Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/162/02. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The draft report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Khunti et al. This work was produced by Khunti et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Khunti et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction: background and rationale

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Yates et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Type 2 diabetes: prevalent but preventable

In 2019, the International Diabetes Federation estimated that 463 million people were living with diabetes. This figure is predicted to rise to 700 million by 2045. 2 Type 2 diabetes (T2D), the most common form of diabetes, has been estimated to be the third leading cause of mortality globally and its growing prevalence over recent decades, both in the UK and worldwide, is one of the greatest health challenges facing modern society. A diagnosis of T2D drastically increases lifetime health-care expenditures. 3 Health-care expenditures associated with T2D are, therefore, substantial; in the UK, diabetes currently accounts for approximately 10% of the total health resource expenditure and is projected to account for approximately 17% by 2035 as a result of the sharply increasing prevalence of T2D and its related complications. Some 80% of the costs of diabetes are attributable to complications, which include limb amputation, blindness, kidney failure and stroke. 4

This rising burden of T2D has precipitated three decades of research and health-care policies aimed at preventing diabetes in individuals deemed to be at high risk of developing the disease. High-risk status is defined as an intermediary category of glucose control that is outside the normal range but below the threshold for diagnosis of T2D. Historically, this intermediary range has been classified through impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance following an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). 5 Supporting international consensus, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recognises that glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the range of 42–47 mmol/mol (6.0–6.4%) can also be used to identify people who are at high risk of developing T2D, alongside the traditional definitions. 6,7 This high-risk category is referred to variously as ‘intermediate hyperglycaemia’, ‘impaired glucose regulation’, ‘non-diabetic hyperglycaemia’ and ‘prediabetes’. Although we acknowledge that there is debate around these terms, we have chosen to use the term ‘prediabetes’ here to facilitate readability. Some 25–50% of individuals in these risk categories go on to develop T2D within a 10-year period and, without intervention, as many as 70% will eventually develop T2D during their lifetime. 8

Large prevention trials globally, including in Europe, the USA, China and India, have demonstrated that lifestyle interventions aimed at weight loss, a healthy diet and increased physical activity can lead to a 50% reduction in the risk of developing T2D,9 with health benefits sustained over the longer term after the intervention has ceased. 10–12 Such interventions were subsequently modelled to be cost-effective. 13 Translational research has further demonstrated that lifestyle interventions can lead to weight loss and a reduction in diabetes risk when implemented in routine clinical settings,14,15 albeit with lower effectiveness than that demonstrated in large efficacy trials. This has led to the commissioning and delivery of lifestyle diabetes prevention programme within routine care internationally. The largest national scheme is ‘Healthier You: the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme’, which has been rolling out diabetes prevention across primary care in England16 and now aims to support 200,000 referrals per year.

However, despite the concerted efforts made to translate research into practice by enabling lifestyle interventions to be delivered to those at risk of T2D, success has been limited. Important questions remain as to how we can engage at-risk individuals with diabetes prevention programmes and sustain that engagement over time. These are questions that need to be answered if we are to optimise the prevention of diabetes in the future.

Physical activity for prevention

Physical inactivity is directly involved in the pathogenesis of prediabetes and T2D, and in observational cohort studies it has consistently been associated with an increased risk of the disease. 17 Conversely, high levels of physical activity have been associated with a lower risk of developing diabetes. Importantly, even moderate levels of physical activity have been shown to offer substantial clinical benefits. 18 For example, evidence from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study demonstrated that the risk of diabetes was reduced by > 60% in those with prediabetes who walked for 150 minutes per week compared with those who walked for < 60 minutes per week in their leisure time. 19 Similarly, a large international cohort study demonstrated that each 2000-steps-per-day increase in walking activity (equivalent to 20 minutes of brisk walking) decreased the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality and morbidity by 8% in people at high risk. 20 We have also demonstrated that each 30-minute increase in moderate to vigorous physical activity in adults at risk of diabetes leads to a decrease in HbA1c of 0.11%, equivalent to an 8-kg reduction in body weight. 21

Although the seminal diabetes prevention trials were successful at initiating weight loss, we have previously shown, in a systematic review of the evidence, that these same trials were unable to demonstrate clinically significant increases in physical activity over the longer term (> 12 months), and that there have not been any long-term interventions primarily focused on physical activity in those with prediabetes. 22 We therefore concluded that, at the gold standard randomised controlled trial (RCT) level of evidence, the effect of physical activity on diabetes risk is equivocal, and that strategies for effective pragmatic physical activity promotion in this population need to be researched thoroughly.

Harnessing structured education for physical activity promotion

Structured education refers to educational interventions, generally delivered in a small-group setting, that are aimed at the promotion of self-management and health behaviours and are underpinned by established health behaviour theories, a written curriculum and standardised educator training and quality assurance pathways. It is widely used as a central component of diabetes management pathways within routine care and has been recommended by NICE since 2003. 23 One of the most prominent structured education programmes for people diagnosed with T2D available to commissioning organisations nationally in the UK, and, to our knowledge, the only programme to have undergone a multicentre RCT to quantify clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, is the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) programme. 24,25 The DESMOND trial reported reductions in cardiovascular disease risk profile, reduced depression, enhanced smoking cessation and weight loss, and had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £2092 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, which makes it significantly cheaper than would normally be considered cost-effective by UK decision-makers. 24,25 The widespread existing infrastructure of the DESMOND model is now being adapted to the area of prevention, as it offers a feasible and scalable model for implementing diabetes prevention programmes in primary care and public health settings. 26

Pilot work undertaken by our group, concluding with a single-centre RCT, demonstrated that the approach used in the DESMOND programme can be successfully adapted to promote physical activity among those identified as having prediabetes and that the effectiveness of structured education can be enhanced by pedometer use. 27 The Prediabetes Risk Education and Physical Activity Recommendation and Encouragement (PREPARE) structured education programme was found to increase physical activity levels and substantially reduce fasting and post-challenge glucose levels in a multiethnic population over 12 months when combined with pedometer use. 27 Following this proof of principle, the PREPARE programme was subsequently developed into the Walking Away from T2D programme (referred to hereafter as ‘Walking Away’) that was broadened into an intervention for a wider high-risk population (not just those with diabetes, but those with any risk factors for T2D) for which a full educator training and quality assurance programme was also developed and piloted (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Walking Away was subsequently commissioned into routine primary care pathways throughout England as a low-resource prevention programme. A later trial of this implementation work, supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (now Applied Research Collaboration) infrastructure, demonstrated small changes (410 steps per day increase) to physical activity over 12 months, with evidence of greater behaviour change in those with prediabetes (513 steps per day increase). 28 Therefore, although Walking Away has been shown to be potentially effective in promoting physical activity behaviour change when delivered in primary care, particularly to those with prediabetes, work is needed to investigate whether or not greater and longer-lasting physical activity behaviour change can be achieved by integrating other low-cost pragmatic approaches enhanced with technological interventions and whether or not the intervention is effective and cost-effective when delivered to multiethnic communities that are reflective of modern Britain.

Using mobile health technologies to increase scalability

New technologies, such as the internet [electronic health (eHealth)], mobile devices and wearables [mobile health (mHealth)], have the potential to enhance behaviour change interventions by offering scalability, interactivity and reach, and have the capacity to offer highly tailored, interactive behaviour change maintenance support.

Text messaging interventions have been used to support medication adherence, physical activity, weight loss, smoking cessation and the prevention/management of chronic disease, either as a standalone intervention or in combination with other modes of delivery, such as face to face. 8,29–32 However, these interventions have tended not to be evidence based and to offer general rather than highly tailored support. A recent systematic umbrella review showed that such distal technologies in the management of people with T2D led to modest changes in HbA1c. 33 Uncertainty remained, however, about the long-term effectiveness of theory- and evidence-based physical activity interventions using mHealth, which is suitable for integration into routine and evidence-based diabetes prevention pathways and programmes in primary care. 34 Such interventions are likely to have particular salience for the promotion of physical activity given that self-monitoring interventions based on pedometers or wearables have been shown to be effective in promoting increased physical activity across different populations. 35 They were, therefore, ideally suited for integration with the eHealth or mHealth platforms. 36

Ethnicity

In industrialised societies, certain minority ethnic groups are known to have a substantially higher risk of T2D than others. Prevalence and progression rates for diabetes are up to four times higher among South Asian people, who constitute the largest ethnic minority group in the UK, than among the general population. 37 This elevated risk of chronic disease is compounded by lifestyle factors, most notably physical inactivity; South Asian people residing in the UK have been shown to be substantially less active and to have lower levels of cardiovascular fitness than the general population. 38–40 These differences in physical activity behaviour and levels of cardiorespiratory fitness have been linked to the increased prevalence of chronic disease and the higher rates of insulin resistance observed in South Asian populations;40,41 South Asian people, therefore, represent a priority target population in the prevention of T2D. However, evidence is limited that diabetes prevention programmes in a European context have been successful in changing lifestyle behaviours and improving health in minority ethnic groups. The largest trial to date, the Prevention of Diabetes and Obesity in South Asians (PODOSA) trial,42 demonstrated a small effect on weight (reduction of 1.64 kg) following a family-based intervention programme, but no significant effect on physical activity.

Principal research objectives

The principal research objectives of the PROPELS study were to:

-

develop a tailored mHealth intervention to provide follow-on support for participants referred to the Walking Away programme

-

investigate whether or not Walking Away can lead to sustained increases in physical activity after 4 years in an ethnically diverse population at high risk of T2D, when delivered at two levels of ongoing follow-on maintenance support (with and without the mHealth intervention developed in the previous objective)

-

compare the effectiveness of the tested interventions in white European and South Asian subgroups

-

conduct a within-trial and long-term economic evaluation of each tested intervention using the costs and benefits arising from the study, rates of progression to diabetes, biomedical outcomes, NHS resource use and quality of life.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Yates et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

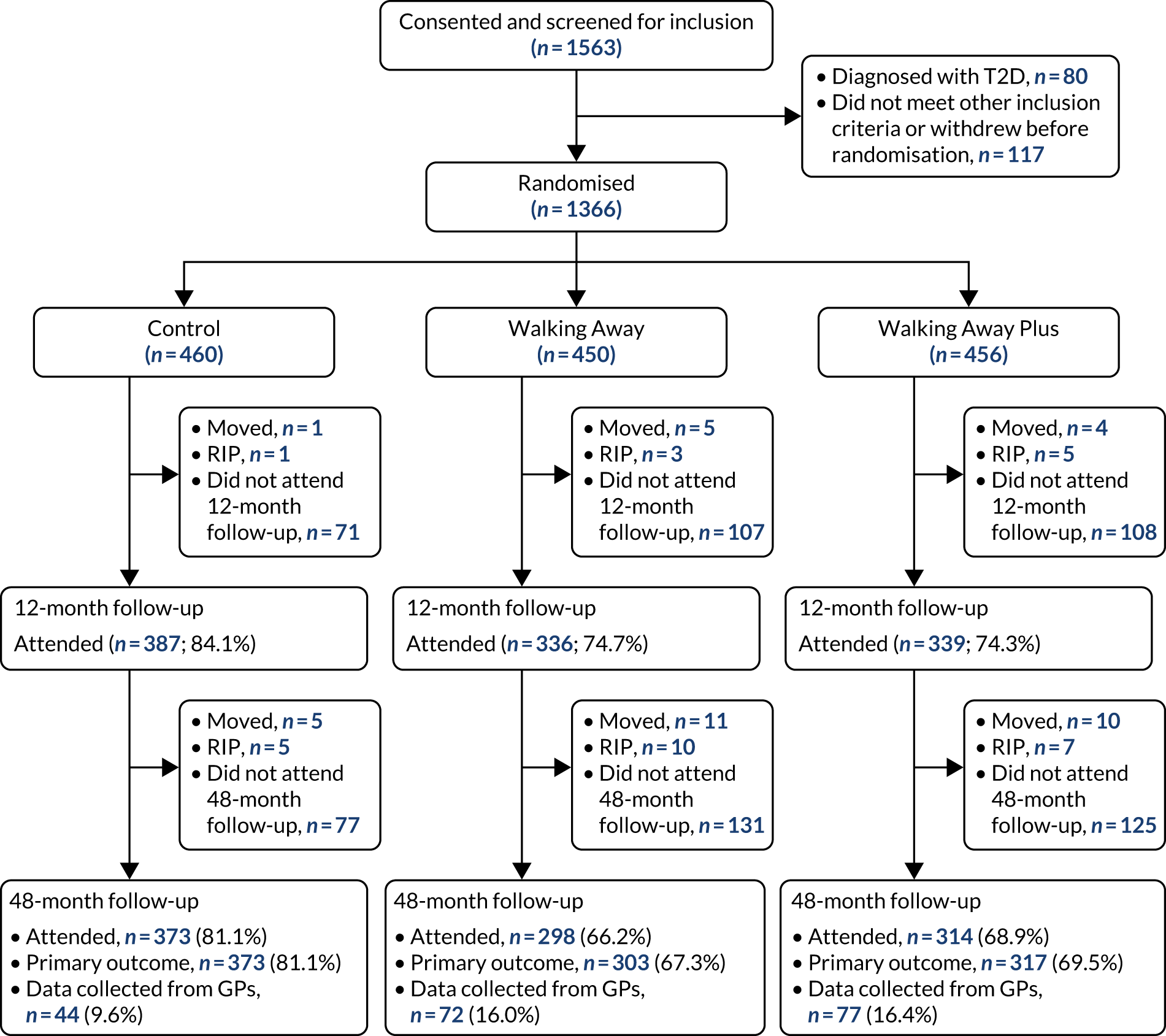

The PRomotion Of Physical activity through structured Education with differing Levels of ongoing Support for those with prediabetes (PROPELS) study was a multicentre RCT that compared two modes of a physical activity intervention with a control condition. The RCT was centred on the established Walking Away intervention. The PROPELS trial comprised two phases: the development and piloting phase of a mHealth intervention to provide follow-on support for Walking Away, and a multicentre RCT to test the efficacy of the intervention in a diverse multiethnic population. This chapter will focus on the design and methods of the RCT, and, therefore, it closely reflects the previously published study protocol. 1

Recruitment of participants

Participants were recruited across two demographically distinct centres, Leicester and Cambridge, UK, with a required sample size of 1308 (see Sample size). The primary method of recruitment was through primary care by using data collected by the NHS Health Checks programme, a screening programme run in England designed to identify and treat vascular disease risk (heart disease, stroke, diabetes and kidney disease) in all individuals aged 40–74 years, which has led to many primary care practices recording their patients’ HbA1c or fasting glucose values. 43

In both Leicester and Cambridge, our research teams worked in collaboration with practices providing the Health Checks programme to recruit individuals who were identified as having prediabetes and were not currently on a systematic diabetes prevention pathway. To help this process, recruited practices were trained to run an established automated diabetes risk score within their practice database. 44 A function within the risk score used a Morbidity Information QUery and Export SynTax (MIQUEST) search to identify all individuals who had had a previous blood glucose or HbA1c result recorded in the prediabetes range at any point during the 5 years preceding recruitment. 44 In Cambridge, participants meeting the inclusion criteria were also recruited from existing population-level research studies (specifically the Fenland Study45).

Eligible individuals identified as having a HbA1c or blood glucose value in the prediabetes category during the previous 5 years were sent an invitation letter, a brochure about the study and a reply slip. Those recruited directly from primary care were sent the invitation letters by the primary care practice at which the search was conducted. Those recruited from existing research databases were sent the invitation by the principal investigator of that study. Individuals who were interested in taking part were asked to return the reply slip directly to the PROPELS trial research team. An appointment was then arranged for a baseline visit and the individual was sent the full study patient information sheet along with a confirmation letter.

To allow for increased generalisability and the ability to stratify results by ethnicity (see Sample size), recruitment was purposely targeted so that 25% (n = 327) of the total cohort would be of South Asian ethnic origin; therefore, we aimed to recruit 66% (n = 863) of participants from Leicester and Leicestershire, which has a more ethnically diverse population than Cambridgeshire. Leicester city is, in fact, one of the most ethnically diverse places in the UK; according to 2011 census figures,46 37% of its population are Asian/Asian British (predominantly of Indian heritage).

Eligibility/exclusion criteria

Individuals were eligible for the trial if they:

-

were aged 40–74 years, or 25–74 years if they were South Asian

-

had had a recorded plasma glucose or HbA1c value in the prediabetes range during the previous 5 years (see Table 1)

-

had access to a mobile telephone and were willing to use it as part of the study.

Individuals were excluded from the trial if they were:

-

unable to take part in ambulatory-based activity

-

pregnant

-

involved in other related intervention studies

-

diagnosed with diabetes, or diabetes was detected at baseline visit

-

unable to understand basic written and verbal English

-

unable to give informed consent.

