Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the Evidence Synthesis Programme on behalf of NICE as award number NIHR133547. The protocol was agreed in April 2021. The draft manuscript began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Asgharzadeh et al. This work was produced by Asgharzadeh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Asgharzadeh et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) was formerly known as insulin-dependent diabetes. It is the result of an autoimmune process that leads to the destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. The cause of this autoimmune process is not known.

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Insulin is essential for survival. Diabetes is characterised by high blood glucose levels, known as hyperglycaemia. Injected insulin lowers blood glucose. It can cause abnormally low glucose, known as hypoglycaemia. The aim of insulin treatment is to keep plasma glucose as close to normal as possible and so prevent the development of the long-term complications of diabetes due to hyperglycaemia.

Treatment also aims to reduce the increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) seen in diabetes. Deficiency of insulin can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), which can be fatal.

Epidemiology

Type 1 diabetes usually comes in late childhood or early adolescence but can develop at any age. T1DM accounts for 5–10% of diabetes cases. The prevalence of T1DM is higher in adults than in children; the highest prevalence is observed in adults aged ≥ 30 years. 1,2 There are about 250,000 people with T1DM in the UK.

Impact of health problem

Hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia can be mild, moderate or severe.

People with diabetes are rightly scared of hypoglycaemia, and this fear may lead to them allowing blood glucose to run higher than is desirable, which can increase the risk of long-term complications. Episodes of hypoglycaemia are usually called ‘hypos’.

The American Diabetes Association3 defines hypoglycaemia as follows:

-

Severe hypoglycaemia: an event requiring the assistance of another person to actively administer carbohydrate, glucagon or other resuscitative actions. These episodes may be associated with sufficient neuroglycopaenia to induce seizure or coma.

-

Documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia: an event during which typical symptoms of hypoglycaemia are accompanied by a measured plasma glucose concentration of (3.9 mmol/l).

-

Asymptomatic hypoglycaemia: an event not accompanied by typical symptoms of hypoglycaemia but with a measured plasma glucose concentration of 70 mg/dl (3.9 mmol/l).

Non-severe hypoglycaemia can be mild or moderate. Mild hypoglycaemia may present with symptoms, such as sweating, shaking, hunger and nervousness. Some symptoms are due to the release of adrenaline. Mild hypoglycaemia is easily self-managed by taking rapidly absorbed carbohydrate.

Moderate hypoglycaemia can cause difficulty concentrating or speaking, confusion, weakness, vision changes and mood swings.

Mild and moderate hypos can usually be managed by people with diabetes themselves, but moderate hypos often lead to the interruption of activities.

Severe hypoglycaemia can lead to cognitive impairment, unconsciousness and convulsions and can be fatal. People having severe hypos need assistance and may need to attend an accident and emergency department or seek support from paramedics. They may require admission to hospital.

Hypoglycaemia can trigger an adrenergic response that acts as a warning that glucose should be consumed. Unfortunately, in some people, after repeated hypos, this warning may be lost. This is known as hypoglycaemic unawareness, and such people are at increased risk of severe hypoglycaemia and its effects. These individuals are covered by the recommendation in NICE diagnostics guidance (DG21)4 and technology appraisal guidance TA1515 on insulin pumps.

Nocturnal hypoglycaemia occurs during sleep and may not be detected. However, it may disturb sleep and wake the person up. It can have two adverse effects. One is rebound hyperglycaemia, the result of the body’s reactions to hypoglycaemia, such as releasing other hormones that increase blood glucose, meaning that nocturnal hypoglycaemia may result in unusually high blood glucose levels around breakfast time. The other consequence is that nocturnal hypoglycaemia may itself contribute to hypoglycaemic unawareness.

Past appraisals

In a technology appraisal (TA53) of long-acting insulin analogues (at that time only glargine),6 the NICE Appraisal Committee accepted that both hypoglycaemic episodes and the fear of such episodes recurring caused significant disutility. A utility decrement of 0.0052 per non-severe hypoglycaemic event (NSHE) was accepted. As regards fear of hypos, NICE’s guidance (TA53)6 states:

The Committee accepted that episodes of hypoglycaemia are potentially detrimental to an individual’s quality of life. This is partly the result of an individual’s objective fear of symptomatic hypoglycaemic attacks as indicated in the economic models reviewed in the Assessment Report. In addition, as reported by the experts who attended the appraisal meeting, individuals’ quality of life is affected by increased awareness and uncertainty of their daily blood glucose status and their recognition of the need to achieve a balance between the risk of hypoglycaemia and the benefits of longer-term glycaemic control. The Committee understood that improvement in this area of concern regarding the balance between hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia could have a significant effect on an individual’s quality of life.

Guidance on the Use of Long‑acting Insulin Analogues for the Treatment of Diabetes – Insulin Glargine. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta53. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

© NICE (2022)

However, the guidance did not specify the amount of utility lost because of fear of hypos, and nor did the Technology Assessment Report7 because it was based on the industry submission from Aventis, which was classed as confidential. However, clearly the utility gain from reducing the fear of hypoglycaemia was enough to change a substantial cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) to an affordable one. There is the probability that a reduction in the rate (events recorded/unit time) of severe hypoglycaemia events may reduce the fear of severe hypoglycaemia events, although the impact of this seems likely to be variable across patients. The quality-of-life impact arising from this would be over and above the direct quality-of-life impact of the severe hypoglycaemia events themselves.

In the type 2 guidelines developed in 2008, fear of severe hypos was estimated to reduce quality of life by 0.020. The assessment group (Waugh et al., Aberdeen8) considered the reasonableness of this:

This fear effect may only apply to a sub-group of patients, but as an illustration of the possible impact of this, the social tariffs derived by Dolan and colleagues9 suggest that a move from level 2 within the anxiety subscale of EQ-5D to level 1 would be associated with a 0.07 QoL gain. In a similar vein, the coefficients derived by Brazier and colleagues10 for the SF-6D questionnaire for the consistent model using standard gamble valuations suggest that a movement within the social dimension from health problems interfering moderately to not interfering would be associated with a 0.022 QoL improvement. Similarly, an improvement in the mental health subscale from feeling downhearted some of the time to little or none of the time would be associated with a 0.021 QoL improvement.

Waugh et al.

Studies of the disutility of hypoglycaemia

Brod et al. 11 carried out a survey to estimate the effect of non-severe hypos on work in terms of productivity, costs and self-management. The authors used telephone interviews and focus groups, supplemented by a literature review. Respondents were required to have had a NSHE in the previous month. A NSHE was defined as a hypo event not requiring assistance from anyone else, with or without blood glucose measurement, and with or without symptoms. The respondents were asked about duration, effect on work, and likely cause of the hypo, and whether the hypo occurred at work, at other times of the day, or during sleep. Seven hundred and thirteen respondents had T1DM, and half of this group had NSHEs at least once per week, with 27% having at least one per month. Twenty-two per cent had hypos only a few times per year.

About 95% of people identified hypos by symptoms, and about 60% of episodes were confirmed by a blood glucose test. The average duration of a NSHE was 33 minutes, but the effect on self-management lasted a week, with an extra six blood glucose tests, a reduction in insulin dose by an average of 6.5 units per day for 4 days in 25% of people, and an unplanned contact with a healthcare professional in 25%.

The effects on work included:

-

Leaving early or missing a full day in 18% of people. The average work time lost was 10 hours.

-

Missing meetings or being unable to finish a task in 24% of people.

Work time was lost not only because of NSHEs occurring at work but also because of those outside work, including nocturnal hypos. No breakdown by insulin regimen was reported, such as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) compared with multiple daily injection (MDI).

Leckie et al. 12 recruited 243 people with diabetes (216 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and some with T2DM on insulin) who were in employment. The participants’ insulin regimens included mostly MDI, but 51 were taking twice-daily mixtures of soluble and Neutral Protamine Hagedorn. Over a 12-month follow-up, every month they recorded their hypo events, the severity of these and the effect on work. A total of 1955 NSHEs were reported, plus 238 severe hypos (some involving unconsciousness and seizures, and a few resulting in soft-tissue injuries). However, 66% of patients had no severe hypos. Most (62%) of the severe episodes occurred at home and 52% occurred during sleep, but 15% occurred at work. Fifty-five per cent of the NSHEs occurred at home and 30% occurred at work. It should be noted that the mean HbA1c in most patients was > 9%, except for patients who had more than two severe hypos over the year, in whom it was 8.4%, still far above the target.

Frier et al. 13 carried out a survey of 466 people with T1DM about the frequency of non-severe hypoglycaemia and found that people with T1DM had an average of 2.4 episodes per week (median 2 episodes per week), with around one-quarter of these being nocturnal. The after-effects include fatigue and reduced alertness, and they persisted longer after nocturnal NSHEs (10 hours) than after daytime episodes (5 hours). Among those in employment, 20% of NSHEs led to a loss of work time. Most did not contact their healthcare professionals. Self-testing of blood glucose increased in the week after the episode, with an average of four extra tests. The survey showed that NSHEs are troublesome for patients and have effects lasting at least into the following day. The commonest after-effects were tiredness, reduced alertness and feeling emotionally down.

Choudhary et al. 14 reported that the use of pumps with a low glucose suspend (LGS) facility meant that 66% of NSHEs lasted < 10 minutes and only 12% lasted up to 2 hours. Nocturnal hypos were greatly reduced.

About 30% of people with T1DM have an impaired awareness of hypos,15 and these people are three to six times more likely to have severe hypos. The Gold scale rates awareness on a scale of 1–7, where 7 means a complete absence of symptoms of hypoglycaemia. Structured education, such as Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating (DAFNE), restores awareness in about half of people with impaired awareness. Better control of hypoglycaemia avoidance can also restore awareness. A trial by Little et al. 16 (the HypoCOMPass trial) showed that better control for 24 weeks improved the Gold score by 1 point and reduced the fear of hypo level from 58 to 45 (higher scores indicate greater fear, with the maximum being 132) without adversely affecting HbA1c.

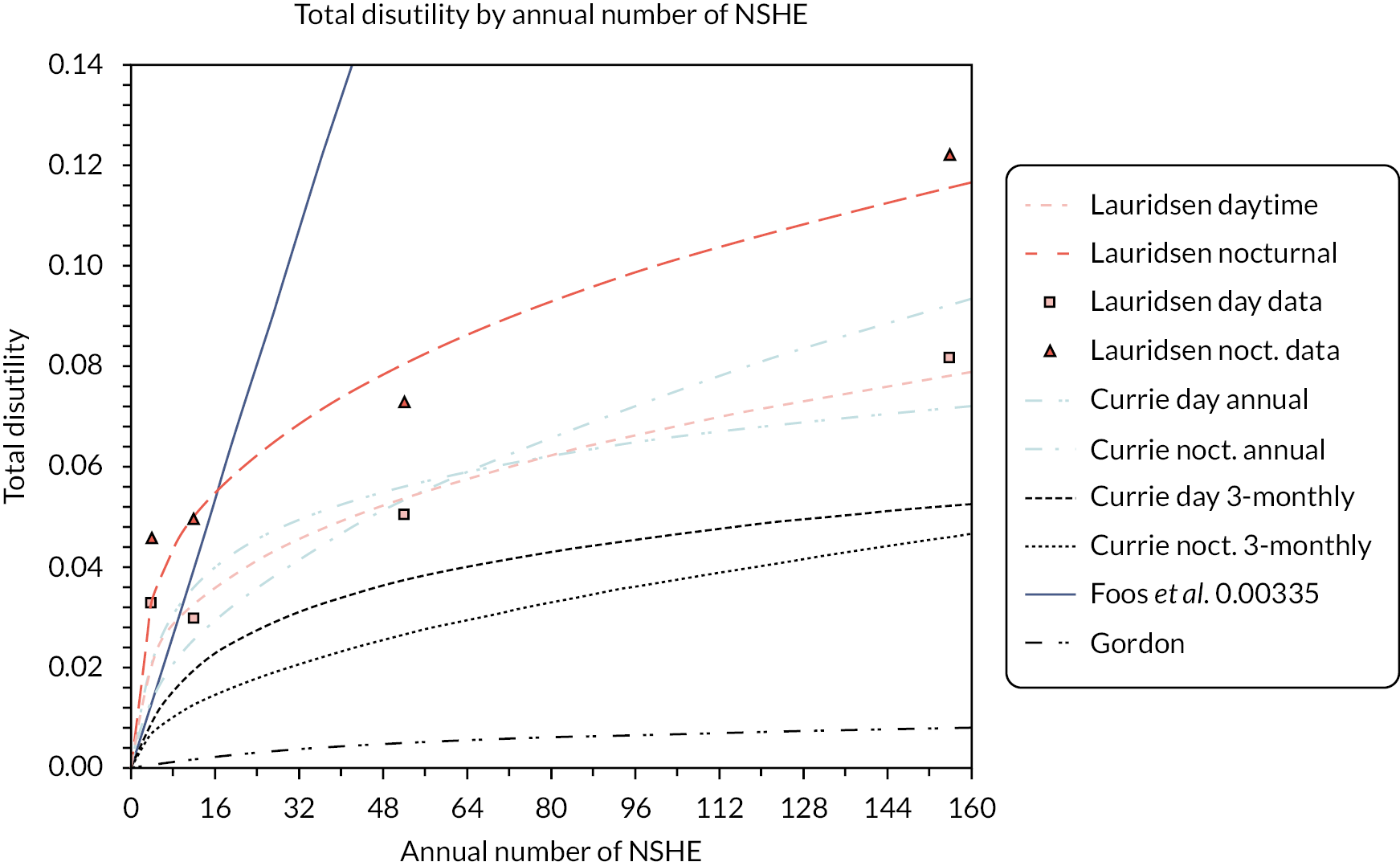

Evans et al. 17 used the time trade-off (TTO) method to estimate the disutility of hypos on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scale (0–1, where 1 is perfect health and 0 is death). They interviewed 551 people with T1DM and 8286 people with no diabetes. They note that hypos can affect HRQoL in two ways: first through the direct effects of the episodes, and second through fear of future hypos, which can lead to precautions, such as taking an insufficient insulin dose (increasing the risk of complications), restricting physical activity, and overeating. In addition, repeated hypos can lead to hypoglycaemic unawareness, which increases the risk of future hypos. The authors estimated that daytime NSHEs reduce HRQoL in a range of 0.032 for one event per month to 0.071 for three episodes per week. Nocturnal NSHEs reduce it by slightly more. Severe events, even only once or twice per year, reduce HRQoL by about 0.08.

The general public’s valuation of disutility per event per year ranged from 0.004 for non-severe daytime hypos to 0.06 per severe event. People with T1DM had slightly lower estimates of the disutility of severe events, at 0.047.

Using data from this study, Lauridson et al. 18 reported that the disutility of NSHEs may diminish if there are repeated events.

The study by Harris et al. 19 reports the Canadian results from this study.

Levy et al. 20 elicited utility values for non-severe hypoglycaemia from 51 Canadians (but only half had T1DM) and control participants with no diabetes. The disutility from a single NSHE was 0.0033. Levy et al. 20 argue that a minimum significant utility loss is 0.03, which would be reached by people having 10 NSHEs per year.

