Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/118/01. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The draft report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Oliveira et al. This work was produced by Oliveira et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Oliveira et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Background

Looked-after children are a very vulnerable group who are at greatly increased risk of experiencing mental health problems and poor long-term social, emotional and educational outcomes. 1,2 Despite this, remarkably few interventions exist that have proven efficacy for intervening in the case of or preventing poor outcomes for these children. 3 Accordingly, there is an urgent need to develop new and effective interventions to improve the outcomes of children in care. In particular, looked-after children are at a fivefold increased risk of all childhood mental, emotional and behavioural problems, and are six to seven times more likely to have conduct disorders. In adulthood, they are between four and five times more likely to self-harm. 1

Critically, the number of children in care has risen steadily in the UK in recent years. Figures from the Department for Education show that, in 2019, the number of children looked after by local authorities in England increased by 4% since 2018, to 78,150. 4 Although the number of children entering care during the year decreased by 2% (to 31,680), the number of children leaving care during the year also decreased 2% (to 29,460), suggesting that some children are spending longer in care. Children ceasing to be looked after during 2018–19 as a result of adoption, in particular, fell by 7% (to 3570), a continuing drop seen since 2015. On the other hand, children who ceased to be looked after as a result of a special guardianship order (SGO) increased by 11% to 3830. There has been a slight decrease in the proportion of looked-after children who are placed in foster care, but foster care remains the most common type of placement. In 2019, 72% of looked-after children were in foster care; the great majority were placed with a foster carer who was not a relative or friend.

Given the size and disproportionately at-risk nature of this group, and the level of responsibility borne by foster carers, there is great need for evidence-based foster carer-led interventions to support them in improving the short- and long-term outcomes of looked-after children.

The most common primary reason for children becoming looked after is abuse or neglect (63%), followed by family disfunction (14%); other parenting difficulties account for the majority of the remaining cases, with child factors (e.g. child disability) identified in a minority of cases as the primary reason. 4 Thus, children who are looked after have typically been exposed to harmful experiences; abuse, neglect and major disruptions in parent–child bonds are prominent. 5 Although these experiences almost certainly affect child development in a number of ways, one very well-documented and important area is in the development of attachment. 6 Attachment is a critical early-appearing developmental phenomenon that is observable from the first year of life, in which children maintain proximity to and selectively seek comfort from their carers when they are worried, anxious or distressed, and attachment is thought to be critical for their optimal long-term development. Attachment is believed to be largely instinctive, but the way in which a child’s attachment behaviour is manifested or organised is dependent on the environment and, particularly, on the quality of care. 7 A large body of research has demonstrated that suboptimal and disordered patterns of attachment behaviour can arise when children experience insensitive, frightening, neglectful or abusive care, or frequent change of carers. 7,8 These early difficulties in attachment leave a child at risk of poor social and emotional outcomes. 9,10 In contrast, a secure attachment, whereby a child is able to openly communicate their attachment needs and be readily comforted by contact, is consistently associated with better developmental outcomes across a range of areas7,9–12

Following an extensive review of the literature, a recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline13 identified three clinically important forms of suboptimal attachment patterns that should be considered important targets for intervention among children in care. These patterns, referred to collectively as ‘attachment problems’ by the guideline group, are reactive attachment disorder (RAD), disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED) and disorganised attachment. RAD and DSED are observed almost exclusively among children who have been subjected to extreme neglect and/or repeated changes in caregivers, whereas disorganised attachment may arise in the context of abuse, neglect or highly insensitive/atypical parenting. 10

Reactive attachment disorder is considered an attachment disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition14 (DSM-5) (previously referred to as the RAD-inhibited subtype in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition), and refers to a pervasive absence of attachment behaviour by young children towards their carers, combined with highly withdrawn and fearful behaviour and emotional volatility. RAD is observed at relatively high rates among children raised in institutions (43% in Zeanah et al. 5), but there is considerable uncertainty regarding its prevalence among children in UK foster care (Zeanah et al. 5 reported 35% RAD in a US foster care sample).

Although DSED has traditionally been defined as an attachment disorder (previously referred to as RAD-disinhibited subtype), it has been reclassified as a disorder of social behaviour in the DSM-5. These children show a striking lack of reticence with strangers, are prone to engaging in inappropriately intimate social (including physical) contact with strangers, and may wander off with strangers. Despite this behaviour with strangers, they show attachment behaviour, sometimes even of the secure type, to their primary caregivers in standard separation–reunion procedures such as the Strange Situation Procedure. 8 The evidence is quite clear that RAD and DSED are different disorders, showing distinct characteristics, aetiologies and courses. 10 Although the precise relation between DSED and the attachment construct is controversial, it is generally accepted that it reflects a lack of selectivity in social approach, which is at least closely related to attachment. 15

Disorganised attachment is observed in around 3–15% of normative populations, and it is much more prevalent among children raised in highly deprived circumstances or those exposed to abuse (48% of abused pre-schoolers are disorganised according to meta-analytic work; see van IJzendoorn et al. 16). Disorganised attachment is also observed at elevated rates in children in foster care compared with controls (d = 0.41; see van den Dries et al. 17). Disorganised attachment is not a disorder and is arguably more accurately described as a relational or developmental vulnerability factor that increases the likelihood of adjustment difficulties in the future.

A large number of intervention studies have shown that it is possible to increase the rate of secure attachment and reduce rates of disorganised attachment in a range of normative, at-risk and clinical populations by improving the sensitive responsiveness of parental care. 13,18,19 Such interventions often combine a number of treatment elements, but share the common objective of helping parents to become sensitively attuned to a child’s attachment cues, and to respond to them consistently and appropriately.

Video-feedback techniques are a commonly used and effective strategy for helping parents to increase their sensitivity to attachment cues and video-feedback-based interventions reliably increase rates of secure attachment and reduce rates of disorganised attachment (d = 0.44, k = 5). 19 Indeed, video-feedback interventions may be particularly helpful for high-risk children who have experienced significant disruptions in care. Three trials have used video-feedback interventions focused on improving caregiver sensitivity as a means of reducing attachment difficulties (specifically disorganised attachment) among children who had been adopted or maltreated, and all reported positive, significant and sizeable treatment effects (Bernard et al. :20 d = 0.72; Juffer et al. :21 d = 0.80; and Moss et al. :22 d = 0.90).

Two independent and wide-ranging reviews, one commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme19 and the other conducted by NICE,13 concluded that interventions promoting sensitivity had the best evidence of effectiveness for reducing attachment problems among children in care. The NICE guidance13 specifically recommended video-feedback methods because of their good clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness profiles.

The Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD)23 is the most rigorously tested sensitivity-focused video-feedback intervention; it has repeatedly been shown to improve parental sensitivity to attachment cues (d = 0.47, k = 12)24 and has been used in a broad range of contexts and age ranges (up to the age of 5–6 years), making it an attractive choice for a brief and cost-effective treatment for children in foster care.

It is critical to note, however, that the HTA programme review19 also highlighted the fact that no study had yet tested whether or not any intervention can effectively treat RAD. Given the likely high prevalence of RAD in the foster care population, this is a serious research gap. 8 It is also noteworthy that no studies have tested the effectiveness of the VIPP-SD for improving attachment security and reducing attachment problems in a UK health-care setting for any target group, although a trial for children at risk of behavioural problems is due to report its findings imminently (UK Clinical Research Network identifier: 18423). 25 However, that trial does not target children in care and will not include children with RAD. Finally, although the VIPP-SD has been trialled for children who have been adopted, (see Juffer et al. 24 and van den Dries et al. 17) no studies, to our knowledge, have tested the effectiveness of the VIPP-SD for children in foster care at the time of the current study (but see Schoemaker et al. ,26 who have recently published the findings from their study with foster children in the Netherlands).

Although we currently lack evidence regarding the most effective treatments for RAD, the most promising approach for young children with difficulties falling under this rubric (primarily, failing to show attachment behaviour when distressed) is to focus on improving parental awareness and understanding of the child’s distress, and encouraging comfort-seeking by supporting what contemporary attachment theory and research indicates is the central driver of secure attachment: parental sensitive responsiveness. Such an intervention would also benefit from incorporating support for carers in managing challenging behaviour. 27 The VIPP-SD represents the most thoroughly tested video-feedback intervention for promoting sensitive responsiveness, includes techniques for behaviour management and is specifically recommended by NICE for treating attachment problems for children in care. It is, therefore, a strong candidate for the treatment of RAD symptoms in the foster care context.

