Notes

Article history

The research reported in this monograph was funded as project number 96/17/01.

Declared competing interests of authors

Colette Hoare has been funded by the NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA) R&D programme. Professor Hywel Williams: four of Hywel Williams' staff are currently employed on NHS HTA or Regional Research and Development grants.Two other Cochrane Skin Group staff members receive NHS R&D core support. He is a paid editor for the Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin. He is also a life member of the National Eczema Society. He does not work as a consultant to any Pharmaceutical Company although he has received payment from Novartis for lectures on the epidemiology of atopic eczema in 1999. One of his research staff was previously funded by Crookes Healthcare International to conduct a pilot study into the role of nurses in running dermatology follow-up clinics. Professor Alain Li Wan Po has acted as occasional lecturer or consultant for Boots HealthCare Ltd, Novartis, Zyma, SmithKline Beecham, Yamanouchi and Warner Lambert.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2000. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising.

Chapter 1 Background and aims

The problem of atopic eczema

What is atopic eczema?

Atopic eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterised by an itchy red rash that favours the skin creases such as folds of elbows or behind the knees. The eczema lesions themselves vary in appearance from collections of fluid in the skin (vesicles) to gross thickening of the skin (lichenification) on a background of poorly demarcated redness. Other features such as crusting, scaling, cracking and swelling of the skin can occur. 1 Atopic eczema is associated with other atopic diseases such as hay fever and asthma. People with atopic eczema also have a dry skin tendency, which makes them vulnerable to the drying effects of soaps. Atopic eczema typically starts in early life, with about 80% of cases starting before the age of 5 years. 2

Is atopic eczema ‘atopic’?

Although the word ‘atopic’ is used when describing atopic eczema, it should be noted that around 20% of people with otherwise typical atopic eczema are not atopic as defined by the presence of positive skin prick test reactions to common environmental allergens, or through blood tests, which detect specific circulating immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. 3 The word ‘atopic’ in the term atopic eczema is simply an indicator of the frequent association with atopy and the need to separate this clinical phenotype from the ten or so other forms of eczema such as irritant, allergic contact, discoid, venous, seborrhoeic and photosensitive eczema, which have other causes and distinct patterns. The terms atopic eczema and atopic dermatitis are synonymous. The term atopic eczema or just eczema is frequently used in the UK, whereas atopic dermatitis is used more in North America. Much scientific energy has been wasted in debating which term should be used.

How is atopic eczema defined in clinical studies?

Very often, no definition of atopic eczema is given in clinical studies such as clinical trials. This leaves the reader guessing as to what sort of people were studied. Atopic eczema is a difficult disease to define as the clinical features are highly variable. This variability can be in the skin rash morphology (e.g. it can be dry and thickened or weeping and eroded), in place (e.g. it commonly affects the cheeks in infants and skin creases in older children) and time (it can be bright red one day and apparently gone in a couple of days). There is no specific diagnostic test that encompasses all people with typical eczema and which can serve as a reference standard. Diagnosis is therefore essentially a clinical one.

Up until the late 1970s, at least 12 synonyms for atopic eczema were in common usage in the dermatological literature, and it is not certain if physicians were all referring to the same disease when using these terms. A major milestone in describing the main clinical features of atopic eczema was the Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria of 1980. 4 These are frequently cited in clinical trial articles, and they at least provide some degree of confidence that researchers are referring to a similar disease when using these features. It should be borne in mind however that these criteria were developed on the basis of consensus, and their validity and repeatability is unknown in relation to physician's diagnosis. 3 Some of the 30 or so minor features have since been shown not to be associated with atopic eczema, and many of the terms, which are poorly defined, probably mean something only to dermatologists. Scientifically developed refinements of the Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria, mainly for epidemiological studies, have been developed by a UK working party, and these criteria have been widely used throughout the world. 5 According the these criteria,6 in order to qualify as a case of atopic eczema, the person must have:

-

an itchy skin condition plus three or more of:

-

past involvement of the skin creases, such as the bends of elbows or behind the knees

-

personal or immediate family history of asthma or hay fever

-

tendency towards a generally dry skin

-

onset under the age of 2 years

-

visible flexural dermatitis as defined by a photographic protocol.

Binary or continuous disease?

It is unclear whether atopic eczema is an ‘entity’ in itself or whether it is part of a continuum when considered at a population level. Some studies have suggested that atopic dermatitis score is distributed as part of a continuum. 3 Although it may be appropriate to ask the question: “How much atopic eczema does he/she have?” as opposed to “Does he/she have atopic eczema – yes or no?”, most population and clinical studies require a categorical cut-off point and tend to include well-defined and typical cases.

Is it all one disease?

It is quite possible that there are distinct subsets of atopic eczema, for example those cases associated with atopy and those who have severe disease with recurrent infections. Until the exact genetic and causative agents are known, it is wiser to consider the clinical disease as one condition. Perhaps sensitivity analyses can be done for those who are thought to represent distinct subsets (e.g. those who are definitely atopic with raised circulating IgE to allergens, or those with severe disease and associated asthma). 3

The prevalence of atopic eczema

Atopic eczema is a very common problem. Prevalence studies in the last decade in Northern Europe suggest an overall prevalence of 15–20% in children aged 7–18 years. 7 Standardised questionnaire data from 486,623 children aged 13–14 years in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) suggest that atopic eczema is not just a problem confined to Western Europe, with high prevalence found in many developing cities undergoing rapid demographic change. 8 There is reasonable evidence to suggest that the prevalence of atopic eczema has increased two- to three-fold over the past 30 years, the reasons of which are unclear. 9 No reliable incidence estimates are available for atopic eczema.

Age

Atopic eczema is commoner in childhood, particularly in the first 5 years of life. One study of 2365 patients who were examined by a dermatologist for atopic eczema in the town of Livingston, Scotland, suggested that atopic eczema is relatively rare over the age of 40, with a 1-year period prevalence of 0.2%. 10 Nevertheless, adults over 16 years made up 38% of all atopic eczema cases in that community. Adults also tend to represent a more persistent and severe subset of cases.

Severity distribution

Most cases of childhood eczema in any given community are mild. One recent study by Emerson and colleagues found that 84% of 1760 children aged 1–5 years from four urban and semi-urban general practices in Nottingham were mild, as defined globally by the examining physician, with 14% of cases in the moderate category and 2% in the severe category. 11 Disease severity was not the only determinant of referral for secondary care, however. This severity distribution was very similar to another recent population survey in Norway. 12

How does atopic eczema affect people?

Direct morbidity has been estimated in several studies using generic dermatology quality-of-life scales. It has been found that atopic eczema usually accounts for the highest scores when compared with other dermatological disease. Specific aspects of a child's life that are affected by atopic eczema are:

-

itch and associated sleep disturbance (Figure 1)

-

ostracism by other children and parents

-

the need for special clothing and bedding

-

avoidance of activities such as swimming, which other children can enjoy, and

-

the need for frequent applications of greasy ointments and visits to the doctor.

Family disturbance is also considerable with sleep loss and the need to take time off work for visits to healthcare professionals. 7

FIGURE 1.

Despite the public's tendency to trivialise skin disease, the suffering associated with the intractable itching of atopic eczema can be greater than other illnesses such as asthma and heart disease. 7

Economic costs

In financial terms, the cost of atopic eczema is potentially very large. One recent study of an entire community in Scotland estimated the mean personal cost to the patient at £25.90 over a 2-month period with the mean cost to the health service of £16.20. 13 If these results were extrapolated to the UK population, the annual personal costs to patients with atopic eczema based on lower prevalence estimates than recent studies suggest would be £297 million. The cost to the health service would be £125 million and the annual cost to society through lost working days would be £43 million making the total expenditure on atopic eczema £465 million per year (1995 prices). Another recent study from Australia found that the annual personal financial cost of managing mild, moderate and severe eczema was Aus$330,818 and $1255, respectively, which was greater than the costs associated with asthma in that study. 14

What causes atopic eczema?

Genetics

There is strong evidence to suggest that genetic factors are important in the predisposition to atopic eczema. In addition to family studies, twin studies have shown a much higher concordance for monozygotic (85%) when compared with dizygotic twins (21%). 15 Preliminary work has suggested that a marker for IgE hyper-responsiveness might be located on chromosome 11q, but this has not been consistent. It is possible that the tendency to atopic eczema might be inherited independently from atopy.