Adler et al. 21 found that severe, frequent and nocturnal hypoglycaemia reduced quality of life, ranging from 0.84 in people with diabetes who had the least severe state (non-severe, daytime only, only once per year, not causing any worry) to 0.40 (severe frequent hypoglycaemia day and night, causing anxiety).

Currie et al. 22 surveyed 1305 UK patients with T1DM and T2DM using both the Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey (HFS) and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). Each severe hypoglycaemic event (SHE) avoided was associated with a change of 5.9 on the HFS. Given a further estimate that each unit change on the HFS was associated with an EQ-5D quality-of-life change of 0.008, this led to an estimated benefit from reduced fear of SHEs of 0.047 per annual event avoided. This was coupled with a direct utility loss associated with a SHE in T1DM of 0.00118 to yield an overall patient benefit of 0.05 per unit reduction in annual SHEs. Currie et al. 22 also reported direct disutilities in T1DM of 0.0036 per NSHE.

Conclusions on hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia remains a major problem in T1DM and has not improved over recent decades. This may be because the increased emphasis on improving glycaemic management, through more intensive insulin treatment, has offset other advances in treatment; tightly managed diabetes can make it more likely that hypoglycaemia might occur. The frequency and severity of hypos can be reduced by structured education and using CSII (insulin pumps), but hypos remain a problem that leads to economic disutilities. For individual events, disutilities and costs are much greater for severe hypos, but the much larger number of NSHEs lead to significant impacts on quality of life.

Current service provision

Management of disease

In people without T1DM, the pancreas produces a little insulin throughout the day but peaks of insulin release after meals. The release after meals is very fast and enables the body to handle and store nutrients. The pancreas releases insulin into the portal vein that goes into the liver, its main site of action.

Treatment with insulin is aimed at replicating the function of the pancreas. Insulin is injected under the skin (subcutaneously). Modern insulin regimens have two components: short-acting insulin to cover mealtimes, and long-acting insulin to cover the rest of the day, usually given twice per day. The long-acting form is called basal, and the combination is often referred to as ‘basal-bolus’ insulin, or as MDI – with three injections of short-acting insulins and two of long-acting insulins (glargine or detemir). However, subcutaneous insulin injections cannot achieve as rapid an effect as pancreatic insulin, and because of the slower onset of action and more prolonged effects, hyperglycaemia is common shortly after meals, often followed by later hypoglycaemia.

Control within target of plasma glucose by intensified insulin therapy requires more than just insulin injections. It also requires regular monitoring of blood glucose by finger-pricking and measurement using a portable meter, or by using a continuous blood glucose measurement device, and then adjusting the insulin dose to take account of calorie intake from food and energy expenditure on exercise. People with diabetes usually manage their own diabetes, supported by structured education packages, such as DAFNE.

The aim of treatment is to manage hyperglycaemia and avoid hypoglycaemia. Glycaemic management is assessed using glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), which gives an average measure over 2–3 months. The NICE target for T1DM is 48 mmol/mol (formerly 6.5%), but few people with T1DM achieve this. With the spread of continuous glucose measurement devices, ‘time in range’ is increasingly used as another measure of glycaemic management.

The alternative to MDI is CSII using an insulin pump. CSII was approved by NICE with restrictions. 5

NICE guidance: Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion for the treatment of diabetes mellitus [TA151].

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (or ‘insulin pump’) therapy is recommended as a treatment option for adults and children aged ≥ 12 years with T1DM provided that:

-

attempts to achieve target haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels with MDI result in the person experiencing disabling hypoglycaemia. For the purpose of this guidance, disabling hypoglycaemia is defined as the repeated and unpredictable occurrence of hypoglycaemia that results in persistent anxiety about recurrence and is associated with a significant adverse effect on quality of life

or

-

HbA1c levels have remained high [i.e. at 8.5% (69 mmol/mol) or above] on MDI therapy (including, if appropriate, the use of long-acting insulin analogues) despite a high level of care.

CSII therapy is recommended as a treatment option for children aged < 12 years with T1DM provided that:

-

MDI therapy is considered to be impractical or inappropriate, and

-

children on insulin pumps would be expected to undergo a trial of MDI therapy between the ages of 12 and 18 years.

The guidance on the use of the VeoTM pump also had restrictions. 4

NICE guidance: Integrated sensor-augmented pump therapy systems for managing blood glucose levels in type 1 diabetes [the MiniMedTM Paradigm Veo system and the Vibe and G4 PLATINUMTM continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) system] (DG21)

-

The MiniMed Paradigm Veo system is recommended as an option for managing blood glucose levels in people with T1DM only if they have episodes of disabling hypoglycaemia despite optimal management with CSII.

-

The MiniMed Paradigm Veo system should be used under the supervision of a trained multidisciplinary team who are experienced in CSII and CGM for managing T1DM only if the person or their carer agrees to use the sensors for at least 70% of the time; understands how to use it and is physically able to use the system; and agrees to use the system while having a structured education programme on diet and lifestyle, and counselling.

-

People who start to use the MiniMed Paradigm Veo system should continue to use it only if they have a decrease in the number of hypoglycaemic episodes that is sustained. Appropriate targets for such improvements should be set.

The guidance did not comment on reduction of severity of hypos.

In people with no diabetes, hypoglycaemia is rare, because if the blood glucose drops, a counter-regulatory mechanism kicks in, including the release of glucagon (which raises blood glucose) and adrenaline and the cessation of insulin release. In people receiving MDI, there are pools of long-acting and short-acting insulin under the skin (subcutaneous) that, unlike pancreatic insulin, cannot be switched off. People receiving CSII have only a little short-acting insulin, so stopping the pump gives a quick response. (There can be a hazard here, in that should a pump fail, the patient soon will have no insulin and be at risk of hyperglycaemia and DKA.)

Interventions to reduce hypoglycaemia

One intervention to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia is structured education, such as the DAFNE programme. Structured education is recommended in NICE guideline NG17. 2 The assessment report for the original appraisal of patient education in diabetes has been published in the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) monograph series. 23

Iqbal and Heller24 have provided a more recent review of the role of structured education and hypoglycaemia. They note that until recently, severe hypoglycaemia had not become less frequent over the last 20 years despite advances in treatment. They conclude that structured education can reduce the incidence of severe hypoglycaemia by about 50%, and that there is some evidence, albeit from an observational study with no control group, that the DAFNE-Hypoglycaemia Awareness Restoration Training (DAFNE-HART) programme can reduce hypoglycaemia even in patients with hypoglycaemia unawareness.

Continuous glucose monitoring

There are various forms of CGM. The term ‘continuous’ is slightly misleading: glucose levels are measured every few minutes. The device measures the level of glucose under the skin (‘interstitial glucose’), which reflects the level in the blood, but with a slight delay.

There are three elements in CGM:

-

a sensor that sits just underneath the skin and measures glucose levels

-

a transmitter that is attached to the sensor and sends the results to a display device

-

a display device that shows the glucose level.

The person with diabetes checks the CGM data and adjusts insulin dose, calorie intake or activity levels to maintain blood glucose levels.

So, the traditional ‘loop’ involves CGM, the patient using the data, and insulin dosage.

Autosuspend pumps

The mechanism here is that the CGM–patient–pump loop is augmented by direct communication between CGM device and the pump. If blood glucose is falling too low, the CGM device communicates with the pump and switches off the insulin infusions for, say, 2 hours. This is particularly useful in nocturnal hypoglycaemia when the patient is asleep.

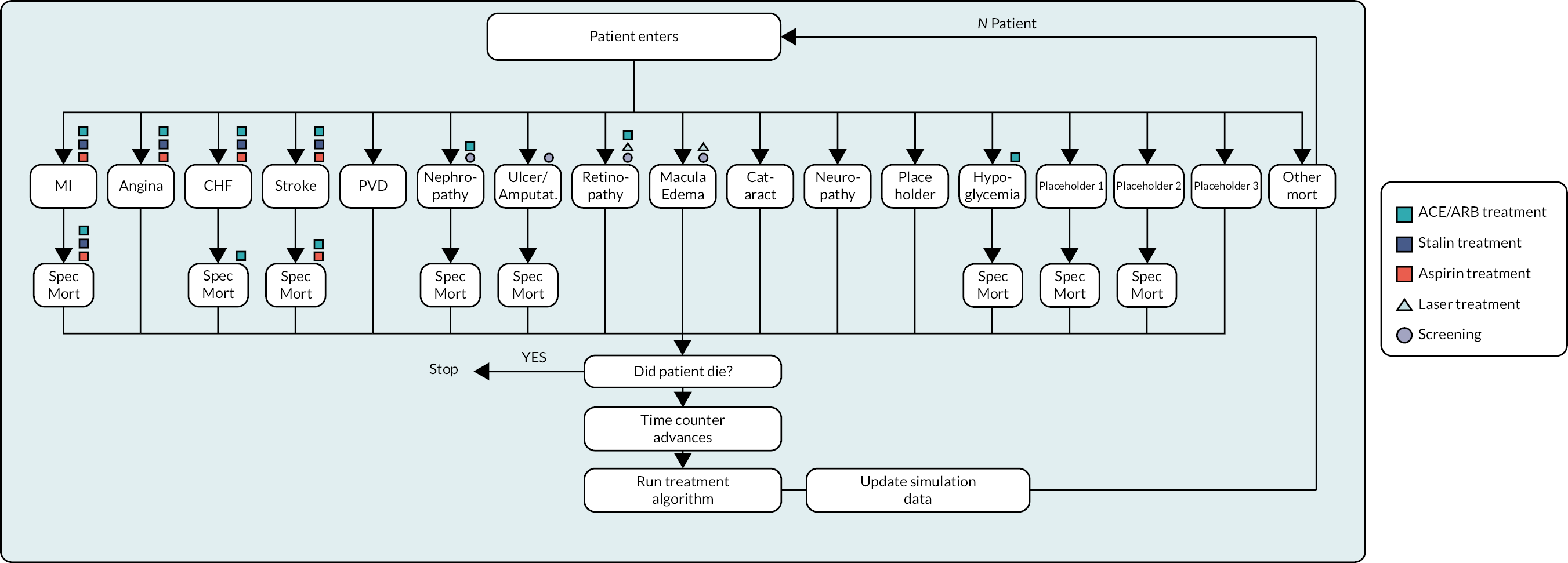

Closed-loop systems

This term refers to systems with three components: the CGM, a microprocessor with algorithms and a pump. In effect, the microprocessor replaces the person. The microprocessor (in effect a small computer) receives data from the CGM and adjusts the infusion rate from the pump.

Devices such as the Veo only control the pump when hypoglycaemia is occurring. They may switch off the insulin infusion when blood glucose falls too low, or if it is heading in that direction.

Closed-loop systems can also control insulin infusion if blood glucose is too high. The most advanced system is the iLet from BetaBionics, which is a dual pump that infuses insulin if blood glucose is too high and glucagon if it is too low.

Relevant national guidelines, including National Service Frameworks

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline covers care and treatment for adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with T1DM, including advice on diagnosis, education and support, blood glucose management, cardiovascular risk, and identifying and managing long-term complications. 2 Evidence reviews by NICE evaluated the most effective method of glucose monitoring to improve glycaemic management in adults with T1DM. Overall, 17 studies were included in the clinical effectiveness analysis to examine real-time continuous glucose monitoring (rtCGM) versus intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring (isCGM), rtCGM versus standard self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), and isCGM versus SMBG. Two UK studies among 14 primary studies that contained cost–utility analyses were included in this evidence review. The results show time in range (TIR) to be a better measure than HbA1c as it captures variation and can be more directly linked to risk of complications. There was a clinically meaningful positive effect on TIR for rtCGM versus both isCGM and SMBG, as well as for isCGM versus SMBG, on the pre-set minimally important difference of a 5% change. 25 The authors clarified that the service user should consult with a member of the diabetes care team who has expertise in the use of CGM. This guideline reported both published UK cost-effectiveness studies (one on rtCGM and one on isCGM) and found these technologies to be cost-effective compared with intermittent capillary blood glucose monitoring. Based on the results of economic modelling (using clinical data from the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) included in the clinical review), isCGM glucose monitoring was clearly cost-effective for the overall population of people with T1DM, and this finding was robust to all the sensitivity analyses undertaken. 25

The Scottish Health Technologies Group (SHTG) review examined the cost-effectiveness of using closed-loop systems and the artificial pancreas for the management of T1DM compared with current diabetes management options, and considered clinical effectiveness, safety and patient aspects. 26

The evidence reviewed on clinical effectiveness consisted of small crossover RCTs that tested the use of closed-loop systems over relatively short periods of time in people with well-managed diabetes who had had the condition for several years and often had experience with using insulin pumps. The results of a network meta-analysis (NMA) and three pairwise meta-analyses show significant improvements in mean percentage TIR for people with T1DM using a closed-loop system compared with other insulin-based therapies. The pairwise meta-analyses also reported statistically significant reductions in mean percentage time spent in hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia. High heterogeneity was present in all meta-analyses, for all outcomes. This is potentially a result of the small study size, multiple different closed-loops systems in the intervention group, and the use of a variety of insulin therapy methods in the control groups. It should be noted that some of the secondary evidence reviewed might have been based on technologies that have since been superseded by newer models because of the rapidly changing nature of these systems.

In addition, adverse events were rarely reported in either the closed-loop system or the control groups.

The SHTG economic model showed that closed-loop systems were associated with the highest costs and QALYs in a Scottish adult population with T1DM, except in the comparison with CGM + CSII. The base-case results showed that the technology is cost-effective compared with CGM + CSII, but not cost-effective in comparison with flash or CGM combined with MDI in people with well-controlled T1DM. There are some uncertainties because of a lack of published studies underpinning the assumptions in the model.

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of intervention

The intervention of interest is a class of automated insulin delivery systems called HCL systems, which have three components: a CGM, a microprocessor with control algorithms and a pump. The microprocessor receives data from the CGM and adjusts the infusion rate from the pump to help keep glucose levels in a healthy range. These systems are aimed at reducing user or caregiver input in insulin dosing, and some only require users to deliver meal boluses by entering the estimated amount of carbohydrates in meals at the time they are eaten. Carbohydrate counting is essential for diabetes management and necessitates matching insulin doses to food choices. Some people find carbohydrate counting challenging because they do not have the skills, tend to eat out (which can be difficult to estimate) or have unhealthy eating habits.

Several HCL systems are available in the UK. Some of these systems have received regulatory approval for a fixed combination of CGM, control algorithm and insulin pump. However, some systems involve combining interoperable devices. The following systems are representative of the intervention of interest and have been identified by NICE as currently available in the UK.

Advanced hybrid closed loop

Hybrid closed-loop (HCL) systems use control algorithms to automate basal insulin delivery based on glucose sensor values in order to increase the time that a patient spends in the target range and thus reduce the frequency and duration of hypoglycaemia. The user of the HCL system is required to enter their carbohydrate intake before each meal, so that the appropriate mealtime insulin bolus can be delivered by the system.

Advanced HCL (AHCL) systems have additional features that include automated correction of bolus insulin delivered up to every 5 minutes when glucose levels are elevated. These systems may also enable greater personalisation of insulin delivery and monitoring and can include meal detection modules that allow the system to deliver more aggressive auto-correction boluses. 27

A number of HCL models, systems and apps are presented in Appendix 1.

