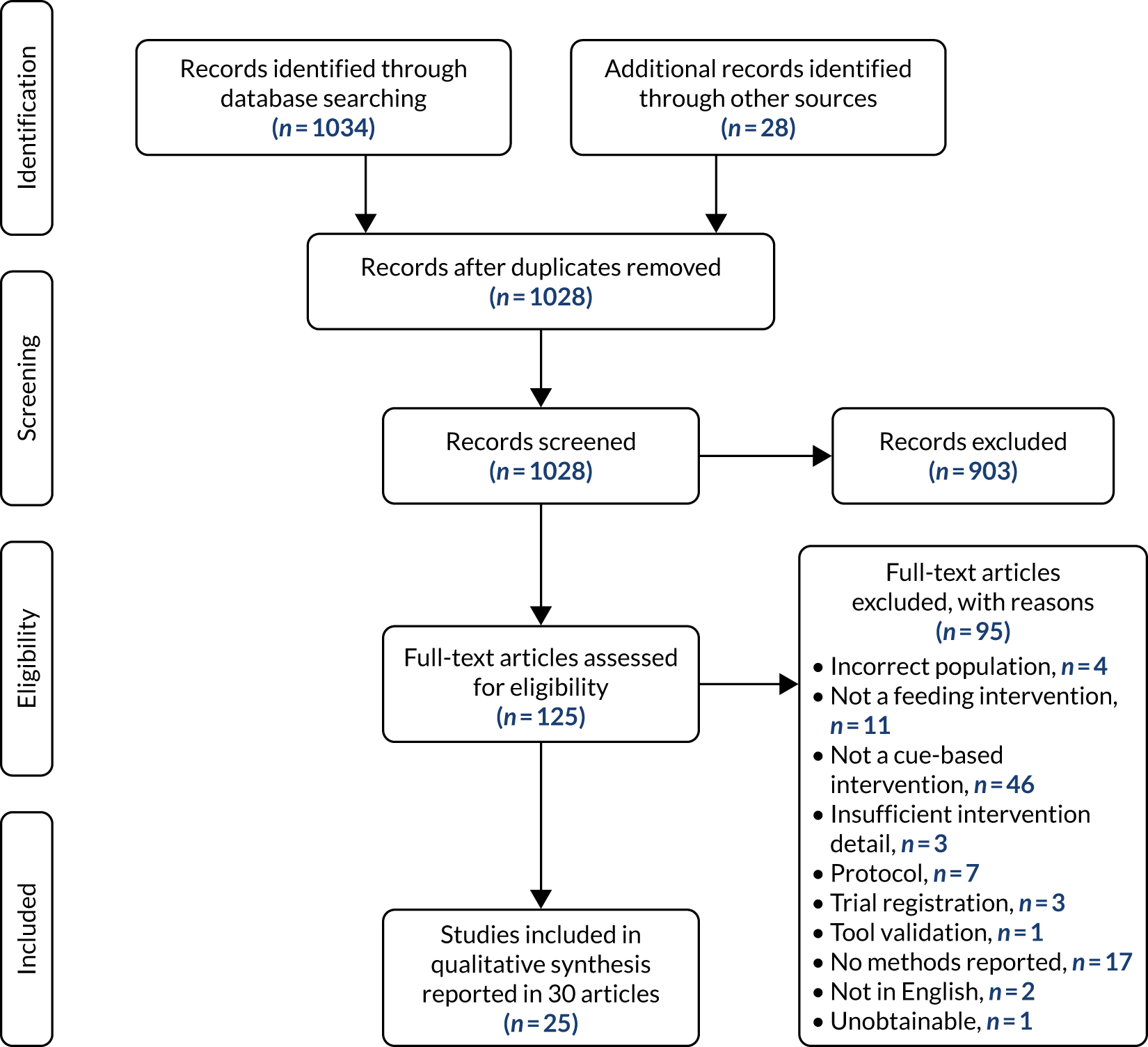

As a result of the search strategy, we screened 1028 studies and subsequently included a total of 25 unique studies reported in 30 publications (Figure 2 reports the numbers of records at each stage in the screening process).

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics

Twenty-five studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Studies were heterogeneous regarding methodology, inclusion/exclusion criteria and reported outcomes. All were published between 1982 and 2018, almost half (n = 12) since 2015. We found no economic evaluations.

The countries the studies were conducted in were the USA (n = 16),18,26–40 Canada (n = 4),41–44 Italy (n = 2),45,46 Australia,15,47 Sweden16 and the UK. 48 Fourteen of the intervention sites were neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) of level 3 or above;26,27,29,33,35–39,42,44–46,48 two were classified as below level 3. 28,43 The remaining studies did not specify the unit level (n = 9). 15,18,30–32,34,40,41,47

Regarding study design, 10 studies were RCTs, nine of which compared cue-based feeding with prescribed volume-driven scheduled feeding30–32,35–37,39,41,44 and one compared assessment of feeding cues at 3- and 6-hourly intervals. 29 Of the remaining 15 studies, nine reported quality improvement projects introducing cue-based feeding to protocols. 26–28,34,38,40,42,43,47 All but one study38 compared pre- and post-implementation infant outcomes. Likewise, two of the six observational studies compared intervention group outcomes with a historic cohort of preterm infants. 18,33 Of the remaining four, three did not have a comparison group15,45,46 and White and Parnell’s48 observational study documented experiences of introducing and implementing a cue-based feeding intervention.

Study participants were either preterm or very preterm infants. Infants were included in the studies based on their age either at birth or at the start of the intervention. Most studies classified the participant’s age based on gestation; however, post-conceptional age and post-menstrual age were also used. Infant characteristics such as sex, birthweight, additional medical complications and ethnicity were recorded in several studies and were tested as confounding factors in analyses. Maternal characteristics were not reported in 22 studies; among those that did report maternal characteristics,29,38,44 the information recorded was not consistent. Only nine studies reported whether infants were breastfed or bottle fed. 26,27,31–34,36,43,44

Common exclusion criteria included infants with major neurological, congenital, chromosomal and gastrointestinal complications that may affect an infant’s ability to feed. Mechanical respiratory support was also a common exclusion criterion; however, Dalgleish et al. 42 and Davidson et al. 27 included infants with respiratory complications. Only one study did not report exclusion criteria. 34

Interventions and their specific components

Over half of the studies (n = 14) implemented a specifically designed cue-based feeding protocol. Six studies27,28,33,34,40,46 used Ludwig and Waitzman’s infant-driven feeding protocol49 (or a modified version). The remaining feeding interventions included an adapted version of the Anderson Behavioural State Scale,50 Glass and Wolf’s Stepwise Oral Feeding in Infants Scale,51 the Preterm Infant Breastfeeding Behaviour Scale52 or the Co-Regulated Feeding Intervention. 53 Two of these scales had been published previously by an author of the included study. 15,38 The components of each intervention are detailed in Appendix 2.

Intervention training

Eighteen of the studies described training neonatal staff and parents to recognise infant cues. Over half of the studies (n = 14) documented examples of feeding cues; however, only nine discussed stop cues. Ten studies included recognising a successful feed. Only four studies described all three elements. 18,27,42,48 Although all studies explored the impact of cue-based feeding on preterm infant outcomes, schedules were still evident in the feeding protocols. Fourteen studies had maximum time limits, which, if exceeded, meant that gavage feeds would be used. Likewise, if a full feed was not taken within a specified time, the remaining milk was given by tube to ensure that the infant received the prescribed intake. Just over half of the studies included fidelity testing achieved through observations, and video-recordings of feeds with inter-rater reliability testing by researchers.

