Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 04/26/02. The protocol was agreed in July 2009. The assessment report began editorial review in November 2009 and was accepted for publication in June 2010. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Anne Fry-Smith was one of the authors of the technology assessment reports compiled to inform the following technology appraisals: TA130 adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis; and TA36 etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. She also formed part of the Evidence Review Group for the single technology appraisal of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in 2009.

Dr David Moore and Kinga Malottki were part of the Evidence Review Group for the single technology appraisal of certolizumab pegol for rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr Pelham Barton constructed the Birmingham Rheumatoid Arthritis Model, which has been used in several National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) technology assessments/appraisals related to rheumatoid arthritis.

Angelos Tsourapas was part of the Evidence Review Group for the single technology appraisal of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in 2009.

Dr Paresh Jobanputra has participated in several technology assessments/appraisals related to rheumatoid arthritis as the clinical expert of the assessment group. He works as consultant rheumatologist in a large department of rheumatology. His department has taken part in clinical trials of etanercept, adalimumab, rituximab and tocilizumab. The department receives funding for nurses from Schering-Plough Ltd to administer infliximab to patients currently being treated with this drug. Currently he is the chief investigator of a clinical trial comparing adalimumab versus etanercept (ISRCTN95861172). He has, in the past, received support for educational purposes from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (etanercept), Abbott (adalimumab) and Roche (rituximab). He has also been involved in an advisory board for Roche in relation to tocilizumab and rituximab, and has accepted support from UCB Pharma for the purposes of study leave to attend an American College for Rheumatology conference in 2009. He has not been involved in any pharmaceutical company submissions to the NICE and has no stocks or shares in any of these companies. Dr Jobanputra was also part of the Evidence Review Group for the single technology appraisal of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in 2009.

Dr Martin Connock was part of the Evidence Review Group for the single technology appraisal of tocilizumab and certolizumab pegol for rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr Yen-Fu Chen was one of the authors of the technology assessment report that was compiled to inform technology appraisal No. 130 entitled adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) typically begins in middle age and more affects more women than men. Pathologically the disease is characterised by an inflammatory reaction and increased cellularity of the lining layer of synovial joints. Joints such as the proximal interphalangeal joints, metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists, elbows, cervical spinal joints, knees, ankle and foot joints are commonly affected. Affected joints become stiff after periods of inactivity, for example in the morning, become swollen and are variably painful. Other organ systems may also be affected. Patients commonly experience fatigue and blood abnormalities such as anaemia and a raised platelet count. Weight loss, lymph node enlargement, lung diseases (such as pleurisy, pleural fluid and alveolitis), pericarditis, vascular inflammation (vasculitis), skin nodules and eye diseases (reduced tear production or inflammation) may also occur.

The severity of disease, its clinical course and individual responses to treatment vary greatly. Symptoms of RA may develop within days or evolve over many weeks and months. 1 Several distinct patterns of joint disease are recognised, including predominantly small or medium joint disease; predominantly large joint disease; flitting or transient attacks of joint pain (palindromic rheumatism); pain and stiffness of the shoulder and pelvic girdles (polymyalgic disease); disease associated with weight loss and fever (systemic onset); or any combination of these. Pain and disability in early RA is linked to disease severity and to measures of psychological distress. 2 Disease progression can be relentless or punctuated by partial or complete remissions of variable and unpredictable intervals.

Diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is diagnosed from a constellation of clinical, laboratory and radiographic abnormalities. Diagnosis may be obvious or may need specialist assessment or a period of clinical observation. Internationally agreed classification criteria for RA are used widely in contemporary research studies,3 but it is widely acknowledged that current criteria need to be revised. Current criteria include morning stiffness in joints exceeding 1 hour, physician-observed arthritis of three or more areas, arthritis involving hand joints, symmetrical arthritis, rheumatoid skin nodules, a positive blood test for rheumatoid factor (RF) and radiographic changes typical of rheumatoid disease. Such criteria have limited utility in routine practice and most clinicians diagnose RA without reference to them, as many patients do not meet formal disease classification criteria early in their disease. 4

Epidemiology

Rheumatoid arthritis affects around 0.5%–1% of the population, three times as many women as men and at age of onset peaks between the ages of 40 years and 70 years. Prevalence of disease at 65 years of age is six times that at 25 years of age. Recent estimates from England and Wales show an annual incidence of 31 per 100,000 women and 13 per 100,000 men, suggesting a decline in recent decades, and a prevalence of 1.2% in women and 0.4% in men. 5 The National Audit Office (NAO) estimates that around 580,000 people have RA in England and that 26,000 patients are diagnosed each year. 6

Aetiology

A specific cause for RA has not been identified. There appear to be many contributing factors including genetic and environmental influences. Genetic influence is estimated at 50%–60%. 7 The risk of RA in both members of a pair of monozygotic twins is 12%–15% and a family history of RA gives an individual a risk ratio of 1.6 compared with the expected population rate. 8 Many of the genes associated with susceptibility to RA are concerned with immune regulation. For example, the human leucocyte antigen HLA-DRB1, which contributes the greatest risk, and PTPN22, which makes the second most important genetic contribution in Caucasian populations, are both involved in T-lymphocyte activation and signalling. 9,10

Infectious agents have been suspected but no consistent relationship with an infective agent has been shown. Sex hormones have also been suspected because of the higher prevalence of RA in women and a tendency for disease to improve in pregnancy. However, a precise relationship has not been identified. A causal link with lifestyle factors such as diet, occupation or smoking has not been shown.

Pathology

Synovial joints occur where the ends of two bones, covered with hyaline cartilage, meet in a region where free movement is desirable. This joint space is encapsulated by a fibrous capsule lined on the inside by a synovial membrane, which functions to secrete fluid to lubricate and nourish hyaline cartilage. In RA the synovial layer of affected joints becomes enlarged as a result of increased cellularity or hyperplasia, infiltration by white blood cells and formation of new blood vessels. This is accompanied by increased fluid in the joint cavity, which contains white blood cells and a high level of protein (an exudate), contributing to the joint swelling. Bony erosions of cartilage and bone occur where synovial tissue meets cartilage and bone. This occurs through the combined actions of synovial tissue (pannus) and resident cartilage and bone cells. Erosions and loss of cartilage are rarely reversible. Such damage, therefore, compromises the structure and function of a normal joint.

Pathogenesis and biological targets in rheumatoid arthritis

A detailed discussion of the pathogenesis of RA is beyond the scope of this report. This subject is reviewed comprehensively elsewhere. 11–13 The synovial membrane in RA contains activated immune cells such as B and T lymphocytes and macrophages. These cells accumulate in synovial tissue. Cells resident in normal joints including synovial fibroblasts, cartilage cells (chondrocytes) and bone cells (osteoclasts) are also activated. Different cytokines, or small proteins, are produced by particular resident and infiltrating cells and aid intercellular communication and influence cellular and tissue behaviour.

A number of cytokines involved in this inflammatory cascade are seen as potential targets for intervention in RA. Drugs that target cytokines and which are licensed or are at a late stage of development currently include anakinra (directed against interleukin-1), tocilizumab [(TOC, RoActemra®, Roche) targeting interleukin-6] and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors [including adalimumab (ADA, Humira®, Abbott Laboratories), certolizumab (Cimzia®, UCB), etanercept (ETN, Enbrel®, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), golimumab (Simponi®, Schering-Plough Ltd) and infliximab (IFX, Remicade®, Schering-Plough Ltd)]. Other agents include abatacept [(ABT, Orencia®, Bristol-Myers Squibb Ltd) also known as CTLA4Ig], which interferes with T-cell activation, and rituximab (RTX, Mabthera®, Roche), which depletes B lymphocytes. Many other potential targets have been identified and a number of novel agents are in clinical trials. 14

Management of rheumatoid arthritis

The current management of RA is described in detail in a recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline. 15 An exhaustive review of management is not provided here. We focus on aspects of disease management that are relevant to the decision problem in this appraisal.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesics are commonly used for symptom relief in RA. These drugs do not modify the disease process and key recommendations in NICE guidance centre on minimising the use of NSAIDs because of the potential toxicity of these agents. Corticosteroids are used widely and in a variety of ways. High doses given orally or parenterally (by a variety of routes) are used for the short-term control of disease while waiting for the effects of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Low-dose glucocorticoids are also commonly used either as sole therapy or in combination with DMARDs. Low-dose glucocorticoids have important disease-modifying effects in RA. 16

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs may be divided into conventional DMARDs, which include azathioprine (AZA), ciclosporin A (CyA), gold [GST (given by intra-muscular injection)], hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), leflunomide (LEF), methotrexate (MTX) and sulfasalazine,17–19 and newer targeted biological agents, described below. Conventional DMARDs such as penicillamine are now used rarely. 18 Conventional DMARDs may be used in combination, especially where there is a poor response to a single DMARD. For example, in early disease MTX is commonly combined with sulfasalazine and HCQ. There are few direct comparisons of individual DMARDs in early disease, but MTX is regarded as the standard against which other drugs should be compared. Most conventional DMARDs have specific dosing and monitoring schedules that require regular visits to a health-care facility and blood tests. How this is managed varies greatly in the UK; for example, in some centres all patients are seen in hospital clinics for drug monitoring whereas in others this occurs largely in the community.

The key objective in early RA management is to achieve remission. Many patients with early inflammatory arthritis (which often does not meet international classification criteria for RA) are able to achieve remission and treatment may be withdrawn in a proportion without relapse. 20 This occurs in randomised trials or therapeutic studies with conventional DMARDs21–24 used as monotherapy or in combination, conventional DMARDs combined with TNF inhibitors and also in observational studies. While these reports focus on the excellent outcomes achieved, it is important to recall that 57% of patients with early RA treated with a protocol designed to minimise disease do not achieve remission, around one-third do not achieve their treatment goal and between 31% and 54% of patients have progressive joint damage depending on the treatment strategy after 4 years of treatment. 25

The NICE RA guidance recommends the use of MTX combined with another DMARD and corticosteroids (used short term) for disease control in early, severe RA. Practice varies; however, and evidence for combining DMARDs is limited and controversial. 26–28 Not all rheumatologists accept the need for DMARD combinations. Some prefer to step up therapy by adding another DMARD to MTX if the disease is inadequately controlled and others choose to replace the first DMARD with a second drug. 29 A necessity for long-term use of multiple medications plainly requires an open dialogue and shared decision making between patients and health professions,30 especially where expert opinion differs.

In England and Wales patients who have failed to respond to (or tolerate) at least two DMARDs, including MTX at optimal doses, are eligible for TNF inhibitors subject to NICE guidance. Patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors may be treated with RTX, a monoclonal antibody that depletes B lymphocytes. Other biological therapies such as anakinra, ABT and TOC are not currently approved for use by NICE. The relevant NICE guidance concerned with biologic therapies is described briefly below (see Current service provision).

Controlling symptoms of joint pain and stiffness, minimising loss of function, improving quality of life (QoL) and reducing the risk of disability associated with joint damage and deformity are central objectives in the management of RA at all stages. These objectives are not met with drug therapy alone: patients often need advice and support from a multidisciplinary team including specialist nurses, podiatrists, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Since RA is a heterogeneous disease, which may vary over time, a long-term plan with regular clinical evaluation to assess disease status, disease complications, comorbidity, patient preferences and psychosocial factors is essential and is aided by well-informed and satisfied patients and carers. 31,32 Indeed a key element of a Scottish trial reporting excellent outcomes was frequent specialist review with a focus on tight disease control. 21

With advanced joint damage surgical intervention such as joint replacement arthroplasty, joint fusion or osteotomy may be necessary. Long-term observations show that around a quarter of patients with RA undergo a total joint arthroplasty. 33 It cannot, of course, be assumed that all such surgery is directly attributable to RA, especially as osteoarthritis is the most prevalent form of arthritis. Other surgical interventions such as removal of synovial tissues and rheumatoid nodules, peripheral nerve decompression (such as in carpal tunnel syndrome) or soft tissue procedures such as tendon release or repair may be necessary at any stage of disease.

Assessment of response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic therapies

ACR response criteria

Modern clinical trials rely on composite end points such as the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) definition of improvement and the Disease Activity Score (DAS). The ACR response requires an improvement in the counts of the number of tender and swollen joints (using designated joints) and at least three items from the following: observer evaluation of overall disease activity; patient evaluation of overall disease activity; patient evaluation of pain; a score of physical disability [such as the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ); see below]; and improvements in blood acute phase responses [e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP)].

Response is defined as ACR20, ACR50 or ACR70, where figures refer to the percentage improvement of these clinical measures. This creates a dichotomous outcome of responders and non-responders. Achieving an ACR20 response has been regarded as a low hurdle, but in clinical practice patients who achieve this hurdle often gain a worthwhile clinical response, especially in early RA. ACR response criteria are described in more detail in Appendix 1.

DAS response criteria

The DAS score is calculated using a formula that includes counts for tender and swollen joints, an evaluation by the patient of general health (on a scale of 0 to 100) and blood acute phase (usually a log of the ESR, but more recently using CRP). DAS response criteria are described in more detail in Appendix 1. Originally DAS was based on an assessment of 53 joints for tenderness and 44 joints for swelling. Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), based on an evaluation of 28 joints, is used widely in routine clinical practice, partly as a result of NICE guidance on use of TNF inhibitors. DAS28, like DAS, is a continuous scale with a theoretical range from 0 to 10. Thresholds have been suggested for the scale such that a score greater than 5.1 is regarded as indicating high disease activity, a score of less than 3.2 low disease activity and a score of less than 2.6 remission. 34,35 Achieving a DAS28 score of less than or equal to 3.2 and improving the score by greater than 1.2 is regarded to be a good response while achieving a score of less than or equal to 3.2 and improving by greater than 0.6 but less than 1.2 is regarded as a moderate response. Current NICE guidance for TNF inhibitors demands that patients should improve DAS28 by 1.2 in order to justify continuing treatment. It has been suggested that NICE guidance should be altered to allow patients who have attained a moderate response to continue treatment with a TNF inhibitor. 36

While DAS28 scores are a very valuable tool for assessing treatment responses in groups of patients, scores have important limitations when used for individual patient decisions. For example, DAS28 does not incorporate ankle and foot disease. Thus, a patient with disease localised here may not attain a sufficiently high score to be eligible for a TNF inhibitor. DAS28 also shows poor concordance with clinical judgement (based on a wide range of parameters). 37 In addition, the degree of measurement error in a test–retest reliability study indicates that the faith placed in DAS28 as the sole decision-making tool is misplaced. 38 For example, the smallest detectable difference which should be exceeded if a clinician is to be 95% confident that a change exceeds measurement variability was 1.32 for DAS28.

The Health Assessment Questionnaire

The HAQ is a family of questionnaires designed to assess functional capacity of patients. 39 The most widely used version of HAQ is the modified HAQ (MHAQ) score which comprises eight items such as an ability to dress, get in and out of bed, lift a cup, walk outdoors and wash. MHAQ is reported as an average score across the eight categories such that 0 indicates an ability to achieve tasks without difficulty and 3 reflects an inability to achieve tasks. Scores therefore range between 0 and 3 with an interval of 0.125. Low scores indicate better function. Care is needed in the interpretation of HAQ scores in published studies because there are several modifications to HAQ. The HAQ score is described in more detail in Appendix 1.

Radiographic measures

Radiographic outcomes are believed by many to be the most important outcome measure in RA. However, variation in joint inflammation has a more profound and immediate impact on disability compared with the slow and cumulative effect of radiographic damage on disability. 40 The most commonly used tools for assessing joint damage are the Sharp and Larsen methods and their modifications (see Appendix 1), which rely on evaluations of plain radiographs of hands and feet. Plain radiographs are rather insensitive to change but are cheap and widely available. A majority of patients show only mild or no progression on plain radiographs over periods of 1–2 years, highlighting one of their limitations in modern clinical trials. 41

Prognosis

The impact of RA on an individual can be viewed from a variety of perspectives including employment status, economic costs to the individual or society, QoL, physical disability, life expectancy and medical complications such as extra-articular disease and joint deformity, radiographic damage or the need for surgery. In general, persistent disease activity is associated with poorer outcomes, although in the first 5 years of disease physical function is especially labile. Greater physical disability at presentation is associated with greater disability later in disease. Other factors linked with poorer function include older age at presentation, the presence of rheumatoid nodules, female sex, psychological distress and degree of joint tenderness. 42 Continued employment is related to the type of work and other aspects of the workplace such as pace of work, physical environment, physical function, education and psychological status; work disability is not necessarily linked to measures of disease activity. 43,44 Radiographic damage in RA joints is also influenced by RF status, age, disease duration and extent of disease and perhaps genetic factors.

Life expectancy in RA is reduced and is related to age, disability, disease severity, comorbidity and RF status, in particular. 45–48 For example, a 50-year-old woman with RA is expected to live for 4 years less than a 50-year-old woman without RA. 49 Patients with RA have a significantly increased risk of ischaemic heart disease. Heart disease is the principal reason for an approximately 60% increased mortality risk in RA. 50 However, other factors such as infection associated with aspects such as comorbidity, including lung disease, extra-articular manifestations of disease, reduced white cell count and corticosteroid use, also contribute. 51,52

Burden of illness

Early in disease indirect costs exceed costs due to health-care utilisation and medication (direct costs) by twofold. 53 It is also clear that informal caregivers shoulder a considerable burden in terms of forgone paid employment, leisure activity and personal health. 54 Inevitably, in a disease characterised by chronic pain, discomfort and physical impairment, the burden on individuals and families is increased. Medication costs, especially in those treated with biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors, account for a majority of the direct costs of RA. 55 Some drug intervention studies have shown reduced work absence with aggressive treatment strategies,56 although only one-third of employed patients cease work because of disease and, unsurprisingly, manual workers are much more likely to stop work. 57 It is estimated that the total costs of RA to the UK economy is between £3.8 and £4.8 billion. 6

Current service provision

Services for patients with RA have been reviewed in detail in a recent report by the NAO. 6 Diagnosis and management of RA is led primarily by consultant rheumatologists employed by acute hospital trusts. People who may have RA often seek help late and may suffer owing to delayed treatment and referral. There are around 460 consultant rheumatologists in England, giving a ratio of 1 : 100,000 rheumatologists per head of population (the ratio in Wales is 1 : 106,000). Consultants are supported by specialist nurses and the NAO census identified 377 specialist rheumatology nurses in England. Considerable variations and deficiencies in service provision were identified by the NAO. Specific recommendations for improving services were made by the NAO in the following areas:

-

timely diagnosis and treatment

-

better integration between primary and secondary care services

-

improved holistic care including strategies to improve self-management and providing support for maintaining employment.

Description of the technologies

Five intervention technologies are considered in this report. Three are TNF inhibitors (ADA, ETN and IFX), and one each a T-cell costimulation modulator (ABT) and a selective CD20 B-cell depleting agent (RTX). The technologies are described below. Licensed indications and relevant NICE guidance are detailed in Table 1.

| Drug | Indications and population | Doses and routes of administration | Synopsis of relevant NICE guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABT | Moderate-to-severe RA – in combination with MTX. Patients with insufficient response to DMARDs including at least one TNF inhibitor | Intravenous infusion over 30 minutes. Dose according to weight, range 500–1,000 mg. Infusions at 0, 2 and 4 weeks followed by 4-weekly maintenance infusions indefinitely |

TA141 Not recommended |

| ADA | Moderate-to-severe RA – in combination with MTX (unless MTX inappropriate). Patients with insufficient response to DMARDs including MTX | Subcutaneous injection of 40 mg every other week indefinitely. Dose may be increased to 40 mg weekly if patients experience a decrease in their response (monotherapy) |

TA130 and TA36 (for ADA, ETN and IFX) DAS28 score of > 5.1 measured on at least two occasions, 1 month apart Previous trial of two DMARDs including MTX (unless contraindicated) necessary Normally used in combination with MTX – unless intolerant or inappropriate when monotherapy with ADA and ETN may be given Only continue after 6 months if DAS28 improves by > 1.2 Alternative TNF inhibitor may be considered if treatment is withdrawn due to an adverse effect before the initial 6-month assessment of efficacy Dose escalation above licensed starting dose is not recommended TA36 does not recommend the consecutive use of TNF inhibitors. This recommendation is not reproduced in the NICE RA guideline. TA130 does not report on consecutive use |

| ETN | Moderate-to-severe RA – monotherapy or in combination with MTX in those with an inadequate response to DMARDs. Patients with severe RA not previously treated with MTX may also be treated | Subcutaneous injection of 25 mg twice a week or 50 mg weekly given indefinitely | |

| IFX | Moderate-to-severe RA – in combination with MTX (unless contraindicated) in those with an inadequate response to DMARDs. Patients with severe RA not previously treated with MTX or other DMARDs may also be treated | Intravenous infusion over 2 hours at a dose of 3 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks followed by 8-weeky maintenance infusions indefinitely. If response lost or inadequate, stepwise increases in dose by 1.5 mg/kg every 8 weeks may given up to a maximum of 7.5 mg/kg. Alternatively, dosing at 3 mg/kg may be given as frequently as 4-weekly | |

| RTX | Severe RA in combination with MTX in patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to other DMARDs including one or more TNF inhibitor | Intravenous infusion given as a course of two infusions (1,000 mg each) 2 weeks apart. Further infusions may be given but a precise limit is not given. Repeat course of treatment must not be given within 16 weeks |

TA126 Use in combination with MTX in severe RA not responding to DMARDs including at least one TNF inhibitor Continue only if DAS28 improves by > 1.2 Repeat courses to be given no more frequently than every 6 months |

Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody, made from human peptide sequences, which neutralises the biological functions of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) by binding to TNF cell-surface receptors. ADA is licensed for use in RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn’s disease.

Etanercept

Etanercept is a combination protein consisting of the extracellular portion of two TNFα receptors (75-kDa TNF receptors) combined with a human fragment crystallisable (Fc) portion of the human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1). ETN inhibits TNFα activity by binding soluble and cell-bound TNFα with high affinity and by competing with natural TNFα receptors. ETN is licensed for use in RA, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Infliximab

Infliximab is a recombinant chimeric human–murine monoclonal antibody that binds soluble and membrane-bound TNFα thereby, inhibiting the functions of TNFα. IFX is licensed for use in RA, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis.

Other tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

Certolizumab pegol has been granted a marketing authorisation in the European Union (EU) for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RA. It is administered by subcutaneous injection. Certolizumab pegol was the subject of a separate NICE single technology appraisal (STA),58 with guidance published in February 2010. Golimumab is currently being assessed by the European Medicines Agency. A positive opinion has been given for the granting of marketing authorisation in RA. Golimumab has been referred to NICE, but the appraisal has been suspended because the manufacturer is not in a position to submit evidence to NICE.

Special precautions for use of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

TNFα is a key component of host defence against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), especially by forming granulomas and preventing dissemination of mycobacteria. 59,60 Inhibition of TNFα increases the risk of MTB and other granulomatous diseases, such as those due to Listeria monocytogenes (a bacterium associated with food-borne diseases) and Histoplasma capsulatum (a fungus which, in endemic areas, causes lung disease in people with a compromised immune system). Recommendations for screening patients for tuberculosis (TB) before treatment have been published. 61 In the UK this is done most commonly by taking a medical history focusing on TB and a pre-treatment chest radiograph. Some centres also perform a tuberculin skin test,62 although interpretation of such tests is complicated by the UK’s previous vaccination programme for TB prevention and also the fact that many patients with RA respond poorly to tuberculin (possibly because of current immunosuppressive therapy but also because of the disease). 63

Routine monitoring of blood tests is not necessary for patients taking TNF inhibitors, but is needed for concomitantly used DMARDs such as MTX. TNF inhibitors can induce anti-nuclear and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies in the blood of some patients treated with TNF inhibitors. These antibodies are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a potentially serious rheumatic disease. Cases of drug-induced SLE have been reported with TNF inhibitors, but are rare. 64

Other technologies

Rituximab

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody which binds the CD20 cell surface marker found on B lymphocytes and depletes these cells. CD20 occurs on normal and malignant B lymphocytes (as in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas). Normal plasma cells, an important component of host defence, and haematopoietic stem cells do not carry CD20. RTX is licensed for use in RA, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. A small number of cases of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy, a rare but usually fatal demyelinating brain disease, have been reported in RA patients following RTX treatment. 65

Abatacept

Abatacept is a fusion protein consisting of CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4) linked to a modified Fc portion of the human IgG1. ABT works by blocking activation of certain populations of T lymphocytes. ABT is currently licensed for use only in RA.

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab was the subject of a separate NICE STA,66 with guidance published in August 2010. This guidance is likely to have a key impact on the treatment pathways considered in this review. TOC is a humanised monoclonal antibody that inhibits the activity of the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). In the EU it is licensed for use only in moderate-to-severe RA patients who are intolerant, or have responded inadequately, to one or more DMARDs or TNF inhibitors. The drug is recommended for use in combination with MTX, but may be used alone in patients intolerant of MTX or for whom it is contraindicated. TOC is given by intravenous (i.v.) infusion over 1 hour once a month indefinitely.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, biologics, treatment sequences and combinations

Rheumatoid arthritis is characterised, in many patients, by an excellent initial response to a DMARD with subsequent loss of response with time. Most randomised trials are of a relatively short duration (typically less than 12 months) and do not study a treatment pathway. Trials of DMARDs sequences are increasingly common. 25,67,68 Remission is possible in early disease with MTX alone or in combination with other agents such as sulfasalazine, HCQ, CyA and TNF inhibitors. The optimal sequence is yet to be determined, and perhaps the choice of drug is not relevant, but the key to successful management appears to be regular patient review with a focus on optimal disease control.

The NICE RA guidance is consistent with this approach, although recent trials indicate that early use of MTX in combination with a TNF inhibitor provides better outcomes. 25,69 NICE recommends that TNF inhibitors are used only in those not responding to MTX and another DMARD. Delayed addition of a TNF inhibitor need not necessarily compromise medium-term outcomes23,25,69 and may be justified on health-economic grounds.

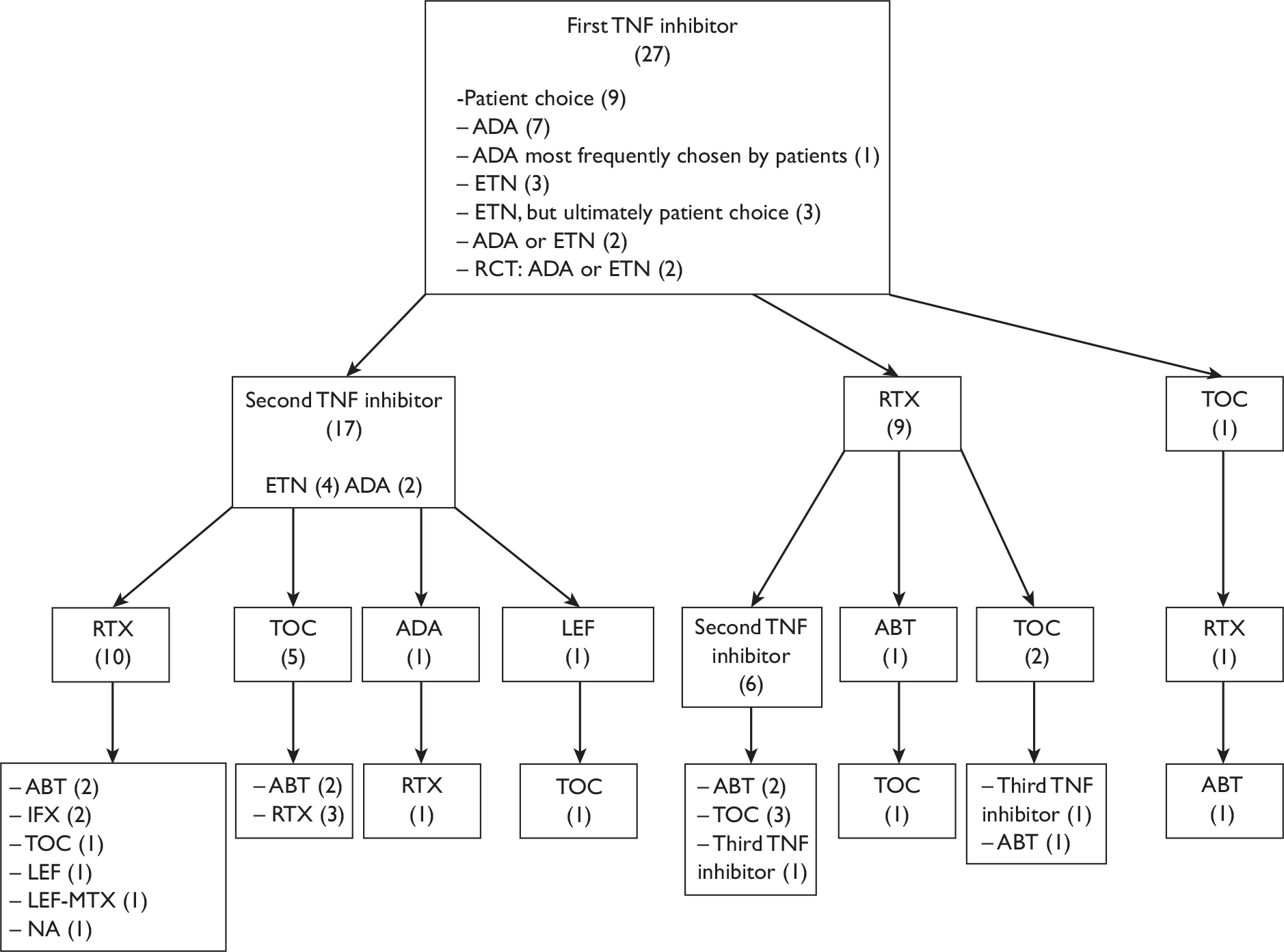

What steps should be taken when a first TNF inhibitor and several DMARDs including MTX fail? This technology assessment report sets out to examine clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence from available randomised controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies and economic evaluations. A small survey conducted as part of this technology assessment on a convenience sample of consultant rheumatologists in the West Midlands indicated considerable variability in approach for patients who fail a first TNF inhibitor. The most common suggested approaches were to consider a second TNF inhibitor or RTX (in combination with MTX). Further details of this survey can be found in Appendix 11.