Identification of important subgroups

The NICE scope (March 2022) includes people with T1DM (of any age), and the following subgroups if evidence permits:

-

Women with T1DM who are pregnant and those planning pregnancy (not including gestational diabetes). Note that in this assessment this subpopulation does not need to fulfil the criterion of prior use of at least one technology.

-

Children with T1DM.

-

If possible, evidence should be analysed based on the following age groups:

-

≤ 5 years

-

6–11 years

-

12–19 years.

-

-

People with extreme fear of hypoglycaemia.

-

People with diabetes-related complications that are at risk of deterioration.

Current usage in the National Health Service

The management of T1DM involves lifestyle adjustments, monitoring of blood glucose levels, and insulin replacement therapy, with the aim of recreating normal fluctuations in circulating insulin concentrations. Blood glucose levels are monitored to determine the type and amount of insulin needed to regulate blood glucose levels and reduce the risk of complications.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines recommend that adults and pregnant women with T1DM be empowered to self-monitor their blood glucose, supported by structured education packages (e.g. DAFNE) on how to measure glucose levels and interpret the results. 2 NICE also recommends that children and young people (CYP) with T1DM and their families or carers be offered a continuing programme of education from diagnosis. Several systems of monitoring glucose levels and delivering insulin are available in clinical practice. The system recommended for an individual is based on their age, whether they are pregnant, their glycaemic control and their personal preferences.

Blood glucose monitoring

Capillary blood glucose monitoring

Blood glucose concentrations in diabetes can vary considerably from day to day and over a 24‑hour period. Routine blood glucose testing is typically done using capillary blood glucose monitoring. Capillary blood glucose monitoring involves pricking a part of the body (usually the finger) with a lancet device to obtain a small blood sample at certain times of the day. The drop of blood is then applied to a test strip, which is inserted into a blood glucose meter for an automated determination of the glucose concentration in the blood sample at the time of the test. Blood glucose measurements are taken after several hours of fasting, usually in the morning before breakfast, and before and after each meal to measure the change in glucose concentration.

Real-time continuous blood glucose measurement

Real-time continuous blood glucose measurement is an alternative to routine finger-prick blood glucose monitoring for people (including pregnant women) aged ≥ 2 years who have diabetes, have MDI of insulin or use insulin pumps, and are self-managing their diabetes. This involves measuring interstitial fluid glucose levels throughout the day and night.

A rtCGM system comprises three parts:

-

a sensor that sits just underneath the skin and measures glucose levels

-

a transmitter that is attached to the sensor and sends glucose levels to a display device

-

a display device that shows the glucose level – a separate handheld device (known as a ‘standalone’ CGM) or a pump (known as an ‘integrated system’).

With most rtCGM systems, calibration by checking the finger-prick blood glucose level is needed once or twice per day. rtCGM systems monitor glucose levels regularly (approximately every 5 minutes), and alerts can be set for high, low or rate of change.

Flash/intermittently scanned glucose monitoring

Flash glucose monitoring (FGM) systems comprise a reader and a sensor applied to the skin to measure interstitial fluid glucose levels. It provides a reading or trends only when the sensor is scanned.

Glycated haemoglobin

Longer-term control is measured using HbA1c levels, which reflect the average blood glucose levels over 2–3 months. HbA1c is correlated to CGM results over the preceding 8–12 weeks. 28 NICE guidelines on diabetes (T1DM and T2DM) in CYP, in adults, and in pregnancy recommend that people with T1DM aim for a target HbA1c level of ≤ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) to minimise the risk of long-term complications from diabetes. Control above target glucose levels may trigger a discussion about different options for insulin administration.

Insulin regimens

Multiple daily injections

Insulin is injected subcutaneously. Modern insulin regimens have two components: short-acting insulin to cover mealtimes, and long-acting insulin to cover the rest of the day, which is usually given twice per day. The long-acting form is called basal, and the combination is often referred to as ‘basal-bolus’ insulin, or as MDI, with three injections of short-acting insulins and one or two of long-acting insulin. However, subcutaneous insulin injections cannot achieve as rapid an effect as pancreatic insulin, and because of the slower onset of action and more prolonged effect, hyperglycaemia is common shortly after meals, often followed by hypoglycaemia later.

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

The alternative to MDI is CSII using an insulin pump. It makes use of an external pump that delivers insulin continuously from a refillable storage reservoir by means of a subcutaneously placed cannula. CSII was approved by NICE as a treatment option for adults and children aged ≥ 12 years with T1DM, provided that:

-

attempts to achieve target HbA1c levels with MDI result in the person experiencing disabling hypoglycaemia. For this guidance, disabling hypoglycaemia is defined as the repeated and unpredictable occurrence of hypoglycaemia that results in persistent anxiety about recurrence and is associated with a significant adverse effect on quality of life or

-

HbA1c levels have remained high [i.e. at ≥ 8.5% (69 mmol/mol)] on MDI therapy (including, if appropriate, the use of long-acting insulin analogues) despite a high level of care.

CSII therapy is recommended as a treatment option for children aged < 12 years with T1DM provided that:

-

MDI therapy is considered to be impractical or inappropriate, and

-

children on insulin pumps would be expected to undergo a trial of MDI therapy between the ages of 12 and 18 years.

For pregnant women with T1DM, NICE recommends that CSII be offered to those who are using MDI and do not achieve blood glucose management without significant disabling hypoglycaemia.

Integrated sensor-augmented pump therapy systems

Integrated sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy systems combine rtCGM with CSII. The systems are designed to measure interstitial glucose levels (every few minutes) and allow immediate real‑time adjustment of insulin therapy. The systems may produce alerts if the glucose levels become too high or too low. NICE’s DG21 on integrated SAP therapy systems for managing blood glucose levels in T1DM recommends the MiniMed Paradigm Veo system as an option for managing blood glucose levels in people with T1DM only if they have episodes of disabling hypoglycaemia despite optimal management with CSII. 4 As with other pumps, the user can programme one or more basal rate settings for different times of the day/night. A built-in bolus calculator works out how much insulin is needed for a meal following the input of carbohydrates consumed. The advanced feature of SAP is that the rtCGM–patient–pump loop is augmented by direct communication between the rtCGM device and the pump. If blood glucose is falling too low, the rtCGM device communicates with the pump and automatically switches off (suspends) the insulin infusions. Depending on the device, either the user must restart insulin delivery or the pump resumes insulin delivery after 2 hours.

Low glucose suspend/predictive low glucose suspend

Sensor-augmented pump systems can operate in standard (manual) and advanced (automatic) modes. In the manual open loop mode, the continuous glucose monitor and glucose pump do not communicate with each other, and insulin doses are programmed by the user, who makes manual adjustments.

In advanced, automatic mode, the CGM device and pump can communicate with each other automatically, based on real-time glucose data, to adjust the insulin basal rate and suspend the insulin infusion without the input of the wearer in order to prevent potential hypoglycaemia. Glucose suspension can be a simple ‘low glucose suspend’ function, in which insulin infusion is suspended when the glucose monitoring system detects that glucose levels have fallen below a specific hypoglycaemia threshold. In this case, insulin is suspended for a period of time and may resume when the system determines that glucose levels have returned to within the target range or when the glucose suspension is overridden by the patient.

Predictive low glucose suspend (PLGS) is a more advanced use of technology in which prediction algorithms are used that essentially forecast future hypoglycaemia (e.g. within the next half-hour) and pre-emptively suspend insulin delivery before hypoglycaemia develops. PLGS systems will then automatically resume insulin infusions if the user overrides the suspension, or if glucose levels begin to rise or rise above a specific threshold. 29,30

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Interventions

The interventions of interest are HCL systems, a class of automated insulin delivery system that have three components: a CGM, a microprocessor with control algorithms and a pump.

Several HCL systems are available in the UK, such as MiniMed 670G and MiniMed 780G. The systems are representative of the intervention of interest and have been identified by NICE as currently available in the UK.

Population including subgroups

The population and subgroups are per NICE scope (published March 2022).

| Populations | People who have T1DM and who are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, real-time continuous glucose monitoring, flash glucose monitoring.a,b |

| If evidence permits, the following T1DM subpopulations will be included: | |

|

Relevant comparators

| Comparator |

|

| Where evidence permits, scenarios assessing the following comparators will be presented for women with T1DM who are pregnant/planning pregnancy: | |

|

Outcomes

Intermediate measures

-

Time in target range (percentage of time a person spends with blood glucose level in target range of 3.9–10 mmol/l).

-

Time below and above target range.

-

Change in HbA1c.

-

Rate of glycaemic variability.

-

Fear of hypoglycaemia.

-

Rate of SHE (events recorded/unit time).

-

Rate of severe hyperglycaemic events (events recorded/unit time).

-

Episodes of DKA (events recorded/unit time).

-

Rate of ambulance call-outs (events recorded/unit time).

-

Rate of hospital outpatient visits (events recorded/unit time).

-

Measures of weight gain.

Clinical outcomes

-

Retinopathy.

-

Neuropathy.

-

Cognitive impairment.

-

End-stage renal disease (ESRD).

-

CVD.

-

Mortality.

Additional clinical outcomes in women who are pregnant/have recently given birth

-

Premature birth.

-

Miscarriage related to fetal abnormality.

-

Increased proportion of babies delivered by caesarean section.

-

Macrosomia (excessive birthweight).

-

Respiratory distress syndrome in the newborn.

Device-related outcomes

-

Adverse events related to the use of devices.

Patient-reported outcomes

-

HRQoL.

-

Psychological well-being.

-

Impact on patient (time spent managing the condition, time spent off work or school, ability to participate in daily life, time spent at clinics, impact on sleep).

-

Anxiety about experiencing hypoglycaemia.

-

Acceptability of testing and method of insulin administration.

Carer-reported outcomes

Impact on carer (fear of hypoglycaemia, time spent managing the condition, time spent off work, ability to participate in daily life, time spent at clinics, impact on sleep).

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The overall objectives of this project are to examine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose levels in people who have T1DM. The key questions for this review are provided below.

Key question 1

What is the clinical effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in people who have T1DM and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

Subquestions

-

What is the clinical effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in pregnant women who have T1DM?

-

What is the clinical effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in children who have T1DM and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

-

What is the clinical effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in people who have T1DM, an extreme fear of hypoglycaemia, and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

-

What is the clinical effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in people who have T1DM, have diabetes-related comorbidities that are at risk of deterioration, and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

Key question 2

What is the cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in people who have T1DM and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

Subquestions

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in pregnant women who have T1DM?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in children who have T1DM and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in people who have T1DM, have an extreme fear of hypoglycaemia, and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose in people who have T1DM, have diabetes-related comorbidities that are at risk of deterioration, and are having difficulty managing their condition despite prior use of at least one of the following technologies: CSII, rtCGM, FGM?

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

The systematic review methods followed the principles outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Reviews31 and the NICE Diagnostics Assessment Programme Manual. 32 A PRISMA Checklist for systematic review reporting is provided in Report Supplemenatry Material 1

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Identification of studies

Search strategy

The search strategy comprised the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic bibliographic databases and other online sources

-

contacting experts in the field

-

scrutiny of references of included studies, relevant systematic reviews, and the most recent NICE guidance on systems that combine CGM and CSII. 4

A comprehensive search was developed iteratively and undertaken in a range of relevant bibliographic databases and other sources, following the recommendations in chapter 4 of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 33 Search terms were related to type 1 diabetes (including a separate set of terms relating to pregnant women and women planning pregnancy) and technologies to manage blood glucose levels. Search strings applied in the previous technology assessment on integrated SAP therapy systems (DG21)34 were used as the basis for developing selected lines relating to T1DM, insulin pumps, SAP and MDI, and other systematic reviews informed the lines relating to pregnancy. 35–37 The main MEDLINE search strategies were independently peer reviewed by a second information specialist.

Date limits were used to identify records added to databases since the searches for DG21 (run in 2014). 34 Searches were conducted in March and April 2021, and updated in April 2022, in the following resources: MEDLINE ALL (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings (via Web of Science), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via Wiley), CENTRAL (via Wiley), ClinicalTrials.gov; the HTA database [via Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)], the international HTA database (INAH); and the NIHR Journals Library. Searches were also conducted of the following websites:

-

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

-

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

-

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH).

-

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU)

The search was developed in MEDLINE (via Ovid) and adapted as appropriate for other resources. Full search strategies are provided in Appendix 2.

Records were exported to EndNote X9, where duplicates were systematically identified and removed. Where available, alerts were set up so that the team were aware of any new, relevant publications added to databases after the original search date.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that satisfied the inclusion/exclusion criteria reported in Appendix 3 were included.

Research papers were included in which it could not be established if all study participants had difficulty managing their condition (defined by HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, non-fasting plasma glucose, or TIR as above), if the group mean met this criterion.

Papers that fulfilled the following criteria were excluded:

-

non-human studies, letters, editorials and communications qualitative studies

-

studies conducted outside routine clinical care settings, for example, inpatient research facilities, diabetes summer camps

-

studies where > 10% of the sample did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. > 10% were inpatients)

-

studies without extractable numerical data

-

studies that provided insufficient information for assessment of methodological quality/risk of bias

-

articles not available in the English language

-

studies evaluating individual components and not complete HCL systems

-

studies of DIY (do-it-yourself) closed-loop systems, which are not approved by regulatory bodies38

-

studies evaluating automated insulin delivery systems that only suspend insulin delivery when glucose levels are low/are predicted to get low.

Review strategy

Prioritisation strategy for full-text assessment

We applied a two-step approach for identifying and assessing relevant evidence. We applied stricter criteria at the point of data extraction/risk of bias than at title and abstract assessment to prioritise and select the best available evidence. 39–41 The elements used to prioritise evidence (study design, study length, sample size) were chosen in collaboration with NICE and diabetes clinicians as those that would provide the most applicable evidence.

Step 1

The studies were scoped in EndNote before deciding which studies qualified for full-text assessment (step 2). Records were coded in terms of study design and study duration. RCTs were prioritised over controlled trials. Non-randomised controlled trials/comparative effectiveness studies were prioritised over non-comparative studies. Longer-term studies (≥ 6 months) were prioritised over shorter-term studies.

Step 2

Studies identified in step 1 went through the standard systematic reviewing approach of full-text assessment. We followed the predefined PICO (see Chapter 2) to assess the eligibility of studies.

Prioritisation strategy for data extraction and risk of bias

Given the limited time and resources available, deprioritised studies, that is the large number of observational studies that otherwise met the inclusion criteria for this review, were narratively reported and listed. RCTs were prioritised for data extraction and quality assessment. 41

Data extraction strategy

We extracted the following study characteristics (informed by the scope): details on study design (parallel, factorial or crossover) and methodology, participant characteristics, intervention characteristics, comparator characteristics, outcomes, outcome measures and additional notes (such as funding).

Two reviewers extracted data independently using a piloted data extraction form. Disagreements was resolved through consensus, with the inclusion of a third reviewer if required.

Critical appraisal strategy

The risk of bias of randomised trials was assessed using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials. 42 Risk of bias in controlled trials, non-randomised trials and cohort studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions tool. 43 Risk of bias for case–control studies and controlled before-and-after studies was assessed using Effective Practice and Organisation of Care risk of bias tool. 44 Two reviewers assessed risks of bias. Disagreements were resolved through consensus, with the inclusion of a third reviewer if required.

