Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/13/02. The contractual start date was in April 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in October 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Santer et al. This work was produced by Santer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Santer et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced with permission from Renz et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Acne vulgaris (hereon acne) is one of the most common inflammatory dermatoses seen globally. 2 Acne typically starts in adolescence with 15–20% of people affected showing moderate or severe acne, often persisting to adulthood. 3 Acne induced scarring occurs in approximately 20% of people with acne and negative social and psychological impact can be substantial. 4,5 The prevalence of acne in adult women is considerable6–10 and results in substantial health service use. 11

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance recommends topical combination preparations containing retinoids, benzoyl peroxide or antibiotics as first line treatment for mild/moderate acne or, for moderate/severe acne, a combination treatment alone or together with oral lymecycline or doxycycline. 12 The NICE guideline recommends that treatment regimens that include an antibiotic (topical or oral) should not be continued for more than 6 months unless exceptional circumstances apply, although other guidelines limit the use of oral antibiotics to 3 months. 13–15

In the UK, oral isotretinoin can be used under the supervision of a dermatologist for indications including severe acne, such as acne at risk of scarring that has not responded to other recommended treatments. Oral isotretinoin is a highly effective treatment for acne but may be contraindicated or deemed unacceptable by some due to concerns about potential serious adverse effects and teratogenicity, which requires robust pregnancy prevention management. In addition, referrals from primary to secondary care for oral isotretinoin often involve long waits, a situation worsened by the impact on health services of the coronavirus pandemic.

A third of people who consult with acne are prescribed prolonged courses of oral antibiotics16 and acne has been shown to account for the majority of antibiotic exposure amongst young people. 17 This may be because people with acne find topical treatments difficult to use, or experience side effects such as stinging or redness (although these can be mitigated with appropriate advice). 16 Sebum is integral to acne pathogenesis, yet antibiotics have no effect on sebum production18 and are therefore less effective than is sometimes estimated by clinicians19 and patients. 20 Rising rates of antibiotic resistance mean that non-antibiotic alternatives are urgently needed. 21,22

Spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic, is widely used in the UK for indications including hypertension23 and has been prescribed off licence for women with acne for many years due to its anti-androgenic properties. US and European Guidelines suggest a role for spironolactone in the management of female acne. 13,14 Spironolactone is more widely used in the USA, where database studies have shown that women who have taken spironolactone for acne were found to receive almost three fewer months of oral antibiotics than those who were not. 24 However, despite expert opinion suggesting spironolactone has a role in acne management, systematic reviews have highlighted a paucity of high-quality evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 25,26

This trial aimed to answer whether spironolactone improves acne-related quality of life (QoL) in adult women with persistent facial acne compared to placebo. As we wished to evaluate spironolactone as it would be used in a real-life context in the clinical pathway, we chose a pragmatic trial design, which included concomitant use of topical treatments in both groups.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

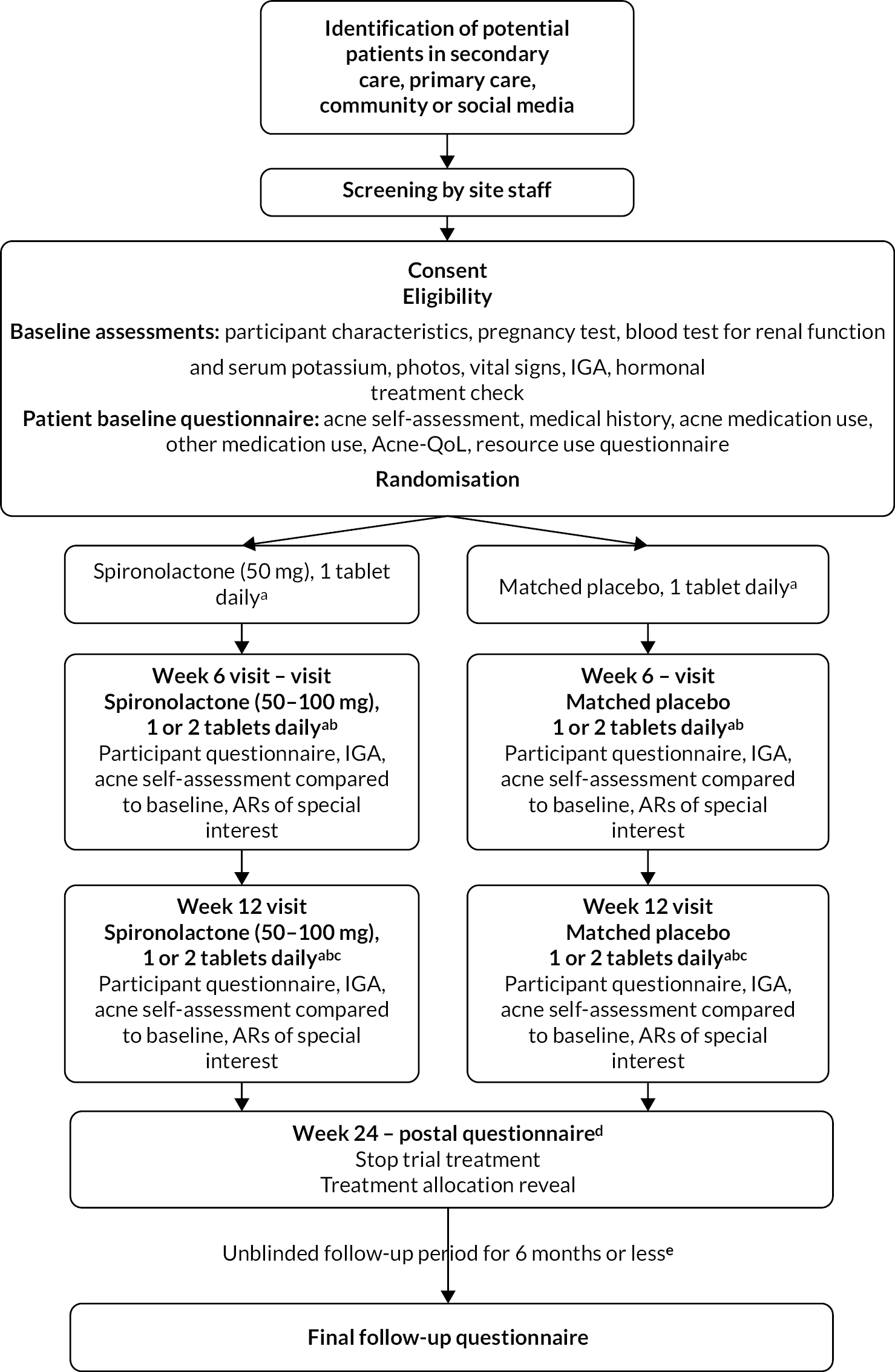

The spironolactone for adult female acne (SAFA) trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, double-blind, superiority RCT with two (1 : 1) parallel treatment groups – spironolactone plus standard topical therapy compared to placebo plus standard topical therapy – to investigate the clinical effectiveness (see Chapter 3) and cost-effectiveness (see Chapter 4) of spironolactone for persistent facial acne. A pragmatic trial design was chosen in order to test the intervention in a population as similar as possible to the context in which the intervention would be used clinically. 27,28 We therefore chose a participant-reported outcome measure, allowed concomitant use of topical treatments and pursued follow-up for as long a duration as possible. Because we wished to include clinically important outcomes to inform decision-making by health professionals and patients, we also looked systematically for adverse effects. The trial protocol paper was published in a peer-reviewed journal1 and is available in full (see www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/13/02). The study design is represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow diagram. AR, adverse reaction; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment. a, Allow use of topical therapy (creams/lotions/gels). b, Escalate dose if study tablet is tolerated, otherwise maintain on 1 tablet. c, Option to add antibiotic taken by mouth/change topical therapy if response to study tablet is inadequate. d, Participants in either arm may seek to use spironolactone or other acne treatments after this time. e, All participants are followed up until the last participant has reached week 24 after baseline.

Ethical approval for the trial was given by Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 in January 2019 (18/WA/0420). The trial was registered prospectively ISRCTN (ISRCTN12892056) and EudraCT (2018-003630-33).

Changes to protocol

Ethical approval for the trial was given by Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 in January 2019 (reference number: 18/WA/0420). The trial is registered on ISRCTN (ISRCTN12892056) and EudraCT (2018-003630-33). A table of changes made to the protocol is given in Appendix 1 (see Table 41). These can be summarised as:

-

clarification of exclusion criteria

-

changes to social media recruitment strategy

-

changes to recruitment material to attempt to improve response rates to mail-out (including development of brief summary sheet in addition to full participant information sheet, signposting to video)

-

adaptations to allow retention of research participants during COVID through flexible trial procedures, clinical trials unit (CTU) taking over some roles from recruiting sites and subsequent changes to reopen to recruitment following COVID

-

downward revision of target sample size to reflect the correlation of the Acne-Specific Quality of Life (Acne-QoL) subscale at 12 weeks with baseline

-

addition of qualitative substudy [not funded by Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and not reported further here].

Participants’ eligibility criteria

Participants were invited through primary care, secondary care and advertising through community and social media, and trial procedures were carried out in secondary care (further details below).

Eligibility criteria reflected safety (i.e. contraindications to spironolactone treatment, including intention to become pregnant), likely appropriateness of use of spironolactone to reflect real life context (e.g. acne sufficient to warrant oral treatment, not previously used spironolactone) and recent changes to therapy that may have impacted on acne (e.g. starting or stopping hormonal treatment within past 3 months).

Inclusion criteria

-

Women aged 18 years or over.

-

Facial acne vulgaris, symptoms present since at least 6 months.

-

Acne of sufficient severity to warrant treatment with oral antibiotics, as judged by the trial clinician; women with an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) ≥ 2 were eligible to participate in the trial.

-

Women of childbearing potential at risk of pregnancy must be willing to use their usual hormonal or barrier method of contraception for the first 6 months of the trial [while taking the trial investigational medicinal product (IMP)] and for at least 4 weeks (approximately one menstrual cycle) afterwards.

-

Willing to be randomised to either treatment.

-

Willing and able to give informed consent.

-

Sufficient English to carry out primary care Acne-QoL.

Exclusion criteria

-

Acne grades 0–1 using IGA (i.e. clear or almost clear).

