Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0609-10135. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elizabeth Murray reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and National School of Primary Care Research during the conduct of the study, and grants from NIHR outside the submitted work. She is also managing director of the not-for-profit HeLP Digital community interest company (CIC), which was established to disseminate the HeLP-Diabetes programme across the NHS. She does not take any remuneration for this work. Kingshuk Pal reports personal fees from HeLP Digital CIC outside the submitted work. Fiona Stevenson reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of this study. Maria Barnard reports sponsorship for attendance at educational conferences from Novo Nordisk A/S, personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceutica NV and that Janssen-Cilag International NV Sponsor was a sponsor of the multicentre CREDENCE trial (which Whittington Health NHS Health Trust is a site for) outside the submitted work. Lucy Yardley reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study; grants from NIHR, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Medical Research Council (MRC), medical charities and European Commission outside the submitted work; and membership of the Health Technology Assessment Efficient Study Designs Board and Public Health Research Research Funding Board. Susan Michie reports grants during the conduct of the study from NIHR, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, MRC, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Department of Health and Social Care, Public Health England, Cancer Research UK, the British Psychological Society and EC outside the submitted work. David Patterson was one of the founders, and is now Chief Medical Officer, of Helicon Health Ltd, a spin-out company from UCL Business. He does not believe there is any actual conflict of interest between Helicon Health Ltd and this work – other than the fact that his knowledge of information technology and devices was growing during this academic work. Ghadah Alkhaldi reports personal fees from the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau, outside the submitted work. Brian Fisher reports that he is the Director of Patient Access to Electronic Record Systems Ltd (now Evergreen Life), which was intended to offer links from the HeLP-Diabetes programme to the patient record outside the submitted work. Orla O’Donnell reports working as the Chief Operating Officer for the HeLP Digital CIC from the end of the programme grant until 1 May 2017. Andrew Farmer reports grants from NIHR and MRC outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Murray et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Structure and overview of report

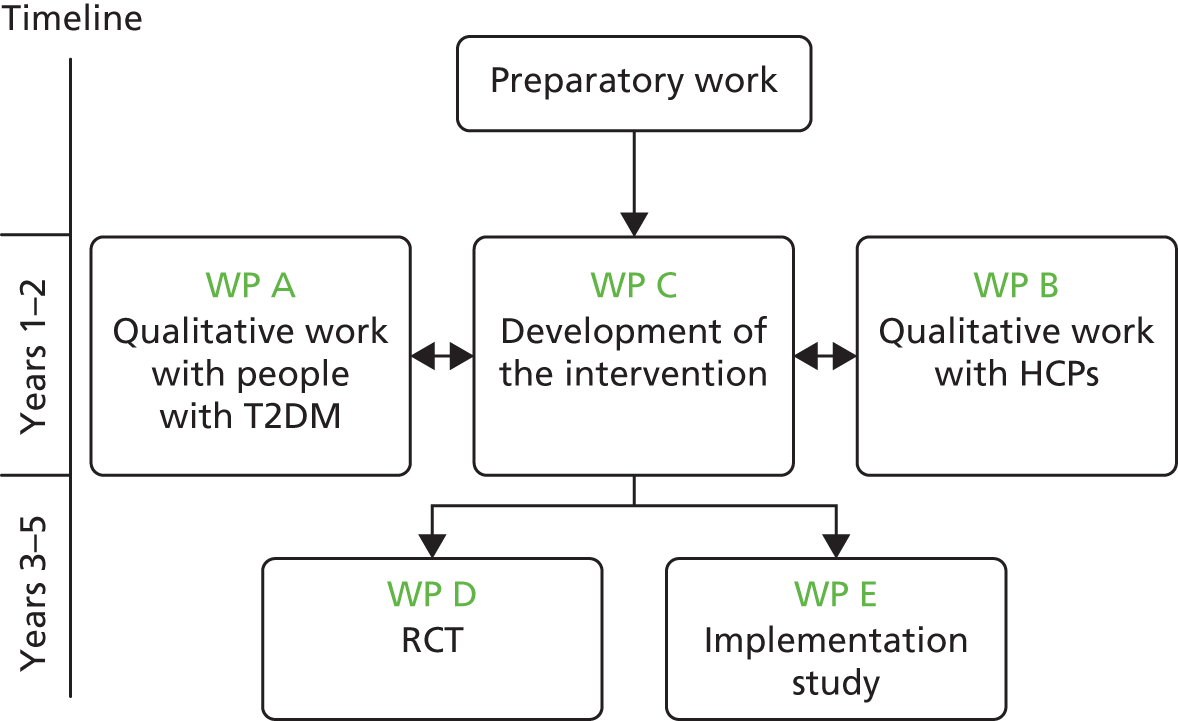

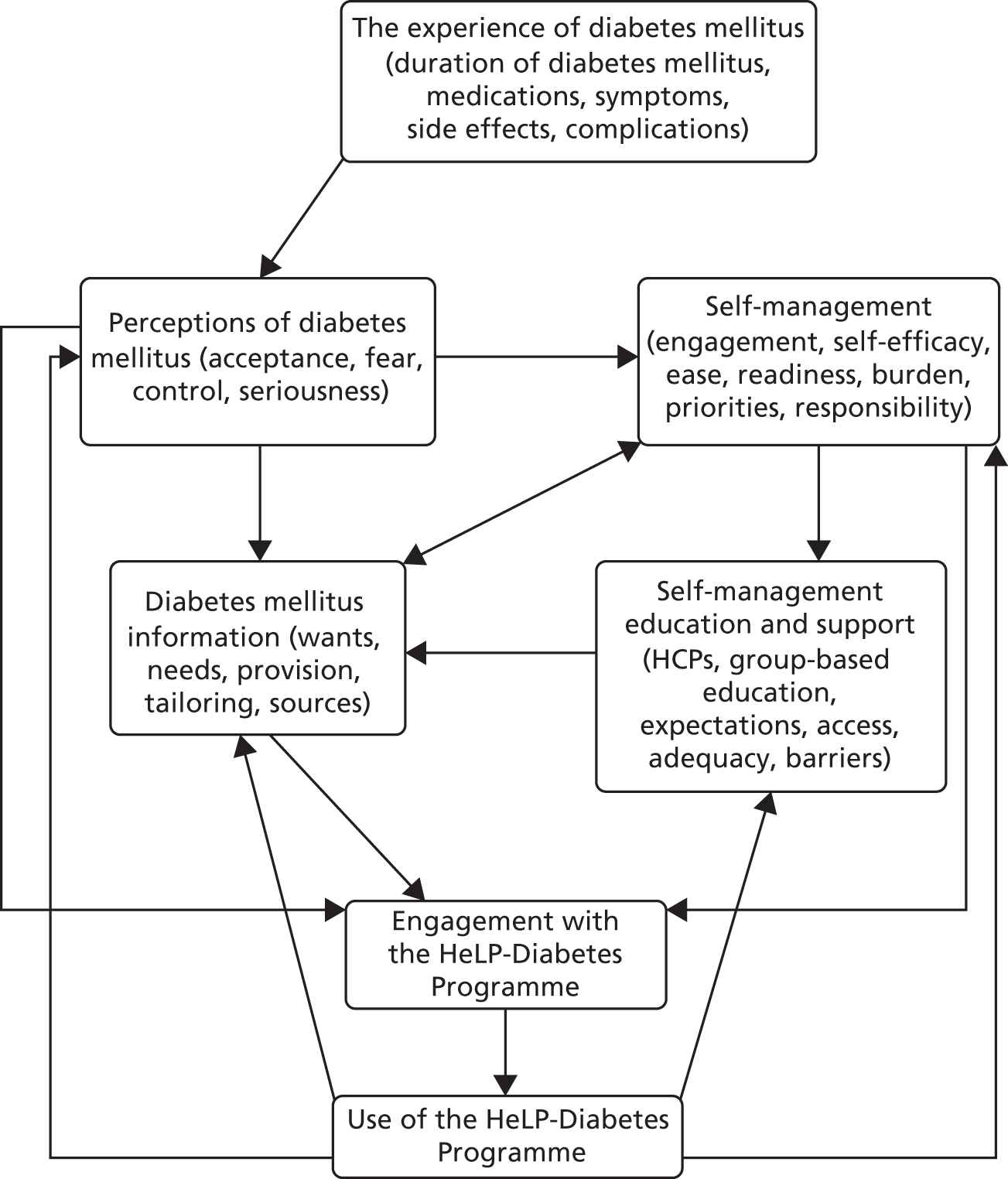

This chapter summarises the contents of the subsequent chapters. The overall structure of the programme of research is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of overall programme with constituent work packages. HCP, health-care professional; RCT, randomised controlled trial; WP, work package.

Summary of Chapter 2: rationale and background

Chapter 2 outlines the rationale for the programme of work, explains why diabetes mellitus is a priority area for the NHS and explores the importance of good self-management in improving health outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus and the problems with current service provision. It suggests reasons why a web-based self-management programme could help address some of these problems and sets out the challenges identified during the planning stage and our approach to these challenges.

As theoretical underpinning is associated with clinical effectiveness in web-based programmes, we had a strong theoretical framework, which is outlined in Chapter 2. Inevitably, there were substantial contextual changes during the 5-year programme of research and these had a considerable impact on the research. These contextual changes are described at the end of this chapter.

Summary of Chapter 3: aims, objectives and additional work undertaken

Chapter 3 describes the aims and objectives of the programme grant and outlines the methods used to address each objective. We were fortunate to be able to undertake a number of studies additional to those originally planned and these are also outlined in this chapter.

Summary of Chapter 4: what do people with type 2 diabetes mellitus want and need from a web-based self-management programme?

Chapter 4 reports on a qualitative study that aimed to determine patient perspectives of the essential and desirable features of a web-based self-management programme for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), including features that would encourage use, such as access to their electronic medical record (EMR) and facilitation by health-care professionals (HCPs).

Summary of Chapter 5: what requirements do health-care professionals have of a web-based self-management programme for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus?

Chapter 5 reports on a qualitative study that aimed to determine the perspectives of HCPs of the essential and desirable features of a web-based self-management programme for people with T2DM and what could be done to encourage uptake and use in the NHS. Additional objectives were to explore HCPs’ views on the type and quantity of facilitation that could be provided in general practice and on patient access to part or all of their EMR.

