Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/57/32. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The draft report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in January 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Thornhill et al. This work was produced by Thornhill et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Thornhill et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this chapter have been adapted with permission from the study protocol. 1

Infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a life-threatening infection of the endocardial lining of the heart, particularly the heart valves, with a high morbidity rate and ≈ 30% first-year mortality. 2 The infection leads to the formation of infected heart valve vegetations that may lead to obstruction of normal blood flow through the heart, destruction or perforation of valve leaflets, and damage to the chordae tendineae that can cause severe valvular regurgitation. These in turn may lead to heart failure. In addition, there may be perivalvular abscess formation, and fragments of infected vegetations may break off and embolise to distant capillary beds, causing strokes, retinal haemorrhages, brain abscesses and other distant site infections, vasculitis and characteristic nail bed splinter haemorrhages. 2

Currently, there are ≈ 3000 IE cases and ≈ 900 IE-related deaths annually in England, and the number has nearly doubled in the last 10 years. 3,4 All patients require hospitalisation and intensive long-term treatment with antibiotics. 2 A large proportion of patients require surgery to replace damaged heart valves and the long-term morbidity rate is high. 2 The resultant cost to individuals, families, society and the NHS is extremely high. 5

Risk of infective endocarditis

Although IE is relatively rare, affecting only 3–10 per 100,000 people per year,3,4,6,7 patients at increased risk of IE are comparatively common and increasing in number. A large number of individuals with predisposing cardiac conditions are at increased risk of IE. 7 Guideline committees around the world have generally stratified individuals into those at high, moderate and low risk of contracting IE, or developing complications from IE. 8–11 High-risk individuals include (1) those with a history of IE; (2) those with prosthetic heart valves, including transcatheter, bioprosthetic or homograft valves; (3) those for whom prosthetic material was used for valve repair; (4) those with any type of cyanotic congenital heart disease; and (5) those with any type of congenital heart disease repaired with prosthetic material, who are at high risk for 6 months following the repair or for life if there is a residual shunt of valvular regurgitation. Those at moderate risk include those with valvular stenosis or regurgitation, a bicuspid aortic valve or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The role of oral bacteria

Infective endocarditis can result from bloodstream infection caused by a spectrum of bacterial and fungal organisms entering the circulation. However, certain organisms seem to have a higher propensity than others for causing IE. The possibility that some cases of IE might be linked to invasive dental procedures (IDPs) was first suggested by Lewis and Grant in 192312 and supported in 1935 by Okell and Elliott,13 who demonstrated that 61% of individuals develop a transient bacteraemia with oral viridans group streptococci (OVGS) following a dental extraction and that OVGS could be isolated from the heart valve vegetations of 40–45% of individuals with IE.

Use of antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures to prevent infective endocarditis

Following the development of antibiotics, Glaser et al. 14 and Hirsch et al. 15 demonstrated that penicillin given prophylactically could reduce the bacteraemia caused by dental extractions, and this paved the way for the American Heart Association (AHA) to issue the first guidelines on the use of antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) to prevent IE in 1955. 16

Antibiotic prophylaxis was soon adopted globally as a standard of care for preventing IE in those at increased risk of IE who were undergoing IDP. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has never been a trial of AP to define its efficacy in IE prevention. 17 Furthermore, multiple studies have shown that low-level bacteraemia occurs frequently following daily activities such as tooth brushing, flossing and mastication, particularly in those with poor oral hygiene. 18 Some have argued that the risk of developing IE posed by these daily activities far exceeds any risk associated with IDP,19 and thus the case for giving AP to cover IDPs is flawed. 19 This, along with concerns about the risk of adverse drug reactions5,20 and the development of antibiotic resistance,21 has led to reductions in the number of individuals targeted for AP.

In 2007, the AHA recommended restricting AP to those at high risk of IE and its complications who were undergoing IDP. 11 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published similar guidance in 2009. 9 In the UK, however, where the important role of daily activities in causing OVGS IE was most strongly argued,19 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded in 2008 that ‘the evidence does not show a causal relationship between having an interventional procedure and the development of IE’ and that ‘it is biologically implausible that a dental procedure would lead to a greater risk of IE than regular tooth brushing’ and recommended the complete cessation of AP (© NICE 2008 Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng64. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.). 22,23

Nonetheless, concerns remain that IDPs could pose a risk for those at increased risk of IE and most guideline committees (e.g. AHA, ESC, Japanese Cardiac Society) continue to recommend AP for those at highest risk who are undergoing IDP. 9,11,24 In 2016, even NICE softened its position and no longer precludes the use of AP for those at increased risk of IE undergoing IDPs. 25,26

Lack of evidence to support the use of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis

Despite the wide adoption of AP before IDPs to prevent IE in many parts of the world, to the best of our knowledge, there has never been a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of AP’s efficacy. The evidence base for the use of AP is mainly limited to case–control studies, in which reduction in bacteraemia was used as a surrogate measure for reduction in IE, and the evidence base for the use of AP is therefore limited and heterogeneous. Many of the studies are of poor methodological quality. 17

There are several reasons why a RCT of AP has not been performed to date and is unlikely to be performed in the foreseeable future. 27 AP is not a treatment, but rather a prevention strategy, and IE is comparatively rare. This means that hundreds of individuals at risk of IE would need to receive AP to prevent one case of IE. Data from a study published in The Lancet suggested that the number of individuals that would need to receive AP to prevent one case of IE was 277 [95% confidence interval (CI) 156 to 1217 individuals]. 6 The need to randomise patients to placebo or active prophylaxis would double the size of the study.

Furthermore, AP has to be administered immediately before performing an IDP for it to be effective. This means that the decision to provide AP has to be made by dentists. However, each dental practice sees only a small number of individuals at risk of IE. Therefore, large numbers of dental practices across the country would need to be involved in recruiting and randomising patients to AP or placebo. All of this means that the size, cost and complexity of a RCT to evaluate AP would be substantial.

Several attempts have been made to fund such a RCT, including by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and the US National Institutes of Health. Ultimately, the high cost of such studies has prevented these and other agencies from funding such a trial. A further barrier to a RCT, particularly in countries in which AP is the current standard of care, are ethics and medicolegal concerns about withholding AP from individuals at high risk of IE who would be randomised to placebo prophylaxis. This is because of concern that individuals randomised to placebo prophylaxis could develop IE and die. So far, this concern has prevented attempts to perform a RCT of AP in countries outside the UK. 27 Collectively, these factors explain why a RCT has not taken place to date and may never be conducted. 27

The aim of the study

Before a RCT would be meaningful, we need to be certain that there is an association between IDPs and IE; that is the purpose of the Invasive Dentistry–Endocarditis Association (IDEA) study. Indeed, such a study could render a RCT unnecessary. Without an association between IDPs and IE, there is no rationale for the use of AP. The IDEA study links national data concerning courses of dental treatment and hospital admissions for IE to investigate if there is a temporal link or association between IDPs and the subsequent development of IE.

The advantage of performing this study in England is that, between March 2008 and March 2016, NICE recommended against AP and there was a high level of compliance with this recommendation. 3,6,28 Any association between IDP and IE should therefore be fully exposed.

Chapter 2 Overview of prespecified study methodology

Introduction

The aim of this study was to investigate if there is a temporal association between IDPs and the development of IE.

Antibiotic prophylaxis makes sense only if there is a temporal association between IDPs and IE. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have specifically looked for the existence of such an association and the results of these investigations have been contradictory.

In 1995, Lacassin et al. 29 performed a small case–control study in France in which they compared the occurrence of IDPs in the 3 months prior to hospital admission in 171 patients with IE with a control population. They found a significantly elevated risk of IE in those who had undergone an IDP and estimated that AP could reduce the risk of IE by 5–10%. However, they acknowledged that their study was underpowered and the case–control design was criticised regarding the risk of selection bias and confounding due to potential differences in IE risk factors between cases and controls.

In 1998, Strom et al. 30 performed a similar case–control study in the Philadelphia area comparing the incidence rate of IDPs in the 3 months prior to hospital admission in 273 IE cases and control subjects. They found no evidence for an association between IDP and IE. However, the authors acknowledged that the study was underpowered to identify an association and was at risk of selection bias and confounding due to differences in the risk of IE in cases and control subjects.

In 2017, Tubiana et al. 31 examined the relationship between IE and IDPs in the 3 months prior to IE hospital admission in a cohort study of 138,876 high-risk individuals with prosthetic heart valves, of whom 267 developed IE associated with oral streptococci. They reported no significant association between IDP and the development of IE, but acknowledged a lack of power to demonstrate an association in their cohort study.

In an attempt to avoid the issues of selection bias and risk factor confounding, Porat Ben-Amy et al. 32 performed a case-crossover design study to address the same problem. They identified 170 patients with IE and used a patient questionnaire to identify any dental visits over the previous 2 years. The frequency of dental visits in the 3 months immediately before IE diagnosis was compared with the frequency in earlier 3-month periods. Again, the study suffered from a small sample size and recall bias caused by patients’ difficulty recalling the timing and nature of dental procedures performed over the preceding 2 years.

More recently, Chen et al. 33 performed a larger case-crossover design study using a Taiwanese longitudinal health insurance database. They identified 739 patients with IE and compared the incidence rate of IDPs in the 3 months immediately prior to IE diagnosis (cases) with earlier 3-month periods (matched control periods). They did not find a significant difference in the incidence rate of IDPs between cases and controls. However, they acknowledged the small number of IE cases in their study and the likelihood that they had insufficient statistical power to detect an association between IE and IDPs.

In 2017, after this study had already started, Tubiana et al. ,31 alongside the cohort study described above, reported the results of a further case-crossover analysis of 648 prosthetic valve patients who developed oral streptococcal IE. They found a higher frequency of IDP in the 3-month case period before IE hospital admission than in the control periods (5.1% vs. 3.2%, respectively; odds ratio 1.66, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.63; p = 0.03). 31

Apart from the Tubiana et al. case-crossover study,31 all of these studies were underpowered. 29,30,32,33 Even more importantly, they were all (including the study by Tubiana et al. 31) performed in populations in which the standard of care was to prescribe AP prior to IDP. At the time of the Lacassin et al. 29 and Strom et al. 30 studies, patients at moderate and high risk of IE would have been provided with AP, and in the case of the Porat Ben-Amy et al. 32, Chen et al. 33 and Tubiana et al. 31 studies it was recommended that those at high risk were provided with AP. Clearly, if AP has efficacy for preventing IE, any association between IDPs and IE would be underestimated in a situation where patients at increased risk of IE were being provided with AP.

The purpose of the IDEA study was to perform a much larger case-crossover study in a population in which the standard of care was not to provide AP. This is why we chose a study period from April 2009 to March 2016. Although the NICE guidelines recommending cessation of AP came into effect in March 2008 (and AP prescribing fell quickly after their introduction),6 by waiting an extra year before collecting data we could ensure that any carryover effect of AP prescribing was minimised. This should have optimised the chances of identifying any association between IDPs and IE that might exist and provide much more reliable data on this important issue. Because the UK was the only country in the world where AP was not recommended during this period, it was the only place where a study investigating the association between IDPs and IE could be performed without the effect of AP concealing any association.

The case-crossover design eliminates selection bias and confounding for risk of IE because each case acts as its own control. 34,35 Furthermore, by linking national dental and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data, we did not have to rely on patient recall to determine the timing and nature of any dental procedures that were performed.

Because the case-crossover methodology addresses problems of selection bias and confounding, and provides greater statistical power for addressing cause and effect issues of this type, we prespecified a case-crossover methodology for our primary analysis. This case-crossover methodology was first proposed by Maclure34 for studying the effect of transient events in triggering a subsequent acute outcome while eliminating control selection bias and confounding by constant within-subject characteristics. In case-crossover studies, each individual acts as their own control. The study examines individuals with a specific outcome – in this case, those who develop IE – and looks at their exposure to events that might precipitate that outcome – in this case, IDPs.

Primary aim of the study

Our primary aim was to perform a case-crossover design study34 to quantify the number of IDPs in the 3 months immediately preceding a hospital admission for IE (the case or exposure period) and to compare this with the number of IDPs in the preceding 12 months (i.e. months 4–15; the matched control periods) to determine if there is an association between IDPs and IE.

We chose a 3-month case/exposure period because previous research has shown that ≈ 90% of IE cases associated with an identifiable potential cause result in hospital admission and a definitive diagnosis of IE within 3 months. 36 A 3-month period is widely accepted within research studies for defining IE cases associated with a causal invasive procedure. 29–33 The preceding 12-month period was selected as the control period.

Possible outcomes

If there is a link between IDPs and IE, we would expect courses of dental treatment involving an IDP to occur with significantly higher frequency in the 3-month case/exposure period immediately preceding hospital admission for IE than in the matched control period.

Alternatively, if there is no link between IDP and IE, we would expect there to be no significant difference in the number of IDPs in the 3-month case/exposure period immediately preceding hospital admission for IE and the number of IDPs in the control period.

Data sources

All hospital admissions in England are recorded in the NHS Digital HES database. 37 We submitted a request to NHS Digital to search the HES database using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), codes to identify all IE hospital admissions between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2016 and create two data sets:

-

Data set 1 – patient-identifying information (i.e. NHS number, name, date of birth, sex, address) for those admitted with IE. This list of identifiers, along with a unique HES study identifier generated randomly for each patient by NHS Digital, was transferred directly to the NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA).

-

Data set 2 – for all IE admissions identified, NHS Digital produced a full set of clinical, diagnostic and procedural HES data for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 March 2016. Data set 2 included the same unique study identifiers used in data set 1, but no other patient-identifying information. Data set 2 was transferred to the study team.

The NHSBSA maintains dental records for all patients receiving NHS dental treatment in England. Using the personal identifiers received in database 1, we requested that they extract the dental records of each of these individuals for the period 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2016, thereby providing the dental records of each individual for the year preceding their hospital admission for IE. The NHSBSA was requested to remove all patient identifiers (except the unique HES study identifier) from these data to create data set 3, which was transferred to the study team. Thus, the study team received and were able to link the medical (data set 2) and dental (data set 3) records of each individual using the common HES study identifier (common to all three data sets) without receiving patient-identifying details.

The study period from 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2016 was chosen for several reasons. First, in March 2008, the NICE guidelines recommending that dentists should cease to provide AP to patients for preventing IE came into effect and, by March 2009, AP prescribing had decreased by 76%. 3,22 Therefore, if IDPs are a risk factor for IE, the risk will have been maximised since then.

Second, from April 2008, dentists working in the English NHS were required to record if a patient had received a dental extraction, scale and polish or endodontic treatment (i.e. an IDP) as part of their course of dental treatment using NHS form FP17. Patient-identifying data, other types of dental treatment (i.e. non-invasive), and the start and end dates of the course of treatment are also recorded. Dentists must complete a FP17 form for each patient they treat and send it to the NHSBSA, where data are recorded to receive payment. Compliance is therefore high.

By waiting to commence data collection for 1 year after the introduction of the NICE guidelines and inclusion of dental procedure recording on the FP17 form, we minimised any carryover effect of AP prescribing or changeover effect on the recording of dental data.

Approvals

Because this study uses national data and necessitated the transfer of individually identifying information between NHS Digital and the NHSBSA, we were required to obtain both national Research Ethics Committee approval (reference 17/SC/0371) and Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) approval (reference 17/CAG/0076) under Regulation 5 of the Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 200238 to process patient-identifiable information without consent. We also had to obtain approval from NHS Digital Data Access Request Service (DARS) and the Independent Group Advising on the Release of Data (IGARD).

Identifying invasive dental procedures

Since April 2008, dentists working in the English NHS must record if a patient has had a dental extraction, dental scaling or endodontic treatment as part of any course of dental treatment. These procedures were considered IDPs for the purposes of this study. 11,39 We also identified ‘non-invasive’ courses of dental treatment, which included courses of treatment restricted to a simple dental examination, with or without radiography, and excluded any operative (including restorative) treatment. Courses of treatment that did not include IDPs or non-invasive dental procedures, as defined above, were labelled indeterminate courses of dental treatment. These included courses of dental treatment that involved restorative dental treatments, but no IDP.

Identifying infective endocarditis admissions and infective endocarditis risk stratification

An IE admission was defined as a hospital provider spell, that is ‘the total continuous stay of a patient on premises controlled by a Health Care Provider’, in line with the NHS Business definition (Information from NHS Digital, licensed under the current version of the Open Government Licence; www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/). 40 Each spell may comprise a number of consultant episodes, each with a primary ICD-10 discharge diagnosis code and up to 20 secondary or supplementary codes. An IE admission was defined as any spell where an ICD-10 I33.0 primary diagnosis code was used for any consultant episode. Patients discharged alive with a hospital stay of < 3 days in length (admission date – discharge date), re-admission within 30 days or elective admission [i.e. admission method recorded as waiting list (category 11), booked (category 12) or planned (category 13)] were excluded from analysis. We have labelled this definition of IE cases as the ‘narrow’ definition of IE or ‘IE narrow’. A recent analysis of English hospital admissions for IE showed that the use of this narrow definition of IE cases had the highest specificity (0.97) and positive predictive value (PPV; 0.88) for identifying Duke criteria-positive IE cases of any ICD-10 diagnostic codes, but low sensitivity (0.41). 41

To increase sensitivity for identifying IE cases, we also performed the analysis using the same criteria and any hospital admission with a primary or secondary ICD-10 discharge diagnosis code (i.e. I33.0, I33.9, I39.0, I39.1, I39.2, I39.3, I39.4 or I39.8), or a primary discharge diagnosis code of I38.X. This definition, labelled the ‘broad’ definition of IE or ‘IE broad’, has been shown to have higher sensitivity (0.65), but lower specificity (0.83, PPV 0.80). 41

To stratify individuals into those at high, moderate, or low/unknown risk of developing IE, the database was searched back to 1 January 2000 to identify any ICD-10 diagnosis or Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures, version 4 (OPCS-4), procedure codes occurring before an IE admission that would have placed an individual at high or moderate risk of IE, as defined by the 2007 AHA guidelines (see Appendix 1, Tables 24 and 25). 11,42 After an individual had an IE hospital admission, they were considered at high risk for further episodes of IE. New IE episodes were distinguished from re-admissions by accepting only IE admissions that were > 6 months apart as new episodes. 7,43 Individuals with a congenital heart condition that was completely repaired with prosthetic material or a device were considered to be at high risk of developing IE for 6 months after the procedure, and were then considered at low risk of developing IE, in line with AHA guidelines. 11 Individuals not identified as being at moderate or high risk were considered to be at low/unknown risk of IE.

Sample size and power calculations

Use of publicly available annualised data from NHS Digital allowed us to estimate that there were 10,593 IE diagnoses in England between 1 April 2009 and 31 March 2015. It also confirmed that the incidence rate of IE was increasing year on year. Between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2016, we therefore expected the number of IE cases to be at least 10,593, and this is the figure we used in our power calculations. Publicly available NHSBSA dental services data for the same period showed that 56% of the population were regular NHS dental attenders (not accounting for any of those only attending an NHS dentist in an emergency). 44

Preliminary analysis of the dental data showed that there were 176.4M courses of dental treatment between 1 April 2009 and 31 March 2015. Of these, ≈ 90.6M included an IDP and ≈ 85.8M did not include an IDP. IDPs included ≈ 13.2M extractions, ≈ 78.6M scale and polishes and ≈ 3.6M endodontic treatments. The numbers of IDPs and the number of each type of IDP are therefore likely to be larger for the period from 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2016.

A case-crossover design study34 is a type of self-controlled case-series. 45–47 Sample sizes for self-controlled case series are given by Muscoda46 and available from the HyLown Consulting webpage. 48

The cases in our study were those patients with IE admissions who underwent an IDP in the 15 months before admission: the ‘observation period’. The ‘risk period’ was the last 3 months of the observation period (i.e. the 3 months just before the admission) and the ‘control period’ was the previous 12 months. Our data spanned the period between April 2009 and March 2016. In the 6 years from April 2010 to March 2016, we expected to identify 10,593 patients with IE admissions in HES data for England whose exposure to IDPs was observed in the 7 years of NHS dental service data from April 2009 to March 2016. We know that 56% of the population regularly use NHS dentists, and that at least half of all courses of dental treatment include an IDP. If we assume that regular NHS dental patients are seen once every 2 years, then we would expect that each patient would have an IDP at least every 4 years. Bearing in mind that IDPs include common procedures, such as a scale and polish, as well as less common procedures, such as extractions, this estimate was probably conservative.

Assuming that there was no association between IDPs and IE, we estimated that our sample size would consist of 10,593 × 0.56 × 0.25 = 1483 patients with admissions for IE who underwent an IDP in the previous 12 months. This gave 80% power to detect a relative incidence rate of 1.18 (i.e. + 18%) in the 3-month ‘risk period’ compared with control periods. If regular NHS dental patients have an IDP once every 2 years, then we should have 2966 cases and 80% power to detect a relative incidence rate of 1.12 (i.e. + 12%). This should give us the statistical power to detect any association between IDPs and IE that is likely to be of clinical significance, and it will greatly exceed the power of any previous study.

Statistical analysis

The planned case–cohort analysis used a longitudinal Poisson regression in which the outcome was the number of IDPs. Specifically, the primary planned analysis was to divide time into four intervals, each of 3 months, with the number of IDPs in the 3 months immediately prior to IE compared with that in months 3–6, 6–9 and 9–12. Hypothesis tests, using Wald tests, were performed to compare case and control periods. A larger number of IDPs in the case period than in the control periods would suggest that there is an association between IE and IDP events.

A second planned analysis was to consider the relative incidence rate of IDPs to non-IDPs during the case and control periods.

Alternative case and control periods were also considered, including:

-

4-monthly – months 0–4 (case) compared with months 4–8 and 8–12 (controls)

-

quarterly, but removing month 1 – months 2–4 (case) compared with months 5–7, 8–10 and 11–13 (controls).

In all cases, the model was a longitudinal Poisson regression using an exchangeable correlation matrix and robust standard errors. The Poisson model was tested for overdispersion by fitting a population-averaged negative binomial model with an overdispersion parameter proportional to the mean. The overall comparison of case and control periods was the averaged coefficient across the three control periods and all IE cases; however, period-specific incidence rates are also reported.

Reporting guidance

As this was an observational study, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement reporting guidance checklist for cohort studies49 was used to guide our reporting of this study.

Causes and consequences of delays in receipt of data

The project start date was 1 September 2016, and the original project end date was 30 November 2018. Within this, we had allowed 14 months to obtain all the regulatory permissions and receive the data needed for the study from NHS Digital and the NHSBSA (i.e. we should have received the data by 30 September 2017). However, we did not receive both data sets until 21 May 2020, some 32 months late. There were many delays in the regulatory and contractual process that led to this.

First, at the outset of the study, the Health Research Authority (HRA) informed us that we did not require NHS research ethics approval for the study, but would require CAG approval. As the University of Sheffield requires us to obtain University ethics approval for any studies not covered by NHS ethics approval, we sought and obtained this before submitting a CAG application. The CAG, however, rejected our application and indicated that it would not consider it without prior NHS ethics approval. The CAG would not accept the University of Sheffield ethics approval. It rejected the HRA advice on this. We therefore sought NHS ethics approval through the National Research Ethics Service (NRES). However, NRES insisted that this was not necessary for our study and that it was the CAG’s responsibility to provide any approval. It took some time to resolve this conflict of opinion and advice between HRA, NRES and CAG. Eventually, NRES undertook the ethics review, and once it had issued a favourable opinion we were allowed to submit the CAG application. Owing to these delays, we finally received CAG approval on 27 September 2017.

Second, once we had CAG approval, we submitted our application to the DARS at NHS Digital to obtain Section 263 approval under the Health and Social Care Act50 for the use of confidential patient information. Having already obtained both research ethics and CAG approval, we expected a relatively rapid turnaround. However, owing to the delays in obtaining these, we were caught by the introduction of a new regulatory step in the NHS Digital CAG approval process, with the additional need to obtain approval from the newly established IGARD. This changed the information we were required to submit. Nonetheless, we submitted our application to the new 13-stage DARS/IGARD process on 27 October 2017.

In January 2018, DARS/IGARD informed us that NHS Digital had reservations about providing the NHSBSA with a list of patients diagnosed with IE, as this would mean that NHSBSA staff would know that everyone on that list had had IE. To avoid this, it was suggested that the data sent to the NHSBSA should contain details of patients admitted for other conditions as well. As we thought it would be interesting to investigate any association between IDP and other acute medical conditions [e.g. myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and pulmonary embolism (PE)] as well, we suggested adding patients diagnosed with these conditions to the data set extracted by NHS Digital. Thus, NHSBSA staff would not know which of these conditions any individual might have experienced. This, however, resulted in a much larger data set, which in turn caused concern within the NHSBSA about its ability to manage a much larger data set with its existing resource and staff. We were eventually informed that we had received DARS/IGARD approval on the 23 February 2018.

Third, the data access charge estimates from NHS Digital and the NHSBSA on which our grant application was costed produced a combined cost of just under the £20,000 requested. However, because of the delays and the DARS/IGARD/NHS Digital requirement that we include non-IE data, both NHS Digital and the NHSBSA very substantially increased their data access charges: NHS Digital increased from £9560 to £25,800 and the NHSBSA increased from under £10,000 to £21,081.45 (i.e. £46,881.45 total). This was beyond the grant’s ability to fund. In discussion with NIHR, it was decided that we should seek a 4-month extension to the study (new end date 31 March 2019) and a budget increase to cover the increase in data access charges. The contract variation request was submitted to NIHR on 22 March 2018 and approved on 1 August 2018.

Fourth, during this period, NHS Digital and the NHSBSA also changed their views several times about the nature of the data-sharing agreement (DSA) arrangement they wanted to cover this study. NHS Digital’s opinion changed from wanting just an agreement between it and the University of Sheffield, to a three-way agreement involving NHS Digital, the NHSBSA and the University of Sheffield, and then to a series of two-way agreements. In late March 2018, NHS Digital finally informed us that it would enter into only a two-way agreement between NHS Digital and the University of Sheffield, and it would not permit the NHSBSA to be a signatory to the agreement (despite the NHSBSA being named in the agreement as a data processor). We therefore had to seek legal advice about how to proceed, as the NHSBSA was one of the named data processors and insisted on being a signatory to any agreement. We were advised to set up two separate DSAs – one between NHS Digital and the University of Sheffield, and another between the University of Sheffield and the NHSBSA. This was finally agreed by all parties in April 2018.

Fifth, simultaneous negotiations about the large increase in data access charges ultimately resulted in a reduction in the NHS Digital charge to £10,200. However, the NHSBSA informed us of a possible further increase in the data access charges. The reason it gave was that the government now required it to outsource all of its data activities to the private company Capita plc (London, UK), and Capita plc would want to perform its own costing, as the NHSBSA was no longer in a position to perform the work. The involvement of Capita plc was new information for us and meant that the DSAs and DARS approvals were no longer valid. NHS Digital required both the NHSBSA and Capita plc to be named as data processors on the DSAs, and we had to obtain separate details and evidence of the data security arrangements of Capita plc as well as the NHSBSA. It took time to identify the right people within Capita plc to provide the necessary details and several problems arose. These problems were due to NHS Digital/DARS’s dissatisfaction with the information provided by Capita plc and Capita plc’s unfamiliarity with the requirements of NHS Digital. The delays were exacerbated by these organisations’ failure to communicate directly with each other and the study team had to act as an intermediary in these processes and communications.

On 10 August 2018, we were finally able to provide NHS Digital/DARS with all of the information it required to approve the study and sign the DSAs. On 14 September 2018, NHS Digital/DARS informed us that it was now satisfied with all of the information and that the DSAs between NHS Digital and the University of Sheffield, and between the University of Sheffield and Capita plc were ready for signing. After much chasing, we received an e-mail from NHS Digital on 12 October 2018 informing us that it had had a change of mind and decided to send the project back to IGARD for review. By 23 November 2018, we had still not heard the outcome of that review or received either data set, and it was evident that it would be impossible to complete the project before the extension’s end date of 31 March 2019. In further discussions with NIHR, it was decided to stop all further work and expenditure (apart from data access charges) on the project on 30 November 2018 and effectively freeze the project until we could be certain of receiving both data sets.

