Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/138/03. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The draft report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Antony Bayer was a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Dementia Themes Call Board from 2010 to 2011. Greta Rait is a member of the HTA Mental Health Methods Group and Panel. Jo Rycroft-Malone is the Director of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme and editor of the National Institute for Health Research HSDR journal. The authors declare no other financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Bunn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This chapter includes text from the protocol, which was published by Bunn et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Introduction

Dementia and diabetes mellitus are common long-term conditions that may coexist in a large number of older people. 2,3 People with dementia may be less able to understand and manage their diabetes and may be at risk of complications such as hypoglycaemic episodes, cardiovascular conditions and amputations,4–6 which place a huge burden on health and social care economies. 7 Moreover, the impact of dementia and diabetes on patients and their families is considerable. There is a need to consider what kind of programmes or interventions are needed for the effective management of diabetes in people with dementia, including how interventions work, for whom and in what contexts; the barriers to, and facilitators of, the effective management of diabetes in people living with dementia; and how interventions might be tailored to this patient group.

Dementia and diabetes in older people

In the UK, there are an estimated 850,000 people living with dementia,8 the most common form being Alzheimer’s disease. 9 The number is forecast to exceed 2 million by 2050. 10 The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the UK is also rising rapidly: since 1996, the number of people diagnosed with diabetes has more than doubled, from 1.4 million to almost 3.5 million. 11,12 The risk of both conditions increases with age. Dementia affects 1 in 20 people aged > 65 years and 1 in 5 people aged > 80 years. 13 In 2010, the prevalence of all types of diabetes was 0.4% in people aged 16–24 years, rising to 15% of people aged 70–84 years. 14 Owing to the high prevalence rates of both conditions in older people, they may inevitably coexist. A scoping review found data to suggest that rates of diabetes in people with dementia are between 13% and 20%. 2

There is increasing evidence that diabetes – in particular type 2 diabetes – is associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Observational studies report that type 2 diabetes is associated with both of the major subtypes of dementia, with an approximate 2.5-fold increased risk of incident vascular dementia and a 1.5-fold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. 15,16 The association between vascular dementia and diabetes is not entirely surprising because diabetes is a risk factor for lacunar infarction and major stroke, and vascular disease is an essential aetiological factor of vascular dementia. 15 Although the underlying pathological pathways between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease are not entirely clear, it is thought that metabolic factors may play a role,15 leading to Alzheimer’s disease being labelled by some as ‘type 3 diabetes’. 17

Dementia has been consistently and independently associated with an increased risk of hypoglycaemia,18,19 possibly because of an increased likelihood of errors in self-medication (e.g. with insulin or sulphonylurea treatments), irregular eating habits and an inability to recognise and treat hypoglyceamia. 20 Furthermore, there are a number of age-related changes that may affect diabetes treatment and management. Deficits in renal and liver functioning associated with increasing age can have an impact on medication effectiveness, making the older person either more or less sensitive to a drug’s potency. 21 In addition, older people may be more likely to demonstrate ‘hypoglycaemic unawareness’, whereby the central nervous system shows greater insensitivity to hypoglycaemic symptoms. 22 Hypoglycaemia is a serious cause of morbidity and mortality in frail older people23 and may increase the risk of robust individuals with diabetes becoming frail. 24 The relationship between dementia, frailty and hypoglycaemia is complex, and it has recently been reviewed. 25

Current guidance on the management of diabetes in people with dementia

Clinical guidance on the management of diabetes in older adults26–30 suggests that glycaemic targets should be individualised for older people and that care should be personalised to take into account factors such as age, dementia, frailty, comorbidities and polypharmacy. 31 However, despite this guidance, and although the harms of intensive treatment are likely to exceed the benefits for older people with complex or poor health status, a substantial proportion of older adults is potentially overtreated. 32 This may be because clinicians are not aware of existing guidelines, because they are uncertain about when and how to de-intensify diabetes medications and/or because they apply performance targets [such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)] to the management of older people with diabetes rather than individualising care. 33

Self-management

The main approach to the management of long-term conditions such as diabetes revolves around self-management (SM) strategies that focus on the attitudes and self-efficacy of the patient. The successful SM of chronic conditions is based on the idea that the patient collaborates with health-care professionals (HCPs) in the management of the condition, allowing the patient to become knowledgeable about their condition, share in decision-making and receive educational support. 34 In relation to diabetes, self-care has been defined as ‘an evolutionary process of development of knowledge or awareness by learning to survive with the complex nature of the diabetes in a social context’,35 and consists of seven key behaviours: healthy eating, being physically active, monitoring blood sugar, complying with medications, good problem-solving skills, healthy coping skills and risk-reduction behaviours. 36

Although SM is well established as fundamental to the management of long-term conditions, there has been a paucity of literature about SM for people living with dementia. This may be due to the general belief of the ‘hopelessness’ of dementia promulgated by both professionals and lay people, coupled with limited research focusing on the daily needs and lives of those living with dementia. 37 Recently, these negative perceptions of people living with dementia have been challenged, and a more strength-based approach drawing on personhood has emerged. 38 There are, however, clearly differences between the skills needed to self-manage dementia and those required for diabetes, and people living with dementia are often reliant on others, usually family carers, to facilitate their access to services and support and to help them manage the condition. 39

Although there are differences in the physical and cognitive effects of the different types of dementias, all are usually progressive, involve increasing physical and mental deterioration, and lead to a person with dementia becoming increasingly dependent, all of which has an impact on their ability to understand and manage their diabetes. 2,4,6 Dementia has an impact on a person’s ability to undertake self-care management tasks such as managing medication, monitoring blood glucose and maintaining a healthy-eating regimen. 39–41 There are additional difficulties related to insulin management. Interviews conducted as part of a recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) study suggest that, as people living with dementia become unable to manage their own medication, they find injections distressing and painful. 39 The situation can be further complicated by the presence of behavioural and psychological symptoms which may have an impact on diabetes self-care regimens42 and lead to dementia becoming the focus of attention to the detriment of diabetes management. 43 Physical frailty or end-stage dementia compounds the complexity of diabetes management, with decisions needing to be made about whether to maintain strict treatment or consider admission into nursing home care. 44 Therefore, for people with dementia, SM needs to be conceptualised as a multidimensional, complex phenomenon affecting individuals, dyads and families, and interventions may need to target family carers. 41,45

Rationale for the research

As the population ages and the proportion of people with dementia and diabetes increases, the delivery of health and social care for this group becomes increasingly complex and challenging. 39 There is, however, currently no systematic approach to the management of dementia and diabetes,28 and many care pathways for diabetes do not take into account the needs of people with dementia. 46 Moreover, there is a gap in provision of services in mental health trusts for diabetes care and, similarly, a gap in acute hospital trusts for dementia care. 28 Recent guidance on the management of diabetes in people with dementia outlines a number of recommendations, including better case-finding of both conditions, better training for staff, adequate carer support, and care that is tailored to the needs of the individual. 28,31 However, currently there is little research evaluating interventions to improve the management of diabetes in people living with dementia; indeed, many diabetes-related studies exclude people with dementia or cognitive impairment.

Interventions designed to improve the management of diabetes in people with dementia are likely to be multicomponent, specific to different stages of the dementia trajectory, and dependent on the behaviours and choices of those delivering and receiving the care. They are also likely to be contingent on contextually situated decision-making. There is a need, therefore, to synthesise the different strands of research evidence in order to develop a theoretical understanding of the realities of working in and across complex, overlapping systems of care, and why and how different interventions may work. Realist synthesis is a systematic, theory-driven approach that aims to make explicit the mechanism(s) of how and why complex interventions work (or not) in particular settings or contexts. 47–49 Realist synthesis takes account of a broad and eclectic evidence base including the experiential and clinical knowledge that relates to the physiology and management of diabetes in older people, and specifically older people with dementia.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim was to identify the key features or mechanisms of programmes and approaches that aim to improve the management of diabetes in people with dementia, to understand how those mechanisms operate in different contexts to achieve particular outcomes for this population, to make explicit the barriers to and facilitators of implementation, and to identify areas needing further research.

We used an iterative four-stage approach that optimised the knowledge and networks of the research team. The synthesis was based on the stages set out by Pawson et al. 48,50 and follows the Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) publication standards. 47 The objectives were to:

-

identify how interventions, or elements of interventions, to manage diabetes in people with dementia are thought to work, on what range of outcomes (i.e. organisational, resource use, and patient care and safety) and for whom they work (or why they do not work) and in what contexts

-

identify the barriers to and facilitators of the acceptability, uptake and implementation of interventions designed to manage diabetes in people with dementia

-

establish what evidence there is on the feasibility and potential value of interventions to manage diabetes in people with dementia

-

establish what is known about the design of diabetes management technologies and identify the potential benefits of involving end-users (people with dementia and their carers) in their development.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter includes text from the protocol, which was published by Bunn et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