Environment

While genetic factors are probably a very important factor for disease predisposition, there are numerous general and specific clues that point strongly to the crucial role of the environment on disease expression. 16 It is difficult to explain the large increase in atopic eczema prevalence over the past 30 years, for instance, in genetic terms. 9 It has been shown that atopic eczema is commoner in wealthier families. 17 It is unclear whether this positive social class gradient is a reflection of indoor allergen exposures or whether it reflects a whole constellation of other factors associated with ‘development’. Other studies have shown an inverse association between eczema prevalence and family size. 18 This observation led to the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, that is that children in larger families were protected from expressing atopy because of frequent exposure to infections. 19 Some evidence for this protective effect of infections on atopic eczema has been shown in relation to measles infection in Guinea Bissau. 20

Migrant studies also point strongly to the role of environmental factors in atopic eczema. It has been shown that 14.9% of black Caribbean children living in London develop atopic eczema (according to the UK diagnostic criteria) compared with only 5.6% for similar children living in Kingston, Jamaica. 21 Other migrant studies reviewed elsewhere have consistently recorded large differences in ethnic groups migrating from warmer climates to more prosperous cooler countries.

Further work has suggested that the tendency to atopy may be programmed at birth and could be related to factors such as maternal age. 22 The observation that many cases of atopic eczema improve spontaneously around puberty is also difficult to explain in genetic terms alone. 2 Specific risk factors for eczema expression in the environment are still not fully elucidated. Allergic factors such as exposure to house dust mite may be important but non-allergic factors such as exposure to irritants, bacteria and hard water may also be important. 23

Pathophysiology

A number of mechanisms and cells are thought to be important in atopic eczema and these are reviewed in detail elsewhere. 1,24 Microscopically, the characteristic appearance of eczema is that of excess fluid between the cells in the epidermis (spongiosis). When severe, this fluid eventually disrupts the adjacent cells in the epidermis to form small collections of fluid, which are visible to the naked eye as vesicles. In the chronic phase, atopic eczema is characterised by gross thickening of the epidermis (acanthosis) and an infiltrate of lymphocytes in the dermis. The theory that unifies the various abnormalities of atopic eczema suggest that blood stem cells carrying abnormal genetic expression of atopy cause clinical disease as they infiltrate and remain in the mucosal surfaces and skin. There appears to be a failure to switch off the natural predominance of Th2 helper lymphocytes, which normally occurs in infancy, and this leads to an abnormal response of chemical messengers called cytokines to a variety of stimuli. The underlying mechanism of disease may be either abnormalities of cyclic nucleotide regulation of marrow-derived cells or allergenic over-stimulation that causes secondary abnormalities. Some studies have suggested a defect in lipid composition and barrier function of people with atopic eczema – a defect that is thought to underlie the dry skin tendency and possibly enhanced penetration of environmental allergens and irritants, leading to chronic inflammation.

Does atopic eczema clear with time?

Although the tendency towards a dry and irritable skin is probably lifelong, the majority of children with atopic eczema appear to ‘grow out’ of their disease, at least to the point where the condition no longer becomes a problem in need of medical care. A detailed review of studies that have determined the prognosis of atopic eczema has been reported elsewhere. 2 This review suggested that most large studies of well-defined and representative cases suggest that about 60% of childhood cases are clear or free of symptoms from disease in early adolescence. Many such apparently clear cases are likely to recur in adulthood, often as hand eczema. The strongest and most consistent factors that appear to predict more persistent atopic eczema are early onset, severe widespread disease in infancy, concomitant asthma or hay fever and a family history of atopic eczema.

How is atopic eczema treated?

The management of atopic eczema in the UK was summarised in a paper jointly produced by a British Association of Dermatology and Royal College of Physicians Working Party in 1995. 25 The article described the management of atopic eczema in three stages. The first line of treatment involved providing an adequate explanation of the nature of disease as well as advice on avoiding irritants. The role of emollients in adequate quantities was emphasised, as well as prompt treatment of secondary infections. Topical steroids were highlighted as the mainstay of treatment, though care regarding the duration of treatment, site and age of the person treated was emphasised. Antihistamines were only recommended for their sedative action. Cognitive behavioural techniques were also mentioned as being important to some families. Allergen avoidance, for example the reduction of house dust mite or dietary intervention, was described as a second-line treatment, as was treatment with ultraviolet light under specialist care. Third-line treatment (always under the care of a specialist) included such treatments as short bursts of systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, evening primrose oil and Chinese herbal medicines.

These recommendations were made on the basis of consensus from a wide range of practitioners and patient advocates. Although some recommendations were based on RCTs, many were not. It is unclear, therefore, how many of these recommendations are truly beneficial to patients. New developments since the publication of these recommendations include increased use of a double layer of protective bandages (‘wet-wraps’) with or without topical steroids, ‘newer’ once-daily topical corticosteroids such as mometasone and fluticasone, and possibly some increased use of potent systemic agents such as cyclosporin A. Other new potent topical preparations such as tacrolimus and ascomycin derivatives are probably going to become available in the near future. 26

How is care organised in the UK?

Most children with atopic eczema in the UK are probably managed by the primary care team. This includes advice from pharmacists, health visitors, practice nurses and family practitioners. About 4% of children with atopic eczema are referred to a dermatologist for further advice. 11

The quality of service provided by secondary care for eczema sufferers has recently been audited by the British Association of Dermatologists. Although most departments provided a high-quality service, some aspects of care, such as the administration of simple standardised record forms could be improved. 27,28

Compliance (or more correctly, concordance) seems to be a major cause of apparent treatment failures and a recent study suggested that this was often due to a poor understanding of the chronic nature of the disease, a fear of topical corticosteroids and the belief that all atopic eczema is caused by a specific allergy. A survey in Nottingham has found that most mothers worry that topical steroids cause adverse effects, though many were not able to distinguish between weak and strong ones. 29

The National Eczema Society is the UK's self-help organisation for atopic eczema sufferers and people with other forms of eczema. It has a well-organised information service and national network of activities geared to help eczema sufferers and their families. Sources of alternative care for atopic eczema sufferers abound in the community ranging from the highly professional to elaborate expensive diagnostic and therapeutic measures of dubious value.

How are the effects of atopic eczema captured in clinical trials?

Outcome measures used in trials have recently been reviewed by Finlay. 30 Most outcome measures have incorporated some measure of itch as assessed by a doctor at periodic reviews or patient self-completed diaries. Other more sophisticated methods of objectively recording itch have been tried. Finlay drew attention to the profusion of composite scales used in evaluating atopic eczema outcomes. These usually incorporate measures of extent of atopic eczema and several physical signs such as redness, scratch marks, thickening of the skin, scaling and dryness. Such signs are typically mixed with symptoms of sleep loss and itching and variable weighting systems are used. It has been shown that measuring surface area involvement in atopic eczema is fraught with difficulties,31 which is not surprising considering that eczema is, by definition, ‘poorly-defined erythema’. Charman and colleagues recently performed a systematic review of named outcome measure scales for atopic eczema and found that of the 13 named scales in current use, only one (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis, SCORAD) had been fully tested for validity, repeatability and responsiveness. 32 Quality-of-life measures specific to dermatology include the Dermatology Quality of Life Index30 and SKINDEX. 33 The Children's Dermatology Life Quality index has been used in atopic eczema trials in children.

The authors are aware that most clinical trials of atopic eczema have been short term, that is about 6 weeks. This seems inappropriate in a chronic relapsing condition. Very few studies have considered measuring number and duration of disease-free relapse periods. It is impossible to say whether modern treatments have increased chronicity at the expense of short-term control in the absence of such long-term studies.

Why is a systematic review needed?

The authors suspect that little research has been done into primary and secondary prevention of atopic eczema. Research is also probably very limited in non-pharmacological areas of treatment such as psychological approaches to disease management. Even for traditional pharmaceutical preparations, the choice of treatments for atopic eczema by patients or their practitioners is complicated by a profusion of preparations whose comparative efficacy is unknown. 5 Thus, the current British National Formulary lists 19 classes of topical corticosteroids available for treating atopic eczema and a total of 63 preparations that combine corticosteroids with other agents such as antibiotics, antiseptics, antifungals and keratolytic agents. 34 How can a family practitioner make a rational choice between so many preparations?35

Systemic treatments for severe atopic eczema have only been partially evaluated. There are plenty of trials, for instance on expensive drugs such as cyclosporin A (which may have serious long-term adverse effects), yet to the best of our knowledge, there is not a single controlled trial on oral azathioprine – a much cheaper and possibly safer and more effective treatment that is currently widely used by British dermatologists. 36 In other areas, there is a profusion of small studies, which do not have the power to adequately answer the therapeutic questions posed.

The authors are also aware that many clinical trials have not asked patients enough of what they think about the various treatments under test. There is an opportunity in a systematic review, therefore, to redress the balance of outcome measures used in clinical trials towards the sort of measures that are clinically meaningful to patients and their carers.

Public concern over long-term adverse effects such as skin thinning and growth retardation from use of topical corticosteroid preparations has not been matched by long-term studies on atopic eczema sufferers. Individuals with atopic eczema often resort to self-prescribed diets, which can be nutritionally harmful, or they may turn to ‘alternative’ tests and treatments which may turn out to be beneficial or expensive and harmful.

