Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10163. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Cordingley et al. This work was produced by Cordingley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Cordingley et al.

SYNOPSIS

Context of the IMPACT programme

Psoriasis is a common, lifelong inflammatory skin disease, the severity of which can range from limited disease involving a small body surface area to extensive skin involvement. 1 It is associated with high levels of physical and psychosocial disability2–4 and a range of comorbidities, and it is currently incurable.

The majority of patients develop the first signs of psoriasis before the age of 40 years;5 thus, the disease makes significant demands on these patients through their productive adult life. 6 The long-term, visible and fluctuating nature of psoriasis means that its effects can be as disabling as other long-term conditions, with significant experiences of stigmatisation, low self-esteem and even suicidal thinking. 7–9 The relationships between physical or clinical severity of psoriasis and the degree of psychological or social disability relating to the condition are complex. It is not unusual for individuals with psoriasis affecting small body surface area to experience significant and disabling impairment to quality of life. 10 However, most of those with moderate to severe psoriasis experience some level of psychological distress at some point in their lives, depending on the time of onset. 11

In the UK, the majority of patients with psoriasis are managed in primary care by their general practitioner (GP) or, occasionally, by primary care dermatology services. At the time of the original IMPACT programme proposal in 2009, we had indications that dissatisfaction with psoriasis care was widespread and a large survey from the Psoriasis Association of the UK and Ireland reported that one-quarter of respondents had not consulted a health-care professional about their psoriasis in the previous 2 years. 12 There was evidence that, even in secondary care services, clinicians did not detect or attend to high levels of associated distress. 11

Psoriasis and comorbidities

Common comorbidities of psoriasis include psoriatic arthritis (PsA),13,14 Crohn’s disease,15 metabolic syndrome16–19 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. 20 In addition, people with psoriasis often have conditions that are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as obesity,21 hypertension, hyperlipidaemia22,23 and type 2 diabetes. 24

In the few years prior to initiation of the Identification and Management of Psoriasis Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) programme, the findings of a number of studies supported the idea of a direct association between psoriasis and the development of CVD,18,25 with some estimating that the relative risk of CVD in those with severe psoriasis is triple that in the non-psoriasis population. 26 The main hypothesis accounting for the association was that increased systemic inflammation, as may occur in psoriasis, exacerbates other chronic inflammatory processes, including the development of atherosclerosis, which could lead to myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke. 15,27 However, the possible link between psoriasis and CVD is complex for several reasons: people with psoriasis are more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles (increased likelihood of smoking, little physical activity and obesity),28 there is a higher prevalence of co-existing CVD risk factors (such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia)23 and therapies for psoriasis may increase (e.g. ciclosporin)28 or decrease (e.g. methotrexate)29 the CVD risk. All of these aspects may confound the associations between psoriasis and other disorders. 30,31

There were some preliminary research findings that indicated that reducing behavioural CVD risk factors through, for example, weight loss, improving diet and/or increasing physical activity can reduce psoriasis severity32,33 at the same time as reducing CVD risk. However, our research team had recognised that psychological distress can impede people’s capacity to make behavioural changes that would improve both skin and heart health. This led to a question about whether or not it would be possible to develop interventions that would reduce psoriasis severity and risks of associated comorbidities and that took account of the existing challenges faced by some people with psoriasis.

Health-care professionals managing people with psoriasis could be well placed to support patients’ lifestyle behaviour change (LBC) in terms of timeliness of patient contact and access; however, the capacity of services to deliver behavioural change interventions was unknown. There was no published literature on whether or not LBC skills are included in the training curricula for relevant health-care professionals, or whether health-care professionals were equipped with the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage psoriasis as a complex, long-term condition, including supporting patients with lifestyle change. The views of health-care professionals about managing patients with psoriasis in primary care were also unknown.

Importance and relevance of the IMPACT programme

All evidence at the time of the original IMPACT programme proposal highlighted the enormous unmet need in terms of service access and provision for individuals with psoriasis, particularly in primary care, despite growing awareness in the dermatology community of very significant levels of distress and psychological and social impacts in this group. Unmet needs included extremely limited access to appropriate treatments, poor referral practices and the limited knowledge base of primary care professionals and patients. Knowledge about comorbidities, their association with disease mechanisms, and the impact of psoriasis was also poor in primary care and this corresponded with an apparently low prioritisation of service provision or development. It was clear that a large segment of the population with psoriasis were not benefiting from either recent developments in the understanding of the disease or interventions that could reduce their risk of comorbidities.

The growing interest in the apparent increase in risk for CVD conferred by psoriasis was an additional impetus. Again, the emerging evidence about risk mapped onto clinical observations in the dermatology community that poor health behaviours were more prevalent in patients with psoriasis than in patients with other skin diseases. 34 The third component in this mix, one that was identified quickly because of the strong interest in behavioural medicine in the existing dermatology research group, was the potential role of psychological and behavioural factors as important mediators and/or moderators of these risk factors. Thus, a comprehensive research strategy was developed to investigate whether or not it would be possible to identify opportunities in existing health-care pathways that would help us, first, to identify those at most risk of psoriasis-related comorbidities and, second, to intervene to improve health outcomes in an economically efficient way.

Original aims and objectives

The programme of work set out to identify optimal methods of investigating and managing psoriasis-related comorbidities. It broadly aimed to apply existing knowledge of psoriasis as a complex, multifaceted condition requiring holistic management to find ways to improve the care and self-care of people living with this condition.

