Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/110/02. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The draft report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in January 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Armstrong-Buisseret et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common condition that predisposes women to potentially serious comorbidities, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and preterm birth, miscarriage and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. 1–5 Typical symptoms include vaginal discharge accompanied by an unpleasant fishy odour that frequently occurs in association with menstruation and can have a significant impact on the woman’s quality of life. 5

In women of reproductive age, the pH of the vagina is normally moderately acidic, in part because of the presence of lactobacilli species that produce lactic acid, which helps to prevent the overgrowth of other vaginal bacteria. An alteration in the usual vaginal flora occurs in BV, with a loss of lactobacilli and an associated increase in pH to more alkaline levels, which allows the proliferation of other primarily anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella. 5,6 The exact pathophysiological mechanism responsible for BV remains to be elucidated, although the sexual transmission of bacteria and the development of a biofilm containing specific bacterial species may be contributory factors to the dysbiosis observed in the vaginal flora. 5,7,8

Guidelines recommend the use of antibiotics as the first-line treatment for BV, with oral metronidazole (Flagyl, Sanofi) having been a standard choice for over 25 years and producing cure rates of up to 85% at 4 weeks post treatment. 9–11 However, antibiotic side effects can affect adherence to treatment and, although antibiotics may be initially effective, BV symptoms frequently recur within a few months. 10,12–14 This results in repeated antibiotic use and the potential for antibiotic resistance to develop.

Public Health England data from 2018 indicate that over 86,000 women had a diagnosis of BV when presenting at a sexual health clinic in England15 and symptoms are likely to recur in about one-third of women in the 3 months following initial treatment. 10,12–14 New treatment options are, therefore, required to reduce antibiotic use, provide better efficacy and lower recurrence rates.

Rationale for the VITA trial

Given that intravaginal lactic acid gel (pH 4.5) replicates the production of lactic acid by lactobacilli in the normal vagina, the use of lactic acid gel as treatment for BV could reduce antibiotic exposure in the population, as recommended in the Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance 2019–2024: The UK’s Five-year National Action Plan16 and A European One Health Action Plan Against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). 17 The avoidance of systemic antibiotics would help maintain the balance of the gut bacteria (microbiome) in individual participants and reduce the potential for the development of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the community. In addition, it would provide an alternative treatment for women who have failed to respond to current treatment for BV with systemic antibiotics.

The aim of the metronidazole Versus lactic acId for Treating bacterial vAginosis (VITA) trial was to determine whether or not using intravaginal lactic acid gel to replace vaginal acidity would be better than oral metronidazole for the symptomatic resolution of recurrent BV. Previous small studies of daily intravaginal acid gel or pessary for the treatment of BV have reported inconsistent results, with little difference between dosing regimens (23–93% efficacy with the more common once-daily dosing vs. 18–100% with twice-daily dosing). 13,18–23 For the VITA trial, a once-daily dose of 4.5% intravaginal lactic acid gel for 7 days was used because this was likely to be a more acceptable regimen than twice-daily dosing. UK management guidelines for BV10 do not currently include lactic acid as a recommended treatment because there is insufficient evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on reproducible efficacy. It was, therefore, anticipated that the VITA trial would advance our understanding by assessing whether or not lactic acid gel is effective and well tolerated for the treatment of recurrent BV, and whether or not it can reduce antibiotic usage in this large group of women. The comparator was 400-mg oral metronidazole tablets twice daily for 7 days and was chosen because it is recommended as first-line therapy in the UK national BV treatment guidelines,10 being active against a wide range of the anaerobic bacteria associated with BV and being commonly used in clinical practice supported by evidence from RCTs. 24

In addition, a qualitative assessment was performed to explore factors affecting the acceptability of, and adherence to, intravaginal treatment for BV and how these could be improved. A pragmatic trial design was used to maximise its relevance to patients and clinicians and to facilitate rapid adoption of the trial results into clinical practice.

Bacterial vaginosis is a common disease with serious physical and psychological sequelae. There is, therefore, the potential for a substantial health gain if a more effective and well-tolerated regimen, which also reduces antibiotic exposure, can be identified. The prospects for the study findings to influence clinical practice were high based on the multicentre approach including primary care, robust study design, existing widespread availability of lactic acid gel and identified need to limit antibiotic use to reduce the development of AMR.

Chapter 2 Methods

Text in the this chapter is reproduced with permission from Armstrong-Buisseret et al. 25 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The full VITA trial protocol is available on the National Institute for Health Research project web page (www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/15/110/02) and a summary protocol has been published. 25 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines have been followed for data analysis and reporting. 26

Regulatory approval for the trial was given by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency on 12 July 2017 (reference 16719/0230/001–0001; European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials 2016-004483-19) and ethics approval was given by the London – Harrow Research Ethics Committee on 9 September 2017 (reference 17/LO/1245). Local research and development departments gave their own approval prior to recruitment commencing at each participating site. The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register as ISRCTN14161293 on 8 September 2017 (https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN14161293; accessed 27 April 2021).

There were no updates made to the protocol after the original approved version (version 1.0); however, the following changes were introduced to the trial procedures and the collection and analysis of some outcome measures:

-

As per the protocol, the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) health survey was administered at baseline, 2 weeks and 6 months. In addition, it was administered at 3 months (which was also included as a secondary outcome), although this was inadvertently not stated in the protocol.

-

Participant-reported outcomes were collected via web-based questionnaires as detailed in the protocol. During the course of the trial, a follow-up telephone call was introduced to try to improve the collection of key outcomes for participants for whom the week 2 and 6-month web-based questionnaires had not been completed, despite several reminders being sent. The key outcome information was a subset of the information included in the web-based questionnaires. Collection of these data via a telephone call was not specifically stated in the protocol; however, consent to be contacted via telephone was included on the informed consent form.

-

To assist with interpretation of the primary outcome, additional subgroup analyses for symptom resolution at week 2 were included as follows, although these were inadvertently not stated in the protocol:

-

number of episodes of BV in the 12 months before baseline (1, 1–3 or > 3)

-

total time with BV in the 12 months before baseline (< 2 weeks, ≥ 2 weeks and < 3 months, ≥ 3 months).

-

-

An additional secondary objective was included that was to compare the time to resolution of BV symptoms, although this was inadvertently not stated in the protocol.

Trial objectives

The primary objective was to determine whether or not intravaginal lactic acid gel is better than oral metronidazole for symptomatic resolution of recurrent BV.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

compare the time to first recurrence of BV symptoms

-

compare the frequency of BV episodes over 6 months

-

compare the frequency of BV treatments required over 6 months

-

compare microbiological resolution of BV on microscopy 2 weeks after presentation

-

compare the time to resolution of BV symptoms

-

compare the tolerability profiles of lactic acid gel and metronidazole

-

compare the adherence to lactic acid gel with adherence to metronidazole tablets

-

compare the acceptability of use of lactic acid gel with that of the use of metronidazole tablets

-

determine the prevalence of concurrent STIs at baseline and week 2

-

compare quality of life (measured using the SF-12 health survey27)

-

compare the cost-effectiveness of intravaginal lactic acid gel with that of oral metronidazole tablets.

In addition, samples for further microbiological analysis, including gene sequencing, were collected for future investigation into the factors associated with successful treatment.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was participant-reported resolution of BV symptoms at week 2. Secondary outcome measures were as follows:

-

time to first recurrence of BV as reported by participants

-

number of participant-reported BV episodes over 6 months

-

number of participant-reported BV treatment courses over 6 months

-

microbiological resolution of BV on microscopy of vaginal smears taken at week 2 and analysed at a central laboratory

-

time to participant-reported resolution of BV symptoms

-

tolerability of lactic acid gel and metronidazole assessed by participant reporting of side effects (including nausea, vomiting, taste disturbance, vaginal irritation, diarrhoea and abdominal pain) and via participant interviews

-

participant-reported adherence to treatment

-

acceptability of treatments via qualitative assessment in a subgroup of participants

-

prevalence of concurrent STIs (gonorrhoea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis) from vaginal swabs taken at baseline and week 2, and analysed at a central laboratory

-

quality of life as assessed by the SF-12 health survey27 at baseline, 2 weeks, 3 months and 6 months

-

comparative cost-effectiveness of intravaginal lactic acid gel and oral metronidazole tablets.

Participant-reported outcome measures were collected using web-based questionnaires, with several reminders sent to encourage completion. During the later stages of the trial, a follow-up telephone call was attempted to collect key outcomes from the week 2 and 6-month questionnaires when these had not been completed.

Trial design and setting

The VITA trial was an open-label, multicentre, parallel-arm RCT. Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to receive either intravaginal lactic acid gel treatment (intervention) or oral metronidazole tablets (control). The treatment was for 7 days, with follow-up taking place at 2 weeks, 3 months and 6 months after randomisation. A health economic evaluation was performed to assess the cost-effectiveness of the study treatments from a UK NHS perspective (see Chapter 4). In addition, a subgroup of participants were interviewed to further explore the adherence, tolerability and acceptability of treatment (see Chapter 5).

Women presenting with symptoms of BV and a history of one or more episodes within the previous 2 years that had been resolved with treatment were approached by a member of the site research team to determine whether or not they were interested in participating in the trial. In normal clinical practice, a diagnosis of BV would be made based on an assessment of symptoms alone or in conjunction with the microscopy appearances of a vaginal smear; therefore, microscopy confirmation of BV was not required for entry into the trial.

