Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/51. The contractual start date was in August 2009. The draft report began editorial review in December 2012 and was accepted for publication in June 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Marion Walker is a member of the Global Stroke Community Advisory Panel (GSCAP), funded by Allergan. Hywel Williams is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Logan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction

In 2009 the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme funded a proposal to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of delivering a targeted outdoor mobility therapy provided within stroke services aimed at helping people get out of the house more often following a stroke. This report details the results of the Getting out of the House Study.

The effect of stroke on functioning, and rehabilitation

Stroke can have a devastating effect on people’s lives, with half of survivors being dependent on others 6 months later,1 one-third feeling socially isolated, one-quarter having abnormal moods, and half not getting out of their houses as much as they would like. 2 These are worldwide health-care issues but, with 130,000 people a year having a stroke in England and Wales,3 and stroke increasing with age, the number of people needing UK health and social care services is set to rise. The cost of stroke to the UK NHS is estimated to be over £2.5B per year3 in addition to the cost to social care services and to the stroke survivors. In the UK most people who have a stroke are admitted to hospital for acute care but are discharged on average 19.5 days later. 4 Treatment is then transferred to community-based teams and social care services.

Stroke unit care has been found to be the best way to organise inpatient care for stroke patients,5 allowing them to be transferred to evidenced-based Early Supported Stroke Discharge services6 when they go home. Once home, stroke rehabilitation interventions provided by occupational therapists have been shown to increase activity7 , 8 by helping people to regain independence in personal and domestic activities of daily living. Most stroke rehabilitation research has been conducted on people in the first year after their stroke. Although many consequences of stroke persist beyond a year there is little evidence for the benefit of interventions delivered after 1 year. 9 The early treatment and rehabilitation of stroke necessarily focuses on reducing neurological impairments but as time goes by after a stroke the activity and participation become more important. Also, the first goal of patients in hospital tends to be to get home, which requires a focus on self-care activities, but, once home, they set goals in terms of being able to optimise participation, and these tend to require an ability to get out of the house or to engage in social activities. However, these rehabilitation areas are rarely targeted.

Outdoor mobility after a stroke, and rehabilitation

Stroke can leave people with long-term and persistent impairments, leading to activity limitations and restriction in participation. These restrictions occur in addition to other impairments resulting from comorbidities, such as osteoarthritis or dementia, making recovery and evaluation of treatments difficult and complicated. In addition, stroke often leaves people with perceptual and cognitive impairments that can reduce performance of everyday activities, such as shopping, hobbies, cooking or using the bus. Lowering of mood, feelings of becoming a different person and lack of confidence are also common after stroke. 10 These hidden impairments often go untreated and, alongside the more obvious physical ones, contribute to activity limitations especially when people are discharged from health services. There is evidence that stroke patients may delay getting back to a normal life, even although they may have made a good physical recovery. 11 Hellstrom et al. 12 argued it is not until people go home after a stroke and attempt to try everyday activities that the real impact is realised. 12 In response to this, it is recommended that all stroke patients receive a 6-month review, with rehabilitation being available to enable people to maintain participation, reduce long-term misery and improve quality of life. These are priority areas identified in the Department of Health of England and Wales Stroke Strategy. 13

Limitations in outdoor mobility affect 42% of stroke patients,2 with 33% remaining permanently dependent on others long term. 3 Stroke patients can become housebound, leading to poor mental health, isolation and misery. 14 This can be devastating for patients and carers, and increase their reliance on home visits from medical staff, home care, social services and home adaptations. Stroke tends to affect older people, median age 77 years [interquartile range (IQR) 68–84 years],15 and, as outdoor mobility – including walking outside – declines with age, mobility disorders may also be due to impairments and social factors associated with ageing and comorbidity. People aged ≥ 80 years of age make half the number of outdoor journeys and travel less than one-quarter of the distance of those aged 50–54 years. 16 There is evidence that elderly people find it difficult to participate in transport services, owing to an inability to carry heavy loads and a fear of crime when outside at night. 14 People who are dependent on walking frames are, on average, getting out of the house less than twice each week. 17 Outdoor mobility is usually achieved by a combination of walking, cars and public transport, with very few people using specialist transport such as the provision of a taxi service for people with disabilities. 16 , 18

Specific outdoor mobility rehabilitation interventions exist for people with limited vision, learning disabilities and those who use wheelchairs19 but these are not routinely used for people who have had a stroke. The National Clinical Stroke Guidelines do not contain any evidence-based recommendations to guide therapists in how to treat outdoor mobility limitations. 20 However, the clinical guidelines recommend that stroke patients are encouraged to take physical exercise, as there is an increasing body of evidence that exercise is of benefit to stroke survivors. 21 In the UK the routine treatment for outdoor mobility problems is to provide information in a leaflet and verbally, delivered by a health-care professional. A Cochrane review22 concluded that the passive provision of leaflets is not effective and leaflets can be difficult to understand after a stroke. It is more likely that a multimodal rehabilitation intervention that includes exercises to decrease impairments (these can be physical and mental), education to provide information and behaviour change regimes, use of adaptive equipment and support from other people, both formal or informal sources, would be more effective at improving outdoor mobility. This study aimed to fill this evidence gap.

Justification for the current study

An outdoor mobility intervention for people with stroke was developed using qualitative interview findings, published literature, correspondence with the Department of Transport and expert opinion. 23 This intervention was evaluated in a single-centre randomised controlled study. 24 The study found clear benefits in outdoor mobility for people who received the intervention. The patients who received the intervention took twice as many journeys, many of these walking, as those in the control group, 4 and 10 months after recruitment into the study, and were significantly more likely to be satisfied with their outdoor mobility activity. Although the study was based on a real clinical need, recruited to target, had excellent follow-up and was published in a peer-reviewed journal, it had some limitations. The intervention was delivered by a single therapist, who was a stroke specialist, with experience in the delivery of community-based treatment. It was delivered in one UK city and no health economic evaluation was completed. Although this study has already influenced practice, alone it is insufficient to inform evidence-based guidelines.

Thus, the next step was to conduct a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT), using the lessons learned from the single-centre study. We completed a multicentre RCT to try and answer the following questions.

-

Whether:

-

the results of the pilot study were generalisable to other therapists and other sites.

-

the intervention could be implemented across a health system.

-

the intervention improves overall health and, if so, whether such an approach is conventionally cost-effective.

-

Structure of the Health Technology Assessment monograph

The monograph has been separated into methods and results for the randomised controlled study, including delivery of the intervention and clinical effectiveness, followed by methods and results for both the economic evaluation and the qualitative substudy. Finally, all results are discussed, followed by overall conclusions.

Appendices include the summary of the intervention manual and the statistical analysis plan.

Chapter 2 Randomised controlled study methods

This chapter describes the methods for the delivery and assessment of the intervention and collection of data to assess clinical effectiveness.

Summary of study design

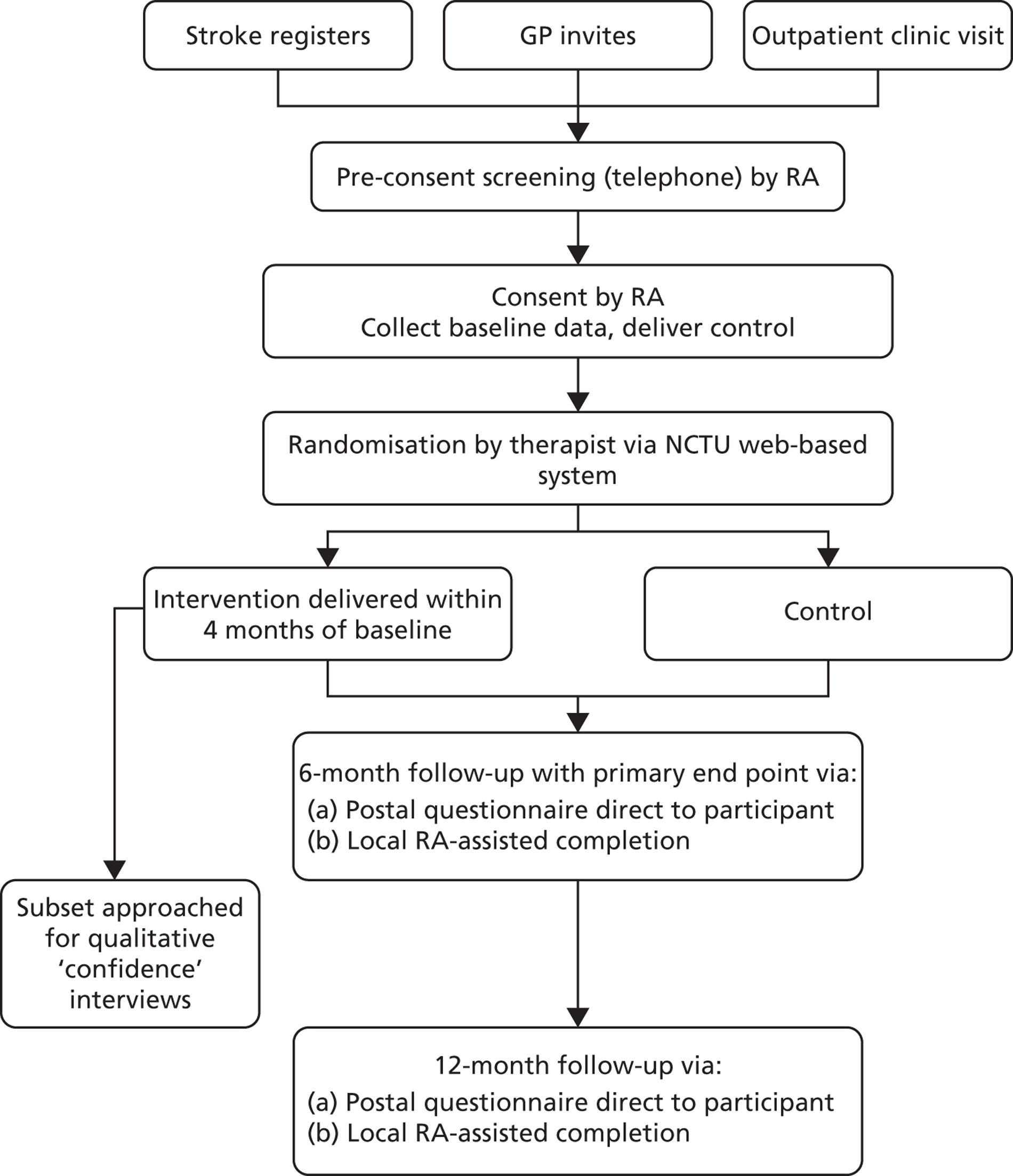

The Getting out of the House Study was a multicentre, parallel-group RCT comparing clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness for two groups, an intervention group and a control group. The methodology used was, as far as possible, a replication of that used in the single-centre study. 24 Figure 1 summarises the study design. Patients aged ≥ 18 years, who had experienced a stroke > 6 weeks previously were considered initially eligible for the study. The majority of patients were contacted by a patient invitation letter sent from either their general practitioner or from the local community rehabilitation or local hospital stroke service register. If interested, patients replied to their local research team, who contacted them and screened them by telephone call to further determine eligibility. Final confirmation of eligibility and subsequent consenting was carried out by the research assistant (RA) at the patient’s home. Following consent, a baseline assessment was completed and all participants received the control. They were provided with travel diaries in the form of 12 months of ‘travel calendar’ to record the number of journeys that they made and any falls that they had. All participants were then randomised by the local therapist, using the web-based randomisation system that was controlled by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU), to either targeted outdoor mobility therapy (the intervention) or no further therapy contact (control). Those randomised to the intervention received up to 12 visits over a maximum of 4 months (from baseline). No further therapy contact was received after 4 months, allowing 2 months before the primary and secondary outcome data were collected. Outcomes were assessed at 6 and 12 months after recruitment by postal questionnaire and by monthly travel diaries. Local RAs blinded to treatment allocation were available to assist the participant with completion of questionnaires if needed. RAs recorded incidents where they were unblinded. A subset of participants at a single site were asked to participate in a nested qualitative study investigating confidence issues surrounding stroke.

