Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1211-20010. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Foster et al. This work was produced by Foster et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Foster et al.

Synopsis

Background and rationale for the programme

Musculoskeletal pain such as back pain, neck, shoulder, knee and multisite pain is common and costly in terms of the burden on individuals, the NHS and society. 1 For some people these musculoskeletal problems are painful but short-lived; however, for others the painful episode fails to resolve or recurs, impacting day-to-day function including ability to work and leading to extensive NHS and societal costs.

Most patients with musculoskeletal problems are managed in primary care, where 20% of the registered practice population will consult their general practitioner (GP) annually with a musculoskeletal problem, accounting for 1 in 6 GP consultations. 2 There is limited evidence to guide how best to direct the right patient to the right treatment in primary care in ways that improve patient outcomes such as pain and function, and make the best use of health-care resource. The sheer number of patients with musculoskeletal pain and the wide variation in their prognosis means that it not appropriate to offer intensive or expensive treatments to all. 3

Stratified care involves targeting treatments according to patient subgroups, in the hope of maximising treatment benefit and reducing potential harm or unnecessary interventions. 4 Building on a previously successful model of prognostic stratified care for patients in primary care with low back pain,5–7 the aims of this programme were to adapt, finalise and test a prognostic stratified primary care model for a much larger group of patients with the five most common musculoskeletal pain presentations.

Aims of the research programme

The aims of this programme were to adapt, finalise and test a prognostic stratified primary care model for primary care patients consulting with the five most common pain presentations (back, neck, shoulder, knee or multisite pain), comparing it with usual primary care. A series of studies involving different methods (a prospective longitudinal cohort study, interviews with patients and clinicians, an evidence synthesis, consensus group workshops, the development of tools and training to support GPs to use the stratified care approach, and clinical trials including analyses of general practice medical record data and health economic analyses) were carried out to address the following research questions:

-

Can one prognostic tool [the Keele STarT MSK Tool (Subgrouping for Targeted Treatment for Musculoskeletal pain)] identify the risk of poor outcome for a wide range of patients with the most common musculoskeletal pain presentations in primary care, and does it discriminate subgroups at low, medium and high risk of persistent disabling pain?

-

What are the most appropriate treatment options that should be recommended for patients in each risk subgroup?

-

What are the views and experiences of patients and clinicians about using a prognostic stratified care approach in the management of musculoskeletal pain?

-

What is the feasibility of (1) delivering the stratified care intervention in primary care and (2) conducting a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test this new model of care?

-

In adults with the most common musculoskeletal pain presentations in primary care, does prognostic stratified care (involving use of the Keele STarT MSK Tool and recommended matched treatments) lead to better patient outcomes, greater cost-effectiveness and different clinical decision-making than usual non-stratified primary care?

In addition, a stratified care clinician training and support package comprising electronic templates, a stratified care tool and recommended treatment options to support delivery of stratified primary care was developed.

The research was carried out between June 2014 and September 2020.

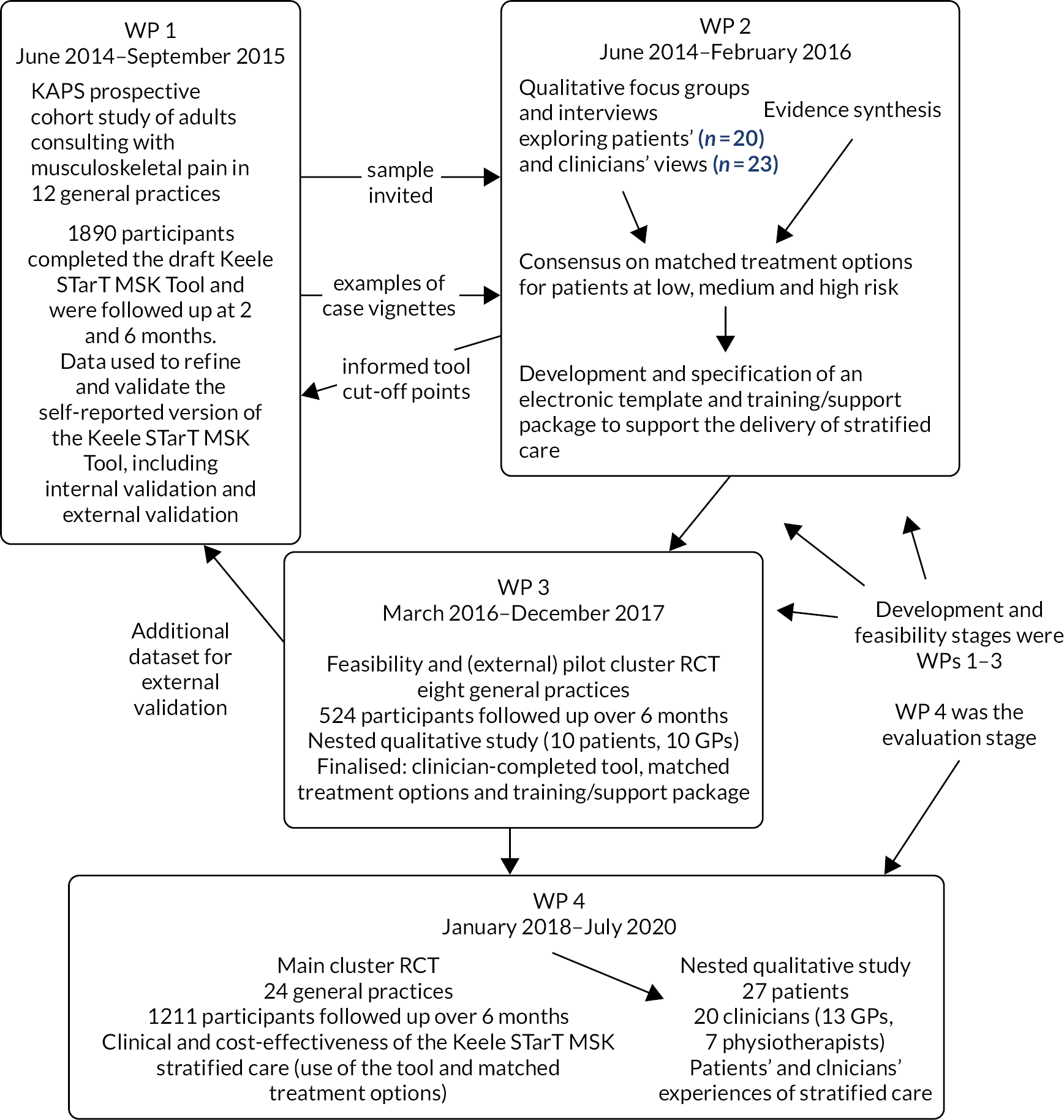

The inter-relationships between the four work packages are summarised in Figure 1 (below). The prospective cohort study in work package 1 provided the sampling frame for the qualitative interviews in work package 2. The feasibility and pilot RCT in work package 3 provided the data set for the external validation of the Keele STarT MSK Tool in work package 1.

FIGURE 1.

The Keele STarT MSK research programme pathway diagram. KAPS, Keele Aches and Pains Study.

Work package 1

Previously, we showed that stratified care involving targeting treatments according to patient subgroups based on the STarT Back tool5 was clinically effective and cost-effective for patients with low back pain.6 Preliminary analyses of a modified version of the STarT Back tool amended to better suit patients with a broader range of musculoskeletal pain presentations (e.g. back, neck, upper limb, lower limb or multisite pain) showed promise, but highlighted that modifications to this draft Keele STarT MSK Tool were required because risk varied for patients with pain at different body sites.8 In addition, the new Keele STarT MSK Tool needed to be validated with the target patient group: those consulting in general practice with musculoskeletal pain.

Research aim and objectives

The aim of this work package was to refine and validate an instrument, the Keele STarT MSK Tool, designed to identify risk of poor outcome in primary care patients with the most common musculoskeletal pain presentations.

The four specific objectives were as follows:

-

confirm the validity and optimise the predictive performance of the Keele STarT MSK Tool

-

determine the screening tool risk strata cut-off points based on optimal predictive values and suitability for matched treatment options

-

estimate the proportions of patients classified at low, medium and high risk of poor outcome and describe their characteristics

-

describe current health-care resource use by all patients and in each risk stratum.

Methods

We carried out a prospective cohort study of consecutive consulters in UK general practice [named the Keele Aches and Pains Study (KAPS)]. The protocol for the study has been published. 9

Patients aged ≥ 18 years presenting with one or more of the five most common musculoskeletal pain presentations (back, neck, shoulder, knee or multisite pain) were identified at 12 general practices in the West Midlands in England. Participants were recruited between July 2014 and February 2015. Patients were excluded if there were indications of potentially serious underlying pathology (such as cancer or infection), they had urgent care needs, they were vulnerable or if they were unable to communicate in English. We mailed out information about the study and baseline questionnaire and, for those providing consent, we sent further questionnaires at 2 and 6 months’ follow-up and analysed their primary care electronic medical records (EMRs). We estimated that we would need to identify approximately 3000 eligible patients to recruit 1800 participants at baseline (based on a 60% response rate). We anticipated that this would provide 1250 patients at 6 months follow-up, including 125 patients at high risk of poor outcome (the smallest subgroup), which would provide adequate power for validation of the draft Keele STarT MSK Tool.

Our main outcome measures were physical function [Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) physical component score (PCS)], pain intensity [0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS)], pain interference [Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain interference scale] and health-related quality of life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)], measured at 2 and 6 months’ follow-up. For dichotomous outcomes, poor outcome on the PCS was defined as scores of < 37.17 at 2 months and < 39.61 at 6 months, based on lower tertiles from an independent study of UK primary care musculoskeletal pain patients. 10 Poor outcome on pain intensity was defined as NRS scores of ≥ 5 points. 11 Secondary outcomes are detailed in our protocol paper by Campbell et al. (2016). 9 The baseline questionnaires also included the draft Keele STarT MSK Tool (identical to the modified STarT Back tool) presented in our paper by Hill et al. (2016). 8 The responses to the KAPS baseline and follow-up questionnaires are provided in Appendix 1.

Analysis

Predictive performance was determined using linear regression of the association between baseline tool score and PCS and pain intensity at 2 and 6 months’ follow-up. Performance was assessed based on model fit (R2) and discrimination (c-statistic) and calibration (calibration slope and Hosmer–Lemeshow test).

Item redundancy and weighting was investigated within multiple linear regression models for estimating PCS score at 2 and 6 months, and pain intensity at 2 and 6 months. If items did not add significant predictive performance and/or if average standardised beta weight was small (i.e. < 0.05) in most analyses, then the item was deemed statistically redundant. The research team, in consultation with members of our patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) group, considered face validity in decisions about the removal of statistically redundant items.

The tool cut-off point for identifying the high-risk subgroup (compared with those at medium/low risk) was based on classification on the full score most likely to attain positive predictive values and specificity ≥ 0.8, and positive likelihood ratio ≥ 5, for predicting pain and function at 2 and 6 months’ follow-up. The tool cut-off point for categorising the low-risk subgroup (compared with those at medium/high risk) was based on the classification most likely to achieve negative predictive values and sensitivity ≥ 0.80, and negative likelihood ratio ≤ 0.2. 12–14 All decisions about tool cut-off points were based on statistical information in the sample overall and within pain sites, plus suitability for matched treatments.

Health-care utilisation data were collected from patient questionnaires and medical record review at 6 months’ follow-up. Information included primary and secondary care contacts, prescribed medications, treatments, tests and investigations. Unit costs were obtained primarily from standard national sources such as NHS Reference costs,15 Unit Costs of Health and Social Care16 and the British National Formulary (BNF),17 and applied to resource use data.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise data on health-care utilisation and a total health-care cost per patient over 6 months was also estimated. Mean total costs for each patient risk subgroup were calculated and non-parametric bootstrapping (1000 replications) was used to estimate bias-corrected CIs around differences in mean costs.

External validity

Independent testing was carried out within the Keele STarT MSK feasibility and pilot trial data set in work package 3, with the Keele STarT MSK Tool completed during GP–patient consultations, and using pain intensity at 6 months’ follow-up as the outcome (see Work package 3 and the pilot trial findings publication by Hill et al. 18). Discriminant and predictive validity were investigated using model fit and discrimination as above. Descriptive analysis of outcomes within risk strata of the final Keele STarT MSK Tool were investigated.

Key findings

Overall, 4720 patients visited their GP about back, neck, knee, shoulder or multisite pain and were invited to participate in the cohort study. A total of 2057 patients responded (43.6% response rate), and 1890 consented to participate (40.2% adjusted response rate owing to incomplete/ineligible questionnaires and refusals). The mean age of participants was 58 years (range 18–96 years), and 61% were female. Response rates at 2 and 6 months were 75.8% (n = 1425) and 78.7% (n = 1452), respectively.

The mean baseline physical function (PCS) score was 36.2 [standard deviation (SD) 10.1], mean baseline pain intensity was 5.3 (SD 2.4) and 22% of the sample reported having pain for less than 3 months. Multisite pain was the most commonly reported reason for consulting the GP, followed by low back pain and knee pain (further baseline characteristics are shown in Appendix 1, Table 1). Response rates to the 2- and 6-month follow-up questionnaires were 75.8% and 78.7%, respectively. At 2 and 6 months, mean PCS scores rose to 38.1 and 38.6, respectively (indicating modest improvements in physical function); 47.7% (n = 560) at 2 months and 53.4% (n = 581) at 6 months were categorised as having a poor outcome on the PCS. Mean pain intensity reduced to 4.4 at 2 months and 4.1 at 6 months, with 45.6% (n = 582) and 42.3% (n = 482) categorised as having a poor pain outcome, respectively.

| Characteristic | Cohort study (N = 1890) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 58.3 (16.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 1145 (60.6) |

| Index pain site, n (%) | |

| Knee | 349 (18.5) |

| Neck | 57 (3.0) |

| Back | 408 (21.6) |

| Shoulder | 103 (5.4) |

| Multisite | 973 (51.5) |

| Live alone, n (%) | 394 (21.0) |

| Employed, n (%) | 747 (41.1) |

| Time off work in last 6 months, n (%) | 318 (16.8) |

| Pain at consultation, mean (SD) | NA |

| Pain intensity, mean (SD) points | |

| Mean of least, average and current pain | 5.3 (2.4) |

| Usual pain | 6.2 (2.5) |

| Duration: time since no pain, n (%) (n = 29 missing) | |

| < 3 months | 403 (21.7) |

| 3–6 months | 225 (12.1) |

| 7–12 months | 212 (11.4) |

| 1–5 years | 521 (27.6) |

| ≥ 6 years | 500 (26.5) |

| SF-36 component scales, mean score (SD) (n = 116 missing) | |

| Physical | 36.2 (10.1) |

| Mental | 43.6 (13.2) |

| PROMIS pain interference, mean (SD) points (n = 46 missing) | 62.1 (8.1) |

| Pain self-efficacy, mean (SD) points (n = 31 missing) | 37.2 (16.1) |

| Catastrophising, mean (SD) points (n = 13 missing) | 9.7 (8.9) |

| Long-term medical conditions, n (%) | |

| Diabetes | 217 (11.5) |

| Breathing problems/COPD/asthma | 334 (17.7) |

| Heart problems or high blood pressure | 579 (30.7) |

| Chronic fatigue, ME, fibromyalgia, widespread pain | 84 (4.5) |

| Anxiety, depression, stress | 446 (23.6) |

| Other | 495 (26.2) |

| Health literacy problems, n (%) | |

| Never/rarely | 1555 (82.3) |

| Sometimes/often/always | 325 (17.3) |

| EQ-5D-5L score, mean (SD) | 0.56 (0.27) |

Objective 1: confirm the validity and optimise predictive performance of the Keele STarT MSK Tool

We investigated whether or not adding, removing or replacing items from the draft tool led to improvements in predictive performance and face validity. A list of candidate items was included in the baseline questionnaire; these covered domains including vitality/fatigue, comorbidity, coping, sleep problems, previous treatment success, pain interference, pain self-efficacy, pain persistence, pain-related depression and fear-avoidance beliefs. Three candidate items were used to replace items in the draft tool because they improved model fit (R2) from 0.334 to 0.405 and discrimination (c-statistic) from 0.804 to 0.815 against physical function (PCS) at 6 months follow-up, and were perceived to improve face validity.

