Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1210-12016. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Harding et al. This work was produced by Harding et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Harding et al.

Synopsis

Background

A recent report by the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that diabetic retinopathy (DR) remains one of the most common causes of visual loss in adults worldwide. 1 Screening for DR aims to detect sight-threatening DR (STDR) and refer people with diabetes (PWD) to the hospital eye service (HES) for timely treatment. Systematic programmes of screening are universally recognised to be important in preventing visual impairment (VI). 2

In England, annual eye screening for STDR for PWD over the age of 12 years commenced in the early 1990s and developed into the National Diabetic Eye Screening Programme (NDESP), with complete coverage achieved by 2008. 3

As in many other countries, the programme screening interval was set at 12 months in England and Wales for all PWD,4 while in the HES follow-up intervals are variable. Evidence to support the delivery of the pathway is limited to screening research cohorts and with minimal input from users.

There has been a rapid increase in the prevalence of diabetes, increasing faster in low- and middle-income countries than high-income countries,5 and resources are stretched. Much evidence supporting extended intervals suggests that it is safe to screen low-risk people at longer intervals6–8 and this has been introduced in some countries. However, the underpinning evidence for this change comes from observational studies in areas with low incidence rates6,9–11 and from modelling studies,12–14 and is not conclusive. In England and Wales, extended intervals have not been adopted, largely because of safety concerns highlighted by a recent systematic review calling for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and cost-effectiveness data,8 and recent problems in cancer screening programmes. 15

The emerging technologies of digital data linkage and risk prediction offer opportunities to personalise the approach to screening. By varying the frequency of screening depending on a person’s own risk of progression, an individualised approach can be developed with further potential improvements in effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

There are potential opportunities for reallocation of resources within the NHS by varying the screen interval, but no cost-effectiveness research data other than from limited modelling. The safety and acceptability of extending the screen interval in low-risk groups have not been investigated.

Estimates of the incidence and prevalence of DR are important in designing screening programmes and clinical services. The landmark epidemiological studies on DR that have provided these data are over 30 years old. 16,17 Since then, there have been changes in diagnostic criteria for diabetes,18,19 and diabetes and blood pressure (BP) control have improved in some populations. 20 At the time of the design of this programme, there were few data on incidence and prevalence in screening populations, mainly those from our own work in the 1990s. 6 As systematic programmes have been introduced and detected early disease, incidence in screened populations has changed, characterised as the ‘first pass effect’. Clinical studies of interventions aimed at early disease utilise cohorts, such as those undergoing systematic screening, and require prevalence and incidence data for study design and comparison.

Aims and objectives of the ISDR programme of applied research

Our aim in this National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Programme Grant for Applied Research (PGfAR) on individualised screening for DR (ISDR) was to conduct a mixed quantitative and qualitative programme of research to strengthen the evidence base for DR screening in the United Kingdom (UK) and beyond. We structured the programme in work packages, reordered here to aid the narrative in our report. A very active patient and public involvement (PPI) group was involved throughout, so we describe their involvement first, with additional detail in Supplementary Material 1.

Data warehouse (work package B1)

The aim of work package B1 was to collate, link and store patient data from routinely collected sources in a study data warehouse (DW) to support the development of a risk-calculation engine (RCE), the RCT and epidemiological, qualitative and cost-effectiveness studies.

The Liverpool Risk Calculation Engine (work package C)

The aim of work package C was to develop an individualised (personalised) method of calculating screen intervals using a RCE based on individual risk factors (see Eleuteri et al. 21).

RCT to evaluate the safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening (work package E)

The aim of work package E was to investigate the safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of longer screening intervals in low-risk PWD and shorter intervals in high-risk PWD (see Broadbent et al. 22,23).

Health economics (work package D)

The aim of work package D was to estimate the likelihood that individualised screening is more cost-effective than current practice (see Broadbent et al. 23).

Qualitative study with patients and healthcare professionals on changing screening intervals (work package F)

The aim of work package F was to explore the underlying perceptions of screening and early detection, and to test the acceptability of our new method of screening to PWD and healthcare professionals (HCPs) (see Byrne et al. 24).

Observational cohort study in people attending DR screening (work package B2)

The aim of work package B2 was to conduct a whole-population longitudinal observational cohort study to estimate up-to-date rates of incidence of DR and STDR in PWD in Liverpool (see Cheyne et al. 25).

Knowledge transfer and preparation for implementation (work package G)

To disseminate the research findings to clinical and academic beneficiaries, develop an NHS implementation plan through a dissemination event and develop any intellectual property (IP).

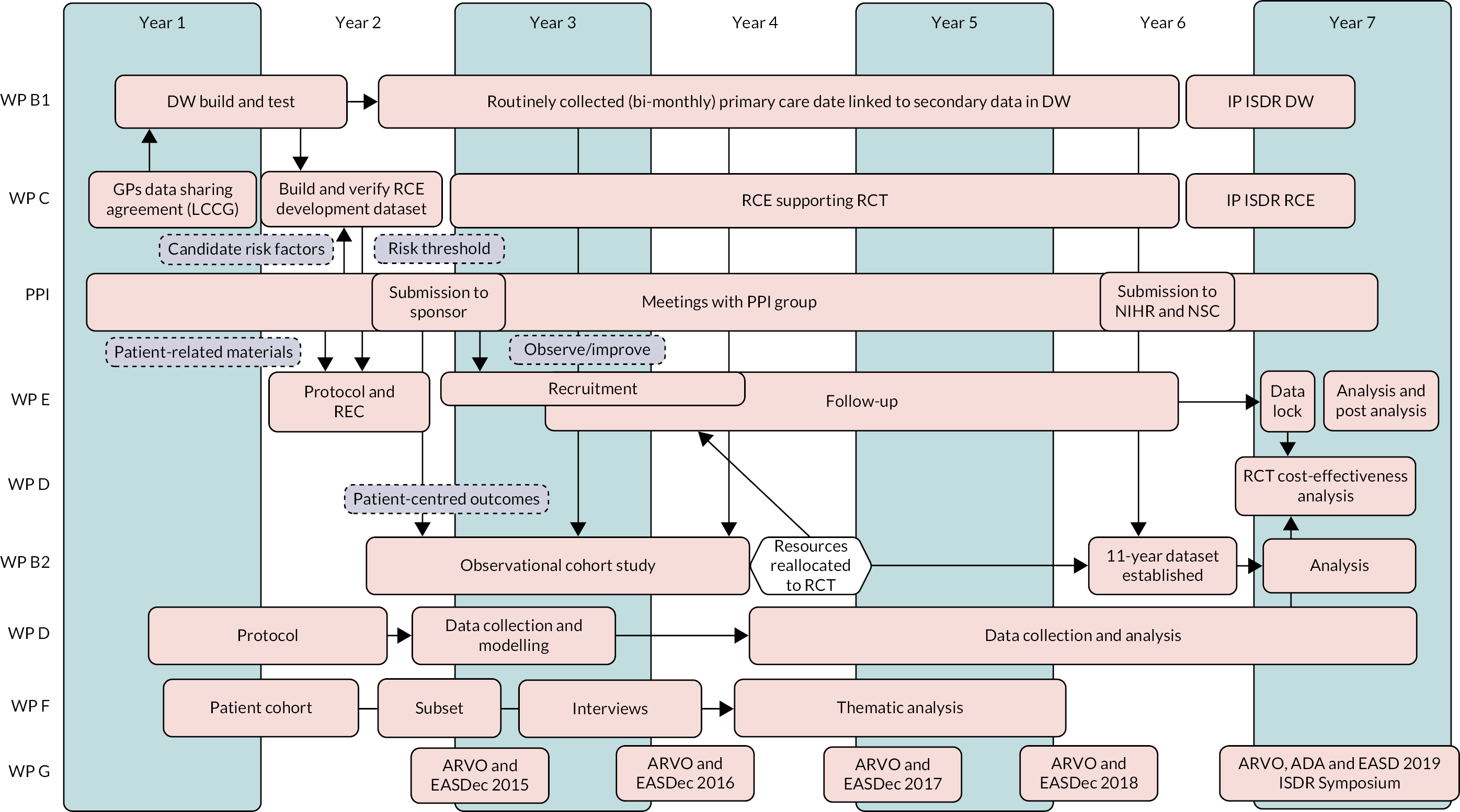

Figure 1 shows the stages and development of the work packages, how the work packages interconnect and the contribution of each work package (WP) to the whole programme.

FIGURE 1.

Pathway diagram showing the work flow in the ISDR Programme Grant for Applied Research, the work packages and their interrelationships. WP B1 DW development; WP C RCE; PPI (involvement shown in dashed boxes); WP E RCT; WP D Health economics; WP B2 Observational cohort study; WP F Qualitative study; WP G Dissemination. Resources were reallocated to the RCT from the cohort study in year 4 to support delayed recruitment (white hexagon and arrow). Arrows indicate input into specific item(s) of a WP. ADA, American Diabetes Association; ARVO, Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; EASD, European Association for the Study of Diabetes; EASDec, European Association for the Study of Diabetes eye complications study group; LCCG, Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group; NSC, National Screening Committee.

Changes to the programme

A number of changes to the planned programme of work occurred in the early years of the programme:

-

We planned to conduct a systematic review (WP A in the grant application). However, a systematic review in this area by Taylor-Phillips et al. 8 was published early in the programme in 2016. To replicate this was inefficient and, therefore, we conducted a literature review instead. Taylor-Phillips et al. 8 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend a move to extended interval screening and mixed and poorly designed cost-effectiveness studies. They provided further confirmation of the need for a RCT with a robust economic analysis.

-

A decision was made by the NIHR PGfAR team in May 2016 to move resources from the cohort study to support the RCT (WP E), which was behind with recruitment. This meant that the cohort study needed to be scaled back. We were able to report findings in an 11-year cohort of PWD being screened in Liverpool, but not the people attending the HES.

-

The observational cohort study (WP B2) utilised data prospectively collected from 2005. However, we were unable to obtain data on people who had died prior to the start of the programme. This resulted in the cohort needing to be considered as partly retrospective, making analysis more difficult to interpret.

-

We were unable to recruit non-attenders in the screening programme, a secondary aim in our qualitative study (WP F), despite multiple attempts in an identified cohort.

-

We had intended to interview participants longitudinally in the qualitative study. However, insufficient participants responded to our invitation, so we revised our sample to reach 60 single interviews.

Patient and public involvement in the ISDR programme

Public engagement is considered a key element in healthcare research by UK and international funders to ensure that research is relevant. Effective engagement empowers patients, ensures research is fit for purpose and develops patient-centred outcomes. NIHR describes involvement of the public in research under its ‘INVOLVE’ guidance. 26

Aims

We set out to involve members of the public in all aspects of our programme, the RCT in particular, and to support the research team to make the research relevant, attainable and applicable to patients and HCPs.

Methods

Seven PWD were recruited to the programme with the help of local and national service-user groups. Some members were recruited during the development phase of the programme, with all of the current group retaining membership during the course of the research grant.

The methods developed for the PPI group within ISDR are listed below:

-

We held regular meetings preceded by lunch in a venue located within the university campus. The location helped to create a relaxed and social atmosphere.

-

We sent the agenda prior to meetings, and any information related to agenda items with items signposted for discussion with and decisions by the group.

-

We made significant efforts to ‘translate’ any scientific or medical information.

-

Our discussions of items often created more questions from our PPI members and a need for other information. We realised early on in the meetings that we often needed at least two (and sometimes three) sessions to discuss agenda items and arrive at a considered position. Much of the information that we gave was technical, scientific or medical and there was often an associated high amount of material. We were asking our PPI group to make significant research decisions, such as the level of risk for the RCE, that would affect other PWD.

-

We worked with the PPI group in their decision-making to ensure that they were able to arrive at decisions without any doubts around their understanding or favouring a decision. This involved the following:

-

The chief investigator (CI) of the programme attended every PPI meeting and gave an update on the RCT.