-

Has ever taken spironolactone.

-

Oral antibiotic treatment (lasting longer than 1 week) for acne within the past month.

-

Oral isotretinoin treatment within the past 6 months.

-

Started, stopped or changed long-term (lasting more than 2 weeks) hormonal contraception, co-cyprindiol or other hormonal treatment within the past 3 months.

-

Planning to start, stop or change long-term (lasting more than 2 weeks) hormonal contraception, co-cyprindiol or other hormonal treatment within the next 3 months.

-

Pregnant/breastfeeding.

-

Intending to become pregnant in the next 6 months.

-

Contraindicated to spironolactone:

-

currently taking potassium-sparing diuretic, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker or digoxin

-

hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, lactase deficiency or glucose–galactose malabsorption (as the spironolactone and placebo tablets contain lactose)

-

androgen-secreting adrenal or ovarian tumour

-

Cushing syndrome

-

congenital adrenal hyperplasia

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2

-

serum potassium level above the upper limit of reference range for the laboratory processing the sample.

-

Participant identification

Potential participants were identified through primary and secondary care, community advertising and social media advertising. All trial documentation such as invitation letters and patient information sheets directed potential participants to the trial specific website (see www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/13/02) which provided information about the trial, eligibility questions, as well as contact details. CTU trial staff triaged interested potential patients to the closest open recruiting trial centre.

Primary care

Targeted mailings

General practitioner (GP) practices local to the recruiting trial sites were identified as participant identification centres (PICs). PICs searched patient lists for potential participants and sent the invitation packs using a secure online mailing service.

Opportunistic recruitment

General practitioners local to recruiting trial sites were provided with business cards containing broad eligibility criteria and a QR code linking to the trial-specific website. GPs were asked to give these cards to patients during consultations if the GPs felt that the patient may potentially be eligible.

Secondary care

Trial staff at recruitment sites screened referral letters and opportunistically invited patients in outpatient clinics. Where there was an available database and patients had given permission to be contacted about research, potential patients were contacted by the local site trial team by e-mail or mail-out.

Community advertising

The trial was advertised through media local to recruiting trial sites and advertising in appropriate institutions, such as posters in universities, pharmacies and hospitals, directing potential patients to the trial-specific website.

Social media advertising

Digital marketing company

An external digital marketing company conducted a social media advertising campaign (on Facebook/Instagram) which displayed advertisements to people who had shown an interest in acne or relevant organisations linked with the condition and who met the profile demographic (gender, age and location). The adverts were shown to people in the area of three initial trial centres. People interested in the trial were able to click on a link to the trial-specific website. If an individual no longer wanted to see the trial advert, they had the option of clicking a link that closed the advert and was not shown again. Adverts managed by the external digital marketing company were run over 3 non-consecutive months. The advertising campaign was stopped due to a pause in recruitment related to COVID-19 in March 2020.

In-house by Southampton clinical trial units

Social media advertising campaigns on Facebook and Instagram (co-ordinated in Facebook Ads Manager) were run in-house and co-ordinated by Southampton clinical trial units (CTU) from June 2020 to August 2021 (non-consecutive). Adverts were displayed to people who had shown an interest in acne or relevant organisations linked with the condition and who fitted the profile demographic (gender, age and geographical location). People interested in the trial could then click on a link to the trial-specific website. If an individual no longer wanted to see the trial advert, they could click a link that ensured it was not shown again.

Baseline and follow-up data collection

Baseline and follow-up appointments were carried out by secondary care dermatology centres to ensure standardisation of the clinical assessments, as Investigator Global Assessment of acne is not generally assessed in primary care and was an important secondary outcome. See Figure 1 for illustration of participant flow through the trial and Table 1 for schedule of observations.

| Outcome measure | 6 weeks | 12 weeks (primary end point) | 24 weeks (end of treatment) | Follow-up (52 weeks or sooner)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome measure | ||||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score | X | |||

| Secondary outcome measures | ||||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score | X | X | X | |

| Acne-QoL other subscalesb | X | X | X | X |

| Acne-QoL total score | X | X | X | X |

| Participant self-assessed overall improvementc | X | X | X | X |

| Investigator’s Global Assessmentd | X | X | ||

| Participant’s Global Assessmente | X | X | X | X |

| Participant satisfaction with trial treatmentf | X | |||

| Health-related quality of life using EQ-5D-5Lg | X | X | X | X |

| Resource use/costs incurred | X | X | X | X |

| Cost-effectivenessh | X | |||

Baseline assessment

After initial telephone contact from site staff to carry out initial eligibility check, potential participants were invited to attend a baseline appointment (face-to-face) at their local trial site. Baseline appointment included:

-

discussion of participant information sheet and written informed consent

-

clinician assessed the eligibility

-

pregnancy test

-

blood test for renal function and potassium level

-

height, weight, waist circumference, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) characteristics, blood pressure

-

acne medication and oral medication use

-

Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) to assess acne severity

-

the site team also took photos on an instant camera or the participant took selfies of their acne in order to compare progress at the follow-up visits

-

questionnaires as outlined in schedule of observations (see Table 1).

Participants were offered a £20 voucher at baseline appointment to thank them for their time and a £10 voucher at subsequent appointments (weeks 6 and 12).

Follow-up

As shown in Figure 1, initial trial design included follow-up based on week-6 and week-12 visits which were initially intended to be held face-to-face in secondary care clinics, in order to discuss dose adjustment (see Interventions below), carry out IGA and reiterate contraceptive counselling. However, following redesign of trial delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic, sites were given the option of holding follow-up visits either remotely or face-to-face (if local trust guidance permitted). Additionally, (1) participants had the option to send digital photos of their acne for the clinician to assess during the consultation and grade the participant’s acne using IGA and (2) site teams had the option to post the trial medication directly to the participants. These modifications ensured that participants who had been recruited to the trial were not lost to follow-up and also allowed for flexibility during subsequent lockdowns.

Week 6 and 12 follow-up visits (remote or face-to-face)

Participants attended their week-6 and week-12 visit either remotely or face-to-face. If attending remotely, participants were asked to send photos (‘selfies’) of their face for the site team to score the IGA, providing the usual data protection measures of secure storage of the photos and prompt deletion (once no longer needed) were applied.

At week 6, the site team assessed treatment response and whether the participant was experiencing side effects from the study medication before escalating the dose to two tablets daily. If the dose hadn’t been increased to two tablets daily at week 6, treatment response was assessed again at week 12 and increased to two tablets daily. The participant’s GP was informed of the dose increase (if applicable).

At weeks 6 and 12, the participant completed a participant questionnaire on acne medication use, adverse reactions (ARs), self-assessment of acne improvement compared to baseline, resource use in the period between baseline and week 6, Acne-Quality of Life Questionnaire (Acne-QoL), EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) and NHS resource use in the period between baseline and week 6 and between week 6 and week 12.

The investigator assessed the participant’s acne using the IGA and recorded the number of remaining tablets in the IMP bottle prescribed at week 6 or week 12 respectively.

Week 24 (postal questionnaire)

The participant completed the week-24 questionnaire containing the Acne-QoL, EQ-5D-5L, self-assessment of acne improvement compared to baseline, number of tablets left from week 12 IMP bottle(s), acne medication use, ARs, serious adverse events (SAEs), satisfaction with the trial treatment and NHS resource use in the period between week 12 and week 24.

Unblinded follow-up period (questionnaire)

Participants were unblinded at week 24 (if returning the week 24 questionnaire) or at week 28 (if the week 24 questionnaire was not returned) and then entered an unblinded follow-up period. Originally, all participants were to be followed up for 52 weeks and would be sent the final follow-up questionnaire 52 weeks after baseline. However, in order to deliver the trial on time, the unblinded follow-up period was truncated so that, once the last participant received the week 24 questionnaire, all remaining participants who had not already received the final follow-up questionnaire were sent it at this point.