Methods of data analysis/synthesis

We synthesised the RCT evidence statistically. The NMA was conducted using a frequentist approach and a random-effects model.

Subgroup analyses were undertaken where possible for the different combinations of interventions study participants had previously used to manage their blood glucose (i.e. flash glucose monitor and multiple daily insulin injections, flash glucose monitor and CSII, rtCGM and multiple daily insulin injections, rtCGM and CSII, self-blood glucose monitoring and CSII).

Pairwise and network meta-analysis

The analysis compared HCL systems and relevant comparators for managing blood glucose levels in T1DM. The primary effectiveness outcome was HbA1c. Other clinically relevant outcomes include the ‘time in target range’, which gives the percentage of time that a person spends with blood glucose level in target range of 70–180 mg/dl, and adverse events (e.g. severe hypoglycaemia, DKA).

Decisions about information to include in the NMA were informed by relevance to the decision problem and sufficient similarity across studies (e.g. patient characteristics and study design) to reduce the risk of violating underlying assumptions of transitivity/coherence when pooling direct and indirect evidence across studies. We used an iterative process45 to define the extent of the treatment network and to identify studies for inclusion. This involved first defining an initial core set of interventions that met the criteria set out in the projects’ scope and included trials of such interventions in T1DM populations.

Publication bias was assessed visually using a comparison-adjusted funnel plot, where publication bias is present if the funnel plot is asymmetrical. Egger’s test was also used, where publication bias is considered to exist if the p-value is < 0.05.

Transitivity was assessed by looking at the distributions of potential effect modifiers across all studies included in the systematic review.

To check for consistency of each network, net splitting can be performed, which splits the estimates in the network into direct and indirect estimates. Statistically significant inconsistency is present between the direct and indirect estimates if the p-value of the difference between effect estimates (ES) is < 0.05. However, owing to the small number of studies and treatments in each network, net splitting was not feasible. Loop consistency was also not tested as there were no closed loops in the networks for any of the outcomes.

Treatments were ranked using P-score, which measures the certainty that one treatment is better than another treatment, averaged over all competing treatments.

Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version 4.1.0 (Posit Software, Boston MA, USA).

Dealing with missing data

We conducted the review according to the registered protocol.

Chapter 4 Patient and public involvement and engagement

At the start of the project, we followed the collaborative consultation approach that was considered most suitable for this review. One service user participated as a consultant. The consultant provided feedback on the scope, review and writing of the plain language summary, answered technical and user queries about T1DM technologies and provided feedback on our interpretation of the condition/technology. A public user was a member of the NICE committee. The public representative accessed our report, attended meetings, presented their views at the committee meetings and raised discussion points on the report findings.

Chapter 5 Equality, diversity and inclusion

We set out to explore the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HCL systems for managing glucose levels in people who have T1DM. We examined the evidence in different age groups (children and adults) and in pregnant women. The evidence did not permit an examination of the effectiveness of HCL systems by patient ethnicity as these data were not clearly reported across studies.

Results

Number of studies identified

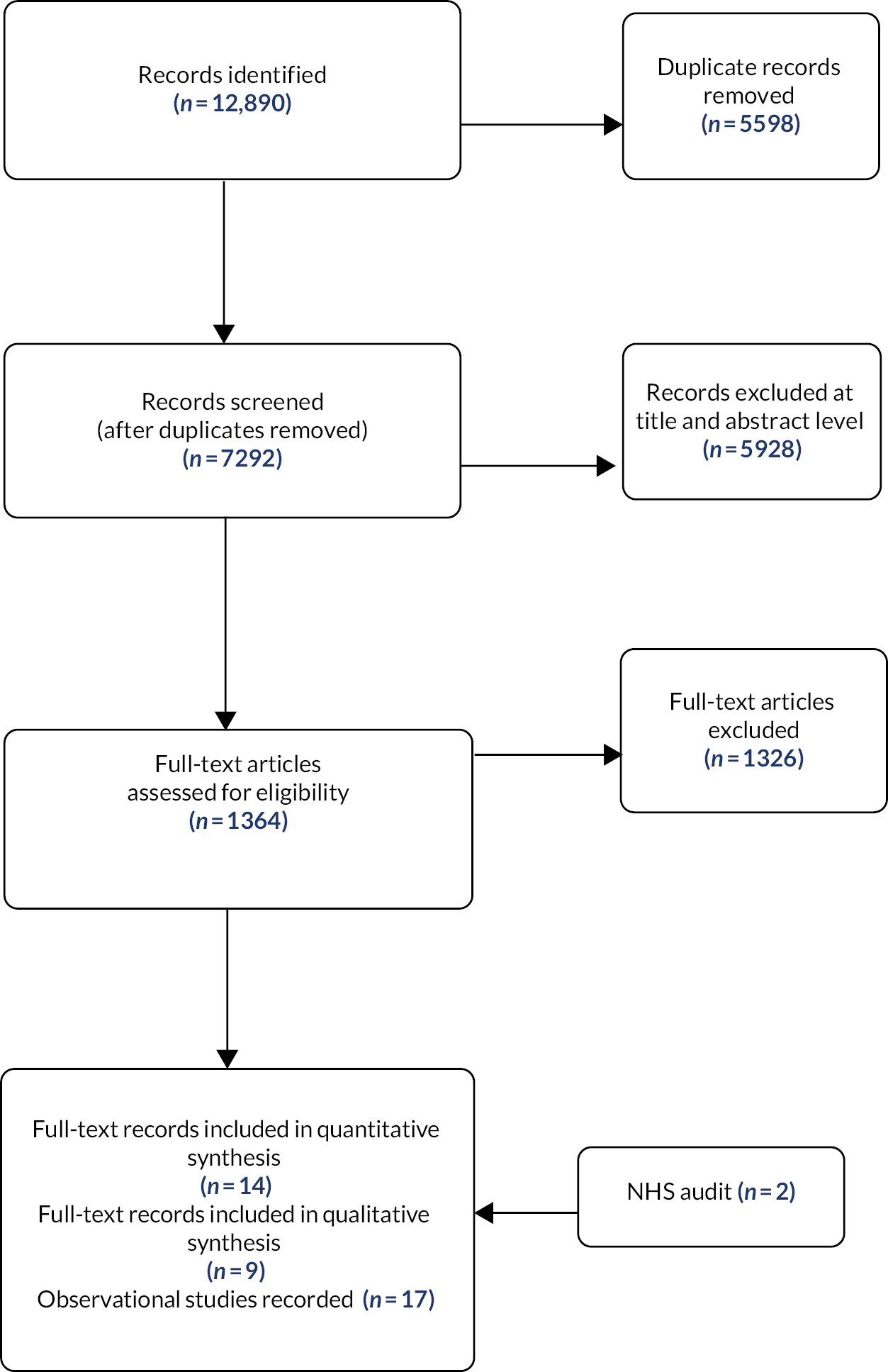

The literature search provided 12,890 records potentially related to the area of interest; 7292 records remained after duplicates were removed. After the abstract screening, 1364 records were identified for full-paper screening. A further 1326 articles were excluded at the full-text stage mainly as a result of incorrect intervention/comparators, study design, incorrect population, abstract/poster presentation only or further duplication identified. Fourteen records (12 RCTs)27,46–58 and nine observational studies27,59–64 are presented for this systematic review of clinical effectiveness. Three papers drew on the same study participants. External submissions, including NHS England evidence and company submissions, are also presented in this report.

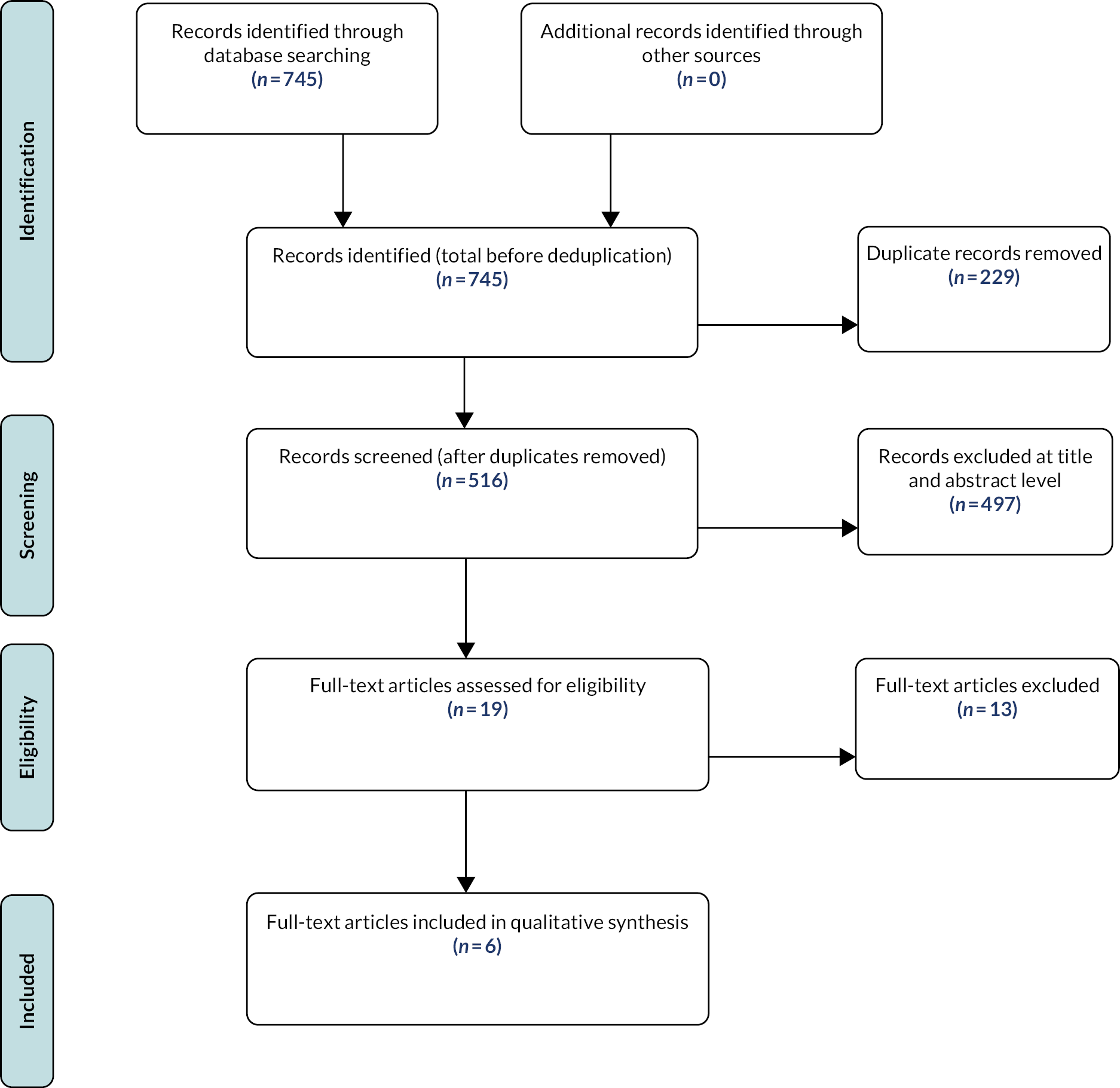

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram (14 RCTs were included; however, two studies were treated as single-arm studies).

Number and type of studies included

Randomised controlled trials

Twelve RCTs (one53 with two relevant intervention arms)46–56,58 were identified that yielded data of potential relevance to the decision problem assessing HCL against a comparator. RCTs in which HCL treatment was received for ≥ 4 weeks (range 4–26 weeks) were included if the comparator was relevant to the decision problem (comparators were classified as CSII + CGM and LGS/PLGS).

Most of these studies reported results for outcomes relevant to monitoring glycaemic management.

These data were assembled using CGM technology that accumulates a large number of data, and they assessed change in % TIR over a specified period of observation (start/baseline to final). Most studies reported change in HbA1c% level (final minus start/baseline) values. The RCTs thus provided quantitative data potentially amenable to NMA. Two publications27,57 were derived from the Fuzzy Logic Automated Insulin Regulation (FLAIR) study and presented data comparing HCL with AHCL; as HCL has been viewed here as a generic intervention, the FLAIR study can be considered more similar to a single-arm study (with two subgroups) than to an RCT and is considered in Table 2.

These RCTs were heterogeneous in multiple respects, including trial design (parallel-group or crossover design with washout phase between different treatments), participants’ age, number of participants and other demographics including run-in times, duration of observation periods, and numbers and types of previous treatments. Studies screened relatively small numbers of patients. The number of participants randomised ranged from 16 to 135, and studies were included whose authors classified recruiting participants variously as very young children, children, adolescents, young adults and older adults.

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of patients recruited in RCTs with treatment lasting 4–26 months. Most studies were conducted in children or young adults. For young children it would likely be difficult to clearly establish whether they were having difficulty in managing glycaemia prior to recruitment. Only McAuley et al. 50 and Boughton et al. 47 looked at HCL use in elderly patients (aged > 60 years); in the control arm, for practical reasons and because of their familiarity with the method, the participants continued with their previous method of glycaemic management, which presumably was long-established (i.e. they were not ‘re-trained’ in a new non-HCL method). In treatment arms, participants were trained in the use of devices before performance was assessed. Both these studies in elderly people enrolled relatively few patients.

| Study | Change in HbA1c% | % time > 10 mM | % time 3.9–10 mM | % time < 3.9 mM | % time < 3.5 mM | % time < 3.3 mM | % time < 3.0 mM | % time < 2.8 mM | Hypo events | Ketotic events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ware et al. 202255 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Population (N = 74): diagnosed ≥ 0.5 years previous; pump ≥ 3 months; HbA1c < 11% no previous HCL. Very young children aged 1–7 years | ||||||||||

| von dem Berge et al. 202254 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Population (N = 38): pump ≥ 3 months; total insulin > 8 U/day; HbA1c 7.4% (± 0.9); no severe hypo in last 3 months. Pre-school and school children aged 2–14 years | ||||||||||

| Thabit et al. 201553 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Population (N = 25): diagnosed ≥ 0.5 years previous; aged ≥ 6 years; pump ≥ 3 months; HbA1c < 10%. Children/adolescents aged 6–18 years Population (N = 33): diagnosed ≥ 0.5 years previous; aged ≥ 18 years; pump ≥ 0.5 year; HbA1c 7.5–10% |

||||||||||

| Ware et al. 202256 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Population (N = 135): diagnosed ≥ 1 year previous; pump ≥ 3 months; HbA1c 7.5–10%. Children/adolescents aged 6–18 years | ||||||||||

| Tauschmann et al. 201852 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Population (N = 86): diagnosed ≥ 1 year previous; aged ≥ 6 to 20 years; pump ≥ 3 months; HbA1c 7.5–10%; no CGM previous 3 months. Children and young adults aged 22 years (13–26 years) | ||||||||||

| Benhamou et al. 201965 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Population (N = 63): diagnosed ≥ 2 years previous; aged ≥ 18 years; ≤ 50 U per day; HbA1c ≤ 10%. Adults aged 48.2 years (± 13.4 years) | ||||||||||

| Boughton and Hovorka 201947 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Population (N = 37): diagnosed ≥ 2 years previous; aged ≥ 18 years; ≤ 50 U per day; HbA1c ≤ 10%. Adults aged 48.2 years (± 13.4 years) | ||||||||||

| McAuley et al. 202250 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Population (N = 30): diagnosed ≥ 10 years; age ≥ 60 years; using insulin pump; HbA1c ≤ 10.5%; no dementia. Elderly people aged 67 years (± 5 years) | ||||||||||

| Collyns et al. 202148 and Wheeler et al. 202258 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Population (N = 60): diagnosed ≥ 1 years; age 7–80 years; pump ≥ 6 months; daily insulin minimum 8 units; HbA1c < 10%; no pregnancy. Children aged 7–13 years, n = 19; adolescents aged 14–21 years, n = 14; adults aged 22–80 years, n = 26 | ||||||||||

| Kariyawasam et al. 202249 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Population (N = 22): diagnosed ≥ 1 year; age 6–12 years; pump ≥ 3 months; HbA1c ≤ 9.0%; hospital 3 days then 6 weeks post-hospital phase. Young people aged 6–12 years | ||||||||||

| Stewart et al. 201851 | ✓ | ✓ | a | ✓ | ||||||

| Population (N = 16): women (singleton pregnancy); diagnosed ≥ 1 year prior to pregnancy; aged 18–45 years; HbA1c (8% (± 1.1); excluded if insulin dose ≥ 1.5 U per kg | ||||||||||

