Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/167/102. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The draft report began editorial review in May 2020 and was accepted for publication in November 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Benger et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Taylor et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and distribute this work, for non-commercial use, with no derivatives, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background and rationale

In the UK, the reported incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is 123 cases per 100,000 population per annum. 2 Despite recent improvements, survival rates from cardiac arrest remain poor, with approximately 7–9% of UK patients surviving to hospital discharge, compared with estimates of between 5% and 25% internationally. 3–7 During a cardiac arrest, the brain is exposed to a period of hypoxaemia and ischaemia, which may result in death or cognitive deficits. 8 Optimal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and rapid return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) are key factors associated with avoiding or minimising neurological impairment in survivors of OHCA,9,10 and early effective airway management, which involves techniques and medical procedures to prevent and relieve airway obstruction, is fundamental to this. 1 The scene of an OHCA is often a challenging and unpredictable environment, which can affect these key interventions.

Tracheal intubation (TI) is the placement of a flexible plastic tube into the trachea (windpipe) to keep an airway open. Traditional teaching suggests that TI is the most effective way to manage the airway during OHCA. 11 However, this assumption has not been well tested,12 and pre-hospital intubation attempts by paramedics can cause complications, such as interruptions in chest compressions, unrecognised oesophageal intubation (particularly if waveform capnography is not available) and delays in accessing definitive care. 1,13,14

Supraglottic airway devices (SGAs) are an alternative to intubation. They are quicker and easier to insert and may avoid the complications of TI. 15 SGAs are used safely to manage the airway during routine anaesthesia. 1,16–18 They are also in widespread use in NHS ambulance services. In 2015/16, the London Ambulance Service alone reported 92.4% (3142/3401) successful SGA placements compared with 86.1% (1411/1639) successful TIs for OHCA. 6 However, these data are from a single ambulance service and do not describe the associated clinical outcomes.

Equipoise between the two techniques has led to calls for a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) to compare the two. 19–22 Relatively small gains in survival of 2–3% would be clinically meaningful and worthwhile,23 provided the intervention is cost-effective. This means that large sample sizes are necessary and missing data could substantially undermine the validity of trial results.

The Resuscitation Council UK 2015 guidelines24 state that the optimal airway technique for cardiac arrest is still unknown and is likely to depend on the skills of the operator, the anticipated pre-hospital time and patient-dependent factors. Evidence-based interventions are urgently required to address the currently poor survival rate following OHCA. The AIRWAYS-2 trial was designed to answer important questions about initial advanced airway management (AAM) during OHCA, examining both survival rates and quality of life (QoL) associated with this survival.

To assess the feasibility of recruiting paramedics and enrolling patients to a trial comparing the techniques, we carried out a feasibility study (REVIVE-AIRWAYS)25 between March 2012 and February 2013. This was completed in a single ambulance service and assessed the feasibility of recruiting paramedics and enrolling patients to the trial comparing two SGAs [the i-gel® (Intersurgical Ltd, Wokingham, UK) and the LMA® Supreme™ Airway (Teleflex Medical Europe Ltd, Athlone, Ireland)] with current practice (including TI). 25 REVIVE-AIRWAYS demonstrated that the trial was feasible and informed the detailed design of the AIRWAYS-2 trial.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the AIRWAYS-2 trial was to determine whether or not the i-gel, a second-generation SGA (the trial SGA), is superior to TI in non-traumatic OHCA in adults, in terms of both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

The trial objectives were to estimate:

-

The difference in the primary outcome of modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at hospital discharge (or 30 days post OHCA if the patient was still in hospital) between groups of patients managed by paramedics randomised to use either the i-gel or TI as their initial AAM strategy following OHCA. The mRS is a measure of functional outcome used to measure disability or dependence in the daily activities of people.

-

Differences in secondary outcome measures relating to airway management, hospital stay and recovery at 3 and 6 months between groups of patients managed by paramedics randomised to use either the i-gel or TI.

-

The relative cost-effectiveness of the i-gel compared with TI, including estimation of major in-hospital resource use (e.g. length of stay in intensive and high-dependency care), and associated costs in each group.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Taylor et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and distribute this work, for non-commercial use, with no derivatives, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Robinson et al. 26 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from JAMA 2018;320(8):779–91. 27 Copyright © 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Trial design