Assessing study quality

We classified the 25 included studies into three main types: (1) RCTs (10 studies), (2) non-randomised prospective studies with a control group (three studies) and (3) not experimental, not prospective or did not report any information about a comparison group (12 studies). We assessed RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool25 and non-randomised prospective controlled studies using the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions54) tool. The remaining studies were not assessed as, by their nature, they were already considered to be at high risk of bias (Table 1).

| RCT (first author) | Domain of biasa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomisation | Allocation | Blinding P | Blinding O | Incomplete O | Selective R | |

| Collinge41 | ? | ? | H | ? | L | ? |

| Gray29 | L | L | H | ? | L | L |

| Kansas30 | ? | ? | H | ? | ? | ? |

| McCain31 | L | ? | H | ? | ? | ? |

| McCain32 | L | ? | H | H | L | ? |

| Pridham35 | L | ? | H | ? | ? | ? |

| Pridham36 | L | ? | H | ? | H | ? |

| Puckett44 | L | H | H | ? | ? | ? |

| Saunders37 | ? | L | H | ? | H | ? |

| Waber39 | H | H | H | ? | H | ? |

We assessed risk of bias in the included RCTs (see Table 1). We extended the risk-of-bias assessment adopted in the original Cochrane review1 to include all elements of bias as well as assessing risk of bias in the newly included study (Gray et al. 29).

Blinding of participants and personnel was not possible in studies of this type of intervention, hence all studies were assessed as high risk of bias for this element. Limited reporting across studies made it difficult to assess all methodological elements, hence the relatively common use of the assessment ‘unsure’ (‘?’) across the data set. Although blinding was an issue in the latest study to be included in the review,29 it was assessed in all other elements to be of low risk.

We also assessed risk of bias in the non-randomised studies we included that had a control group but were not RCTs (Table 2).

| Non-RCT (first author) | Domain of biasa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confounding | Selection | Classification | Deviations | Missing data | Outcome | Selective R | |

| Kirk18 | H | H | L | L | L | L | L |

| Ward47 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Wellington40 | H | H | L | L | L | H | L |

The studies by Kirk et al. 18 and Wellington et al. 40 were potentially at high risk of bias due to confounding and selection of participants. It was difficult to assess the study by Ward et al. 47 since only a conference abstract was available from which to understand the methods applied.

We did not assess risk of bias in the 12 studies15,26–28,33,34,38,42,43,45,46,48 that were not experimental, not prospective or did not report any information about a comparison group, as, by their nature, such studies are deemed to be at risk of bias due to limitations with the methods that they employ.

Across all the studies (randomised and non-randomised) included in this review, methodological shortcomings across the data set undermine confidence in the findings generally. Only one study, the most recently found RCT published by Gray et al. ,29 was deemed to be at low risk of bias across the majority of the key bias domains (blinding of participants and personnel excepted).

Theory and behaviour change

Only two studies discuss the theoretical basis of their interventions. Thoyre et al. 38 credit two theories, namely the dynamic systems theory55 and guided participation,56,57 as the driving concepts for the extension of the co-regulated feeding intervention used in their research. Messer33 cites the synactive theory58 of Als as the theoretical base of the intervention developed for her doctoral study.

We mapped all the studies’ intervention components according to 93 hierarchically clustered techniques described in the BCT taxonomy (v1). 23 Where a technique was identified, we assessed whether the definition of the technique was fully or only partially met. Detailed assessments of all studies are available on request. Here, we summarise the main top-level findings from this analysis.

Table 3 shows that, across the included studies, 22 BCTs were identified. The majority of these were found to have been used in only one or two studies. The most commonly adopted BCT was the use of instructions to inform those delivering the intervention on how to perform the behaviour (17 studies with a total of 34 instances where this occurred). On its own, instructions to perform a behaviour that requires effort is not particularly effective. 59 The combination of BCTs is known to make interventions more effective. Of note, one study used nine BCTs,42 one used six26 and another used five. 45 This was taken into account in planning the intervention to maximise the use of BCTs that can together produce a more effective intervention.

| BCT | Number of specific components | Studies (first author) |

|---|---|---|

| Problem-solving | 2 | Thoyre38 |

| Goal-setting (outcome) | 1 | Chrupcala26 |

| Action-planning | 4 | Dalgleish,42 Giannì,45 Giannì,46 Gray29 |

| Monitoring of outcomes of behaviour without feedback | 2 | Chrupcala,26 Pridham35 |

| Biofeedback | 1 | Thoyre38 |

| Feedback on outcomes of behaviour | 1 | Gray29 |

| Social support (practical) | 3 | Giannì,45 Messer,33 Nyqvist15 |

| Instructions on how to perform the behaviour | 34 | Chrupcala,26 Collinge,41 Dalgleish,42 Davidson,27 Gelfer,28 Giannì,45 Kirk,18 Marcellus,43 McCain,31 McCain,32 Messer,33 Pridham,35 Pridham,36 Puckett,44 Saunders,37 Thoyre,38 Wellington40 |

| Information about antecedents | 2 fully, 1 partially | White48 |

| Information about health consequences | 3 fully, 2 partially | Dalgleish,42 Giannì,45 White48 |

| Salience of consequences | 1 | Thoyre38 |

| Information about social and environmental consequences | 1 fully, 1 partially | Dalgleish,42 Giannì45 |

| Information about the emotional consequences | 1 fully, 1 partially | Dalgleish,42 Giannì45 |

| Demonstration of the behaviour | 4 | Messer,33 Thoyre,38 Waber39 |

| Social comparison | 2 | Dagleish,42 Davidson27 |

| Prompts/cues | 4 | Chrupcala,26 Dagleish,42 McCain,32 Messer33 |

| Behavioural practice/rehearsal | 2 | Davidson,27 Thoyre38 |

| Credible source | 2 fully, 1 partially | Chrupcala,26 Dalgleish,42 Messer33 |

| Reducing the social environment | 1 | Chrupcala26 |

| Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour | 1 | White48 |

| Adding objects to the environment | 6 fully, 2 partially | Chrupcala,26 Dalgleish,42 Puckett,44 Saunders,37 Wellington,40 White48 |

| Identity associated with changed behaviour | 1 | Thoyre38 |

Outcome measures

In total, 33 outcome measures were identified during the review. As with the inclusion criteria, the definition of age differed across the studies, and when this is taken into account the number of measures increases to 41. The five most common outcome measures reported were (1) daily weight gain (n = 11), (2) total length of stay length in the NNU (n = 10), (3) length of time to full oral feed (n = 9), (4) respiratory complications or oxygen therapy requirements (n = 9) and (5) daily volume intake (n = 8). The full list of measures reported and the studies that have used them can be found in Appendix 3.

Only two papers used qualitative methods in their research. Marcellus et al. 43 explored parents’ experiences of implementing cue-based feeding through focus groups. Thoyre et al. 38 analysed video- and audio-recording and field notes of training sessions to assess the acceptability of guided participation as a method of introducing parents to cue-based feeding.

Evidence of effectiveness

This review was an update of the previous Cochrane review. 1 That review included nine small-scale, methodologically limited RCTs, leading the authors to conclude that there was a lack of strong or consistent evidence that responsive feeding affected important outcomes, and that there was low-quality evidence that feeding in response to cues may lead to earlier establishment of full oral feeding. 1

Our updated search found one further trial to include. 29 This trial was also relatively small scale (involving 55 infants), but was deemed to be at low risk of bias across the majority of the key bias domains. The study found that, among preterm infants fed when oral feeding cues are present, a 6-hour schedule did not alter the time to full oral feeding and had no effect on rate of tachypnoea or apnoea or length of hospital stay compared with a 3-hour feeding schedule. The study also found that a 6-hour oral feeding schedule led to only small reductions in the number of oral feeding attempts per day. The inclusion of this study, therefore, does not alter the conclusions of the previous Cochrane review. 1

Analysis of policies and guidelines

The aim of the guideline and policy review was to inform the development of the Cubs intervention by considering current cue-based feeding practices within NNUs worldwide.