There are many and increasing permutations of treatment sequences. Combinations of biologic agents are not licensed and where combinations have been tried there is an increased risk of serious infections. Potential drug toxicity of newly licensed agents is an important unknown. Other considerations include practical matters to do with drug delivery such as i.v. or subcutaneous administration and availability of infusion facilities. Patients with RA tend to be risk averse70 and strategies mandating targeted disease control in late ‘stable’ RA are commonly resisted by doctors and patients. 71 However, in those with active and progressive disease new therapies are needed. This review seeks to explore some aspects of these uncertainties as determined by a protocol agreed with NICE and interested parties.

Degree of diffusion and anticipated costs

The number of RA patients currently being treated with TNF inhibitors is unknown. By July 2009, 12,626 patients who started treatment with a TNFα inhibitor were registered with the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Registry (BSRBR). This register has stopped recruiting patients with RA starting ADA, ETN and IFX. So far 2,876 (23%) have ceased taking the first prescribed TNFα inhibitor and switched to a second TNFα inhibitor [1,881 switched owing to the lack of efficacy and 995 because of an an adverse event (AE)]. Of these the mean and maximum observed duration of treatment with a second TNFα are currently 18 months and 64 months, respectively. By August 2009 the BSRBR had registered 442 patients treated with RTX from a target of 1,100. 72

The drug costs of biologic agents are similar for the agents given by subcutaneous injection at around £9,000 per annum. Costs of i.v. administered drugs vary depending on patient weight and frequency of treatments courses (with RTX). Likely drug costs for these agents range between £7,000 and £10,000 per annum.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problems

According to the final scope issued by NICE for this technology appraisal, the decisions to be made are:

-

Decision problem 1: whether there are significant differences in clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness between ADA, ETN, IFX, RTX and ABT (referred to as ‘the interventions’ hereafter), when used within their licensed indications in adults with active RA who have had an inadequate response to a first TNF inhibitor prescribed according to current NICE guidance.

-

Decision problem 2: whether the interventions are clinically effective and cost-effective compared with previously untried conventional DMARDs (such as LEF and CyA).

-

Decision problem 3: whether the interventions are clinically effective and cost-effective compared with other biologic agents (including TOC, golimumab and certolizumab pegol).

-

Decision problem 4: whether the interventions are clinically effective and cost-effective compared with supportive care (including conventional DMARDs to which patients have had inadequate response).

-

Decision problem 5: whether the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the interventions differ significantly between certain subgroups of patients (see Definition of the interventions).

The assessment report set out to address these decision problems as they apply to potential patient pathways in the UK. The nature of evidence and the timelines for this technology appraisal constrain the focus of the assessment report to key clinically relevant questions.

Definition of the interventions

The interventions being considered are:

-

Adalimumab: a TNF inhibitor administered by subcutaneous injection and usually prescribed in combination with MTX, except in cases where MTX is not tolerated or is contraindicated.

-

Etanercept: a TNF inhibitor administered by subcutaneous injection in combination with MTX, except in cases where MTX is not tolerated or is contraindicated.

-

Infliximab: a TNF inhibitor administered by i.v. infusion in combination with MTX.

-

Rituximab: a monoclonal antibody directed at CD20+ B cells, administered by i.v. infusion in combination with MTX.

-

Abatacept: a T-cell costimulation modulator, administered by i.v. infusion in combination with MTX.

Population and relevant subgroups

The population being considered is adults with active RA who have had an inadequate response to a first TNF inhibitor.

Potentially relevant subgroups are numerous and include:

-

patients having had primary or secondary (had initial response, but subsequently lost the response over time) failure of response to the first TNF inhibitor or having withdrawn from the first TNF inhibitor mainly owing to adverse effects

-

subgroups defined by autoantibody status [e.g. presence or absence of RF and/or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies]

-

subgroups defined by different doses of the intervention (within licence)

-

patients with comorbidities for which some treatments may be contraindicated (e.g. heart failure).

The specific subgroups examined in the effectiveness review of this report were determined in light of available evidence and in consultation with clinical experts. Subgroups were not considered in the economic modelling as compelling evidence of differential effectiveness between subgroups was lacking from the effectiveness review.

Clarification of population of interest

The NICE guidance states that an alternative (second) TNF inhibitor may be considered for patients in whom treatment is withdrawn because of an AE before the initial 6-month assessment of efficacy. This group of patients (withdrawal because of an early AE) is strictly speaking outside the remit of this technology appraisal and should ideally be excluded from the technology assessment. However, in practice, the reason for the withdrawal of a TNF inhibitor may not be clear-cut as a decision to withdraw may be related to both efficacy and adverse effects (and the balance of risk and benefit for the patient).

Relevant comparators

Potential comparators include:

-

supportive care (including corticosteroids and ongoing or reinstated conventional DMARDs, such as MTX, sulfasalazine to which the patients have had inadequate response previously)

-

conventional DMARDs which have not been tried prior to trying a TNF inhibitor for example AZA, CyA and GST, either as monotherapy or combined with other DMARDs or corticosteroids

-

biologic agents including TOC, golimumab and certolizumab pegol

-

the interventions being considered compared with each other.

Clarification of comparators

The assessment report focuses on key clinically relevant questions, including, where data allow, comparing each of the interventions with supportive care and comparing each of the interventions against each other. This was based on the following considerations:

-

The majority of patients considered in this technology appraisal may have already had inadequate response to at least two conventional DMARDs, including MTX tried for an adequate length of time and at adequate doses, as indicated in the current NICE guidance. These DMARDs may still be continued in the comparator (and intervention) arm(s) of trials in patients who have responded inadequately to these options. In such cases continued use of these DMARDs was regarded as supportive care rather than as a credible alternative treatment option. Therefore, a clear distinction was made between conventional DMARDs depending on whether the patients had tried them before and if there was a history of inadequate response to the DMARD tried.

-

Only conventional DMARDs to which the patients have not had inadequate response or have not tried were to be regarded as separate comparators. The evidence for use of conventional DMARDs in patients who have failed to respond to TNF inhibitors was expected to be very limited.

-

Although conventional DMARDs which are continued and to which the patients had an inadequate response were regarded as supportive care, subgroup analysis was considered (where relevant and evidence permits) to assess whether the presence or absence of these (failed) DMARDs in the control and intervention groups influenced the estimated treatment effects of the interventions.

-

Tocilizumab, golimumab and certolizumab pegol were potentially relevant comparators. These drugs are not yet available in the UK, but all are (or are potentially) the subject of STAs by NICE. The inclusion of these three drugs in the final scope as comparators means that there were no formal submissions from their manufacturers for this technology appraisal. This may have had implications with regard to the acquisition of evidence for these comparators. It was proposed that TOC, golimumab and/or certolizumab pegol could have been reviewed in the assessment report as a comparator if marketing authorisation of the technology was obtained before the submission of the protocol for this assessment report. This condition was not met.

Relevant outcomes

Key outcomes considered appropriate to the decision problem were:

-

withdrawals (with reason)

-

treatment response (ACR)

-

disease activity (DAS)

-

physical function (HAQ)

-

joint damage/radiological progression

-

pain

-

fatigue

-

serious AEs (including death)

-

other AEs potentially associated with treatment

-

health-related QoL (HRQoL).

Key issues

Key issues have been mentioned, where relevant, earlier in this section and also in the background section of this report.

Further key issues predominantly concern the limited availability of evidence from controlled trials and the impact this has on the assessment of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of each of the interventions compared with the potential comparators (and the other interventions), and the ability to identify relevant subgroups in whom the technologies are more or less beneficial.

Place of the intervention in the treatment pathway(s)

Based on the final scope, the interventions are to be used when patients have had an inadequate response to a TNF inhibitor.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The overall aims and objectives were to address the decision questions outlined in section Decision problems. These aims were to be achieved by:

-

A systematic review of RCTs of the efficacy, tolerability and safety of ADA, ETN, IFX, RTX and ABT for the treatment of RA in adults who have had an inadequate response to a first TNF inhibitor.

-

As the volume of RCT evidence was expected to be relatively small, relevant non-randomised comparative studies and uncontrolled studies were also reviewed.

-

A systematic review of published studies on the cost and cost-effectiveness of the technologies in the treatment of RA in adults who have had an inadequate response to a first TNF inhibitor.

-

A review of economic evaluations included in any manufacturer’s submissions (MSs) for this appraisal.

-

A focused, model-based economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the technologies from the perspective of the UK NHS.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Search strategy

The following resources were searched for relevant studies:

-

Bibliographic databases: Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) 2009 Issue3, MEDLINE (Ovid) 1,950 to July week 1 2009, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid) 13 July 2009, EMBASE (Ovid) 1980–2009 week 28. Searches were based on index and text words that encompassed the condition, RA, and the interventions ADA, IFX, ETN, RTX and ABT.

-

Citations of included studies were examined.

-

Reference lists of identified systematic reviews were checked.

-

Further information was sought from contacts with experts.

-

Research registries of ongoing trials including the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database, Current Controlled Trials and Clinical Trials.gov using terms for the particular drugs.

-

Manufacturer submissions.

The searches were not limited by date of publication or language.

Search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

Study selection

All articles identified in the searches were imported into a reference manager database (reference manager v.11, Thomson ResearchSoft). Duplicate entries were allowed to be removed by the inbuilt feature in reference manager and removed when encountered by reviewers. Titles and abstracts were independently checked for relevance based on the population and intervention by two reviewers. If articles were considered relevant by at least one of the reviewers a full paper copy was ordered.

Full papers were assessed for relevance by two independent reviewers using an inclusion/exclusion checklist (see Appendix 6) based on the following criteria:

-

population: a majority of adults with active RA who have had an inadequate response to a TNF inhibitor

-

intervention: ADA, ETN, IFX, RTX, or ABT

-

outcomes: clinical outcomes related to efficacy, safety or tolerability

-

study design: primary study (except case reports) or a systematic review

-

study duration: at least 12 weeks

-

participant numbers: for non-randomised studies – at least 20 patients in one arm.

Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Conference abstracts were not sought. If they were identified as relevant in the first stage of study selection, an attempt was made to match them with journal publications. If this was not possible, contact with authors was not attempted owing to time constraints and they were not included in the analysis.

A list of excluded studies and the reason for exclusion were recorded (see Appendix 4).

Included systematic reviews were not themselves systematically reviewed, but were utilised to identify further primary studies.

Additional references identified from systematic reviews or industry submissions were entered into the reference manager database. The same process was applied to additional the references as to the references identified from initial searches.

Data extraction

Data were extracted into a standard form (see Appendix 8) for all included studies by one reviewer. A second reviewer checked the accuracy of the extracted information. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by referral to a third reviewer if necessary.

Information regarding study design and characteristics of study participants was extracted. Data on the following outcomes were sought from included studies:

-

treatment withdrawal (and reasons for withdrawal)

-

ACR20, ACR50, ACR70

-

disease activity (e.g. DAS28 or DAS)

-

physical function (e.g. HAQ)

-

joint damage/radiological progression (measured by a scoring system)

-

pain

-

fatigue

-

extra-articular manifestations of the disease

-

serious AEs (including death)

-

other adverse effects potentially associated with treatments

-

HRQoL.

Data for any outcomes other than those listed above were also extracted if they were considered relevant to this report.

Additional data from industry submissions were extracted by only one reviewer owing to time constraints.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and if necessary a third reviewer was consulted.

For randomised trials the following criteria were considered:

-

Randomisation: whether allocation was truly random. Randomisation using a computer or a random number table was considered adequate, whereas the use of alternation, case record numbers, or dates of birth and day of the week was considered inadequate.

-

Allocation concealment: whether allocation concealment was adequate. Any of the following methods was considered adequate: centralised (e.g. allocation by a central office unaware of subject characteristics) or pharmacy-controlled randomisation; pre-numbered or coded identical containers which are administered serially to participants; on-site computer system combined with allocations kept in a locked unreadable computer file that can be accessed only after the characteristics of an enrolled participant have been entered; or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes.

-

Blinding: use of blinding and who was blinded (patients, study investigators/outcome assessors, data analysts).

-

Patients withdrawn: what was the percentage of patients withdrawn from the study?

-

Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis: whether ITT analysis was used.

For non-randomised studies the following criteria were considered:

-

Study design: if the study was controlled or uncontrolled, prospective or retrospective.

-

Inclusion criteria: if inclusion criteria were clearly stated.

-

Consecutive patients: if consecutive patients were included in the study.

-

Patients withdrawn: what was the percentage of patients withdrawn from the study?

The results of quality assessments are reported in relevant sections of the report.

Data analysis/synthesis

Outcomes of interest

Selected outcomes of interest were specified in the review protocol, based upon the final scope issued by NICE for this technology appraisal. These were:

-

treatment withdrawal (and reasons for withdrawal)

-

ACR20, ACR50, ACR70

-

disease activity (e.g. DAS28 or DAS)

-

physical function (e.g. HAQ)

-

joint damage/radiological progression (measured by a valid scoring system)

-

pain

-

fatigue

-

extra-articular manifestations of the disease

-

serious AEs (including death)

-

other adverse effects potentially associated with treatment

-

HRQoL.

Handling of data and presentation of results

Comparisons with supportive care

Studies were considered to compare interventions with supportive care if they:

-

had an arm receiving supportive care

-

had a placebo arm.

Owing to the paucity of evidence from controlled studies of TNF inhibitors, evidence from uncontrolled studies (i.e. single-group before-and-after studies) is also considered in this section.

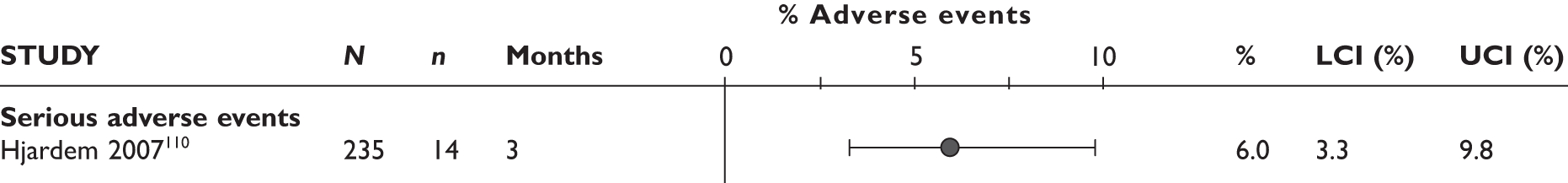

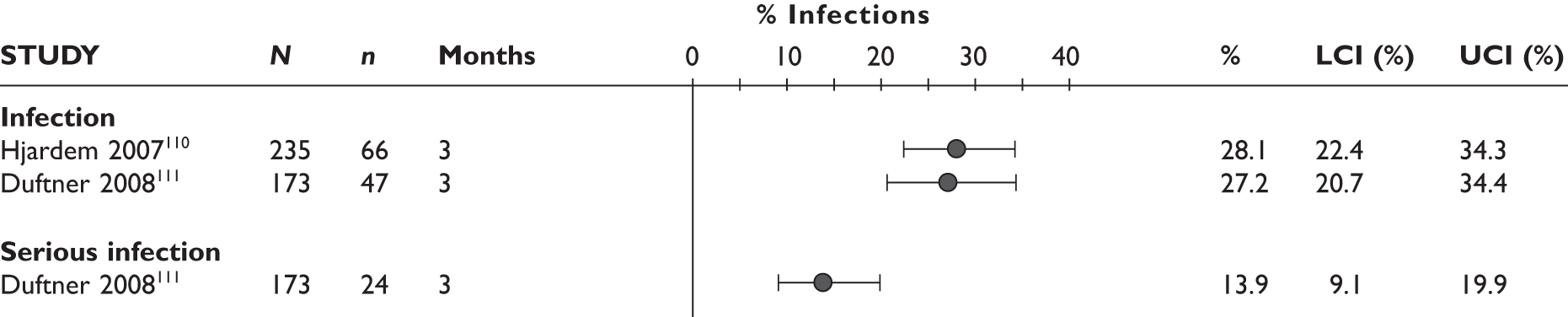

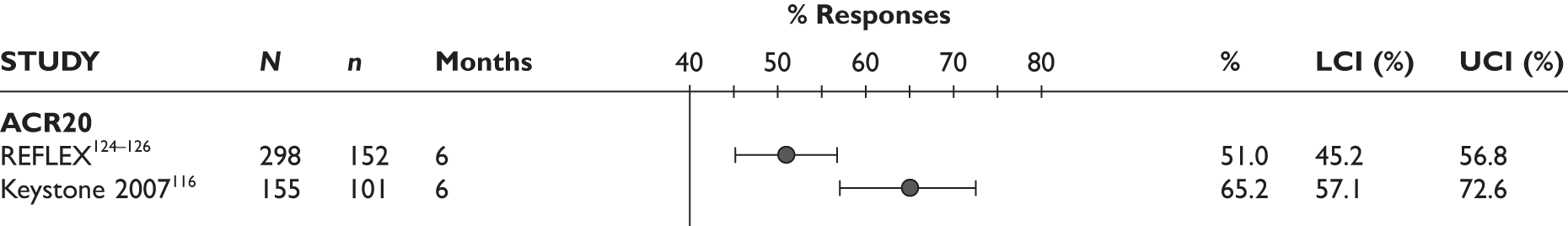

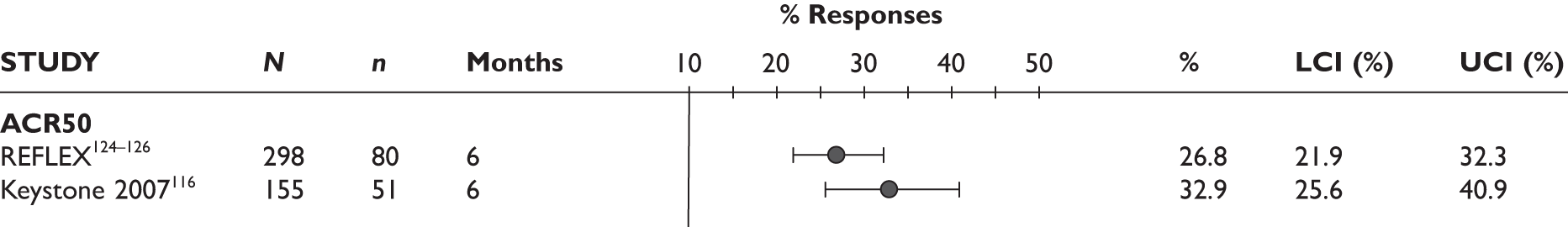

Studies were considered separately for each of the interventions. In addition, TNF inhibitors were discussed together as a class of drugs. Results were presented in figures and discussed in the main text of the report for the following outcomes:

-

withdrawals (for any reason, owing to the lack of efficacy and owing to AEs)

-

ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70

-

DAS

-

European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response

-

HAQ

-

QoL

-

joint damage

-

serious AEs

-

infections and serious infections

-

injection/infusion reaction.

For other outcomes only figures were created, and these can be found in Appendix 10.

Dichotomous measures data are presented as relative risks (RRs) (for RCTs) and percentages (for other study designs). For continuous outcomes, mean differences (for RCTs) and means (for other study designs) were used.

Where available, data were analysed for 3, 6, 9, 12, etc. months’ duration of follow-up. They were assumed to be 3-month data if they were collected between 3 and 4 months from the initiation of treatment, 6-month data if they were collected between 5 and 7 months from the initiation of treatment. If more than one estimate was available for a time interval, the value nearest to the assumed follow-up was used.

Pooling of results was not attempted for the assessment of effectiveness of individual technologies because the majority of included studies had no control group and there was substantial methodological and clinical heterogeneity between included studies. Given the relatively small number of patients that can be analysed in subgroup analyses, some pooling of data using a random-effects model was attempted. The results were presented with I2 statistics mainly for demonstrating consistency of findings between studies (see Subgroup analyses).

Comparisons with newly initiated and previously untried conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

No studies were identified and therefore analyses were not undertaken.

Comparisons with other biologic agents

No studies were identified and therefore analyses were not undertaken.

Comparisons between technologies (head-to-head comparisons)

No studies were identified and therefore direct comparisons were not undertaken.

Indirect comparison (IC) was undertaken when data were available from RCTs. It was conducted using the method by Bucher et al. 73 The results of the analyses were presented in tabular format.

Subgroup analyses

The following subgroups were specified in the review protocol:

-

patients having withdrawn from the first TNF inhibitor owing to the lack of response (primary failure), loss of response (secondary failure) or AEs/intolerance

-

subgroups defined by autoantibody status (e.g. presence or absence of RF or anti-CCP antibodies)

-

subgroups defined by different doses of the intervention (within licence)

-

patients with comorbidities for which some treatments may be contraindicated (e.g. heart failure).

No subgroup data concerning the last two categories (varied doses; comorbidities) were identified, and thus no subgroup analysis was performed for these. Subgroup analyses relating to the reasons of withdrawal from the first TNF inhibitor were carried out as two separate comparisons:

-

withdrawal owing to lack of response versus withdrawal due to loss of response

-

withdrawal owing to lack of efficacy (which includes both lack of response and loss of response) versus withdrawal due to AEs/intolerance.

In addition to the above, subgroup data in relation to the identity of the first TNF inhibitor which the patients received before discontinuation and the number of prior TNF inhibitor(s) that the patients had tried before switching were reported in some studies. These were considered potentially of clinical relevance and thus subgroup analyses on these were also performed where data were available [commercial-in-confidence information (or data) removed].

Ongoing studies

Ongoing primary studies were identified in the searches. They were not included in the systematic review, but discussed in Ongoing studies.

Assessment of publication bias

All manufacturers of the interventions provided a list of all company-sponsored RCTs and other non-randomised or uncontrolled studies that are relevant for this appraisal. Requests of clarification of trial data that are potentially available but not reported in published papers were also made to the manufacturers of RTX and ABT.

The number of relevant studies for individual technology was too small to allow a formal assessment of publication bias.

Sensitivity analyses

The protocol specified that if evidence permits sensitivity analyses may be carried out taking into account the following factors:

-

quality measures of studies such as blinding and randomisation

-

factors associated with the characteristics of the study population

-

factors associated with study design such as study duration and drug doses

-

exclusion of data supplied as commercial/academic in confidence.

However, sensitivity analyses were not performed as no pooling of study results was undertaken.

Changes to the original protocol

During the study selection process, several potentially relevant studies including mixed proportion of patients with or without prior treatment with a TNF inhibitor were identified. No criterion relating to inclusion or exclusion of these studies was specified in the original protocol. It was agreed by consensus within the project team that studies that included less than 50% of patients with RA who have failed a TNF inhibitor were excluded, unless results from these patients were described separately and the number of these patients was greater than or equal to 20.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Results: quantity and quality of research available

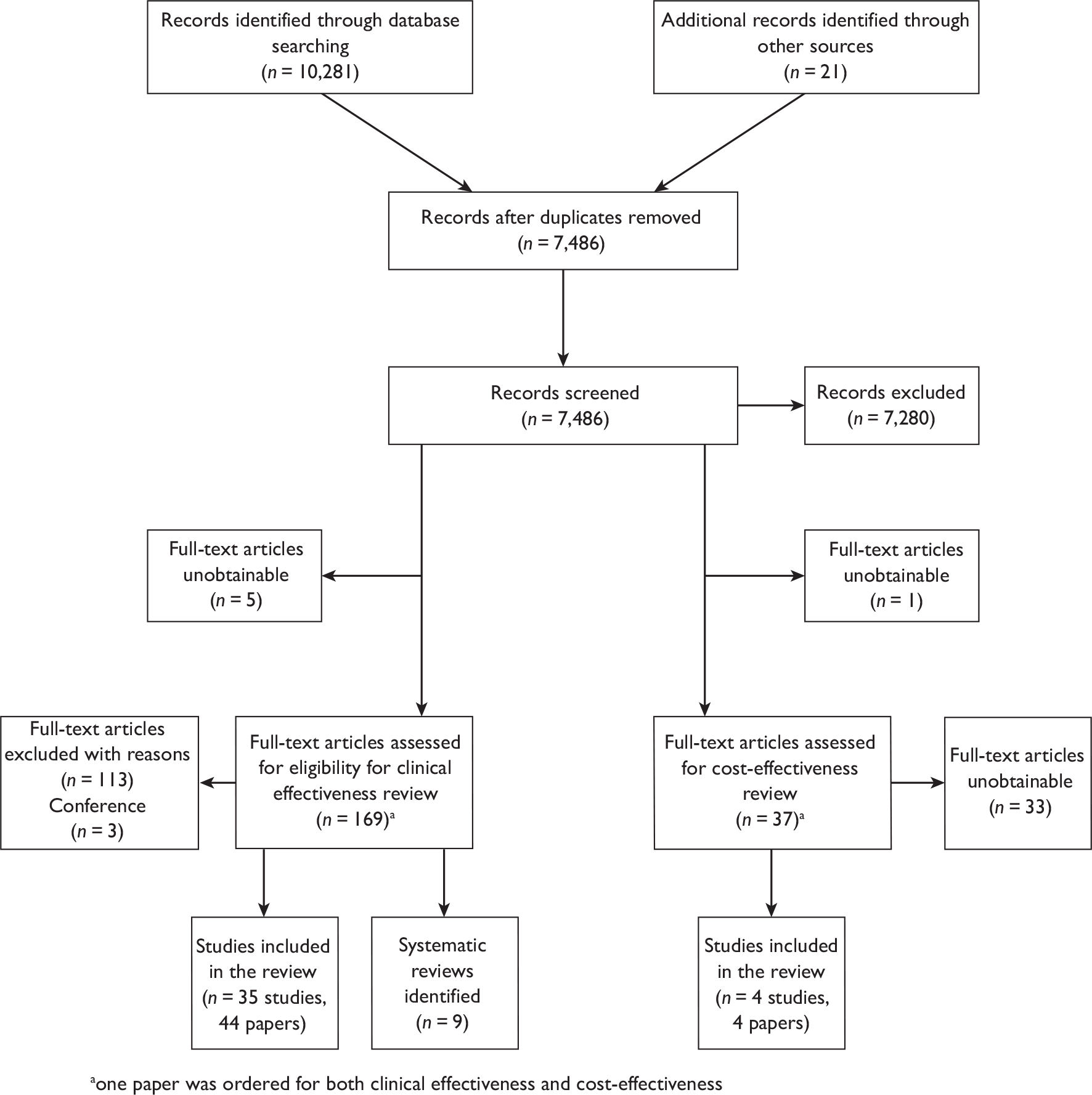

The searches resulted in the identification of 10,281 records and an additional 17 were identified from industry submissions and 15 from reference lists of included studies.

