Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/44/05. The contractual start date was in May 2008. The draft report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Christie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to CASCADE

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is one of the most common chronic conditions of childhood and adolescence. Treatment is a taxing regimen of daily insulin therapy, blood glucose (BG) self-monitoring, controlling and calculating carbohydrate (CHO) intake and matching insulin to CHO, together with careful exercise management. Insulin replacement therapy easily controls hyperglycaemia and ketoacidosis, but the main treatment issue is supporting self-management by families and young people to maximise normality of BG and quality of life (QoL), preventing long-term complications.

Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes

There is a significant increase in the number of children and young people diagnosed with T1D and other variants of diabetes. The current prevalence of T1D in the UK is 1 per 700–1000 children, yielding a total population of over 29,000. 1 Peak age for diagnosis is between 10 and 14 years of age. 2

Diagnosis in the under-fives has risen relentlessly over the last 10–15 years. The reason for this is not clear. Changing incidence rates of childhood obesity have been suggested (‘The Accelerator Hypothesis’), with little to support this other than observational studies. 3 Young children have lower insulin needs and unpredictable food intake, and are poorly served by conventional multiple injection therapies. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends insulin pump therapy at diagnosis for management of this age group to avoid persistent hyperglycaemia and inadvertent hypoglycaemia, which may be detrimental to the developing brain. 4

Type 1 diabetes is a major health burden for the individual and society. Early onset in children is associated with an increased risk of developing complications in their 30–40s, and the estimated cost of care and lost earnings in the USA has been estimated to escalate from teenage years to 60 years of age. T1D is also associated with a high mortality, both at diagnosis and especially in the critical period of transition to adult services.

Monitoring of glycaemic control

Avoiding hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia requires BG monitoring using two modalities. The first is regular self-monitoring of current BG, ideally six or more times a day. Greater frequency of BG self-monitoring is associated with better glycaemic control. Regular monitoring allows correction of high or low BG into the normal range (4–7 mmol/l), and aids accurate dosing of insulin for CHO intake with meals and snacks. Potentially painful finger-pricks needed for BG measurement are a significant disincentive to frequent testing for many and may impair QoL.

The second is assessment of long-term glycaemic exposure by measuring the glycosylated fraction of haemoglobin (HbA1c). This estimates the exposure of red cells to glucose in the bloodstream over a 8- to 12-week period. The recommended target for prevention of long-term complications is a HbA1c value of < 7.5% (< 58 mmol/mol). In the UK National Paediatric Diabetes Audit (NPDA), < 16% of children and adolescents reached this target. 5

Short-term complications

Diabetic ketoacidosis

In T1D, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) results from either insufficient insulin or lack of insulin efficacy (e.g. during intercurrent illness). DKA carries a significant mortality rate (0.2%), largely from cerebral oedema and hypokalaemia. DKA is often present at diagnosis. Approximately 25% of all newly diagnosed children are admitted in DKA at diagnosis (35% in those of < 5 years). 6,7

Hypoglycaemia

The most common short-term complication of T1D is low BG (hypoglycaemia). Hypoglycaemia is a result of an imbalance of insulin to both ingested CHO and the current BG level. Hypoglycaemia (BG level of < 4.0 mmol/l) initially causes symptoms associated with activation of the sympathetic nervous system (i.e. adrenaline release). Severe hypoglycaemia (BG level of < 2.5 mmol/l) results in insufficient glucose for neuronal activity (neuroglycopenia), resulting in impaired consciousness, bizarre behaviour, seizures, coma and death. Persistent or frequent recurrent hypoglycaemia may impact on short- and long-term neurocognitive functioning. 8

Consequences of long-term hyperglycaemia

Microvascular and macrovascular disease due to persistent exposure to excess glycaemia reduces life expectancy (on average by 23 years in people with T1D). 9 Microvascular complications may present within 5–10 years post diagnosis and are frequently seen in adolescence and early adulthood, and include significant visual loss, chronic renal failure and dialysis, and autonomic symptoms that include impaired peripheral sensation, pain, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary problems. The International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) recommend screening for retinopathy (by retinal review) and microalbuminuria (through urine albumin–creatinine ratio) at 11 years (with 2 years’ diabetes duration), at 9 years (with 5 years’ duration) and after 2 years’ duration in adolescence. 10

Macrovascular disease presents later in adult life with problems including heart attacks, strokes and lower limb problems including ulcers and gangrenous extremities requiring amputation. High glucose variability, i.e. rapid alternation of hyper-, normo- and hypoglycaemia, may independently increase risk of cardiovascular end points, although this remains controversial. 11

Suboptimal BG control through childhood and adolescence is a significant risk factor for complications in later adult life. 12 Key outcome studies [e.g. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)] have demonstrated improved diabetes control in childhood (or later improved control) can reduce the incidence and progression of microvascular complications. 13,14

The relationship between HbA1c and relative risk of developing eye, kidney and nerve problems is not linear. Small changes from very poor to reasonable control (e.g. 12–9%) reduces risk fivefold but does not reduce it to the population background. Only moving towards near-normal values of HbA1c will effectively reduce the risk in T1D to that of the general population.

Chronic hyperglycaemia leads to persistent glucose wasting in the urine, resulting in calorie insufficiency, poor or absent weight gain, and thus poor growth and pubertal delay. Optimising adherence to insulin therapy can reverse this.

Common comorbid conditions

The most common conditions comorbid with T1D are autoimmune conditions. These include thyroid disease (most commonly primary hypothyroidism), adrenal hypofunction (Addison’s disease) and coeliac disease, although other autoimmune conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, are described in association with diabetes.

Management of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents

The goals of diabetes management are adequate glycaemic control while maintaining high QoL. Studies from the 1990s onwards have made it clear that tight glycaemic control is important to attain and maintain from the point of diagnosis. 14

The basic principle of insulin replacement therapy is to mimic the normal physiology of insulin secretion by:

-

Ensuring that there is always insulin around in the background throughout the 24-hour period. At night this is essential to switch off hepatic glucose production.

-

Deliver a bolus of insulin in a dose-dependent manner for whatever amount of CHO is consumed.

-

Bring any BG that is high or low back into target range.

-

Insulin can be delivered through multiple daily injections (MDIs) or through constant subcutaneous infusion of insulin. Intensive regimens are considered best practice and in many centres are commenced at diagnosis.

-

As regimens become more ‘physiological’, so too do requirements for adherence to achieve the best levels of glycaemic control.

Technological approaches

Advancing technologies such as the artificial pancreas are providing promising results in adults with diabetes. 15 Technological advances underpin increasingly sophisticated insulin delivery and self-monitoring devices. 15,16 Recent reviews report a wide range of current options. 17–22 Individual and group technology-based interventions include digital devices, video games, online chat rooms and social networks designed to engage, motivate, support and inform young people, although effect on glycaemic control remains modest. 23–30

The multidisciplinary team

Safe and effective diabetes care for children and young people requires a well-resourced multidisciplinary team (MDT) competent in integrating clinical, educational, dietetic, lifestyle, mental health and foot care aspects of diabetes. 31

Intensification of treatment supported by the MDT can produce dramatic improvements in HbA1c. Poor control is common when children are asked to take responsibility for self-care without sufficient cognitive and social maturity. 32 Involving families,33 supporting parental monitoring34 and facilitating shared responsibility for disease management contribute to good glycaemic control and adherence. The challenge is to find patient-centred models of care that can be implemented in clinics and create similar improvements in HbA1c level to those achieved in the DCCT, with subsequent reductions in the development of diabetes-related complications.

Psychosocial aspects of diabetes

Adolescence disrupts the precarious balance managing diet, activity and insulin. 35 There is an increased risk of depression, anxiety, disordered eating, disrupted body image, adverse effects on behaviour and increases in suicidal thoughts in this age group. Depression is associated with both poor glycaemic control and low regimen adherence. 36–44 Other outcomes include increased vigilance by parents and diabetes teams and family conflict. Given the significant number of young people who have unique needs as a consequence of this particular developmental stage, training in adolescent health and medicine is increasingly important.

Reactions to a diagnosis of diabetes

Initial reaction to a diagnosis of diabetes can be devastating. A loss of spontaneity and restrictions on activities create a sense that things will never be the same. 45 Adjustment improves with time after diagnosis. However, parents were clear that they never fully ‘accept’ the diagnosis. 46,47 Episodes of grief are described 7 years post diagnosis triggered by regimen changes, injections, hospitalisation, discussions about diabetes control and worry about complications, attending clinics and meeting new medical teams – reminding them that their child is different. 48

Parents worry over the long term, uncertainty about the future, medical procedures and finance. Loss of pay and costs of travelling to appointments creates additional stress. 45 For some, balancing a career and managing the complexities and demands of a child’s treatment regimen becomes untenable.

Adherence to the treatment regimen

Adherence is a common problem in adolescents in general. 49,50 Although adherence to different components of the regimen may be unrelated to each other,51 insulin omission is common in adolescent girls who are concerned with body weight issues. 52–56 Failure to monitor BG or adjust insulin is also common. 57 Demographic, psychosocial and health-care system factors all influence adherence. Poorer adherence is reported in children and adolescents with T1D from ethnic minority backgrounds, of low socioeconomic status (SES) and from single-parent families. 58 Adolescence is also a risk factor for low adherence and poor glycaemic control. This is related to the effects of diabetes on major developmental changes that occur in adolescence and include hormonal changes associated with puberty, resulting in decreased insulin sensitivity negatively affecting BG metabolism, leading to increases in BG levels. 59 Alongside these physical factors, self-management, increasing independence, emerging sexuality and increased stress from peer and academic pressures are all associated with deteriorating glycaemic control in adolescence. 60

Healthier family functioning just after diagnosis and greater family support are associated with better adherence over time. 61–63 Good family communication patterns,64 low family conflict65,66 and good problem-solving67 are also associated with better adherence. Frustration and guilt at failure to achieve optimal outcomes can be exacerbated by existing psychological issues within families.