FIGURE 1.

Study design flow chart. GP, general practice.

Primary objective

To test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treating people who have had a stroke with an outdoor mobility rehabilitation intervention in addition to routine care compared with routine care alone.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to measure whether the intervention was associated with:

-

improved:

-

mobility in and outside the house

-

patient well-being

-

participation in everyday activities

-

carer well-being

-

health-related quality of life.

-

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the Social Function domain score of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items, version 2 (SF-36v2)25 measured at 6 months, as recorded in their questionnaire response. This is one of the eight domains of the SF-36v2 and was scored and transformed on to a scale of 0 (worst possible health state) to 100 (best possible health state).

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

functional activity in participants measured by the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) scale26 , 27

-

mobility reported by participants in the completion of the Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI)28

-

the number of journeys as recorded by participants in the travel calendars

-

satisfaction with outdoor mobility (SWOM) as reported by participants in the completion of a yes/no question: ‘Do you get out of the house as much as you would like?’

-

psychological well-being as reported by participants in the completion of General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ-12). 29

-

carer psychological well-being as reported by participants in the completion of GHQ-1229

-

health-related quality of life as reported by participants in the completion of European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)30 and Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D)25 (based on a subset of questions from the SF-36 v231)

-

the resource use of health and social care, carer input and provision of equipment as reported by participant in the completion of the service use questionnaire and data collected relating to intervention visits

-

participant mortality (death data) as collected from NHS Information Centre (IC)/NHS Central Register.

Recruitment process

There were three methods of patient identification: searching general practice (GP) databases, searching stroke registers in secondary care hospitals, community hospitals or primary care community teams and approaching patients attending post-stroke outpatient clinics as they were discharged from rehabilitation. If the search team also had access to local stroke service rehabilitation records they cross referenced for any active stroke-related rehabilitation that may be ongoing.

All potential participants received a version of the participant information sheet (PIS) prior to the baseline visit and had sufficient time to consider the information. In addition, if required, an aphasic PIS and a summary PIS were available for participants and their carers.

Other recruitment strategies included placing adverts within local newspapers, local trust publications and relevant websites (e.g. the Stroke Association), establishing a study website, various articles within local trust publications and local press, visiting local stroke groups and widespread distribution of the study poster to relevant areas (e.g. GPs, rehabilitation teams, stroke groups, etc.).

Sample size

Our sample size calculations were based on the primary outcome measure, the Social Function domain of the SF-36v2 at 6-month follow-up. Although this was not used in the pilot study, a recent study had suggested a minimally clinically important difference (MCID) for the Social Function domain was 12.5 points. 32 The estimate of the standard deviation (SD) was taken from Brittle’s study33 and this closely matched the standard deviation obtained by assuming that the distribution of the nine possible integer-valued scores followed a roughly right-angled triangular distribution (i.e. that was positively skewed). This followed the general approach suggested by Deming34 for schematic distributions. Assuming a power of 90% and a two-sided significance level of 5%, we estimated that to detect a difference in mean SF-36 scores of 12.5 points, assuming a common SD of 28.2 points,33 a sample size of 135 patients per group was required. This calculation assumed an attrition rate of 20% over a 6-month period.

Clustering by delivery of treatment was allowed for by generating simulated data to mimic the multilevel structure of the proposed study, with site-specific variation between therapists. The likely existence of sharing of therapists by patients was addressed by a multiple membership model, and the variance of the treatment effect so found was compared with that of a regression model ignoring clustering (both models treating centre as a fixed effect). The data sets and analyses were performed in Stata v10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The variance inflation observed was insensitive to variation in the simulated between-site variance and the average between-therapist variance, and a rounded value of 2.5 was selected as the multiplier for a sample size based on a naive analysis. After the allowance for clustering by delivery of treatment, a sample size of 338 participants per arm was required, with an overall sample size of 676, allowing for 20% lost to follow-up.

Revised sample size

Owing to an increase in the expected number of sites, the sample size was revised.

As more information had become available after the original sample size calculation was performed we developed an alternative method of calculating a sample size that was easier to replicate. This analytic approach was based on the same assumptions of the original sample size calculation and assumed that within each site there would potentially be four therapists delivering the intervention in the intervention group and one therapist delivering the control in both groups. In these calculations we assumed a therapist effect intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 (Professor Stephen Walters, University of Sheffield, 30 October 2008, personal communication) and a site effect ICC of 0.04 [obtained from Aberdeen University’s database of ICCs (www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/epp/iccs-web.xls)]. For comparison, based on seven sites this method gave a sample size of 746, allowing for 20% lost to follow-up. This method was adopted to provide a revised sample size.

As the number of sites had increase from the assumed 7 to 14 (at that time) we conducted further power calculations assuming a lower sample size and investigated the effect of varying the number of sites. This was based on detecting a difference in means of 12.5 (as in the original sample size calculation) and assuming a total sample size of 440 with the number of sites ranging from 7 (as originally planned) to 14. These calculations were based on the same assumptions made in the analytic sample size above (i.e. SD = 28.2 sites, two-sided significance level of 5%, ICC of 0.02 for therapist effect, and ICC of 0.04 for centre effect). These indicated that a sample size of 440 would have a power of 86% (assuming no attrition) and a power of 82% (assuming lost to follow-up rate of 20%) to detect a difference in means of 12.5 if there were seven sites and if there were 12 or more sites the corresponding power would be at least 90%. There were a total of 15 sites in this study so this met the latter calculations.

Sample size calculations can be performed only if a number of assumptions are made and although our calculations were based on the best estimates we could obtain at the time that there was some uncertainty about the true values of the ICCs used to adjust for clustering. Therefore, we decided to be cautious and aimed to recruit a sample size of 506 participants (440 + 15%) to ensure that we had recruited enough participants. This was agreed with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Setting and locations

The study was coordinated by the NCTU and involved 15 sites from across England, Scotland and Wales. Initially seven sites were planned but during the course of recruitment an additional eight were added.

The sites were a mixture of settings, split in broad terms as follows.

Primary care community stroke rehabilitation service

-

NHS Nottingham City.

-

NHS Nottinghamshire County.

-

Gateshead Primary Care Trust (PCT).

-

NHS North Somerset.

-

Wolverhampton PCT.

-

Kent Community Health Trust.

-

Tower Hamlets PCT.

-

Norfolk Community Health and Care NHS Trust/NHS Norfolk.

-

NHS Bristol.

Secondary care community stroke rehabilitation service

-

NHS Lanarkshire.

-

NHS Grampian.

-

Cardiff and Vale University Health Board.

-

Cwm Taf Health Board.

Secondary care stroke service

-

United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust.

-

Southend Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible for the study if they provided written informed consent and if they:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

had experienced a stroke at least 6 weeks previously, and

-

wished to get out of the house more often.

Patients were not eligible for the study if they were:

-

not able to comply with the requirements of the protocol and therapy programme – in the opinion of the assessor

-

still in post-stroke intermediate care or active rehabilitation, or

-

previously enrolled in this study.

Patients who had suffered a transient ischaemic attack were not included.

Screening and baseline assessment

The majority of preconsent screening was undertaken over the telephone by the RA in response to a patient reply to a patient invitation, and involved a general discussion of the study background and participation requirements. In addition, key eligibility questions were asked in relation to wishing to get out of the house more often and establishing potential outdoor mobility goals related to the intervention manual. Following this process, if the potential participant remained eligible then a baseline visit would be arranged.

The baseline visit was conducted in the potential participant’s home. The visit consisted of four elements: first, confirming eligibility against inclusion and exclusion criteria; second, consenting (see Consent, below); third, baseline data collection; and, fourth, delivery of the control (see Control, below).

Only limited numbers of data were collected, including basic demographics, time since stroke and contact details.

Consent

Participant information sheets were available in several different formats, including full length, abbreviated leaflet style, summary and aphasic. In practice, a combination of all four of these were often used, as appropriate, for each individual participant. Only people who had the mental capacity to consent to participation, defined against the criteria in the English Mental Capacity Act,35 were eligible to take part. If there were communication problems then the participant’s carer or relative was involved in the process. In addition, owing to potential physical limitations with completion of the consent forms, it was acceptable for the participant to mark the consent form, accompanied by a witness signature to complete the consent process. If the physical challenges were more severe then a witness (usually a member of the participant’s family, carer or neighbour) could complete the consent form on the participant’s behalf.

During the baseline visit, carer information sheets and questionnaires were provided to all carers. They were allowed to complete them immediately or later, and the process of completing and returning the questionnaire was considered to be implied consent.

Control information

All participants in the study received the control information during the baseline visit by the RA. The control information was provision of verbal and written local mobility and transport information. This information was site specific. Each site collated a pack of local information and leaflets as guided by the research team. They were asked to include information about bus times, local community transport, taxi services, wheelchair services, disabled persons’ car badges, wheelchair borrowing schemes and mobility equipment. These individualised packs were given to the participant after their content had been discussed.

Randomisation

Following consent and completion of the baseline assessments and delivery of the control information, the participant’s details were passed to the local therapist. The therapist accessed the remote, secure web-based electronic case report form (eCRF) and randomisation system developed and maintained by the NCTU and entered basic demographic details. Once these details had been entered irrevocably into the system, the group to which the participant was randomly allocated was provided to the therapist. Randomisation was created using Stata/SE version 9 statistical software with a 1 : 1 allocation to intervention group or control. Participants and therapists were aware of the intervention allocation, whereas the RA responsible for assisting with collection of the outcome measures was kept blinded to the allocation throughout the study.

