Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 06/59/01. The protocol was agreed in November 2006. The assessment report began editorial review in March 2008 and was accepted for publication in December 2008. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the problem

Hearing loss

Loss of hearing is a common problem, generally associated with increasing age. 1 In the UK about 40% of those over 50 years of age have some degree of deafness. 2 A person who can detect tones at an average level below 20 decibels hearing level (dB HL) is considered to have normal hearing. Those with a severe loss of hearing cannot detect tones at an average level below 70–94 dB HL in their better-hearing ear. Those with a profound loss of hearing cannot detect tones at an average level below 95 dB HL in their better-hearing ear.

Traditional acoustic hearing aids may improve hearing function but are diminishingly ineffective for many people with severe to profound sensorineural loss of hearing. 3 For some of this group the advent of cochlear implants has provided an alternative treatment. 4

Epidemiology

Incidence and/or prevalence

Children (0–16 years)

An estimated 371 [95% confidence interval (CI) 327–421] children in England and 21 (95% CI 18–24) children in Wales are born annually with permanent severe to profound deafness. 5 The prevalence for severe to profound deafness is about 59 cases per 100,000 children. 5 About 1 in 1000 children is severely or profoundly deaf at 3 years old. This rises to 2 in 1000 children aged 9–16 years. 6

Adults (over 16 years)

Significant hearing loss affects one-third of those over 60 years and half of those over 75 years. 4 In the UK around 3% of those over 50 years and 8% of those over 70 years have severe to profound hearing loss. 2 People with severe to profound hearing loss make up around 8% of the adult deaf population. 2 This number is likely to rise with the increasingly elderly population. In those over 60 years the prevalence of hearing impairment is higher in men than in women (55% and 45%, respectively, for all degrees of deafness). 1

Aetiology

Children

A 15-year study by Fortnum and colleagues7 that examined birth cohorts of those born in the UK between 1980 and 1995 found nearly 3600 (21%) cases of children with permanent severe hearing loss (71–95 dB) and 4262 (25%) cases with permanent profound hearing loss (> 95 dB). The aetiology of severe hearing loss was 22% more likely than other levels of deafness to have perinatal causes (p < 0.001). Those with profound deafness were more likely to have a genetic (42%; p < 0.001), postnatal (20%; p < 0.001) or prenatal (12%; p < 0.001) aetiology. Fortnum and colleagues also looked at the subset of children with cochlear implants. Here, significantly more of these children had a postnatal aetiology (47.7%; p < 0.001) than those profoundly deaf children not implanted.

Adults

The most common cause of eventual severe to profound deafness in the elderly is presbycusis. 1 This is progressive hearing loss due to the failure of hair-cell receptors in the inner ear, in which the highest frequencies are affected first. Hearing loss may also be due to noise exposure, ototoxic drugs, metabolic disorders, infections or genetic causes. 8 Communication problems from deafness may lead to social isolation and depression. 9–11

Pathology

Hearing impairment can be classified as conductive or sensorineural. Conductive deafness is caused by disease of the external, or more commonly middle, ear, which prevents the conduction of sound waves to the cochlea where they are sensed. Cochlear implantation is not a treatment for conductive deafness, which will not be considered further.

Sensorineural hearing loss occurs when there is damage to the inner ear (cochlea) or to the nerve pathways from the inner ear (retro cochlea) to the brain. Sensorineural hearing loss is permanent and not only involves a reduction in the ability to hear faint sounds but also affects speech understanding and discrimination.

Sensorineural hearing loss can be caused by disease, birth injury, drugs that are toxic to the auditory system, and genetic syndromes. It may also occur as a result of noise exposure, viruses, head trauma, ageing and tumours. It can be much more severe than conductive hearing loss, causing insensitivity to even the loudest sounds (total deafness).

Co-morbidities

Hearing loss is often associated with other health problems; Fortnum and colleagues7 found that 27% of children who were deaf had additional disabilities. In total, 7581 disabilities were reported in 4709 children; however, this may be an underestimate as ‘no disability’ and ‘missing data’ responses were not distinguished. Abutan and colleagues1 found that 11% of adults over 60 years with hearing loss also had tinnitus. About 23,000 (0.3%) of the population of deaf people are also blind and 250,000 (2.7%) of hearing-impaired people have some degree of additional sensory disability. 2 Additionally, 45% of severely or profoundly deaf people under 60 years have other disabilities, usually physical; this rises to 77% of those over 60 years. 2

Measurement of hearing sensitivity

The degree of sound intensity that can be heard is measured in decibels (dB); this is a relative not an absolute measure. Hearing loss is characterised as the additional intensity that pure tones must possess to be detected by an individual relative to the intensity that can be detected by young adults free from auditory pathology. The additional intensity is measured in units of decibels hearing level (dB HL) and is usually averaged across frequencies from 500 to 4000 Hz.

Communication with hearing loss

People with hearing loss communicate face to face in two different ways:

-

oral communication – this includes auditory–oral skills, which can range from emphasising auditory information without lip-reading to cued speech in which hand cues supplement lip-reading

-

total communication – this emphasises both signed and spoken communication with considerable variation from one setting to another in the emphasis placed on each modality.

Of those with severe or profound deafness, about 450,000 cannot hear well enough to use a voice telephone. 2

It is estimated that about 50,000 people, mainly those who were born deaf or who lost their hearing early in life, use British sign language as their first language. 2 It is difficult to accurately estimate the number of lip-readers as this skill is used in varying degrees by most deaf people. 2

Impact of deafness

Children

In children, hearing loss may have significant consequences for linguistic, cognitive, emotional and social development. 12 Many deaf children live in relative isolation in their early years and their first contact with other deaf children may be when they attend school. 13

Early life may be dominated by trying to adapt to their impairment. This may involve learning to lip-read and/or using cued speech or sign language, either at mainstream or special schools. 14 The inability to communicate wants and needs may alienate children from family members. 12

At school, deaf children may also exhibit more behavioural problems than their hearing peers. Greater problems are evident in those with bilateral severe to profound deafness. 13,15 Congenitally deaf children fare poorly academically. 13,15 In the longer term children with uncorrected hearing loss are at an increased risk of becoming underemployed. 16,17

Measurement of quality of life in young children (i.e. < 5 years) is often by proxy through parents (or teachers). 18,19 In total, 90% of deaf children have two hearing parents and 95% have at least one. 13,20 There are no standardised measures to assess quality of life specific to deaf children, deaf adolescents or their parents. 15 However, two generic profile measures have been used to assess quality of life in deaf children, the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ)15,21 and the Munich Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children (KINDLr). 19,22 Both have been used to assess quality of life in children with severe to profound deafness, including those who are prelingually deafened, either using an acoustic hearing aid or with a cochlear implant. Prelingual deafness refers to deafness occurring before a child has developed speech, with an age of 3 years often taken as a proxy for this. Postlingual deafness refers to deafness occurring after this time.

An Australian cross-sectional study15 used the 28-item short version of the parent proxy report CHQ to compare quality of life in children aged 7–8 with significant congenital hearing loss (with mild to profound hearing impairment, including cochlear implant users) with their hearing peers. The CHQ has 12 subscales – physical functioning, role (social–physical), role (social–emotional), bodily pain, behaviour, mental health, self-esteem, general health, parent impact (emotional), parental impact (time) and family activities – and produces two summary scores (physical and psychosocial). The CHQ has only been provisionally validated. 23 Children with congenital hearing loss scored significantly worse in six domains [role (social–physical), behaviour, mental health, parent impact (emotional), parental impact (time) and family activities]. The psychosocial summary score (out of 100) was also significantly lower in children with congenital hearing loss (49.2, SD 9.6) than in children with normal hearing (53.1, SD 8.2). Ceiling scores of 100 were reported on four subscales in both groups. 15 The study did not control for differences in parental level of tertiary education or co-morbidity.

An Austrian study22 used the KINDLr to assess the quality of life of children (aged 8–16 years) with cochlear implants. It has six domains (physical health, general health, family functioning, self-esteem, social functioning and school functioning). Total self-reported scores for boys (67.5, SD 9.6) and girls (63.1, SD 8.6) were significantly below those of their hearing peers (76.8, SD 8.6 and 76.7, SD 8.7 respectively).

Adults

Studies indicate that deafness may adversely affect the quality of life of adults24–29 and that of their family members. 31,32 Mulrow and colleagues33 reported that 82% of the elderly deaf stated that deafness had an adverse effect on their quality of life and 24% felt depressed.

Commonly reported difficulties identified by postlingually deaf adults include feelings of isolation, loss of confidence and tinnitus. 10 In social settings, in particular those with background noise, communicating with others can be very challenging. 17 In a study of 47 severely to profoundly postlingually deafened adults in Wales,34 nearly two-thirds identified feelings of isolation, loss of confidence and loss of social life as causing them difficulties. Such difficulties may influence the viability of personal networks and, therefore, the sense of self. 16 These effects can lead to reduced feelings of well-being. 17 The difficulties caused by hearing loss may result in withdrawal from social activities, reducing intellectual and cultural stimulation and cognitive functioning. 12,17

In an Italian study of 1191 non-institutionalised elderly,35 those with hearing impairment had twice the risk [odds ratio (OR) 2.1, 95% CI 1.36–3.25] of poor functioning in daily living activities compared with non-impaired elderly, with over 20% of the elderly deaf having a level of functioning classified as poor by the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale. A similar relationship between hearing loss and self-sufficiency was seen among middle-aged adults (51–61 years) living in the community. 36

A US cross-sectional study31 of 178 adults (17–84 years) with profound postlingual deafness showed that 13% showed clinically elevated levels of depressed mood (T-score ≥ 70) and 16% had feelings of significant social isolation on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Their levels of anxiety in social contexts, measured using the Social Avoidance and Distress (SAD) scale, were also greater than those of people diagnosed with simple phobias. 31 A follow-on study involving 95 of these participants also showed that they had lower levels of social participation than 44 age-matched hearing control subjects. 31 Candidates experienced lower levels of pleasant social events (16%) and non-social events (19%) than control subjects (23% and 27% respectively; p < 0.05). 31

Dalton and colleagues27 used the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) to measure the impact of hearing impairment on quality of life in 2688 adults. The SF-36 measures physical functioning, role limitation because of health problems, social functioning, role–emotional, general health, bodily pain, mental health and vitality on a scale from 0 to 100. They found that severity of hearing loss was significantly associated with worse quality of life. Those with moderate to severe hearing loss (> 40 dB) had the lowest scores. Scores were 1.9–5.9 points lower than in those without hearing loss across six of the eight domains. The greatest differences were in the domains of role (physical) (5.9), physical functioning (5.2), vitality (4.2) and role (emotional) (3.9). There was no association with general health (2.1) or bodily pain (1.9), although scores did decline with hearing loss. 27 There was also a statistically significant difference in the two adjusted summary component scores in physical and mental health between people with no hearing loss (40.3, SE 1.87 and 50.2, SE 1.59 respectively) and those with moderate to severe hearing loss (38.8, SE 1.89 and 49.0, SE 16.1 respectively). 27 The impact of increasing deafness on quality of life has been shown in other studies. 37 It is not clear to what extent these relationships are causally related to the hearing impairment rather than to other disabilities or diseases associated with ageing or the aetiology of deafness (e.g. premature birth).

In a Dutch study38 of 46 people waiting for cochlear implants, SF-36 scores in those with profound postlingual deafness, mean age 51 years (SD 16), were between 60.2 (SD 41.5) [role (physical) domain] and 79.2 (SD 24.8) (physical functioning domain). A Norwegian study39 of 27 postlingually deaf, cochlear implant candidates compared pre- and postimplantation scores. They found that postimplantation participants had similar physical functioning scores (80.8) as preimplantation participants but higher role (physical) scores (71.0, SD 40.0). The vitality domain had the lowest scores (58.8, SD 21.8).

Tinnitus

Tinnitus is often associated with sensorineural hearing loss. 28,40 One in five people reported tinnitus as severely annoying,28,40 affecting speech discrimination, concentration and sleeping patterns. 29,41 The Norwegian study40 found that 67% of people with subjective hearing loss had tinnitus. Similarly, the prevalence of tinnitus was 70% in those with severe to profound deafness. 40

In an American study29 25% of adults with tinnitus attending an audiology clinic had moderate to severe depression, impacting on their quality of life. Self-assessment using the Quality of Well-being Scale (QWBS) was 0.53 (SD, 0.15), with a score of 0 equating to death and 1 to complete functioning. Thus, combined with hearing loss, tinnitus may exacerbate problems with maintaining a social life. 29

Quality of life in families of people with hearing loss

As the majority of parents and relatives of deaf people have no previous experience of deafness13 they may need to spend time and effort managing communication problems or assisting their deaf relative when engaging in social activities. 42,43 Over time this additional load may result in reduced physical health and elevated levels of emotional and psychological distress,15,42 the magnitude of which may be moderated by personal and external resources or the severity of the impairment. 32 However, the evidence for effects on health in families with a hearing-impaired child is inconclusive. 32

Whose quality of life? – The deaf world perspective

The deaf world community do not consider that deafness is an impairment. 44 From their perspective, deafness is a variation of normality. 45,46 Therefore, people who use sign language do not require hearing to be functional, productive and happy. 44 Growing up or living in a deaf community provides social and emotional support against the difficulties commonly associated with deafness,13,47 as well as a cultural identity. 47 As such, the hearing world may undervalue the quality of life experienced by deaf people. A Dutch study44 has shown that degree of deafness is not associated with a respondent’s happiness or perceived quality of life. Wald and Knutson47 have shown that deaf people who have a deaf identity have higher self-esteem than with those who do not. Some deaf activists argue that providing cochlear implants for prelingually deaf children will result in a declining deaf community. 46 They believe that the provision of cochlear implants poses a long-term indirect threat to the survival of the deaf world.

However, in assessing arguments about the ethics of providing cochlear implantation to deaf children, it is necessary to dissociate the needs of a community for recruits to ensure its survival from issues of what is right and best for children. Indeed, Arlinger17 has shown that deaf people are not always aware of all of the consequences of their condition and therefore may underestimate the impact of deafness on the quality of their own lives.

Current service provision

Relevant national guidelines

-

National action plan for audiology – Improving Access to Audiology Services in England. 48 This framework document sets out how health reform levers can be brought to bear to improve quality, efficiency and access to audiology services. It also describes national work intended to support this for adults and children.

-

MHAS – Modernisation of Hearing Aid Services (Adults)

-

MCHAS – Modernisation of Hearing Aid Services (Children) (2001)

-

NHS Newborn Hearing Screening Programme – seeks to identify deafness within 26 days of birth.

Significance to the NHS

Although deafness per se is not an illness, it does impact on NHS resources through the need for procedures of diagnosis and assessment and the possible provision of acoustic hearing aids and cochlear implants with the associated follow-up and support required.

Cochlear implants have been available in England and Wales since the late 1980s. Currently there are 14 tertiary implant centres in England and three in Wales. Treatment is provided by multidisciplinary teams of clinical scientists in audiology, audiologists, surgeons, speech and language therapists, hearing therapists and administrators. Within paediatric services, teams also include teachers of the deaf. Some units use or have access to clinical and/or educational psychology, link nurses and paediatricians. 49

The recently published best practice guidance Improving Access to Audiology Services in England48 seeks to improve the responsiveness of audiological services to cut waiting times to a maximum of 18 weeks.

Management of hearing loss

NHS Newborn Hearing Screening Programme

Nationally all newborns are screened for hearing problems within 26 days of birth with positive cases referred to NHS audiology departments. If confirmed deaf the baby should be provided with a hearing aid within 2 months. Referrals to other services are usually coordinated by the audiology department. These include:

-

paediatric services, to assess for possible co-morbidities

-

ear, nose and throat services, to consider surgery, including possible referral to a tertiary centre for cochlear implant assessment

-

educational services

-

social services.

Variation in services for hearing loss

There is geographical variation in the way that hearing impairment is managed in different parts of the UK. In general, models of adult services tend to follow the MHAS. Differences occur in the types of digital hearing aids fitted, the diagnostic facilities available and the access to hearing therapists. The professionals providing services may also vary. The larger departments and teaching hospitals tend to employ clinical scientists (audiology) whereas local district general hospitals are more likely to employ audiologists.

Paediatric services also vary; there are different models of newborn hearing screening, with some being maternity-unit based and others community based. In some areas second-tier paediatric services are delivered in the community, usually by community paediatricians with support from audiologists. In other areas these services have been integrated into the main audiology department and are clinical scientist/audiologist led. Hearing aid services for paediatrics will usually follow the MCHAS model.

The referral process for cochlear implants may also vary, but referrals will go to the major centres (14 in England and three in Wales). Similar protocols are used for adults and children.

There may be slight variation nationally in the initial screening and diagnostic services described above. Although follow-up care may vary more, the following description may be considered reasonably typical (expert advisory group, 2006, personal communication).

For children, following diagnosis and fitting with an initial hearing aid 2 months later, services generally conform to the following pattern:

-

visit to the audiology department every 2 weeks for new ear moulds for 6 months

-

visit from educational services every week

-

formal diagnosis of level of hearing loss at 3 months

-

potential cochlear implant use considered very early on, i.e. usually within the first year

-

audiological assessment at 6 months, then every 6 months until 2 years old or until hearing aid use is stable and consistent

-

once stable audiological checks every 6 months until 5 years old, then annually until adult services take over at 18 when there are 4-yearly reassessments.

Adults make up the vast majority of people seen in the NHS for hearing problems. The NHS provides over 2,600,000 adult hearing aid services per year; 600,000 of these are assessments of hearing, 500,000 are hearing aid fittings, 500,000 are follow-up appointments and more than 1,000,000 are for ‘repairs’ of devices. 50 Services are coordinated by audiology departments. Adults normally have a 4-yearly review, although this varies across the UK (Dr Jonathan Parsons, Mid, East Devon and Exeter Area Primary Care Trust, 2006, personal communication).

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of intervention

Cochlear implants first became available on the NHS in the 1980s. These were single channel devices that used simple coding strategies to interpret speech into intelligible sounds. These early devices gave 15–35% word or sentence understanding. 51 Cochlear implants and their coding strategies have been continually developed since then, with step changes in the quality of performance coming from the arrival of multichannel devices and whole speech coding strategies in the mid-1990s, giving up to 90% understanding of words or sentences. 51 It is these later multichannel whole-speech processing devices that this technology assessment will consider.

Aim of cochlear implants

The aim of cochlear implants is to improve quality of life by enabling people with hearing loss to hear and interpret sounds, thus improving their ability to understand others, communicate effectively and move safely in their environment.