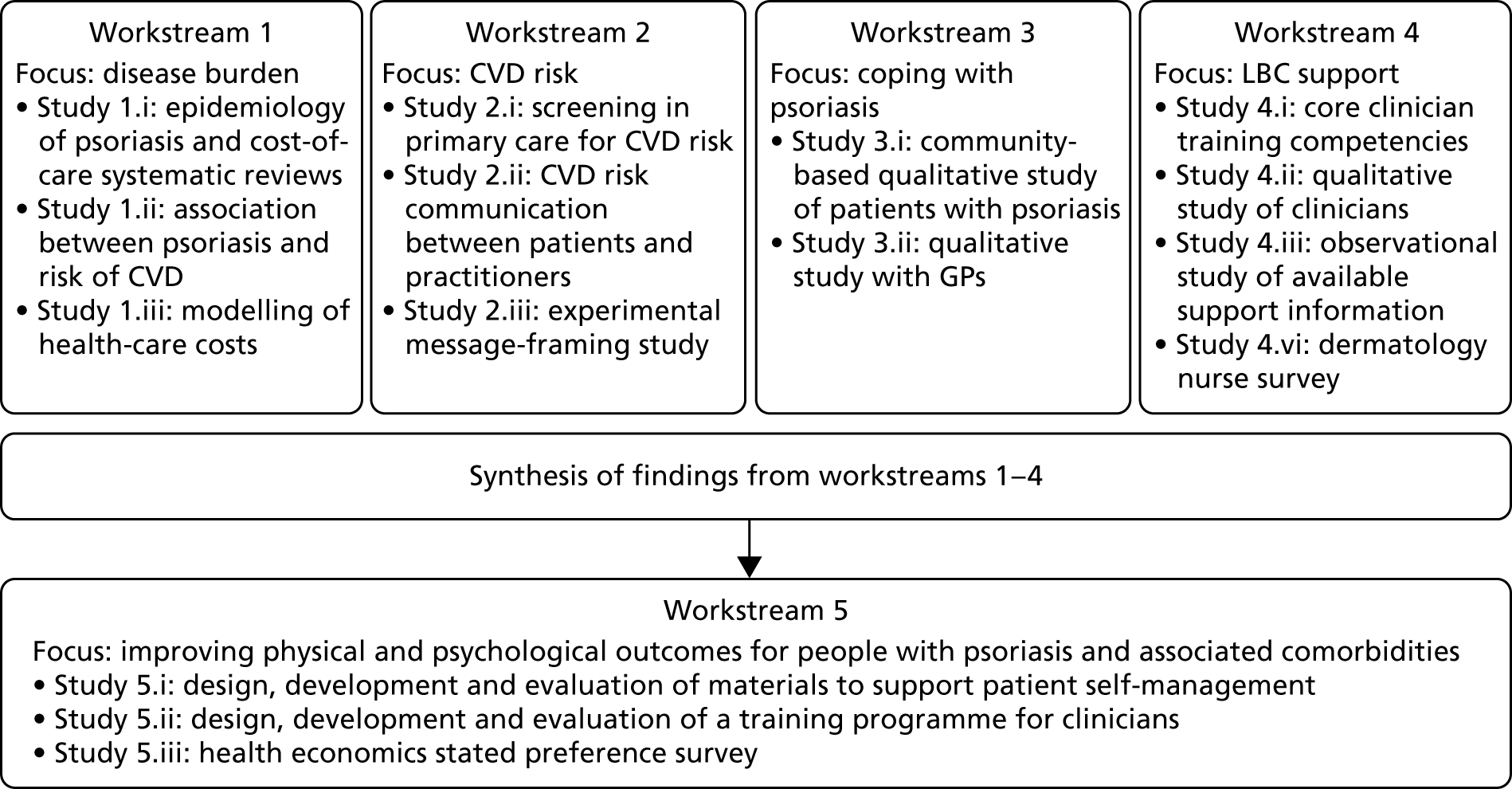

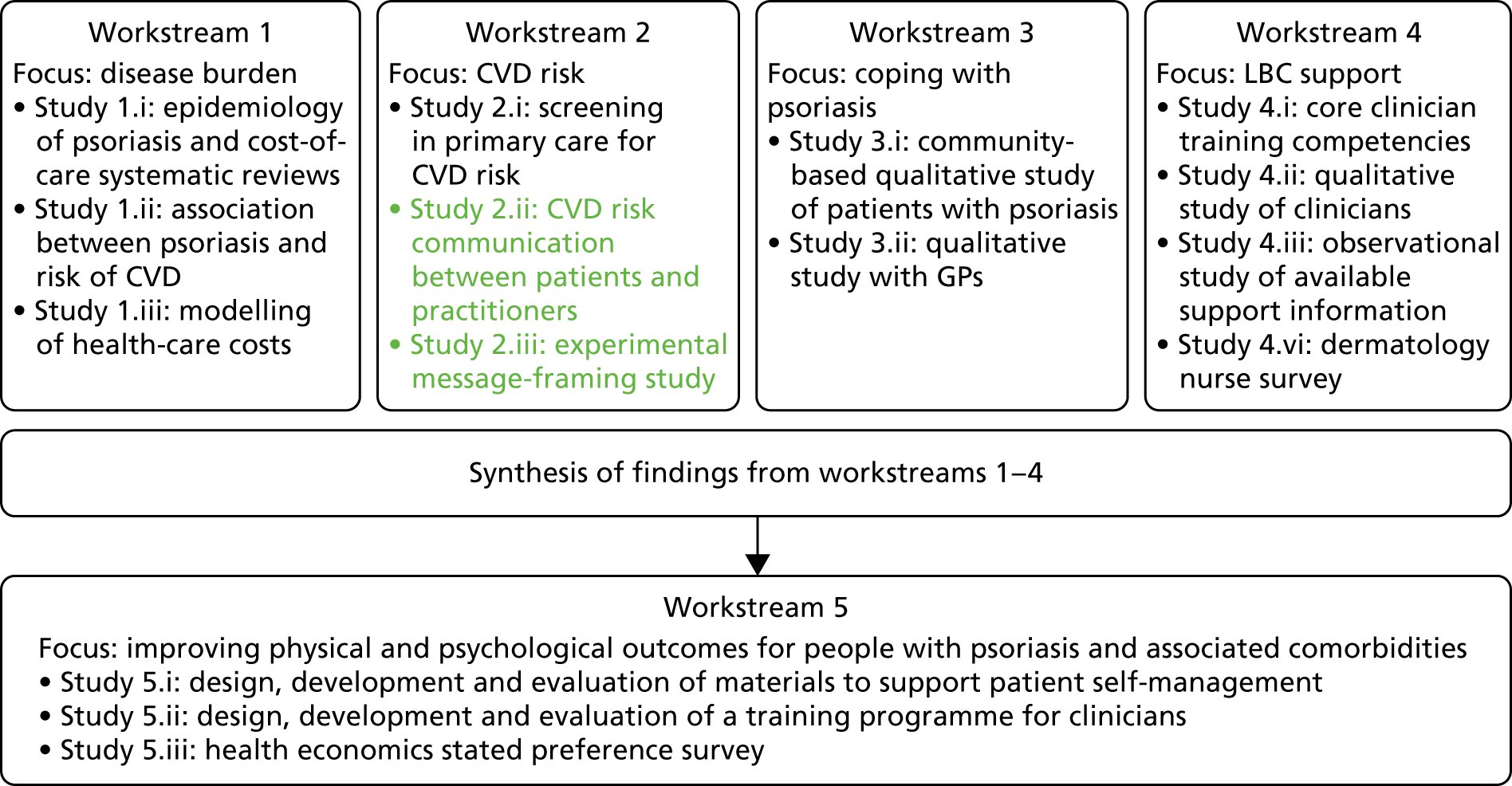

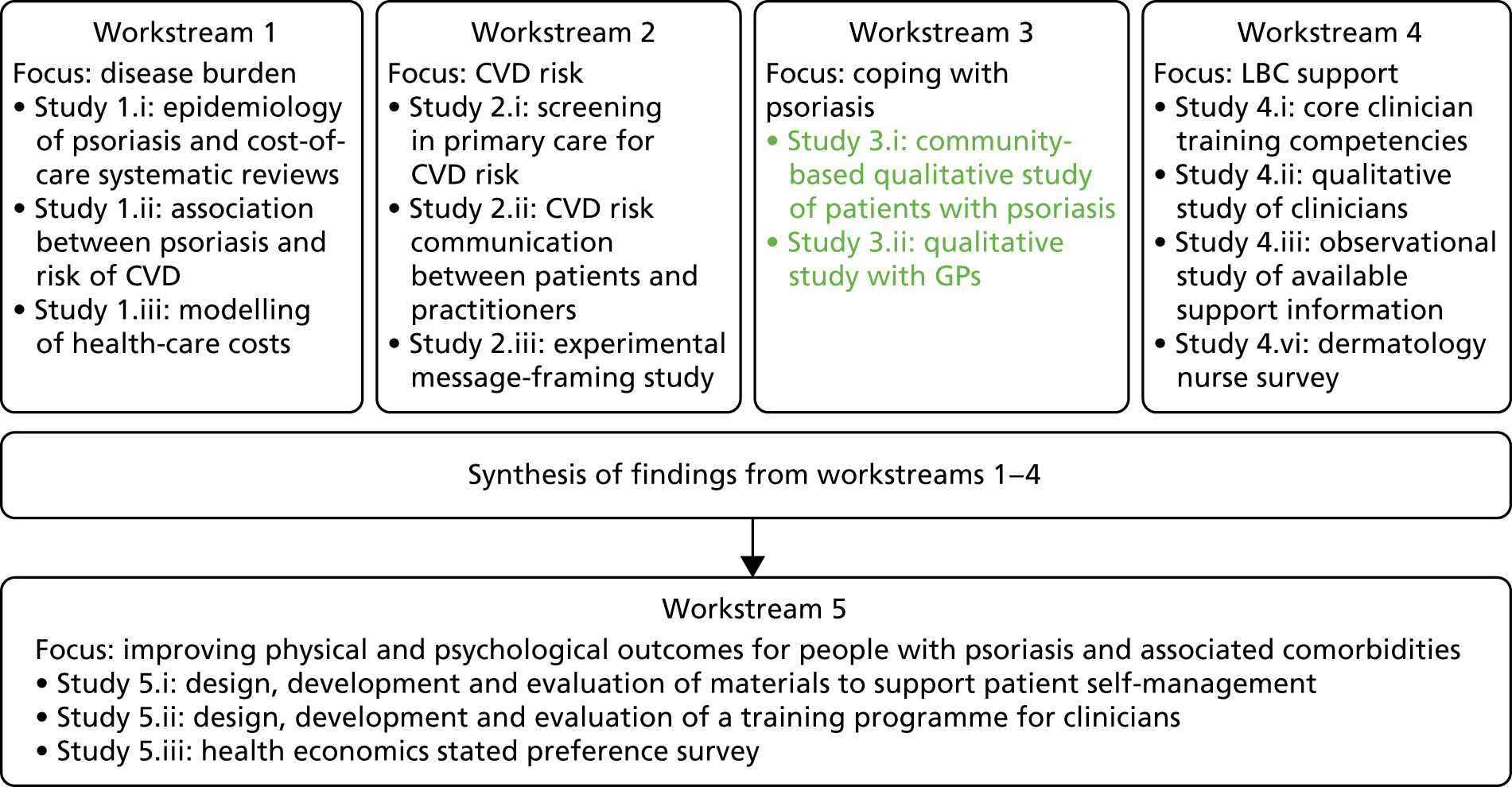

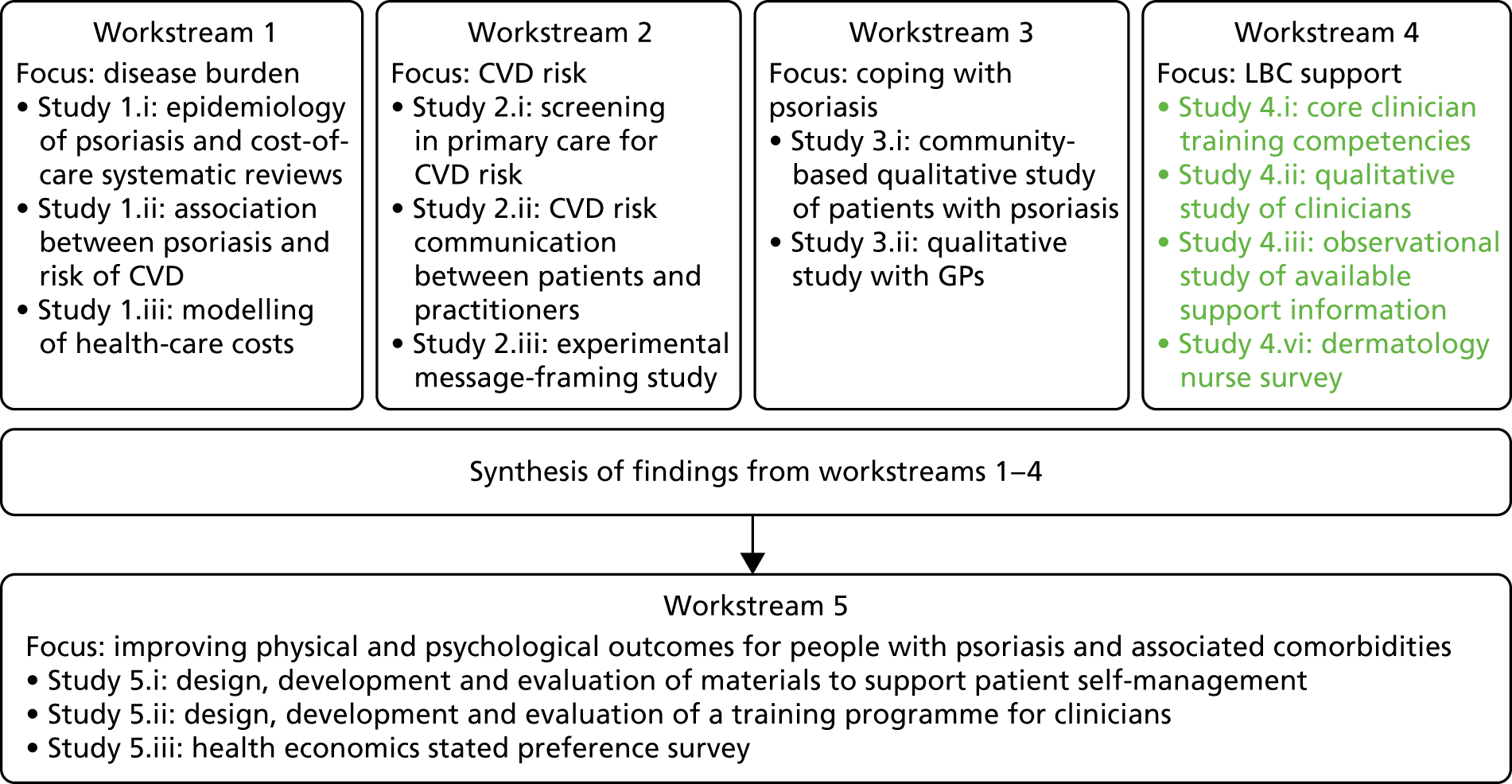

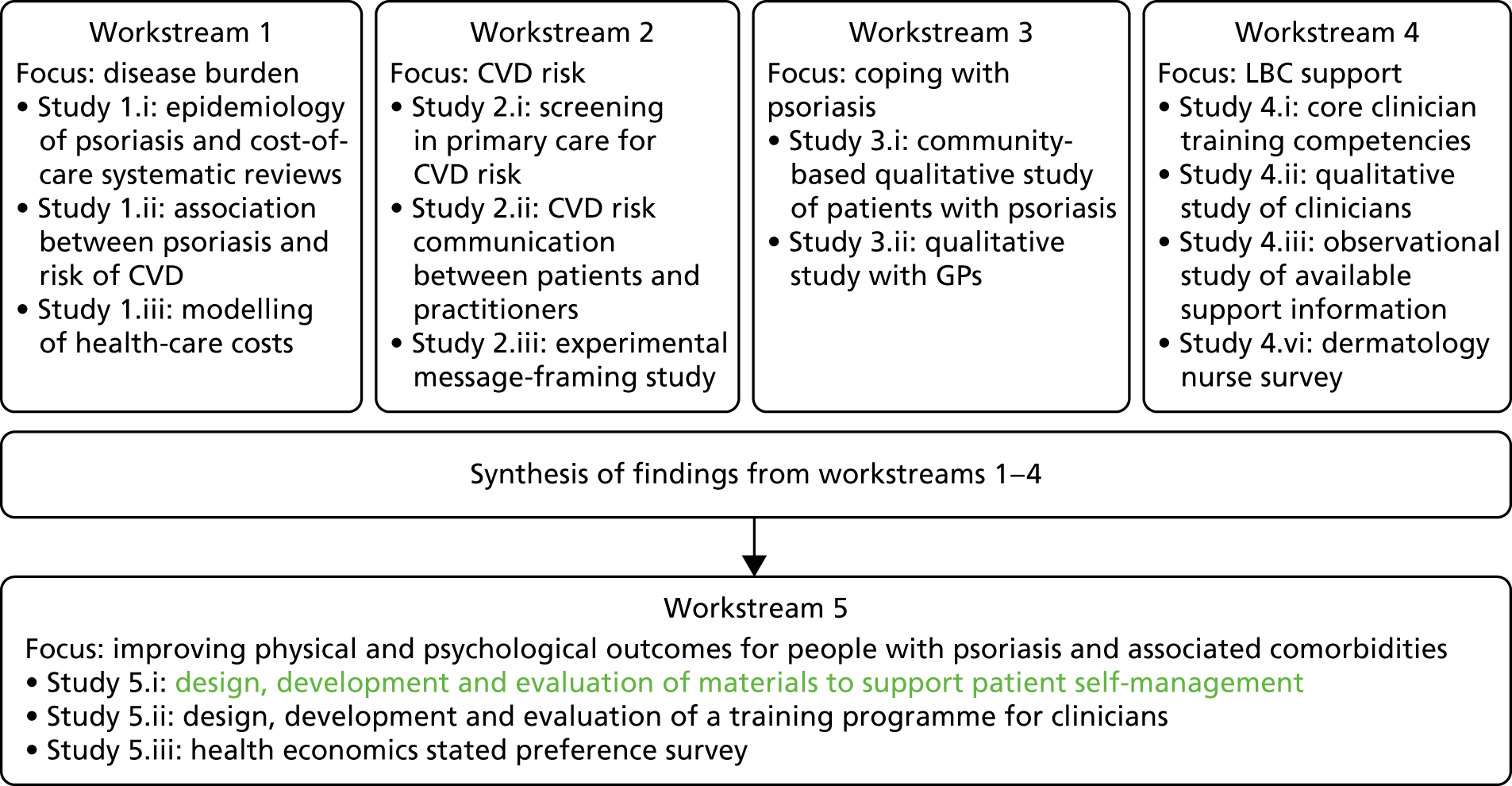

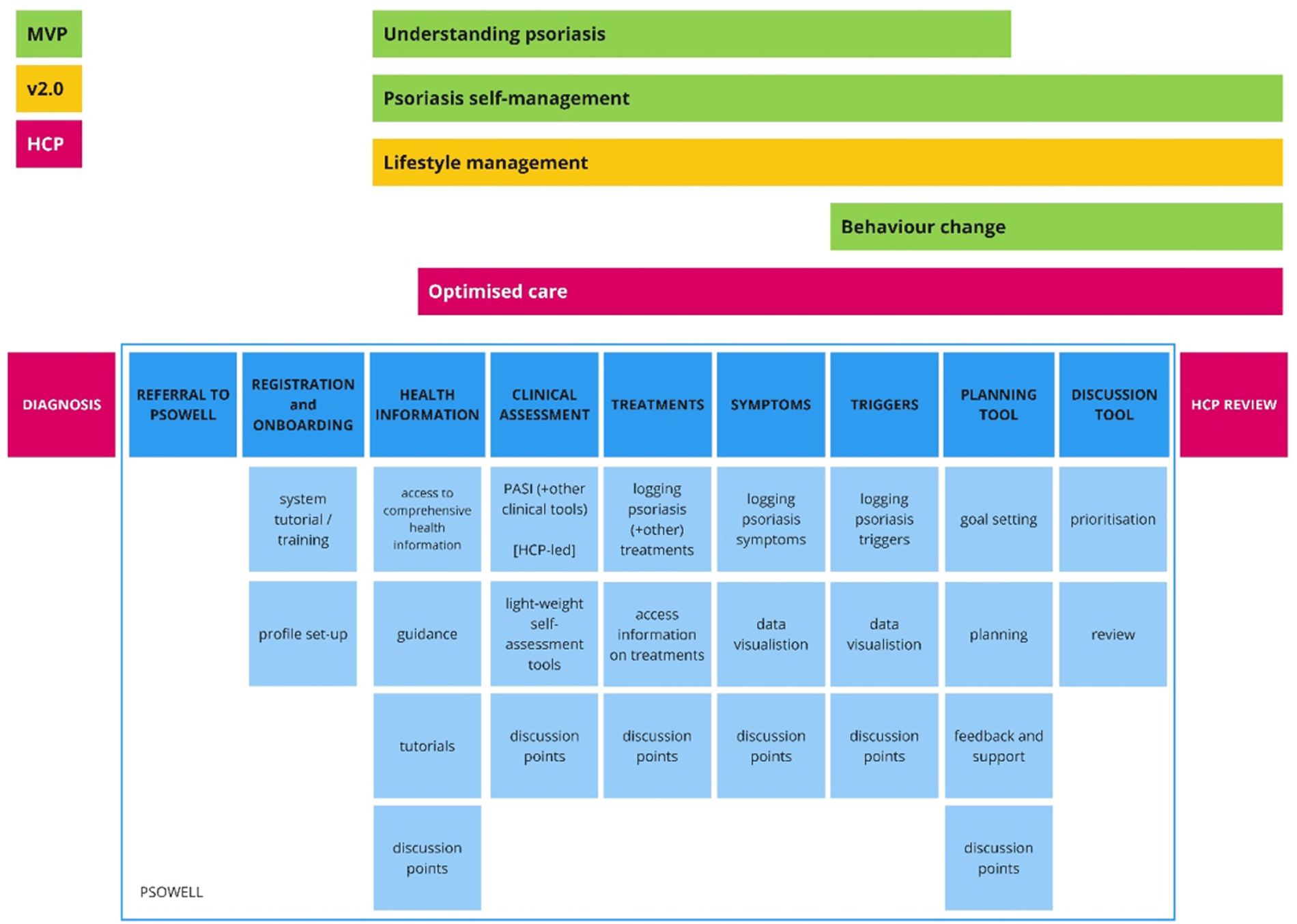

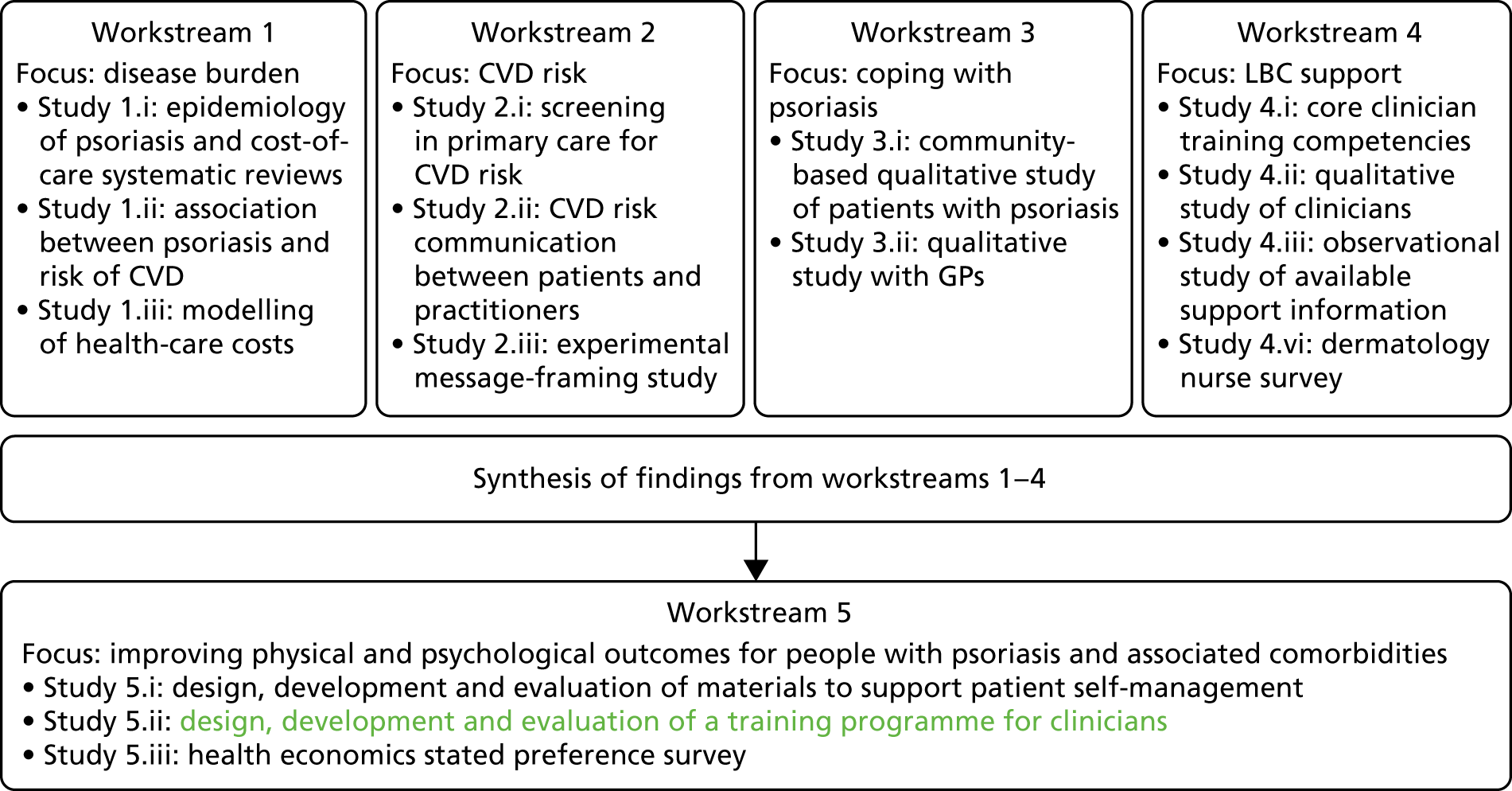

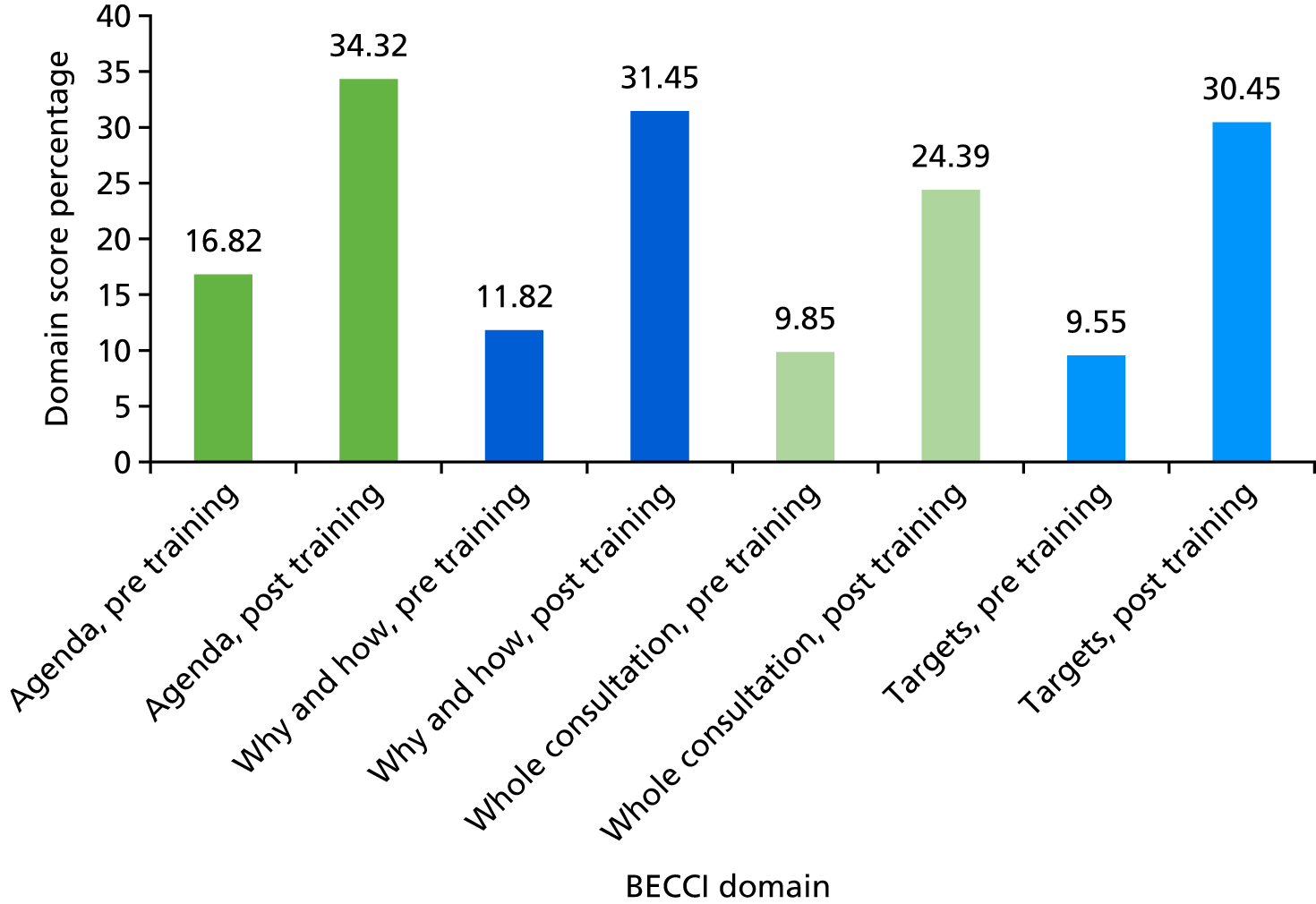

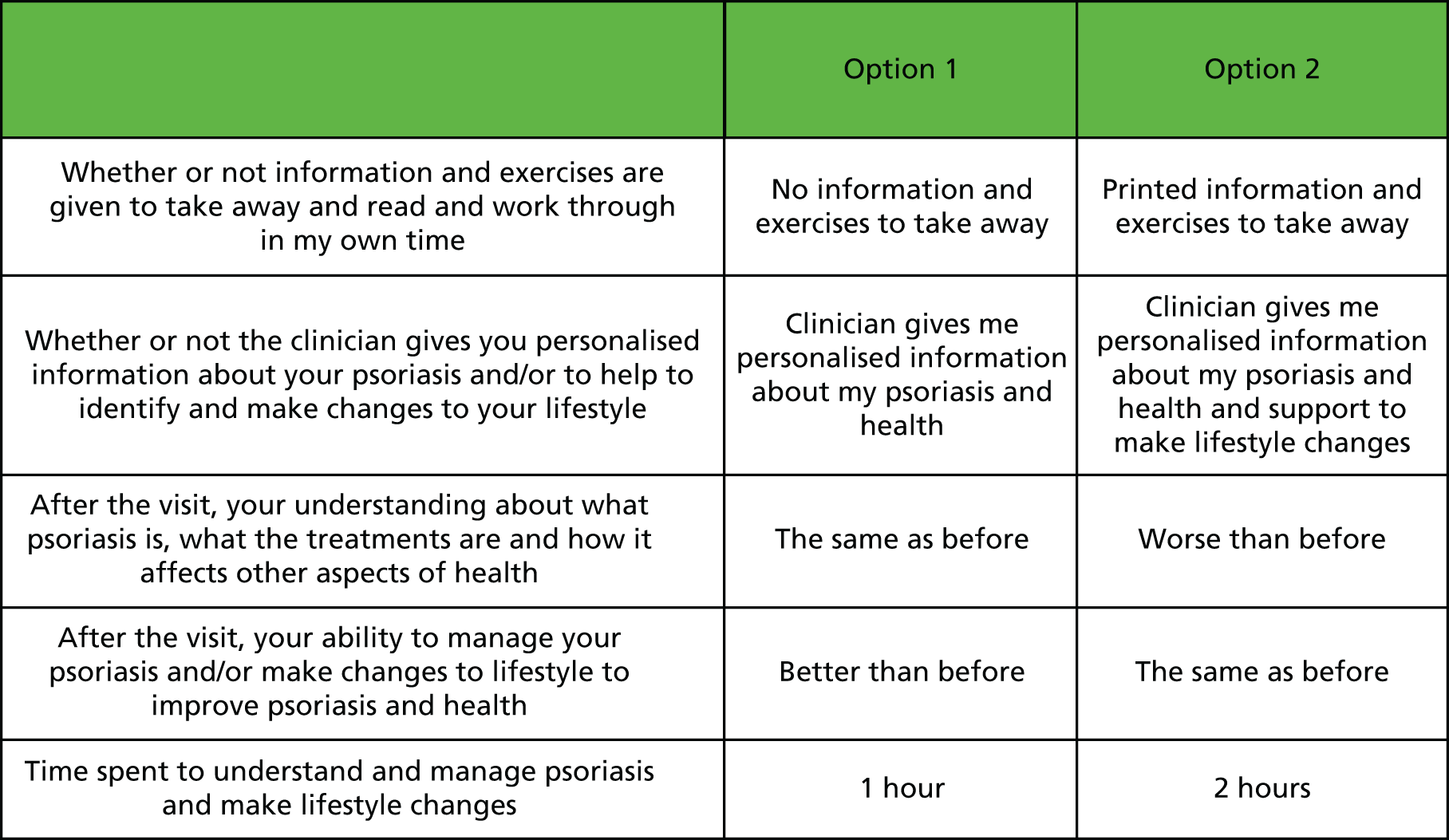

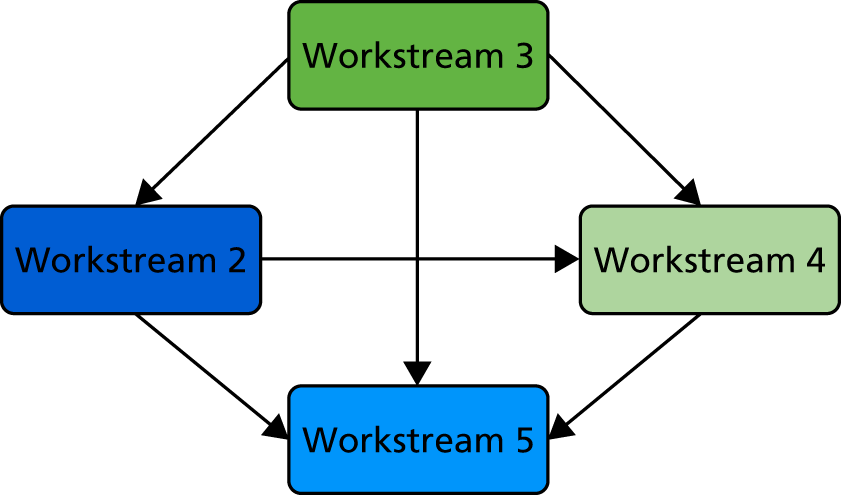

The original IMPACT programme application proposed five workstreams (Figure 1) to address gaps in knowledge and thereby provide a platform from which to develop services. Each workstream was set up to address specific aims, with the findings from workstreams 1–4 being used to inform the development of interventions based on primary care to improve outcomes for people with psoriasis addressed in workstream 5.

FIGURE 1.

Relationships between IMPACT programme workstreams.

Modifications to original aims

During a number of the studies, opportunities were identified to supplement the original plans with additional studies; these included workstreams 2, 3 and 4 (Table 1). Thus, as well as meeting our original objectives, we undertook additional work.

| Workstream | Programme objective | Study undertaken | Report section |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Objective 1: to confirm which patients with psoriasis are at highest risk of developing additional long-term conditions and identify service use and costs to patient | Study 1.i: epidemiology of psoriasis and costs of care. Systematic reviews | Epidemiology of psoriasis and its association with risk of cardiovascular disease |

| Study 1.ii: association between psoriasis and risk of CVD (1.i/ii) | Epidemiology of psoriasis and its association with risk of cardiovascular disease | ||

| Study 1.iii: modelling of health-care costs for people with psoriasis | Health economics modelling of costs of interventions for people with psoriasis | ||

| 2 | Objective 2: to apply knowledge about risk of comorbid disease to the development of targeted screening services to reduce risk of further disease and to investigate how this affects patient experience | Study 2.i: screening in primary care for CV risk in psoriasis patients | Cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis: screening study and pulse wave velocity measures in people with psoriasis |

| Study 2.ia: assessing the impact of psoriasis severity on artery health (pulse wave velocity) | Cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis: screening study and pulse wave velocity measures in people with psoriasis | ||

| Study 2.ii: mixed-methods interview study of patients and practitioners in primary care screening | Cardiovascular disease risk communication and reduction in psoriasis | ||

| Study 2.iii: experimental study of message-framing | |||

| 3 | Objective 3: to learn from patients with psoriasis about helpful and unhelpful coping (self-management) strategies | Study 3.i: main community qualitative study of people with psoriasis | Coping with psoriasis: learning from patients |

| Study 3.ii: adjunct qualitative study with GPs | |||

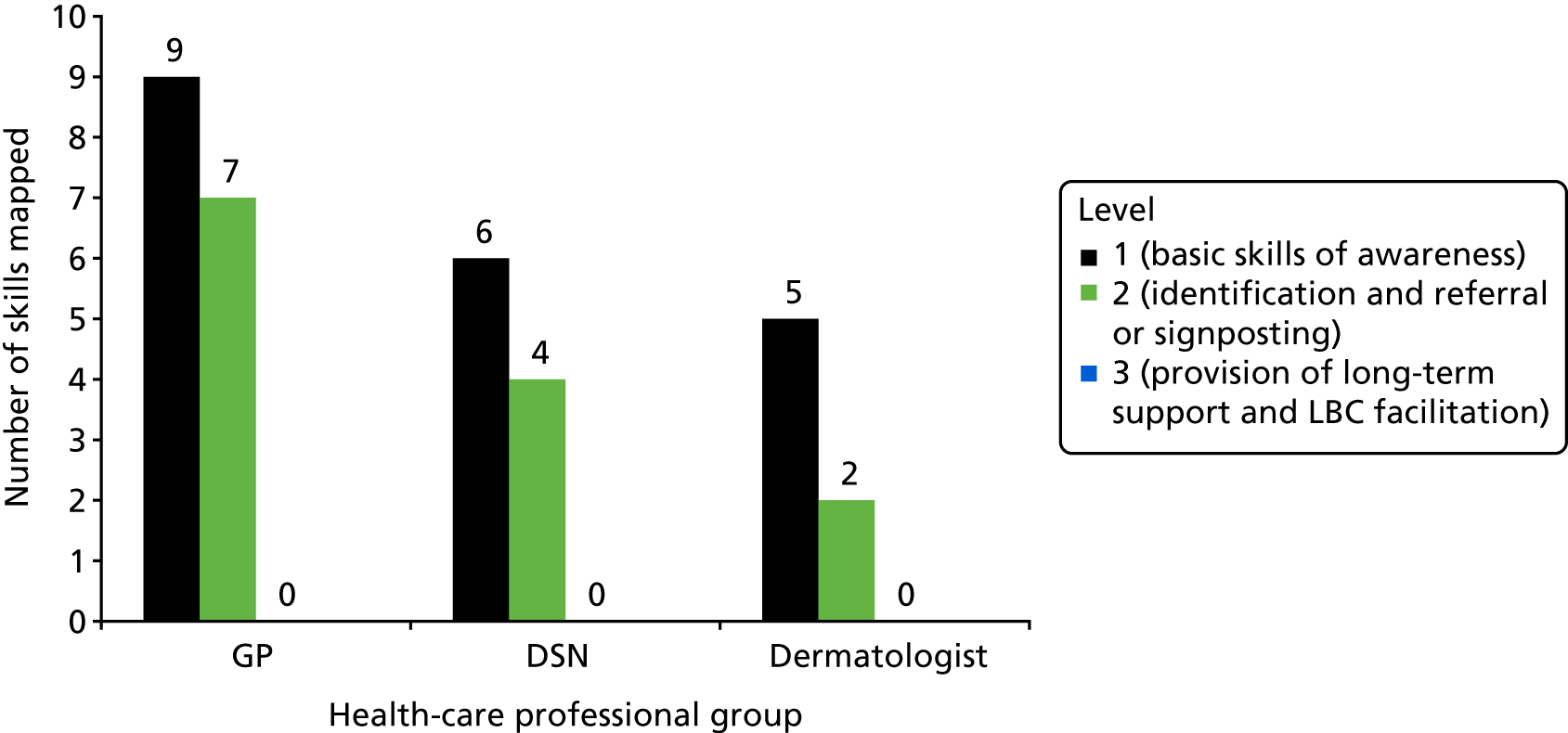

| 4 | Objective 4: to identify the barriers for professionals providing patients with support in LBC | Study 4.i: content analysis of core training competencies for health-care professionals | Understanding the professional role in supporting lifestyle change in patients with psoriasis |

| Study 4.ii: in-depth qualitative interview study of health-care professionals | |||

| Study 4.iii: observational study of available support information | |||

| Study 4.iv: a survey of DSNs | |||

| 5 | Objective 5: to develop patient self-management resources and staff training packages to improve the lives of people with psoriasis | Study 5.i: design, development and evaluation of materials to support patient self-management | Psoriasis and Wellbeing (PSO WELL): developing patient materials to broaden understanding of psoriasis as a long-term condition, psoriasis-associated comorbidities and the role of self-management |