Sixth, around the same time, the NHSBSA informed us that Capita plc’s contract to undertake all of the NHSBSA’s data-processing activities was coming to an end, with all data-processing activity being brought back in house. However, because the NHSBSA no longer had the staff and resources to undertake this work and because of the challenges associated with repatriating the work to the NHSBSA, it was unlikely that the NHSBSA would be able to deal with our data request for at least 1 year.

Seventh, in early 2019, we finally received IGARD approval again and the DSAs were finally signed off on 21 March 2019. In June 2019, NHS Digital finally provided the NHSBSA with data set 1 and the study team with data set 2. Unfortunately, the NHSBSA Dental Information Services Team in Eastbourne was still not in a position to extract the dental data we needed, despite now having all the information they needed from NHS Digital. After much further negotiation, the Eastbourne NHSBSA team enlisted the support of the NHSBSA Data Analytics Learning Laboratory team in Newcastle to carry out the work. This necessitated further adjustments to the DSA’s data security details, but, on 30 October 2019, we finally received a guarantee from the NHSBSA’s Chief Insight (Data) Officer that the NHSBSA would provide the dental data before 1 April 2020.

Eighth, we informed NIHR of this and it was agreed that we should request a further contract variation to allow the project to restart on 1 April 2020, with an end date of 31 March 2021. This contract variation was submitted on 25 October 2019. On 5 February 2020, NIHR approved the contract variation, with a financial reconciliation that would allow us to restart on 1 April 2020 and fund our work until 31 March 2021. However, although providing funding until 31 March only, NIHR extended the study end date by a further 3 months until the 30 June 2021. We finally received the dental data from the NHSBSA on 21 May 2020.

Ninth, with the release of the dental data to the study team, the NHSBSA informed us that it was unable to supply all of the data we had requested (i.e. data from 1 April 2009 until 31 March 2015). It informed us that this was because they have a policy of destroying data that are ≥ 10 years old. NHSBSA was, therefore, able to supply us with data only from 1 April 2010 until 31 March 2015, that is 60 months of data rather than the 72 months of data we had requested and had used to calculate the sample size and power of the data. Had the data been made available to us as planned by 30 September 2017 (or even up to 18 months after that), we could have still received the whole data set.

Last, on 16 March 2020, the government announced the UK COVID-19 lockdown. This necessitated a rapid change to home working that slowed the NHSBSA’s final delivery of the dental data. We finally received the data on 21 May 2020. The need for home working also had some effect on the study team’s ability to work with and analyse the data, which were stored on University of Sheffield computers, but had to be handled remotely due to home working. It also meant that the study team members could not work as closely and seamlessly together as normal. However, we adapted very effectively to home working.

These events were important because they caused enormous delays and disruptions to the study and led to a substantial (≈ 20%) loss of data, as noted above. Once we had received the data, we identified further problems that are described in the following chapters.

Chapter 3 Data checking, data linkage and preliminary analysis

We finally received the hospital admissions data from NHS Digital in June 2019 and received the dental data from the NHSBSA on 21 May 2020. Each data set was checked for completeness, integrity, fidelity to specification and duplicates. It was also cleaned and manipulated to comply with the methodological requirements. The two data sets were then linked using the common, random, individual-specific study identifier.

Data on infective endocarditis hospital admissions

The imported IE hospital admissions data from NHS Digital were manipulated to comply with the IE case definition. As described in Identifying infective endocarditis admissions and infective endocarditis risk stratification, we used two different definitions of an IE hospital admission:

-

a narrow definition – any consultant episode for which an ICD-10 I33.0 primary discharge diagnosis code was used

-

a broad definition – any consultant episode for which a primary or secondary ICD-10 discharge diagnosis code of I33.0, I33.9, I39.0, I39.1, I39.2, I39.3, I39.4 or I39.8, or a primary discharge diagnosis code of I38.X was used.

As a patient may be under the care of more than one consultant and even be transferred between hospitals during a single spell of admission for IE, we combined such episodes into a single continuous hospital admission spell or ‘index’ admission (i.e. we removed non-index admissions data).

New IE cases result in urgent or emergency hospital admission. However, some patients with an existing IE diagnosis are admitted to hospital for evaluation, or may be re-admitted for further evaluation or treatment. As these do not represent a new IE diagnosis, we excluded the following from analysis: all elective admissions (i.e. where admission method was recorded as waiting list, booked or planned), any hospital admission with a duration of < 3 days and any re-admission within 6 months. For the IE admission data counts at each stage of these manipulations, see Appendix 1, Table 26.

Because new IE episodes were distinguished from re-admissions by accepting only IE admissions > 6 months apart as new episodes,7,43 we analysed the data to determine how many patients had more than one IE admission and how many of those were > 6, > 12 or > 18 months apart. For data using the narrow and broad definitions for an IE admission, see Appendix 1, Table 27.

Data on courses of dental treatment

The data on courses of dental treatment received from the NHSBSA were checked, cleaned and characterised (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Dental treatment start date | |

| Number | 3,751,621 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010a |

| Latest | 17 March 2016 |

| Dental treatment end date | |

| Number | 3,745,728 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010 |

| Latest | 17 March 2016 |

| Dental treatment duration (days) | |

| Number | 3,745,728 |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 10.8 (30.6) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 0 (0, 1848) |

| Match descriptionb | |

| Number | 3,751,621 |

| Legacy index does not appear in patient dimension, n (%) | 1,427,382 (38.0) |

| Legacy index matches multiple NHS numbers, n (%) | 140,076 (3.7) |

| Legacy index has unique 1 : 1 NHS number match, n (%) | 2,168,752 (57.8) |

| Legacy index matches a unique NHS number, but other LIDs also match the same NHS number, n (%) | 15,411 (0.4) |

| Dental procedure type | |

| Number | 3,751,621 |

| IDP, n (%) | 1,819,776 (48.5) |

| Non-invasive procedure, n (%) | 956,634 (25.5) |

| Indeterminate procedure, n (%) | 975,211 (26.0) |

| IDP type | |

| Number | 1,819,775 |

| Endodontic treatment, n (%) | 39,490 (2.2) |

| Extractions, n (%) | 286,360 (15.7) |

| Scale and polish, n (%) | 1,384,950 (76.1) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 108,975 (6.0) |

| Antibiotics usec | |

| Number | 3,751,621 |

| No, n (%) | 3,682,646 (98.2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 68,975 (1.8) |

During this process, NHSBSA dental data were linked to NHS Digital data on IE admissions using the person-specific study identifier generated by NHS Digital. Dental data with no associated IE admission data were removed and any courses of dental treatment that overlapped were combined into a single course of dental treatment. The counts of dental treatment courses at each stage of data cleaning and manipulation are provided in Appendix 1, Table 28.

Using the two different definitions for an IE admission (narrow and broad), we then determined the number of these admissions for which we had 12 months of linked data on preceding dental courses of treatment. We quantified this in two ways: (1) starting from the day of IE hospital admission (months 0–12) and (2) skipping the first month before hospital admission (months 1–13). The counts for these are shown in Appendix 1, Table 29.

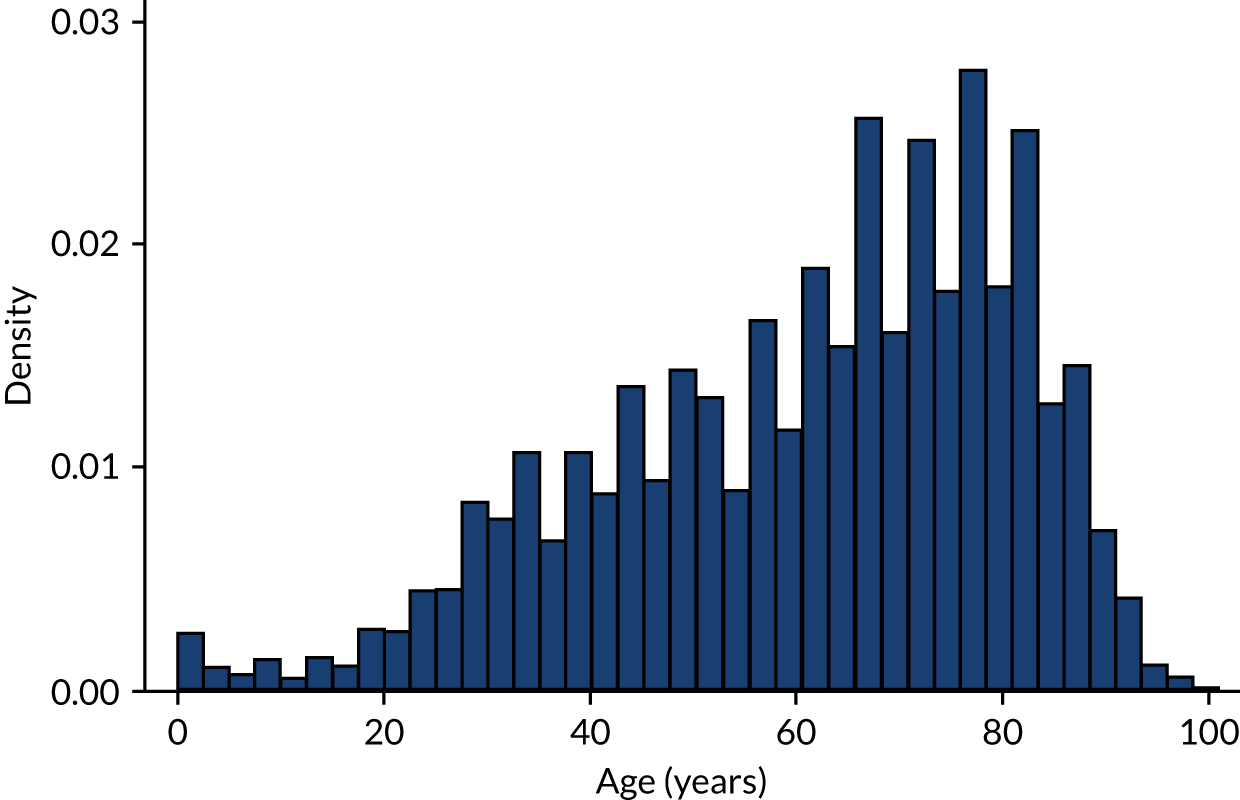

Infective endocarditis patient characteristics using the narrow definition of infective endocarditis

Using the narrow definition of IE, we analysed the age, sex and previous IE risk status (high, moderate or low/unknown risk) of each IE admission patient. We also identified the specific heart condition that categorised an individual as high risk or moderate risk for IE, and if there was any IE causal organism data for that individual. We quantified this information for all IE admissions in the data set and for those IE admissions for which we had linked dental data (Table 2; see also Appendix 2, Figures 19 and 21).

| Characteristic | IE narrow admission | |

|---|---|---|

| All | With linked dental data | |

| Age of the patient (years) | ||

| Number | 11,570 | 3163 |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 61.2 (19.8) | 61.6 (18.7) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 65 (0, 101) | 66 (1, 96) |

| Sex | ||

| Number | 11,575 | 3160 |

| Male, n (%) | 7900 (68.3) | 2135 (67.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 3675 (31.7) | 1030 (32.5) |

| Level of IE risk before IE admission | ||

| Number | 11,575 | 3160 |

| High risk, n (%) | 3285 (28.4) | 1050 (33.2) |

| Moderate risk, n (%) | 1875 (16.2) | 520 (16.4) |

| Low/unknown risk, n (%) | 6415 (55.4) | 1590 (50.2) |

| Reason for high-risk stratification, n (%)a | ||

| Previous IE | 530 (16.1) | 155 (14.8) |

| Previous IE: I38X | 180 (5.5) | 35 (3.3) |

| Replacement heart valve | 2090 (63.6) | 700 (66.7) |

| Repaired heart valve | 280 (8.5) | 105 (10.0) |

| Cyanotic congenital heart disease | 155 (4.7) | 35 (3.3) |

| Repaired congenital heart disease | – | – |

| Palliative shunt or conduit | 35 (1.1) | 20 (1.9) |

| Prosthetic heart/ventricular assist device | – | – |

| Reason for moderate-risk stratification, n (%)a | ||

| Previous rheumatic fever | 580 (30.9) | 155 (29.8) |

| Non-rheumatic valve | 1190 (63.5) | 340 (65.4) |

| Congenital valve anomalies | 55 (2.9) | 20 (3.9) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 50 (2.7) | 10 (1.9) |

| Causal organism reported | ||

| Number | 11,575 | 3160 |

| No, n (%) | 3175 (27.4) | 870 (27.5) |

| Yes, n (%) | 8400 (72.6) | 2290 (72.4) |

| Type of causal organism | ||

| Number | 8400 | 2290 |

| Oral streptococci, n (%) | 2620 (31.2) | 755 (33.0) |

| Other streptococci, n (%) | 610 (7.3) | 175 (7.6) |

| Staphylococci, n (%) | 2630 (31.3) | 680 (29.7) |

| Other causal organism, n (%) | 1395 (16.6) | 375 (16.4) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 1145 (13.6) | 305 (13.3) |

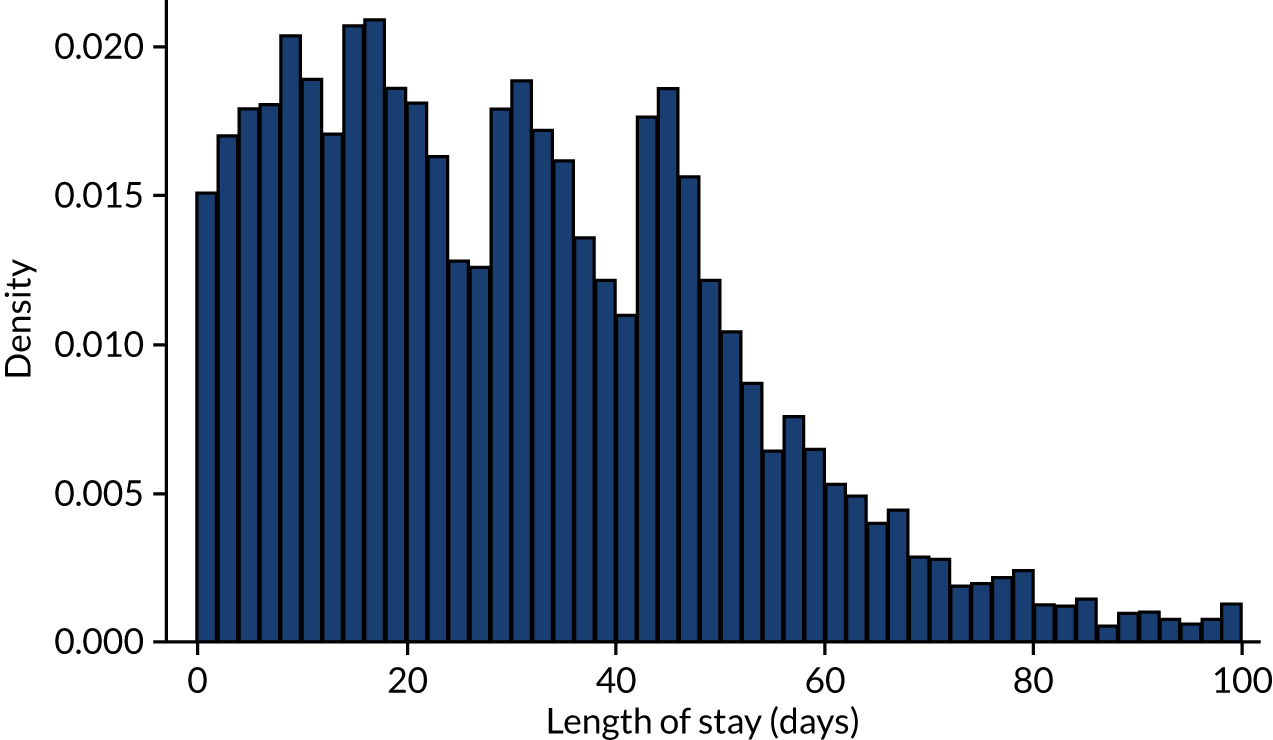

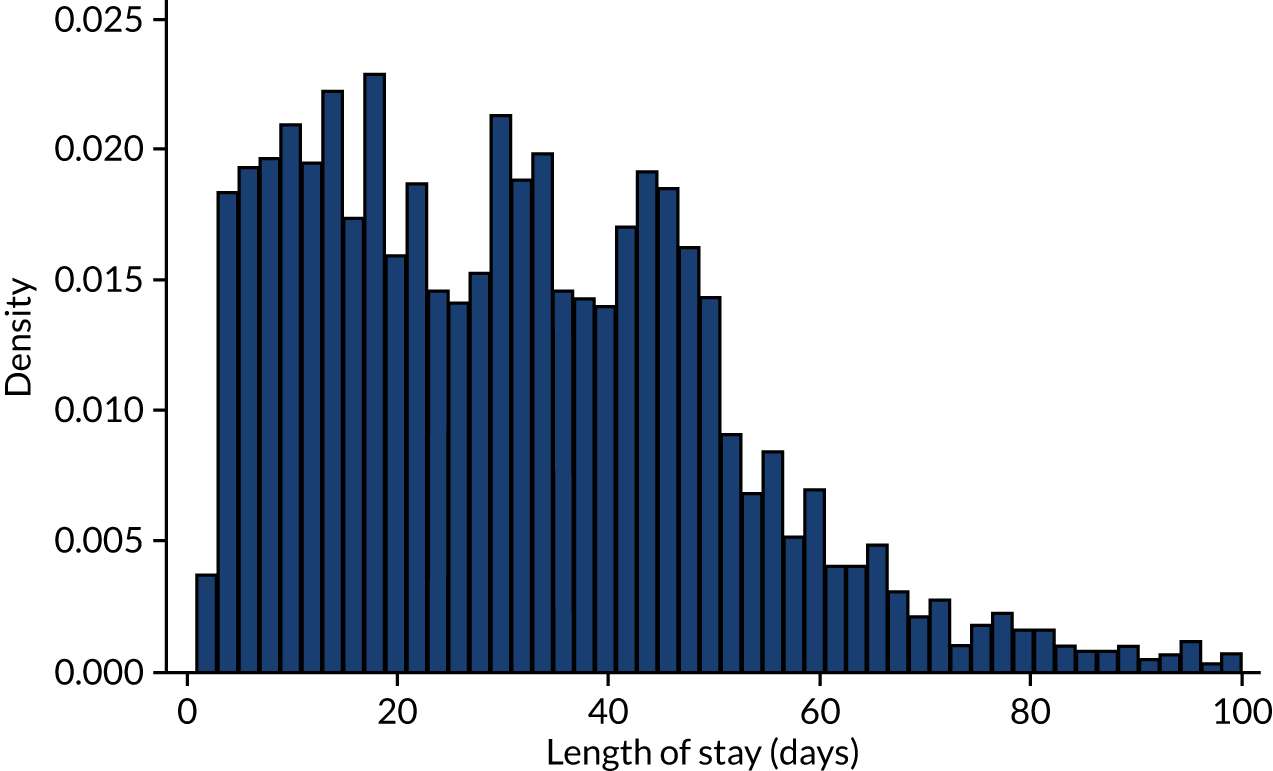

We also extracted the following data for each IE admission: whether the admission was an elective or non-elective admission, the start and end date of the admission episode, the length of hospital stay, and whether the patient was discharged from hospital alive or dead (providing the inpatient IE mortality rate). Table 3 provides these data for all IE admissions recorded using the narrow definition of IE and those narrow-definition IE admissions that had linked dental data. For the duration of hospital admission for all narrow-definition IE admissions, see Appendix 2, Figure 21, and for the duration of hospital admission for all narrow-definition IE admissions with linked dental data, see Appendix 2, Figure 22.

| Characteristics | IE narrow admission | |

|---|---|---|

| All | With linked dental data | |

| Admission method | ||

| Number | 11,575 | 3165 |

| Non-elective, n (%) | 11,250 (97.2) | 3165 (100.0) |

| Elective, n (%) | 325 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Admission date | ||

| Number | 11,574 | 3163 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010a | 1 April 2011a |

| Latest | 28 March 2016 | 26 March 2016 |

| Discharge date | ||

| Number | 11,297 | 3134 |

| Earliest | 2 April 2010 | 6 April 2011 |

| Latest | 31 March 2016 | 31 March 2016 |

| Hospital length of stay | ||

| Number | 11,297 | 3134 |

| Mean (standard deviation) (days) | 31.7 (24.5) | 32.0 (21.7) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) (days) | 29 (0, 315) | 30 (1, 208) |

| Discharged alive? | ||

| Number | 11,285 | 3130 |

| No, n (%) | 1720 (15.2) | 410 (13.1) |

| Yes, n (%) | 9560 (84.7) | 2720 (86.9) |

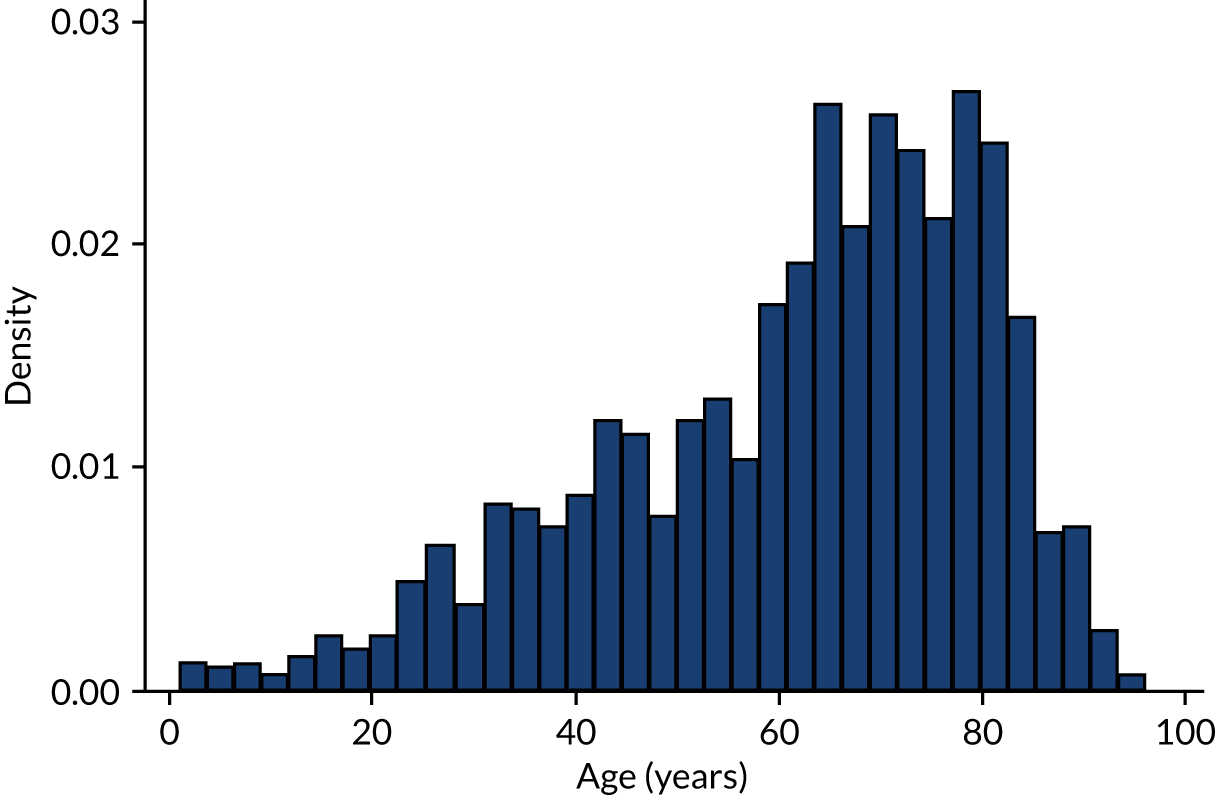

Infective endocarditis patient characteristics using the broad definition of infective endocarditis

Using the broad definition of IE, we analysed the age, sex and previous IE risk status (high, moderate or low/unknown risk) of each IE admission patient. We also identified the specific heart condition that categorised an individual as at high or moderate risk for IE, and if there were any IE causal organism data for that individual. We quantified this information for all IE admissions in the data set and for those IE admissions for which we had linked dental data (Table 4).

| Characteristic | IE broad admission | |

|---|---|---|

| All | With linked dental data | |

| Age of the patient (years) | ||

| Number | 17,732 | 4293 |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 60.9 (21.0) | 62.3 (18.6) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 66 (0, 103) | 66 (1, 103) |

| Sex | ||

| Number | 17,740 | 4490 |

| Male, n (%) | 11,665 (65.8) | 2830 (65.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 6075 (34.2) | 1460 (34.0) |

| Level of IE risk before IE admission | ||

| Number | 17,740 | 4295 |

| High risk, n (%) | 4075 (23.0) | 1250 (29.1) |

| Moderate risk, n (%) | 3065 (17.3) | 745 (17.3) |

| Low/unknown risk, n (%) | 10,600 (59.8) | 2300 (53.6) |

| Reason for high-risk stratification, n (%)a | ||

| Previous IE | 405 (9.9) | 100 (8.0) |

| Previous IE: I38X | 115 (2.8) | 20 (1.6) |

| Replacement heart valve | 2860 (70.2) | 920 (73.6) |

| Repaired heart valve | 405 (9.9) | 135 (10.8) |

| Cyanotic congenital heart disease | 220 (5.4) | 50 (4.0) |

| Repaired congenital heart disease | – | – |

| Palliative shunt or conduit | 50 (1.2) | 20 (1.6) |

| Prosthetic heart/ventricular assist device | 10 (0.3) | – |

| Reason for moderate-risk stratification, n (%)a | ||

| Previous rheumatic fever | 1000 (32.6) | 235 (31.5) |

| Non-rheumatic valve | 1915 (62.5) | 465 (62.4) |

| Congenital valve anomalies | 75 (2.5) | 25 (3.4) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 75 (2.5) | 20 (2.7) |

| Causal organism reported | ||

| Number | 17,740 | 4295 |

| No, n (%) | 6730 (37.9) | 1385 (32.2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 11,010 (62.1) | 2910 (67.8) |

| Type of causal organism | ||

| Number | 11,010 | 2910 |

| Oral streptococci, n (%) | 3020 (27.4) | 850 (29.2) |

| Other streptococci, n (%) | 780 (7.1) | 215 (7.4) |

| Staphylococci, n (%) | 3540 (32.2) | 895 (30.8) |

| Other causal organism, n (%) | 2130 (19.3) | 545 (18.7) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 1540 (14.0) | 405 (13.9) |

We also extracted the admission data for each IE admission recorded using the broad definition of IE and those broad-definition IE admissions that had linked dental data (Table 5).

