Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/39/02. The contractual start date was in May 2008. The draft report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stephen Allen has undertaken research in probiotics supported by Cultech Ltd, Baglan, Port Talbot, UK; the Children and Young People’s Research Network, Cardiff University, Wales; the Knowledge Exploitation Fund, Welsh Development Agency and the National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society, UK. He has also been an invited guest at the Yakult Probiotic Symposium in 2011 and received research funding from Yakult, UK, in 2010.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Allen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD), defined as diarrhoea in association with antibiotic treatment and without an alternative cause, occurs in 5–39% people within 12 weeks of exposure to antibiotics. 1,2 The predominant mechanism underlying AAD is disruption of the commensal gut flora. This impairs colonisation resistance and facilitates the emergence of a range of gut pathogens. 2,3 The major diarrhoeal pathogen associated with antibiotic treatment is Clostridium difficile, which accounts for 15–39% of AAD cases. 4 Altered commensal flora may also result in diarrhoea through changes in the metabolism of carbohydrates, short-chain fatty acids and bile acids, and some antibiotics cause diarrhoea through direct effects such as increased gut motility. 2,5

Clostridium difficile is an anaerobic bacterium that produces resistant spores that persist long term in the environment. Transmission is faecal–oral and 4–21% patients may acquire the infection during admission to hospital through contact with colonised patients, contaminated fomites and the hands of health-care staff. C. difficile diarrhoea (CDD) occurs in both endemic and outbreak scenarios. 6 Since 2003, an increase in the frequency and severity of CDD in North America and Europe has been attributable to the emergence of the hypervirulent 027 strain, which may produce higher amounts of toxin. 7–9

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea occurs typically in older people admitted to hospital. 1,2 ADD complicates treatment with many antibiotic classes but especially broad-spectrum penicillins, cephalosporins, clindamycin and long-duration antibiotic treatments. 10 Additional risk factors include prolonged hospital stay, previous hospital admission, previous gastrointestinal surgery and use of a nasogastric tube (NGT). 3 In a retrospective study of European hospitals, risk factors for CDD included age ≥ 65 years, severe comorbidity and recent treatment with cephalosporins and aminopenillin-beta (β)-lactamase inhibitor combinations. 11 In a prospective study of people aged > 18 years admitted to Canadian hospitals, age, exposure to antibiotics, treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and previous hospital admission within the last 2 months predicted CDD. 12

The severity of AAD varies greatly. Although usually a mild, self-limiting illness, it is associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased health-care costs. C. difficile infection may remain asymptomatic, but intestinal pathology results from secretion of toxins A and B causing increased mucosal fluid secretion and inflammation. Symptoms range from mild, self-limiting diarrhoea to severe diarrhoea complicated by pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon and death. 6,8

Estimates of the financial burden of C. difficile infection (CDI) to the health-care service have varied between $2454 and $16,464 for every health-care-acquired case in the USA,13–15 £4107 in the UK16 and €7147 in Germany. 17 The annual cost of health care for CDD in the USA has been estimated to be $3B. 18,19 Nosocomial CDI increases hospital stay by between 7 and 26 days,16,17,20 and prolonged hospital admission was identified as the main cost driver in most studies. 13,15,16 Furthermore, an increase in length of hospital stay due to more severe disease in recent years has resulted in a rise of the incremental cost of CDI. 21

Treatment

Uncomplicated AAD usually responds to withdrawal of the offending antibiotics. CDD usually responds to treatment with metronidazole or vancomycin, but 20–25% patients go on to suffer from a recurrent form of the disease. Novel modes of treatment include probiotics, immunoglobulin infusion and faecal transplant from healthy donors. 3,6

Prevention of antibiotic-associated and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea

The frequency and severity of CDD in hospitals in the industrialised world have led to comprehensive strategies for prevention. These include decontamination of the environment, hand washing and isolation of patients with diarrhoea. 6 Antibiotic stewardship programmes have also been effective in reducing infection rates. 6,22,23

Probiotics

Probiotics are defined as live microbial organisms which, when administered in adequate numbers, are beneficial to health. 24 Although clinical trials are undertaken to determine whether or not a microbial preparation has a health benefit in a specific population, the term ‘probiotic’ is commonly used to refer to the preparation being evaluated and it is used in this sense here. Bacteria used as probiotics are among the organisms ‘generally regarded as safe’ by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 25 Live bacteria from several genera and the yeast Saccharomyces boulardii have been administered to vulnerable groups such as preterm infants and people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection without adverse effects. 26 Adverse events occurring in clinical trials evaluating the prevention of AAD have not been ascribed to probiotic intake. 26 Administration of lactic acid bacteria has been associated in rare cases with septicaemia in immunocompromised people and endocarditis in people with artificial heart valves. 27 Despite the apparent low risk of adverse events, careful assessment of safety in clinical trials is recommended. 26

Rationale

Specific probiotic strains have been identified in vitro and in vivo to possess several mechanisms that may prevent or ameliorate AAD and CDD through enhanced barrier function of the gut epithelium. 28 First, potential pathogens are killed or inhibited by the secretion of antimicrobial peptides and probiotics compete for attachment sites on intestinal mucus and epithelium. Acidification of the gut contents through the production of lactic acid also inhibits pathogen growth. Second, mucosal immunity is enhanced through increased secretory immunoglobulin A production and stimulation of antimicrobial peptide secretion by host cells. Finally, through direct effects on the epithelium, probiotics increase the secretion of mucus, enhance tight junction integrity and decrease epithelial cell apoptosis.

At the time that probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in the elderly (PLACIDE) was developed, meta-analyses had suggested that probiotics may be effective in the prevention of AAD. McFarland pooled data from 25 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which included a total of 2810 adults and children. 29 There was significant heterogeneity (χ2 = 82.5; p < 0.001) in a fixed-effects model. In random-effects analysis, the relative risk (RR) for AAD was 0.43 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31 to 0.58] in participants receiving a probiotic. This meta-analysis included all of the trials included in previous systematic reviews, which had broadly similar findings. 30–33 Although meta-analysis has provided some evidence that probiotics may be effective in the prevention of AAD, the marked differences between trials in the microorganisms evaluated (single strains and mixtures of bacteria, the yeast S. boulardii), administration regimens (mode of delivery, number of organisms, probiotics combined with prebiotics), patient populations (age and exposure to antibiotics) and period of follow-up for AAD probably underlie the statistical heterogeneity in the results and weaken the evidence for probiotic effectiveness.

Much less evidence from clinical trials was available for probiotics in the prevention of CDD. A pilot study in elderly hospitalised patients reported that 30 out of 138 (21.7%) patients developed diarrhoea and 5 out of 69 (7.2%) in the placebo group compared with 2 out of 69 (2.9%) who had received a combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum tested positive for C. difficile toxin. Stool culture suggested that the main effect of the probiotic was neutralisation of toxin rather than prevention of colonisation. 34 Thomas et al. had assessed Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for the prevention of AAD in 267 adults who were monitored for an average of 21 days, but the number of patients from whom stool samples had been collected and in which C. difficile was detected was too small to assess probiotic effect. 35 In randomised trials of 19336 and 180 adult patients,37 the occurrence of CDD was similar in those receiving S. boulardii and those receiving the placebo. Although there was trial evidence for probiotics in the treatment of established CDD or the prevention of recurrence,29 we are not aware of any other studies that had assessed probiotics in the prevention of CDD in adults.

We are not aware of any studies that have assessed the effect of probiotic on quality of life (QoL) in patients at risk of AAD.

Selection of the probiotic preparation

Although several mechanisms whereby probiotic organisms enhance gut barrier function have been identified,28 it remains unclear which of these are most relevant to the prevention or amelioration of AAD and to what extent these mechanisms are common to many different probiotic organisms or are strain specific. Therefore, the scientific evidence to inform the selection of a specific probiotic intervention for the prevention of AAD is limited. The meta-analyses included trials that had evaluated many different bacterial preparations and the yeast S. boulardii. 29 The bacterial interventions included single strains, mixtures of different organisms and mixtures of probiotics with prebiotics. Dosages (number of organisms) and modes of administration also varied markedly between studies. Factors associated with greater efficacy in preventing AAD in meta-analysis included the use of S. boulardii or L. rhamnosus GG, mixtures of probiotics and preparations with high numbers of organisms. 29 Efficacy was similar for bacterial preparations [five trials conducted on 384 adults and children; odds ratio (OR) 0.34; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.61] and yeast preparations (four trials conducted on 830 participants; OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.62). 31

In an attempt to maximise gut colonisation and, therefore, colonisation resistance, we used a multistrain preparation of Lactobacillus sp. and Bifidobacterium sp., bacterial species that had been evaluated extensively in clinical trials, with a high number of viable bacteria (total 6 × 1010 organisms per day). We intended to undertake a pragmatic trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the probiotic preparation in older people receiving antibiotics in secondary health-care settings representative of those in industrialised counties and with the causes of diarrhoea determined by routine laboratory practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

Probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile in the elderly was a prospective, multicentre, pragmatic, two-armed, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with equal randomisation.

Approvals obtained

The Research Ethics Committee (REC) for Wales approved the study on 27 November 2008 (number 08/MRE09/18).

A clinical trial authorisation (CTA) was granted for the live bacterial preparation by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on 6 October 2008 (CTA number AAD-CDD-001). The details of the REC for Wales, local RECs, competent authorities and research and development department approvals are provided in Appendix 1. The trial was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) ISRCTN70017204 and EudraCT number 2007–002876–32.

Trial sites

Inpatients were recruited from medical and surgical wards of secondary care hospitals from two NHS regions: the Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board (ABMUHB) in South West Wales (Singleton, Morriston and Princess of Wales hospitals), and the County Durham and Darlington Foundation Trust (CDDFT; the University Hospital of North Durham and Darlington Memorial Hospital). Details of the trial sites are included in Appendix 2.

Participant inclusion criteria

People aged ≥ 65 years who were admitted to hospital and had been exposed to one or more antibiotics within the preceding 7 days, or were about to start antibiotic treatment, were eligible to join the study. Approval to invite the patient to participate in the study was secured from the patient’s consultant.

Participant exclusion criteria

People were excluded if they:

-

already had diarrhoea, which was defined as three or more watery or loose stools (Bristol Stool Form Scale types 5–7)38 in the preceding 24 hours

-

were sufficiently immunocompromised to require isolation and/or barrier nursing

-

had a severe illness requiring high-dependency or intensive care

-

had a prosthetic heart valve

-

had suffered from CDD in the previous 3 months

-

had inflammatory bowel disease that had required specific treatment in the previous 12 months

-

had suspected acute pancreatitis, which was defined as abdominal pain with serum amylase or lipase greater than three times the institutional upper limit of normal

-

had a known abnormality or disease of mesenteric vessels or coeliac axis that may compromise gut blood supply

-

had a jejunal tube in situ or were receiving jejunal feeds

-

had a previous adverse reaction to probiotics

-

were unwilling to discontinue their existing use of probiotics.

Investigational medicinal products

The active preparation consisted of a vegetarian capsule containing 6 × 1010 live bacteria as lyophilised powder comprising two strains of L. acidophilus [CUL60, National Collection of Industrial, Food and Marine Bacteria (NCIMB) 30157 and CUL21, NCIMB 30156; 3 × 1010 colony-forming units (cfu)] and two strains of Bifidobacterium (B. bifidum CUL20, NCIMB 30153 and Bifidobacterium lactis CUL34, NCIMB 30172; 3 × 1010 cfu). Obsidian Research Ltd, Port Talbot, UK, prepared the investigational medicinal products (IMPs) according to the randomisation schedule. The organisms were available commercially through BioCare® Ltd (Lakeside, Birmingham, UK) and Pharmax (Bellevue, WA, USA). The placebo capsules were identical to the probiotic capsules but contained inert maltodextrin powder. The dose was one capsule per day with food and, where possible, between antibiotic doses, for 21 days.

Each participant was provided with a bottle labelled with his or her unique study number and containing 21 capsules. The IMPs were given to participants on the day of recruitment and administration during the hospital stay was supervised by the research nurses in ABMUHB and by the ward nurses in CDDFT. To prevent cross-contamination, strict hygiene procedures were followed, for example where capsules were opened, and the contents were mixed with fluids for administration to participants with difficulty swallowing. Although the live bacteria had a shelf life of 2 months at room temperature, participants were instructed to keep the capsules in the refrigerator following discharge from the hospital and encouraged to complete the 21-day course.