| Study 5.ii: design, development and evaluation of a training programme for individuals | Psoriasis and Wellbeing (PSO WELL): developing a patient-centred approach using motivational interviewing skills with dermatology clinicians to support healthy living in people with psoriasis | ||

| Study 5 iii: health economics stated preference survey | Valuing the interventions with a stated preference survey |

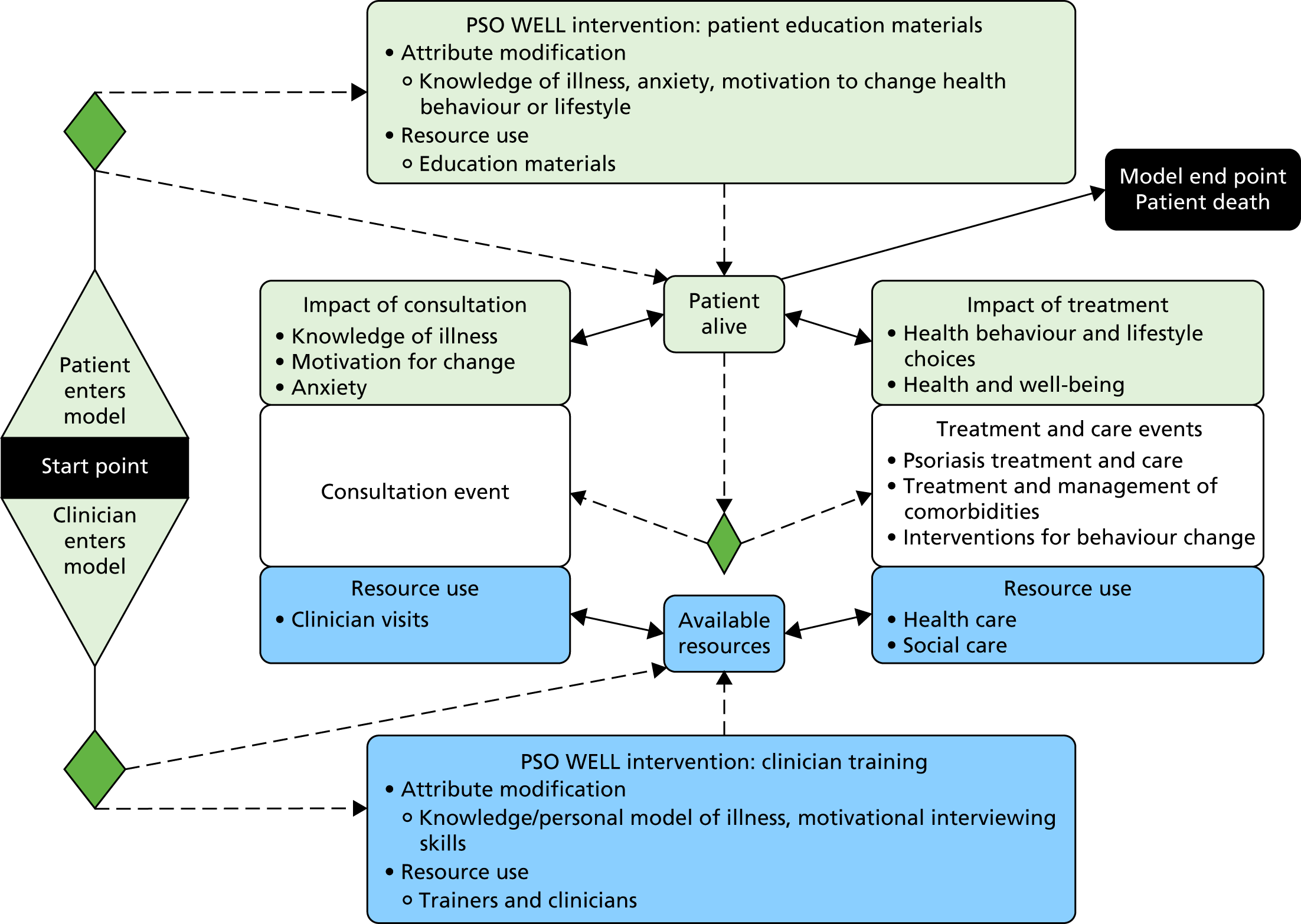

An economic model was planned as part of workstream 1 to explore whether or not systematic screening of people with psoriasis for CVD risk factors in primary care is cost-effective compared with usual care. This plan was modified because the modelling work fitted better as part of workstream 5. The reasons for this change are given as follows. First, the findings of workstream 1 indicated that psoriasis alone was not independently associated with the risk of major cardiovascular (CV) events over the follow-up period, although people with psoriasis also have a higher rate of acquired CVD risk factors. Second, workstreams 2, 3 and 4 found that many psoriasis patients are not engaged with NHS services and that effective control of CVD risk factors known to the patient and the general practice may be clinically more important than the detection of new risk factors. Third, the economic systematic review and findings from workstreams 3 and 4 suggested that it would be more informative to focus available resources on developing a more complex economic model to account for the interactions between patient and health-care professional characteristics, treatment and organisational factors. Finally, the interventions designed in workstream 5 are designed to provide information about the lifestyles associated with CVD risk and how to manage them. Accordingly, a more complex model was designed to account for the interactions between patients and health-care practitioners and includes CVD risk and management as part of the treatment and care events that a patient may experience. This model can be adapted to include new interventions for explicit management of known CVD risk factors in people with psoriasis as they are developed.

Other changes to our original plans occurred because of major changes to NHS funding and/or service structures. These changes meant that we needed to adjust our approach, particularly in relation to the final workstreams, which occurred towards the second half of the funding period. For example, the end of the administrative role of primary care trusts (PCTs) meant that we no longer had a direct link with the original PCT partner in research. In addition, the roles of health trainers had not been rolled out as we had anticipated for the final workstream; indeed, some of our original NHS partners removed these services altogether. Furthermore, the transition of some public health-care services to local authorities rather than the NHS meant that these services were further separated from the GP links that had been there when the original proposal was submitted. Although these did necessitate adjustments to the original plans, we were still able to meet the objectives by, for example, adapting the staff development intervention to general practice and secondary care dermatology services.

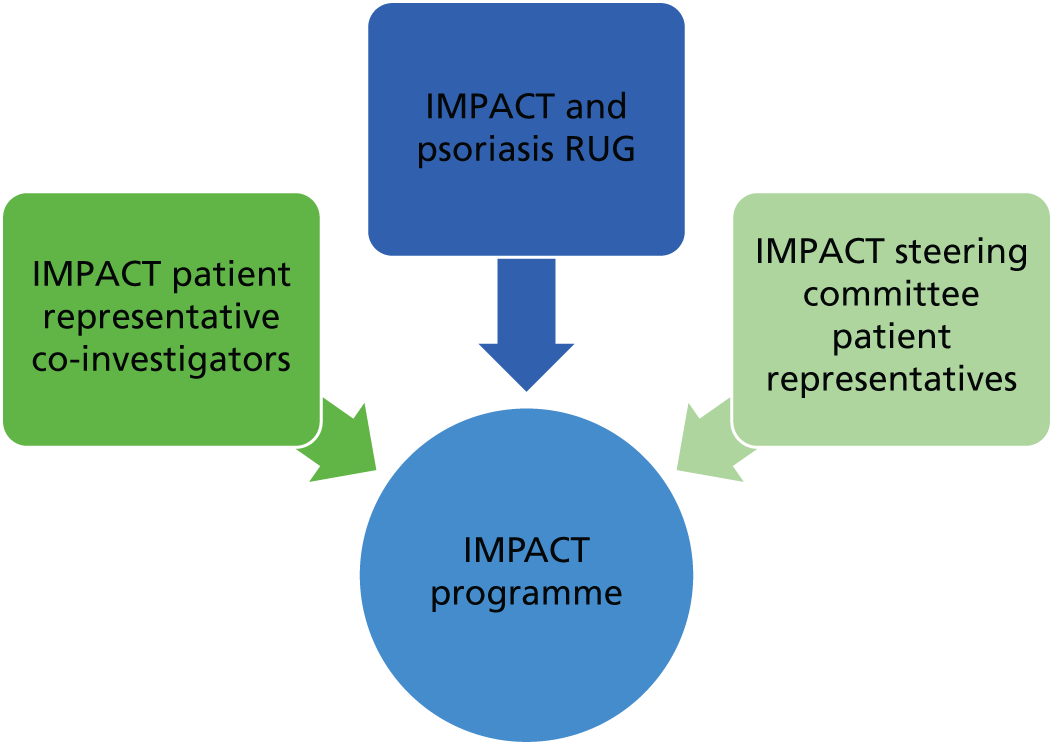

Patient and public involvement throughout the programme

The Psoriasis Association has worked closely with the IMPACT programme team from inception. Helen McAteer, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Psoriasis Association, is a co-investigator on the research programme, contributing to the research strategy and successful delivery of the programme. An IMPACT programme research user group (RUG) (comprising patients and carers) was set up in the first year of the programme grant to advise and work in partnership with the research team across workstreams at a practical and logistical level. In addition, three patient representatives were recruited to sit on the steering committee and contribute to the annual independent expert advisory panel meetings from a patient and public involvement (PPI) perspective. More detail on the PPI approach can be found in Patient, public and practitioner involvement in the IMPACT programme.

