Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1109. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in September 2012 and was accepted for publication in March 2013. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Challis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the programme of work contained in this report and sets the current provision of specialist mental health services for older people in the context of their development from the late 1960s to the present day. It also highlights the marked lack of evidence currently available to inform service planning for this client group.

ObjectivesIn this context, the chapter sets out the three fundamental concerns the programme sought to address. These were the best combination of inpatient, residential and community services to provide for older people with mental health problems; the factors that make for the effective working of community mental health teams for older people (CMHTsOP); and the quality and quantity of mental health support provided to older care home residents. A trial of depression management in care homes as part of the third objective was removed at review by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) prior to the award of funding.

Background

This study addresses the urgent need for better evidence to inform the provision of care for older people with mental health problems, a significant and growing group whose care costs constitute a substantial proportion of the health and social care budget. Entitled National Trends and Local Delivery in Old Age Mental Health Services, the research explores the most appropriate and cost-effective ways of organising and delivering care for this client group at the macro (strategic planning) and mezzo (provider unit) levels, locally and nationally.

The rising number of older people in the UK presents a considerable challenge to policy-makers, commissioners and service providers nationwide. More than 10 million people in the UK are aged ≥ 65 years, and this figure is anticipated to rise by almost two-thirds in the next 20 years. Moreover, the fastest growth in numbers will be among the ‘oldest old’, the biggest users of care services. Population projections suggest that by 2033 the number of people aged ≥ 85 years will have doubled. 1,2

Although many older people will lead healthy, fulfilling lives, increasingly involving work or roles as volunteers or carers,3,4 this demographic change will have a significant impact on the ability of services to meet the needs of older people with mental health problems, not least because the prevalence of dementia increases exponentially with age. Some 5% of the population aged > 65 years and 20% of those aged > 80 years have dementia, while approximately 15% of all older adults have depression. Others are affected by anxiety, schizophrenia, paranoid states and substance misuse. 5–7

Such disorders carry very high costs, both personal and economic, for many are subject to relapse or of long duration. Mental health problems can affect every aspect of a person’s functioning, exacerbate physical ill health and cause significant personal and family distress. 7,8 They are also associated with increased service use. 9,10 Relatively conservative estimates suggest that 40% of older adults visiting their general practitioner (GP), 50% of general hospital inpatients and 60% of care home residents have a mental health problem,11 and older people with mental illness make greater demands on home care services than the older population as a whole. 12–14 Indeed, the total economic costs of dementia have been put at £23B per year,15 more than the annual cost for stroke, cancer and heart disease combined. 16 This provides a marked incentive to make the best use of resources, particularly in a climate of economic constraint. 17

Although old age psychiatry was not formally recognised as a specialty within the NHS until 1989, the need for specialist services for older people with mental health problems was first recognised in the 1940s, prompted by the already increasing number of older people, the differentiation of clearly demarcated syndromes of psychiatric disorder in later life and the inadequacies of care in long-stay institutions. 18–21 Until then older people with mental health problems had generally been cared for by general psychiatrists, but in the late 1960s and early 1970s the first consultant psychogeriatricians were appointed and reports of specialist services began to emerge. 20,22,23 Steady service development followed, and by 1980 there were approximately 120 consultant psychiatrists with a substantial time commitment to the care of older people. Many of these staff were based in hospitals, with beds in long-stay wards and a high proportion of chronically ill patients. 24

The pattern of service development over subsequent decades reflects a move away from the medical assessment of patients in largely hospital-based services towards the multidisciplinary assessment, treatment and support of patients in predominantly community-orientated services. 25 This shift was in keeping with the growing policy imperative for community care,26–28 and was stimulated by a variety of considerations including costs and cost-effectiveness,10,29 with institutional care generally perceived to be more expensive than care in the community. 30 There was also a growing belief that most older people, including those with complex needs could, and would rather be, cared for in their own homes. 10,31 However, such preferences are themselves likely to be influenced by the relative availability and quality of care in different settings, the availability of informal care, and cultural expectations about family obligations and personal cost. 32

As the number of NHS hospital beds fell throughout the 1980s, the care home sector grew, boosted by a paradoxical financial incentive whereby people eligible for supplementary benefit could have their care in private and voluntary sector homes funded through income maintenance support with no medical or social work assessment required. 33–35 The resulting concerns about service funding and organisation led to the 1990 NHS and Community Care Act,36 which stressed the role of local authorities as arrangers/purchasers rather than providers of care and highlighted the need for a comprehensive review of individuals’ health and social care needs before admission to long-term care. Mechanisms to increase choice and flexibility, match services with need, and promote accountability and quality were described, and a special transitional grant was made available to fund community care packages as well as care home placements. 33,35,37–39 Designed as a corrective to the institutional bias of the previous decade, by the mid-1990s dependency levels in residential settings were considerably greater than in the mid-1980s40 and have risen further since. 41,42

Despite little government guidance on the role of mental health services for older people, specialist services continued to grow rapidly throughout the 1980s and 1990s. 43,44 The dominance of ‘the medical model’ declined further, and an increasing emphasis was placed on the need for health and social services to work together. 3 By the end of the twentieth century, localities aimed to offer mental health services that were ‘comprehensive, accessible, responsive, individualised, multidisciplinary, accountable and systematic’. 44 However, many areas could not live up to such aspirations, and variation in service practice was deemed likely to have a negative impact on equity, efficiency and patient outcomes. 43,45–47

The publication of the National Service Framework for Older People (NSFOP) in 200131 and a string of linked initiatives11,48,49 were widely welcomed as an attempt to address these inconsistencies and improve the quality of care. Outlining a 10-year programme of reform, the NSFOP aimed to deliver fair, integrated and high-quality services based on eight national standards, one of which concerned the provision of care for older people with mental health problems and their carers. Integrated health and social care services, including a broad range of hospital- and community-based facilities, were to deliver effective diagnosis, treatment and support. 31 Multidisciplinary community mental health teams for older people (CMHTsOP) were given a key role in the provision of specialist care for people with severe or complex mental health problems at home, as well as providing support and advice to staff working in primary, care home and general hospital services. In comparison with the previously published framework for adults of working age, however, the framework contained less prescriptive models of service and no dedicated resources. 50

Despite such high ambitions, recent years have witnessed several reports expressing profound criticism of the care received by older people with mental health problems, including the ongoing difficulties of getting services to work together. 50–53 Although specialist mental health services have continued to grow, there remains significant disquiet about the degree of variation in practice and investment, whereas the ongoing efficiency savings demanded from local authorities have led to tighter eligibility criteria and fewer people receiving services. 2,54–56 The National Dementia Strategy was designed to address at least some of these concerns, and early priority has been given to the need to provide good quality diagnosis and intervention for all; improve the quality of care in general hospitals and care homes; and reduce the use of antipsychotic medication (a particular concern in care homes). 57–59 Although it has been argued that the primary function of long-stay facilities is to provide care for people with advanced dementia60 and the proportion of residents with depressive symptoms is also high,61–63 evidence suggests that care home staff are often ill equipped to meet such needs and that many mental health problems go undetected and undertreated. 63,64

The need for new research

Although a consensus exists on the need to improve mental health care for older people, and on its underlying principles, evidence on the relative clinical effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness of different service models is sparse. 7,65,66 Relatively few studies have made useful service comparisons enabling inferences to be drawn about the best ways of delivering care, and evidence from other countries with different service arrangements is not always transferable to the UK. 7,49 In the absence of clear evidence, local service development and commissioning have reflected both historical funding patterns and individual enthusiasm and commitment. 66,67 There is then an obvious need to help health and social care commissioners and providers make informed decisions about resource allocation and address any unwarranted variation in supply. 68,69 The programme of work detailed in this publication seeks to contribute to that process focused on three fundamental concerns at different levels of the health delivery system in England:

-

to refine and apply ‘the balance of care (BoC) approach’ (a systematic framework for choosing between alternative patterns of support by identifying people whose care needs could be met in more than one setting, and comparing their costs and outcomes) to the care of older people with mental health problems

-

to identify whether, how and at what cost the mix of services provided for this client group might be more optimally developed in a particular locality

-

to enable other health and social care decision-makers to apply the BoC framework independently

-

to identify core features of national variation in the structure, organisation and processes of community mental health teams (CMHTs)

-

to examine whether or not different CMHT models are associated with different costs and outcomes

-

to identify core features of national variation in the nature and extent of specialist mental health outreach services for older care home residents

-

to scope the evidence on the association between different models of outreach and resident outcomes; and

-

to disseminate the findings and service development tools from the work to NHS trusts, commissioners, local authorities and national policy-makers.

First, at the macro level, the programme examines the combination or mix of inpatient, residential and community services, health and social care, provided for older people with mental health problems, and whether or not the balance between them can be altered beneficially (workstream 1). As noted earlier, the configuration of supply and investment in localities varies and is subject to debate. However, there is relatively little evidence about the characteristics of those people who benefit most from different services or the relative cost-effectiveness of institutional and non-institutional care. 7,65,70 Against this background, Chapter 2 reports the findings of a systematic review of the past use of ‘the balance of care’ approach, which offers a systematic framework for choosing between alternative patterns of support by identifying people whose care needs can be met in more than one setting and comparing the costs and outcomes of different options. 71,72 Building on this, Chapters 3–5 outline the results of a new development to this approach and demonstrate its utility in planning care for older people with mental health problems through a detailed evaluation of the mix of services needed in three areas of north-west England.

Second, at the mezzo level, the programme explores the factors which make for the effective working of CMHTs for older people (workstream 2). The provision of integrated, multidisciplinary CMHTs has formed a central plank of mental health policy for older people with mental health problems. 11,31,48,57 However, although there is a modest evidence base to support a range of individual-level interventions undertaken by staff in such teams,7,65 comparatively little is known about the service design features or models of teams associated with better outcomes, or their relative costs. 49,70 To this end, Chapter 6 details the findings of a systematic literature review to establish the known nature and extent of variation in teams’ structures and processes over time, and the strength of the evidence-base linking variations in team approaches to service user, staff and service outcomes. This is complemented by the results of a national survey of the composition and working practices of contemporary CMHTs, and the findings of an evaluation of the relative costs and outcomes of different team models using a multiple case study approach (see Chapters 7–11).

Lastly, the programme provides a detailed picture of the support available to meet the mental health needs of older care home residents (workstream 3). Improving access to specialist care and advice for this population has recently become a prominent concern11,57 and many specialist services already provide support for care home staff. 73 However, relatively little is known about the quality and availability of the services they offer. This work seeks to address that gap and reports the findings of a systematic literature review that examined how the structure, organisation and activities of specialist mental health services vary in their provision of outreach to older care home residents, as well as the impact of such services on resident outcomes (see Chapter 12). This is augmented by the results of two national surveys, one of CMHTs outreach services, and one of care home managers (see Chapters 13 and 14). Although a proposed trial of depression management for older care home residents was not funded, this work provides a valuable scoping of a critically important area in old age mental health services.

In summary, the programme presents both national data that will act as a benchmark for future service development and monitoring, and new information on the most cost-effective ways of organising and providing services to facilitate evidence-based development. As befits complex evaluations, it displays a concern for both measurement and meaning, process and outcomes,66,74 and draws on a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. Given the breadth and depth of this programme, the material presented necessarily covers only a proportion of the work undertaken and forms just one element of a comprehensive dissemination strategy. Nevertheless, the findings will be useful to a range of different stakeholders, including service providers, commissioners, policy-makers, carers and older people themselves.

Chapter 2 The balance of care approach to health and social care planning: a systematic review of the literature

The ‘balance of care’ model, a framework for estimating the local economic consequences of adjusting the supply of health and social care services for specified client groups, has been widely used but with variations in methodology and application.

ObjectivesTo synthesise existing applications of the BoC model since its inception 40 years ago, and to highlight methodological lessons for future research.

MethodA systematic literature review adopted a bibliographic database search [MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Web of Science] for empirical applications of the BoC model, supplemented by hand searches and expert knowledge, with no restriction to jurisdiction, time or provenance.

ResultsForty-two papers were identified encompassing 33 separate studies, concentrated in the UK but showing an even spread over the past four decades. Most studies focused on older people’s services and on the margins between hospital, residential and community care. The review revealed a narrow approach to service costing: few studies considered the impact of changing the BoC on wider public agencies (e.g. housing/benefit costs) or informal carers. Furthermore, just eight studies made use of data on service user outcomes and there was a lack of clarity as to how this was incorporated into the BoC approach. More generally, the review found variation in reporting standards.

ConclusionsFuture studies should widen their scope, to incorporate a broader range of cost implications; more alternative care scenarios; and the potential benefits to service users/carers. Local practitioners and service users could be involved in developing alternative care options and establishing preferences for these.