Randomisation was based on a computer-generated pseudorandom code using random permuted balanced blocks of randomly varying size, set up and maintained by the NCTU in accordance with its standard operating procedure and held on a secure server. The randomisation was stratified by age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years) and site. Sixty-five years of age was chosen as a cut-off point because Mobility Allowance – a monetary allowance – was no longer available for people aged > 65 years and over. Access to the sequence was confined to the NCTU Informartion Technology (IT) Manager. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until all participants had been randomly assigned to a treatment group and recruitment, data collection and all other study-related assessments were complete.

If the participant was randomised to the intervention group then the therapist contacted the participant to arrange an initial goal-setting visit. If the participant was randomised to the control group the therapist would either, based on site staff preference, not contact the participant or contact the participant to explain their allocation. It was not recorded which approach was used for which participant.

Intervention

The development of the intervention followed the guidelines. 36 Qualitative interviews23 were used to identify ‘barriers and need’ theories. A group of senior and specialist therapists met to discuss the interviews and developed an intervention based on the results, their clinical skills and training. The intervention training manual that was used to train therapists in each site was developed using a systematic approach. Initially, a literature review was performed using the search strategy for the following terms ‘rehabilitation’, ‘stroke’, ‘occupational therapy’ and ‘outdoor mobility’, with the results reviewed by a panel of expert stroke clinicians from which a draft training manual was developed. This was then reviewed by a focus group of therapists (n = 15) who had either delivered the intervention in the pilot study or were clinical experts in stroke. The intervention training manual used for this study contained:

-

standardised assessments

-

case vignettes of treatment plans

-

goal planning and activity analysis guidelines

-

protocol for a first outing walking, using the bus and using a taxi

-

checklist of benefits and barriers to going outside

-

motivational and confidence-building strategies

-

examples of skills needed to catch a bus or train

-

examples of skills needed to be able to operate an outdoor mobility scooter.

The aim of the intervention was to increase outdoor mobility participation by alleviating physical difficulties, developing skills to maximise the individual’s potential and overcoming psychological barriers. The main component of the intervention was for participants to repeatedly practise outdoor mobility. This included buses, taxis, walking, voluntary drivers and mobility scooters until they felt confident to go alone or with a companion. The number of intervention sessions depended entirely on the participant. If they felt they did not require any further intervention, for whatever reason, then the intervention stopped. If they felt they required additional intervention for whatever reason, they could continue the intervention up to a maximum of 12 visits. We recorded the duration of each intervention visit, including the time taken to deliver the intervention, and travel to and from the participant’s home. A description of the intervention has been published37 and a training manual developed. A more detailed summary of the training manual can be found in Appendix 2 .

Training therapists to provide the intervention

Therapists in each site were trained by Pip Logan [chief investigator (CI) and sole therapist in the pilot study] to deliver the intervention using the intervention training manual and a standard presentation over the course of 2 hours. Following this face-to-face training, the majority of therapists attended an update session each year. On an ongoing basis they were able to e-mail other therapists on the study to discuss treatments and were able to contact the study CI with any queries relating to the intervention.

Each therapist was registered on the eCRF database and when the record of a particular intervention visit was added to the eCRF then a therapist, or therapists, had to be assigned to that particular visit, therefore providing an accurate record of the delivery of the intervention, which could be correlated against the training records.

Data collection

There were four methods of data collection: eCRF, questionnaire booklets, travel diaries and intervention records. The NCTU performed quality control checks on all aspects of data collected and entered onto the eCRF to ensure accuracy and completeness. Specifically, a 100% check of primary end points and a 10% check of all other data were completed.

Electronic case report form

Only the therapist [and principal investigator (PI)] at each site had access to the eCRF. The baseline demographic details, including the NHS number, were recorded and supplied to the NHS IC/NHS Central Register to allow mortality checks prior to follow-up. In addition, data for duration of visit, the occurrence of any adverse events and end of intervention details was also collected and directly entered on the eCRF, often transcribed from paper records (either study worksheets or the intervention records).

Questionnaire booklets

Baseline participant questionnaires were completed by participants, with assistance from the RA if needed, during the baseline screening assessment. Alternatively, the RA left the questionnaire for the participant to complete later and post direct to the NCTU. We asked participants to record at baseline and both the 6- and 12-month assessments, whether they completed the questionnaire themselves or required assistance. This was to indicate who physically completed the questionnaire and it was assumed that the participant answered the questionnaires regardless of who filled in the form. If the RA assisted with completion of the baseline questionnaire, they informed the NCTU that the participant would also require assistance at 6 and 12 months. The RA sent the baseline questionnaire booklets to the NCTU for entry onto the database. Baseline carer questionnaires were either completed during the baseline screening assessment, if the carer was available, or left with the participant for completion later.

Six- and 12-month participant and carer questionnaire data were collected either by post or with assistance of a blind-to-allocation RA. Following baseline assessment, each participant was assigned to the postal approach unless otherwise indicated by the RA. The NCTU tracked all questionnaires with the option to send a reminder letter or to telephone to assess the situation. If difficulties were encountered at any time during the study then participants were switched from the postal approach to the RA approach. These methods were found to be successful in the single-centre pilot study, with a 90% postal return rate of active participants (i.e. those who had not withdrawn, died or been lost to follow-up) with the further 10% collected by an independent assessor, the equivalent of the RA in this study.

Travel diary

Travel diaries were completed by all participants on a daily basis. This was in the form of a calendar with the participants entering the number of journeys made for each day. In addition, in order for the study team to assess safety, participants indicated whether they had experienced a fall on each day. The participant was provided with a 12- or 13-month calendar, depending on the date of the baseline visit. Training in the completion and return of the travel diaries was provided by the RA at baseline. A prepaid envelope was sent to participants at the end of each month for them to return the diaries. No reminder letters were sent.

Data from travel diaries were entered on to the database on a month-by-month basis but only if a journey was recorded (i.e. ≥ 1 journey for any given day). Months that contained only ‘0’ were also recorded. If the month was blank then no data were entered for that particular month.

Intervention records

As well as the intervention duration being recorded in the eCRF, therapists also completed a paper intervention record form detailing goals set, visit-by-visit clinical details plus a breakdown of therapy activities. These were collected at the end of the study and collated into a separate database. Therapists were trained to use the form as part of the intervention training. The type and duration of intervention within any given visit were recorded under the following headings: goal setting, mobility, confidence, adaptive equipment, information, other rehabilitation and referral on to other agencies. For each intervention visit the therapist recorded how many minutes they spent on each activity, they listed the agreed outdoor mobility goals and kept running records of each treatment session as they would in routine clinical care. The intervention records were kept in the NHS clinical setting until the end of the study when they were copied and collated by the central coordinating centre.

Treatment fidelity

To assess the fidelity of the intervention therapy provided, 20% of clinical records were monitored (10% of all participants). A RA who was independent of the site visited the site and checked the treatments being delivered against a predefined checklist by accompanying the therapist on a number of treatment visits and by monitoring the intervention records. The last question on the checklist (a yes/no question as to whether the assessor believed that treatment provided met the required standard) was used to indicate whether the intervention had been delivered as specified and, therefore, implied fidelity of treatment.

Adverse events/safety evaluation

The main risk identified from this study was the potential to increase the chance of a participant having a fall, as a result of increased mobility. For adverse event purposes we adopted the following definition: ‘A recordable adverse event is any fall that occurs during or following the first outdoor mobility intervention and for the remaining period of intervention in the study that specifically requires the assistance of a health-care professional’. If these criteria were met then an adverse event form was completed. We adopted the following approach to capture this information – the therapist would ask, during an intervention visit, the following questions:

-

‘Have you had any falls since my last visit?’

-

If yes, ‘How many?’

-

‘How many required health-care professional help?’

Therefore, adverse events were only recorded from the intervention group, as the control group did not receive any visits post baseline. No other adverse events were collected. The occurrence of a serious adverse event as a result of participation within this study was not expected and no serious adverse event data were collected.

In order to capture information from both groups for comparison and a further measure of safety, we adopted a second approach. Participants indicated a fall on the travel diary by marking or circling the preprinted ‘f’, denoting that ≥ 1 fall had occurred for that participant on that day. These would not be classed or recorded as adverse events. Also, a comparison was made of any untoward changes in the well-being score of all participants by comparing the baseline GHQ-12 score with the 6- and 12-month score.

In the event of a pregnancy occurring in a study participant then they were allowed to continue in the study regardless of which arm they had been randomised to.

Concealment of allocation during outcome assessments

Participants and therapists were aware of treatment allocation. However, the treatment allocation was concealed from the RA so that they were able to assist the participant with completion of the 6- and 12-month questionnaires, if necessary. In order to measure concealment of allocation we asked the RAs to complete a blinding assessment for each post-randomisation visit, indicating whether they were unblinded prior to or during the visit.

Participant retention and withdrawals

To try and reduce the bias in participant retention caused by people wishing to withdraw before the primary end point because they were not allocated to the intervention group, we allowed participants to stop completing the travel diaries and asked them whether they would be happy to remain in the study and complete the 6-month questionnaire.

No specific withdrawal criteria were defined for this study. If a participant left the study prematurely (i.e. prior to completion of the protocol), the primary reason for discontinuation was determined and recorded if at all possible. Withdrawn participants were not replaced. Participants were made aware (by the information sheet and consent form) that should they withdraw, the data collected prior to the withdrawal date would not be erased and would still be used in the final analysis.