-

We created a ‘research translator’, a member of the team who checked on the PPI group’s understanding and expectations.

-

We invited experts from the ISDR research team to give presentations and answer any queries from members of the PPI group.

-

We fed back at every meeting the progress of the PPI group’s decisions on every aspect of the RCT.

-

-

Members of the PPI group were also on the Programme Steering Committee, Programme Investigators Committee and Trial Steering Committee and had a macro view of the research process. Before each of these meetings, a pre meeting took place between the PPI member and one of the investigators.

-

Operational, logistical or political issues were discussed with the group for potential strategies.

Results: summary of patient and public involvement contributions to the ISDR programme

We met with our PPI group 19 times between 2013 and 2019, as detailed in Supplementary Material 1. In summary, they:

-

contributed to the programme development grant and research and programme grant application

-

developed with the research team candidate risk factors associated with progression of DR (WP C)

-

prioritised research questions by identifying the most important patient-centred outcomes (WP B2)

-

were heavily involved in setting the acceptable risk threshold in the RCE to be tested in the RCT (WPs C and E)

-

assisted in the preparation of patient-related materials, such as consent forms and patient information booklets (WP E)

-

suggested measures to improve study recruitment by observing screening clinics and the ISDR RCT consent process (WP E)

-

made suggestions to the clinical director of the Liverpool Diabetic Eye Screening Programme (LDESP) to improve screening attendance

-

served on oversight committees and helped to resolve issues during the lifetime of the grant

-

participated in cost-effectiveness analyses and suggested ways in which savings could be used to improve future services (WP D)

-

commented on this report and draft papers from the RCT and a paper on the acceptability of variable-interval risk-based screening to HCPs and PWD (WP F)

-

were involved in a PPI session in the dissemination conference (WP G).

Discussion: reflections/critical perspective

Members of our PPI group had a very positive impact on all aspects of the programme and strongly supported the research team. Their activities have been wide-ranging, not only in the technical details of the RCT, but also in their lobbying for variable-interval screening. As PWD, they were primarily concerned about the safety of the trial and improving the health of others, and mindful of the potential consequences of making the wrong decision and its impact on others’ lives. Our key lessons on successful PPI are set out in Box 1.

-

Co-investigators and preferably the CI to attend all PPI meetings.

-

Identify a ‘research translator’ or ‘research connector’ with sufficient knowledge of the research objectives and empowered to constructively challenge the research team.

-

Identify critical decisions in the research design to be taken by the group and develop a process to reach a clear conclusion. Needs to extend beyond reviewing patient information sheets and consent forms.

-

Avoid overload – plan to address two to three topics at each meeting and develop over a series of meetings.

-

Go slowly – give time for PPI members to express their opinions.

-

Assess levels of knowledge at all stages.

-

Hold regular meetings in a relaxed environment.

-

Ensure an appropriate spread of ages, experience and, where relevant, disease type.

-

Work hard at maintaining engagement over the duration of the research.

-

Ensure adequate funding is available.

-

Patients and members of the public can become ‘patient experts’.

-

Complex nuanced decisions can be reached.

-

Patient-centred outcomes can change research questions.

-

Well-argued patient opinions that are much more powerful than views of academics.

-

A research team with greatly improved communication skills and a clearer insight of the potential impact of their research.

Over the extended duration of our research programme, our PPI members developed wide expertise and became ‘patient experts’. Further work to develop systems to retain and build on this expertise could provide a useful resource for funding bodies and policy-makers.

Interrelation to other work packages and overall aims of the programme

The PPI group members supported most work packages of the programme, including B2 (observational cohort study), C (RCE), D (health economics), E (RCT) and F (qualitative study).

The ISDR study data warehouse

Research aims

To design and develop a purpose-built DW to support the development of the RCE, the delivery of the RCT, and the economic, qualitative and cohort studies.

Methods

Using Structured System Analysis and Design Methodology,27 the ISDR business intelligence (BI) team designed and built the ISDR DW and supporting architecture. The DW centralises data into a single Microsoft SQL (structured query language) server data repository hosted on a secure private local area network within the Department of Medical Physics and Clinical Engineering at the Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospital Trust (RLBUHT). All incoming and outgoing file transfers were carried out using secure networks and encryption methods, and received local information governance approvals (Privacy Impact Assessment, Data Governance Committee, Caldicott Guardian).

The following data sources interacted with the ISDR DW:

-

Demographic and systemic risk factor data from general practices (GPs) via the Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (LCCG) (Egton Medical Information Systems, EMIS Web, EMIS Health; www.emishealth.com).

-

Demographic, retinopathy grading and visual acuity (VA) data from –

-

the LDESP, collected in the Orion/Digital healthcare database between 1995 and 2013 and in OptoMize from 2013

-

HES-based screen-positive assessment clinics, collected in a bespoke Microsoft Access database (Diabolos) (1991–2015) and the hospital patient electronic notes system (PENS) (from 2016).

-

-

Appointment and treatment records from the hospital’s integrated patient-management system.

-

An ‘opt-out register’. PWD who were registered with GPs in Liverpool were informed of the project in a letter addressed from the screening programme. Their consent for inclusion in the DW was obtained via an ‘opt-out’ method and a record of those patients who opted out was kept in a register.

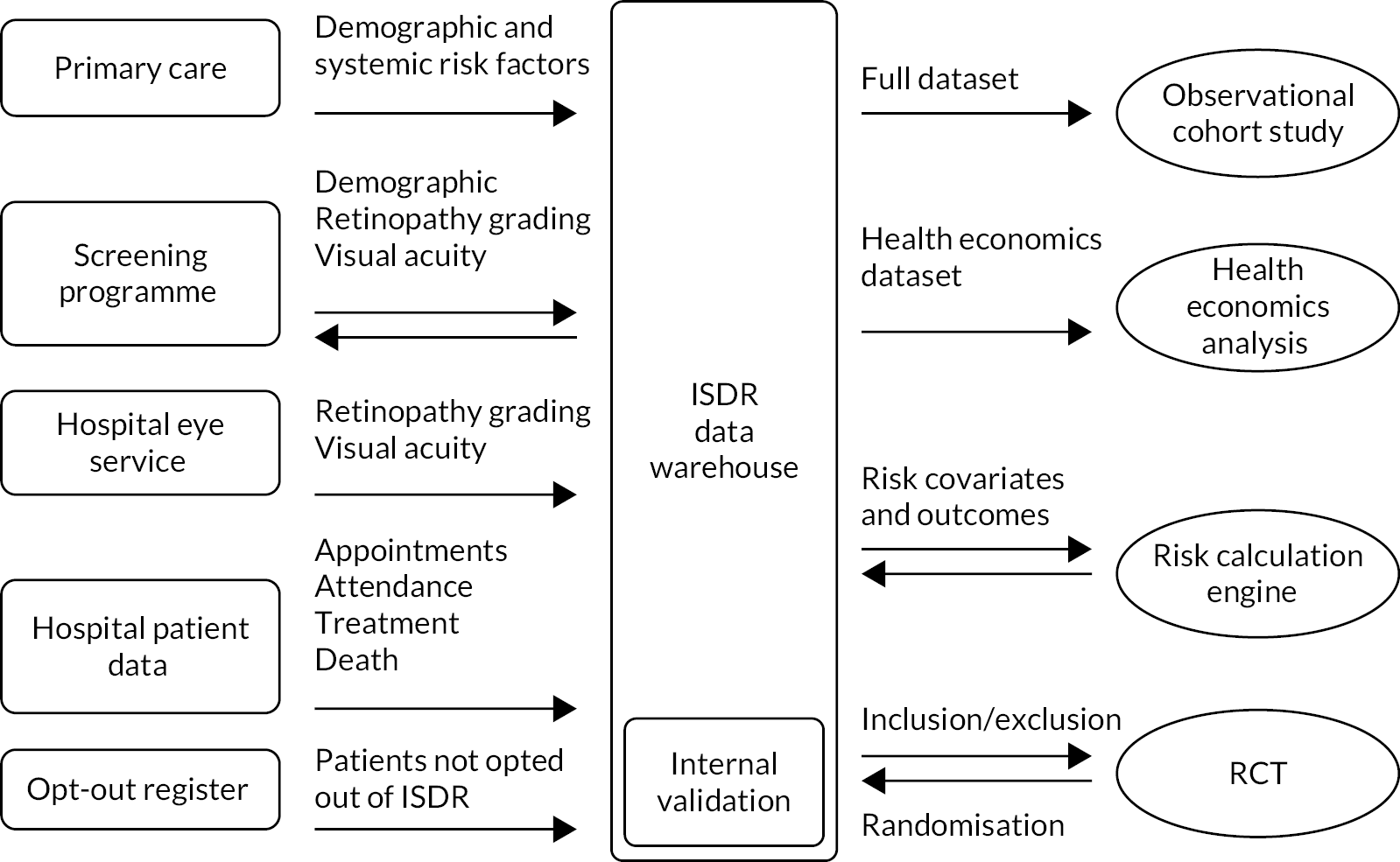

The flow of data in the programme is illustrated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Diagrammatic representation of ISDR DW data flows.

The DW received all relevant data from PWD streamed from primary and secondary care. The RCE was fed directly from the DW. Risk factors included were demographic (e.g. age, deprivation and ethnicity), ocular (e.g. previous and current retinopathy severity, previous treatment and VA) and systemic (e.g. diabetes control and duration, BP, and lipids). The data fields are listed in more detail in Supplementary Material 2, Table 1.

To ensure the credibility of data coming from multiple sources, which contained data with varying quality, covariates in the source data were examined for outliers and distribution inconsistencies. Credibility limits were developed using a statistical methodology. This set of scripts cleansed and validated incoming data for the DW. Input and output schemas (see Supplementary Material 2, Table 2) were developed for each data transfer element, as indicated by the arrows in Figure 2.