Programme management

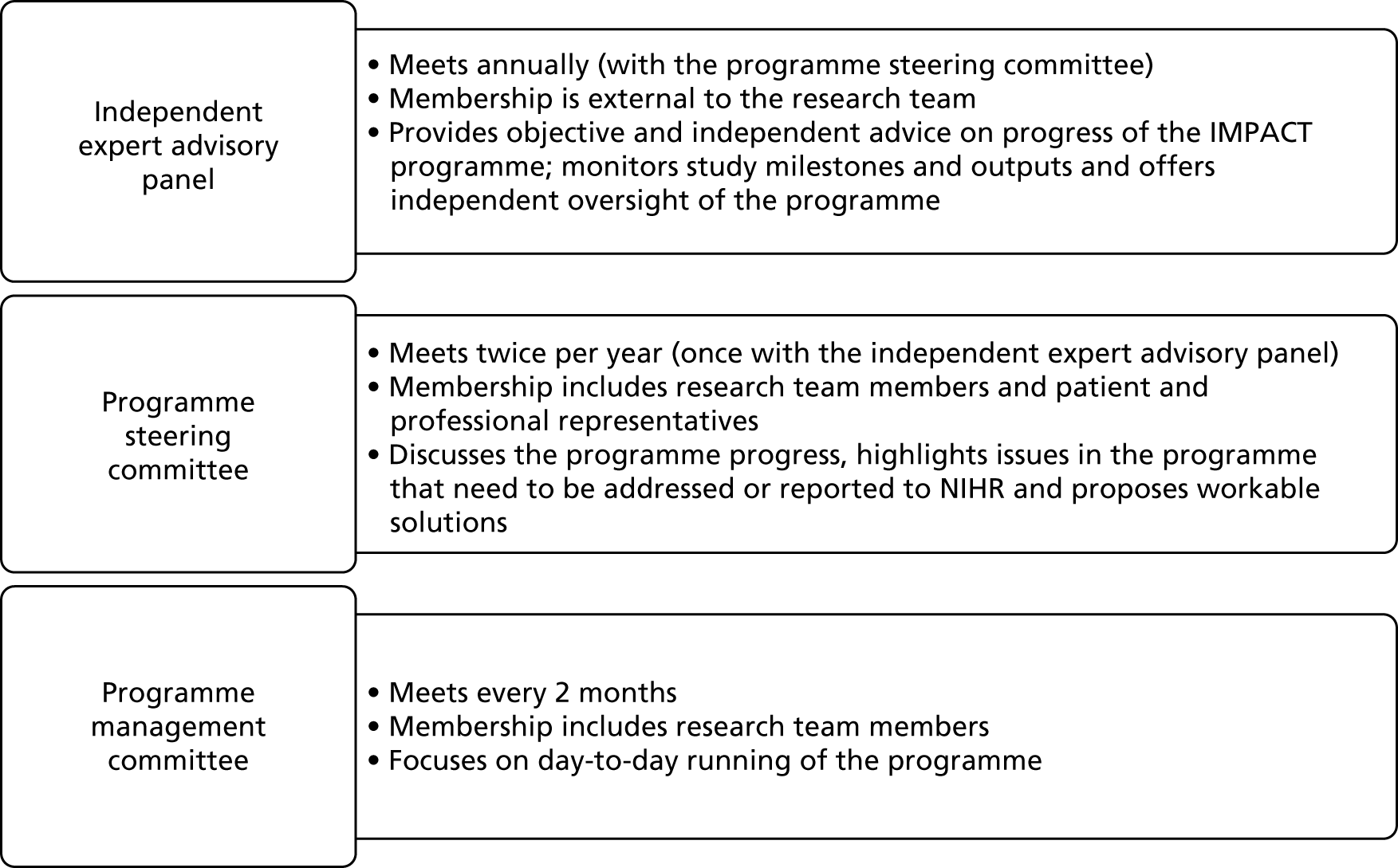

Management systems were set up from the beginning of the IMPACT programme to ensure effective running and timely delivery of the ambitious programme. There were three main management structures. Day-to-day management was overseen by the programme manager with regular input from the principal investigator. In each workstream, academic leads managed their research teams.

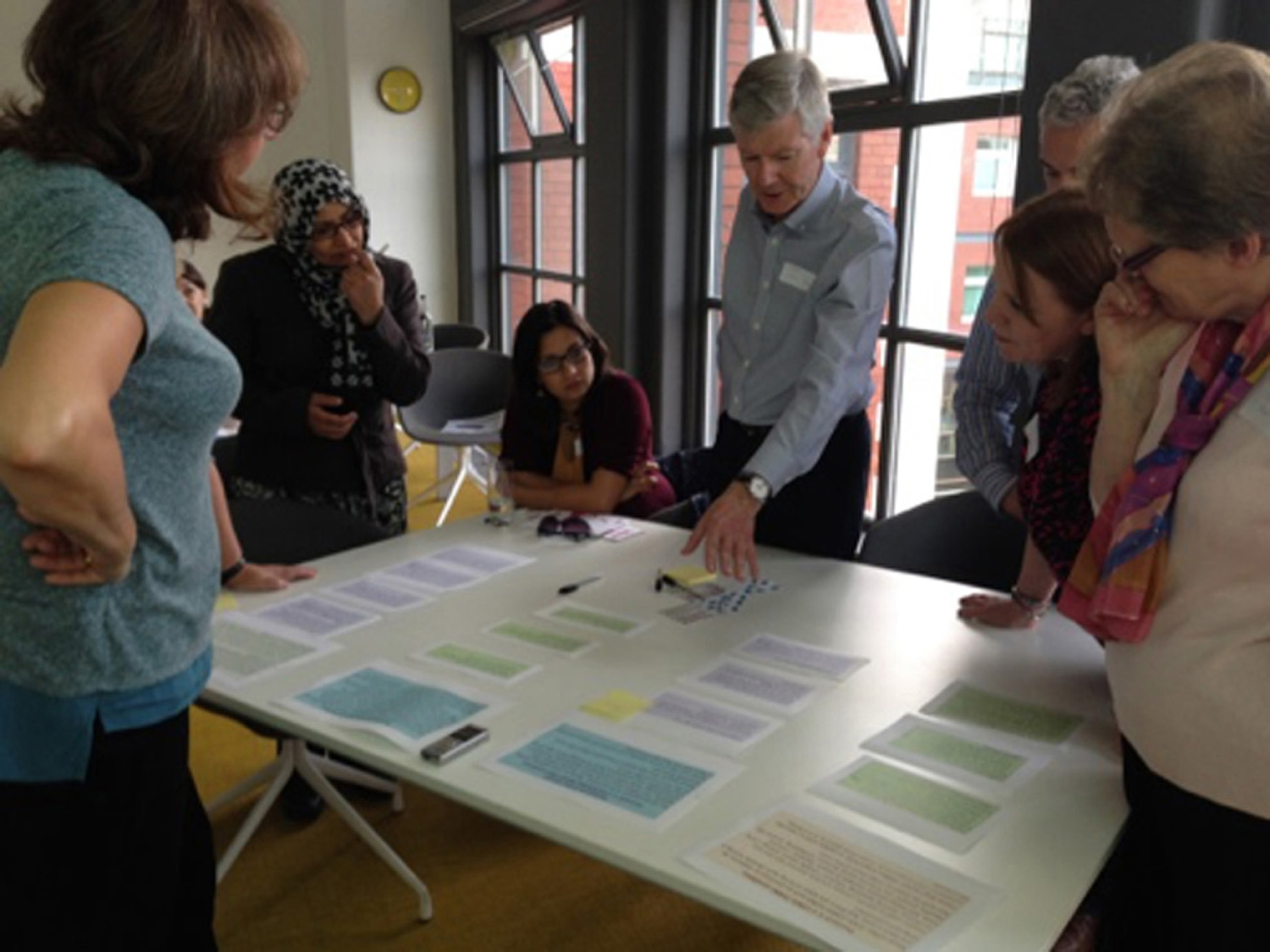

The independent advisory panel comprised individuals with an expertise in psoriasis or inflammatory disease and three patient representatives. All panel members were independent of the programme research team. An annual report was presented to this group followed by a full day’s face-to-face meeting with all researchers and investigators. At the end of this meeting the independent panel presented a written response to the programme team. Full investigator meetings (FIMs) comprised the principal investigator and all co-investigators. These were held monthly to monitor progress. Three patient representatives sat on the independent advisory panel. These individuals also attended RUG meetings. More details about the roles and experiences of patients and research users are provided in Patient, public and practitioner involvement in the IMPACT programme. Communication between co-investigators and researchers was aided by the fact that research staff and academics often spanned more than one workstream. Considerable planning and time were invested in annual whole-day training and development events in which all co-investigators and researchers presented and discussed findings with each other. These served as opportunities to interrogate findings and develop strategies for achieving the next research objectives, but were also important for team building. Extensive advance preparation for these meetings meant that they were very productive and focused. Particular attention was paid to supporting patient representatives to take an active part in these meetings (see Patient, public and practitioner involvement in the IMPACT programme).

Programme achievements

The programme has achieved its intended objectives, including the final aim of fully evaluated interventions for patients and professionals (workstream 5). In addition, we have improved understanding of the complex relationship between psoriasis and CVD (workstreams 1 and 2), undertaken in-depth qualitative research (workstreams 3 and 4) and conducted discrete event simulation (DES) modelling to capture the complexity of psoriasis, lifestyle and patient–health care relationships and estimate the cost-effectiveness of new interventions (workstream 5).

The work has been disseminated via academic, professional and public involvement routes including publication in academic journals, professional resource materials, presentations and a number of high-profile public engagement events. Highlights include:

-

17 peer-reviewed journal papers with at least three more in preparation

-

23 peer-reviewed oral and 43 peer-reviewed poster presentations

-

two successful national public engagement events, one city-wide and one national

-

sets of evaluated patient materials with outcomes assessed

-

an evaluated training intervention for health-care professionals.

Epidemiology of psoriasis and its association with risk of cardiovascular disease

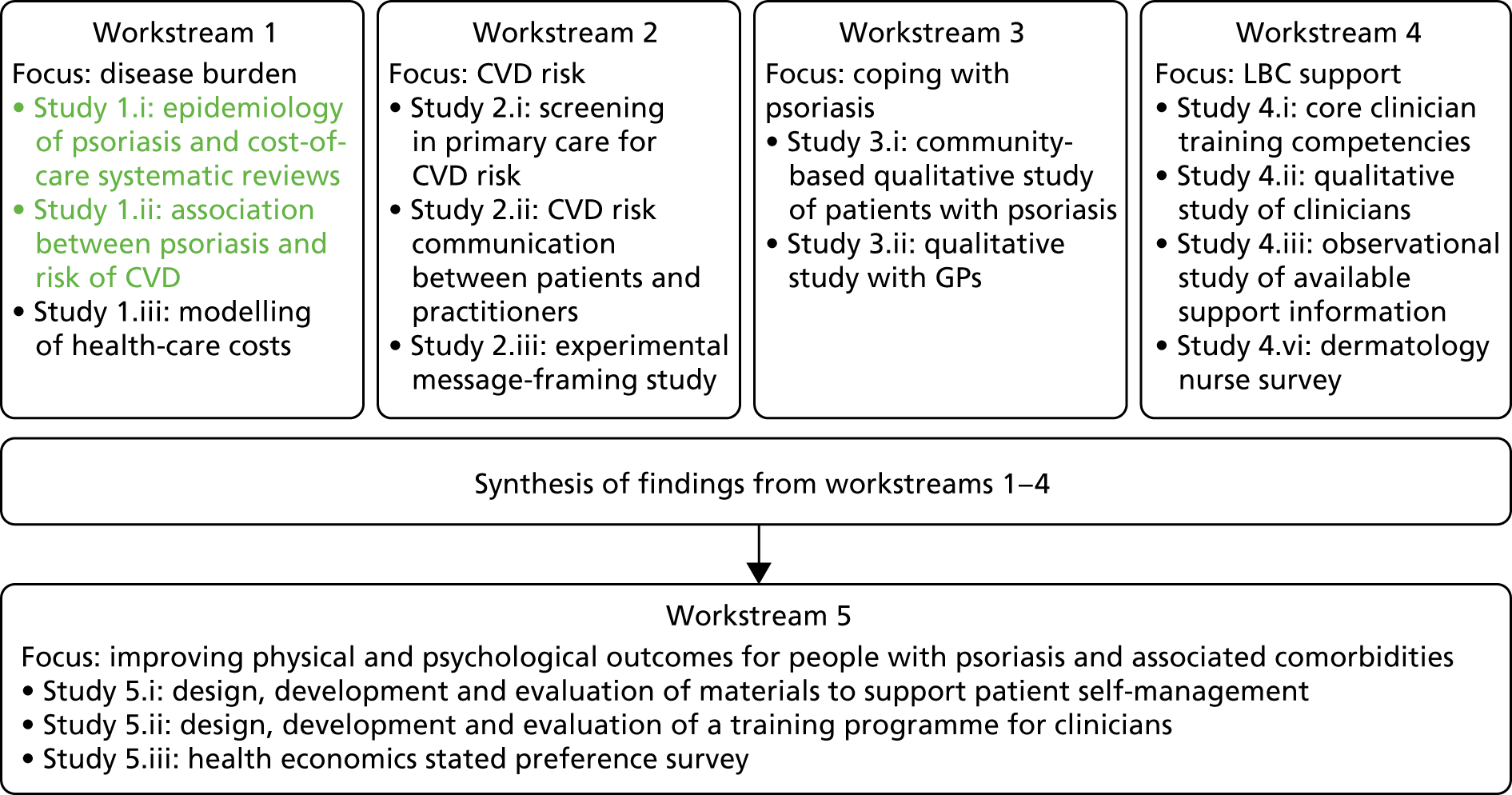

Workstream 1 studies 1.i and 1.ii (Figure 2) address objective 1 of the programme: to confirm which patients with psoriasis are at highest risk of developing additional long-term conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Workstream 1: relationship of studies 1.i and 1.ii to other IMPACT programme workstreams.

Publications relating to this section and workstream are listed in Publications and cited throughout this section.

Prevalence and incidence of psoriasis: a systematic review

The worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis is poorly understood. A systematic review that provided a detailed critique of the existing literature on the worldwide incidence and prevalence of psoriasis was undertaken as part of workstream 1, comparing studies in relation to geography, age and gender. See Parisi et al. 1

The results from the systematic review confirmed that psoriasis is a common disease, and is less common in children and more common in adults. Prevalence rates showed a worldwide geographic variation that probably reflects the fact that psoriasis is a complex disease influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. The incidence of psoriasis in the UK is estimated to be 140 per 100,000 person-years. 35 Studies on the prevalence of psoriasis in the UK highlight that the disease is uncommon before the age of 9 years (0.55%)36 and has an estimated prevalence of between 1.30% [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21% to 1.39%]37 and 2.60% (95% CI 2.47% to 2.78%)38 in adults and between 1.48% (95% CI 1.20% to 1.80%) and 1.87% (95% CI 1.89% to 1.91%)6,36,39 taking into account all ages.

Furthermore, some studies have found an increasing trend in the prevalence of psoriasis with age;36,39 however, there is no agreement about whether or not the prevalence differed between men and women. 36,39 The systematic review served to inform the recently published World Health Organization’s Global Report On Psoriasis40 and a subsequent call for further epidemiological research on the disease.

Systematic review of published economic evaluations

Although the economic systematic review and economic model of costs were both conceived as part of workstream 1, they were developed in parallel with other workstreams. In particular, the economic model drew on the findings of these to inform its structure and to populate it with data. The methods and results of the systematic review are reported here and those of the economic model are reported in Valuing the interventions with a stated preference survey.

A systematic review of published economic evaluations was conducted to understand what was known about the cost-effectiveness of psoriasis management. 41 The review’s aims were to identify full economic evaluations that compared the costs and health benefits of alternative interventions, summarise what was known about the relative cost-effectiveness of different interventions and assess the quality of the evidence, uncertainties and evidence gaps. The review highlighted inconsistencies between analyses and uncertainties where models have so far struggled to accurately characterise the disease. The review informed the need to develop a new model structure and the direction such a model should take.

The databases EMBASE, MEDLINE and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) were searched for full economic evaluations in January 2012, and updated with a search of NHS EED in April 2014. Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to screen abstracts and titles and select papers for review. Studies were included in the review if they compared services or treatments for psoriasis in adult patients, measured health outcomes and costs, and used either primary data or synthesised data in a full economic evaluation. The search identified 1355 articles. Three reviewers independently performed the primary and secondary screening of identified papers, cross-checking their results with each other. The full paper was obtained and reviewed for titles and abstracts when one or more reviewer was uncertain. Any discrepancies or uncertainties about the inclusion of papers in the secondary screening were resolved by discussion between the reviewers, with reviewer four acting as arbiter for any remaining uncertainty or disagreement. Two reviewers extracted data from the studies included for full review. Predefined data extraction forms and quality assessment forms were used (see Appendix 1). A total of 37 papers met the inclusion criteria and reported 71 treatment comparisons. The treatments evaluated in the 71 comparisons were systemic (n = 45), topical (n = 22), phototherapies (n = 14) and combinations (n = 4). The 37 economic papers reviewed mainly evaluated individual therapeutic agents rather than packages of care. Typically, these evaluations did not consider the context in which the treatment was delivered. Four articles and seven comparisons directly addressed the organisation and delivery of care. These included a programme to support patients’ self-management at home, online care management and home-based phototherapy. Four of the papers explored differing time and convenience demands on patients.

The review indicated that most of the economic evaluations were modelling studies, synthesising data from several sources. In summary, the systematic review identified a number of key areas of uncertainty in the existing psoriasis economic literature, which future economic analyses should seek to improve on. A limited effectiveness evidence base is over-represented in the available economic evidence and, overall, there was a lack of high-quality head-to-head clinical comparisons of different interventions. Repeated use of previous model structures was commonplace. When different sources of evidence or models have been used, uncertainty persists owing to diversity in setting, perspective and study design.

Many of the studies were limited in terms of reporting the methods used. In addition, the short-term follow-ups used in clinical trials of new interventions meant that 27 out of 37 economic evaluations were restricted to a time horizon of ≤ 1 year, despite the chronic nature of psoriasis. The review found that parameter uncertainty was not typically incorporated into analyses to a suitable degree.

Although the current evidence base is inconclusive about the relative cost-effectiveness of individual treatments, it contributes valuable data and methods to inform complex decisions and develop robust evaluation methods.

Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriasis: a population cohort study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The severity of psoriasis can range from limited disease involving small body surface area to extensive skin involvement. As described in Synopsis, people affected by the disease often have an impaired quality of life. People with psoriasis may have other comorbid conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus, which are associated with an increased risk of CVD.

In the last decade, a number of studies have suggested an association between psoriasis and CVD. It has been argued that increased systemic inflammation in those with psoriasis exacerbates other chronic inflammatory diseases including atherosclerosis, which could lead to MI or stroke (see Synopsis).

However, any purported association between psoriasis and CVD is complex for several reasons: those with psoriasis are more likely to engage in unhealthy lifestyle habits (increased likelihood of smoking, low levels of physical activity and obesity),28 have higher prevalence of CVD risk factors (e.g. diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia)23 and therapies that may raise (e.g. ciclosporin)28 or lower (e.g. methotrexate)29 the CVD risk. Each of these are aspects that may confound the association between the two conditions. 30

After controlling for several major CVD risk factors, a number of studies have suggested an increased risk of fatal and non-fatal CVD events in patients with psoriasis. 18,42–51 By contrast, other studies have concluded that psoriasis is not an independent risk factor for CVD. 52–55 In a recent systematic review, Samarasekera et al. 56 concluded that a possible association between severe psoriasis and CVD may exist; however, the authors warn that the existing studies were limited by failing to adequately adjust for important risk factors.