Thus, there is considerable uncertainty about the effectiveness of the prevention and treatment of atopic eczema. This combination of high disease prevalence, chronic disability, high financial costs, public concerns regarding adverse effects, lack of evaluation of non-pharmacological treatments, concern regarding the clinical relevance of trial outcome measures and the profusion of treatments and care settings of unknown effectiveness is why a scoping systematic review of atopic eczema treatments is needed. It is hoped that the review will form the basis for identifying, prioritising and generating further primary, secondary and methodological research.

Summary of the problem of atopic eczema

-

The terms atopic eczema and atopic dermatitis are synonymous.

-

The definition of atopic eczema is a clinical one based on itching, redness and involvement of the skin creases.

-

About 20% of people with clinically typical atopic eczema are not ‘atopic’.

-

The word ‘atopic’ in atopic eczema serves to distinguish it from the ten or so other types of ‘eczema’.

-

Atopic eczema affects about 15–20 % of UK schoolchildren.

-

About 80% of cases in the community are mild.

-

Adults form about one-third of all cases in a given community.

-

Disease prevalence is increasing for unknown reasons.

-

The constant itch and resultant skin damage in atopic eczema can lead to a poor quality of life for sufferers and their families.

-

The economic costs of atopic eczema to both State and patient are high.

-

Genetic and environmental factors are both critical for disease expression.

-

Non-allergic factors may be just as important as allergic factors in determining disease expression and persistence.

-

Imbalances of T-lymphocytes and skin barrier abnormalities are both important in explaining the pathological processes of atopic eczema.

-

About 60% of children with atopic eczema are apparently clear or free of symptoms by adolescence.

-

Early onset, severe disease in childhood and associated asthma/hay fever are predictors of a worse prognosis.

-

Current first-line treatment in the UK includes emollients, topical corticosteroids, and sedative antihistamines.

-

Second-line treatments include allergen avoidance and ultraviolet light.

-

Third-line treatments include systemic immunomodulatory treatments such as cyclosporin A and azathioprine.

-

Most people with atopic eczema are managed by the primary care team.

-

Some people with atopic eczema seek alternative treatments.

-

A systematic review is needed to map out where high quality research has been conducted to date with the aim of resolving some areas of uncertainty and in order to identify knowledge gaps to be addressed by further primary research.

Research questions asked in this review

The remit of this project is to provide a summary of RCTs of atopic eczema with the main aim of informing the NHS R&D Office and other research commissioners of possible research gaps for further primary, secondary or methodological research. It is also hoped that the review will be of some use to healthcare providers, physicians involved in the care of people with atopic eczema and also to atopic eczema sufferers and their families by placing current treatments in context with their evidence base. The main research questions asked in this review are therefore:

-

What therapeutic interventions have the RCTs of atopic eczema covered so far? The main output of this coverage question is a summary of research gaps for further research, with research commissioners, charities and researchers as the main target audience.

-

What treatment recommendations can be made by summarising the available RCT evidence using qualitative and quantitative methods? The main output for this question are detailed summaries of available RCT evidence for different interventions for atopic eczema along with the authors' interpretation of the data based on the quality, magnitude of treatment effect, and clinical relevance of that evidence.

An impossible task?

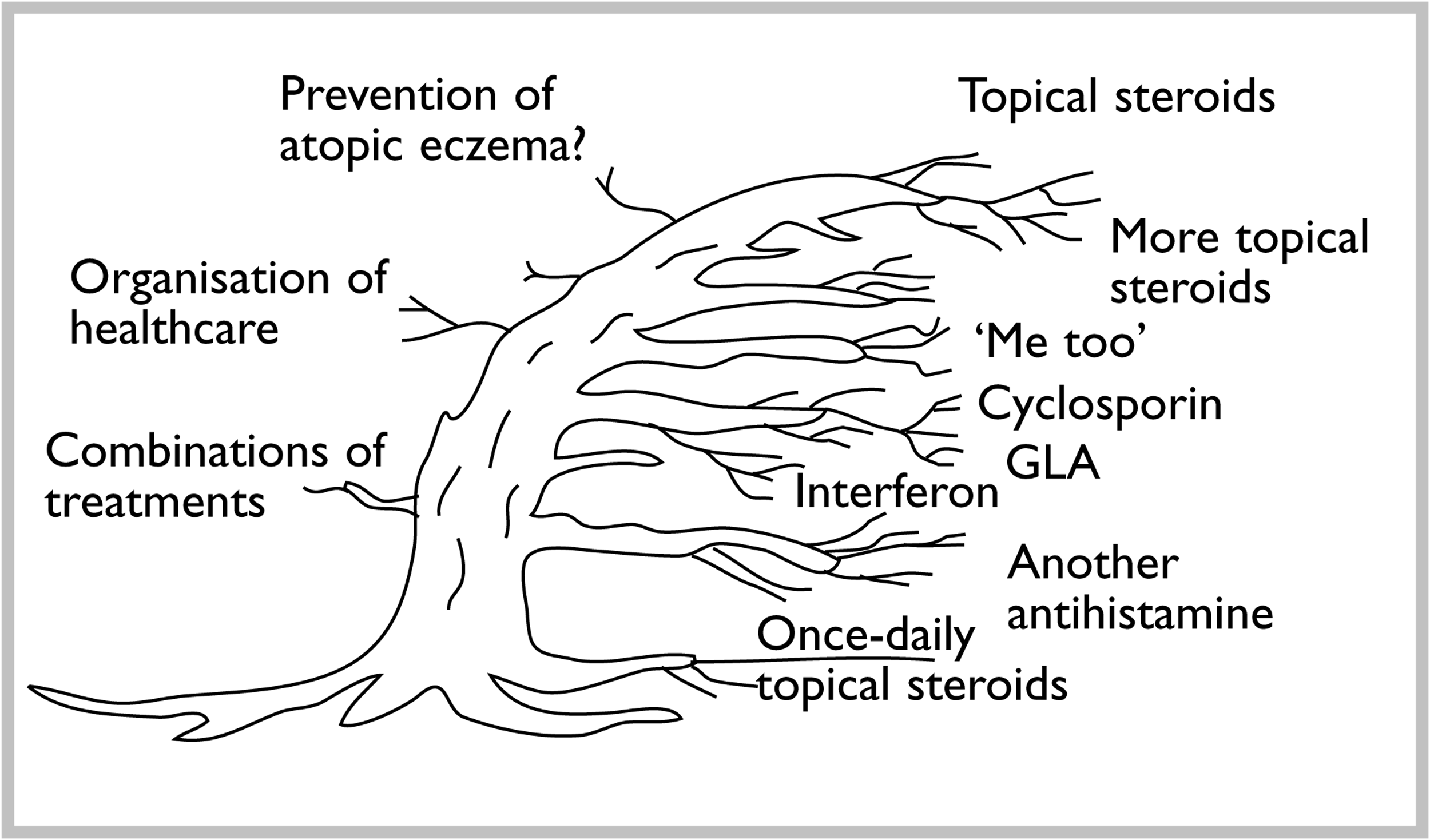

It is unrealistic to attempt to summarise the entire ‘treatments of atopic eczema’ into a single Cochrane-style systematic review, as such a task would take years and cover several volumes. Atopic eczema is a complex disease with at least 40 different treatment approaches and specific questions that can be asked of each treatment group. What is more realistic is to produce a ‘sketch’ or ‘map’ of RCTs of atopic eczema, to quantitatively summarise a few areas of conflicting studies where possible, and to qualitatively review the others in a form that would be helpful to clinicians and patients. Such an approach could also act as ‘seed reviews’ for subsequent, more detailed Cochrane systematic reviews.

A question or data-driven review?

The very broad-ranging scoping nature of this review implies that it cannot be hypothesis-driven. Even in just one area of atopic eczema management such as dietary prevention, there are at least six separate systematic reviews that can be asked of the available data:

-

Does maternal avoidance of certain potentially allergenic foods prevent atopic eczema and if so, by how much in offspring at high risk (i.e. family history of atopy) versus those at normal risk?

-

Does dietary manipulation in pregnancy reduce the severity of atopic eczema in offspring?

-

Does exposing infants to allergens at an early stage of their immune development help by making them tolerant to substances that they will inevitably encounter in later life?

-

Does exclusive breastfeeding protect against atopic eczema?

-

Does prolonged breastfeeding with supplementation protect against atopic eczema?

-

Does the early introduction of solids bring on atopic eczema?

Trying to answer similar questions for each of the 40 or so interventions used for the treatment of atopic eczema would be impossible in one short report.

