Notes

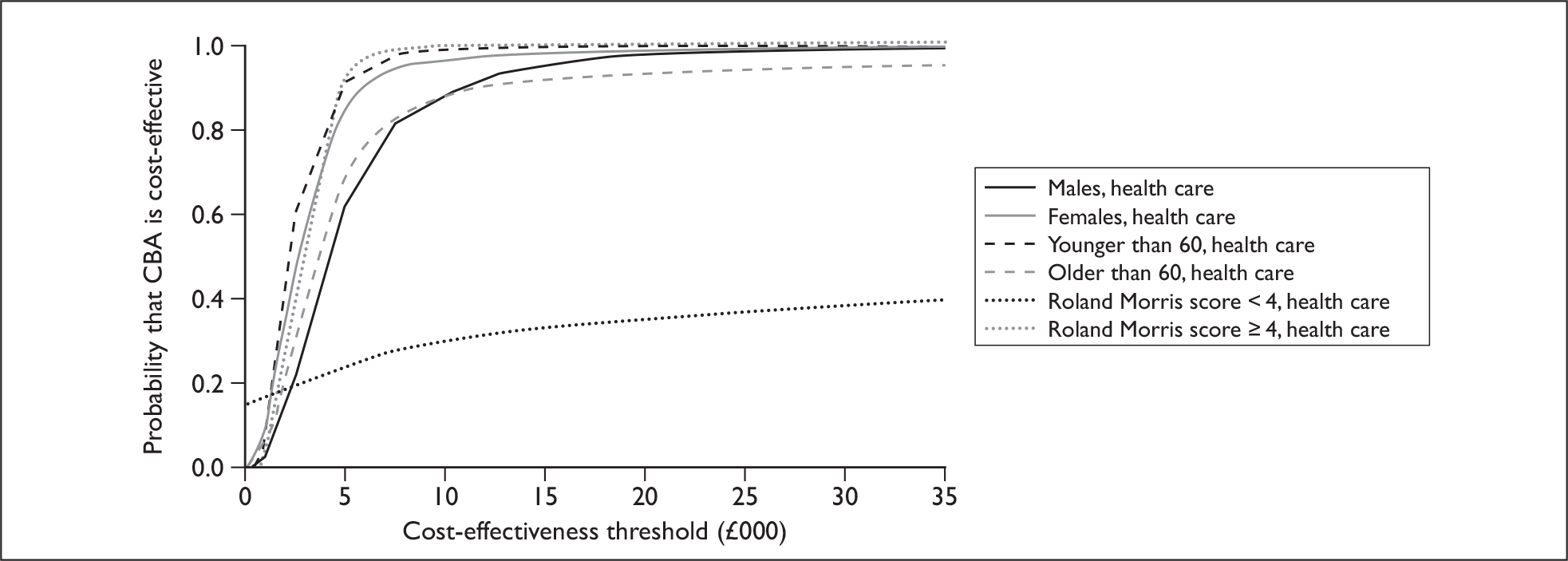

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 01/75/01. The contractual start date was in October 2003. The draft report began editorial review in January 2009 and was accepted for publication in August 2009. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a major public health problem in Western industrialised societies. 1 In the UK, the annual period prevalence is approximately 37%2,3 and LBP is so common that it affects almost everyone at some time during his or her lifetime. 4 For the majority, LBP follows a recurrent, fluctuating time course, with about 70% of patients having at least one recurrence within 12 months. 5,6 Annually around one in three people have an acute bout of LBP, but symptoms resolve quickly and pose no ongoing problem. 7 A significant proportion of people self-manage LBP without consulting the NHS. Estimates suggest that between 7% and 20% of the adult population who experience LBP consult a general practitioner (GP)8 and this results in 2.6 million additional consultations annually. 9 Of these people, 75% have symptoms 1 year later10,11 and about 30% develop persistent disabling LBP.

The direct health-care costs associated with LBP in 1998 were £1628 million; the majority of this expenditure was on physiotherapy and general practice. 1 During the years 1994 and 1995, 116 million production days were lost in the UK as the result of LBP, costing an estimated £10,668 million in production and informal care costs. 1 The majority of these costs are generated by those with the most chronic symptoms, and as a consequence the prevention and amelioration of chronic disabling pain is now the focus of research and clinical activity in this field. 12

This introduction provides a background to our sampling strategy, risk factors for developing chronic LBP and reasons why cognitive behavioural approaches (CBAs) may be helpful in LBP, an overview of current management of LBP, and the evidence to support CBA at the time the trial was designed.

Sampling approach and risk factors for the development of chronic low back pain

The population of people who suffer from low back pain is highly diverse. There have been a number of attempts to define different subgroups but none are satisfactory or in widespread use. We focused our trial on non-specific LBP, which is a term used to describe the majority of presentations, i.e. those in which no serious cause (infection, cancer or fracture) for LBP can be identified. The primary focus of our trial was the prevention or amelioration of disabling LBP in those with established (subacute or chronic) symptoms. We defined LBP according to Croft et al. 11 and used the International Society of Pain (ISAP) definitions of acute, subacute and chronic duration (Table 1). The ISAP provides a simple and widely used definition of back pain syndromes, although this does not include activity limitation.

| Low back pain – pain of musculoskeletal origin in the area bounded by the 12th rib and below by the gluteal folds (Croft et al. 1998)11 |

|---|

| Acute pain – lasting 6 weeks or less |

| Subacute pain – lasting 6–12 weeks |

| Chronic pain – lasting more than 3 months (International Association for the Study of Pain, Merskey et al. 1979)13 |

Considerable advances have been made in identifying risk factors and understanding the processes involved in the development of chronic LBP. 14 Psychological, social and behavioural risk factors have been found consistently to be stronger predictors of chronic disability than the physical factors associated with the initial onset of pain. 15 This does not mean that physical symptoms are unimportant; for example, pain radiating down the leg is acknowledged to be a risk factor for developing chronic symptoms. 16,17 However, a recent prospective study found only a weak association between structural changes and pain and no association with disability or future health care. 18

Psychological risk factors play an important role in the progression of LBP to chronic disabling LBP. A review of psychological risk factors found that coping strategies, beliefs, distress, depressive mood and somatisation were associated with the development of persisting pain and disability. 19,20 Of these, ‘fear of movement’ (which is a negative health belief about the relationship between pain and re-injury such that if I increase my back pain, I am causing further damage, so I should avoid movement), has been that most consistently and strongly associated with the progression to chronic disability. 21,22 Participation in physical recreational activity is associated with lower LBP and a reduced risk of progression to disability. 23 There is now a widely held belief that increasing physical activity and/or exercise participation is important in managing LBP. 24 Physical activity is usually characterised as a behavioural factor.

Social factors are also important. A systematic review of social risk factors identified low social support in the workplace, heavy manual work and low job satisfaction as strong risk factors for the occurrence of chronic back pain. 25 More recent studies have also found strong correlations between chronic back pain and low socioeconomic status, educational level, work satisfaction and female gender. 6,26,27

Epidemiological evidence suggests that interventions that address this range of psychological, behavioural and social risk factors offer hope in reducing the burden of LBP. Recent clinical guidelines6,26 stress the importance of assessing psychosocial factors and emotional distress, and suggest that such assessments might assist in targeting intervention more appropriately. Cognitive behavioural approaches encompass a range of interventions that aim to directly change behaviour using models of learning, and to indirectly change behaviour by changing beliefs and behavioural risk factors However, it is broadly acknowledged that there is insufficient evidence to determine the optimal methods of assessment and intervention and that large-scale evaluation is required.

Current management in the UK

The majority of LBP is managed in primary care, with a small number of people referred to secondary care, often only for a single consultation and with little consistency or rationale. 28 About 9% of the population with LBP attend for physiotherapy treatment, usually after primary-care consultation. 1 Chiropractic and osteopathy are used less often. 1

Since 2000, there has been a major change in the approach to managing LBP in primary care known as the active management (AM) strategy, which forms the core of all international guidelines. 29–31 The AM strategy discourages bed rest for LBP and instead advocates physical activity. 10 Appropriate medication is encouraged, although many classes of pain medication have been shown to have limited long-term benefits and are recommended most often for the management of acute LBP. 32,33 An information booklet called The Back Book34 has facilitated implementation of the AM guidelines in the UK. The Back Book was designed to challenge negative beliefs and behaviours, rather than merely to impart factual information. A randomised controlled trial evaluating The Back Book showed a positive effect on patients’ beliefs and clinical outcomes, maintained at 1 year, for those with both acute and recurrent back pain. 25,35

A 2007 systematic review36 evaluating the effectiveness of advice for the management of LBP compared advice offered to acute, subacute and chronic LBP patients. The review suggests that advice to stay active is sufficient for acute LBP patients and could be more widely implemented in practice. There is uncertainty about the management of both subacute and chronic LBP. No conclusions could be drawn from the evidence base about the optimal method of advice, and although there are suggestions in the literature that additional treatments may be beneficial, differences in case definitions of LBP and the treatments tested make it difficult to draw substantial conclusions about what type of advice is optimal for various presentations of LBP.

Unlike most guidance, and at the time of planning this trial, most UK guidelines tentatively recommended early referral to physical treatments, including acupuncture, spinal manipulation and exercise. 1 The evidence for these treatments has strengthened during the lifetime of the Back Skills Training (BeST) trial. More recent studies have raised some doubt about the effectiveness of traditional physiotherapy approaches to LBP; for example a comparison of routine physiotherapy with a single session of advice for LBP found no difference in treatment outcomes. 37 An Australian study of participants with subacute LBP, found physiotherapist-directed exercise and advice were each slightly more effective than placebo, with greatest effectiveness when combined. 38 A Cochrane review concludes that exercise therapy appears to be slightly effective at decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic LBP. 39 A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of spinal manipulation therapy for LBP concluded that there is no evidence to suggest that manipulation is superior to other standard treatments for acute LBP. 40 However, a recent large UK trial comparing manipulation with exercise and a combination of manipulation and exercise found small medium-term benefits in each treatment arm, and greater benefits if treatments were combined. 24

We selected the active management strategy and The Back Book as the intervention for the control arm of the trial, as these were recommended as best practice strategies within UK guidance at the time of starting and during the conduct of the trial.

Cognitive behavioural approaches in low back pain

The CBA includes a range of therapies deriving from cognitive and behavioural psychological models that aim to teach an individual to tackle their problems using specific psychological and practical skills. 41

Cognitive behavioural approaches for managing LBP were first introduced in the UK as part of inpatient pain management programmes for those with very chronic/severe LBP. Intensive (> 100 hours of therapy) multidisciplinary bio-psychosocial rehabilitation programmes were found to improve pain and function for patients in the secondary-care setting. 42 Systematic reviews suggest that the type of CB treatments for chronic LBP (> 12 weeks) that could be delivered in primary care appear to have short-term benefits but, possibly, no sustained long-term benefits. 43

Although there has been no formal systematic review, trials of CBA in populations with acute and subacute LBP report a mixed picture, including some improvement in disability. 44–46

Although some trials pointed to the potential for CBA in treatment of subacute and chronic LBP, there was a mixed picture of results. Few programmes found sustained benefits. Differences in results may be attributable to poor research design, but more likely they are the result of variable adherence to the principles of CBA and differences in how the programmes are delivered. These include the amount of contact time, level of expertise, components included in programmes and method of delivery. Indications are that the important attributes of effective interventions are ensuring that the health-care professionals who deliver the interventions are able to elicit psychosocial risk factors, implementing a CB framework that results in modification of beliefs as well as behaviours (as opposed to delivering skills alone), and delivering a treatment that is credible to patients. 47,48

The aim of this study was therefore to develop and test a group-based CBA intervention that could be delivered within the UK NHS and that could be accessed from primary care. We carried out a definitive randomised controlled trial with a parallel economic and qualitative study that would provide a comprehensive evaluation of CBA as a treatment for subacute and chronic LBP, and provide the NHS with evidence to support decision-making in this area of clinical practice.

Chapter 2 Characteristics and description of the intervention

Introduction

A detailed description of the theoretical basis of the intervention, as well as dose and mode of delivery is an essential step in the reporting of randomised trials of complex interventions. 49 Our approach was to draw together the essential elements of a CBA, ensuring that the intervention was consistent with the principles of CB therapy, and that we targeted health behaviours and beliefs that are broadly accepted as being on the causal pathway between LBP and disability. The intervention was developed by systematically reviewing experimental and observational literature, and linking the results of these reviews into a CB framework. We also considered the optimal delivery method to balance clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

The CB model states that the way a person thinks about their problem will produce emotions, including associated physical sensations, which then drive behaviour. 50 Often, the behaviour will inadvertently maintain the thoughts or beliefs, so creating a maintenance or vicious cycle effect. The following sections provide a rationale for the risk factors selected as treatment targets for the CBA.

