Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/18/01. The contractual start date was in August 2011. The draft report began editorial review in September 2012 and was accepted for publication in April 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Note

this is a ‘short report’ that has been produced with only one-third of the resources that would be available for a full technology assessment report and it cannot be as comprehensive as a full report would be.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Waugh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

People can have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with none of the classical symptoms, such as the passing of larger volumes of urine (polyuria) and thirst. Some may have had some symptoms when diagnosed, but have not recognised them as due to diabetes.

Sometimes by the time people are diagnosed with diabetes, they have developed complications such as retinopathy, due to an effect of diabetes on small blood vessels (microvascular disease). About half of the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) recruits had some sign of complications at entry, mostly retinopathy in 36%,1 although the proportion who have retinopathy at diagnosis is now lower than in past studies, with only about 2% having referable retinopathy at first screening. 2 (Note that patients who had established macrovascular complications, such as angina, were excluded from UKPDS.)

However, the main risk to health in undiagnosed T2DM is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), in particular ischaemic heart disease (IHD), because of damage to the arteries (macrovascular disease). Indeed, the first manifestation of diabetes could be a heart attack, often fatal.

Early detection of diabetes would lead to measures to reduce the risk of heart disease, such as the use of statins to lower cholesterol, and treatment for raised blood pressure (BP), as well as reduction of blood glucose levels, initially by diet and exercise, and supplemented with glucose-lowering drugs if necessary.

It is known that a proportion of people with T2DM are undiagnosed. In the age group of 52–79 years, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)3 in 2004–5 found that almost 20% of those with diabetes were undiagnosed, with a higher percentage in men (22%) than women (12%). The overall prevalence was 9.1%, with 1.7% undiagnosed. Predictors of undiagnosed diabetes included body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and triglycerides. Diagnosis was based on a single fasting plasma glucose (FPG) value of ≥ 7.0 mmol/l and would therefore miss those whose diabetes is manifested mainly by postprandial hyperglycaemia.

The authors of the ELSA study3 note that the proportion undiagnosed has fallen, and attribute this to increased opportunistic screening in general practice.

The results from the pilot screening programme in England support this, with an overall prevalence of 4.08%, including 0.54% undiagnosed. However, uptake of screening was only 61%4 and the non-responders might have had a higher proportion with undiagnosed diabetes.

Prevalence

The increase in reported prevalence of T2DM depends on a number of factors, including:

-

An increase in the incidence of T2DM, related to rising levels of overweight and obesity. Data from the Framingham study show that almost all of the increase in the USA in diabetes prevalence is in the obese category. 5

-

Demographic change – half of all people with diabetes are > 65 years of age, so an increase in the number of people over that age will increase the prevalence of diabetes.

-

A fall in the age at onset of T2DM – people contracting diabetes earlier in life, probably because of earlier weight gain and reduced physical activity compared with previous generations. 6

-

Changes in the definition of diabetes, with the diagnosis made at a lower level of FPG.

-

Better survival with diabetes because of improved control of blood glucose level, hypertension and cholesterol level.

-

More complete recording of diabetes on general practitioner (GP) computer systems.

-

Better detection of undiagnosed diabetes by opportunistic case-finding or practice-based screening, linked with greater public awareness of diabetes.

The York and Humber Public Health Observatory (YHPHO) diabetes report7 estimated that 40% of the rise in crude prevalence was due to changing age and ethnic group structure, and 60% to obesity and overweight.

The prevalence of T2DM is closely linked with that of overweight. The proportion of the population that is overweight or obese (BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2) has been increasing in recent years.

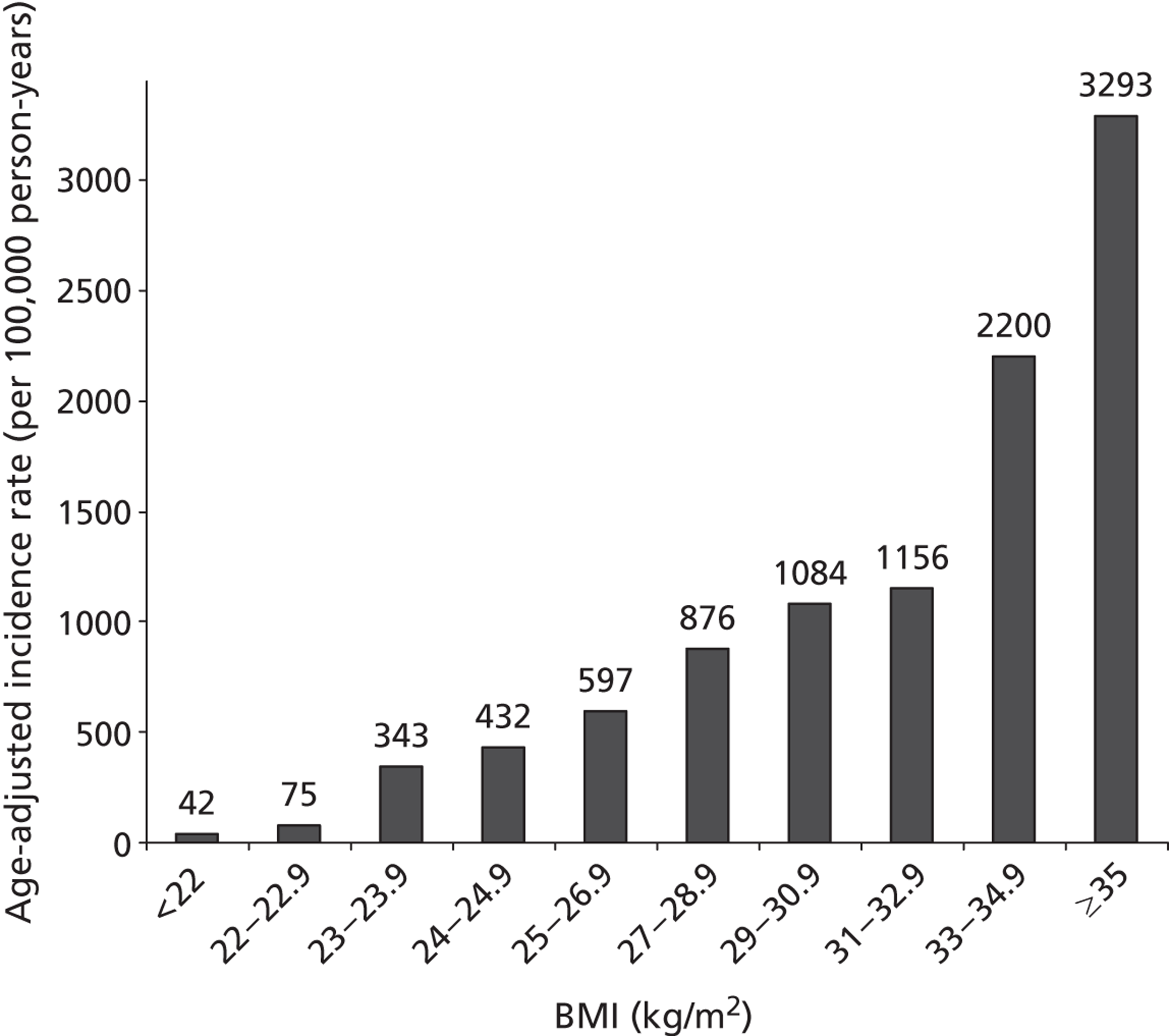

The importance of BMI in the incidence of T2DM is shown in Figure 1. There is a close relationship between BMI and the incidence of T2DM, and it is worth noting that it starts well below the obesity range.

FIGURE 1.

Age-adjusted incidence rates of diabetes as a function of baseline BMI in 30- to 55-year-olds (both sexes), based on data from Ford et al. (1997). 8

In the Cambridge centre of the ADDITION (Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study in General Practice of Intensive Treatment and Complication Prevention in Type 2 Diabetic Patients Identified by Screening) study, high proportions of people with screen-detected diabetes had risk factors for CVD. 9 Almost all were overweight or obese (mean BMI = 32.5 kg/m2); 86% had hypertension, 75% had dyslipidaemia, and many of those with hypertension and dyslipidaemia did not have good control of BP or lipids. Hence, those detected by screening form a group in which CVD risk can be reduced by combined treatment. The ADDITION study is described in detail in Chapter 4. Another implication is that first-stage screening based on weight would identify most people with undiagnosed diabetes.

Screening

The UK National Screening Committee (NSC) has reviewed its policy on screening for T2DM at intervals. A review in 2006 was underpinned by a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report that included a systematic literature review and economic modelling of the case for population screening. 10 The HTA report found that the case for screening for undiagnosed diabetes and for IGT was becoming stronger because of greater options for the reduction of CVD and because of the rising prevalence of obesity, and hence of T2DM. (Details of methods are given in Appendix 1.)