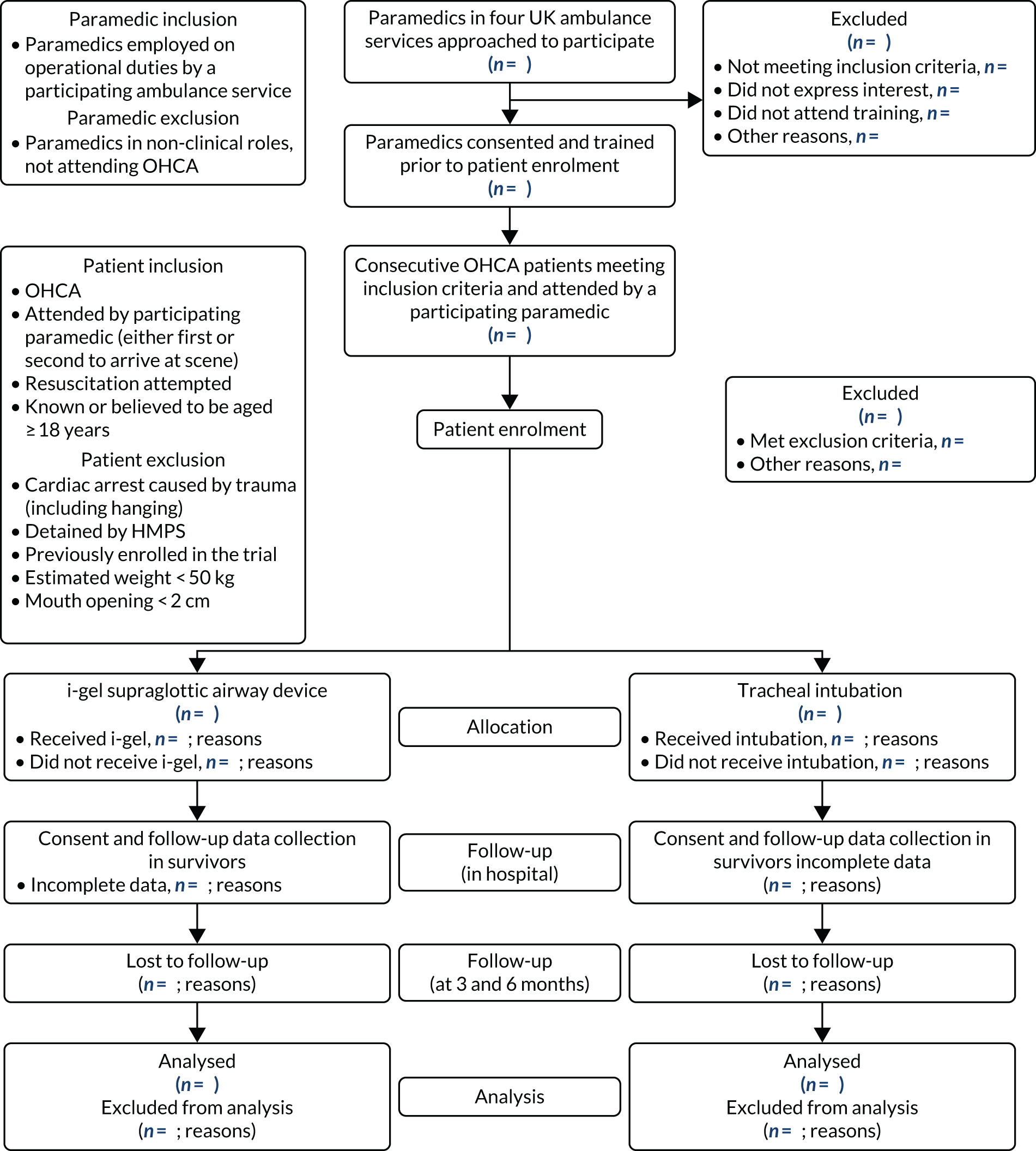

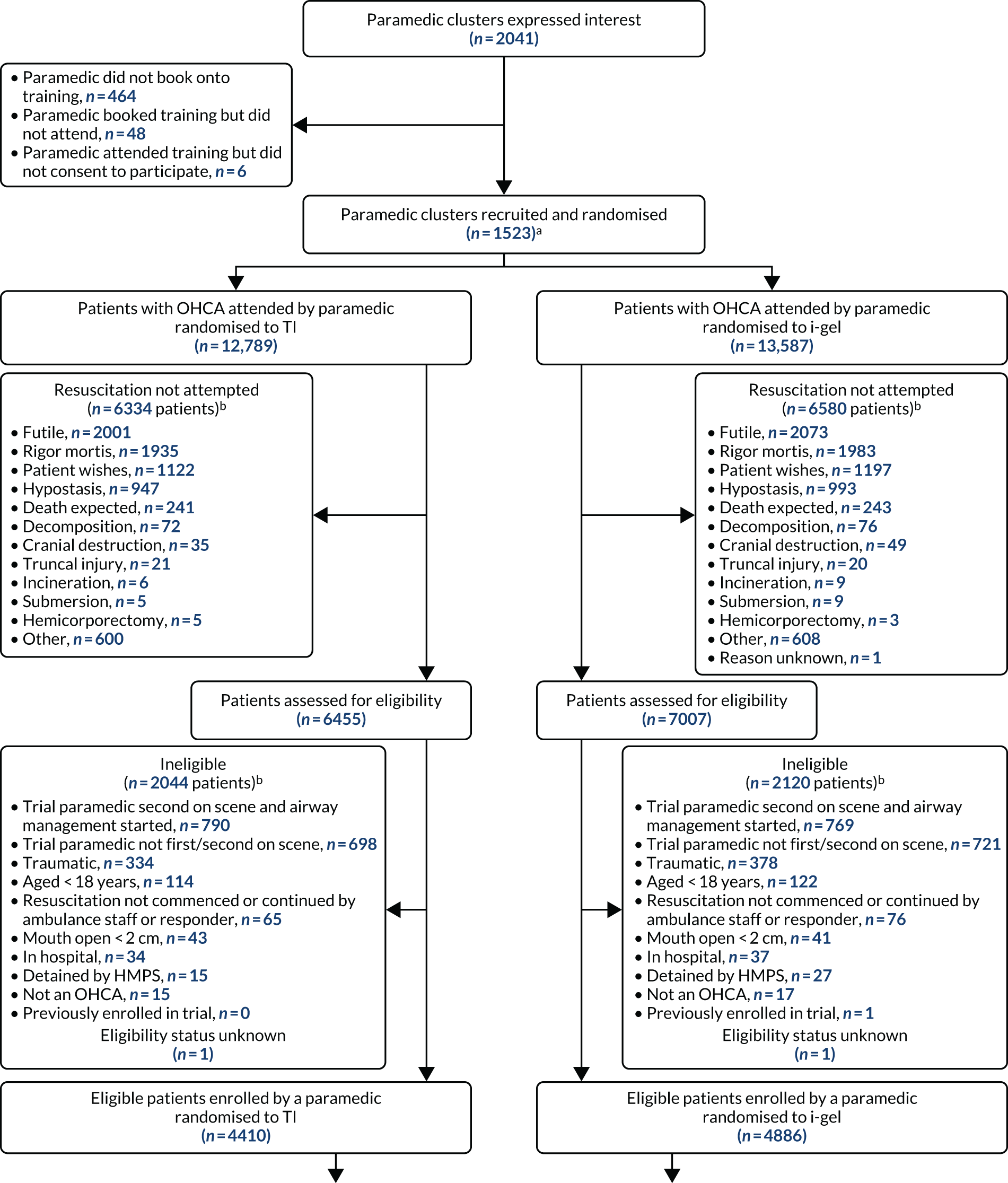

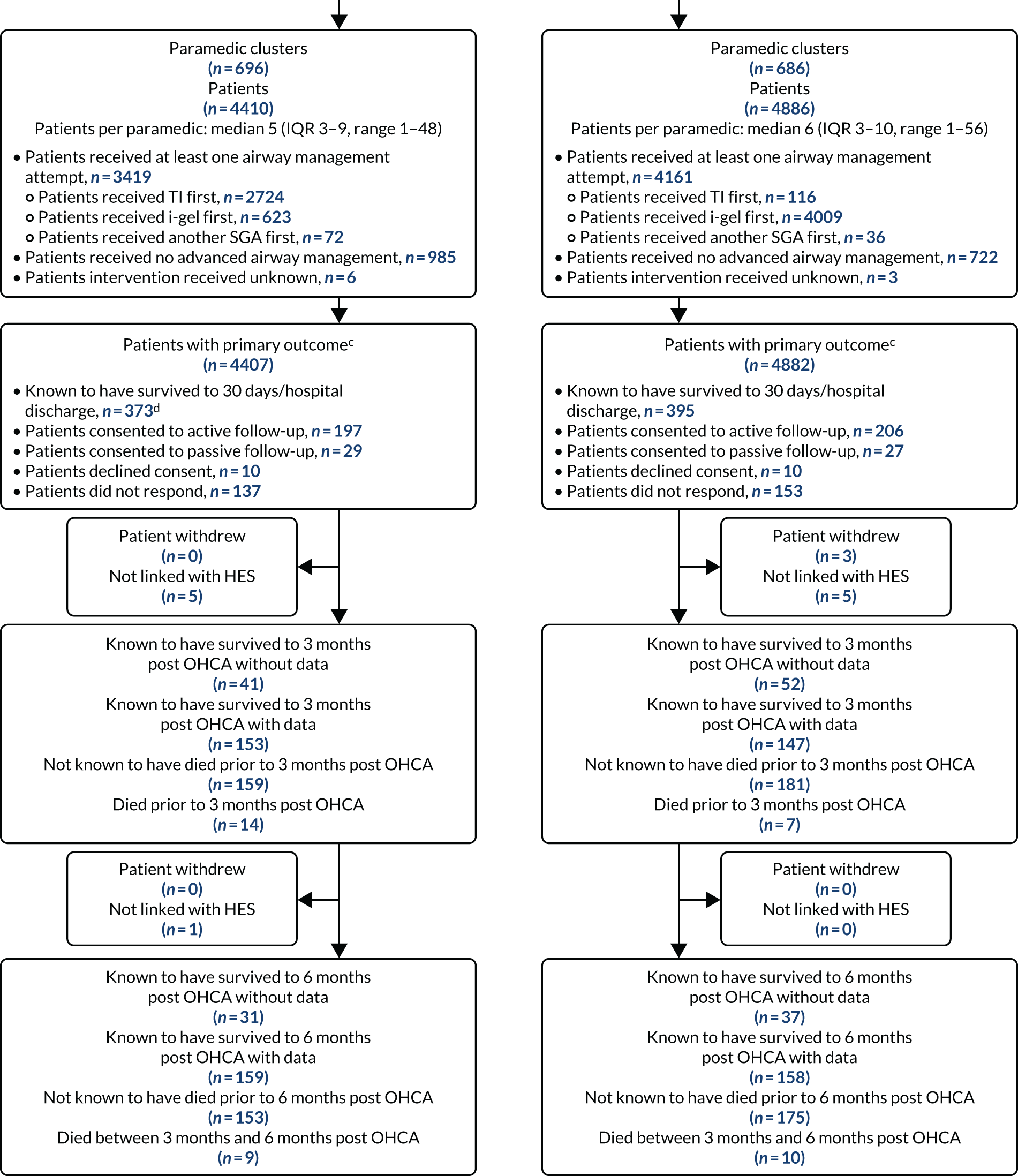

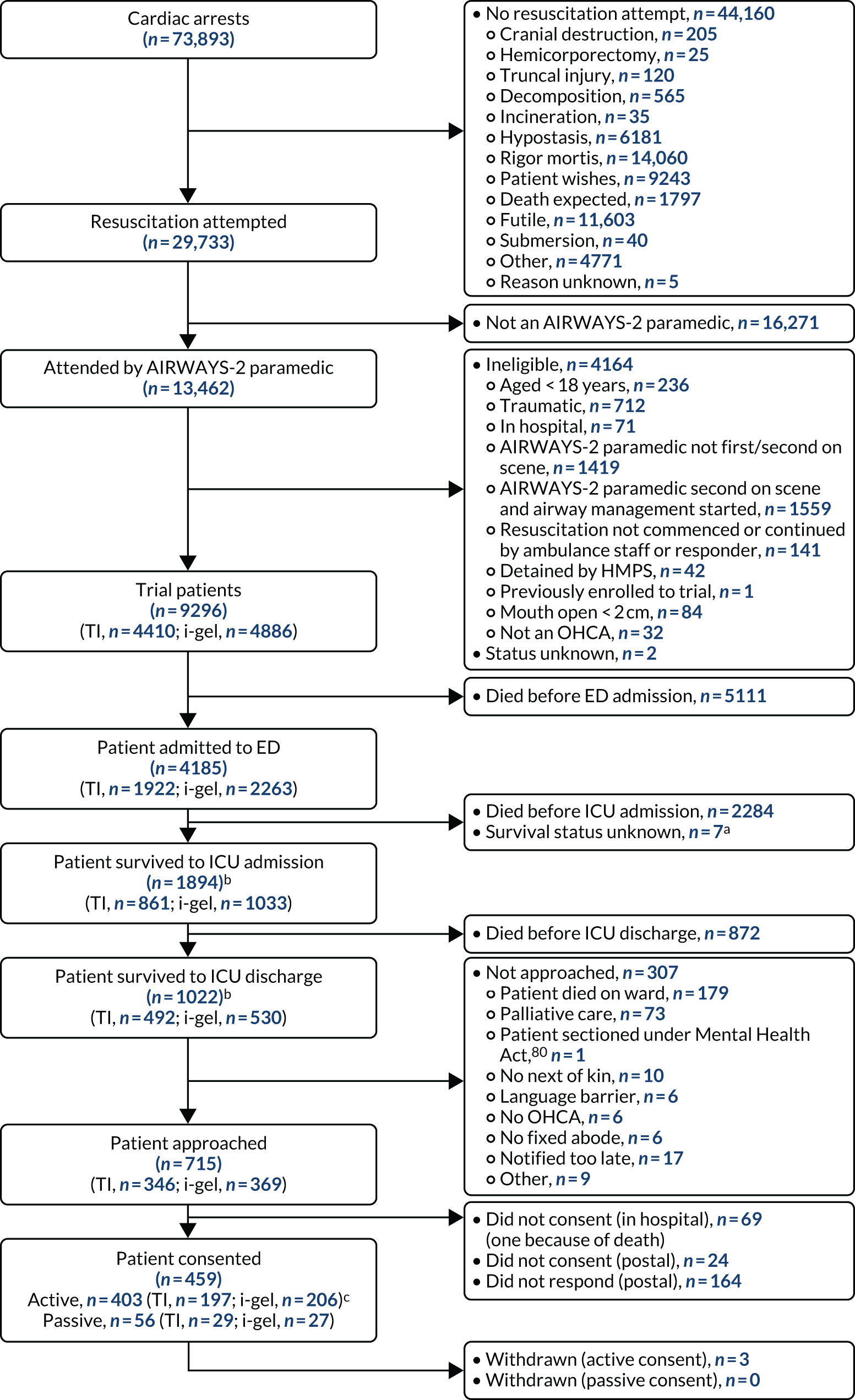

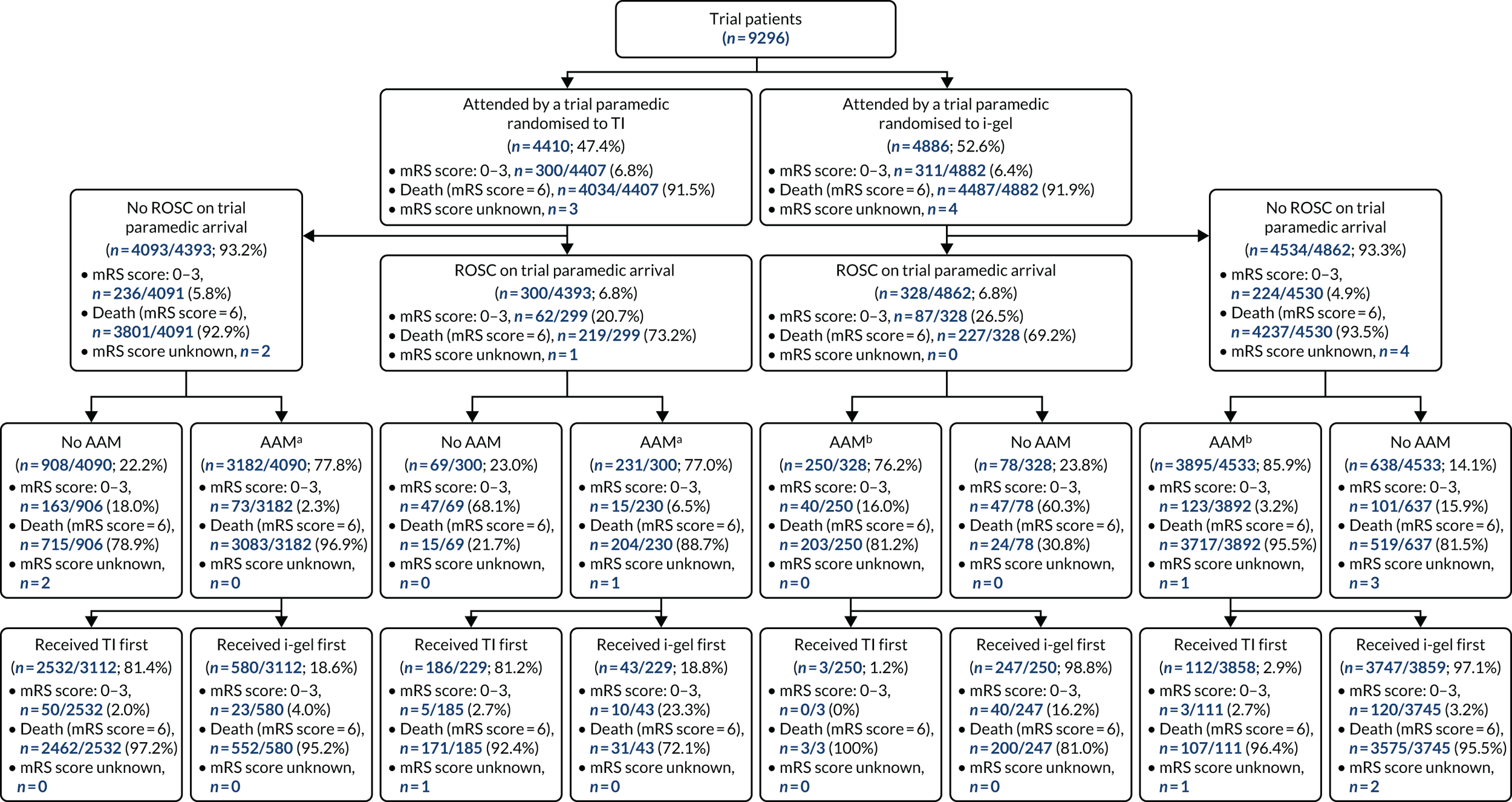

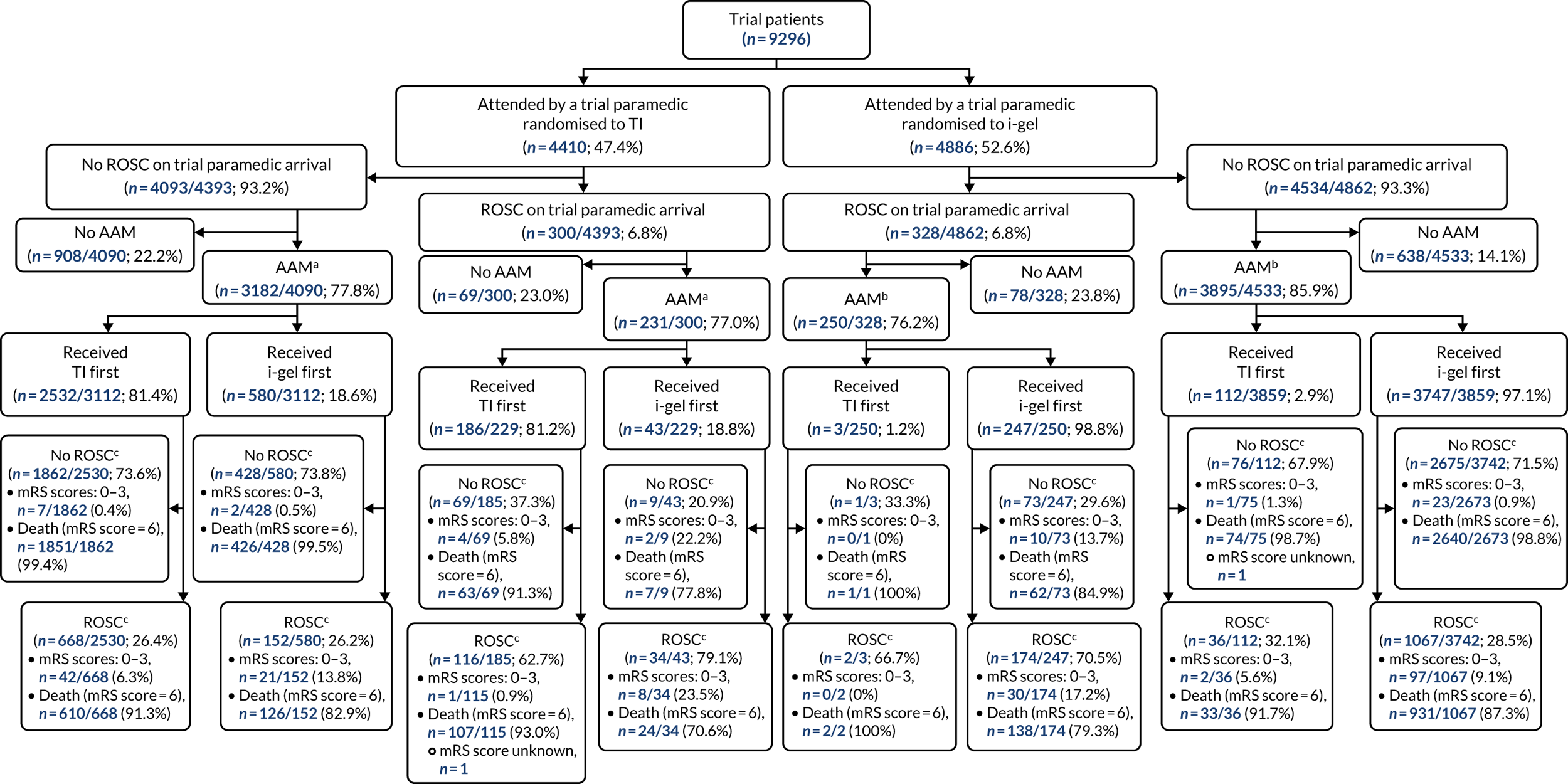

The AIRWAYS-2 trial was a pragmatic, open, parallel, two-group, multicentre cluster RCT. The trial schema is presented in Figure 1. The trial objectives were addressed by randomising paramedics, rather than patients, to either the i-gel or TI. All enrolled patients were then treated according to the enrolling paramedic’s allocation. This trial is registered as ISRCTN08256118.

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema. HMPS, Her Majesty’s Prison Service. n values missing as this is the methods section and this figure shows the flow of patients through the trial. n values appear in Chapter 3.

All enrolled patients transferred to the emergency department (ED) required follow-up data to be collected in hospital. Hospitals identified as potential receiving sites for OHCA patients were any of those within or bordering the geographical area served by the four participating ambulance services. It was not possible to predict or influence which hospital an enrolled patient would be taken to and this meant that all 95 hospitals served by the four ambulance services needed to participate in the trial. If a hospital refused to take part or could not provide the necessary approval, the trial could not collect data for enrolled patients taken to that hospital. 26 It was also required that all 95 hospitals started their participation in the trial at the same time, that is as soon as patient enrolment began. Ethics review and approval was provided by South Central – Oxford C Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference 14/SC/1219). Owing to the immediate and incapacitating nature of OHCA, patients were unable to provide consent at the scene. Every eligible patient attended by a participating paramedic was automatically enrolled in the trial under a waiver of consent provided by the Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) (reference 14/CAG/1030). Patients who survived to discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU) were approached to provide consent for ongoing trial follow-up. A consultee could also provide an opinion on the likely views of a patient in instances where the patient was incapacitated.

Changes to trial design after commencement of the trial

During the trial, several amendments were made to the trial protocol. For a more detailed description of these amendments, see Appendix 2. The protocol version in use at the start of the trial was version 2.0. The current full trial protocol can be found on the project web page (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/12167102#/; accessed 3 March 2021).

Throughout the trial, adjustments had to be made to the collection of data for the economic evaluation. We aimed from the outset to make use of routinely collected data from NHS Digital Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)/Office for National Statistics (ONS) data linked to the trial cohort. However, as the trial progressed, it became clear that there was a risk that the HES/ONS routine data would take too long to arrive and might not be available in time for the final analyses. The initial application to NHS Digital for the data was made in July 2016. There were various delays to the application process that were beyond the control of the trial team. In late 2017, it was agreed that the trial team would try to acquire a set of routine data by other means so that data would be available should the HES/ONS data not be available in time for analysis. It was agreed with the sponsor (South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust) and REC that a sample of sites could be approached and asked to complete brief data collection forms to be used to estimate resource use by collecting information on admissions, cross-sectional imaging [computerised tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance scans] and interventions received by AIRWAYS-2 participants at their sites. In February 2018, a sample of sites was approached to collect this additional retrospective health economics data. A total of 24 hospitals across the four regions were approached, with 18 hospitals returning completed data collection forms for around 850 patients. However, these data were not used in the final analyses because the HES/ONS data became available.

Some changes were made to the statistical analysis plan (SAP) after the trial had started. For a more detailed description of these changes, see Appendix 3. The initial SAP was finalised in February 2018. In April 2018, version 2.0 of the SAP was signed off.

Participants

Paramedic population

Paramedics were eligible if they were employed by one of the four participating ambulance services (see Settings) and undertook general operational duties and, therefore, could be despatched to attend an OHCA as the first or second paramedic to arrive at the patient’s side. Paramedics had to be registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and be qualified to practise TI in their clinical role. Paramedics were required to undergo trial-specific training prior to providing consent to participate.

Patient eligibility criteria

The trial population was adults who had a non-traumatic OHCA. Patients were treated in accordance with the allocation of the attending paramedic.

The trial inclusion criteria were:

-

patient known or believed to be aged ≥ 18 years

-

patient has had a non-traumatic cardiac arrest outside hospital

-

patient attended by a paramedic who was participating in the trial and was either the first or second paramedic to arrive at the patient’s side*

-

resuscitation was commenced or continued by ambulance staff or responder. †

*The participating paramedic managed the patient’s airway according to their allocation. If both the first and second paramedic were participating in the trial, the patient’s airway was managed in accordance with the allocation of the first paramedic to arrive at the patient’s side (usually designated as the ‘attendant’ in the ambulance service). If the first paramedic to arrive was not an AIRWAYS-2 paramedic (i.e. a paramedic who provided consent and was randomised) but the second paramedic was, the patient was enrolled in the trial unless an advanced airway intervention had already occurred (advanced airway intervention being defined as either a SGA or a tracheal tube being present in the patient’s mouth) at the point that the second paramedic arrived at the patient’s side. If a third or subsequent paramedic arrived at the patient’s side, and the first two paramedics were not participating in the trial and the third or subsequent paramedic was participating in the trial, the patient was excluded (some of these exclusions had to be determined retrospectively).

†Circumstances in which resuscitation should and should not be attempted are described in national guidelines; the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) Recognition of Life Extinct (ROLE) criteria28 are currently used by all ambulance trusts to determine when a resuscitation attempt is inappropriate and these criteria were applied in the trial. These criteria were objectively defined, but the frequency of attempted resuscitation in both groups was examined regularly by the Data Monitoring and Safety Committee (DMSC) to identify any bias in the commencement of resuscitation attempts.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

patient detained by Her Majesty’s Prison Service (HMPS)

-

patient previously enrolled in the trial (determined retrospectively)

-

resuscitation considered inappropriate28

-

advanced airway device inserted by another HCPC-registered paramedic, doctor or nurse already in place when the AIRWAYS-2 paramedic arrived at the patient’s side (when the first paramedic to arrive was not participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial)

-

known to already be enrolled in another pre-hospital randomised trial

-

mouth opening < 2 cm.

This last exclusion criterion was applied because successful insertion of a SGA requires mouth opening of > 2 cm. There was a risk of post-randomisation bias being introduced by this exclusion criterion, but in our feasibility trial only 2 out of 711 patients (0.3%) were excluded on these grounds. We monitored this exclusion, under the guidance of the DMSC, and had the exclusion rate exceeded 1% we would have taken action to address this through enhanced training and supervision.

Standardised guidelines, based on those produced by the JRCALC, were applied to determine patients for whom a resuscitation attempt was inappropriate. This was the case where there was no chance of survival; where the resuscitation attempt would be futile and distressing for relatives, friends and health-care personnel; and where time and resources would be wasted undertaking such measures.

When any one or more of the following conditions existed, resuscitation and enrolment in the trial would not take place:

-

massive cranial and cerebral destruction

-

hemicorporectomy

-

massive truncal injury incompatible with life (including decapitation)

-

decomposition/putrefaction

-

incineration

-

hypostasis

-

rigor mortis

-

a valid ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ order or an advanced directive (living will) that states the wish of the patient not to undergo attempted resuscitation

-

patient’s death expected owing to terminal illness

-

submersion of adults for > 1 hour

-

efforts would be futile, as defined by the combination of all three of the following being present –

-

> 15 minutes since the onset of collapse

-

no bystander CPR prior to arrival of the ambulance

-

asystole (flat line) for > 30 seconds on the electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor screen (exceptions: drowning and drug overdose/poisoning).

-

Patients were also excluded from the trial if an immediate family member, relative or close friend who was present at the scene of the cardiac arrest indicated to the participating paramedic at the start of the resuscitation attempt that the person had previously expressed an opinion that they would not wish to take part in the AIRWAYS-2 trial. In practice, no patients were excluded for this reason.

Changes to trial eligibility criteria after commencement of the trial

In January 2015, the paramedic exclusion criteria were refined to define routine attendance at OHCA as attending at least two OHCA patients per year in whom resuscitation was attempted. The patient inclusion criterion regarding enrolment by the second trial paramedic on scene (where the first paramedic was not participating in the trial) was refined to state that the second paramedic could enrol the patient unless an AAM intervention had already occurred. Two additional patient exclusion criteria were added: ‘advanced airway device already in place when AIRWAYS-2 paramedic arrives at patient’s side (when the first paramedic to arrive is not participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial)’ and ‘known to already be enrolled in another pre-hospital randomised trial’.

In April 2015, the paramedic inclusion criteria were updated to state that paramedics soon to be employed by a participating ambulance trust could participate, and that paramedics must be qualified to practise TI in their current clinical role. The patient inclusion criterion ‘must be in non-traumatic cardiac arrest outside hospital’ was changed to ‘patient has had a non-traumatic cardiac arrest outside hospital’, and the patient inclusion criterion ‘resuscitation is attempted or continued by emergency medical services (EMS) staff’ was changed to ‘resuscitation was commenced or continued by ambulance staff or responder’. The patient exclusion criterion ‘advanced airway device already in place when AIRWAYS-2 paramedic arrives at patient’s side (when the first paramedic to arrive is not participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial)’ was changed to ‘advanced airway device inserted by another HCPC-registered paramedic already in place when AIRWAYS-2 paramedic arrives at patient’s side (when the first paramedic to arrive is not participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial)’ and the patient exclusion criterion ‘estimated weight < 50 kg’ was removed.

In August 2015, the patient exclusion criterion ‘advanced airway device inserted by another HCPC-registered paramedic already in place when AIRWAYS-2 paramedic arrives at patient’s side (when the first paramedic to arrive is not participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial)’ was changed to ‘advanced airway device inserted by another HCPC-registered paramedic, doctor or nurse already in place when AIRWAYS-2 paramedic arrives at patient’s side (when the first paramedic to arrive is not participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial)’. The reason for this minor amendment was to update the protocol so that it reflected clinical practice (i.e. a trial paramedic would not remove an airway device that had already been inserted by a nurse or doctor).

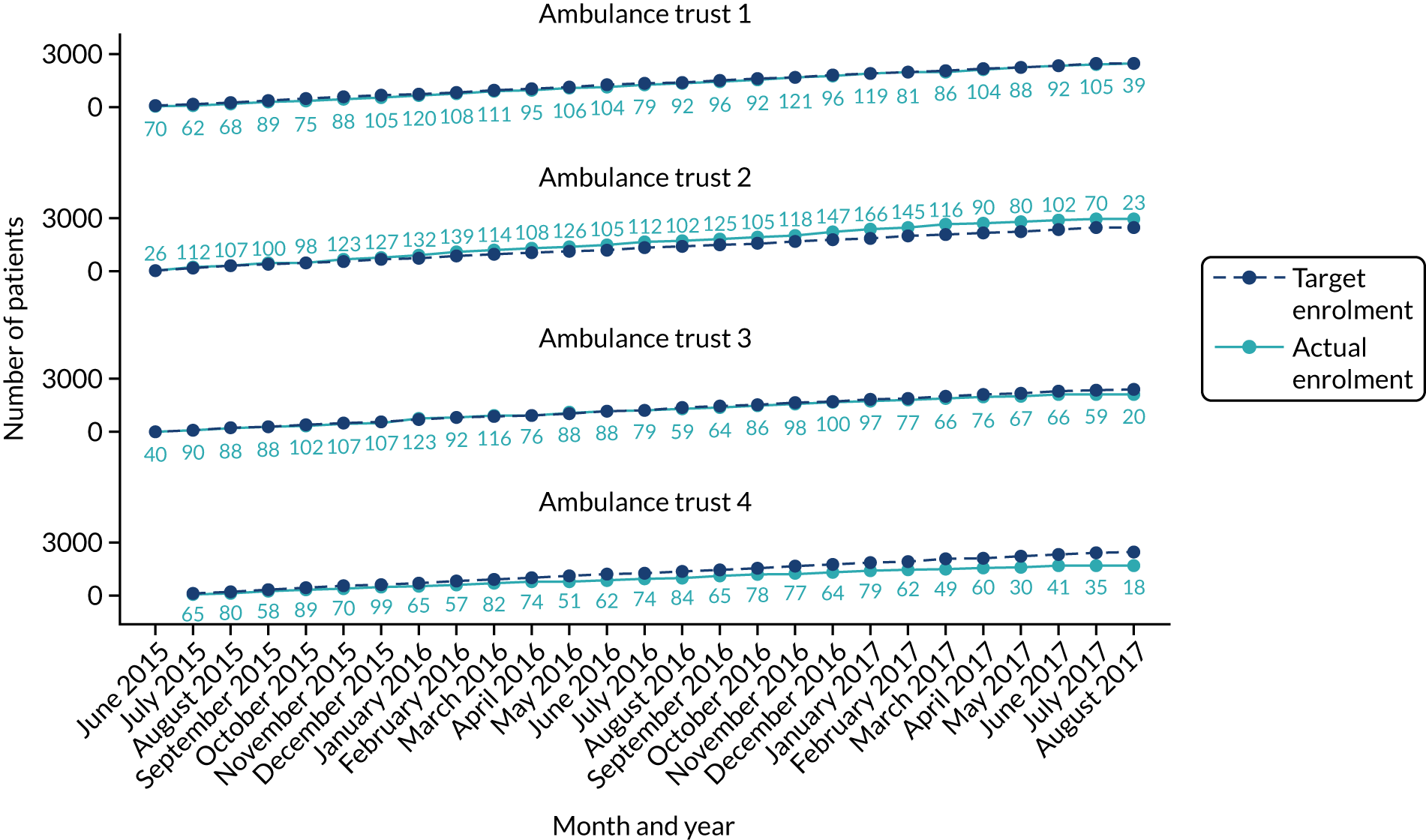

Settings

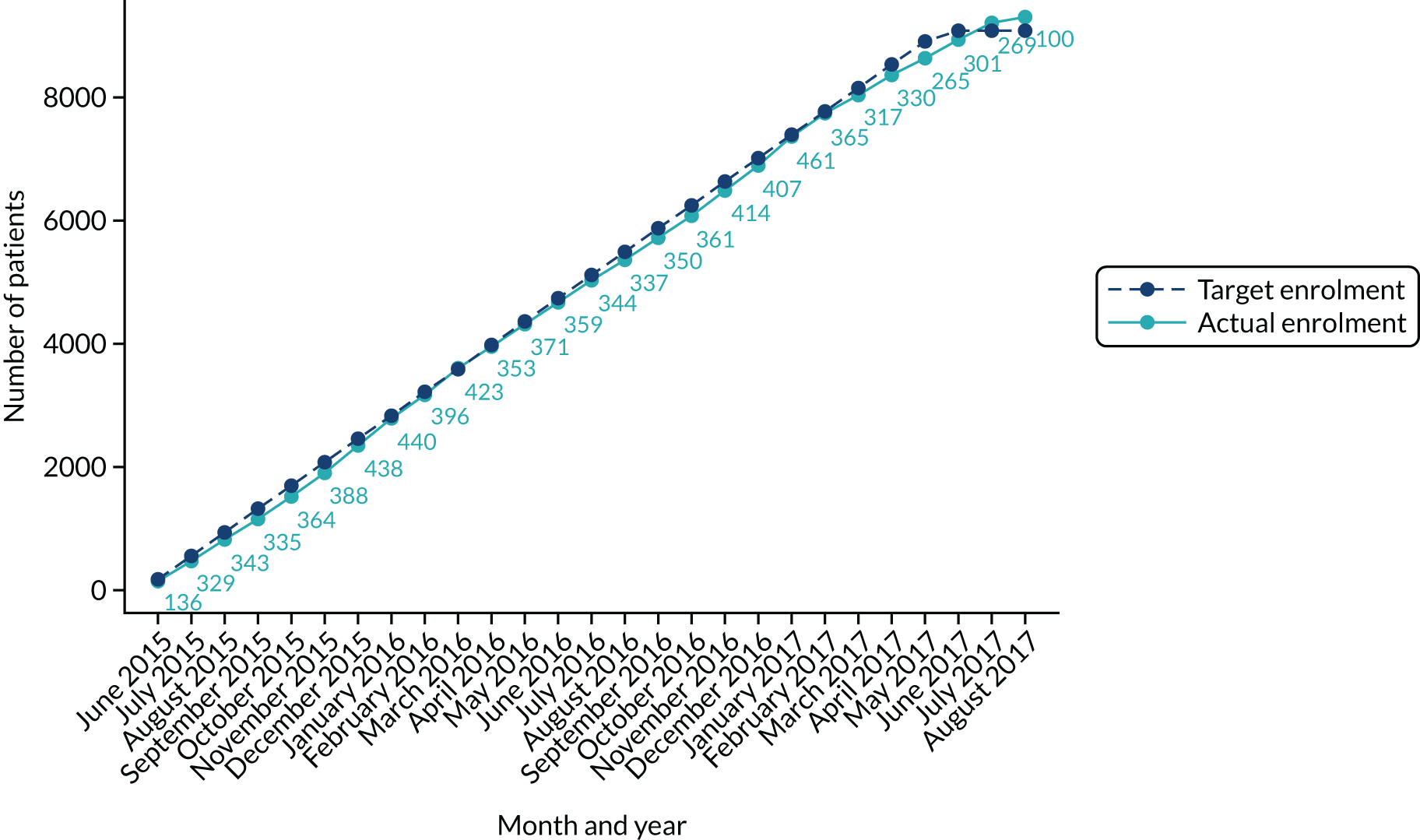

The trial involved collaboration with four NHS ambulance services – South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (SWAST), East of England Ambulance Service NHS Trust (EEAST), East Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Trust (EMAS) and Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust (YAS) – and the 95 NHS hospitals served by these ambulance services. The four ambulance services covered 21 million people (40% of England’s population). Each ambulance service employed a research paramedic to work on the trial, liaising with the trial co-ordination team and AIRWAYS-2 paramedics. All eligible patients attended by an AIRWAYS-2 paramedic between June 2015 and June 2016 were automatically enrolled in the trial and treated according to the attending paramedic’s trial allocation. 1

Interventions

Tracheal intubation (control group)

Tracheal intubation, the placement of a cuffed tube in the patient’s trachea to provide oxygen to the lungs and remove carbon dioxide (CO2), has been generally recognised as the ‘gold standard’ of airway management. TI is used universally in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest following their admission to hospital.

i-gel (intervention group)

The intervention was insertion of the i-gel, a second-generation SGA, as an alternative to TI. Because of its speed and ease of insertion, this device is being increasingly used as the SGA of choice during OHCA in England. 29,30

Aspects of airway management common to both groups

A common approach to airway management, from basic to advanced techniques, was agreed by the participating ambulance services. This included the use of bag–mask ventilation (BMV) and simple airway adjuncts prior to AAM.