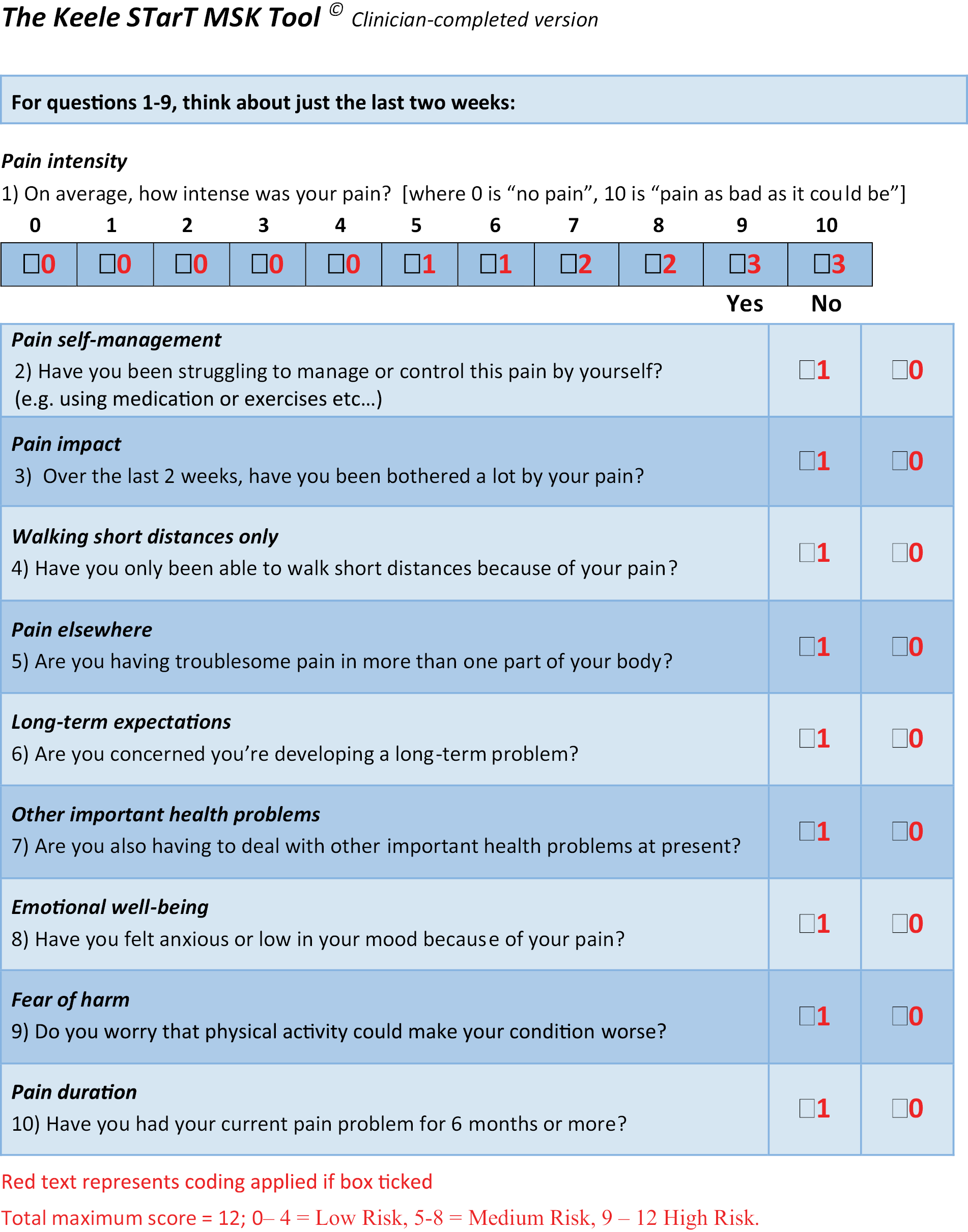

We then examined this amended version of the Keele STarT MSK Tool within the independent sample of 524 patients in the feasibility and pilot RCT described in Work package 3 (mean age 61 years, 61% female). Analyses indicated unacceptable reductions in model fit (R2 0.149) and discrimination (c-statistic 0.685). We, therefore, returned to the KAPS data set, and identified additional items that further improved the tool. Investigation of item redundancy, in combination with assessment of face validity by the team led to the removal of two items. This led to a final 10-item Keele STarT MSK Tool with scale range 0–12 (0 = lowest risk of poor outcome, 12 = highest risk of poor outcome). Each item is scored 0 or 1 except the item on pain intensity, which is scored on a subscale of 0 to 3, indicating increasing severity of pain; this weighting reflects a higher standardised beta coefficient compared with other items in the final model. The final model fit at 6 months’ follow-up was 0.422 and discrimination 0.839 for physical function (PCS), and 0.430 and 0.822 for pain intensity; there was acceptable performance across the five musculoskeletal pain presentations. Multiple imputation indicated that tool performance was robust to missing data. The final model also resulted in improved model fit (R2 0.224) and discrimination (c-statistic 0.725) for pain intensity in the external data set from work package 3.

Objective 2: determine the screening tool risk strata cut-off points

The cut-off points determined to provide the best combination of sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios, in combination with suitability for the recommended matched treatments (identified in work package 2), overall and across pain sites, were 0–4 for low risk, 5–8 for medium risk, and 9–12 for high risk, on the full scale.

Objective 3: estimate the proportions of patients classified at low, medium and high risk of poor outcome and describe their characteristics

The KAPS cohort participants were classified as 25% at low risk, 42% at medium risk and 33% at high risk. There were clear and consistent differences between risk subgroups on key variables at both baseline and follow-up. For example, mean baseline physical function (PCS) scores were 45.8 for patients at low risk, 36.8 for those at medium risk and 28.4 for those at high risk, with mean 6-month follow-up scores of 48.0, 39.0 and 30.2, respectively. Pain intensity showed comparable differences, with mean scores at 6 months of 1.9 for the low-risk subgroup, 4.0 for the medium-risk subgroup and 6.2 for the high-risk subgroup. There were also clear differences in the other key outcomes, pain interference (PROMIS pain interference scale) and health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L), as well as differences on the secondary outcome measures. Further details are presented in Appendix 1, Table 2. These patterns were still evident when the data were examined by site of pain presentation (back, neck, shoulder, knee and multisite pain).

| Keele STarT MSK Tool subgroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic/outcome | All | High risk | Medium risk | Low risk |

| SF-36 PCS, mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 36.2 (10.1) | 28.4 (7.3) | 36.8 (8.1) | 45.8 (8.0) |

| 6 months | 38.6 (11.4) | 30.2 (8.8) | 39.0 (10.0) | 48.0 (8.2) |

| Poor outcome at 6 months, n (%) | 581 (53.4) | 287 (87.5) | 257 (53.7) | 43 (15.1) |

| Pain intensity, mean (SD) points | ||||

| Baseline | 5.3 (2.4) | 7.2 (1.6) | 5.3 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.6) |

| 6 months | 4.1 (2.8) | 6.2 (2.3) | 4.0 (2.4) | 1.9 (1.9) |

| Poor outcome at 6 months, n (%) | 482 (42.3) | 263 (75.1) | 200 (40.7) | 33 (11.1) |

| PROMIS pain interference scale, mean (SD) points | ||||

| Baseline | 62.1 (8.1) | 68.8 (4.9) | 61.9 (5.6) | 53.6 (6.6) |

| 6 months | 59.1 (9.0) | 65.9 (6.7) | 58.4 (7.3) | 51.3 (7.4) |

| EQ-5D-5L score, mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 0.56 (0.27) | 0.33 (0.26) | 0.62 (0.18) | 0.78 (0.11) |

| 6 months | 0.62 (0.26) | 0.42 (0.28) | 0.66 (0.19) | 0.81 (0.15) |

| Pain self efficacy questionnaire, mean (SD) points | ||||

| Baseline | 37.2 (16.1) | 24.3 (13.6) | 39.3 (12.7) | 51.6 (8.8) |

| 6 months | 39.9 (16.1) | 27.0 (14.5) | 42.1 (13.2) | 52.3 (10.0) |

| SF-36 mental component score, mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 43.6 (13.2) | 35.1 (12.3) | 45.4 (11.7) | 52.4 (9.1) |

| 6 months | 47.7 (11.9) | 40.2 (13.0) | 49.2 (10.4) | 54.1 (7.5) |

| Pain catastrophising, mean (SD) points | ||||

| Baseline | 9.7 (8.9) | 16.3 (9.2) | 8.3 (6.8) | 3.4 (4.7) |

| 6 months | 7.8 (8.4) | 13.8 (9.3) | 6.9 (7.1) | 2.4 (4.0) |

| Sleep problems, n (%) | ||||

| Baseline | 1193 (63.1) | 464 (82.1) | 449 (63.7) | 161 (38.4) |

| 6 months | 675 (54.3) | 266 (76.4) | 261 (53.5) | 82 (28.0) |

| Global change: ‘much improved’ at 6 months, n (%) | 353 (24.3) | 38 (9.0) | 118 (21.0) | 167 (50.1) |

Objective 4: describe health-care resource use by all patients and in each risk stratum

Overall, there was a mean of 1.44 GP visits for musculoskeletal pain per participant over the 6-month follow-up period (not including the index consultation); this ranged from a mean of 0.66 visits in the low-risk subgroup, to 1.40 in medium risk, to 2.22 in the high-risk subgroup. The risk subgroups differed on all areas of health-care utilisation, for example the mean number of prescriptions ranged from 1.80 per person in the low-risk subgroup to 10.45 per person in the high-risk subgroup over the 6-month period. Further details are given in Appendix 1, Table 3.

| Health-care resource | Overall (N =1253)a | Keele STarT MSK risk subgroupb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (N = 298) | Medium (N = 491) | High (N = 350) | ||||||

| Primary care health-care utilisation, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| GP consultations | ||||||||

| Practice | 1.44 (2.191) | 0.66 (0.959) | 1.40 (2.154) | 2.22 (2.738) | ||||

| Home | 0.12 (0.862) | 0.04 (0.249) | 0.07 (0.363) | 0.18 (0.821) | ||||

| Nurse consultations | ||||||||

| Practice | 0.19 (0.774) | 0.08 (0.348) | 0.18 (0.777) | 0.29 (1.029) | ||||

| Home | 0.05 (0.578) | 0.04 (0.695) | 0.05 (0.662) | 0.06 (0.400) | ||||

| Other primary care consultationsc | ||||||||

| Practice | 1.06 (2.823) | 0.53 (1.500) | 1.28 (3.227) | 1.27 (3.186) | ||||

| Home | 0.10 (0.951) | 0.01 (0.141) | 0.13 (1.295) | 0.14 (0.841) | ||||

| Secondary care health care-utilisation, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| Consultantd | ||||||||

| NHS | 0.44 (1.349) | 0.17 (0.505) | 0.42 (1.196) | 0.75 (1.982) | ||||

| Private | 0.21 (1.010) | 0.11 (0.737) | 0.26 (1.038) | 0.26 (1.234) | ||||

| Physiotherapist | ||||||||

| NHS | 0.51 (1.667) | 0.34 (1.191) | 0.50 (1.542) | 0.77 (2.238) | ||||

| Private | 0.33 (1.519) | 0.20 (1.094) | 0.41 (1.531) | 0.39 (1.900) | ||||

| Acupuncture | ||||||||

| NHS | 0.08 (0.917) | 0.03 (0.337) | 0.10 (0.337) | 0.11 (1.436) | ||||

| Private | 0.07 (0.596) | 0.06 (0.562) | 0.10 (0.706) | 0.10 (0.553) | ||||

| Osteopath | ||||||||

| NHS | 0.01 (0.135) | 0.01 (0.116) | 0 | 0.02 (0.232) | ||||

| Private | 0.04 (0.536) | 0.02 (0.173) | 0.03 (0.241) | 0.09 (0.953) | ||||

| Other secondary care health-care utilisation and OTC medication, n (%) | ||||||||

| Overnight stay in hospital | 43 (3.4) | 2 (0.7) | 19 (3.9) | 21 (6.0) | ||||

| Treatments or investigations | 345 (28) | 43 (14.5) | 144 (29.5) | 129 (36.9) | ||||

| OTC medication | 608 (49) | 121 (40.7) | 256 (52.4) | 180 (51.6) | ||||

| Prescribed medication, n (%) e | ||||||||

| Total number of prescriptions, N | 7039 | 536 | 2125 | 3659 | ||||

| Simple analgesic | 865 (12.3) | 62 (11.6) | 309 (14.5) | 406 (11.1) | ||||

| Topical analgesic | 624 (8.9) | 81 (15.1) | 180 (8.5) | 285 (7.8) | ||||

| Compound analgesic | 1504 (21.4) | 130 (24.3) | 509 (23.9) | 697 (19.1) | ||||

| NSAID | 1001 (14.2) | 128 (23.9) | 397 (18.7) | 391 (10.7) | ||||

| Skeletal muscle relaxant | 245 (3.5) | 12 (2.2) | 50 (2.4) | 173 (4.7) | ||||

| Neuropathic pain medication | 734 (10.4) | 21 (3.9) | 186 (8.8) | 483 (13.2) | ||||

| Opioid medication | 1818 (25.8) | 45 (8.4) | 411 (19.3) | 1177 (32.2) | ||||

| Corticosteroid injection | 77 (1.1) | 20 (3.7) | 31 (1.5) | 19 (0.5) | ||||

| Other treatmentsf | 171 (2.43) | 37 (6.9) | 52 (2.5) | 28 (0.8) | ||||

Total mean health-care costs per participant over the 6 months were £132.92 (SD £167.88), £279.32 (SD £462.98) and £476.07 (SD £716.44) for patients in the low-, medium- and high-risk subgroups, respectively.

Alterations to initial plans and work package limitations

We anticipated 60% participation among those invited to participate in the KAPS cohort study, based on previous similar studies, but only 40% consented to participate. With approval from the Programme Steering Committee (PSC), we extended recruitment by 3 months to achieve the required sample, but the lower initial response rate may have introduced further bias into the characteristics of the study sample. This is most likely to be reflected in the proportions of participants in each subgroup. However, it is unlikely to strongly affect the data analyses and findings because these were internal comparisons and there was still sufficient variation within the sample, and sufficient numbers, to carry out the analyses.

All the key outcomes were available within our purposely designed development data set (the KAPS prospective cohort) but of those outcomes, only pain intensity was available in the independent validation data set (the feasibility and pilot trial in work package 3). As the tool appeared robust across outcomes in the cohort data set, it seems unlikely that it would show substantially different findings in the trial data set for outcomes of physical function (as measured by the PCS), but this cannot be empirically demonstrated.

The decision was made to examine the performance of the tool developed in the cohort study within the independent pilot trial data set; this took place after the publication of the KAPS cohort protocol paper but was agreed with the PSC. This decision was taken because the predictive performance of the initial refined tool was not as high as required. After examination of the tool in the external data set indicated sub-optimal performance, the requirement for candidate items to be potentially modifiable by treatment was removed because the team wanted to examine the potential for including non-treatment-modifiable factors in the tool such as ‘pain duration’, which was included in the final version to increase its predictive abilities.

A limitation of work package 1 as planned was that although we conducted the refinement and validation of the Keele STarT MSK Tool as a patient-completed set of questions, its use as completed by clinicians during a clinical consultation was not investigated.

Conclusions

A new tool was refined and validated, the Keele STarT MSK Tool, with which to subgroup adults consulting with back, neck, shoulder, knee or multisite pain in primary care into those at low, medium and high risk of poor outcome. The tool is available on request from www.keele.ac.uk/startmsk/startmskresearch/. It clearly and simply allocates patients to subgroups with distinct characteristics, different health-care usage and different prognoses, and its performance is acceptable upon independent validation. This study confirms that generic prognostic factors can be combined in one simple stratification tool and that this tool can be used to identify the risk of poor outcome (low, medium or high) in a wide range of patients consulting with different musculoskeletal pain presentations in primary care.

Interrelationship with other parts of the programme

The Keele STarT MSK Tool was refined and validated in this work package, ready for use in work package 3 (feasibility and pilot RCT) as one of two components of the new stratified care intervention. The data from work package 3 was used to examine the external validity of the tool, prior to work package 4 (Keele STarT MSK trial). Participants in the work package 1 KAPS cohort formed the sampling frame for (1) invitation to participate in the qualitative interviews in work package 2 and (2) selection of example patient case vignettes to aid the development of consensus on matched treatments in work package 2. In addition, the recommended matched treatment options generated in work package 2 contributed to decisions about the cut-off points on the tool used to allocate patients to low-, medium- or high-risk subgroups.

Work package 2

In parallel with the prospective cohort study (KAPS) in work package 1, work package 2 comprised three studies (an evidence synthesis, qualitative interviews and a consensus study) that together informed the final stage in this work package: the development and specification of the stratified care electronic template and GP training and support package to support the delivery of stratified primary care. These studies have been published in Babatunde et al. ,19 Saunders et al. 20 and Protheroe et al. 21

Research aims and objectives

The aim of this work package was to define and agree the matched treatment options for patients in each of the three risk subgroups and develop a training and support package for the delivery of stratified primary care.

The specific objectives were as follows:

-

summarise current best evidence on available treatments for the five most common musculoskeletal pain presentations in primary care

-

explore patients’ and GPs’ views on the acceptability of prognostic stratified care, and the anticipated barriers to and facilitators of its use in clinical practice

-

agree, through expert consensus, the most appropriate matched treatment options that should be recommended for patients in each risk subgroup

-

develop and specify a training and support package to support the delivery of stratified primary care.

Methods and key findings for each study

Evidence synthesis

Methods

A systematic search and appraisal of evidence about the effectiveness of first-line available treatments for the five most common musculoskeletal pain presentations was conducted. The evidence synthesis followed a pyramidal approach using national clinical guidelines, policy documents, clinical evidence pathways and systematic reviews as a starting point. This was supplemented by systematic searches of bibliographic databases to identify and retrieve more recently published trials that had not yet been summarised in systematic reviews or guidelines, or identify where evidence gaps existed. Full details are available from the published paper. 19

Currently available treatments for patients with musculoskeletal pain consulting in primary care that were considered include self-management advice and education, exercise therapy, manual therapy, pharmacological interventions (oral and topical analgesics and local joint injections), aids and devices, and other treatments [ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), laser, acupuncture and ice/hot packs]. Referral options for psychosocial interventions (cognitive–behavioural therapy and pain-coping skills) and surgery were also included. Comparison groups could include usual care, no intervention or other active interventions. Subsequently, data on study populations, interventions, and the outcomes of the intervention on patients’ pain and function were extracted. Secondary outcomes such as psychological well-being/depression, catastrophising, quality of life, work-related outcomes (e.g. days off work and return to work), and cost of treatment were also extracted. The methodological quality of included systematic reviews was assessed using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR)22 and the overall strength of evidence on the effectiveness of each treatment was rated using a modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. 23

Key findings

In addition to clinical guidelines, policy and care pathway documents, a total of 146 systematic reviews (71 Cochrane and 75 non-Cochrane) met the selection criteria and were included. Methodological quality was lower for non-Cochrane reviews, because these are susceptible to publication bias (≈ 80% of studies); full details are available in the published paper. 19 Study quality was not always incorporated into the evidence synthesis nor appropriately used to formulate conclusions in over a third of the included studies.