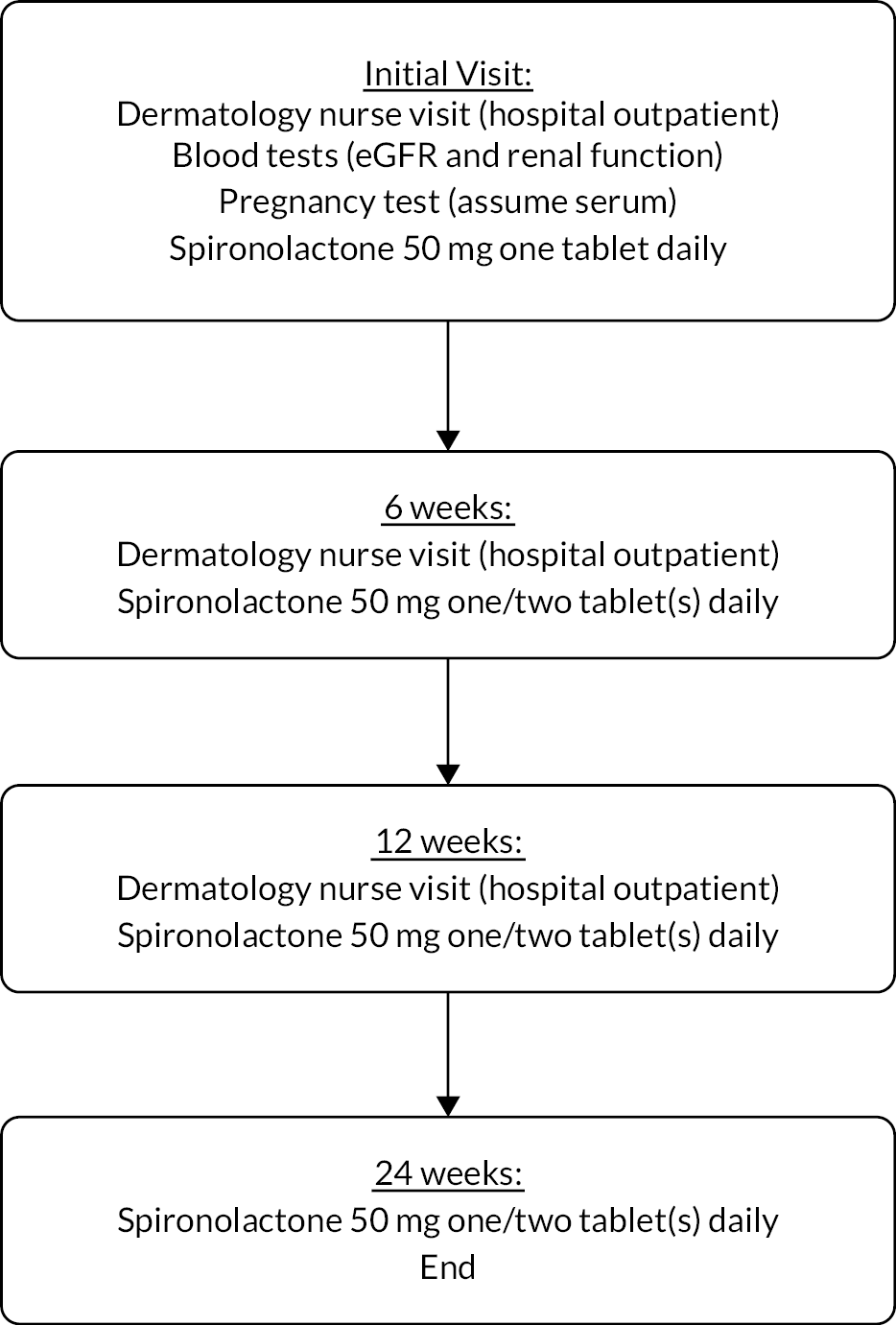

Interventions

Trial participants received one tablet per day (50 mg spironolactone or matched placebo) for the first 6 weeks of the trial. At or any time after the week-6 visit, the dose was escalated to two tablets daily (total 100 mg spironolactone or matched placebo) by the trial clinician, providing the participant was tolerating any side effects. All participants were instructed to take their total dose once per day in the morning to avoid diuresis later in the day.

All participants were instructed that they could continue to use their usual topical treatments throughout the trial, but adherence to topicals was not actively promoted. Participants were asked not to change their topical treatments or hormonal treatments between baseline and week 12.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was comparison of mean Acne-QoL symptom subscale score between groups at 12 weeks, adjusted for baseline variables. Of the many different participant-reported outcome measures available, the Acne-QoL is the most extensively validated. 29,30 The Acne-QoL contains 19 questions with 7 response categories, each referring to the past week, organised into 4 domains (self-perception, role-social, role-emotional, acne symptoms).

Effectiveness of acne treatments is usually judged clinically at 8–12 weeks so primary outcome at 12 weeks was chosen. A survey carried out prior to the trial (reported in the published protocol paper1) suggested that people with persistent acne may not be willing to stay on a trial treatment of unknown benefit for longer than 12 weeks, which is why this time point was chosen, with blinded treatment continuing to 24 weeks to assess medium term outcomes and continuing to follow-up participants beyond this to investigate longer-term outcomes.

No changes were made to trial outcomes after the trial commenced.

Secondary outcomes

-

Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 6 weeks and at end of treatment (24 weeks). 29,30

-

Acne-QoL other subscales (self-perception, role-emotional and role-social), and total score, at 6, 12 and 24 weeks.

-

Participant self-assessed overall improvement at 6, 12 and 24 weeks recorded on a six-point Likert scale with photographs taken at the baseline visit to aid recall, as was carried out in the previous HTA-funded trial on acne. 31

-

FDA IGA of acne at 6 and 12 weeks (5-point scale: 0 – Clear; 1 – Almost clear; 2 – Mild; 3 – Moderate; 4 – Severe). 32

-

PGA at 6, 12 and 24 weeks (5-point scale same as IGA but written in plain language).

-

Participant satisfaction with trial treatment (asked prior to revealing treatment allocation at 24 weeks).

-

Health-related quality of life using EQ-5D-5L at 6, 12 and 24 weeks.

-

Cost at 6, 12 and 24 weeks (participant report) and cost-effectiveness over 24 weeks.

Other outcomes

-

Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at up to 52 weeks.

-

Acne-QoL other subscales (self-perception, role-emotional and role-social), and total score, at up to 52 weeks.

-

Participant self-assessed overall improvement at up to 52 weeks recorded on a six-point Likert scale.

-

Participant’s Global Assessment at up to 52 weeks.

-

ARs of special interest.

-

Use of other oral acne treatment (e.g. antibiotics, isotretinoin) (participant report).

-

Health-related quality of life using EQ-5D-5L up to 52 weeks.

-

Cost up to 52 weeks (participant report).

-

Participant experiences during the trial (qualitative interviews).

Sample size

Original sample size calculation

Based on comparison of mean Acne-QoL scores between groups at 12 weeks, power 90%, alpha 0.05 and seeking a difference between groups of two points on the symptom subscale [standard deviation (SD) 5.8, effect size 0.35], we calculated that 346 participants would be needed. Allowing for 20% loss to follow-up gave a total target of 434 participants (217 per group). 30,33

Revised sample size

No assumption was made initially regarding anticipated correlation between baseline and 12 weeks Acne-QoL subscale (r = 0). Following preliminary data, an adjustment was made on the basis of correlation between baseline and 12-week Acne-QoL subscale (r = 0.293). A deflation factor of 1-ρ2,34 allowing a reduction in the required sample size (including allowing for 20% loss to follow-up) to 398 participants (199 per group). This revision was approved in consultation with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), Data Monitoring Committee, REC and the Funder.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to either spironolactone plus standard topical therapy or matched placebo plus standard topical therapy, using an independent web-based system (TENELEA) using varying blocks of size two and four, stratified by recruitment centre and by baseline severity (IGA ˂ 3 vs. IGA 3 or 4).

Participants, local site staff and investigators were blind to treatment allocation until the end of the treatment phase (week 24). At this point participants and local site staff were unblinded. The research team remained blinded to treatment allocation until all analyses were complete and checked; however the statisticians were unblinded throughout the course of the trial.

Participants were asked prior to unblinding to guess which treatment they thought they had received, although it is noted that this may measure an individual’s prior belief in interventions’ effectiveness rather than a successful guess of treatment allocation.

Withdrawal, unblindings and protocol deviations

Participants were free to withdraw from the treatment or trial at any time without providing a reason:

-

participants could stop treatment but remain in follow-up (level 1 withdrawal)

-

participants could stop treatment and withdraw from follow-up (level 2 withdrawal)

-

participants could stop treatment and withdraw from follow-up and their data would not be used within the analysis (level 3 withdrawal).

Emergency unblinding was available in case of adverse events (AEs) where treatment allocation may affect the required participant care. If unblinding was performed, site staff informed Southampton Clinical Trial Unit (SCTU) trial team with details (date, time, reason for unblinding, name of staff requesting the code break and name of person breaking the code) and unblinding reports were filed in the participant medical records at site.

Serious adverse events were reviewed in a blinded manner.

If a participant became pregnant while taking part in the trial, the local site team was required to inform the SCTU as soon as they became aware of the pregnancy. The pregnancy itself was not a SAE; however the outcome of the pregnancy may be a SAE. When becoming pregnant, the participant was asked to stop taking the trial medication and was withdrawn from the trial (level 2 withdrawal).

If an informed consent for pregnancy follow-up was completed, the SCTU Quality and Regulatory team would enquire about the outcome of the pregnancy with the site staff.

If no informed consent for pregnancy follow-up was received, no further follow-up of the pregnancy outcome was possible.

There were a total of 206 protocol deviations (Table 2). Most of these related to the visit schedule, where appointments were late or cancelled, primarily due to the pandemic, meaning no IGA was recorded. The 31 deviations related to study procedure primarily related to the timing of tests at baseline or the timing of receiving IMP. The 12 deviations related to patient identifiable data involved the use of the safa@soton.ac.uk when not appropriate. The 15 deviations related to consent procedures related primarily to sites using an older version of the consent form.

| Reason for deviation | Number |

|---|---|

| Consent procedures | 15 |

| Case report form completion | 6 |

| Delegation log | 1 |

| Standard operating procedure adherence | 4 |

| Inclusion/exclusion | 5 |

| Lab assessments/procedures | 3 |

| Study procedures | 31 |

| SAE reporting | 3 |

| Registration/randomisation/unblinding | 5 |

| Study drug management | 13 |

| Visit schedule | 104 |

| Patient identifiable data | 12 |

| Other | 4 |

Statistical methods

A statistical analysis plan was written and reviewed by the TSC and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) prior to the trial database being locked.

The complete cases population consisted of all participants who had been randomised to a treatment arm, regardless of compliance, and had complete data for the outcome and time point being analysed. The level of missing data is reported for all outcomes, unless otherwise stated. The frequency and pattern of missing data were examined, and a sensitivity analysis was carried out using a chained-equations multiple imputation model, including all outcomes and covariates used in the final analysis.

For the primary analyses, descriptive statistics were used to characterise recruited participants and assess baseline comparability between groups. For the primary outcome, a linear regression model was used to analyse Acne-QoL symptom subscale at week 12, adjusting for baseline variables (including stratification factors, baseline Acne-QoL symptom subscale score, topical treatment use, hormonal treatment use, age and PCOS status). A 95% confidence interval (CI) for the least squares mean difference between groups in Acne-QoL symptom subscale at week 12 was calculated. The same analysis methods were used to summarise Acne-QoL symptom subscale at other time points (weeks 6, 24 and up to week 52 after baseline) and for the other Acne-QoL subscales (self-perception, role-emotional and role-social) and total score.

Investigator’s Global Assessment and PGA at 6, 12 and 24 were dichotomised as success or failure as recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration32 (with success for IGA and Participant’s Global Assessment defined as clear or almost clear (grade 0 or 1) and at least a two-grade improvement from baseline; this represents a clinically meaningful outcome). The dichotomised outcomes were summarised by frequencies and percentages and compared by group using logistic regression, adjusting for stratification factors [recruitment centre and baseline acne severity (IGA < 3 vs. IGA ≥ 3)], baseline Acne-QoL symptom subscale score, topical treatment use (yes/no), hormonal treatment use (yes/no), age and PCOS status (as below).

Participants’ comparison with baseline photo at weeks 6, 12 and 24 weeks was presented by frequencies and percentages and compared by group using logistic regression with success defined as slight improvement/moderate improvement/excellent improvement/completely cleared and failure defined as no improvement/worse. Participants’ satisfaction with trial treatment was also presented with frequencies and percentages and compared by group using logistic regression.