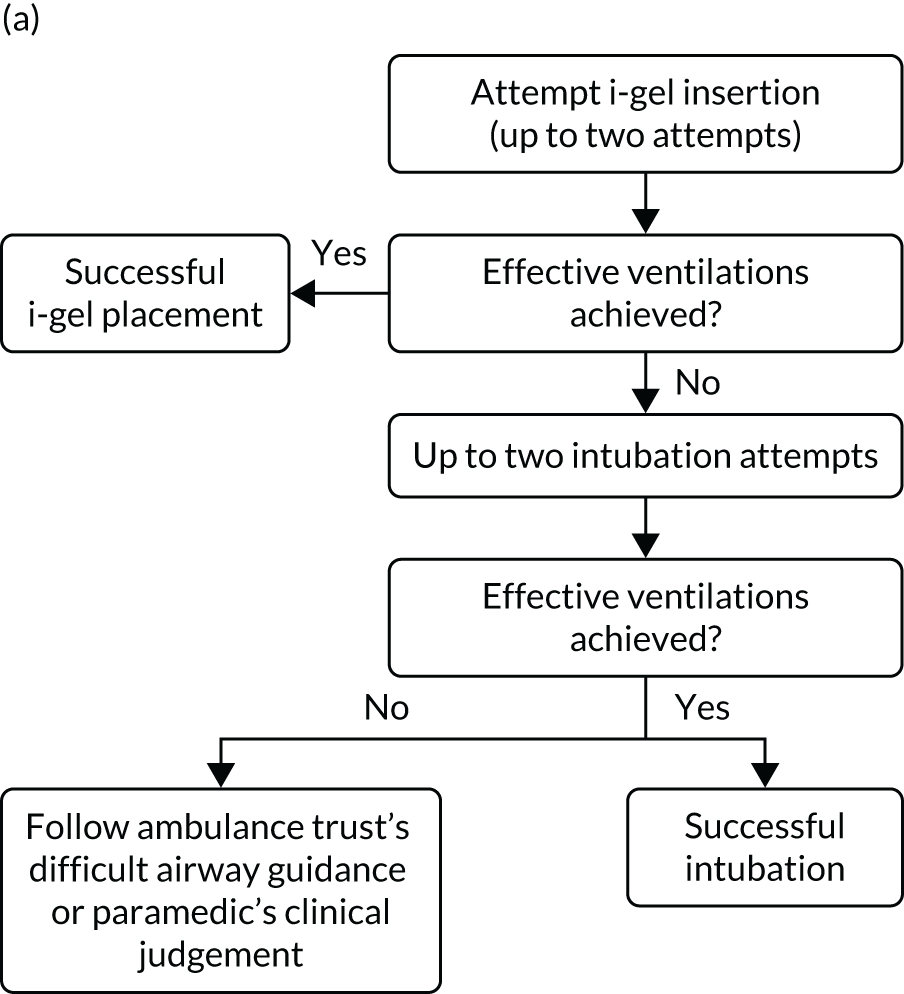

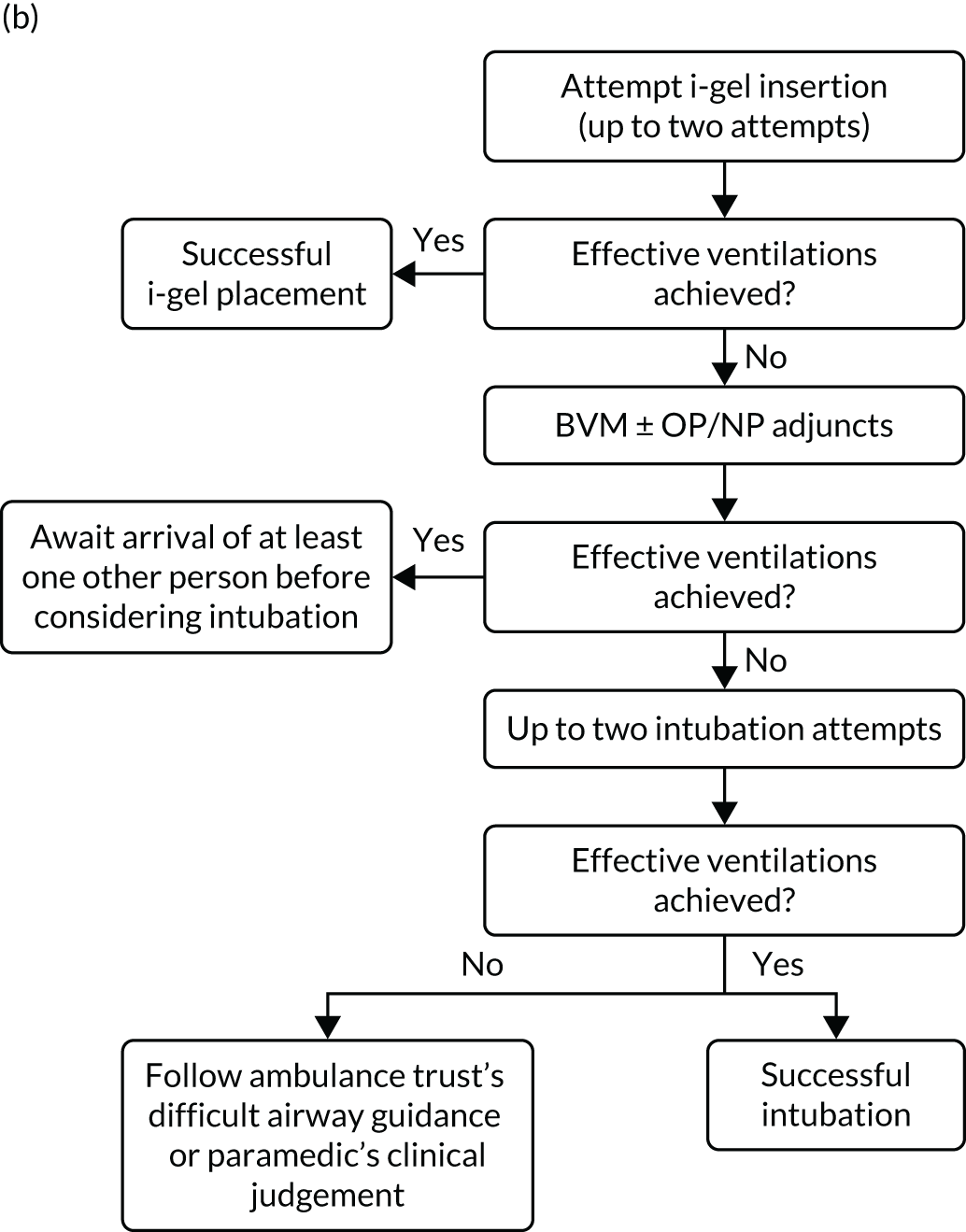

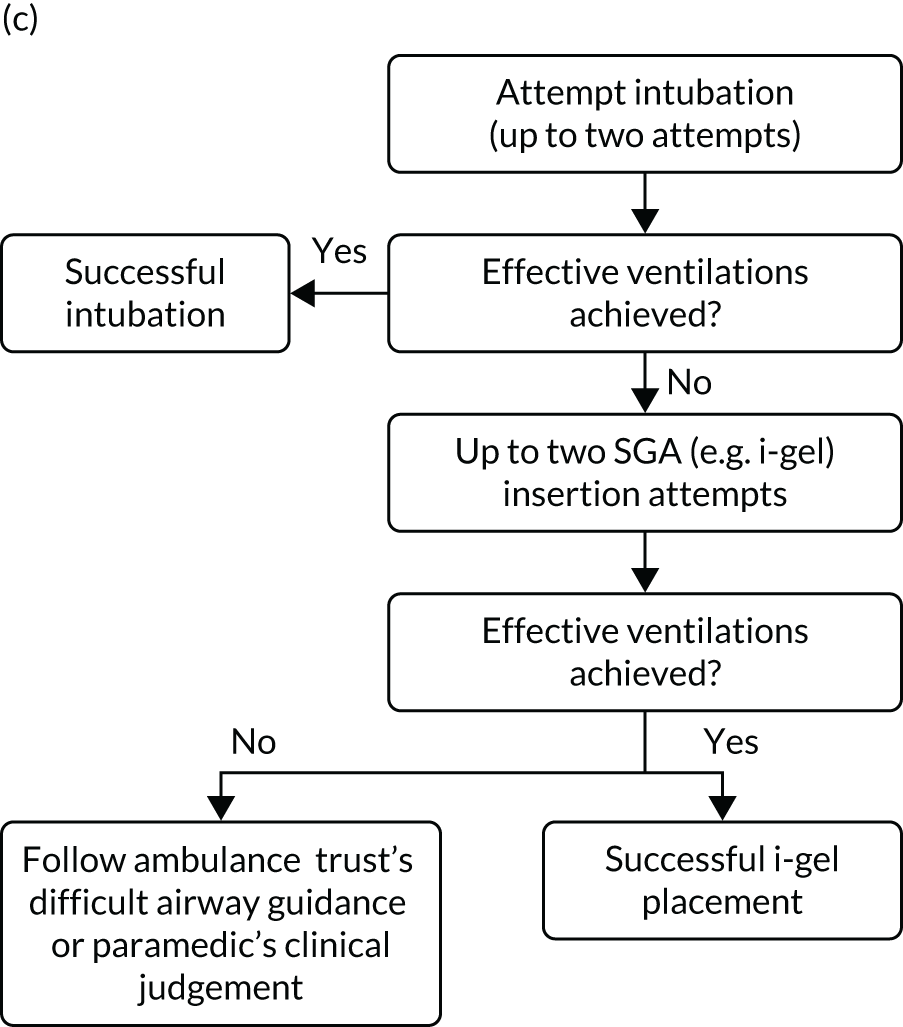

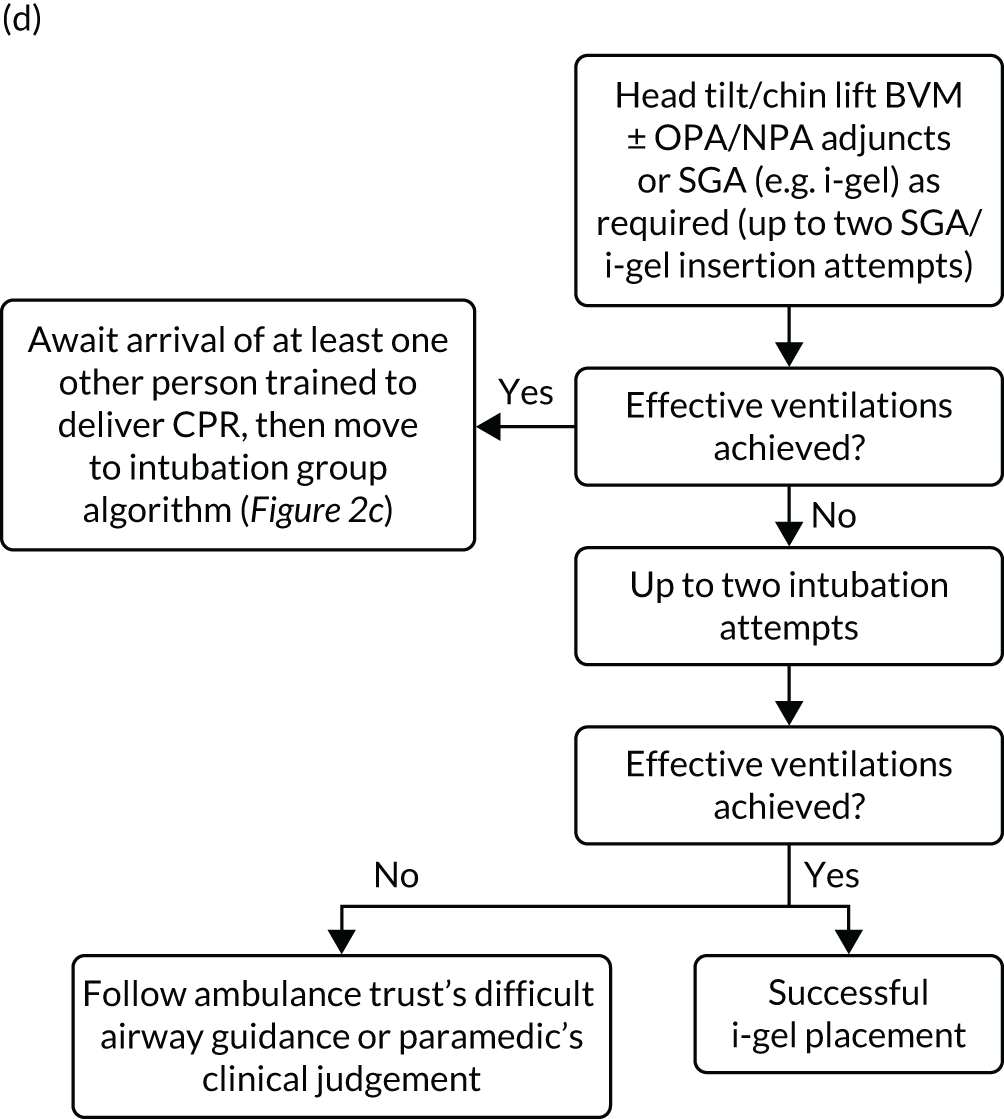

A standardised airway management algorithm1 (Figure 2) was developed by the four participating ambulance services to guide further actions should the initial approach to airway management prove unsuccessful.

FIGURE 2.

The AIRWAYS-2 trial treatment trial algorithm. (a) i-gel group: AIRWAYS-2 paramedic and at least one other person trained in CPR; (b) i-gel solo: single AIRWAYS-2 paramedic response; (c) intubation group: AIRWAYS-2 paramedic and at least one other person trained in CPR; and (d) intubation solo: single AIRWAYS-2 paramedic response. NP, nasopharyngeal; NPA, nasopharyngeal airway; OP, oropharyngeal; OPA, oropharyngeal airway. This figure is reproduced with permission from Taylor et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and distribute this work, for non-commercial use, with no derivatives, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Care proceeded as normal for OHCA patients enrolled in the trial, aside from the initial AAM. All other interventions proceeded in accordance the standard resuscitation guidelines,24 which are disseminated widely in the UK and internationally. Patients who died at the scene were managed in accordance with nationally disseminated protocols. 28 Patients who did not die at scene were transported to hospital and treated using standard post-OHCA care pathways.

Owing to the emergency nature of the trial, we expected deviations from the AIRWAYS-2 trial treatment algorithm (see Figure 2). Protocol deviations could arise because paramedics have both strategies available to them. Usual practice follows a ‘step-wise’ approach from simple to more advanced techniques, but paramedics had clinical discretion to adapt airway management during OHCA to the patient’s anatomy, position and perceived needs. The trial protocol specified two attempts using the allocated strategy before proceeding to the alternative, but paramedics had discretion to deviate from the protocol on clinical grounds. Allowing discretion was necessary to avoid a paramedic feeling obliged to undertake an intervention that they believed to be against the patient’s best interests. This was also necessary to gain REC approval and professional support. 27

True crossover was defined as the patient receiving the incorrect intervention on the first airway management attempt; other deviations could occur during subsequent airway attempts. To try to reduce deviations as much as possible, monthly monitoring was carried out; research paramedics were required to follow up protocol deviations with the relevant AIRWAYS-2 paramedic and reiterate the correct procedures. We estimated that ≥ 80% adherence to the AIRWAYS-2 trial protocol was necessary to maintain the integrity of the trial, with < 10% true crossover. 1

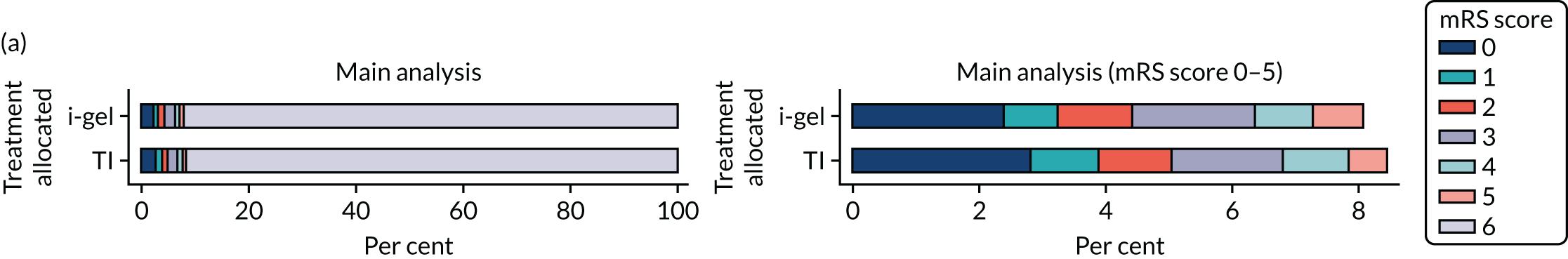

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was mRS score measured at hospital discharge (or 30 days post OHCA if the patient was still in hospital). The mRS is a 7-point scale (0 to 6) widely used in OHCA research. 31,32 Scores are usually dichotomised as good outcome (0–3) or poor outcome/death (4–6; 6 indicates death). The full scale is:

-

0 – no symptoms at all

-

1 – no significant disability despite symptoms; able to carry out all usual duties and activities

-

2 – slight disability; unable to carry out all previous activities, but able to look after own affairs without assistance

-

3 – moderate disability; requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance

-

4 – moderately severe disability; unable to walk and attend to bodily needs without assistance

-

5 – severe disability; bedridden, incontinent and requiring constant nursing care and attention

-

6 – dead.

Patients were conveyed to and followed up in hospital, where mRS scores were collected by assessors blinded to treatment allocation. mRS score was determined by a research nurse, who assessed the patient using a simple flow chart that has been used previously to assess cardiac arrest survivors. 33

With the permission of the Health Research Authority CAG, we were able to collect survival data and mRS score at hospital discharge or 30 days after OHCA for all enrolled patients, regardless of their consent status, thereby ensuring close to 100% ascertainment of the primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes

The trial sought consent from survivors to collect additional data at hospital discharge, 3 months post OHCA and 6 months post OHCA (depending on consent option chosen). The three consent options were:

-

Active follow-up – data were collected from the patient’s medical records and they were invited to complete questionnaires about their ongoing health and well-being at 3 and 6 months post OHCA.

-

Passive follow-up – data were collected from the patient’s medical records, but they were not contacted again or invited to complete follow-up questionnaires.

-

No further involvement – no further information was collected, but it was clearly stated that the information already collected would be retained and included in the data analysis. Anonymity of the participant was assured.

A proportion of participants who experience an OHCA remain incapacitated; therefore, the trial was designed so that a personal consultee (usually a close relative) could provide an opinion on the follow-up option that would probably be preferred by the patient. 26

The following secondary outcomes were collected for all eligible patients, with all but the last two reported by participating paramedics:

-

initial ventilation success, defined as visible chest rise

-

regurgitation (stomach contents visible in the mouth or nose) and aspiration (stomach contents visible below the vocal cords or inside a correctly placed tracheal tube or airway channel of a SGA)

-

loss of a previously established airway (patients with AAM only)

-

sequence of airway interventions delivered (patients with AAM only)

-

ROSC

-

airway management in place when ROSC was achieved, or resuscitation was discontinued

-

chest compression fraction (in a subset of patients in two ambulance services)

-

time to death.

For patients who survived to admission to hospital (estimated to be ≈ 20% of enrolled patients before the trial started), length of intensive care stay and length of hospital stay were also collected. For patients who survived to hospital discharge (estimated to be ≈ 9% of enrolled patients before the trial started), QoL using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), was collected at the time of discharge. For patients who survived beyond hospital discharge, date of death was collected (if applicable), mRS score was collected at 3 and 6 months post OHCA, and QoL (using the EQ-5D-5L) was collected at 3 and 6 months post OHCA.

Chest compression fraction was measured in a subset of patients. Good-quality, continuous CPR is associated with increased survival and improved neurological outcomes following cardiac arrest,19,34 and compression fraction is the standardised way of measuring and expressing this. 35 In this trial, standard resuscitation protocols were agreed with all participating ambulance services. These specified that patients receive continuous chest compressions as soon as an advanced airway device (i-gel or tracheal tube) was placed successfully. Therefore, patients in both groups should receive continuous chest compressions.

The compression fraction is defined as the proportion (or percentage) of resuscitation time without spontaneous circulation during which chest compressions are administered; the higher the compression fraction, the better the quality of CPR and the more likely it is that the patient will survive. 36 Comparison of the compression fraction between the two groups could help to explain the trial findings. Measuring and reporting compression fraction allows heterogeneity between trials to be more consistently described. A suggested mechanism by which SGAs may improve the outcomes of OHCA is a reduction in interruptions to CPR (with an accompanying increase in compression fraction).

Compression fraction is not routinely measured during OHCA in England but it is technically possible. 37 Measurement of compression fraction requires the use of a modified defibrillator, but it was not practical or affordable to measure this in all enrolled patients. Instead, the trial implemented technology that enabled compression fraction to be routinely measured during CPR in a subset of enrolled patients and collected these data alongside the other outcome measures. The technology used was the CPR card (Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway), a small disposable device placed in the centre of the patient’s chest during CPR. The specific device we used gives no feedback to the user but records data that can be retrieved subsequently.

Resource use data to be used for the trial cost-effectiveness analysis and longer-term function were also collected (see Economic evaluation).

Adverse events

Serious adverse events (SAEs) and other adverse events (AEs) were recorded and reported in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines38 and the sponsor (South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust)’s Research Related Adverse Event Reporting Policy.

Data on AEs were collected from the start of the intervention for the duration of the participant’s post-operative hospital stay and for the 6-month follow-up period if the patient consented to ongoing data collection. Any elective surgery/intervention/treatment (e.g. planned non-cardiac surgery) during the follow-up period that was planned prior to enrolment to the trial was not reported as an unexpected SAE.

Serious adverse events

Because all patients in this trial were in an immediately life-threatening situation, events related to cardiac arrest resuscitation (including death and hospitalisation) were expected; therefore, we obtained permission from the sponsor (South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust) and the REC to report events as SAEs or serious adverse device events (SADEs) only if their cause was clearly unrelated to the cardiac arrest.

Unexpected adverse events

Events were reported as SAE/SADEs only if they were serious, potentially related to trial participation (i.e. may have resulted from trial treatment such as use of the SGA device) and were unexpected (i.e. the event was not an expected occurrence for patients who have had a cardiac arrest).

Examples of events that may have been a SAE/SADEs were the use of a SGA causing a new injury that endangered the patient, malfunction of the device causing injury to ambulance clinicians and malfunction of the device leading to inadequate ventilation.

Changes to trial outcomes after commencement of the trial

In April 2015, the primary outcome measure was amended to state that mRS score could be measured either at hospital discharge or 30 days post OHCA, instead of at hospital discharge only. The reason for this change was that some patients were proving to have very long hospital stays. Indeed, in some cases a patient could remain an inpatient for years, meaning that they would never record a primary outcome measure. It was noted that for patients who survived to hospital discharge (or were still inpatients 30 days after their OHCA) the mRS score would be determined by a research nurse who would assess the patient using a simple flow chart that has been used previously to assess patients who have had a cardiac arrest. 33 Any patient who did not survive to discharge would automatically be assigned a score of 6 (dead).

Sample size

In the REVIVE-AIRWAYS feasibility trial, 9% of enrolled patients survived to hospital discharge. 25,39 This was in line with the prevailing rate of overall survival to discharge reported by EMS in England. 4 No data were available for mRS score. However, death and poor functional outcome after OHCA are closely related because death is the most common outcome. 33 Using survival as a proxy for mRS score, a 2% improvement in the proportion of patients achieving a good neurological outcome (defined as an mRS score of 0–3) would be clinically significant, and similar to the 2.4% difference in survival to discharge between TI and SGAs reported in a retrospective analysis. 13

To identify a difference of 2% (8% vs. 10%, i.e. centred on 9%), we calculated that 4400 patients per group (at the 5% level for statistical significance and 90% power) would be required. However, each OHCA was not an independent observation, as the patients are nested within a limited number of paramedics who participated in the trial. Using data from our feasibility trial of 171 paramedics attending 597 OHCAs, we estimated that the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) would be < 0.001. However, when estimating the sample size we assumed a conservative estimate for the ICC of 0.005. Therefore, we required a sample size of 9070 patients (4535 per group).