Nine relevant systematic reviews74–82 were identified in addition to the reports conducted for previous NICE appraisals in RA. Examination of these nine reviews did not identify any further primary studies that met all the criteria for inclusion in either the clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness sections of this report.

Duplicates had been removed, leaving 7,486 records. Screening of the title and abstract of these articles indicated that 174 were directly relevant to the clinical effectiveness section of this report. Full paper copies of these articles were ordered. Five of them were unobtainable. 83–87 Inclusion criteria were applied to the remaining 169 articles. Of these, 113 were excluded for not meeting at least one of the inclusion criteria. Three articles were identified as conference abstracts88–90 and, as these could not be matched to full publications, they were excluded. Details of excluded studies together with reasons for exclusion can be found in Appendix 4.

A flow diagram presenting the process of identification of relevant studies can be found in Appendix 3.

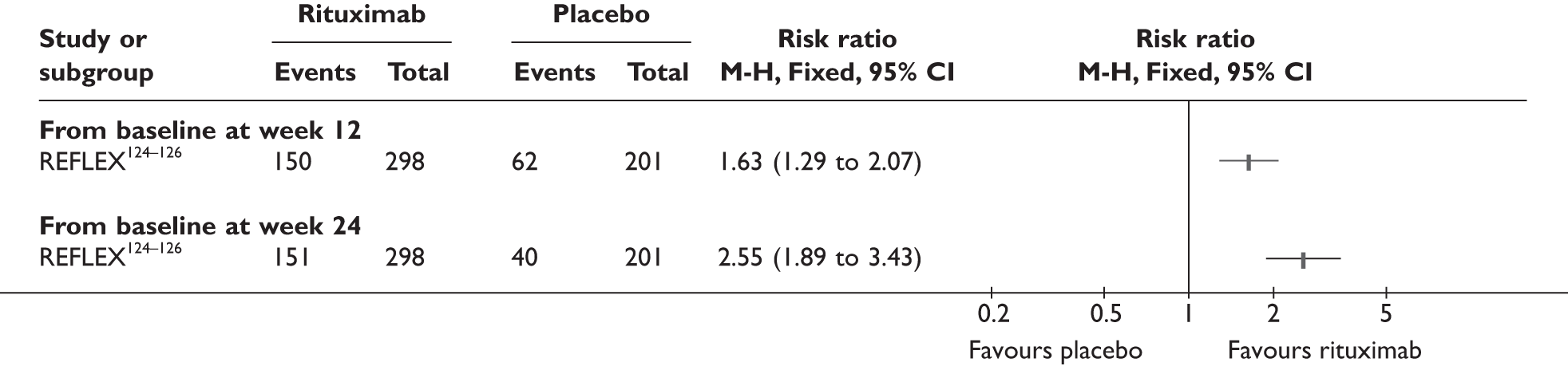

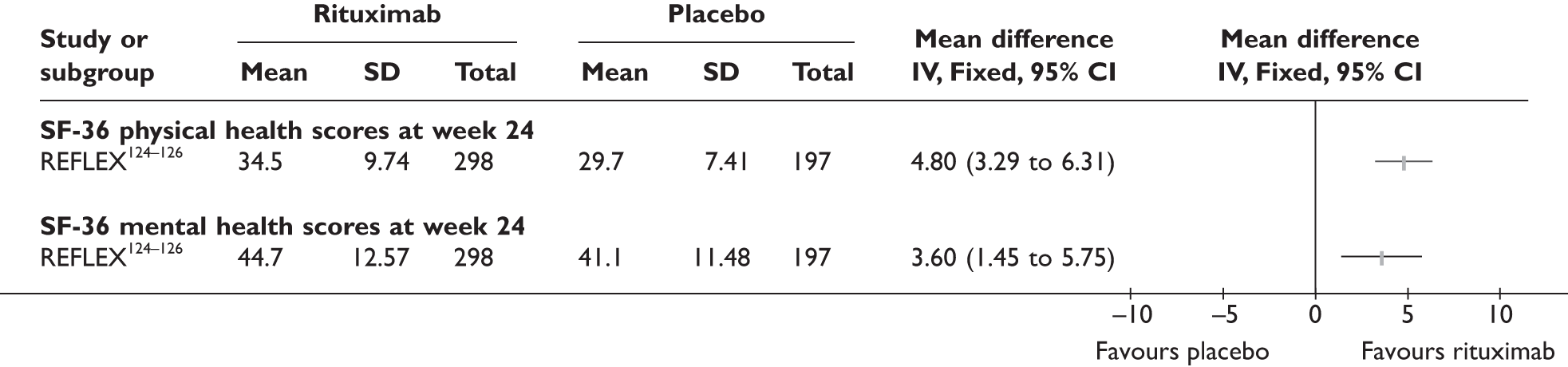

There were 35 studies described in 45 papers meeting the inclusion criteria. Five of the studies were RCTs, one was a comparative study, one was a non-randomised controlled study and 28 were uncontrolled studies [including one long-term extension (LTE) of an RCT].

A randomised study on RTX [study for understanding rituximab safety and efficacy (SUNRISE)91] that was not yet published in full was identified. Data from this study were requested from the manufacturer; however, the clinical study report was received too late to be included in the analyses.

Table 2 presents mapping of studies to relevant interventions and comparators.

| Comparators | Interventions (newly initiated) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADA | ETN | IFX | TNF inhibitors | RTX | ABT | |

| Nonea |

Bennett 200592 (n = 26, 52 weeks) Wick 200593 (n = 27, 24 weeks) Nikas 200694 (n = 24, 52 weeks) Bombardieri 200795,96 (n = 899, 12 weeks) van der Bijl 200897 (n = 41, 16 weeks) |

Haraoui 200498 (n = 25, 12 weeks) Buch 200599 (n = 207, 12 weeks) Cohen 2005100 (n = 24, 13 weeks) Buch 2007101 (n = 95, 12 weeks) Iannone 2007102 (n = 37, 24 weeks) Laas 2008103 (n = 49, >36 weeks) Bingham 2009104 (n = 201, 16 weeks) |

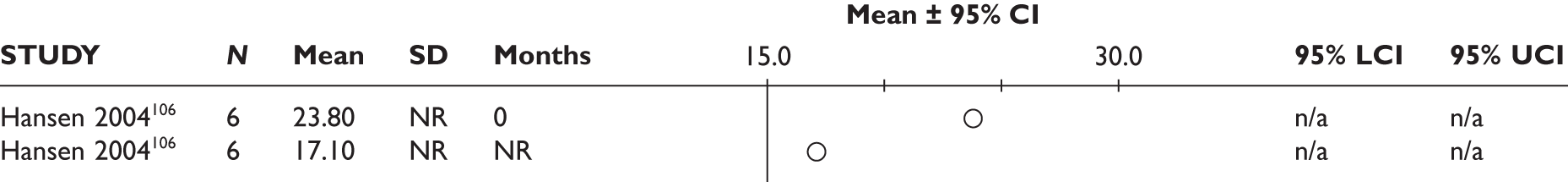

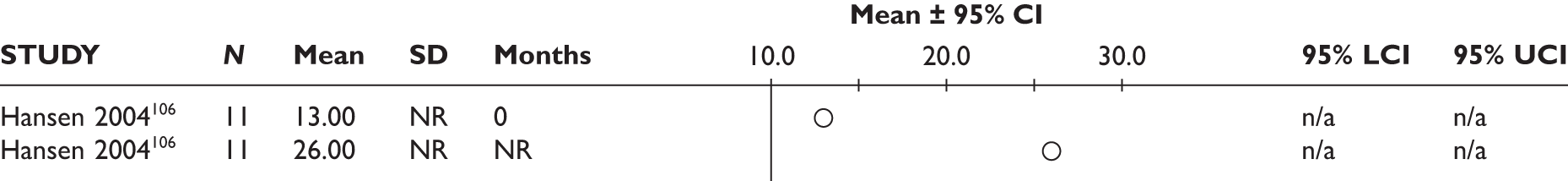

Ang 2003105 (n = 24, unclear) Hansen 2004106 (n = 20, unclear) Yazici 2004107 (n = 21, unclear) |

Gomez-Reino 2006108 (n = 488, 104 weeks) Solau-Gervais 2006109 (n = 70, > 13 weeks) Hjardem 2007110 (n = 235, 13 weeks) Duftner 2008111 (n = 109, up to 208 weeks) Karlsson 2008112 (n = 337, 13 weeks) Blom 2009113 (n = 197, 48 weeks) |

Bokarewa 2007114 (n = 48, 52 weeks) Jois 2007115 (n = 20, 26 weeks)b Keystone 2007116 (n = 158, 24 weeks) Assous 2008117 (n = 50, 26 weeks) Thurlings 2008118 (n = 30, 24 weeks) |

ATTAIN LTE119 (n = 317, < 260 weeks) ARRIVE120 (n = 1,046, 24 weeks) |

| Supportive carec | Hyrich 2009121–123 (n = 736, > 24 weeks) |

REFLEX124–126 (n = 517, 48 weeks) SUNRISE91 (n = 559, > 48 weeks) |

ATTAIN127–132 (n = 391, 26 weeks) | |||

| Ongoing biologicsd | OPPOSITE133 (n = 27, 16 weeks) |

Weinblatt 2007134 (n = 121, 52 weeks) ASSURE135 (n = 167, 52 weeks) |

||||

| Newly initiated DMARD | ||||||

| ADA | ||||||

| ETN | ||||||

| IFX | ||||||

| TNF inhibitors | ||||||

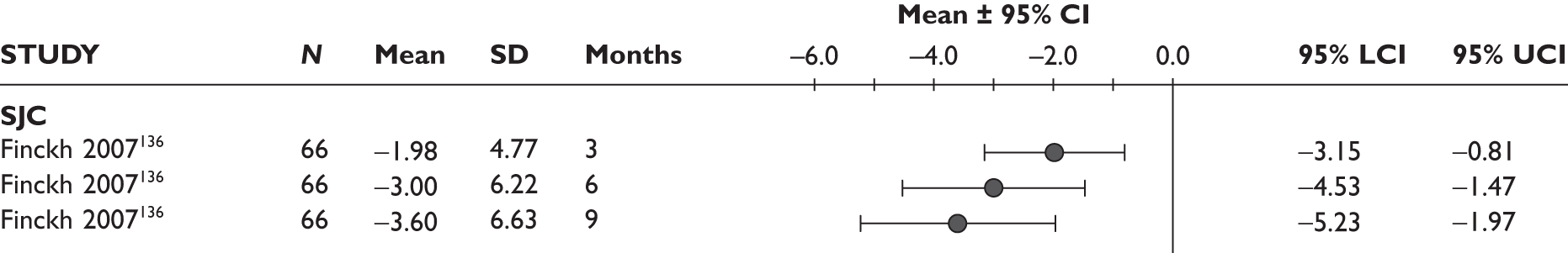

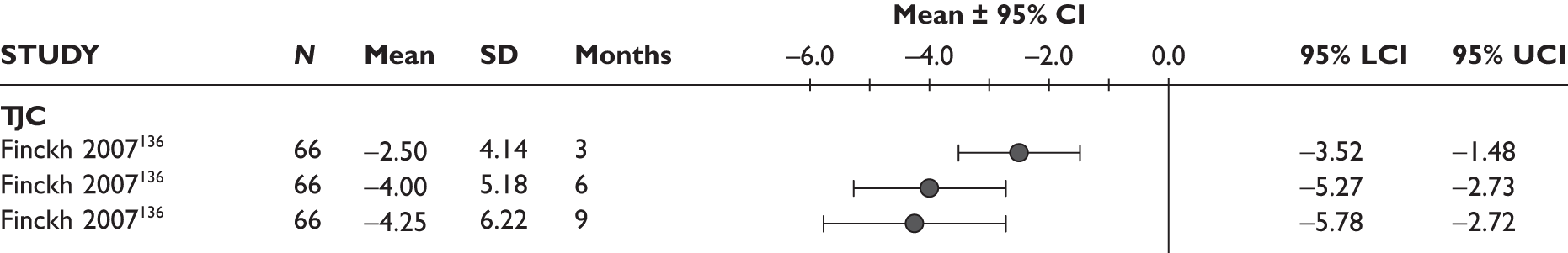

| RTX | Finckh 2009136,137 (n = 318, > 44 weeks) | |||||

| ABT | ||||||

| TOC | ||||||

| Golimumab | ||||||

| Certolizumab pegol | ||||||

The assessment of effectiveness of the technologies is reported below in six sections, one for each of the technologies and one for TNF inhibitors as a class (see Effectiveness of the technologies compared with supportive care). Studies directly comparing the technologies and ICs are reported in Evidence from comparative studies and Indirect comparisons sections respectively.

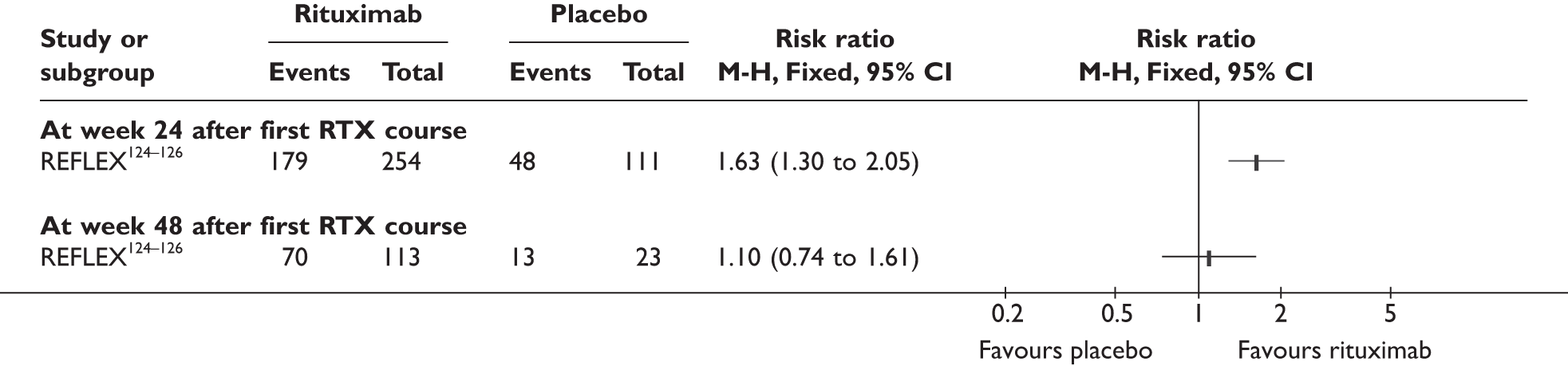

Effectiveness of the technologies compared with supportive care

This section describes evidence relating to each of the technologies compared with supportive care, which includes treatments received by the placebo group in placebo-controlled trials and ongoing conventional DMARDs or biologics to which the patients had had inadequate response. Owing to the paucity of evidence from controlled studies for TNF inhibitors, evidence from uncontrolled studies (i.e. single-group before-and-after studies) is also considered in this section.

Adalimumab

Overview of evidence

Five studies in six publications92–97 met the inclusion criteria. No RCT was found. Four studies had comparator arms in which the patients were TNF inhibitor naive. 92–94,96 These arms were excluded here. One of the four studies93 also had a small comparator arm of nine patients, which did not meet the inclusion criteria of this report of greater than or equal to 20 patients for an arm to be included; thus, data from this arm were excluded.

One multicentre study was conducted in 12 countries, 11 of which were European, including the UK. Other studies were conducted in the UK, Sweden and Greece. It was unclear in which country one of the studies was conducted.

Sample sizes were small, ranging from 24 to 41 patients, that are relevant to the review in four studies; in one study there were 899 patients. Patients included all had previous treatment with either one or two TNF inhibitors, most frequently IFX. Reasons for switching TNF inhibitors were lack of efficacy only in one study,93 lack of efficacy or intolerance in two studies96,97 and lack of efficacy or AEs in two studies. 92,94 Details on ADA treatment were not reported in one study; in all the other studies ADA was given 40 mg subcutaneously every other week. Study duration ranged from 12 weeks to over 1 year. Further details are outlined in Table 3.

| Study | Country | Design | Reason for switching (n) | Prior TNF inhibitors (n) | Treatment arms (no. of patients) | Duration of follow-up | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett 200592 | UK | Uncontrolled prospective | Primary (8) and secondary (13) failure, AEs, other | IFX, ETN, anakinra (1) | ADA, (26) | > 52 weeks | Primary and secondary failures – all IFX |

| Wick 200593 | Sweden | Uncontrolled retrospective | Secondary failure | IFX (1) | ADA, (27) | 3, 6 months | |

| Nikas 200694 | Greece | Uncontrolled prospective | Lack of efficacy, AEs | IFX (1) | ADA, (24) | 12 months | Possibly one or two active TB patients (outside study inclusion criteria) |

| Bombardieri 2007 (ReAct)95,96 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, UK | Uncontrolled prospective | Primary and secondary failure, intolerance | IFX, ETN, or both (≥ 1) | ADA, (899) | 12 weeks | |

| van der Bijl 200897 | Unclear | Uncontrolled prospective | Primary and secondary failure, intolerance | IFX (1) | ADA, (41) | 16 weeks (follow-up to 56 weeks; treatment for and efficacy measured at 16 weeks) | Pre-existing antirheumatic therapy (in about 12 patients) was continued and remained stable until week 16 |

Patient characteristics

Data on patient characteristics can be found in Table 4. Characteristics of the patients included in the five studies varied in some aspects:

| Study | Number of patients/% female | Age (years), mean (SD) | RA duration (years), mean (SD) | RF positive (%) | % of patients on concomitant DMARDs and steroids | Number of previous DMARDs, mean (SD) | Number of previous TNF inhibitors, mean (SD) | HAQ, mean (SD) | DAS28, mean (SD) | TJC/SJC, mean (SD) | ESR (mm/hour), mean (SD) | CRP (mg/dl), mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett 200592,a | 26/87 | 54 (range 19–77) | NR | NR | MTX (37); LEF (3); HCQ (3); AZA (1). All above with or without low-dose prednisone | 3.4 (range 2–7) | 1 (IFX, ETN, anakinra) | 2.07 (NR) | 6.3 (NR) | NR | NR | NR |

| Wick 200593 | 27/84b | 50 (15) | NR | NR | MTX (85); steroids (NR) | 2.0 (NR) | 1 (all IFX) | 1.39 (0.52)c | 5.5 (1.6)c | Tender 8 (5)c; swollen 10 (5)c | 41.7 (27.5)c | 43.9 (45.2)c |

| Nikas 200694 | 24/92 | 57 (11) | 16.6 (7.0) | 63 | MTX (83); CyA (4); LEF (13); steroids (100) | NR | 1 (all IFX) | NR | 5.6 (0.8) | Given graphically only | Given graphically only | Given graphically only |

| Bombardieri 200795,96 | 899/81 | 53 (13) | 12.0 (8.0) | 72 | DMARDs (31), steroids (77) | 5.0 (1.9) | ≥ 1 (IFX and/or ETN) | 1.85 (0.66) | 6.3 (1.1) | Tender 15 (7); swollen 11 (6) | NR | NR |

| van der Bijl 200897 | 41/88 | 55 (NR) | 11.6 (7.4) | NR | One DMARD (66); steroids (NR) | NR | 1 (all IFX) | 1.85 (0.49) | 6.1 (0.9) | Tender 6 (1); swollen 8 (5) | NR | 25.1 (32.0) |

-

Where reported 81%–92% were female.

-

The mean age of the patients ranged from 50 to 57 years.

-

The mean RA duration ranged from 11.6 to 16.6 years, but was not reported in two studies.

-

The percentage of RF-positive patients was reported only in two studies (63% and 72%).

-

Concomitant DMARDs: where reported 37%–85% patients were on MTX other DMARDs included CyA (4%), leflunonide (3%–13%), HCQ (3%) and AZA (1%).

-

The percentage of patients on concurrent steroids was reported in two studies and ranged from 77% to 100%.

-

Where reported the mean number of previous DMARDs used ranged from 2 to 5.

-

The mean number of previous TNF inhibitors was greater than or equal to 1 in the biggest study, and it was exactly 1 in all the other studies.

-

The HAQ scores ranged from 1.29 to 2.07 in four studies, but were not reported in one study.

-

The mean DAS28 scores were very similar, ranging from 5.5 to 6.3.

-

The mean number of tender and swollen joints at baseline was reported in three studies and ranged from 6 to 15 and from 8 to 11, respectively.

-

Baseline ESR was reported in only one study (41.7 mm/hour) and CRP in only two studies (25.1 mg/dl and 43.9 mg/dl).

Quality assessment

The studies were all uncontrolled; four of them were prospective and one was retrospective. 93 Criteria for patient inclusion were clearly stated in four studies; however, in three of these it was unclear whether consecutive patients were included. The highest percentage of patients withdrawn from a study was 26.8%. There were no withdrawals from the retrospective study. In general, the higher withdrawal rates occurred with the longer follow-up durations. Further details on the quality assessment of the studies are given in Table 5.

| Study | Study design | Inclusion criteria clearly defined? | Were consecutive patients included in the study? | Patients withdrew (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett 200592 | Prospective uncontrolled | Yes | Yes | NRa | |

| Wick 200593 | Retrospective uncontrolled | No | NA | 0 | |

| Nikas 200694 | Prospective uncontrolled | Yes | Unclear | 16.7 | |

| Bombardieri 200795,96 | Multicentre, uncontrolled open-label | Yes | Unclear | 9.9 | |

| van der Bijl 200897 | Pilot uncontrolled open-label prospective | Yes | Unclear | 26.8 |

Results

Tables 6 and 7 show what outcomes were measured in each study. Outcomes in Table 6 are reported and discussed in the main text of this report and those in Table 7 are reported in Appendix 10 only.

| Study | Total withdrawal | Withdrawal by reason | ACR (20/50/70) | DAS28 | EULAR response | HAQ | QoL | Joint damage | Serious AEs | Infection/serious infection | Injection/infusion reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett 200592 | ✓ | ✓ time range | ✓ time range | ||||||||

| Wick 200593 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Nikas 200694 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bombardieri 200795,96 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| van der Bijl 200897 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Study | Other measures of disease activity | Fatigue | Pain | TJC/SJC | CRP/ESR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett 200592 | |||||