Description of cochlear implants

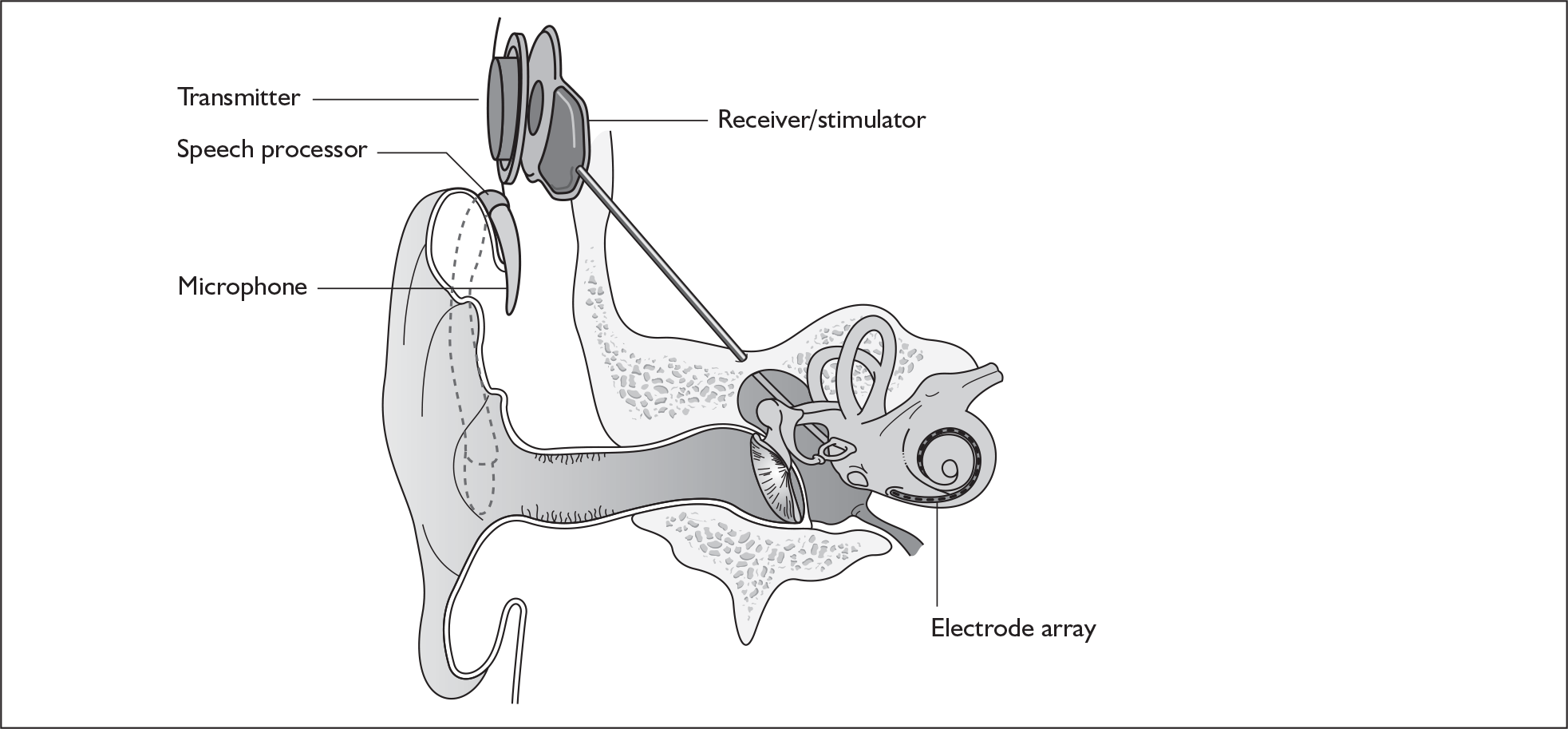

Cochlear implant systems consist of the following components (Figure 1). A microphone, worn behind the ear, is connected by a wire to a sound processor. The sound processor is connected by a wire to a transmitter coil, worn on the side of the head. The transmitter coil transmits electrical power (by induction) and data (as a radio-frequency signal) to a receiver coil. The receiver coil is part of a receiver/stimulator package that is placed in a depression fashioned surgically in the mastoid bone behind the ear. The transmitter coil is held in place, and is aligned with the receiver coil, because the coils surround magnets of opposing polarity. The stimulator is a microprocessor that receives electrical power and digital data from the receiver coil. The microprocessor translates the data into biphasic charge-balanced electrical pulses, which are delivered to an array of electrodes that are placed surgically within the cochlea. The primary neural targets of the electrodes are the spiral ganglion cells, which innervate fibres of the auditory nerve.

FIGURE 1.

Ear with cochlear implant.

When the electrodes are activated by a signal they send a current along the auditory nerve, which produces a sensation of hearing. This is not a restoration of hearing. A normal ear can resolve patterns of sound energy in about 60 distinct bands of frequency in the range from 100 Hz to 20,000 Hz. The best that users of implants achieve is 6–8 bands, regardless of whether they have 24, 16 or 12 electrodes (Professor Quentin Summerfield, University of York, May 2007, personal communication).

One of the limitations of implants arises because electrical stimulation spreads widely within the cochlea. This means that a single electrode excites spiral ganglion cells that would normally respond to a wide range of frequencies. In comparison, the tuning of the basilar membrane in the normal cochlea restricts the spread of excitation to a narrow range of spiral ganglion cells.

Initially, sound processors were about the size of a packet of cigarettes and were worn clipped to clothing or, in the case of a young child, held in a harness. More recently, miniaturisation of electronic circuitry and the increased capacity of small batteries have allowed the processor to be combined with the microphone in an assembly worn behind the ear, like an acoustic hearing aid. Body-worn processors are still used by infants because the processor can be held securely in place in a harness. Behind-the-ear assemblies are used by older children and adults.

Insertion procedure

The procedure for cochlear implant surgery takes between 2 and 3 hours under general anaesthetic. It involves the insertion of the electrode array into the cochlea through a tunnel that has been drilled above the external ear canal, bypassing the mastoid cavity. 52

Criteria for candidacy for cochlear implantation

Currently there are no nationally agreed criteria for candidacy for cochlear implantation, although the British Cochlear Implant Group (BCIG) is due to produce a position statement in 2007. A summary of its recent audit of UK practice can be found in Appendix 4.

The joint submission to NICE of the British Academy of Audiology (BAA), BCIG and the British Association of Otorhinolaryngologists (ENT UK) in March 200749 states that, in broad terms, criteria for candidacy in the UK are based on:

-

failure to achieve adequate benefit from conventional acoustic amplification in cases of severe to profound sensorineural deafness

-

organisation of the cochlea together with the presence of viable spiral ganglion cells and auditory nerve capable of stimulation

-

the ability to gain surgical access to the cochlea

-

the ability of the patient to utilise the auditory input from the cochlear implant.

A number of other issues should be considered in relation to candidacy:

-

In the UK there are no upper or lower age limits for consideration for cochlear implantation; however, hearing evaluation tests mean that implantation is unlikely before 9 months.

-

Profound deafness of greater than 30 years has been linked to poorer outcomes;53 however, positive outcomes are possible and therefore skilled candidate selection is essential.

-

Progressive and fluctuating loss can give rise to a greater degree of difficulty experienced by the patient than the audiogram may suggest at any particular time. Patients within these groups require careful multidisciplinary monitoring and intervention in a timely fashion. 54

-

Patients with a profound unilateral loss, or an asymmetric profound/severe loss, can also experience high levels of difficulty in adapting to a cochlear implant.

It might be assumed that the inability to detect tones at severe and profoundly deaf levels correlates directly with speech perception; however, while there is some correlation this is not total (Professor Quentin Summerfield, University of York, May 2007, personal communication). This raises a problem because in clinical situations older children and adults are assessed for implant suitability on the basis of functional outcomes, i.e. ability to understand prerecorded sentences without lip-reading; however, the inclusion criteria of most research studies are based on the average ability to detect tones in the better-hearing ear. Thus, people who are classified as profoundly deaf do not form a homogeneous group, so that a person may meet the candidacy criteria on functional outcomes but not on audiological ones. This causes a potential mismatch between clinical assessment for candidacy and the research on which effectiveness for particular levels of deafness is based.

Assessment for cochlear implantation

Assessment for cochlear implantation is undertaken by a multidisciplinary team whose aim is to select people who are medically, audiologically and psychologically suitable. Assessment comprises a number of evaluations:

-

Audiological – This involves a pure-tone audiogram to give an indication of the degree of hearing deficit. If this results in a likely indication for cochlear implantation then patients undertake a 3-month trial with acoustic hearing aids to confirm that these do not provide sufficient support.

-

Functional hearing – This is tested using optimally fitted acoustic hearing aids to find out if cochlear implants are likely to improve hearing outcomes.

-

Speech, language and communication – This is difficult in prelingual children and requires a specialist speech and language therapist to assess abilities in relation to normal development and contribute to judgements about the level of functional hearing. Most adult candidates are postlingually deafened and so their ability to communicate and comprehend in social situations is assessed.

-

Medical – This involves an assessment of fitness for surgery, the aetiology of hearing loss and whether there are other disabilities or medical conditions present that may affect the success of implantation.

-

Radiological – This involves an examination of the anatomical structure of the cochlea and the auditory nerve for anomalies that might contraindicate surgery or require a modified implantation. This is carried out using computerised tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging scanning, under general anaesthetic in young children.

-

Psychological assessment – This may be carried out to ensure that realistic expectations of the benefits and the demands of training are understood. Children may also be evaluated by teachers of the deaf.

Setting and equipment required

Specialist surgical equipment is needed to perform the operation, in particular, specialist drills for shaping the mastoid bone and monitoring equipment to check the integrity of the facial nerve. Intraoperative CT scanning may be used to check the position of the electrode array.

Follow-up required for children

Cochlear implantation requires a commitment from the child’s carers to long-term involvement in rehabilitation. Children receive individualised programmes of audiological training once they have shown that they are able to detect sound after implantation (the device is switched on approximately 1 month after insertion). Intensive training over several months is undertaken by a speech and language therapist and a teacher of the deaf. Tuition addresses sound discrimination, recognition with associated meaning and the appropriate response to verbal cues (comprehension). The development of speech is encouraged by imitation and concurrent articulation, progressing to sentence production. Complete training may take many years; however, initial benefit occurs within 6–18 months. Typically, a child’s progress is assessed at approximately 3, 6 and 12 months post implant and then annually. These evaluations involve a variety of measures to test understanding of others’ speech and the intelligibility of their own to others.

Identification of important subgroups

As far as the included data permit we look at the issues of pre- and postlingual implantation in children and differences in outcomes between adults who were born deaf and those who later became deaf.

Bilateral implantation

Bilateral implantation has the potential to provide a number of benefits above those of unilateral implantation:

-

Localisation of sounds. The ability to detect the direction that a sound comes from can be measured either by the minimum audible angle in the frontal horizontal plane, which is a measure of the least separation that two sources of sound need to have to be able to tell which direction the sound comes from, or by the accuracy with which someone can localise the sources of sound to more than two locations.

-

Measures of the ability to use both ears to improve the accuracy with which speech is understood in noise:

-

– binaural summation is shown when both speech and noise come from the same place, and ability with both ears is significantly better than ability with the better-hearing single ear

-

– the head shadow effect is shown when speech and noise come from separate locations, and ability is better when listening with both implants than with a single implant for the ear closer to the noise

-

– binaural squelch is shown when speech and noise come from separate locations, and ability is better when listening with both implants than with a single implant for the ear closer to the speech.

-

-

The assurance that the better of the two ears receives an implant.

-

That two ears are often better than one even when there is no difference between the sound reaching the two ears.

These potential benefits of bilateral implantation are outcomes that are measured in the systematic review in Chapters 4 and 5.

Current usage in the NHS

By the year ending March 2007 there were 374 adults and 221 children implanted with cochlear implants in England and eight adults and 22 children in Wales. A further 451 adults and 446 children are under assessment. A summary of the results of an audit by the BCIG of cochlear implant services for the year ending March 2007 is shown in Table 1. Ages ranged from babies of less than 12 months to adults of over 80 years. 49

| Total registered | Implanted, current year | Under assessment | Waiting time first OPD1 (mean months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children | Adults | Children | Adults | Children | Adults | Children | |

| England | 2599 | 2474 | 374 | 221 | 416 | 434 | 5.4 | 5.6 |

| Wales | 72 | 45 | 8 | 22 | 35 | 12 | 4 | 5 |

Bilateral implantation in the UK

Throughout the UK there had been 115 bilateral implantations by the year ending April 2006; of these, 33 were simultaneous implantations (both ears implanted in the same operation) and 82 were sequential implantations (ears implanted in different operations). In the year ending March 2007 there were an additional 32 child and 11 adult bilateral implantations. There had also been 34 bilateral reimplantations to this date either because of contraindication of more surgery to the first ear or because residual function of the first device was considered likely to contribute to the benefit from a second implant. 49

Estimated future demand

The BAA, BCIG and ENT UK joint submission to NICE in March 200749 estimated (based on the assumption that 25% of severely deaf people with > 85 dB HL may benefit from an implant) that in 2005 there were potentially 625 children and 1620 adults per year who could benefit from implantation.

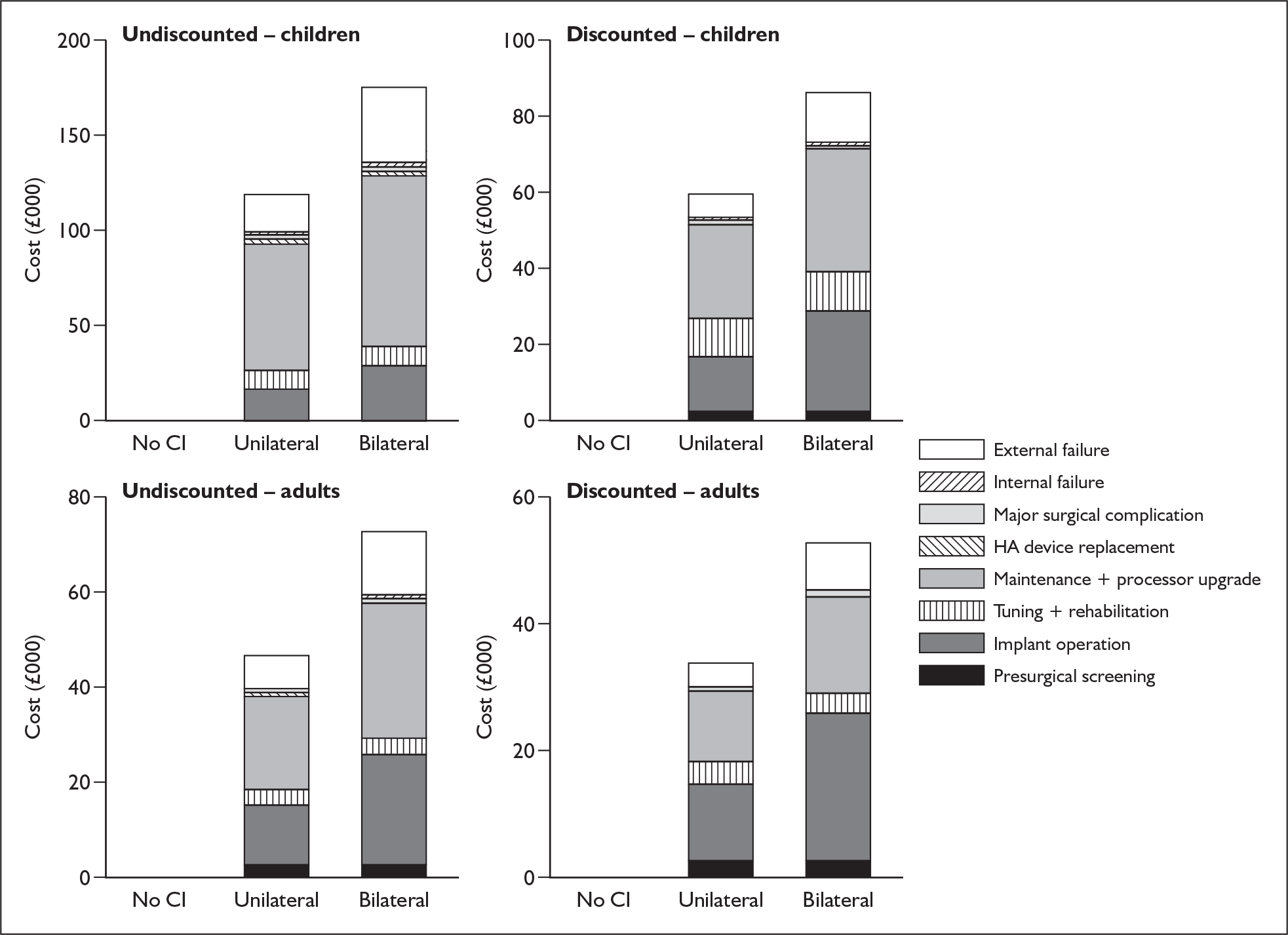

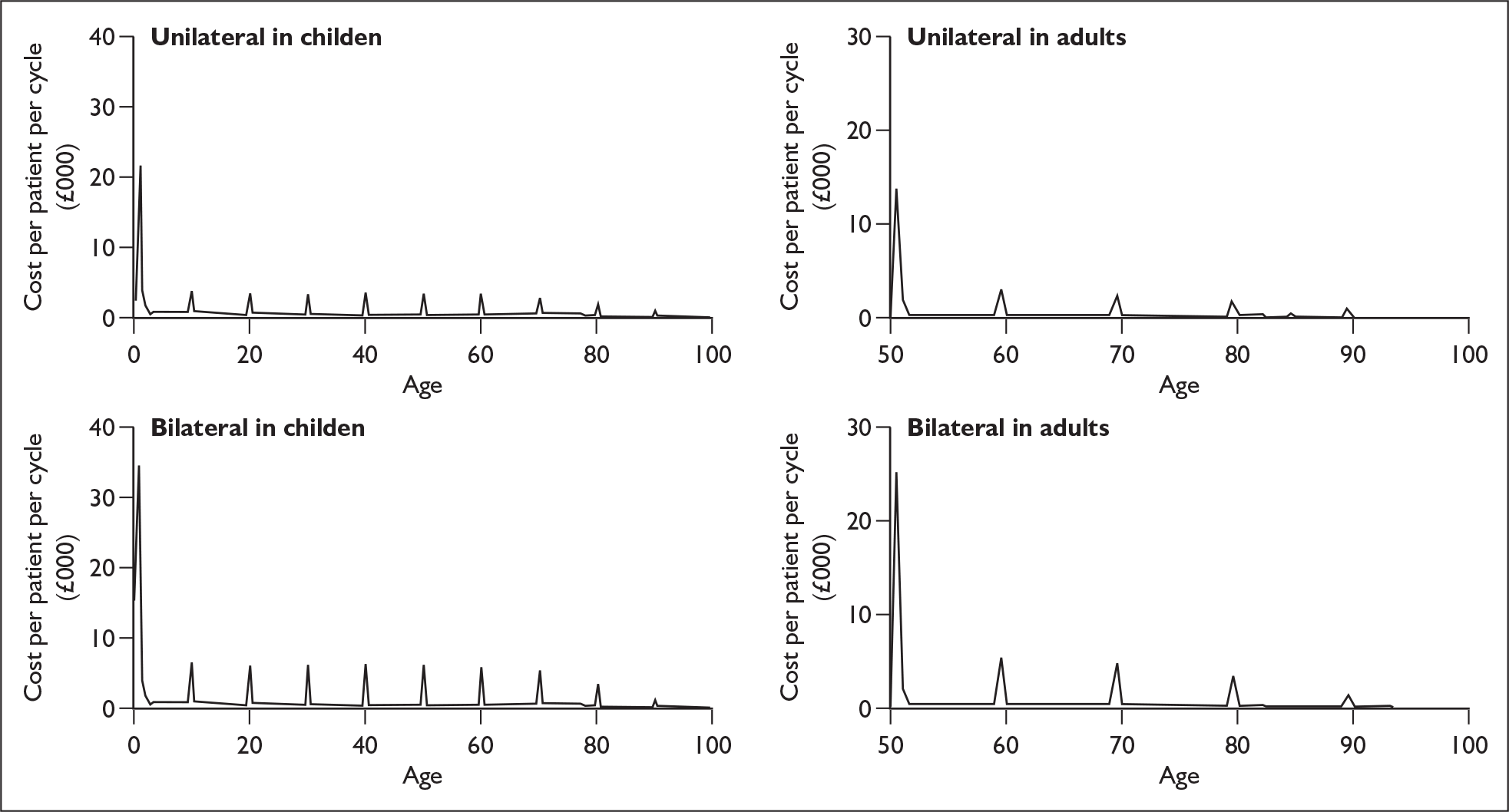

Anticipated costs associated with cochlear implantation

The costs of cochlear implantation to the NHS mainly comprise the resources involved in assessing deaf people for possible implantation, the purchase costs of the devices (implanted components and speech processors), the costs of surgery and postsurgical care, the costs of tuning (setting the implant to individual requirements) and training to use the devices, and any costs over the lifetime of the implant recipient associated with hardware failures, other complications or routine external device replacements or upgrades.

