Notes

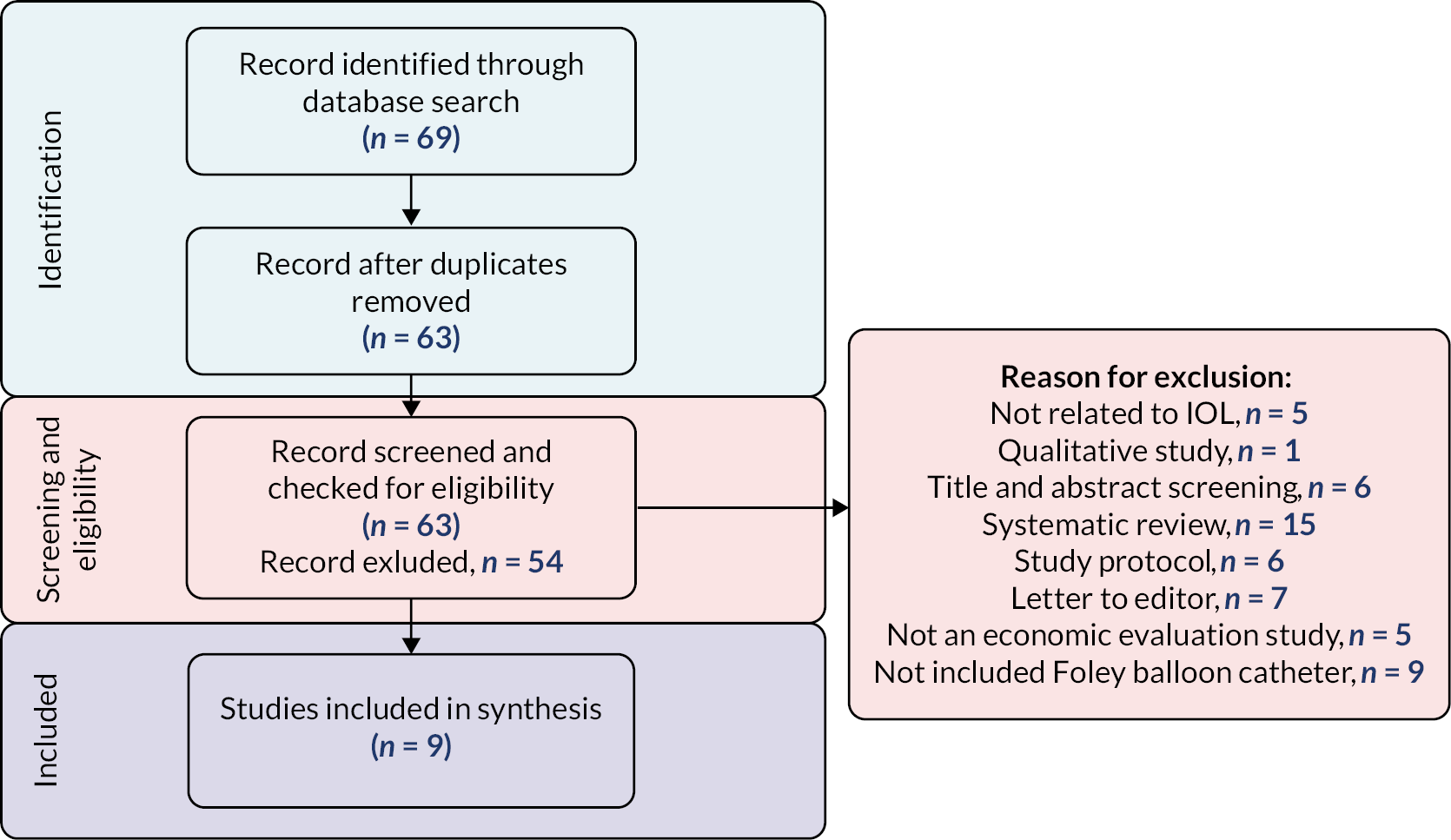

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR127569. The contractual start date was in December 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Black et al. This work was produced by Black et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Black et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Induction of labour (IOL) is the most common obstetric intervention offered to women when risks of continuing the pregnancy are thought to outweigh risks of birth. Rates of IOL in the UK were above 40% in the 1970s, but halved over the next decade, before increasing again from the late 1990s. 1 Current IOL rates mean that 33% of pregnant women in England have their labour induced, compared with 21% 10 years ago. 2 Elective IOL at term, when compared with expectant management of pregnancy, reduces caesarean birth and maternal hypertensive disease, as well as being associated with a reduction in perinatal mortality and maternal complications. 3–5 It thus seems likely that demand for IOL will continue. Maternity services are struggling to accommodate increasing rates of IOL. 6 Although IOL (compared with expectant management) reduces overall hospital stay, it increases the amount of time spent on antenatal wards and on labour wards, with a major impact on maternity resources and staffing, and on women’s experience of labour. 3,7–9

Cervical ripening is a key component of IOL, whereby application of a drug or mechanical method over several hours, causes softening, shortening and opening of the cervix in preparation for labour. 10 Cervical ripening may itself initiate labour but is often followed by artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) with or without intravenous infusion of oxytocin (both inpatient procedures). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends that all women having IOL have prior cervical ripening, unless there is a contraindication. 11

Traditionally, all cases of cervical ripening have been performed in hospital, to allow monitoring of maternal and fetal well-being and recognition of complications such as uterine hyperstimulation (frequent/sustained contractions that increase the risk of hypoxic birth injury; incidence 2–3%). 12 More recently, however, a rising number of maternity units give women the option of home cervical ripening. Home cervical ripening means that women attend hospital for initial assessment and administration of cervical ripening agent before returning home (to their own home or that of a friend/relative/birth partner) for a period of time (usually 24 hours), before reassessment in hospital. This arrangement has the potential to reduce women’s overall hospital stay during IOL, thus reducing costs to health service providers. However, the safety and acceptability of home cervical ripening has not been fully evaluated. Any NHS cost savings could potentially be offset by increased costs of any additional morbidity resulting from home cervical ripening; costs to parents may be increased and acceptability of home cervical ripening is not fully understood. Health services need to balance the full resource impact of IOL with the need to provide safe and acceptable care.

In the CHOICE study, we addressed the question ‘Is it safe, effective, cost-effective and acceptable to women to carry out home cervical ripening during induction of labour (IOL)?’ We also performed descriptive analyses of the process and outcomes of IOL. These analyses will provide information to help women and their caregivers make informed decisions around when and how to have IOL.

Rationale and justification for study

As the rate of IOL is increasing, home cervical ripening may provide opportunities to reduce the burden on the NHS. However, there are evidence gaps in whether home cervical ripening is safe, acceptable to women, reduces hospital stay and is cost-effective. NICE identified the need to assess the safety, efficacy and clinical and cost-effectiveness of outpatient and inpatient IOL in the UK setting, considering women’s views. 11 Maternity service users have identified IOL as an important research topic and women have reported specific negative experiences such as increased pain and anxiety and lack of support, which may be alleviated by home cervical ripening. 9,13

Home cervical ripening has the potential to reduce separation of women from their families and increase choice regarding the timing and setting for labour and delivery. Existing evidence suggest that home cervical ripening is feasible and adverse outcomes appear to be rare, but trials have been underpowered to confirm safety. 14 Importantly, studies have not confirmed anticipated reductions in length of hospital stay or cost-effectiveness. 4,15 However, no studies have investigated the acceptability to women or their families, or whether choice is increased in a UK setting, apart from a small feasibility study conducted by some of the investigators in qCHOICE. 9 This study will provide much needed evidence on women’s and partners experiences of home cervical ripening, IOL and costs from the service user perspectives.

Despite the lack of evidence on home cervical ripening, the practice is becoming increasingly common in UK practice. In preparation for this study (August 2018), we obtained information on IOL policies from 128/167 (77%) obstetric units in Scotland and England and found that 54% (69 of 128) of units offered, or would shortly start to offer, home cervical ripening. This was a large and rapid increase – a 2014 survey found only 17% of UK maternity units offered home cervical ripening. 16

There is variation in the population of women offered home cervical ripening between hospitals. However, most units only offer home cervical ripening to women with ‘low risk’ pregnancies (i.e. women with uncomplicated pregnancies). Most units that offered home cervical ripening in 2018 (> 90%) used topical prostaglandin applied intravaginally as a slow-release pessary of 10 mg dinoprostone, which stays in place for 24 hours. This was in line with NICE guidance, which recommended prostaglandin as the primary method of IOL for all women. 11 Balloon catheters, which involve inserting either the balloon from a foley catheter or a specially designed cervical ripening catheter into the cervix and inflating it with saline to mechanically open the cervix, have also been shown to be effective. 11 Compared with prostaglandin, balloon catheters have a lower incidence of uterine hyperstimulation (2% vs. 3%) and operative delivery indicated by fetal heart rate abnormalities (12% vs. 18%). 12 However, they may be less acceptable to women. 17 Whereas in 2014 no units offered home cervical ripening with balloon catheters, our survey suggested that at least six UK units currently, or soon would, offer balloon catheters as the primary method of home cervical ripening. 16 Other methods of cervical ripening are not currently used at home. Oral misoprostol has high rates of uterine hyperstimulation and is not used outside hospitals in the UK. 18 Osmotic dilators (an alternative mechanical method) are under evaluation in hospitals (SOLVE trial; ISRCTN20131893) but have not yet been shown to be effective or established in UK practice.

The aim of the overall CHOICE study was to assess the safety, clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of home cervical ripening. This was to be achieved by performing a prospective multicentre observational cohort study, using real-world data obtained from hospital electronic health records (CHOICE prospective observational cohort study) linked with a process evaluation using a questionnaire-based survey and nested case studies (qCHOICE) with economic evaluation.

Chapter 2 Observational cohort study

Observational cohort study objectives/research questions

This study addressed the research question:

Is home cervical ripening:

-

as safe as in-hospital cervical ripening in terms of neonatal unit (NNU) admission (primary outcome) and other secondary outcomes of maternal and neonatal morbidity?

-

effective in reducing the amount of time women spend in hospital during the IOL process?

-

cost-effective from the NHS perspective?

Preplanned primary comparison

The planned primary comparison was home dinoprostone (a prostaglandin) cervical ripening (exposure) versus in-hospital dinoprostone cervical ripening (comparison) from 39 weeks of gestation. A secondary exploratory comparison was planned to be undertaken to explore home cervical ripening with balloon catheter (exposure) versus home cervical ripening with dinoprostone (comparator).

Additional supplementary research questions to be applied to the cohort study, should numbers suffice, were:

-

How do IOL rates, methods and outcomes vary across the UK?

-

What are the outcomes of IOL in different subgroups of women (e.g. women with multiple pregnancy, women with IOL after a previous caesarean section) and at each week of gestation (37, 38, 39, 40 and 41+ weeks)?

-

Can we predict which women will have caesarean section after IOL?

However, these supplementary questions are not addressed in this report.

Revised primary comparison

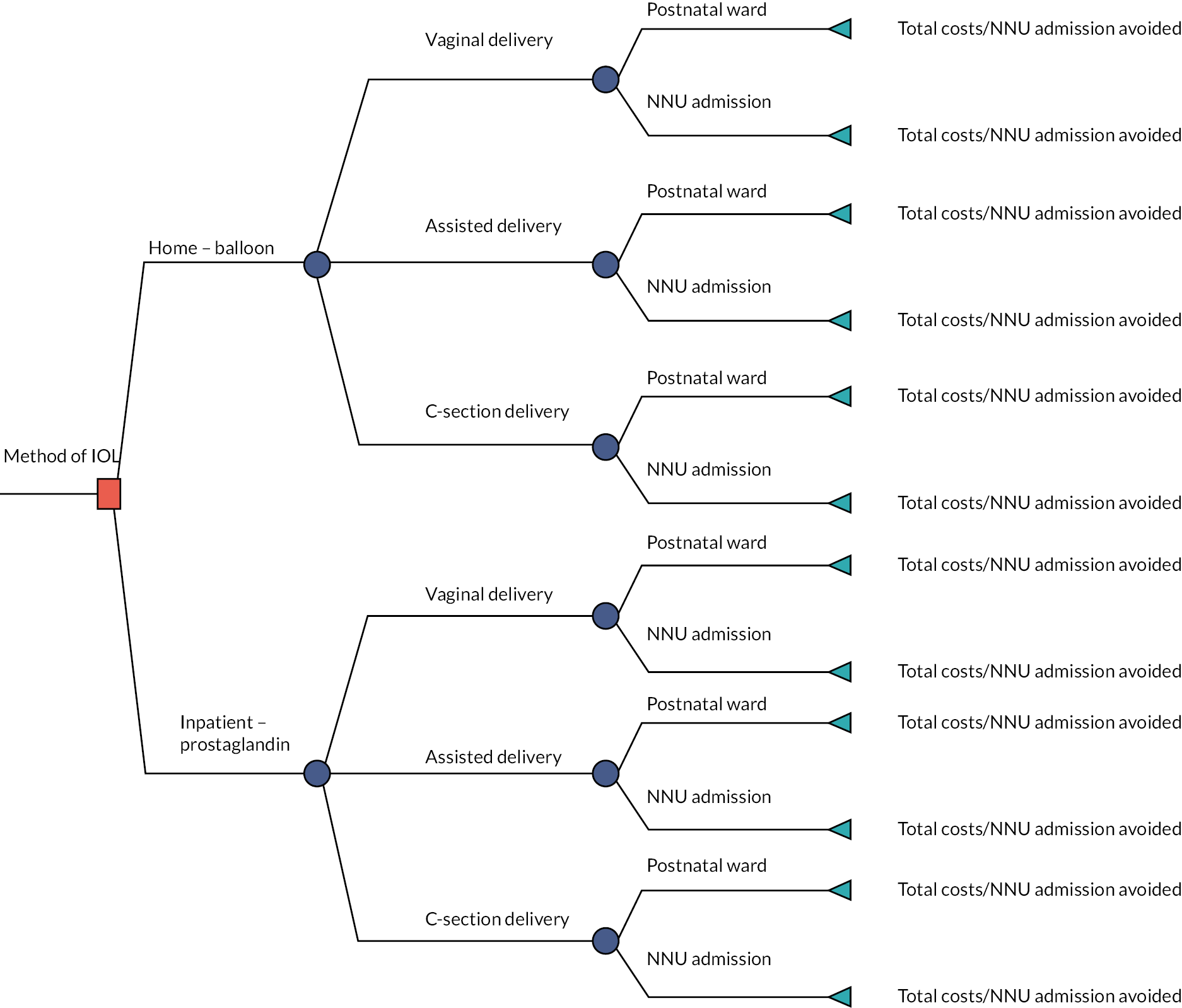

Following preplanned pilot analysis at 156 site months of data collection, the primary comparison was changed to ensure feasibility and to reflect current practice. The revised primary comparison became ‘Home balloon cervical ripening (exposure) versus in-hospital prostaglandin cervical ripening (comparator) from 37 weeks gestation’.

