Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in October 2019. This article began editorial review in June 2023 and was accepted for publication in August 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health Technology Assessment editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Smith et al. This work was produced by Smith et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Smith et al.

Introduction

The prevalence of depression among young people is high worldwide, with rates having increased significantly since the 1980s. 1–3 Although depression prevalence varies widely across studies and countries,4 estimates are reported to be between 4% and 11% in mid-to-late adolescence (15–16 years old) and up to 20% by late adolescence (up to 18 years old),3–5 and adolescence is stated as a high-risk period for the development of depression. 6 Depression among adolescent females compared with adolescent males is estimated at 2 : 1,1–4,7–11 with more girls than boys aged 13–15 years being diagnosed with depression. 12 Studies of longitudinal GHQ-12 (General Health Questionnaire-12) scores from 1991 to 2008 suggest that British 16- to 24-year-old girls had a small but statistically significant additional increase in mental distress not found in boys, despite an overall increase for both genders over the same period. 13 While some studies have explored differences,4,12,14–17 trends also show higher prevalence rates in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+) people18 as well as in those with minority ethnic backgrounds, with these trends not fully understood. 19

Recent research suggests that young people who seek help benefit from contact with mental health services. 8 Despite this, it is known that 34–56% of young people with depression globally do not access mental health services or delay seeking help, increasing the risk of recurrent episodes. 6,8 Recent meta-analyses suggest that antidepressants for children and adolescents do not generally perform better than placebo20 and pose an increased risk of suicidal ideation and aggressive behaviour. 21 Therefore, it is important to identify a range of effective non-pharmacological alternatives. Cognitive–behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy are options, with cognitive–behavioural therapy shown to be effective in lowering the risk of depression in children and adolescents living with subclinical depression22 and interpersonal psychotherapy showing benefits for adolescents with depression,23,24 yet few trials compare their efficacy with that of alternative treatments. 25 When treatment outcomes have been compared across therapy types, no evidence has been shown of superiority, and only 8–27% of 11 to 17 year olds completed the recommended number of sessions. 24,26 These findings are echoed in national data, which show that only 36% of people complete the full Improving Access to Psychological Therapies treatment. 27

Despite clear evidence of exercise’s effectiveness in supporting adults with depression,28 the evidence base for its effectiveness in young people living with depression is scarce and of poor quality. Cochrane and other systematic reviews have examined the effects of exercise interventions in reducing anxiety in children and adolescents29–32 but for various methodological reasons studies have been unable to draw firm conclusions. There is need for well-powered and robust trials with help-seeking young people in real-world treatment settings that explore effectiveness alongside the mechanisms by which exercise may act on depression in young people.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the ways by which exercise may be beneficial for managing depression. 33 These include social mechanisms such as diversions from depressive thoughts, opportunities to learn new skills and increased socialisation,34 as well as physical mechanisms such as the release of endorphins and serotonin35 and the reduction of inflammation. 36,37 The optimal intensity of exercise required to prevent and manage depressive symptoms has not yet been established. Moderate levels of exercise have been shown to positively affect inflammation,38,39 but, more recently, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has been suggested to promote anti-inflammatory effects during recovery. 40

In summary, evidence is required to determine whether exercise is a promising and acceptable intervention for young people living with depression. 24 There is a clear need to test the feasibility of a high-quality trial in this area, in terms of the recruitment and retention of young people and the development, training and delivery of the intervention as planned, and to provide data to inform a full trial. 24 The current study was designed to ascertain the feasibility of conducting a high-quality RCT with help-seeking young people living with depression.

Aims and objectives

The primary objective of the READY (Randomised control trial of Energetic Activity for Depression in Young people) RCT was to establish the feasibility and acceptability of delivering a randomised controlled trial to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an exercise intervention to treat depression in young people aged 13–17 years. The design included an embedded process evaluation, with user and stakeholder input at three sites.

The trial aimed to evaluate (1) a high-intensity exercise intervention, (2) a low-intensity exercise intervention and (3) an active control group of social (non-exercise-based) activities, and specifically to:

-

Examine the feasibility of delivering the intervention across three sites –

-

Explore adherence to the intervention protocol by exercise professionals, including contamination of delivery between the exercise arms.

-

Examine the acceptability of the exercise interventions to young people.

-

Examine adherence to the intervention and maintenance of exercise.

-

-

Establish potential reach and representativeness –

-

Examine demographic patterns of participants referred into the study (e.g. religion, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status).

-

-

Examine the feasibility of delivering a randomised trial at scale –

-

Estimate referrals, recruitment and retention rates.

-

Examine referral pathways.

-

Estimate rates of adherence to exercise.

-

Determine the acceptability of the interventions.

-

Explore the feasibility of collecting outcome and resource use data.

-

Evaluate the safety of the trial interventions.

-

Confirm the number of required sites and sample size for the main RCT.

-

Note that the study protocol lists six aims, which are reduced to the three core aims here relating specifically to the feasibility of the study, mapping to aims 3, 5 and 6 in the original protocol.

Methods

This section contains text reproduced with permission from Howlett et al. 24 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design

The full READY trial methodology is reported in the protocol paper24 and this manuscript is reported in line with the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials) reporting guidelines for parallel-group randomised trials. 41

We conducted a three-arm, multisite, 12-week feasibility cluster RCT with 6-month follow-up to determine the feasibility of undertaking a full randomised trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of exercise as an intervention for treating depression in young people. The design had an embedded process evaluation to examine the acceptability, delivery and adherence of the intervention. An economic evaluation tested the feasibility of collecting resource use data and intervention costs.

Setting

The trial was conducted in Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and Norfolk. Young people seeking support for depression were identified from general practitioner (GP) practices, NHS Single Point of Access (SPA), Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) or schools or self-referred to the study. Interventions were delivered by registered exercise professionals (REPs) employed by local physical activity providers (e.g. Watford Football Club Community and Sports Trust, Active Luton, Norwich City Football Club Community Sports Foundation) in local community venues (e.g. sports facilities and community halls). At the time the study was designed, Sport England was funding a national network of exercise providers, often supported by football clubs. By the time the study was established, much of this funding had been withdrawn. However, there remains a range of providers that are committed to engaging with local communities to provide interventions of this kind (e.g. charitable trusts, sports clubs and local community organisations). While this removes access to a national network, it does mean that there is much more flexibility for local solutions. The study was conducted between October 2020 and August 2022.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Help-seeking adolescents aged 13–17 years with a Child Depression Inventory version 2 (CDI-2) score of 17–36 inclusive (indicating mild to moderate symptoms). (Although a lower threshold on the CDI-2 is sometimes used, the handbook specifies a threshold of 17 for mild depression. This also reduces the risk of observing floor effects on improvement following an intervention.)

-

Current treatment with antidepressants or other drugs or psychological therapy was allowed.

-

Young people understood their role in the trial and were able to complete all trial activities.

-

Young people provided assent/consent to participate where apropriate, with consent from parent/carer for those under 16 years.

-

Parent/carer/guardian agreeing to participate in the study provided information on the young person’s mental health and caregiver burden.

-

Young people and parent/carer were able to complete the questionnaires in English.

Exclusion criteria

-

Considered unsuitable by a clinician.

-

Current treatment or comorbid conditions presenting contraindications to engaging in the study.

-

Active psychosis, significant substance abuse, self-harm or suicidal ideation presenting significant risk (assessed as part of the Development and Wellbeing Assessment).

Intervention

The intervention was delivered to groups in 24 sessions over 12 weeks, with assessment at baseline (prior to the first session) and follow-up at 14 weeks and 26 weeks from baseline. Sessions were each delivered by a REP, supported by a mental health support worker (MHSW).

Young people were randomly assigned to one of the following three groups:

-

high-intensity physical exercise of alternating training sessions42,43 (e.g. basketball, football, circuit training to music, boxing drills)

-

low-intensity physical exercise of alternating training sessions44 (e.g. chair-based exercises and multiactivity sessions)

-

social active control including activities such as quizzes, computer-based games and group discussions, with the activities agreed on by the group.