Cochlear implant devices are currently purchased by the NHS under a long-term procurement contract (framework agreement) between the four main manufacturers and the NHS Supply Chain (formerly part of the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency). This contract (contract reference number CM/RSG/05/3419) was established in November 2005 and applies until 31 October 2008, with an option to extend for a further 24 months (www.pasa.nhs.uk/PASAweb).

The suppliers and different products included in this agreement are listed in Table 2, together with the price for each product (the ‘applicable national price band’ for buying a full implant system for an NHS trust). The full agreement involves adjustment of these price bandings according to actual sales volumes (price adjustments not shown here). The price of single systems varies from £12,250 to £15,600. One of the suppliers, Neurelec, provides a two-system pack of Digisonic SP cochlear implant devices. The same supplier also offers a 24-channel ‘binaural’ device, which comprises one device and two electrode arrays. Although this is part of the NHS Supply Chain contract it is not shown here because it is not a bilateral cochlear implant.

| Supplier | Product | Cost (£)a | Cost (£) if low sales | Cost (£) if high sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Bionics | CLARION ICS HiRes 90K Bionics Ear (HF IJ CI-1400–01) | 14,900 | 16,550 | 12,900 |

| HiRes CI 24R with HiFocus Helix Electrode (CI-1400–02H) | 14,900 | 16,500 | 12,900 | |

| Cochlear UK | Nucleus CI 24R (ST) ‘K’ with a Sprint or ESPrit 3G Speech Processor | 14,350 | 14,350b | 14,350b |

| Nucleus CI 24R (CA) Advanced with a Sprint or ESPrit 3G Speech Processor | 14,350 | 14,350b | 14,350b | |

| Nucleus CI11 + 11 + 2 Double Array with a Sprint or ESPrit 3G Speech Processor | 14,350 | 14,350b | 14,350b | |

| Nucleus Freedom with either BTE or BWP optionc | 15,250 | 15,250b | 15,250b | |

| Nucleus Freedom with both BTE and BWP optionc | 15,550 | 15,550b | 15,550b | |

| MED-EL | Pulsar CI-100 (implant and patient kit) | 15,600 | 17,375 | 13,500 |

| Pulsar CI-100 (implant alone) | 13,500 | 13,500 | 13,500 | |

| Neurelec | DIGISONIC SP with Digi SP or Digi SP*K (model no. DX10/SP/K) | 12,250 | 12,250 | 10,200 |

| DIGISONIC SP for bilateral implantation – two full systems (model no. DX10/SP-BILAT) | 18,375 | 18,375 | 15,300 |

Bilateral implantation essentially involves the use of two systems in the same person. However, a range of price discounts are offered by manufacturers to reduce the per system price (usually by offering a percentage discount on the second implant system). These price discounts are discussed more fully in the assessment of cost-effectiveness (Chapter 6).

The other main costs associated with cochlear implantation have been estimated in two relatively recent UK-based studies. 52,54 They are summarised in Table 3 and discussed in more detail in the assessment of cost-effectiveness (Chapter 6). Note that the costs of tuning and maintenance in Table 3 include some costs for repairs and replacements, which under current warranty arrangements would be covered by the manufacturer.

| Cost type/stage of use | Children (£) | Adults (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | 2843 | 4011 |

| Implantation (excluding hardware costs) | 3480 | 2814 |

| Tuning (first year post implantation) | 9148 | 5262 |

| First year of maintenance | 4716 | 1060 |

| Second year of maintenance | 3640 | 1018 |

| Each subsequent year | 1897 | 861 |

These NHS costs reflect the current organisation of NHS service provision for cochlear implantation, which is via 20 regional tertiary cochlear implant centres in the UK (14 in England, three in Wales, two in Scotland and one in Northern Ireland).

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

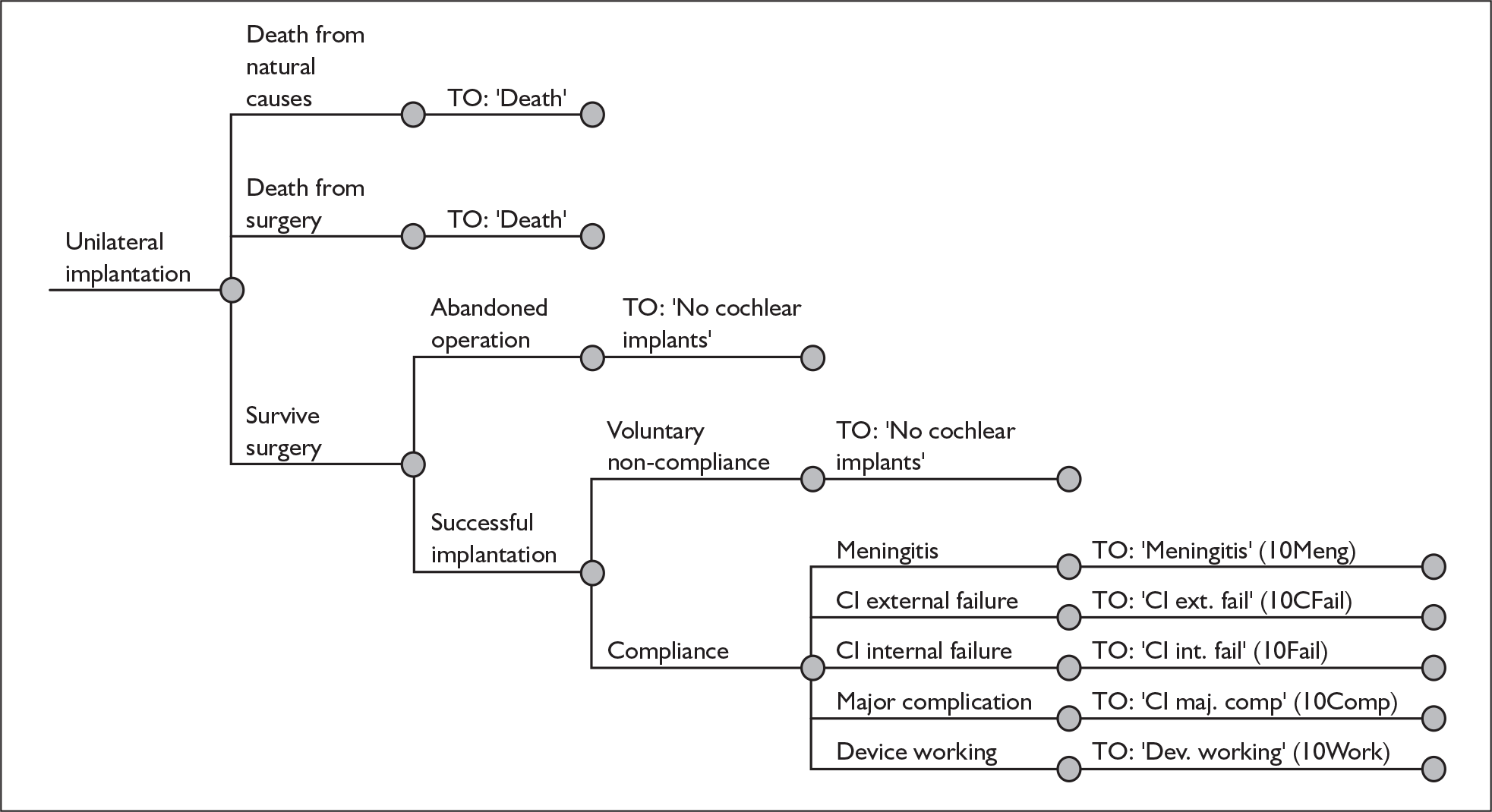

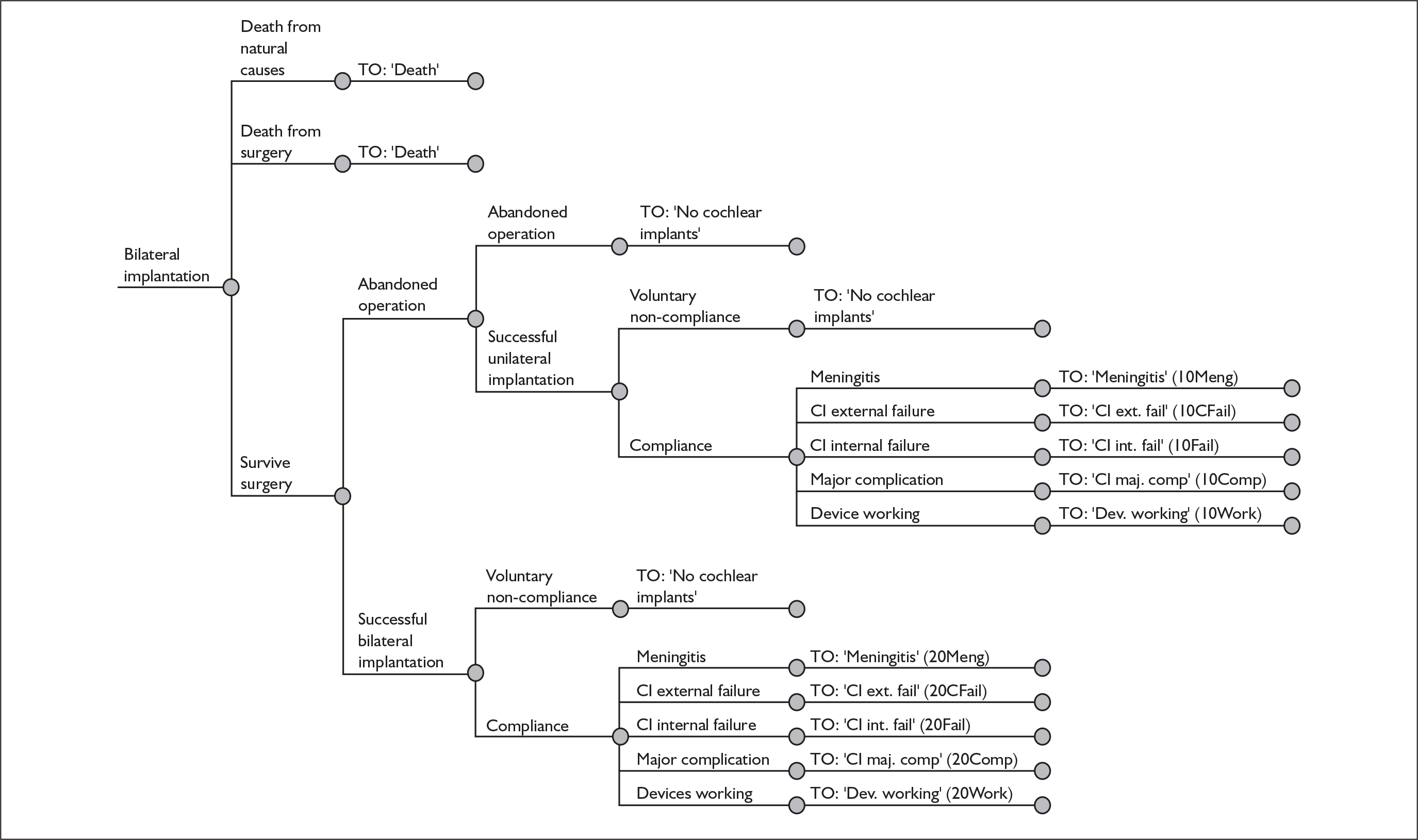

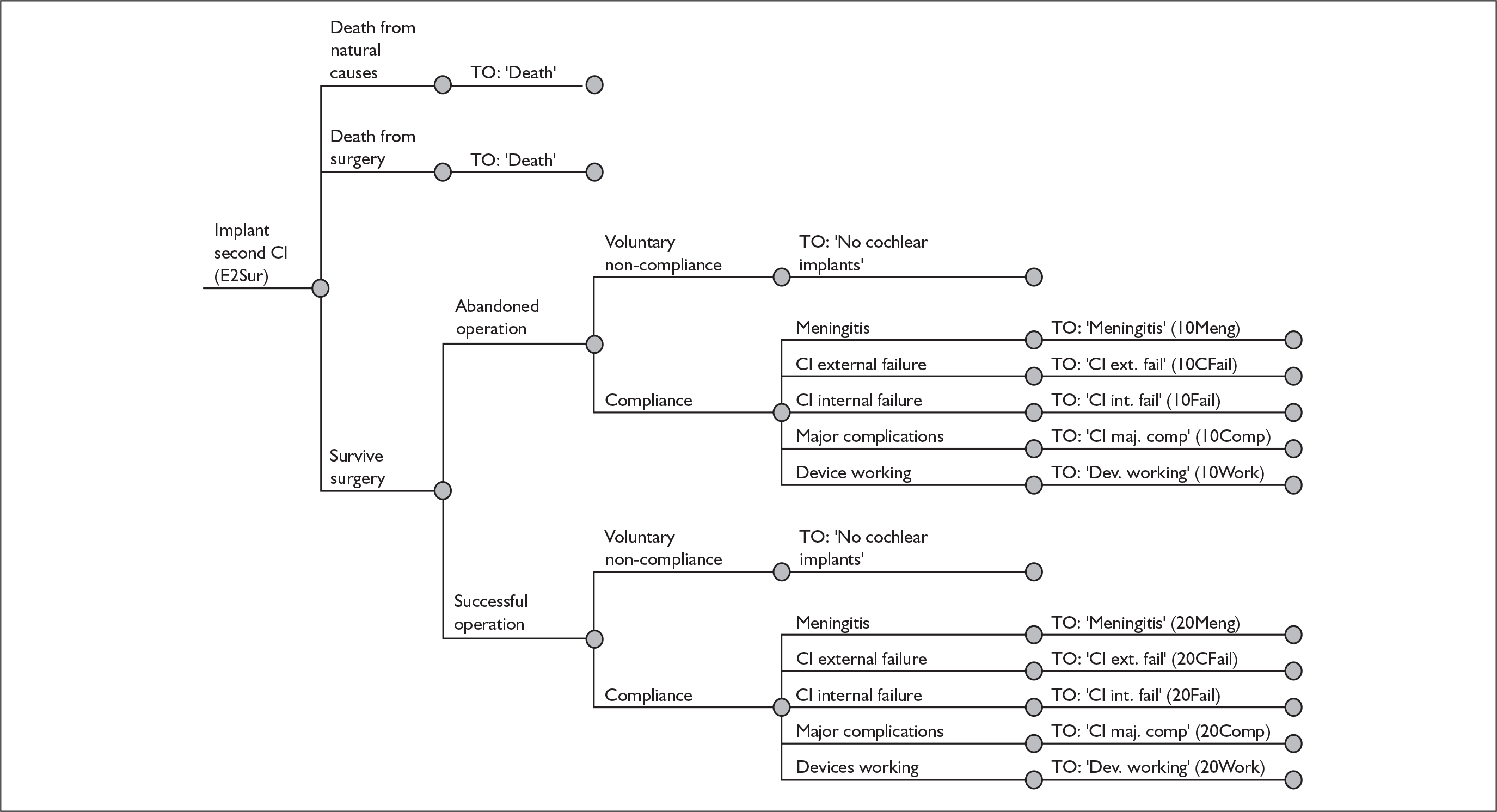

The purpose of this report is to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cochlear implants for severe to profound deafness in children and adults.

Because cochlear implants may be placed in either one or both ears, and because having one cochlear implant may be an intermediate step between having none and having two, there are in fact two decision problems in the severely and profoundly deaf population: (1) should people without a cochlear implant have one implanted and (2) should people who already have one (unilateral) cochlear implant receive a second one in the other ear (i.e. bilateral cochlear implantation).

More fully, therefore, the policy questions to be answered are:

-

For severely or profoundly deaf people (who may be either using or not using a hearing aid), is it effective and cost-effective to implant a first (i.e. unilateral) cochlear implant?

-

For severely or profoundly deaf people with a single cochlear implant (either unilateral or unilateral with a hearing aid), is it effective and cost-effective to implant a second (i.e. bilateral) cochlear implant?

In the clinical effectiveness systematic review these questions are answered by looking at eight independent comparisons. These are:

-

In children:

-

– unilateral cochlear implants versus non-technological support (no devices of any kind)

-

– unilateral cochlear implants versus acoustic hearing aids

-

– unilateral cochlear implants versus bilateral cochlear implants

-

– bilateral cochlear implants versus unilateral cochlear implants and acoustic hearing aids.

-

-

In adults:

-

– unilateral cochlear implants versus non-technological support (no devices of any kind)

-

– unilateral cochlear implants versus acoustic hearing aids

-

– unilateral cochlear implants versus bilateral cochlear implants

-

– bilateral cochlear implants versus unilateral cochlear implants and acoustic hearing aids.

-

Although the two policy questions above set out the two main logical comparisons (going from using no cochlear implant to one cochlear implant, and going from using one to two cochlear implants), there is also the clinical reality – and different decision problem – of going straight from having no cochlear implant to bilateral implantation. This is why, in the absence of reliable outcome (especially utility) data to answer the second policy question, the cost-effectiveness of simultaneous and sequential bilateral cochlear implantation is assessed in this report, that is, in deaf adults and children who are not currently cochlear implant users.

Interventions

This assessment considers multichannel cochlear implants using whole-speech processing coding strategies, for example advanced combination encoder (ACE), spectral peak (SPEAK), continuous interleaved sampling (CIS) and speech and motion sensor (SMP) (i.e. devices that are the same as, or comparable with, those currently available on the NHS).

Population including subgroups

The population is children and adults with severe to profound deafness. People with a severe loss of hearing cannot detect tones at an average level below 70–94 dB HL in their better-hearing ear. People with a profound loss of hearing cannot detect tones at an average level below 95 dB HL in their better-hearing ear.

The assessment considered the following groups of people depending on the availability and quality of the data:

-

children who were born deaf or who became deaf before the age of 3 years (prelingually deaf)

-

children who were post lingual (3 years or older) when they became deaf

-

adults who became deaf after learning spoken language compared with adults who were born deaf or who became deaf before acquiring spoken language

-

adults who were born deaf.