This review is therefore unashamedly a data-driven one. It is a review that aims to map out what has been done in terms of RCTs in atopic eczema to date and to reflect and comment on the coverage of already researched areas in relation to questions that are commonly asked by physicians and their patients.

The authors are aware that there is a danger that a data-driven review can serve to amplify and perpetuate current trends in evaluating minor differences between a profusion of similar pharmacological products. The authors have mitigated against this inevitable hazard by drawing attention to gaps that have not been addressed when summarising the reported studies, and also by including a comprehensive section on ‘unanswered questions’ in chapter 14 of this report, based on the views of contemporary researchers, physicians and patients.

Chapter 2 Methods

General methods structure

This review has been prepared along the guidelines developed by the University of York37 and those issued by the NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme38 and uses methods developed by the Cochrane Collaboration39 where possible.

Types of studies included in the review

Only RCTs of treatments for atopic eczema were included in the data summaries as other forms of evidence are associated with higher risks of bias. In order to be included as an RCT, a randomisation procedure was described, the study compared two or more treatments in human beings, and the study was prospective. In addition, the RCTs had to be concerned with therapeutic issues in relation to the prevention or treatment of atopic eczema. Thus, RCTs that involved evaluating cellular or biochemical responses of patients with atopic eczema after testing or injecting them with substances such as histamine were not included. Although they might inform future therapy, they were not therapeutic trials. Studies of possible increased incidence of drug adverse effects in atopic people compared with non-atopic people were also excluded. Studies also had to include at least one clinical outcome. Therefore, studies that only reported changes in blood tests or cellular mechanisms were excluded.

| Definite atopic eczema | Possible atopic eczema | Not atopic eczema |

|---|---|---|

| (include if study was an RCT) | (implies original paper must be obtained and read before a judgement is made to include or exclude by one of the authors based on additional features such as a good clinical description of atopic eczema with atopy) | (implies that the authors did not accept this term as representing atopic eczema) |

| Atopic eczema | Periorbital eczema | Seborrheic eczema |

| Atopic dermatitis | Childhood eczema | Contact eczema |

| Besnier's prurigo | Infantile eczema | Allergic contact eczema |

| Neurodermatitis atopica (German) | ‘Eczema’ unspecified | Irritant contact eczema |

| Flexural eczema/dermatitis | Constitutional eczema | Discoid/nummular eczema |

| Endogenous eczema | Asteatotic eczema | |

| Chronic eczema | Varicose/stasis eczema | |

| Neurodermatitis | Photo-/light-sensitive eczema | |

| Neurodermatis (German) | Chronic actinic dermatitis | |

| Dishydrotic eczema | ||

| Pompholyx eczema | ||

| Hand eczema | ||

| Frictional lichenoid dermatitis | ||

| Lichen simplex | ||

| Occupational dermatitis | ||

| Prurigo |

Study participants

Studies were included if participants were babies, children or adults who have atopic eczema (syn. atopic dermatitis) according to Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria,4 or as diagnosed by a physician. Terms used to identify trial participants with definite, possible and definitely not atopic eczema are shown in Table 1. Those studies using terms in the ‘definitely not atopic eczema’ category such as allergic contact eczema were excluded. Those studies using terms in the ‘possible atopic eczema’ category, such as ‘childhood eczema’ were scrutinised by one of the authors and only included if the description of the participants clearly indicated atopic eczema (i.e. itching and flexural involvement).

Main outcome measures

Changes in patient-rated symptoms of atopic eczema such as itching (pruritus) or sleep loss were used where possible. Global severity as rated by patients or their physician were also sought. If these were not available, then global changes in composite rating scales using a published named scale, or where not possible, the author's modification of existing scales or new scales developed within the study were summarised. Adverse events were also included if reported. The selection of outcome measures was explored in more detail in a focus group of consumers held by one of the authors.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes measures were changes in individual signs of atopic eczema as assessed by a physician, for example:

-

erythema (redness)

-

purulence (pus formation)

-

excoriation (scratch marks)

-

xerosis (skin dryness)

-

scaling

-

lichenification (thickening of the skin)

-

fissuring (cracks)

-

exudation (weeping serum from the skin surface)

-

pustules (pus spots)

-

papules (spots that protrude from the skin surface)

-

vesicles (clear fluid or ‘water blisters’ in the skin)

-

crusts (dried serum on skin surface)

-

infiltration/oedema (swelling of the skin), and

-

induration (a thickened feel to the skin).

Search strategy

Electronic searching

In order to retrieve all RCTs on atopic eczema treatments in accordance with inclusion criteria, a systematic and mainly electronic search strategy was carried out. The Cochrane Collaboration Handbook39 and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines for systematic reviews37 were used as templates.

The following electronic databases have been searched:

-

MEDLINE40 (1966 to end of 1999)

-

EMBASE41 with its higher yield of non-English reports (1980 to end of 1999)

-

The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCTR)42 and

-

The Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Trials Register. 43

Disease terms for atopic eczema (as a textword and MeSH term) are shown in appendix 1.

Possible trials were identified from each of the four databases by:

-

MEDLINE (Index Medicus online): the Cochrane Collaboration ‘highly sensitive electronic search string’ for RCTs was used (appendix 1). Years 1966–December 1999 were searched and yielded over 3000 references using the disease search terms in appendix 1. An iterative approach was used with retrieved papers. Once trials on specific drug types were obtained, an additional MEDLINE search was carried out employing these specific drug terms (e.g. tacrolimus) or their developmental names (e.g. FK506) combined with a general skin search (appendix 1). References were checked for possible additional RCTs of atopic eczema. Review articles were also retrieved in hard copy form and references were checked for further RCTs.

-

EMBASE (Excerpta Medica online): due to the different format of this database, an alternative search strategy was employed which was developed by the BMJ Publishing Group for its Clinical Evidence series (appendix 1). 44 Years 1980–December 1999, (the only years fully searchable on OVID), were searched. This yielded over 1000 references using the same eczema terms as for MEDLINE in Table 1. Trials that might have been on the EMBASE database from 1974 to 1979 would have been picked up by CCTR (see below), which has compiled its search of the entire EMBASE database since its inception in 1974.

-

CCTR: the Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 1999 was searched for controlled trials within the CCTR section by exploding the disease-specific search terms separated by the boolean ‘AND’ with the advanced search option. These include clinical controlled trials (quasi randomisation) and RCTs (randomisation).

-

Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register: this was searched with the disease-specific terms and kind help of the Cochrane Skin Group Trials Search Coordinator.

Handsearching

As there are over 200 specialist dermatology journals and none specific to atopic eczema, separate handsearching was not done for this report. Some trials published in journals not listed in the main bibliographic databases or published within the body of a letter to the editor might therefore have been missed. However, results of handsearching of specialist dermatology journals by the Cochrane Skin Group are kept on the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register of trials, which was searched. This included results of handsearching the following dermatology journals as at July 2000:

-

Acta Dermato-Venereologica Supplementum 1970–91

-

Archives of Dermatology 1976–98

-

British Journal of Dermatology 1991–97

-

Clinical & Experimental Dermatology 1976–99

-

Cutis 1967–99

-

International Journal of Dermatology 1985–98

-

Journal of Investigative Dermatology 1991–97

-

Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1987–99.

In addition, conference proceedings of previous symposia such as the Atopic Dermatitis Symposium, held every 3 years (initially set up by Professor Georg Rajka), and all meeting abstracts for the annual meetings of the Society of Investigative Dermatology, European Academy of Dermatology and British Association of Dermatologists have been handsearched by one of the authors and the results made available to the Skin Group Specialised Register. Furthermore, one of the authors has been prospectively handsearching five dermatology journals (Clinical Experimental Dermatology, British Journal of Dermatology, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Journal of Investigative Dermatology and Paediatric Dermatology) since January 1998, and any possible atopic eczema trials were accessed further by the team.

Other trial source

In addition to checking citations in retrieved RCTs and review articles, additional trials were sought by personal contact with atopic eczema researchers, and by writing to 37 pharmaceutical companies with a product or developing product in the area of atopic eczema.

Filtering

With the 3899 references yielded from the initial searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and CCTR a filtering process began. This was carried out manually to assess whether the reference fitted the preliminary labels of ‘trial’ and ‘atopic eczema’.

Not all references had abstracts; therefore, ‘titles only’ had to be included as possible trials to avoid premature judgement. Where doubt existed from the abstract or title, the full paper was requested and scrutinised further by two of the authors. Papers labelled as ‘rejects’ were categorised with another label to specify why they were not suitable for inclusion. This was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer in any cases of possible uncertainty.

All papers were catalogued on a specialised ProCite database. 45

Non-English studies

Studies published in non-English languages were screened by international colleagues (listed in the acknowledgement section) to see if they were possible RCTs with full data abstraction if this proved to be the case.