Introduction, background and aims

The growing demand for public services alongside resource scarcity make the efficient use of available resources an increasing imperative. 75,76 Against this background, one longstanding issue has been the concern to provide the most cost-effective mix of hospital-based, residential and community-based services and to this end, the policies of many developed countries have converged, with each designed to reduce the growth of institutional care and promote the use of community support. 77 However, despite policy initiatives dating back to the 1960s, there remains considerable variation in the balance of resources invested in different services in different areas, and relatively few tools with which to evaluate the options for improvement. 26,27,78,79 The ‘balance of care approach’, a specific application of marginal analysis, which provides a systematic framework for exploring the potential costs and outcomes of changes in the provision of community and institutional services, offers the potential to examine service efficiency. 71,72

Although the origins of the BoC model have been attributed to a national policy analysis tool developed by the then Department for Health and Social Security (DHSS) in the early 1970s,80 over time the approach has taken on a number of manifestations, some more sophisticated than others. However, all are predicated on the belief that although resources are scarce, there are significant amounts of money that can be moved from one client group/service to another81 and are grounded in the principles of cost–benefit analysis. 82 Thus, they do not try to identify total need but instead ask whether or not any redeployment of available resources could increase total benefit. 71,80

At the heart of this approach is the identification of those people whose care needs could be met in more than one setting. Although it is generally accepted that there are some people for whom a particular location, say residential care, is the only appropriate one, the approach is particularly concerned with those individuals who could be supported in more than one setting, say residential care or extra care housing (ECH) (people ‘on the margins of care’). It then examines the costs and consequences of the possible alternatives with a view to informing the strategic planning process. The defining features of BoC studies are thus:

-

the identification and measurement of those client characteristics that affect decisions about where best to care for them (e.g. dependency and cognition)

-

the specification of resources and service inputs required

-

some means of allocating clients to the most appropriate setting; and

-

a determination of the relative costs (and ideally outcomes) of care in different settings. 71,72

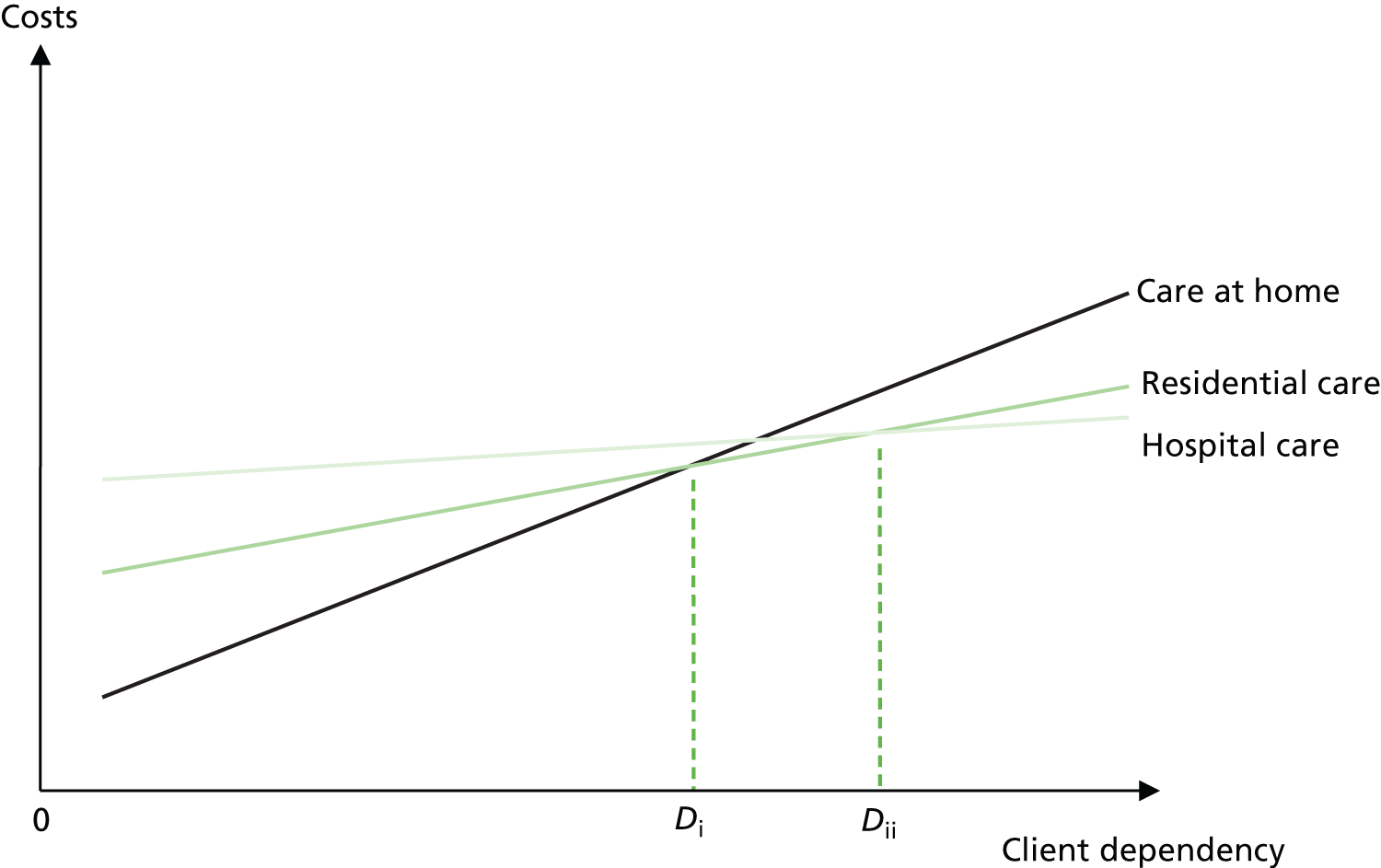

The central premises of the model are formally illustrated in Figure 1, in which the three upwards-sloping lines represent the association between the costs and characteristics of people supported at home, in residential care and in hospital. Each assumes that costs and dependency are positively correlated. However, their position and gradient differ, indicating that for people with low dependency, care at home is cheaper than residential care, which in turn is cheaper than hospital care, whereas for people with high dependency, this hierarchy reverses. Indeed, if the outcomes for people in all three settings were equally acceptable, the most cost-effective place to support people with low levels of dependency (between 0 and Di) would be their own homes, whereas for people with moderate dependency levels (between Di and Dii) it would be residential care, and for people with dependency levels greater than Dii, hospital.

FIGURE 1.

Costs by dependency for people at home, in residential care and in hospital.

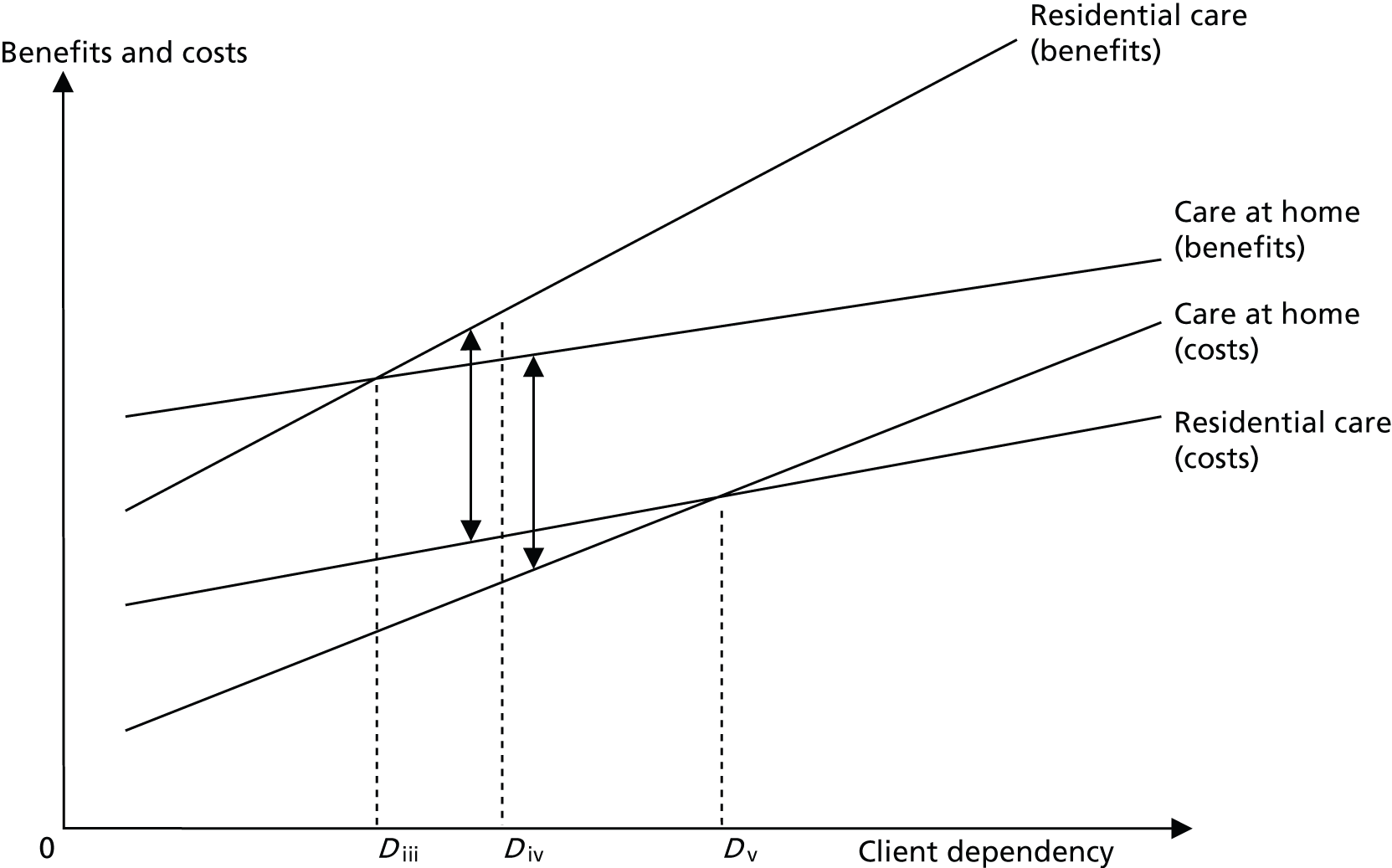

This is the BoC approach at its most basic. However, in reality people’s preferences for different modes of care vary and, following Knapp,83 Figure 2 thus considers marginal costs and benefits. In order to keep the diagram relatively clear, just two alternatives are shown.

FIGURE 2.

Costs and benefits by dependency for people at home and in residential care.

Although the lines representing the relationship between cost and dependency are the same in Figure 2 as in Figure 1, two new lines representing the relationship between benefit and dependency have been added. These are again assumed to be positively correlated, and, as with the cost-dependency lines, cross. Thus people with dependency between 0 and Diii gain more benefit from community services, whereas people with dependency higher than Diii gain more from residential care.

When considering both costs and benefits the situation becomes more complicated. Nevertheless, the most cost-efficient placement for people with dependency levels beneath Diii is clearly home, where the benefits are greater and costs lower than residential placement, whereas the most cost-efficient placement for people with dependency above Dv is residential care, where these arguments reverse. For people with dependency between Diii and Dv, however, residential care is more beneficial and more expensive, and it is the point at which marginal social cost equals marginal social benefit (Div) that determines the most cost-effective placement. For people with dependency below Div, this is care at home, whereas for people with dependency above Div, residential care is optimal.

Although not all applications have explicitly applied the above framework, over the years a number of BoC studies have been reported in the literature. This work is, however, not easy to access, for studies have been generated by a variety of organisations and span several decades. Moreover, no systematic review of the model’s use has been conducted, so an overall picture of past research that can inform its future application and development is lacking. This chapter was designed to fill this gap by identifying how key elements of the BoC approach have been operationalised and illuminating its strengths and weaknesses. The principal research question was ‘How has the BoC approach to health and social care planning been used over the past 40 years?’

Method

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was undertaken following established guidance. 84,85 An initial search for existing reviews was executed in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Health Technology Assessment database, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database and Social Care Online in June 2008. The following databases were then searched for individual studies on 22 and 23 October 2008, from the earliest to the most recent dates available: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), HEMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) and Web of Science. No attempt was made to limit the searches by language (although the search terms were in English), nor to a particular geographical location or time period.

The search strategy aimed to capture not only those studies that explicitly employed the BoC approach, but applications based on the same principles, and an iterative approach was taken to the identification of potential search terms to identify that combination yielding the greatest number of relevant publications. The final strategy sought references containing any of the following phrases:

-

‘balance of care’

-

‘margin(s) of care’

-

‘marginal analysis’ or ‘marginal analyses’,

in their title or abstract, as well as work citing Mooney, an early key exponent of the approach. 71,82,86 The Web of Science search also contained terms to limit the topic area to health/social care. An example is given in Appendix 1.

Additional searches for the term ‘balance of care’ were subsequently undertaken in the System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe; the websites of a number of specialist research centres and Google; the reference lists of relevant publications were scrutinised for further studies; and experts were asked to identify missing studies.