Interventions were adapted due to COVID-19 restrictions (see Report Supplementary Material 5 and Report Supplementary Material 6). One main change was to ensure that participants did not share any equipment. Therefore, multiactivities were included, such as circuit training (high-intensity exercise) and chair-based exercises (low-intensity exercise). This also meant that participants were able to participate remotely if they were isolating at home. Furthermore, in the low-intensity group, to maximise attendance in the light of concerns about mental health and COVID-19, a hybrid option was offered. Young people in person were given an activity to engage in and young people logging in online were provided instructions on how to use common household objects such as stuffed socks to engage in games themselves that would mirror the activity in person. Original and alternative adapted exercises are shown in Report Supplementary Material 1 and Report Supplementary Material 2.

All intervention groups were offered a behaviour change ‘healthy living’ component to begin each session, to facilitate exercise adherence during 12 weeks of intervention, and to maintain physical activity over the longer term. 24 Group sessions were run in community settings or online where necessary and led by a REP who had been trained by a health psychologist and researcher with expertise in behaviour change (Angel Chater and Neil Howlett) for the study.

The minimum planned group size was nine participants to ensure that each group was of sufficient size to facilitate delivery. Each group was planned either as a single-sex group or to include at least two girls or two boys. Owing to the nature of the intervention, neither participants nor delivery staff were blinded to group allocation. All participants in the study continued to receive usual care.

In addition, the initial plan was for groups to have a minimum of nine participants. This was based on feedback from our early public involvement and engagement work with young people, who said that this sort of group size would be ideal as it would not be too large and overwhelming but also they would not be the sole focus of the deliverers. Where there were smaller group sizes during the feasibility trial, particularly in the high-intensity group, additional support was provided to the young people who did attend to ensure that they felt as comfortable as possible in smaller groups or on their own. This involved offering greater flexibility in the activities with which the young people could choose to engage.

Participants were followed up at 14 and 26 weeks with questionnaires on depression, quality of life, self-esteem and service use. Some young people and intervention staff were interviewed to understand their experiences of the exercise sessions and participation. Full details of the interventions and measures used were published as a protocol and in pilot work. 24,45

Screening, eligibility assessment and recruitment process

Potentially eligible young people were identified from CAMHS (tier 2 and tier 3), SPA caseloads and/or waiting lists, and searches of GP records. Young people (or parents/carers on their behalf) were also able to self-refer via the study website. The study was advertised on social media and on leaflets and posters displayed in GP surgeries, local community centres, schools and other venues. Members of the research team were also invited into schools to promote the study.

Those who met the initial consultation criteria (e.g. able to travel to the venue or attend online if necessary) and consented to their details being passed to the study team were scheduled an informed consent meeting to obtain consent (if they were aged ≥16 years) or assent (if they were aged <16 years) to participate, with consent from parents/carers if their child was <16 years old.

Screening measures were then completed online (Table 1). If eligible, the young person was assigned to a group, and if ineligible, they were referred back to their referring service and signposted to services, if appropriate.

| Time point | Study period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Randomisation | Baseline | Exercise sessions | + 14 weeks | + 26 weeks | Follow-up | |

| Enrolment | |||||||

| Eligibility screen | X | ||||||

| Referral to research team | X | ||||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||

| Randomisation | X | ||||||

| Interventions | X | ||||||

| Assessments | |||||||

| CDI-246 | X | X | X | X | |||

| Demographic information | X | ||||||

| DAWBA47 (includes SDQ) CYP completed | X | ||||||

| DAWBA (includes SDQ) carer completed | X | ||||||

| PAR-Q | X | ||||||

| PANAS48 | X | X | X | ||||

| Self-efficacy scale49 | X | X | X | ||||

| Social Support Scale50 | X | X | X | ||||

| Caregiver burden51 | X | X | X | ||||

| Adherence | X | ||||||

| Peak and average heart rate | X | ||||||

| Ratings of perceived exertion52 | X | ||||||

| Measured physical activity | X | X | X | ||||

| Y-PAQ53 | X | X | X | ||||

| COM-B measures54 | X | X | X | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L55 | X | X | X | ||||

| CSRI56 | X | X | X | ||||

| CHU-9D57 | X | X | X | ||||

| Focus groups | X | ||||||

| Adverse event monitoring | X | X | X | X | X | ||

Once a group of nine young people had been formed, the trial manager randomised the group as a whole to one of the three intervention arms using a web-based REDCAP (Research Electronic Data Capture) randomisation tool. Randomisation was allocated with a block size of three for each study site.

Baseline and follow-up measures

Young people and parents completed online measures at baseline and at 14 and 26 weeks. These included data collection on psychological, carer burden, physical activity and adverse events. Attendance, adherence and physical exertion data were recorded at each session by the REP. Heart rate data during the session were recorded using chest band monitors. All measures are listed in Table 1.

Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the study participants or the delivery staff. However, all study assessments were completed online independently by the study participants, reducing response bias during assessment. All data analysis was undertaken blinded to allocation.

Feasibility assessment

Feasibility criteria were predefined based on the stop–go criteria for the full trial:24,58

-

Referrals and recruitment –

-

Recruitment of three sites providing mental health services to young people.

-

Identification of 30–50 patients per month from record screening at CAMHS and GP practices at each site.

-

Referral of 16–20 patients per month at each site for eligibility screening.

-

Recruitment of > 10% of eligible young people.

-

Identification of an additional five sites in the main trial (based on referral data).

-

-

Acceptability –

-

Acceptability of interventions and questionnaires to young people.

-

Young people’s attendance at sessions to be > 66%.

-

REP and MHSW acceptance of training and willingness to deliver sessions.

-

Adherence to the intervention protocol by deliverers.

-

-

Completion of trial measures –

-

> 80% of main outcome measures completed at 14 weeks.

-

Successful completion of resource use data for 80% of patients at baseline and 26 weeks.

-

Feasibility of collecting average and peak heart rate and accelerometer data at 14 and 26 weeks.

-

Process evaluation

As a response to the low recruitment rate, interviews were conducted with recruitment staff to obtain a better understanding of the key barriers and to identify solutions for improving recruitment. Three online interviews were conducted with four participants from three sites to obtain a detailed description of the steps involved in identifying, determining eligibility and enrolling young people; the staff member’s perceptions of the understanding and expectations of carers and young people about trial participation; and to identify key points in the recruitment process where carers and young people declined to take part or were excluded.

We aimed to observe 5–10% of intervention sessions and used a log to record observations and ascertain fidelity to the training and potential contamination.

We conducted focus group/interviews with participants after they completed interventions. Semistructured topic guides were used to explore the acceptability of intervention and study methods and the barriers to and facilitators of participation/intervention delivery. These focus groups/interviews were audio-recorded.

The focus groups/interviews were transcribed verbatim. We aimed to thematically analyse these using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software, but, due to the small number of participants, we changed our approach. The two core members of the physical education team reviewed all transcripts and made independent notes summarising the key themes and findings to address the physical education aims. The key themes and findings were then synthesised, along with the intervention observations, to explore implementation fidelity and identify any modifications the study needed.

Patient and public involvement

Young people were actively involved in developing the research proposal, research process and all aspects of the trial. 24 This included ongoing consultation and establishment of a dedicated READY young people’s advisory group (YPAG) involving young people aged 13–17 years from across the study area who had lived experience of depression (either personally or through siblings/friends). They were recruited from three young people’s groups: Young Healthwatch Central Bedfordshire, the Youth Council of Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust and Breckland Youth Advisory Board from Norfolk. Regular online and face-to-face YPAG meetings were held in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) INVOLVE guidance59. Three parents/carers and two Public Involvement in Research group members were on the Trial Steering Committee.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

Equality, diversity and inclusion was built into the study design at every stage, as reflected in the study design, the public and patient involvement (PPI) programme and the process evaluation. Study locations were selected to reflect a range of deprivation levels, ethnic populations and city and rural locations. PPI included a wide range of young people from various backgrounds and the process evaluation planned to explore barriers to recruitment of and engagement from particular groups.

Data analysis

Sample size

A sample size of 81 randomised young people at three sites (27 per site, nine in each of three groups) from Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and Norfolk was required. This target enabled at least 20 participants per arm to complete and allowed for each of the three interventions to be completed at each of the study sites, giving nine groups in total with nine participants in each group. This was deemed sufficient to estimate the recruitment rates and completion rates, providing a point estimate within ±6% assuming an 80% confidence interval and 80% completion.