The major outcomes reported in the RCTs related to monitoring glycaemic management. These included change in HbA1c% and % time within, above or below a defined blood glucose level (mmol/l), including % time within range indicating satisfactory control (3.9–10 mmol/l, % time in a hyperglycaemic range (> 10 mmol/l), and % time in a hypoglycaemic range, variously < 3.9, < 3.5, < 3.3, < 3.0 and < 2.8 mmol/l depending on the study. Low rates (events recorded/unit time) of severe hypoglycaemia and of ketotic episodes were also reported; it may be that the small number of participants and relatively short treatment periods mean that accurate estimates of the rates of these events are difficult to obtain. The outcomes reported in RCTs are summarised in Tables 2 and 3.

| Study | Design | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| NHS pilot study adults; HCL | Analysis of an audit of routinely available data (from 31 diabetes centres) of a cohort of NHS adult patients with elevated HbA1c who received HCL intervention starting between August and December 2021. Data collection to May 2022 | Outcome values reported for start of HCL and at end of study |

| Forlenza et al.64 2022; HCL | A prospective study. Selection of patients for enrolment unclear. Enrolled patients were screened for inclusion according to prespecified criteria, and those satisfying criteria entered a run phase followed by 3-month study phase. Methods were referenced to an earlier study | Results represent a subset of children able to use the HCL system |

| Beato-Vibora et al.60 2021; ‘group 4’ HCL (MM670G) | Cross-sectional study of HCL (MiniMed 670G System with Guardian Sensor 3) recipients followed (at a hospital) for about 13 months (other treatment modalities were also reported) | |

| Bassi et al.59 2022; two AHCLs (A, MM780G; B, Control-IQ) | Retrospective comparison of two AHCLs (Medtronic 780G and Control-IQ) after propensity matching of patients who upgraded to an AHCL system for 1 month; HbA1c was not reported | Propensity matching selects patient subgroups and may render study population less ‘real world’ |

| Beato-Vibora et al.61 2021; AHCL MM780G | Prospective study of patients transferred to an AHCL system (c780G AHCL) from previously used modality. Method of patient selection unspecified | |

| Breton and Kovatchev62 2021; AHCLAHCL slim X2 pump with Control-IQ | A retrospective analysis of a sample (n = 7801) of a self-selected group of patients who used AHCL slim X2 pump with Control-IQ. Subjects self-selected by uploading data to ‘Tandem’s t:connect web application as of February 11, 2021’; 9451 patients met inclusion criteria; 83% had T1DM; results for 7801 T1DM subjects were presented | Non-self-selectors not represented. Ratio of self-selectors to non-self-selectors not reported |

| Carlson et al.63 2022; AHCL MM | Prospective ‘safety’ study of (a) adolescent and (b) adult patients using an AHCL (MiniMed closed-loop system) for 45 days. Industry-sponsored study | Restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria |

| Bergenstal et al.27 2021; HCL MM 670G; AHCL as but with updated software. Crossover study | Because in the present report HCL and AHCL are both considered HCL interventions, Bergenstal et al.26 has been classified as an ‘observational’ single-arm study (single population) observed prospectively for two examples of the HCL intervention. There was no washout period at time of switch between the two HCL interventions; the first HCL intervention used was determined randomly | |

| NHS pilot study CYP; HCL | Analysis of an audit of routinely available data (from eight paediatric centres) of a cohort of young NHS patients with elevated HbA1c who received HCL intervention starting between August and December 2021. Data collection to May 2022 | Outcome values reported for start of HCL and at end of study |

| Study | Population at recruitment | Age description | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS pilot study adults; HCL (report provided to EAG by NICE, 17 June 2022) | NHS services adults with T1DM managed with an insulin pump and flash glucose monitor with an HbA1c ≥ 8.5%; aged > 18 years | Adult; median 40 years (IQR 28–50 years) | 640 (63 lost to follow-up) |

| Forlenza et al.64 2022; HCL | Diagnosed ≥ 0.25 years; pump ≥ 3 months; HbA1c < 10%; total insulin ≥ 8 U per day; no severe hypo in last 3 months | Children; 2 to < 7 years | 46 |

| Beato-Vibora et al.60 2021; ‘group 4’ HCL (MM670G) | T1DM for 29 years (± 9.4 years); pregnant women excluded. Cross-sectional study | Adult; 38 years (± 11 years) | 43 |

| Bassi et al.59 2022; two AHCLs (A = MM780G; B = Control-IQ) | Diagnosed ≥ 1 years; previous CSII or MDI; use of CGM: ≥ 1 month before and after starting the AHCL. Dropouts from AHCL before 1 month of use were excluded | 24.4 years (± 15.7 years) | A 51; B 39 |

| Beato-Vibora et al.61 2021; AHCL MM780G | HbA1c% 7.23 (± 0.86); pregnant women excluded | Adult 43 years (± 12 years) | 52 |

| Breton and Kovatchev62 2021; AHCLAHCL slim X2 pump with Control-IQ | Users of AHCL; patients in US ‘Tandem’s Customer Relations Management database’ | Range 6–91 years | 7801 |

| Carlson et al.63 2022; AHCL MM | Diagnosed ≥ 2 years; T1DM for at least 2 years. Minimum daily insulin ≥ 8 U; HbA1c% < 10; willingness to use device. Excluded if history of severe hypos, diabetic ketosis | Adolescents and adults. 38.3 years (± 17.6 years) | 157 |

| Bergenstal et al.27 2021; HCL MM 670G; AHCL as but with updated software. Crossover study | Diagnosed ≥ 1 year; aged 14–29 years; HbA1c 7.0–11.0%; excluded if ≥ 1 severe hypo | 14–29 years | 112 |

| NHS pilot study CYP; HCL (report provided to EAG by NICE, 17 June 2022) | Children or young people aged 1 to < 19 years; TIDM for ≥ 1 year; minimum of 2 prior HbA1c measures | 6.6 years (± 3.7 years), range 2–18.9 years | 251 |

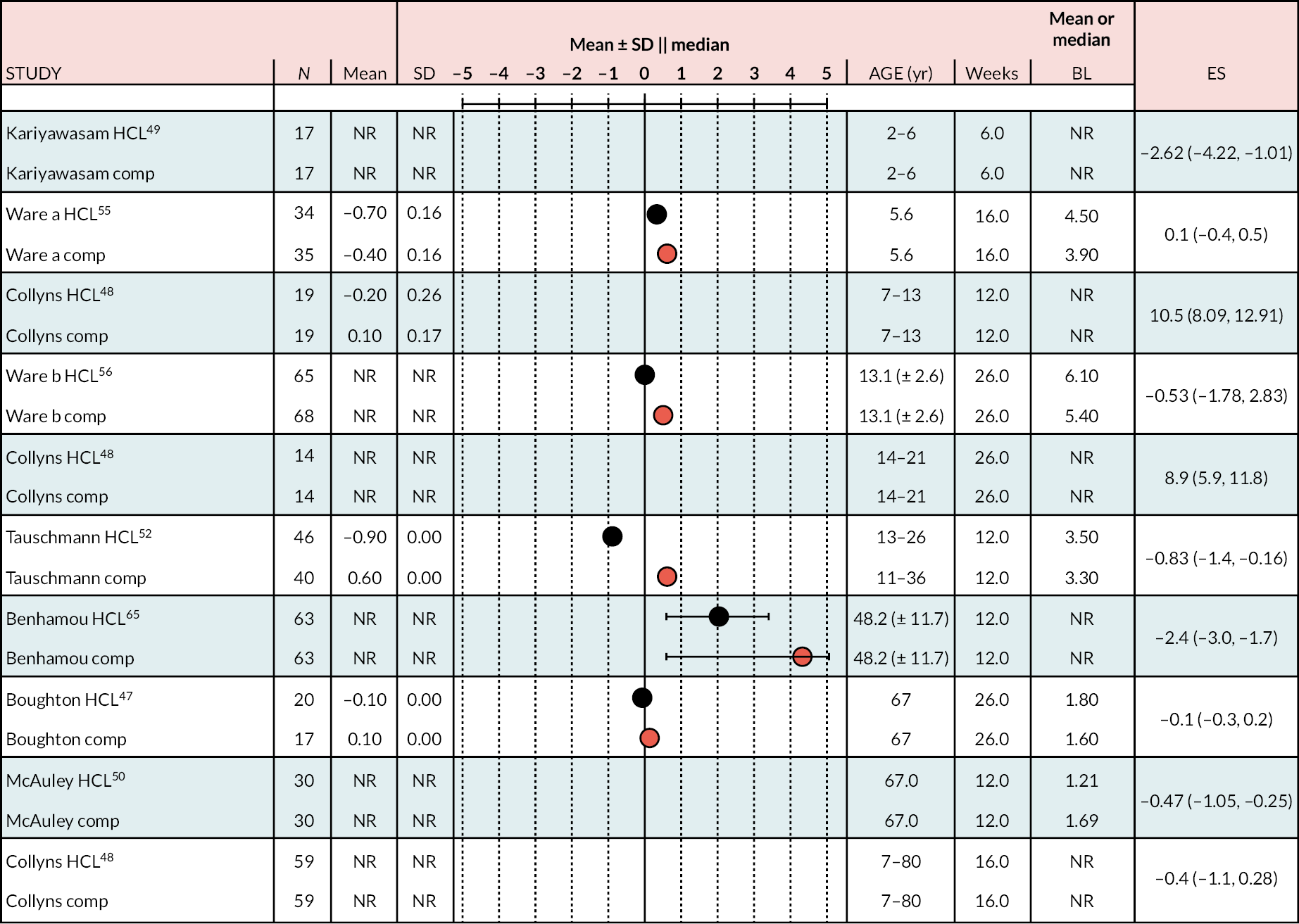

Outcome results reported in the RCTs are summarised in Appendix 4, Table 25. Glycaemic management outcomes by study arm were reported in various ways, as mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median [interquartile range (IQR)] values; often start/baseline values for each arm were not reported or were unclear so that change from baseline was sometimes unreported and only end-of-treatment values were provided. Trials reported a difference and its range between arms, whether this was represented as a median or a mean for a particular outcome. These reported values were available for NMA. Where necessary some outcome results have been calculated from numerical data in the relevant published reports; these, together with most other data reported, were often strongly rounded to only a few significant figures. Appendix 4, Table 25, summarises the data extracted from the included RCTs.

Because many different outcomes were reported by authors, Appendix 4, Table 25 is organised by columns specifying outcomes in the following order: HbA1c%; % time > 10 mmol/l; % TIR (3.9–10 mmol/l); % time < 3.9 mmol/l; % time < 3.5 mmol/l; % time < 3.0 mmol/l; % time < 2.8 mmol/l; non-severe hypo events; severe hypo events; DKA events.

Each study outcome value within these columns is represented by trial arm as (1) start of study, (2) end of study and (3) end of study minus start of study difference. The start/baseline value was not necessarily the same in both arms of a trial.

The last row for each study represents the value reported for the difference between arms and is labelled NET effect.

Authors reported values sometimes as mean (SD), sometimes as median or median (IQR), and sometimes as mean [95% confidence interval (CI)]. Values that are medians are asterisked.

Individual study details are itemised as n = number of participants; age of participants in years; interventions HCL, CSII + CGM OR LGS/PLGS; Tx = treatment period in weeks; study design, parallel-arm or crossover study.

Data input for meta-analyses

Outcome results reported in the RCTs are summarised in Appendix 4, Table 25. For reader information, some summary values (e.g. change from start to end in a trial arm) that were unreported in published reports have been estimated from numerical data elsewhere in the trial reports.

The results from standard random-effects meta-analyses are presented as forest plots. The effect size is the mean difference (MD) between trial arms in the mean change from start to end of study (MD is sometimes called weighted MD).

Published data available for extraction and further use in meta-analysis presented several difficulties. Most data reported were strongly rounded so that outcomes (end of study minus start of study) by study arm, and also net effect (MD) of intervention versus comparator, were usually reported to only two significant figures. These estimates were sometimes reported as a mean (SD, or 95% CI) or as a median (IQR). This was not consistent for a particular outcome across different studies; for example, the hyperglycaemic outcome ‘time in range at glucose concentration > 10 mmol/l’ was reported in some studies as median (IQR) and in others as mean (SD). The measure chosen by authors appeared to depend on the skewness of the data distribution. Sometimes start/baseline or end-of-study values for each arm were not reported or were unclear, and change from baseline in each arm was sometimes unreported.

Trials reported the difference between arms (difference between intervention and comparator in change from start to end of study) sometimes as mean (SD) difference and sometimes as median (IQR) differences for a particular outcome. As meta-analysis of medians is problematic, where reported values were deemed useful, median (IQR) values were converted to means and variance values using the Vasserstats website (http://vassarstats.net/median_range.html). The difference between arms reported in some RCTs was developed using complex models and therefore did not necessarily correspond to separate data reported for each arm. In these circumstances the model-adjusted outcome was used for meta-analysis.

These characteristics of the available data represent limitations to the accuracy of meta-analytic results.