The comparison between having no cochlear implant and having one cochlear implant was analysed separately for those already using hearing aids and those only using non-auditory methods to aid communication. (However, we acknowledge that many people who only use non-auditory methods may either be clinically ineligible to receive a cochlear implant or would choose not to have one for the same reasons that they may choose not to use hearing aids.)

The comparison between having one and two cochlear implants was analysed separately for those with a contralateral hearing aid and those with a cochlear implant but no hearing aid in their other ear. This is because the use of a hearing aid, either with or without a cochlear implant, indirectly reflects both the severity and the cause of deafness; they are thus more appropriately defined as subgroups rather than comparators in this assessment.

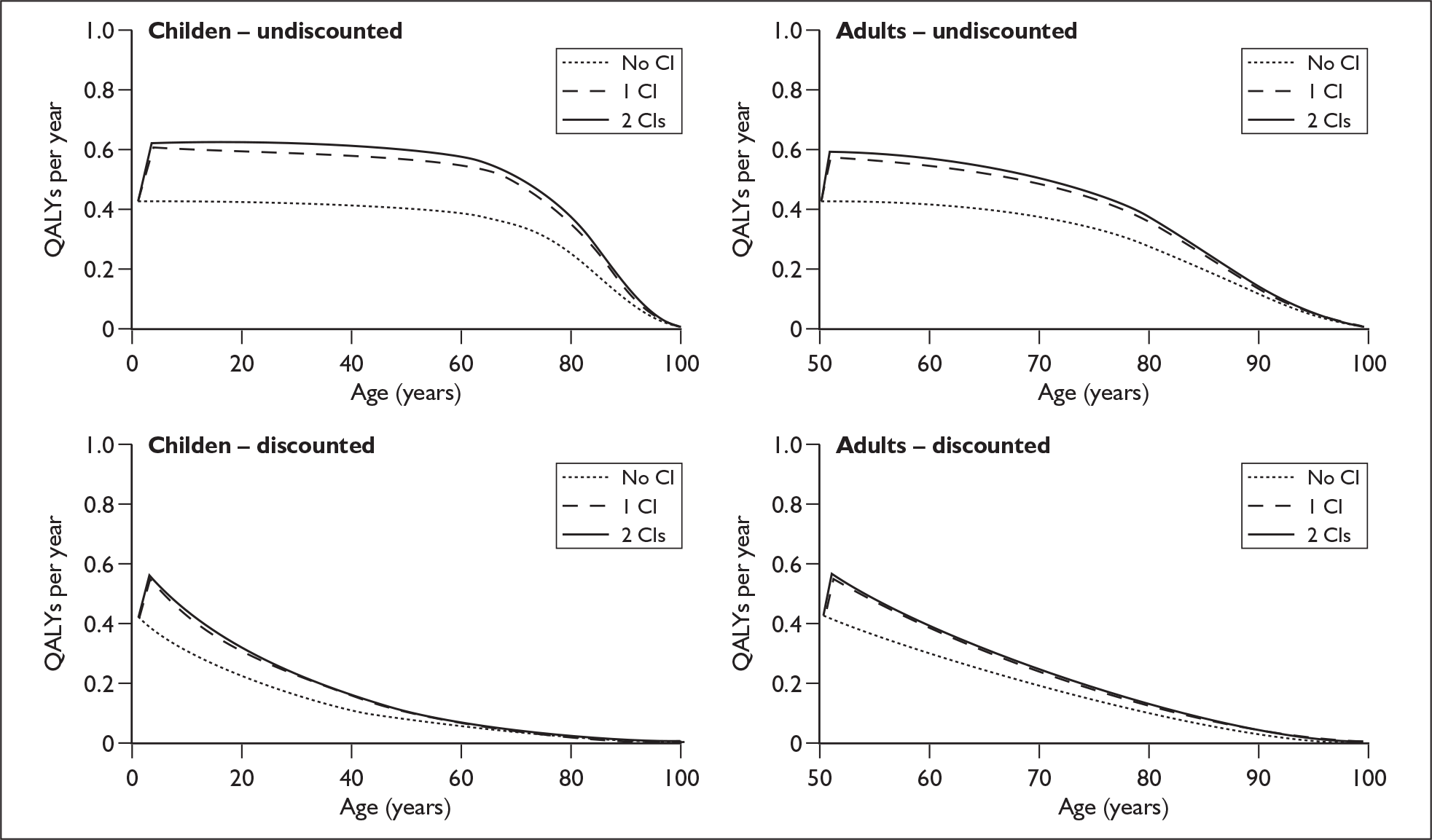

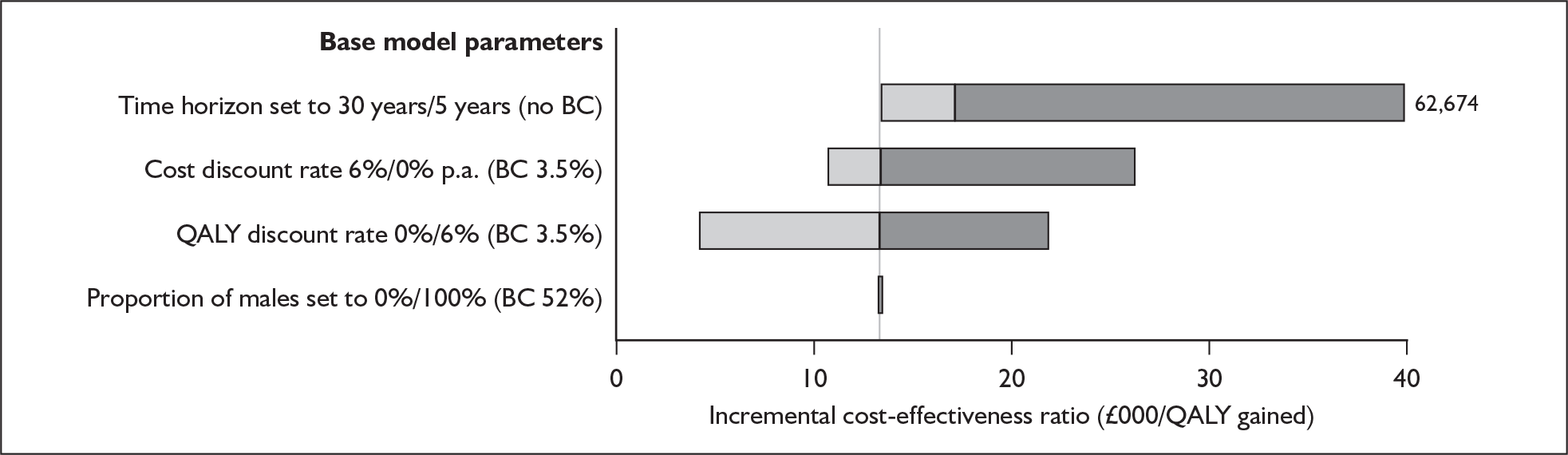

The extent to which the degree of residual hearing (e.g. severe deafness, profound deafness) and the presence of other additional needs (e.g. dual sensory impairments, learning disabilities) may influence costs and outcomes could be considered but was constrained by lack of data; no utilities were found for severe deafness or co-disabilities. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis, including the wider costs and benefits of educational placement, which are not reflected in health-related quality of life measures, was conducted.

Outcomes

The outcome measures found in the studies included in the systematic reviews were:

-

sensitivity to sound

-

speech perception

-

speech production

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

health-related quality of life

-

educational outcomes.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

This project will review the evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cochlear implants for children and adults who have severe to profound or profound deafness. The assessment will look at multichannel devices used in one or both ears and will draw together the relevant evidence about unilateral and bilateral cochlear implants and try to determine what, if any, is the incremental cost-effective benefit of the population using one implant rather than acoustic hearing aids or non-auditory support and if there is an additional benefit from using two cochlear implants.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness systematic review methods and search results

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

The clinical effectiveness of cochlear implantation was assessed by a systematic review of published research evidence. The review was undertaken following the general principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 57

Identification of studies

Electronic databases were searched for published systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses, randomised controlled trials (RCT) and ongoing research in October 2006 and this search was updated in July 2007. The updated search revealed one new cross-sectional study. Appendix 1 shows the databases searched and the strategies in full. Bibliographies of articles were also searched for further relevant studies, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Regulatory Agency Medical Device Safety Service websites were searched for relevant material. The search was limited to English language papers only.

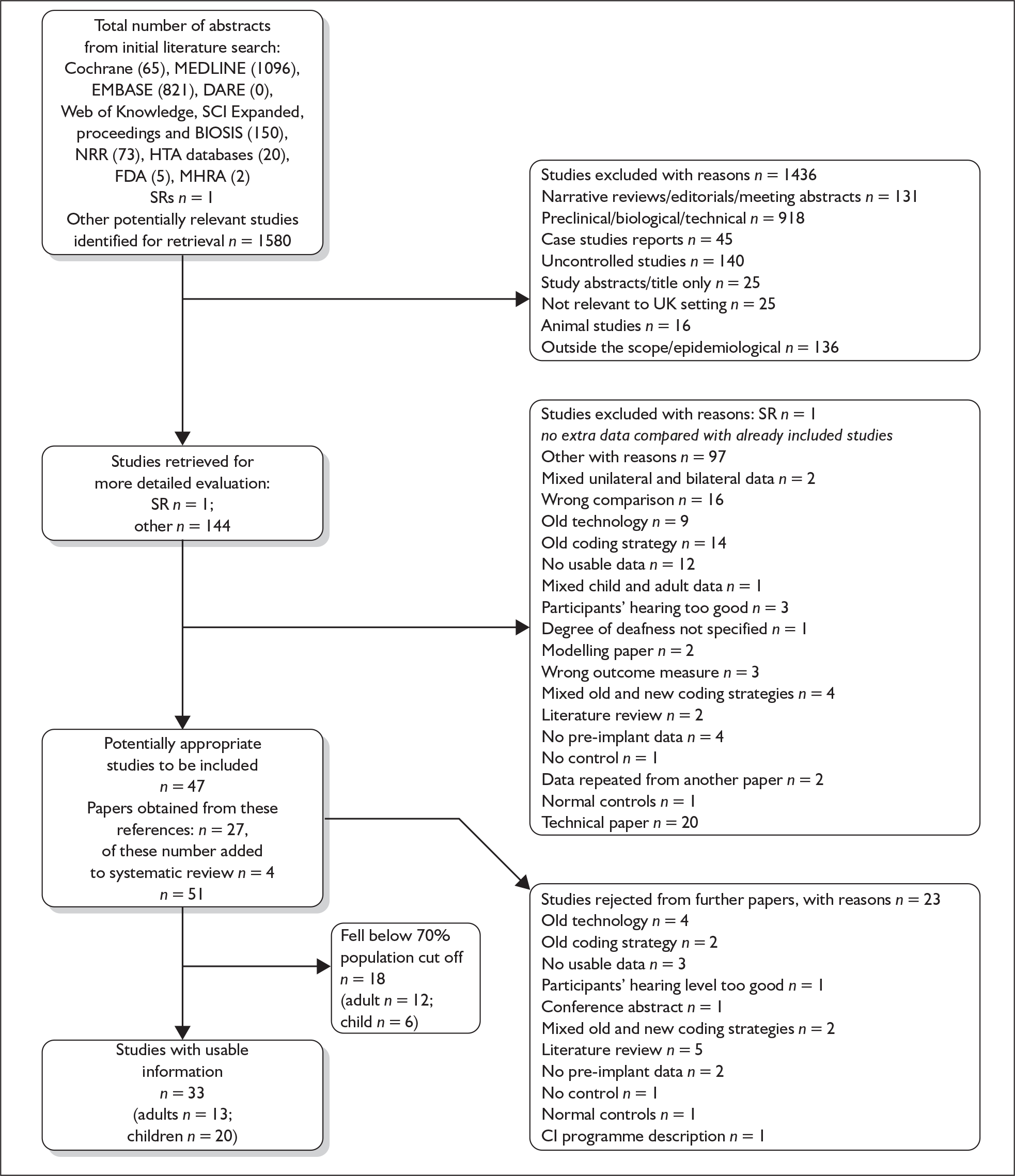

Relevant studies were identified in two stages. Abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two researchers (MB and JE) and screened for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts of the identified studies were obtained. Two researchers (MB and JE) examined these independently for inclusion or exclusion and disagreements were again resolved by discussion. The process is illustrated by the flow chart in Appendix 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Intervention

This assessment considers one or two multichannel cochlear implants using whole-speech processing coding strategies that attempt to transmit as much sound signal information as possible, for example ACE, SPEAK and CIS, rather than earlier feature extraction strategies. In cases in which the coding strategy was not disclosed in the research paper, attempts were made to contact authors for this information. When there was no response it was assumed that studies which collected data after 1995 used whole-speech processing and that those before did not.

This distinction between coding strategies was made following expert advice that whole-speech processing strategies are considered more effective and that older coding strategies are no longer being implanted by the NHS (Professor Quentin Summerfield, University of York, January 2007, personal communication). The devices currently supplied to the NHS and those in the included studies are shown in Table 4. There are currently 11 cochlear implant devices sold on contract to the NHS. Only two of these were used in the studies included in this report. Fourteen others were used in the studies but are no longer supplied under contract to the NHS.

| Supplier | Brand and model no.a | Year of introduction |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Bionics | HiRes 90K with HiFocus Helix Electrode CI-1400-02H | 2005 |

| CLARION ICS HiRes 90K Bionic Ear HF I J CI-400-01 | 2003 | |

| CLARION CII HiFocus | 2001 | |

| BI CLARION Platinum Aura | ||

| CLARION multistrategy implant with CIS | 1994 | |

| CLARION 1.2 | ||

| Cochlear UK | Nucleus Freedom with either the BTE or BWP option | 2006 |

| Nucleus CI 24R (ST) ‘K’ with a Sprint or ESPrit 3G speech processor | ||

| Nucleus CI 24R (CA) Advanced with a Sprint or ESPrit 3G speech processor | 2003 | |

| Nucleus CI11+11+2 double array with a Sprint or ESPrit 3G speech processor | 2000 | |

| Nucleus 24 contour | 1997 | |

| Nucleus 24 | 1997 | |

| Nucleus 22 with SPEAK | 1994 | |

| Nucleus multichannel | ||

| MED-EL | Pulsar CI-100 (implant and patient kit) | 2004 |

| Pulsar CI-100 (implant alone) | 2004 | |

| COMBI 40+ | 1996 | |

| COMBI 40 | 1996 | |

| Neurelec | DIGISONIC SP with Digi SP or Digi SP*K, model no. DX10/SP-K | |

| DIGISONIC SP binaural 24 channel, model no. DX10/SP-BIN | ||

| DIGISONIC SP for bilateral implantation, two full systems, model no. DX10/SP-BILAT | ||

| Manufacturers not reported | Tempo+ | |

| Spectra | ||

| CIS Pro+ | ||

| SPRINT |

Comparator

One cochlear implant was compared with non-auditory support, acoustic hearing aids and two cochlear implants. Two cochlear implants were compared with one cochlear implant plus a contralateral acoustic hearing aid.

Population

The population was children aged from 12 months to 18 years and adults.

Outcomes

These included:

-

sensitivity to sound

-

speech perception

-

speech production

-

psychological outcomes

-

educational outcomes

-

adverse events

-

health-related quality of life.

Relevance to the UK NHS of the technology

Studies were included if they were in health-care settings that were considered to be sufficiently similar to the UK to be relevant to this assessment (e.g. Europe, North America and Australasia).

Overview of the policy questions

This technology assessment report seeks to respond to the following NHS policy questions:

-

For severely or profoundly sensorineurally deaf people (who may be either using or not using acoustic hearing aids), is it effective and cost-effective to implant a first (i.e. unilateral) cochlear implant? This first question is addressed by the following comparisons:

-

unilateral cochlear implant versus no other hearing aid (non-technological support)

-

unilateral cochlear implant versus an acoustic hearing aid.

-

-

For severely or profoundly sensorineurally deaf people with a single cochlear implant (either unilateral or unilateral with a hearing aid), is it effective and cost-effective to implant a second (i.e. bilateral) cochlear implant? This second question is addressed by the following comparisons:

-

bilateral cochlear implants versus unilateral cochlear implant

-

bilateral cochlear implants versus unilateral cochlear implant and acoustic hearing aid.

-

Study design hierarchy

Systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials

All systematic reviews and RCTs were included, including those with waiting list controls. Systematic reviews ideally only consider well-conducted RCTs; however, in this instance the evidence base is methodologically highly variable across the policy questions of interest. The inclusion criteria for studies of clinical effectiveness were as follows.

Controlled studies

Other types of controlled studies (i.e. non-RCTs, cross-sectional studies and pre/post studies with people acting as their own controls) were included. These designs, including within-subject designs, were considered acceptable because levels of sensitivity to sound outcome at preimplantation were near or at zero and because hearing loss was unlikely to improve over time. Thus, benefits seen over time can be attributed to the intervention. However, with speech outcomes for children it could be expected that there would be a natural improvement over time. Prospective cohort designs, in which other people acted as control subjects, were included when baseline levels of hearing loss between the two groups were similar.

The inclusion of prospective cohort studies in a systematic review requires caution. The absence of randomisation introduces the possibility of bias in the selection of participants so that the group receiving the intervention may have different characteristics from the control group. These dissimilarities may cause confounding. Further bias may occur in measurement, for example ceiling effects from the benefit of a unilateral cochlear implant may obscure the benefit of an additional implant.

A number of the included studies were prospective case series; although these had the advantage of allowing participants to be their own controls, the validity of the results obtained is uncertain as familiarity with test materials, and therefore procedural learning, may affect results. 58 In observational studies confounding is a greater issue than lack of statistical power. A review59 evaluating non-randomised intervention studies has concluded that:

Results from non-randomised studies sometimes, but not always, differ from results of randomised studies of the same intervention. Non-randomised studies may still give seriously misleading results when treated and control groups appear similar in key prognostic factors.

Data abstraction strategy

Data were independently abstracted by one of five researchers (MB, SM, JE, ZL and CM). Each data extraction form was checked by another researcher. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Critical appraisal strategy

Assessments of study quality were performed using the indicators shown in the following sections. Results were tabulated and these aspects described in Chapter 4 and Chapter 5.

Internal validity

Consideration of internal validity addressed the selection of appropriate study groups, the identification of sources of possible confounders and their effects on analyses, whether the study was prospective, the blinding of assessors and data analysts, the validity and reliability of outcome measures, the reporting of attrition and the appropriateness of data analysis.

External validity

External validity was judged according to the ability of a reader to consider the applicability of findings to a patient group in practice. Study findings can only be generalisable if they (1) describe a cohort that is representative of the affected population at large or (2) present sufficient detail in their outcome data to allow the reader to extrapolate findings to a patient group with different characteristics. Studies that appeared representative of the UK population with regard to these factors were judged to be externally valid.

Data synthesis

The high degree of clinical heterogeneity of the studies combined with generally poor reporting of methods, plus a preponderance of non-randomised studies, meant that quantitative pooling of the data has not been possible. Instead, narrative syntheses of studies with tabulated quantitative results have been given.

Clinical effectiveness search results

Structure of the clinical effectiveness results section

The assessment of clinical effectiveness will be presented as follows:

-

a brief summary of the history of cochlear implant research

-

an overview of the quantity and quality of included studies

-

a description of the outcome measures used in the included studies.