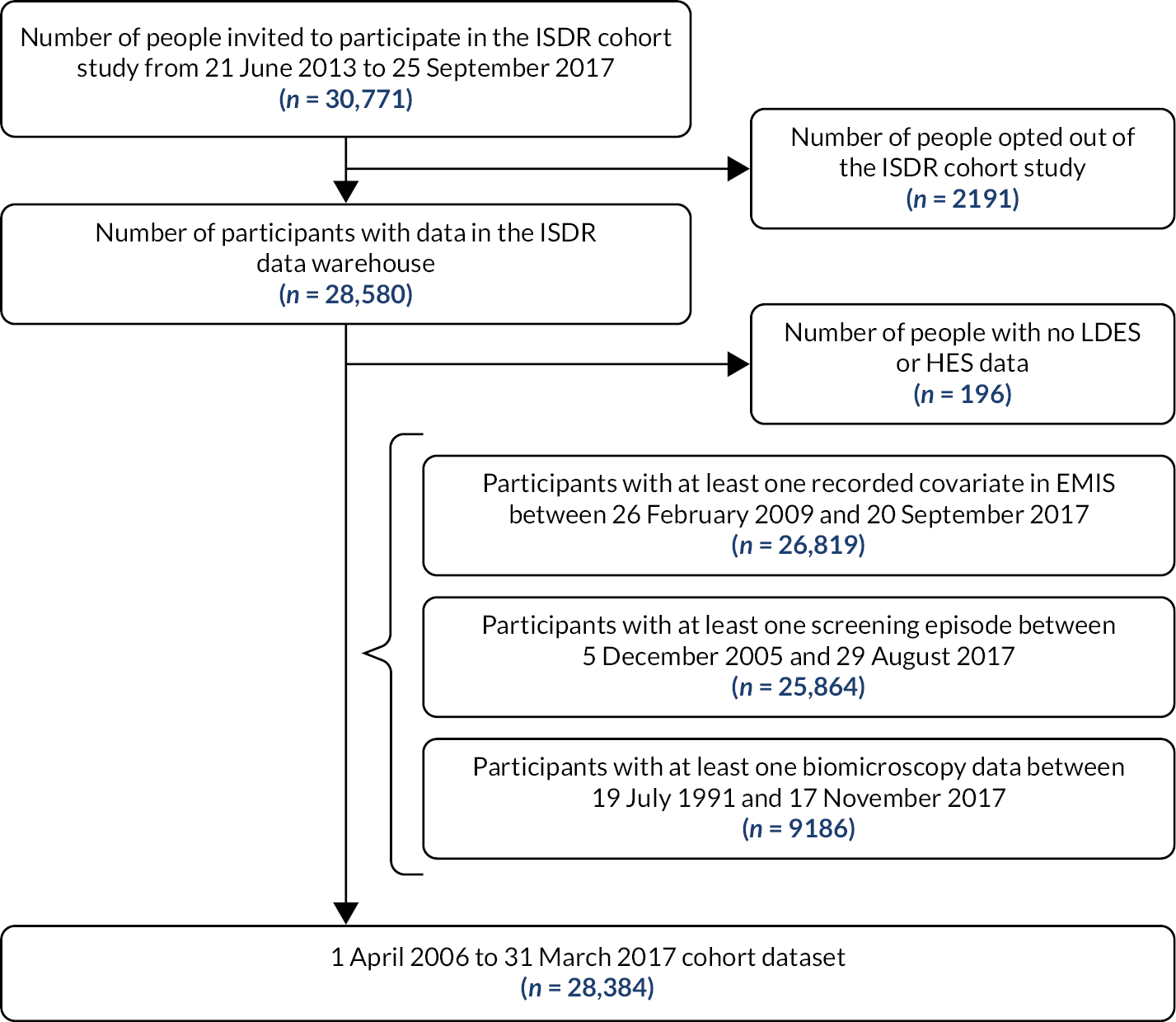

Results

The ISDR DW held data from 2009 on 28,556 participants as of January 2020 (end of the programme) over 11 screening cycles. Data linkage was achieved for all participants. The ISDR DW received test and preliminary data sets from early 2013. One of the main data sets was the ‘ISDR Cohort Study Dataset’, which supported WP B2. This contained data for 28,384 participants in October 2017, equivalent to 318,053,075 data points; a data point is a discrete unit of information,28 an example being a single recording of weight for a patient.

Discussion: challenges in the DW

The ISDR programme collated and linked large-scale routinely collected clinical data across different domains in a single repository. It successfully supported all aspects of the programme and routine patient management in the local screening programme. The DW is dynamic in that it updates on a regular basis. It demonstrated resilience and the potential to be developed into a routine health informatics tool in the NHS for personalised medicine.

We faced a number of challenges. No existing ‘off the shelf’ databases existed. The data were complex and came from multiple data sources. The Liverpool CCG had to set up and run a set of manual processes throughout the lifetime of the project to link the various domains within primary care. There was variability in data quality, which required bespoke processing and the development and application of credibility limits before the data could be considered adequate for a clinical application. Systems were of widely differing design: some were commercial (OptoMize) and some were developed in house (Diabolos, PENS). Systems had to be ‘cracked’ before the relevant data could be extracted. Data labels had to be investigated and tested. Several clinical system upgrades took place during the lifetime of the programme, which tended to occur unannounced, resulting in some lengthy delays and wasted effort.

The multidisciplinary nature of the programme meant that several members of the team had very little understanding of the requirements of database development and engineering, and similarly the database team struggled with adequate engagement with the clinical teams. There appears to be a lack of bioinformatic expertise to act as a bridge between the technical BI and computer science teams on the one hand and the clinical/research end-users on the other. This needs urgently addressing.

We learnt several important lessons. Establishing a real-time data repository within an NHS environment to underpin personalised medicine requires:

-

sufficient time for interdisciplinary team working on data sanity checks, outlier/credibility handling protocols, logic rule development and imputation strategies

-

investment in developing cross-disciplinary bioinformatics expertise to link technical teams and clinical/research end-users.

Interrelation to other work packages and overall aims of the programme

In addition to the underpinning role of the DW across much of the programme, it has led to development of new IP covered in WP G. Imputation strategies needed to be developed in several WPs to deal with missing data.

The Liverpool Risk-Calculation Engine

A peer-reviewed publication21 reports additional information on the continuous Markov process, imputation, covariate selection, threshold setting and model checking.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Broadbent et al. 22 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Research aims

To develop and internally validate a RCE to estimate the risk of progression to screen-positive or referable DR and assign individualised screening intervals (WP C).

Methods

Data set

Data from established screening and primary care systems were combined in the ISDR DW. A set of candidate covariates was selected for the model in partnership with our PPI group. A review of the literature around the known risk factors was presented by the research team, and additional candidate covariates were proposed by the PPI team to create a ‘long list’. The ISDR DW was explored with this set of candidates in mind, and a RCE development data set was extracted containing covariates with ≥ 80% completeness in PWD who were screen-negative at the first of at least two episodes that occurred in a 5-year sample period.

Model

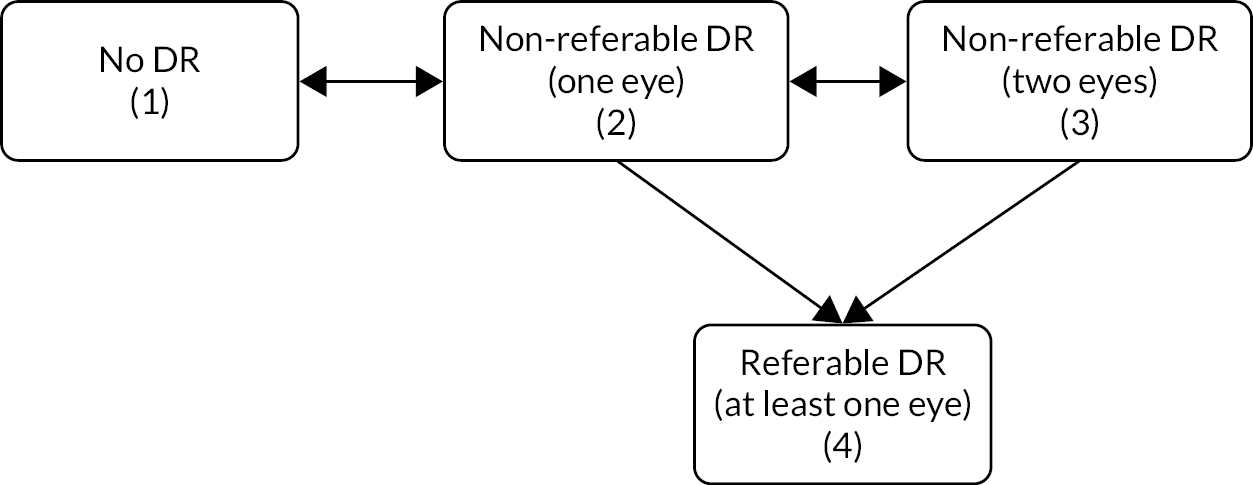

We selected a continuous-time Markov process to allow for a set of individuals to transition among states over time. 29 The state at each time point was defined by the level of retinopathy, including separation by one or both eyes (Figure 3):30 state 1 – no DR detected; state 2 – non-referable DR in one eye only; state 3 – non-referable DR in both eyes; and state 4 – referable DR (screen-positive for at least one eye).

FIGURE 3.

States and transitions in the continuous-time Markov process in the Liverpool Risk-Calculation Engine.

Only one baseline screening event was used. The risks or intensities for each of six transitions between these states were entered into the model within a probability matrix. The interval censoring seen in screening data required special methodology. Missing clinical data were handled using multiple imputation.

Ten covariates met the entry criteria and were ranked using Wald statistics. A set of nested models were built to estimate corrected Akaike’s information criterion (AICc). The model with the smallest AICc was chosen to give the best fit to the data.

We checked the RCE development data set using random samples of event vectors. The model was checked for the influence of outliers, regression and distributional assumptions; Pearson-type goodness of fit and corrected C-index were calculated. Bootstrapping and fourfold cross-validation were used for internal validation. Further internal validation was conducted using a geographical split based on deprivation index. 31

Implementation

The effect of a set of risk thresholds (5%, 2.5%, 1%) on screening interval allocation was investigated and a final threshold was selected in discussion with the PPI group.

A small sample of cases assigned by the RCE to 6-, 12- and 24-month intervals were independently checked against patient records for clinical credibility.

After design and testing, the RCE was implemented within the Liverpool Clinical Trials Centre for testing within the RCT (see Randomised controlled trial to evaluate the safety and cost-effectiveness of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening). Data were received from the DW electronically on a daily basis.

Results

Data extracted into the RCE development data set were from 11,806 PWD attending the LDESP between 20 February 2009 and 4 February 2014.

Covariates meeting the selection criteria are listed in Table 1. Those that gave the best fit and were included in the final model were disease duration, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), age at diagnosis, systolic BP and total cholesterol. Although the retinopathy stage is not technically a covariate, it is included in the table to show the improvement in predictive power when covariates are added to the model.

| Covariates | Wald statistic | Rescaled AICc | Explained likelihood (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retinopathy (baseline) | 893.65 | – | |

| + Disease duration (years) | 293.4 | 423.23 | 48 |

| + HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 201.2 | 68.61 | 85 |

| + Age at diagnosis (years) | 44.2 | 10.85 | 92 |

| + Systolic BP (mmHg) | 18.9 | 6.61 | 94 |

| + Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 18.7 | 0 | 96 |

| + Disease type | 15.2 | 0.99 | 97.5 |

| + Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 8.2 | 5.61 | 98.6 |

| + eGFR (ml/min–1 1.73 m2 –1) | 5.4 | 13.63 | 99.4 |

| + Sex | 5.1 | 24.95 | 99.9 |

| + HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.73 | 40.99 | – |

The risk model is summarised in three equations. The first gives the hazard rates (or intensities or ‘risks’) of going from one state to another for each transition:

where i, j = {1, 2, 3, 4} and βCij is the model parameter for covariate C (or baseline intensity when C = 0); AgeD is age at diagnosis and DiseaseD is disease duration. From this equation, a transition intensity matrix is derived for the four states described above:

Probabilities of transition occurring at a specific time are obtained by using the third equation:

Tables 2 and 3 show the estimated baseline hazard ratios and probabilities of each transition state. Further details are available elsewhere. 30

| Transition | HR for transition (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | Disease duration | HbA1c | Cholesterol | SBP | |

| 1 to > 2 | 1.00450 (1.00115 to 1.00787) | 1.0280 (1.0213 to 1.0348) | 1.0101 (1.00743 to 1.0128) | 0.963 [0.923 to 1.00521] | 1.00409 (1.00104 to 0.0073) |

| 2 to > 1 | 1.00580 (1.00237 to 1.00919) | 0.983 (0.975 to 0.992) | 0.998 (0.995 to 1.00140) | 1.0153 [0.973 to 1.0592] | 0.999 (0.996 to 1.00244) |

| 2 to > 3 | 0.989 (0.984 to 0.994) | 1.0261 (1.0173 to 1.0350) | 1.00621 (1.00221 to 1.0102) | 0.965 [0.901 to 1.0333] | 0.998 (0.993 to 1.00255) |

| 2 to > 4 | 1.0245 (0.990 to 1.0605) | 0.989 (0.931 to 1.0510) | 1.00554 (0.983 to 1.0285) | 1.0231 [–0.27 to 0.37] | 1.00342 (0.977 to 1.0310) |

| 3 to > 2 | 1.00839 (1.00329 to 1.0135) | 0.959 (0.949 to 0.968) | 0.990 (0.985 to 0.994) | 1.0836 [1.0147 to 1.157] | 0.997 (0.993 to 1.00126) |

| 3 to > 4 | 0.986 (0.977 to 0.995) | 1.00420 (0.989 to 1.0200) | 1.0164 (1.00888 to 1.0239) | 1.0346 [0.918 to 1.166] | 1.00501 (0.996 to 1.0141) |

| Transition | Probability (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| 1 to > 2 | 0.114 (0.111 to 0.118) |

| 2 to > 1 | 0.552 (0.541 to 0.565) |

| 2 to > 3 | 0.141 (0.134 to 0.148) |

| 2 to > 4 | 0.0163 (0.0139 to 0.0202) |

| 3 to > 2 | 0.283 (0.272 to 0.294) |

| 3 to > 4 | 0.0574 (0.0485 to 0.0678) |

Data and model checking

Homogeneity in the RCE was checked by smoothed summary residuals compared with follow-up time with 95% CI. The calibration curves for the Cox–Snell residuals were close to the theoretical optimal calibration. The Pearson-type statistic denoted not enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis of good fit. Cross validation showed that the training and test performance measures were essentially the same. Fitting the model to the most deprived subjects produced only very small changes in risk allocation of the non-deprived group.