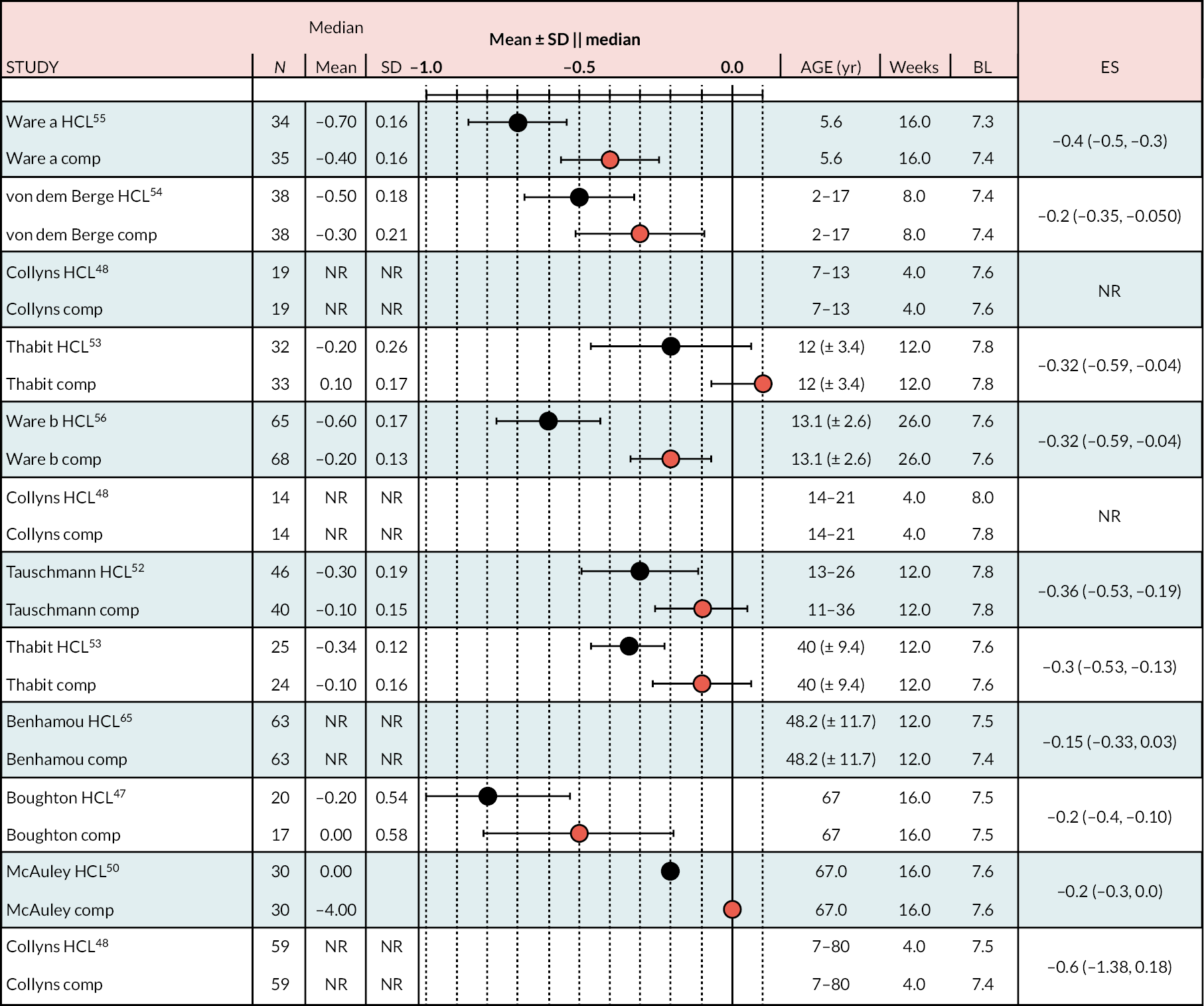

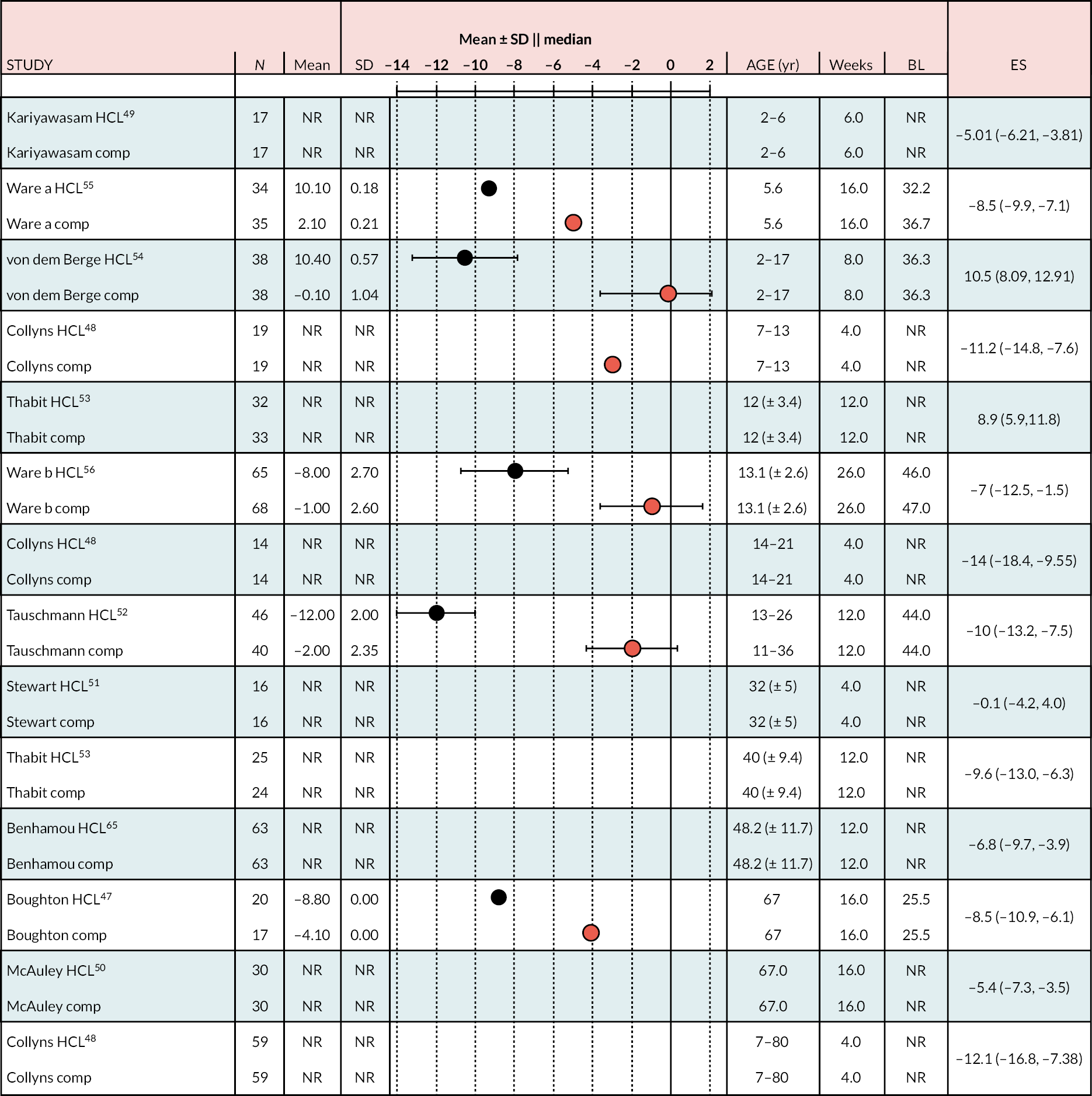

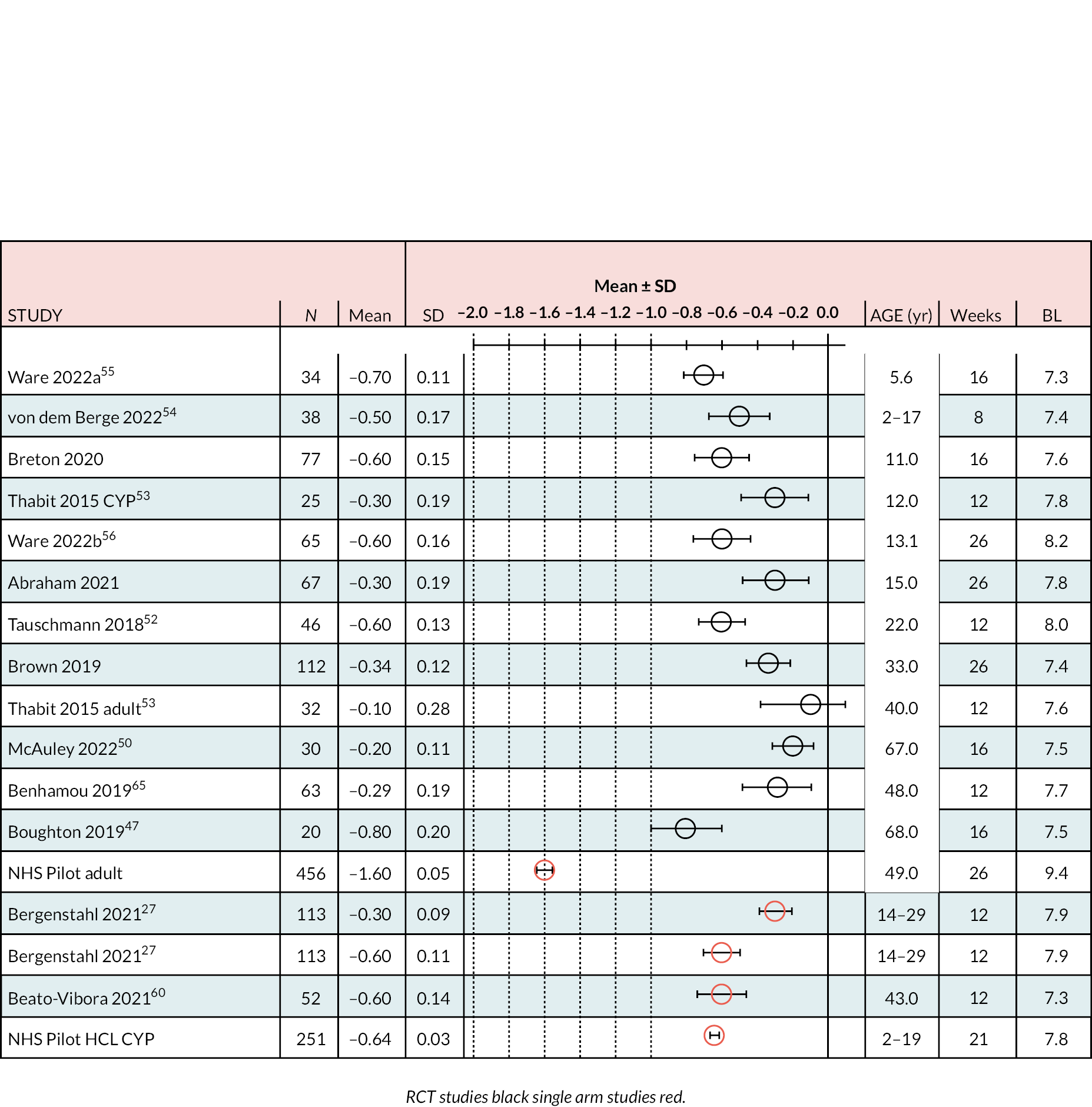

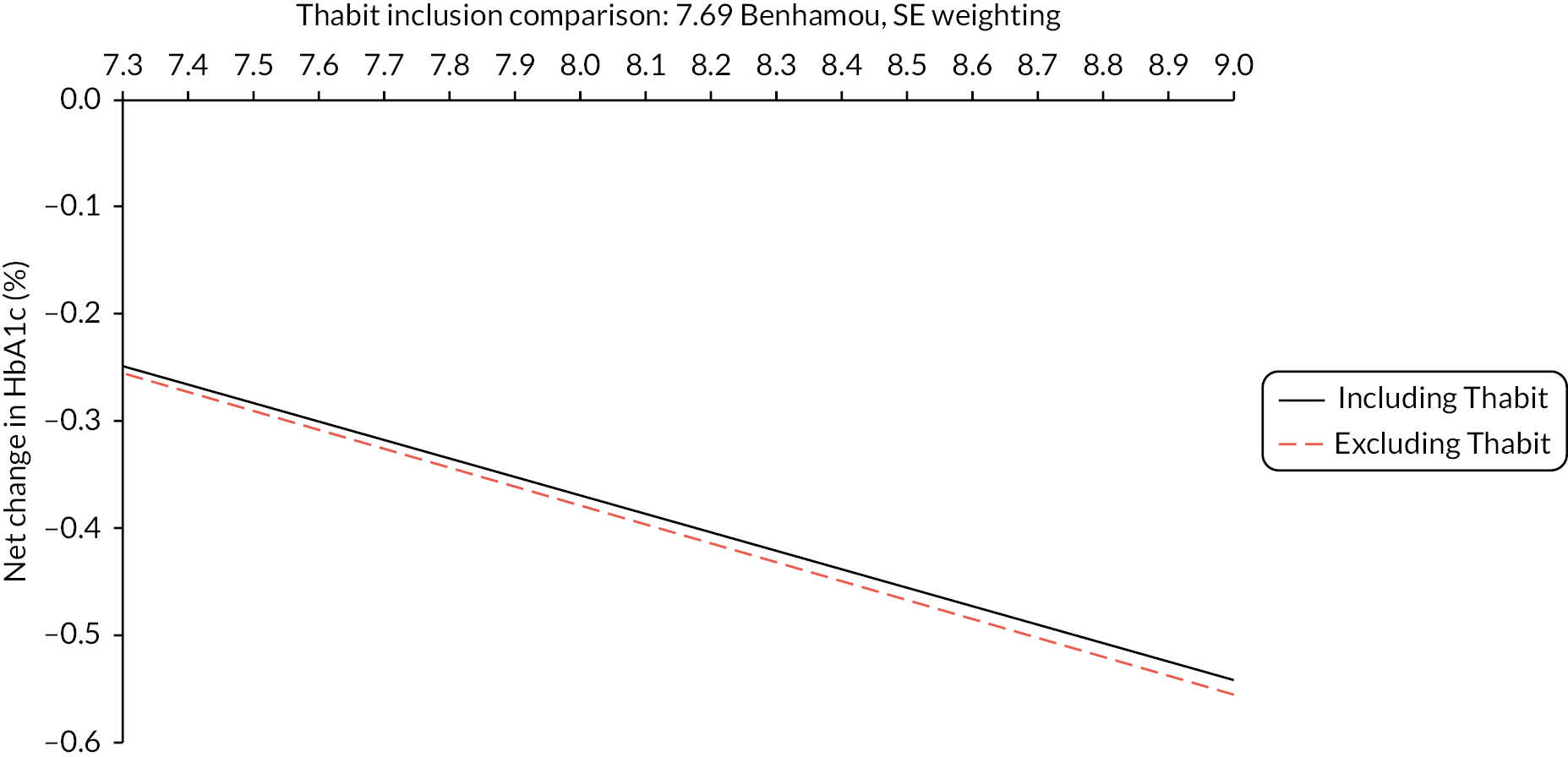

Glycated haemoglobin per cent

Figure 2 shows the reported change (start to end of study) in HbA1c% for each arm over the treatment period. The standard meta-analysis shows the MD between treatment arms. A negative ES is presented in Appendix 5, Figure 19, comparing HCL with comparator, infers superior management of glycaemia with HCL.

FIGURE 2.

Change (end minus start as mean ± SD or median) by arm in HbA1c% over treatment period in RCTs.

