Notes

Article history

This themed issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a collection of research commissioned by the NIHR as part of the Department of Health’s (DH) response to the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. The NIHR through the NIHR Evaluation Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) commissioned a number of research projects looking into the treatment and management of H1N1 influenza. NETSCC managed the pandemic flu research over a very short timescale in two ways. Firstly, it responded to urgent national research priority areas identified by the Scientific Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE). Secondly, a call for research proposals to inform policy and patient care in the current influenza pandemic was issued in June 2009. All research proposals went through a process of academic peer review by clinicians and methodologists as well as being reviewed by a specially convened NIHR Flu Commissioning Board.

Declared competing interests of authors

Vaccines were manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline vaccines and Baxter, both of whom donated the vaccine but had no role in study planning or conduct. AJP, AF, PTH, SNF and ACC act as chief or principal investigators for clinical trials conducted on behalf of their respective NHS Trusts and/or universities, sponsored by vaccine manufacturers, but receive no personal payments from them. AJP, AF, PTH and SNF have participated in advisory boards for vaccine manufacturers but receive no personal payments for this work. MDS, SL, PTH and AF have received financial assistance from vaccine manufacturers to attend conferences. All grants and honoraria are paid into accounts within the respective NHS Trusts or universities, or to independent charities.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The first illness caused by a new influenza A virus was confirmed in the UK on 27 April 2009. Since then, the virus has become much more common in both the UK and across the world, and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on 11 June 2009. Children have experienced pandemic influenza A(H1N1) infections at four times the rate of adults and are hospitalised more frequently. 1,2 Although most childhood disease has been mild, severe disease and deaths have occurred, mainly in those with comorbidities. 3–5 As children are also very effective transmitters of the virus,6–8 they are a high-priority group for vaccination against pandemic influenza in many countries. 8–10

In response to this pandemic, the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation (WHO-SAGE), held an extraordinary meeting on 7 July 2009 to consider the role for immunisation in the prevention of this disease. 11 The key recommendations of this report were:

-

All countries should immunise their health-care workers as a first priority to protect the essential health infrastructure. As vaccines that are available initially will not be sufficient, a step-wise approach to vaccinate particular groups may be considered. WHO-SAGE suggested the following groups for consideration, noting that countries need to determine their order of priority based on country-specific conditions: pregnant women; those aged above 6 months with one of several chronic medical conditions; healthy young adults of 15–49 years of age; healthy children; healthy adults of 50–64 years of age; and healthy adults of 65 years of age and above.

-

Since new technologies are involved in the production of some pandemic vaccines, which have not yet been extensively evaluated for their safety in certain population groups, it is very important to implement postmarketing surveillance of the highest possible quality. In addition, rapid sharing of the results of immunogenicity and postmarketing safety and effectiveness studies among the international community will be essential for allowing countries to make necessary adjustments to their vaccination policies.

-

In view of the anticipated limited vaccine availability at a global level, and the potential need to protect against ‘drifted’ strains of virus, WHO-SAGE recommended that promoting production and use of vaccines, such as those that are formulated with oil-in-water adjuvants and live attenuated influenza vaccines, was important.

-

As most of the production of the seasonal vaccine for the 2009–10 influenza season in the northern hemisphere is almost complete and is therefore unlikely to affect production of pandemic vaccine, WHO-SAGE did not consider that there was a need to recommend a ‘switch’ from seasonal to pandemic vaccine production.

The UK Department of Health provided two H1N1 vaccines for the national immunisation programme: a split-virion, egg culture-derived AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and a non-adjuvanted Vero cell culture-derived whole-virion vaccine manufactured by Baxter. 12 Both manufacturers initially gained marketing authorisation approval from the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) for a pandemic strain vaccine under the ‘mock-up’ dossier route, based on limited clinical trial data for a candidate H5N1 vaccine. These vaccines were modified to cover the novel influenza AH1N1 strain.

Novel adjuvants had not been routinely used in early childhood prior to this pandemic, but were believed to provide enhanced immunogenicity, particularly in infants in whom traditional influenza vaccines have limited efficacy,9 and potentially allow antigenic sparing and induction of cross-clade immunity. 13–15

Although whole-virion influenza vaccines have previously been associated with unacceptable reactogenicity rates,16 H5N1 ‘mock-up’ whole-virion vaccines were well tolerated,17 and these vaccines avoid problems with egg-allergic individuals. 18 Use of cell culture for manufacture was expected to shorten production times, by avoiding the bottleneck of supply of hens’ eggs. 12,19

Although substantial safety data regarding the use of trivalent seasonal split and subunit non-adjuvanted inactivated influenza vaccines in children existed, similar safety and efficacy data for novel H1N1 vaccines were lacking. 20–23 The need for comparative immunogenicity and reactogenicity data for these two products in children was identified by the UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (UK-SAGE) as a high priority to help guide national recommendations on which to use in a paediatric population.

This study was therefore conducted to compare the immunogenicity, reactogenicity and safety of the two H1N1 vaccines in children aged 6 months to 12 years in a multicentre, open-label, randomised head-to-head trial. Immunogenicity was assessed by both the haemagglutination inhibition assay and microneutralisation assay.

Chapter 2 Methods

Vaccines

Two novel H1N1 vaccines were compared: a split-virion, AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine (GSK Vaccines, Rixensart, Belgium) and a non-adjuvanted whole-virion vaccine (Baxter Vaccines, Vienna, Austria).

The split-virion adjuvanted vaccine was constructed from the influenza A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) v-like strain antigen (New York Medical College x-179A), generated by classical reassortment in eggs, combining the HA, NA and PB1 genes of influenza A/California/07/2009 (H1N1)v to the PR8 strain backbone. 23,24 Each dose (0.25 ml, one-half of the adult dose) contained 1.875 µg of haemagglutinin antigen and the oil-in-water emulsion-based adjuvant AS03B [containing squalene (5.345 mg), DL-α-tocopherol (5.93 mg) and polysorbate 80 (2.43 mg) and thiomersal], and was supplied as suspension and emulsion in multidose vials. Opened vials were used within 24 hours but not stored overnight.

The non-adjuvanted whole-virion vaccine derived from Vero cell culture was supplied in multidose vials. Opened vials were used within 3 hours; each dose (0.5 ml) contained 7.5 µg of haemagglutinin from influenza A/California/07/2009 (H1N1).

Study design

Between 26 September and 11 December 2009, we conducted an open-label, randomised, parallel-group, phase II study at five UK sites (Oxford, Bristol, Southampton, Exeter and London) in children aged 6 months to 12 years, comparing the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of two novel H1N1 vaccines in a two-dose regimen.

The study was approved by the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (EUDRACT 2009–014719–11), the Oxfordshire Ethics Committee (09/H0604/107) and the local NHS organisations by an expedited process. 25 The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the standards of Good Clinical Practice (as defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation) and UK regulatory requirements.