Setting the risk threshold

The PPI group identified acceptable screen intervals of 6, 12 and 24 months, and risks of 1% and 2.5% of missing screen-positive disease at any future screen episode. Exploration of the effect of different risk thresholds on allocation to the three different screen intervals showed that, as the threshold decreased, the proportion of incorrect allocations decreased for screen-positives (overestimation) and increased for negatives (underestimation). For all three, there was a reduction in the overall number of screening episodes required. The research team and PPI group considered that a 2.5% criterion showed a satisfactory distribution across the three screening intervals and a reasonable reduction in episodes, and this was selected for implementation.

Discussion

We have developed and tested a RCE in which an individual’s risk can be predicted from routinely collected clinical data, referenced to the clinical histories of the local population, and using covariates of local relevance. The risk can be reassessed at each screening episode as new clinical information is acquired.

Strengths of our model include the strongly embedded PPI group, which allowed us to develop an appropriate preliminary covariate list, acceptable screen intervals and risk threshold. The model internally handles interval censoring, inherent to retinopathy data in screening. 29 It predicts the probabilities of transition for all patient states and embeds a model for multiple imputation of missing covariates.

Potential limitations include not adjusting for misclassification of retinopathy during grading. This could be addressed by adding a misclassification model but at the cost of substantially more observations and computational complexity. Some potentially useful covariates were not informative in the Liverpool setting: ethnic diversity and prevalence of abnormal estimated glomerular filtration rate levels were low, and ‘type of diabetes’ may not have been accurately recorded. We used the date of the first HbA1c test to improve data on ‘duration of diabetes’. This was helpful in people with long durations but less reliable since the introduction of HbA1c as a primary screening test.

The model consistently showed good levels of prediction for the 2.5% risk threshold. The numbers of screen-positive cases with overestimated screening dates and screen-negative cases with underestimated screening dates were smaller. The majority of people were correctly allocated (78% of screen-positives, 80% of screen-negatives), with a reasonable allocation across the 6-, 12- and 24-month intervals (approximately 10% : 10% : 80%). The number of patients who had a screen-positive event before the allocated screening date reduced by > 50% and the overall number of screening episodes by 30%.

Our RCE development process is suitable for a wide range of geographical locations and populations, with a minimum prerequisite of a disease register with adequate historical data. Revision/addition of covariates can be accommodated based on the strength that they add to a locally developed model. We give the key steps to developing and building such a system in Box 2.

-

Approvals and systems for regular data transfers.

-

Patient and professional groups for covariate selection.

-

First iteration data set.

-

Explore data and verify.

-

Set data range criteria for local relevance.

-

Lock risk engine development data set.

-

Handle missingness with multiple imputation.

-

Select preliminary Markov model using all available covariates selection (model fitting).

-

Assign informedness to covariates.

-

Review with local patient and professional groups.

-

Finalise covariates and fix model structure.

-

Build test model.

-

Agree choice of screen intervals.

-

Run diagnostics and validation.

-

Final model version (revise if required).

-

Secure domain for implementation model.

-

Determine frequency to update data (recommend 2 monthly).

-

Re-tune model (recommend 3 yearly).

The use of near real-time data and a model developed from local data in our approach is novel. Aspelund et al. 13 reported on a risk-estimating model using retinopathy data collected in Iceland between 1994 and 1997, and risks for covariates estimated from data published in the 1980s. This was tested in a prospective cohort of people with type 2 diabetes. 32 Discriminatory ability was good (C-statistic 0.83) but 67 out of 76 people (88.2%) who developed STDR developed it after the time predicted by the model. This overestimation of risk highlights the weakness of using historical data. In 2020, van der Heijden et al. 33 reported a systematic review of risk-prediction models in DR screening. Discrimination was reported in seven studies with C-statistics ranging from 0.55 to 0.84. Our study21 was published subsequently and, therefore, was not included. The corrected C-index in the Liverpool RCE was 0.687.

Access to clinical information is not routinely available. We had to overcome significant challenges in developing a near real-time data flow; this may be too difficult in some populations. However, we determined that including clinical data would aid acceptance among the professional community, offer better prospects for generalisability and allow inclusion of more frequent screening for high-risk individuals. Our view is supported by our own data,6 those of others34 and our PPI group. We recognise that estimates of resource requirements for introduction of our type of RCE are not available.

External validation of models is required before general implementation. 32,35 An implementation phase will include model updating (temporal validation and model tuning) and the opportunity for comparative cross-population (external) validation to correct for potential over-performance. 36

Conclusions

This research programme indicates that the Liverpool RCE is feasible, reliable, safe and acceptable to patients. Our evidence suggests that a RCE could offer potential significant transfer of resources into targeting high-risk and hard-to-reach groups, as well as improved cost-effectiveness. Based on the internal validations we performed, it showed sufficient performance for a local introduction and testing of safety and acceptability within a RCT. However, we did not provide evidence of external validation.

Interrelation with other parts of the programme and overall aims of the programme

The RCE was developed using data from primary and secondary care linked through the ISDR DW developed specifically for this programme. It was required for the development of the RCT and is part of the developed IP. It will form part of any potential future benefit from the programme if deployed within the NHS and other countries. The health economics team worked with the RCE team ensuring that the economic model followed the structure and content of the RCE and could be fully integrated alongside it.

Randomised controlled trial to evaluate the safety and cost-effectiveness of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening

Peer-reviewed publications are available on the ISDR RCT and its protocol. 22,23 Additional information is available in these publications on trial methods, sample size revisions, withdrawals, and additional secondary safety and efficacy data. Our economic analysis is described in Cost-effectiveness of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening for diabetic retinopathy.

We followed the CONSORT 2016 reporting guidelines for non-inferiority and equivalence trials.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Byrne et al. 24 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Research aims

We designed a RCT to investigate the safety, feasibility, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of extending screening intervals in low-risk PWD and reducing screening intervals in high-risk PWD (WP E). We utilised the emerging methodology and technologies of personalised risk prediction37,38 and an innovative data linkage system to develop an individualised variable-interval risk-based screening approach. Individualised clinical care offers opportunities for improved patient engagement.

We tested the hypothesis of equivalence between the attendance rates as a primary measure of safety, for individualised and annual screening. An equivalence design was selected, instead of a superiority trial, because the aim was to demonstrate equivalence between attendance rates rather than difference. Our PPI group was involved in all aspects of design, delivery and interpretation (see Patient and public involvement in the ISDR programme).

Methods

This was a single site, two-arm, parallel assignment, equivalence RCT conducted in all screening clinics in the LDESP, part of the NDESP. The trial was conducted with the Liverpool Clinical Trials Centre.

The main inclusion and exclusion criteria were: registered with a GP whose postcode was within the city boundaries of Liverpool, aged ≥ 12 years, attending screening for DR and had not opted out of data-sharing. Age-appropriate patient information leaflets were sent to eligible patients with their screening appointment. Participants provided written informed consent. For children aged 12–15 years, proxy consent by the parent/guardian was provided and, where appropriate, assent from the child. Preston Research Ethics Committee approved the trial (14/NW/0034). The trial registry number is ISRCTN87561257.

Allocation was randomly 1 : 1 to individualised variable-interval risk-based screening recall at 6, 12 or 24 months (intervention arm, high-, medium-, low-risk respectively), or annual screening (control arm, current routine care).

The ISDR DW automatically populated the majority of the fields in the baseline and follow-up electronic CRFs, including data for randomisation. Screening staff and clinical assessors were masked to intervention arm, risk-calculation and interval.

Procedures

Allocation of participants by the RCE (see The Liverpool Risk-Calculation Engine) at baseline and each follow-up was against the risk of becoming screen-positive at 6-, 12- and 24-month intervals. The interval was allocated against the criterion deemed appropriate by the PPI group of less than 2.5% risk of becoming screen-positive before the next appointment. Independent risk factor covariates were retinopathy levels in both eyes, age, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, systolic BP and total cholesterol. Participants in the fixed-interval control arm continued with annual screening. For those in the individualised arm, the interval could change at each visit.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of attendance rate at the first follow-up visit assessed the safety of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening. Non-attendance was defined as failure to attend any appointment within 90 days of the follow-up invitation date. Secondary outcomes measuring efficacy and safety were screen-positive disease, number of cases of STDR detected, median VA [logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR)] and rates of VI (VA ≥ 0.30 logMAR). All cases of STDR that occurred between baseline and 24 months (+ 90 days) were included in the analysis. A medical retina specialist determined if referred STDR was true- or false-positive using slit-lamp biomicroscopy at a dedicated HES clinic.

Statistical analyses and sample size calculations

The primary analysis was to test for equivalence in attendance rates between individualised and annual screening. The estimated minimum number of patients required was 4460 (90% power, 2.5% one-sided significance level, 5% equivalence margin, 6% loss to follow-up). Primary analysis was per protocol (PP). Intention-to-treat (ITT) and multiple imputation analyses were also conducted.

A secondary aim was to investigate whether or not personalised screening could be considered as non-inferior for the detection of STDR when compared with annual screening; this used a 1.5% non-inferiority margin.

Within the three risk groups, equivalence in attendance rates between the two arms and non-inferiority in the detection of STDR in the individualised arm were explored. For this analysis, participants in the control arm were allocated to risk groups based on the RCE risks at baseline. Generalised linear models were fitted with arm, level of risk and their interaction added as factors.