Throughout the report, these main two comparator groups are referred to as ‘home balloon’ and ‘hospital prostaglandin’, respectively.

Observational cohort study methods

Study design as planned at study outset

We planned to perform a prospective multicentre observational cohort study with an internal pilot phase. 19 We set out to obtain data from electronic health records from at least 14 maternity units offering only in-hospital cervical ripening and 12 offering dinoprostone home cervical ripening. The expected sample size was 8533 women with singleton pregnancies undergoing IOL at 39 + 0 weeks’ gestation or more. To achieve this and to contextualise our findings, we planned to collect data relating to a cohort of approximately 41,000 women undergoing IOL after 37 weeks. We planned to use mixed-effects logistic regression for the non-inferiority comparison of NNU admission and propensity score matched adjustment to control for treatment indication bias.

A secondary exploratory comparison was planned if sufficient cases allowed: home cervical ripening with balloon catheter (exposure) versus home cervical ripening with dinoprostone (comparator), to explore whether there are any indications of different safety profiles of these two methods of home cervical ripening.

Changes to study design

Results of the planned interim analysis after 156 site months of data led to a change in study design and expected sample size. Three key changes were made:

-

Data would be obtained from a total of 26 NHS maternity units, of which 18 offered only in-hospital cervical ripening (predominantly with prostaglandin) and 8 offered home cervical ripening using balloon catheters, meaning that around 25,000 women would be in the initial data extract from which the analysis sample would be drawn.

-

Instead of including a population of women from 39 weeks’ gestation onwards, women were included if they underwent IOL at 37 completed weeks of gestation onwards.

-

Instead of comparing home cervical ripening using dinoprostone with in-hospital cervical ripening using dinoprostone, home cervical ripening with balloon would be compared with in-hospital cervical ripening using any prostaglandin.

-

Planned analysis would use multivariable logistic regression without propensity score matching for the primary outcome. All other outcomes would be reported using descriptive statistics.

Justification of change in study design

It was recognised following the pilot analysis that it was not feasible to answer the original research question relating to safety of home cervical ripening using dinoprostone, as dinoprostone was so infrequently used in home settings. If the number of home cervical ripening cases using dinoprostone had continued to accrue at the same rate, it was calculated that it would take over 10 years to reach the planned sample size. Instead, it was recognised that as balloon cervical ripening had become the dominant method in home settings, a pragmatic research question would ask what the difference in safety (and cost) is between home cervical ripening using balloon and in-hospital cervical ripening using any prostaglandin.

It was also recognised that home cervical ripening using balloon was being used for multiple indications from 37 weeks’ gestation and was not limited to post-dates IOL. Thus, it was considered relevant to include women from 37 completed weeks of gestation in the primary analysis.

To complete the study within the funded period, it was decided to cease data collection on 30 June 2022, 1 month earlier than originally planned. This decision was made to maximise time available for data analysis within funded study resources and to ensure that the maximum descriptive analyses could be performed to provide details of the context in which the study was set. This was considered particularly relevant given the perceived practice changes that had occurred during the study period, including those changes in setting related to the COVID-19 pandemic, increased IOL rates, wide variation in indications for IOL, substantial delays during IOL and earlier gestation at onset of IOL.

Participants

Data on all women having IOL at 37 + 0 weeks’ gestation or more were extracted. Women who opted out of data provision were excluded from the data set by the BadgerNet (System C, Stratford-upon-Avon, UK) maternity system analysts before data were extracted, so the number of such women is not known to the research team.

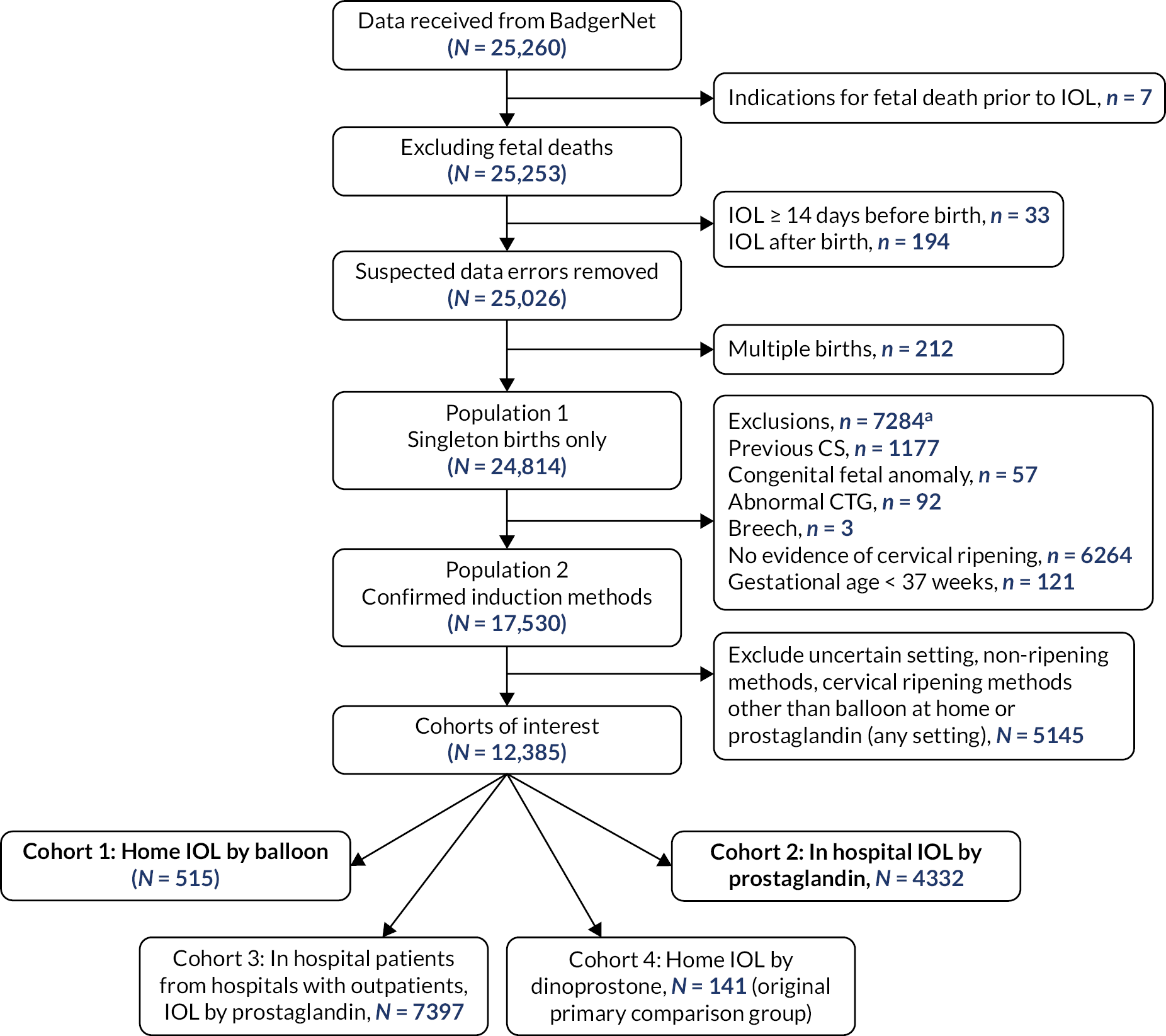

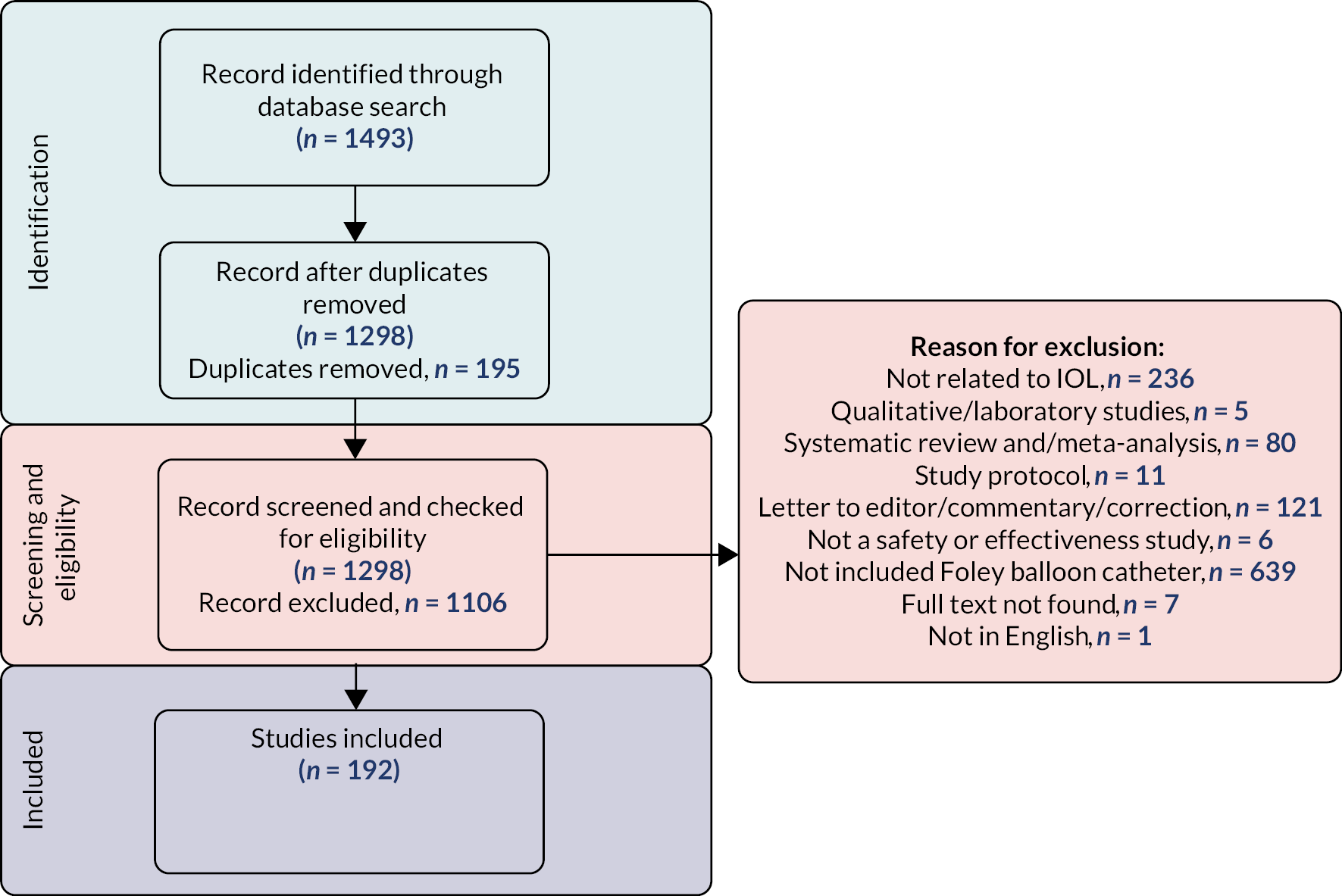

More stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied at the analysis stage. These are summarised in the flowchart in Figure 1. In the primary analysis, a cohort of women was created with broadly comparable level of risk in pregnancy (i.e. those without key risk factors for adverse maternal or perinatal outcomes defined below) in whom there was no contraindication to home cervical ripening, who had singleton pregnancies with IOL at 37 weeks’ gestation or more. This group included women having IOL for post dates, because of maternal or clinician preference, for maternal age, for discomfort or social indications, for hypertension, diabetes, fetal concerns (oligohydramnios, reduced liquor volume, macrosomia, intrauterine growth restriction, static growth, polyhydramnios), fetal movement concerns, obstetric cholestasis, antepartum haemorrhage, previous obstetric history, prelabour rupture of membranes (ROM) documented as primary or other indication for IOL (prolonged ROM, spontaneous ROM and suspected spontaneous ROM) and other maternal reasons, such as raised body mass index (BMI), in vitro fertilisation pregnancy, musculoskeletal pain, thrombophilia. Exclusion criteria consisted of previous caesarean section, antepartum stillbirth (before cervical ripening initiated), congenital fetal anomaly, abnormal cardiotocograph (CTG)/Doppler, breech presentation.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of CHOICE observational cohort study populations and analysis cohorts by setting and method of cervical ripening. a, Some participants may have more than one reason for exclusion. CS, caesarean section.

Participants were identified from data recorded in specified fields in BadgerNet electronic maternity records. We used data fields indicating IOL, estimated due date and date of IOL to identify women having IOL at 37 weeks of gestation or more.

Women were made aware of the CHOICE study through posters in participating sites, business cards, information leaflets, online adverts on hospital/maternity websites and relevant social media sites, and information in maternal electronic maternity records.

Women were able to opt out of data provision by notifying their clinician or midwife or e-mailing the study research midwife at the local site, following which their opt-out status was recorded on their electronic record. This became a conditional field, where there must be no opt-out selected for the data to be extracted for the study. There was no restriction on co-enrolment in other studies.

Study settings

The study was performed in 26 UK obstetric units, 8 of which offered cervical ripening both in-hospital (mix of methods) and at home (predominantly balloon method) and 18 of which offered exclusively in-hospital cervical ripening (predominantly prostaglandin method). All included sites used the BadgerNet maternity record system.