The feasibility study was not powered to detect a difference in clinical outcomes between the interventions.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent move to online recruitment and delivery significantly impacted recruitment, and for clarity agreed changes to the target sample size are noted here. Owing to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, and slow recruitment to the study, the sample size was amended twice with funder agreement. On review in June 2021, a revised sample size of 48 was agreed (six groups of eight participants, TSC minutes October 2021). For pragmatic reasons in December 2021 as the period for recruitment came to an end, a revised target of 27 participants was agreed.

Feasibility outcomes

Referral and recruitment (number screened, eligible, consented and randomised) and retention (number withdrawn or lost to follow-up) during the study are presented using CONSORT diagrams. Session attendance and heart rate adherence are reported overall and per week by treatment group, with descriptive statistics of average and peak heart rate, and proportions of session delivery type given. No formal hypothesis testing was undertaken, and all analyses are based on intention-to-treat.

The feasibility and acceptability of outcome measures were assessed by the level of data completeness, giving the numbers and proportions of those returned and completed. Descriptive statistics of outcome measures are reported by treatment group at baseline and at 14 and 26 weeks. For categorical variables, numbers and percentages of non-missing values are presented. For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation are reported, unless the data are heavily skewed, in which case the median and interquartile range are given.

The aim of the analysis is to estimate the parameters required for the sample size calculation of the main trial, namely the standard deviation. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Health economics

The aim of the economic component of this feasibility study was to test the methods and data collection tools proposed for the economic evaluation in the main trial. 24 We evaluated the completeness of data collection from patient questionnaires completed at baseline and at 14 and 26 weeks for resource use, the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five levels (EQ-5D-5L), the Child Health Utility 9D (CHU-9D) and an indicative cost estimate of the exercise intervention.

This included:

-

data collected on staff and fees for using relevant facilities

-

intervention costs in the three groups using study records and expert opinion

-

participant attendance at sessions.

Health and social care service used a modified Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)60 completed by the young person in consultation with the MHSW and with input from the parent/carer where necessary. Details of the proposed health economic evaluation have been published. 56

As recruitment in this feasibility study was lower than expected, we revised a few originally proposed health economic methods. First, we did not calculate a cost per person of the intervention; instead, we reported the costs and estimated an indicative cost based on a group size that might be more reflective of likely group sizes in practice. Second, numbers meant that cost estimates related to service use would not be informative. Instead, tables were produced showing average number of items for each resource category type. Estimates provided total numbers of items, not disaggregated. This demonstrates what resource items occur most frequently and enabled a judgement of the likely resource use items that would be important drivers of the total cost.

Third, we did not estimate quality-adjusted life-years and instead just reported EQ-5D-5L and CHU-9D values at the three time points (Table 2). Analyses were conducted in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and IBM SPSS version 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Because of the short follow-up, discounting was not used.

| Baseline | 14 weeks | 26 weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | |

| EQ-5D-5L | 13 | 0.63 (0.21) | 10 | 0.71 (0.24) | 9 | 0.73 (0.16) |

| CHU-9D | 13 | 0.73 (0.071) | 10 | 0.77 (0.12) | 9 | 0.74 (0.11) |

Ethical considerations

The trial was undertaken in accordance with the principles of ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) Good Clinical Practice, and all relevant ethics and governance processes, including the Health Research Authority approvals. Processes to manage risk were put in place to ensure timely and appropriate clinical support for the young person where necessary. Parent/carer involvement was encouraged through engagement in the study assessments and by providing a study information pack. Ethics approval was received from the East of England – Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire Research Ethics Committee (reference 20/EE/0047).

Trial registration

This trial is registered as ISRCTN66452702 (registered 9 April 2020, www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN66452702).

Results

Referrals, recruitment and retention (objective 3)