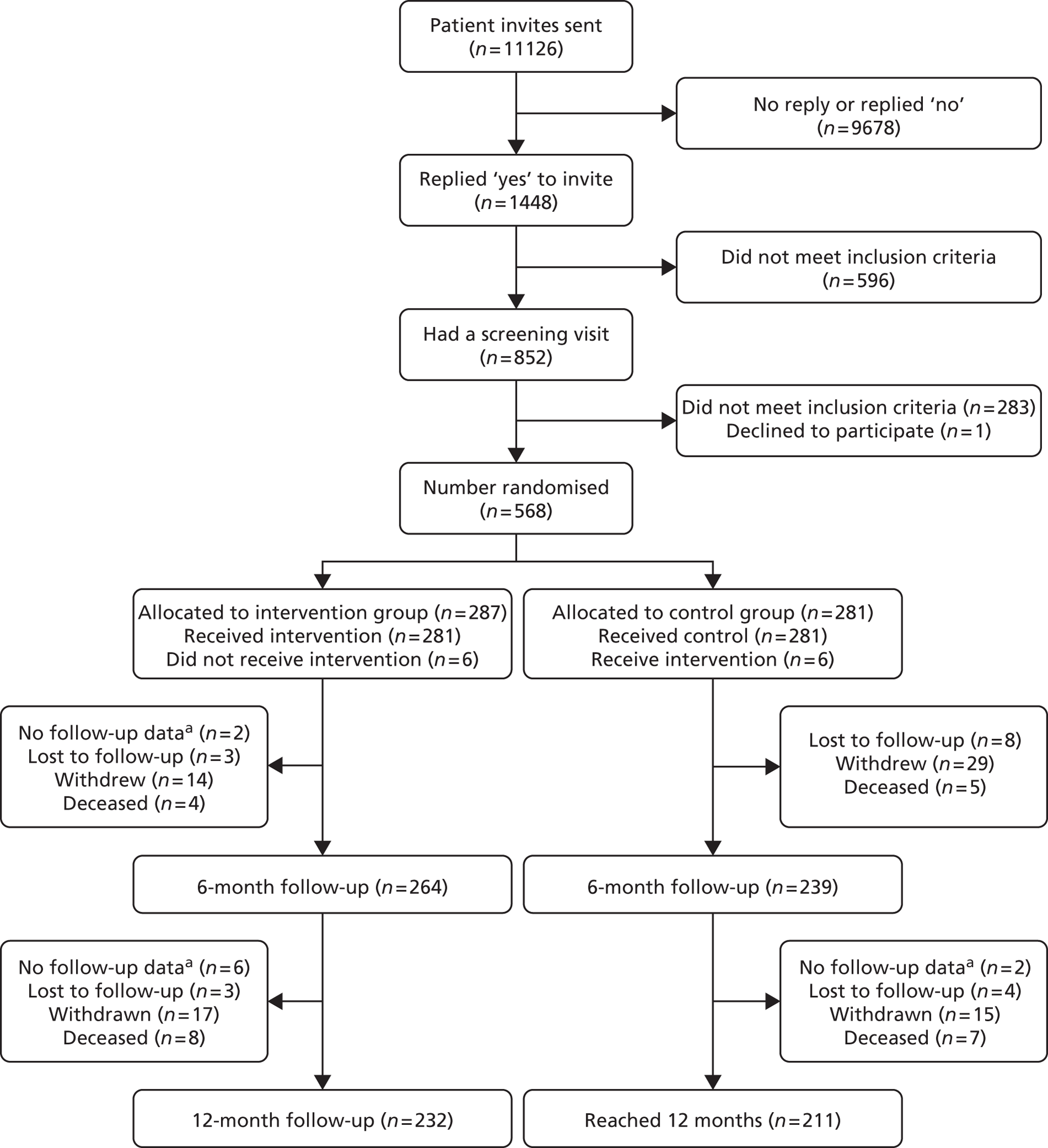

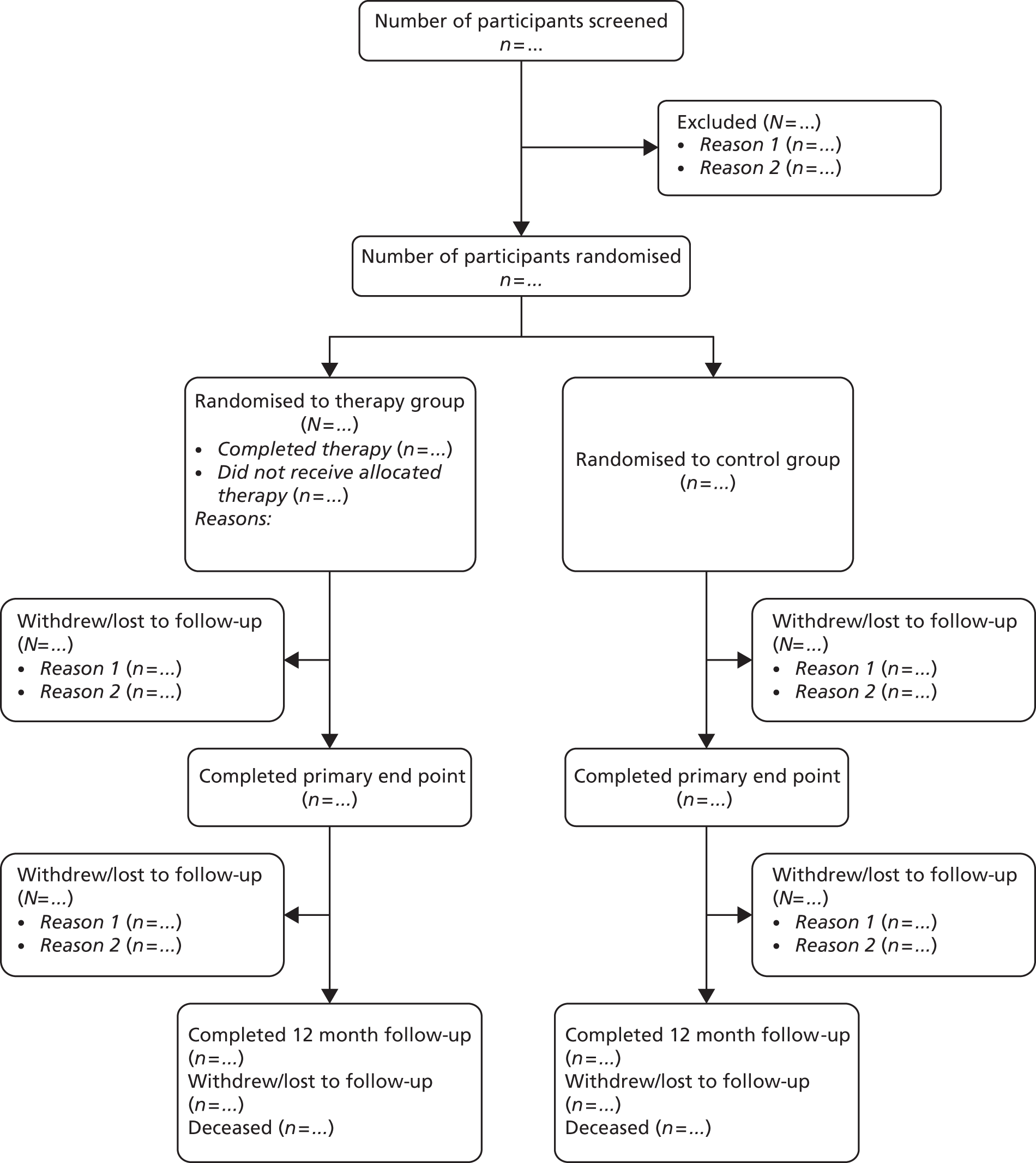

For this study, and in reference to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram (see Figure 3 ), the following definitions were applied in relation to the participants and the data:

Withdrawn consent The participant formally withdrew from the study and no further data were collected from that point. This was measured in relation to completion of 6- or 12-month follow-up and not the time of withdrawal, for example, if a participant withdrew after 7 months and did not complete their 6-month follow-up then they would be recorded as ‘withdrawn prior to 6-month follow-up’.

Lost to follow-up The study coordinating centre and/or local site staff were unable to contact the participant. This was recorded in relation to completion of 6- or 12-month follow-up as above.

No follow-up data The study coordinating centre and/or local site staff were in contact with the participant but follow-up data were not received; however, the participant was not formally withdrawn from the study. These participants at 6-month follow-up were classed as ‘no follow-up data’ on the CONSORT diagram and continued to participate in the study. These participants at 12 months’ follow-up were also classed as ‘no follow-up data’ on the CONSORT diagram.

Statistical methods

Full descriptions of the statistical methods of analysis are detailed in the statistical analysis plan (see Appendix 1 ).

Intervention and goals descriptive analysis A description of the components of the intervention was undertaken with the type of intervention therapy received by participants (e.g. mobility, goal setting, confidence, etc.) summarised in terms of number and percentage of participants who received the different types of therapy sessions and the mean, SD, median, IQR, and the minimum and maximum of the number of sessions for each type of therapy session. The goals set by each participant during the intervention sessions were recorded verbatim and this information was then sorted into categories of the goal types. These data were then analysed through calculating the number and percentage of participants who set each type of goal.

Comparison between treatment arms

All analyses were undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis, in that participants were analysed according to the group to which they were randomised, regardless of whether they received the intervention or not. Analyses were conducted on available case data. A sensitivity analysis, using multiple imputation (MI) to replace missing values, was performed for all outcome measures except travel journeys (see Sensitivity analysis adjusting for missing data section below for further information).

Basic data explorations using summary and graphical statistics (i.e. box plots, etc.) were conducted to check for outliers. If, after additional investigation, there was no evidence that these were errors then the analyses were repeated after Winsorising the data to assess the robustness of the results. Winsorising involves replacing extreme values (outliers) with a specified percentile of the data. 38 In this case, we replaced data values below the 5th percentile with the 5th percentile value and to replace data values above the 95th percentile with the 95th percentile value.

Descriptive analyses

Continuous data that were approximately normally distributed were summarised in terms of the mean, SD and number of observations. Skewed data were presented in terms of the median, lower and upper quartiles, minimum, maximum, and number of observations. Categorical data were summarised in terms of frequency counts and percentages.

Analysing primary and secondary outcomes

The mean social function score of the SF-36v2 was compared between treatment groups using a multiple membership form of mixed-effects multiple regression analysis, adjusting for site (as a random effect), age and baseline social function score as covariates, and therapist as a multiple membership random effect. A three-level hierarchical regression model was used with site at level 3, multiple membership effect of therapists at level 2, and participants at level 1. Regression coefficients and 95% credible intervals were presented. The robustness of these findings was assessed by repeating the analysis and including baseline variables that are likely to be associated with the outcome variable (namely gender and residential status) as covariates in the model.

Satisfaction with outdoor mobility was compared between treatment groups using a multiple membership form of a mixed-effects logistic regression model adjusting for site (as a random effect), baseline answer to the question and age as covariates, and therapist as a multiple membership random effect. Odds ratios and 95% credible intervals were presented.

Travel journeys were compared between treatment groups using a multiple membership form of a mixed-effects Poisson regression model, adjusting for site (as a random effect) and age as covariates, and therapist as a multiple membership random effect. Rate ratios and 95% credible intervals were presented. Travel journeys were presented as number of journeys per day. The analysis assumed that for a particular month for which journeys had been recorded then all other days were imputed with ‘0’. All months that were returned blank were not included in the analysis. When no travel diary was returned then that month was not included in the analysis.

All remaining secondary outcome variables were analysed using the same methods as for the primary outcome measure. We acknowledge the potential for type 1 errors associated with significance testing for multiple end points and, therefore, we consider the analyses of the secondary outcome measures to be partly exploratory in nature, and partly confirmatory of the findings for the primary outcome measure.