| Characteristic | IE broad admissions | |

|---|---|---|

| All | With linked dental data | |

| Admission method | ||

| Number | 17,740 | 4295 |

| Non-elective, n (%) | 16,680 (94.0) | 4295 (100.0) |

| Elective, n (%) | 1060 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Admission date | ||

| Number | 17,741 | 4293 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010a | 1 April 2011a |

| Latest | 31 March 2016 | 30 March 2016 |

| Discharge date | ||

| Number | 17,259 | 4255 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010 | 6 April 2011 |

| Latest | 31 March 2016 | 31 March 2016 |

| Hospital length of stay | ||

| Number | 17,259 | 4255 |

| Mean (standard deviation) (days) | 29.6 (29.1) | 31.7 (24.2) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) (days) | 24 (0, 1,027) | 28 (0, 229) |

| Discharged alive? | ||

| Number | 17,235 | 4250 |

| No, n (%) | 2820 (16.4) | 655 (15.4) |

| Yes, n (%) | 14,420 (83.7) | 3595 (84.6) |

Dental data matched to infective endocarditis admissions

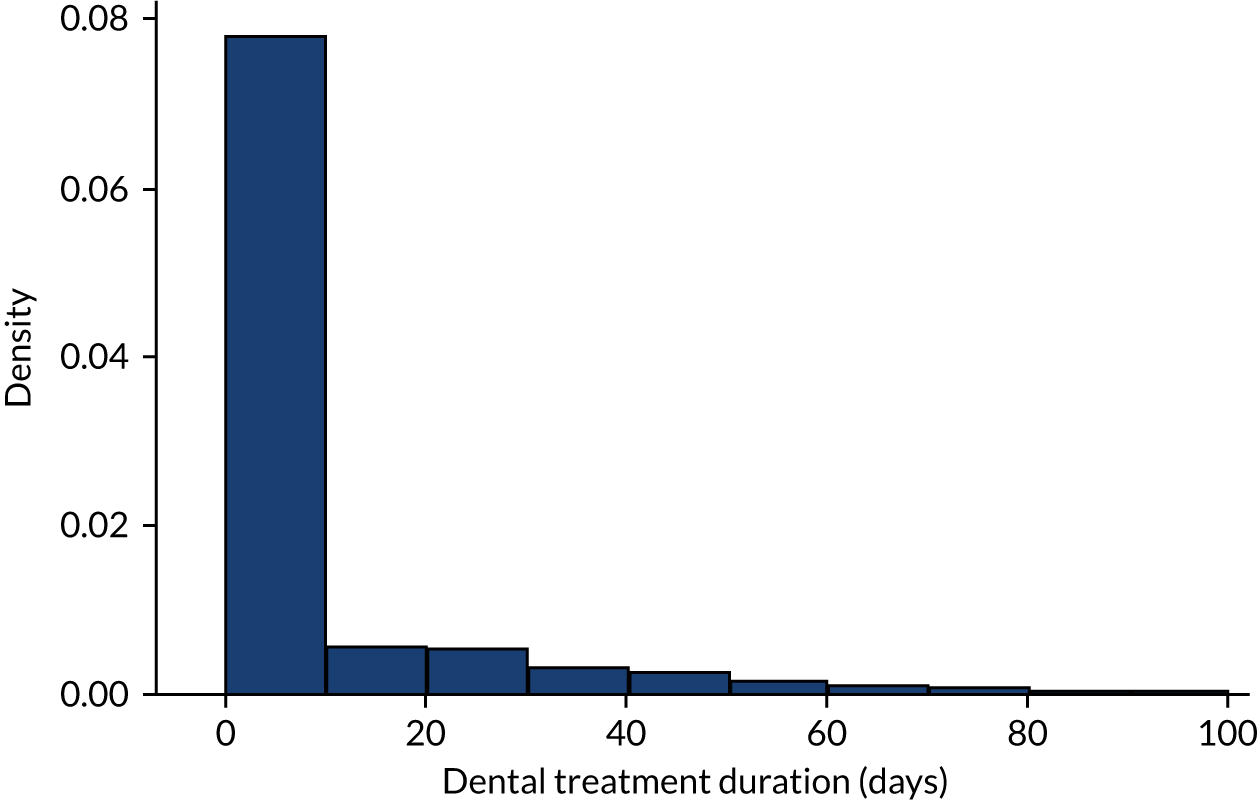

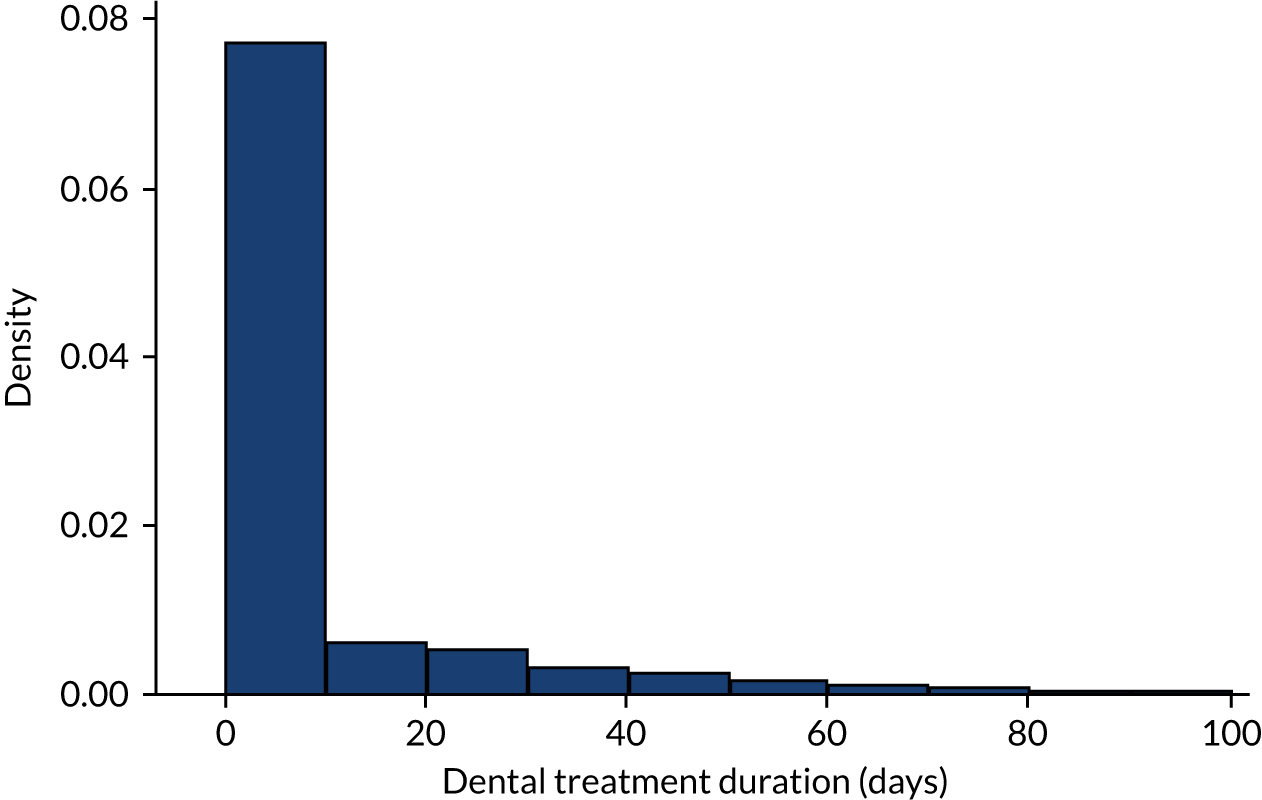

Having cleaned the data sets, we were able to look in more detail at all of the dental data provided by the NHSBSA and compare these with the dental treatment data in the 12 months immediately prior to admission for those individuals admitted to hospital with an IE diagnosis. We did this for individuals admitted to hospital using both the narrow and broad definitions of IE (see Data on infective endocarditis hospital admissions). The numbers of courses of dental treatment for each definition were compared (Table 6). We plotted the distribution of courses of dental treatment of different length for the entire dental data set (see Appendix 2, Figure 23), and for those courses of dental treatment matched to patients who developed IE (see Appendix 2, Figure 24).

| Characteristics | Courses of dental treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Courses matched to narrow definition of IE | Courses matched to broad definition of IE | |

| Dental treatment start date | |||

| Number | 3,751,621 | 5426 | 7338 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010 | 7 April 2010 | 7 April 2010 |

| Latest | 17 March 2016 | 2 March 2016 | 7 March 2016 |

| Dental treatment end date | |||

| Number | 3,751,621 | 5426 | 7338 |

| Earliest | 1 April 2010 | 23 April 2010 | 12 April 2010 |

| Latest | 17 March 2016 | 4 March 2016 | 7 March 2016 |

| Dental treatment duration | |||

| Number | 3,751,621 | 5426 | 7338 |

| Mean (standard deviation) (days) | 10.8 (30.5) | 12.0 (34.9) | 11.9 (33.9) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) (days) | 0 (0, 1848) | 0 (0, 725) | 0 (0, 725) |

| Match descriptiona | |||

| Number | 3,751,620 | 5425 | 7340 |

| Legacy index does not appear in patient dimension, n (%) | 1,427,380 (38.0) | 2545 (46.9) | 3695 (50.3) |

| Legacy index has multiple matching NHS numbers, n (%) | 140,075 (3.7) | 160 (2.9) | 190 (2.6) |

| Legacy index has unique 1 : 1 NHS number match, n (%) | 2,168,750 (57.8) | 2710 (50.0) | 3445 (46.9) |

| Legacy index matches a unique NHS number, but other LIDs also match the same NHS number, n (%) | 15,410 (0.4) | 10 (0.2) | 10 (0.1) |

| Procedure type | |||

| Number | 3,751,620 | 5425 | 7340 |

| Invasive procedure, n (%) | 1,819,775 (48.5) | 2585 (47.6) | 3455 (47.1) |

| Non-invasive procedure, n (%) | 956,635 (25.5) | 1460 (26.9) | 2000 (27.2) |

| Indeterminate procedure, n (%) | 975,210 (26.0) | 1380 (25.4) | 1885 (25.7) |

| Invasive procedure type | |||

| Number | 1,819,775 | 2585 | 3455 |

| Endodontic treatment, n (%) | 39,490 (2.2) | 65 (2.5) | 75 (2.2) |

| Extractions, n (%) | 286,360 (15.7) | 445 (17.2) | 615 (17.8) |

| Scale and polish, n (%) | 1,384,950 (76.1) | 1885 (72.9) | 2520 (72.9) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 108,980 (6.0) | 185 (7.2) | 245 (7.1) |

| Antibiotics useb | |||

| Number | 3,751,620 | 5425 | 7340 |

| No, n (%) | 3,682,645 (98.2) | 5325 (98.2) | 7205 (98.2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 68,975 (1.8) | 105 (1.9) | 135 (1.8) |

Timing of dental procedures in the 12 months before infective endocarditis hospital admission