The maternity units included were selected to represent the diverse range of maternity service settings in the UK, and included urban tertiary referral units, mid-sized urban district general hospitals and small, more isolated, rural units.

Participating trusts/boards/units included:

-

NHS Borders

-

NHS Fife

-

NHS Grampian

-

NHS Highland

-

NHS Lanarkshire

-

NHS Tayside

-

Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Maternity)

-

Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust

-

Darlington Memorial Hospital

-

University Hospital of North Durham (Maternity)

-

Dorset County Hospital

-

Epsom Hospital (Maternity)

-

St Helier Hospital (Maternity)

-

Hereford County Hospital (Maternity)

-

Princess Royal University Hospital

-

King’s College Hospital (Maternity)

-

Chorley and South Ribble Hospital

-

Royal Preston Hospital

-

Cumberland Infirmary (Maternity)

-

West Cumberland Hospital (Maternity)

-

Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead (Maternity)

-

Warwick Hospital

-

Queen Elizabeth Hospital Kings Lynn (Maternity)

-

New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton (Maternity)

-

Walsall Manor Hospital

-

Worcestershire Royal Maternity Hospital

No data were collected from each site for the first 14 days after their ‘go live’ date to ensure that women had the opportunity to see and read study materials such as posters and study cards, and to opt-out of data collection if preferred.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics

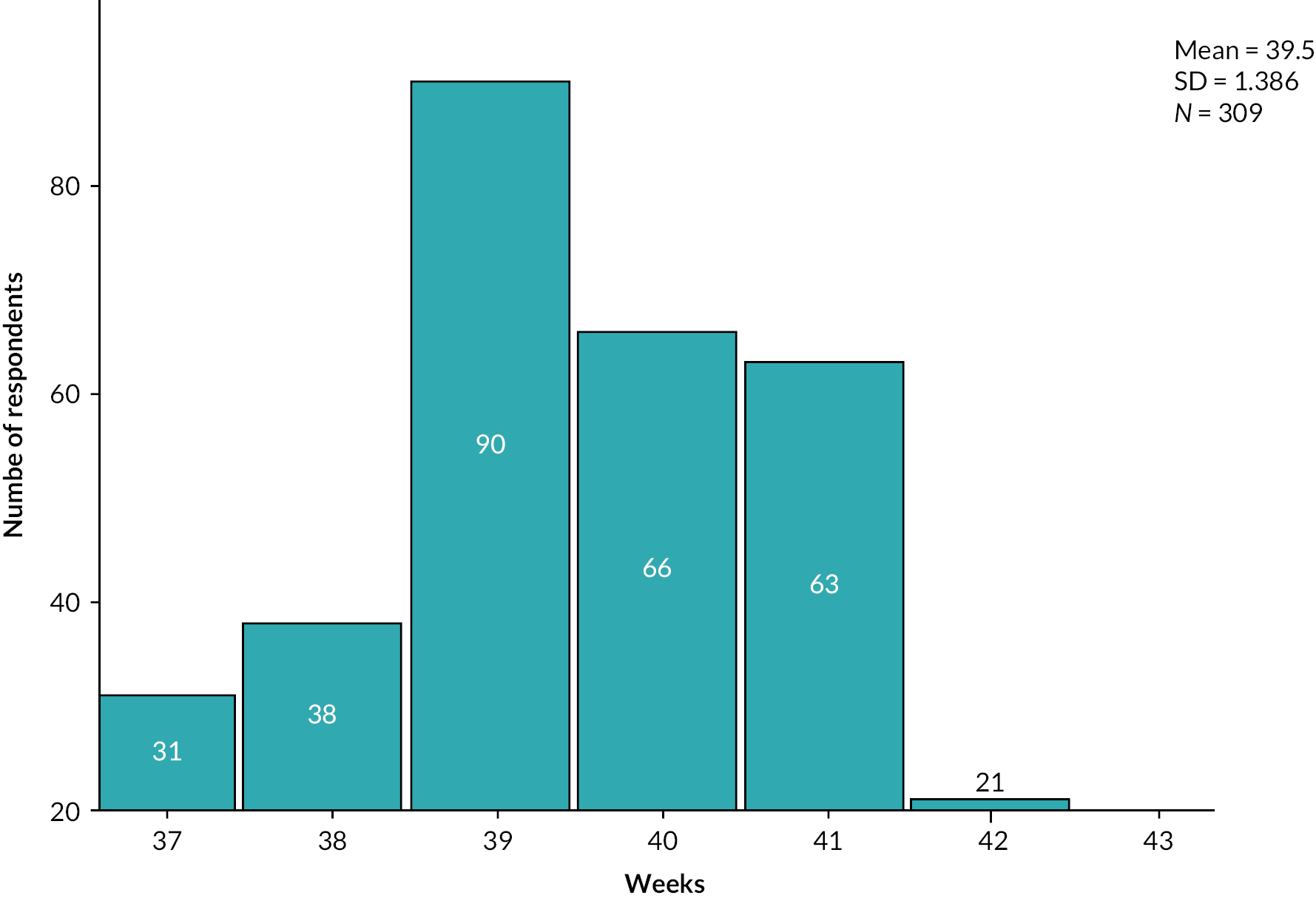

The following demographic and clinical characteristics were described across cohorts: number of women undergoing IOL by study site; age of women in years; BMI of women; class III obesity at booking (≥ BMI 40 kg/m2); marker of deprivation [index of multiple deprivation (IMD)]; parity (number of parity 0, 1, 2, 3 +); gestation at IOL (completed weeks) plus number at each completed week; birth weight (grams) and indication for IOL.

Indications for IOL (as defined by study sites) were categorised as follows: post dates; hypertension (pregnancy-induced hypertension or pre-eclampsia), antepartum haemorrhage; diabetes; obstetric cholestasis; obstetric history; maternal age; maternal request (including social indications); other maternal reasons (including raised BMI, in vitro fertilisation; musculoskeletal pain, thrombophilia); fetal concern (excessive growth, polyhydramnios, reduced liquor volume, small for gestational age, static growth, suboptimal growth, abnormal dopplers); previous precipitate labour; ROM (preterm, prolonged, suspected, confirmed); reduced fetal movements (isolated or recurrent episodes).

Exposures

The exposure group consisted of women who, at the start of the cervical ripening process, planned to have home cervical ripening and who underwent this procedure using a balloon catheter as the first method of IOL. This group is referred to as the ‘home balloon’ group in the report.

The comparator group included women who planned to have in-hospital cervical ripening from maternity units not offering home cervical ripening, and who underwent this using prostaglandin methods. This design minimised potential bias arising from the fact that, in maternity units which offer both home and in-hospital cervical ripening, the risk of complications in the babies of women having home cervical ripening (lower-risk pregnancies) is inherently different from that of babies of women having in-hospital cervical ripening (higher-risk pregnancies).

A further two cohorts were identified (in-hospital cervical ripening using prostaglandin where the hospital also offers home cervical ripening, and at home cervical ripening using dinoprostone – the original exposure group), to provide context to the primary outcome, although the latter group was not used in any of the secondary outcome analyses. Figure 1 outlines the derivation of each cohort.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was admission to a NNU/special care baby unit for 48 hours or longer, initiated within 48 hours of birth. NNU admission is a marker of neonatal morbidity and is the leading core outcome defined for studies of IOL. 19 Any increase in NNU admission of term babies is undesirable due to the separation of mother and baby. However, NNU admission rates are highly variable between maternity units and are likely to depend on local policies and culture. 20 For this reason, we used a primary outcome that represents more severe neonatal morbidity (admission to a NNU within 48 hours of birth for 48 hours or longer), which is less likely to be influenced by site-specific factors than NNU admissions for shorter durations.

Secondary outcomes

The core outcomes set for IOL includes many outcomes for inclusion in studies of IOL. 13 These outcomes were prespecified as exploratory secondary outcomes in the published study protocol. Further mother and baby outcomes were suggested by our lay consultation as important to include. Not all these outcomes were included in the updated statistical analysis plan following pilot analysis, as many outcomes were recognised to be poorly recorded or not recorded at all within the pilot data extract. The outcomes considered for reporting (where enough data exist) are outlined below.

Maternal outcomes

Mode of birth (unassisted vaginal, caesarean, forceps/ventouse-assisted); postpartum haemorrhage 1000 ml or more; maternal pyrexia 38 °C or more after starting cervical ripening (exploratory outcome); obstetric anal sphincter injury; retained placenta.

Offspring outcomes

Apgar score at 1, 5 and 10 minutes; NNU admission (any); duration of NNU stay; duration of NICU stay; neonatal seizures; meconium-stained liquor, mechanical ventilation; intracranial haemorrhage; serious morbidity (at least one of neonatal seizures, intracranial haemorrhage, stillbirth, neonatal death); stillbirth after admission/first attendance for IOL (excluding deaths from congenital anomalies); early neonatal death up to 7 days after birth (day 0–6; excluding deaths from congenital anomalies); hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy.

Effectiveness outcomes

Birth in obstetric unit; birth in alongside midwifery unit (if available at that site); methods used to start (first method) IOL (e.g. type of prostaglandin, ARM); number of IOL methods used by type; number of women undergoing cervical ripening as part of IOL at any point (balloon, prostaglandin or cervical dilator); number of women undergoing each type of cervical ripening, first versus subsequent; number of women in whom more than one cervical ripening agent was used; number of women receiving oxytocin during labour.

Labour progress

Cervical dilation at commencement of IOL; time (duration in minutes before birth) cervix fully dilated; cervical dilation at time of caesarean section; length of time between IOL starting and transfer to labour ward (minutes); length of time between IOL starting and birth (minutes); duration of antenatal hospital stay for cervical ripening (in-hospital) (minutes); duration of discharge during cervical ripening (at-home; minutes); duration of antenatal hospital stay for cervical ripening (at home; minutes); duration of labour ward admission until birth (minutes); duration of postnatal hospital stay (mother; minutes); total hospital stay (minutes); oxytocin use.

Reporting of small numbers

To preserve anonymity of participants, it was agreed that where fewer than five outcomes were reported in a group then findings for that outcome would not be reported by group.

Changes to outcomes

The primary outcome remained the same, although following the pilot analysis, it was agreed that it was unlikely that there would be sufficient power to achieve our primary objective of assessing safety of home versus in-hospital cervical ripening. To compare outcomes across groups, a simplified analysis with two non-matched cohorts replaced the original analysis plan, which had involved a propensity-score matching process.

Sample size

The original sample size required 1920 home IOL with dinoprostone to be matched with 1920 in-hospital IOL with prostaglandin from hospitals not offering home IOL. However, at the time of the pilot study, only 150 women had been given prostaglandin for IOL at home, with even fewer having received dinoprostone. Our stop–go criteria at this point required us to have achieved at least 400. With the changes in practice necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, 1920 was not going to be achievable in a practicable time frame. The requirement to match was dropped to increase the power from the in-hospital cohort.

Overall, the lower numbers of women in the home setting than expected meant that the study was deemed to be underpowered to assess the primary outcome in any other way than exploratory. The primary end point was presented with a 95% confidence interval (CI), but should only be considered as hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing.

Data sources

Data were collected directly from electronic maternity and neonatal records for participants who had babies cared for by neonatal staff. These data are recorded by clinical staff (midwives, doctors and neonatal nurses) while providing antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care. Existing data fields were used. Data were assumed to reflect the understanding of the clinical staff who entered the data. Diagnoses were assumed to reflect national guidance.

Unless women opted out of secondary data use, deidentified data were transferred from BadgerNet participating sites to a secure University of Edinburgh server for analysis.

No personal data were collected. Potentially identifiable data, such as the date and time of birth, date of events such as commencing cervical ripening and hospital discharge, were converted into gestation at birth (weeks + days); and antenatal and postnatal events into ‘t – x’ and ‘t + x’ minutes, respectively.

Data from a total of 40 tables in the BadgerNet system were extracted. These included details of the following:

-

neonatal care admission

-

critical incident affecting baby

-

birth details of baby

-

discharge details of baby

-

baby examination details

-

baby feeding details

-

operative birth details

-

internal transfer of baby

-

medications administered to baby

-

microbiological tests performed in relation to baby

-

baby patient index (demographic and clinical details)

-

risk assessment relating to baby

-

transfer of baby’s care

-

maternal admission

-

maternal analgesia

-

maternal antenatal assessment

-

maternal care plan

-

maternal communication details

-

maternal critical incident

-

maternal discharge details

-

maternal perineal tears or trauma

-

maternal health history

-

maternal induction of labour details

-

maternal induction of labour booking details

-

maternal internal transfer

-

maternal labour and birth details

-

maternal lifestyle

-

maternal death

-

maternal observations

-

maternal partogram

-

maternal patient index

-

maternal pre-operative checklist

-

maternal previous pregnancy

-

maternal risk assessment

-

maternal ROM

-

maternal sepsis pathway

-

maternal transfer of care

-

maternal transfusion

-

maternal vaginal examination

-

summary of neonatal care.

Algorithm to determine setting of cervical ripening

Women in the study data set were categorised as having either had home cervical ripening, in-hospital cervical ripening or unclear setting of cervical ripening. The categorisation took place using the following variables: mother_induction (first induction), mother_admission (admissions after IOL), mother_patientindex, mother_discharge (excluding discharge before IOL), mother_communication (phone call between ‘patient’ and other), mother_previouspregnancy and baby_deliverydetails.

The main analysis population was identified following the exclusion of cases listed below:

-

Remove if fetal death is reason for IOL.

-

Remove if IOL time < 14 days before birth (likely coding error).

-

Remove if IOL time is after birth (likely coding error).

-

Remove multiple births (population 1 in flowchart).

-

Remove if reason for IOL is:

-

congenital fetal abnormality

-

abnormal CTG

-

breech.

-

-

Remove if any previous pregnancy involved caesarean section.

-

Remove if not confirmed IOL.

-

Remove if gestational age at IOL < 37 weeks (population 2 in flowchart).