Then, separately for children and adults we present:

-

a critical review of the evidence for cochlear implantation with each comparison reviewed in turn, including the type and quality of studies; a summary table of key quality indicators; study results, presented as a narrative description and as tables giving a visual overview of study results; and a summary of the comparison results

-

at the end of the child and adult comparisons a review of studies reporting quality of life outcomes outside the population intervention comparator outcome setting (PICOS) criteria

-

at the end of the children’s section a review of studies reporting educational outcomes outside the PICOS criteria

-

at the end of the child and adult sections a summary of all of the clinical effectiveness studies

-

a review of the safety and reliability of cochlear implants.

Summary of cochlear implant research history

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the earliest research prototype cochlear implants provided totally deaf people with a sensation of sound. This enabled them to identify environmental sounds and possibly a few words. The research issues at that time were those of safety and efficacy and understanding the differences in outcome that people experienced.

In 1993 an RCT50 compared single channel and multichannel devices and showed that multichannel implants had significant advantages. This study led to the end of single channel implantation. Also, in the early 1990s the Iowa research group60 compared the leading makes of multichannel implants by allocating recipients alternately to either device. As well as showing no differences between devices, this group demonstrated that a large number of people would be needed to show significant differences between devices. Thus, the research agenda shifted to studies of small numbers of carefully selected people to test different processing strategies, and large-scale RCTs were not undertaken.

Quantity and quality of studies found

The systematic search of electronic databases for clinical effectiveness studies produced 1581 abstracts/titles.

From the search results 1436 items were excluded; reasons for these exclusions included that items were narrative reviews, preclinical or technical papers, uncontrolled studies, conference abstracts, not relevant to the UK setting, animal studies or outside the PICOS criteria for this assessment. The movement of papers can be seen in the QUOROM flow chart in Appendix 2. One meta-analysis and 144 other primary research papers were obtained for further examination. This led to the exclusion of 97 papers, leaving 47.

Further papers (n = 27) were obtained from the reference lists of the included papers; when these had been assessed four papers were added to the review giving a total of 51 primary research papers in the review of clinical effectiveness.

Because of the large number of eligible studies (n = 51), some of which included a very small sample size (range n = 3 to n = 311), and constraints on resources, we evaluated sufficient studies for each of the eight comparisons (see Chapter 2, Decision problem) to have at least an arbitrary 75% of the total eligible study population for that comparison, starting with the largest studies. We would have preferred to make these further exclusions on grounds of quality; however, on examination it was found that the heterogeneity amongst the studies was such that there was no logical way to pursue this. The 75% population cut-off left a total of 33 studies (13 adult studies and 20 child studies). All of the excluded studies used non-randomised designs.

The main theoretical implication of not including all eligible studies is that the excluded studies may contain evidence that contradicts that presented. In reality this is unlikely to be the case as, although there is a large amount of heterogeneity between the included studies in terms of design, numbers, outcome measures, etc., the results all go in the same direction. It is therefore unlikely that the excluded smaller studies would contradict this finding. Another potential problem could occur if data were pooled, as the results of the excluded studies could change the central estimate; however, in this review, because of heterogeneity, there is no pooling of data. Furthermore, the excluded studies may contain particular information that is not available in the other studies.

The meta-analysis by Cheng and colleagues61 was a comparison of published and unpublished literature on child cochlear implantation. However, all of the included studies were of old technologies excluded from this review. Table 5 provides a summary of the types and numbers of studies included. The relaxing of criteria to include non-RCTs permits the introduction of many sources of bias and limits the possible statistical analyses.

| Comparison | Design | Total studies | n in each group | % of potential participants included | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting list RCTs | Pre/post studies | Cross-sectional studies | Prospective cohort studies | ||||

| Adult groups | |||||||

| One CI vs NT | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 984 | 89 |

| One CI vs AHA | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 248 | 91 |

| Two CI vs 1CI | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 147 | 77 |

| Two CI vs 1CI and AHA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Total adults | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 1379 | 88 |

| Child groups | |||||||

| One CI vs NT | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 848 | 97 |

| One CI vs AHA | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 535 | 87 |

| Two CI vs 1CI | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 61 | 84 |

| Two CI vs 1CI and AHA | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 69 | 100 |

| Total children | 0 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 1513 | 93 |

| Total both groups | 2 | 19 | 8 | 4 | 33 | 2892 | 90 |

A summary of ongoing trials can be found in Appendix 14.

Definitions of study design used in this report

-

Waiting list RCTs – These are RCTs in which participants are randomly allocated to have the intervention immediately or to go onto a waiting list and have the intervention in the future. Outcomes from both groups are then compared at baseline and at the same time points from baseline. The weakness of this design is that confounding variables may affect the control group in the time before they receive the intervention.

-

Pre/post studies – This design consists of measuring and comparing outcomes before and after the intervention, with participants usually acting as their own controls. The main weaknesses of this design are its inability to account for maturation effects and selection bias.

-

Cross-sectional studies – These measure differences in outcomes between intervention and control groups at one point in time. Usually the intervention and control groups are two different groups of people. However, in the case of cochlear implants they may be the same, as the external component of an implant can be removed and outcomes measured without the device. The main weaknesses of this design are that it cannot report changes over time and if different groups are measured then selection bias may occur.

-

Prospective cohort studies – In this design the intervention group is compared with control subjects who have been selected to have similar characteristics. The weakness of this design is the lack of randomisation, which would control for selection bias and potential confounders.

Summary tables for each comparison are shown at the beginning of the relevant section.

Only seven studies reported both sensitivity to sound and functional measures of severity of deafness. Moreover, there were insufficient studies (with the same comparators) to reveal any apparent relationships between the preimplantation sensitivity to sound hearing level and size of functional outcome.

Of the studies reporting both types of measures of deafness (sound sensitivity and functional ability) only one62 used health utility outcomes; this study classified implant recipients according to preimplantation speech perception using standard sentence tests and when using optimally fitted hearing aids. This can be viewed as a classification according to level of ‘functional hearing’, and was predictive of levels of utility gain with implantation. Given that, in the current UK NHS, ability to benefit from cochlear implantation is primarily judged on the basis of level of functional hearing ability, it is unfortunate that the vast majority of the evaluative research on this technology only reports the audiologically measured severity of deafness of implantation candidates.

Number and type of studies excluded

Studies of single channel implants or those that used feature extraction or compressed analogue coding strategies were excluded as they are not comparable with current NHS practice. In total, 132 studies were excluded from the clinical systematic review. This was for a variety of reasons, for example the outcome measures or comparisons were outside our inclusion criteria, they included technologies that are no longer in current use, none of the data published was usable, they described technical details of the technologies, they were literature reviews or conference proceedings or they had very small sample sizes.

Quality of life and educational outcome studies

The study selection process found only three studies that included measures of quality of life, and no studies with educational outcomes. Therefore, the searches were screened again for studies with these outcomes using broader inclusion criteria that allowed normal-hearing control subjects and no control subjects; further searches were carried out; and references from included studies were checked. Seven studies were identified that included educational outcomes for children with cochlear implantation. For the quality of life of cochlear implant users four studies in children and six studies in adults were found. Quality of life and educational outcomes are therefore reported separately for children and adults in Chapters 4 and 5 respectively.

Outcome measures

This section reports an overview of outcome measures used in the included studies. The outcome measures selected by the authors of the included studies reflect the hypothesised benefits that may come from cochlear implantation. These are enhanced auditory receptive skills with evidence of emergence of aural/oral communication modes, followed by useful levels in ability in spoken language; improved performance at school in terms of academic achievement and reduced levels of specialist educational support, leading to enhanced social skills; a successful transition to secondary education; and better educational outcomes with better further educational and employment prospects, which may lead to greater independence and quality of life.

The outcome measures can be categorised as sensitivity to sound, speech perception, speech production, quality of life and educational. Because of the large numbers of measures (n = 62) reported in the included studies they are described in more detail in Appendix 5. Here we present a brief description of the different types of outcome measure followed by a list of outcomes by type and the number of studies that used each one. In Tables 6–10, measures shaded in dark grey were used with adults, those shaded with light grey were used with adults and children and those unshaded were used with children.

| Measure | No. of studies using this measure |

|---|---|

| Basal auditory ability64 | 1 |

| CAP – Categories of Auditory Performance65 | 1 |

| MAA – Minimal audible angle | 3 |

| MAIS (IT-MAIS) – Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale62 | 2 |

| PTA – Pure-tone audiometry | 2 |

| SSQ – Speech Hearing, Spatial Hearing and Qualities of Hearing questionnaires63 | 1 |

| Measure | No. of studies using this measure |

|---|---|

| One-syllable test70 | 1 |

| Two-syllable test70 | 1 |

| AB monosyllables – Arthur Boothroyd monosyllabic word test71 | 1 |

| AVGN – A normalised index of audiovisual gain | 1 |

| BKB – Bamford–Kowal–Bench sentences67 | 5 |

| CAP – Categories of Auditory Performance72 | 1 |

| CDT – Connected discourse tracking73 | 1 |

| CID sentences – Central Institute for the Deaf sentences74 | 1 |

| CNC – Consonant Nucleus Consonant monosyllabic word test75 | 4 |

| Common Phrases Test76 | 3 |

| CUNY – City University of New York77 | 5 |

| ESP – Early Speech Perception battery68 | 5 |

| FMWT – Freiburger monosyllabic word test78 | 1 |

| GASP – Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure69 | 7 |

| Gottinger speech lists79 | 1 |

| HINT – Hearing in Noise Test80 | 3 |

| HINT-C – Hearing in Noise Test for Children80 | 3 |

| HSM sentences – Hochmaier, Schultz and Moser sentence test81 | 2 |

| IMST – Iowa Matrix Sentence Test82 | 1 |

| LNT – Lexical Neighbourhood Test83 | 2 |

| MAC – Minimal Auditory Capabilities84 | 1 |

| Minimal Pairs Test76 | 1 |

| MLNT – Multisyllabic Lexical Neighbourhood Test85 | 2 |

| Mr Potato Head86 | 3 |

| NU-6 – Northwestern University Auditory Test number 687 | 1 |

| OLSA – Oldenburg sentence test88 | 1 |

| PB-K – Phonetically Balanced Kindergarten Word List89 | 5 |

| RITLS – Rhode Island Test of Language Structure90 | 1 |

| SECSHIC – Scales of Early Communication Skills for Hearing Impaired Children91 | 1 |

| TAC – Test for Auditory Comprehension of Language92 | 1 |

| TAPS – Test for Auditory Perception and Speech93 | 1 |

| TROG – Test for the Reception of Grammar94 | 1 |

| Measure | No. of studies using this measure |

|---|---|

| CRISP – Children’s Realistic Intelligibility and Speech Perception test95 | 2 |

| IPSyn – Index of Productive Syntax96 | 1 |

| SIR – Speech Intelligibility Rating97 | 1 |

| Measure | No. of studies using this measure |

|---|---|

| APHAB – Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit98 | 1 |

| AQoL – Assessment of Quality of Life99 | 2 |

| Everyday Life Questionnaire100 | 1 |

| EQ-5D – EuroQol 5 dimensions101,102 | 1 |

| GBI – Glasgow Benefit Inventory103 | 2 |

| GHSI – Glasgow Health Status Inventory104 | 2 |

| HHIA – Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults105 | 1 |

| HPS – Hearing Participation Scale106 | 1 |

| HUI-3 – Health Utilities Index 3107 | 2 |

| IRQF – Index Relative Questionnaire Form108 | 1 |

| KINDLr – Munich Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children109 | 1 |

| NCIQ – Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire110 | 1 |

| PQLF – Patient Quality of Life Form108 | 1 |

| Quality of life questionnaire111 | 2 |

| SF-36 – Short-Form 36112 | 1 |

| Symptom Checklist 90-R113 | 1 |

| Tinnitus Questionnaire114 | 1 |

| ULS – Usher Lifestyle Questionnaire115 | 1 |

| VAS quality of life scale – Visual analogue scale101,102 | 1 |

| Measure | No. of studies using this measure |

|---|---|

| AMP – Assessment of Mainstream Performance116 | 1 |

| SIFTER – Screening Instrument for Targeting Educational Risk117 | 1 |

Sensitivity to sound measures

Six different sensitivity to sound measures were used in 10 studies, nine of which were studies of children (Table 6).

Some of these measures used everyday sounds, for example the basal auditory ability test, which determines whether a child can correctly associate a common sound with its source, such as a door bell. Real-life listening behaviours of children were measured by proxy from carer questionnaires with the Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale (MAIS). 63 Other instruments were laboratory-based, measuring the ability to detect the direction of sound (Speech, Spatial and Quality of Hearing questionnaires64) or the smallest change in position that could be discriminated (minimal audible angle, MAA).

Speech perception measures

Most studies reported speech perception measures. In total, 32 measures were used; 11 measures were used for adults, one measure was used for adults and children (Bamford–Kowal–Bench sentences67) and 20 were used only on children (Table 7). The tests consisted of lists of phonemes, words or sentences that had to be correctly identified. Some tests included word recognition tasks in which a word is spoken and the correct picture has to be pointed to [e.g. the Early Speech Perception (ESP) battery68]. Other tests [e.g. the Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure (GASP)69] required a verbal response and so could also be used to measure speech production. These outcome measures place varying cognitive demands on people to complete the tasks, i.e. perception, discrimination, recognition and understanding at different levels (word, sentence, phoneme). This means that the tests and results are not all comparable and cannot be considered as equally difficult.

Speech production measures

Speech production measures were less frequently used, including three measures in four studies, all of which were in children (Table 8). Measures evaluated the intelligibility of whole speech by a range of listeners (Speech Intelligibility Rating) and parts of speech such as noun phrases (Index of Productive Syntax).

Quality of life measures

Quality of life with cochlear implants was measured in 23 studies using 19 different instruments (children, five; adults, 13; both, one) (Table 9). A range of experience was covered by the measures, which included ad hoc, condition-specific questionnaires (Everyday Life Questionnaire) to generic, validated measures of utility (Health Utilities Index 3). Other instruments measured particular aspects of quality of life and psychological, social, emotional and physical states (Glasgow Health Status Inventory) or focused on specific diseases or symptoms (Usher Lifestyle Questionnaire and the Tinnitus Questionnaire).

Educational measures

Only two questionnaire measures of educational outcomes were used (Table 10). These measured the skills that deaf children need to succeed in mainstream education [Assessment of Mainstream Performance (AMP)] and school performance [Screening Instrument for Targeting Educational Risk (SIFTER)].

Other considerations about measures and their implementation

There is some evidence that the choice of speech recognition test can affect outcomes; sentences that have more syllables per minute are harder to recognise. 118 It has also been shown that a known voice is easier to understand than an unknown one. 119

Chapter 4 Results of the clinical effectiveness evidence for children

The majority of studies reported results in figures (usually bar charts) rather than in the text or in tables. To maximise accurate data extraction the figures had to be enlarged (×400%) to enable reading of the study results. Thus, values may deviate from values measured by the original authors. Summary tables of study characteristics and results can be found in Appendix 3.

Unilateral cochlear implants versus non-technological support – children

This section considers studies in which the comparisons did not include devices of any kind.