Protocol for participants found to have type 2 diabetes at baseline

At Leicester, individuals who had a HbA1c value in the diabetes range at baseline (Table 1) were recalled for a second, confirmatory, test, and if diabetes was confirmed they were referred back to their physician for routine care. At Cambridge, the individual’s primary care clinician was informed of the need to confirm diagnosis as appropriate. Individuals found to meet the World Health Organization and NICE47,48 criteria for a diagnosis of diabetes were excluded from the study.

| Variable | Normal glycaemia | Prediabetes (inclusion criteria for PROPELS)b | T2D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper value | Lower value | Upper value | Lower value | |

| HbA1c (%)a | < 6.0 | ≥ 6.0 | < 6.5 | ≥ 6.5 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | < 42 | ≥ 42 | < 48 | ≥ 48 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l)a | < 5.5 | ≥ 5.5 | < 7.0 | ≥ 7.0 |

| 2-hour post-challenge glucose (mmol/l) | < 7.8 | ≥ 7.8 | < 11.1 | ≥ 11.1 |

Protocol for participants found to have normal glycaemia at baseline

Individuals who were found to have normal glycaemia at baseline were included in the study, provided that they met the inclusion criterion of a historical blood glucose level in the prediabetes range during the previous 5 years.

Randomisation and blinding

Once baseline data had been collected, participants were randomised (stratified by sex and ethnicity) using an online randomisation tool hosted at the University of Leicester Clinical Trials Unit. Individuals were randomised (1 : 1 : 1) to one of three study arms:

-

control arm

-

Walking Away arm

-

Walking Away Plus arm.

The only exception to this was that individuals recruited from the same household were randomised to the same study arm. Participants were informed by letter of their allocated treatment. Study arm allocation was concealed from the study measurement teams conducting the 12- and 48-month follow-up and the research staff processing the accelerometer data.

Owing to the nature of the trial, patients and intervention providers were not blinded to study arm allocation. However, those processing the accelerometer data to generate the primary outcome were blinded to allocation.

Control study arm: detailed advice leaflet

Participants allocated to the control study arm received an advice leaflet (see Report Supplementary Material 1) detailing the likely causes, consequences, symptoms and timeline associated with prediabetes, as well as information about how physical activity can reduce the risk of developing T2D. The leaflet was informed by Leventhal’s common sense model,49 which also underpinned the structured education programme. Participants also continued to receive routine care from their GP.

Walking Away study arm: group-based behaviour change intervention with annual refresher sessions

Participants assigned to the Walking Away study arm were given the same advice leaflet that those in the control study arm received and were invited to attend, within 3 months of their baseline clinic visit, a 3-hour behaviour change intervention titled ‘Walking Away from Type 2 Diabetes’ (Walking Away), along with annual refresher sessions. The intervention is described in full in Chapter 3.

Walking Away Plus study arm: group-based behaviour change intervention, annual refresher sessions plus a mHealth intervention to provide follow-on support

Participants received the same advice leaflet and were invited to attend the Walking Away programme and annual refresher sessions as described above. In addition, they were provided with follow-on support in the form of a tailored text messaging and telephone intervention. The text messaging and telephone aspect of the intervention, hereinafter referred to as ‘the mHealth intervention’, was developed within the PROPELS programme of work; its content and the process of its development are described in full in Chapter 3.

Data collection

Data collection clinics were run by research nurses in the Leicester Diabetes Centre and in the MRC Epidemiology Unit in Cambridge and at other local community centres and clinic areas. All staff members were trained in study procedures and data were collected in accordance with the sponsor’s standardised operating procedures (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before data collection commenced. Details of all clinical assessments taken are provided in Table 2. After each visit, participants were sent a letter detailing selected clinical results, and the results were also sent to the participant’s general practitioner.

| Clinical assessment | Time point (months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12 | 48 | |

| 7-day step count and physical activity (accelerometer) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blood pressurea | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Body fat percentage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| BIPQ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dietary questions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Enactment of techniques (groups 2 and 3 only) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| EQ-5D; SF-8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Family history of disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fasting and 2-hour post-75 g challenge glucose and insulin (Leicester only) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| HbA1ca | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Heighta | ✓ | ✓ | |

| HADS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lipidsa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Liver function testsa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Medication status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Muscular/skeletal injury | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| NEWS | ✓ | ||

| Walking self-efficacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| RPAQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sleep | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Smoking status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Urea and electrolytesa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Use of health resources | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Waist circumferencea | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Weighta | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

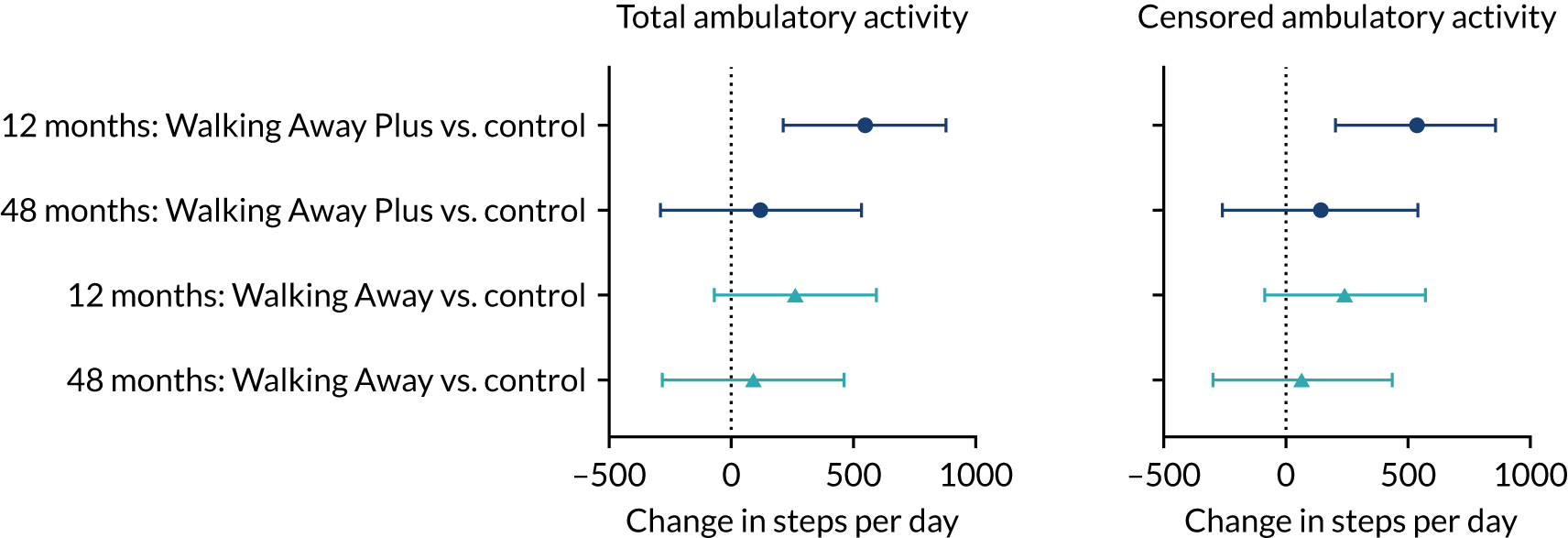

Primary outcome measure: change in ambulatory activity at 48 months

The primary outcome measure was the change in ambulatory activity (steps per day) at 48 months, assessed using an accelerometer (Actigraph GT3X+, ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA), with an intermediary assessment at 12 months. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on a waistband (on the right anterior axillary line) during waking hours for 7 consecutive days following their baseline and follow-up visits. At the end of the 7 days, participants were asked to return the accelerometer and log sheet to the research team in a prepaid envelope. Raw acceleration data were captured and stored at 100 Hz. For the purposes of this study, data were integrated into 60-second epochs. At least 3 days’ valid wear was required to count as a valid recording. Non-wear time was determined by ≥ 1-hour of consecutive zero counts. Data processing was undertaken on a commercially available analysis tool (Kinesoft, Saskatoon, SK, Canada).

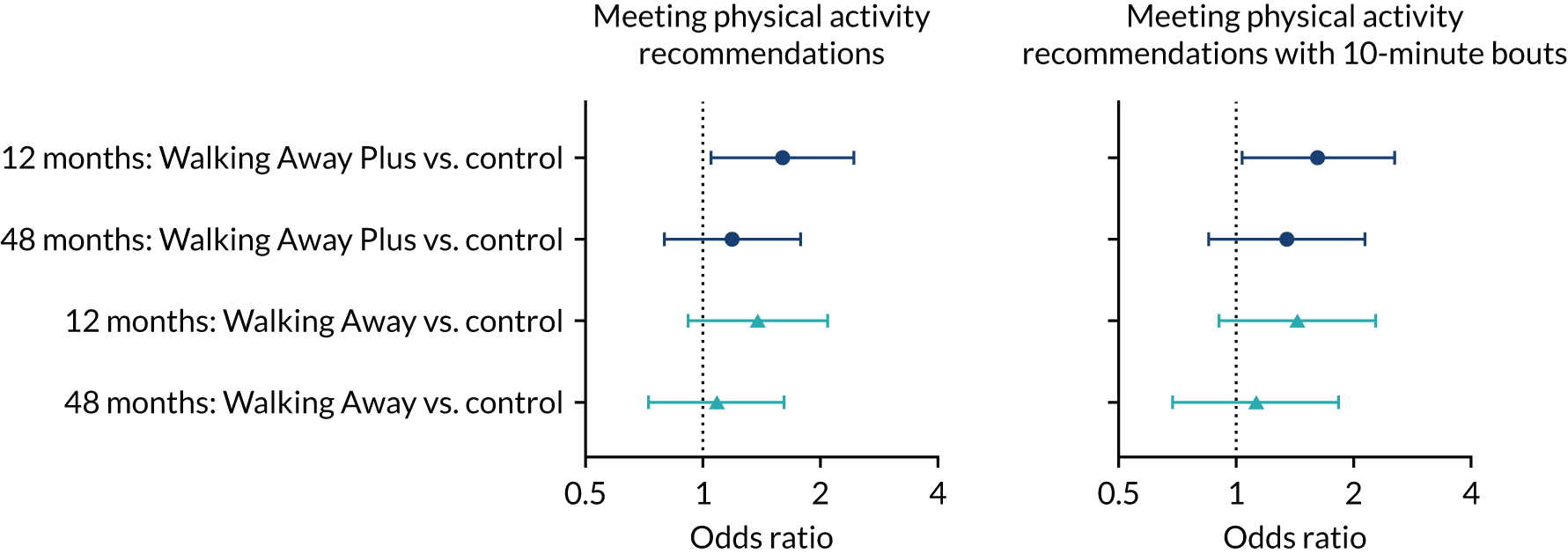

Secondary outcomes and descriptive data

Objectively assessed time spent sedentary and in light- and moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity

The accelerometer that was used to measure the primary outcome detailed above also provided secondary outcome data on the number of censored steps taken per day, defined as steps taken above an intensity (500 counts per minute) used to distinguish between purposeful and incidental ambulation. 50 Commonly used Freedson cut-off points were used to distinguish between time spent sedentary and time spent in light, moderate and vigorous physical activity. 51 Compliance with the physical activity recommendations of undertaking at least 150 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity per week was also assessed;52 this was calculated as (1) the accumulation of 150 minutes overall of at least moderate-intensity physical activity to meet the Chief Medical Officer’s updated physical activity guidelines52 and (2) the accumulation of 150 minutes per week of at least moderate-intensity physical activity in bouts of at least 10 minutes in duration.

Objectively assessed time spent in the postures of sitting/lying, standing and walking

Concurrently with, and in addition to, the ActiGraph accelerometer, participants were asked to wear an activPAL3™ device. This is a small, slim, monitor worn on the thigh that uses accelerometer-derived information about thigh position to determine body posture (i.e. sitting/lying, standing or stepping). The activPAL3™ was initialised using the manufacturer’s software with the default settings (i.e. 20 Hz, 10 seconds’ minimum sitting-upright period) and participants were asked to wear the device continuously (24 hours per day). The activPAL3™ was covered with a nitrile sleeve and fully wrapped in one piece of waterproof dressing [Hypafix Transparent (BSN Medical, Hamburg, Germany)] to allow participants to wear the device during bathing activities and was secured to the midline anterior aspect of the upper thigh using hypoallergenic waterproof dressing (Hypafix Transparent). Data were analysed using a bespoke open-source processing package [ProcessingPAL; URL: https://github.com/UOL-COLS/ProcessingPAL/releases/tag/V1.2 (accessed 16 November 2021)]. Data on waking wear time, time spent sedentary, time spent standing and time spent walking were utilised for this study.

Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire

Self-reported physical activity was measured using the Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire (RPAQ), which assesses physical activity across four domains (domestic, recreational, work and commuting) over the previous month. RPAQ has shown moderate to high reliability for assessing physical activity energy expenditure, and good validity in ranking individuals according to their time spent in vigorous intensity physical activity and overall physical activity energy expenditure. 53

Biochemical variables and diabetes diagnosis

Venous sampling was used to assess standard biomedical outcomes, comprising HbA1c, lipid profile (triglycerides, HDL, LDL and total cholesterol), urea and electrolytes (sodium, potassium, urea and creatinine), and liver function tests (albumin, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and alanine transaminase). Assays were completed in quality-controlled clinical laboratories at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. At the Leicester site only, participants were assessed for fasting and 2-hour post-challenge glucose and insulin levels following a 75-g OGTT; the OGTT results will be analysed at a later date and used to provide greater clinical insight into how physical activity affects metabolic health.

For the purposes of the main trials, the classification of glycaemic status was based on HbA1c values using World Health Organization and NICE guidelines47,48 (see Table 1). During the trial, participants at the Leicester site who were found to have a HbA1c value in the diabetes range (≥ 6.5% or 48 mmol/mol) were recalled for a second, confirmatory, test, and if diabetes was confirmed they were referred to their clinician. At Cambridge, the response to a HbA1c value in the diabetes range was to send a letter to the individual’s primary care clinician informing them of the need to confirm a diagnosis.

Protocol for participants found to have type 2 diabetes during the trial

Participants diagnosed with T2D during the trial were retained and continued to be offered all study and interventional procedures, as the primary outcome measure was change in physical activity.

Standard anthropometric and demographic measurements

Height, body weight, body fat percentage and waist circumference were measured to the nearest 0.5 cm, 0.1 kg, 0.5% and 0.1 cm, respectively. Waist circumference was measured using a soft tape measure mid-way between the lowest rib and the iliac crest. Arterial blood pressure was obtained from the right arm of the participant when seated; three measurements were taken and the average of the last two measurements was used. Information on ethnicity, medication history, current smoking status, family history of diabetes in first- and second-degree relatives, and muscular/skeletal injury that prevents physical activity were obtained by self-report. Social deprivation was determined by applying the English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) to participants’ postcodes. For descriptive purposes, data are categorised at the national quintile values to show that the distribution within the recruited population is generalisable to the national average.

Genetics

A blood sample for future genetic analysis was also collected from those who consented.

Cardiovascular risk

Secondary outcomes were used to estimate cardiovascular risk, calculated through the Framingham Risk Score. 54 The Framingham Risk Score has been shown to perform reasonably well in multiethnic UK populations, although it may underestimate risk in South Asian ethnic minorities. 55 However, the secondary outcomes in the PROPELS trial did not allow a more comprehensive risk score to be employed.

Sleep

Participants self-reported on two single-item questions asking about sleep duration in the last night and average sleep duration during a usual week.

Self-reported dietary behaviour

Dietary behaviour was captured in two short questionnaires used in previous research studies by our group, which were administered to participants for self-completion. The questions were based on an abbreviated dietary food frequency questionnaire developed for the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study and a questionnaire of dietary intentions developed for the international NAVIGATOR (Nateglinide And Valsartan in Impaired Glucose Tolerance Outcomes Research) study. 56,57 The food frequency questionnaire captured portions per week of fresh fruit, green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, oily fish, other fish, chicken, meat, eggs, cheese and wholemeal/brown bread. In addition, alcohol intake (drinks per day) was captured. Dietary intentions captured the degree (on a 5-point Likert scale) to which each participant was actively trying to limit the amount of total fat, saturated fat, sugar or salt in their diet.

Health-related quality of life: EuroQol-5 Dimensions, SF-8 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Health-related quality of life was measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L),58 and the Short Form (SF-8) Health Survey. 59 The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is a standardised questionnaire developed for use as a measure of health outcomes. It defines health in terms of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. It is widely used to calculate QALYs, which are essential for cost-effectiveness analysis. The SF-8 is a self-administered questionnaire that measures eight health domains (general health, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, mental health and emotional roles) using eight questions. The standard (4-week) recall format was used. Data from SF-8 responses were used to derive a physical component score and a mental component score.

Depression and anxiety symptomology were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to produce independent subscales for anxiety and depression. 60

Health, medication and smoking status

Medical history and medication status were measured using an interview-administered protocol. Data on family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, smoking status and muscular/skeletal injury were obtained by self-report. All adverse events that were reported to the study sponsor (University of Leicester) were also recorded.

Health resources

A health resources questionnaire was used to record the number of times that the participant had seen a health-care practitioner (e.g. a GP, nurse or other health worker) over the previous 12 months and the number of times that they had been to hospital. In addition, the number of contacts and costs associated with the intervention were captured by the research team and were included in the cost-effectiveness analysis of the intervention.