For most musculoskeletal pain presentations, non-pharmacological treatments, especially exercise therapy and psychosocial interventions, were found to lead to medium to large improvements for pain and function in the short and long term. Corticosteroid injections lead to short-term benefit for patients with knee and shoulder pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids reduced pain in the short-term but effect sizes were modest and the potential for adverse effects needs careful consideration. With the exception of acupuncture, which was found to be beneficial for relieving pain in the short-term, the clinical effectiveness of other treatments (ultrasound, TENS, laser and ice/hot packs) either alone or in combination was not substantiated by strong evidence for pain and function. The effectiveness of surgery as a first-line treatment option was not established. Evidence of long-term effectiveness of surgery was also limited except where directly indicated by specific serious pathology such as end-stage degenerative knee joint disease, or where persistent pain and functional limitations were refractory to conservative treatments.

Current evidence was equivocal on the optimal dose and application of most treatments. There was little evidence specifically about characteristics that might identify those patients most likely to respond to different treatments (e.g. pain severity or duration, previous pain episodes, or function).

In summary, the evidence synthesis showed that primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain can be managed effectively with non-pharmacological treatments, such as self-management advice, exercise therapy and psychosocial interventions, with short-term benefits only from pharmacological treatments.

Qualitative focus groups and interviews

Methods

Four focus groups and six one-on-one telephone interviews were conducted with GPs (n = 23), and three focus groups with patients (n = 20). Data were analysed thematically, and identified themes mapped onto the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF),24 a behaviour change theory that synthesises 112 psychological constructs determining behaviour change into 14 domains in order to identify barriers to and facilitators of behaviour change. Full details of methods and results are available in our published paper by Saunders et al. 20

Key findings

In brief, four key themes were identified.

Theme one: acceptability of clinical decision-making guided by stratified care

Several GPs were receptive to the principles of stratifying patients, and felt that using the prognostic tool could complement their usual approach to clinical decision-making. Most GPs felt that having matched treatment options recommended to them was acceptable, as long as they felt these made clinical sense. Patients also perceived stratified care as being acceptable; expressing positive views about receiving appropriate management as a result of stratification.

Some GPs, however, expressed concerns relating to stratified care not adding significantly to GPs’ clinical decision-making and potentially leading to reduced clinical autonomy. Patients, too, stressed the importance of GPs’ clinical judgement and experience in treatment decision-making, and were concerned that some GPs may rely solely on the stratification tool results.

Theme two: impact on the therapeutic relationship

Some GPs felt that stratified care could enhance the therapeutic relationship with the patient because they perceived that patients would respond positively to them investing more time asking questions about their musculoskeletal problem, a view also evident among patients. The contrasting view was also presented by GPs, however, that the prognostic tool could impede the GP’s efforts to build therapeutic rapport. GPs also anticipated potential conflict if the recommended matched treatment options were not in line with patients’ treatment preferences, which was again echoed in the patient data.

Theme three: embedding a prognostic approach within a biomedical model

Some GPs expressed concern that an overreliance on prognostic stratified care may result in GPs becoming less proficient in diagnosing musculoskeletal conditions, leading to the fear that serious underlying pathologies could be missed. The importance of diagnosis was also highlighted by some patients, who felt that a diagnostic scan was the most effective route to the resolution of their symptoms. However, some GPs placed less emphasis on diagnosis and saw added value in the stratified care approach allowing them to give patients prognostic information in the face of diagnostic uncertainty.

Theme four: practical issues in using stratified care

Some GPs expressed concerns that completing a prognostic tool could detract from salient elements of the consultation and disrupt its flow. There was some scepticism from patients about whether or not stratified care would be used in practice, owing to the time-constraints of consultations. GPs also highlighted that matched treatment options must correspond to locally available services. However, some GPs identified past experience of using similar tools for other conditions as an enabler to the delivery of stratified care.

Summary

When looking across the themes, the theoretical domains of knowledge, skills, professional role and identity, environmental context and resources, and goals were identified as salient to GPs’ and patients’ perceptions of stratified care. It was found that for GPs and patients to see stratified care as useful, it must be perceived to add to existing clinical knowledge and skills, while not undermining GPs’ and patients’ identities and roles or their perceived goals of the consultation; particularly, not undermining GPs’ clinical autonomy or disrupting therapeutic rapport. The need for the tool and matched treatment options to be integrated into the environmental context of consultations with minimal disruption was highlighted.

Consensus on matched treatment options

Methods

Three multidisciplinary consensus group meetings were conducted with clinicians between April and May 2015. In total, 20 participants attended at least one meeting (group 1, n = 18; group 2, n = 16; group 3, n = 12). Nominal Group Technique (NGT)25 was used, a systematic approach to building consensus using structured in-person meetings of stakeholders that follows a distinct set of stages. NGT participants were provided with summaries of best evidence about treatment effectiveness from the earlier evidence synthesis study in this work package, presented as novel ‘evidence flowers’. 26 These included summary tables of evidence about treatment effectiveness for each of the five pain presentations (back, neck, shoulder, knee and multisite pain) and each patient risk subgroup (low, medium and high risk). Participants could suggest additional treatment options that they felt were appropriate but missing from the evidence synthesis. Participants were also provided with anonymised case vignettes drawn from KAPS cohort participants in work package 1. These vignettes included key characteristics of patients in each risk subgroup in order to inform discussions and consensus decision-making about matched treatment options.

For each potential treatment option, participants anonymously rated, on a Likert scale, their appropriateness for patients with each musculoskeletal pain presentation and in each risk subgroup. Mean scores were calculated, then treatments were organised in rank order and further discussed, before participants again rated the appropriateness of each treatment option. Treatments were included in the final list if they achieved reasonable consensus (a mean rating of > 3.5 out of 7 on a Likert scale). Full details of methods and results are available in the published paper. 21

Key findings

In total, 17 treatment options were recommended: four for patients at low risk, 10 for patients at medium risk and 15 for patients at high risk. As the risk of poor outcome increased, recommended treatment options increased in both number and intensity. For all five pain presentations, ‘education and advice’ and ‘simple oral and topical pain medications’ were recommended for all risk subgroups. For patients at low risk, across all five pain presentations ‘review by primary care practitioner if not improving after 6 weeks’ was also recommended. Treatment options for those at medium risk differed slightly across pain presentations, but all included: ‘consider referral to physiotherapy’ and ‘consider referral to musculoskeletal interface clinic’. Treatment options for patients at high risk also varied by pain presentation. Some of the same options were included as for patients at medium risk, and additional options included ‘opioid medication’ and ‘consider referral to expert patient programme’ (across all pain presentations), and ‘consider referral for surgical opinion’ (for back, neck, shoulder and knee pain). ‘Consider referral to rheumatology’ was agreed for patients at medium and high risk with multisite pain. 21 These recommended matched treatments were summarised in table format ready to be incorporated into the electronic template and training/support package in the final stage of this work package.

Development and specification of an electronic template and training/support package

Methods

Using the results of the previous three studies in this work package, a training and support package to support the delivery of stratified care by GPs was developed and specified. This drew on previous evidence showing that clinical decision support systems are most effective when combined with education for the professionals using them and that their perceived usefulness is a key factor driving engagement and acceptance by clinicians. 27