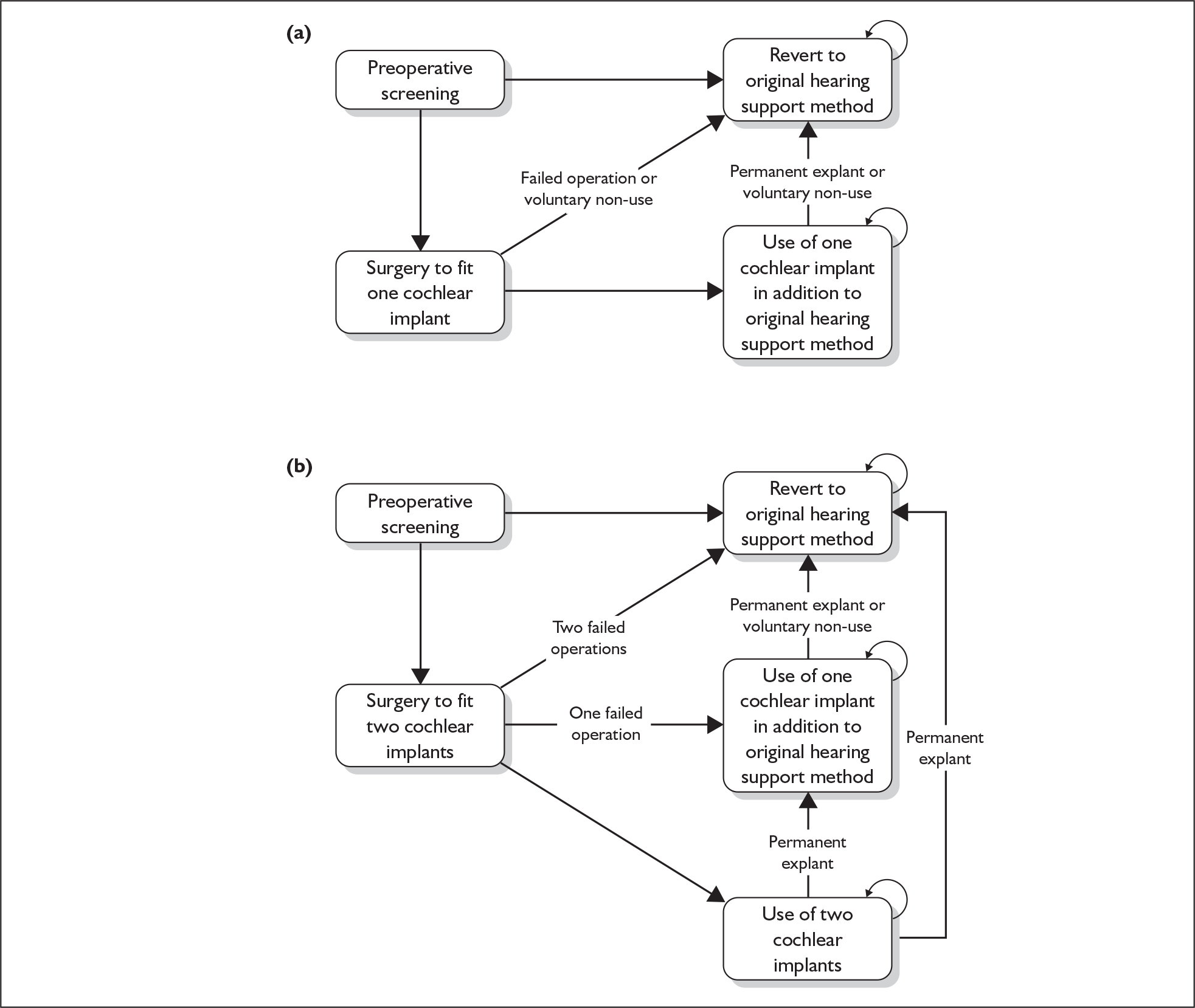

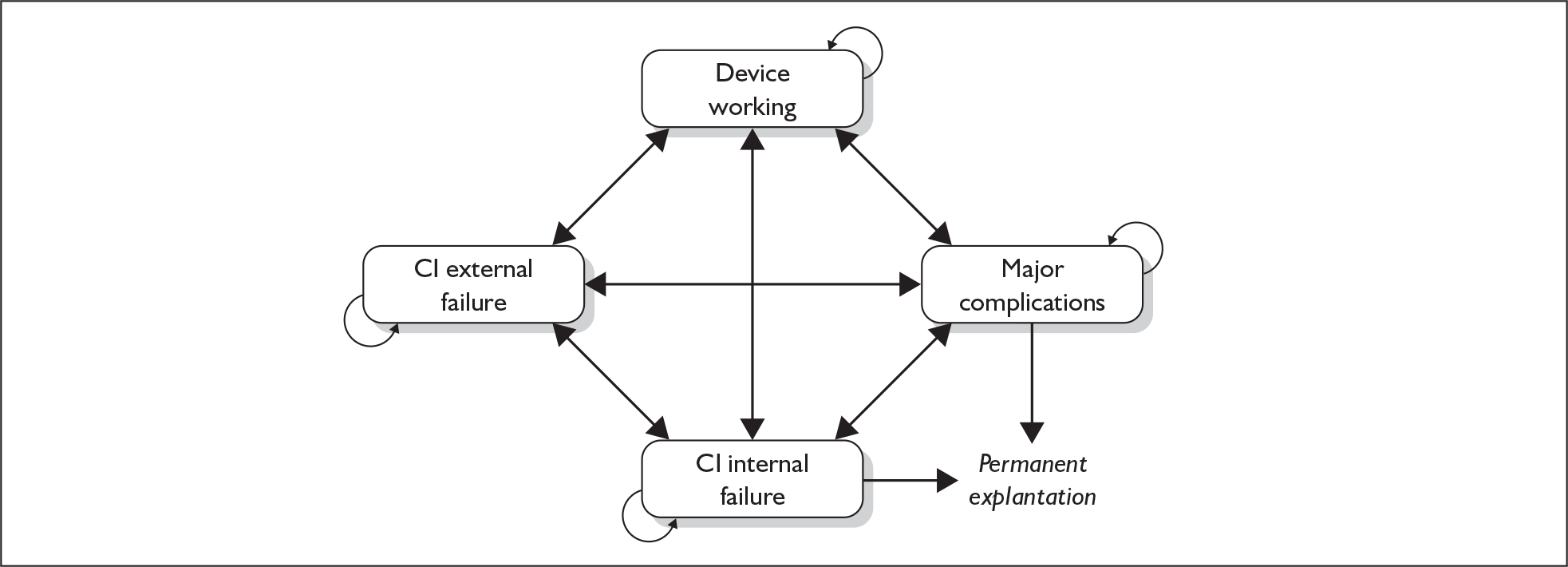

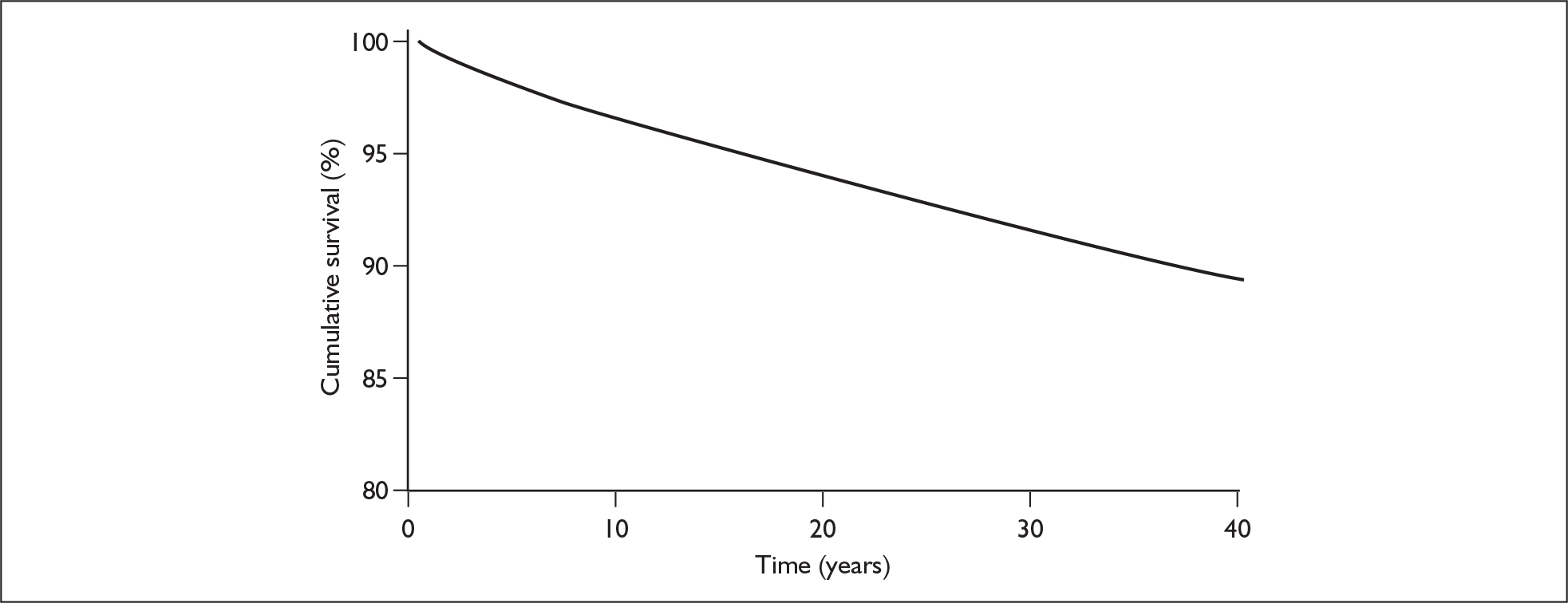

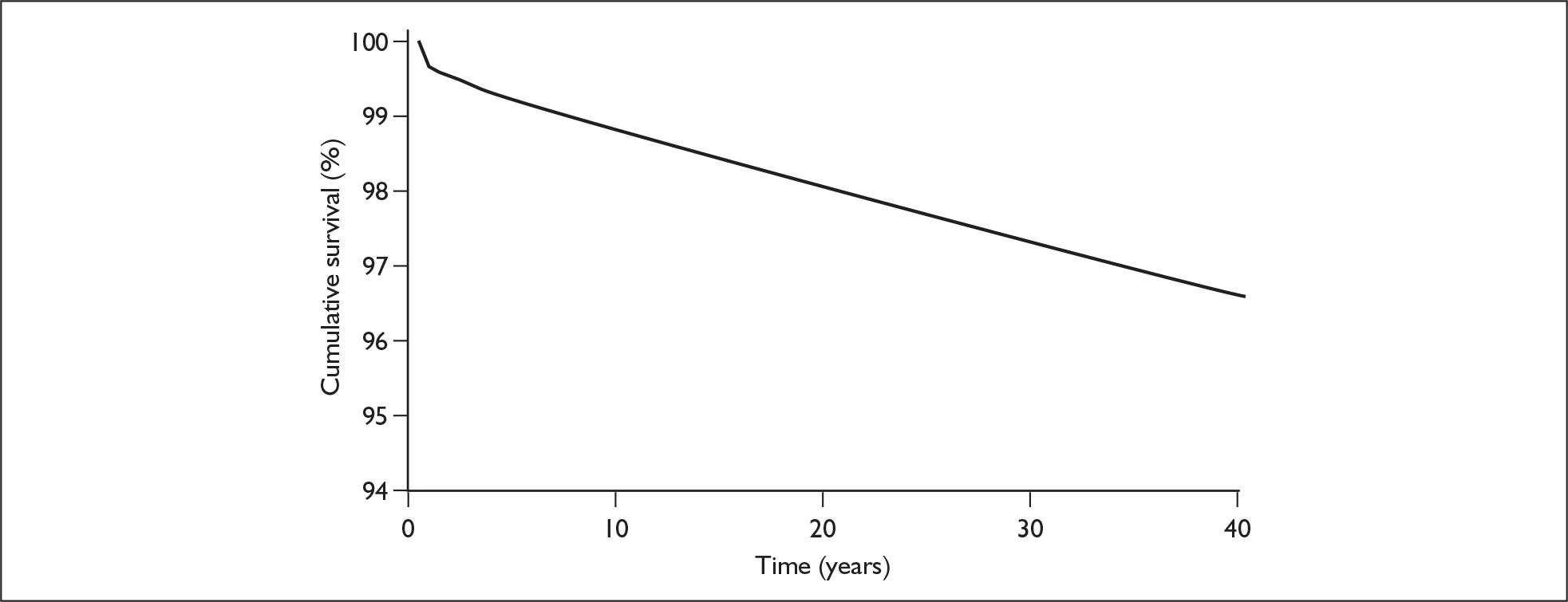

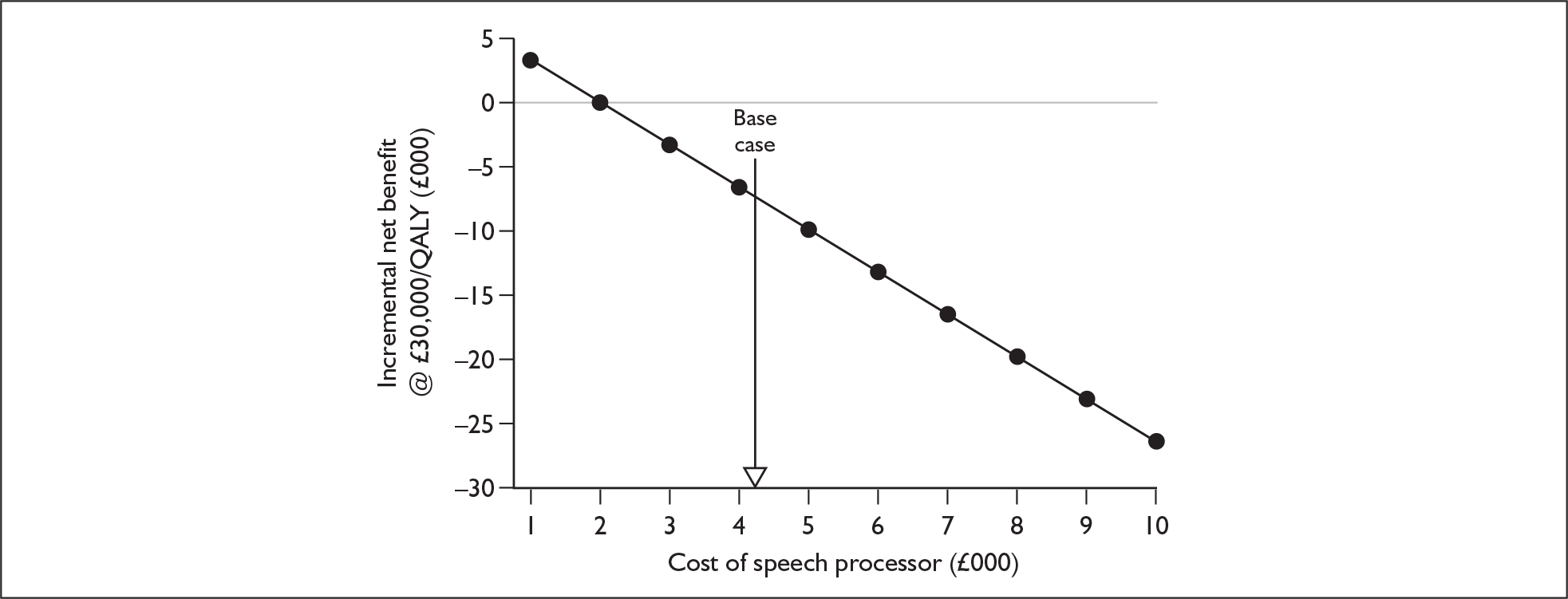

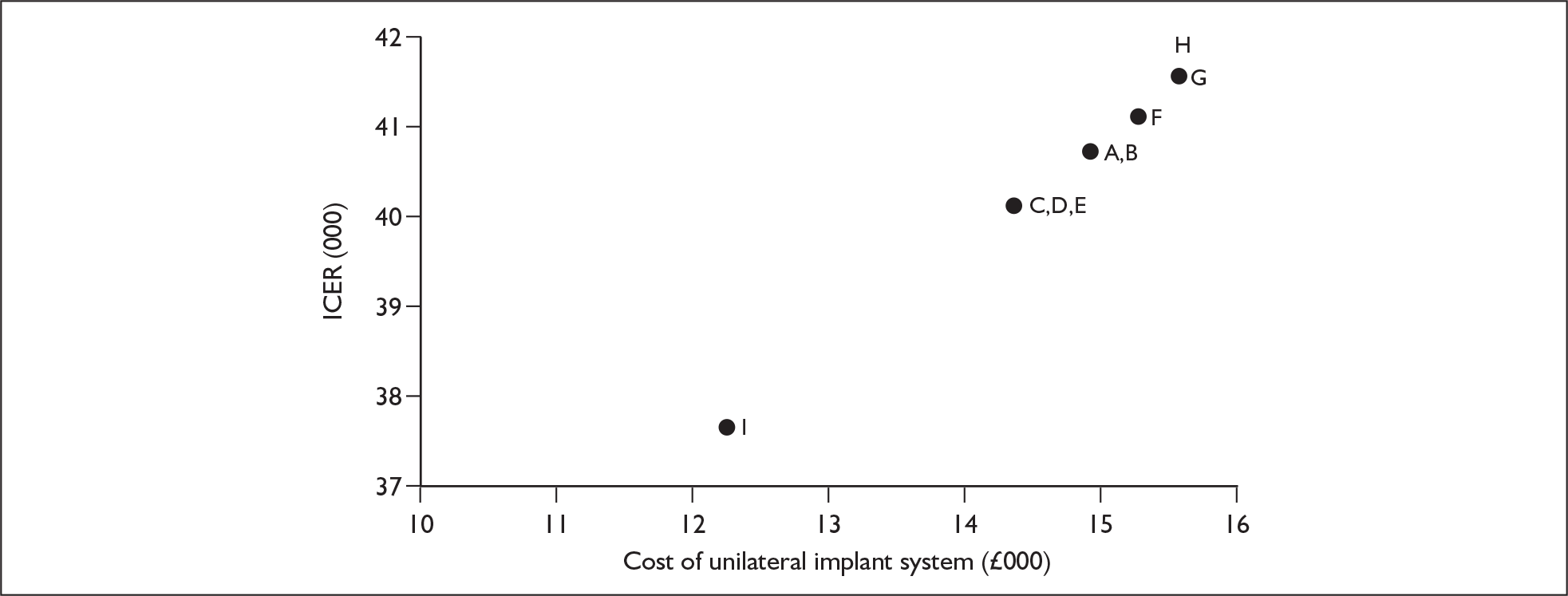

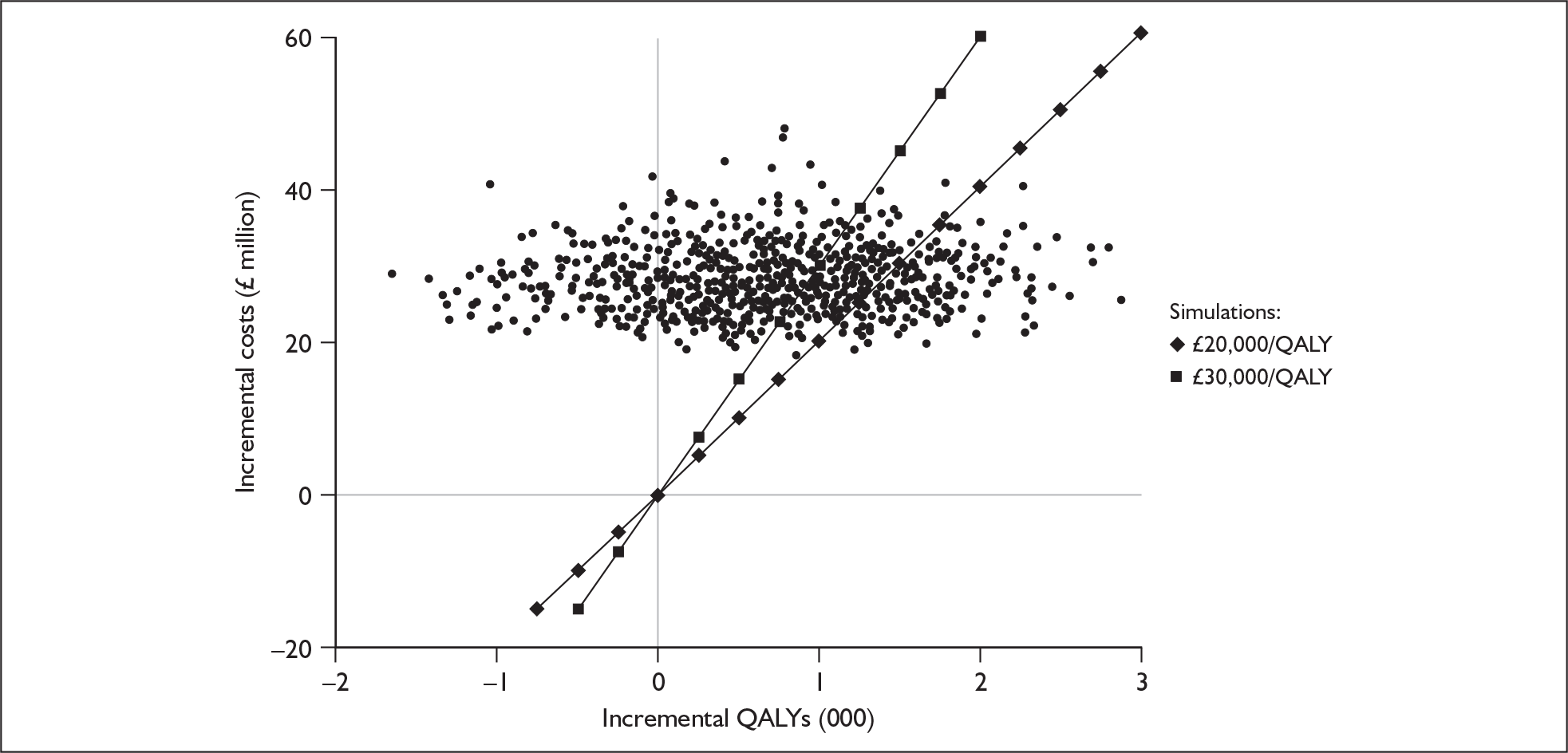