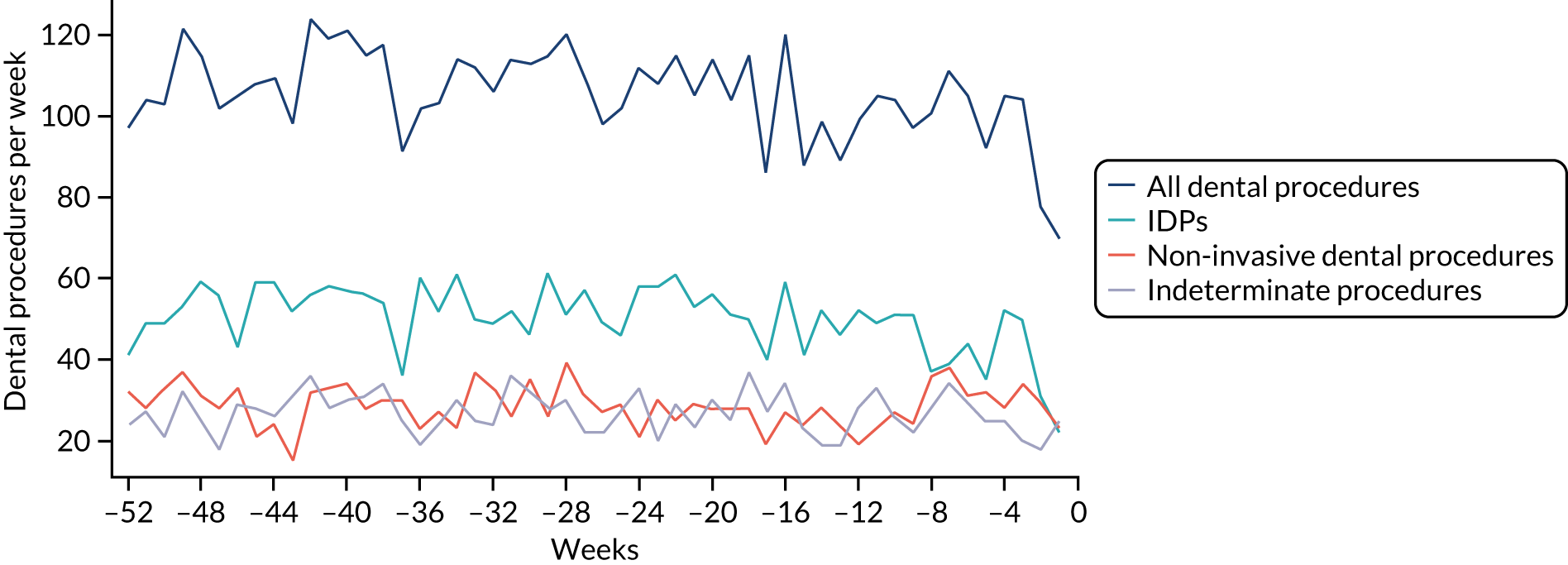

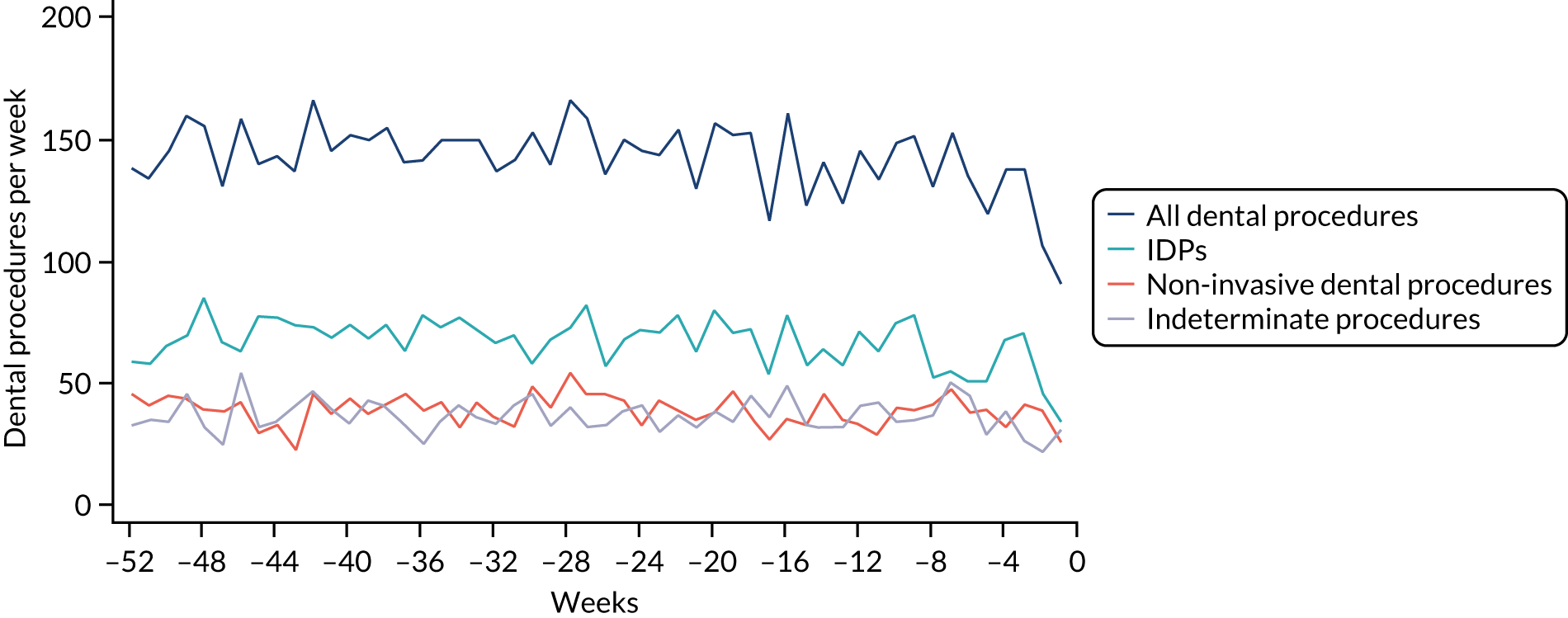

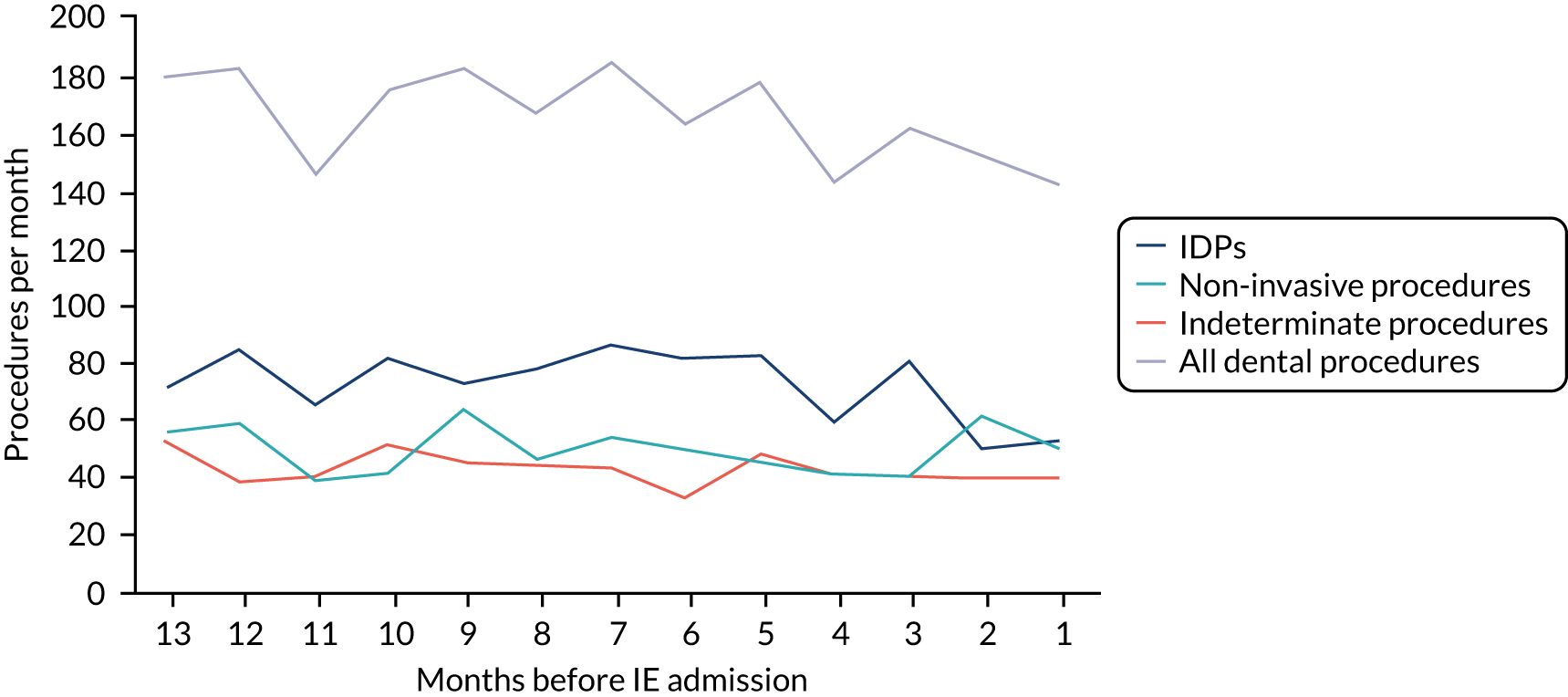

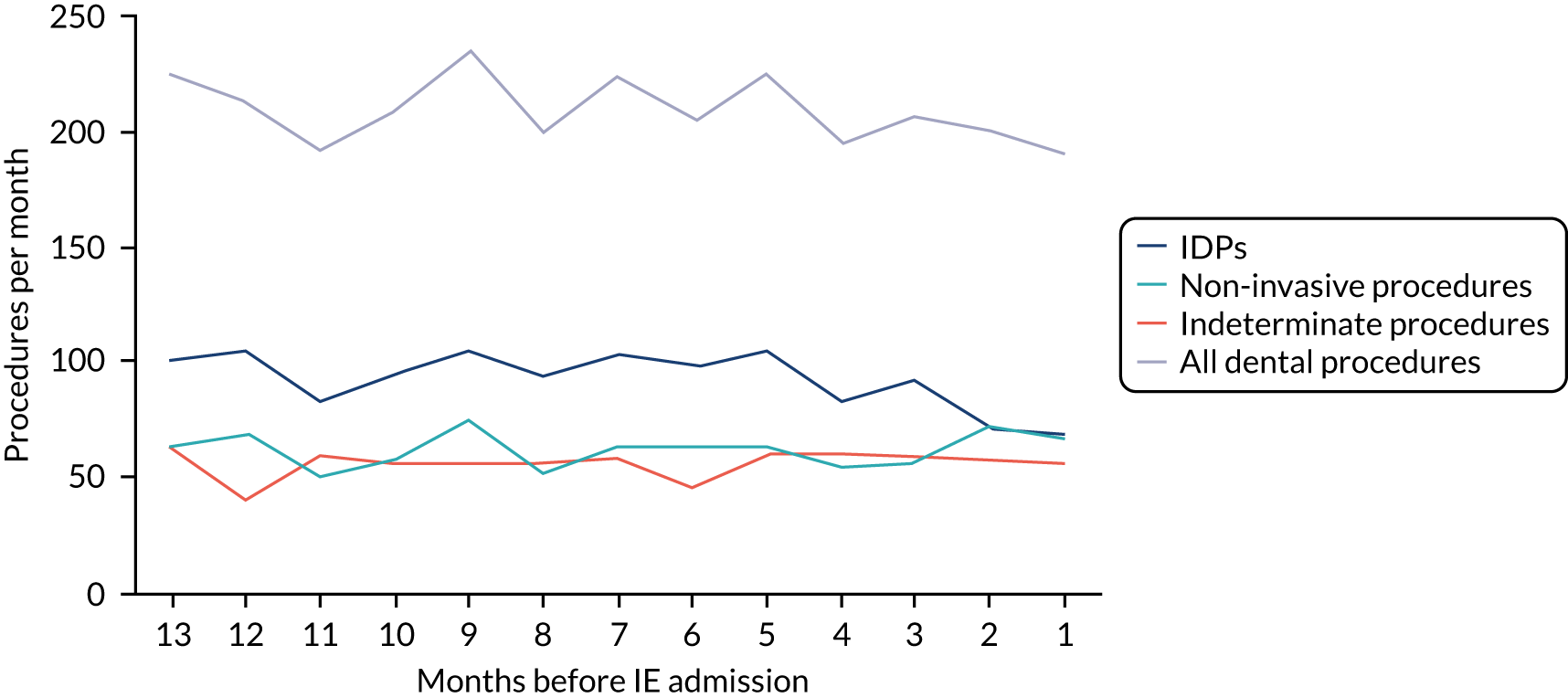

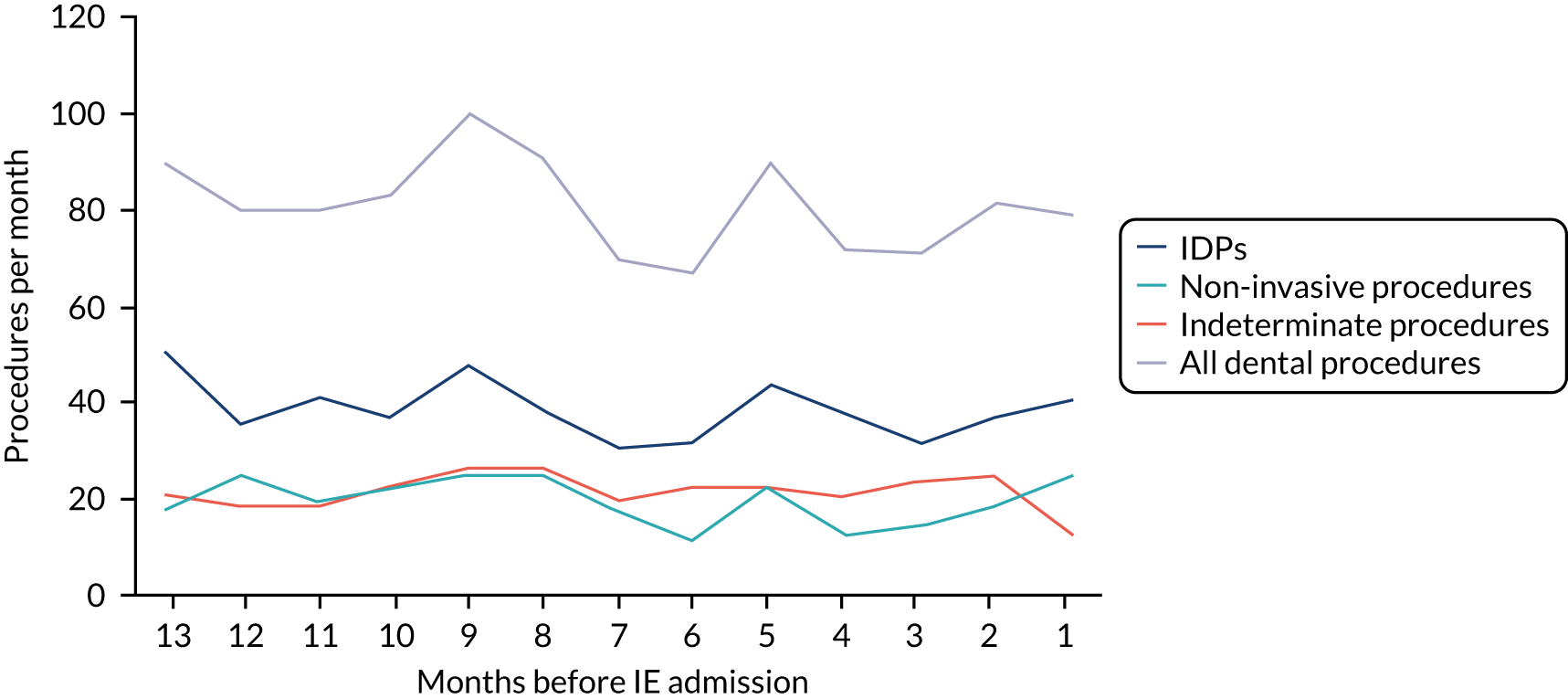

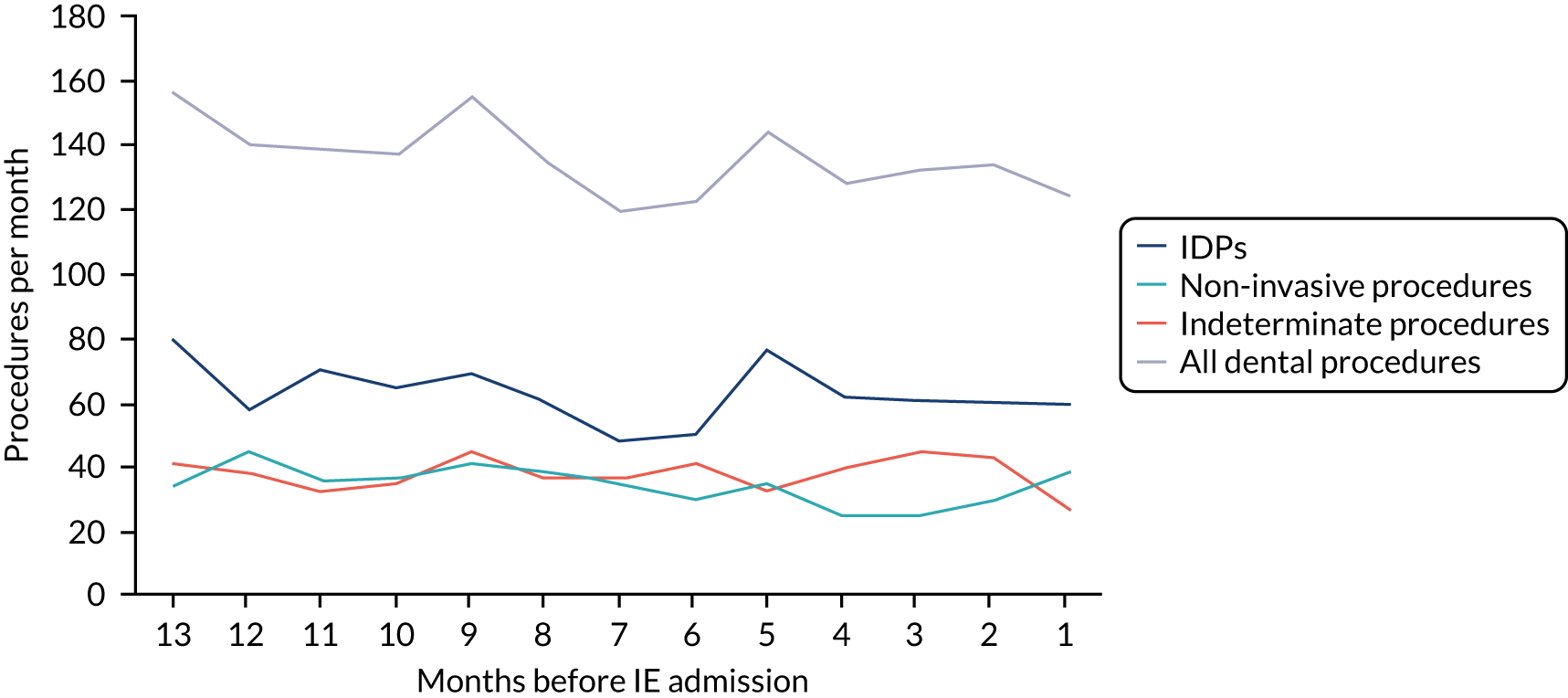

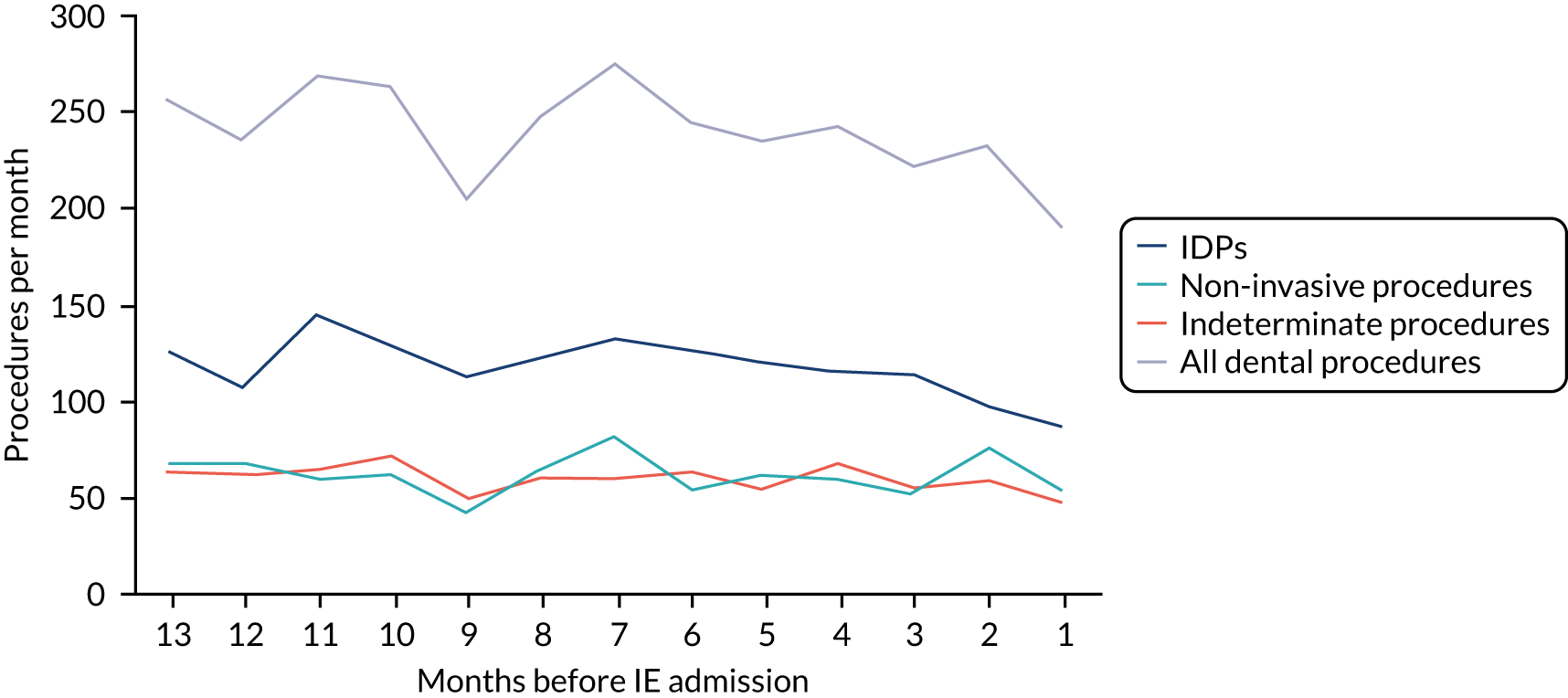

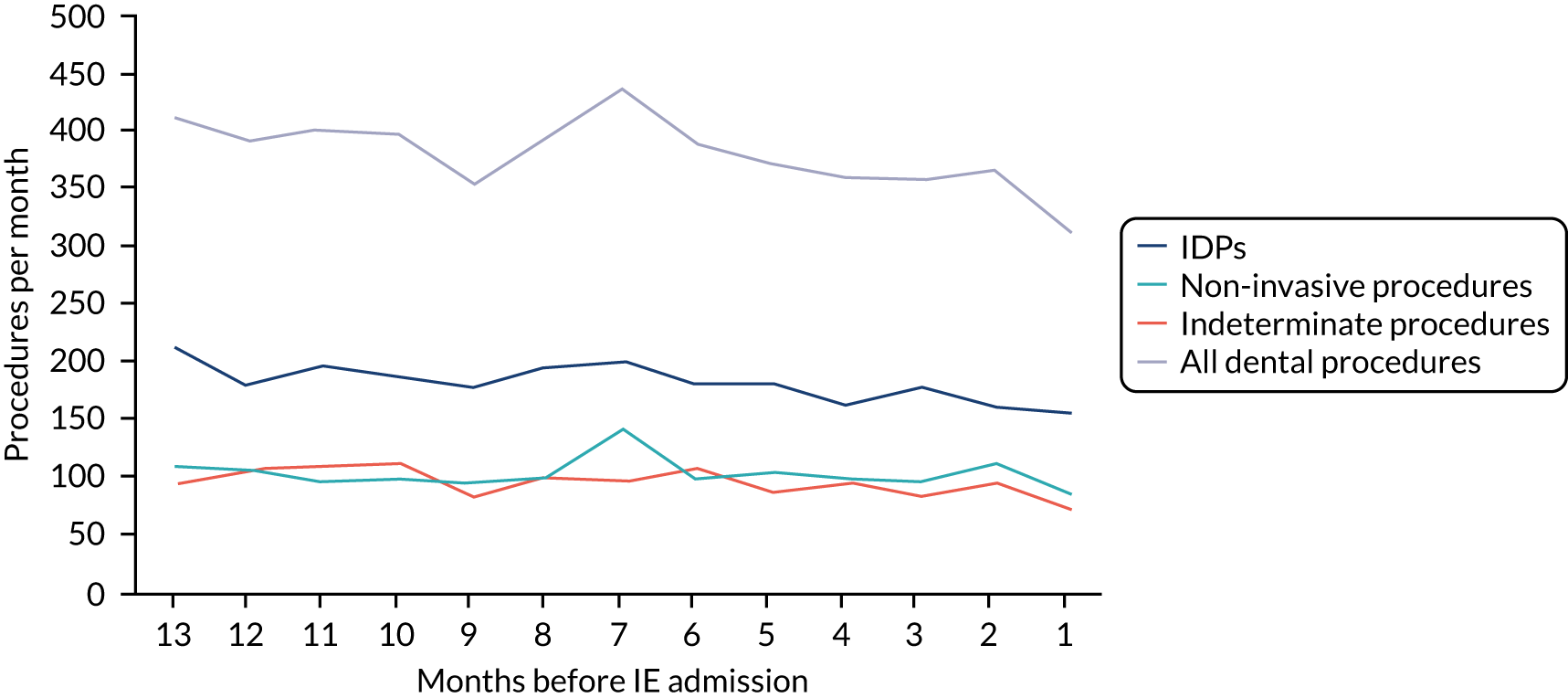

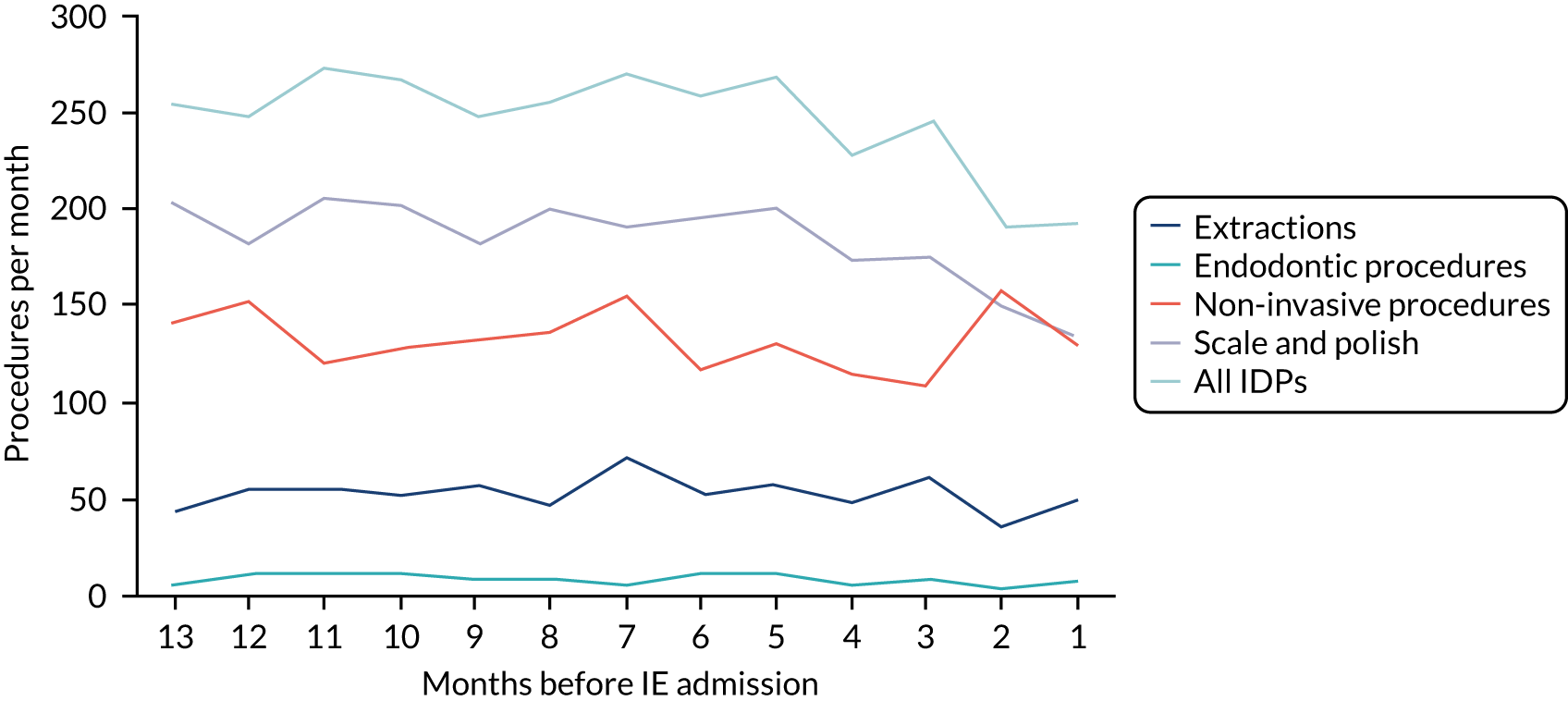

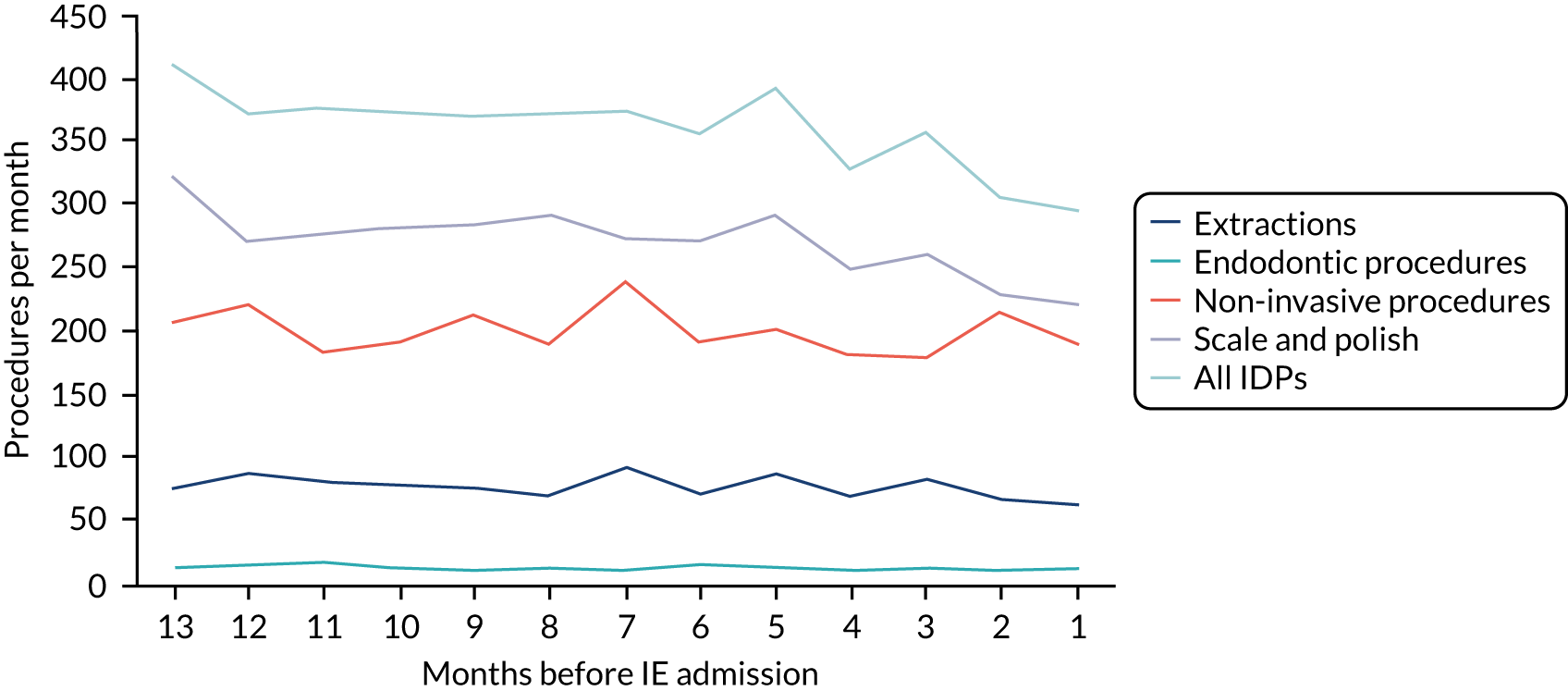

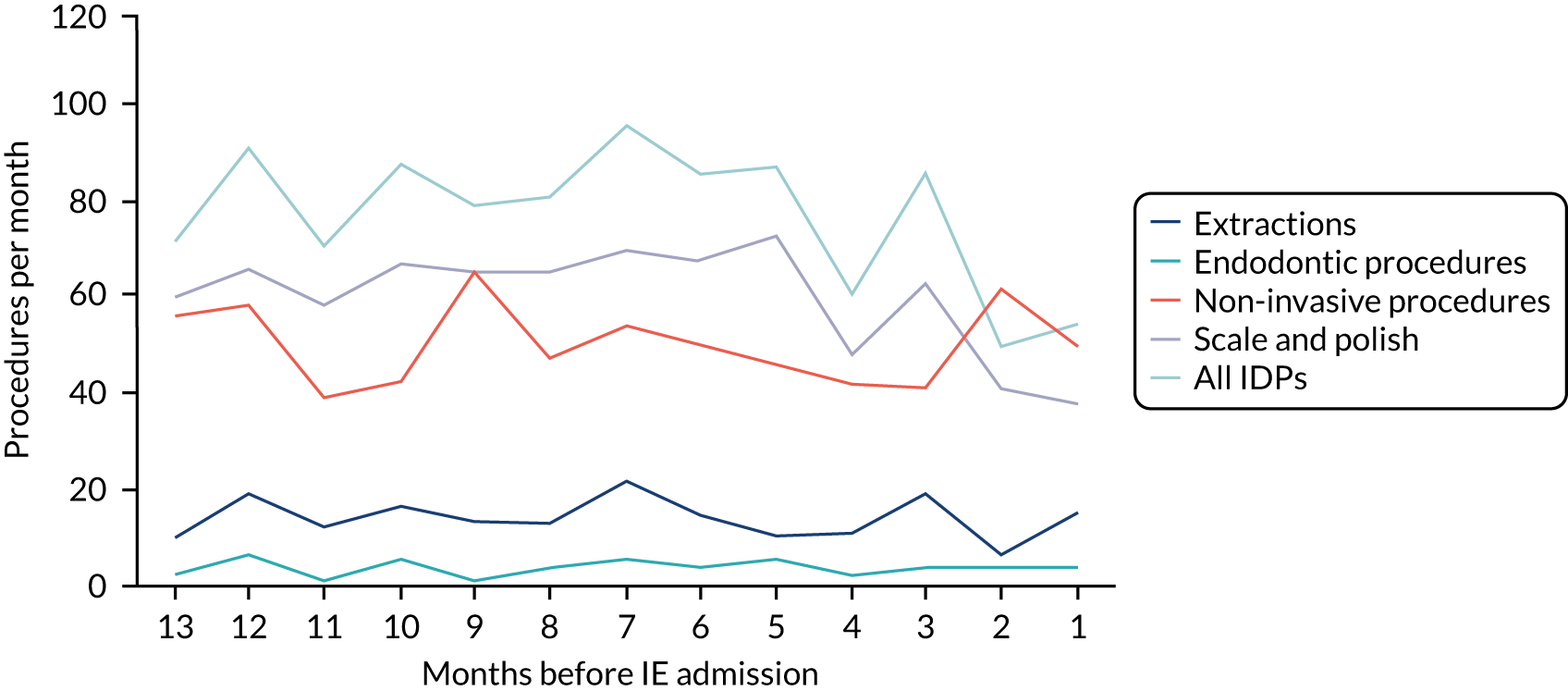

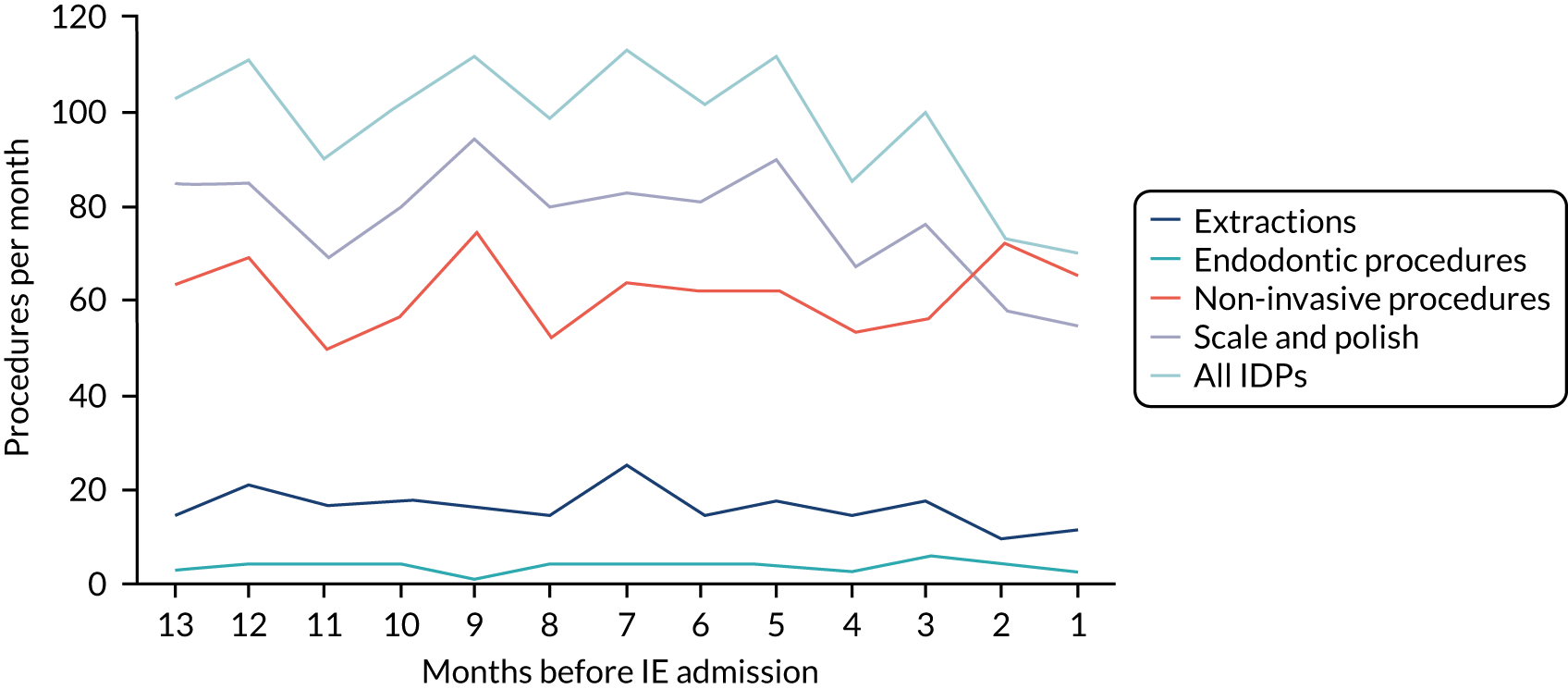

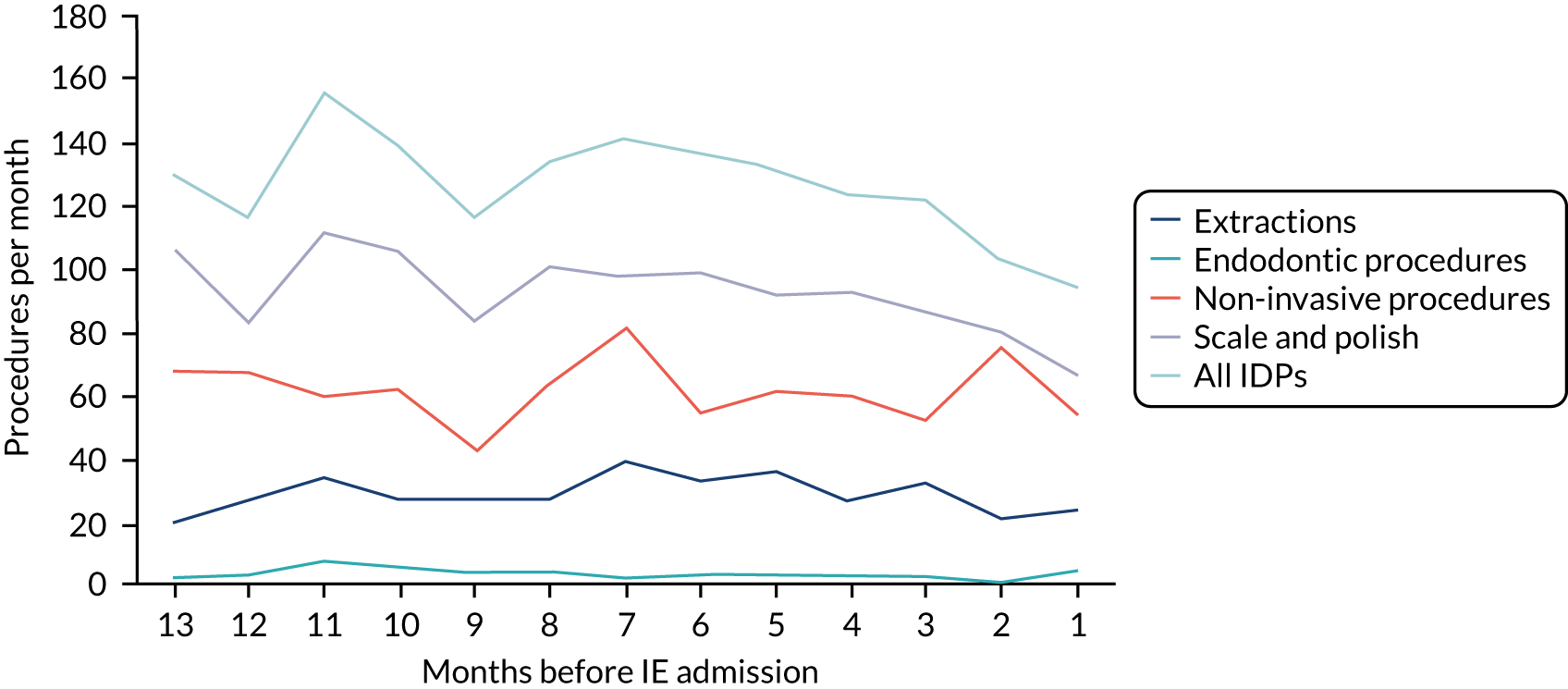

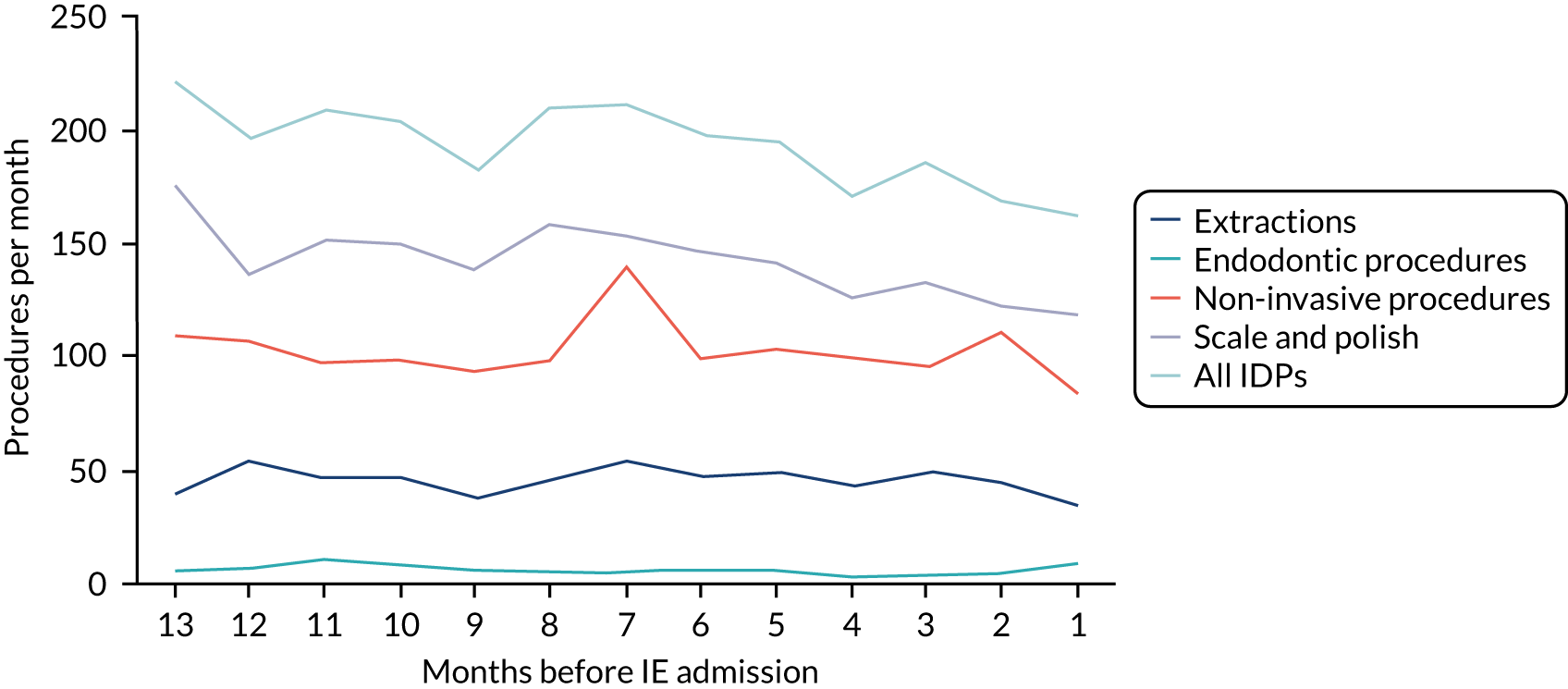

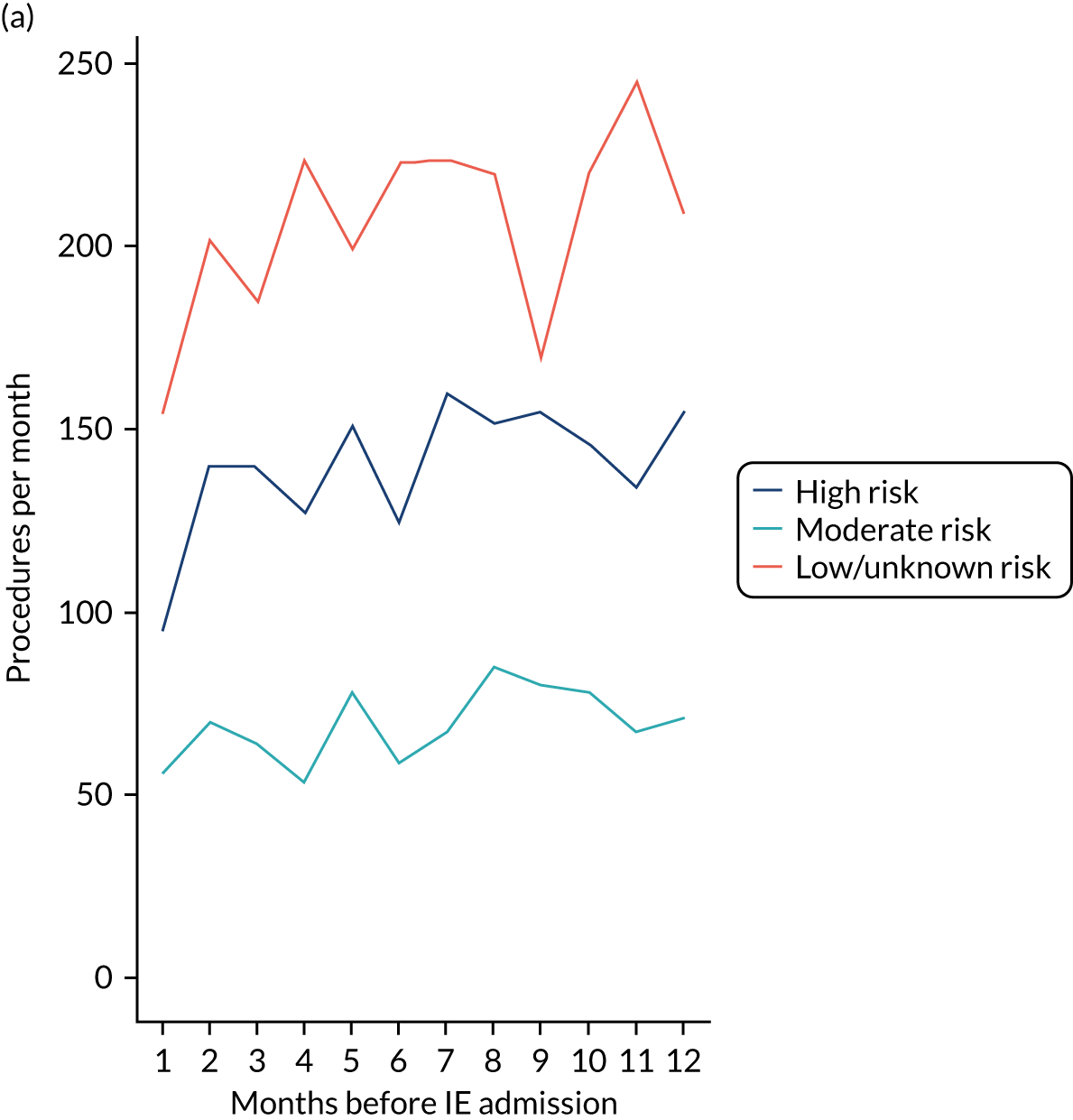

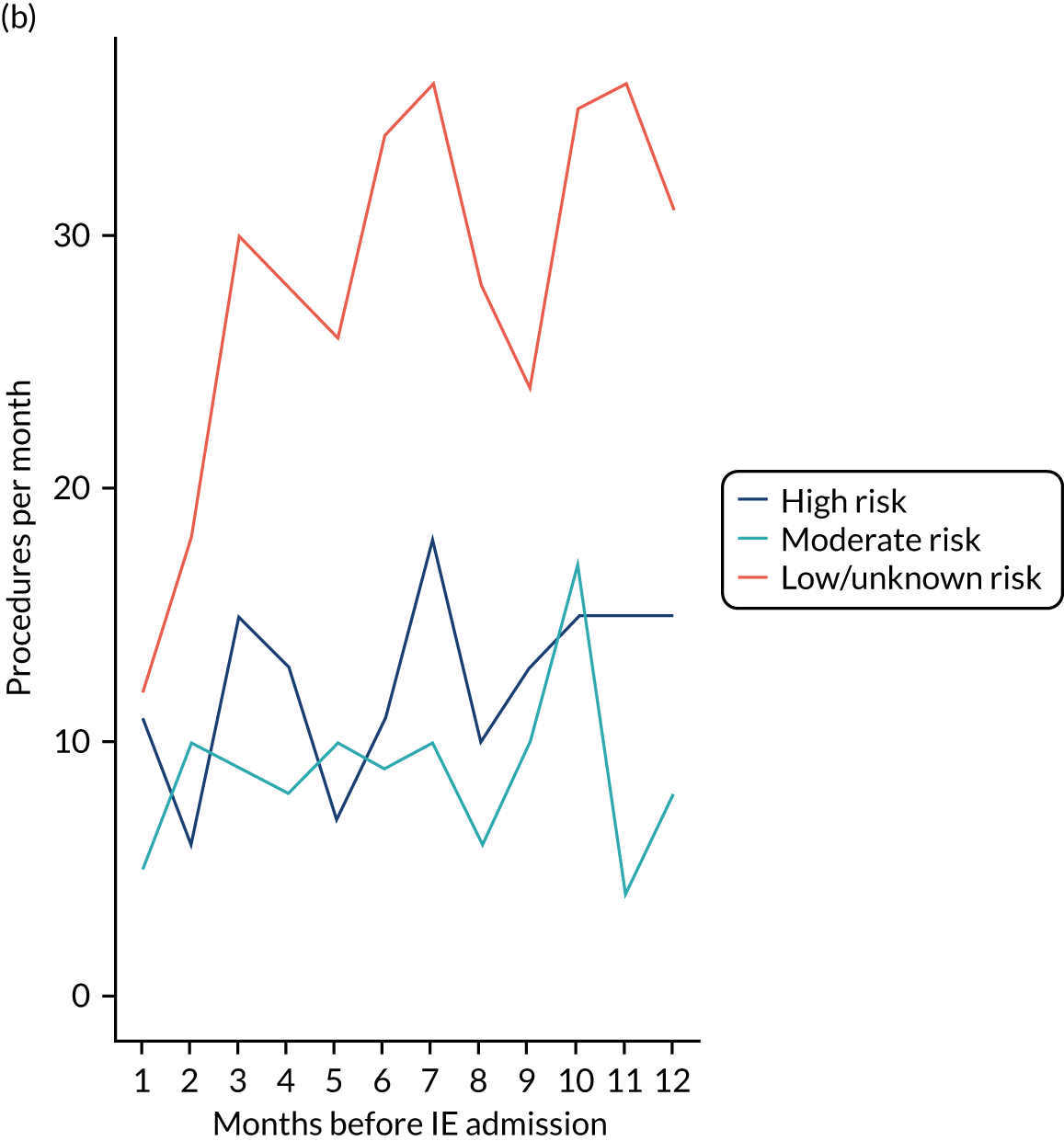

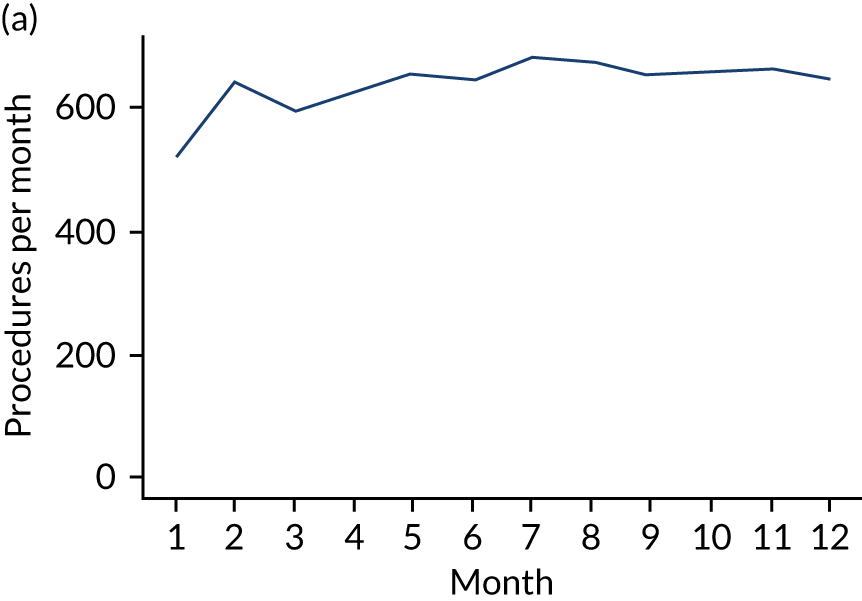

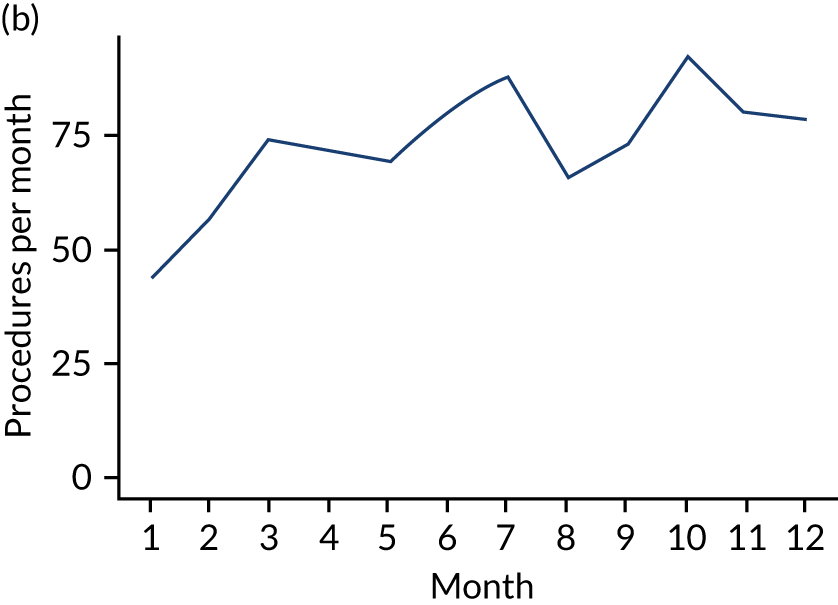

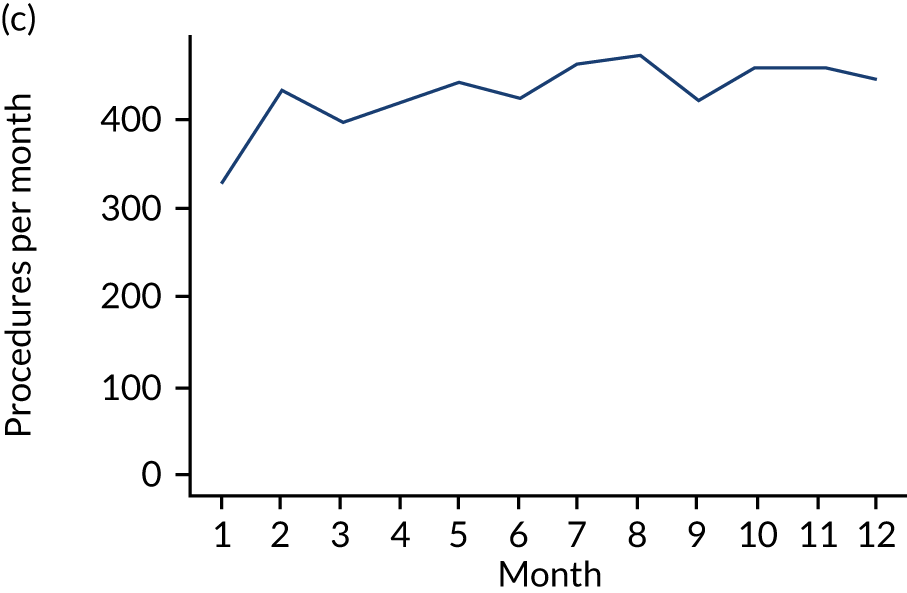

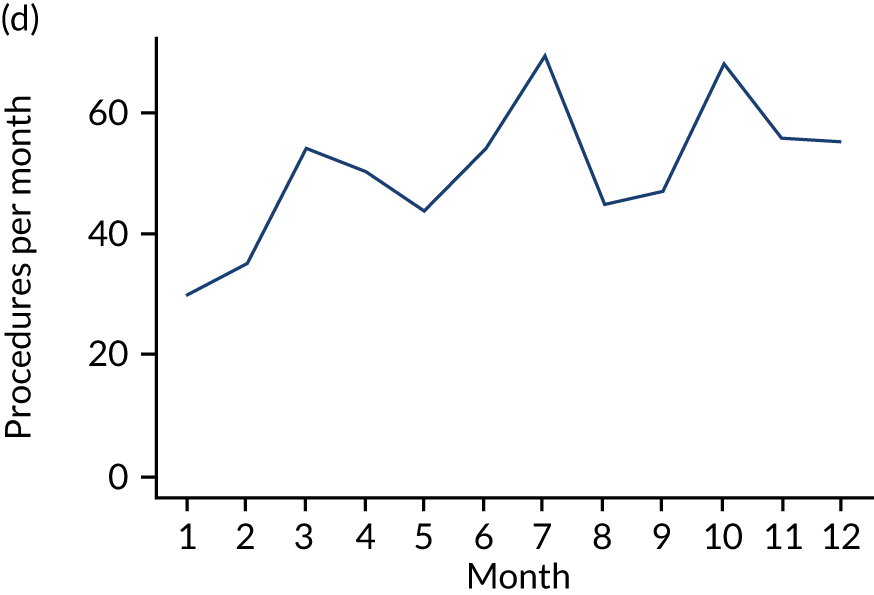

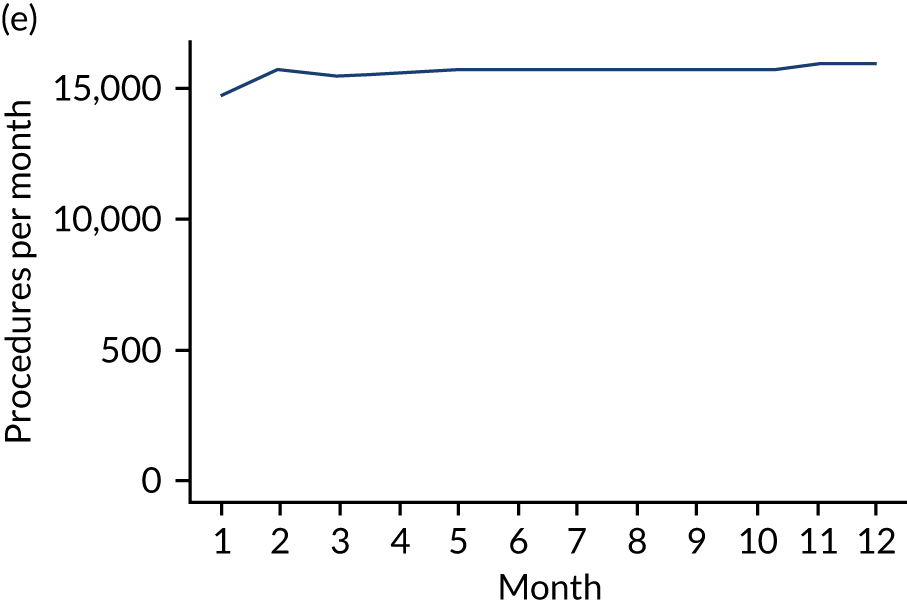

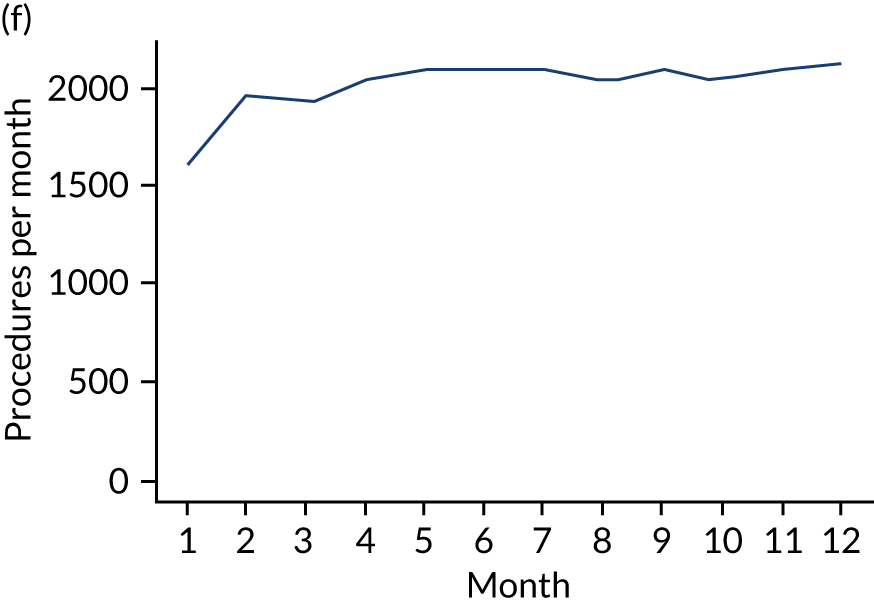

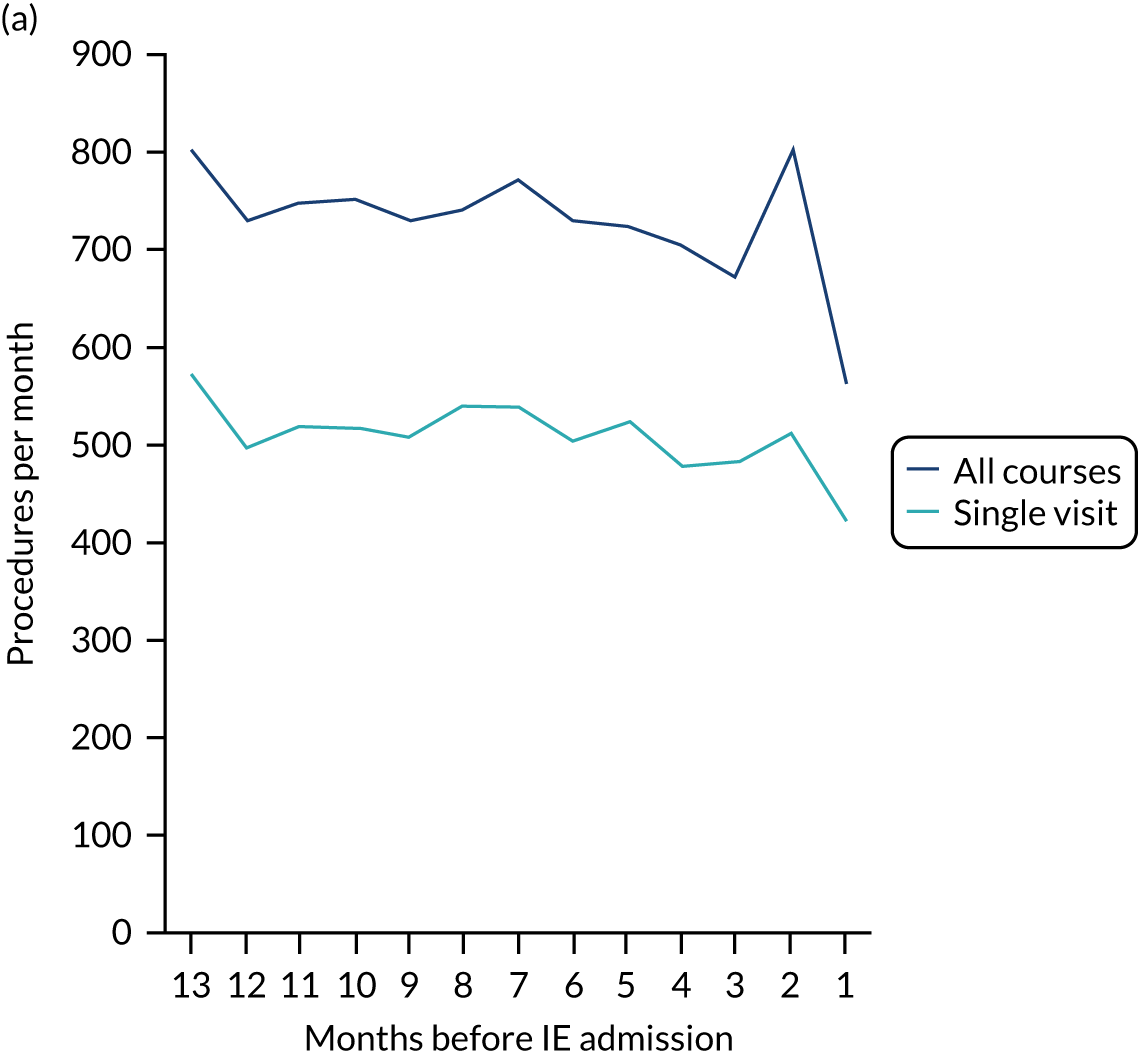

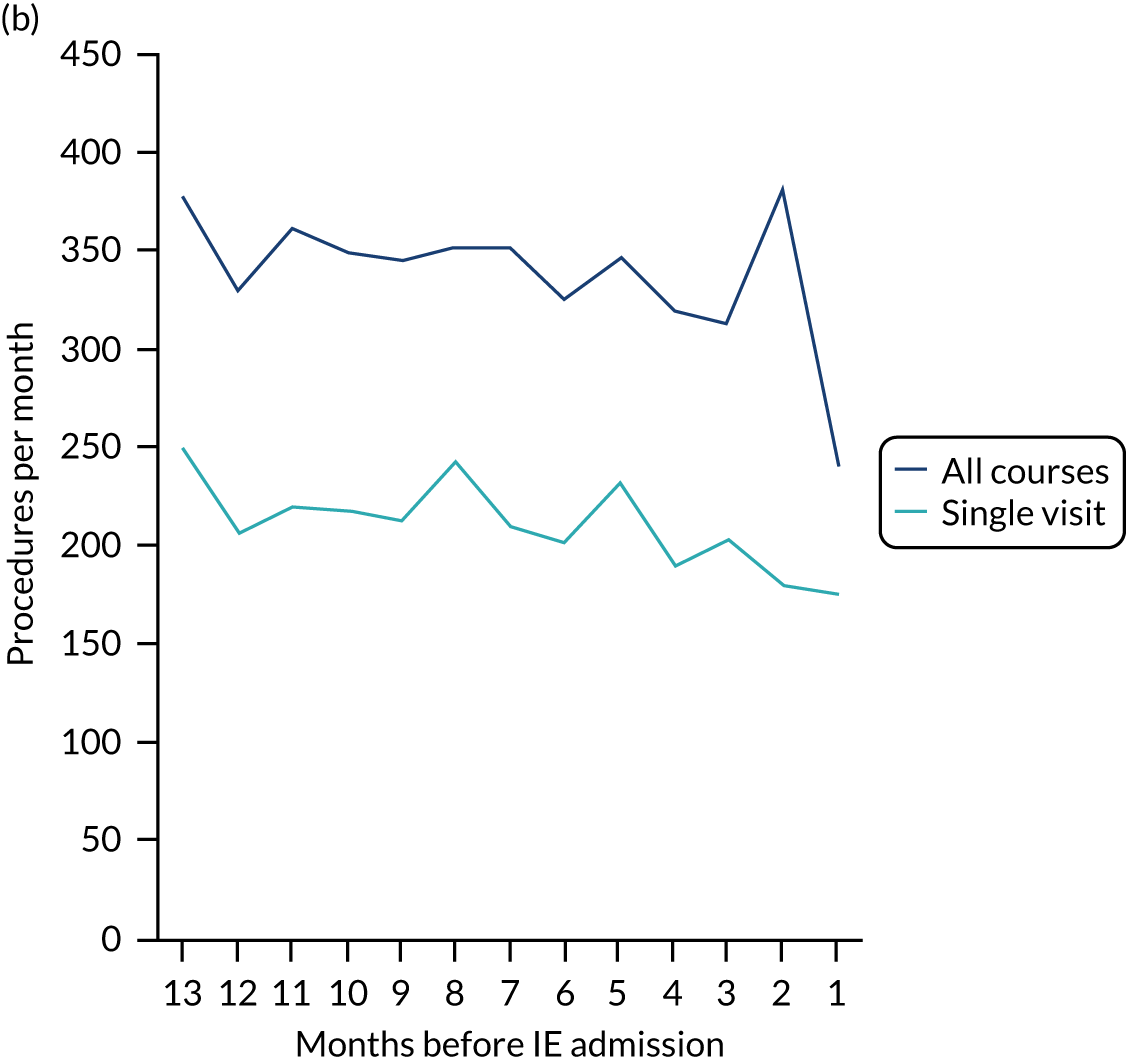

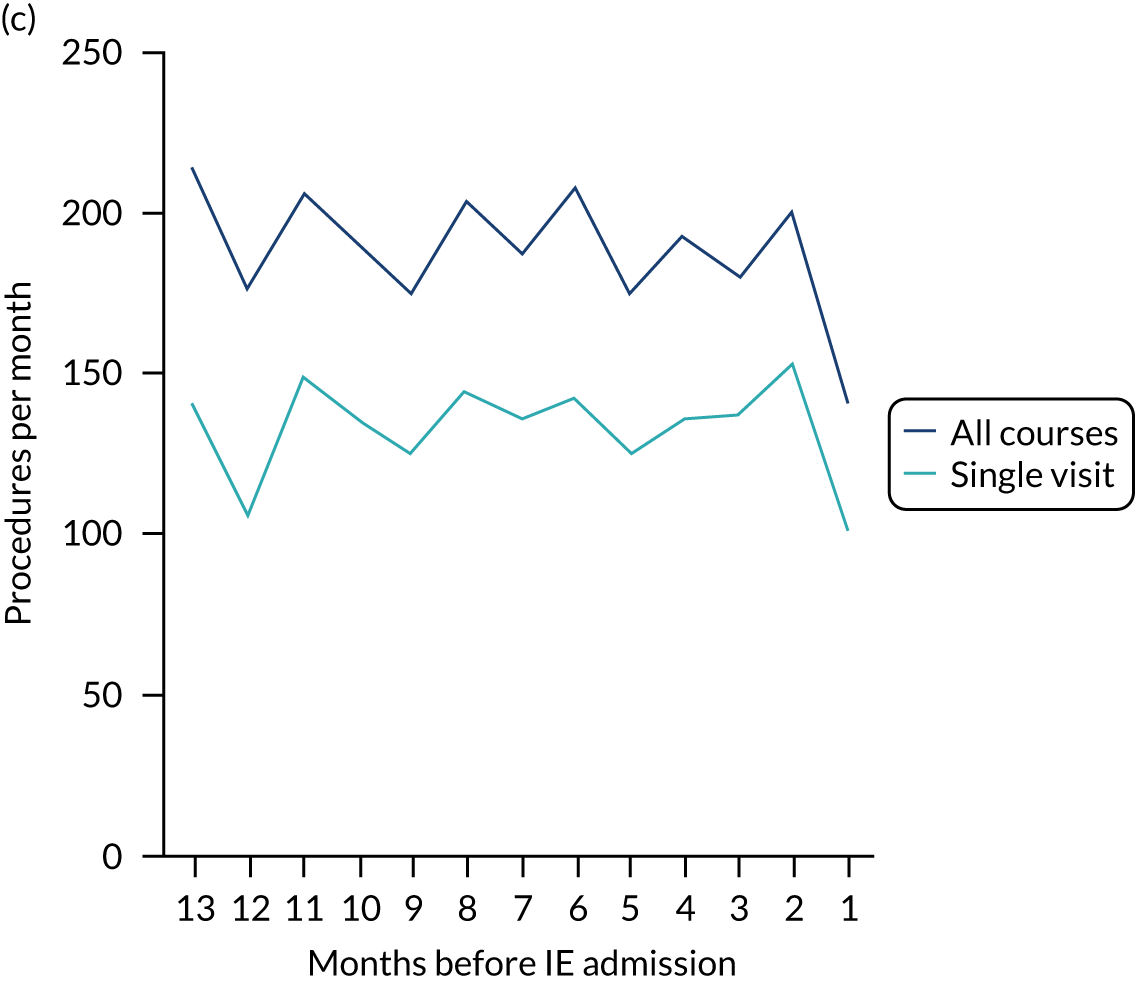

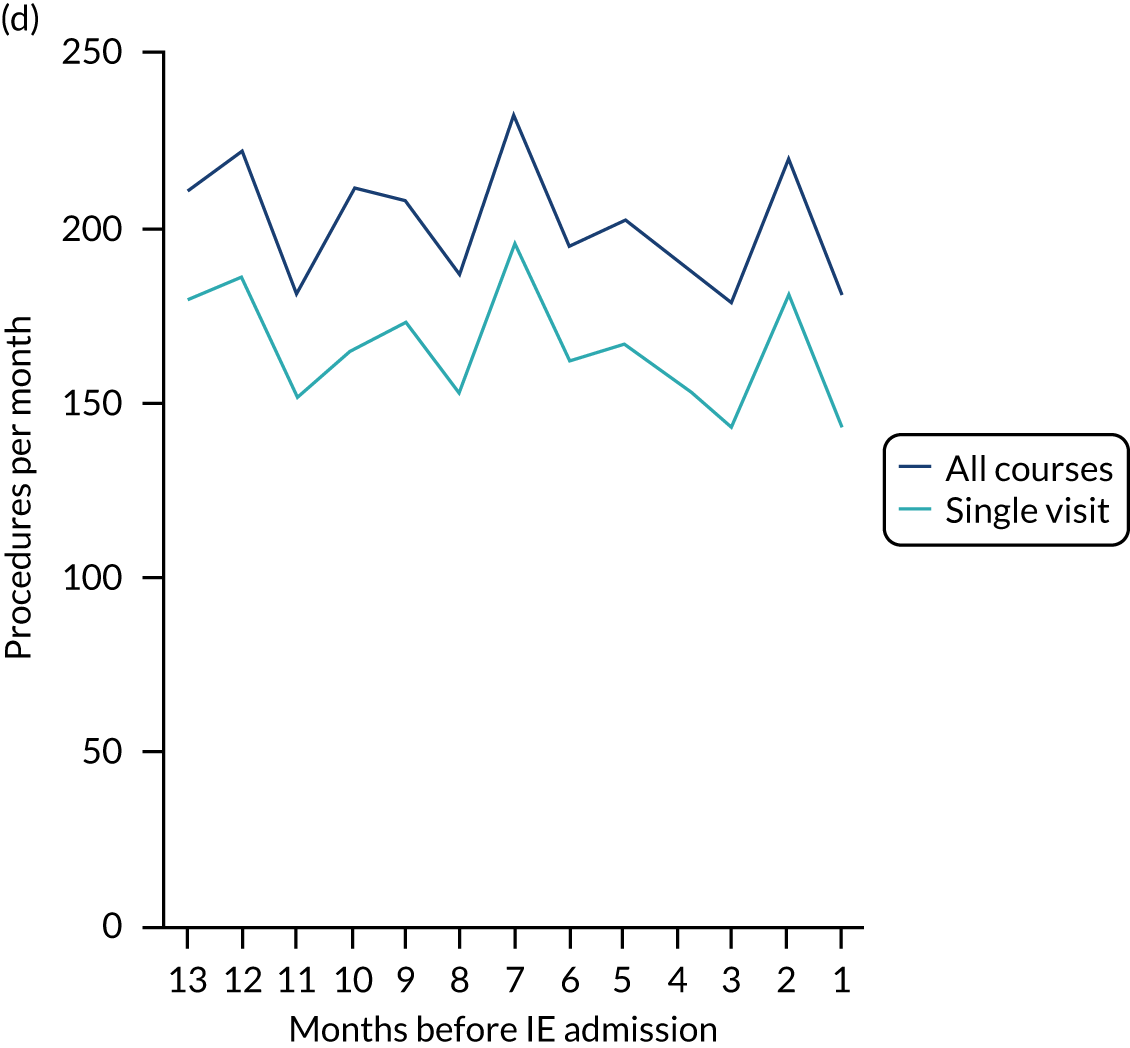

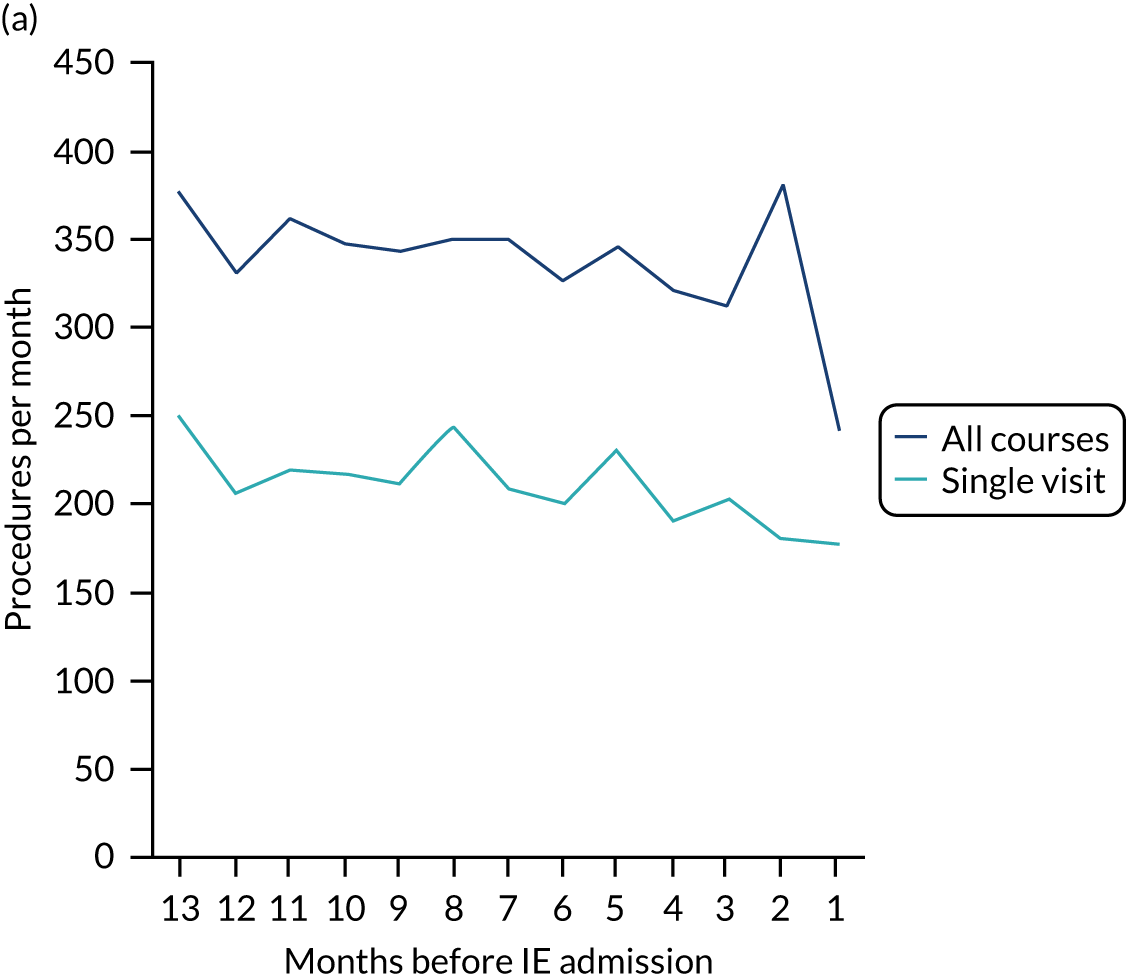

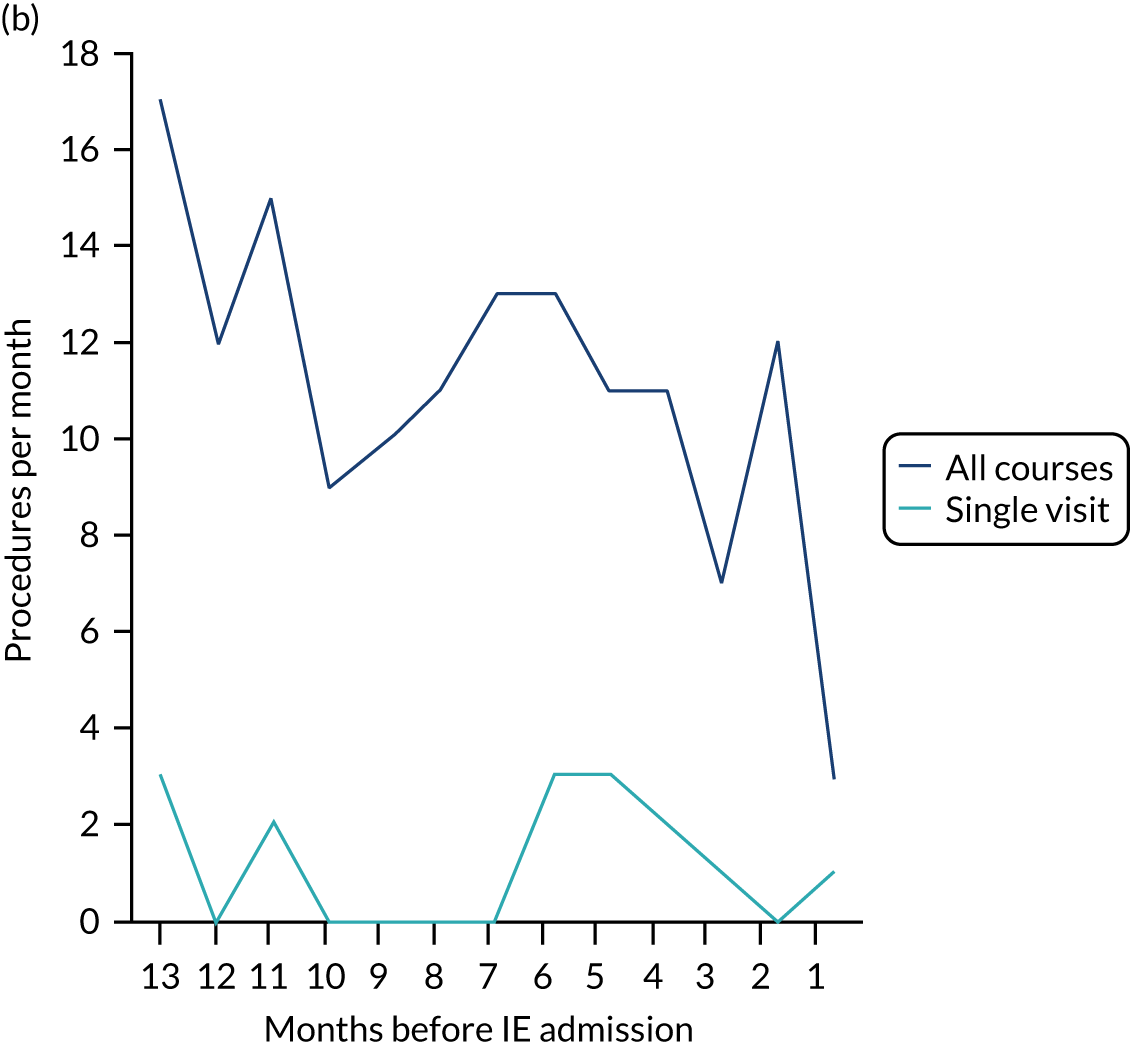

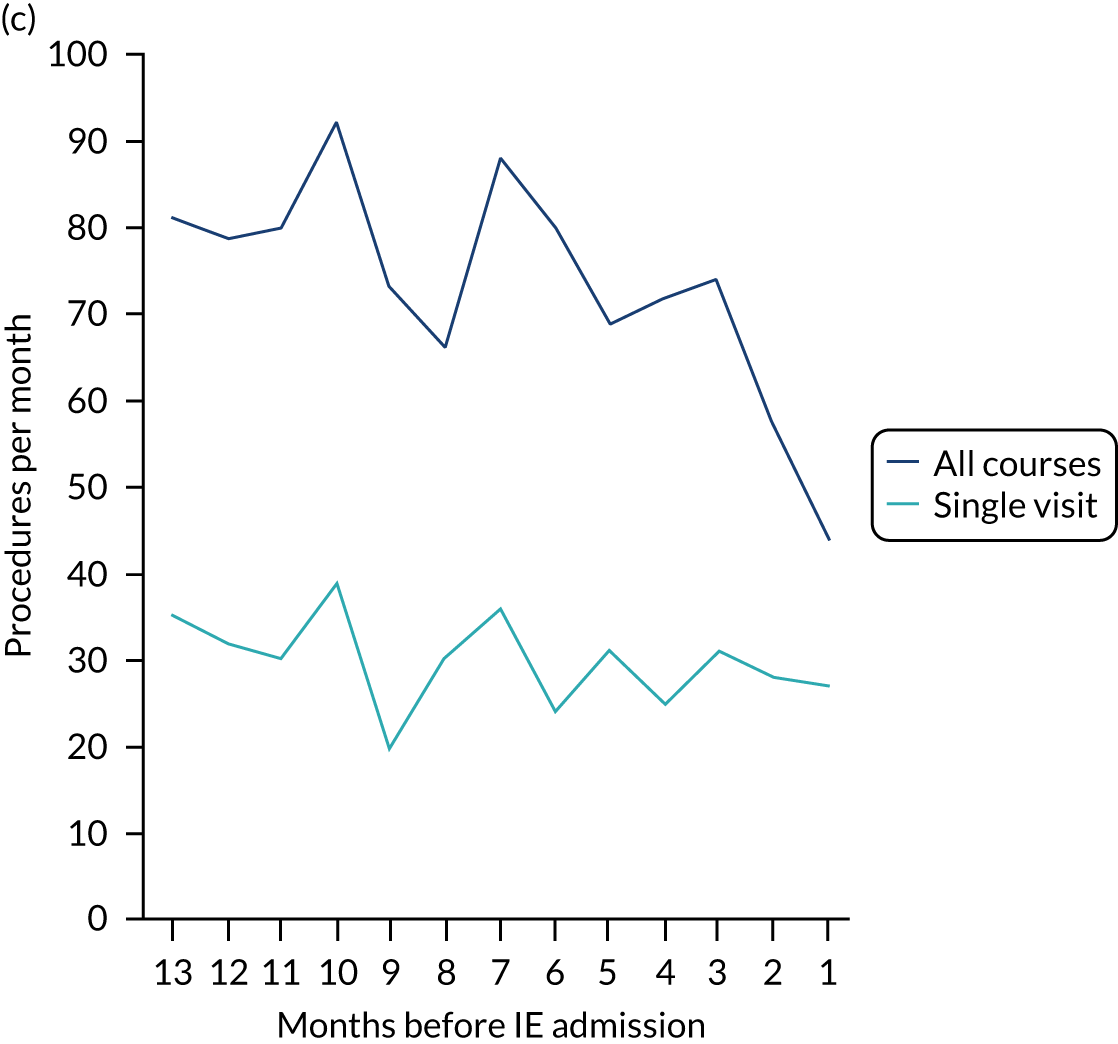

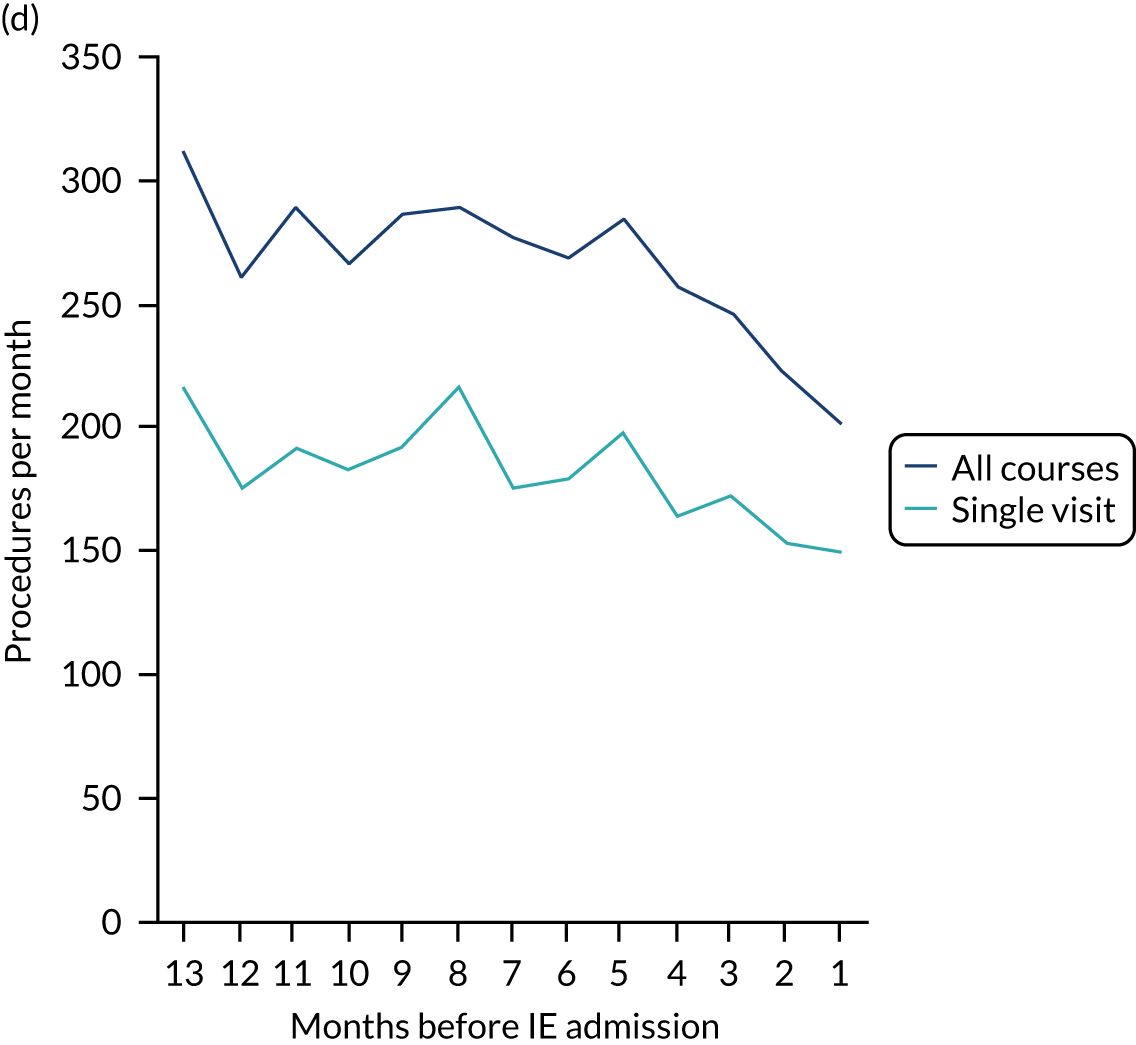

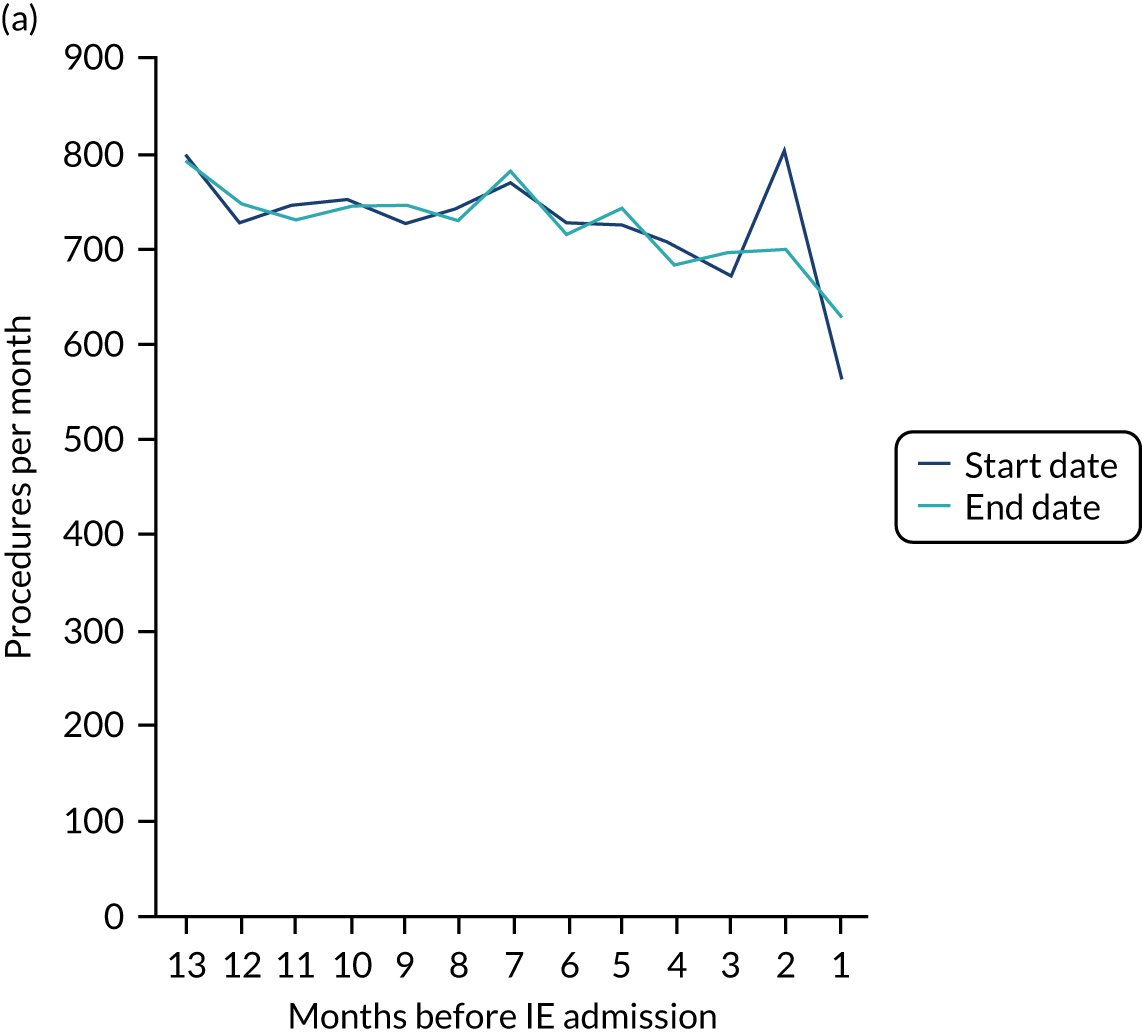

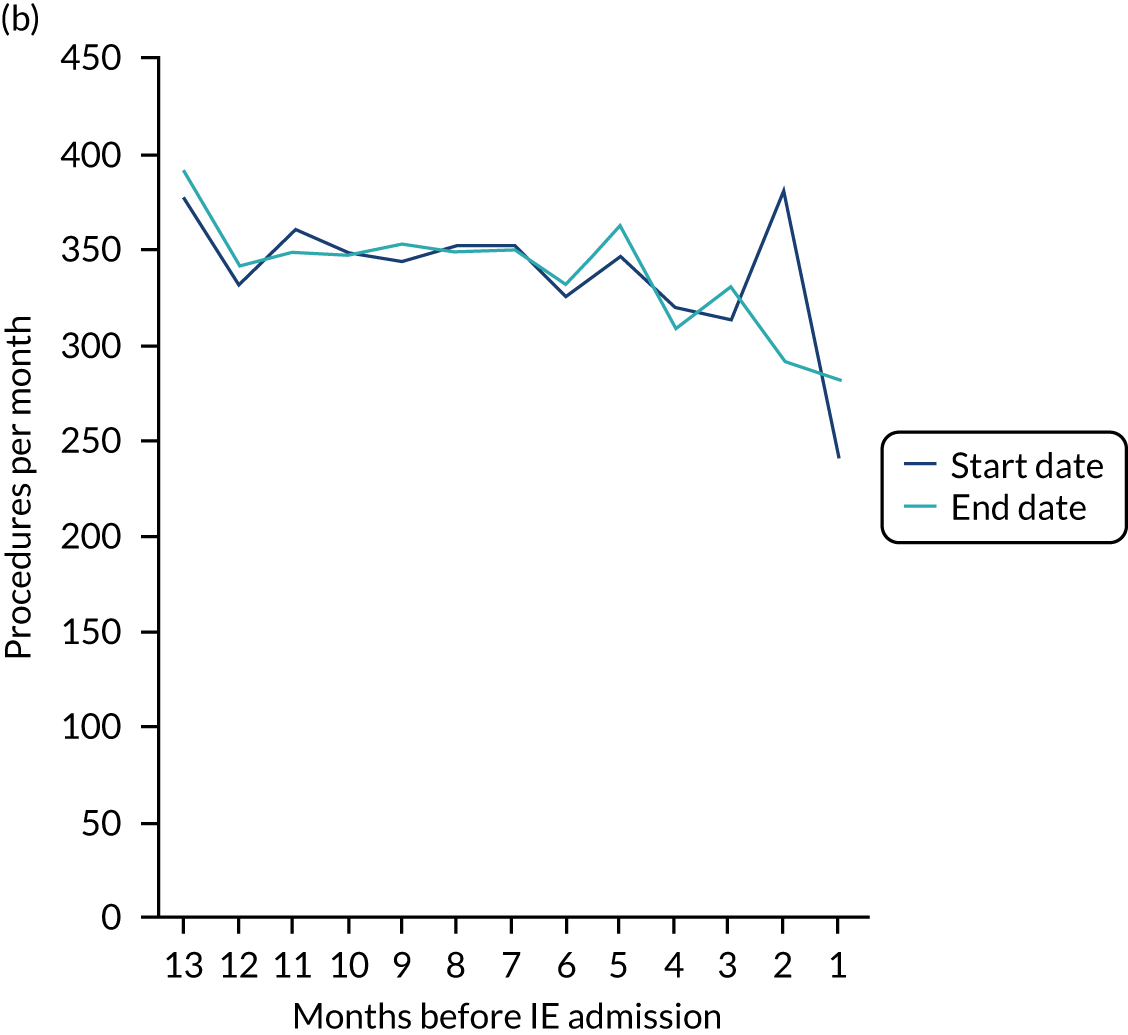

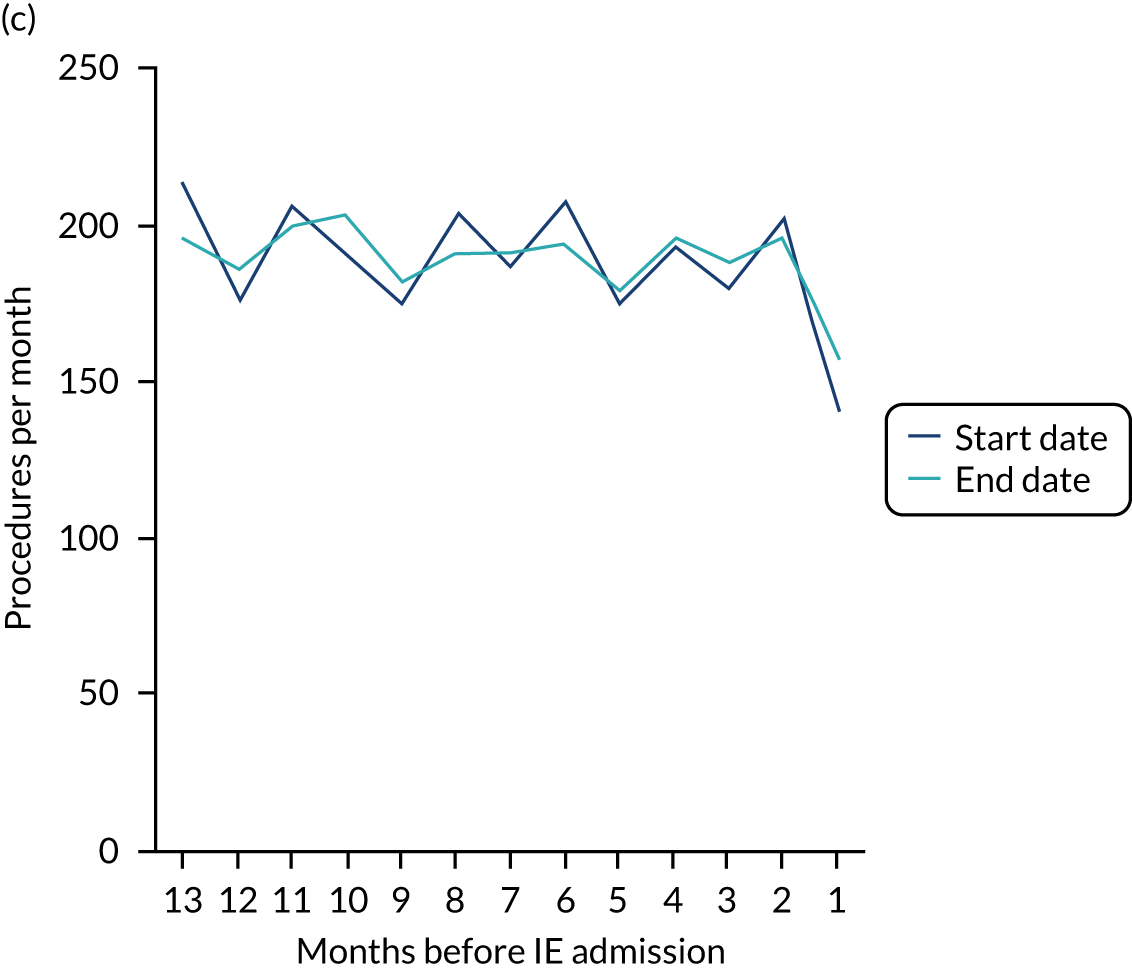

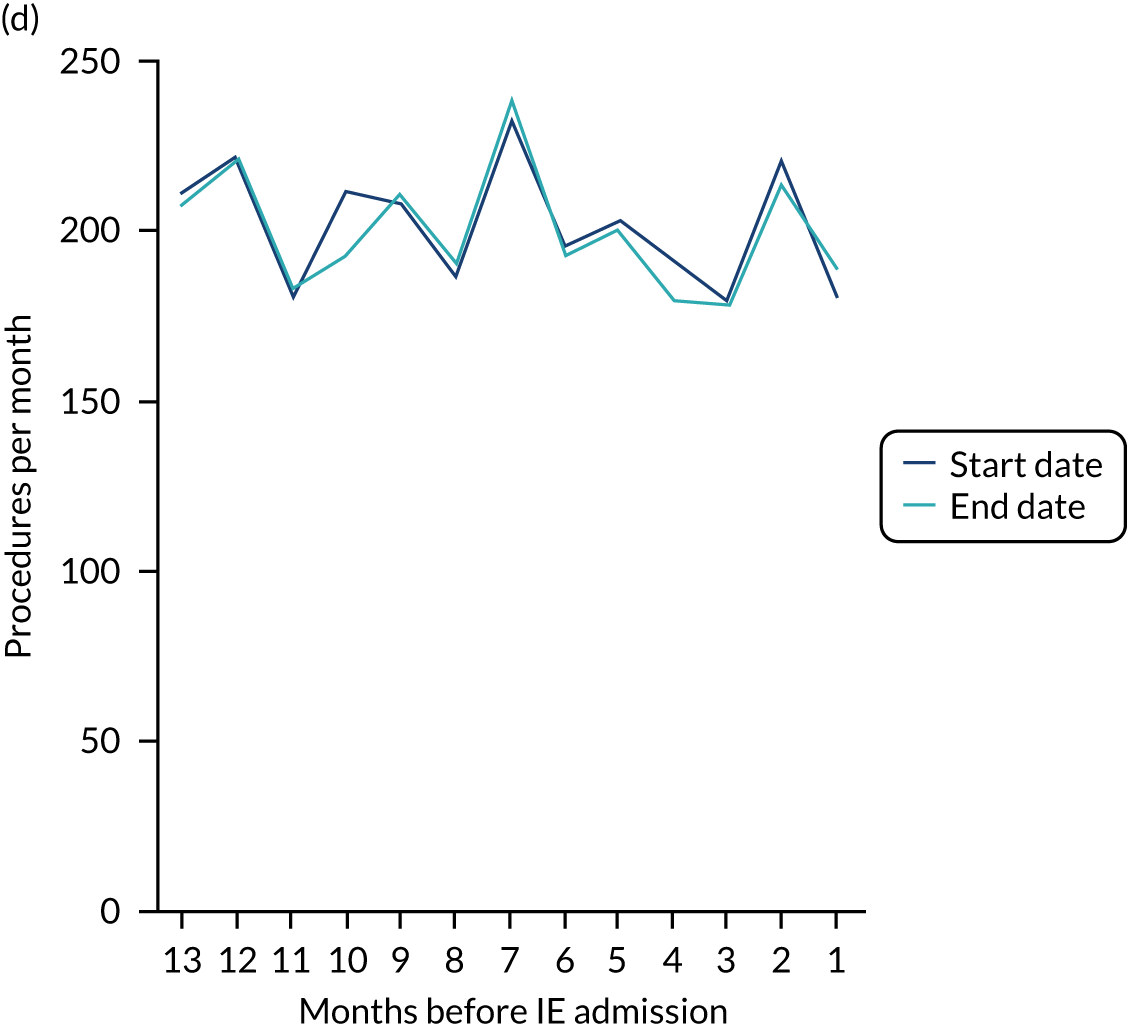

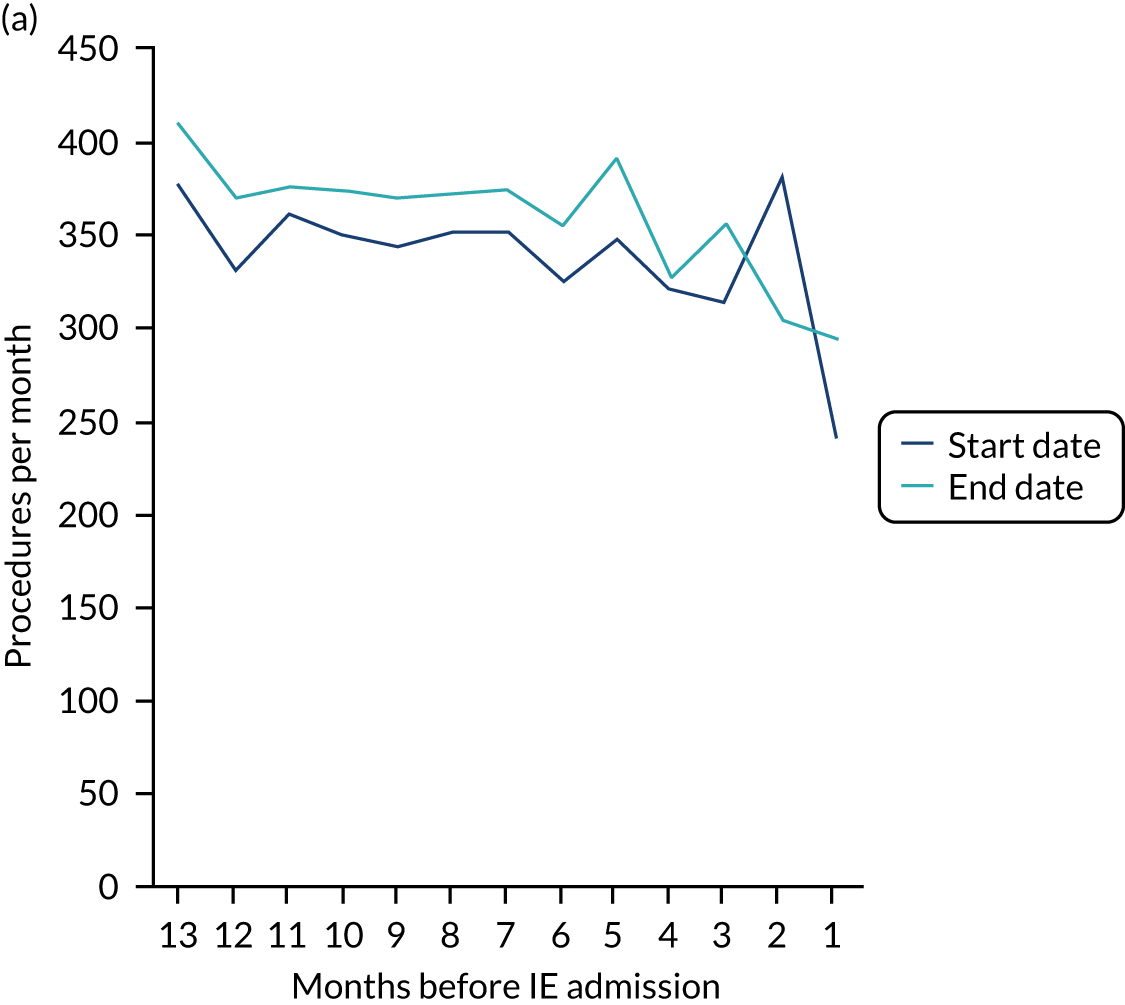

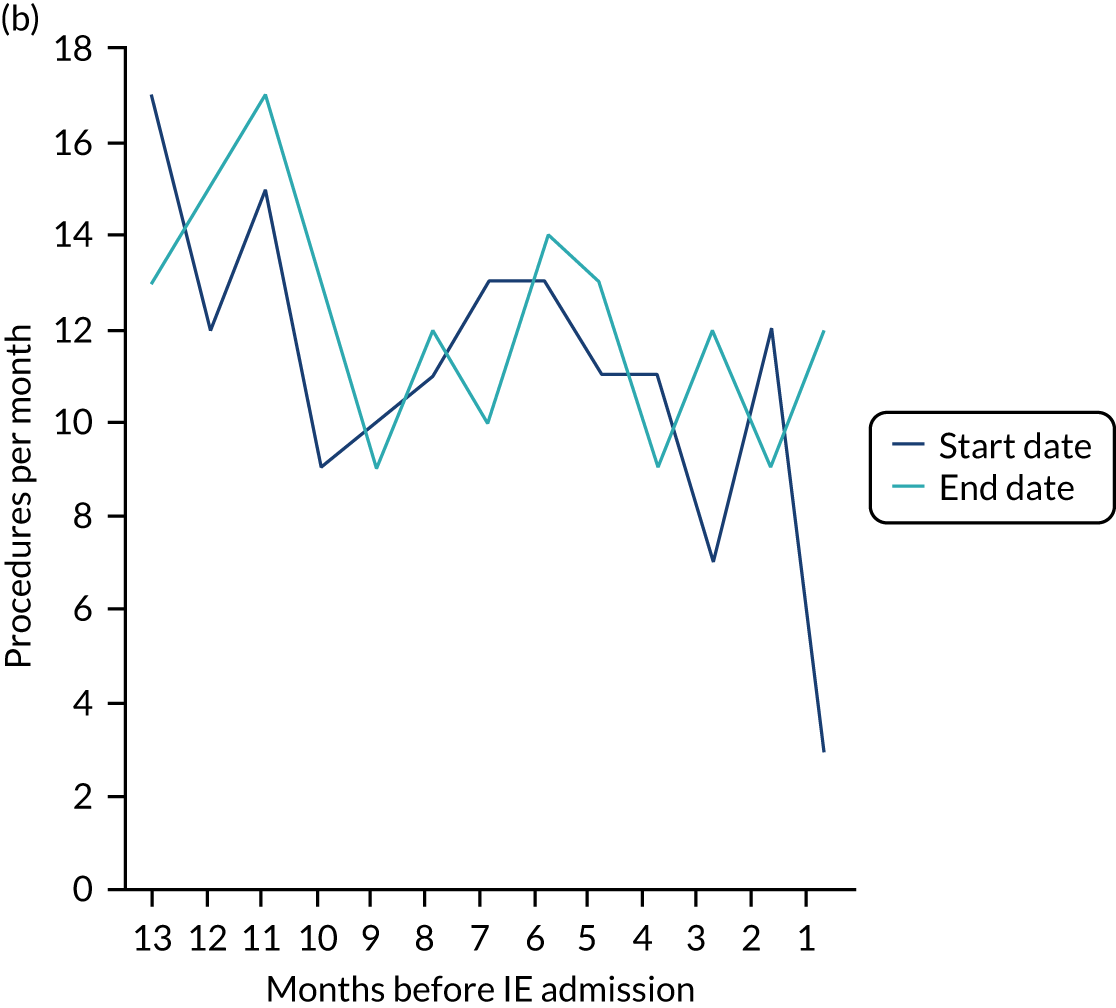

Because a case-crossover analysis compares the number of events (IDPs) in the case period immediately before the outcome (IE) with the number in earlier control periods, the duration and timing of the case and control periods is crucial. Although we had predefined a 3-month case period, this was based on the choices made in other studies, rather than on evidence. We therefore plotted the weekly numbers of all dental procedures, IDPs, non-invasive dental procedures and indeterminate procedures over the 52 weeks immediately preceding each IE hospital admission for which we had linked dental data. We repeated this analysis using the narrow (Figure 1) and broad (Figure 2) definitions for IE.