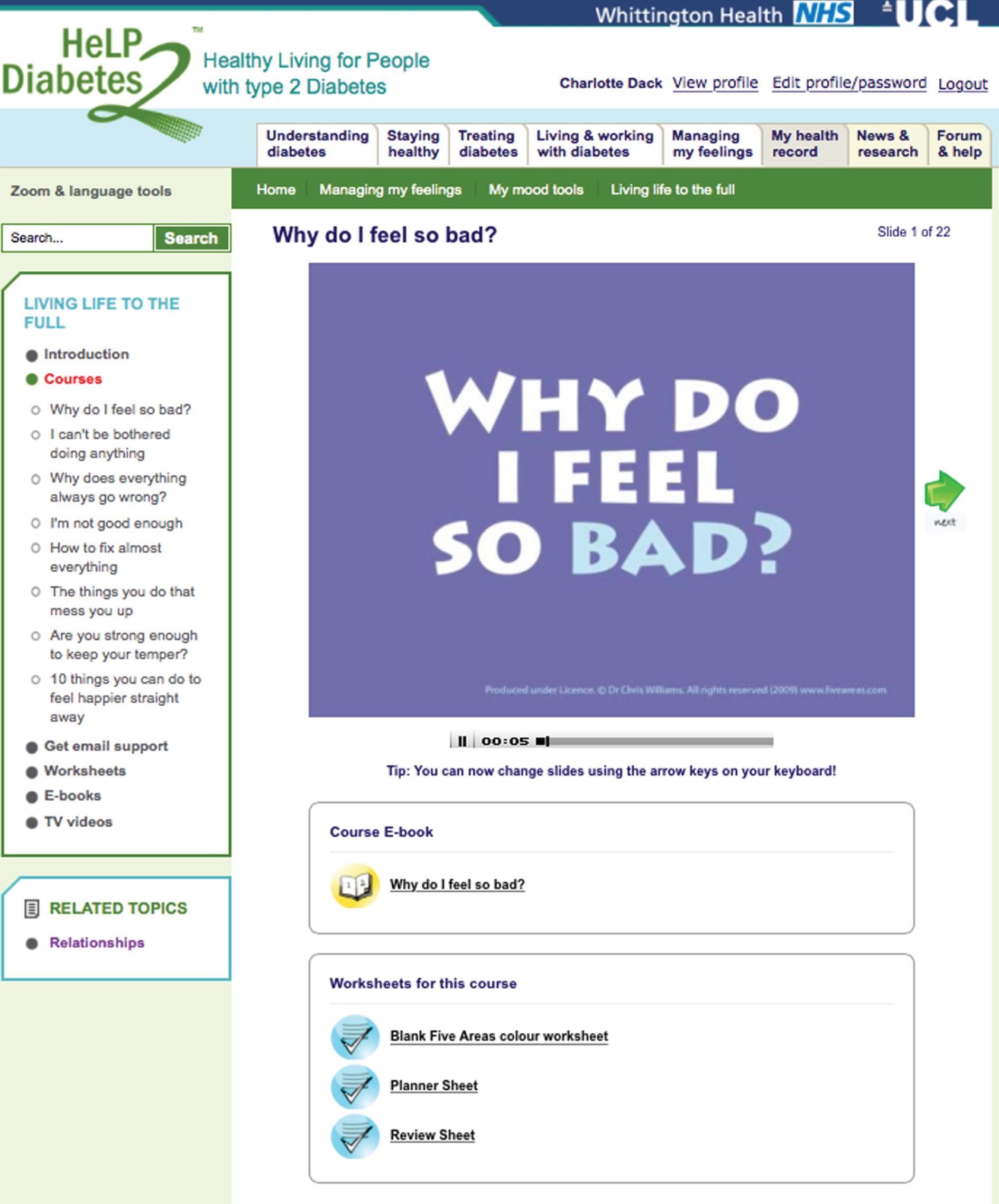

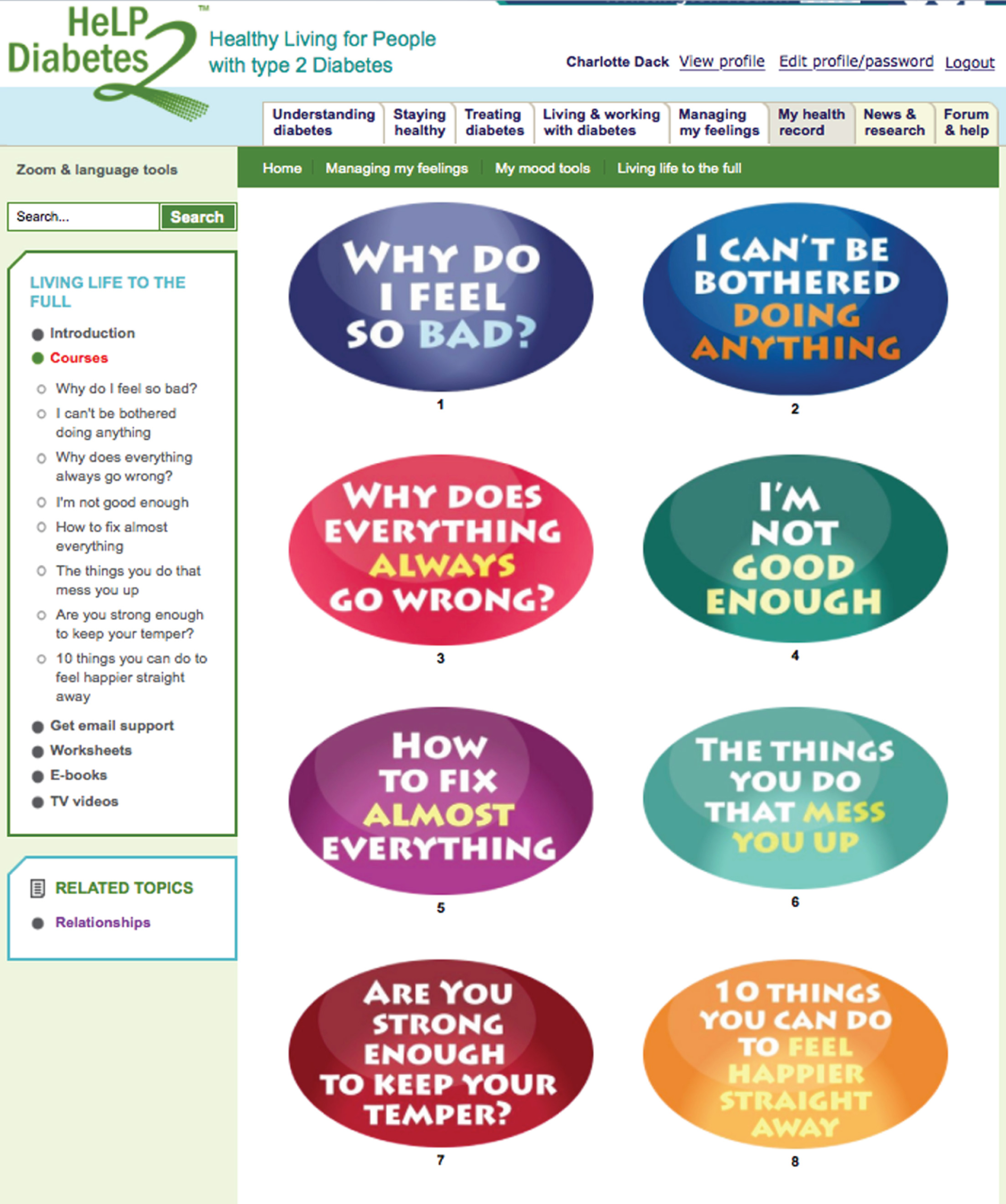

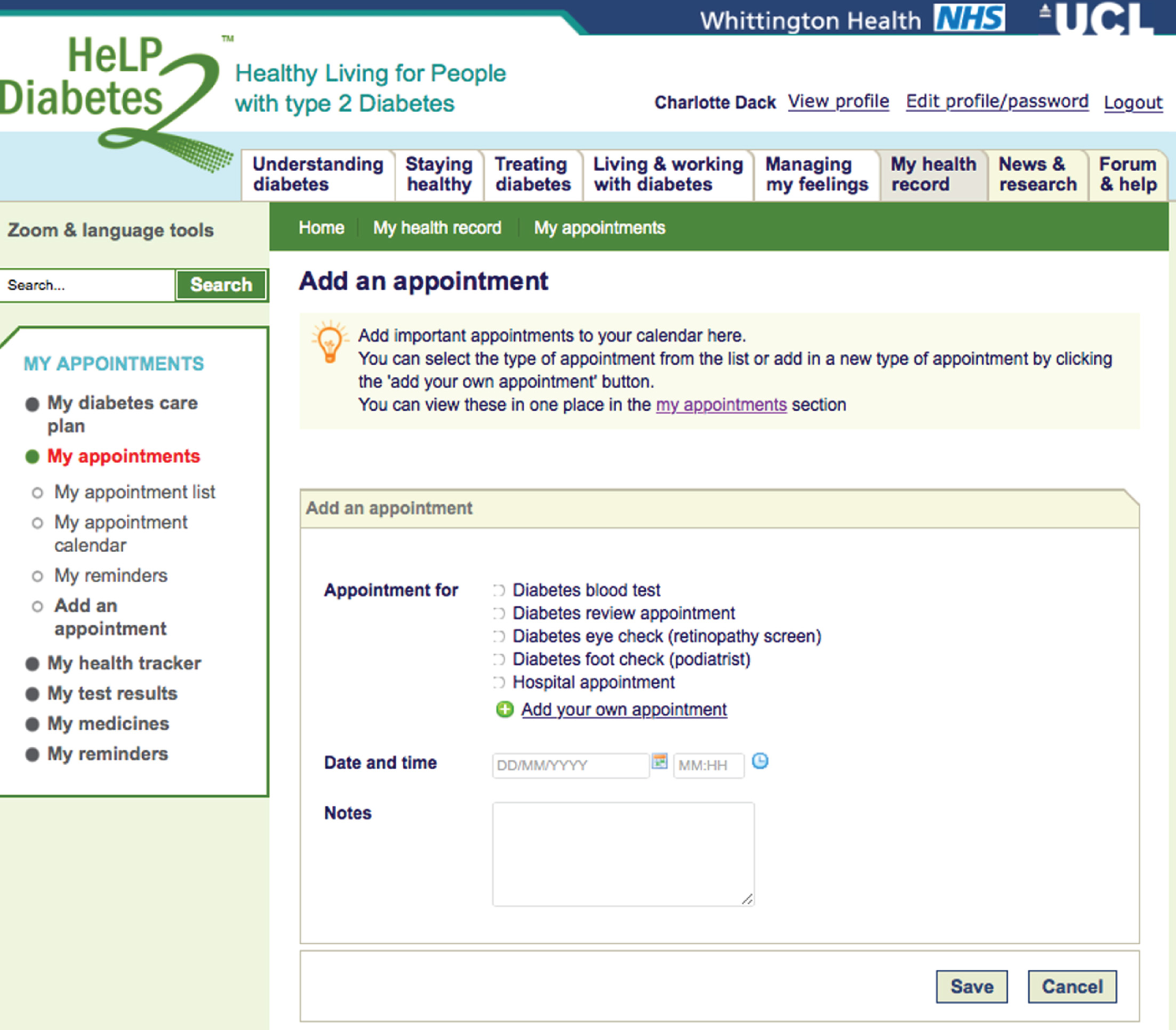

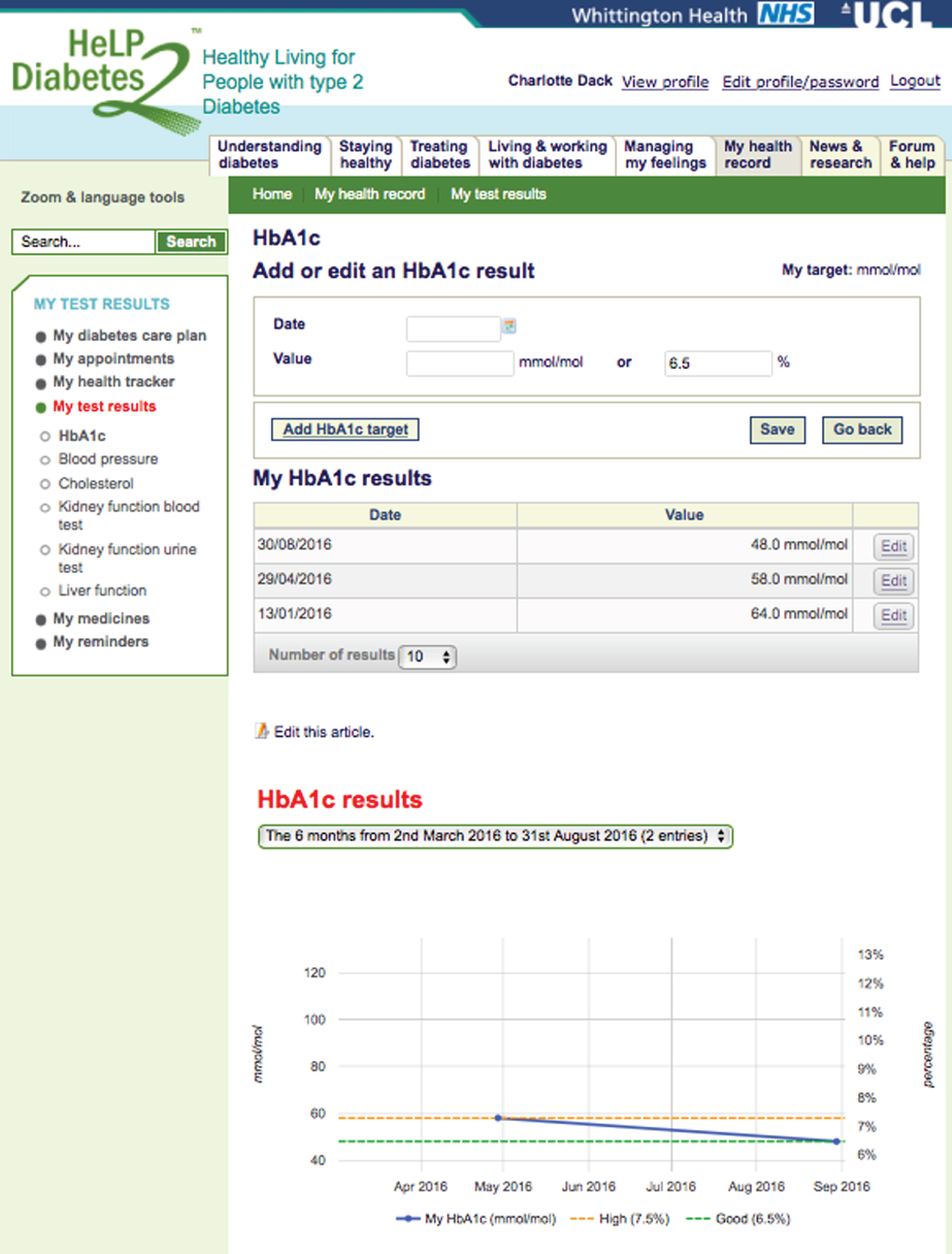

Summary of Chapter 6: the Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes programme: a web-based self-management programme for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus

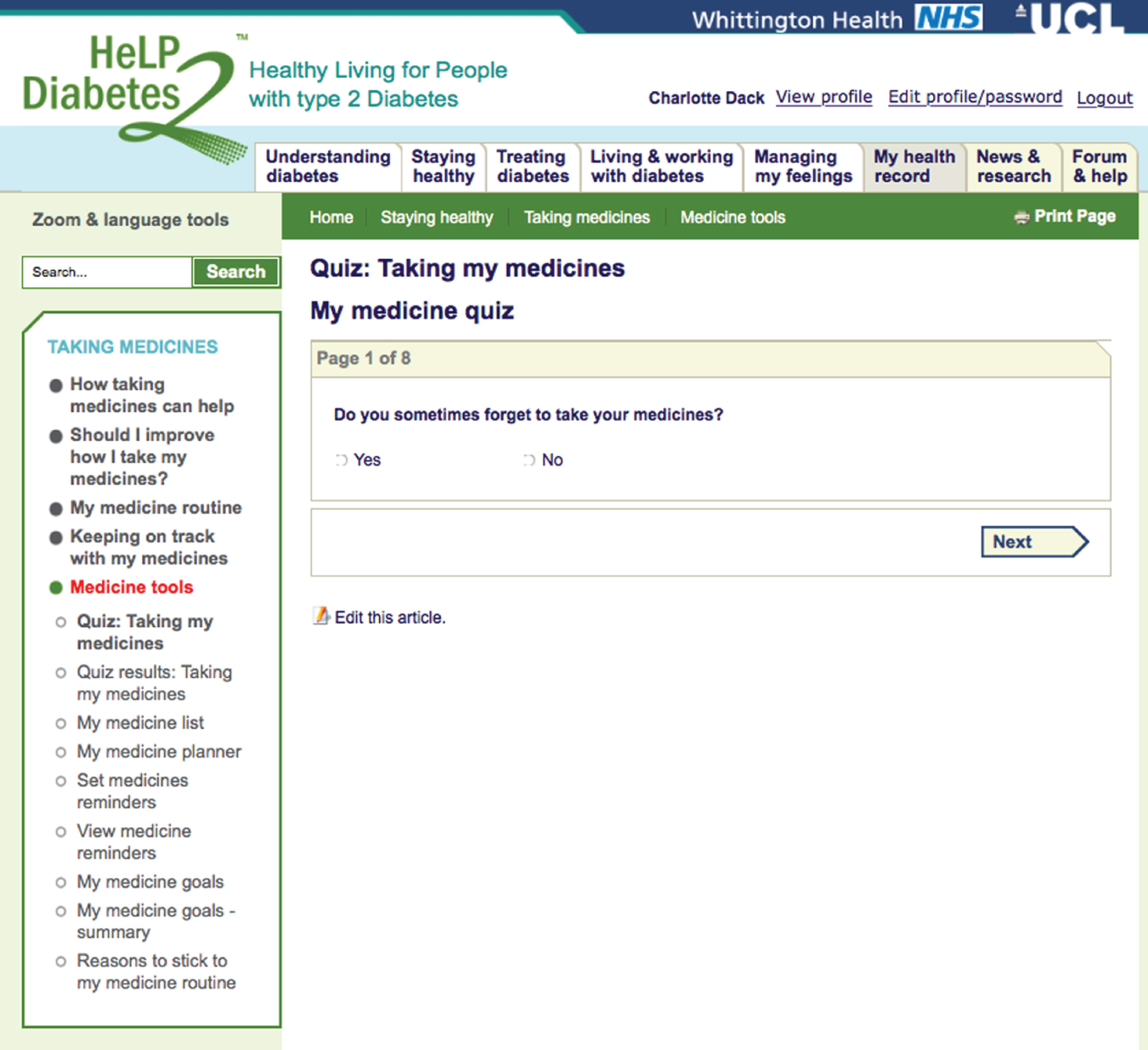

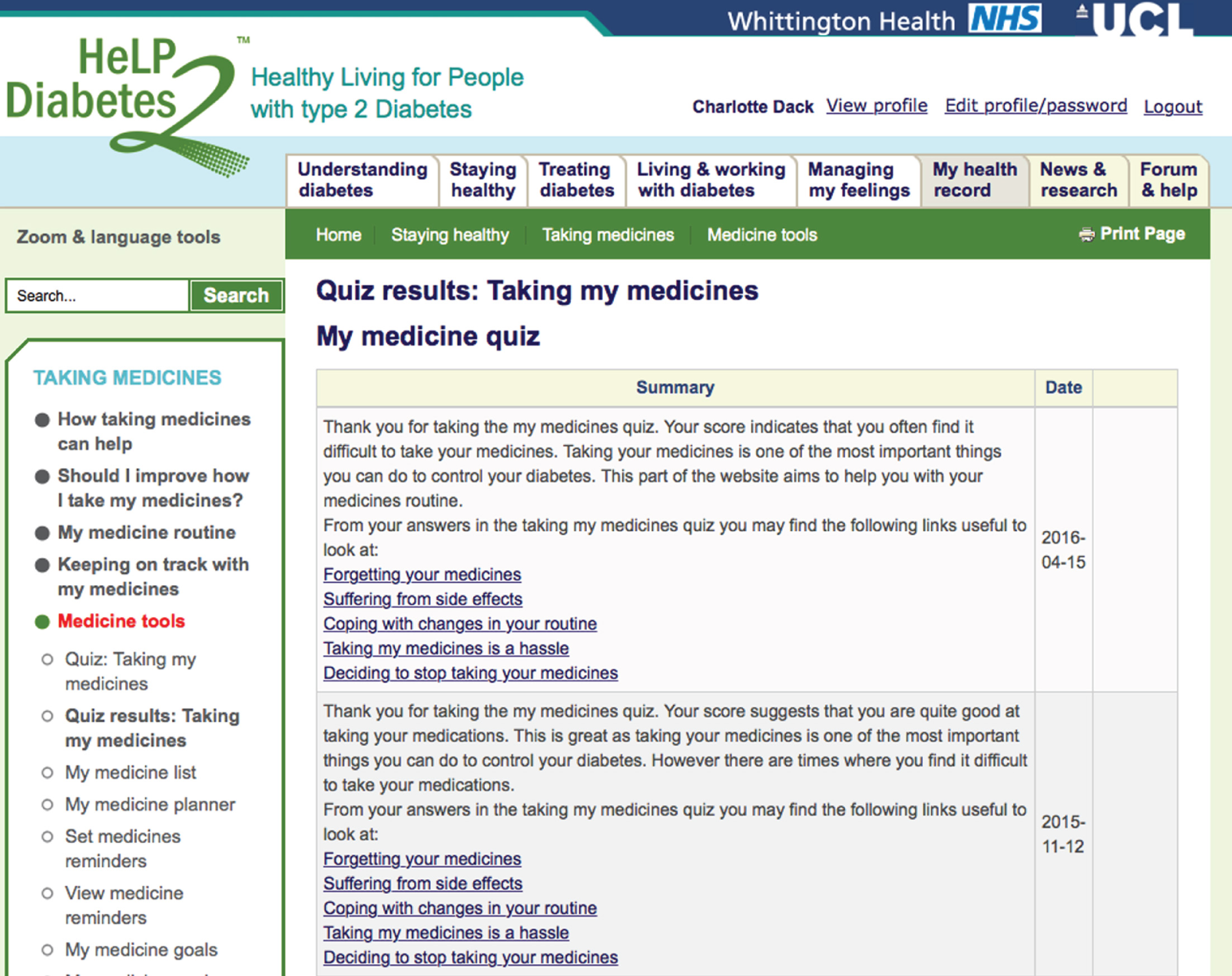

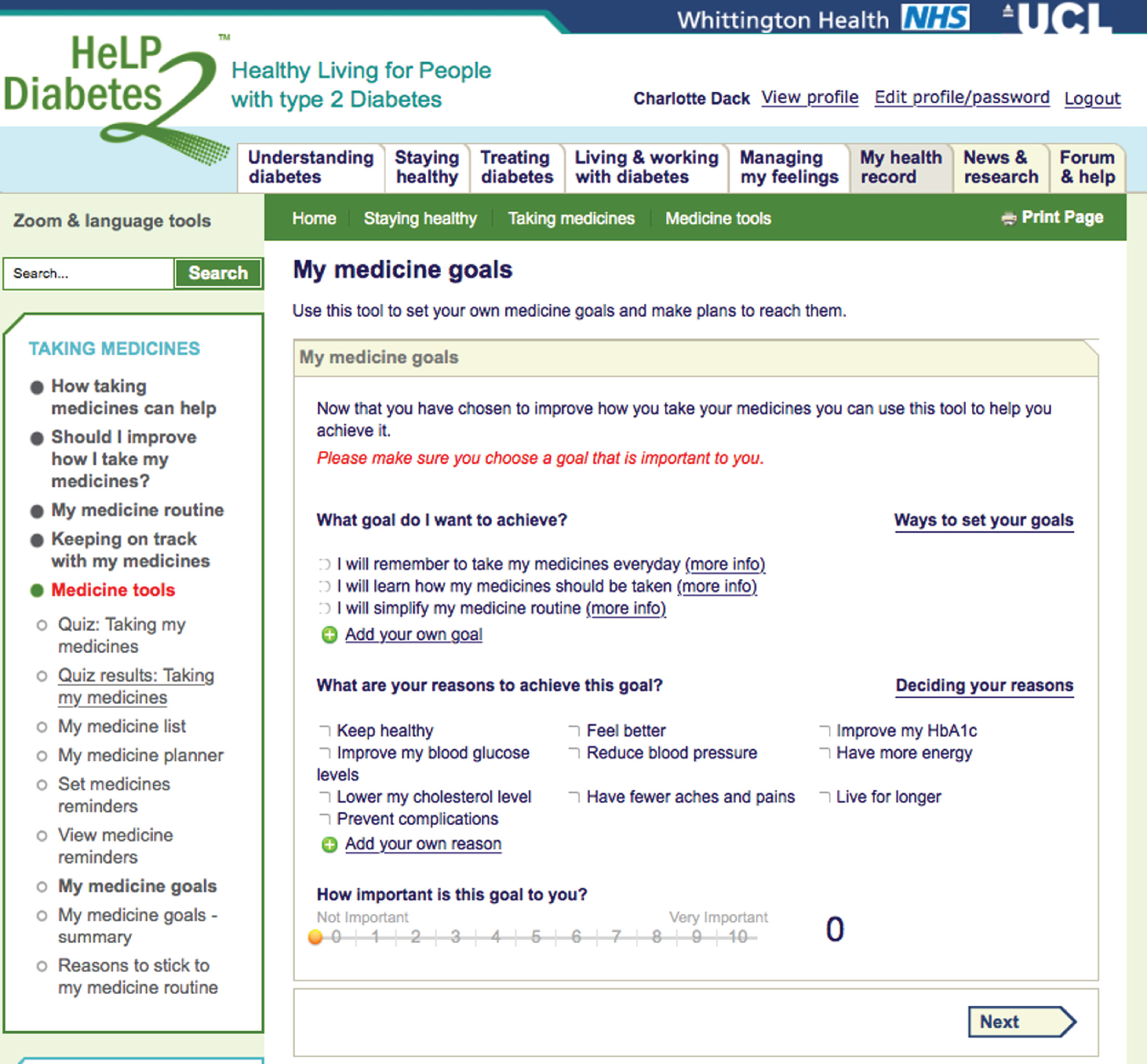

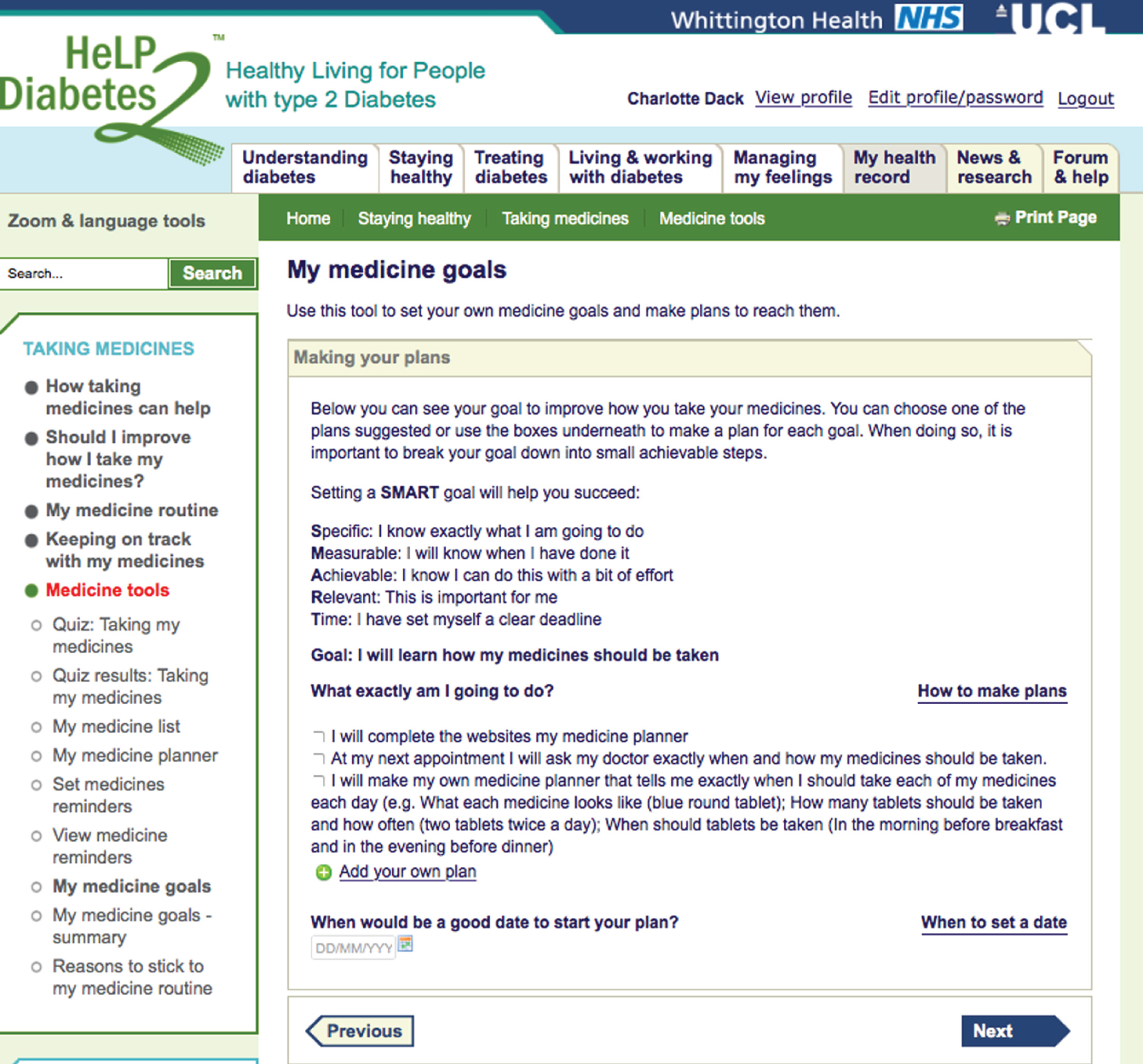

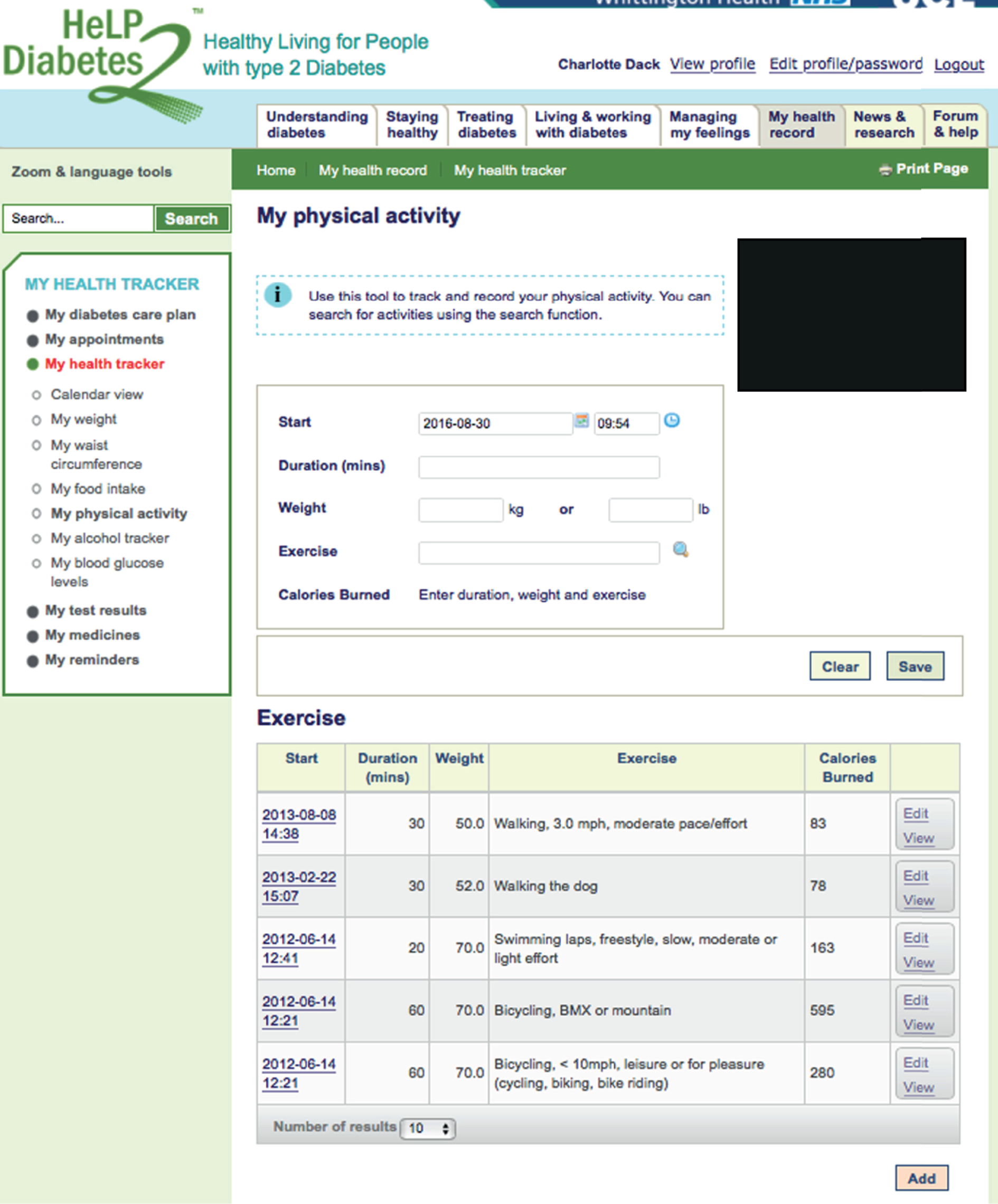

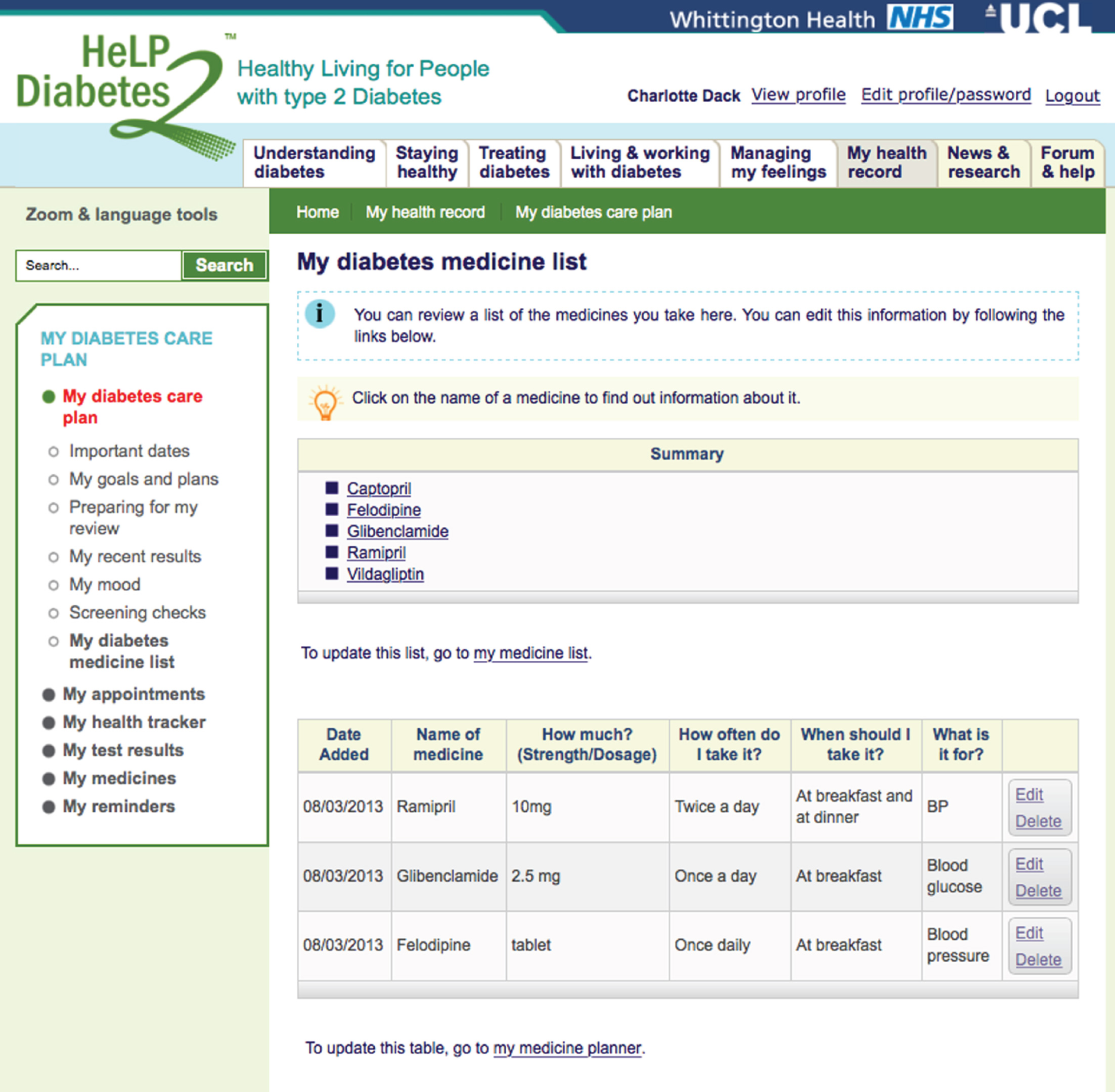

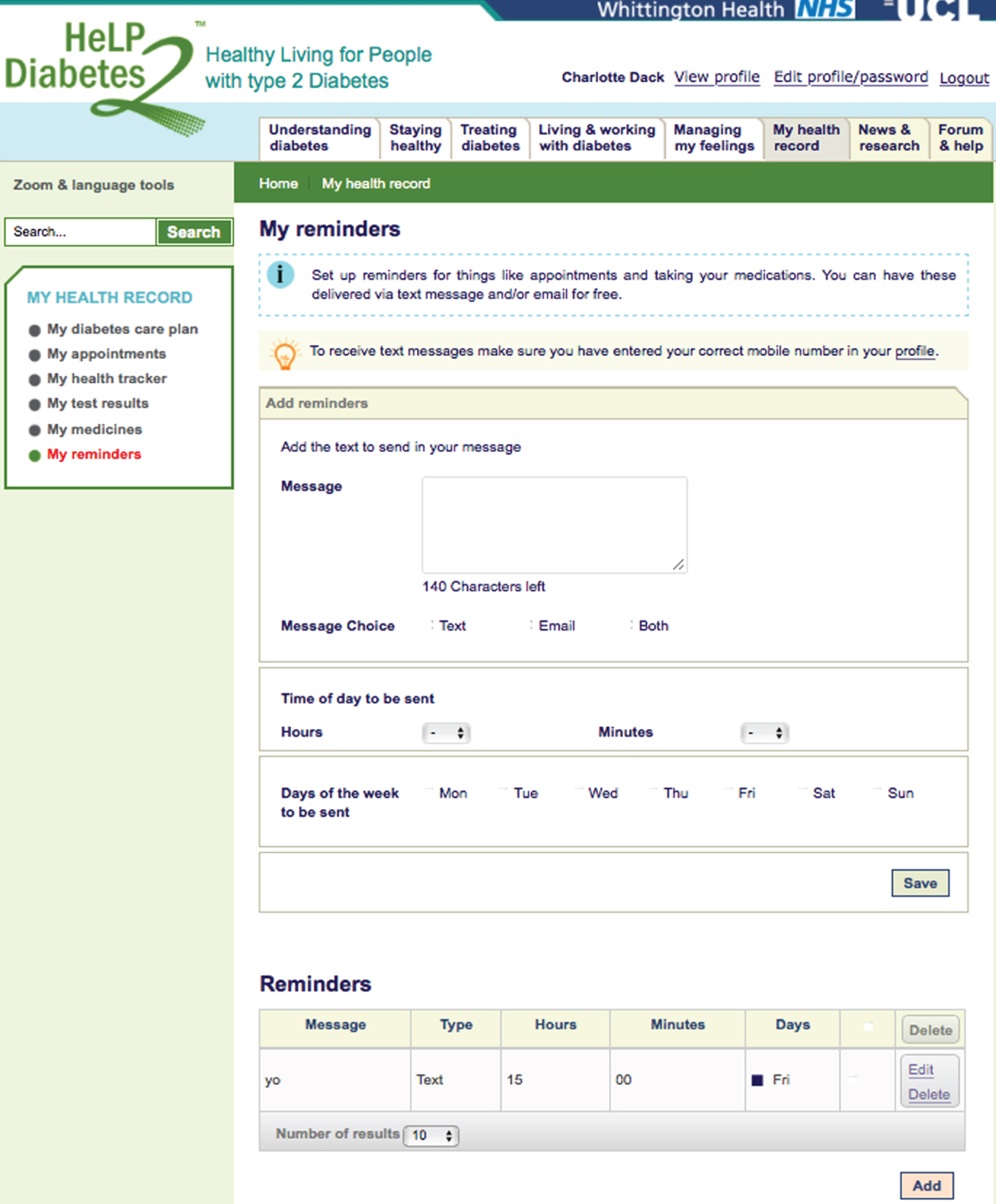

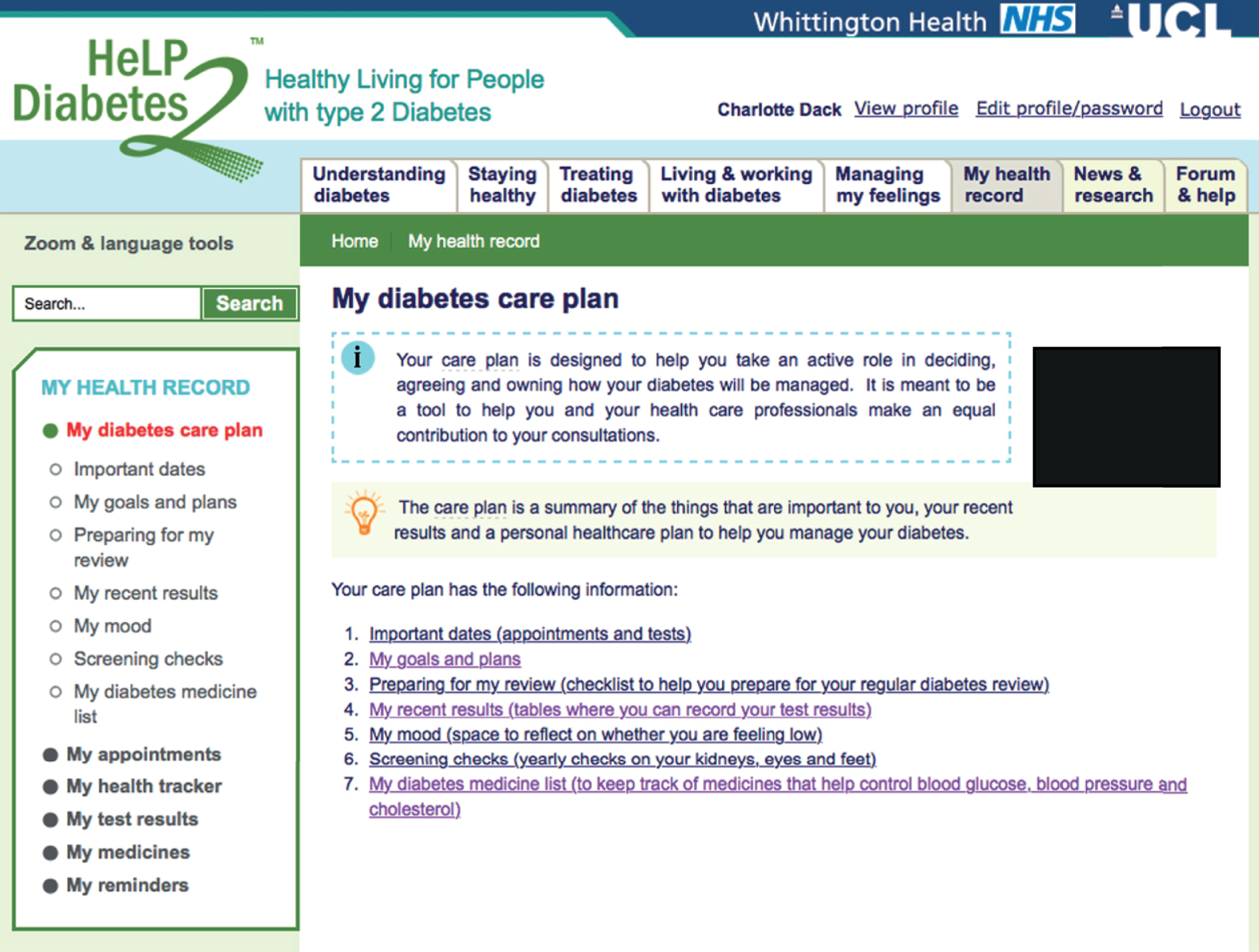

Chapter 6 describes the process of developing the Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes (HeLP-Diabetes) programme, including determining and creating the content and functionality. The process was iterative and involved a large multidisciplinary team, with extensive user input through participatory design. We then describe the intervention, procedures for maintaining and updating the intervention and techniques for promoting engagement.

Summary of Chapter 7: randomised controlled trial of the Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes programme

Chapter 7 describes the design and results of a multicentre individually randomised controlled trial in primary care to determine the clinical effectiveness of the HeLP-Diabetes programme.

Summary of Chapter 8: health economic analysis

Chapter 8 presents the within-trial health economic analysis of the HeLP-Diabetes programme.

Summary of Chapter 9: design and evaluation of a plan for implementing the Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes programme into routine NHS care

Chapter 9 describes the design and evaluation of a plan for implementing the HeLP-Diabetes programme into routine care. The aim of this work was to determine how best to integrate an eHealth intervention for patients into routine care, using the HeLP-Diabetes programme as an example.

Specific objectives were to design an implementation plan, evaluate its clinical effectiveness and any reasons for observed variation in implementation and modify the original plan in the light of these emerging data. We were interested in maximising uptake and use by people with T2DM, in exploring ways of overcoming the ‘digital divide’ and the impact that the intervention had on patient outcomes outside a trial.

Summary of Chapter 10: discussion

Chapter 10 summarises the overall findings of the programme of work, considers the strengths and limitations of the work done and the implications for practice, policy and research.

Chapter 2 Rationale and background

Chapter summary

This chapter outlines the rationale for the programme of work, explains why diabetes mellitus is a priority area for the NHS and explores the importance of good self-management in improving health outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus and the problems with current service provision. It suggests reasons why a web-based self-management programme could help address some of these problems and sets out challenges identified during the planning stage and our approach to these challenges.

As theoretical underpinning is associated with effectiveness in web-based programmes, we had a strong theoretical framework, which is outlined here. From its conception, this programme of work was planned and executed with substantial input from people with T2DM, who acted as research partners. This input (also called patient and public involvement; PPI) is summarised in this chapter. Inevitably, there were significant contextual changes during the 5-year programme of research, and these had considerable impact on the research. These contextual changes are described at the end of the chapter.

Diabetes mellitus: a health service priority

In the UK, diabetes mellitus is a NHS priority, affecting around 6% of the population, about 4 million people in the UK,1 of whom around 90% have T2DM. Diabetes mellitus is also a global health priority. Current estimates suggest that there are over 400 million people living with T2DM across the world, with a prevalence of 8.3% in adults aged 20–79 years; numbers are rising and by 2035 there may be 600 million people living with this condition. 2,3

Diabetes mellitus can cause significant morbidity and mortality: complications include cardiovascular disease (leading to heart attack and stroke), peripheral vascular disease (leading to leg ulcers, infection and amputation), nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy. People with T2DM are at increased risk of mental health problems, with nearly double the prevalence of depression compared with those without diabetes mellitus (19.1% vs. 10.7%)4 and 25% higher risk of anxiety. 5 There is also a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus-related distress, defined as ‘the concerns and worries about diabetes and its management’. 6 Surveys of populations who have diabetes mellitus have reported rates of diabetes mellitus-related distress of 45%. This matters not only because high levels of distress have an adverse effect on quality of life, but also because high levels of distress are associated with poor diabetes control and increased rates of complications.

Overall, diabetes mellitus has a significant negative impact on life expectancy, reducing it by anything from 3.3. to 18.7 years. 7

There are substantial health-care costs associated with diabetes mellitus, both for health-care systems and for individuals. Around 10% of the NHS budget is estimated to be spent on managing diabetes mellitus and its complications. 8 In 2010, direct costs of diabetes mellitus in the UK were estimated at £13.8B annually. 9 By far the largest proportion of direct health-care costs are as a result of inpatient treatment of complications. 10,11 Overall, health-care costs related to diabetes care are rising because of a combination of increasing prevalence, increased costs of drugs used to treat diabetes mellitus and increased numbers of consultations. 12

Diabetes mellitus self-management education

The Wanless13 report of 2002 argued that two factors were critical to improving health outcomes and containing health-care costs: (1) a population actively engaged in self-care of their health and (2) a responsive health service with high rates of technology uptake. This report reflected and triggered considerable interest in self-management interventions, defined as ‘primarily designed to develop the abilities of patients to undertake management of health conditions through education, training and support to develop patient knowledge, skills or psychological and social resources’. 14

In the field of diabetes mellitus, landmark trials such as the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) trial15 and the X-PERT programme16 suggested that educating patients about their diabetes mellitus and helping them improve self-management skills could improve glycaemic control, at least in the short term. 17,18 Early studies suggested that the risk of developing complications could be reduced fourfold by appropriate diabetes mellitus self-management education (DSME). 19

Providing people with diabetes mellitus with access to structured DSME at diagnosis, with annual reinforcement thereafter, was thus incorporated into national guidelines. 20 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) included structured education in the clinical guideline for T2DM in 200921 and in the quality standard for diabetes mellitus in adults in 2011. 22 However, uptake remained low, with data from the National Diabetes Audit suggesting that only 7.6% of people with diabetes mellitus reported being offered structured education in 2009–10 and 10.3% in 2010–11,23 with even fewer attending.

Reasons for this low uptake were thought to include provider difficulties in implementing and resourcing high-quality education programmes and patient difficulties in attending the available programmes. 24,25 The dominant model for self-management education is group-based education, usually offered over 1 full day or 2 half-days. Attending groups may be difficult for people who work, have family or caring commitments or simply do not like group-based formats. Moreover, patient needs evolve with time, for example as changes are made to their medication (such as higher doses or additional or different drugs) or as they develop complications. These events are likely to bring new information needs and may be associated with further emotional distress.

Potential benefits of web-based diabetes mellitus self-management education

The web appeared to have considerable potential to improve access to, and uptake of, DSME. Internet access in the UK in 2011 was 73%,26 having increased year-on-year with an expectation of continued growth; indeed, latest estimates suggest that 86% of households had internet access in 2015. 27

Computer and web-based interventions were known to have specific advantages, including convenience (accessible at any time), anonymity (important to people with a stigmatised condition such as T2DM) and easy updating. A particular potential benefit appeared to be the ability to provide the entire range of support needed for a person’s illness journey, since diagnosis to end-stage disease. Good design could ensure that users accessed only the information and services needed at that time but, as needs evolved, they could find resources to match. The processing power and connectivity of desktop, laptop or handheld computers and smartphones allowed for interactive, tailored interventions that could respond to data entered by users with personalised information and advice. Such interventions could provide support for behaviour change,28–31 improve mental health and emotional distress32–35 and offer peer support. 36 There was evidence to support their use in long-term conditions (LTCs),37 including in diabetes mellitus,38 asthma39 and hypertension. 40

Potential pitfalls of web-based diabetes mellitus self-management education

Even at the time that this grant was conceived (i.e. 2009–10), it was clear that the potential benefits of web-based self-management interventions were hard to achieve and that there were a number of pitfalls. Challenges that were particularly evident were:

-

very variable clinical effectiveness between different interventions, with no real understanding of the causes for this43,44

-

significant problems with implementation of digital interventions, with, at that time, almost no examples of their successful integration into routine health care45

-

the digital divide – the divide between those who did and did not use digital technologies. 46

This programme of work was undertaken with these challenges in mind. The process of developing the self-management programme was designed to optimise uptake and use, while maximising the likelihood of clinical effectiveness and future implementation into routine NHS services.

Addressing the challenges

Low uptake and usage

We tackled the problem of low uptake and low usage in several ways. First, we followed the principles of participatory design and heavily involved members of the target user population in the development of the intervention. The aim of participatory design is to ensure that the intervention meets user requirements and is appealing and easy to use.

As the intervention was designed to be used by people with T2DM, in partnership with their HCPs, we defined the target population as people with T2DM and the HCPs with responsibility for them, including general practitioners (GPs), practice nurses, specialist diabetes nurses, consultants in diabetes medicine and dietitians.