Inflammatory arthritis, a common comorbidity in patients with psoriasis and a recognised risk factor for CVD,57–59 has rarely been considered as a possible confounder. It is also important to note that, in many studies using electronic medical record databases, severe psoriasis is typically defined by exposure to systemic or biologic therapies that may also be used to treat inflammatory arthritis. This raises the possibility of misclassification of severe psoriasis when not taking account of the presence of inflammatory arthritis. Furthermore, little consideration has been given in earlier studies to the time-varying nature of the development of risk factors, or the severity of psoriasis. 30

A large population-based cohort study was undertaken with the aim of investigating whether or not psoriasis is an independent risk factor for major CV events [including MI, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), unstable angina and stroke] when taking into account relevant risk factors for CVD. See Parisi et al. 30

Methods

Study design

Using a primary care database from the UK [specifically the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD)], a population-based cohort study was conducted that included people with and people without psoriasis. The CPRD comprises the entire medical history (demographics, treatments, clinical events, test results and referrals to hospitals) of patients registered in a general practice in the UK. The database is broadly representative of the UK population in terms of age and gender. The protocol of this study was approved by the CPRD’s Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol reference number 11_134A). The study is reported according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. 60

At the time data were extracted (September 2012), data were available for 652 practices and > 12 million patients.

Study population

An inception cohort of adult (aged ≥ 20 years) patients with psoriasis and a matched comparison group of up to five people without psoriasis were identified between 1994 and 2009. Patients with and patients without psoriasis were included if they had no history of CVD or diabetes mellitus before index date (first diagnosis of psoriasis or corresponding consulting date for comparison patients) and were registered for ≥ 2 years in the general practice before entry into the study cohort.

Comparison patients were individuals who had never received a diagnosis for psoriasis. For each patient with psoriasis up to five comparison patients were matched on age, gender and general practice. Furthermore, to ensure that comparison patients visited the practice at approximately the same time as when patients with psoriasis received their first diagnosis of psoriasis, comparison patients were also matched on index date (psoriasis diagnosis date) in a 6-month window. All patients were followed up from their respective index date (first diagnosis of psoriasis) or consulting date (for the comparison cohort) and ended at the earliest date of the occurrence of a major CV event (MI, ACS, unstable angina or stroke), transfer out of the practice, death date or end of follow-up (31 December 2011).

Definition of exposure

Patients with a first diagnosis of psoriasis between 1994 and 2009 and received a recognised treatment for psoriasis {(emollients, topical treatment, phototherapy, systemic therapy or biologics [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline CG153]} were included in the cohort. 61 Patients were classified as having severe psoriasis if they had received a systemic treatment (acitretin, etretinate, ciclosporin, hydroxycarbamide, methotrexate, fumaric acid), phototherapy or a biologic therapy (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab); if they had received none of these they were classified as having mild psoriasis. 30

Outcome of interest

The outcome of interest was a combined CV end point, including the first event of fatal or non-fatal MI, ACS, unstable angina or stroke. In the main analysis, the outcome of interest was identified using data from CPRD by using the Read code classification, which is a hierarchical coding system used to record diagnoses in primary care. 62 To assess the robustness of the main findings to potential outcome misclassification, in a sensitivity analysis, the combined CV end point was identified using primary care data (CPRD) and the national mortality records [from the Office for National Statistics (ONS)] of those patients in practices providing linked data between CPRD and ONS. In this situation, both Read codes and the International Classification of Diseases codes were used.

Covariates

To assess whether or not there is a relationship between psoriasis and risk of major CV events, a statistical model was built including multiple risk factors (other than psoriasis). This approach will help us to understand whether or not any observed association between psoriasis and major CV events could be accounted for by other concomitant diseases/risk factors that are known to be linked to CVD. Risk factors included in the model were age, gender, depression and calendar year calculated at baseline and having or developing severe psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis (which included both diagnostic codes for PsA or rheumatoid arthritis). Diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, atrial fibrillation (AF), transient ischaemic attack, congestive heart failure, thromboembolism, valvular heart disease and smoking status were modelled as time-varying risk factors; therefore, an individual’s classified status could change during the study period. Psoriasis was defined as being severe from the date of first exposure to phototherapy, systemic or biologic treatment. It was considered as severe from that point onward. Smoking status was classified as ‘current’, ‘former’, ‘never smoker’ or ‘unknown smoking status’. This enabled switching from one smoking class to another during follow-up. 30 Additional risk factors such as a high body mass index (BMI) score and a high score on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD),63 which is a measure of socioeconomic status, were included only in sensitivity analyses owing to the high proportion of missing data.

All code lists used for the exposure and outcome are available for download [URL: www.clinicalcodes.org (accessed 15 May 2019)]. 64

Statistical analysis

Medians and interquartile ranges were used to summarise continuous variables; proportions were used to summarise discrete covariates. The combined CV end-point events and incidence rates per 1000 person-years with 95% CIs were calculated for patients with and patients without psoriasis, and by disease severity. The estimate of the age- and gender-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for each variable were made using Cox proportional hazard regression. Cox regression with a shared frailty model was used to estimate the fully adjusted HRs and 95% CIs. The assumption of proportionality for each variable and the model overall was tested by using Schoenfeld residuals.

Using the initial cohort identified from CPRD, multiple sensitivity analyses were performed. These included assessing whether or not a more complex or parsimonious multivariate model (by including different sets of risk factors) would change the conclusions. BMI and IMD scores contained a high proportion of missing data; therefore, they were included in the model only in sensitivity analyses. Smoking status had a small proportion of missing values; therefore, it was included in the main analysis and a category was introduced to account for missing values. Accordingly, sensitivity analyses explored the impact of using multiple imputation to estimate missing BMI and IMD scores so that they could be included in the model.

Additional sensitivity analyses were (1) including only those patients with at least one GP visit per year, (2) including only those patients with ≥ 6 months of follow-up, (3) testing for an interaction between the presence of psoriasis or severe psoriasis with age and (4) additional adjustment for patients exposed to methotrexate, ciclosporin or oral retinoids.

Finally, a subgroup analysis was performed by linking data from CPRD to the mortality data contained in the ONS. The nested cohort included patients identified from CPRD practices linked to the ONS and who had an index date (first diagnosis of psoriasis or corresponding consulting date) between 1998 and 2009; they were followed up until 2011. The outcome was the first fatal or non-fatal major CV event (MI, ACS, unstable angina or stroke) recorded in CPRD or ONS.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata® 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The number of patients meeting all inclusion criteria who formed the final cohort was 48,523 patients with psoriasis and 208,187 comparison patients. Overall, there was a higher proportion of females (56.40%) and the median age at index date was 47 years (see table 1 of Parisi et al. 30).

At baseline, patients with psoriasis had a higher prevalence of the majority of risk factors (inflammatory arthritis, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, depression, current or ex-smoker, overweight or obese) than the comparison group (see original table 1). At the end of follow-up, patients with psoriasis had a higher prevalence of all time-varying risk factors except for AF, transient ischaemic attack and congestive heart failure (see original table 2). Inflammatory arthritis was present in 2.39% of patients with psoriasis and 0.98% of the comparison patients at baseline. It was also present in 4.69% of the patients with psoriasis and 1.38% of the comparison patients by the end of follow-up. In addition, at baseline, 1.03% of patients with psoriasis had been treated with phototherapy or systemic or biologic therapies. This increased to 4.29% of patients by the end of follow-up. Just over 50% (50.62%) of those treated with systemic or biologic therapies had also been diagnosed with inflammatory arthritis by the end of the follow-up period. 30

The most commonly used systemic treatment used in patients with psoriasis was methotrexate. Original table 3 shows the distribution of phototherapy, systemic therapy or biologic received by patients with psoriasis.

Patients included in the study were followed up for a median time of 5.2 years. Over this period, 1257 (2.59%) patients with psoriasis had a major CV event, compared with 4784 (2.30%) comparison patients (see original table 4 of the published paper). The unadjusted incidence rate of a major CV event per 1000 person-years was higher in the psoriasis group than in the comparison group [4.13 per 1000 person-years, 95% CI 3.91 to 4.36, and 3.87 per 1000 person-years, 95% CI 3.76 to 3.98, respectively] (see original table 4).

There were time-varying effects related to risk of outcome for hypertension, transient ischaemic attack, AF and gender (revealed in Schoenfeld residuals). Allowing each of these variables to have different effects for the first 3 years of follow-up and the later follow-up did, however, remove the non-proportionality (p = 0.12).

In the age- and gender-adjusted analysis, all the variables tested were significantly associated with the risk of major CV events. In particular, the HRs of major CV events due to psoriasis and severe psoriasis were 1.10 (95% CI 1.04. to 1.17) and 1.40 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.84), respectively. However, both HRs were attenuated and became non-significant in the fully adjusted model (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.08, and HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.69, respectively) (original table 5 of the published paper).

In addition, in the multivariate analysis, each of the following risk factors was significantly related to the risk of major CV events (original table 5): inflammatory arthritis (HR 1.36, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.58), diabetes mellitus (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.31), chronic kidney disease (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.31), hypertension (HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.45), transient ischaemic attack (HR 2.74, 95% CI 2.41 to 3.12), AF (HR 1.54, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.73), valvular heart disease (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.44), thromboembolism (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.49), chronic heart failure (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.39 to 1.78), depression (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.34), current smoker (HR 2.18, 95% CI 2.03 to 2.33), age (HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.07) and male gender (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.69 to 1.98). Hyperlipidaemia was not significantly related to the risk of major CV events (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.11).

Interaction terms between psoriasis or severe psoriasis and age were tested; however, they were not included in the multivariate model because they were non-significant (p = 0.40 and p = 0.25, respectively).

The sensitivity analyses did not change the main findings. The HRs of major CV events due to psoriasis or severe psoriasis when taking into account the different sets of risk factors can be found in original table 6 of the published paper. In particular, the HR of major CV events due to severe psoriasis changed from 1.28 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.69) to 1.46 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.92) when inflammatory arthritis was not included in the model.

When using multiple imputation and adding BMI and IMD scores to the fully adjusted model, the HRs of major CV events were > 1 but still non-significant (see original table 6).

Likewise, the results obtained by analysing data from patients with at least one GP visit per year, patients with ≥ 6 months’ follow-up or results that took into account patients exposed to methotrexate, ciclosporin or oral retinoids gave the same results as the main findings (see original table 6).

Finally, the subgroup analysis that analysed data from CPRD linked to the ONS mortality data and patient-level socioeconomic status (IMD) yielded similar results to the main findings. Here, the fully adjusted HRs of major CV event due to psoriasis and severe psoriasis were 1.02 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.11) and 1.10 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.68), respectively (see original table 6).

Discussion

This study investigates whether or not psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk of CVD. The results confirm that patients with psoriasis have more prevalent comorbid conditions associated with CVD. However, taking into account other established risk factors for CVD, psoriasis itself was not found to be directly associated with short- to medium-term (3–5 years) risk of major CV events. These results highlight that individuals who have psoriasis co-occurring with inflammatory arthritis have a 36% higher risk of a major CV event than those who do not.

Similar to other studies,18,23,46 our research highlights that patients with psoriasis have a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors. Our findings are comparable to those reported by Brauchli et al. 52 and Wakkee et al. ,55 neither of which found an overall higher risk of MI associated with psoriasis. However, our research is more robust because the sample size was larger, 55 we used more stringent inclusion criteria (e.g. psoriasis cases were identified on the bases of diagnosis and treatment received)52 and in our analysis we accounted for important confounders including inflammatory arthritis. 52,55

Our finding that psoriasis is not an independent risk factor for a major CVD event was in contrast to other influential studies that reported that it was an independent risk factor. 42,44,65

In a study that utilised the Health Improvement Network database, Ogdie et al. 65 reported an increased risk of major adverse CV events in patients with either mild or severe psoriasis. It is possible that the cohort of patients with psoriasis used in that study had a longer disease duration than patients identified in our cohort. Different study designs were used (prevalent vs. incident cohort). An important issue is raised by the use of a prevalent cohort, namely that it is associated with the problem of left censoring. For example, those with the most severe psoriasis or CVD could have died prior to cohort entry, meaning that these studies can address only the question of what happens to individuals with psoriasis who have already survived. 30

Another study that reported an increased and significant risk of coronary heart disease in patients with severe psoriasis was conducted by Dregan et al. ,44 using the CPRD; however, it is possible that they misclassified severe psoriasis on the basis of treatments received without taking account of the possibility of comorbid inflammatory arthritis. 30

Using a Danish nationwide database, Ahlehoff et al. 42 reported increased risks of CVD in patients with severe psoriasis with and without PsA. However, in that study, patients with severe psoriasis were classified using hospitalisation for psoriasis or PsA, which could be subject to surveillance bias. 30,42 Furthermore, comorbidities were assigned by linking with prescribed treatments instead of diagnostic codes, which could lead to potential misclassification.

There are a number of additional differences between our study and earlier studies. We examined a wider range of risk factors in the analyses41,43,64 and modelled these to account for development of new risk factors over time. We examined psoriasis severity as a time-varying covariate, so that patients with severe psoriasis become ‘at risk’ only once they started phototherapy, systemic therapy or biologic therapies (rather than simply whether or not they had ‘ever’ been exposed to systemic treatment. That approach would have meant that an individual would have been classified as having severe psoriasis for the whole observation period).

Some strengths and limitations of the study can be listed. Selection bias was minimised, as was information bias and detection bias by identifying patients from the same database. We selected patients with and patients without psoriasis from the same general practice and during the same time-window.

Furthermore, our findings were consistent after multiple sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Several additional strengths can be identified in our study. (1) Important confounders were taken into account to investigate the association between psoriasis and major CV events. These included both traditional and non-traditional CVD risk factors, in particular inflammatory arthritis. (2) We present a large population-based study representative of the UK. (3) Only those with at least a diagnostic code of psoriasis plus a treatment for psoriasis were included in the cohort to minimise the risk of disease misclassification. (4) More advanced methodology was employed, such as the use of the shared frailty model. These methods take better account of the matched nature of the data, and the use of time-varying covariates. 30

Some limitations also need to be taken into account. Given that this was an observational study, the risk of residual confounding was considered. The CPRD is a primary care database and therefore diagnoses of psoriasis were not necessarily confirmed by dermatologists; phototherapy and systemic and biologic therapies were used as a surrogate to classify disease severity rather than standard clinical assessments, such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) or the body surface area affected by psoriasis. The size of the group of individuals with or developing severe psoriasis may be underpowered to investigate that end point of interest. The duration of follow-up was > 5 years (on average) for those with psoriasis and > 3 years for those who developed severe psoriasis during the observation period. It may be the case that chronic inflammation takes longer to produce adverse CV outcomes and therefore studies involving longer follow-up periods are recommended. 30

Due to the small number of patients exposed to biologics it was not possible to discern whether or not biologic therapy reduces the risk of major CV events. The specific aim of the current study was to investigate whether or not psoriasis was independently associated with the risk of major CV events. Thus, to minimise the risk of bias, patients from our cohort who had a history of either CVD or diabetes mellitus were excluded. 30

Key conclusions

-

Adults with psoriasis are more likely to have prevalent conditions associated with CVD.

-

However, psoriasis alone is not independently associated with the short- to medium-term (i.e. 3–5 years) risk of major CV events, after adjusting for important CVD risk factors.

-

Despite this, the co-occurrence of inflammatory arthritis and psoriasis is an independent risk factor for major CV events.

Implications

-

Screening psoriasis patients for inflammatory arthritis is important, as is screening to prevent development of CVD risk factors in people with psoriasis.

-

Patients with inflammatory arthritis are at an increased risk of CVD; this may be an additional reason to minimise a patient’s cumulative inflammatory burden.

Cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis: screening study and pulse wave velocity measures in people with psoriasis

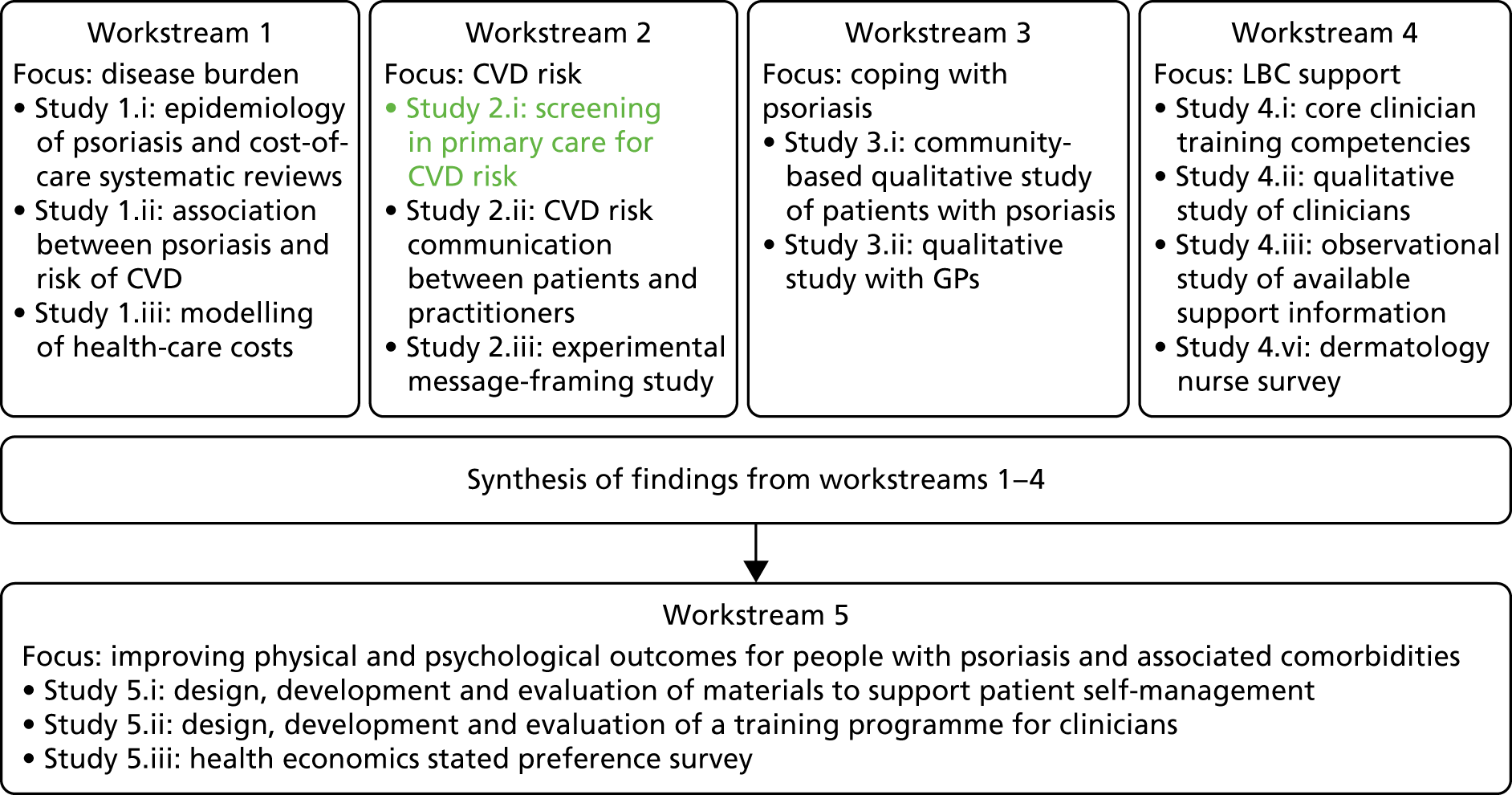

Workstream 2 (Figure 3) addresses objective 2 of the IMPACT programme: to apply knowledge about the risk of comorbid disease to the development of targeted screening services to reduce the risk of further disease.