Recruitment was by media advertising and direct mailing. Children aged 6 months to < 13 years, for whom a parent or guardian had provided written informed consent and who were able to comply with study procedures, were eligible for inclusion. In addition, verbal assent was sought from participants aged 7 years and older. Those with laboratory-confirmed pandemic H1N1 influenza or with clinically diagnosed disease meriting antiviral treatment were excluded to target an immunologically naive population. For safety reasons, those with allergy to egg or any other vaccine components and coagulation defects were excluded. Other exclusions included those with significant immunocompromise, immunosuppressive therapy, recent receipt of blood products, intent to immunise with another H1N1 vaccine, or, participation in another clinical trial. Participants were grouped into those aged 6 months to < 3 years (younger group) and 3 years to < 13 years of age (older group). Participants were randomised by study investigators (1 : 1 ratio) to receive one of the two vaccines (randomisation group stratified for age group with block sizes of 10 and concealed until immunisation by opaque envelope generated by the Health Protection Agency). Vaccines were administered by intramuscular injection (deltoid or anterior-lateral thigh, depending on age and muscle bulk) at enrolment and at day 21 (± 7) days. Sera were collected at study days 0 and 21 (–7 to +14) after second vaccination.

Safety and tolerability assessments

From days 0–7 post vaccination, parents or guardians recorded axillary temperature, injection site reactions, solicited and unsolicited systemic symptoms, and medications (including antipyretics/analgesic use) in diary cards. Primary reactogenicity end points were frequency and severity of fever, tenderness, swelling and erythema post vaccination. Secondary end points were the frequency and severity of non-febrile solicited systemic reactions or receipt of analgesic/antipyretic medication. Solicited systemic reactions were different in those under and over 5 years of age to reflect participants’ ability to articulate symptoms. Erythema and swelling were graded by diameter as mild (1–24 mm), moderate (25–29 mm) or severe (≥ 50 mm). Other reactions were graded by effect on daily activity as none, mild (transient reaction, no limitation in activity), moderate (some limitation in activity) or severe (unable to perform normal activity) or by frequency/duration into none, mild, moderate and severe categories.

Medically significant adverse events (any ongoing solicited reaction or any event necessitating a doctor’s visit or study withdrawal after day 7 post vaccination) were recorded on a diary card. Monitoring of adverse events of special interest, as recommended by the EMEA,26 was undertaken (for full details, see Appendix 1, subappendix E).

All data from case report forms and participant diary cards were double-entered and verified on computer.

Assays

Antibody responses were measured by microneutralisation and haemagglutination inhibition assays on sera using standard methods27,28 at the Centre for Infections, Health Protection Agency (UK). Assays were performed with the egg-grown NIBRG-121 reverse-genetics virus based on influenza A/California/07/2009 and A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (see Appendix 1).

The primary immunogenicity objective was a comparison between vaccines of the percentage of participants demonstrating seroconversion by the microneutralisation assay, with seroconversion defined as a fourfold rise to a titre of ≥ 1 : 40 from prevaccination to 3 weeks post second dose. A secondary objective based on the microneutralisation assay was a comparison between vaccines of the percentage with post-second-dose titres ≥ 1 : 40. Further secondary objectives based on the haemagglutination inhibition assay were comparisons between vaccines of the percentage with fourfold rises to titres ≥ 1 : 32 post second dose, the percentage with post-second-dose titres ≥ 1 : 32, geometric mean fold rises from baseline to post second dose, and geometric mean titres post second dose.

For microneutralisation assays, the initial dilution was 1 : 10 and the final dilution was 1 : 320, unless further dilutions were necessary to determine fourfold rises from baseline. For haemagglutination inhibition assays, the initial dilution was 1 : 8 and the final dilution was 1 : 16,384. For both assays, negative samples were assigned a value of one-half of the initial dilution. Sera were processed in 1 : 2 serial dilutions in duplicate and the geometric mean of each pair used.

Statistical analysis

With 200 participants in each age and vaccine group, the study had 80% power to detect differences of –14% to 12% around a 70% reactogenicity and seroconversion rate. Planned recruitment was up to 250 participants per group to allow for dropout and non-availability of sera.

Proportions with local or systemic reactions, and with seroconversion or titres above given thresholds, were calculated for each age and vaccine group. Comparisons between vaccines were made using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. For reactions, comparisons between doses were made using the sign test for paired data.

Geometric mean haemagglutination inhibition titres and fold rises were calculated for each age and vaccine group, along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Logged postvaccination haemagglutination inhibition titres were compared between vaccines using normal errors regression in a univariable model and then in a multivariable model adjusting for age, study site, sex, and interval from second vaccine dose to obtaining final serum sample. The interaction between age and vaccine was also investigated.

A planned interim analysis on the reactogenicity data from the first 500 participants was performed to provide rapid data to the UK Department of Health. The study site investigators remained blinded to the results of this analysis while visits were ongoing.

Data analysis was undertaken with stata software, version 10. The level of statistical significance was 5%. The data were analysed per protocol. As planned, no intention-to-treat analyses were conducted, as < 10% of subjects would have been classified differently in such an analysis.

Summary of protocol changes

-

Version 1.1 – increased sample size to 1000 participants, clarification of the role of the Data Monitoring Committee, procedures for vaccine labelling, specification of needle size for immunisation

-

Version 1.2 – addition of an interim analysis of the safety data, change in indemnity information

-

Version 2 – modification of serious adverse event reporting timelines and procedures, and addition of monitoring and reporting of adverse events of special interest

-

Version 3 – addition of the possibility of using a half-adult dose of vaccine if that became the recommended dose; the suggested dose for the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine in children did become half of the adult dose before the trial commenced and therefore this was used; and the recommendation remained to use a full adult dose of the whole-virion vaccine.