Psychosocial variables

High self-esteem, appropriate health beliefs (e.g. perceived threat of diabetes low and perceived benefits to cost ratio high)68–70 and the ability to cope with the stress of negative life events (ranging from a new diagnosis to daily hassles) predict better adherence. 58,71 Peer support is positively related to adherence, particularly for dietary and exercise behaviours. 72 However, pressure to conform to social situations and be accepted by peers is related to decreased glucose monitoring. 49,73,74 Young people who see themselves as having little internal control over their health and who attribute negative events to external sources (i.e. out of their control) have lower adherence. 75

When young people identify other people’s reactions to their self-care as negative, they are also more likely to have adherence difficulties. 72,76,77 Maladaptive coping, such as risk behaviours or withdrawal from family or peer interaction, is associated with poor adherence. 78,79

Psychological and psychoeducational interventions

Person-centred therapies, motivational interviewing (MI), positive reinforcement behavioural contracts, negotiation of diabetes management goals and training in communication, coping and collaborative problem-solving skills are potential approaches to decreasing psychological distress and improving glycaemic control and QoL.

Managing the demands of a diabetes regimen

Stress management programmes using cognitive-restructuring and problem-solving strategies have limited impact. 80,81 In contrast, individual and group interventions focusing on peer group support, problem-solving and coping skills impact on short-term glycaemic control, showing positive effects on adherence including improved self-perception and increased knowledge about diabetes and decreases in diabetes-related conflict. 82,83 A problem-solving skills programme improved BG monitoring but failed to show improvements in problem-solving or HbA1c level. 84 In contrast, social problem-solving, social skills training, cognitive–behaviour techniques and conflict resolution skills for children transferring to intensive diabetes regimens reported improvement in glycaemic control and QoL, maintained at 1-year follow-up. 85–87 The groups did not affect adverse outcomes of hypoglycaemia, DKA or weight gain in boys but decreased the incidence of weight gain and hypoglycaemia in girls.

Diabetes summer camps offering peer interaction, sports and recreational activities alongside diabetes self-management training are highly evaluated; however, only show short-term changes in self-management and knowledge and fail to demonstrate lasting improvements in HbA1c level without ongoing support. 88,89

Focusing on psychological therapies

The effectiveness of psychological and psychoeducational interventions to improve adherence, glycaemic control, psychosocial functioning and QoL is debated, not only in T1D,90,91 but also in paediatric chronic illness in general. 92 Systematic reviews offer limited evidence that psychological interventions in children and young people with diabetes improve adherence and glycaemic control, with small to medium effects on physical and psychosocial outcomes. 91,93 Interventions that result in modest improvements focus on increasing knowledge/skills, addressing specific psychosocial issues and addressing self-management behaviours, but are often not sustained. Continuous support delivered by a diabetes MDT may be equally as important as short-term interventions. DeWit et al. 94,95 reported that asking young people about QoL during clinic visits improved QoL and satisfaction with care but had no effect on glycaemic control.

A recent meta-analysis of 15 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of adherence interventions in 997 adolescents with T1D found a mean effect size of 0.11 (95% CI −0.01 to 0.23). 96 Modest improvements in glycaemic control were found in interventions that included emotional, social or family targets in addition to specific behavioural goals. 96 Interventions are most likely to be effective if they help the adolescent connect the many different aspects of diabetes management with all aspects of daily living. 97

Family interventions

Because of the complexity of diabetes management and the importance of family involvement and support, most interventions include a family component. In a review of family interventions, a positive effect was reported in 5 out of 19 studies, suggesting that family interventions may improve diabetes-related knowledge and glycaemic control. 98 A teamwork intervention increased family involvement and prevented an expected deterioration in glycaemic control. 98,99 However, the quality of family relationships may not be causally related to adherence, therefore decreasing family conflict and improving parent–child relationships alone may not result in improved adherence or glycaemic control.

Multisystemic therapy and an intensive home and community family intervention, incorporating developmentally appropriate negotiated responsibility,100 significantly improved adherence to BG testing, improved glycaemic control and decreased the number of inpatient admissions. 101,102

Behavioural family systems therapy (BFST) was developed for families of adolescents with clinically significant conduct-related problems. 103 The intervention includes cognitive restructuring of irrational beliefs and targets problematic family characteristics, family communication and problem-solving. Initial adaptations for children and families with diabetes addressed general developmental issues, such as managing curfews, chores and focused less on diabetes treatment-related treatment adherence or management. 104–106 BFST enhanced family communication, improved parent–adolescent relations, reduced behaviour problems and general and diabetes-related family conflict. 104–108 The effects on psychological adjustment depended on the adolescent’s age and gender but overall there was little effect on adjustment to diabetes or diabetic control. 104,105

A revised Behavioural Family Systems Therapy–Diabetes integrated empirically supported intervention strategies focusing on specific behaviours, as well as the social context of diabetes treatment-related behaviour including:

-

targeting at least two or more diabetes problems

-

behavioural contracting109

-

parental simulation of living with diabetes100

-

involving peers, siblings, and teachers, and running sessions in different locations.

Family conflict decreased as well as improvements in adherence. HbA1c level was significantly reduced, particularly among adolescents with poor metabolic control. Change in treatment adherence correlated significantly with change in HbA1c level at each follow-up. 105,106,111

These approaches show encouraging results; however, they are resource-intensive, requiring highly skilled practitioners who are able to travel into the family home. Although effective, this strategy is unlikely to be incorporated into UK clinical practice until shown to be clearly cost-effective.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) can be delivered only by trained practitioners and usually requires 6–12 sessions. The client connects thoughts, feelings and behaviours. This requires a degree of engagement and participation that is often missing in adolescents. Although effective, standardised interventions for behaviour problems or depression in adolescents are available, no studies have targeted specific psychological disorders in adolescents with diabetes. A review found that the majority of studies used non-standardised approaches. 112

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a person-centred therapy that works to resolve ambivalence about behaviour change. It creates a shared agenda, inviting the client to identify his/her goal (e.g. young people may say they want to talk about problems at school, whereas parents may want to talk about blood tests). The clinician negotiates how to explore these issues during the consultation. MI invites the client to be in charge of making changes, and looks for statements about intention to change and optimism about the future. The client identifies importance of change, confidence in their ability to change and when change will be a priority.

Motivational interviewing in paediatric populations has been increasingly explored. 113–115 Early work demonstrated the potential of MI to decrease harm-reduction behaviours in relation to alcohol and polysubstance use. 113,114 A review of nine RCTs in health-related domains, including diabetes, reported seven with positive findings on the effectiveness of MI. All RCTs that specifically addressed T1D related to the adolescent age group. 113,114,116 Two studies using MI alone117,118 found a significant reduction in HbA1c level, reduced fear of hypoglycaemia, and improved QoL and positive well-being. MI combined with other therapeutic approaches, such as dietary advice or CBT, has reported reductions in HbA1c level, a greater sense of control, improved perceptions of diabetes and improved self-esteem. 119–121

Attempts to incorporate MI into other formats, for example a six-session ‘personal trainer’ intervention delivered by non-clinical practitioners,122 have shown promising results, lowering HbA1c levels in older teenagers.

One response to the scarcity of mental health resources in the UK has been to ‘skill up’ staff and introduce components of successful interventions into routine consultations. MI122,123 and other brief therapy approaches have the potential to offer diabetes teams ways to communicate with young people and encourage greater self-management. 124,125 However, a recent study that attempted to deliver MI components as part of routine consultations proved challenging to implement and had no impact on either HbA1c level or psychosocial measures. 123–125

Solution-focused brief therapy

Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) relies on the clinician noticing what works successfully during conversations and doing more of this. 124 SFBT assumes the clients are the expert in their own situation and invites them to describe their preferred future and focus on what is already working. This creates opportunities to notice small changes and identify what makes this possible. 126 The clinician does not attempt to find the cause or ‘take the problem away’. The clinician and family work collaboratively to find already existing solutions to manage injections, finger-pricks or eating difficulties. They work together to stop diabetes getting in the way of family communication and find ways to manage sadness or anger. The family takes the lead in relation to ‘non-adherence’, focusing on what is working for them.

Solution-focused brief therapy is an effective approach for most, including those with severe and chronic problems. 127 The latest outcome evaluation research128 reviewed 109 SFBT studies including two meta-analyses and 19 RCTS. Nine RCTs found that SFBT has a greater effect than other approaches, for example CBT. Of the comparison studies, 34 out of 43 favoured SFBT. Solution-focused practice has been recommended within clinical practice guidelines. 120,129,130 SFBT combined with MI has been successfully integrated into diabetes clinical service,124 reducing HbA1c level in children and adolescents. 121

Solution-focused conversations create a different experience for families. Young people who have been blamed or criticised and described as non-adherent or manipulative ‘grow visibly taller in their chair’ given the opportunity to talk about their strengths and abilities and describe positive steps they are already taking to get their lives back on track.

This approach is increasingly relevant to the management of long-term chronic illness and models of empowerment. Nurses trained in SFBT showed positive changes in their practice and improved willingness to communicate with troubled people. 124,131 Changes to practice centred on the rejection of problem-orientated discourses and reduced feelings of inadequacy and emotional stress.