The National Screening Committee criteria

The NSC has a list of criteria for assessing possible population screening programmes. It is usually expected that all should be met before a screening programme is introduced. 11

The last HTA report10 concluded that some criteria had not been met, including:

-

criterion 12, on optimisation of existing management of the condition

-

criterion 13, which requires that there should be evidence from high-quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showing that a screening programme would reduce mortality or morbidity

-

criterion 18, that there should be adequate staffing and facilities for all aspects of the programme

-

and possibly criterion 19, that all other options, including prevention, should have been considered; the issue here is whether or not all methods of improving lifestyles in order to reduce obesity and increase physical activity have been sufficiently tried; the rise in overweight and obesity suggests that health promotion interventions have not so far been effective.

There have been several developments since the last review that affect the case for screening.

Criteria 12 and 18

There have been some improvements that affect criterion 12. The introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework as part of changes to the GP contract in 2004 provided incentives to improve selected aspects of clinical care, including diabetes and hypertension. For example, 79% of practices were meeting the BP 5 target of the Quality and Outcomes Framework, of getting a recent BP value of < 150/90 mmHg. The audits of diabetes care in England and Wales showed that 67% (England) and 68% (Wales) of patients with T2DM had glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels of < 7.5% [note: the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines target for T2DM was 6.5%]; 69% and 61%, respectively, had BPs of ≤ 140/8 mmHg. In both countries, 78% of patients were meeting the total cholesterol target of ≤ 5.0 mmol/l, and 41% were meeting the more stringent target of ≤ 4.0 mmol/l.

However, the National Audit Office (NAO) report on adult diabetes services identifies shortcomings in care in many primary care trusts (PCTs), as reported in the following extracts. 12

7. In 2009–10, national clinical audit data found that only half of the increasing number of people with diabetes received all the recommended care processes that could reduce their risk of developing diabetes-related complications

8. Less than one in five people with diabetes are achieving recommended treatment standards that reduce their risk of developing diabetes-related complications

9. There is significant variation in the quality of care received by people with diabetes across the NHS

And:

The Department of Health has failed to deliver diabetes care to the standard it set out as long ago as 2001. This has resulted in people with diabetes developing avoidable complications, in a high number of preventable deaths and in increased costs for the NHS.

The expected 23 per cent increase by 2020 in the number of people in England with diabetes will have a major impact on NHS resources unless the efficiency and effectiveness of existing services are substantially improved.

Amyas Morse, head of the NAO, 23 May 2012

Hence, criterion 12 is far from met and the audit report also implies that criterion 18 is also not met.

Criterion 13

One trial13 of screening for diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors has been carried out in Ely in England. In this study, one-third of people aged 40–65 years, not known to have diabetes, were randomly selected and invited for screening, using the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), in 1990; 68% attended, of whom 4.4% were found to be diabetic. They were invited for rescreening for diabetes in 1994–6 and 2000–2. The results of the OGTT, and of cholesterol and BP levels, were fed back to GPs, who took whatever action they deemed appropriate. No standardised advice on diabetes management was given.

In 2000–2, half of those not invited for screening at baseline (i.e. another third) were randomly invited for screening. Uptake was lower, at 45%. The remaining third were not invited.

All participants, whether or not invited, were flagged at the Office of the Registrar General, now the Office for National Statistics, so that mortality data could be obtained.

In the 1990–9 period, the relative risk (RR) of mortality for the invited group compared with those non-invited, was 0.96 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 1.20] before adjustment for age, sex and deprivation, and 0.79 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.00) afterwards.

In the 2000–8 period, the RR for the invited group was 1.20 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.51) before adjustment and similar afterwards.

The only significant differences in mortality were between those invited who attended and those invited who did not attend – about a threefold increase in the latter. This is as expected, as those who accept screening invitations have other protective health behaviours.

In terms of morbidity, at the 13-year follow-up, health status and cardiovascular morbidity were assessed in the screened group (43% attended) and in a randomly selected and invited sample of half of those previously not screened (42% attended). There were no differences in health status or cardiovascular morbidity.

Hence, criterion 13 is not met – we have a RCT but no benefit was shown. It should be noted that the numbers of people found to have diabetes were low, so it would be difficult to show any effect of intervention in them. The ADDITION study addresses this issue and is described in detail later in this review.

Criterion 19

This criterion is about prevention.

A recent study14 examined the incidence of T2DM and concluded that about 90% could be avoided by adherence to five lifestyle factors:

-

physical activity

-

a healthy diet

-

BMI of < 25 kg/m2

-

not smoking

-

moderate alcohol consumption.

That study14 was in people aged > 65 years, but similar findings have been seen in all age groups. Similar findings were reported from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). 15 Participants were divided into six groups according to how many lifestyle goals were achieved, so that group 5 achieved all and group 0 none.

Table 1 shows the incidence of diabetes for each group, expressed as a ratio to group 0.

| Success score | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 0.85 (0.57 to 1.28) |

| 2 | 0.66 (0.40 to 1.09) |

| 3 | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.26) |

| 4–5 | 0.23 (0.10 to 0.52) |

| Test for trend p = 0.0004 |

Hence, we know what people should do to avoid getting T2DM. The problem is that we do not know how to persuade them to do it. The rising trends in obesity and overweight show that health promotion measures have so far failed.

Developments

In 2008, the NSC recommended the introduction of a Vascular Risk Management Programme in which ‘the whole population would be offered a risk assessment that could include, among other risk factors, measurement of BP, cholesterol and glucose’. The NSC concluded that: ‘targeted screening for T2DM was feasible but should be undertaken as part of an integrated programme to detect and manage vascular risk factors in certain subgroups of the population who are at high risk of T2DM’ (UK NSC, DPH Newsletter, 2008, March). 17 This policy acknowledges that the relationship between blood glucose levels and CVD is a continuous one and, therefore, the detection of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), in addition to the detection of diabetes, could be part of a programme of CVD prevention.

That programme is for England only. One effect of devolution is that policy and practice have been diverging in the four territories. Hence, different approaches to diabetes screening may emerge.

In Wales, there has been a pilot of screening in community pharmacies. This lasted for only 2 weeks but more than 17,500 people had their risk of diabetes assessed, of whom 8.4% were identified as high risk. They were referred to their GPs for further testing. 18

If we screen for diabetes, we will identify, depending on the screening strategy used and cut-offs chosen, more people with lesser degrees of hyperglycaemia, such as IGT, than with T2DM. 10 Before a screening programme is started, we should therefore consider how best to manage such people. Another HTA review19 was commissioned to examine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to prevent or reduce progression to diabetes in people with IGT. It is summarised in Chapter 5, with details of methods provided in Appendix 1.

This report builds on and updates these two HTA reports, produced for the Department of Health (England) and the NSC by the Aberdeen Health Technology Assessment Group and colleagues in the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) in Sheffield. It also draws on a research review, carried out by the former Diabetes and Health Technology Assessment Group in the Department of Public Health in the University of Aberdeen, to support a working group of the Scottish Public Health Network (SPHN) set up to review screening and prevention of T2DM. The report of the working group is available on the SPHN website (www.scotphn.net) and its remit and conclusions are given in Appendix 1. We have reviewed studies published since these reports were undertaken, to update the evidence base.

What should we be screening for?

Diabetes is defined on the basis of high blood glucose levels. The key feature of the classification is that the diagnosis is based on the level at which the risk of retinopathy starts. At the risk of a little oversimplification, people with glucose levels below the threshold do not get retinopathy; those with levels above the threshold are at risk of retinopathy, with the risk increasing as glucose levels rise further. This was based on three studies, described in the report of the expert committee of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). 20 A very large recent study from the DETECT-2 (Evaluation of Screening and Early Detection Strategies for Type 2 Diabetes and Impaired Glucose Tolerance) Group21 also found clear thresholds for moderate retinopathy of 6.5 mmol/l for FPG and 6.5% for HbA1c. The threshold for the 2-hour plasma glucose (PG) level was less distinct, at around 10.1–11.2 mmol/l.

The DETECT-2 Group21 used ‘moderate retinopathy’. Some retinopathy, such as microaneurysms only, has been reported in IGT from the Diabetes Prevention Program. 22

However, the risk of heart disease increases at lower levels of hyperglycaemia than diabetes. So for public health purposes, there could be advantages in having screening for diabetes done as part of assessment of cardiovascular risk and the English vascular risk assessment programme provides an opportunity for that.

Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance

In IFG, FPG is above the upper limit of normal but below the diabetes level of 7.0 mmol/l. The European definition uses a cut-off for FPG of 6.1 mmol/l. In the USA the cut-off for IFG is 5.5 mmol/l. The European definition omits a group with FPG above normal (up to 5.4 mmol/l) but < 6.1 mmol/l.

Impaired glucose tolerance is defined as a postload level of > 7.8 mmol/l but < 11.1 mmol/l.

These conditions are often referred to as ‘pre-diabetes’, but this term is somewhat misleading because under half go on to get diabetes. However, those with IGT are at increased risk of vascular disease compared with people with normal glucose tolerance (NGT).