Sensitivity analysis adjusting for missing data

We assessed the effect of missing data on the overall conclusions of the study using MI. We used the Stata ‘ice’ command to generate 10 imputed data sets, and estimated the intervention effect in each imputed data set. We then used ‘Rubin’s Rules’ to combine these estimates into a pooled estimate of the intervention effect. 39

This process was conducted for all outcomes (except the travel journeys) for 6- and 12-month data. We considered the use of this process for the travel journeys to be inappropriate because, in addition to imputing the total number of journeys made, we would also have had to impute the number of days on which journeys were taken. Furthermore, there was no prior information available at baseline on the number of journeys made or the numbers of days on which the participants had made journeys that could be used to predict the data for 6 and 12 months.

Multiple membership random effect

In many studies, outcome measures are influenced by an intervention, such as a drug or a single person delivering an intervention, and, in these studies, assessing the effects of the drug or person on the outcome is clear. In our study, participants in the control group were treated by only one therapist but in the intervention group participants may have been treated by multiple therapists and some therapists may have delivered more therapy sessions to a specific individual than others. This means that the outcome obtained from a participant receiving treatment from different therapists may have been influenced by more than one person and, as some therapists may have delivered more therapy sessions to a participant than others (and the therapists may differ in their effectiveness), it is important to take account of this in the analysis. We used multiple membership random-effects models to deal with this situation and adjusted for the effect of the therapist by placing weights on the therapists delivering the intervention. We placed the greatest weight on the therapist who delivered the most therapy sessions for a particular participant. If two therapists delivered the same number of therapy sessions to a participant, equal weight was applied to each therapist, whereas if one therapist delivered one-third of the therapy sessions and another therapist delivered two-thirds of the therapy sessions (i.e. twice as many), the therapist who provided the most sessions was given the greatest weight (in this case, twice the weight of the other therapist). For participants treated by only one therapist, all weight was placed on that therapist, as only that therapist influenced the outcome. The weight applied to each therapist treating an individual therefore reflected the potential amount of influence that they may have had on the outcome with low weights indicating less influence on the outcome than higher weights.

Presentation of primary and secondary results

All main 6- and 12-month primary and secondary outcome data were presented descriptively by treatment group using means and SDs for continuous data or frequency counts and percentages for categorical data (unadjusted results), and then the results of the multivariable analysis – adjusting for therapy effect and site effect – were presented as differences in means for continuous data, odds ratios or rate ratios for binary and count data, respectively (adjusted results), with 95% credible intervals as a measure of significance. In addition, the ICCs indicating the size of the therapy effect and site effect were presented, apart from travel journey, for which these effects were not calculable. The interpretation of the results of the multivariable analysis of the 6- and 12-month primary and secondary outcome data are as follows:

-

Difference in means Where a score of ‘0’ indicates ‘no difference’ and hence if the 95% credible interval crossed the value ‘0’ then the result (difference in means between the two treatment groups) was not statistically significant. This approach was used for the primary outcome, NEADL, RMI and GHQ-12 outcome measures.

-

Odds ratio Where a score of ‘1’ indicates ‘no difference’ and hence if the 95% credible interval crossed the value ‘1’ then the result (the odds of getting out of the house as often as they would like in the intervention group relative to the control group) was not statistically significant. This approach was used only for the outcome SWOM.

-

Rate ratio Where a score of ‘1’ indicates ‘no difference’ and hence if the 95% credible interval crossed the value ‘1’ then the result was not considered to be statistically significant. This parameter was used for travel journeys.

Exploratory/other analyses

The following analyses were prespecified in the analysis plan:

-

NEADL by category Descriptive summaries (by treatment group) for the NEADL scale categories ‘Mobility’, ‘Kitchen’, ‘Domestic’ and ‘Leisure’.

-

Number of sessions by site Descriptive analysis of number of intervention visits by site compared with perceived successful completion of the intervention.

-

Number of travel journeys by intervention session Descriptive analysis comparing the number of travel journeys within the intervention group by participants who had received fewer than six sessions or six or more sessions. The pilot study found that a median of six sessions were effective, hence the pre-existing threshold of fewer than six or ≥ six or more sessions was used in this analysis.

-

Falls by age category and treatment allocation The total number (%) of ‘fall-days’ was described by treatment arm and age category (< 60 years of age and ≥ 60 years).

-

Satisfaction with outdoor mobility changes over time To explore the effect of the control information a descriptive comparison in the change of the SWOM scores from baseline to 6 months for each group.

-

Six-month follow-up by approach A descriptive comparison of collection of 6-month follow-up data from postal or RA approach.

Compliance in reference to CONSORT

Compliance in this study was effectively a measure of completeness of follow-up data. Baseline questionnaires were required to be completed before randomisation so that baseline CONSORT-presented numbers randomised. The CONSORT diagram presented compliance for this study as the number of returned questionnaires for the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, regardless of completeness of the questionnaire booklets.

For individual analyses of outcome measures, as the analysis relies on a comparison between follow-up data and the baseline data, the ‘n’ presented in the results section was a measure of the number of participants who completed the outcome measure at both baseline and follow-up. Data from participants who answered some, but not all, of the questions within a questionnaire based outcome measure were still included in the analysis; however, if the whole of the questionnaire was missing then their data were not used.

Study management and oversight

A number of committees were assembled to ensure the management and conduct of the study, and to uphold the safety and well-being of participants.

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group (TMG) oversaw the operational aspects of the study, which included the processes and procedures used and the day-to-day activities involved in study conduct.

Trial Steering and Data Committee

The Trial Steering and Data Committee (TSDC) had the overall responsibility for ensuring a scientifically sound study design, a well-executed study, and accurate reporting of the study results.

The data monitoring part of this committee evaluated the outcome and safety data in the context of the overall study and the currently existing information about the study. They considered the appropriate time frame for reviewing the data during the course of the study. The TSDC had access to grouped study data.

However, as part of the process of calculating a revised sample size, an ad hoc independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) was convened, which reviewed the suitability and legitimacy of the proposed revision.

Amendments to the study

Eligibility To simplify the screening process we removed ‘Able to comply with the requirements of the protocol’ as an inclusion criterion, and ‘Significant cognitive impairment which will impede ability to complete the assessments’ and ‘Diagnosis likely to interfere with rehabilitation or outcome assessments e.g. terminal illness’ as exclusion criteria. In their place we added a single exclusion ‘Not able to comply with the requirements of the protocol and therapy programme, in the opinion of the assessor/GP/investigator’. These amendments were made prior to the start of recruitment. We amended ‘At least 6 weeks but no longer than 5 years since stroke’ to ‘At least 6 weeks since stroke’ as an inclusion, as there was no valid reason for the 5-year limit and participant invitations asked participants whether the mobility issues were as a result of their stroke, so time frame was not relevant. Hence it was more inclusive to potential participants. This amendment was made after 4 months of recruitment.

Sample size Following consultation with the funders and the TSC, it was agreed that we would calculate a revised sample size, based on an increase in the number of sites. This revision is described in the ‘Revised sample size’ section earlier in the chapter. Independent statisticians from outside the study checked the validity of all calculations and assumptions. These amendments were made after 16 months of recruitment.

Summary of changes to recruitment material After initially using a standard PIS, in full and summary form, we introduced a supplementary PIS leaflet, in addition to rewording the PIS, consent form and patient invites. These were amended in order to make the aims of the study more transparent and patient friendly. Another significant change was the introduction of an aphasia-specific PIS consisting of images and key words. Though initially designed for aphasic patients it was used extensively, in conjunction with more standard formats, for other stroke patients. These amendments were made after 4 months of recruitment.

Qualitative study A study investigating confidence after stroke was incorporated into the existing study protocol with a view to interviewing existing study participants about issues relating to confidence and how it affected their recovery from stroke. This part of the study was only in Nottingham for 10 participants. The qualitative study is described in more detail in Chapter 5 . This amendment was made after 11 months of recruitment.

Recruitment timelines Initial recruitment timelines were 12 months; however, final recruitment timelines were extended to 22 months. This was managed through a combination of efficiencies within the overall project timelines and an extension to the overall project from 36 months to 40 months.

Chapter 3 Results: randomised controlled study

This chapter reports recruitment and retention of participants, and collection and analysis of study data specifically relating to the delivery and fidelity of the intervention, primary outcome measured at 6 months, and secondary outcomes measured at 6 and 12 months.