This involvement was a three-stage process: (1) we undertook qualitative work with the patients and HCPs to identify the ‘wants and needs’ for such a programme; (2) we recruited patients and professionals to contribute on an ongoing basis to the intervention’s development, including seeking input on decisions for content, look and feel, tone, navigation and functionality; and (3) we undertook user testing of the intervention, asking patients and HCPs to review the programme and identify errors in content, bugs or glitches in functionality and problems with design or navigation. This process is described in detail in Chapters 4–6.

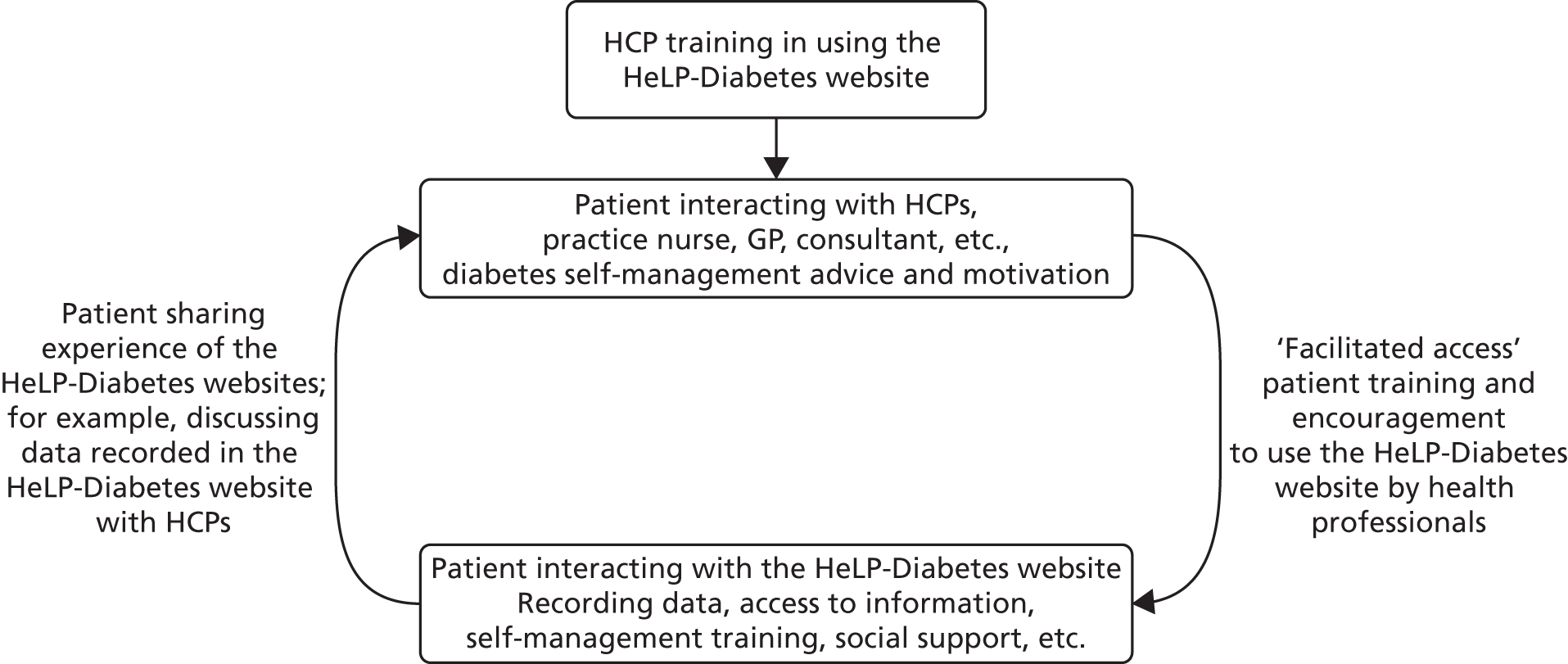

Second, we thought that uptake and use would be enhanced by ensuring that the self-management programme was integrated into people’s routine health care and seen by patients and HCPs as an integral part of the total care package. Previous data have shown that patient-centred clinician communication improves diabetes mellitus self-management behaviours. 47,48 Educational and self-help programmes that are actively supported by clinicians can improve health outcomes for people with LTCs,49 and in people with low health literacy the impact that written material has is increased by verbal recommendations from the HCP. 50 Thus, we conceived of the intervention as a web-based programme together with interactions between HCPs and patients around the programme (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The intervention: not just a computer program.

We thought there were at least three ways that HCPs could promote the programme to patients: first, by introducing them to the programme, explaining how it could help them with managing their diabetes mellitus and achieve better health status and quality of life and providing some initial training. Second, we thought that telephone calls would help to encourage the uptake and use of our self-management programme, particularly when patients were new to it and might need a bit of encouragement or help. This was based on experience from the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme, which facilitated access to computerised cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) through graduate mental health workers who first introduced patients to specific computerised CBT programmes and then telephoned them regularly to encourage adherence to the programme. Third, we hoped that HCPs would refer to our self-management programme in consultations, for example when discussing care plans with patients, or by reviewing any self-monitoring data the patient had entered into the programme.

One inference of this approach of integrating our programme into routine health care was that some linkage between the self-management programme and the patient’s EMR would be useful, and such a linkage formed part of our original grant application.

Variable effectiveness and problems with implementation

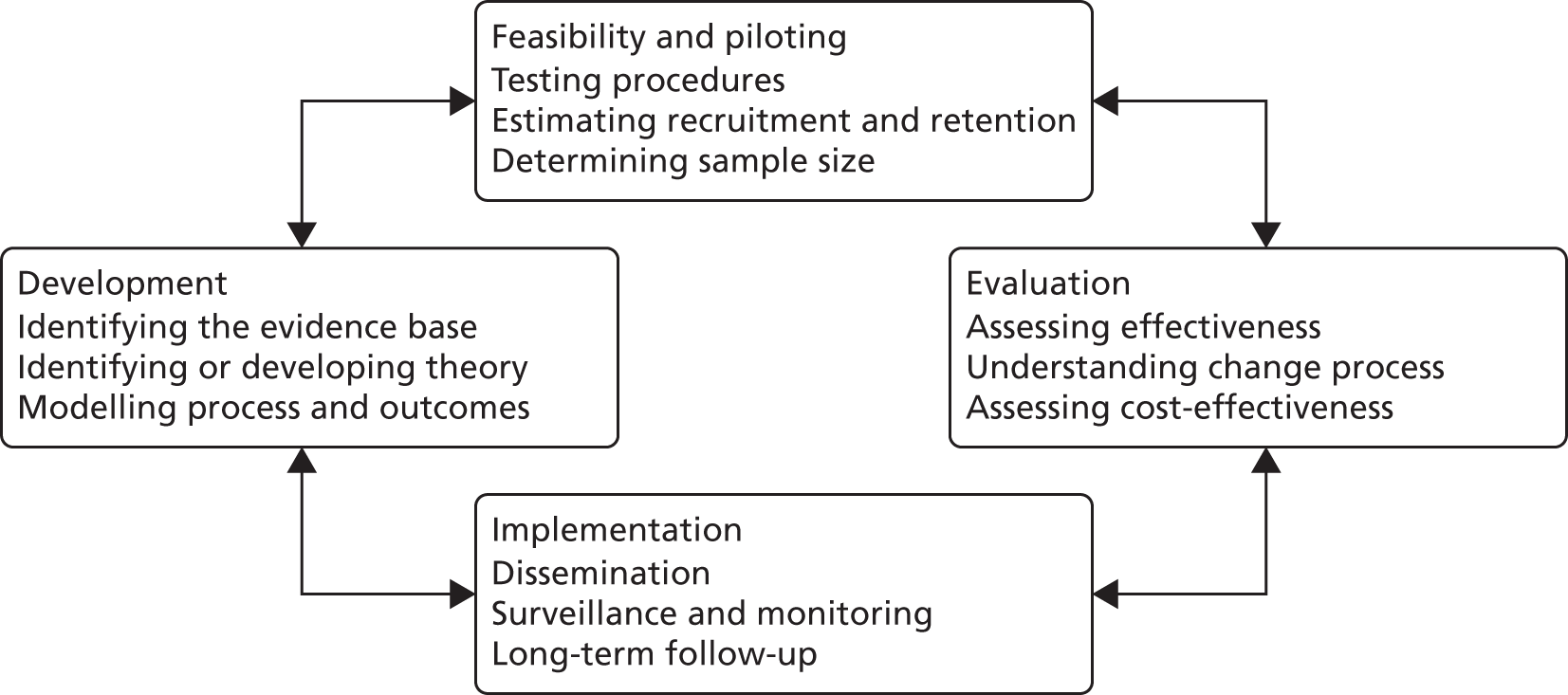

At the time we wrote the grant and developed the intervention, relatively few data existed to explain why some web-based interventions were effective and others were not. 43,44 What few data existed supported the expectation that interventions that were based on theory were more likely to work than those that were not. In the light of this, and following Medical Research Council (MRC)’s guidance for development of complex interventions (Figure 3),51–53 we adopted a strong theoretical framework to guide the development of the intervention. We also followed best practice in using theory to guide us in considering implementation from the outset, aiming to ensure that the intervention was maximally ‘implementable’ and would fit easily into existing NHS structures and workflows.

FIGURE 3.

The MRC framework. 51 Reproduced from Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance, Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, Medical Research Council Guidance, 337, a1655,51 Copyright © 2008, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited.

We used three theoretical frameworks or approaches to guide us:

-

Corbin and Strauss’ model54 of the work of managing a LTC

-

Abraham and Michie’s taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCTs)55

-

normalisation process theory (NPT). 56

We worked within the paradigm of evidence-based medicine, identifying and applying the best-available evidence for treatment of diabetes mellitus and for any decisions made during development (e.g. around maximising acceptability, uptake, usage and clinical effectiveness).

Corbin and Strauss’ model for managing a long-term condition

In their seminal work Unending Work and Care, published in 1988, Corbin and Strauss54 conceptualised the work of living with a LTC as comprising three tasks: medical management, role management and emotional management. Medical management consists of adopting healthy behaviours (e.g. not smoking, exercising regularly, eating healthy food), working with health professionals (e.g. keeping appointments and following instructions) and taking medicines. Emotional management entails addressing the powerful negative emotions associated with being diagnosed with a LTC, such as anger, guilt, shame and despair. Role management requires coming to terms with the disruption of one’s biographical narrative and sense of self,57 including adjusting to the ‘patient’ role and managing the impact that one’s diagnosis has on relationships with friends, family and colleagues. This conceptualisation was used to create a map of the overall content required in the self-management programme.

Abraham and Michie’s taxonomy of behaviour change techniques

The Corbin and Strauss model and conventional diabetes education curricula both stress the need for behaviour change as part of self-management. For people with T2DM, the key target behaviours are to stop smoking (for smokers), improve their diet, increase physical activity, moderate alcohol consumption and take medicines.

There are a plethora of psychological theories predicting behaviour, many of which include overlapping concepts. 58 Rather than opt for one specific theory, and because we were more interested in changing behaviour than predicting it, we adopted the Abraham and Michie taxonomy of BCT. 55 This taxonomy identified techniques used to change behaviour and there is a growing body of evidence around which techniques are effective. 59–61 One advantage of this taxonomy was that it allowed for those components that were likely to lead to the desired behaviour changes to be implemented elsewhere. 62

Normalisation process theory

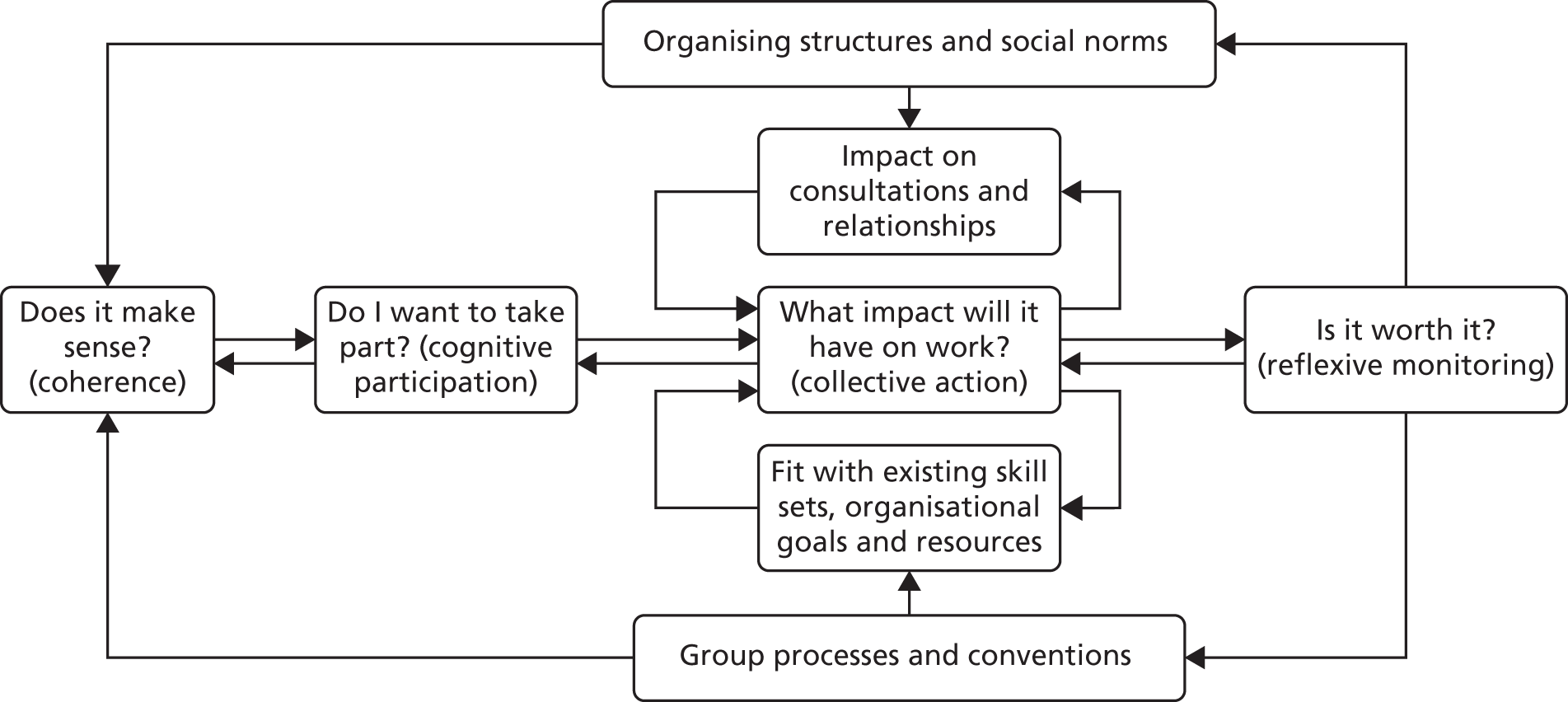

The NPT56 is a mid-range sociological theory that explains why interventions do or do not ‘normalise’, that is become integrated into routine practice. It focuses on the work of implementation, integration and embedding new practices, ways of working or other interventions. It has four main constructs: coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Normalisation process theory.

Coherence refers to the ease with which the intervention can be described, understood and distinguished from other interventions or practices. This construct also includes an understanding of the problem that the intervention is designed to address, how the intervention could benefit its target population and what work will be needed for these potential benefits to be realised. Cognitive participation is about the decision whether or not to participate in the intervention. This will include an assessment of the relative benefits of participation (to patients, professionals or the health-care system) weighed against the costs of participation, in particular the expected impact on workload. Collective action is about the impact that the intervention has on the work undertaken by professionals within the organisation and reflexive monitoring is the process of considering whether or not the benefits of the intervention are worth the effort required to implement it. Within this construct is the possibility of altering or adapting the intervention to make it easier to implement in any given setting or organisation.

In turn, collective action has four subsidiary constructs: interactional workability, relational integration, skillset workability and contextual integration. Interactional workability refers to the degree to which the intervention facilitates or impedes the work of professional–patient interactions (consultations). Relational integration is the degree to which the intervention promotes or hinders good communication and relationships between different professional groups, including the degree to which accountability and responsibility are aligned. Skillset workability refers to the degree to which the intervention fits with existing skillsets or roles and the amount of training required to use the intervention. Finally, contextual integration is about the degree to which the intervention fits with existing policies, priorities and practices within the organisation.

The NPT56 predicts that interventions that improve consultations, promote good relationships between professionals, with accountability and responsibility well aligned, that need little training and that fit well with organisational priorities are more likely to normalise than those that do not.

Applying NPT to the development process meant that we were mindful of the following needs for the final self-management programme:

-

it should be easily described, easy to differentiate from other programmes and have clear benefits

-

it should fit with organisational and professional priorities, including enabling people with T2DM to self-manage care, reducing demand on professional time, adhering to NICE guidance and being accessible to a wide range of people

-

it should fit easily into existing working practices and be compatible with existing technology

-

it should make consultations between HCPs and patients easier and more productive and should be very easy to use.

Further details about how we applied NPT to the development of the intervention, and how NPT informed our implementation strategy, can be found in Chapters 5, 6 and 8.

Evidence-based medicine

We applied the paradigm of evidence-based medicine in two ways: first, we ensured that all the information, guidance and advice for patients in the intervention was evidence based and compatible with NICE, or other, national guidelines. Second, we applied the best-available evidence to the whole process of intervention development, drawing on data on best practice from computer science, eHealth, biomedical, health education and health services research.

The digital divide

The term ‘digital divide’ refers to the gap between those who do and do not have access to, or make use of, information and communication technologies. 46 At the time that this grant started (i.e. 2011), there were marked inequalities in internet access, with age, income, educational status and health status all being associated with access. Figures from the 2011 Oxford Internet Institute survey26 showed that, although about 85% of people who were at prime working age (25–55 years) used the internet regularly, only 33% of those aged ≥ 65 years did. Some 99% of households with total annual household income of ≥ £40,000 had internet access, but only 43% of households with an annual income of ≤ £12,500 did. Internet use was around 95% among people with degree-level education, but only 54% in those with a basic or secondary school education. The level of internet use in people with a disability was 41%; however, among people without a disability it was 78%. 26

There was evidence that the digital divide could be overcome with appropriate infrastructure, resources, training and design of interventions. Infrastructure requirements included provision of access to the internet, and the UK has benefited from a policy environment that promoted universal access. For example, most public libraries provide up to 1 hour per day per user of free access to an online computer and many local authorities fund community cluster rooms with associated training opportunities. 63 Provision of appropriate resources and training has been shown to enable diverse disadvantaged populations to make meaningful use of internet resources, including homeless drug users,64 vulnerable elderly people,65 parents of children attending early learning centres66 and people with cardiovascular disease67 or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)68 from underserved communities.

We took a multipronged approach to attempting to narrow the digital divide and to ensure that our proposed intervention would be used by people from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. We thought that people would be more likely to use the programme if it were recommended by trusted HCPs and integrated into routine care. Our previous research had shown that even short training sessions could enable some people who were not used to using computers to be able to use well-designed web-based interventions,69 although some people needed ongoing support. We thought that ongoing engagement would be promoted by HCPs referring to the programme in their consultations with the patient. Finally, we aimed to ensure that the intervention could be easily used by people with low literacy or computer literacy skills, by aiming for intuitive navigation, having liberal use of graphics, using text written for a reading age of 12 years and ensuring that key information was provided in video format, as well as text.

Patient and public involvement

The entire programme of research had very strong PPI input. At the initial development of the grant application, a named PPI co-investigator and two named PPI collaborators were recruited. These PPI members were equal partners in the research team and contributed equally to the decisions made during the programme. All three were members of the overall steering group for the programme. In common with our other co-investigators and collaborators, circumstances changed for some of these key PPI members, leading to their resignation from the programme. In each case, they were replaced. In addition to the overall steering group, each individual work package (WP) had a project management group. Each project management group had at least one, and usually two, PPI members who contributed to the oversight and conduct of the project on an equal footing with the other members of the management group. There was PPI membership of both the trial management group and the trial steering committee. As members of the project and trial management groups and the trial and overall steering committees, PPI members contributed to discussions on recruitment, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the data and to dissemination. All recruitment and participant-facing materials were designed in collaboration with our PPI members and were revised in accordance with their input. Our PPI collaborators are listed in the Acknowledgements. They were recruited through advertisements and publicity in diabetes networks and interested applicants were sent job descriptions and person specifications. We held interviews with applicants to clarify what was required, select appropriate candidates and match successful applicants to available roles. This process was repeated at various points during the programme, as individual PPI members left or moved on. For the development of the intervention, we recruited a much larger group of PPI. This is described in detail in Chapter 6.

Context changes since grant awarded

Health and Social Care Act 2012

There were a number of significant changes in context between the time that funding for our programme of research was confirmed (in 2010) and its completion (in 2016). By far the biggest of these was the Health and Social Care Act 2012,70 which was described as the ‘biggest single reorganisation’71 and the ‘longest and most complex piece of legislation’ in the history of the NHS. 72

Among its many components was the abolition of primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities, which had been responsible for commissioning services. PCTs were replaced by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), which were intended to control around 60% of the NHS budget, be led by GPs supported by other clinicians and managers and were tasked with meeting the needs of their populations.