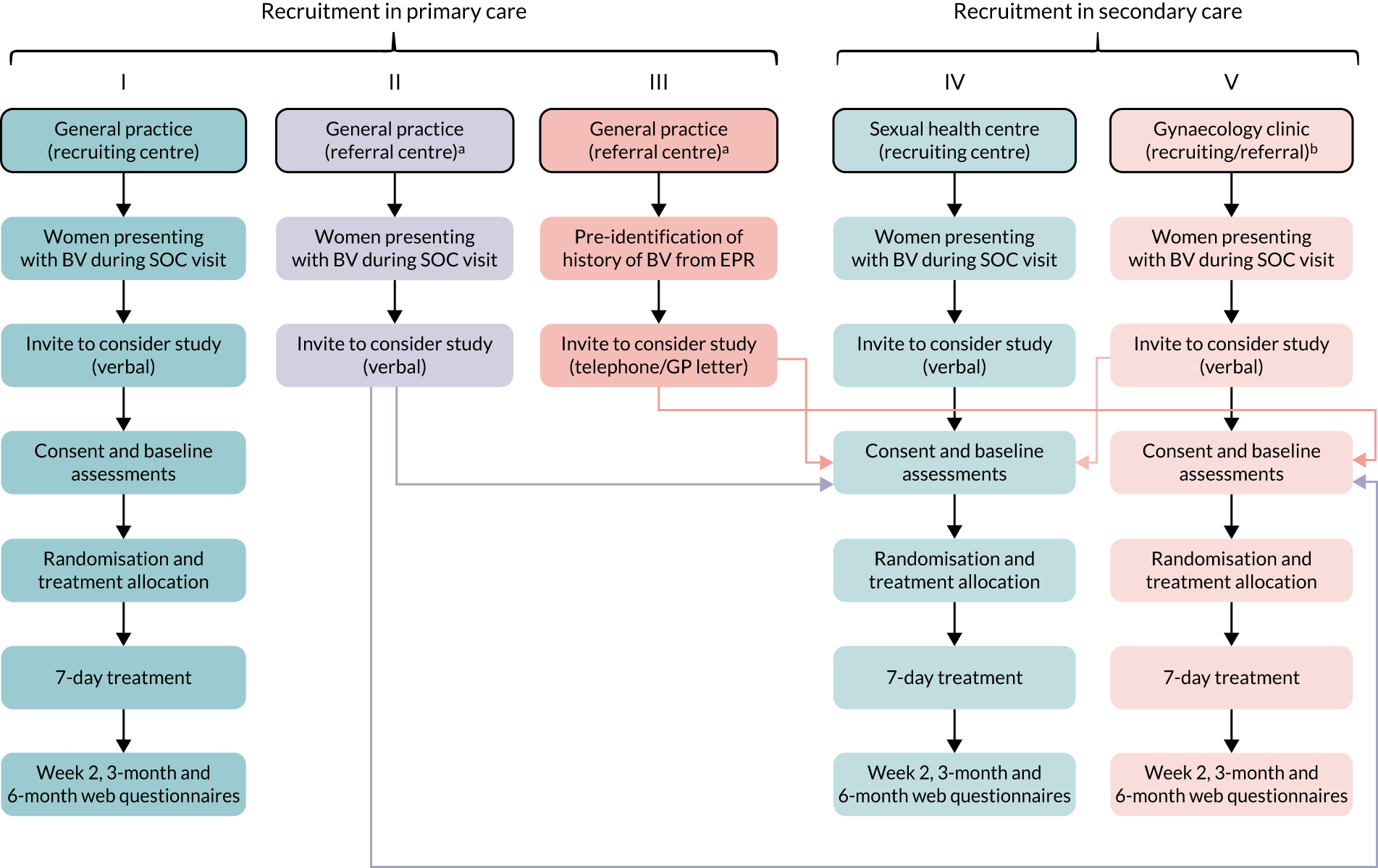

Recruitment was planned to take place in approximately 25 primary care general practices and 15 sexual health centres and gynaecology clinics via several routes in the UK (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The VITA trial participant pathways in primary and secondary care settings. EPR, electronic patient record; SOC, standard of care. a, Acting as a participant identification centres: identification and referral of women with BV to recruiting centre; b, identification and recruitment at local clinic or referral to a recruiting sexual health centre depending on local facilities. Reproduced with permission from Armstrong-Buisseret et al. 25 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Primary care (general practices)

-

Opportunistic identification of women presenting with BV in general practices that were VITA trial recruiting centres with trained research staff on site. Participants were identified, consented, randomised and prescribed study treatment at the practice. These research-ready sites required on-site availability of trained research nurses and facilities to directly consent and randomise patients.

-

Opportunistic identification and referral of women with BV attending general practices without on-site research staff (participant identification centres) to local participating VITA trial recruiting centres for invitation to participate in the trial.

-

Pre-identification of women with a history of BV by general practitioners (GPs) from electronic patient records/primary care databases. GPs would provide potential participants with information on the trial via telephone or letter and invite them to attend a local recruiting centre for consent if they developed BV and were interested in participating.

In addition, GP practices could use computerised ‘pop-up’ alerts to support the identification and recruitment of suitable women when they presented with possible BV symptoms.

Secondary care

-

Opportunistic identification of women presenting with BV in sexual health centres that were VITA trial recruiting centres with trained research staff on site. Participants were identified, consented, randomised and dispensed study treatment at the centre. These research-ready sites required on-site availability of trained research nurses and facilities to directly consent and randomise patients.

-

Opportunistic identification of women presenting with BV in gynaecology clinics that either were VITA trial recruiting centres with trained research staff on site where participants would be identified, consented, randomised and prescribed study treatment within the clinic; or acted as VITA trial referral clinics (participant identification centres) where women presenting with BV could be referred to a nearby participating recruiting sexual health centre for invitation to participate in the trial.

Participants and eligibility

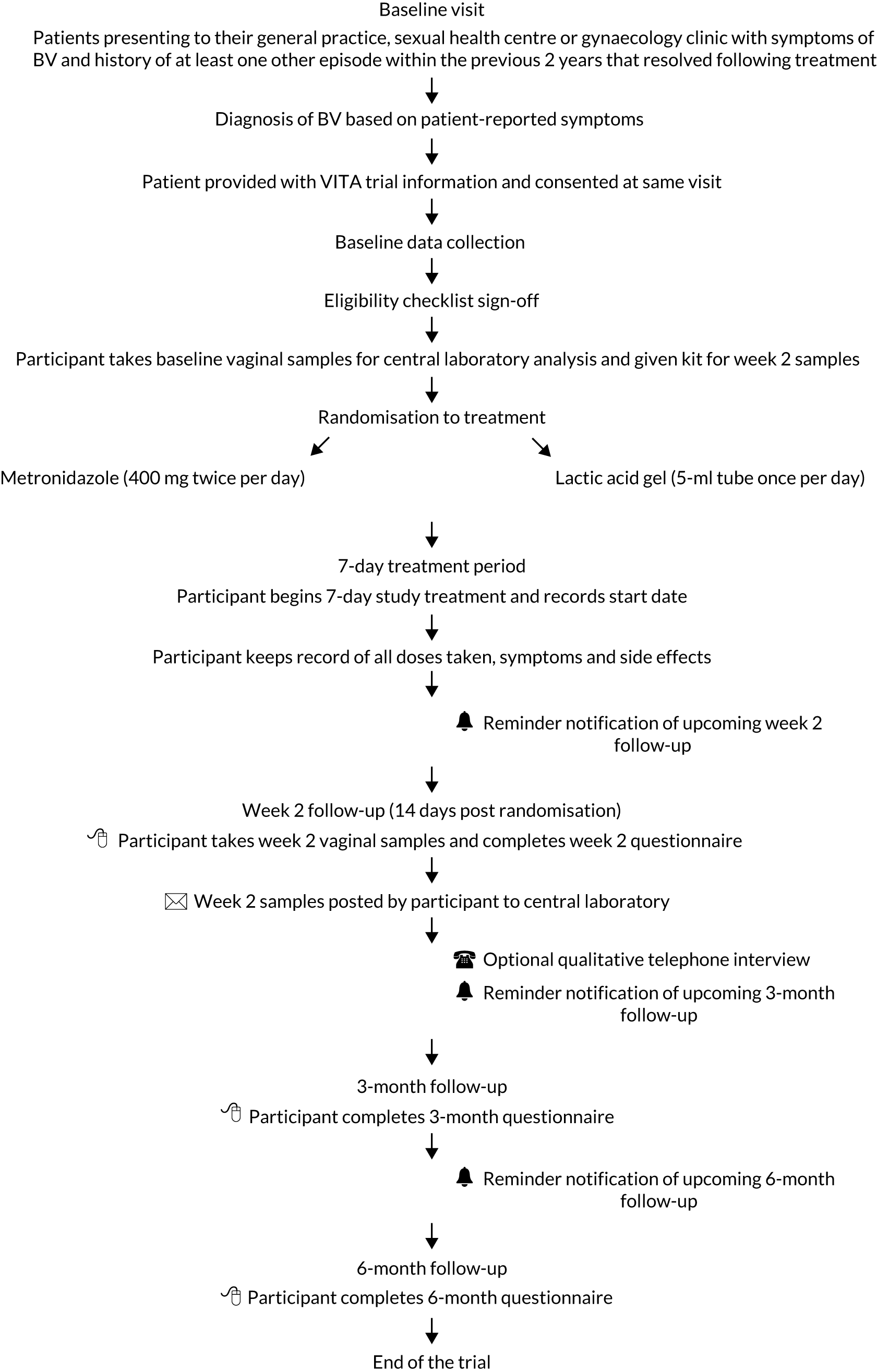

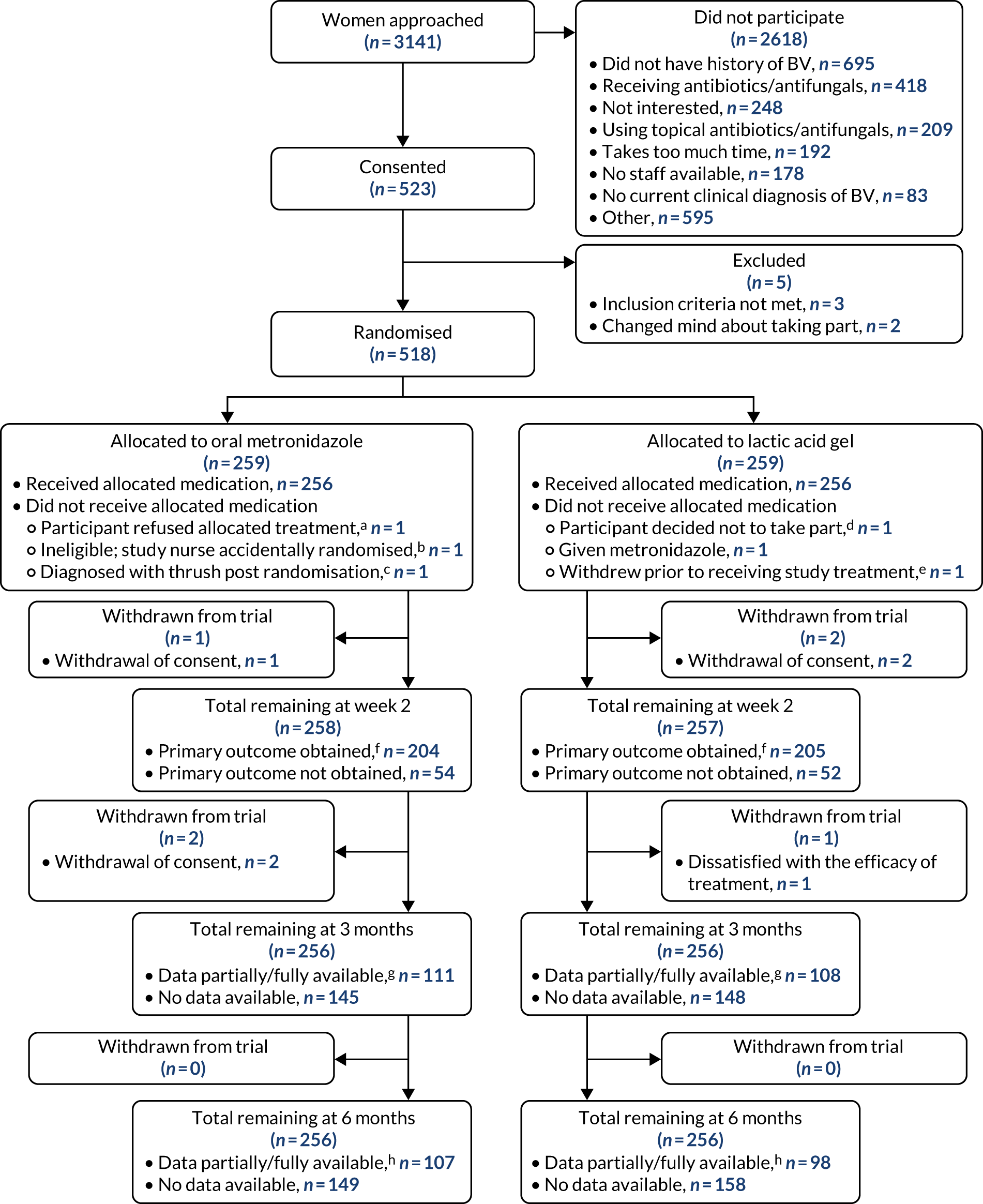

The flow of participants from presentation to follow-up is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow through the trial. Reproduced with permission from Armstrong-Buisseret et al. 25 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Inclusion criteria