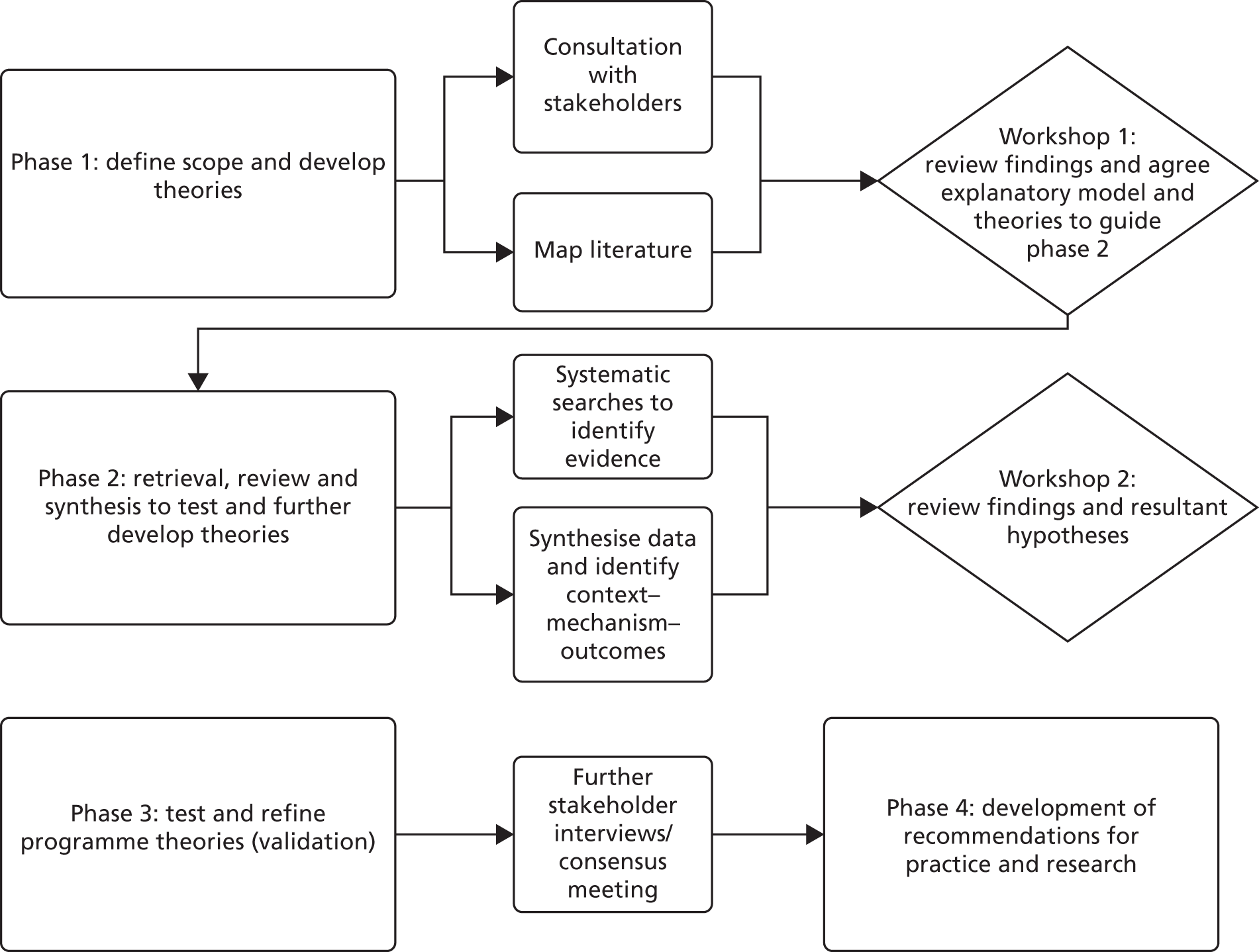

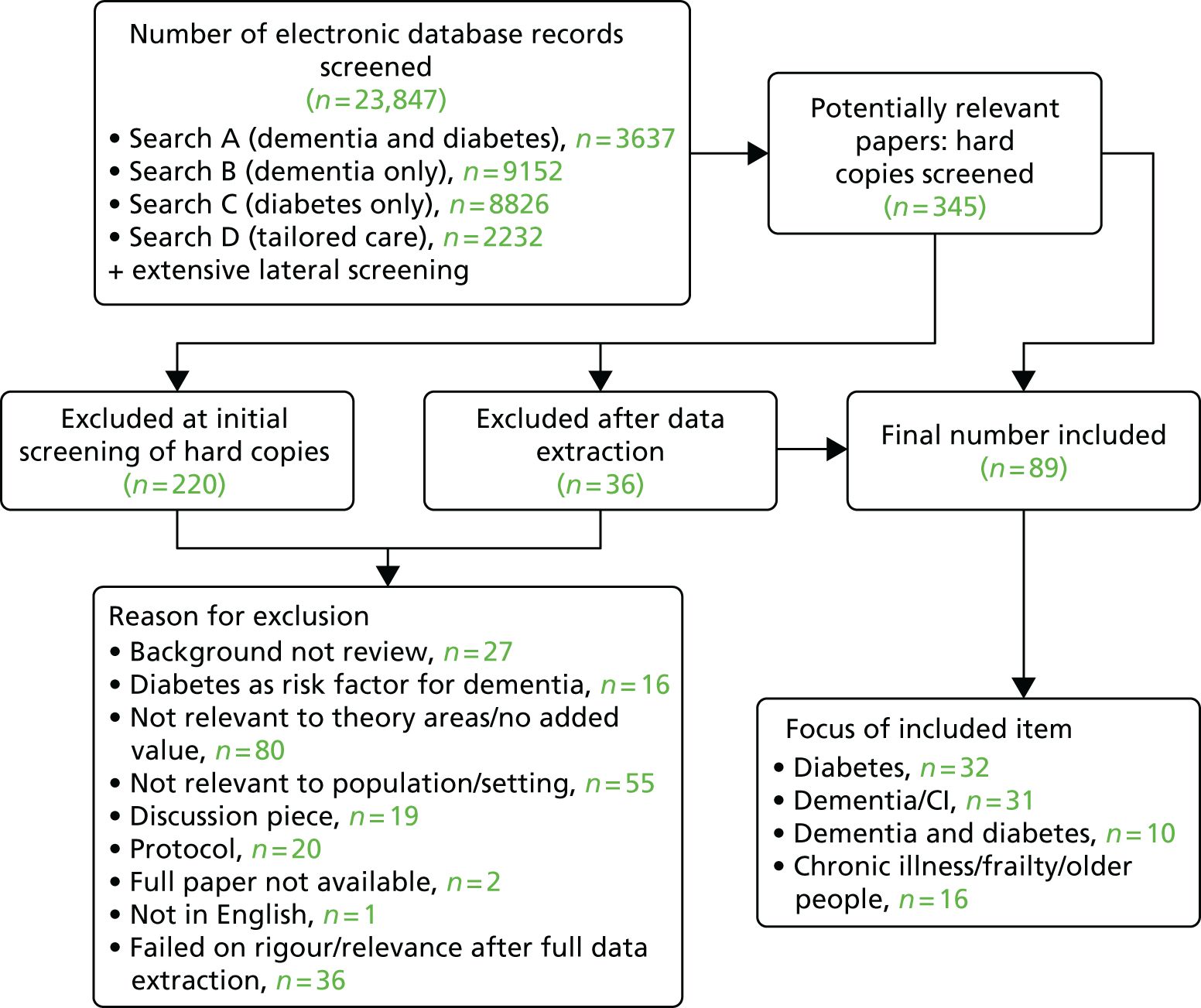

We used an iterative four-stage approach that optimised the knowledge and networks of the research team. The review was based on the stages for realist review set out by Pawson et al. 50 and follows the RAMESES publication standards for realist syntheses. 47 Figure 1 provides an overview of the study design.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of study design.

Rationale for using realist approach

The rationale for using a realist synthesis approach is that interventions for the management of diabetes in people living with dementia are likely to be multicomponent and will be dependent on the behaviours and choices of those delivering and receiving the care. Realist review is a theory-driven interpretive approach to evidence synthesis47,48,51 that assumes that there is more to reality than how we see it. There is an external reality or world that can be observed and measured, but how this reality is articulated and responded to is constantly being shaped by individuals’ perceptions and reasoning and/or dominant social and cultural mores. It is this constant interaction that creates particular responses that lead to observed outcomes. 52

Realist synthesis, therefore, endeavours to go beyond lists of barriers to and enablers of care, to unpack the ‘black box’ of how interventions might help people living with dementia manage their diabetes. The much-repeated statement used to explain the focus and purpose of realist synthesis is that it makes explicit ‘what works, for whom, why and in what circumstances’. It uses a theory-driven approach to articulate how particular contexts (C), including resources, have prompted certain mechanisms (M) or responses to lead to the observed outcomes (O). The iterative process of the review tests those theories that are thought to work (initial programme theory) against the observations reported in the evidence included in the syntheses. 53 The definitions of key realist terminology used in the review are provided in Box 1. The review process results in the emergence of ‘demi-regularities’ or patterns, which provide insight into how interventions work or not, and in what contexts. A realist synthesis enables us to take account of a broad evidence base, including experiential and clinical knowledge that relates to the physiology and management of diabetes in older people, and specifically older people living with dementia.

-

Context (C): the ‘backdrop’ conditions (which may change over time), for example provision of training in diabetes and/or dementia care delivery systems. Context can be broadly understood as any condition that triggers and/or modifies the behaviour of a mechanism.

-

Mechanism (M): a mechanism is the generative force triggered in particular contexts that leads to outcomes. Often denotes the reasoning (cognitive or emotional) of the various ‘actors’ (i.e. people living with dementia and diabetes, relatives and HCPs). Mechanisms are linked to, but are not the same as, a service’s strategies or interventions. Identifying the mechanisms goes beyond describing ‘what happened’ to theorising ‘why it happened, for whom and under what circumstances’.

-

Outcomes (O): the outcome is a result of the interaction between a mechanism and its triggering context. This may include greater engagement in SM behaviours or a reduction in adverse events.

-

Programme theory: those ideas about what needs to be changed or improved in how diabetes is managed for people living with dementia, what needs to be in place to achieve an improvement(s) and how programmes are believed to work. It specifies what is being investigated and the elements and scope of the review.

Changes in the review process

As recommended in the RAMESES publication standards,47 changes in the review process are documented in Table 1.

| Protocol | Revisions/changes | Agreed |

|---|---|---|

| The inclusion criteria stated that we would include people ‘resident in the community or a care home or other long-term setting’ | At the second project workshop (involving eight members of the RMT) it was decided that further refinement was needed of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The RMT felt that the issues of managing diabetes for people living with dementia in care homes are different from those for people living in their own homes and that literature relating to care homes should be excluded | Research management team (April 2016) and supported by the PAG. The PAG agreed that the decision was appropriate because there were significant differences between the two environments |

| The protocol stated that in phase 3 we would review the hypotheses and supporting evidence through telephone interviews with up to 15 stakeholders | We conducted only seven individual interviews in phase 3. However, in addition, hypotheses (CMOs) and supporting evidence were presented and discussed at a consensus meeting involving 24 participants |

Phase 1: defining the scope of the realist review – concept mining and theory development

In phase 1, we were concerned with developing an initial programme theory/theories or hypotheses about why diabetes management programmes for people living with dementia work or do not work. This scoping or concept mining involved a variety of evidence sources, including the commissioning brief, policy/guidance and grey and published literature. In addition, we consulted with a range of content experts via interviews with stakeholders and discussions with the Research Management Team (RMT) and Project Advisory Group (PAG). The PAG included experts in the fields of diabetes, dementia, older people’s health and realist methods (see Appendix 1). The first RMT meeting included an open discussion in which the team were asked to draw on their expertise to articulate:

-

the dominant approaches and assumptions that informed current thinking about what supported the management of diabetes in people living with dementia

-

important outcomes.

Scoping interviews

To complement the expertise provided by the team, we interviewed 19 stakeholders (Table 2).

| Group | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Clinicians with a special interest in the management of diabetes in older people | To understand organisational process and protocols and current ‘best practice’ for older people with diabetes. To be aware of factors which facilitate the implementation of guidelines |

| 2. Providers of care in primary and secondary care (e.g. diabetes specialist nurses, GPs and other clinicians) | To gain the perspectives of clinicians who are likely to be providing diabetes care for people living with dementia |

| 3. User representatives, including recipients of care and their family carers, and relevant diabetes or dementia charities | To give the closest possible approximation of the views of people living with dementia and diabetes |

| 4. Dementia specialists from primary, secondary and tertiary care and the voluntary sector (e.g. old-age psychiatrists, dementia specialist nurses and GPs with an interest in dementia) | To understand organisational process and protocols and current ‘best practice’ for caring for people living with dementia. To be aware of factors which facilitate the implementation of guidelines |

| 5. Academics and those involved in developing education and guidance for older people with diabetes | To ensure that we are up to date with the most relevant current research |

In the first instance, stakeholders were identified through the clinical and research networks of the RMT and PAG. A process of snowballing was used to identify additional participants.