Data assessment

After assessment of retrieved papers for inclusion/exclusion criteria, the final list of included RCTs were subject to data abstraction with view to pooling or qualitative summary. Data abstraction forms were developed and used for those treatment groups where pooling appeared likely. Data for pooling were abstracted by two authors with discrepancies checked by a third if required. Data for qualitative summary were abstracted by one author and checked by a second.

Study quality

Methodological quality of each study was assessed using a previously described scheme where the three potential sources of bias were evaluated,46 namely:

-

the quality of the randomisation procedure

-

the extent to which the primary analysis included all participants initially randomised (i.e. an intention-to-treat analysis)

-

the extent to which those assessing the outcomes were aware of the treatments of those being assessed (blinding).

These three factors have been consistently shown to predict possible bias in effect estimates. 47 A descriptive component, rather than a score-based system, was used to quality rate the studies so that readers can see which aspects of the study reporting were deficient. Due to the sheer size of this scoping review, report authors were not blinded to the identity of the RCT authors when quality rating or data abstracting. Such blinding would have needed to be very thorough (to the point of having to conceal the interventions) as many of the RCTs are well known to one of the abstracting authors.

Quantitative data synthesis

Where pooling made sense clinically in terms of the interventions, study participants and common clinical outcomes, a meta-analysis was performed using both a fixed- and random-effects model depending on whether there was evidence of statistical heterogeneity. Odds ratios of improvement compared with the comparison intervention was used in the pooling exercises. The inverse of the variance of the outcome measures was used as weights for pooling the data from different trials. Sources of heterogeneity, such as differences in patients or formulation of interventions, were explored within the meta-analysis.

Methods of presenting qualitative results

Summarising the evidence of treatment and harm from 283 RCTs covering at least 47 different interventions in a way that would be helpful to healthcare commissioners, providers, physicians and users is challenging. There is always a conflict in such a situation of providing too much information resulting in loss of the general picture or of omitting important details in some specific areas. Readers are therefore encouraged to read the original studies for themselves where doubt occurs as to the reported data or author's conclusions in this paper.

For qualitative data summaries, the authors have adopted two systems.

-

Where six or more RCTs are identified, these are summarised in tabular form, noting the interventions and comparator plus any other treatments permitted concurrently during the study (co-treatments), study population and sample size, study design and duration, outcome measures used in the study, main reported results, quality of reporting and specific comments relating to the study. The table is introduced with a brief summary of the rationale for use of the drug and the way it is used, and appended by any additional general comments and a summary of key points.

-

Interventions with five or fewer RCTs have been summarised in text form in a way similar to that used in the BMJ Publishing Group's Clinical Evidence series. 44 After a brief introduction, the evidence of benefits from included RCTs is presented for each study, followed by a section on harms of treatment, followed by a section on author's interpretation of the data.

In many of the studies, over ten outcome measures have been reported, and it would have been impractical to document every one when presenting the reported results in the above two formats. In deciding which results to highlight in the ‘main reported results’ sections therefore, the authors have adopted a systematic approach of:

-

patient-rated global improvement or itch or sleep loss, then

-

global severity score based on several skin signs, or

-

individual skin sign scores,

in that order of preference. In many studies evaluating multiple clinical signs of atopic eczema, only those that were statistically significant (post-hoc) were highlighted in the paper's conclusions or abstract. The authors have mitigated against this post hoc bias by reporting results relating to excoriations, erythema, extent or lichenification (in order of preference) if global or other more clinically meaningful summary measures were not reported.

If pre-existing systematic reviews were identified for any of the interventions, these were highlighted at the beginning of the results sections and described in more detail. Help in deciding which outcomes were important to patients was obtained by running a focus group of four participants recruited through the Cochrane Skin Group Consumer Network.

Separating trial data from authors' opinions

Throughout the report, the authors of the current review have been careful to make a clear distinction between the facts abstracted from individual studies and the respective author's interpretation of what those results or lack of results mean. Thus, actual data on efficacy and possible harms have been clearly separated from the author's ‘comment’ section. In the comment sections of the tables, the authors have commented on issues such as clinical relevance, quality of reporting, possible sources of bias, generalisability of the study, clinical implications and research gaps.

Identifying treatments with no RCTs and future research priorities

Given the inescapable fact that a data-driven review can only identify treatments for which some evidence exists, the authors sought to list those other treatments that are currently used throughout the world in atopic eczema which are not necessarily supported by RCTs. This was done by mailing colleagues through professional networks, requesting them to add any interventions that were missing from a list of treatments supported by RCTs drawn up by the authors. Eighteen out of 23 physicians from six different countries responded to this request.

In order to help the authors identify future research priorities, another sample of colleagues was approached asking them to indicate the top five ‘unanswered’ questions in atopic eczema therapy today. Three purposive samples were sent this question on a personal letter: 12 colleagues internationally renowned for clinical atopic eczema research in the UK and abroad, four general practitioner colleagues with a known interest in skin disease, eight consultant dermatologists in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland working in district general hospitals who did not have a declared special interest in atopic eczema, six consumer members of the Cochrane Skin Group and the seven Steering Group members of the European Dermato-Epidemiology Network (EDEN). Responses were collated by the authors and new themes were added as they became apparent.

Chapter 3 Results

Included studies

A total of 283 trials were finally included. In order to help summarise the interventions, groupings were constructed on the basis of: whether treatments dealt with prevention of new disease or treatment of established disease, and similar pharmacological drug type (e.g. topical steroids), similar intervention type (e.g. dietary measures) or convenience (e.g. non-pharmacological treatments) (Table 2).

| Intervention groupings | No. of studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| A. Prevention of atopic eczema | 20 | |