Results

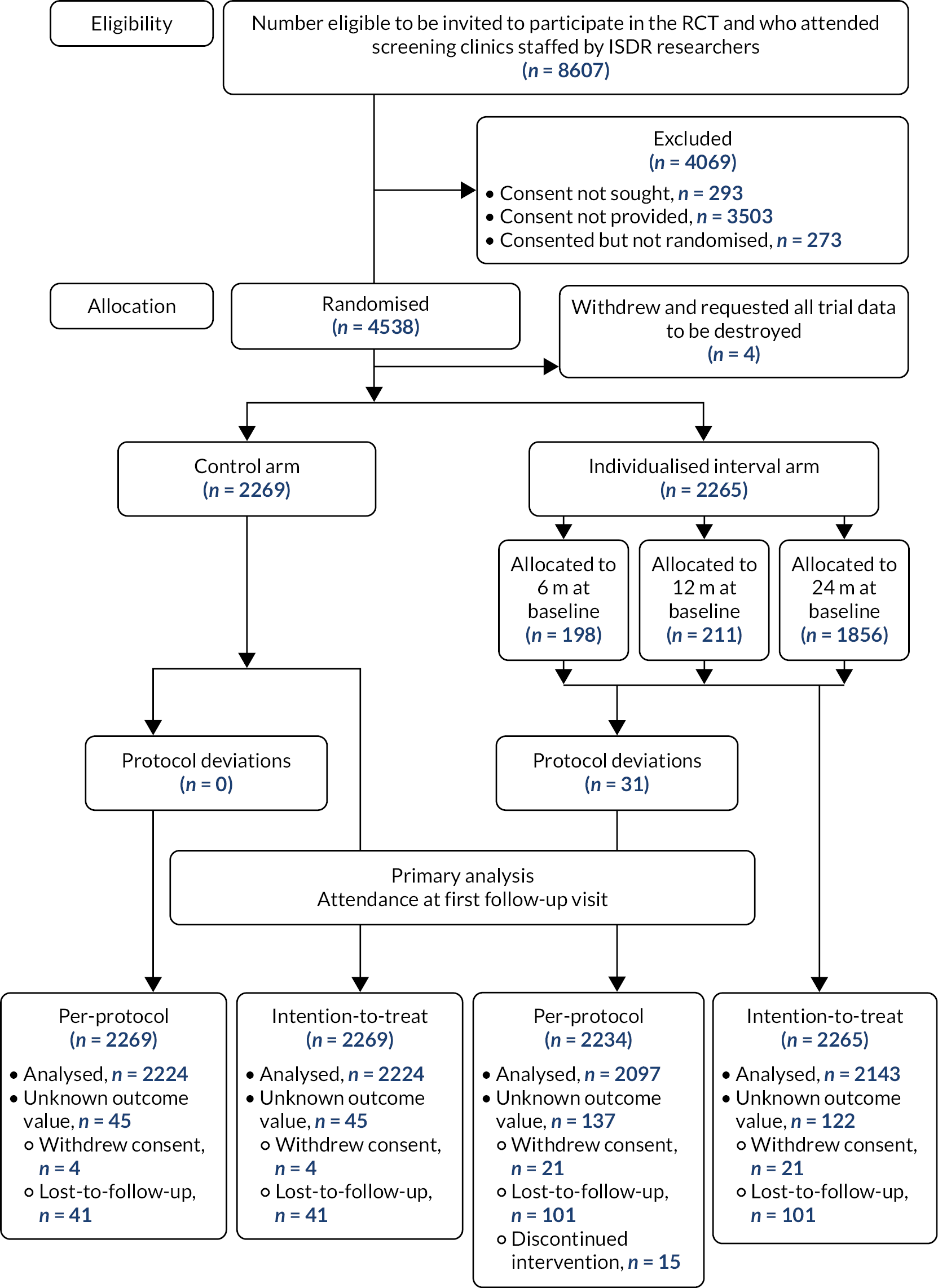

The trial opened on 1 May 2014, randomisation took place from 12 November 2014 to 14 June 2016 and last follow-up was 16 August 2018. In total, 4069 out of 8607 eligible people were excluded, which meant that there were 4538 individuals who were randomised and allocated to a trial arm (2269 fixed interval, 2265 individualised, 4 withdrawals). In the individualised arm, at baseline 198 participants were allocated their first screening recall at 6 months, 211 at 12 months and 1856 at 24 months, which reflects the allocation to high, medium and low risk by the RCE. The trial profile is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram showing the numbers for eligibility, allocation, withdrawals in the PP and ITT data sets for the primary analysis.

Baseline characteristics in the PP data set are shown in Table 4; the ITT data set had similar characteristics. Participants had a median age of 63 years (range 14–100 years), 60.4% were male, 94.6% were white and 88.5% had type 2 diabetes. Those in the high-risk group were more likely to have type 1 diabetes, a longer diabetes diagnosis and higher HbA1c, and less likely to have ever smoked, when compared to those in the medium- and low-risk groups.

| Baseline characteristic | Arm | Baseline risk group | Overall total (N = 4503) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed (12 m) (N = 2269) | Individualised (N = 2234) | High (N = 197) | Medium (N = 211) | Low (N = 1826) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 1358 (59.9) | 1360 (60.9) | 124 (62.9) | 135 (64.0) | 1101 (60.3) | 2718 (60.4) |

| Female | 911 (40.1) | 874 (39.1) | 73 (37.1) | 76 (36.0) | 725 (39.7) | 1785 (39.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 2140 (94.3) | 2120 (94.9) | 180 (91.4) | 204 (96.7) | 1736 (95.1) | 4260 (94.6) |

| Asian | 48 (2.1) | 30 (1.3) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) | 25 (1.4) | 78 (1.7) |

| Black | 40 (1.8) | 43 (1.9) | 6 (3.0) | 3 (1.4) | 34 (1.9) | 83 (1.8) |

| Chinese | 7 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 13 (0.3) |

| Other | 25 (1.1) | 29 (1.3) | 8 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (1.2) | 54 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 9 (0.4) | 6 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.3) | 15 (0.3) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Smoker | 419 (18.5) | 364 (16.3) | 26 (13.2) | 39 (18.5) | 299 (16.4) | 783 (17.4) |

| Ex-smoker | 877 (38.7) | 899 (40.2) | 69 (35.0) | 76 (36.0) | 754 (41.3) | 1776 (39.4) |

| Non-smoker | 965 (42.5) | 967 (43.3) | 102 (51.8) | 96 (45.5) | 769 (42.1) | 1932 (42.9) |

| Unknown | 8 (0.4) | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 12 (0.3) |

| Diabetes type, n (%) | ||||||

| Type 1 | 80 (3.5) | 99 (4.4) | 38 (19.3) | 14 (6.6) | 47 (2.6) | 179 (4.0) |

| Type 2 | 2024 (89.2) | 1962 (87.8) | 140 (71.1) | 180 (85.3) | 1642 (89.9) | 3986 (88.5) |

| Unknown | 165 (7.3) | 173 (7.7) | 19 (9.6) | 17 (8.1) | 137 (7.5) | 338 (7.5) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Observed, n | 2269 | 2234 | 197 | 211 | 1826 | 4503 |

| Median (IQR) | 63.3 (55.0–71.0) | 62.8 (54.8–70.3) | 58.3 (49.9–66.2) | 60.9 (53.4–69.8) | 63.7 (55.9–70.8) | 63.1 (54.9–70.7) |

| Range | 14.1–100.7 | 15.4–91.3 | 17.5–86.8 | 15.4–86.8 | 16.8–91.3 | 14.1–100.7 |

| Disease duration (years) | ||||||

| Observed, n | 2267 | 2231 | 197 | 209 | 1825 | 4498 |

| Unknown, n | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Median (IQR) | 6.9 (4.2–10.9) | 7.0 (4.2–11.2) | 11.1 (7.3–16.1) | 9.8 (6.3–13.7) | 6.4 (4.0–10.1) | 7.0 (4.2–11.0) |

| Range | 0.6–66.4 | 1.0–44.7 | 1.2–44.7 | 1.1–37.2 | 1.0–39.1 | 0.6–66.4 |

| HbA1c | ||||||

| Observed, n | 2269 | 2232 | 197 | 211 | 1824 | 4501 |

| Unknown, n | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Median (IQR) (mmol/mol) | 51 (44–61) | 52 (44–63) | 67 (53–84) | 58 (51–67) | 50 (44–60) | 51 (44–62) |

| Range |(mmol/mol) | 26–146 | 28–155 | 33–134 | 34–155 | 28–104 | 26–155 |

| Median (IQR) (%) | 6.8 (6.2–7.7) | 6.9 (6.2–7.9) | 8.3 (7.0–9.8) | 7.5 (6.8–8.3) | 6.7 (6.2–7.6) | 6.8 (6.2–8.8) |

| Range (%) | 4.5–15.5 | 4.7–16.3 | 5.2–14.4 | 5.3–16.3 | 4.7–11.7 | 4.5–16.3 |

| Systolic BP | ||||||

| Observed, n | 2268 | 2234 | 197 | 211 | 1826 | 4502 |

| Unknown, n | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Median (IQR) (mmHg) | 130.0 (121.0–138.0) | 130.0 (122.0–138.0) | 130.0 (124.0–138.0) | 132.0 (124.0–140.0) | 130.0 (122.0–138.0) | 130.0 (122.0–138.0) |

| Range (mmHg) | 84.0–213.0 | 90.0–204.0 | 93.0–175.0 | 95.0–204.0 | 90.0–200.0 | 84.0–213.0 |

| Diastolic BP | ||||||

| Observed, n | 2208 | 2180 | 193 | 201 | 1786 | 4388 |

| Unknown, n | 61 | 54 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 115 |

| Median (IQR) (mmHg) | 76.0 (70.0–80.0) | 76.0 (70.0–80.0) | 77.0 (70.0–80.0) | 77.0 (70.0–80.0) | 76.0 (70.0–80.0) | 76.0 (70.0–80.0) |

| Range (mmHg) | 46.0–140.0 | 46.0–130.0 | 54.0–105.0 | 57.0–130.0 | 46.0–110.0 | 46.0–140.0 |

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| Observed, n | 2258 | 2224 | 196 | 209 | 1819 | 4482 |

| Unknown, n | 11 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 21 |

| Median (IQR) (mmol/l) | 4.0 (3.4–4.7) | 4.0 (3.4–4.7) | 4.0 (3.4–4.9) | 4.0 (3.4–4.6) | 4.0 (3.5–4.7) | 4.0 (3.4–4.7) |

| Range (mmol/l) | 1.4–8.1 | 1.8–9.7 | 2.0–9.0 | 2.2–7.6 | 1.8–9.7 | 1.4–9.7 |

| Retinopathy level, n (%) | ||||||

| R0 R0 | 1857 (81.8) | 1800 (80.6) | 1 (0.5) | 44 (20.9) | 1755 (96.1) | 3657 (81.2) |

| R1 R0 | 262 (11.5) | 296 (13.2) | 58 (29.4) | 167 (79.1) | 71 (3.9) | 558 (12.4) |

| R1 R1 | 146 (6.4) | 137 (6.1) | 137 (69.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 283 (6.3) |