Polycystic ovary syndrome status was defined as patients who stated they had a diagnosis or those who had suspected PCOS. Suspected PCOS was derived based on the Rotterdam criteria,35 where suspected PCOS is defined as having two or more of: oligo/anovulation (missed/infrequent periods), hyperandrogenism (evidence of excess facial and body hair or female pattern baldness) or polycystic ovaries on ultrasound. Since ultrasound was not performed in this study, participants needed to have both of the other criteria to qualify as having suspected PCOS.

Exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate how the treatment effect differs by whether participants have symptoms consistent with PCOS as recorded at the baseline visit, by age (below 25 years and 25 years and over),36 by higher and lower IGA scores at baseline (as per stratification), by the use of hormonal co-treatments (yes/no) and by the use of topical co-treatments (yes/no). Descriptive statistics were also used to observe the differences in mean Acne-QoL score pre- and post-COVID pandemic and amongst different ethnicities.

A complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was undertaken in order to compare ‘compliant’ participants (i.e. those who reported that they took their study medication) in the intervention group with those in the control group who would have complied with the intervention, given the opportunity to do so. Compliance was defined as taking at least 80% of the prescribed medication over the 12- to 24-week period. To explore the sensitivity of this analysis to the definition of ‘compliance’, we also completed two further sensitivity analyses defining compliance as taking 100% of the trial medication and 50% of the trial medication. Compliance was presented by frequencies and percentages and compared by groups with a single-equation instrumental-variables regression model adjusting for baseline variables.

Adverse reactions of special interest and SAEs were summarised by group with frequencies and percentages and compared with Pearson’s χ² tests.

The same analysis methods were applied to the outcomes collected at up to 52 weeks; however, the interpretation of these results was assessed with caution as participants were no longer blind to treatment use and could have started a different acne treatment. All analyses were carried out using Stata and/or SAS. No interim analysis was planned or conducted.

Health economics

For health economics methodologies, please see Chapter 4.

Trial oversight

The day-to-day management of the trial was co-ordinated through SCTU and through regular meetings with the Trial Management Group (TMG). The conduct of the trial was overseen by a TSC and a DMEC.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Trial population

A total of 1267 women were assessed for eligibility; 413 were consented and randomised from 10 hospitals in England and Wales. Recruitment period ran from 5 June 2019 to 31 August 2022 with a pause in recruitment from 23 March to 11 June 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All sites open by end of 2020 were affected by COVID-19, mostly due to staff redeployment and the pause of research at trusts, with each site closed for an average of 6 months with a range from 3 to 10 months (Table 3). Last participant’s final follow-up questionnaire was returned in March 2022 with data cleaning complete in April 2022.

| Site | Opened | Closed | Restart | Time closed total (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Birmingham) | 13 January 2020 | 23 March 2020 11 January 2021 |

16 October 2020 20 April 2021 |

7 |

| Bristol Royal Infirmary | 24 June 2019 | 23 March 2020 | 15 January 2021 | 3 |

| Epsom Hospital | 22 October 2019 | 23 March 2020 | 13 May 2021 | 10 |

| Harrogate District Hospital | 22 May 2019 | 23 March 2020 | 6 July 2020 | 4 |

| Poole General Hospital | 24 July 2019 | 23 March 2020 | 9 September 2020 | 6 |

| St Mary’s General Hospital (Portsmouth) | 17 June 2019 | 23 March 2020 | 21 July 2020 | 4 |

| Queen’s Medical Centre (Nottingham) | 19 October 2020 | 9 November 2020 | 10 May 2021 | 6 |

| University Hospital of Wales (Cardiff) | 28 October 2020 | 12 November 2020 | 5 May 2021 | 6 |

| Singleton Hospital (Swansea) | 13 January 2021 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| St Mary’s Hospital (HQ) (London) | 21 May 2021 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

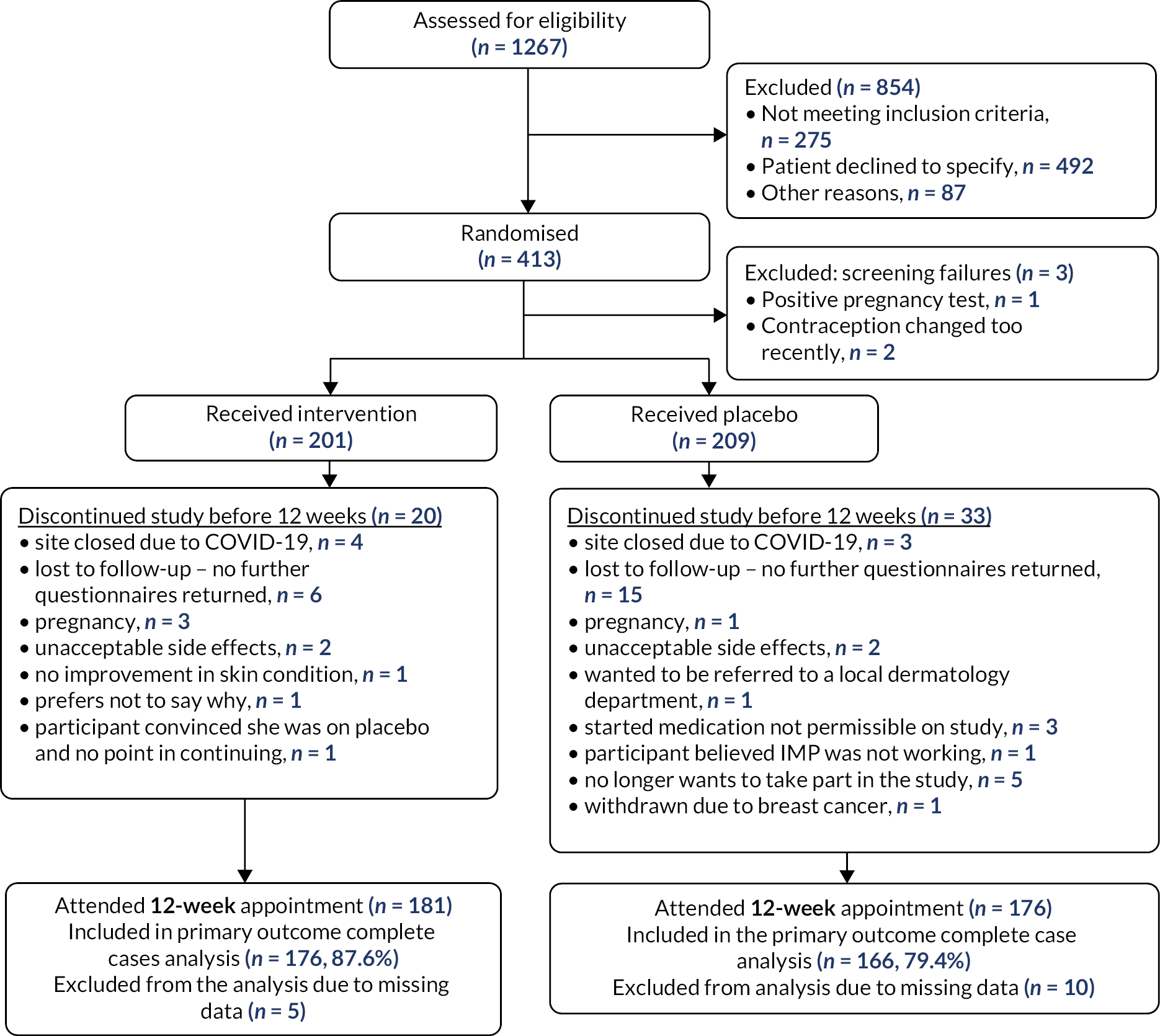

There were three post-randomisation screen failures (two where it was found after randomisation that contraception had been changed recently and the third where the pregnancy test was incorrectly done after randomisation) leading to 201 women being assigned the intervention and 209 being assigned placebo. Site closures due to COVID-19 resulted in the loss to follow-up of seven participants (Figure 2). Loss to follow-up was one of the main reasons for participant discontinuation in the trial, with 6 discontinuing for this reason before 12 weeks in the intervention group and 15 in the control group. There were seven pregnancies in total, with three in the intervention group and four in the control group. The primary outcome data was provided for 176/201 (87.6%) of participants in the intervention group and 166/209 (79.4%) in the control group.

FIGURE 2.

Consort diagram.

Social media advertising accounted for 47.6% (195/410) of the participant recruitment, 19.8% (81/410) through secondary care, 15.6% (64/410) through primary care, 6.6% (27/410) through community advertising, 6.6% (27/410) word of mouth and 3.9% (16/410) through the participants finding the trial via online search.

Baseline characteristics

Information on stratification factors (recruiting centre and baseline acne severity judged by IGA) can be seen in Table 4. The percentage of women who had an IGA score of more than or equal to three, denoting moderate or severe acne, was 53.7%.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centre – n (%) b | |||

| Bristol Royal Infirmary | 34 (16.9%) | 36 (17.2%) | 70 (17.1%) |

| Epsom Hospital | 7 (3.5%) | 8 (3.8%) | 15 (3.7%) |

| Harrogate District Hospital | 43 (21.4%) | 46 (22.0%) | 89 (21.7%) |

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust – Queen’s Medical Centre Campus | 14 (7.0%) | 14 (6.7%) | 28 (6.8%) |

| Poole General Hospital | 26 (12.9%) | 26 (12.4%) | 52 (12.7%) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Birmingham) | 23 (11.4%) | 25 (12.0%) | 48 (11.7%) |

| Singleton Hospital (Swansea) | 3 (1.5%) | 4 (1.9%) | 7 (1.7%) |

| St Mary’s General Hospital (Portsmouth) | 42 (20.9%) | 42 (20.1%) | 84 (20.5%) |

| St Mary’s Hospital (HQ) (London) | 6 (3.0%) | 5 (2.4%) | 11 (2.7%) |

| University Hospital of Wales (Cardiff) | 3 (1.5%) | 3 (1.4%) | 6 (1.5%) |

| Missing – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Baseline severity – n (%) b | |||