Individuals had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria to be included in the trial:

-

aged ≥ 16 years

-

clinical diagnosis of BV based on patient-reported symptoms of discharge with an unpleasant (typically fishy) odour, with or without positive microscopy according to local site practice

-

history of at least one previous episode of BV in the past 2 years (clinically diagnosed or patient reported) that had been resolved with treatment

-

willing to use either intravaginal lactic acid gel or oral metronidazole tablets for the management of BV

-

willing to take their own vaginal samples

-

willing to avoid vaginal douching during treatment

-

willing to provide contact details and be contacted for the purpose of collecting follow-up information

-

willing to avoid sexual intercourse or use effective contraception for the 7-day duration of study treatment (condoms were not considered to be effective contraception owing to a potential interaction with the lactic acid gel)

-

access to the internet and e-mail and willing to complete web-based follow-up questionnaires in English

-

written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals were excluded from the trial if they met any of the following exclusion criteria:

-

contraindications or allergy to lactic acid gel or metronidazole tablets

-

pregnant or breastfeeding

-

patients currently trying to conceive and not willing to avoid sexual intercourse or use effective contraception for the 7-day duration of study treatment

-

using oral antibiotics (other than the study treatment) or antifungal agents concurrently, within the last 2 weeks or planned use within the next 2 weeks

-

using topical vaginal antibiotics, antifungals or acidifying products (other than the study treatment) concurrently, within the last 2 weeks or planned use within the next 2 weeks

-

previous participation in this study

-

current participation in another trial involving an investigational medicinal product (IMP).

Contraindications and concomitant medications

Metronidazole

As per the exclusion criteria, any known hypersensitivity to metronidazole, other nitroimidazole derivatives or any of the ingredients in metronidazole tablets would exclude patients from the trial. Sites were advised to refer to the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for metronidazole for details, but to take particular note of the following:

-

Alcohol was to be avoided (including products containing alcohol) during the course of treatment and for 48 hours afterwards.

-

Warfarin (warfarin, Ranbaxy) – elevated international normalised ratio (INR) and bleeding events have been reported with concurrent use of warfarin and metronidazole.

Lactic acid gel

There is no SmPC for lactic acid gel, but sites were advised to take particular note of the following:

-

Shellfish allergy – some lactic acid gel brands may contain glycogen obtained from oysters.

-

Condom use – the effects of lactic acid gel on condom degradation have not been fully determined. Therefore, it was advised that condoms should not be assumed to be an effective method of contraception during the 7-day treatment period with lactic acid gel.

Concomitant medications

Concomitant medications relevant to BV, such as oral or topical antibiotics and/or antifungals, were recorded at baseline to determine participant eligibility.

Screening and consent

Screening

Women either pre-identified by or presenting to referring or recruiting general practices, sexual health centres or gynaecology clinics who had symptoms of BV (and a history of one or more episodes within the previous 2 years that resolved following treatment) were invited (by telephone or letter) or approached by a member of the site research team to determine whether or not they were interested in participating in the trial. If they were interested, they were given a participant information sheet.

Women who were identified in general practices and gynaecology clinics that were acting as referral centres were introduced to the trial and directed to a local recruiting practice, sexual health centre or gynaecology clinic for consent if they were interested in participating in the trial.

A screening log was maintained at each recruiting site detailing all patients approached about the study, the number of patients agreeing to participate, the reasons for not participating and, where relevant, the route of referral.

Consent

Women were given time to read the participant information sheet and had the opportunity to ask the site research team any questions about the trial prior to consent. Written informed consent was requested during the same clinic visit by the principal investigator (PI) or the delegated study doctor or nurse prior to performing any trial-related procedure. A copy of the completed informed consent form was given to the participant, a copy was filed in the medical notes and the original copy was placed in the investigator site file.

The consent process included optional consent to be approached by researchers from the University of Warwick for a qualitative telephone interview. When participants who had given this optional consent were contacted to arrange an interview, verbal consent that they remained willing to take part was recorded by the researcher before the interview began.

Participants recruited from sexual health centres and gynaecology clinics were also asked for their optional consent to inform their GP that they were taking part in the trial.

Randomisation and blinding

After obtaining informed consent, baseline data were collected by a member of the site research team. Participant eligibility was confirmed by the PI (or the delegated study doctor) prior to randomisation. Participants were randomised 1 : 1 to receive lactic acid gel or metronidazole using a remote internet-based randomisation system developed and maintained by Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). The concealed allocation system used a minimisation algorithm with the following variables and levels: site, type of site (general practice and sexual health clinic), number of episodes of BV in the previous 12 months (0, 1–3 and > 3) and whether or not they had had a female sexual partner in the previous 12 months (yes/no). The allocation system was held on a secure University of Nottingham server.

Given that this was an open-label trial, there was no blinding to treatment allocation of the participants, site research teams or trial team. However, the central laboratory staff performing BV microscopy and STI testing were blinded to participant’s treatment allocation. In addition, the trial statistician remained blinded to treatment allocation until after database lock. Analyses requiring knowledge of treatment codes were conducted by an independent statistician. Data presented to both the trial team and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) were aggregated, that is they were not split by treatment allocation.

Trial intervention

There were two treatment arms in the trial:

-

lactic acid gel – 5 ml of gel inserted into the vagina before bedtime each day for 7 days

-

metronidazole tablets – 400 mg taken orally twice daily, approximately 12 hours apart, for 7 days.

Metronidazole tablets were an IMP in the trial and are licensed for use in the treatment of BV as per the SmPC. Lactic acid gel is a registered medical device consisting of a colourless viscous gel administered through an intravaginal tube applicator. Known side effects of lactic acid gel include vaginal irritation, for example redness, stinging and itching. In rare cases an allergic skin reaction, for example severe redness, swelling or burning, may occur.

Treatment supplies, labelling and storage

Participants received their study treatment via the routine method of dispensing used in the setting of each recruiting site. This could be via dispensing directly from standard clinic stocks or the provision of a standard prescription to be taken to a pharmacy for dispensing. Any licensed brands of metronidazole or lactic acid gel could be used and the brand of lactic acid gel was recorded by the participant in the web-based questionnaire.

Trial-specific labelling was not required given that the IMP has a marketing authorisation in the UK and was being used within the terms of its marketing authorisation. The IMP was dispensed to a trial participant in accordance with a prescription given by an authorised health-care professional and was labelled in accordance with the requirements of Schedule 5 to The Medicines for Human Use (SI 1994/31 94) (Marketing Authorisations Etc.) Regulations 199428 that apply to relevant dispensed medicinal products.

The IMP was stored in accordance with usual site policy and as per manufacturer’s instructions. Accountability records for treatment dispensing were in accordance with local site procedures and no additional trial-specific accountability was mandated.

Dosing schedule

It was requested that treatment was started on the day of receipt, and participants were advised to record their actual start date and time (morning or evening) of dosing in a paper patient diary that was given at the baseline visit. If they were menstruating at the time, those on the lactic acid gel arm were advised to delay starting treatment until menstruation had finished. Participants were also asked to use this diary with log all subsequent doses taken and/or missed doses over the treatment period to aid compliance with the treatment schedule and to record any symptoms, side effects or additional health-care use. The patient diaries were intended to be used as an aid for participants when completing their web-based questionnaires at 2 weeks, 3 months and 6 months.

No treatment or dose modifications were expected in this trial. Where a dose was accidentally missed, participants were advised to follow the manufacturer’s instructions or to seek advice from their physician. In the case of any missed dose, participants were advised to continue to complete their treatment course. Lactic acid gel was to be inserted vaginally before going to bed. Metronidazole tablets were to be taken during or after meals with a glass of water and not to be crushed or chewed, and were to be swallowed whole.

Trial assessments and procedures

All assessments and procedures performed at each time point for participants are indicated in Table 1. Assessments carried out at baseline included:

-

Demographics.

-

Symptoms.

-

Previous BV episodes.

-

Medical history.

-

Sexual history.

-

Concomitant medication.

-

Contraception and condom use.

-

Verbal confirmation that the participant was not pregnant.

-

SF-12 health survey.

-

Vaginal samples for BV/STI screening. Participants took their own vaginal samples following instruction from site personnel, and sites sent the baseline samples to a central laboratory at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, which is accredited under the UK Accreditation Service to perform the tests.

| Trial procedure | Baseline | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post randomisation | 2 weeks | 3 months | 6 months | |

| Assessments | |||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||

| Baseline data collection | ✗ | ||||

| Eligibility screen | ✗ | ||||

| Vaginal swabs for BV/STI screen | ✗ (participant) | ✗ (participant) | |||

| Randomisation | ✗ | ||||

| Posting of vaginal swabs to central laboratory | ✗ (site) | ✗ (participant) | |||

| Intervention | |||||

| Lactic acid gel (intervention arm) | ✗ (7-day treatment) | ||||

| Metronidazole (control arm) | ✗ (7-day treatment) | ||||

| Follow-up | |||||

| Participant web-based questionnaires | ✗ (site) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Telephone interviews for the qualitative substudy | ✗ (2–4 weeks from randomisation) | ||||

After randomisation into the trial, participants took their first dose of study treatment and continued taking study treatment for 7 days.

At 2 weeks, participants took their own vaginal samples using kits provided at the baseline visit and sent them to the central laboratory using pre-addressed and prepaid envelopes. They also completed a web-based questionnaire (see Appendices 1 and 2) with details of symptoms, treatment adherence and tolerability, any known side effects, health-care use, additional BV treatments, sexual history, contraception/condom use and another SF-12 health survey. A £15 voucher was provided to each participant on completion of the week 2 questionnaire as a thank you for their time. If requested to do so by a participant, the time frame for completing the questionnaire was extended.

Participants were also asked to complete two further web-based questionnaires at 3 months (see Appendix 3) and 6 months (see Appendix 4), with details of BV recurrence, sexual history, health-care use, additional BV treatments, contraception/condom use and the SF-12 health survey. Those not responding to requests to complete the week 2 and 6-month web-based questionnaires were contacted by telephone to collect follow-up data.

Participants could discontinue study treatment at any time but remain in the trial, taking week 2 vaginal samples and completing all follow-up questionnaires. They could also withdraw from the follow-up assessments at any time. Reason(s) for withdrawal were requested, but participants were not obliged to provide these.

Collection and analysis of vaginal samples

The central laboratory performed the following tests on vaginal samples taken at baseline and at week 2:

-

Microscopic assessment of BV based on a Gram-stained vaginal smear using the Ison–Hay scoring system. 29

-

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis. Positive results were returned within 1–2 months to the recruiting site to review (PI and research nurse) and to arrange further testing or treatment in accordance with local protocols.