General practice data

The research team attempted to collect relevant biochemical data, diabetes diagnosis data and other medical event data from during the trial directly from participants’ GP practices for those lost to follow-up. Collected data were matched to the nearest follow-up time point.

Potential mediators of behaviour change

Perceptions of diabetes risk: Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire

The validated Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (BIPQ) was used to measure perceptions and perceived knowledge of diabetes risk at 12 and 48 months. 61 BIPQ is an eight-item instrument that uses an 11-point Likert scale (where 0 = no effect and 10 = complete effect) to measure five cognitive diabetes risk representations (consequences, timeline, personal control, treatment control and identity), two emotional representations (concern and emotion) and risk comprehensibility (perceived knowledge).

Walking self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was assessed at baseline and 12 and 48 months using six items to measure participants’ confidence in their ability to walk for 10, 30 and 60 minutes each day. Items used a 100% confidence rating scale (on which 0% represented no confidence and 100% represented complete confidence).

Self-reported use of behaviour change strategies

Participants in the Walking Away and Walking Away Plus study arms reported their use of behaviour change strategies called ‘action control’ measures62 at 12 and 48 months using a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = most of the time and 5 = never). The items assessed included how often participants set goals, formed action plans, used a pedometer, completed a physical activity log, were aware of their activity levels and were trying to be more physically active.

Uptake and adherence to Walking Away and Walking Away Plus interventions

Measures of uptake and adherence to the interventions included (1) attendance at the initial Walking Away group session, (2) attendance at the group annual refresher sessions at 12, 24 and 36 months, (3) the proportion of telephone calls completed, (4) the number of participants who registered for the text messaging service, (5) the number of STOP messages received for test messaging (i.e. number opting out of the text messaging and pedometer support), (6) the proportion of intended texts sent, and (7) the number of step count texts received from participants relative to the number of requests they were sent (engagement).

Qualitative substudies

A number of qualitative substudies were conducted to contribute to the process evaluation of the intervention:

-

Focus groups were held with the educators who delivered the programme and the telephone calls; these were held approximately 12 months after the educators had delivered the final sessions.

-

Focus groups and telephone interviews were held with participants from the two intervention arms at approximately 48 months. Purposive sampling aimed to achieve a sample that was diverse in terms of both demographic characteristics and level of engagement with the intervention [e.g. from those who attended all Walking Away group sessions (groups 2 and 3) and/or responded frequently to text messages (group 3) to those who attended fewer group sessions (groups 2 and 3) and/or requested to stop the text messages (group 3)].

These qualitative substudies focused on two novel aspects of the PROPELS intervention: its duration (4 years, compared with many previous interventions of only 1 year) and the maintenance support through telephone calls and text messaging. We were specifically interested in understanding the influences on engagement with the intervention; whether or not and how participants reported that the intervention helped them to increase and/or maintain physical activity; and how participants and educators thought that the intervention could be improved.

The procedure for conducting the interviews and focus groups and analysing the scripts is described in Chapter 5.

Sample size

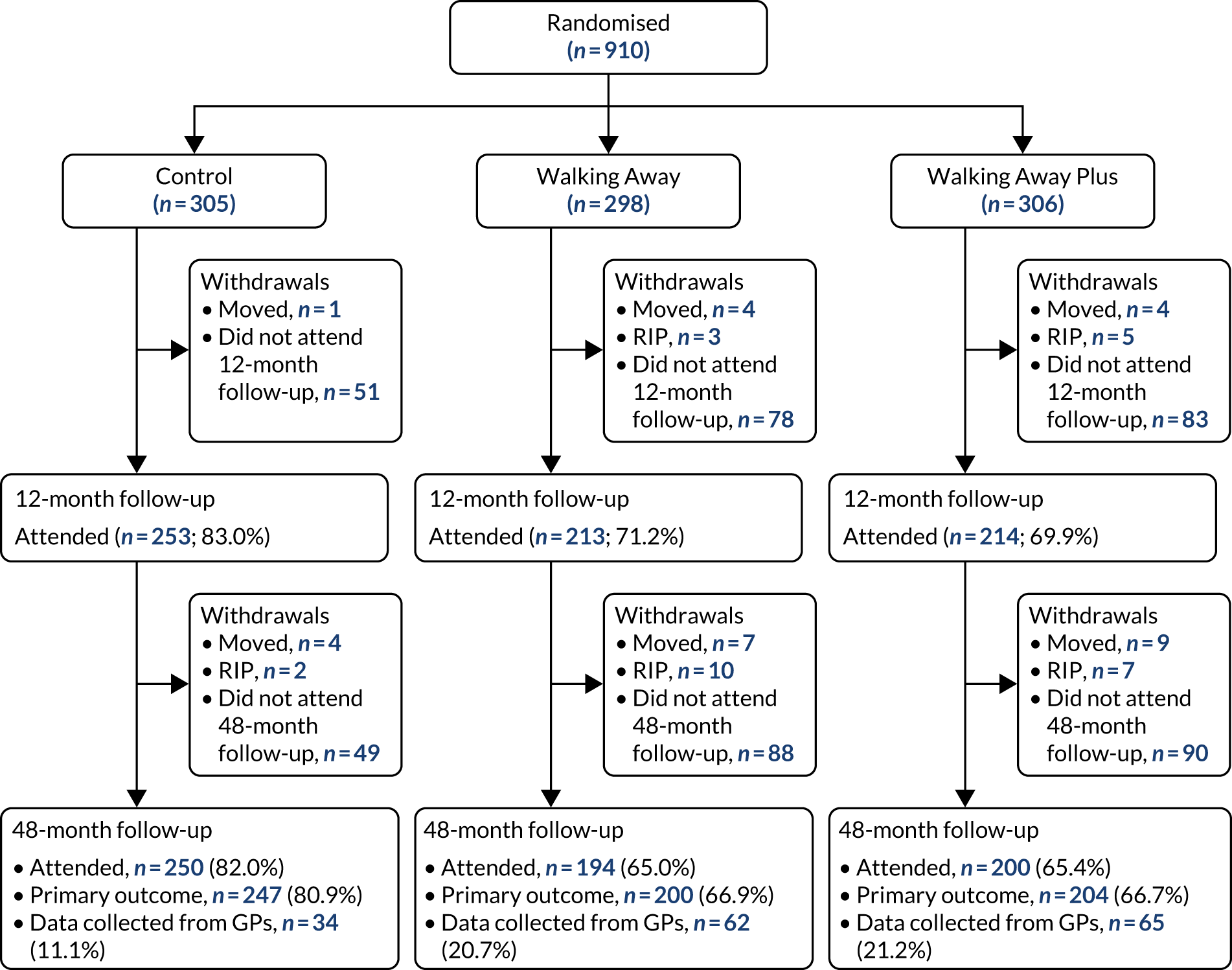

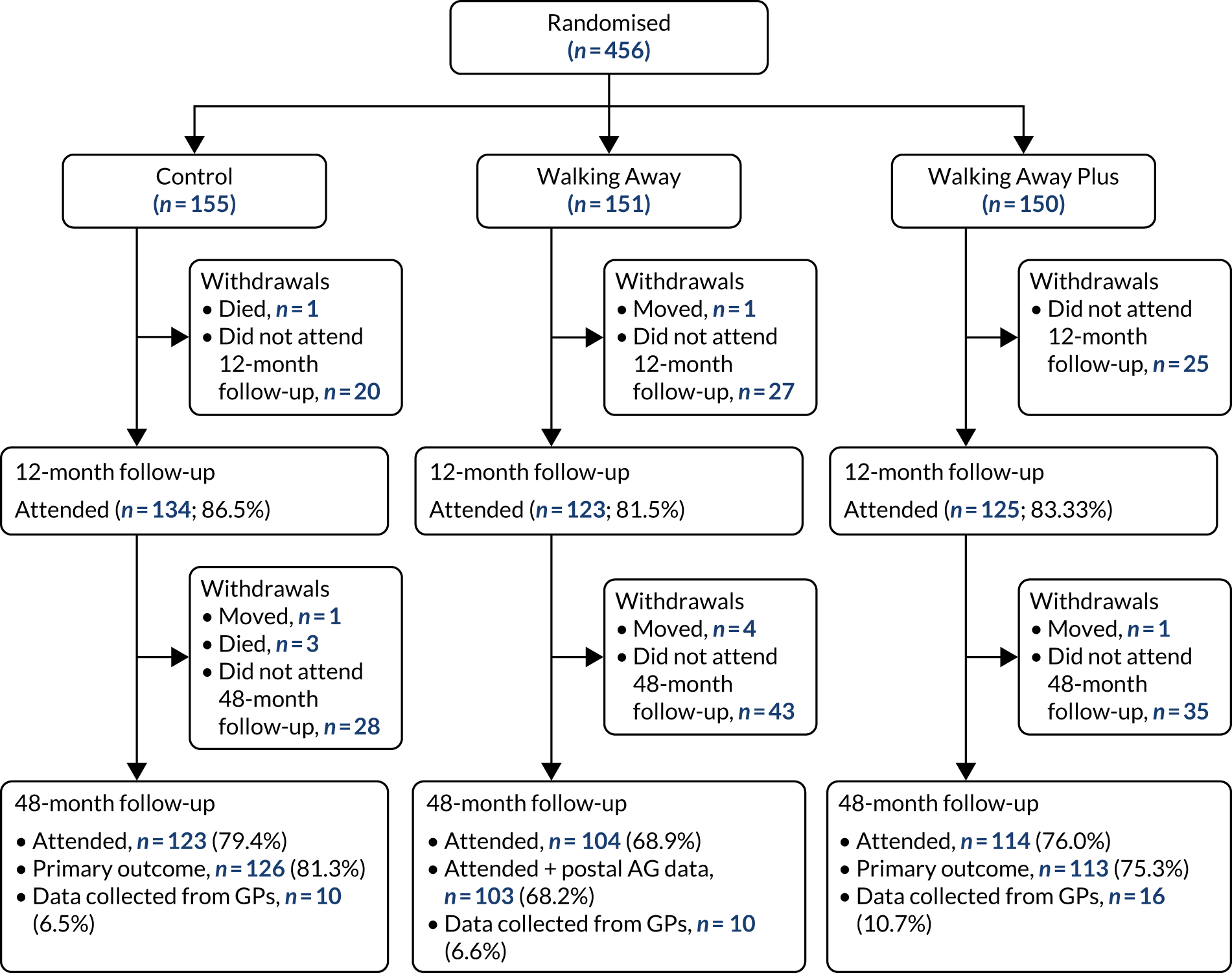

For 1 – beta = 0.8, alpha = 0.025 (allowing for two a priori comparisons against control conditions), a standard deviation (SD) 4000 steps per day27,63–65 and a dropout rate of 30% (lost to follow-up and incomplete primary outcome data) over 4 years, we required 436 participants in each study arm (1308 in total) to be able to detect a difference in change in ambulatory activity of 1000 steps per day (equivalent to 10 minutes of walking per day or 70 minutes of walking per week) between the intervention study arms and the control study arm. Assuming that 25% of participants in the total cohort were South Asian, we had 80% power to detect a difference of 2000 steps per day when comparing the two intervention comparisons with the control study arm (α = 0.025) in the South Asian population.

It should be noted that this sample was intended to be updated based on relevant information that was published after the development of the protocol. Based on pooled longer-term outcome data for steps per day from two primary care-based trials that, collectively, recruited 1688 individuals, the baseline-adjusted SD at 1, 2 and 3 years post randomisation was approximately 2000 steps per day. 66 Furthermore, recent evidence has suggested that even small differences in objectively assessed physical activity are clinically important,67 with 500 steps per day defined as the minimum clinically important difference in those at risk of T2D. 66 Had the study been powered on these parameters, the overall sample size would have been unchanged, as the standardised differences (1000/4000 vs. 500/2000) are identical. Therefore, it can be noted that the study is likely to be powered to detect a smaller difference in ambulatory activity in the overall population of 500 steps per day and a difference in the South Asian population of 1000 steps per day.

Diabetes progression

We assumed a conversion rate to T2D in the control study arm of at least 24% over the entire 4 years of the study and would, therefore, have 80% power to detect a 40% reduction in the relative risk of T2D in both intervention study arms compared with the control study arm (α = 0.025). We used an estimated conversion rate at the lower level reported for traditionally defined prediabetes. 5,68

Statistical analysis

See Appendix 1 for the full statistical analysis plan (SAP) developed for this study, as well as the SAP revision history (see Table 26), SAP responsibilities (see Table 27) and SAP signatories (see Table 28). The SAP was finalised and published on the trial registry (ISRCTN83465245) before the database was locked. The trial statistician was not blinded to study arm allocation.

Analysis of the primary outcome: change in ambulatory activity (steps per day) at 48 months

The analysis involved two a priori comparisons in which each intervention arm was compared with the control study arm. Should either of these comparisons reveal a significant difference, a third a priori comparison would have been undertaken to compare the difference between intervention arms; this will be included as a secondary analysis. Data were analysed at the patient level using a modified intention-to-treat protocol; participants with complete data were analysed in the study arm to which they had been randomised, regardless of the dose of intervention they actually received. Analyses of covariance models were used, adjusting for wear time at baseline, wear time at 48 months, number of valid days at baseline, number of valid days at 48 months, the three randomisation stratification variables (centre, ethnicity and sex) and ambulatory activity at baseline as covariates. Missing data at baseline were replaced using the indicator method. 69

Ethnicity and other subgroup analyses for primary outcome

For the primary outcome only, interactions between randomised study arm and (1) sex (men/women), (2) age (< 60 years/≥ 60 years), (3) ethnicity (white European/South Asian/other), (4) family history of T2D (yes/no), (5) prediabetes status at baseline (yes/no), (6) baseline obesity status [< 30 kg/m2 (27.5 kg/m2 for South Asians), ≥ 30 kg/m2 (27.5 kg/m2 for South Asians)] and (7) baseline deprivation (split at median IMD score into high vs. low) were tested by including the relevant interaction parameters in the analysis model.

If the p-value of any of the interactions tested above was < 0.05, then the estimates and 97.5% confidence intervals (CIs) of the two intervention effects (Walking Away vs. control and Walking Away Plus vs. control) on the primary outcome were reported in the relevant subgroups.

Sensitivity and per-protocol analysis for the primary outcome

To access the possible impact of excluding those with data lost to follow-up from the analysis, the primary analysis was repeated replacing missing data using multiple imputation by chained equations, across 10 imputed data sets. In addition, to access whether or not adherence to the intervention affected the results, the primary analysis was repeated when restricted to a per-protocol data set in accordance with the following criteria:

-

control – all individuals

-

Walking Away – attended initial education and at least one follow-up annual refresher session

-

Walking Away Plus – attended initial education and at least one follow-up annual refresher session and registered with the text message service and received the initial telephone call and received at least one further telephone call during the trial.

Analysis of continuous secondary outcomes

Ambulatory activity at 12 months and all other continuous secondary outcomes at 12 and 48 months were analysed using the same strategy and at the same time points as described for the primary outcome, with the exception that accelerometer wear values were removed from non-accelerometer-derived outcomes.

Analysis of binary secondary outcomes

The odds of compliance with moderate to vigorous physical activity recommendations at 12 and 48 months were analysed using logistic regression, adjusted for the randomisation stratification variables (centre, ethnicity and sex) and compliance with moderate to vigorous physical activity recommendations at baseline as covariates.

The odds of diabetes at 12 and 48 months were analysed using logistic regression, adjusted for randomisation stratification variables (centre, ethnicity and sex). Those who were diagnosed with diabetes but had a HbA1c value subsequently recorded in the non-diabetes range were still classified as having diabetes.

Potential mediators of behaviour change and self-reported use of behaviour change strategies

To avoid multiple testing with measures that were not study outcomes, data on illness perceptions, self-efficacy and self-reported use of behaviour change strategies are reported descriptively, but were not subject to statistical testing.

Statistical significance and reporting of data

As the primary outcome involved two comparisons with the control (Walking Away and Walking Away Plus), the significance level was adjusted accordingly to account for this multiple testing. Therefore, statistical significance was considered at a p-value of < 0.025, rather than the tradition p-value of < 0.05. The results of the statistical analyses are, therefore, reported as means (97.5% CIs) to be consistent with the lower significance level.