Correctly reading and being consistently sensitive and attuned to a child’s attachment cues may be maximally difficult; therefore, enhanced support and training may be necessary when a child has attachment problems and a complex and traumatic history. A recent modified VIPP-SD programme designed for children in foster care [the Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline, Foster Care (VIPP[SD]-Foster Care or VIPP-FC for short)]28 pays particular attention to the need to help carers recognise signals, which may be quite challenging and difficult to understand, that are more commonly observed in children in foster care, so that the carers are better equipped to respond sensitively and to support the child’s secure attachment to them as their carer. In particular, children in foster care tend to demonstrate attachment signals that are very subtle, highly distorted or absent, for example not crying when hurt because they are not used to being comforted, or becoming angry or fearful when comforted. By helping foster carers become aware of these subtle, distorted or absent signals and training them to respond appropriately, it is hoped that the child can learn that foster carers can be relied on in times of need and that it is safe to show their distress and seek comfort. For many children in foster care, their experience of physical interactions with carers has been extremely negative; hence, the VIPP-FC also specifically addresses how to gently and sensitively support a child’s needs for physical contact and comfort. 28

Rationale for the study

There is an urgent need to address the lack of evidence underpinning prevention and intervention work for young children in foster care with attachment needs. 13 The current report presents the results of a feasibility study investigating the acceptability of the VIPP-FC and the practical feasibility of implementing a randomised study of its efficacy. As part of this feasibility work, we explore the views of foster carers and professionals about the challenges of and barriers to supporting children with attachment needs in the foster care context, and the challenges of and potential solutions to running a research trial in this context. We undertook a small-scale trial to test a range of critical feasibility questions and conducted qualitative interviews with recipients of the VIPP-FC to better understand its strengths and limitations and foster carers’ experiences of the process of change. The present study represents an important step towards addressing a serious gap in the capacity of the NHS and social care services to meet the needs of looked-after children, in a context in which comparatively few research trials of therapeutic interventions have been undertaken.

Overview of study aims and design

In this study, we aimed to conduct a series of studies that represent key preparatory steps necessary to pave the way for a full-scale randomised trial of the VIPP-FC for children in foster care, who are at risk of attachment difficulties. This study comprised the following:

-

Modifying the existing VIPP-FC clinical manual to be suitable for the UK foster care context and to meet the requirements of children with attachment difficulties commonly presenting among children in foster care, such as those under the rubric of the RAD label.

-

Testing the acceptability of the intervention from the point of view of practitioners and foster carers, and working with local authorities, foster carers, parents and young people to establish the optimal systems, procedures and ethics considerations required to identify and support children with attachment difficulties in UK foster care populations.

-

Investigating the feasibility of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the modified intervention.

The study was divided into three phases. Phase 1 involved the refinement of the VIPP-FC manual through iterative consultation with an expert advisory group (including the developers, expert clinicians and foster carers), leading to the production of an initial, revised treatment manual. Phase 2a involved the initial testing of the treatment (no random allocation) with a small series of children with RAD-type difficulties and their foster carers, the results of which informed a further revision of the VIPP-FC clinical manual; in parallel with this, phase 2b involved a scoping study of the organisational, ethics and practical landscape within which a trial of VIPP-FC for foster children would need to operate. Phases 1 and 2 informed the final research protocol for the feasibility trial conducted in phase 3. Phase 3 involved recruiting a new group of children in foster care and undertaking a pilot RCT of VIPP-FC (with random allocation). This last phase also included a series of qualitative interviews with the recipients of the VIPP-FC to illuminate feasibility and acceptability questions.

As a treatment development and feasibility study, we adopted a mixed-methods approach, in which quantitative and qualitative data were collected sequentially and integrated at the analysis stage to obtain a better understanding of the treatment development process; the organisational and professional context that will constrain the operation of a future trial; and carers’, practitioners’ and care managers’ experiences and views of the programme, as well as evaluating the feasibility of a randomised trial using a small-scale pilot. In doing so, we adopted a pragmatic implementation-focused approach to establishing the initial feasibility of evaluating a complex intervention such as this, in line with the approach advocated in the Medical Research Council’s guidance. 29

The clinical intervention and the assessment framework were grounded in attachment theory and methods, which conceive of attachment as a critical biobehavioural process that develops in the context of routine caregiving interactions, serving to support children’s needs for comfort when they are anxious or feel vulnerable. 21 In addition to providing a rich and evidence-based account of the environmental mechanisms that shape the development of attachment (mechanisms which are the targets of attachment-focused interventions), attachment research provides a well-developed set of systematic and rigorously evaluated tools for measuring attachment at different ages. In the current study, we used gold-standard instruments for evaluating attachment difficulties [the Disturbances of Attachment Interview (DAI) and the Strange Situation Procedure] to show that their use is feasible in a clinical trial in this context, which will ensure confidence in the findings of any future full-scale trial.

Data management

The data in all phases of this study were collected and processed in accordance with the Data Protection Act (1998)30 and the General Data Protection Regulation (2018). 31 Management of the data was overseen by the chief investigator with support from the Trial Co-ordinating Team. Study data were collected by an experienced research assistant who had been trained to work with high-risk populations, with support from one or two other research assistants. Regular supervision by the chief investigator, Trial Co-ordinating Team and research assistants ensured the reliability of data collection. When necessary, the research assistants were fully trained and certified in administering all research measures. For data that required coding using standardised measures, we employed trained reliable coders, ensuring sufficient inter-rater reliability among coders. Although a number of NHS trusts and higher education institutions were involved in this study, all data were collected, collated and stored at University College London (UCL).

All data collected containing non-identifiable information were entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA), a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases. 32,33 A master log of participants who were randomised was kept in the trial master file, detailing names and randomisation codes. Paper forms were kept in a locked filing cabinet, and electronic files were kept in an encrypted hard drive and on the UCL Data Safe Haven platform. Screening data and consent forms signed online were completed in REDCap within the UCL Data Safe Haven, as they contained identifiable information. Video- and audio-recordings were stored in the UCL Data Safe Haven or Citrix (Citrix Systems, Inc., Fort Lauderdale, FL, and Santa Clara, CA, USA), two secure and accredited technical solutions for storing, handling and analysing identifiable data.

Study management

Structured oversight of the project was undertaken by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Both had an independent chairperson and the recommended proportion of independent members (subject experts and a public member), and were convened in accordance with guidelines for the NIHR HTA programme. The TSC and DMEC met regularly to guide the conduct of the study and agreed the details of project set-up, initiation and changes to the design and supervision of the study.

Ethics amendments and protocol modifications

During the study, we submitted three substantial amendments and five non-substantial amendments. See Appendix 1 for an outline of the reasons for the amendments.

The protocol went through six versions. The key changes introduced in the earlier stages of the study were (1) a mechanism to facilitate access to participants (to avoid the team being dependent on the return of paper questionnares to contact foster carers) by adding the possibility of social workers obtaining verbal consent from foster carers for their contact details to be passed on to the research team, and (2) allowing the possibility for the RCT to begin before the case series ended to avoid delaying the start of the RCT owing to difficulties in recruiting to the case series. After the RCT began, the key changes to the protocol were as follows: (1) adding online screening to aid recruitment; (2) the introduction of a reward for participants returning screening questionnaires (either on paper or online) to aid recruitment; (3) a change in target population – opening up the eligibility criteria to allow children who did not meet the criteria for RAD as defined by the DSM-5; this was a solution agreed with the TSC to allow thorough testing of the intervention; (4) allowing practitioners other than Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) professionals to deliver the intervention to increase clinical capacity; (5) the addition of new sites; and (6) an extension of study dates. See Appendix 1 for an outline and dates of approval of these changes.

Patient and public involvement

Involvement of foster and kinship carers was integral to this study: in its preparation, in the refinement of methods and procedures throughout, and in the dissemination of the findings and discussions regarding a future trial.

The research team included an experienced foster carer who was closely involved, particularly in the early stages of the study, in setting up and refining the procedures. For example, this foster carer team member recommended that carers be offered the possibility of completing screening online and that a contact sheet should be the first step in the online screening to allow us to contact foster carers even if they did not complete all of the steps of the online screening. They also supported the introduction of a voucher to encourage and thank participants for completing the screening questionnaires (until this point, participants were rewarded after baseline and follow-up assessments only). This foster carer team member was also involved in the development of the modified treatment manual. In addition, we recruited one foster carer to sit on the DMEC and another to sit on the TSC.

We established a foster carers advisory group composed of three members, which contributed to several aspects of study design, implementation and dissemination. The foster carers advisory group members were appropriately supported by the study team and remunerated for their time in accordance with INVOLVE guidelines. 34 Owing to ongoing difficulties in scheduling face-to-face meetings at times that worked for all three members, this group provided their input remotely. One of the key aspects of the study about which we consulted this group was the screening packs; specifically, in the face of the low return rate in the case series (see Chapter 3), we intended to rethink the packs, fine-tune their contents and make them more attractive. Carer feedback was incorporated into the substantial amendment, such as the introduction of a colourful front sheet with a summary of what is required and rewording the participant information sheet to make it clearer that we were interested in hearing from everyone, even if they thought that the social and emotional problems described did not apply to the child in their care. They were also consulted for their opinions on the usefulness of adding the online screening and to get their feedback on the qualitative interview schedules.

We also consulted the Parent and Young People Panel from the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families about the screening packs and its feedback was incorporated in the packs, specifically, changing the order of the questionnaires in the pack to have the ‘friendlier’ one first and rewording instructions to avoid missing data, which initially occurred with one of the questionnaires (on which it was not clear that a respondent was required to answer all questions).