FIGURE 1.

Weekly number of dental procedures over the 52 weeks preceding IE hospital admission using the narrow definition of IE. The x-axis shows the number of weeks before an IE hospital admission (using the narrow definition of IE), with the time of admission being week 0 and using the start date for each course of dental treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Weekly number of dental procedures over the 52 weeks preceding IE hospital admissions using the broad definition of IE. The x-axis shows the number of weeks before an IE hospital admission (using the broad definition of IE), with the time of admission being week 0 and using the start date for each course of dental treatment.

Concerns raised by the timing of dental procedures in the 12 months before infective endocarditis admission

The results shown in Figures 1 and 2 were a surprise for two main reasons. The first was that we had anticipated that, if there were a link between IDP and IE, this would occur in the 3 months (12 weeks) immediately preceding any admission to hospital for IE. This 3-month window was derived from the period used in other IE studies,29–33 and we adopted this to define the case period in our planned (prespecified) case-crossover analysis comparing the incidence rate of IE in the case period (months 0–3) with that in the earlier control period (months 4–15). However, the time course studies did not support this. They showed that any change in IE incidence rate was largely confined to the 4 weeks immediately before admission. It is notable that although several studies have adopted 3 months as the exposure period between a triggering event (e.g. an IDP) and the onset of IE, none of these studies had actually plotted a time course to confirm this relationship. Indeed, the only study to specifically investigate the time between exposure and onset of IE (the incubation period) found that this period was as short as 7 days in 62% of cases, that 92% of IE cases developed within 4 weeks of an exposure and that only 8% of exposures occurred ≥ 4 weeks before IE diagnosis. 36 Our time course data are, therefore, much more consistent with a 4-week exposure/case period than the 12-week case period we predefined for our analysis.