Interview procedures

Interviews were conducted either face to face or via telephone by one of three researchers (FB, PRJ and BR). Participants were given a copy of the study information sheet, which provided contact details of the research team, and a consent form, which they were asked to read and sign. Interviews were conducted using an interview schedule and were audio-recorded and transcribed. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Hertfordshire Health and Human Sciences Ethics Committee with delegated authority (CSK/SF/UH/00106). The interview schedules were designed to explore:

-

participants’ experiences of (a) working with people living with dementia and diabetes, (b) living with dementia and diabetes or (c) acting as an informal carer to someone with dementia and diabetes

-

current problems and challenges facing people and families who have to manage dementia and diabetes, and what needs to be in place to address the effects of dementia

-

what good diabetes care looks like for people living with dementia and what is needed to achieve it

-

changes required to improve the management of diabetes in people living with dementia.

First search and mapping of the literature

Literature for the scoping was initially drawn from a number of sources. This included searches recently undertaken for a scoping review for a NIHR study about dementia and comorbidity2 and for the development of clinical guidance on dementia and diabetes. 28 These were supplemented by a search of ProQuest Pro (2010–December 2015): this contains 13 databases, including British Nursing Index, PsycINFO and SocialSciences collection; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, EBSCOhost, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Key words used in the searches included dementia OR Alzheimer’s disease OR vascular dementia OR mild cognitive impairment OR MCI OR frail elderly OR severe mental illness AND diabetes, T1DM OR T2DM AND self-management OR self-care OR chronic illness OR case-management OR assistive technology OR telemedicine/care OR family carer OR social support OR eating/meal times OR medicine management OR adherence OR exercise/leisure, OR health and social care professionals.

Records were originally categorised as diabetes biology/pathophysiology, candidate theories, case management, SM and technology. Portable Document Format (PDF) files of potentially relevant papers were stored in a private group on Mendeley (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) to which all members of the research team had access. Records were screened by two reviewers independently (from FB, PRJ, BR and DT) and decisions were recorded on a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

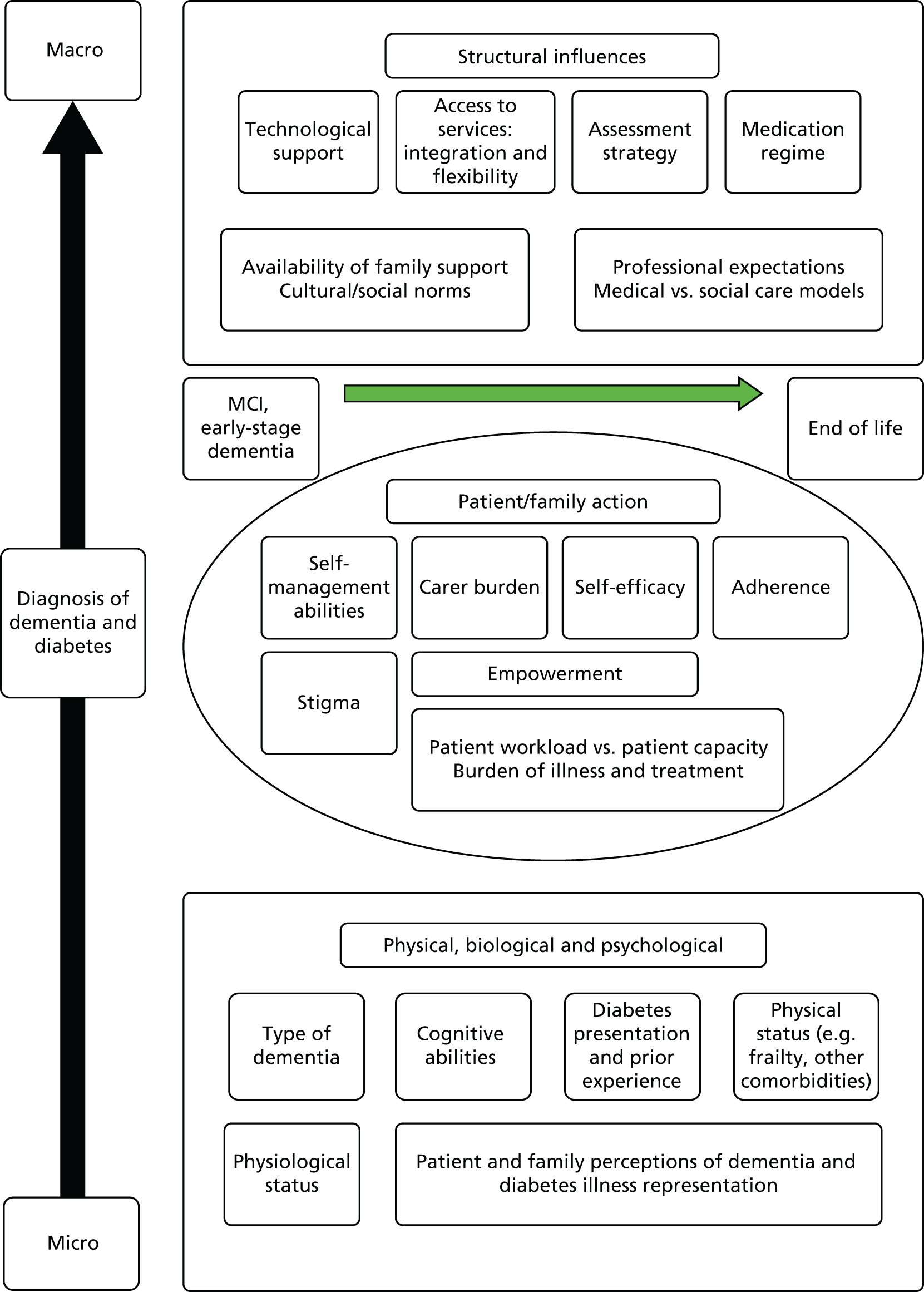

The initial scoping of the literature produced minimal research that investigated how diabetes is managed in people living with dementia, apart from the recognition that cognitive decline may be accelerated in people with diabetes. As an initial step to literature scoping, a framework was required that could link the management of diabetes (in older people) to the management of dementia (mild cognitive impairment to the end of life). Following the first project management meeting, a potential conceptual framework was identified based on the work of Glass and McAtee54 and extended by Greenhalgh et al. 55 This framework was used as a way of identifying key theories that could influence the management of dementia and diabetes care and linking the management of diabetes (in older people) and the management of dementia (mild cognitive impairment to the end of life). The framework highlights the complex influences that affect the management of diabetes in people living with dementia (Figure 2) and was used as a guide to ‘sketch the terrain’47 to be investigated and, through this process, to assist in refining the elements and scope for the review.

FIGURE 2.

Nested hierarchy of influences around diabetes management in people living with dementia. MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

From the literature and from listening to stakeholder transcripts, a series of explanatory accounts were built up that contained ‘if–then’ statements that helped to specify context and mechanism. ‘If–then’ statements are the identification of an intervention/activity linked to outcome(s), and they contain references to contexts and mechanisms (although these may not be very explicit at this stage) and/or barriers and enablers (which can be both mechanism and context). 56 The ‘if–then’ statements provided a helpful way of structuring our thinking. They also helped to focus the process of taking ideas and assumptions about how interventions work and testing them against the evidence we found. Initially, we generated 20 ‘if–then’ statements, which, after further discussion, were reduced to three (Box 2).

-

If interventions designed to promote SM use a comprehensive toolbox approach tailored to individual needs (including, for example, skill building, education, how to manage emotions, and coping mechanisms), then the person living with dementia and diabetes (and their family/carers) is (are) more likely to engage positively with managing their diabetes because they feel more in control (are more autonomous, confident, motivated, empowered), which results in (for the individual):

-

If models of care reflect a person-centred partnership approach (incorporating holism, and that are participatory, relational), and are balanced (with focus on diabetes management, therapeutic alliance), then relationships between the person living with dementia and diabetes (and family/carers) and HCPs are more likely to be effective because there is mutual trust and understanding and better communication between them, which results in:

-

If local specialist and primary services reflect a seamless approach that is responsive and accessible for people living with dementia and diabetes (including having the right systems, processes and people in place), then the person (and their family/carers) and the HCP will feel better supported and informed, which results in:

The ‘if–then’ statements were discussed with the PAG members, who made several suggestions that influenced our thinking and the development of our theory areas. For example, they suggested that we map what constitutes good diabetes care (e.g. that specified in current guidelines) against the barriers created by dementia. Members also felt that the review should not be too biomedically focused.