| IGA 2 or less | 92 (45.8%) | 98 (46.9%) | 190 (46.2%) |

| IGA 3 or more | 109 (54.2%) | 111 (53.1%) | 220 (53.7%) |

| Missing – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Baseline demographics and source of recruitment are described in Table 5. The average age of participants was 29 years old and the average body mass index was 26. The majority of women were white and almost 50% were recruited through social media advertising.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at baseline b | |||

| Mean | 29.6 | 28.7 | 29.2 |

| SD | 7.4 | 7.0 | 7.2 |

| Range | 18–59 | 18–51 | 18–59 |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 158 (84.0%) | 170 (84.6%) | 328 (84.3%) |

| Asian or Asian British | 5 (2.7%) | 4 (2.0%) | 9 (2.3%) |

| Black, African, Black British or Caribbean | 4 (2.1%) | 2 (1.0%) | 6 (1.5%) |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 6 (3.2%) | 3 (1.5%) | 9 (2.3%) |

| Other ethnic group | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 4 (1.0%) |

| Prefer not to say | 14 (7.4%) | 19 (9.5%) | 33 (8.5%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 13 (6.5%) | 8 (3.8%) | 21 (5.1%) |

| Body mass index b | |||

| Mean | 25.7 | 26.5 | 26.1 |

| SD | 5.3 | 5.9 | 5.6 |

| Range | 17.7–50.1 | 16.6–50.1 | 16.6–50.1 |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Waist circumference (cm) b | |||

| Mean | 80.3 | 81.7 | 81.0 |

| SD | 12.2 | 13.2 | 12.7 |

| Range | 60.0–122.0 | 60.0–127.0 | 60.0–127.0 |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Where did the participant hear about the trial? – n (%) b | |||

| Community advertising | 12 (6.0%) | 15 (7.2%) | 27 (6.6%) |

| GP | 35 (17.4%) | 29 (13.9%) | 64 (15.6%) |

| Participant’s online search | 6 (3.0%) | 10 (4.8%) | 16 (3.9%) |

| Secondary care | 38 (18.9%) | 43 (20.6%) | 81 (19.8%) |

| Social media advertising | 98 (48.8%) | 97 (46.4%) | 195 (47.6%) |

| Word of mouth | 12 (6.0%) | 15 (7.2%) | 27 (6.6%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

The acne assessment information recorded at baseline can be seen in Table 6. It was observed that 1% of women described their acne as almost clear, 21% described their acne as mild severity, 53% described their acne as moderate severity and 25% as severe; 0.5% of women did not answer. This is in contrast with the clinicians’ views (IGA), who described 46% of women as having mild severity, 41% as moderate severity and 13% as severe. Hormonal contraception was being used by 58% of women, with 71% using the progesterone-only pill or other progesterone-only contraception.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How would you describe the acne on your face at the moment? – n (%) b | |||

| Clear | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Almost clear | 3 (1.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1.0%) |

| Mild severity | 37 (18.4%) | 49 (23.4%) | 86 (21.0%) |

| Moderate severity | 115 (57.2%) | 101 (48.3%) | 216 (52.7%) |

| Severe | 44 (21.9%) | 58 (27.8%) | 102 (24.9%) |

| Not answered | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Using the IGA scale for acne, how would you describe the participant’s facial acne – n (%)b | |||

| Clear | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Almost clear | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Mild severity | 92 (45.8%) | 98 (46.9%) | 190 (46.3%) |

| Moderate severity | 84 (41.8%) | 82 (39.2%) | 166 (40.5%) |

| Severe | 25 (12.4%) | 29 (13.9%) | 54 (13.2%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| If completed, how was IGA carried out? n – (%)b | |||

| Face-to-face | 198 (98.5%) | 208 (99.5%) | 406 (99.0%) |

| Photo | 3 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Video consultation | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Medical history information is presented in Table 7. More than half of the women in the trial had acne for over 5 years. The average age acne started was 16 years old and 19% of women either reported having a diagnosis of PCOS or, based on the information they provided to us, they met the Rotterdam criteria and therefore had suspected PCOS (see Methods section).

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How long have you had your current episode of acne? – n (%) b | |||

| Less than 6 months | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 6 months to 2 years | 48 (23.9%) | 56 (26.8%) | 104 (25.3%) |

| 2–5 years | 44 (21.9%) | 49 (23.4%) | 93 (22.7%) |

| Over 5 years | 109 (54.2%) | 104 (49.8%) | 213 (52.0%) |

| Not answered | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Age acne started (years) b | |||

| Mean | 16.1 | 16.7 | 16.4 |

| SD | 5.4 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Range | 9.0–46.0 | 8.0–40.0 | 8.0–46.0 |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| PCOS diagnosis or suspected PCOS – n (%)b,d | |||

| Yese | 30 (15.4%) | 47 (23.3%) | 77 (19.4%) |

| No | 165 (84.6%) | 155 (76.7%) | 320 (80.6%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c,f | 6 (3.0%) | 7 (3.4%) | 13 (3.2%) |

The details of acne medication use are described in Table 8. There was a high proportion of women (85%) who said they had used or are currently using topical treatments. Benzoyl peroxide and combination were currently being used by 13% of women. Approximately 30% of women were taking topical treatments once a day. The full table of acne medication use at baseline can be seen in the Appendix 2 (see Table 42).

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you used, or are you currently using, topical treatments (creams/lotions/gels) for your acne? – n (%) b | |||

| Yes | 169 (84.9%) | 171 (82.2%) | 340 (83.5%) |

| No | 30 (15.1%) | 37 (17.8%) | 67 (16.5%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| If ʻYesʼ d | |||

| Benzoyl peroxide | 22/165 (13.3%) | 30/168 (17.9%) | 52/333 (15.6%) |

| Azelaic acid | 10/165 (6.1%) | 15/167 (9.0%) | 25/332 (7.5%) |

| Topical adapalene | 22/167 (13.2%) | 21/167 (12.6%) | 43/334 (12.9%) |

| Nicotinamide | 9/165 (5.5%) | 3/167 (1.8%) | 12/332 (3.6%) |

| Antibiotic | 8/167 (4.8%) | 6/167 (3.6%) | 14/334 (4.2%) |

| Combination | 28/167 (16.8%) | 21/168 (12.5%) | 49/335 (14.6%) |

| Other | 20/137 (14.6%) | 25/148 (16.9%) | 45/285 (15.8%) |

| Not sure | 7/134 (5.2%) | 7/147 (4.8%) | 14/281 (5.0%) |

| If topical treatments have been prescribed, how often are they used? b | |||

| Not at all | 17 (8.5%) | 32 (15.3%) | 49 (12.0%) |

| Less than once a day | 16 (8.0%) | 19 (9.1%) | 35 (8.6%) |

| Once a day | 62 (31.0%) | 58 (27.8%) | 120 (29.3%) |

| Twice a day | 25 (12.5%) | 20 (9.6%) | 45 (11.0%) |

| More than twice a day | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Not been prescribed topical treatments | 64 (32.0%) | 64 (30.6%) | 128 (31.3%) |

| Not answered | 15 (7.4%) | 14 (6.7%) | 29 (7.1%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Is the participant currently using any hormonal treatment? – n (%) b | |||

| Yes | 81 (40.1%) | 91 (43.5%) | 172 (42.0%) |

| No | 120 (59.7%) | 118 (56.5%) | 238 (58.1%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| If ʻYesʼ, please state which hormonal treatment e | |||

| Combined oral contraceptionf | 27 (33.3%) | 22 (24.2%) | 49 (28.5%) |

| Progesterone-only pill or other progesterone-only contraceptiong | 54 (66.7%) | 69 (75.8%) | 123 (71.5%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)c | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Table 9 presents the baseline values for all outcome measures. The mean Acne-QoL acne symptom subscale score at baseline was 13.0 (SD 4.7). The mean score of the other subscale scores including role-social, role-emotional and self-perception were 12.4 (SD 6.7), 10.7 (SD 6.6) and 8.9 (SD 6.5), respectively. The Acne-QoL total score at baseline was 45.0 (SD 21.1).

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne-QoL acne symptom subscale score at baseline | |||

| N | 201 | 209 | 410 |

| Mean (SD) | 13.2 (4.9) | 12.9 (4.5) | 13.0 (4.7) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)a | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at baseline | |||

| N | 201 | 209 | 410 |

| Mean (SD) | 12.4 (6.6) | 12.5 (6.8) | 12.4 (6.7) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)a | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at baseline | |||

| N | 201 | 209 | 410 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.8 (6.7) | 10.6 (6.4) | 10.7 (6.6) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)a | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at baseline | |||

| N | 201 | 209 | 410 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.2 (6.6) | 8.6 (6.4) | 8.9 (6.5) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)a | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Acne-QoL total score at baseline | |||

| N | 201 | 209 | 410 |

| Mean (SD) | 45.6 (20.9) | 44.6 (21.2) | 45.0 (21.1) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)a | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Treatment information

Participants initially received one tablet per day (50 mg spironolactone or matched placebo) then at or any time after the 6-week visit, the dose was escalated to two tablets daily if the treatment was tolerated. Table 10 shows that the majority of women (98.1%) were advised to increase to two tablets per day at their 6-week visit. The percentage of women on two tablets per day between 6 and 12 weeks was 96% and between 12 and 24 weeks was 90%, with similar percentages for both groups.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants with 6-week treatment information available – n (%)b | 188 (93.5%) | 193 (92.3%) | 381 (92.9%) |

| No. of participants who were advised to increase the dose to two tablets per day at 6-week visitc | 182 (98.9%) | 182 (97.3%) | 364 (98.1%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)d | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| No. of participants with 12-week treatment information available – n (%)b | 181 (90.1%) | 177 (84.7%) | 358 (87.3%) |

| No. of participants whose dose per day between 6-week and 12-week visit wasc | |||

| One tablet | 4 (2.2%) | 4 (2.3%) | 8 (2.2%) |

| Two tablets | 174 (96.1%) | 169 (95.5%) | 343 (95.8%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)d | 3 (1.7%) | 4 (2.3%) | 7 (2.0%) |

| No. of participants with a 24-week treatment information eCRF available – n (%)b | 168 (83.6%) | 146 (69.9%) | 314 (76.4%) |

| No. of participants whose dose per day between 12-week and 24-week visit was c | |||

| One tablet | 7 (4.2%) | 3 (2.1%) | 10 (3.2%) |

| Two tablets | 150 (89.3%) | 132 (90.4%) | 282 (89.8%) |

| Not answered | 9 (5.4%) | 11 (7.5%) | 20 (6.4%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)d | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.6%) |