In vitro antibiotic testing demonstrated that the lactobacilli and bifidobacteria were sensitive to broad-spectrum antibiotics. All four strains were sensitive to ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, linezolid and tetracycline.

After recruitment of the first 50 participants, a research nurse perceived a slight difference in the colour of the powder contained in the probiotic and placebo capsules, which were transparent. Therefore, the IMPs were resupplied in opaque capsules according to the original random allocation sequence. No unmasking of participant allocation occurred.

To ensure the quality of the IMPs, unused capsules were collected from participants on an opportunistic basis (e.g. from participants who withdrew before completing the 21-day course). A laboratory independent of the research team performed quantitative bacterial culture. The findings were sent to the independent statistician to check against the randomisation sequence and for the total count of viable organisms.

Objectives

Primary objectives: to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a live preparation of two strains of lactobacilli and two strains of bifidobacteria in the prevention of AAD and CDD in people aged ≥ 65 years who were exposed to oral or intravenous antibiotics and who were representative of patients admitted to secondary care NHS facilities in the UK.

Secondary objectives: to assess the effect of the probiotic on the duration and severity of AAD, the acceptability of the probiotic preparation, serious adverse events (SAEs) of the probiotic preparation and its effect on QoL.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes: the occurrence of AAD within 8 weeks and CDD within 12 weeks of recruitment.

Secondary outcomes: the severity and duration of AAD; the severity and duration of CDD and incidence of recurrence within the follow-up period; the number of days with abdominal pain, bloating, flatus and nausea; the incidence of pseudomembranous colitis, the need for colectomy; well-being and QoL; duration of hospital stay; frequency of SAEs; the acceptability of the live bacterial preparation (to identify if the participants had any difficulty taking the bacterial preparation vs. the placebo); the viability of the bacterial preparation at point of administration and death.

Sample size

Based on a review of previous clinical trials, we estimated that AAD would occur in 20% and CDD in 4% of participants in the placebo arm. The detection of a 50% reduction in CDD to a frequency of 2% in the active arm with 80% power at the 5% significance level required 2478 subjects (1239 in each arm). This number of participants would provide a power of > 99% to detect a 50% reduction in the risk of AAD (to 10% frequency) and a power of 90% to detect a 25% risk reduction in AAD (to 15% frequency) in the active arm at the 5% significance level. We planned to recruit 2974 participants to allow for 10% drop-outs and 10% loss to follow-up due to deaths unrelated to diarrhoea.

Randomisation

The independent statistician prepared a random allocation sequence using blocks of variable sizes and stratified by hospital using SAS® PROC PLAN, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The sequence allocated participants in a 1 : 1 ratio to the two arms of the study.

Blinding

The allocation sequence was not available to any member of the research team until databases had been completed and locked. In view of the established safety record of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria27 and the sensitivity of the organisms used in this study to broad-spectrum antibiotics, there was no provision for the emergency unblinding of participants. Therefore, copies of the random allocation sequence were not held at the recruitment sites.

Recruitment

The research nurses received training in ‘Good Clinical Practice’ and were fully conversant with all aspects of the trial. Specific training was given in assessment of patient eligibility, recruitment and obtaining informed consent, the trial protocol, reporting of adverse events and collecting information. Presentations were made to clinical, nursing and pharmacy staff to ensure their familiarity with the purpose and conduct of the trial. Permission to approach patients and invite them to join the study was obtained from hospital consultants.

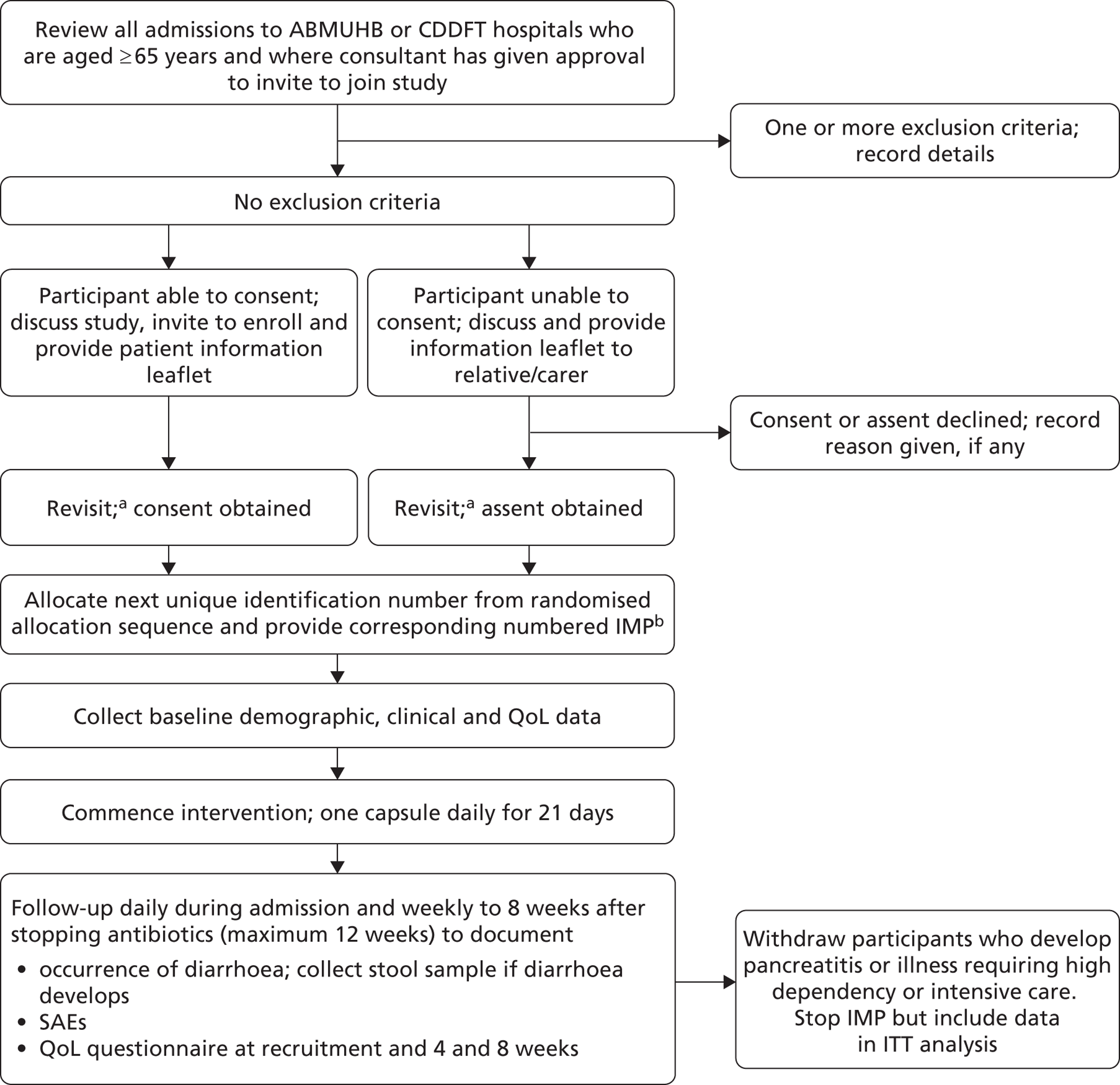

Research nurses visited wards daily to identify eligible patients and provide them with verbal and written information (see Appendix 3). Patients were revisited either later the same day or the next day after they had had the opportunity to discuss with relatives/carers and health-care personnel whether or not they wished to join the study. For people unable to provide consent, information was provided to their relatives/carers and assent sought (see Appendix 3). Although reasons for not joining the study were requested, patients and their relatives/carers were free to decline to participate without giving a reason. Patients in whom consent or assent was obtained were allocated the next unique study number in the random sequence for that site and the research nurses provided them with the corresponding trial preparation.

Baseline assessment

Information recorded at recruitment included basic demographic characteristics, use of cigarettes and alcohol, source of admission, principal diagnosis or reason for admission, comorbid illnesses, duration of hospital stay prior to recruitment, non-antibiotic drug treatment, indication for antibiotic treatment and antibiotics prescribed (see Appendix 4).

Participant follow-up

Participants were visited daily by the research staff during hospital stay. Changes to antibiotic treatment, gastrointestinal symptoms (including the presence of diarrhoea), compliance, difficulties taking the IMPs and occurrence of SAEs were recorded onto standard forms (see Appendix 4). The same information was requested weekly, after discharge from hospital, via a telephone questionnaire and continued for 8 weeks post recruitment. In addition, participants were encouraged to contact a named member of the research staff to report potential SAEs at any time during follow-up. Review of laboratory data regarding stool assays was continued until 12 weeks after recruitment.

Trial completion

Participants had completed the trial when they:

-

had completed follow-up

-

had withdrawn and declined collection of further follow-up data

-

were lost to follow-up

-

had died.

A chart showing participant flow through the study is included as Appendix 5.

Measurement of primary outcomes

Diarrhoea was defined as three or more loose stools (stool consistency 5–7 on the Bristol Stool Form Scale)38 in a 24-hour period. Diarrhoea was also diagnosed in participants with frequent stools that they described as loose but who were unable to describe stool consistency using the Bristol Stool Form Scale. The presence of diarrhoea according to these criteria was confirmed by the research nurses during admission with either the patient, their carers or a member of the medical staff. After discharge, this was confirmed during telephone interview.

Stool samples for analysis were collected only during episodes of diarrhoea, including diarrhoea that occurred after discharge from hospital. Stools were analysed for diarrhoeal pathogens according to routine NHS laboratory practice. Analyses included bacterial culture for Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter and Escherichia coli 0157 and wet film for ova, cysts and parasites. Detection of viruses depended on the clinical context (e.g. suspected norovirus outbreak). In ABMUHB, C. difficile toxins were detected by an in-house tissue culture assay with confirmation by enzyme immunoassay Premier™ Toxins A&B (Meridian Bioscience, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). In CDDFT, toxins were detected by the VIDAS® C. difficile A&B (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l’Etoile, France). To improve the detection of CDD from June 2010, CDDFT also introduced detection of the C. difficile antigen glutamate dehydrogenase C. DIFF QUIK CHEK® (TECHLAB® Inc., Blacksburg, VA, USA) to be used in conjunction with the toxin assay. Further stools samples were requested if a cause of diarrhoea was not identified and especially if there was clinical suspicion of CDD. Stools positive for C. difficile toxin were cultured and the isolates sent to a central reference laboratory for ribotyping.

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea was defined as occurring in association with antibiotic therapy but without diarrhoeal pathogens detected on routine laboratory analysis or an alternative explanation (e.g. laxative treatment). Among patients with AAD, CDD was diagnosed in those with stools testing positive for C. difficile toxins.

Measurement of secondary outcomes

Information regarding the severity and duration of AAD and CDD, number of stools per day and stool consistency, incidence of recurrence of CDD within the follow-up period, the number of days with abdominal pain, bloating, flatus and nausea, duration of hospital stay and acceptability of the live bacterial preparation was collected by the research nurses during follow-up (see Appendix 4). CDD was investigated and managed according to the current hospital practice and clinical and laboratory information from clinical records was recorded (see Appendix 4). Information regarding the occurrence of pseudomembranous colitis, the need for colectomy and death was also collected from the patient’s case records. The information from follow-up and patient case records was used to classify the severity of CDD according to UK national guidelines (see Appendix 6). 39 The severity of CDD was classified independently by two assessors, WH and SA, and differences resolved by discussion.

Quality of life was assessed by the generic Short Form questionnaire-12 items version 2 (SF-12 v2) administered by research nurses at baseline and at 4 and 8 weeks. SF-12 v2 QoL subscales (social function, role function–emotional, role function–physical, general health, mental health, bodily pain, vitality, physical functioning), physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores were calculated and quality assured according to the QualityMetric Incorporated guidance40 with imputation of missing scores using the SF-12 v2 Missing Data Estimator software where possible. 40 SF-12 v2 subdomain, PCS and MCS scores were allocated a value of 0 for the lowest/worse score and 100 for the highest/best score.

Serious adverse events were identified and reported according to standard guidelines. 41 Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions were to be reported immediately to the independent safety monitor and, if appropriate, the ethics committee in accordance with local and national requirements, which were identified as:

-

any manifestation of infection (e.g. abscess, bacterial endocarditis, bacteraemia) in which lactobacilli or bifidobacteria were isolated from pathological specimens

-

the development of pancreatitis, which was defined as abdominal pain with serum amylase or lipase concentration equal to or greater than three times the institutional upper limit of normal

-

the development of multiorgan failure

-

the development of bowel ischaemia.