| Wick 200593 | |||||

| Nikas 200694 | ✓a | ✓a | ✓a | ||

| Bombardieri 200795,96 | ✓ | ||||

| van der Bijl 200897 | ✓ |

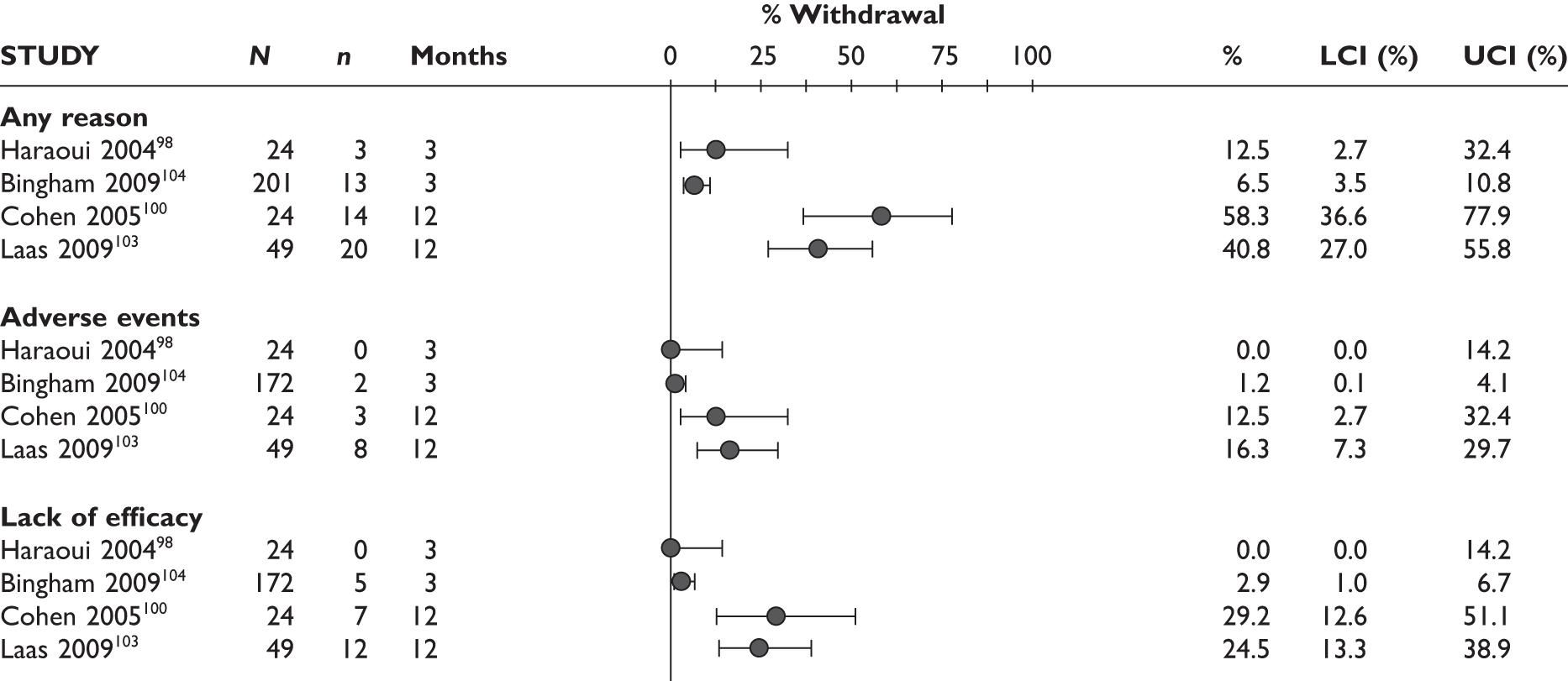

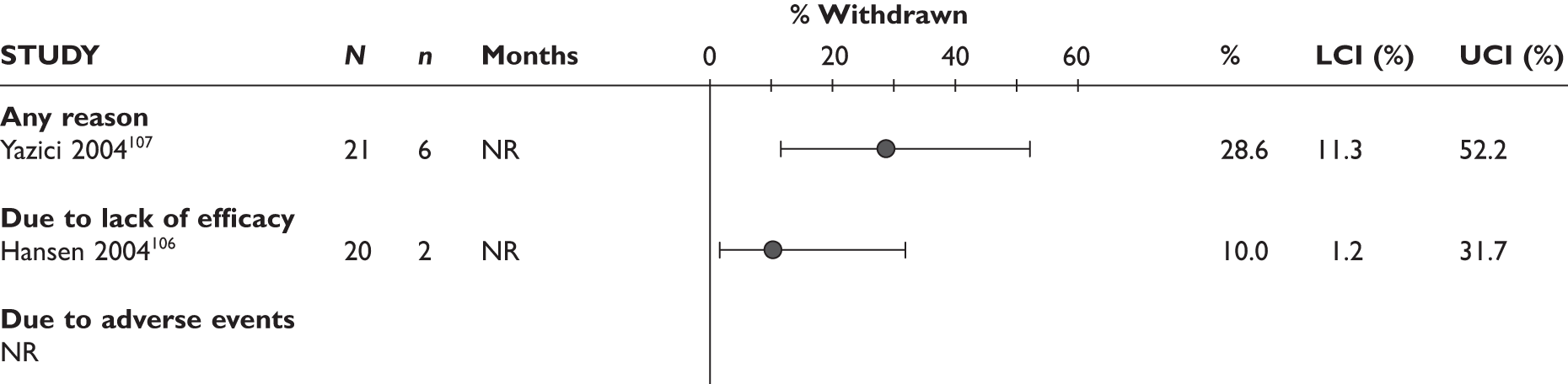

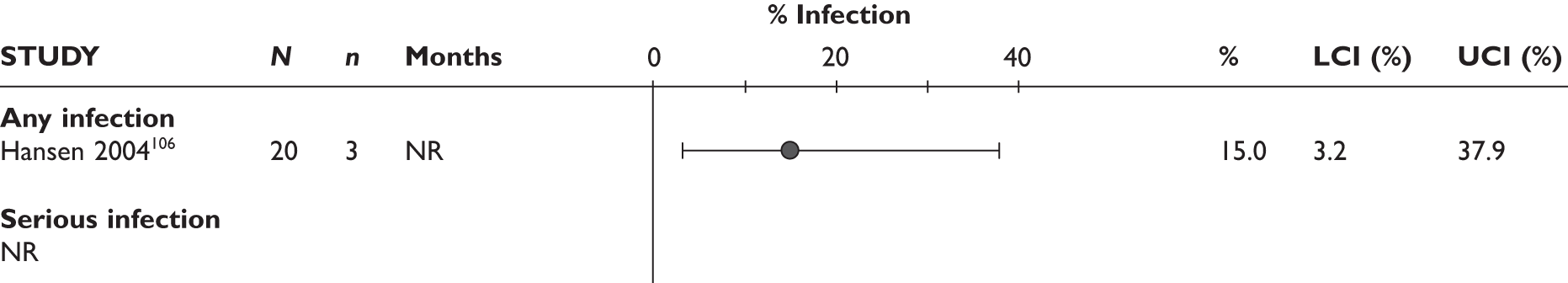

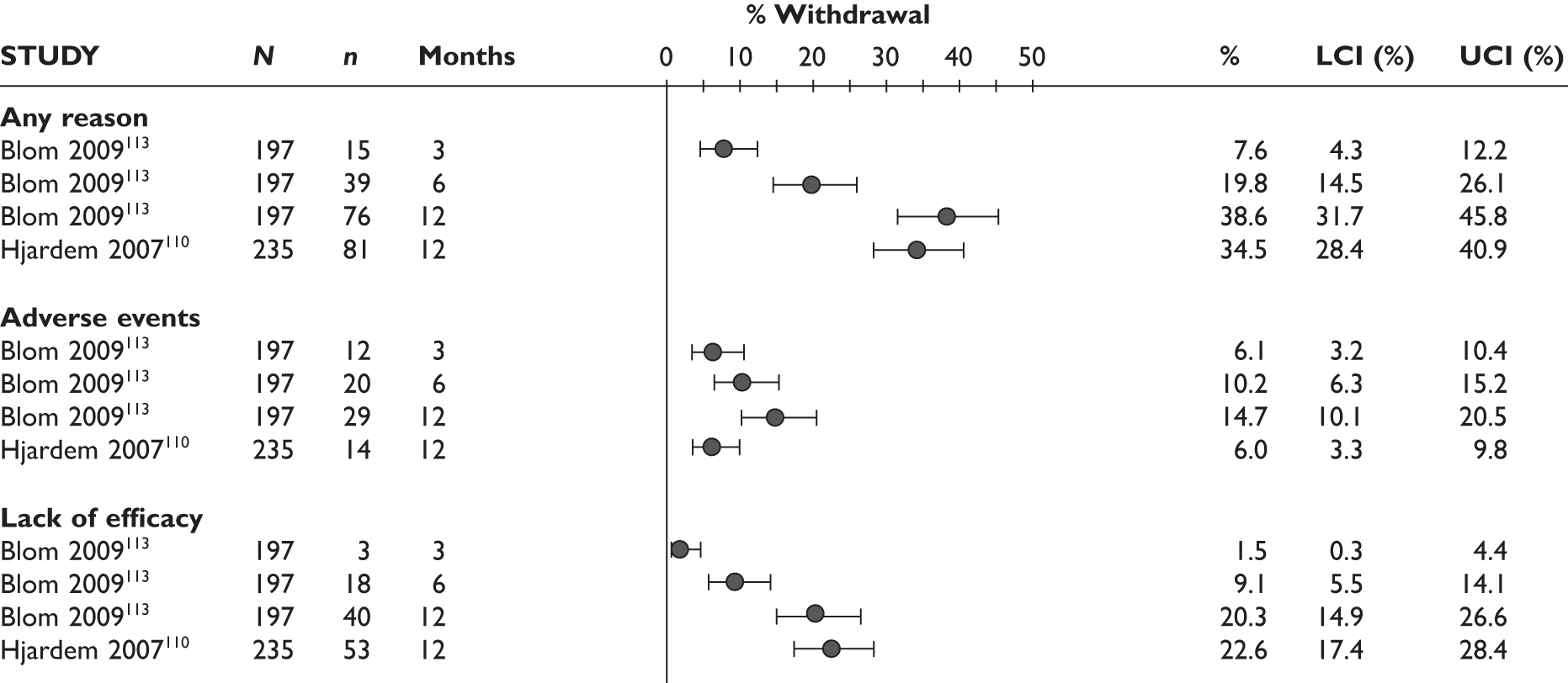

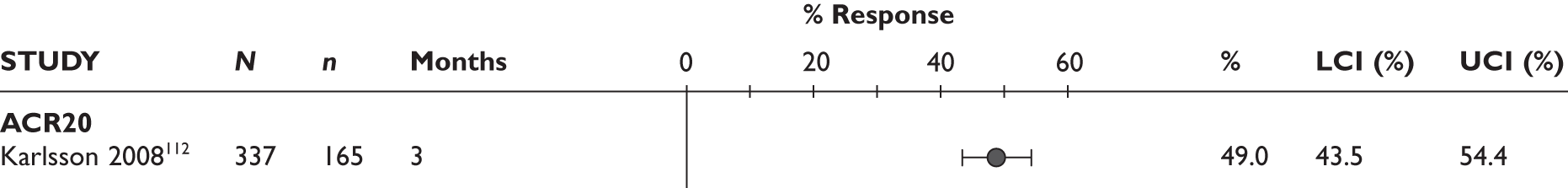

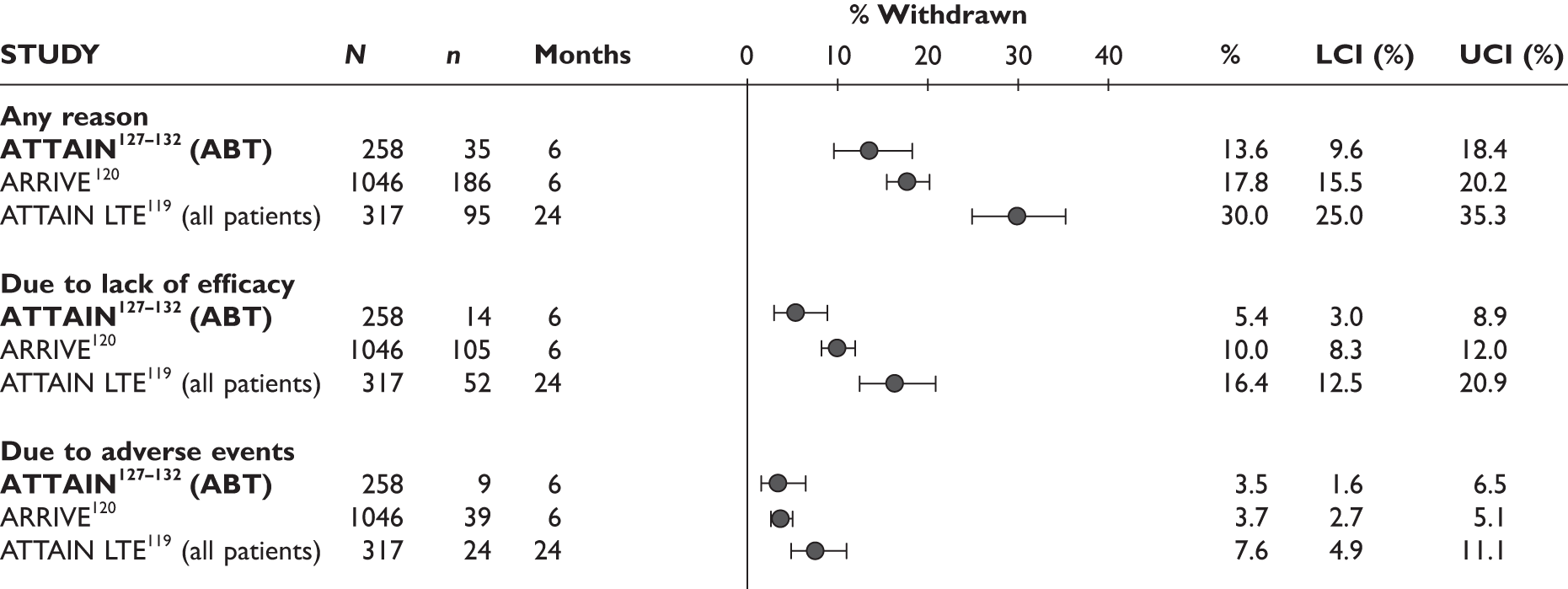

Withdrawals

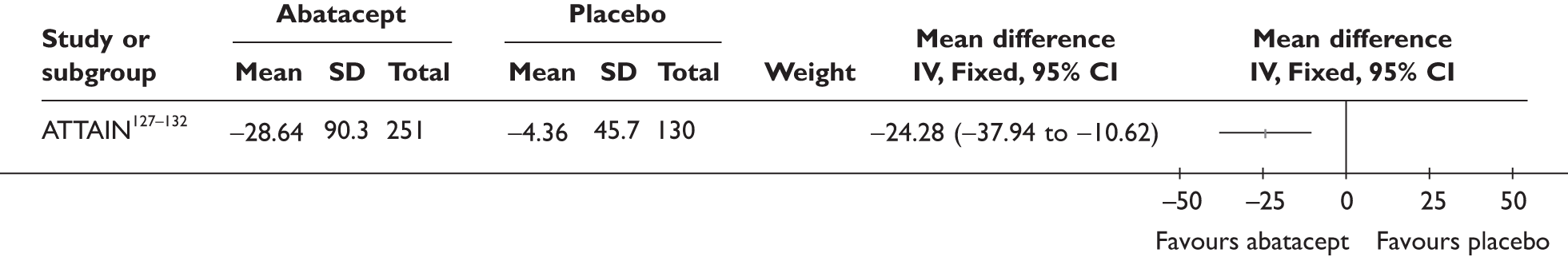

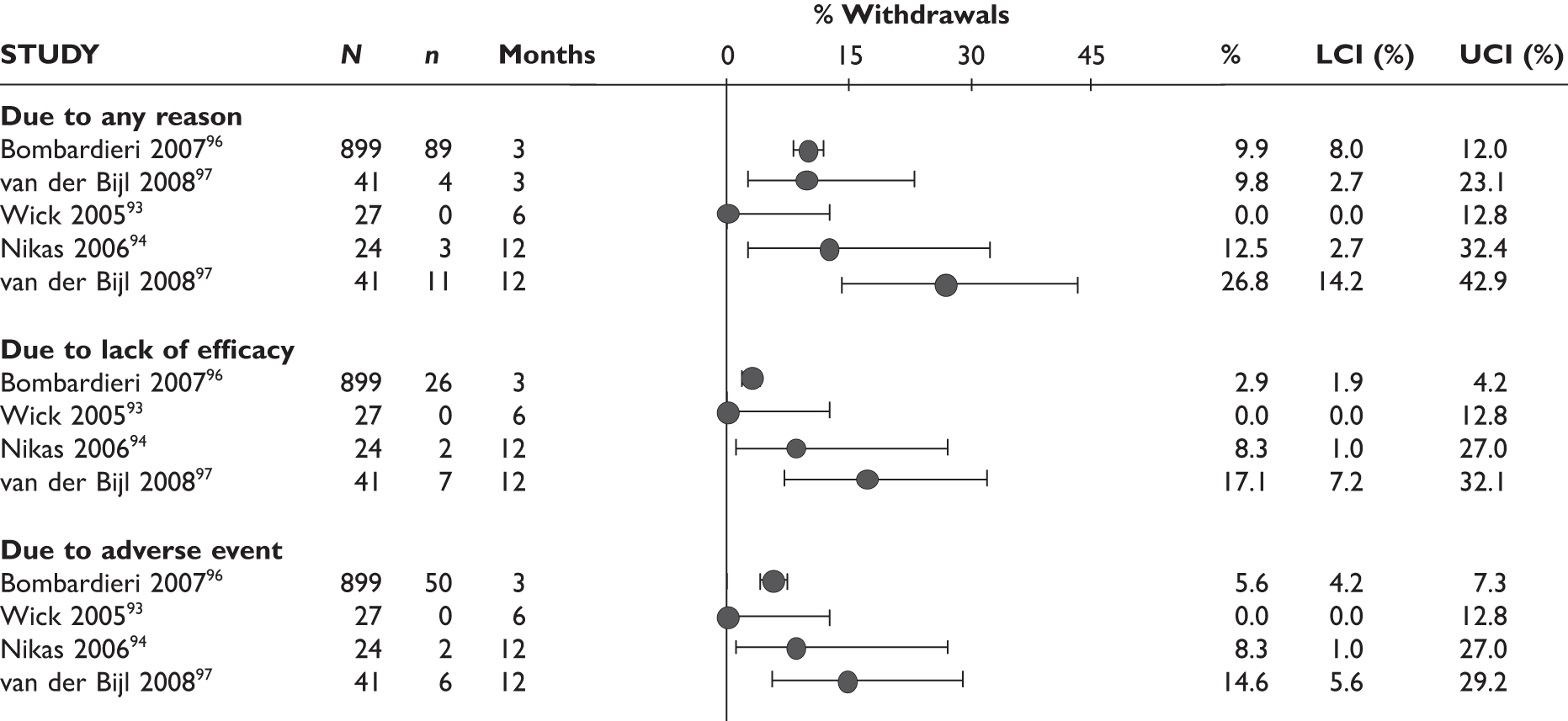

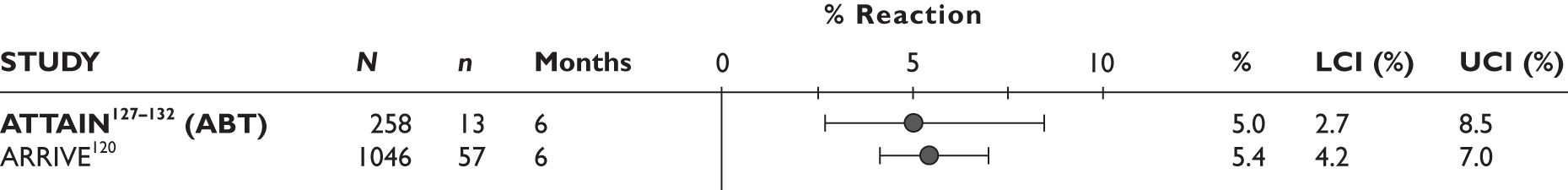

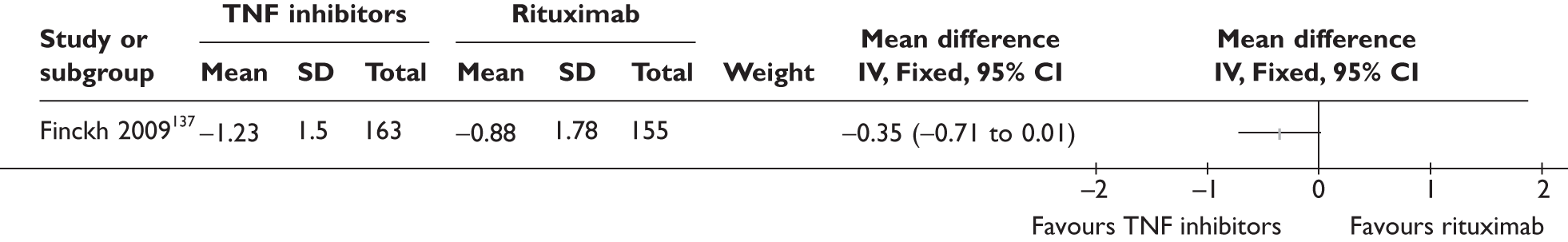

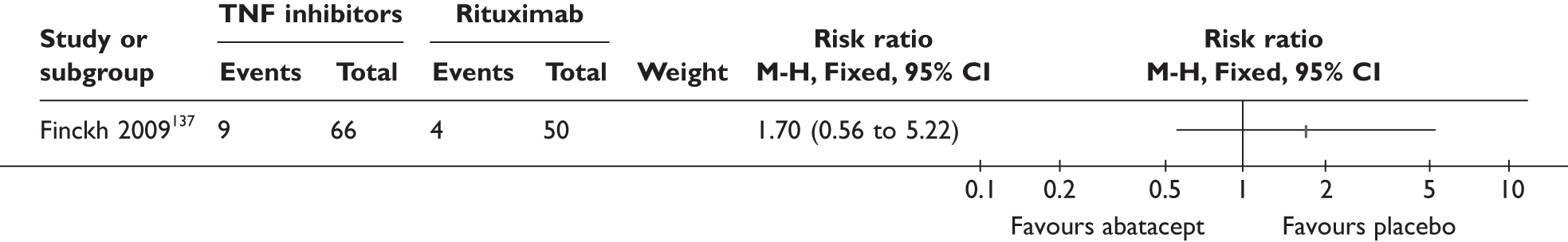

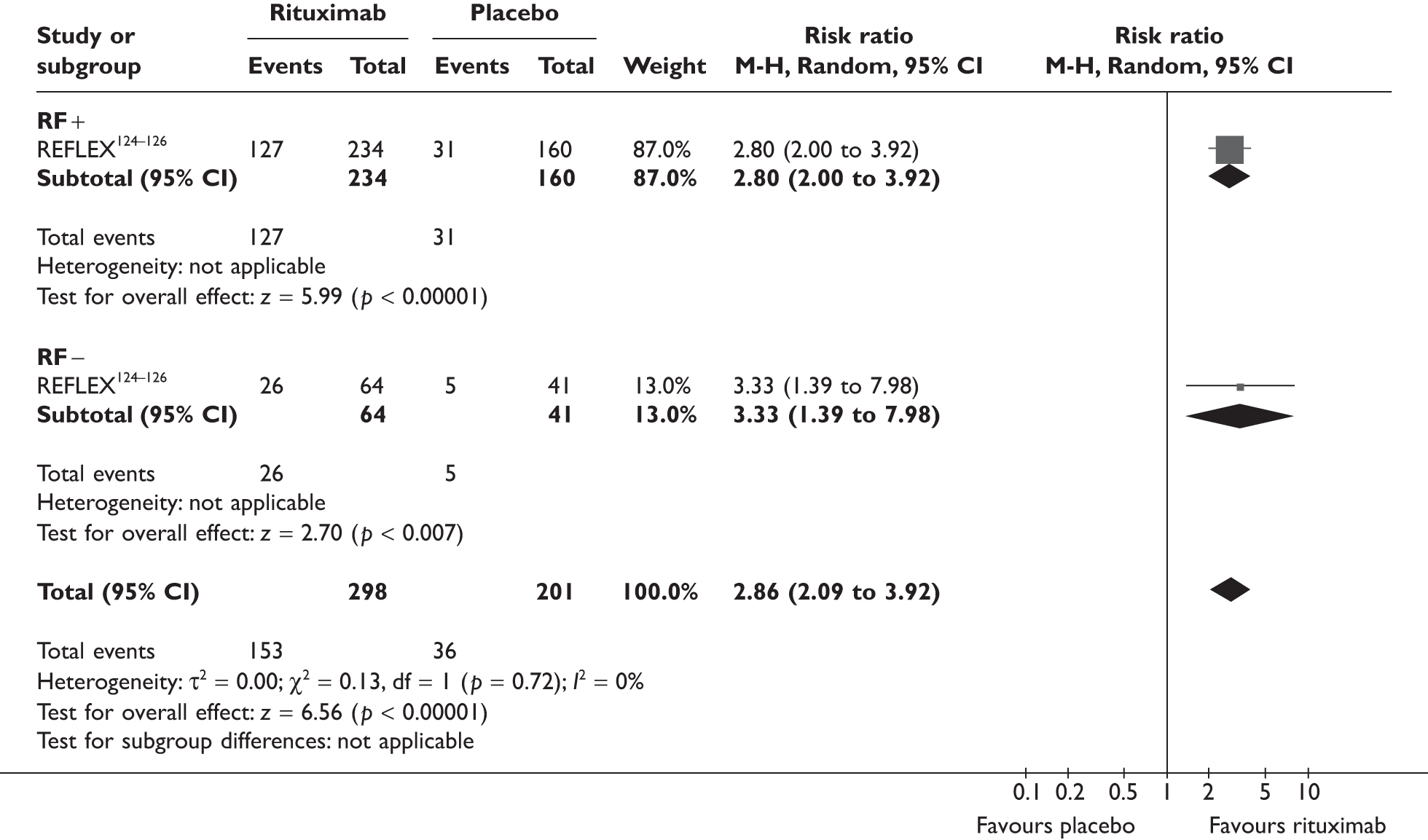

Withdrawal rates are presented in Figure 1. At 3 months, the percentage of patients withdrawn was very similar in the two studies that reported this outcome (9.9% and 9.8%). No patients withdrew in a retrospective study during 6 months. Withdrawal rates reported at 1 year were 12.5% and 26.8% in the two studies that reported this outcome. The percentage of patients withdrawn owing to lack of efficacy and owing to AEs at 3 months was reported only in the biggest study and was 2.9% and 5.6%, respectively. The percentage of patients withdrawn owing to lack of efficacy and owing to AEs at 12 months was measured in two studies: 8.3% and 17.1% withdrew because of lack of efficacy and 8.3% and 14.6% withdrew because of AEs.

FIGURE 1.

Adalimumab: withdrawals from studies by reason. LCI, lower confidence interval; UCI, upper confidence interval.

One study92 reported withdrawal data based on all 70 patients, including 44 patients who received a prior TNF inhibitor as well as TNF inhibitor-naive patients; the withdrawal data were not included in this report.