SFBT techniques may be relevant to nursing and a useful, cost-effective approach to the training of communication skills . . . provides a framework and easily understood tool-kit that are harmonious with nursing values.

Bowles, Mackintosh and Torn131

Case management/educational approaches

Other interventions have focused on case management and/or diabetes education. Enhanced case management increased the frequency of clinic visits, reduced hypoglycaemia and hospital admissions and improved glycaemic control in ‘high-risk’ youths. 132 Education and telephone case management has improved adherence and self-efficacy but with little influence on HbA1c level. 133,134 The NICE Health Technology Appraisal on patient education models (http://publications.nice.org.uk/guidance-on-the-use-of-patient-education-models-for-diabetes-ta60) and National Diabetes Support Team (NDST) identified a lack of nationally evaluated paediatric education programmes. 135 Very few, if any, paediatric clinics in the UK offer an evaluated structured education programme as part of routine clinical care. 4

In the last 5 years, a number of studies were initiated to tackle this issue. Programmes vary in methodology, style of intervention and number of patients recruited. Appendix 1 describes details of the most recent nine trials. All have failed to show positive change in glycaemic control. 136–138

The CASCADE study

The Child and Adolescent Structured Competencies Approach to Diabetes Education (CASCADE) intervention is a competency-driven, motivational, patient-centred structured intensive psychoeducational programme designed to improve diabetic control, self-management and QoL in children and adolescents. Intervention content and development are described in Chapter 2 . CASCADE is a complex intervention developed using the Medical Research Council (MRC) complex intervention evaluation framework. 139 We have already conducted the Phase I study [Modelling – defining components of the intervention and Phase II study (Exploratory Trial Phase)]. The present study is a multicentre cluster RCT with integral process and economic evaluation to investigate the effectiveness of CASCADE.

Research objectives

To:

-

assess the feasibility of the CASCADE intervention within a standard clinic setting for a diverse range of young people

-

investigate the effects on long-term glycaemic control of diabetes

-

evaluate the impact of the intervention on QoL using well-validated and reliable self-report and parental measures

-

investigate the impact on psychosocial functioning, including (1) emotional and behavioural adjustment of children and young people; (2) family functioning; and (3) self-management, decision-making and self-efficacy

-

investigate cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

Type 1 diabetes in children and young people is increasing worldwide, with a particular increase in those of < 5 years. Effective glycaemic control requires a careful balancing act between insulin, food and physical activity. Intensive regimens are best practice, and in many centres these are commenced at diagnosis. Modern diabetes regimens can be oppressive for children, young people and families. Despite intensive regimens offering the best possible control, fewer than one in six children and young people achieve HbA1c values in the range identified as providing best future outcomes. One-third of all children with T1D in the UK are at significant risk for developing long-term complications. The challenge of how to address non-adherence is significant. Evidence to support one approach over another remains limited. Moderate evidence supports the effectiveness of psychological interventions in improving adherence. However, only 20% of children and adolescent services in the UK report adequate access to psychological services. 140

There is an urgent need for pragmatic, feasible and effective structured education programmes that are deliverable within clinics to targeted groups, which improve both glycaemic control and QoL. CASCADE was designed to respond to policy goals addressing strengths and weaknesses of other approaches. The aim was to refine and test the effectiveness of a pragmatic intervention delivered by trained educators. The intervention offers both structured education – to ensure that young people know what they need to know – and a delivery model designed to motivate self-management through empowerment techniques. The next chapter discusses the background to the development of structured education approaches and the CASCADE intervention.

Chapter 2 The development of the CASCADE intervention

Introduction

The CASCADE intervention is a manual-based structured education programme incorporating psychological approaches to increase engagement and enhance behaviour change in children, young people and families. The intervention has four modules led by a paediatric diabetes specialist nurse (PDSN) with a minimum of one additional member of the diabetes team.

This chapter outlines:

-

the background to structured education programmes

-

the CASCADE educational approach

-

the CASCADE underpinning philosophy

-

a summary of each CASCADE module

-

the educational theory and key components of the training workshops.

Structured education programmes

There are no effective structured education programmes for children and young people with diabetes in the UK. Patient-centred care and timely access to specialist education and support form the central pillars of the Diabetes National Service Framework,141 the NICE guidance for T1D4 and ‘Making Every Young Person with Diabetes Matter’. 142 The NICE Health Technology Appraisal on patient education models (http://publications.nice.org.uk/guidance-on-the-use-of-patient-education-models-for-diabetes-ta60) recommends that ‘structured patient education should be made available at the time of initial diagnosis and then as required on an ongoing basis, based on formal, regular assessment of need’.

At a recent structured education conference only 4 of 38 local structured educational programmes were paediatric. A number of programmes have recently been evaluated using different methodological approaches. Each differs in hours of education per patient, time period of the course, number of trained educators and number of patients taught per year (see Appendix 1 ).

International guidelines on how to establish, evaluate and improve diabetes education include the American Diabetes Association143 and ISPAD Consensus Guidelines. 144

The NDST guide to commissioning structured education identifies criteria by which to evaluate the effectiveness of patient education, including (1) quality assurance; (2) developmentally appropriate educational approaches; (3) a structured curriculum incorporating audit; (4) an underpinning philosophy; and (5) trained educators. 135 Although nationally evaluated structured education programmes exist for adults [Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE); Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND); and Xpert],145–147 no UK paediatric clinics offer structured education that meets these standards. 135

The CASCADE intervention was developed in response to the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) review of psychoeducational interventions in childhood diabetes. 91 The intervention is based on Phase 1 pilot work and a non-randomised trial delivered by psychologists. 121 CASCADE was designed with robust quality assurance, developmentally appropriate educational approaches, a structured curriculum that incorporates an audit programme and most importantly an underpinning philosophy and trained educators. It uses approaches important in predicting success in improving long-term diabetic control as well as simply transferring knowledge.

Quality assurance

The programmes DAFNE and DESMOND have developed robust quality assurance processes;145,146 however, no standard template exists for paediatric and adolescent diabetes teams to assess patient knowledge and skills. The structure of quality assurance is crucial to ensure a rigorous process, with clear, written standards that can be monitored, regularly reviewed and updated. The quality assurance process include three main elements:

-

A defined programme with clear content, structure, curriculum and underlying philosophy. The training programme for educators should be included within the quality assurance process.

-

Quality assurance tools based on the programme structure, and a set of observable behaviours required to deliver the programme.

-

Internal and external processes to assess delivery and programme organisation.

Educational approach

Developmental level and perceived learning needs

Children of < 12 years use concrete thinking to combine, separate, order and transform objects and actions. An eight-year-old relies on parents to help test BG, supervise injections or manage hypoglycaemia at school or out with friends. Educational material and conversations about health care need to be simple, concrete and involve shared goals with the parent and child.

Adolescents start to develop a sense of identity, increasing their need for independence with a move from parental to peer influence. Another change is the beginning of complex thinking processes (formal logical operations), including abstract thinking (thinking about possibilities), reasoning from known principles (form own new ideas or questions), the ability to consider many points of view according to varying criteria (compare or debate ideas or opinions) and the ability to think about the process of thinking. Adolescence is a transitional time with expectations of increasing responsibility for independent diabetes self-management.

Age and developmental status are powerful contextual variables that influence diabetes self-management. An evolutionary concept analysis identifies three attributes of diabetes self-management in children and adolescents. 148 The first is process, which is proactive, flexible, and involves a shift of shared responsibility between the child and family, and collaboration with health-care providers (HCPs). The second is performance of simple to complex activities related to the adjustment of regimens, including self-adjustment of insulin. The third is where children and parents engage in this process to accomplish certain goals. Successful completion of process, performance and goals are developmentally influenced.

The CASCADE intervention was designed to be accessible for children and young people between 8 and 16 years. Four modules lasting approximately 120 minutes each are delivered to groups of three to four families with children and young people aged 8–11 years or 12–16 years over 4 months. Everyone in the group is included in all discussions, and encouraged to share ideas and thoughts and develop their own solutions to their goals by evaluating decisions made in the past and think about possibilities for the future.

Interventions that incorporate parents are generally associated with favourable outcomes. 145,146,149–151 Young people are invited to bring parents or significant family members to CASCADE unlike other current structured education courses. 137

Learning methods

Families work in the large group or individual family or peer groups (young people and parents). Delivery is non-didactic. Families are invited to discuss diabetes information from a position of their own knowledge and expertise. Their right to choose different behaviours is acknowledged. The literacy level for written material was age appropriate with additional visual and written information (handouts, charts, diagrams, flow charts). Children, young people and parents are invited to consider attitudes towards changing self-care behaviours and complete exercises that look at the pros and cons of changing behaviour and assess readiness to change. It is more important that the HCP ‘hear and understand what the child has to say, than the child hears and understands what the healthcare worker is telling them’. 152

The CASCADE structured curriculum

Modules were designed to develop confidence managing different aspects of diabetes, including how to adapt insulin dose, how to eat normally and how to manage exercise and illness. The curriculum conformed to the agreed core content for education programmes set out by the Diabetes Education network and Diabetes UK (DUK) (see Appendix 2 ).