Methods

An internet search, using the advanced Google interface, was conducted in July 2018. Search phrases were ‘cue-based feeding protocol’, ‘cue-based feeding protocol NNU’, ‘cue-based feeding guidelines UK’, ‘cue-based feeding NNU guidelines UK’ and ‘responsive feeding policy’. Potentially relevant documents were identified by reading the meta-descriptions of the generated web pages. The identified documents were read in full by a single reviewer to assess for relevance to cue-based feeding for preterm infants. The results of the search and review were discussed with the study’s chief investigator, and a final decision on inclusion or exclusion was made. All included documents were then read to identify their main points, especially around inclusion criteria, feeding methods and outcome measures, that could inform the Cubs intervention. These data were extracted and tabulated.

Results

Of the 15 documents included in the review, six were hospital guidelines and policies, five were training presentations, three were information or guidance sheets and one was a literature review. Six of the documents were from the UK (of which four were NHS guidelines and two were from UNICEF UK BFI), five were from Canada, three were guidelines from USA hospitals, and the remaining document was a guideline based on a literature review. The majority of the documents specified that the recommendations were for both breastfeeding and bottle-feeding transition (n = 11). Two did not specify this. Of the remaining two, one was written specifically for bottle-feeding transition and the other focused on bottle feeding but did have pictures of a mother breastfeeding included in the presentation.

Table 4 details the main points of each included guideline or policy and how it aided the development of the Cubs intervention. Some points have been modified based on evidence-based literature, and this is also indicated in the table. The decisions about which components of the guidelines and policies were used to develop the intervention were based on discussions within the research team and consultation with the Stakeholder Advisory Group. To be taken forward, the components had to be feasible within a UK setting and consistent with our understanding of cue-based feeding as well as the evidence base from our systematic review.

| First author and document title | Breastfeeding and/or bottle feeding | Purpose and main points |

|---|---|---|

|

Lubbe60 Clinicians’ guide for cue based transition to oral feeding in preterm infants: an easy to use clinical guide |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Published literature review producing an evidence-based guideline for cue-based feeding in pre-term babies ✓ Parent to be educated to recognise their baby’s feeding cues ✗ Babies should gain weight at a rate of 15 g/kg per day ✓ Supplementary feeding when required ✓ Babies must be physiologically stable prior to transition to oral feeds. ✗ Semi-demand feeding after discharge • Eight feeds in 24 hours ✗ Babies < 2.5 kg should be fed every 3 hours. More flexibility can be given to babies > 2.5 kg |

|

Nationwide Children’s Hospital61 Cue-based Feeding In High Risk Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Infants: Barriers, Outcomes and Opportunities |

Not specified |

A presentation introducing cue-based feeding with the aim to standardise feeding approaches and foster a cultural shift within NNUs ✓ Provide training ✓ Documentation of feeds to assist communication ✓ Audits of implementation ✓ Cue-based feeding responding to start and stop cues ✓ Supportive feeding techniques ✗ Introduces cue-based feeding scales/intervention within literature |

|

Surerus62 Cue Based Infant Driven Feedings |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Presentation of the results from implementation of a cue-based feeding protocol in a special care nursery ✓ Staff training session on cue-based infant-driven feeding ✗ Infant-driven feeding scale implemented ✓ Use of visual aids ✓ Parent education on feeding readiness, stress cues and calming a stressed baby ✗ Output was measured ✗ Daily weight measured for first 3 days of intervention ✓ Nasogastric tube remained in place to be used if baby showed signs of stress during feeding ✓ Length of stay was an outcome measure ✗ Parent confidence was measured ✗ Increase in staff knowledge was measured |

|

Baptist Health63 Cue-based Feeding |

Not specified |

Training presentation for staff to implement cue-based feeding within a NICU • Feeding-readiness assessment before every feed using scale ✗ Baby to be 32 weeks’ gestation ✓ Baby to be physiologically stable ✓ Recognition of hunger cues ✓ Monitor feeding tolerance for example negative physiological changes ✗ Monitor weight ✓ Feed via nasogastric tube, if required ✓ Assess feeding quality after every feed |

|

Southern West Midlands Newborn Network64 Bottle Feeding Guideline |

Bottle feeding |

Guideline for hospitals with the network on bottle feeding ✓ Maximise parents’ involvement in feeding and care ✗ Minimum gestational age of 34 weeks ✗ Care activities should conserve energy ✓ Observe for physiological stability prior to feed ✓ Observe for feeding cues ✗ Provide a calm environment to feed ✗ Slow flow teats ✗ Bottle feed swaddled ✗ Bottle feed in a side-lying position ✗ Paced feeding ✗ Maximum feed time of 30 minutes, with rests if required ✓ Staff training and updates |

|

Southern West Midlands Maternity and Newborn Network65 Progression from Tube to Oral Feeding (Breast or Bottle) |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Guideline introducing a modified responsive feeding flow chart for preterm infants progressing from tube to oral feeding • Cue-based feeding is slowly introduced to the feeding schedule • Flow chart for clinical staff to follow ✓ Quality of feed is defined and more important than the quantity fed ✓ Quality of each feed assessed ✓ A successful feed would be one based on start and stop cues • No longer than 4 hours between feeds but preferred to be no longer than 3 hours ✓ Nasogastric tube in place during transition ✓ Offer breastfeeding whenever cueing is seen, regardless of planned feeding schedule ✓ Encourage parent involvement in care ✓ Top-up when assessment of feed indicates it is required ✗ Weight measured every 2 days ✗ Monitor output ✗ Bottle feeding should be paced ✗ Bottle feed in an elevated side-lying position ✓ Recognise stress cues and stop feed immediately ✗ Monitor volume intake for bottle feeders and ensure prescribed volume is achieved ✓ Bottle feeding assessment chart ✓ Breastfeeding assessment charts |

|

UNICEF UK The Baby Friendly Initiative66 Responsive Feeding: Supporting Close and Loving Relationships |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Information sheet detailing the UNICEF BFI standards of responsive feeding ✓ Breastfeeding when baby shows hunger cues or signs of distress ✓ Staff training on the new UNICEF UK BFI standards ✓ Engaging conversations with mothers around their expectations of feeding |

|

Winnipeg Regional Health Authority67 Enteral Feeding and Nutrition for the Preterm and High Risk Neonate |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Clinical guidelines for enteral feeding of preterm and high-risk neonates ✗ Weekly head and length measurements ✗ Twice-weekly weights measured, adjusting volume of feed for baby accordingly ✓ When necessary, allow rest time during feed ✓ Skin to skin ✓ Kangaroo care ✗ Baby born at a gestation < 33 weeks progress through the SINC (safe individualised nipple competence) protocol ✗ First oral breastfeed should be at a pumped breast ✓ Infants must have physiological stability prior to feeding ✗ Non-nutritive sucking • Assess feeding progression every 24 hours ✓ Stop feeding at signs of physiological instability and give remaining feed by naso-gastric tube ✗ Consider weight testing for breastfeeding baby • Cue-based or semi-demand feeding when baby shows adequate progression • Feed every 3 or 4 hours ✗ Side-lying bottle feeding |

|

UNICEF UK The Baby Friendly Initiative68 Guidance for Neonatal Units |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Guidance documents from UNICEF on BFIs within NNUs ✓ Education for all clinical staff on feeding cues ✗ Promotion of breastfeeding ✓ Support and work in partnership with parents ✓ Recognition of behavioural cues by both staff and parents ✓ Written and visual aids to support conversations and information-sharing ✓ Recognising and responding to stress signals ✓ Frequent skin to skin ✓ Bottle feed in response to cues ✓ Monitor regulation of sucking and breathing when bottle feeding ✓ Nasogastric tube feeds when required ✓ Avoid force feeding • Feed in a semi-upright supported position ✗ Oral care with EBM ✗ Early expressing of breast milk and support to sustain expressing ✓ Skin to skin ✓ Educating and supporting parents to recognise and be responsive to their baby’s cues • Minimum of 8 feeds in 24 hours ✓ Update parents of care their baby received in their absence |

|

Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Trust and Barts Health NHS Trust69 Every Feed Matters: Developmentally Supportive Feeding on the NICU |