Study selection and data extraction process

The process of selecting studies had two stages. First, one researcher screened the titles and abstracts of all citations against the initial inclusion criteria (Box 1), while a second researcher confirmed the exclusion of each rejected reference. Where decisions were not clear, the full text was reviewed, and, if uncertainty persisted, this was resolved through discussion. One researcher then read the full text of the retained references and extracted data about the key characteristics of studies meeting the full inclusion criteria (in summary, empirical studies providing data about client characteristics, service use and costs). A second researcher confirmed the inclusion of, and independently extracted data from, approximately one-third of these references, and double-checked the inclusion of, and data extracted from, all other retained publications. They also confirmed the screening-out of each excluded reference, with any inconsistencies/disagreements again resolved by discussion.

Include: peer and non-peer-reviewed journal articles, books/book chapters, reports, discussion papers.

Exclude: other grey literature.

Study designInclude: all studies, empirical and non-empirical designs.

Focus of interventionInclude: references focusing on the prospective strategic planning of health and/or social care (including reports of implementation issues).

Exclude: references not concerned with any aspect of health or social care; descriptive accounts of past or current services; references concerned with a particular type of clinical care/treatment; references with a policy focus; references with a managerial/financial focus.

ParticipantsInclude: references concerned with the planning of care for any health or social care client group.

Exclude: references concerned with individual care planning for specific patients.

Outcomes: no outcome criteria will be applied.

Second screen Study designInclude: empirical studies and other applications.

Exclude: non-empirical work, including descriptive accounts of planning models, their development, limitations and assumptions.

Focus of interventionInclude: studies that can contribute to planning decisions by simulating resource allocation options AND draw on data about client dependency AND draw on data about service receipt AND provide information about the relative costs of care in different settings.

Exclude: studies utilising other approaches to health and social care planning.

A standardised electronic form based on guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination85 was used to extract all data. This was tested and refined on a sample of five studies before full data extraction began. It contained 15 domains covering studies’ aims, settings, populations, data collection processes, analyses and conclusions (see Appendix 2).

Quality assessment

Two researchers working independently and then together determined the extent that the reported studies exhibited a number of features of good practice. These were drawn from established criteria for systematic reviews and economic evaluations, reporting standards for economic submissions to major health and social science journals and expert opinion85,87,88 (Box 2) and included questions about studies’ design, conduct and analysis. Clear coding guidance was given (see Appendix 3). Where two or more publications related to a single study, these were considered both separately and together, resulting in two sets of codes, by reference and by study.

-

Was the purpose of the study clear?

-

Was the number of cases the analysis was based on large enough to instil confidence in the results?

-

Were the cases the analysis was based on broadly typical of the population of interest?

-

Where decisions about care were based on case types, did these have face validity?

-

Were those service user characteristics most likely to be important in determining individuals’ placements/care packages considered?

-

Was the approach to costing comprehensive?

-

Were the cost data used valid?

-

Was the approach to costing fit for purpose?

-

Were the dates to which resources and prices referred reported?

-

Were appropriate adjustments made for inflation?

-

Was there any attempt to investigate cost shifting?

-

Were any outcomes measured/considered?

-

Where decisions about alternative care packages were not based on research or policy, were they made by appropriate personnel?

-

Was there an attempt to optimise the care provided?

-

Were sensitivity analyses conducted to investigate uncertainty in estimates (of costs or consequences) and test the robustness of the results?

-

Were key assumptions noted?

Lastly, four summary measures were constructed to depict the proportion of good practice indicators

-

exhibited by

-

not applicable to

-

not clearly described in, or

-

not exhibited by,

for each study. In essence, these counted the number of responses in each category and expressed them as a percentage of the total.

Results

Included/excluded literature

The search for systematic reviews identified no relevant publications. However, a small selective review of past BoC studies undertaken by one of the authors helped conceptualise the current review. 72