This reorganisation resulted in huge workloads for those involved as they struggled to come to terms with new priorities and responsibilities, evolving structures and changes in personnel. This was often accompanied by uncertainty about roles and responsibilities, loss of existing staff with relevant expertise and loss of organisational memory. 73–75

This massive reorganisation occurred at the same time as the NHS entered a period of significant financial austerity. After a period of year-on-year growth in budget, the NHS was charged with making financial savings of £20B over 5 years from 2011–15 while maintaining (or improving) the quality of the service. 76 This required efficiency savings of around 4% per year, compared with maximum previous efficiency savings of around 2% per year. It was recognised that meeting this ‘unprecedented challenge’ would require new ways of working, with an emphasis on reducing hospital admissions for people with LTCs, as well as there being a pay freeze for NHS staff. 76

Not entirely coincidentally, English general practice was, at the same time, entering a period of ‘crisis’,77 with a rapidly rising workload because of increased numbers and complexity of consultations but no concomitant rise in HCP numbers and static or falling incomes. 78,79 As a result, general practices were under enormous pressure. Many were unable to fill vacant clinical posts (both doctors and nurses were hard to recruit), leading to excessive workloads for remaining clinicians. 80 This was reflected in long waiting times for appointments and many GPs reporting low morale, burn out and resistance to change. 80 Although some practices showed considerable resilience, others went into a spiral of decline. 77

This turbulent background had a considerable impact on our research, particularly when it came to implementing the self-management programme into routine care (see Chapter 9).

Closure of the Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework

Our original application included an individually randomised controlled trial of the intervention to be run in primary care. At the time the proposal was submitted, we had a close collaboration with the MRC’s General Practice Research Framework (GPRF) and had designed the trial with the resources and expertise of the GPRF in mind. GPRF practices had trained research nurses available to participate in studies and, therefore, we designed a study that was predicated on unblinded practice nurses undertaking clinical tasks and delivery of the intervention and blinded research nurses undertaking research tasks, including data collection.

However, in 2012, the GPRF was subsumed into the wider National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Primary Care Research Network (PCRN). The PCRN operated a different model of supporting primary care research, with resources focused on promoting recruitment. Most PCRN hubs did not have the resources available to support data collection. This had quite an impact on the feasibility of the trial and, although in the end we were able to recruit sufficient practices and exceed our planned sample size, there were a number of challenges en route that required us to show agility and adaptability (see Chapter 7).

Changes to the Quality and Outcomes Framework

In 2013, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) was changed to include an incentive for GPs to refer people newly diagnosed with diabetes mellitus to structured education within 9 months of diagnosis. This had an immediate impact on referral rates, which rose from 15% in 2012 to 75% in 2014. Our programme was not designed as ‘structured education’ for newly diagnosed people, but rather as ongoing self-management support for people throughout their illness journey. This mismatch between policy and our intervention affected our research and required us to adapt some of our original ideas. In particular, it led us to develop an additional structured component to our intervention, aimed at newly diagnosed people (see Chapter 3).

Chapter 3 Aims, objectives and additional work undertaken

Chapter summary

This chapter describes the aims and objectives of the programme grant and outlines the methods used to address each objective. We were fortunate to be able to undertake a number of studies that were in addition to those originally planned, and these are also outlined in this chapter.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of this programme grant was to develop, evaluate and implement a web-based self-management programme for people with T2DM (at any stage of their illness journey), with the goal of improving access to, and uptake of, self-management support and, hence, improve health outcomes in a cost-effective manner. Particular attention was paid to working with users (patients and HCPs) to identify and meet user ‘wants and needs’, overcoming the digital divide and ensuring ‘implementability’.

Specific objectives were grouped under the headings Development, Evaluation and Implementation.

Development

-

Determine patients’ perspectives of the essential and desirable features of the intervention (wants and needs).

-

Determine HCPs’ perspectives of the essential and desirable features of the intervention that would encourage uptake and use in the NHS.

-

Determine the overall content and function of the intervention.

-

Determine the optimal facilitation required to encourage use of the intervention.

-

Determine feasibility, acceptability and short-term effects of facilitated access to the intervention in a naive population.

Evaluation

-

Determine the effect of the intervention on clinical outcomes and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in people with T2DM.

-

Determine the incremental cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with usual care from the perspectives of health and personal social services and wider public sector resources.

Implementation

-

Implement the intervention in two PCTs (later redesignated as CCGs).

-

Determine the uptake, use and effects of the intervention in an unselected population in routine care.

-

Determine factors that inhibit or facilitate integration into existing services and use of the intervention.

-

Determine the resources needed for effective implementation.

Methods

The programme grant application described five WPs that together addressed all 11 objectives. Table 1 shows how each WP related to the objectives.

| WP | Objectives | Design | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1. Determine patient wants and needs | Qualitative study, using focus groups and individual interviews with a diverse range of people with T2DM | Understanding of patients’ wants and needs from such an intervention, illustrated with examples of good and bad practice |

| 4. Determine optimal facilitation to encourage use of intervention | Information on why, when and how people thought they would use such an intervention, and what would encourage them to use it | ||

| B | 2. Determine HCPs’ perspectives of essential and desirable features | Qualitative study, using focus groups and individual interviews with HCPs who are caring for people with T2DM in primary and secondary care | Understanding of content that HCPs want to see, benefits and problems that they foresee and how they envisaged using it in routine practice |

| 4. Determine optimal facilitation to encourage use of intervention | Information on what degree of facilitation or support that GPs thought would be feasible to offer routinely in primary care | ||

| C | 3. Determine the content and function of intervention | Participatory design, working with the research team, people with T2DM, HCPs, software engineers and web designers to determine and create content, navigation and functionality including usability testing and piloting. All decisions were underpinned by theory and evidence | An acceptable, comprehensive and comprehensible self-management programme called the HeLP-Diabetes programme |

| 5. Determine the feasibility, acceptability and effects of intervention | |||

| D | 6. Determine the effect of the intervention on patients | Individually randomised controlled trial in primary care | Data on the impact of the HeLP-Diabetes programme on diabetes control (as measured using HbA1c levels), diabetes mellitus-related distress (as measured using the PAID scale), QALYs and service use |

| 7. Determine cost-effectiveness | |||

| E | 8. Implement the HeLP-Diabetes programme in two PCTsa | Mixed-methods implementation study | Data on adoption, uptake and use of the HeLP-Diabetes programme by CCGs,a practices and patients |

| 9. Determine uptake | Data on the impact that the HeLP-Diabetes programme has on people with T2DM outside the trial setting | ||

| 10. Determine inhibiting or facilitating factors | Data on the costs and resources required for different models of implementation and associated advantages and disadvantages | ||

| 11. Determine the resources needed for effective implementation |

The first 2 years of the grant (March 2011–February 2013) were dedicated to developing the self-management programme. This work was divided into three WPs: WP A focused on ascertaining patients’ wants and needs for the programme, WP B on identifying HCPs’ wants and needs and WP C on the design and development of the self-management programme itself, which was called the HeLP-Diabetes programme.

The last 3 years of the grant focused on evaluation and implementation, with two WPs running in parallel: WP D was an individually randomised controlled trial in primary care and WP E was an implementation study in two CCGs. Both of these studies started on time in March 2013. WP E was completed on time, but delays in recruitment for the trial (WP D) led to a request for a 6-month no-cost extension. With this extension, we were able to recruit the required sample size, complete the 12-month follow-up, and analyse and disseminate the results.

Additional studies undertaken

Some of the (many) advantages of having a programme grant were the financial stability and duration of funding. This allowed for long-term planning and enabled the core University College London (UCL) team to attract a number of additional students and fellows who worked alongside them, contributing to the main body of work and undertaking additional projects. These additional studies are outlined in the following text and included:

-

the development and formative evaluation of a cardiovascular risk calculator for people with T2DM

-

an evaluation of the impact that the HeLP-Diabetes programme had on the psychological well-being of patients with T2DM: a mixed-methods cohort study

-

a systematic review of technological prompts to improve engagement with digital health interventions

-

two RCTs81 of the use of e-mail and text messages to improve engagement with the HeLP-Diabetes programme

-

a systematic review82 of the implementation of eHealth interventions: an update of a review of reviews

-

the development and formative evaluation of a structured education programme for newly diagnosed patients with T2DM: the HeLP-Diabetes programme – Starting Out

-

the development of a digital T2DM prevention programme: HeLP Stop Diabetes.

In addition, the overall programme of work generated three Doctors of Philosophy (PhDs) and one Doctor in Clinical Psychology. One PhD was undertaken by co-investigator Dr Kingshuk Pal, an academic GP. His PhD focused on the development of the HeLP-Diabetes programme; his thesis was submitted in 2016 and he passed his viva with minor corrections. The second was undertaken by Jamie Ross. Her thesis was based on the implementation study in WP E and she successfully submitted and passed her viva with minor corrections in 2016. The third was undertaken by Ghadah Alkhaldi, whose PhD studentship was funded by the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau. Her thesis focused on the promotion of user engagement with digital health interventions, using the HeLP-Diabetes programme as an example. Her thesis was also submitted in 2016 and she too passed her viva with minor corrections. The doctorate in clinical psychology was undertaken by Megan Hoffman and her doctorate was awarded in 2014. The empirical part of the doctorate explored the impact that the HeLP-Diabetes programme had on the emotional well-being in people with T2DM.

The development and formative evaluation of a cardiovascular risk calculator for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus83

Dates: 2012–13.

Lead: Dr Tom Nolan (GP academic registrar).

Collaborators (additional to programme grant co-investigators and UCL team): Professor David Spiegelhalter (Winton Professor of Public Understanding of Risk, Statistical Laboratory, Centre for Mathematical Sciences, University of Cambridge) and Mike Pearson (Statistical Laboratory, Centre for Mathematical Sciences, University of Cambridge).

Additional funding: none.

Background

As part of our overall goal of enabling people with T2DM to understand the risks of diabetes mellitus and the benefits of self-management and medication, we thought it helpful to develop a risk calculator for people with T2DM and explore its effects on their understanding of their personal risk and the impact that this had on their motivation to manage their diabetes mellitus.

The calculator would provide users with an easily understandable presentation of their personal risk, along with estimates of how this risk could be reduced, for example by stopping smoking, losing weight, becoming more active or taking medication. The underlying intention was to motivate users with the thought that it might also help them to prioritise one particular behaviour (e.g. taking prescribed medication or becoming more active).

As Winton Professor of Public Understanding of Risk, David Spiegelhalter had tremendous expertise in presenting risk in a comprehensible format, as well as an interest in exploring the impact that such risk presentation has. Together with Mike Pearson, he had recently developed a cardiovascular risk calculator for people without diabetes mellitus, and was interested in collaborating with us to develop a similar calculator for people with T2DM.

Method

There were three components to this study:

-

Developing the risk estimates, based on the UK Prospective Diabetes Study data. Michael Sweeting, the grant statistician, undertook this, by adapting methods developed by David Spiegelhalter. We worked with T2DM patients to identify which potential risk factors were of most interest to users.

-

Transferring the algorithms and risk estimates into an online risk calculator, which captured data entered by users and used this to provide personalised estimates of risk. The authors followed best practice, according to the literature, in how these risk estimates were presented and worked with users to optimise navigation and usability.

-

Undertaking qualitative evaluation with users to explore understanding and impact of the risk information.

Outcome

Despite following accepted best practice and making every effort to ensure that the information presented was readily comprehensible, our evaluation showed that users struggled to understand their personal risk. Moreover, even when personal risk was understood, user reactions were complex and, overall, were unlikely to lead to desired changes in behaviour. In the light of this, the risk calculator was not included in the final HeLP-Diabetes programme intervention.

An evaluation of the impact that the Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes programme had on the psychological well-being of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a mixed-methods cohort study84

Dates: 2012–14.

Lead: Megan Hoffman (Doctor of Clinical Psychology student). The doctorate was awarded in 2014.

Collaborator (additional to programme grant co-investigators and UCL team): Professor Chris Barker (Professor of Clinical Psychology, Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, UCL).

Additional funding: none.

Background

Megan Hoffman was a student on the doctoral clinical psychology course at UCL. She was interested in the psychological well-being of people with T2DM and exploring whether or not the HeLP-Diabetes programme could improve well-being.

Method

Megan Hoffman undertook a single-arm mixed-methods study in primary care, recruiting patients with T2DM and facilitating their use of the HeLP-Diabetes programme. She collected quantitative and qualitative data at baseline and after 6 weeks. Quantitative data comprised self-completed validated outcome measures for diabetes mellitus-related distress [as measured using Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) scores], depression and anxiety scores [as measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)] and scores on the Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (DMSES). Qualitative data comprised semistructured interviews: at baseline participants were asked about their current problems with diabetes mellitus and what help they would like, and at follow-up whether or not the intervention had made any difference and which parts they had found particularly helpful or unhelpful.

Outcomes

The planned sample size (n = 19) was recruited. Participants showed a statistically significant reduction in diabetes mellitus-related distress [baseline: mean PAID score of 26.32 points, standard deviation (SD) 20.88 points; 6 weeks: mean PAID score of 20.94 points, SD 16.53 points; p = 0.04]. Qualitative data showed that, overall, participants found the intervention helpful. Negative impacts reported related to feeling guilty about non-use.

A systematic review of technological prompts to improve engagement with digital health interventions85,86

Dates: 2013–15.

Lead: Ghadah Alkhaldi (PhD student). PhD awarded in 2016.

Collaborator (additional to programme grant co-investigators and UCL team): Dr Fiona Hamilton (NIHR Lecturer in Primary Care, Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health, UCL).

Additional funding: PhD studentship funded by the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau.

Background

A well-recognised problem with digital interventions is the lack of engagement. Although this can be overcome by human facilitation, this increases costs and may undermine the economic arguments for digital interventions. Hence, there is an interest in exploring the extent to which automated prompts can improve engagement. Ghadah Alkhaldi joined the UCL team as a PhD student and focused her PhD on the use of automated or technological prompts to increase engagement with the HeLP-Diabetes programme. As part of this, she undertook a systematic review to determine what impact such prompts could have with engagement.

Method

Ghadah Alkhaldi used standard (Cochrane) systematic review methods, with systematic searching, double-screening of abstracts and full papers and independent checking of data extraction.

Outcomes

Technological prompts, such as e-mail and text messages, can have a small positive impact on engagement, but there were insufficient data to determine optimal content, frequency or mode of delivery of such prompts.

Two randomised controlled trials of the use of e-mail and short message services to improve engagement with the Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes programme81

Dates: 2014–16.

Lead: Ghadah Alkhaldi (PhD student). PhD awarded in 2016.

Collaborator (additional to programme grant co-investigators and UCL team): Dr Fiona Hamilton (NIHR Lecturer in Primary Care, Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health, UCL).

Additional funding: PhD studentship funded by the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau.

Background

Following her systematic review, Ghadah Alkhaldi explored how best to use e-mail and/or text messages to improve engagement with the HeLP-Diabetes programme.

Methods

Ghadah Alkhaldi employed mixed methods, initially developing e-mail prompts and newsletters in collaboration with our user panel and then using quantitative data to identify which prompts or newsletters were associated with increased numbers of visits to the HeLP-Diabetes programme website. Subsequent ‘think-aloud’ interviews explored which features or prompts were particularly attractive or compelling. Finally, two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were undertaken to test the hypotheses generated by the qualitative interviews.

Outcomes

Prompts and newsletters had a small positive impact on engagement, but it was not possible to identify the characteristics of effective prompts compared with ineffective ones.

A systematic review of the implementation of eHealth interventions: update of a review of reviews82

Dates: 2014–16.

Lead: Jamie Ross [research associate (RA) and PhD student], supervised by Professor Elizabeth Murray and Dr Fiona Stevenson. PhD awarded in 2016.

Collaborator (additional to programme grant co-investigators and UCL team): Rosa Lau (PhD student).

Additional funding: none.

Background

A systematic review of reviews of factors influencing implementation of eHealth interventions had been completed in 2009. A very large number of studies had since been published, including a large number of additional systematic reviews; however, most focused on specific eHealth topics or types of intervention. Therefore, the authors undertook an update of the original review of reviews.

Methods

Jamie Ross conducted a systematic review of reviews.

Outcomes

The field had moved on very considerably in the intervening years, in terms of both the quality of available reviews and the insights generated. The available data fitted well with the recently developed Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

The development and formative evaluation of a structured education programme for newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes: The Healthy Living for People with type 2 Diabetes programme – Starting Out (papers not yet published)

Dates: 2014–16.

Lead: Shoba Poduval (academic GP fellow).

Collaborators (additional to programme grant co-investigators and UCL team): Helen Gibson and Rebecca Owen (diabetes specialist nurses).

Additional funding: the National School of Primary Care Research funding round 9.

Background

During the implementation study (WP E), it became clear that, although both people with T2DM and HCPs appreciated the support across the whole of the illness journey provided by the HeLP-Diabetes programme, a slimmer, more structured intervention was needed for newly diagnosed people. GP incentives from the QOF were limited to referral to structured education, and referral to programmes that were accredited by the Quality Institute for Self-Management Education and Training (QISMET) was preferred. QISMET accreditation was available only to programmes with a structured curriculum and clear learning goals. In the light of this, we decided to develop a structured education programme based on the HeLP-Diabetes programme but amended for use by newly diagnosed people and augmented by e-mail and telephone support to improve uptake and completion rates.

Methods

We worked with patients and diabetes nurse educators to develop a structured education programme based on the HeLP-Diabetes programme. The structured education programme’s curriculum addressed the three core tasks identified by Corbin and Strauss54 (medical, emotional and role management) while also meeting NICE and QISMET’s guidance for the content of diabetes mellitus-structured education programmes. This was iteratively user-tested and piloted, with revisions made after each cycle of testing.

Outcomes

HeLP-Diabetes: Starting Out is a structured education programme comprising four mandatory sessions, with an optional fifth and final one. Each session contains three or four modules, with each module taking 10–15 minutes to work through. Users are encouraged to proceed through one session per week, working through as many modules as they choose at each sitting. E-mail and telephone support is provided by specialist diabetes nurse educators to promote engagement. The authors are currently seeking further funding to undertake a feasibility study and then a Phase III RCT.

The development of a digital diabetes prevention programme: HeLP Stop Diabetes (papers not yet published)

Dates: 2016–18.

Lead: Marie-Laure Morelli (academic GP trainee).

Collaborator (additional to programme grant co-investigators): Paulina Bondaronek (PhD student).

Additional funding: the National School of Primary Care Research funding round 11.

Background

With the rapid increase in prevalence of diabetes mellitus, prevention became a national priority. Initial commissioning of T2DM prevention programmes has focused on face-to-face or group-based programmes; however, these are expensive and it is unclear what the uptake will be. A digital T2DM prevention programme could offer a cost-effective alternative to group-based programmes and may improve uptake. In the light of this potential, we are undertaking preliminary work to explore the acceptability, feasibility and desirable content of a digital intervention to prevent diabetes mellitus in high-risk individuals.

Methods

We will conduct qualitative interviews and focus groups to determine user requirements for a digital T2DM prevention programme.

Outcomes

This work has been seriously delayed as a result of the reorganisation of the Health Research Authority, such that it took 10 months to obtain ethics and research governance approvals. Marie-Laure Morelli was then on maternity leave until September 2017; the work restarted on her return and is still underway.

Chapter 4 What do people with type 2 diabetes mellitus want and need from a web-based self-management programme?

Chapter summary

Chapter 4 reports on a qualitative study that aimed to determine patient perspectives of the essential and desirable features of a web-based self-management programme for people with T2DM, including features that would encourage use, such as access to their EMR and facilitation by HCPs.