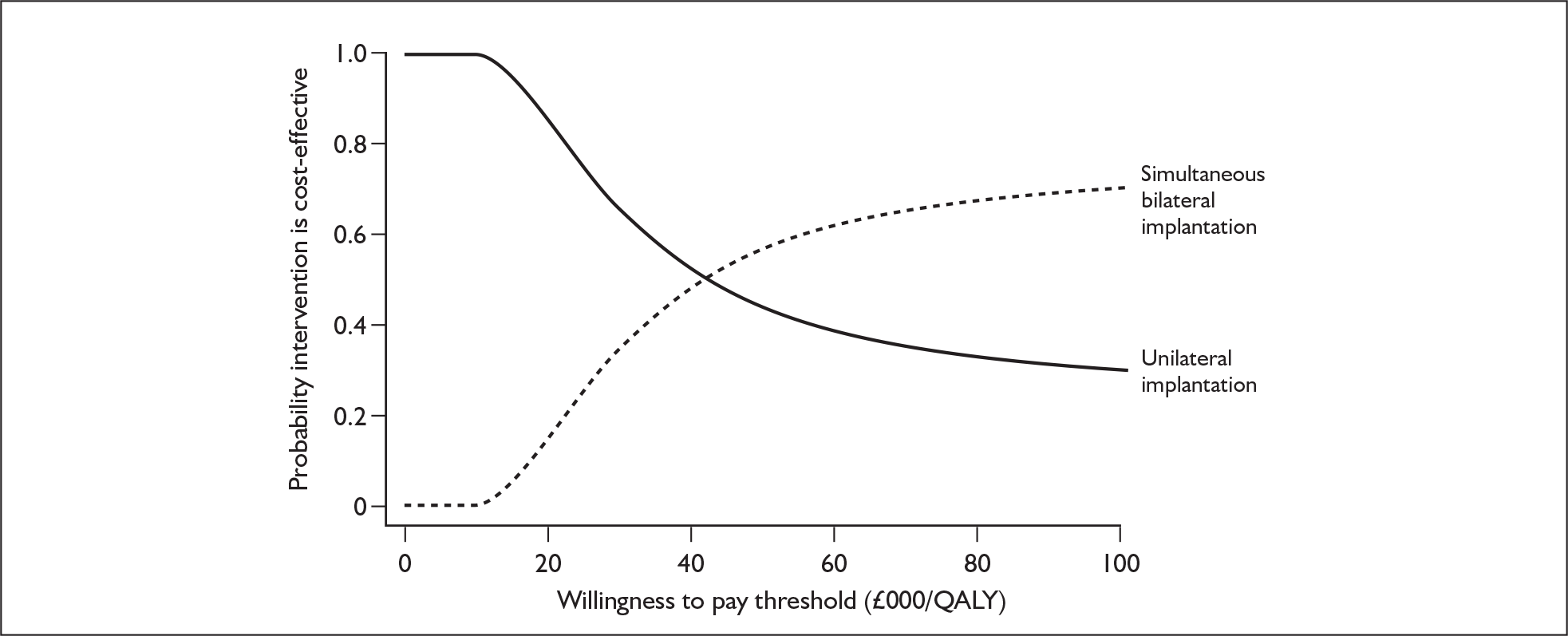

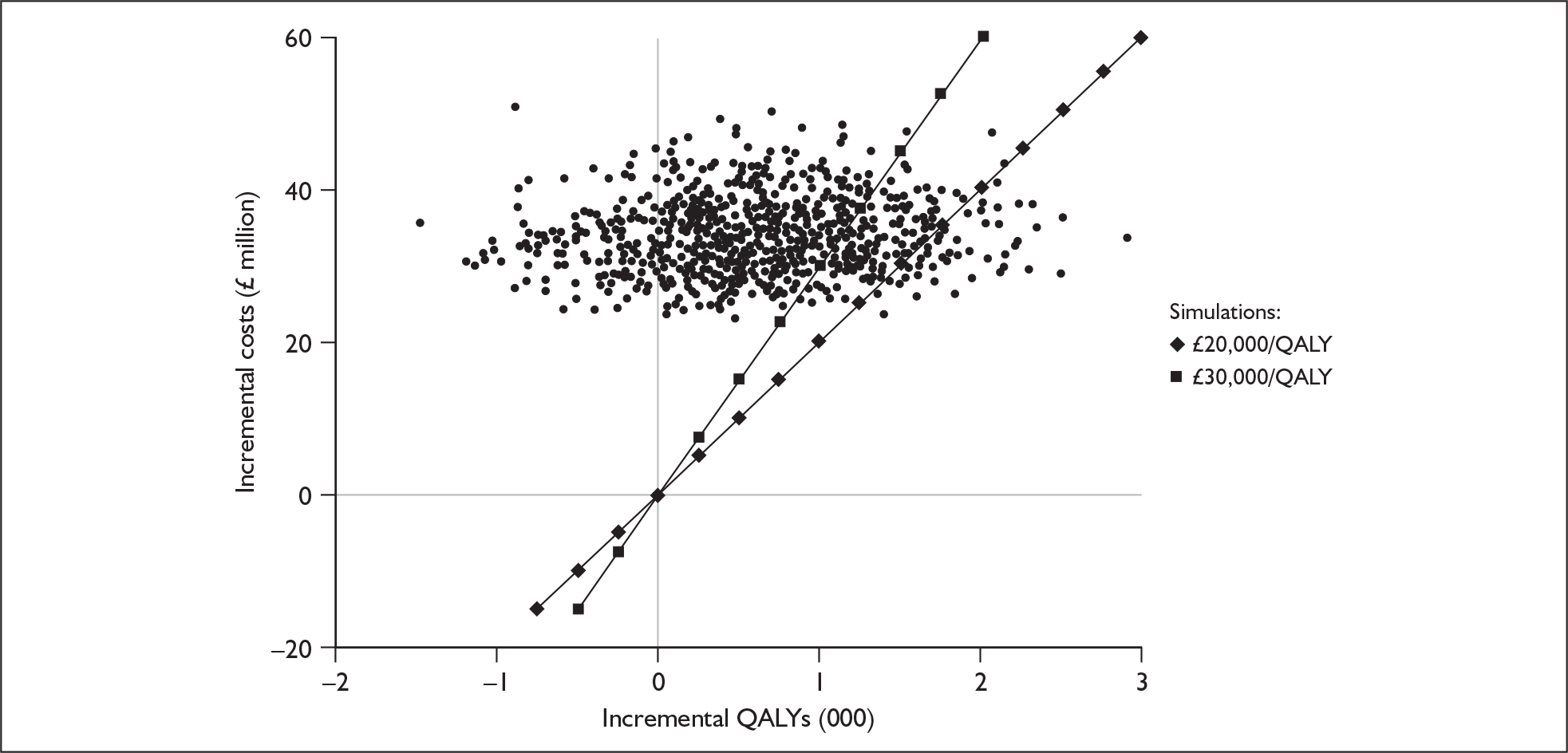

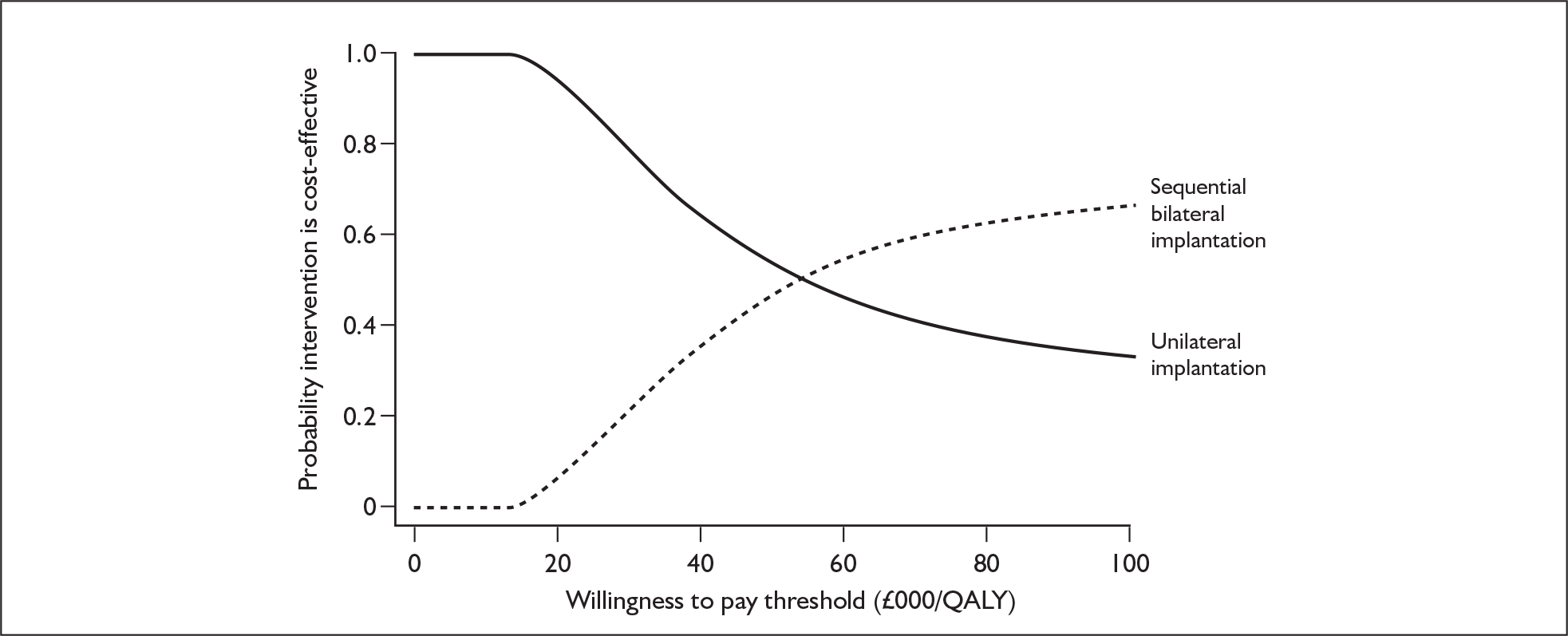

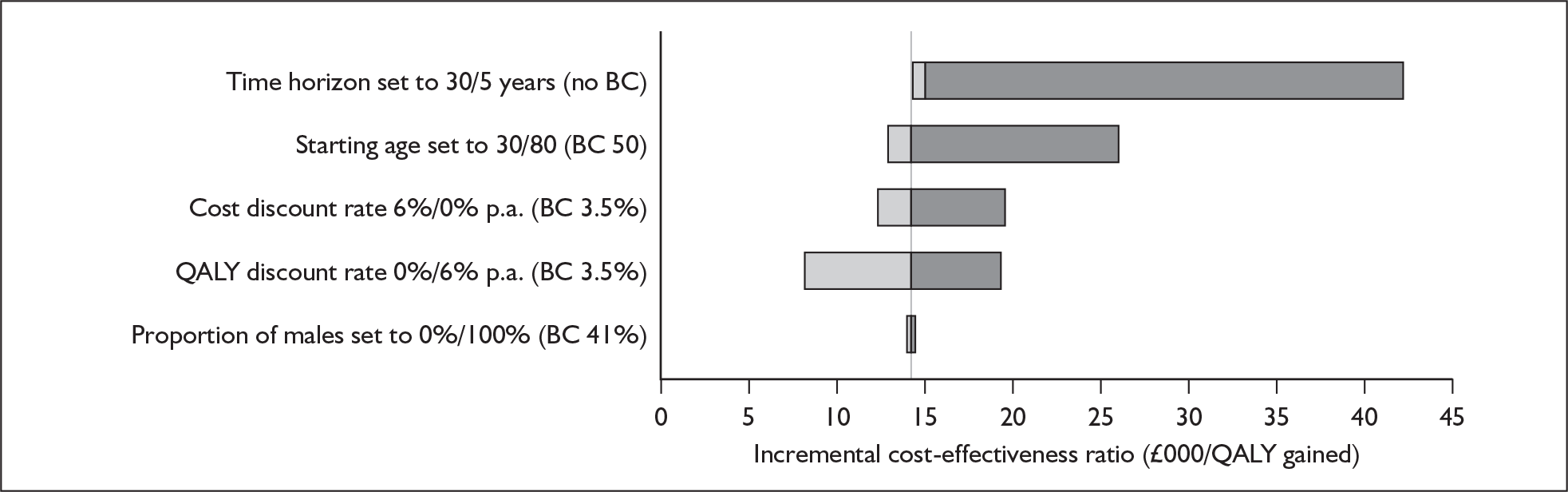

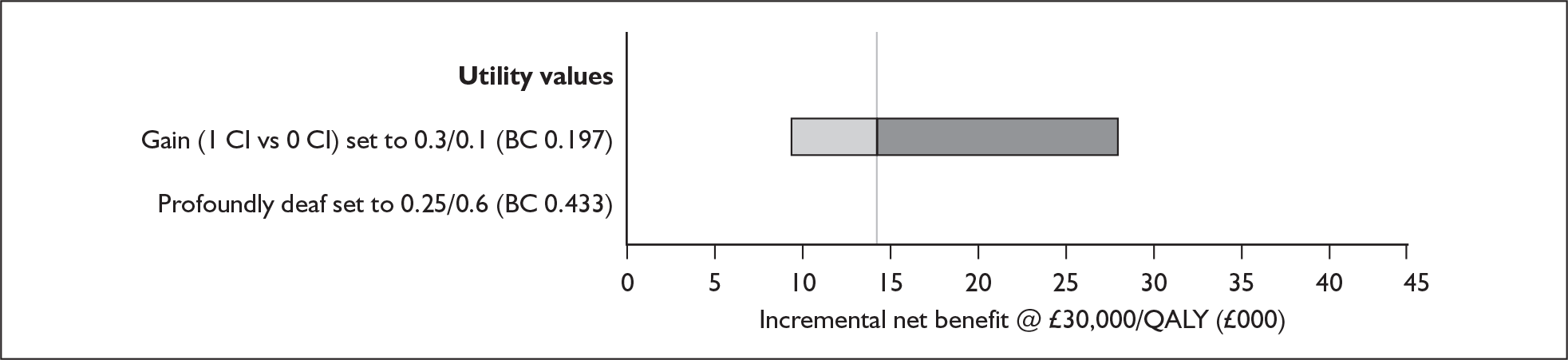

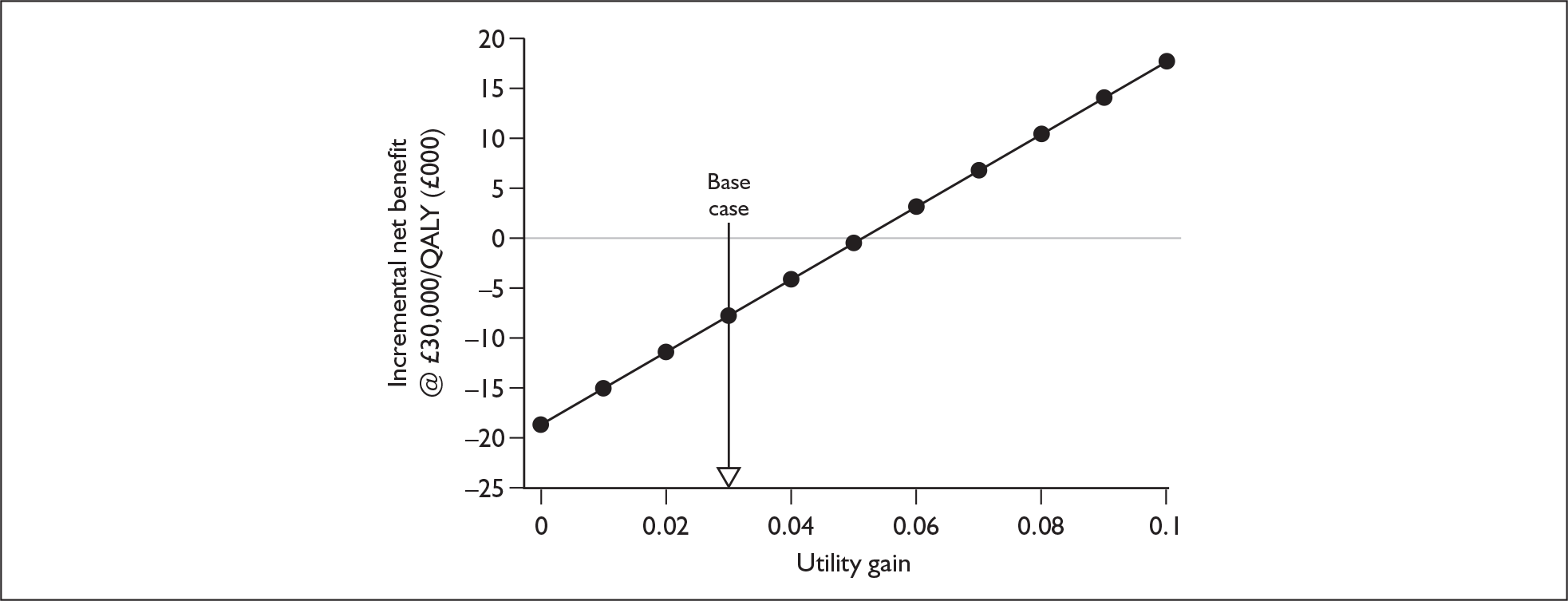

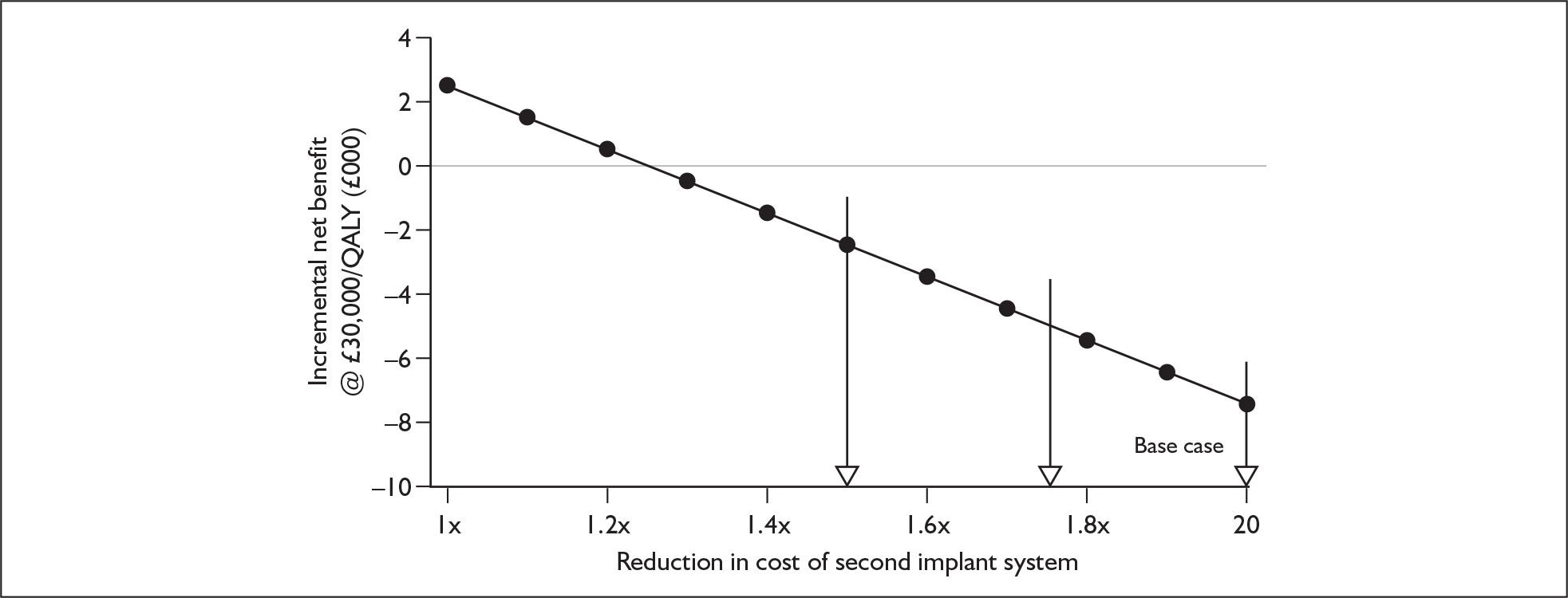