These trial-related tests did not form the basis for patient management at the baseline visit; clinicians took additional tests that were processed locally to inform immediate patient care as indicated by the patient’s clinical presentation.

Substudies

Optional consent was sought from trial participants to store residual vaginal swabs taken at baseline and week 2 for future ethics-approved research, including microbiological analysis and gene sequencing into the factors associated with BV and its successful treatment.

Adverse events and pregnancy reporting

The safety profiles of the treatments in this trial are well characterised. To provide secondary outcome data to compare the tolerability of the two treatments, specified side effects experienced during study treatment were reported. The following were regarded as expected for the purpose of the trial and were reported on the week 2 questionnaire completed by the participant: nausea, vomiting, taste changes, vaginal irritation, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were not anticipated in this low-risk trial, but were recorded if reported by participants and were followed up until resolution or stabilisation.

Although lactic acid gel is considered safe for use in pregnancy and metronidazole is frequently prescribed for treatment of BV in pregnancy, caution is advised for their use in pregnant women and participants were asked to confirm that they were not pregnant as part of the screening process. Participants were also asked to confirm their pregnancy status during their follow-up period. Any pregnancies reported during the period between randomisation and week 2 were followed up for outcomes.

Data management

All baseline trial data were entered by site staff into a trial-specific database through the electronic case report form (MACRO 4.2.1 version 3800; Elsevier, London, UK), with participants identified by their unique trial number and initials only. All data collected after the baseline visit, that is at week 2, 3 months and 6 months, were entered by participants into the trial-specific database using a web-based questionnaire. The database was developed and maintained by NCTU. Access to the database was restricted and secure, and all data transactions were logged in a full audit trail.

Participant contact details were stored in a separate secure database using encryption with restricted password-protected access. Only appropriate members of the site team and the trial team had access to these data.

Statistical considerations

Analysis of outcome measures

A full statistical analysis plan was developed and agreed to prior to database lock and unblinding of the analysing statistician, and all analyses were carried out using Stata® version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables were summarised in terms of the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, lower and upper quartiles, minimum, maximum and number of observations. Categorical variables were summarised in terms of frequency counts and percentages. Descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical measures were used to assess the balance between the treatment arms at baseline, but no formal statistical comparisons were made.

The primary approach to between-arm comparative analyses was by modified intention to treat, that is it included all participants who were randomised and without imputation of missing outcome data. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of missing data, additional baseline variables and adherence to allocated treatment.

Evaluation of the primary outcome was performed using a generalised estimating equation for the binary outcome that included factors used in the minimisation, with site as the panel variable. This was changed prior to database lock (and before finalising the statistical analysis plan and unblinding the trial statistician) from the originally planned mixed-effects model owing to model non-convergence because some sites had very small numbers of participants. It had been planned to also include whether or not vaginal douching had occurred in the 3 months prior to randomisation, but model convergence issues resulted in this being excluded from the model. The comparison of lactic acid gel with oral metronidazole was presented using the risk difference of the proportion of participants who reported resolution of symptoms at week 2, along with the 95% confidence interval (CI). The adjusted risk ratio and 95% CI were also presented. Owing to non-convergence of several of the models, sensitivity analyses also used a random-effects logit model including the same factors, presenting the odds ratio and 95% CI.

Secondary outcomes were analysed using appropriate regression models dependent on data type (e.g. binary, continuous, count and survival), and included factors used in the minimisation and baseline value of the outcome where measured. The analyses of secondary outcomes were considered supportive to the primary outcomes, and estimates and p-values, where presented, were interpreted in this light.

Presentations of quantitative tolerability data were descriptive. Frequency counts and percentages of the proportion of participants reporting nausea, vomiting, taste disturbance, vaginal irritation, abdominal pain and diarrhoea were presented by treatment arms.

Planned subgroup analyses

The primary analysis for symptom resolution was investigated to determine whether or not treatment effectiveness differed according to the following subgroups:

-

presence of concomitant STI (yes/no)

-

BV confirmed by positive microscopy (yes/no)

-

number of episodes of BV in the 12 months before baseline (0, 1–3 and > 3)

-

total time with BV in the 12 months before baseline (< 2 weeks, ≥ 2 weeks and < 3 months, ≥ 3 months).

A further subgroup analysis was planned to determine whether or not treatment effectiveness differed according to the type of centre at which the participant presented (sexual health vs. GP/other clinics); however, this was not performed given that no gynaecology clinics and only one GP practice took part in the trial. Between-group treatment effects were provided for each subgroup, but interpretation of any subgroup effects was based on the treatment–subgroup interaction and 95% CI, estimated by fitting an appropriate interaction term in the regression models. Given that the trial was powered to detect overall differences between the groups rather than interactions of this kind, these subgroup analyses were regarded as exploratory. An interaction term could not be fitted when investigating the subgroup for the presence of concomitant STI at baseline owing to the small number of participants with a STI.

Feasibility

There was no planned interim analysis of treatment efficacy. However, an assessment of recruitment and adherence to treatment was performed using data from the first 6 months of participant recruitment. This was to determine how feasible it was that the trial would be able to adequately address its primary and secondary objectives.

The TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) used the following criteria as a guide to determine whether or not the trial should progress:

-

Review of the number of participants completing their week 2 assessment against the following targets –

-

> 90% – continue the trial

-

65–90% – review recruitment and retention procedures to identify underlying problems and put in place strategies to address these, with review in 6 months

-

35–65% – review recruitment and retention procedures to identify underlying problems and put in place strategies to address these. Ongoing review over 6 months and terminate the trial if the recruitment trajectory does not indicate that full recruitment can occur within an acceptable recruitment period

-

< 35% – terminate the trial.

-

-

Review of adherence to lactic acid gel and metronidazole against the following predefined targets –

-

median adherence 5–7 days per week – continue the trial

-

median adherence 3–4 days per week – review data from the qualitative interviews on adherence and tolerability to identify underlying problems and put in place strategies to address these, with review in 6 months

-

median adherence < 3 days per week – terminate the trial.

-

Power calculation/sample size calculation

Assuming that 80% of participants receiving oral metronidazole would achieve resolution of symptoms,24,30–32 1710 participants (855 in each treatment arm) were required for analysis to detect a 6% increase in response rate to 86% in those receiving lactic acid gel (risk ratio 1.08) at the 5% significance level (two-sided) with 90% power. To allow for loss to follow-up of 10% (i.e. non-collection of the primary outcome), a total of 1900 participants were required to be recruited.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives provided input during the development of the grant application into the trial design, including feedback on the importance of the research question, the effect size used in the power calculation and ideas on how to make participation in the trial appealing to potential recruits. They also requested the addition of the secondary outcome of time to recurrence of BV because it was felt that this was an important measure. In addition, PPI representatives reviewed all participant-facing documents prior to submission for ethics approval. These documents included the participant information sheet; informed consent form; participant invitation letter; participant kit instruction leaflet; all participant questionnaires, reminders and diaries; all advertising materials; and the qualitative interview schedule.

The PPI representatives sat on the TSC as independent members and contributed to the oversight of the trial, including reviewing and interpretating the results and providing input to the Plain English summary. Once the trial results have been published, a summary will be disseminated to participants, and PPI representatives will be invited to review the summary prior to distribution.

Chapter 3 Clinical results

Sites

Recruitment was originally planned to take place at approximately 25 primary care general practices and 15 sexual health outpatient and gynaecology clinics in the UK. However, during the course of the trial, a total of one general practice and 21 sexual health centres were opened to recruitment; the general practice and 19 of the sexual health centres recruited at least one participant. Although the Primary Care Clinical Research Network was involved in the planning of the trial, fewer primary care centres than expected had sufficient research nurse resources to support recruitment and, with approval from the TSC, additional sexual health centres were identified to take part. One gynaecology clinic was approached but none was identified that was willing to participate in the trial.

Recruitment

Recruitment took place between October 2017 and June 2019. It was originally planned that recruitment would continue until 1900 participants had been randomised, with an initial projected date for completion of recruitment of November 2019. However, in May 2019 the DMC reviewed the unblinded trial data at a planned meeting and its recommendation from this review was that trial recruitment should be stopped, because its opinion was that the primary research question had been answered with the number of participants, recruited at that time. There were no concerns raised around any safety issues. To ensure that this was a robust decision, further analyses were conducted that were reviewed by the DMC in June 2019, and its recommendation remained the same. The TSC supported this opinion and recruitment into the trial was terminated on 28 June 2019, with follow-up of ongoing participants continuing for 6 months (completed 26 February 2020 to allow sufficient time for receipt of the final questionnaires after sending all reminders), as per the protocol. No additional information about the reason for the recommendation was provided to any member of the trial team.

During the recruitment period, a total of 3141 patients were approached (Figure 3), of whom 2618 (83%) were excluded prior to consent; the main reason given was not having a history of at least one previous episode of BV within the last 2 years (n = 695) (see Appendix 5, Table 28). A total of 523 (17%) participants consented to take part in the trial, of whom five were excluded after consent because they were not eligible (n = 3) or they changed their mind about participating (n = 2) (see Figure 3). This gave a total of 518 participants who were randomised into the trial (metronidazole arm, n = 259; lactic acid gel arm, n = 259), who represented 16% of those presenting with BV and 99% of those who consented.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram. a, Prescribed lactic acid gel as refused allocated study treatment; b, ineligible as taking warfarin, prescribed lactic acid gel instead; c, no study treatment given as participant received medication to treat thrush; d, preferred metronidazole after being randomised to lactic acid gel; e, included as one of the two withdrawn before week 2 in the next box down; f, includes outcomes obtained from the week 2 questionnaire for which a date of resolution was given without an answer to the ‘Have your BV symptoms cleared’ question, and primary outcome data collected by telephone, includes outcomes obtained from the 3-month questionnaire asking about resolution by week 2; g, at least one data item entered on the questionnaire; and h, at least one data item entered on the questionnaire or obtained by telephone.

A total of three participants (metronidazole arm, n = 1; lactic acid gel arm, n = 2) withdrew their consent in the first 2 weeks, resulting in 258 participants in the metronidazole arm and 257 in the lactic acid gel arm remaining in the trial at week 2 (see Figure 3). A further three participants withdrew between week 2 and 3 months, two from the metronidazole arm (both because of withdrawal of consent) and one from the lactic acid gel arm (because of being dissatisfied with the efficacy of the treatment), giving a total of 512 participants remaining in the trial at 3 months (256 per arm). There were no known participant withdrawals between 3 months and 6 months.

Of the 22 sites that were opened, 20 screened and recruited at least one participant (see Appendix 5, Table 29).