Study recruitment and follow-up

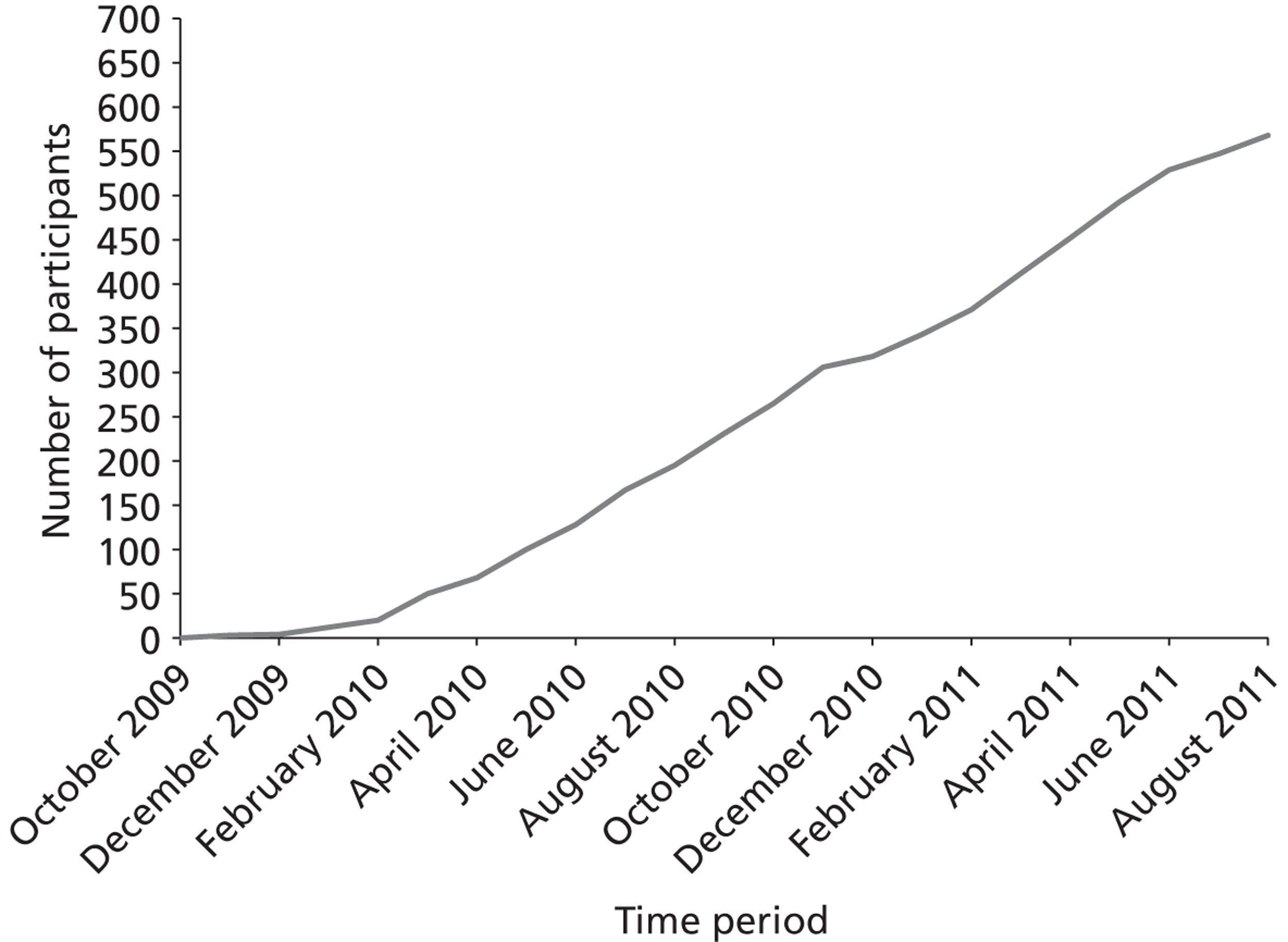

The study recruited 568 out of 506 (112.3%) of the required sample size from November 2009 to August 2011. Participants were recruited from 15 sites across England, Scotland and Wales, with an average recruitment of 38 participants (range from 5 to 99) per site, with nine sites recruiting > 30 participants. The participant involvement in the trial ended in August 2012, following completion of recruitment and follow-up. Figure 2 shows that, after an initial lag phase, steady recruitment was achieved with no noticeable seasonal variation.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment rate.

Table 1 provides a breakdown of screening figures collected from all sites, in terms of number of invitations sent, number of ‘yes’ replies, number of home screening visits, number randomised and the proportion of recruits per 100 invites. The different approaches were used to varying extents: GP-based approaches being responsible for recruiting 158 out of 568 (27.8%) of randomised participants at a rate of 2.5 per 100 invites, and stroke register-based approaches recruiting 410 out of 568 (72.2%) of randomised participants at a rate of 8.5 per 100 invites. The stroke register data includes participants recruited at outpatient clinics.

| Approach | Invites | ‘Yes’ replies (% of invites) | Screening visits (% of ‘yes’ replies) | Randomised (% of ‘yes’ replies) | Recruits/100 contacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP database | 6329 | 679 (10.7) | 261 (38.4) | 158 (23.3) | 2.5 |

| Stroke register | 4797 | 769 (16.0) | 591 (76.9) | 410 (53.3) | 8.5 |

| Overall | 11,126 | 1448 (13.0) | 852 (58.8) | 568 (39.2) | 5.1 |

Follow-up (CONSORT)

Figure 3 shows the CONSORT diagram for the study. The identification of participants was from 11,126 invites, either by letters of invitations or face-to-face approach. The exact breakdowns were not recorded; however, the majority were by letter of invitation. We had ‘yes’ replies from 1448 out of 11,126 (13.0%) approaches to participate in the study with 9678 out of 11,126 (87%) either not responding or providing negative replies. We did not record the number of ‘no’ replies. After initial pre-consent screening, usually by telephone, a further 596 out of 11,126 (5.4%) were considered ineligible. The main reason for ineligibility was that the potential participants felt they got out of the house as much as they wished already. Therefore, 852 out of 11,126 (7.7%) had a further screening visit in their own home from the RA. Overall, 568 out of 852 (66.7%) were found to be eligible to take part. Of the 11,126 letters sent, 568 people were included (5.1%). Of the 284 out of 11,126 (2.6%) who did not enter the study, only 1 out of 11,126 (0.01%) explicitly refused to participate (owing to their desire to be in the intervention group only).

FIGURE 3.

Final CONSORT diagram. a, Participant remained in the trial but no data were collected at that time point.

The baseline questionnaire was completed by 567 out of 568 (99.8%) participants, with the one outstanding being left with the participant and never being received by the study coordinating centre.

Following randomisation, 287 out of 568 (50.5%) participants were allocated to the intervention group and 281 out of 568 (49.5%) to the control group. In the control group, 1 out of 281 (0.4%) participants received two intervention visits in error. In the intervention group, 281 out of 287 (97.9%) of participants received at least one intervention visit. There was no evidence of crossover between the two groups.

Six-month follow-up was measured by the receipt of the 6-month questionnaire booklet by the research team. For the intervention group, 264 out of 287 (92.0%) reached 6-month follow-up. Of the 23 out of 287 (8.0%) who did not reach 6-month follow-up, 3 out of 287 (1.0%) were lost to follow-up, 14 out of 287 (4.9%) withdrew consent and 4 out of 287 (1.4%) died. A further 2 out of 287 (0.7%) did not complete the follow-up but remained in the study, with 266 participants remaining in the intervention group after 6-month follow-up. For the control group, 239 out of 281 (85.1%) reached 6-month follow-up. Of the 42 out of 281 (14.9%) who did not reach 6-month follow-up, 8 out of 281 (2.8%) were lost to follow-up, 29 out of 281 (10.3%) withdrew consent and 5 out of 281 (1.8%) died. Therefore, there were 239 participants remaining in the control group after 6-month follow-up.

Completion of 6- and 12-month follow-ups was defined as return of the fully/partially completed questionnaire booklet to the NCTU. It does not indicate the level of completeness. Six- and 12-month results for individual measures presented later in the chapter indicate the number of participants from which we have analysable data.

There was a differential follow-up rate between the two groups for the 6-month follow-up, with 92.0% collected for the intervention group and 85.1% collected for the control group. However, these were both less than the predefined 20% attrition rates.

Successful data collection at 12-month follow-up was measured by receipt of the 12-month questionnaire booklet. For the intervention group, 232 out of 287 (80.8%) reached 12-month follow-up. Of the 34 out of 287 (266 – 232 = 34; 11.8%) who did not reach 12-month follow-up, 3 out of 287 (1.0%) were lost to follow-up, 17 out of 287 (5.9%) withdrew consent and 8 out of 287 (2.8%) died. A further 6 out of 287 (2.1%) did not complete the follow-up but remained in the study. For the control group 211 out of 281 (75.1%) reached 12-month follow-up. Of the 28 out of 281 (239 – 211 = 28; 10.0%) who did not reach 12-month follow-up, 4 out of 281 (1.4%) were lost to follow-up, 15 out of 281 (5.3%) withdrew consent and 7 out of 281 (2.5%) died. A further 2 out of 281 (0.7%) did not complete the 12-month follow-up but remained in the study.

As with the 6-month follow-up, there were differential follow-up rates between the two groups for the 12-month follow-up. A total of 232 out of 287 (80.8%) of questionnaires were collected for the intervention group and 211 out of 281 (75.1%) collected for the control group. Although the control group follow-up rate was within the defined 20% attrition rate, the overall number of participants with 12-month follow-up data (n = 443) was within the threshold to ensure that the study had adequate power.

Table 2 summarises the results of who completed the questionnaire and indicates a consistent proportion of participants completed the questionnaires themselves, whereas at 6 and 12 months there were consistent completion rates for both carer and other (16% and approximately 37%, respectively). The ‘other’ completions at baseline were due to the presence of the RA.

| Questionnaire | Who completed the questionnaire | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| You (%) | Carer (%) | Other (%) | |

| Baseline (n = 567a) | 234 (41.3) | 32 (5.6) | 301 (53.1) |

| 6-month follow-up (n = 503) | 230 (45.7) | 81 (16.1) | 192 (38.2) |

| 12-month follow-up (n = 443) | 208 (47.0) | 74 (16.7) | 161 (36.4) |

Carer questionnaire follow-up

We received 192 carer questionnaires at baseline, with 100 out of 192 (52.1%) and 92 out of 192 (47.9%) from carers of participants in the intervention and control groups, respectively. We received 148 carer questionnaires at 6-month follow-up, with 84 out of 100 (84.8%) and 64 out of 92 (69.6%) from carers of participants in the intervention and control groups, respectively. We received 127 carer questionnaires at 12-month follow-up, with 71 out of 100 (71.0%) and 56 out of 92 (60.9%) from carers of participants in the intervention group and control, respectively.

Travel diary follow-up

Owing to the volume of travel diaries and the challenges of tracking their status, a decision was taken not to send reminders if the travel diary was not received. Overall, 70.6% of all expected travel diary months were received and assigned, regardless of whether they contained data, to 508 out of 568 (89.4%) of participants ( Table 3 ); 73.6% were received for the intervention group and 67.5% from the control group. Overall, 55.1% of participants returned diaries for the full 12 months.

| Travel diaries | Overall (expected n = 7363) | Control group (expected n = 3644) | Intervention group (expected n = 3719) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total received | 5198 | 70.6 | 2462 | 67.5 | 2736 | 73.6 |

Baseline characteristics

Table 4 presents a summary of key baseline characteristics of each group. Baseline characteristics of the sample showed the majority of participants to be women, living with others, with a mean age of 71 years (SD 12.1 years). At baseline there was a slight gender imbalance, with a higher proportion of men in the control group than the intervention group (47% vs. 42.2%). Residential status was well balanced between groups with only a slightly higher proportion living alone in the control group (35.2% vs. 33.4%). The average time since stroke was 37 months (SD 43.8 months) for the control group and 43 months (SD 60.1 months) for the intervention group.

| Variable | Parameter | Allocation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |||

| Total | n (%) | 281 (49.5) | 287 (50.5) | |

| Age at inclusion (years) | Mean (SD) | 71.5 (12.1) | 71.7 (12.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 75 (63–81) | 73 (64–81) | ||

| Min. to max. | 36–95 | 32–96 | ||

| Sex | Women | n (%) | 149 (53) | 166 (57.8) |

| Men | 132 (47) | 121 (42.2) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | n (%) | 263 (93.6) | 270 (94.1) |

| Black: Caribbean | 7 (2.5) | 4 (1.4) | ||

| Black: African | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Black: other | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1) | ||

| Pakistani | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Indian | 5 (1.8) | 4 (1.4) | ||

| Bangladeshi | 2 (.7) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Chinese | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Mixed | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Not given | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Residential status | Lives alone | n (%) | 99 (35.2) | 96 (33.4) |

| Lives with others | 170 (60.5) | 179 (62.4) | ||

| Living in care home | 12 (4.3) | 12 (4.2) | ||

| Time since stroke (months) | Mean (SD) | 37 (43.8) | 43.2 (60.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 21.3 (10.2–47.6) | 24.5 (12.8–44) | ||

| Min. to max. | 1.6–392.6 | 2–479.3 | ||

| Social functioning score | Mean (SD) | 50.1 (30.7) | 45.9 (30.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (25–75) | 37.5 (25–62.5) | ||

| Min. to max. | 0–100 | 0–100 | ||

| NEADL score | Mean (SD) | 10.1 (5.7) | 8.8 (5.2) | |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (5–14) | 9 (4–13) | ||

| Min. to max. | 0–22 | 0–22 | ||

| RMI score | Mean (SD) | 8.9 (4.1) | 8.1 (3.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (6–12) | 8 (5–11) | ||

| Min. to max. | 0–15 | 0–15 | ||

| SWOM | Yes | n (%) | 20 (7.1) | 18 (6.3) |

| No | 259 (92.2) | 268 (93.4) | ||

| General Health Questionnaire (participant) | Mean (SD) | 15.1 (6.8) | 14.9 (6.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 13 (10–19) | 14 (10–19) | ||

| Min. to max. | 1–36 | 1–35 | ||

Baseline scores for mobility, activity measures, GHQ-12 and SWOM were similar in the two groups. However, for the primary outcome measure of quality of life (social functioning score), the control group had a higher mean (50.1 vs. 45.9) and median (50 vs. 37.5) than the intervention group.