Additional data collected

Information was collected to identify subgroups of participants who may be at increased risk of AAD and CDD. This included potential risk factors at baseline, antibiotic treatment and duration of hospital stay.

Data management

All data were collected on standardised forms that were checked for missing values by the trial manager. Routine laboratory records were accessed to record results of stool analyses. Data were entered into Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and included range checks and double entry. Databases were compared using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to identify data entry errors.

Antibiotics were classified according to British National Formulary categories (see Appendix 7). 42 Indications for antibiotic treatment were classified according to the system organ class (SOC) terminology of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). 43 Participants were allocated to each SOC for either suspected or proven infection of that organ or system. Antibiotic treatment for suspected infection where no system or organ was identified was classified as ‘suspected sepsis but site unclear’. SAEs were coded according to the most appropriate preferred terms (PTs) of the MedDRA. 43

After data cleaning, databases were locked and forwarded to the trial statistician for analysis. Initial analysis according to the randomisation sequence identified the two arms of the study as only ‘A’ or ‘B’. The identity of the two arms was only revealed after the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee had reviewed these data and approved the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and baseline data were summarised by recruitment hospital and treatment group. Continuous variables were summarised using number of observations, median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables by the number and percentage of events.

Analysis of primary and secondary end points was performed in a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) population that excluded a small number of subjects who withdrew shortly after randomisation and did not have follow-up data. The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions. Risk difference and RR together with the 95% CIs were calculated using a generalised linear model that included treatment as a single predictor. Similarly, CIs for the ORs of AAD and CDD were estimated from logistic regression models. Secondary continuous outcomes with no repeated measurements were summarised using number of observations, median and IQR. The t-test or Mann–Whitney method were used to compare continuous variables. Duration data were summarised by median and IQR and compared using the Mann–Whitney method. No transformation was used for any variables.

Analysis of primary end points was also performed by logistic regression model adjusting for the following prespecified baseline characteristics and potential risk factors for AAD that may be likely to affect the occurrence of the primary end point:

-

centre

-

age

-

sex

-

antibiotic class

-

duration of antibiotic treatment

-

antacid therapy (including PPI treatment)

-

NGT in situ

-

previous gastrointestinal surgery

-

recent previous hospital admission

-

duration of hospital stay.

We intended to include all 10 prespecified variables in the logistic model but some were not entered because their effects were inestimable. A per-protocol (PP) population excluded participants who did not receive any IMP doses or in whom compliance was unclear. Additional analyses also assessed probiotic effect on primary outcomes in participants who took all 21 doses, 14 or more doses, or seven or more doses of the IMP. Analysis methods for the PP population were similar to those described for the modified ITT population. All analyses were performed on both the modified ITT and PP populations.

SAS version 9.2 was used for data analyses.

Quality of life analysis

The main analysis compared the change from baseline in SF-12 v2 PCS and MCS composite scores at 4 weeks in the two study arms. We also compared SF-12 v2 PCS and MCS composite scores at 8 weeks and scores for individual SF-12 v2 subdomains (social function, role function–emotional, role function–physical, general health, mental health, bodily pain, vitality and physical functioning) at 4 and 8 weeks. Composite scores were compared using mixed model analysis using the SF-12 v2 score at baseline as a covariate, treatment, visit, interaction between the treatment and visit as fixed effects, and subject as a random effect. During the trial, some subjects dropped out, resulting in some incomplete observations. These incomplete observations were not computed but were assumed to be missing at random in the mixed model analysis. The treatment difference, together with the 95% CI at each visit, was derived from the mixed model.

Economic analysis

The cost-effectiveness evaluation was undertaken from the perspective of the UK NHS. Costs were assigned to the resources utilised by each participant. These consisted of the bacterial preparation, staff time involved in administering the preparation, treatment relating to potential adverse events, the assessment of cases of diarrhoea (stool collection and culture/toxin assay, endoscopy) and diarrhoea management costs (laundry, antibiotics, increased hospital stay and comorbidities). Unit costs (cost year 2011) were derived from published information44–46 and through discussions with relevant clinical and finance department staff. Missing data were addressed using the imputation-based method for QoL data and censored data relating to costs using the weighted cost method with known cost histories. 47 In view of the short timescale of the project, there was no discounting of the costs or benefits. Costs and benefits would have been discounted at the conventional rate of 3.5% if the time scale of the follow-up had exceeded 1 year.

Cost differences between the two arms of the study were determined and used in conjunction with differences in outcomes in undertaking a cost–consequences analysis, with cost per case of AAD averted as the primary outcome measure. We planned to undertake subgroup analyses to determine the relative cost-effectiveness of preventative strategies in different risk groups as indicated in the covariate analysis. In addition, a cost–utility analysis considered the differences in costs between the two study arms and differences in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) derived from European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) responses.

Resource use and costs

Health-care contacts

The number of health-care contacts, duration of initial hospital stay, days spent in care facilities and number and duration of readmissions were recorded routinely within the trial. If the discharge date was not known, the end of follow-up was assumed to be the discharge date. A weighted unit cost of £334.17 was applied for every day a participant spent in hospital (NHS reference costs 2011; extrapolated). 44 For the base-case analysis, all other health-care contacts were treated as general practitioner (GP) visits and published care home costs were applied on a daily rate basis. 45

Antibiotics

Antibiotic use was collected throughout the 8-week follow-up period and costed using published sources. 46 Staff time was assumed to be 5 minutes for the administration of oral antibiotics and 20 minutes for intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics. As 66% of doses during the study period were delivered orally and 34% intravenously, staff cost per dose was weighted to 10.1 minutes per dose and costed at £16.33 per dose. 45 Missing data on antibiotic dose were replaced by the most common value. If no data were available on number of doses per day or duration of antibiotic course, it was assumed that the patient was receiving a full course of the recorded antibiotic.

Intervention implementation

For the cost-effectiveness analysis, it was assumed that every patient would receive a course of 21 oral capsules containing the probiotic formulation at a retail cost of £10 and that capsules that were not taken by the participant would go to waste (as a high proportion of participants finished their course at home after hospital discharge). While the patient was in hospital, staff time of 5 minutes was allocated for administration of each dose. The number of days in hospital (and thus number of nurse contacts) was calculated individually for each patient according to his or her intervention start and hospital discharge dates. Nursing time was allocated even if the patient declined the intervention, as time would have been used for patient interaction and assessment of the situation. No staff time was allocated after the patient withdrew or died. Nursing time was costed at £8.08 per 5 minutes. 45 The cost of placebo formulation and staff cost for administration in the control group were excluded from the cost-effectiveness analysis as ‘routine use’ was considered.

Episodes of diarrhoea

Costs regarding health-care resource use, antibiotics and increase in length of hospital stay associated with diarrhoea were collected routinely during the trial. Other costs, such as diagnostics, clinical review, cleaning, laundry and isolation, were sourced from outside the trial setting. Resource use and costs of laboratory tests for C. difficile detection were obtained using a microcosting approach based on internal standard operating procedures and discussions with key laboratory staff and purchasing officers. Costs of other diagnostic tests (Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, E. coli 0157 and norovirus) were taken from the literature. 48 Published reference costs44 were used to estimate the costs of diagnostic (endoscopy, abdominal computerised tomography and radiography) and therapeutic (colectomy) procedures, which were then weighted to reflect the probability of the event occurring in a population suffering from diarrhoea based on recent publications. 49,50 Costs of patient assessment, including for review of antibiotic treatment and nutritional requirements, and infection control measures were based on discussions with infection control nurses, clinicians and microbiologists. The medical team in the base case was assumed to consist of the treating clinician (costed as registrar), a gastroenterologist, a microbiologist, an infection control nurse, a ward nurse and a pharmacist. Staff time was estimated to be 45 minutes for the registrar and 15 minutes for the other professionals and unit costs were obtained from the literature. 45 Cleaning after patient discharge from the hospital or relocation after a diarrhoea episode was costed based on discussions with key members of infection control staff and includes domestic staff time, specialist cleaning agents (hypochlorite; TUFFIE 5®, Vernacare UK, Bolton, UK) and special cleaning equipment as well as laundry, steam cleaning and use of an autoclave. Costs were obtained from hospital human resource and purchasing departments, wholesalers, published literature51 and microcosting. All costs were allocated once per patient diarrhoea episode.

Daily costs of diarrhoeal disease included daily cleaning and bed and ward closures. Costing of daily cleaning included domestic staff time, specialist cleaning agents and special cleaning equipment. Costs were obtained from human resources and purchasing departments as well as wholesalers. A lost bed-day due to closures was costed at £334.17 by published reference costs44 and weighted for specialties (e.g. whether or not the bed is in intensive care) and activity. 44 Data on frequency of ward closures due to CDD and number of positive cases identified per year were obtained from discussions with key staff and Public Health Wales reports. 52 It was assumed that 1 in 115 cases resulted in an outbreak and subsequent ward closure. Based on an average ward size of 28 beds in Singleton and Morriston hospitals, ward closures could cost up to £9356.76 per day and occur in 0.87% of positive cases. Thus, a weighted cost of £81.40 was applied to each diarrhoea case per day to account for potential ward closures.

The cost per stool included disposables such as gloves and aprons, laundry and staff time for patient check-ups, spot cleaning and changing of beds. Costing of spot cleaning included nursing time, specialist cleaning agents and special cleaning equipment. Data on number of stools per day, duration of diarrhoea episode in days and whether or not the episode was managed in hospital were collected routinely as part of the trial. These data were used to calculate the cost of a diarrhoea episode individually for each patient by applying the one-off episode costs (microbiology, review, procedures, end cleaning) and adding daily and per stool costs according to duration and stool frequency. No cost was applied to participants whose diarrhoea was managed entirely at home. Episodes managed in care homes were treated as hospital episodes.

Cost-effectiveness analyses

Patient responses from EQ-5D questionnaires at baseline and after 4 and 8 weeks were translated into utility scores using a scoring algorithm. We planned to use health and cost outcomes to calculate the cost of probiotics per QALY gained in a cost–utility analysis, to obtain the cost per case of diarrhoea averted in a cost-effectiveness analysis and to present and compare outcomes in tabular form in a cost–consequences analysis. The results of cost-effectiveness analyses were expressed as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) and calculated by dividing the cost difference between the two alternatives being compared by the difference in the effect/benefit. In cost–utility analysis, the effect was expressed in QALYs. The cost per QALY was calculated by dividing the difference in costs by the difference in QALYs for each comparison.

Generally, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence considers an intervention cost-effective if one of the following applies. 53

-

The intervention is less costly and more clinically effective than all other relevant alternatives. In this case, no ICER is calculated as the strategy in question dominates the alternatives.

-

The intervention has an ICER of < £20,000 per QALY compared with the next best alternative. This means that an investment of up to £20,000 in order to achieve an additional QALY is considered cost-effective.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses investigated the robustness of the results to changes in estimated costs and outcomes and probabilistic sensitivity analysis used bootstrap resampling to determine the probability that preventative strategies were within certain thresholds. We planned to assess the budgetary impact from a NHS perspective of adopting a policy of administering the bacterial preparation to prevent or ameliorate AAD and CDD in the target population.