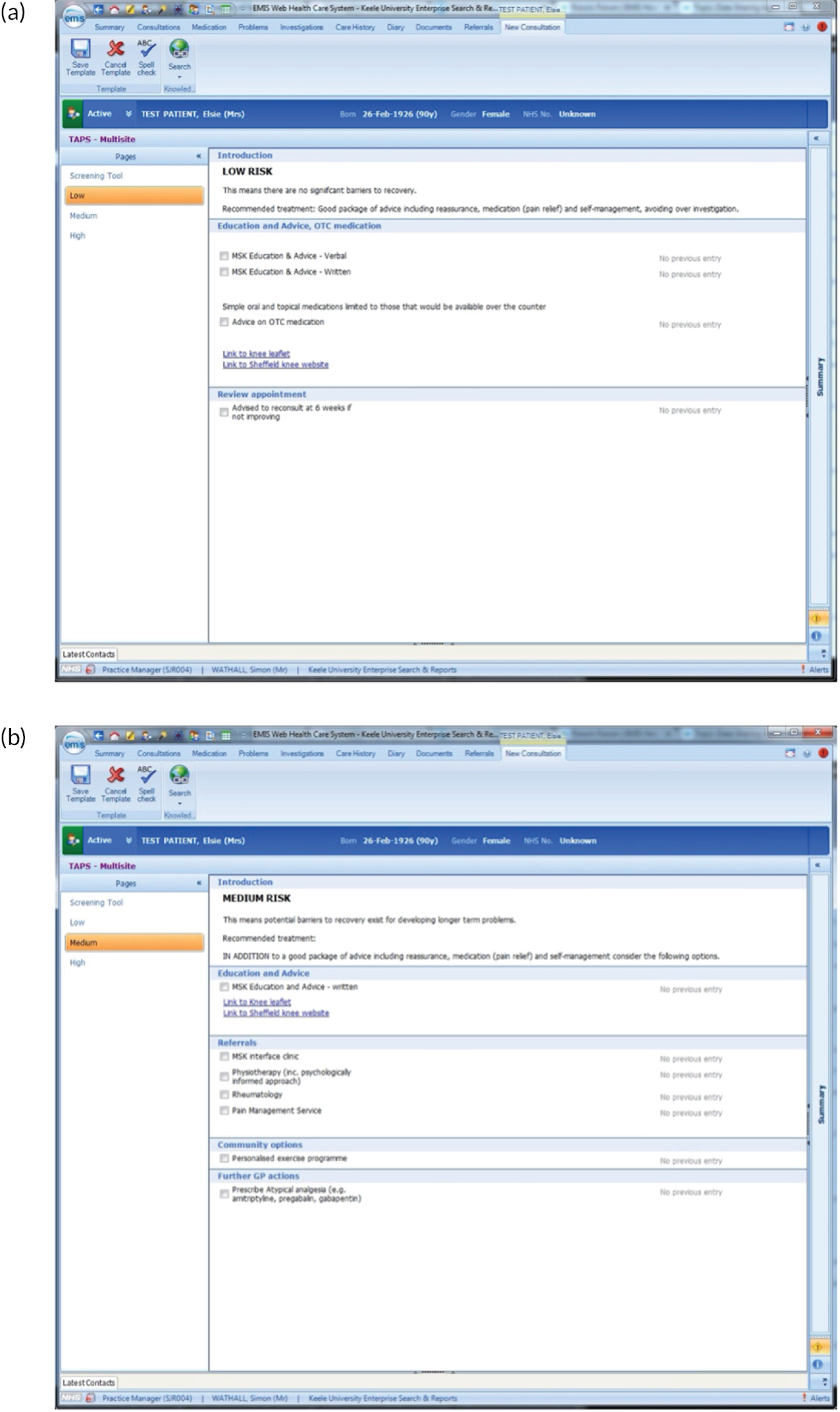

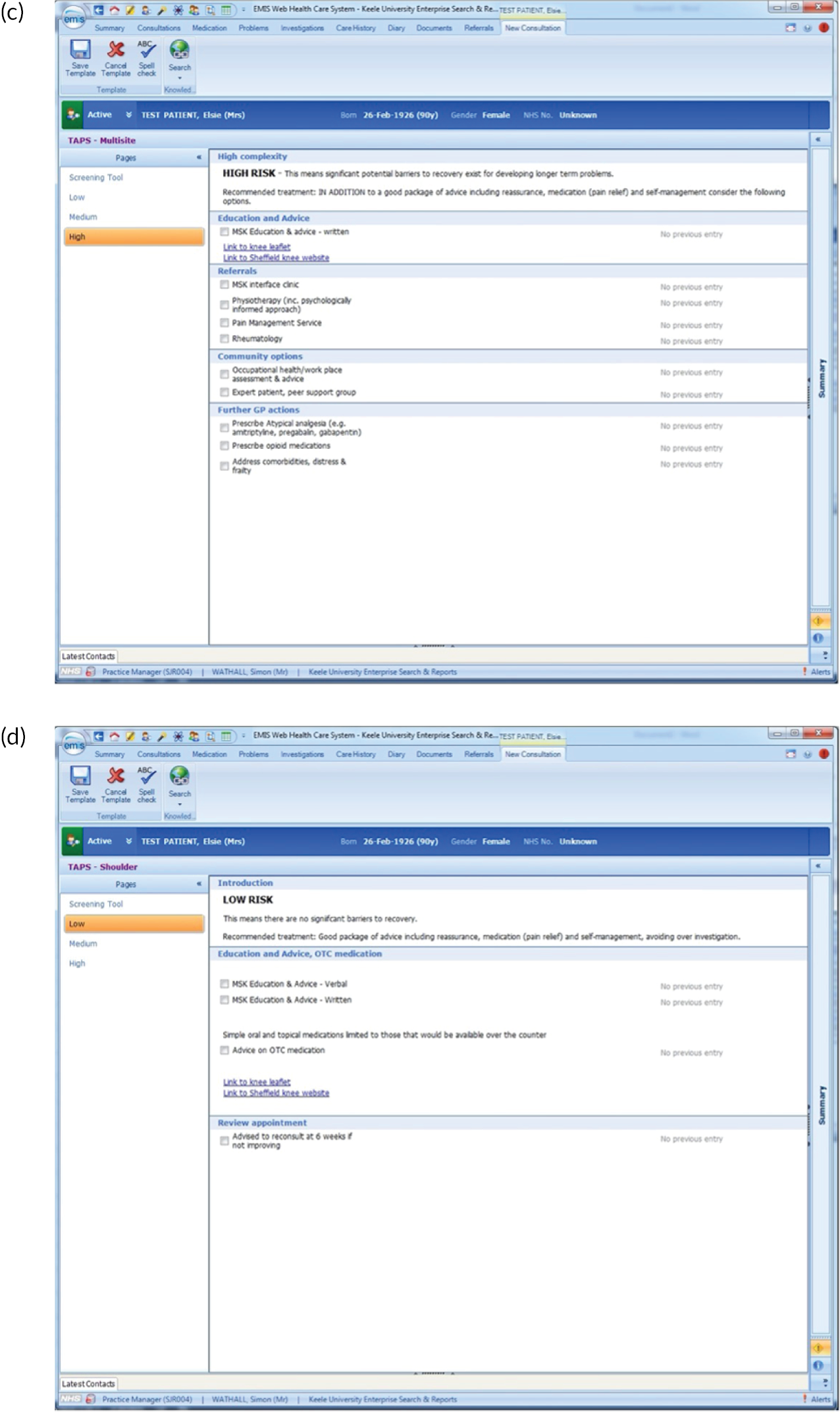

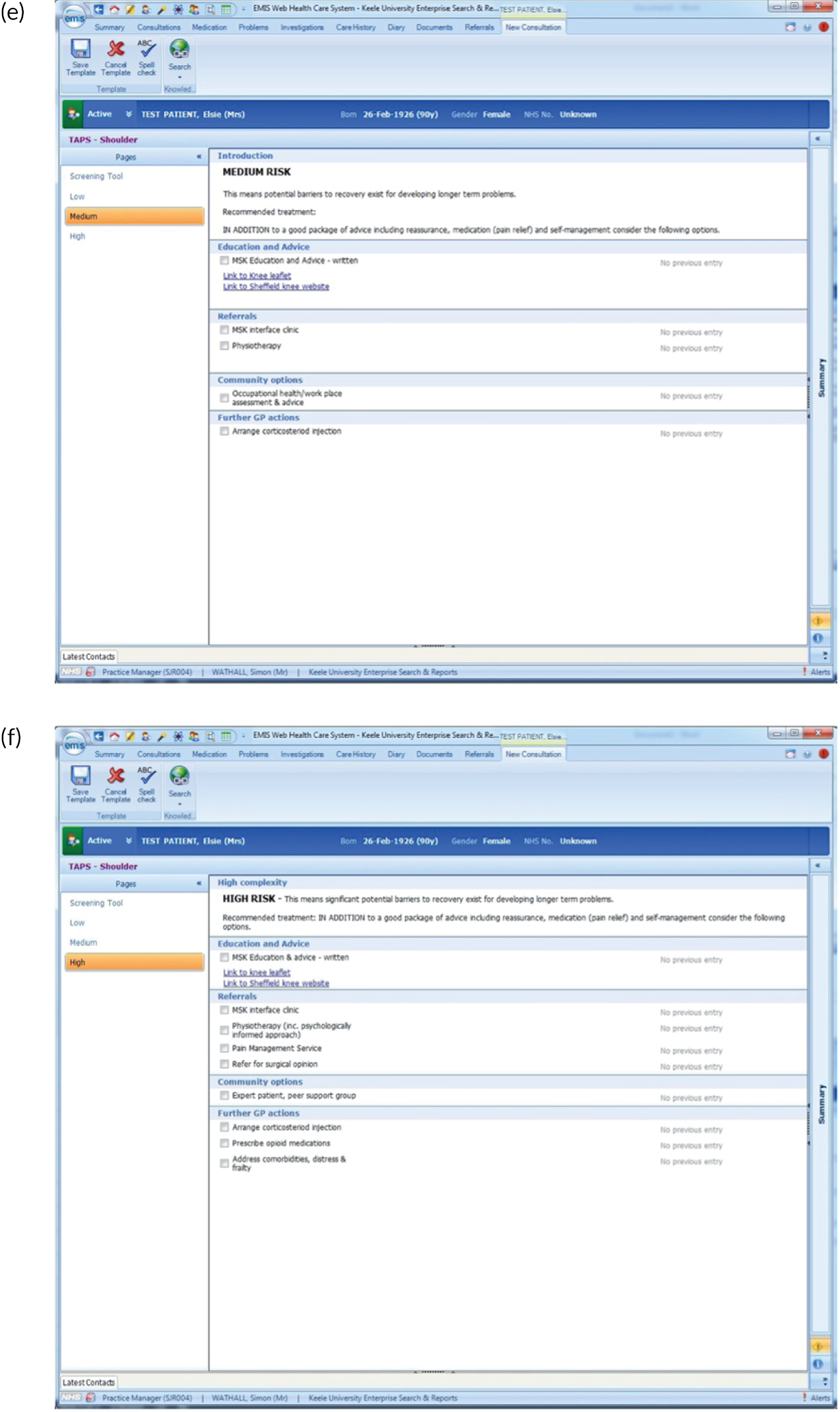

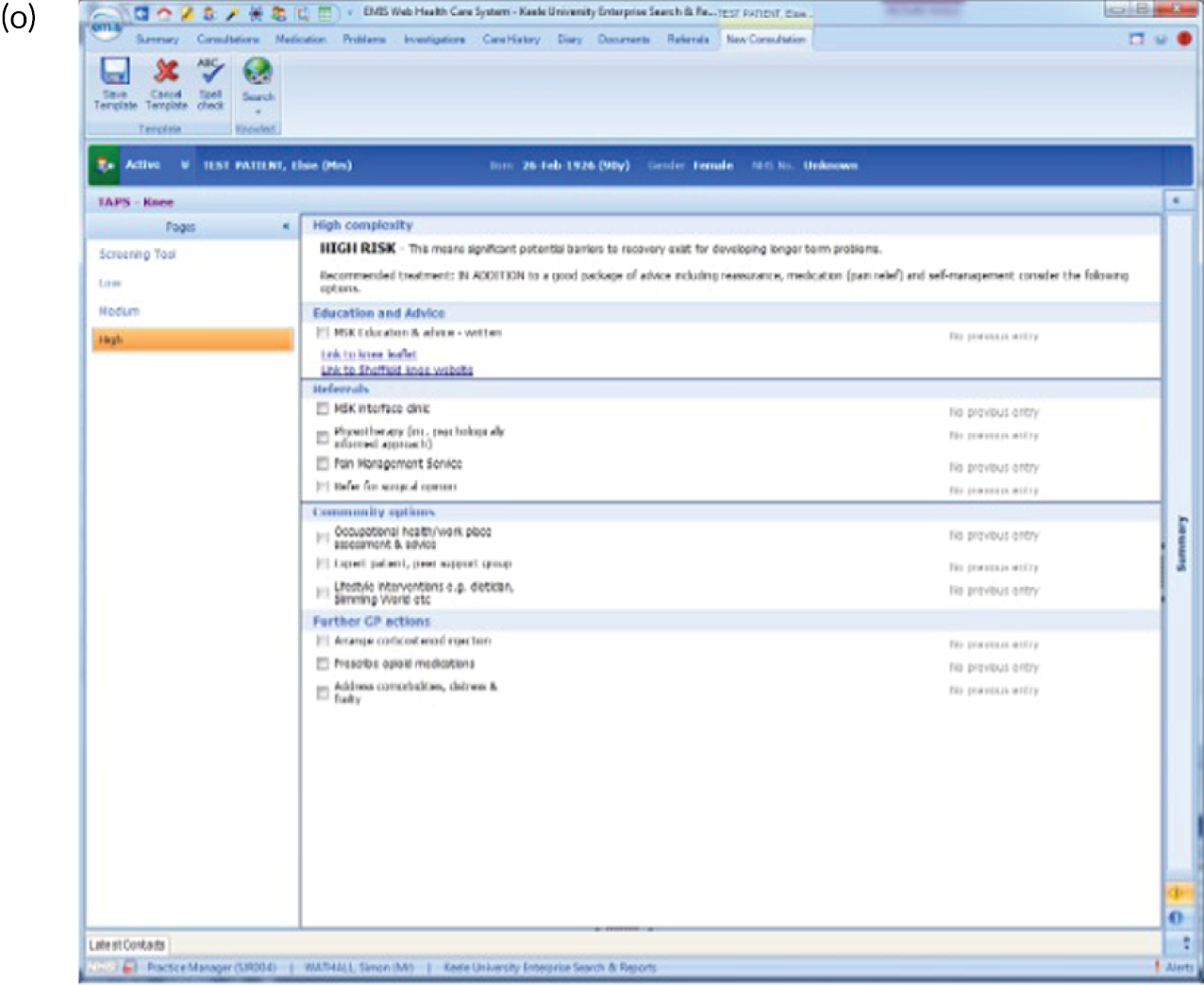

One of the barriers to the use of stratified care identified in the qualitative focus groups and interviews was the time taken to include it within short primary care consultations. To make it as easy as possible for GPs to deliver stratified care, an electronic platform or electronic template was developed within the EMIS Web (EMIS Health, Leeds, UK) clinical electronic health record (EHR). This included both components of the stratified care intervention (the Keele STarT MSK Tool and the recommended matched treatments). EMIS allows bespoke protocols and data entry templates to be designed then implemented in target general practices. A version of the tool for use during face-to-face consultations was developed and embedded within the EMIS system, which triggered automatically on entering a relevant musculoskeletal pain diagnosis or symptom into the patient’s EHR, and asked the GP to complete the Keele STarT MSK Tool. This led to the automatic calculation of the patient’s risk score, classification into one of the three risk subgroups (low, medium or high risk of poor outcome), and the recommended matched treatment options. In addition, to support the delivery of ‘education and advice’ for all patient risk subgroups, integrated self-management information resources were embedded into the electronic template which could be easily printed to be shared with the patient.

The electronic template was developed to meet both the needs of the research and the requirements of the user, that is to complement the consultation, be easy to use in the time-pressured environment of brief consultations and to record key clinical information enabling assessment of intervention fidelity for the trials in later work packages of the programme. GPs were involved in the development of the template from the initial stages through to user testing. For user testing GPs were sampled to include new, inexperienced, experienced and GPs, and those unfamiliar with EMIS Web, and invited to evaluate a draft version of the template. GPs provided feedback on ease of use, time taken, layout, format and text descriptors, leading to refinement of the template for use within face-to-face consultations in later work packages. Further details showing screenshots of the EMIS template are given in Appendix 2. Delivering stratified care within a musculoskeletal pain consultation required the GP to engage with the EHR and trigger the stratified care template, to use the Keele STarT MSK Tool and to share the recommended matched treatment options with the patient and agree on treatment(s). Informed by the findings of the qualitative focus groups and interviews earlier in this work package, we developed a training and support package for GPs, drawing on well-recognised adult learning principles. 28–30 The training and support package aimed to address GPs’ beliefs about the validity, value and feasibility of the stratified care approach and ensure they had the skills required to deliver this in practice. This included discussion among GPs about how they consult and make treatment decisions, introducing the principles of stratified care and how it differs from usual care, and an opportunity to try using the stratified care template and reflect on its use. Given that performance monitoring and feedback are important elements for encouraging behaviour change, the training and support package also included a plan for data collection and feedback at the individual GP, practice and trial arm level during GP practice review visits in later work packages.

Key findings

A bespoke electronic template was designed, specified, user-tested and amended, ready to support GPs to deliver stratified care (i.e. to use both the Keele STarT MSK Tool and recommended matched treatment options). In addition, a training and support package for use with GPs participating in the trials in later work packages was developed. Full details of the content of the GP training package are given in Appendix 2, Table 4. It was initially developed to be delivered in two approximately 1-hour sessions with GPs in those practices randomly allocated to the stratified care arm of the feasibility and pilot trial in work package 3, and then further refined for use in the main trial in work package 4.

| Timing | Topic | Detail | Methods and resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 minutes | Introductions | Personal introductions, roles, etc. Brief outline of the practice and its population Special interests of GPs |

Pre-trial background sheet completed by practice Informal chat to get people warmed up |

| 10 minutes | Brief outline of study its background and scope | Origins of research in STarT Back Explain prognostic risk Clinical conditions and sites involved What we are investigating, in general terms |

Few slides – scant detail Interactive presentation and brief Q/A |

| 10 minutes | GPs’ current management of these conditions | Diagnostic approaches: biomechanical/biopsychosocial – use shoulder pain as example Investigations routinely used: what and where Advice generally given to these patients Sickness certification Medication preferences and usage Physiotherapy, etc. availability and usage Referral options and patterns for different pain sites: musculoskeletal, surgical etc Significant constraints they experience Patients’ expectations, e.g. imaging, certificates, referral |

Pre-trial background sheet General discussion to gauge GPs’ philosophy and general approaches: helps build relationship and aid to tailoring our approach to training Avoid detail on specific conditions within musculoskeletal Flip chart to explore treatment/referral options for the practice |

| 20 minutes | GPs’ usual consultation habits | Map out their usual consultation process/flow Is computer used during or after consultations? Read coded diagnosis entered at provisional stage or not Any existing use of templates and decision aids? Use of interactive tool plus printed advice, e.g. PILS |

More informal discussion A4 sheet with a few prompt statements for GPs Pads of paper for GPs’ notes Sticky-note pads to capture notes and queries for later |

| 20 minutes | Stratified care approach | What is stratified care and how does it differ? | Interactive presentation and Q/A Slides: |

| Why it may have advantages for patients and NHS Basis for prognostic stratification tool Expected proportion in each risk group The tool identifies potential treatment targets How this complements usual diagnostic clinical practice Matched treatment options and how we devised them No change in local pathways during the study: treatment options are pointers to be used with these pathways |

|

||

| 45 minutes | The Keele STarT MSK tool in practice | Overview of questionnaire and matched treatments Key GP behaviours the tool tries to nudge/change Providing the tool score to onward treating clinicians Trying out the tool: paper exercise – |

Discussion around slides Pyramid slide for overview Questionnaire and matched treatments Giving patients score and recommended options Communicating score in referrals |

|

Paper copies of vignettes and risk tool Live EMIS system with template Demo of template use All GPs trying out template, using vignettes, with no attempt at consultation elements Vignettes needed: low risk knee-pain, medium-risk shoulder pain, High risk multisite pain with co-morbidity |

||

| Demonstration of integrated template by facilitator All GPs trying it out with support |

|||

| 5 minutes | Suggested preparation for Session 2 | Try template a few more times with dummy patients Look at treatment options and linked patient info |

Replace this with a short break if running 2 sessions together: would need refreshments |

Alterations to initial plans and work package limitations

We conducted more focus groups with patients than planned (four rather than two) to ensure that larger numbers of patients’ views were included. Based on pragmatic considerations, only one physiotherapist focus group was conducted (rather than the two planned). In the original plans for the consensus group study, 70% or more was the intended cut-off point to recommend treatment options, but this was reduced to 50% or more given the challenge in gaining higher levels of consensus with our highly multidisciplinary group of clinicians. We may have reached higher levels of consensus about recommended matched treatments, or a smaller set of recommended matched treatment options, had we included a more homogenous group of clinicians.

In the evidence synthesis, despite an extensive search, we found a paucity of evidence about treatments for multisite musculoskeletal pain. The control interventions were often not well described, and it is possible this led to overestimation of the effectiveness of some treatments in some included studies. In the qualitative study, patients’ and clinicians’ views were sought prior to finalisation of the stratification tool and recommended matched treatments. Discussions were deliberately based on the general principles of prognostic stratified care so that the views of patients and clinicians could inform the specific stratified care approach. Experiences of clinicians delivering, and patients receiving, the stratified care intervention in this programme were sought in work packages 3 and 4.

Interrelationship with other parts of the programme

The qualitative focus group and interview study and the consensus group study both drew on participants from the KAPS cohort in work package 1. The agreed recommended matched treatment options from this work package informed the cut-off points of the Keele STarT MSK Tool in work package 1 and along with the electronic template and GP training/support package, were tested for feasibility of delivery in work package 3 (feasibility and pilot trial).

Work package 3

Research aims and objectives

The aims of this work package were to test the feasibility of a future main cluster RCT to compare stratified care with usual primary care, and to test the feasibility of delivery of the stratified care approach.

The four specific objectives were as follows:

-

estimate participant recruitment and follow-up rates for the main cluster RCT

-

examine evidence of selection bias between trial arms and between participants and non-participants

-

assess GP fidelity to the stratified care intervention (i.e. use of the stratification tool and matched treatment options)

-

conduct secondary descriptive analyses of GP decision-making and patient outcomes.

Methods

Full details of methods and results have been published in two papers: Hill et al. 18 and Saunders et al. 31 The design was a pragmatic pilot, parallel two-arm (stratified vs. non-stratified care), cluster RCT in eight UK GP practices (four allocated to the intervention and four as control). Practices were randomised with stratification by practice size, and the trial statistician and outcome data collectors were blind to allocation. Participants were adult consulters with one of the five most common musculoskeletal pain presentations (back, neck, shoulder, knee or multisite pain) and without indicators of serious pathologies, urgent medical needs or vulnerabilities. Potentially eligible patient records were electronically tagged following consultation at participating practices and individual patients were sent postal invitations to participate in data collection. The target sample was 500 participants.

Delivery of the stratified care intervention by GPs was supported by the bespoke EHR template which included the Keele STarT MSK Tool validated in work package 1 to stratify patients into low, medium or high risk of poor outcome and the 17 recommended matched treatment options agreed in work package 2. Patients at low risk were matched to options that supported self-management, including over-the-counter (OTC) medication, and unnecessary investigations or referrals were discouraged. For those at medium risk, in addition to the low-risk treatment options, recommendations included referral to conservative non-pharmacological treatments (e.g. physiotherapist-led exercise therapy) and workplace assessment and advice. For those at high risk, in addition to the low- and medium-risk options, recommendations included referral for corticosteroid injections, specialist clinical services (including rheumatology, orthopaedics and pain clinics) and opioid medications. Full details of the matched treatment options are described in Appendix 3, Box 2, and also in figure 2 of our pilot trial publication by Hill et al. 18

General practitioners in the four practices randomised to deliver stratified care were invited to participate in the training/support package developed in work package 2, facilitated by an experienced GP trainer and the trial lead. The sessions lasted a total of 3–4 hours at each practice and covered the rationale for stratified care, how it differs from usual care, and familiarisation with the EHR template and its fit within the flow of a musculoskeletal consultation. The sessions also provided an opportunity for discussion and questions or concerns to be addressed. GPs also received a training update halfway through their practice’s recruitment period at which feedback data were shared about individual GP intervention fidelity, with peer-to-peer comparisons and discussion. Further details about the training and GP peer-to-peer comparisons are available in Appendix 3, Tables 5 and 6.

| Anonymised GP identifier | Patients, n (invited, n = 127; consented, n = 65) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back | Knee | Multisite | Neck | Shoulder | No time | Patient not present | Patient declined | Suspected serious pathology | Vulnerable patient | GP escaped | Grand total | |

| a | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 46 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 84 | |

| b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||

| c | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| d | 11 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 21 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 59 | |

| d | 7 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 19 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 77 | |||

| e | 1 | 2 | 2 | 45 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 74 | |||

| f | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| g | 1 | 1 | 51 | 30 | 1 | 84 | ||||||

| h | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 20 | ||||

| i | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||

| j | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 51 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 84 | ||

| k | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 15 | |||||

| l | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| m | 16 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 71 | ||

| n | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 44 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 85 | ||

| o | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 16 | |||||||

| p | 5 | 5 | ||||||||||

| q | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Grand total | 61 | 36 | 6 | 16 | 8 | 272 | 133 | 100 | 8 | 12 | 39 | 691 |

| Percentage for general practice (%) | 9 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 39 | 19 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 100 |

| Percentage for all general practices in the trial (%) | 12 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 12 | 27 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 100 |

| Patients (n) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anonymised GP identifier | ||||||||||||||

| Decision made | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | Grand total | Proportion of total from this GP surgery (%) | Proportion of total from all TAPS practices (%) |

| Low – per protocol | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 16 | 13 | 16 | ||||||

| Medium – per protocol | 5 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 57 | 45 | 44 | |||

| High – per protocol | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 24 | 19 | 18 | ||

| Low – no treatments selected | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 3 | ||||||

| Medium – no treatments selected | 7 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 9 | 5 | |||||||

| High – no treatments selected | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||

| Low – with medium treatments | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Low – with high treatments | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Medium – low treatments only | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | |||||||||

| Medium – with high treatment | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| High – low treatments only | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| High – with medium options selected | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Grand total | 11 | 20 | 21 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 16 | 4 | 26 | 15 | 127 | 100 | 100 |

A set of pre-defined feasibility success criteria were used to evaluate recruitment, follow-up rates, selection bias and GP intervention fidelity. To determine whether or not these success criteria were met, four sources of data were used:

-

the general practices’ EHR participant identification screen, which captured point-of-consultation data in all 8 general practices, including patients’ pain intensity and location (back, neck, shoulder, knee or multisite pain)

-

an initial and 6-month postal questionnaire which collected outcomes such as physical function, risk subgroup, overall musculoskeletal health, fear avoidance beliefs, patient-perceived reassurance (from their GP), health-related quality of life, satisfaction with care received, provision of written educational material from their GP, global rating of change in the musculoskeletal problem, employment characteristics, work absence and productivity and patient demographic descriptors (see our published paper by Hill et al. 18 for full details, and also see Appendix 3, Table 7, for a summary of the participant self-reported measures)

-

monthly follow-up using either short message service (SMS) texts or brief paper questionnaires to capture pain intensity, musculoskeletal pain-related distress and self-efficacy

-

an anonymised general practice EHR audit to collect data to describe GP decision-making including prescriptions, referrals, imaging requests, sick certifications and repeat GP visits over a 6-month period following the index consultation when the stratified care template was first fired.