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the participants were similar between the two treatment arms (Table 2). The age of the participants ranged from 16 to 58 years, with a mean of 29 (SD 8.3) years. Forty-eight per cent of the participants were of white ethnicity and 23% were black Caribbean. Vaginal douching was carried out by 12% of the participants in the 3 months before baseline. A total of 198 (38%) participants had experienced more than three episodes of BV in the previous 12 months, and BV was confirmed microscopically at baseline in 436 (84%) participants by local laboratories and in 266 (51%) participants using Ison–Hay grade 329 by the central laboratory.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm | Total (N = 518) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | ||

| Age at randomisation (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.0 (8.41) | 29.4 (8.12) | 29.2 (8.26) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 27 (23, 34) | 27 (23, 34) | 27 (23, 34) |

| Minimum, maximum | 16, 58 | 18, 57 | 16, 58 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 125 (48) | 126 (49) | 251 (48) |

| Black Caribbean | 62 (24) | 57 (22) | 119 (23) |

| Mixed race | 24 (9) | 27 (10) | 51 (10) |

| Black African | 26 (10) | 15 (6) | 41 (8) |

| Other | 8 (3) | 8 (3) | 16 (3) |

| Other Asian (non-Chinese) | 5 (2) | 6 (2) | 11 (2) |

| Indian | 4 (2) | 5 (2) | 9 (2) |

| Black (other) | 1 (< 0.5) | 6 (2) | 7 (1) |

| Chinese | 1 (< 0.5) | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Pakistani | 3 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) | 4 (1) |

| Bangladeshi | 0 | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Not given | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Vaginal douching in the past 3 months, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 36 (14) | 25 (10) | 61 (12) |

| No | 223 (86) | 233 (90) | 456 (88) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Frequency of douching per month, n (%) | |||

| 0–2 | 9 (25) | 6 (24) | 15 (25) |

| 3–4 | 9 (25) | 5 (20) | 14 (23) |

| 5–6 | 1 (3) | 3 (12) | 4 (7) |

| ≥ 7 | 17 (47) | 11 (44) | 28 (46) |

| Current use of oral contraceptive pill, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 45 (17) | 44 (17) | 89 (17) |

| No | 214 (83) | 214 (83) | 428 (83) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Type of contraceptive pill, n (%) | |||

| Combined oral contraceptive pill | 27 (60) | 30 (68) | 57 (64) |

| Progesterone-only pill | 18 (40) | 14 (32) | 32 (36) |

| Past history of BV | |||

| Approximate age when BV first occurred (years) | |||

| n | 258 | 258 | 516 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.8 (7.26) | 23.4 (6.49) | 23.6 (6.88) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 22 (18, 27) | 22 (19, 27) | 22 (19, 27) |

| Minimum, maximum | 14, 58 | 11, 50 | 11, 58 |

| Number of previous episodes of BV in the past 12 months, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 6 (1) |

| 1–3 | 157 (61) | 157 (61) | 314 (61) |

| > 3 | 99 (38) | 99 (38) | 198 (38) |

| Approximate total length of time in past year with BV symptoms, n (%) | |||

| < 2 weeks | 56 (22) | 40 (15) | 96 (19) |

| ≥ 2 weeks and < 3 months | 135 (52) | 130 (50) | 265 (51) |

| ≥ 3 months | 68 (26) | 88 (34) | 156 (30) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| BV confirmed at baseline visit (local laboratory), n (%) | |||

| Yes | 217 (84) | 219 (85) | 436 (84) |

| No | 31 (12) | 29 (11) | 60 (12) |

| Not tested | 11 (4) | 10 (4) | 21 (4) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Baseline sample Ison–Hay grade for BV (central laboratory),a n (%) | |||

| 0 (no bacteria) | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 2 (< 0.5) |

| 1 (normal flora) | 48 (19) | 62 (24) | 110 (21) |

| 2 (intermediate BV) | 62 (24) | 61 (24) | 123 (24) |

| 3 (confirmed BV) | 138 (53) | 128 (49) | 266 (51) |

| U (Gram-positive cocci) | 3 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) | 4 (1) |

| Missing | 7 (3) | 6 (2) | 13 (3) |

The differences in BV microscopy results obtained from local and central laboratory analyses of samples are available in Appendix 5, Table 30.

Medical and sexual histories are summarised in Appendix 5, Tables 31 and 32. The vast majority of participants were HIV negative (99%) and around half (48%) reported having had thrush in the 12 months before baseline. A total of 365 (71%) participants had a sexual partner at baseline and 51 (10%) had a female sexual partner in the 12 months before baseline.

Participant-reported symptoms at baseline are summarised in Table 3, and included 470 out of 518 (91%) participants with genital discharge, 440 out of 518 (85%) with an offensive vaginal smell, 193 out of 518 (37%) with vaginal irritation and 406 out of 518 (78%) had both discharge and an offensive smell.

| Symptom | Treatment arm | Total (N = 518) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | ||

| Abnormal genital discharge,a n (%) | |||

| Yes | 239 (92) | 231 (89) | 470 (91) |

| No | 20 (8) | 27 (10) | 47 (9) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| For those with discharge, length of time present during this episode (days) | |||

| n | 239 | 231 | 470 |

| Mean (SD) | 31 (58.6) | 31 (57.0) | 31 (57.7) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 14 (7, 28) | 14 (7, 28) | 14 (7, 28) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 365 | 1, 365 | 1, 365 |

| Offensive vaginal smell,b n (%) | |||

| Yes | 227 (88) | 213 (82) | 440 (85) |

| No | 32 (12) | 45 (17) | 77 (15) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| For those with smell, length of time present during this episode (days) | |||

| n | 227 | 212 | 439 |

| Mean (SD) | 26 (45.0) | 32 (55.2) | 29 (50.2) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 10 (5, 28) | 14 (7, 30) | 14 (6, 28) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 351 | 1, 365 | 1, 365 |

| Presence of both discharge and smell, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 211 (81) | 195 (75) | 406 (78) |

| No | 48 (19) | 63 (24) | 111 (21) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Vaginal irritation, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 100 (39) | 93 (36) | 193 (37) |

| No | 159 (61) | 165 (64) | 324 (63) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| For those with irritation, length of time present during this episode (days)c | |||

| n | 100 | 93 | 193 |

| Mean (SD) | 27 (101.8) | 22 (48.1) | 25 (80.4) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 7 (3, 21) | 7 (3, 14) | 7 (3, 20) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 999 | 1, 364 | 1, 999 |

Data completeness

All of the 518 randomised participants were considered in the analysis of primary and secondary outcomes. Details of where data were missing, for example because of questionnaires or samples not being returned, are given below.

Questionnaires and telephone calls

The completion of data via web-based questionnaires and telephone calls was similar between the two treatment arms (see Appendix 5, Tables 33 and 34). The web-based questionnaire response rates were 318 out of 515 (62%) at week 2, 219 out of 512 (43%) at 3 months and 176 out of 512 (34%) at 6 months (see Appendix 5, Table 33). Further key data were obtained by telephone, with week 2 primary outcome information on BV resolution provided by an additional 88 out of the 202 participants for whom contact was attempted (success rate of 44%); secondary outcomes on recurrence were given by an additional 29 out of the 105 participants for whom contact was attempted at 6 months (success rate of 28%).

The median (minimum–maximum) time from randomisation to return of the week 2 questionnaires was 15 (14–55) days, with most of the questionnaires being returned within 28 days. For week 2 telephone data, the median time for obtaining these was 55.5 (29–155) days. This latter time was much longer than that for the questionnaires because the decision to collect data by telephone was made part-way through the trial to try to improve response rates. In addition, participants were given up to 28 days after randomisation to return questionnaires before a telephone call was attempted. The median time to return of the 3- and 6-month questionnaires was 93 (89–113) days and 186 (181–208) days, respectively. Six-month telephone data were collected after a median (minimum–maximum) time of 231 (203–265) days.

Week 2 vaginal samples

Week 2 vaginal samples were received by the central laboratory from 301 (58%) participants and numbers were similar between the treatment arms (see Appendix 5, Table 35). Overall, 280 out of 515 (54%) participants reported a primary outcome at week 2 and returned their week 2 samples, with similar numbers in both treatment arms (see Appendix 5, Table 35).

Nucleic acid amplification test analysis for sexually transmitted infections

Kits were provided for participants to take vaginal swab samples at baseline and week 2 for NAAT analysis of STIs. At each time point, one swab sample was placed into a tube containing a transport fluid and the tube was shipped directly to the central laboratory that was responsible for performing the analysis. On 16 January 2019, an issue was identified at three sites that some kits had been given to participants that contained time-expired NAAT sample tubes. The manufacturer of the tubes confirmed that there were no stability data past the point of expiry; therefore, it was decided that any samples received in expired tubes would be considered as void. An investigation took place into the expiry dates of existing stock at all sites and it became apparent that use of expired sample tubes was a wider issue.

Given that the expiry dates of sample tubes were not recorded by the manufacturer, site or NCTU, an audit was conducted at the central laboratory on 4 June 2019 of all NAAT samples received to determine whether or not sample tubes had expired prior to the date that each sample was taken. This audit revealed that the central laboratory had discarded some residual samples in error; therefore, for some participants it was not possible to determine whether or not the sample tubes had expired before use. For those baseline NAAT samples that were available at the central laboratory and for which expiry dates could be checked, a total of 339 samples were confirmed as being valid and within the expiry date, and a further 32 samples were confirmed as being void (i.e. the tube had expired prior to use) (see Appendix 5, Table 36). Expiry status could not be confirmed for 138 baseline samples because, although the central laboratory records indicated that these had been received, the residual samples had since been discarded. The remaining nine baseline samples either were not received by the central laboratory according to their records (n = 7) or were received but without accurate identifiable information (n = 2). For those week 2 NAAT samples that were available at the central laboratory and for which expiry dates could be checked, a total of 224 samples were confirmed as being valid and within the expiry date, and a further 19 samples were confirmed as being void (i.e. the tube had expired prior to use) (see Appendix 5, Table 36). Expiry status could not be confirmed for 58 week 2 samples because, although the central laboratory records indicated that these had been received, the residual samples had since been discarded. The remaining 214 week 2 samples either were not received by the central laboratory according to their records (n = 213) or were received but without accurate identifiable information (n = 1).

Sites followed their usual guidelines for treatment of suspected STIs during the participant’s baseline visit and clinical care of participants was not dependent on these NAAT results, which were taken purely for trial purposes.

Protocol non-compliance

Of the 518 participants who were randomised, six did not receive their allocated treatment (metronidazole arm, n = 3; lactic acid gel arm, n = 3) as a result of refusing to take the allocated study treatment (n = 1), being found to be ineligible post randomisation (n = 1), being diagnosed post randomisation with thrush, requiring antifungal treatment (n = 1), declining to take part post randomisation (n = 1), being given the other study treatment (n = 1) or withdrawing prior to receiving study treatment (n = 1) (see Figure 3). For a further two participants allocated to the lactic acid gel arm, the wrong value of the minimisation variable ‘any female sexual partners in previous 12 months’ was entered onto the system; they both received lactic acid gel and continued in the trial. No further incidents of non-compliance were recorded.

Primary outcome

Primary outcome data were available for 409 (79%) participants (see Figure 3): 321 who entered their primary outcome data into the questionnaire and 88 for whom primary outcome data were collected via a follow-up telephone call. Of the 321 participants who provided the primary outcome on the questionnaire, 316 entered this on the week 2 questionnaire (314 answered yes or no to the primary outcome question and two did not respond to the yes/no question but provided a date of resolution) and a further five with missing primary outcome data at week 2 provided a response on the 3-month questionnaire indicating either that their BV had resolved by week 2 or that their BV was ongoing.