Paramedic sample size

In our feasibility trial the mean number of patients enrolled per participating paramedic was 3.6 per year. Therefore, to enrol the 9070 patients within the 2-year period of the trial, we estimated that we would need to recruit at least 1300 paramedics. Across the four ambulance services participating in the AIRWAYS-2 trial, there were > 4300 eligible paramedics; therefore, we needed to enrol > 30% of these paramedics.

Interim analyses

A formal 1-year interim analysis of trial data for patients enrolled within the first year of the trial was performed. The purpose of this interim analysis was (1) to determine whether or not there was an unexpected large difference in the primary outcome or in the mortality rates between the two treatment groups that might justify stopping the trial early and (2) to establish whether or not the assumptions underpinning the sample size calculations were still valid. The data and results from this interim analysis were not shared outside the DMSC.

Modified Rankin Scale score and all-cause mortality were the only outcomes that were formally compared. The analyses of mRS score included several subgroup and sensitivity analyses. All other outcomes were described but not formally compared. The criteria for recommending stopping the trial were agreed at the first meeting of the DMSC and documented in the DMSC charter. The agreed threshold for stopping was a p-value ≤ 0.001 for the group comparison in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis of the primary outcome. The results of this analysis, along with patient enrolment figures and success rates, were sent to the DMSC in a preliminary report in July 2016. No adjustments to the sample size or statistical significance levels were made.

Randomisation

In the AIRWAYS-2 trial, the potential participants were unconscious and in need of immediate emergency care, and clinical necessity was therefore the overriding priority. For this reason, it was not deemed feasible to randomise individual patients and a cluster randomised design was considered most appropriate. We chose to randomise the paramedics, treating each participating paramedic as a ‘cluster’. This choice meant that the trial had many clusters, with average cluster size being relatively small (the median number of OHCAs attended by a paramedic annually was three in our previous feasibility trial25), minimising the effect of ICC and the risk of chance imbalances between groups.

Paramedics working in SWAST, EMAS, EEAST or YAS who consented to participate in the trial were randomly allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to one of the two groups: i-gel or intubation (i.e. each paramedic was a randomised cluster). This ensured that the number of paramedics in each group was equal; however, some imbalance in the number of patients enrolled was possible as a result of chance.

The random allocation sequence was generated by the trial statistician using the ralloc command in Stata® version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Blocked randomisation of varying sizes (4, 6, 8) was used and randomisation was stratified by ambulance service, years of paramedic experience (< 5 years’ vs. ≥ 5 years’ full-time operational experience) and urban/rural location of the base ambulance station (≥ 5 miles vs. < 5 miles from the nearest hospital with an ED that receives cardiac arrest patients).

The random allocation sequence was embedded in the database and randomisation was performed by research paramedics using a secure computer system developed by Clinical Trials and Evaluation Unit (CTEU) Bristol, with allocation concealment that could not be changed once allocated. The allocation was not revealed until enough information to identify the paramedic had been entered into the system. 1

To avoid bias caused by paramedics withdrawing from the trial based on their allocation, paramedics were not randomised until halfway through a trial-specific training session; prior to randomisation the trial design and the need for individual equipoise was explained. If the paramedic was willing to treat all OHCA patients they attended during the trial period by either intervention, they gave consent to take part in the trial. The paramedic was then randomised and completed the training session with training that was specific to their allocation. 1 Training comprised theoretical and simulation-based practice over 1 hour, with a brief assessment to confirm competence. For TI, a two-person technique using an intubating bougie was recommended. End-tidal CO2 monitoring was used to confirm correct device placement in all patients.

Blinding

Because of the nature of the intervention, paramedics could not be blinded and were aware of treatment allocations. Therefore, it was necessary to ensure that all eligible patients were enrolled to avoid selection bias. The trial adopted a model whereby every eligible patient attended by a participating paramedic was automatically enrolled in the trial under the waiver of consent provided by the CAG. In this way, the participating paramedics could not influence whether or not a patient was enrolled. However, a disadvantage of this model of automatic enrolment was that the trial protocol might not be followed because the enrolling paramedic could not recall the protocol details (attendance at an OHCA is relatively rare and stressful for paramedics) or the paramedic mistakenly believed the patient to be ineligible.

Ambulance control room personnel were blinded to the allocation of paramedics and followed established protocols when allocating resources to a possible cardiac arrest. This ensured that there was no bias in despatch.

Patients were unaware of their treatment allocation at the time of the intervention and this was likely to be maintained throughout the trial. Research staff assessing outcomes at hospital discharge and at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups were also blinded to treatment group.

Emergency department staff could not be blinded to the treatment group (intubation or i-gel) to which the patient was allocated because the patient would arrive in the ED with either the intubation tube or the i-gel obviously visible in situ. However, we were able to blind clinical staff who cared for the patients beyond the ED to the method of initial airway management used. Therefore, the care of the patient beyond the ED was not affected by knowledge of the intervention used.

Data collection

Data collection included the following elements:

-

a log of all paramedics approached and a record of those who consented to take part in the trial

-

a log of all patients who had an OHCA who were attended by a paramedic within one of the four participating ambulance trusts

-

a log of those attended by an AIRWAYS-2 paramedic (together with details of whether or not resuscitation was attempted)

-

a log of all OHCA patients attended by an AIRWAYS-2 paramedic (where resuscitation was attempted) assessed against the eligibility criteria and, if ineligible, reasons for ineligibility

-

a screening log of all OHCA patients enrolled in the trial who survived to ICU/coronary care unit (CCU) discharge

-

survivors who were approached for consent (including the date that they were given the patient information leaflet) and outcome of the consent process

-

for those who consented to active follow-up, responses to QoL and mRS questionnaires collected at the time of consent and at follow-up at 3 and 6 months

-

key data items from routine data sources for survivors who consented and for those who died prior to discharge from ICU/CCU

-

demographic characteristics of surviving OHCA patients who did not consent and withdrew from the trial.

These data were requested without any direct patient identifiers to maintain anonymity. The following information was sought: NHS number, date of birth, sex and data to characterise socioeconomic status (partial postcode).

Data collection occurred during the out-of-hospital treatment phase, during the inpatient phase of care, at hospital discharge and at 3 and 6 months (± 4 weeks) after the index OHCA (Table 1).

| Data item | Out-of-hospital treatment phase (data collection by paramedics) | Hospital discharge (data collection by hospital staff) | 3 months post OHCA | 6 months post OHCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | ✓ | |||

| Airway management | ✓ | |||

| Demography | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Survival | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Patient movements | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Approached for consent | ✓ | |||

| mRS score | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| EQ-5D-5L score | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Economic data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| SAEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Length of hospital stay/ward movements | ✓ |

Training in data collection and case report form (CRF) (see Appendix 9) completion was provided by the research nurse in each region, co-ordinated and supported by the central trial team at CTEU Bristol. A fixed fee per patient was included in the trial research costs to support the collection of trial-specific outcome data.

To minimise bias, outcome measures were defined as far as possible based on objective criteria. All personnel carrying out an outcome assessment beyond ED care were blinded to help minimise bias.

Identification of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

All eligible patients attended by a participating paramedic were automatically enrolled in the trial under a waiver of consent. Therefore, it was essential to establish mechanisms that would reliably identify every one of these patients. We achieved this by identifying every OHCA (where resuscitation was attempted) that occurred in the participating ambulance services throughout the trial period, along with the subset of patients eligible for trial inclusion. The process to achieve this is described in the following paragraph. It allowed regular review by the DMSC and supported a complete ITT analysis (see Statistical methods, Sensitivity analyses of the longer-term secondary outcomes).

In April 2011, the Department of Health and Social Care introduced survival from cardiac arrest as part of the Ambulance Service National Quality Indicator set. 40 ROSC and survival to hospital discharge rates are reported for all patients who have resuscitation started or continued by a NHS ambulance service after an OHCA. 41 For this reason, all cardiac arrests are routinely identified by ambulance services in England, with regular data collection and return. This process was being strengthened through the introduction of an electronic patient record and a national OHCA registry, based at the University of Warwick. 42 To ensure near-complete patient identification, we used a triangulation method developed during the feasibility trial. 25 Data were collected on all OHCAs occurring within an ambulance service from three separate sources:

-

Direct paramedic report – participating paramedics were asked to complete a CRF immediately after each eligible OHCA that they attended, and to notify the co-ordinating research paramedic by telephone, text or e-mail.

-

Daily review of the ambulance computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system by a project research paramedic to identify all 999 calls from the previous 24 hours identified as suspected or confirmed cardiac arrest, and follow up with the relevant ambulance staff to determine whether or not OHCA had occurred.

-

Regular review of the OHCA data routinely collected by that ambulance trust and reported as part of the Ambulance Service National Quality Indicator set. 40 This is usually based on the clinical record (paper or electronic) routinely completed by ambulance staff after each case that they attend.

Source 1 was the primary data source for the AIRWAYS-2 trial. However, by triangulating data from all three sources it was possible to reliably identify all, or nearly all, OHCAs where resuscitation was attempted during the trial. Although it was possible for an eligible OHCA to be overlooked by this triangulation process, it would require that a cardiac arrest not be reported to the research team by a participating paramedic, not be identified as an OHCA on the CAD and not be picked up by the ambulance trust’s routine identification and reporting system. We estimated that the chance of this happening was very low, thereby ensuring an exceptionally high rate of eligible patient identification that reduced any bias to an absolute minimum.

Out-of-hospital treatment phase (data collection by paramedics)

After treating an eligible OHCA patient, the participating paramedic responsible for airway management completed a CRF to capture baseline and secondary outcome data. The CRF was completed at the same time as routine ambulance service paperwork: immediately after the patient had been handed over to the receiving hospital team or resuscitation attempts had been discontinued at the scene. The CRF was then returned as soon as possible (preferably within 24 hours) to the co-ordinating research paramedic by a secure method chosen by each ambulance trust (e.g. post, secure fax or e-mail). Occasionally, the participating paramedic would not complete the form immediately, in which case they were contacted by the research paramedic subsequently and encouraged and supported to do so.

Even when this did not occur, relevant data could be extracted from the routine ambulance service record within 48 hours, allowing the patient to be followed up to seek consent and collect primary and secondary outcome data. Ambulance services reliably collect data regarding the individuals attending each patient and the time of staff arrival; therefore, for every eligible patient, the attending ambulance paramedic(s), trial allocation and a range of baseline data could be determined with near-100% accuracy.

Hospital discharge (data collected by hospital staff)

Once a patient had been admitted to hospital, the consent and follow-up process was co-ordinated by a research nurse allocated to each participating ambulance service. This was identified as a separate, hospital-based post to ensure that consent and follow-up was blinded to treatment. The research nurse was usually based in the main ‘heart attack centre’ or major receiving hospital for that region. 43

Each research nurse received regular lists of enrolled patients who had been brought to the receiving hospitals in that ambulance service region. The research nurse co-ordinated the process of identification, consent and follow-up data collection with support from the central team. Although the research nurse undertook this personally where necessary, in most cases the consent and follow-up processes were undertaken by existing research staff at the receiving hospitals.

Statistical methods

Enrolled patients who were subsequently identified as being ineligible remained in the trial and were included in analyses, with the exception of (1) patients who were subsequently found to have been previously enrolled in the trial, (2) patients who were inadvertently enrolled in the trial owing to being treated as a trial participant by a paramedic who arrived later than second at the patient’s side and (3) patients who were subsequently identified as being children (aged < 16 years; individuals aged 16 and 17 years were included in analyses). Analyses were undertaken according to the principle of ITT and reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 44,45

Analysis of the primary outcome, and exploratory analyses of secondary outcomes, were performed according to a pre-specified SAP, which was finalised before data lock and any comparative analysis but after the end of patient enrolment due to staff changes in the statistical team. Some typographical errors were corrected in version 2 and some points were clarified, but no substantive changes were made. No comparative post hoc analyses were performed. 27

Non-adherence to allocated group was documented. The trial was analysed on an ITT basis (i.e. outcomes were analysed in accordance with the treatment allocation of the first trial paramedic on scene, irrespective of future management and events, and every effort was made to include all participants treated by a trial paramedic who met the inclusion criteria). Follow-up for the outcome measures during the participant’s stay in hospital and at the 3-month and 6-month time point should have been complete for all participants who consented to take part in the trial.

All analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 unless otherwise stated. For hypothesis tests, two-tailed Wald p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical tests to compare data not listed as outcomes were not performed. All ratio effects are presented as i-gel divided by TI and all difference effects are presented as i-gel minus TI.

Where possible, adjusted differences in proportion of patients (ADPs) experiencing a good outcome were calculated by fitting a model with a binomial family, an identity link and clustered sandwich estimator for paramedic. Risk ratios (RRs) were also calculated, where possible, by fitting a model with a Poisson family, logit link and a clustered sandwich estimator for paramedic.

Data presentation

Continuous variables were summarised using the mean and standard deviation (SD), or the median and interquartile range (IQR) if the distribution was skewed. Categorical variables were summarised as number and percentage.

Adjustment in models

The intention was to adjust all models for paramedic as a random effect and for the three stratification factors included in the randomisation as fixed effects [NHS ambulance trust (YAS, SWAST, EMAS and EEAST), paramedic experience (≥ 5 years and < 5 years) and distance from paramedic’s base ambulance station to the nearest hospital (≥ 5 miles and < 5 miles)]. Where it was not possible to fit paramedic as a random effect, the clustering within paramedic was accounted for using a clustered sandwich estimator, or clustered bootstrap where this was not possible.

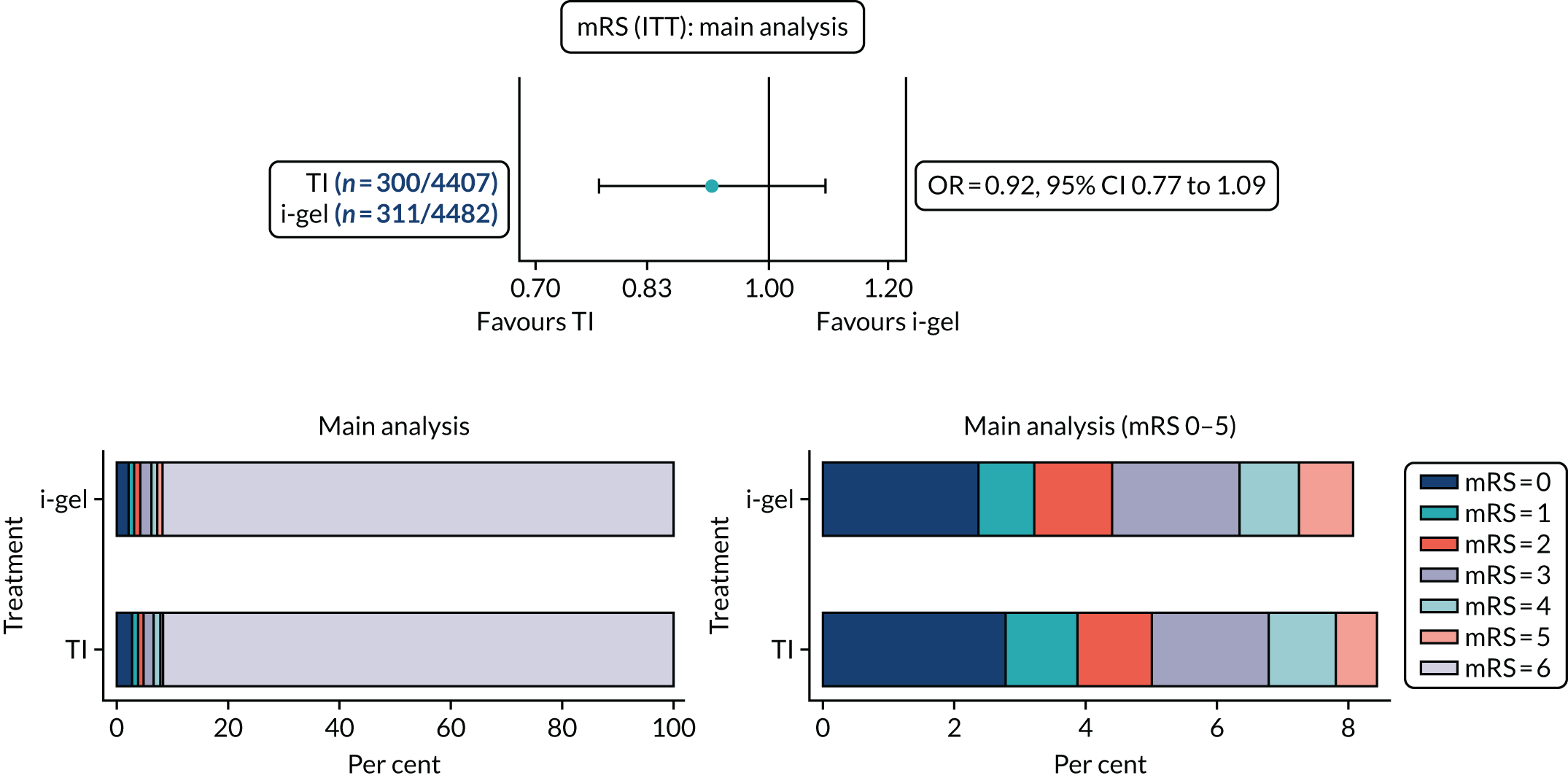

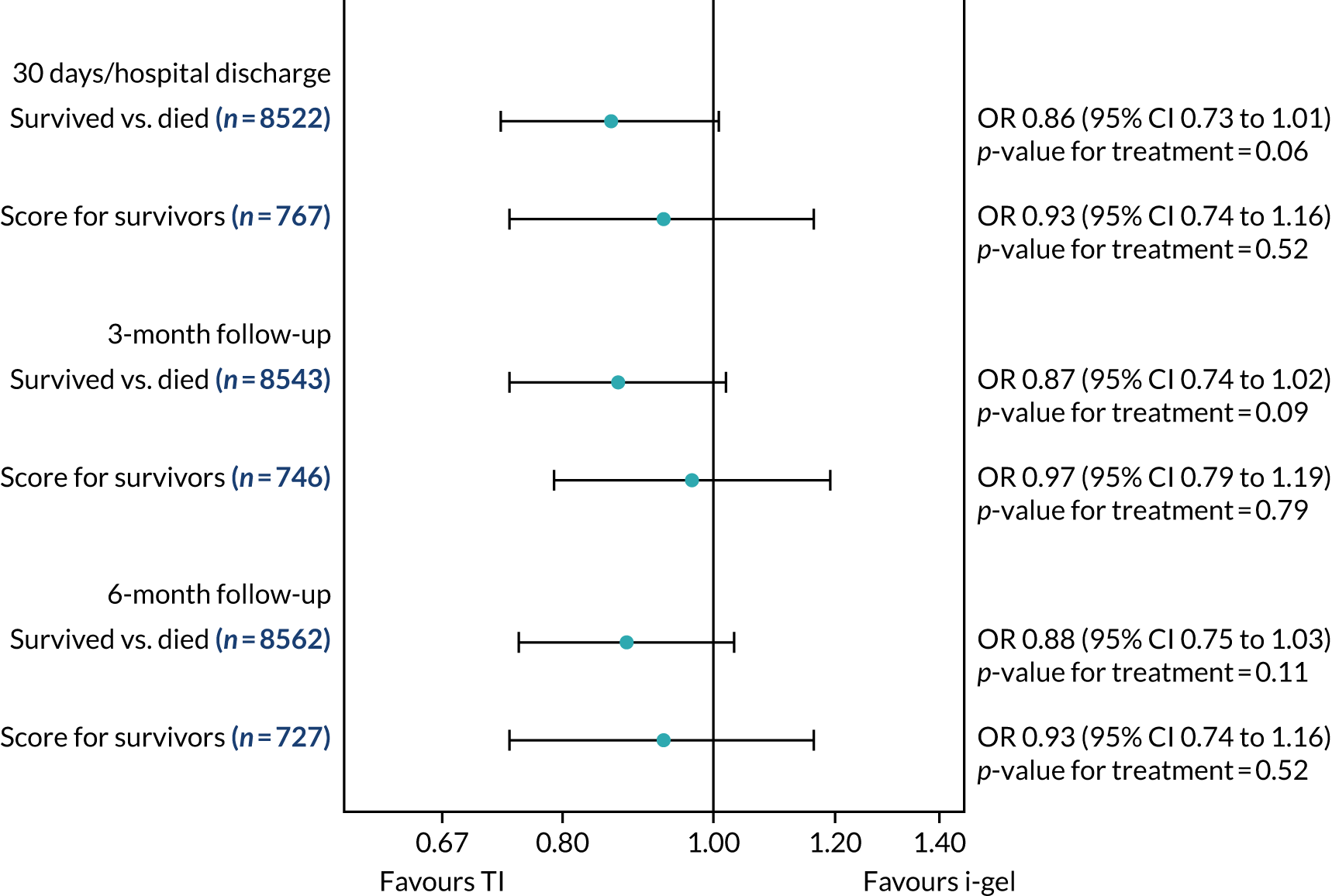

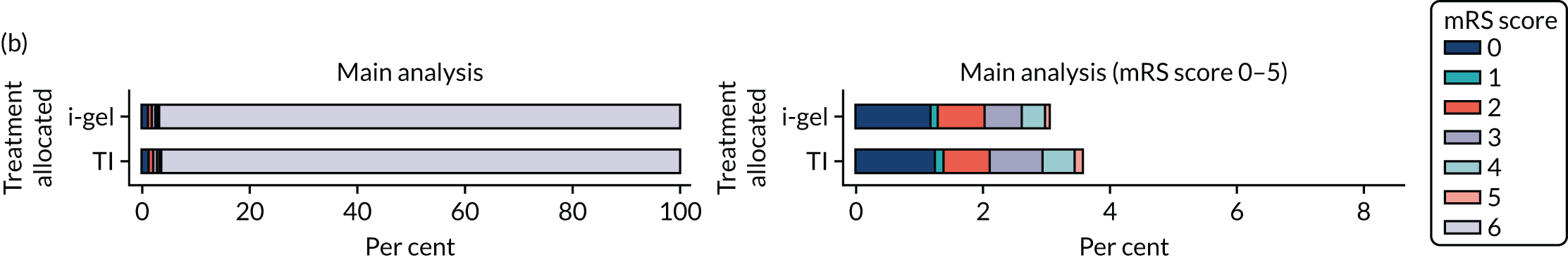

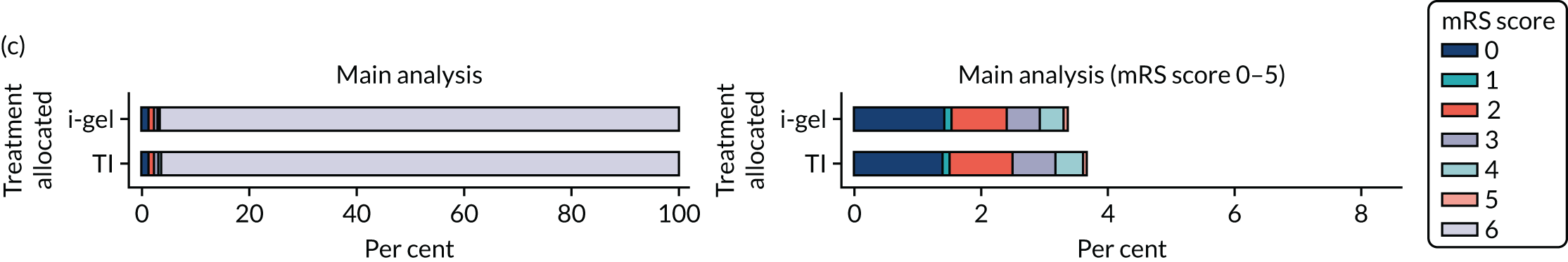

Primary and secondary pre-hospital discharge outcome models

The primary outcome of mRS score at discharge or 30 days post OHCA [presented dichotomously as good functional recovery (0–3) or poor functional recovery/death (4–6; 6 indicates death)], and other binary outcomes were analysed using a multilevel logistic regression model. Repeated mRS scores were analysed using multilevel logistic regression at the separate time points owing to convergence issues. The treatment effects for these models were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Compression fraction was transformed owing to skewness and the log of 100 minus the compression fraction was fitted using a multilevel Gaussian model, with the treatment effect presented as a geometric mean ratio (GMR) and 95% CI.