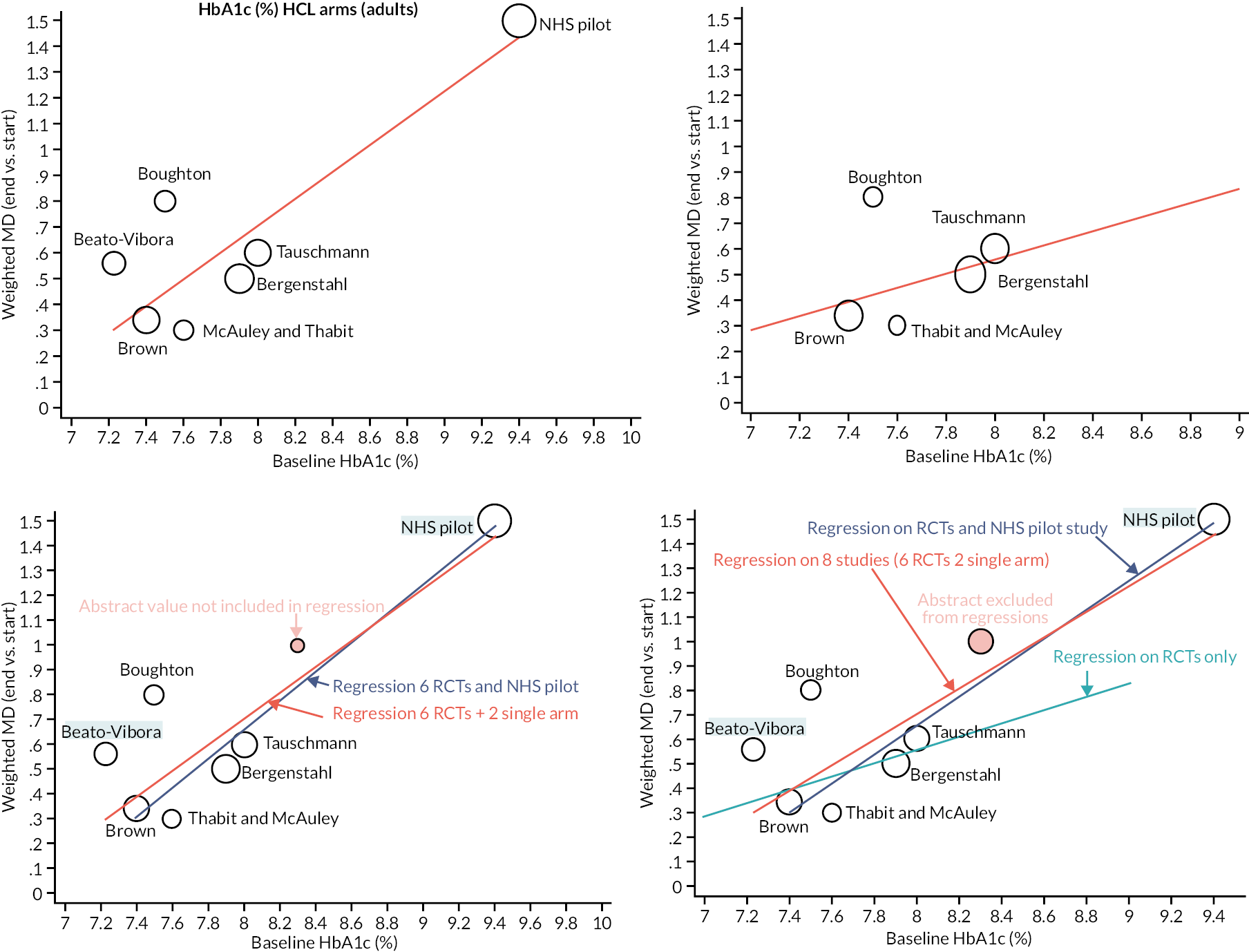

The range of mean baseline HbA1c% in the RCTs was narrow: 7.4–8.3. In all studies the reduction in HbA1c% (end minus start of study) was greater in the HCL arm than in the comparator arm (either CSII + CGM or LGS/PLGS). The change in HbA1c% over the treatment period is modest in the HCL arm (range −0.2 to −0.8). Net effect sizes (MD between treatments, HCL vs. comparator) are modest, ranging from approximately −0.15 to approximately −0.4. Relative to the NHS ‘real world’ adult pilot study, in RCTs the start/baseline HbA1c% is lower (NHS baseline = 9.4 HbA1c%) and the MD is smaller (NHSES = −1.6). In the NHS pilot study (described in Methods for assessing cost-effectiveness evidence) treatment with HCL brings the mean HbA1c% to 7.9, approaching a level comparable with the upper range values seen in RCTs after HCL use. Not included in the forest plot is the FLAIR study27 comparing two AHCL versus HCL with baseline HbA1c% = 7.9. Change from baseline was similar to that in the RCTs: −0.5 (± 0.10) with HCL and −0.3 (± 0.09) with AHCL.

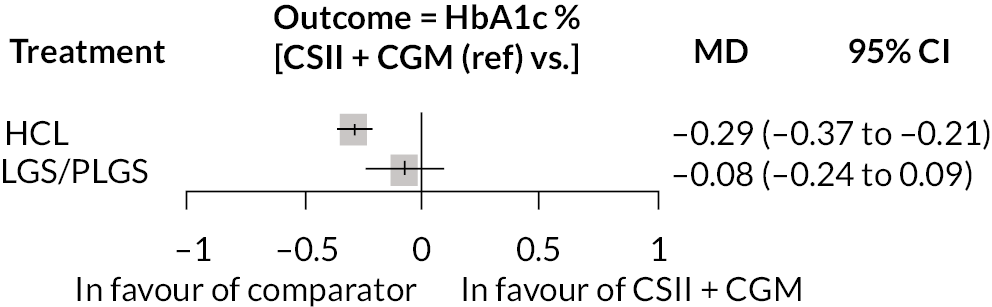

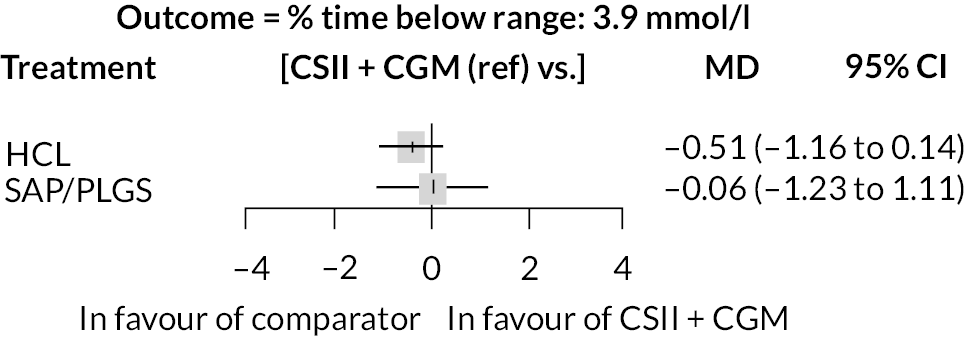

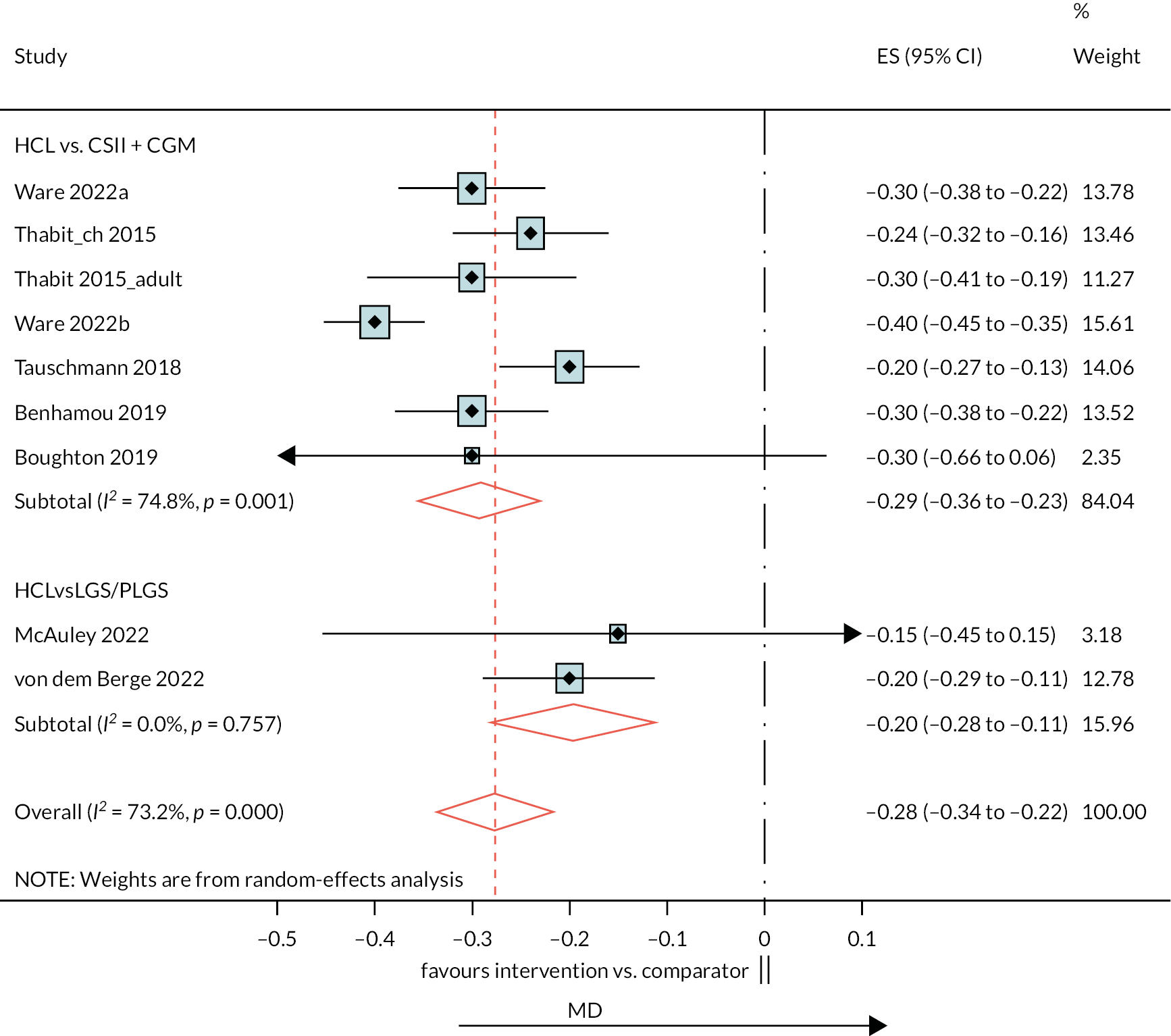

Ten estimates from nine studies (Figure 3) were included in this NMA because estimates from the Thabit study arms were split into adult and children estimates. The reference treatment class was CSII + CGM, where estimates > 0 favoured CSII + CGM. The forest plot of the NMA is presented in Figure 3. Compared with CSII + CGM, treatment with HCL decreased HbA1c% by 0.28 (95% CI −0.34 to −0.21). There was no statistically significant difference between CSII + GCM and LGS/PLGS.

FIGURE 3.

Results of the NMA of the outcome change in HbA1c% during observation period.

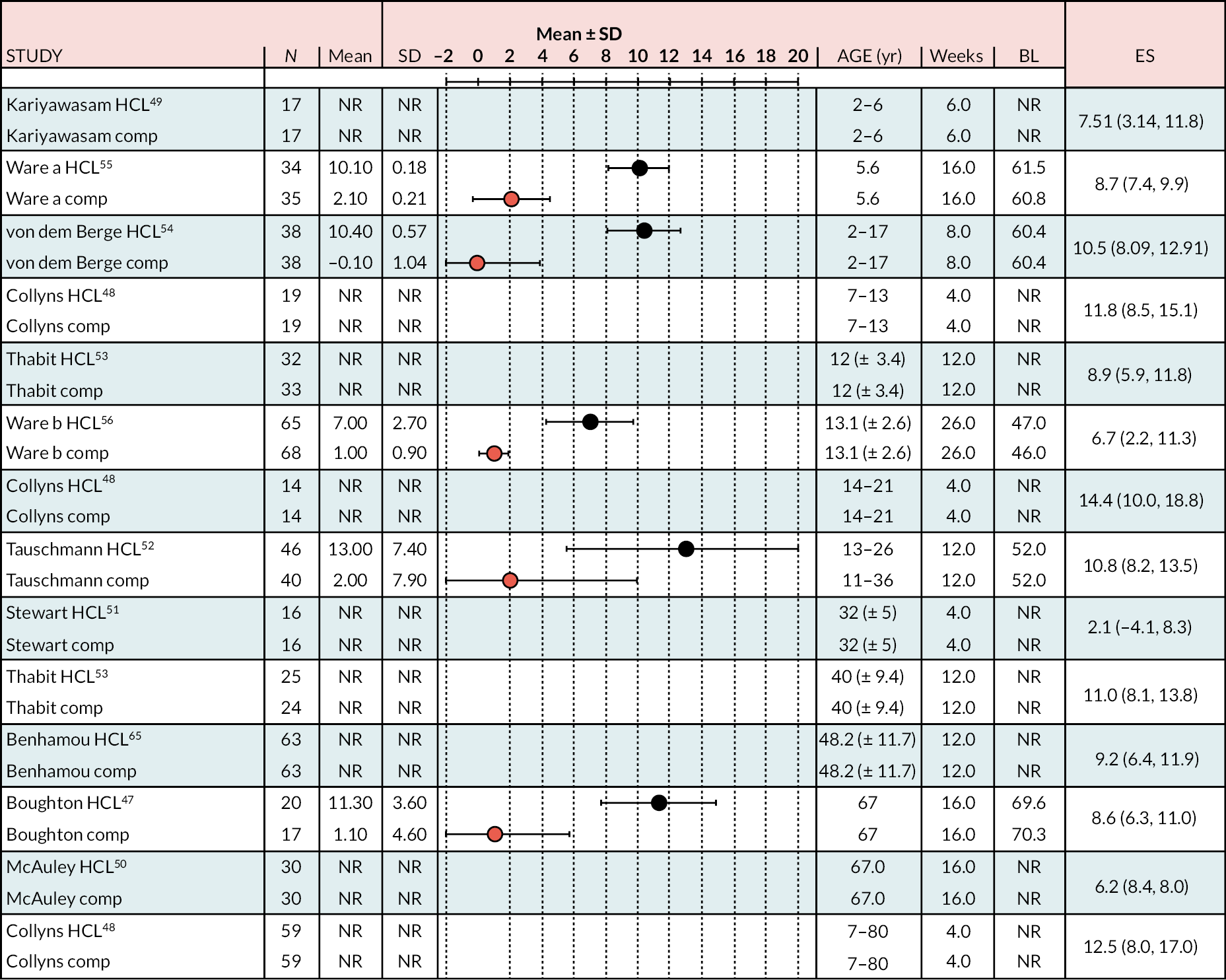

Per cent time within range (between 3.9 and 10.0 mmol/l)