FIGURE 3.

Workstream 2: relationship of study 2.i to other IMPACT programme workstreams.

This section describes a study66 and a substudy. The first part of this section briefly summarises a study of screening for CVD risk in primary care. 66 The second part of this section reports the small substudy that investigated the utility of pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurement as a potential target method for screening.

Screening for cardiovascular disease risk in primary care

Background

Since 2006, the possibility that people with psoriasis experience an increased rate of fatal and non-fatal CVD in comparison with the general population has been an increasing focus of discussion. 67 At the time of this study it was unclear whether such an enhanced risk was due to an increased prevalence of traditional CV risk factors (e.g. hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia); an increased prevalence of some of the more recently recognised CV risk factors, such as physical inactivity and depression; or the severity of the psoriasis. There was very little information on the prevalence of traditional CV risk factors in patients with psoriasis in the UK and this small body of research may have been limited by selection bias, inappropriate choice of control groups or reliance on risk factors measured for other clinical reasons.

Primary care patients aged ≥ 40 years are supposed to be offered CV risk assessment as a matter of routine in the UK. However, this is not the case for patients aged < 40 years. This could be a problem for those diagnosed with psoriasis if, as reported by Gelfand et al. ,18 they have up to three times the expected CVD risk. Without robust data it would be difficult to make a case for systematic screening of patients with psoriasis for CV risk factors over and above what might be offered to the general population. 31,67–69

Previous primary care-based studies have neither assessed how systematic screening for CVD risk factors might influence their estimated prevalence in patients with psoriasis nor estimated the potential benefits of identifying such risk factors and subsequent intervention.

Objectives

Our objectives were to:

-

investigate whether or not screening for CVD risk factors in primary care could influence the estimated prevalence of CVD in patients with psoriasis

-

assess whether or not the prevalence of screen-detected CVD risk factors or estimated CVD risk varies by age, psoriasis severity and the presence of PsA

-

estimate the clinical benefits of normalising modifiable risk factors.

Method

Exposure and outcome measures

A number of exposure and outcome measures were included in the study. These were PsA, severe psoriasis, hypercholesterolaemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, alcohol excess, suboptimal levels of risk factors on therapy, rheumatoid arthritis and chronic kidney disease. These are defined in Rutter et al. 66

Selection of general practices, participants and sample size

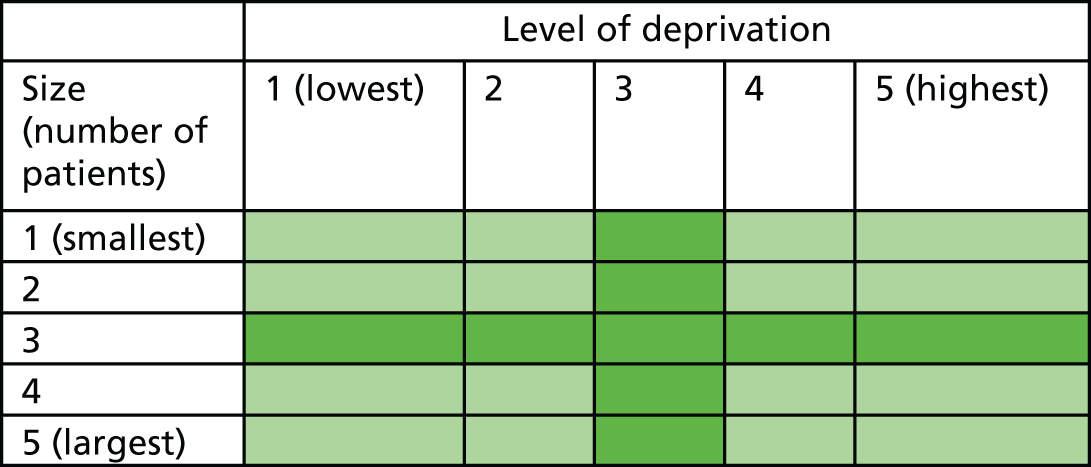

General practices from two PCTs in north-west England were identified. We aimed to recruit large and small general practices from deprived and affluent areas by grouping eligible general practices in quintiles by size, using the numbers of registered patients, and by level of deprivation, using the IMD (based on practice postcode). A five-by-five sampling frame was constructed (Figure 4) and practices in the nine middle quintiles were removed. Practices were then randomly selected from the remaining four quadrants: small and deprived, small and affluent, large and deprived, and large and affluent. Removing the nine middle quintiles increased the likelihood of ensuring maximum differences between the quadrants.

FIGURE 4.

Sampling frame for practices.

Forty-four eligible general practices were sent letters of invitation and information sheets and were followed up by telephone, e-mail or visit. Only five practices were recruited via this route; consequently, the recruitment strategy was widened to include three more PCTs. In these PCTs, practices were identified via the comprehensive local research network. In total, 13 practices were finally recruited and reimbursed for their participation (i.e. block payments were made to participating practices to compensate for time incurred by administrators identifying psoriasis patients in each practice).

We aimed to recruit 320 people to yield estimates of the prevalence of CVD risk factors to within ≈1.9% of the true value for rarer factors and to within ≈5.3% of the true value for common factors.

Accordingly, we aimed to include ≈80 people with psoriasis in each of four age/sex categories: males aged < 40 years; females aged < 40 years; males aged ≥ 40 years and females aged ≥ 40 years. The age of 40 years was the cut-off because routine screening for CVD risk factors is usually offered routinely once every 5 years to all patients aged ≥ 40 years. Participating general practices identified patients with psoriasis aged > 18 years using Read codes known to map to the condition and medications/topical preparations for psoriasis (see Rutter et al. 66). Exclusion criteria were severe mental health problems, no capacity to consent, recent bereavement and terminal illness.

Eligible patients were sent an invitation from their own GP to attend a CVD risk screening assessment at their general practice. The invitation included an information leaflet about the study and a reply slip on which the patient was asked to indicate if they had psoriasis and if they were interested in participating. Smaller practices mailed all eligible patients on their list; larger practices mailed an agreed number (depending on practice capacity), using a randomised numbered list to select invitees. Patients replying positively were telephoned by a researcher, who arranged attendance for CVD risk factor screening at the patient’s own general practice.

Data collection

The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (REC) [North West Research Committee, Greater Manchester East (reference number: 11/NW/0654)]. All participants gave informed written consent before any data collection. Data were collected from the patient (via a self-completed questionnaire in advance of their appointment), from the practice (from medical records) and from a face-to-face assessment, and included items needed to calculate the individual probability of a CV event over the next 10 years using the standard UK CVD risk calculator QRISK®2 (ClinRisk Ltd, Leeds, UK).

When patients consented to having their medical records examined, a designated member of the practice staff recorded (if appropriate):

-

most recent cholesterol reading and pre-treatment value

-

most recent blood pressure reading and pre-treatment value

-

relevant medication

-

information about the following known CVD risk factors – smoking status, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, type 2 diabetes, AF, chronic kidney disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Information from the medical records, along with self-reported risk factors, was used to assess whether or not risk factors were newly detected by screening.

Patients were asked about their history of psoriasis; family history of psoriasis; previous treatments for psoriasis; current medication; history of CV conditions including heart attack, stroke, angina and AF; family history of CV conditions; and history of rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, depression and type 2 diabetes.

The practice nurse or GP then:

-

Recorded the current smoking status and number of units of alcohol consumed per week reported by the patient.

-

Generated the patient’s BMI. Each practice was provided with a new set of weighing scales for this purpose to ensure consistent/accurate measurements.

-

Measured hip and waist circumferences (cm).

-

Measured sitting blood pressure three times in the same arm after a 5-minute rest and the mean of the last two readings. Each practice was provided with a new blood pressure monitor for this purpose.

-

Took fasting blood samples, to be analysed at a local hospital biochemistry department for the measurement of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting lipids [total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglycerides], fasting glucose, and liver and renal function.

If patients were found to have high levels of anxiety or depression, they were notified using a standardised form containing their Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores, with accompanying advice to speak to their GP.

Patients were recalled for follow-up discussion of the screening if deemed necessary by the practice.

Statistical methods

Data are reported as mean [standard deviation (SD)] or median (range), depending on distribution. Groups were compared using chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data and Student’s t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests for continuous data.

The prevalence of risk factors was compared with that in a general population sample drawn from the 2011 Health Survey for England (HSE). 70 To facilitate the comparison, sampling weights were used to standardise HSE estimates to the age, ethnicity and gender distribution of the psoriasis sample.

The individualised probability of a CV event over the next 10 years (using QRISK2) was calculated for patients not already deemed to be at high CVD risk (see above) by using Stata 13 plugins and the QRISK®-2013 source code (ClinRisk Ltd). Also using the QRISK2 calculator, the ‘optimised CVD risk’ was calculated for each of these individuals using an ideal set of values for modifiable risk factors (no smoking, cholesterol/HDL ratio 5, systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg, BMI of 25 kg/m2), but leaving non-modifiable factors such as age, gender, diabetes and family history unchanged. The absolute change in predicted risk through risk factor optimisation was calculated as the optimised minus the predicted risk before risk factor optimisation.

A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.

Results

Practice and participant recruitment

Practice sizes ranged from 3070 to 16,746 registered patients; IMD scores ranged from 48.79 (least deprived) to 9.77 (most deprived). Details can be found in Appendix 2.

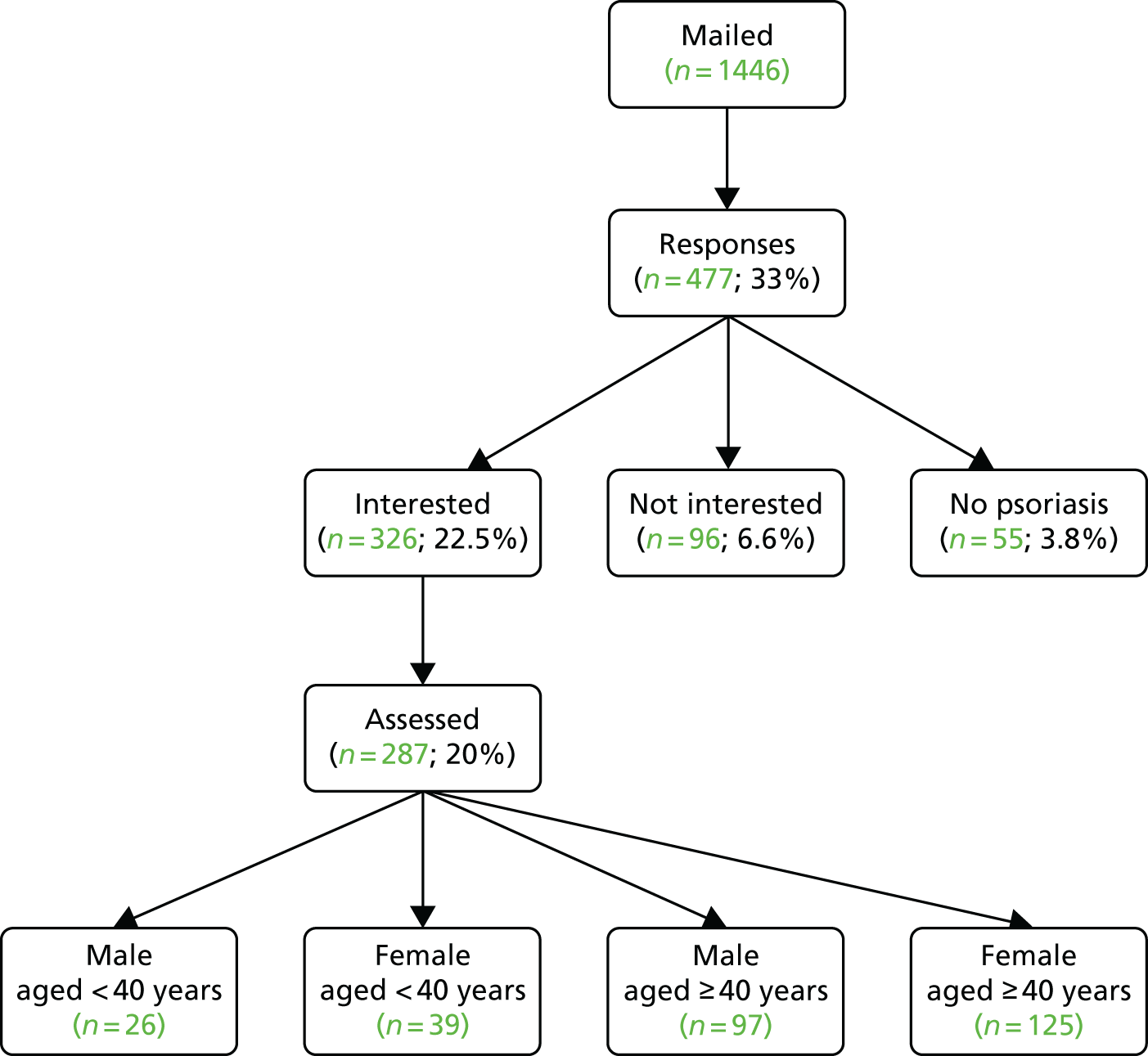

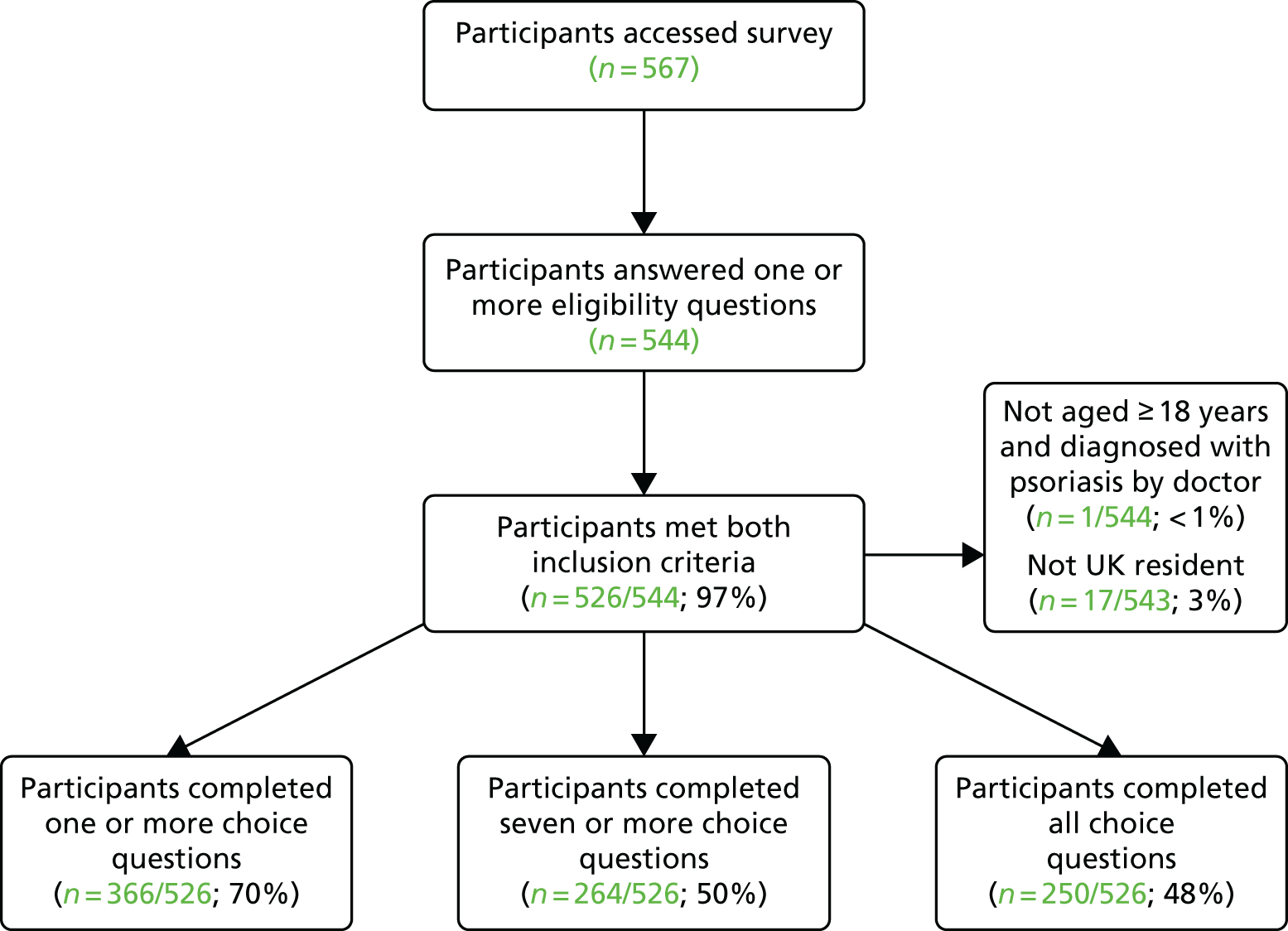

The process of participant recruitment is shown in Figure 5. A total of 1446 people with psoriasis were invited to attend for risk factor review, of whom 287 (19.8%) completed the review.

FIGURE 5.

Flow chart of responses.

Nine practices (P1, P2, P4, P5, P6, P7, P8, P12 and P13) provided more detailed information about patient response to the screening invitation, permitting a breakdown of response rates by patient age and sex (Table 2). Acceptance rates were lower among younger (< 40 years) than among older (≥ 40 years) patients; there were no appreciable differences by gender.

| Patient sex, age (years) | Invited (n) | Attended (n) | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, < 40 | 231 | 25 | 11 |

| Female, < 40 | 209 | 39 | 19 |

| Male, ≥ 40 | 346 | 82 | 24 |

| Female, ≥ 40 | 444 | 117 | 26 |

| All patients | 1230 | 263 | 21 |

Of those screened, 173 (60%) patients were invited to a follow-up appointment by their practice, 109 patients were not given a follow-up appointment and the outcome for five patients was unknown.

Nearly one-quarter of participants had severe psoriasis and around one-third were clinically obese. One-third of participants self-reported high cholesterol levels and high blood pressure and over two-thirds of these people were receiving medication for these conditions (lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medications). A history of coronary or cerebrovascular disease or AF was self-reported by < 10% of participants.