The following secondary outcomes were described but not formally compared: sequence of airway interventions delivered, airway management in place when ROSC was achieved or resuscitation was discontinued, and length of ICU stay. Time to death or last follow-up was formally compared in place of length of ICU and hospital stays. For time to death (up to 72 hours), patients who were known to be alive longer than 72 hours post OHCA were censored at 72 hours (i.e. given a time to death of 72 hours). For time to death or last follow-up, survivors who did not consent to active or passive follow-up were censored at ICU discharge, survivors who consented and provided 6 months’ follow-up data were censored at 6 months post OHCA, survivors who consented and provided 3 months’ but not 6 months’ follow-up data were censored at 3 months post OHCA, and survivors who consented and provided 30 days’/hospital discharge data but not 3 months’ or 6 months’ follow-up data were censored at hospital discharge.

Both time to death or last follow-up and time to death (up to 72 hours) were analysed using Cox proportional hazards models stratified by NHS ambulance trust to allow for varying baseline hazards and adjusted for paramedic experience and distance from base ambulance station. These models were adjusted for clustering of paramedic using a clustered sandwich estimator and presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs.

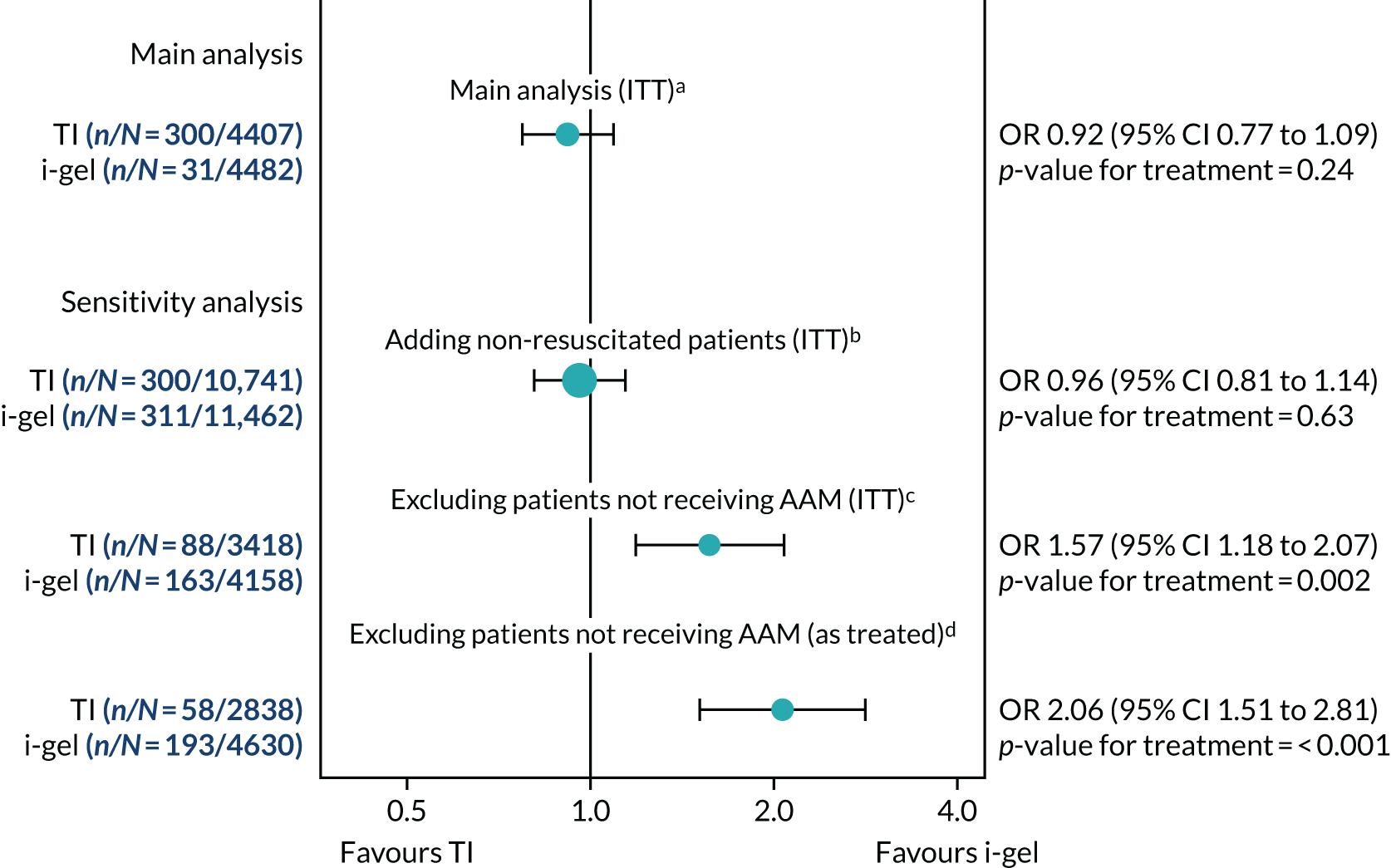

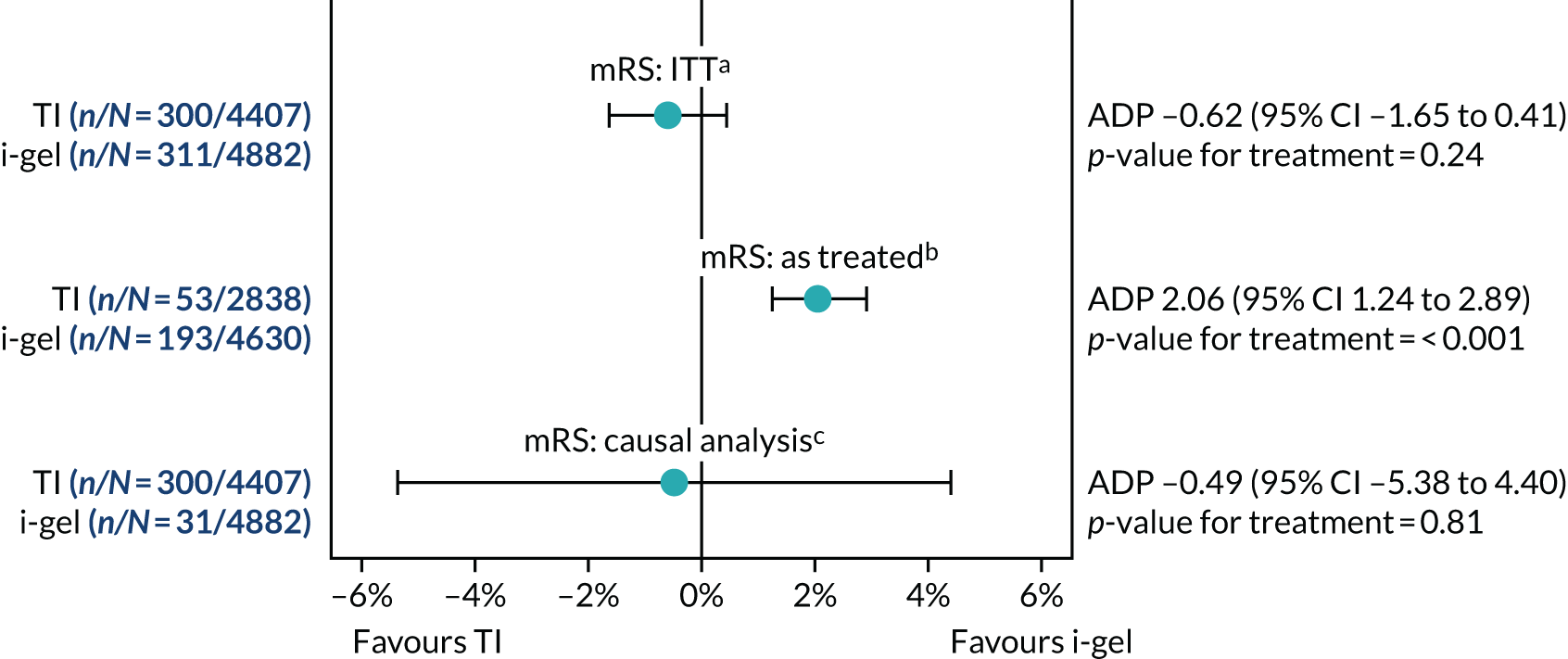

Sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome

Three pre-specified exploratory sensitivity analyses were performed for the primary outcome. The first extended the trial population to include patients attended by a participating paramedic but who were not resuscitated (i.e. trial patients plus non-resuscitated patients). This was prompted by feedback from a pre-planned, closed interim analysis of half the sample considered by the DMSC. 27 The second and third sensitivity analyses, restricted to the cohort of patients who received AAM (as allocated and treatment received comparisons), were planned from the outset. All three sensitivity analyses were analysed using multilevel logistic regression.

Additional analyses of the primary outcome

In the sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome restricted to the cohort who received AAM, patients who did not receive either trial treatment were excluded. Owing to concerns that this analysis could be prone to bias, one additional analysis was performed to assess the causal effect of the treatment received on the primary outcome. This analysis used two-stage least squares with two instruments: randomisation and an indicator of whether one or two paramedics initially attended the OHCA. In the first stage, the treatment received was regressed on the two instruments and the interaction between the two instruments. Predicted probabilities were obtained from the first-stage model. In the second stage, the mRS score was regressed on these predicted probabilities and the stratification factors used in randomisation. For more information relating to the model fitted, see Appendix 4.

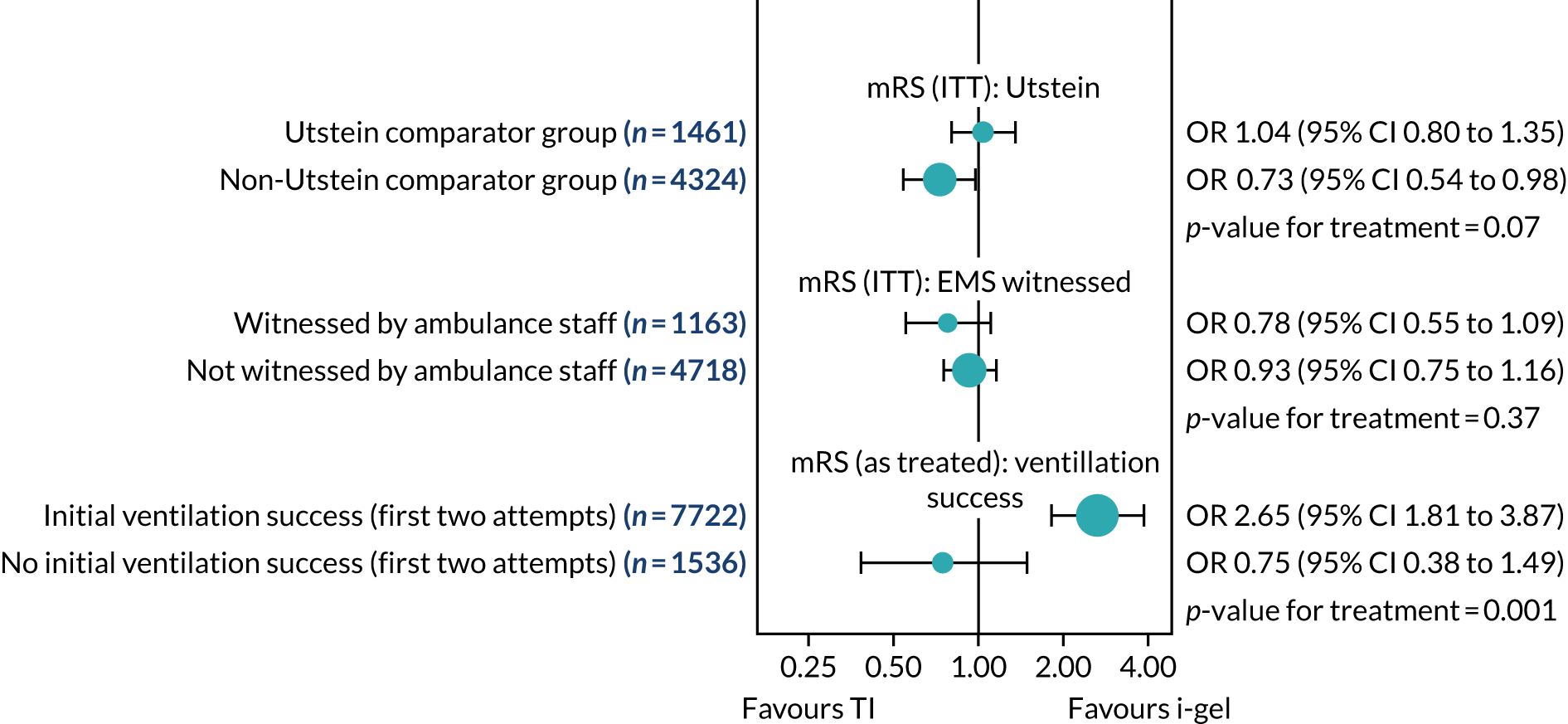

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome

Two subgroup analyses were planned: (1) Utstein comparator group (OHCA with a likely cardiac cause that was witnessed and had an initial rhythm amenable to defibrillation,46 estimated to make up ≈ 20% of the total) versus non-comparator group and (2) OHCA witnessed by paramedic (estimated to make up 6% of the total) or not. These two subgroup analyses were analysed on an ITT basis.

Because of concerns about ventilation success raised during the trial, an additional subgroup analysis of the primary outcome comparing patients whose i-gel or intubation airway management attempt(s) were or were not ‘successful’ during the first and/or second attempt was also performed. This analysis was performed on an as-treated basis (i.e. according to the first AAM the patient had received). In addition, this third unplanned subgroup analysis included patients who had received at least one AAM using an i-gel and/or TI only.

The treatment effects in subgroups were compared by testing for an interaction between paramedic allocation and the subgroup variable. We described the outcomes in the subgroups and tested for differences in the primary outcome between subgroups by including interaction terms in the models, although we recognised that the power to detect such differences was low as the proportions in the subgroups were unequal.