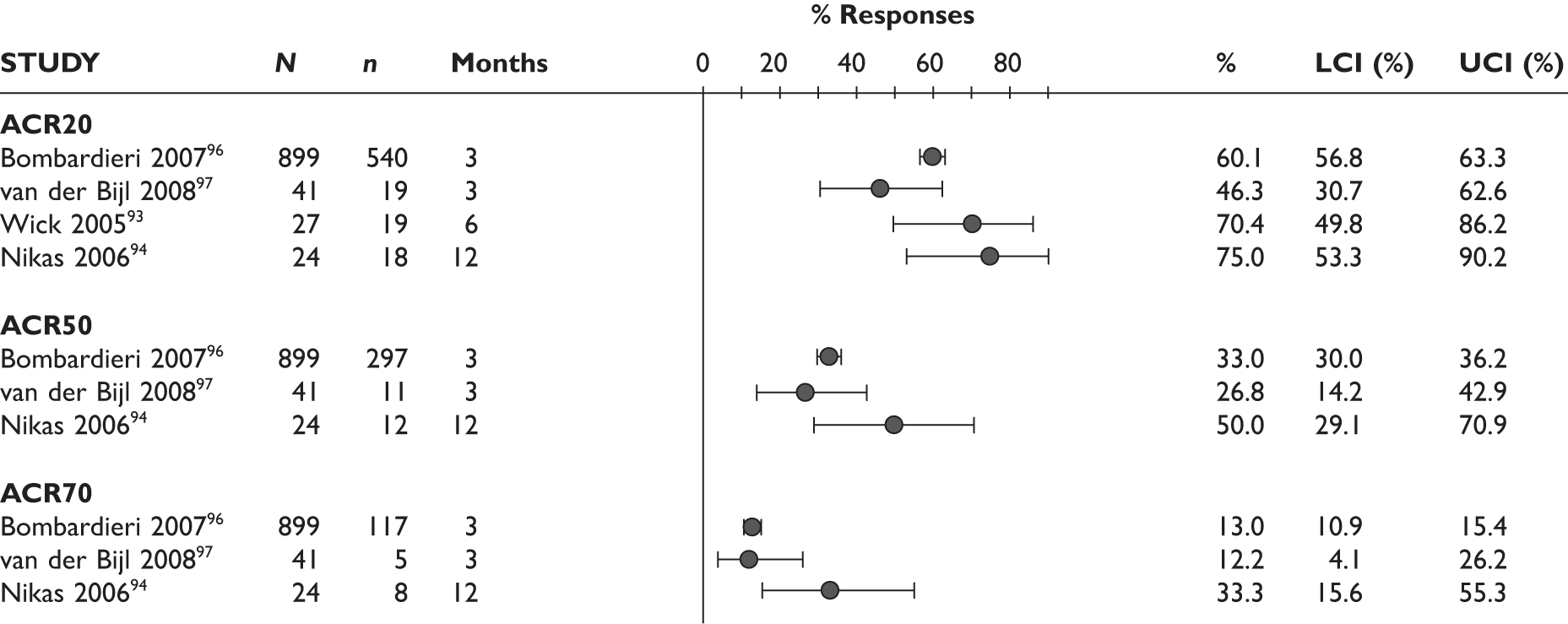

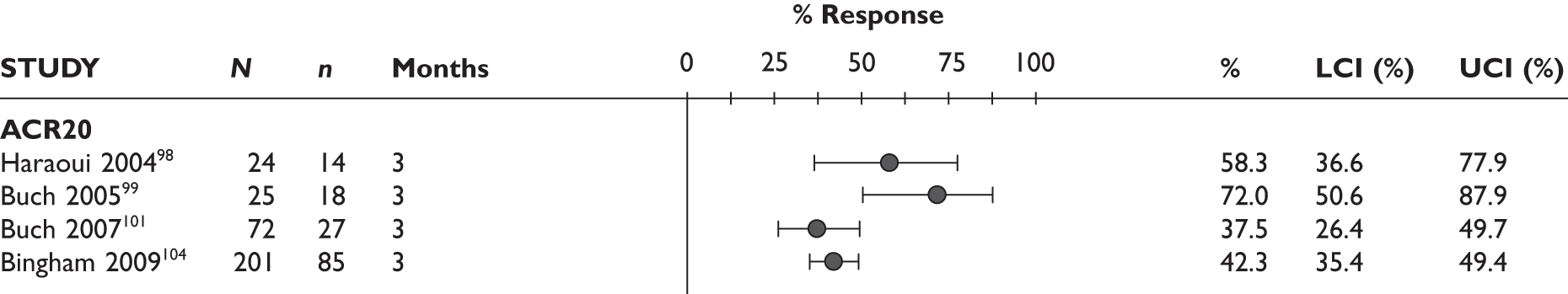

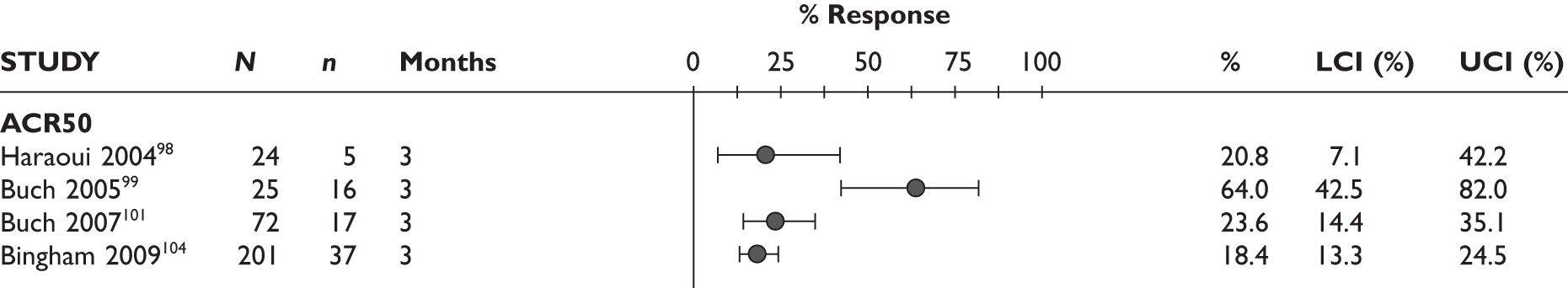

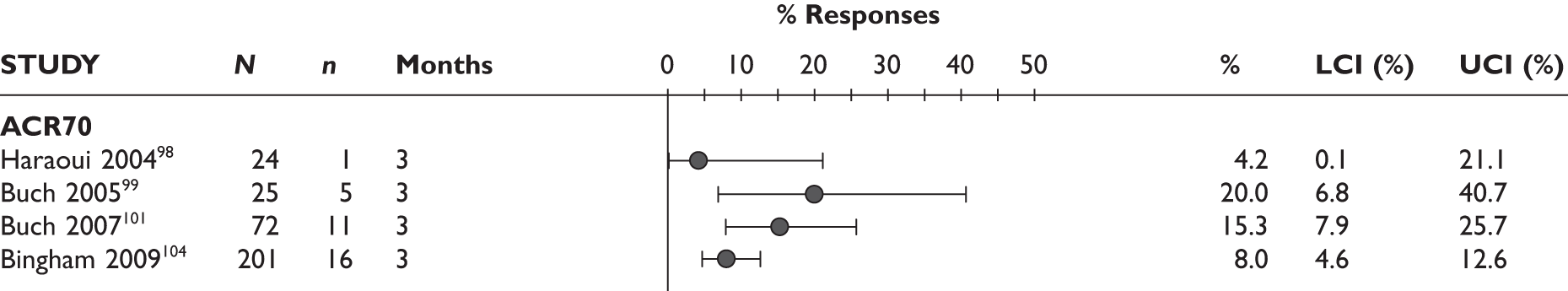

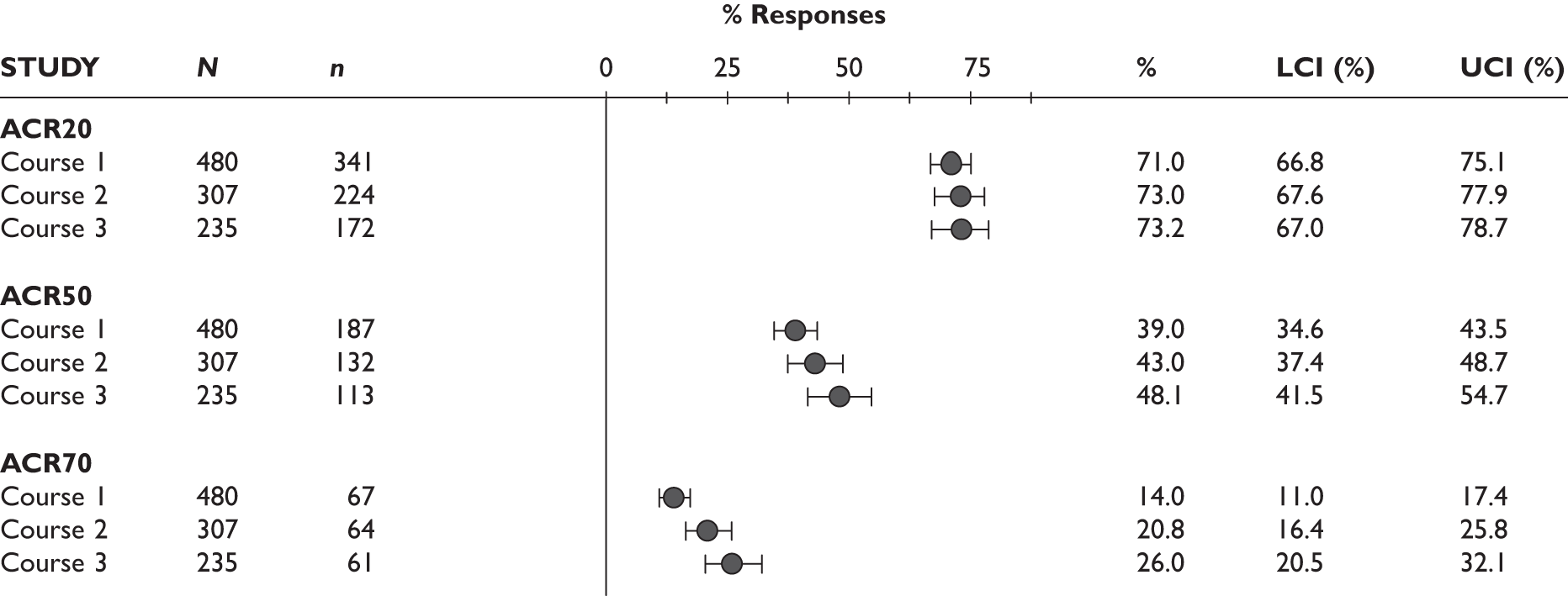

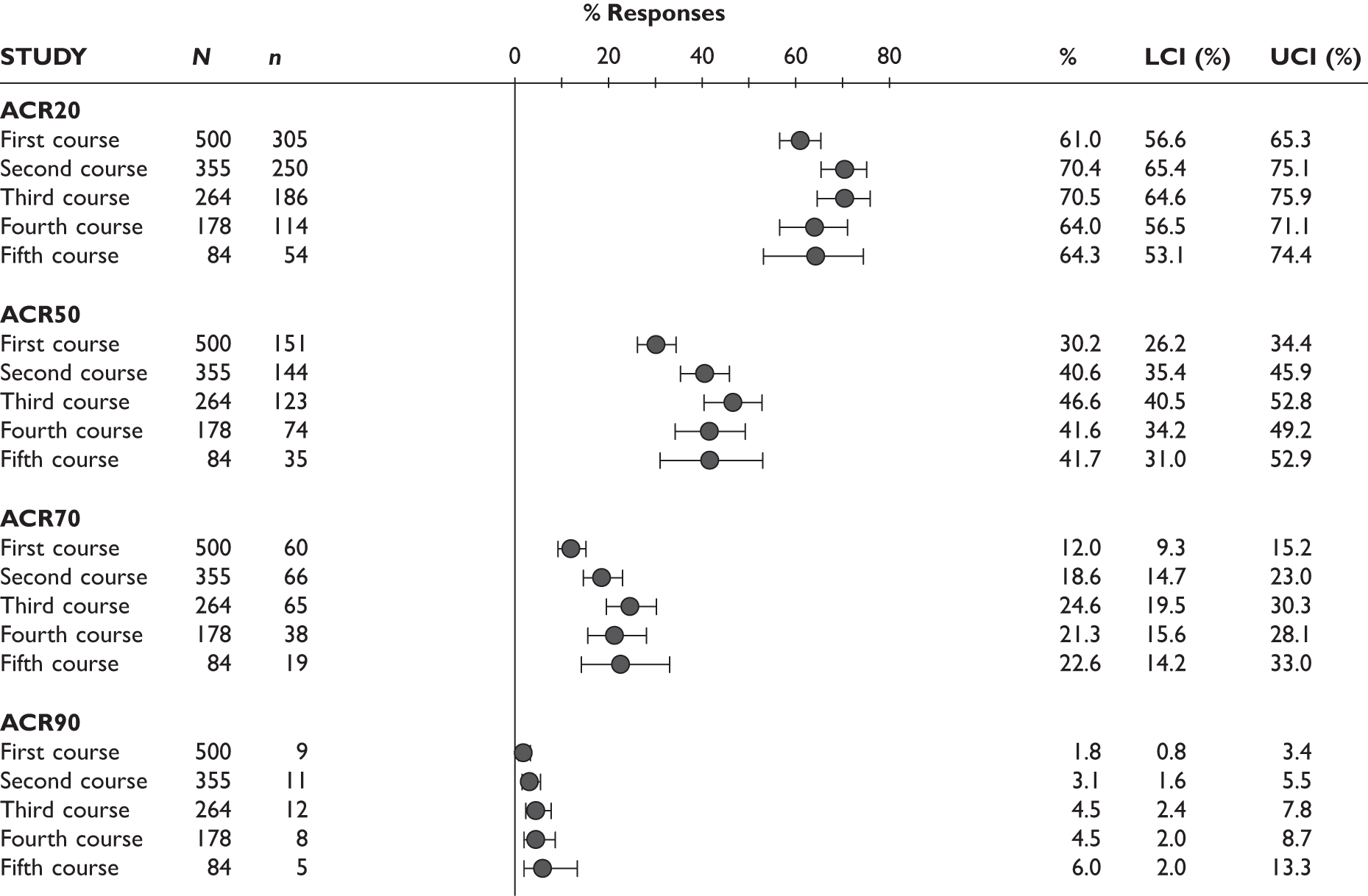

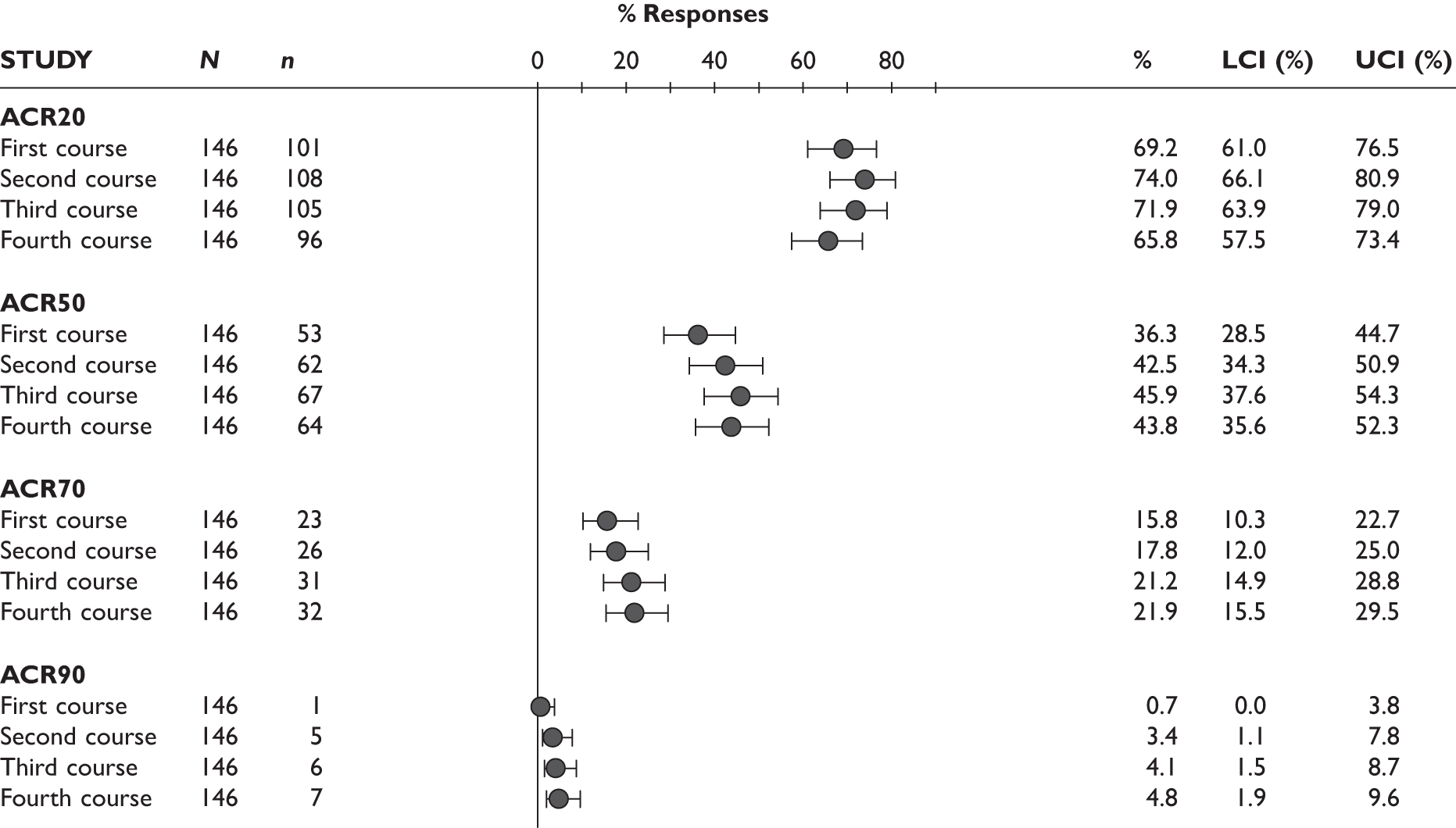

ACR20 response

The ACR20 response was assessed in four studies (Figure 2). Two studies assessed it at 3 months and the response was achieved by around half of the patients (46% and 60%). In the other two studies, the percentage of patients who achieved ACR20 response was 70% at 6 months and 75% at 12 months.

FIGURE 2.

Adalimumab: ACR (20, 50, 70) responses. LCI, lower confidence interval; UCI, upper confidence interval.

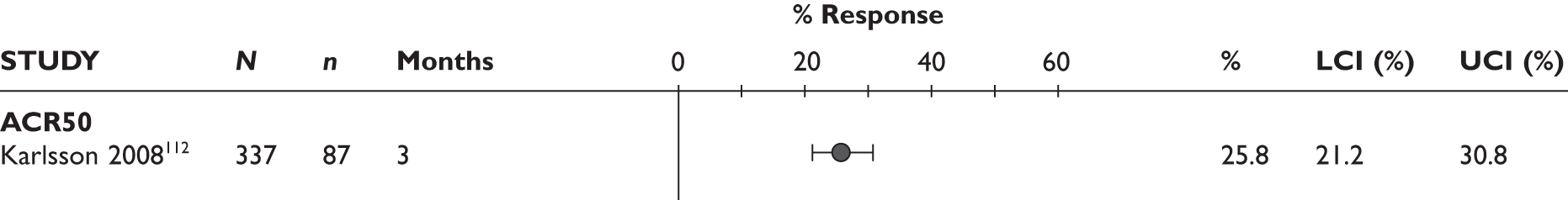

ACR50 response

The ACR50 response was measured in three studies (Figure 2): 26.8%–33% of patients achieved ACR50 response at 3 months. When measured at 12 months in the other study, half of the patients achieved this response.

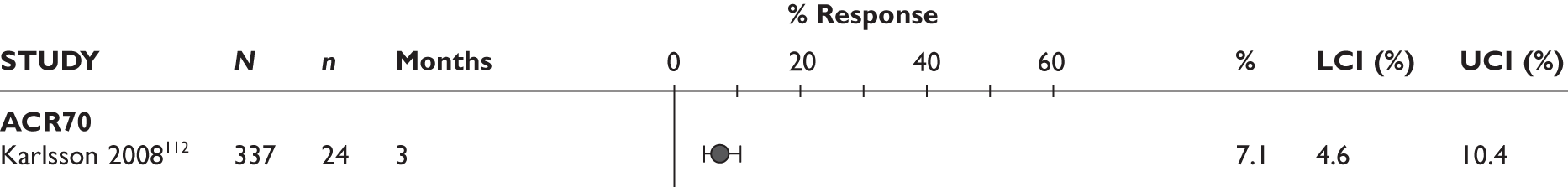

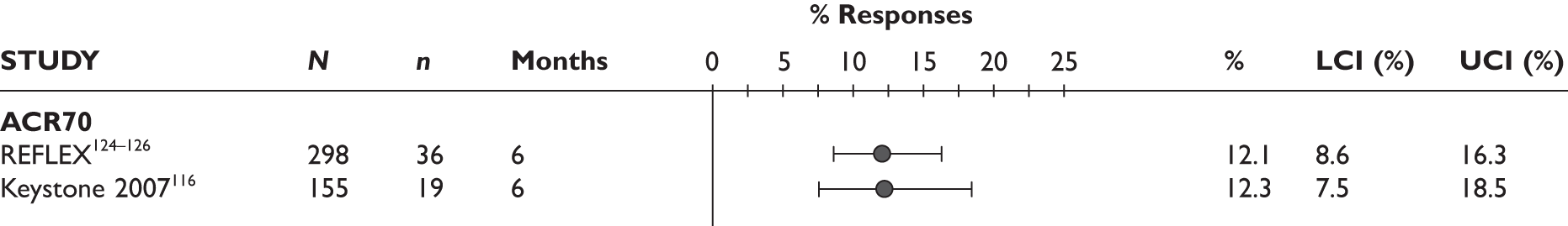

ACR70 response

The ACR70 response was measured in three studies (Figure 2). ACR70 response at 3 months was similar in two studies that measured this outcome (13% and 12%). ACR70 response at 12 months was reported in one study, with 33% of the patients achieving this response.

A similar pattern was seen for ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70, with a relatively higher percentage of patients achieving a response with longer duration of treatment.