Chapter 3 Results

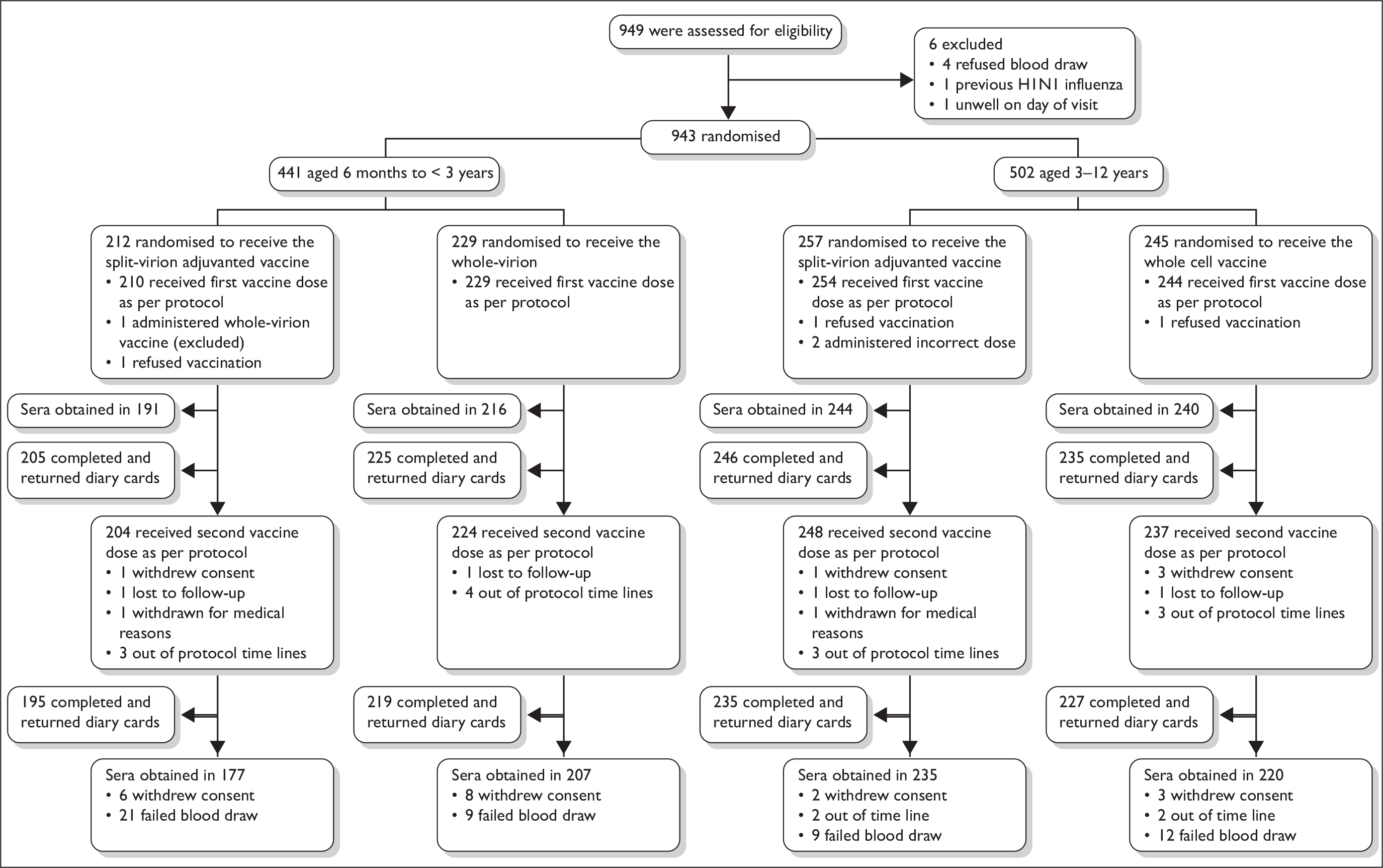

Recruitment visits were attended by 949 participants, of whom 943 were enrolled and 937 included in the per-protocol analysis (Figure 1 and Table 1). Overall, 913 participants received the second vaccine dose per protocol, at a mean interval of 20 days (range 14–28 days). Sera were obtained in 827 participants (88.2%) after the second vaccine dose as per protocol, at a mean interval of 20 days (range 14–35).

FIGURE 1.

Enrolment and follow-up of study participants.

| Characteristic | Age of participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months to < 3 years | 3–12 years | |||

| Split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine (n = 210) | Whole-virion (n = 229) | Split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine (n = 254) | Whole-virion vaccine (n = 244) | |

| Race or ethnic group (no.) | ||||

| White | 189 | 201 | 231 | 222 |

| Indian | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pakistani | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Asian other | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixed ethnic group | 14 | 19 | 9 | 10 |

| Black African | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Black Caribbean | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Chinese | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Sex (no.) | ||||

| Male | 116 | 123 | 131 | 121 |

| Female | 94 | 106 | 123 | 123 |

| Previous seasonal influenza vaccine (no.) | 5 | 5 | 22 | 28 |

| Age (years/months) | ||||

| Median | 23 months | 23 months | 82 months | 84 months |

| Range | 6–35 months | 6–35 months | 36–151 months | 36–155 months |

| Site in the UK | ||||

| Bristol | 44 | 46 | 41 | 42 |

| Exeter | 16 | 23 | 24 | 19 |

| Oxford | 70 | 79 | 66 | 59 |

| Southampton | 67 | 58 | 72 | 80 |

| St George’s | 13 | 23 | 51 | 44 |

Safety and tolerability

Solicited reactions are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Measurement | Level | Vaccine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split-virion AS03B adjuvanted | Whole-virion | ||||

| Dose 1,a n (%) | Dose 2,b n (%) | Dose 1,c n (%) | Dose 2,d n (%) | ||

| Pain | Mild | 77 (28.5) | 79 (31.1) | 48 (17.2) | 46 (17.0) |

| Moderate | 6 (2.2) | 19 (7.5) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Severe | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 85 (31.5)e,f | 100 (39.4)e,f | 51 (18.3)e | 47 (17.3)e | |

| Redness | 1–24 mm | 67 (24.8) | 59 (23.2) | 64 (22.9) | 52 (19.2) |

| 25–49 mm | 9 (3.3) | 8 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥ 50 mm | 0 (0) | 11 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 76 (28.1) | 78 (30.7)e | 64 (22.9) | 52 (19.2)e | |

| Swelling | 1–24 mm | 42 (15.6) | 37 (14.6) | 26 (9.3) | 17 (6.3) |

| 25–49 mm | 8 (3) | 6 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | |

| ≥ 50 mm | 2 (0.7) | 7 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 52 (19.3)e | 50 (19.7)e | 26 (9.3)e | 18 (6.6)e | |

| Any local reaction | Severe | 4 (1.5)f | 15 (5.9)e,f | 0 (0) | 0 (0)e |

| Decreased feeding | Mild | 67 (24.8) | 70 (27.6) | 75 (26.9) | 59 (21.8) |

| Moderate | 17 (6.3) | 27 (10.6) | 17 (6.1) | 14 (5.2) | |

| Severe | 5 (1.9) | 6 (2.4) | 2 (0.7) | 8 (3) | |

| Any | 89 (33) | 103 (40.6)e | 94 (33.7) | 81 (29.9)e | |

| Decreased activity | Mild | 34 (12.6) | 45 (17.7) | 26 (9.3) | 33 (12.2) |

| Moderate | 17 (6.3) | 33 (13) | 24 (8.6) | 11 (4.1) | |

| Severe | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Any | 55 (20.4)f | 81 (31.9)e,f | 52 (18.6) | 47 (17.3)e | |

| Increased irritability | Mild | 89 (33) | 84 (33.1) | 64 (22.9) | 45 (16.6) |

| Moderate | 28 (10.4) | 34 (13.4) | 28 (10) | 26 (9.6) | |

| Severe | 6 (2.2) | 4 (1.6) | 7 (2.5) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Any | 123 (45.6)e | 122 (48)e | 99(35.5)e | 77 (28.4)e | |

| Persistent crying | Mild | 52 (19.3) | 49 (19.3) | 32 (11.5) | 35 (12.9) |

| Moderate | 8 (3) | 13 (5.1) | 12 (4.3) | 13 (4.8) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Any | 61 (22.6) | 63 (24.8) | 46 (16.5) | 49 (18.1) | |