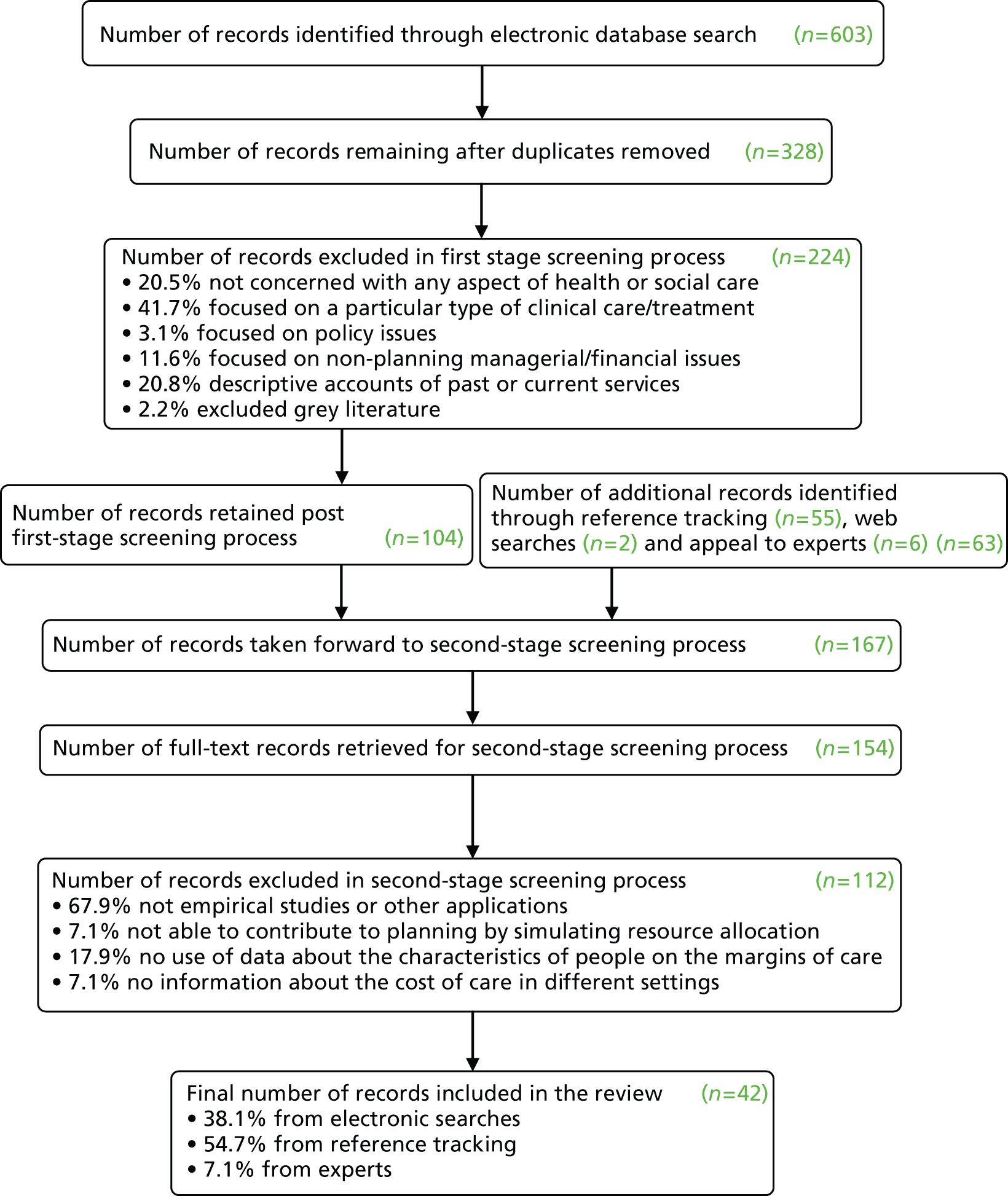

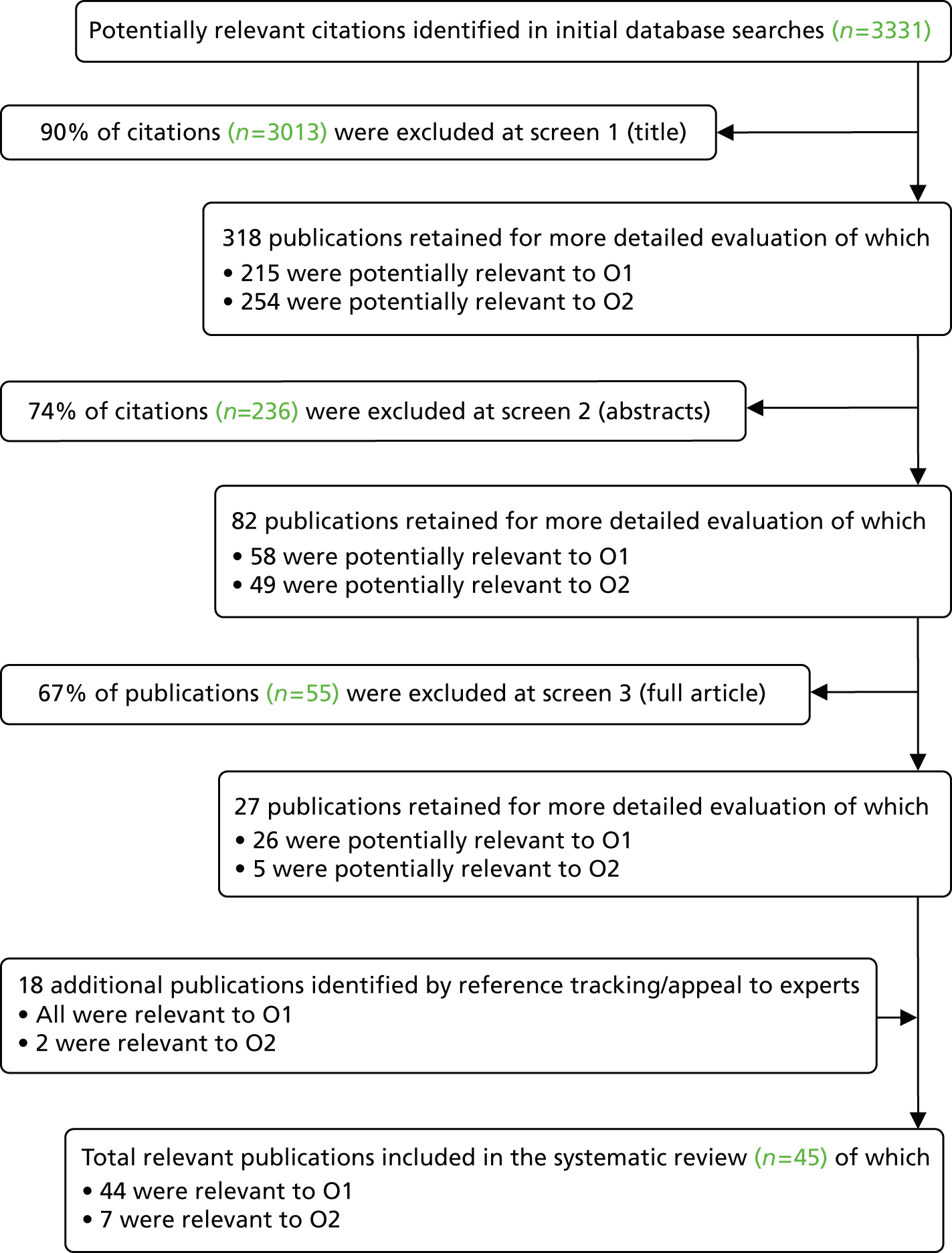

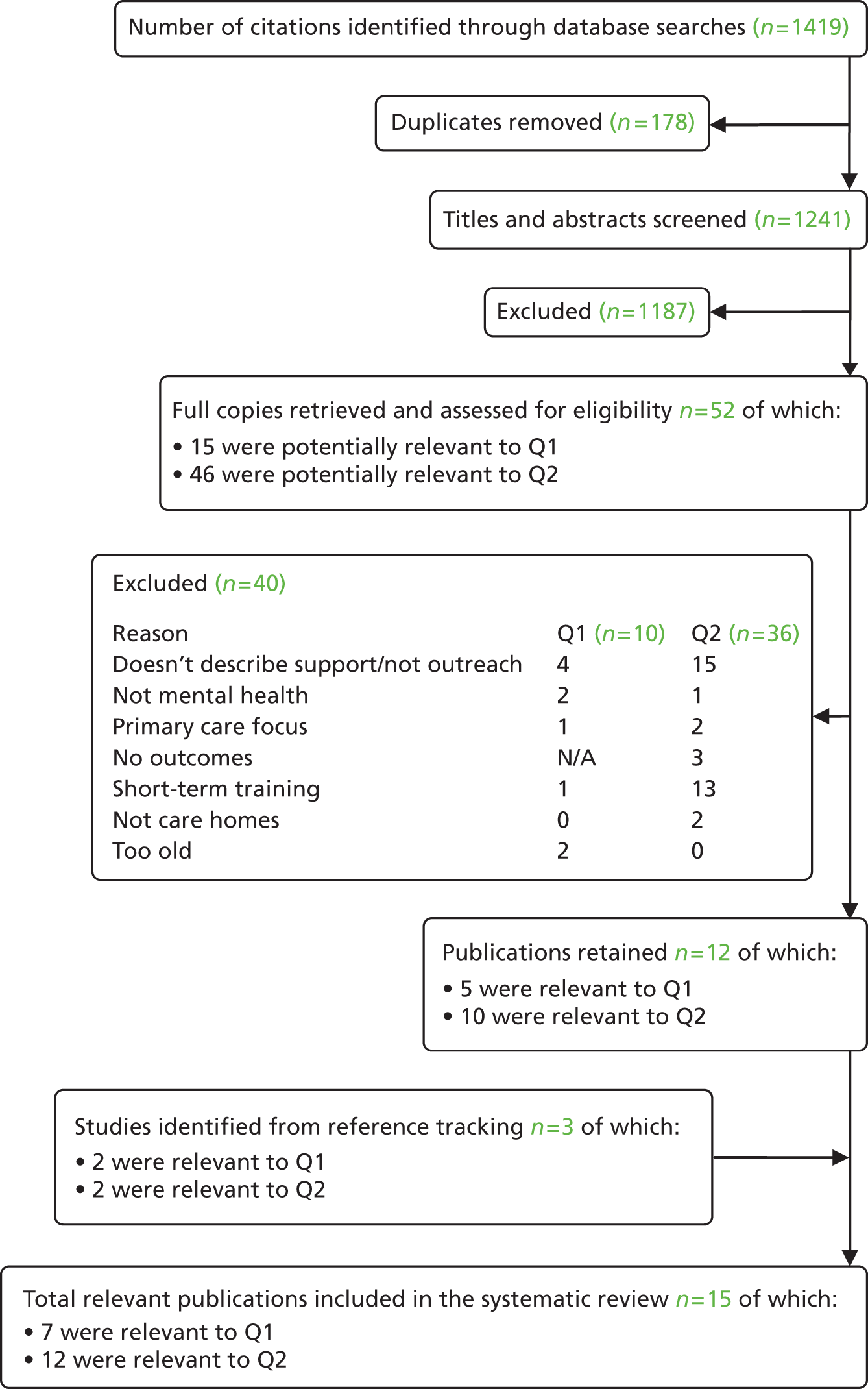

The electronic database search identified 328 references, of which 16 met the inclusion criteria. A further 26 citations were identified by reference tracking and experts, giving 42 citations in the final review (Figure 3). Of these, 22 were published in 22 different journals, whereas the remainder constituted a disparate mix of monographs, book chapters, discussion papers and reports. Slightly more references were identified from the 1980s and 1990s than from previous or subsequent decades. However, given the potential delay in recent reports reaching electronic databases, the general picture was suggestive of a steady flow of publications (Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

| Decade of publication | Number | Number by publication type | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s | 9 | Journal article | 5 | 21.4 |

| Book chapter | 0 | |||

| Report | 2 | |||

| Other | 2 | |||

| 1980s | 13 | Journal article | 5 | 31.0 |

| Book chapter | 2 | |||

| Report | 5 | |||

| Other | 1 | |||

| 1990s | 12 | Journal article | 7 | 28.6 |

| Book chapter | 3 | |||

| Report | 0 | |||

| Other | 2 | |||

| 2000+ | 8 | Journal article | 5 | 19.0 |

| Book chapter | 0 | |||

| Report | 1 | |||

| Other | 2 | |||

Thirty-three discrete studies were described in this data set, which included multiple reports of the same study and single publications describing multiple studies. Given that the review sought to elucidate the BoC methodology, it was the studies per se that were of interest, and this is the unit of analysis reported in the rest of this chapter. As there was too much information to present everything, the following material and references have been chosen to illustrate important points. Additional information is given in Appendices 4 and 5, and in Tucker et al. 89

Coverage of included studies

Table 2 confirms the longevity of the BoC approach and highlights its limited geographical employment. The origins of the BoC model have been attributed to the British government,81,90 and the vast majority of subsequent studies have been undertaken in the British Isles. 91–96 Nothing in the approach, however, limits its use to this policy context, as demonstrated by studies from Italy97 and Canada,98 nor to the national level, with local studies predominating. 71,97–101

| Study | Decadea | Location | Main population | Settings explored | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1970s | Essex | Older people | Residential, community | Wager 197291 |

| 2 | 1970s | UK | Multiple patient groups | Hospital, residential, community | McDonald et al. 1974;80 Gibbs 197890 |

| 3 | 1970s | London (multiple sites) | Older people | Residential, community | Plank 197799 |

| 4 | 1970s | Birmingham | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Opit 197792 |

| 5 | 1970s | Essex | Older people | Residential, community | Whitfield and Symonds 1976109 |

| 6 | 1970s | Devon | Multiple patient groups | Hospital, residential, community | Canvin et al. 1978;119 Boldy et al. 1981,120 1982121 |

| 7 | 1970s | Aberdeen | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Mooney 1977,115 1978;71 Fordyce et al. 1981;116 Mooney et al. 198686 |

| 8 | 1970s | England (multiple sites) | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Wright et al. 1981102 |

| 9 | 1970s | Devon | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | DHSS 1981124 |

| 10 | 1970s | Avon | Older people | Residential, community | Avon County Council SSD 1980110 |

| 11 | 1980s | East Sussex | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Klemperer and McClenahan 1981105 |

| 12 | 1980s | Wiltshire | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Klemperer and McClenahan 1981105 |

| 13 | 1980s | England (multiple sites) | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Audit Inspectorate 198393 |

| 14 | 1980s | England and Wales (multiple sites) | Children/adults with learning difficulties | Hospital, residential, community | Audit Inspectorate 198394 |

| 15 | 1980s | England and Wales (multiple sites) | Children | Residential, community | District Auditors 1981127 |

| 16 | 1980s | Kent | Adults with learning difficulties | Long-term hospital, residential, community | Challis and Shepherd 1983106 |

| 17 | 1980s | Ireland | Older people | Residential (two options) | O’Shea and Costello 199195 |

| 18 | 1980s | Ireland | Older people | Hospital, community | O’Shea and Corcoran 1989,113 1990114 |

| 19 | 1980s | London | People with HIV/AIDS | Hospital, community | Rizakou et al. 1991;126 Rosenhead et al. 1990125 |

| 20 | 1990s | Oxfordshire | Older people | Residential, community | Bebbington et al. 1990103 |

| 21 | 1990s | South Belfast | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | McCallion 1993107 |

| 22 | 1990s | England | Older people with cognitive impairment | Hospital, residential, community | Kavanagh et al. 1993,122 1995123 |

| 23 | 1990s | North London | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Forte and Bowen 1994108 |

| 24 | 1990s | Sandwell | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Forte and Bowen 1997100 |

| 25 | 1990s | North Midlands | Older people | Hospital, residential, community | Forte and Bowen 1997100 |

| 26 | 1990s | England and Wales (multiple sites) | Functional mental illness | Acute hospital, residential | Knapp et al. 1997112 |

| 27 | 1990s | North-east Italy | People with HIV/AIDS | Acute hospital, residential, community | Tramarin et al. 199797 |

| 28 | 1990s | Gateshead | Older people | Residential, community | Challis et al. 2000;101 Challis and Hughes 2002104 |

| 29 | 2000s | UK, but not clear where | People using dialysis services | Acute hospital (three options) | Rutherford and Forte 2003111 |

| 30 | 2000s | England (multiple sites) | Older people | Residential, community | Clarkson et al. 200596 |

| 31 | 2000s | England | Older people | Residential, community | Wanless et al. 200610 |

| 32 | 2000s | Cumbria | Older people with mental health problems | Acute hospital, residential, community | Tucker et al. 2005,117 2008118 |

| 33 | 2000s | Toronto, Canada | Older people | Residential, community | Williams et al. 200998 |

The original model’s applicability across multiple client groups was not found in later studies, with all but two focusing on just one population, older people. 10,102–104 Again, however, there seems nothing to restrict the model’s use to this group (as illustrated by the diversity of groups represented in Table 2), nor to a particular setting. Thus, while more than half of studies echoed the then DHSS’s interest in shifts between hospital, residential and community services,105–108 almost one-third focused simply on the residential/domiciliary margin. 96,99,109,110 The remainder included studies of the potential to locate renal dialysis services in three alternative hospital settings111 and divert acute psychiatric inpatients to supported hostels. 112 Furthermore, although most studies focused only on downward shifts from supposedly more costly, institutional settings to cheaper, community provision,91,97,98 a handful considered moves in both directions. 71,113,114

Approaches to profiling clients

One key feature of BoC studies is their depiction of the needs of people supported in different settings, and in the majority of studies (n = 20) this information was collected via some form of local survey, typically completed by practitioners110,115–118 and/or researchers. 119–121 Those studies that employed secondary data generally obtained this from national data sets or surveys in other areas. 96,122,123

Although all bar two studies provided information about their data sources, only just over a half provided enough detail to judge whether or not the cases forming the basis of their analyses were (a) sufficient in number to instil confidence in the results and (b) broadly typical of the population of interest (n = 18 in each instance). In the vast majority of studies where this information was provided, cases seemed valid and representative. Nevertheless, one study’s sample was judged too small (13 people in each setting),95 and another failed to address an important subsection of the target group. 109

Detailing the original BoC philosophy, Arthur Andersen and Company81 state that when considering alternative care options it is preferable to look at groups of clients, not individuals. In practice, this means dividing the population into categories of clients (case types) with similar needs for support on the basis of those characteristics deemed most significant in determining the locus of and/or costs of their care. Of the 33 studies in this review, 23 took this approach. Table 3 lists the variables most frequently used, with the person’s ability to undertake daily activities of living,103–105,120,121 the extent of their informal care93,96,101 and the impact of their mental state/behaviour108,117,118,124 commonly thought important. Those studies concerned with the location for a specific treatment (as opposed to where different groups of people might reside) also considered such factors as the distance a person would have to travel97,111 and the severity of their illness. 97,125,126 Less frequently mentioned variables included age, gender and level of risk.

| Attribute | Number of studies employing this attribute (maximum n = 23) | Percentage of studies employing this attribute |

|---|---|---|

| Dependency/disability | 18 | 78 |

| Informal support | 16 | 70 |

| Mental state/behaviour | 13 | 57 |

| Incontinence | 7 | 30 |

| Housing/place of residence | 6 | 26 |

Most studies used between three and five attributes, each with two or three levels (e.g. the presence or absence of cognitive impairment), resulting in between 16 and 48 possible case types. The subgroups used in four studies were, however, considered too broad to identify clinically recognisable groups. For example one broke the population into just three ‘standard’ groups of children,127 which would not be clinically recognisable groups.

Approaches to profiling services

Although a comparison of the services people currently receive and alternative ways of meeting their needs is central to the BoC approach, the very first DHSS studies assumed that the total amount of resources available would be curbed by limits on the overall supply of services. 90,119 By contrast, later adaptations of the DHSS model ran both with and without resource constraints,128 whereas other studies tended not to restrict resources to pre-specified levels,98,122,123 though sometimes suggested that account be taken of likely financial constraints. 101,117 In order to estimate the total resource requirements of the various options, the aggregate resources proposed for the care of different individuals/case types were then compared with the resources actually used by the same population.

The range of resources considered varied according to studies’ aims, populations and margins of interest, but generally included those public services likely to account for a significant proportion of total client group spending. Hospital and care home beds, as well as commonly utilised community services, therefore featured frequently. 10,80,113,114,124 The sources of service receipt data were generally poorly detailed. However, some studies employed aggregate measures of available resources taken from routinely collected statistics,80,93,94 whereas others undertook individual-level data collections similar to those above. 71,92,99

Approaches to identifying alternative care arrangements

In the original DHSS studies, alternative care services were identified by modellers after consultation with a team of medical, nursing and social work advisors and ‘mathematical programming’ was used to estimate how practitioners might allocate these based on existing patterns of resource allocation. 80,105 Subsequent BoC studies have, however, generally taken a simpler approach. Many asked practitioners (individuals, monodisciplinary or multidisciplinary groups) to identify the most appropriate form of care for particular case types/individuals (facilitating the incorporation of new services),101,117,118,120,121 whereas others asked practitioners to identify those people in location A who could be cared for in location B. 71,91,113,114 An alternative was to draw on policy documents,103 research recommendations10,121,122 or comparative provision elsewhere. 93,94

Approaches to costing

A comparison of the costs of current and alternative care forms a key element of BoC studies. Few studies provided detailed descriptions, and it was not always clear what costs were included. Furthermore, there is not necessarily one single ‘right’ concept of costs. 129 Thus, in studies exploring how public expenditure might be reduced, it could be argued that only public costs are relevant, whereas this is inadequate when valuing wider social opportunity costs. 130 The consideration of costs undertaken in this review therefore addressed a number of different questions (Table 4).

| Question | Insufficient data to judge | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was the approach to costing comprehensive? | 1 | 5 | 27 |

| 2. Were the cost data used valid? | 11 | 21 | 1 |

| 3. Was the approach to costing fit for purpose? | 21 | 11 | 1 |

| 4. Were the dates to which resources and prices referred reported? | 0 | 20 | 13 |

| 5. Were appropriate adjustments made for inflation? | 20 | 13 | 0 |

| 6. Was there any attempt to investigate cost shifting? | 5 | 4 | 24 |

Less than one-sixth of studies undertook a comprehensive costings approach encompassing not only those costs incurred by public agencies, but also the costs of housing, personal consumption/living expenses and informal care. 92,95,112,122,123 A further fifth incorporated some of these elements. 71,91,110 The remainder considered only public expenditure which, depending on their foci, covered the costs incurred by health and/or social services. 103,106,118,120,121 Interestingly, although many aspired to a comprehensive costing approach, there was little evidence that one framework had come to dominate the field. However, there appeared to be an order in which non-public costs were considered with more studies including housing than living expenses, and informal care costs least likely to be examined.