We found that nearly half the cohort had at least one screen-detected risk factor and one-fifth had two or more risk factors for CVD. There was no evidence that the prevalence of screen-detected risk factors varied by age, psoriasis severity or the presence of self-reported PsA. Comparison with the weighted HSE data suggests differences between our study participants and the general population on one risk factor (where p < 0.001). Hypertension was higher (p < 0.001) in study participants than in the general population. This applied to the full cohort (n = 287) and the subset of people (n = 269) who were not taking ciclosporin, which can cause hypertension.

Among the study participants receiving treatment for CVD risk factors, nearly half (46%) had suboptimal therapy levels for blood pressure and/or total cholesterol and one-quarter (26%) of participants had suboptimal levels for glucose assessed by HbA1c.

In our study, just over one-third of participants not already considered ‘high risk’ according to NICE guidelines were assessed to be at high risk of CVD using the 10-year risk threshold of > 10% (QRISK2). 53 The mean predicted lifetime CVD risk estimated by QRISK2 was 35%. Thirteen per cent of participants had a high lifetime CVD risk of > 50%. After adjusting for age, there were no statistically significant differences in CVD risk between participants who had severe psoriasis and self-reported PsA and those without these conditions.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first UK primary care-based study to report that CVD risk factor screening augments the estimated prevalence of CVD risk factors in psoriasis, and it is the first study to assess lifetime CVD risk and the potential benefits of optimising modifiable CVD risk factors. We have shown that the proportion of patients with screen-detected CVD risk factors was unrelated to age, psoriasis severity or the presence of self-reported PsA. When known and screen-detected risk factors were considered, hypertension was more prevalent in patients with psoriasis, in keeping with data from two other studies. 53,71

Although we had an adequate sample size, we did not show statistically significant differences in the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of obesity, smoking or diabetes compared with the general population. Although more than one in three participants (37%) were at high 10-year CVD risk, only one in eight (13%) participants overall had a high lifetime risk of > 50%. Therefore, the estimation of lifetime risk does not appear to be particularly beneficial in patients with psoriasis.

We observed many patients with suboptimal management of known risk factors. Previous studies have shown undertreatment of CVD risk factors in patients with psoriasis72 and one study suggests that hypertension is more difficult to manage in these patients,73 perhaps because psoriasis or its treatment somehow increases blood pressure or reduces concordance with therapy.

A few studies have reported the prevalence of screen-detected CVD risk factors in patients with psoriasis in highly selected patient groups. 74–77 Several large studies, some of which were population based,23,78 have reported a higher prevalence of known CVD risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, obesity, smoking, renal disease and metabolic syndrome. 23,78–82 However, control groups in these studies included people with ‘forms of dermatitis’,81 other hospitalised patients77,82 and people taking part in other research projects,77 which makes interpretation, comparison and clinical implications challenging. Other studies have reported the prevalence of known CVD risk factors in patients with psoriasis but without a control group. 83,84 Our study demonstrated that using a standard approach to CVD screening of patients with psoriasis who attend primary care is an effective means of identifying individuals with CVD risk factors who would have otherwise been missed.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include (1) we selectively sampled practices across a broad range of socioeconomic settings to ensure a meaningful sample size in four age/sex subgroups; (2) the prevalence of important CVD risk factors was established with clinically meaningful precision in these subgroups; (3) we reported how CVD risk factor screening, when added to information on known risk factors, influenced the detected prevalence of CVD risk factors; (4) we used QRISK2 to estimate the 10-year risk of CV events in patients with psoriasis not already judged to be at high CVD risk; (5) psoriasis severity was assessed; (6) we compared prevalence data to population-based controls matched for age, sex and ethnicity; (7) we assessed the benefits of optimising risk factors within 10-year and lifetime time frames; and (8) these data can be used to inform policy on primary care-based risk factor screening.

Limitations of the study include (1) risk factors were measured on one occasion, which may have led to some misclassification; (2) we did not validate diagnoses of psoriasis or PsA; (3) our cohort was largely white, limiting the generalisability of findings; (4) the participation rate was 20%; and (5) men aged < 40 years were under-represented. We suspect that patients who did not participate would be more likely to have an adverse risk factor profile than those who enrolled. Response rates were lower in men than in women, suggesting that men would be less likely to attend for routine screening, even though, being at higher risk, they are more likely to benefit from intervention.

Clinical implications

Cardiovascular risk factor screening is a means of identifying a high proportion of patients (1) at high CVD risk, (2) with screen-detected risk factors and (3) with suboptimally managed known risk factors. ‘Health checks’ have recently come under criticism for failing to improve long-term health outcomes,85,86 perhaps because of overmedication or social class biases in attendees. 87 An alternative explanation has been made by our research team in a parallel study that recorded and analysed CVD consultations (see Cardiovascular disease risk communication and reduction in psoriasis). The study found that risk information was seldom discussed with patients; instead, practitioners prioritised information collection (see Cardiovascular disease risk communication and reduction in psoriasis). 88 Thus, although the current study has shown that screening identifies modifiable CVD risk factors, caution is required before recommending this as a strategy.

Accordingly, our findings in this study need to be considered alongside those showing limited response of clinicians to identified risk before universal CVD screening for people with psoriasis can be recommended. 88

Workstream 2.i substudy: assessing the impact of psoriasis severity on artery health (pulse wave velocity)

Background

As already stated, emerging evidence indicates that there is an association between psoriasis and CVD. 18,89–93 Arterial stiffness is an important surrogate marker of CVD and can be assessed non-invasively at the brachial artery by measuring the velocity of the arterial pulse wave occurring after cardiac contraction. This measurement is known as the PWV94–96 and is a strong predictor of CV events and all-cause mortality. 97

We have previously shown that patients with PsA have a higher risk of CV events than the general population. 30 Measurements of arterial stiffness could identify patients at higher risk of CVD and be incorporated in screening algorithms to identify individuals for more intensive risk factor intervention. Previous studies have indicated that psoriasis is associated with increased arterial stiffness and arterial stiffness has been found to be higher in patients with PsA than in the general population. 98,99 However, no study has either assessed whether or not arterial stiffness is related to the presence of PsA in a cohort of patients with psoriasis or related the age at onset of psoriasis or its severity to arterial stiffness.

Aims

To assess whether PWV is related to (1) the severity of psoriasis, (2) the presence of PsA and/or (3) the age at onset of psoriasis.

Method

Selection of participants

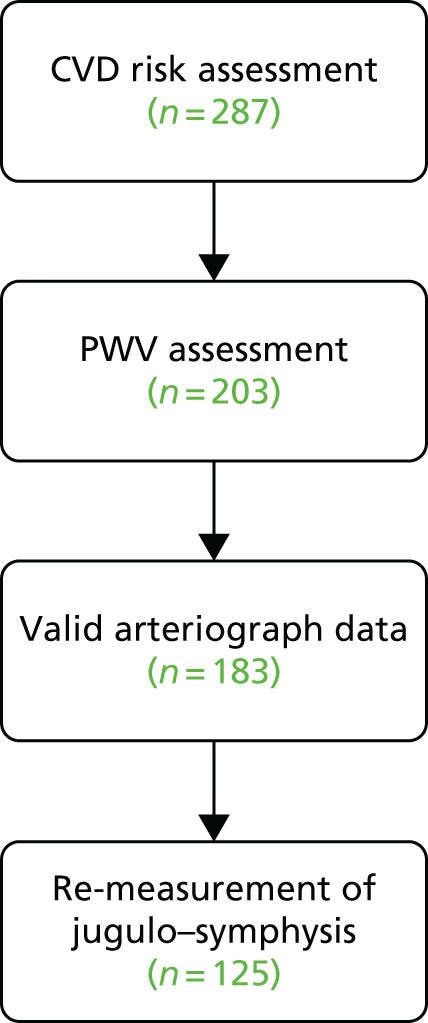

Thirteen general practices across north-west England identified patients with psoriasis and invited them for a CVD risk assessment (study 2.i). This PWV substudy recruited from the 287 people who attended the CVD risk assessments (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Recruitment to PWV substudy.

Data collection

Patients attended their own general practice surgery or a local dermatology research department for PWV measurement. Haemodynamic factors, including PWV, were measured using an arteriography device. 100 In addition, a research nurse also conducted a skin assessment using the PASI and patients completed the Simplified Psoriasis Index (SPI)101 assessment. Data on CVD risk factors, and other relevant demographic and medical data, were collected as described in Screening for cardiovascular disease risk in primary care.

The PWV data for the study were collected by four research nurses using three arteriography devices. Early analysis and reliability testing revealed that there was no significant difference in measurements between devices, but there was a significant difference between individual nurses’ measurements (between-observer and within-observer variation); the differences were accounted for by inconsistency in the calliper measurement between the suprasternal notch and the symphysis pubis, known as the jugulo–symphysis measurement used in the calculation of PWV. To reduce observer error and to improve the accuracy of this study, the jugulo–symphysis distance was remeasured in as many participants as possible by a single research assistant.

Data handling

All data were entered into a study-specific database by the research nurse conducting the assessment or by a researcher who entered the data from the hard copy of the information collected by the research nurse. All data were double-checked for correct entry.

Data analysis

As PWV was skewed, it was log-transformed before analysis. Linear regression was used to assess the associations between PWV and CV risk factors, with log PWV as the outcome variable. Severe psoriasis and PsA were also evaluated as potential determinants of PWV: severe psoriasis was defined as Self-Administered Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (SAPASI)102 score of > 10 or use of a disease-modifying therapy [psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA), methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin, fumaric acid esters, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab or ustekinumab]. Psoriatic arthropathy was defined as positive responses to any three out of the first five Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool questions or a positive response to the question ‘Have you ever been told that you have arthritis associated with psoriasis?’.

Relationships between arterial stiffness and measures of psoriasis were adjusted for traditional CVD risk factors, psychological variables and the presence of PsA (when appropriate).

Data analysis was performed using the Stata 13 package. Two-tailed p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Sample size

In a small study of 52 patients and 50 controls, Yiu et al. 103 showed that patients with psoriasis had higher PWV than control participants [mean 14.5 m/second (SD 2.5 m/second) vs. mean 13.2 m/second (SD 1.6 m/second), respectively; p < 0.01]. Using this difference in means (1.3 m/second) and the SD data provided, we would have 87% power to detect this difference (two-tailed, p < 0.05) with 50 individuals in each group. Therefore, a sample size of 102 (52 patients and 50 controls) would be adequately powered to demonstrate a 1.3-m/second difference in PWV between study groups. This difference in PWV is likely to be clinically important; a recent meta-analysis has suggested that an increase in aortic PWV of 1.3 m/second would be predicted to be associated with a multivariable-adjusted risk increase of 18% for total CV events and 20% for CV mortality and total mortality. 97

Our assessment included multivariable-adjusted analysis including several continuous and categorical covariates [psoriasis (yes/no), QRISK2, HbA1c, metabolic syndrome (yes/no), physical activity, depression], which increased the sample size by a modest amount.

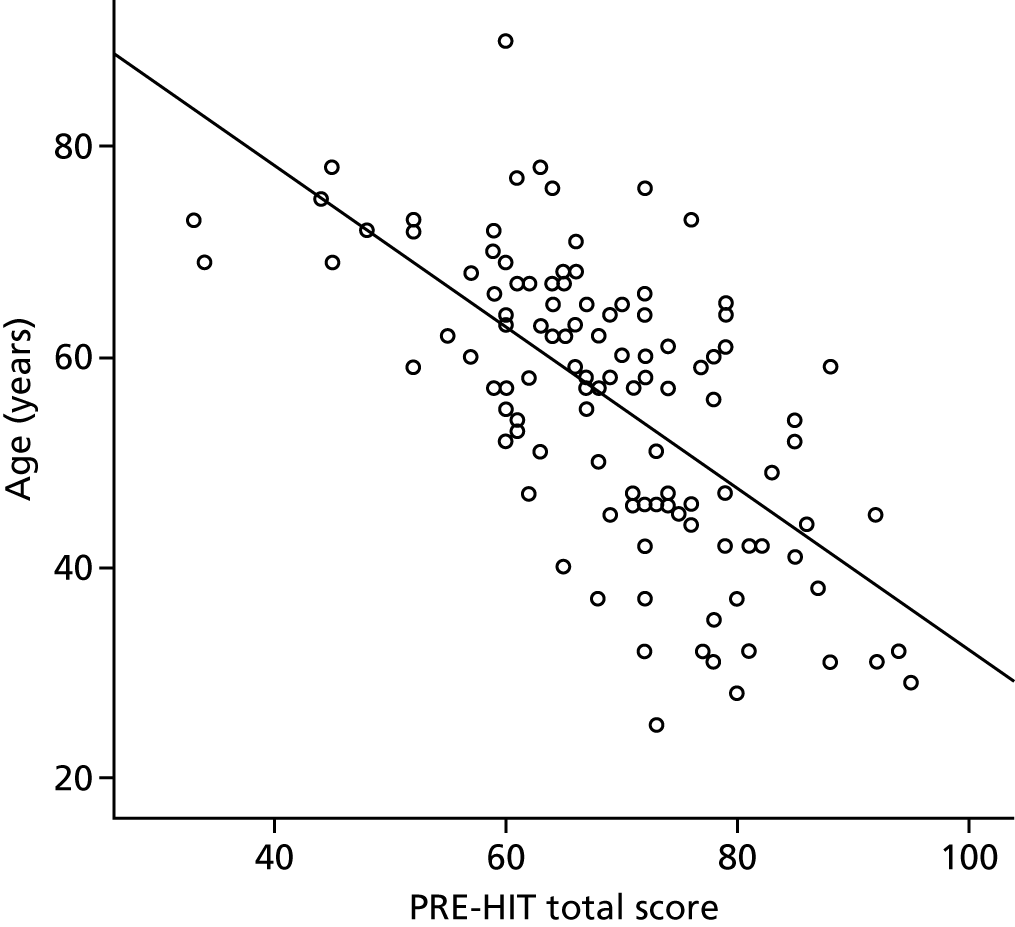

Results

A total of 125 subjects were recruited: 66 female and 58 male. The median age was 58 years [interquartile range (IQR) 45–66 years]. There were 27 subjects with severe psoriasis and 44 with PsA. The median SAPASI score was 3.6 (IQR 1.4–6.2).

Mean PWV was 8.83 m/second (95% CI 8.08 to 9.58 m/second) in subjects with severe psoriasis and 8.80 m/second (95% CI 8.40 to 9.19 m/second) in those without; the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.9). Controlling for CV risk factors as psoriasis-associated factors had little effect on the difference between these two groups (see Appendix 3, Table 12). PWV was significantly higher in subjects with PsA (mean 9.34 m/second, 95% CI 8.74 to 9.95 m/second) than in those without (mean 8.52 m/second, 95% CI 8.11 to 8.93 m/second; p-value for difference = 0.03). However, controlling for age and sex reduced the difference between the two groups until it was no longer statistically significant. The difference remained non-significant after controlling for CV risk factors and disease characteristics (see Appendix 3, Table 13).

There was no significant association between PWV and SAPASI score (p = 0.23). However, after controlling for age and gender, PWV increased with increasing SAPASI score (increase of 1.1% per unit increase in SAPASI score, 95% CI 0.3% to 1.8%) because the higher SAPASI scores tended to occur in younger subjects. This association was reduced to a non-significant level by controlling for CV risk factors (see Appendix 3, Tables 12–14).

There was a tendency for PWV to be higher in subjects with a higher age at onset of psoriasis (p = 0.001), but this effect became non-significant after controlling for age. Controlling for CV risk factors and psoriasis-related factors had no further impact on this association.

Conclusions

Main findings

There was no significant relationship between arterial stiffness and either the severity of psoriasis or patient age at onset after adjusting for age. This is in contradiction to other, smaller, studies that appeared to demonstrate a positive association between increased arterial stiffness and psoriasis. 103–105 Patients with PsA had higher levels of arterial stiffness and were older than patients without the condition, but this relationship became non-significant after adjusting for age. It is likely that the current study is a true representation owing to the removal of confounders and the larger sample size.

Clinical implications

The results suggest that patients with either severe psoriasis or early-onset PsA do not have higher levels of arterial stiffness than those with clinically less severe disease. The results do not support screening patients with psoriasis for arterial stiffness as a means of identifying individuals at high CVD risk. However, patients with psoriasis do have an increased prevalence of traditional risk factors and comorbid conditions associated with CVD. Thus, this still suggests that lifestyle modification and behaviour change to reduce acquired risk factors for CVD are an important part of managing psoriasis patients.

Strengths and limitations

The study involved a large, well-characterised patient cohort; however, the absence of a control population without psoriasis means that there was potential for limited statistical power to identify significant relationships.

Key conclusions

-

Screening for CVD risk factors in patients with psoriasis identified that approximately 40% of individuals were at high (> 20%) CVD risk over the next 10 years and had potentially modifiable CVD risk factors.

-

Management was suboptimal in a high proportion of patients with known risk factors.

-

In a group of patients with psoriasis, disease severity, age at onset of psoriasis and the presence of PsA were not independently related to higher levels of arterial stiffness.

-

There was no increased prevalence of raised arterial stiffness in patients with psoriasis or PsA.

Implications

-

These data provide valuable augmenting information about the prevalence of CVD risk factors and the potential value of primary care-based screening of patients with psoriasis.

-

It is important to intervene early to identify or prevent the development of poor lifestyle behaviours in patients with psoriasis with appropriate lifestyle management and behaviour change interventions.

-

Such interventions will, in turn, not only militate against development of CVD, but optimise psoriasis outcomes and improve the management of psoriasis per se (e.g. as has been shown for weight reduction).