Resolution of BV symptoms was higher in the metronidazole arm than in the lactic acid gel arm: 143 out of 204 (70%) participants in the metronidazole arm reported resolution at week 2, compared with 97 out of 205 (47%) participants in the lactic acid gel arm. The adjusted risk difference was –23.2% (95% CI –32.3% to –14.0%) and the adjusted risk ratio was 0.67 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.79) (Table 4). The analysis was adjusted for site, number of BV episodes in the 12 months before baseline (0, 1–3 or > 3) and female partner in the 12 months before baseline (yes/no), but not for vaginal douching owing to non-convergence of the model.

| Resolution of BV at week 2 | Treatment arm, n (%) | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI)a | Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI)a | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | ||||

| Yes | 143 (70) | 97 (47) | –23.2% (–32.3% to –14.0%) | 0.67 (0.57 to 0.79) | 0.38 (0.25 to 0.57) |

| No | 61 (30) | 108 (53) | |||

| Missing | 55 | 54 | |||

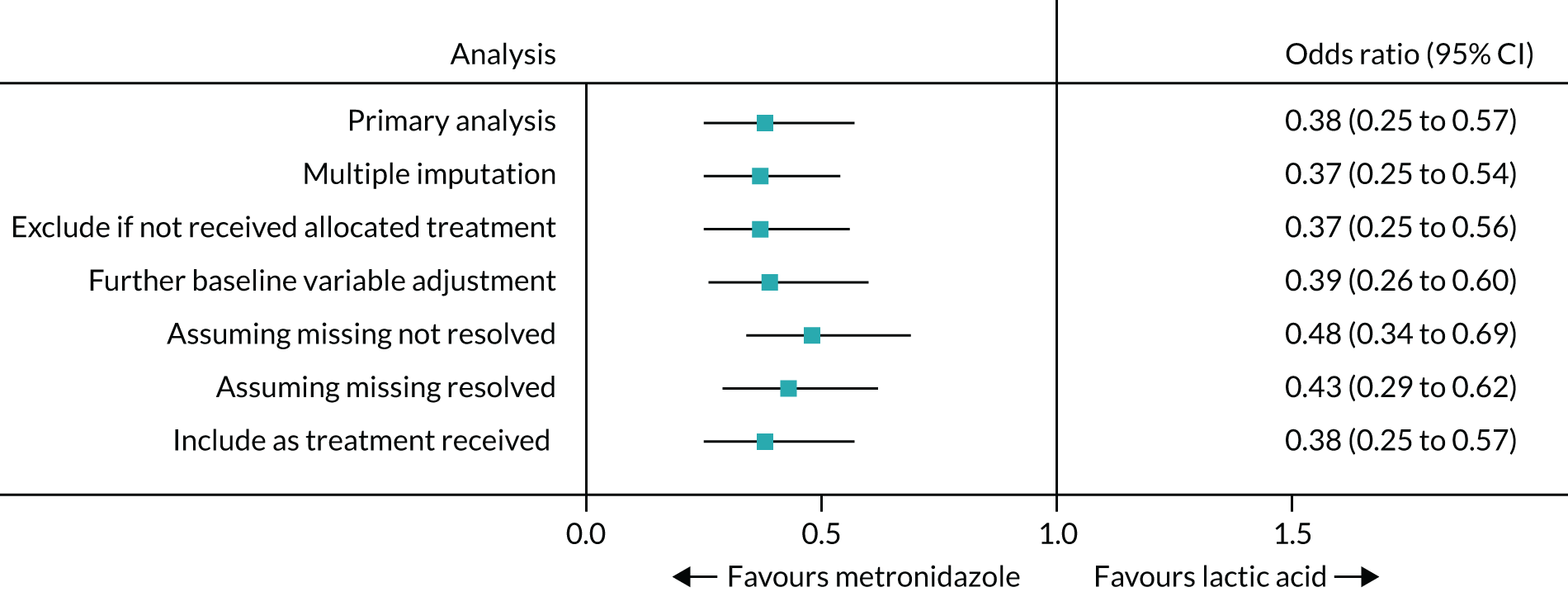

The sensitivity analyses showed similar results (Table 5 and Figure 4; see also Table 4). Odds ratios were presented for comparison of the sensitivity analyses owing to non-convergence of two of the models for treatment difference.

| Scenario | Resolution of BV symptoms, n (%) | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI)a | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple imputation of missing resolution datab | |||

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | (70) | Not estimablec | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.54) |

| Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | (47) | ||

| Excluding those who did not receive allocated treatment | |||

| Oral metronidazole (N = 256) | 143 (70) | –23.5% (–32.6% to –14.3%) | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.56) |

| Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 256) | 96 (47) | ||

| Further adjustment for baseline variablesd | |||

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | 143 (70) | Not estimablec | 0.39 (0.26 to 0.60) |

| Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | 97 (47) | ||

| Assuming missing symptom resolution as not resolved | |||

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | 143 (55) | –17.8% (–26.2% to –9.3%) | 0.48 (0.34 to 0.69) |

| Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | 97 (37) | ||

| Assuming missing symptom resolution as resolved | |||

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | 199 (77) | –18.5% (–26.3% to –10.7%) | 0.43 (0.29 to 0.62) |

| Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | 153 (59) | ||

| Included in arm as treatment received | |||

| Oral metronidazole (N = 258) | 144 (71) | –23.6% (–32.8% to –14.5%) | 0.38 (0.25 to 0.57) |

| Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 258) | 96 (48) | ||

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot for the primary outcome and sensitivity analyses.

A planned post hoc investigation showed that resolution rates were lower in both treatment arms when the data were collected via questionnaires than via telephone calls (see Appendix 5, Table 37). Of the 158 participants in the metronidazole arm who provided resolution data via a questionnaire, 105 (66%) reported that symptoms had resolved, whereas of the 46 who provided these data via a telephone call, 38 (83%) reported that symptoms had resolved. Of the 163 participants in the lactic acid gel arm who provided resolution data via a questionnaire, 75 (46%) reported that symptoms had resolved, whereas of the 42 who provided the data via a telephone call, 22 (52%) reported that symptoms had resolved.

Of those participants who reported resolution of symptoms at week 2, 154 in the metronidazole arm and 158 in the lactic acid gel arm also gave information on whether or not any additional treatment had been taken for their BV (Table 6). A total of 22 out of 154 (14%) participants in the metronidazole arm and 20 out of 158 (13%) participants in the lactic acid gel arm had taken additional treatment, of whom 12 out of 22 (55%) and 7 out of 20 (35%), respectively, had resolution of their symptoms. Although resolution rates were lower for those taking additional treatment, the difference between treatment arms was similar with an unadjusted risk difference for resolution with additional treatment of –19.5% (95% CI –49.0% to 10.0%) compared with –19.6% (95% CI –31.1% to –8.1%) for resolution without additional treatment (see Table 6).

| Resolution of BV | Treatment arm, n (%) | Unadjusted risk difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | ||

| With additional treatment | |||

| N | 22 | 20 | |

| Yes | 12 (55) | 7 (35) | –19.5% (–49.0% to 10.0%) |

| No | 10 (45) | 13 (65) | |

| Without additional treatment | |||

| N | 132 | 138 | |

| Yes | 90 (68) | 67 (49) | –19.6% (–31.1% to –8.1%) |

| No | 42 (32) | 71 (51) | |

There were no statistically significant treatment-by-subgroup interactions. The number of valid STI samples available at baseline and week 2 was small owing to the expiry date issue and, consequently, the number of participants with a STI (from a valid sample) at baseline and who had resolution data at week 2 (n = 8) was too small to allow any analysis. In each of the other subgroups, resolution rates were consistently higher in the metronidazole arm than in the lactic acid gel arm (Tables 7 and 8). Treatment outcomes in the subgroup of participants who had confirmation of a BV diagnosis by positive microscopy are given in Microbiological resolution of bacterial vaginosis on microscopy of vaginal smears at week 2.

| Baseline subgroup | Treatment arm: BV resolution at 2 weeks, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | |||||

| Yes | No | Missing | Yes | No | Missing | |

| Presence of concomitant STI at baselinea | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (100) | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 (100) | 0 |

| No | 85 (67) | 41 (33) | 26 | 66 (50) | 67 (50) | 36 |

| Missing | 53 | 20 | 22 | 31 | 3 | 18 |

| BV confirmed by positive baseline microscopy (central laboratory Ison–Hay grade 3) | ||||||

| Yes | 83 (75) | 28 (25) | 27 | 49 (49) | 52 (51) | 27 |

| No | 58 (65) | 31 (35) | 25 | 46 (46) | 55 (54) | 24 |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Number of episodes of BV in 12 months before baseline | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 2 | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 0 |

| 1–3 | 91 (75) | 31 (25) | 35 | 61 (51) | 59 (49) | 37 |

| > 3 | 51 (63) | 30 (37) | 18 | 34 (41) | 48 (59) | 17 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total time with BV in 12 months before baseline | ||||||

| < 2 weeks | 31 (72) | 12 (28) | 13 | 20 (57) | 15 (43) | 5 |

| ≥ 2 weeks and < 3 months | 78 (73) | 29 (27) | 28 | 54 (53) | 48 (47) | 28 |

| ≥ 3 months | 34 (63) | 20 (37) | 14 | 23 (34) | 45 (66) | 20 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Subgroup | Treatment difference (95% CI)a | Estimate of treatment–subgroup interaction (95% CI); p-valueb |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of concomitant STI at baseline | ||

| No (n = 259) | –17.8% (–29.6% to –6.0%) | Not enough data to analyse |

| Yes (n = 8)c | –100% (not calculable) | |

| BV confirmed by positive baseline microscopy (central laboratory Ison–Hay grade 3)d | ||

| No (n = 190) | –19.6% (–33.5% to –5.8%) | 2.1% (–11.6% to 15.7%); 0.77 |

| Yes (n = 212) | –26.3% (–38.9% to –13.6%) | |

| Number of episodes of BV in 12 months before baseline | ||

| 0 (n = 4) | –33.3% (–86.7% to 20.0%) | |

| 1–3 (n = 242) | –23.8% (–35.6% to –11.9%) | –2.0% (–21.2% to 17.0%); 0.83 |

| > 3 (n = 163) | –21.5% (–36.5% to –6.5%) | |

| Total time with BV in 12 months before baseline | ||

| < 2 weeks (n = 78) | –15.0% (–36.1% to 6.2%) | |

| ≥ 2 weeks and < 3 months (n = 209) | –20.0% (–32.8% to –7.1%) | –3.1% (–27.8% to 21.6%); 0.81 |

| ≥ 3 months (n = 122) | –29.1% (–46.2% to –12.0%) | –11.1% (–38.5% to 16.4%); 0.43 |