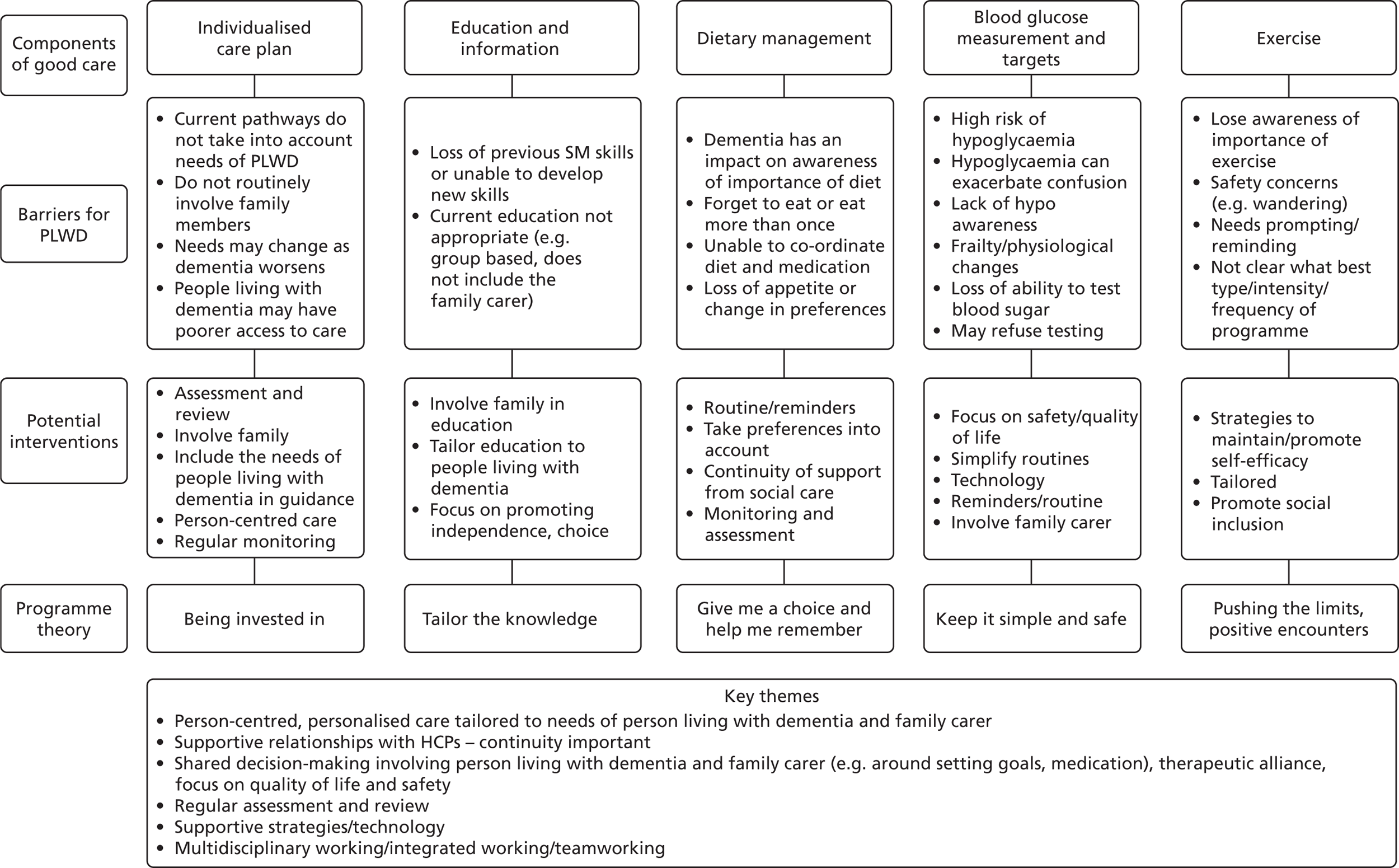

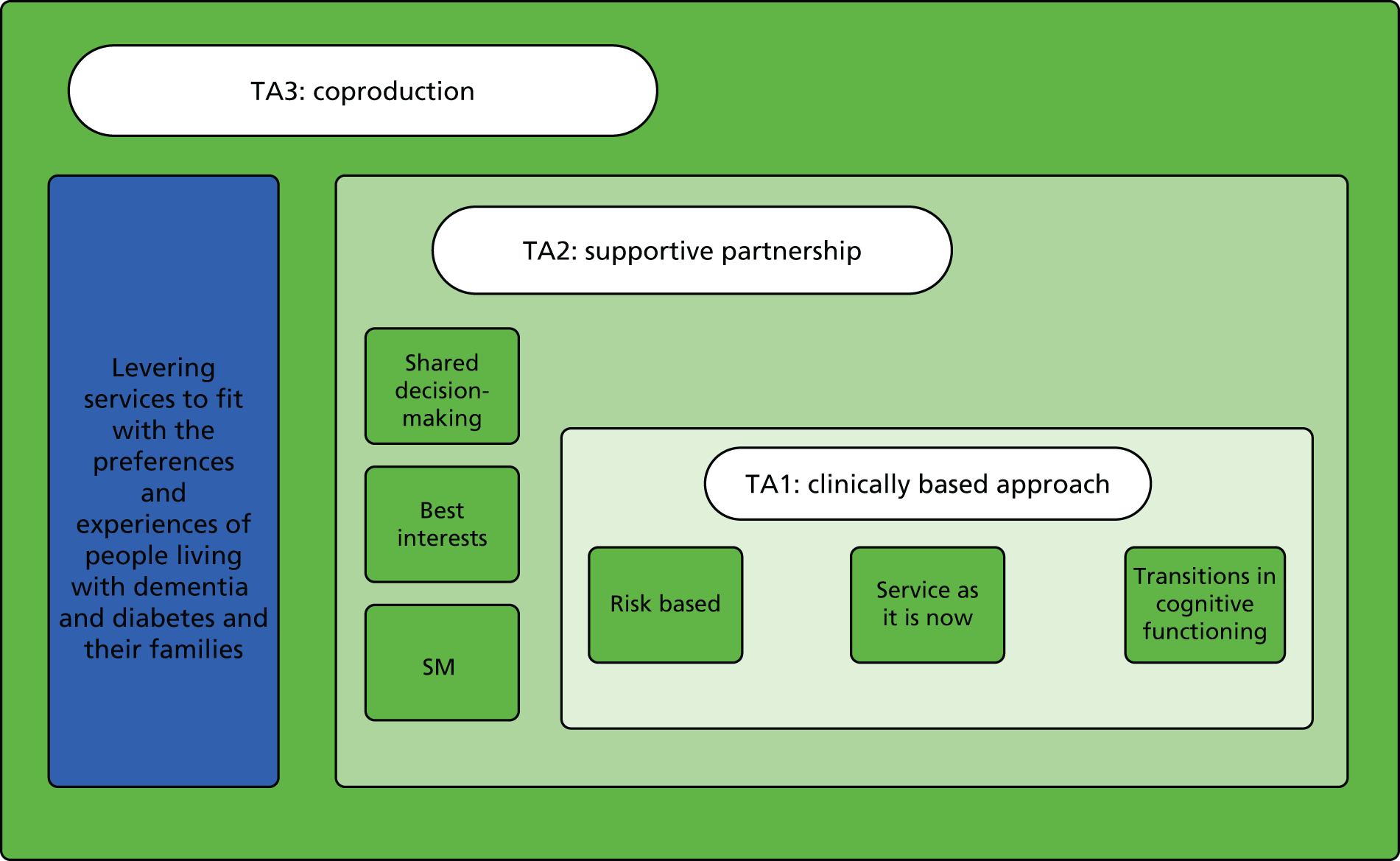

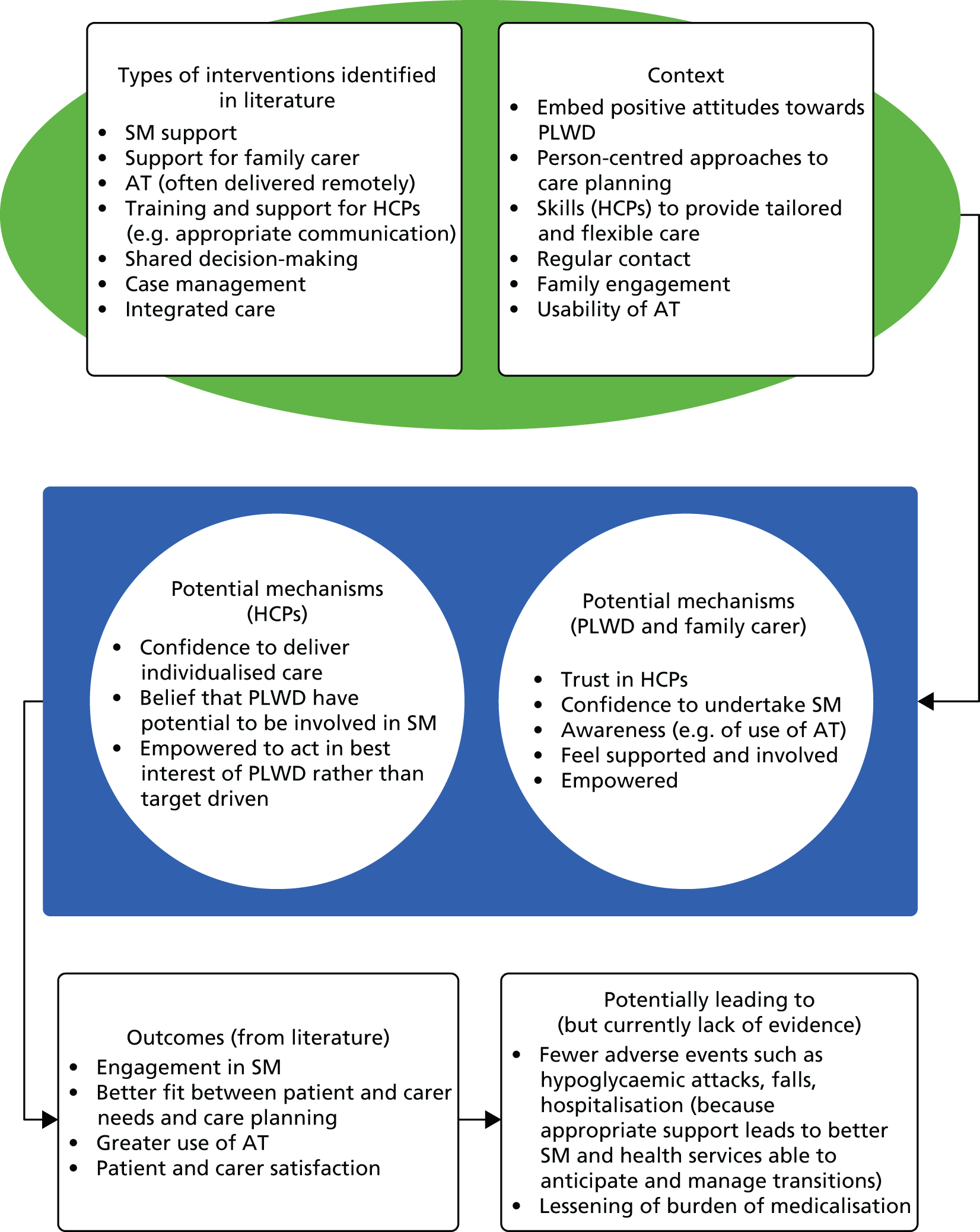

In response, we mapped ideas about ‘good’ diabetes care against the barriers for people living with dementia identified by the literature and the stakeholder interviews. We also identified potential interventions and emerging theory (Figure 3). This became theory area 1: clinically based approach. Theory area 1 was, however, felt to be rather biomedically focused, and additional theory areas around supportive partnerships (theory area 2) and coproduction (theory area 3) were developed to reflect other areas identified in the scoping. Figure 4 provides an overview of all of the initial theory areas.

FIGURE 3.

Good diabetes care mapped against potential barriers, interventions and emerging programme theory areas. PLWD, people living with dementia.

FIGURE 4.

Initial programme areas that emerged from phase 1. TA, theory area.

Phase 2: retrieval, review and synthesis

Searching processes

In phase 2 we undertook systematic searches of the evidence to test and develop the theories identified in phase 1. The main inclusion criteria were:

-

people with mild, moderate or advanced dementia [of any type, e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s disease dementia, frontotemporal dementia (Pick’s disease) and alcohol-related dementia] and type 1 or type 2 diabetes, resident in the community

-

studies of any intervention designed to promote the management of diabetes in people living with dementia and the prevention of potential adverse effects associated with poorly managed diabetes, such as falls, blindness, vascular complications and renal failure

-

studies that provide evidence on barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation and uptake of interventions designed to improve the physical health of people living with dementia (e.g. dementia-friendly initiatives, the impact of the cognitive vs. behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia and the impact of the progression of dementia on family carers and service providers)

-

studies that offer opportunities for transferable learning, such as those that evaluate interventions for people living with dementia and other clinical conditions, or those that look at the way in which services are delivered and implemented for people living with dementia (e.g. interventions to improve access or continuity, tailor care to the needs of individuals with dementia or support family carers).