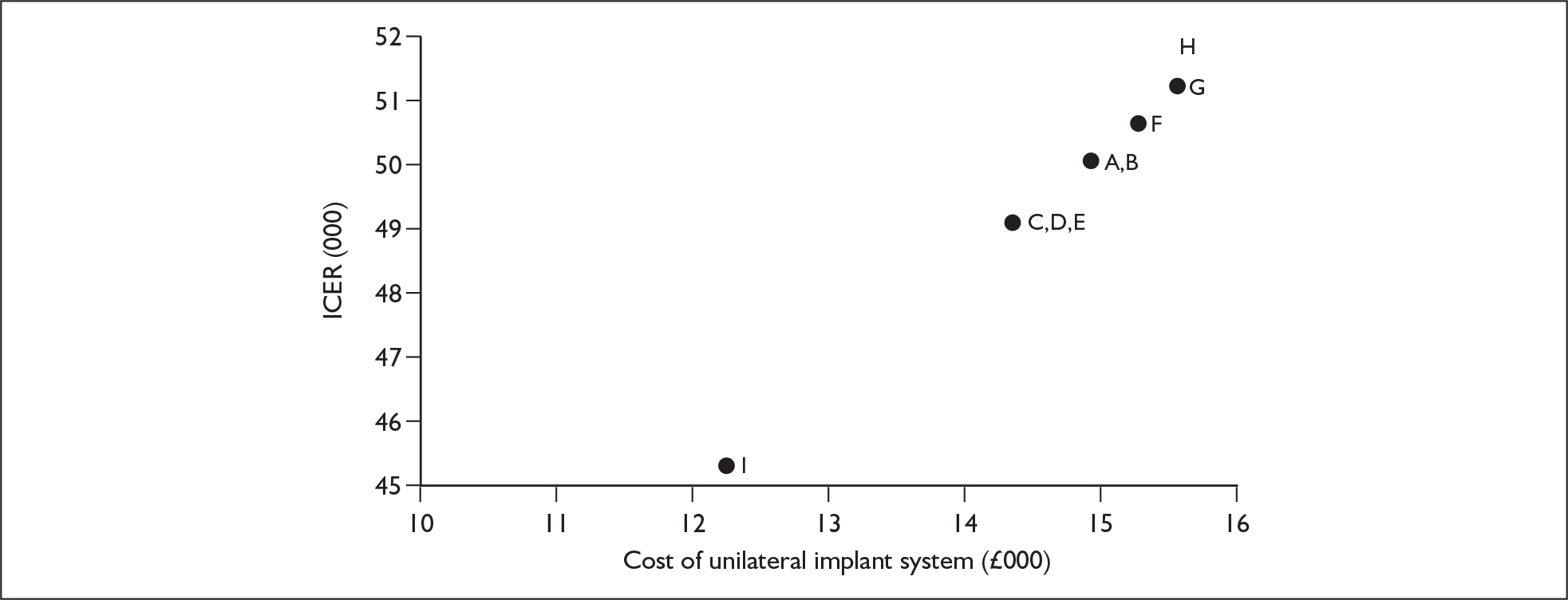

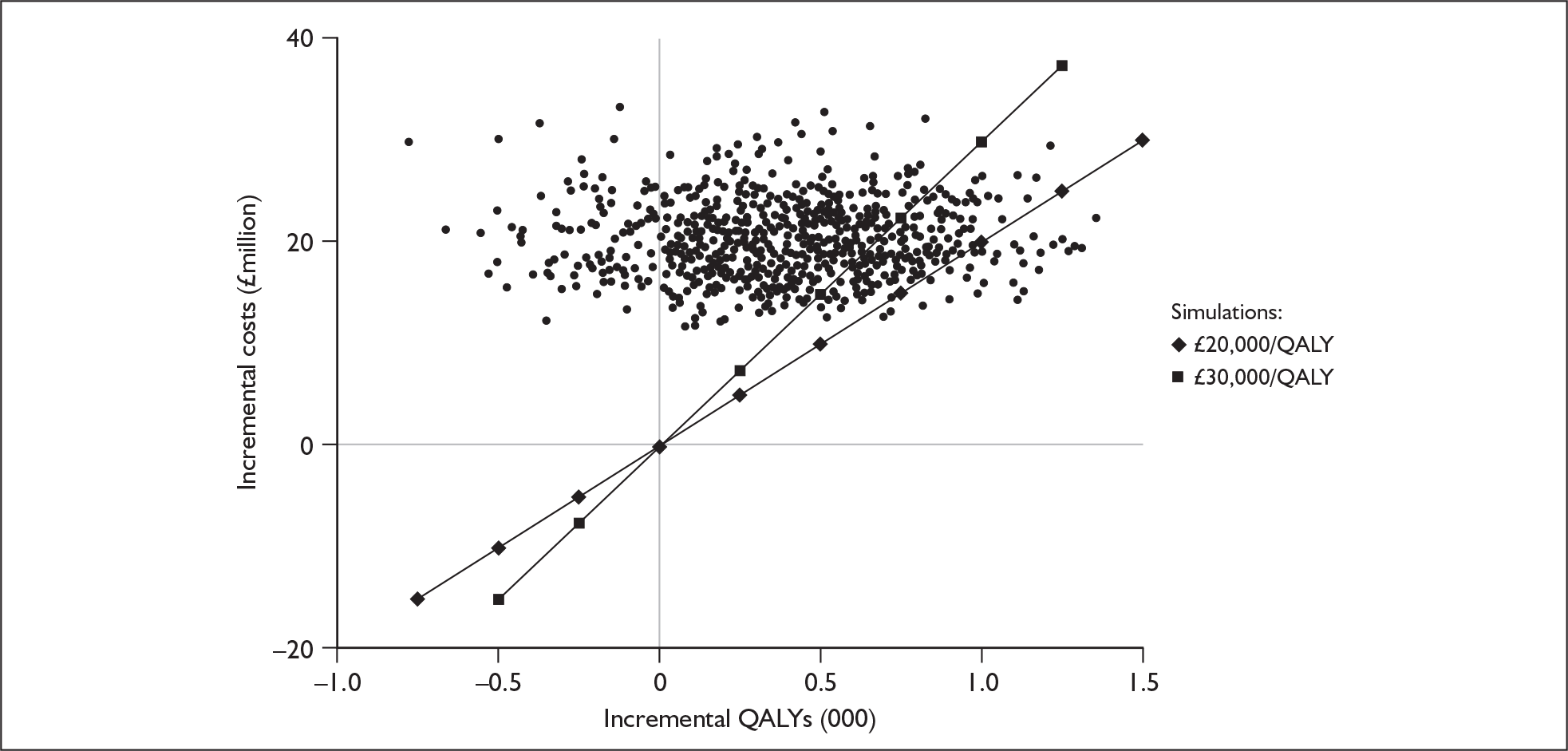

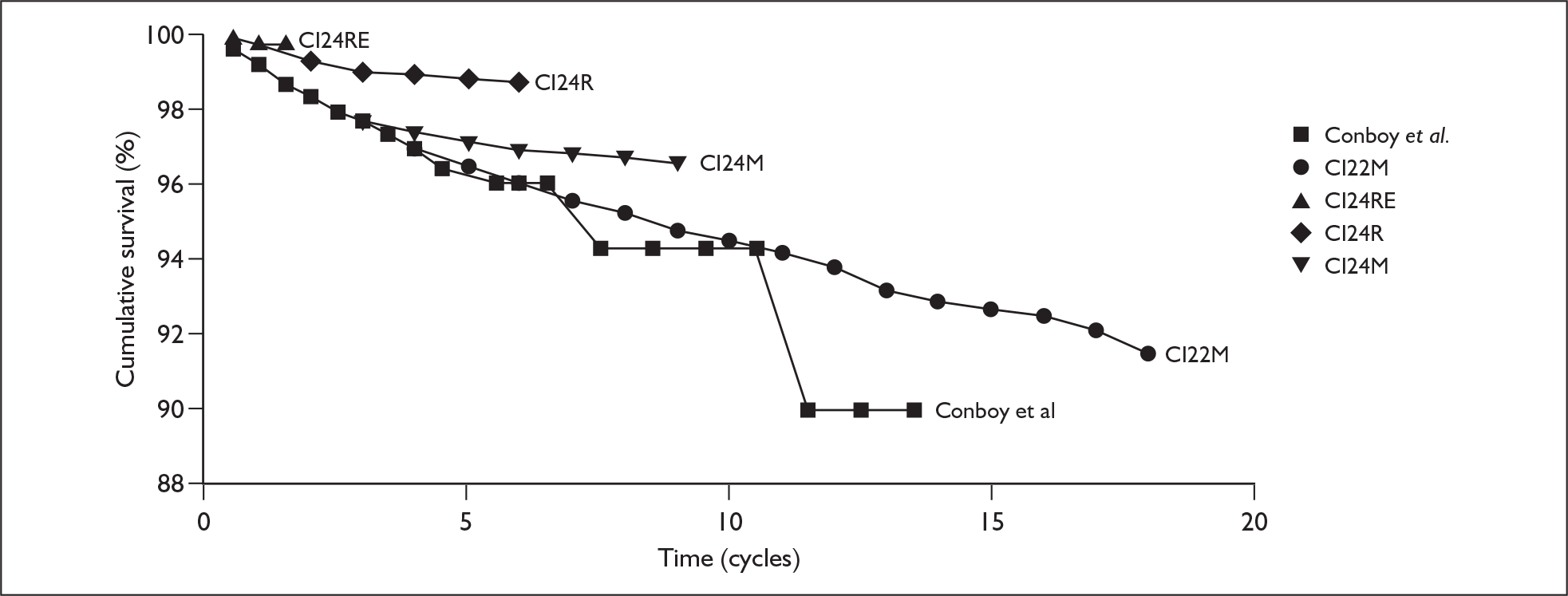

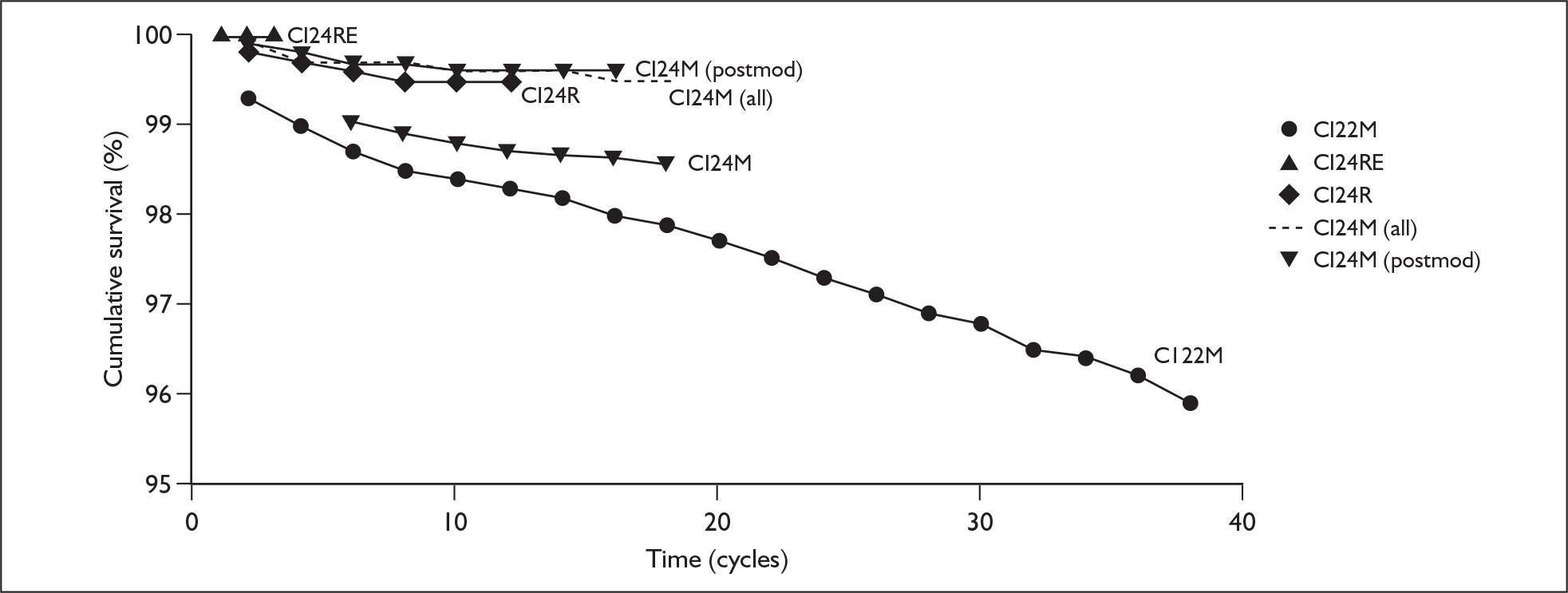

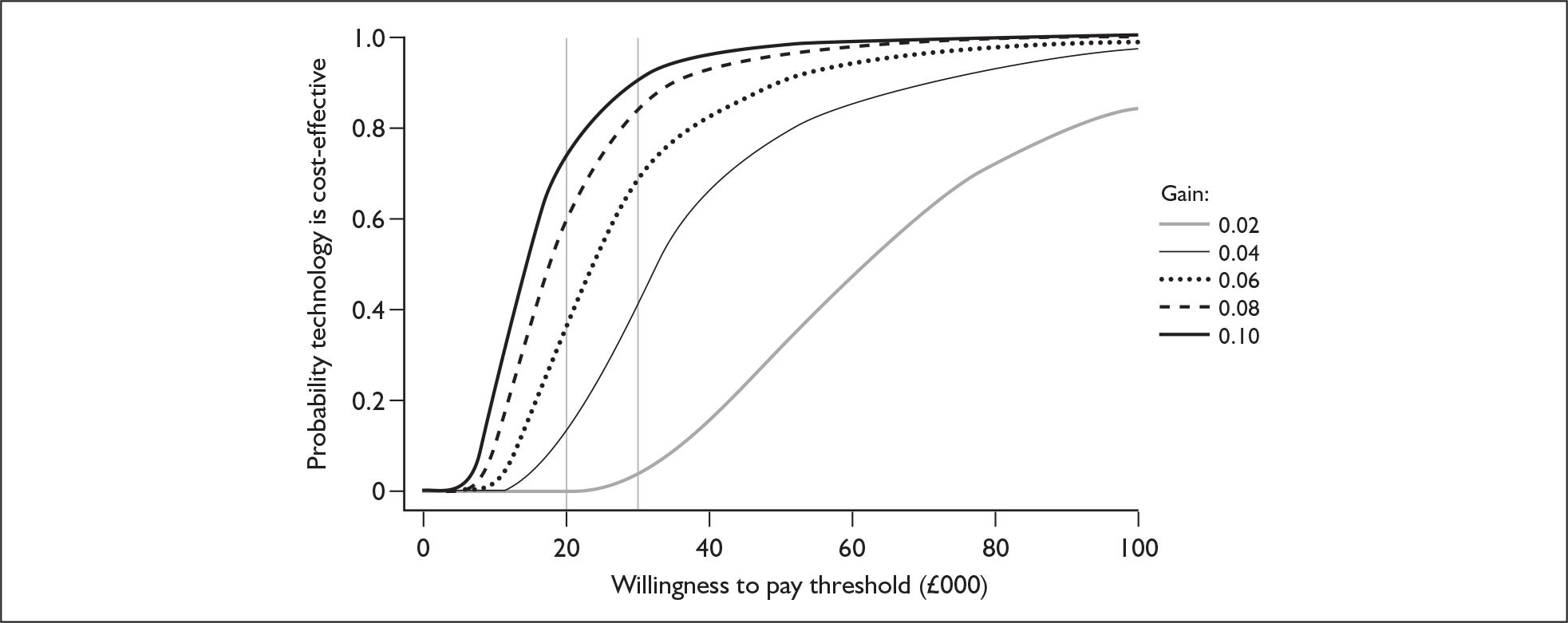

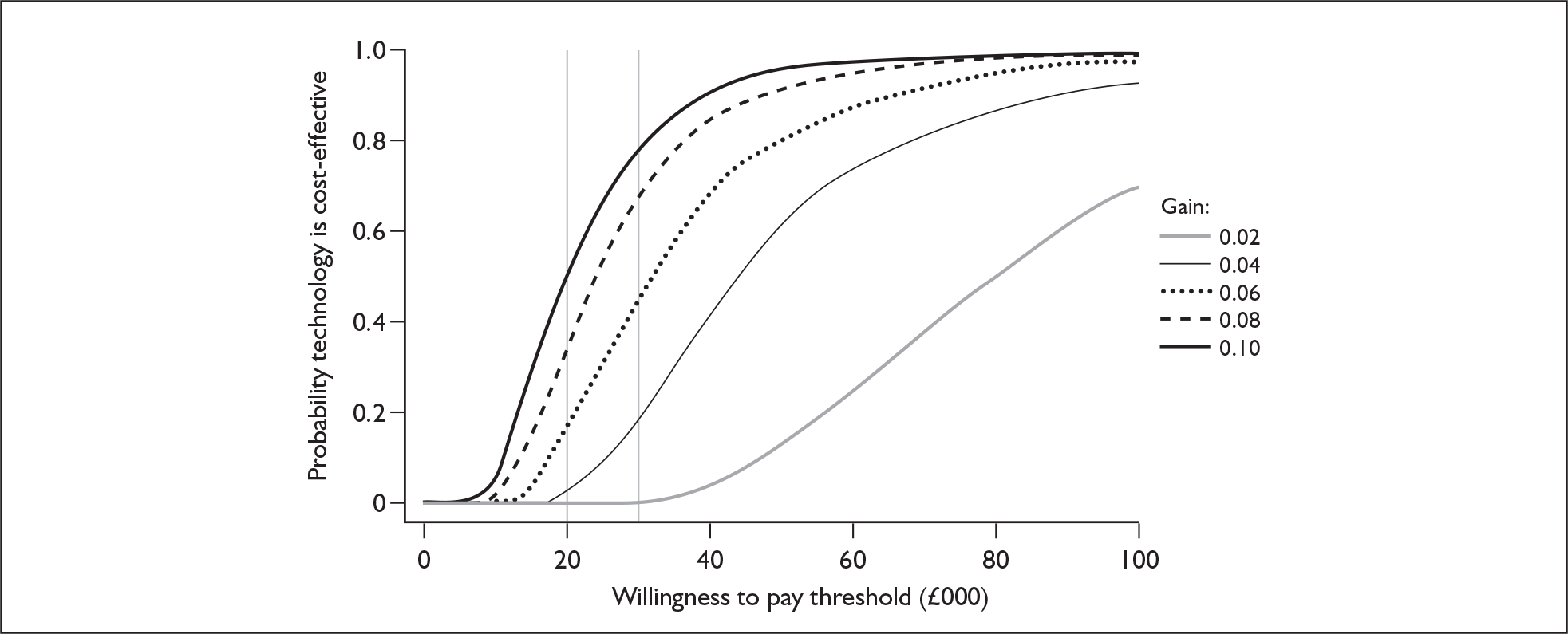

Type and quality of studies