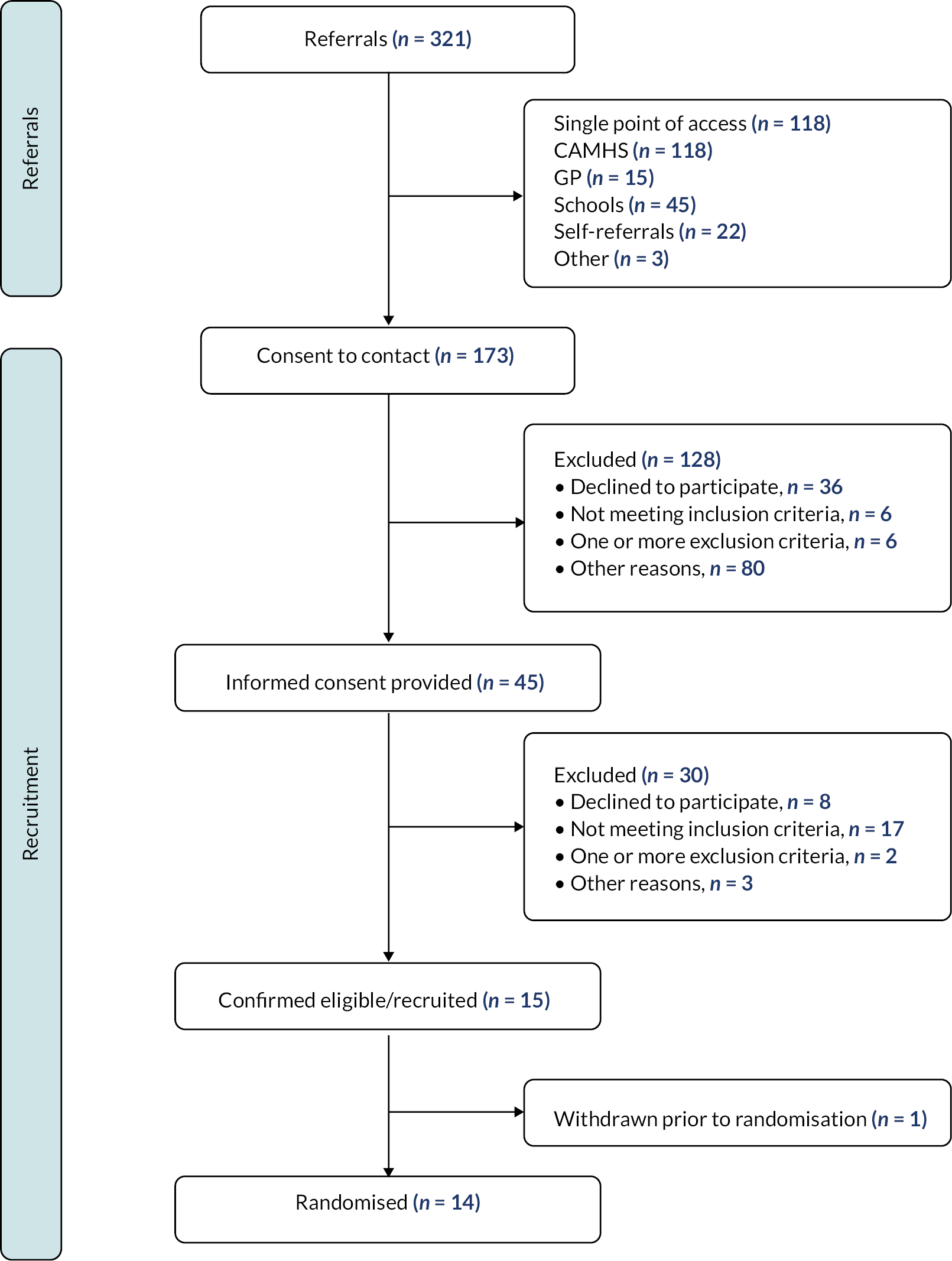

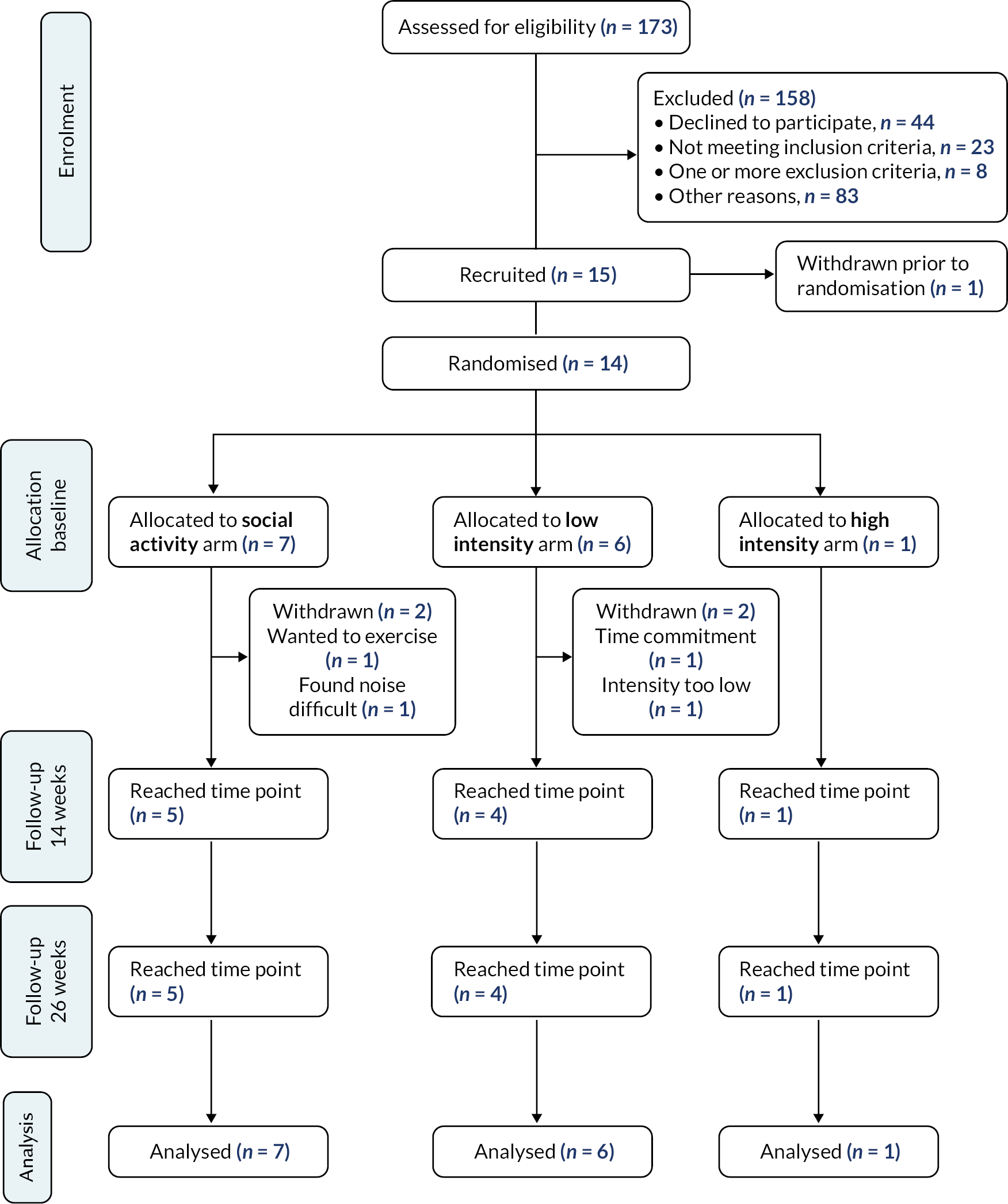

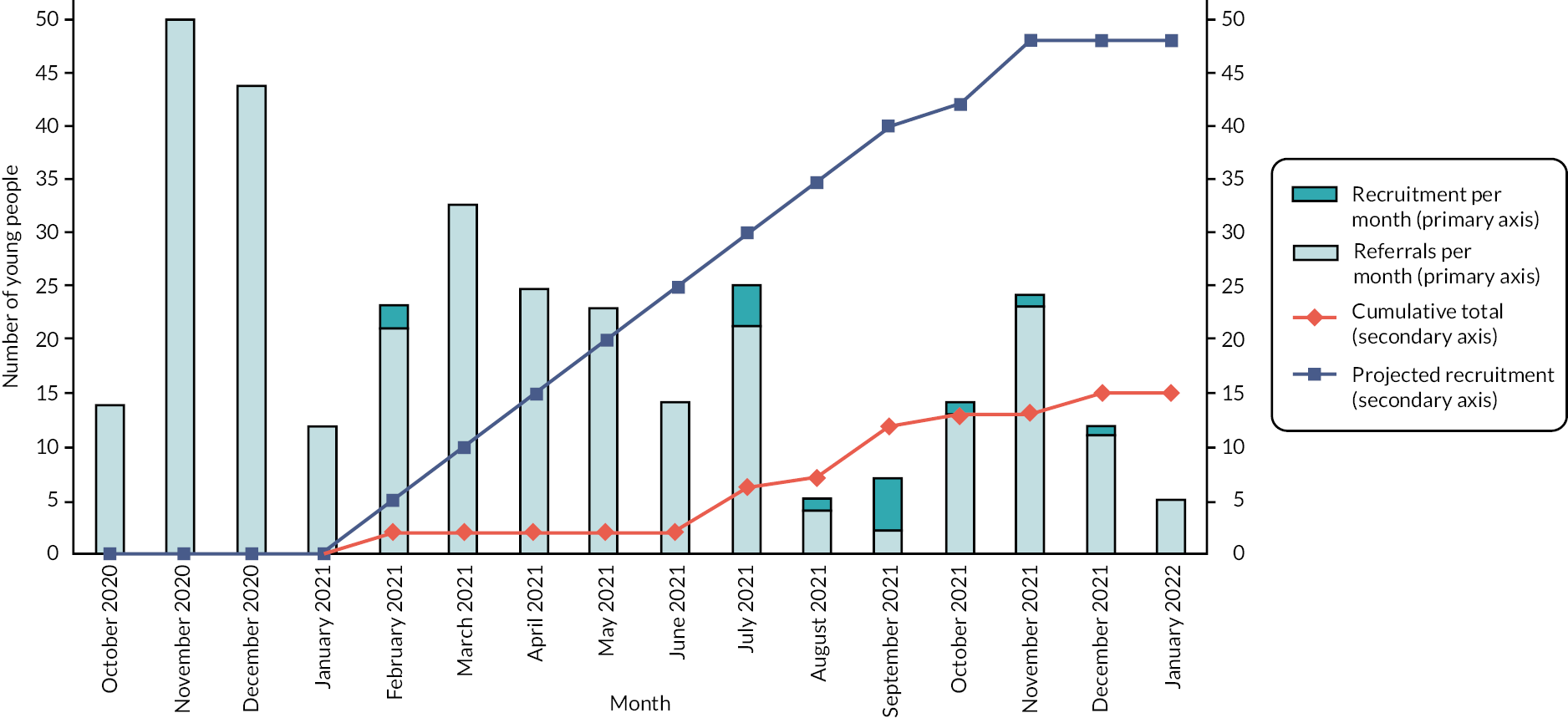

The CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1 (recruitment) and Figure 2 (overall progression). Cumulative referral and recruitment is shown in Figure 3. There were 321 young people referred to the study, 173 assessed for eligibility, 15 recruited and 14 randomised. The sample size achieved was 14 (social control, n = 7; low intensity, n = 6, high intensity, n = 1). Four participants withdrew (before 14 weeks) during the study (social group, n = 2; low intensity, n = 2). The recruitment rate was 0.31 participants per month, per site.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT study flow diagram: recruitment.

FIGURE 2.

CONSORT study flow diagram: overall progression.

FIGURE 3.

Referral and cumulative study recruitment.

The high-intensity group with only one participant was included for ethical reasons. A number of participants withdrew before group randomisation, leaving only one young person who had agreed to be randomised as the recruitment for the study came to an end. As this young person had committed to the study, a decision was made to run the intervention for that person, accepting that there would only be one person in the group.