Bottle feeding (although images of breastfeeding also included) |

Presentation on the role of speech and language therapists in the transition to oral feeding in NNUs and how neonates develop to oral feeding ✓ Importance of supporting neonates to develop positive emotions relating to feeding ✗ Non-nutritive sucking ✓ Skin to skin ✓ Touch ✓ Feeding should be based on quality rather than quantity ✓ Babies display readiness and stress cues ✗ Stress cues are not as well known as readiness cues ✓ Physiological and behavioural responses to stress displayed by babies ✗ Paced bottle feeding ✓ Bottle feed in an elevated side-lying position ✗ Swaddled when bottle feeding |

|

Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust70 Trust Infant Feeding Policy |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

NHS infant feeding policy aiming to increase breastfeeding rates and improve safe feeding among bottle fed baby ✓ Skin to skin ✗ Encourage and support expressing ✓ Recognition and responding to feeding cues for breastfeeding and bottle feeding ✓ Mothers taught to recognise effective feeding ✗ Paced bottle feeds ✓ No force feeding through the recognition of stop cues ✓ Sharing of information to enable parents to make informed decision-making |

|

Alberta Health Services71 Oral Feeding Guideline |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Clinical guideline aiming to reduce risk and enhance baby’s feeding experience ✓ Feeding commenced based on baby’s readiness to oral feed not their gestation ✗ Non-nutritive sucking to develop sucking skills ✓ Skin-to-skin care ✓ Identification of cues ✗ Bottle feeding side-lying position ✓ Feed at baby’s pace ✓ Tube feed when required ✗ Test weighing for breast-fed babies to calculate milk intake ✗ Use bottles for top-up for breastfed babies if required, after nasogastric tube removed ✗ Maximum feed time of 30 minutes • Encourage cue-driven rather than volume-driven feeding once nasogastric tube removed |

|

McMaster Children’s Hospital and St Joseph’s Healthcare72 Cue-based Feeding in the Neonatal Nurseries |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Information sheet for parents on the Infant Driven Feeding Scale ✓ Advocates cue-based feeding ✗ Infant Driven Feeding Scale used to aid transition ✓ Combines clinical planning and baby’s readiness to oral feed ✓ Quality of feed is more important than the quantity of intake |

|

Wolf 201873 FUN-damentals of feeding in the NICU |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Presentation, providing the evidence supporting a cue-based feeding approach within a NICU and offers a number of interventions available to aid transition ✗ Non-nutritive sucking ✓ Skin to skin ✗ Oral motor stimulation ✗ Oral care with EBM ✗ Step wise plan ✗ Alberta Oral Feeding Progression Plan ✗ Co-regulated feeding ✓ Describes subtle stress cues given by a baby ✓ Stop cues • Side-lying feeding position for bottle feeding |

|

BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre74 Cue-based Feeding Guideline: NICU |

Breastfeeding and bottle feeding |

Health authority guideline for introducing cue-based feeding in their NICU ✓ Assess baby’s ability to oral feed ✓ Provide opportunities when readiness cues are shown ✓ Respond to stop cues ✓ Assess feeds based on quality being more important than quantity of intake ✓ Parents are partners in decision-making and care of their baby • Open to all babies ✗ Education for mothers on expressing ✓ Skin to skin ✓ Comforting touch encouraged ✓ Training for family members to recognise start and stop cues ✗ Pacing of bottle feeding |

Summary

The systematic review included 25 studies, of which 10 were RCTs, nine were quality improvement projects and six were observational studies. The quality of the studies was low, with all but one having a high risk of bias. Two key components of all the interventions were a cue-based feeding protocol and training for staff and parents. Only two interventions reported a theoretical basis. Across all studies, 22 BCTs were identified, of which the most common was providing instructions on how to perform the required behaviour. The studies incorporated 41 different outcomes, the most common of which were daily weight gain, length of stay in NNU, and length of time to full oral feeding. Although we found one additional small trial, our results do not change the conclusions of the Cochrane review22 that the evidence in favour of cue-based feeding is of low quality and should be treated cautiously. The analysis of policies and guidelines included 15 documents: six from the UK, five from Canada, three from the USA and one based on a literature review. The findings highlighted common features that were taken forward to the consensus-building workshop to inform the development of the Cubs intervention (see Chapter 7).

Chapter 4 Case studies of cue-based feeding

In this chapter we report three rapid organisational case studies of units that had embedded cue-based feeding, and highlight the learning for the development of the Cubs cue-based feeding intervention.

Aims

The aim was to generate a contextualised picture of cue-based feeding strategies for preterm infants in NNUs by exploring experiential knowledge and clinical or behavioural approaches that facilitated the practice. The case study goals were to confirm and detail key practices identified through literature review and consultation, with neonatal medical and nursing expertise provided by the Stakeholder Advisory Group.

The three participating NNUs were the Princess Royal Maternity (Glasgow) in Scotland, and Uppsala University Hospital (Uppsala) and Falun Hospital (Falun), both in Sweden. These units were identified by members of the Stakeholder Advisory Group as suitable for inclusion on the basis of pre-existing or embedded cue-based feeding approaches.

Method

Case studies can be focused on a group of people for a particular purpose and be designed to examine examples or phenomena that illuminate activity and behaviour within a real-life context. 75 The case studies described here involved observational visits to the clinical area, informal interviews with key informants (including senior nurses and consultant neonatologists) and access to relevant documentation, policies, guidelines and training materials.

Based on the characteristics of the trials included in Watson and McGuire,1 key features that were anticipated would inform the Cubs intervention included how to recognise infants’ readiness-to-feed cues; frequency of assessment of readiness to feed; understanding infants’ cues of physiological stability or instability during a feed; how to recognise satiation cues and when to stop an oral feed; minimum and maximum time between feeds; how to assess need for and when to give ‘top-up’ feeds by tube; stages of transition to full oral feeding; monitoring infant well-being, and mother/parent confidence and satisfaction with feeding. This information was reviewed and refined by expert neonatal medical and nursing partners to create a template for case study data collection, prior to visiting the units.

The template consisted of 46 questions grouped into broad categories to organise the collection of observational, documentary and verbal information on cue-based feeding strategies. The categories included population (infants eligible for cue-based feeding); feeding cues (how cues were defined); practicalities of feeding (‘the what’ and ‘the how’ of administering enteral nutrition); clinical markers (what guided clinical decisions or precautions were taken); written resources and policies; parent and staff experiences, and general reflections.

Each unit was visited once between July and October 2018. The visits lasted between 4 and 5 hours and were conducted by two members of the research team: a health psychologist and a neonatal nurse specialist, each experienced in their respective fields. Both researchers were always present and completed the template separately, making contemporaneous notes and observations during the visit. After visits were completed, notes were transcribed, compared and analysed based on the aims and goals of the case studies.