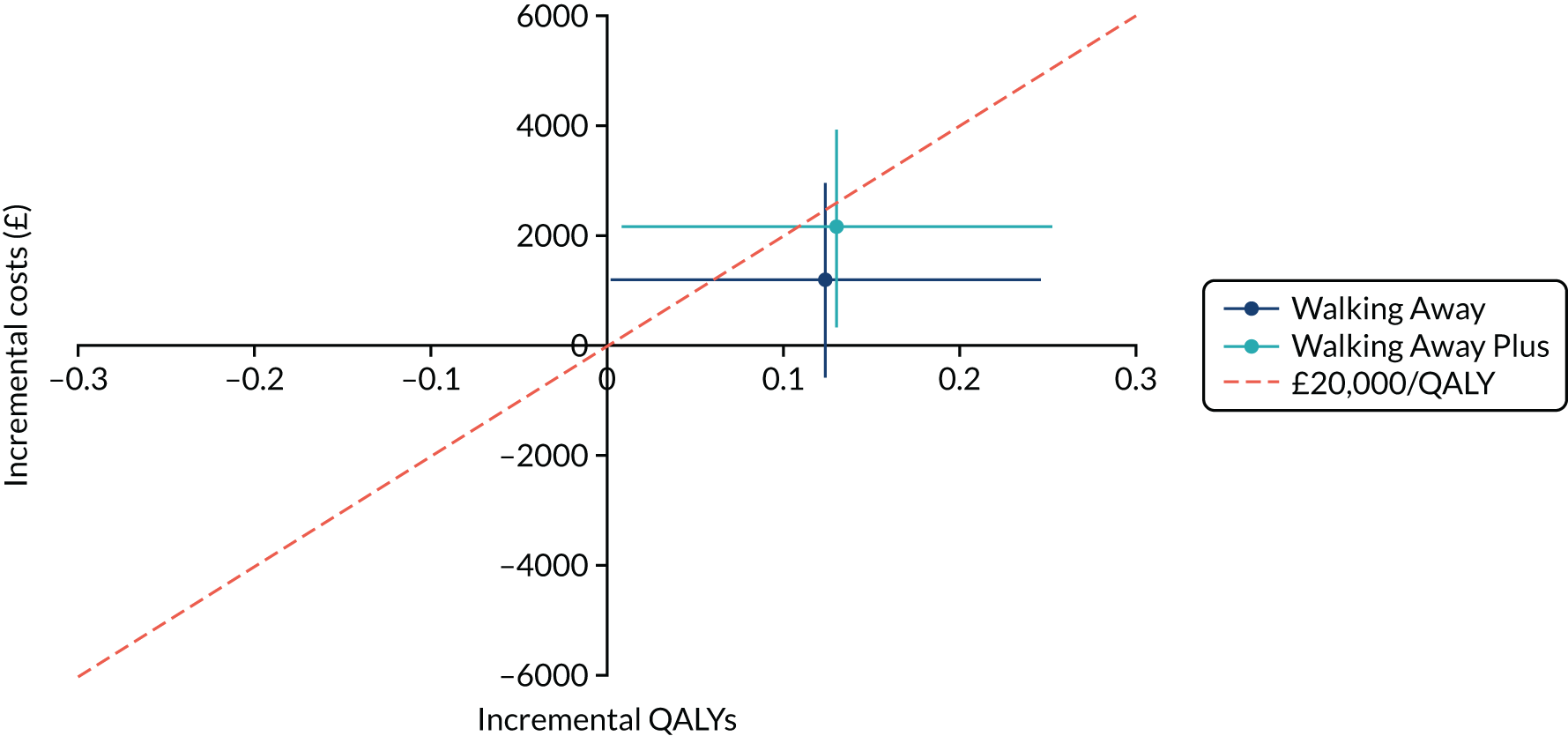

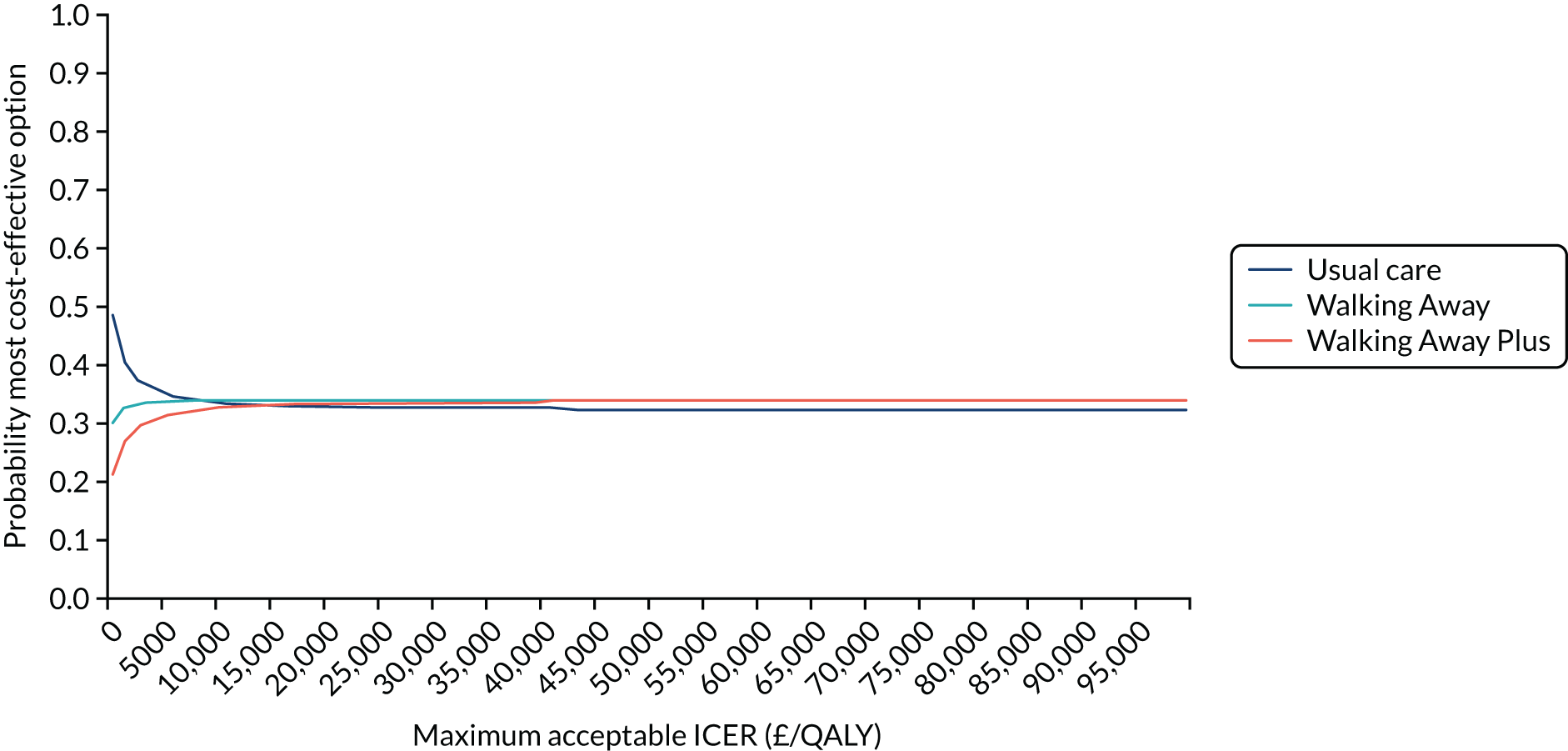

Health economics

Two separate health economics analyses were carried out to assess the cost-effectiveness of the trial interventions. The primary analysis was a model-based analysis using the School for Public Health Research Diabetes Prevention Model (henceforth ‘the model’),70 which extrapolated trial outcomes over a lifetime horizon. The secondary analysis was an evaluation of the within-trial costs and outcomes, which assessed the costs and benefits of the interventions for the 4-year follow-up period of the trial. Both analyses took an NHS and Personal Social Services perspective, in line with current NICE guidelines. Costs for both analyses were valued in 2017/18 Great British pounds. Unit costs were obtained from nationally representative sources, such as NHS reference costs. 71 Any cost sources used from previous years were inflated to 2017/18 prices using the hospital and community services index and/or the new health services index. 72 The detailed methods of these analyses are described in Chapter 6 of this report and are summarised briefly below.

The cost of the interventions

Two different sets of intervention costs were calculated. One was the expected costs of the interventions as they would be implemented in the real world. The intention in using the costs of interventions as we expect them to be implemented is to correct for budgetary inefficiencies that are an artefact of the trial process and would not be expected to occur in a real-world setting. To estimate these, we combined data collected in the study, data from other similar educational interventions and expert opinion. These costs were used as our base-case costs in both analyses.

The other type of intervention was the cost of interventions in the PROPELS trial, regardless of whether or not these costs reflect realistic costs, if Walking Away or Walking Away Plus were to be implemented. These costs will be presented as a sensitivity analysis.