The algorithm used to determine induction of labour setting (‘IOL type’) was as follows (where 'y' = yes and 'n' = no):

-

If the hospital does not offer home cervical ripening, then IOLtype = ‘In hospital only’.

-

If the hospital is a mixed hospital (allows both at home and in-hospital cervical ripening) AND dischargedhome = ‘y’, then IOLtype = ‘home’.

-

If the hospital is a mixed hospital (allows both at home and in-hospital cervical ripening) AND dischargedhome = ‘n’, then IOLtype = ‘inhospital mixed’.

-

For those still undefined at this point:

-

If baby born outside hospital, then IOLtype = ‘home’.

-

If the hospital allows home IOL AND there is no admission time, then IOLtype = ‘inhospital mixed’ (data sets only include admissions after IOL, so mother must already be in hospital if there is no admission time after IOL has commenced).

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND there is no discharge note AND first admission > 120 hours, then IOLtype = ‘uncertain’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND there is no discharge note AND first or second admission is 6–120 hours after birth, then IOLtype = ‘home’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND there is no discharge note AND only one admission AND admission ≤ 6 hours after birth, then IOLtype = ‘uncertain’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND there is no discharge note and time from IOL to discharge > 24 hours, then IOLtype = ‘inhospital mixed’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND IOL time < discharge time AND discharge ≤ 24 hours after birth, then IOLtype = ‘inhospital mixed’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND IOL time < discharge time AND discharge ≤ 24 hours before birth, then IOLtype = ‘home’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND first admission < 6 hours after birth, then IOLtype = ‘home’.

-

If place of birth in hospital that allows home IOL AND first discharge is after birth, then IOLtype = ‘inhospital mixed’.

-

If there is a record of a phone call between patient and other during period between IOL and birth, then IOLtype = ‘home’.

-

Definition of cohorts

-

If IOLtype = ‘home’ and induction method = ‘cervical balloon’, then cohort = 1.

-

If IOLtype = ‘In hospital only’ and induction method = ‘prostaglandins’, then cohort = 2.

-

If IOLtype = ‘inhospital mixed’ and induction method = ‘prostaglandins’, then cohort = 3.

-

If IOLtype = ‘home’ and prostaglandin type = ‘propess’, then cohort = 4.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

As proposed, we carried out a pilot phase analysis to determine the parameters of the primary outcome and feasibility of obtaining the planned sample size for the original preplanned analysis at 156 site months, using criteria as shown in Table 1. This was based on an evaluable comparison group of 1920 women in each arm, so acted as an inherent check on home cervical ripening eligibility and uptake rates. We assessed variation of the primary outcome at the pilot stage, along with that of other measures of neonatal morbidity included as secondary outcomes (e.g. any NNU admission). We retained the preplanned parameters of NNU admission used in the primary outcome after analysis of pilot data. We redefined the comparison groups following assessment of the pilot analysis data, which demonstrated much lower uptake of home cervical ripening using dinoprostone than expected, higher uptake of home cervical ripening using balloon, a much wider range of indications of IOL in home cervical ripening groups and earlier gestation at IOL in both settings. The decision to redefine the comparison groups was made in consultation between the expert project management group, the study steering committee and the funder.

| Criteria | Stop | Change | Go |

|---|---|---|---|

| N matched women in each arm | < 400 (< 4 SD of target) | 400–549 (2–4 SD of target) | 550–650 (2 SD of target) |

| ICC for NNU admission | > 0.0125 | > 0.01 but ≤ 0.0125 | ≤ 0.01 |

| ACTION | Stop study – unfeasible to assess safety outcomes | Consult with funder for extension to data collection period | Continue study as proposed |

Statistical methods

All analyses were fully specified in an updated comprehensive statistical analysis plan (version 2.0) and agreed by the steering committee. Analyses were carried out in accordance with relevant guidance, including Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. 15

The original design, which informed the sample size calculation, was a non-inferiority design, chosen with a non-inferiority margin of 4% (deemed as likely to be an important difference on consultation with women and clinicians) for the primary outcome of NNU admission within 48 hours of birth for 48 hours or more.

The non-inferiority margin was established based on a combination of what is acceptable to women and partners and what costs are acceptable to healthcare providers. However, following the pilot phase and the expected inability to reach the required sample size, the principal analysis as defined originally, was deemed unlikely to be sufficiently powered, and the primary analysis was changed to an estimation problem, rather than a hypothesis testing problem.

For the principal analysis of the primary outcome, we used mixed-effects logistic regression for the comparison of NNU admission within 48 hours of birth for 48 hours or longer (yes/no). Within the mixed model, site has been included as a random effect and all other factors are fixed effects. A random intercept for each site was included, rather than a common intercept to allow for baseline differences, with the assumption of no correlation between sites.

Potential confounding variables were identified from the pre-planned list including:

-

Gestational age at commencement of IOL (in weeks).

-

Maternal age at delivery (in years).

-

BMI at booking (or earliest record) in kg/m2.

-

Maternal medical conditions such as diabetes (pre-existing or gestational).

-

Hypertensive disorder (proteinuria, hypertension, pre-eclamptic toxaemia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia).

-

Other maternal risk factors (obstetric cholestasis, thrombophilia, in vitro fertilisation, past obstetric history).

-

Fetal concerns (fetal growth or liquor concerns, reduced fetal movement, other fetal reason).

-

ROM.

-

Smoking.

-

Deprivation.

-

Parity.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe all secondary outcomes. We described the duration of hospital stay during IOL, time spent at home, total hospital stay and time to birth using medians and interquartile ranges, while categorical outcomes such as mode of birth were described using proportions and percentages.

As outlined in the exposures section, data were reported for cohort 1 (women who had balloon cervical ripening at home), cohort 2 (women who had in-hospital cervical ripening using prostaglandin) and cohort 3 (women who had in-hospital cervical ripening using prostaglandin in a hospital that also offers home cervical ripening). Data from the larger cohort of women having IOL from 37 + 0 weeks’ gestation (population 2) and those relating specifically to in-hospital cervical ripening in units also offering home cervical ripening (cohort 3) were used to contextualise the findings on the background of unit practices and populations undergoing IOL. This was due to the considerable inter-unit variation in both the rates of IOL and the risk profile of women giving birth that needed to be considered. This helped to demonstrate the generalisability of the findings.

Missing data

We expected that up to 10% of women would have missing data on the primary outcome, eligibility criteria, setting of cervical ripening and/or have only part of the baseline data (age, comorbidities and any relevant identified hospital-level factors). Due to a lack of opportunity to put bespoke fields in place to address missing data as planned, only complete case analyses were conducted. Some of these missing fields made it difficult to identify whether women had gone home for IOL or were in hospital, and as such could not be included in the analysis data set. It is possible that, with better ability to determine which fields must be completed, we could have increased the sample size, as approximately 36% of the singleton births had insufficient detail. However, given the relative proportion of home IOL to the final complete cohort, it is still unlikely that we would have achieved sufficient power.

Additional analyses

The primary outcome was adjusted for potential confounders (as described above), but no further adjusted or subgroup analyses were performed.

Observational cohort study results

Recruitment context

Unexpectedly, the CHOICE study took place in an NHS under pressure to manage high IOL rates (range 31–49% of all births in study sites) during the COVID-19 pandemic, with long delays during the IOL process. Home cervical ripening using balloon was performed in women for a wide array of indications (low to moderate-risk groups) and from 37 weeks’ gestation onwards.

COVID-19 pandemic impact

The observational cohort study was due to commence site recruitment in spring of 2020. All sites were due to go live simultaneously. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the CHOICE study was halted from all recruitment for 10 months in total. Following the restart of research, every research and development department had differing timelines for processing of CHOICE permissions for their site, with several unable to progress these for several months. This led to much less recruitment than planned and a much later pilot analysis than planned. The pilot analysis was however carried out at the same number of site months as originally intended (156 site months). Following completion of the pilot analysis (May 2022) only one further month of data extraction was planned, thus ending data extraction on 30 June 2022. This decision was taken to ensure that the study would be completed on time, within budget and with maximal use of available data (estimated at end of data collection period to include around 25,000 cases of IOL and around 500 having cervical ripening at home using balloon methods).

The data collection period extended from 3 February 2021 to 30 June 2022, 14 days after the first ‘go live’ date as shown in Table 2.

| Site | Live date | Months live |

|---|---|---|

| NHS Borders | 23 August 2021 | 10 |

| NHS Fife | 19 August 2021 | 10 |

| NHS Grampian | 18 October 2021 | 8 |

| NHS Highland | 13 September 2021 | 9 |

| NHS Lanarkshire | 5 July 2021 | 11 |

| NHS Tayside | 19 July 2021 | 11 |

| Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Maternity) | 02 August 2021 | 10 |

| Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust | 8 March 2021 | 15 |

| Darlington Memorial Hospital | 1 April 2022 | 2 |

| University Hospital of North Durham (Maternity) | 1 April 2022 | 2 |

| Dorset County Hospital | 12 August 2021 | 10 |

| Epsom Hospital (Maternity) | 5 May 2021 | 13 |

| St Helier Hospital (Maternity) | 5 May 2021 | 13 |

| Hereford County Hospital (Maternity) | 4 May 2021 | 13 |

| Princess Royal University Hospital | 22 March 2022 | 3 |

| King’s College Hospital (Maternity) | 22 March 2022 | 3 |

| Chorley and South Ribble Hospital | 6 September 2021 | 9 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 6 September 2021 | 9 |

| Cumberland Infirmary (Maternity) | 26 July 2021 | 11 |

| West Cumberland Hospital (Maternity) | 26 July 2021 | 11 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead (Maternity) | 20 January 2021 | 17 |

| Warwick Hospital | 15 September 2021 | 9 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital Kings Lynn (Maternity) | 10 September 2021 | 9 |

| New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton (Maternity) | 15 July 2021 | 11 |

| Walsall Manor Hospital | 20 April 2022 | 2 |

| Worcestershire Royal Maternity Hospital | 7 June 2021 | 12 |

Participant flow

Participants were identified from the data transferred from BadgerNet as illustrated in Figure 1. Data for a total of 25,260 women were extracted.

Losses and exclusions

As outlined in the flowchart, seven women were excluded due to fetal death occurring before IOL started. A total of 212 women with multiple pregnancies were excluded. Additional exclusions (7284 in total) were those women where home cervical ripening would be contraindicated (previous caesarean birth, congenital fetal anomaly, abnormal CTG, breech fetal presentation, gestational age < 37 completed weeks) and those where there was no documented evidence that any cervical ripening had taken place. Further exclusions involved women where there was assumed to be a higher level of clinical risk than those who had cervical ripening at home since these women had in hospital cervical ripening in hospitals that also offered home cervical ripening (n = 7397, cohort 3). The final exclusions from the primary analysis were those women who had cervical ripening using dinoprostone at home (n = 141, cohort 4) given that these were no longer included in the primary comparison.

Data on study population

Following initial exclusions, the total number of women who were coded as having had an IOL at each site is shown in Table 3 (population 1 as per Figure 1). Following exclusion of those in whom the method of IOL could not be established, the numbers of women with confirmed method of IOL at each site are shown in Table 3 (population 2). The IOL rate at each site (calculated as a proportion of all births at each site during the study period) is shown in Table 3 where denominator data were provided by sites.

| Hospital or NHS trust | All in data set (population 1), N (%) | Confirmed inductions with or without cervical ripening (population 2), N (%) | IOL rate during CHOICE study period (% of all registerable births)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS Borders | 260 (1.0) | 170 (1.0) | 31.7 |

| NHS Fife | 1199 (4.8) | 756 (4.3) | 39.0 |

| NHS Grampian | 1190 (4.8) | 759 (4.3) | 33.0 |

| NHS Highland | 639 (2.6) | 462 (2.6) | 41.0 |

| NHS Lanarkshire | 1825 (7.4) | 1050 (6.0) | 33.5 |

| NHS Tayside | 1200 (4.8) | 753 (4.3) | Unknown |

| Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Maternity) | 1373 (5.5) | 852 (4.9) | 39.0 |

| Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust | 4063 (16.4) | 2664 (15.2) | 34.6 |

| Darlington Memorial Hospital | 156 (0.6) | 143 (0.8) | 46.3 |

| University Hospital of North Durham (Maternity) | 209 (0.8) | 164 (0.9) | 46.3 |

| Dorset County Hospital | 463 (1.9) | 387 (2.2) | 35.7 |

| Epsom Hospital (Maternity) | 896 (3.6) | 653 (3.7) | 33.3 |

| St Helier Hospital (Maternity) | 890 (3.6) | 793 (4.5) | 33.3 |

| Hereford County Hospital (Maternity) | 821 (3.3) | 585 (3.3) | 38.2 |

| Princess Royal University Hospital | 299 (1.2) | 142 (0.8) | Unknown |

| King’s College Hospital (Maternity) | 272 (1.1) | 160 (0.9) | 30.6 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 1223 (4.9) | 1070 (6.1) | 40.7 |

| Cumberland Infirmary (Maternity) | 586 (2.4) | 435 (2.5) | 36.5 |

| West Cumberland Hospital (Maternity) | 355 (1.4) | 191 (1.1) | 36.5 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead (Maternity) | 1258 (5.1) | 1009 (5.8) | 49.4 |

| Warwick Hospital | 851 (3.4) | 608 (3.5) | 34.8 |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Kings Lynn (Maternity) | 667 (2.7) | 558 (3.2) | 40.1 |

| New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton (Maternity) | 1776 (7.2) | 1380 (7.9) | 37.8 |

| Walsall Manor Hospital | 283 (1.1) | 224 (1.3) | Unknown |

| Worcestershire Royal Maternity Hospital | 2057 (8.3) | 1561 (8.9) | 41.1 |

| Total | 24,814 (100) | 17,530 (100) |

Following further exclusions (see Figure 1), the final comparison groups for the main analysis comprised 515 women who underwent home cervical ripening using balloon methods (cohort 1), 4332 women who underwent in-hospital cervical ripening using prostaglandin methods (cohort 2) and 7397 women in the additional comparison group (providing background context) who underwent in-hospital cervical ripening with prostaglandin at a site that also offered home cervical ripening (cohort 3) as shown in Table 4.

| IOL type | Mixed hospital, at home balloon cervical ripening (cohort 1), N (%) | In hospital only, prostaglandin cervical ripening (cohort 2), N (%) | Mixed hospital, in-hospital prostaglandin cervical ripening (cohort 3), N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 515 (100) | 4332 (100) | 7397 (100) |

Not all units offered cervical ripening using balloon method. The number of women undergoing balloon cervical ripening at any point during IOL by site is reported in Table 5.

| Hospital or NHS trust | Women having balloon cervical ripening at any point among all confirmed inductions (population 2), n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| NHS Borders | 93/170 (54.7) |

| NHS Fife | 12/756 (1.6) |

| NHS Grampian | 401/759 (52.8) |

| NHS Lanarkshire | 16/1050 (1.5) |

| NHS Tayside | 235/753 (31.2) |

| Ashford and St Peter’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Maternity) | 59/852 (6.9) |

| Darlington Memorial Hospital | 28/143 (19.6) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Kings Lynn (Maternity) | 27/558 (4.8) |

| University Hospital of North Durham (Maternity) | 74/164 (45.1) |

| Dorset County Hospital | 20/387 (5.2) |

| Epsom Hospital (Maternity) | 108/653 (16.5) |

| St Helier Hospital (Maternity) | 174/793 (21.9) |

| Worcestershire Royal Maternity Hospital | 6/1561 (0.4) |

| Cumberland Infirmary (Maternity) | 6/435 (1.4) |

| West Cumberland Hospital (Maternity) | 8/191 (4.2) |

| Total | 1267/9225 (13.7) |

Cervical ripening using cervical dilator was performed at two sites as shown in Table 6.

| Hospital or NHS trust | Women having cervical ripening using cervical dilator at any point among all confirmed inductions (population 2), n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Kings Lynn (Maternity) | 58/1009 (5.8) |

| Warwick Hospital | 12/608 (2.0) |

All sites used prostaglandin as a method of cervical ripening in some cases, as is shown in Table 6.