The other surprise was that our time course data showed a decrease in the number of all types of dental procedures in the 4 weeks preceding IE admission. If there was a link between IDPs and IE, we would have expected an increase in the number of IDPs in the 4 weeks before IE admission, but this was not the case. Alternatively, if there was no association between IDPs and IE, we would expect no change in the number of IDPs in the 4 weeks preceding IE admission, but this was also not the case. The decrease in all types of dental procedures was unexpected and raised concerns that this might be caused by some other issue affecting the data on dental treatment in the weeks before admission to hospital with IE.

We therefore undertook further investigations to examine the possible reasons for this observation.

Chapter 4 Investigation of the reasons for the decrease in the number of dental procedures in the 4 weeks before infective endocarditis admission

Initial considerations

The time course data prompted a reconsideration of the ideas underlying our study and further discussion with our clinical colleagues.

One consideration was the fact that the main association between IDPs and IE (if it exists) should be for those at the highest risk of IE. As the proportion of the entire population that is at high risk of IE is very small, we might be losing any signal of an association within the larger population. There is also some debate about which IDPs are real risk factors for IE. The procedure around which there is most consensus is dental extractions; in countries where AP is recommended for IE, it is universally recommended for individuals at high risk of IE who are undergoing dental extractions.

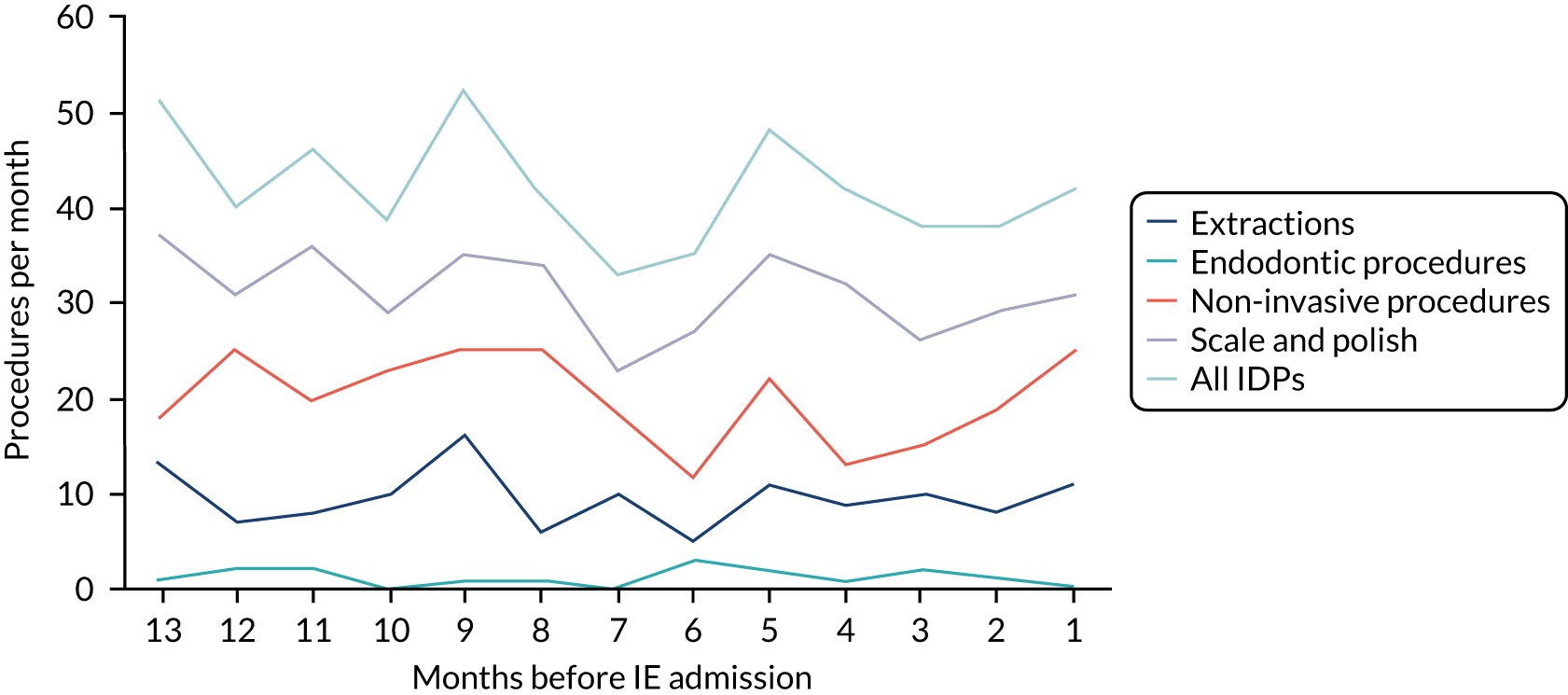