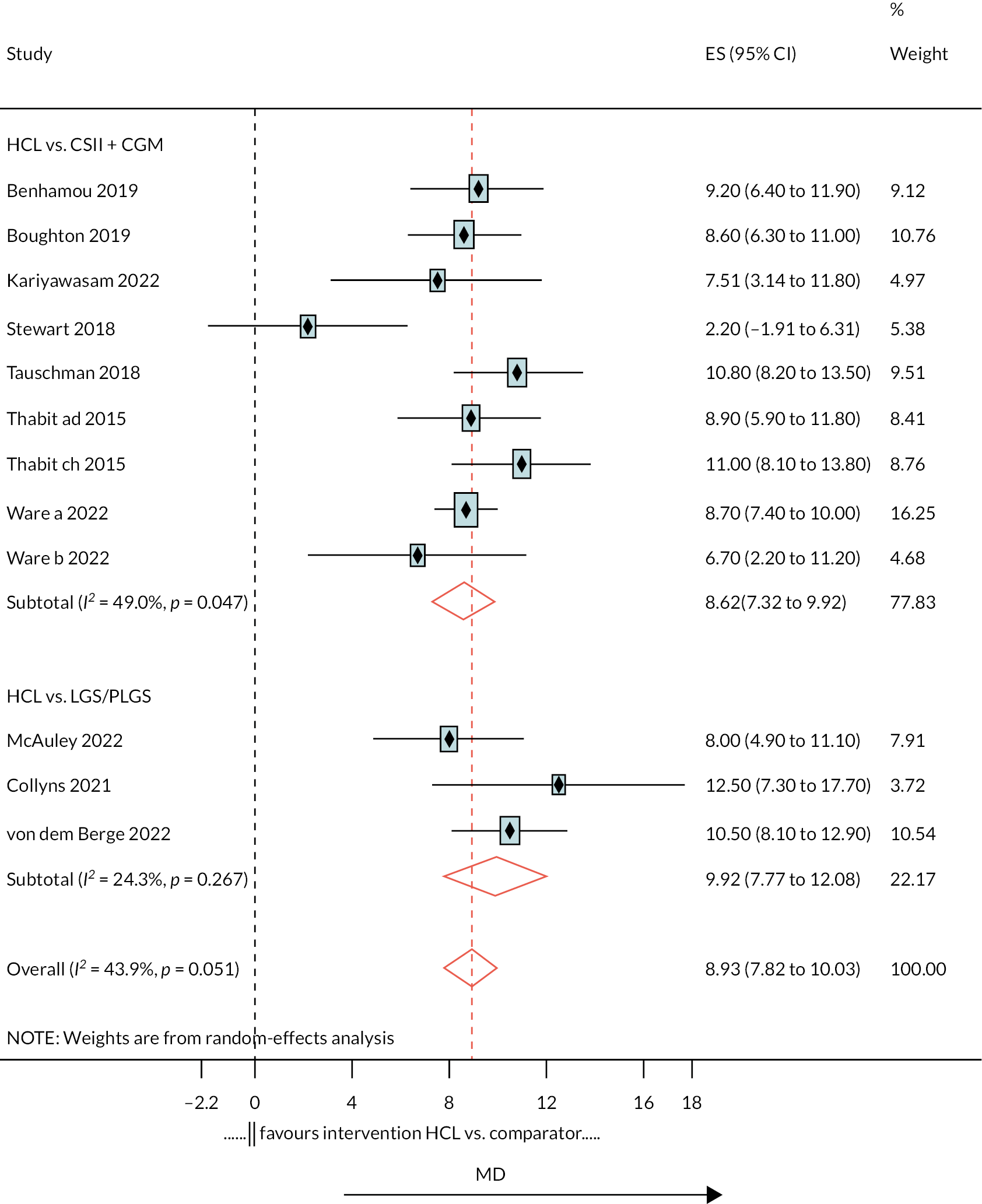

In all the RCTs, the increase in % TIR was greater in the HCL arm than in the comparator arm (Figure 4), in all cases reaching statistical significance (p < 0.05). The lowest mean start/baseline value % TIR was 40%; in all other RCTs it was > 50%. In the NHS pilot study (described in Methods for assessing cost-effectiveness evidence), the start/baseline value was 34.2%, allowing considerable scope for improvement with HCL treatment, which was 28.5% (unadjusted; 95% CI 31.4 to 13.5). The change from start/baseline in the HCL arm of RCTs recruiting adults of similar age to those in the adult NHS pilot study ranged from ≈ 10% to ≈ 15%, approximately half of that in the pilot. The improvement in % TIR appears to be greater the smaller the start or baseline level.

FIGURE 4.

Change (end minus start as mean ± SD or median) by arm % TIR (3.9–10.0 mmol/l) over treatment period.

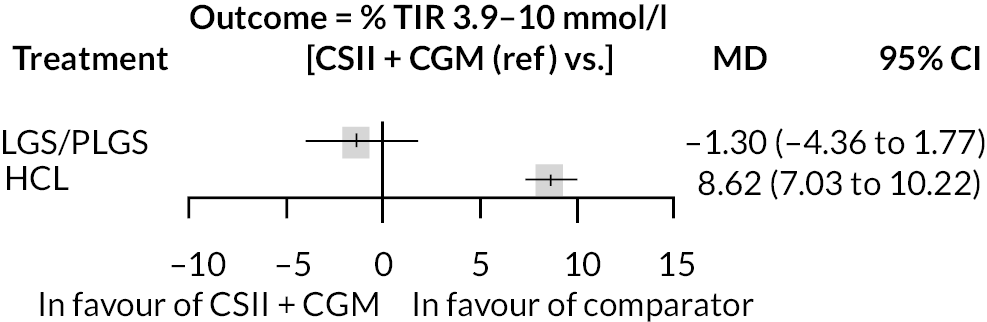

The meta-analysis pooled estimate for the comparison of HCL with CSII + CGM was considerably influenced by the inclusion of the Stewart et al. 51 study (see Appendix 6, Figure 20). This study included only pregnant women, and treatment duration was shorter than in other studies. The exclusion of Stewart et al. resulted in greater pooled estimate for HCL versus CSII + CGM (MD 9.1). There were 13 estimates from 12 studies that were included in this NMA, as estimates from Thabit were split into adult and children estimates. The reference treatment class was CSII + CGM, where estimates < 0 favoured CSII + CGM. The forest plot of the NMA is presented in Figure 5. Compared with the CSII + CGM treatment classification, HCL significantly increased % TIR (between 3.9 and 10.0 mmol/l), with a MD of 8.6 (95% CI 7.03 to 10.22). There was no statistically significant difference between CSII + GCM and LGS/PLGS.

FIGURE 5.

Results of the NMA of the outcome time in target range (% between 3.9 and 10.0 mmol/l).

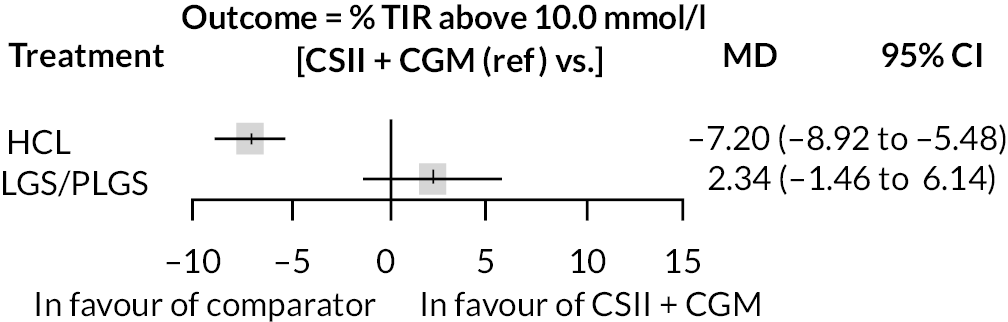

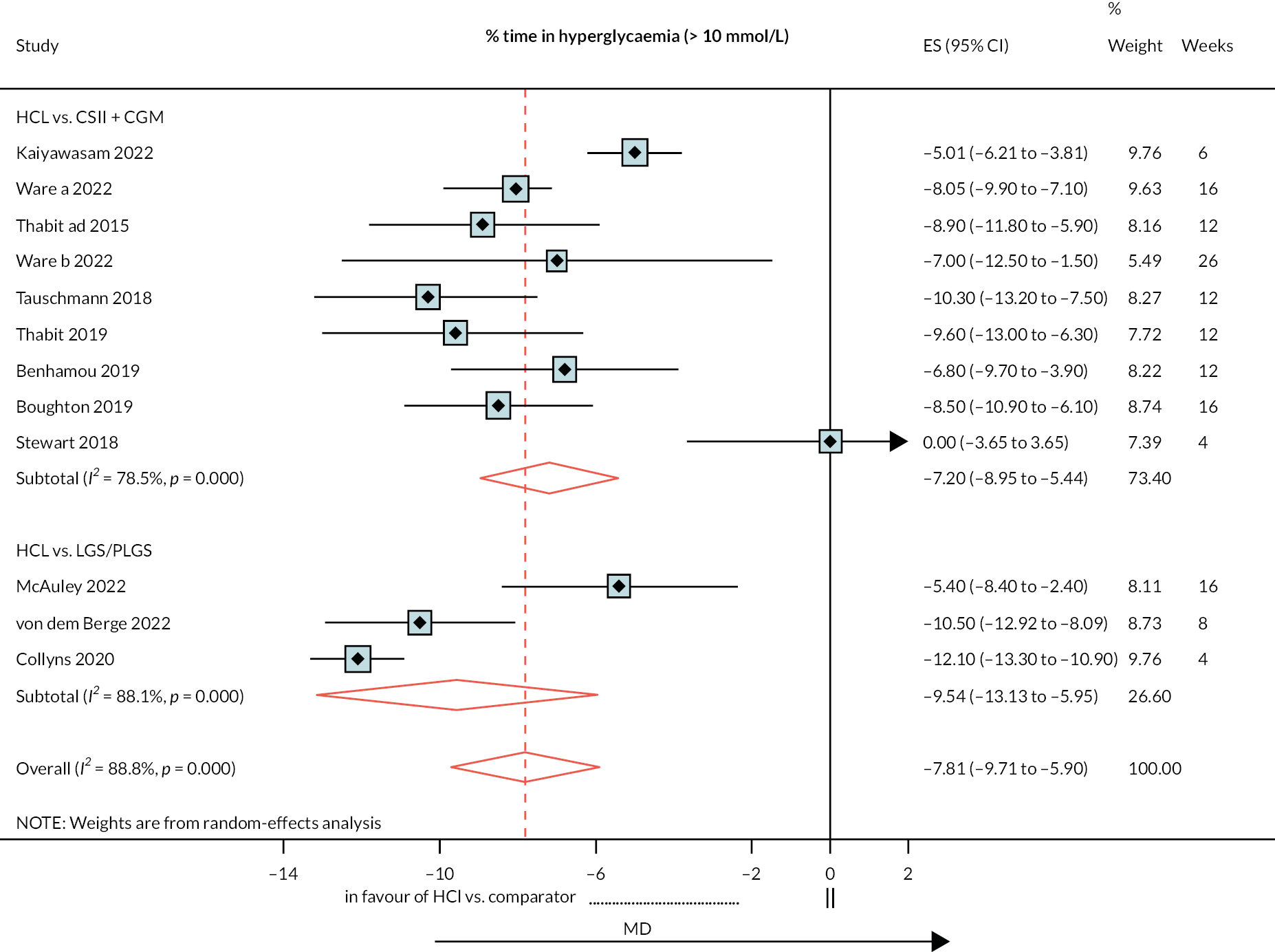

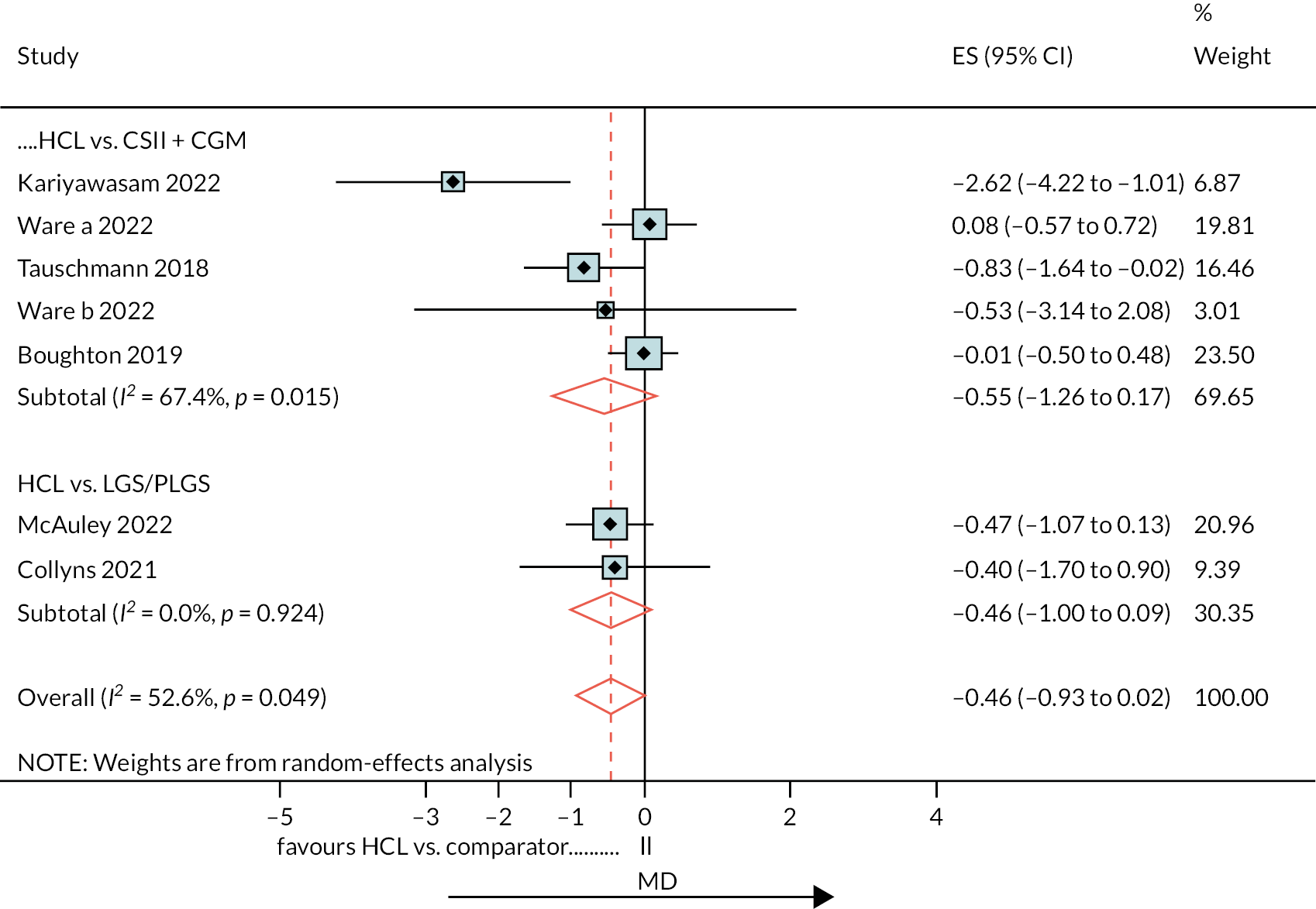

Per cent time above range (> 10.0 mmol/l)