Satisfaction with outdoor mobility scores indicated that overall 93.3% of participants were not currently satisfied with their level of outdoor mobility. The remaining participants who indicated SWOM (n = 38) were spread across both groups, in all sites except one, and had no other unusual characteristics.

It is important to clarify the relationship between the ‘SWOM’ (Do you get out of the house as much as you would like?) question as part of the baseline questionnaire and the eligibility criteria of ‘Wishing to get out of the house more often’. On 38 out of 568 (6.7%) occasions, 20 out of 281 (7.1%) in the control group and 18 out of 287 (6.3%) in the intervention group, the participant indicated that he or she met the eligibility criteria during the consent process but answered ‘Yes’ to the ‘SWOM’ question during completion of the baseline questionnaire. On further investigation it appeared that certain participants were viewing these questions within a different context. The eligibility question was related to aspirational view of getting out of the house (i.e. ‘Wishing to get out of the house more often’), whereas the SWOM question was related to day-by-day coping views of getting out of the house. Hence these participants were not classed as ineligible and were included in the analyses.

Delivery of the intervention

Number of therapists by site

There were 29 therapists taking part in this study, who delivered at least one treatment session. There was no restriction on how many therapists delivered the intervention at each site. This was mainly determined by how the service was structured, availability of staff to perform the research activity, and delivery of research and treatment costs to the relevant department. The therapists ranged from junior to senior (Agenda for Change bands 4–740). Three were physiotherapists, 17 were occupational therapists and nine were assistant practitioners. The number of therapists per site ranged from 1 to 4, with a median of two per site. A small proportion of visits were attended by two therapists (65/1939; 3.4%). These were mainly as a result of training junior staff and training as part of handover to replacement staff. Generally, only one therapist delivered the intervention while the second therapist observed as part of training.

Number and duration of intervention sessions

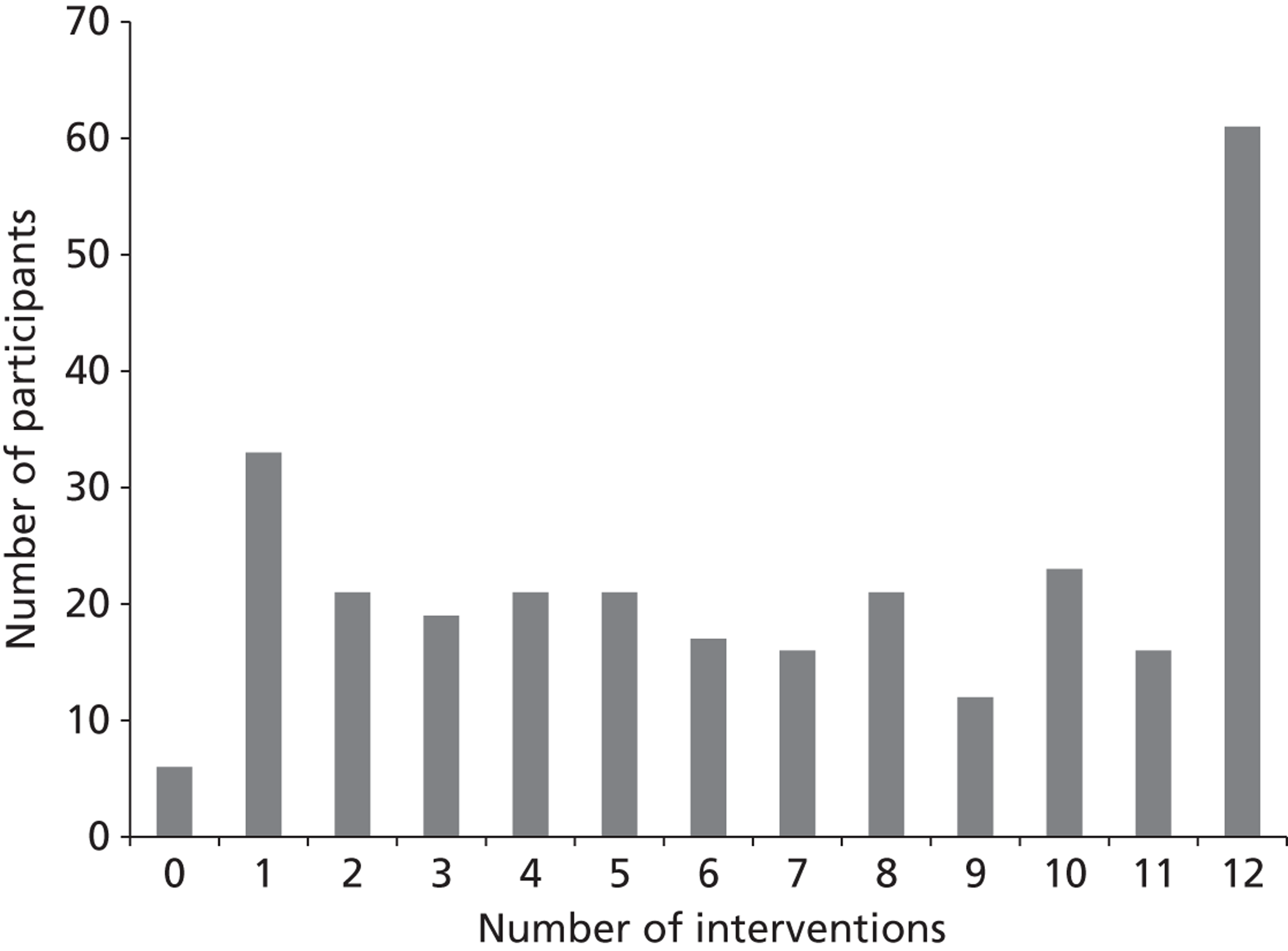

The intervention group received a median of seven intervention sessions (IQR 3–11 sessions), mean 6.80 sessions (SD 4.01 sessions). Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of intervention visits received by participants, ranging from zero intervention sessions (6/287, 2.1%) to the maximum 12 (61/287, 21.3%); 138 out of 287 (48.1%) received less than the median of seven visits, with 149 out of 287 (51.9%) receiving ≥ 7 visits. These were calculated from eCRF intervention visit data.

FIGURE 4.

Range of intervention visits.

Of the 287 intervention participants, paper intervention records completed by the therapists were returned for 269 out of 287 (93.7%) participants, 264 out of 287 (92.0%) of whom had received at least one treatment session. The median duration in total, in minutes, of intervention provided for these 264 participants was 369.5 minutes (IQR 170–691.5 minutes), mean 454.6 minutes (SD 352.20 minutes). These were calculated from intervention records data.

Description of set goals

Table 5 summarises the types of goals set for each participant. Of the 287 participants in the intervention group, information on goals set was recorded for 243. Participants were able to set more than one goal during the process. However, we have no direct measure, relating to individual goals set, to indicate the proportion of goals that were achieved. Instead, we have an overall measure of whether the intervention was delivered to the satisfaction of the therapist, detailed later in Table 11 . The most common goal was a long walk of > 100 m, set by 55.1% of participants, whereas increasing confidence was set for 36.2%. There was a wide range of goals set and the vast majority were considered appropriate for an intervention aimed at getting participants out of the house and were also considered attainable.

| Goal type | n participants | Percentage of 243 participants |

|---|---|---|

| Long walk > 100 m | 134 | 55.1 |

| Increase confidence | 88 | 36.2 |

| Short walk < 100 m | 83 | 34.2 |

| Othersa | 78 | 32.1 |

| Stamina | 56 | 23.1 |

| Access local shop | 54 | 22.2 |

| Bus | 50 | 20.6 |

| Attending social clubs/social activity | 46 | 18.9 |

| Training outdoor mobility equipment | 37 | 15.2 |

| Mobility scooter | 29 | 11.9 |

| Increase independence | 28 | 11.5 |

| Access town centre | 23 | 9.5 |

| Powered wheelchair | 16 | 6.6 |

| Crossing roads | 14 | 5.8 |

| Taxi | 12 | 4.9 |

| Car transfers | 12 | 4.9 |

| Increase journeys | 12 | 4.9 |

| Driving | 10 | 4.1 |

| Dial-a-Ride | 8 | 3.3 |

| Walk inside | 6 | 2.5 |

| Day centre | 6 | 2.5 |

| Shopmobility | 6 | 2.5 |

| Car | 1 | 0.4 |

Description of the key elements of the intervention

The average duration of an intervention visit, including travel to and from the participant’s home, was 96.6 minutes with a range of 10–390 minutes. A total of 1856 out of 1939 (95.7%) intervention visits were completed within the protocol guidelines of 4 months post baseline visit. The other 4.3% were outside the 4-month protocol guidance, although not all were recorded as protocol deviations by the therapists.

Table 6 summarises the proportion and type of intervention delivered to participants. Goal setting was delivered for 243 (92.1%) participants, with a median of two sessions provided (IQR 1–4 sessions). Mobility training was delivered the most often for a median of 5.5 visits for 222 participants (84.1%), and had the longest duration, with a median of 212.5 minutes (IQR 80–390 minutes) (data not reported in the table). Confidence building was used with 202 (76.5%) participants, with a median of four sessions provided (IQR 2–8 sessions). The least used treatment method was adaptive equipment training, with 63 (23.9%) participants receiving a median of one session (IQR 1–2 sessions). All treatment techniques listed on the record form were used at least once by each site.

| Intervention type | Participants, n (%)a | No. of sessions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Min. to max. | ||

| Goal setting | 243 (92.1) | 3.32 (3.13) | 2 (1–4) | 1, 12 |

| Mobility | 222 (84.1) | 6.06 (3.89) | 5.5 (2–10) | 1, 12 |

| Information | 205 (77.7) | 3.89 (3.28) | 3 (1–10) | 1, 12 |

| Confidence | 202 (76.5) | 5.13 (3.53) | 4 (2–8) | 1, 12 |

| Other rehabilitation | 139 (52.7) | 3.55 (2.91) | 2 (1–5) | 1, 11 |

| Referral | 104 (39.4) | 2.04 (1.32) | 2 (1–3) | 1, 7 |

| Adaptive equipment | 63 (23.9) | 1.92 (1.24) | 1 (1–2) | 1, 6 |

Treatment fidelity

Of the 15 sites delivering the intervention, 14 were assessed for fidelity of treatment.