Of those in the exposed group (‘home balloon’) around 1 in 20 (24/515, 4.7%) received prostaglandin for cervical ripening after their balloon method was used.

The total number of women undergoing confirmed IOL (population 2) by parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The number of women undergoing IOL by setting (whether home or in-hospital, regardless of method) is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 3. Further breakdown of first method used in IOL (including but not exclusive to cervical ripening) by site is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 4. Median number of IOL attempts made by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 5–7. Median number of different methods used in IOL are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 8–10. Number of women having balloon method for cervical ripening at any point by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 11–13. Number of women having prostaglandin method for cervical ripening at any point by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 14–16. Number of women having non-ripening IOL methods at any point by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 17–19. Number of women having any cervical ripening method at any point by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 20–22. Subsequent method used in IOL after balloon or prostaglandin by site, parity, gestation and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 23–40. The proportion of women using more than one method of cervical ripening by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 41–43.

In all groups, the median cervical dilatation at onset of IOL was 1 cm, with an interquartile range of 0–1. A full breakdown of cervical dilatation at onset of IOL is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 44–46.

Cohort characteristics

Characteristics of women included in the exposed group (‘home balloon’), in the comparison group (‘hospital prostaglandin’) and in the background context group (women who had in-hospital cervical ripening using prostaglandin in hospitals that also offered home cervical ripening – ‘hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital’) are presented in Table 7. This demonstrated similarities across the groups with respect to maternal age, median BMI and the range of gestations at which cervical ripening was performed. Further breakdown of maternal age by site, parity, gestation and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 47–50, respectively. Further breakdown of maternal BMI by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 51–53, respectively.

| Exposed: home balloon, N = 515 | Comparison: hospital prostaglandin, N = 4332 | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin, mixed hospital, N = 7397 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity N (%) | |||

| 0 | 339 (65.8) | 2465 (56.9) | 3973 (53.7) |

| 1 | 118 (22.9) | 1131 (26.1) | 1936 (26.2) |

| 2 | 40 (7.8) | 463 (10.7) | 906 (12.2) |

| 3 + | 18 (3.5) | 273 (6.3) | 582 (7.9) |

| Gestation N (%) | |||

| 37 weeks | 50 (9.7) | 584 (13.5) | 1056 (14.3) |

| 38 weeks | 85 (16.5) | 894 (20.6) | 1547 (20.9) |

| 39 weeks | 163 (31.7) | 1267 (29.2) | 2330 (31.5) |

| 40 weeks | 81 (15.7) | 826 (19.1) | 1448 (19.6) |

| 41 weeks | 129 (25) | 753 (17.4) | 980 (13.2) |

| 42 weeks | 7 (1.4) | 8 (0.2) | 36 (0.5) |

| Maternal age (years) | Median 30 (IQR 26–34) | Median 29 (IQR 25–33) | Median 30 (IQR 26–34) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Median 26.8 (IQR 23.4–31.6) | Median 27.4 (IQR 23.6–32.2) | Median 27.0 (IQR 23.5–32.1) |

| Class III obesity n/N (%) | 24/487 (4.9) | 259/4013 (6.5) | 430/6962 (6.2) |

| Birthweight | Median 3540 g (IQR 3200–3830) | Median 3414 g (IQR 3080–3720) | Median 3380 g (IQR 3050–3710) |

| IMD N (%) | |||

| 1 | 58 (11.3) | 1239 (28.6) | 2272 (30.7) |

| 2 | 95 (18.5) | 770 (17.8) | 1709 (23.1) |

| 3 | 96 (18.7) | 920 (21.3) | 1352 (18.3) |

| 4 | 153 (29.8) | 824 (19.0) | 1206 (16.3) |

| 5 | 112 (21.8) | 573 (13.2) | 852 (11.5) |

The proportion of women in the home balloon group who were in their first pregnancy was 65.8%, while in the hospital prostaglandin group 56.9% were in their first pregnancy.

Class III obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) was present in 4.9% of women in the home balloon group and 6.5% in the hospital prostaglandin group. Further breakdown of class III obesity by site, parity, gestation and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 52–55.

The proportion of women in the home balloon group who were 41 weeks’ gestation at onset of IOL was 25%, while in the hospital prostaglandin group it was 17.4%. Respective proportions at 42 weeks’ gestation were 1.4% and 0.2%. Further breakdown of gestation by site, parity and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 56–58.

Median birth weight in the home balloon group was 3540 g compared with 3414 g in the hospital prostaglandin group. Further breakdown of birth weight by site, parity, gestation and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 59–62.

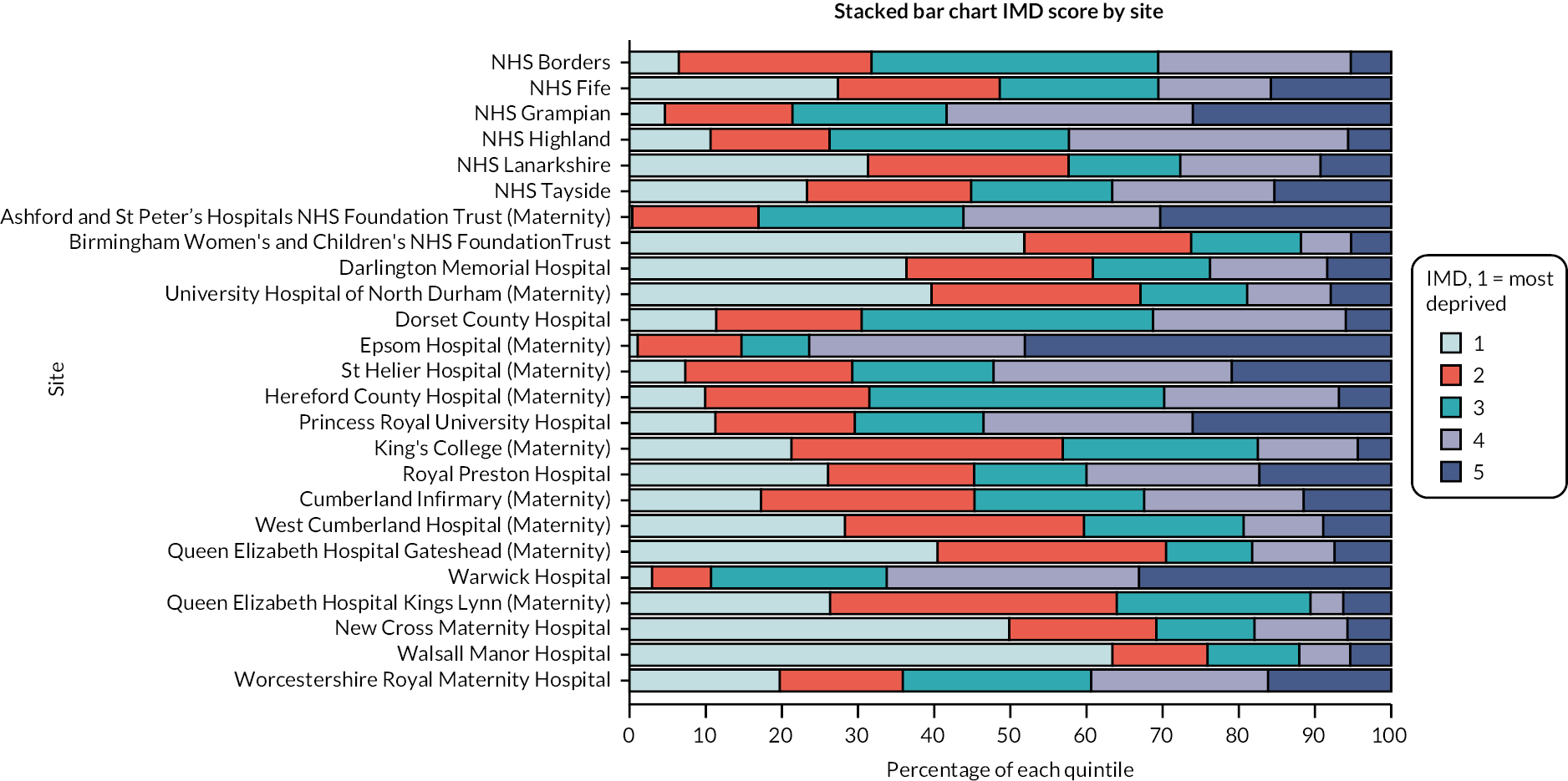

Index of multiple deprivation was 11.3% in the home balloon group being in the most deprived category compared to 28.6% in the hospital prostaglandin group. The wider group of women in the ‘hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital’ group had 30.7% of women in the most deprived category.

Index of multiple deprivation by site is indicated in Figure 2. Further breakdown of IMD by parity, gestation and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 63–74.

FIGURE 2.

CHOICE cohort study participant IMD by study site (all IOL cases with confirmed method). Chorley and South Ribble Hospital is not included in the figures as fewer than five women from the unit were included in the study population.

Indications for induction of labour

Recorded indications for IOL appeared similar across the two groups except for the expected higher proportion of ‘post dates’ indication (27.2% vs. 15.8%) reflecting the higher proportion of women beyond 41 weeks gestation in the home balloon group, as shown in Table 8. More than one indication was recorded in some cases.

| Exposed: home balloon,a n/N (%) |

Unexposed: hospital prostaglandin, n/N (%) | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital,a n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-dates | 150/515 (27.2) | 686/4332 (15.8) | 833/7397 (11.3) |

| Hypertensive disorder | 33/515 (6.4) | 361/4332 (8.3) | 583/7397 (7.9) |

| Diabetes | 59/515 (11.5) | 664/4332 (15.3) | 1050/7397 (14.2) |

| Obstetric cholestasis | 8/515 (1.6) | 103/4332 (2.4) | 191/7397 (2.6) |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | – | 11/4332 (0.3) | 50/7397 (0.7) |

| Maternal age | 14/515 (2.7) | 99/4332 (2.3) | 262/7397 (3.5) |

| Fetal concernsb | 166/515 (32.2) | 1491/4332 (34.4) | 2510/7397 (33.9) |

| Precipitate labour | – | 9/4332 (0.2) | – |

| Reduced fetal movement | 88/515 (17.1) | 895/4332 (20.7) | 1448/7397 (19.6) |

| ROM | – | 167/4332 (3.9) | 629/7397 (8.5) |

| Maternal request | 19/515 (3.7) | 70/4332 (1.62) | 200/7397 (2.7) |

| Other maternal reasons | 86/515 (16.7) | 441/4332 (10.2) | 868/7397 (11.7) |

Approximately one in three inductions (32.2% and 34.4%) were carried out due to fetal concerns in both home balloon and hospital prostaglandin groups. Fetal concerns included oligohydramnios, macrosomia, intrauterine growth, growth liquor concerns, polyhydramnios, reduced liquor volume, small gestational age, static growth, suboptimal growth, abnormal dopplers or other fetal reason.

A total of 17.1% of IOL in the home balloon group had the indication of reduced fetal movement, while 20.7% in the hospital prostaglandin group had this indication.

Diabetes was the indication for IOL in 11.5% of the home balloon group and 15.3% of the hospital prostaglandin group.

Hypertensive disorders were the indication for IOL in 6.4% of the home balloon groups and 8.3% of the hospital prostaglandin group.

Maternal age was the indication for IOL in 2.7% of the home balloon group and 2.3% of the hospital prostaglandin group.

Obstetric cholestasis was the indication for IOL in 1.6% of the home balloon group and 2.4% of the hospital prostaglandin group.

In total 3.7% of IOL were carried out due to maternal request in the home balloon group compared to 1.6% in the hospital prostaglandin group.

Further breakdown of indications for IOL by site, parity and gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 75–110.