Descriptive statistics of participant characteristics and outcomes at baseline are given in Table 3. As there was only one participant in the high-intensity group, data from this group have not been reported. The low-intensity group was predominately male (5 of 6, 83.3%), whereas all participants in the social group were female. Seven of the 13 young people identified as White British (54%), with 1 from another white background, and 4 of 13 (31%) reported a non-white ethnicity. The CDI-2 score ranged from 16 to 31, and the young people reported a significant amount of time in moderate activity per week (610–1052 minutes).

| Social (N = 7) | Low intensity (N = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 16 (13–17) | 14 (14–16) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 0 | 5 (83.3%) |

| Female | 7 (100%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Self-identified gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 0 | 5 (83.3%) |

| Female | 7 (100%) | 0 |

| Gender diverse/non-binary | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White British | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| Other white background | 0 | 1 (16.7%) |

| Indian | 3 (42.9%) | 0 |

| Pakistani | 1 (14.3%) | 0 |

| Asian | 1 (14.3%) | 0 |

| CDI-2 total score, median (IQR) | 23.00 (16.00–31.00) | 22.00 (21.00–30.00) |

| YPAQ, median (IQR) | ||

| Sports (minutes/week) | 30 (0–195) | 0 (0–0) |

| Leisure (minutes/week) | 180 (0–480) | 55 (0–120) |

| School (minutes/week) | 65 (60–100) | 60 (30–240) |

| Other (minutes/week) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–180) |

| Sedentary time (minutes) | 5212 (4958–5691) | 4885 (4492–5044) |

| Light activity (minutes) | 755 (658–881) | 851 (825–851) |

| Moderate activity (minutes) | 691 (610–1009) | 784 (749–1052) |

| Vigorous activity (minutes) | 14 (4–25) | 29 (2–35) |

Figure 3 summarises the cumulative recruitment of young people into the study. Initially the focus for identifying potential recruits was on the triage services (the SPA, or other regional variations) for referrals to mental health support into CAHMS. Although a large number of young people were referred through these triage services, this led to a small number of young people being randomised (2 from 126). Reasons for ineligibility were age (too young, n = 5) or a CDI-2 score that was too low (n = 9) or too high (n = 8). Alternative routes of recruitment via GPs and schools were also tested. Four GP practices sent 460 letters, referred 45 young people and screened 15, with 6 randomised (40% of referrals). Among schools, there were 45 referrals and 5 randomised (11%). For comparison, 2 from 46 referrals were randomised from referral agencies (4%).

Following randomisation, the overall retention rate was 71.4% (see Figure 2; Table 4). Attendance at sessions (Table 3) was 78.7% overall, ranging from 66.7% (week 4) to 90.5% (week 12). The young people in the high-intensity group (n = 1) appeared to show, overall, a consistently high attendance, with the social group (n = 7) overall showing lower attendance (lowest 57.1% at week 4). Table 4 shows that most sessions were delivered face to face, with 9.1% of the social control sessions delivered online due to COVID-19 infections. The low-intensity group was delivered in a hybrid format with 34.6% attendance online.

| Outcome | Social (N = 7), n (%) | Low intensity (N = 6), n (%) | High intensity (N = 1), n (%) | Overall (N = 14), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial retention rate | 5 (71.4) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (100) | 10 (71.4) |

| Number of invited sessions | 151 | 97 | 24 | 272 |

| Adherence: attendance a | ||||

| Overall | 110 (72.9) | 81 (83.5) | 23 (95.8) | 214 (78.7) |

| Adherence: heart rate (average) b , c , d | ||||

| Week 2 | 0/2 (0) | No data | 0/ 2 (0) | |

| Week 4 | 2/2 (100) | 0/1 (0) | 2/3 (66.6) | |

| Week 5 | 1/1 (100) | No data | 1/1 (100.0) | |

| Week 8 | 0/ 2 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 0/ 3 (0) | |

| Session delivery | ||||

| Face to face | 100 (90.9) | 53 (65.4) | 23 (100) | 176 (82.2) |

| Online | 10 (9.1) | 28 (34.6) | 0 | 38 (17.8) |

With regard to heart rate data (Table 5), the young people in the high-intensity group did not achieve the target heart rate, and three participants in the low-intensity group did achieve target (33.3% of non-missing values). The average and peak heart rate reported by group shows a higher peak and average heart rate in the high-intensity group than in the low-intensity group, indicating that there was a difference in the heart rate achieved by the study participants.

| Heart rate type | Low intensity (N = 6) | High intensity (N = 1) | Overall (N = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, mean (standard error) | Average | 92.9 (7.1) | 152.5 (15.5) | 106.1 (10.6) |

| Peak | 140.9 (4.1) | 183.0 (6.0) | 150.2 (7.0) |

Data completeness at baseline (see Report Supplementary Material 2) is high, with all outcomes at baseline achieving 83.3–100% except the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour change) motivation subscale, which was 66.7% in the low-intensity group.

Data completeness of outcomes at 14 weeks is given in Report Supplementary Material 3. All outcomes achieved 100% completion rate, except for the parental burden scale total (BSFC) in the social group (80.0%) and the accelerometer data (social group, 80.0%; low-intensity group, 50.0%). Data completeness of outcomes at 26 weeks is given in Report Supplementary Material 4. Completion rate of all outcomes at 26 weeks was 100% in the high-intensity group and 80.0% in the social group. For the low-intensity group, 100% was achieved for all outcomes, except the Youth Physical Activity Questionnaire at 75.0% and the accelerometer data at 50.0%. Efficacy outcomes at follow-up are not reported but can be supplied on application.

A note on study timelines

In the original study plan, recruitment was set to run for 6 months (from October 2020 to March 2021). As outlined elsewhere here, the pandemic had a significant impact on recruitment, and both the target sample size and the recruitment period were modified over time. A review with the funder of study progress was undertaken in June 2021. The decision was made to extend recruitment to December 2021, with a modified sample size of 48. The sample size was subsequently reduced to 27 for pragmatic reasons, and recruitment was finally completed by mid-January 2022.

Process evaluation

In the process evaluation, we examined the feasibility of delivering the intervention across the three sites (objective 1) to address adherence to intervention protocol by exercise professionals, adherence to interventions by participants, acceptability, and barriers to recruitment and participation by young people.

The additional investigation into recruitment processes was undertaken while recruitment was ongoing. We found four main barriers to recruitment.

-

Length of time between identifying potentially eligible young people and trial participation commencing. The need to deliver group activities in each trial group meant that some young people were put ‘on hold’ until enough young people had been recruited to the allocated arm, leading to substantial delays (in some cases of >6 months). This meant that some young people might have lost interest in participating or did not want to participate if only a few other young people were in their allocated group.

-

Staff were unsurprised that young people suffering from low mood, and potentially from social anxiety, were reluctant to participate in a study requiring them to meet with other young people they did not know to carry out activities that they were perhaps not confident in participating in.

-

Staff argued that the thresholds of the trial (CDI-2 score of > 16) screening measures were too high for many of the young people who would benefit from taking part in the trial. Staff felt that several young people who were highly motivated to participate were excluded on this basis (n = 9).

-

The decision to participate in the trial was not always driven by the young person. Staff received referrals and had subsequent contact with carers who were anxious that the young person in their care receive some support. Without buy-in from the young people themselves, this ultimately affected whether they took part.

Two key solutions to overcoming these barriers were proposed by staff. First, staff felt that recruitment in schools might help to increase rates of recruitment, leading to shorter waiting times before commencing intervention sessions. Second, staff wondered if eligibility screening thresholds could be relaxed to enable participation of a wider pool of young people who had reported having low mood and were motivated to participate.

The main process evaluation was otherwise completed as planned. One focus group/interview took place per site. Separate sessions were arranged for young people and staff. Four young people from the social control group took part in a focus group. One young person from each of the low-intensity and high-intensity groups took part in separate interviews. Two staff from the social control condition took part in a focus group and five staff from the low-intensity group took part in a focus group. The staff from the high-intensity group were invited to participate in a focus group but did not respond to the invitation; two out of the three staff had previously taken part in a focus group for the social control group.

Independent observations were undertaken for 8 of the 72 intervention sessions (11%). This comprised three social control sessions, three low-intensity exercise sessions and two high-intensity exercise sessions. Most sessions were observed by two team members who completed independent observations, leading to 13 intervention observation logs completed. There were five team members in total who conducted observations. Where issues with fidelity to the intervention manual were noted by the observers, these were discussed within the team and brought to the attention of the REP where appropriate.

Synthesis of process evaluation findings

There was positive feedback on the study processes and logistics: randomisation, session logistics and completion of questionnaires, although a few participants reported that the questionnaires were long.

Contamination between different conditions did not appear to be an issue. Face-to-face delivery appeared to be optimum for developing rapport and engagement and ensuring that young people engaged with the activity appropriately and safely. Online delivery was seen as an important option as it allowed some young people to engage who would otherwise not participate in the first instance and because it allowed people to attend even if they had to isolate due to COVID-19-related restrictions. However, delivery and social engagement were more challenging. When young people attended online, they often did so with their camera off and with minimal engagement via talking or using the chat function. This was very different from the in-person experience. In addition, the REPs sometimes did not know who was attending in person or online prior to the session. Lack of equipment was also an issue, with REPs suggesting alternatives during the session (e.g. socks instead of a ball), and, in future, equipment should be provided to young people engaging online so they have this ready for the session.