Secondary outcomes

Time to first recurrence of bacterial vaginosis

Among those participants who reported symptom resolution by week 2 (metronidazole arm, n = 143; lactic acid gel arm, n = 97), data on recurrence at 3 months were available for 73 (51%) and 50 (52%) participants, respectively, and at 6 months for 72 (50%) and 46 (47%) participants, respectively (Table 9). Of these participants, 37 out of 73 (51%) in the metronidazole arm and 23 out of 50 (46%) in the lactic acid gel arm reported recurrence by 3 months, whereas 51 out of 72 (71%) and 32 out of 46 (70%) reported recurrence by 6 months, respectively (see Table 9). The median [standard error (SE)] times to recurrence, allowing for censored times (when there was no reported recurrence up to 6 months, the 6-month data were used to calculate the censored time; if there was no reported recurrence up to 3 months and 6-month data were missing, the 3-month data were used; times were not available for recurrences reported by telephone at 6 months), were 92 (34.6) days in the metronidazole arm and 124 (SE not calculable) days in the lactic acid gel arm. It was possible to calculate only the lower limits of the 95% CIs (as there were not enough uncensored ‘events’) and these were 71 and 74 days, respectively (see Table 9). Including only those who had a time to recurrence gave median times of 54 (n = 43) days and 66 (n = 25) days in the metronidazole and the lactic acid gel arms, respectively. Times to first recurrence were not compared between treatment arms using statistical tests given that they comprised only those who had symptom resolution within 2 weeks and any comparison would, therefore, not be between randomised arms. A post hoc investigation showed that baseline characteristics were similar between treatment arms for the subset of participants resolving by week 2 (see Appendix 5, Table 38).

| Resolution/recurrence of BV | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | |

| Resolved by 2 weeks (n) | 143 | 97 |

| Recurred within 3 months, n/N (%) | 37/73 (51) | 23/50 (46) |

| Recurred within 6 months, n/N (%) | 51/72 (71) | 32/46 (70) |

| Number with time to recurrence (including censored times) (n) | 73 | 50 |

| Median time to recurrence (SE) (days) | 92 (34.6) | 124 (–)a |

| 95% CI (days) | (71 to –)a | (74 to –)a |

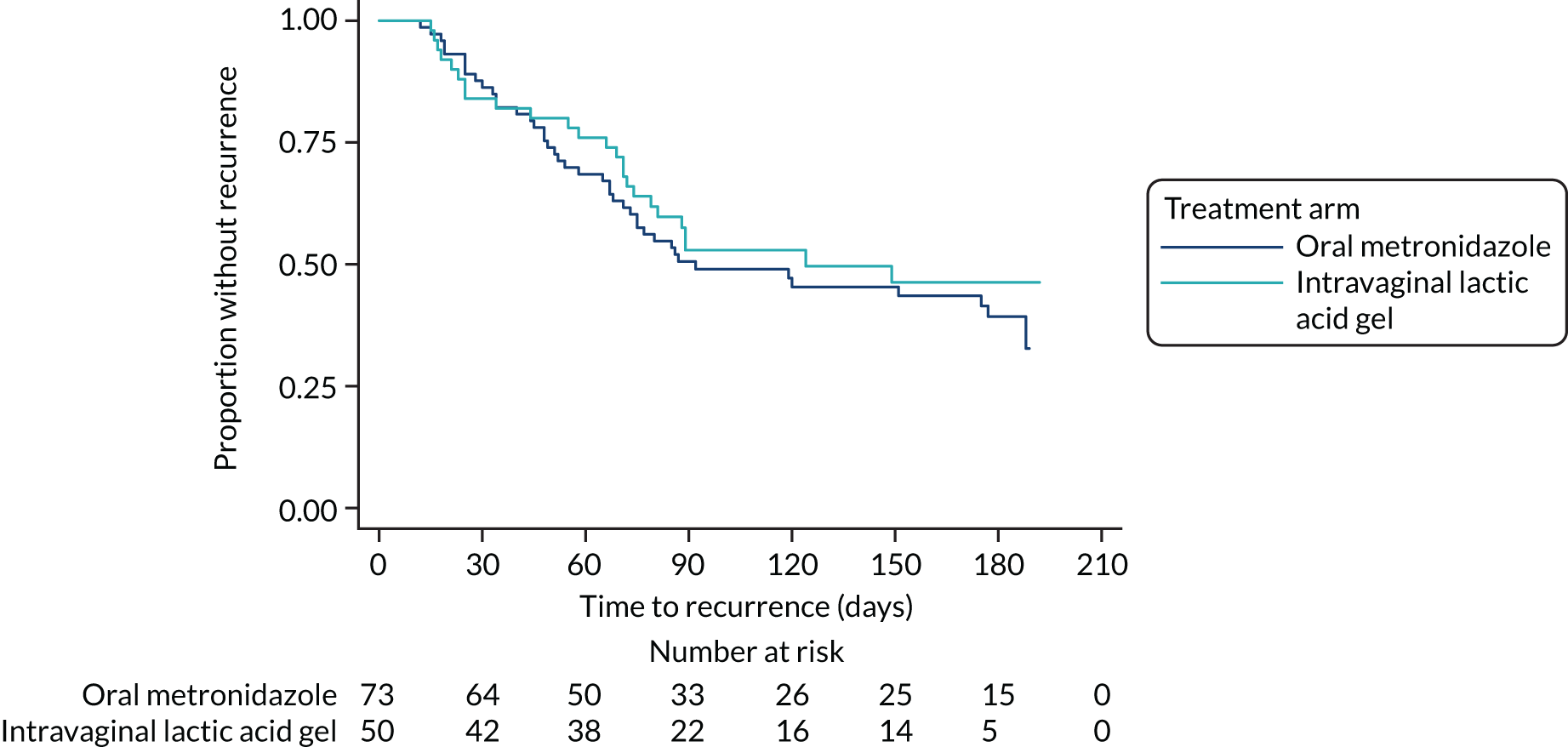

A Kaplan–Meier plot of recurrence against time is shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier plot of recurrence of BV symptoms against time.

There were few participants (n = 13) who resolved, had time to recurrence data and reported that additional treatment was taken during the first 2 weeks; therefore, the difference between those with and those without additional treatment could not be assessed (see Appendix 5, Table 39).

Time to recurrence was censored at 6 months if data were available at both 3 months and 6 months, but no recurrence had been reported. Of the times used in the analysis, 30 (41%) in the metronidazole arm and 25 (50%) in the lactic acid gel arm were censored times.

Including only those with data at both 3 months and 6 months gave the percentage recurring at 6 months as 60% (32/53) in the metronidazole arm and 56% (18/32) in the lactic acid gel arm. This removes inflation of the recurrence rate resulting from needing an episode at only one time for recurrence, but data at both times to record no recurrence.

Number of participant-reported bacterial vaginosis episodes over 6 months

The number of participants whose symptoms resolved by week 2 and who had complete episode data available at both 3 months and 6 months was small (metronidazole arm, n = 48; lactic acid gel arm, n = 29). There was little difference between treatment arms in the number of subsequent episodes of BV between week 2 and 6 months for those who had resolved by week 2. Both treatment arms had a median of one episode over the 6-month period, with a maximum of six episodes in the metronidazole arm and 10 episodes in the lactic acid gel arm (Table 10). The adjusted incidence rate ratio was 0.97 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.69). The analysis was adjusted for site, number of BV episodes in the 12 months before baseline and female partner in the 12 months before baseline (yes/no). Although vaginal douching could be included in the negative binomial model, it made little difference to the estimates (incidence rate ratio 1.00, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.72) and it was more consistent with the other analyses not to include this variable. The incidence rate is defined as the number of episodes per time at risk, that is if both treatment arms were followed up for the same length of time (in this case 6 months), the ratio of episodes in the metronidazole arm compared with the lactic acid gel arm was estimated as 0.97.

| Resolution/persistence of BV | Treatment arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | |

| Resolved by week 2 | n = 143 | n = 97 |

| Number of episodes within 3 months per participant whose symptoms resolved within 2 weeks | ||

| Total resolved by week 2 with 3-month episode data | 71 | 46 |

| Median number of episodes (25th, 75th centile) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 4 | 0, 8 |

| Number of episodes within 6 months per participant whose symptoms resolved within 2 weeks | ||

| Total resolved by week 2 with complete episode dataa | 48 | 29 |

| Median number of episodes (25th, 75th centile) | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 2) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 6 | 0, 10 |

| Did not resolve by week 2 | n = 61 | n = 108 |

| Number of episodes within 3 months per participant whose symptoms did not resolve within 2 weeks | ||

| Total not resolved by week 2, with 3-month episode data | 26 | 40 |

| Median number of episodes (25th, 75th centile) | 1 (0, 2) | 1.5 (0, 2) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 6 | 0, 5 |

| Number of episodes within 6 months per participant whose symptoms did not resolve within 2 weeks | ||

| Total not resolved by week 2, with complete episode dataa | 16 | 25 |

| Median number of episodes (25th, 75th centile) | 1 (0, 2) | 3 (1, 4) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 13 | 0, 93b |

Number of participant-reported bacterial vaginosis treatment courses over 6 months

Data on the number of BV treatment courses over the 6 months of the trial (excluding the study treatment) for those who had resolved by week 2 were available for 59 out of 143 (41%) participants in the metronidazole arm and 35 out of 97 (36%) participants in the lactic acid gel arm (see Appendix 5, Table 40). For those resolving by week 2, the median number of BV treatment courses received between week 2 and 6 months was similar between the treatment arms (metronidazole arm, median = 1; lactic acid gel arm, median = 1), with an adjusted incidence rate of 1.03 (95% CI 0.53 to 2.01) (see Appendix 5, Tables 40 and 41), and are explored further in the health economic analysis (see Chapter 5).

Microbiological resolution of bacterial vaginosis on microscopy of vaginal smears at week 2

The number of participants with central laboratory microbiological confirmation of BV (Ison–Hay grade 3) on vaginal smears taken at baseline was 138 participants in the metronidazole arm and 128 participants in the lactic acid gel arm (Table 11). Of those participants, 77 (56%) in the metronidazole arm and 73 (57%) in the lactic acid gel arm had central laboratory BV results available at week 2. Microbiological resolution of BV at week 2 in those with confirmed BV at baseline was higher in the metronidazole arm (59/77 participants; 77%) than in the lactic acid gel arm (31/73 participants; 42%), with an adjusted risk difference of –34.3% (95% CI –49.1% to –19.5%) (see Table 11). Microbiological resolution was defined as having Ison–Hay grade 3 at baseline followed by Ison–Hay grades 0, 1, 2 or U at week 2.

| Resolution of BV | Treatment arm, n (%) | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI)a | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral metronidazole (N = 259) | Intravaginal lactic acid gel (N = 259) | |||

| Number with baseline-confirmed BV (Ison–Hay grade 3 by central laboratory) | 138 | 128 | ||

| Microbiological resolution of BV by week 2 | ||||

| Yes | 59 (77) | 31 (42) | –34.3% (–49.1% to –19.5%) | 0.22 (0.10 to 0.46) |

| No | 18 (23) | 42 (58) | ||

| Missing | 61 | 55 | ||

Of those participants with microbiological confirmation of BV at baseline, resolution of symptoms occurred in 83 out of 111 (75%) participants in the metronidazole arm and 49 out of 101 (49%) participants in the lactic acid gel arm.

When rates of resolution were compared between microbiological results and participant-reported symptomatic results, they were similar (60% indicating microbiological resolution and 61% indicating symptomatic resolution) (see Appendix 5, Table 42). However, these results were not consistent in about one-third of cases with data; that is, 25 out of 145 (17%) samples did not indicate microbiological resolution while the participant did report symptomatic resolution, and a further 24 out of 145 (17%) samples showed microbiological resolution without symptomatic resolution.