Outcomes and estimation

Primary outcome

The total number of babies with a NNU stay within 48 hours of birth for 48 hours or more was divided by the population of babies without a NNU stay within 48 hours of birth for 48 hours of more, in the home balloon and hospital prostaglandin groups to calculate odds. The odds of the primary outcome in the home balloon group (16/499) was compared with the odds in the hospital prostaglandin group (206/4126) in the form of a ratio, as shown in Table 9. However, due to the influence of practice at various sites, this odds ratio was adjusted for site.

| Home balloon, n/N (%) | Hospital prostaglandin, n/N (%) | Bivariate odds ratio (95% CI),a N = 4847 | Multivariable odds ratio (95% CI),b N = 4366 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NNU admission for at least 48 hours within 48 hours of birth | 16/515 (3.1) | 206/4332 (4.8) | 0.75 (0.35 to 1.64) | 0.81 (0.36 to 1.81) |

While adjusting for nothing other than site, the odds ratio of the primary outcome for home balloon to hospital prostaglandin is 0.75. This means that the chances of the primary outcome (NNU admission for 48 hours or more within 48 hours of birth) in the home balloon group are lower than in the hospital prostaglandin group, by 25%. Even with the adjustment for other potentially confounding factors, this remains similar (at 19% lower in home balloon group than hospital prostaglandin group). However, as expected, the 95% CI is quite large, meaning that the true odds ratio of home balloon to hospital prostaglandin groups could theoretically be between about one-third (0.36 or 74% lower odds) to almost twice as much (1.81 or 81% higher odds).

The effect of potential confounding factors was explored by including them in a multivariable model. The results are shown in Table 10. Most potential confounding factors had adjusted odds ratios of close to one, with confidence intervals crossing unity, indicating little influence on the primary outcome. However, women who had given birth to one or two previous babies had lower odds of the primary outcome than women with no previous births. Women in the third quintile of deprivation (IMD 3) had lower odds of the primary outcome than women in the most deprived quintile.

| n/N (%) | Multivariable odds ratio (95% CI), N = 4366 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gestation (weeks – referent 37 weeks) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.99) | |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 135/2549 (5.3) | Reference |

| 1 | 31/1107 (2.8) | 0.46 (0.31 to 0.70) |

| 2 | 8/458 (1.8) | 0.25 (0.12 to 0.53) |

| 3 + | 9/252 (3.6) | 0.50 (0.24 to 1.04) |

| Maternal age (year) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) | |

| Booking BMI (n = 4500) (kg/m2) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) | |

| Hypertension | ||

| None | 163/3831 (4.3) | Reference |

| Hypertension | 20/535 (3.7) | 0.71 (0.43 to 1.18) |

| Diabetes | ||

| None | 143/3616 (4.0) | Reference |

| Diabetes | 40/750 (5.3) | 1.17 (0.77 to 1.78) |

| Other maternal risk factor a | ||

| None | 176/4151 (4.2) | Reference |

| Maternal risk factora | 7/215 (3.3) | 0.66 (0.30 to 1.48) |

| Fetal risks b | ||

| None | 131/2875 (4.6) | Reference |

| Fetal riskb | 52/1471 (3.5) | 0.72 (0.47 to 1.09) |

| Reduced fetal movement | ||

| None | 144/3484 (4.1) | Reference |

| Reduced fetal movement | 39/882 (4.4) | 0.98 (0.66 to 1.46) |

| Other fetal concerns c | ||

| None | 169/3907 (4.3) | Reference |

| Other fetal concernsc | 14/459 (3.1) | 0.86 (0.46 to 1.61) |

| Prelabour ruptured membranes | ||

| None | 171/4219 (4.1) | Reference |

| Prelabour ruptured membranes | 12/147 (8.2) | 1.54 (0.80 to 2.97) |

| Smoking status at booking | ||

| Non-smoker | 162/3855 (4.2) | Reference |

| Smoker | 21/511 (4.1) | 1.18 (0.72 to 1.93) |

| IMD | ||

| 1 (most deprived) | 56/1138 (4.9) | Reference |

| 2 | 33/782 (4.2) | 0.90 (0.57 to 1.41) |

| 3 | 24/911 (2.6) | 0.54 (0.32 to 0.90) |

| 4 | 37/903 (4.1) | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.33) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 33/632 (5.2) | 1.11 (0.68 to 1.84) |

Further breakdown of the primary outcome by gestation are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 111 and 112.

Of the 7397 women in the hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital group, 556 (7.52%) experienced the primary outcome.

Of the 141 women who had home cervical ripening with dinoprostone (Propess®, FerringPharmaceuticals, West Drayton, UK) prostaglandin (cohort 4 in the flowchart in Figure 1, and the original exposure before pilot analysis), 10 experienced the primary outcome, a proportion of 7.09%.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary maternal outcomes compared by exposure group are reported in Table 11. Postpartum haemorrhage of 1000 ml or more occurred in similar proportions in all groups at 11–12%. Third- or fourth-degree perineal tears affected around 1 in 50 women in each group. Maternal pyrexia was reported in 1.75% of home balloon cases and 1.4% hospital prostaglandin cases.

| Home balloon, N = 515 (%) | Hospital prostaglandin, N = 4332 (%) | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital, N = 7397 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum haemorrhage ≥ 1000 ml | 65 (12.6) | 482 (11.1) | 866 (11.7) |

| Third- or fourth-degree perineal tear | 11 (2.1) | 86 (2.0) | 141 (1.9) |

| Maternal pyrexia in labour | 9/515 (1.8) | 59/4332 (1.4) | 188/7397 (2.5) |

Further breakdown of postpartum haemorrhage over 1000 ml by site and setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 113 and 114. Further breakdown of maternal pyrexia and retained placenta by setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 115 and 116, respectively.

Neonatal care admission affected around 8% of babies in both home balloon and hospital prostaglandin groups. In the hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital group (cohort 3 in the flow diagram in Figure 1), the proportion of babies admitted to neonatal care was 14%, as shown in Table 12. Median Apgar scores were the same across the three groups. Further breakdown of Apgar scores by setting are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 117–121. Further breakdown of NNU admission by setting is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 122.

| At home balloon | Hospital prostaglandin | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal care admission (any) n/N (%) | 40/515 (7.8) | 371/4332 (8.6) | 1049/7397 (14.2) |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes | Median 9 (IQR 9–9), N = 511 | Median 9 (IQR 9–10), N = 4323 | Median 9 (IQR 9–10), N = 4331 |

| Apgar score at 10 minutes | Median 9 (IQR 9–9), N = 44 | Median 9 (IQR 9–10), N = 558 | Median 9 (IQR 9–10), N = 1296 |