Identifying the targets for a cognitive behavioural intervention for low back pain

The key modifiable risk factors appear to be psychological and behavioural factors that have a mediating effect on activity levels. Psychological constructs, including catastrophising, passive coping, fear avoidance and depression lead to decreased activity levels or, for some, overactivity. These changes in activity levels are implicated in the development of chronic disabling LBP through a pathway of deconditioning, and worsening pain. We specified the targets of the CB intervention:

-

to increase activity levels

-

to manage periods of overactivity

-

to specifically address catastrophising and fear avoidance

-

to improve coping skills.

There is consistent evidence across various reviews that coping skills, catastrophising and fear avoidance are key factors in the progression of acute LBP to chronic disability. Distress has also been identified as an important risk factor;51 however, it is difficult to define distress separately from the other psychological constructs and mood. 6,18,52

Many studies have pointed to the importance of coping strategies and beliefs held by patients. 19,53 A sense of personal control and self-efficacy are associated with active coping strategies (e.g. taking exercise). A lack of personal control and feelings of helplessness are associated with passive (maladaptive) coping strategies such as rest and catastrophising. 54–57

The strong link between beliefs predicting behaviour has been shown in two studies. 3,58 A reduction in patients’ belief that they were disabled and that increased pain signified harm and the need to restrict activity, was strongly associated with a reduction in pain behaviours, physical disability and depression. These beliefs are commonly referred to as ‘catastrophic beliefs’ and lead to avoidance of the feared activity or pain. This behaviour has been labelled ‘fear avoidance’ and has been consistently and strongly associated with the progression of acute LBP to disability. 21,22,59–61 In addition, catastrophising is associated with hypervigilance for symptoms, which increases pain perception. 62,63 Interventions that have used CBA to target catastrophising and fear avoidance behaviours appear to reduce disability in the short term. 64

At the other end of the activity level spectrum, there are people who increase their activity levels in response to pain. 65 This overactivity has been linked to mood and to unhelpful beliefs66 and can lead to poor control over pain and subsequent activity.

Depression is associated with the risk of developing chronic LBP,67 with a hypothesised pathway of apathy, demotivation and low mood resulting in decreased activity and poor outcome. Exercise is effective in the management of depression68 and has the potential to reverse this cycle. 69

Pain intensity has been positively and consistently associated with a poor outcome. 70 However, pain intensity is not independent of other psychological constructs such as catastrophising. 71 Education on pain mechanisms appears effective in changing beliefs and improving physical functioning. 72

Low levels of physical activity have been shown to correlate with future episodes of persistent LBP. 23,73,74 In addition, a significant proportion of the LBP population will reduce their activity levels in response to developing LBP. 75 The resultant ‘deconditioning or disuse syndrome’ describes the physical decline in strength, mobility, endurance and coordination that is postulated to contribute to ongoing pain. 76

Several systematic reviews have investigated the efficacy of exercises in the treatment of LBP and found modest improvements in pain and function. 77–78 Hayden et al. 79 went on to perform a meta-regression to identify features of the exercise programmes associated with successful outcomes. They concluded that the most effective exercises were conducted as part of an individualised supervised programme and included stretching and strengthening exercises. Although counterintuitive, particularly for those suffering LBP, exercise does not increase recurrence of pain. 80–82 There have been relatively few interventions that have focused on improving general or functional activities. 78

The intervention did not intend to target social factors that are not modifiable within the context of a primary care-based intervention (e.g. educational level, work-related risk factors, job satisfaction). Models of pain based on disc degeneration, posture, injury, weight and leg-length discrepancy were excluded because there is little evidence to support a relationship between these factors and chronic LBP. 83,84

Framework and structure of the cognitive behavioural intervention

The British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) has developed definitions of CB therapy41 and suggests that the following components are essential:

-

The intervention should be delivered collaboratively, i.e. intervention draws on the expertise of therapist and client and direction of treatment is determined jointly.

-

The intervention should use a goal-oriented approach, i.e. treatment is centred around achieving the client’s goals.

-

The intervention should use the CB model, i.e. intervention links thoughts, feelings and behaviours.

-

The intervention should explore unhelpful beliefs through CB questioning techniques, e.g. the use of open questions to help the client consider alternative ways of thinking.

-

The intervention should focus on the development of specific psychological and practical skills to enable the client to tackle problems independently, e.g. problem-solving and relaxation skills.

-

The intervention should use homework to achieve skill development, e.g. practising skills discussed during treatment sessions.

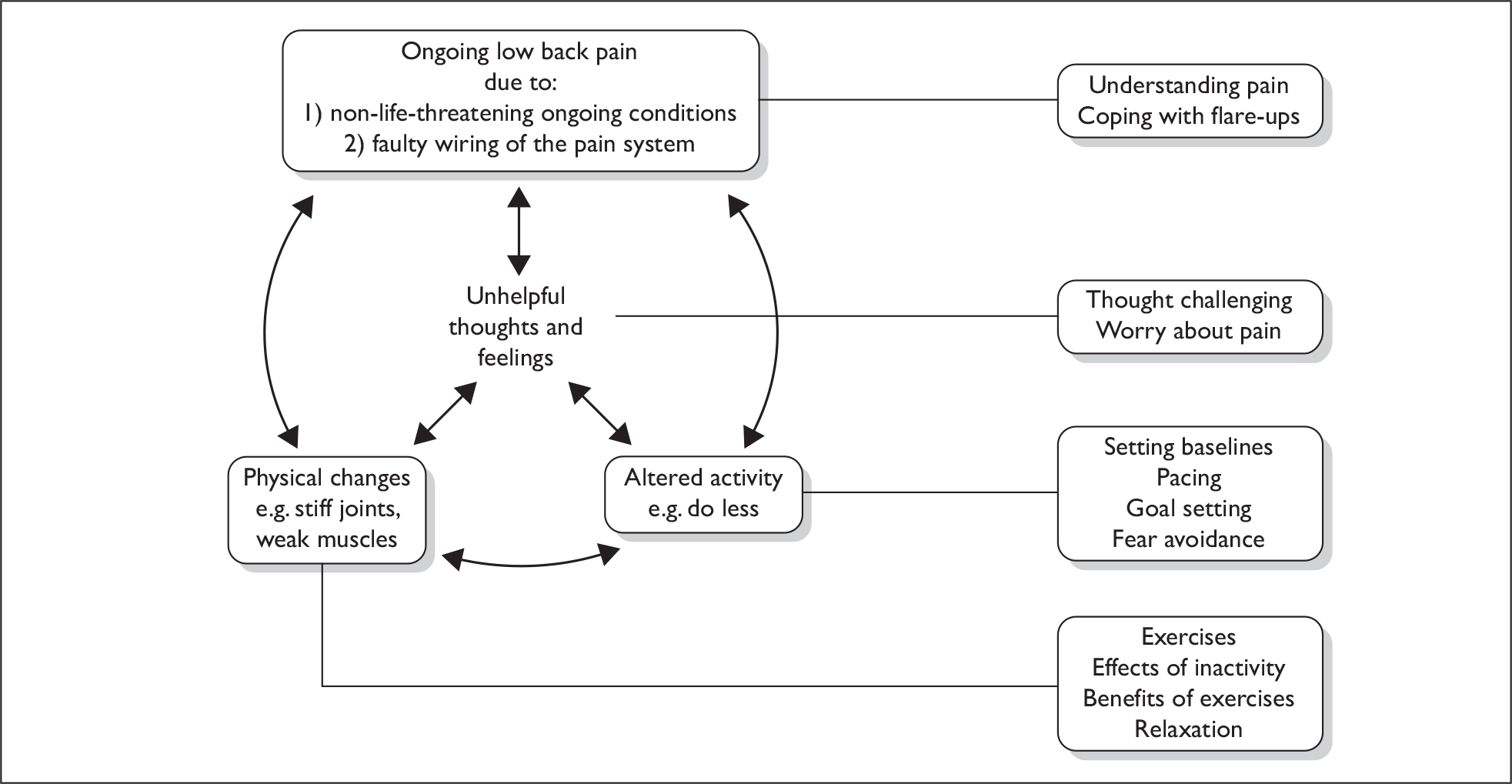

We designed an intervention comprising an assessment followed by six group sessions based on these principles. The CB model we developed to underpin the interventions is shown in Figure 1. The figure depicts the concept that back pain leads to altered activity and associated physical changes, which in turn leads to maintenance or worsening of pain. These relationships are mediated by unhelpful thoughts and feelings. The shaded boxes indicate the key skills developed by the BeST intervention, and their hypothesised mode of action.

FIGURE 1.

Integrated model of LBP. Text in boxes indicates how sessions target components.

Group format

The intervention was designed for group delivery. A review of outcomes in individual versus group CB therapy found little difference in efficacy. 85 Group treatment has the potential to maximise cost-effectiveness86 as well as providing additional non-specific effects. These benefits include participant modelling of helpful coping strategies, support and increased opportunity for developing problem-solving, a key skill in self-management. 87

Assessment session

We chose an initial one-to-one assessment session of up to 90 minutes, which would allow the therapists to better understand an individual’s problems and negotiate goals. This assessment also included the negotiation of a simple home exercise programme as we considered promotion of physical activity central to the intervention (this could be as little as one activity). These exercises were checked and progressed on at least one occasion during the group sessions. Goal setting for the programme was an important product of the assessment. Goals were set collaboratively in the assessment session and reviewed as a group in the second session.

Group session length

Group sessions were of 90 minutes’ duration, with a frequency of once per week for 6 weeks (i.e. a total of 10.5 hours including the assessment). The length of the sessions and overall programme was designed to facilitate attendance while ensuring sufficient time to develop skills. A small study on pain management programmes found no difference in outcomes between group or individual treatment and programmes that were 15, 30 or 60 hours in duration. 88 However, very brief interventions of less than 1 hour were found not to be effective. 89

Group session content

The content of each session was prespecified and documented in the therapist’s manual. Details of the session contents are given in Table 2. Therapists were requested not only to cover the content of the sessions but also to respond flexibly to participants’ needs as necessary.

| Session number | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Assessment | ||||||

| History taking, including current problems and eliciting beliefs on LBP and activity | ||||||

| Collaborative goal setting with plan to start activity goal | ||||||

| Exercises chosen collaboratively from options with level negotiated | ||||||

| Exercises practised and progression discussed | ||||||

| Understanding pain | ✓ | |||||

| Group activity to demonstrate hurt does not equal harm | ||||||

| Current thinking on causes of long-term pain explained | ||||||

| Discussion on group’s experience of alternative treatments for LBP with reference to research evidence and need to self-manage | ||||||

| Benefits of exercise | ✓ | |||||

| Discussion of physical impact of inactivity or altered activity and how changes impact on pain (disuse syndrome) | ||||||