In all except one study the data used appeared valid, that is related to costs drawn from empirical sources in keeping with the study’s coverage. The costs of local public services were typically supplied by the relevant agencies’ finance departments, whereas national costs were calculated from statistics provided by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy131 or the average local costs in the studied sites. Living costs were generally taken from the Family Expenditure Survey,132 whereas housing cost sources included the estimates of an experienced valuer, national survey data and rateable values. Just two studies described the valuation of informal care costs, with one basing these on the replacement costs of formal care services,10 and the other considering the costs of foregone paid work, non-market work and leisure time. 113,114

Where costs were valid and in keeping with studies’ aims they were deemed ‘fit for purpose’. Thus, studies undertaken from a provider/commissioner perspective (interested in public expenditure) that included the most important health and/or social care costs and used valid data were scored positively, as were those that sought to calculate comprehensive costs and included the four elements detailed above. In almost two-thirds of cases, however, there was insufficient information to make this judgement. Furthermore, a substantial number of studies failed to report the year to which costs referred, whether appropriate adjustments were made for inflation or the extent to which any reallocation of resources would change the distribution of the cost burden between health and social care/the public and private sector. There were no reports of the transaction costs that might be incurred in reallocating resources between care locations or creating new services.

Approaches to the inclusion of outcomes

Consideration of the relative benefits of alternative care options was widely advocated, although only four studies reported collecting any outcome information. 97,99,101,127 A further four demonstrated awareness of existing outcome data. 10,91,102,122,123 Not all of those studies that collected outcome information explained how it was used. However, one used data on fostering breakdown to explore concerns that greater use of fostering might increase placement failure,127 whereas another used information on (among other things) the extent to which people’s needs were met and how satisfied they were to indicate care quality. 99

Most of those studies that drew on existing evidence were more explicit. One cited research on the relative benefits of community and institutional care to support its plans to increase domiciliary support,91 whereas another discussed possible changes to the support of older people with cognitive impairment based on evidence of the quality and effectiveness of each option. 122,123 More recently still, Wanless et al. 10 created an outcomes-led estimate of the costs of addressing the social care needs of vulnerable older people. This work aside, several studies used practitioners to make explicit judgements of best placements, on the assumption that ‘best interests’ evaluations of outcome were included,96,117,118 whereas others simply presented decision makers with the relevant cost data alongside a description of the individuals likely to be affected by any reallocation of resources, leaving them to judge the relative benefits of any proposed transition in terms of, say, equity, continuity, normalisation and/or effectiveness.

Good practice indicators

The preceding sections have summarised the extent to which studies exhibited the criteria of good practice identified in Box 2 and demonstrated how key elements of the BoC framework have been operationalised, but have not addressed the overall design or reporting of individual studies.

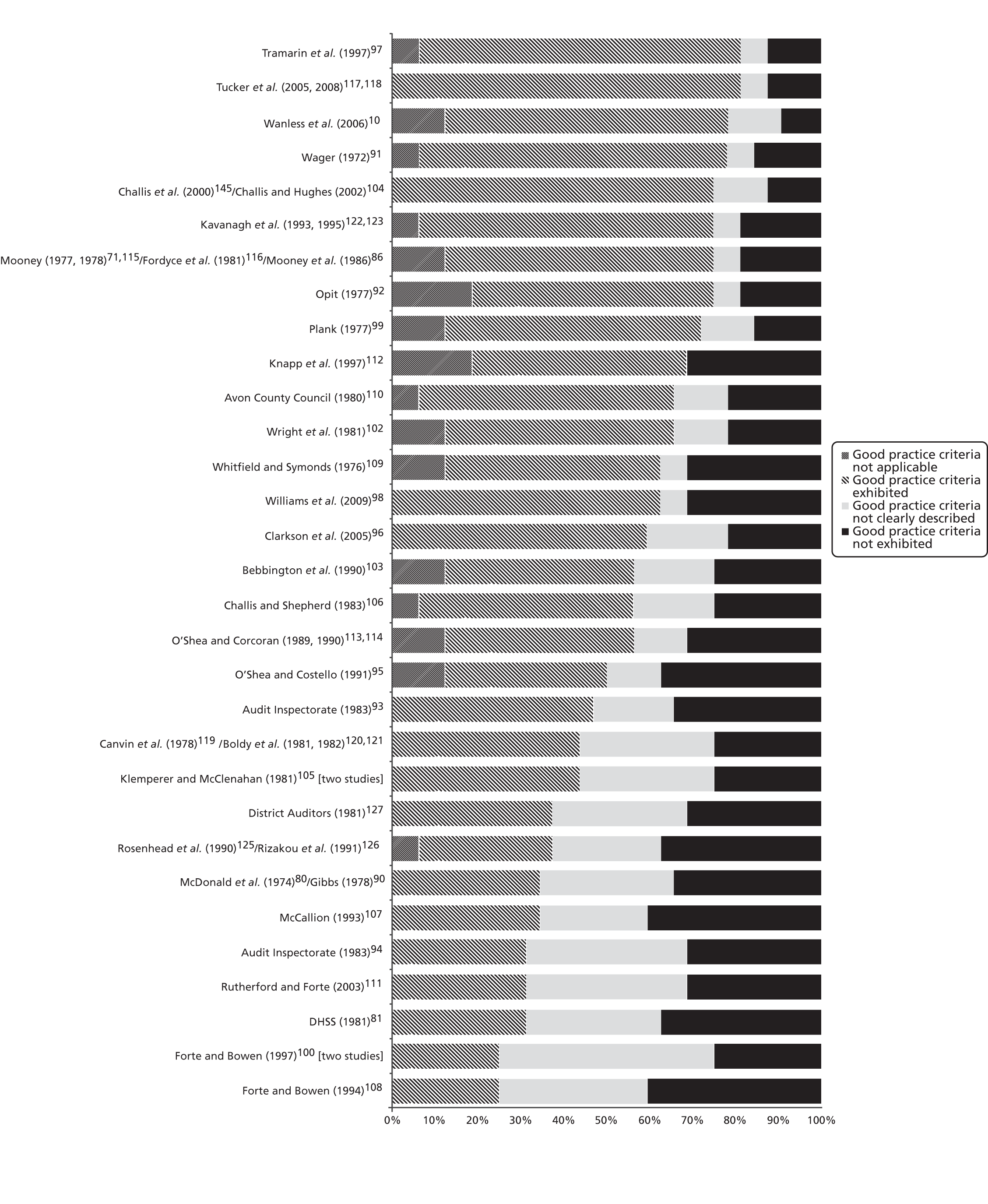

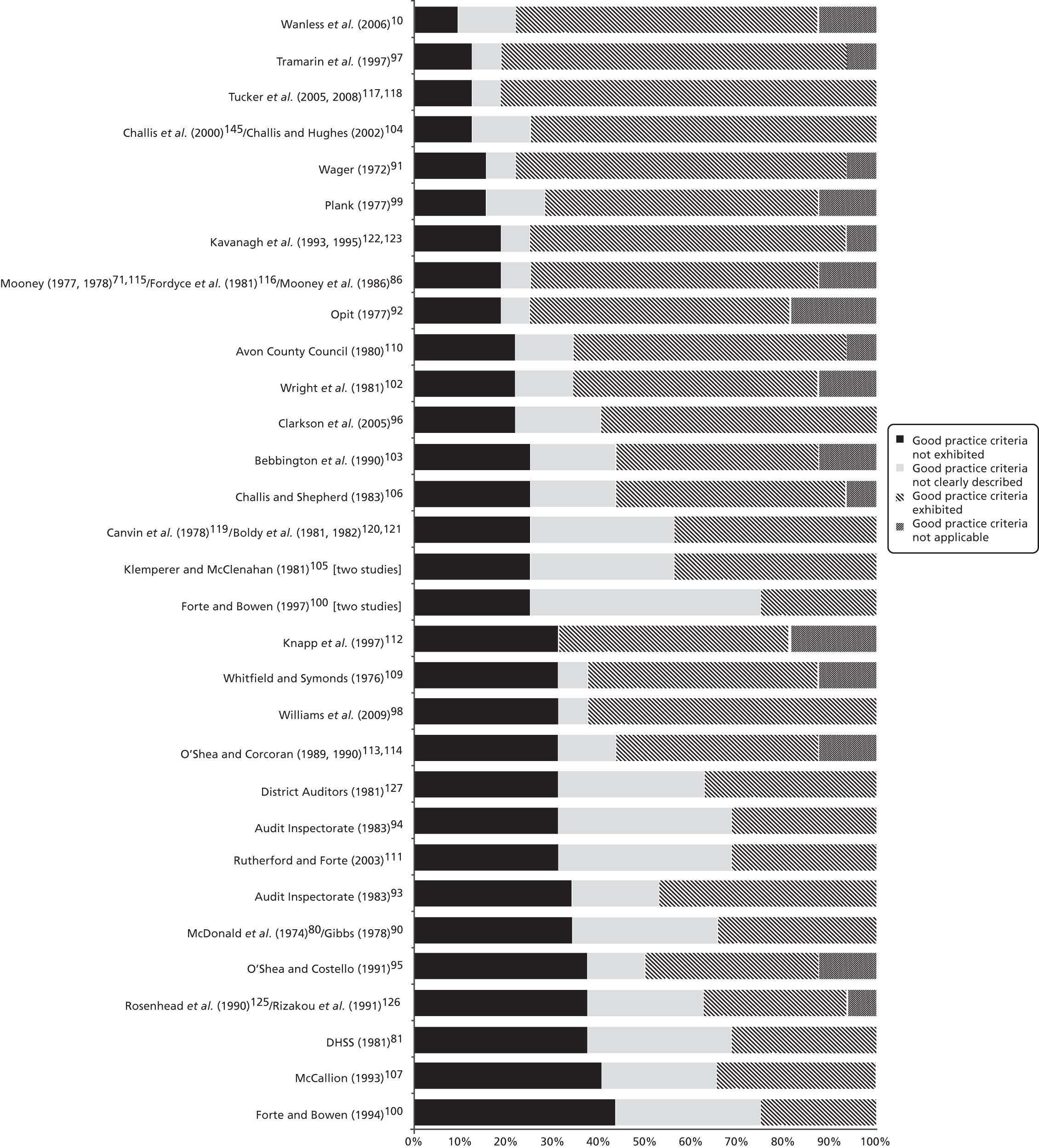

To assist such a comparison, Figure 4 ranks the studies by the number of good practice indicators exhibited (most to least). As can be seen, not one study exhibited all 16 components, whereas approaching half (n = 15) exhibited < 50%. As one moves down the figure, however, the proportion of items not reported increases more than the proportion definitely not exhibited, suggesting that study designs may be less variable than reporting standards. This distinction is reinforced by Figure 5, which ranks the studies from least to most good practice indicators not exhibited, and although the upper sections of Figures 4 and 5 are similar, the ordering of those studies in the middle and lower sections changes considerably. Interestingly, there is no indication that studies with multiple publications or described at more length performed systematically better than studies described in single publications or at less length. Moreover, there is no straightforward association with year of publication, since most of the more recent studies are in the upper half, as are some of the earliest.

FIGURE 4.

Ranking of studies by good practice criteria exhibited (most to least).

FIGURE 5.

Ranking of studies by good practice criteria not exhibited (least to most).

Discussion

The strategic allocation of resources has been described as one the most difficult tasks facing health and social care decision-makers. The NHS and local authorities deliver a complex range of services, with benefits that are imperfectly understood, to a population that is heterogeneous in its needs and expectations. 133 The enduring appeal of the BoC approach, which offers service commissioners and providers a formal structure for exploring potential changes in service mix, is thus unsurprising. However, it is clear that there is not one standard approach. The studies included in this review spanned an array of programme areas/services at local, regional and national levels. Although some were large in scale and ambition, others had more modest aims. Nonetheless, in identifying service users on the margins of care, articulating costs and identifying the values placed on different care settings, each exposed its key assumptions to critical debate. Furthermore, there is some suggestion that, despite certain shortcomings, the most recent studies were among the more robust.

Methodological considerations

This review faced a number of methodological challenges, not least of which was the desire to examine not only that work that explicitly used the BoC model, but that sharing the same approach. Although the selected search terms may not have captured all relevant studies, experts highlighted only a handful of additional publications suggesting the final list was relatively complete, and just two unsourced references related to studies not captured elsewhere. The lack of methodological detail given in many publications was also problematic, and no suitable validated quality assessment tool was identified. The components of the constructed checklist were, however, selected with due consideration for the scope and purpose of the exercise (if not necessarily all of equal importance), and highlighted a number of areas in need of methodological refinement.