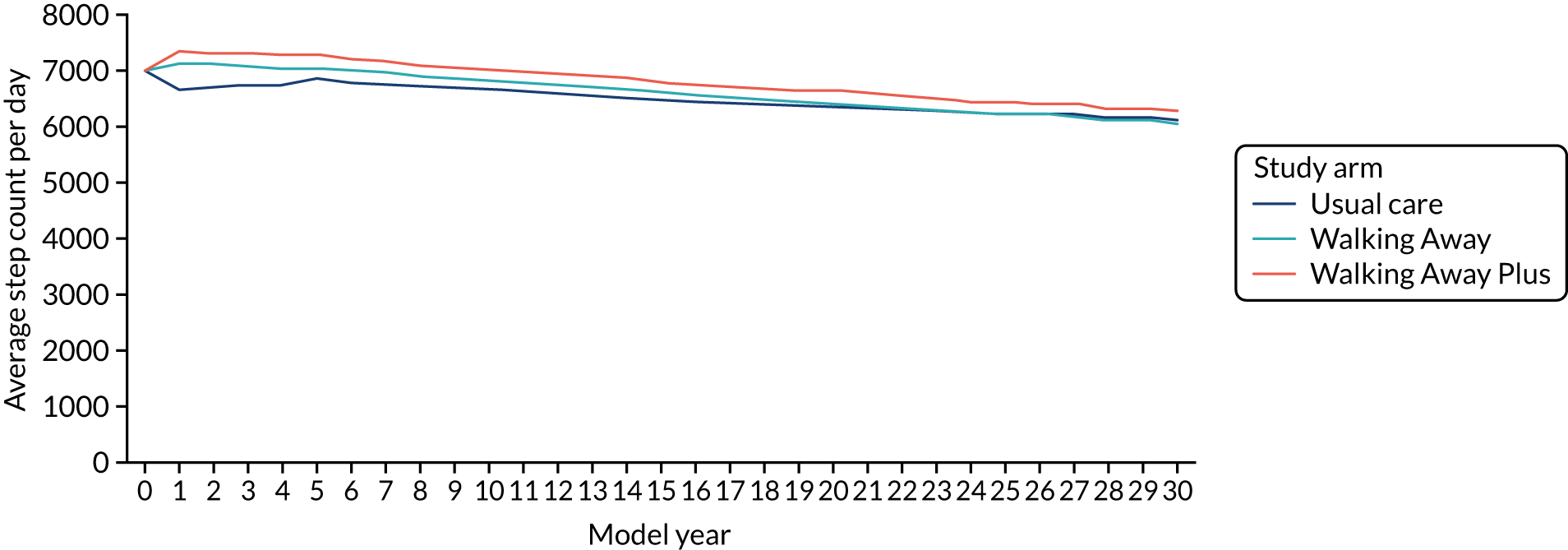

Model-based analysis

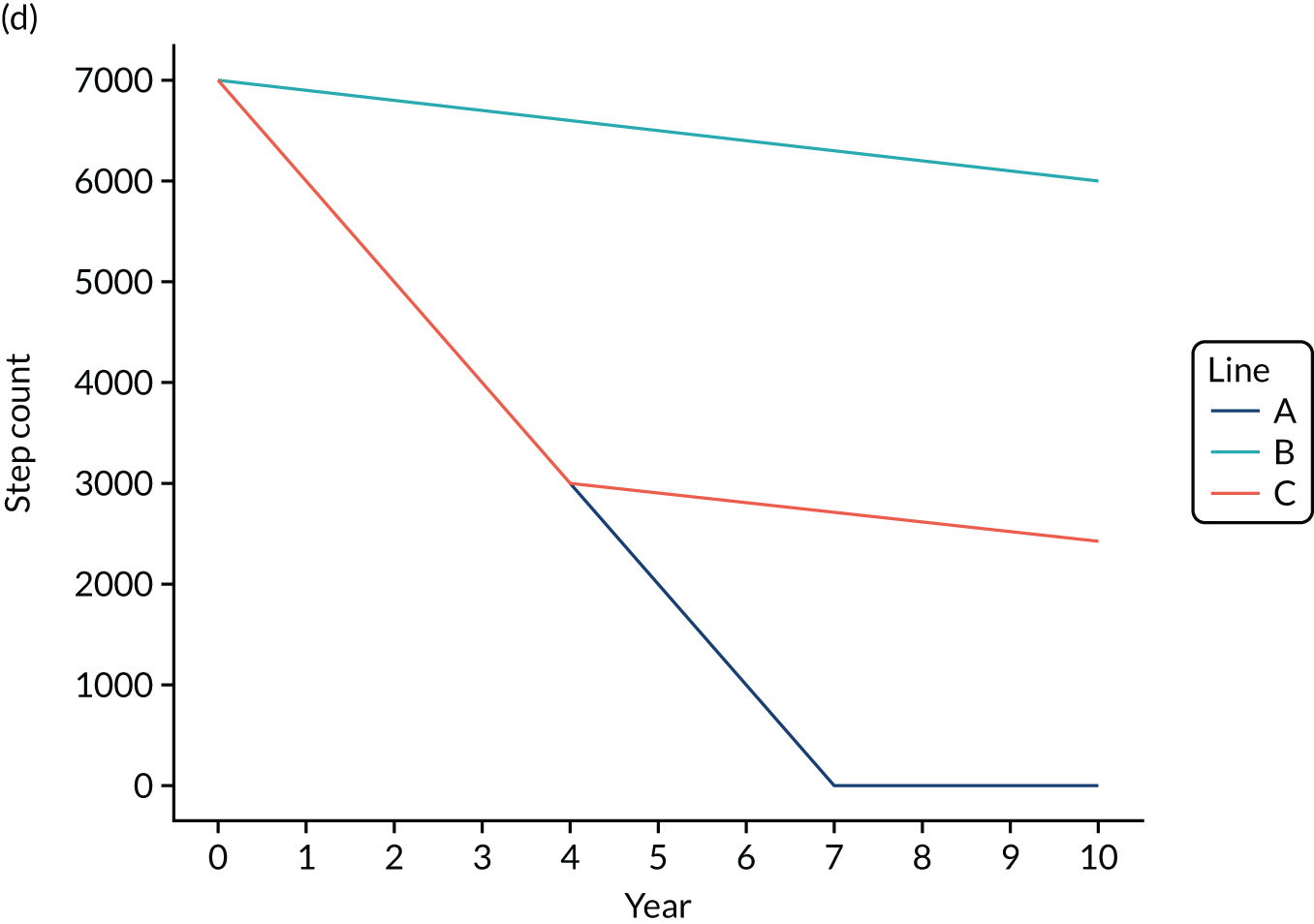

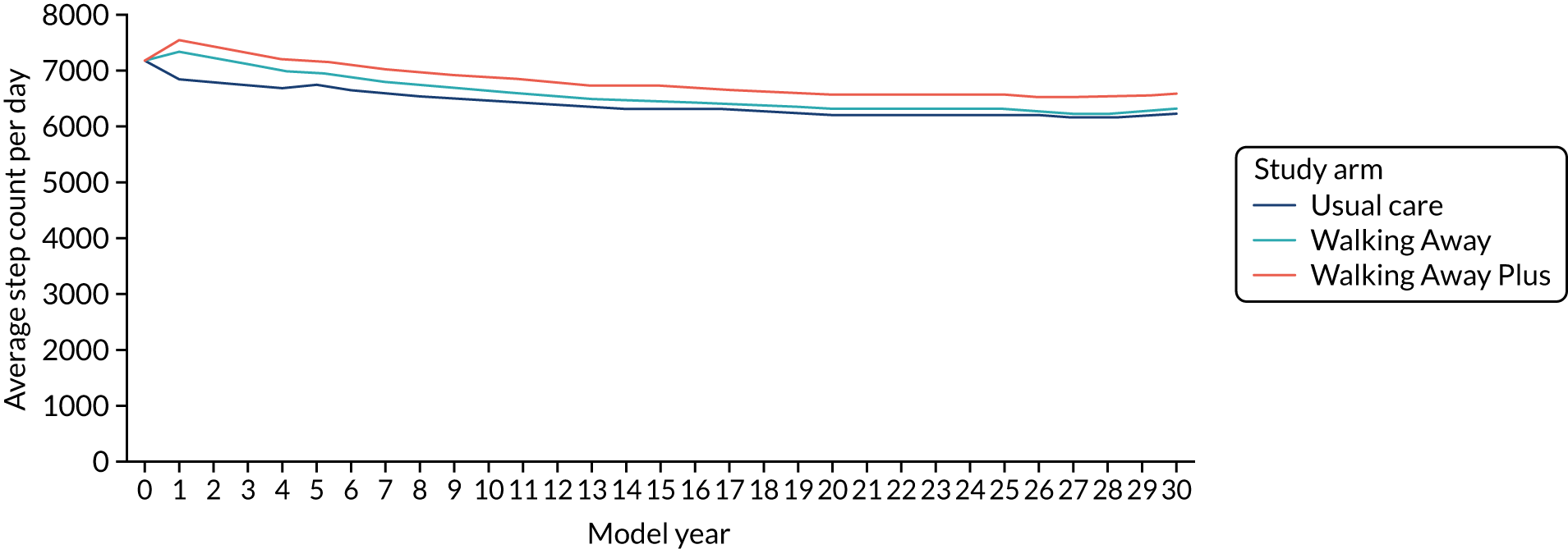

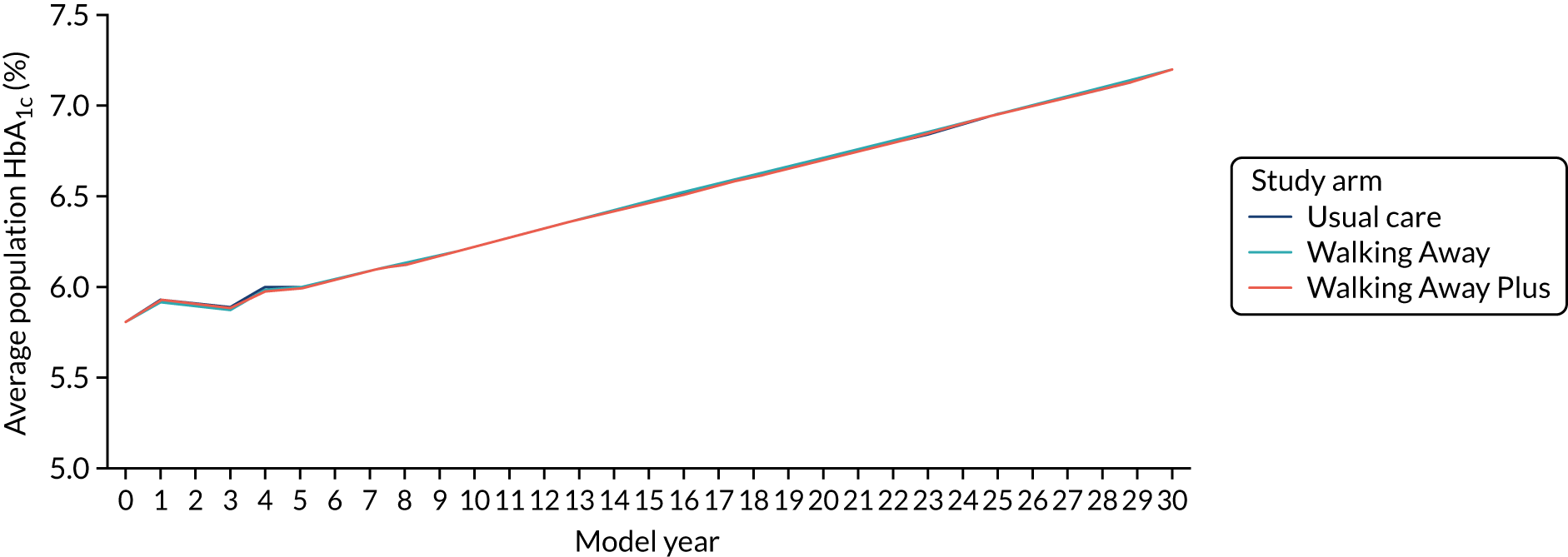

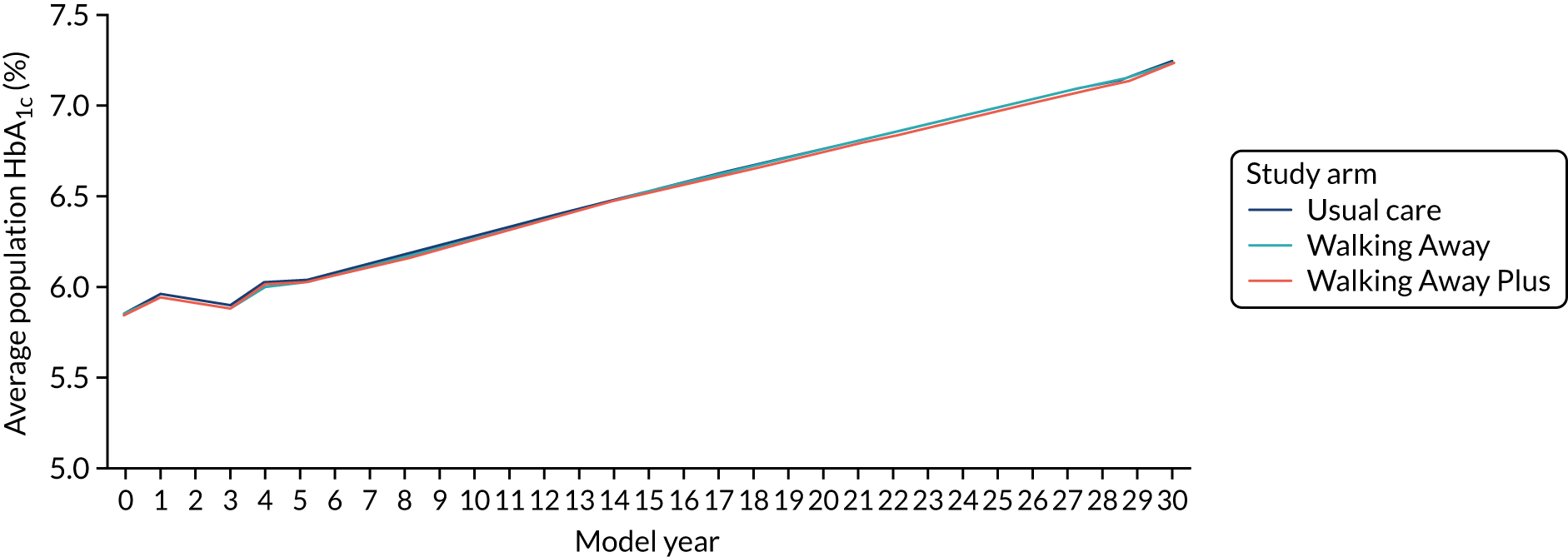

The School for Public Health Research model was used to simulate the long-term incidence of T2D, complications of T2D and other related conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and depression. The model is well validated for use in diabetes prevention interventions73 and was adapted to the specific requirements of the PROPELS trial in three ways:

-

The rates of progression to T2D in the first 4 years of the model were based on a statistical model derived from data collected in the trial.

-

Daily step count was added as a new population characteristic to incorporate the primary outcome variable of the trial.

-

The existing cardiovascular risk function was adapted to incorporate the independent effect of ambulatory activity on cardiovascular risk, as reported in the NAVIGATOR trial. 20

The model population was simulated based on an analysis of the baseline characteristics of the trial participants. Additional characteristics required for the model that were not collected in the trial were imputed using Health Survey for England data. 74 Owing to over recruitment of South Asian participants in the trial compared with the general population of the UK, analyses were performed separately for South Asian and non-South Asian populations. These results were then aggregated proportionally to the ethnic structure of the UK to provide an estimate of cost-effectiveness that was representative of the UK population as a whole.

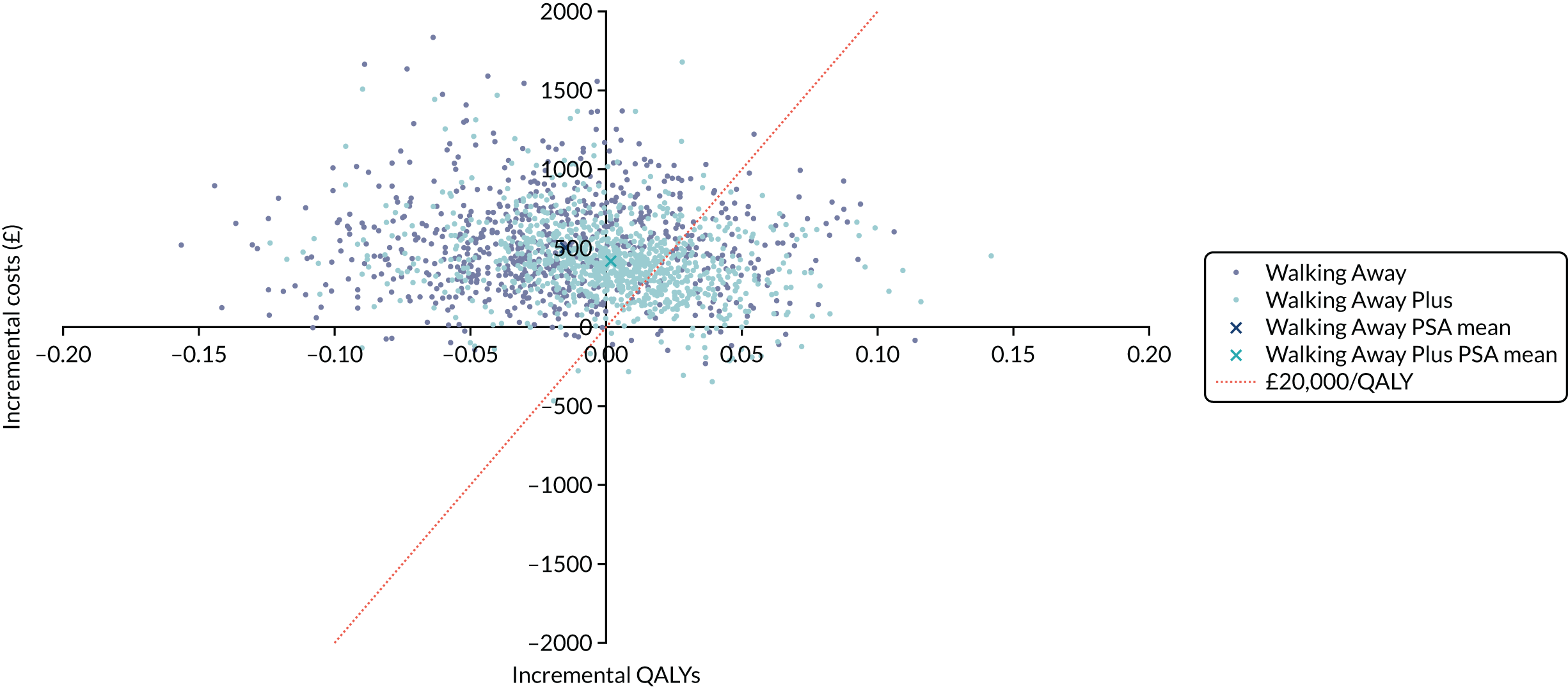

The primary model outcomes were aggregated lifetime costs and lifetime QALYs, both of which were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum in line with NICE recommendations. 75 Relevant clinical outcomes, including the number of diabetes diagnoses, incidence of diabetes complications and incidence of related conditions (including cardiovascular events), are also reported.