| Vomiting | Mild | 28 (10.4) | 28 (11) | 29 (10.4) | 26 (9.6) |

| Moderate | 6 (2.2) | 5 (2) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 34 (12.6) | 33 (13) | 32 (11.5) | 29 (10.7) | |

| Diarrhoea | Mild | 54 (20) | 49 (19.3) | 58 (20.8) | 46 (17) |

| Moderate | 9 (3.3) | 6 (2.4) | 10 (3.6) | 12 (4.4) | |

| Severe | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Any | 66 (24.4) | 58 (22.8) | 71 (25.4) | 62 (22.9) | |

| Any symptoms | Severe | 14 (5.2) | 19 (7.5) | 12 (4.3) | 14 (5.2) |

| Fever | ≥ 38°C | 24 (8.9)f | 57 (22.4)e,f | 26 (9.3) | 34 (12.5)e |

| GP visit for any reason | Any | 14 (5.2) | 14 (5.5) | 11 (3.9) | 16 (5.9) |

| Hospital visit for any reason | Any | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Analgesic or antipyretic medication | Any | 85 (31.5)f | 111 (43.7)e,f | 77 (27.6) | 64 (23.6)e |

| Measurement | Level | Split-virion AS03B adjuvanted | Whole-virion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose 1,a n (%) | Dose 2,b n (%) | Dose 1,c n (%) | Dose 2,d n (%) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Pain | Mild | 89 (49.2) | 78 (44.3) | 68 (37.6) | 65 (37.1) |

| Moderate | 44 (24.3) | 43 (24.4) | 4 (2.2) | 8 (4.6) | |

| Severe | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Any | 136 (75.1)e | 125 (71)e | 72 (39.8)e | 74 (42.3)e | |

| Redness | 1–24 mm | 41 (22.7) | 40 (22.7) | 38 (21) | 34 (19.4) |

| 25–49 mm | 8 (4.4) | 8 (4.5) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) | |

| ≥ 50 mm | 7 (3.9) | 9 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 56 (30.9) | 57 (32.4)e | 41 (22.7) | 38 (21.7)e | |

| Swelling | 1–24 mm | 24 (13.3) | 28 (15.9) | 21 (11.6) | 24 (13.7) |

| 25–49 mm | 9 (5) | 6 (3.4) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | |

| ≥ 50 mm | 8 (4.4) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Any | 41 (22.7)e | 39 (22.2) | 25 (13.8)e | 26 (14.9) | |

| Any local reaction | Severe | 13 (7.2)e | 15 (8.5)e | 2 (1.1)e | 2 (1.1)e |

| Loss of appetite | Mild | 33 (18.2) | 26 (14.8) | 17 (9.4) | 16 (9.1) |

| Moderate | 5 (2.8) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Severe | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Any | 42 (23.2)e | 33 (18.8) | 21 (11.6)e | 20 (11.4) | |

| Generally unwell | Mild | 39 (21.5) | 31 (17.6) | 27 (14.9) | 14 (8) |

| Moderate | 20 (11) | 13 (7.4) | 16 (8.8) | 12 (6.9) | |

| Severe | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 62 (34.3) | 46 (26.1)e | 45 (24.9)f | 26 (14.9)e,f | |

| Headache | Mild | 51 (28.2) | 38 (21.6) | 50 (27.6) | 36 (20.6) |

| Moderate | 25 (13.8) | 21 (11.9) | 10 (5.5) | 10 (5.7) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 77 (42.5) | 60 (34.1) | 61 (33.7) | 46 (26.3) | |

| Nausea/vomiting | Mild | 30 (16.6) | 25 (14.2) | 20 (11) | 15 (8.6) |

| Moderate | 4 (2.2) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Any | 34 (18.8) | 27 (15.3) | 22 (12.2) | 17 (9.7) | |

| Diarrhoea | Mild | 24 (13.3) | 11 (6.3) | 25 (13.8) | 17 (9.7) |

| Moderate | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Any | 28 (15.5)f | 14 (8)f | 27 (14.9) | 21 (12) | |

| Muscle pain | Mild | 40 (22.1) | 29 (16.5) | 22 (12.2) | 17 (9.7) |

| Moderate | 19 (10.5) | 13 (7.4) | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.9) | |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 59 (32.6)e | 44 (25)e | 25 (13.8)e | 22 (12.6)e | |

| Joint pain | Mild | 17 (9.4) | 15 (8.5) | 19 (10.5) | 13 (7.4) |

| Moderate | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Any | 20 (11) | 19 (10.8) | 23 (12.7) | 15 (8.6) | |

| Any symptoms | Severe | 5 (2.8) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) |

| Fever | ≥ 38°C | 14 (7.7) | 11 (6.3) | 6 (3.3) | 5 (2.9) |

| GP visit for any reason | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Hospital visit for any reason | 66 (36.5)e | 50 (28.4)e | 40 (22.1)e | 29 (16.6)e | |

| Analgesic/antipyretic medication | Any | 66 (36.5)e | 50 (28.4)e | 40 (22.1)e | 29 (16.6)e |

The split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine was associated with more frequent severe local reactions than the whole-virion vaccine after either dose in those aged over 5 years (dose 1, 7.2% vs 1.1%, p = < 0.001; dose 2, 8.5% vs 1.1%, p = 0.002) and after dose 2 in those under 5 years (5.9% vs 0.0%, p < 0.001). There were also more systemic reactions among participants 6 months to < 5 years of age with more irritability after either dose (dose 1, 45.6% vs 35.5%; dose 2, 48% vs 28.4) and, after dose 2, more decreased feeding (40.6% vs 29.9%) and decreased activity (31.9% vs 17.3%). Participants aged over 5 years experienced more muscle pain after either dose (dose 1, 32.6% vs 13.8%; dose 2, 25% vs 12.6%) and were more often generally unwell after dose 2 (26.1% vs 14.9%).

In younger children, dose 2 of the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine was more reactogenic than dose 1, with more fever ≥ 38°C (22.4% vs 8.9%, p < 0.001), local severe reactions (5.9% vs 1.5%, p = 0.02) and decreased activity (31.9% vs 20.4%, p = < 0.001). The second dose of the whole-virion vaccine was associated with decreased frequency of being generally unwell (14.9% vs 24.9%).

More recipients of the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine used antipyretic/analgesic medication after either dose of vaccine in the older participants (dose 1, 36.3% vs 22.1%; dose 2, 28.4% vs 16.6%) and after the second dose in younger participants (43.7% vs 23.6%, p < 0.001).