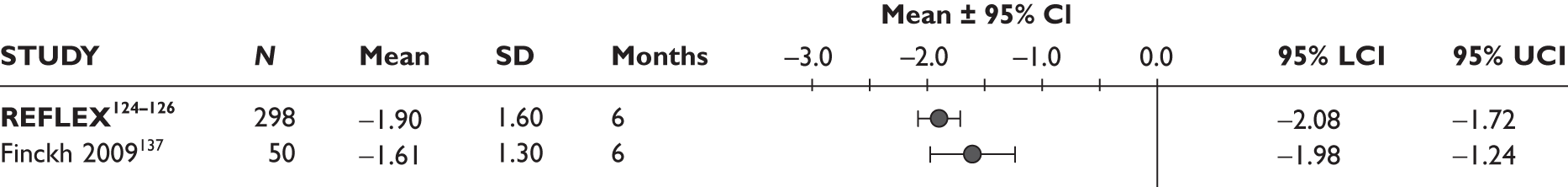

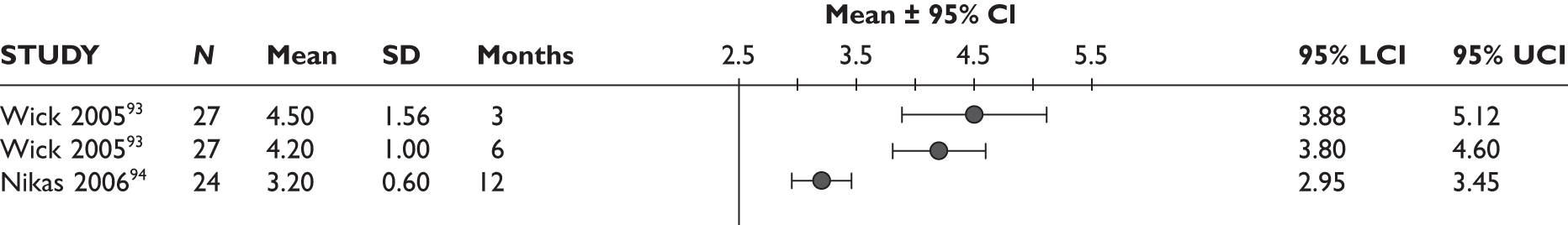

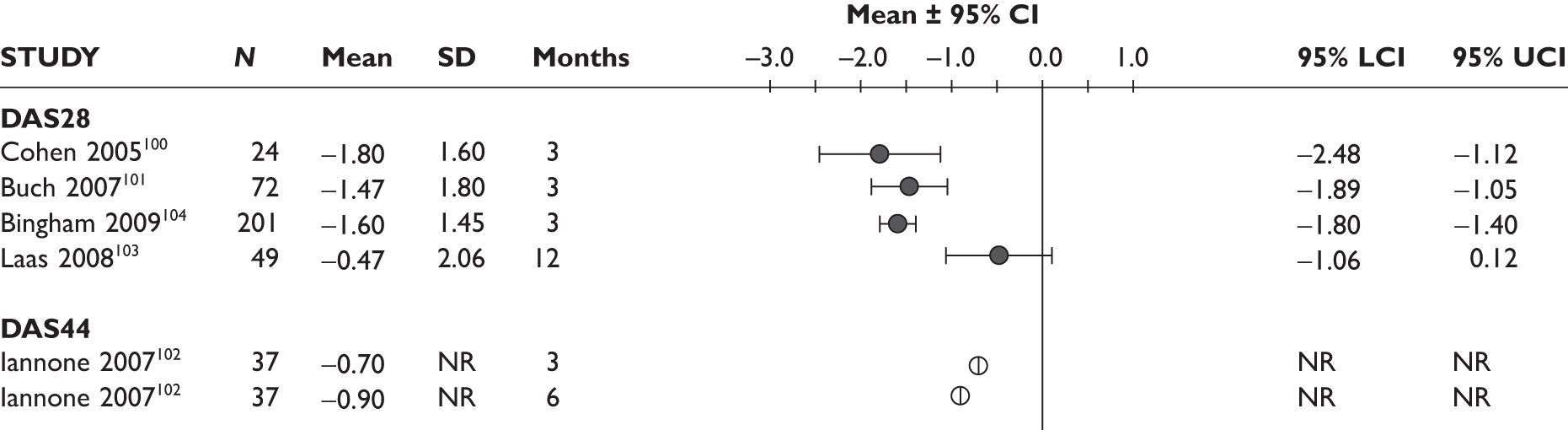

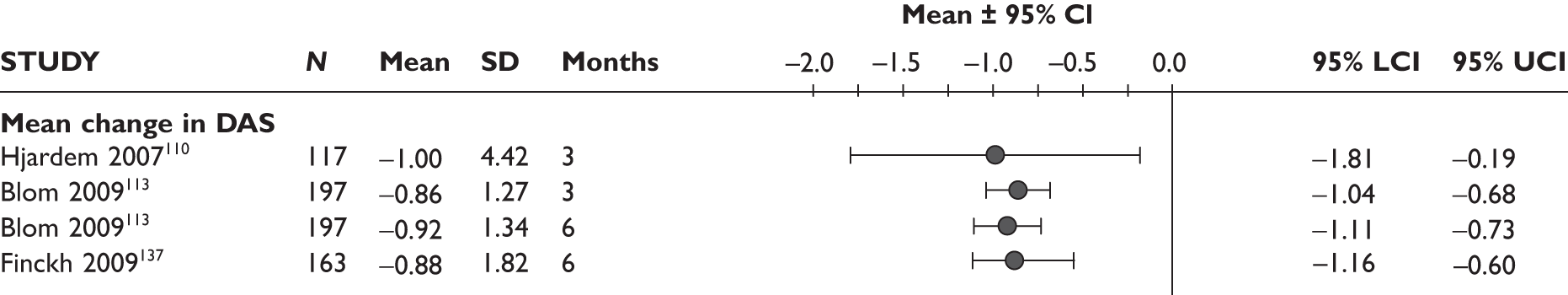

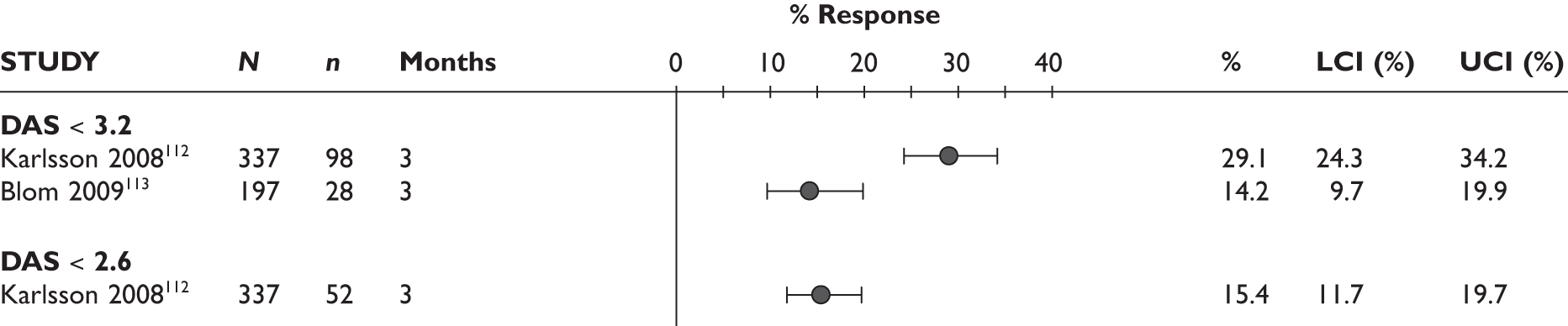

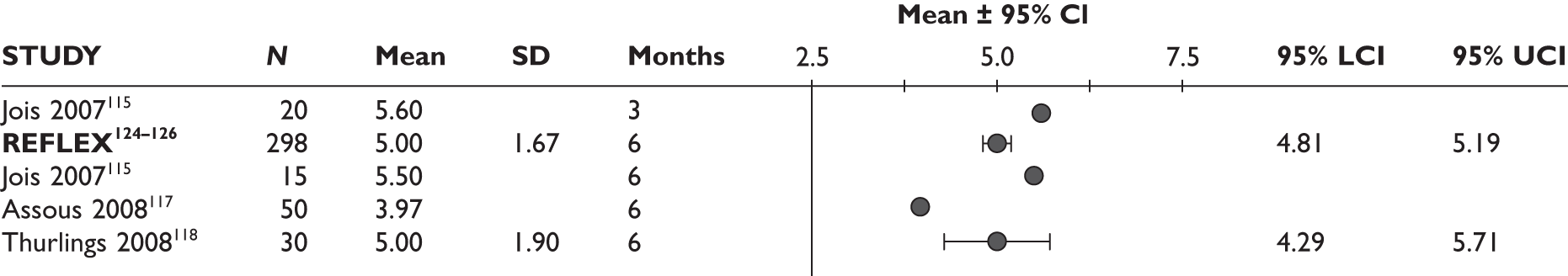

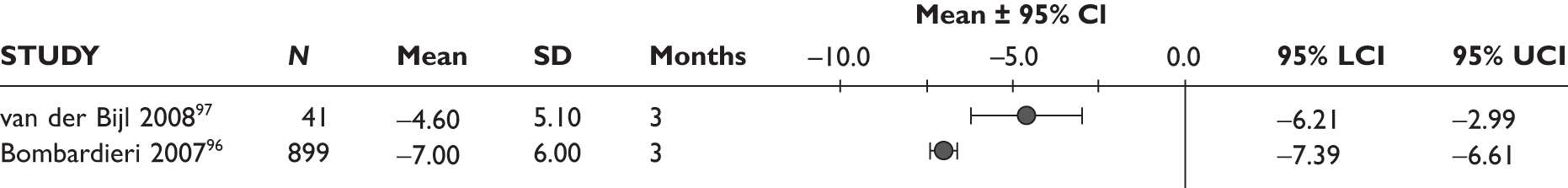

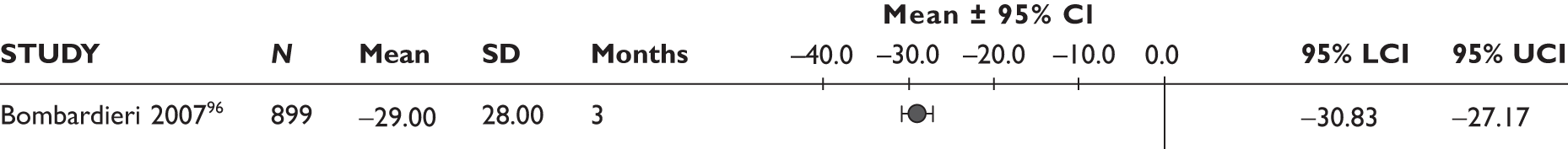

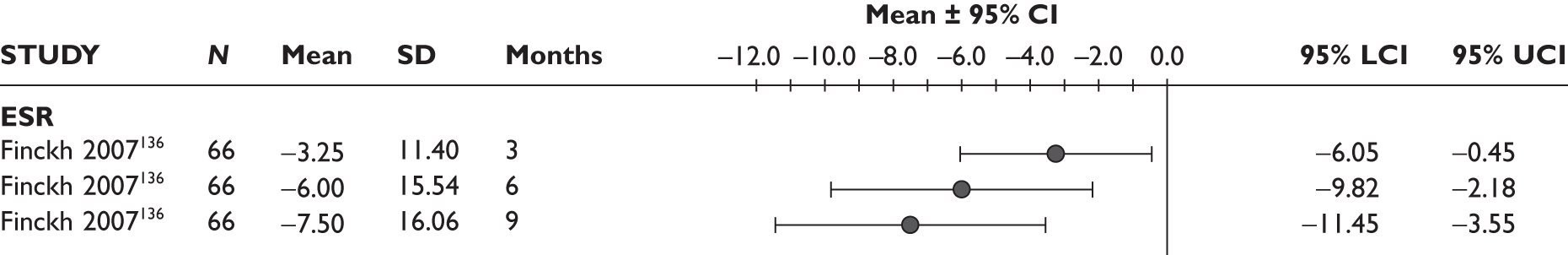

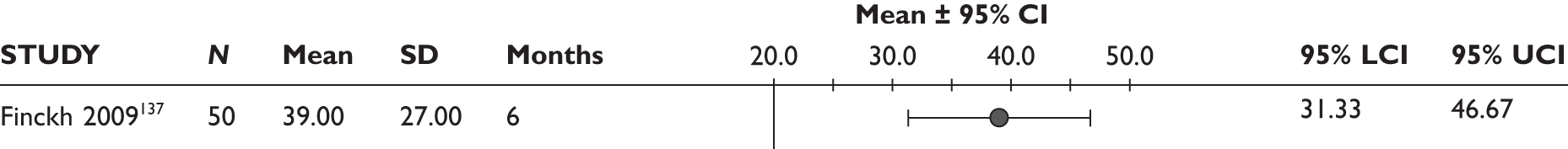

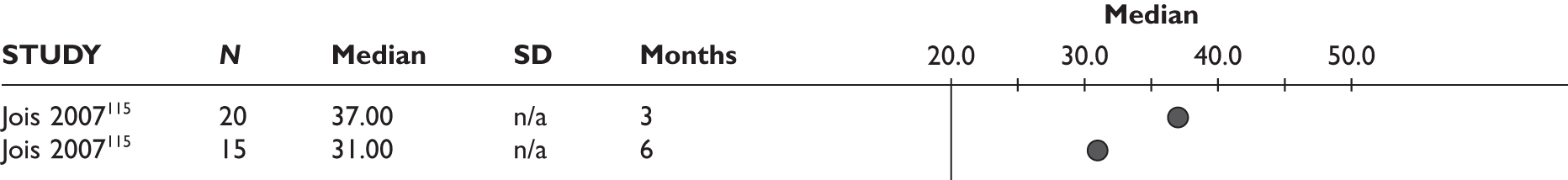

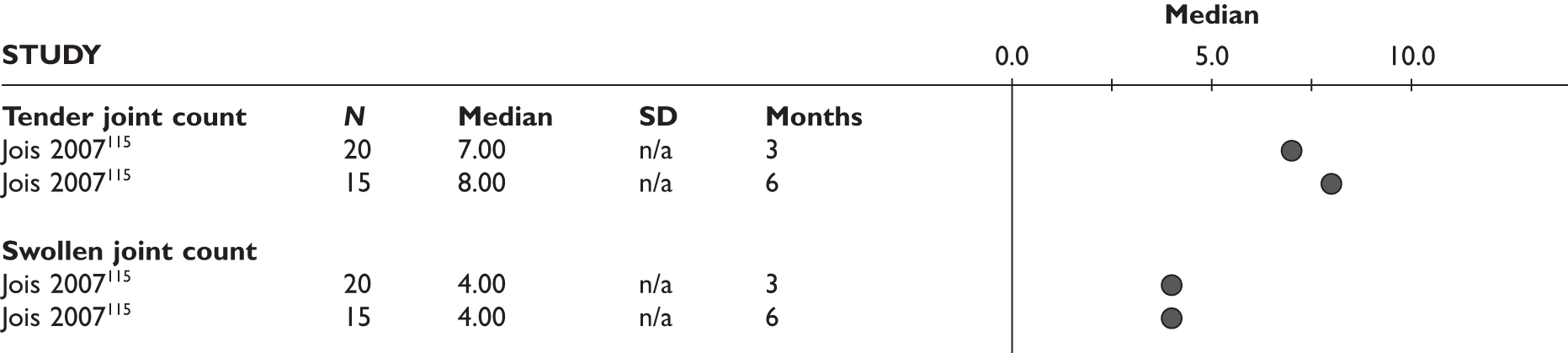

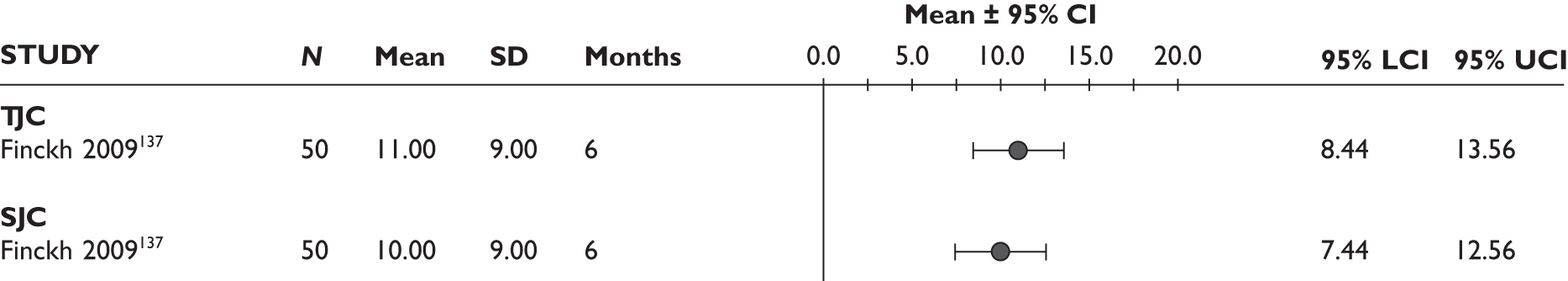

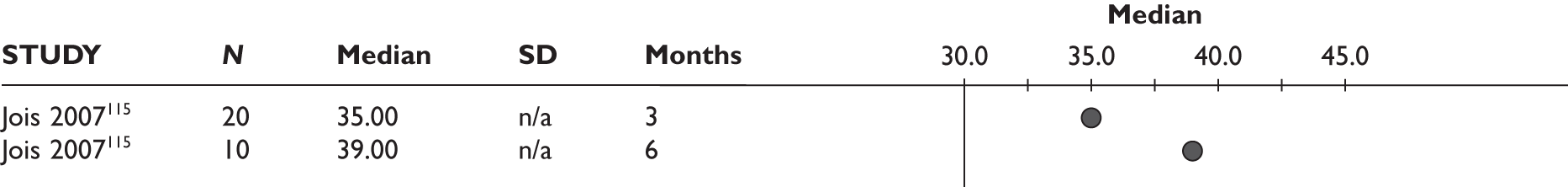

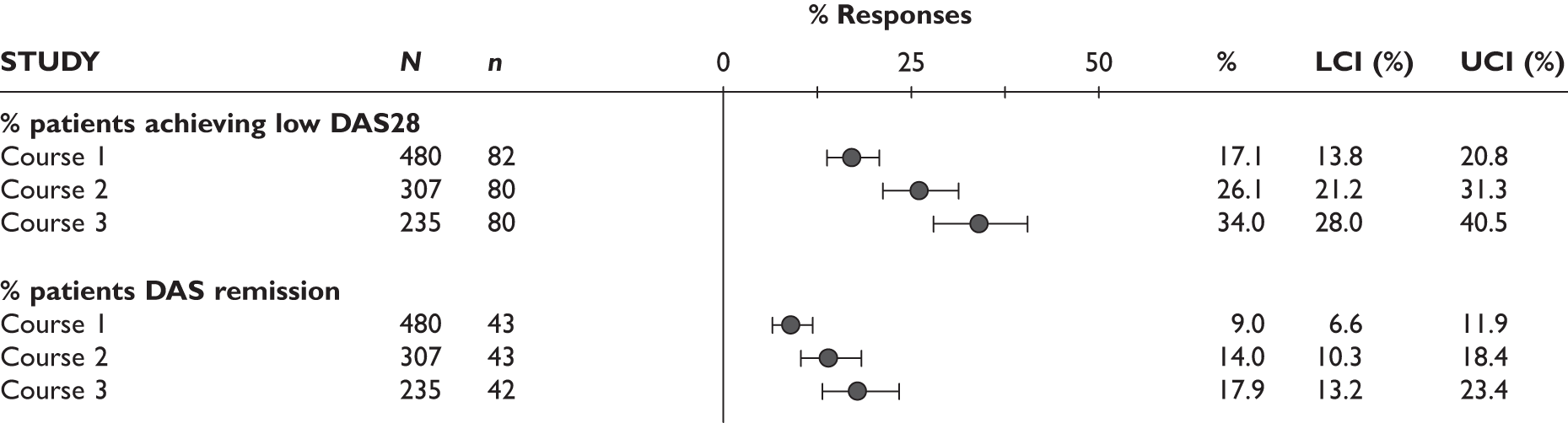

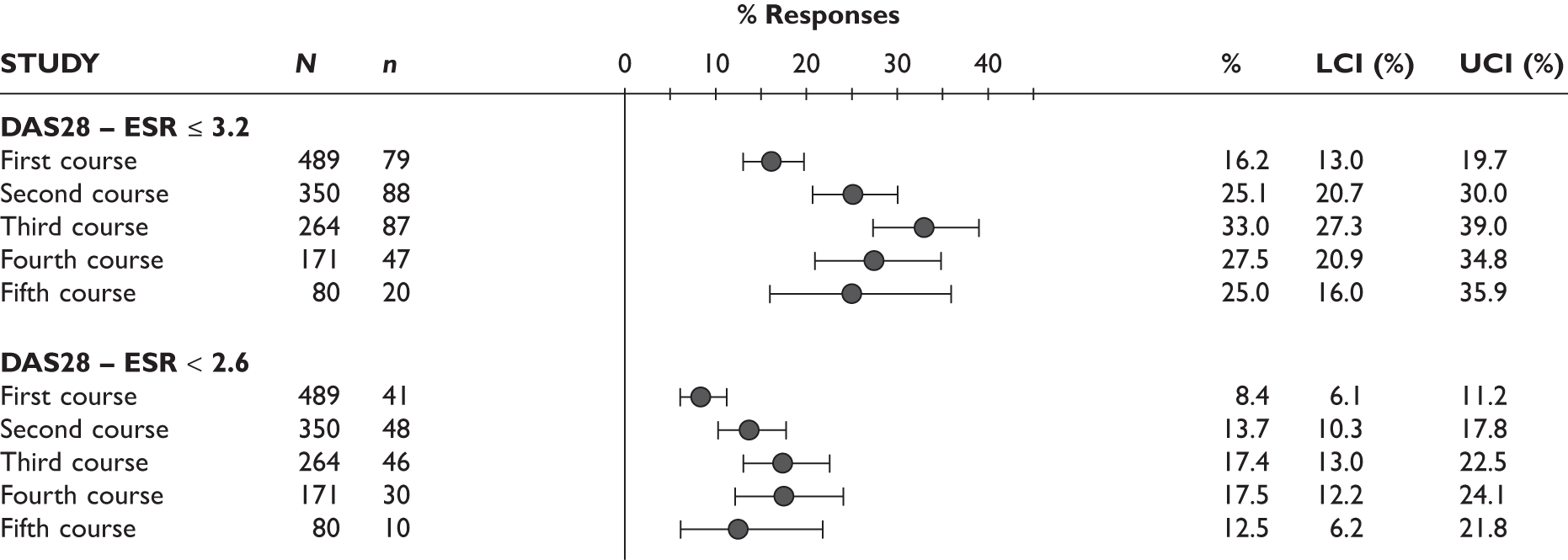

DAS28

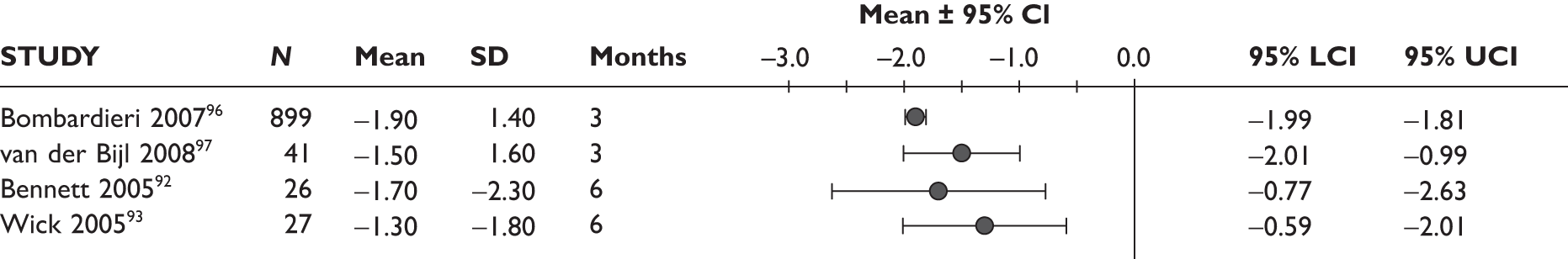

One study measured DAS28 at 3 and 6 months and another study at 12 months; the mean scores were 4.5, 4.2 and 3.2, respectively. See Figure 3 for details. The mean changes from baseline to 3 months and to 6 months [note: in the Bennett et al. study92 it was measured after mean treatment duration of 8.5 (range 1–19) months], were reported in four studies including the biggest study. They all showed that treatment with ADA significantly improved DAS28 scores (mean changes ranged from –1.30 to –1.90). See Figure 4 for details.

FIGURE 3.

Adalimumab: DAS28 scores. LCI, lower confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; UCI, upper confidence interval.

FIGURE 4.

Adalimumab: mean changes in DAS28 scores. LCI, lower confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; UCI, upper confidence interval.

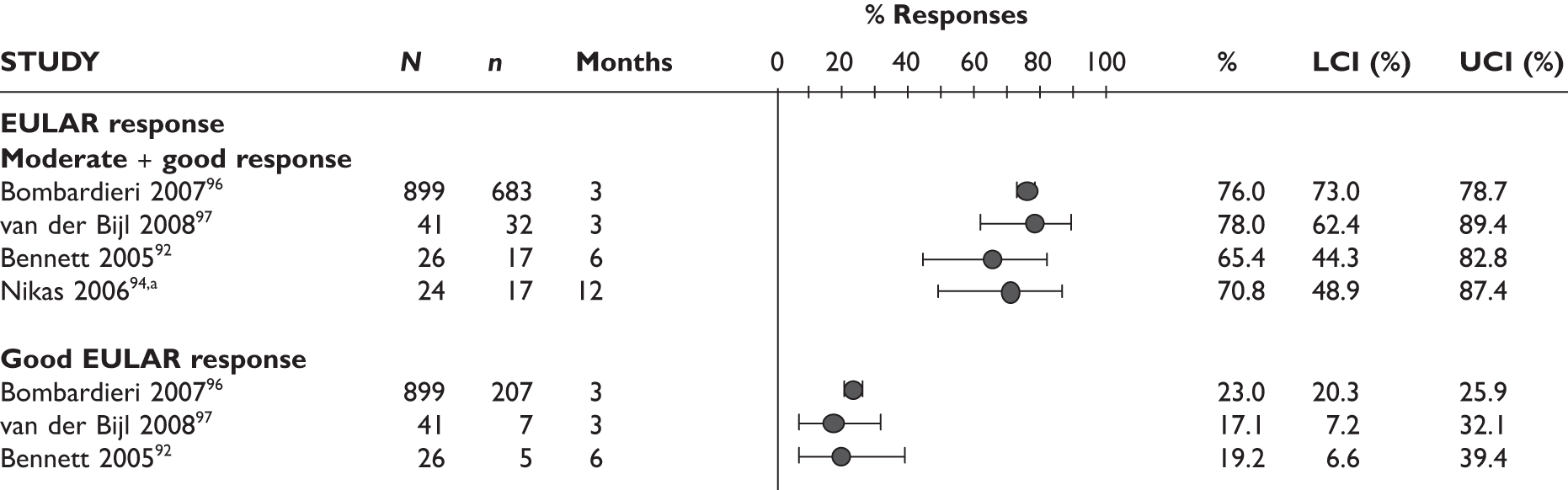

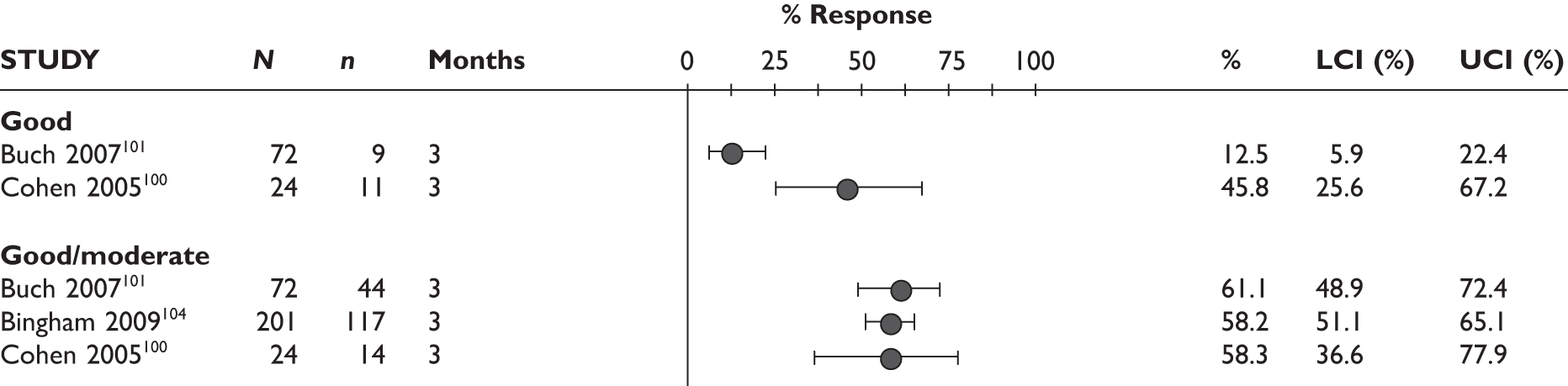

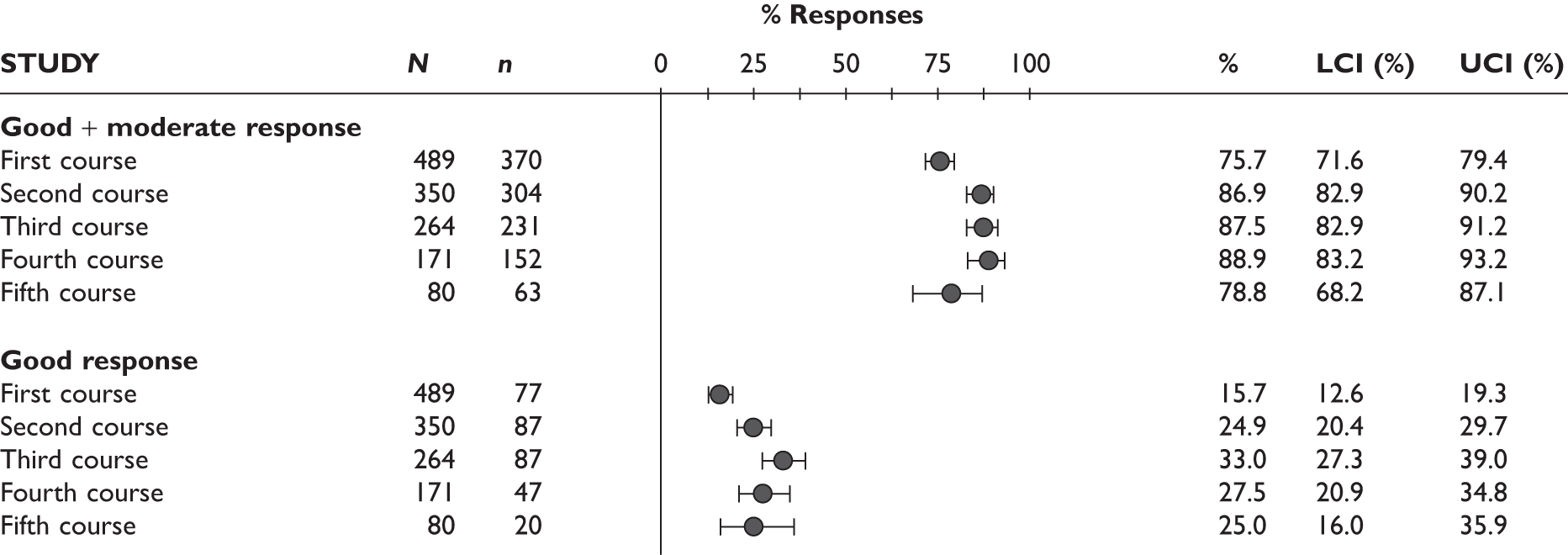

EULAR response

Two studies reported EULAR response at 3 months; most of the patients had a good/moderate response (76% and 78%) and 17%–23% had a good response. The Bennett et al. study92 measured EULAR response after a mean treatment duration of 8.5 months (range 1–19 months); the response rate was 65%, of whom 46% had a moderate response and 19% had a good response. See Figure 5 for details.

FIGURE 5.

Adalimumab: EULAR response. (a) Nikas et al. 94 only reported ‘EULAR response’ without providing further detail. LCI, lower confidence interval; UCI, upper confidence interval.