One issue is about the value of categorisation. With continuous variables such as PG, subdividing the range into categories such as IGT is always somewhat arbitrary. Chamnan et al. (2011)23 from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Epidemiology Unit in Cambridge have made a convincing case for using hyperglycaemia as a continuous variable as part of overall cardiovascular risk assessment. They point out that someone with HbA1c in the IGT range (6.0–6.4%) but no other raised CVD risk factors, will have a much lower risk than someone with a HbA1c level ≤ 5.5% but high values for other risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

Microvascular disease, such as retinopathy, is specific to diabetes. However, the macrovascular disease seen in diabetes is broadly the same disease as seen in people without diabetes. The difference in diabetes is an increased risk and a more diffuse distribution of arterial disease. They are more likely to die after a heart attack than people without diabetes. This is particularly important as the heart attack may occur without any prior warning of heart disease, such as angina.

The increase in cardiovascular risk starts below the level of blood glucose used to define diabetes, so if reduction of heart disease is one of the aims of screening, we should consider screening not just for diabetes, but also for IGT. The risk of CVD in IGT is slightly less than with T2DM, but the number of people with IGT is much higher than those with undiagnosed diabetes, and so the cardiovascular population impact of IGT is much greater than for undiagnosed diabetes [for a review, see Waugh et al. (2007)10].

The importance of large vessel disease can be seen in the end points reported in the UKPDS. 24 The majority of adverse events were due to large vessel disease.

If we are considering screening based on risk factors then those in the UKPDS who were overweight (defined as > 120% ideal body weight for height) may be more similar to those who would be found by screening. As in the total UKPDS group, the end points in the control group were dominated by large vessel disease, with 157 macrovascular end points and 19 microvascular ones in the control group of 411 patients. 25

The risks of CVD in those with IFG and IGT have been reported to be higher than in people with normal glucose levels. Table 2 shows results from the DECODE (Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative Analysis of Diagnostic Criteria in Europe) meta-analysis.

| FPG and 2-hour PG levels both normal | 1.0 |

| IFG – raised FPG but 2-hour PG levels normal | 1.18 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.42) |

| IGT alone – raised 2-hour PG levels but normal FPG | 1.56 (95% CI 1.33 to 1.83) |

Hence IFG alone, without IGT, is associated with a slight increase in mortality [although CIs overlap with no increase], but IGT carries more risk, possibly as a consequence of stronger associations with hypertension and dyslipidaemia than for IFG. The risk of CVD is also more closely related to the 2-hour PG than FPG, even in people with normal glucose levels. 27

Similar findings were reported from a meta-analysis by Coutinho et al. (1999)28 of 20 studies examining cardiovascular mortality (19 studies) or morbidity (four studies). A FPG level of 6.1 mmol/l carried 1.3 times the risk of the reference one of 4.2 mmol/l; a 2-hour glucose level of 7.8 mmol/l carried a RR of 1.6 compared with a 2-hour PG level of 4.2 mmol/l.

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration study,29 which had data from 698,782 people, also found that IFG had little effect on cardiovascular risk, with RRs of 1.11 for the 5.6 to < 6.0 mmol/l range and 1.17 for the 6.0–6.9 mmol/l range.

More recent work has suggested that the excess risk from IGT is lower than previously thought. A meta-analysis by Sarwar et al. (2010)30 reported a RR of 1.05 for every 1-mmol/l increase in postload glucose. They found a stronger link between HbA1c level and coronary heart disease (CHD), with a RR of 1.2 for every 1% rise in HbA1c.

The meta-analysis included early data from the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab) study, but at a time when there were only 31 CHD cases. A later paper from AusDiab, by Barr et al. (2009)31 reported a linear relationship between HbA1c level and CHD mortality, with the risk at HbA1c 6% being double that at 4.5%. The Edinburgh Artery Study, reported by Wild et al. (2005)32 was not included in the meta-analysis. Wild et al. (2005)32 reported that isolated postload hyperglycaemia conferred little increase in cardiovascular risk.

The Hoorn study33 from the Netherlands found the reverse – postload hyperglycaemia in the IGT range was associated with an RR of 1.48, but the number of events was small and the 95% CI was 0.7 to 3.2. FPG in the IFG range was associated with a RR of 1.4, but, after adjustment for factors including hypertension and lipids, the RR was reduced to 1.07 (the same adjustment reduced the IGT RR from 1.9 to 1.48).

In the Rancho Bernardo study, Barrett-Connor et al. (1998)34 found that the risk of cardiovascular mortality was increased in women with isolated postchallenge hyperglycaemia [age-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 2.6, 95% CIs 1.5 to 4.8] but not in men (age-adjusted HR 0.7, 95% CI 0.3 to 1.6). The point estimates for the Edinburgh Artery Study32 participants were similar, with odds ratios (ORs) for cardiovascular mortality of 2.7 (95% CI 0.6 to 11.6) for women and 0.8 (95% CI 0.09 to 6.7) for men. However, a Paris study35 found that the heart disease mortality rate in men with normal fasting glucose but IGT was three times that of those with NGT.

IGT is common – it affects 17% of Britons aged 40–65 years. 36

Unlike with retinopathy, there is no sudden inflexion in the risk curve for CVD according to blood glucose levels, but rather a continuum of risk. Indeed, even within what is regarded as being the normal range, higher blood glucose levels have higher IHD rates. In the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) study in Norfolk,37 the relationship between HbA1c and cardiovascular risk started well within the non-diabetic range (Table 3).

| HbA1c band (%) | RR of CVD | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| < 5 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 5–5.4 | 1.23 | 0.89 |

| 5.5–5.9 | 1.56 | 0.98 |

| 6.0–6.4 | 1.79 | 1.63 |

| 6.5–6.9 | 3.03 | 2.37 |

| > 7 (newly diagnosed diabetes) | 5.01 | 7.96 |

| Prior diabetes | 3.32 | 3.36 |

However, in a more recent paper from the EPIC-Norfolk study, Chamnan et al. (2011)23 report that the risk associated with hyperglycaemia across the whole range, from just above normal to diabetes, depends more on associated risk factors. They analysed data from a subgroup of 10,144 subjects whose had HbA1c level had been measured. The subgroup arose because funding of HbA1c testing was not initially available so no particular bias arises. All subjects were free of CVD at baseline, and were followed up for 10 years through linkage with mortality and hospital admission data. The CVD event rates per 1000 person-years were for bands of baseline HbA1c:

-

< 5.5% 7.0

-

5.5–5.9% 12.3

-

6.0–6.4% 16.5

-

diabetes 28.9.

The authors report that each 1% increase in HbA1c level increased the risk of CVD by 27%, and that individuals with HbA1c levels of ≥ 6.5% were more than twice as likely to have an event as those with HbA1c levels of < 5.5%. These figures do not appear to match the event rates above.

Chamnan et al. (2001)23 give RRs for different bands, taking a HbA1c level of < 5.5% as the reference of 1.0. RRs were 1.31 for HbA1c band 5.5–5.9%, 1.50 for 6.0–6.4%, 2.19 for 6.5–6.9% and 3.21 for ≥ 7%. These are somewhat different from the Khaw et al. (2004)37 results.

Notably, the risk associated with different bands was determined more by the presence of other CVD risk factors, so that people with a low HbA1c level but other risk factors had higher CVD risk than someone with a high HbA1c level but no other raised CVD factors. This is reminiscent of an earlier study from this group,38 which showed that adding HbA1c value to the Framingham score added little to the predictive value.

Chamnan et al. (2001)23 therefore argue against basing management on defined categories such as IGT, and suggest that risk factors such as PG, BP and lipid levels are continuous variables. They recommend that management should be based on an overall assessment of cardiovascular risk.

In a 2009 paper, Chamnan et al. (2009)39 reported the findings of a high-quality systematic review of risk scores for CVD in people with diabetes. Their main findings were, in brief:

-

Scores were developed for different purposes: ranking of risk to determine priority for treatment (especially when statins were introduced); assessing the potential absolute benefit of treatment; and motivating patients to change behaviour.

-

They identified 17 scoring systems, but that number included five variants of the Framingham score and two of a Hong Kong system.

-

Eight scores were developed in diabetes populations, and five of these [UKPDS, DARTS (Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland), Swedish National Diabetes Register, ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study) and Hong Kong] included HbA1c level.

-

Most scores developed in general population groups had diabetes as a binary variable.

-

Most of the scores developed in general populations underestimated CVD risk in diabetic groups, with underestimates ranging from 11% to 64%.

-

However, in populations with low CVD risk, scores overestimated CVD risk.

As noted above, the addition of diabetes or HbA1c to the score had only modest effect, because it carries less weight than age, cholesterol level, BP and smoking.

These findings have an implication when considering screening for T2DM. Much of the benefit in detecting undiagnosed diabetes comes from treatment of associated metabolic conditions, such as hyperlipidaemia and hypertension. So the better controlled those conditions are in the general population, including those with undiagnosed diabetes, the less there is to gain by detecting diabetes.