It is also important to note that, in the context of the feasibility nature of the case series and pilot RCT, we continuously asked participating foster carers for their views regarding the study procedures and measures. For example, as a result of this feedback, we offered participants the possibility of completing the screening questionnaires during a home visit; we kept the out-of-home research visits short and in locations that were easy for participants to get to; we provided extra instructions and support to complete the outcome measure that carers had more difficulty with (the computer-based questionnaire); and we introduced communications by text message, as this was a preferred method for many foster carers. It was clear that most foster carers had a preference for face-to-face contact with the research team and that they often experienced what one of them called ‘questionnaire fatigue’. This is an obstacle for a recruitment system that relies on questionnaire return, as the questionnaires often get ‘thrown onto the pile’ without being given appropriate consideration. We introduced several changes (the key changes are outlined in Ethics amendments and protocol modifications) to deal with this frequently reported obstacle.

A crucial patient and public involvement part of this study was the running of two conferences/seminars for all stakeholders: one mid-study, in September 2018, and another near the end of the study, in December 2019. Both were half-day, free events, during which we presented the project and preliminary findings and heard from world-renowned guest speakers, who were all experts in attachment and development of looked-after children. The events were very well received, with an audience that included foster carers, social workers, service managers and VIPP-SD/VIPP-FC interveners. The second event included a foster carers’ forum, where carers who had participated in the study discussed their experiences and insights and offered feedback to the study team. A key learning point from these events was that foster carers enjoyed contributing to the research, both those who received the intervention and those who did not, once they were ‘in’. This reinforces our conclusion from the conversion numbers in earlier stages versus later stages of the study (discussed in more detail in Chapter 5) that, once in direct contact with the team, foster carers tended to find the study very acceptable. Foster carers who could not attend the events were very pleased to receive the final study newsletter with a summary of the findings.

Feedback from the foster carers at all stages of the study was invaluable. In future studies involving this population, foster carer involvement should be sought at all stages of the project, bearing in mind that flexibility is needed to accommodate their busy schedules and child-care commitments.

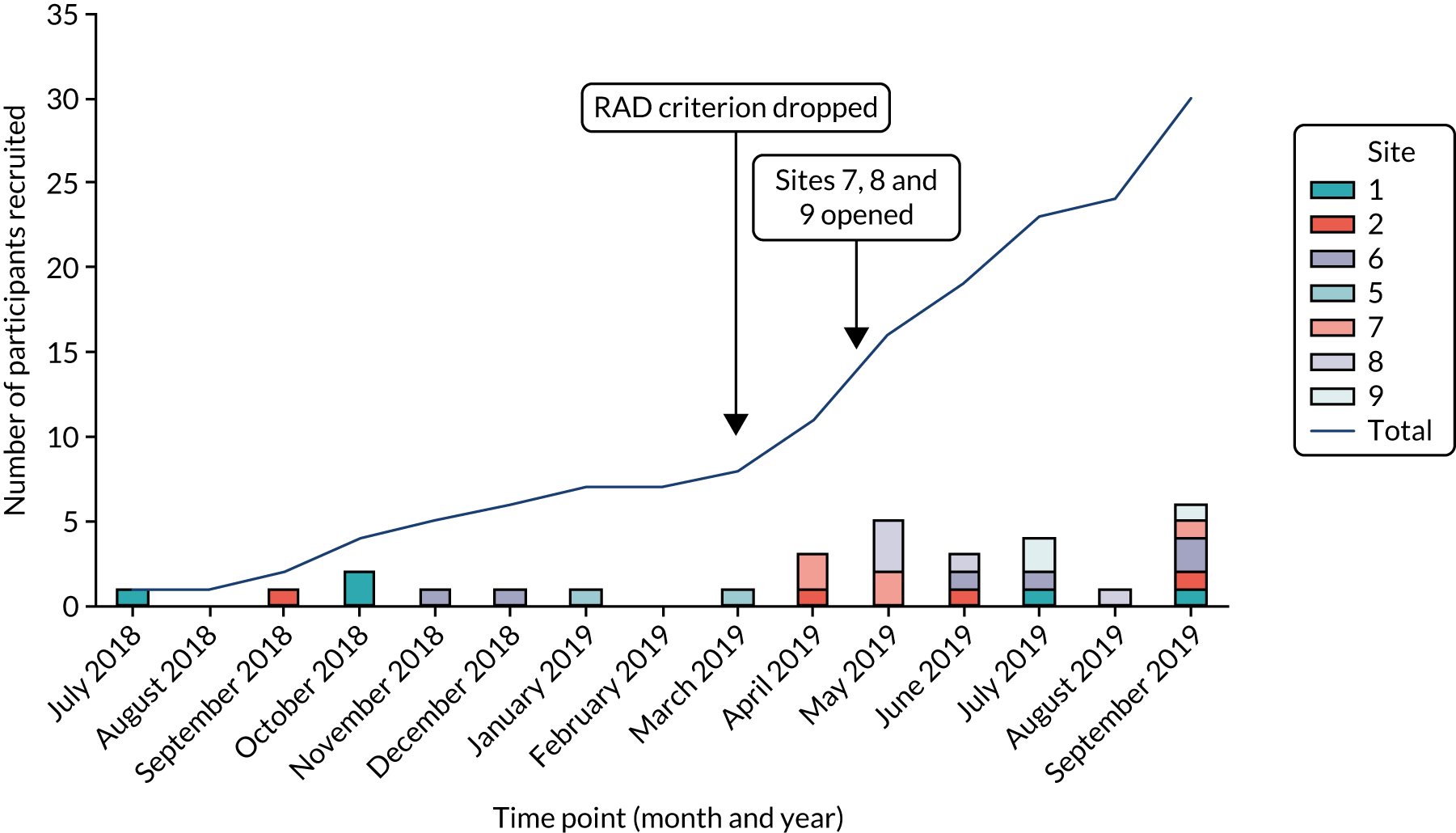

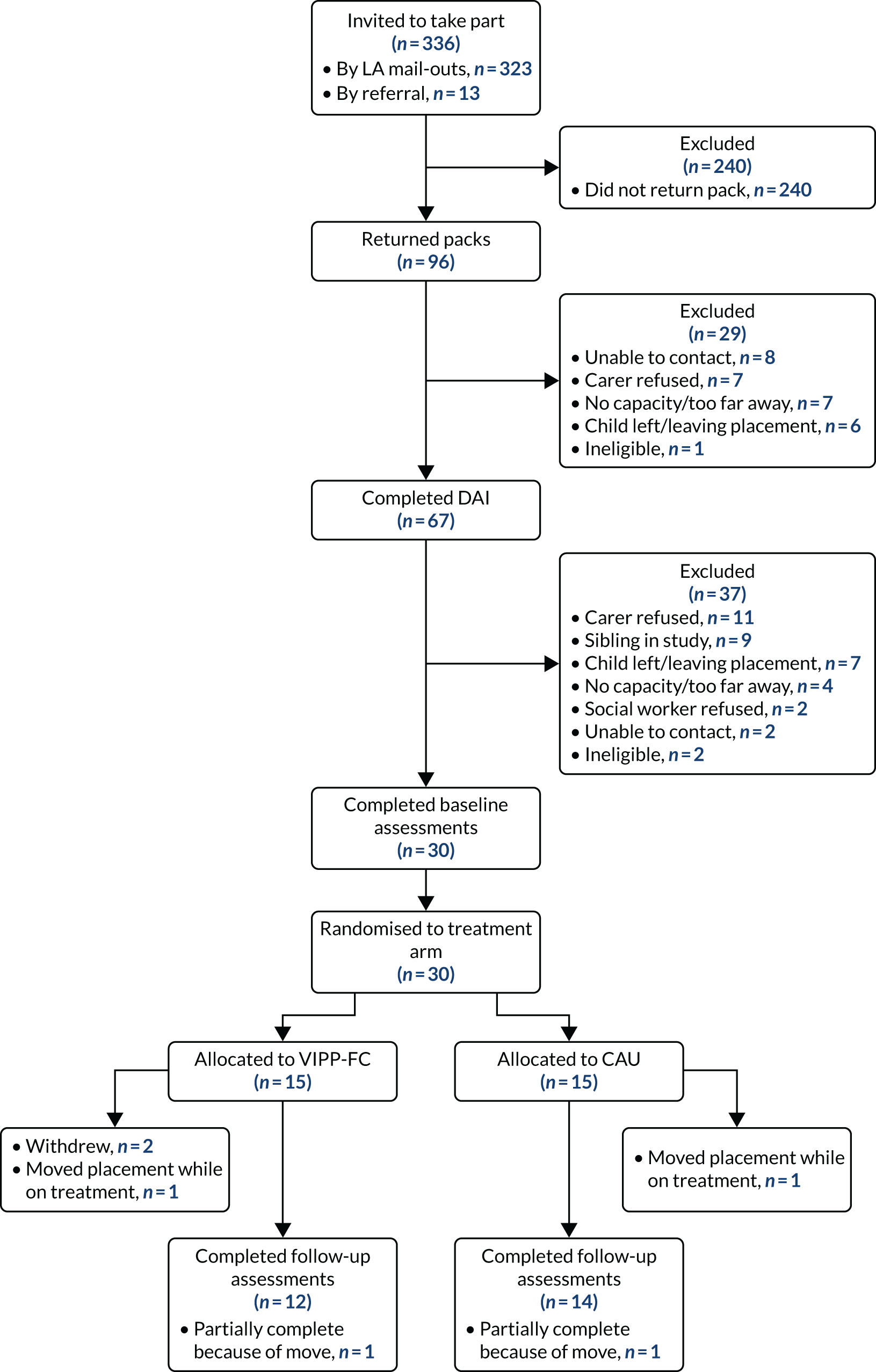

Timeline

The study began in May 2017 and the final outcome assessments from the feasibility RCT were completed in January 2020. As outlined in Chapter 5, Results and Discussion there were numerous challenges in identifying and recruiting foster carers to the trial, which meant that, among other significant adjustments to the initial design, the timeline for recruitment was extended considerably: originally planned to cover March 2018–March 2019, recruitment to the feasibility and pilot trial began in May 2018 and ended in September 2019.