| Discussion on effects of activity/exercise | ||||||

| Introduction to LBP model (Figure 1) | ||||||

| Pain fluctuations | ✓ | |||||

| Overactivity/underactivity cycle explained | ||||||

| Use of pacing | ||||||

| Group problem-solving for overactivity, e.g. gardening | ||||||

| Working out starting point for exercises or activities | ✓ | |||||

| How to use baseline setting | ||||||

| How to set goals | ✓ | |||||

| SMART system used to break down an example goal | ||||||

| Feedback from group on how progressing with goals from assessment | ||||||

| Group problem-solving problems with goals | ||||||

| Unhelpful thoughts and feelings | ✓ | |||||

| Styles of unhelpful thinking discussed, including catastrophising | ||||||

| Link with unhelpful behaviours | ||||||

| Identifying unhelpful thoughts | ||||||

| Group problem-solving for challenging unhelpful thoughts | ||||||

| Restarting activities or hobbies | ✓ | |||||

| Discussion on activities commonly avoided in LBP | ||||||

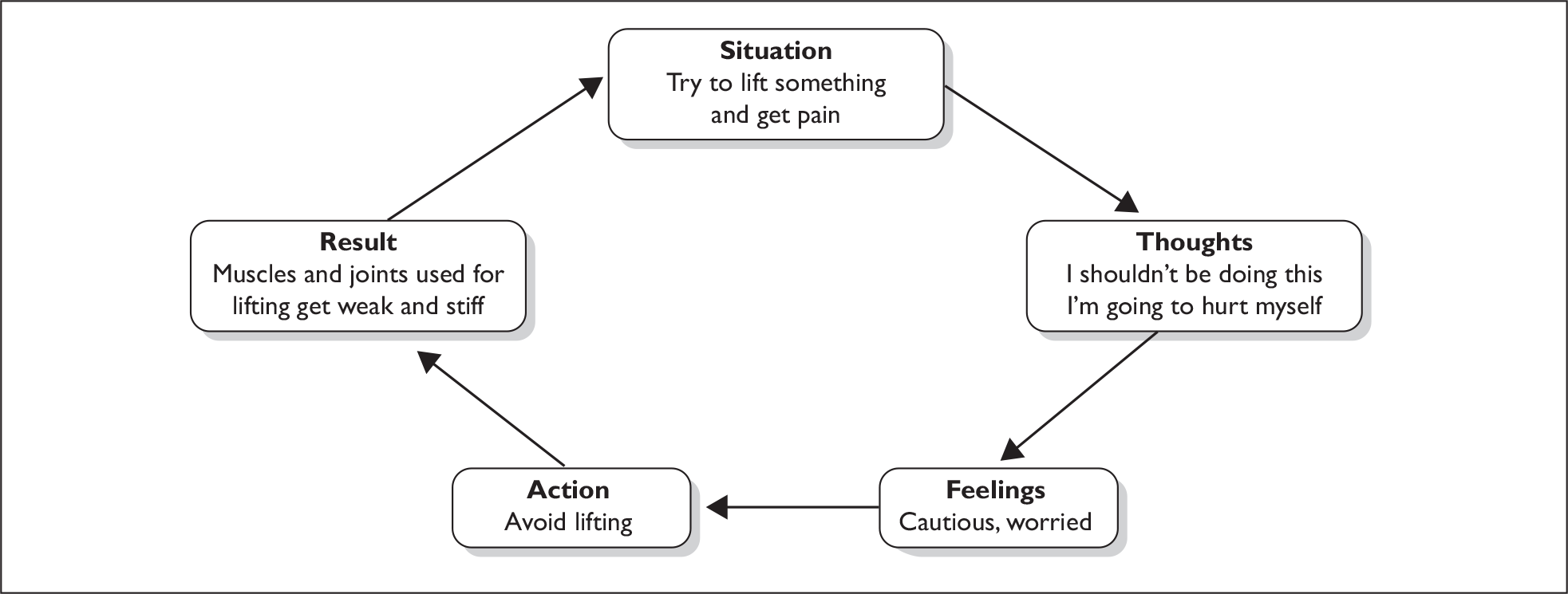

| Fear avoidance cycle (Figure 2) | ||||||

| Group problem-solving out of cycle | ||||||

| Development of specific goals relating to restarting activities | ||||||

| When pain worries us | ✓ | |||||

| Effect of attention to pain explored through group activity | ||||||

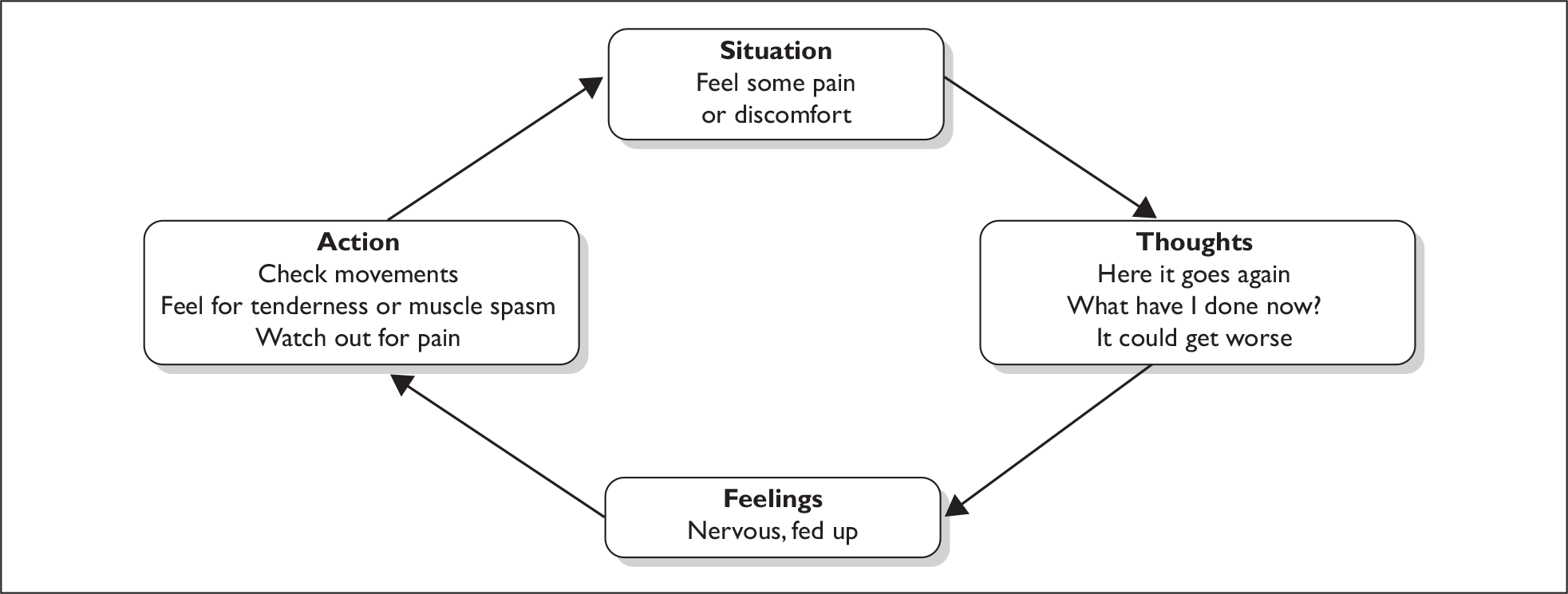

| Hypervigilance cycle (Figure 3) used to link unhelpful thoughts and behaviours | ||||||

| Group problem-solving out of cycle | ||||||

| Discussion on the use of medication/distraction/alternating activities | ||||||

| Coping with flare-ups | ✓ | |||||

| Discussion on causes of flare-ups | ||||||

| Plan of what to do in and out of flare-ups | ||||||

| Revision of topics over previous sessions and questions | ||||||

Group structure

Each session was structured in line with standard CB therapy approaches to include agenda setting, topics and homework review. The work of the previous session was reviewed briefly at the beginning of each session, and all sessions included a 10-minute break midway through to allow participants to move around and exercise (if they wished to). Each session started with agenda setting, which included asking participants what they wanted to cover in the sessions. Homework was reviewed at some point during each session to allow for group problem-solving.

Each session focused on one or more of the components of the CB model shown in Figure 1. We used simple CB maintenance models for fear avoidance and hypervigilance to provide a structure and rationale for the skills being taught in the sessions (Figures 2 and 3). These provide a conceptual framework for the relationship between thoughts, feelings and behaviours which could be communicated to participants, and form the foundation of discussions to enable problem-solving to break vicious cycles.

FIGURE 2.

Fear avoidance cycle used in BeST session 4.

FIGURE 3.

Hypervigilance cycle used in BeST session 5.

We prespecified a benchmark in attendance to define those who we believed had been compliant with the intervention, and those who had not. This threshold was attendance at the assessment session and at least three of the six group sessions. Although not evidence based, we hypothesised that this was the minimum number of sessions required to cover the key components of CBA as defined by the BABCP. 41

Group size, equipment and space required for running the groups

The only equipment needed was exercise mats, a flipchart easel, pad and pens. The optimal size for a therapy group has not been determined. A size of six to 10 is popular in practice as it is thought to encourage group discussion and problem-solving. Therefore we determined that the venue had to be sufficiently large to seat up to 10 participants in a circle with space to move around and place exercise mats on the floor during the break if participants wanted to do some exercises or have their exercises reviewed by the therapist running the group. Before running the groups, each therapist was provided with all the necessary paperwork and materials.

Targeting of specific risk factors

Catastrophic thoughts were targeted in several ways: pain education, teaching participants how to identify these thoughts and challenging beliefs, specific education on fear avoidance and hypervigilance using vicious cycles, and through the therapist’s use of questioning. The CB model identifies three levels of thinking. 50 The most ‘superficial’ of these is negative automatic thoughts and these will tend to directly relate to the present situation. For example, a participant faced with a lifting task might have the thought ‘I’ll hurt myself’. Other levels of thinking include ‘assumptions’ or ‘rules’ such as ‘In order to be safe, I need to be careful at all times’ and ‘core beliefs’ or ‘schema’ such as ‘I am vulnerable’. These two deeper levels of thinking are usually related to more global domains about the person. They can be targeted directly within the context of CB psychotherapy. Within the trial, we trained health professionals to identify the negative automatic thoughts related to LBP. The questioning techniques that were adopted by the therapists in the trial were not designed to delve for deeper meanings such as the ‘downward arrow technique’,90 but to help patients explore alternative ways of thinking around their LBP, known as ‘guided discovery’. 91

Depression and underactivity were targeted through education on the effects of inactivity and the benefits of exercise, and through providing participants with the skills needed to increase their activity levels: goal setting, baseline setting, pacing and techniques to manage increases in pain.

Overactivity was targeted through thought challenging and developing pacing skills.

Passive coping was addressed through developing problem-solving skills and alternative helpful pain management techniques, such as relaxation, using medication and planning for potential flare-ups.

Participant information folder

A high-quality participant information folder was designed for the intervention and provided to each participant at the first assessment appointment (Figure 4). The folder contained an overview of the sessions, how and where the groups would be run, therapist contact details, what participants should expect and exercise sheets. During the assessment these exercise sheets were personalised and the goal sheets were filled in. To support participants in working towards their goals while waiting for the group sessions to start, there were information sheets on goals and how to set baselines (starting level for activity). In addition, there were information sheets on sleep, medication and communicating with health professionals.

FIGURE 4.

Participant information folder.

At each group session participants were given sheets to add to their folders that summarised the content of the session and provided details of their ‘homework’ task. If a participant missed any sessions, either the inserts were provided at subsequent sessions or they were sent through the post if the participant was unable to attend any other sessions. As the folder was only provided at the therapist assessment, any participant who did not attend for this session received only the active management intervention.

Pilot study and refining of the intervention

Several pilot groups were run as part of the study pilot procedures. An independent researcher collected feedback comments, which were given anonymously to the intervention development team. Comments were very positive, although more supervision of exercises was requested. As a result the therapists were instructed to ensure that each participant had at least one opportunity to have their exercises reviewed during the programme.

Therapist recruitment and training

A 2-day programme was developed to train registered health professionals (physiotherapists, psychologists, nurses or occupational therapists). The length of training reflects the typical length of informal training programmes for qualified staff currently available in the UK. We trained a spectrum of health professionals. This was a pragmatic decision – LBP is a common condition and there are unlikely to be sufficient numbers of psychologists to meet demand. It is recognised that generic pain management skills cross professional boundaries. 92 For example, when CBAs have been applied in diabetes self-management, the treatment effect sizes are found to be the same for psychological specialists and non-specialist clinicians. 93 Although there are high rates of distress and low mood among LBP sufferers in primary care, these symptoms are generally not severe. Therefore, a prolonged training programme in psychological management for the therapists in the trial was not felt necessary.

With this in mind the training was designed to ensure that individuals with different professional backgrounds would be equipped with the same basic knowledge and skills and that the intervention was effective regardless of which health-care professional delivered it. This included equipping psychologists with knowledge of LBP, physical activity and exercise prescription.

The training covered an understanding of LBP and the risk factors associated with chronicity, understanding the CB model, developing basic CB skills such as questioning techniques, developing group facilitation skills and learning the topics to be covered in each session, including pain management techniques. Training was delivered by a cotrained CBT therapist/physiotherapist and a clinical psychologist and was documented in an extensive training manual. 49

Therapist support

In addition to the training already described, each therapist received a comprehensive treatment manual detailing the rationale and content of each session, including suggested dialogue. In response to feedback from the first training session a website and DVD were developed. The website contained all support materials, including trial updates and a ‘frequently asked questions’ section; a screen print is shown in Figure 5. The website also had a forum for posting questions to be answered by the trial intervention team and by other therapists. This section was not used; therapists preferred to e-mail or phone the trial team directly.

FIGURE 5.

Screen print of BeST Therapist webpage.

The DVD was a recording of sessions 1 and 3 run for volunteers from the research department as group participants. Feedback from therapists indicated that they found the DVD very useful before running the programme for the first time.

Within psychological therapies it is usual practice to have regular supervision sessions with a senior therapist to discuss cases. This is not normal practice within most of the other professions allied to medicine. For the purposes of the trial we allowed for flexible supervision, which consisted of discussions either face-to-face on-site visits or via phone or e-mail, whichever was convenient and appropriate for the issues to be discussed. Supervision was provided during the course of the trial by the clinical research fellow, which was on average 1.5 hours per group run. This supervision usually centred on difficulties encountered in the groups, for example difficulties in setting goals with some individuals.

Satisfaction with training

All therapists were asked to provide anonymous feedback in a questionnaire sent out 2 weeks after training; 72% of therapists rated the training as ‘very good’ with the remaining 28% rating it as ‘good’. Confidence to deliver the intervention was rated as ‘fairly confident’ or ‘very confident’ by at least 75% of all therapists for each of the skills taught. The exception was ‘thought challenging’. A significant proportion of therapists rated themselves as ‘a little confident’ (45%) or ‘not at all confident’ (10%) in these techniques. As this skill was new to the majority of therapists this rating was to be expected.