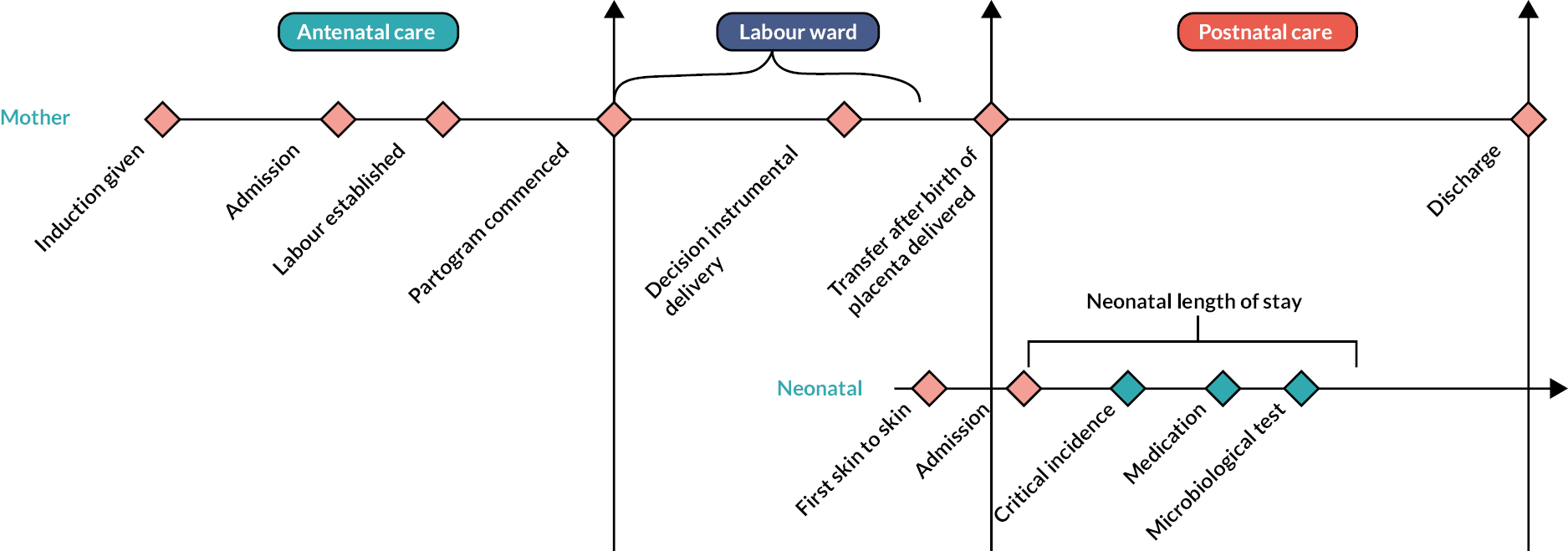

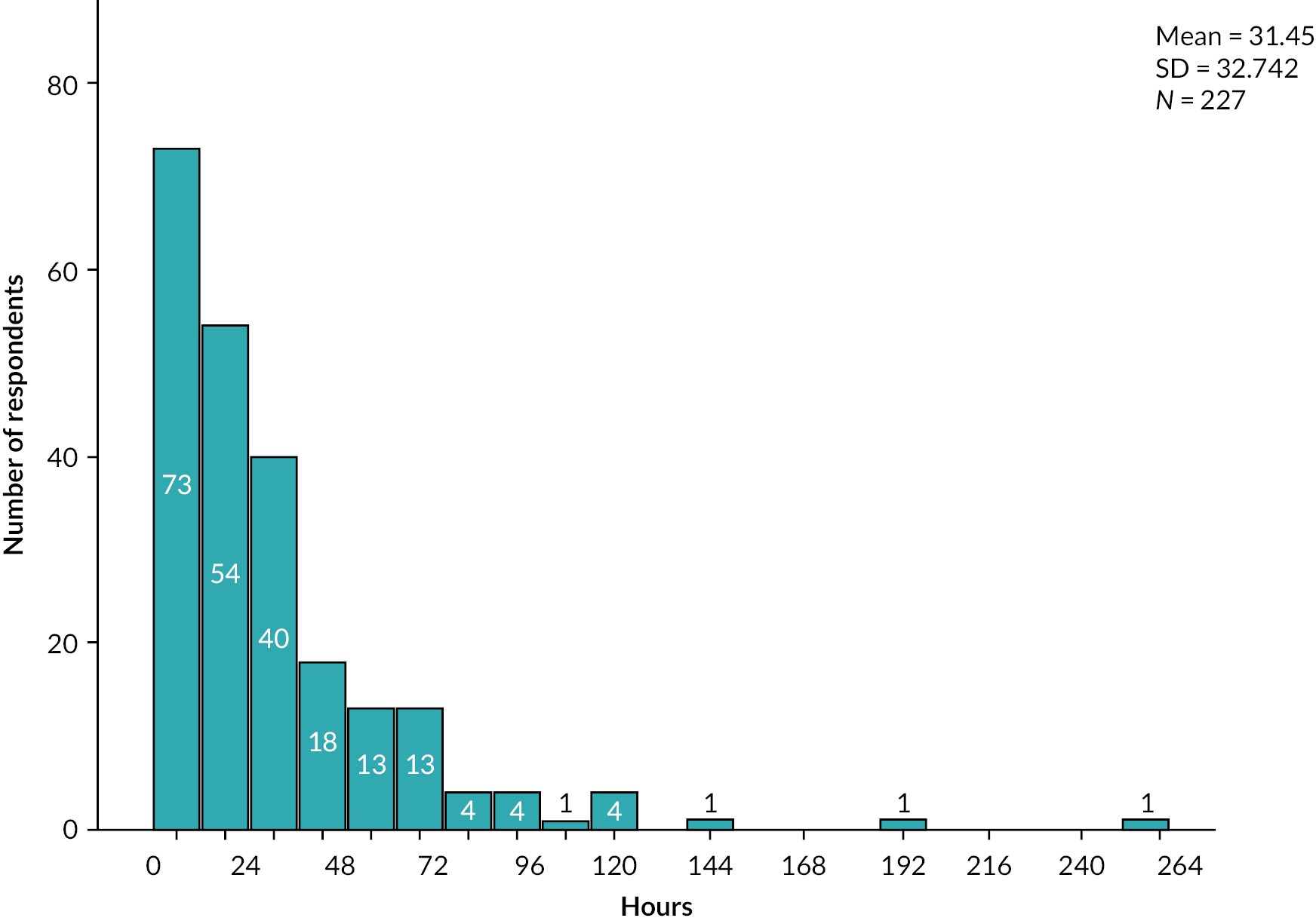

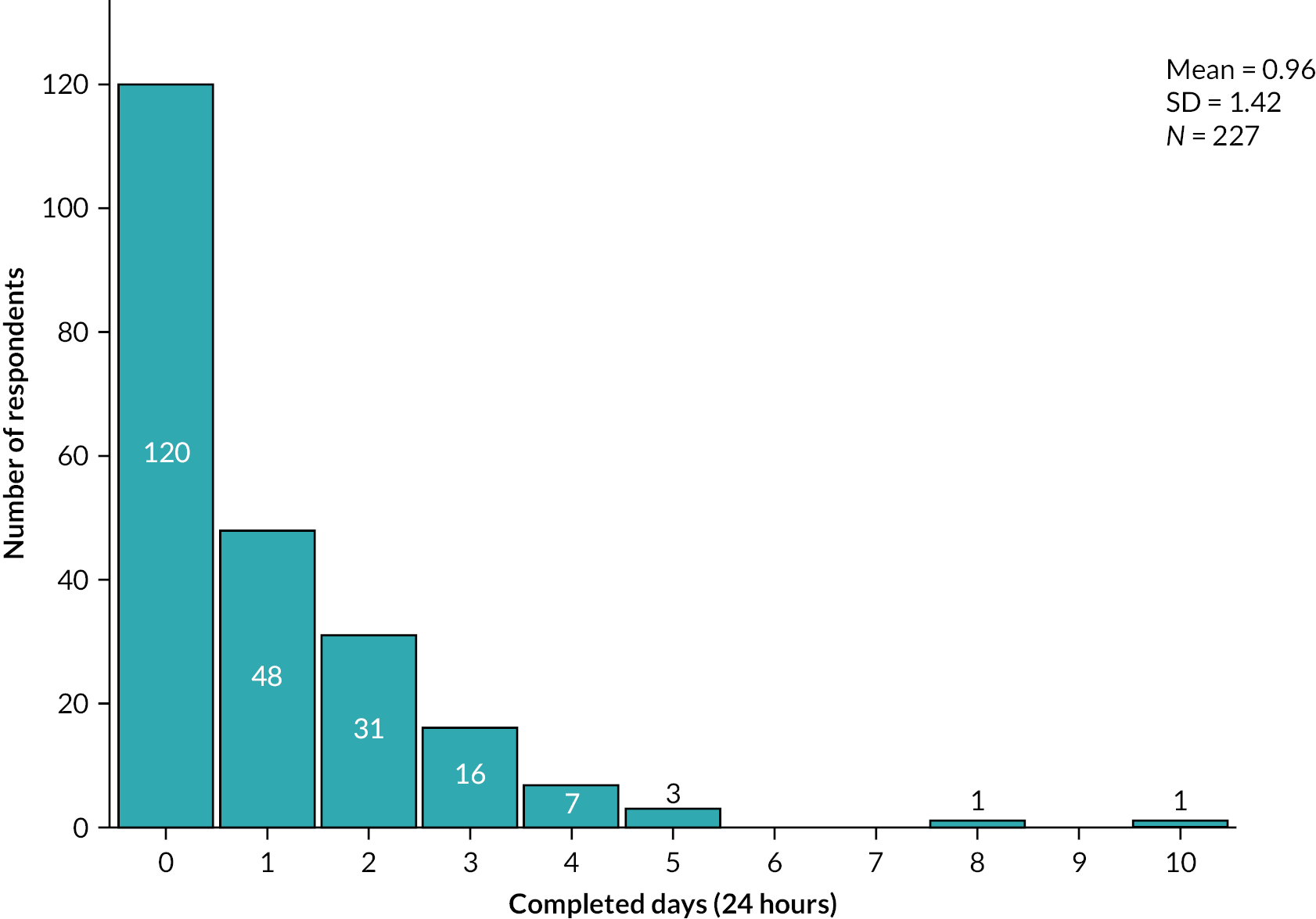

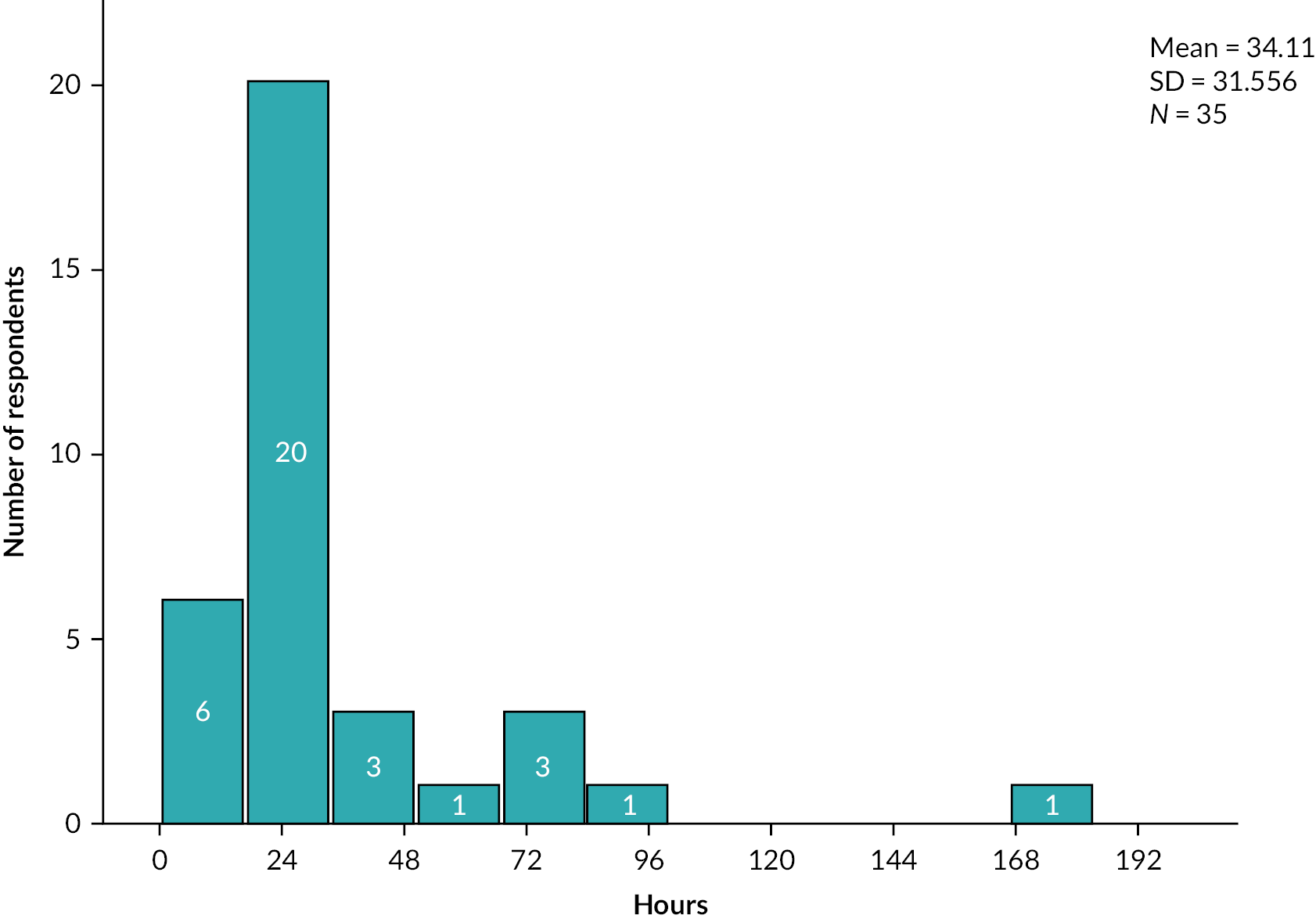

Describing induction of labour practice

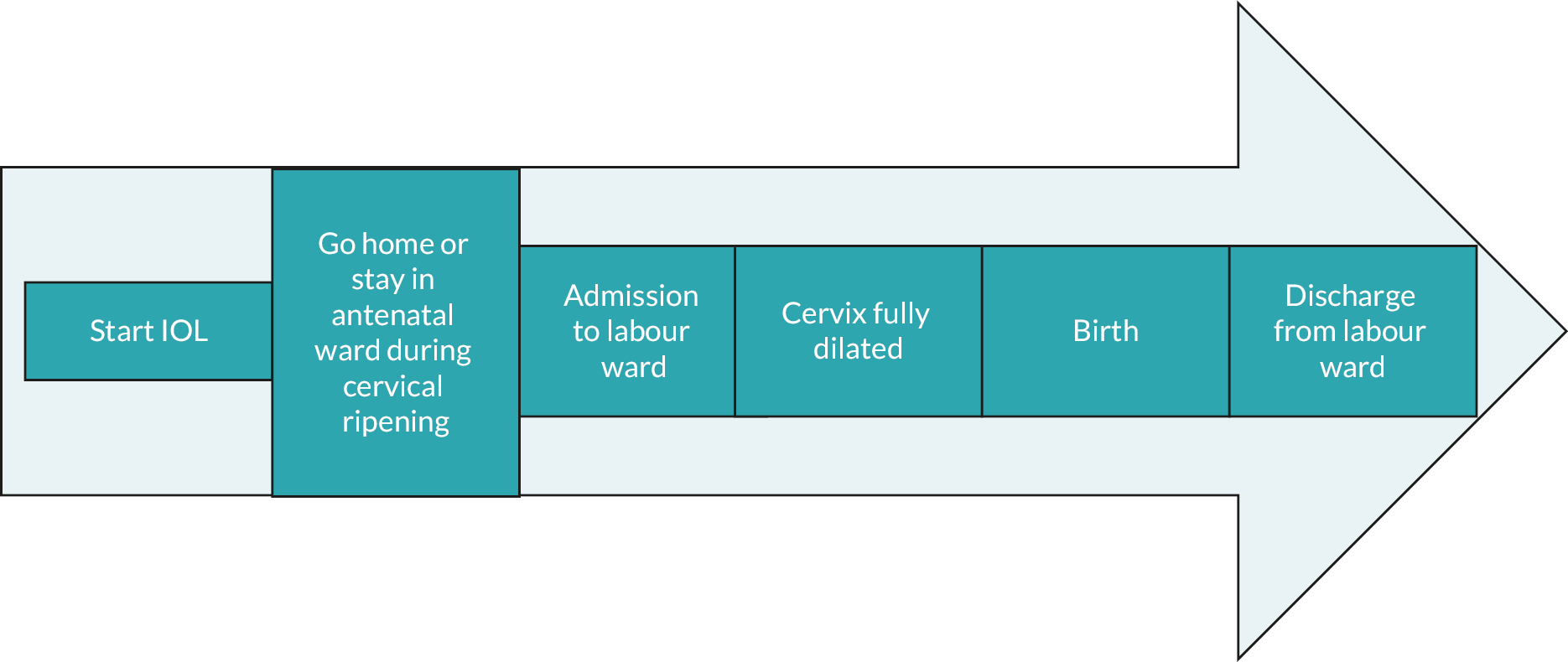

As shown in Figure 3, each induced labour follows a pattern of phases. The duration of each distinct phase (based upon location and labour events) is shown in Table 13. This shows that the home balloon group had an average duration of labour from IOL onset to birth of 2574 minutes (IQR 1777–3978 minutes) while the hospital prostaglandin group had a duration of 1906 minutes (IQR 1042–3514 minutes). These durations are broken down as follows: the home balloon group took 1875 minutes (IQR 1181–3080 minutes) to reach labour ward care while the hospital prostaglandin group took 1490 minutes (IQR 745–2915 minutes). The home balloon group took 624 minutes (IQR 383–950 minutes) to get from labour ward entry to birth, while the hospital prostaglandin group took 376 minutes (IQR 144–691 minutes). The average duration of the second stage of labour (from full dilatation of the cervix to birth) was 66 minutes (IQR 16–150 minutes) in the home balloon group and 29 minutes (IQR 9–96 minutes) in the hospital prostaglandin group. Women in the home balloon group spent on average 1043 minutes at home during cervical ripening.

FIGURE 3.

Simple timeline of potential events during IOL.

| Phase of labour | Home balloon, median minutes (IQR) | Hospital prostaglandin, median minutes (IQR) | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital, median minutes (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOL onset to entry to labour warda | 1875 (1181–3080), N = 487 | 1490 (745–2915), N = 3565 | 1215 (650–2390), N = 5997 | |

| IOL onset to entry to labour warda by parity | Parity 0 | 1960 (1335–3130), N = 323 | 1618 (830–3060), N = 2038 | 1341 (709–2650), N = 3317 |

| Parity 1 | 1804.0 (1050–2955), N = 110 | 1337 (645–2733), N = 921 | 1052 (572–1945), N = 1522 | |

| Parity 2 | 1815.5 (1007–2998), N = 36 | 1211 (630–2625), N = 378 | 1115 (6510–2260), N = 698 | |

| Parity 3 + | 1887 (1141–3021), N = 18 | 1273 (667–2825), N = 228 | 1154 (586–2228), N = 460 | |

| IOL onset to entry to labour warda by gestation at induction onset | 37 weeks | 1995 (1288–3807), N = 47 | 1805 (859–3415), N = 461 | 1481 (705–2712), N = 838 |

| 38 weeks | 1875 (1050–3344), N = 83 | 1753 (881–3445), N = 712 | 1373 (677–2500), N = 1235 | |

| 39 weeks | 2130 (1280–3030), N = 157 | 1548 (810–3075), N = 1051 | 1336 (695–2740), N = 1866 | |

| 40 weeks | 1920 (1102–3575), N = 77 | 1258 (692–2619), N = 698 | 1025 (593–1995), N = 1205 | |

| 41 weeks | 1643 (1169–2808), N = 116 | 1115 (640–2300), N = 637 | 990 (577–1758), N = 826 | |

| 42 + weeks | 1800 (1365–3312), N = 7 | 1893 (750–2850), N = 6 | 785 (575–1551), N = 27 | |

| IOL onset to cervix fully dilated | 2285 (1638–3691), N = 324 | 1657 (910–3045), N = 2941 | 1411 (830–2497), N = 4910 | |

| IOL onset to cervix fully dilated by parity | Parity 0 | 2463 (1805–3860), N = 186 | 1858 (1070–3245), N = 1513 | 1660 (1005–2835), N = 2355 |

| Parity 1 | 2103 (1360–3300), N = 94 | 1423 (760–2724), N = 876 | 1166 (712–2118), N = 1490 | |

| Parity 2 | 2062 (1365–2919), N = 30 | 1395 (710–2760), N = 350 | 1190 (720–2230), N = 655 | |

| Parity 3 + | 2208 (1735–3384), N = 14 | 1387 (755–3010), N = 202 | 1197 (715–2205), N = 410 | |

| IOL onset to cervix fully dilated by gestation at induction onset | 37 weeks | 2340 (1740–4507), N = 35 | 1916 (950–3490), N = 394 | 1667 (890–2895), N = 701 |

| 38 weeks | 2310 (1435–3789), N = 59 | 1873 (1050–3638), N = 616 | 1555 (895–2647), N = 1021 | |

| 39 weeks | 2519 (1804–3644), N = 104 | 1773 (995–3196), N = 878 | 1465 (850–2615), N = 1591 | |

| 40 weeks | 2275 (1615–3653), N = 52 | 1491 (803–2535), N = 557 | 1238 (750–2165), N = 962 | |