The methods, the results and an interim discussion for each study phase are presented separately in the following chapters, followed by a general discussion and conclusions.

Chapter 2 Manual development and programme modification

Phase 1 of the study aimed to refine the Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD) programme (which has previously been adapted for foster care in the Netherlands) for the context of children in foster care in the UK. This intervention is named the Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline, Foster Care [VIPP-FC (UK)]. In this chapter, we provide a succinct description of VIPP-SD and summarise the adaption process.

The VIPP-SD is a brief home-based attachment and parenting intervention. It is highly acceptable to families, has a clear and empirically supported model of change and has good evidence of efficacy with families of young children in many settings. 21 Practitioners who are trained and accredited to deliver the intervention visit families at home for six 90-minute sessions. Sessions 1–5 take place biweekly and focus on improving the carer’s sensitivity to the child. Session 6 is a booster session; it can take place approximately 1 month after session 5 and focuses on consolidating the information provided in sessions 1–5 and teaching carers sensitive discipline skills. In the original intervention programme, there is usually an additional booster session.

Sessions involve both the carer and the child, and start by video-recording carer–child interactions, following specific intructions that are given to the parent/carer (e.g. to play with a certain toy, to read a book together, to share a meal). The intervener films clips that provide the basis for themed discussions in the next session, when the intervener plays the clips back to the carer and discusses what they are observing. Themes include recognising the child’s attachment signals and expressions, providing prompt and adequate responses to them, promoting empathy for the child, praising positive behaviour and appropriate ignoring of negative behaviour. Carers are also given exercises and tips. Session content is consistent across families, although its presentation and the video feedback are tailored to the specific needs of each family. This description of the VIPP-SD also applies to the modified VIPP-FC. A summary of the VIPP-FC adaptation process follows.

Methods

Prior to this study, the intervention manual for the VIPP-SD had been modified for a foster care population, resulting from pilot clinical work conducted in the Netherlands. 28 We proposed to further modify this revised intervention (VIPP-FC) to specifically account for the clinical features of RAD, as well as to incorporate local (UK) health and social care policies and practices. In addition, given the differences between foster care in the Netherlands and foster care in the UK, other potential differences between the two groups of children and carers had to be considered.

An expert advisory group of the programme developers, UK clinicians (including colleagues in CAMHS, social care and the third sector) and foster carers was set up to review the existing VIPP-FC manual and advise the Manual Development Working Group (composed of members of the study team), which implemented the recommended changes. The consultation and revision processes were iterative, consisting of three advisory meetings and three rounds of manual revision. The Manual Development Working Group made an initial adaptation of the existing VIPP-FC manual for the context of children in foster and kinship care in the UK; this draft version of the manual was used in a small case series (phase 2a). After the completion of the intervention programme with participants in the case series, the Manual Development Working Group met again and further modified the manual. This modified manual was then used in the feasibility RCT (phase 3) of the research project and was reviewed once the RCT was completed.

Results

Although the adaptation process was planned to primarily focus on adapting the VIPP-SD/Dutch VIPP-FC for use in a population of children with high levels of difficulty in the domain of RAD symptoms, the Manual Development Working Group decided early on that the existing (Dutch) VIPP-FC manual was already constructed to handle clinical issues linked to RAD presentations. Therefore, the modifications that resulted from the work of the Manual Development Working Group dealt primarily with either contextual characteristics of the UK foster care population or more general needs that many children in this setting may present with, rather than RAD symptoms per se. These are described in more detail in the next two sections.

Initial adaptation of the VIPP-SD programme for the foster care population

Although the Leiden group’s original version of VIPP-SD for foster care was tailored to be appropriate for children in foster care,28 the adaptation undertaken in the Dutch context did not reflect the UK setting; as previously noted, the majority of changes recommended by the Manual Development Working Group reflect these differences in context and practice between the UK and the Netherlands. Before outlining the second phase of adaptation for the UK context, we summarise the main differences between the original VIPP-SD manual and the adapted VIPP-FC manual, as adapted by the Leiden group for the Dutch foster care context.

On the whole, the original VIPP-SD manual and the VIPP-FC manual were very similar, with similar tasks, visits and messages. However, the VIPP-FC manual included some extra key themes introduced in the manual specifically for foster children:

-

Additional content highlighting that foster children do not always show what they are feeling, as they may not be used to having their needs met, hence the need to address the more subtle signals of the child.

-

Additional content about not asking for help – children in foster care do not always behave in the ways that carers would expect them to, hence the need to react to the absence of attachment behaviour as well (e.g. if they do not cry when they hurt themselves, the carer should show them attention anyway to demonstrate that they can be trusted when something is wrong). These were added by the Leiden developers to encourage children to learn that they can rely on their carers. These modifications, in particular, relate to difficulties in the domain of RAD symptoms.

-

Additional content regarding the importance of physical contact – how it can cause anxiety for children who have experienced maltreatment and how gently encouraging it can help them overcome these anxieties, particularly if it is done in a structured and sensitive way (such as a song involving touch).

-

Additional content encouraging carers to compliment/praise small steps in the right direction – this is even more important for allowing foster children to know that they are doing something right.

-

Additional content about strategies to manage indiscriminate friendliness.

-

Alternative tasks to those in the original manual; for example, some short extra tasks were added that involve physical touch in a game/song to introduce physical touch in a safe way for the child.

-

‘Don’t touch’ task puts more emphasis on maintaining eye contact with the child than in the original VIPP-SD version, and also a suggestion of naming a book or toy to play with after they have calmed down so that they can more easily imagine the reward they will receive if they are able to wait.

Revisions to the VIPP-FC manual: the work of the manual development group

The modifications made to the VIPP-FC manual for this study were based on discussions within and feedback from the Manual Development Working Group, as well as on learning acquired during the case series, feedback from which was also reviewed by the Manual Development Working Group (see Chapter 3). Some modifications reflect changes to the manual itself, such as the wording of certain messages or tasks, whereas others have to do with the broader context for delivery of the intervention, such as introduction of forms and letters to aid in the delivery of the VIPP-FC in UK mental health services. There follows a summary of all of these modifications:

-

An additional guidance document was written to be used alongside the manual for interveners working with specific types of carers/children. This document aimed to guide interveners on where they should adapt their wording to ensure that the language they use is sensitive and tailored to the circumstances of a child and their foster carer; for example, the VIPP-FC manual regularly asks the intervener to refer to the child having had ‘previous adverse experiences’, but this was considered not always appropriate for some carers, such as when the carer is a relative of the birth parent or when the carer has had the child since birth. The four main groups that required the modified wording were (1) a child in a SGO, (2) a child in kinship care, (3) a child who has been with the family since birth and (4) a child who is likely to stay with the family on a long-term basis. As an example, for the fourth group of children, we removed a paragraph that referred to the importance of the carer’s relationship with the child even if they were not going to remain with them long term.

-

Following feedback from the Manual Development Working Group, we changed the word ‘obey’ to ‘do what you ask them to do’ throughout the manual as it was felt to be a little outdated and because it has negative connotations that contrast with the sensitive parenting that the VIPP-SD is trying to encourage.

-

We shortened the manual to from seven to six visits as it was deemed more suitable for the sometimes short-term nature of placements within the population of foster children and to minimise the chances that the intervention work would be disrupted by a change in placement. The timing of the last two visits was also changed so that there was only a 2-week gap instead of a gap of 3 or 4 weeks, again to ensure that the programme could be finished relatively swiftly.

-

A games booklet was introduced to the manual (adapted from a version created by the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust for use with adopted families) to give to the carer in visit 4, which includes numerous songs involving actions and touch for the carer to use as a resource with the child (and with other children they may care for currently or in the future).