| Prevention by allergen avoidance during pregnancy | 8 | 48–55 |

| Prevention by allergen avoidance after birth | 12 | 56–67 |

| B. Established atopic eczema | 254 | |

| Topical corticosteroids | 83 * | 68–150 |

| Other topicals | 12 | |

| Coal tar | 1 | 151 |

| Emollients | 6 | 152–157 |

| Lithium succinate | 1 | 158 |

| Tacrolimus | 3 | 159–161 |

| Ascomycin | 1 | 162 |

| Antimicrobial/antiseptics | 10 | 163–172 |

| Antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers | 51 | |

| Antihistamines | 21 | 173–193 |

| Chromone compound/sodium cromoglycate | 20 | 84, 194–121 |

| Nedocromil sodium | 3 | 213–215 |

| Ketotifen | 2 | 216,217 |

| Doxepin | 4 | 218–221 |

| Tiacrilast | 1 | 222 |

| Dietary interventions | 37 | |

| Dietary restriction in established atopic eczema | 9 | 223–231 |

| Evening Primrose Oil | 14* | 232–245 |

| Borage oil | 5 | 246–250 |

| Fish oils | 4 | 251–254 |

| Pyridoxine | 1 | 255 |

| Vitamin E and multivitamins | 3 | 256–258 |

| Zinc supplementation | 1 | 259 |

| Non-pharmacological | 18 | |

| House dust mite reduction | 8* | 260–267 |

| Avoidance of enzyme-enriched detergents | 1 | 268 |

| Specialised clothing | 3 | 269–271 |

| Salt baths | 1 | 272 |

| Nurse education | 1 | 273 |

| Bioresonance | 1 | 274 |

| Psychological approaches | 3 | 106,275,276 |

| Ultraviolet light | 7 | 277–283 |

| Systemic immunomodulatory agents | 30 | |

| Allergen–antibody complexes | 2* | 284,285 |

| Cyclosporin A | 13* | 286–298 |

| Levamisole | 1 | 299 |

| Platelet activating factor antagonist | 1 | 300 |

| Interferon-gamma | 3 | 301–303 |

| Thymodulin | 2 | 304,305 |

| Thymostimulin | 2 | 306,307 |

| Thymopentin | 4 | 308–311 |

| Immunoglobulin | 1 | 312 |

| Transfer factor | 1 | 313 |

| Complementary therapies | 8 | |

| Chinese herbs | 4 | 314–317 |

| Homeopathy | 1 | 318 |

| Aromatherapy | 1 | 319 |

| Hypnotherapy/biofeedback | 1 | 320 |

| Massage therapy | 1 | 321 |

| Miscellaneous | 7 | |

| Nitrazepam | 1 | 322 |

| Ranitidine | 1 | 323 |

| Theophylline | 1 | 324 |

| Salbutamol | 1 | 325 |

| Papaverine | 2 | 326,327 |

| Suplatast tosilate | 1 | 328 |

| Total RCTs | 283 |

Excluded studies

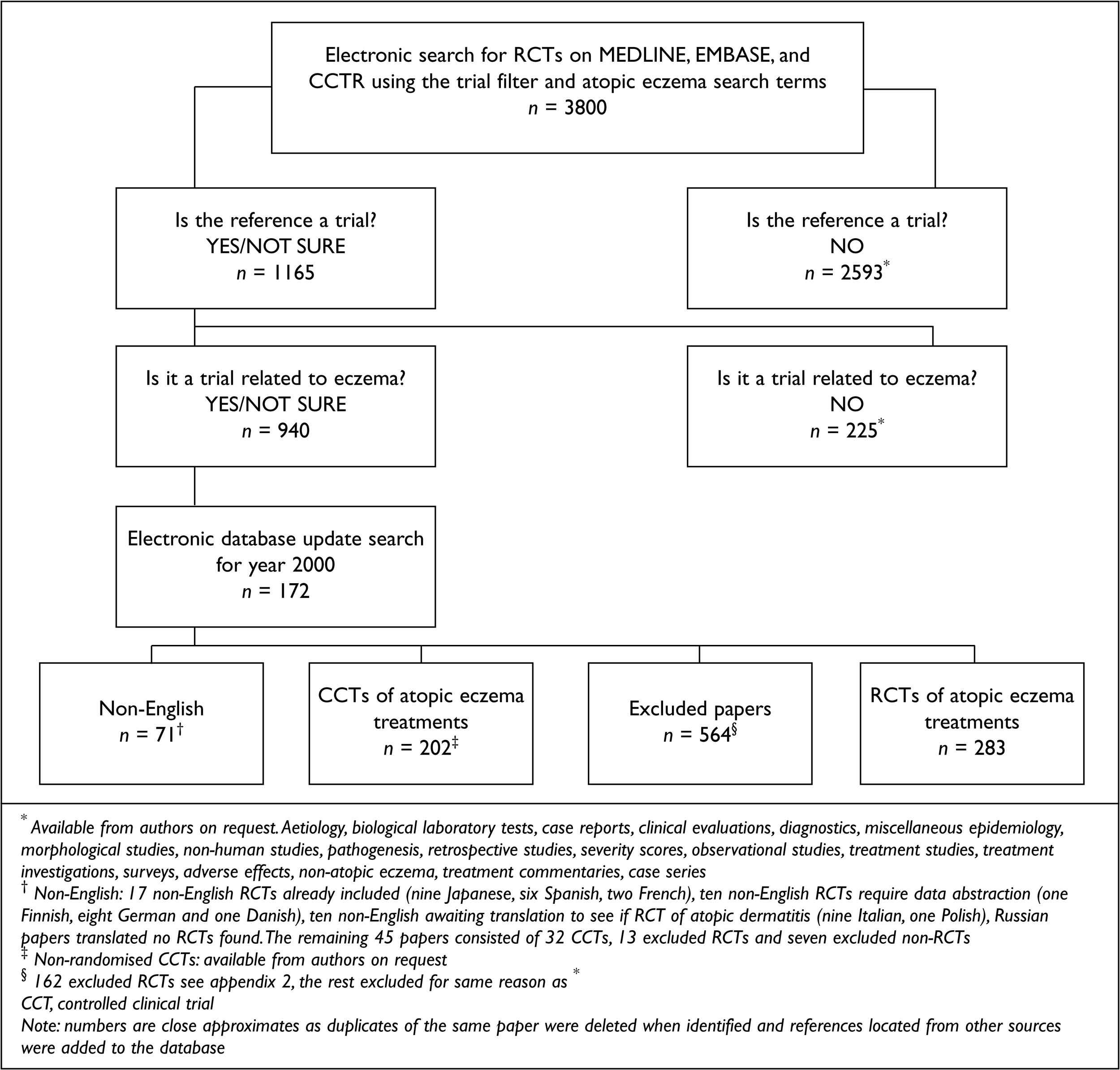

Details of excluded studies are shown in Figure 2. Further details on the 146 RCTs that included atopic eczema participants and which were excluded in the final stages are shown in appendix 2. The commonest reasons for exclusion were ‘eczema’ unspecified and combining the results of atopic eczema patients with patients who had other dermatoses.

FIGURE 2.

Details of excluded studies and process involved

Prevention of atopic eczema

Given the high and rising prevalence of atopic eczema, prevention of atopic eczema has to be a desirable goal. It seems to be a far more logical one than treating sick individuals who present themselves after a long chain of pathological effects with potentially toxic and expensive medicines, which at best only ameliorate disease symptoms. Disease prevention can be considered at several levels: that of preventing allergen sensitisation at birth (which may or may not lead to atopic disease), prevention of manifest atopic eczema in childhood, the prevention of severe disease (without necessarily altering the total prevalence of disease) and the prevention of other atopic diseases such as asthma, which may follow atopic eczema. When considering disease prevention, it is important to be clear about whether a high-risk approach (i.e. intervening with parents who have atopic disease) or a low-risk population-based approach is being used in order to try and prevent atopic eczema developing in their offspring. Although it may sound an obvious strategy to simply target children known to be at high risk of developing atopic eczema, it has been previously suggested that a high-risk approach would prevent about 31% of children from developing atopic eczema compared with about 50% if the entire population was targeted. 5 It is also important that studies that purport to prevent atopic eczema follow-up children for a long time (i.e. 4 years or more), to ensure that the programme does not just simply delay the onset of disease to a time when it could have an even more damaging effect on the child's development.

Most prevention studies have focused on the role of allergen avoidance (mainly dietary) in early life, and these are summarised in the next sections. The authors were not able to find any RCT evidence of other forms of disease prevention such as avoidance of soaps, regular use of emollients or deliberate exposure to allergens at a critical time of thymic development during infancy to try to induce tolerance to allergens.

One small study62 on 40 pregnant Venezuelan women with a history of atopic disease, randomised 20 mothers to an educational and nutritional programme (which was not clearly defined) and 20 to no intervention in an open fashion, and followed the offspring to evaluate the efficacy of the programme in preventing atopic disease. No cases of atopic eczema (definition based on the Hanifin and Rajka guide) were noted in the 20 intervention children aged 4 years, whereas ten out of 20 children in the non-intervention group had developed atopic eczema by this time. Similar beneficial differences were noted for bronchial hyper-reactivity and rhinitis. Randomisation was not described, and the study was unblinded.

One ambitious RCT of a cohort of 817 infants aged 1–2 years with atopic eczema, the Early Treatment of the Atopic Child (ETAC) study,329 tested the hypothesis that long-term treatment with the non-sedating antihistamine cetirizine, at a dose of 0.25 mg/kg twice daily, could prevent the development of asthma. Although there was no overall difference in the incidence of asthma between the cetirizine and placebo intention-to-treat populations, there was a reduced risk for developing asthma in subgroups who were sensitised to grass pollen and house dust mite, who made up 20% of the study population. Data on the severity of atopic eczema in the two treatment groups have not been published to date.

Atopic eczema prevention by allergen avoidance during pregnancy

Dietary prevention

The idea of trying to prevent atopic eczema by avoiding potentially allergenic foods and other allergens such as house dust mite during pregnancy and early life is an attractive one. Parents often believe that foods are an important cause of atopic eczema and expectant mothers are often highly motivated to do what they can to prevent illness in their offspring, particularly if there is a strong family history of atopic disease.

Many questions can be asked in relation to such prevention, for example:

-

Does avoidance of certain potentially allergenic foods prevent atopic eczema and if so by how much in offspring at high risk (i.e. family history of atopy) versus those at normal risk?

-

Does exposing infants to allergens at an early stage of their immune system development help by making them tolerant to such substance, which they will inevitably encounter in later life?

-

Does such a programme simply delay the onset of disease and does it decrease disease severity?

-

Do the benefits to children outweigh the rigorous long-term measures needed to undertake such dietary exclusions?

-

Does exclusive breastfeeding protect against atopic eczema or does prolonged breastfeeding protect against atopic eczema?

-

Does the early introduction of solids bring on atopic eczema?

All of these questions require different studies. Most have been observational in nature. This is understandable for breastfeeding, as the decision to breastfeed is not something that can be easily subject to an RCT. The decision to breastfeed can also be inextricably linked to possible confounding factors such as social class and family history of atopy, rendering observational studies of such issues difficult to interpret. These have been reviewed by Kramer. 330

A Cochrane systematic review331 has evaluated three trials of maternal antigen avoidance during pregnancy for preventing atopic disease in general in infants of women at high risk of atopy. 48,52,53 Kramer's review331 of 504 women showed that the combined evidence did not suggest a strong protective effect or maternal antigen avoidance during pregnancy on the development of atopic eczema and other allergic diseases in the first year of life of their children and some evidence that such avoidance could lead to lower birth weight. The trials also suggested a non-significant increase in pre-term birth in the intervention groups. Cord blood IgE levels were similar in both groups.