| 41 weeks | 2025 (1495–3300), N = 69 | 1240 (785–2323), N = 493 | 1240 (750–2040), N = 618 | |

| 42 + weeks | 1635.0 (1435–4302), N = 5 | < 5 | 1138 (690–1700), N = 17 | |

| Entry to labour ward to birtha | 624 (383–950), N = 487 | 376 (144–691), N = 3565 | 412 (168–723), N = 5997 | |

| Entry to labour ward to birtha by parity | Parity 0 | 741 (488–1033), N = 323 | 544 (258, 833), N = 2038 | 568 (299–858), N = 3317 |

| Parity 1 | 434 (281–687), N = 110 | 223 (85–444), N = 921 | 238 (85–479), N = 1522 | |

| Parity 2 | 459 (330–677), N = 36 | 210 (73–438), N = 378 | 238 (90–486), N = 698 | |

| Parity 3 + | 344 (235–567), N = 18 | 260 (85–477), N = 228 | 257 (102–481), N = 460 | |

| Full dilation of cervix to birth | 66 (16–150), N = 324 | 29 (9–96), N = 2941 | 29 (10–105), N = 4910 | |

| Full dilation of cervix to birth by parity | Parity 0 | 116 (59–181), N = 186 | 76 (30–154), N = 1513 | 85 (31–171), N = 2355 |

| Parity 1 | 20 (7–82), N = 94 | 12 (5–29), N = 876 | 14 (6–38), N = 1490 | |

| Parity 2 | 12 (6–19), N = 30 | 8 (4–20), N = 350 | 9 (4–24), N = 655 | |

| Parity 3 + | 8 (5–17), N = 14 | 6 (3–18), N = 202 | 8 (3–19), N = 410 | |

| Full dilation of cervix to birth by gestation at induction onset | 37 weeks | 19 (7–118), N = 35 | 20 (7–58), N = 394 | 18 (7–67), N = 701 |

| 38 weeks | 27 (10–106), N = 59 | 25 (7–90), N = 616 | 26 (8–89), N = 1021 | |

| 39 weeks | 82 (17–159), N = 104 | 30 (10–99), N = 878 | 30 (9–110), N = 1591 | |

| 40 weeks | 71 (22–143), N = 52 | 31 (10–97), N = 557 | 36 (11–119), N = 962 | |

| 41 weeks | 94 (20–162), N = 69 | 42 (14–119), N = 493 | 52 (14–140), N = 618 | |

| 42 + weeks | 87 (60–165), N = 5 | – | 29 (10–105), N = 4910 | |

| Induction start to birth | 2574 (1777–3978), N = 515 | 1906 (1042–3514) N = 4332 | 1649 (934–2935), N = 7397 | |

| Induction start to birth | Parity 0 | 2791 (1920–4215), N = 339 | 2210 (1284–3928), N = 2465 | 2009 (1213–3374), N = 3973 |

| Parity 1 | 2315 (1426–3387), N = 118 | 1485 (807–2881), N = 1131 | 1228 (724–2247), N = 1936 | |

| Parity 2 | 2165 (1352–3017), N = 40 | 1461 (766–2859), N = 463 | 1285 (753–2419), N = 906 | |

| Parity 3 + | 2231 (1744–3386), N = 18 | 1514 (772–3188), N = 273 | 1295 (727–2426), N = 582 | |

| Induction start to birth | 37 weeks | 2623 (1857–4693), N = 50 | 2111 (1059–4099), N = 584 | 1842 (979–3173), N = 1056 |

| 38 weeks | 2519 (1676–4019), N = 85 | 2173 (1147–4161), N = 894 | 1813 (990–3141), N = 1547 | |

| 39 weeks | 2780 (1993–4007), N = 163 | 1992 (1096–3747), N = 126 | 1695 (935–3197), N = 2330 | |

| 40 weeks | 2427 (1704–4072), N = 81 | 1702 (945–3051), N = 826 | 1483 (880–2622), N = 1448 | |

| 41 weeks | 2309 (1541–3589), N = 129 | 1607 (912–2809), N = 753 | 1495 (868–2435), N = 980 | |

| 42 + weeks | 1977 (1632–4467), N = 7 | 2624 (954–3560), N = 8 | 1271 (826–2164), N = 36 | |

| Discharge during balloon cervical ripening at home | 1043.5 (642.00–1683.0), N = 110 | N/A | N/A | |

| Last admission to birth during balloon cervical ripening at home | 802 (510–1184), N = 493 | N/A | N/A | |

| Birth to discharge from labour ward care | 2075 (1356–2959), N = 514 | 1691 (1015–2554), N = 4225 | 2026 (1401–3071), N = 7350 |

Similar findings were observed when broken down by parity. For first births, the average total time from IOL onset to entry to labour ward was 1960 minutes (IQR 1335–3130 minutes) in the home balloon group and 1617 minutes (IQR 830–3060 minutes) in the hospital prostaglandin group. From labour ward entry to birth duration was 741 minutes (IQR 488–1033 minutes) in the home balloon group and 544 minutes in the hospital prostaglandin group.

Further breakdown of duration of each phase of labour by site, parity, gestation and setting is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 123–150.

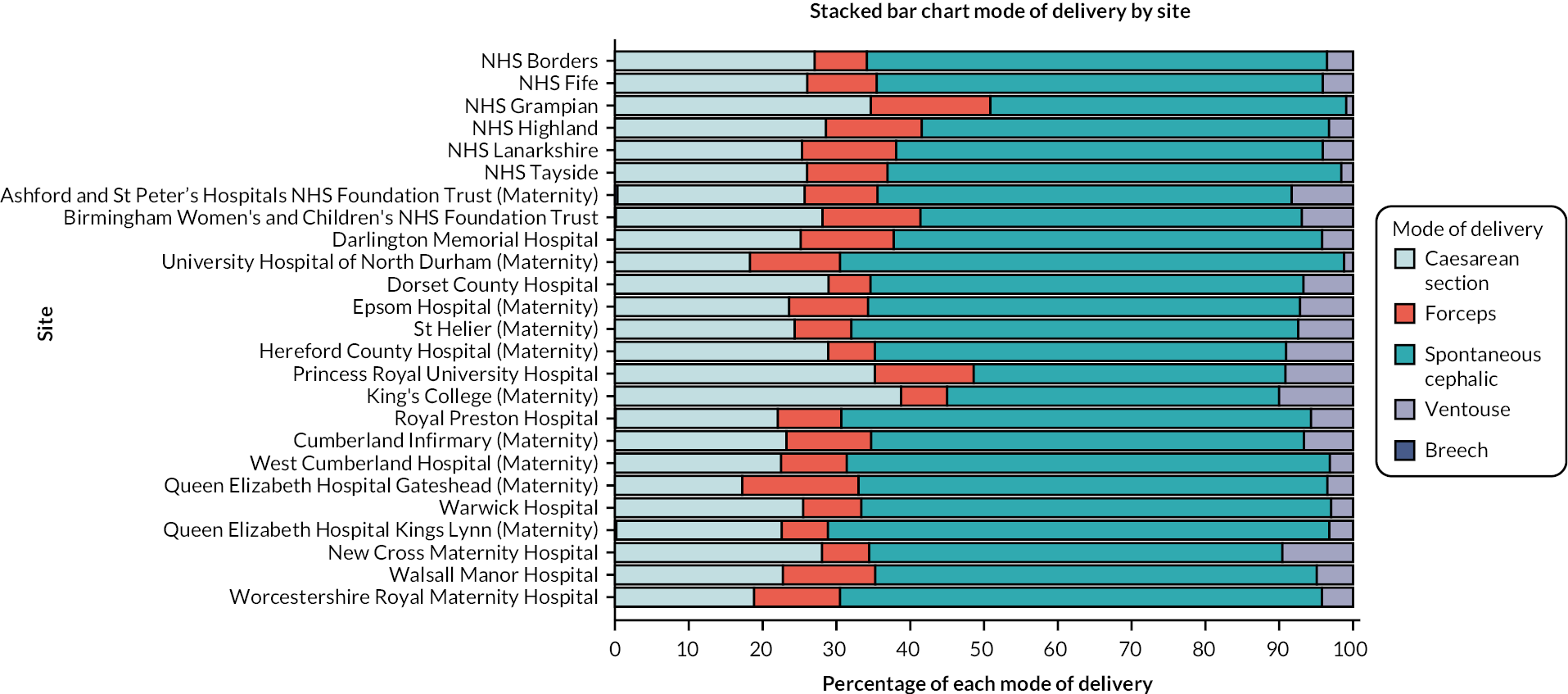

Breakdown of type of birth by exposure and comparison groups is provided in Table 14.

| Type of birth | Home balloon, N = 515 (%) | Hospital prostaglandin, N = 4332 (%) | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital, N = 7397 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unassisted vaginal birth | 259 (50.3) | 2509 (57.9) | 4151 (56.1) |

| Caesarean birth | 175 (34.0) | 1174 (27.1) | 1995 (27.0) |

| Forceps | 74 (14.4) | 395 (9.1) | 808 (10.9) |

| Ventouse | 7 (1.4) | 254 (5.9) | 436 (5.9) |

Type of birth in all IOL with known method (population 2) by site is shown in Figure 4 and type of birth by cohort and site is shown in Table 15. The breakdown of birth type by parity and gestation are shown in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 151–159.

FIGURE 4.

CHOICE cohort type of birth following confirmed IOL by study site.

| Study site | Birth type | Home balloon, N = 515 (%) | Hospital prostaglandin, N = 4332 (%) | Background context group: hospital prostaglandin – mixed hospital, N = 7397 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS Borders | Unassisted vaginal | 19 (57.6) | – | 17 (56.7) |

| Forceps assisted | < 5 | – | < 5 | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | < 5 | |

| Caesarean | 10 (30.3) | – | 11 (36.7) | |

| NHS Fife | Unassisted vaginal | – | 372 (59.0) | – |

| Forceps assisted | – | 58 (9.2) | – | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | 25 (4.0) | – | |

| Caesarean | – | 176 (27.9) | – | |

| NHS Grampian | Unassisted vaginal | 111 (47.2) | – | 25 (24.0) |

| Forceps assisted | 43 (18.3) | – | 13 (12.5) | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | < 5 | |

| Caesarean | 79 (33.6) | – | 63 (60.6) | |

| NHS Highland | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 167 (50.0) |

| Forceps assisted | – | – | 48 (14.4) | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | – | 10 (3.0) | |

| Caesarean | – | – | 109 (32.6) | |

| NHS Lanarkshire | Unassisted vaginal | < 5 | – | 443 (55.8) |

| Forceps assisted | < 5 | – | 103 (13.0) | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | 32 (4.0) | |

| Caesarean | < 5 | – | 216 (27.2) | |

| NHS Tayside | Unassisted vaginal | 89 (49.2) | – | 41 (50.6) |

| Forceps assisted | 21 (11.6) | – | 9 (11.1) | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | < 5 | |

| Caesarean | 69 (38.1) | – | 30 (37.0) | |

| Ashford and St Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 339 (54.9) |

| Forceps assisted | – | – | 59 (9.5) | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | – | 54 (8.7) | |

| Caesarean | – | – | 164 (26.5) | |

| Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 1190 (52.1) |

| Forceps assisted | – | – | 289 (12.6) | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | – | 158 (6.9) | |

| Caesarean | – | – | 646 (28.3) | |

| Darlington Memorial Hospital | Unassisted vaginal | 6 (54.5) | – | 26 (41.9) |

| Forceps assisted | < 5 | – | 10 (16.1) | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | < 5 | |

| Caesarean | < 5 | – | 22 (35.5) | |

| University Hospital of North Durham (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | 28 (65.1) | – | < 5 |

| Forceps assisted | 5 (11.6) | – | < 5 | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | < 5 | |

| Caesarean | 10 (23.3) | – | < 5 | |

| Dorset County Hospital | Unassisted vaginal | – | 144 (53.3) | – |

| Forceps assisted | – | 16 (5.9) | – | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | 17 (6.3) | – | |

| Caesarean | – | 93 (34.4) | – | |

| Epsom Hospital (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | < 5 | – | 103 (62.4) |

| Forceps assisted | < 5 | – | 10 (6.1) | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | 13 (7.9) | |

| Caesarean | < 5 | – | 39 (23.6) | |

| St Helier Hospital (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | < 5 | – | 208 (67.3) |

| Forceps assisted | < 5 | – | 15 (4.9) | |

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | – | 18 (5.8) | |

| Caesarean | < 5 | – | 68 (22.0) | |

| Hereford County Hospital (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 268 (54.1) |

| Forceps assisted | – | – | 30 (6.1) | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | – | 46 (9.3) | |

| Caesarean | – | – | 151 (30.5) | |

| Princess Royal University Hospital | Unassisted vaginal | – | 59 (41.8) | – |

| Forceps assisted | – | 19 (13.5) | – | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | 13 (9.2) | – | |

| Caesarean | – | 50 (35.5) | – | |

| King’s College Hospital (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 51 (44.0) |

| Forceps assisted | – | – | 8 (6.9) | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | – | 9 (7.8) | |

| Caesarean | – | – | 48 (41.4) | |

| Royal Preston Hospital | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 554 (64.2) |

| Forceps assisted | – | – | 70 (8.1) | |

| Ventouse assisted | – | – | 54 (6.3) | |

| Caesarean | – | – | 184 (21.3) | |

| Cumberland Infirmary (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | – | 165 (56.7) | – |

| Forceps assisted | 34 (11.7) | |||

| Ventouse assisted | 15 (5.2) | |||

| Caesarean | 77 (26.5) | |||

| West Cumberland Hospital (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | – | 40 (60.6) | – |

| Forceps assisted | 7 (10.6) | |||

| Ventouse assisted | < 5 | |||

| Caesarean | 17 (25.8) | |||

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead (Maternity) | Unassisted vaginal | – | – | 473 (63.7) |

| Forceps assisted | 115 (15.5) | |||

| Ventouse assisted | 22 (3.0) | |||

| Caesarean | 133 (17.9) | |||

| Warwick Hospital | Unassisted vaginal | – | 281 (63.1) | – |