-

The Goal-Based Outcome form was incorporated into the manual. This change reflects a standard requirement in CAMHS in the UK, where this form is used as a routine outcome measure and has also been incorporated more generally into clinical practice. The Goal-Based Outcome form is completed during a discussion with the carer in visit 1, to gauge and manage their expectations and goals for the programme, and to reframe or find common ground from which to work if their aims are out of the scope of the programme. The intervener also completes a final Goal-Based Outcome form with the carer at the end of the programme in visit 6 to assess if and how the goals were met, and if not, why not.

-

Some extra guidance was added for the intervener supporting them in explaining or framing the importance of the work, even if the placement is expected to be short. The guidance helps the practitioner to explain that research supports the view that responsive and sensitive care is important for children even when relationships do not last, and that the relationship they build with them in this early stage of life can act as a foundation for the child’s future relationships and well-being. This was to counter beliefs that foster carers might have that it is best not to ‘bond’ with the child if they are not likely to be with them long term, and to help them understand how important it is for the child to experience warm and supportive care, regardless of the length of the placement.

-

In keeping with the need for close communication between members of a child’s professional team, a closing letter was introduced in which interveners are instructed to write a letter about how the programme went, what improved and what issues may still require support at the end of the programme, which is sent to the social worker, copying in the foster/kinship carer.

-

All names of Dutch games/songs were changed to English ones and additional instructions were added to explain how they worked, in case carers were not familiar with them.

-

Photograph booklets were provided for the carer and child at the end of the programme with stills from their VIPP-FC/research videos depicting memorable moments of shared sensitive interaction. It was decided that this booklet with stills was a more acceptable option than providing the video clips themselves, owing to the complexities of consent and data protection of video material in this population.

As previously mentioned, the majority of these modifications were introduced during the initial phase of the work of the Manual Development Working Group, and some were added after the Manual Development Working Group considered feedback from practitioners and supervisors after the case series cases were completed. Although the manual was open to further modifications on review of the RCT cases, no additional changes were deemed necessary to the manual and programme themselves. Nevertheless, challenges with interveners’ capacity and availability, as well as interveners having dual roles in some cases (e.g. interveners who also worked in other roles in the local authority or mental health service provider), throughout the RCT led to discussion of the best model for the delivery of the VIPP-FC, which we return to in Chapter 8.

Discussion

The VIPP-SD is a well-evidenced parenting intervention informed by both attachment and social learning models. It uses video feedback as the primary means of introducing change by focusing the caregiver’s attention on moments of connection and examples of sensitive care highlighted by a trained intervener, who uses their knowledge and skills to frame their feedback into a coherent, attachment-informed message, drawing attention to the child’s cues and communications, the carer’s sensitive response and the positive effect that this has on the child. Despite its extensive track record for promoting sensitivity in parenting in a range of populations, VIPP-SD has not been used before in the context of UK foster care and has only recently been adapted for the foster care context in its country of origin, the Netherlands. Transporting the VIPP-FC to the context of UK foster care requires careful attention to the particular needs and ways of communicating and interacting that children in foster care may present with, as well as the professional context and systems around the child, so that it can be used efficiently by practitioners in CAMHS and other related sectors. Our initial appraisal and adaptation of the VIPP-FC treatment manual suggests that it is well suited to the needs of children in foster care and the Manual Development Working Group’s suggested modifications should make it suitable and appropriate for the UK CAMHS context. The acceptability of the intervention from the point of view of foster carers is considered in greater depth in Chapter 7.

Chapter 3 Case series

Overview

Phase 2a of the study consisted of a small case series. Using a preliminary version of the treatment manual, resulting from the work of the Manual Development Working Group, we trained a group of practitioners in the modified Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline, Foster Care (VIPP-FC) to work with a target of six children in foster care and their carers. We proposed to purposively recruit a sample reflecting variations in age and presentation of RAD symptoms, to road-test the modified VIPP-FC treatment manual and examine its clinical suitability for these children in real-world clinical practice. During this phase of the study, we recruited from a single local authority and identified a small number of cases using screening measures of RAD with the help of the children’s services. The case series also allowed us to undertake preliminary tests of the feasibility and acceptability of the screening process and the proposed research assessments. The case series was originally planned to run in two local authorities. However, shortly before we were due to begin work, the partner trust in one site lost their contract to deliver CAMHS locally, which meant that we were unable to proceed with that site for the case series.

Methods

Ethics considerations

Two key ethics issues required careful consideration in this study: consent and the RAD label/diagnosis. The determination of who must provide consent for a child in foster care to take part in a research study and how this should be done is recognised in the literature as a complex problem. 35 An important aim of the current study was to investigate the range of views on how this should be achieved, from local authorities in different regions and from parents and carers. However, the starting point for the purposes of this study was to follow a procedure used in another NIHR pilot trial being conducted by our group for older children in foster care [aged 6–16 years; NHS Research Ethics Committee reference number 15/EE/0032; award ID: PB-PG-0614-34079 (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/PB-PG-0614-34079)]. The consent protocol for that study was developed from a review of the literature and consultation with a local authority director of social care and their legal department. The general principle informing the protocol was that written, informed consent to take part in the study must be received from all parents and from the local authority when holding parental responsibility, and that every effort should be made to secure the consent of parents when they do not have sole legal parental responsibility.

On the basis of these considerations, to take part in the intervention phase of the study (i.e. after initial screening), parents of children on full care orders were sent information sheets and an opt-out letter (with a 14-day period for opting out) in all but exceptional circumstances. Specifically, children on a full care order could enter the study without parental consent if the local authority [which shares parental responsibility with the birth parent(s)] deemed it not in the child’s best interests to seek it, or when every attempt had been made to inform parents of the study and to secure consent, but this had failed. For all other children, full written consent was obtained from the child’s parent(s). The child’s social worker initially made contact with the parent(s) and provided parents with the information sheets. It was at the discretion of the social worker whether to seek verbal consent for parents’ contact details to be passed on to the research team so that a meeting could be arranged to sign the full written consent or to seek the full signed consent from the parents themselves. In either case, the research team’s contact details were always provided to parents in case they wished to ask more in-depth questions. Active refusal of consent by a parent was always respected, regardless of the care order. Furthermore, a parent’s decision to withdraw their child once the child had started in the study was always respected, regardless of the care order.

Full informed consent was obtained from all participating foster carers and from the local authority. As the children were all aged ≤ 6 years, they did not provide written consent, but the researchers were trained to obtain verbal assent in an age-appropriate fashion for children old enough to do so (age ≥ 4 years).

Throughout our discussions with colleagues in the local authorities, a recurrent theme was professionals’ concerns regarding the diagnostic term ‘RAD’. In particular, professionals expressed conerns that if this diagnosis became a part of a child’s social work record, this may have direct implications for the child’s subsequent care, including their likelihood of being adopted. For a more in-depth discussion of this issue, see Chapter 4: stakeholder interviews drew attention to the potential difficulties associated with using diagnostic terms and a diagnostic criterion as part of the eligibility criteria for entry to the study, as well as the complications associated with information-sharing regarding diagnoses.

Because we included children presenting with varying degrees of RAD-type behaviour and as our assessments were based on research instruments rather than full clinical assessments, we did not use the term ‘RAD’ in our communications with participating families (e.g. in participant information sheets or verbally) to refer to the set of behaviours the study was focused on. Instead, we described the specific behaviours that are considered under the rubric of RAD, which tend to carry fewer unhelpful connotations (e.g. difficulties in seeking comfort from available caregivers). The same avoidance of diagnoses applied to written correspondence with foster carers and social workers about each child.

Target population

The target population was children in foster care aged between 11 months and 6 years, and their foster or kinship carer(s).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Families recruited to the study were eligible if the following criteria were met:

-

parental figure –

-

foster carer(s) who is (are) primary carer(s) for the child

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

proficient in English

-

-

child –

-

living with foster carer(s) in a placement planned to last at least 4 months

-

has lived with foster carer for at least 4 weeks

-

presence of RAD symptom(s) as defined by the DSM-5

-

aged between 11 months and 6 years.

-

Exclusion criteria

-

Parental figure: already engaged in a similar parenting intervention.

-

Child: severe developmental disability.

As a pragmatic study, we deliberately minimised exclusion criteria; this was to enable the later feasibility trial to reach a participant population that is broad and reasonably representative so that we could address the clinical suitability of VIPP-FC for a wide range of children in foster care. We did, however, collect detailed information about factors that might be relevant to the suitability of the VIPP-FC intervention for children with RAD, such as co-occurring conditions, placement variables and care order.

It is a pragmatic requirement of this form of intervention that the foster carer has some proficiency in English language because of the reliance of this programme on dialogue between the carer and practitioner as part of the video-feedback procedure. Thus far, the Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD) has not been tested using interpreters, and we considered that this project was not the appropriate context in which to do such testing. Furthermore, on the basis of consultation with colleagues in the local authorities, we determined that comparatively few foster carers would not have adequate command of English language to participate in the programme. The research assistant in contact with the foster carer made a judgement regarding the suitability of their English-language proficiency, making sure that they met the minimal requirements necessary to take part in the study.