Findings

The results of each case study are presented based on key differences in their approach in terms of the population of infants eligible, how the cues were assessed and implementation considerations.

Unit 1 (Princess Royal Maternity, Glasgow, UK)

Population of eligible infants

Infants receiving intensive care were excluded from the study. Infants > 32 weeks’ gestation and not requiring intensive care were offered cue-based oral feeding. Infants < 32 weeks’ gestation were assessed for clinical stability and required a medical decision to be offered cue-based feeding.

Assessment of cues

Eligible infants were assessed using a five-step ‘readiness to feed’ scale. The absence or presence of recognised start or stop cues was identified by staff and/or parents and allocated the appropriate score. Oral feeding was withheld, offered or discontinued on this basis. Cue assessments were documented using the five-step tool framework before and during feeds.

Implementation

All staff were trained in the approach to cue-based feeding as a targeted quality improvement strategy. The five-step ‘readiness to feed’ scale applied to both breast- and bottle-fed infants, but an additional tool was used to guide reduction of supplementary feed volumes via gastric tube (top-ups) for breastfed infants. Infants had a prescribed volume to achieve in 24 hours which aimed for an increasing body weight trend over 1 or more days. The tool to guide reducing feeds recommended chunked reductions (i.e. by one-quarter, by half) in top-up volumes, based on quality-of-feed observations and through discussion with the mother. Kangaroo care was strongly encouraged when parents were available and wished to do this; however, infants were often dressed by the time cue-based feeding commenced so oral feeds were not necessarily pre-empted by this.

Unit 2 (Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden)

The population of eligible infants

A limited number of infants were excluded because they were orally ventilated (oral feeding therefore was not possible) or exclusion was medically indicated (generally infants with significant gastrointestinal disorders). The use of cue-based feeding was fully infant-driven with no minimum gestational age or formal assessment. Infants were offered the mother’s choice of oral feed as soon as they actively sought out the breast during kangaroo care. Unrestricted and prolonged kangaroo care was proactively offered in all cases, even in the case of infants born at as early as 21–22 weeks’ gestation.

Assessment of cues

Experiential, informal observation of start and stop cues was made by staff, many of whom had completed a 4-day training programme on infant neurodevelopment: Family and Infant Neurodevelopmental Education (FINE). There was also support from qualified Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP)76 trainers. This knowledge was translated to parents and new staff through informal bedside teaching from the time of admission, regardless of the gestation of the infant. Although the quality of feeds was documented, cues were not, with responsibility for cue recognition shifting quickly to parents.

Practicalities of implementation

Pre- and post-feed test weighing was routinely used to assess the intake of breastfed infants. There were no limits on time or frequency of feeds, but a prescribed daily volume was set by medical guidance. A template specified by how much the total volume of feed could be reduced over 24 hours, which allowed flexibility from feed to feed. Many variables identified in the policy guidance (e.g. frequency, quality, sleep states, weight at feeds and over time) could influence the duration over which this occurred. Some clinical nursing judgement was required to negotiate these variables in combination with test weighing and discussion with the mother regarding top-ups.

Unit 3 (Falun Hospital, Falun, Sweden)

The population of eligible infants

The population of eligible infants was similar to that of Uppsala University Hospital; however, as this was a unit offering a lower level of intensive care facilities, complex infants or those of < 28 weeks’ gestational age were transferred to a tertiary unit. Infants who were > 28 weeks’ gestation were included unless they were ventilated or their exclusion was medically indicated (generally because of suspected gastrointestinal infection, as more serious issues would result in a transfer to higher care).

Assessment of cues

The UNICEF image chart and a ‘wheel of cues’ were used to assess when to start feeds, but an informal judgement-based approach was used to decide when to stop feeds. Any instability or issues with a specific feed informed the approach at the next feed. Documentation included quality of feed and start cues, but not stop cues. Training for most staff was informal and ad hoc (supported by one staff member with NIDCAP training). Kangaroo care was unrestricted, and parents were encouraged to learn and respond to cues early.

Practicalities of implementation

A combination of cue and scheduled approaches was in evidence; for example, very frequent feeding would see an adjustment in top-ups. A formal tool was used to guide small reductions in prescribed volumes gradually using daily weight. This assumed eight feeds a day and a 5 ml reduction in each feed, over 1 day, and further reductions (in 5-ml increments) were applied if daily weight gain was medically acceptable.

Clinical considerations

Although there were key differences in the approach to cue-based feeding, there were clinical similarities across the three sites; for example, a maximum limit of 3 hours between feeds was applied regardless of cues, and this was relaxed only when feeding was established. There was a clear focus on the importance of assessing the efficacy of breastfeeding rather than just applying the tools available to support the identification of feeding cues. All units used prescribed daily feed volumes and relied on weight and head circumference trends to ensure that nutritional, growth and development needs were achieved. This was an important feature of NNU care and a key driver in the clinical management of infants in this environment.

Facilitators

Operational approach

There were similarities in operational approach and unit ethos demonstrated by the enabling of kangaroo care, encouragement of breastfeeding and enabling of parents to be primary caregivers. Managerial support was also a principal factor in driving change, particularly for access and time for education and training for staff, the development of protocols and policy guidance, and the provision of accessible educational materials for all at the cot-side.

Education

There was recognition across all three units that the education of staff and parents is fundamental to embedding cue-based feeding approaches. Teaching was strongly orientated towards parents assuming responsibility as the primary interpreters of infant cues. A range of methods were used to increase the knowledge and practice of cue-based feeding. Educational materials such as posters or charts were available at the bedside for easy reference, and all units used the UNICEF cue guide featuring images of term-born infants. Interactional learning also took place, including bedside teaching, peer-to-peer education and reflective learning. Each unit also utilised champions or trained supporters who exhibited behavioural modelling and offered informal teaching.

Environment/equipment

The provision of rooms for parents to stay near their infants was standard, although there were differences in the type of accommodation available. In Glasgow, single rooms were available within the unit. They were relatively self-contained and situated in a designated ‘rooming-in suite’ and offered to mothers of infants transitioning to discharge. Fathers could also be accommodated. One double room within the NNU was used only for the parents of the sickest infants. The Swedish units were spacious by comparison and could accommodate adult beds in each intensive care space to enable parents to sleep adjacent to their infants. The two Swedish units did not use the traditional infant incubators (‘closed’ unit with side panel access) predominant in Glasgow; rather, they exclusively used open beds with removable hoods. As care was stepped down to high-dependency or special care, infants moved into private rooms with their parents (and sometimes siblings or extended family) for the rest of the stay. Kitchen facilities equivalent to a typical home were available to families in Sweden, including freezers, full-sized cookers and dining space. In Glasgow, the available facilities were more limited, comprising a kettle, fridge and microwave, in addition to a sitting area.

Sociocultural factors

Differences in the social care policies of Sweden and the UK resulted in a significant difference in the lived experience of staff and families in NICUs. The Swedish national insurance system facilitates parents’ presence at the NICUs. Both parents can access a benefit that covers up to 80% of their salary and allowed them to take leave from work to attend to their child in hospital. Parents are also entitled to 480 days of shared paid parental leave for every child, which does not start until infants are discharged home and can be taken up until the child is 8 years old. In Scotland, at the time, there was no equivalent to the child-in-hospital benefit support, with standard maternity/paternity leave commencing from the child’s birth. Additional unpaid parental leave amounting to a maximum of 18 weeks (90 days) can be taken at any time until the child is aged 18 years. This represents a significantly less generous package in both time and financial support. This clearly influenced the way in which staff and parents could approach time in the unit. The sites at Falun and Uppsala applied a ‘zero separation of family’ philosophy (an expectation matched by parents), with a family member in attendance 24 hours per day, whereas in Glasgow parents were strongly encouraged to be present, but any expectation was mitigated by what families could reasonably achieve.