Further evidence on the associations between hyperglycaemia and cardiovascular risk comes from the Telde study from Spain,40 which compared risk factors in four groups – NGT, IFG, IGT and combined IFG and IGT – recruited from a population-based study. Novoa et al. (2005)40 reported that, compared with the NGT group, the other three had higher proportions with hypertension, high BMI, higher triglycerides and higher insulin levels, reflecting insulin resistance.

Even when fasting and 2-hour postload glucose levels are within the normal range, there are associations with cardiovascular mortality. Ning et al. (2005)27 from the DECODE study group showed that those with the highest (but still normal) 2-hour glucose levels had insulin resistance and increased cardiovascular mortality.

There is also a relationship between HbA1c level and peripheral vascular disease. Muntner et al. (2005)41 report data from the 1999–2002 NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). The data shown in Table 4 follow multivariate adjustment. Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) was defined as an ankle–brachial BP ratio of < 0.9.

| HbA1c band (%) | RR of peripheral arterial disease |

|---|---|

| < 5.3 | 1.0 |

| 5.3–5.4 | 1.41 |

| 5.5–5.6 | 1.39 |

| 5.7–6.0 | 1.57 |

However, CIs were wide and only the last figure had a 95% CI that did not overlap with 1.0.

Decision point

Hence, if one aim of screening is to reduce heart disease, we should look not only for diabetes, but also for IGT. Even if we did look only for diabetes, we would identify many with IFG and/or IGT, depending on which test was used and what cut-offs were chosen.

The aims of treatment might be:

-

For those with definite diabetes, reduction of the risk of retinopathy and nephropathy, by reduction of PG, initially trying diet and exercise, but using drug therapy when indicated.

-

For those with PG levels in the IFG and IGT ranges, prevention of progression to diabetes, by diet and exercise, or by drug therapy (metformin) if indicated.

-

For all of the above, measures to reduce cardiovascular risk, by measures other than the glucose control ones already mentioned, such as qualitative improvements in diet, cholesterol-lowering measures (such as statins), BP control and anti-obesity measures.

There could be large implications for workload and costs. About 0.5% of the population may have undiagnosed diabetes, but there may be 10% with IGT. Before any screening was started, there would need to be careful planning of workload, involved in both screening and follow-up. Screening might be introduced in a phased manner in order to avoid overload.

Chapter 2 Screening strategies and tests

The strategies to be considered will vary according to what is done at present.

Should screening be selective or universal over the age of 40 years?

It is assumed that screening will be selective by age because T2DM is much less common in younger age groups. The first question is whether or not other selection criteria should be applied. Given the link between T2DM and overweight, the obvious next criterion is BMI.

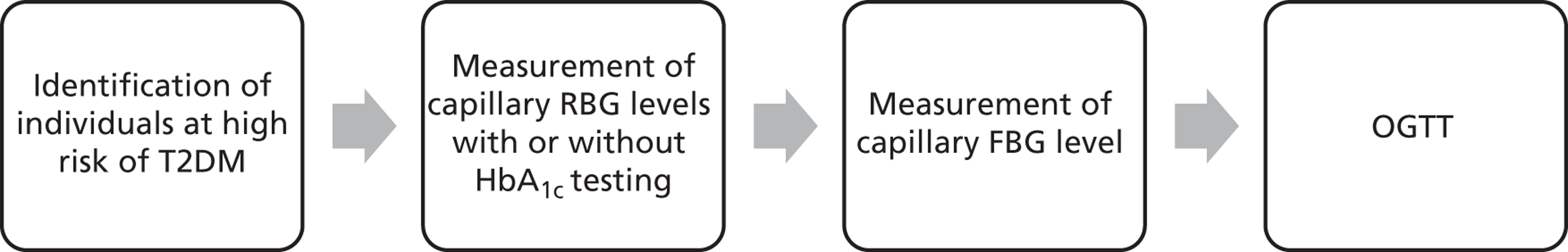

Organised screening could be a three-stage process, with the first stage being selection from the general population (using general practice registers or self-completed questionnaires) of those likely to be more at risk than average, the second being testing of blood glucose levels, and the third being confirmation (or not) of raised blood glucose level.

Testing only people who are at higher than average risk means that a higher proportion of those who will be tested for glucose will be positive. The number needed to screen to detect each true-positive will be lower, and the whole programme will be more cost-effective. However, the distribution of risk needs to be considered. As the risk threshold is raised, the proportion of those with diabetes will rise, but the absolute number detected may fall. Because of the shape of the distribution curve, most people with undiagnosed diabetes may be in the middle risk band.

Many risk-scoring systems have been used around the world5,42 based on different questionnaires. Risk factors were listed by Paulweber et al. (2010)43 in an analysis to support development of European guidelines. This analysis identified both non-modifiable and modifiable factors, listed in Table 5.

| Non-modifiable risk factors | Modifiable risk factors |

|---|---|

| Age | Overweight and obesity |

| Family history/genetic predisposition | Physical inactivity |

| Ethnicity | Disturbances in intrauterine development/prematurity |

| History of GDM | IFG/IGT |

| POS | Metabolic syndrome |

| Dietary factors | |

| Diabetogenic drugs | |

| Depression | |

| Obesigenic/diabetogenic environment | |

| Low socioeconomic status |

Different risk scores seem to have different specificity and sensitivity. The commonly used Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) score is based on a sample from the population in Finland. This scorecard predicts the probability of T2DM development over the following 10 years. It uses information such as age, BMI, sex, antihypertensive medication history and some lifestyle factors. This risk score has high sensitivity towards undiagnosed diabetes. It has been validated both in Germany44 and Italy. 45

Risk factors

Age has been mentioned above. The cost-effectiveness of screening will be lower at younger ages, as the number needed to be screened to find each case will increase and also because the event rate from CVD will be lower. However, although the prevalence of diabetes is greater in the older age groups, the excess mortality may fall. Tan et al. (2004)46 found that in men diagnosed with T2DM, aged > 65 years, in Tayside, there was no excess mortality compared with the general population. The situation in women was different, with a RR of death of 1.29 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.45). The implication of this might be that if the main aim of screening is to reduce heart disease mortality and morbidity, screening for diabetes in men should not include the over-65s. However, if the aim is to detect undiagnosed diabetes, we should screen older age groups – perhaps to the age of 75 years.

The age at which screening should start has been debated. Kahn et al. (2010)47 modelled a range of screening strategies based on a US population, starting at ages 30, 45 and 60 years, or at diagnosis of hypertension, and found that the lowest costs per quality-adjusted-life year (QALY) were obtained by starting at age 45 years or at diagnosis of hypertension, and screening at 3-or 5-yearly intervals. In practice, the age at which screening will start will be determined by each health department, with the age threshold in England being determined by the Government's decision on the vascular screening programme.

Body mass index is the second factor. The risk of T2DM is greatly increased by excess weight. But there is also a link with the distribution of body fat, with abdominal (especially visceral) fat distribution carrying a higher risk. Waist measurement could be used as a risk factor – for example, > 40 inches in men or > 35 inches in women. However, waist data are unlikely to be held on GP computer systems.

Comorbidities affect risk. The risk of diabetes is associated with other metabolic conditions, such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, and with the presence of vascular disease, such as PVD or IHD. There will be data on comorbidities on GP systems, even if just the fact of prescriptions for antihypertensive or lipid-lowering drugs or steroids.

A family history of diabetes, or of premature vascular disease or hypertension, also increases the risk.

Some ethnic groups have a higher risk of T2DM than others, although this is less if adjustments are made for BMI and fat distribution. In the Manchester survey48 the prevalence of known diabetes in a poor inner city area was 8% and 3.7% in European men and women, and 14% and 18.2% in Pakistani men and women. The Pakistani women had higher BMI than the Europeans – 29.6 kg/m2 compared with 27.2 kg/m2, respectively – and a higher waist–hip ratio – 0.88 compared with 0.81, respectively. Pakistani and European men had similar BMIs (27.4 and 27.5 kg/m2, respectively) but the Pakistani waist–hip ratio was higher [0.96 (95% CI 0.94 to 0.97) vs 0.92 (95% CI 0.92 to 0.94), respectively]. However, the most striking differences were in physical activity. The proportions taking at least 20 minutes of exercise three times a week were 38% and 29% for European men and women, and 7% and 5% for Pakistani men and women, respectively. Physical activity reduces insulin resistance even if there is little or no weight loss.

Risk-scoring systems

There are various scoring systems. The Finnish questionnaire-based system, FINDRISC, includes age, BMI, waist measurement, physical activity, diet (vegetable, fruit and berry consumption), treatment for hypertension, any previous hyperglycaemia and family history. 49

It might be easier if we could use a smaller set of indicators, and there would be little difference in predictive power, as age and BMI provide most of that. 50

One advantage of using a smaller set of risk indicators is that computer systems in general practices will usually have the necessary data – certainly age, drug treatment, comorbidities and, usually, BMI. They are less likely to have family history, and probably will not have waist measurements. But it means that the first stage of any screening system could use existing data at little extra cost.