During univariate sensitivity analysis, all ICERs were recalculated after changing the value of a range of parameters individually to estimate the robustness of the ICER (Table 1). Prolonged inpatient stay is the main cost driver when considering the cost of diarrhoea. 13,15,16 Other potentially important cost differences between the probiotic and placebo arms included staff time, which is naturally subject to variation, and diarrhoea-associated costs such as cleaning, laundry, microbiology, assessment, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. As these costs were thought to make up a large proportion of the total health-care costs, the impact of changes to parameters contained within these costs was evaluated.

| Parameter | Minimum | Maximum | Change from base case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Costing of diarrhoea (£) | |||

| Microbiology ABMUHB | 30.17 | 109.88 | 50% discount on consumables; two samples tested per patient |

| Microbiology CDDFT | 27.51 | 90.56 | 50% discount on consumables; two samples tested per patient |

| Ward and bed closures | 0.00 | 497.61 | No cost effect; double the amount of wards closed per year |

| Clinical assessment and review | 103.01 | 259.67 | Reduced staff time, no gastroenterologist; increased staff time |

| Cleaning, laundry and disposables | 57.15 | 85.73 | ± 20% |

| Other costs (£) | |||

| Cost of one hospital inpatient day | 267.34 | 401.00 | ± 20% |

| Other parameters | |||

| Staff time/dose probiotics (minutes) | 2.5 | 10 | Half; double |

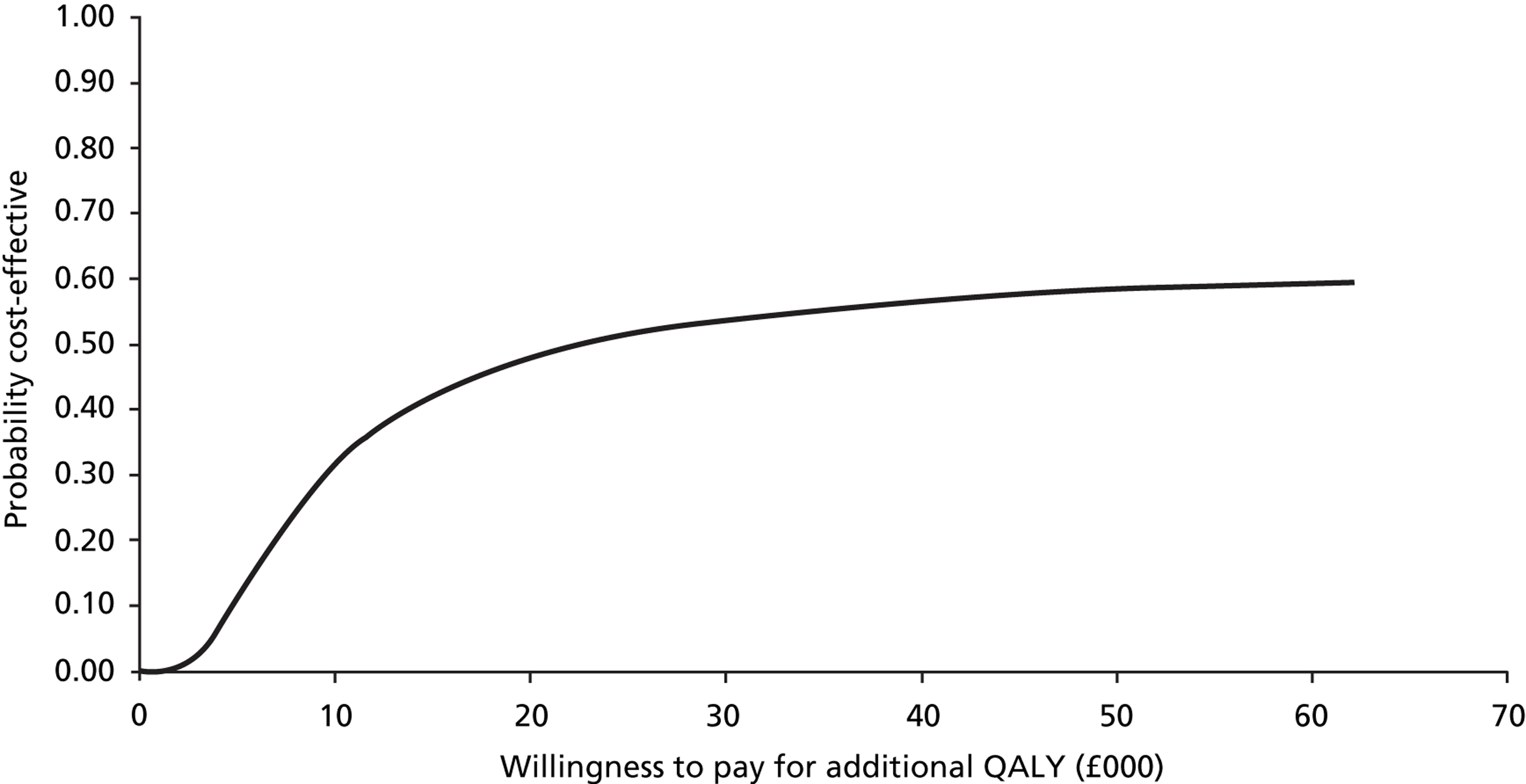

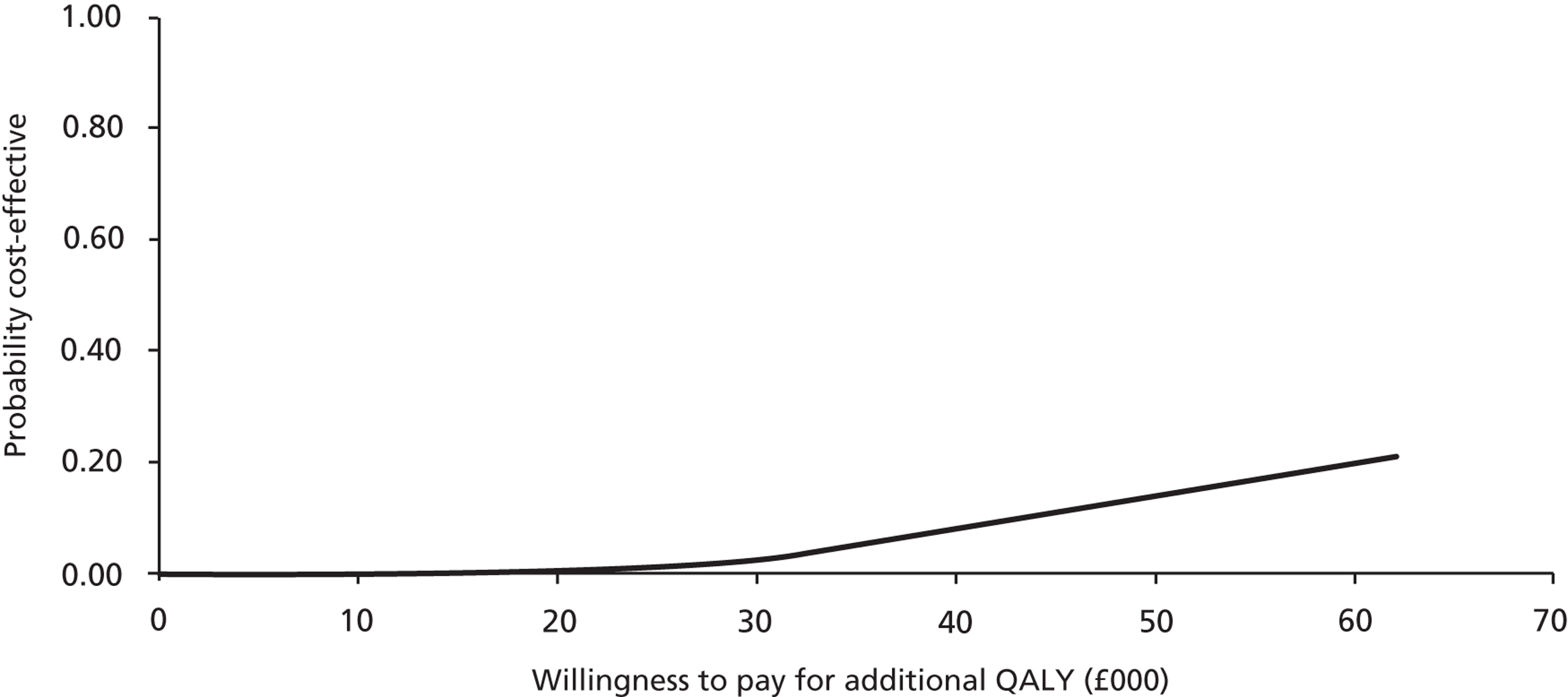

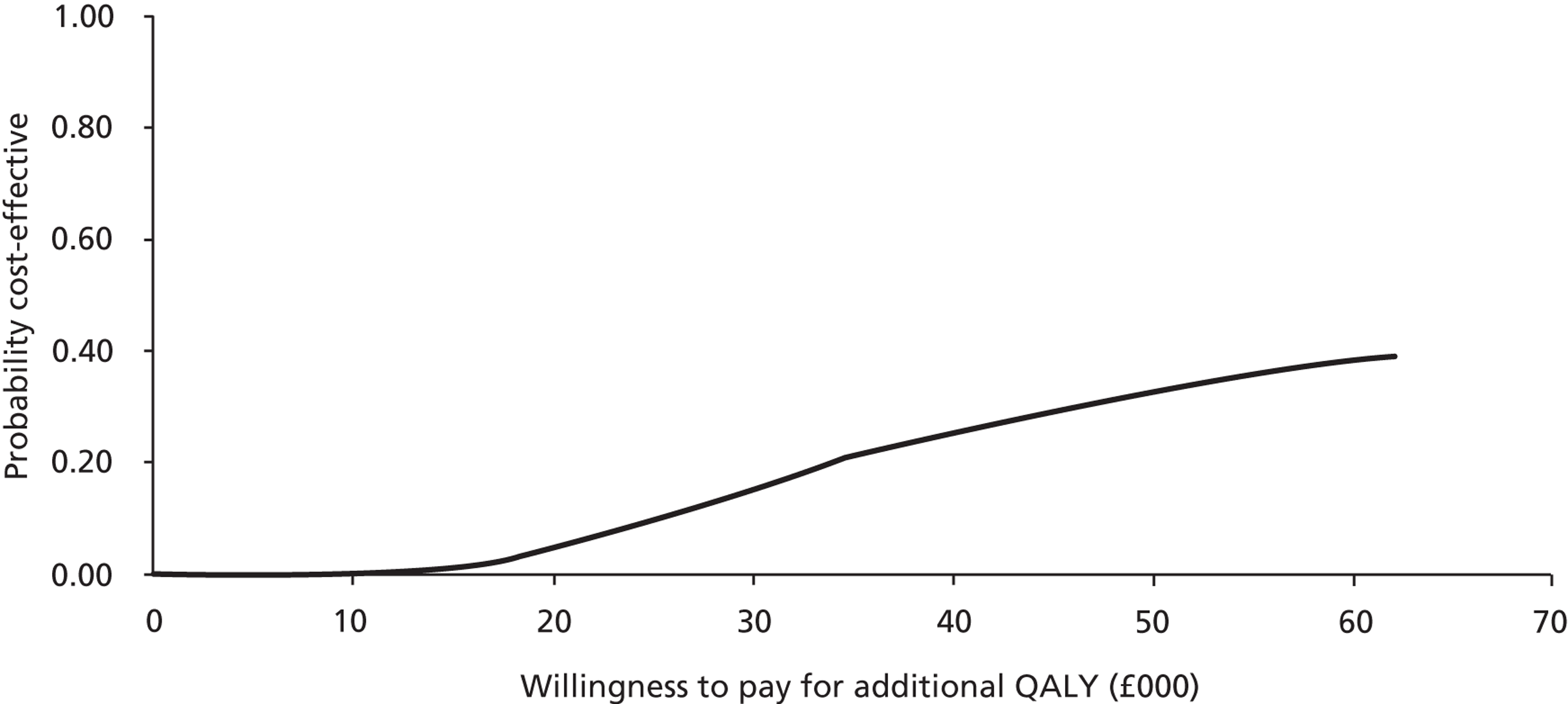

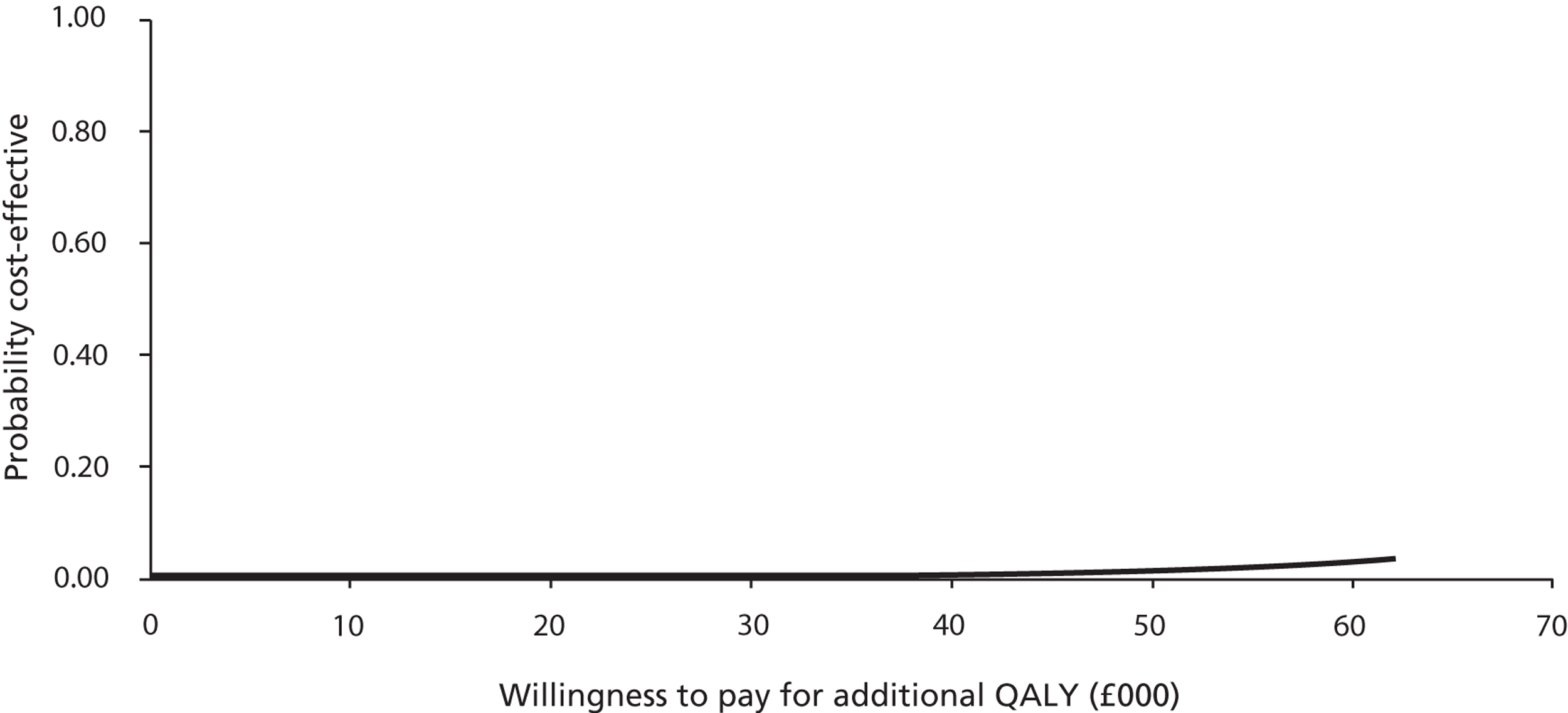

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis with changes to the values of all chosen parameters (usually within the 95% CI or a reasonable, defined range) calculated the probability that the intervention was cost-effective when all uncertainty associated with the individual parameters was considered. Results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis were expressed as per cent probability that the intervention was cost-effective. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were generated to depict the probability of the intervention being cost-effective at different willingness-to-pay thresholds.

Chapter 3 Protocol changes

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In practice, on assessment for eligibility, some patients were severely ill and not expected to survive for the intended period of follow-up; therefore, they were not approached regarding joining the study. Similarly, participants who were nil by mouth at initial assessment were not approached.

Follow-up

We had intended that diarrhoea outcomes would be assessed during antibiotic treatment and for 8 weeks after stopping antibiotics. However, prolonged follow-up for participants on long courses of antibiotics was not feasible. In practice, daily follow-up during hospital stay or weekly follow-up after discharge from hospital was continued to 8 weeks after recruitment. Review of laboratory data regarding stool assays was continued until 12 weeks after recruitment.

Assessment of quality of life

We considered modifying tools validated to measure QoL in treatment-induced diarrhoea in people with HIV54 and older patients with faecal incontinence. 55 However, we considered that completion of additional questionnaires would be too onerous for elderly inpatients and these were not pursued.

Chapter 4 Results

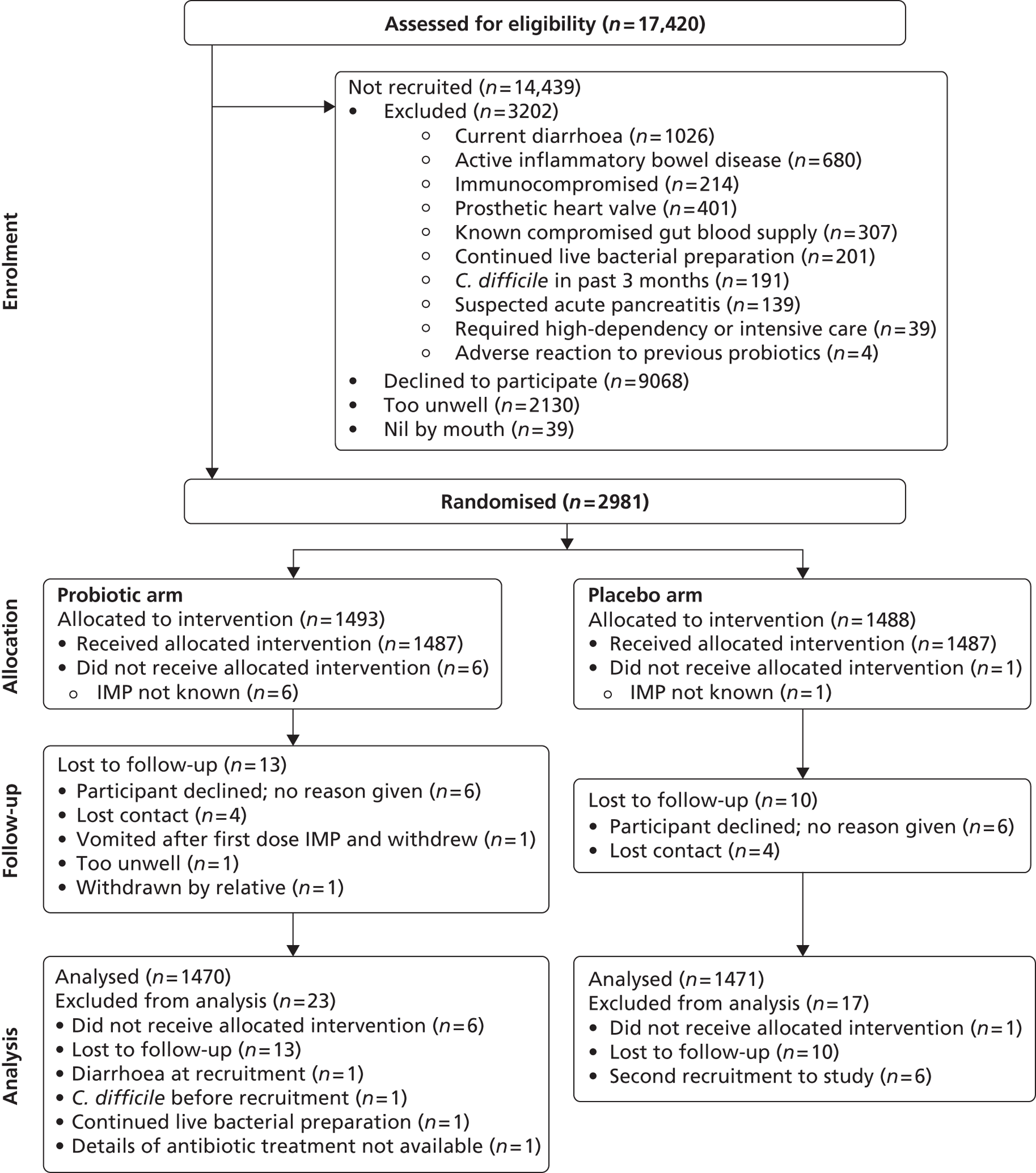

A total of 17,420 in-patients aged ≥ 65 years and who had been exposed to one or more antibiotics were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). Exclusion criteria were present in 3202 (18.4%) patients, 9068 (52.1%) declined to participate, 2130 (12.2%) were too unwell to join the study and 39 (0.2%) were nil by mouth. We recruited 2981 (17.1%) patients, at randomisation 1493 (50.1%) were allocated to the probiotic and 1488 (49.9%) to the placebo arm.

FIGURE 1.

Trial profile.