Measuring change using a competencies framework

The aim of patient education is for people with diabetes (or their carers) to improve and put into practice knowledge and skills with confidence, enabling them to become experts at managing their (or their child’s) diabetes on a day-to-day basis. HCPs need to collaborate with education specialists to formulate appropriate and reliable evaluation methods that can be used in addition to measuring changes in HbA1c. 153

The CASCADE modules are informed by an eight-level competency system that assesses skills and knowledge designed by Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles ( Table 1 ). 154

| Competency | Level |

|---|---|

| Safety | 1 |

| Basics | 2 |

| CHO management | 3 |

| Correction doses | 4 |

| Daily changes | 5 |

| Base dose adjustment | 6 |

| Advanced management | 7 |

| Maximised control, basal and bolus therapy | 8 |

Families must demonstrate a minimum of competency level 5 to start on pump therapy. The assessment, completed in a clinical interview, in conjunction with insulin pump therapy showed significant and sustained reductions in HbA1c level over a 2-year period. 154

The manual

The manual provides a written curriculum. It includes Microsoft PowerPoint 2003, version 11 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides from each training session with reading lists and copies of key reading for each module.

Underpinning philosophy and delivery techniques

Psychological approaches used in CASCADE are MI and SFBT (see Chapter 1 ). Specific components integrated into each module to enhance engagement, develop confidence and motivation are described below.

Key communication skills

Key skills in motivational conversations are asking open-ended questions, affirming, reflective listening and summarising. Educators use open questions to elicit information and broaden and deepen conversations. Affirming positive actions and intentions of young people and families focuses on positive outcomes. Educators use reflective listening and simple summaries to show that they are listening.

Identifying skills abilities and strengths

Solution-focused brief therapy assumes that people possess the knowledge and resources they need to tackle their problems. 126 At the beginning of each module, educators invite descriptions of what has gone well, listening out for examples of skills, abilities and resources. Children, young people and families note positive change and identify what they are doing differently. The aim is for both educators and families to have ‘determined curiosity and relentless optimism’.

‘How come?’ and ‘What else?’

Describing examples of when they have been in charge of diabetes since the last session orientates people towards what is already working and acknowledges when their preferred future is happening. Educators ask families what they had noticed had worked (‘What else?’) and ask what made the positive changes possible (‘How come?’).

Focusing on the future

Families imagine themselves in the future having overcome difficulties or problems and describe this problem-free preferred future. Families think about what they will be doing differently, or more, or less of, and how this will have changed their relationships with friends and family. ‘Stepping into the future’ invites families to identify ‘their’ goal for change.

Scaling

Scaling helps families think about how close they currently are to their preferred future and break this into small and achievable steps. Scaling reinforces positive change and prevents young people from feeling stuck when change is difficult to notice. Asking how someone had moved a half or a whole point towards a goal reinforces a sense of personal agency having taken a step forward (or prevented themselves from slipping backwards).

Considering the pros and cons of behaviour change

Motivational interviewing assumes that young people and families are, to a greater or lesser extent, ambivalent about current self-management behaviours and the degree to which they put pre-existing knowledge into action. The majority of young people with high HbA1c levels will have had many conversations with diabetes consultants, nurses and dietitians, and possibly psychologists or counsellors. Uncertainty about implementing change can be expressed across emotional, practical and behavioural domains. In each module the young person and their parent/carer are invited to identify advantages and disadvantages of behaviours related to diabetes self-management (e.g. BG monitoring, using different insulin regimens, correcting for high or low BG) to help the educator understand the young person’s position and clarify the ‘pros and cons’ of change for the young person.

Establishing the importance and confidence of change

Importance and confidence are central to exploring the young person’s ambivalence to change. 156 Young people and parents scale (between 0 and 10) importance of change, confidence changing and how ready they feel they are to do things differently after completing a pros and cons exercise. The family identify what needs to be different for change to happen. If confidence is low the young person can think how to build confidence before making changes. If importance is low the group can think about what would need to happen for change to be more important.

Evocation not education: avoiding giving a choice or answer

The majority of young people with high HbA1c are aware of what they ‘need’ to do but are not willing, able or ready to put this knowledge into practice. Educators ask if it is ‘OK’ to discuss information about different topics and invite the group to talk about existing knowledge first. These ‘scaffolding’ questions help individuals discover further information for themselves, or ‘draw it out’. 157 Additional learning is a collaborative effort between individuals and trainers, reducing the sense of an expert imposing knowledge and moving towards a shared venture. This active rather than passive approach has been shown to be effective in eliciting behaviour change in other areas. 158

The CASCADE modules

The teaching plan includes session activities, objectives, time guides and resources, including key information essential for the educator, learning objective for the family and brief descriptions of each activity. Young people and parents completed homework tasks including a post-module quiz, designed to consolidate information, after each group. The educators encouraged the young person to complete the quiz with parents who could not attend, facilitating communication of key messages delivered during the module. The quiz and pre-prepared handouts could be sent to families if they missed a session.

Each module (apart from the first) starts with a review of the previous module creating an opportunity to highlight changes that have taken place and congratulate young people on successes. It also creates an opportunity to review the previous module for any family who missed the session.

Module 1: the relationship between food, insulin and blood glucose

Readings: (1) educator notes about CHO foods, BG and a healthy diet and (2) ISPAD guidelines on nutritional management in childhood and adolescent diabetes. 159 The introduction identifies strengths, resources and abilities. Focusing on the future, identify how things will be in the future if families get what they want from CASCADE. They scale how close they currently are to this. The session focuses on understanding food groups, particularly CHO. It talks about the role of insulin and different insulin regimens. Finally, families and young people consider the pros and cons of matching insulin to food to attain better glycaemic control.

Module 2: blood glucose testing

Readings: Implications of the DCCT13 and assessment and management of hypoglycaemia in children and adolescents. 160

After reviewing module 1, educators discuss the recommended target HbA1c. The group identify factors that cause BG to rise and fall and explore individual hypoglycaemia definitions, reviewing symptoms according to severity. Families discuss ways to treat hypoglycaemia and assess the pros and cons of BG testing.

Module 3: adjusting insulin – pros and cons

Reading: insulin analogues in diabetes care,161 using CHO counting162 and guidelines on assessment and monitoring of glycaemic control. 163

Following the review families discuss symptoms of hyperglycaemia and ketones. A brainstorming session considers when, how and who to contact for help with managing hyperglycaemia. The session focuses on managing high BG using temporary insulin changes and explains how to correctly calculate correction doses. The group explores the advantages of identifying trends in relation to permanent insulin dose changes and considers the advantages and disadvantages of CHO counting as a way of improving glycaemic control.

Module 4: living with diabetes

Reading: guidelines on exercise164 with a set of PowerPoint slides used in the workshop to explain the principles of exercise and management of insulin and CHOs.

Following the review, families identify the effect that low and high BG has on performance and concentration, and discuss effective strategies to bring BG into target range before starting exercise. Participants work in family groups to identify how different activities affect BG and discuss the timing of insulin injections in relation to exercise before considering the advantages of using CHO before, during and after exercise (to keep their BG stable during different exercise).

At the end of module 4, young people and families complete a ‘blueprint for success’. This marks the end of the sessions and acknowledges the steps into the future the young person has already made. It creates an opportunity to review the programme and strengthens long-term motivation to change by reviewing previous successful goals.

Trained educators

The Department of Health and DUK have both highlighted the importance of structured training for educators involved in delivering patient education. Members of UK paediatric and adolescent diabetes teams have a varying amount of training in relation to age-specific and developmental milestones for children and adolescents with no current consensus regarding uniformity of roles and qualifications for different members of teams delivering structured education.

Each diabetes team in the CASCADE intervention arm identified two primary site educators, one of whom had to be a PDSN. The 2006 Royal College of Nursing (RCN) document on specialist nursing services for children and young people with diabetes states that a PDSN based in hospital or community, working as a member of the team specialising in the management of childhood diabetes, should be able to provide:

. . . a source of specialist advice for children, young people and families on the nursing care and management of diabetes, including the provision of basic dietary advice and the management of acute complications.

. . . individual specialist teaching for children, young people and families, facilitating the development of self care skills and knowledge, at time of diagnosis and in planned, ongoing, age appropriate education, both individually and in groups.

Royal College of Nursing165

The second trainer could be any HCP within the team. These two trainers were expected to deliver the groups to families within their service. Teams were invited to bring along additional members to the training if they so wished.

Training and intervention

Pilot for intervention manual and training workshops

The intervention manual was piloted with a family known to the University College London Hospitals (UCLH) team. Content, delivery and resources were discussed to ensure that the principles and messages were clear and understandable. Training workshops were piloted with two UCLH PDSNs not involved in the intervention development, and five local PDSNs from centres not recruited to CASCADE. Feedback on the length of training (2 days), content and delivery was positive. Small changes were incorporated before training of the intervention sites began.

Training workshops

Key messages, based on the fundamental principles of CASCADE ran through all of the workshops:

-

Assume basic diabetic knowledge already provided at, and subsequent to, diagnosis.

-

Non-didactic educational principles and psychological models underpin behaviour change.

-

Not additional work for staff but working differently.

-

No right or wrong ways of saying things – just more or less helpful ways of talking.

-

Builds on families’ knowledge, skills and abilities, and uses their experience and expertise.

-

Assumes families have knowledge about how to manage diabetes and want to change their behaviours.

-

Use open questions; affirm and positively connote behaviours.

-

Reflect on what is heard and summarise to show good listening skills.

-

Explore the advantages and disadvantages of changing.

-

Focus on advantages of change and disadvantages of the status quo.

-

Encourage staff to be interested in the person rather than the problem.

-

Identify ways that people are already doing what they want to do by focusing on what is going well rather than what is not going well.