One scoring system using data that should be available on GP systems was developed by Hippisley-Cox et al. (2009),51 and comprises the following factors: ethnicity, age, sex, BMI, smoking, family history of diabetes, Townsend deprivation score, treated hypertension, CVD and current use of corticosteroids. It was developed using the QResearch database (Version 19; University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK ) and is known as the QD score. The authors report receiver operating characteristic (ROC) statistics of 0.85 for women and 0.83 for men for detection of diabetes. The results indicate that people from South Asian ethnic groups have different risk factors. These include different lifestyle habits, particularly smoking, along with a family history of diabetes. These factors make them more vulnerable to getting diabetes earlier in life than Caucasians, with a four- to fivefold variation in risk among different ethnicities. So ethnicity should be included in the risk evaluation.

There has been an independent validation of the QD score by Collins and Altman,52 which reported that it performed well in distinguishing between those who develop diabetes and those who do not.

Other scoring systems include the Cambridge Risk Score (CRS), again based on data available in GP systems (see Appendix 2). 53 Those in the highest quintile of the CRS had 22 times the risk of diabetes as those in the lowest quintile, and 54% of incident cases were in the top quintile. 50 It takes into account ethnicity. This score is also validated in the Danish population. 54

Body mass index is probably the single most powerful factor, and other factors may add much less to the detection rate. One review of risk scores by Witte et al. (2010)55 for predicting undiagnosed diabetes concluded that a combination of age and BMI was as good as more complex scores. However, if all of the data are on GP systems, then they may as well be used.

A very thorough systematic review of risk-scoring systems by Noble et al. (2011)56 identified 145 risk prediction models, and described 94 in detail. They noted that almost 7 million people had been in risk-scoring studies, with ages ranging from 18 to 98 years, and follow-up ranging from 3 to 28 years. They estimated that risk scores for diabetes were appearing at a rate of one every 3 weeks. Noble et al. (2011)56 set out to look for scores that were ‘sufficiently simple, plausible, affordable and widely implementable in clinical practice’. They noted that some scores included expensive laboratory biomarkers.

Noble et al. (2011)56 applied a set of quality criteria to the scores. These were:

-

generalisability external validation by a separate research team on a different population

-

statistically significant calibration i.e. that predictions match observations

-

discrimination that the score reliably distinguishes high-risk people from low-risk people

-

usability defined as the score having 10 or fewer components.

They noted that there were two broad categories of score: those that were completed by people themselves, based on questionnaires, and those that were based on data held by health-care providers such as GPs.

Noble et al. (2011)56 did not recommend any one system, making the point that the choice would depend on local circumstances. However, they did identify seven very good systems. These included two from the UK, the CRS and the QD score. In terms of area under ROC curves (AUROCs), the QD score came out better, with external validation AUROCs of 0.80 for men and 0.81 for women, compared with the Cambridge AUROC of 0.72. It should be noted that AUROCs can be altered by changing thresholds for positivity. The Cambridge score of 0.72 uses a threshold of 0.38.

Both of these scores include age, sex, family history of diabetes, BMI, current use of corticosteroids, treatment for hypertension and smoking. The QD score adds ethnicity, deprivation score and CVD. All of the QD components should be on GP computer systems.

Hence, if screening for T2DM in the UK was to be based in primary care and to use a first stage of selection by risk, the QD score seems best.

Another of the Noble et al. (2011)56 ‘top seven’ scores was FINDRISC, which has been validated in a UK population. So if screening in the UK or part thereof was to be based on self-scoring by completion of questionnaires, then FINDRISC could be used. The cut-off might be 12, based on ROC curves from a study by Martin et al. (2011)57 of Munich, Germany. Martin et al. (2011)57 measured HbA1c levels in 12,773 blood donors of whom almost 8% scored 12 points or more in the FINDRISC questionnaire and had HbA1c values of ≥ 5.6%. The 8% and age- and sex-matched controls were invited for an OGTT. Unfortunately, only about 10%, 671 participants, came for the OGTT, some citing reasons such as time costs.

Using a FINDRISC score of 12 as the cut-off, over half had some degree of impaired glucose regulation (IGR) in the OGTT: 9.7% diabetes, 32.6% IFG, 5.7% IGT, 11.8% both IFG and IGT, and 40% having normal glucose levels. Martin et al. (2011)57 compared the percentages of those with diabetes in two FINDRISC subgroups: medium risk, with scores 12–14, and high risk, with scores ≥ 15. Half (31) of the newly diagnosed group were in the high-risk group and 40% in the medium-risk group. The proportions with IFG, IGT or the combination were similar in the medium- and high-risk groups.

Martin et al. (2011)57 state that:

The high acceptance of the FINDRISC questionnaire and the HbA1c testing contrasted with the rather low number of participants that were willing to participate in the OGTT. This finding indicates that simple screening procedures are necessary to achieve compliance and that the OGTT is not attractive for people who would otherwise be accessible for diabetes screening.

They conclude that a combination of FINDRISC cut-off of 12 and HbA1c value of 5.9% would be optimal, as that would identify 56 of the 65 people diagnosed with diabetes.

Abbasi et al. (2012)58 used data from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-NL) study to validate 25 models for predicting future T2DM. Two approaches were used, depending on what data were available, with data from 38,379 people being used for validating ‘basic’ models (with no blood test data) and data from 2506 individuals used for validating prediction models that included biochemical data. Most models performed well, but most overestimated the risk. The measure of capture used was the c-statistic, which is comparable with the AUROC. FINDRISC had a c-statistic of 0.81 at 7.5 years, in both full and concise form. QD score was lower, at 0.76. AUSDRISK scored 0.84 and EPIC-Norfolk37 0.81.

One issue has been raised by Griffin et al. (2000)53 and the Dutch Hoorn group. 59 Griffin et al. (2000)53 wondered about the dangers of reassurance in those who have high-risk scores but who do not have hyperglycaemia – will they feel they are able to persist with unhealthy lifestyles? And in the Hoorn study, Spijkerman et al. (2002)59 found that the group with high-risk scores, but who did not have diabetes on glucose testing, had a CVD risk that was almost as high as those who were glycaemia-positive. As there were more of the risk-positive but glucose-negatives, they had more cardiac events, leading the authors to comment that:

It may be of greater public health benefit to intervene in the screen positive group as a whole rather than only in the relatively small group who on subsequent biochemical testing have an increased glucose concentration.

However, a recent study by Paddison et al. (2009)60 from the Cambridge MRC group found that people with negative diabetes screening tests were not so reassured that they would have an adverse shift in health behaviours.

In the EPIC-Norfolk study,38 adding a measure of hyperglycaemia, in this case HbA1c, to the Framingham risk score, added little to the predictive value for CHD. That might imply that glucose testing would not be necessary. However, their focus was on CVD, and detection of diabetes would also lead to reduction of microvascular events, for example by screening for retinopathy.

The tests for blood glucose include:

-

casual (non-fasting) blood glucose

-

FPG

-

glucose tolerance testing, combining fasting and 2-hour levels (OGTT)

-

the 50-g glucose challenge test (GCT), which has been used mainly for screening for gestational diabetes

-

HbA1c, which reflects blood glucose over the previous 3 months [assuming red blood cells (RBCs) of normal longevity and the absence of haemoglobin variants].

Casual blood glucose is usually discounted because of its variability and poor sensitivity (at levels which give acceptable specificity). 61

The OGTT is expensive, inconvenient (and sometimes unpleasant – in some people the glucose load causes nausea) and has poor reproducibility. It may also not fit easily into the primary care setting in which most T2DM is diagnosed,62 although some practices have carried out oral glucose tolerance testing. 63

The choice of test depends on what we are screening for. FPG is reliable, in the sense of showing less day-to-day variability than OGTTs, and will identify people with diabetes and IFG. However, it will miss those people with IGT, who have a higher IHD risk than those with IFG.

As with all tests, there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, nicely shown by Hu et al. (2010)64 (Table 6).

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Likelihood ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||

| FPG ≥ 5.6 mmol/l | 92.5 | 54.3 | 2.02 | 0.14 |

| FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/l | 54.5 | 100 | Infinite | 0.46 |

| FPG ≥ 6.1 mmol/l | 81.5 | 80.5 | 4.18 | 0.23 |

| HbA1c ≥ 6.1% | 81.0 | 81.0 | 4.26 | 0.23 |

| FPG > 6.1 mmol/l and HbA1c > 6.1% | 66.0 | 96.3 | 17.84 | 0.35 |

Note that although the cut-offs of FPG 6.1 mmol/l and HbA1c 6.1% give the same sensitivity (they were chosen from ROC curves) they will not identify exactly the same people.

Glycated haemoglobin

An expert group in the UK65 has issued a position statement on the implementation of the World Health Organization (WHO) 2011 guidance on the use of HbA1c levels in the diagnosis of diabetes. The WHO guidance was that, given good quality assurance (QA) testing, a HbA1c value of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) was recommended as the cut-off point for diagnosing diabetes but that a lower value did not exclude diabetes.