We therefore stratified individuals in the data set according to their IE risk status (high, moderate or low/unknown) and looked at the number of dental extractions in the 12 months before an IE hospital admission (see Appendix 2, Figure 25).

A decrease in the number of non-extraction dental visits was still evident in the data in the 4 weeks before IE admission, and this was as true for those at low/unknown risk of IE as for those at high or moderate risk of IE. This decrease was also evident for dental extractions in those at low/unknown risk of IE, but there was little evidence of any change in the general trend for those at moderate or high risk of IE (although the numbers were very small).

The decrease in the number of all types of dental visits (both extraction and non-extraction), particularly in those at low/unknown risk of IE, suggested some inherent reduction in the number of dental visits or a loss of data in the 4 weeks before hospital admission for IE. There was no reduction (or a much smaller reduction) in the number of dental extractions for those at high risk of IE compared with those at low/unknown risk of IE in the 4 weeks before IE admission. This suggests that those at high risk of IE who are undergoing dental extractions may be more likely to be admitted to hospital with an IE diagnosis in the subsequent 4 weeks than those at low/unknown risk of IE.

Infective endocarditis diagnosis is not simple, and patients who develop IE often become quite ill before a diagnosis is made. Symptoms may mimic the symptoms of flu, making diagnosis difficult, and may include a high temperature, night sweats, shortness of breath on exertion, tiredness, muscle and joint pains, and weight loss. 51 We speculated that one explanation for the unexplained decrease in all types of dental visits in the 4 weeks before IE admission might be because patients were incubating IE and becoming too ill to visit the dentist, cancelling appointments or failing to attend. However, it was also possible that something else could be causing a loss of data on dental treatments in the days before a hospital admission.