Assessment of treatment fidelity

Quality of the intervention delivery was checked via three processes:

-

a site visit was made to a group session for each therapist during their first programme of intervention

-

subsequent groups had one session randomly selected for audio recording

-

treatment records were screened for each participant.

The session content and skills demonstrated by the therapist were assessed via these processes using a checklist that included items shown in Table 3. The audio recordings were used as an observational tool as part of a process of evaluation to determine treatment fidelity, and were not used for further training and feedback.

| Item | Not achieved (% of total) | Partially achieved (% of total) | Satisfactorily achieved (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Set agenda | 5 (14) | 8 (23) | 22 (63) |

| Homework reviewed | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 34 (97) | |

| Topics covered | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 32 (91) | |

| Break | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 35 (100) | |

| Homework set | 0 (0) | 5 (14) | 30 (86) | |

| Feedback elicited | 6 (17) | 7 (20) | 22 (63) | |

| Exercises checked in break | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 34 (97) | |

| Style | Encouraged group participation | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 31 (89) |

| Listened appropriately | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 35 (100) | |

| Empathy demonstrated | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 32 (91) | |

| Elicited beliefs/thoughts | 2 (6) | 11 (31) | 22 (63) | |

| Questioning style demonstrated | 2 (6) | 8 (23) | 25 (71) | |

| Referred to CB model | 4 (11) | 4 (11) | 27 (77) | |

| Appropriate pacing of session | 1 (3) | 7 (20) | 27 (77) | |

| Appeared professional | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 35 (100) | |

| Environment | Comfortable | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 34 (97) |

| Spacious | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 35 (100) | |

Summary

A CB intervention was designed that targeted known modifiable risk factors for the development of chronic disabling LBP. The intervention adhered strongly to the principles of a CBA and was structured with sufficient flexibility to allow delivery in a variety of settings and by a range of different health professionals. The training and support package was practical to allow for roll out within the NHS if the intervention proved effective.

Chapter 3 Methods

Aims

There were two aims:

-

To estimate the clinical effectiveness of AM in general practice versus AM in general practice plus a group-based, professionally-led CB package (AM+CBA) for subacute and chronic LBP in terms of:

-

– reduction in disability associated with LBP

-

– reduction of pain or improved tolerance of pain symptoms

-

– reduction of further medical, rehabilitation or surgical treatment for LBP

-

– improvements in quality of life.

-

-

To measure the cost of each strategy, including treatment and subsequent health-care costs, over a period of 12 months and to estimate cost-effectiveness. The methods employed in the economic analysis are detailed in Chapter 6.

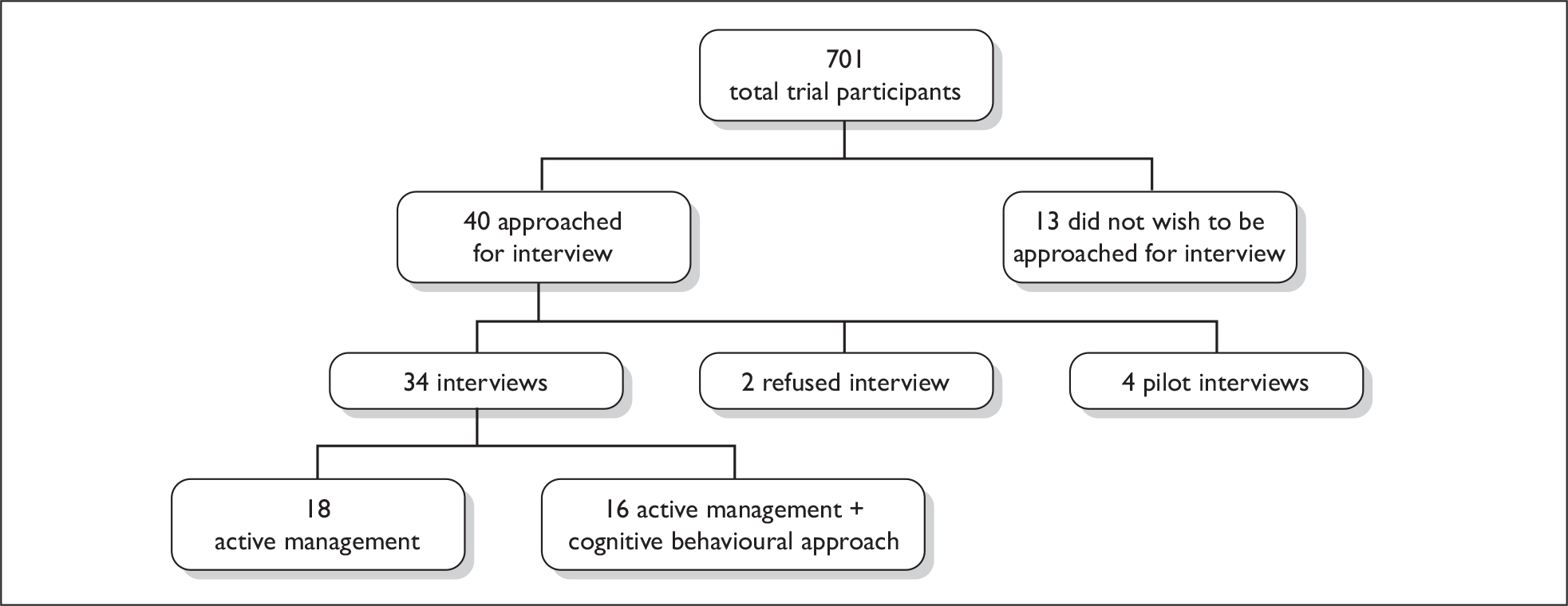

In addition, we planned to interview a selection of participants to gain insight into the experience of LBP and of the treatments delivered as part of the trial (for the methods used, see Chapter 5).

Research methods

Study design

The study comprised a pragmatic, multicentred randomised controlled trial, with investigator-blinded assessment of outcomes.

Setting

Fifty-six general practices were recruited from seven regional clusters across the UK.

Practices

The original plan had been to recruit clusters of general practices that had participated in the UK Back pain Exercise and Manipulation trial (UK BEAM) that had been run by the Medical Research Council (MRC) General Practice Research Framework (GPRF). 94 However, when conducting the pilot study, it became evident that there were insufficient GPRF practices interested in participating in this new study within each area to ensure a flow of recruitment sufficient to sustain the group-based service delivery model. Therefore, alternative strategies were used. The majority of practices were recruited through collaboration with the primary-care trusts (PCTs), and had not been involved in the UK BEAM study. Fewer than 5% of practices were involved in the BEAM study. This strategy was implemented successfully, although it was labour intensive and caused a delay in starting recruitment. By June 2004, all PCTs in England had been contacted and where interest was expressed a series of visits was undertaken. Initially, seven PCTs were recruited. By the end of November 2004, two PCTs withdrew their consent to participate for logistical reasons, and by July 2005, five clusters (Coventry, Norwich, Langbaurgh, Heart of Birmingham and Solihull) had launched the BeST trial in their PCT. To speed up recruitment and meet target dates for the end of recruitment, two additional PCTs, South and North Warwickshire, were launched in January and March 2006 respectively.

Participants

Our aim was to recruit people with subacute and chronic LBP, who were experiencing symptoms that were at least moderately troublesome. Low back pain presents in a wide variety of ways, and typically patients present with a spectrum of severity and chronicity. The treatment for acute LBP (defined as a first episode that has occurred for less than 6 weeks) is agreed, and although not evidence based, it is generally recognised that psychological therapies are most likely to benefit those with subacute and chronic conditions. 95 We wished to exclude people who had transient, minimally troublesome symptoms.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

For entry into the trial, the following inclusion criteria had to be fulfilled:

-

participants had attended general practice reporting LBP of at least moderate troublesomeness for > 6 weeks

-

participants had to be aged 18 years or older

-

participants were able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were not eligible for BeST if they:

-

were aged < 18 years

-

had been managed previously in a CB programme

-

had factors associated with serious pathology [these included cauda equina symptoms, systemic illness (including cancer, human immunodeficiency virus infection, fever), widespread neurology, severe unremitting night-time pain, violent trauma (fall from height, road traffic accident) and substantial unexplained weight loss]

-

had severe psychiatric or personality disorders sufficient to merit exclusion as determined by the GP.

Treatments

Active management (reference group)

Both the treatment and reference (control) groups received an intervention that was consistent with best practice in primary care (see Chapter 1, Current management in the UK). Nurses were trained in the approach using a 1-hour training session that included methods to cascade the information within their practice environments. The nurses provided the AM to all trial participants and, in addition, provided each with a copy of The Back Book. 35,96 The active management intervention lasted approximately 15 minutes.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (for the experimental arm only)

In addition to AM, participants randomised to CBA received up to six sessions of group therapy (for details, see Chapter 2).

Study procedures

From initial identification of participants to randomisation

Participants consulting their GP in the previous 6 months with LBP were identified from computerised searches of primary-care records or from general practice attendances.

A list of potential participants was screened by GPs, who identified those patients who should be excluded on the basis of serious illness or mental-health problems. The GPs were encouraged to make prospective referrals of any participants they considered suitable for the trial, although only a small number of participants were referred this way. In some practices, searches were repeated after 12 months to identify further participants.

Once potential participants had been identified, an invitation letter (including an information sheet) to participate in the trial, and an initial approach questionnaire (see Appendix 1) was sent out to determine interest and eligibility. The GP signed the approach letter. Potential participants were given approximately 2 weeks to send the initial approach questionnaire back. If there was no reply after 2 weeks a second letter was sent out. Those participants who expressed an interest in the trial and appeared to meet the initial inclusion criteria were contacted by a research nurse and the first of two assessment appointments with the research nurse was scheduled. The reasons for decline/withdrawal/exclusion were documented at all stages.

At the first nurse assessment, the trial was explained in more detail to the participant. In general these appointments were carried out face-to-face at the participant’s own GP surgery, although sometimes the appointment was conducted over the telephone. Each of the nurses was provided with a laptop and the nurse determined whether the subject was eligible by completing the computerised first nurse assessment questionnaire (see Appendix 2). Those participants who were temporarily excluded (e.g. because they were awaiting or receiving treatment) were issued a temporary exclusion letter (see Appendix 3). The temporarily excluded participants were allowed to enter the trial once they had become eligible by contacting the nurse and arranging an appointment. For those participants interested in taking part in the trial who met all the study inclusion criteria, a second appointment was made (appointment two – nurse randomisation appointment). This appointment was arranged for within 1–2 weeks of the first nurse appointment to allow time for the participant to consider whether they would like to enter the trial. For those participants who did not attend either of the two nurse appointments, a reminder telephone call was made and the opportunity was provided for another appointment to be made if the participant wished.

At the nurse randomisation appointment, the nurse randomisation assessment questionnaire (see Appendix 4) was completed. If the participants satisfied the eligibility criteria and provided informed consent then they were asked to (1) sign the informed consent form (see Appendix 5) and (2) complete the baseline questionnaire (see appendix 6). Every participant randomised then had an active management session supplemented by The Back Book96 and it was stressed that they should read and follow the advice given.

The nurse then filled in the randomisation form (see Appendix 7). The information on this checklist was telephoned through to the randomisation office at the MRC Clinical Trials Unit in London (see Randomisation, below). The unit then provided the nurse with the additional treatment allocation for that participant. The nurse would then let the participant know to which treatment they had been randomised. If the randomisation appointment occurred at a time when the randomisation office was closed, the randomisation form was faxed and the treatment allocation was provided once the office reopened.

From randomisation to follow-up

For those participants randomised to AM+CBA, the nurse sent a notification letter to the therapist and provided the participant with a copy. The nurse also advised the participant that the therapist would contact them to arrange a time to start their treatment within the next 2 weeks and asked the participant to contact the therapist if this did not happen. The nurse e-mailed the therapist with confirmation of final numbers referred into the group to check that the number of referrals made matched the number of referrals received.

Follow-up

Follow-up was conducted at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation using self-administered questionnaires. The majority of questionnaires were completed in postal format (see Appendix 8). Response was tracked carefully by the trial office, and a reminder questionnaire was sent after 2 weeks if a follow-up questionnaire had not been returned. If the questionnaire had still not been returned after a further 2 weeks, participants were telephoned to check that the questionnaires had been received and to arrange for another to be sent if needed. If the questionnaire remained unreturned after a further 2 weeks a telephone call was made to the participant to request a core set of data that was collected over the telephone at a time convenient to the participant. All people who provided core outcomes were willing to continue to participate in the trial. Core outcomes are detailed in Appendix 9.

The clinical record form was stamped with the date and initialled on receipt at the Warwick Trials Unit Office. It was then checked for correctness and completeness and coded for the data input clerk. Any queries were checked with the statistician. Missing data were clarified with participants where possible.