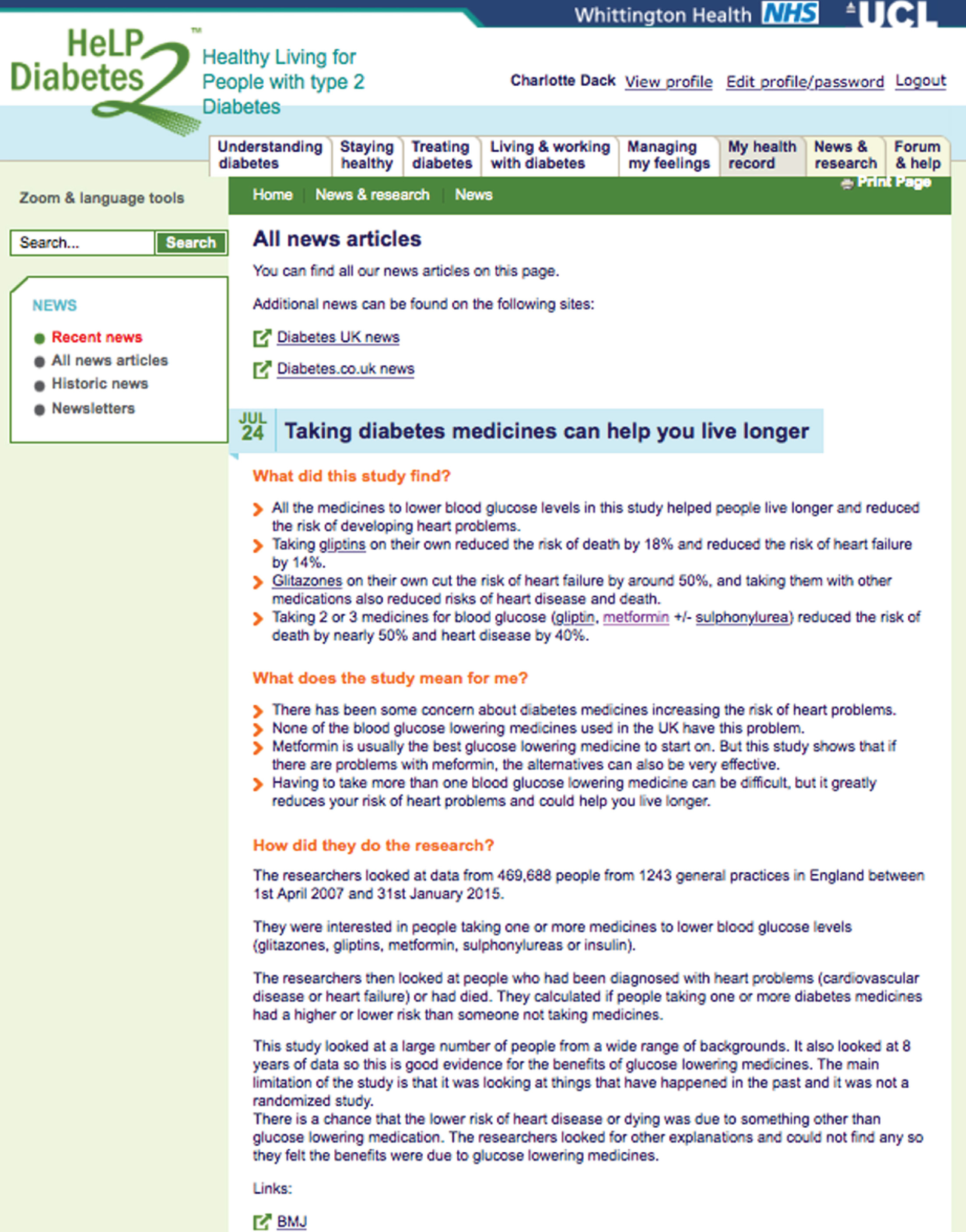

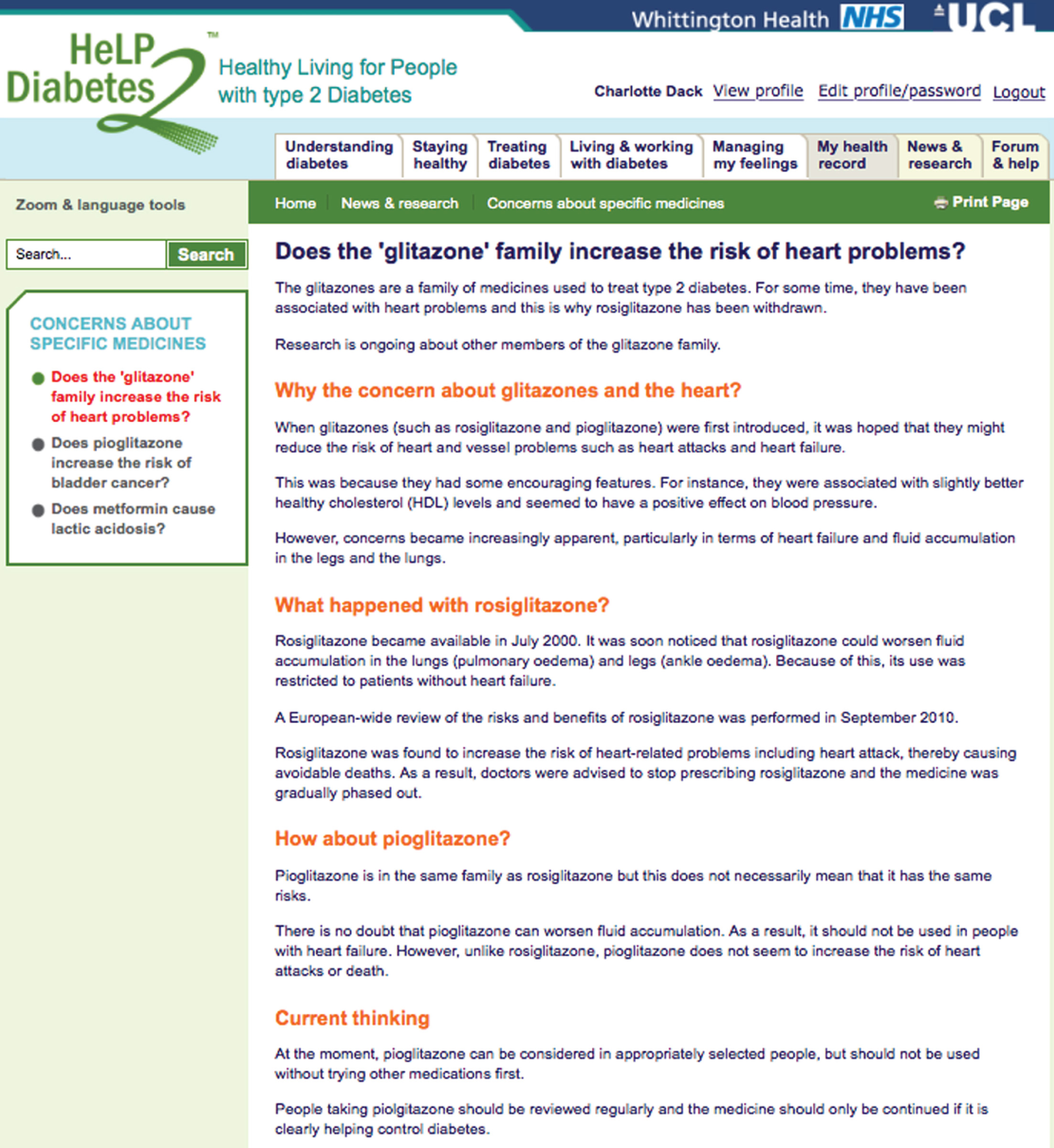

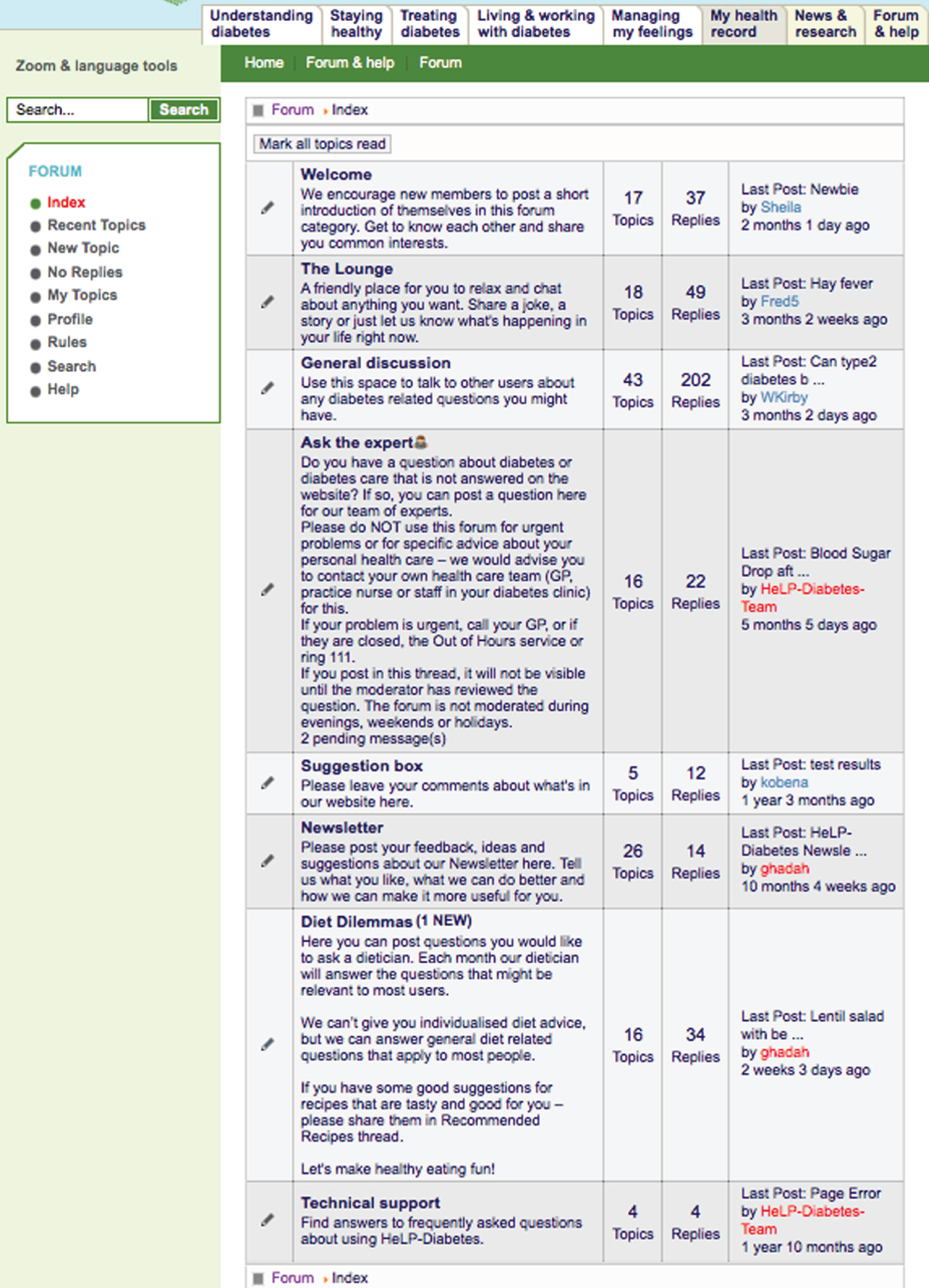

We undertook focus groups with a maximum variety sample of people with T2DM. Participants in focus groups were shown three existing diabetes mellitus self-management websites, selected to illustrate a range of features, and then asked to consider what they liked or disliked about each programme, as well as what would be included in an ideal programme. A thematic analysis of these data was used to clarify the necessary and desirable content, functionality and approach of our proposed intervention. We subsequently undertook a more deliberative approach, exploring underlying experiences and the meaning ascribed to them by participants.

The four focus groups had a total of 20 participants. A strong shared sense of the overwhelming burden that the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus placed on participants underpinned all of the data generated; it had had severe negative impacts on their emotional well-being, work, social life and physical health. Although participants’ experience of health-care services varied, there was agreement that even the best services were unable to meet all users’ needs and that a web-based self-management support programme could, therefore, be extremely useful in meeting these unmet needs.

Participants had clear views about the features that they would want or need from such a programme, as well as the features that would help generate trust and encourage engagement. They also clearly identified features that would be off-putting and lead to disengagement. These views informed the development of the HeLP-Diabetes programme.

Background

The rationale for focusing on T2DM and for considering a web-based self-management programme has been described in Chapter 2. In this chapter, we describe the rationale for the study objectives and the selected methodology.

Rationale for study objectives

Establishing user requirements for any proposed intervention is a necessary first step. 87 We conceptualised these requirements as ‘wants and needs’, for which ‘wants’ are features that users actively desire and would make them want to use the intervention and ‘needs’ are features that evidence suggested would improve health outcomes.

We postulated that combining wants with needs should combine the attractiveness and appeal of many commercial digital interventions (including games) with the clinical effectiveness of face-to-face interventions. As an example, there was evidence from the literature that forums, where users could interact online, were associated with increased use of an intervention, as people wanted the opportunity to interact with others in similar situations (a ‘want’). 88 However, nothing suggested that this improved health outcomes. 89 In contrast, improving medication adherence is likely to improve health outcomes (a ‘need’), but including such a facility in an intervention is unlikely to promote engagement with, and use of, the intervention. Our goal was to understand both wants and needs with a view to creating an intervention that met both and, hence, was both useful and used.

We were also aware that patients and HCPs used different criteria for assessing web-based self-management interventions90 and that HCPs’ perceptions of patient requirements were often inaccurate. 91 For example, there is evidence that HCPs overestimate patients’ concerns about complications and underestimate their concerns about dietary restrictions. 92 Hence, we were clear that we needed separate, parallel studies to determine patients’ and HCPs’ perceptions of the essential and desirable features of such an intervention.

Previous research by Kerr et al. 90 had established some generic patient requirements for self-management interventions for LTCs. Kerr et al. 90 convened 10 focus groups with 40 patients and carers who generated detailed quality criteria relating to information content, presentation, interactive components and trustworthiness. Participants in that study stated that information needed to be detailed, specific and of practical use. They also advised that long-term use required increasing the depth of information as self-management experience increased, as well as providing new and up-to-date information. Participants wanted information about their condition and the treatments available, practicalities around day-to-day living (holidays, travel and eating out), local services and resources, new research and areas of scientific uncertainty and other people’s experiences and information for family members. They felt that it was important for users to control how much information they accessed at any time and the topic of the information. This was particularly important for ‘bad news’, which they did not want forced on them.

These criteria focused on the need for excellent website design, easy navigation giving intuitive and speedy access to relevant content and an attractive appearance, using colours, graphics, videos, animations, photographs and text broken up into small sections. The tone should be straightforward but not patronising; medical terms and jargon should be explained but not avoided. The criteria for interactive components were that they should be optional, use online assessments to provide tailored advice and monitoring and include an ‘Ask the Expert’ facility and online forum. Finally, trustworthiness was vital and could be established and maintained by information being accurate and regularly updated, the intervention having no commercial links or advertisements and the website being authored or sponsored by a known and trusted organisation, such as the NHS or a local hospital or well-known university or charity. 90

However, technology and website use had changed considerably since the above research was published. Website use had become much more interactive and peer to peer (the so-called Web 2.0). 93 Moreover, although this research had included people with T2DM, it had not specifically focused on diabetes mellitus; rather, it had looked to draw out criteria that were transferable across a range of LTCs. There were no studies in the literature that we could identify that specifically explored the wants and needs of people with T2DM for web-based self-management programmes.

As described in Chapter 2, well-recognised limitations of web-based interventions are non-use and high rates of attrition. 41 In our original grant application, we postulated that engagement with the intervention was likely to be enhanced by HCPs recommending and endorsing both initial and ongoing use. Evidence from internet cognitive–behavioural therapy (ICBT) suggested that facilitated or supported use of ICBT was more effective than unsupported use. 94 However, we also recognised that it is hard to change professional behaviour,95 and that HCP time is a scarce (and expensive) resource. Therefore, we wanted to explore with people the type of facilitation they would find useful and what they thought was realistic.

We were also specifically interested in the possibility of linking the self-management programme with patients’ EMRs. While the work for WP A was being done, there was considerable discussion about the relative advantages and disadvantages of such access. Some pilot studies had suggested that it was feasible, did not lead to excess workload or patient anxiety but did lead to correction of inaccurate data in the record, better-informed patients and more productive consultations. 96–98 However, mainstream opinion, as represented by, for example, the British Medical Association, was unconvinced, citing concerns about privacy, confidentiality, causing unnecessary anxiety among patients and about it resulting in additional workload for doctors. 99 We wanted to explore with patients what they thought about having access to their EMR and, in particular, what information they wanted to see and why. We planned to see whether or not it was possible to find a solution that addressed patients’ wants and needs while respecting clinicians’ concerns.

As an example of the changing context during our research programme, shortly after this study was completed, the Department of Health and Social Care issued new policy, mandating that all patients should have access to their EMR. 100

Rationale for study methods

Two key methodological decisions were to use focus groups for data collection, and, as part of the focus groups, to show participants three existing examples of self-management websites for people with T2DM. These decisions were based on our previous experience with this methodology,90 which had proven feasible and yielded rich data. This work was in turn based on a study by Coulter et al. ,101 which determined quality criteria for traditional paper-based information materials for users.

The use of qualitative methodology allowed participants to explore issues of importance to them, in their own words, generating their own questions and focusing on their own priorities; this was particularly important when exploring self-management and interventions to empower patients. We opted for focus groups, rather than individual interviews, as we wanted participants to explore their underlying reasons for differing perspectives. Group discussions can yield rich data when participants explore and clarify their views through interactions with each other. 102 Group dynamics also involve many different forms of day-to-day communication, such as jokes, anecdotes, teasing and arguing. These natural interactions may allow a more nuanced appreciation of what people know or experience and can reveal ‘shared truths’. 103 A disadvantage of focus groups is that some participants may find it difficult to discuss sensitive or potentially embarrassing topics, such as sexual dysfunction, which can be a common complication of diabetes mellitus. Therefore, we planned to use focus groups as our primary method of data collection, while reserving the option of individual interviews if it appeared that some topics were not being adequately addressed.

The decision to show participants three websites at the start of each focus group was based on the observation that it is much easier to critique existing interventions than to think in the abstract about what one might want. Moreover, the experience of using such interventions allowed users to think about features they looked for, even if they were not present. Our experience from our earlier work had confirmed that participants could review three websites in the time available that, with careful selection, it was possible to ensure that most of the features of interest were included in the websites presented and that there was sufficient difference between the websites to enable participants to compare and contrast them in a fashion that generated useful data. 90

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the study was to determine patients’ perspectives of the essential and desirable features of a digital self-management intervention for adults with T2DM (i.e. T2DM-specific wants and needs regarding information content, presentation, interactive components and trustworthiness). Additional objectives were to determine the optimal facilitation required to encourage use of the intervention and to explore patient views about integrating the self-management programme with EMRs.

Data from this study contributed to the following objectives of the programme grant:

-

determine patients’ perspectives of the essential and desirable features of the intervention (wants and needs)

-

determine the overall content and function of the intervention

-

determine the optimal facilitation required to encourage use of the intervention

-

determine feasibility and acceptability of facilitated access to the intervention.

Methods

Design

The design was a qualitative study using focus groups for data collection.

Ethics

Ethics approval was provided by the North West London Local Research Ethics Committee on behalf of the National Research Ethics Service (reference number 10/H0722/86).

Setting and participants

As our goal was to develop an intervention that appealed to a wide spectrum of the total population of adults with T2DM, we aimed to recruit a diverse sample that reflected the target population, namely adults with T2DM who could understand spoken or written English. An additional inclusion criterion was the ability to speak English in order for the individual to be able to participate in the focus group. Factors that the literature suggested were likely to influence wants and needs included demographic factors (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, first language), clinical factors (e.g. duration of diabetes mellitus since diagnosis, current treatment, presence or absence of diabetes mellitus-related complications and previous experience of self-management programmes) and factors related to health and computer literacy (such as educational attainment, previous experience with computers and access to the internet). 46,104–106 Hence, our goal was to recruit a sample that varied across these characteristics.

To achieve this, we adopted a broad recruitment strategy. We placed online advertisements on the Diabetes UK website, a local council website, a black and minority ethnic forum and other diabetes mellitus forums. In addition, we advertised in Balance magazine, which is published bimonthly by Diabetes UK and distributed freely to all Diabetes UK members. We distributed flyers, leaflets and posters through community support groups for people with T2DM, general practices and community diabetes clinics. Most responses were from local support groups and readers of Balance.

Participants who responded to the advertisements were sent an information sheet and consent form and invited to complete a questionnaire to collect the demographic, clinical and literacy factors as described. This information was used to recruit a maximum variation sample. Recruitment and data collection continued until we reached theoretical saturation, that is, until no new data emerged in subsequent focus groups. The research team met after each focus group to discuss the results and consider whether or not there were areas or topics that needed further probing in subsequent groups.

Data collection

Focus groups were run in a community centre with online computer cluster rooms in London, UK. Focus groups lasted 3 hours and were led by at least two facilitators. Each focus group started with round table introductions of the facilitators and participants, as well as a description of the task and the structure of the session. Participants were then asked to move to the personal computers, with each participant having their own computer to use. We asked participants to visit three self-management websites for T2DM. These had been selected by the research team to demonstrate the range of interventions and component parts available. They varied in terms of content, complexity, tone, navigation and presence of interactive features, such as forums, ‘Ask the Expert’ sections or self-monitoring tools.

Participants were asked to spend 20–30 minutes on each site and were given a structured note pad to jot down thoughts as they occurred. Facilitators were on hand to help participants access the three selected sites and to address any problems that arose (e.g. people with little computer experience could find some sites difficult to navigate).

Once participants had explored all three interventions, the group reconvened for some rest and refreshment before starting the group discussion. This discussion was guided by one of the facilitators, with the other observing and noting group dynamics, thinking about the emerging data, occasionally checking or following up on specific themes or ideas that seemed to be emerging and making notes on key points. The lead facilitator followed a topic guide to steer the conversation.

This topic guide reflected the objectives of the study and was informed by our previous work and our theoretical approaches, particularly NPT56 and the Corbin and Strauss model54 of LTC self-management. The topic guide was piloted in an individual interview with one of our PPI representatives and no changes were required. It started by asking participants about their overall impressions of the utility of the three sites and whether or not a self-management website could be useful for people with T2DM. Subsequent areas for discussion included specific likes or dislikes about the three programmes, with the reasons for these reactions, and this led into a discussion on the ‘ideal’ content and form for a new programme.