Adverse events

In participants receiving the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine, three adverse events of special interest occurred. One was an episode of reactive arthritis, in a participant aged 11 months, in the leg in which vaccine had been administered 2 days previously; this was considered possibly related. In brief, this participant became febrile to 39.1°C on the evening of vaccination. Two days later he was noted to be hesitant to weight bear on his right leg and was crawling unusually. Hospital review showed a well, afebrile child with a slightly erythematous and warm right knee with a reduced range of movement. There was no other obvious joint involvement and the vaccination site appeared normal. Blood tests were performed, including a C-reactive protein (1.00 mg/l) and white cell count (13.9 × 109), which were normal; throat swab and blood cultures were also taken, which showed no growth on either culture. Radiographs of both pelvis and right knee were normal. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis, possibly related to the vaccination, was made. The participant made a full recovery after 10 days. The second was a self-terminating generalised seizure 22 days post second vaccination in a participant aged 11 years 7 months with a previous history of possible seizure following head injury; this was considered unrelated to vaccination. The third was a possible seizure 20 days post second vaccination in a participant aged 12 years and 7 months, with a history of seizure following head injury; this was considered unrelated to vaccination.

In participants receiving the whole-virion vaccine, one adverse event of special interest occurred. This was a right focal seizure in a participant, aged 11 months, associated with fever, 9 days post second vaccination; this was considered unrelated to vaccination.

Five serious adverse events occurred, not in the category of adverse events of special interest and all considered unrelated to vaccination. In participants receiving the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine, these included an episode of exacerbation of asthma and an episode of tonsillitis with associated exacerbation of asthma; in participants receiving the whole-virion vaccine, these included an episode of exacerbation of asthma, a chest infection and vaccine failure with microbiologically confirmed influenza A(H1N1) 17 days post completion of vaccine course.

Immunogenicity

Prior to vaccination, 4.0% of participants (2.9% younger group, 5.0% older group) had microneutralisation titres ≥ 1 : 40, suggesting pre-existing immunity. Antibody responses are shown in Tables 4–6 and Figure 2.

| Vaccine | Age | Pre-vaccine | Post second dose | Fold rise | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % MN ≥ 1 : 40 (95% CI) | n/N | % MN ≥ 1 : 40 (95% CI) | n/N | % ≥ fourfold to ≥ 1 : 40 (95% CI) | ||

| Whole-virion | < 3 years | 9/216 | 4.2 (1.9–7.8) | 166/206 | 80.6 (74.5–85.8) | 157/196 | 80.1 (73.8–85.5) |

| 3–12 years | 11/240 | 4.6 (2.3–8.1) | 211/220 | 95.9 (92.4–98.1) | 208/217 | 95.9 (92.4–98.1) | |

| All | 20/456 | 4.4 (2.7–6.7) | 377/426 | 88.5 (85.1–91.3) | 365/413 | 88.4 (84.9–91.3) | |

| Split-virion, AS03B-adjuvanted | < 3 years | 3/191 | 1.6 (0.3–4.5) | 175/177 | 98.9 (96.0–99.9) | 163/166 | 98.2 (94.8–99.6) |

| 3–12 years | 13/244 | 5.3 (2.9–8.9) | 234/235 | 99.6 (97.7–99.9) | 226/228 | 99.1 (96.9–99.9) | |

| All | 16/435 | 3.7 (2.1–5.9) | 409/412 | 99.3 (97.9–99.8) | 389/394 | 98.7 (97.1–99.6) | |

| Vaccine | Age | Pre-vaccine | Post second dose | Fold rise | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % HI ≥ 1 : 32 (95% CI) | n/N | % HI ≥ 1 : 32 (95% CI) | n/N | % ≥ fourfold to ≥ 1 : 32 (95% CI) | ||

| Whole-virion | < 3 years | 8/216 | 3.7 (1.6–7.2) | 136/207 | 65.7 (58.8–72.1) | 126/197 | 64.0 (56.8–70.7) |

| 3–12 years | 7/240 | 2.9 (1.2–5.9) | 198/220 | 90.0 (85.3–93.6) | 192/217 | 88.5 (83.5–92.4) | |

| All | 15/456 | 3.3 (1.9–5.4) | 334/427 | 78.2 (74.0–82.0) | 318/414 | 76.8 (72.4–80.8) | |

| Split-virion, AS03B-adjuvanted | < 3 years | 3/191 | 1.6 (0.3–4.5) | 174/175 | 99.4 (96.9–99.9) | 163/164 | 99.4 (96.6–99.9) |

| 3–12 years | 13/244 | 5.3 (2.9–8.9) | 233/235 | 99.1 (97.0–99.9) | 225/228 | 98.7 (96.2–99.7) | |

| All | 16/435 | 3.7 (2.1–5.9) | 407/410 | 99.3 (97.9–99.8) | 388/392 | 99.0 (97.4–99.7) | |

| Vaccine | Age | Pre-vaccine | Post second dose | Fold rise | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | n | GMT (95% CI) | ||

| Whole-virion | < 3 years | 216 | 4.6 (4.2–5.1) | 207 | 44.0 (35.6–54.3) | 197 | 9.5 (7.8–11.6) |

| 3–12 years | 240 | 4.6 (4.2–4.9) | 220 | 106.3 (90.2–125.3) | 217 | 22.7 (19.3–26.8) | |

| All | 456 | 4.6 (4.3–4.9) | 427 | 69.3 (60.3–79.6) | 414 | 15.0 (13.2–17.2) | |

| Split-virion, AS03B-adjuvanted | < 3 years | 191 | 4.2 (4.0–4.5) | 175 | 461.0 (409.0–519.6) | 164 | 107.4 (93.9–122.9) |

| 3–12 years | 244 | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 235 | 377.3 (339.2–419.7) | 228 | 78.5 (69.9–88.1) | |

| All | 435 | 4.5 (4.3–4.8) | 410 | 411.0 (379.4–445.2) | 392 | 89.5 (81.9–97.8) | |