The baseline and follow-up data were single-entered into the database by the data input clerk. The accuracy of the data entry was checked by taking a 10% random sample (70 participants) and completing a 100% correctness check on all the variables on the database against the record forms (baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months). There is no firm guidance as to what constitutes an acceptable error rate. Shen97 suggests a very conservative error rate of 0% for the primary outcome and 0.5% for the secondary outcomes. This was achieved in BeST.

The baseline and follow-up data were validated continuously through the trial and reported at intervals to the Data Monitoring Committee (see Data monitoring and ethics committee, p. 27). After the final validation checks, the database was ‘frozen’. If changes were required thereafter, these were formally documented. The clinical outcome data were validated in sas (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The health economic data were validated in sas and then transferred to stata (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis.

The validation checks carried out included:

-

eligibility criteria

-

consecutive date checks

-

range checks

-

missing data checks.

Outcome assessments

Demography and baseline assessments

Appendix 11 lists the demographic and clinical data that were collected at each of the three prerandomisation stages. The baseline assessments are listed in Appendix 6.

The data included date of birth, sex, LBP/symptoms in the past 6 weeks, frequency of back pain in the past 6 weeks, troublesomeness in the past 6 weeks, ethnic origin, age when left full-time education and employment details.

Although we had proposed to collect the Acute Low Back Pain Screening Questionnaire (ALBPSQ)98 as part of the baseline assessment, this was dropped in the set-up phase of the study to reduce respondent burden, and in recognition that many of the other measures were capturing duplicate information.

Clinical outcomes

We were guided in the selection of outcome measures by three principles. First, we wished to be consistent with the international recommendations for clinical trials of LBP interventions. 99,100 Second, we considered more recent methodological studies of LBP outcome measures. Third, we did not want to overburden participants with too many outcomes.

The International Forum of LBP has recommended that trials should measure five domains: pain symptoms, function, generic health status, work disability and satisfaction of care. 99,100 Table 4 details the measures used in this trial101 and the time points of data capture.

| Domain | Measures | Time points |

|---|---|---|

| Primary measures | ||

| Pain-associated disability | Roland Morris Questionnaire102 | 0, 3, 6, 12 |

| Pain | Modified Von Korff Scale103 | 0, 3, 6, 12, Tela |

| Disability | ||

| Secondary measures | ||

| Occupational and other limitations | Numbers of days off work, reduced activity and bed rest | 0, 3, 6, 12, Tela |

| Health-related quality of life | Short Form-12 version 2104 | 0, 3, 6, 12, Tela |

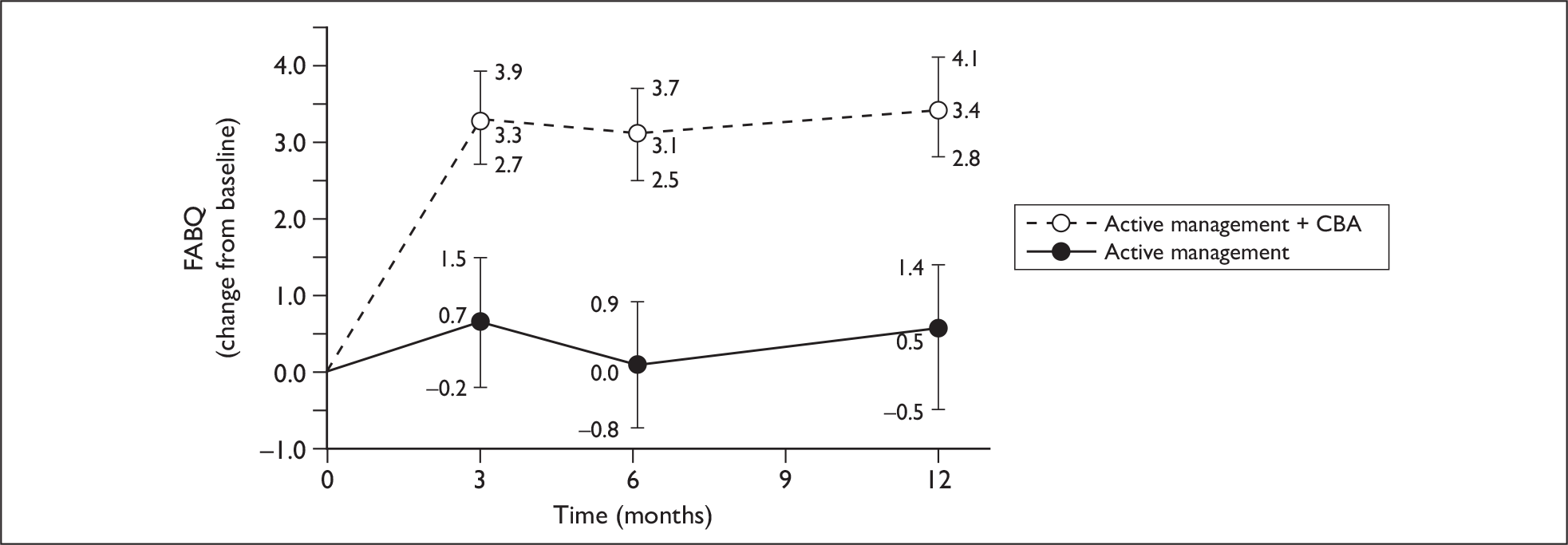

| Back pain beliefs | Fear avoidance scale (first five items only)105a | 0, 3, 6, 12 |

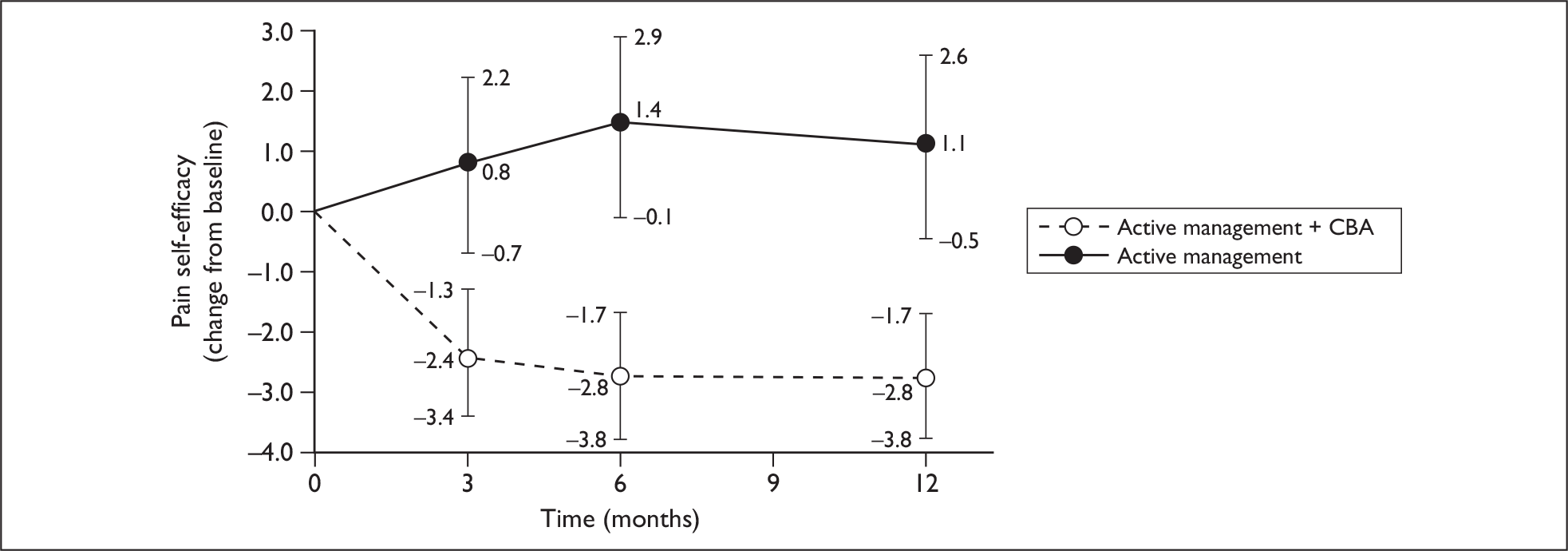

| Self-efficacy | Pain self-efficacy questionnaire106 | 0, 3, 6, 12 |

| Satisfaction with treatment | Single-item rating of satisfaction with treatment99 | 3, 6, 12 |

| Global rating of change | Seven-point rating99 | 3, 6, 12 |

| Economic analysis | ||

| Resource use | Resource use questionnaire | 3, 6, 12 Tela |

| Health-related quality of life; time trade-off score | EuroQoL five dimensions (health utility)107 | 0, 3, 6, 12, Tela |

A copy of all follow-up questionnaires is provided in Appendix 8.

Primary outcomes

We selected two primary outcome measures a priori because of concerns with the scaling of the Roland Morris Questionnaire.

Roland Morris Questionnaire

The Roland Morris Questionnaire (RMQ) is the most widely used measure of LBP disability in primary-care trials. Originally derived from the Sickness Impact Profile, it contains 24 items relating to a range of functions commonly affected by LBP. 102 It takes less than 5 minutes to complete. It has good reliability101 but there are concerns that it does not conform to many of the assumptions that underpin its use in statistical analysis (scaling and normality of distribution). Data from the Oxfordshire Low Back Pain Trial suggested that it had a marked ceiling effect, failing to capture important clinical information on improvement in participants with subacute or chronic LBP attending NHS physiotherapy. It has been shown to be differentially sensitive at low, mid and high ranges, with (not unsurprisingly) better sensitivity in the middle range. 108,109 In the low to mid range, the RMQ is less sensitive to within-group changes than the Aberdeen Low Back Pain Score, but better at detecting between-group differences. 101

Completion of the RMQ scale comprises a mark next to each appropriate statement.

The total number of marked statements is added up to form a score (out of 24), and a low score is associated with less disability.