-

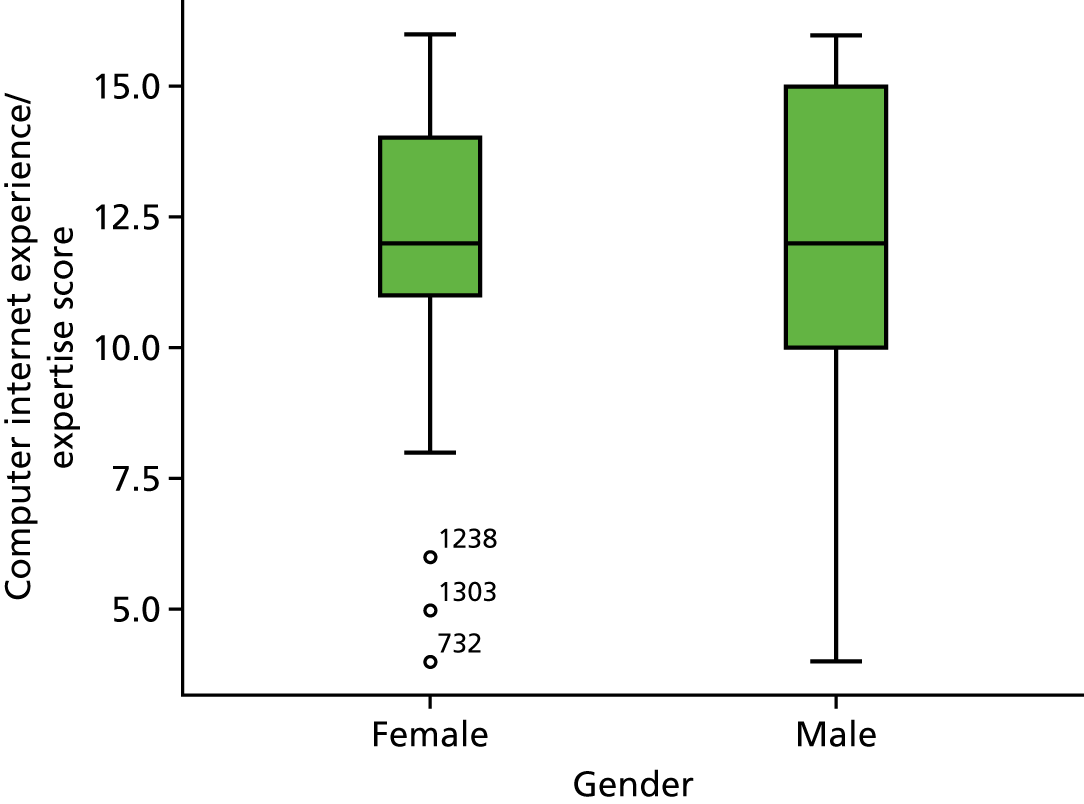

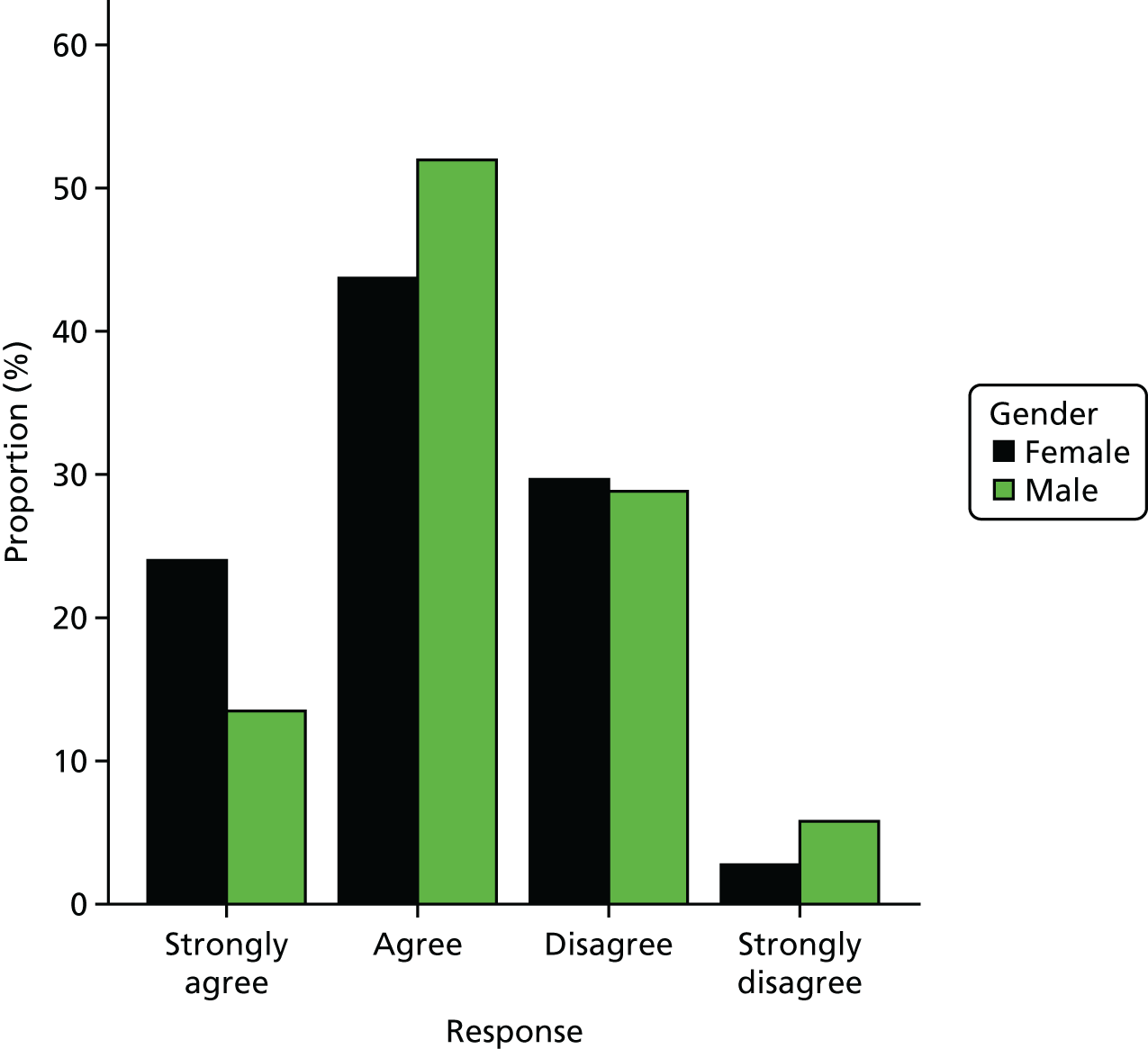

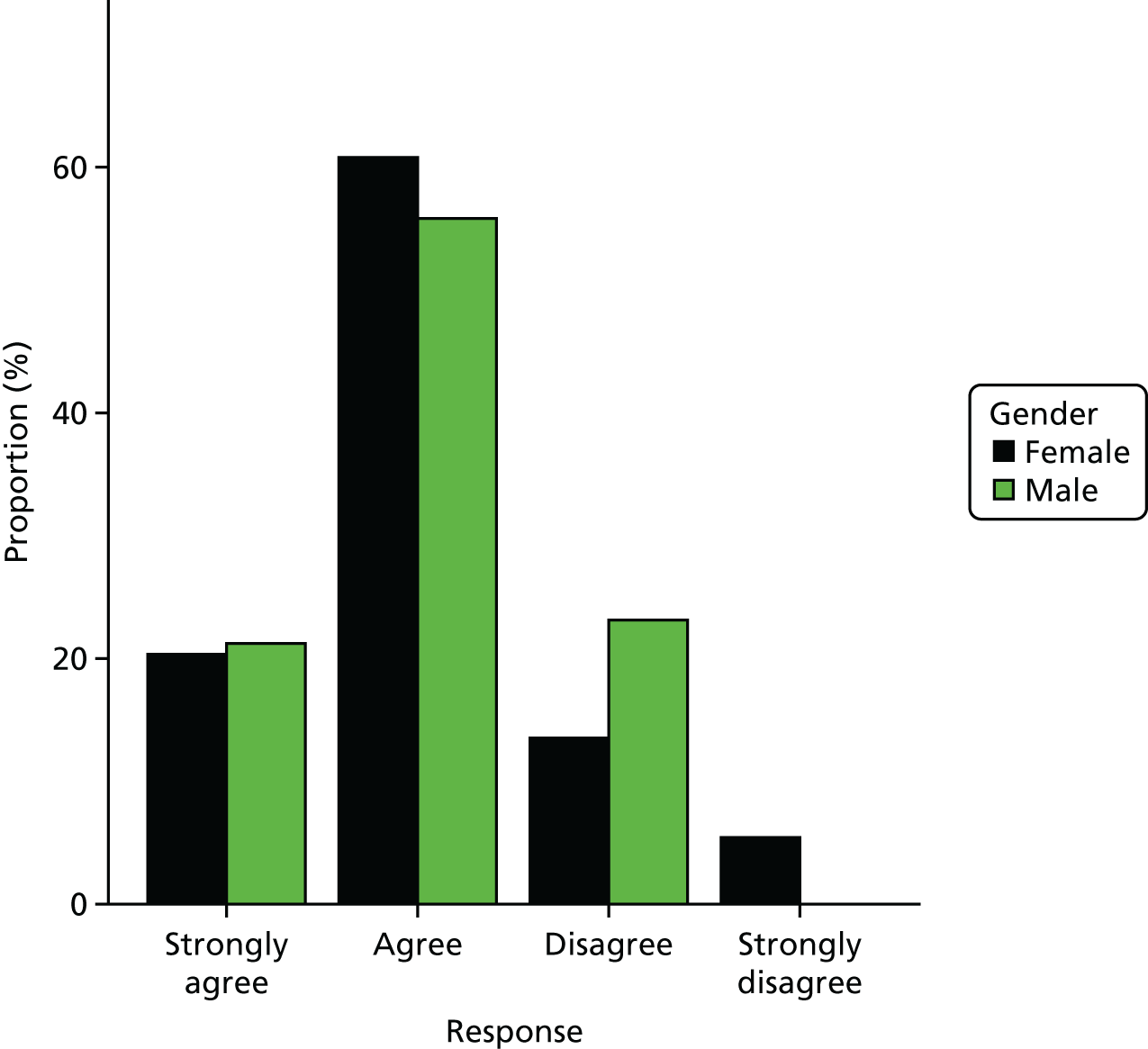

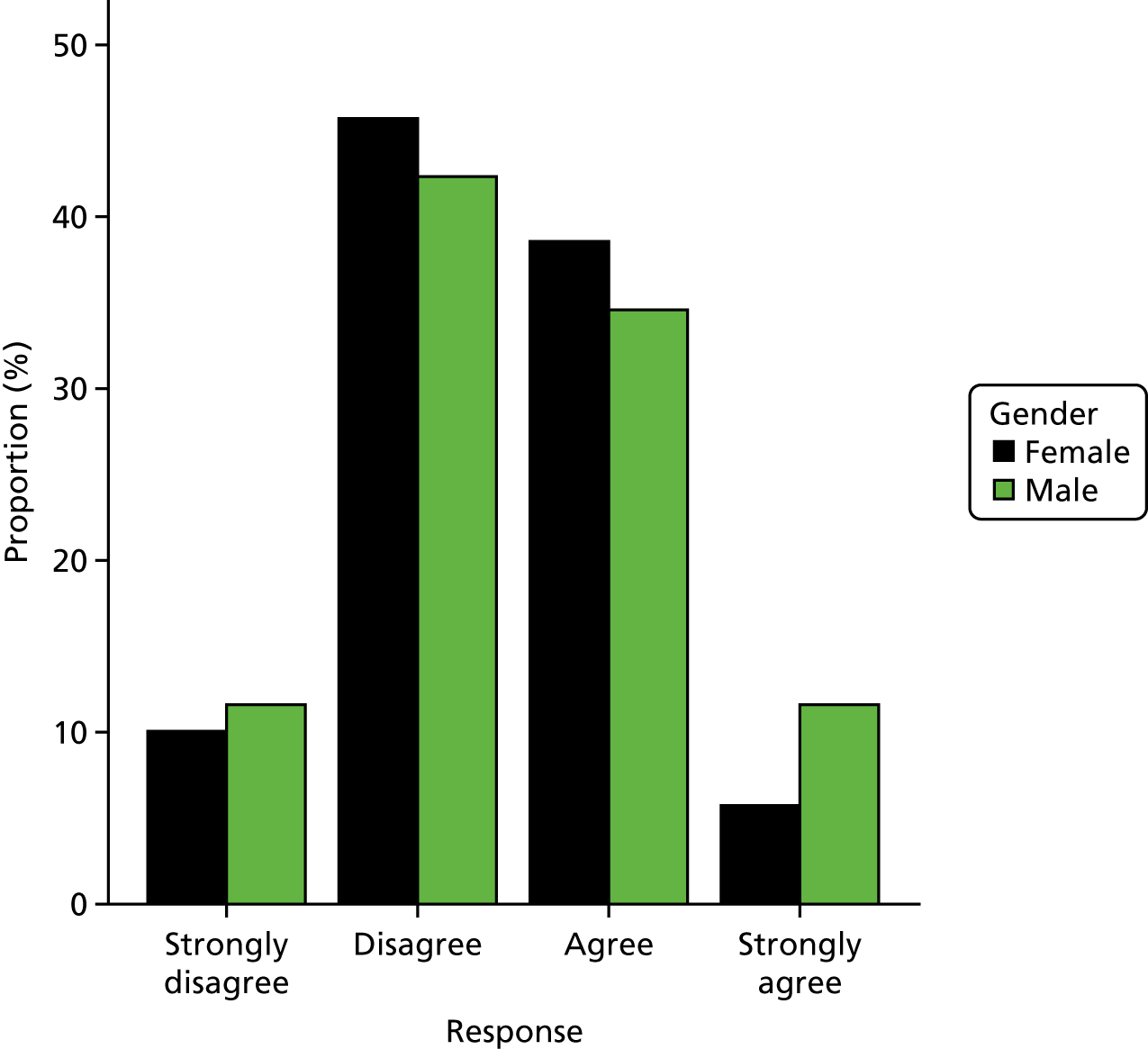

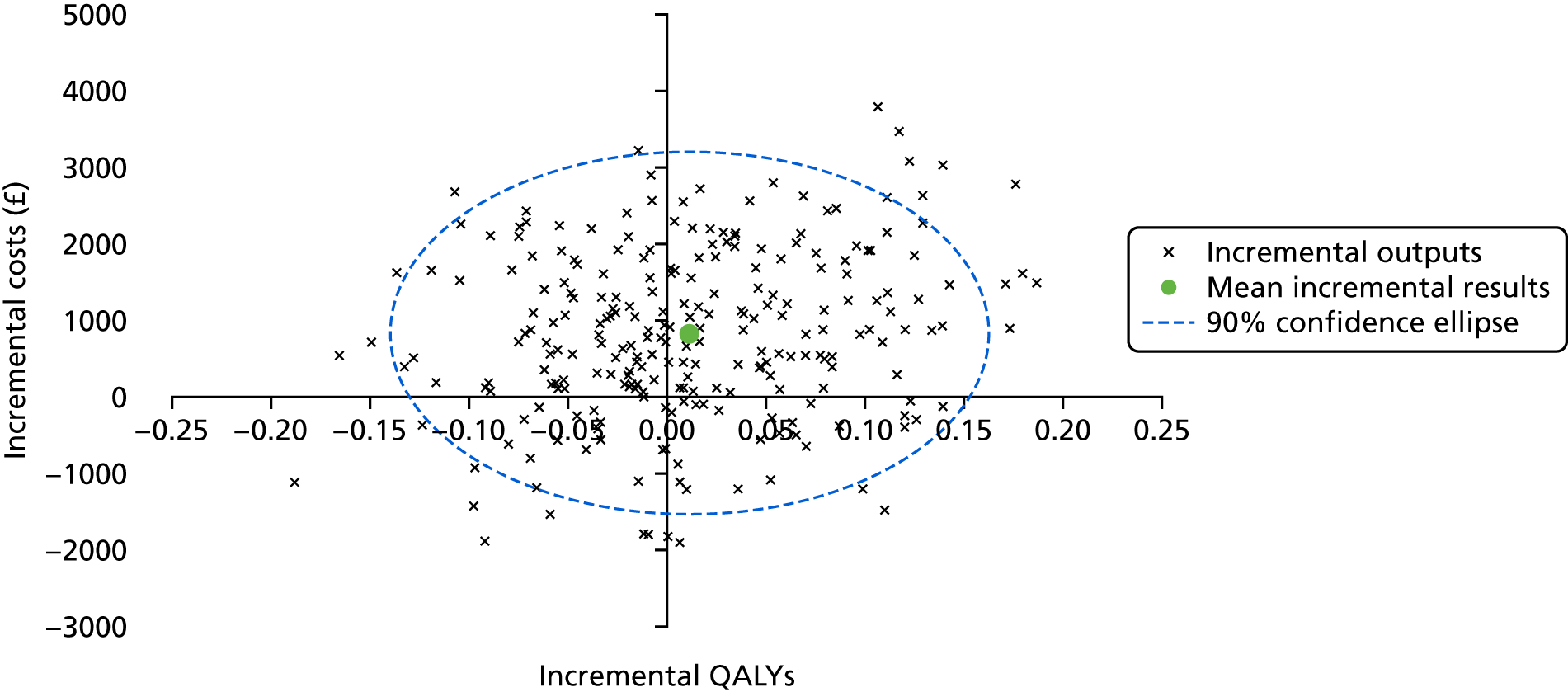

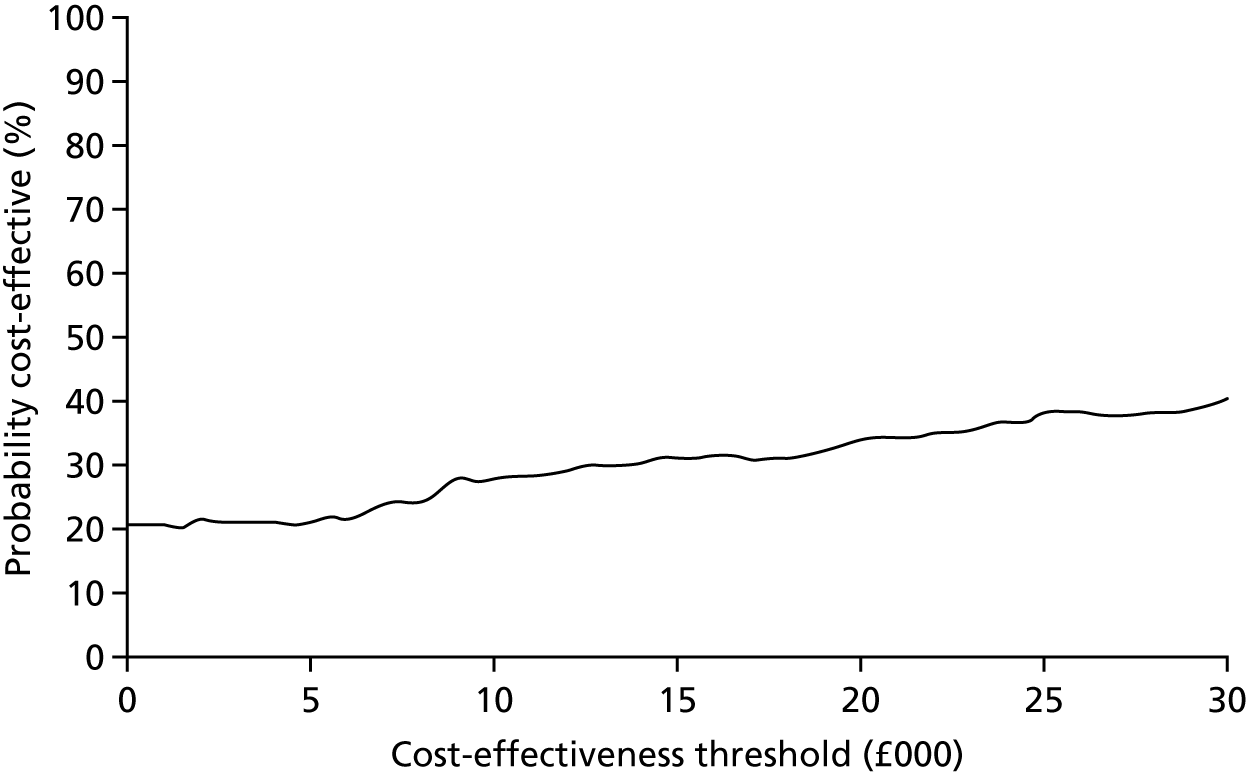

There is no support for screening for arterial stiffness in clinical practice.