Key learning

In Sweden, cue-based feeding practices were more established than in Glasgow, where the practice had been introduced only during the preceding year. Both Swedish units reported that, historically, there were some challenges, with older, more experienced, staff expressing a preference for scheduled feeding. However, there were key factors that helped address their concerns about risks. NNUs across Sweden collected extensive mortality and morbidity outcome comparison data for their infants. The unit in Uppsala was able to identify better outcomes than other units across several measures in these data. Staff in the unit believed that this was attributable to its approach to kangaroo care and, by extension, the fact that practices that were facilitated by this, such as cue-based feeding, became more acceptable. Staff at the unit in Falun also described similar challenges, with some staff resisting cue-based feeding, but they believed that a recent move to a purpose-built unit with better facilities to facilitate zero separation and increased kangaroo care helped to reduce resistance. Staff in Glasgow did not report any significant challenges in implementing their cue-based feeding strategy, identifying a willingness to accept the change as quality improvement.

Access to training was not perceived as sufficient in every area. Staff in Falun expressed a desire for more formalised education to be available either for or by NIDCAP trainers, particularly to help to support decision-making on the quality of feeds. Experience was seen as an important facet of managing the approach to top-ups in Falun, and there was some difficulty in articulating the clinical decision-making that guided this, suggesting that unconscious competence77 was directing the decision. It was evident across the case study sites that assessing the quality of feeds and the approach to top-ups required some degree of clinical judgement, as it was impossible to ascertain the volume an infant had swallowed at a breastfeed. This may explain the preference for scheduled feeding among more experienced staff in Sweden. Despite differences in approach, each unit had operationalised elements of top-up management to provide a degree of certainty in achieving prescribed volumes and nutritional needs by reducing reliance on interpretation or judgement. In Glasgow, this involved using minimum gestational age, increasing the infant’s likelihood of sufficiently mature reflexes, as well as a quality feed tool to guide the decision. Falun’s semi-scheduled approach meant that relatively small incremental volume reductions were of low impact and could be carefully guided by weight trends over time, and Uppsala utilised test weighing to make assessments of actual intake.

What should not be underestimated, in terms of the impact on families’ experience of cue-based feeding approaches, was the sociocultural difference evident between Scotland and Sweden. Very few infants received bottles in Falun or Uppsala and there was very little bottle-feeding equipment and very few breast milk substitutes available in the units to offer this, as breastfeeding was the accepted norm. Sweden has a very high breastfeeding rate compared with the UK. Staff here also expressed their ardent belief in preterm infants’ ability to demonstrate and follow through on cues in their own time, especially if they received unrestricted kangaroo care. Their commitment to unrestricted kangaroo care was demonstrated by having adult beds at the cot side and the use of ‘open’ incubators to reduce physical barriers. Sweden also had many advantages in terms of well-funded social welfare benefits, extensive parental leave and spacious well-facilitated ‘living’ environments available to Swedish families. There was an implicit recognition in these measures that families’ and infants’ normal state is to be together at all times. This did not just facilitate a zero-separation philosophy from staff and families, it demanded it. The feasibility of this approach is unlikely to be replicable to the same extent in the UK. Reduced family–infant interaction has an impact on the opportunity for kangaroo care and may affect opportunities for cues generally to be both recognised and responded to from a very early stage. This, arguably, suggests that a higher level of nursing input into the delivery of care and caveats for introducing cue-based approaches may be necessary.

Limitations

The limitations of these case studies are that they represented an informal, time-limited snapshot of cue-based feeding approaches in three purposefully selected NNUs. A large amount of information was collected, and presentation of the results represents a rapid ethnography78 rather than an in-depth analysis of behaviours and practice. A key strength of these case studies was using two researchers with significant experience in neonatal intensive care nursing and in health psychology. The combination of the differing lenses on the clinical and behavioural aspects of cue-based feeding afforded a rounded perspective on which to inform the development of an intervention.

Chapter 5 Survey of neonatal units to determine current practice

As there is no consensus on how to manage the transition from tube feeding to full oral feeding and there was no information about current approaches and practices across the UK, we conducted a telephone survey of a purposive sample of UK NNUs.

Aim

The aims of the survey were to map and understand the range of approaches to the transition from tube feeding to full oral feeding in the UK including the scope of routine data collection systems, training needs of staff, and the variation in practice to understand ‘usual care’ that would form the control arm of a future trial.

Method

A purposive sample of 20 NNUs was selected from across the 220 units in the UK. The selection of units was based on the geographical location, designated unit level, cot capacity, population and urban–rural setting. Initially, units were contacted on behalf of the study team by regional representatives of the Neonatal Networks. Where there was no response, contact was followed up by a representative from the relevant Clinical Research Network for the trust/health board. Out of the 20 units sampled, 18 units indicated a willingness to take part; two units did not respond to the invitation.

Each unit that indicated a willingness to participate nominated an individual, or individuals, to be interviewed. Once units had agreed to be contacted, an introductory call was made by a researcher from the study team. The purpose of this call was to discuss the aim of the telephone survey, to discuss the participant information sheet and to arrange a suitable time and date for a telephone interview. Verbal consent was sought at the outset of the telephone interview.

The interviews were conducted by a member of the research team using a semistructured interview schedule based on the aims of the survey. The duration of interviews ranged from 18 to 56 minutes; the mean length was 35 minutes. The units varied from level 1 (special care) to level 3 (neonatal intensive care). The number of cots in the units ranged from 6 to 53. The job roles of interviewees included infant feeding advisor (n = 6), specialist speech and language therapist (n = 5), staff nurse (n = 4), senior charge nurse (n = 2), clinical/practice educator (n = 2), unit manager (n = 1), clinical nurse lead (n = 1), neonatologist (n = 1) and neonatal consultant (n = 1). There were four participants in one interview, two in another, and the remaining participants had individual interviews.

Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using a thematic approach. 79 Initial coding was conducted independently by two researchers. The final themes were discussed and agreed with the research team.

Approvals were granted by NHS East of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (LR/18/ES/0059) and the Health Research Authority.

Findings

An overarching theme was typologies of change. This referred to the various stages in the process of change towards introducing cue-based feeding described by participants. Three typologies of change were evident in the descriptions of units’ approaches to the transition from tube to oral feeding: ‘not considering change’, ‘considering change’ and ‘making changes’. A further subtheme was ‘variations in practice’. Descriptions of these subthemes utilised the characteristics, ethos and practices of units, as well as the micro language, namely change talk,78 to categorise the stage of change of each unit at the time of the telephone survey.

Not considering change

Three of the 17 units were not contemplating changes to their protocol around the transition from tube to oral feeding. These units were typically smaller (range 10–22 cots) and were level 1 (n = 1) or level 2 units (n = 2). None had Bliss accreditation, while only one was part of a hospital which had UNICEF UK BFI accreditation. Rates of breastfeeding and kangaroo care were generally low (30–40%). The predominant model of care in these units was described as family-centred care.

Although unit policy was not to implement cue-based feeding policies, there were individual members of staff who advocated cue-based feeding:

I keep pushing [for changes] . . . I put up [information on responsive feeding] on the notice board and then I’ll say to staff ‘oh that baby is looking for a feed’ and they will do it if I say to them. But if I wasn’t there they wouldn’t do it or would just give a tube feed.

Unit 4

Within these units, the biggest barrier to implementing a cue-based feeding protocol was suggested to be the attitudes of other staff, both nursing and medical, which tended to be focused on feed volumes:

Adverse events have occurred when bottle feeding because I suppose it’s nursing staff who think no you will finish this, you will take this and just the old system . . . you have to take this amount so you will take it.