Lessons for future applications

Key lessons arising from this review focus on the need to minimise bespoke data collections, the formation of case types, the choice of margins, the delineation of care alternatives, the measurement of costs and the inclusion of outcome data.

Data collection

Past studies have relied mainly on local data collections. Such exercises can be time-consuming and expensive. It is thus suggested that future studies ascertain precisely what routinely collected data is available before undertaking additional collection, and limit this to that information essential to the planning exercise.

Case types

The use of case types has been widely adopted and reduces demands on busy practitioners. Nonetheless, the formation of case types requires careful thought, given the trade-off to be made between the number of characteristics taken into account and the number of people captured by each type. Attention should also be given to whether or not the selected attributes form single scales. Thus, although some commonly used variables (e.g. physical dependency) lend themselves to this, others (e.g. behavioural problems) can encompass a number of different dimensions needing different care. 102 Furthermore, some way must be found of incorporating those less objectively measurable characteristics (e.g. clients’/carers’ preferences) that affect placement decisions and surely influence the relationship between resources and outcomes. 130

Margins

Although a number of past studies have focused on services administered by either health or social services, in today’s more complex planning environment the viability of many people’s care depends on both. Future applications should thus consider taking a cross-agency approach. Similarly, whereas previous applications tended to focus on just one or two settings, in light of the increasing development of new forms of support, a careful determination is needed of both the choices available and the widest margins of care. 130,134,135

Care alternatives

The engagement of local practitioners in generating care options is widely acknowledged as a strength of past BoC studies. However, thought should be given to the selection of staff involved, for different professional groups hold different values and opinions,136 while the extent to which staff can think beyond current practice is fundamental to the method. Some studies have addressed this using multidisciplinary groups of professionals,97,117,118 encouraging participants to be more explicit about the rationale for their choices, and, through consensus decision-making processes, facilitating peer review. Such approaches could be widened to include other stakeholders, including the public.

Costs

Although most past studies examined only public expenditure, few saw this as ideal, acknowledging it significantly underestimated the burden of community care. As other studies illustrated, however, there are a number of ways of incorporating housing, living and informal care costs into the methodology. Future studies should also give thought to the practical problems of reallocating resources between care settings/providers, for although it is often assumed the monies released from one service can be used to pay for another, in practice this may be difficult, particularly if it involves a transfer between agencies. 137 In addition, capacity cannot always be reduced/increased in a linear fashion and there may be a need for new and old services to run in parallel, at least in the short-term. Hence, the transaction costs of shifting resources should be considered.

Outcomes

Despite widespread support for including outcome data in the model, few past studies have attempted to do this. This is potentially the biggest challenge facing future applications, for without this information the approach risks being perceived as a cost-minimisation tool. With adequate benefit information, it could become a much more sophisticated and flexible toolset. Decisions to be made include whose perspective to consider, which outcomes are important, and how best to measure them. 71

Conclusions

Some 40 years after the development of the BoC approach, its utility appears as high as ever. A number of factors account for this. First, the search for the most appropriate and efficient ways of caring for different client groups is an enduring one, and is of relevance to service providers/planners at many levels within the health and social care system. Second, the approach is pragmatic, incorporating a mixture of local data, research, practitioners’ and clients’ views, yet based on sound economic principles. It accepts service planning is not fully informed, but provides a systematic and explicit framework to guide the exploration of alternative actions. Third, the approach both involves and cedes control to local stakeholders, who inform the study’s scope, suggest alternatives and choose solutions, engendering the support of the people who will need to implement change. Fourth, precisely because the approach is applied within a particular geographical area/service, and is based on local data, the findings are of immediate and specific relevance to local decision-makers. Indeed, as demographic profiles and relative marginal service costs vary, decisions made in one area/service will, and should, differ from those in another.

There is, however, undoubtedly the potential to improve the methodology, as specified above, providing important pointers for future studies. There are, in addition, a number of gaps in the research, including the need for future qualitative studies on current decision-making and resource allocation processes and a follow-up evaluation of past BoC studies to determine their success in facilitating change.

Chapter 3 Services for older people with mental health problems. The North-West Balance of Care Study: method

Introduction, aims and objectives

Following on from Chapter 2, the research detailed in the next three chapters employs a BoC approach to explore a more appropriate and efficient mix of services for older people with mental health problems in three areas of north-west England. The BoC approach was described in Chapter 2, and will not be repeated here. It identifies groups of people whose needs can be met in more than one setting (marginal cases), and examines the costs and consequences of these alternatives. Although 33 studies have employed variants of the BoC model over the last 40 years, only two have considered the services needed by older people with mental health problems. Moreover, several methodological shortcomings were evident in previous use of the framework.

This study was designed to build on past applications and had three main aims:

-

to demonstrate the potential of the BoC approach to inform strategic service planning for this client group

-

to develop and refine the methodology and

-

to enable other health and social care decision-makers to apply the framework independently.

In order to achieve these aims the research sought to:

-

apply the BoC framework to the care of older people with mental health problems, examining whether, how and with what consequences the mix of institutional and community services provided by health and local authorities could be improved

-

expand the number of settings considered

-

further investigate the potential for diverting older people from acute mental health inpatient care

-

examine the implications of taking a comprehensive, as opposed to a public, expenditure costing approach

-

explore different ways of incorporating final outcome data into the analysis

-

improve understanding of the determinants of the BoC in the main study site; and

-

inform the production of a BoC workbook.

Overview

The research was undertaken in three areas of north-west England – sites X, Y and Z – and explored the support needed by older people with mental health problems in five key settings in which this client group receive support from specialist secondary mental health and local authority (LA) social care services:

-

acute mental health inpatient wards

-

care homes (with and without nursing)

-

ECH

-

home with specialist mental health support from a CMHT; and

-

home with social services but no specialist mental health support.

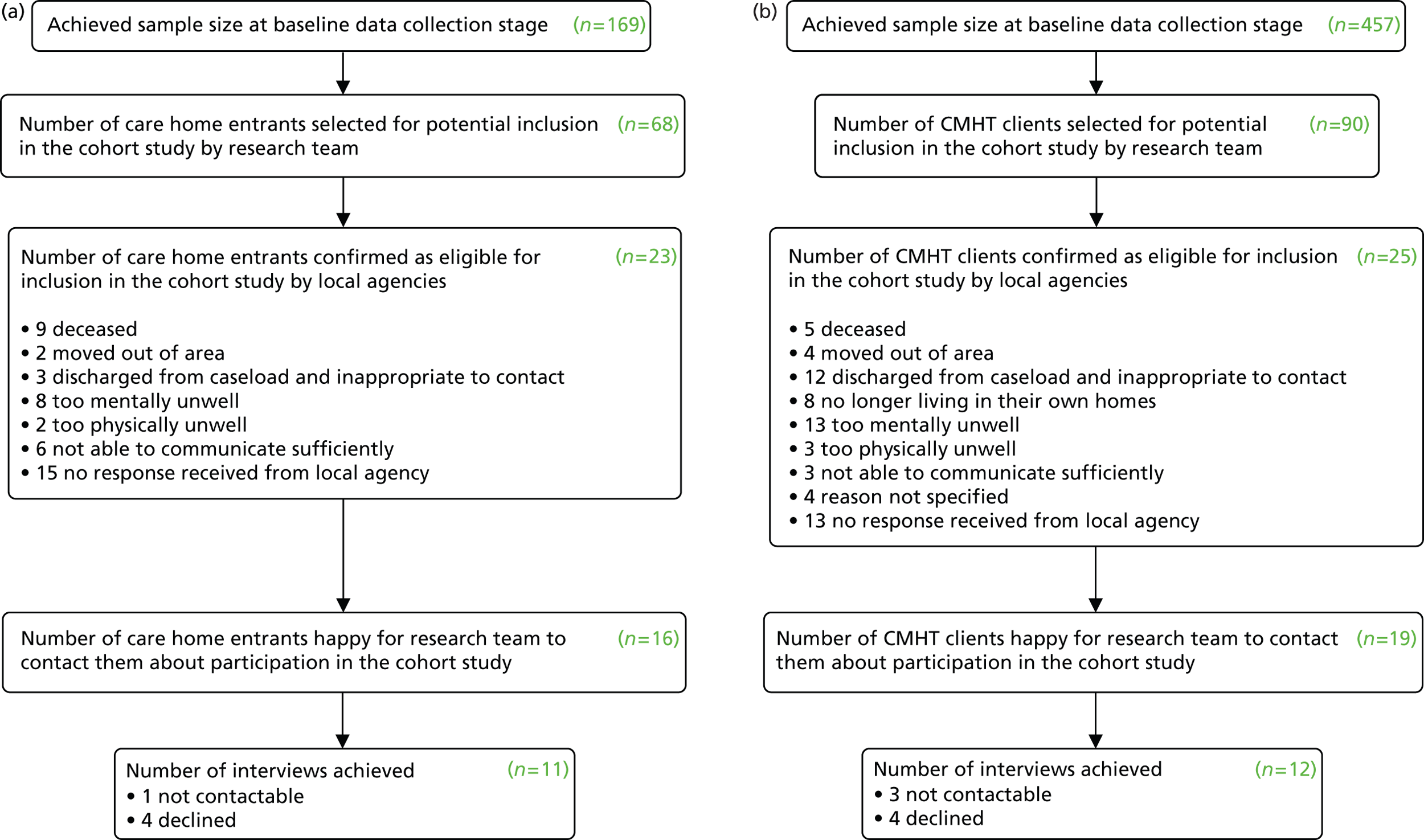

The approach drew on both quantitative and qualitative methods in a sequential mixed-methods design and was grounded in the experience and knowledge of local practitioners and service users. It contained seven work packages encompassing 17 interlinked activities, described below. The work packages are numbered 1 to 7 and the activities within work packages are numbered to reflect their work packages (e.g. activity 3.1). Although one locality, site X, served as an exemplar for the use of the BoC methodology across the entire spectrum of services, facilitating a whole systems analysis, data about ECH tenants and care home and hospital inpatient admissions were sought in all three sites to increase sample sizes and permit between-area comparisons. This was only partially successful, for the council in site Z, which had originally intended to participate in the study, was subsequently unable to do so, and substantial delays in obtaining research governance approval from the mental health trust in site Z reduced the amount of data it could provide.

Ethical approval was granted by Cambridgeshire 3 Research Ethics Committee (reference number 10/H0306/51) and research governance procedures in each participating organisation were fulfilled.

Work package 1: profiling service provision and service users

Activity 1.1

Multiple, secondary data sources were used to develop an overview of the existing distribution of resources for older people with mental health problems, providing a baseline against which future changes in service provision could be considered. These data were compared with published national findings in order to benchmark service provision in the study sites against other areas, providing a wider context for the research.

Activity 1.2

Front-line practitioners completed bespoke surveys providing information about the sociodemographic, functional, clinical and service receipt characteristics of service users in each setting (the baseline data collection) drawing on routinely collected data (Box 3). In the ECH, care home and inpatient samples, they also indicated which of a list of factors identified from the literature contributed to the admission. The questionnaires (see Appendices 6 and 7) were designed to collect the minimum amount of information necessary to profile the populations of interest, including standardised measures such as the modified Barthel Index,138–140 the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS)141 and, where available, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE),142 Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)143 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 144

| Setting | Population of interest | Approach to sampling | Information domains | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute mental health inpatient wards | All older people (aged ≥ 65 years) admitted to an acute mental health assessment ward excepting admissions for planned respite Target sample: 300 |

Consecutive admissions in the following time periods: Site X: October 2010–March 2011 Site Y: November 2010–April 2011 Site Z: April–September 2011 Discharge information collected until December 2011 (Information provided by nominated nursing staff shortly after admission) |

Sociodemographic information Admission details Daily functioning Clinical characteristics Informal care Formal service receipt Discharge arrangements |

Site X, two wards Site Y, two wards Site Z, three wards |

| Care homes | All older people (aged ≥ 65 years) with mental health problems admitted to a care home with the approval of Social Services’ Older People’s Resource Allocation Panels and/or known to CMHTs excepting admissions for planned respite and people moving from one care home to another Target sample: 350 |

Consecutive admissions approved/known about in the following time periods: Site X: October 2010–April 2011 Site Y: January–May 2011 Site Z: February–May 2011 (Information provided by service users’ care co-ordinators shortly after admission. Forms completed by staff in social services. Older people’s teams contained a preliminary mental health screen to exclude service users with no indication of mental health problems) |

Sociodemographic information Admission details Daily functioning Clinical characteristics Informal care Formal service receipt Funding arrangements |

Site X LA Site Y LA Site X CMHT Site Y CMHT Site Z six CMHTs |

| ECH | All older people (aged ≥ 65 years) with mental health problems on the caseloads of the Social Services Older People’s Teams or CMHTs resident in (specialist or non-specialist) ECH Target sample: 30 |