Training took place on two separate days with at least two intervention sites invited on each day. The following basic principles were emphasised:

-

Follow the manual as much as possible to maintain treatment fidelity.

-

Always have two people delivering each module.

-

Divide the different components in the module in whatever way works best for site educators.

-

Read key readings for each module to ensure knowledge of educational content.

Session 1 (morning of day 1)

The background to CASCADE was introduced with key delivery principles. These were to:

-

Deliver the intervention to all recruited families in each intervention clinic.

-

Offer four modules monthly to groups of three or four families with children in the same age group.

-

Offer groups if only one or two families turn up for a module. If only one family turns up, reschedule or complete the module on their own and then join another group for future modules.

-

If families miss a module they can continue with the next module and, where possible, be helped to catch up by discussing the module content with one of the site educators and/or being given the handouts from the module they missed.

The session introduced the basic principles of SFBT and MI and provided opportunities to try out the techniques embedded throughout the four modules.

Session 2 (afternoon of day 1)

This session introduced modules 1 and 2. Delivery and communication style was modelled by the UCLH trainers. Site educators participated in each exercise, giving answers or comments that they thought children might offer or the information they thought correct. The UCLH trainers worked together; one delivering the activities, while the second trainer commented on the process and performance, and invited discussion of content and delivery style. The trainers highlighted SFBT and MI techniques used in each activity.

Session 3 (morning of day 2)

Modules 3 and 4 were described using the same format as session 2.

Session 4 (afternoon of day 2): envisaging the future

Session 4 explored practicalities of running groups, organising sessions and how to engage and motivate participants to attend. After a brief slide presentation on groups, educators then worked in their clinic groups. They were asked to imagine themselves in 12 months’ time, having completed all of the CASCADE groups, and consider:

-

What made completing CASCADE possible?

-

What aspects of the process had gone well?

-

What had been possible challenges and barriers that they had overcome?

They were invited to identify their skills, abilities and knowledge that contributed to this ‘ideal outcome’ making the groups possible. As each ‘outcome’ was described, trainers asked questions to generate details about solutions, such as ‘How did you achieve this?’ ‘Which days worked best for you?’ The shared ideas from each clinic generated practical and achievable solutions to potential problems in advance to support group organisation (e.g. in one training session good attendance was ‘achieved’ by staff phoning families a week before the start as a reminder). Other ideas highlighted during this session included:

-

Enthusiasm for the project, successful recruitment and practicing sessions in front of peers for feedback.

-

Resources in place for delivering the programme; finding an appropriate venue for running sessions with staff and time to plan, organise and deliver sessions.

-

Good communication between educators, supportive management and other team members who would be receptive to the approaches and non-directive in communicating with young people.

-

Sessions delivered at the right pace, working as a team with families with good attendance and age groups that bonded well. Involving everyone in the group with good use of techniques and listening skills.

-

Positive feedback from young people and families. Families happy, more confident and accessing services appropriately.

-

All HbA1c levels of < 7.5%.

One-day refresher training

A 1-day refresher workshop was offered to all members of each intervention site when all workshops were finished. The morning session provided the training in the delivery process with a description of the four modules in the afternoon.

Ongoing support

Site educators could contact trainers at any time during the delivery of groups with queries or concern about timing of the groups, clarity in relation to aspects of the manual or what to do if a family did not turn up to training or composition of groups.

Chapter 3 Methods

Trial design

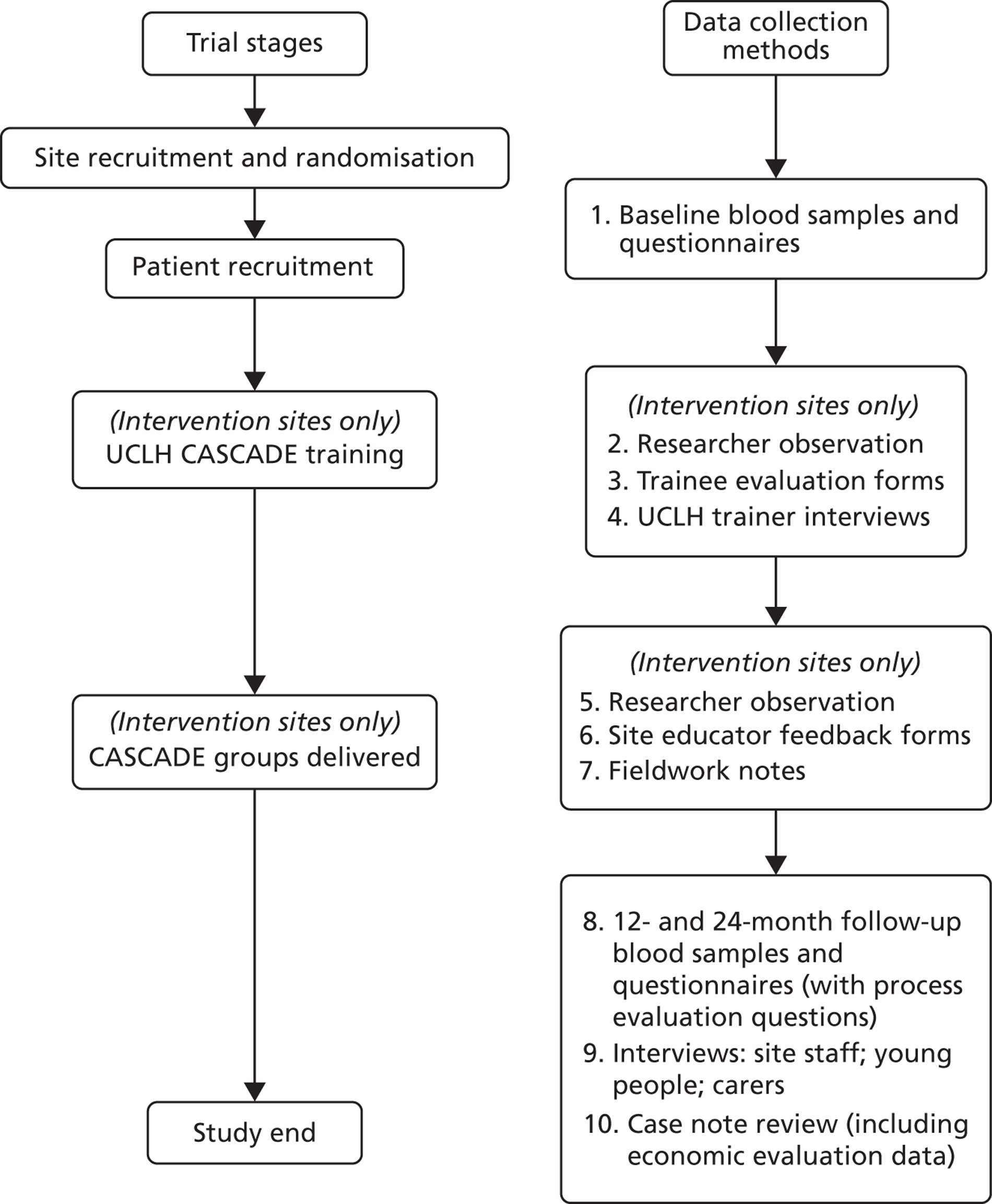

The study was a pragmatic, cluster RCT with paediatric/or adolescent diabetes clinic as the unit of randomisation. Integral process and economic evaluations were completed ( Figure 1 ). The protocol was published in BioMed Central trials. 166 A list of all substantial amendments made to the final protocol after trial commencement is shown in Appendix 3 .

FIGURE 1.

Data collection timing and methods.

Trial objectives

The primary trial objectives were to determine whether a structured, intensive educational programme could be provided within a standard clinic setting for a diverse range of young people with T1D and to assess whether the CASCADE intervention improved long-term clinical outcomes (HbA1c levels).