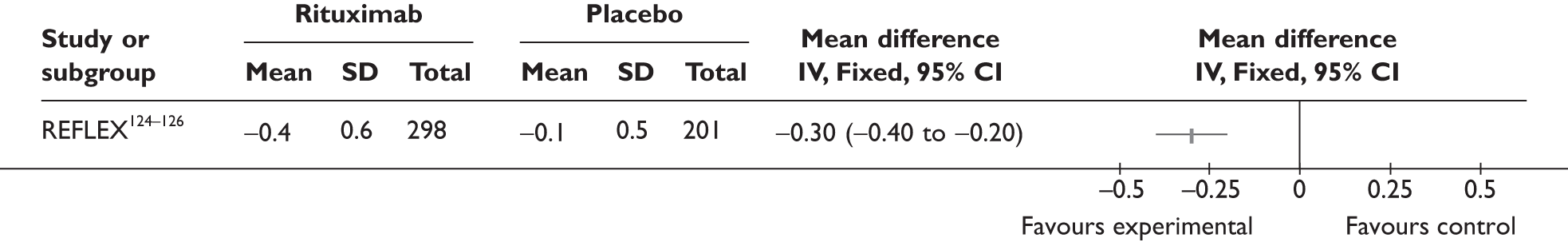

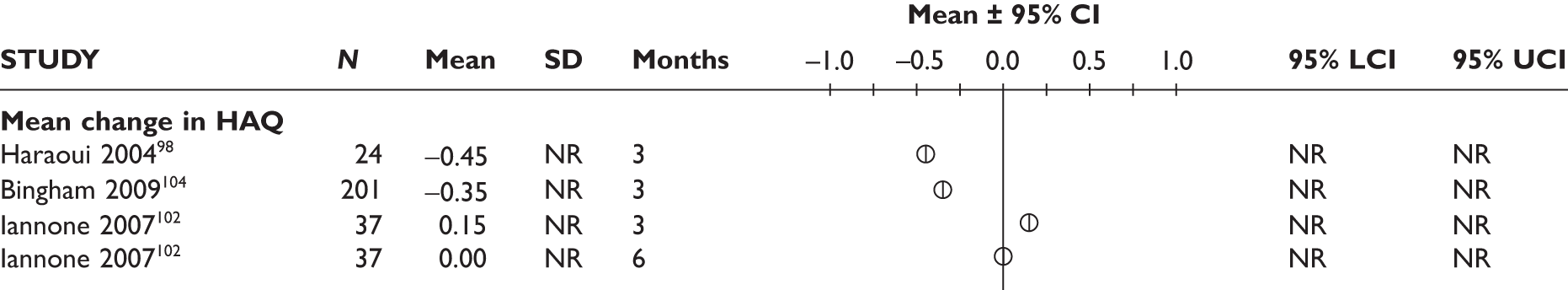

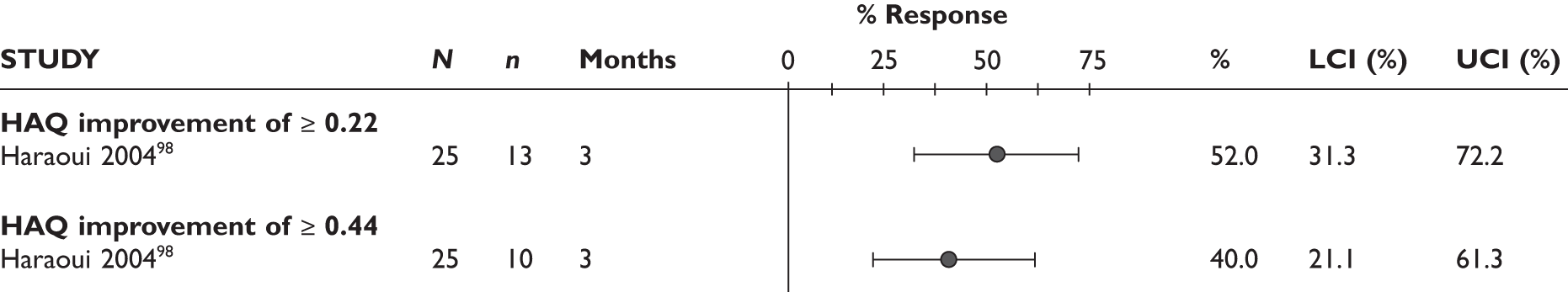

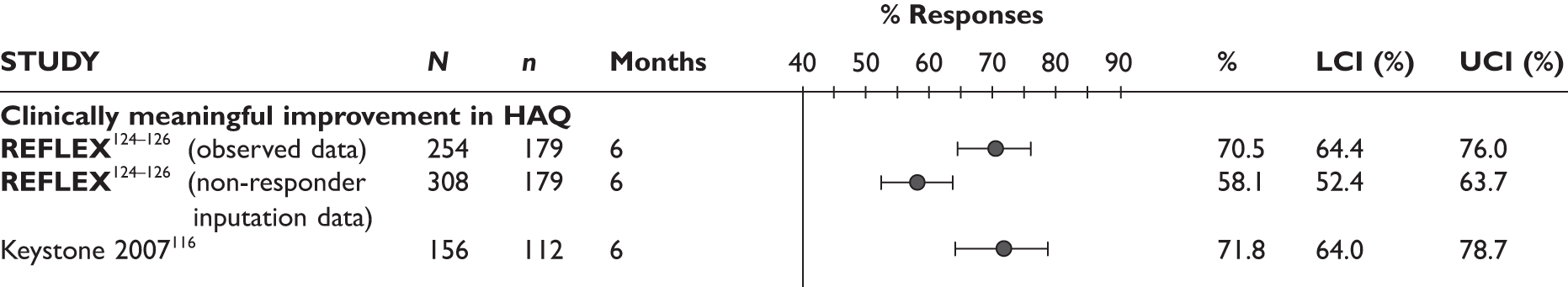

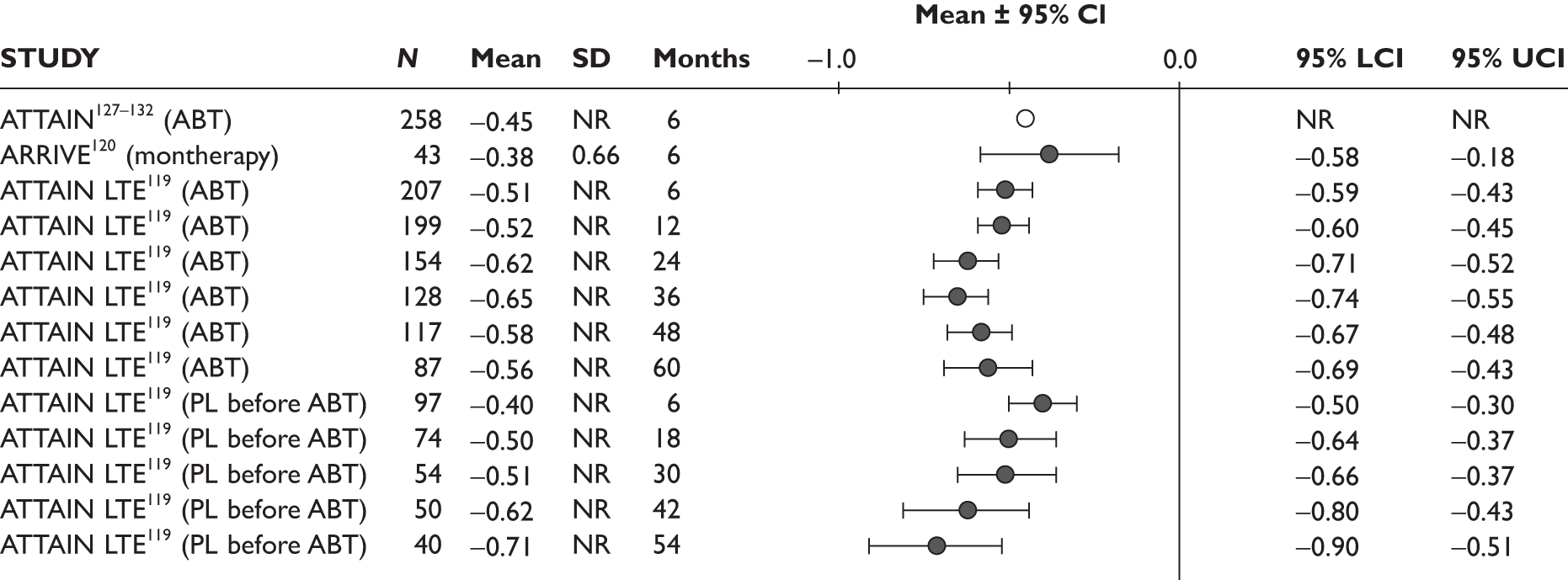

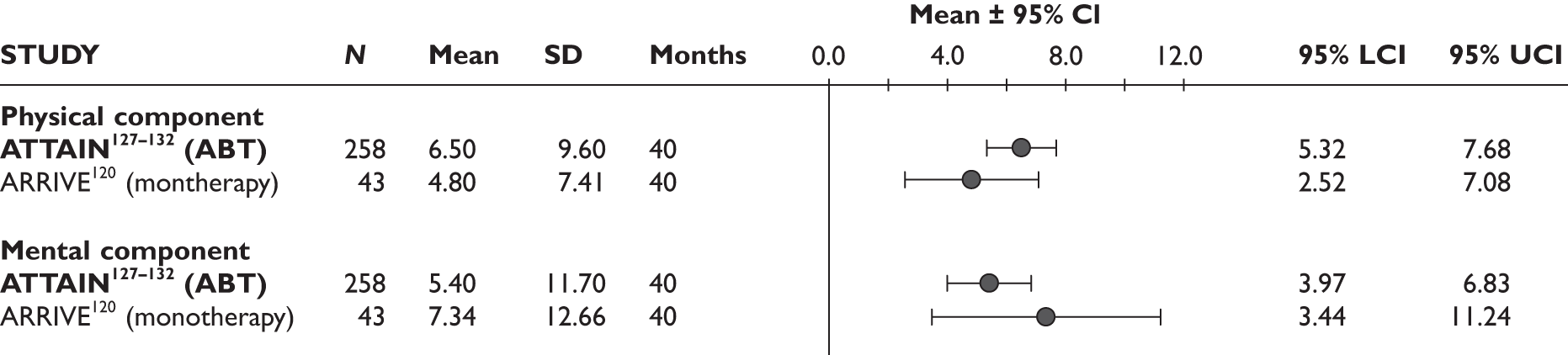

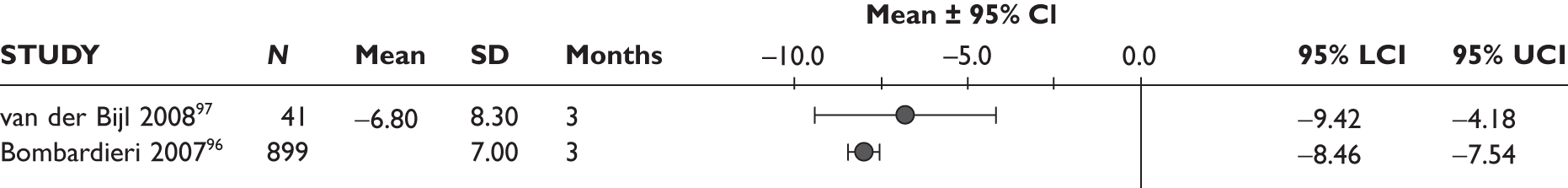

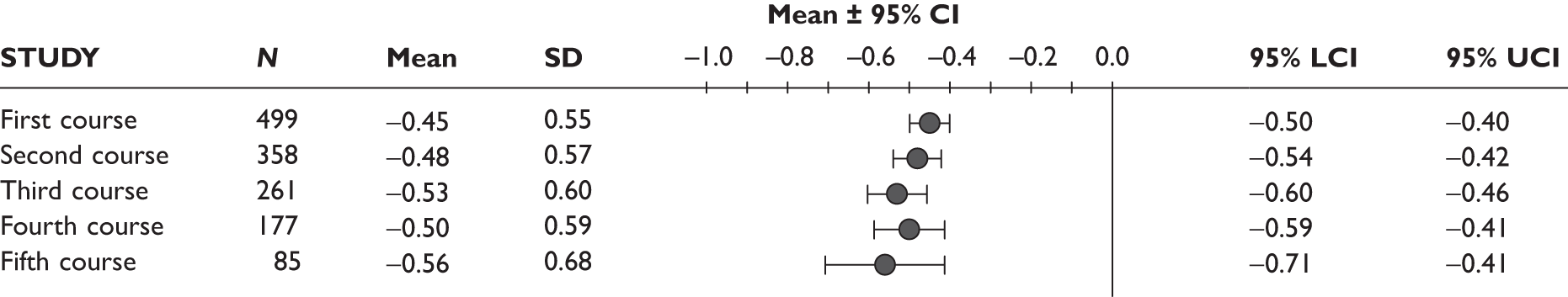

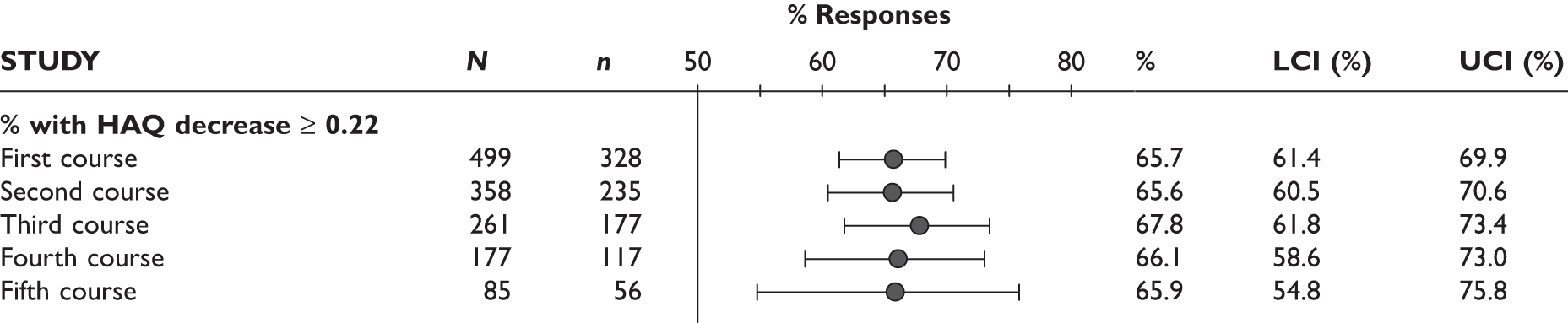

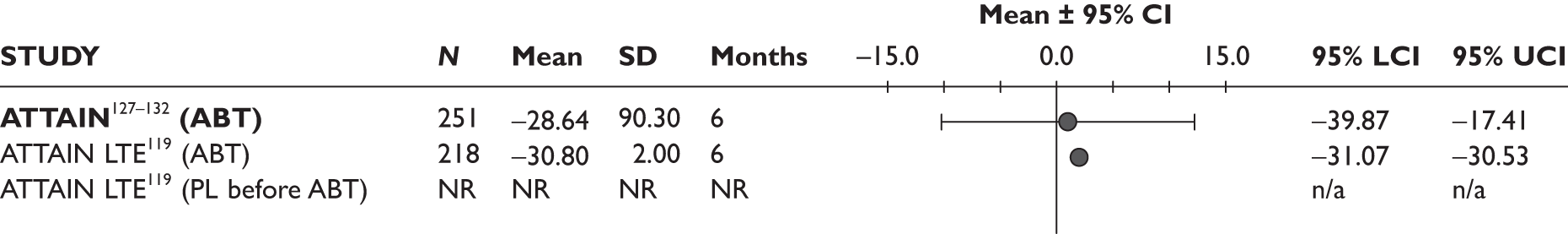

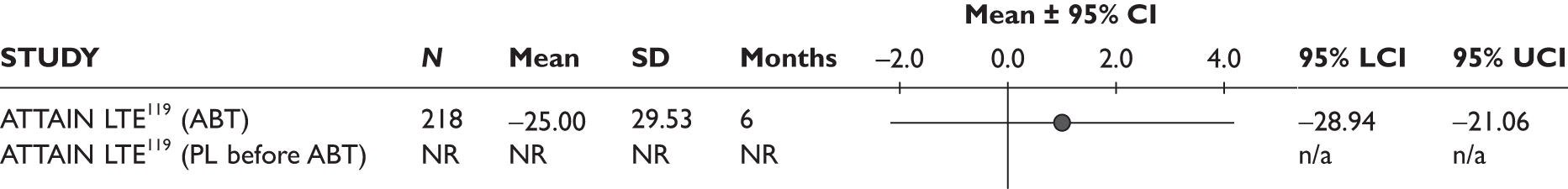

Health Assessment Questionnaire

Mean change in HAQ score was reported in three studies. Figure 6 shows that the mean HAQ score measured at 3 months in two studies, including the biggest study, and at mean 8.5 months (range 1–19 months) in the Bennett et al. study92 in all cases showed a significant decrease, ranging from –0.21 to –0.48, with the largest improvement observed in the biggest study.

FIGURE 6.

Adalimumab: mean change in HAQ scores. LCI, lower confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; UCI, upper confidence interval.

Joint damage

None of the studies reported this outcome measure.

Quality of life

None of the studies reported this outcome measure.

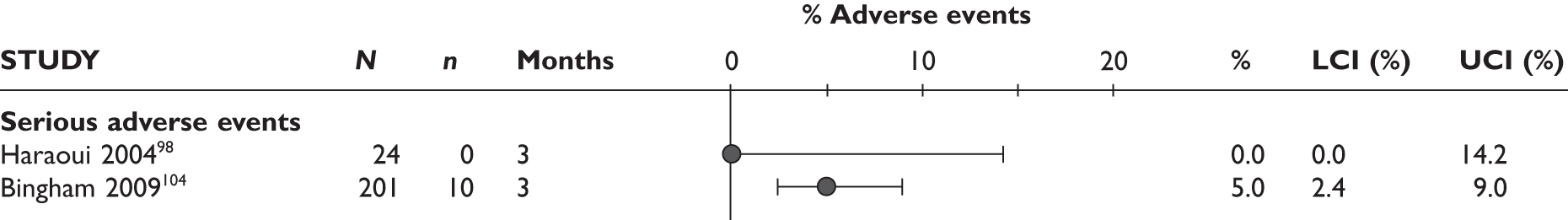

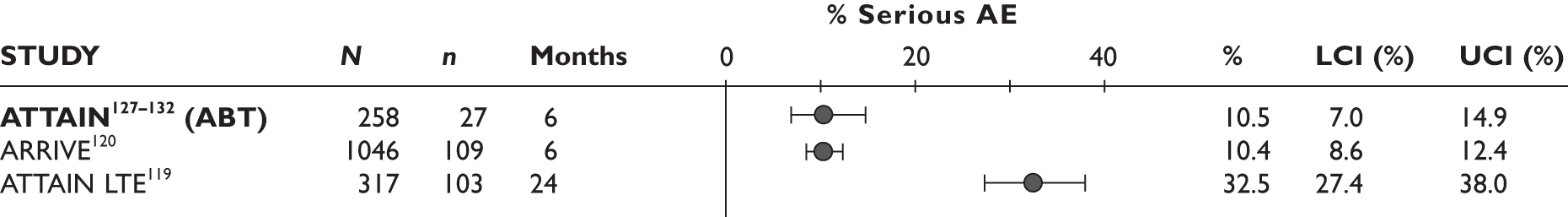

Serious adverse events

One study (the largest) reported that 18% of the patients experienced serious AEs and 13% withdrew because of AEs; none of these was lupus related or a demyelinating disorder. 96,97

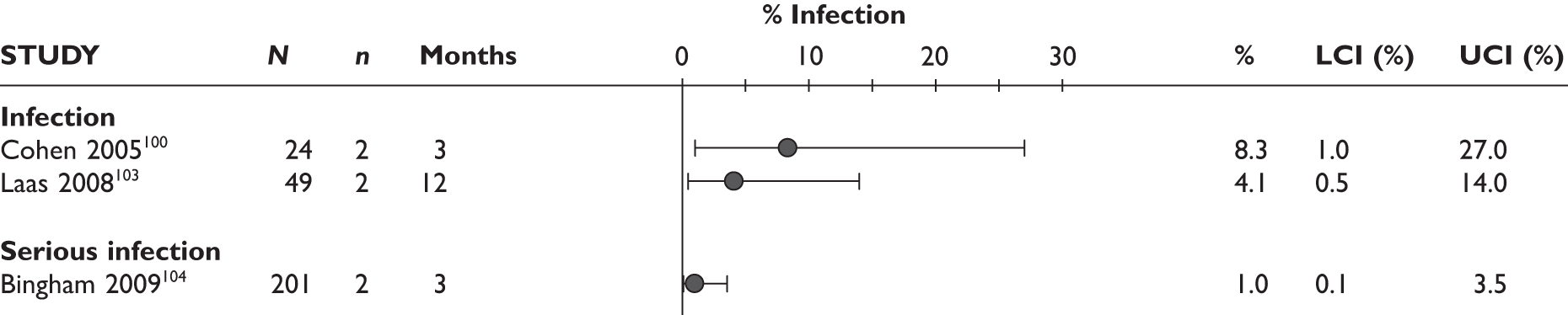

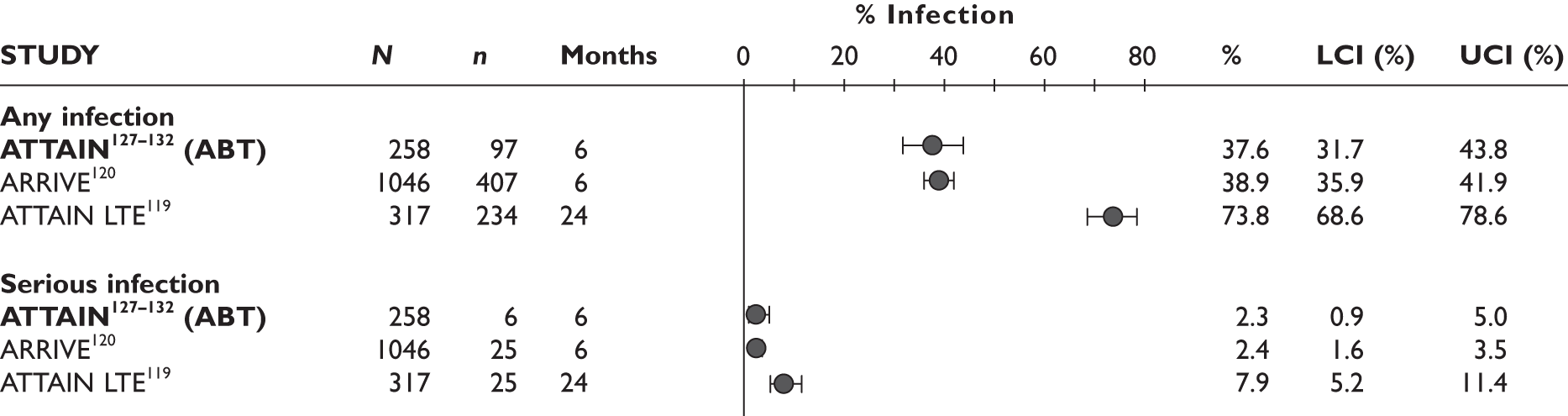

Any infections/serious infections

The largest study reported that the serious infection rate was 10.0/100 patient-years. The prevalence of TB infection was 0.4/100 patient-years in this study. In another study97 one patient developed pulmonary TB at 11 months. In the latter study, serious infection with cellulitis was also reported in one patient. One patient in a 12-month study by Nikas et al. 94 had to stop the study because of herpes zoster infection; it was not reported at which time point the treatment was stopped.