Seven RCTs48–50,52–55 that have looked at dietary manipulation during and after pregnancy are summarised in Table 3. All included studies have involved children at high risk of developing atopic eczema because of atopic disease in close family members. Although some of the interventions are broadly similar, pooling is probably not justified in view of the differences in foods avoided, duration of avoidance after birth and whether the mother continued to avoid the foods during lactation. Some key points emerging from these five studies are as follows.

-

Lack of blinding seriously threatens the validity of the studies. Even if assessors were reported to be blind to the dietary allocation, it is possible that unblinded parents revealed their allocation to assessors. Independent assessment of disease status (e.g. by using coded photographic records) is one way of reducing such a possibility.

-

Disease definition is often quite vague or nonexistent in these studies. Disease definition is particularly important in the first year of life to separate atopic eczema from simple irritant eczema and seborrhoeic dermatitis of infancy.

-

Studies that have examined avoidance of potentially allergenic foods during pregnancy produce conflicting results with two suggesting benefit and four no benefit. The highest quality reported study54 found no benefit.

-

Methodological difficulties such as failure to comply with protocols, lack of blinding and complex interventions can probably be overcome by closer involvement with consumers and by use of more objective outcome measures.

| Study | Interventions | Study population and sample size | Trial design, description and follow-up | Outcome measures | Main reported results | Quality of reporting | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chandra et al., 198653 | Dietary antigen avoidance of milk, dairy products, egg, fish, beef and peanuts throughout pregnancy and lactation vs no dietary restriction | 121 women with a previous history of a child with atopic eczema | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up until age 1 year | Proportion of infants who developed atopic eczema and severity/extent of atopic eczema | Of 109 mothers who completed study, 17 out of 55 (30.9%) children born to the dietary restriction group had eczema by 1 year compared with 24/54 (44.4%) children in the control group (p = 0.069) | Concealment of allocation unclear | Unclear if reported benefit was sustained after age 1 year |

| (Canada) | Severity scores lower in intervention group | Unblinded study | Lack of blinding serious threat to validity of study findings | ||||

| No ITT analysis (12/121 drop-outs some of whom withdrew for undisclosed reasons) | More mothers in the control group formula-fed, which could explain increased eczema | ||||||

| Miskelly et al., 198854 | Pregnant mothers restricting their daily milk intake to half a pint during pregnancy and during lactation and addition of soya-based milk if needed vs no such restrictions | 487 mothers with at least one family member suffering from atopic disease (238 intervention, 249 control) | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up until age 1 year | Atopic eczema, wheeze, nasal discharge and skin-prick tests | Eczema during first year in 41% of intervention group vs 34% in control group (p > 0.05) | Clear description of method of randomisation and concealment in sealed envelopes | High-quality study that tested hypothesis that cows' milk in early life increase risk of allergic disease and found no evidence to support this |

| Wales | Similar for wheeze and nasal discharge | Physician examining children reported to be unaware of allocation status | Definition of atopic eczema vague | ||||

| Clear description of flow of study participants | |||||||

| ITT analysis carried out | |||||||

| Lilja et al., 198948 | Maternal diet low in hens' egg and cows' milk (‘reduced diet’) vs diet with one hen's egg and 1 l of milk in last 3 months of pregnancy | 162 mothers with respiratory allergy to animal dander and/or pollens giving birth to 166 infants | Prospective randomised study with children followed-up to age 18 months of age | Proportion developing atopic diseases and positive skin-prick tests | Of 163 evaluable children, no difference in prevalence of asthma, rhinitis, urticaria or atopic eczema | Method and concealment of allocation unclear | Marked differences (64% vs 46%) in mothers with personal history of atopic eczema in the ‘reduced’ vs high dairy intake groups at baseline |

| Sweden | Proportion of obvious, probable and possible cases of atopic eczema in reduced group was 33% compared with 28% in other group | Study assessors reported to be unaware of diet allocation | No definition of atopic eczema given | ||||

| No ITT analysis | |||||||

| Zeiger & Heller, 1995,49 199351 | Mothers who avoided cows' milk, eggs and peanuts during last trimester of pregnancy and lactation and whose children avoided cows' milk until 1 year, egg until 2 years and fish until 3 years vs mothers and their children who followed standard feeding practices | 288 children born to parents at high risk of atopic disease | Prospective randomised study with children followed-up to age 7 years | Proportion developing atopic eczema and other atopic diseases, food allergy and skin-prick tests | Of 165 children evaluable at age 7 years, no differences in atopic eczema prevalence, allergic rhinitis, asthma, serum IgE noted | Concealment of allocation unclear | Very large drop-out from original randomisation |

| USA | Period of prevalence for atopic eczema in intervention group at age 7 years (estimated from graph) = 7%, identical to control group | Study patients were unblinded due to nature of intervention | Bias mis-classification of outcome cannot be ruled out due to unblinding | ||||

| Investigators recording atopic eczema also probably not blinded | Some changes between the 2 groups that were apparent at age 2 years (food allergy and milk sensitisation) were no longer present at age 7 years | ||||||

| No ITT analysis | Differences in eczema treatment not recorded | ||||||

| Falth-Magnusson & Kjellman,199252 | Total abstinence of cows' milk and eggs from week 28 of pregnancy until delivery vs normal food throughout pregnancy | 209 pregnant mothers from families with at least one allergic family member | Prospective randomised study with children followed-up to age 5 years | Prevalence of allergic disease including atopic eczema, skin-prick testing, and IgE | Of 209 evaluable children at age 5 years, 29% of children in the dietary group vs 24% in the control group had reported atopic eczema (p > 0.05) | Method and concealment of allocation unclear | Similar limitation of unblinding to other studies, though similar proportion with objective atopy argues against bias by observers |

| Sweden | Proportion with asthma, hay fever and objective atopy very similar in both groups | Study unblinded | Atopic eczema mainly based on history with some physical examination | ||||

| No ITT (hough very few drop-outs) | Remarkably high follow-up rate for such a long study (95%) | ||||||

| Hide et al., 1994,50 199655 | Mothers during last trimester of pregnancy and during lactation excluded dairy products, egg, fish and nuts or soy-based milk plus measures to reduce house dust mite at home vs mothers whose infants were fed conventionally with no control of house dust mite | 120 children identified before birth as being at high risk for atopy | Prospective randomised study with children followed-up to age 4 years | Atopic eczema (prevalence and severity), asthma, rhinitis and skin-prick tests | At age 2 years, 13.8% in the prophylactic and 24.2% in the control group had examined atopic eczema | Method and concealment of allocation unclear | Promising and persistent difference in atopic eczema prevalence in intervention group |

| England | At age 4 years, this difference persists (8% and 15% with atopic eczema, respectively) | Study participants unblinded but some attempt at blinding study assessor | Unclear if reported benefit was die to prenatal diet, feeding practices after birth or reduction in house dust mite | ||||

| No differences in eczema severity | No ITT analysis | ||||||

| Atopy also significantly less common in intervention group |

Prevention of atopic eczema through allergen avoidance and dietary manipulation after birth

One Cochrane systematic review331 of maternal antigen avoidance during lactation pooled three studies53,61,332 and found some benefit on the prevention of atopic disease in offspring from maternal avoidance of allergenic foods while breastfeeding. Methodological shortcomings in all three trials (mainly loss of blinding) argue for caution in interpreting the results. RCTs that have examined the usefulness of manipulating the diet of lactating mothers and their infants after birth with a view to preventing atopic eczema56–61,63–67 are summarised in Table 4. A further trial332 has been excluded because no separate data on atopic eczema have been given. These studies share similar methodological concerns regarding disease definition and unmasking of blinding.

Other summary points are as follows.

-

The Moore and colleagues63 study illustrates the difficulty of trying to randomise mothers to breastfeed.

-

There is no evidence to support the use of soya milk as opposed to cows' milk supplementation to children as a means of preventing or delaying onset of atopic eczema.

-

There is some evidence to support the use of extensively hydrolysed cows' milk formulae over regular cows' milk formulae in preventing atopic eczema in high-risk families, though the extent to which these unpalatable formulations can be taken up in practice is unclear.

-

There is some evidence that maternal avoidance of allergenic foods during lactation may reduce the incidence of subsequent atopic eczema and other allergic disease.

-

Some studies (e.g. Chandra et al. ,61 Marini et al. ,65 and Porch et al. ,57) mix up results of observational data with randomised participants in such a way as to render it difficult to make valid comparisons.

-

Most of the studies refer to children born to families with atopic disease.