The population known to CMHTs on a nominated day in June 2011; plus the population of site X’s LA ECH schemes who took up tenancies in the year preceding June 2011. (Note: Local staff advised that contemporary information was unlikely to be available about longer-term residents) (Information provided by service users’ care co-ordinators in June/July 2011. Forms relating to site X LA tenants contained a preliminary mental health screen to exclude service users with no indication of mental health problems) |

Sociodemographic information Admission details Daily functioning Clinical characteristics Informal care Formal service receipt |

Site X LA Site X CMHT Site Y CMHT Site Z six CMHTs |

| Home with specialist mental health support | All older people (aged ≥ 65 years) on the caseloads of the trusts’ CMHTsOP who were not long-term residents of care homes or ECH Target sample: 900 |

All clients with an organic mental illness plus a one in four systematic random sample from a clinician-generated list of clients with functional mental health problems stratified by practitioner Samples selected on nominated days in: Site X: November 2010 Site Y: December 2010 Site Z: June 2011 (Information provided by service users’ care co-ordinators in the month following sample selection) |

Sociodemographic information Daily functioning Clinical characteristics Informal care Formal service receipt |

Site X CMHT Site Y CMHT Site Z six CMHTs |

| Home with social services support (but no specialist mental health input) | All older people (aged ≥ 65 years) with mental health problems on the caseloads of the older people’s locality teams who were not currently receiving specialist mental health care or living in care homes or ECH Target sample: 100 |

A random sample of 199 active cases stratified by care co-ordinator were selected in July 2011 (Note: Local staff advised that contemporary information was unlikely to be available about inactive cases) (Information provided by service users’ care co-ordinators in the 2 months following sample selection) Forms contained a preliminary mental health screen to exclude service users with no indication of mental health problems |

Sociodemographic information Daily functioning Clinical characteristics (partial) Informal care Formal service receipt |

Site X LA |

All information supplied to the research team was provided in a fully anonymised form. However, in order to facilitate the identification of people for whom outcome data would be sought in Activity 4.4, each proforma included a unique study or non-sensitive agency number. As the participating social services’ documentation did not reliably distinguish older people with mental health problems from other older people, the relevant forms also contained a brief screen to identify the study population for whom the full data set was then collected.

The sampling strategy aimed to identify individuals at a point on the care pathway where real life choices are made between settings, while simultaneously generating sufficient numbers for the formation of case types (see Activity 2.1) and the power required by the planned outcome analysis (see Activity 4.4). The focus on people with an organic mental illness in the CMHT sample was also influenced by the need to match CMHT clients with care home admissions (see Activity 4.4), whereas the small size of the ECH sampling frame necessitated a whole population approach.

Data were initially entered onto SPSS for Windows (version 19; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and checked for errors, while subsequent analyses were conducted with Stata (versions 10 to 12; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Where data permitted, critical gaps were filled by model-based imputation routines and scores for summary measures were calculated from their constituent elements (see Appendices 8 and 9). Differences between groups were explored using appropriate statistical tests.

Work package 2: developing case types and formulating vignettes

Activity 2.1

The study samples were divided into relatively homogeneous subgroups (case types) on the basis of those client characteristics deemed likely to be important in determining the locus of/and/or costs of their care. The attributes employed (Box 4), were informed by the literature review (see Chapter 2), the wider literature on care home and inpatient admission predictors and exploratory analyses of the empirical data. Further details are given in Appendix 10. As each of the three variables used in the domiciliary, ECH and care home settings had three levels, this gave 27 possible different combinations or case types, whereas the four variables used in the inpatient classification generated 72 possible subgroups.

| Setting of interest | Attributes | Number of case types |

|---|---|---|

| Home, ECH, care home entrants | A three-level rating of dependency based on a modified version of the Barthel ADL Index:

|

27 |

| Inpatient admissions | A three-way grouping of primary diagnosis:

|

72 |

Activity 2.2

Vignettes were formulated to exemplify the most prevalent case types for care home admissions in site X (see Appendix 11). Based on real individuals, they took the form of brief case histories which systematically incorporated information about the three key variables as well as individuals’ falls risk, physical health, living situation, service receipt, location immediately prior to admission and preferences. A few control vignettes were also constructed to depict two of the same case types in the CMHT sample as well as the most commonly populated CMHT case type, and the homeogeneity of the needs of the people represented by each vignette was checked.

A similar process was used to formulate vignettes representing the inpatient sample, but depicting the most prevalent case types across the three sites to facilitate wider exploration of the appropriateness of inpatient admission. They also included information about individuals’ mental health history (see Appendix 12). In one instance, where the needs of the individuals represented by a particular case type appeared too heterogeneous, the relevant case type was divided according to the individuals’ usual place of residence (i.e. home or care home).

To adhere to the study timeline, this exercise was started approximately half-way through the baseline data collection exercise.

Work package 3: identifying marginal case types and alternative care arrangements

Two different approaches to the identification of people on the margins of care were explored.

Activity 3.1

First, an empirical analysis was undertaken of the extent to which the same case types were found in the two domiciliary, ECH and care home samples.

Activity 3.2

Second, local staff attending a series of practitioner workshops identified those commonly populated care home and inpatient case types whose needs could be met by other services, scoping the potential for downwards substitution from the two most intensive settings. Box 5 sets out the workshops’ key characteristics.

| Primary case types of interest | Practitioners involved | Locality |

|---|---|---|

| Care home residents | Mental health nursing, support worker, managerial, social care and housing staff | Site X only |

| Acute mental health inpatients | Mental health community and inpatient nursing, medical, occupational therapy, counselling, managerial, commissioning and social care staff | Sites X, Y and Z (three separate exercises) |

Participants in the care home workshop worked in five small groups, with each group pseudo-randomly allocated a set of pre-selected care home and domiciliary control vignettes.

Working alone, practitioners first indicated where they believed the depicted ‘client’ would be most appropriately cared for and, where care home placement was felt preferable, recorded the main reason for their decision. They also indicated if their decision would be different if (a) the service user lived with or without a coresident carer and (b) was at home or in hospital at the point of assessment. Working collectively, each group then identified between two and four cases that could appropriately be diverted from care home admission (‘marginal care home cases’) and compiled care plans specifying the alternative community resources required.

In this exercise participants were asked to put aside short-term constraints in current services and be creative, while remembering that all services inevitably have funding implications. To help practitioners to think creatively, they were given a care planning sheet containing a list of services already available in other areas.

Employing a similar process, participants at the inpatient workshops first individually indicated whether it was ‘completely’, ‘possibly’ or ‘not’ appropriate to admit the ‘client’ to a mental health bed. To construct a hierarchy of appropriateness, case types were then scored: two points were given for each respondent stating ‘completely’; one point for each respondent stating ‘possibly’; the points were totalled; and totals expressed as a percentage of the maximum possible. Working in small groups, practitioners then formulated care plans to enable the four to six lowest scoring admissions in each workshop (‘marginal inpatient cases’) to be diverted from hospital care.

Activity 3.3

Statistical modelling was undertaken to illuminate the decision-making process. The individual decisions made during workshops (clustered by rater) formed the analysis data set, and a series of logistic regression analyses were undertaken to explore the factors associated with those care home and inpatient case types that were definitely not divertible, as well as rater characteristics that may have influenced these decisions.

Work package 4: identifying the costs and outcomes of alternative packages of care

This study component sought to estimate the costs of alternative support for marginal care home and inpatient cases and to identify different potential outcome evidence for inclusion in the BoC analysis.