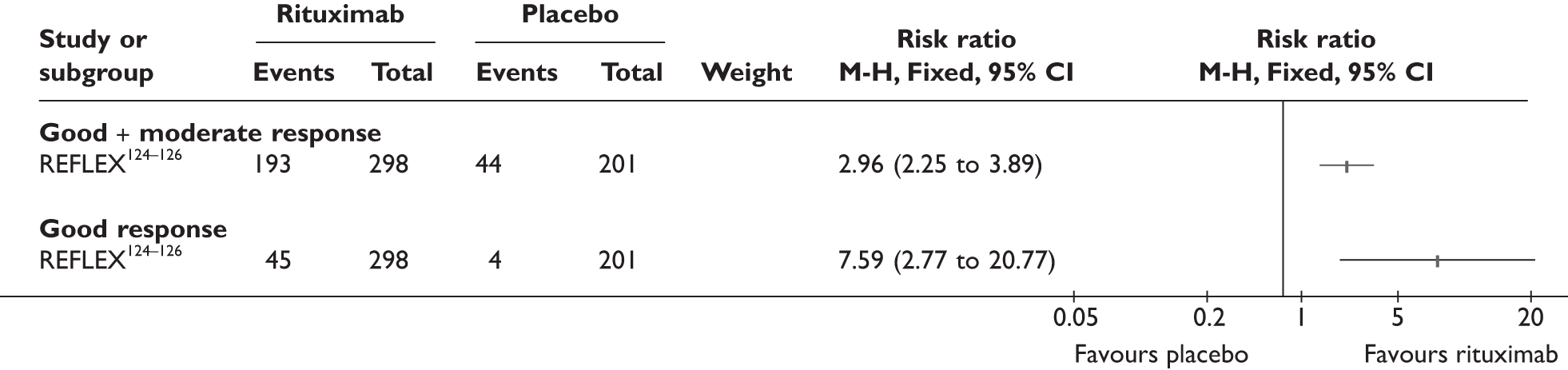

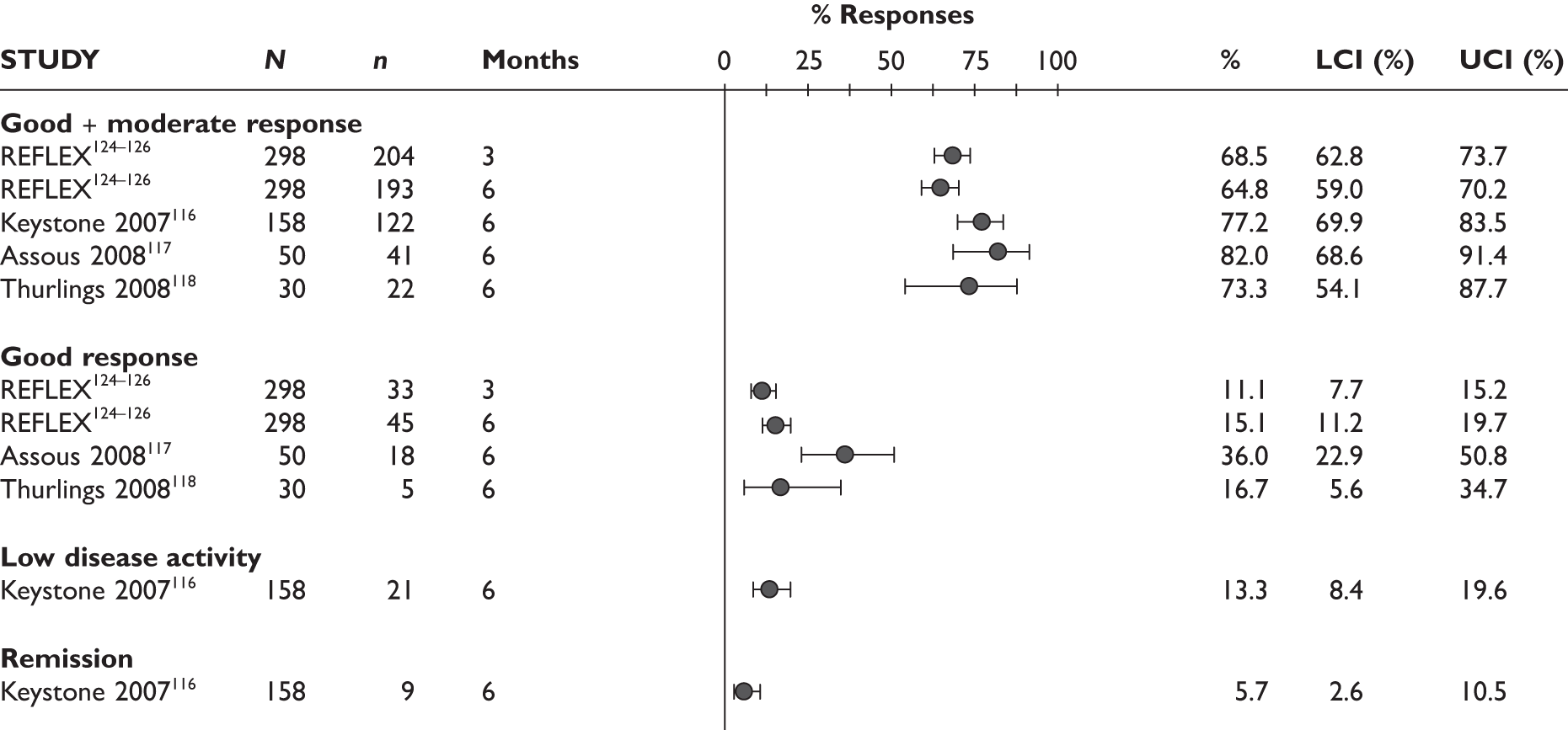

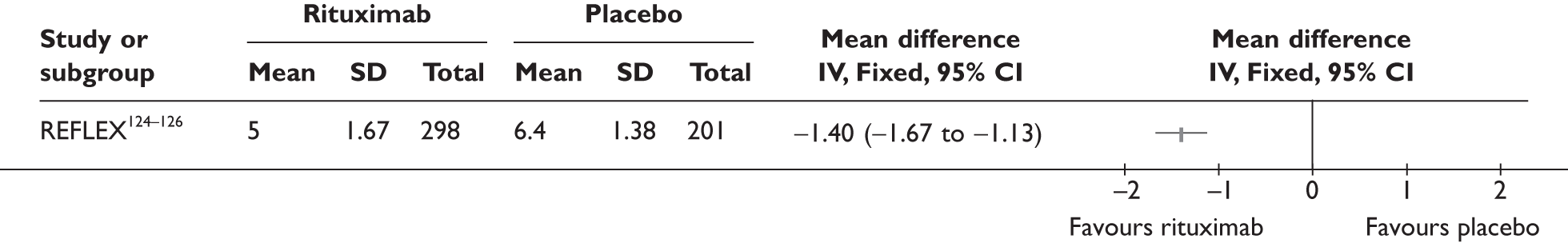

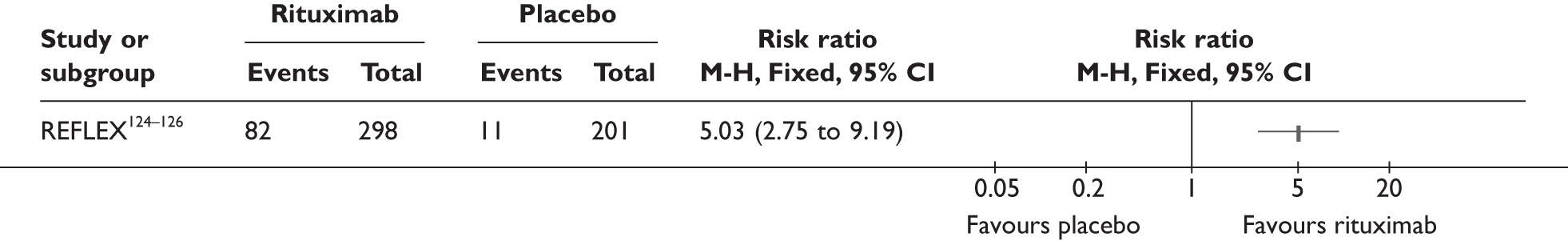

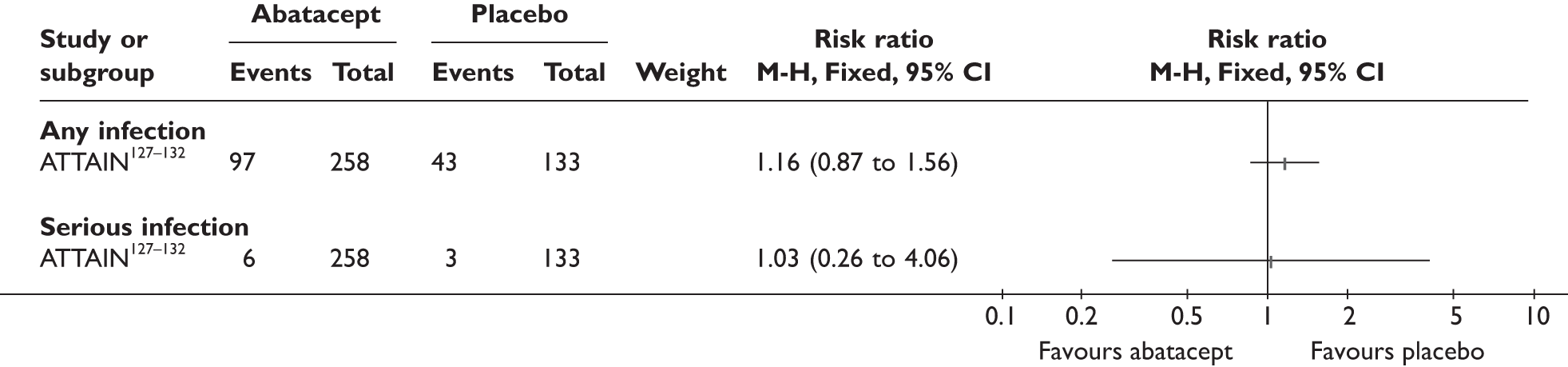

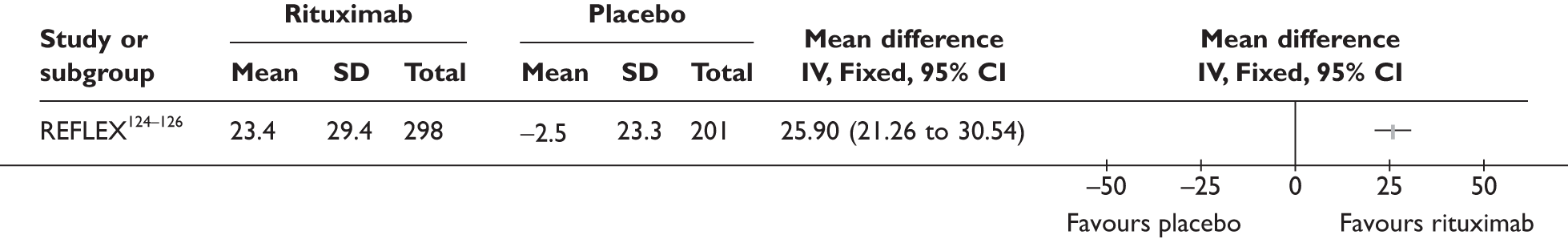

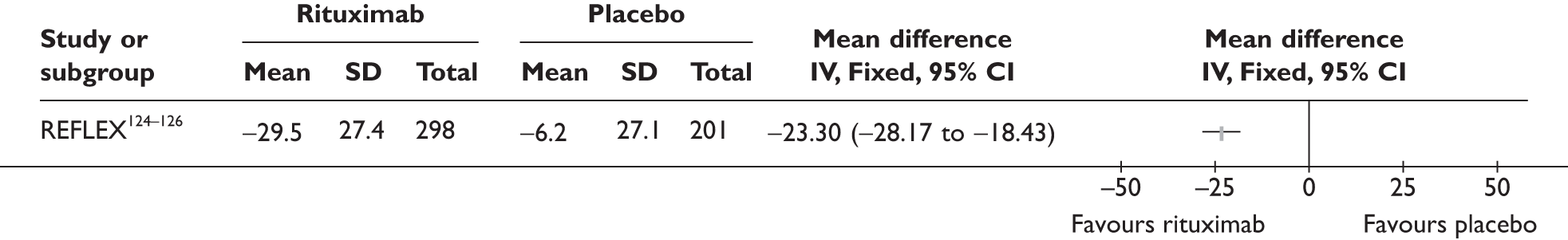

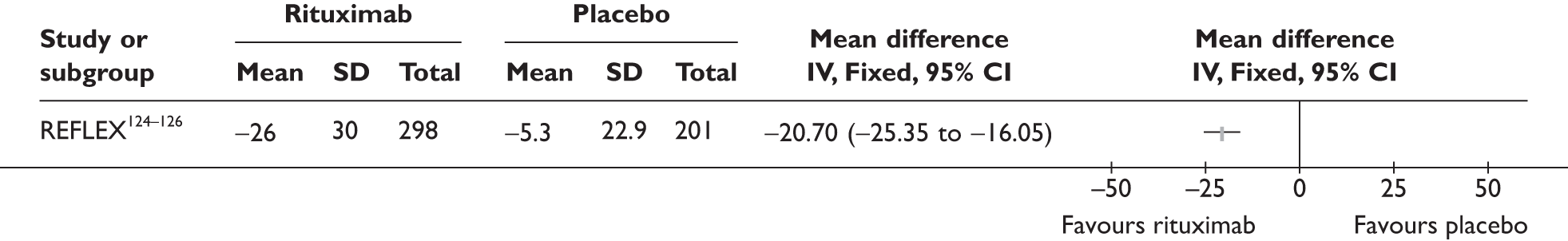

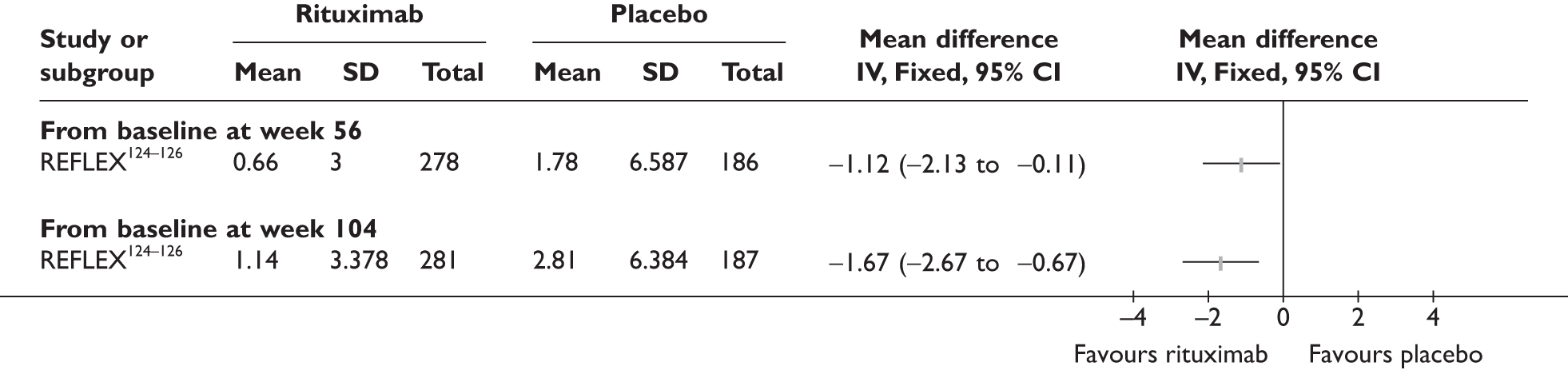

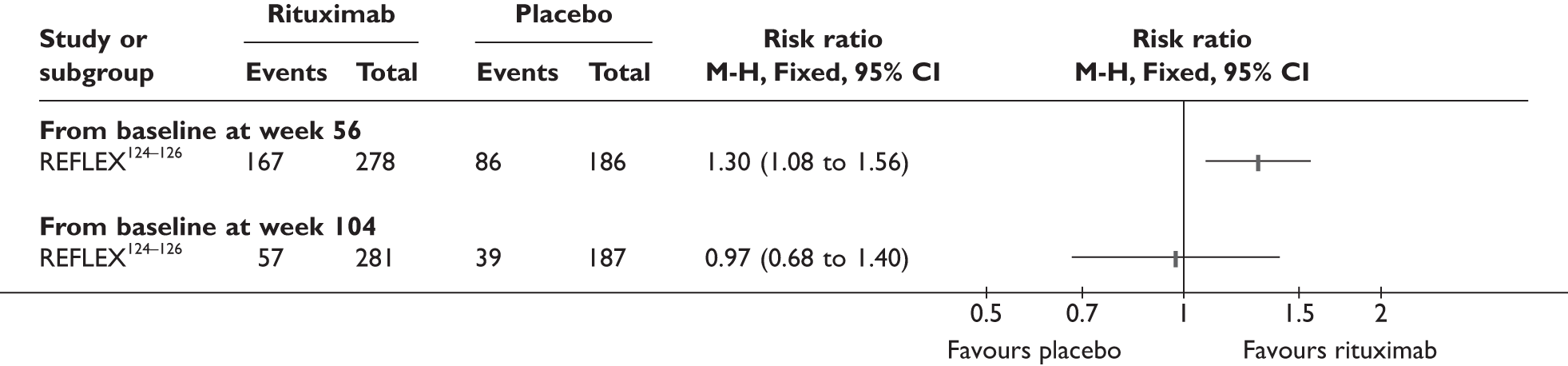

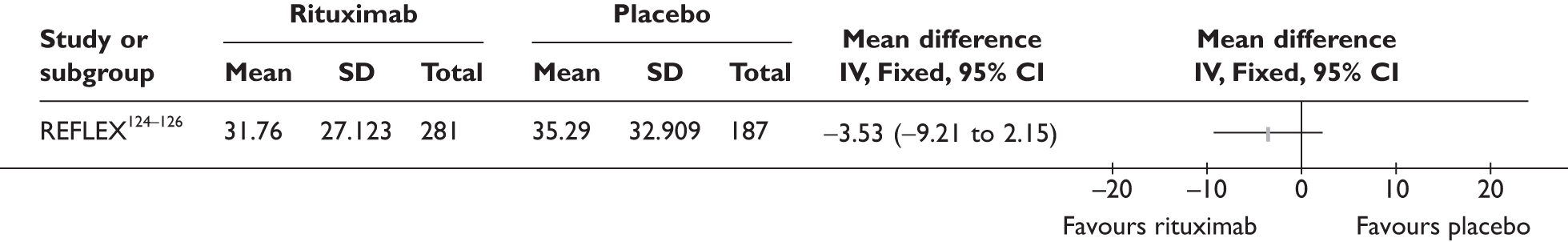

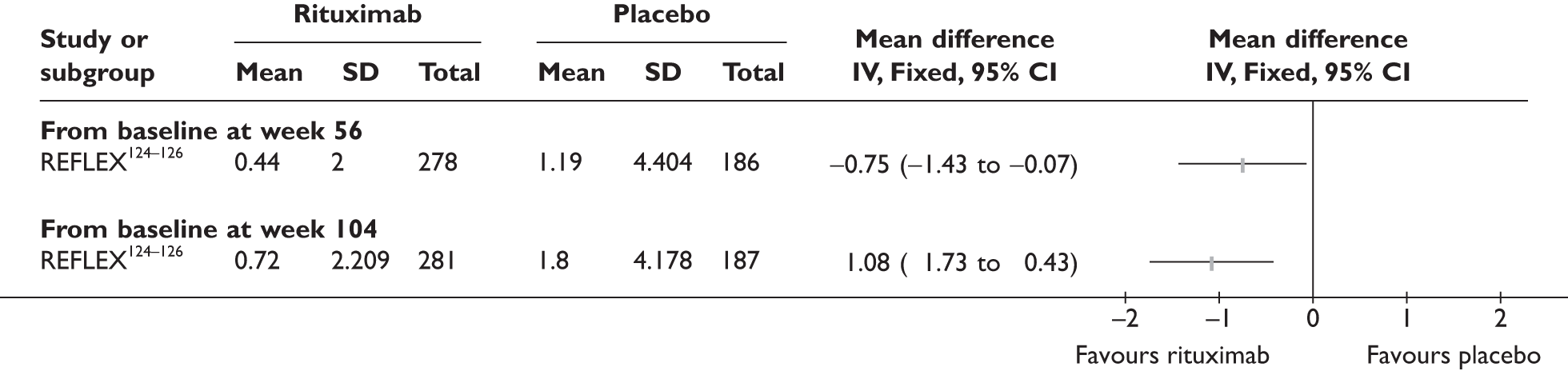

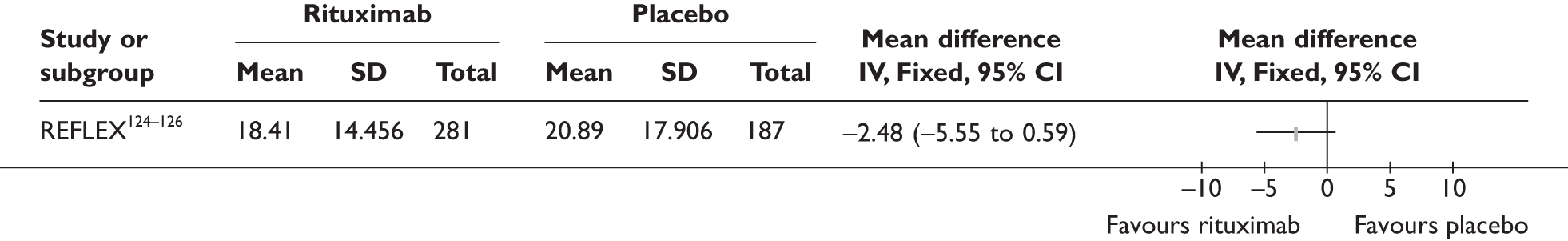

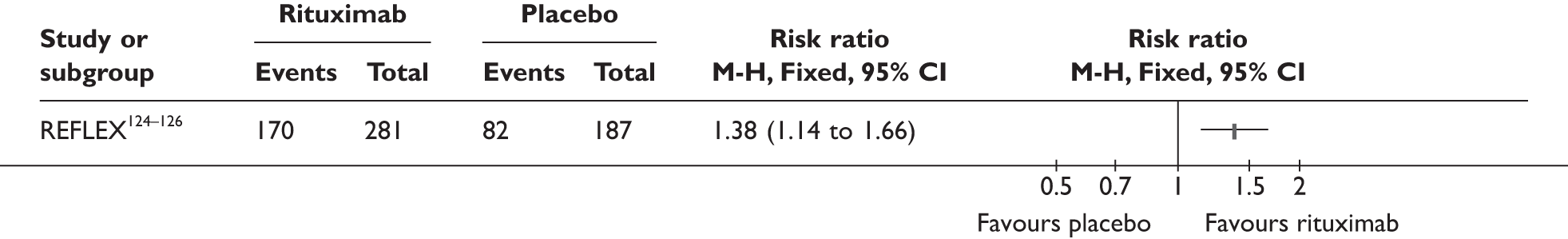

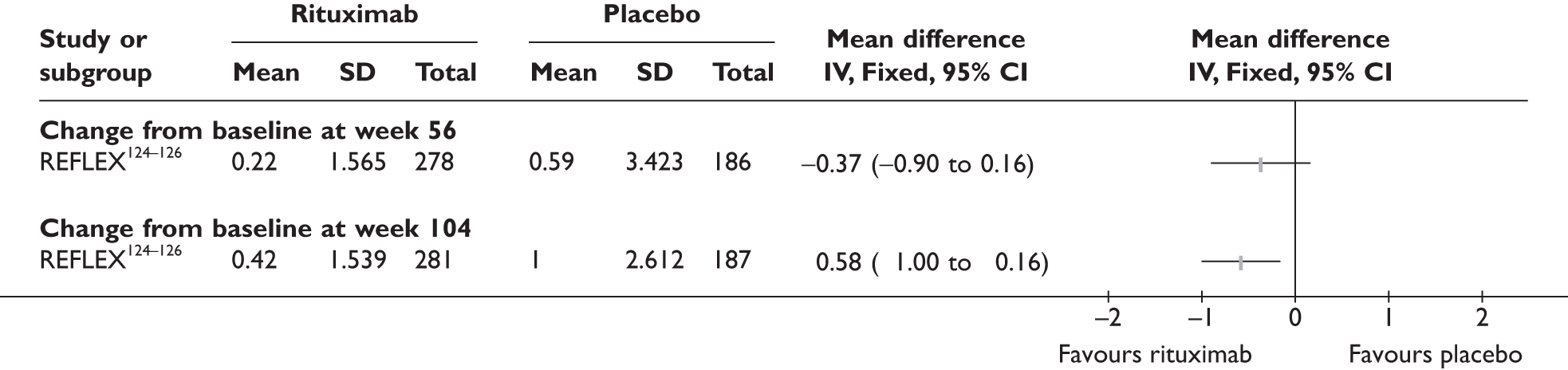

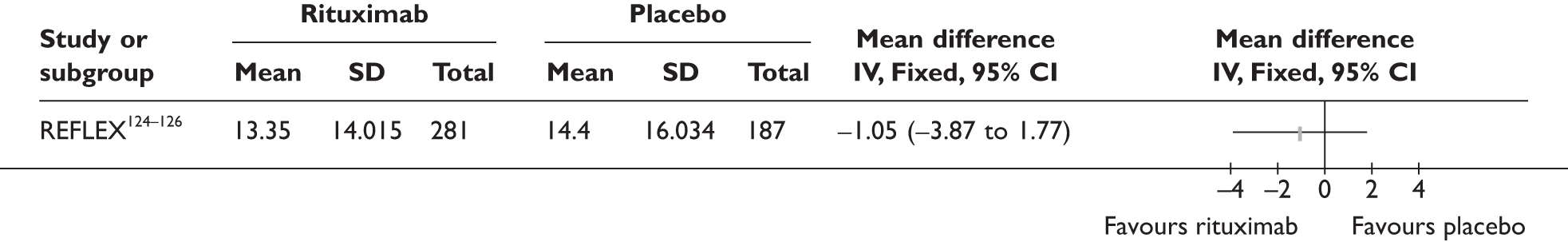

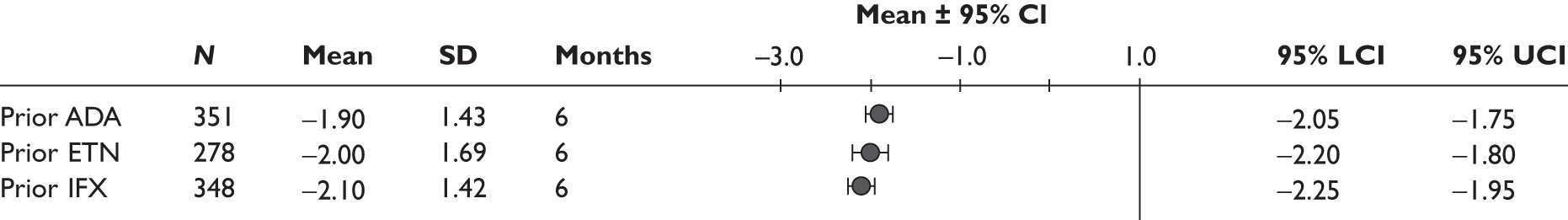

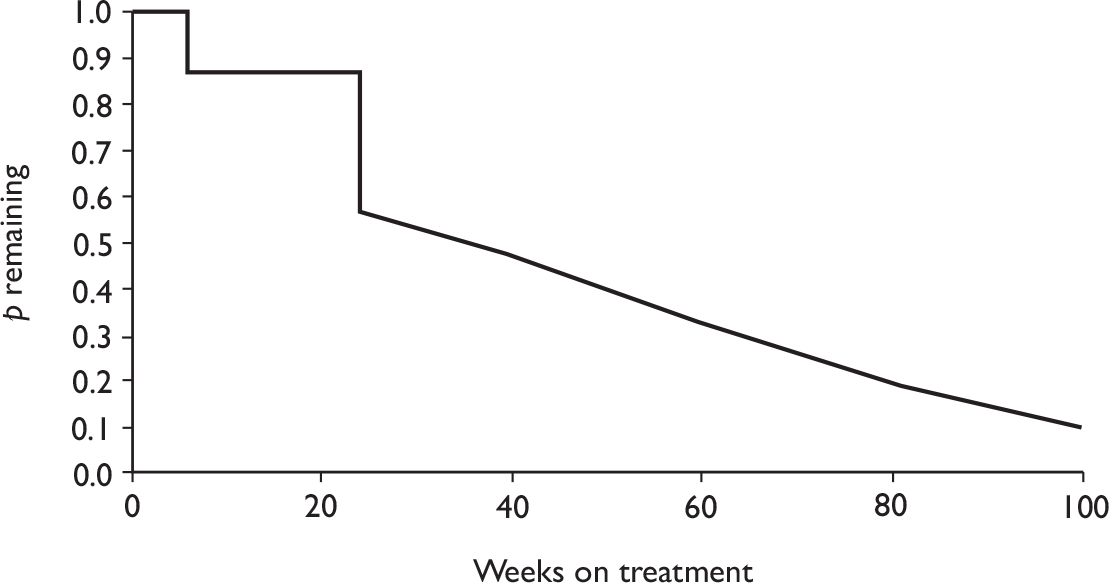

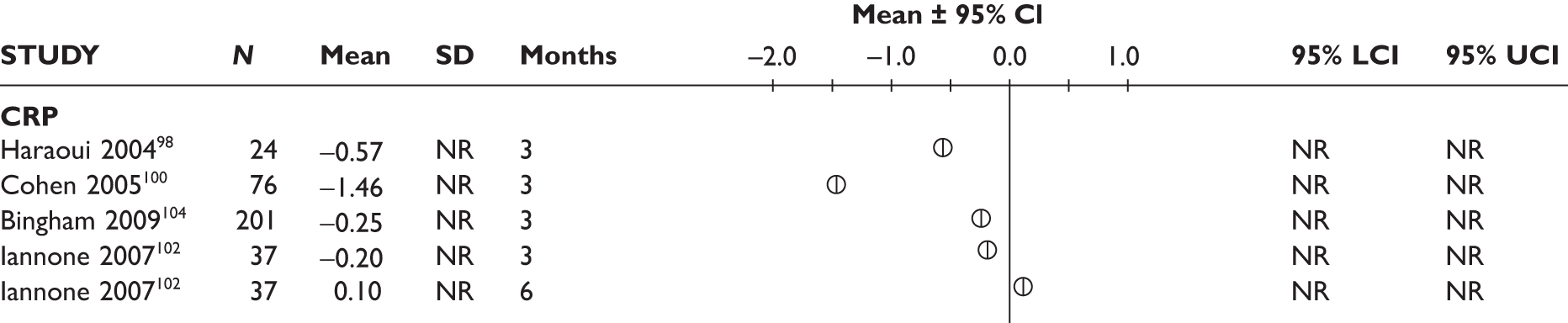

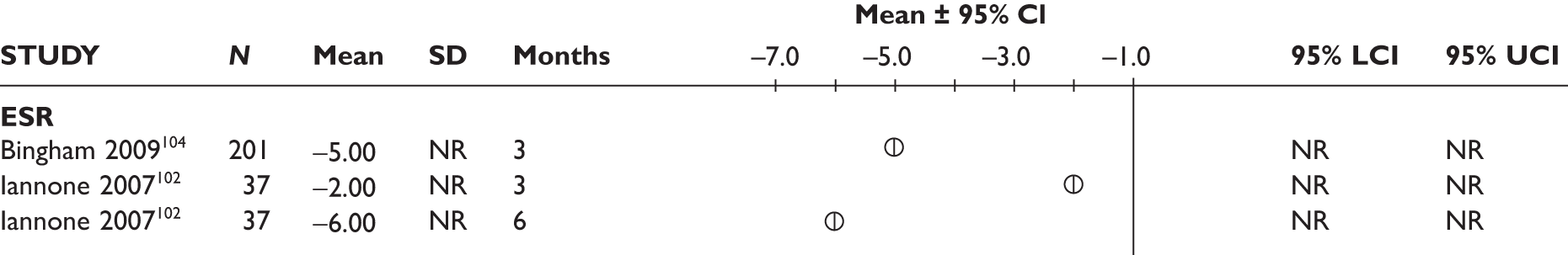

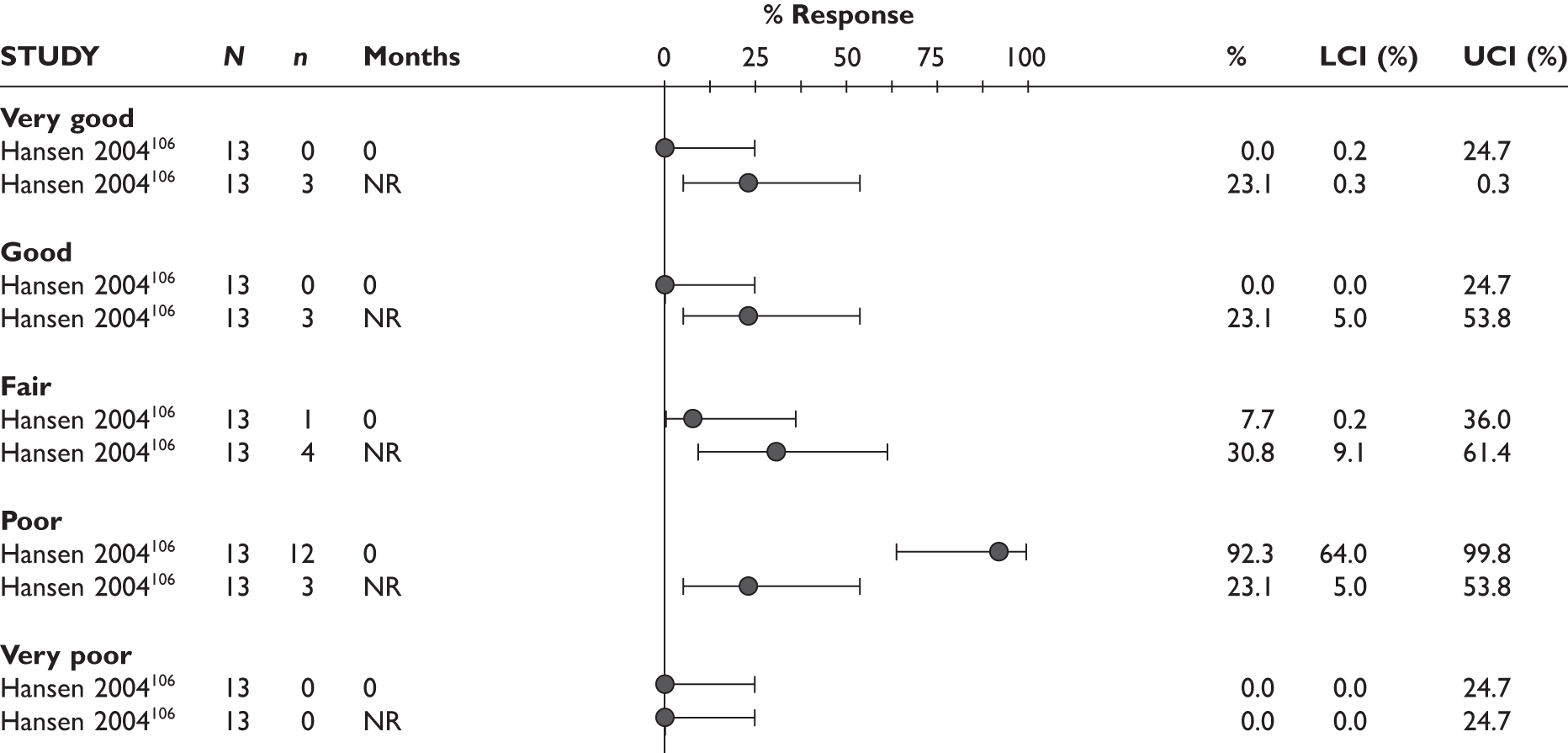

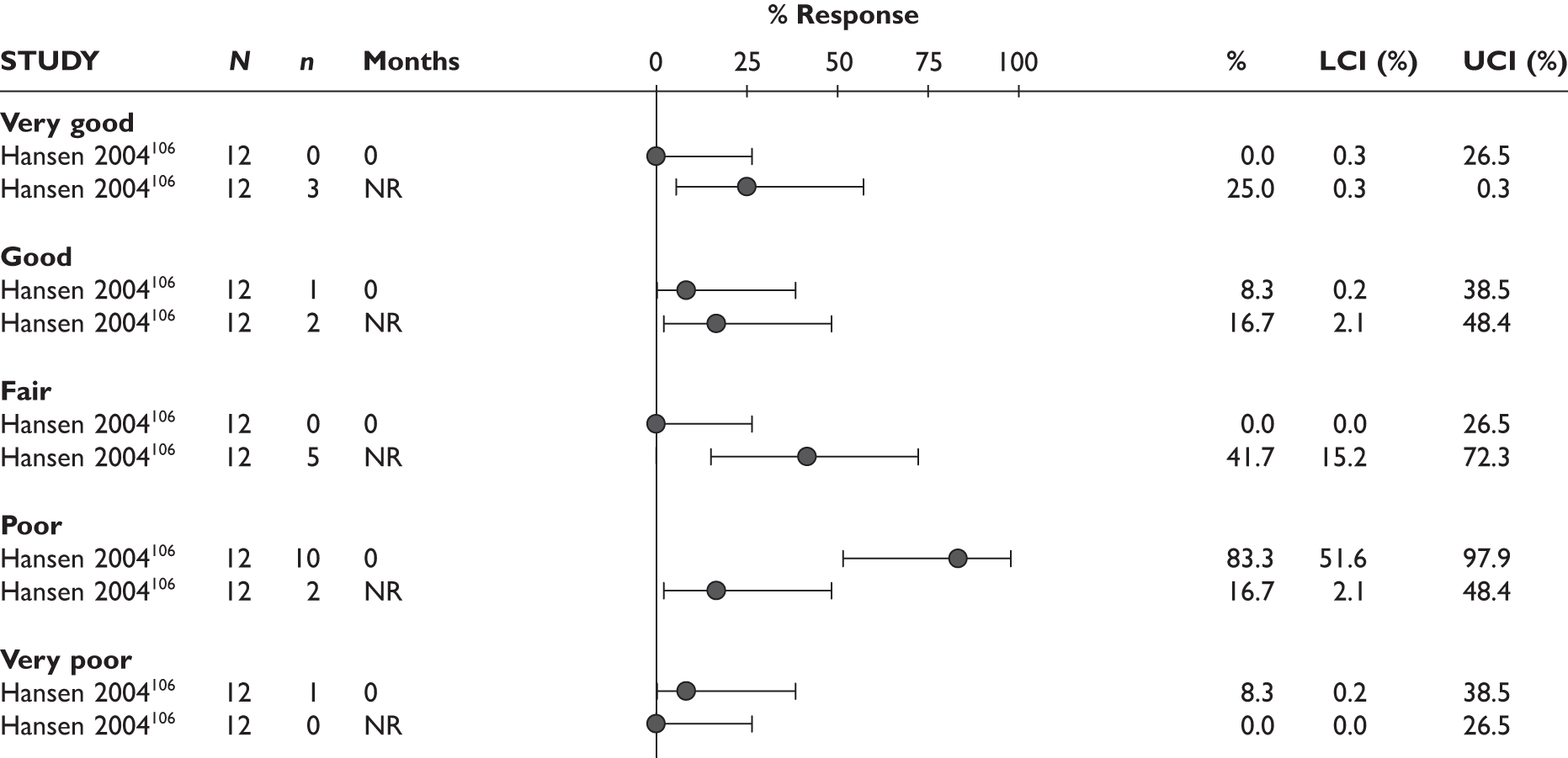

Injection site reaction/infusion reaction