The purpose of the searches was not to identify an exhaustive set of studies but rather to be able to reach conceptual saturation in which sufficient evidence was identified to meet the aims of the review. 74 A diversity of evidence provides an opportunity for richer data mining and theory development. Therefore, we included studies of any design, including randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled studies, uncontrolled studies, interrupted time series studies, cost-effectiveness studies, process evaluations, surveys, and qualitative studies of participants’ views and experiences of interventions. We also included grey literature, policy documents and information about locally implemented programmes in the UK. As is usual with a realist review, the process of identifying relevant information and deciding what to include was iterative, involving tracking backwards and forwards between the literature and our review questions. 50 As such, the identification of relevant literature carried on during the course of the review, and some studies initially thought to be relevant were later excluded.

The search terms were devised in conjunction with an information scientist and chosen to reflect the theory areas identified in phase 1. The searches were split into three main categories:

-

A – theory areas + dementia AND diabetes

-

B – theory areas + dementia

-

C – theory areas + diabetes.

The main searches were category A, which included terms for the theory areas combined with both dementia and diabetes. However, because the scoping had identified little literature that covered both dementia and diabetes, we also searched for literature that focused on the theory areas and either dementia only (B searches) or diabetes only (C searches). As a result of discussions at the second project team workshop, an additional search was conducted (search D). This focused on tailored and individualised care for people with complex health needs (e.g. comorbidity and frailty). For full search terms, see Appendix 2.

For searches A, B and C, we searched the following electronic databases from 1990 to March 2016: MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, Scopus, The Cochrane Library (including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews), DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects), the HTA database, NHS EED (NHS Economic Evaluation Database), AgeInfo (Centre for Policy on Ageing – UK), Social Care Online, the NIHR portfolio database, NHS Evidence, Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and Google Scholar. For search D, we searched PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, Google Scholar and The Cochrane Library (1990–April 2016). An alert was set up in PubMed so that the team received weekly updates of new records identified by the search terms (March 2016–December 2016).

Previous dementia reviews undertaken by members of the project team have highlighted the importance of lateral searching for identifying studies for dementia-related reviews. 75 Therefore, in addition to the electronic database searches, we undertook lateral searches, which included checking reference lists, and citation searches using the ‘cited by’ option on Google and the ‘related articles’ option on PubMed.

Selection and appraisal of documents

Search results were downloaded into bibliographic software and, when possible, duplicates were deleted. Records from search A were split into two files and each file was screened independently by two reviewers (file 1 by PRJ and DT and file 2 by FB and BR). After each pair of reviewers had discussed the results of their screening, all four authors met to resolve any disagreements and amend the inclusion criteria as necessary. Records from the other searches (B and C) were screened by one reviewer, with 10% checked by a second. When studies appeared potentially relevant, PDF files were obtained, stored in Mendeley and screened by two reviewers. To enable us to keep track of the large number of records screened, and the changes in inclusion criteria, decisions made at different times were recorded in the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet created in phase 1.

Data extraction

A bespoke data extraction form was developed based on our three main theory areas. The form was piloted on six records by team members (FB, PRJ, BR and DT) and further refined as necessary. Once the final fields for data extraction were agreed, an electronic version was created in Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The data extraction form included fields relating to study aims, design and methods, the types of participants (e.g. dementia only, diabetes only, dementia and diabetes, other), outcomes, information relevant to the theory areas, and emerging context–mechanism–outcomes (CMOs) (see Appendix 3). Data were extracted by one reviewer, with 50% checked by a second. It should be noted that ‘data’ in a realist sense are not just restricted to the study results or outcomes measured. Therefore, author explanations and discussions can provide a rich source, or ‘nugget’, of ‘data’, and these were included in the data extraction form.

A test of whether or not to include an item in a realist review is to use ‘good enough and relevant enough’. 76 For a previous realist review,77 members of the research team created a set of constructs to ensure that the test of ‘good enough and relevant enough’ was transparent and clear to all team members. ‘Good enough’ was deconstructed as the quality of evidence expressed through fidelity, trustworthiness and value. ‘Relevant enough’ related to the contribution of the evidence to the theories and its potential contribution to the review. This set of constructs was added to the data extraction form in the form of a flow chart.

Analysis and synthesis processes

Realist reviews identify the task of synthesis as one of refining theory. Programmes operate through highly elaborate implementation processes. A realist review starts with a preliminary understanding of those processes, the initial programme theories (phase 1), and then seeks to refine them by extracting and evaluating the identified literature (phase 2).

The analytical task involved synthesising across the extracted information the relationships between mechanisms (e.g. underlying processes, structures and entities), contexts (e.g. conditions, types of setting, organisational configurations) and outcomes (i.e. intended and unintended consequences and impact). From the data fields in Microsoft Access, tables were constructed as the basis for further discussions about the emerging contingencies seen within and across the extracted data. These data were discussed with the wider RMT during a second half-day workshop. From these tables, we attempted to identify prominent recurrent patterns of contexts and outcomes (demiregularities) in the data and then sought to explain these through the means (mechanisms) by which they occurred. 78 This deliberative and iterative process enabled iteration from plausible hypotheses to the uncovering of potential CMO configurations.

The research team (FB, PRJ and BR) managed this extraction and synthesis process on a day-to-day basis, with regular consultation [via e-mail and telephone/SkypeTM (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) conferencing]. Data synthesis involved individual reflection and team discussion that:

-

questioned the integrity of each theory

-

adjudicated between competing theories

-

considered the same theory in different settings

-

compared the stated theory with actual practice.

Phases 3 and 4: test and refine programme theories (validation) and develop actionable recommendations

To enhance the trustworthiness of the resultant hypotheses, and to develop a final review narrative to address what is necessary for the effective implementation of programmes to manage diabetes in people living with dementia, we reviewed the hypotheses and supporting evidence through consultation with the PAG and with stakeholders, some of whom had participated in the scoping. Stakeholder consultation was carried out by telephone interviews (n = 7) and by group discussions at a consensus conference involving 24 participants. Participants at the conference were purposively sampled to ensure that all of the key stakeholder groups in phase 1 were represented.

Consensus conference

The meeting began with a presentation from the research team in which the development of the hypotheses was outlined. This was followed by small group discussions about the proposed CMO configurations. Participants were split into three groups, with each including a mix of specialists in dementia and diabetes and at least one service user representative. Each group included two members of the research team, one to facilitate the group and one to take notes. At this stage there were six CMOs and each group was asked to focus on two. To encourage a quick generation of ideas, participants had just 10 minutes to write their recommendations on the ideas templates. The templates required participants to name what they thought the CMO might look like in practice (what needs to be in place), and what were the priorities and mediating factors. The facilitator for each group then asked participants to share their thoughts and these were recorded by the note-taker. Finally, the conference facilitator consolidated the recommendations by asking each of the groups to put forward their ideas to the larger group. Recommendations were discussed and recorded on a flip chart at the front of the room.

Following the consensus conference, members of the core project team (FB, PRJ and BR) met to review and discuss the outputs of the conference and amend the CMOs as appropriate. The revised CMOs were then checked against data from the literature and against transcripts of all the stakeholder interviews. The final CMOs and the supporting evidence are presented in Chapter 3.

Patient and public involvement

A well-established Public Involvement in Research Group at the University of Hertfordshire trains and provides support to public members and has a broad membership of service users and carers. Two members of this group (Dr Paul Millac and Mrs Diane Munday), both of whom have experience of caring for a family member with dementia and/or diabetes, were involved throughout the project. They were involved in defining the scope of the review (e.g. commenting on stakeholder interview transcripts), overseeing the project as members of the PAG and verifying findings as participants at the consensus meeting. As part of the realist review process, we also recruited additional patient and public involvement representatives for stakeholder interviews and the consensus conference. They were involved in defining the scope of the review and validation of the findings.

Chapter 3 Results

Description of studies

We included 89 papers. 25,28,30,37,39,42,43,45,57–73,79–142 These comprised 79 research papers and 10 guidelines or discussion pieces. Other papers cited in this chapter are for background information and did not undergo full data extraction. Twenty-two of the 79 research papers were reviews. Of those, 15 were systematic reviews,79,80,82,84,89,90,93,101,125–127,131,132,137,143 one was a realist review134 and six were non-systematic reviews. 25,37,45,66,73,105 The rest of the research papers (n = 57) related to primary research. Several studies were reported in more than one publication: the 57 primary research papers reported 51 studies. The main types of primary research were qualitative studies, RCTs or controlled studies. The rest were a mix of designs, including feasibility studies, surveys, before-and-after studies and observational studies. Ten papers25,28,39,42,59,64,66,83,123,142 focused on people living with dementia and diabetes; the rest were concerned with diabetes (n = 32), dementia (n = 31) or other groups, such as those with chronic illness or frailty. An overview of the selection process can be seen in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Flow chart detailing study selection process. CI, cognitive impairment.