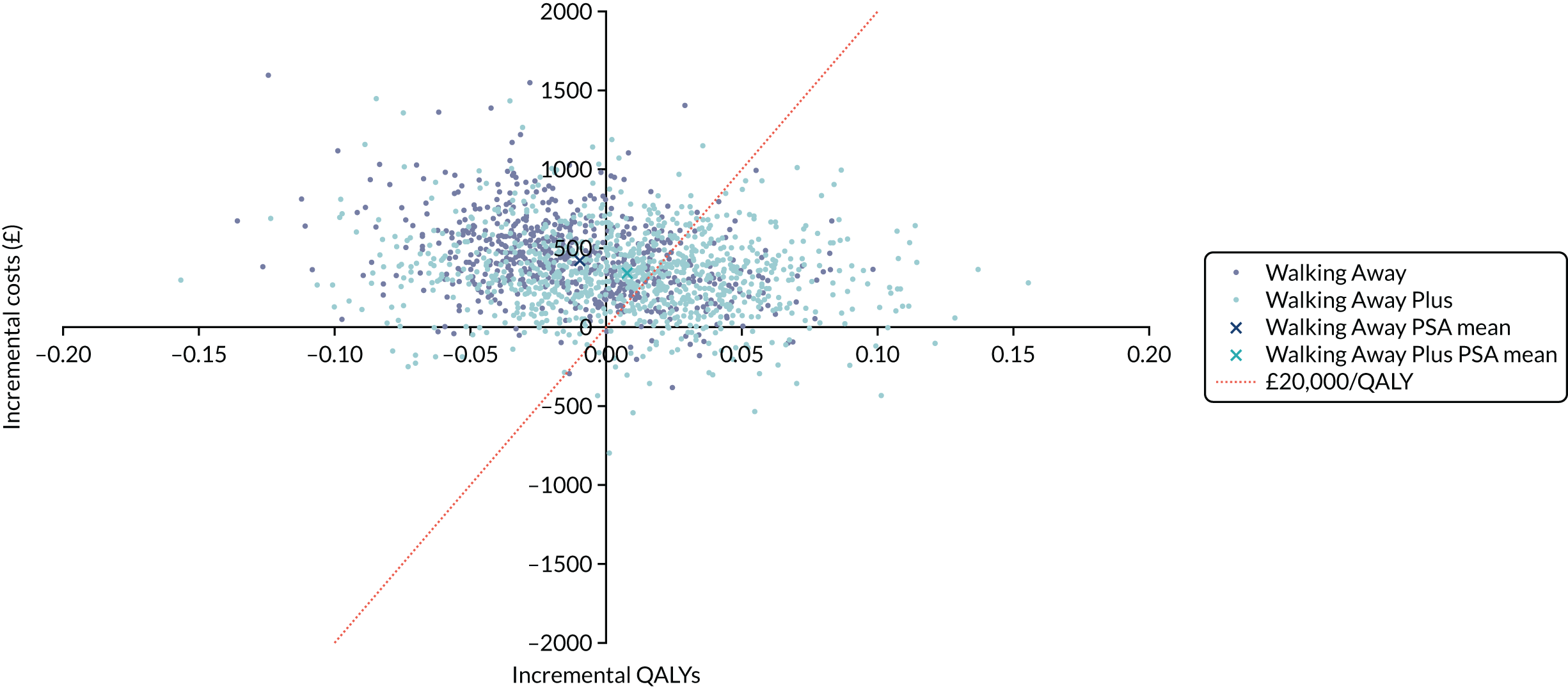

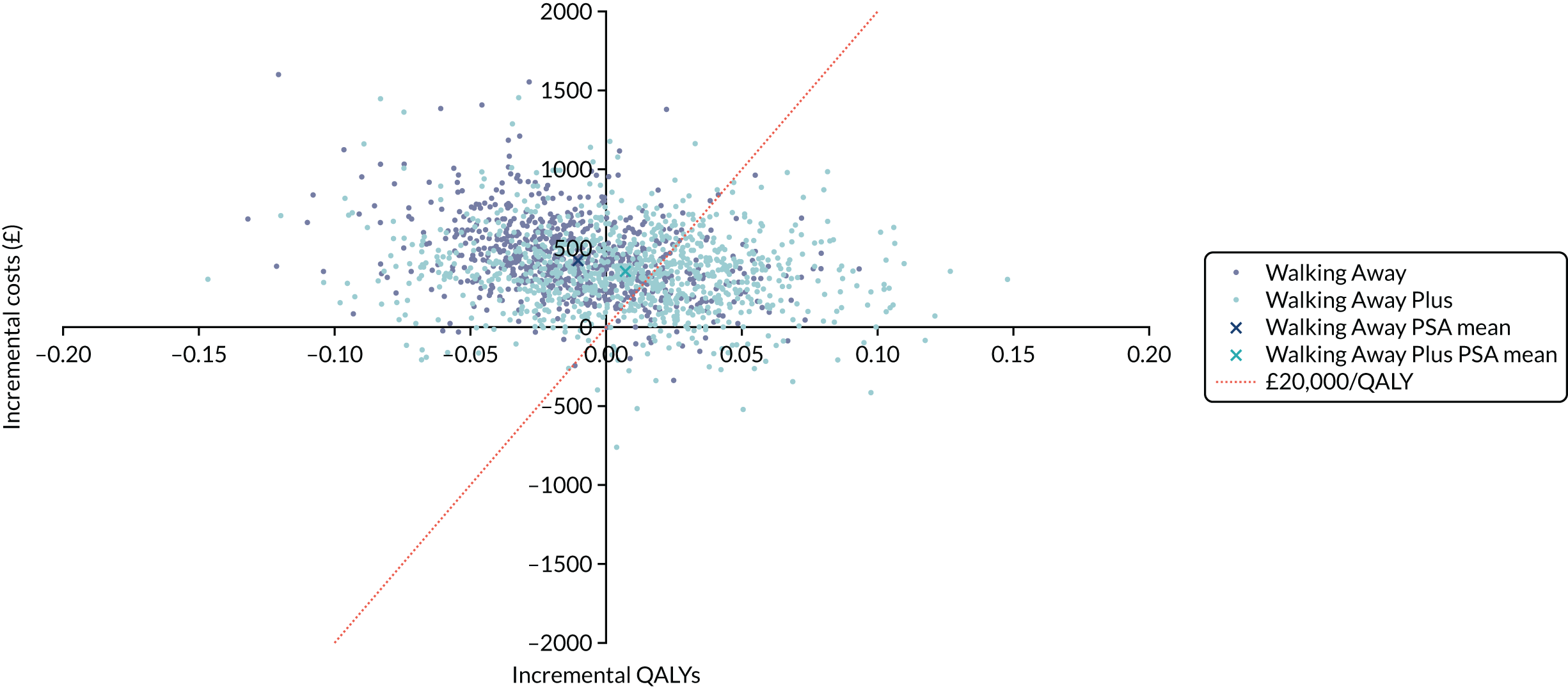

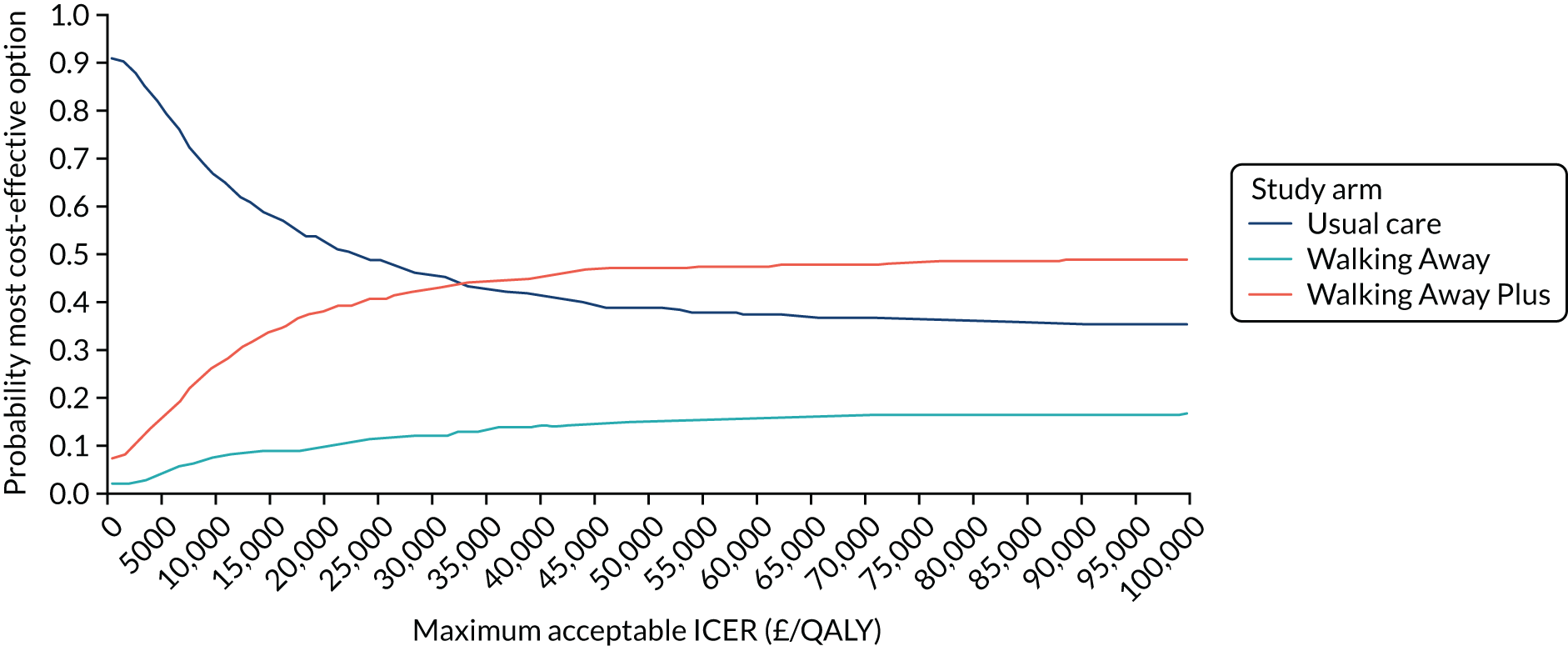

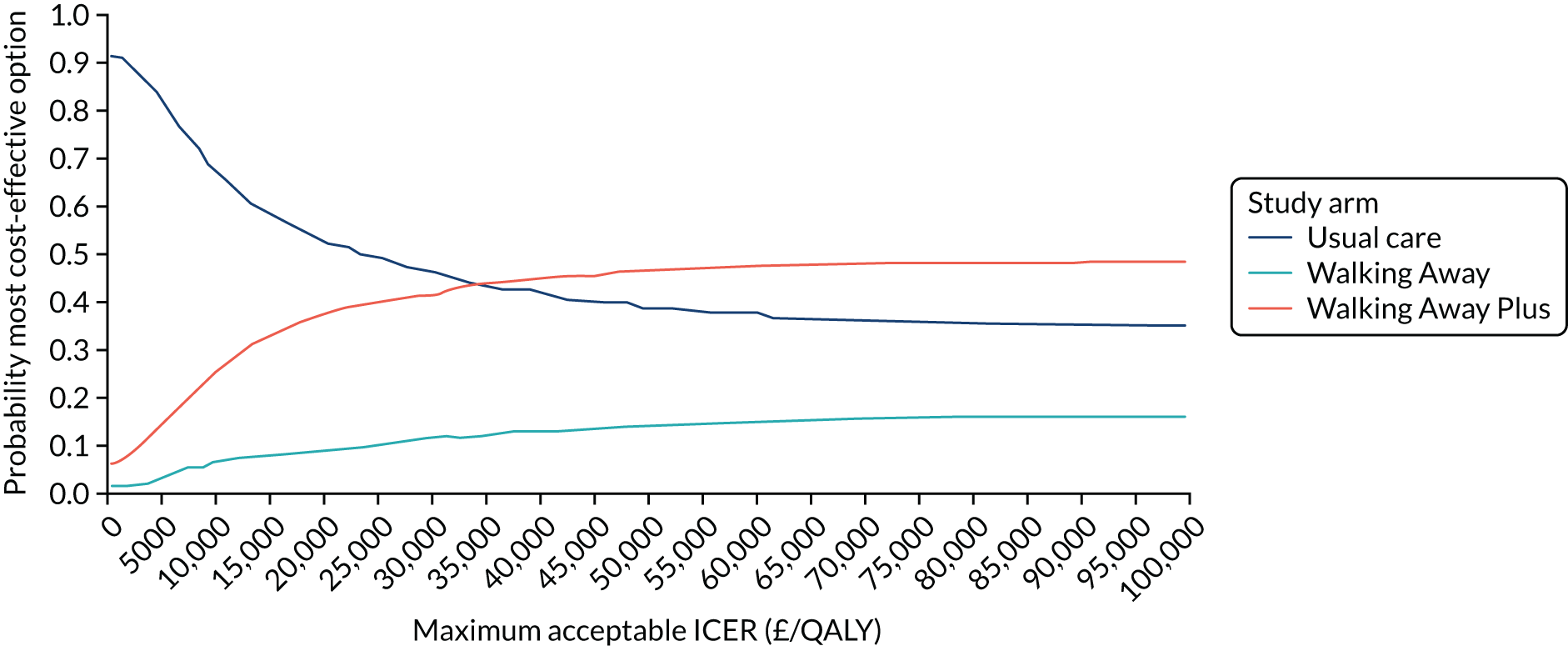

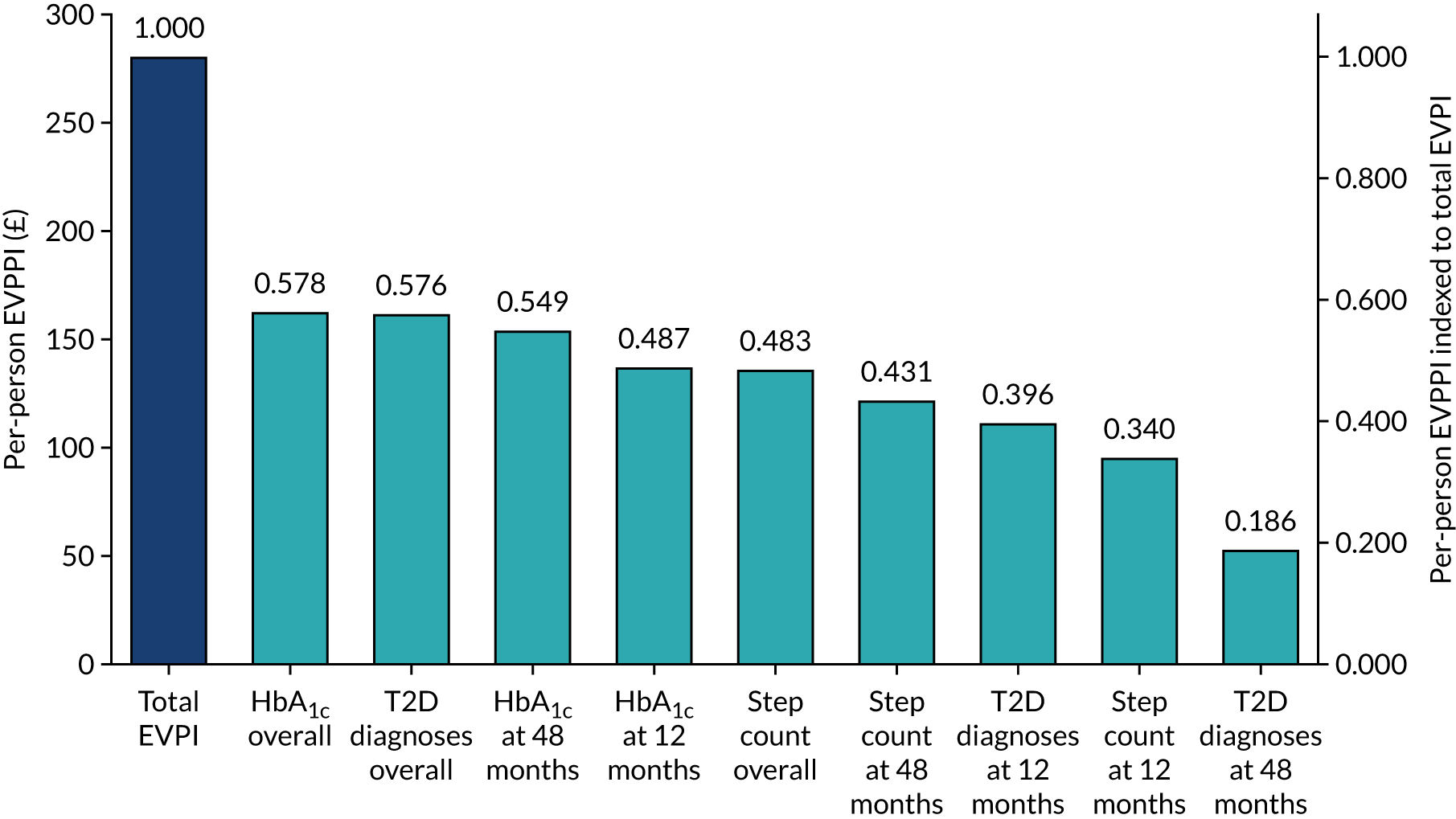

Cost-effectiveness was reported as an ICER and net monetary benefit assuming a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per QALY, as recommended by NICE. 75 Uncertainty around these results was explored through probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) and value-of-information techniques. We also conducted scenario analyses, as outlined in Chapter 6.

Within-trial analysis

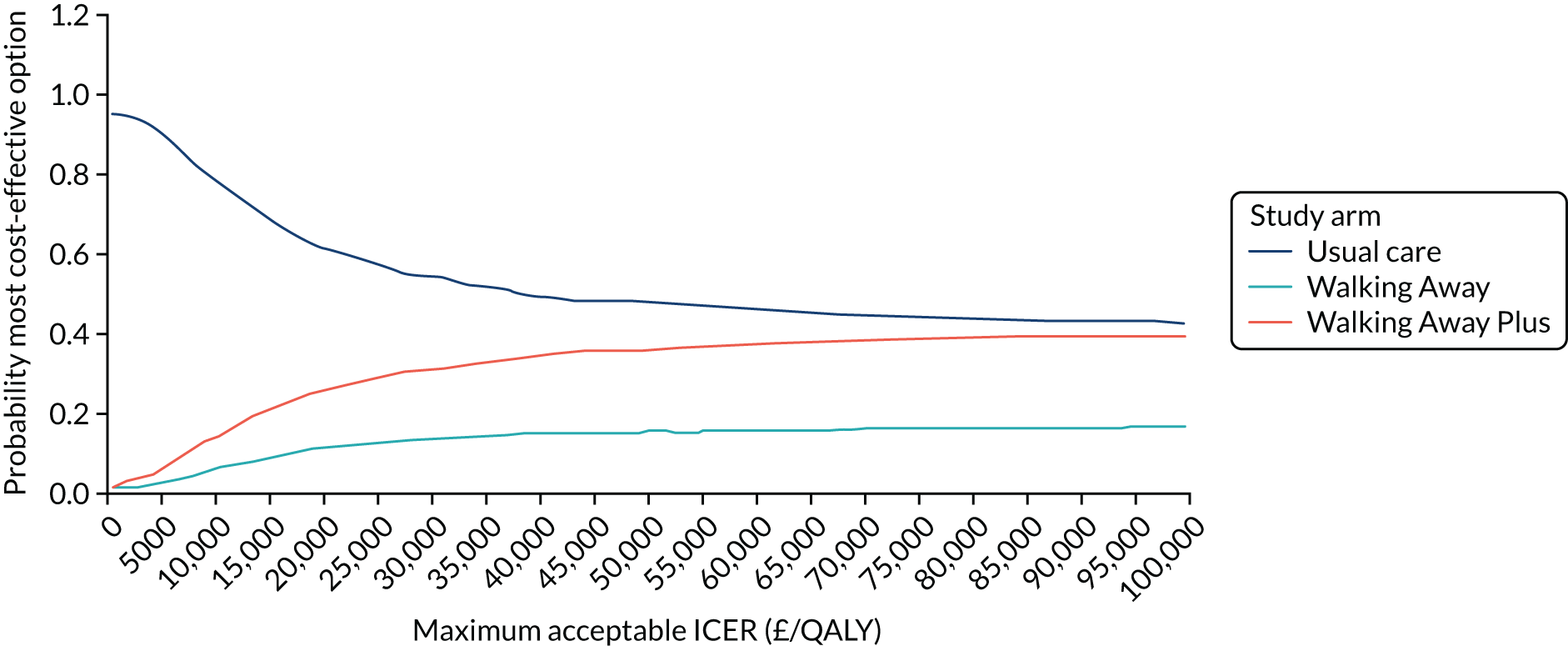

The within-trial analysis was conducted in line with Ramsey et al. ’s76 2015 recommendations for cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials. Resource use was calculated using data collected as part of the trial, and the cost of this was valued using standard unit sources, including, but not limited to, the British National Formulary77 and NHS Reference Costs. 78 The outcome measure was QALYs. Utility values were calculated by mapping the EQ-5D-5L data collected in the trial to the EQ-5D-3L scores, as recommended by NICE. 75 The resulting scores were valued using the standard EQ-5D-3L tariff for the UK population. 79 The total QALYs were estimated using an area-under-the-curve method. The costs and QALYs accrued after the first year were discounted at 3.5% in line with NICE guidance. 75 As for the model-based evaluation, the results are presented as an ICER and net monetary benefit, assuming a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per QALY. 75

Research governance

The study was conducted in accordance with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. The sponsor institution responsible for verifying research governance arrangements was the University of Leicester.

Trial Steering Committee

The trial was overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC), which was responsible for the overall management and oversight of the trial. The TSC was made up of:

-

Simon Heller, Professor of Clinical Diabetes, University of Sheffield (chairperson)

-

Richard Morris, Professor in Medical Statistics, University of Bristol

-

Des Johnston, Professor of Clinical Endocrinology, Imperial College London.

The TSC met approximately every 6 months, normally within 2 months of a meeting of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

A fully independent DMEC reported to the TSC. Although it was highly unlikely that the non-pharmaceutical, non-invasive interventions proposed would result in any substantial negative effects on trial participants, the DMEC held responsibility for the interests of participant safety and data integrity and reviewed all reported adverse events. It also assessed data at 12 months, with predefined rules for stopping the trial for futility if specific criteria were met. These criteria were based on whether or not there was evidence that the intervention was causing harm, defined as a decrease in the primary outcome (ambulatory activity) in the intervention arms compared with the control arm, based on the 99% CI and 95% CI. If a decrease was seen based on the 99% CI in both arms, then the trial would be terminated. If a decrease was seen based on the 95% CI, then secondary outcomes would be considered in making a recommendation for termination. These criteria were not met.

In addition, the DMEC reviewed and signed off the statistical analysis plan. The DMEC comprised Graham Hitman, Professor of Molecular Medicine and Diabetes, Queen Mary, University of London (chairperson); Naveed Sattar, Professor of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow; and Michael Campbell, Emeritus Professor of Medical Statistics, University of Sheffield.