The main points in the UK expert group statement are:

-

UK laboratories meet QA requirements.

-

HbA1c testing should be based on laboratory measurement of a venous blood sample. Point of care results should always be confirmed in a laboratory.

-

One positive HbA1c result is enough in the presence of symptoms, but should be repeated in the absence of symptoms. (The implication for screening is that repeats would be required.)

-

People with HbA1c values in the range 6.0–6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol) were at high risk of diabetes and should receive lifestyle advice, be warned to report symptoms and should have their HbA1c level checked annually.

-

Some people with HbA1c values of < 6.0% (42 mmol/mol) may be at high risk of diabetes, and they should be monitored as above.

The ADA Expert Committee66 on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus summarised the advantages and disadvantages of HbA1c for the diagnosis of diabetes. The Committee listed the advantages as:

-

HbA1c testing measures average glycaemic levels over a period of 10 weeks or so, and is therefore more stable than FPG testing, and especially 2-hour OGTT.

-

Fasting is not required and the test can be carried out at any time of day.

-

The precision of HbA1c testing can be as good as that of PG testing.

-

HbA1c level is the test used for monitoring control of diabetes and correlates well with the microvascular complications; it may be useful to use the same test for diagnosis and monitoring.

-

It has been shown by meta-analysis that when using a statistical cut-point of two standard deviations (SDs) above the non-diabetic mean value, HbA1c testing is as good as FPG testing and 2-hour PG in terms of sensitivity (66%) and specificity (98%).

The disadvantages were identified as:

-

Internationally, there had been a profusion of assay methods and reference ranges. However, this can be overcome by standardisation to the DCCT (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial) assay.

-

HbA1c level may be affected by other conditions that affect the life of the RBC; results may then be misleading. This could be a particular problem in ethnic groups in which haemoglobinopathy is common.

-

A chemical preparation for uniform calibration standards had become available only recently and was not universally available.

However, with the exception of the other conditions, these disadvantages need not apply in a national screening system that would include quality control measures. Therefore, there is a case for using HbA1c as the screening test, particularly in view of its correlation with cardiovascular risk across a wide spectrum. As mentioned above, Khaw et al. (2004)37 noted that the rise in cardiovascular events with rising HbA1c level starts well below the diabetic range. Indeed, they point out that when both diabetes and HbA1c level are included in the statistical analysis HbA1c dominates; as Gerstein (2004)67 argues in an editorial:

. . . the glycosylated haemoglobin level is an independent progressive risk factor for cardiovascular events, regardless of diabetes status.

The glucose levels for the diagnosis of diabetes were based on the relationship between PG and retinopathy. Recently, a similar study by Sabanayagam et al. (2009)68 has examined the relationship between HbA1c level and retinopathy. Using the presence of moderate retinopathy as the indicator of diabetes, the authors suggest a HbA1c threshold of 6.6%. This is very close to the 6.5% suggested by the DETECT-2 Group. 21

The ADA position statement69 in January 2010 recommended a cut-off of 6.5% for diagnosing diabetes, based on retinopathy risk. They recommended a cut-off of 5.7%, and hence a range of 5.7% to < 6.5%, for identifying those at high risk of diabetes. The arguments in favour of the 5.7% cut-off were that:

-

The 6.0% to < 6.5% range misses a lot of patients who have IFG or IGT and who are at increased risk of diabetes. They cite studies reporting that people in the 5.5% to < 6.0% range have a 5-year incidence of diabetes of 12–25%.

-

That unpublished NHANES data show that a HbA1c value of 5.7% corresponds with a FPG of 6.1 mmol/l (i.e. IFG).

-

That other unpublished NHANES data show that a HbA1c cut-off of 5.7% has modest sensitivity (about 40%) but good specificity (81–91%) for IFG and IGT

-

That other unpublished analyses indicate that a HbA1c value of 5.7% is associated with a similar risk of diabetes to the high-risk group in the Diabetes Prevention Program.

As always, there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. If we used a low cut-off of HbA1c of 5.7%, there would be more false-positives. However, they are at higher risk of CVD than the rest of the population and would benefit from lifestyle measures. The only harm might be from the labelling as ‘pre-diabetic’.

In July 2009, an expert committee appointed by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and ADA published a report70 on the role of the HbA1c assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. The key recommendations of this report were that:

-

HbA1c assay should be used as a diagnostic test for diabetes with a threshold of ≥ 6.5% for defining diabetes.

-

That HbA1c measurement has several advantages (both logistical and technical) over fasting glucose.

-

Individuals whose HbA1c values are close to the 6.5% threshold for diabetes (i.e. ≥ 6.0%) should receive demonstrably effective interventions aimed at preventing progression to diabetes.

-

Testing should be by clinical laboratory instruments, not point-of-care instruments.

A cut-off level of 6.0% might pick up most people with IFG, but not all. Selvin et al. (2010)71 (from the ARIC study) reported that a HbA1c cut-off level of ≥ 6.5% would detect 49% of those with FPG of ≥ 7.0 mmol/l, and a cut-off of 6.0% would detect 75% of those diabetic by FPG. In the band below (HbA1c level of 5.5% to < 6.0%), only 3% were diabetic by FPG. In this band, the mean HbA1c level was 5.7% and mean FPG was 5.8 mmol/l. A cut-off of 5.5% would detect 91% of those with diabetic FPGs.

In Germany, Peter et al. (2001)72 examined the value of HbA1c testing using a cut-off of 6.5% in patients shown to be diabetic by OGTTs. Sensitivity was only 47% and specificity was 98.7%. Using a lower cut-off of 6.1% gave sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 92%.

In Wales, Morrison et al. (2011)73 reported a sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 57% using a 6.5% threshold.

A very useful study by Schottker et al. (2011)74 compared FPG and HbA1c testing in the ESTHER (Epidemiologische Studie zu Chancen der Verhütung, Früherkennung und optimierten Therapie chronischer Erkrankungen in der älteren Bevölkerung) study in Germany among almost 10,000 subjects aged 50–74 years. They excluded people with diabetes at baseline and re-tested the others at 2 and 5 years. They classified those who had pre-diabetes at baseline using FPG levels of 100–125 mg/dl and HbA1c levels of 5.7–6.4%. In this group, 23% had pre-diabetes only by FPG testing; 23% had pre-diabetes by both FPG and HbA1c testing, and 54% had it only by HbA1c testing. Hence, in total, FPG testing detected 46% and HbA1c testing detected 77%. They did not carry out OGTTs.

Schottker et al. (2011)74 determined the risks of incident diabetes over the next 5 years. Compared with those who had neither raised FPG or HbA1c levels, the RRs were:

-

IFG alone 4.23

-

pre-diabetic HbA1c alone 3.05

-

both FPG and HbA1c pre-diabetic 7.81.

They concluded that screening for future diabetes should use both FPG and HbA1c testing. They did not report incidence of CVD.

Moves towards global standardisation of HbA1c measurement will help. 75 HbA1c testing has advantages of not requiring people to be fasting, and its diagnostic accuracy now rivals that of PG. However, it should be noted that any cut-off will be arbitrary because for vascular disease there is a continuum of risk, unlike the dichotomy seen with moderate retinopathy.

There are ethnic differences in HbA1c levels and the cut-off may have to be adjusted for different groups. A study from China by Bao et al. (2010)76 suggested a cut-off of 6.3%.

We need to distinguish the use of HbA1c testing for diagnosing diabetes from its value in predicting vascular risk. In the latter case, it is correct to say that HbA1c level is a good predictor of vascular risk on its own, but that once other traditional markers of vascular risk – such as hypertension, smoking, lipid level – are added, HbA1c testing gives limited marginal benefit. 38

Reservations about the use of glycated haemoglobin

Various concerns about reliance on HbA1c level as the diagnostic test for diabetes have been raised. Some of these come from the clinical biochemists and, therefore, need to be recognised.

The Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) position statement77 on using HbA1c testing for diagnosis (not screening) lists the advantages and disadvantages (Table 7).

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| No need for fasting | Abnormal haemoglobins |

| Low biological variability | Anaemias |

| Measure of glycaemia over a period of months | Ageing and ethnicity |

| Analytical standardisation | Residual analytical variations |

Each of the first three disadvantages leads to misleading results.

The ABCD choose a HbA1c range of 5.8–7.2% for intermediate hyperglycaemia and recommend another test, such as FPG or an OGTT, to confirm or exclude diabetes. They suggest that combined HbA1c and FPG testing could be used for diagnosis.

Schindhelm et al. (2010)78 also warn that laboratory assays for HbA1c level still show significant variability, noting that coefficients of variance ranged among methods from 1.7% to 7.6%. However, if there was a national screening system with QA systems, this should be less of a problem.

There has been debate about the lower cut-off level for HbA1c. The SPHN working group79 noted that some groups advocate a HbA1c range of 5.7–6.4% for defining non-diabetic hyperglycaemia (NDH), whereas others suggest 6.0% as the lower limit. Unfortunately, most studies simply report results for the whole band, whereas what we need is a comparison of the 5.7–5.9% range with the 6.0–6.4% range.