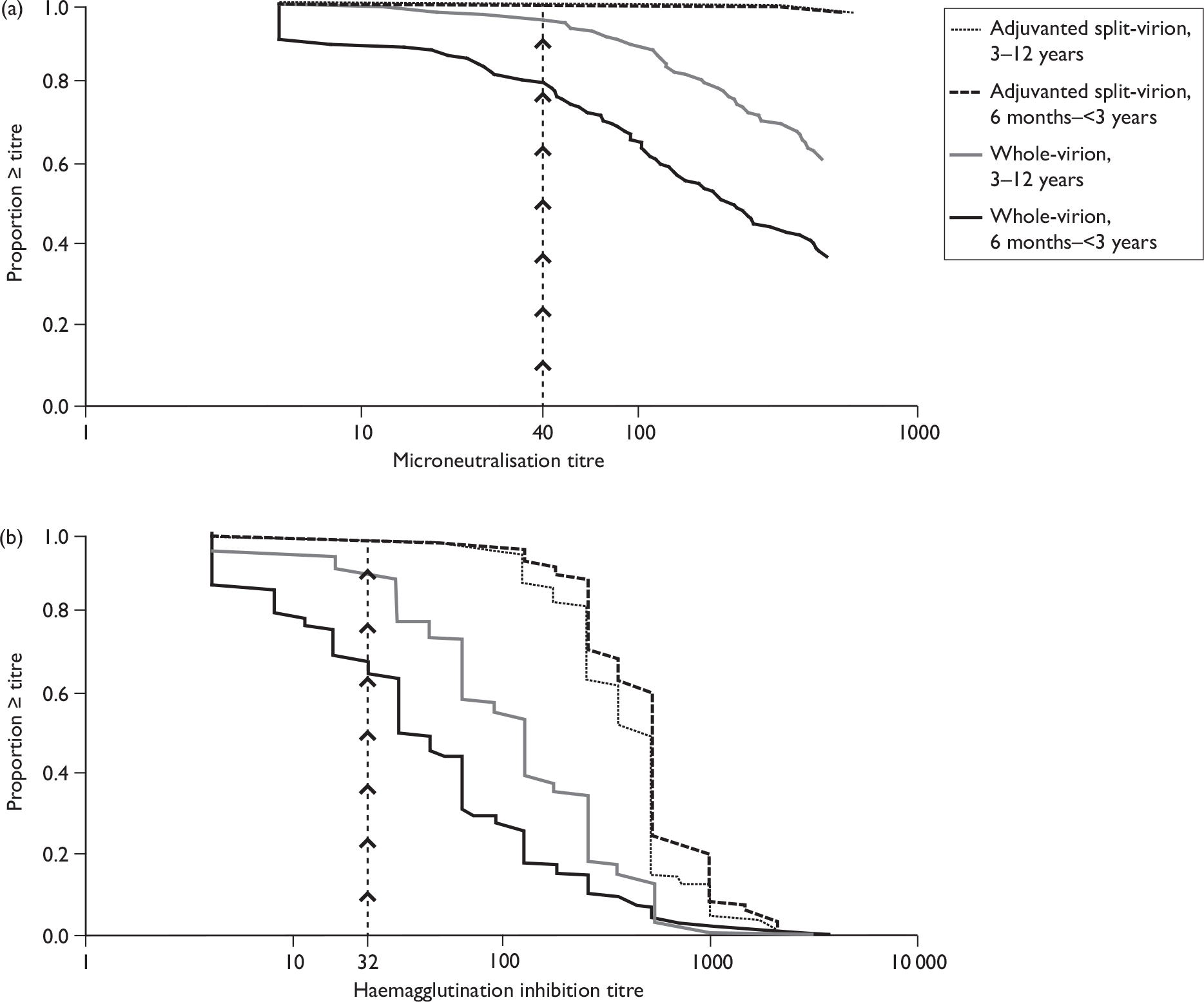

FIGURE 2.

Reverse cumulative distribution curves of antibody titres as measured by microneutralisation curves and haemagglutination inhibition assays by age group and vaccine. Arrows indicate seroprotection thresholds.

Seroconversion rates were higher with the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine than with the whole-virion unadjuvanted vaccine both by microneutralisation assay (younger group, 98.2% vs 80.1%, p < 0.001; older group, 99.1% vs 95.9%, p = 0.03) and haemagglutination inhibition assay (younger group, 99.4% vs 64.0%; older group, 98.7% vs 88.5%, p = < 0.001 for both groups). Compared with the whole-virion vaccine, the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine was associated with a higher percentage of participants with microneutralisation titres ≥ 1 : 40 (99.3% vs 88.5%, p < 0.001), a higher percentage with haemagglutination inhibition titre ≥ 1 : 32 (99.3% vs 78.2%, p < 0.001), higher geometric mean haemagglutination inhibition titres (411.0 vs 69.3) and greater geometric fold rise in haemagglutination inhibition titre from baseline (89.5 vs 15.0) (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Although 95% CIs for the degree of pre-existing immunogenicity for the two groups overlapped, the 95% CIs did not overlap for post second dose immunogenicity results.

The multivariable analysis on logged haemagglutination inhibition titres showed a significant interaction between age and vaccine (p < 0.001), with 10.5-fold (95% CI 8.1 to 13.5) higher titres induced by the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine in the younger participants compared with 3.6-fold (95% CI 3.0 to 4.3) higher titres in older children. This difference in the age effect by vaccine was further evaluated by including age as a continuous variable in the multivariable model, which showed a 3% decrease in titre per year of age (95% CI 0.5 to 5, p = 0.02) for the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine and a 16% increase per year (95% CI 12 to 21, p < 0.001) for the whole-virion vaccine.

Chapter 4 Discussion

This is the first paediatric head-to-head study of the GSK split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted H1N1 pandemic vaccine and the Baxter whole-virion non-adjuvanted vaccine. The vaccine containing the novel adjuvant was more immunogenic than the whole-virion vaccine, especially in young children, but was also more reactogenic. Children with comorbidities are at increased risk of severe H1N1 disease, and for this reason we did not exclude children with pre-existing medical conditions (except immunodeficiency), making our findings relevant to the general paediatric population. A UK vaccination programme, principally using the adjuvanted split-virion vaccine29 was announced in August 2009, initially targeting those with comorbidities,30 but the programme was widened to all children aged 6 months to 5 years in December 2009 following a review of interim data from this study and other data. 29

The haemagglutination inhibition assay is used extensively in the serological assessment of immunity to influenza viruses and as licensure criteria. 27,31–33 However, the haemagglutination inhibition assay measures only antibody directed to the receptor binding site, whereas the microneutralisation assay may be more sensitive, as it detects antibody directed at this and other antigenic sites in the virus,31,34,35 and was therefore chosen as the primary immunogenicity end point.

Only 3.5% of participants had prevaccination antibody levels ≥ 1 : 32 by haemagglutination inhibition, suggestive of prior infection with the pandemic strain H1N1. 1 This was lower than that found in a recent serosurvey in England, which was conducted after the first wave, and may reflect geographical differences in exposure risk. 1 Moreover, we excluded children with a history of confirmed H1N1 disease or who had been treated for suspected infection. Follow-up took place during the second wave of the UK pandemic, but any boosting effect of natural infection would be expected to be similar between vaccine groups.

An important finding of this study was that the whole-virion vaccine showed a strong age-dependent response, with a 16% increase in immunogenicity per year with age. Similarly, the immunogenicity of both seasonal influenza vaccines16 and other non-adjuvanted H1N1 vaccines22 in young children is less than in older children and adults. New-generation adjuvants (such as MF59 and AS03B) have been used to improve immunogenicity13,14,35 and in this study the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine was highly immunogenic, even in young children, but was slightly less immunogenic in older children than in infants (3% per year with age), a pattern not previously described for inactivated vaccines.

Other H1N1 vaccines, including both adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted vaccines, are immunogenic in children but contain considerably more antigen than the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine used in this trial. 21,36,37 Antigen sparing is important in a pandemic setting where vaccine requirements exceed manufacturing capability. 38 Pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine trials demonstrated the need for a two-dose regimen in immunologically naive individuals,24 and two-dose regimens of several H1N1 vaccines are more immunogenic than single-dose regimens. 21,22,36 However, limited data have suggested that a single-dose regimen of the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine used in this trial may be sufficient to meet licensing criteria,23,24 and the UK has recently recommended a single-dose regimen in healthy children. 29 When we were designing this study, a two-dose pandemic vaccine schedule was planned for children, and for this reason our pragmatic trial did not include a blood test after one dose to simplify the study in the face of the need for rapid recruitment. With the subsequent change to a single-dose regimen in the UK, our results would have been strengthened by addition of assessment of immunogenicity after a single dose. Furthermore, a comparison with a non-adjuvanted split-virion vaccine would be of interest but none was used in the UK during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and we limited the study to these two novel vaccines.