At this point, participants were encouraged to indulge in ‘blue-sky thinking’ and come up with ideas for features they really wanted, even if they had never seen anything similar. Participants were also asked why and when they might use such a programme, what would encourage them to use it, whether or not they would like to share health-related data with their HCPs and whether or not they would like an HCP to facilitate use and, if so, how.

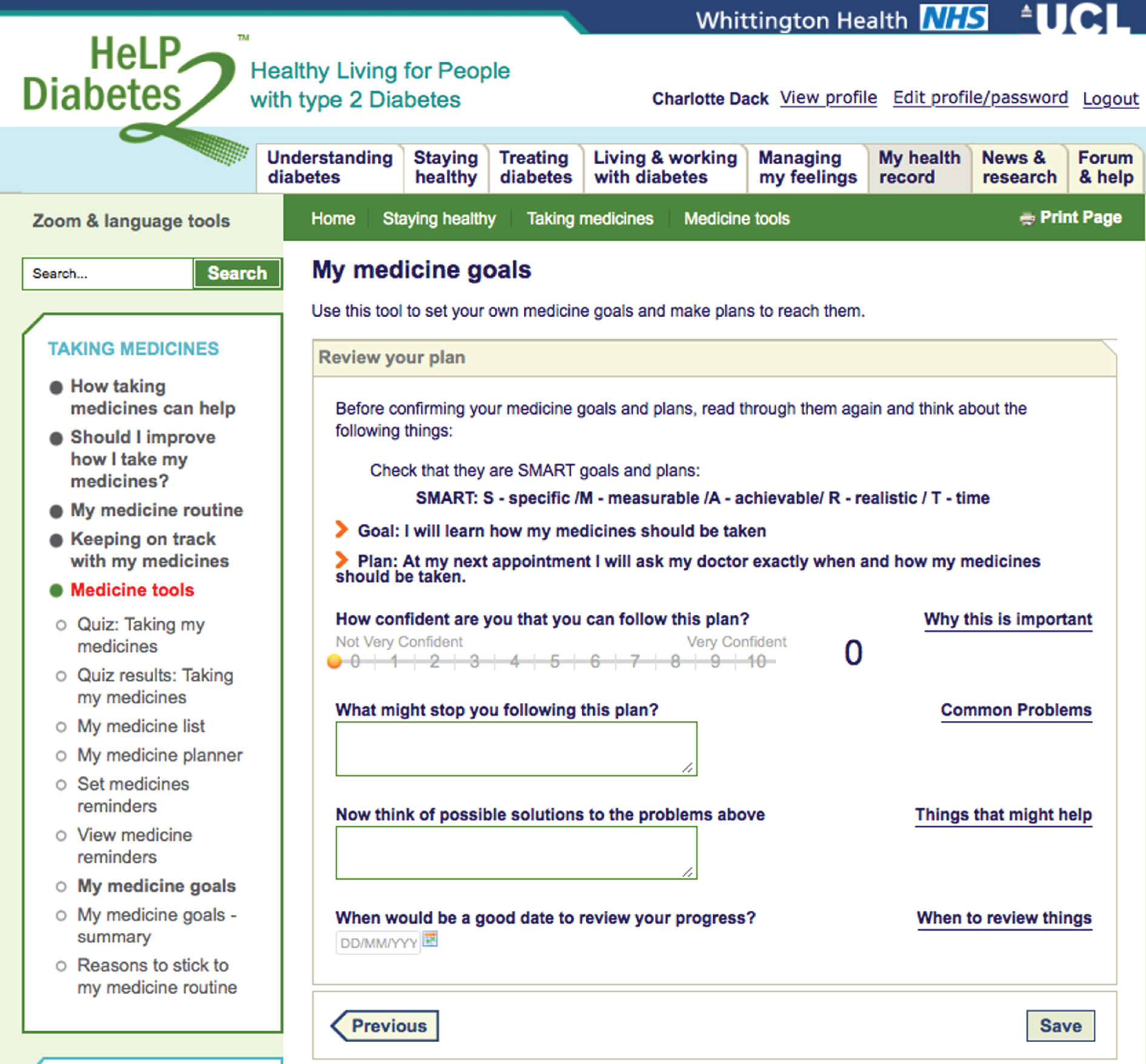

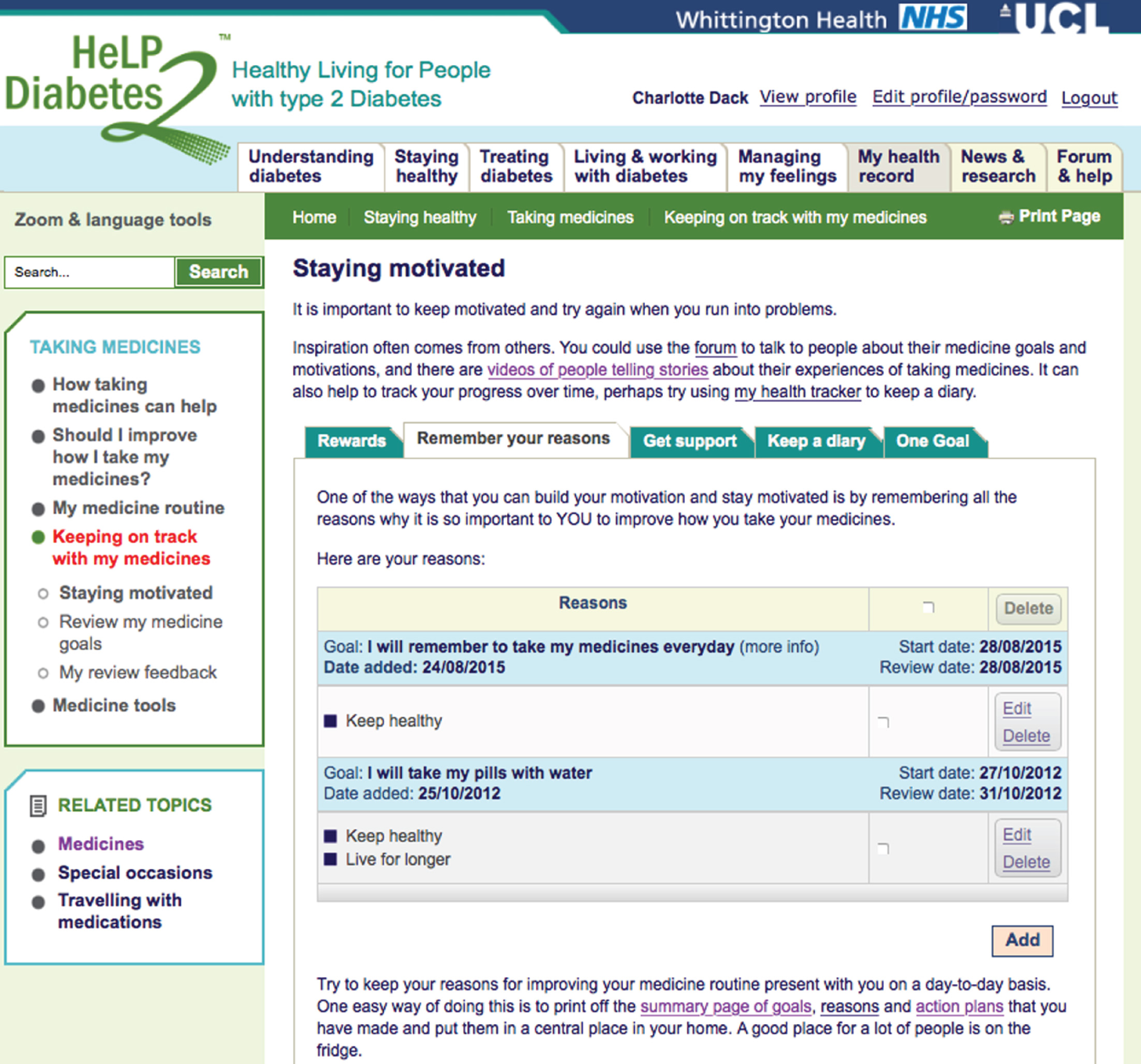

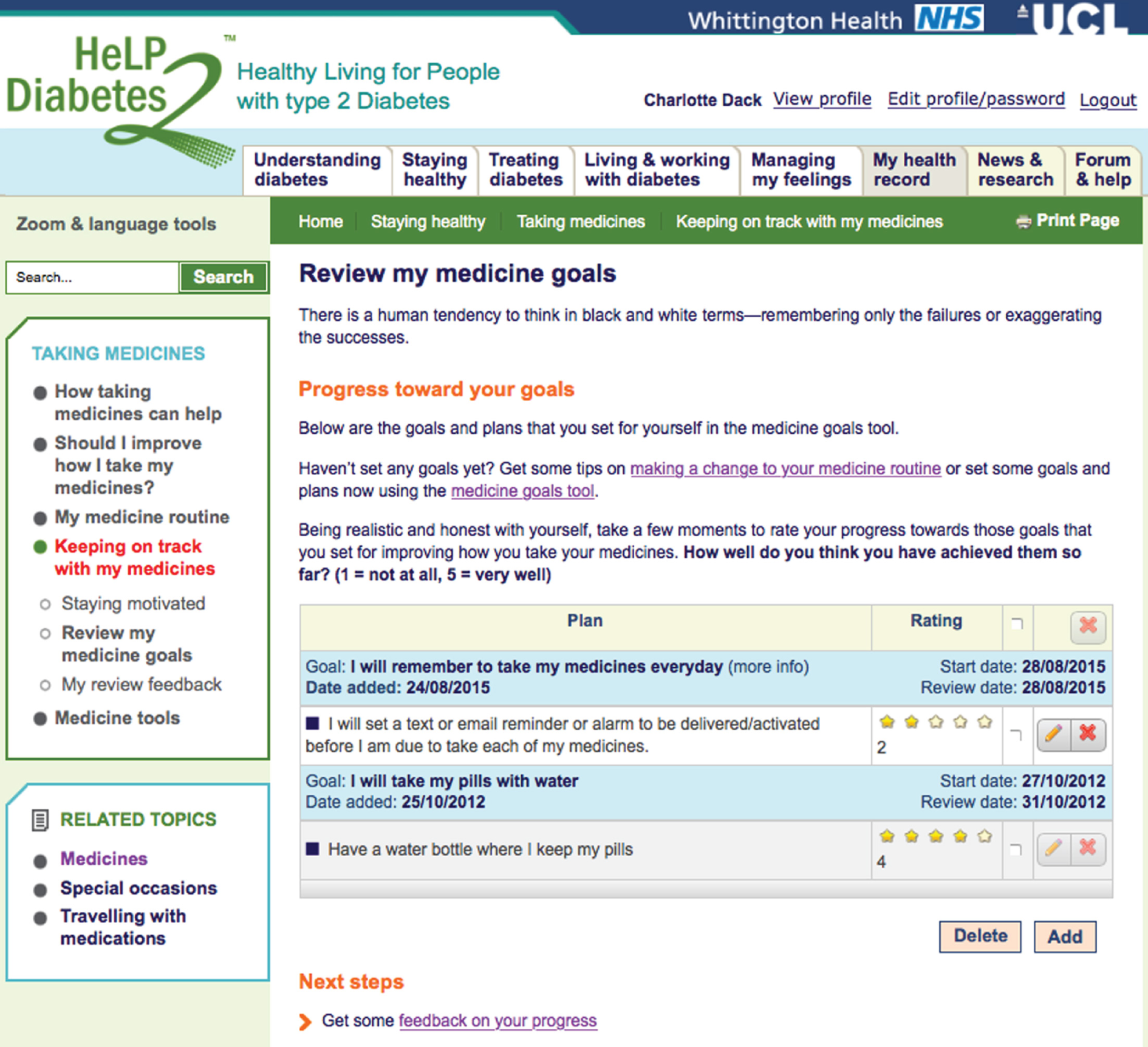

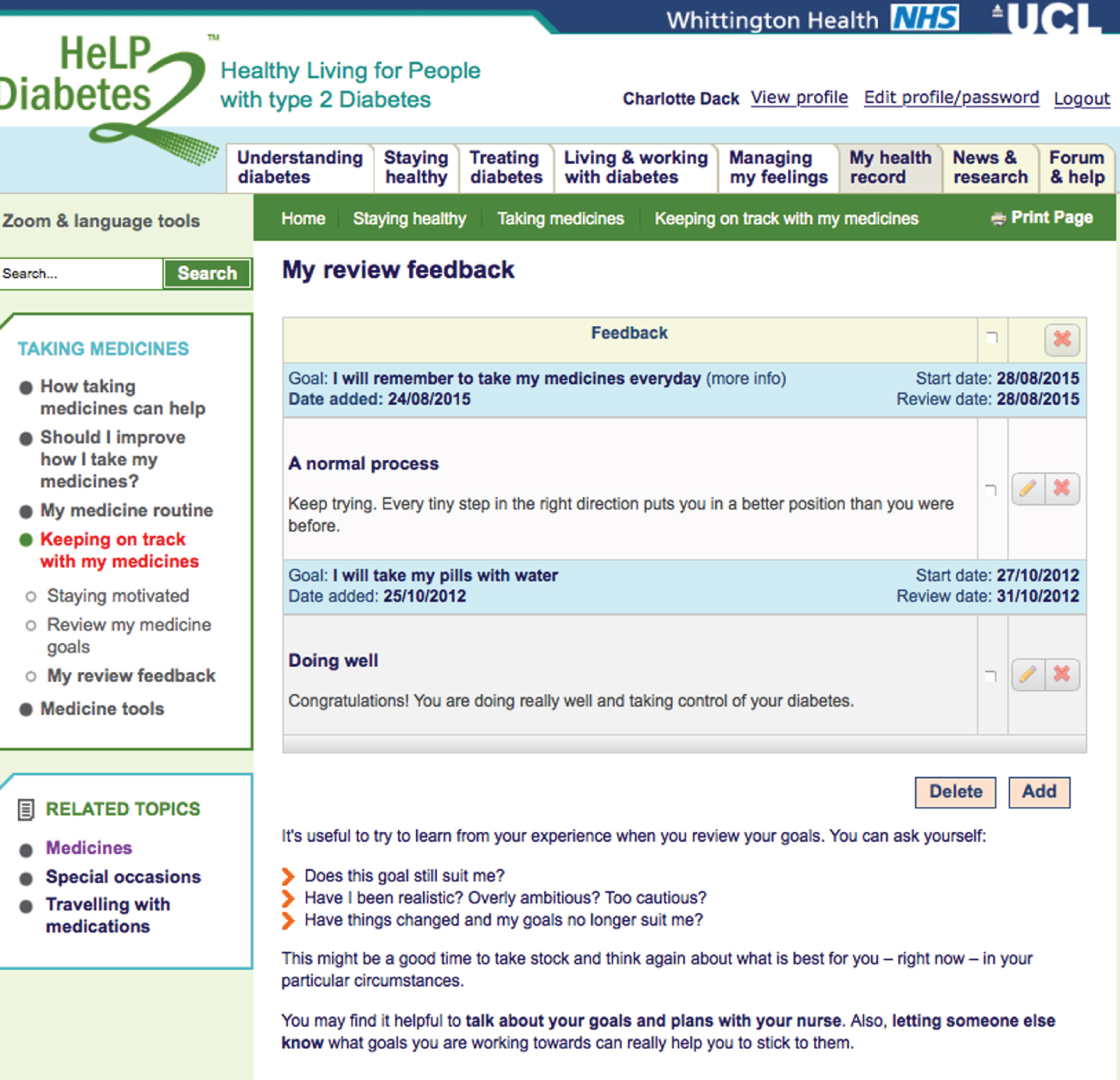

The focus groups were audio-taped and the tapes transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company. The transcripts were checked and corrected by the group facilitators, and the notes taken by the second facilitator were included in the data set.