House dust mite

No RCTs evaluating the sole use of anti-house dust mite measures to prevent atopic eczema were identified. The study by Hide and colleagues55 evaluated the combined effect of dietary allergen reduction and house dust mite reduction during pregnancy and after birth, but it is impossible to say from this study whether it was the diet, house dust mite reduction or both that was responsible for the observed benefit. Future studies evaluating a combination of interventions simultaneously should consider factorial designs in order to tease out which components of the intervention have been beneficial.

| Study | Interventions | Study population and sample size | Trial design, description and follow-up | Outcome measures | Main reported results | Quality of reporting | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kjellman & Johansson 197956 | Supplementing breastfeeding with either soy or cows' milk from weaning to age 9 months | 48 children whose parents both had atopic disease | Parallel study with children followed-up for 4 years | Obvious and probable atopic disease (atopic dermatitis, asthma, gastrointestinal allergy, urticaria and rhinitis) | 13/25 infants in the soy group compared with 11/25 in the cows' milk group developed obvious or probable atopic dermatitis (NS) | Method of randomisation and concealment not specified | Small study, which did not provide any evidence to suggest that soy supplements had any benefit for a range of allergic diseases over cows' milk |

| Sweden | No significant differences in other allergic diseases between the two groups | Probably single-blind | |||||

| Two drop-outs with no ITT analysis | |||||||

| Moore et al., 198563 | Breastfeeding for at least 3 months and avoidance of solids for this time with soya-based supplementation if required vs standard advice plus cows' milk formula if needed | 525 mothers (250 in experimental and 275 in control group) | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up until aged 1 year | Prevalence of eczema at 3, 6 and 12 months | Because only 26% of mothers in experimental and control groups exclusively breast-fed their infants, results were not analysed as a randomised study but as an observational one | Method of randomisation and concealment of allocation unclear | An ambitious large study that illustrates the difficulty in randomising mothers to breastfeed |

| England | Person recording skin lesions reported to be unaware of feeding group | ||||||

| No ITT analysis | |||||||

| Chandra et al.,67 1989a | Four different infant feeding formulae: hydrolysate cows' milk formula vs soy-based formula vs conventional cows' milk vs exclusive breastfeeding for 4 months or more | 288 ‘high-risk’ infants with family history of atopic disease among first-degree relatives. 72 children in each of the four intervention groups | Prospective RCT with infants followed up for 6 months | Atopic eczema development, eczema severity, wheezing illness, nasal discharge | Of 263 evaluable children, 7.4% in the hydrolysate group, 29.9% in the conventional milk group, 27.9% in the soya group and 18.3% in the exclusive breast-fed group had atopic eczema (not tested for statistical significance in paper) | No details on randomisation procedure or concealment thereafter | Unclear if all four groups were randomised and at what point |

| Canada | Eczema severity score did not differ between all four groups | Two examining physicians reported to be blind to formula status of child | Description I methods suggest that the exclusive breast-fed group were not randomised at all | ||||

| Incidence of any disease of allergic atopic eczematiology was lowest in hydrolysate group (p < 0.005) | No ITT analysis | Atopic eczema notoriously difficult to separate from seborrhoeic eczema at up to age 6 months | |||||

| Chandra et al., 1989b61 | Two studies: | 97 mothers who chose to breastfeed and 124 who did not | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up for 18 months | Development of atopic eczema and eczema severity | Eczema less common and milder in severity in babies who were breastfed and whose mothers were on a restricted diet (11/49 (22%) vs 21/48 (48%)) | Method of concealment of allocation unclear | Unclear if blinding of assessors was successful |

| Canada | i) mothers who planned to breastfeed allocated to either diet restricted (milk, dairy products, eggs, fish, peanuts and soybeans) or normal diet while breastfeeding | In infants fed hydrolysate, soy or cows' milk, 9/43 (21%), 26/41 (63%) and 28/40 (70%), respectively developed eczema | No blinding of eczema in breast-fed groups | Vague definition of atopic eczema, which could easily be confused with seborrhoeic eczema of infancy | |||

| ii) mothers who did not plan to breastfeed allocated to one of three formula feeds (hydrolysate, soy milk or conventional cows' milk) | Blinding of observers reported for formula-fed babies | Several exclusion from each group after randomisation | |||||

| No ITT analysis | |||||||

| Lucas et al., 199060 | Two trials: | 777 preterm infants (birth weight < 1850 g) born to parents at no increased of atopic disease | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up for 18 months after term | Development of eczema, asthma or wheezing, and allergic food reactions | No difference in the incidence of allergic disease between dietary groups in either trial at 18 months after term | Randomisation and concealment described | Large study with high-quality reporting |

| England | i) evaluated donor milk vs preterm formula as sole diet or (separately randomised) as a supplement to mother's expressed milk | In subgroup with a family history of atopy, early exposure to cows' milk increased risk of developing eczema (odds ratio 3.6 in those with a family history vs 0.7 in those without; p < 0.05) | Observers reported to be blind to infants' initial diet | Description of atopic eczema based on ‘characteristic distribution’ unclear | |||

| ii) infants allocated term vs preterm formula | ITT analysis | Finding of increased risk in atopic families post hoc and needs testing in other studies | |||||

| Validity of results to non-preterm infants unclear | |||||||

| Mallett & Henocq, 199259 | Infants assigned to hydrolysate formula vs adapted cows' milk formula | 177 infants (92 in hydrolysate group and 85 in adapted formula group) selected from a birth cohort whose immediate family had a history of allergic disease confirmed by medical records | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up for until aged 4 years | Atopic eczema occurrence and severity, asthma, food intolerance and objective tests of atopy (total IgE) | Eczema significantly more common at 4 months, age 2 and age 4 years | No details on randomisation procedure or concealment thereafter | Unblinded study |

| France | Both interventions were either alone or with breastfeeding for 4 months | At age years, 7.1% (5/70) of children had eczema in the hydrolysate group compared with 25.9% in the cows' milk group (p < 0.001) | No mention of blinding in study | No definition of eczema given | |||

| No evidence of protective effect of hydrolysate for asthma | No ITT analysis with a 30% drop-out rate at age 4 years | Despite randomisation, 58% in hydrolysate group vs 33% in cows' milk group chose to breastfeed, which could confound results | |||||

| Vandenplas et al., 199566 | Assignment to partial whey-hydrolysate formula vs regular cows' milk during first 6 months of life | 75 infants with atopic disease in at least two first-degree relatives and whose mothers chose not to breastfeed | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up for until aged 5 years | Cows' milk protein sensitivity, atopic eczema prevalence and severity, allergic rhinitis and asthma | Of 58 evaluable children at age 5 years, 7/28 children on whey had developed eczema vs 8/30 on cows' milk (NS) | No details on randomisation procedure or concealment thereafter | No description of atopic eczema definition |

| Belgium | No difference in eczema severity | Some attempt at blinding of mothers and observers | Due to the obvious taste difference to hydrolysate, unblinding highly likely | ||||

| Cumulative atopic disease of any type was 29% vs 60% in the whey vs cows' milk group | No ITT analysis with a 23% drop-out rate at age 5 years | ||||||

| Marini et al., 199665 | Hydrolysed milk formula vs conventional cows' milk formula | Children born to mothers with high atopic risk participating in an allergen avoidance programme (n = 279) whose mothers had insufficient breast milk | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up for until aged 3 years | Atopic eczema, recurrent wheeze, rhinitis, urticaria and gut symptoms | Unclear which results refer to the randomised groups | Randomisation procedure or concealment thereafter unclear | Small underpowered randomised study occurring within a large case control study |

| Italy | These mothers randomised to breastfeeding plus hydrolysate (n = 32) and breast plus cows' milk (n = 28) | Of the 25 evaluable children on hydrolysate plus breast milk, three (12%) had eczema at 3 years vs 3/22 (13.6%) evaluable children in the breastfeeding plus cows' milk group (NS) | Mothers unblinded; physicians reported to be unaware of dietary allocation | Very difficult to relate results to original randomisation schedule as so many groups from the observational part of the study mixed together | |||

| No ITT analysis with a 22% drop-out rate at age 3 years | |||||||

| Odelram et al., 199664 | Hydrolysed cows' milk formula vs ordinary cows' milk formula | 82 infants with at least two atopic family members or one atopic parent whose mothers exclusively breast-fed for 9 months | Prospective RCT with infants followed-up for until aged 18 months | Atopic eczema occurrence, asthma, rhinitis and food allergy | Of the 82 randomised infants, 11 mothers chose to continue exclusive breastfeeding and these joined nine other children to form a nonrandomised comparison group of 20 children | Method of randomization described | Small study where there is loss of originally randomised groups due to mothers' preferences |

| Finland and Sweden | Lactating mothers and their infants also avoided milk egg and fish until 12 months | Also skin-prick tests and IgE analysis | Data for atopic eczema in the remaining 32 children randomised to hydrolysate and 39 to ordinary cows' formula, were not given, but reported as not statistically significant | Study not blinded | Authors point out the difficulties in randomising such a group and conclude that “we can spare high atopy-risk families this (hydrolysate) extra burden” | ||

| No ITT analysis | |||||||