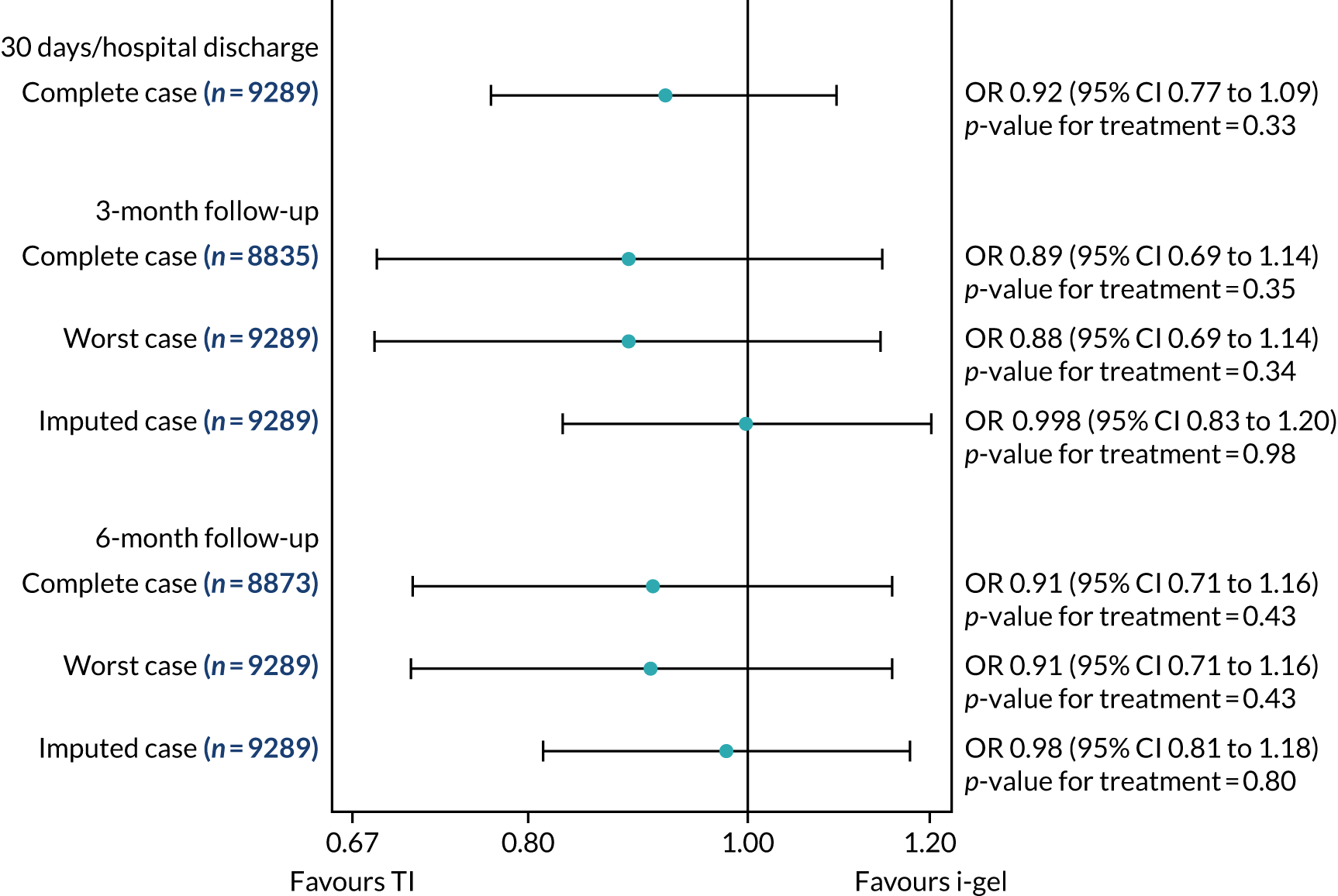

Longer-term secondary outcomes

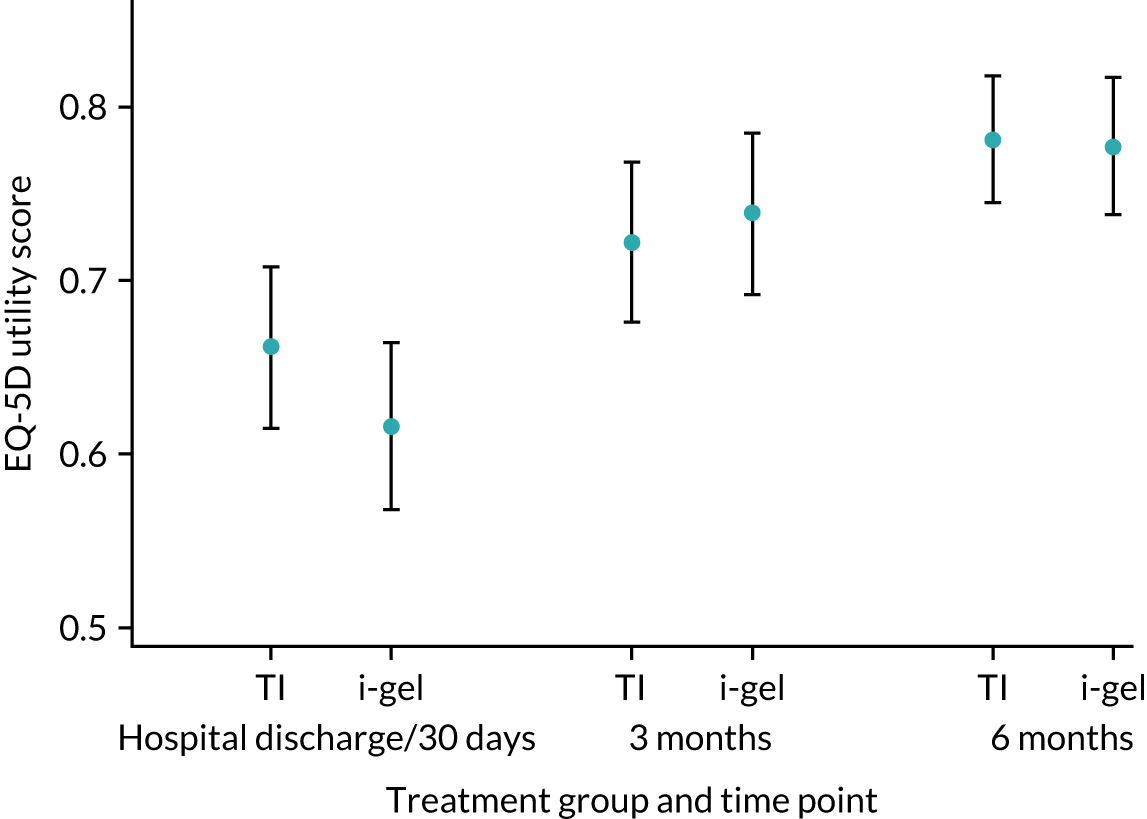

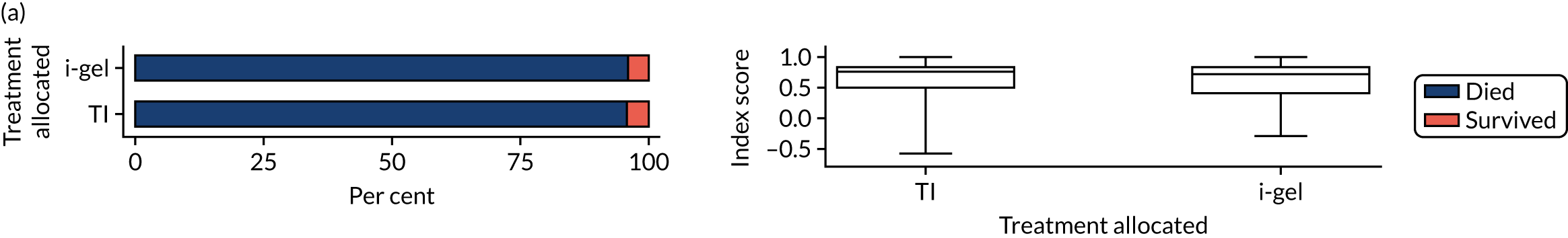

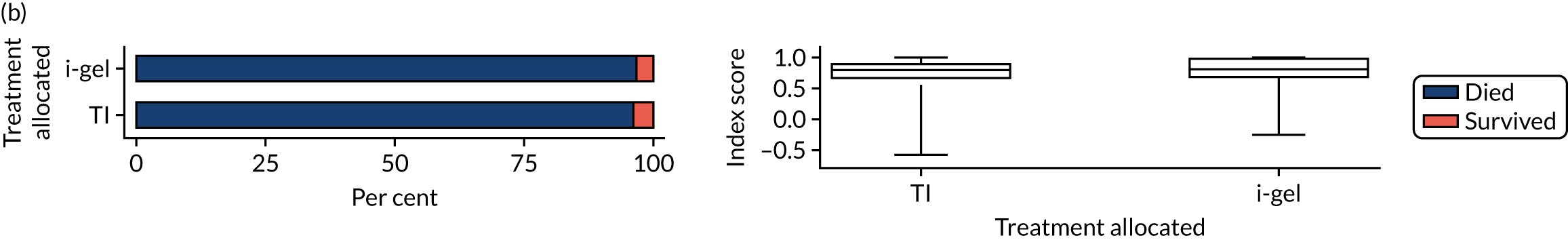

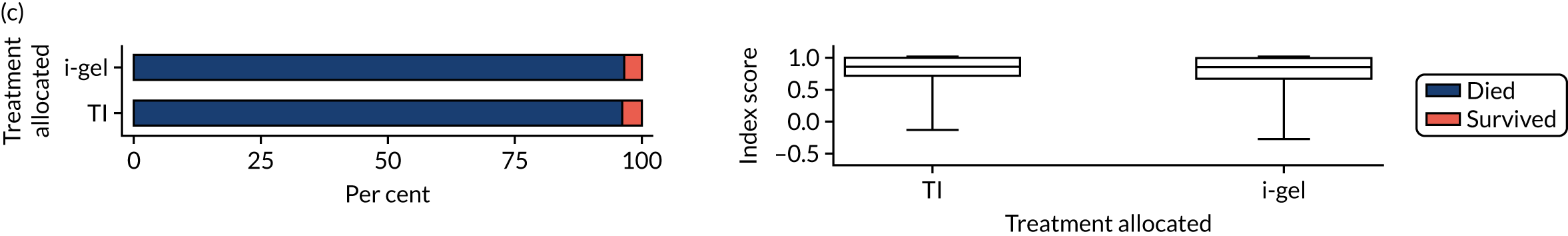

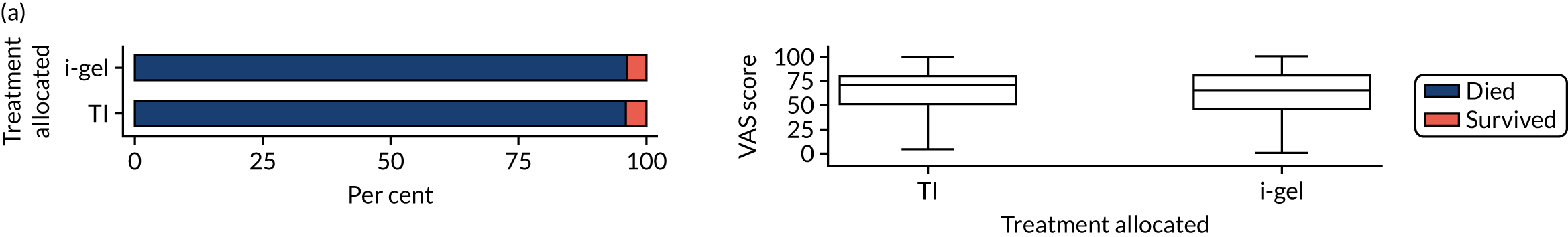

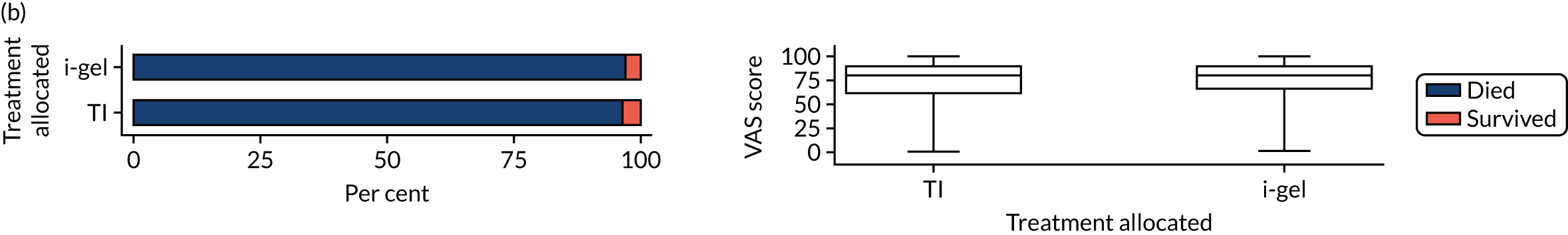

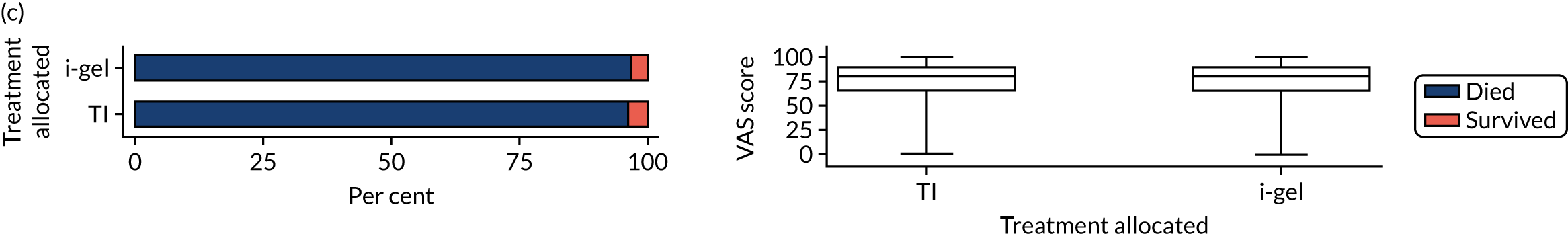

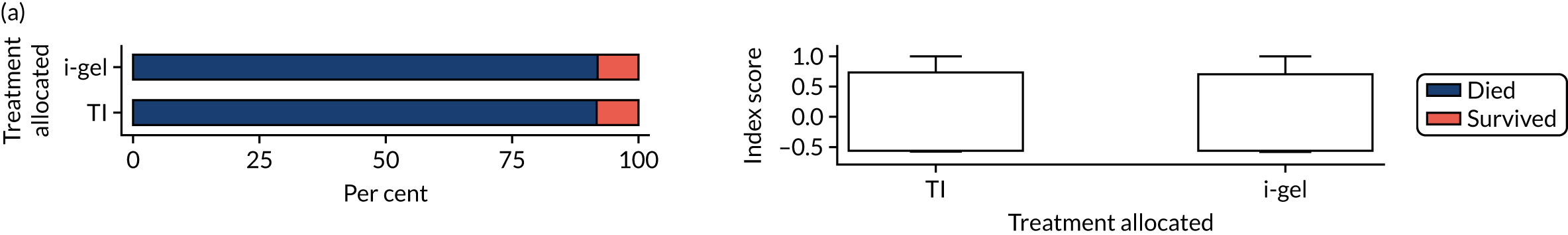

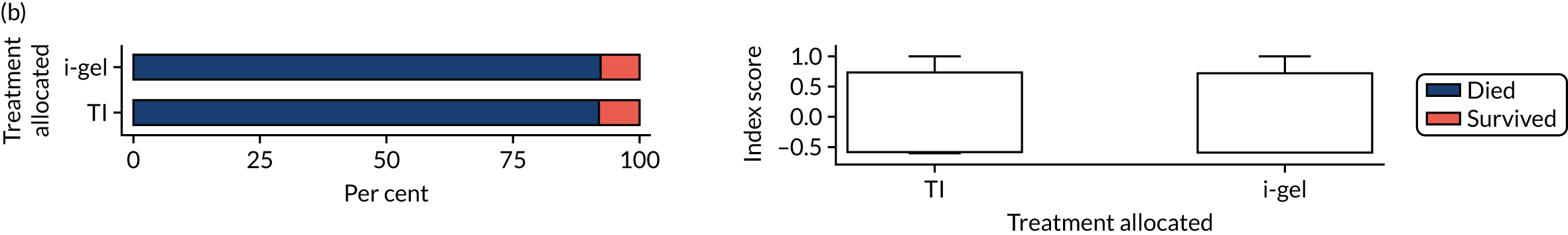

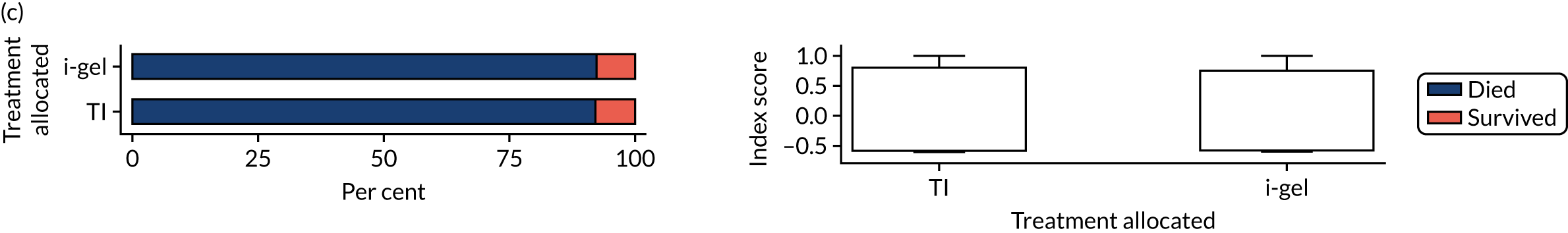

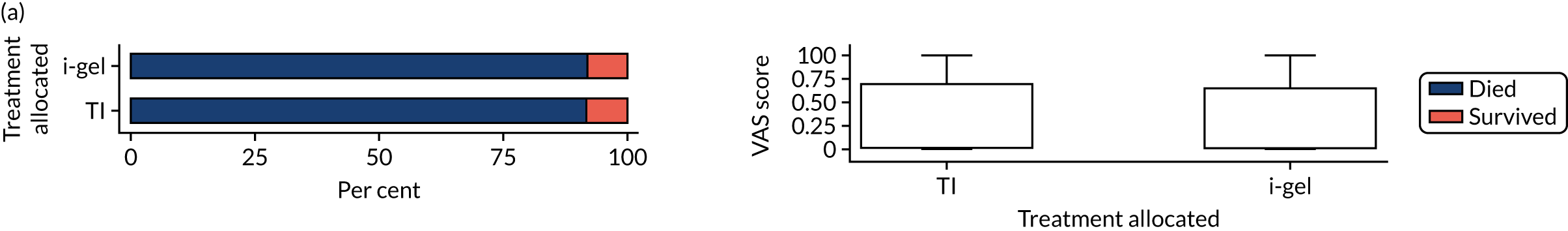

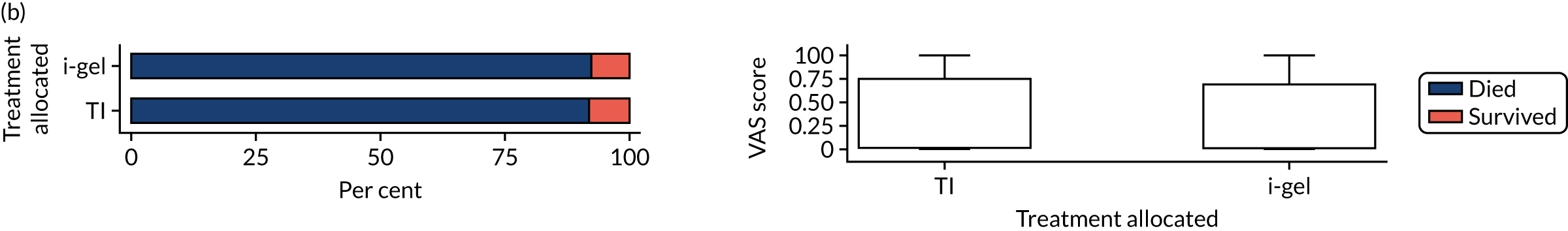

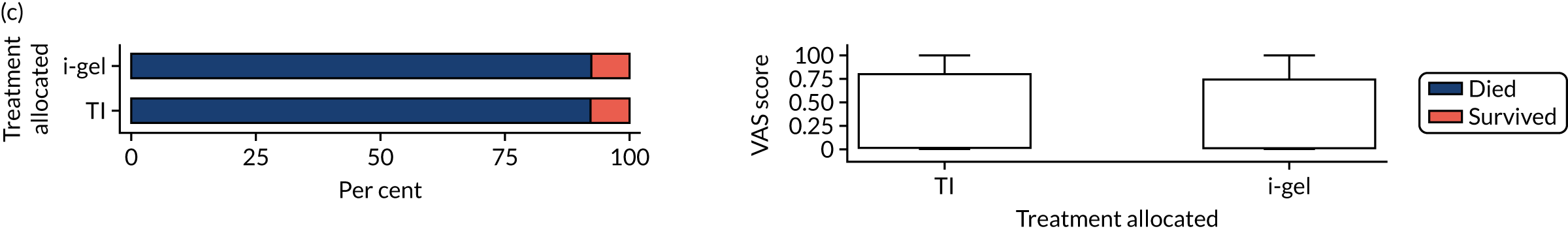

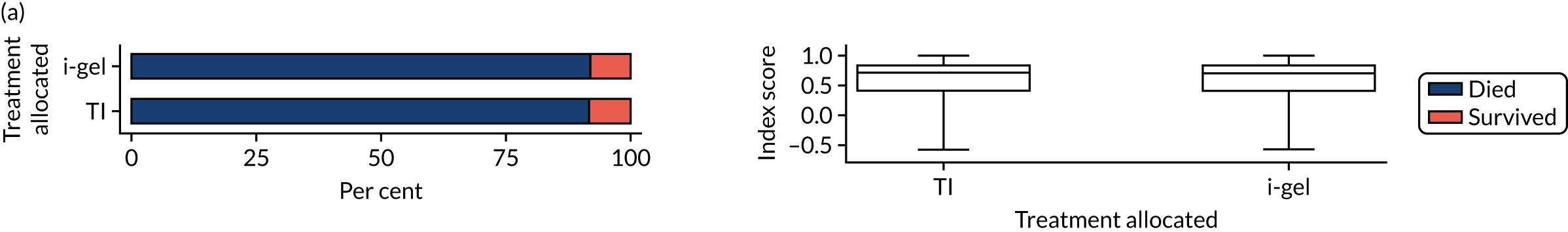

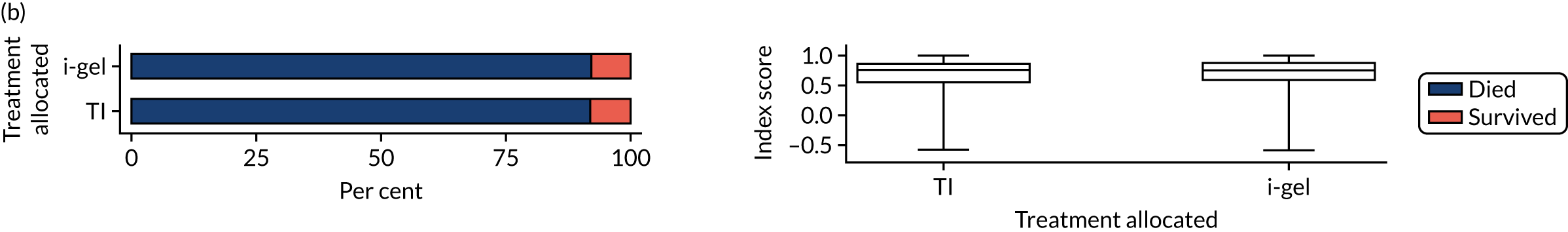

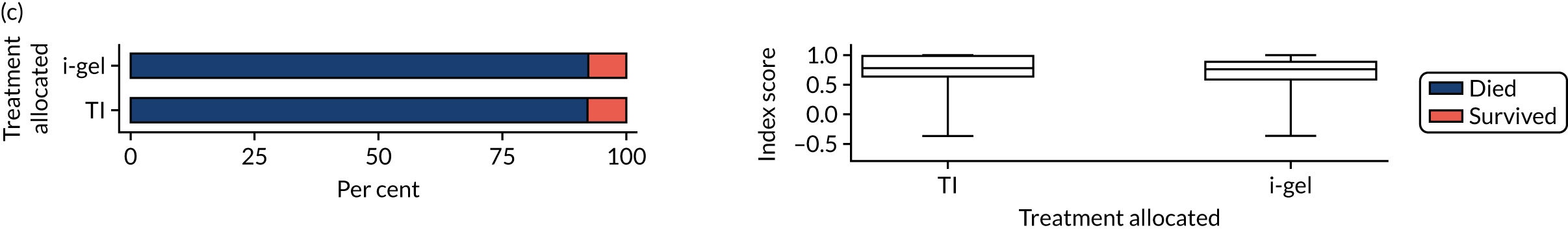

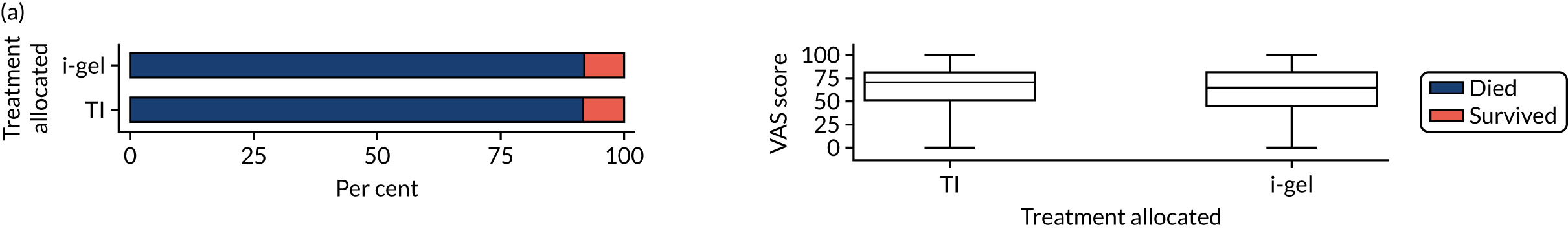

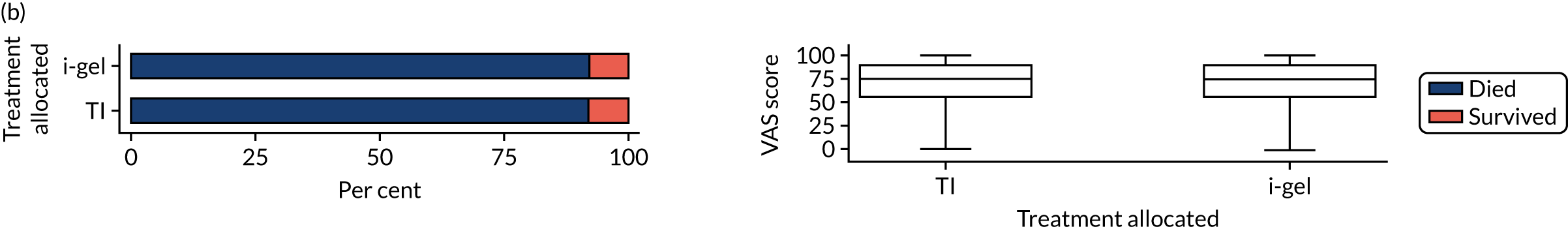

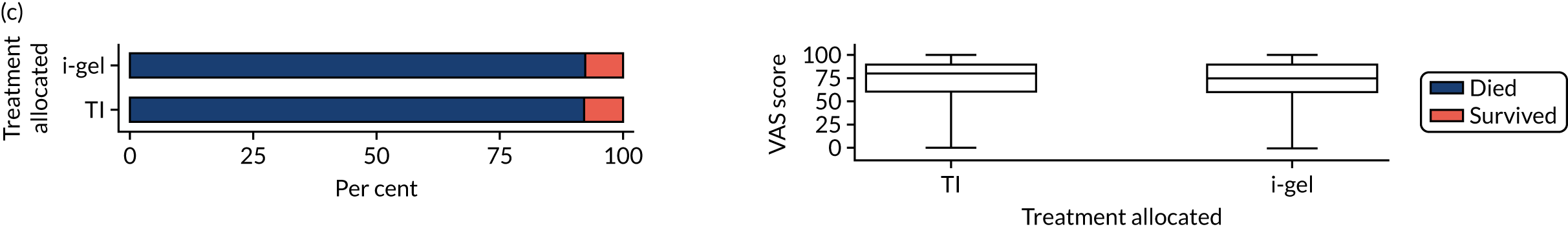

The longer-term secondary outcomes were mRS score measured at 3 months and 6 months and QoL [single summary index and visual analogue scale (VAS)] measured at 30 days/hospital discharge, 3 months and 6 months. These longer-term outcomes were obtained from patients who had survived to the follow-up time points and had provided active consent.

The five dimensions of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression – were described for actively consented survivors. These five dimensions were transformed into a single summary index score using a method that mapped these scores onto the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), value set. 47 A value of 0 was assigned for both VAS and single summary index for patients who had died.