Unit 4

I think a big thing is the dependence still on the quantity that is recorded to get into a baby . . . although we wouldn’t like to still think of ourselves as medicalised it’s still mls to kg.

Unit 12

The variation in staff’s practices relating to the transition from tube to oral feeding seemed to be based on individual experience, confidence and attitudes:

. . . there can be quite a noticeable difference between staff and how they cut down on milk. It really depends on their confidence and experience . . . there is a lot of trial and error in deciding how well an infant is transitioning from tube to oral feeding and it depends on your experience and confidence in identifying this.

Unit 13

For these units, routine, in terms of sticking to a schedule, was important for staff:

I do feel we still have people who go ‘no, you’re not due for another hour’ and really the baby is showing signs . . . I do feel it’s become ingrained in neonatal units . . .

Unit 13

Considering changes

Many of the participating units (n = 13) were considering what changes could be made in their approach towards the transition from tube to oral feeding, in the form of departmental procedures, training for staff, or support for parents. These units were more likely to have Bliss and/or UNICEF UK BFI accreditation and to report an increase in breastfeeding rates in the previous year. These units tended to be small to medium-sized units and to be moving towards the implementation of family integrated care:

We are trying to bring in family integrated care and move away from medicalised types of care. We want to shift old thinking on cue-based feeding.

Unit 1

This change in the model of care the unit subscribed to was reported also to lead to changes in the overall ethos of the unit and relationship with parents. Interviewees suggested that parents were viewed as partners in care and encouraged to be actively involved in providing care alongside nursing staff:

We encourage parents to be on the unit as much as possible and encourage them to feel a valued partner in their baby’s care.

Unit 3

Although these units were considering what changes could be made, some staff were described as actively implementing cue-based feeding. However, these staff were reported to be in the minority and change at a wider systemic level was needed. As unit-wide change was yet to take place, the approach to feeding was still reported to be largely focused on volume and schedule.

In terms of the approach to the transition from tube to oral feeding, these units described using non-nutritive sucking prior to starting oral feeds, and would base the decision to transition on the infant’s gestational age. Units that had greater multidisciplinary input (e.g. speech and language therapists) appeared to be more likely to be encouraging the practice of cue-based feeding.