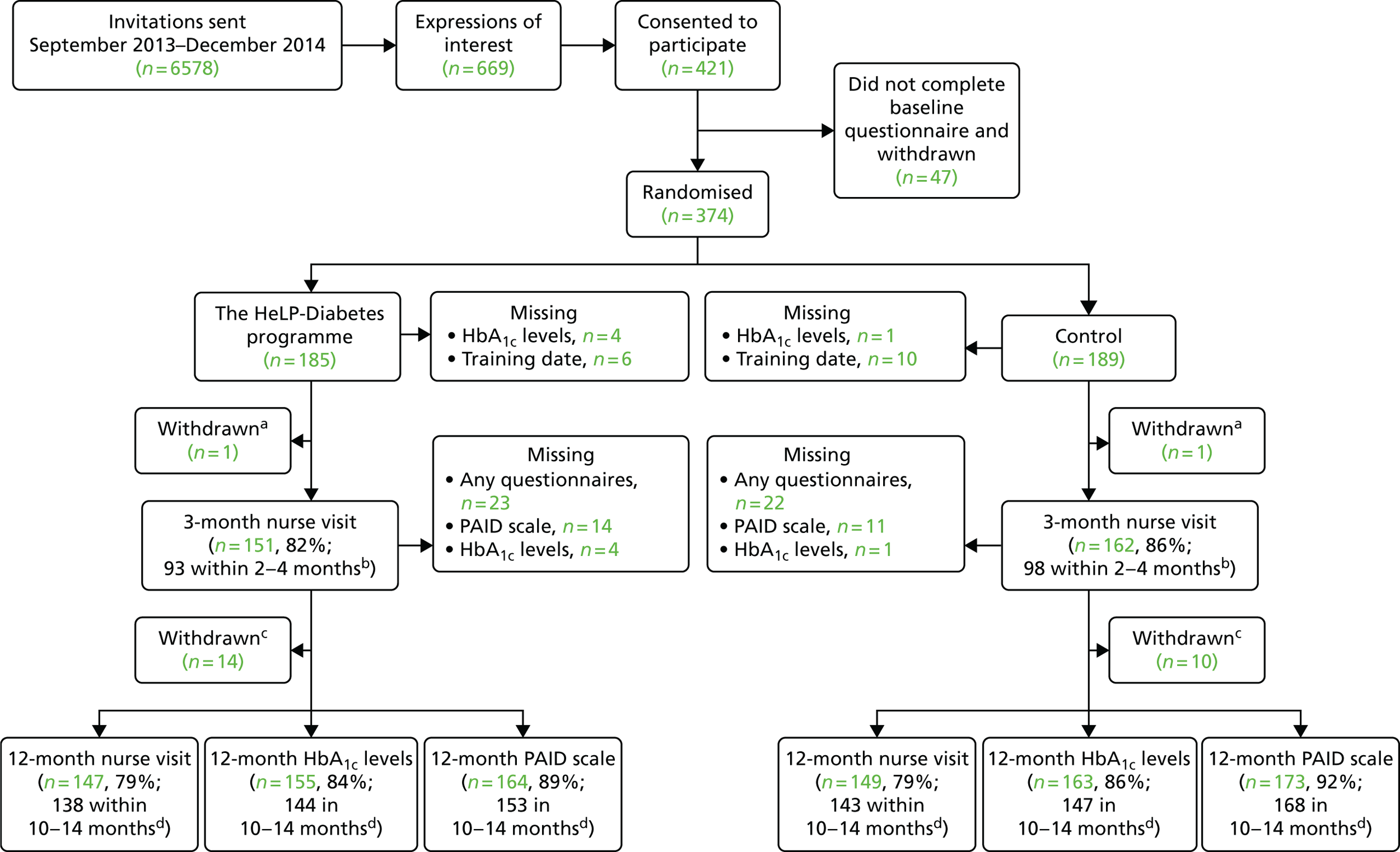

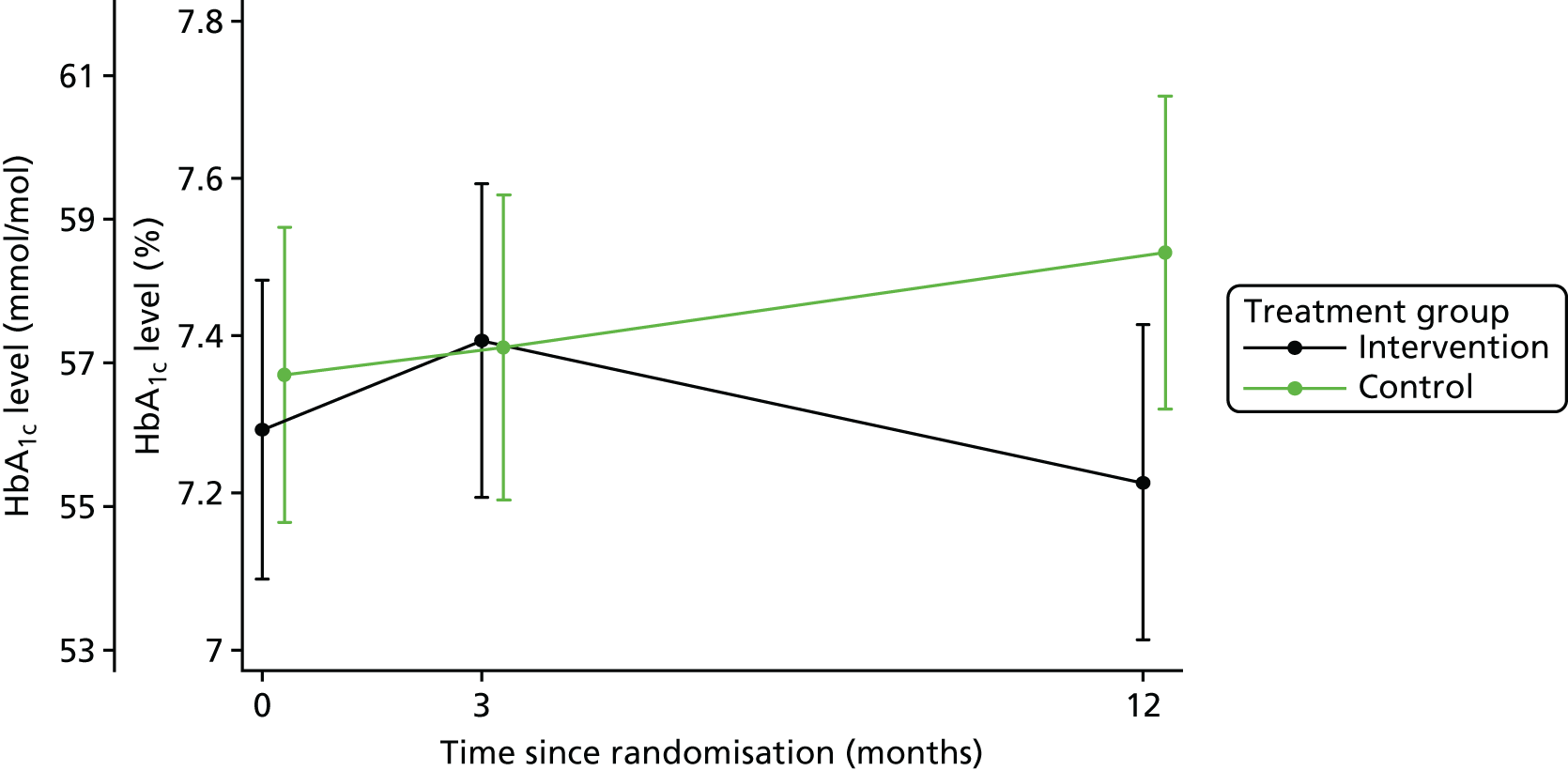

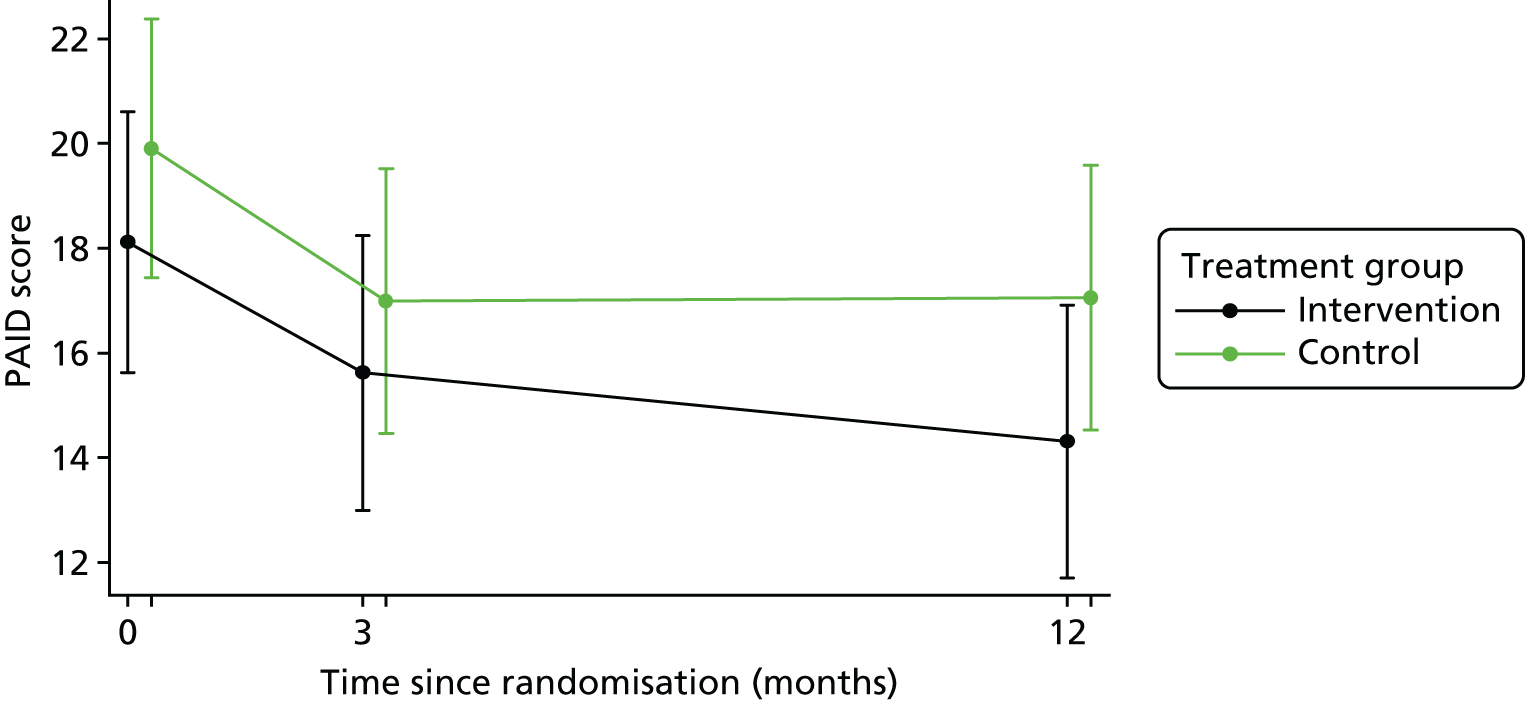

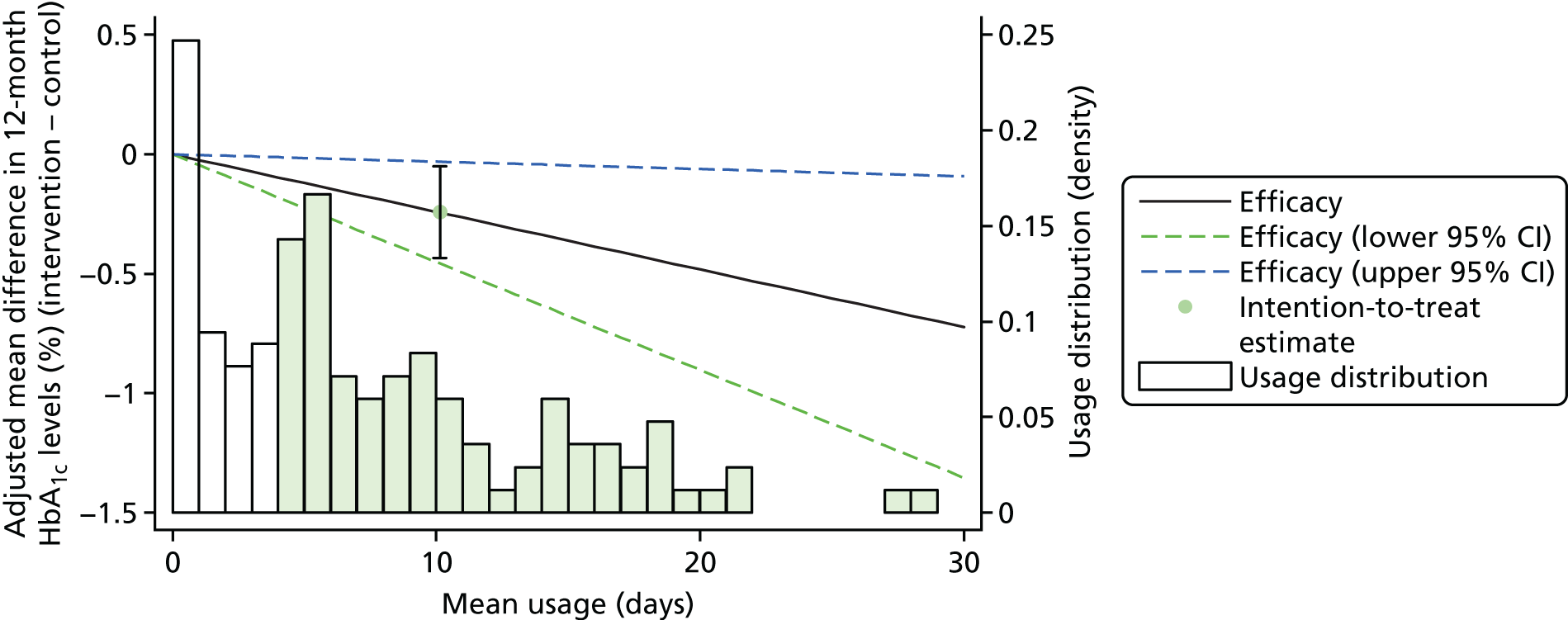

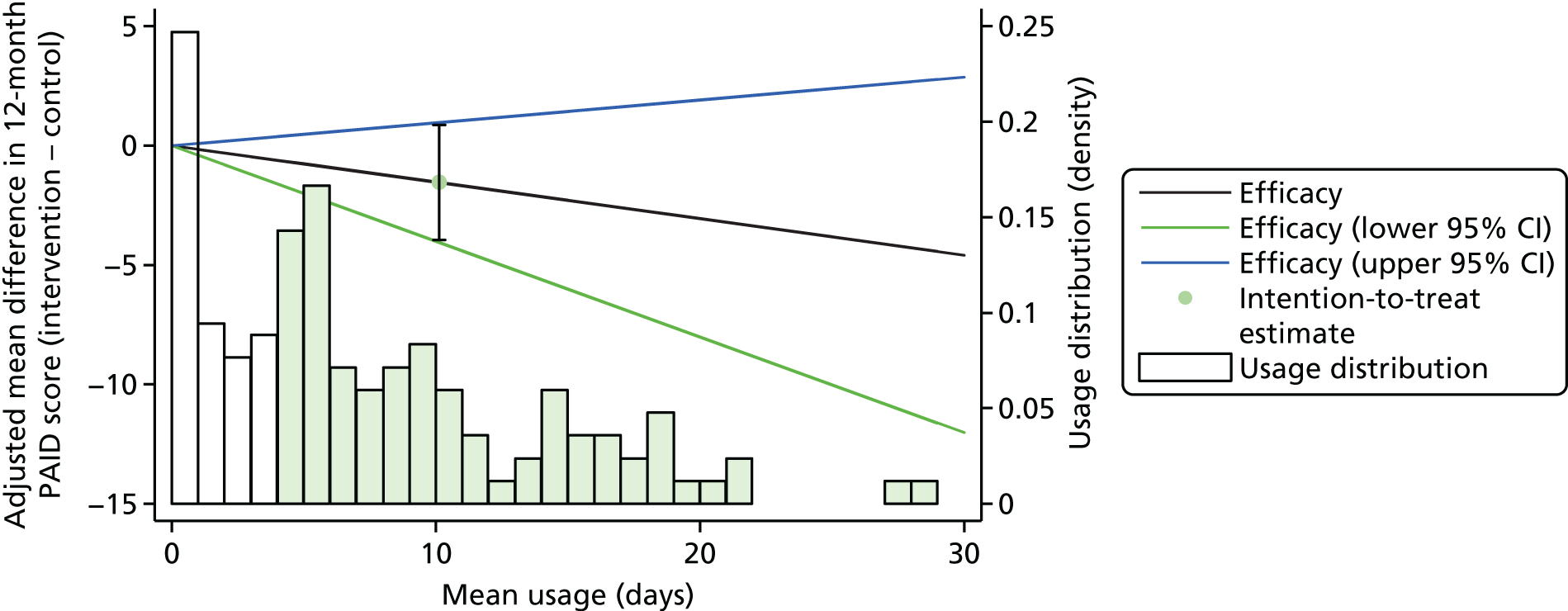

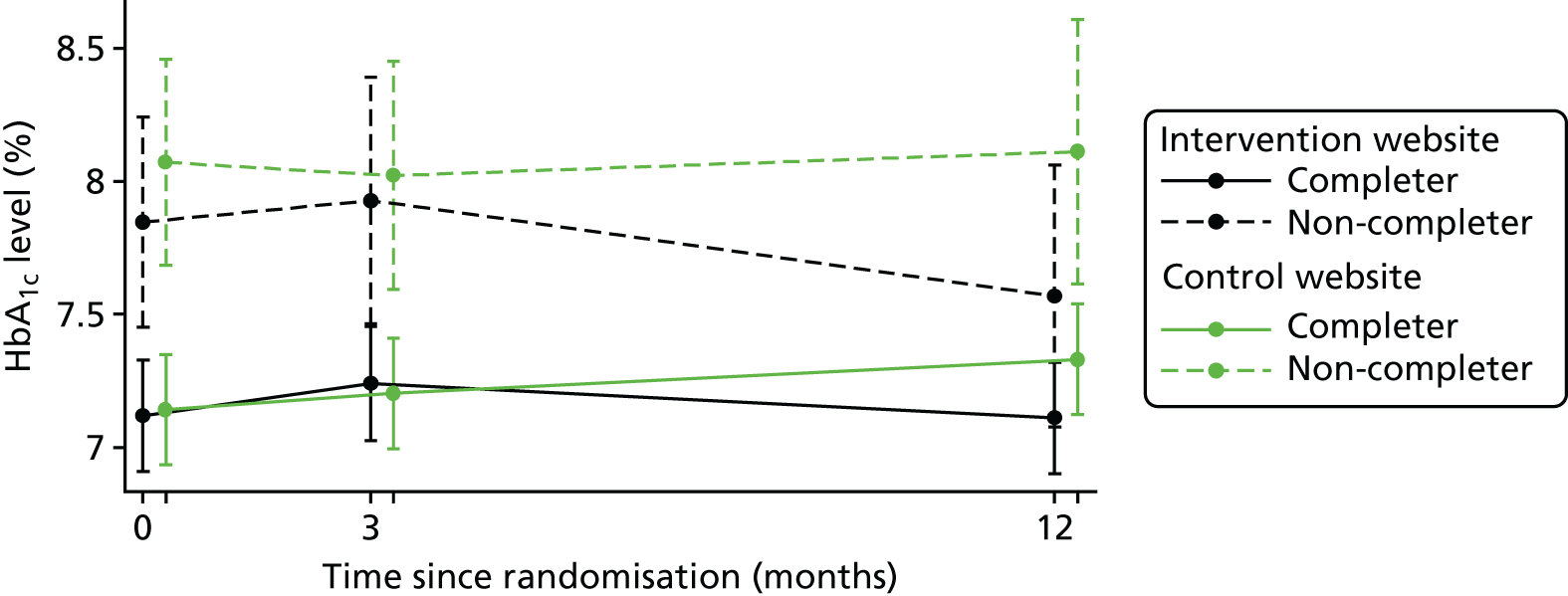

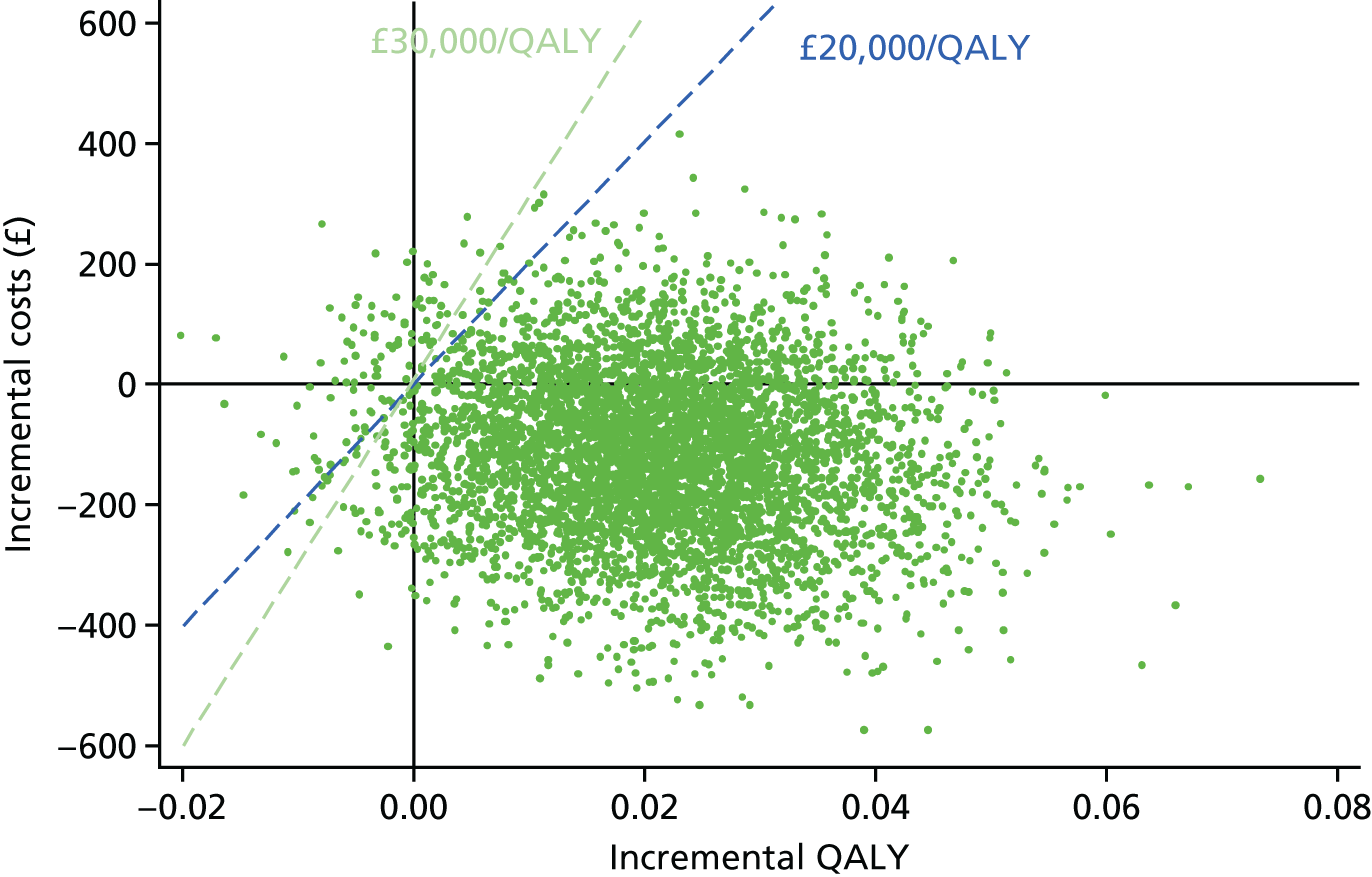

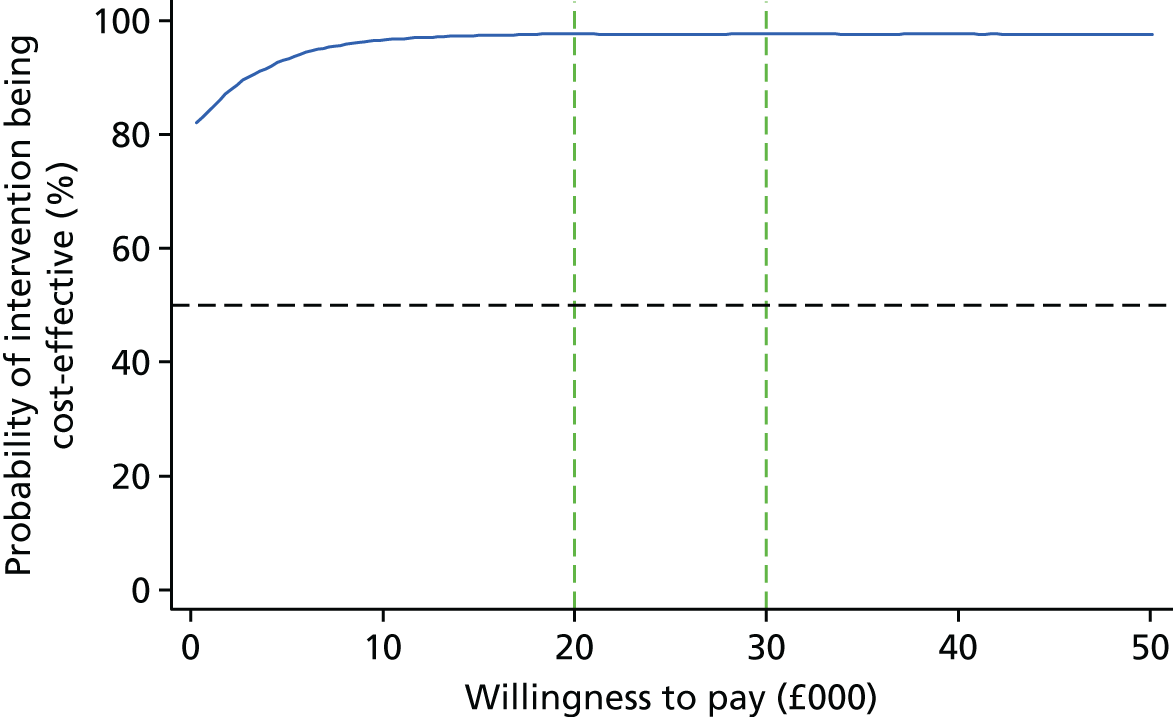

Data analysis