Primary outcome

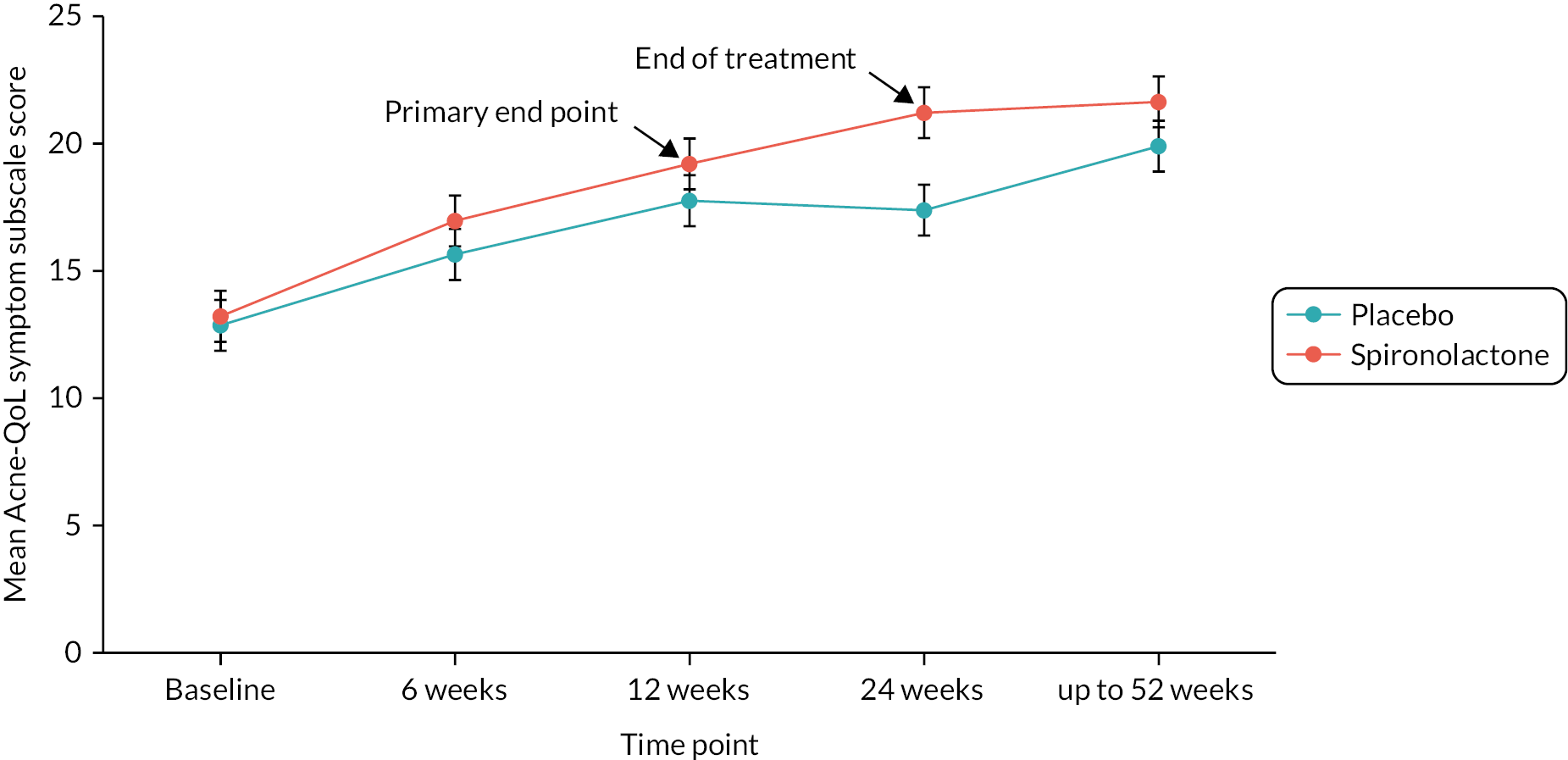

Figure 3 displays the mean Acne-QoL symptom subscale over time for each treatment group. The acne symptoms of women improve over time for both groups, with higher scores seen in the spironolactone group, indicating greater improvement. After 12 weeks, improvement continues in the spironolactone group; however the placebo group flattens out. The largest difference between the groups can be seen at 24 weeks. It is important to note that at 24 weeks treatment ended; at this point participants could obtain any treatment that they wanted which could explain the smaller difference in scores at 52 weeks.

FIGURE 3.

Mean Acne-QoL symptom subscale score by time point for each treatment group.

Table 11 presents the primary end-point information. The mean Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks was 19.2 (SD 6.1) in the spironolactone group and 17.8 (SD 5.6) in the placebo group. In the unadjusted model, the mean difference was 1.48 with 95% CI 0.30 to 2.67. The primary analysis adjusted for stratification factors (site and baseline IGA), baseline Acne-QoL symptom subscale score, topical treatment use, hormonal treatment use, age and PCOS status, resulting in mean difference 1.27 (95% CI 0.07 to 2.46). This represents a statistically significant improvement in the spironolactone group. The sensitivity analysis on multiply imputed data gave similar results and inferences (see Table 11).

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12-weeks | |||

| N | 176 | 166 | 342 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.2 (6.1) | 17.8 (5.6) | 18.5 (5.9) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted – only including baseline Acne-QoL score) | 1.48 (0.30 to 2.67) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted)b | 1.27 (0.07 to 2.46) | REF | N/A |

| Missing data imputed (adjusted – 100 imputations) | 1.26 (0.04 to 2.48) | REF | N/A |

Secondary and tertiary outcomes

Details of Acne-QoL information at 12 weeks are displayed in Table 12. There was a statistically significant improvement in mean total Acne-QoL score and all Acne-QoL subscales at 12 weeks in the spironolactone group compared to placebo.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 176 | 165 | 341 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.7 (6.1) | 17.0 (6.7) | 17.8 (6.4) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.88 (0.64 to 3.13) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.99 (0.70 to 3.28) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 175 | 166 | 341 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.2 (7.8) | 17.5 (8.1) | 18.9 (8.1) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 2.66 (1.08 to 4.25) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 2.75 (1.11 to 4.39) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 175 | 166 | 341 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.2 (8.5) | 16.9 (8.2) | 18.1 (8.4) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 2.21 (0.55 to 3.86) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 2.10 (0.39 to 3.82) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL total score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 176 | 166 | 342 |

| Mean (SD) | 77.0 (26.5) | 69.0 (26.2) | 73.2 (26.6) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL total score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 8.18 (2.98 to 13.38) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 8.03 (2.68 to 13.37) | REF | N/A |

Details of Acne-QoL information at 24 weeks is displayed in Table 13. The mean Acne-QoL symptom subscale score was 21.2 (SD 5.9) in the spironolactone group and 17.4 (SD 5.8) in the placebo group. The mean difference between the groups in the adjusted analysis was 3.45 with 95% CI 2.16 to 4.75, which represents a statistically significant greater improvement in the spironolactone group. The results for all the other Acne-QoL subscales and for total Acne-QoL score at 24 weeks were also statistically significant in favour of the spironolactone group.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| N | 163 | 136 | 299 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.2 (5.9) | 17.4 (5.8) | 19.5 (6.1) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks (95 CI%) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 3.77 (2.50 to 5.03) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 3.45 (2.16 to 4.75) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| N | 163 | 136 | 299 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.6 (5.6) | 16.7 (6.8) | 18.3 (6.3) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at 24 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 3.03 (1.78 to 4.28) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 3.06 (1.77 to 4.35) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| N | 164 | 137 | 301 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.1 (7.3) | 16.5 (8.2) | 19.0 (8.0) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at 24 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 4.50 (2.81 to 6.18) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 4.35 (2.64 to 6.05) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| N | 164 | 137 | 301 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.3 (7.7) | 16.3 (8.7) | 19.1 (8.5) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at 24 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 4.98 (3.23 to 6.74) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 4.77 (2.97 to 6.56) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL total score at 24 weeks | |||

| N | 164 | 137 | 301 |

| Mean (SD) | 83.0 (25.0) | 66.7 (27.5) | 75.6 (27.4) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL total score at 24 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 16.25 (10.66 to 21.84) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 15.73 (10.04 to 21.42) | REF | N/A |

Table 14 describes Acne-QoL information at 6 and (up to) 52 weeks, although these time points are less informative as 6 weeks would clinically be judged to be too early to expect to see a treatment difference from spironolactone for acne and after 24 weeks participants were unblinded and able to seek any treatment that they wished, including spironolactone in the control group.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 6 weeks | |||

| N | 176 | 179 | 355 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.0 (5.7) | 15.6 (5.7) | 16.3 (5.7) |