| Conceptual domain | Operational definition | Empirical measure used | Number of items | Time point of data collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age at index consultation | Date of birth | 1 | GP EMR audit |

| Sex | Sex | Male/female | 1 | GP EMR audit |

| Index pain location | Site of index pain complaint | Choice of anatomical region | 1 | GP EMR audit |

| Pain intensity | Usual pain intensity | 0–10-point NRS | 1 | GP EMR audit, I, 6FU, MF, MDC |

| Socioeconomic status (IMD) | The individual’s (1) current or (2) most recent job title | Job title: categorised as manual/non-manual | 2 | GP EMR audit |

| GP practice | GP practice consulted for musculoskeletal pain | Taken from medical record | 1 | GP EMR audit |

| Episode duration | Time since last whole month pain free | Episode duration | 1 | I |

| Health literacy screen | Health literacy | Single question: Likert scale | 1 | I |

| Comorbidities | Self-reported diagnosed comorbidities from a provided list | Yes | 1 | I |

| Widespread pain | Presence of widespread pain | Yes/no | 1 | I |

| Support needed | Support to complete questionnaire | Yes/no | 1 | I |

| Living arrangements | Lives alone | Yes/no | 1 | I |

| Previous episodes | Number of previous pain episodes | Number | 1 | I |

| Perceived reassurance from GP consultation | ECRQ | 12 items with 7-point Likert scale | 12 | I |

| Receipt of written education material from GP | Single item to ask if patient received written information at their GP visit | Yes/no/do not remember | 1 | I |

| Pain self-efficacy | Single item: confidence to manage pain | 0–10-point NRS | 1 | I, MF |

| Psychological distress | Single item regarding level of distress | 0–10-point NRS | 1 | I, MF |

| Employment status and absence from work | Employment status at time of questionnaire | Yes/no and details | 1 | I, 6FU |

| Risk status: development version of the Keele STarT MSK Tool | Risk of persistent disabling pain | Yes/no | 9 | I, 6FU |

| Musculoskeletal health | Impact from musculoskeletal symptoms | MSK-HQ | 14 | I, 6FU |

| Overall rating of change | Change since index pain consultation | Single question: –5 to +5 scale | 1 | I, 6FU |

| Physical activity level | Days past week of moderate activity | 1–7 days | 1 | I, 6FU |

| Fear avoidance beliefs | Fear of movement | TSK-11 | 11 | I, 6FU |

| Satisfaction | Satisfaction with care | Single question – Likert scale | 1 | I, 6FU |

| Physical function | ||||

| Back pain patients | Site-specific physical function | RMDQ: original version | 24 | I, 6FU |

| Neck pain patients | Site-specific physical function | NDI | 10 | I, 6FU |

| Shoulder pain patients | Site-specific physical function | SPADI | 13 | I, 6FU |

| Knee pain patients | Site-specific physical function | KOOS-PS | 7 | I, 6FU |

| Multisite pain | Site-specific physical function | SF-12 PCS | 12 | I, 6FU |

| Health-related quality of life | Utility-based quality of life | EQ-5D-5L | 5 | I, 6FU, MDC |

| Health-care costs | ||||

| Performance at work | How productivity at work is affected | 0–10-point NRS | 1 | I, 6FU |

| Work absence | Number of days absent from work | Yes/no and details | 1 | I, 6FU |

| Health-care resource use | Use of primary care, other NHS services and private health care | Yes/no and, if yes, details of resources used | 3 | 6FU |

Nested qualitative study

Stimulated recall interviews were conducted with patients and GPs in the stratified care arm of the feasibility and pilot trial (n = 10 patients, n = 10 GPs), prompted by consultation recordings, in order to explore the feasibility of delivering stratified care in consultations. Data were analysed thematically and mapped onto the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) behaviour change model, exploring the capability, opportunity and motivation GPs and patients had to engage with stratified care (see our published paper by Saunders et al. 30 for full details of the methods and results of the nested qualitative study).

Key findings

Participants were recruited between October 2016 and May 2017 from eight general practices, during which GPs screened 3063 patients (stratified care n = 1591, usual care n = 1472) and completed the bespoke EHR template with 1237 eligible patients (stratified care n = 513, usual care n = 724). A total of 524 participants (42% of those who received the bespoke EHR template) consented to providing questionnaire outcome data (stratified care n = 231, usual care n = 293) over 6 months’ follow-up. Follow-up questionnaires and EHR audit data collection were completed by December 2017.

Objective 1: estimating participant recruitment and follow-up rates

Recruitment took 28 weeks (target 12 weeks) and 91% of participants provided follow-up data (target > 75%). Anonymised EHR data were available for 1281 patients (529 from stratified care practices and 752 from usual care practices). Although the high follow-up rate exceeded the target, the slow recruitment rate was a key concern, suggesting that the main cluster RCT would struggle to recruit the numbers originally intended (target n = 3600) within the available timeline. This led to the decision to revise the sample size for the main trial (for full details see the flowchart in our published paper by Hill et al18).

Objective 2: evidence of selection bias

Most participant characteristics (e.g. sex) were similar between the two arms of the pilot trial, although there were a few minor differences between participants in the trial compared with non-participants (e.g. participants were slightly older and from more deprived areas). Baseline values of the primary outcome measure intended for the main trial (pain intensity) was 6.22 [standard deviation (SD) 2.17, n = 230] in the stratified care arm compared with 6.21 (SD 2.32, n = 293) in the usual care arm, and the proportions of patients at low, medium and high risk of poor outcome were 31%, 55% and 14%, respectively, in the stratified care arm compared with 33%, 54% and 13%, respectively, in the usual care arm (for full details see table 1 in our published paper by Hill et al.). 18 Overall, the data suggested little evidence of selection bias and, therefore, no changes were required to identification or recruitment procedures for the main trial.

Objective 3: assessing general practitioner fidelity to the stratified care intervention

The fidelity of participating GPs to both components of the stratified care intervention was assessed (i.e. use of the stratification tool and matching patients to recommended treatment options). The pre-specified target for use of the stratification tool was for 50% of eligible patients, but the bespoke EHR data showed that GPs actually used the tool for 40% of eligible patients. Key reasons for the lower level of fidelity to the use of the tool were identified in the nested qualitative study (see Nested qualitative study key findings). However, in the consultations in which GPs used the risk stratification tool, their fidelity to matching patients to the recommended treatment options was high, with 81% of patients at low risk, 89% of those at medium risk and 87% of those at high risk being correctly matched to a recommended treatment, as recorded using the bespoke EHR template.

Objective 4: descriptive analyses of general practitioner decision-making and patient self-reported outcomes

Based on the anonymised EHR data, key descriptive differences in GP decision-making were identified when comparing stratified care with usual care practices. For example, 20% fewer patients were given a prescription for opioid medication (opioid medications were listed as a matched treatment option only for patients at high risk of poor outcome in the pilot trial) and 53% fewer patients were recorded as having musculoskeletal pain-related imaging in stratified care practices. In addition, referral to physiotherapy for patients at medium or high risk of poor outcome was recorded as occurring more frequently in stratified care than in usual care practices. By contrast, the numbers of corticosteroid injections, sick certifications and repeat musculoskeletal pain-related GP consultations over 6 months’ follow-up were recorded as similar in stratified care and usual care practices.

Based on the participant self-reported data in the postal questionnaires, patients received more written self-management information from GPs in stratified care practices than usual care practices (71% compared with 17%). Descriptive data on patients’ follow-up outcomes demonstrated that participant’s mean 6-month pain intensity was 3.93 (SD 2.98) in stratified care practices and 4.18 (SD 2.88) in usual care practices, with a change in 6-month pain intensity from baseline of −2.6 (SD 3.1, n = 207) in stratified care practices compared with −1.9 (SD 3.1, n = 266) in usual care practices. Most other outcomes were similar at 6 months’ follow-up (e.g. patient satisfaction with GP care) although there was less musculoskeletal pain-related time off-work in participants in stratified care practices (17.4%) than usual care practices (25.4%) (full details are available in table 4 of our published paper by Hill et al.). 18 We did not statistically compare participant outcomes between the two arms in the pilot trial.

Nested qualitative study key findings

Qualitative interviews with GPs revealed that the main reasons for lower than anticipated fidelity in using the Keele STarT MSK Tool with eligible patients were GPs perceiving that using the tool increased their consultation workload; GPs preferring to only use the bespoke EHR template when musculoskeletal pain was the primary reason for the consultation; GPs being reluctant to use the tool when their clinics were running late or were very busy; and that often patients had left the consultation room before GPs used their EHR system to record their consultations. It was also noted that some GPs rarely coded musculoskeletal pain consultations in the EMIS system and that others tended to use ‘synonym’ codes, which are a set of diagnostic codes that were not able to activate the bespoke EHR template, or caused it to activate for some non-musculoskeletal pain problems (e.g. chest pain). It was agreed that for the main trial the GP training package needed to include ways to mitigate these challenges.

Patients reported positive views, reporting that that stratified care enabled a more ‘structured’ consultation and felt that the tool items were useful in making GPs aware of patients’ worries and concerns. However, the closed nature of the tool’s items was seen as a barrier to opening up discussion during consultations. Both patients and GPs identified ‘cumbersome’ items that made it more difficult to use (i.e. ‘capability’ within the COM-B theoretical model). Their feedback suggested that four of the items needed modification to be less ‘clunky and awkward’ to ask patients. For example, item 4 asks: ‘Do you have any other important health problems?’ which was felt to confuse patients when asked by their own family doctor whom the patient expected to know their health problems well. Most GPs reported that the matched treatment options aided their clinical decision-making (i.e. ‘motivation’), but identified some options that were not commonly available to them (e.g. occupational health/workplace assessment referral or supported self-management), not needed (e.g. review if not improving after 6 weeks) or that they felt were appropriate but missing from the recommendations (e.g. consider imaging). They also expressed concerns about potentially overloading physiotherapy services with referrals and sought reassurance that linked physiotherapy services had sufficient capacity. For full details of the nested qualitative study results, see our published paper by Saunders et al. 31

Alterations to initial plans and work package limitations

The learning from this work package led to important changes to the original plans, all of which were agreed with the PSC and funder, prior to the main Keele STarT MSK cluster trial in work package 4, which were as follows:

-

This feasibility and pilot trial changed from the intended internal pilot phase to an external pilot trial, given it took twice as long as expected (28 weeks rather than 12) to recruit participants and only 2 of the 4 pre-specified success criteria were met.

-

The main trial sample size was reduced (from n = 3600 to n = 1200) by focusing on the overall between-arm comparison rather than also powering the trial to detect between-arm differences at the level of patient risk subgroups (i.e. low, medium and high risk).

-

The items within the Keele STarT MSK Tool were amended following further statistical analysis using the point-of-consultation data from the pilot trial to identify items that improved the tool’s predictive validity, and a clinician-completed version (interview style rather than self-report style) was developed. A license to obtain both the self-report and clinician-completed versions of the tool is available on request at www.keele.ac.uk/startmsk. The clinician-completed version of the tool is also available in Appendix 3, Figure 2.

-

The number of recommended matched treatment options was reduced slightly from 17 in the pilot to 14 in the main trial and some options were recommended for additional patient subgroups (e.g. opioid medications). Following meetings with linked physiotherapy services, participating GPs were also reassured that these NHS physiotherapy services were informed about the trial and had capacity to receive referrals.