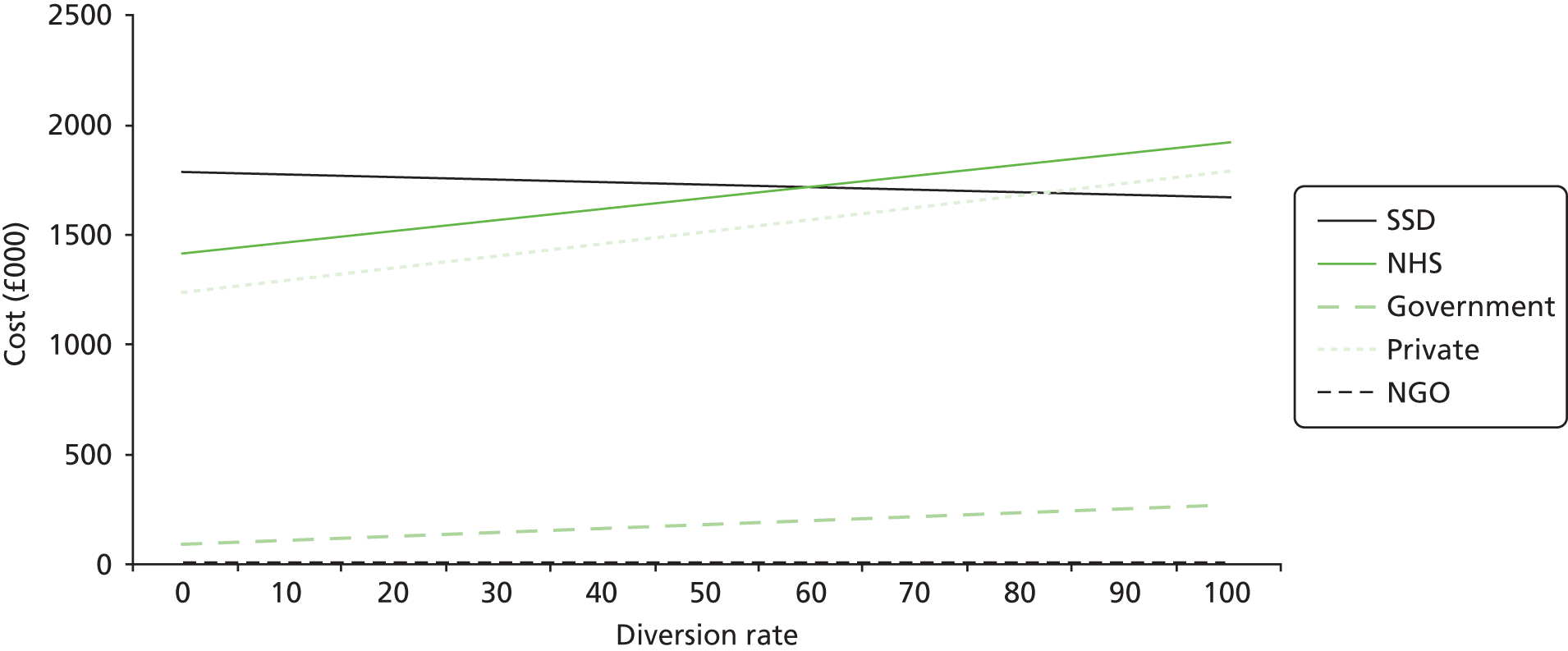

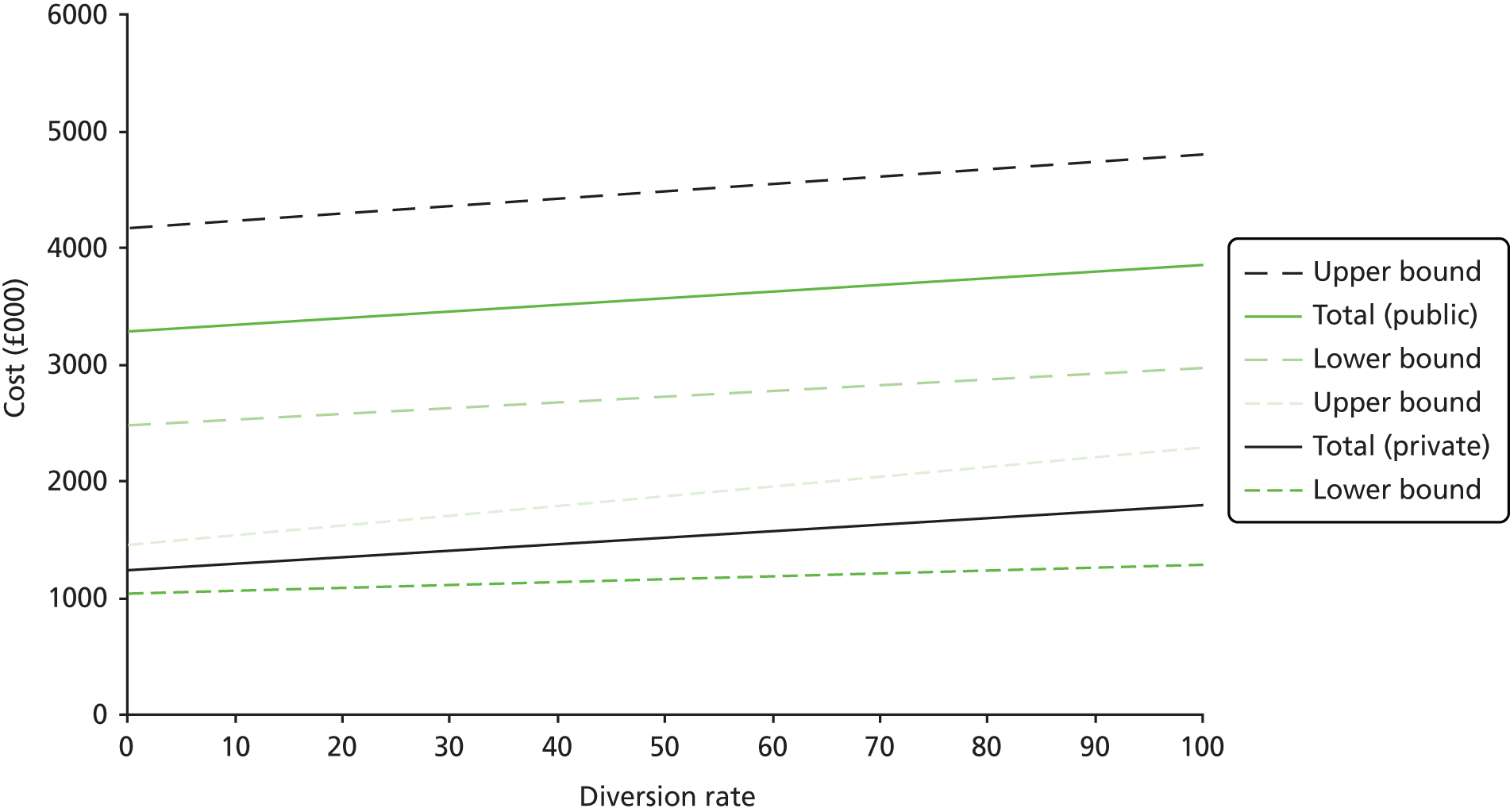

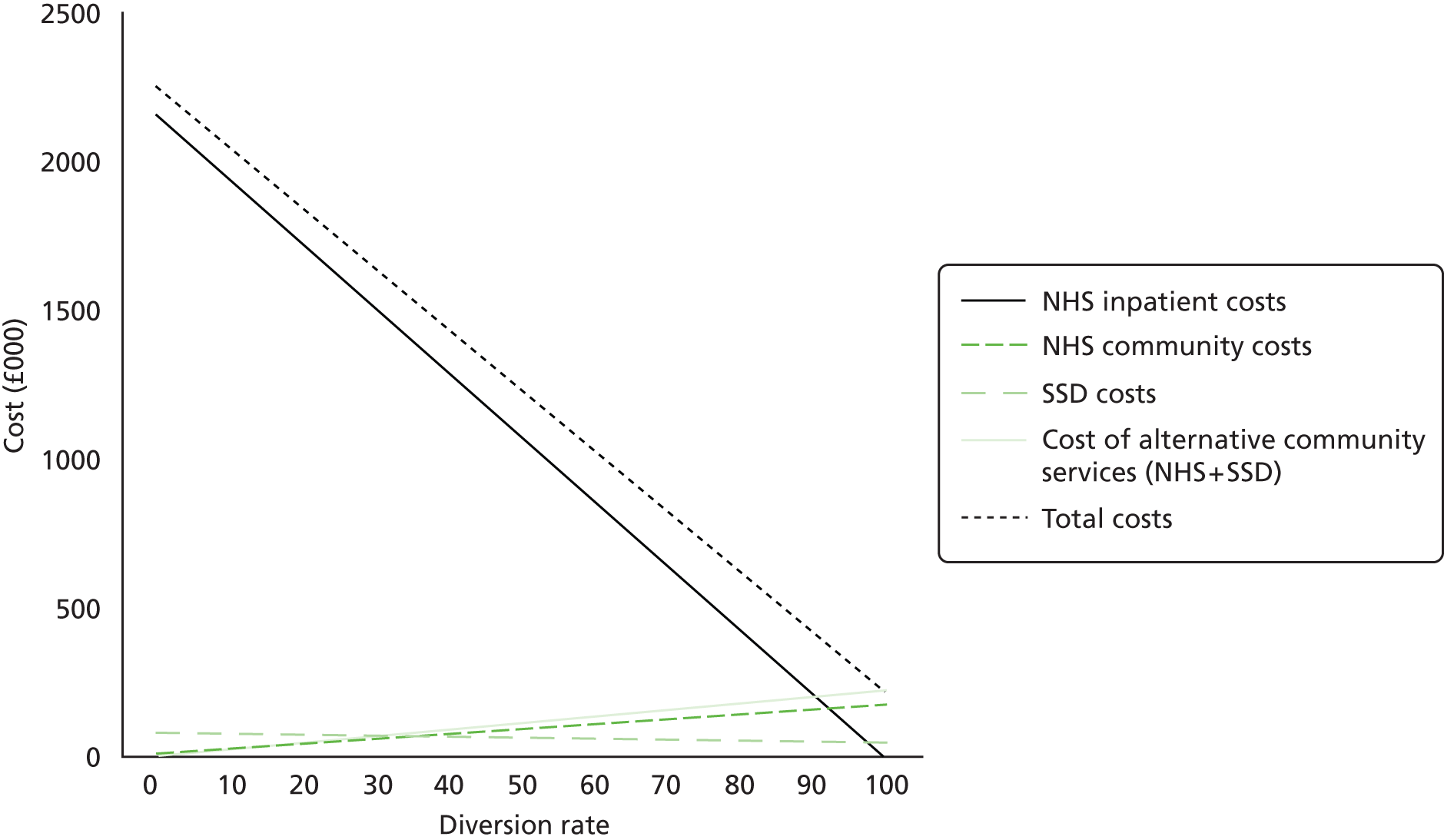

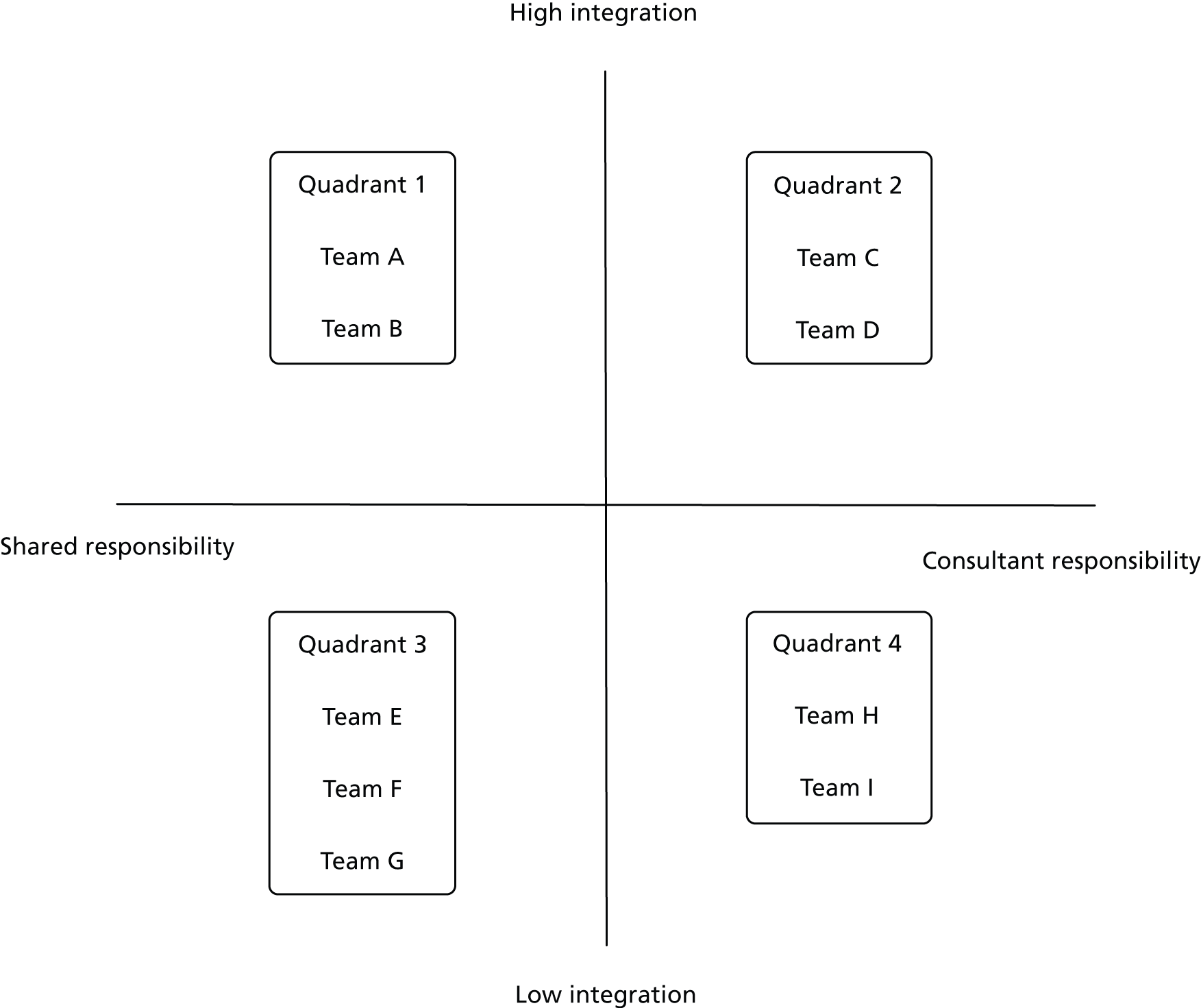

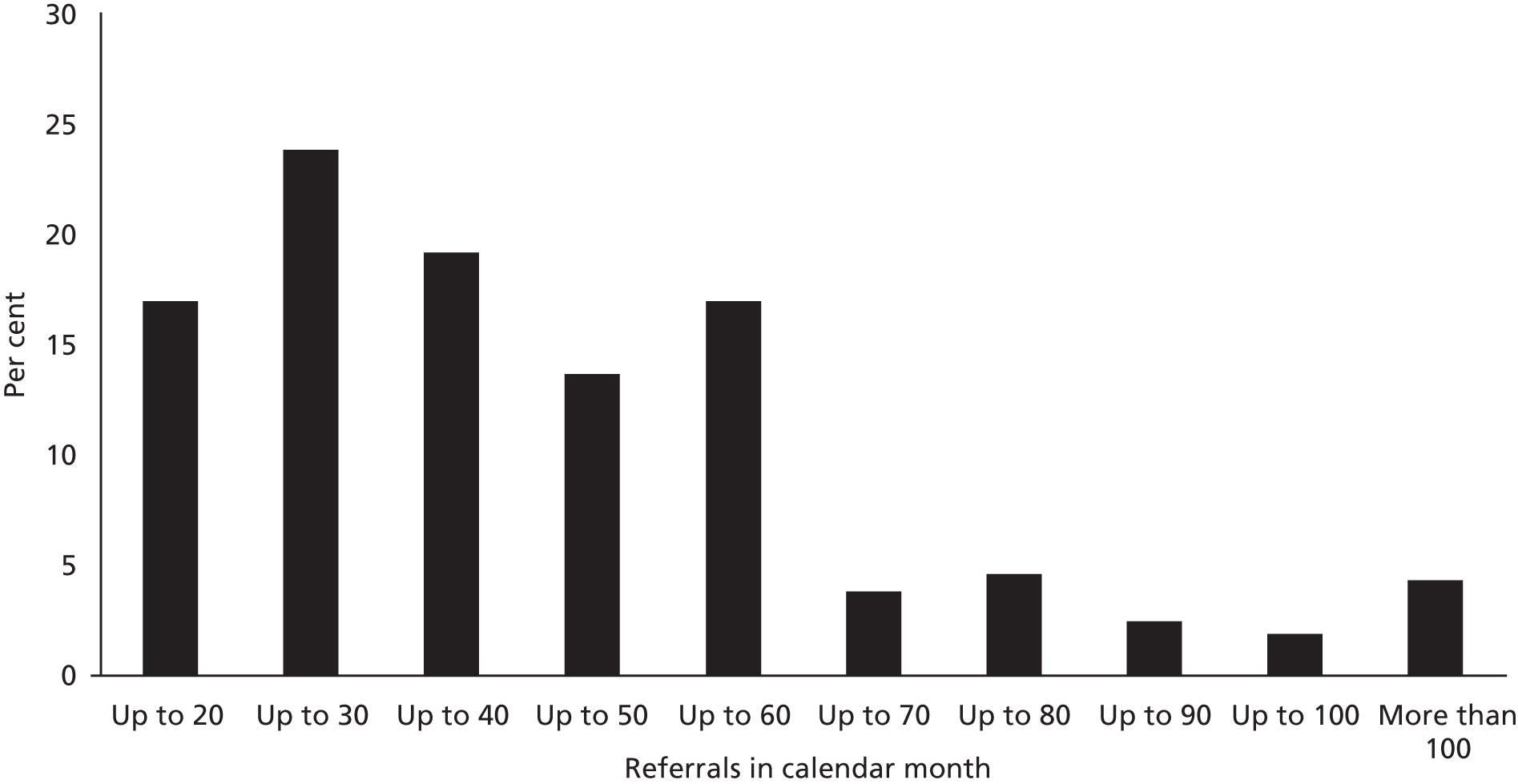

Activity 4.1