In total, 2941 (98.7%) were included in the analysis according to treatment allocated; 23 in the probiotic arm and 17 in the placebo arm were excluded. The identity of the IMP was unknown in seven participants (six allocated to the probiotic and one to the placebo arm) due to an error in IMP labelling at one hospital site. No outcome data were available in 23 patients who were lost to follow-up. In each arm of the study, these included six patients who declined further participation shortly after randomisation without giving a reason and contact was lost with four patients from each arm. Exclusion criteria were present at recruitment in three patients and the details of antibiotic treatment could not be determined in one patient in the probiotic arm. Six participants were recruited to the study for a second time and all were allocated to the placebo arm. Possible carry-over effects from their first involvement in the study could not be excluded and; therefore, data from their second involvement were excluded.

Participant characteristics according to intervention arm

Consent to participate in the trial was provided directly by 1398 patients (95.1%) in the probiotic arm and 1392 patients (94.6%) in the placebo arm. For patients unable to give consent themselves, assent was usually provided by a family member: daughter [in 24 cases (1.6%) in the probiotic arm and 34 cases (2.3%) in the placebo arm], wife [in 19 cases (1.3%) in the probiotic arm and 13 cases (0.9%) in the placebo arm], or son [in 15 cases (1.0%) in the probiotic arm and 18 cases (1.2%) in the placebo arm].

Baseline demographic and patient characteristics were similar in the two intervention arms except for a greater proportion of males than females in the probiotic arm and vice versa in the placebo arm (Table 2). The frailty of the study population is reflected in the median age of 77.1 years and common occurrence of comorbid illnesses: 54.6% of participants suffered from hypertension, 24.1% from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and 22.9% from diabetes. Participant age ranged from 65.0 to 107.5 years in the probiotic arm and from 65.0 to 104.4 years in the placebo arm. More participants were recruited during the winter than in the summer months. The majority of patients were admitted to hospital from home and approximately one-third had been admitted to hospital within the previous 8 weeks. Very few people of non-white ethnic origin were recruited. Cigarette smoking was uncommon, but approximately one in three participants drank alcohol. Recent consumption of foods containing live bacteria was uncommon among all participants and occurred with a similar frequency in both study arms.

| Characteristic | Probiotica (n = 1470) | Placeboa (n = 1471) | Total (n = 2941) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (IQR) | 77.2 (70.8–83.6) | 77.0 (71.3–83.5) | 77.1 (71.0–83.5) |

| Male, n/N (%) | 777/1470 (52.9) | 679/1471 (46.2) | 1456/2941 (49.5) |

| Ethnicity, n/N (%) white | 1459/1461 (99.9) | 1461/1464 (99.8) | 2920/2925 (99.8) |

| Recruited during winter (October–March), n/N (%) | 845/1470 (57.5) | 845/1471 (57.4) | 1690/2941 (57.5) |

| Where admitted from | n = 1469 | n = 1468 | n = 2937 |

|

1345 (91.6) | 1334 (90.9) | 2679 (91.2) |

|

58 (3.9) | 67 (4.6) | 125 (4.3) |

|

37 (2.5) | 39 (2.7) | 76 (2.6) |

|

29 (2.0) | 28 (1.9) | 57 (1.9) |

| Hospital | |||

|

102 (6.9) | 101 (6.9) | 203 (6.9) |

|

742 (50.5) | 737 (50.1) | 1479 (50.3) |

|

94 (6.4) | 97 (6.6) | 191 (6.5) |

|

269 (18.3) | 278 (18.9) | 547 (18.6) |

|

263 (17.9) | 258 (17.5) | 521 (17.7) |

| Cigarette smoker, n/N (%) | 140/1470 (9.5) | 120/1471 (8.2) | 260/2941 (8.8) |

| Drinks alcohol, n/N (%) | 459/1470 (31.2) | 482/1471 (32.8) | 941/2941 (32.0) |

| Comorbid illnesses | |||

|

779/1455 (53.5) | 812/1457 (55.7) | 1591/2912 (54.6) |

|

350/1459 (24.0) | 354/1462 (24.2) | 704/2921 (24.1) |

|

357/1465 (24.4) | 314/1468 (21.4) | 671/2933 (22.9) |

|

237/1462 (16.2) | 232/1465 (15.8) | 469/2927 (16.0) |

|

127/1455 (8.7) | 139/1461 (9.5) | 266/2916 (9.1) |

|

61/1449 (4.2) | 80/1459 (5.5) | 141/2908 (4.8) |

|

28/1465 (1.9) | 26/1465 (1.8) | 54/2930 (1.8) |

|

978/1452 (67.4) | 1010/1458 (69.3) | 1988/2910 (68.3) |

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery, n/N (%) | 203/1448 (14.0) | 212/1449 (14.6) | 415/2897 (14.3) |

| NGT in situ, n/N (%) | 5/1469 (0.3) | 2/1464 (0.1) | 7/2933 (0.2) |

| Hospital admission in last 8 weeks, n/N (%) | 488/1470 (33.2) | 448/1471 (30.5) | 936/2941 (31.8) |

| Median number of hospital admissions in last 8 weeks (IQR) | 1465 0.0 (0.0–10) | 1467 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 2932 0.0 (0.0–1.0) |

| Live bacteria consumed in last 7 days, n/N (%) | 72/1470 (4.9) | 45/1471 (3.1) | 117/2941 (4.0) |