Treatment fidelity forms were completed for 59 out of 287 (20.6%) intervention participants. Fidelity of treatment assessments were not performed equally across sites, ranging from the intervention sessions for 10 out of 59 (17.0%) participants assessed at one site to 1 out of 59 (1.7%) participant at each of two sites, and no participants at one site.

Initially, the fidelity of treatment assessment was a combination of checking treatment records against a predefined checklist and also accompanying the treating therapists on visits. However, owing to the possibility that accompanying the therapists on visits might influence how a therapist undertook these sessions, it was decided that only reviewing the participants’ notes would be completed for the remainder. Of the 59 fidelity of treatment assessments, 12 (20.3%) were completed using the visit and the treatment notes and 47 out of 59 (79.7%) were completed by just assessing the treatment notes.

The final question asked the assessor to make a judgement as to whether the intervention had met the standard based on the checklist. They indicated that in 100% of the cases they believed it had.

Completion of intervention

At the end of the participant’s intervention period the therapist indicated in 193 out of 287 (67.3%) of participants that they, the therapists, felt that the participant had completed the intervention to the therapist’s satisfaction (i.e. a surrogate marker for achieving their set goals).

Contamination

There was one participant allocated to the control group who received two intervention visits in error. This was recorded as a protocol deviation and is reported later in the chapter. The nature of the study, with the intervention requiring a visit to the participant’s home, as well as the fact that all participants were not currently within the rehabilitation service, meant that participants in the control group were unlikely to have any contact with local site therapists and hence contamination was unlikely to occur. There is no evidence of any contamination within this study.

Numbers analysed

Figure 2 illustrates the flow of participants and their data; however, it does not provide the details on an outcome-by-outcome basis. A partially completed outcome at the particular follow-up was required for unadjusted measures. In order for any unadjusted outcome measure (apart from travel journeys) to be calculated, the particular measure must be at least partially completed at both baseline and at the particular follow-up. For travel journeys, the participant had to return at least one travel diary to be included in either unadjusted or adjusted analysis. Table 7 details the number of participants analysed for both adjusted and unadjusted outcome measure analysis.

| Outcome | Numbers analysed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | |||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| SF-36 (SF domain) | 500 | 493 | 425 | 422 |

| NEADL | 494 | 493 | 438 | 437 |

| RMI | 499 | 497 | 442 | 440 |

| GHQ-12 | 495 | 493 | 436 | 434 |

| GHQ-12 (carer) | 148 | 145 | 127 | 125 |

| SWOM | 494 | 491 | 432 | 429 |

| Travel journeys | 504 | 504 | 504 | 504 |

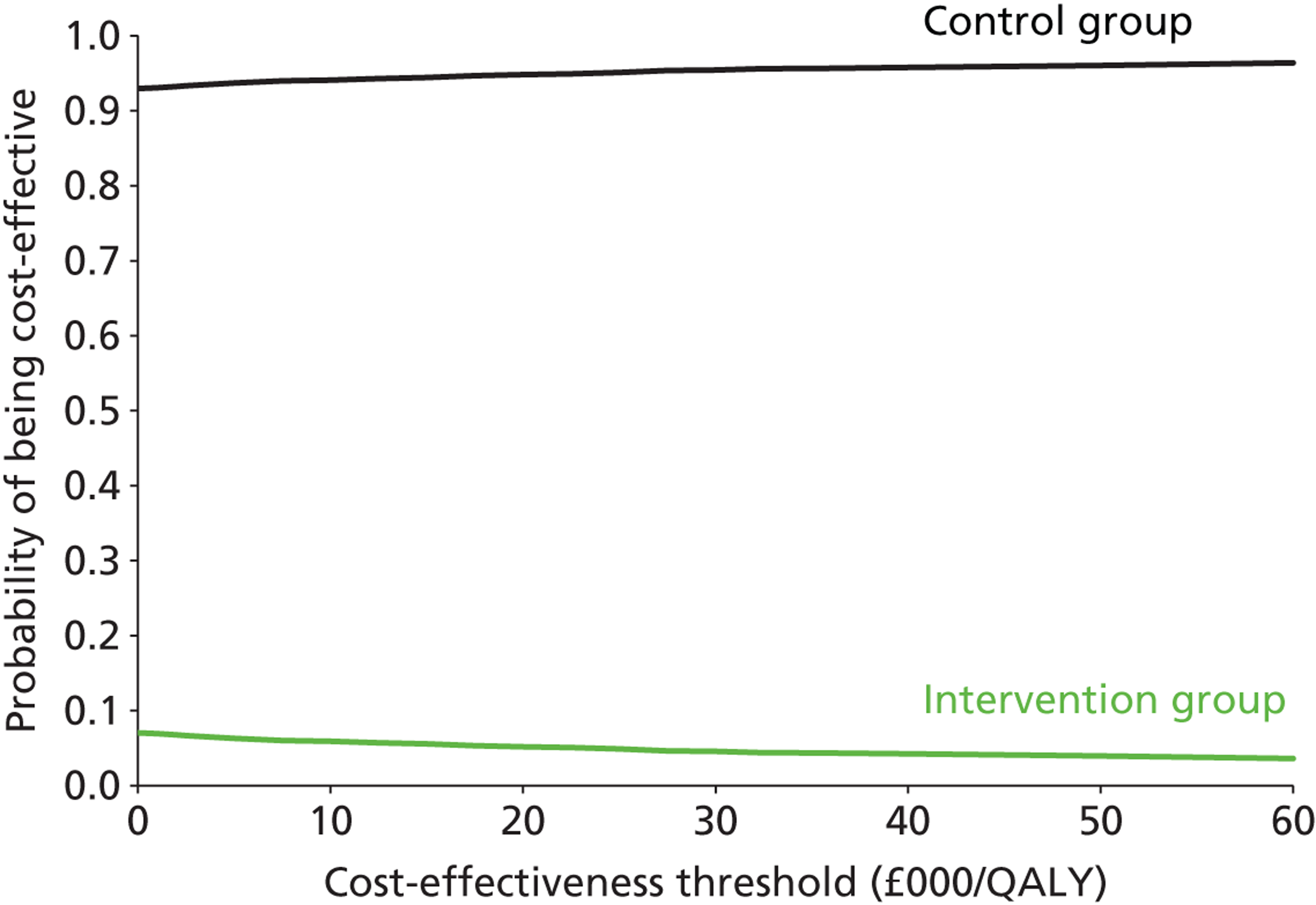

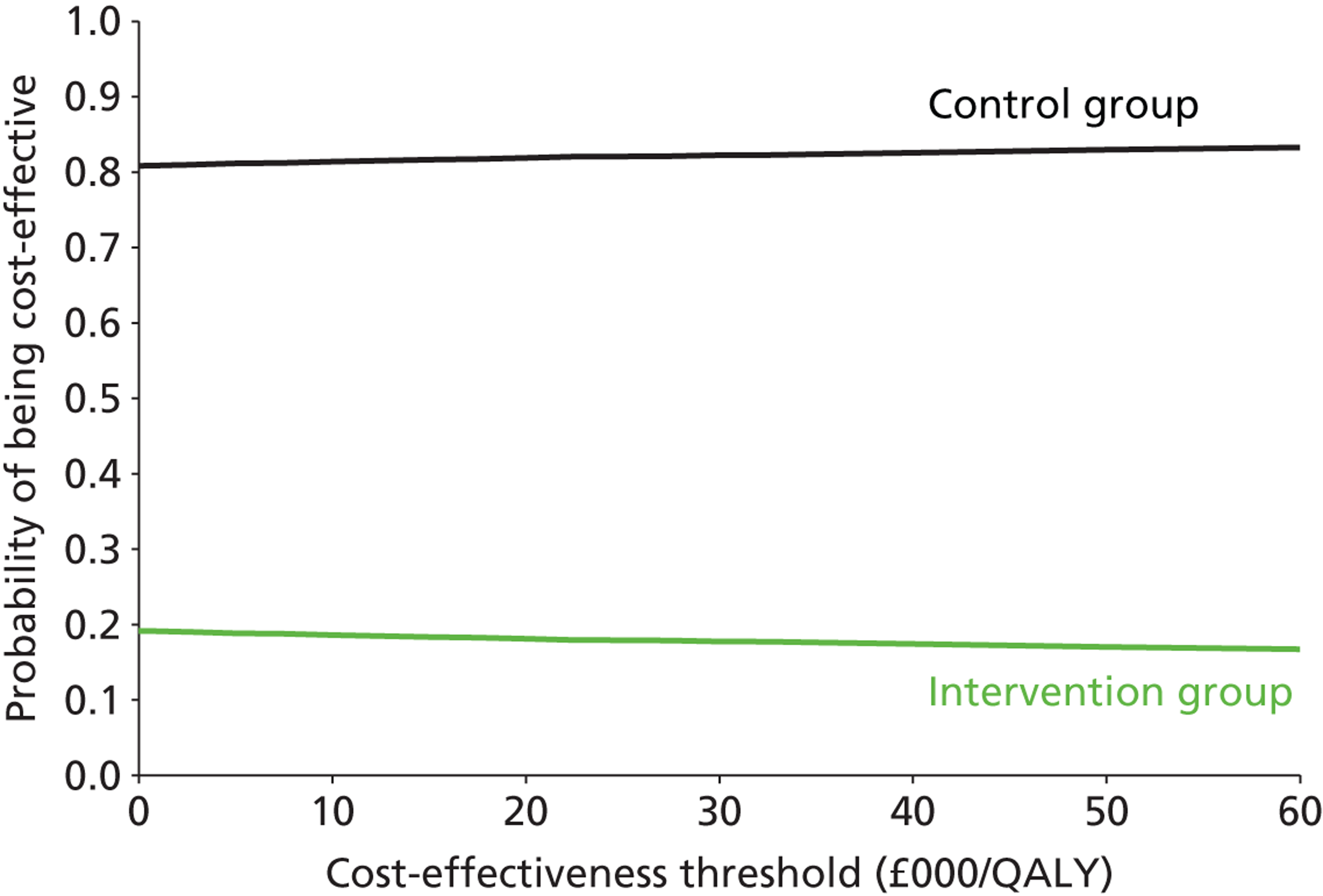

Primary outcome