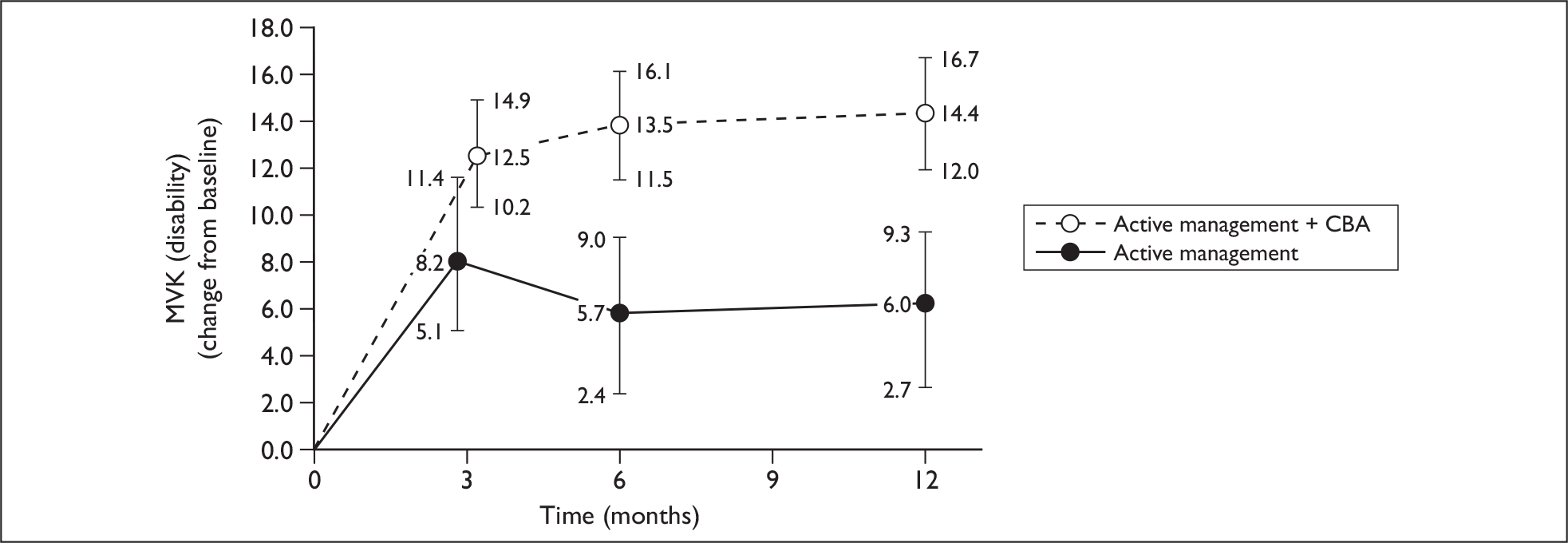

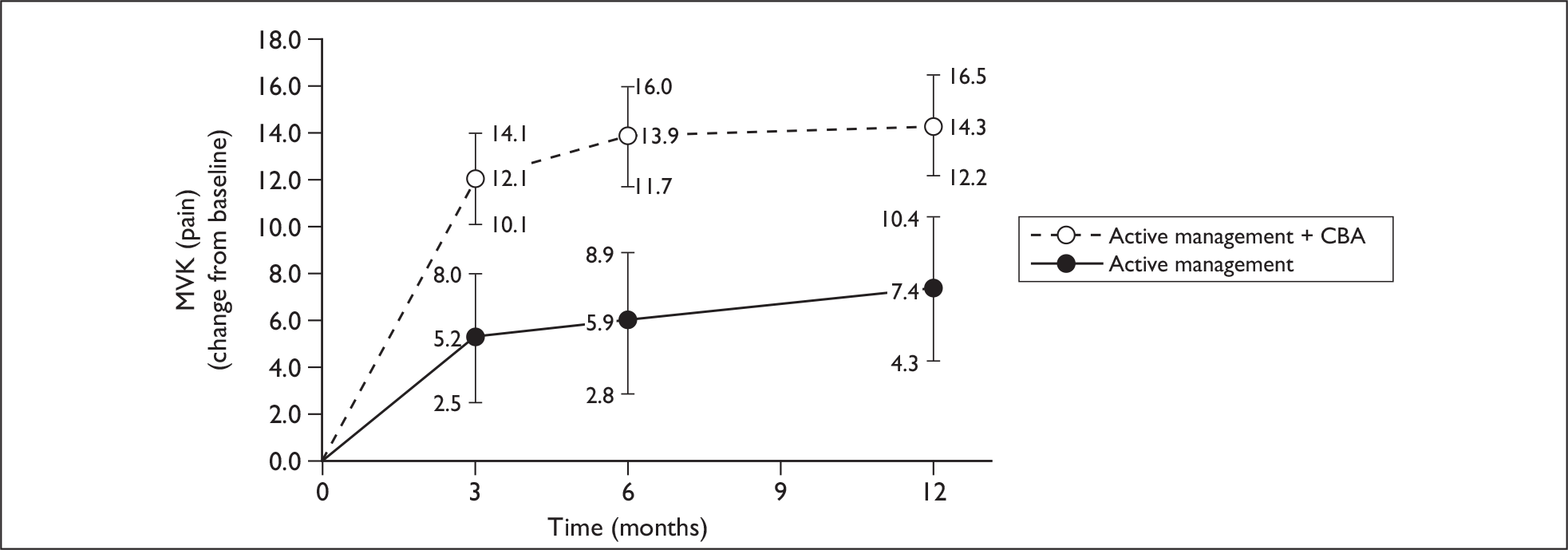

Modified Von Korff Scale

The Modified Von Korff Scale (MVK)103 assesses two dimensions – pain and disability associated with back pain in the last 4 weeks. It is made up of six items, each of which is scored on a scale of 0 (no pain/disability) to 10 (worst pain/disability). The first three of these items relate to disability and ask about how back pain interferes with (1) daily activity, (2) recreation and (3) ability to work. The last questions relate to pain and assess the (1) worst pain, (2) average pain and (3) rating of back pain today. The questionnaire was administered at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months.

The scale has two dimensions:

The higher the score, the more severe the disability or back pain.

Secondary outcomes

Occupational disability and limited activity days

Three separate questions were used to elicit the number of days in the period from 0 to 3 months, 3 to 6 months and 6 to 12 months that participants:

-

had to cut down on normal activities (for more than half a day)

-

had time off work because of low back or leg pain (sciatica).

These questions were recommended by the International Forum, and have been used widely (summarised in Deyo et al. 99).

Participant satisfaction

Participant satisfaction was assessed using the single-item question recommended by the International Low Back Pain Forum:99 ‘Over the course of treatment for your LBP or leg pain, how satisfied were you with your overall medical care?’ We modified this question slightly to reflect care over the duration of the study, and by changing the term ‘medical care’ to ‘one related to health care’. The question that was asked was ‘How satisfied are you with the treatment you received?’ Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’.

Psychological and behavioural measures

We included these measures because they measure constructs hypothesised to lie on the causal pathway of effect, and we hoped that they would provide some explanation as to why the treatment may or may not be effective.

The Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) is a measure of the degree of fear of pain and disability, and the avoidance of physical activities that can result. Each item is scored from 0 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). This scale has two dimensions (fear avoidance beliefs about work and fear avoidance beliefs about physical activity). We selected only the section of the measure concerned with physical activity as it has generic applicability.

The scores from each of these items are summed to provide a total score. Minimal scale score is 0 and maximum scale score is 24.

The higher the scale scores the greater the degree of fear and avoidance beliefs shown by the participant.

This is a measure of the patient’s confidence to carry out a range of activities despite the back pain. There are 10 items, ranging from 0 (not at all confident) to 6 (completely confident).

The scores are totalled with the total ranging from 0 to 60.

A lower score indicates reduced self-efficacy of the participant.

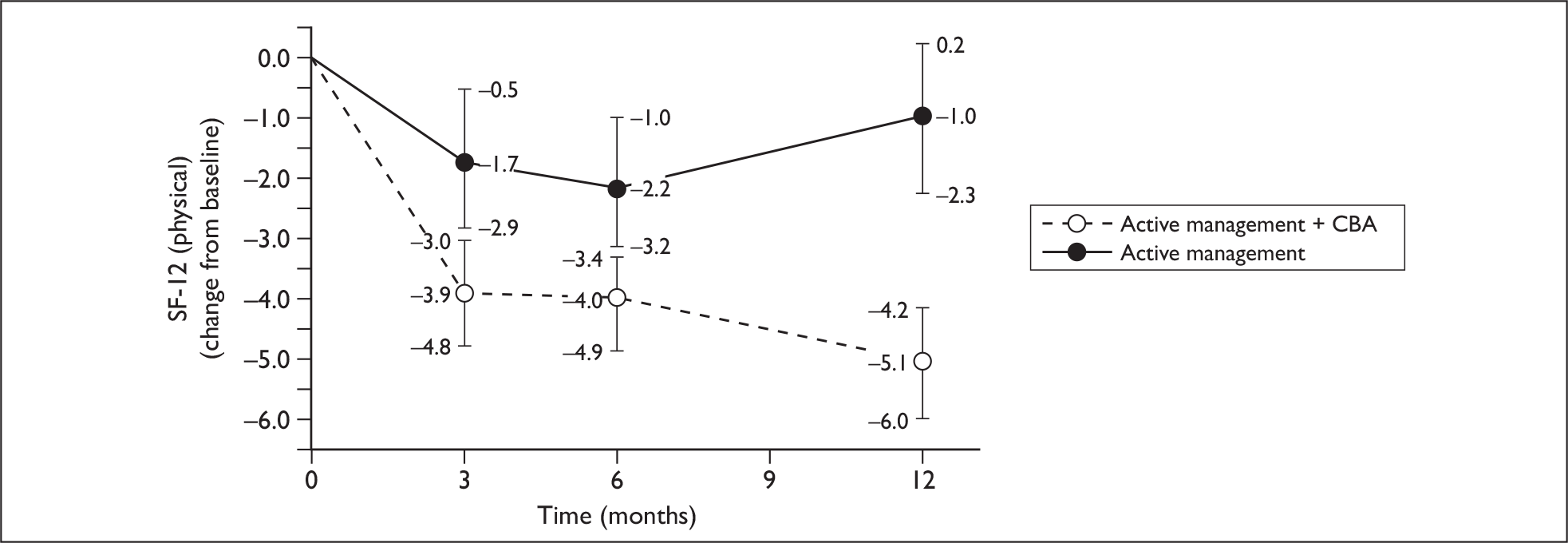

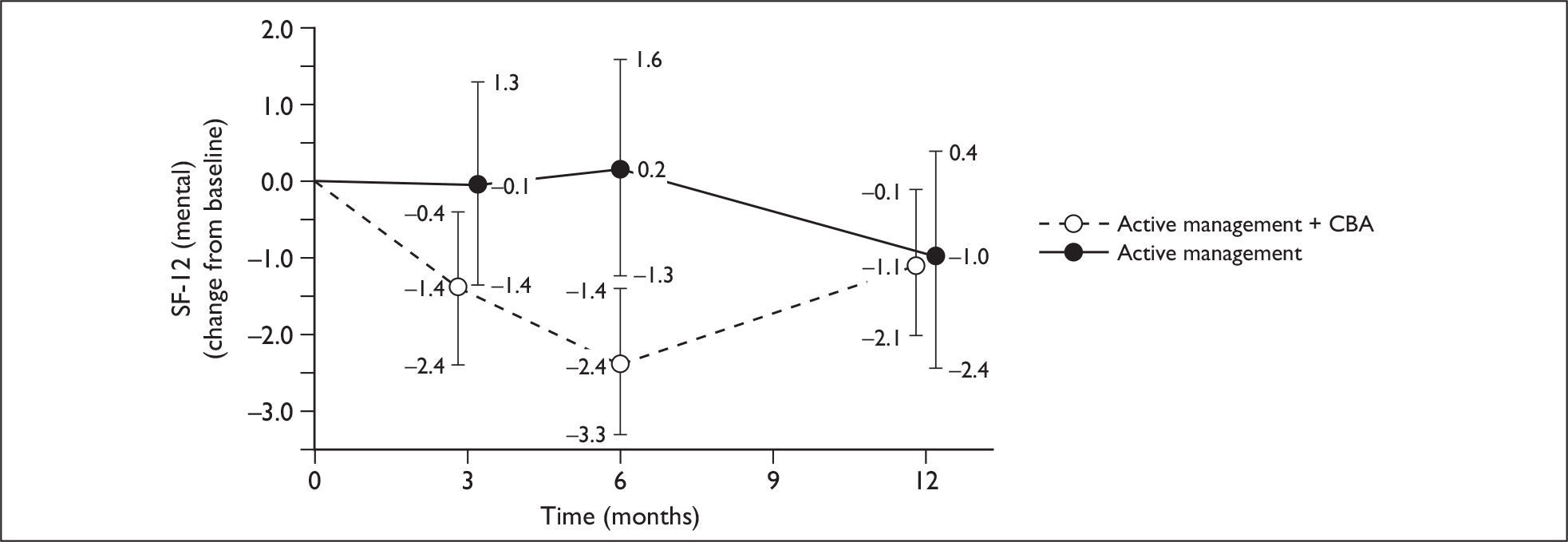

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using the Short Form-12 (SF-12) version 2. The SF-12 (a short version of the SF-36) is a measure of health-related quality of life and is widely used in back pain trials. The SF-12 has performed well in previous clinical trials of LBP using postal follow-up. 110

The SF-12 manual was used to score the SF-12. Results were expressed in terms of two meta-scores: physical and mental components.

The SF-12 is scored so that a high score indicates better physical functioning. The physical and mental scores have a range of 0–100 and were designed to have a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 in a representative sample of the US population (see Table 5 for age-specific SF-12 scores). Scores > 50 therefore represent above-average health status. On the other hand, people with a score of 40 function at a level lower than 84% of the population (one SD) and people with a score < 30 function at a level lower than approximately 98% of the population (two SDs).

| Age (years) | Physical component | Mental component |

|---|---|---|

| 45–54 | 50 | 50 |

| 55–64 | 47 | 51 |

| 65–74 | 44 | 52 |

| ≥ 75 | 39 | 50 |

Health economics – EuroQoL five dimensions

The EuroQoL five dimensions (EQ-5D)111 measure was collected at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months’ follow-up.

The instrument (see Appendix 8) contains a description of the health state in five dimensions or items: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. It measures health on five dimensions and a tariff is available for deriving a single utility score. Completion takes less than 5 minutes. 107

The items are three levels of severity for each item: 1 (no problems), 2 (some problems) and 3 (unable to do/extreme problems). For each item, the respondents must indicate the level of severity that best describes their personal health state at the time of giving the answers. The subject’s global health state is defined as the combination of the level of problems for each of the five dimensions. Health states defined by the EQ-5D can be converted to a single summary by applying scores from a standard set of weights (or preferences) derived from general population samples. 107

The weightings represent the strength of societal preference for a described health state and are scored between 0 (death or worst imaginable health state) and 1 (full health or best imaginable health state). The quality adjustment is then multiplied by the expected life-years in the assessed health state to arrive at the total quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) achieved. The total utility associated with a health-care intervention is then the sum of utility weights declared by respondents multiplied by the time spent in those states.