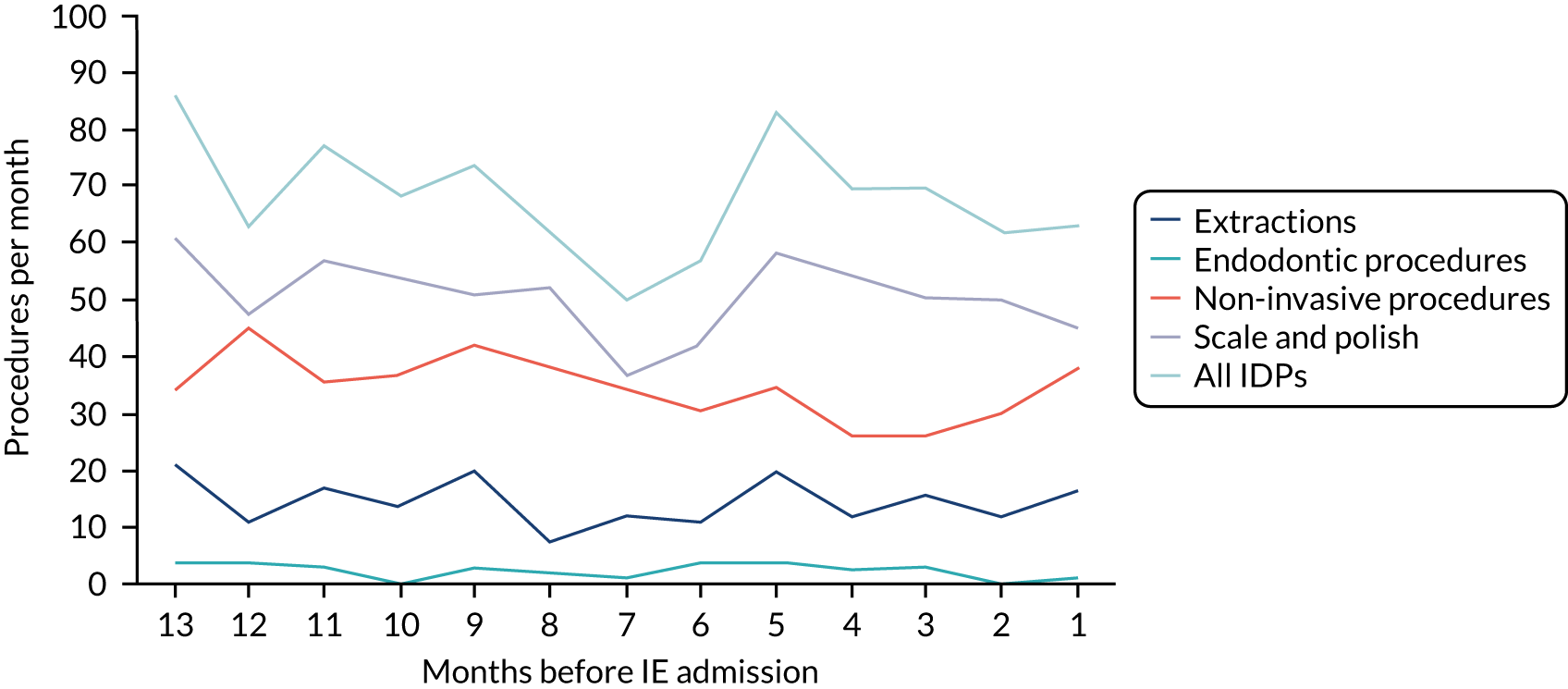

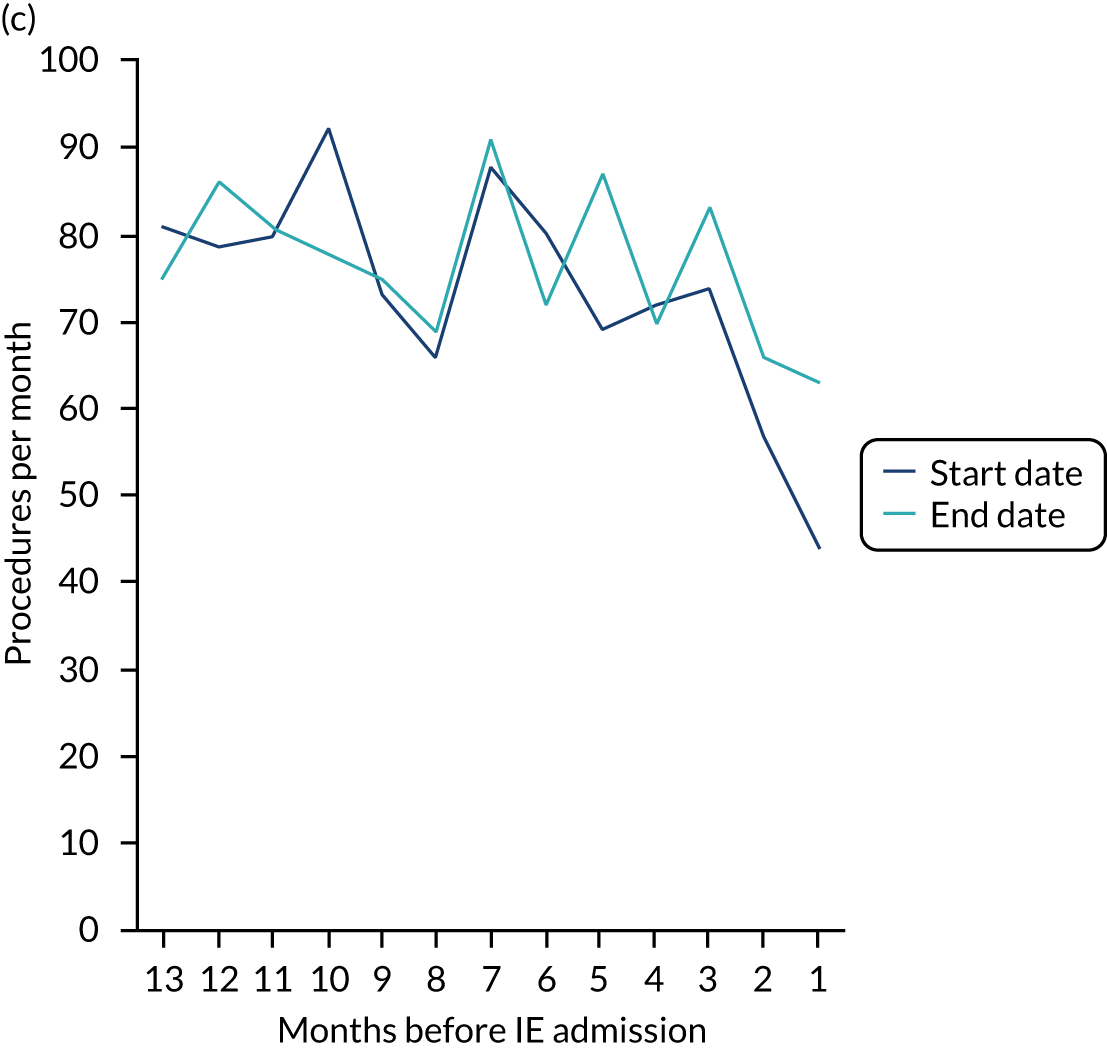

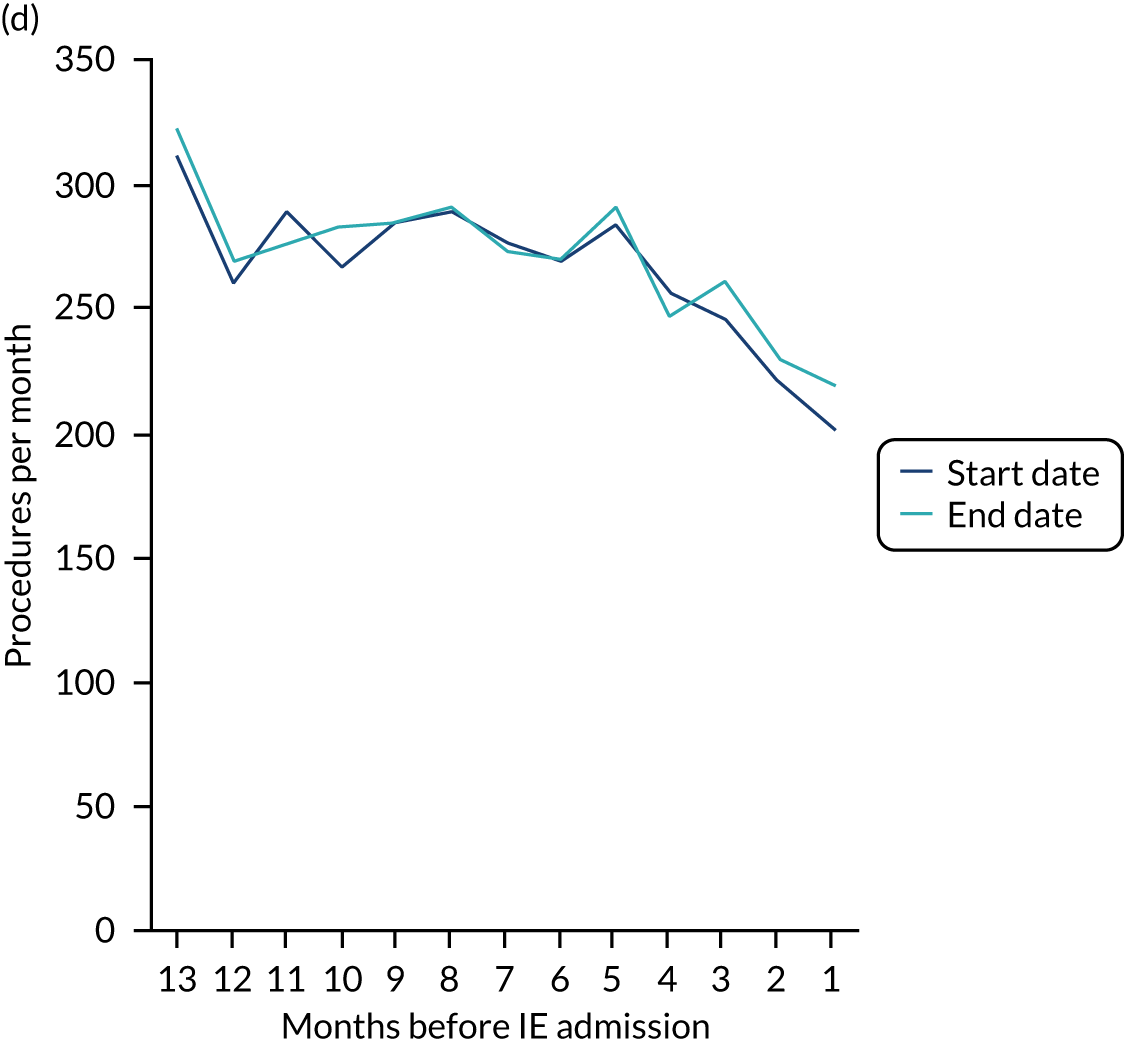

There was no direct way we could test if patients were too unwell to visit the dentist, but we realised that we might be able to address this indirectly by looking at the number of dental treatments in the weeks prior to other types of hospital admission. Within our data set, we had the data to perform this analysis for acute hospital admissions for MI, PE and stroke, and we had the research ethics approval to support this. Unlike hospital admission for IE, hospital admission for the majority of MI, PE and stroke patients occurs without warning or prior illness that might prevent dental attendance. Hence, if illness in the lead-up to hospital admission with IE was the cause of the decrease in dental attendance in the 4 weeks prior to their hospital admission, we would not expect to see a similar decrease in the numbers admitted to hospital with MI, PE or stroke. We therefore directly compared the monthly number of extraction and non-extraction dental visits in the 12 months before hospital admission for individuals admitted to hospital with IE (using both the narrow and broad definitions of IE), MI, PE and stroke (see Appendix 2, Figure 26).

The time course data showed a decrease in the number of dental visits (both extraction and non-extraction) in the 4 weeks before hospital admission for IE (both narrow and broad definition), MI, PE or stroke. In other words, the decrease in the number of dental visits was common to all types of acute hospital admission, not specific to IE admissions. This strongly suggested that there was a universal reduction in the number of dental visits or a loss of data occurring in the 4 weeks before emergency hospital admissions for serious illnesses with a significant mortality.

To explore possible reasons for this, we conducted a series of discussions with the NHSBSA and general dental practitioners.

For each course of NHS dental treatment, dentists complete a FP17 form. This is sent electronically to the dental division of the NHSBSA, based in Eastbourne, where it is analysed. The main purpose of the form is to ensure that dentists are fulfilling their dental services contract with the NHS, but it is also used to account for the patient charges that dentists are obliged to collect from patients, and the payment of dentists.

Patient charges and payments to dentists are based on bands of treatment (i.e. bands 1–3) or special treatment categories (e.g. prescription only and denture repairs). These are detailed in Part 5 of the form. Treatment bands do not provide much detail of the treatment provided and only cover broad cost categories of treatment. For this reason, in April 2008, the form was changed to collect some basic information on the types of dental treatment provided. This information is collected in Part 5a of the form, the ‘Clinical Data Set’, which is intended to provide the NHS and researchers with more information on the types of treatment provided by dentists.

Collection of these data became a mandatory requirement for all dentists from 1 April 2008, but some leeway was permitted in the first 12 months after its introduction. It is for this reason that we were only able to collect data for this study from April 2009. For the purposes of the study, we considered the following items in the ‘Clinical Data Set’ to be IDPs: item 1, ‘Scale and polish’; item 5, ‘Endodontic treatment’; and item 7, ‘Extractions’ (for more details, see Identifying invasive dental procedures). Part 2 of the form collects the patient details and Part 3 provides the course of treatment start and end dates; this information was also important to the study.

Results of the investigation conducted into the reasons for the decrease in the recorded number of dental treatments in the weeks preceding infective endocarditis hospital admission

We engaged in a series of discussions with staff at the NHSBSA Dental Data Processing Centre at Eastbourne to investigate if there could have been any data loss. These discussions eventually revealed that although we had asked for the details of all courses of dental treatment during the period 1 April 2009 through 31 March 2015, these had not in fact been provided. There were two main reasons for this.

The first reason was that, because of all the regulatory, administrative and organisational delays in providing us with the data, the NHSBSA did not actually perform the data extraction until April 2020 (instead of by 31 October 2017, as originally planned). NHSBSA also informed us that it had introduced a policy of destroying all data that was ≥ 10 years old. Because of this, it had supplied us with data only from 1 April 2010 until 31 March 2015 (i.e. 60 months’ data rather than the 72 months’ data we had requested – a 17% reduction in the size of the data set).

The second was that the NHSBSA also informed us that it had not provided us with any data for courses of dental treatment that had no Part 5a Clinical Data Set content. We were surprised to hear that any FP17 could be returned and processed that did not contain Part 5a information, as dentists have been required to complete Part 5a since April 2008. However, further questioning revealed that the NHSBSA do not enforce this requirement for incomplete courses of treatment, although it does enforce it for all complete courses of dental treatment.

Dentists are required to record the date when a patient is accepted for a course of dental treatment (even if only for an oral examination with no actual treatment) in Part 3 of the FP17 form. Because many courses of treatment are a single visit (e.g. a patient has a dental examination but no treatment), there is a tick box for when a course of treatment starts and finishes on the same day. If a dentist ticks this box or provides an end date for the course of treatment, they must also complete Part 5, which provides details of the band of dental treatment provided and is used to manage the business transactions involved (i.e. patient charges and payment due to the dentist). When this is complete, the dentist must also record clinical details in Part 5a.

However, Part 3 of the form also contains three tick boxes for incomplete courses of treatment (i.e. courses of treatment for which there is a start date but no end date). To deal with the business aspects of an incomplete course of treatment, the dentist is required to tick one of three boxes in Part 3 to denote what band of dental treatment they provided and any patient payment collected. However, the NHSBSA do not require dentists to complete Part 5a of the form (where the clinical details are recorded), as long as one of these three boxes is ticked. Furthermore, the NHSBSA does not perform follow-up to ensure that these details are provided in such situations, whereas it does perform follow-up if an end of treatment date was entered or the ‘Completion same day as acceptance’ box was ticked. Because such courses of dental treatment contain no clinical details of the treatment provided, the NHSBSA removed these from the provided data set. This meant that we had no data for any incomplete courses of treatment.

We investigated the possibility of the NHSBSA providing us with these data. However, we identified this problem only in November 2020, by which time any re-run of the data by the NHSBSA would have resulted in a further loss of 7 months of data owing to its policy of destroying data that are ≥ 10 years old. Moreover, although we would receive the start date for these incomplete courses of treatment, we would not receive any clinical details of the treatment provided and would hence be unable to determine whether or not the treatment was invasive – the essential item of information for our study.

We also talked to a number of dentists working in general dental practice to obtain a better understanding of how they handled incomplete courses of treatment. It would appear that, although some dentists record the clinical details for incomplete courses of treatment, many do not, as it is time-consuming and an unnecessary requirement for payment. Furthermore, some dental practice software used in completing such forms does not allow the inclusion of treatment details for an incomplete course of treatment. The information from dental practitioners therefore confirmed the information from the NHSBSA and suggested inconsistencies in the way incomplete courses of treatment are recorded.

We also asked dentists to tell us about the types of situation that most often result in an incomplete course of treatment. These included patients abandoning a course of treatment, moving out of the area, being admitted to hospital as an emergency with a serious life-threatening disease or dying. Emergency admission to hospital, death and serious illness were considered not uncommon reasons for a patient to fail to complete a course of treatment.

This observation is important, as IE hospital admissions are nearly all unexpected emergencies. Around 20% of patients admitted to hospital with IE die during the initial admission, and around 30% die within 1 year of the admission. Owing to their serious nature and the frequent need for long-term intravenous antibiotics and cardiac surgical intervention, hospital stays for IE are among the longest of any condition.

Furthermore, survivors often have serious debilitating and long-term morbidity. This suggests that, if a patient is admitted to hospital with IE soon after initiating a course of dental treatment, there is a significant possibility that the course of treatment will not be completed, and that the clinical treatment data will not be provided to the NHSBSA. In addition, many patients admitted with IE, particularly those requiring valve intervention, will be evaluated and treated by the maxillofacial surgery team while in hospital before valve surgery, providing another reason for any course of treatment initiated by the patient’s primary care dentist to be abandoned and incomplete.

In any of these circumstances, the record of the treatment being started will be lost from the data provided to us by the NHSBSA. Furthermore, the fact that data loss is most likely in the period immediately before IE admission explains (at least in part) the decrease in the number of all types of dental procedures in the 4 weeks before emergency hospital admission that we saw with other serious acute medical conditions associated with a significant mortality rate and long-term morbidity (i.e. MI, PE and stroke). Unfortunately, this data loss, which was focused on the weeks before high-mortality-rate emergency hospital admissions, directly and adversely impacted our case-crossover analysis, which relies on comparing the number of IDPs in the weeks immediately before IE admission (when the data loss is focused) with that in earlier periods (when data loss would be much less likely to occur).

In conclusion, we have two major reasons for data loss: (1) loss of all types of data from earlier years owing to the NHSBSA’s policy of destroying data that are ≥ 10 years old, and (2) loss of clinical treatment data for incomplete courses of dental treatment. Although the former significantly reduces the sample size and, therefore, the statistical power of the study, it does not affect the comparison of case and control periods in our case-crossover analysis. Unfortunately, however, the loss of data from incomplete courses of treatment is disproportionally focused on case periods, rather than control periods. This is therefore likely to significantly bias the outcome of any case-crossover analysis.

Chapter 5 The search for alternative methods of analysis

Initial considerations

The loss of data in the critical few weeks before IE hospital admission seriously undermined our ability to investigate any link between IDPs and IE using the study’s case-crossover methodology design. Our investigations determined that this data loss was, at least in part, due to the NHSBSA not requiring dentists to provide clinical details for incomplete courses of dental treatment.

We therefore investigated ways of using the data to answer the original question that did not depend on the incomplete course of treatment data. Possibilities included using:

-

data for single-visit courses of dental treatment

-

courses of dental treatment defined by the end date.

Single-visit courses of dental treatment

Single-visit courses of treatment are courses of dental treatment that start and finish on the same day (i.e. the start and finish dates are the same). Restricting the data to single-visit treatments would ensure that all courses of treatment recorded were complete before IE hospital admission and, therefore, could not be affected by any data lost as a result of incomplete courses of treatment. However, using single-visit treatment could introduce a new bias if the mix of invasive and non-invasive dental treatments was significantly different for single-visit courses of treatment and longer courses of treatment.

The entire dental data set consisted of 3,751,621 records, of which 2,629,502 (70.1%) were single session (i.e. the start date and end date were identical). Of those, 6623 (0.25%) related to individuals requiring IE hospital admission within 13 months of that date – using the broad definition of an IE hospital admission.

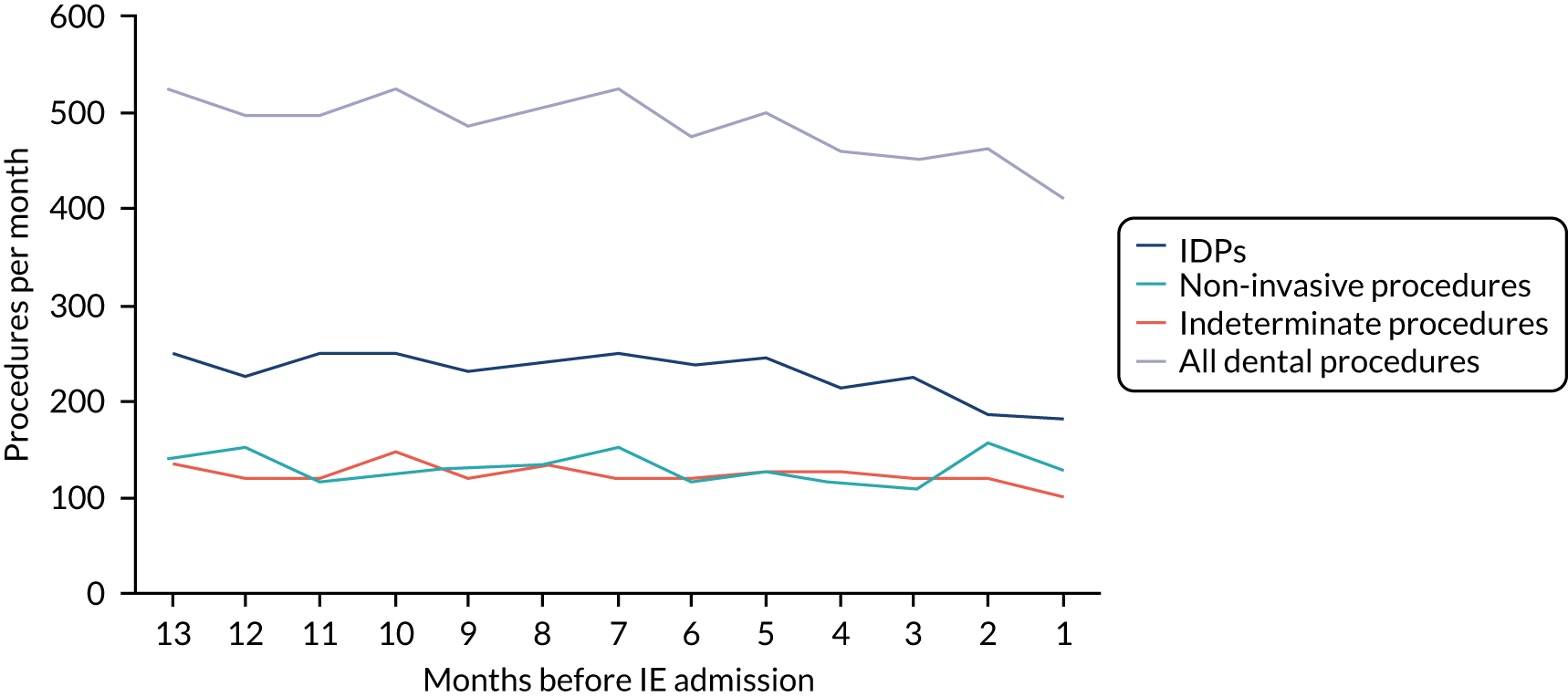

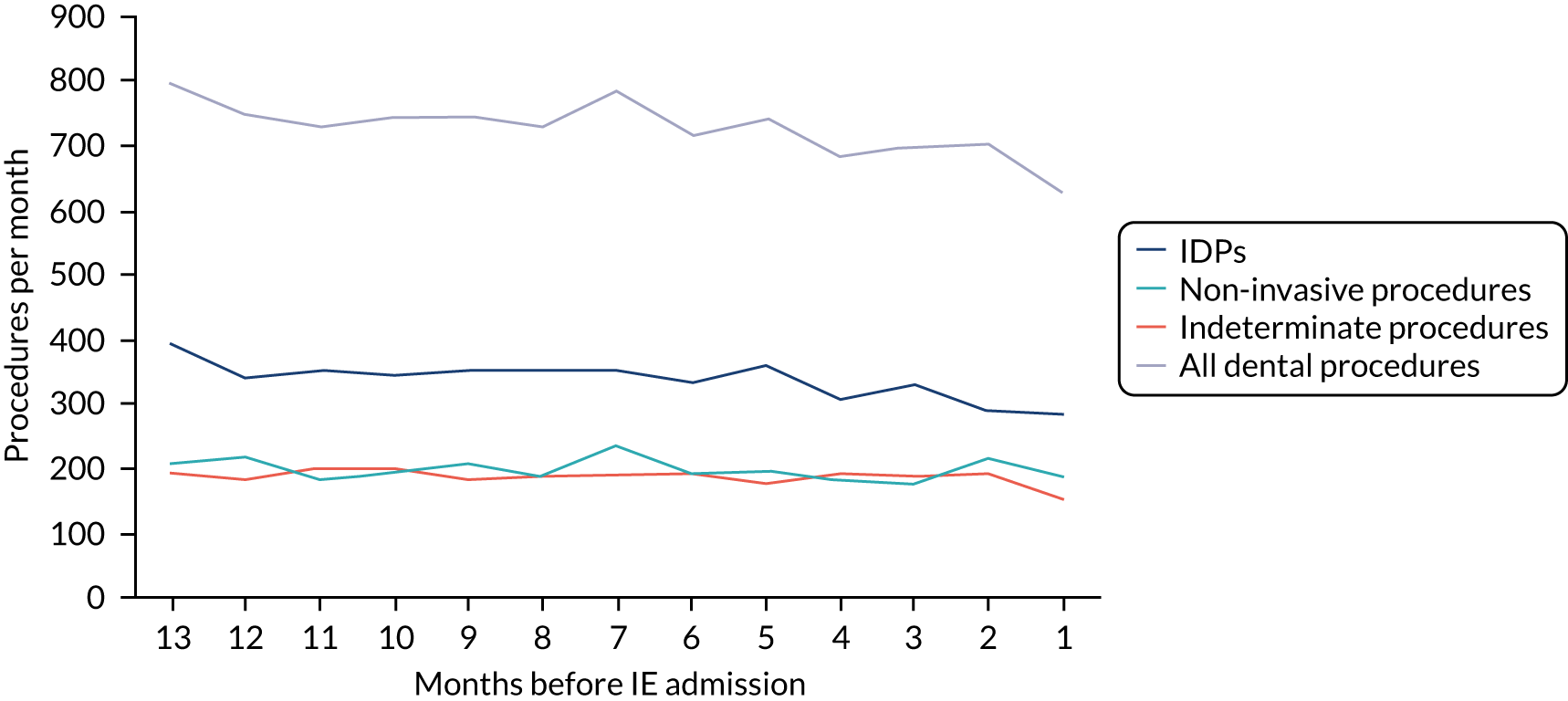

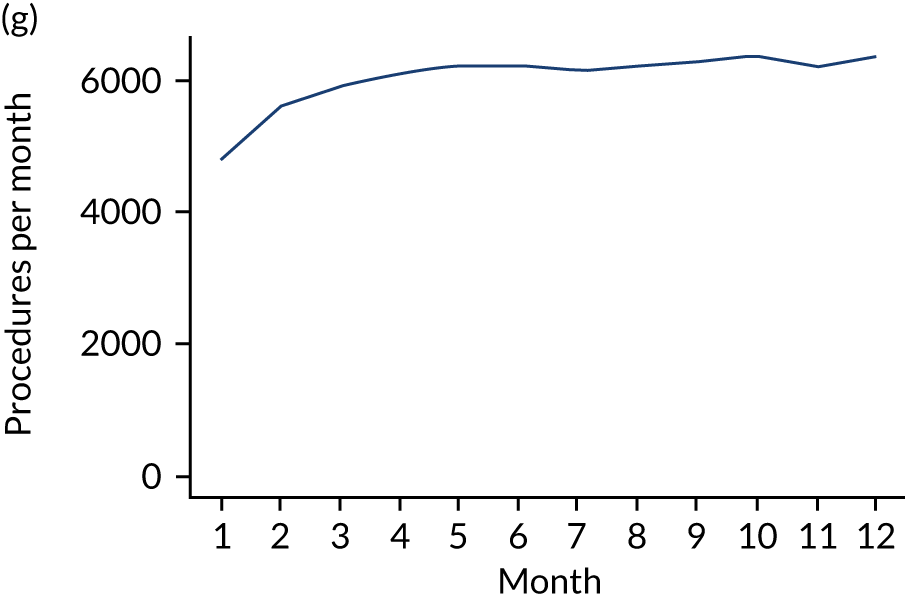

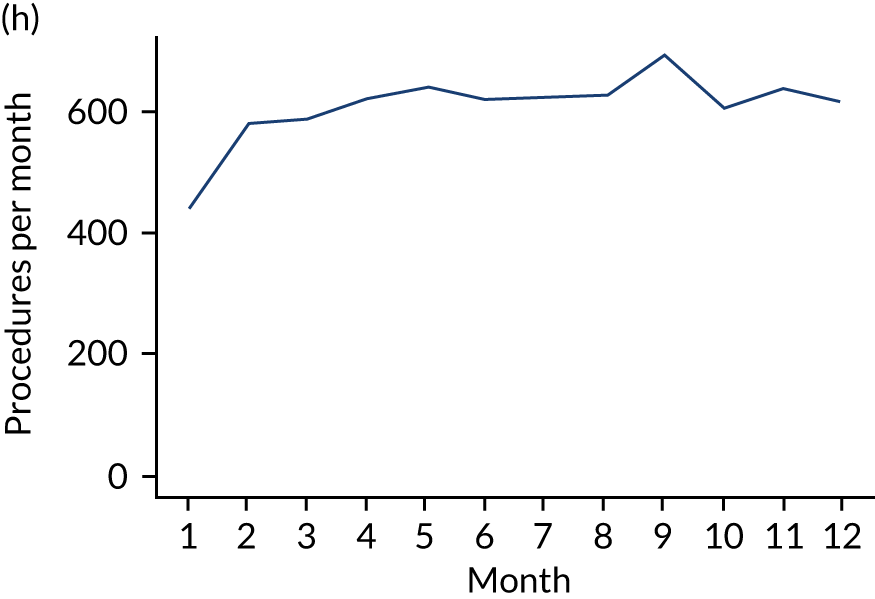

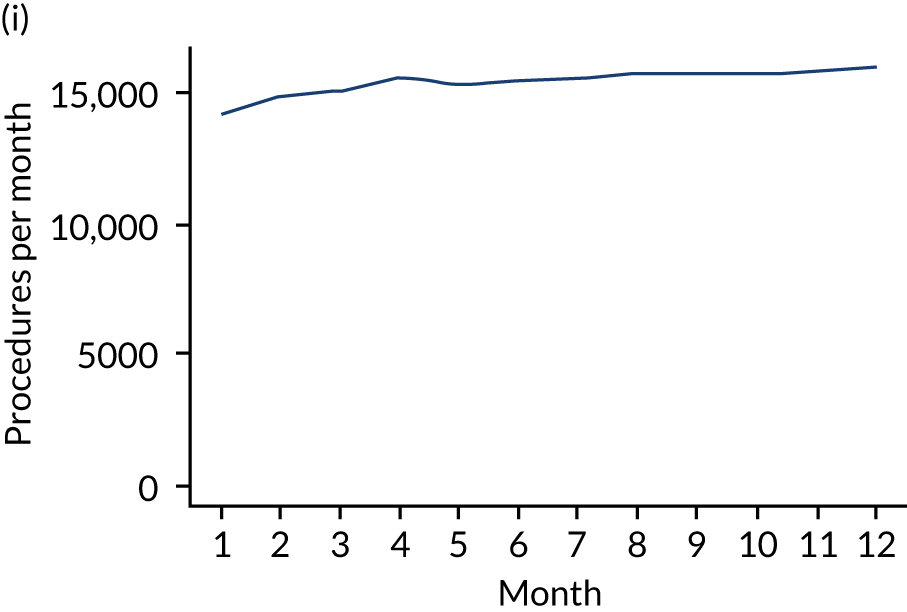

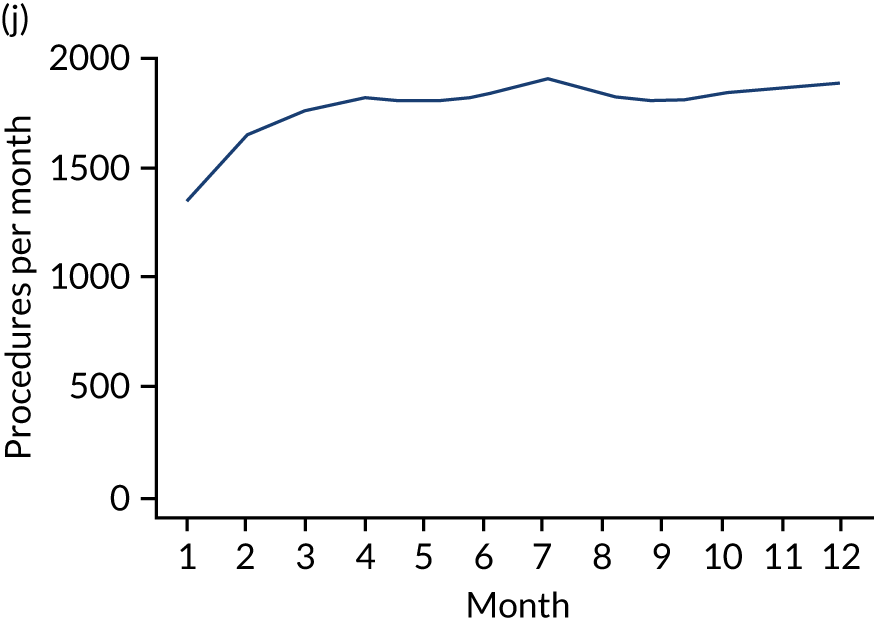

These single-visit courses of treatment were divided into those that included an IDP, an indeterminate procedure or a non-invasive procedure. They were tabulated according to the number of months (30-day periods) before the IE admission (Table 7; see also Appendix 2, Figure 27).