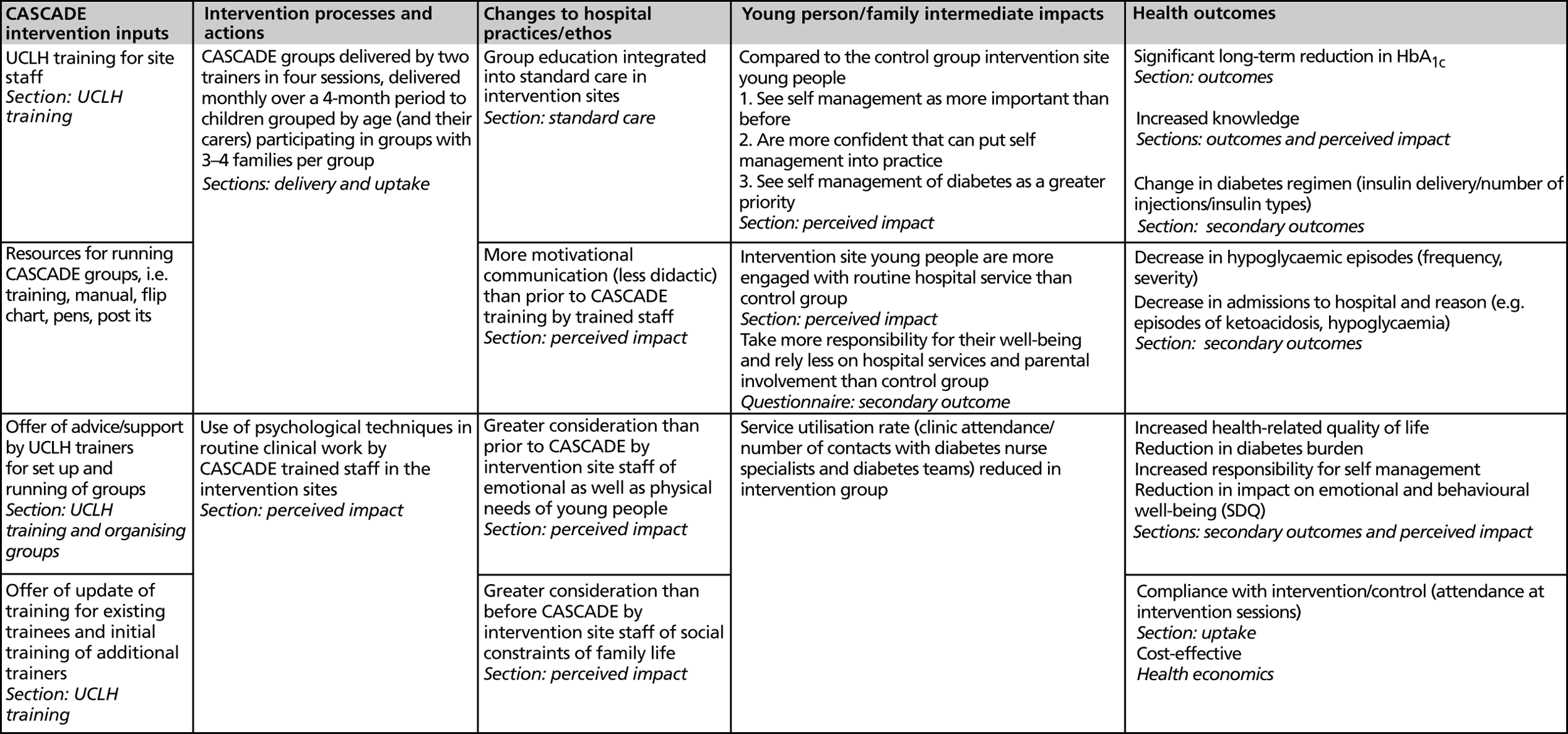

Secondary objectives included determining the impact of the intervention on other markers of diabetes control, psychological wellbeing and costs (see Outcomes, below). The logic model which informed evaluation of the intervention is shown in Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2.

CASCADE logic model.

Ethics committee approvals

The trial was performed in accordance with the recommendations of guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human participants adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, 1964, amended at the 59th World Medical Association General Assembly, Seoul, October 2008. The study was approved by the University College London (UCL)/UCLH REC reference number 07/HO714/112 (see Appendix 4 ). Subsequent amendments to the original ethics approval are detailed below. Site-specific approval was granted at each site.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary trial outcome was glycaemic control, assessed at the individual level using venous HbA1c value. Intravenous HbA1c samples for patients and questionnaires from patients and carers were collected at baseline. The original protocol stated outcomes would be collected 12 and 24 months post intervention. A substantial amendment to collect follow-up data 12 and 24 months after the date of baseline blood sample was approved and reported in protocol v6 301010 (HTA progress report 5). Where possible, data were collected within 3 months either side of the expected collection date.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were outcomes directly and indirectly related to diabetes management, including hypoglycaemic episodes and hospital admissions, choice of diabetes regimen, knowledge and skills associated with diabetes management, responsibility for diabetes management, compliance with intervention and clinic utilisation. Information about psychological functioning in terms of emotional and behavioural adjustment and general and diabetes-specific QoL was measured using well-validated, reliable self-report and parental measures.

Questionnaire development

Specific versions of questionnaires were created for 8- to 12-year-olds, 13- to 16-year-olds and carers (questionnaires are available from the corresponding author). Those on pump therapy completed modified questionnaires reflecting differences in regimen. Demographic information and clinical data included years since diagnosis, insulin type dose, number of injections and time at current clinic. Carer outcomes included demographic information [age, gender, ethnic origin, socioeconomic status (SES)]. Questionnaires contained a number of validated instruments detailed below.

Psychosocial outcomes

Validated instruments appropriate for age were used wherever possible. Parental and self-report of health-related QoL was measured using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL). 167 The scale has good internal consistency, reliability and validity for both the generic and diabetes modules. The physical psychosocial health summary score produce an overall total score. The T1D module has four scales: Treatment I and II, Worry, and Communication, which combine to produce a total diabetes score.

The five-item ‘Impact Supplement’ of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (parent and child report versions) assessed the impact of identified emotional and behavioural difficulties on the young person’s life. 168

Young people were also asked to rate how happy they were with current weight and if they had skipped insulin using two self-report questions designed specifically for the study.

Diabetes outcomes directly related to patient management (parental report and case note review)

-

Diabetes regimen (insulin dose/number of injections/insulin types).

-

Hypoglycaemic episodes (frequency, severity) in last 6 months.

-

Admissions to hospital in last 6 months and reason (e.g. episodes of ketoacidosis, hypoglycaemia).

Diabetes outcomes indirectly related to patient management

-

Knowledge and skills associated with diabetes. 155

-

The Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire (DFRQ)169 (parent and child report) reflects the sharing of diabetes-related responsibilities (such as deciding what to eat at meals and snacks, rotating injection sites and telling teachers about diabetes) within families. Parent and child versions of the questionnaire are scored separately. Higher responses (on both) indicate greater responsibility taken by the young person for their care. A dyadic score for the parent–child pair reflects agreement about who is taking responsibility. High dyadic scores when neither reports taking responsibility is linked to poor health outcomes.

-

The Diabetes Self-Efficacy Scale assesses confidence managing diabetes-related tasks. 170

Compliance with intervention/control

-

Attendance at intervention sessions.

-

Service utilisation rate.

-

Clinic attendance.

-

Contacts with PDSNs and diabetes teams.

Data were collected through process evaluation (PE) and case note review (CNR).

Service user perspectives

Service user perspectives were sought on the structure and content of all the questionnaires. Initial questionnaires were reviewed by a young woman with diabetes as part of the trial management group. One individual with research responsibilities for a diabetes charity and the mother of a girl with diabetes who was also research trained provided comments about the length, general tone and specific items on the questionnaire. Early data collection proved problematic as questionnaires were too long and were often only partially completed. After consulting a patient organisation and a carer researcher, the self-efficacy scale was removed and questions assessing knowledge and skills about self-management were removed from the 8- to 12-year-old child version.

Baseline data collection

Wherever possible, baseline data were collected at the point of consent. Otherwise it was collected at the next possible opportunity. A substantial amendment to allow researchers to collect follow-up questionnaire data by telephone was approved in June 2009 (progress report 3).

Primary outcome data collection

Arrangement for collection varied widely between and within sites. Research nurses or a member of the local clinical team trained in venesection took the sample in the paediatric outpatient clinic or occasionally at the patient’s home or GP surgery. Hospital phlebotomists also collected samples. Approximately 4 ml of blood was collected and stored in a tube prefilled with diluent and preservative. The samples were sent to a single UK laboratory (UCLH Special Biochemistry, London) for measurement of HbA1c concentrations. This ensured direct comparability of results from all clinics. Current legislation requires that non-infectious diagnostic specimens are transported in accordance with guidelines UN 3373 and need to conform to secure packing instructions P650 (The European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road; Regulations concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Rail; the International Air Transport Association). The research team provided the appropriate packaging. Samples were transported using a courier or more often delivered by hand by researchers or via the Royal Mail (identified as a biological substance, category B). HbA1c assays were carried out on a Tosoh G8 instrument (Tosoh Bioscience, Tessenderlo, Belgium) with International Federation of Clinical Chemistry aligned calibrators and results reported directly to the data manager following adjustment against the DCCT international standard.

When a sample was lost or spoiled in transit, the research team used their discretion with regard to requesting a repeat sample. A small number of young people were recruited in whom it was subsequently found they had variant haemoglobin, meaning that HbA1c levels could not be accurately measured. This issue came to light when the UCLH laboratory reported abnormal results for baseline blood samples. The clinic principal investigator (PI) was informed. These patients remained in the study and provided completed questionnaires but their HbA1c data were not used and no further study blood samples taken.

Secondary outcome data collection

For collection of secondary outcome data the researcher provided patients and carers with a copy of the appropriate questionnaire. Participants were encouraged to self-complete the questionnaires independently (i.e. parents and children were asked not to confer). The researcher provided help when required. If a young person and/or their carer was not able to complete the questionnaire in the clinic, either owing to insufficient time or the parent not being present, the researcher would go through the questionnaire with the young person/parent on the telephone. Patients recruited by site staff or research network nurses were contacted by telephone to complete the questionnaire.

The PI from each clinic ensured appropriate access to advice and psychological support should any participant express any concerns or worries with regard to taking part in research activities. In exceptional circumstances, for example disclosures of significant risk (to self or others), feedback to the family/carer and clinical team would be made by the research team. Participants were reminded that DUK provides an independent voice of support, through ‘Careline’, a dedicated helpline for all people with diabetes, friends, family, carers and HCPs.

Follow-up data collection

The process for collecting data at 12 and 24 months was the same as for baseline. A letter was sent to the young person and their parent/carer a few weeks prior to their clinic appointment, approximately 1 year after the baseline blood sample and 1 year later for the second-year follow-up. Families were asked to come to clinic early if possible to meet with the researcher and advised that a £10 high street gift voucher would be offered as a thank you for their participation. A substantial amendment to the protocol was submitted and approved (progress report 5, protocol v6) allowing the team to offer an additional £10 high street gift voucher at the second follow-up.