Resource use questionnaire

Resource use was monitored for the economic analysis and to gain insight into other treatments being used either as a consequence of or alongside the treatments being tested in the trial. A self-report questionnaire was administered to ascertain whether participants had additional hospital treatment for their LBP during the follow-up period, specifying whether this was NHS or private treatment; any GP consultations; and any manipulation, massage, etc. which they received during follow-up. Participants were also asked about the number and types of any medications and treatments, including pain-relieving medications. Participants were asked to distinguish between prescription and out-of-pocket expenses. We used a structured closed questionnaire to ascertain these data, based on a questionnaire that had been used in previous LBP trials. 37 Participant self-reported information on service use had been shown to be accurate in terms of intensity of use of different services. 112

Other treatments

There was a possibility that participants would seek other forms of treatment during the follow-up period. The resource use questionnaire allowed us to monitor changes in the amount or types of analgesia used, use of physical treatments (osteopathy, chiropractic or physiotherapy), alternative therapies, or referral to secondary-care services. Participants and GPs were encouraged to refrain from referral of participants to other treatments where possible during the first 3 months after randomisation and while participants were attending the CBA course.

Randomisation

The randomisation system

Initially a web-based randomisation system was planned. This system was very difficult to implement as it depended on the research nurses being able to access an NHS web link or secure internet link in the practices. The nurses were not always able to have access to practice computers and were often allocated rooms without internet access. Instead, an independently administered telephone randomisation service was used at the MRC Clinical Trials Unit in London. Random allocations were generated by an independent statistician in a ratio of 2 : 1 in favour of the intervention arm of the trial. Randomisation reports were sent to the trial office on a weekly basis.

Method of randomisation

We used stratified block randomisation. The randomisation was stratified by region (recognising the heterogeneity likely to exist between regions). It was important to balance the severity of back pain (moderately versus very/extremely troublesome) over the two treatment arms in case there was a difference in response based on severity. Block lengths were sufficiently large to ensure that predictions of treatment allocation could not be made, and that the allocation ratio of 2 : 1 could be achieved.

In the initial application, randomisation was based on equal assignment (a ratio of 1 : 1) over the two therapy groups. It was recognised, during the trial set-up stages, that such an allocation would produce an insufficient yield of participants to run the groups for the AM+CBA arm. As a result, random allocation was conducted using a 2 : 1 (AM+CBA : AM) ratio. This had little impact on the power of the trial and considerably improved efficiency.

The details required by the randomisation officer are shown on the randomisation form (see Appendix 7).

Quality assurance

We implemented a quality assurance protocol to monitor and ensure that research nurses were adherent to the trial protocol. Each research nurse was visited on at least two occasions by a senior research nurse from the MRC GPRF, and observed taking consent and delivering the active intervention component of the intervention. Problems were minimal.

Compliance

We measured compliance with the intervention by the number of sessions attended. This information was ascertained from records collected by the therapist providing the treatment.

Formal approvals

The original ethics approval for the project was dated 26 March 2003 with a substantial amendment approving protocol amendments on 22 July 2004. Further amendments for the qualitative interview study and consent, change to patient information sheets and promotional posters were all approved on 5 March 2005. An amendment to the randomisation procedure was submitted on 24 May 2005 and approved via chairman’s action on 14 July 2005. Further chairman’s action approval was received on 7 September 2005 for a change in trial personnel. A substantial amendment was approved on 25 January 2006 for version control. Chairman’s action was sought on 5 July regarding follow-up procedures and approval was received on 1 September 2006.

Adverse events

Risks and benefits

The risks to participants in this trial were considered small. The potential benefits were minimisation of back pain symptoms and prevention of chronic problems.

Potential side effects and monitoring

It was anticipated that there were unlikely to be any serious side effects from the treatments. Possible potential side effects were worsening of symptoms if other more effective treatments were withheld. All adverse events were reported to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Serious adverse events were defined as those that resulted in death or admission to hospital as a result of the intervention, or that caused unwarranted distress to a participant. All deaths and potential events were reported to the Chief Investigator, who determined whether the event might have been or was attributable to the intervention. Events were reported to the ethics committee and to the DMEC.

Sample size

The primary outcome measures were the RMQ and MVK assessed over 12 months.

Increasingly it has been recognised that advances in modern health care are most likely to yield moderate improvements, but in the context of highly prevalent conditions like LBP, these are considered worthwhile. 113

Choice of treatment effect

Deciding the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) between groups was problematic, particularly for the RMQ. Previous trials (including the UK BEAM, Oxfordshire Low Back Pain Trial and York Back Pain and Exercise Trial) adopted a clinically significant difference between groups of 2.5 RMQ points, based on the views of an expert group of clinicians and researchers. This equates to a large standardised effect size of 0.65,114 assuming an SD of 4.0. Differences of this magnitude had not been observed in several large trials (effect sizes were 0.35 for BEAM and 0.36 for the York Low Back Pain Trial115). Careful back tracking through trials (reviewed by Bombardier et al. 100) suggested that the MCID had been derived from a few studies of short-term benefits (< 8 weeks) of therapies in LBP. This is the stage at which one would expect to see the largest differences between groups because of the natural history of LBP. Powering a trial on the short-term clinical benefit was unlikely to be sufficient to monitor longer-term impacts of public-health significance. The majority of outcomes reported for CBA suggest moderate benefits at 1 year, with a between-group effect size of approximately 0.35 for the majority of outcomes reported in efficacy trials. 116 This equates to a between-group difference of approximately 1.4 change points on the RMQ disability score (i.e. new treatment approaches are approximately half as good again as the comparative treatment at reducing disability). We therefore considered that an effect size of 0.35 would be a suitable target for the CBA to be worthwhile.

The power of the trial

We selected a power of 90% recognising that economic analyses required greater power. Based on the experience of previous trials, the number of participants we intended to recruit was adequate for the purposes of the economic analysis. 117

We selected a significance level of 0.01 because of the need for a definitive trial. The sample size was sufficient to detect worthwhile benefits in the range of secondary outcome measures at conventional levels of statistical significance.

Adjustment for cluster effects of group interventions

The unit of randomisation was the individual, but the sample size estimate was inflated to account for the occurrence of cluster effects relating to grouping of patients together in each CB programme, and the clustering of outcomes around individual therapists (therapist effects). Previous studies of LBP report the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for therapist effects to be 0.01,94 although comparative data on group effects were not available. The ICC of 0.01 was used as an estimate for the therapist and group effects. Based on collecting outcome data on an average of seven people per group we inflated our sample size by 1.07.

Loss to follow-up

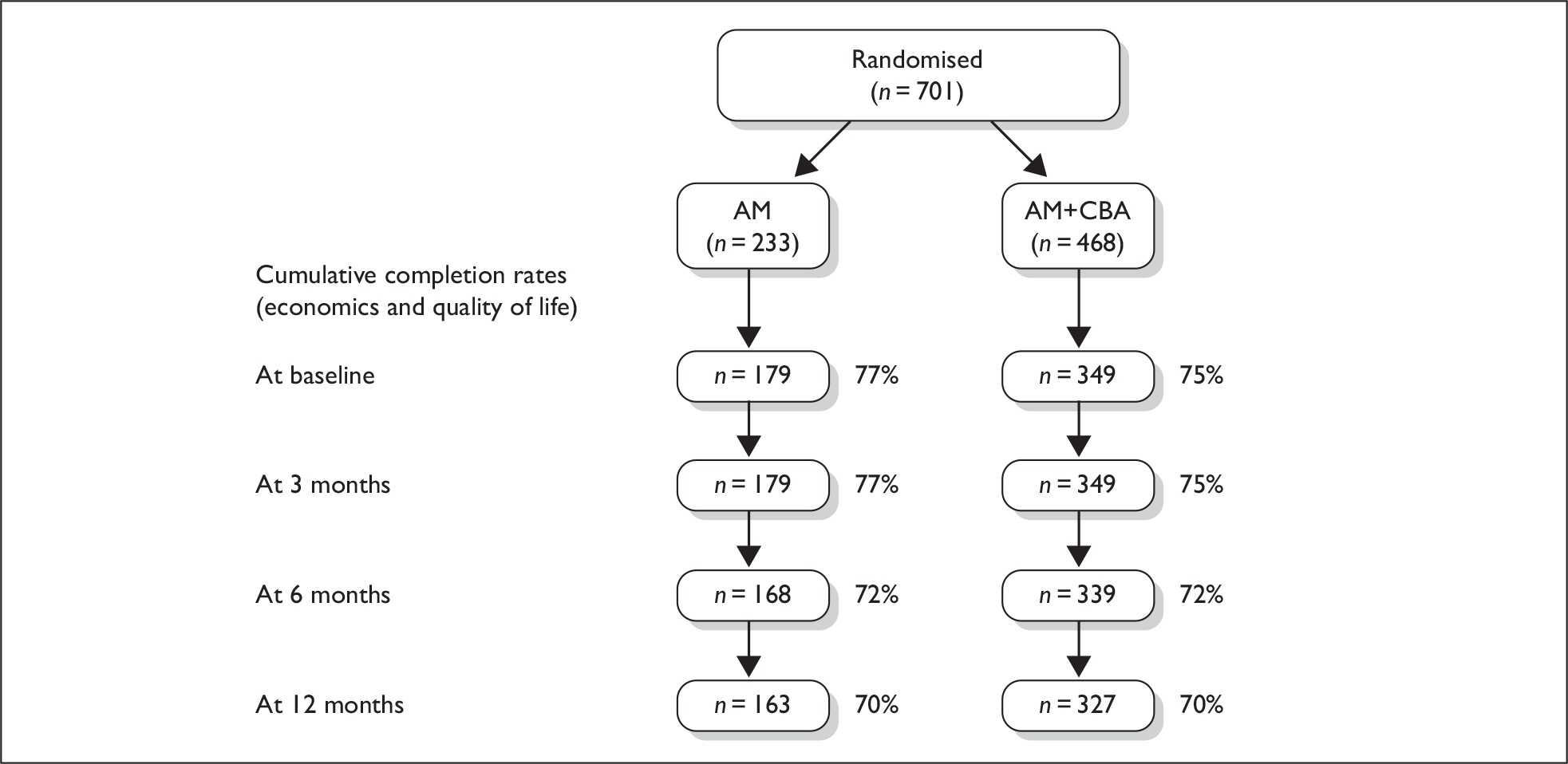

We assumed a loss to follow-up of 25% at 12 months, as achieved in the BEAM trial. 94

Sample size estimate

The sample size was estimated at the outset of the trial, and subsequently revised during trial set-up as we examined the practical aspects of setting the trial up. In the original sample size estimate [Health Technology Assessment (HTA) application], we used an effect size of 0.35 SD points, 90% power and p < 0.01 and inflation factor for clustering yielding an estimate of 262 in each group. We specified that we wished to detect a between-group difference of approximately 1.4 change points and a standardised effect size of 0.35. Assuming loss to follow-up of 25% and a balanced allocation between treatment and control (1 : 1), we aimed to recruit 350 in each group (700 in total).

As we progressed with the early phases of the trial, and with the experience gained in another trial we were conducting of group treatments, we opted to use an unbalanced randomisation (2 : 1 in favour of the intervention). The reason was pragmatic; we could not sustain a flow of participants to fill the groups in a reasonable time frame using balanced randomisation. A randomisation balance of 2 : 1 can be adopted with inconsequential loss of power, but further imbalances necessitate an increase in study size. 118,119 We estimated that a change to unbalanced randomisation without further inflation of the sample size would still allow us to detect clinically worthwhile benefits (effect size 0.42 and a between-group difference of 1.8 RMQ points. 118 We chose not to increase the sample size target, recognising that if loss to follow-up was 25% as predicted the study still had power to detect clinical worthwhile improvements. At the end of the trial, follow-up was better than anticipated, and we retained power to detect the original differences specified.

Using the proposed 700 participants and a 2 : 1 randomisation, we needed approximately 233 participants in the AM group and 467 participants in the AM+CBA arm.

Pilot study

We undertook a series of pilot studies to refine the study procedures and ensure that the intervention was acceptable and deliverable in the format intended.

The intervention was piloted at the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre NHS Trust in Oxford in the first instance. Two CBA cycles were completed and participants provided feedback on the contents and revised contents of the intervention. We then piloted the intervention in primary care along with the study procedures.

We planned to carry out the pilot study in three general practices in the Coventry area and to recruit 30–40 participants. In fact it was carried out in only one of the practices for the following reasons:

-

one practice dropped out when they learnt more about the trial

-

we were forced to run the pilot over the July/August period because of a 7-week delay in the Central Office for Research Ethics Committees confirming ethical approval because of an internal Central Office for Research Ethics Committees communication problem (as a consequence the research nurse who was secured to run the second practice was unavailable – she had to cover leave, went on holiday and was subsequently stranded abroad by hurricanes; however, this practice participated in the main trial).

We tested one of the two recruitment strategies – identification of participants through participant record searches but not prospective identification of participants via the GPs. In general the pilot study had been successful and useful in refining the study methods and in particular, methods related to the approach to participants.

Data management

All the databases were developed in Microsoft access 2002.

The prerandomisation and randomisation information was captured on laptops, whereas the baseline and follow-up data were collected using postal clinical research forms or by telephone and then entered into the database manually. Computerised validation checks were incorporated into the data sets to minimise data errors.