Cederberg et al. (2010)80 used the 5.7% cut-off and compared it with IGT and IFG as revealed by OGTTs. Diabetes was preceded by raised HbA1c, IGT and IFG levels in 33%, 41% and 22% of cases, respectively, after 10 years. The converse may be more important – diabetes was not preceded by raised HbA1c in 67%, although if screening were to be introduced in the UK, the repeat testing interval would most likely be 5 years.

Mostafa et al. (2010)81 from Leicester used data on OGTTs and HbA1c from a cohort of 8696 subjects to compare proportions with abnormal results. Using the OGTT, 3.3% were diabetic, and of these about one-third had a HbA1c level of < 6.5%. Using a HbA1c level of 6.5% as the threshold for diabetes increased the prevalence to 5.8%, but on OGTT over half had IGT or IFG. Of 595 people, 198 were identified as diabetic by both OGTT and HbA1c testing, 93 by only OGTT, and 304 only by HbA1c. The paper does not give details of how many who were diabetic by OGTT, had the diagnosis made by the FPG or the 2-hour PG, or both. All of those who were recognised as diabetic on OGTT had the OGTT repeated – one-third were not diabetic on the second OGTT. Mostafa et al. (2010)81 noted that a HbA1c cut-off level of 5.7% would identify 51% of their cohort as abnormal.

A later abstract from the same group82 reported that HbA1c testing and the OGTT gave similar numbers for incident diabetes – but not the same people.

Borg et al. (2010)83 from Denmark also compared the characteristics of those diagnosed by OGTT and HbA1c but, again, give no details of the OGTT time points responsible for diagnosis. Using a HbA1c cut-off level of ≥ 6.5%, 6.6% were identified as diabetic compared with 4.1% using the OGTT. Almost 58% of those recognised as diabetic using the OGTT were not picked up by HbA1c testing. In terms of cardiovascular risk profile, those people considered diabetic by HbA1c testing, but not using the OGTT, had as high a risk (actually higher, but not statistically significantly so). Hence, OGTT and HbA1c testing appear to be detecting groups that only partly overlap.

Lorenzo et al. (2010)84 from the IRAS (Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study) reported that HbA1c testing was less sensitive than IFG or IGT for detection of risk (not diabetes), but what was meant by this was that HbA1c testing classified fewer individuals as having abnormal glucose tolerance – it was not about diabetes. No specificity was reported.

Valdes et al. (2011)85 from Asturias found that for prediction of diabetes in those not diabetic when first screened, FPG (2-hour post challenge) and HbA1c testing had similar ROC curves [area under curve (AUC) 0.83, 0.79 and 0.80, respectively], but that a combination of HbA1c and FPG testing did better (AUC 0.88).

The incremental risks of higher HbA1c levels vary among outcomes. Selvin et al. (2010)86 took a HbA1c range of 5.0% to < 5.7% as the reference range (RR = 1.0). For diabetes, RRs for HbA1c levels of 5.7% to < 6.5% and ≥ 6.5% were 3.0 and 13.7, respectively, but for CHD the RRs were 1.6 and 1.9, respectively. 86

Skriver et al. (2010)87 from the Danish arm of the ADDITION trial, have provided data on the specificity of HbA1c testing. A high-risk group (identified by questionnaire and then by a second-stage casual blood glucose or HbA1c level) underwent OGTTs and then the HbA1c levels of those with NGT (defined by OGTT) were examined. Only 0.4% had HbA1c of ≥ 6.5%; 6.7% had HbA1c levels in the range 6.0–6.49%, and 93% had HbA1c levels of < 6.0%.

The sensitivity of HbA1c testing was assessed in a Paris study by Cosson et al. (2010). 88 In a group mainly composed of obese women, they compared FPG and HbA1c with the 2-hour OGTT. Using FPG testing alone, 70% of people with IGR would have been missed because most had isolated IGT. The sensitivity of HbA1c testing for detecting an abnormal 2-hour PG using a cut-off of ≥ 6% was only 37%.

From Brazil, Cavagnolli et al. (2011)89 also reported low sensitivity. They carried out OGTTs in 498 people of whom 115 were recognised as diabetic by the OGTT: 26 by FPG alone, 54 by 2-hour PG alone and 35 by both. But only 56 were identified as diabetic by HbA1c levels of ≥ 6.5%. HbA1c testing was stronger in specificity. Using a cut-off of ≥ 6.0% identified 167 people, of whom 65 had diabetes, 41 had IFG, 52 had IGT, and only nine had NGT.

Pajunen et al. (2010)90 (from the DPS) carried out two OGTTs to be sure of correctly diagnosing people with IGT. They then monitored participants for the development of diabetes. They found that the sensitivities of HbA1c levels of ≥ 6.5% for detecting new diabetes were 35% in women and 47% in men compared with two OGTTs. A cut-off level of 6.0% gave sensitivities of 67% and 68%. Specificities were better; using a cut-off HbA1c level of < 6.5% gave specificities of 90% in women and 91% in men.

Turning to the usefulness of HbA1c testing for detecting IGT at baseline, Pajunen et al. (2010)90 report that HbA1c levels in patients with IGT confirmed by two OGTTs were:

-

< 5% 8.5% of participants

-

5.0–5.9% 69.5% of participants

-

6.0–6.4% 14.3% of participants

-

6.5% or > 7.7% of participants.

So a HbA1c cut-off level of 6.0% missed most people with IGT.

Pajunen et al. (2010)90 compared those who developed diabetes and had a HbA1c level of ≥ 6.5% with those who developed diabetes and had a HbA1c level of < 6.5%. The former group had significantly higher weight, BMI and FPG, but there were no differences in BP or cholesterol levels. They then reclassified the DPS patients as diabetic or not, based on a HbA1c level of ≥ 6.5% and found that the results of the study, in terms of preventing progression to diabetes, would not have been statistically significant.

Older studies were reviewed by Bennett et al. (2006). 91 They identified nine studies that assessed the value of HbA1c testing in screening for diabetes, using the OGTT as the reference standard. They concluded that the HbA1c cut-off level should be 6.1%, which, for diabetes, had a sensitivity ranging from 78% to 81% and specificity of 79–84%. FPG testing, with a cut-off level of > 6.1 mmol/l, had poorer sensitivity (ranging from 48% to 64%) but better specificity (ranging from 94% to 98%). HbA1c and FPG testing had, at those cut-off levels, only 50% sensitivity for detecting IGT. Bennett et al. (2006)91 noted that the need for cut-off levels varied among different populations.

Glucose challenge test

The 50-g GCT has been used extensively in screening for gestational diabetes but has seldom been studied in screening for T2DM. It can be used for people who have not fasted, which makes it more convenient.

Abdul-Ghani and De Fronzo (2009)92 have reviewed the evidence on relationships of FPG and PG at all time points after the 75-g OGTT. They make a convincing case for the 1-hour PG being the strongest predictor of later diabetes. This would suggest that it would be worth researching the value of the 50-g 1-hour GCT in screening for IGT and diabetes.

A study published since that review provides further support for the superiority of the 1-hour PG, although it was based on the 75-g OGTT, not the 50-g GCT: Joshipura et al. (2011)93 reported that among a group of non-diabetic people aged 40–65 years in Puerto Rico, the 1-hour PG had stronger associations with metabolic factors – such as BMI, waist circumference and body fat percentage – than the 2-hour PG.

In a recent study, Abdul-Ghani et al. (2011)94 compared various measures of blood glucose for predicting future T2DM. A HbA1c level of 5.65% had an AUROC of 0.73, and FPG (126 mg/dl) had an AUROC of 0.75. However, the 1-hour PG (155-mg/dl cut-off) had a greater AUROC of 0.84. Adding HbA1c testing to the 1-hour PG increased the AUROC slightly, to 0.87. The 2-hour PG had an AUROC of 0.79.

Phillips et al. (2009)95 compared the non-fasting GCT with HbA1c testing and the OGTT (undertaken 1 week later) and found AUROCs of 0.90 for diabetes, and 0.79 for pre-diabetes (defined as IGT of IFG based on the 6.1-mmol/l threshold). For HbA1c testing (probably > 6.0%, although not clear) the AUROCs were 0.82 for diabetes and 0.68 for pre-diabetes.

From the same group, Chatterjee et al. (2010)96 examined the cost-effectiveness of screening by random PG, the 1-hour 50-g GCT and the 75-g OGTT, compared with no screening. Their model included costs of testing and treatment (with metformin). They concluded that the GCT would be the most cost-effective test and also that screening would be cost-effective compared with no screening. This study is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

Jones et al. (2013)97 from Exeter reported results from a group of 2253 people aged > 40 years and not known to have diabetes. They were participating in the ‘Exeter 10,000’ study. They had two risk scores applied: Leicester and Cambridge. The latter was more sensitive (69%) but less specific (57%) than the Leicester one (62% and 69%). However, the interest here is in the results of HbA1c and FPG testing; both result in diabetes being diagnosed in about 16%, but half of those diagnosed as having diabetes or at high risk by HbA1c testing were not diagnosed by FPG testing and vice versa.