There was ongoing support from research nurses from networks that had capacity to continue to support the study at one or both follow-up time points. National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) flexibility and sustainability funding supported a part-time researcher from June 2010 to June 2011 to assist with follow-up data collection where research network nurses were not available.

During the first- and second-year follow-up, some patients transitioned to adult services. The risk of data loss was minimised by requesting that, wherever possible, clinics delayed transition. If this was not possible the research team wrote to the adult consultant to introduce the study and reassure him/her that the research team would take responsibility for overseeing data collection.

Trial Steering Committee and Data and Ethics Monitoring Committee

The NIHR-HTA appointed a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and independent Data and Ethics Monitoring Committee (DMEC). The TSC met with the trial management group every 6 months. The DMEC reviewed, in strict confidence, data from the trial approximately halfway through the recruitment period. The Chair of the DMEC could also request additional meeting/analyses. In the light of these data and other evidence from relevant studies, the DMEC would inform the TSC if in their view:

-

There was proof that data indicated any part of the protocol under investigation was either clearly indicated or contra-indicated, either for all patients or a particular subgroup of patients, using the Peto and Haybittle stopping rule. 171,172

-

There were major ethical or safety concerns.

Details of committee membership are provided in Appendix 5 .

Centre recruitment and consent

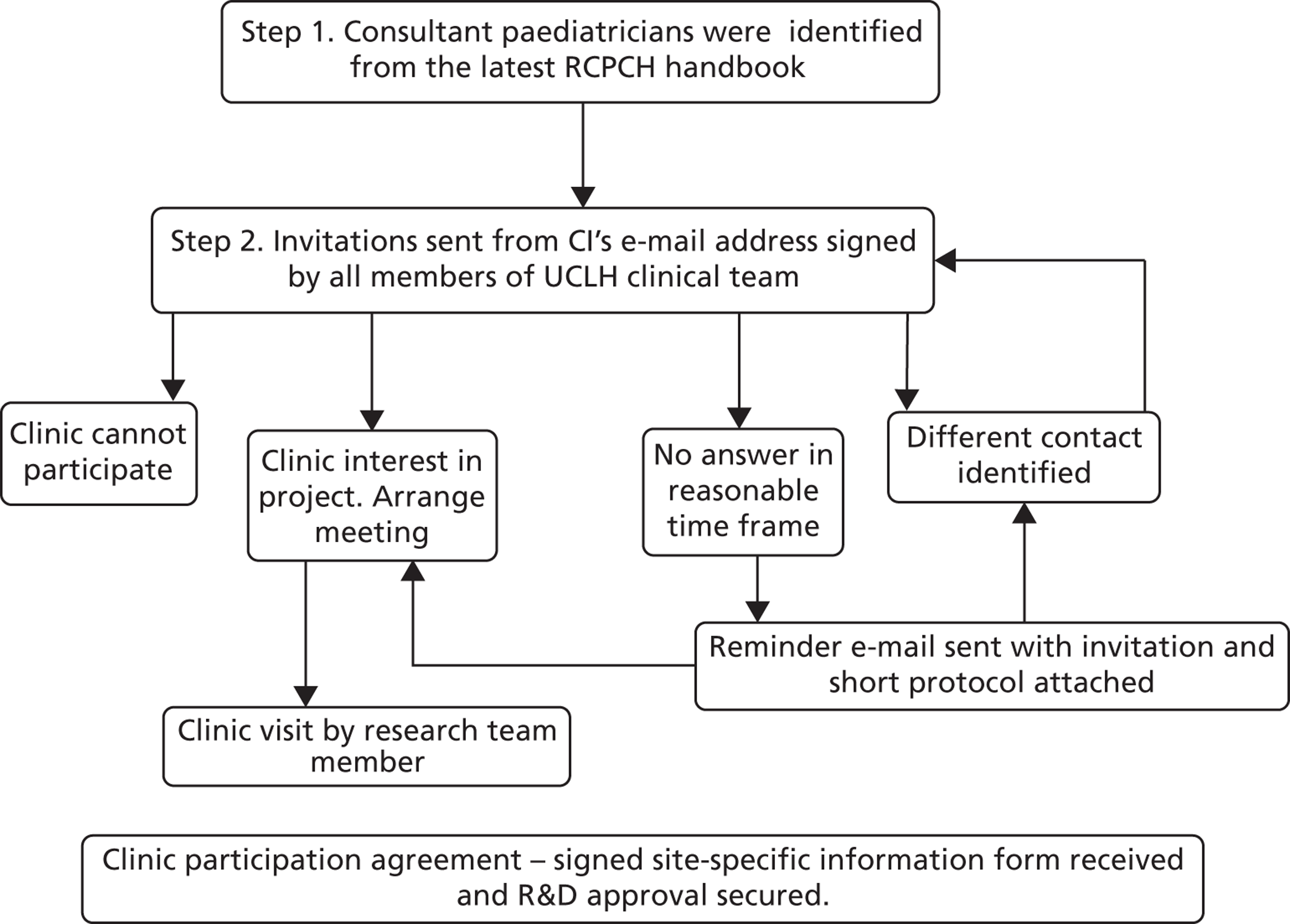

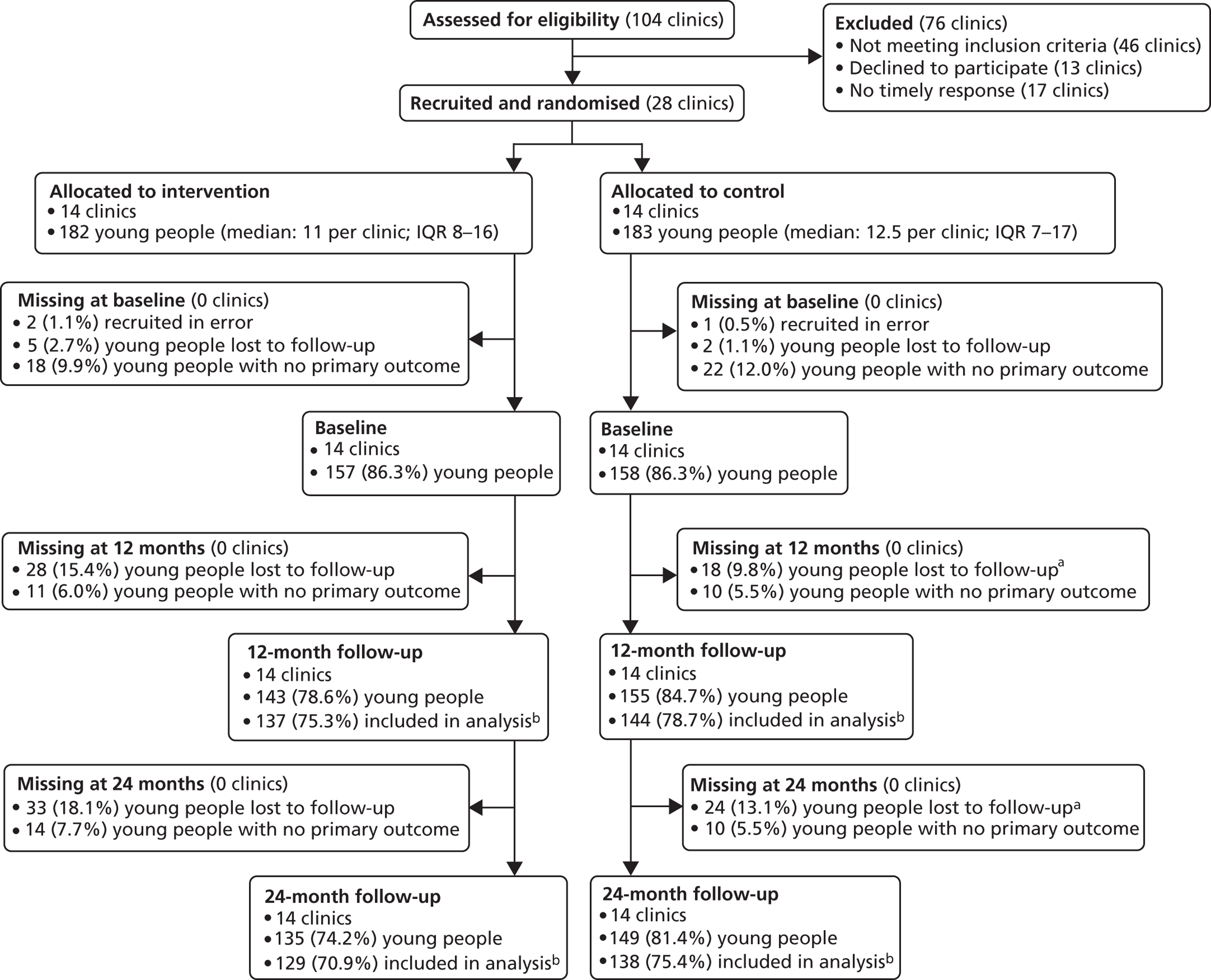

A database of potential diabetes clinics was created from a list of hospitals and consultant paediatricians identified from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) handbook. The Chief Investigator e-mailed the clinical lead for each potential clinic on behalf of the UCLH team to invite them to participate. Clinical teams in a few sites, hearing about the study, approached the study team to request inclusion. Clinical teams that expressed an interest were contacted by the research team to discuss the study in more detail and ensure that they met inclusion criteria. Consent to randomisation was obtained from the responsible clinician who agreed to act as PI ( Figure 3 ). Research and development (R&D) approval was then arranged with the participating acute trusts.

FIGURE 3.

Centre recruitment and consent process. R&D, research and development.