Even during interpandemic periods, children experience significant morbidity and mortality from influenza infection, and their role in virus transmission results in a much wider burden. 16 The favourable immunogenicity and reactogenicity of the split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine demonstrated in this study suggest that novel adjuvants may also have a role in seasonal influenza vaccines.

Whole-virion influenza vaccines have previously been associated with high reactogenicity rates. 16 This study provides the first data showing that a whole-virion H1N1 vaccine in children was well tolerated. Increased reactogenicity was seen with an MF59-adjuvanted H1N1 vaccine in children,37 as well as in adult trials of oil-in-water adjuvanted vaccines. 13–15,23,35 The AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine in this trial was similarly associated with more local reactions, and some increase in systemic reactions, compared with the whole-virion vaccine. The higher reactogenicity observed with the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine may influence parental uptake of the vaccine. No data on the parental feelings on the tolerability were collected, so the likely effective of this cannot be assessed. Our observed local and systemic reactogenicity rates were generally in keeping with data in the Summary of Product Characteristics. 23,24 However, although we found the rate of fever to be slightly higher in infants after the second dose compared to the first, these are one-half of the reported rate (43.1% of 51 infants). 24

Chapter 5 Conclusions

This is the first direct comparison of two commercially available novel H1N1 vaccines. The split-virion AS03B-adjuvanted vaccine was more immunogenic and induced high seroconversion rates in young children. These data provide important information to guide immunisation policy in an influenza pandemic and indicate the potential for improved immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccines in children.

Implications for health care, recommendations for research

Further studies evaluating the breadth and duration of the immune response to single- and two-dose regimens are needed, in particular the persistence of antibody and the degree of cross-clade protection. Our observation that the split-virion adjuvanted vaccine was slightly less immunogenic in older children than in infants (3% per year with age) is a pattern that is not previously described for inactivated vaccines. Further research is needed to see if this is a consistent finding with adjuvant use, and, if so, what the underlying mechanisms are. The role of adjuvants in seasonal influenza vaccines to provide enhanced immunogenicity in infants is also needed.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to the parents and children who participated in the trials and are grateful for the clinical and administrative assistance of the Department of Health (DH); the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR); National Research Ethics Service (NRES); Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA); National Health Service (NHS); Thames Valley, Hampshire and Isle of Wight, and South London NIHR Comprehensive Local Research Networks (CLRNs); NIHR Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN), the Southampton University Hospitals NHS Trust Research and Development Office, Child Health Computer Departments of Primary Care Trusts in Oxford, Southampton, Bristol, Exeter and London (Wandsworth); the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). We are also grateful to the Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections for both administrative assistance and laboratory support. This study was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme and was supported by the NIHR Oxford Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre programme (including salary support for AR, TMJ and MDS), and the Thames Valley, Hampshire and Isle of Wight and Western (salary support for CDS) CLRNs. This study was adopted by the NIHR MCRN and supported by their South West Local Research Network. AJP is a Jenner Institute Investigator.

Dual publication: reproduced with permission of the BMJ publishing group.

Contributions of authors

Professor Andrew Pollard (Professor of Paediatric Infection and Immunity) contributed to the design of the study, participant enrolment, and data interpretation, and was chief investigator.

Dr Matthew Snape (Consultant Paediatrician and Vaccinologist) contributed to design of the study, participant enrolment and data interpretation, and was principal investigator at the Oxford site.

Professor Elizabeth Miller (Head, Immunisation Department) was lead investigator, contributing to study design and data interpretation, and overseeing data management, statistical analysis and laboratory processing.

Dr Saul Faust (Senior Lecturer in Paediatric Immunology and Infectious Diseases) contributed to design of the study, participant enrolment and data interpretation, and was principal investigator at the Southampton site.

Professor Adam Finn (David Baum Professor of Paediatrics) contributed to design of the study, participant enrolment and data interpretation, and was principal investigator at the Bristol site.

Dr Paul Heath (Executive Officer Paediatric Studies, Senior Lecturer, Honorary Consultant Paediatrician) contributed to design of the study, participant enrolment and data interpretation, and was principal investigator at the St George’s London site.

Dr Andrew Collinson (Consultant Paediatrician) contributed to design of the study, participant enrolment and data interpretation, and was principal investigator at the Exeter site.

Nick Andrews (Senior Statistician) was responsible for statistical analysis.

Katja Hoschler (Advanced Healthcare Scientist/Clinical Scientist) was responsible for laboratory analysis.

Woolf Walker (Welcome Trust Clinical Research Fellow, Paediatrics), Clarissa Oeser (Clinical Research Fellow, Vaccines), I Okike (Clinical Research Fellow, Vaccines), Shamez Ladhani (Consultant in Paediatric Infectious Diseases), Suzanne Wilkins (Clinical Research Nurse, Paediatrics) and Michelle Casey (Children’s Senior Research Sister) enrolled patients and/or contributed to data collection.

Amanda Reiner (Project Manager) and Tessa John (Clinical Team Lead, Paediatric Vaccine Research) were responsible for project management, including coordination across sites, study logistics and preparation of regulatory submissions, as well as contributing to patient enrolment and data collection.

Polly Eccleston (Data Manager) contributed to data management.

Ruth Allen (Research Network Manager) contributed to project management at the Bristol and Exeter sites.

Elizabeth Sheasby (Quality Manager) contributed to study management.

Pauline Waight (Senior Scientific Data Analyst) was responsible for data management.

Claire Waddington (Clinical Research Fellow, Vaccinology) drafted this report, which was subsequently reviewed by all authors, and contributed to design of the study, participant enrolment and data interpretation.

Publication

Waddington C, Walker WT, Oeser C, Reiner A, John T, Wilkens S, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of AS03B adjuvanted split-virion versus non-adjuvanted whole-virion H1N1 influenza vaccine in UK children aged 6 months–12 years: open label, randomised, parallel group, multicentre study. BMJ 2010; c2649. DOI 10.1136/bmj.c2649.

Disclaimers

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

- Miller E, Hoschler K, Hardelid P, Stanford E, Andrews N, Zambon M. Incidence of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: a cross-sectional serological study. Lancet 2010;375:1100-8.

- Health Protection Agency . Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in England: An Overview of Initial Epidemiological Findings and Implications for the Secondwave n.d. www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1258560552857.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Surveillance for paediatric deaths associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection – United States, April–August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly 2009;58:941-7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Hospitalised patients with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection – California, April–May, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:536-41.

- Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, Schmitz AM, Benoit SR, Louie J, et al. Hospitalised Patients with 2009 H1N1 Influenza in the United States, April-June 2009. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2605-15.

- Kuehn BM. CDC names H1N1 vaccine priority groups. JAMA 2009;302:1157-8.