Data integrity

The study was reviewed by the NHS National Research Ethics Service Committee East Midlands – Leicester and the Comprehensive Local Research Network (ethics number 12/EM/0151). All data were entered (through secure web-based access) and held in a specifically designed database in the Leicester Clinical Trials Unit. The database was designed with internal validity and quality control checks; potential errors were highlighted to, and corrected by, the study team. Data were released to the study statistician at predefined time points.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the NHS National Research Ethics Service, East Midlands – Leicester Committee, which co-ordinates ethics permissions across the following study and recruitment sites:

-

University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust

-

Leicester City Clinical Commissioning Group

-

West Leicestershire Clinical Commissioning Group

-

East Leicestershire and Rutland Clinical Commissioning Group

-

University of Cambridge

-

MRC Epidemiology Unit

-

Cambridge and Peterborough Clinical Commissioning Group

-

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Amendments

The PROPELS protocol was subject to 14 amendments, none of which changed the main aims or objectives of the trial; for a list, see Appendix 3.

Trial registration

The trial was registered with ISRCTN as ISRCTN83465245: The PRomotion Of Physical activity through structured Education with differing Levels of ongoing Support for those with pre-diabetes (PROPELS) (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN83465245).

Chapter 3 Intervention description and development

This chapter details the content of Walking Away and the development work that informed the text messaging and telephone (mHealth) support element used in the Walking Away Plus study arm. The intervention description was developed in accordance with the principles of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist.

Walking Away: group-based behaviour change intervention with annual refresher sessions

Walking Away is an established programme that was developed within the infrastructure of NIHR CLAHRC (Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care) East Midlands for implementation in primary care; it has been described in detail elsewhere. 80 Walking Away went on to be implemented nationally through commissioned diabetes prevention services. Walking Away formed the core intervention programme that was evaluated within PROPELS. Based on learning generated by the development and trial work supported by the CLAHRC, minor revisions were made to Walking Away so that it could be used within PROPELS. In particular, the way that risk was communicated was broadened to emphasise that the risk of diabetes increases as the number of related risk factors increases to extend the focus beyond glycaemia.

Walking Away is underpinned by a theoretical framework focusing on linking motivational and volitional determinants of health behaviour. It draws on mutually complementary health behaviour theories and behaviour change techniques, including Bandura’s social cognitive theory,81 Gollwitzer’s implementation intentions,82 Leventhal’s common sense model83 and Chaiken’s dual process theory,84 and is modelled on the person-centred philosophy and learning techniques developed for the DESMOND programme. 24 DESMOND is a self-management programme for people living with T2D that is commissioned and delivered both nationally and internationally.

Walking Away: the initial education session

Walking Away was delivered by two trained educators to groups of up 10 participants, with participants invited to bring a family member or a guest if they wished. Sessions were delivered in a variety of settings chosen for proximity to the recruiting GP surgeries, including at the surgeries themselves, in nearby community centres and at hospital sites.

The curriculum for the initial education session, examples of activities and the underlying theories and behaviour change techniques are presented in Table 3. Walking Away was aimed at increasing participants’ knowledge of diabetes risk, changing their outcome expectations about how physical activity can lead to decreased diabetes risk, and strengthening their self-efficacy for engaging in increased physical activity. The programme was designed to harness key behaviour change techniques related to self-regulation, including goal-setting, action-planning, self-monitoring and barrier identification/problem-solving to ensure that motivation for behaviour change translated into actual behaviour change. Self-monitoring was supported through the provision of a pedometer [Yamax SW200 (Yamax, Shropshire, UK)]. Participants used their daily habitual step count (measured at baseline prior to the education programme) to set personalised steps-per-day activity goals.

| Module | Main aims | Example activity | Theoretical underpinning | Behaviour change techniques employed (mapped from Michie et al.85) | Time weighting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Welcome/housekeeping | 5 minutes | |||

| Patient story | Give participants a chance to share their knowledge and perceptions of being identified as ‘at risk’ of T2D and highlight any concerns that they may want the programme to address | Participants are asked to share their story, how they were diagnosed as being ‘at risk’ of developing T2D and their current knowledge of being ‘at risk’ | Common sense model83 | Provide normative information about others’ behaviour | 25 minutes |

| Professional story | Use simple non-technical language, analogies, visual aids and open questions to provide participants with:

|

Individuals are helped to plot their individual risk (fasting and 2-hour blood glucose levels, cholesterol and blood pressure levels – assessed at baseline) |

Common sense model83 Dual process theory Social cognitive theory81 |

Provide information on consequences of behaviour | 35 minutes |

| Risk story |

|

Participants explored the broader risk factors for T2D beyond glucose values, including generating a list of non-modifiable (e.g. family history and age) and modifiable risk factors (e.g. overweight, blood pressure, cholesterol levels). Participants were then supported to plot their own risk factors onto a risk chart to work out their individual risk areas |

Social cognitive theory81 Dual process theory84 |

Provide information on consequences of behaviour | 25 minutes |

| Break | Refreshments and informal discussion | 10 minutes | |||

| Physical activity | Use simple non-technical language, analogies, visual aids and open questions to help participants:

|

|

Social cognitive theory81 Implementation intentions81 Dual process theory84 |

|

55 minutes |

| Diet | Increase participants’ knowledge about diet and give them an accurate understanding of the link between dietary macro-nutrients and metabolic dysfunction | Participants are asked to group models of fats and oils into saturated, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated categories |

Social cognitive theory81 Dual process theory |

Provide information on consequences of behaviour | 20 minutes |

| Conclusion | Questions and future care | Signpost to locally available groups/programmes | 5 minutes |

Participants were encouraged to increase their activity levels by up to 3000 steps per day, equivalent to around 30 minutes of walking. Goal attainment was encouraged through the behaviour change technique of setting graded tasks, whereby the use of proximal objectives, such as increasing ambulatory activity by 500 steps per day every 2 weeks, is used to work up to overall goals. Participants were encouraged to make an action plan detailing where, when and how they would reach their first proximal goal, to repeat action-planning for each new proximal goal, to wear their pedometer on a daily basis and to self-monitor their ambulatory activity using a specifically designed steps-per-day diary. Although this was primarily a physical activity intervention, a short time was allocated to covering the key dietary messages because participant groups had requested this during the intervention development process for Walking Away.

Walking Away: the annual refresher sessions

As for the original Walking Away RCT, after the initial education session, participants were offered annual group-based maintenance sessions at 12, 24 and 36 months (‘refresher sessions’). Refresher sessions each lasted 2.5 hours and were designed to revisit the key messages of the initial session, strengthen self-efficacy through sharing successes and prompt problem-solving in relation to barriers, goal-setting and self-monitoring using pedometers. The annual nature of the group sessions was designed to fit with primary care pathways, in which annual clinical follow-up is recommended for those with a high risk of chronic disease, such as prediabetes. 43,86

Walking Away Plus: with enhanced mHealth follow-on support

Participants assigned to the Walking Away Plus study arm were invited to attend the Walking Away initial education session and annual refresher sessions, as described above. In addition, they were provided with a mHealth follow-on support intervention in the form of tailored text messaging and telephone support.

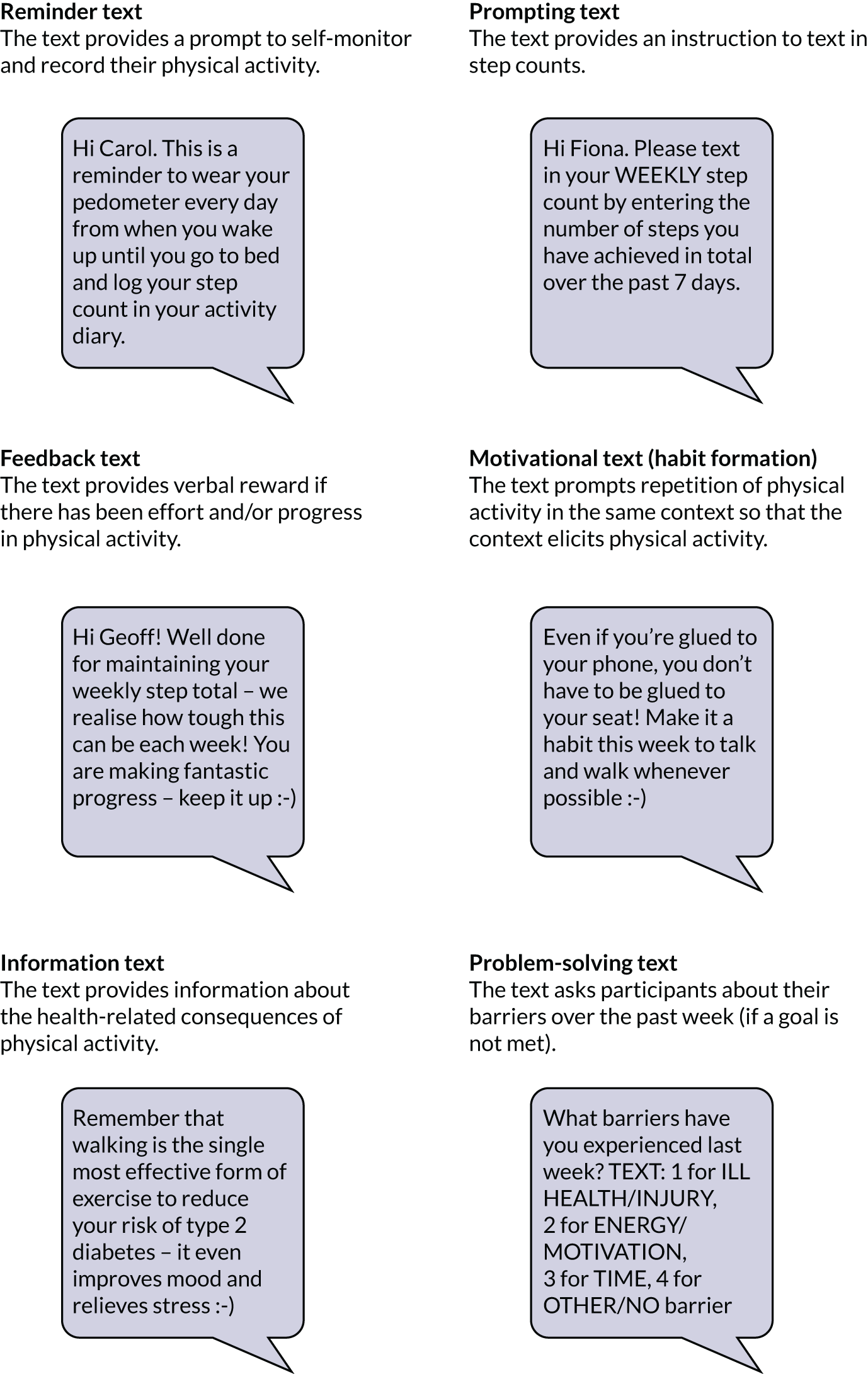

Text messaging system

Text messages were used to prompt pedometer use and provide tailored feedback on meeting steps-per-day goals. The frequency of texts received varied over time to coincide with the initial and annual refresher face-to-face group sessions (Table 4).

| Time point from education attendance | Type of contact and frequency | Content (behaviour change techniques and their delivery) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 months | Initial group session (3 hours) |

|

| 1 week | First telephone call from educator (15 minutes) | The educator prompted the participant to set an action plan and personal short- and long-term goals informed by the baseline steps, and asked the participant about their confidence in achieving goals and their previous levels of physical activity. Educator recorded this information on an online form, which was saved to a database for use in tailoring subsequent text messages |

| 0–2 months | Text message contact (1–3 text messages per week) |

|

| 2–6 months | Text message contact (one per week) |

|

| 6 months | Telephone contact (15 minutes) |

|

| 7–12 months | Text message contact (once per month) |

|

| Optional | Telephone contact (15 minutes) |

|

| 12 months | Walking Away refresher session (2.5 hours) | See Walking Away study arm |

The text messaging system was hosted on a secure University of Cambridge server. The program consists of two parts:

-

a set of tables in a MySQL database

-

a set of PHP (hypertext preprocessor) scripts.

The MySQL tables contain data from participants, which were obtained in two ways:

-

data elicited by educators during telephone calls (see Telephone support)

-

data extracted from text messages participants sent to the system, such as the number of steps participants reported having taken and a STOP message sent by a participant indicating that they did not wish to receive any further text messages.

A messages table contained the bank of messages that were developed for the PROPELS trial. Schedule tables specified the days and time slots when text messages should be sent. Matrix tables specified which variables should be used to individually tailor each message.

Messages were tailored in two ways:

-

Different participants received different messages depending on the values of the relevant tailoring variables.

-

Tags were embedded in some messages enabling variable values to be inserted dynamically (e.g. #nname# to insert the participant’s nickname).

Other tables stored the educators’ identification numbers, messages sent by participants to the system and messages sent by the system to participants. Messages sent to participants included query messages, for example asking them to text in their weekly step count.

Participants registered with the system by sending a text that included the keyword ‘PROPELS’ and their nickname to a specified number. The system was fully automated except for the educator interface, which allowed manual data entry. The main PHP (hypertext preprocessor) script was set to run every 15 minutes from 06.05. The first time that it ran each day it set up the text messages to be sent that day. Then, every 15 minutes it checked whether or not the time for sending the messages had been exceeded. If it had, the messages were sent.

A message was ‘sent’ by sending a HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) request to a company called FastSMS, which relayed the message over the mobile telephone network. Other scripts sent birthday and New Year messages, processed incoming texts (relayed from FastSMS) and queried the database to produce reports, for example of messages sent that day.

Telephone support

Telephone support from trained educators was used to support and tailor the text messaging system. An educator telephoned the participant approximately 1 week after the Walking Away session to confirm short- and long-term step goals and an action plan for the next 6 months, and to elicit information needed to enable the text messaging system to be tailored to variables such as confidence in increasing physical activity, previous experience of physical activity and potential mobility issues that prevented walking from being the primary activity. The collected information was captured in an online form and saved to a database for use in the text messaging programme. Participants also continued to receive two telephone calls annually to review their progress.

Structure and intensity of mHealth follow-on support

The structure and intensity of the mHealth intervention used in the PROPELS trial is detailed in Table 4.

This annual structure was repeated each year following each group education refresher session for the 4 years that constituted the intervention period.

The mHealth intervention content and the structure used were developed and piloted within the PROPELS programme of work. This development work, along with examples of the content used, is detailed below.

Development of the mHealth follow-on support intervention: a pragmatic framework for developing and piloting a text messaging intervention

The robust development of mHealth behaviour change interventions can be time-consuming, and yet in RCT protocols87,88 this is often allocated limited time. The time constraints of the PROPELS RCT protocol provided for 12 months to conceptualise, develop and test the follow-on support programme prior to the commencement of the RCT. Our methods offer a pragmatic framework for developing and piloting a text messaging intervention – drawing on relevant behaviour change theory and using rigorous qualitative methods incorporating user engagement – that lends itself well to replication and application to the development of similar interventions.

The structured, iterative process that we used to develop the PROPELS follow-on support programme involved undertaking concurrent and sequential research with the target population while maintaining a strong focus on the integration of theory and evidence. The methods that we employed combined features of published mHealth development frameworks89,90 and multiple iterative phases of qualitative research similar to a user-centered design process. 88 Our framework for intervention development and piloting was informed by the model by Dijkstra and De Vries89 for developing computer-generated tailored interventions (to conceptualise the programme) and the mHealth development and evaluation framework by Whittaker et al. 90 and Fjeldsoe et al. 91 The high level of engagement with our target population enabled us to refine the design to optimise its acceptability to users.

The four phases of the development process are described below.

Phase 1: conceptualisation

In line with Dijkstra and De Vries’89 model for developing computer-generated tailored interventions, our first step was a focused literature review to identify the key psychosocial determinants of increasing and/or maintaining physical activity levels among adults at risk of developing T2D; these determinants of physical activity were then translated into the key objectives of the PROPELS follow-on support programme.

Our literature review focused on text messaging interventions to promote physical activity, but also reviewed physical activity behaviour change interventions more broadly within our target population to identify salient behaviour change techniques. 92 The main findings from our focused literature review are summarised below.

Text messaging for physical activity promotion

Two comprehensive meta-analyses demonstrated a growing evidence base for text messaging interventions to promote health. In the first, which focused on physical activity promotion using mobile devices,93 most of the included interventions delivered through text messaging were passive, sending participants relay messages (e.g. goal intentions) or generic, non-tailored information about health benefits, and most of the participants were younger adults. However, one exception to this was a pilot study in older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,94 which provided the control (self-monitoring) study arm with a pedometer and mobile telephone, prompted them to text in details about their symptoms and exercise, and responded with a standard message to thank them and encourage them to continue submitting data. Intervention (coaching) study arm participants received additional ongoing reinforcement coaching messages. Objectively measured step count increased in the self-monitoring group only. Although this intervention was feasible to deliver, delivery was not automated, as text responses were manually adjusted by a nurse, and scalability was limited by all participants being provided with a telephone. The second study of interest was a RCT in middle-aged healthy adults of a fully automated intervention, consisting of a wrist-worn device, an interactive website to provide feedback on physical activity and text messaging reminders of activity plans, which reported significant increases in objectively measured activity compared with no support. 95

The second meta-analysis investigated the efficacy of different formats of text messaging-based interventions for various health behaviours and outcomes and found that message tailoring and personalisation were significantly associated with greater intervention efficacy;96 interventions that involved decreasing frequency of messages over the course of the intervention were more effective than interventions that used a fixed message frequency;96 and text message-only physical activity interventions without tailored feedback did not increase physical activity. 97

This pointed to tailored feedback being a promising component of mHealth physical activity interventions and suggested that physical activity interventions using text messages may be more effective if they incorporate active components, such as self-monitoring, provide tailored feedback and personalised messages, and decrease the frequency of text messages over time.