Of the 57 papers reporting primary research, the majority were from the UK (n = 2928,39,60,67,85–87,91,92,97,103–105,109–111,115,118–121,123,132,133,138–142), the USA (n = 1842,45,59,62–64,68,70,71,81,98–100,107,112,116,117,140) or Europe (n = 1058,61,72,95,96,106,113,114,122,124). As there was limited literature directly relevant to our target group, which we had anticipated, we included studies that offered opportunities for transferable learning, for example SM strategies for people living with dementia or diabetes care for older people. This evidence offered the opportunity to consider which challenges or issues were specific to people with dementia and diabetes and which were more general to other populations with diabetes (e.g. related to visual or sensory loss or other age-related problems). The types of papers we included, together with a summary of areas on which they focused and the sorts of outcomes they reported, can be seen in Table 3. Further details of individual studies are provided in Appendix 4. It is worth noting that much of the evidence on which we drew, particularly that relating to people with dementia and older people with diabetes, was detailing the absence or lack of care for these groups. Therefore, although there is literature that makes recommendations about what ought to be in place for these vulnerable groups, there is a lack of evidence that tests out these ideas.

| Focus | Included studies | Methodological approach | Types of outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

Dementia AND diabetes (n = 10)

|

Abdelhafiz et al., 201625 |

|

|

| Brown et al., 201583 | |||

| Bunn et al., 201639 | |||

| Bunn et al., 2017142 | |||

| Camp et al., 201559 | |||

| Feil et al., 200942 | |||

| Feil et al., 201164 | |||

| Hackel, 201366 | |||

| Sachar, 2012123 | |||

| Sinclair et al., 201428 | |||

|

Dementia NOT diabetes (n = 31) Includes: |

Alsaeed et al., 201679 |

|

Patient outcomes include:

|

| Bahar-Fuchs et al., 201380 | |||

| Boots et al., 201482 | |||

| Boots et al., 201661 | |||

| Clare et al., 201385 | |||

| Clare et al., 201086 | |||

| Dhedi et al., 201487 | |||

| Dugmore et al., 201589 | |||

| Fleming and Sum, 201490 | |||

| Gibson et al., 201591 | |||

| Giebel et al., 201592 | |||

| Gillespie et al., 201293 | |||

| Goodwin et al., 2013138 | |||

| Graff et al., 200665 | |||

| Graff et al., 200896 | |||

| Graff et al., 200795 | Carer outcomes include:

|

||

| Iliffe et al., 200667 | |||

| Jekel et al., 2015101 | |||

| Knapp et al., 2015105 | |||

| Laakkonen et al., 2016106 | |||

| Lingler et al., 2016107 | |||

| Martin et al., 2013109 | |||

| Martin et al., 2015110 | |||

| Mountain, 200637 | |||

| Mountain and Craig, 2012115 | |||

| Quinn et al., 2015143 | |||

| Quinn et al., 2016136 | |||

| Schaller et al., 2016124 | |||

| Span et al., 2013127 | |||

| Suh et al., 2004128 | |||

| Toms et al., 2015132 | |||

|

Diabetes NOT dementia (n = 32) Participants include older adults, those with complex health needs (comorbidity, frailty, etc.), people with mental illness and adults with T2DM Includes: |

Aikens et al., 201563 |

|

|

| Bailey et al., 201681 | |||

| Baxter, 201457 | |||

| Beverly et al., 201470 | |||

| Branda et al., 201371 | |||

| Chrvala et al., 201684 | |||

| Care Quality Commission, 2016139 | |||

| Donald et al., 201388 | |||

| Goeman et al., 201694 | |||

| Heisler et al., 200398 | |||

| Hsu et al., 201699 | |||

| Huang et al., 2005100 | |||

| Jowsey et al., 201469 | |||

| Jowsey et al., 2016102 | |||

| Markle-Reid et al., 2016108 | |||

| Mathers et al., 2012111 | |||

| Mayberry et al., 201168 | |||

| Mayberry et al., 2016112 | |||

| McBain et al., 2016137 | |||

| McBain et al., 2016140 | |||

| Munshi et al., 2011117 | |||

| Munshi et al., 2013116 | |||

| Newton et al., 2016118 | |||

| Penn et al., 2015119 | |||

| Piette and Kerr, 200643 | |||

| Reinhardt Varming et al., 2015122 | |||

| Schulman-Green et al., 2016125 | |||

| Sherifali et al., 2015126 | |||

| IDF, 201330 | |||

| Sun et al., 2013129 | |||

| Tan et al., 2015130 | |||

| Taylor et al. 2016141 | |||

|

Other (e.g. people with chronic illness, frail older people, people with multimorbidity or LTCs) (n = 15) Includes: |

Anderson et al., 201573 |

|

|

| Bergdahl et al., 201372 | |||

| Davis et al., 201262 | |||

| De Vriendt et al., 201558 | |||

| Greenhalgh et al., 201397 | |||

| Kennedy et al., 2013103 | |||

| Kennedy et al., 2014104 | |||

| Kennedy et al., 201460 | |||

| Metzelthin et al., 2013;113 and Metzelthin et al., 2013114 | |||

| Procter et al., 2014120 | |||

| Ryan and Sawin, 200945 | |||

| Taylor et al., 2014131 | |||

| Wherton et al., 2012133 | |||

| Yardley et al., 2015134 |

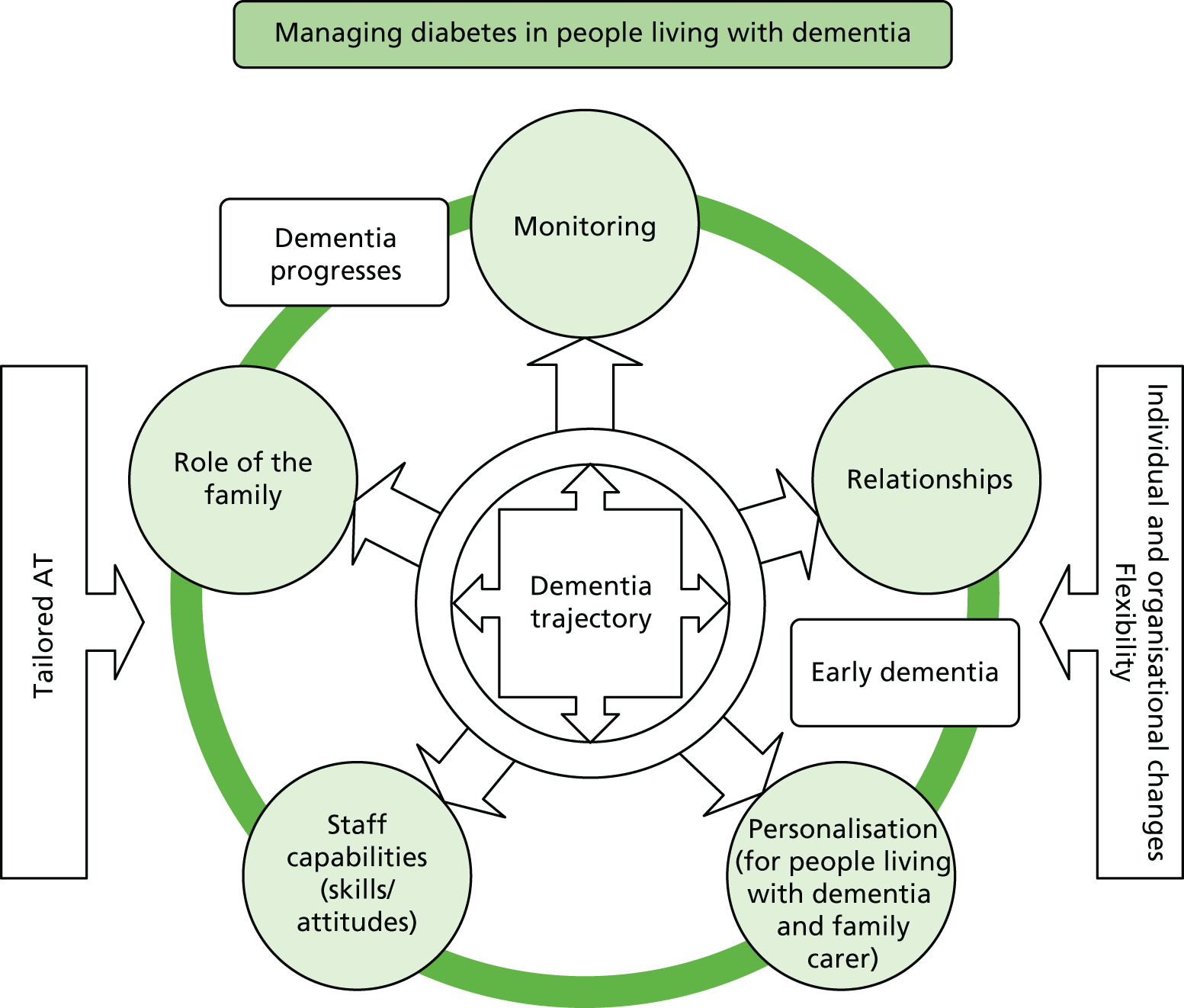

Context–mechanism–outcome configurations

The theory development, refinement and testing process (see Chapter 2) led to the development of six CMO configurations (Table 4). Together, these explanations or hypotheses constitute a programme theory about ‘what works’ (or ‘what might work’) in the management of diabetes in people living with dementia. These CMO configurations were developed from evidence taken from interviews and the literature, and then were further tested in the literature and verified with stakeholders. The CMOs are not mutually exclusive and we would suggest that it is how the different elements of each interact that is important.

| Title | Context | Mechanism and outcome | Included evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: embedding positive attitudes towards people living with dementia | If health and social care delivery systems propagate and reinforce positive attitudes towards people living with dementia and diabetes and their families through tailored SM support . . . | . . . then this fosters a belief in staff that people living with dementia and diabetes have the potential to be involved in SM and the right to access diabetes-related services (even when the trajectory is one of deterioration), (M) prompting treatment confidence in people living with dementia and diabetes (M), which leads to engagement in SM practices by people living with dementia and diabetes, their family carers and HCPs (O) | 28,37,39,59,60,62,65,67,80,85,86,95,96,104–106,109,110,115,121,131,132,134,136,142 |

| 2: person-centred approaches to care planning | If delivery systems promote a person-centred and partnership approach to care, allowing HCPs to understand the individual needs and abilities of people living with dementia and diabetes and their families . . . | . . . then (1) HCPs feel confident that they are acting in the best interests of people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (M), and (2) this generates trust between HCPs and people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (M), leading to a better fit between care planning and patient and carer needs, and (potentially) a lessening of the burden of medicalisation experienced by people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (O) | 45,58,59,65,67,69,71–73,79,87,94,95,98,100,102,108,111,114,116,118,122,125–127,130,132,134,137,138 |

| 3: developing skills to provide tailored and flexible care | If HCPs are expected to develop skills that enhance the delivery of individualised and tailored care to people with dementia and diabetes (e.g. enablement rather than management, listening/communication/negotiation, shared decision-making) . . . | . . . then this legitimises the work creating the expectation in patients and in HCPs that diabetic care for people living with dementia is important (M), leading to the provision of more tailored diabetes care (O) and better engagement in SM by people living with dementia and diabetes and their family carers (O) | 25,60,67,69,71,79,88,89,98,103,104,111,113,114,116,117,119,122,123,129,134 |

| 4: regular contact | If HCPs maintain regular contact over time (e.g. face to face, by telephone or by e-mail) with the person living with dementia and diabetes and their family carer, monitoring and anticipating needs throughout the dementia trajectory . . . | . . . then HCPs feel more equipped to meet patients’ needs (M), and people living with dementia and diabetes and their families believe themselves to be supported (M) through the transition from functional independence to functional dependence (M), leading to improved diabetes management (O) | 28,43,59,61,62,64,66,79,83,84,87,116–119,124,128,130 |

| 5: family engagement | If family carers are routinely involved in care planning and information sharing, and are given the support they need to take on the tasks associated with managing diabetes in people living with dementia (e.g. medicine management, recognition of hypoglycaemia) . . . | . . . then family carers will feel supported and that their contribution is recognised and appreciated (M), leading to the development of effective SM strategies on the part of the family carer (O) | 39,42,63,64,69,72,79,82,95,107,108,115,124,130,142 |

| 6: usability of AT | As the dementia trajectory progresses, AT needs to be tailored and adapted to the needs and requirements of people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (includes social, environmental and cultural needs), with the focus on maintaining autonomy for the people living with dementia and diabetes . . . | . . . leading to people living with dementia and diabetes and their families gaining an understanding (awareness) of the usefulness of AT in their management of dementia and diabetes (M), leading to more effective and sustained use of AT to maintain autonomy and diabetes SM strategies (O) | 39,59,61,63,68,90,91,93,97,99,101,105,112,120,127,133,135 |

We now present each of the six CMOs in more detail. Further evidence supporting the CMOs can be seen in Appendices 5 and 6; this includes evidence from the papers (see Appendix 5) and interviews (see Appendix 6).