Although the programme is suitable for children with a range of levels of cognitive ability, and would be appropriate for children with physical and mild to moderate disabilities, it has not been used before among children with very severe global delay; such global delay would also substantially complicate, if not preclude, a reliable RAD assessment. Therefore, children with global developmental delay would need to be excluded from the study. This exclusion criterion was assessed by asking carers if the child had any medical diagnoses relating to severe developmental delays.

Owing to the risk of participant overburden and the contamination/confounding of treatment effects, it would be problematic for families to be engaged in similar parenting interventions simultaneously; hence, this was also an exclusion criterion. We did not consider it to be problematic that families were involved in other forms of social, psychological or medical treatment; therefore, no such exclusion criteria were applied. Furthermore, we explicitly assessed the presence or absence of comorbid psychiatric conditions in the child because these may be important factors influencing both clinical management and outcome, and are also likely to be quite prevalent. Exclusion on that basis would therefore be inappropriate. However, when other diagnoses were identified that warranted intervention (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), we notified the child’s social worker and foster carer and recommended a referral.

Extensive consideration was given to the range of care arrangements that should be eligible for this pilot project. Children in foster care can be subject to a range of different care orders and placement arrangements (e.g. interim care order, full care order, section 20 voluntary placement36). Children placed in family and friends care may be placed under a SGO, a residence order or a care order and, rarely, as an informal placement. These issues are primarily relevant to the feasibility of intervention delivery, rather than child mental health need (as children in all of these circumstances are likely to present with raised rates of attachment problems and RAD). In consultation with colleagues in the local authorities, we decided that this is an important feasibility question and exclusion on the basis of placement setting or type of order would unhelpfully limit the learning that the feasibility study could produce. Regarding family and friends care in particular, there was a clear view from our consultation, which was highly consistent with recommendations made by NICE, that family and friends care, which is increasingly common, should be within the scope of this study. 13 Children placed under a section 2036 (a voluntary placement, whereby the parents retain full parental responsibility) or on an interim care order may present the most difficulties from a practical point of view because the duration of the placement will be uncertain. Nevertheless, it is not uncommon for such placements to last at least 6 months (i.e. long enough for an intervention to be put in place) and duration cannot be predicted in advance. Therefore, our view, which was supported by our discussions with local authorities, was that an inclusive strategy should be taken.

One critical point to emerge from these discussions was that there may be great value in considering adaptations to the intervention that allow for the programme to ‘follow the child’ when there is a transition in the placement arrangements (e.g. to adoption, to a more permanent foster care placement or back to the child’s parents). A lack of continuity in care is a problem highlighted by many in the field and by children in care themselves. 13,27 We planned to discuss this process carefully with the study advisory groups and we proposed to test, in a small number of cases as they arose, the workability of the plan they recommended. In such cases, we anticipated that the work would not begin again, but would focus on transferring what had been learnt during treatment to the subsequent placement and supporting a smooth transition.

Recruitment

Screening and identification stage

The screening process involved close collaboration with the partner local authority, which sent out information sheets, initial consent forms and screening measures to the foster carers in the study locality. In addition, as noted previously, the local authority sent out a letter to all parents explaining the study and the opting-out process, including the contact details of the research team. They communicated to their staff members within the children’s social care team to raise awareness of the study and draw attention to the support required from children’s social workers. We originally planned to invite all foster carers or special guardians registered with the local authority caring for children aged ≤ 6 years. In practice, the local authority applied its own exclusion criteria at this point (e.g. excluding highly complex cases undergoing assessments for court or cases with restricted files), as we note in Results and Conclusion.

We also contacted and sent leaflets to several foster care agencies inviting them to take part in the study. When direct self-referrals or clinician referrals were received by the research team, foster carers/clinicians were asked for the child’s social worker’s contact details in order for the local authority to initiate the screening process, including contacting the birth parents. Regardless of the route of recruitment to screening, a minimum 2-week period was given between sending out the letter to parents and initiating the child’s participation in the study.

Once initial consent forms and screening measures had been received by the research team, research assistants contacted participants, thanking them for their response and reiterating the research process. Invitations and follow-up telephone calls were made to all foster carers to take part in a face-to-face interview assessment to confirm eligibility, unless it was clear from the information provided at that point that they would not be eligible (e.g. the child had already left placement or the placement was very far from the borough). Owing to the comparatively small number of carers who could be invited to take part, we opted to invite all foster carers who returned the questionnaires to take part in the DAI so that we gained experience of the acceptability of the interview and a reasonable level of initial data on the performance of the screening questionnaires. As the screening/identification stage involved no direct contact with the child and involved minimal burden or risk, we obtained active consent from the foster carer only. However, a letter was sent to all birth parents with an explanation of the study and the process of opting out (except in circumstances in which the local authority deemed it inappropriate to inform the parents). If, after the 2-week period for opting out, the local authority or the research team had not been contacted by the parent to opt out, the screening process was initiated. Foster carers received an information sheet explaining the study fully and a contact telephone number of a member of the research team in case they had any questions. The information sheet explained that completing the screening measures did not entail any obligation to participate in the subsequent stages of the study (i.e. the baseline research assessments, treatment and follow-up assessments).

Post-screening stage

If eligibility was confirmed, foster carers were invited to the next stage of the study, involving baseline assessments, receiving the VIPP-FC and completing follow-up (i.e. post-treatment) assessments. The baseline assessment took place as soon as possible after all consents had been obtained (the target was within 4 weeks). At this point, we initiated the more comprehensive consent process (i.e. consent to baseline/follow-up assessments and treatment). Consent from birth parents (if applicable) and consent from the social worker or team manager were obtained before the baseline study visit. At the baseline study visit, we obtained the foster/kinship carer’s consent, as well as the child’s assent, if they were aged > 4 years.

The baseline assessment took place in our partner CAMHS, in the local authorities’ premises, or at UCL, depending on the preference of the foster carer. Carers were paid £30 at both the baseline and follow-up (i.e. post-treatment) outcome assessments to thank them for their time, and were reimbursed any travel expenses. Children were given a sticker after each visit.

Sample

For this (non-randomised) case series, we aimed to recruit six cases for piloting the clinical intervention, and testing screening and assessment procedures. As noted previously, we proposed to include a mixture of cases obtaining high RAD scores on the screening measures and cases falling below this threshold to explore whether or not the intervention required adjustment for these groups of children, and to maintain the pace of manual development in the event that prevalence was lower than expected.

Screening measures

There is no pre-existing established tool to screen for RAD. This is a significant gap in health technology in this field, as early detection may be critical for improving outcomes for children in care. In this study, we used two different instruments that each have their individual limitations, but may be useful in combination for screening for symptoms of RAD. The Attachment Screening Assessment (ASA) (Danya Glaser, Saul Hillman, Yael Shmueli-Goetz and Vivian Prior, the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families and UCL, 2013, personal communication) is a new instrument designed specifically to capture behaviours reflective of the DSM-5 symptoms of RAD and DSED, as well as standard Ainsworth-type attachment classifications. 37 In pilot work (Ching Yiu Ng and Saul Hillman, the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families and UCL, 2015, personal communication), the RAD items in particular have been found to discriminate well between children in care and those from the community, as well as children with greater overall psychopathology on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). However, the ASA has thus far not been validated against formal diagnostic assessments, which limits the extent to which it can be used alone as a screening measure. The Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) includes a recently revised set of items for DSM-5 RAD. 38 We proposed to use these two instruments so that we could test the optimal configuration of measures for case identification.

Primary outcome: attachment measure

The DAI is a semistructured interview to evaluate the presence of signs of disordered attachment. 39 For each of 12 sections, the interviewer asks multiple questions and follows up with probes sufficient to yield a rating reflecting the degree of evidence of disturbed or disordered attachment: 0 = none/never, 1 = somewhat/sometimes and 2 = considerable/frequently. The first five sections of the interview address signs of emotionally withdrawn/inhibited attachment disturbance (i.e. RAD), yielding total scores ranging from 0 to 10 points. The inhibited attachment disturbance items are 1 – does not differentiate among adults, 2 – does not actively seek comfort when hurt/upset or does not seek comfort preferentially, 3 – does not respond to comfort when hurt/frightened, 4 – does not respond reciprocally with familiar caregivers and 5 – does not regulate emotions well. The next three sections address signs of indiscriminate behaviour and the last four sections address other signs of disturbances in attachment behaviour (known as ‘secure base distortions’). There is sound evidence for the validity of this measurement system. First, it distinguishes between institutionalised and non-institutionalised children, reliably identifies signs of attachment disturbance in maltreated children and validly distinguishes RAD from DSED. 5,39–41 Second, it has shown very good inter-rater reliability and high levels of internal consistency. 39,40,42 Third, criterion validity has been demonstrated through the convergence of attachment disorder diagnosis by different measurements. Construct validity has also been demonstrated by the association of DAI ratings with quality of care. 43

Secondary outcome measures

Attachment insecurity and disorganisation

Strange Situation Procedure

Participants were observed with their foster carer while in an unfamiliar room for the Strange Situation Procedure. The Strange Situation is a standardised procedure lasting a maximum of 21 minutes. It is divided into a series of episodes involving brief separations and reunions with the parent/caregiver; exposure to an unfamiliar, but friendly, female adult; and a period of time alone. These episodes are video-recorded for subsequent rating by trained coders, resulting in a classification of the infant–caregiver dyad into one of the four attachment categories: secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant or disorganised. For children aged > 24 months, an adaptation of the administration of the Strange Situation (mainly concerning the timing of each episode) and the respective coding system for the pre-school years was implemented (Jude Cassidy, Pennsylvania State University, 1992, personal communication; Robert Marvin, University of Virginia, 1992, personal communication; and the MacArthur Working Group on Attachment, University of Virginia, 1992, personal communication). Even though the pre-school rating system was originally created for children up to the age of 54 months, we did not anticipate problems in extending it to the 6-year-old participants. Indeed, the pre-school system was created based on the assumption that the ‘strategies’ associated with each one of the three organised attachment categories remain the same throughout development.