From the perspective of both the REPs and the young people, the main challenge of running sessions with fewer participants than intended was the impact on social engagement. This was particularly the case for the high-intensity condition, which was more akin to a personal training session than a group exercise with a social component. The young people in the group from the same school commented that this commonality helped them to form a rapport. Notably, many of them had not known each other before the intervention.

Flexibility of activity type is important to allow REPs to tailor activities. There were mixed findings around whether skills/sports-based activities should be included as some young people struggled but others enjoyed the competitiveness. Planned behaviour change technique (BCT) components were not consistently delivered as a separate ‘healthy living’ component as REPs prioritised physical activity, but exercise-related BCTs were embedded throughout the session (e.g. instructions on how to perform, and demonstration of, behaviour).

The mental health check-in was experienced by young people as awkward and checklist-like. However, co-delivery worked well as REPs and MHSWs had clearly defined roles and expertise, experience and skills, and employing a ‘youth worker’ style approach was important for successful delivery. More structured support and supervision for the MHSW was needed in case of disclosures and adverse events. The timing of training is important, as it impacts on delivery, that is, it needs to occur close to the first intervention sessions. Overall, the intervention was seen as acceptable and enjoyable, with some (albeit limited) reports of increased mood in the exercise groups, although support was needed for continued activity.

Reach and representativeness (stated objective 2).

We examined the demographic patterns of participants referred into the study (see Table 1). With a small sample it is difficult to comment on the inclusiveness of the target population with certainty. However, the numbers provide preliminary evidence of the ability to recruit young people from ethnically diverse populations (7 out of 13 were White British, 1 ‘other’ white, and 4 of 13 of non-white ethnicity).

Health economics

The intervention was provided in three venues, with an average venue cost of £1061 for the 24 sessions over 12 weeks. Each session was attended by a REP and a MHSW (assistant psychologist). The REPs and MHSWs were costed assuming agenda for change grade 4. 61 It was assumed that 90 minutes was required to allow for travel for each staff type. This gave an estimate of £2663 for the 24 sessions for staff time. Including the costs of the venue gave estimates of total costs of £3749, £3698 and £3398 for the social activity, low-intensity and high-intensity groups, respectively. It is difficult to compare the cost per person for the three groups as numbers are likely to be higher in actual practice and the high-intensity group had only one participant. If we assume that in practice groups would be offered to eight people, then the approximate costs per person of the intervention would be £460, or approximately £20 per person per session.

Of the 14 individuals randomised, the CSRI was completed for 13 (social, n = 7; low intensity, n = 5; high intensity, n = 1). At the first follow-up 10 had completed CSRI (social, n = 5; low intensity, n = 4; high intensity, n = 1) and at the final follow-up the CSRI was completed for eight individuals (social, n = 4; low intensity, n = 3; high intensity, n = 1). Table 6 shows the quantities of the different resources reported in the CSRI at baseline, 14 weeks and 26 weeks. Common items of resource use were seeing a classroom assistant at school, secondary care contacts with CAMHS, seeing a GP, and having some form of counselling. Resource use appeared to be highest at baseline and during the first period (up to 14 weeks), with lower resource use in the second, follow-up period (up to 26 weeks), even allowing for the reduced numbers of participants followed up for 6 weeks.

| Category | Baseline | 14 weeks | 26 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|

| School based | |||

| Educational psychologist | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Welfare officer | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Classroom assistant | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Special educational needs | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| School nurse | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| School counsellor | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other school based | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Drugs | |||

| Drugs – depression related | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Drugs – other | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| Secondary care | |||

| CAMHS | 6 | 12 | 0 |

| Other outpatient | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Community health and social care | |||

| Q5 – GP | 14 | 6 | 1 |

| Q5 – paediatrician | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Q5 – psychiatrist | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| Q5 – other HC | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Q5 – counselling (individual therapy) | 19 | 28 | 16 |

| TaQ5 – after-school club | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Q7 – service use by family | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 91 | 61 | 25 |

For both the EQ-5D-5L and the CHU-9D, 13 were completed at baseline (social, n = 7; low intensity, n = 5; high intensity, n = 1), 10 were completed at 14 weeks (social, n = 5; low intensity, n = 4; high intensity, n = 1) and 9 were completed at 26 weeks (social, n = 4; low intensity, n = 4; high intensity, n = 1). The mean scores on the EQ-5D-5L and CHU-9D for the three time periods are given in Table 7. Where these instruments had been completed, they were completed in full and there was a response for each question and hence overall scores for all participants who returned these instruments could be calculated. Scores for the two instruments were generally similar. Mean values were generally higher for the CHU-9D than for the EQ-5D-5L, although this difference had narrowed at the 26-week follow-up. Correlations between all 32 responses for these instruments at all three time points were calculated. The EQ-5D-5L and the CHU-9D appeared highly correlated (0.821, significant at the 0.01 level). Correlations between these preference-based instruments and the CDI-2 were –0.537 and –0.565 for the EQ-5D-5L and the CHU-9D, respectively, both significant at the 0.01 level. These correlations are negative, as decreases in both the EQ-5D-5L and the CHU-9D indicate worse health, whereas decreases in the CDI-2 represent improved health. These results indicate cautious support for the use of either the EQ-5D-5L or the CHU-9D in future studies of depression in adolescents.

| Feasibility outcome | Result | Target – stop–go criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | Three sites recruited | Three sites |

| Referrals for screening | Average cumulative referrals 20 per month across two sites | 16–20 YP per month/site |

| Randomised (% of eligible YP) | 8.1% (14/173) | > 10% of eligible YP |

| Retention | 71.4% (10/14 randomised) | High level of retention of YP |

| Adherence to sessions | Sessions attended/sessions invited. 78.7% (214/272) overall | YP’s attendance at sessions to be >66% |

| Acceptability | Acceptability was good Completion of questionnaires was high (> 80%), and attendance at sessions was high (79%) |

Acceptability of intervention and questionnaires to YP |

| The REPs and MHSWs were willing to engage in the training, and to deliver intervention sessions | REP and MHSW acceptability of training and willingness to deliver sessions | |

| Adherence to the intervention protocol | Issues with the structure and content of the intervention sessions were identified, particularly with the behaviour change ‘healthy living’ element | Adherence to the intervention protocol by intervention staff |

| Completion of trial measures | > 80% data completion (see Report Supplementary Material 2–4) Economic (resource use) outcomes: CSRI completed 14 weeks 76.9% (10/13); 26 weeks 61.5% (8/13) EQ-5D-5L and CHU-9D 76.9% (10/13) 14 weeks; 69.2% (9/13) 26 weeks Heart rate data not reliably collected during sessions. Data collected indicated adherence to session target 65% of accelerometer data returned at 26 weeks |

>80% of main outcome measures completed at 14 weeks Successful completion of resource use data for 80% of patients at baseline and 26 weeks Feasibility of collecting average and peak heart rate and accelerometer data at 14 and 26 weeks |

| Identify additional sites for full trial | Interest to participate from three additional sites | Identify five additional sites |

Impact of patient and public involvement input

At the pre-application consultation stage, young people with depression and experience of CAMHS (aged 14–15 years) identified the importance of emotional support for young people participating in the study, leading to the addition of MHSWs to co-facilitate the activity groups alongside the REPs. A LGBTQ+ group of young people (16–19 years old) and an ethnically mixed group of young women from Luton (aged 15–17 years) helped us consider the complexity of gender in relation to exercise and depression, and to enhance inclusion and diversity in our PPI. In addition, the Public Involvement in Research group at the University of Hertfordshire provided advice to the team at different stages of study development and reviewed research ethics documents.

In total, we held 12 READY YPAG meetings (a mix of face-to-face and online meetings), involving 46 young people and 10 youth leaders, between November 2019 and March 2023. YPAG members provided valuable advice to the research team regarding key stages of the research, including recruiting and engaging with schools; using social media relevant to young people; reviewing research ethics documents and data collection materials; providing advice on moving the intervention online (during the pandemic) and post-COVID-19; and co-authoring a research article about the READY YPAG. In addition, three parents of young people are on the Trial Steering Committee, and they have contributed valued advice to the research team.