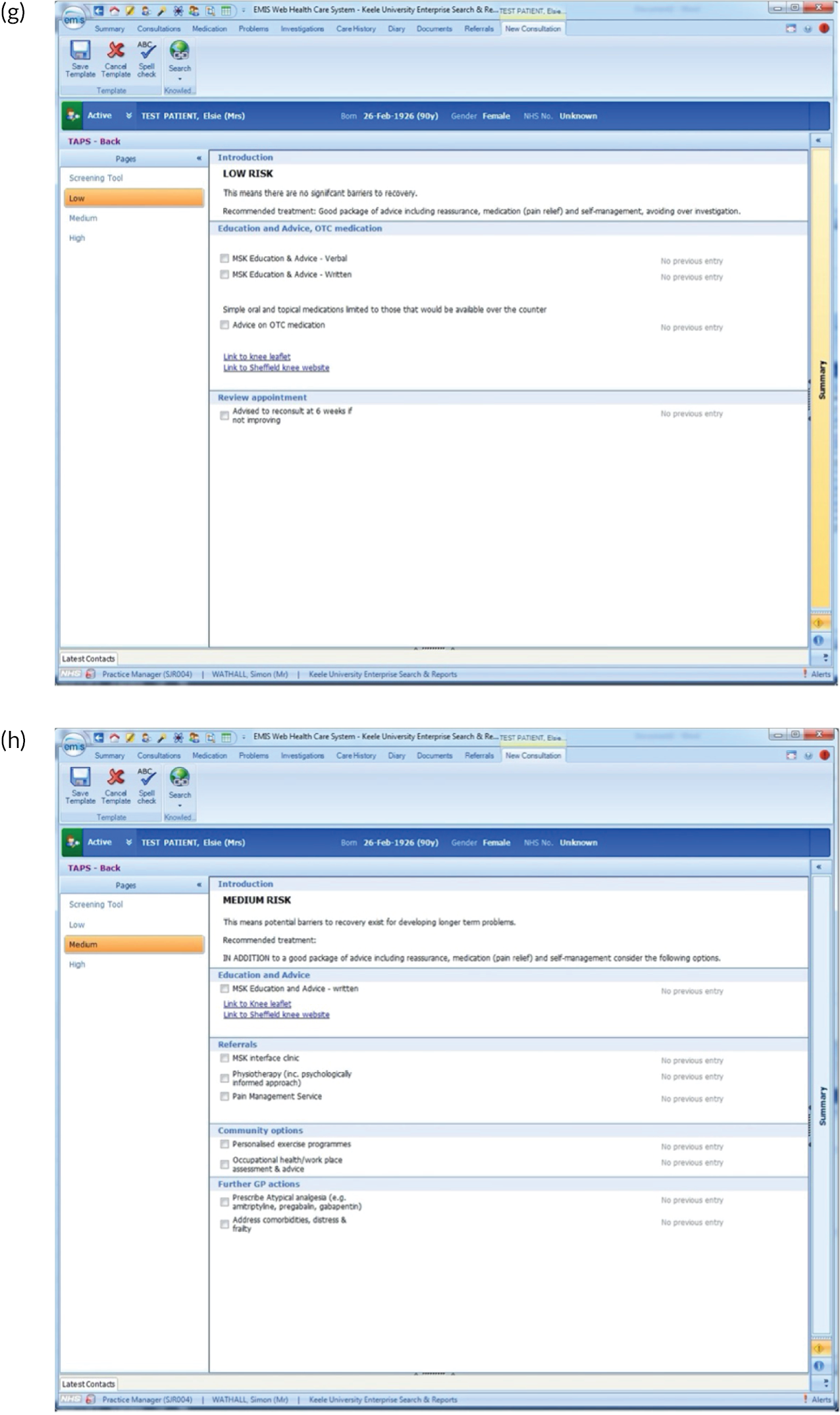

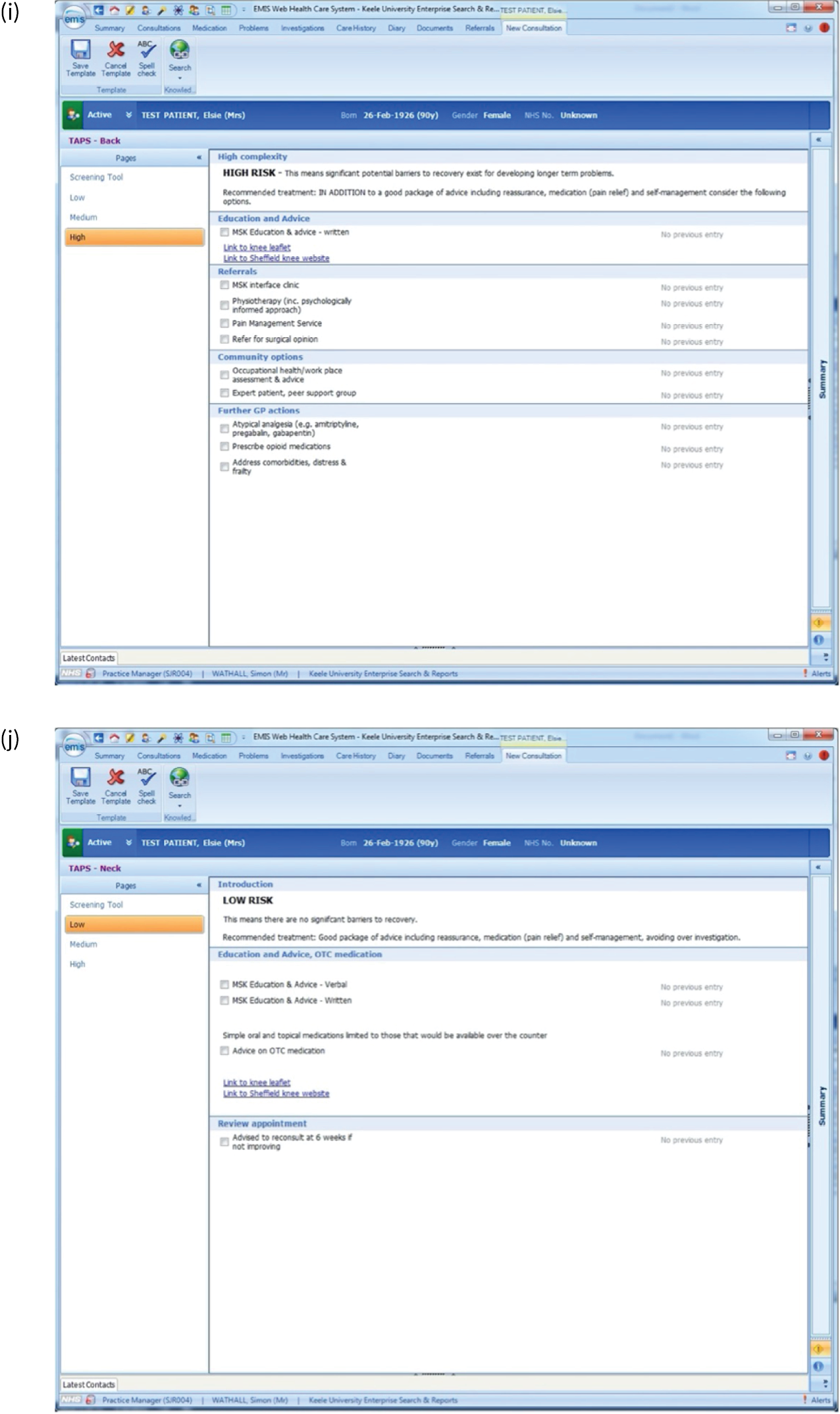

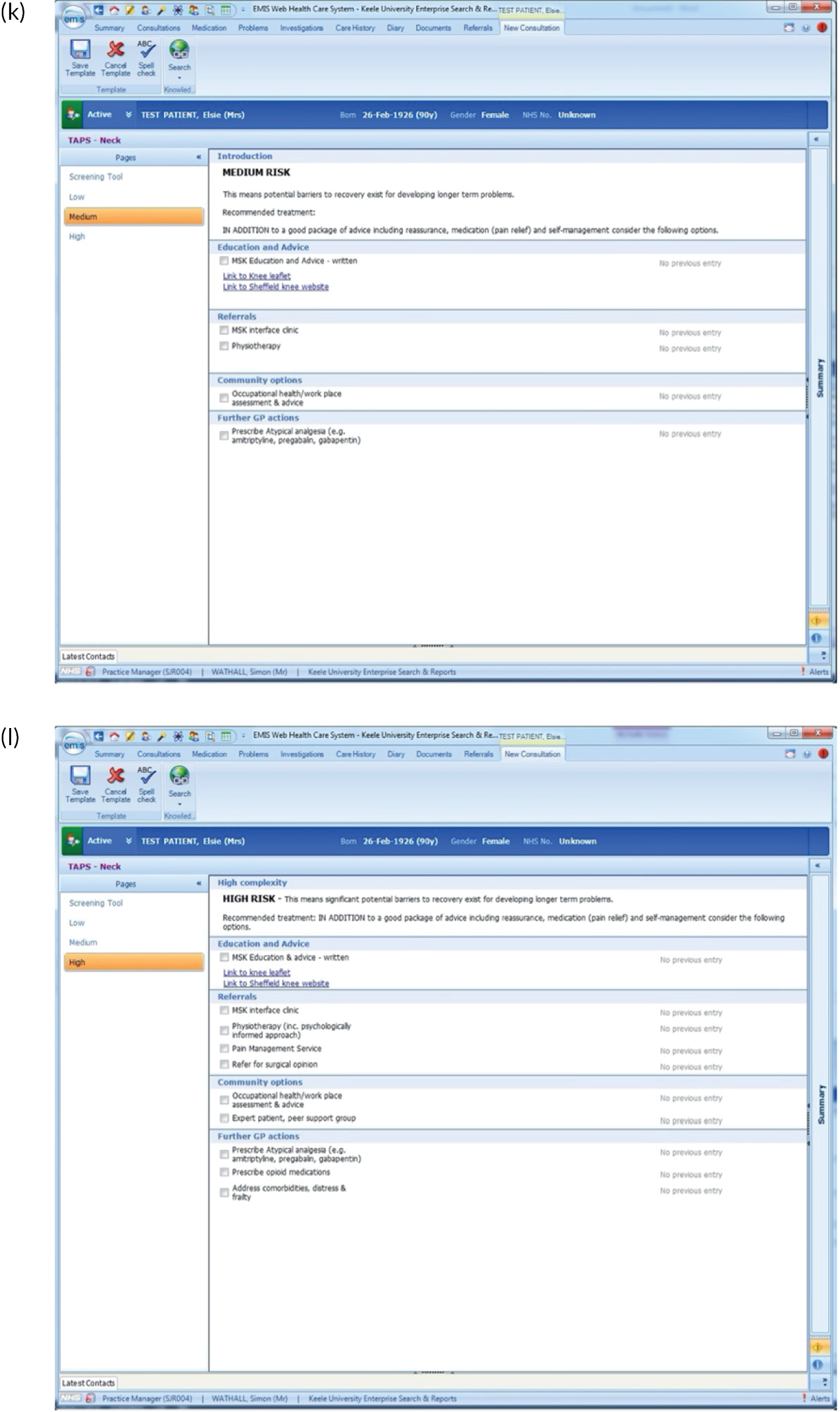

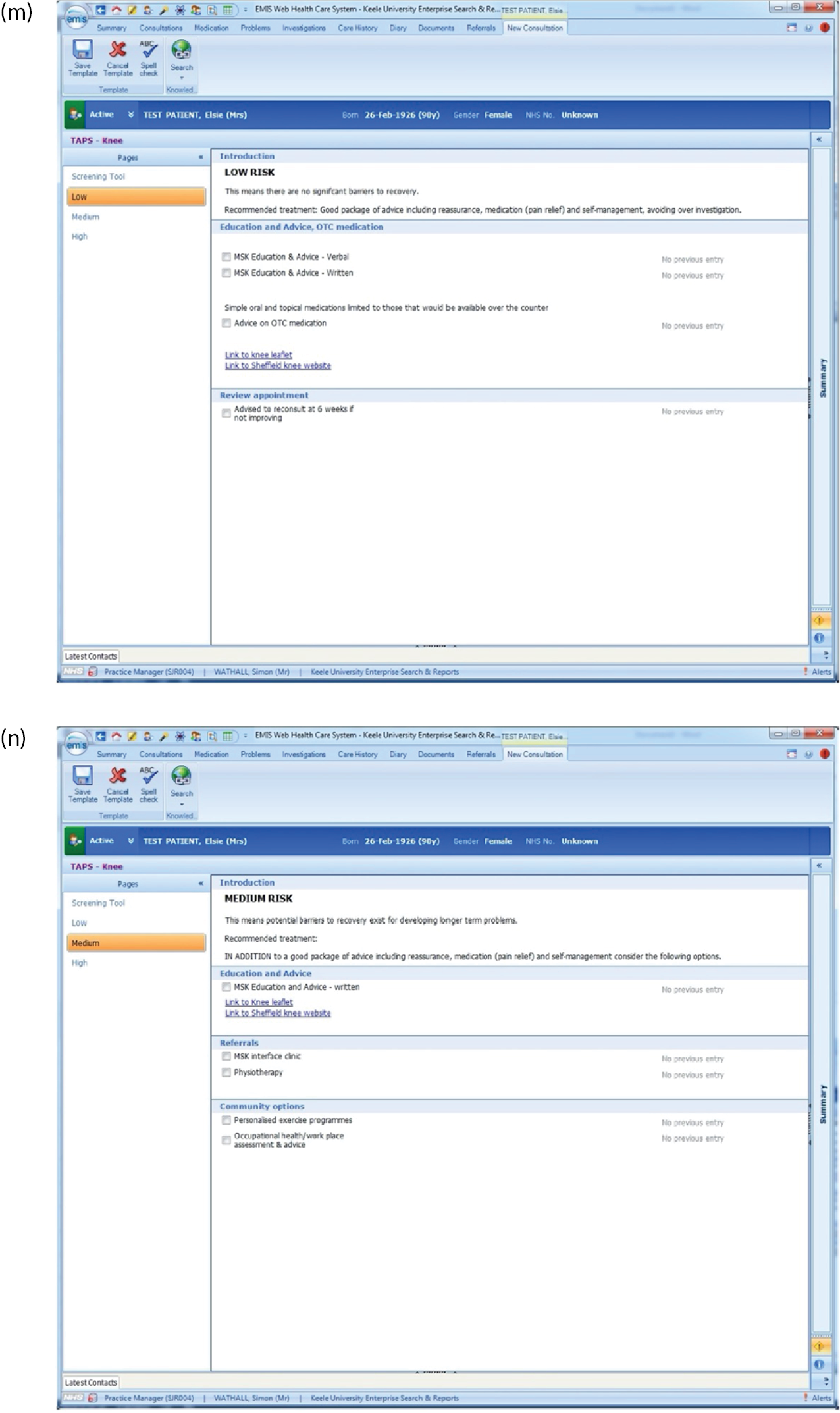

FIGURE 2.

EMIS templates for matched treatment options. (a) Multisite pain patients classified as low risk; (b) multisite pain patients classified as medium risk; (c) multisite pain patients classified as high risk; (d) shoulder pain patients classified as low risk; (e) shoulder pain patients classified as medium risk; (f) shoulder pain patients classified as high risk; (g) back pain patients classified as low risk; (h) back pain patients classified as medium risk; (i) back pain patients classified as high risk; (j) neck pain patients classified as low risk; (k) neck pain patients classified as medium risk; (l) neck pain patients classified as high risk; (m) knee pain patients classified as low risk; (n) knee pain patients classified as medium risk; and (o) knee pain patients classified as high risk.

There were several research limitations that need to be highlighted. First, there is an inherent potential risk of bias from those involved in developing a new clinical tool being the researchers who test it in practice. In addition, although the qualitative research revealed useful insights about why GPs found the tool difficult to use and explored the perceptions of patients regarding the services and treatment options available to them, more information about the reasons for both of these elements would have been useful. A further limitation is that there may have been a difference in the suitability of the approach according to the length of condition duration (i.e. acute vs. chronic pain) that we have not yet been able to fully explore.

Interrelationship with other parts of the programme

This work package evaluated the feasibility of using the Keele STarT MSK Tool and matched treatment options that were agreed in work packages 1 and 2 and comprised the external feasibility and pilot trial that informed the main trial in work package 4. In addition, the data from this pilot trial were used for the external validation of the Keele STarT MSK Tool at the point of consultation.

Work package 4

Research aims and objectives

The aim of this work package was to determine whether or not stratified care (i.e. the use of the Keele STarT MSK Tool to subgroup patients and matching subgroups to recommended treatment options) leads to superior clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness compared with usual primary care in patients with one of the five most common musculoskeletal pain presentations (back, neck, shoulder, knee or multisite pain).

The four specific objectives were as follows:

-

determine the comparative clinical effectiveness of stratified care compared with usual primary care for patient outcomes

-

investigate GP fidelity to delivery of stratified care and the impact on clinical decision-making

-

undertake an economic evaluation of stratified care versus usual care

-

conduct a nested qualitative study to understand how stratified care was perceived and operationalised by clinicians and patients.