Primary safety findings

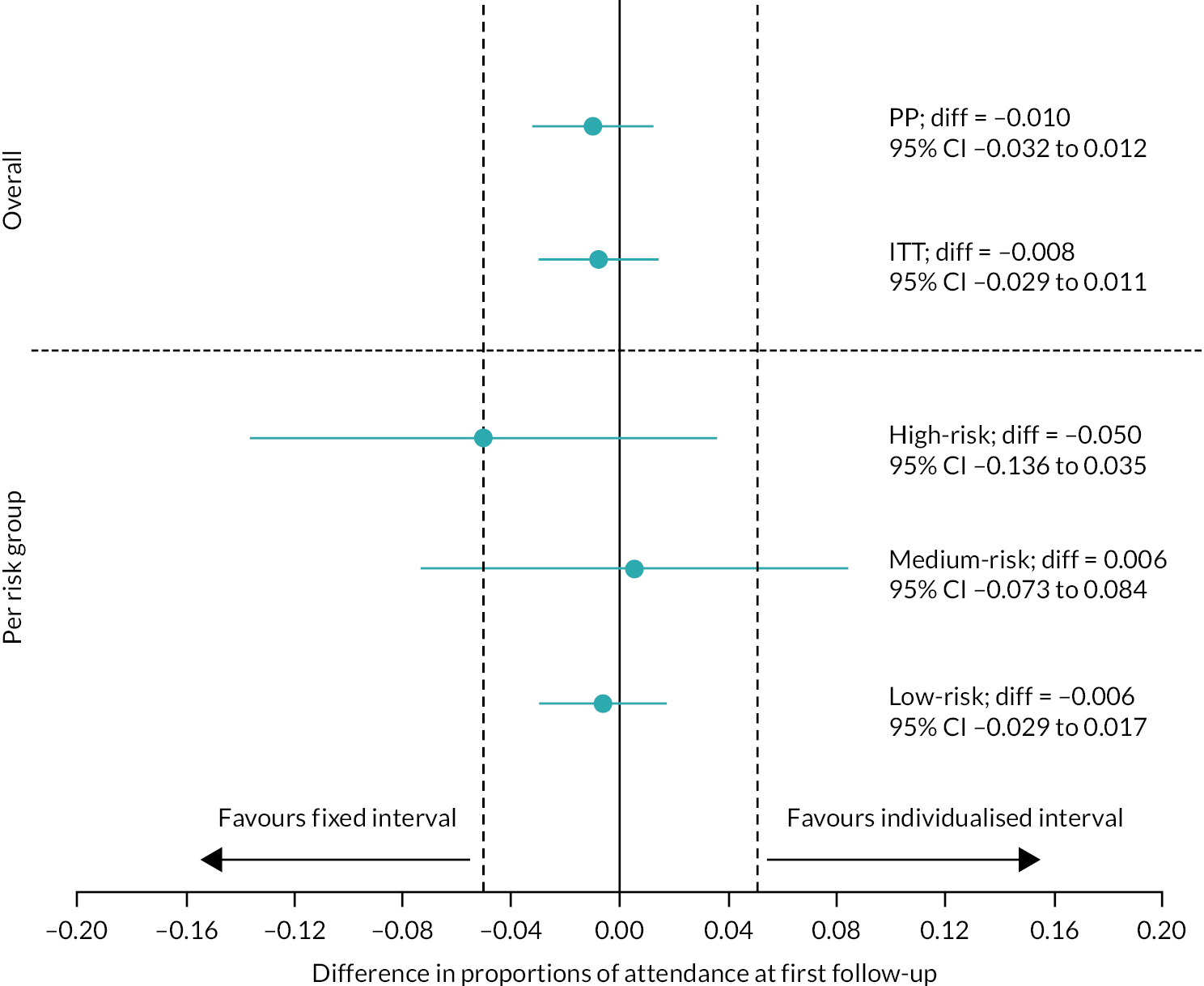

Attendance rates at the first follow-up visit for the control and individualised arms (primary outcome) were 84.7% (1883/2224) and 83.6% (1754/2097), respectively (difference –1.0%, 95% CI –3.2% to 1.2%, PP analysis). Against an acceptability range of 0.05, these attendance rates were equivalent (Figure 5 upper panel, Table 5). PP and ITT analyses with multiple and simple imputation confirmed equivalence in attendance rates between the two arms.

FIGURE 5.

Plot showing point estimates and 90% CIs for participants attending the first follow-up visit in the two arms. Upper panel: primary analysis. Lower panel: high-, medium- and low-risk groups in the individualised arm.

| Approach | Control arm | Individualised arm | Difference in proportions (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Attended/STDR detected (n) | Proportion | N | Attended/STDR detected (n) | Proportion | |||

| Primary outcome: attendance at first follow-up | ||||||||

| PP | ||||||||

| Overall | 2224 | 1883 | 0.847 | 2097 | 1754 | 0.836 | –0.010 (–0.032 to 0.012) | |

| High risk | 203 | 157 | 0.773 | 195 | 141 | 0.723 | –0.050 (–0.136 to 0.035) | |

| Medium risk | 169 | 138 | 0.817 | 208 | 171 | 0.822 | 0.006 (–0.073 to 0.084) | |

| Low risk | 1852 | 1588 | 0.857 | 1694 | 1442 | 0.851 | –0.006 (–0.029 to 0.017) | |

| Multiple imputation | 2269 | 1910 | 0.842 | 2234 | 1870 | 0.837 | –0.005 (–0.026 to 0.017) | |

| ITT | ||||||||

| Overall | 2224 | 1883 | 0.847 | 2143 | 1798 | 0.839 | –0.008 (–0.029 to 0.014) | |

| Multiple imputation | 2269 | 1913 | 0.843 | 2265 | 1903 | 0.840 | –0.004 (–0.025 to 0.018) | |

| Secondary outcome: STDR within 24 months | ||||||||

| PP | ||||||||

| Overall | 2042 | 35 | 0.017 | 1956 | 28 | 0.014 | –0.003 (–0.011 to 0.005) | |

| High risk | 176 | 20 | 0.114 | 127 | 17 | 0.134 | 0.020 (–0.053 to 0.100) | |

| Medium risk | 157 | 5 | 0.032 | 179 | 7 | 0.039 | 0.007 (–0.038 to 0.051) | |

| Low risk | 1709 | 10 | 0.006 | 1650 | 4 | 0.002 | –0.003 (–0.009 to 0.001) | |

| Multiple imputation | 2269 | 39 | 0.017 | 2234 | 36 | 0.016 | –0.001 (–0.009 to 0.007) | |

| ITT | ||||||||

| Overall | 2042 | 35 | 0.017 | 2056 | 32 | 0.016 | –0.002 (–0.010 to 0.006) | |

| Multiple imputation | 2269 | 39 | 0.017 | 2265 | 39 | 0.017 | –0.001 (–0.008 to 0.008) | |

Equivalence in the analysis of the three risk groups in the individualised arm (see Figure 5, lower panel, and Table 5) was found for the low-risk group (control 85.7%, individualised 85.1%, difference –0.6%, 95% CI –2.9% to 1.7%). For the medium-risk group, equivalence was not confirmed (control 81.7%, individualised 82.2%, difference 0.6%, 95% CI –7.3% to 8.4%); differences were very small but equivalence was not confirmed because of the relatively wide CIs. Attendance rates were lower in the high-risk group (control 77.3%, individualised 72.3%, difference 5.0%, 95% CI –13.6% to 3.5%) than in the medium- and low-risk groups. Although the hypothesis of equivalence was not supported in this group, the attendance rates observed over 12 months (percentage with at least one attended appointment) were higher in the individualised arm (89.1%) than in the control arm (77.3%).

Secondary safety findings

There was no evidence of a loss of ability to detect STDR in the individualised arm (1.4% vs. 1.7%, difference –0.3%, 95% CI –1.1% to 0.5%, prespecified non-inferiority margin 1.5%) (see Table 5). Similar results were obtained in the ITT and imputation analyses. Non-inferiority was found for the low-risk group (control 0.6%, individualised 0.2%, difference –0.3%, 95% CI –0.9% to 0.1%), but not the high- and medium-risk groups; this was probably explained by the small numbers.

We did not detect any clinically significant worsening of diabetes control. There was no difference in the proportions of participants in each group who had a significant (≥ 11 mmol/mol) increase in HbA1c during the trial: control 15.2%, individualised 14.6%, high 13.4%, medium 15.0% and low 14.7%. We did not detect any differences in logMAR VA (p = 0.64) or in rates of VI in the better eye at the last attended visit between the two arms. Findings for worse eye VA and VI were similar.

Efficacy

In total, 43.2% fewer screening attendances were required in the individualised arm than in the control arm (2008 vs. 3536). Higher rates of screen-positive by screen episode attended were seen in the individualised arm than in the control arm [control 4.52% (160/3536), individualised 5.08% (102/2008)]. Within the individualised arm, the high-risk group had the highest screen-positive rate [high 10.72% (34/317), medium 6.02% (15/249), low 3.7% (53/1442)]. In the low-risk group, most of the screen-positive cases were a result of other eye disease; the rates of screen-positive for DR were low at 0.5% (7/1442). Screening episodes that detected STDR were earlier in the individualised arm than in the control arm: 6–12 months 17.9% (5/28) versus 2.9% (1/35), 12–18 months 32.1% (9/28) versus 60.0% (21/35), respectively.

The number of appointments over the 2 years per participant in the individualised arm varied by allocated group at baseline: 1.83, 1.06 and 0.85 in the high-, medium- and low-risk groups, respectively. The RCE was stable throughout the RCT. A total of 132 participants were switched by the RCE to a longer screening interval and 176 to a shorter screening interval.

Discussion

Our study, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the largest ophthalmic RCT performed in individualised DR screening to date, shows that all parties involved in diabetes care can be reassured that extended and individualised (personalised) interval screening can safely be introduced in an established screening programme. We have shown that variable-interval risk-based screening, as developed by us in Liverpool, is equivalent to the current standard of annual screening, in our setting. Our secondary safety findings support this primary result. In the individualised arm, we did not detect any drop in rates of detection of STDR, worse VA or higher rates of VI, or worsening glycaemic control. Attendance levels were maintained throughout the study.

We have also shown improved efficacy for our personalised approach, reducing the number of appointments by 43.2%. In the individualised arm, there were higher proportions of screening episodes that were screen-positive and screening episodes that detected STDR were earlier than in the control arm. In the setting of a RCT, the RCE showed feasibility and reliability with good discrimination.

A move to longer screening intervals for people at low risk of DR has been suggested in the literature prior to39 and during40–42 our programme, but without convincing evidence on safety. 8 Overall, 19.0% of people invited to take part in our study explicitly stated that they wished to remain on annual screening or did not want a change of interval. We did not detect a worsening in glycaemic control. Our findings give substantial reassurance that a 24-month interval for low-risk individuals with diabetes is safe in a setting such as ours. However, for resource-poor or rural settings in low- and middle-income countries, further research is required before longer intervals can be contemplated.

Our findings have some limitations when considering wider application. We developed and applied our approach to screening in a single centre with relatively low rates of baseline DR and low rates of progression to sight-threatening disease. Our programme has been running for over 30 years. Participants’ glycaemia and BP control were relatively good. Our results should be generalised with caution to other settings with higher prevalence, poorer control of diabetes, wider ethnic group representation, or in programmes in set-up. Our study has important strengths including the RCT design, its size, independent oversight, and involvement of an expert patient group.

Our approach allowed us to target high-risk people using a 6-month screening interval. Attendance rates at first visit in this group were lower in the individualised arm (72.3% vs. 77.3% in the control group) but disease was detected earlier through more frequent screening (1.7 visits, 89.1% attendance over the first 12 months vs. 77.3% estimated in controls) than in the control arm. The rates of detection of STDR were higher in the high- and medium-risk individualised groups (13.4% and 3.9% vs. 1.7% in controls). The proportion of screening episodes that were positive was higher in the individualised arm at 5.1% than in the control arm at 4.5%. By contrast, there very low rates of screen-positive episodes in the low-risk group (0.2%). These rates are similar if slightly lower than the 0.3–1.0% reported over 2 years in people with no retinopathy in either eye in a study of seven screening programmes in England. 41

The value of adding in clinical data is a matter of debate. Our PPI group advised strongly during the design phase of the study that including clinical data was important to them. It allows the introduction of a high-risk group and better targeting than stratification (see Further analysis for post-RCT analysis). 30 We would suggest that the advantages for patient and clinician engagement outweigh the added cost and complexity. Around 15% of people had at least one change in risk-based interval: 59% people allocated to the medium (annual) group experienced a change of interval, adding further evidence to move away from a fixed interval for all.

Interrelation to other work packages and overall aims of the programme

Data collated in the ISDR DW (WP B1) informed the RCE (WP C), which in turn supported the RCT. The PPI group developed the risk criteria, actively supported with the production of patient-related materials and observed clinics to improve recruitment.

Cost-effectiveness of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening for diabetic retinopathy

A peer-reviewed publication24 describes the cost-effectiveness study24 and additional information is available in this publication on methods and results. We followed the CHEERS reporting guidance.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Bryne et al. 24 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Research aims

We conducted an economic analysis within our RCT to investigate the cost-effectiveness of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening from an NHS and a societal perspective (WP D).

Our review of the literature showed limited evidence on cost-effectiveness of screening. Study designs have been heterogeneous and relied on modelling rather than direct observation. One systematic review of screening called specifically for cost-effectiveness studies. 8

Methods

Within-trial analysis

The costs of routine screening were directly measured using a mixed micro-costing and observational health economics analysis. Societal costs, including participant and companion costs, which were collected using a bespoke questionnaire, comprised time lost from work (productivity losses) and travel and parking costs. A detailed workplace analysis, measuring resources and staff time to deliver the screening programme, was observed at each screening centre. This ingredient-based bottom-up approach enabled a current resource-based cost to be attributed to the individual patient cost of screening, taking into account both attendees and the related cost of non-attendance. We estimated the additional costs of running the RCE using a screen population of size of 22,000 (Liverpool). Treatment costs were excluded because the design was a within-trial analysis. The study was not designed to make economic inference of eye screening in general.