Co-occurring disorders/difficulties

The DAWBA was used to assess the presence of psychiatric symptomatology co-occurring with RAD through the foster carer interviews. The DAWBA is a well-validated diagnostic interview schedule that has been recently extended to children as young as aged 2 years and has been updated for the DSM-5. The DAWBA has been used extensively in clinical trials and epidemiological studies. The system has high levels of inter-rater reliability and provides automated algorithms for scoring and assigning diagnoses. It should be noted that, owing to some limitations in the validity of the DAWBA for assessing RAD, we relied on the DAI as the main instrument to identify RAD symptoms.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a very widely used carer-reported questionnaire for assessing children’s emotional and behavioural problems, and yields well-validated continuous measures of internalising problems, externalising problems, total problems and specific ‘syndrome’ scales for narrow-band symptom areas (such as attention problems, aggression, social problems). 44 It is valid for children from the age of 1.5 years and has age-appropriate forms for children aged 1.5–5 years and ≥ 5 years.

Broader impact measures

To assess quality of caregiving, we rated the observed carer sensitivity and other related parameters of parenting (e.g. co-operation, positive regard for the child). We used standardised observational procedures for assessing carer sensitivity during free play and routine caregiving interactions. Specifically, we video-recorded an interaction between carer and child for 10 minutes (excluding instructions), during which a set of structured instructions given to the carer were followed: (1) to teach the child how to play with a challenging toy for their age, (2) to then play with the child using no toys, (3) free play with the toys and (4) to help the child tidy up the toys. These video-recordings were subsequently scored blind to treatment condition and status (pre vs. post) by trained and reliable coders. The scoring system used was the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) sensitivity scales, which have been validated in numerous studies. 45

We also administered two parenting-related questionnaires. The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form was used to assess carer well-being, carer strain and the carer–child relationship. 46 The Brief Parental Self-Efficacy Scale is a measure of beliefs and confidence about parenting skills. 47

The Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS) assesses resource use for health economic evaluation. 48 Previous versions of the CA-SUS measuring service use by pre-school children with autism and young looked-after children formed the basis of a modified version suitable for the current population, with modifications being determined, initially, by expertise in the research group and, subsequently, by testing for acceptability and comprehensiveness. Specifically, this initial draft version was tested and modified in two ways. First, after a sufficient number of cases, the interviewers and the CA-SUS authors discussed necessary amendments and clarifications that were incorporated into the previous (draft) version. Second, the measure’s comprehensiveness in capturing all relevant services was assessed. Testing was important to identify items that were redundant or important services that had been omitted.

The proposed battery of outcome assessments was similar to those we have used in other trials and cohort studies,25,49,50 and our previous experience was that it would not be excessively burdensome. However, we planned consultation with foster carers (through the foster carers advisory group), as well as with those taking part in the study, regarding the level of acceptability and burden. Establishing the optimal balance between participant time/burden and the robustness of the outcome assessments was an important aim of this project as preparation for a full-scale trial.

The research team attempted to follow-up all families involved in the study, including children who moved to a different placement during the time of the research. Any additional relevant consent that was required as a result of placement changes was obtained (e.g. consent from the new carer).

One of the aims of the case series was to establish initial feasibility of the intervention protocol and the acceptability of the programme and outcome assessments to foster carers. Accordingly, research assistants closely monitored the recruitment and assessment processes and requested continuous feedback from carers to make any necessary adjustments to the protocol for the feasibility RCT (phase 3). In addition, treatment progress and process were closely monitored, and feedback was presented and discussed by the Manual Development Working Group (from phase 1) to allow consideration of further appropriate manual modifications. Practitioner feedback forms were used to provide additional qualitative feedback about the experience of using the VIPP-FC in practice. The results of the case series also informed revision of the research protocol in preparation for phase 3.

Intervention

Intervention description

The VIPP-SD is a brief home-based attachment and parenting intervention. It is highly acceptable to families, has a clear and empirically supported model of change and has strong evidence of efficacy with families of young children in many settings. 21 We proposed to have staff who had received training in the intervention visit families at home for six 90-minute sessions over 4 months. Sessions 1–5 take place biweekly and focus on improving carer sensitivity to the child. Session 6 is a booster session; it can take place approximately 1 month after the fifth session and focuses on consolidating the information provided in sessions 1–5 and teaching carers sensitive discipline skills.

Sessions involve both the carer and child, and start by video-recording carer–child interactions, which provides the basis for themed discussion in the next session when the intervener feeds back the clips, pausing the video at certain moments to highlight and provide messages according to manualised themes. Themes include recognising the child’s attachment signals and expressions, providing prompt and adequate responses to them, promoting empathy for the child, praising positive behaviour and appropriate ignoring of negative behaviour. Carers are also given exercises and tips. Session content is consistent across families, although its presentation and the video feedback are tailored to the specific needs of each family.

The VIPP-SD has recently been modified specifically for the Dutch foster care context by the developers of the programme in the Netherlands. This modified programme (VIPP-FC) pays particular attention to the need to help carers recognise signals that are specific to foster children, which may be quite challenging and difficult to understand, so that they are better equipped to respond sensitively and to support the child’s secure attachment to them as their carer. The VIPP-FC is thus designed to specifically address the attachment difficulties often shown by children in foster care. In particular, these children tend to demonstrate attachment signals that are very subtle, highly distorted or absent, for example not crying when hurt because they are not used to being comforted, or becoming angry or fearful when comforted. By helping foster carers become aware of these subtle, distorted or absent signals and training them to respond appropriately, the child can learn that foster carers can be relied on in times of need and that it is safe to show their distress and seek comfort.

Many children in foster care have extremely negative experience of physical interactions with carers; hence, the VIPP-SD modified for foster care also specifically addresses how to gently and sensitively support a child’s needs for physical contact and comfort. 28

The intervention manual and delivery were further modified for this study to meet the systems and circumstances of the UK foster care context, as described in Chapter 2. We will refer to the modified intervention as VIPP-FC.

Training of interveners

We trained a group of individuals from an NHS Specialist Looked-after Children’s CAMHS team in the delivery of the VIPP-FC modified intervention. The interveners of the case series were already VIPP-SD trained, experienced practitioners. Each intervener was trained by an accredited VIPP-SD trainer and was required to undertake supervised practice before becoming a study therapist. Accredited supervision face to face, by telephone and by e-mail was provided to all practitioners.

Treatment fidelity

We ensured fidelity through supervision of three visits per case. All interveners completed logbooks for each visit, outlining how closely they followed the manual, if they completed all the filming tasks and if they included key messages in their feedback to the carer; logbooks were required for each different visit. They were also required to audio record at least one of their feedback sessions per case.