- Glezen WP, Couch RB. Interpandemic influenza in the Houston area, 1974–76. N Engl J Med 1978;298:587-92.

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation . Report of the Extraordinary Meeting on the Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Pandemic n.d. www.who.int/wer/2009/wer8430.pdf.

- Jefferson T, Rivetti A, Harnden A, Di Pietrantonj C, Demicheli V. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2.

- Ferguson N. Poverty, death, and a future influenza pandemic. Lancet 2006;368:2187-8.

- World Health Organization . Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Briefing Note 2: WHO Recommendations on Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Vaccines n.d. www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_vaccine_20090713/en/print.html.

- Barrett PN, Mundt W, Kistner O, Howard MK. Vero cell platform in vaccine production: moving towards cell culture-based viral vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2009;8:607-18.

- Chu DW, Hwang SJ, Lim FS, Oh HM, Thongcharoen P, Yang PC, et al. Immunogenicity and tolerability of an AS03(A)-adjuvanted prepandemic influenza vaccine: a phase III study in a large population of Asian adults. Vaccine 2009;27:7428-35.

- Leroux-Roels I, Roman F, Forgus S, Maes C, De Boever F, Drame M, et al. Priming with AS03(A)-adjuvanted H5N1 influenza vaccine improves the kinetics, magnitude and durability of the immune response after a heterologous booster vaccination: an open non-randomised extension of a double-blind randomised primary study. Vaccine 2010;28:849-57.

- Leroux-Roels I, Borkowski A, Vanwolleghem T, Drame M, Clement F, Hons E, et al. Antigen sparing and cross-reactive immunity with an adjuvanted rH5N1 prototype pandemic influenza vaccine: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:580-9.

- Zangwill KM, Belshe RB. Safety and efficacy of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in young children: a summary for the new era of routine vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:189-97.

- Ehrlich HJ, Muller M, Oh HM, Tambyah PA, Joukhadar C, Montomoli E, et al. A clinical trial of a whole-virus H5N1 vaccine derived from cell culture. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2573-84.

- Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, Brathwaite N, Lucas JS, Warner JO. Recommendations for the administration of influenza vaccine in children allergic to egg. BMJ 2009;339.

- Oxford JS, Manuguerra C, Kistner O, Linde A, Kunze M, Lange W, et al. A new European perspective of influenza pandemic planning with a particular focus on the role of mammalian cell culture vaccines. Vaccine 2005;23:5440-9.

- Kelly H, Barr I. Large trials confirm immunogenicity of H1N1 vaccines. Lancet 2009;75:6-9.

- Liang XF, Wang HQ, Wang JZ, Fang HH, Wu J, Zhu FC, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 vaccines in China: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;375:56-6.

- Plennevaux E, Sheldon E, Blatter M, Reeves-Hoche MK, Denis M. Immune response after a single vaccination against 2009 influenza A H1N1 in USA: a preliminary report of two randomised controlled phase 2 trials. Lancet 2010;375:41-8.

- Roman F, Vaman T, Gerlach B, Markendorf A, Gillard P, Devaster JM. Immunogenicity and safety in adults of one dose of influenza A H1N1v 2009 vaccine formulated with and without AS03(A)-adjuvant: preliminary report of an observer-blind, randomised trial. Vaccine n.d.;28:1740-5.

- European Medicines Agency (EMEA) . Pandemrix. Summary of Product Characteristics, Approved by the European Commission on 22 December 2009 2009. www.ema.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/pandemrix/D-H1N1%20single%20PDFs/SPC/emea-spc-h832pu17en.pdf.

- Pollard AJ, Reiner A, John T, Sheasby E, Snape M, Faust S, et al. Future of flu vaccines. Expediting clinical trials in a pandemic. BMJ 2009;339.

- European Medicines Agency (EMEA) . CHMP Recommendations for the Core Risk Management Plan for Influenza Vaccines Prepared from Viruses With the Potential to Cause a Pandemic and Intended for Use Outside of the Core Dossier Context 2008. www.ema.europa.eu/pdfs/human/pandemicinfluenza/4999308en.pdf.

- Rowe T, Abernathy RA, Hu-Primmer J, Thompson WW, Lu X, Lim W, et al. Detection of antibody to avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in human serum by using a combination of serological assays. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:937-43.

- Ellis JS, Zambon MC. Molecular analysis of an outbreak of influenza in the United Kingdom. Eur J Epidemiol 1997;13:369-72.

- UK Department of Health . A(H1N1) Swine Flu Influenza: Phase Two of the Vaccination Programme; Children over 6 Months and under 5 Years: Dosage Schedule Update 2009. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/lettersandcirculars/Dearcolleagueletters/DH_110182.

- UK Department of Health . Priority Groups for the Vaccination Programme 2009. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Flu/Swineflu/InformationandGuidance/Vaccinationprogramme/DH_105455.

- Stephenson I, Heath A, Major D, Newman RW, Hoschler K, Junzi W, et al. Reproducibility of serological assays for influenza virus A (H5N1). Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:1252-9.

- US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for Industry: Clinical Data Needed to Support the Licensure of Pandemic Influenza Vaccines 2007. www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Vaccines/ucm074786.htm.

- European Medicines Agency (EMEA) . Guideline on Influenza A Vaccines Prepared from Viruses With the Potential to Cause a Pandemic and Intended for Use Outside of the Core Dossier Content 2007. www.ema.europa.eu/pdfs/human/vwp/26349906enfin.pdf.

- Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, Zhong W, Butler EN, Sun H, et al. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1945-52.

- Clark TW, Pareek M, Hoschler K, Dillon H, Nicholson KG, Groth N, et al. Trial of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent MF59-adjuvanted vaccine: preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2424-35.

- Nolan T, McVernon J, Skeljo M, Richmond P, Wadia U, Lambert S, et al. Immunogenicity of a monovalent 2009 influenza A(H1N1) vaccine in infants and children: a randomised trial. JAMA 2009;303:37-46.

- Arguedas A, Soley C, Lindert K. Responses to 2009 H1N1 vaccine in children 3 to 17 years of age. N Engl J Med 2009;362:370-2.

- Collin N, de Radigues X. Vaccine production capacity for seasonal and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza. Vaccine 2009;27:5184-6.

Appendix 1 Protocol, version 3, dated 25 September 2009

Appendix 2 Information booklet

Appendix 3 Consent form

Appendix 4 Child information sheet

Appendix 5 Diary cards

Appendix 6 Memory aid card

Appendix 7 Recruitment poster

List of abbreviations

- CI

- confidence interval

- EMEA

- European Medicines Agency

- GSK

- GlaxoSmithKline

- UK-SAGE

- UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies

- WHO

- World Health Organization

- WHO-SAGE

- WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation

All abbreviations that have been used in this report are listed here unless the abbreviation is well known (e.g. NHS), or it has been used only once, or it is a non-standard abbreviation used only in figures/tables/appendices, in which case the abbreviation is defined in the figure legend or in the notes at the end of the table.