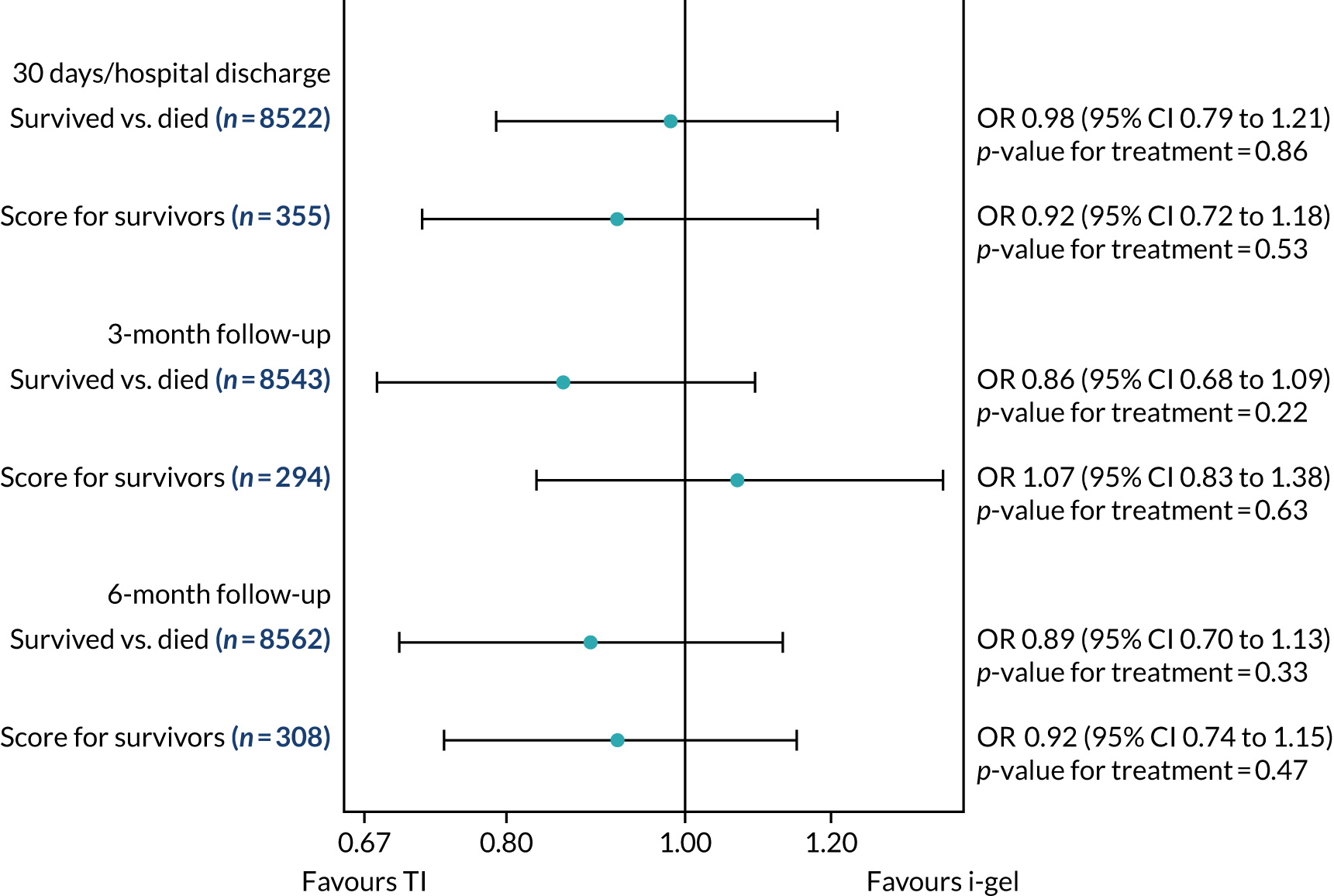

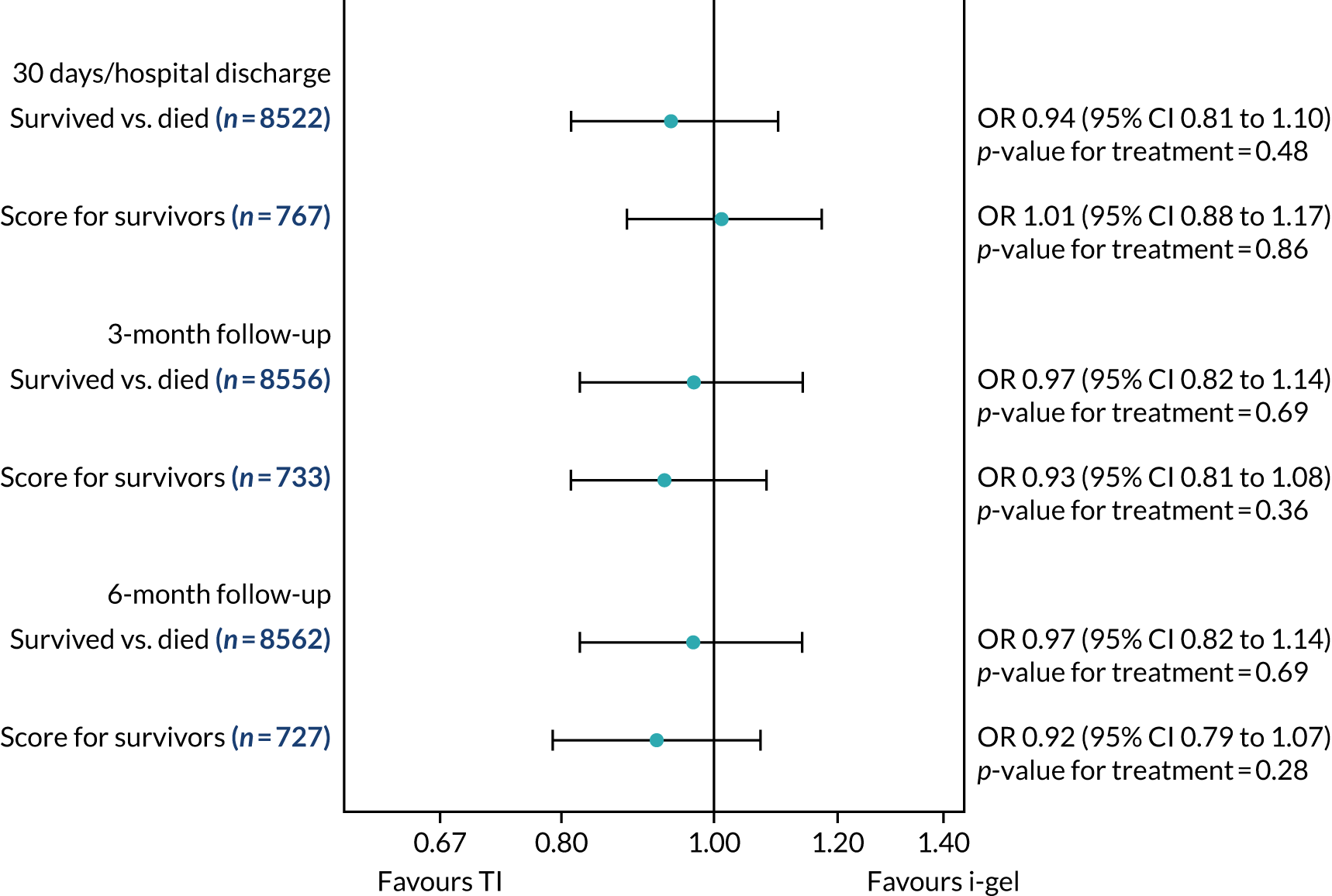

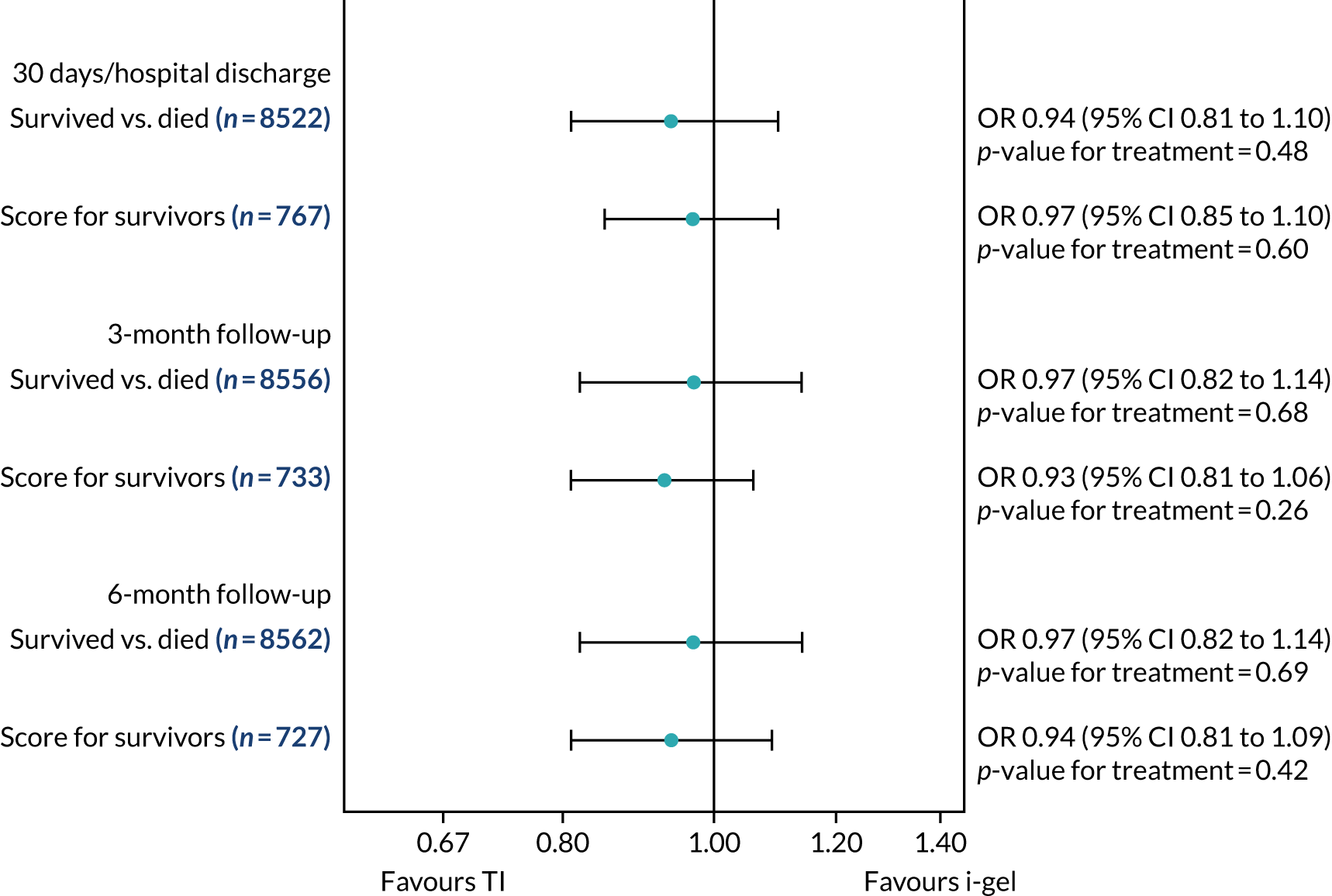

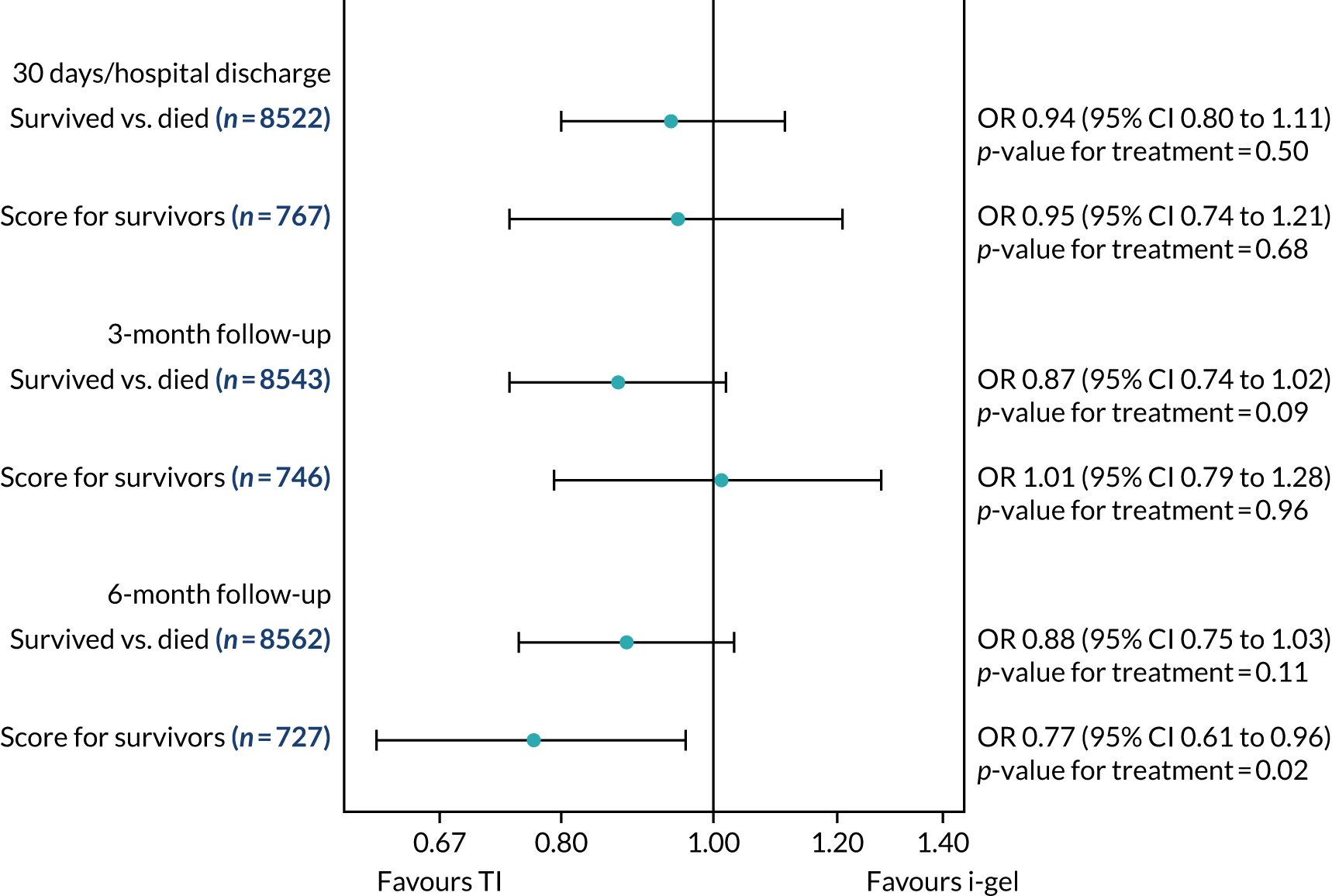

Only patients with outcome data were included in the main analyses of these outcomes (complete-case analysis). The dichotomised mRS scores were analysed using multilevel logistic regression with paramedic fitted as a random effect. Both the single summary index and VAS scores had large spikes at 0 due to the large number of deaths, which meant that a normal or log-normal regression model was inappropriate. Consequently, these two QoL outcomes were analysed using a two-part beta-binomial model. For the purposes of modelling, the QoL scores of survivors were transformed as follows:

where y is the QoL score, a is the lowest possible score (single summary index –0.59, VAS 0), b is the highest possible score (index 1, VAS 100), N is the total number of survivors with data and yn is the transformed score. 48 This transformation was necessary for the purposes of beta regression as it guaranteed that the transformed scores were between 0 and 1 (excluding 0 and 1).

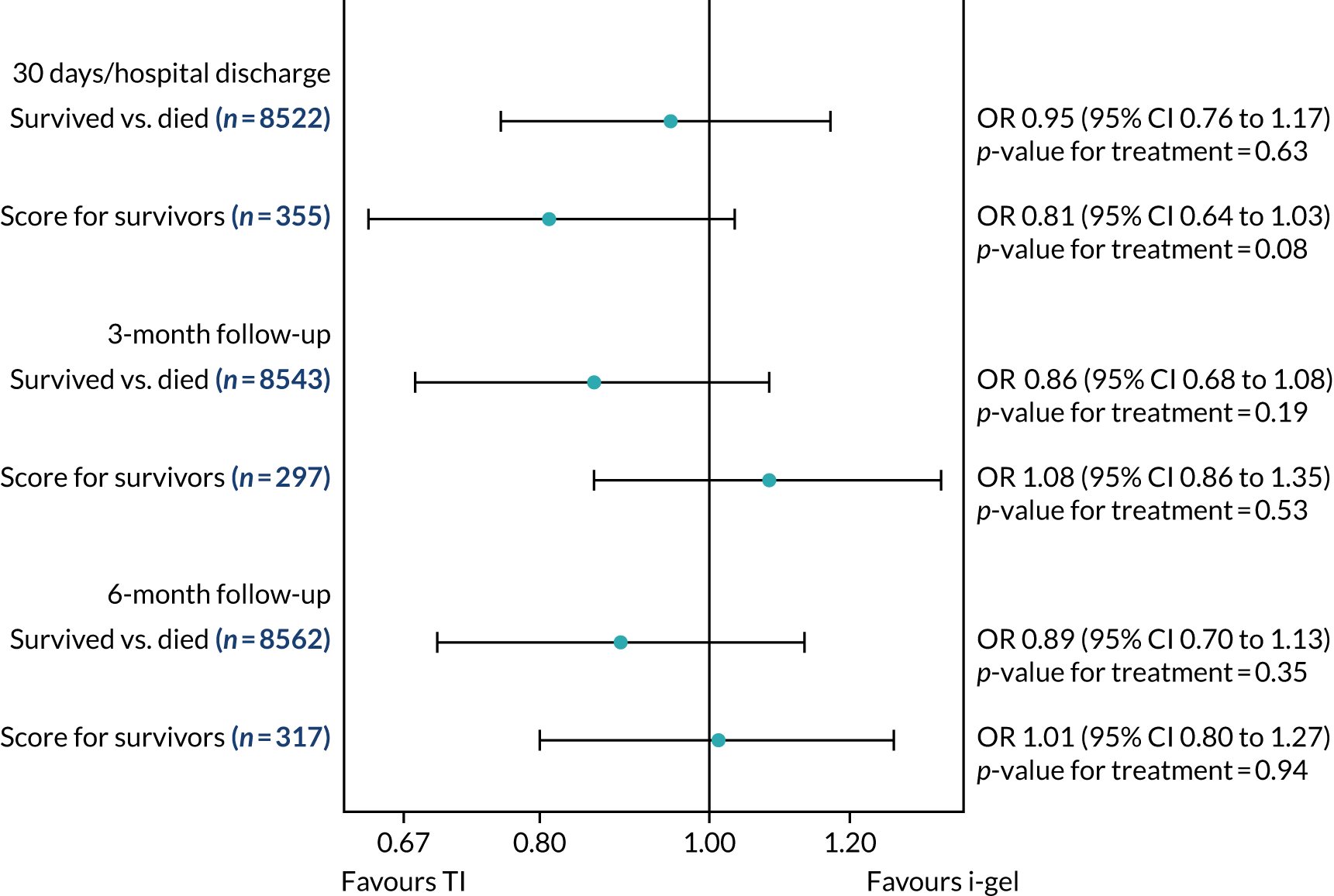

Two estimates were produced from the two-part beta-binomial model. The first, which is the binomial part, is the OR for survival (‘alive vs. dead’). The second estimate, which is the beta part, relates to the QoL of survivors (‘score for survivors’). Thus, these models were able to assess whether or not the use of the i-gel reduces the risk of death and, if the patient survives, assess whether or not it improves the patient’s QoL. An estimate > 1 for ‘alive vs. dead’ means that the odds of survival in the i-gel group is higher than in the TI group. Similarly, an estimate > 1 for ‘score for survivors’ means a better QoL in the i-gel group than in the TI group.

All longer-term outcomes were fitted to each time point separately because convergence issues prevented the fitting of longitudinal models. Convergence issues were also encountered when including paramedic as a random effect in the QoL models. Thus, the CIs were estimated using clustered bootstrapping. 49,50 A total of 1000 cluster bootstrap samples were created by sampling the paramedic clusters with replacement to obtain 1375 paramedic clusters in each bootstrap sample. The ‘alive vs. dead’ and ‘score for survivors’ estimates were obtained from each of the 1000 cluster bootstrap samples by applying the two-part beta-binomial model. The SD of each set of estimates (SDbootstrap) was then used as an approximation of the standard error (SE) and the 95% CIs were estimated using the formula:

Both the clustered bootstrap and two-part beta-binomial models were performed in SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA; SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration) and all other analyses were performed in Stata.

Sensitivity analyses of the longer-term secondary outcomes

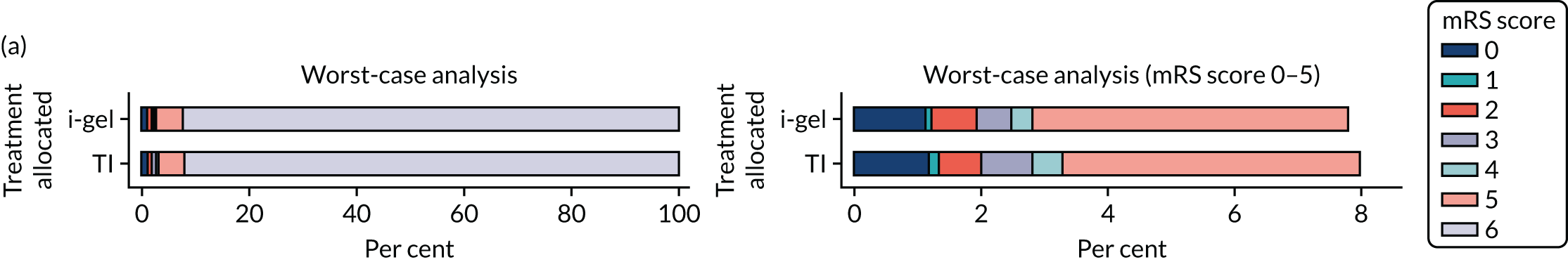

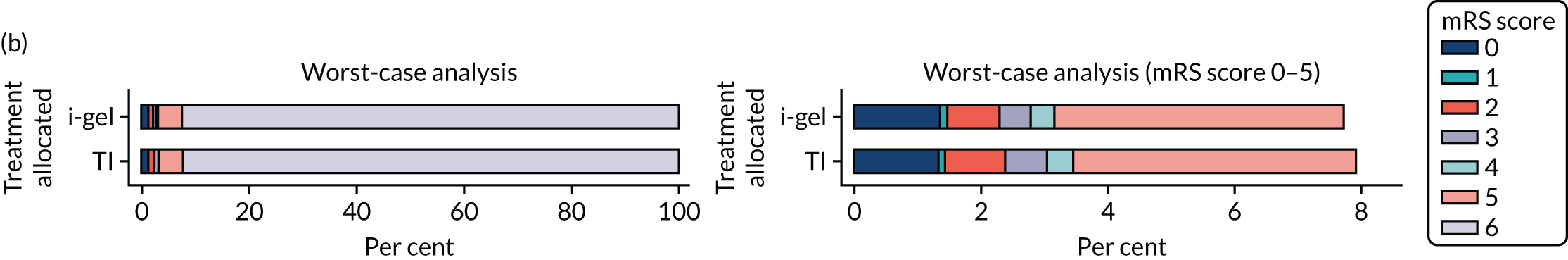

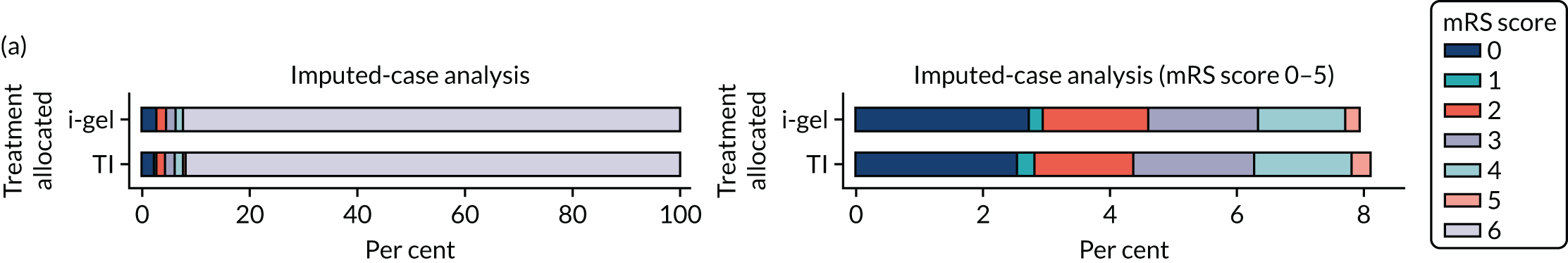

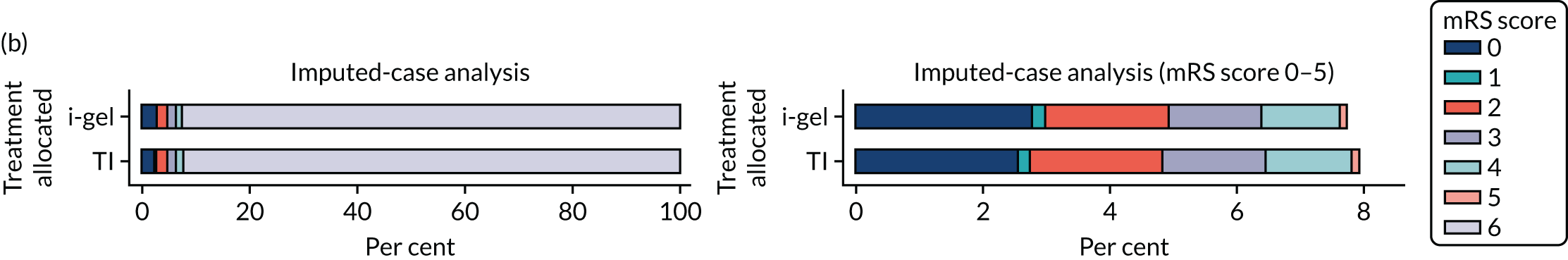

Two sensitivity analyses were performed on the longer-term secondary outcomes to examine the effect of missing data. The first was the ‘worst-case scenario’, in which the worst possible score for a survivor was assigned to known survivors with missing data. In this scenario, patients whose survival status was unknown were assumed to have died. The ‘imputed case scenario’ was the second sensitivity analysis. In this scenario, multiple imputation (60 imputations) was performed using the ice command in Stata. Estimates were combined using Rubin’s rules.