Feasibility outcomes (objective 3)

The study tested the feasibility of delivering a full RCT of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of exercise to treat depression among young people. It examined recruitment, retention, adherence to interventions by young people and to protocol by intervention staff, data completion, acceptability, and barriers to and facilitators of engagement of young people.

Table 7 summarises the feasibility stop–go criteria. The most important finding is that the trial failed to recruit to target, achieving a sample size of 14 in total against a reduced target of 27. However, other aspects of the feasibility study indicate more positive outcomes. Considerable numbers of young people were identified, with more than 20 identified per month on average in two study sites. In addition, retention in the study was strong (71%), and attendance at intervention sessions remained high (> 66%). Qualitatively the exercise professionals and health support workers providing the intervention were willing to engage and reported a positive experience overall. Some issues were identified with delivery of the behaviour change element of the intervention, which can be addressed in a future study. Where young people remained in the study, data completion was very high for most data, apart from some measures of heart rate that proved challenging to collect, partly due to the nature of the process of data collection, and potentially due to COVID-19-related restrictions. The young people wore the accelerometers, and data on physical activity were successfully collected at baseline and 26 weeks. The interest from other study sites was strong, although given the challenges in recruiting study participants engagement with additional sites was not pursued. In general, if engagement with young people can be addressed, it is possible that a large-scale randomised trial could be completed in the future.

Discussion

It is widely recognised that young adolescents experiencing depression have poor outcomes. 62 There are gaps in the evidence base on effective interventions to reduce depression and improve the well-being of young people with depression. 28–32 The READY trial tested the feasibility of conducting a large RCT of exercise in young people aged 13–17 years experiencing depression. 24 We summarise the main findings, lessons learnt and implications for future research.

Summary of findings

We report on our stated objectives to examine the feasibility of delivering the intervention and to establish the feasibility of conducting a RCT. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the recruitment and delivery of interventions. Young people can be identified through a wide range of NHS and non-NHS sources. Although the study had a good number of referrals, the original target for recruitment was reduced from 81 to 27, and only 14 (8% screened) were randomised; of these, only one person was randomised to the high-intensity group. Therefore, the study did not recruit sufficient young people to demonstrate feasibility to proceed to a full-scale trial. The study did provide valuable insights and demonstrated that the intervention was acceptable, and that, once engaged, young people do complete the study. Retention rates (71%) and data completion rates (> 80%) were good and give a good indication that the key barrier to successfully delivering a study is getting the young people to engage at the outset. Through strong PPI engagement we were able to develop some recruitment strategies and identify key influencing factors to enhance engagement with and delivery of interventions. Owing to the limited number of randomised young people, there are limits to our understanding of the reach and representativeness in the study sample.

Lessons learned

Recruitment challenges (objectives 1 and 2)

Recruitment was initially delayed by 6 months due to the COVID-19 pandemic. When recruitment commenced in October 2020, referrals via referral agencies, including SPA and CAMHS, were high, but they declined steadily from January 2021 until the services withdrew support from April 2021 due to pandemic pressures. We explored with the Clinical Research Network (CRN) the possibility of placing a person in CAMHS to support the identification and referral of young people, but this was not possible due to the complexity of governance arrangements (combined with time pressures).

The focus of the NHS services was young people who had moderate to severe depression and were outside the depression range criterion for the study. Young people with lower levels of depression who were suitable for the study were not routinely contacted by the referral agency in person but received a letter referring them back to their GP. Information about the READY trial sent to young people in this group led to few referrals.

Engaging with primary care was difficult, largely because CRN support was redirected to prioritise COVID-19 research during the pandemic, and GP practices focused on research recovery programmes as the pandemic restrictions lifted. The potential for referrals from this route is significant as we know that those young people who are ineligible for CAMHS are referred back to their GP. 63,64

Potentially eligible young people identified through GP practices were only contacted once by letter, and it is likely that telephone reminders might have improved recruitment,65 although the effectiveness of various recruitment strategies is not established for this population. 66 Recruiting through GP practices is effective and relatively inexpensive (costing approximately £150 per site). It also demonstrated that more thoroughly screening the referral lists and directly contacting young people and their families leads to greater engagement.

Our active engagement with schools restarted in September 2021. READY trial presentations varied in type (assemblies, workshops, physical education sessions) depending on schools’ requirements and reached over 1000 young people. However, the second wave of COVID-19 infections that followed meant that planned in-person visits were cancelled, although pre-recorded presentations were sent to schools to be shared with pupils. Remote engagement did not work as well as engagement in-person (11% conversion from referral to recruitment).

Our PPI, process evaluation and feedback from the stakeholder group, youth workers and study staff indicate that in-person contact is important. Engagement with young people is challenging and relies on building trust, which can be difficult with remote communication such as e-mail, phone and video calls. Depression itself can be characterised by withdrawal from social contact, making building trust more challenging. 67,68 Our study design was set up for a face-to-face setting, which was disrupted by the pandemic. While it is impossible to quantify the extent to which the failure to recruit can be ascribed to the problem of building rapport and trust with young people, there are significant indications from multiple observations that this may be a key feature in successfully recruiting to this type of intervention.

Delivery challenges

We examined the feasibility of delivering the intervention (objective 1).

We delivered some hybrid sessions with both face-to-face and online participation because of the pandemic. They were delivered successfully and allowed some young people to remain engaged with the intervention. It is an important mechanism requiring further acceptability assessment.

The social nature of the exercise was seen as important by the young people who attended in person, and they felt that it contributed to enjoyment of the session. Therefore, a lack of social interaction in online sessions and in sessions with fewer in-person attendees than intended may impact on intervention outcomes.

The mental health check-ins often interrupted the flow of the intervention sessions, and young people could not always engage with these checks as privacy was important. Hybrid delivery often led to disconnection and a challenge with maintaining group dynamics with both online and in-person sessions, and some young people online and some physically in the room.

Competency in sports affected some participants’ enjoyment of groups, for example if a young person did not feel confident/skilled playing football or table tennis. In response to this, the REPs modified the exercises in line with participant feedback successfully and the young people reported more enjoyment in the modified exercises.

Streamlined management of hybrid sessions, including clear communication allowing for session organisation, and provision of necessary equipment to young people engaging online needs to be considered for future studies.

Strengths and limitations

The READY YPAG has been pivotal in this trial by providing the experiences and views of young people that have helped to guide key decisions at different stages of the research process. Training sessions provided for young people included an introduction to research designs and methods; mental health, well-being and self-care; careers in health and social care; and health research.

A key achievement of the PPI in this trial was our success in maintaining active engagement with young people in the YPAG, particularly during the national pandemic and lockdowns. On reflection, we think this is because we recruited YPAG members from existing health-related youth groups, with youth workers who were committed to supporting the YPAG and the involvement of the young people, which included support with YPAG meetings and other activities. We consulted the YPAG members regarding how to run the meetings, and at each meeting we provided feedback on how we have implemented their advice in the research. At our final meeting, YPAG members told us that they had felt valued and listened to and that their involvement had had great personal benefits, including learning about research and supporting their own mental well-being and that of loved ones.

We have identified challenges around the recruitment process and delivery of the interventions.

Access to schools and GP practices for further recruitment opportunities was not possible until after June 2021. These constraints severely hampered efforts to engage with and recruit young people to the trial for a significant period. New initiatives at the time of writing delivered through the CRN [e.g. the Transforming Research Delivery Team (Agile Team) and CRN support for GP recruitment] offer the opportunity to develop processes to engage with GPs for identifying young people who were not eligible in CAMHS and would be an important opportunity to improve recruitment. Unfortunately, the timing did not enable us to take this up for the feasibility phase but was planned for the main trial.

While we approached individual schools, a wider promotion strategy via academies and school networks needs to be considered. Such strategies could involve the CRN initiatives to introduce schools to research and help them to become ‘research ready’ schools. Although the study team were well placed to engage with this initiative, unfortunately due to the time delays in the feasibility phase we were unable to pursue this but would have done so in preparation for the main trial. Other strategies include accessing school networks through the local county councils, which now have school co-ordinators who link with local schools and their mental health teams; and appropriate charities such as HAVENS Schools that provide an intervention for anxiety in schools in Hertfordshire, but the team needed time to understand more fully how the charity works with schools to inform the READY trial. The READY team also worked with an external company (PREGO) that specialises in working with schools to promote new initiatives. While this company was instrumental in enabling the READY team to communicate effectively with the schools, a review of the work done by PREGO and how to work with it effectively over the main trial was planned.