Context–mechanism–outcome 1: embedding positive attitudes towards people living with dementia

Programme theory

If health and social care delivery systems propagate and reinforce positive attitudes towards people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (C), through tailored SM support, then this fosters a belief in staff that people living with dementia and diabetes have the potential to be involved in SM and the right to access diabetes-related services (even when the trajectory is one of deterioration), (M) prompting treatment confidence in people living with dementia and diabetes (M), which leads to engagement in SM practices by people living with dementia and diabetes, their family carers and health-care professionals (HCPs) (O).

Stigma and barriers to care for people living with dementia

There is evidence that social stigma surrounds both dementia and diabetes not only in the general population but also among HCPs. 144 Stigma associated with dementia has an impact on the person living with dementia and may lead to them having poorer access to care than people with similar comorbidities but without dementia. 39 Stigma is also felt by the family carer, for example through increased social isolation. People with diabetes may also be stigmatised and blamed for their condition because of lifestyle choices and/or obesity. 144 Recent work by members of the team around community engagement and dementia-friendly health care has argued that without a foundation of awareness about what it is like to live with dementia, related initiatives will not succeed. A reliance, for example, on single initiatives such as dementia champions is insufficient. 145,146

People with dementia and comorbidity face many problems in accessing health care. This includes a lack of services designed around the needs of people living with dementia, poor communication between services, a lack of training on dementia care for health and social care staff and a reliance on others (such as family carers) to recognise a need for services and seek help. 39 A recent mixed-methods study, which included qualitative interviews and focus groups with clinicians, highlighted deficiencies in access to care and continuity of care for people with dementia and comorbidity. Access to care was affected by clinicians’ previous experiences and their attitudes towards risk. For example, there were contrasting opinions about the appropriateness of taking someone with dementia off insulin. 39,142 Stakeholders also highlighted the need to ensure that people living with dementia received equitable care:

. . . you shouldn’t be sort of swayed one way or the other, just because someone has dementia . . . I think certainly when they first start on their journey I think it’s really important that we do everything we can [of cross-disciplinary training to facilitate appropriate care].

Diab 1 (stakeholder interviews)

Involving people with dementia in self-management

We found 10 studies37,59,62,106,109,110,115,121,132,136 looking at SM interventions for people living with dementia or cognitive impairment, only one of which included people with dementia and diabetes. 59 This controlled study evaluated the impact of personalised education sessions on people with diabetes and cognitive impairment. 59 In this US-based study, certified diabetes educators delivered personalised education sessions over the internet to older adults with type 2 diabetes and cognitive impairment (mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia). They found a significant increase in self-efficacy but no difference in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) at 6-month follow-up. The authors say that the face-to-face nature of the contact (via Skype) was beneficial for establishing good rapport with participants. Mountain37 suggests that the lack of studies on SM for people living with dementia is a result of negative perceptions of the abilities of people with early dementia, which ‘leaves them on the periphery of any benefits that can be derived from the current focus of policies that support people with long term conditions’. 37

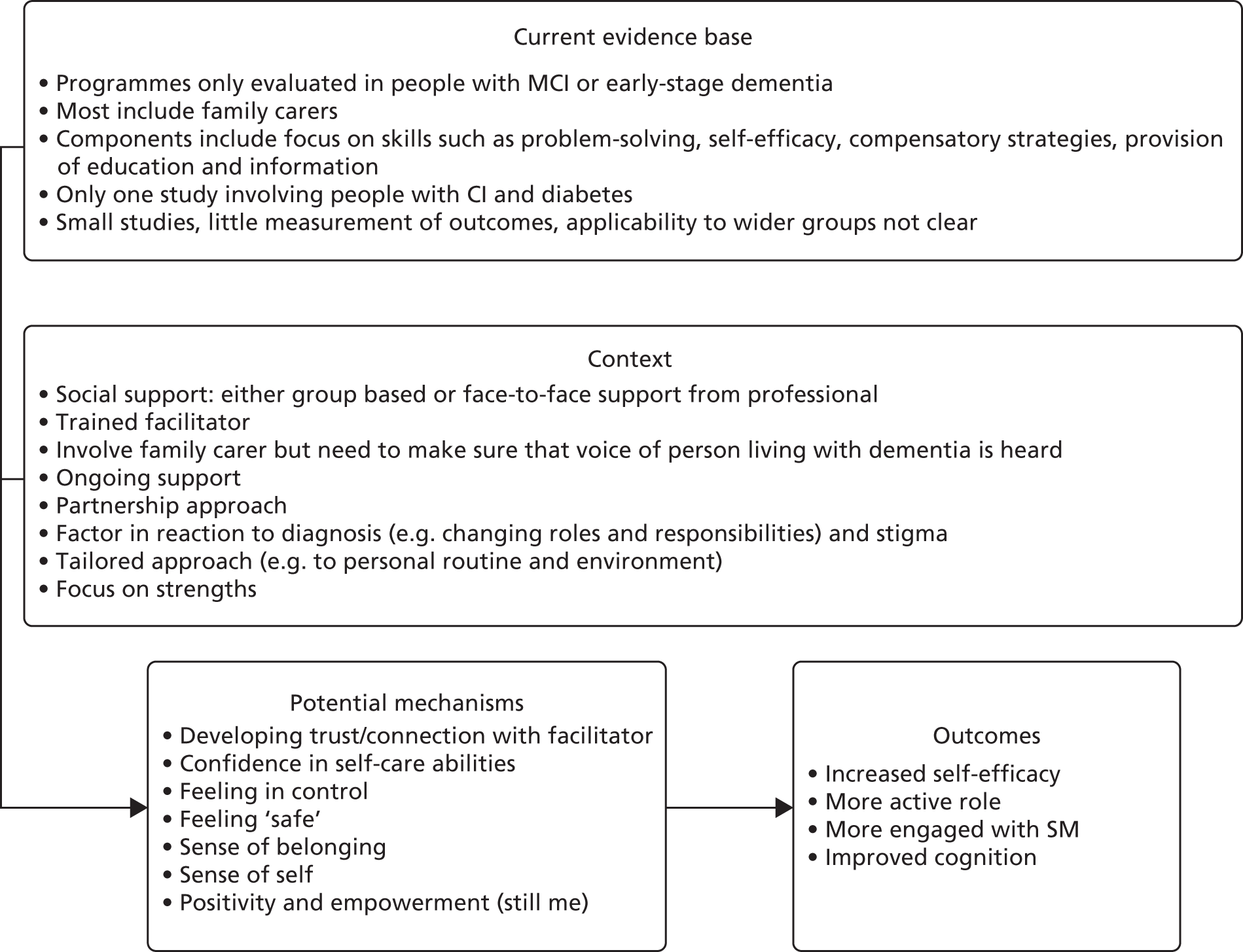

Studies on SM for people with dementia are mostly qualitative or small pilot or feasibility studies, and most do not report measurable health outcomes. They also tend to focus on couples or people who have a partner, which excludes many who might potentially benefit. 147 This literature does, however, provide valuable insights into what needs to be in place to support independence and appropriate outcomes in people living with dementia, much of which might form the basis for programmes for people with dementia and diabetes. Potentially important components of such programmes include the need to focus on the abilities and strengths of people with dementia rather than their disabilities,109,110 on emotions rather than problems,109 on building confidence62,121 and on respecting participant autonomy and enhancing empowerment. 106 Social interaction may also be important. 106,110,143 A small feasibility study121 suggested that SM interventions may foster independence and reciprocity, and promote social and clinical support. A larger RCT involving 136 people living with dementia–spouse dyads found that a group-based intervention to promote SM in people newly diagnosed with dementia led to improvements in health-related quality of life in spouses and in cognition in people living with dementia, although quality-of-life improvements in spouses were not maintained at longer-term (9-month) follow-up. 106 Further details of these studies can be seen in Appendix 7 and an overview of some key potential aspects of context, mechanism and outcomes can be seen in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Summary of evidence around SM programmes for people living with dementia. CI, cognitive impairment; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Fostering confidence

The importance of confidence as a mechanism is underlined in a number of studies. For example, a systematic review130 of self-care interventions for older adults with diabetes (not dementia) found that interventions using concepts of self-efficacy, self-determination and proactive coping were effective in influencing diabetes self-care behaviours, leading to improved health outcomes. For example, proactive coping helped people to anticipate threats and act accordingly. In addition, work by Clare et al. 86 and Claire148 suggests that there is a link between independence, functional ability and self-care behaviour and feelings of confidence or self-efficacy in people living with dementia and their family carers. Clare et al. 86 argue that a loss of confidence can promote disability:

Negative influences can contribute to the development and maintenance of ‘excess’ disability – where the extent of functional disablement is greater than would be predicted by the degree of impairment: an example would be where an individual loses confidence.

Clare et al. 86

Therefore, interventions that promote confidence or self-efficacy may lead to increased engagement in SM activities. This ties in with literature on enablement, in which the focus is on what the person with dementia can do both cognitively and functionally to maintain their quality of life. 148 The process of enablement has been sponsored by the Department of Health in England in their 2010 guidance Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained,149 which made it clear that HCPs need to be proportionate in their assessment of risk with people living with dementia and that a ‘safety first’ management perspective disempowers people living with dementia. Although we found no literature on enablement for people living with dementia and diabetes, there is some evidence that teaching goal-directed activities can improve the cognitive functioning of people living with dementia. 85,86 It has been suggested that the enablement philosophy can also be applied to identifying and treating accompanying physical illness and providing information and support to caregivers,148 although this has not been tested in people living with dementia and diabetes.

We included several studies that focused on the functional abilities of older people with multimorbidity. A case study138 of co-ordinated care for people with complex chronic conditions supported the idea that care co-ordination programmes should focus on supporting service users and carers to become more functional, independent and resilient. The authors suggested that this is preferable to a purely clinical focus on managing or treating medical symptoms. Two studies58,65 involved occupational therapists (OTs) delivering interventions aimed at improving the functional abilities of older people with multimorbidity. One, which found improvements in activities of daily living, suggested that an important aspect of the intervention was that OTs used motivational interviewing and goal-setting to understand patient priorities and to negotiate solutions in partnership. 58 In the other, a RCT of community OT for people living with dementia and their carers, the authors found that 10 sessions of OT led to improvements in mood, quality of life and health status at the 12-week follow-up. 65,95,96 The intervention involved the use of compensatory strategies to adapt activities of daily living to the disabilities of patients and adapt environments to their cognitive disabilities. Primary caregivers were trained to use effective supervision, problem-solving and coping strategies to sustain both their own and the patient’s autonomy and social participation. A potential mechanism was an increased sense of control.