Database specifications were set up by the statistician and programmer for each variable collected at baseline and follow-up assessments.

Statistical analysis

Prerandomisation and randomisation

The trial has been reported in accordance with the CONSORT120 guidelines that have now been extended to consider the reporting of complex interventions. All statistical tests were two-sided. The statistical analyses were carried out using sas (version 9.13) and stata (version 9). The health economic analyses were carried out using stata. The demographic profile of the sample was summarised as the mean, SD, range and number of participants missing. The categorical data have been summarised using the number (and percentage) of participants within each category.

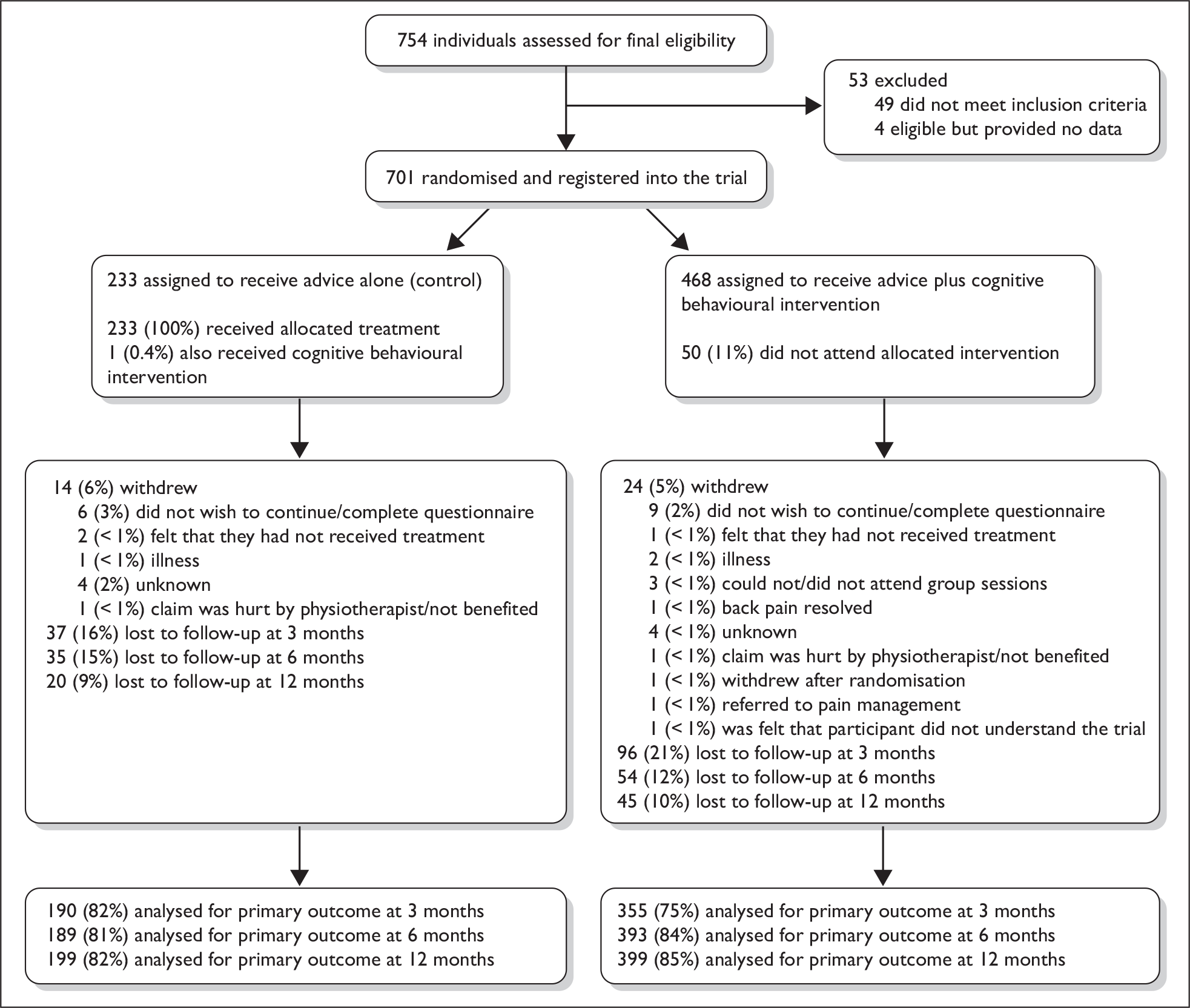

CONSORT flowchart

The CONSORT flowchart details the number (and percentage) of participants who were recruited into the trial from the second nurse’s assessment time point. The flowchart depicts the passage of participants through the trial (prerandomisation, intervention allocation, follow-up and primary data analysis).

Recruitment of randomised participants

The number (and percentage) of participants at baseline and follow-up was detailed as follows:

-

with data/clinical research forms present

-

with core data present

-

with no data present.

The follow-up (response) rates were derived from the total data present (i.e. sum of first two bullet points). The cumulative number of withdrawals over each time period was calculated and the frequency of loss to follow-up, blank questionnaire return and withdrawal (with reasons) was summarised.

The primary analysis method was ‘intention-to-treat’. The participants were analysed according to the therapy to which they were randomised, irrespective of the treatment they actually received.

Intention-to-treat formed the basis for computing the proportion of participants at different stages of the trial from randomisation to 12-month follow-up. The main summary tables and analysis are based on the intention-to-treat population unless otherwise specified.

Per protocol analysis

Participants who did not adhere to the treatment at the prespecified level of three or more sessions or who were incorrectly randomised were removed to form a per protocol sample. These analyses were undertaken using the primary outcomes and informed the sensitivity analysis.

Clinical outcomes: baseline and follow-up

Two sets of analyses were carried out:

-

primary analysis observed case analysis

-

sensitivity analysis missing data imputed at case level and questionnaire level and per protocol analysis.

Change from baseline to each of the follow-up assessments

Outcomes were summarised as the change from baseline score. The absolute scores were not used because the distribution of the data was, for some outcome measures, substantially non-normal. This was expected, particularly for the RMQ. A range of transformation methods were investigated, but none was able to normalise the data.

We needed to identify a method of summarising the data that would allow us to implement parametric methods including random effects and hierarchical modelling. Non-parametric covariance analysis121 is substantially limited in both scope and interpretation and was rejected because it does not allow consideration of clustering effects within the model. Similarly, more sophisticated statistical methods of modelling the probability density function122 while allowing for non-normality are significantly limited in interpretation and do not allow for consideration of clustering effects.

The interpretation of change from baseline scores is listed in Table 6.

| Questionnaire/score | Interpretation of absolute score | Change from baseline (baseline – follow-up) |

|---|---|---|

| RMQ | Lower score implies less disability; higher score implies more disability | –ve implies deterioration; +ve implies improvement |

| MVK (disability) | Lower score implies less disability; higher score implies more disability | –ve implies deterioration; +ve implies improvement |

| MVK (pain) | Lower score implies less pain; higher score implies more pain | –ve implies deterioration; +ve implies improvement |

| FABQ | Lower score implies less fear/avoidance; higher score implies more fear/avoidance | –ve implies deterioration; +ve implies improvement |

| Pain self-efficacy | Lower score implies less confidence; higher score implies greater confidence | –ve implies became more confident; +ve implies became less confident |

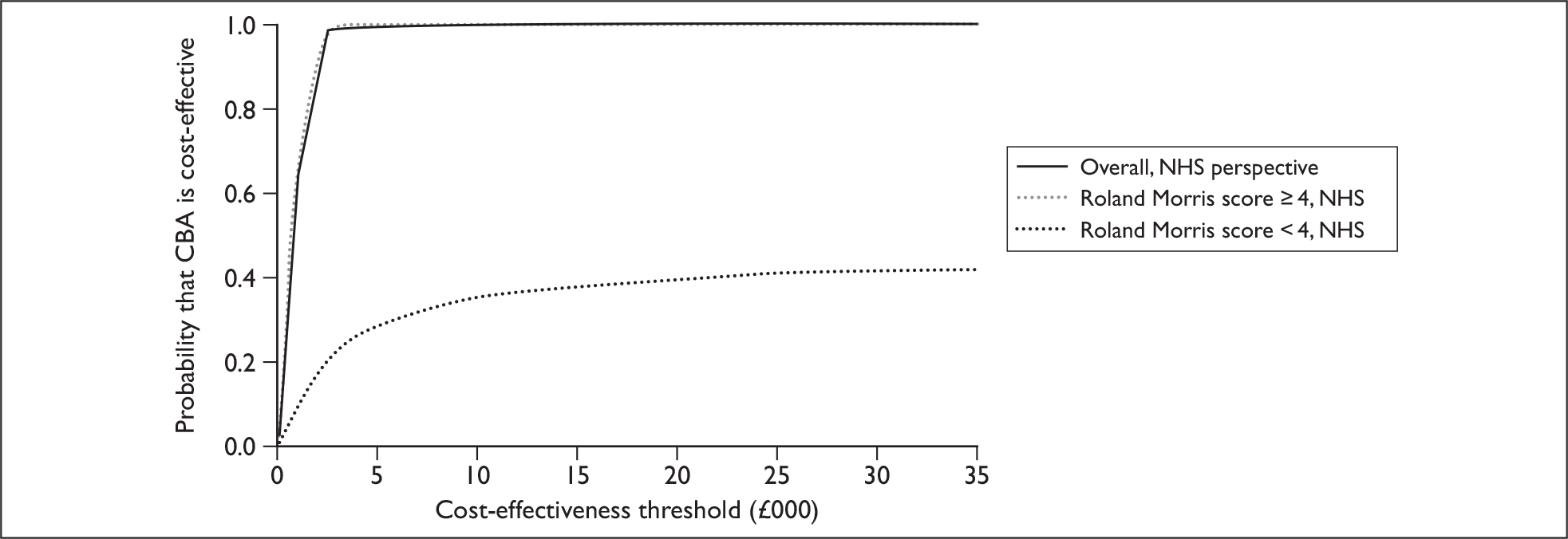

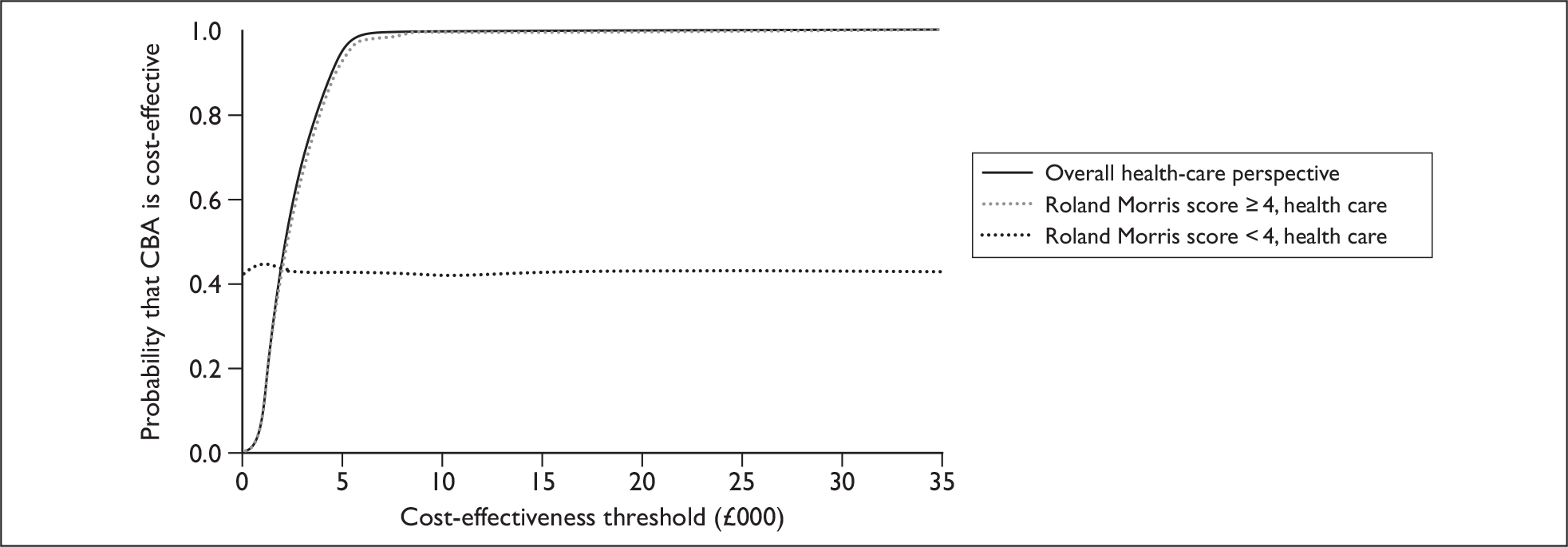

| SF-12 (physical and mental) | Lower score implies poor functioning; higher score implies better functioning | –ve implies functioning has improved; +ve implies functioning has deteriorated |