Difficulties in developing ways of working directly with young people and their families to enhance recruitment clearly impacted young people’s participation in the trial and hence the recruitment rate.

Our PPI and process evaluation undertaken during the trial indicates that young people and families respond more fully when contacted in person, but due to the pandemic we were unable to place a person in the referral agencies. This role would be to actively screen lists for appropriate patients and telephone families to talk to them about the trial.

Complexities around delivering hybrid sessions for the interventions were difficult to manage and resolve, so early PPI engagement with the format and delivery of interventions is crucial as remote engagement was problematic.

Willingness of professionals to deliver the sessions

In general, the REPs were willing to deliver the exercise sessions, and the inclusion of a MHSW did provide additional support where required. Issues were identified with the format of the intervention as planned, and especially with the ‘healthy living’ behaviour change component of the intervention, which the REPs found difficult to deliver. It may be that the specific BCT section required a less familiar style of delivery, and the physical activity was seen as the priority. This may have been addressed by holding the initial REP training sessions closer to the delivery of the intervention and also having regular check-ins with the study team. In addition, observations of all sessions within the first 2 weeks would have helped to identify and address any issues with BCT delivery. For the social control group, the BCTs were also felt to be targeted around exercise and therefore not relevant. Consideration of how to present this component of the intervention for the REPs delivering the control group needs further consideration. We also note that recruiting providers to deliver the intervention was possible, and that there are providers in many locations that would be willing to take on delivery of this kind of intervention.

Recruiting young people and finding study sites

Several of the issues discussed above point to potential barriers to recruiting young people into a study. Key among these barriers must be establishing trust between a study team and the potentially eligible young people. On the other hand, the study demonstrated that identifying potentially eligible young people was possible, with considerable numbers of young people identified through the referral agencies (the SPA to CAMHS), through primary care practices and through schools. However, once young people have been identified, finding effective ways to engage them constitutes a critical barrier to successful recruitment in any future study. The effect of the pandemic, which emphasised withdrawal to a group of children already prone to being weary about engaging with the wider world, among other things, is much more difficult to judge. However, the consistent failure of studies in the literature to recruit to target69 points to this issue as important to address in general. The young people in focus groups did not note any issues about disclosing their depression, although we note that it is possible that young people feeling uncomfortable about this might not have consented to take part in the trial.

The impact of the pandemic on study feasibility

Taking the data as a whole, there are several reasons to assume that the pandemic had a significant impact on the feasibility of delivering the trial as intended. The data clearly show that young people seeking help for mental health can be identified in significant numbers (via triage services, GP practices, schools and social media). Although there are fewer data available, it is also clear that once the young people had been randomised to the study, completion of and engagement with the intervention sessions and completion of the study measures were maintained at a high level. While some issues are yet to be addressed with how the intervention was delivered, the study team identified a range of services that were willing to deliver the intervention, and the staff in these services remained committed to engaging with the young people in the study groups. Last, the study data collection methods were robust, with few missing data due to process errors.

There were a range of processes and procedures that were complicated by pandemic restrictions. Delivering the interventions online was possible, but the engagement of the young people involved was uncertain. The ability of the study team to gain approvals for amendments was also significantly impacted, limiting the range of in-trial adjustments that could have been implemented. Although these impacts were important, their impact on trial feasibility is most likely limited.

The key barrier to delivery in this trial appears to have been the ability to engage with the young people identified during screening and encourage them to take part in the trial. Evidence suggests that building rapport and trust with young people is a key element of successful engagement with this group. 65–71 Although undertaking recruitment online might have solved a particular issue in ensuring limited social contact as required by the pandemic-related restrictions, it is clear that this impacted significantly on the staff’s ability to engage and build rapport with the young people being screened for inclusion.

Overall, it is reasonable to conclude that the trial may well have been feasible if face-to-face recruitment had been possible, as described in the original bid documents.

Future research and implications for decision-makers

Developing appropriate recruitment strategies via NHS, GP practices, schools and social media and early engagement with the local CRN to support the process would help recruitment. Collaborations between the NHS services and sports delivery partners could help to increase capacity to deliver interventions. However, in-person contact rather than remote consultations and delivery are likely to be important.

The role of community engagement (social media, public health agencies, community groups) needs to be further explored. Strong PPI and engagement via young people’s advisory groups (including YPAGs) is important to ensure that research is relevant to young people.

A range of sources suggest that a key task is to build engagement and trust with young people seeking help. Hard-pressed services with little time tend to resort to remote forms of communication that may not be helpful in establishing engagement with young people. An important question then remains around understanding how to provide the available resources that would allow successful engagement and improve recruitment into research studies.

The available evidence suggests that the intervention merits further evaluation, assuming that the shortcomings related to recruitment and engagement can be addressed to enhance participation in a trial. This would include building on our process evaluation and conducting in-depth face-to-face work with young people and their families to better understand their concerns. The evidence base suggests that the trial processes as otherwise designed worked well, and the interventions were largely delivered as envisaged. There remains a significant need to provide evidence-based support for this group of young people.

Conclusions

Key learning points

A large-scale RCT is not feasible based on this study, and further work is needed to develop screening and recruitment routes for young people. Our study has highlighted the difficulty in recruiting young people aged 13–17 years into this type of research study. Working through referral agencies, primary care practices and schools enabled significant numbers of young people to be identified, but this did not always lead to recruitment into the study. Anecdotally, from contact with youth workers and observations by recruiting staff, face-to-face contact enables trust to be established with the young people and could be key to successful engagement. There is a need to identify resources for a dedicated team to work with young people and their families to promote engagement. This was further supported by our PPI and process evaluation, undertaken during the trial, indicating that young people and their families respond more fully when contacted in person. The representativeness of our sample is uncertain as we did not achieve our intended sample size to establish feasibility. Future studies need to consider lower thresholds on the CDI-2 screening score to encourage young people with low mood to participate. Furthermore, although this study could have been feasible in the absence of the pandemic, complexities highlighted around the format of hybrid session delivery and the reasons for participant withdrawal or the low uptake among those referred to the study conducted during the pandemic need to be further examined.

What this adds to existing knowledge

Although we know that recruiting young people to mental health research studies can be challenging,70–72 our study highlights the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on conducting mental health research in this group. It identifies the mechanisms to be considered around wider recruitment strategies and emphasises the importance of face-to-face communications with young people and their families. Our PPI activities and engagement of young people enabled us to plan our research through the changing phases of the pandemic and helped to highlight ways of building trust with young people and their families and potentially overcoming barriers to recruitment had circumstances been more favourable.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Megan Smith (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1482-2350): Conceptualisation, Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing, Other contributions.

Ryan James (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5448-5424): Resources, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Neil Howlett (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6502-9969): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Silvana Mengoni (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9431-9762): Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Julia Jones (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3221-7362): Funding acquisition, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing, Other contributions.

Erika Sims (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7898-0331): Conceptualisation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

David Turner (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1689-4147): Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Kelly Grant (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5319-8127): Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Allan Clark (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2965-8941): Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing, Other contributions.

Jamie Murdoch (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9021-3629): Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Lindsay Bottoms (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4632-3764): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Jonathan Wilson (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5279-6237): Conceptualisation Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Shivani Sharma (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7682-2858): Funding acquisition, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Angel Chater (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9043-2565): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Cecile Guillard (https://orcid.org/0009-0002-8844-9955): Conceptualisation, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Timothy Clarke (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3901-9601): Methodology, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Andy Jones (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3130-9313): Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Lee David (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5319-6156): Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Solange Wyatt (https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0829-4436): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

Claire Rourke (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7631-9275): Conceptualisation, Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing.

David Wellsted (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2895-7838): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing, Other contributions.

Daksha Trivedi (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7572-4113): Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – reviewing and editing, Other contributions.

Karen Irvine: Conceptualisation.

Antony Colles: Conceptualisation.

Maria Leathersich: Conceptualisation, Data curation Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software Supervision.

Martin Pond: Data curation, Resources, Software.

Sue Stirling: Formal analysis.

Ann Marie Swart: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Other contributions.

Jonathan Hill: Other contributions.

Jonathan Sinclair: Other contributions.