Theory and behaviour change techniques

Looking beyond text messaging interventions, health behaviour change interventions that combine self-monitoring with at least one other self-regulatory behaviour change technique (e.g. goal-setting) have been found to be significantly more effective at increasing physical activity than those that do not. 98 These behaviour change techniques fit with the process of self-regulation or, more specifically, control theory,99 which proposes that setting goals, self-monitoring behaviour, receiving feedback and reviewing goals following feedback are central to behavioural self-management.

We, therefore, structured the PROPELS follow-on support programme around the use of behaviour change strategies, which informed the selection and sequencing of the primary behaviour change techniques that featured in the various components of the programme. 92 Accordingly, during the educator telephone call at week 1, physical activity goals and an action plan were established. The text messaging component drew on a range of behaviour change techniques to:

-

encourage self-monitoring of physical activity behaviour

-

provide tailored feedback regarding physical activity progress to highlight the discrepancy between goals and current behaviour

-

review behavioural goals.

A more detailed explanation of all of the behaviour change techniques employed in the PROPELS follow-on support programme has already been reported. 100

In interventions among people with or at risk of T2D, those that included a larger number of behaviour change techniques,101 or a larger number of behaviour change techniques and specific behaviour change techniques such as goal-setting,102 have been associated with greater weight loss. There is also consistent evidence demonstrating the importance across general populations and in high-risk groups of several other key determinants of physical activity behaviour change, including attitudes toward physical activity,103 intrinsic motivation104 and (maintenance) self-efficacy,105 especially when targeted in conjunction with the use of behaviour change techniques. 106 With this in mind, the text message component of the PROPELS follow-on support programme also targeted these other determinants of physical activity behaviour change. Given the uncertainty that remains about the acceptability of the aforementioned behaviour change techniques when delivered by text message, one aim of phases 2–4 was to explore the acceptability and feasibility of this approach with our target population.

Phase 2: formative research

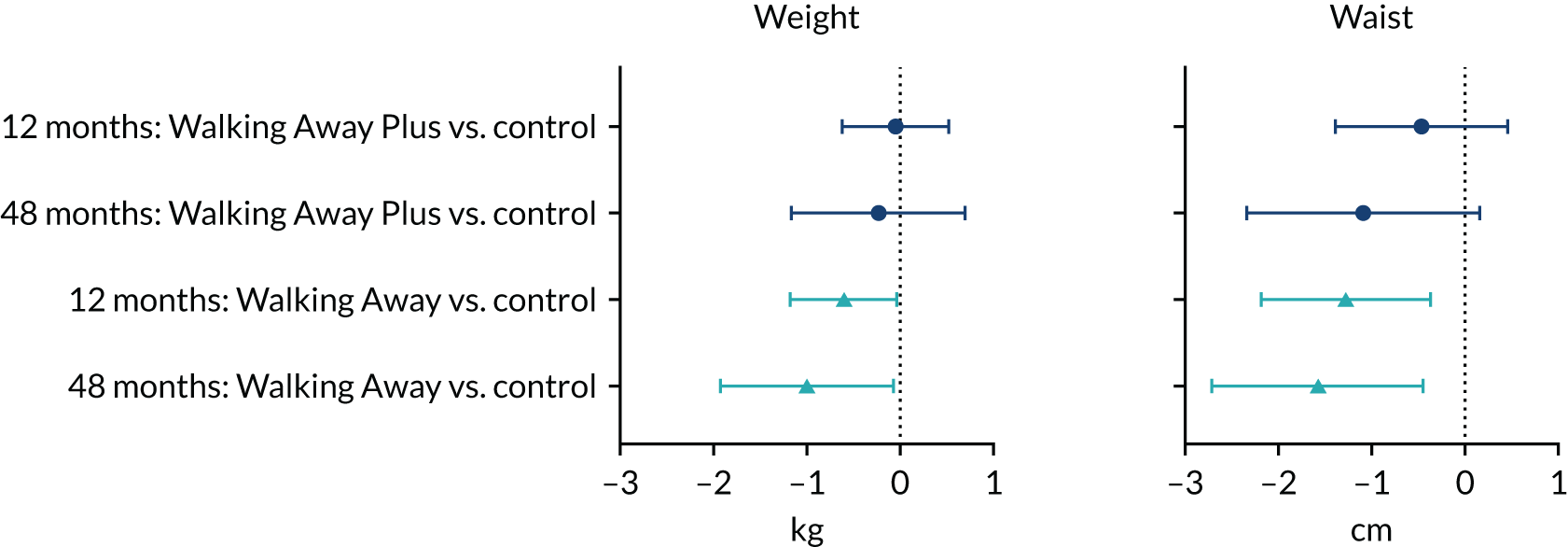

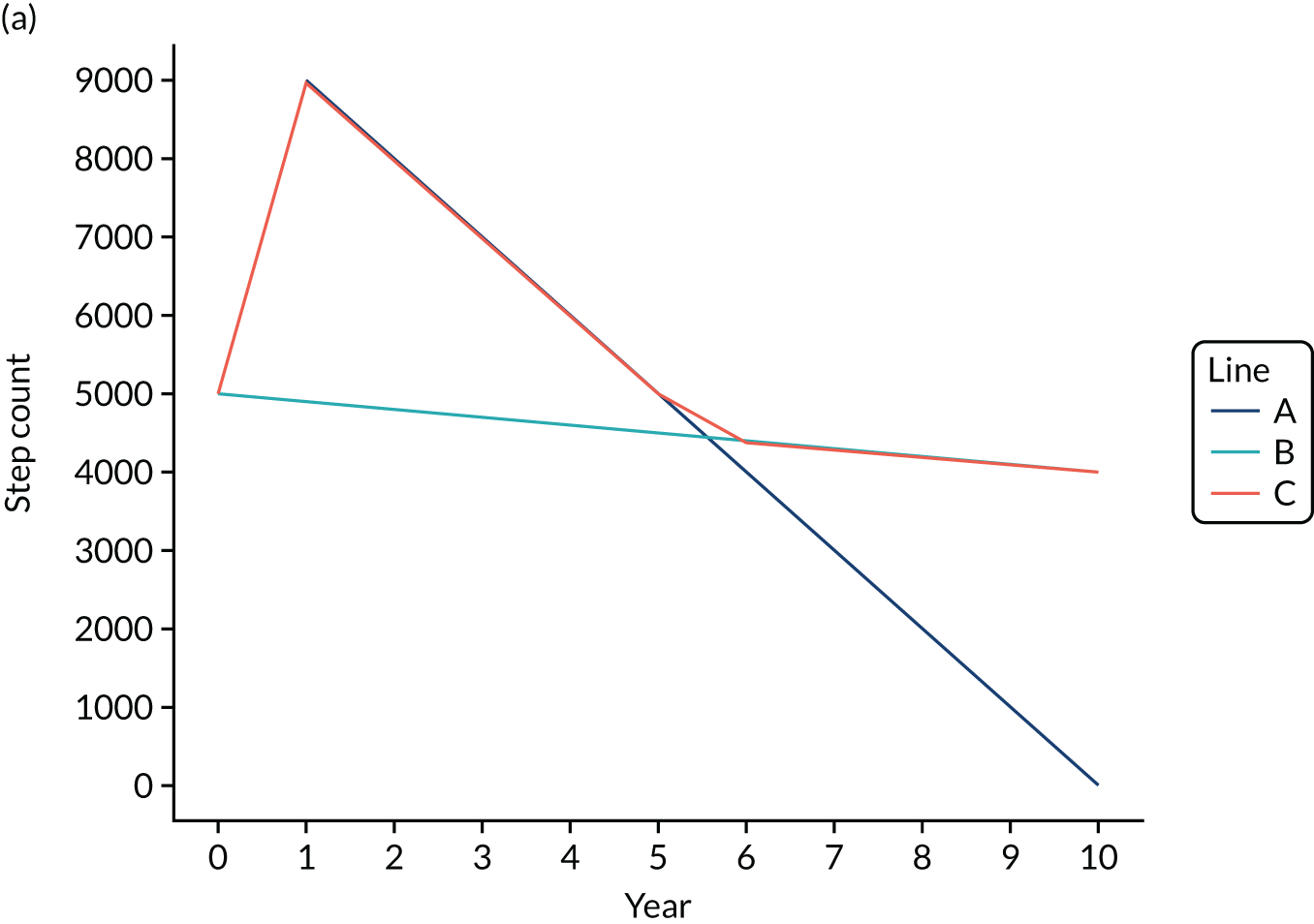

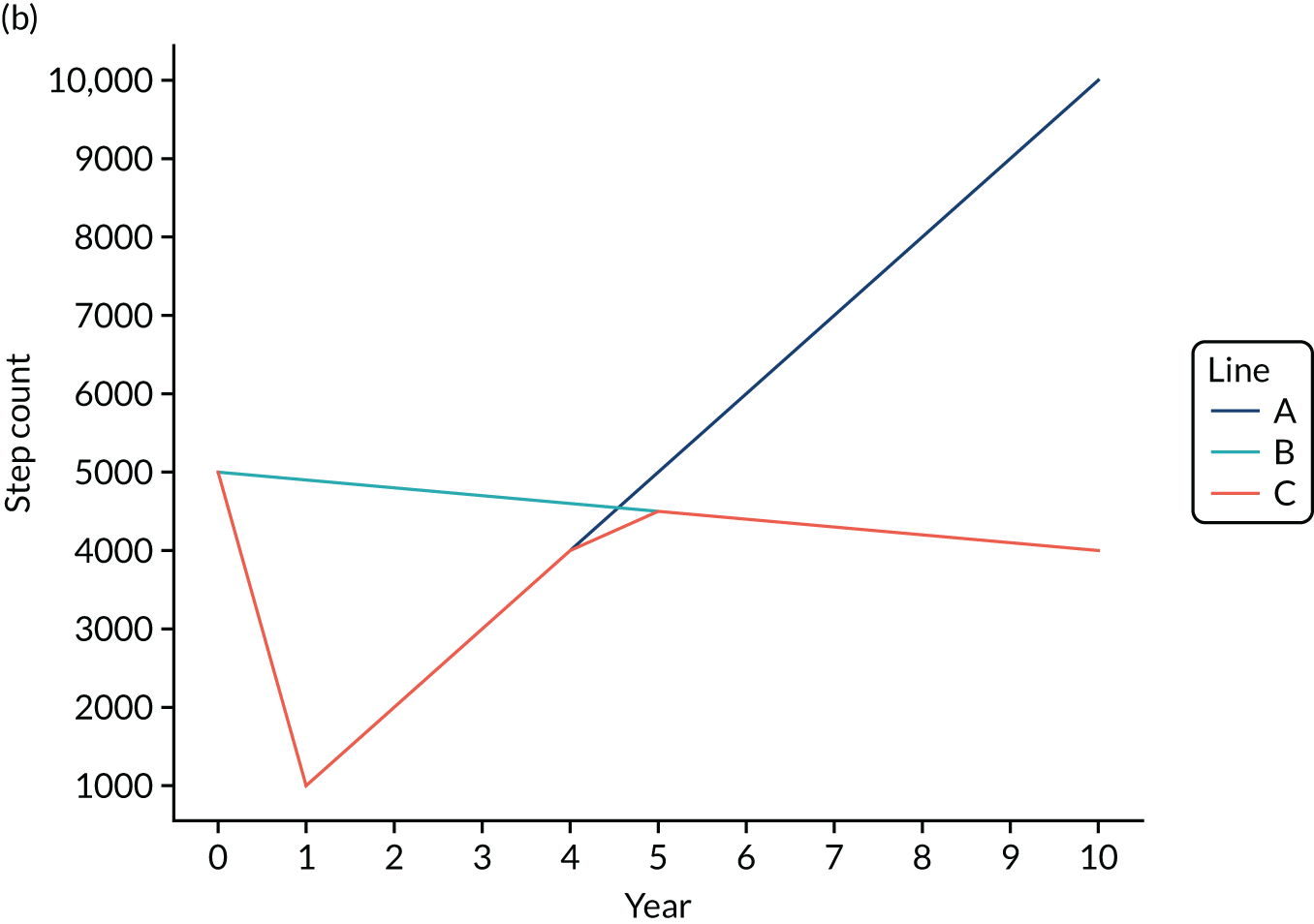

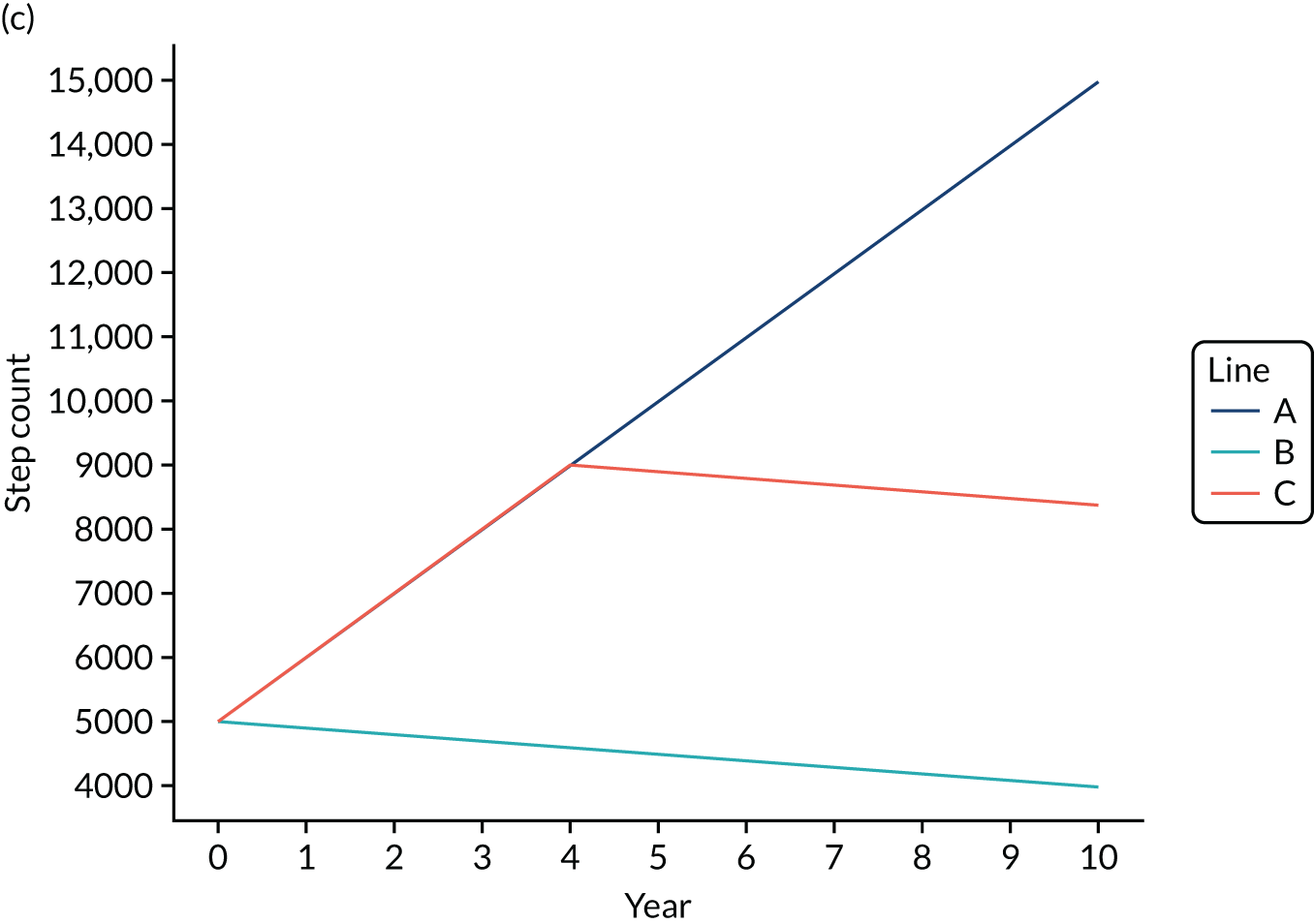

Concurrently with phase 1, informal observations were conducted of Walking Away sessions across the diverse regions in which it had been commissioned into routine care pathways for the prevention of T2D, and discussions were held with Walking Away educators who were involved in an ongoing evaluation of Walking Away taking place in primary care. 80 The aim of this was to ensure familiarisation with the delivery of Walking Away, develop initial ideas about the possible structure and content of the PROPELS follow-on support, understand the cultural and ethnic diversity of our target population, explore educators’ views about supplementing Walking Away with text messaging and pedometer support, and inform the development of topic guides for subsequent focus groups.