Although these studies do not focus on SM for dementia and diabetes, and although they focused on people living with mild or early-stage dementia, they may provide transferable learning for the development of SM support for people living with dementia and diabetes, for example the focus on family relationships, maintenance of an active lifestyle, psychological well-being and techniques for coping with memory changes. Furthermore, they promote positive attitudes, with an emphasis on equality and collaboration between participants and facilitators. 106 Working with families is clearly key. However, studies highlight the need to ensure that the voice of the person living with dementia is heard and that their needs are balanced with those of the carer. 115 Qualitative studies on SM support for people living with dementia found that information provision may be aimed at carers, leaving people living with dementia feeling powerless,115 that carers may inadvertently take control away from people living with dementia109 and that people living with dementia can find support inappropriate or stifling. 132 As one stakeholder put it:

. . . an intervention should work at a level that people . . . particularly early stages of dementia . . . can be included . . . so it’s not decisions being made about them . . .

Dem 1

Further RCTs of SM support for people with diabetes and cognitive impairment are under way but these focus on intellectual disability150 and learning disability151 rather than dementia. Although the results are not available, the protocols do provide information about components of the intervention. For example, the intervention being evaluated by Walwyn et al. 151 involves establishing participants’ daily routines and lifestyles, identifying all supporters and helpers and their roles, setting realistic goals for change and monitoring progress against agreed-on goals, while the Taggart et al. 150 study involves evaluating an adapted version of DESMOND (The Diabetes and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed patients with T2D programme). 152 The adapted version includes longer sessions, increased use of pictures in the educational information, greater involvement of carers, more repetition and interactive sessions, and a strong focus on celebration and fun,153 components that would appear appropriate for people living with dementia.

Context–mechanism–outcome 1 summary

Interventions for people with dementia and diabetes need to address the stigma that this group faces. There is evidence that people living with dementia have the potential to be involved in SM, although most research currently focuses on SM skills in people with mild or early-stage dementia, and there is little evidence relating to SM in people with dementia and a comorbid condition such as diabetes. However, the literature identified important components of interventions that are likely to be transferable to people with dementia and diabetes; for example, focusing on strengths and abilities, being emotion focused rather than problem focused, respecting autonomy and working to build confidence and empowerment. The involvement of family carers in programmes is key, but it is important to balance the needs of the people living with dementia with those of the carer to ensure that people living with dementia are not disempowered.

Context–mechanism–outcome 2: person-centred approaches to care planning

Programme theory

If delivery systems promote a person-centred and partnership approach to care, allowing HCPs to understand the individual needs and abilities of people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (C), then (1) HCPs feel confident that they are acting in the best interests of people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (M), and (2) this generates trust between HCPs and people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (M), leading to a better fit between care planning and patient and carer needs, and (potentially) a lessening of the burden of medicalisation experienced by people living with dementia and diabetes and their families (O).

Identifying patient and carer priorities

People living with dementia and diabetes have two chronic conditions with different trajectories. Dementia will generally ‘have a progressive or stepwise pattern of progression in illness severity, symptoms and disability over time, which will require continual adaptation to new issues or limitations’,154 whereas diabetes may have a more constant course with longer periods in which to adapt, but the trajectory of each is likely to have an impact on the other. Supporting people living with dementia and diabetes, and their families, with these ambiguous trajectories along the route from early-stage dementia to end-of-life care is a difficult clinical enterprise. Delivering appropriate and sustainable care for people living with dementia and diabetes requires a change from a curative, biomedical strategy to a more person-centred approach whereby patient priorities are at the forefront. 155 The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centred care as being ‘respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’, and is a hallmark of high-quality care. 156

Maintaining independence and engagement with day-to-day activities was a clear priority for participants in all groups (e.g. people with dementia and diabetes, older people with diabetes, people with dementia). 59,70,100,113,114,132 For example, a qualitative study100 of older patients with type 2 diabetes found that their primary goal in diabetes SM was engagement with their day-to-day activities, rather than maintaining biomedical parameters. The authors concluded that HCPs have to prioritise each patient’s life experience when providing advice about diabetes management. This was supported by our stakeholder interviews, as seen in the following quotation from a general practitioner (GP):

But actually at this stage [referring to when people have complex health needs] people are interested in autonomy, mobility you know, retaining as much function and independence as they can, being a burden on their families you know, so all the normal things and they’re often much, much more important than a lot of the medical stuff.

Diab 12

Person-centred approach to self-management in people living with dementia and diabetes

A recognition of patient motivators and goals, and negotiation of a mutually agreed management plan, could improve adherence to SM regimens. 98,102,118,125,157 For example, in a qualitative study of older adults with diabetes (aged ≥ 65 years), participants reported a variety of motivators for maintaining SM once a routine had been established. HCPs needed to understand what these motivators were and work with patients towards their SM goals. Feedback from participants included the observation that HCPs did not listen to, or were dismissive of, their concerns and, as a result, this reduced the trust that they had in their HCP. 118

A Cochrane review137 looked at SM interventions for people with diabetes and severe mental illness. Searches, which were conducted in 2016, identified only one RCT that met the inclusion criteria. This was a small study (n = 64) involving adults with type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (average age 54 years). The intervention, which involved a 24-week education programme, had no significant impact on glycaemic control, although there were small improvements in diabetes knowledge and self-efficacy. The authors suggested that the lack of impact could, in part, be explained by the lack of a person-centred approach within the programme.

We found only limited evidence that evaluated the impact of our identified context on glycaemic control or adverse events. Of the six included sources that focused on people with dementia and diabetes, only one59 evaluated an intervention. This was a controlled study evaluating the provision of personalised education sessions for diabetes and cognitive impairment. The study showed an increase in self-efficacy and a short-term effect on glycaemic control (HbA1c levels initially declined but had returned to baseline after 6 months). The authors suggested that this supported a need for long-term connection and maintenance programmes for this group.

Trusting relationships

A key element of achieving a person-centred or partnership approach to care is building a long-term trusting relationship with the people living with dementia and diabetes and their family69,70,72,73,79,102,125,142 that involves listening and valuing the patient’s subjective health experiences:

It’s allowing a two-way exchange of information, isn’t it, about how different conditions might affect things.

Res 1

The impact that a trusting relationship between HCPs and people with dementia can have on patient care is illustrated in a qualitative study87 exploring GPs’ perceptions of what is meant by a ‘timely’ diagnosis of dementia and how this differs from an early diagnosis. The timely diagnosis was seen as requiring a more patient-centred approach that recognises the issues that families go through in reconciling the stigma of diagnosis and consequences for the future. The authors argue that a ‘diagnosis’ of dementia was not a discrete act ‘. . . but a collective, cumulative, contingent process’. 87 The GPs in this study saw the diagnosis as a journey for both them and the patient and their family in reaching a nuanced and contingent resolution, leading to a co-constructed diagnosis. This study, like others,39 highlights how vital relationship continuity can be in creating trust and helping to secure appropriate and timely care for people living with dementia.

A feasibility study122 explored the use of patient-centred consultations for improving medication adherence and management among older people with diabetes. The intervention included the use of dialogue tools whereby the patient was asked to describe their day living with diabetes, to ‘. . . encourage participants to reflect, engage in dialogue, and verbalize their experiences’. 122 The findings showed that people living with type 2 diabetes felt listened to, which generated a trusting relationship with their HCP. Participants also reported feeling more capable of managing their diabetes, although, as this was a feasibility study, the authors did not measure the impact of the intervention on glycaemic control. HCPs reported that the process supported patient-centred partnership but the authors cautioned that the dialogue tools are, by themselves, not enough to ensure patient-centeredness; adequate communication skills are also required to prevent the process becoming a tick-box exercise.

We know that for people who have previously self-managed their diabetes (often for many years), the transition to needing SM support can be difficult and distressing. 39,142 Although we found some literature on enablement for people living with dementia (see Context–mechanism–outcome 1: embedding positive attitudes towards people living with dementia), we found no evidence about how (or whether or not) a patient’s previous diabetes knowledge or SM strategies are acknowledged or used by HCPs.

Shared decision-making

The management of people living with dementia and diabetes represents a complex process with difficult trade-offs to be made, so methods of involving patients and families in shared decision-making are important aspects of achieving person-centred care. In a multicentre cluster RCT of older people with type 2 diabetes (not dementia), Branda et al. 71 introduced a decision aid that encouraged shared decision-making between participants with diabetes and HCPs. There was no difference in glycaemic control between the decision-aid intervention group and the control group. However, the decision aids did facilitate patient-centred practice and co-construction of decision-making related to diabetes management. The participants also felt more engaged in their diabetes management despite the lack of clinical outcomes. Similarly, Mathers et al. ,111 in a RCT of a decision aid for patients with type 2 diabetes (adults aged between 42 and 87 years), found no statistical effect on glycaemic control (HbA1c decreased in both intervention and control groups), but decision-making by patients was more autonomous and promoted more realistic expectations and greater knowledge. The authors suggested that this can lead to better long-term SM practices.

Both of these studies involved the use of a decision aid in a single consultation between a clinician and a person with diabetes. In the Mathers et al. 111 study, the mean duration of the consultation was 15.31 minutes. People living with dementia and diabetes are likely to need interventions that involve more frequent contact and include repetition and reinforcement. Decision-making involving people living with dementia is likely to be complicated by issues of consent, concordance and the appropriateness of treatment for people with dementia.

Context–mechanism–outcome 2 summary

Self-management of diabetes in people with dementia is likely to be contingent on the development of a trusting relationship between the HCP and the person living with dementia and diabetes and their family, involving understanding and incorporating patient priorities and how these may change over time. This in turn facilitates a person-centred approach to care planning and diabetes management. There is currently little research that looks at person-centred approaches to diabetes management in people living with dementia, and further research is needed to develop interventions that support partnership working and incorporate the consideration of the risk-benefit balance for different treatment options.

Context–mechanism–outcome 3: developing skills to provide tailored and flexible care

Programme theory

If HCPs are expected to develop skills that enhance the delivery of individualised and tailored care to people with dementia and diabetes (e.g. enablement rather than management, listening/communication/negotiation, shared decision-making), then this legitimises the work and creates the expectation in patients and in HCPs that diabetic care for people living with dementia is important (M), leading to the provision of more tailored diabetes care (O) and better engagement with SM by people living with dementia and diabetes and their family carers (O).

Tailored and flexible