The first 868 participants enrolled into the RCT completed the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),43 and Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3)44 instruments at baseline and follow-up visits. Health state utilities were mapped45 from the EQ-5D-5L to the EQ-5D three-level version and used a UK population tariff. 46 We applied a relevant Canadian tariff 47 to health state classifications of the HUI3 in the absence of an English or UK valuation set. Discounting was not applied as both costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were assumed to be assigned and incurred on an annual basis.

A 90-day attendance window was utilised with a further 90 days added at 24 months to allow for the compounding lag in scheduling.

QALYs were constructed using AUC, and incremental QALYs estimated through ordinary least squares regression (for the univariate distributions of complete cases) and seemingly unrelated regressions (for the joint distributions of multiply imputed sets) on baseline utilities. Unadjusted estimates were used as sensitivity analyses. We bootstrapped these regressions to characterise sampling distributions and derive 95% bias-corrected CIs around trial arm means and mean differences. 48 ITT analyses were conducted in Stata/SE (Release 16; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) from an NHS/societal perspective, and post-multiple imputation analyses followed Rubin’s combination rules for estimation within multiply imputed sets. 49 Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were generated from mean differences in QALYs and NHS screening costs, as well as incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) derived from a £20,000 threshold. 50 Multiple imputation of chained equations was run using available case data. Bootstrapping was used to characterise sampling distributions and derive 95% CIs around mean differences.

Results

The costs of screening are shown in Table 6. Costs per attendance (n = 16,736) were £11.73 for programme costs, £10.00 for photography and £7.00 for grading, with a total NHS cost of £28.73. The cost for non-attendance at £12.73 was principally the programme cost, with a small contribution for lost photographer time. Additional productivity losses and out-of-pocket payments by the patient accounted for £9.00.

| Variable | Top-down annual total (£) | Per attendance (n = 16,736) (£) | Per non-attendance (n = 6179) (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programme costs | |||

| Staff (including oncosts) | 242,715 | 10.59 | 10.59 |

| Stationery | 3056 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| IT | 22,988 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total | 268,759 | 11.73 | 11.73 |

| Photography | |||

| Staff | 157,528 | 9.08 | 0.91 |

| Cameras and equipment | 11,777 | 0.68 | 0.07 |

| Medical consumables | 4229 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Total | 173,534 | 10.00 | 1.00 |

| Grading (P3–P6) | |||

| Staff | 117,234 | 7.00 | 0.00 |

| Total NHS cost | 559,528 | 28.73 | 12.73 |

| Societal costs associated with screening attendance | |||

| Patient-borne costs | – | 2.64 | – |

| Productivity loss | – | 6.36 | – |

| Total societal cost | – | 9.00 | – |

| Estimated Liverpool RCE costs | Annual total | Per patient | |

| Database administrator | 34,000 | 1.54 | |

| CCG administrator (20% FTE) | 6000 | 0.27 | |

| RCE total | 40,000 | 1.81 | |

The estimated cost of running the RCE was £40,000 per annum for a total screen population of 22,099 in Liverpool allocated to the intervention arm as £1.81 per person.

Table 7 shows summary health economic and cost-effectiveness data. There was no statistically significant difference in QALY scores between the trial arms (EQ-5D 0.006, 95% CI −0.039 to 0.06; EuroQol Visual Analogue Score 0.004, 95% CI −0.049 to 0.052; and HUI3 −0.017, 95% CI −0.083 to 0.04). We observed incremental cost savings per participant of £17.34 (£17.02 to £17.67) from an NHS perspective (not including treatment costs), corresponding to a potential reduction in total programme costs of 20% (95% CI from £193,983 to £154,386), and £23.11 (95% CI £22.73 to £23.53) from a societal perspective, and an INMB for the EQ-5D-5L of £736 (95% CI –£239 to £1718) and £178 (95% CI –£919 to £1338) for the HUI3 £26.19 (95% CI £24.41 to £27.87).

| Variable (n/N) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete case | Multiple imputed | |

| EQ-5D (539/868) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.012 (–0.097 to 0.119) | 0.043 (0.032 to 0.055) |

| Baseline adjusted | 0.006 (–0.039 to 0.06) | 0.044 (0.038 to 0.05) |

| EQ-VAS (548/868) | ||

| Unadjusted | –0.033 (–0.109 to 0.044) | 0.013 (0.005 to 0.022) |

| Baseline adjusted | 0.004 (–0.049 to 0.052) | 0.022 (0.017 to 0.028) |

| HUI3 (408/868) | ||

| Unadjusted | –0.016 (–0.135 to 0.116) | 0.068 (0.056 to 0.081) |

| Baseline adjusted | –0.017 (–0.083 to 0.04) | 0.051 (0.045 to 0.058) |

| Costs (4389/4534) | ||

| NHS screening | –17.44 (–18.57 to –16.31) | –17.34 (–17.67 to –17.02) |

| Societal | –23.26 (–24.65 to –21.92) | –23.11 (–23.53 to –22.73) |

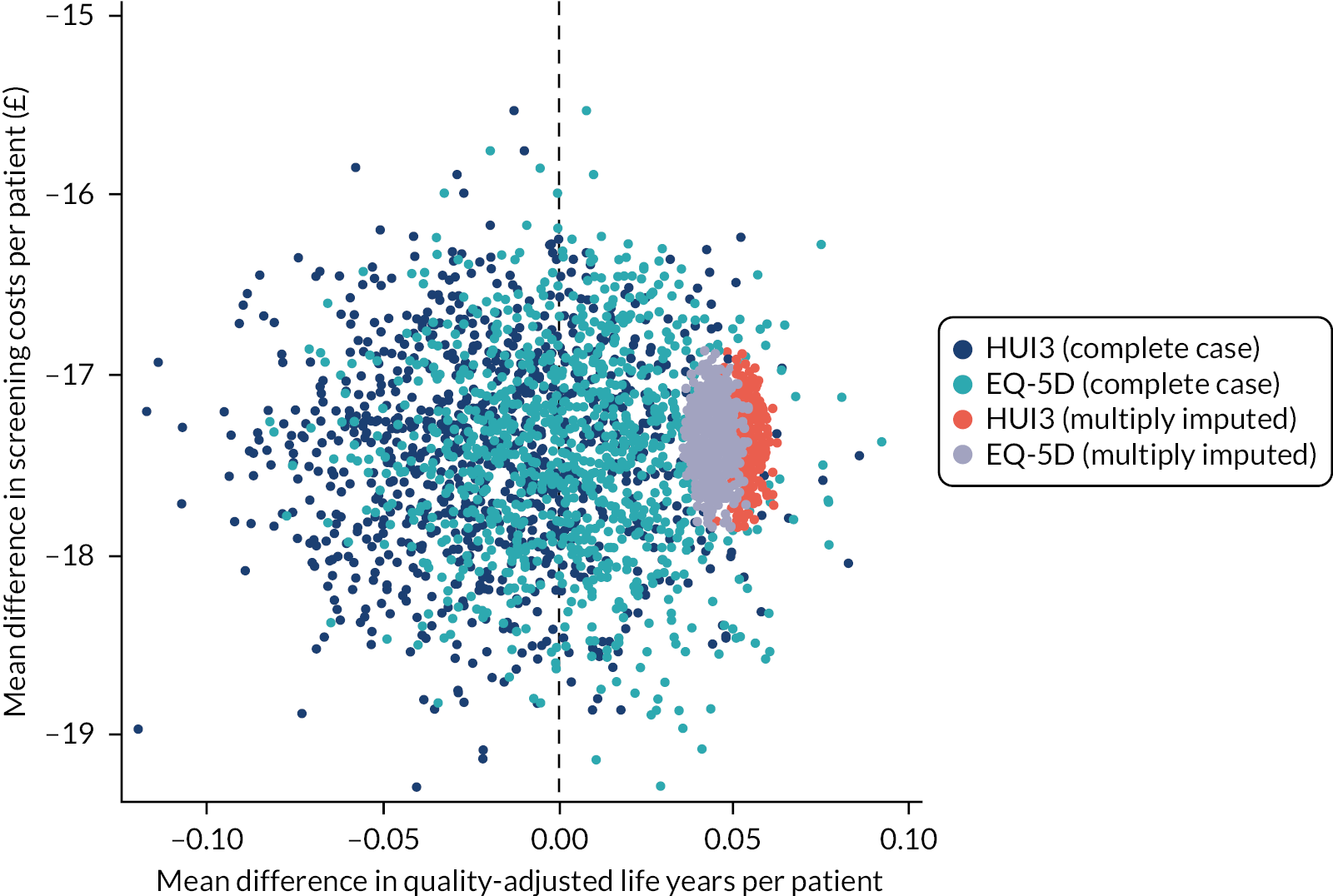

Results following multiple imputation indicated the dominance of the individualised arm in both QALY gain (EQ-5D-5L and HUI3) and cost savings (screening and societal) (Figure 6). All ICER point estimates fell in the south-east and south-west quadrants of the cost-effectiveness plane, signifying the dominance in cost savings, with mean differences in QALYs clustered around the zero threshold, EQ-5D-5L reporting a marginal benefit, and the HUI3 reporting an incremental distribution of near equivalence between the arms.

FIGURE 6.

Baseline adjusted EQ-5D, HUI3, and NHS perspective incremental cost-effectiveness of individualised vs. annual screening from 1000 iteration bootstraps.

Economic model

Risk-based cohort model

We worked with the RCE team (WS C) to develop a risk-based economic model that closely followed the structure and content of the RCE. The economic model was designed to be fully integrated and usable with the risk engine. We evaluated three alternative screening programmes: (1) current practice, (2) biennial stratification (as proposed by the English NDESP) and (3) ISDR individualisation using the ISDR RCE.

A microsimulation state transition (semi-Markov) model was developed based on DR disease states, as identified through photographic screening, with time- and event-dependent transition probabilities. The patient-level simulation (an individual sampling model) tracked individual characteristics through time, so that their changing risk of disease onset could be used to determine their pathways through the model. The simulation incorporates both disease states and events that determine individuals’ pathways through the model, which are observed in discrete units of time. Parameters used in this analysis were drawn from both published literature and local data.

Model structure

The disease states used in the model were defined in the terms used by the NDESP, namely ‘R0M0’ gradings. Retinopathy is graded as R0 (no retinopathy), R1 (background), R2 (pre proliferative) or R3 (proliferative). Maculopathy is graded as either M0 (absent) or M1 (present).

All individuals were in the screening programme, except for those who had experienced a screen-positive event and were, therefore, in follow-up and may have been receiving treatment. However, those who receive treatment that was successful may have been referred back to the screening programme. Therefore, the model allows for individuals to be in either screening or follow-up, whether or not they received treatment.

Individuals who went on to receive treatment were subject to different progression rates. Therefore, it was necessary to divide the model further based on the stages of the treatment pathway. The model allowed for four separate groups of individuals: (1) those in screening who had not received treatment, (2) those in screening who had previously received treatment, (3) those in follow-up who had not yet received treatment and (4) those in follow-up who had previously received treatment. This increases the number of disease-specific states fourfold, giving 38 states.