Participant characteristics according to centre

Overall, 1873 (63.7%) inpatients were recruited in hospitals in ABMUHB (Singleton, Morriston and Princess of Wales) and 1068 (36.3%) in CDDFT (Durham and Darlington). In ABMUHB, recruitment began with a pilot study of 50 patients in Morriston Hospital on 1 December 2008 to evaluate the recruitment methods and data collection forms. Methods were found to be reliable and these patients were included in the final analysis. Recruitment continued until 28 February 2012 and a total of 1479 patients (50.3% of total) were recruited (see Table 2). Recruitment in Singleton Hospital began on 9 June 2009 but was terminated on 9 February 2011, after 203 (6.9%) patients had been recruited, because of falling numbers of eligible patients due to service reconfiguration. To maintain patient numbers, recruitment was undertaken at Princess of Wales Hospital from 5 May 2011 to 10 January 2012 and 191 (6.5%) patients were recruited. The start of recruitment was delayed in CDDFT for operational reasons. Darlington Memorial Hospital recruited 521 (17.7%) patients from 12 October 2009 to 27 February 2012 and University Hospital of North Durham recruited 547 (18.6%) patients from 17 November 2011 to 28 February 2012 (see Table 2).

Baseline participant characteristics were generally similar across the hospital sites (Table 3) with some exceptions. The greater proportion of males in the probiotic arm and females in the placebo arm occurred in all centres except for Singleton Hospital, where there were more females than males in the probiotic arm (data not shown). Participants recruited at Singleton Hospital were more likely to be female and tended to be older than participants from other hospitals. The period during which recruitment in each centre occurred was reflected in the lower proportion of patient recruitment during the winter months in Princess of Wales than in other hospitals. The frequency of COPD and hospital admission in the previous 8 weeks were both more common in hospitals in CDDFT than in ABMUHB.

| Variable | ABMUHBa | CDDFTa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singleton | Morriston | Princess of Wales | Durham | Darlington | |

| Number participants recruited | n = 203 | n = 1479 | n = 191 | n = 547 | n = 521 |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 79.9 (74.1–86.3) | 76.8 (70.6–83.4) | 76.0 (70.4–82.7) | 77.7 (71.3–84.2) | 76.4 (70.8–82.1) |

| Male, n (%) | 85 (41.9) | 755 (51.0) | 93 (48.7) | 271 (49.5) | 252 (48.4) |

| Ethnicity, n/N (%) white | 203/203 (100.0) | 1467/1469 (99.9) | 188/188 (100.0) | 543/544 (99.8) | 519/521 (99.6) |

| Recruited during winter (October–March) n/N (%) | 130/203 (64.0) | 819/1479 (55.4) | 66/191 (34.6) | 368/547 (67.3) | 307/521 (58.9) |

| Where admitted from | |||||

|

184 (90.6) | 1312 (88.8) | 184 (96.3) | 506 (93.0) | 493 (94.6) |

|

14 (6.9) | 61 (4.1) | 3 (1.6) | 28 (5.1) | 19 (3.6) |

|

2 (1.0) | 64 (4.3) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) |

|

3 (1.5) | 41 (2.8) | 3 (1.6) | 6 (1.1) | 4 (0.8) |

| Cigarette smoker, n/N (%) | 16/203 (7.9) | 122/1479 (8.2) | 18/191 (9.4) | 66/547 (12.1) | 38/521 (7.3) |

| Drinks alcohol, n/N (%) | 66/203 (32.5) | 487/1479 (32.9) | 43/191 (22.5) | 160/547 (29.3) | 185/521 (35.5) |

| Comorbid illnesses | |||||

|

88/198 (44.4) | 827/1467 (56.4) | 106/186 (57.0) | 261/545 (47.9) | 309/516 (59.9) |

|

54/201 (26.9) | 216/1468 (14.7) | 53/189 (28.0) | 216/544 (39.7) | 165/519 (31.8) |

|

48/202 (23.8) | 336/1477 (22.7) | 40/191 (20.9) | 138/543 (25.4) | 109/520 (21.0) |

|

43/202 (21.3) | 194/1473 (13.2) | 26/191 (13.6) | 96/542 (17.7) | 110/519 (21.2) |

|

20/202 (9.9) | 99/1467 (6.7) | 13/188 (6.9) | 68/540 (12.6) | 66/519 (12.7) |

|

17/202 (8.4) | 73/1458 (5.0) | 3/191 (1.6) | 32/539 (5.9) | 16/518 (3.1) |

|

3/202 (1.5) | 22/1475 (1.5) | 5/191 (2.6) | 13/542 (2.4) | 11/520 (2.1) |

|

91/199 (45.7) | 929/1470 (63.2) | 132/187 (70.6) | 420/542 (77.5) | 416/512 (81.3) |

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery, n/N (%) | 21/194 (10.8) | 201/1460 (13.8) | 18/188 (9.6) | 81/537 (15.1) | 94/518 (18.1) |

| NGT in situ, n/N (%) | 1/203 (0.5) | 1/1477 (0.1) | 1/191 (0.5) | 2/541 (0.4) | 2/521 (0.4) |

| Hospital admission in last 8 weeks, n/N (%) | 50/203 (24.6) | 311/1479 (21.0) | 30/191 (15.7) | 304/547 (55.6) | 241/521 (46.3) |

| Number of hospital admissions in last 8 weeks, n, median (IQR) | 201, 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1473, 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 191, 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 546, 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 521, 0.0 (0.0–1.0) |

| Live bacteria consumed in last 7 days, n/N (%) | 7/203 (3.4) | 65/1479 (4.4) | 6/191 (3.1) | 12/547 (2.2) | 27/521 (5.2) |

Indications for initial antibiotic treatment

Indications for antibiotic treatment classified according to the MedDRA SOC43 were similar in the two study arms (Table 4). The most common indication was ‘respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders’. Antibiotic treatment for suspected sepsis where the site was unclear was given to a small proportion of patients. About one in four patients in each arm of the study received antibiotics for prophylaxis rather than the treatment of infection and nearly all of these were for surgical and medical procedures.

| Indication for initial antibiotic treatment | Probiotic (n = 1470) (%) | Placebo (n = 1471) (%) | Total (n = 2941) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) |

|

5 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) |

|

4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

|

14 (1.0) | 8 (0.5) | 22 (0.7) |

|

32 (2.2) | 23 (1.6) | 55 (1.9) |

|

2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

|

67 (4.6) | 56 (3.8) | 123 (4.2) |

|

18 (1.2) | 17 (1.2) | 35 (1.2) |

|

3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) |

|

265 (18.0) | 278 (18.9) | 543 (18.5) |

|

2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

|

501 (34.1) | 525 (35.7) | 1026 (34.9) |

|

166 (11.3) | 147 (10.0) | 313 (10.6) |

|

338 (23.0) | 363 (24.7) | 701 (23.8) |

|

2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

| Suspected sepsis but site unclear | 49 (3.3) | 39 (2.7) | 88 (3.0) |

In keeping with differences in the frequency of COPD according to centre, a greater proportion of the patients in hospitals in CDDFT than ABMUHB were treated for ‘respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders’ (Table 5).

| Indication for initial antibiotic treatment | ABMUHB | CDDFT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singleton (n = 203) (%) | Morriston (n = 1479) (%) | Princess of Wales (n = 191) (%) | Durham (n = 547) (%) | Darlington (n = 521) (%) | |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Cardiovascular disorders | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Eye disorders | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 (0.0) | 17 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 7 (3.4) | 24 (1.6) | 5 (2.6) | 13 (2.4) | 6 (1.2) |

| Infections and infestations | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 2 (1.0) | 100 (6.8) | 6 (3.1) | 5 (0.9) | 10 (1.9) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 (0.0) | 18 (1.2) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (0.9) | 10 (1.9) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 56 (27.6) | 284 (19.2) | 37 (19.4) | 105 (19.2) | 61 (11.7) |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 90 (44.3) | 331 (22.4) | 64 (33.5) | 313 (57.2) | 228 (43.8) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 25 (12.3) | 162 (11.0) | 21 (11.0) | 52 (9.5) | 53 (10.2) |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 9 (4.4) | 488 (33.0) | 49 (25.7) | 28 (5.1) | 127 (24.4) |

| Vascular disorder | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Suspected sepsis but site unclear | 12 (5.9) | 42 (2.8) | 1 (0.5) | 18 (3.3) | 15 (2.9) |

Antibiotic exposure

All of the participants were receiving one or more antibiotics when they started the IMPs. The date the participant began taking the antibiotics before recruitment was known in 1448 participants in the probiotic and 1443 in the placebo arm. The median (IQR) period of exposure to antibiotics before starting the IMP was 3.0 days (2.0–6.0 days) in both study arms (p = 0.38).

During the period 7 days before, and 8 weeks following, recruitment, the most commonly used antibiotic class was the penicillins, with over half of all participants receiving a broad-spectrum penicillin. About one in four participants were exposed to a cephalosporin. Antibiotic exposure was similar in the two study arms (Table 6).

| Antibiotic (classes and individual drugs) | Probiotic (n = 1470) (%) | Placebo (n = 1471) (%) | Total (n = 2941) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillins | 1052 (71.6) | 1061 (72.1) | 2113 (71.8) |

| Benzylpenicillin | 115 (7.8) | 99 (6.7) | 214 (7.3) |

| Penicillinase-resistant penicillin – flucloxacillin | 322 (21.9) | 310 (21.1) | 632 (21.5) |

| Broad-spectrum penicillins | 822 (55.9) | 829 (56.4) | 1651 (56.1) |

|

310 (21.1) | 323 (22.0) | 633 (21.5) |

|

2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

|

612 (41.6) | 623 (42.4) | 1235 (42.1) |

| Anti-pseudomonas penicillins | 127 (8.6) | 118 (8.0) | 245 (8.3) |

|

3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) |

|

125 (8.5) | 118 (8.0) | 243 (8.3) |

| Cephalosporins | 359 (24.4) | 356 (24.2) | 715 (24.3) |

| First generation | 77 (5.2) | 74 (5.0) | 151 (5.1) |

|

77 (5.2) | 73 (5.0) | 150 (5.1) |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Second generation | 290 (19.7) | 304 (20.7) | 594 (20.2) |

|

27 (1.8) | 24 (1.6) | 51 (1.7) |

|

1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

|

284 (19.3) | 293 (19.9) | 577 (19.6) |

| Third generation | 11 (0.7) | 10 (0.7) | 21 (0.7) |

|

1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

|

7 (0.5) | 7 (0.5) | 14 (0.5) |

|

3 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) |

| Other antibiotics | |||

| Carbapenems and other β-lactams | 33 (2.2) | 29 (2.0) | 62 (2.1) |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

|

2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

|

31 (2.1) | 26 (1.8) | 57 (1.9) |

| Tetracyclines | 211 (14.4) | 222 (15.1) | 433 (14.7) |

|

0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

|

199 (13.5) | 213 (14.5) | 412 (14.0) |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

|

10 (0.7) | 4 (0.3) | 14 (0.5) |

|

2 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) |

| Aminoglycosides | 182 (12.4) | 196 (13.3) | 378 (12.9) |

|

182 (12.4) | 195 (13.3) | 377 (12.8) |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Macrolides | 249 (16.9) | 251 (17.1) | 500 (17.0) |

|

13 (0.9) | 11 (0.7) | 24 (0.8) |

|

203 (13.8) | 210 (14.3) | 413 (14.0) |

|

43 (2.9) | 41 (2.8) | 84 (2.9) |

| Clindamycin | 18 (1.2) | 14 (1.0) | 32 (1.1) |

| Sulphonamides and trimethoprim | 228 (15.5) | 242 (16.5) | 470 (16.0) |

|

0 (0.0) | 6 (0.4) | 6 (0.2) |

|

228 (15.5) | 236 (16.0) | 464 (15.8) |

| Metronidazole | 171 (11.6) | 142 (9.7) | 313 (10.6) |

| Quinolones | 185 (12.6) | 180 (12.2) | 365 (12.4) |

|

171 (11.6) | 157 (10.7) | 328 (11.2) |

|

14 (1.0) | 21 (1.4) | 35 (1.2) |

|

2 (0.1) | 5 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) |

|

0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Glycopeptides | 103 (7.0) | 75 (5.1) | 178 (6.1) |

|

82 (5.6) | 61 (4.1) | 143 (4.9) |

|

27 (1.8) | 20 (1.4) | 47 (1.6) |

| Anti-tuberculous antibiotics | 26 (1.8) | 20 (1.4) | 46 (1.6) |

|

1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

|

26 (1.8) | 20 (1.4) | 46 (1.6) |

|

1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Others | 38 (2.6) | 53 (3.6) | 91 (3.1) |

|

1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

|

3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) |

|

26 (1.8) | 45 (3.1) | 71 (2.4) |

|

9 (0.6) | 8 (0.5) | 17 (0.6) |

Antibiotic exposure varied according to centre (see Appendix 9, Table 31). In hospitals in CDDFT, exposure to broad-spectrum penicillins was greater than in hospitals in ABMUHB (67.8–70.6% vs. 47.3–57.1%, respectively), but exposure to cephalosporins was lower (1.9–3.3% vs. 13.6–29.1%, respectively), as was exposure to quinolones (6.9–7.5% vs. 8.4–21.2%, respectively).