In the worst-case scenario, multilevel logistic regression was performed for the mRS score at 3 months and 6 months post OHCA. The two-part beta-binomial model was used to analyse the QoL outcomes at 30 days/hospital discharge, 3 months and 6 months post OHCA. For the QoL outcomes, the 95% CIs were adjusted using the clustered bootstrap method described in Longer-term secondary outcomes.

In the ‘multiple imputed case scenario’, the variables included in the multiple imputation model were age; sex; length of ICU stay; treatment group; the randomisation stratification variables; and QoL and mRS scores at 30 days/hospital discharge (whichever was earlier), 3 months and 6 months post OHCA. Predictive mean matching was used for continuous variables. The percentages of missing data were calculated for patients who survived to 30 days/hospital discharge (whichever was earlier) for all QoL and mRS score outcomes and time points in turn. The number of imputations (which was 60) was based on the maximum missingness percentage. For mRS score at 3 months and 6 months post OHCA, multilevel logistic regression with paramedic as a random effect was performed on the multiple imputed data sets and the estimates were pooled using Rubin’s rules. In this scenario, the QoL secondary outcomes were analysed using the two-part beta-binomial model. To obtain the cluster bootstrap-adjusted 95% CIs, the clustered bootstrap was performed to produce the 1000 bootstraps samples. This was followed by multiple imputation (60 imputations) on each of the bootstrap samples as recommended by Schomaker and Heumann. 51 Rubin’s rules were then used to combine the treatment estimates in each of the 1000 bootstrap samples and, as described in Longer-term secondary outcomes, the SDs of these two sets of treatment estimates were used as proxies for the SEs in the calculation of the CIs. These analyses were completed using Stata for the multiple imputation and SAS for the clustered bootstrap and model fitting.

Frequency of analyses

The original intention was for the primary analysis to take place when follow-up was complete for all enrolled participants. Formal interim analysis was planned at the mid-point of patient enrolment (after 12 months) and was presented to the DMSC. Safety data were reported together with any additional analyses the committee requested. In these reports the data were presented by group, but the allocation remained masked.

During the sixth DMSC meeting in September 2017, the DMSC recommended that the primary outcome be analysed prior to completion of patient follow-up and published first. There were three main reasons for early reporting: (1) to realise patient benefit as soon as possible, (2) to inform policy and guidance at a time of increased interest in the future of TI52 and (3) to co-ordinate with publication of the PART, a comparable trial undertaken in North America. 53 The DMSC was happy for this to take place if all relevant data fields could be locked down. This proposal was discussed with and agreed by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) at their fourth meeting in October 2017.

Economic evaluation

Economic evaluation aims and objectives

The economic evaluation aimed to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of the i-gel compared with TI in non-traumatic OHCA adults in line with the AIRWAYS-2 trial.

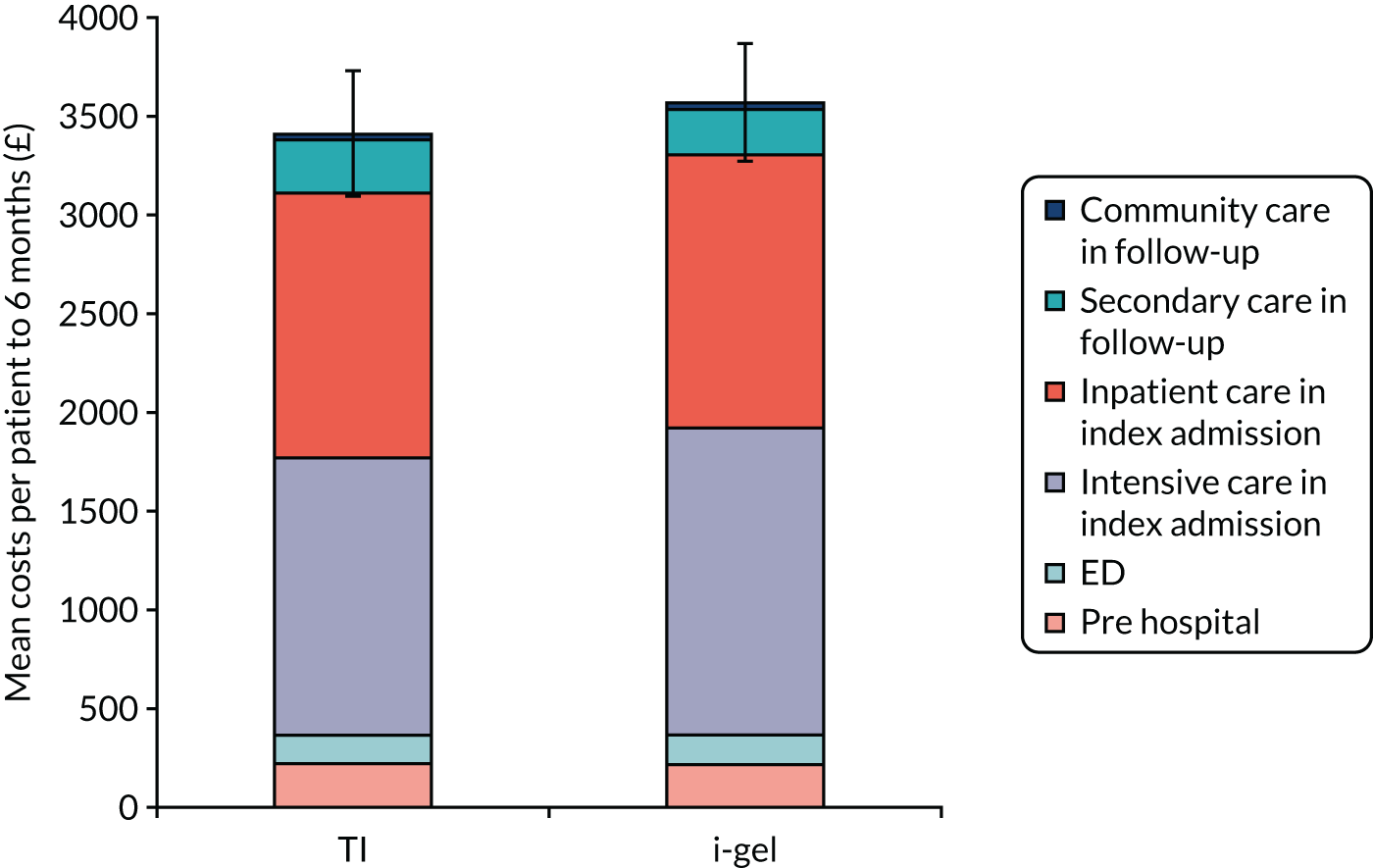

Economic evaluation overview

The perspective of the evaluation was that of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS), as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 54 The perspective for outcomes was that of the patients undergoing treatment. The primary outcome measure for the cost-effectiveness analysis was quality-adjusted life-year (QALYs), estimated using the EQ-5D-5L. 55,56 Good practice guidelines on the conduct of economic evaluations were followed. 54,57,58 Table 2 summarises the key aspects of the economic evaluation methods.

| Aspect of methodology | Strategy used in base-case analysis |

|---|---|

| Form of economic evaluation | Cost-effectiveness analysis for comparison between the i-gel and TI |

| Perspective | NHS and PSS |

| Time horizon | A within-trial analysis, taking a 6-month time horizon |

| Data set | All trial patients were included (see Data set) |

| Costs included in analysis | Pre hospital:

|

| Utility measurement | EQ-5D-5L (administered at hospital discharge and at 3 and 6 months post OHCA) |

| QALY calculations | Assume that patients’ utility changes linearly between utility measurements |

| Missing data | Multiple imputation |

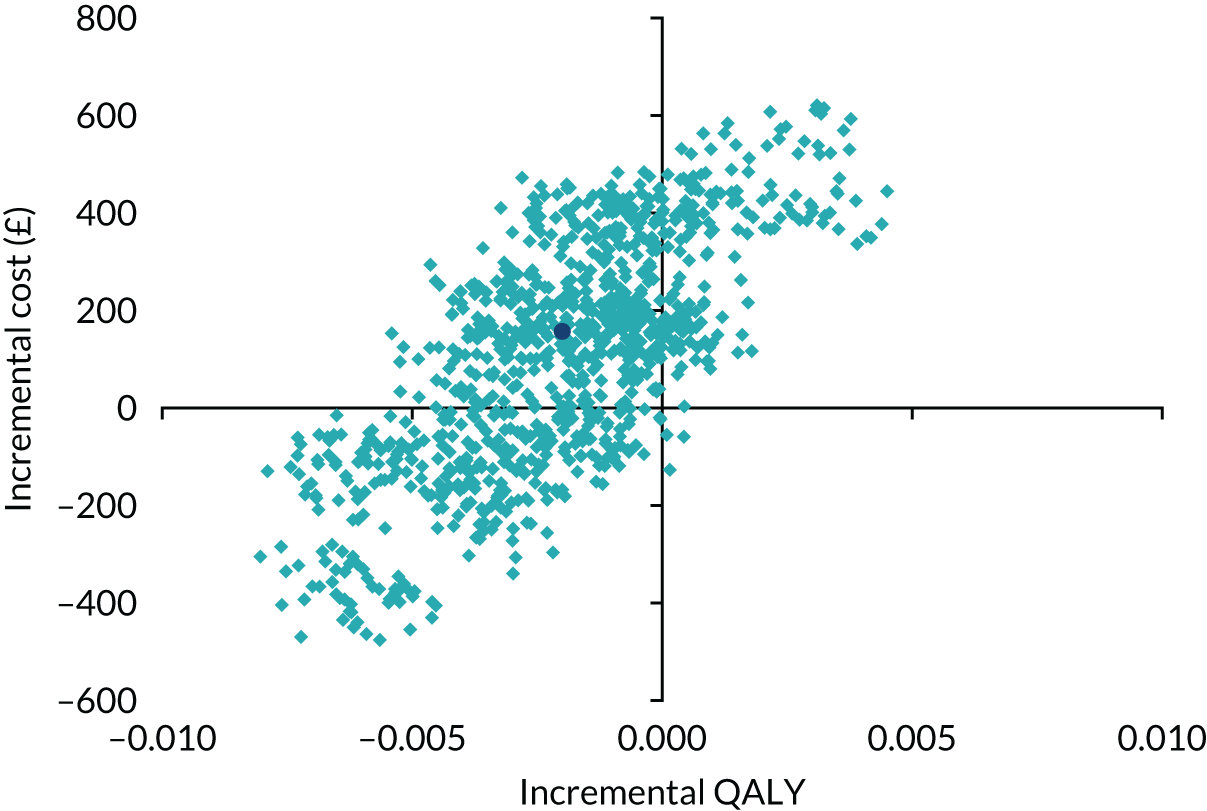

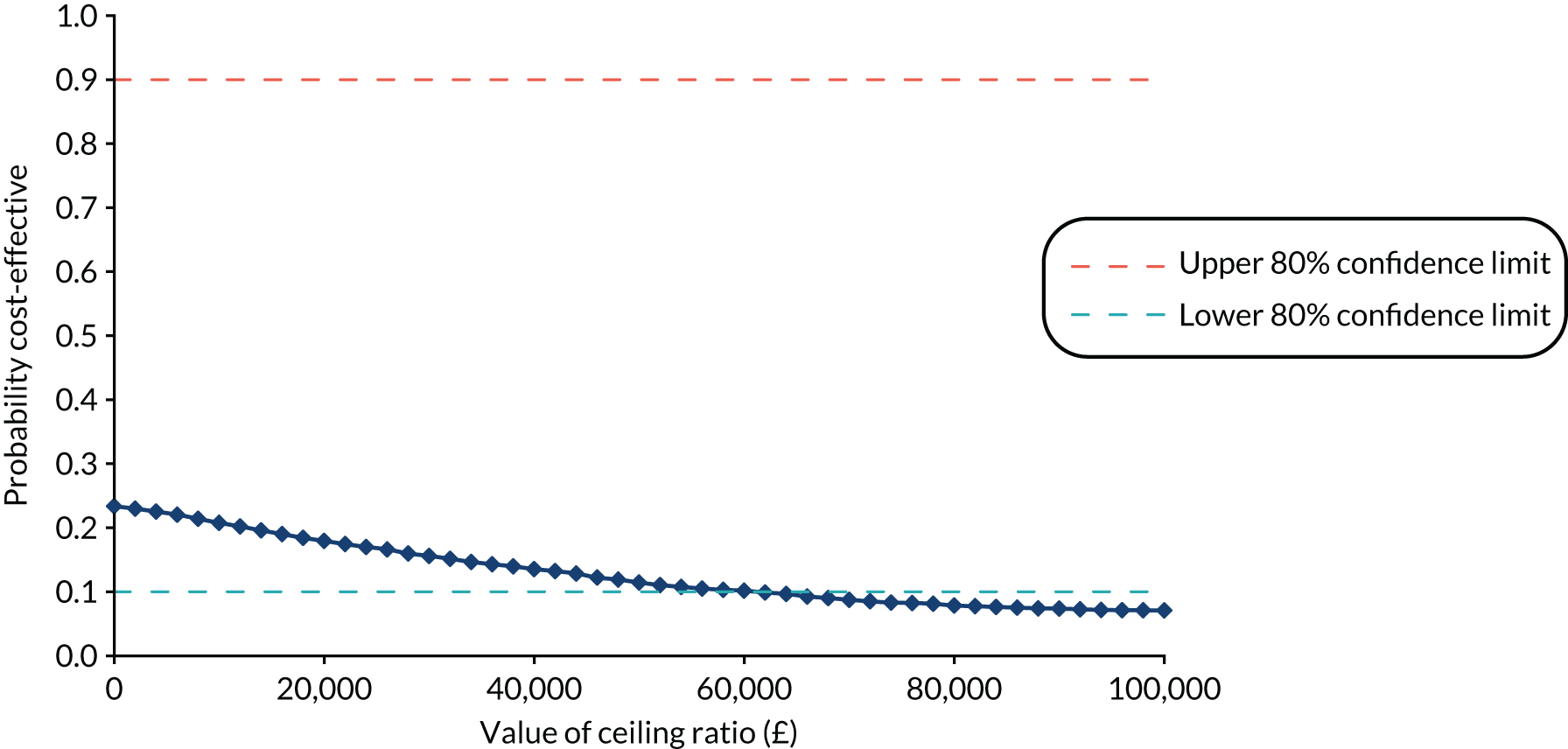

Form of analysis, primary outcome and cost-effectiveness decision rules

A cost-effectiveness analysis (specifically a cost–utility analysis) using QALYs as the primary outcome measure was conducted, as advocated by NICE. 54 QALYs combine both quantity of life and QoL into a single measure. Incremental costs (the difference in mean costs between the i-gel and TI groups) were divided by incremental QALYs (the difference in mean QALYs between the groups) and presented as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which quantifies the incremental cost per QALY gained by switching from using TI to i-gel. The economic evaluation analyses were performed on an ITT basis.

The i-gel was considered cost-effective if the ICER fell below £20,000, which is generally considered to be the threshold that NICE adopts for considering an intervention to be cost-effective. 59

Time horizon

A within-trial analysis, taking a 6-month time horizon, was conducted. It was anticipated that all major resource use would occur within this time frame and, therefore, be captured. Our time horizon began when the first paramedic arrived at the OHCA scene and continued until 6 months later.

Data set

The base-case analysis included all trial patients (see Economic evaluation overview), except seven patients who were transported to hospital but could not be identified and were lost to further follow-up (three randomised to TI and four randomised to i-gel). It was felt that there was insufficient information on these patients to reasonably impute their follow-up data.

Collection of resource use and costs

Resource use data were collected on all significant health service resource inputs for the trial patients to the end of the 6-month follow-up period. Detailed resource use data on the pre-hospital phase in the patient care pathway were collected on the trial CRFs, and inpatient data were largely obtained from HES data sets. CRFs for the pre-hospital phase were completed by the paramedics attending the OHCA patients and by the research paramedics using data from the ambulance CAD system. A small amount of inpatient resource use was captured on the in-hospital CRFs, and primary and community care resource use post hospital discharge was captured on the follow-up questionnaires at 3 and 6 months post OHCA for patients who consented to follow-up. The main resource use categories costed are listed in Table 3, along with details of the sources of unit cost information for each resource category.

| Resource | Source(s) | Source(s) of unit cost information |

|---|---|---|

| Airway devices used and management at the scene (pre hospital) | Trial CRF | NHS Supply Chain Online Catalogue60 |

| Ambulance staff (and vehicles) attending the scene (pre hospital) | Trial CRF | NHS Employers Agenda for Change pay scales 2017/18;61 ambulance trusts |

| Index ED attendance | Trial CRF; HES | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 62 |

| Admission to a ward, and length of stay by level of care | Trial CRF; HES | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 62 |

| Operations and procedures (e.g. CT scan, percutaneous coronary intervention) | HES (or trial CRF) | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 62 |

| Hospital re-admissions | HES (or trial CRF); 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 62 |

| Outpatient and ED attendances | HES | NHS Reference Costs 2017/18 62 |

| Community health-care contacts | 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2018 63 |

| Long-term care, or stays in nursing/residential homes | Trial CRF (discharge destination); 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2018 63 |

| Equipment and aids | 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2018 63 |

Availability of resource use and cost data

Given the large numbers of patients and hospitals involved in the AIRWAYS-2 trial, the trial CRFs asked limited numbers of questions on health-care resource use. The intention was to make use of routinely held data and collect the majority of secondary care resource use from HES. Because we had several issues obtaining data from four HES data sets (ED, inpatients, critical care and outpatients), we made contingency plans early in the trial to mitigate the risk of not receiving all the HES data we would need for the trial cost-effectiveness analysis.

At the outset of the trial, some additional resource use data items were added to the trial data collection forms. Detailed information on trial CRFs captured the date and time of movements between different levels of care during the inpatient admission. An additional question was also added to the 3- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires asking about overnight hospital stays. However, without HES data we would have no information on interventions and procedures patients receive in hospital (notably CT and percutaneous coronary interventions) nor any information after hospital discharge about further contact with secondary care (re-admissions, outpatient appointments, subsequent ED visits) beyond the information described above on the number of additional nights in hospital captured on the follow-up questionnaires.

To further mitigate against a possible lack of HES data as the trial neared completion, we asked the top five hospitals (i.e. the five hospital trusts that had received the most patients) in each of the four ambulance trust regions enrolling patients to the trial for some additional data for up to 50 AIRWAYS-2 patients taken to their hospital. For the index admission, this additional retrospective CRF captured the number of CT and magnetic resonance imaging scans, angiograms performed (and whether or not these included a percutaneous coronary intervention) and any other surgery. For the period from hospital discharge to 6 months post OHCA, the trial CRFs captured information on hospital re-admissions (length of stay and number of days in intensive care) and any other surgery. We sought information on a random sample of 50 patients taken to each hospital (or all patients taken there if this was < 50), sampled in the following ratio: one-third died in the ED, two-thirds admitted to hospital. This extra data collection was made possible by support from the NIHR critical care clinical specialty leads and research nurses.

The intention was for these secondary care resource use data, captured for a sample of AIRWAYS-2 patients on trial CRFs, to be summarised and costed. The mean resource use and associated costs would then be calculated for three subgroups of patients:

-

patients who died in ED

-

patients who survived to hospital admission but died in hospital

-

patients who survived to hospital discharge.

The mean costs of procedures and scans in hospital, and re-admissions, calculated for these subgroups would then be applied to all AIRWAYS-2 patients who were brought to hospital. However, these data were not used, because HES data were obtained and used in our primary analysis. However, having collected these additional data, an extension to this work will compare this resource use and associated costs with the HES data.

Although there was very good case ascertainment for three of the HES data sets received, there were considerably fewer patients in the critical care data set than expected. Based on CRF data, 1450 patients were admitted to intensive care following their OHCA; however, the HES critical care data set contained records for only 314 patients. Given this wide disparity between data sources, we did not use the HES critical care data set; time in intensive care was taken from the CRFs instead. NHS Digital has kindly investigated this issue. The original request for each identified patient was for data from the date of OHCA to 6 months post OHCA. It appears there may be an issue with dates: from a preliminary check, HES critical care records relating to ≈ 1250 patients were identified when data from date of OHCA minus 7 days through to 6 months were extracted, much more in line with expectations. However, it is still unclear why this issue exists. There was a considerable amount of data cleaning required for the resource use figures. For further details, see Appendix 5.

Attaching unit costs to resource use

Unit costs for hospital and community health-care resource use were largely obtained from national sources, for example NHS Reference Costs for ward costs, scans and surgery,62 and Unit Costs of Health and Social Care for community costs. 64,65 Resources were valued in 2017/18 Great British pounds, and any unit costs not in 2017/18 prices have been adjusted to 2017/18 prices using the NHS Cost Inflation Index (NHSCII). 66 For a summary of the sources of unit cost information, see Table 3. For further details on all unit costs and their sources, see Appendix 6.

Measurement of health-related quality of life and quality-adjusted life-years

Measurement of health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D-5L, advocated for use in economic evaluations by NICE,54 was used to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL). 55,56 The EQ-5D descriptive system is a generic measure of health outcome covering five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Responses to this multiattribute utility scale can be converted to a single index value. The EQ-5D also includes a VAS for patients to rate their overall current health, but that response was not used in the economic evaluation. The EQ-5D-5L was completed by patients at three time points: at hospital discharge (or 30 days if sooner) and at 3 and 6 months post OHCA. Although data were gathered using the EQ-5D-5L (i.e. the five-level version, with five possible responses for each dimension), responses recorded on the instrument were converted into a single index value using the original three-level UK valuation set. 67 Scores were then used to facilitate the calculation of QALYs. Utility values were calculated by mapping the five-level descriptive system to the three-level valuation set using the crosswalk developed by van Hout et al. ,68 in line with NICE recommendations at the time of analysis. 69

Baseline utility