Summary

There is no perfect screening test. HbA1c testing is accepted for diagnosis in people who are suspected to have diabetes, using a level of 6.5%, but is less reliable for screening because of its sensitivity. But it is convenient and a good marker of cardiovascular risk.

The OGTT has higher sensitivity but is inconvenient, and uptake is poorer.

The 50-g GCT looks good, and does not require fasting, but the evidence base is sparse.

The combination of HbA1c and FPG testing might be a compromise option, but will miss some people who diagnosed as diabetic on the 2-hour OGTT.

Suggested conclusions

The first step in screening for diabetes and IGT should be selection by risk factor score.

The second stage should use HbA1c level as the screening test, with 6.0% as the cut-off.

In the third stage, the diagnosis of diabetes should be confirmed by a second test of blood glucose: either FPG or HbA1c testing. Two HbA1c results of ≥ 6.5% would confirm the diagnosis.

Given the lack of agreement on the use of HbA1c testing alone, we recommend that if the first HbA1c value is in the 6.0–6.49% range then the third stage should meantime use both HbA1c testing and either FPG testing, with 7.0 mmol/l used as the diabetes cut-off as in the standard definitions, or a 2-hour OGTT. It is unlikely that people with HbA1c values in the range 6.0–6.49% will have FPG values of ≥ 7.0 mmol/l; this recommendation can be reviewed in the light of experience and FPG dropped if it does not contribute. However, more people may have postload hyperglycaemia and we might expect some with HbA1c values in the 6.0–6.49% range to have 2-hour PG in the diabetic range.

We recommend research into the usefulness of the 50-g non-fasting GCT as a screening test.

Chapter 3 Do different screening tests identify groups at different cardiovascular risk?

Concern has been raised that screening by HbA1c and FPG testing might pick up different groups. This was examined by Carson et al. (2010)98 using NHANES data, with cut-off levels of 6.5% for HbA1c and 7.0 mmol/l for FPG. There was some disagreement between the tests, but 96% were not diagnosed as diabetic by both, and 1.8% were diagnosed as diabetic by both. In 0.5% of people, diabetes was diagnosed by HbA1c testing but not FPG testing, but 82% of this group had IFG and would be treated correctly. In the 1.8% diagnosed as diabetic by FPG testing but not by HbA1c testing, almost half were in the HbA1c range 6.0% to < 6.5% and would also be treated.

However, there is less agreement between HbA1c and FPG testing when it comes to diagnosing ‘pre-diabetes’. Mann et al. (2010),99 also using NHANES data, compared results using a HbA1c cut-off level of 5.7% and FPG of 6 mmol/l among participants who also had an OGTT. The prevalence of pre-diabetes using the range 5.7% to 6.4% was 12.6%, of whom 4.9% were negative by FPG (PG level of < 100 mg/dl). However, almost 21% were identified as positive by FPG testing (in range 100–125 mg/dl) but negative by HbA1c testing. One could speculate that the last group had isolated IFG and hence were at lower risk of CVD, whereas the HbA1c-positive but FPG-negative group may have had IGT. There were some differences among the HbA1c-positive, FPG-negative groups and the FPG-positive, HbA1c-negative groups, with more of the former found to be hypertensive (41% vs 34%) and with slightly higher total cholesterol results (212 mg/dl vs 205 mg/dl).

Previous studies have reported that in pre-diabetes, HbA1c level has a stronger relationship with the 2-hour PG than the FPG,100 and that IFG is associated with beta cell dysfunction, whereas those with IGT and normal FPG levels have insulin resistance.

In monitoring people with pre-diabetes for progression to diabetes, there is a case for using both HbA1c and FPG testing. De Vegt et al. (2001)101 from the Hoorn study showed that having both IFG and IGT was associated with a much higher risk of progression to diabetes than either alone (rates of 40% vs 10% and 11%).

Recent papers: cohort studies

The ADDITION study102 followed up 20,916 participants for a median of 7 years, all of whom had a HbA1c level of > 5.8% or a random PG level of > 5.5 mmol/l. A HbA1c level of > 6.5% was associated with increased HRs for all-cause mortality in the NGT groups, and in groups with IGT but not IFG. This relationship was present in both the subsets, with high and low heart risk scores at baseline. In people with IFG but not IGT, increasing HbA1c level was not associated with significantly changing HR. Limited comparisons can be made between the effectiveness of HbA1c, FPG and IGT for predicting cardiovascular risk factors because the population investigated was selected partly on the basis of HbA1c risk score.

The ARIC Study71,103 followed a cohort of 11,057 people, without diabetes or heart failure at baseline, for a median of 14.1 years. This study found that a HbA1c level of between 6.0% and 6.4% is associated with a doubling of risk – adjusted for age, race and sex – for incident heart failure in comparison with a HbA1c level of between 5.0% and 5.4% (Table 8). The HR is reduced to 1.4 after adjustment for a range of CVD risk factors and fasting glucose levels. Compared with the group with HbA1c levels of 5.0–5.4%, the group with HbA1c levels of 6.0–6.4% were more likely to be smokers (31% vs 18%), had higher BMIs (29.7 kg/m2 vs 26.6 kg/m2), were more likely to be treated for hypertension (42% vs 23.5%) and had a much higher proportion of African American people (51% vs 12%).

A FPG of 6.1–6.9 mmol/l was not indicative of an increased risk of incident heart failure above a reference category of 5.0 to 5.5 when adjusted for covariates and HbA1c levels (see Table 8). Of the people with elevated HbA1c levels (6.0–6.4%), the greatest risk for incident heart disease was observed in those with lower FPG:

-

HR 3.57 (1.45–8.79) for FPG of < 5.0 mmol/l

-

HR 2.19 (1.40 to 3.43) for FPG of 5.0–5.5 mmol/l

-

HR 1.29 (0.86 to 1.94) for FPG of 5.6–6.0 mmol/l compared with reference category HbA1c 5.0–5.4%, FPG 5.0–5.5 mmol/l.

Each 1% increase in HbA1c level was associated with a 39% increase in heart failure risk after adjustment for covariates.

| HbA1c level (%) | HR adjusted for age, race and sex only (95% CI) | HR adjusted for age, race, sex and other covariates including FPG (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 5.0–5.4 | Reference | Reference |

| 5.5–5.9 | 1.44 (1.24 to 1.68) | 1.16 (0.98 to 1.37) |

| 6.0–6.4 | 2.04 (1.63 to 2.54) | 1.40 (1.09 to 1.79) |

| FPG level (mmol/l) | HR adjusted for age, race and sex only (95% CI) | HR adjusted for age, race, sex and other covariates including HbA1c (95% CI) |

| 5.0–5.5 | Reference | Reference |

| 5.6–6.0 | 1.13 (0.95 to 1.34) | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.20) |

| 6.1–6.9 | 1.49 (1.23 to 1.79) | 1.11 (0.90 to 1.35) |

Hence, HbA1c level predicted heart failure but FPG level did not.

The Strong Heart Study104 followed a cohort of 4549 American Indian adults for a median of 15 years. There was a non-significant trend towards higher risk of CVD in people with elevated but non-diabetic HbA1c and FPG. This trend was stronger for HbA1c than FPG but both were non-significant. Elevated HbA1c of over 6.5% was associated with an increased HR for CVD 1.40 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.93) when correcting for a range of risk factors including FPG although the CI almost intersects zero (Table 9). Elevated FPG of over 126 mg/dl (7 mmol/l) was associated with a non-significant trend towards an increased HR for CVD 1.25 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.62) when correcting for a range of risk factors including HbA1c (see Table 9).

| HbA1c level (%) | HR for CVD adjusted for age and sex only (95% CI) | HR for CVD adjusted for age, race, sex and other covariates including FPG (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| < 5 | Reference | Reference |

| 5.0 to < 5.5 | 1.29 (1.04 to 1.61) | 1.17 (0.94 to 1.46) |

| 5.5 to < 6 | 1.21 (0.95 to 1.55) | 1.09 (0.85 to 1.39) |

| 6.0 to < 6.5 | 1.30 (0.91 to 1.85) | 1.13 (0.79 to 1.61) |

| ≥ 6.5 | 1.93 (1.43 to 2.59) | 1.40 (1.02 to 1.93) |

| FPG level: mg/dl (mmol/l) | HR adjusted for age and sex only (95% CI) | HR adjusted for age, race, sex and other covariates including HbA1c (95% CI) |

| < 100 (< 5.6) | Reference | Reference |

| 100 to < 126 (5.6 to 6.9) | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.41) | 1.10 (0.90 to 1.34) |

| ≥ 126 (7) | 1.51 (1.18 to 1.92) | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.62) |

These two cohort studies provide evidence that when considering cardiovascular risk, HbA1c is more predictive than FPG.