Fewer than 1 in 10 participants received only a single dose of an antibiotic and most received antibiotics for ≥ 7, with one-third treated for at least 14 days (Tables 7 and 8). The majority of participants were exposed to antibiotics from two or more classes. Exposure to combination therapy and duration of antibiotic therapy was similar in the two study arms.

| Combination antibiotic therapya | Probiotic (n = 1470) | Placebo (n = 1471) | Total (n = 2941) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) participants who received an antibiotic from | |||

| One class only | 310 (21.1) | 310 (21.1) | 620 (21.1) |

| Two classes | 407 (27.7) | 397 (27.0) | 804 (27.3) |

| Three or more classes | 753 (51.2) | 764 (51.9) | 1517 (51.6) |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | Probiotica (n = 1406) | Placeboa (n = 1398) | Total (n = 2804) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) participants who received | |||

| Single dose | 133 (9.5) | 123 (8.8) | 256 (9.1) |

| 1–6 days’ treatment | 389 (27.7) | 398 (28.5) | 787 (28.1) |

| 7–13 days’ treatment | 402 (28.6) | 426 (30.5) | 828 (29.5) |

| ≥ 14 days’ treatment | 482 (34.3) | 451 (32.3) | 933 (33.3) |

Non-antibiotic drug treatment

Use of drugs other than antibiotics was common, with many participants receiving antihypertensive therapy, aspirin, PPIs or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy. Non-antibiotic drug treatment was similar in the two study arms (Table 9).

| Drugs | Probiotic,a n/N (%) | Placebo,a n/N (%) | Total, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antacid therapies | |||

| PPI | 582/1459 (39.9) | 567/1460 (38.8) | 1149/2919 (39.4) |

| H2 blocker | 96/1449 (6.6) | 74/1454 (5.1) | 170/2903 (5.9) |

| Antacid | 30/1457 (2.1) | 34/1460 (2.3) | 64/2917 (2.2) |

| Other drugs | |||

| ACE inhibitor | 425/1449 (29.3) | 436/1453 (30.0) | 861/2902 (29.7) |

| Antihypertensive | 679/1450 (46.8) | 716/1453 (49.3) | 1395/2903 (48.1) |

| Aspirin | 597/1458 (40.9) | 589/1458 (40.4) | 1186/2916 (40.7) |

| Oral hypoglycaemic agent | 208/1460 (14.2) | 188/1460 (12.9) | 396/2920 (13.6) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 158/1450 (10.9) | 135/1454 (9.3) | 293/2904 (10.1) |

| Insulin | 96/1459 (6.6) | 78/1460 (5.3) | 174/2919 (6.0) |

| Feed containing probiotic | 8/1459 (0.5) | 9/1457 (0.6) | 17/2916 (0.6) |

Primary outcomes

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (including CDD) occurred with a similar frequency in the probiotic arm (159 participants, 10.8%) and placebo arm (153 participants, 10.4%; RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.28; p = 0.71; Table 10). This included 12 participants with frequent stools that they described as looser than normal but who were unable to describe stool consistency using the Bristol Stool Form Scale. 38

| Outcome | Probiotic n/N (%) | Placebo n/N (%) | RR (95% CI) [p-value] | OR (95% CI) [p-value] | Risk difference (95% CI) [p-value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AADb | 159/1470 (10.8) | 153/1471 (10.4) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.28) [0.72] | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.32) [0.72] | 0.42 (−1.81 to 2.64) [0.72] |

| CDD | 12/1470 (0.8) | 17/1471 (1.2) | 0.71 (0.34 to 1.47) [0.35] | 0.70 (0.34 to 1.48) [0.35] | −0.34 (−1.05 to 0.37) [0.35] |

Clostridium difficile diarrhoea was uncommon and occurred in 12 (0.8%) participants in the probiotic arm and 17 (1.2%) participants in the placebo arm (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.34 to 1.47; p = 0.35; see Table 10). Based on this effect size and the low prevalence of CDD, the number needed to treat to prevent one case is 295. This would be reduced to 95 for an effect size at the lower limit of the 95% CI (a threefold reduction in CDD in the probiotic arm). The corresponding number needed to harm (the upper 95% CI) is 267.

Secondary outcomes

Clostridium difficile was isolated from stools in two participants with mild loose stools (not meeting the study criteria for diarrhoea) in the probiotic arm. One participant in each arm had an episode of CDD after an initial episode of AAD that was not associated with CDI; the participant allocated to the placebo arm required surgery for CDD and the participant allocated to the probiotic arm had gallstones and died during the episode of CDD. One patient with known carcinoma of the head of the pancreas with a biliary stent in situ died during an episode of CDD that occurred after withdrawal from the trial.

The adjusted treatment effect on occurrence of AAD from covariate analysis was similar to the unadjusted effect after controlling for nine prespecified covariates. Covariate analysis identified that the occurrence of AAD could be predicted by the duration of antibiotic treatment, antacid therapy and duration of hospital stay (Table 11).

| Variablea | Comparison | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | Probiotic vs. placebo | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.27) |

| Centre | Singleton vs. Darlington | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.25) |

| Morriston vs. Darlington | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.21) | |

| Princess of Wales vs. Darlington | 1.08 (0.62 to 1.88) | |

| Durham vs. Darlington | 0.93 (0.62 to 1.41) | |

| Age | ≤ 77 years vs. > 77 years | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.35) |

| Sex | Male vs. female | 1.07 (0.83 to 1.37) |

| Antibiotic class | Penicillins vs. other | 0.93 (0.70 to 1.22) |

| Cephalosporins vs. other | 1.41 (0.97 to 2.04) | |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | ≤ 8 days vs. > 8 days | 0.48 (0.36 to 0.62) |

| Any antacid therapy | No vs. yes | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.95) |

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery | No vs. yes | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.33) |

| Recent previous hospital admission | No vs. yes | 1.05 (0.80 to 1.38) |

| Duration of hospital stay | < 7 days vs. ≥ 7 days | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.99) |

The frequency of AAD was similar in each centre: Morriston 162/1479 (11.0%), Singleton 20/203 (9.9%), Princess of Wales 21/191 (11.0%), Durham 56/547 (10.2%) and Darlington 53/521 (10.2%; p = 0.97). Subgroup analyses showed that the distribution of cases of AAD according to prespecified potential risk factors for AAD, including those identified as risk factors in covariate analysis, was similar in the two intervention arms and there was no evidence of a statistically significant interaction between prespecified potential risk factors for AAD and intervention arm (Table 12).

| Category | Probiotic,a n/N (%) | Placebo,a n/N (%) | RR (95% CI) | p-value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre | ||||

| Singleton | 11/102 (10.8) | 9/101 (8.9) | 1.21 (0.52 to 2.79) | 0.28 |

| Morriston | 81/742 (10.9) | 81/737 (11.0) | 0.99 (0.74 to 1.33) | |

| Princess of Wales | 15/94 (16.0) | 6/97 (6.2) | 2.58 (1.05 to 6.37) | |

| Durham | 26/269 (9.7) | 30/278 (10.8) | 0.90 (0.54 to 1.47) | |

| Darlington | 26/263 (9.9) | 27/258 (10.5) | 0.94 (0.57 to 1.57) | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 77 years | 86/730 (11.8) | 70/732 (9.6) | 1.23 (0.91 to 1.66) | 0.15 |

| > 77 years | 73/740 (9.9) | 83/739 (11.2) | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.18) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 91/777 (11.7) | 68/679 (10.0) | 1.17 (0.87 to 1.57) | 0.25 |

| Female | 68/693 (9.8) | 85/792 (10.7) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.24) | |

| Antibiotic class | ||||

| Penicillins | 78/761 (10.2) | 77/777 (9.9) | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.39) | 0.87 |

| Cephalosporins | 31/227 (13.7) | 26/220 (11.8) | 1.16 (0.71 to 1.88) | |

| Other | 50/482 (10.4) | 50/474 (10.5) | 0.98 (0.68 to 1.43) | |

| Duration of antibiotic treatment | ||||

| ≤ 8 days | 48/694 (6.9) | 52/709 (7.3) | 0.94 (0.65 to 1.38) | 0.66 |

| > 8 days | 107/712 (15.0) | 99/689 (14.4) | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.35) | |

| PPI treatment | ||||

| No | 86/877 (9.8) | 79/893 (8.8) | 1.11 (0.83 to 1.48) | 0.55 |

| Yes | 72/582 (12.4) | 72/567 (12.7) | 0.97 (0.72 to 1.32) | |

| Any antacid therapy (including PPI treatment) | ||||

| No | 77/802 (9.6) | 74/834 (8.9) | 1.08 (0.80 to 1.47) | 0.73 |

| Yes | 81/657 (12.3) | 77/627 (12.3) | 1.00 (0.75 to 1.34) | |

| NGT in situ | ||||

| No | 159/1464 (10.9) | 153/1462 (10.5) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.28) | – |

| Yes | 0/5 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) | ||

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery | ||||

| No | 132/1245 (10.6) | 129/1237 (10.4) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.28) | 0.71 |

| Yes | 25/203 (12.3) | 23/212 (10.8) | 1.14 (0.67 to 1.93) | |

| Recent previous hospital admission | ||||

| No | 107/982 (10.9) | 105/1023 (10.3) | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.37) | 0.85 |

| Yes | 52/483 (10.8) | 47/444 (10.6) | 1.02 (0.70 to 1.48) | |

| Duration of hospital stay | ||||

| < 7 days | 39/524 (7.4) | 40/498 (8.0) | 0.93 (0.61 to 1.42) | 0.54 |

| ≥ 7 days | 117/928 (12.6) | 111/949 (11.7) | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | |

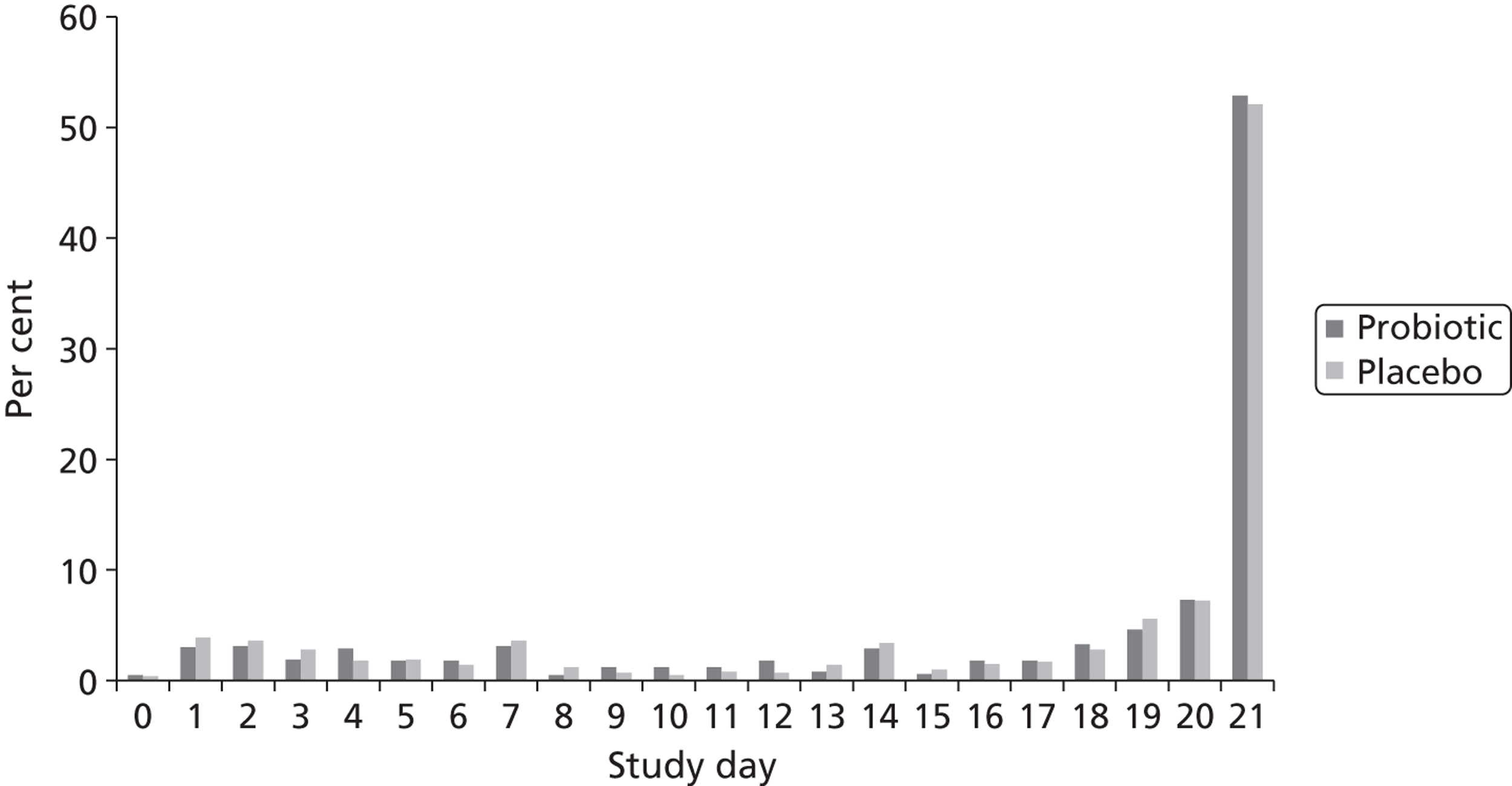

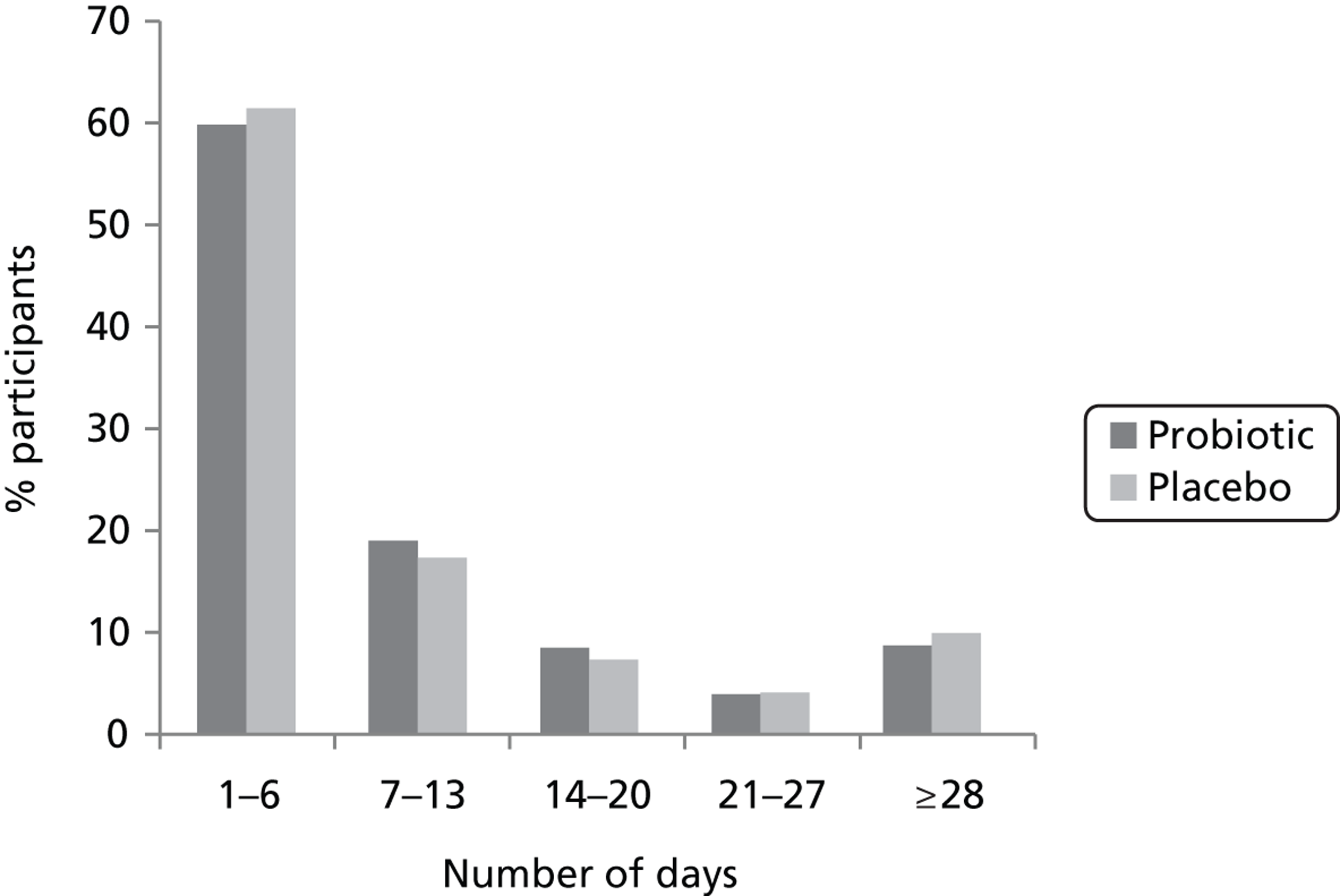

Most episodes of AAD (73.7%) occurred within 4 weeks of recruitment. On average, episodes of AAD lasted for 2 days with four stools in 24 hours and of consistency seven on the Bristol Stool Form Scale (Table 13). The most commonly associated symptoms were urgency, abdominal pain and nocturnal diarrhoea. The latter tended to occur more frequently in the placebo than the probiotic group (p = 0.051) and other characteristics of the diarrhoea episodes were similar in the two study arms (see Table 13). Most episodes of AAD were managed in hospital and stool samples were collected and tested for diarrhoeal pathogens in 58.6% of all cases. For many episodes of AAD, the short duration and occurrence after discharge from hospital complicated the collection of a stool specimen for testing for pathogens.

| Outcome | Probiotica | Placeboa | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration (days), n, median (IQR) | 135, 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 125, 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 260, 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 0.11 |

| Number stools per 24 hours, n, median (IQR) | 158, 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 152, 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 310, 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 0.69 |

| Stool consistency, n, median (IQR) | 152, 7.0 (6.0–7.0) | 145, 7.0 (6.0–7.0) | 297, 7.0 (6.0–7.0) | 0.85 |

| Nausea, n/N (%) | 35/154 (22.7) | 37/145 (25.5) | 72/299 (24.1) | 0.57 |

| Vomiting, n/N (%) | 20/155 (12.9) | 16/149 (10.7) | 36/304 (11.8) | 0.56 |

| Bloating, n/N (%) | 32/154 (20.8) | 31/146 (21.2) | 63/300 (21.0) | 0.92 |

| Flatus, n/N (%) | 41/153 (26.8) | 45/146 (30.8) | 86/299 (28.8) | 0.44 |

| Abdominal pain, n/N (%) | 55/154 (35.7) | 65/147 (44.2) | 120/301 (39.9) | 0.13 |

| Tenesmus, n/N (%) | 8/154 (5.2) | 7/145 (4.8) | 15/299 (5.0) | 0.88 |

| Fever, n/N (%) | 6/152 (3.9) | 4/143 (2.8) | 10/295 (3.4) | 0.59 |

| Faecal incontinence, n/N (%) | 27/151 (17.9) | 31/147 (21.1) | 58/298 (19.5) | 0.48 |

| Nocturnal diarrhoea, n/N (%) | 44/151 (29.1) | 59/148 (39.9) | 103/299 (34.4) | 0.051 |

| Urgency, n/N (%) | 78/151 (51.7) | 85/146 (58.2) | 163/297 (54.9) | 0.26 |

| Blood in stool, n/N (%) | 3/135 (2.2) | 3/134 (2.2) | 6/269 (2.2) | 0.99 |

| Mucus in stool, n/N (%) | 7/132 (5.3) | 12/131 (9.2) | 19/263 (7.2) | 0.23 |

| Managed in hospital, n/N (%) | 93/157 (59.2) | 75/146 (51.4) | 168/303 (55.4) | 0.17 |

| Stool sample tested, n/N (%) | 93/158 (58.9) | 88/151 (58.3) | 181/309 (58.6) | 0.92 |

As with AAD, the adjusted treatment effect for CDD was similar to the unadjusted estimate (Table 14). Covariate analysis showed that duration of antibiotic treatment was associated with CDD.

| Variablea | Comparison | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | Probiotic vs. placebo | 0.65 (0.29 to 1.47) |

| Centre | Singleton vs. Darlington | 0.52 (0.04 to 6.08) |

| Morriston vs. Darlington | 1.56 (0.34 to 7.20) | |

| Princess of Wales vs. Darlington | 0.00 (0.00 to incalculable) | |

| Durham vs. Darlington | 0.75 (0.10 to 5.46) | |

| Age | ≤ 77 vs. > 77 years | 0.95 (0.42 to 2.18) |

| Sex | Male vs. female | 1.12 (0.49 to 2.58) |

| Type of antibiotics | Penicillins vs. other | 0.43 (0.15 to 1.21) |

| Cephalosporins vs. other | 1.80 (0.69 to 4.67) | |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | ≤ 8 days vs. > 8 days | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.56) |

| Any antacid therapy (including PPI treatment) | No vs. yes | 0.49 (0.21 to 1.12) |

| Previous gastrointestinal surgery | No vs. yes | 1.41 (0.41 to 4.88) |

| Recent previous hospital admission | No vs. yes | 0.97 (0.40 to 2.34) |

| Duration of hospital stay | < 7 days vs. ≥ 7 days | 0.00 (0.00 to incalculable) |

The frequency of CDD was similar in each centre: Morriston 21/1479 (1.4%), Singleton 2/203 (1.0%), Princess of Wales 0/191 (0.0%), Durham 3/547 (0.5%) and Darlington 3/521 (0.6%; p = 0.15). In subgroup analysis, there was a statistically significant interaction between intervention arm and age (p = 0.0015; Table 15). In patients aged > 77 years, the frequency of CDD was significantly lower in the probiotic arm than in the placebo arm. In contrast, the frequency of CDD was similar in the two intervention arms for patients aged ≤ 77 years. In addition, the interaction between treatment group and duration of antibiotic treatment was of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.054). There was no evidence of a significant interaction between the intervention arm and other prespecified potential risk factors for CDD (Table 15).

| Category | Probiotic,a n/N (%) | Placebo,a n/N (%) | RR (95% CI) | p-value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre | ||||

| Singleton | 1/102 (1.0) | 1/101 (1.0) | 0.99 (0.06 to 15.62) | 0.91 |

| Morriston | 8/742 (1.1) | 13/737 (1.8) | 0.61 (0.25 to 1.47) | |

| Princess of Wales | 0/94 (0.0) | 0/97 (0.0) | – | |

| Durham | 1/269 (0.4) | 2/278 (0.7) | 0.52 (0.05 to 5.67) | |

| Darlington | 2/263 (0.8) | 1/258 (0.4) | 1.96 (0.18 to 21.50) | |

| Age | ||||