Results

Screening response rates

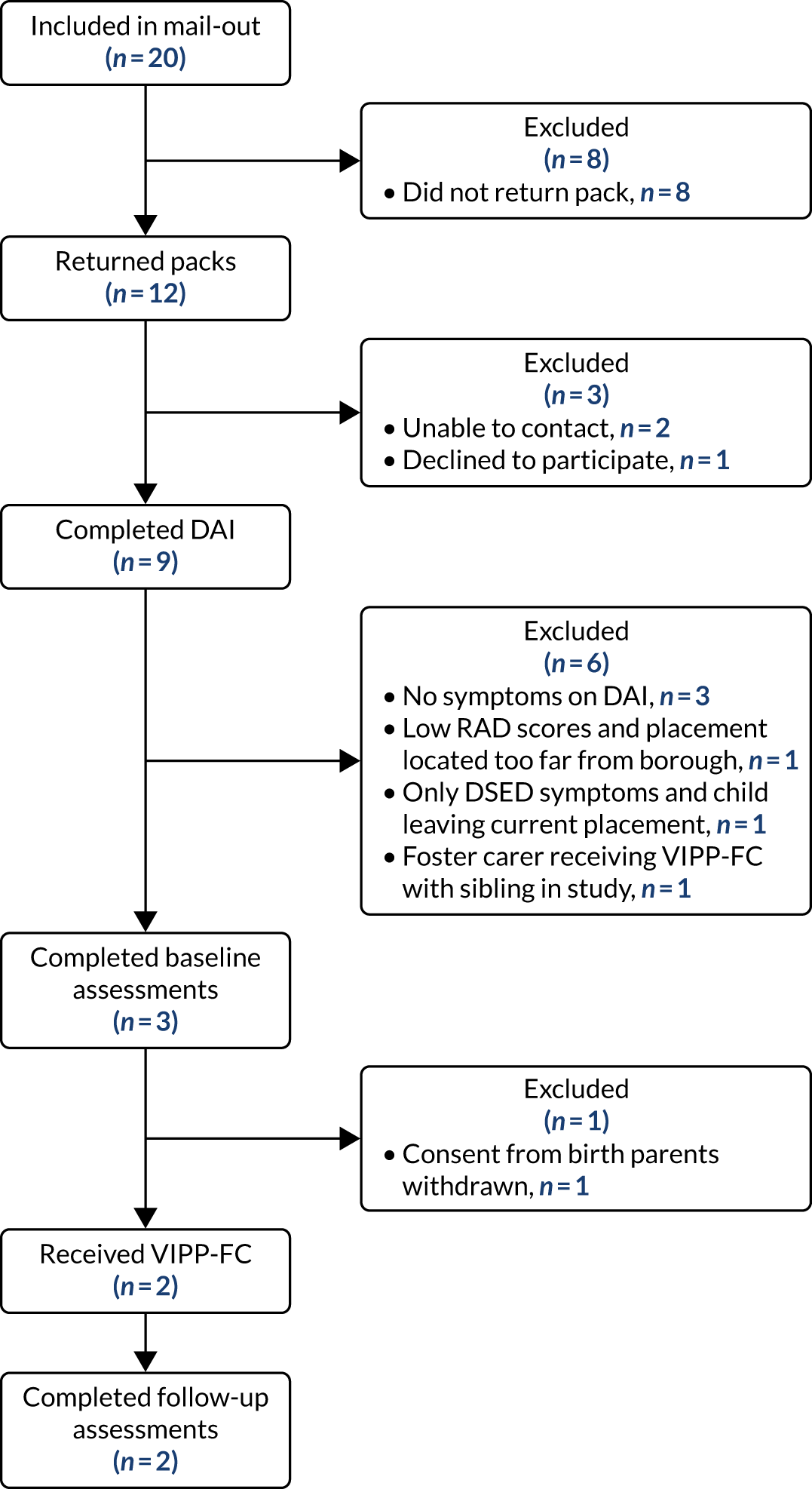

We present the overall response and retention rates in the form of a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram in Figure 1. As is evident from the diagram, we achieved a relatively good response rate of 60%, or 12 out of 20 carers.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the case series.

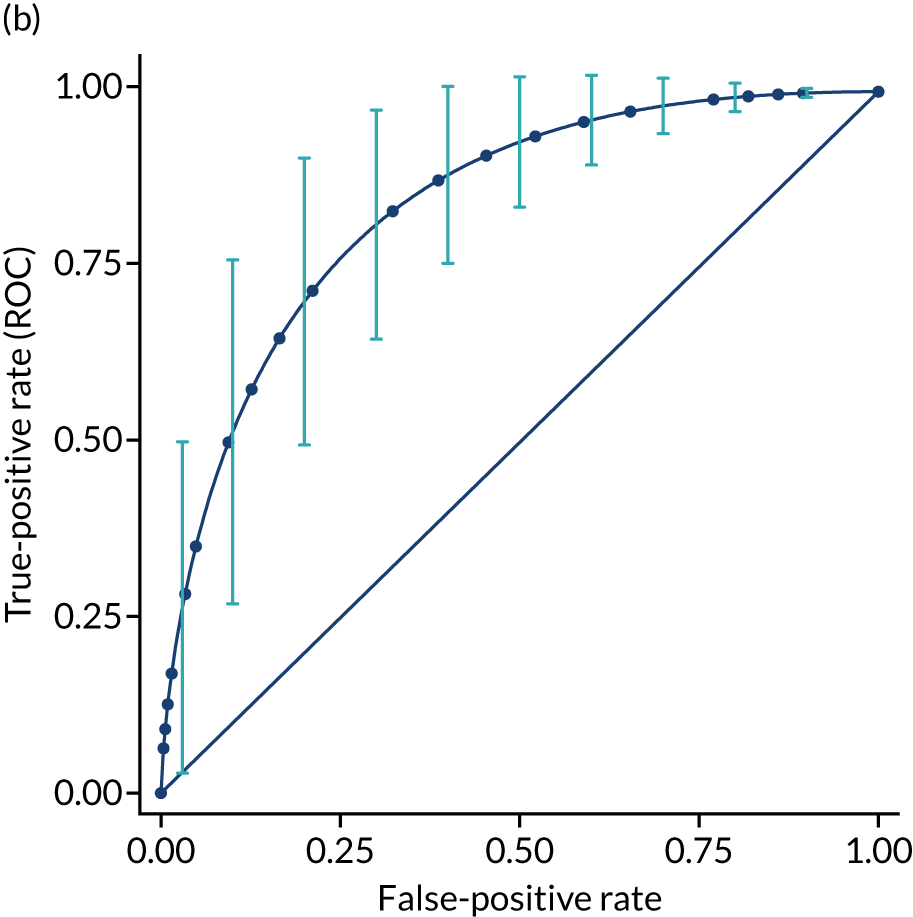

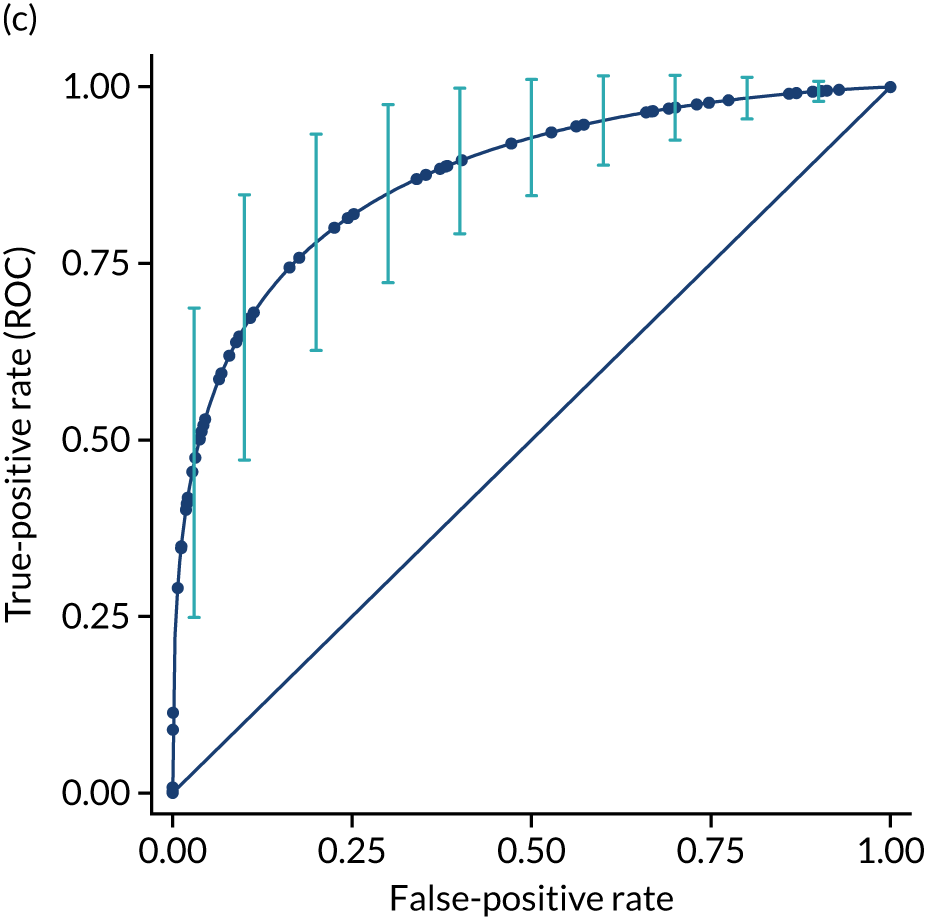

Performance of the screening questionnaires

We found a moderate prevalence of RAD symptoms in this sample. Specifically, five out of the nine completing the DAI scored positive for at least one RAD symptom/sign, and four scored positive for more than one. It is unclear, of course, if the prevalence in this small sample is representative of the population of children in foster and kinship care or placed with guardians in the UK, and, with such a small sample size and low sample rate, the estimate has a very high degree of uncertainty attached to it.

Treated cases

Of the nine children whose carers completed the DAI, only three were eligible to proceed to treatment (see the reasons for exclusion in Figure 1). These three children underwent all baseline assessments with their carer. After the assessments were completed, one of them left the study because the child’s birth parents (who had received opt-out letters) contacted the social worker to refuse the child’s participation.

Hence, two children went on to receive the VIPP-FC, each provided VIPP-FC by a different CAMHS practitioner. They both completed all six sessions and all of the follow-up (i.e. post-treatment) research assessments.

Process observations: recruitment and consent