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 52 weeks | |||

| N | 95 | 81 | 176 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.7 (6.3) | 20.0 (5.7) | 20.9 (6.1) |

| Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at 6 weeks | |||

| N | 176 | 179 | 355 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.2 (6.5) | 15.2 (6.8) | 15.7 (6.6) |

| Acne-QoL role-social subscale score at 52 weeks | |||

| N | 95 | 81 | 176 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.1 (5.7) | 17.8 (6.4) | 19.1 (6.1) |

| Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at 6 weeks | |||

| N | 178 | 183 | 361 |

| Mean (SD) | 15.7 (7.8) | 14.4 (7.6) | 15.0 (7.7) |

| Acne-QoL role-emotional subscale score at 52 weeks | |||

| N | 96 | 82 | 178 |

| Mean (SD) | 22.4 (7.7) | 18.6 (8.7) | 20.7 (8.4) |

| Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at 6 weeks | |||

| N | 178 | 183 | 361 |

| Mean (SD) | 15.2 (8.2) | 13.4 (8.0) | 14.3 (8.2) |

| Acne-QoL self-perception subscale score at 52 weeks | |||

| N | 96 | 82 | 178 |

| Mean (SD) | 22.6 (7.9) | 18.8 (8.7) | 20.8 (8.5) |

| Acne-QoL total score at 6 weeks | |||

| N | 179 | 184 | 363 |

| Mean (SD) | 63.3 (26.1) | 57.7 (26.0) | 60.4 (26.2) |

| Acne-QoL total score at 52 weeks | |||

| N | 96 | 82 | 178 |

| Mean (SD) | 86.3 (26.1) | 74.7 (28.0) | 81.0 (27.5) |

Information on participant’s and investigator’s global assessment (PGA and IGA, respectively) at 12 and 24 weeks can be seen in Table 15. PGA and IGA were dichotomised as success or failure with success defined as clear or almost clear (grade 0 or 1) and at least a two-grade improvement from baseline, in line with FDA guidance. The adjusted odd ratio for PGA score at 12 weeks was not statistically significant; however the PGA at 24 weeks showed a statistically meaningful result with adjusted odds ratio 3.76 and 95% CI 1.95 to 7.28. This implies that the odds of success on the PGA was higher in the spironolactone group. The adjusted odds ratio for IGA at 12 weeks was also statistically significant with odds ratio 5.18 and 95% CI 2.18 to 12.2. Therefore, the odds of success on the IGA were significantly higher in the spironolactone group.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGA score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 176 | 166 | 342 |

| Success | 36 (20.5%) | 20 (12.1%) | 56 (16.4%) |

| Failure | 140 (79.6%) | 146 (88.0%) | 286 (83.6%) |

| Complete cases (unadjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.91 (1.05 to 3.45) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.69 (0.89 to 3.19) | REF | N/A |

| PGA score at 24 weeks | |||

| N | 164 | 136 | 300 |

| Success | 53 (32.3%) | 15 (11.0%) | 68 (22.7%) |

| Failure | 111 (67.8%) | 121 (89.0%) | 232 (77.3%) |

| Complete cases (unadjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.93 (2.09 to 7.37) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.76 (1.95 to 7.28) | REF | N/A |

| If completed, how was IGA carried out? – n (%)3 | |||

| Face-to-face | 97 (57.7%) | 95 (59.8%) | 192 (58.7%) |

| Photo | 55 (32.7%) | 47 (29.6%) | 102 (31.2%) |

| Video consultation | 16 (9.5%) | 17 (10.7%) | 33 (10.1%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)4 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| IGA score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 168 | 160 | 328 |

| Success | 31 (18.5%) | 9 (5.6%) | 40 (12.2%) |

| Failure | 137 (81.6%) | 151 (94.4%) | 288 (87.8%) |

| Complete cases (unadjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.78 (1.73 to 8.27) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 5.18 (2.18 to 12.28) | REF | N/A |

Table 16 presents participants’ self-assessed overall improvement and participants’ satisfaction with trial treatment. Participant self-assessed overall improvement was measured by asking a single question ‘Using the photograph taken at your first visit if you have it, how do you think your acne today compares to your acne then?’ on a six-point Likert scale from 1 ‘Worse’ to 6 ‘Completely Cleared’. Participants in the spironolactone group were more likely than those in the placebo group to report overall acne improvement, compared with baseline photo, at both 12 weeks {72.2% vs. 67.9% [adjusted OR 1.16 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.91)]} and at 24 weeks {81.9% vs. 63.3% [adjusted OR 2.72 (95% CI 1.50 to 4.93)]}. Post hoc analyses showed that this equated to number needed to treat (NNT) of 23 at 12 weeks and NNT of 5 at 24 weeks. Participants were asked about their satisfaction with the trial treatment through a single question ‘Do you think the tablets you received in this trial have helped your skin?’. This was measured on a scale of 0 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘a lot’) with higher scores indicating increased satisfaction with treatment. There was a significantly higher proportion of people who were satisfied (scored 3 or more) with the trial treatment compared with placebo, 70.6% versus 43.1%. The adjusted odds ratio was statistically significant with odds ratio 3.12 (95% CI 1.80 to 5.41). Therefore, the odds of participant satisfaction were significantly higher in the spironolactone group.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant’s self-assessed overall improvement at 12 weeks a | |||

| N | 169 | 159 | 328 |

| 1–2 | 47 (27.8%) | 51 (32.1%) | 98 (29.9%) |

| 3–6 | 122 (72.2%) | 108 (67.9%) | 230 (70.1%) |

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.2) |

| Complete cases (unadjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI)b | 1.23 (0.76 to 1.96) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI)b | 1.16 (0.70 to 1.91) | REF | N/A |

| Participant’s self-assessed overall improvement at 24 weeks a | |||

| N | 160 | 128 | 288 |

| 1–2 | 29 (18.1%) | 47 (36.7%) | 76 (26.4%) |

| 3–6 | 131 (81.9%) | 81 (63.3%) | 212 (73.6%) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.4) |

| Complete cases (unadjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI)b | 2.62 (1.53 to 4.50) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI)b | 2.72 (1.50 to 4.93) | REF | N/A |

| Participant’s satisfaction with trial treatment at 24 weeks c | |||

| 0–2 | 42 (29.4%) | 70 (56.9%) | 112 (42.1%) |

| 3–5 | 101 (70.6%) | 53 (43.1%) | 154 (57.9%) |

| Not sure | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not answered | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Complete cases (unadjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.18 (1.91 to 5.27) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) – odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.12 (1.80 to 5.41) | REF | N/A |

Table 17 details the information on other oral acne treatment used at 24 and 52 weeks. At the time of the final follow-up questionnaire, 35% of women in the intervention group and 28% in the control group reported that they were taking spironolactone. This shows that, following unblinding at 24 weeks, a substantial proportion of women in the intervention group had continued this medication and a substantial proportion in the control group had commenced it after unblinding. Although numbers are small, it is notable that fewer women in the intervention group than the control group reported that they were taking oral antibiotics or isotretinoin at the time of the final follow-up questionnaire.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| At 24 weeks | |||

| Are you using topical treatment? | |||

| N | 168 | 146 | 314 |

| Yes | 112 (66.7%) | 99 (67.8%) | 211 (67.2%) |

| No | 52 (31.0%) | 37 (25.3%) | 89 (38.3%) |

| Not answered | 4 (3.4%) | 10 (6.7%) | 14 (4.5%) |

| Are you using oral antibiotic? | |||

| N | 168 | 146 | 314 |

| Yes | 4 (2.4%) | 6 (4.1%) | 10 (3.2%) |

| Not answered | 164 (97.6%) | 140 (95.9%) | 304 (96.8%) |

| Are you using combined oral contraceptive? | |||

| N | 168 | 146 | 314 |

| Yes | 26 (15.5%) | 16 (11.0%) | 42 (13.4%) |

| Not answered | 142 (84.5%) | 130 (89.0%) | 272 (86.6%) |

| Are you using oral isotretinoin? | |||

| N | 168 | 146 | 314 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Not answered | 168 (100.0%) | 146 (100.0%) | 314 (100.0%) |

| Are you using progesterone-only contraception? | |||

| N | 168 | 146 | 314 |

| Yes | 47 (28.0%) | 48 (32.9%) | 95 (30.3%) |

| Not answered | 121 (72.0%) | 98 (67.1%) | 219 (69.8%) |

| At 52 weeks | |||

| Are you using topical treatment? | |||

| N | 103 | 89 | 192 |

| Yes | 88 (85.4%) | 79 (88.8%) | 167 (87.0%) |

| No | 5 (4.8%) | 2 (2.2%) | 7 (3.6%) |

| Not answered | 10 (9.7%) | 8 (9.0%) | 18 (9.4%) |

| Are you using oral antibiotic? | |||

| N | 103 | 89 | 192 |

| Yes | 6 (5.8%) | 12 (13.5%) | 18 (9.4%) |

| Not answered | 97 (94.2%) | 77 (86.5%) | 174 (90.6%) |

| Are you using spironolactone? | |||

| N | 103 | 89 | 192 |

| Yes | 36 (35.0%) | 25 (28.1%) | 61 (31.8%) |

| Not answered | 67 (65.0%) | 64 (71.9%) | 131 (68.2%) |

| Are you using combined oral contraceptive? | |||

| N | 103 | 89 | 192 |

| Yes | 13 (12.6%) | 8 (9.0%) | 21 (10.9%) |

| Not answered | 90 (87.4%) | 81 (91.0%) | 171 (89.1%) |

| Are you using oral isotretinoin? | |||

| N | 103 | 89 | 192 |

| Yes | 2 (1.9%) | 6 (6.7%) | 8 (4.2%) |

| Not answered | 101 (98.1%) | 83 (93.3%) | 184 (95.8%) |

| Are you using progesterone-only contraception? | |||

| N | 103 | 89 | 192 |

| Yes | 33 (32.0%) | 32 (36.0%) | 65 (33.9%) |

| Not answered | 70 (68.0%) | 57 (64.0%) | 127 (66.1%) |

Additional analyses

Subgroup analysis

Table 18 describes the subgroup analysis that was performed to compare results in certain pre-specified populations. Interaction terms were included in the model; however age (categorised as below 25 years and 25 years and over)36 and treatment were the only significant interaction terms. The coefficient and 95% CI for this interaction was: 4.2 (1.3 to 7.1). The difference in Acne-QoL symptom subscale score in the 25 years and above population was 2.42 (95% CI 1.00 to 3.84), which was statistically significant and reached the desired two-point mean difference between groups in favour of spironolactone. The population of those below 25 years was considerably smaller (44 participants) and therefore it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions, although the difference of –0.87 (95% CI –3.67 to 1.92), which does not favour the spironolactone group, suggests that spironolactone may be less effective in younger women.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Including only participants with PCOS or suspected PCOS | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 26 | 35 | 61 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.4 (6.0) | 17.3 (5.2) | 17.3 (5.5) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 0.60 (–2.14 to 3.34) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.37 (–1.40 to 4.14) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants without PCOS or suspected PCOS | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 144 | 124 | 268 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.4 (6.2) | 17.7 (5.8) | 18.6 (6.0) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.74 (0.36 to 3.12) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.46 (0.12 to 2.80) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants 25 years and above | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 132 | 120 | 252 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.0 (6.0) | 17.4 (5.6) | 18.7 (5.9) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 2.63 (1.27 to 3.98) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 2.42 (1.00 to 3.84) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants below 25 years | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 44 | 46 | 90 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.9 (5.8) | 18.7 (5.6) | 17.8 (5.8) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | –1.79 (–4.13 to 0.55) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | –0.87 (–3.67 to 1.92) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants with a BMI ≤ 25 | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 99 | 82 | 181 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.8 (5.7) | 17.7 (5.2) | 18.9 (5.5) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 2.17 (0.60 to 3.75) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.89 (0.32 to 3.46) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants with a BMI > 25 | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 77 | 84 | 161 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.4 (6.6) | 17.8 (6.0) | 18.1 (6.3) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 0.61 (–1.19 to 2.40) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 0.34 (–1.56 to 2.24) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants with baseline IGA < 3 | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 79 | 80 | 159 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.4 (5.8) | 18.2 (5.8) | 19.3 (5.9) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.90 (0.20, 3.61) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.63 (–0.10 to 3.35) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants with baseline IGA ≥ 3 | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 97 | 86 | 183 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.3 (6.2) | 17.4 (5.4) | 17.8 (5.8) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.06 (–0.60 to 2.73) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.35 (–0.33 to 3.03) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants not taking hormonal treatment | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 102 | 90 | 192 |