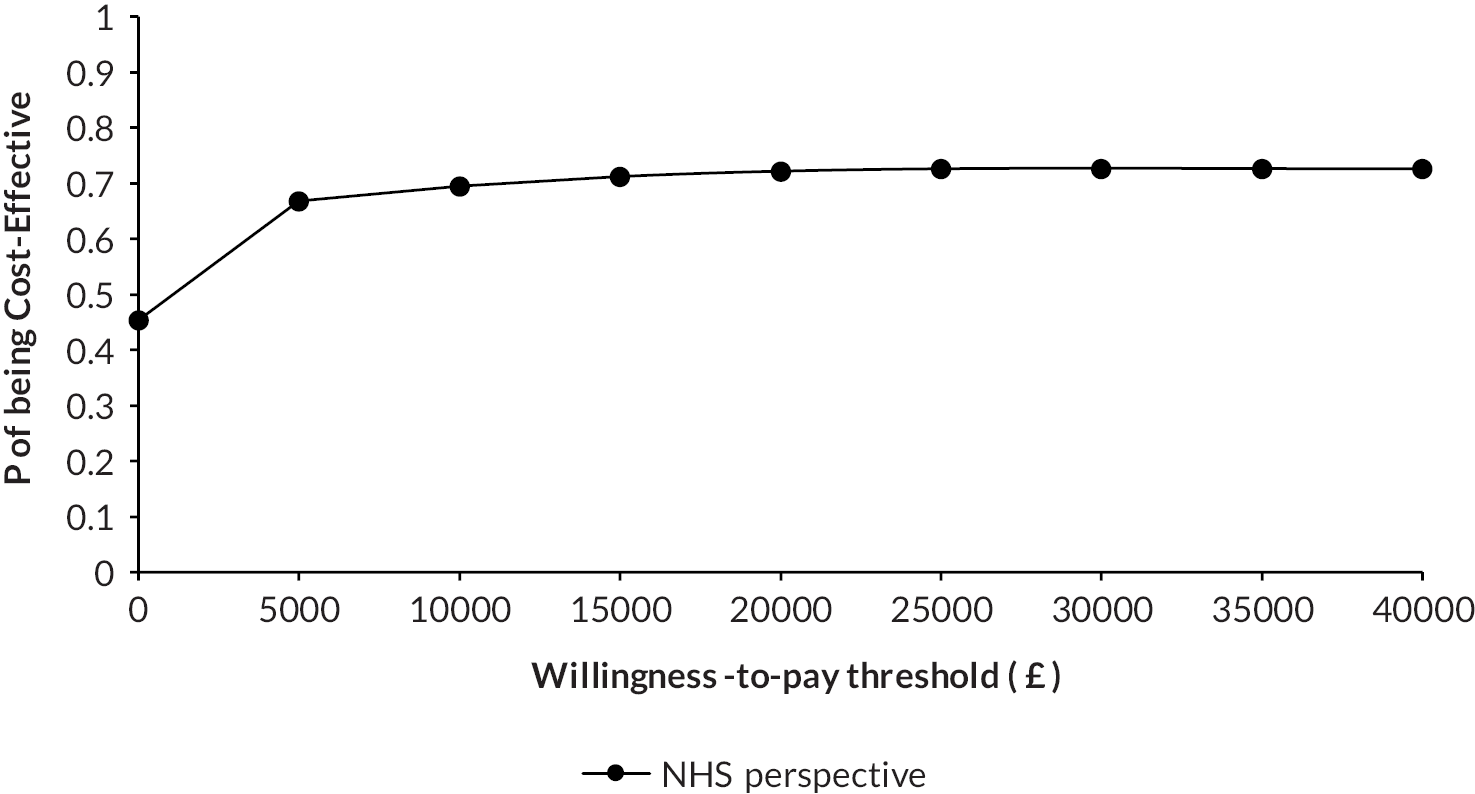

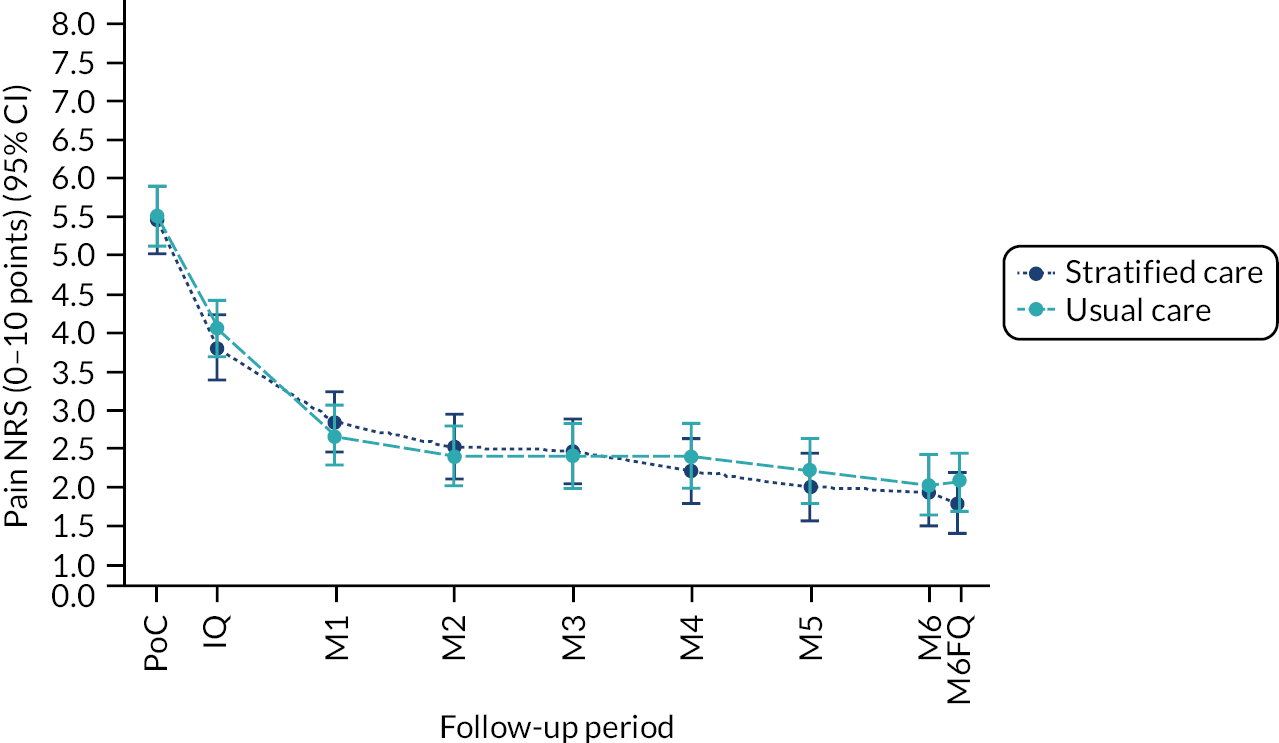

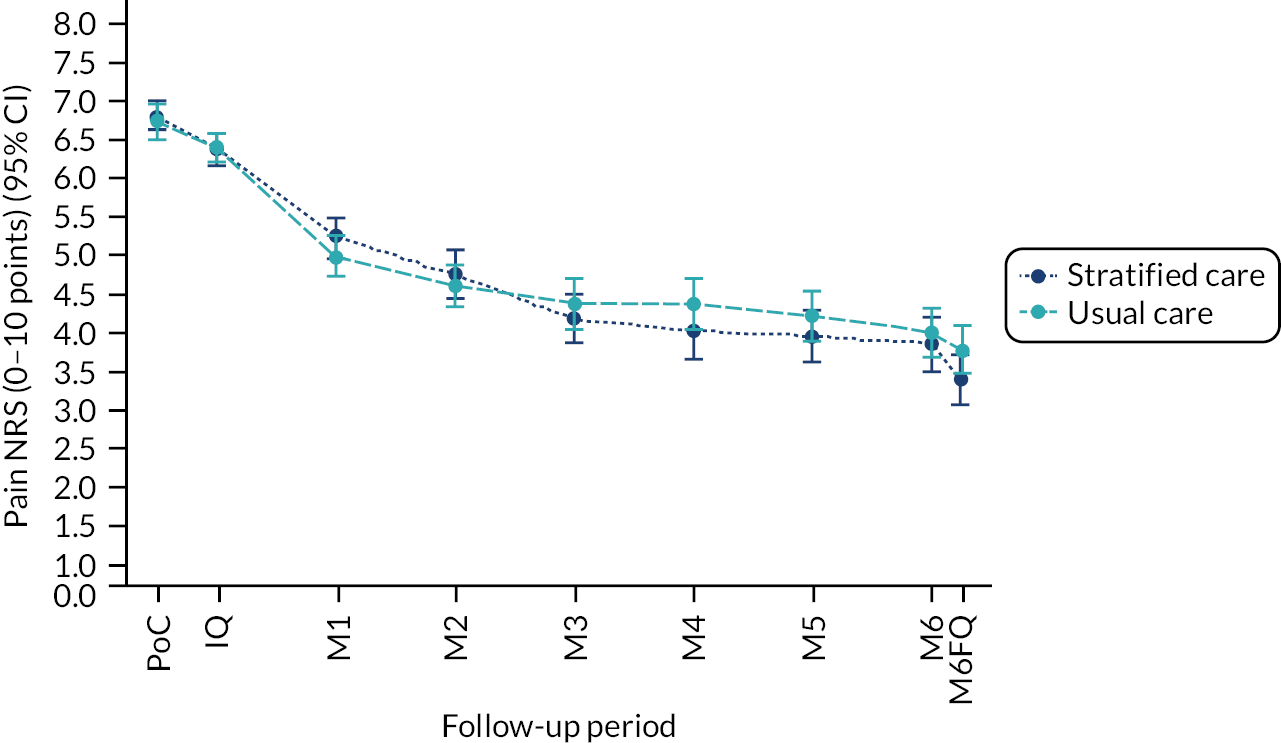

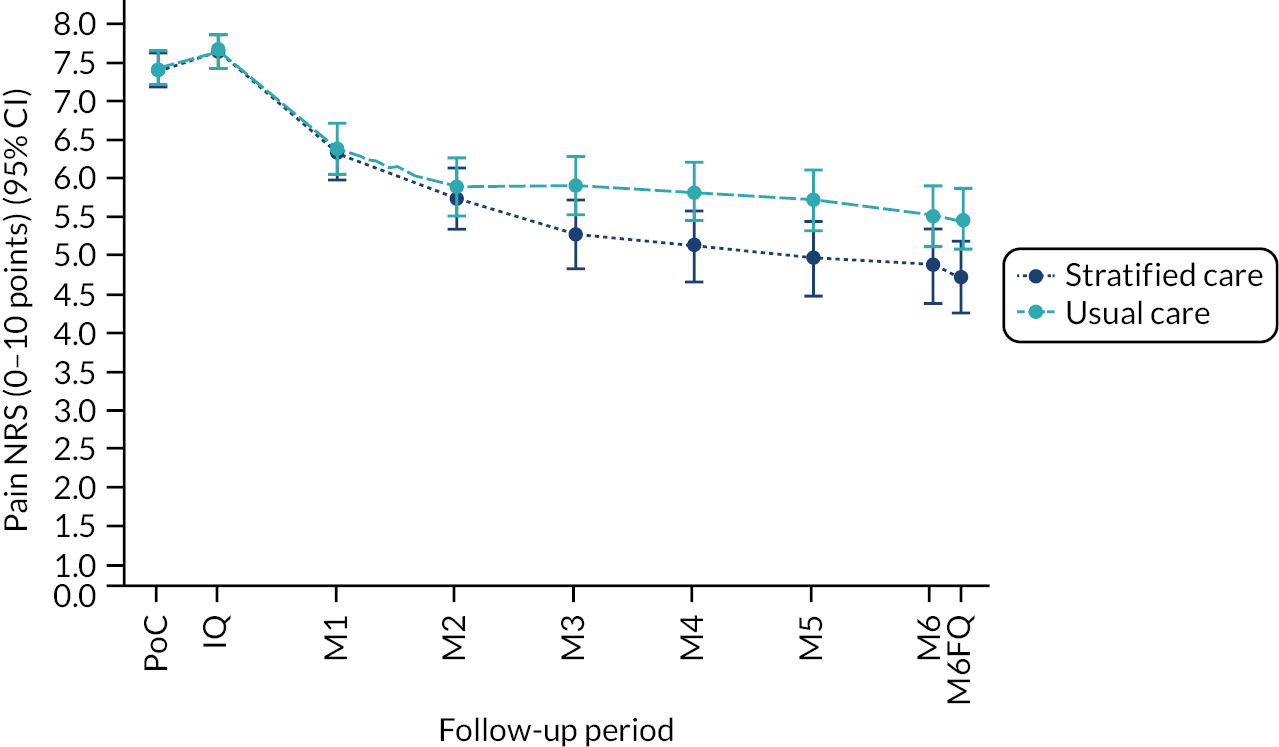

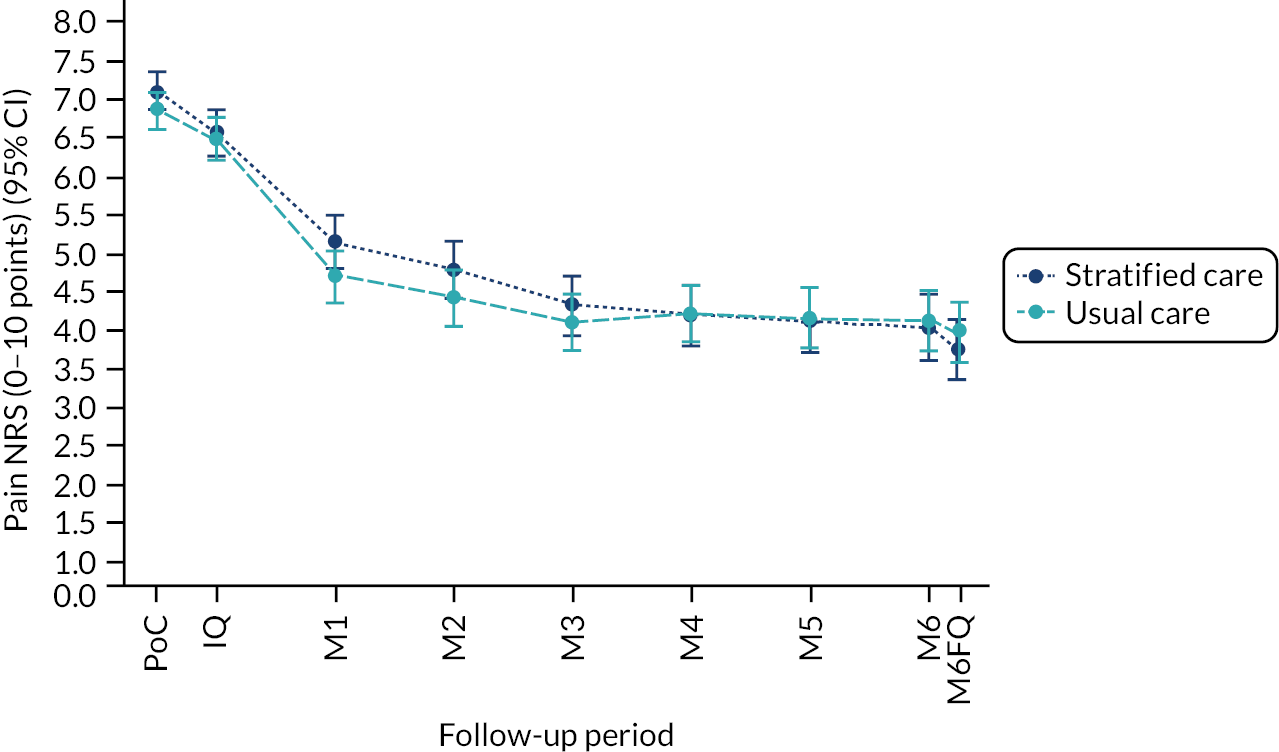

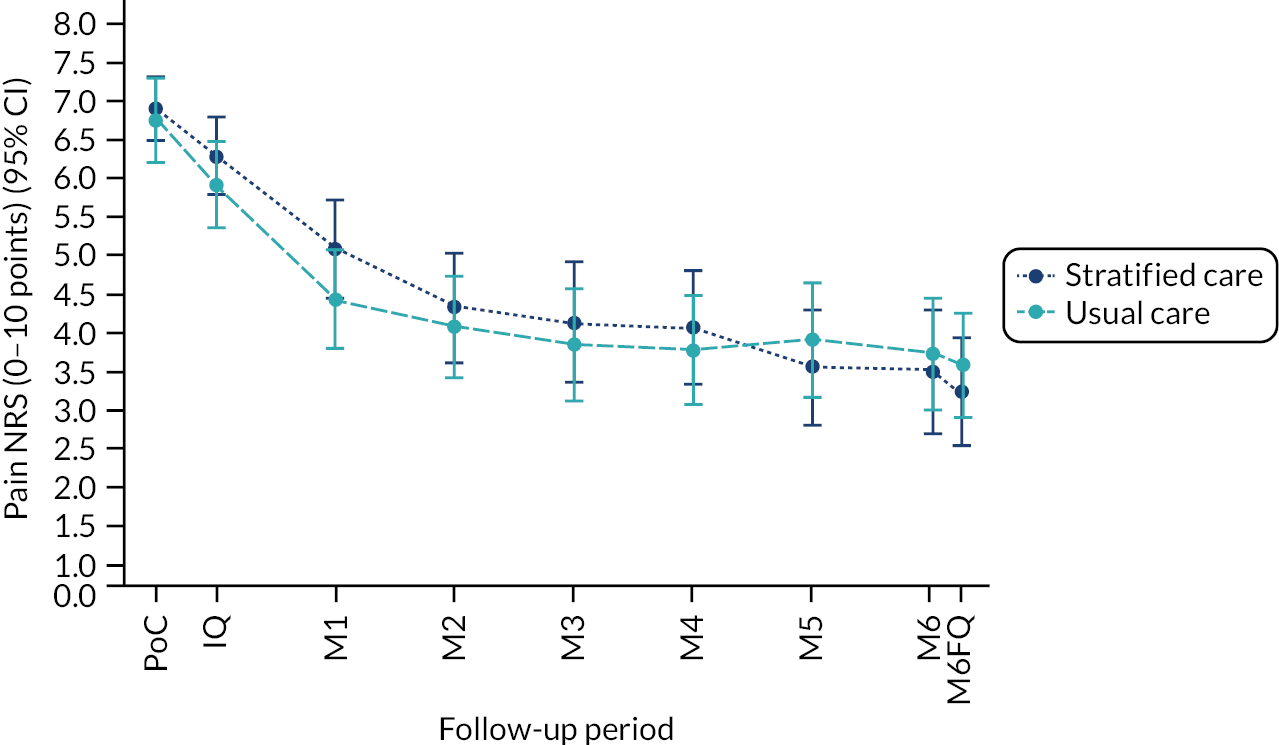

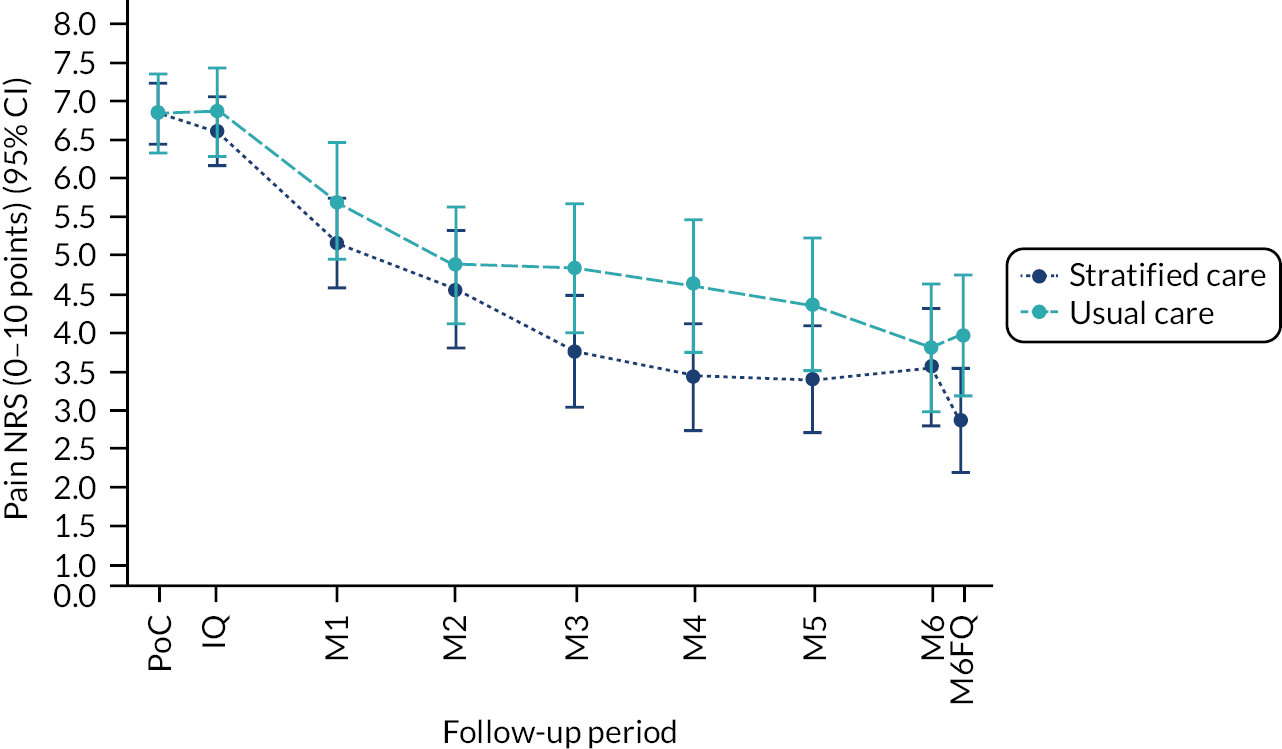