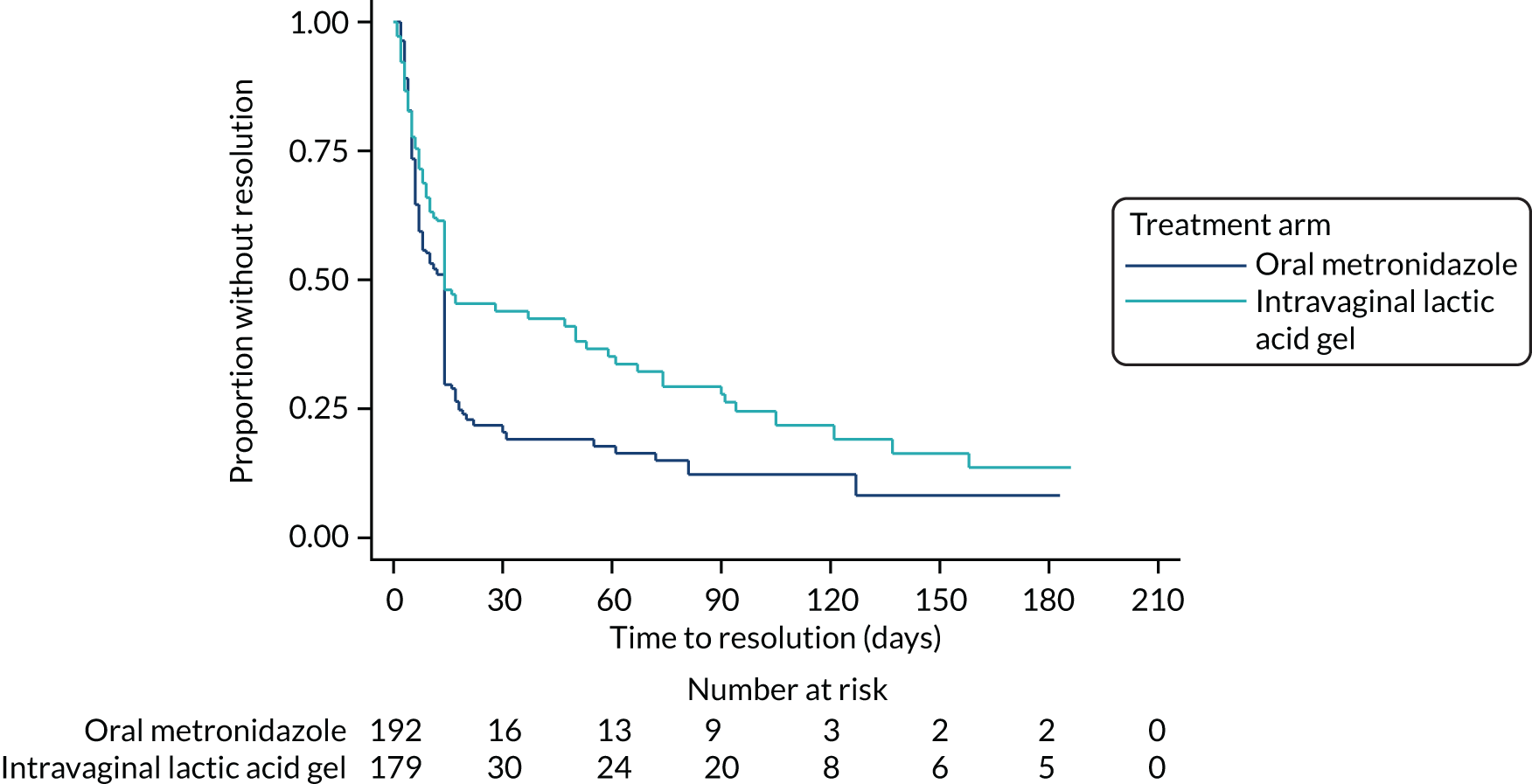

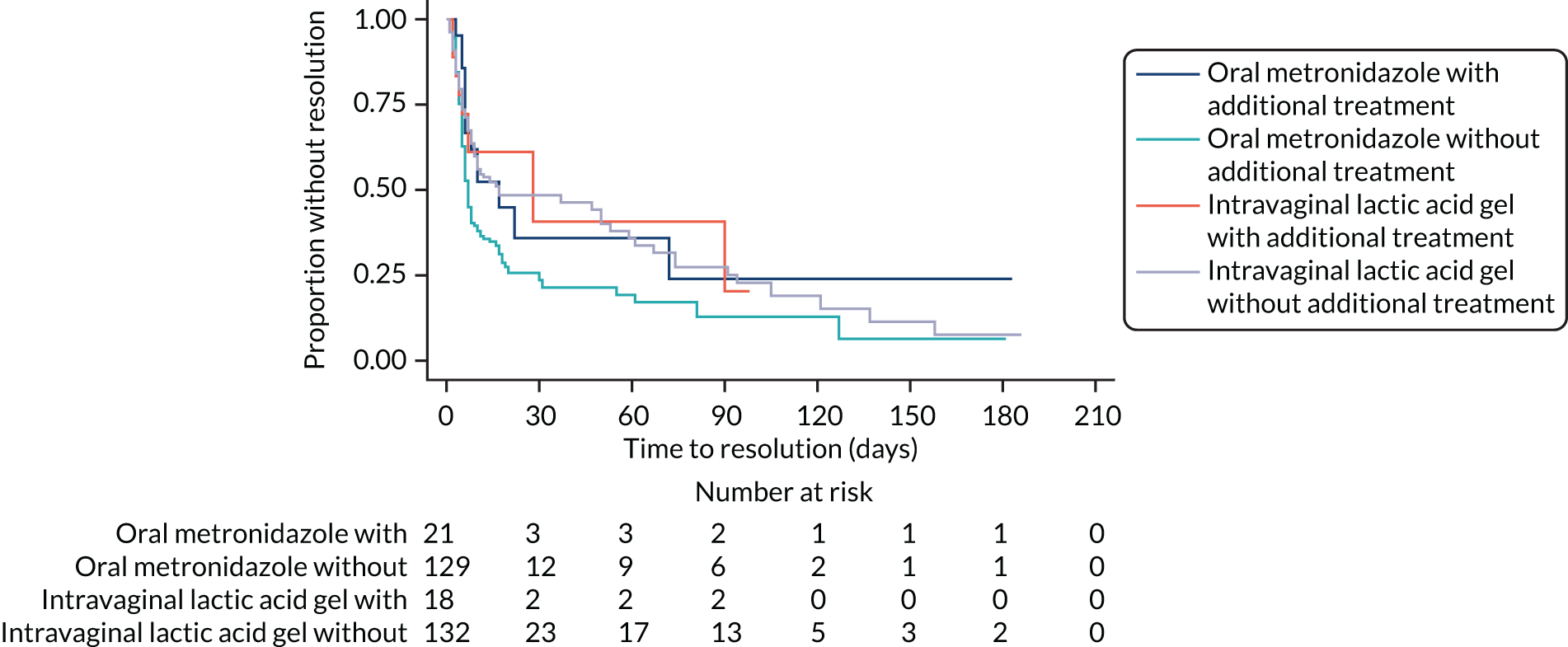

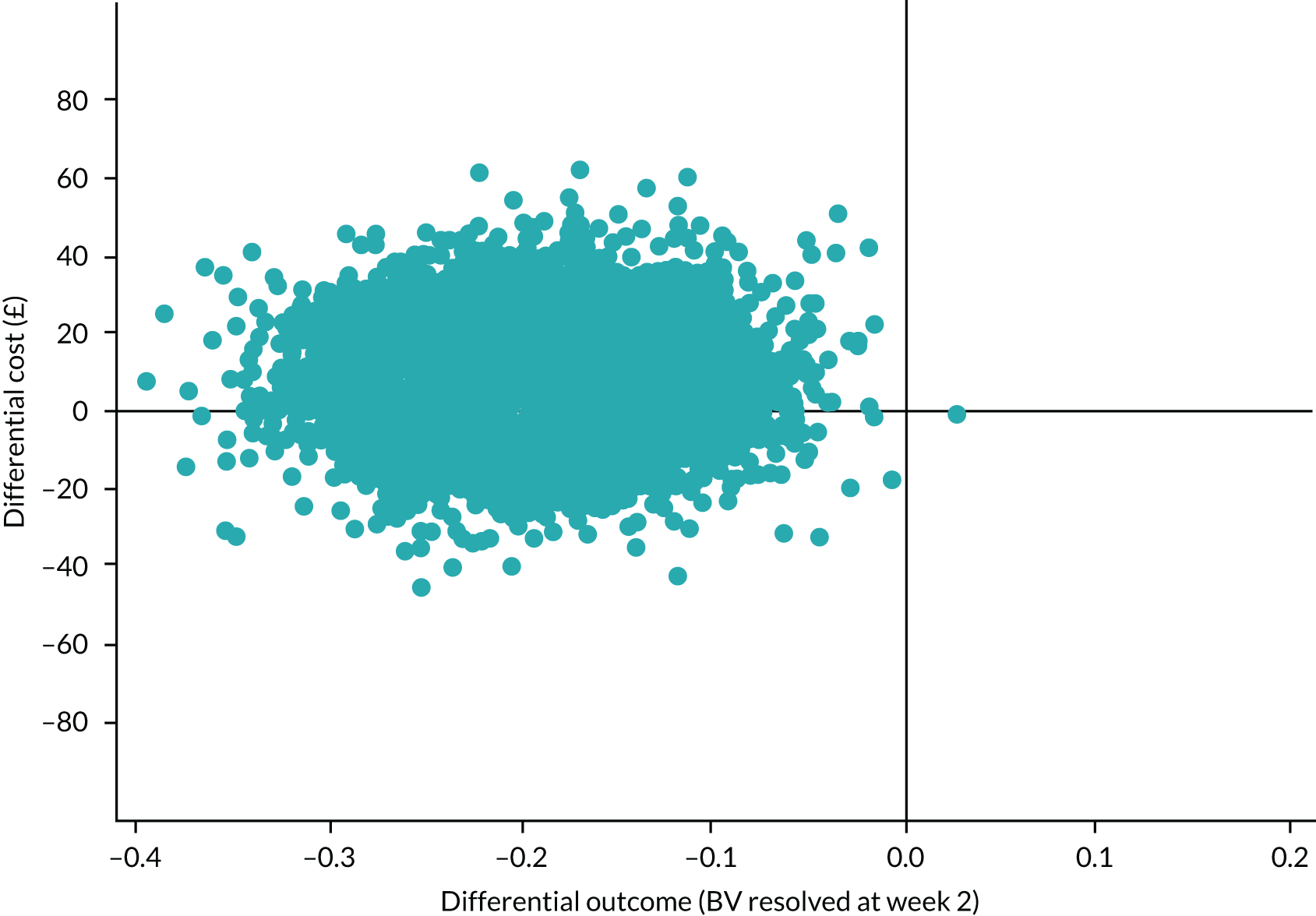

Time to participant-reported resolution of bacterial vaginosis symptoms