| Mean | 18.8 (6.1) | 17.5 (5.7) | 18.2 (5.9) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.49 (–0.12 to 3.11) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.79 (0.12 to 3.46) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants taking the combined oral contraceptive a | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 27 | 18 | 45 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.1 (6.7) | 19.2 (6.1) | 20.4 (6.5) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 2.13 (–1.89 to 6.14) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 2.70 (–1.77 to 7.17) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants taking progesterone-only contraception | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 47 | 58 | 105 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.9 (5.8) | 17.7 (5.3) | 18.2 (5.5) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 0.58 (–1.33 to 2.50) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.03 (–0.83 to 2.90) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants who reported they were not taking topical treatment at baseline | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 24 | 27 | 51 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.8 (5.8) | 17.2 (6.7) | 17.9 (6.3) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.96 (–1.19 to 5.10) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.91 (–1.82 to 5.65) | REF | N/A |

| Including only participants who reported they were taking a topical treatment at baseline | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 150 | 138 | 288 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.2 (6.1) | 17.9 (5.4) | 18.6 (5.8) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12-weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 1.27 (–0.17 to 2.56) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 1.22 (–0.09 to 2.53) | REF | N/A |

Summary statistics are presented in Table 19 for the primary outcome pre and post COVID as well as for ethnicity. The mean Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks pre and post COVID was similar for both groups. Those who identified as non-white had on average a better score in the placebo group; however this population was small (n = 22), therefore it is difficult to draw meaningful conclusions.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre COVID | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 35 | 32 | 67 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.1 (6.3) | 17.7 (4.7) | 19.0 (5.7) |

| Post COVID | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 141 | 134 | 275 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.0 (6.1) | 17.8 (5.8) | 18.4 (6.0) |

| Ethnicity – white | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 143 | 149 | 292 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.6 (6.1) | 17.4 (5.6) | 18.5 (5.9) |

| Ethnicity – non-white | |||

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 12 weeks | |||

| N | 15 | 7 | 22 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.1 (5.6) | 19.9 (5.3) | 17.3 (5.7) |

Complier-average causal effect analysis

The results of the CACE analysis performed on self-reported treatment adherence at 24 weeks can be seen in Table 20. ‘Compliance’ was defined as participants reporting that they had taken either 50%, 80% or 100% of the prescribed medication over the 12- to 24-week period. Compliance was only considered over the 12- to 24-week period due to the collection of these data before this time point being poorly reported in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as pill count at 6 and 12 weeks was initially planned but often not possible. When considering 80% as the threshold for compliance, we observed 74% of women complied. The adjusted mean difference between groups was 5.13 (95% CI 3.17 to 7.08), suggesting a greater treatment effect amongst women who took 80% or more of the prescribed medication. For all thresholds of compliance (50%, 80% and 100%), the proportion of participants achieving ‘compliance’ were similar in both spironolactone and placebo groups, suggesting that spironolactone was well-tolerated.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| CACE analysis – 50% compliance | |||

| Was the participant compliant? | |||

| Yes | 144 (98.0%) | 115 (98.3%) | 259 (98.1%) |

| No | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (1.7%) | 5 (1.9%) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks (95% CI) | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 4.33 (2.82 to 5.84) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 3.89 (2.48 to 5.30) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| CACE analysis – 80% compliance | |||

| Was the participant compliant? | |||

| Yes | 110 (74.8%) | 85 (72.7%) | 195 (73.9%) |

| No | 37 (25.2%) | 32 (27.4%) | 69 (26.1%) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 5.67 (3.60 to 7.74) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 5.13 (3.17 to 7.08) | REF | N/A |

| Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| CACE analysis – 100% compliance | |||

| Was the participant compliant? | |||

| Yes | 33 (22.4%) | 29 (24.8%) | 62 (23.5%) |

| No | 114 (77.6%) | 88 (75.2%) | 202 (76.5%) |

| Mean difference Acne-QoL symptom subscale score at 24 weeks | |||

| Complete cases (unadjusted) | 18.89 (9.64 to 28.14) | REF | N/A |

| Complete cases (adjusted) | 17.13 (8.34 to 25.93) | REF | N/A |

Adverse reactions

Adverse reactions of special interest were included in the participant questionnaire and can be seen in Tables 21–23. Table 21 shows that menstrual irregularities are reported by approximately a quarter of women at all time points, with similar rates in spironolactone and placebo groups. Table 22 shows that menstrual irregularities are also similar across both groups when comparing across all time points. Table 23 shows that most ARs were experienced at similar rates in the spironolactone group compared to the placebo group. Pearson’s χ² test showed that the only statistically significant difference was that headaches were more commonly reported amongst women on spironolactone.

| Characteristic | Spironolactone (n = 201) | Placebo (n = 209) | Total (n = 410) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced irregular menstrual bleeding at baseline a | |||

| Yes | 44 (22.2%) | 58 (28.0%) | 102 (25.2%) |

| No | 119 (60.1%) | 107 (51.7%) | 226 (55.8%) |

| Don’t have periods | 35 (17.7%) | 42 (20.3%) | 77 (19.0%) |

| Missing from eCRF – n (%)b | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 5 (1.2%) |

| Experienced irregular menstrual bleeding at 6 weeks a | |||

| Yes | 45 (25.3%) | 46 (25.3%) | 91 (25.3%) |

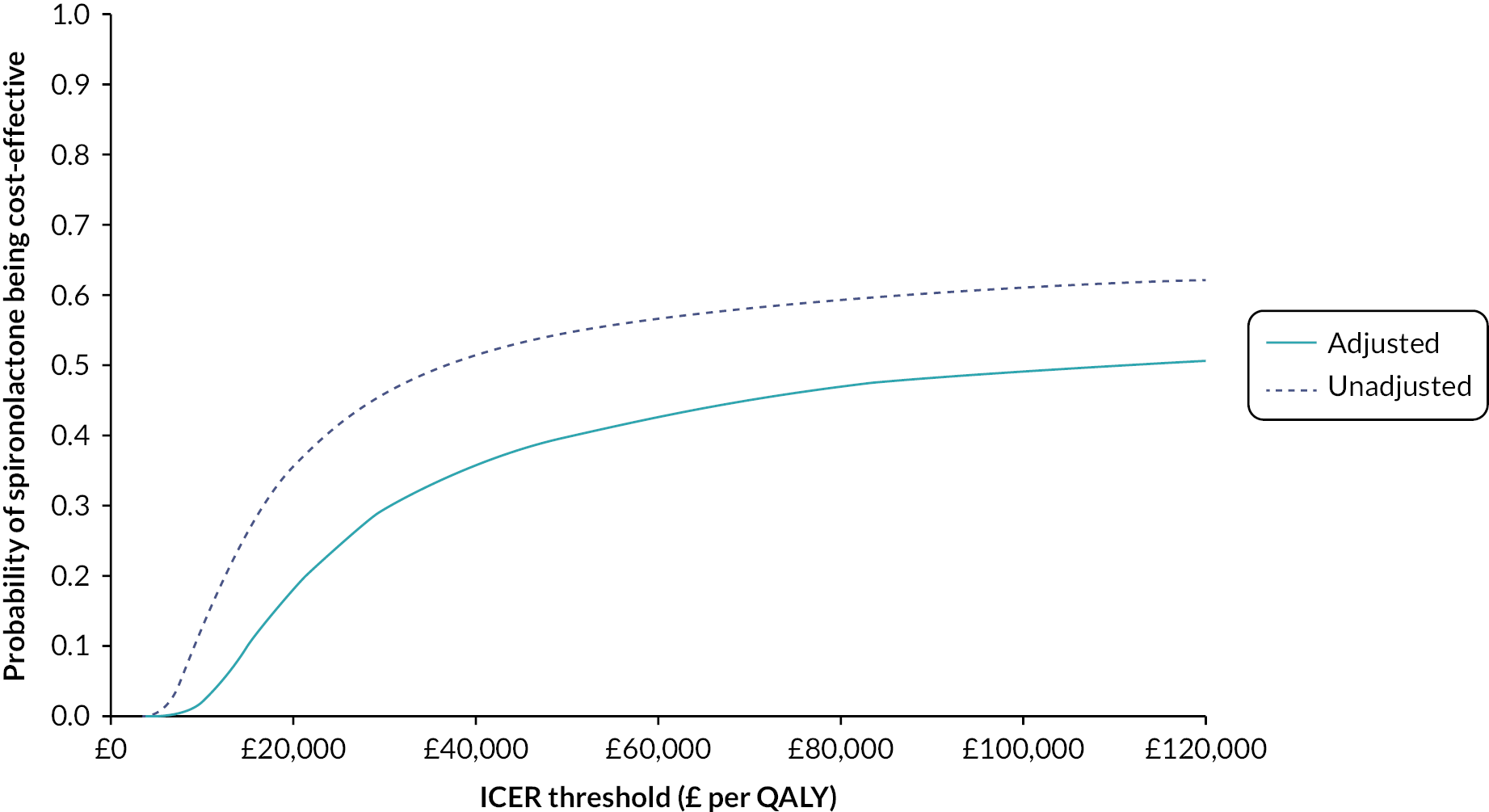

| No | 100 (56.2%) | 102 (56.0%) | 202 (56.1%) |