Eligibility criteria for clusters

-

NHS paediatric diabetes service – clinic had to be staffed by at least one paediatrician and paediatric nurse with an interest in diabetes.

-

Located within London, the south-east (SE) and the Midlands (maximum train journey time 2 hours).

-

Not running a group education programme at time of recruitment or during trial.

-

Not taken part in a similar paediatric diabetes trial within the last 12 months.

-

At least 40 eligible patients on current patient list.

Patient recruitment and consent

Prior to randomisation, clinics were asked to review patient lists to identify patients eligible to participate in the study. Guidance regarding patient eligibility was provided in writing, over the phone and sometimes face to face. The following criteria were used to determine eligibility.

Inclusion criteria for patients

-

Diagnosis of T1D with duration ≥ 12 months.

-

Aged 8–16 years.

-

Mean 12-month HbA1c value ≥ 8.5 mmol/l.

-

Under the care of a paediatric and/or adolescent diabetes clinic conducted by a specialist, or general paediatrician with an interest in diabetes.

Exclusion criteria for patients

-

Significant mental health problems unrelated to diabetes requiring specific mental health treatment.

-

Significant other chronic illness in addition to diabetes that may confound the results of the intervention. Patients with coeliac disease or hyperthyroidism were included.

-

Significant learning disability or insufficient command of English to enable full participation in the planned intervention. Young people with good command of English but whose parents have poor command of English would be eligible to attend by themselves if they wished as long as parents had given informed consent. Another relative who was one of the primary diabetes carers (e.g. sibling, aunt or uncle) who had good command of English could participate instead of the parents.

-

Participated in diabetes treatment trials in the 12 months prior to collection of baseline data.

Sample size

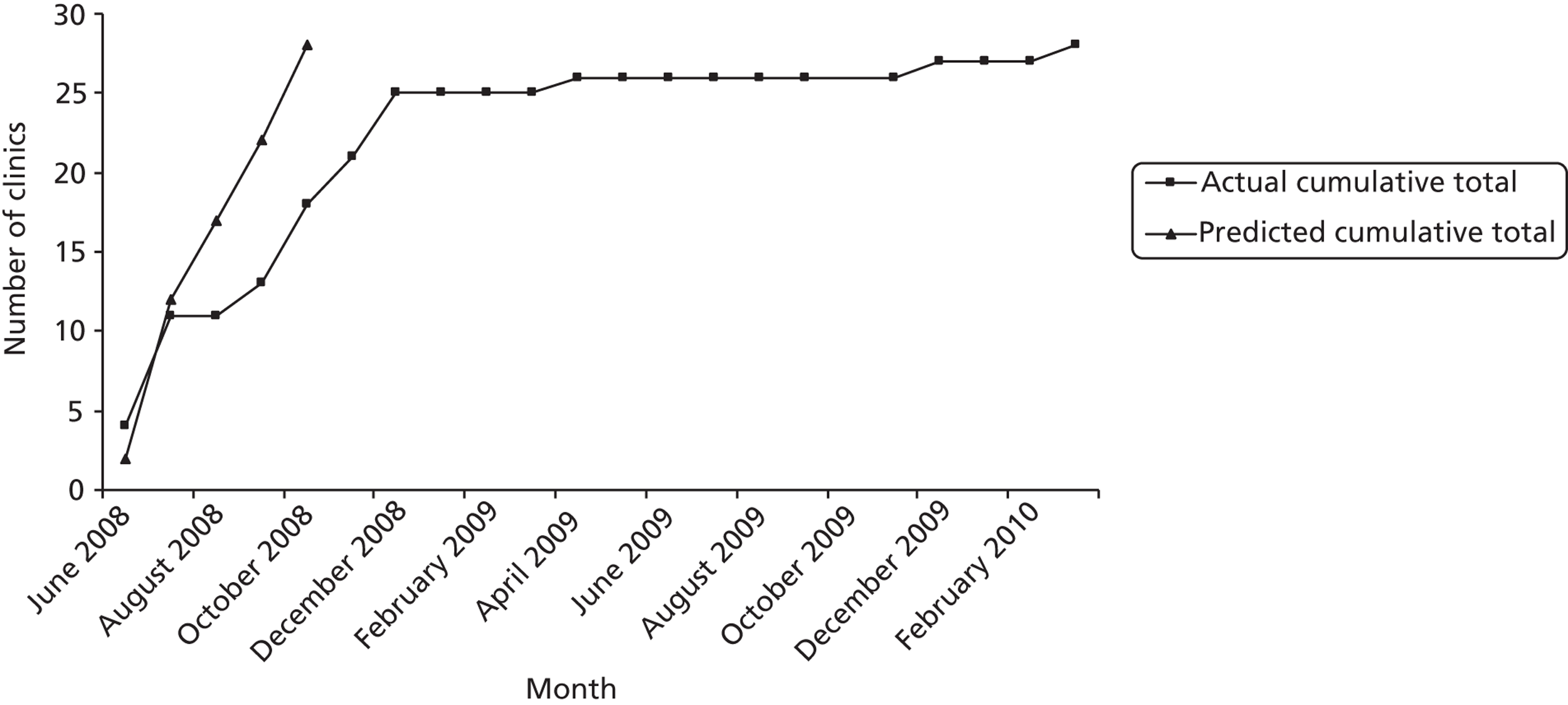

Based on NPDA figures, we calculated the average number of eligible patients would be 80–100 patients per site. A recruitment rate of 25% was predicted based on a previous study by the Chief Investigator. 121 The standard deviation (SD) of HbA1c in the target population is approximately 1.5%. The proposal was to recruit sufficient young people to allow the trial to detect a difference between groups of 0.5 SD, i.e. 0.75%, with 90% power at a significance level of 0.05 (two tailed), considered to represent a moderate size of effect. Power calculations were based upon an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) (the variability in outcome between clinics divided by the sum of the within-cluster and between-cluster variances) of 0.1. In the absence of reliable data on which to calculate an ICC for the clinic population, this was chosen to be compatible with databases of ICCs such as www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/epp/cluster.shtml. With these assumptions, 13 clinics in each arm with an average of 20 young people in each would be required to detect a difference of half a SD (0.75) with > 90% statistical power at 5% significance. Given the possible loss to follow-up of approximately 10%, the target recruitment was inflated to 22 young people from each clinic. The original target sample size was therefore 572 children and young people recruited from 26 sites.

Early in the trial, the average number of eligible patients per clinic reported was 48 patients, with a range of 19–97 patients. This was considerably fewer than the 80–100 patients per clinic originally estimated.

Given the lower than expected number of eligible patients per clinic, the predicted recruitment rate of 25% would mean an average of only 11 patients per clinic was likely to be available (a total possible sample size of 286). Maintaining the original predicted effect size of 0.5 SD the reduced sample size would have power of only 80%.

A preliminary exploration of baseline data suggested that the ICC was 0.01, which was significantly lower than the original assumption of 0.1. Using this revised ICC and increasing the number of recruited clinics to 28, a minimum of 11 patients per clinic provided 87% power to detect the proposed effect size with 5% level of significance. This created a revised patient recruitment target of 308. The rationale for this was sent to the DMEC, TSC and NIHR-HTA and was approved on 21 December 2009.

In order to meet this overall target, the target recruitment rate per clinic was also raised from 25% to 33%. In clinics where eligible lists were particularly small, or patient recruitment began late, 33% was felt to be unrealistic and a minimum of seven recruits was set in these clinics. Where eligible patient numbers were felt to be particularly small, clinical teams were asked to review patient lists to identify any additional eligible patients who may have been inadvertently missed. Where requested, the research team visited clinical teams to help with this process.

Recruitment process

The research team provided electronic templates of letters and pre-printed information leaflets. Invitation packs were posted by clinics to the parent/guardian of all eligible patients and included:

-

an invitation letter (printed on trust headed paper) to parent/guardian

-

participant information leaflet for parent/guardian explaining the study

-

a separate non-sealed envelope containing an age appropriate invitation letter for the young person (printed on trust headed paper) and an age-appropriate information leaflet

-

separate invitation letters and participant information leaflets for 8- to 10-year-olds and 11- to 16-year-olds.

Administrative support to send out invitation packs was provided by the research team if requested by the site. The team liaised with site staff and travelled to outpatient clinics when eligible patients were attending routine appointments. Initial recruitment was carried out by two full-time members of the research team. Eligible children, young people and carers were approached in clinic and asked if they had received the invitation pack in the post. If not a duplicate pack was provided and patients were then approached at the next convenient opportunity. The trial was described as a comparison of different ways of helping young people to manage their diabetes. Participants were told that if they were in the intervention arm they would, in addition to standard care, be invited to a series of four 2-hour group sessions. If they were in the control arm they would continue with standard care only. It was made clear that all approaches had potential advantages and disadvantages. They were informed that the children and young people were required to give a venous blood sample and complete a questionnaire at three time points, and that the parent/carer would be required to complete a questionnaire at the same time points. Eligible patients that asked for more time to think about the study before consenting were followed up (by phone, letter or at subsequent clinic appointments).

Informed written consent or assent was obtained from both the young person and one parent/carer. The right of a child or parent to refuse participation without giving reasons was respected. The child/young person or their parent remained free to withdraw at any time from the study without giving reasons and without prejudicing further treatment. If a participant withdrew consent from further trial participation their data remained on file and was included in the final study analysis. If a participant withdrew consent for their data to be used, the data were destroyed immediately. 173,174

Additional strategies to support recruitment process

Five additional sessional workers were used to support recruitment on an ‘as required’ basis to increase capacity and maximize flexibility within the team.