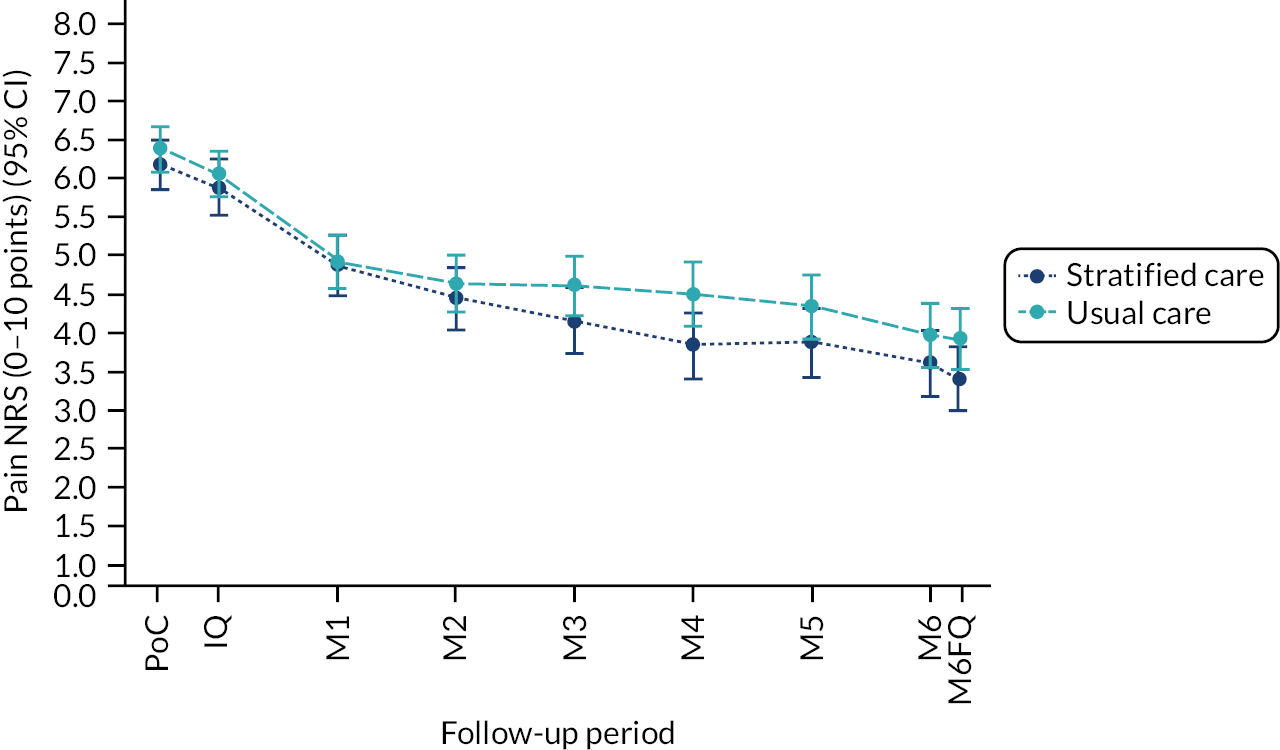

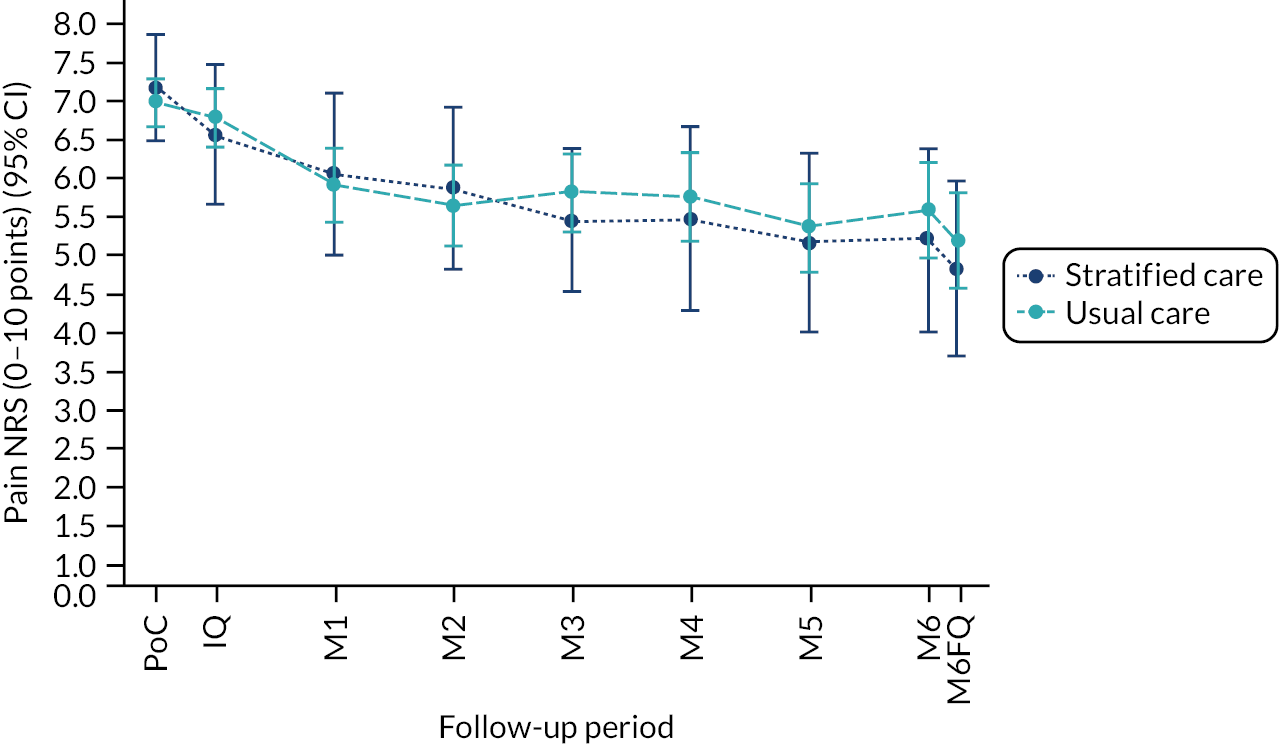

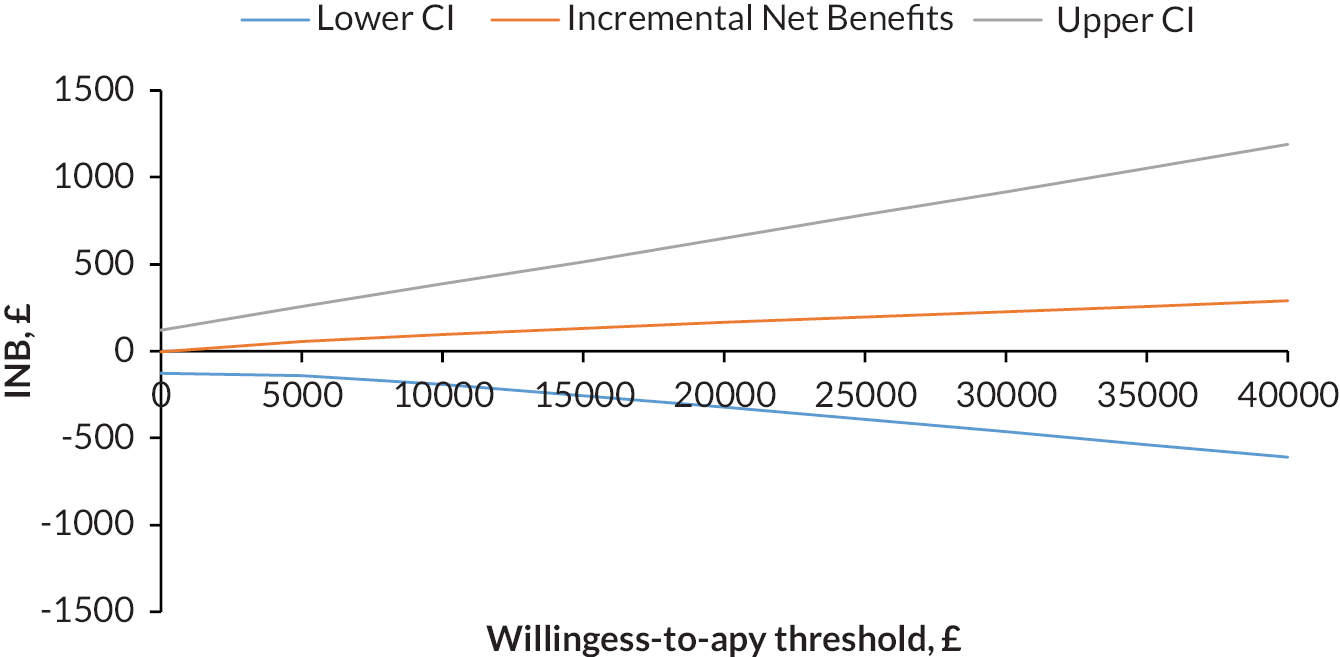

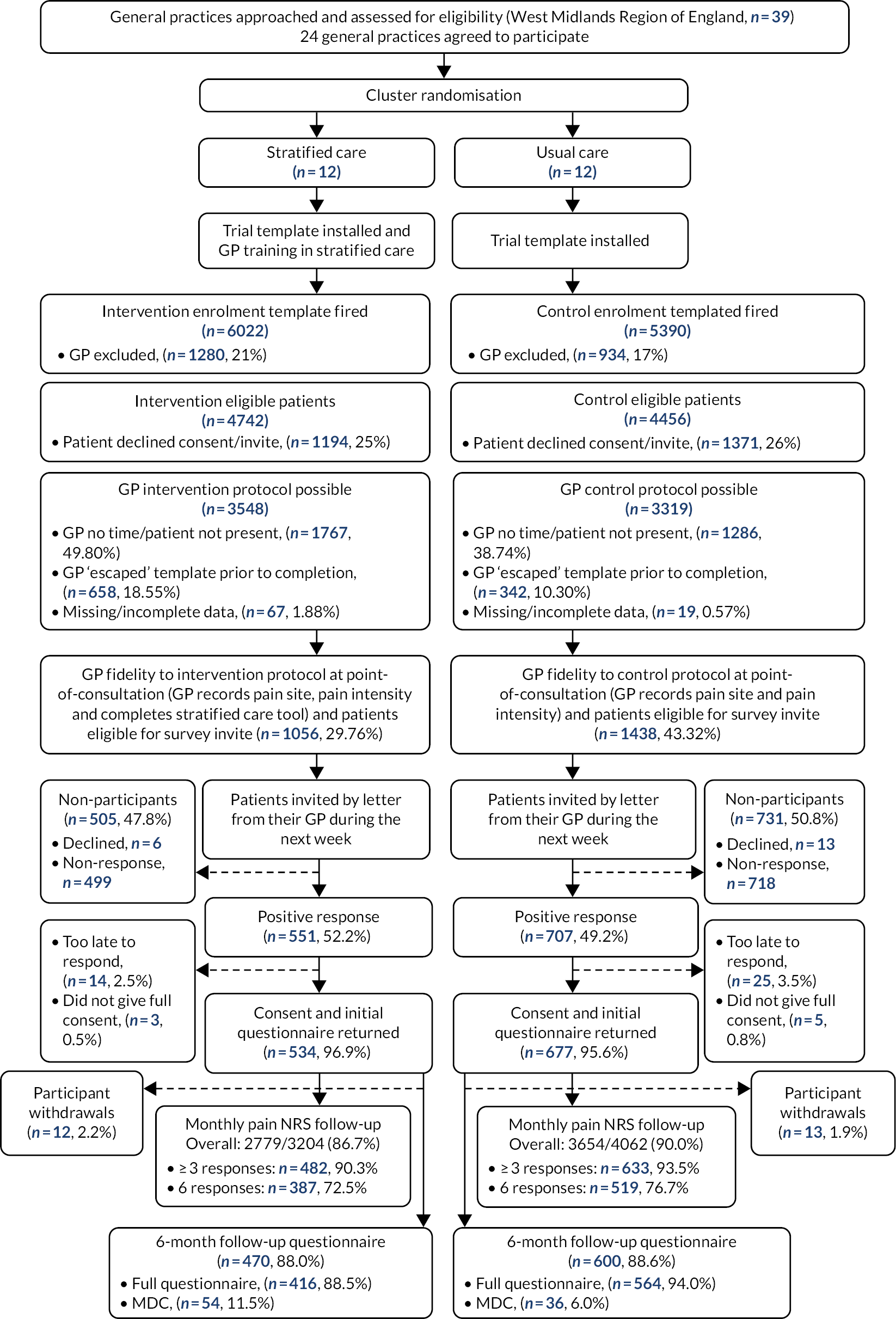

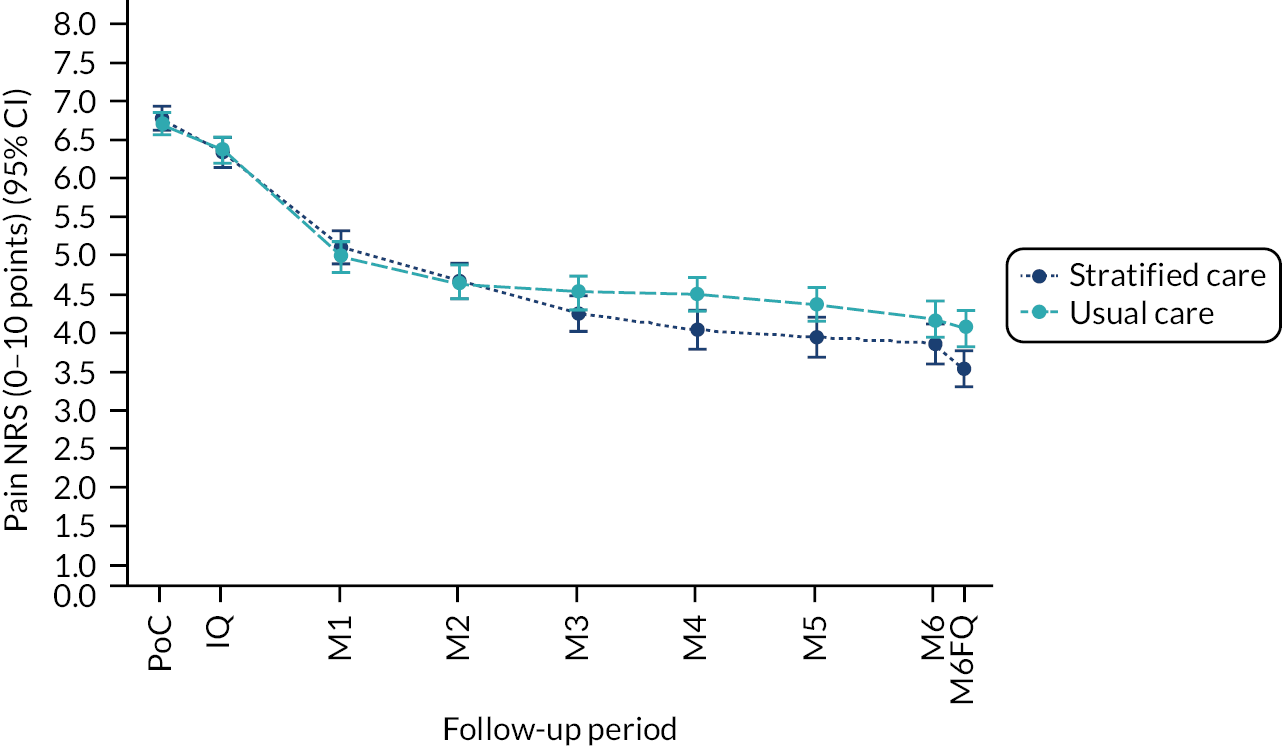

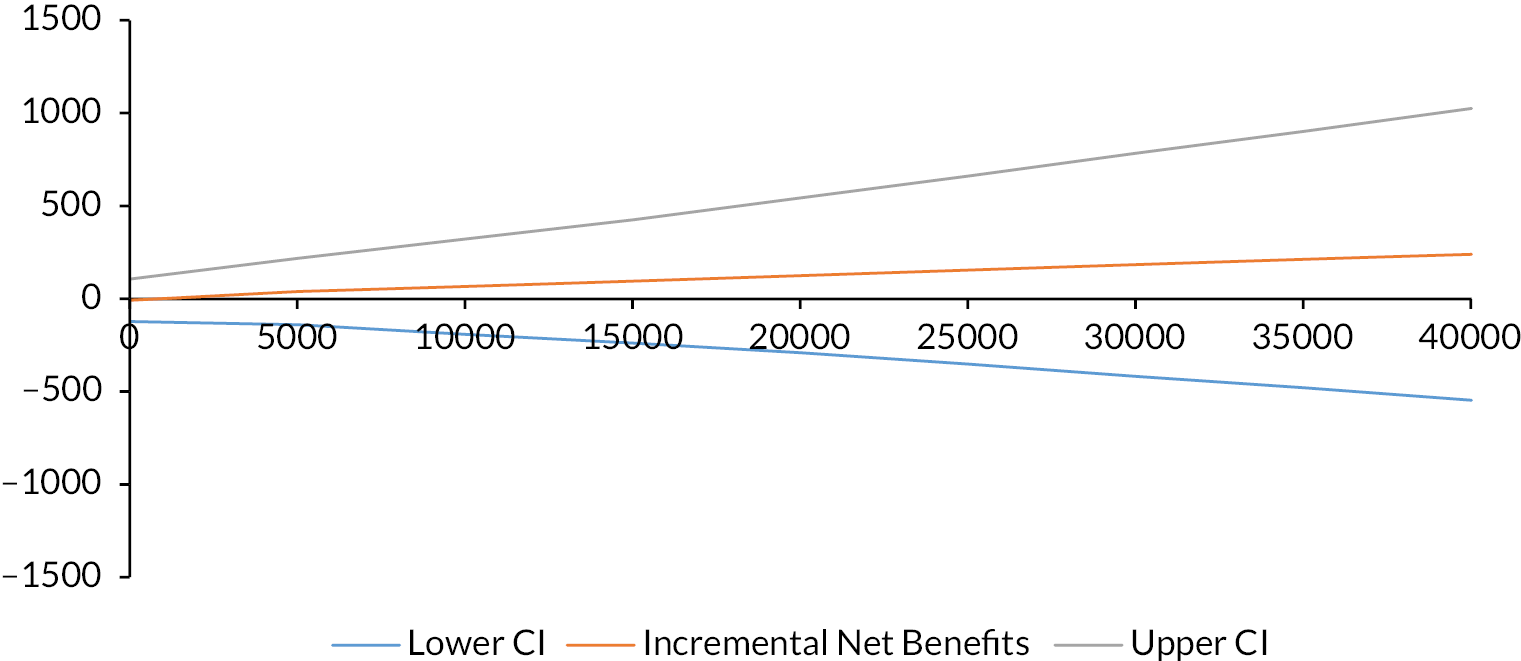

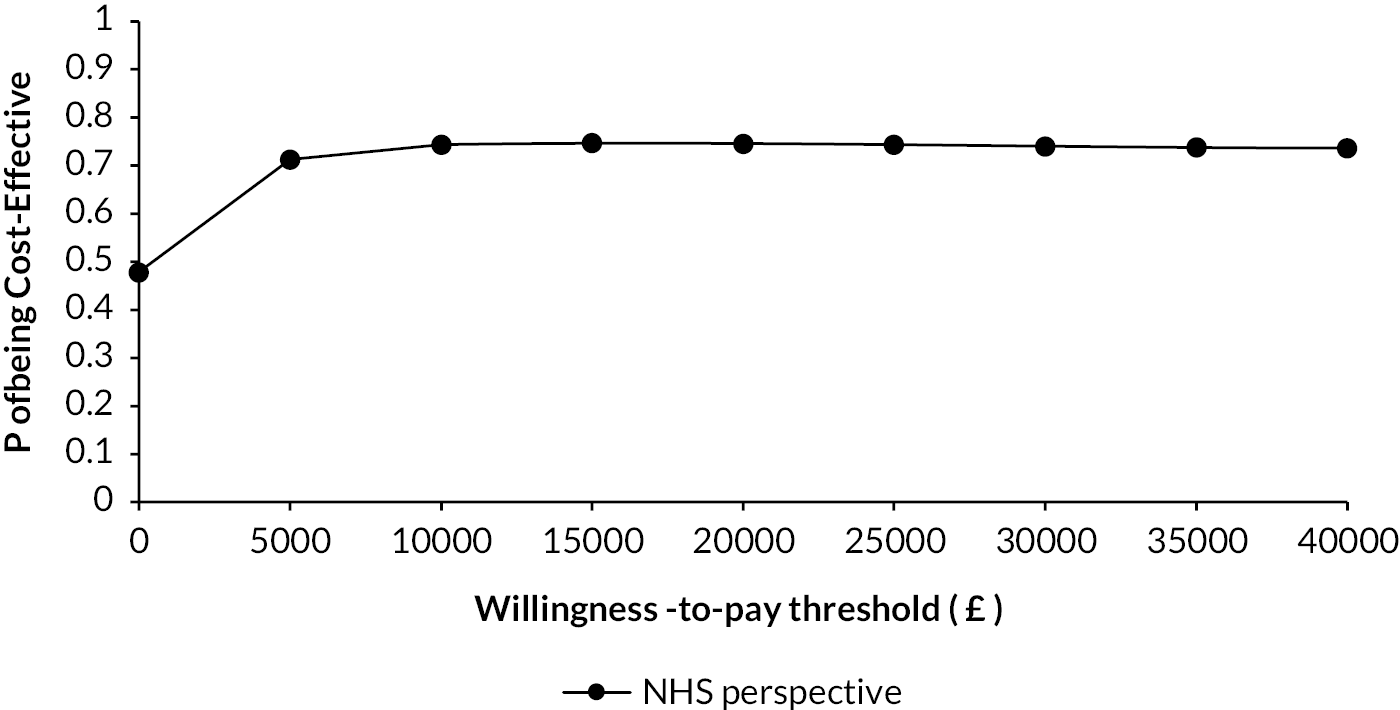

Methods