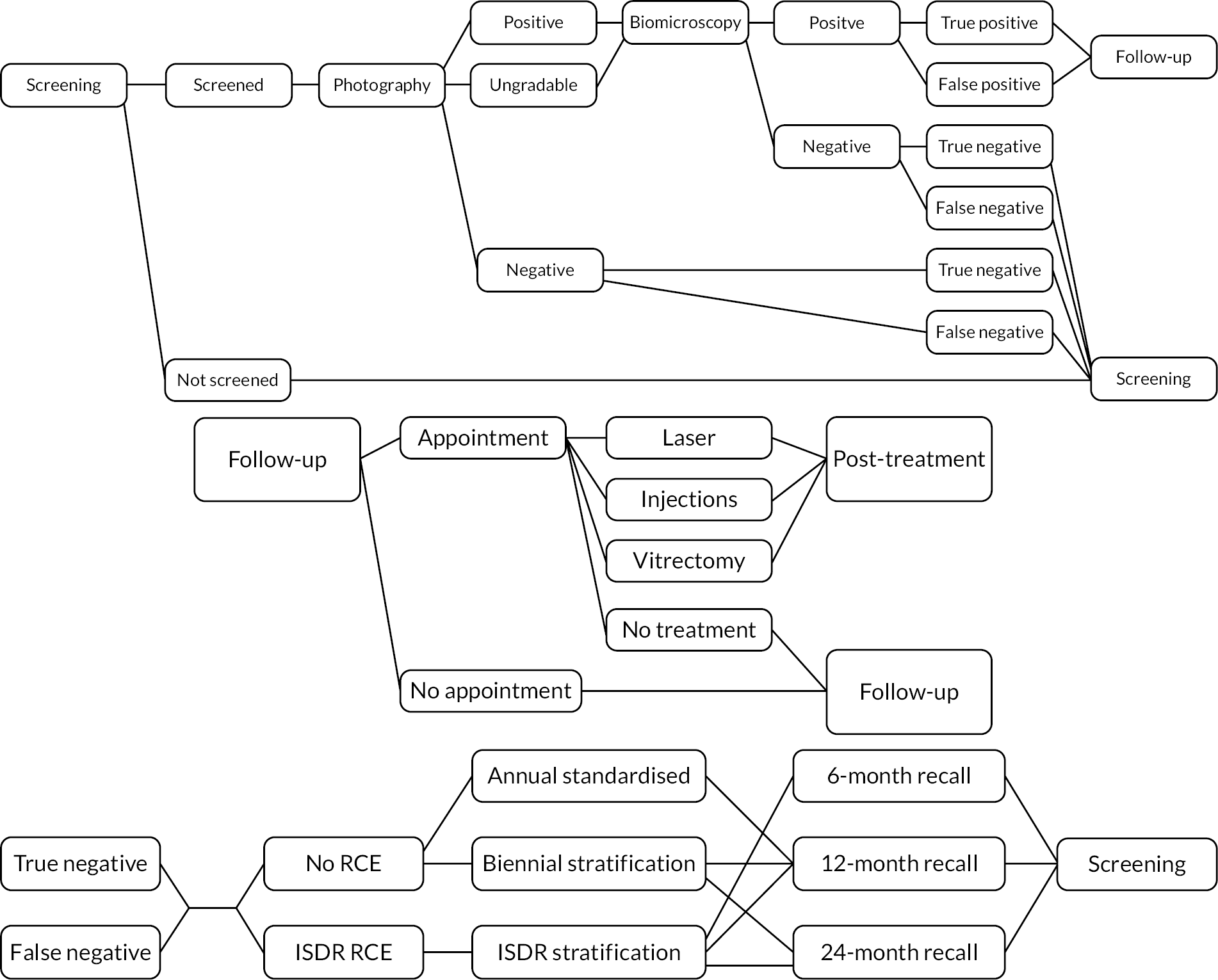

The comparators for analysis (described above) are similarly included as an additional event process, applied to all people whose screening outcome is negative and who are referred back to screening. These event pathways are outlined in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Event pathways in the economic model developed within the ISDR programme of applied research. Upper panel: pathway within screening programme; middle panel: pathway within HES for screen-positive individuals; lower panel: pathway showing comparison between three screening models.

The model was developed using Microsoft Excel 2013. The intent was to run the model from NHS and Personal Social Services perspectives over a life-time horizon with cycles occurring monthly, and transitions and events occurring at the end of each cycle. The computational and mathematical requirements of such a large-scale model proved non-operational by the end of the programme, requiring around 4 days of processing. Work continued to produce a final version of the model based on 10,000 people.

Discussion

Our data provide evidence that an individualised screening approach may provide cost savings within the programme. We feel that the assumptions and costs applied throughout were conservative and took care not to overstate the benefits of this approach or underplay any of the costs, for example providing a realistic estimate of replicating the cost of a risk engine elsewhere.

By moving to variable-interval risk-based screening, patients were not compromised on safety or quality of life. We calculated potential incremental cost savings over the 2-year time horizon within the trial of £17.34 NHS costs, rising to £23.11 per patient from a societal perspective. In a population such as in Liverpool, this may amount to potential annual savings in the region of £199,000 in NHS screening programme costs. For England [screening population 2.76M (2018–19)51], this could amount to around £23.9M in the NHS, not including treatment costs, rising to £31.9M from a societal perspective. Such resources could be used to target groups that are hard to reach and those at high risk of VI, and more cost-efficiently screen the expanding population of PWD. Individualised screening (on average) reduces the number of attendances required, given that patients in low-risk groups would be spared the inconvenience and additional personal cost of attending non-essential appointments. In brief, fewer visits reduce both patient and hospital costs and the trial shows that this can happen without negative clinical consequences.

Strengths of this within-trial cost-effectiveness study are the detailed characterisation of the costs to the health service and society of a person attending screening and the large number of observations. Our work is limited by the 2-year time horizon, which is short for a long-term disease, such as diabetes. Our work could have been further strengthened by taking a long-term time horizon to capture lifetime costing differentials and years of sight loss averted. Treatment costs were excluded as per the within-trial analysis and the study objectives of comparing screening options rather than of a lifetime analysis of screening. We did explore adding a post-screening analysis to include treatment costs but considered it very unlikely to be informative because the numbers progressing to treatment were very small (two in each group).

It may have been useful to collect utility data for the entire cohort. We elected not to undertake this to minimise disruption at screening clinics. Multiple imputation indicated that quality-of-life (QoL) data were robust. At a 2-year time horizon, the effects of screening intervals on QoL appear to be close to negligible, where our between-arm utilities and incremental QALYs demonstrated near-equivalence.

Although the intention had been to report cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, the dominance in cost reduction of variable-interval risk-based screening and little fluctuation in QALYs across all instruments rendered this metric uninformative, as the proportion cost-effective was inelastic to varying thresholds. See Strengths and limitations for a further discussion of strengths and limitations.

In 2015, Scanlon et al. 42 reported a cost-effectiveness model developed in a historical data set of 10,942 people in Gloucestershire with screening and clinical data over at least 3 years and validated it in three other English programmes. They reported a 3-yearly screening interval to be the most cost-effective in the absence of personalised risk-based intervals. Using their risk-based strategy, the most cost-effective options were to screen those at low risk every 5 years and those at medium and high risk every 3 and every 2 years, respectively. We now add robust RCT evidence to support the introduction of variable-interval risk-based screening.

Interrelation to other work packages and overall aims of the programme

The health economics and RCE teams (WS C, WS D) worked closely together. The economic model was designed to be fully integrated and usable with the RCE. This is an important element should the Liverpool approach be rolled out into wider practice. Co-ordination occurred with WP F to enable a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of valuation in QoL in DR screening. This was important as this group was under-represented in the trial itself.

Qualitative study with patients and healthcare professionals on changing screening intervals

A peer-reviewed publication is available24 and includes example narratives of the key findings. COREQ reporting guidelines were followed.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Byrne et al. 24 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Research aims

We aimed to explore perceptions of changing from annual to individualised variable-interval risk-based screening and to gain wider insights into users’ perceptions to enable successful implementation (WP F). We also wanted to explore the wider aspects of DR screening in general.

Methods

Setting

We conducted our qualitative studies within the setting of our RCT. This allowed for the first time a real rather than theoretical investigation of the perceptions around the acceptability of implementation of varying intervals and the use of a risk calculator in a population from an established screening programme and in a geographical location where annual fixed-interval screening was already established.

Design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted after informed consent was obtained to gather views on variable-interval risk-based screening. Interviews with PWD were conducted before the start of the RCT (phase 1, baseline) and subsequently with a second group (phase 2) during the RCT. All interviews with HCPs took place prior to commencement of the RCT. The research team and PPI group created interview topic guides (see Supplementary Material 3) covering participants’ background, beliefs and attitudes towards diabetes, management of diabetes, medical management and contact, and future management of screening. For HCP interviews, discussions included participants’ background in diabetes, types of patients they see and potential issues with changing screening intervals. Interviews lasted 30–90 minutes, with most lasting around 45 minutes.

Participants

Participants aged over 16 years who were PWD attending the eye screening programme were identified in two GPs in Liverpool. The practices were approached by a research nurse. The practices reflected the range of socioeconomic status, with one located in a disadvantaged location and the other in an affluent location.

We used purposive sampling to identify potential participants aiming to reflect the characteristics of the local diabetic population and of HCPs involved in eye screening. Suitability of potential PWD participants was reviewed by a GP in the practice prior to contact by the research team.

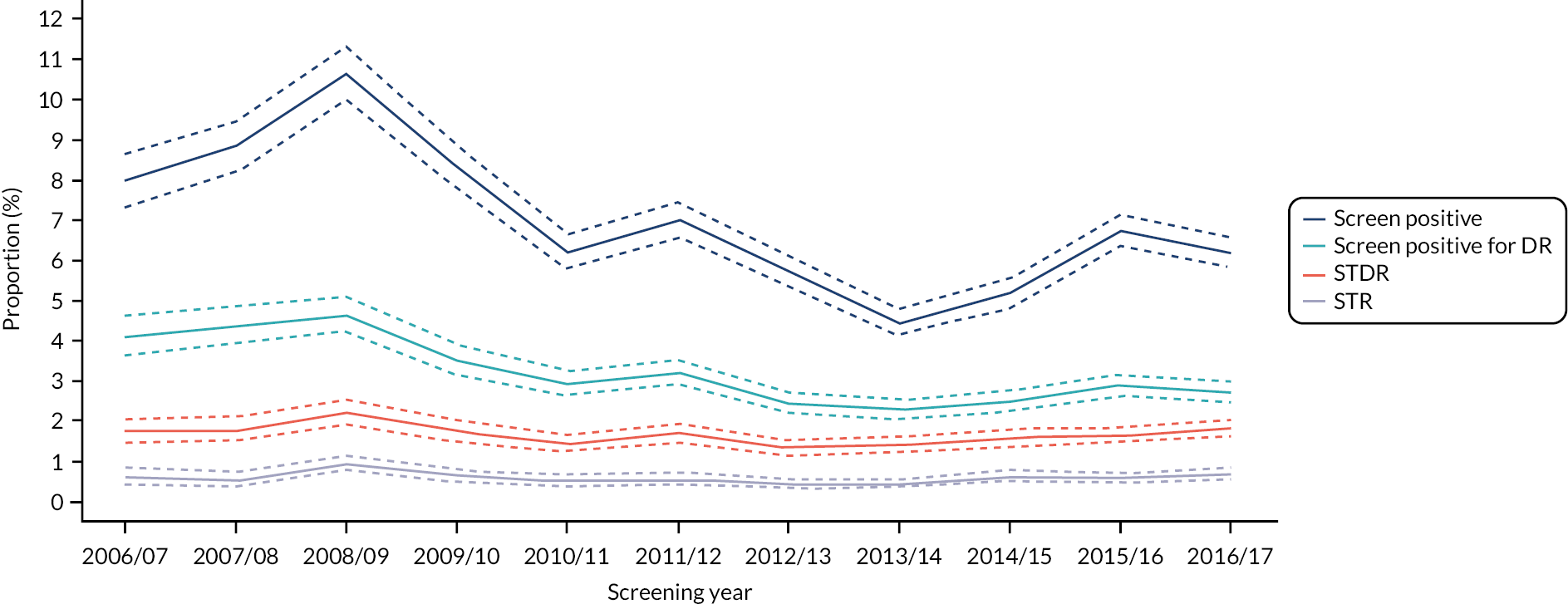

All participants received a brief overview of individualised variable-interval risk-based screening. Most patient interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, although some chose to complete them in a university office and one completed their interview in their own office.