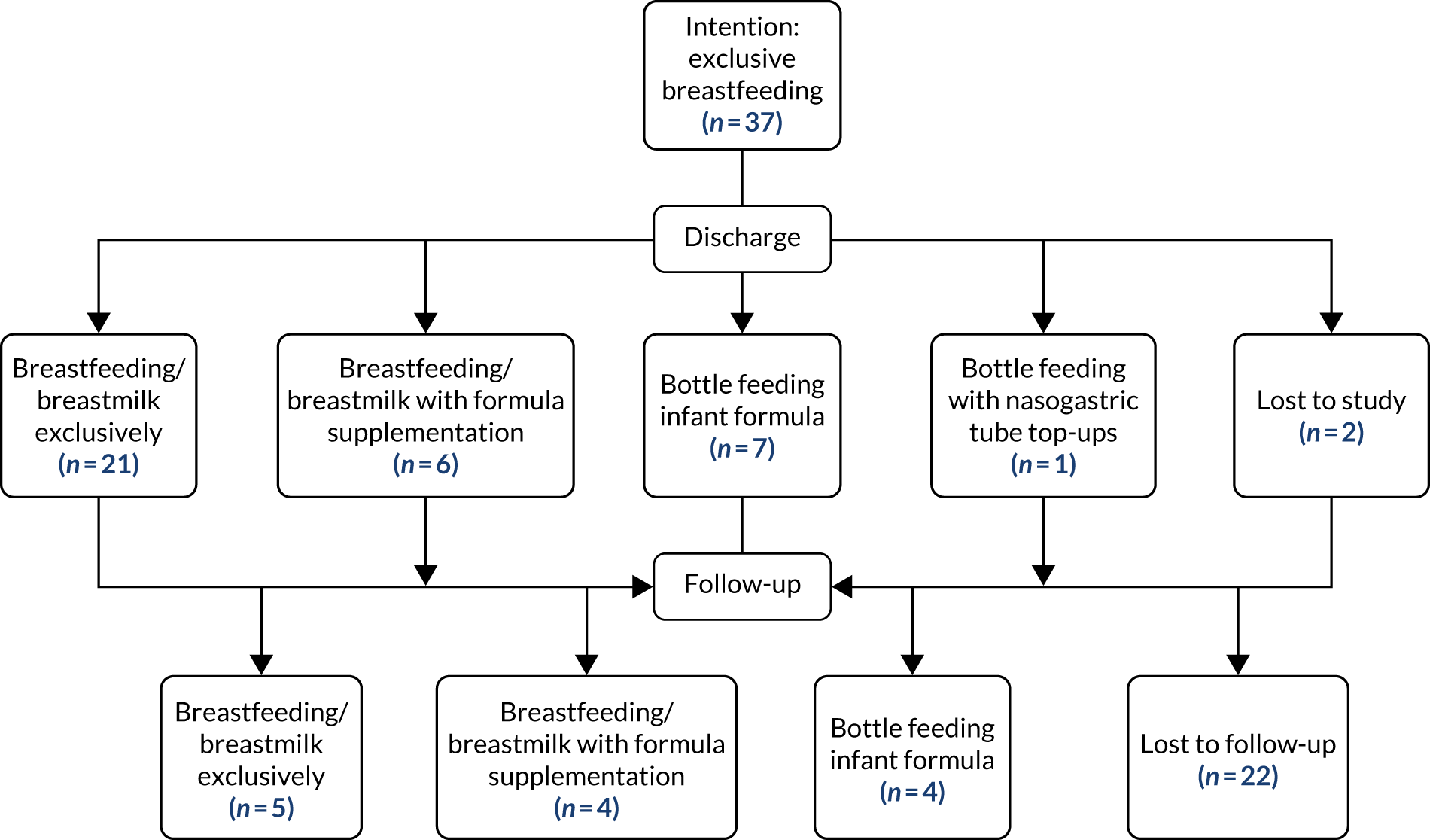

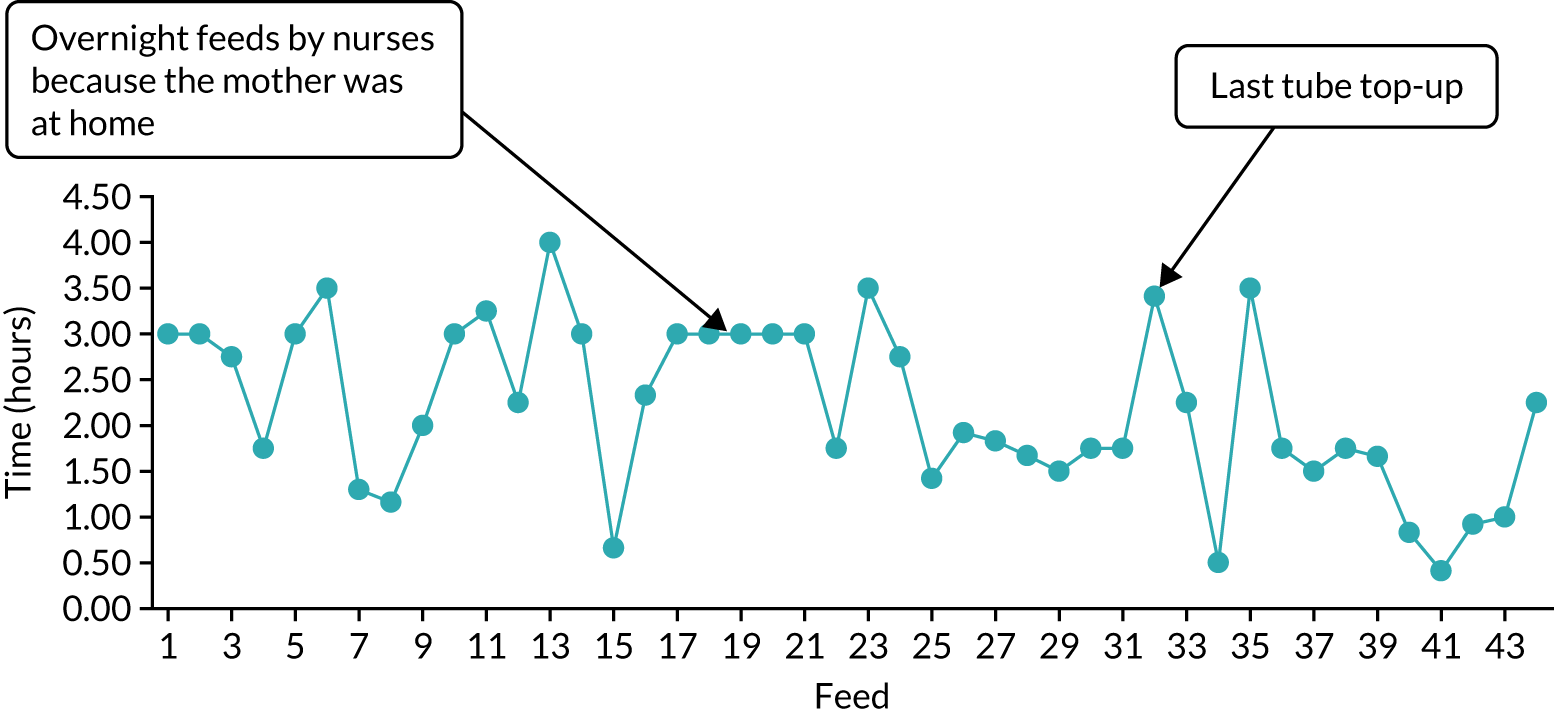

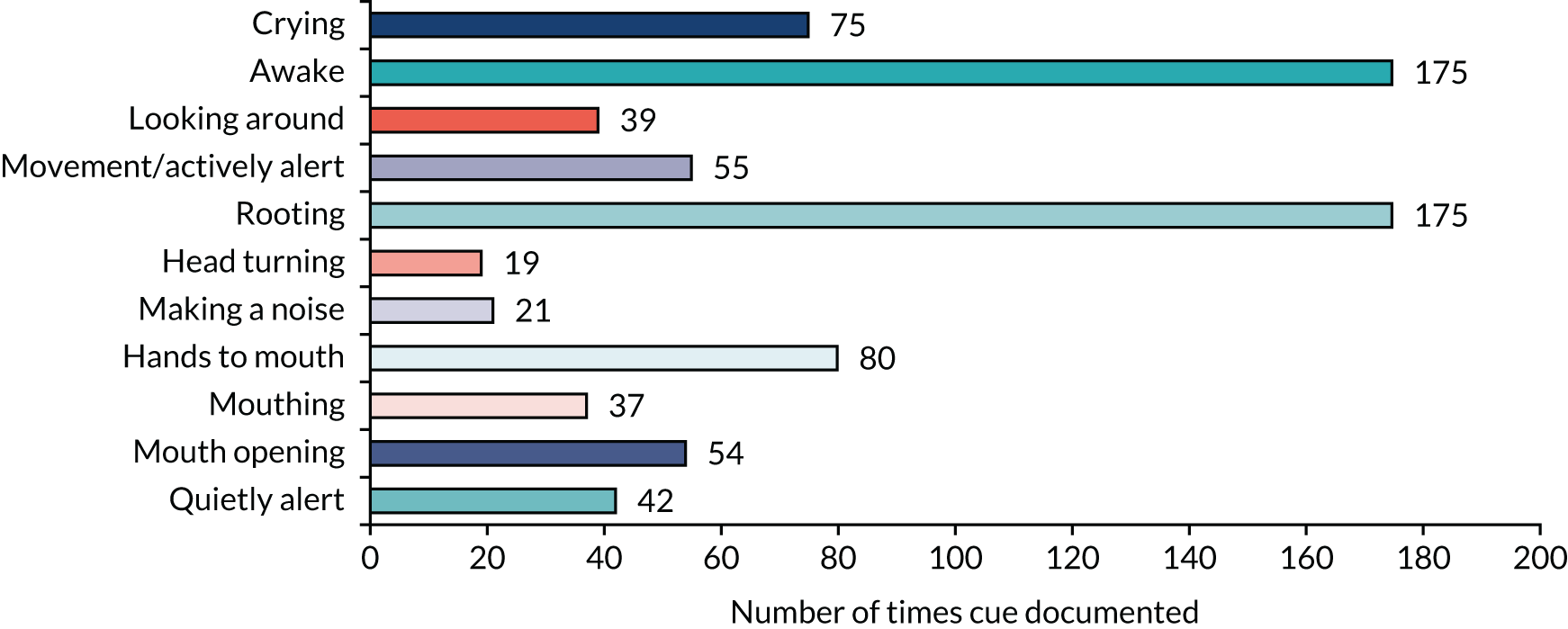

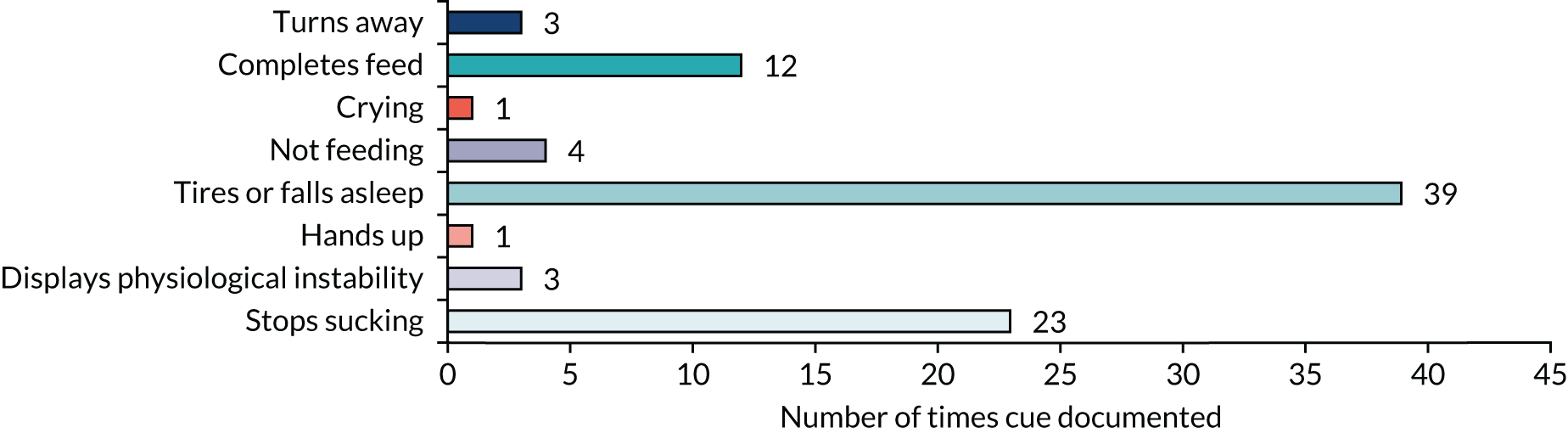

Making changes